1. Overview

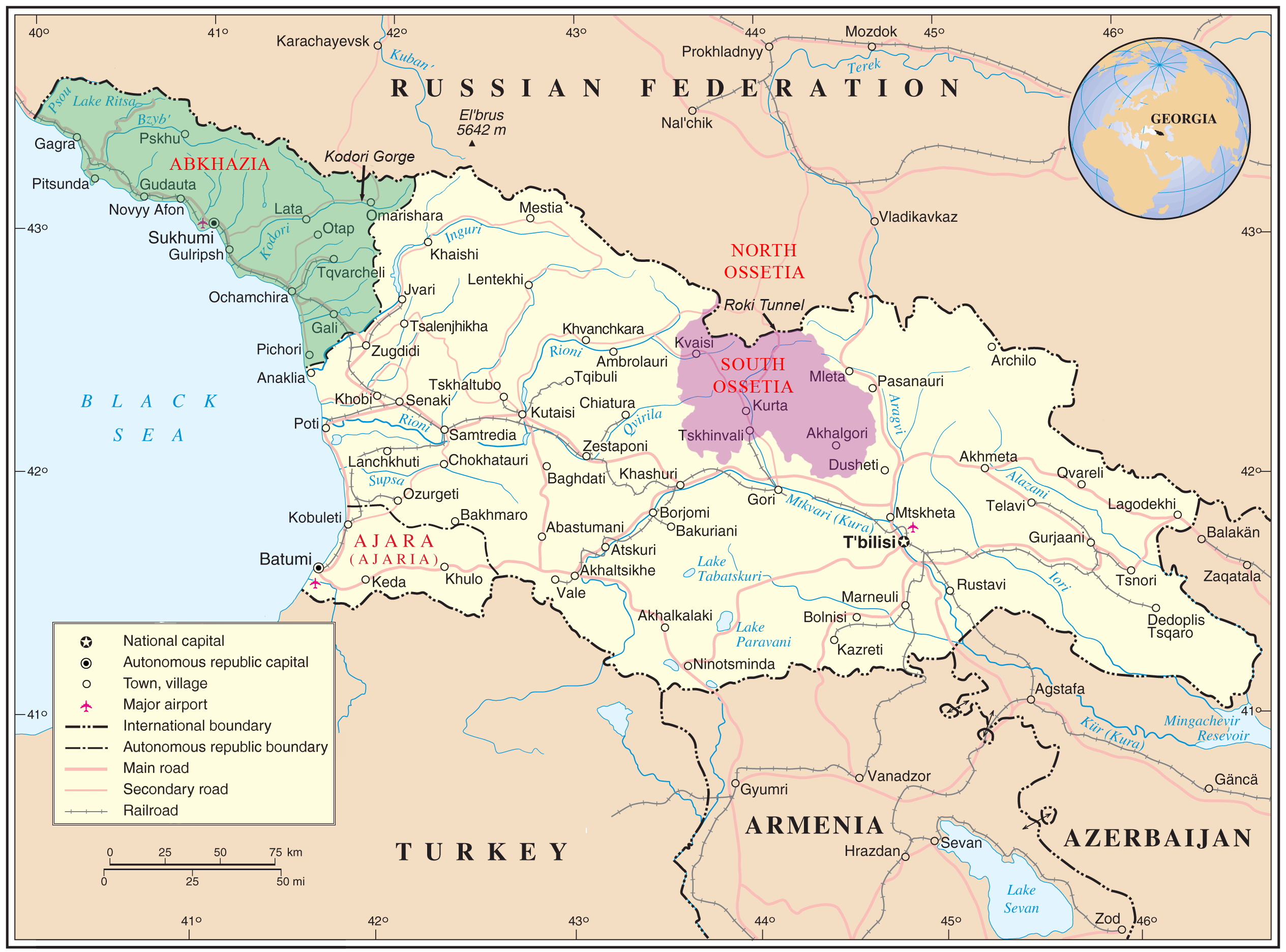

Georgia is a country situated at the intersection of Eastern Europe and West Asia, part of the Caucasus region. It is bounded by the Black Sea to the west, Russia to the north and northeast, Turkey to the southwest, Armenia to the south, and Azerbaijan to the southeast. The nation covers an area of approximately 27 K mile2 (69.70 K km2) and has a population of around 3.7 million people. Its capital and largest city is Tbilisi.

Historically, the territory of modern Georgia has been inhabited since prehistory, boasting some of the world's oldest evidence of winemaking, gold mining, and textiles. The classical era saw the emergence of kingdoms like Colchis and Iberia, which formed the core of the Georgian state. The adoption of Christianity in the early 4th century played a pivotal role in unifying the Georgian people and shaping their cultural identity, leading to a Golden Age under rulers like King David IV and Queen Tamar during the High Middle Ages. Subsequent centuries brought invasions by Mongols, Timurids, Ottomans, and Persians, leading to fragmentation and foreign domination before the Russian Empire gradually annexed Georgian lands in the 19th century.

Georgia briefly declared independence as the Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921) after the Russian Revolution, but was soon incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. This period saw industrialization and collectivization but also significant political purges and suppression of dissent, particularly under Stalin, a native Georgian. An independence movement in the late 20th century led to Georgia's secession from the Soviet Union in 1991. The post-Soviet era was marked by economic crises, political instability, and secessionist conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The 2003 Rose Revolution ushered in a period of pro-Western reforms aimed at democratic and economic modernization, though these years also faced criticism regarding human rights and authoritarian tendencies. Tensions with Russia culminated in the Russo-Georgian War of 2008, resulting in the continued Russian occupation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Since 2012, the Georgian Dream coalition has been in power, navigating ongoing domestic political developments, foreign policy aspirations including European Union candidacy, and significant social issues, including recent large-scale protests over laws perceived as threatening democratic freedoms and concerns about democratic backsliding.

2. Etymology

The etymology of "Georgia" and its native name "Sakartvelo" has various historical and linguistic roots, with their usage differing across languages and contexts.

2.1. Names of Georgia

Ancient Greeks, including authors like Strabo, Herodotus, Plutarch, and Homer, along with Roman writers such as Titus Livius and Tacitus, referred to early western Georgians as Colchians and eastern Georgians as Iberians (IberoiGreek, Ancient (Latin script); ἸβηροιGreek, Ancient in some Greek sources).

The first recorded mention of the name "Georgia" in Italian appears on the mappa mundiworld mapLatin of Pietro Vesconte, dated 1320. In its early appearances in the Latin world, the name was often spelled "Jorgia." Traveler Jacques de Vitry offered a lore-based explanation, attributing the name's origin to the popularity of Saint George among Georgians. Jean Chardin, another traveler, thought "Georgia" derived from the Greek word γεωργόςgeorgósGreek, Ancient, meaning "tiller of the land." However, these centuries-old explanations are now largely rejected by the scholarly community. The prevailing theory points to the Persian word gurğgurgh (Persian transliteration)Persian (Latin script) or gurğāngurghan (Persian transliteration)Persian (Latin script) (گرگPersian), meaning "wolf," as the likely root. This Persian root is believed to have been subsequently adopted into numerous other languages, including Slavic and West European tongues.

The native name for the country is საქართველოSakartveloGeorgian, meaning "land of the Kartvelians." This name is derived from the core central Georgian region of Kartli, recorded from the 9th century, and was used in an extended sense to refer to the entire medieval Kingdom of Georgia by the 13th century. The Georgian circumfix sa-...-o is a standard geographic construction designating "the area where X dwell," where X is an ethnonym. The self-designation used by ethnic Georgians is ქართველებიKartvelebiGeorgian (i.e., "Kartvelians"), first attested in the Umm Leisun inscription found in the Old City of Jerusalem.

The medieval Georgian Chronicles present an eponymous ancestor of the Kartvelians, Kartlos, a great-grandson of Japheth, whom medieval chroniclers believed to be the origin of their kingdom's local name. However, scholars generally agree that the word Kartli is derived from the Karts, a proto-Kartvelian tribe that emerged as a dominant regional group in ancient times. The name საქართველოSakartveloGeorgian consists of two parts. Its root, ქართველ-იkartvel-iGeorgian, specifies an inhabitant of the core central-eastern Georgian region of Kartli, or Iberia as it is known in sources of the Byzantine Empire.

2.2. State name

The official name of the country is "Georgia," as stipulated in Article 2 of the Georgian Constitution, adopted in 1995. In Georgia's two official languages, Georgian and Abkhaz, the country is named საქართველოSakartveloGeorgian and ҚырҭтәылаKərttʷʼəlaabkhazian respectively. Prior to the 1995 constitution and following the dissolution of the USSR, the country was commonly referred to as the "Republic of Georgia," and this name is still occasionally used.

Several languages continue to use variants of the Russian name for the country, "Gruzia." The Georgian authorities have actively campaigned to replace this exonym with "Georgia" in international usage. Since 2006, countries like Israel, Japan, and South Korea have legally changed their official appellation for the country to forms derived from the English "Georgia." In 2020, Lithuania became the first country to adopt SakartvelasSakartvelasLithuanian (derived from the native Georgian name) in all official communications.

3. History

Georgia's history stretches from prehistoric settlements through ancient kingdoms, a medieval golden age, periods of foreign domination and fragmentation, Russian annexation, a brief 20th-century independence, Soviet rule, and the complexities of its post-Soviet restoration of sovereignty, including internal conflicts and democratic transitions.

3.1. Prehistory

The earliest traces of archaic humans in what is now Georgia date back approximately 1.8 million years, represented by the Dmanisi hominins, a subspecies of Homo erectus. These fossils are among the oldest known hominin remains in Eurasia. The Caucasus region, buffered by these mountains and benefiting from the Black Sea ecosystem, appears to have served as a refugium throughout the Pleistocene. The first continuous primitive human settlements in Georgia date to the Middle Paleolithic period, around 200,000 years ago. During the Upper Paleolithic, settlements developed primarily in Western Georgia, in the valleys of the Rioni and Qvirila rivers.

Evidence of agriculture in Georgia dates back to at least the 6th millennium BC, particularly in Western Georgia. The basin of the Mtkvari River (Kura) became stably populated in the 5th millennium BC, as shown by the rise of various cultures closely associated with the Fertile Crescent, including the Trialetian Mesolithic, the Shulaveri-Shomu culture, and the Leyla-Tepe culture. Archaeological findings indicate that early inhabitants of Georgia were responsible for the first use of fibers, possibly for clothing, over 34,000 years ago. The region is also recognized as one of the earliest sites of winemaking, with evidence dating back to the 7th millennium BC. Furthermore, the Sakdrisi site shows signs of gold mining from the 3rd millennium BC.

The Kura-Araxes culture, Trialeti culture, and Colchian culture coincided with the development of proto-Kartvelian tribes. These tribes, which may have originated from Anatolia during the expansion of the Hittite Empire, included groups such as the Mushki, Laz, and Byzeres. Some historians suggest that the collapse of the Hittite world during the Late Bronze Age collapse led to an expansion of these tribes' influence towards the Mediterranean Sea, notably with the formation of the Kingdom of Tabal.

3.2. Antiquity

The classical period in Georgia saw the rise of several significant states. In western Georgia, the kingdom of Colchis emerged, famously known in Greek mythology as the location of the Golden Fleece sought by Jason and the Argonauts. Archaeological evidence points to a wealthy kingdom in Colchis as early as the 14th century BC, with an extensive trade network connecting it to Greek colonies on the eastern Black Sea shore, such as Dioscurias and Phasis. This region was later annexed by the Kingdom of Pontus and subsequently by the Roman Republic in the first century BC.

Eastern Georgia, initially a decentralized mosaic of various clans ruled by individual mamasakhlisi (patriarchs), was conquered by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. This eventually led to the creation of the Kingdom of Iberia under the protectorate of the Seleucid Empire. Iberia represented an early example of advanced state organization with a single king and an aristocratic hierarchy. Iberia engaged in various wars with the Roman Empire, the Parthian Empire, and the Kingdom of Armenia, frequently shifting its allegiance but remaining a Roman client state for much of its history.

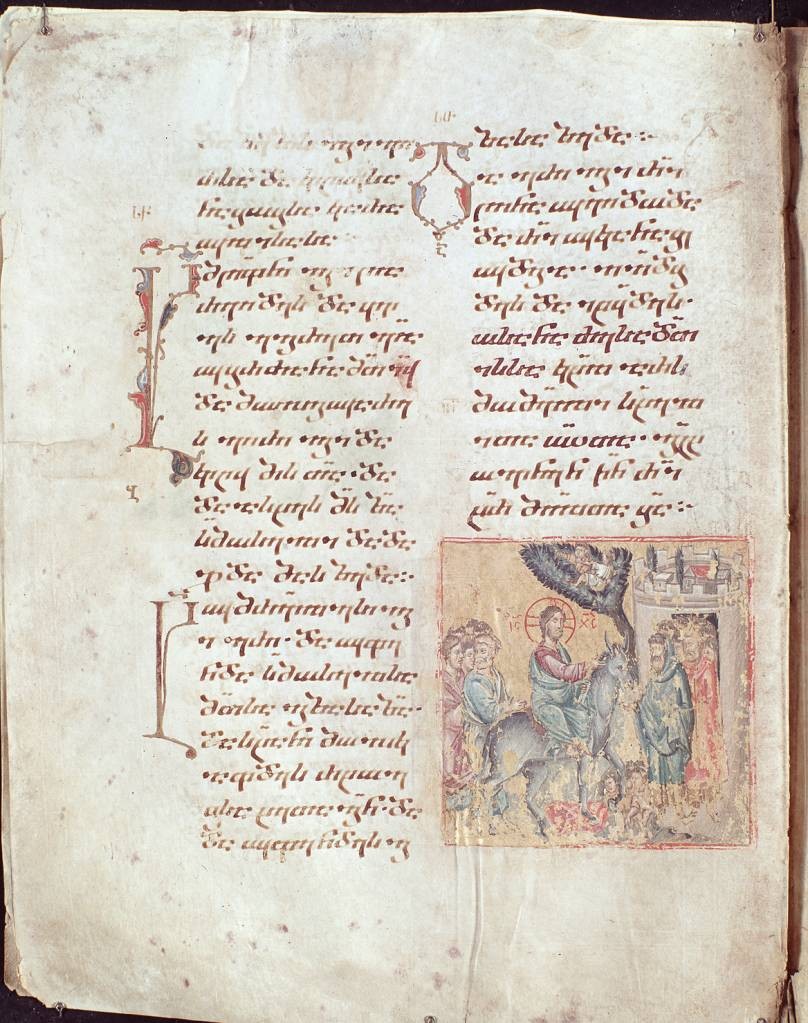

A pivotal moment in Georgian antiquity was the adoption of Christianity as the state religion of Iberia in 337 AD under King Mirian III. This event, spurred by the missionary work of Saint Nino, marked the beginning of the Christianization of the Western Caucasus. It solidified Iberia's alignment with Rome's sphere of influence and led to the abandonment of the ancient Georgian polytheistic religion, which had been heavily influenced by Zoroastrianism. The societal impact of Christianity was profound, fostering a sense of unity among Georgian-speaking peoples and laying cultural foundations that would endure for centuries.

However, the Peace of Acilisene in 384 AD formalized the Sasanian Persian control over the entire Caucasus. Despite this, Christian rulers of Iberia occasionally rebelled, leading to devastating wars in the 5th and 6th centuries. A notable figure during this period was King Vakhtang Gorgasali, who is credited with expanding Iberia to its largest historical extent by capturing all of western Georgia and founding a new capital in Tbilisi. The adoption of Christianity also spurred the development of a unique Georgian alphabet and literary tradition, further strengthening cultural identity in the face of external pressures and contributing to a distinct societal fabric that differentiated Georgians from their Zoroastrian overlords and pagan neighbors.

3.3. Medieval unification and Golden Age

The early medieval period saw the fragmentation of Georgian lands following the Sasanian Empire's abolition of the Iberian monarchy in 580 AD. The region was embroiled in the Roman-Persian Wars, with both Persia and Constantinople supporting various factions. By the end of the 6th century, the Byzantine Empire established control over Georgian territories, ruling Iberia indirectly through local Kouropalates. The Arab invasions in the 7th century further complicated the political landscape, leading to Muslim domination in southeastern Georgia and the establishment of feudal states like the Emirate of Tbilisi and the Principality of Kakheti. Western Georgia largely remained a Byzantine protectorate.

The lack of central authority allowed the Bagrationi dynasty to rise in the early 9th century. Ashot I (813-830) consolidated lands in Tao-Klarjeti and expanded his influence, eventually being recognized as Presiding Prince of Iberia. His descendant, Adarnase IV, unified most Georgian lands (excluding Kakheti and Abkhazia) and was crowned King of the Iberians in 888, restoring the monarchy. In Western Georgia, the Kingdom of Abkhazia became a powerful state in the 8th century. Dynastic struggles later weakened Abkhazia, while David III of Tao-Klarjeti empowered the Bagrationi. Bagrat III, heir to the Bagrationi dynasty, successively became King of Abkhazia (978), Prince of Tao-Klarjeti (1000), and King of the Iberians (1008), culminating in his coronation as King of Georgia in 1010, unifying most Georgian feudal states. This unification laid the groundwork for a period of cultural and political flourishing. Societal structures during this time were largely feudal, with a strong aristocracy and a peasantry tied to the land. The Georgian Orthodox Church played a crucial role in legitimizing royal power and fostering a common cultural identity.

The 11th century was marked by geopolitical and internal challenges, with noble factions opposing state centralization, often backed by the Byzantine Empire. However, the rise of the Seljuk Empire in the 1060s led to a normalization of Byzantine-Georgian ties. After the Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Manzikert (1071), Georgia found itself at the forefront of conflicts with the Turks.

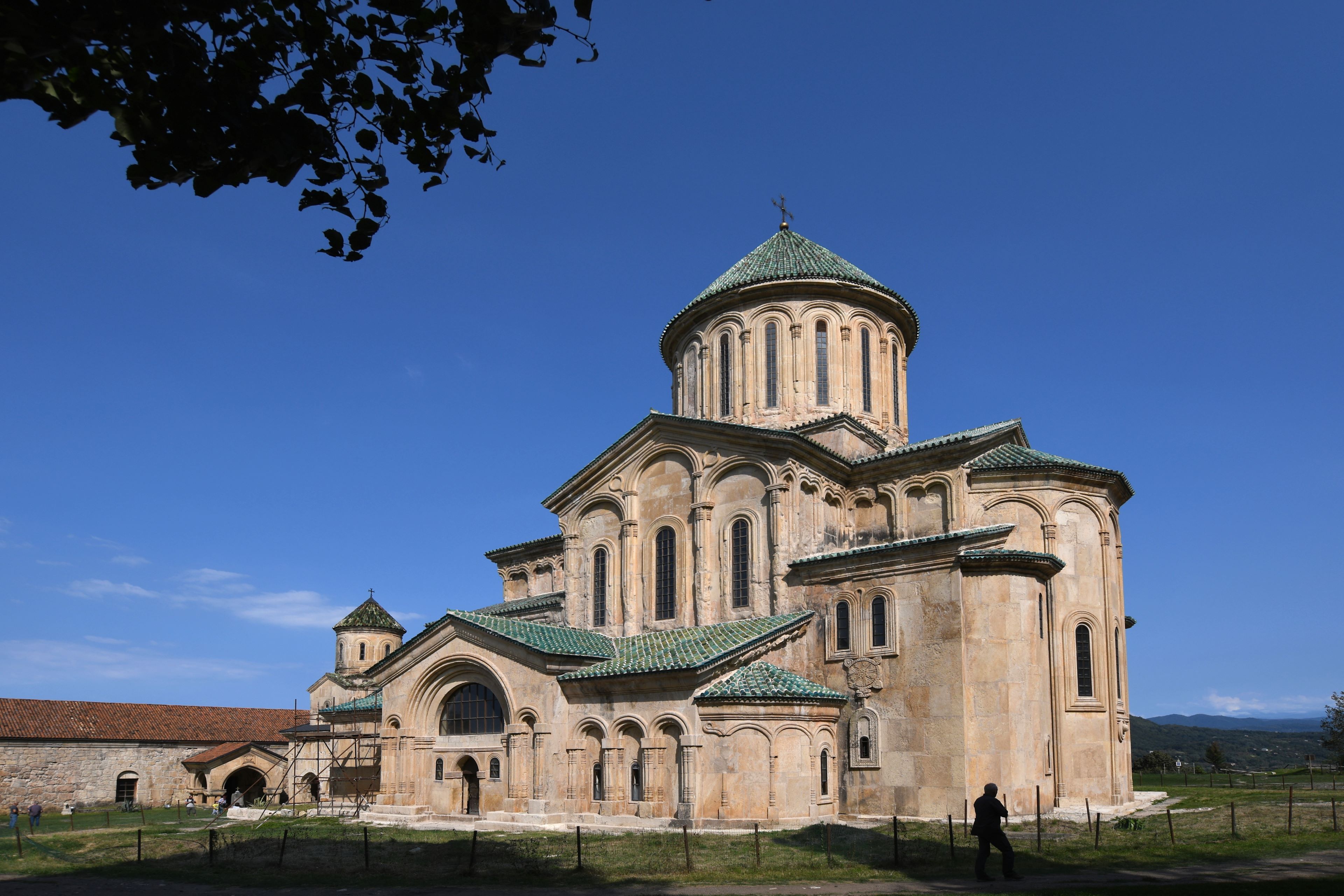

The Kingdom of Georgia reached its zenith from the 12th to the early 13th centuries, a period known as the Georgian Golden Age, particularly under King David IV "the Builder" (r. 1089-1125) and his great-granddaughter Queen Tamar (r. 1184-1213). This era was characterized by significant military victories, territorial expansion, and a cultural renaissance in architecture, literature, philosophy, and the sciences. David IV suppressed feudal dissent, centralized power, and decisively defeated larger Turkish armies at the Battle of Didgori (1121), abolishing the Emirate of Tbilisi. His reign saw the construction of monumental cathedrals and monasteries like Gelati Monastery, which became a major cultural and educational center. The societal structure, while still feudal, saw a strengthening of the monarchy and a more organized military and administrative system.

Queen Tamar's 29-year reign is considered the most successful in Georgian history. Titled "king of kings," she neutralized opposition and pursued an energetic foreign policy, capitalizing on the decline of the Seljuks and Byzantium. Supported by a powerful military elite, Tamar consolidated an empire that dominated the Caucasus, extending over parts of modern-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, eastern Turkey, and northern Iran. She also used the power vacuum left by the Fourth Crusade to establish the Empire of Trebizond as a Georgian vassal state. Culturally, her reign saw the creation of the epic poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin by Shota Rustaveli, a national epic. The arts, philosophy, and sciences flourished, supported by royal patronage. Society during the Golden Age experienced relative stability and prosperity, with significant advancements in legal codes and administration. The church continued to be a powerful institution, and monastic centers served as hubs of learning and culture.

3.4. Mongol and Timurid invasions and fragmentation

The flourishing period of the Kingdom of Georgia faced a severe setback when Tbilisi was captured and destroyed by the Khwarezmian leader Jalal ad-Din in 1226. This was followed by devastating invasions by the Mongols under Genghis Khan. The social and political consequences were catastrophic, leading to widespread destruction, depopulation, and the imposition of heavy tribute. Georgian rulers became vassals of the Mongol Khans, and the kingdom's unity began to erode.

There was a brief resurgence under King George V "the Brilliant" (r. 1299-1302 and 1314-1346), who managed to expel the Mongols, reunite eastern and western Georgia, and restore some of the country's former strength and Christian culture. He implemented administrative reforms and attempted to revive the economy. However, this revival was short-lived. After George V's death, internal feudal strife re-emerged as local rulers sought independence from central Georgian rule.

The kingdom was further weakened by several disastrous invasions by Timur (Tamerlane) between 1386 and 1403. These invasions were marked by extreme brutality, massacres, and the systematic destruction of towns, agricultural lands, and cultural monuments. The social fabric was torn apart, and the population significantly declined. The central authority collapsed, and the unified Kingdom of Georgia disintegrated by the 15th century into smaller, rival kingdoms and principalities. These included the kingdoms of Kartli, Kakheti, and Imereti, and principalities such as Samtskhe, Mingrelia, Guria, Svaneti, and Abkhazia. This fragmentation left Georgia vulnerable to constant raiding by neighboring powers like the Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu Turkomans, preventing any significant recovery and leading to a prolonged period of political instability and economic decline. The once-strong feudal system fractured, and local lords gained more autonomy, further weakening any prospect of reunification.

3.5. Ottoman and Persian domination

From the 16th to the 18th centuries, the fragmented Georgian kingdoms and principalities became pawns in the rivalry between two major regional powers: the Ottoman Empire and successive Persian empires (namely the Safavids, Afsharids, and Qajars). The Peace of Amasya in 1555 formally divided Georgia between these two empires, with western Georgia falling under Ottoman influence and eastern Georgia (Kartli and Kakheti) under Persian suzerainty.

This period was characterized by constant warfare, raids, and deportations, which devastated the population and economy. Georgian rulers often tried to maneuver between the Ottomans and Persians, seeking autonomy or alliances with other powers, including Russia. There were numerous local rebellions and efforts to preserve Georgian culture and the Georgian Orthodox Church in the face of pressure to convert to Islam, particularly in regions under direct Ottoman or Persian administration.

Despite the political turmoil, some Georgian rulers managed to achieve temporary stability and cultural revivals. For instance, King Vakhtang VI of Kartli in the early 18th century was a notable legislator, scholar, and patron of arts, who established the first printing press in Georgia. However, his efforts to gain Russian support against Persian and Ottoman domination ultimately failed.

The social structure remained largely feudal, but the constant warfare and foreign interference weakened the traditional aristocracy and led to increased suffering for the peasantry. The population of Georgia dwindled significantly due to wars and forced deportations, particularly the massive deportations of Georgians to Persia by Shah Abbas I in the early 17th century. Cultural life, though strained, persisted, with continued production of religious art and literature. The struggle for survival and cultural preservation became a defining feature of this era, deeply impacting the Georgian collective memory and national identity.

3.6. Russian Empire

The gradual annexation of Georgian territories into the Russian Empire began in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In 1783, King Heraclius II of the eastern Georgian Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti signed the Treaty of Georgievsk with Russia, making his kingdom a Russian protectorate in exchange for military protection against Persia and the Ottoman Empire. However, Russia failed to provide adequate assistance when Persia, under Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, invaded in 1795, sacking Tbilisi and massacring its inhabitants.

Following the death of Heraclius II's successor, King George XII, Tsar Paul I of Russia violated the terms of the Treaty of Georgievsk and, in 1801, formally annexed Kartli-Kakheti. The Bagrationi dynasty, which had ruled Georgia for centuries, was deposed, and Russian imperial administration was established. Over the following decades, other Georgian kingdoms and principalities were progressively absorbed: the Kingdom of Imereti in western Georgia was annexed in 1810, Guria in 1829, Mingrelia (Samegrelo) in 1857, Svaneti in 1858, and Abkhazia in 1864. Territories like Adjara, previously lost to the Ottomans, were recovered through Russian wars against Turkey and incorporated into the empire by 1878.

Russian rule brought an end to centuries of Persian and Ottoman incursions and internal feudal warfare, providing a degree of stability and security. However, it also meant the loss of Georgian sovereignty and the imposition of Russian imperial policies. The Georgian Orthodox Church, a cornerstone of Georgian identity, lost its autocephaly (independence) in 1811 and was subordinated to the Russian Orthodox Church. Russian became the language of administration, and Russification policies were implemented, particularly in education.

Social and economic changes occurred under Russian rule. Serfdom was abolished in Georgia later than in Russia proper (1864-1871, depending on the region), which freed many peasants but often left them with insufficient land and mired in poverty. The growth of capitalism led to the development of some industries, such as manganese mining in Chiatura, and the expansion of cities like Tbilisi (then Tiflis), which became the administrative and cultural center of the Caucasus Viceroyalty. A new urban working class emerged.

The 19th century also witnessed a Georgian national revival movement, led by intellectuals like Ilia Chavchavadze, Akaki Tsereteli, and Vazha-Pshavela. This movement sought to preserve and promote Georgian language, literature, and culture, and laid the groundwork for modern Georgian nationalism. Discontent with Russian autocracy and social inequalities fueled various peasant uprisings and, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the rise of socialist movements, particularly the Menshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Party, which gained significant support in Georgia. The social impact of Russian rule was thus mixed: it brought an end to certain forms of instability but also introduced new forms of oppression and exploitation, while inadvertently fostering the conditions for a modern national consciousness and political mobilization.

3.7. Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921)

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the collapse of the Russian Empire, Georgia declared its independence on May 26, 1918, as the Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG). This brief period of sovereignty was a significant experiment in democratic governance in a region fraught with instability. The Menshevik wing of the Social Democratic Party of Georgia became the dominant political force, with Noe Zhordania serving as its most prominent leader and later Prime Minister.

The DRG established a multi-party parliamentary system and enacted progressive social and political reforms. A constitution adopted in February 1921 enshrined principles of universal suffrage (including for women), freedom of speech, assembly, and religion, an independent judiciary, and minority rights. The government implemented land reforms, aimed at redistributing land from large landowners to peasants, and introduced labor legislation, including an eight-hour workday. Efforts were made to establish a national education system with Georgian as the language of instruction.

Internationally, the DRG sought recognition and support from European powers. It initially existed under German protection and later received de jure recognition from several countries, including Soviet Russia under the Treaty of Moscow (May 1920). However, its international position remained precarious. The republic faced numerous challenges, including economic hardship, border disputes with neighboring Armenia (the Georgian-Armenian War of 1918) and Azerbaijan, and internal threats from Bolshevik agitators. The DRG also conducted military operations to secure its borders, including against Denikin's White Army in the Sochi region.

Despite its democratic aspirations and social reforms, the DRG's independence was short-lived. In February 1921, the Soviet Russian Red Army invaded Georgia, bringing an end to its independence. The government went into exile, primarily in France. Though brief, the DRG period remains a potent symbol of Georgian statehood and democratic ideals, and its legacy influenced the country's aspirations for independence during the Soviet era and beyond. The social reforms, though not fully implemented due to the brevity of independence, represented a significant departure from the autocratic traditions of the Russian Empire and laid a foundation for future democratic development.

3.8. Soviet Georgia (1921-1991)

Following the Red Army invasion of Georgia in February 1921, the Democratic Republic of Georgia was overthrown, and the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (Georgian SSR) was established. Georgia was initially incorporated into the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic along with Armenia and Azerbaijan in 1922, before becoming a direct constituent republic of the Soviet Union in 1936.

Soviet rule brought profound and often brutal transformations to Georgian society. The early years were marked by the suppression of national opposition, culminating in the failed August Uprising of 1924, which was ruthlessly crushed. Joseph Stalin, an ethnic Georgian (born Ioseb Jughashvili), rose to become the leader of the Soviet Union. Ironically, his rule brought some of the harshest repressions to his homeland. During the Great Purge of the 1930s, thousands of Georgian intellectuals, artists, political figures, and ordinary citizens were executed or sent to Gulag labor camps. Prominent Georgian Bolsheviks like Lavrentiy Beria, who later became head of the NKVD, also played significant roles in these purges. The suppression of dissent and any perceived nationalist tendencies was systematic, severely impacting Georgia's cultural and intellectual life. Human rights were non-existent in any meaningful sense, with arbitrary arrests, show trials, and executions being common.

Economically, Soviet Georgia underwent forced industrialization and collectivization. While industrial output increased, particularly in areas like manganese mining and some manufacturing, collectivization devastated the traditional rural economy and led to widespread famine and peasant resistance. The first five-year plans (1928-1932) aimed to transform Georgia from an agrarian society, making it a major center for textile goods among other industries.

During World War II, over 700,000 Georgians (about 20% of the population) fought in the Red Army against Nazi Germany, with an estimated 350,000 killed. Although Axis forces were stopped before reaching Georgian borders, the war had a significant demographic and economic impact.

After Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev's de-Stalinization policies led to some liberalization but also triggered protests in Georgia. The 1956 demonstrations in Tbilisi, sparked by criticism of Stalin, were violently suppressed by Soviet troops, leading to many casualties. This event further fueled anti-Soviet sentiment and Georgian nationalism.

Throughout the later Soviet period, Georgia experienced economic growth and improvements in living standards, but also widespread corruption and a growing informal economy. The Georgian language and culture faced pressures from Russification, though they generally managed to maintain a strong presence. Dissident movements, though suppressed, continued to exist. The 1978 demonstrations against attempts to change the constitutional status of the Georgian language were a notable instance of successful public protest, forcing the authorities to back down.

In the 1980s, under Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of Glasnost and Perestroika, nationalist sentiments surged. Pro-independence movements, led by figures like Zviad Gamsakhurdia and Merab Kostava, gained momentum. The April 9 tragedy in 1989, when Soviet troops violently dispersed a peaceful pro-independence rally in Tbilisi, killing 21 people and injuring hundreds, became a pivotal moment, galvanizing the nation towards independence and discrediting Soviet rule. This event starkly highlighted the Soviet regime's disregard for human rights and national aspirations.

3.9. Restoration of independence and recent history

Georgia's journey after restoring independence in 1991 has been marked by periods of intense political upheaval, armed conflicts, economic struggles, democratic experiments, and ongoing efforts to define its place in the international community, often amidst complex geopolitical pressures. The humanitarian impact of conflicts and the evolution of human rights have been significant features of this era.

Georgia declared independence from the Soviet Union on April 9, 1991, following a referendum in which an overwhelming majority voted in favor. Zviad Gamsakhurdia, a former dissident and leader of the nationalist Round Table-Free Georgia coalition, was elected as the first President. However, his rule quickly became controversial, criticized for authoritarian tendencies and confrontational policies towards ethnic minorities. This led to a violent coup d'état in December 1991-January 1992, plunging the country into a civil war.

Simultaneously, secessionist conflicts erupted in Abkhazia (1992-1993) and South Ossetia (1991-1992). These wars resulted in thousands of deaths, widespread destruction, and the ethnic cleansing and mass displacement of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Georgians from these regions, creating a long-lasting humanitarian crisis of internally displaced persons (IDPs). Georgia effectively lost control over large parts of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which became de facto independent entities heavily reliant on Russian support.

Eduard Shevardnadze, the former Soviet Foreign Minister, returned to Georgia in March 1992 and became head of state. He navigated the country through the civil war and economic collapse of the early 1990s. A new constitution was adopted in 1995, and Shevardnadze was elected president. His tenure saw some stabilization, but was plagued by pervasive corruption, weak state institutions, and unresolved conflicts. The economic situation remained dire for much of the population, and progress on democratic reforms was slow.

3.9.1. Rose Revolution and Saakashvili era (2003-2012)

Allegations of widespread fraud in the November 2003 parliamentary elections sparked mass protests, leading to the bloodless Rose Revolution. Eduard Shevardnadze resigned, and a new generation of pro-Western leaders came to power, headed by Mikheil Saakashvili, who was elected president in January 2004 with a large majority.

The Saakashvili era was characterized by ambitious reforms aimed at modernizing the state, combating corruption, strengthening the economy, and integrating Georgia with Western institutions, particularly NATO and the European Union. Significant successes were achieved in reducing petty corruption (especially in the police force), improving public services, and attracting foreign investment. Economic growth accelerated. The government also sought to reassert central authority over the autonomous republic of Adjara in 2004, successfully ousting its autocratic leader Aslan Abashidze in the Adjara crisis.

However, Saakashvili's government also faced significant criticism. Reforms were often implemented in a top-down manner, and concerns were raised about the concentration of power, an erosion of judicial independence, and pressure on media freedom. Human rights organizations pointed to issues such as the use of excessive force by law enforcement, poor prison conditions, and a politically influenced judiciary. The government's forceful response to opposition protests in 2007 and 2011 drew international condemnation and accusations of authoritarian tendencies. The social impact of economic reforms was uneven, with poverty and unemployment remaining significant challenges for parts of the population. Attempts to regain control over Abkhazia and South Ossetia remained a central, but ultimately unsuccessful, policy goal.

3.9.2. Russo-Georgian War (2008)

Tensions between Georgia and Russia, which had been escalating over Georgia's NATO aspirations and the status of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, culminated in the Russo-Georgian War in August 2008. Hostilities began with clashes between Georgian forces and South Ossetian separatists, followed by a Georgian military operation in Tskhinvali, the South Ossetian capital. Russia responded with a large-scale military invasion, pushing deep into Georgian territory beyond the conflict zones.

The war, which lasted five days, resulted in hundreds of deaths and the displacement of tens of thousands of civilians. There were widespread reports of human rights abuses and ethnic cleansing of Georgians from villages in and around South Ossetia by South Ossetian militias with Russian backing. The humanitarian impact was severe, with many IDPs unable to return to their homes.

A EU-brokered ceasefire agreement was reached, but Russia subsequently recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and established permanent military bases in these territories. Georgia severed diplomatic relations with Russia and declared Abkhazia and South Ossetia as Russian-occupied territories. The war significantly altered the geopolitical landscape of the Caucasus and dealt a blow to Georgia's efforts to restore its territorial integrity. International stances were divided, though most Western countries condemned Russia's actions and reaffirmed support for Georgia's sovereignty.

3.9.3. Georgian Dream era (2012-present)

The 2012 parliamentary elections saw the defeat of Mikheil Saakashvili's United National Movement party by the Georgian Dream coalition, led by billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili. This marked the first peaceful transfer of power through elections in Georgia's post-Soviet history. Ivanishvili became Prime Minister, and constitutional changes shifted significant powers from the presidency to the prime minister and parliament. Giorgi Margvelashvili (Georgian Dream) won the 2013 presidential election.

The Georgian Dream government initially focused on addressing perceived injustices of the Saakashvili era, including prosecuting former officials, which drew criticism from some Western observers as selective justice. Foreign policy continued a pro-Western orientation, including the signing of an Association Agreement with the EU in 2014 and continued cooperation with NATO. In December 2023, Georgia was granted EU candidate status.

Domestically, the Georgian Dream era has been marked by increasing political polarization. While the party has maintained a majority in subsequent elections, including in 2016 and 2020, these have often been marred by opposition claims of irregularities and a decline in democratic standards. Concerns about democratic backsliding have grown, particularly regarding judicial independence, pressure on media and civil society, and the influence of Bidzina Ivanishvili, who, despite formally stepping back from official positions at times, is widely seen as wielding significant informal power.

Recent years have witnessed large-scale public protests. In 2023 and 2024, massive demonstrations erupted against a controversial "foreign influence" or "foreign agent" law, which critics, including the EU and the US, argue is similar to Russian legislation used to stifle dissent and would undermine Georgia's democratic development and EU integration prospects. The government's handling of these protests, including the use of force against demonstrators, further fueled concerns.

Following the 2024 Georgian parliamentary election, which the opposition and some international observers alleged were marred by irregularities, large protests erupted again. In November 2024, the Georgian Dream government announced it would pause EU accession negotiations until 2028, a move that triggered further widespread protests and condemnation from pro-European segments of society and international partners, deepening concerns about the country's democratic trajectory and geopolitical orientation. The social fabric has been strained by these political divisions and debates over national identity and future direction.

4. Geography

Georgia is a mountainous country located in the South Caucasus region, at the crossroads of Eastern Europe and West Asia. It lies between latitudes 41° and 44° N, and longitudes 40° and 47° E. The country covers an area of 27 K mile2 (69.70 K km2), though this figure often includes the territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, over which the central government does not exercise control. Some small slivers of Georgian territory are situated north of the Caucasus Watershed in the North Caucasus.

The physical geography of Georgia is dominated by mountains, with the Likhi Range dividing the country into its eastern and western halves. Historically, western Georgia was known as Colchis and the eastern plateau as Iberia. The terrain includes low-land plains, major river systems, and high mountain peaks, contributing to diverse climatic zones and biodiversity.

4.1. Topography

Georgia's landscape is highly varied. The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range forms the northern border, featuring some of Europe's highest peaks, including Mount Shkhara (17 K ft (5.20 K m)), Georgia's highest point, and Mount Janga (17 K ft (5.06 K m)). Other prominent peaks are Mount Kazbek (17 K ft (5.05 K m)), Shota Rustaveli Peak (16 K ft (4.96 K m)), Tetnuldi (16 K ft (4.86 K m)), Ushba (15 K ft (4.70 K m)), and Ailama (15 K ft (4.55 K m)). The region between Kazbek and Shkhara is heavily glaciated. Main roads into Russian territory pass through the Roki Tunnel and the Darial Gorge.

The southern portion of the country is bounded by the Lesser Caucasus Mountains, generally lower than the Greater Caucasus, with peaks typically not exceeding 11 K ft (3.40 K m). This region includes the Javakheti Volcanic Plateau, numerous lakes such as Tabatskuri and Paravani, mineral water, and hot springs.

The Likhi Range connects the Greater and Lesser Caucasus, dividing western and eastern Georgia. Western Georgia's landscape includes low-land marsh-forests, swamps, and temperate rainforests, particularly along the Black Sea coast. Eastern Georgia has a more continental landscape with semi-arid plains, valleys, and gorges. The two major rivers are the Rioni (west) and the Mtkvari (Kura) (east).

Natural habitat in western lowlands has been altered by agriculture and urbanization. Forests mainly remain on foothills and mountains. Western forests are primarily deciduous below 1969 ft (600 m) (oak, hornbeam, beech, elm, ash, chestnut, box evergreens). Temperate rainforests cover slopes of the Meskheti Range in Adjara and parts of Samegrelo and Abkhazia. Between 1969 ft (600 m) and 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m), mixed deciduous and coniferous forests (beech, spruce, fir) are common. From 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m) to 5.9 K ft (1.80 K m), forests become largely coniferous. The tree line is around 5.9 K ft (1.80 K m), with the alpine zone extending to about 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m).

Eastern Georgia's landscape differs considerably. Low-lying areas (Mtkvari and Alazani River plains) are largely deforested for agriculture. About 85% of eastern forests are deciduous (beech, oak, hornbeam, maple, aspen, ash, hazelnut). Coniferous forests are mainly in the Borjomi Gorge. At higher elevations (above 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m)) in Tusheti, Khevsureti, and Khevi, pine and birch forests dominate. Forests typically occur between 1640 ft (500 m) and 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m), with the alpine zone from 2,000-2,300 meters to 3,000-3,500 meters. The Alazani Valley of Kakheti holds the only remaining large, low-land forests.

4.2. Climate

Georgia's climate is extremely diverse, influenced by its topography. The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range moderates the climate by protecting it from colder northern air masses, while the Lesser Caucasus Mountains partially shield it from dry southern air.

Much of western Georgia lies within the humid subtropical zone, with annual precipitation from 0.0 K in (1.00 K mm) to 0.1 K in (2.50 K mm), peaking in autumn. The climate varies with elevation; lowland areas are relatively warm year-round, while foothills and mountains experience cool, wet summers and snowy winters (snow cover often exceeds 6.6 ft (2 m)). The Black Sea strongly influences coastal western Georgia's climate.

Eastern Georgia has a climate transitioning from humid subtropical to continental, influenced by dry Caspian air from the east and humid Black Sea air from the west (often blocked by the Likhi and Meskheti ranges). Wettest periods are spring and autumn; winter and summer are drier. Eastern Georgia has hot summers in low-lying areas and relatively cold winters. Elevation is crucial, with conditions above 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m) being considerably colder.

4.3. Biodiversity

Georgia's diverse landscape and location contribute to its rich biodiversity, hosting about 5,601 animal species, including 648 vertebrates (over 1% of the world's total), many endemic. Forests host large carnivores like Brown bears, wolves, lynxes, and the rare Caucasian Leopard. The common pheasant (Colchian Pheasant) is an endemic bird. Invertebrate species numbers are high; the spider checklist includes 501 species. The Rioni River may host the critically endangered bastard sturgeon.

Over 6,500 fungi species (including lichens) are recorded, though many more likely exist; an estimated 2,595 may be endemic. About 1,729 plant species are associated with fungi. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists 4,300 vascular plant species, with about 1,000 of Georgia's 4,000 higher plants being endemic.

Georgia has four terrestrial ecoregions: Caucasus mixed forests, Euxine-Colchic deciduous forests, Eastern Anatolian montane steppe, and Azerbaijan shrub desert and steppe. It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index score of 7.79/10 (31st globally), indicating relatively well-preserved forest landscapes. Western Georgian forests below 1969 ft (600 m) are mainly deciduous (oak, hornbeam, beech, elm, ash, chestnut); higher elevations have mixed and coniferous forests (spruce, fir).

4.4. Environmental issues

Georgia faces significant environmental challenges, including air pollution in cities like Rustavi and water pollution in rivers like the Mtkvari and the Black Sea from untreated wastewater, contributing to digestive diseases.

Deforestation has occurred in low-lying areas for agriculture, though mountain forests remain. Soil degradation and erosion affect a substantial portion of agricultural land. Historical pesticide and fertilizer use led to soil contamination.

Improper waste management is an issue, with non-compliant landfills risking soil and water contamination. Hazardous chemical waste is reportedly buried in some mountain regions.

Conservation efforts include national parks and protected areas, vital for preserving Georgia's biodiversity. Balancing economic development with environmental protection is a key challenge, with growing concern over the social impact of environmental problems on local communities' health and livelihoods.

5. Government and politics

Georgia operates as a unitary parliamentary republic with a constitutionally defined structure involving a president, prime minister, and parliament. Its political landscape is characterized by a multi-party system and evolving electoral processes, while its judiciary aims to uphold the rule of law. The country pursues active foreign relations, maintains defense forces, and addresses ongoing human rights issues within its administrative divisions.

5.1. Constitution and government structure

The Constitution of Georgia, adopted in 1995 and significantly amended (notably in 2010 and 2017-2018), is the supreme law, establishing a parliamentary system.

The President of Georgia is the largely ceremonial head of state, elected for a five-year term (by an electoral college from 2024). The current president is Salome Zourabichvili (since 2018), though Mikheil Kavelashvili was inaugurated in the disputed 2024 election.

The Prime Minister of Georgia is the head of government, holding primary executive power, appointed by and accountable to Parliament. The Prime Minister leads the Cabinet. The current Prime Minister is Irakli Kobakhidze, whose legitimacy is also contested.

Legislative authority rests with the unicameral 150-member Parliament of Georgia, elected for four-year terms. Parliament enacts laws, approves budgets, oversees the government, and ratifies treaties. It is located in Tbilisi.

5.2. Elections and political parties

Georgia has a multi-party system, often polarized. Elections are held for the presidency, parliament, and local bodies. Electoral system reforms aim for fairness and proportionality.

Major parties include the United National Movement (UNM) and Georgian Dream. The 2003 elections led to the Rose Revolution. The 2012 elections marked the first peaceful power transfer. Subsequent elections (2020, 2024) have been contentious, with opposition claims of irregularities, fueling political crises and impacting democratic development.

5.3. Judiciary

The judicial system includes district courts, appellate courts, the Supreme Court of Georgia (highest court of cassation), and the Constitutional Court of Georgia. Reforms since the Rose Revolution aimed to enhance judicial independence, efficiency, and public trust. However, concerns about political influence, particularly in judge appointments and accountability, persist, scrutinized by civil society and international observers.

5.4. Foreign relations

Georgia's foreign policy is largely pro-Western, aiming for integration into the European Union (EU) and NATO. It is a member of the United Nations, Council of Europe, OSCE, WTO, BSEC, and GUAM. Georgia actively participates in international peacekeeping.

5.4.1. Relations with Russia

Georgia-Russia relations are complex and tense, primarily due to Russia's support for separatist Abkhazia and South Ossetia (considered occupied territories by Georgia), Georgia's NATO aspirations, and regional geopolitical competition. The Russo-Georgian War in 2008 led to Russia recognizing Abkhazia and South Ossetia's independence and severing diplomatic ties. Ongoing challenges include Russian "borderization" activities impacting local communities' human rights.

5.4.2. Relations with the European Union and NATO

EU and NATO integration is a cornerstone of Georgian foreign policy. Georgia signed an Association Agreement (including a DCFTA) with the EU, in force since 2016, and achieved visa-free travel to the Schengen Area in 2017. Georgia applied for EU membership in 2022 and was granted candidate status in December 2023, contingent on reforms. Recent domestic political developments and a 2024 government announcement to pause EU accession talks until 2028 have raised concerns.

NATO allies agreed at the 2008 Bucharest Summit that Georgia would become a member, though without a timeline. Cooperation has deepened via the NATO-Georgia Commission and the Substantial NATO-Georgia Package (SNGP). Russia strongly opposes Georgia's NATO aspirations.

5.4.3. Relations with the United States

The Georgia-U.S. relationship is a strategic partnership with strong political, military (e.g., Georgia Train and Equip Program), and economic cooperation. The U.S. supports Georgia's sovereignty, territorial integrity, democratic reforms, and NATO aspirations, and has condemned Russia's occupation of Georgian territories. The U.S.-Georgia Charter on Strategic Partnership (2009) frames cooperation.

5.4.4. Relations with neighboring countries

Georgia maintains key relationships with Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

Turkey is a major trading partner and strategic ally, with strong cooperation in energy transit (e.g., Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline), transport (Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway), and trade.

Armenia shares historical ties, with significant economic links and reliance on Georgia for transit. The ethnic Armenian population in Samtskhe-Javakheti is a factor in relations.

Azerbaijan is a crucial energy partner, with Georgia as a transit country for oil and gas. They collaborate on regional projects and are major trading partners.

Georgia aims for balanced relations with neighbors, vital for its economy, security, and transit role.

5.5. Military

The Defense Forces of Georgia (GDF) comprise Land, Air, National Guard, and Special Operations Forces, responsible for national defense and international security. The Coast Guard is under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Conscription accounts for over 20% of the GDF.

Post-2008 war, Georgia has modernized its military with NATO and U.S. assistance. It has significantly contributed to peacekeeping in Iraq and Afghanistan (over 11,000 soldiers served; 32 killed). The 2021 military budget was about 900 million Lari (approx. 300.00 M USD). Georgia develops domestic military equipment via STC Delta.

5.6. Law enforcement and corruption

The Ministry of Internal Affairs oversees police. Radical post-Rose Revolution police reforms (e.g., dismissing the entire traffic police in 2004) significantly reduced petty corruption and improved public trust. U.S. assistance supported these reforms.

While street-level corruption decreased, high-level corruption and political influence over law enforcement remain concerns, potentially increasing in recent years according to observers like Transparency International. Ensuring independence and accountability is critical.

5.7. Human rights

Human rights are constitutionally guaranteed, overseen by an independent Public Defender (Ombudsman). Georgia has ratified treaties like the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

Civil liberties (speech, assembly) face pressure. Media is diverse but polarized, with concerns about ownership concentration and political influence. Minority rights (ethnic, religious) are officially protected but face challenges (e.g., issues for Azerbaijani schools, discrimination against some religious minorities). Women's rights see legislative progress, but domestic violence persists.

LGBTQ+ rights are contentious; individuals face societal hostility and violence despite legal non-discrimination provisions. Recent "anti-LGBT propaganda" law initiatives raise serious concerns. Prison conditions and detainee treatment remain issues. The Public Defender's role is crucial but can be affected by the political climate.

5.8. Administrative divisions

Georgia is a unitary state divided into 9 regions (მხარეmkhareGeorgian), the capital Tbilisi, and two autonomous republics: Adjara and Abkhazia. These are further subdivided into 67 municipalities (მუნიციპალიტეტიmunits'ipalitetiGeorgian) and 5 self-governing cities.

The regions are: Guria (Ozurgeti), Imereti (Kutaisi), Kakheti (Telavi), Kvemo Kartli (Rustavi), Mtskheta-Mtianeti (Mtskheta), Racha-Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti (Ambrolauri), Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti (Zugdidi), Samtskhe-Javakheti (Akhaltsikhe), Shida Kartli (Gori).

The status of Abkhazia (capital: Sukhumi) and South Ossetia (Tskhinvali Region, capital: Tskhinvali) is contested. Abkhazia declared independence in 1999 after the 1992-1993 conflict. South Ossetia's autonomy was abolished in 1990; it declared independence after the 1991-1992 and 2008 wars. Both are de facto independent, recognized mainly by Russia, and considered Russian-occupied territories by Georgia, which maintains governments-in-exile for them.

| Region | Centre | Area (km2) | Population (2014 Census; Note: Data excludes Abkhazia and South Ossetia unless specified by source as estimate) | Density (per km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abkhazia | Sukhumi | 8,660 | 242,862 (est.) | 28.04 |

| Adjara | Batumi | 2,880 | 333,953 | 115.95 |

| Guria | Ozurgeti | 2,033 | 113,350 | 55.75 |

| Imereti | Kutaisi | 6,475 | 533,906 | 82.45 |

| Kakheti | Telavi | 11,311 | 318,583 | 28.16 |

| Kvemo Kartli | Rustavi | 6,072 | 423,986 | 69.82 |

| Mtskheta-Mtianeti | Mtskheta | 6,786 | 94,573 | 13.93 |

| Racha-Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti | Ambrolauri | 4,990 | 32,089 | 6.43 |

| Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti | Zugdidi | 7,440 | 330,761 | 44.45 |

| Samtskhe-Javakheti | Akhaltsikhe | 6,413 | 160,504 | 25.02 |

| Shida Kartli | Gori | 5,729 | 300,382 (est., includes parts of South Ossetia not under Georgian control) | 52.43 |

| Tbilisi | Tbilisi | 720 | 1,108,717 | 1,539.88 |

6. Economy

Georgia's economy has transitioned from a Soviet command system to a market-oriented one, experiencing periods of reform, growth, and challenges like poverty and unemployment. Key sectors include agriculture, industry, and a growing services sector, particularly tourism and transport, all of which have social and environmental implications.

6.1. Economic history and overview

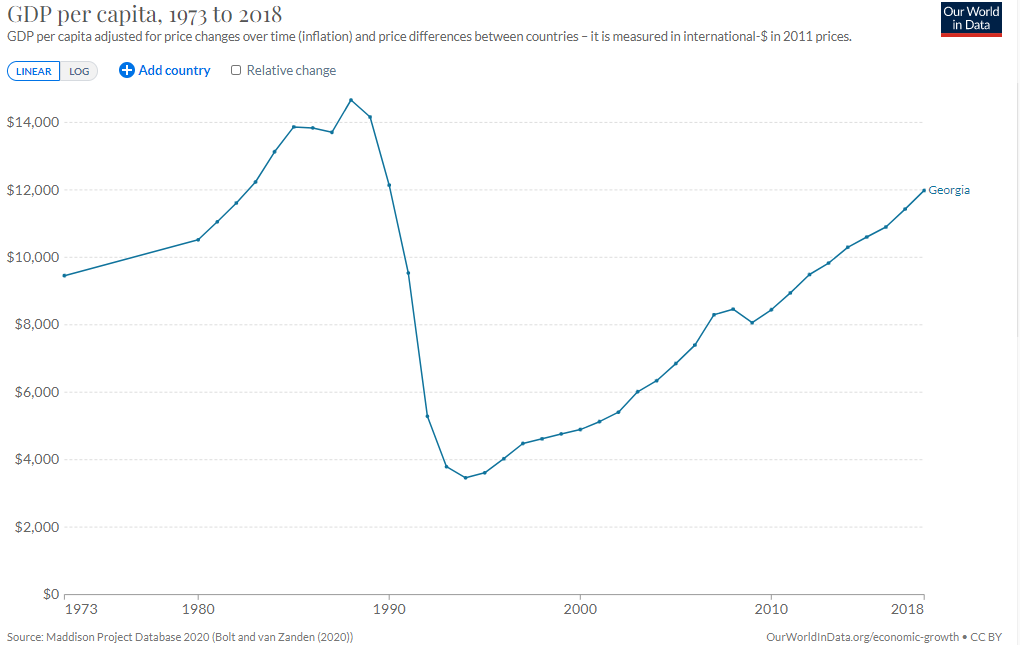

Georgia's economy was part of the Soviet command economy until 1991. Post-independence, it faced severe economic collapse, worsened by civil war and conflicts. Reforms after the 2003 Rose Revolution aimed at liberalization, reducing corruption, and attracting investment, leading to high growth (e.g., 12% real GDP growth in 2007). Georgia ranked highly in the Ease of Doing Business Index (6th globally by 2020) and economic freedom.

Poverty has reduced (from 54% in 2001 to ~10.1% by 2015), but income inequality and unemployment persist. The COVID-19 pandemic and regional instability have impacted performance. Social equity, labor rights, and social safety nets are ongoing concerns. Georgia's Human Development Index (HDI) was 61st in 2019. The economy is increasingly service-oriented (~59.4% of GDP in 2016), with agriculture at ~6.1%.

6.2. Major sectors

The Georgian economy comprises several key sectors:

Agriculture benefits from a diverse climate. Viticulture is renowned. Other products include citrus fruits, tea, and nuts. Challenges include small farm sizes and outdated technology. Labor rights and sustainability are concerns.

Industry includes mining (manganese, copper, gold), manufacturing (processed foods, beverages), and hydropower. Modernization and investment are needed. Environmental impacts from industry are a concern.

The services sector dominates GDP and employment, including:

- Tourism: Rapidly growing, leveraging cultural and natural assets.

- Finance: A relatively stable banking sector.

- Transport and Logistics: Vital due to Georgia's transit corridor role.

- Information Technology (IT): Developing with growth potential.

Fair labor practices and social protections in services are important.

6.3. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing sector, driven by historical sites, natural landscapes, cuisine, wine, and winter sports. Major attractions include UNESCO World Heritage Sites (e.g., Bagrati Cathedral, Gelati Monastery, Mtskheta, Upper Svaneti), cave cities (Vardzia, Uplistsikhe), Old Tbilisi, Sighnaghi, mountain resorts (Gudauri, Bakuriani), national parks, and the Black Sea coast (Batumi). Gastronomy and wine tours (Kakheti) are popular.

International arrivals peaked at 9.3 million in 2019. Government promotion includes marketing, infrastructure development, and visa liberalization. Tourism contributes significantly to GDP and employment but faces challenges like sustainable development, environmental impact, and equitable benefit distribution.

6.4. Transport and infrastructure

Georgia's transport network is crucial for its economy and transit role.

- Roads: Primary domestic transport. Modernization of highways like the East-West Highway (S1, part of TRACECA) is ongoing. Total road length: ~13 K mile (21.11 K km).

- Railways: Georgian Railways operate ~1.0 K mile (1.58 K km), vital for freight transit (Caspian-Black Sea). The Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway (2017) enhances regional connectivity.

- Ports: Poti and Batumi are major Black Sea ports for international trade and transit.

- Airports: Three main international airports: Tbilisi International Airport (largest), Batumi International Airport, and Kutaisi International Airport.

- Pipelines: Key transit for oil (BTC pipeline) and gas (SCP) from Azerbaijan to Turkey/Europe.

Infrastructure development is a priority but raises environmental and social concerns.

6.5. Foreign trade and investment

Georgia has an open economy. Main trading partners: Turkey, Russia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, European Union, China, United States. The EU is key post-DCFTA. FTAs pursued with China, EFTA.

Key exports: Wine, ferroalloys, mineral water, copper ores, re-exported vehicles, nuts, fruits.

Main imports: Petroleum products, vehicles, machinery, pharmaceuticals, food.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) attracted by improved business climate, flowing into energy, tourism, manufacturing, finance. Trade policy impacts on local industry and social welfare require careful management.

7. Demographics

Georgia's population is characterized by its ethnic diversity, with Georgians forming the majority. The country has experienced demographic shifts due to migration and changing birth rates. The Georgian language is official, alongside Abkhaz in Abkhazia, with several minority languages spoken. Eastern Orthodox Christianity is the dominant religion.

7.1. Ethnic groups and population

Georgia's population was ~3.7 million (excluding Abkhazia and South Ossetia), experiencing decline due to emigration, lower birth rates, and conflicts.

Ethnic Composition (2014 census, government-controlled territory):

- Georgians (Kartvelians): 86.8%

- Azerbaijanis: 6.3%

- Armenians: 4.5%

- Russians: 0.7%

- Ossetians: 0.4% (lower due to displacement)

- Yazidis: 0.3%

- Ukrainians: 0.2%

- Kists (ethnic Chechens): 0.2%

- Greeks: 0.1%

- Others: 0.5%

Georgian Jews are an ancient community, numbers reduced by emigration. Historically home to Caucasus Germans, deported during WWII.

Population Trends and Migration: Significant emigration since 1990s (economic hardship, conflicts). Russia is a primary destination. Internal displacement from Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Recent influx of Russian citizens post-2022 Ukraine invasion. Urbanization ongoing, mainly to Tbilisi. Challenges: aging population, low fertility.

7.2. Languages

Official language: Georgian (Kartvelian family, unique to Caucasus). Primary language for ~87.7%. Unique Georgian scripts (Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri, Mkhedruli).

In Abkhazia, Abkhaz (Northwest Caucasian) is also official.

Minority languages: Armenian, Azerbaijani, Russian, Ossetian, Kist, Greek, Ukrainian. Russian prevalence declined since independence; English gaining popularity.

Language policy and minority rights are important, with challenges in implementation.

7.3. Religion

According to the 2014 census for government-controlled territory, the dominant religion in Georgia is Eastern Orthodox Christianity, adhered to by 83.4% of the population, with the majority belonging to the autocephalous Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC). The GOC is one of the world's oldest Christian churches, traditionally believed to have been founded by the Apostle Andrew. Christianity was adopted as the state religion of the Kingdom of Iberia (eastern Georgia) in the early 4th century (around 337 AD) through the missionary work of Saint Nino. The GOC plays a significant role in Georgian national identity and culture, and its special status is recognized in the Constitution and a Concordat between the state and the church, although religious institutions are formally separate from the state.

Muslims constitute 10.7% of the population, primarily ethnic Azerbaijanis (mostly Shia) in Kvemo Kartli and ethnic Georgian Muslims (mostly Sunni) in Adjara. The Kists in Pankisi Gorge and Meskhetian Turks are also Sunni. A minority of Abkhaz are Sunni Muslims.

Followers of the Armenian Apostolic Church are the third-largest group (2.9%), mainly ethnic Armenians in Samtskhe-Javakheti and Tbilisi.

Smaller communities include Roman Catholics (0.5%), Jews, Yazidis, Protestants, and Jehovah's Witnesses.

Religious freedom is constitutionally guaranteed, but societal discrimination and occasional violence against minority groups occur. Church-state relations and the GOC's role are discussed. About 0.5% declared no religion in 2014; 1.2% did not specify.

7.4. Education

Georgia's education system underwent modernization reforms since 2004. Education is mandatory for ages 6-14.

Structure: Elementary (6 years, ages 6-12), Basic (3 years, ages 12-15), Secondary (3 years, ages 15-18) or vocational (2 years). Higher education access via Unified National Examinations.

Higher education: Bachelor's (3-4 years), Master's (2 years), Doctoral (3 years). Certified specialist programs (3-6 years). 75 accredited HEIs (2016). Gross primary enrollment: 117% (2012-2014).

Tbilisi is the main HE center: Tbilisi State University (TSU, 1918), Georgian Technical University (GTU), Tbilisi State Medical University, The University of Georgia, Caucasus University, Free University of Tbilisi.

Reforms focused on curriculum, teacher training, university autonomy, anti-corruption. Challenges: equitable access (rural, minorities), funding, vocational training alignment. English teaching emphasized.

7.5. Health

Georgia's healthcare system transitioned from Soviet centralized to market-oriented with private involvement since early 2000s, aiming to improve access, quality, and efficiency.

Public health indicators improved but challenges remain (lower life expectancy, non-communicable diseases, infectious diseases, maternal/child health).

State financing via universal healthcare program (2013) for basic services. Out-of-pocket payments are significant, creating access barriers.

Infrastructure: hospitals, polyclinics, primary care (public/private mix). Modernization efforts ongoing, but urban-rural disparities persist.

Access to affordable medicines is a challenge (largely private market, high prices).

Focus on strengthening primary care, public health programs, medical professional skills, financial sustainability. Addressing health disparities is crucial.

8. Culture

Georgian culture, ancient and rich, evolved from Iberian and Colchian civilizations, experiencing a Golden Age in the 11th-13th centuries. It has been influenced by Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Iranian empires, as well as the Russian Empire and Soviet Union.

Despite influences, Georgia maintained a unique identity centered on the Georgian language, its distinctive Georgian scripts, and the Georgian Orthodox Church. The national narrative emphasizes cultural preservation and a European/Western identity.

Georgia is known for folklore, traditional polyphonic music (UNESCO Intangible Heritage), traditional dances, unique cuisine, ancient winemaking, distinctive architecture (medieval churches, defensive towers), and rich literature. Modern culture includes achievements in theatre, cinema, and visual arts.

8.1. Architecture and arts

Georgian architecture reflects a diverse history, with unique castles, towers, fortifications, and churches. Upper Svaneti's towers and Shatili village are examples of medieval vernacular and defensive architecture.

Ecclesiastical architecture features a distinctive cross-dome style (from 9th century). Medieval churches like Jvari Monastery, Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, Bagrati Cathedral, and Gelati Monastery (all UNESCO sites) are known for stone carvings and frescoes. Georgian architectural influence is found abroad (e.g., Bachkovo Monastery, Iviron monastery).

Later architecture includes 19th-century buildings in Tbilisi (Rustaveli Avenue, Old Town). Modern architecture is also developing.

Georgian ecclesiastical art (iconography, frescoes, enamelwork like Khakhuli triptych) was highly sophisticated. Niko Pirosmani (late 19th/early 20th c.) is a famous primitivist painter. Other notable 20th-century painters: Lado Gudiashvili, Elene Akhvlediani.

8.2. Literature

Georgian literature dates to the 5th century AD. The unique Georgian scripts (Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri, Mkhedruli) are central.

Early literature: hagiographies, ecclesiastical texts. Medieval masterpiece: The Knight in the Panther's Skin (ვეფხისტყაოსანიVepkhistqaosaniGeorgian), 12th-century epic by Shota Rustaveli, a national epic.

19th-century revival under Russian rule: Romanticism (Nikoloz Baratashvili, Grigol Orbeliani, Alexander Chavchavadze), followed by realism and national awakening figures (Ilia Chavchavadze, Akaki Tsereteli, Vazha-Pshavela).

20th century: Soviet period constraints, but significant writers like Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, Galaktion Tabidze, Mikheil Javakhishvili. Contemporary literature thrives, gaining international recognition.

8.3. Music and dance

Georgian music is known for ancient traditions, especially polyphonic singing (UNESCO Intangible Heritage), typically male choirs with three+ independent vocal parts. The folk song "Chakrulo" is on the Voyager Golden Records.

Diverse regional folk music traditions with characteristic instruments (panduri, chonguri, salamuri, doli, chiboni).

Georgian dances are vibrant, athletic, and graceful, depicting history, work, or celebrations (Kartuli, Khorumi). Professional ensembles like Sukhishvili National Ballet have international acclaim.

Georgia also has classical and contemporary music scenes (pop, rock, electronic, jazz).

8.4. Cuisine

Georgian cuisine is diverse, flavorful, using herbs, spices, and fresh ingredients. Hospitality is key; food is central to social gatherings. The supra (traditional feast) is led by a tamada (toastmaster).

Signature dishes:

- Khachapuri: Savory cheese bread (variations: Imeretian, Adjarian - boat-shaped with egg/butter, Megrelian).

- Khinkali: Large dumplings (spiced meat/broth or vegetarian).

- Mtsvadi: Skewered grilled meat (shashlik).

- Pkhali: Vegetable pâtés (spinach, beets) with walnuts, herbs.

- Badrijani Nigvzit: Fried eggplant with spiced walnut paste.

- Lobio: Hearty bean stew.

- Satsivi: Chicken/turkey in walnut sauce (served cold).

- Churchkhela: Nut candy in thickened grape juice.

Spices: cilantro, blue fenugreek, marigold. Walnuts are a staple. Pickled vegetables (mtsnili) common.

8.4.1. Wine

Georgia is one of the oldest wine-producing regions (evidence ~8,000 years ago). Traditional winemaking using qvevri (large buried clay vessels) is UNESCO Intangible Heritage.

Key aspects:

- Indigenous Grape Varietals: Over 500 (Reds: Saperavi, Tavkveri, Otskhanuri Sapere; Whites: Rkatsiteli, Mtsvane Kakhuri, Kisi, Tsolikouri).

- Qvevri Winemaking: Fermenting grape juice (often with skins/stalks/pips) in qvevris imparts unique characteristics.

- Wine Regions: Kakheti (most famous; sub-regions: Telavi, Kvareli, Tsinandali, Mukuzani), Kartli, Imereti, Racha-Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti, Adjara.

- Cultural Significance: Wine is central to hospitality (supra). The vine is a national symbol (e.g., grapevine cross of Saint Nino).

Georgian wine faced challenges (e.g., 2006 Russian embargo) but gained global recognition, especially qvevri wines.

8.5. Sports

Popular sports: Football (Soccer) (domestic league: Erovnuli Liga; club: FC Dinamo Tbilisi; players: Kakhaber Kaladze, Khvicha Kvaratskhelia).

Rugby union (national sport; Lelos compete in Rugby Europe Championship, Rugby World Cup).

Wrestling (freestyle, Greco-Roman; strong tradition, Olympic medals).

Judo (numerous Olympic/world champions).

Weightlifting (Olympic golds).

Basketball (national team in EuroBasket; NBA players: Zaza Pachulia, Tornike Shengelia; BC Dinamo Tbilisi won EuroLeague 1962).

Other sports: chess (grandmasters: Nona Gaprindashvili, Maia Chiburdanidze), boxing, martial arts.

Motor racing: Rustavi International Motorpark. Traditional games: Lelo. Georgian athletes: 40 Olympic medals (wrestling, judo, weightlifting).

8.6. Media

Media landscape: TV, radio, print, online (state-owned e.g., Georgian Public Broadcaster, and private). Constitution guarantees free speech.

Considered diverse in South Caucasus, but faces challenges:

- Political Polarization: Media often aligned with political factions.

- Ownership Concentration and Influence: Concerns about political/business influence on content.

- Pressure on Journalists: Reports of intimidation, violence.

- Disinformation and Propaganda: Domestic/foreign sources impacting public discourse.

- Financial Viability: Independent media struggle for sustainability.

Georgian Public Broadcaster (GPB) mandate for impartiality; faced criticism. Regulatory/self-regulation mechanisms exist; effectiveness questioned.

Vibrant online media and civil society contribute to pluralism.

8.7. Public holidays and festivals

Georgia observes public holidays reflecting cultural, historical, and religious heritage:

- January 1, 2: New Year's Day

- January 7: Orthodox Christmas

- January 19: Orthodox Epiphany

- March 3: Mother's Day

- March 8: International Women's Day

- April 9: Day of National Unity (commemorates 1989 Tbilisi massacre, independence restoration)

- Easter (movable, Orthodox): Good Friday, Holy Saturday, Easter Sunday, Easter Monday

- May 9: Day of Victory over Fascism (WWII end in Europe)

- May 12: Saint Andrew the First-Called Day

- May 26: Independence Day (1918 First Republic)

- August 28: Mariamoba (Assumption of Mary)

- October 14: Svetitskhovloba (Day of Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, Mtskheta)

- November 23: Giorgoba (Saint George's Day)

Numerous traditional, religious, cultural festivals year-round (harvest festivals e.g., Rtveli, local saint's days, folk festivals).