1. Overview

Serbia, officially the Republic of Serbia, is a landlocked country situated at the crossroads of Southeast and Central Europe, in the Balkan Peninsula and the Pannonian Plain. Belgrade is the capital and largest city. Historically a pivotal nation in the Balkans, Serbia's past includes medieval kingdoms and empires, periods under Ottoman and Habsburg rule, and a central role in the formation and dissolution of Yugoslavia. Contemporary Serbia is a parliamentary republic pursuing European Union integration while navigating challenges related to democratic consolidation, human rights, social progress, and the unresolved status of Kosovo. The nation possesses a diverse geography, an emerging market economy, and a rich cultural heritage shaped by its position between East and West, with ongoing societal emphasis on the development of democratic institutions, the protection of human rights, and the welfare of minorities and vulnerable groups.

2. Etymology

The origin of the name Serbia is unclear. Historically, authors have mentioned the Serbs (Срби / SrbiSrbiSerbian) and the Sorbs of Eastern Germany (Upper Sorbian: Serbja; Lower Sorbian: Serby) in various ways, including Cervetiis (Servetiis), gentis Surbiorum, Suurbi, Sorabi, Soraborum, Sorabos, Surpe, Sorabici, Sorabiet, Sarbin, Swrbjn, Servians, Sorbi, Sirbia, Sribia, Zirbia, Zribia, Suurbelant, Surbia, and Serbulia / Sorbulia. These names were used to refer to Serbs and Sorbs in areas where their historical and current presence is not disputable, notably in the Balkans and Lusatia. However, some sources have used similar names in other parts of the world, such as in Asiatic Sarmatia in the Caucasus.

Two prevailing theories exist regarding the origin of the ethnonym *Sŕbъ (plural *Sŕby). One theory suggests it originates from a Proto-Slavic language with an appellative meaning of "family kinship" and "alliance." Another theory proposes an origin from an Iranian-Sarmatian language with various meanings. In his work De Administrando Imperio, Constantine VII suggests that the Serbs originated from White Serbia near Francia.

From 1815 to 1882, the official name for Serbia was the Principality of Serbia. From 1882 to 1918, it was renamed the Kingdom of Serbia. Later, from 1945 to 1963, the official name was the People's Republic of Serbia, which was again renamed the Socialist Republic of Serbia from 1963 to 1990. Since 1990, the official name of the country has been the Republic of Serbia.

In minority languages spoken in Serbia, the name "Serbia" is rendered as:

- Albanian: SerbiaSerbiaAlbanian

- Bulgarian: СърбияSŭrbiyaBulgarian

- Croatian: SrbijaSrbijaCroatian

- Hungarian: SzerbiaSzerbiaHungarian

- Macedonian: СрбијаSrbijaMacedonian

- Pannonian Rusyn: СербіяSérbiyarue

- Romanian: SerbiaSerbiaRomanian

- Slovak: SrbskoSrbskoSlovak

The official name, "Republic of Serbia", is rendered in these minority languages as:

- Albanian: Republika e SerbisëRepublika e SerbisëAlbanian

- Bulgarian: Република СърбияRepublika SŭrbiyaBulgarian

- Croatian: Republika SrbijaRepublika SrbijaCroatian

- Hungarian: Szerb KöztársaságSzerb KöztársaságHungarian

- Macedonian: Република СрбијаRepublika SrbijaMacedonian

- Pannonian Rusyn: Републіка СербіяRepublíka Sérbiyarue

- Romanian: Republica SerbiaRepublica SerbiaRomanian

- Slovak: Srbská republikaSrbská republikaSlovak

3. History

The history of Serbia spans millennia, from prehistoric settlements through ancient civilizations, the rise and fall of medieval Serbian states, centuries under Ottoman and Habsburg rule, to the struggles for independence and the formation of modern Serbia. Its 20th-century history was largely defined by its central role in various Yugoslav states and the subsequent conflicts during their dissolution, leading to contemporary challenges and aspirations.

3.1. Prehistory and Antiquity

Archaeological evidence of Paleolithic settlements on the territory of present-day Serbia is scarce. A fragment of a hominid jaw found in Sićevo (Mala Balanica) is believed to be up to 525,000-397,000 years old.

Approximately 6,500 BC, during the Neolithic period, the Starčevo and Vinča cultures existed in the region of modern-day Belgrade. These cultures dominated much of Southeast Europe as well as parts of Central Europe and Anatolia. Several important archaeological sites from this era, including Lepenski Vir and Vinča-Belo Brdo, still exist near the Danube river.

During the Iron Age, local tribes of Triballi, Dardani, and Autariatae were encountered by the Ancient Greeks during their cultural and political expansion into the region, from the 5th up to the 2nd century BC. The Celtic tribe of Scordisci settled throughout the area in the 3rd century BC. They formed a tribal state, building several fortifications, including their capital at Singidunum (present-day Belgrade) and Naissos (present-day Niš).

The Romans conquered much of the territory in the 2nd century BC. In 167 BC, the Roman province of Illyricum was established. The remainder was conquered around 75 BC, forming the Roman province of Moesia Superior. The modern-day Srem region was conquered in 9 BC, and Bačka and Banat in 106 AD after the Dacian Wars. As a result, contemporary Serbia extends fully or partially over several former Roman provinces, including Moesia, Pannonia, Praevalitana, Dalmatia, Dacia, and Macedonia. Seventeen Roman Emperors were born in the area of modern-day Serbia, second only to contemporary Italy. The most famous of these was Constantine the Great, the first Christian Emperor, who issued the Edict of Milan, ordering religious tolerance throughout the Empire.

When the Roman Empire was divided in 395, most of Serbia remained under the Byzantine Empire, while its northwestern parts were included in the Western Roman Empire. By the 6th century, South Slavs migrated into Byzantine territory in large numbers. They merged with the local Romanised population, which was gradually assimilated.

3.2. Middle Ages

White Serbs, an early Slavic tribe from White Serbia, eventually settled in an area between the Sava river and the Dinaric Alps. By the beginning of the 9th century, Serbia had achieved a level of statehood. The Christianization of Serbia was a gradual process, finalized by the middle of the 9th century. In the mid-10th century, the Serbian state experienced a period of decline. During the 11th and 12th centuries, the Serbian state frequently fought with the neighboring Byzantine Empire.

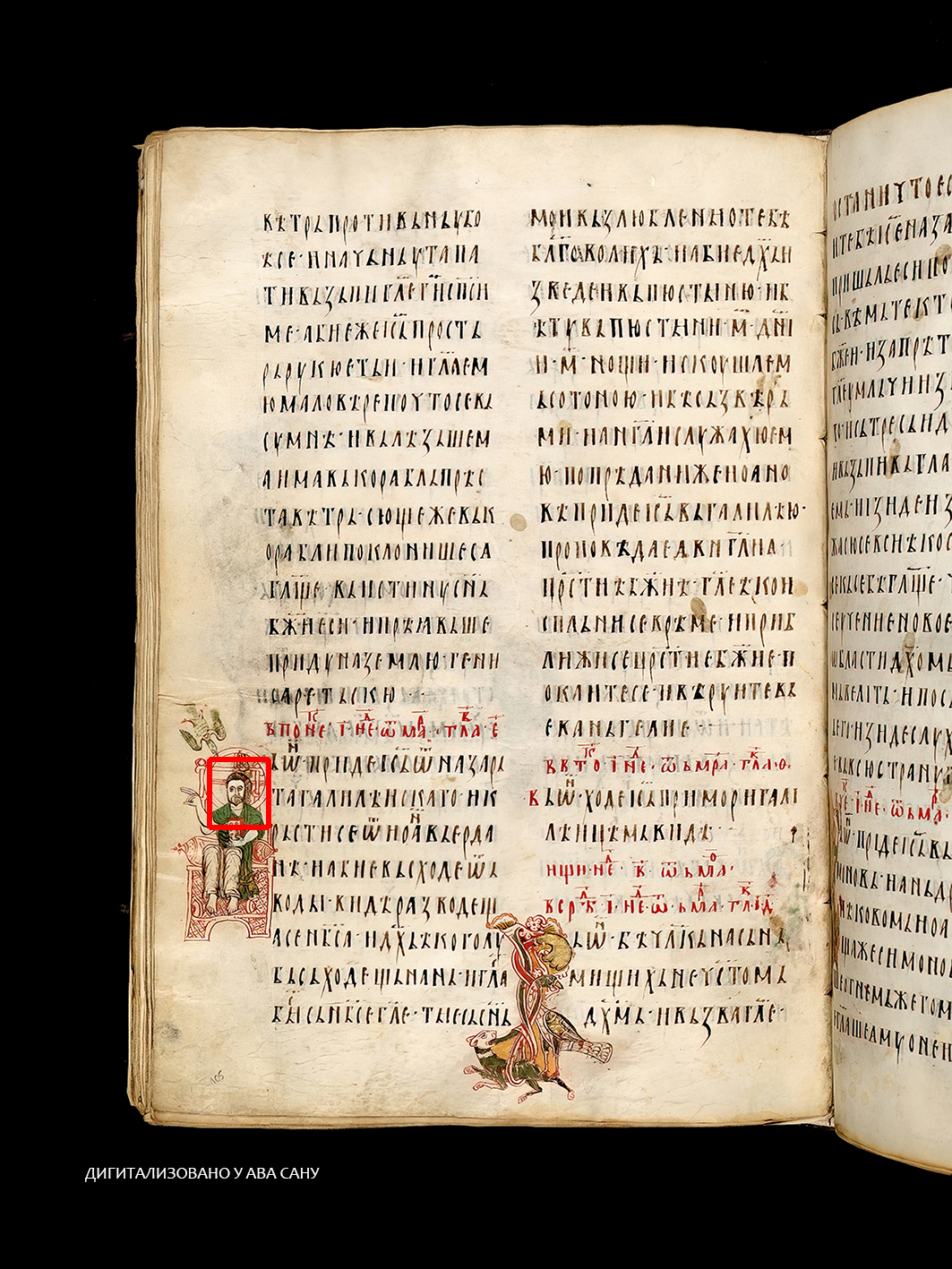

Between 1166 and 1371, Serbia was ruled by the Nemanjić dynasty. Under this dynasty, the state was elevated to a kingdom in 1217 and an empire in 1346 under Stefan Dušan. The Serbian Orthodox Church was organized as an autocephalous archbishopric in 1219, through the efforts of Sava, the country's patron saint. In 1346, it was raised to the Patriarchate. Monuments of the Nemanjić period survive in many monasteries (several of which are World Heritage sites) and fortifications.

During these centuries, the Serbian state and its influence expanded significantly. The northern part, modern Vojvodina, was ruled by the Kingdom of Hungary. The period after 1371, known as the Fall of the Serbian Empire, saw the once-powerful state fragmented into several principalities, culminating in the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 against the rising Ottoman Empire. By the end of the 14th century, the Turks had conquered and ruled the territories south of the Šar Mountains. The political center of Serbia shifted northwards when the capital of the newly established Serbian Despotate was transferred to Belgrade in 1403, before moving to Smederevo in 1430. The Despotate was then under the double vassalage of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. The fall of Smederevo on June 20, 1459, which marked the full conquest of the Serbian Despotate by the Ottomans, also symbolically signified the end of the Serbian state.

3.3. Ottoman and Habsburg Rule

In all Serbian lands conquered by the Ottomans, the native nobility was eliminated, and the peasantry was enserfed to Ottoman rulers. Much of the clergy fled or were confined to isolated monasteries. Under the Ottoman system, Serbs and other Christians were considered an inferior class (known as rayah) and subjected to heavy taxes. A portion of the Serbian population experienced Islamization. Many Serb boys were recruited through the devshirme system, a form of slavery in which boys from Balkan Christian families were forcibly converted to Islam and trained for infantry units of the Ottoman army known as the Janissaries. The Serbian Patriarchate of Peć was extinguished in 1463 but reestablished in 1557, providing for a limited continuation of Serbian cultural traditions within the Ottoman Empire under the Millet system.

After the loss of statehood to the Ottoman Empire, Serbian resistance continued in northern regions (modern Vojvodina), under titular despots (until 1537), and popular leaders like Jovan Nenad (1526-1527). From 1521 to 1552, Ottomans conquered Belgrade and regions of Syrmia, Bačka, and Banat. Wars and rebellions constantly challenged Ottoman rule. One of the most significant was the Banat Uprising in 1594 and 1595, which was part of the Long War (1593-1606) between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans. The area of modern Vojvodina endured a century-long Ottoman occupation before being ceded to the Habsburg monarchy, partially by the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699), and fully by the Treaty of Požarevac (1718).

During the Great Turkish War (Habsburg-Ottoman war of 1683-1699), much of Serbia switched from Ottoman rule to Habsburg control from 1688 to 1690. However, the Ottoman army reconquered a large part of Serbia in the winter of 1689/1690, leading to brutal massacres of the civilian population by uncontrolled Albanian and Tatar units. As a result of these persecutions, several tens of thousands of Serbs, led by Patriarch Arsenije III Crnojević, fled northwards to settle in the Kingdom of Hungary. This event is known as the Great Migration of 1690. In August 1690, following several petitions, Emperor Leopold I formally granted Serbs from the Habsburg monarchy a first set of "privileges," primarily to guarantee them freedom of religion. Consequently, the ecclesiastical center of the Serbs also moved northwards, to the Metropolitanate of Karlovci. The Serbian Patriarchate of Peć was once again abolished by the Ottomans in 1766.

In 1718-1739, the Habsburg monarchy occupied much of Central Serbia and established the Kingdom of Serbia as a crown land. These gains were lost by the Treaty of Belgrade in 1739, when the Ottomans retook the region. Apart from the territory of modern-day Vojvodina, which remained under the Habsburg Empire, central regions of Serbia were occupied once again by the Habsburgs in 1788-1792.

3.4. Revolution and Independence

The Serbian Revolution for independence from the Ottoman Empire lasted eleven years, from 1804 until 1815. The revolution comprised two major uprisings. During the First Serbian Uprising (1804-1813), led by Vožd (leader) Karađorđe Petrović, Serbia was independent for almost a decade before the Ottoman army was able to reoccupy the country. This uprising was significant not only for its military aspects but also for laying the groundwork for a Serbian national consciousness and administrative structures, despite its eventual suppression.

The Second Serbian Uprising began in 1815, led by Miloš Obrenović. It ended with a compromise between Serbian revolutionaries and Ottoman authorities, granting Serbia a degree of autonomy. Serbia was one of the first nations in the Balkans to abolish feudalism. The Akkerman Convention in 1826, the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829, and finally, the Hatt-i Sharif of 1830, recognized the suzerainty of Serbia. The First Serbian Constitution was adopted on 15 February 1835 (Julian calendar), making the country one of the first in Europe to adopt a democratic constitution, though its liberal provisions led to its suspension under pressure from major powers. February 15th is now commemorated as Statehood Day, a public holiday.

Following clashes between the Ottoman army and Serbs in Belgrade in 1862, and under pressure from the Great Powers, by 1867 the last Turkish soldiers left the Principality, making the country de facto independent. By enacting a new constitution in 1869, without consulting the Porte, Serbian diplomats under Jovan Ristić confirmed the de facto independence of the country. In 1876, Serbia declared war on the Ottoman Empire, siding with the ongoing Christian uprisings in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Bulgaria.

The formal independence of the country was internationally recognized at the Congress of Berlin in 1878, which ended the Russo-Turkish War. This treaty, however, prohibited Serbia from uniting with other Serbian regions by placing Bosnia and Herzegovina under Austro-Hungarian occupation, alongside the occupation of the Raška region. From 1815 to 1903, the Principality of Serbia was ruled by the House of Obrenović, save for the rule of Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević between 1842 and 1858. In 1882, the Principality of Serbia became the Kingdom of Serbia, ruled by King Milan I. The House of Karađorđević, descendants of the revolutionary leader Karađorđe Petrović, assumed power in 1903 following the May Overthrow, an event that significantly shifted Serbia's foreign policy towards Russia and contributed to rising tensions with Austria-Hungary.

The 1848 revolution in Austria led to the establishment of the autonomous territory of Serbian Vojvodina. By 1849, the region was transformed into the Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar.

3.5. Balkan Wars and World War I

In the First Balkan War in 1912, the Balkan League (Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, and Bulgaria) defeated the Ottoman Empire and captured its remaining European territories. This victory enabled the territorial expansion of the Kingdom of Serbia into regions of Raška, Kosovo, Metohija, and Vardarian Macedonia. The Second Balkan War soon ensued when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils, turned on its former allies but was defeated, resulting in the Treaty of Bucharest. In two years, Serbia enlarged its territory by 80% and its population by 50%. However, it also suffered high casualties (more than 36,000 dead) on the eve of World War I. Austria-Hungary became wary of the rising regional power on its borders and its potential to become an anchor for the unification of Serbs and other South Slavs, leading to increasingly tense relations between the two countries.

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Young Bosnia organization and an Austrian citizen of Serb ethnicity, provided Austria-Hungary with a pretext to declare war on Serbia on 28 July 1914, setting off World War I.

Serbia won the first major battles of the war, including the Battle of Cer and the Battle of Kolubara, marking significant early Allied victories. Despite initial success, Serbia was eventually overpowered by the combined forces of the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria) in 1915, leading to the Austro-Hungarian occupation. Most of its army and many civilians retreated through Albania to Greece and Corfu, suffering immense losses from combat, disease, and famine. After the Central Powers' military situation on other fronts worsened, the reformed Serb army returned to the Salonica front and led a final breakthrough through enemy lines on 15 September 1918, liberating Serbia and contributing to the defeat of Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary. Serbia, with its campaign, was a major Balkan Entente Power which contributed significantly to the Allied victory in the Balkans in November 1918.

Serbia's casualties in World War I were catastrophic, accounting for 8% of the total Entente military deaths; 58% (243,600) of soldiers of the Serbian army perished. The total number of casualties is estimated to be around 700,000, more than 16% of Serbia's prewar population, and a majority (57%) of its overall male population. Serbia suffered the highest casualty rate in World War I, a testament to the immense human cost and devastation endured by the nation, which had profound long-term demographic and social consequences.

3.6. Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Corfu Declaration of 20 July 1917 was a formal agreement between the government-in-exile of the Kingdom of Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee (representing anti-Habsburg South Slav émigrés). It pledged to unify the Kingdom of Serbia and the Kingdom of Montenegro with Austria-Hungary's South Slav autonomous crown lands: the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, the Kingdom of Dalmatia, Slovenia, Vojvodina (then part of the Kingdom of Hungary), and Bosnia and Herzegovina into a post-war Yugoslav state.

As the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed, the territory of Syrmia united with Serbia on 24 November 1918. Just a day later, on 25 November, the Great People's Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci and other Slavs in Banat, Bačka and Baranja declared the unification of these regions (Banat, Bačka, and Baranja) with the Kingdom of Serbia.

On 26 November 1918, the Podgorica Assembly deposed the House of Petrović-Njegoš and united Montenegro with Serbia. On 1 December 1918, in Belgrade, Serbian Prince Regent Alexander Karađorđević proclaimed the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, under King Peter I of Serbia.

King Peter was succeeded by his son, Alexander, in August 1921. Serb centralists and Croat autonomists clashed in the parliament, and most governments were fragile and short-lived. Nikola Pašić, a conservative prime minister, headed or dominated most governments until his death. In an attempt to resolve the political instability and ethnic tensions, King Alexander established a royal dictatorship in 1929. He changed the name of the country to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and aimed to establish a singular Yugoslav ideology and nation. However, the effect of Alexander's dictatorship was to further alienate the non-Serbs living in Yugoslavia from the idea of unity, exacerbating ethnic divisions rather than healing them.

Alexander was assassinated in Marseille during an official visit in 1934 by Vlado Chernozemski, a member of the IMRO. Alexander was succeeded by his eleven-year-old son Peter II, with a regency council headed by Prince Paul Karađorđević. In August 1939, the Cvetković-Maček Agreement established an autonomous Banate of Croatia as a solution to Croatian concerns about centralization and Serb dominance, but this move came too late to fully resolve the deep-seated ethnic and political issues facing the kingdom on the eve of World War II.

3.7. World War II

In 1941, despite Yugoslav attempts to remain neutral, the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia. The territory of modern Serbia was divided between Hungary, Bulgaria, the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), Greater Albania, and Italian-occupied Montenegro. The remainder of Serbia was placed under the military administration of Nazi Germany, with Serbian puppet governments led by Milan Aćimović and later Milan Nedić, assisted by Dimitrije Ljotić's fascist organization Yugoslav National Movement (Zbor).

The Yugoslav territory became the scene of a brutal civil war between royalist Chetniks commanded by Draža Mihailović and communist Partisans commanded by Josip Broz Tito. Axis auxiliary units like the Serbian Volunteer Corps and the Serbian State Guard fought against both resistance movements. The siege of Kraljevo was a major battle of the 1941 uprising in Serbia, led by Chetnik and Partisan forces against the Nazis. In reprisal for the attack, German forces committed the Kraljevo massacre, executing approximately 2,000 civilians.

The Draginac and Loznica massacre of 2,950 villagers in Western Serbia in 1941 was the first large-scale execution of civilians in occupied Serbia by German forces. The Kragujevac massacre and the Novi Sad Raid of Jews and Serbs by Hungarian fascists were among the most notorious atrocities, with over 3,000 victims in each case. After one year of occupation, around 16,000 Serbian Jews were murdered in the area, or around 90% of its pre-war Jewish population, during The Holocaust in German-occupied Serbia. Many concentration camps were established, with Banjica concentration camp being the largest, jointly run by the German army and Nedić's regime, where primary victims were Serbian Jews, Roma, and Serb political prisoners.

Hundreds of thousands of ethnic Serbs fled the Axis puppet state known as the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) and sought refuge in German-occupied Serbia to escape the large-scale persecution and the Genocide of Serbs, Jews, and Roma committed by the Ustaše regime. The number of Serb victims in the NDH is estimated to be between 300,000 and 350,000. According to Tito himself, Serbs made up the vast majority of anti-fascist fighters and Yugoslav Partisans throughout World War II.

The Republic of Užice was a short-lived liberated territory established by the Partisans in the autumn of 1941 in western occupied Serbia, becoming the first liberated territory in World War II Europe. By late 1944, the Belgrade Offensive, conducted by Partisans with Soviet Red Army support, swung the civil war in favor of the Partisans, who subsequently gained control of Yugoslavia. The Syrmian Front was the last major military action of World War II in Serbia. A study by Vladimir Žerjavić estimates total war-related deaths in Yugoslavia at 1,027,000, including 273,000 in Serbia, reflecting the immense human cost of the conflict.

3.8. Socialist Yugoslavia

The victory of the Communist Partisans resulted in the abolition of the monarchy and a subsequent constitutional referendum. A one-party state was soon established in Yugoslavia by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. It is claimed that between 60,000 and 70,000 people died in Serbia during the 1944-45 communist purges, a period marked by significant human rights violations as the new regime consolidated power. Serbia became a constituent republic within the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (later the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia or SFRY), known as the People's Republic of Serbia (later Socialist Republic of Serbia), and had a republic-branch of the federal communist party, the League of Communists of Serbia.

Serbia's most powerful and influential politician in Tito-era Yugoslavia was Aleksandar Ranković, one of the "big four" Yugoslav leaders. Ranković was later removed from office due to disagreements regarding Kosovo's nomenklatura and the unity of Serbia. His dismissal was highly unpopular among Serbs. Pro-decentralization reformers in Yugoslavia succeeded in the late 1960s in attaining substantial decentralization of powers, creating substantial autonomy in Kosovo and Vojvodina through the 1974 Constitution, and recognizing a distinctive "Muslim" nationality (now Bosniaks). As a result of these reforms, there was a massive overhaul of Kosovo's nomenklatura and police, shifting from Serb-dominated to ethnic Albanian-dominated, often through the dismissal of Serbs. Further concessions were made to the ethnic Albanians of Kosovo in response to unrest, including the creation of the University of Pristina as an Albanian language institution. These changes created widespread fear among Serbs of being treated as second-class citizens in Kosovo and contributed to growing ethnic tensions.

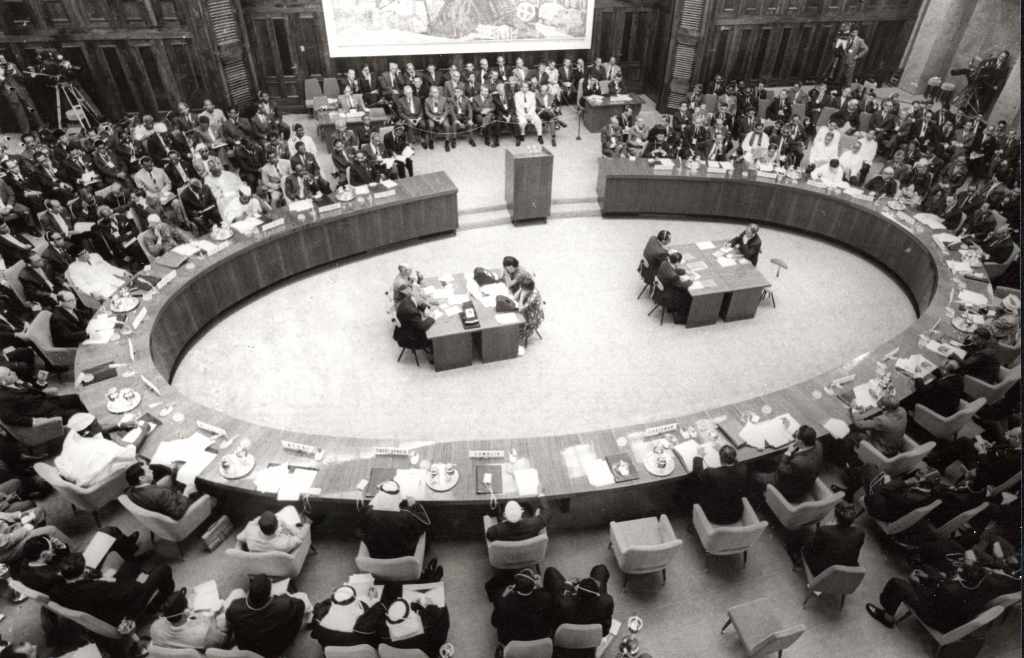

Belgrade, the capital of SFR Yugoslavia and SR Serbia, hosted the first Non-Aligned Movement Summit in September 1961, reflecting Yugoslavia's independent foreign policy and its significant role in global affairs. It also hosted the first major gathering of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) aimed at implementing the Helsinki Accords from October 1977 to March 1978. The 1972 smallpox outbreak in SAP Kosovo and other parts of SR Serbia was the last major outbreak of smallpox in Europe since World War II. The socialist period saw significant industrialization and improvements in living standards for many, but also suppressed political dissent and maintained a complex balance of power among its constituent republics and ethnic groups, which ultimately proved unsustainable after Tito's death in 1980.

3.9. Breakup of Yugoslavia and Political Transition

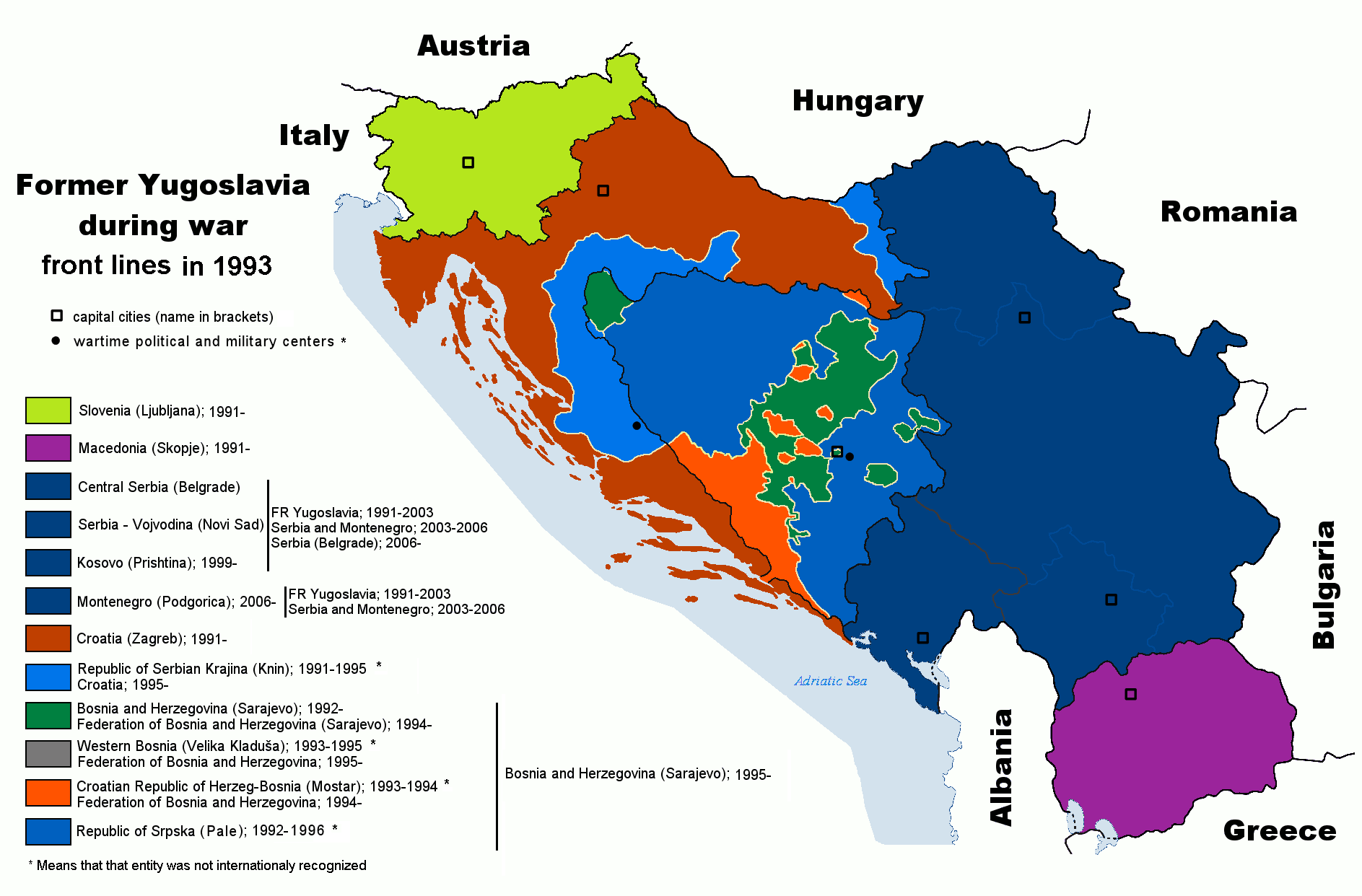

In 1989, Slobodan Milošević rose to power in Serbia. Milošević promised a reduction of powers for the autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina, where his allies subsequently took over power during the Anti-bureaucratic revolution. This ignited tensions with the communist leadership of other Yugoslav republics and awoke ethnic nationalism across Yugoslavia, eventually resulting in its breakup. Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia declared independence during 1991 and 1992. Serbia and Montenegro remained together as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). However, according to the Badinter Commission, the FRY was not legally considered a continuation of the former SFRY but a new state.

Fueled by ethnic tensions, the Yugoslav Wars (1991-2001) erupted, with the most severe conflicts in Croatia and Bosnia, where large ethnic Serb communities opposed independence. The FRY remained outside the direct conflicts initially but provided logistic, military, and financial support to Serb forces, leading to UN sanctions against FRY, political isolation, and economic collapse (GDP decreased from 24.00 B USD in 1990 to under 10.00 B USD in 1993). Serbia was later sued for alleged genocide by Bosnia and Herzegovina (see Bosnian genocide case) and Croatia (see Croatia-Serbia genocide case), but the main charges were dismissed, though Serbia was found to have failed to prevent genocide in Srebrenica.

Multi-party democracy was introduced in Serbia in 1990, but Milošević maintained strong political influence over state media and security apparatus, suppressing dissent. When the ruling Socialist Party of Serbia refused to accept defeat in municipal elections in 1996, Serbians engaged in large protests.

In 1998, continued clashes between the Albanian guerrilla Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and Yugoslav security forces led to the Kosovo War (1998-99). Widespread human rights violations and ethnic cleansing of Albanians by Serbian forces prompted NATO intervention through a bombing campaign against Yugoslavia in 1999. This led to the withdrawal of Serbian forces and the establishment of UN administration in Kosovo. After the Yugoslav Wars, Serbia became home to the highest number of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Europe, a stark reminder of the human cost of the conflicts.

After presidential elections in September 2000, opposition parties accused Milošević of electoral fraud. A campaign of civil resistance, led by the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS), culminated on 5 October when half a million people congregated in Belgrade, compelling Milošević to concede defeat. The fall of Milošević ended Yugoslavia's international isolation. Milošević was sent to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) to face charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The DOS announced that FR Yugoslavia would seek to join the European Union. In 2003, the FRY was renamed Serbia and Montenegro.

Serbia's political climate remained tense. In 2003, Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić, a key figure in the democratic transition, was assassinated. The 2004 unrest in Kosovo resulted in 19 deaths and the destruction or damage of numerous Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries, highlighting ongoing ethnic tensions and the vulnerability of minorities and cultural heritage. The transition period was marked by efforts to democratize, address war crimes through cooperation with the ICTY (though often fraught with domestic political resistance), and rebuild a society deeply scarred by years of conflict and authoritarian rule.

3.10. Contemporary Serbia

On 21 May 2006, Montenegro held an independence referendum, with 55.4% of voters favoring independence. On 5 June 2006, Serbia declared its own independence, marking the re-emergence of Serbia as a sovereign state and the formal dissolution of the union with Montenegro. The National Assembly of Serbia declared Serbia the legal successor to the former state union.

The Assembly of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence from Serbia on 17 February 2008. Serbia immediately condemned the declaration and continues to deny Kosovo's statehood, considering it an integral part of its sovereign territory as the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija. The declaration has sparked varied responses from the international community, with many countries recognizing Kosovo's independence while others, including major powers like Russia and China, do not. Status-neutral talks between Serbia and Kosovo-Albanian authorities, mediated by the EU, have been ongoing in Brussels to normalize relations, a key condition for Serbia's EU aspirations.

Serbia officially applied for membership in the European Union on 22 December 2009, and received candidate status on 1 March 2012. Accession negotiations commenced in January 2014. However, progress has been slow, often linked to the Kosovo issue and concerns about the rule of law, media freedom, and democratic backsliding in Serbia.

Since Aleksandar Vučić and his Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) came to power in 2012, numerous international analysts and organizations have reported a decline in democratic standards, increased authoritarian tendencies, and a deterioration of media freedom and civil liberties. This period has been marked by a concentration of power, pressure on independent institutions, and a challenging environment for opposition parties and critical voices. Protests against the government, citing issues like electoral irregularities, corruption, and erosion of democratic norms, have occurred, notably after the 2023 parliamentary election, which the opposition alleged was fraudulent.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, a state of emergency and curfew were introduced. A constitutional referendum in January 2022 approved amendments concerning the judiciary, presented as a step toward reducing political influence, though concerns remain about their full implementation and impact.

Serbia was chosen to host the international specialized exposition Expo 2027. The government's collaboration with Rio Tinto on a major lithium mining project has sparked significant public debate and protests due to environmental and social concerns, highlighting ongoing tensions between economic development and environmental protection/social welfare. Contemporary Serbia continues to navigate complex domestic and international challenges, including efforts towards EU accession, managing the Kosovo dispute, strengthening democratic institutions, upholding human rights, and ensuring social and economic progress for all its citizens, particularly vulnerable groups.

4. Geography

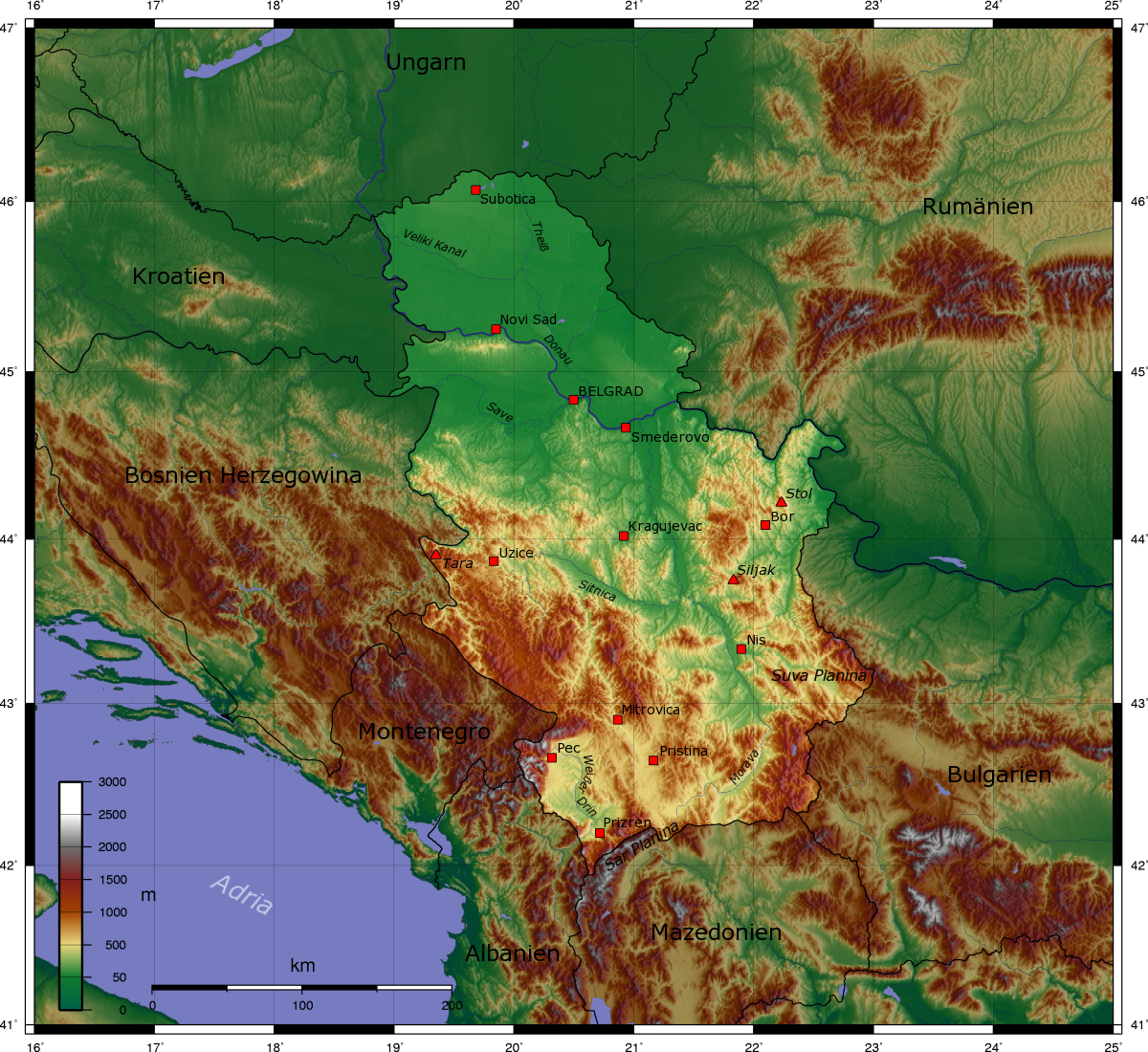

Serbia is a landlocked country situated at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, occupying a significant portion of the Balkan Peninsula and the southern part of the Pannonian Plain. Its geographical position has historically made it a vital transit route. The country is characterized by diverse topography, with fertile plains in the north, rolling hills in the central region, and mountainous terrain in the south.

Serbia lies between latitudes 41° and 47° N, and longitudes 18° and 23° E. The country covers a total area of 34 K mile2 (88.50 K km2) (including the disputed territory of Kosovo); excluding Kosovo, the total area is 30 K mile2 (77.47 K km2). Its total border length amounts to 1.3 K mile (2.03 K km). Serbia borders Hungary to the north, Romania to the northeast, Bulgaria to the southeast, North Macedonia to the south, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to the west, and Montenegro to the southwest. Serbia claims a border with Albania through the disputed territory of Kosovo.

The northern third of the country, primarily Vojvodina and the Mačva region, is dominated by the fertile Pannonian Plain. The easternmost tip of Serbia extends into the Wallachian Plain. The terrain of central Serbia consists chiefly of hills traversed by rivers. Mountains dominate the southern third of Serbia. The Dinaric Alps stretch in the west and southwest, following the flow of the Drina and Ibar rivers. The Carpathian Mountains and Balkan Mountains stretch in a north-south direction in eastern Serbia. Ancient mountains in the southeast corner of the country belong to the Rilo-Rhodope Mountain system.

Elevation ranges from the Midžor peak of the Balkan Mountains at 7.1 K ft (2.17 K m) (the highest peak in Serbia, excluding Kosovo) to the lowest point of just 56 ft (17 m) near the Danube river at Prahovo. The largest lake is Đerdap Lake (63 mile2 (163 km2)) on the Danube, and the longest river passing through Serbia is the Danube (365 mile (587.35 km)).

4.1. Climate

The climate of Serbia is influenced by the landmass of Eurasia, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Mediterranean Sea. With mean January temperatures around 32 °F (0 °C), and mean July temperatures of 71.6 °F (22 °C), it can be classified as a warm-humid continental or humid subtropical climate. In the north, the climate is more continental, characterized by cold winters and hot, humid summers, along with well-distributed rainfall patterns. In the south, summers and autumns are drier, and winters are relatively cold, with heavy inland snowfall in the mountains.

Differences in elevation, proximity to the Adriatic Sea and large river basins, as well as exposure to winds, account for climate variations. Southern Serbia is subject to Mediterranean influences. The Dinaric Alps and other mountain ranges contribute to the cooling of most of the warm air masses. Winters are quite harsh in the Pešter plateau due to the surrounding mountains. One of the notable climatic features of Serbia is Košava, a cold and very squally southeastern wind that originates in the Carpathian Mountains. It follows the Danube northwest through the Iron Gate, where it gains a jet effect, and continues to Belgrade, sometimes spreading as far south as Niš.

The average annual air temperature for the period 1961-1990 for areas with an elevation up to 984 ft (300 m) is 51.620000000000005 °F (10.9 °C). Areas with an elevation of 984 ft (300 m) have an average annual temperature of around 50 °F (10 °C), and those over 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m) in elevation average around 42.8 °F (6 °C). The lowest recorded temperature in Serbia was -39.099999999999994 °F (-39.5 °C) on 13 January 1985, at Karajukića Bunari in Pešter, and the highest was 112.82 °F (44.9 °C) on 24 July 2007, recorded in Smederevska Palanka.

Serbia is among European countries with a very high risk of natural hazards such as earthquakes, storms, floods, and droughts. It is estimated that potential floods, particularly in areas of Central Serbia, threaten over 500 larger settlements and an area of 6.2 K mile2 (16.00 K km2). The most disastrous were the floods in May 2014, which resulted in 57 deaths and inflicted damage exceeding 1.50 B EUR.

4.2. Hydrology

Almost all of Serbia's rivers drain to the Black Sea, primarily via the Danube river. The Danube, the second-longest European river, flows through Serbia for 365 mile (588 km) (21% of its overall length) and represents the major source of fresh water. Its largest tributaries joining within Serbia are the Great Morava (the longest river entirely in Serbia with a length of 306 mile (493 km)), the Sava, and the Tisza rivers. A notable exception is the Pčinja, which flows into the Aegean Sea. The Drina river forms a significant part of the natural border between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia and is a major attraction for kayaking and rafting.

Due to the terrain configuration, natural lakes in Serbia are sparse and small, mostly located in the lowlands of Vojvodina, such as the aeolian Palić Lake or numerous oxbow lakes along river courses (like Zasavica and Carska Bara). However, there are numerous artificial lakes, mostly created by hydroelectric dams. The largest of these is Đerdap Lake (Iron Gates) on the Danube, with 63 mile2 (163 km2) on the Serbian side (total area of 98 mile2 (253 km2) shared with Romania). Other significant artificial lakes include Perućac on the Drina and Vlasina Lake. The largest waterfall, Jelovarnik, located in Kopaonik, is 233 ft (71 m) high. Serbia possesses an abundance of relatively unpolluted surface waters and numerous underground natural and mineral water sources of high quality, presenting opportunities for export and economic improvement, although extensive exploitation and production of bottled water began relatively recently.

4.3. Environment

Serbia boasts a rich ecosystem and significant species diversity. Covering only 1.9% of the total European territory, Serbia is home to 39% of European vascular flora, 51% of European fish fauna, 40% of European reptile and amphibian fauna, 74% of European bird fauna, and 67% of European mammal fauna. Its abundance of mountains and rivers creates an ideal environment for a variety of animals, many of which are protected, including wolves, lynx, bears, foxes, and stags. There are 17 snake species living throughout the country, 8 of which are venomous.

The Tara Mountain in western Serbia is one of the last regions in Europe where bears can still live in absolute freedom. Serbia is also home to about 380 species of birds. Carska Bara, a wetland area, hosts over 300 bird species in just a few square kilometers. The Uvac Gorge is considered one of the last European habitats of the griffon vulture. In the area around the city of Kikinda, in the northernmost part of the country, some 145 endangered long-eared owls have been noted, making it the world's largest settlement of these species. The country is also considerably rich in threatened species of bats and butterflies.

There are 380 protected areas of Serbia, encompassing 1.9 K mile2 (4.95 K km2), or 6.4% of the country. These protected areas include 5 national parks (Đerdap, Tara, Kopaonik, Fruška Gora, and Šar Mountain), 15 nature parks, 15 "landscapes of outstanding features," 61 nature reserves, and 281 natural monuments.

With 29.1% of its territory covered by forest, Serbia is considered a middle-forested country, compared to the world forest coverage of 30% and the European average of 35%. The total forest area in Serbia is 5.6 M acre (2.25 M ha) (2.9 M acre (1.19 M ha) or 53% are state-owned, and 2.6 M acre (1.06 M ha) or 47% are privately owned), which is approximately 0.7 acre (0.3 ha) per inhabitant. Common trees include oak, beech, pines, and firs. Serbia had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.29/10, ranking it 105th globally out of 172 countries.

Environmental challenges in Serbia include air pollution, particularly in industrial areas like Bor (due to copper mining and smelting) and Pančevo (oil and petrochemical industry). Some cities suffer from water supply problems due to mismanagement, lack of investment, and water pollution (e.g., pollution of the Ibar River from the Trepča zinc-lead complex, or natural arsenic in underground waters in Zrenjanin). Poor waste management is another significant environmental problem, with recycling being a fledgling activity; only 15% of its waste is turned back for reuse. The 1999 NATO bombing caused serious environmental damage, with several thousand tonnes of toxic chemicals stored in targeted factories and refineries released into the soil and water basins, the long-term effects of which continue to be a concern for public health and ecosystem integrity.

5. Politics

Serbia is a parliamentary republic with a governmental structure based on the separation of powers into legislative, executive, and judiciary branches, as defined by the Constitution of 2006. The political system has undergone significant transitions since the breakup of Yugoslavia, with ongoing efforts towards democratic consolidation and European integration, though these processes have faced challenges, including concerns about democratic backsliding in recent years.

5.1. Government Structure

The President of the Republic (Predsednik Republike) is the head of state, elected by popular vote for a five-year term and limited by the Constitution to a maximum of two terms. The President is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, has the procedural duty of appointing the prime minister with the consent of the parliament, and holds some influence on foreign policy. Aleksandar Vučić of the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) is the current president. The official residence of the presidency is Novi Dvor in Belgrade.

The Government (Vlada) is the executive branch, composed of the Prime Minister and cabinet ministers. The Government is responsible for proposing legislation and a budget, executing laws, and guiding foreign and internal policies. The Prime Minister is appointed by the President and approved by the National Assembly. The current prime minister is Miloš Vučević of the Serbian Progressive Party.

The National Assembly (Narodna skupština) is the unicameral legislative branch. It has the power to enact laws, approve the budget, schedule presidential elections, select and dismiss the Prime Minister and other ministers, declare war, and ratify international treaties and agreements. It is composed of 250 members elected through proportional representation for four-year terms. Following the 2023 parliamentary election, the populist Serbian Progressive Party and its allies hold a significant majority of seats.

Serbia was ranked 5th in Europe in 2021 by the number of women holding high-ranking public functions, indicating some progress in gender representation in politics, though challenges in achieving full gender equality persist across various sectors of society.

5.2. Law and Judiciary

Serbia has a civil law legal system, with a three-tiered judicial structure. The Supreme Court of Cassation is the court of last resort. Courts of Appeal serve as the appellate instance, while Basic and High courts are the general jurisdictions at first instance. Specialized courts include the Administrative Court, commercial courts (with the Commercial Court of Appeal at second instance), and misdemeanor courts (including the High Misdemeanor Court at second instance). The judiciary is overseen by the Ministry of Justice. Efforts to reform the judiciary to enhance its independence, efficiency, and reduce political influence have been ongoing, particularly in the context of EU accession requirements, with a constitutional referendum in 2022 aimed at such reforms.

Law enforcement is primarily the responsibility of the Serbian Police, which is subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior. The Serbian Police force includes approximately 27,363 uniformed officers. National security and counterintelligence are the responsibility of the Security Intelligence Agency (BIA).

5.3. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Serbia is complex and has been a subject of scrutiny by both domestic and international organizations. While the constitution guarantees fundamental rights and freedoms, challenges persist in their full implementation and protection. Key areas of concern include the rights of ethnic and national minorities, freedom of the press and media, LGBTQ+ rights, and issues related to historical accountability and transitional justice for war crimes committed during the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s.

Ethnic minorities, such as Hungarians, Bosniaks, Roma, Albanians, Croats, and others, are constitutionally guaranteed rights, including language use, education, and cultural preservation, particularly in regions like Vojvodina. However, discrimination and socio-economic marginalization, especially affecting the Roma community, remain significant problems. Anti-minority sentiment and hate speech periodically surface.

Freedom of the press and media has deteriorated in recent years. Reports from organizations like Reporters Without Borders and Freedom House have highlighted increased government pressure on media outlets, biased reporting by pro-government media, threats and attacks against journalists, and a lack of transparency in media ownership and funding. This environment has led to concerns about media pluralism and the ability of citizens to access diverse and objective information.

LGBTQ+ rights have seen some legal progress, but societal acceptance remains low, and LGBTQ+ individuals often face discrimination, harassment, and violence. While pride parades have been held in Belgrade, they often require heavy police protection.

Transitional justice and accountability for war crimes remain sensitive issues. While Serbia has cooperated to some extent with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and domestic war crimes trials have taken place, progress has been criticized as slow and insufficient by human rights groups. There are concerns about the glorification of convicted war criminals by some public figures and media outlets, which undermines reconciliation efforts in the region.

Efforts towards improving the human rights situation are ongoing, often driven by civil society organizations and as part of Serbia's EU accession process, which requires adherence to EU standards on rule of law and fundamental rights. However, significant challenges remain in ensuring that all citizens can fully enjoy their human rights without discrimination and that democratic institutions effectively protect these rights.

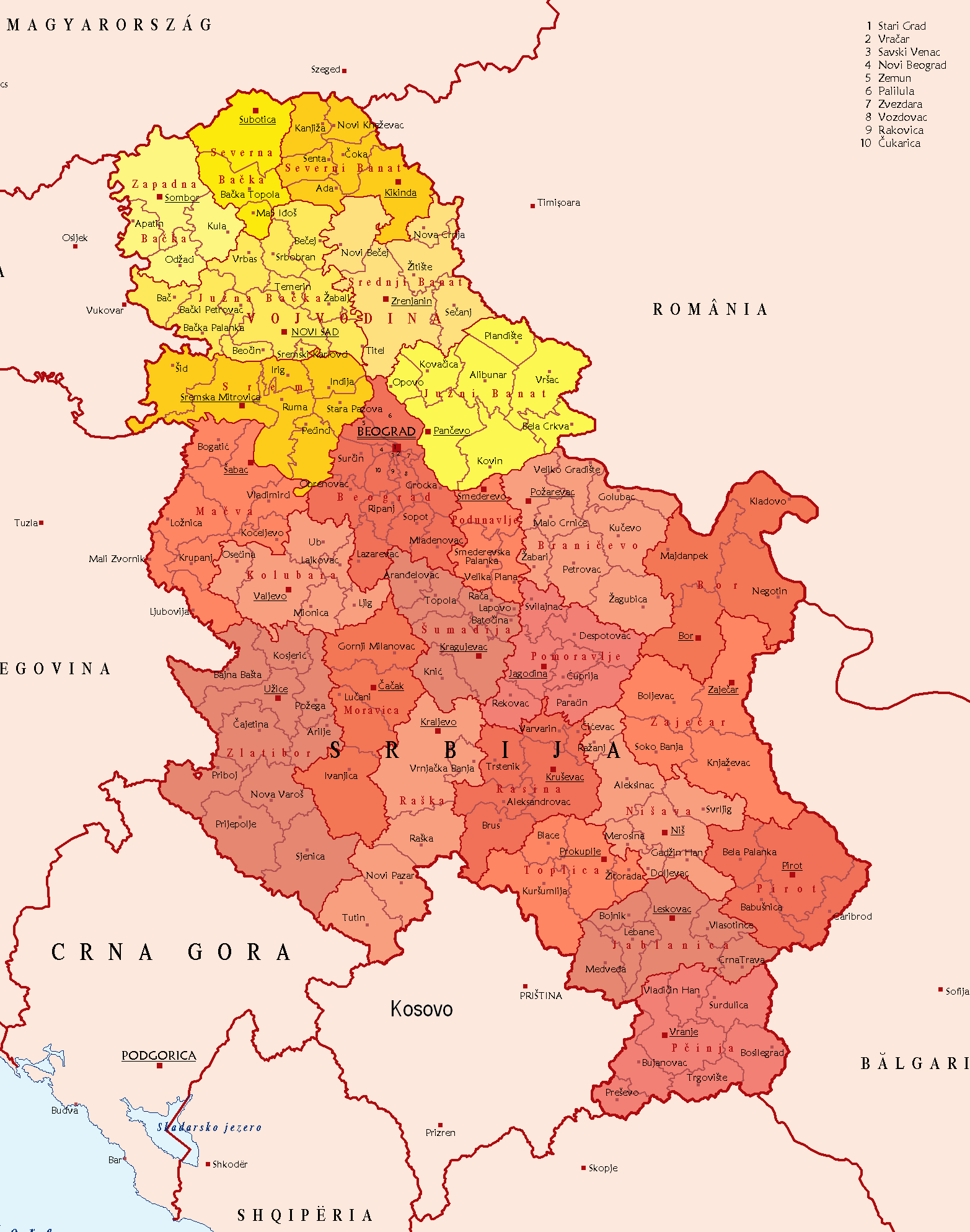

6. Administrative Divisions

Serbia is a unitary state administratively divided into municipalities/cities, districts, and two autonomous provinces. This structure provides for local self-government and varying degrees of regional autonomy.

In Serbia, excluding Kosovo, there are 145 municipalities (opštine) and 29 cities (gradovi), which form the basic units of local self-government. Beyond municipalities and cities, there are 24 districts (okruzi), with the City of Belgrade constituting an additional, distinct district. Except for Belgrade, which has an elected local government with broader responsibilities, districts primarily function as regional centers of state authority and are administrative divisions without their own elected bodies or significant autonomous powers.

6.1. Autonomous Provinces

The Constitution of Serbia recognizes two autonomous provinces:

1. The Autonomous Province of Vojvodina is located in the north. It has a distinct multi-ethnic and multi-cultural identity, with several official languages in use besides Serbian. Vojvodina has its own elected assembly and government with significant powers in areas such as education, culture, healthcare, and economic development.

2. The Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija is located in the south. Serbia considers Kosovo an integral part of its territory with autonomous status. However, following the Kosovo War in 1999, Kosovo was placed under UN administration (UNMIK) as per UNSC Resolution 1244. In 2008, the Assembly of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence. Serbia does not recognize this declaration and continues to claim sovereignty over the territory. The "Kosovo Issue" remains a significant political and diplomatic challenge, with ongoing EU-mediated dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina aimed at normalizing relations. The Serb minority in Kosovo faces particular challenges regarding their rights and security.

The remaining area of Serbia, not included in these two autonomous provinces, is often referred to as Central Serbia. This region does not have its own overarching regional authority equivalent to the autonomous provinces.

6.2. Districts and Major Cities

Serbia is divided into 24 administrative districts (okruzi) plus the City of Belgrade. These districts are primarily units of state administration at the regional level. Below is a list of the districts:

- Bor

- Braničevo

- Jablanica

- Kolubara

- Mačva

- Moravica

- Nišava

- Pčinja

- Pirot

- Podunavlje

- Pomoravlje

- Rasina

- Raška

- Šumadija

- Toplica

- Zaječar

- Zlatibor

- Central Banat (Vojvodina)

- North Bačka (Vojvodina)

- North Banat (Vojvodina)

- South Bačka (Vojvodina)

- South Banat (Vojvodina)

- Srem (Vojvodina)

- West Bačka (Vojvodina)

Districts claimed by Serbia within the disputed territory of Kosovo:

- Kosovo

- Kosovska Mitrovica

- Kosovo-Pomoravlje

- Peć

- Prizren

Major Cities:

Serbia has several major cities that serve as economic, cultural, and administrative centers.

| Rank | City | District | Population (Urban Area) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Belgrade | City of Belgrade | 1,197,714 |

| 2 | Novi Sad | South Bačka | 306,702 |

| 3 | Niš | Nišava District | 178,976 (city proper); 249,501 (wider urban area defined by statistical office) |

| 4 | Kragujevac | Šumadija District | 146,315 |

| 5 | Subotica | North Bačka | 88,752 |

| 6 | Pančevo | South Banat | 73,401 |

| 7 | Zrenjanin | Central Banat | 67,129 |

| 8 | Čačak | Moravica District | 69,598 |

| 9 | Novi Pazar | Raška District | 71,462 |

| 10 | Smederevo | Podunavlje District | 59,261 |

| 11 | Kraljevo | Raška District | 57,914 |

| 12 | Leskovac | Jablanica District | 58,338 |

| 13 | Kruševac | Rasina District | 68,119 |

| 14 | Užice | Zlatibor District | 54,965 |

| 15 | Valjevo | Kolubara District | 56,059 |

Note: Population figures for Niš can vary based on the definition of its urban area. The list prioritizes cities with significant population and economic/cultural importance.

7. Foreign Relations

Serbia's foreign policy is primarily focused on its strategic goal of European Union (EU) membership, maintaining regional stability, and addressing the complex Kosovo issue. The country also cultivates relationships with major global powers and international organizations. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs conducts Serbia's foreign relations, maintaining a network of embassies and consulates worldwide. Serbia is a member of the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and other international bodies. It officially adheres to a policy of military neutrality.

7.1. Relations with the European Union

Serbia officially applied for EU membership on 22 December 2009 and was granted candidate status on 1 March 2012. Accession negotiations formally began in January 2014. The EU is Serbia's largest trading partner and investor. The accession process requires Serbia to undertake comprehensive reforms across various sectors, particularly in the areas of rule of law, judicial independence, fight against corruption and organized crime, fundamental rights, and public administration. Progress in these areas has been noted by the European Commission, but challenges remain, and the pace of reforms has sometimes been criticized as slow. The normalization of relations with Kosovo is a key condition for Serbia's EU accession, with the EU facilitating the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue. The EU provides significant financial and technical assistance to Serbia through instruments like the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA) to support its reform efforts. While the prospect of membership by 2030 has been mentioned, it depends on sustained reform momentum and resolving outstanding issues, particularly concerning Kosovo and alignment with EU foreign policy.

7.2. Kosovo Issue

Following Kosovo's unilateral declaration of independence on 17 February 2008, Serbia has maintained its position that Kosovo is an integral part of its territory, the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija, under UNSC Resolution 1244. Serbia does not recognize Kosovo as a sovereign state and actively campaigns against its membership in international organizations. The international community is divided on Kosovo's status, with many Western countries, including the United States and most EU member states, recognizing its independence, while others, such as Russia, China, and five EU member states, do not.

The status of the Serb minority in Kosovo is a major concern for Serbia. Issues include their security, property rights, cultural and religious heritage protection (especially Serbian Orthodox monasteries), and political representation. The EU has been mediating a dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina since 2011, aimed at normalizing relations and resolving practical issues affecting the daily lives of citizens. Several agreements have been reached, such as the 2013 Brussels Agreement, which included provisions for the establishment of an Association/Community of Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo, though its implementation has been contentious and incomplete.

Humanitarian concerns, including the situation of internally displaced persons (IDPs) from Kosovo residing in Serbia and the rights of all communities in Kosovo, remain relevant. Achieving a comprehensive, legally binding agreement on the normalization of relations is considered crucial for the European perspective of both Serbia and Kosovo. The process is complex, involving deeply entrenched historical narratives, national identities, and geopolitical interests, requiring sustained diplomatic efforts and a commitment to peaceful resolution from all stakeholders.

7.3. Relations with Neighboring Countries and Major Powers

Serbia aims to maintain stable and cooperative relations with its Balkan neighbors. However, historical legacies from the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s sometimes strain these relationships, particularly with Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (especially concerning Republika Srpska). Relations with Montenegro are generally stable despite its independence and recognition of Kosovo. Serbia also engages with North Macedonia, Albania, Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary. Regional cooperation initiatives like the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) and the Berlin Process are important frameworks for Serbia.

Regarding major global powers:

- Russia: Serbia maintains historically close ties with Russia, based on shared Slavic and Orthodox Christian heritage, as well as political and economic interests. Russia is a key supporter of Serbia's stance on Kosovo at the UN Security Council. Serbia relies on Russia for energy supplies and has not joined Western sanctions against Russia following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, a position that has complicated its EU accession path.

- China: Relations with China have strengthened significantly in recent years, particularly in economic and infrastructure development through China's Belt and Road Initiative. China also supports Serbia's position on Kosovo.

- United States: The US supports Serbia's EU integration and the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue. While relations have improved since the 1990s, differences remain, particularly regarding Kosovo and Serbia's ties with Russia. The US is a significant partner in security cooperation and democratic reforms.

Serbia navigates a complex geopolitical landscape, balancing its EU aspirations with its traditional ties and economic partnerships, while striving to protect its national interests, especially concerning Kosovo.

8. Military

The Serbian Armed Forces are subordinate to the Ministry of Defence and are composed of the Army and the Air Force and Air Defence. Although a landlocked country, Serbia operates a River Flotilla which patrols the Danube, Sava, and Tisza rivers. The Serbian Chief of the General Staff reports to the Defence Minister and is appointed by the President, who is the commander-in-chief. The country has a policy of military neutrality.

8.1. Organization and Strength

Traditionally having relied on a large number of conscripts, the Serbian Armed Forces underwent a period of downsizing, restructuring, and professionalization following the Yugoslav Wars and the end of the union with Montenegro. Conscription was abolished in 2011. As of recent estimates, the Serbian Armed Forces have approximately 28,000 active troops. This active force is supplemented by an "active reserve" numbering around 20,000 members and a larger "passive reserve" of about 170,000 personnel.

The Serbian Army is the largest component, equipped with tanks (such as the M-84 and T-72), armored personnel carriers, artillery, and anti-tank systems. Modernization efforts have focused on acquiring new equipment, upgrading existing platforms, and improving training. The Air Force and Air Defence operate fighter aircraft (including MiG-29s), transport aircraft, helicopters, and air defense missile systems. Recent acquisitions and upgrades aim to enhance air surveillance and combat capabilities. The River Flotilla is equipped with patrol boats and minesweepers. Serbia has a significant domestic defense industry that produces a range of military equipment, contributing to both national defense needs and exports.

8.2. Defense Policy and International Activities

Serbia formally adheres to a policy of military neutrality, which was proclaimed by a resolution of the Serbian Parliament in December 2007. This policy means Serbia does not intend to join military alliances like NATO or the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), though it cooperates with both. Joining any military alliance would be contingent on a popular referendum, a stance acknowledged by NATO. The neutrality policy is largely influenced by public opinion, shaped by the legacy of the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia.

Despite its neutrality, Serbia participates in NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) program, engaging in joint military exercises and cooperation in areas like defense reform and peacekeeping training. It signed an Individual Partnership Action Plan (IPAP) with NATO. Serbia also holds observer status in the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) since 2013 and participates in some of its activities.

The Serbian Armed Forces are involved in international peacekeeping operations under the auspices of the United Nations and the European Union. Serbian personnel have been deployed in missions in countries such as Lebanon, Cyprus, the Central African Republic, and Mali. These deployments reflect Serbia's commitment to international peace and security. Serbia also engages in bilateral and multilateral military exercises with various countries to enhance interoperability and share expertise. Modernization of equipment and improvement of personnel training remain key priorities for the Serbian Armed Forces to meet contemporary security challenges. In 2024, the Serbian president approved the reintroduction of mandatory military service, planned to last 75 days, starting from 2025, pending government adoption.

9. Economy

Serbia has an emerging market economy classified in the upper-middle income range. The economy is largely service-based, followed by industry and agriculture. The transition from a socialist system and the impacts of the Yugoslav Wars and international sanctions in the 1990s significantly affected its economic development, but reforms and foreign investment have contributed to recovery and growth in recent decades, albeit with ongoing challenges. The official currency is the Serbian dinar (RSD), and the central bank is the National Bank of Serbia.

9.1. Economic Overview

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Serbia's nominal GDP in 2024 is estimated at 81.87 B USD or 12.38 K USD per capita, while its GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) stood at 185.01 B USD or 27.98 K USD per capita. The services sector dominates the economy, accounting for approximately 67.9% of GDP, followed by industry with 26.1%, and agriculture with 6%.

The Serbian economy faced significant challenges during the global economic crisis of 2008-2009 and subsequent recessions. After a period of strong growth, it experienced negative growth in 2009, 2012, and 2014. Public debt increased substantially during this period but has seen a downward trend in recent years, stabilizing around 50% of GDP. Key economic challenges include unemployment (though it has decreased, it remains a concern, especially for youth), managing public debt, reducing the trade deficit, and implementing structural reforms to improve competitiveness and attract further foreign direct investment (FDI). Since 2000, Serbia has attracted over 40.00 B USD in FDI, with significant investments from companies like Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, Siemens, Bosch, Philip Morris, and Michelin, as well as Russian energy giants Gazprom and Lukoil, and Chinese metallurgy firms Hesteel and Zijin Mining.

The Belgrade Stock Exchange is the country's sole stock exchange. Serbia is ranked 52nd on the Social Progress Index and 54th on the Global Peace Index (as of recent reports). The average monthly net salary in May 2019 was 47,575 dinars (approximately 525 USD at the time). Labor rights and social equity remain important considerations in Serbia's socio-economic development, with trade unions and civil society organizations advocating for better working conditions and social protections.

Serbia has free trade agreements with the EFTA and CEFTA, a preferential trade regime with the European Union, a Generalised System of Preferences with the United States, and individual free trade agreements with Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Turkey. These agreements aim to boost exports, which reached 19.20 B USD in 2018. However, the country still has an unfavorable trade balance, with imports exceeding exports.

9.2. Agriculture

Serbia possesses favorable natural conditions, including fertile land and a suitable climate, for diverse agricultural production. The country has approximately 13 M acre (5.06 M ha) of agricultural land (around 1.7 acre (0.7 ha) per capita), of which about 8.1 M acre (3.29 M ha) is arable land (1.1 acre (0.45 ha) per capita). In 2016, Serbia exported agricultural and food products worth 3.20 B USD, with an export-import ratio of 178%. Agricultural exports constitute more than a fifth of Serbia's total sales on the world market.

Agricultural production is most prominent in the fertile Pannonian Plain of Vojvodina. Other significant agricultural regions include Mačva, Pomoravlje, Tamnava, Rasina, and Jablanica. Crop production accounts for about 70% of agricultural output, with livestock production making up the remaining 30%.

Serbia is one of the world's largest producers of plums (582,485 tonnes, second to China) and raspberries (89,602 tonnes, second to Poland). It is also a significant producer of maize (corn), with 6.48 million tonnes (ranked 32nd globally), and wheat, with 2.07 million tonnes (ranked 35th globally). Other important agricultural products include sunflowers, sugar beets, soybeans, potatoes, apples, pork, beef, poultry, and dairy products.

There are 138 K acre (56.00 K ha) of vineyards in Serbia, producing about 230 million litres of wine annually. The most famous viticulture regions are located in Vojvodina and Šumadija. The agricultural sector plays a crucial role in Serbia's economy, providing employment and contributing significantly to exports.

9.3. Industry

Serbia's industrial sector was severely impacted by UN sanctions and trade embargoes during the 1990s, the NATO bombing in 1999, and the subsequent transition to a market economy in the 2000s. Industrial output experienced a dramatic downsizing, and in 2013, it was expected to be only about half of its 1989 level. However, recent years have seen efforts towards recovery and modernization, supported by foreign direct investment.

Main industrial sectors include:

- Automotive**: Dominated by a cluster located in Kragujevac and its vicinity, with Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (now Stellantis) being a major player. The automotive industry contributes significantly to exports, around 2.00 B USD in some years.

- Mining**: Serbia has comparatively strong mining resources. It is a major producer of coal (18th largest globally, 7th in Europe), extracted from large deposits in the Kolubara and Kostolac basins. It is also a significant copper producer (23rd largest globally, 3rd in Europe), with extraction primarily by Zijin Bor Copper (acquired by Chinese Zijin Mining in 2018). Gold extraction is also developed around Majdanpek. A controversial lithium mining project with Rio Tinto in the Jadar Valley has faced public opposition due to environmental and social concerns.

- Non-ferrous Metals**: Besides copper, Serbia has other non-ferrous metal processing facilities.

- Food Processing**: A well-known sector both regionally and internationally, it is one of the strong points of the economy. International brands like PepsiCo and Nestlé have production in Serbia.

- Electronics**: This industry had its peak in the 1980s and is now smaller, but has seen some revival with investments from companies like Siemens (wind turbines), Panasonic (lighting devices), and Gorenje (electrical home appliances).

- Pharmaceuticals**: Comprises a dozen manufacturers of generic drugs, with Hemofarm in Vršac and Galenika in Belgrade being major domestic producers, meeting a significant portion of local demand.

- Clothing and Textiles**: A traditional industry that continues to contribute to exports.

- Arms Industry**: A legacy of Cold War Yugoslavia, Serbia has a notable arms industry, being a leading weapons manufacturer in the Western Balkans and a significant arms exporter, employing around 20,000 people with exports surpassing 1.60 B USD in 2023.

As of September 2017, Serbia had 14 free economic zones, which have attracted foreign direct investments. The industrial sector's development is crucial for Serbia's economic growth, but it also faces challenges related to modernization, environmental sustainability, and ensuring fair labor practices.

9.4. Energy

The energy sector is one of the largest and most important sectors of the Serbian economy. Serbia is a net exporter of electricity but an importer of key fuels such as oil and gas. The country has abundant coal reserves, particularly lignite, and significant, albeit smaller, reserves of oil and gas.

Serbia's proven reserves of 5.5 billion tonnes of coal lignite are the fifth largest in the world (second in Europe, after Germany). These reserves are primarily found in two large deposits: Kolubara (4 billion tonnes) and Kostolac (1.5 billion tonnes). While small on a global scale, Serbia's oil (77.4 million tonnes of oil equivalent) and gas reserves (48.1 billion cubic metres) have regional importance, being the largest in the former Yugoslavia region (excluding Romania). Almost 90% of discovered oil and gas are found in Banat, and these fields are among the largest in the Pannonian Basin.

Electricity production in Serbia in 2015 was 36.5 billion kilowatt-hours (kWh), while final electricity consumption amounted to 35.5 billion kWh. Most electricity is generated from thermal power stations (72.7% of all electricity), primarily lignite-fired, with hydroelectric power plants contributing a smaller share (27.3%). There are six lignite-operated thermal power plants with an installed capacity of 3936 MW. The total installed capacity of nine hydroelectric power plants is 2831 MW, with the Đerdap 1 (Iron Gate 1) on the Danube being the largest. Additionally, there are mazut and gas-operated thermal power plants with an installed capacity of 353 MW. The entire production of electricity is largely concentrated in Elektroprivreda Srbije (EPS), the state-owned public electric utility power company.

Current oil production in Serbia amounts to over 1.1 million tonnes of oil equivalent, satisfying about 43% of the country's needs, with the rest imported. The national petrol company, Naftna Industrija Srbije (NIS), was acquired by Gazprom Neft in 2008. NIS's refinery in Pančevo (capacity of 4.8 million tonnes) is one of the most modern oil refineries in Europe. It also operates a network of filling stations in Serbia and neighboring countries. There are 96 mile (155 km) of crude oil pipelines connecting Pančevo and Novi Sad refineries as part of the transnational Adria oil pipeline.

Serbia is heavily dependent on foreign sources of natural gas, with only 17% coming from domestic production (totaling 491 million cubic metres in 2012); the rest is imported, mainly from Russia via pipelines through Ukraine and Hungary. Srbijagas, a public company, operates the natural gas transportation system, which comprises 2.0 K mile (3.18 K km) of trunk and regional natural gas pipelines and a 450 million cubic metre underground gas storage facility at Banatski Dvor. In 2021, the Balkan Stream gas pipeline opened through Serbia, enhancing its role as a transit country and potentially improving its energy security. Serbia's energy policy faces challenges related to decarbonization, improving energy efficiency, and diversifying energy sources, particularly in line with EU environmental standards.

9.5. Transport

Serbia has a strategic transportation location, as the country's backbone, the Morava Valley, represents the easiest land route from continental Europe to Asia Minor and the Near East.

The Serbian road network carries the bulk of traffic. The total length of roads is 28 K mile (45.42 K km), of which 598 mile (962 km) are "class-IA state roads" (motorways), 2.8 K mile (4.52 K km) are "class-IB state roads" (national roads), 6.8 K mile (10.94 K km) are "class-II state roads" (regional roads), and 15 K mile (23.78 K km) are "municipal roads". While the motorway network has been expanding, with over 186 mile (300 km) constructed in the last decade and more under construction (e.g., A5 motorway, segments of A2), many other roads are of lower quality compared to Western European standards due to past underinvestment. Coach transport is extensive, connecting almost every place in the country, with major operators like Lasta and Niš-Ekspres. As of 2018, there were approximately 2 million registered passenger cars.

Serbia has 2.4 K mile (3.82 K km) of rail tracks, of which 0.8 K mile (1.28 K km) are electrified and 176 mile (283 km) are double-track. Major rail hubs are Belgrade and Niš. Key railroads include Belgrade-Subotica-Budapest (Hungary), which is being upgraded for high-speed rail (the Belgrade-Novi Sad section opened in 2022, with Novi Sad-Subotica expected by 2025), the Belgrade-Bar (Montenegro) line, and lines forming part of Pan-European Corridor X (Belgrade-Šid-Zagreb (Croatia) and Belgrade-Niš-Sofia (Bulgaria)). Rail services are operated by Srbija Voz (passenger) and Srbija Kargo (freight).

There are three international airports with regular passenger services: Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport, Niš Constantine the Great Airport, and Morava Airport (near Kraljevo). Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport is the busiest, serving as the hub for the flagship carrier Air Serbia, which flies to numerous international destinations and carried 2.75 million passengers in 2022. Vršac International Airport primarily serves as a training facility.

Serbia has 1.1 K mile (1.72 K km) of navigable inland waterways, almost all in the northern third of the country. The Danube is the most important, with other navigable rivers including the Sava, Tisza, Begej, and Timiș. These waterways connect Serbia to Northern and Western Europe via the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal and North Sea route, to Eastern Europe via Black Sea routes, and to Southern Europe via the Sava. Over 8 million tonnes of cargo were transported on Serbian rivers and canals in 2018. Major river ports include Novi Sad, Belgrade, Pančevo, Smederevo, Prahovo, and Šabac.

9.6. Telecommunications

Fixed telephone lines connect 81% of households in Serbia. With about 9.1 million users, the number of mobile phones surpasses the total population by 28%. The largest mobile operator is Telekom Srbija (operating under the mts brand) with 4.2 million subscribers, followed by Yettel (formerly Telenor Serbia) with 2.8 million users, and A1 (formerly Vip mobile) with about 2 million.

Approximately 58% of households have fixed-line (non-mobile) broadband Internet connections, while 67% are provided with pay television services (38% cable television, 17% IPTV, and 10% satellite). The digital television transition was completed in 2015, with the DVB-T2 standard adopted for signal transmission. The development of the ICT sector, including software development and outsourcing, has been a growing area of the Serbian economy, generating over 1.20 B USD in exports in 2018.

9.7. Tourism

Serbia is not a mass-tourism destination but offers a diverse range of touristic products. In 2019, over 3.6 million tourists were recorded in accommodations, with half being foreign. Foreign exchange earnings from tourism were estimated at 1.50 B USD that year.

Tourism primarily focuses on the country's mountains and spas, which are mostly visited by domestic tourists. Belgrade and, to a lesser extent, Novi Sad are preferred choices for foreign tourists, accounting for almost two-thirds of all foreign visits. The most famous mountain resorts include Kopaonik, Stara Planina, and Zlatibor. Serbia has many spa towns, with the largest being Vrnjačka Banja, Soko Banja, and Banja Koviljača. City-break and conference tourism are developed in Belgrade and Novi Sad.

Other touristic products offered by Serbia include natural wonders like Đavolja Varoš (Devil's Town), Christian pilgrimage to numerous Orthodox monasteries across the country (many of which are medieval), and river cruising along the Danube. Serbia hosts several internationally popular music festivals, such as the EXIT Festival in Novi Sad (which has won Best Major Festival at the European Festivals Awards) and the Guča Trumpet Festival, a renowned Balkan brass band event. Other notable festivals include the Nišville Jazz Festival in Niš and the Gitarijada rock festival in Zaječar. The development of rural tourism (agrotourism) and cultural tourism focusing on historical sites and traditions is also gaining traction.

10. Society

Serbian society is characterized by its demographic composition, linguistic landscape, religious makeup, and systems of education, healthcare, and media. It reflects a blend of historical influences and contemporary social trends, with ongoing efforts to address various social challenges and improve the quality of life for its citizens.

10.1. Demographics

As of the 2022 census, Serbia (excluding Kosovo) has a total population of 6,647,003. The overall population density is medium, at 85.8 inhabitants per square kilometer. Serbia has been experiencing a demographic crisis since the early 1990s, with a death rate continuously exceeding its birth rate, leading to a natural population decline. This is compounded by emigration. It is estimated that 500,000 people left Serbia during the 1990s, 20% of whom had higher education, contributing to a significant brain drain. Serbia has one of the oldest populations in the world, with an average age of 43.3 years, and its population is shrinking at one of the fastest rates globally. A fifth of all households consist of only one person, and just one-fourth consist of four or more persons. The average life expectancy in Serbia is 76.1 years.

During the 1990s, Serbia hosted the largest refugee population in Europe. Refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Serbia formed between 7% and 7.5% of its population at the time. About half a million refugees sought refuge in the country following the Yugoslav Wars, mainly from Croatia and, to a lesser extent, from Bosnia and Herzegovina, along with IDPs from Kosovo. The integration of refugees and IDPs, and addressing their long-term needs, remains a social challenge. More recently, tens of thousands of Russians and Ukrainians have immigrated to Serbia following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, with reports of over 300,000 Russian emigrants by January 2024, some facing integration issues.

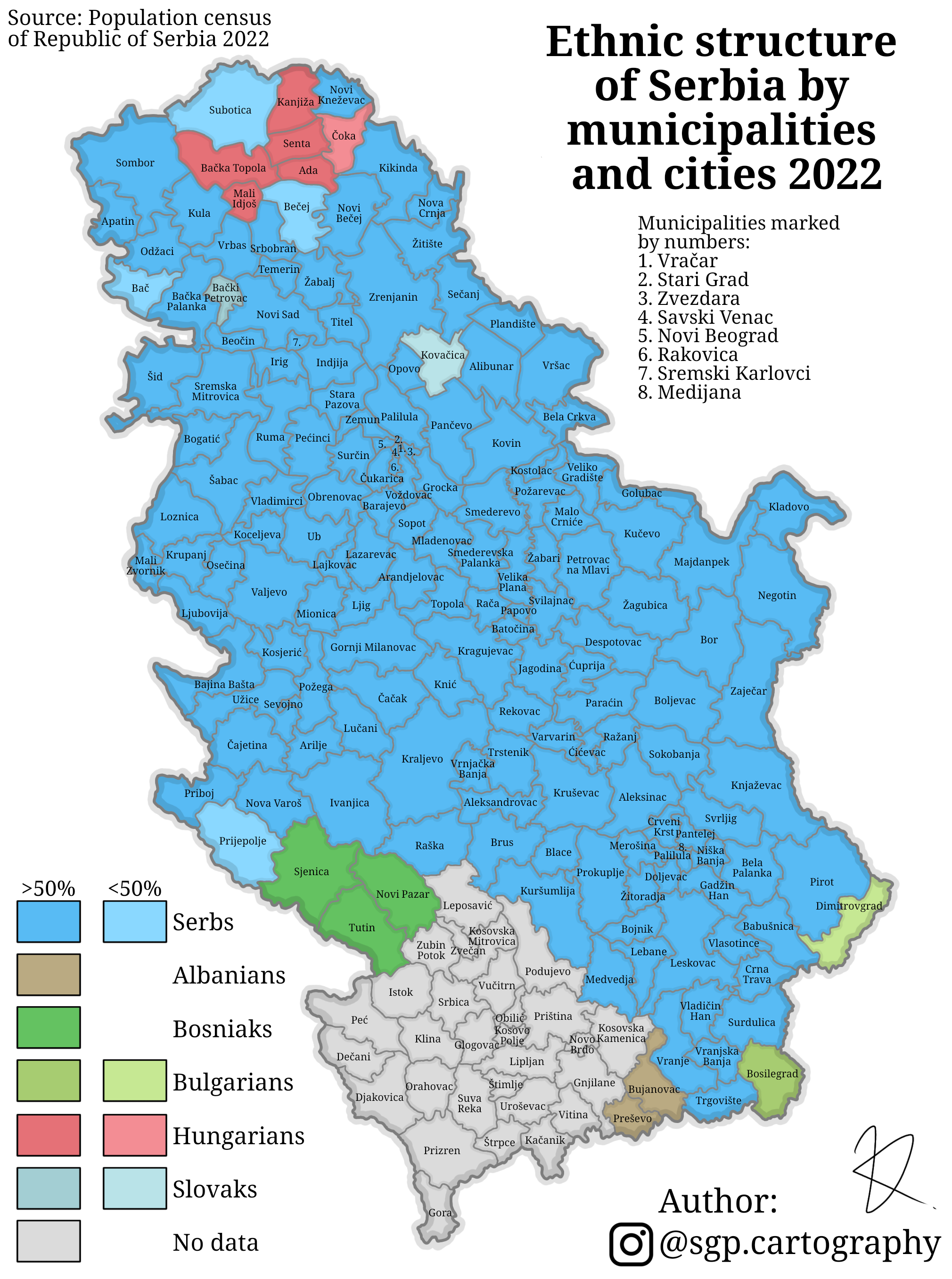

Serbs are the largest ethnic group, with 5,360,239 individuals, representing 81% of the total population (excluding Kosovo). Serbia is one of the European countries with the highest number of registered national minorities. The province of Vojvodina is particularly known for its multi-ethnic and multi-cultural identity. Hungarians, with a population of 184,442, are the largest ethnic minority, concentrated predominantly in northern Vojvodina and representing 2.8% of the country's population (10.5% in Vojvodina). The Romani population stands at 131,936 according to the 2022 census, but unofficial estimates place their actual number between 400,000 and 500,000. Bosniaks (153,801) and Muslims by nationality (13,011) are concentrated in the Sandžak region in the southwest. Other minority groups include Albanians (primarily in southern Serbia outside Kosovo), Croats and Bunjevci, Slovaks, Yugoslavs, Montenegrins, Romanians and Vlachs, Macedonians, and Bulgarians. The Chinese, estimated at 15,000, are the only significant non-European immigrant minority.

The majority of the population, 59.4%, resides in urban areas, with about 16.1% in Belgrade alone. Belgrade is the only city with more than a million inhabitants in its metropolitan area. Other major cities with over 100,000 inhabitants include Novi Sad, Niš, and Kragujevac.

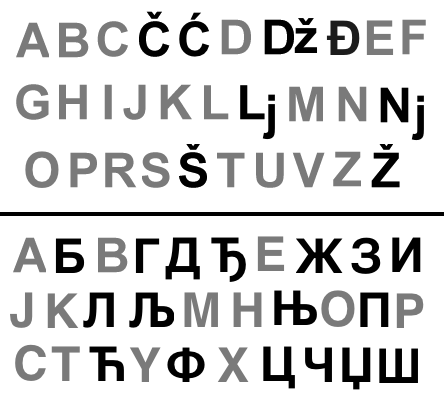

10.2. Language

The official language of Serbia is Serbian, which is native to 88% of the population. Serbian is the only European language with active digraphia, meaning it officially uses both the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets. The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet is designated in the Constitution as the "official script." A 2014 survey showed that 47% of Serbians favored the Latin alphabet, 36% favored the Cyrillic one, and 17% had no preference. Standard Serbian is based on the Shtokavian dialect, specifically its Eastern Herzegovinian variant, and is mutually intelligible with Bosnian and Croatian.

Recognized minority languages in Serbia include Hungarian, Slovak, Albanian, Romanian, Bulgarian, Rusyn, and Macedonian. These languages are in official use in municipalities or cities where the respective ethnic minority exceeds 15% of the total population. In the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, the provincial administration co-officially uses five languages besides Serbian: Slovak, Hungarian, Croatian, Romanian, and Rusyn. This linguistic diversity reflects Serbia's multi-ethnic composition and commitment to minority rights, though challenges in full implementation sometimes occur.

10.3. Religion