1. Overview

The Republic of Latvia is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe, possessing a rich and complex history, a resilient democratic political system, a developing market economy, and a unique cultural heritage. Geographically, it is characterized by lowland plains, extensive forests, and a significant coastline along the Baltic Sea. Historically, Latvian lands have been inhabited by Baltic tribes, later influenced and ruled by German crusaders, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Swedish Empire, and the Russian Empire. Latvia first declared independence in 1918, followed by an interwar period of nation-building that was tragically interrupted by Soviet and Nazi German occupations during World War II. Decades under Soviet rule significantly impacted Latvian society, including its demographic makeup and the suppression of its national identity and human rights. The peaceful Singing Revolution culminated in the restoration of full independence in 1991. Since then, Latvia has focused on democratic consolidation, economic reform, and integration into European and transatlantic structures, joining both NATO and the European Union in 2004, and the Eurozone in 2014. Politically, Latvia is a parliamentary republic with a multi-party system. Its economy has transitioned from a Soviet command system to a market-based one, facing challenges such as the 2008 financial crisis but also periods of significant growth. Latvian society is ethnically diverse, with Latvians constituting the majority alongside a significant Russian minority and other groups; language and citizenship policies, particularly concerning non-citizens, remain important social and human rights topics. The state actively works towards social justice, the protection of human rights, including those of minorities and vulnerable groups like LGBTQ+ individuals, and the strengthening of its democratic institutions. Culturally, Latvia is known for its ancient folk traditions, particularly its dainas (folk songs) and the massive Song and Dance Festival, alongside vibrant contemporary arts. This article explores these facets of Latvia, emphasizing its journey towards democratic development, social equity, and the safeguarding of human rights and cultural identity from a center-left/social liberalism perspective.

2. Etymology

The name Latvia (LatvijaLatviyaLatvian) is derived from the name of the ancient Latgalians, one of four Indo-European Baltic tribes, along with the Curonians, Selonians, and Semigallians. These tribes formed the ethnic core of the modern Latvians, together with the Finnic Livonians. Henry of Latvia, a chronicler in the 13th century, coined the Latinisations of the country's name, "Lettigallia" and "Lethia," both derived from the Latgalians. These terms subsequently inspired the variations of the country's name in Romance languages, such as "Letonia," and in several Germanic languages, such as "Lettland."

3. History

The history of Latvia chronicles the settlement of ancient Baltic tribes, periods of foreign domination by various European powers, the struggle for national identity and independence, devastating occupations in the 20th century, and the eventual restoration of sovereignty and integration into modern Europe. These events have profoundly shaped Latvian society, its demographic composition, and its ongoing efforts towards democratic and social development.

3.1. Medieval Period

Around 3000 BC, the Proto-Baltic ancestors of the Latvian people settled on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea. The Balts established trade routes to Rome and Byzantium, trading local amber for precious metals. By 900 AD, four distinct Baltic tribes inhabited Latvia: the Curonians (kuršikurshiLatvian), Latgalians (latgaļilatgaliLatvian), Selonians (sēļiseliLatvian), and Semigallians (zemgaļizemgaliLatvian), as well as the Finnic tribe of Livonians (lībiešilibieshiLatvian), who spoke a Finnic language. In the 12th century, the territory of Latvia comprised various lands with their rulers, including Vanema, Ventava, Bandava, Piemare, Duvzare, Sēlija, the Koknese, Jersika, Tālava, and Adzele.

Although the local people had contact with the outside world for centuries, they became more fully integrated into the European socio-political system in the 12th century. The first Christian missionaries, sent by the Pope, sailed up the Daugava River in the late 12th century, seeking converts from the indigenous pagan beliefs. Saint Meinhard of Segeberg arrived in Ikšķile in 1184, traveling with merchants to Livonia on a Catholic mission. However, the local people did not convert to Christianity as readily as the Church had hoped. Pope Celestine III had called for a crusade against pagans in Northern Europe in 1193. When peaceful means of conversion failed, Meinhard and his successors plotted to convert Livonians by force of arms.

German crusaders were sent, leading to the establishment of German rule over large parts of what is currently Latvia by the beginning of the 13th century. Bishop Albert of Riga founded Riga in 1201, which soon became the largest city in the southern part of the Baltic Sea. The influx of German crusaders increased, especially in the second half of the 13th century following the decline of the Crusader States in the Middle East. The conquered areas of Latvia and southern Estonia formed the crusader state known as Terra Mariana (Land of Mary) or Livonia, ruled initially by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and later by the Teutonic Order. This period marked the beginning of centuries of German dominance over the native Latvian population, significantly impacting their social structure and land ownership.

In 1282, Riga, and later the cities of Cēsis, Limbaži, Koknese, and Valmiera, became part of the Hanseatic League. Riga developed into an important hub for east-west trade and formed close cultural links with Western Europe. The German settlers, including knights and townsfolk primarily from northern Germany, brought their Low German language to the region, which influenced the Latvian language through numerous loanwords.

3.2. Reformation Period and Polish-Swedish Rule

The 16th century brought significant changes to Livonia with the Reformation, which spread Lutheranism across the region. The Livonian War (1558-1583), fought over the control of Livonia, led to the dissolution of Terra Mariana. Following the war, Livonia (Northern Latvia & Southern Estonia) fell under the hegemony of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The southern part of Estonia and the northern part of Latvia were ceded to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and formed into the Duchy of Livonia (Ducatus Livoniae UltradunensisDuchy of Livonia over the DaugavaLatin). Gotthard Kettler, the last Master of the Livonian Order, formed the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia in 1561, encompassing parts of modern-day western and southern Latvia. Though the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was a vassal state to the Lithuanian Grand Duchy and later of Poland-Lithuania, it retained a considerable degree of autonomy and experienced a golden age in the 16th century, even briefly establishing overseas colonies in Tobago and Gambia. Latgalia, the easternmost region of Latvia, became a part of the Inflanty Voivodeship of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Swedish Empire, and the Tsardom of Russia (later the Russian Empire) struggled for supremacy in the eastern Baltic. After the Polish-Swedish Wars (1600-1629), northern Livonia, including Vidzeme, came under Swedish rule. Riga became the capital of Swedish Livonia and the largest city in the entire Swedish Empire. Fighting continued sporadically between Sweden and Poland until the Truce of Altmark in 1629.

The Swedish period is generally remembered positively in Latvian historiography. During this time, serfdom was somewhat eased, a network of schools was established for the peasantry, and the power of the regional Baltic German barons was diminished. Several important cultural changes occurred. Under Swedish and largely German rule, western Latvia adopted Lutheranism as its main religion. The ancient tribes of the Couronians, Semigallians, Selonians, Livs, and northern Latgallians gradually assimilated to form the Latvian people, speaking one Latvian language. Throughout these centuries, however, an actual Latvian state had not been established. Meanwhile, largely isolated from the rest of Latvia, southern Latgallians adopted Catholicism under Polish and Jesuit influence. The native Latgalian dialect remained distinct, although it acquired many Polish and Russian loanwords.

3.3. Russian Empire Period

The Great Northern War (1700-1721) devastated the Latvian lands. Up to 40 percent of Latvians died from famine and plague, with half the residents of Riga perishing from plague in 1710-1711. The capitulation of Estonia and Livonia in 1710 and the subsequent Treaty of Nystad in 1721 gave Vidzeme to Russia, becoming part of the Riga Governorate. The Latgale region remained part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as the Inflanty Voivodeship until 1772, when it was incorporated into Russia during the First Partition of Poland. The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, a vassal state of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, was annexed by Russia in 1795 in the Third Partition of Poland, bringing all of what is now Latvia into the Russian Empire. All three Baltic provinces (Livonia, Courland, and Latgale, though administered separately) preserved local laws, German as the local language of administration and education for the elite, and their own parliament, the Landtag, dominated by the Baltic German nobility.

The emancipation of the serfs took place in Courland in 1817 and in Vidzeme in 1819. In practice, however, the emancipation was initially advantageous to the landowners and nobility, as it dispossessed peasants of their land without compensation, forcing them to return to work at the estates "of their own free will" or seek opportunities elsewhere. During these two centuries, Latvia experienced an economic and construction boom - ports were expanded (Riga became the largest port in the Russian Empire), railways were built, new factories, banks, and a university were established. Many residential, public (theatres and museums), and school buildings were erected, new parks formed, and Riga's boulevards and some streets outside the Old Town date from this period. Numeracy was also higher in the Livonian and Courlandian parts of the Russian Empire, which may have been influenced by the Protestant religion of the inhabitants.

During the 19th century, the social structure changed dramatically. A class of independent farmers established itself after reforms allowed peasants to repurchase their land, but many landless peasants remained. Many Latvians left for the cities, seeking education and industrial jobs. There also developed a growing urban proletariat and an increasingly influential Latvian bourgeoisie. The Young Latvians (JaunlatviešiJaunlatvieshiLatvian) movement laid the groundwork for nationalism from the middle of the century. Many of its leaders looked to the Slavophiles for support against the prevailing German-dominated social order. The rise in use of the Latvian language in literature and society became known as the First Latvian National Awakening. Russification policies began in Latgale after the Polish-led January Uprising in 1863 and spread to the rest of what is now Latvia by the 1880s. The Young Latvians were largely eclipsed by the New Current (Jaunā strāvaJauna stravaLatvian), a broad leftist social and political movement, in the 1890s. Popular discontent exploded in the 1905 Russian Revolution, which took a nationalist character in the Baltic provinces, leading to widespread unrest and brutal suppression by Tsarist authorities. This period, despite its hardships, strengthened the Latvian national consciousness and desire for self-determination.

3.4. Declaration of Independence and Interwar Period

World War I devastated the territory of what became the state of Latvia, as well as other western parts of the Russian Empire. Demands for self-determination were initially confined to autonomy, until a power vacuum was created by the Russian Revolution in 1917, followed by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between Russia and Germany in March 1918, and then the Allied armistice with Germany on 11 November 1918. On 18 November 1918, in Riga, the People's Council of Latvia proclaimed the independence of the new country, and Kārlis Ulmanis was entrusted to set up a government, taking the position of prime minister.

The Latvian War of Independence that followed was part of a general chaotic period of civil and new border wars in Eastern Europe. By the spring of 1919, there were three governments: the Provisional Government headed by Kārlis Ulmanis, supported by the People's Council and the Inter-Allied Commission of Control; the Latvian Soviet government led by Pēteris Stučka, supported by the Red Army; and the Provisional government headed by Andrievs Niedra, supported by Baltic-German forces composed of the Baltische Landeswehr and the Freikorps formation Eiserne Division (Iron Division). Estonian and Latvian forces defeated the Germans at the Battle of Wenden in June 1919, and a massive attack by a predominantly German force-the West Russian Volunteer Army-under Pavel Bermondt-Avalov was repelled in Riga in November. Eastern Latvia was cleared of Red Army forces by Latvian and Polish troops in early 1920.

A freely elected Constituent Assembly convened on 1 May 1920, and adopted a liberal constitution, the Satversme, in February 1922. With most of Latvia's industrial base evacuated to the interior of Russia in 1915, radical land reform was the central political question for the young state. In 1897, 61.2% of the rural population had been landless; by 1936, that percentage had been reduced to 18%. The interwar period saw significant cultural and educational development, but parliamentary democracy proved unstable.

On 15 May 1934, Kārlis Ulmanis, then Prime Minister, staged a bloodless coup d'état, establishing a nationalist authoritarian dictatorship that lasted until 1940. The constitution was partly suspended, political parties were banned, and the Saeima was dissolved. Ulmanis established government corporations to buy up private firms with the aim of "Latvianising" the economy. This period, while sometimes viewed with nostalgia for its perceived stability and economic progress by some, represented a significant setback for democratic development in Latvia, concentrating power and limiting civil liberties.

3.5. Occupations (1940-1991)

The period from 1940 to 1991 was marked by successive foreign occupations that brought immense suffering and profound changes to Latvian society, interrupting its de facto independence.

3.5.1. Soviet and Nazi German Occupations

Early in the morning of 24 August 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed a 10-year non-aggression pact, known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The pact contained a secret protocol, revealed only after Germany's defeat in 1945, which divided Northern and Eastern Europe into German and Soviet "spheres of influence". Latvia, along with Estonia and Finland (though Finland successfully resisted full occupation), was assigned to the Soviet sphere. After the conclusion of the pact, most of the Baltic Germans left Latvia by agreement between Ulmanis's government and Nazi Germany under the Heim ins Reich programme.

On 5 October 1939, Latvia was forced to accept a "mutual assistance" pact with the Soviet Union, granting the Soviets the right to station between 25,000 and 30,000 troops on Latvian territory. Following an ultimatum, Soviet forces occupied Latvia on 17 June 1940. State administrators were murdered or replaced by Soviet cadres. Rigged elections were held with single pro-Soviet candidates, and the resulting "people's assembly" immediately requested admission into the USSR. Latvia was formally incorporated into the Soviet Union on 5 August 1940, as the Latvian SSR, under the puppet government headed by Augusts Kirhenšteins. This first Soviet occupation was marked by harsh repression. Prior to Operation Barbarossa, in less than a year, at least 34,250 Latvians were deported or killed, primarily during the June deportation in 1941. Most were deported to Siberia, where death rates were estimated at 40 percent, a devastating blow to Latvian society and its intellectual and political elites.

On 22 June 1941, German troops attacked Soviet forces in Operation Barbarossa. Some spontaneous uprisings by Latvians against the Red Army occurred. By early July, Latvia was under the control of German forces. Under German occupation, Latvia was administered as part of Reichskommissariat Ostland. The Nazi occupation brought its own reign of terror. Latvian paramilitary units and Auxiliary Police units established by the occupation authority, such as the Arajs Kommando, participated in the Holocaust and other atrocities against Jews, Roma, and political opponents. Approximately 70,000 Latvian Jews and 20,000 Jews deported from other parts of Europe were murdered. About 30,000 Jews were shot in Latvia in the autumn of 1941. Another 30,000 Jews from the Riga Ghetto were killed in the Rumbula massacre in November and December 1941.

There was a pause in major fighting on Latvian territory, apart from partisan activity (both pro-Soviet and anti-Soviet/anti-Nazi), until after the Siege of Leningrad ended in January 1944. Soviet troops re-entered Latvia in July and captured Riga on 13 October 1944, marking the beginning of the second Soviet occupation. Some Latvian units, including divisions of the Latvian Legion (formed under German command, largely through conscription), continued to fight against the Soviets in the Courland Pocket until the end of World War II in May 1945. The re-occupation by the Soviets led to further repression, deportations, and the imposition of the Soviet system.

3.5.2. Soviet Era (Post-WWII)

The post-war period under the Latvian SSR saw profound political, economic, and social changes, along with sustained efforts to suppress Latvian national identity and human rights. The Soviets re-established control, and further deportations followed as the country was collectivised and Sovietised. An armed resistance movement, known as the Forest Brothers, fought against Soviet rule for several years but was eventually suppressed.

Rural areas were forced into collectivization. An extensive program to impose bilingualism was initiated, limiting the use of the Latvian language in official uses in favor of Russian as the main language. All minority schools (Jewish, Polish, Belarusian, Estonian, Lithuanian) were closed down, leaving only Latvian and Russian as media of instruction. A large influx of laborers, administrators, military personnel, and their dependents from Russia and other Soviet republics occurred. By 1959, about 400,000 Russian settlers had arrived, and the ethnic Latvian population had fallen to 62%. This policy of Russification and demographic change was a deliberate Soviet effort to dilute Latvian national identity and ensure control.

Since Latvia had maintained a well-developed infrastructure and educated specialists, Moscow decided to base some of the Soviet Union's most advanced manufacturing in Latvia. New industries were created, including a major machinery factory RAF in Jelgava, electrotechnical factories in Riga, and chemical factories in Daugavpils, Valmiera, and Olaine. Latvia manufactured trains, ships, minibuses, mopeds, telephones, radios, and hi-fi systems. However, there were often not enough local people to operate the newly built factories, leading to further migration from other Soviet republics, further decreasing the proportion of ethnic Latvians. The population of Latvia reached its peak in 1990 at just under 2.7 million people. Despite industrialization, living standards often lagged, and consumer goods were scarce. Freedom of speech, assembly, and religion were severely curtailed, and any expression of dissent was met with repression.

3.6. Restoration of Independence to Present

In the second half of the 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev started to introduce political and economic reforms known as glasnost and perestroika. In the summer of 1987, the first large demonstrations were held in Riga at the Freedom Monument, a symbol of independence. In the summer of 1988, a national movement, coalescing in the Popular Front of Latvia, emerged. It was opposed by the Interfront. The Latvian SSR, along with the other Baltic states, was allowed greater autonomy. In 1988, the pre-war Latvian flag flew again, replacing the Soviet Latvian flag as the official flag in 1990. This period, known as the Singing Revolution, was characterized by mass peaceful demonstrations and a resurgence of national culture and identity. In 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted a resolution on the Occupation of the Baltic states, in which it declared the occupation "not in accordance with law." Pro-independence Popular Front of Latvia candidates gained a two-thirds majority in the Supreme Council in the March 1990 democratic elections.

On 4 May 1990, the Supreme Council adopted the Declaration "On the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia", and the Latvian SSR was renamed the Republic of Latvia. This declaration stipulated a transitional period for the full restoration of independence. However, the central power in Moscow continued to regard Latvia as a Soviet republic. In January 1991, Soviet political and military forces unsuccessfully tried to overthrow the Republic of Latvia authorities by occupying the central publishing house in Riga and establishing a "Committee of National Salvation." These events, known as The Barricades, saw civilians non-violently defending strategic locations.

The Republic of Latvia declared the end of the transitional period and restored full independence on 21 August 1991, in the aftermath of the failed Soviet coup attempt in Moscow. Latvia resumed diplomatic relations with Western states. The Saeima, Latvia's parliament, was again elected in 1993. Russia ended its military presence by completing its troop withdrawal in 1994 and shutting down the Skrunda-1 radar station in 1998.

A significant challenge in the post-independence period was the issue of citizenship. Citizenship was primarily granted to persons who had been citizens of Latvia on the day of loss of independence in 1940 and their descendants. As a consequence, a large portion of the ethnic non-Latvian population, mostly Russians who had settled during the Soviet era, did not automatically receive Latvian citizenship, becoming non-citizens. This status granted them basic rights but excluded them from voting in parliamentary elections and holding certain public offices. While naturalization processes were established, the status of non-citizens has remained a significant social and human rights issue, drawing international attention. By 2011, more than half of non-citizens had taken naturalization exams and received Latvian citizenship, but in 2015 there were still 290,660 non-citizens. Children born to non-nationals after the re-establishment of independence are automatically entitled to citizenship if their parents choose it.

The major foreign policy goals of Latvia in the 1990s, to join NATO and the European Union, were achieved in 2004. The NATO Summit 2006 was held in Riga. Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga was President of Latvia from 1999 until 2007, the first female head of state in a former Soviet bloc state, and was active in Latvia joining both NATO and the European Union. Latvia signed the Schengen Agreement on 16 April 2003 and started its implementation on 21 December 2007. The government denationalized private property confiscated by the Soviets, returning it or compensating the owners, and privatized most state-owned industries, reintroducing the prewar currency (until the adoption of the Euro in 2014). Despite a difficult transition to a liberal economy and its re-orientation toward Western Europe, Latvia experienced periods of rapid economic growth, though it was severely affected by the 2008-2009 financial crisis, which led to significant austerity measures and social hardship.

In November 2013, the roof collapsed at a shopping center in Riga, causing Latvia's worst post-independence disaster with the deaths of 54 people. In late 2018, the National Archives of Latvia released a full alphabetical index of some 10,000 people recruited as agents or informants by the Soviet KGB, a move that followed two decades of public debate. In May 2023, the parliament elected Edgars Rinkēvičs as the new President of Latvia, making him the European Union's first openly gay head of state, a significant step for LGBTQ+ rights in the region. After years of debate, Latvia ratified the EU Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence, otherwise known as the Istanbul Convention, in November 2023, marking progress in addressing gender-based violence. Contemporary Latvia continues to navigate its complex geopolitical position, strengthen its democratic institutions, address social inequalities, and promote human rights for all its residents.

4. Geography

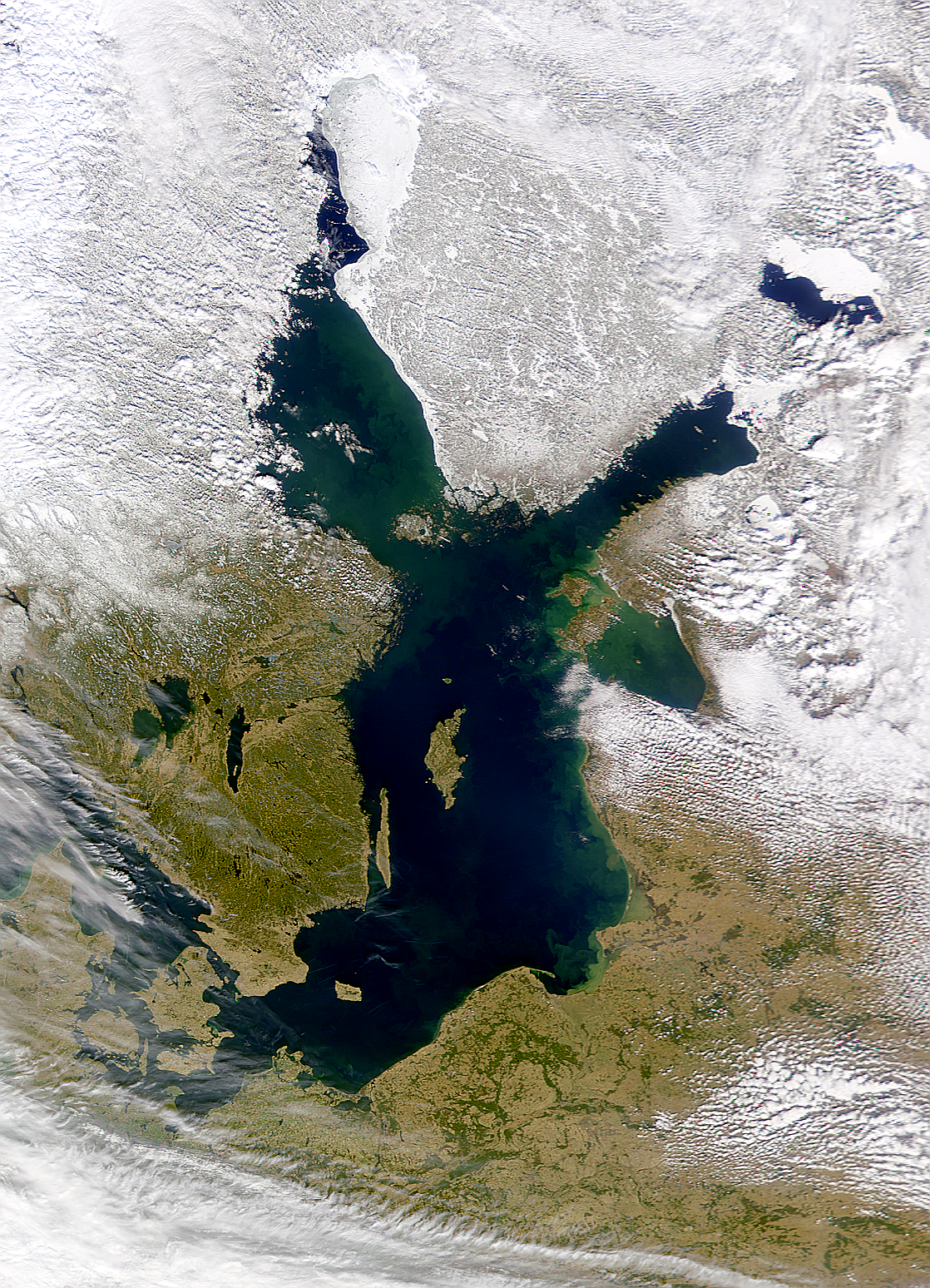

Latvia is situated in Northern Europe, on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It lies within the northwestern part of the East European Craton, between latitudes 55° and 58° N (a small area is north of 58°), and longitudes 21° and 29° E (a small area is west of 21°). The country shares land borders with Estonia to the north (213 mile (343 km)), Russia to the east (171 mile (276 km)), Belarus to the southeast (88 mile (141 km) or 100 mile (161 km) according to different sources), and Lithuania to the south (365 mile (588 km)). It also shares a maritime boundary with Sweden to the west. The total area of Latvia is 25 K mile2 (64.59 K km2) (or 25 K mile2 (64.56 K km2) by some sources), of which 24 K mile2 (62.16 K km2) is land. Agricultural land covers 7.0 K mile2 (18.16 K km2), forest land 13 K mile2 (34.96 K km2) or 8.6 M acre (3.50 M ha), and inland waters 0.9 K mile2 (2.40 K km2). The total length of Latvia's boundary is 1.2 K mile (1.87 K km), with a land boundary of 0.9 K mile (1.37 K km) and a maritime boundary of 309 mile (498 km). The country extends 130 mile (210 km) from north to south and 280 mile (450 km) from west to east.

4.1. Topography and Hydrology

Latvia's topography is characterized by predominantly fertile lowland plains and moderate, gentle hills. Most of its territory is less than 328 ft (100 m) above sea level. The country's highest point is Gaiziņkalns, at 1022 ft (311.6 m).

Latvia has an extensive network of rivers and lakes. There are over 12,500 rivers, which stretch for a total of 24 K mile (38.00 K km). The longest river flowing through Latvian territory is the Daugava River (Western Dvina), which has a total length of 0.6 K mile (1.01 K km), with 219 mile (352 km) of that within Latvia. Other major rivers include the Gauja (281 mile (452 km) in length, the longest river solely on Latvian territory), Lielupe, Venta, and Salaca, the latter being the largest spawning ground for salmon in the eastern Baltic states.

There are 2,256 lakes larger than 2.5 acre (1 ha), with a collective area of 0.4 K mile2 (1.00 K km2). The largest lake is Lake Lubāns (31 mile2 (80.7 km2)), and the deepest is Lake Drīdzis (214 ft (65.1 m) deep). Mires (bogs, fens, and transitional mires) occupy 9.9% of Latvia's territory.

The length of Latvia's Baltic Sea coastline is 307 mile (494 km). An inlet of the Baltic Sea, the shallow Gulf of Riga, is situated in the northwest of the country, characterized by continuous white sand beaches.

4.2. Climate

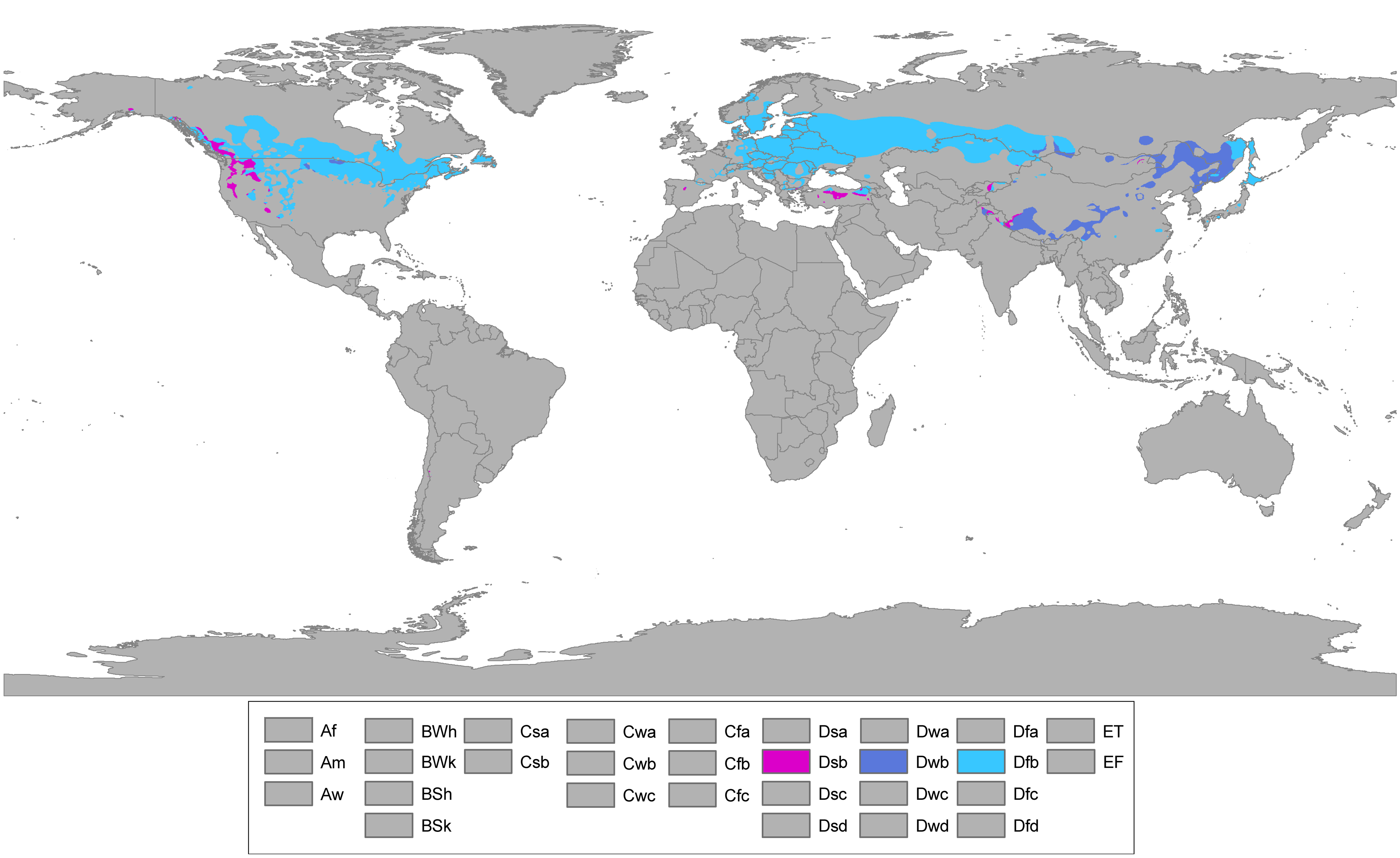

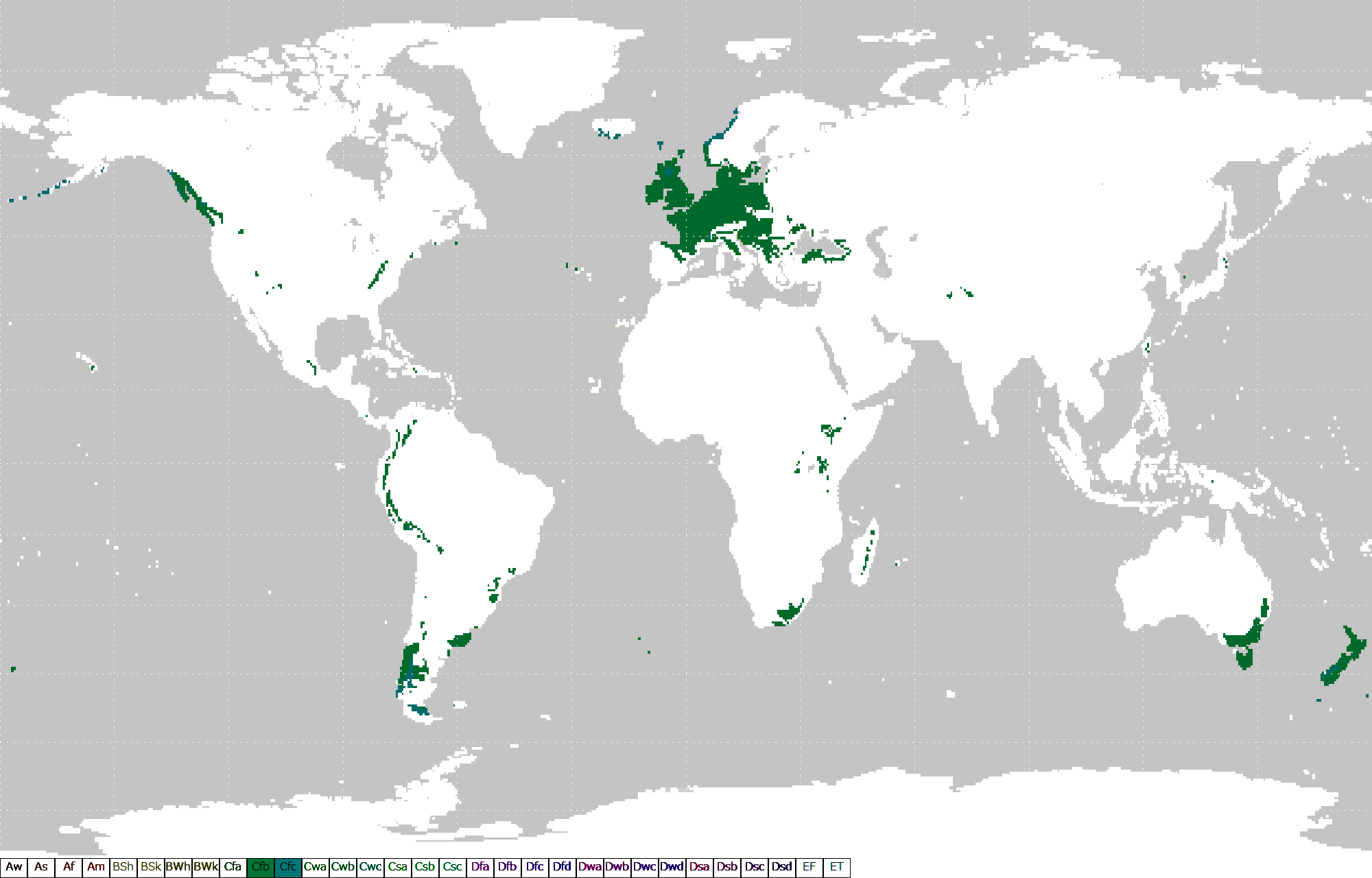

Latvia has a temperate seasonal climate, influenced by its proximity to the Baltic Sea and prevailing westerly winds from the Atlantic Ocean. It is often described as either a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb) or an oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb). Coastal regions, especially the western coast of the Courland Peninsula, possess a more maritime climate with cooler summers and milder winters, while eastern parts exhibit a more continental climate with warmer summers and harsher winters. However, temperature variations are relatively small due to the country's modest size and flat terrain.

Latvia has four pronounced seasons of near-equal length. Winter typically starts in mid-December and lasts until mid-March, with average temperatures of 21.2 °F (-6 °C). Winters are characterized by stable snow cover, bright sunshine, and short days. Severe spells of winter weather with cold winds, extreme temperatures of around -22 °F (-30 °C), and heavy snowfalls are common. Spring arrives in April with mild weather. Summer starts in June and lasts until August, usually warm and sunny, with cool evenings and nights. Average summer temperatures are around 66.2 °F (19 °C), with extremes reaching 95 °F (35 °C). Autumn, from September to October, also brings fairly mild weather.

Precipitation is distributed throughout the year, with the heaviest rainfall typically occurring in late summer.

The highest recorded temperature in Latvia was 100.03999999999999 °F (37.8 °C) in Ventspils on 4 August 2014. The lowest recorded temperature was -45.760000000000005 °F (-43.2 °C) in Daugavpils on 8 February 1956. The year 2019 was the warmest year in the history of weather observation in Latvia, with an average temperature 15 °F (8.1 °C) higher than the norm.

| Weather record | Value | Location | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest temperature | 100.03999999999999 °F (37.8 °C) | Ventspils | 4 August 2014 |

| Lowest temperature | -45.760000000000005 °F (-43.2 °C) | Daugavpils | 8 February 1956 |

| Last spring frost | - | Large parts of territory | 24 June 1982 |

| First autumn frost | - | Cenas parish | 15 August 1975 |

| Highest yearly precipitation | 0.0 K in (1.01 K mm) | Priekuļi parish | 1928 |

| Lowest yearly precipitation | 15 in (384 mm) | Ainaži | 1939 |

| Highest daily precipitation | 6.3 in (160 mm) | Ventspils | 9 July 1973 |

| Highest monthly precipitation | 13 in (330 mm) | Nīca parish | August 1972 |

| Lowest monthly precipitation | 0.0 in (0 mm) | Large parts of territory | May 1938 and May 1941 |

| Thickest snow cover | 50 in (126 cm) | Gaiziņkalns | March 1931 |

| Month with the most days with blizzards | 19 days | Liepāja | February 1956 |

| The most days with fog in a year | 143 days | Gaiziņkalns area | 1946 |

| Longest-lasting fog | 93 hours | Alūksne | 1958 |

| Highest atmospheric pressure | 1067.5 hPa | Liepāja | January 1907 |

| Lowest atmospheric pressure | 931.9 hPa | Vidzeme Upland | 13 February 1962 |

| The most days with thunderstorms in a year | 52 days | Vidzeme Upland | 1954 |

| Strongest wind | 76 mph (34 m/s), gusts up to 107 mph (48 m/s) | Not specified | 2 November 1969 |

4.3. Environment

Latvia boasts a rich natural environment. In a typical Latvian landscape, a mosaic of vast forests alternates with fields, farmsteads, and pastures. Arable land is spotted with birch groves and wooded clusters, which afford a habitat for numerous plants and animals. Latvia has hundreds of kilometres of undeveloped seashore-lined by pine forests, dunes, and continuous white sand beaches.

Latvia has the fifth-highest proportion of land covered by forests in the European Union, after Sweden, Finland, Estonia, and Slovenia. Forests account for 8.6 M acre (3.50 M ha) or 56% of the total land area. About 70% of the mires are untouched by civilization and are a refuge for many rare species of plants and animals.

Agricultural areas account for 4.5 M acre (1.82 M ha) or 29% of the total land area. With the dismantling of collective farms after the restoration of independence, the area devoted to farming decreased dramatically, and farms are now predominantly small. Approximately 200 farms, occupying 6.8 K acre (2.75 K ha), are engaged in ecologically pure farming (using no artificial fertilizers or pesticides).

Latvia has a long tradition of conservation. The first laws and regulations concerning nature protection were promulgated in the 16th and 17th centuries. There are 706 specially state-level protected natural areas in Latvia: four national parks, one biosphere reserve, 42 nature parks, nine areas of protected landscapes, 260 nature reserves, four strict nature reserves, 355 nature monuments, seven protected marine areas, and 24 microreserves. Nationally protected areas account for 4.9 K mile2 (12.79 K km2) or around 20% of Latvia's total land area. The country's national parks are Gauja National Park in Vidzeme (established 1973), Ķemeri National Park in Zemgale (1997), Slītere National Park in Kurzeme (1999), and Rāzna National Park in Latgale (2007). Latvia has ratified the international Washington (CITES), Bern, and Ramsar conventions on environmental protection. Latvia's Red Book (Endangered Species List of Latvia), established in 1977, contains 112 plant species and 119 animal species.

The 2012 Environmental Performance Index ranked Latvia second globally, after Switzerland, based on the environmental performance of the country's policies. Latvia has made efforts to address environmental issues stemming from past industrial or agricultural practices inherited from the Soviet era, focusing on improving water quality, waste management, and promoting sustainable forestry. Access to biocapacity in Latvia is much higher than the world average. In 2016, Latvia had 8.5 global hectares of biocapacity per person within its territory, significantly more than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person. In the same year, Latvia used 6.4 global hectares of biocapacity per person (their ecological footprint of consumption), meaning they use less biocapacity than Latvia contains, resulting in a biocapacity reserve.

4.4. Biodiversity

Approximately 30,000 species of flora and fauna have been registered in Latvia. Larger mammalian wildlife in Latvia include roe deer, wild boar, moose, lynx, bear, fox, beaver, and wolves. The non-marine molluscs of Latvia include 170 species.

Species that are endangered in other European countries but common in Latvia include the black stork (Ciconia nigra), corncrake (Crex crex), lesser spotted eagle (Aquila pomarina), white-backed woodpecker (Picoides leucotos), Eurasian crane (Grus grus), Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber), Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra), European wolf (Canis lupus), and European lynx (Felis lynx).

Phytogeographically, Latvia is shared between the Central European and Northern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Latvia belongs to the ecoregion of Sarmatic mixed forests. As noted, 56 percent of Latvia's territory is covered by forests, mostly Scots pine, birch, and Norway spruce. Latvia had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 2.09/10, ranking it 159th globally out of 172 countries.

Several species of flora and fauna are considered national symbols. The oak (Quercus robur, ozolsozolsLatvian) and linden (Tilia cordata, liepaliepaLatvian) are Latvia's national trees, and the daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare, pīpenepeepeneLatvian) is its national flower. The white wagtail (Motacilla alba, baltā cielavabalta tzielavaLatvian) is Latvia's national bird. Its national insect is the two-spot ladybird (Adalia bipunctata, divpunktu mārītedivpunktu mariteLatvian). Amber, fossilized tree resin, is one of Latvia's most important cultural symbols. In ancient times, amber found along the Baltic Sea coast was sought by Vikings as well as traders from Egypt, Greece, and the Roman Empire, leading to the development of the Amber Road.

Several nature reserves protect unspoiled landscapes with a variety of large animals. At Pape Nature Reserve, where European bison, wild horses, and recreated aurochs (Heck cattle) have been reintroduced, there is now an almost complete Holocene megafauna also including moose, deer, and wolf.

5. Government and Politics

Latvia is a democratic parliamentary republic. Its political system operates under the framework laid out in the Constitution of Latvia (Satversme), originally adopted in 1922, suspended during the authoritarian regime and Soviet/Nazi occupations, and fully restored in 1993. The constitution guarantees fundamental human rights and defines the structure and powers of the state, emphasizing democratic institutions and citizen participation.

5.1. Government Structure

Latvia's government is structured around the principles of separation of powers into legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

The legislature is the unicameral Saeima, which consists of 100 members elected for a four-year term through proportional representation with a 5% electoral threshold. The Saeima enacts laws, approves the national budget, oversees the government, and elects the President. Bills may be initiated by the Government or by members of parliament. Parliamentary elections are held at least every four years, but the President can call for early elections under certain circumstances. The Saeima can force the resignation of a single minister or the entire government through a vote of no confidence.

The executive power is vested in the Cabinet of Ministers, which is headed by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is appointed by the President and must receive a vote of confidence from the Saeima. The Cabinet, consisting of the Prime Minister and other ministers who head various ministries, is responsible for proposing bills and a budget, executing laws, and guiding the foreign and internal policies of Latvia. The position of Prime Minister usually belongs to the leader of the largest political party or a coalition capable of commanding a majority in the Saeima. Coalition governments, often minority governments dependent on support from other parties, are common due to the proportional representation system. The most senior civil servants are the thirteen Secretaries of State.

The President of Latvia is the head of state, elected by the Saeima for a four-year term, with a maximum of two consecutive terms. The President's role is largely ceremonial but includes powers such as formally appointing the Prime Minister, promulgating laws, representing Latvia abroad, and acting as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The President also has the right to initiate legislation and to return laws to the Saeima for reconsideration.

The judiciary is independent. It consists of district (city) courts, regional courts, and the Supreme Court. There is also a Constitutional Court, which reviews the constitutionality of laws.

5.2. Administrative Divisions

Latvia is a unitary state. Following an administrative reform effective from 1 July 2021, the country is divided into 43 local government units: 36 municipalities (novadinovadiLatvian) and 7 state cities (valstspilsētasvalstspilsetasLatvian) with their own city councils and administrations. The state cities are Daugavpils, Jelgava, Jūrmala, Liepāja, Rēzekne, Riga, and Ventspils.

There are four historical and cultural regions in Latvia - Courland (KurzemeKurzemeLatvian), Latgale, Vidzeme, and Zemgale (Semigallia) - which are recognised in the Constitution of Latvia. Selonia (SēlijaSeliyaLatvian), a part of Zemgale, is sometimes considered a culturally distinct fifth region, but it is not part of any formal division. The borders of these historical and cultural regions are usually not explicitly defined and may vary in different sources.

For statistical and planning purposes, Latvia is also divided into planning regions (plānošanas reģioniplanoshanas regjioniLatvian). These were created in 2009 to promote balanced development. The five planning regions are Riga, Courland, Latgale, Vidzeme, and Zemgale. The Riga region includes the capital and surrounding areas. Statistical regions of Latvia, established in accordance with the EU Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS), duplicate this division.

The largest city in Latvia is Riga, the capital. The second largest city is Daugavpils, and the third largest is Liepāja.

5.3. Political Culture

Modern Latvian political culture is characterized by a multi-party system, coalition governments, and ongoing debates on social, economic, and national identity issues. Since regaining independence, Latvia has established democratic norms and institutions, with regular free and fair elections. Civil society organizations play an active role in public discourse and policy-making.

The 2010 parliamentary election saw the ruling centre-right coalition win 63 out of 100 seats, while the left-wing opposition Harmony Centre, supported by Latvia's Russian-speaking minority, gained 29 seats. In November 2013, Prime Minister Valdis Dombrovskis resigned after the Zolitūde shopping centre roof collapse. The 2014 parliamentary election was again won by a centre-right coalition. In December 2015, Prime Minister Laimdota Straujuma, the country's first female prime minister, resigned. A new coalition government led by Māris Kučinskis was formed in February 2016.

The 2018 parliamentary election resulted in a fragmented Saeima. The pro-Russian Harmony party was the largest single party but remained in opposition. A new coalition government led by Krišjānis Kariņš of the centre-right New Unity was formed in January 2019, comprising five parties.

Following the October 2022 parliamentary election, Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš formed the Second Kariņš cabinet in December 2022, a coalition of New Unity, National Alliance, and United List. On 14 August 2023, Kariņš resigned, citing National Alliance's opposition to expanding the coalition. The Siliņa cabinet, led by Evika Siliņa (New Unity) and comprising New Unity, the Union of Greens and Farmers, and The Progressives, was sworn in on 15 September 2023. This marked a shift in coalition dynamics, with The Progressives, a social-liberal party, entering government for the first time.

Key political debates often revolve around economic policy, social welfare, relations with Russia, national identity, and the integration of minorities, including the rights of non-citizens and Russian speakers. The role of civil society and the upholding of democratic norms remain central to Latvia's political culture, especially in the context of regional security challenges.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Latvia is an active member of the international community. It is a member of the United Nations (UN), European Union (EU), Council of Europe, NATO, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), International Monetary Fund (IMF), and World Trade Organization (WTO). It is also a member of the Council of the Baltic Sea States and the Nordic Investment Bank. Latvia was a member of the League of Nations (1921-1946). Latvia is part of the Schengen Area and joined the Eurozone on 1 January 2014.

Latvia has established diplomatic relations with 158 countries. It maintains 44 diplomatic and consular missions abroad, including 34 embassies and 9 permanent representations. There are 37 foreign embassies and 11 international organisations in Riga. Latvia hosts one EU institution, the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC).

Latvia's foreign policy priorities include co-operation in the Baltic Sea region, European integration, active involvement in international organisations, contribution to European and transatlantic security and defence structures, participation in international civilian and military peacekeeping operations, and development co-operation, particularly the strengthening of stability and democracy in the EU's Eastern Partnership countries.

Since the early 1990s, Latvia has been involved in active trilateral Baltic states co-operation with Estonia and Lithuania, and Nordic-Baltic co-operation with the Nordic countries. Latvia is a member of the interparliamentary Baltic Assembly and the intergovernmental Baltic Council of Ministers. The Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB8) is a format for joint co-operation of the governments of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, and Sweden. The Nordic Council of Ministers has an office in Riga.

Latvia participates in the Northern Dimension and Baltic Sea Region Programme. In 2013, Riga hosted the annual Northern Future Forum. The Enhanced Partnership in Northern Europe (e-PINE) is a U.S. Department of State framework for co-operation with the Nordic-Baltic countries. Latvia hosted the 2006 NATO Summit, and the annual Riga Conference has become a leading foreign and security policy forum in Northern Europe. Latvia held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2015.

Relations with Russia have historically been complex and have significantly deteriorated following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Latvia has strongly condemned Russian aggression, provided substantial aid to Ukraine, and taken measures to bolster its own security and reduce dependence on Russia. In January 2023, Latvia withdrew its ambassador from Russia and expelled Russia's ambassador to Latvia, and has implemented travel restrictions for Russian citizens. Cooperation within the Baltic and Nordic regions, particularly on security and energy issues, has intensified. Latvia advocates for strong EU and NATO responses to Russian aggression and supports Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity.

5.5. Military

The Latvian National Armed Forces (Nacionālie Bruņotie SpēkiNatsionalie Brunyotie SpekiLatvian, NAF) consist of the Latvian Land Forces, Latvian Naval Forces, Latvian Air Force, Latvian National Guard (Zemessardze), Special Tasks Unit, Military Police, NAF Staff Battalion, Training and Doctrine Command, and Logistics Command. Latvia's defence concept is based upon a rapid response force composed of a mobilisation base and a small group of career professionals. From 1 January 2007, Latvia switched to a professional fully contract-based army. However, in response to increased regional security threats following Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Latvia announced plans to reintroduce conscription starting in 2023 for men, with voluntary service for women.

Latvia has been a member of NATO since 2004. This membership is a cornerstone of its security policy. Latvia actively participates in international peacekeeping and security operations. Latvian armed forces have contributed to NATO and EU military operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1996-2009), Albania (1999), Kosovo (2000-2009), Macedonia (2003), Iraq (2003-2008, 2005-2006 for different missions), Afghanistan (2003-2021), Somalia (since 2011), and Mali (since 2013). Per capita, Latvia has been one of the largest contributors to international military operations among NATO allies. Seven Latvian soldiers have perished in international operations.

Latvian civilian experts have also contributed to EU civilian missions. Since March 2004, NATO members have deployed fighter jets on a rotational basis for the Baltic Air Policing mission to guard Baltic airspace. Latvia hosts elements of NATO's Enhanced Forward Presence battle group, demonstrating allied commitment to collective defense. Latvia participates in several NATO Centres of Excellence and hosts the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence in Riga.

Latvia co-operates closely with Estonia and Lithuania in several trilateral Baltic defence co-operation initiatives, including the Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT), Baltic Naval Squadron (BALTRON), Baltic Air Surveillance Network (BALTNET), and joint military educational institutions like the Baltic Defence College. In January 2011, the Baltic states were invited to join Nordic Defence Cooperation (NORDEFCO). In response to the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Latvia significantly increased its defense budget, aiming to reach 2.5% of GDP, and has accelerated military procurement and infrastructure development.

5.6. Human Rights

Human rights in Latvia are generally respected by the government, as reported by organizations like Freedom House and the U.S. Department of State. Latvia is ranked above-average among the world's sovereign states in democracy, freedom of the press, privacy, and human development. Latvia has made significant strides in establishing democratic institutions and ensuring civil liberties since regaining independence in 1991.

One of the most prominent human rights issues in Latvia has been the status of its non-citizens, largely Russian-speaking residents who settled in Latvia during the Soviet era or their descendants, who were not automatically granted citizenship after 1991. While non-citizens have basic rights, they cannot vote in parliamentary or municipal elections or hold certain public sector jobs. International bodies, including the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities, have urged Latvia to facilitate their naturalization and allow participation in municipal elections. The number of non-citizens has significantly decreased over the years due to naturalization, death, or emigration, but the issue remains a point of discussion regarding social integration and minority rights. The government has taken steps to simplify naturalization, particularly for children born to non-citizen parents.

The rights of ethnic minorities are protected under the constitution and international laws ratified by Latvia. The country has a large ethnic Russian community, and language policy, particularly concerning education and the use of Latvian as the sole state language, has been a subject of debate and concern among some minority groups and international observers. Efforts have been made to balance the promotion of the Latvian language with the rights of minorities to use and preserve their own languages and cultures.

Regarding LGBT rights, Latvia has seen gradual progress but also faces challenges. Same-sex relationships are not legally recognized to the same extent as heterosexual relationships, and same-sex marriage is constitutionally prohibited since an amendment in 2006 defined marriage exclusively as a union between a man and a woman. However, in 2023, the Saeima passed legislation to allow civil partnerships for same-sex couples, expected to come into force in mid-2024, representing a significant step forward. Public attitudes towards LGBTQ+ individuals are mixed, and events like Riga Pride have sometimes faced opposition, although they have also become important platforms for advocacy and visibility. EuroPride was hosted in Riga in 2015.

Other human rights concerns highlighted by various reports include occasional instances of police misconduct, conditions in prisons, judicial efficiency, and societal discrimination against certain groups. The government generally investigates abuses. Latvia has ratified the Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, reflecting a commitment to address gender-based violence. The impact of historical events, particularly the Soviet and Nazi occupations, continues to influence discussions on human rights, memory politics, and national identity.

Latvia ranks highly in Europe for the proportion of women in leading positions, holding the first rank in Europe and sharing the top global position with five other European countries in women's rights according to the World Bank.

6. Economy

Latvia has an open economy in Northern Europe and is part of the European single market. Following its transition from a Soviet command economy to a market-based system after regaining independence in 1991, Latvia has experienced periods of rapid growth, significant challenges, and ongoing structural reforms. It is a member of the World Trade Organization (since 1999) and the European Union (since 2004). On 1 January 2014, the euro became the country's currency, replacing the lats.

6.1. Economic Overview and Trends

Latvia's transition to a market economy in the 1990s involved large-scale privatization of state-owned enterprises and liberalization of prices and trade. Privatisation is now almost complete, with virtually all previously state-owned small and medium companies privatised, leaving only a small number of politically sensitive large state companies. The private sector accounted for 70% of the country's GDP in 2006.

From 2000, Latvia experienced one of the highest GDP growth rates in Europe, driven by strong domestic demand, foreign investment, and EU fund inflows. However, this rapid, chiefly consumption-driven growth, financed by a significant increase in private debt and a negative foreign trade balance, led to an overheating economy and a large current account deficit (over 22% of GDP in 2007). Real estate prices rose dramatically.

The global financial crisis of 2008 severely impacted Latvia, leading to the Latvian financial crisis of 2008-2010. The economy contracted sharply, with GDP falling by 18% in the first three months of 2009, the biggest fall in the European Union at the time. The crisis was exacerbated by the collapse of Parex Bank, the country's second-largest bank, which required a government bailout. Latvia implemented severe austerity measures as part of an international bailout package led by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the EU. These measures included significant public sector wage cuts, spending reductions, and tax increases, which had considerable social impacts, including a sharp rise in unemployment (peaking over 22%) and emigration.

The economy began to recover from 2010, with growth driven by exports and a gradual return of domestic demand. Latvia successfully exited the bailout program and was often cited as an example of successful internal devaluation. It joined the Eurozone on 1 January 2014. Support for the euro, initially mixed, grew after its introduction.

Recent economic trends show moderate growth. GDP at current prices rose from 23.70 B EUR in 2014 to 30.50 B EUR in 2019. The employment rate rose from 59.1% to 65% in the same period, with unemployment falling from 10.8% to 6.5%. The economy has faced new challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic consequences of the war in Ukraine, including inflation and energy price volatility.

Foreign investment in Latvia is still modest compared with levels in north-central Europe. In 2010, Latvia launched a Residence by Investment program (Golden Visa) to attract foreign investors, requiring an investment of at least 250.00 K EUR.

6.2. Main Industries

Latvia's economy is diversified, with key sectors including:

- Timber and Wood Processing: Forests cover a significant portion of Latvia, making timber and wood products (furniture, paper, construction materials) a major export industry.

- Agriculture and Food Processing: Main agricultural products include grains (wheat, barley, rye), rapeseed, potatoes, and vegetables. Dairy farming and meat production are also important. The food processing industry is well-developed.

- Metalworking, Machinery, and Electronics Manufacturing: This sector produces a range of goods, from metal structures and components to machinery, transport vehicles (like railway cars), and electronic equipment.

- Information and Communication Technologies (ICT): The ICT sector has been growing, with a focus on software development, IT services, and telecommunications.

- Transit and Logistics: Due to its geographical location and ice-free ports, Latvia serves as a transit hub, particularly for goods moving between Russia/CIS countries and Western Europe, although this role has been affected by geopolitical shifts.

- Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals: Latvia has a tradition in chemical and pharmaceutical production.

- Tourism: Riga, with its historic center (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), and other attractions like Jūrmala's beaches and national parks, contribute to the tourism sector.

6.3. Infrastructure

6.3.1. Transport

The transport sector contributes significantly to Latvia's GDP. Key transport facilities include:

- Ports: The three major ports are Riga, Ventspils, and Liepāja, all of which are largely ice-free. They handle a variety of cargo, historically including significant transit volumes of crude oil and oil products from Russia, though this has diminished. Skulte is another port.

- Airports: Riga International Airport (RIX) is the largest airport in the Baltic states, serving as a hub for the national airline airBaltic and offering direct flights to numerous destinations. Liepāja International Airport also handles some commercial flights.

- Railways: The Latvian railway network primarily uses the 0.1 K in (1.52 K mm) Russian gauge. The total network length is approximately 1.2 K mile (1.86 K km), of which about 156 mile (251 km) is electrified. Latvia is a key participant in the Rail Baltica project, a major ongoing infrastructure development aimed at creating a standard gauge (0.1 K in (1.44 K mm)) railway line connecting Helsinki (via ferry), Tallinn, Riga, Kaunas, and Warsaw, thereby integrating the Baltic states with the European standard gauge network. This project is expected to be completed around 2026-2030.

- Roads: Latvia has a network of main roads (A-roads), regional roads (P-roads), and local roads. The Via Baltica (European route E67), connecting Warsaw and Tallinn, and European route E22, are important international transport corridors passing through Latvia. In 2017, there were a total of 803,546 licensed vehicles.

6.3.2. Energy

Latvia's energy sector relies on a mix of domestic production and imports.

- Electricity: A significant portion of Latvia's electricity is generated from hydroelectric power, primarily from three large hydroelectric power stations on the Daugava River: Pļaviņu HES (908 MW), Rīgas HES (402 MW), and Ķeguma HES (248 MW). Wind power is a growing renewable energy source, with several wind farms in operation and more planned. Biomass and biogas power stations also contribute to electricity generation. Latvia is interconnected with the electricity grids of neighboring countries, participating in the Nord Pool spot market.

- Natural Gas: Latvia has historically relied on imports for its natural gas supply, primarily from Russia. The Inčukalns underground gas storage facility is one of the largest in Europe and the only one in the Baltic states, playing a crucial role in regional gas supply security. Following geopolitical shifts, Latvia has been working to diversify its gas supply sources, including through access to liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals in the region.

- Heating: District heating is common in urban areas, often fueled by natural gas or biomass.

Latvia is focused on increasing its energy independence, promoting renewable energy sources, and enhancing energy efficiency in line with EU targets, planning investments of 1.00 B EUR in new wind farms.

7. Society

Latvian society is characterized by its demographic trends, ethnic diversity, unique linguistic landscape, and evolving social structures. The country has undergone significant societal shifts since regaining independence, grappling with issues of integration, population decline, and the development of its education and welfare systems.

7.1. Demographics

As of January 2023, the population of Latvia was approximately 1.88 million. Latvia has experienced a significant population decline since its peak of nearly 2.7 million in 1990. This decline is attributed to several factors, including a low total fertility rate (TFR), negative natural increase (more deaths than births), and net emigration, particularly after Latvia's accession to the EU in 2004, which facilitated labor migration to other EU countries. The government has expressed concern over these trends and is exploring policies to address them.

The TFR in 2018 was estimated at 1.61 children born per woman, below the replacement rate of 2.1. In 2012, 45.0% of births were to unmarried women. Life expectancy in 2013 was estimated at 73.2 years (68.1 years for males, 78.5 years for females). As of 2015, Latvia was estimated to have one of the lowest male-to-female ratios in the world, at 0.85 males per female, particularly pronounced in older age groups. In 2017, there were 1,054,433 females and 895,683 males. While more boys are born than girls annually, the disparity in life expectancy means that above the age of 70, there are significantly more females than males (e.g., 2.3 times as many in 2017).

7.2. Ethnic Groups

| Ethnicity | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Latvians | 62.4% |

| Russians | 23.7% |

| Belarusians | 3.0% |

| Ukrainians | 3.0% |

| Poles | 2.0% |

| Lithuanians | 1.1% |

| Others | 4.8% |

Latvia is an ethnically diverse country. According to 2023 data, Latvians (an ethnic Baltic people) constituted about 62.4% of the population. The largest ethnic minority is Russians, making up 23.7%. Other significant minority groups include Belarusians (3.0%), Ukrainians (3.0%, this figure has likely increased due to refugees from the war in Ukraine), Poles (2.0%), and Lithuanians (1.1%). Other ethnic groups make up the remaining 4.8%.

The current ethnic composition is a result of historical processes, including centuries of foreign rule and significant demographic shifts during the Soviet era, when many people from other Soviet republics, particularly Russia, migrated to Latvia. In some cities, such as Daugavpils and Rēzekne, ethnic Latvians constitute a minority of the total population. Even in the capital, Riga, ethnic Latvians make up slightly less than half the population, although their proportion has been steadily increasing. The share of ethnic Latvians in the country declined from 77% in 1935 to 52% in 1989, but has since risen to over 62%.

The integration of ethnic minorities, particularly the large Russian-speaking community, has been a key social and political issue. This includes matters related to citizenship (the status of non-citizens), language use, and education. Latvia aims to foster a cohesive society while preserving Latvian national identity and language, and ensuring the rights and representation of minorities. Relations with Russia have impacted the Russian minority, particularly since 2022, with Latvia taking measures against individuals deemed to be undermining national security or failing to integrate, including requirements for language proficiency for continued residency for some Russian citizens.

7.3. Language

The sole official language of Latvia is Latvian, which belongs to the Baltic language sub-group of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. It is spoken as a native language by about 62% of the population and is a key element of Latvian national identity.

Another notable indigenous language is the Livonian language, a Finnic language that is nearly extinct but enjoys protection by law. Latgalian, often considered a dialect or historical variant of Latvian, is spoken in the Latgale region and is also protected by Latvian law.

Russian is by far the most widely used minority language. In 2023, 37.7% of the population spoke it as their mother tongue, and a larger percentage speak it fluently as a second language. Its widespread use is a legacy of the Soviet period.

Language policy is a significant aspect of Latvian society and politics. The government promotes the use of Latvian in all official spheres, including education. It is required that all school students learn Latvian. While minority schools have existed, there has been a progressive shift towards Latvian as the primary language of instruction in public education. From 2019, instruction in Russian was gradually discontinued in private colleges and universities, and a transition to Latvian as the sole language of general instruction in public high schools (except for subjects related to minority culture and history) was initiated. Schools still using Russian in 2023 were required to transition to Latvian in all classes within three years. These policies aim to strengthen the role of the state language and foster integration, but have also led to debates and concerns among some minority groups regarding linguistic rights and access to education in their native language.

English is widely taught as a foreign language and is increasingly used in business and tourism. German and French are also included in school curricula. Many Latvians, especially younger generations, are multilingual.

On 18 February 2012, Latvia held a constitutional referendum on whether to adopt Russian as a second official language. The proposal was overwhelmingly rejected, with 74.8% voting against and 24.9% voting for, on a voter turnout of 71.1%. This outcome reaffirmed Latvian as the sole state language.

7.4. Religion

| Religion | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Lutheranism | 34.2% |

| Roman Catholicism | 24.1% |

| Eastern Orthodoxy | 17.8% |

| Old Believers | 1.6% |

| Other Christian denominations | 1.2% |

| Other or none | 21.1% |

The largest religion in Latvia is Christianity, though religious observance is generally low. According to 2011 data, the main Christian denominations are:

- Lutheranism: 34.2% of those affiliated (approximately 708,773 adherents). Lutheranism has strong historical roots, particularly in western and central Latvia, reflecting historical links with German and Nordic cultures.

- Roman Catholicism: 24.1% (approximately 500,000 adherents). Catholicism is predominant in the eastern region of Latgale, due to historical Polish-Lithuanian influence.

- Eastern Orthodoxy: 17.8% (approximately 370,000 adherents). Most Orthodox Christians are part of the Latvian Orthodox Church, which was historically under the Moscow Patriarchate. In September 2022, amid geopolitical tensions, Latvian law was changed to affirm the autocephaly (independence) of the Latvian Orthodox Church from the Moscow Patriarchate, aiming to remove foreign influence over the church, a move reflecting national security concerns.

- Old Believers: 1.6%. This community has a long history in Latvia.

- Other Christian denominations: 1.2%.

A significant portion of the population is not affiliated with a specific religion (21.1% in 2011). In a Eurobarometer Poll in 2010, 38% of Latvian citizens responded that "they believe there is a God," while 48% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force," and 11% stated that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force."

Lutheranism was more prominent before the Soviet occupation, when it was adhered to by about 60% of the population. The Soviet era led to a decline in religious practice for all faiths. Since independence, there has been some revival of religious life.

Dievturība, a Latvian neopagan movement based on Latvian mythology, also exists, with a few hundred adherents. In 2011, there were 416 Jews and 319 Muslims registered.

7.5. Education and Science

Latvia's education system provides for compulsory education up to the age of 16 (typically completing basic education, grades 1-9). The system includes pre-school education, basic education (9 years), secondary education (general or vocational, typically 3 years), and higher education. The language of instruction in public schools is primarily Latvian, with provisions for minority language and culture subjects.

Major universities include the University of Latvia (LU) and Riga Technical University (RTU), both located in Riga and successors to the historic Riga Polytechnical Institute. Other important institutions include the Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies in Jelgava (formerly the Latvia University of Agriculture), Riga Stradiņš University (specializing in medical and social sciences), and the University of Daugavpils. There are also numerous state and private colleges and vocational schools.

Latvia has faced challenges in its education sector, including demographic decline leading to school closures (131 schools between 2006 and 2010) and decreased enrollment. There is ongoing reform to improve quality, efficiency, and relevance to the labor market.

Latvian policy in science and technology aims to transition from a labor-consuming economy to a knowledge-based economy. The government has expressed goals to increase spending on research and development (R&D), with a target of 1.5% of GDP, encouraging private sector investment. Key areas for scientific development include organic chemistry, medical chemistry, genetic engineering, physics, materials science, and information technologies. The Latvian Academy of Sciences is a major scientific institution. Latvia was ranked 42nd in the Global Innovation Index in 2024. The greatest number of patents, both nationwide and abroad, are in medical chemistry.

7.6. Health

Latvia has a universal health care system, largely funded through government taxation. All permanent residents are guaranteed medical care. However, the system has faced challenges, including underfunding, long waiting times for certain treatments, issues with access to the latest medicines, and a shortage of medical personnel, partly due to emigration of healthcare professionals. In international comparisons, Latvia's healthcare system has sometimes ranked among the lower-performing ones in Europe.

Reforms have been ongoing to improve efficiency, quality of care, and accessibility. There has been a consolidation of hospitals; in 2009, there were 59 hospitals, down from 94 in 2007 and 121 in 2006. Key public health concerns include cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and lifestyle-related risk factors. Efforts are being made to promote preventative care and public health initiatives.

8. Culture

Latvian culture is a unique blend of indigenous traditions, historical influences from neighboring Germanic, Slavic, and Nordic cultures, and contemporary European trends. It is characterized by a strong connection to nature, a rich heritage of folklore, and vibrant artistic expressions in music, literature, and the visual arts.

8.1. Traditional Culture and Arts

Traditional Latvian folklore, especially the folk songs known as dainas, dates back well over a thousand years. More than 1.2 million texts and 30,000 melodies of folk songs have been identified and collected, primarily through the work of Krišjānis Barons in the 19th century. These dainas reflect ancient beliefs, customs, and a deep reverence for nature. Folk dances are also an integral part of Latvian traditional culture.

The Latvian Song and Dance Festival (Vispārējie Latviešu Dziesmu un Deju svētkiVisparyeyee Latvyeshu Dzeesmu oon Deyu svehtkiLatvian) is a monumental event in Latvian cultural and social life. Held since 1873, normally every five years, it involves tens of thousands of singers and dancers from across Latvia and the Latvian diaspora, performing in massive choir concerts and intricate dance formations. It is recognized by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Folk songs and classical choir songs are sung, with an emphasis on a cappella singing, though modern popular songs have also been incorporated.

In the 19th century, Latvian nationalist movements emerged, promoting Latvian culture and encouraging Latvians to take part in cultural activities. This period, along with the early 20th century, is often regarded as a classical era of Latvian culture. With the onset of World War II and subsequent Soviet occupation, many Latvian artists and other members of the cultural elite fled the country yet continued to produce their work, largely for a Latvian émigré audience. During the Soviet era, artists and writers were often forced to follow the socialist realism style, though Latvian cultural identity was subtly preserved and expressed.

Since regaining independence, there has been a resurgence and flourishing of Latvian arts. Choir music remains exceptionally strong, with Latvian choirs frequently winning international competitions. Classical music is also prominent, with world-renowned Latvian musicians like conductor Mariss Jansons, Andris Nelsons, and violinist Gidon Kremer. Riga hosted the eighth World Choir Games in 2014, with over 27,000 choristers from over 70 countries. The Riga Jurmala Music Festival, launched in 2019, features world-famous orchestras and conductors.

Visual arts, including painting, sculpture, and graphic arts, have a rich tradition. Posters from the 19th and early 20th centuries show the influence of other European cultures, for example, works by artists such as the Baltic-German artist Bernhard Borchert and the French Raoul Dufy. Contemporary Latvian artists explore a wide range of styles and media. Latvian cinema and theatre are also active, with scenography being a particularly strong field.

8.2. Cuisine

Latvian cuisine is typically based on agricultural products, with meat featuring in most main meal dishes. Fish is commonly consumed due to Latvia's location on the Baltic Sea. Latvian cuisine has been influenced by neighboring countries, particularly Germany, Russia, and Scandinavia. Common ingredients found locally include potatoes, wheat, barley, cabbage, onions, eggs, and pork. Latvian food is generally hearty and can be quite fatty, traditionally using few spices but emphasizing natural flavors.

Some representative Latvian traditional foods include:

- Rupjmaize: A dark rye bread, considered a national staple.

- Grey peas with speck (Pelēkie zirņi ar speķiPelehkiye zirnyi ar spekchiLatvian): A traditional dish, often eaten at Christmas.

- Sklandrausis: A sweet pie made from rye dough, filled with potato and carrot paste, and seasoned with caraway.

- Various soups: Such as sorrel soup (skābeņu zupaskabenyu zupaLatvian), beetroot soup, and cabbage soup.

- Smoked fish: Especially sprats and herring.

- Dairy products: Including biezpiens (quark/curd cheese), sour cream, and kefir.

Kvass, a fermented beverage made from rye bread, is also popular.

8.3. Sport

Various sports are popular in Latvia. Ice hockey is often considered the most popular sport. Latvia has produced many famous hockey players, including Helmuts Balderis, Artūrs Irbe, Kārlis Skrastiņš, Sandis Ozoliņš, and more recently Zemgus Girgensons. Dinamo Riga is the country's most prominent professional hockey club, having played in the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL) and now in the Latvian Hockey Higher League. The national tournament is the Latvian Hockey Higher League, held since 1931. Riga co-hosted the IIHF World Championship in 2006, 2021, and 2023.

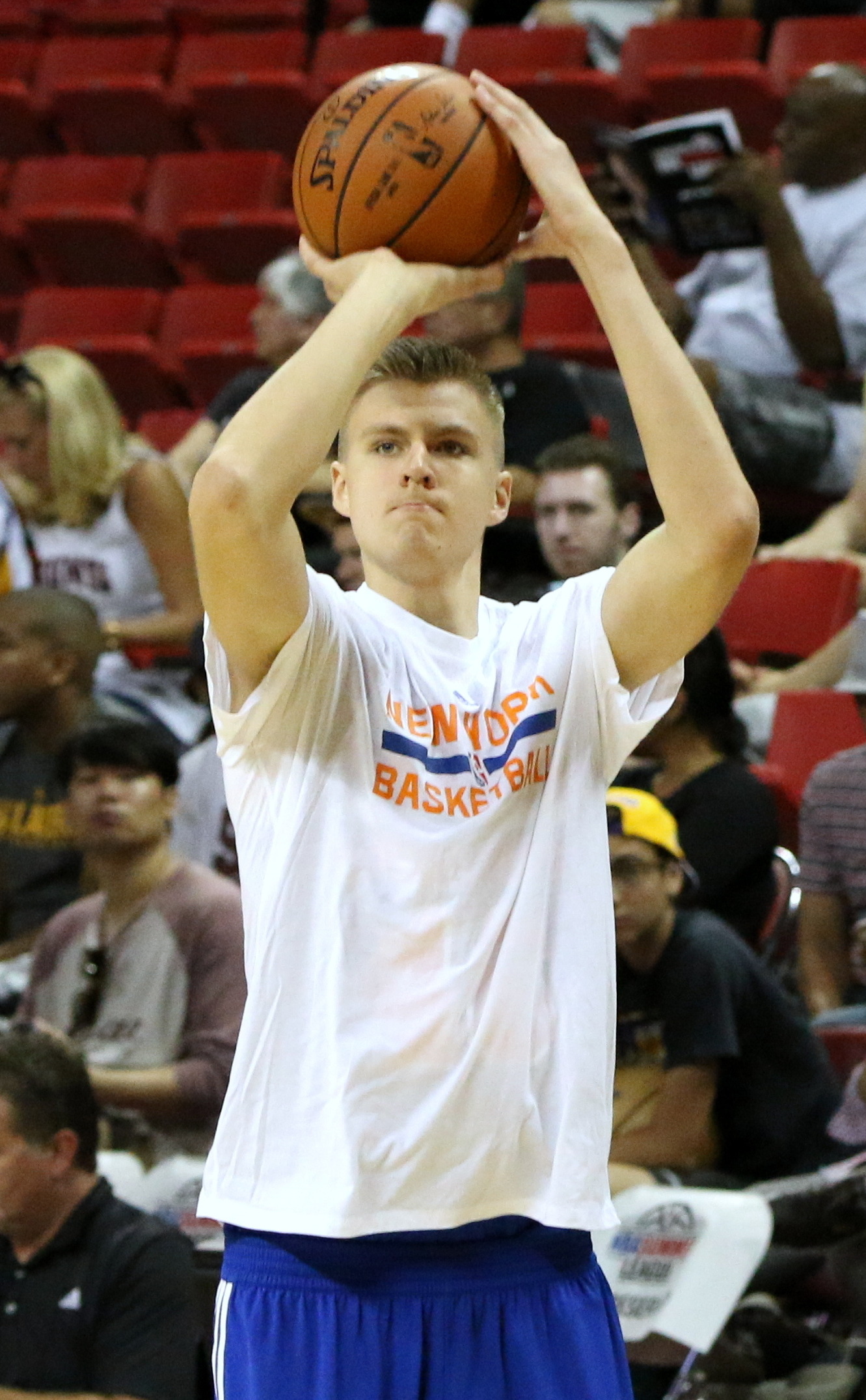

Basketball is the second most popular sport. Latvia has a long basketball tradition, with the men's national team winning the first-ever EuroBasket in 1935 and silver medals in 1939. Notable Latvian basketball players include Jānis Krūmiņš, Valdis Valters, Gundars Vētra (the first Latvian NBA player), Andris Biedriņš, Kristaps Porziņģis, and Dāvis Bertāns. Former club ASK Rīga won the EuroLeague three times. Currently, VEF Rīga and BK Ventspils are strong professional clubs. Latvia co-hosted EuroBasket 2015 and is set to co-host EuroBasket 2025.

Other popular sports include association football (soccer), floorball, tennis, volleyball, cycling, bobsleigh, and skeleton. The Latvian national football team's only major tournament participation was UEFA Euro 2004.

Latvia has participated successfully in both Winter and Summer Olympics. The most successful Olympic athlete in the history of independent Latvia is Māris Štrombergs, a two-time Olympic champion in Men's BMX (2008 and 2012). Latvia has also achieved significant success in bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton at the Winter Olympics.

In boxing, Mairis Briedis is the first and only Latvian to date to win a boxing world title, having held multiple cruiserweight titles.

In tennis, Jeļena Ostapenko won the 2017 French Open Women's singles title, becoming the first unseeded player to do so in the Open Era.

In futsal, Latvia will co-host the UEFA Futsal Euro 2026 with Lithuania.

8.4. World Heritage Sites

Latvia is home to sites recognized by UNESCO for their outstanding universal value:

- Historic Centre of Riga: Inscribed in 1997, the Historic Centre of Riga is noted for its medieval architecture, its extensive and well-preserved Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) buildings (considered one of the finest collections in the world), and its 19th-century wooden architecture.

- Struve Geodetic Arc: Inscribed in 2005, this is a chain of survey triangulations stretching from Hammerfest in Norway to the Black Sea, passing through ten countries. It represents a significant step in the development of earth sciences and topographic mapping. Two of the original station points are located in Latvia.

- Kuldīga Old Town: Inscribed in 2023, the historic old town of Kuldīga is recognized as an exceptionally well-preserved example of a traditional urban settlement that developed from a small medieval village into an important administrative center for the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia between the 16th and 18th centuries. It showcases a blend of traditional log construction with foreign styles and craftsmanship.

These sites highlight Latvia's rich historical and cultural significance on the world stage.