1. Overview

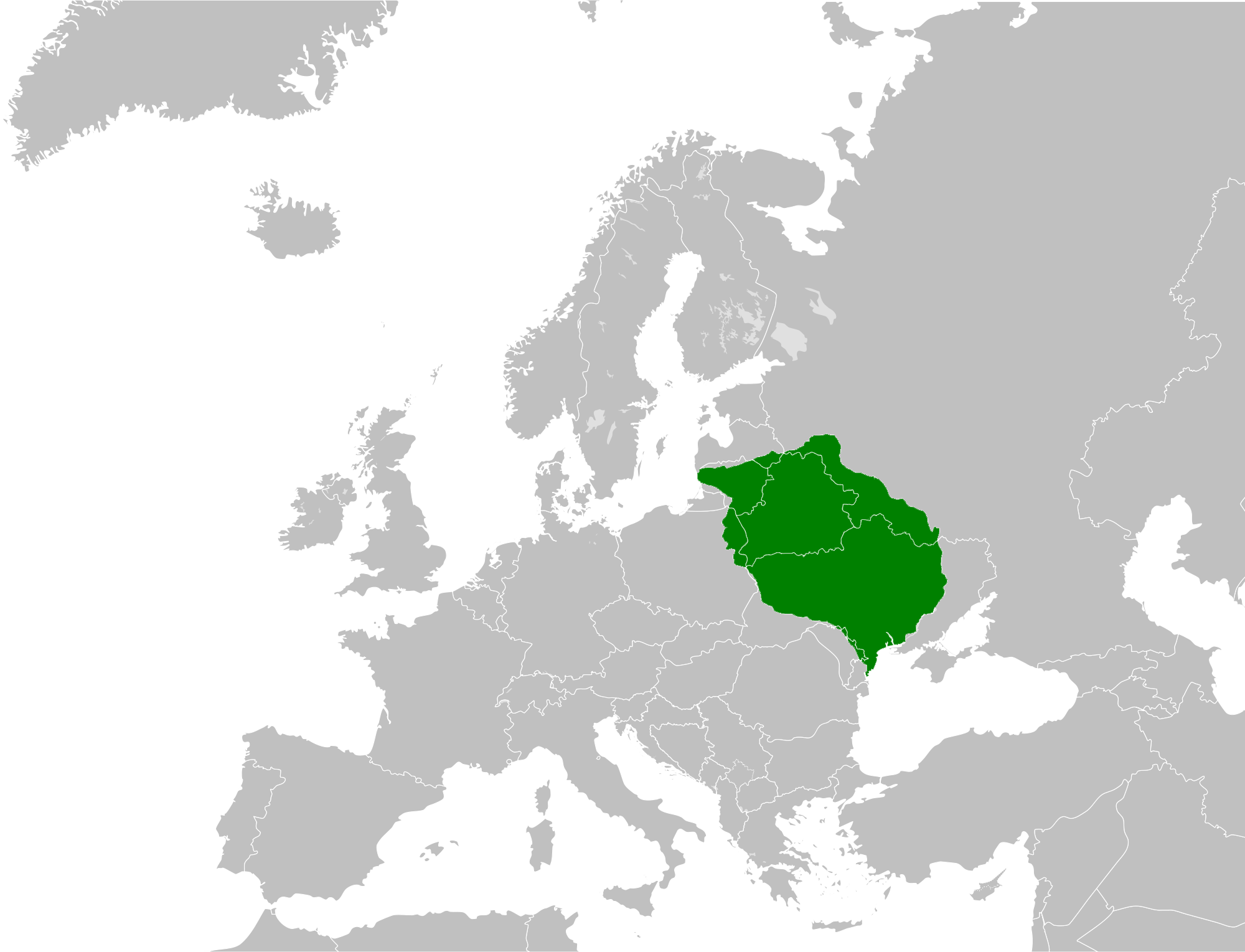

The Republic of Belarus is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital and largest city is Minsk. The country's landscape is predominantly flat, characterized by extensive forests covering about 40% of its territory, numerous lakes, and vast marshlands, including the Polesie marshes, one of Europe's largest.

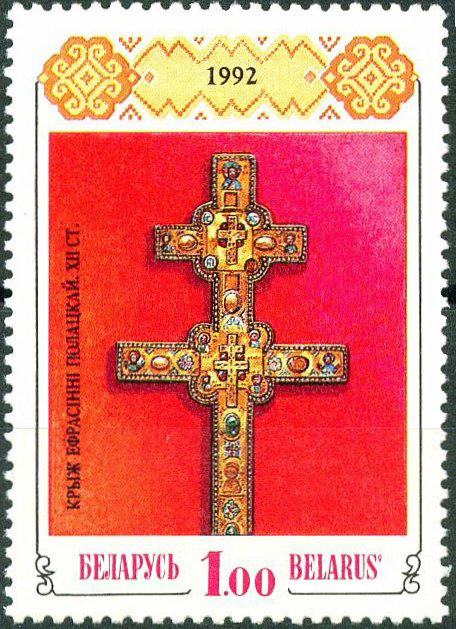

Belarus has a complex history, with its lands being part of various states including Kievan Rus', the Principality of Polotsk, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Russian Empire. The 20th century was particularly tumultuous, featuring a brief period of independence as the Belarusian People's Republic (1918) before becoming the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR), a founding member of the Soviet Union in 1922. World War II brought immense devastation to Belarus, with significant population loss, widespread destruction, and a strong partisan movement. The country declared state sovereignty in 1990 and full independence in 1991 following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Since 1994, Belarus has been led by President Alexander Lukashenko. His long tenure has been marked by a highly centralized, authoritarian government, which has drawn significant international criticism and sanctions due to concerns over human rights, democratic processes, and press freedom, particularly following contested elections and subsequent protests, such as those in 2020. Belarus maintains close political, economic, and military ties with Russia, forming the Union State, and allowed its territory to be used by Russia during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The economy is largely state-controlled, with key industries including heavy machinery (tractors, trucks), chemicals (notably potash), and a growing IT sector.

Socially, Belarus has two official languages, Belarusian and Russian, with Russian being more widely used in daily life. Eastern Orthodoxy is the predominant religion. The nation continues to deal with the long-term environmental and health consequences of the Chernobyl disaster (1986), which severely affected its southern territories. Culturally, Belarus possesses rich traditions in arts, literature (with figures like Francysk Skaryna, Yanka Kupala, Yakub Kolas, and Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich), music, and folk crafts, and is home to several UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

2. Etymology

The name Belarus is closely related to the term Belaya Rus (Белая РусьBelaya Rus'Belarusian), meaning White Rus. The origin of this name is subject to several theories. One ethno-religious theory suggests it described the part of old Ruthenian lands within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania populated mainly by Slavs who were Christianized early, contrasting with Black Ruthenia, which was predominantly inhabited by pagan Balts. Another theory links the name to the white clothing traditionally worn by the local Slavic population. A third theory posits that the old Rus' lands not conquered by the Tatars (such as Polotsk, Vitebsk, and Mogilev) were referred to as White Rus'. A fourth theory, influenced by Mongol and Chinese traditions where colors denote cardinal directions, suggests that white was associated with the west, and Belarus constituted the western part of Kievan Rus' in the 9th to 13th centuries. Some theories also connect "white" with "free" or "liberated" from Mongol dominion, as opposed to "black" for "subjugated."

The name Rus' is often conflated with its Latin forms, Russia and Ruthenia, leading to Belarus sometimes being referred to as White Russia or White Ruthenia. The term first appeared in German and Latin medieval texts; the chronicles of Jan of Czarnków mention the imprisonment of Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila and his mother at "Albae Russiae, Poloczk dictoAlbae Russiae, Poloczk dictoLatin" in 1381. Sir Jerome Horsey, an Englishman with close ties to the Russian royal court, is credited with the first known use of "White Russia" to specifically refer to Belarus in the late 16th century. During the 17th century, Russian Tsars used the term to describe lands acquired from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The term Belorussia (БелоруссияBelorussiyaRussian, a name with a different spelling and stress from РоссияRossiyaRussian, Russia) became prominent during the Russian Empire. The Russian Tsar was often styled "the Tsar of All the Russias," signifying that the empire comprised Great Russia, Little Russia, and White Ruthenia. This asserted that these territories were all Russian and their peoples variants of the Russian people.

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, "White Russia" caused confusion as it was also the name of the military forces opposing the Bolsheviks. During the Byelorussian SSR period, the term Byelorussia was embraced as part of the national consciousness. In western Belarus, then under Polish control, Byelorussia was commonly used in regions like Białystok and Grodno during the interwar period.

The term Byelorussia, and its equivalents in other languages based on the Russian form, was officially used until 1991. On September 19, 1991, the country officially adopted the name Republic of Belarus (Рэспубліка БеларусьRespublika ByelarusBelarusian; Республика БеларусьRespublika BelarusRussian). The shorter form, Belarus (БеларусьByelarusBelarusian; БеларусьBelarus'Russian), is also official. Despite the official change, the term "Belorussia" remains common in Russia. The Belarusian government has requested that other countries use "Belarus" and has suggested "白羅斯" (Bái luó sī) as the Chinese transliteration, moving away from "白俄羅斯" (Bái èluósī - White Russia).

In Lithuanian, besides BaltarusijaBaltarusijaLithuanian (White Russia), Belarus is also known as GudijaGudijaLithuanian. The etymology of Gudija is unclear. One hypothesis suggests it derives from the Old Prussian name GudwaGudwaprg, related to Żudwa, a distorted version of Sudwa or Sudovia, names for the Yotvingians. Another theory connects it to the Gothic kingdom (Oium) that occupied parts of modern Belarus and Ukraine, as the Goths' self-name was Gutans or Gytos. A third hypothesis suggests Gudija meant "the other" in Lithuanian and was used to refer to any non-Lithuanian speaking peoples.

3. History

The history of Belarus encompasses the settlement of early Slavic tribes, the rise and influence of medieval principalities, periods under the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, incorporation into the Russian Empire, a tumultuous 20th century marked by wars, revolution, and Soviet rule, and its eventual independence in 1991 followed by the long-standing presidency of Alexander Lukashenko.

3.1. Early History and Medieval Period

Between 5000 and 2000 BC, the Bandkeramik culture was predominant in the region that now constitutes Belarus. By 1000 BC, Cimmerians and other pastoralist groups roamed the area. The Zarubintsy culture became widespread at the beginning of the 1st millennium AD. Remains from the Dnieper-Donets culture have also been found in Belarus and parts of Ukraine.

The region was first permanently settled by Baltic tribes in the 3rd century AD. Around the 5th century, Slavic tribes began to move into the area, gradually and peacefully assimilating the Balts, partly due to the Balts' lack of military coordination. Invaders from Asia, including the Huns and Avars, swept through the region circa 400-600 AD but did not dislodge the Slavic presence.

In the 9th century, the territory of modern Belarus became part of Kievan Rus', a vast East Slavic state ruled by the Rurikids. The Principality of Polotsk emerged as a significant entity within Kievan Rus' and often asserted its autonomy. Upon the death of Yaroslav the Wise in 1054, Kievan Rus' fragmented into independent principalities. The Battle on the Nemiga River in 1067 is a notable event from this period, and its date is considered the founding date of Minsk.

The Mongol invasions of the 13th century devastated many Rus' principalities. However, the lands of modern-day Belarus largely avoided the brunt of the invasion and were gradually incorporated into the expanding Grand Duchy of Lithuania. There are no records of military seizure; rather, annals suggest an alliance and united foreign policy between Polotsk and Lithuania for decades. This incorporation led to an economic, political, and ethno-cultural unification of Belarusian lands. Nine of the principalities within the Grand Duchy were settled by a population that would eventually form the Belarusian people.

During this period, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was involved in numerous military campaigns. A notable instance was its alliance with the Kingdom of Poland against the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. The joint victory allowed the Duchy to control the northwestern borderlands of Eastern Europe. The Muscovites, under Ivan III of Russia, began military campaigns in 1486 to incorporate former Kievan Rus' lands, including territories of modern-day Belarus and Ukraine. The official language of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was Ruthenian (also known as Old Belarusian or Chancery Slavonic), which was used for administrative and legal documents.

3.2. Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

On February 2, 1386, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland were joined in a personal union through the marriage of their rulers. This union initiated developments that culminated in the formation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally established by the Union of Lublin in 1569.

In the years following the union, a gradual process of Polonization affected both Lithuanians and Ruthenians (ancestors of modern Belarusians and Ukrainians). In culture and social life, the Polish language and Roman Catholicism became increasingly dominant. In 1696, Polish replaced Ruthenian as the official language in administrative use, and Ruthenian was banned from such contexts. However, the Ruthenian peasantry continued to speak their native language and largely adhered to Orthodox Christianity. The Belarusian Greek Catholic Church (Uniate Church) was formed through the Union of Brest in 1595, bringing many Orthodox Christians in the Belarusian lands into communion with the See of Rome while allowing them to retain their Byzantine liturgy in the Church Slavonic language. This period saw significant cultural shifts, with the nobility adopting Polish customs and language, while the peasant majority maintained their distinct cultural and linguistic heritage. The Statutes of Lithuania, a codification of law in the Grand Duchy, were initially issued in Ruthenian and later also in Polish.

3.3. Russian Empire

The union between Poland and Lithuania ended with the Third Partition of Poland in 1795, carried out by Imperial Russia, Prussia, and Austria. The Belarusian territories, acquired by the Russian Empire under Catherine II, were incorporated into the Belarusian Governorate (Белорусское генерал-губернаторствоBelorusskoye general-gubernatorstvoRussian) in 1796 and remained under Russian rule until their occupation by the German Empire during World War I.

Under Tsars Nicholas I and Alexander III, national cultures within the empire were suppressed. Policies of Polonization, which had occurred under the Commonwealth, were replaced by intensive Russification. This included efforts to convert Belarusian Uniates (Greek Catholics) back to Orthodox Christianity. The Belarusian language was banned in schools, while in nearby Samogitia, primary school education with Samogitian literacy was permitted. In the 1840s, Nicholas I prohibited the use of the Belarusian language in public schools and campaigned against Belarusian publications.

Economic and cultural pressures culminated in the January Uprising of 1863, led in Belarusian lands by Konstanty Kalinowski (Kastuś Kalinoŭski). After the failed revolt, the Russian government intensified Russification, reintroducing the Cyrillic script for Belarusian in 1864 and banning documents in Belarusian until 1905. These policies aimed to assimilate the Belarusian population into the broader Russian identity, suppressing local language and culture. Despite these efforts, a Belarusian national movement began to emerge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, seeking to preserve and promote Belarusian identity.

3.4. 20th Century: Revolutions, Wars, and Soviet Era

The 20th century was a period of profound upheaval and transformation for Belarus. It witnessed attempts at national independence, devastating wars, and nearly seven decades as a Soviet republic, all of which deeply shaped its national identity, social structures, and political trajectory, often at a great human cost.

3.4.1. Belarusian People's Republic and Interwar Period

During the negotiations of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between Russia and the Central Powers in World War I, Belarus first declared independence under German occupation on March 25, 1918, forming the Belarusian People's Republic (BNR). However, this state was short-lived and lacked broad international recognition or stable territorial control, as the region was contested by German and Russian forces. The Rada (Council) of the BNR has existed as a government in exile since then, making it one of the longest-serving governments in exile globally. The choice of the name "Belarus" was likely influenced by government members educated in Tsarist universities, emphasizing West-Russianism.

The Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921) followed, leading to the division of Belarusian territory. Under the Peace of Riga (1921), the western part of Belarus was incorporated into the newly re-established Second Polish Republic, while the eastern part became the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR), formally established in July 1920. The BSSR became a founding member of the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1922. The Republic of Central Lithuania, a short-lived political entity centered on Vilnius (Wilno), was created in 1920 following a staged rebellion and was later annexed by Poland in 1922.

In the BSSR during the 1920s and 1930s, Soviet agricultural and economic policies, including collectivization and the five-year plans, led to famine and significant political repression. The Great Purge under Stalin saw the execution or exile of many Belarusian intellectuals and nationalists, including those at Kurapaty.

In Western Belarus, under Polish rule, an early period of liberalization was followed by increasing tensions between the Polish government and ethnic minorities. The Belarusian minority faced Polonization policies, suppression of political organizations like the Belarusian Peasants' and Workers' Union, closure of Belarusian schools and Orthodox churches, and discouragement of the Belarusian language. Belarusian leaders were imprisoned, for example, at the Bereza Kartuska prison.

3.4.2. World War II

In September 1939, following the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland just weeks after Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland initiated World War II. The territories of Western Belorussia were annexed and incorporated into the Byelorussian SSR. The Soviet-controlled Byelorussian People's Council officially took control of these territories on October 28, 1939, in Białystok.

Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 in Operation Barbarossa. The Defense of Brest Fortress became one of the first major battles. The Byelorussian SSR was the hardest-hit Soviet republic during World War II, remaining under German occupation until 1944. The German Generalplan Ost (Generalplan OstGeneralplan OstGerman) called for the extermination, expulsion, or enslavement of most Belarusians to create Lebensraum (living space) for Germans. Most of Western Belarus became part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland. In 1943, German authorities allowed local collaborators to establish a client state, the Belarusian Central Council.

Belarus was home to a vast and diverse partisan movement, one of the largest in Europe. These partisans, including Jewish, Polish, and Soviet groups, played a significant role in disrupting German operations. The partisan legacy became a core part of Belarusian national identity, with Belarus often referred to as the "partisan republic." Many post-war Belarusian leaders, like Pyotr Masherov and Kirill Mazurov, were former partisans.

The German occupation and the war on the Eastern Front devastated Belarus. An estimated 209 out of 290 towns and cities were destroyed, along with 85% of the republic's industry and over one million buildings. Casualty estimates vary, but it is generally accepted that Belarus lost about a quarter of its pre-war population, with some figures suggesting 2.2 to 2.7 million deaths, including combatants and civilians. The Jewish population of Belarus was decimated during the Holocaust. The population of Belarus did not regain its pre-war level until 1971, and the country lost around half of its economic resources. The human cost of the war and the atrocities committed, such as the Khatyn massacre, left deep scars on the nation.

3.4.3. Post-War Soviet Belarus

After World War II, the borders of the Byelorussian SSR and Poland were redrawn in accordance with the Curzon Line, with Byelorussia gaining territory to the west, formerly part of Poland's eastern territories (Kresy). Joseph Stalin implemented a policy of Sovietization to isolate the BSSR from Western influences, which involved sending Russians to key governmental positions and promoting the Russian language and culture. Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin's successor, continued this cultural hegemony, stating, "The sooner we all start speaking Russian, the faster we shall build communism."

Between Stalin's death in 1953 and the 1980s, Belarusian politics was largely dominated by former Soviet partisans, including First Secretaries Kirill Mazurov and Pyotr Masherov. They oversaw Belarus's rapid industrialization, known as the Belarusian economic miracle, transforming it from one of the poorest Soviet republics into one of its wealthiest.

A catastrophic event during this period was the Chernobyl disaster on April 26, 1986, at a nuclear power plant in the neighboring Ukrainian SSR, just 9.9 mile (16 km) from the Belarusian border. Belarus received approximately 70% of the radioactive fallout. About a fifth of Belarusian land, primarily farmland and forests in the southeastern regions (especially Gomel and Mogilev), was severely contaminated. This disaster had long-lasting radiological, health, social, and environmental consequences, including increased rates of thyroid cancer in children and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people from affected areas.

By the late 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of Perestroika and Glasnost led to political liberalization and a national revival in Belarus. The Belarusian Popular Front emerged as a significant pro-independence force, advocating for greater autonomy and the preservation of Belarusian language and culture.

3.5. Independence and the Lukashenko Era

In the late 1980s, Perestroika under Mikhail Gorbachev initiated political liberalization across the Soviet Union. In March 1990, elections were held for the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian SSR. Although opposition candidates, primarily associated with the pro-independence Belarusian Popular Front, secured only about 10% of the seats, the movement for national sovereignty gained momentum. On July 27, 1990, Belarus declared state sovereignty with the Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Following widespread strikes in April 1991 and the failed August Coup in Moscow, Belarus officially declared independence from the Soviet Union on August 25, 1991. The country's name was changed to the Republic of Belarus. On December 8, 1991, Stanislav Shushkevich, Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of Belarus, met with Boris Yeltsin of Russia and Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine in the Białowieża Forest. They signed the Belavezha Accords, formally declaring the dissolution of the USSR and establishing the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

A new constitution was adopted in March 1994, establishing a presidential republic. In the presidential election held in June and July 1994, Alexander Lukashenko, a relatively unknown figure at the time, was elected as the first president of independent Belarus. He garnered 45% of the vote in the first round and 80% in the second, defeating Vyacheslav Kebich. This election is widely considered the only free and fair presidential election in Belarus since independence.

Since taking office, Lukashenko has consolidated power, establishing a highly centralized and authoritarian government. A controversial referendum in 1996 extended his presidential term and significantly expanded presidential powers, effectively weakening the legislature and judiciary. Subsequent presidential elections in 2001, 2006, 2010, 2015, and 2020 saw Lukashenko re-elected with large majorities, but these elections were widely condemned by international observers and opposition groups as fraudulent and undemocratic. Term limits for the presidency were removed following a 2004 referendum.

Lukashenko's rule has been marked by the continuation of Soviet-era policies, such as state ownership of large sectors of the economy, and suppression of political dissent, freedom of the press, and civil liberties. Belarus remains the only country in Europe that continues to use capital punishment. The government has faced international criticism and sanctions from the European Union, the United States, and other Western countries due to human rights abuses, electoral irregularities, and the crackdown on opposition.

Economic relations with Russia have been complex, characterized by periods of close cooperation, such as the formation of the Union State in 2000, and disputes over energy prices (e.g., the 2004 and 2007 energy disputes, and the 2009 "Milk War"). Belarus experienced a severe economic crisis in 2011, with high inflation. The 2011 Minsk Metro bombing killed 15 people; two men were swiftly convicted and executed, though the official account was questioned by some.

The 2020 presidential election led to widespread mass protests across the country, the largest in its history, after official results declared Lukashenko the winner with over 80% of the vote. The opposition, led by Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, alleged widespread fraud. The government responded with a violent crackdown, arresting thousands of protesters and opposition figures, and reports of torture and ill-treatment of detainees were widespread. Many countries, including EU members, the UK, Canada, and the US, refused to recognize Lukashenko as the legitimate president and imposed further sanctions. Tsikhanouskaya and other opposition leaders were forced into exile.

In May 2021, Belarusian authorities forcibly diverted a Ryanair flight to Minsk to arrest opposition activist Roman Protasevich, leading to further international condemnation and sanctions. Later in 2021, Belarus was accused of orchestrating a migrant crisis on its borders with EU countries Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia, allegedly as a form of "hybrid warfare" in response to EU sanctions.

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Belarus allowed Russian troops to use its territory as a staging ground for the offensive, leading to additional international sanctions against the Lukashenko government for its complicity. A constitutional referendum in February 2022 removed Belarus's non-nuclear and neutral status, potentially allowing Russia to deploy nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory, and reset presidential term limits, allowing Lukashenko to potentially remain in power until 2035.

4. Geography

Belarus is a landlocked country located in Eastern Europe, characterized by a generally flat terrain and extensive natural features such as forests, marshes, rivers, and lakes.

This section outlines its topography, borders, climate, water systems, and natural resources, including the environmental impact of the Chernobyl disaster.

4.1. Topography and Borders

Belarus lies between latitudes 51° N and 57° N, and longitudes 23° E and 33° E. Its maximum extent from north to south is 348 mile (560 km), and from west to east is 404 mile (650 km). The country is landlocked and possesses a relatively flat topography, part of the vast East European Plain. The landscape is marked by low hills, extensive plains, and large tracts of marshy land, particularly in the Polesie region, which is one of Europe's largest wetlands.

The highest point in Belarus is Dzyarzhynskaya Hara (Dzyarzhynsk Hill), at an elevation of 1132 ft (345 m) above sea level. The lowest point is on the Neman River, at 295 ft (90 m) above sea level. The average elevation of the country is 525 ft (160 m) above sea level.

Belarus shares international borders with five countries:

- Russia to the east and northeast.

- Ukraine to the south.

- Poland to the west.

- Lithuania to the northwest.

- Latvia to the north.

Treaties in 1995 and 1996 demarcated Belarus's borders with Latvia and Lithuania. Belarus ratified a 1997 treaty establishing the Belarus-Ukraine border in 2009. Final border demarcation documents with Lithuania were ratified in February 2007.

4.2. Climate

Belarus has a temperate-continental climate, transitional between maritime and continental climates, influenced by its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and the vast Eurasian landmass.

Winters are generally mild to cold, with average January minimum temperatures ranging from 24.8 °F (-4 °C) in the southwest (Brest) to 17.6 °F (-8 °C) in the northeast (Vitebsk). Snow cover is common during winter.

Summers are cool and moist, with an average temperature of 64.4 °F (18 °C).

Annual precipitation ranges from 22 in (550 mm) to 28 in (700 mm), with the majority occurring during the warmer months. Significant weather phenomena can include occasional heavy rainfall leading to localized flooding, and in winter, periods of more intense cold or heavy snowfall.

4.3. Water Systems

Belarus possesses an extensive network of rivers and lakes. There are approximately 11,000 lakes in the country, though most are relatively small.

The three major rivers that flow through Belarus are:

- The Neman River (Nieman), which flows westward towards the Baltic Sea (via Lithuania).

- The Pripyat River, which flows eastward into the Dnieper River.

- The Dnieper River, one of Europe's major rivers, which flows southward through Belarus and Ukraine towards the Black Sea.

Other significant rivers include the Berezina River and the Sozh River. These water systems are ecologically important, supporting diverse aquatic life and wetland ecosystems. They also hold economic significance for transportation (historically and for some modern inland navigation), water supply, and recreation. The Dnieper-Bug Canal connects the Pripyat river system with the Western Bug, providing a link between the Black Sea and Baltic Sea basins.

4.4. Natural Resources and Environment

Belarus's main natural resources include extensive forests, which cover about 43% of the country's total land area as of 2020 (an increase from 1990). In 2020, naturally regenerating forests covered approximately 16 M acre (6.56 M ha) and planted forests covered 5.5 M acre (2.21 M ha). A small percentage (2%) of the naturally regenerating forest was reported as primary forest. About 16% of the forest area is within protected areas, and nearly all forest land is under public ownership. The country lies within two ecoregions: Sarmatic mixed forests and Central European mixed forests.

Other significant natural resources include:

- Peat deposits: Belarus has substantial peat reserves, historically used for fuel and agriculture.

- Potash salts: The country is a major global producer of potash, a key component in fertilizers, mined primarily around Salihorsk.

- Building materials: Deposits of granite, dolomite (limestone), marl, chalk, sand, gravel, and clay are found.

- Minor deposits of oil and natural gas exist but are insufficient to meet domestic demand.

A major environmental issue for Belarus is the long-term consequence of the Chernobyl disaster of April 1986. Approximately 70% of the radioactive fallout from the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in neighboring Ukraine descended upon Belarusian territory. About a fifth of Belarusian land, principally farmland and forests in the southeastern regions (Gomel and Mogilev Oblasts), was affected by radiation. This contamination led to significant health problems, including increased rates of thyroid cancer, displacement of populations, and long-term restrictions on land use in the affected areas. The Polesie State Radioecological Reserve was established in the most contaminated zone to monitor and study the effects of radiation. International agencies and the Belarusian government have undertaken efforts to mitigate the radiation levels, including the use of caesium binders and specific agricultural practices like rapeseed cultivation to reduce soil contamination by caesium-137.

5. Politics

Belarus is constitutionally a presidential republic with a formal separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. However, in practice, the political system is highly centralized and authoritarian, with extensive power concentrated in the hands of the President. The country has been described by some Western media and political figures as "Europe's last dictatorship." The international community, particularly Western nations, has frequently criticized Belarus for its record on democratic standards and human rights.

This section examines the structure of the Belarusian government, its electoral processes and political parties, the human rights situation, and issues related to corruption.

5.1. Government Structure

The President of Belarus is the head of state and holds significant executive power. Since 1994, this office has been held by Alexander Lukashenko. The presidential term is five years. Originally limited to two terms by the 1994 constitution, term limits were removed following a controversial referendum in 2004. A 1996 referendum had previously extended the presidential term and expanded presidential powers, which critics argue undermined the balance of power. The President appoints the Prime Minister, members of the government, key judicial figures, and has broad authority over domestic and foreign policy.

The executive branch is headed by the Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers (the government). Roman Golovchenko is the current Prime Minister. The members of the Council of Ministers are appointed by the President and are not required to be members of the legislature.

The National Assembly is the bicameral parliament.

- The House of Representatives (Palata Predstaviteley) is the lower house, with 110 members elected directly by popular vote for four-year terms. It has the power to consider and pass laws, make constitutional amendments, call for a vote of confidence in the prime minister, and make suggestions on foreign and domestic policy.

- The Council of the Republic (Soviet Respubliki) is the upper house, with 64 members. Fifty-six members are indirectly elected by regional councils (eight from each of the six regions and Minsk city), and eight members are appointed by the President. The Council of the Republic has the power to approve or reject bills passed by the House of Representatives, select various government officials (including some judges), and conduct impeachment trials of the president.

Both chambers can veto laws passed by local officials if they contradict the Constitution. However, the legislature's influence is significantly limited by the dominant role of the presidency.

The judiciary comprises the Supreme Court and specialized courts, including the Constitutional Court, which deals with constitutional and business law issues. Judges of national courts are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Council of the Republic. The judicial system has been criticized for lacking independence and being subject to political interference. The Constitution forbids the use of special extrajudicial courts.

5.2. Elections and Political Parties

Belarus holds regular presidential and parliamentary elections. However, since the mid-1990s, these elections have been consistently criticized by international observers, including the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), as failing to meet democratic standards. Concerns have been raised regarding restrictions on opposition candidates, lack of media freedom, opaque vote-counting processes, and the suppression of political dissent.

President Alexander Lukashenko has been re-elected in 1994, 2001, 2006, 2010, 2015, and 2020. The 2020 presidential election was followed by unprecedented mass protests amid widespread allegations of electoral fraud. The government responded with a severe crackdown on protesters and opposition figures.

Political parties in Belarus operate in a restrictive environment. Pro-government parties, such as the Belarusian Social Sporting Party and the Republican Party of Labour and Justice, generally support the president's policies. Opposition parties, including the BPF Party (Belarusian Popular Front) and the United Civic Party, face significant challenges, including difficulties with registration, harassment of members, limited access to media, and exclusion from meaningful political participation. In parliamentary elections, such as the 2004, 2012, and subsequent elections, very few or no opposition candidates have won seats in the House of Representatives. Many elected members are formally non-partisan but are generally aligned with the government. The United Transitional Cabinet of Belarus was formed by exiled opposition figures following the 2020 protests.

Domestic and international concerns persist regarding the fairness of elections and the overall democratic landscape in Belarus. The lack of genuine political competition and the suppression of opposition voices have led to Belarus being described as an autocracy.

5.3. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Belarus has been a subject of significant concern for international organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the UN Human Rights Council, as well as many Western governments. Belarus consistently ranks low in international assessments of democracy and civil liberties. Freedom House labels the country as "Not Free," and it scores poorly on indices related to press freedom and economic freedom.

Key areas of concern include:

- Freedoms of Speech, Press, and Assembly:** Severe restrictions are placed on independent media, with journalists facing harassment, detention, and prosecution. The government controls major television and print media outlets. Public assemblies and protests are tightly controlled, and unauthorized gatherings are often met with force and mass arrests, as seen during the 2020-2021 protests.

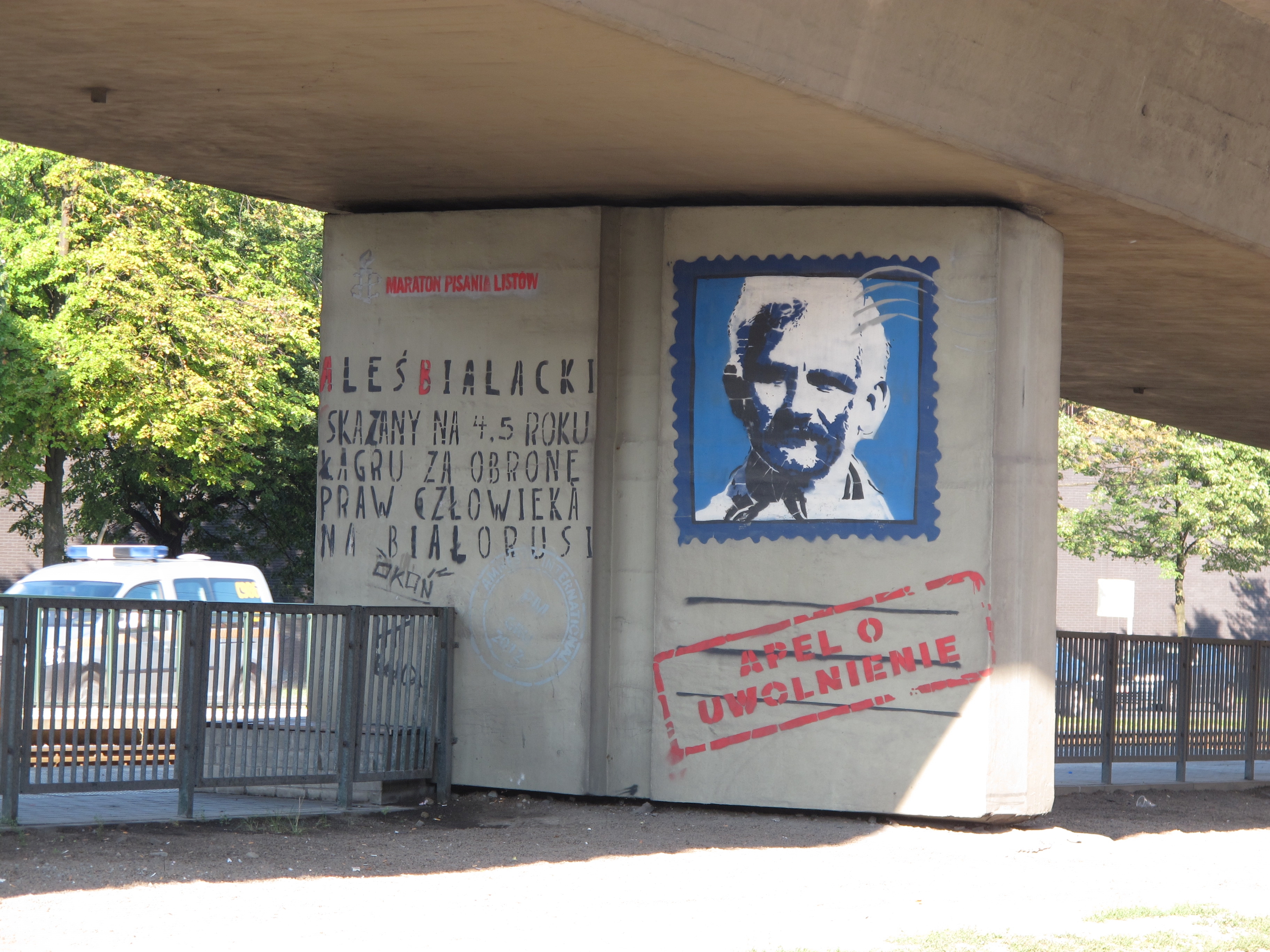

- Treatment of Political Opposition:** Opposition activists, politicians, and their supporters face intimidation, arbitrary detention, politically motivated prosecutions, and imprisonment. Prominent opposition figures have been jailed or forced into exile. Ales Bialiatski, a leading human rights activist and founder of the Viasna Human Rights Centre, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022 while imprisoned.

- National Minorities and Vulnerable Groups:** While the constitution guarantees equality, concerns have been raised about the rights of national minorities, particularly the Polish minority, regarding cultural and educational activities. LGBT rights are severely limited, and individuals face discrimination and lack legal protection.

- Capital Punishment:** Belarus is the only country in Europe and the former Soviet Union that continues to use capital punishment. Executions are carried out by shooting. In March 2023, a law was signed allowing the death penalty for officials and soldiers convicted of high treason.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment:** There have been numerous credible reports, particularly following the 2020 protests, of torture and ill-treatment of detainees by security forces, including physical abuse, denial of medical care, and psychological pressure. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights documented hundreds of such cases.

- International Scrutiny and Sanctions:** The Lukashenko government has faced extensive criticism and economic and targeted sanctions from the European Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and other countries due to democratic backsliding and human rights violations. These sanctions intensified after the 2020 election, the forced diversion of Ryanair Flight 4978 in 2021 to arrest journalist Roman Protasevich, and Belarus's role in facilitating the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- Restrictions on Labor Rights:** In 2014, a law was introduced that restricted collective farm workers (about 9% of the workforce) from leaving their jobs without permission from governors, a measure Lukashenko himself reportedly compared to serfdom. Similar regulations were introduced for the forestry industry in 2012. Laws have also existed that effectively forbid unemployment or working outside state-controlled sectors.

The Council of Europe suspended Belarus's observer status in 1997 due to electoral irregularities and a lack of progress on human rights and democracy.

5.3.1. Corruption Issues

Corruption is a significant issue in Belarus, impacting governance, public trust, and economic development. While the government officially has anti-corruption measures in place, their effectiveness is widely questioned due to a lack of transparency, judicial independence, and genuine political will.

Belarus ranks poorly on international corruption perception indices. Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index consistently places Belarus among countries with high levels of perceived corruption.

Key aspects of corruption in Belarus include:

- State Control and Lack of Transparency:** The extensive role of the state in the economy creates opportunities for corruption, particularly in procurement, state-owned enterprises, and the distribution of resources. Lack of transparency in government operations and decision-making processes further exacerbates the problem.

- Weak Rule of Law and Judicial Independence:** The judiciary is not considered independent and is often subject to political influence. This undermines efforts to prosecute corruption effectively, especially when high-level officials are involved.

- Nepotism and Cronyism:** Allegations of nepotism and cronyism in appointments to state positions and the awarding of contracts are common.

- Restrictions on Civil Society and Media:** The suppression of independent media and civil society organizations limits public oversight and the ability to expose corrupt practices. Whistleblower protection is reportedly weak or non-existent.

- Bribery:** Bribery in various forms is reported to occur, including in interactions with public officials and during tender processes for government contracts.

Anti-corruption campaigns have been launched by the government, but critics argue these are often selective and used to target political opponents rather than address systemic corruption. The lack of independent oversight mechanisms and a free press makes it difficult to assess the true extent of corruption and the effectiveness of anti-corruption efforts.

6. Administrative Divisions

Belarus is a unitary state. Its administrative structure consists of regions (oblasts), districts (raions), and various types of settlements, with the capital city of Minsk holding a special status.

This section outlines these divisions and identifies the major cities.

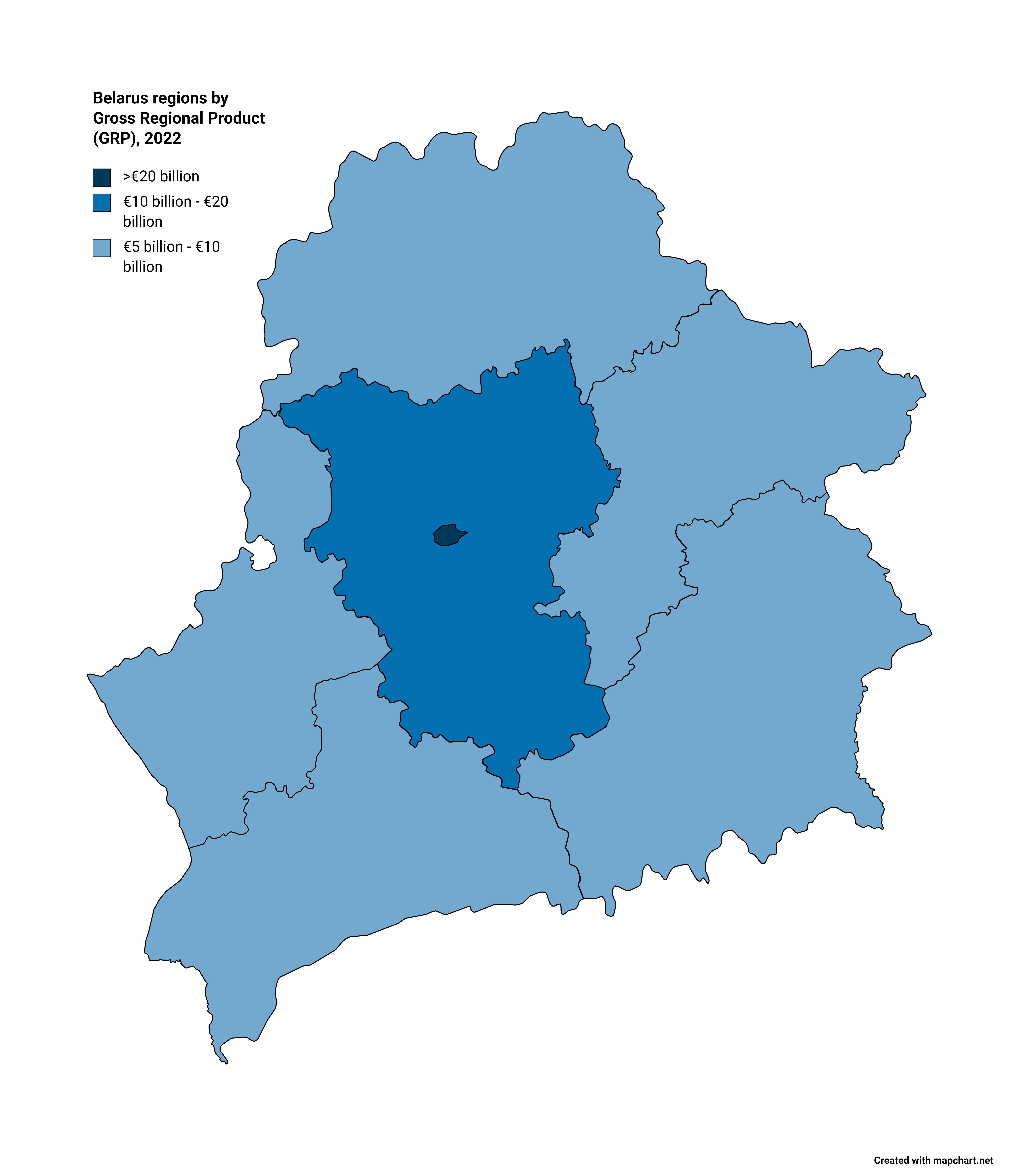

6.1. Regions and Districts

Belarus is divided into six regions, known as oblasts (вобласцьvoblasts'Belarusian; областьoblast'Russian). These are named after their administrative centers:

1. Brest Oblast (Administrative center: Brest)

2. Gomel Oblast (Administrative center: Gomel)

3. Grodno Oblast (Administrative center: Grodno)

4. Mogilev Oblast (Administrative center: Mogilev)

5. Minsk Oblast (Administrative center: Minsk)

6. Vitebsk Oblast (Administrative center: Vitebsk)

The city of Minsk is the capital of Belarus and has a special administrative status equivalent to that of an oblast. Although it serves as the administrative center of Minsk Oblast, it is administered separately. Minsk city is further divided into nine administrative districts (raions).

Each oblast has a provincial legislative authority, the Oblast Council of Deputies (абласны Савет Дэпутатаўablasny Savet DeputataŭBelarusian; Областной Совет депутатовOblastnoy Sovet deputatovRussian), elected by its residents, and a provincial executive authority, the Oblast Executive Committee (абласны выканаўчы камітэтablasny vykanaŭčy kamitetBelarusian; областной исполнительный комитетoblastnoy ispolnitel'nyy komitetRussian), whose chairman is appointed by the President of Belarus.

The oblasts are further subdivided into 118 raions (districts; раёнrajonBelarusian; районrajonRussian). Each raion has its own local council (Raion Council of Deputies) elected by its residents, and a raion administration whose head is appointed by the respective oblast executive authorities.

Local government in Belarus operates on two main levels: basic and primary. The basic level includes the 118 raion councils and councils for 10 cities of oblast subordination. The primary level includes councils for cities of raion subordination, urban-type settlements, and 1,151 village councils (selsoviets). Settlements without their own local council are considered territorial units governed by a council of another primary or basic unit. As of 2019, Belarus had 115 cities, 85 urban-type settlements, and 23,075 rural settlements.

6.2. Major Cities

Besides the capital, Minsk, other major cities serve as administrative, economic, and cultural centers for their respective regions.

| Rank | City | Region | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Minsk | Minsk City | 2,018,281 |

| 2 | Gomel | Gomel | 510,300 |

| 3 | Vitebsk | Vitebsk | 364,800 |

| 4 | Grodno | Grodno | 357,500 |

| 5 | Mogilev | Mogilev | 357,100 |

| 6 | Brest | Brest | 339,700 |

| 7 | Babruysk | Mogilev | 212,200 |

| 8 | Baranavichy | Brest | 175,000 |

| 9 | Barysaw | Minsk | 140,700 |

| 10 | Pinsk | Brest | 126,300 |

Other significant cities include Babruysk, Baranavichy, Barysaw, Pinsk, Orsha, Mazyr, and Salihorsk.

7. Foreign Relations

Belarus's foreign policy has been largely shaped by its close relationship with Russia, its geographical position between Russia and the European Union, and the political orientation of the Lukashenko government, which has often led to strained relations with Western countries.

This section provides an overview of Belarus's foreign policy, its ties with Russia, relations with the European Union, and interactions with neighboring countries and other significant international partners.

7.1. Overview of Foreign Policy

The Byelorussian SSR was one of the two Soviet republics (along with the Ukrainian SSR) that were founding members of the United Nations in 1945, holding a separate vote from the Soviet Union. Since gaining independence in 1991, Belarus has pursued a foreign policy aimed at maintaining its sovereignty while fostering key alliances.

Belarus is a member of several international and regional organizations:

- United Nations (UN)

- Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) - Belarus was a founding member.

- Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) - A Russia-led military alliance.

- Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) - An economic union with Russia, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan.

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)

- Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) - Joined in 1998.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) - Became a full member in 2024.

Belarus has not expressed aspirations to join the European Union (EU) or NATO. Its approach to international cooperation and security often aligns with Russia's positions. The country participates in some EU initiatives like the Eastern Partnership (though participation was suspended in 2021) and the Baku Initiative. Diplomatic relations with many Western countries have been strained due to concerns over human rights, democratic standards, and the suppression of political opposition in Belarus, leading to various sanctions being imposed on the country and its officials.

7.2. Relations with Russia

Relations between Belarus and Russia are exceptionally deep and multifaceted, rooted in shared history, culture, language, and close political, economic, and military ties. Russia is Belarus's primary trading partner, a major source of energy imports (oil and gas), and its closest military ally.

The cornerstone of their bilateral relationship is the Union State of Russia and Belarus, established through a series of treaties in the late 1990s (formally in 1999). The Union State aims for greater integration, including a potential monetary union, single citizenship (not fully realized), and common foreign and defense policies. However, the full implementation of the Union State has faced challenges, including Belarusian concerns about sovereignty and occasional disputes over economic terms, such as energy prices and trade.

Military cooperation is extensive, with joint military exercises, a common air defense system, and close coordination within the CSTO framework. Russia maintains a military presence in Belarus, which became particularly prominent during the lead-up to and during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, when Belarus allowed its territory to be used as a staging ground by Russian forces.

Economically, Belarus is heavily dependent on Russia for subsidized energy and as an export market for its industrial and agricultural products. This dependence has sometimes led to tensions when Russia has adjusted energy prices or trade terms. Despite periods of friction, the strategic alliance remains strong, particularly as Belarus has become more isolated from Western countries.

7.3. Relations with the European Union

Belarus-European Union relations have been complex and often strained. While the EU is a significant trading partner, political relations have been largely shaped by EU concerns over the human rights situation, lack of democratic reforms, and electoral irregularities in Belarus under President Lukashenko.

Belarus was included in the EU's Eastern Partnership program, launched in 2009, which aims to deepen political and economic ties with several Eastern European and South Caucasus countries. However, engagement has been limited by the political climate in Belarus.

The EU has imposed multiple rounds of sanctions on Belarusian officials and entities, particularly following:

- The crackdown on opposition after various presidential elections.

- The 2020 presidential election and the subsequent violent suppression of mass protests.

- The forced diversion of Ryanair Flight 4978 in May 2021 to arrest opposition journalist Roman Protasevich.

- The 2021 migrant crisis on the Belarus-EU border, which the EU accused Belarus of orchestrating.

- Belarus's facilitation of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In response to EU sanctions, Belarus suspended its participation in the Eastern Partnership program in June 2021. The EU does not recognize Alexander Lukashenko as the legitimate president following the 2020 election. Despite the political tensions, some channels for trade and limited dialogue have remained, though heavily impacted by sanctions.

7.4. Relations with Neighboring Countries and Other Nations

- Ukraine:** Historically, Belarus and Ukraine share deep cultural and linguistic roots. After 1991, relations were generally pragmatic. However, since Belarus allowed Russia to use its territory for the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, relations have become extremely tense, with Ukraine viewing Belarus as complicit in the aggression.

- Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia:** These EU and NATO member states share borders with Belarus and have been strong advocates for democratic reforms and human rights in the country. They have hosted many Belarusian opposition figures and activists in exile. Relations have been particularly strained due to the 2021 migrant crisis, which these countries viewed as a hybrid attack orchestrated by Belarus, and Belarus's alignment with Russia. Poland and Lithuania, in particular, do not recognize Lukashenko as the legitimate president.

- China:** Relations with China have strengthened, particularly as Belarus has sought to diversify its foreign partnerships amid strained ties with the West. China has invested in Belarusian infrastructure and industrial projects, such as the Great Stone Industrial Park near Minsk. Lukashenko has made multiple visits to China.

- United States:** Relations with the United States have been consistently poor for much of Lukashenko's rule. The U.S. has been a vocal critic of the human rights situation and lack of democracy in Belarus, imposing sanctions and supporting civil society. The U.S. has not had an ambassador in Minsk for extended periods. The Belarus Democracy Act of 2004 authorized funding for anti-government Belarusian NGOs.

- Other Nations:** Belarus has also cultivated ties with various countries in the Middle East (e.g., historically with Syria), Latin America, and Asia, often as part of its efforts to counter Western pressure.

8. Military

The Armed Forces of the Republic of Belarus (Узброеныя сілы Рэспублікі БеларусьUzbrojenyja sily Respubliki BielaruśBelarusian; Вооружённые силы Республики БеларусьVooruzhonnyye sily Respubliki Belarus'Russian) consist of the Army, the Air Force, and the Air Defence Forces. Viktor Khrenin currently serves as the Minister of Defence, while the President, Alexander Lukashenko, is the Commander-in-Chief. In addition to the armed forces, there are paramilitary organizations such as the Internal Troops (under the Ministry of Internal Affairs) and the State Border Committee.

The modern Belarusian armed forces were formed in 1992 from units of the former Soviet Armed Forces stationed on Belarusian territory following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The transformation process, completed by 1997, involved significant reductions in personnel (by about 30,000 soldiers) and restructuring of command and military formations.

Most service members are conscripts, typically serving for 12 months if they have higher education or 18 months if they do not. Due to demographic declines, the role of contract soldiers has become more important; in 2001, there were approximately 12,000 contract soldiers. In 2005, military expenditure accounted for about 1.4% of Belarus's GDP.

Belarus's national defense policy is heavily influenced by its close alliance with Russia. The two countries are key members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and have a Union State agreement that includes provisions for a common defense policy and a joint Regional Grouping of Forces. Belarus and Russia conduct regular joint military exercises, such as the "Zapad" (West) series. Russia maintains some military installations in Belarus, and its military presence and influence increased significantly in the lead-up to and during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, for which Belarus provided its territory as a staging ground.

Belarus has not expressed a desire to join NATO. It participated in NATO's Partnership for Peace program starting in 1995 and the Individual Partnership Program since 1997, even providing refueling and airspace support for the ISAF mission in Afghanistan at one point. However, relations with NATO have been strained, particularly after the 2006 presidential election and subsequent political developments. Belarus's membership in the CSTO makes NATO membership incompatible.

The primary equipment of the Belarusian military largely consists of Soviet-era hardware, though some modernization efforts have been undertaken, often in cooperation with Russia.

9. Economy

The economy of Belarus is a state-influenced mixed economy that retains many characteristics of the Soviet era, with a significant role for state-owned enterprises. It is classified as a developing country but ranks "very high" on the United Nations' Human Development Index (60th in 2021). This section analyzes its economic model, key industries, trade, currency, energy sector, and labor market, considering aspects of social equity and labor conditions.

9.1. Economic Model and Performance

Belarus's economic system is often described as "market socialism" or a state-directed economy. Following independence in 1991, unlike many other former Soviet republics that pursued rapid privatization, Belarus under President Alexander Lukashenko maintained substantial state control over key industries and eschewed large-scale privatizations. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) continue to dominate large sections of the economy, particularly in manufacturing and agriculture. In 2015, about 39.3% of Belarusians were employed by state-controlled companies, 57.2% by private companies (in which the government had a 21.1% stake), and 3.5% by foreign companies.

Key macroeconomic indicators include:

- GDP:** In 2018, Belarus's GDP (PPP) was estimated at around 185.00 B USD. GDP per capita (PPP) was approximately 19.76 K USD in 2020. Economic growth has fluctuated, with periods of strong growth fueled by favorable terms for Russian energy imports, followed by slowdowns or recessions due to external shocks, internal structural issues, or international sanctions. The economy experienced a severe crisis in 2011 with high inflation.

- Inflation:** Inflation has historically been a challenge. For instance, in 2011, inflation reached 108.7%. In October 2022, President Lukashenko controversially banned price increases to combat food inflation.

- State Intervention:** The government plays a significant role in economic planning, price controls, and resource allocation. Policies have often prioritized social stability and full employment, sometimes at the cost of economic efficiency and market reforms.

The social impact of this model includes relatively low official unemployment rates and a social safety net inherited from the Soviet era. However, wages are generally lower than in neighboring EU countries, and there are concerns about economic freedom and the business environment for private enterprises. The Global Innovation Index ranked Belarus 85th in 2024.

9.2. Major Industries

Belarus has a developed industrial sector, a legacy of Soviet industrialization. Key sectors include:

- Manufacturing:** This is a cornerstone of the economy.

- Heavy Machinery and Vehicles:** Belarus is known for producing tractors (e.g., MTZ/Belarus), trucks (e.g., BelAZ haul trucks, MAZ), agricultural machinery, and machine tools. In 2019, manufacturing accounted for 31% of GDP, employing 34.7% of the workforce.

- Chemicals:** Production of fertilizers (especially potash, with Belarus being a major global producer centered in Salihorsk), synthetic fibers, and other chemical products is significant.

- Petroleum Refining:** Belarus has large oil refineries (e.g., at Mazyr and Navapolatsk) that process imported Russian crude oil for domestic consumption and re-export of refined products. This has been a key source of export revenue, though vulnerable to changes in Russian supply terms.

- Food Processing:** A substantial sector based on domestic agricultural output, including dairy products, meat products, and canned goods.

- Agriculture:** Important agricultural products include potatoes (a traditional staple), grains (rye, barley, oats), sugar beets, flax, and livestock (cattle for meat and dairy, pigs). Much of the agricultural land is managed by large collective or state farms.

- Information Technology (IT):** The IT sector has seen significant growth, becoming an important export earner. The Belarus Hi-Tech Park in Minsk, established in 2005, offers tax incentives and has fostered a vibrant ecosystem for software development, IT outsourcing, and tech startups (e.g., Wargaming, Viber).

- Forestry and Wood Processing:** Given that forests cover about 43% of the country, forestry and wood products are also important.

Social and environmental concerns related to these industries include the impact of heavy industry on the environment, working conditions in state-owned enterprises, and the long-term effects of the Chernobyl disaster on agriculture in affected regions.

9.3. Trade

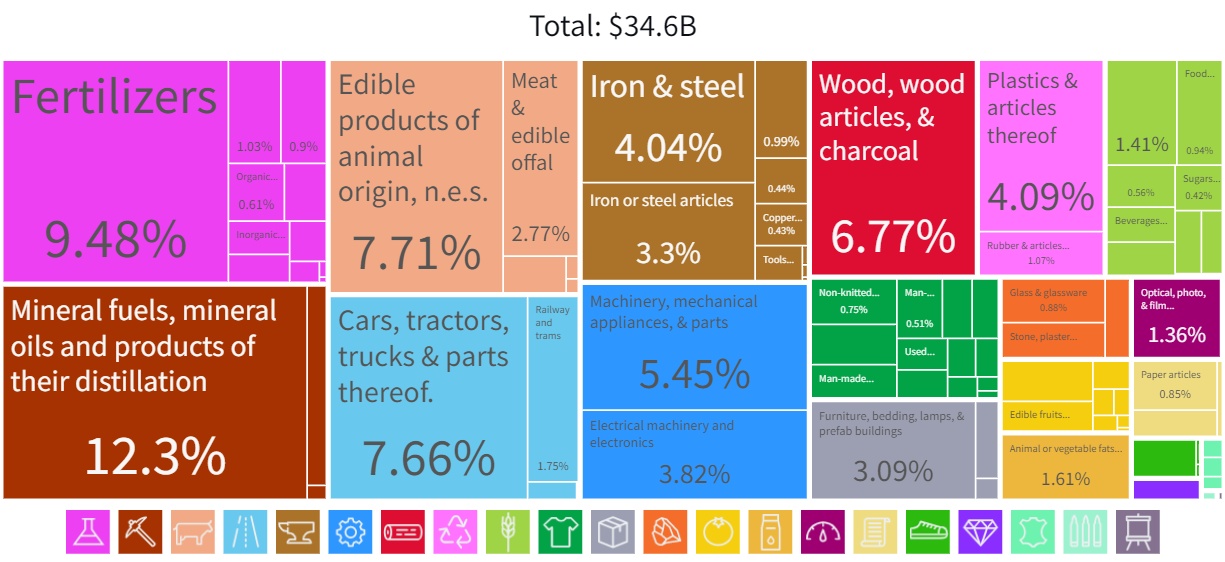

Belarus has trade relations with over 180 countries. Its main trading partners have traditionally been Russia and the European Union (EU).

- Exports:** Key export commodities include refined petroleum products, potash fertilizers, machinery and transport equipment (tractors, trucks), chemicals, food products (dairy, meat), and IT services.

- Imports:** Major imports include crude oil and natural gas (primarily from Russia), machinery, metals, and consumer goods.

- Trading Partners:**

- Russia:** Historically the largest trading partner, accounting for a significant share of both exports and imports (around 45% of exports and 55% of imports in 2007, including petroleum). Belarus is part of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) with Russia, which facilitates trade.

- European Union:** The EU was the second-largest trading partner (around 25% of exports and 20% of imports in 2007). However, trade has been significantly affected by EU sanctions imposed due to political and human rights concerns, especially after 2020.

- Other Partners:** China has emerged as an increasingly important trading and investment partner. Belarus also trades with Ukraine and other CIS countries.

Belarus applied to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1993, but its accession process has been prolonged. International sanctions, particularly from Western countries, have had a substantial impact on Belarus's foreign trade, restricting access to markets and financial services. In 2007, Belarus lost its EU Generalized System of Preferences status due to concerns over labor rights. Further extensive sanctions were imposed by the EU, US, UK, and Canada following the 2020 election, the Ryanair flight diversion, the migrant crisis, and Belarus's involvement in the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. These sanctions target key sectors like potash, oil refining, finance, and aviation.

In January 2023, Belarus controversially legalized copyright infringement of media and intellectual property from "unfriendly" foreign nations.

There are six free economic zones in Belarus, established to encourage investment: FEZ Brest (1996), FEZ Gomel-Raton (1998), FEZ Grodnoinvest (2002), FEZ Minsk (1998), FEZ Mogilev (2002), and FEZ Vitebsk (1999).

9.4. Currency and Finance

The official currency of Belarus is the Belarusian ruble (BYN).

The currency was first introduced in May 1992, replacing the Soviet ruble. It has undergone several redenominations due to high inflation:

- The first coins of the Republic of Belarus were issued on December 27, 1996.

- A redenomination occurred in 2000 (removing three zeros).

- A significant financial crisis in 2011 led to a sharp devaluation of the ruble (by 56% against the USD in May 2011) and high inflation.

- Another redenomination took place in July 2016, introducing the new Belarusian ruble (BYN) at a rate of 1 BYN = 10,000 old rubles (BYR). This was aimed at stabilizing the currency and curbing inflation. Old and new currencies circulated in parallel until December 31, 2016.

Exchange rate policy has varied. For a period, the National Bank of Belarus pegged the ruble to the Russian ruble, but this peg was abandoned in 2007. As part of the Union State discussions, a single currency with Russia (analogous to the Euro) has been considered but not implemented.

The banking system of Belarus consists of two tiers: the National Bank of the Republic of Belarus (the central bank) and commercial banks. As of recent reports, there are around 25 commercial banks, with state-owned banks playing a dominant role in the financial sector. The Belarusian Currency and Stock Exchange is the country's main stock exchange. The financial sector has also been targeted by international sanctions.

9.5. Energy

Belarus is highly dependent on imported energy resources, particularly oil and natural gas, almost exclusively from Russia. This dependency has been a critical factor in its economic and political relations with Moscow.

- Energy Supply and Consumption:** The country's energy mix relies heavily on fossil fuels. Natural gas is the primary fuel for electricity generation and heating.

- Oil and Gas Imports:** Belarus imports large volumes of crude oil from Russia, which is processed at its two major refineries in Mazyr and Navapolatsk. A significant portion of the refined products is then exported, forming a key source of revenue. However, disputes with Russia over the price of oil and gas (e.g., the "energy wars") have periodically impacted the Belarusian economy. Russia has often provided energy to Belarus at subsidized prices as part of their close alliance, but these terms have varied.

- Belarusian Nuclear Power Plant (Astravets NPP):** To reduce its reliance on imported fossil fuels, Belarus constructed its first nuclear power plant near Astravyets, Grodno Region, with Russian financing and technology (Rosatom). The first unit began commercial operation in 2021, and the second unit was expected to follow. The project has faced controversy, particularly from neighboring Lithuania, due to safety concerns and its proximity to the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius. The Baltic states have agreed to stop electricity trade with Belarus once the NPP is fully operational.

- Energy Security:** Diversifying energy sources and improving energy efficiency are stated goals, but progress has been limited due to strong ties with Russia.

- Environmental Considerations:** The reliance on fossil fuels contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. The environmental impact of the Chernobyl disaster also has long-term implications for land use and energy policy in affected regions.

9.6. Employment and Labor

The Belarusian labor market is characterized by high levels of state involvement, a legacy of the Soviet system, and specific policies under President Lukashenko that have drawn international scrutiny regarding labor rights.

- Labor Force and Employment Structure:** The labor force consists of over 4 million people. In 2005, nearly a quarter of the population was employed in industrial factories. Other significant sectors for employment include agriculture, manufacturing sales, trade, and education. As of 2015, approximately 39.3% of Belarusians were employed by state-controlled companies, 57.2% by private companies (in which the government has a 21.1% stake), and 3.5% by foreign companies.

- Unemployment:** Official unemployment rates in Belarus have historically been reported as very low (e.g., 1.5% in 2005). This is partly due to state policies aimed at maintaining employment in SOEs and discouraging official unemployment status. However, hidden unemployment or underemployment may be more significant.

- State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs):** Employment in SOEs remains a major feature. These enterprises often provide not only jobs but also social benefits, reflecting the Soviet-era model.

- Labor Rights and Social Welfare:** Belarus has faced criticism from international organizations like the International Labour Organization (ILO) concerning violations of labor rights, including freedom of association and the right to strike. Independent trade unions face significant obstacles.

- In 2014, a controversial law was announced by President Lukashenko restricting collective farm (kolkhoz) workers (around 9% of the total workforce at the time) from leaving their jobs or changing their living location without permission from governors. Lukashenko reportedly compared this law to serfdom. Similar restrictive regulations were introduced for the forestry industry in 2012.

- Laws have also existed that penalize unemployment (sometimes referred to as "social parasite" laws), requiring those not officially employed to pay a special tax or perform community service, which has also been criticized as a violation of labor rights.

- Social Welfare:** Belarus maintains a comprehensive social welfare system inherited from the Soviet Union, providing pensions, healthcare, and other social benefits. However, the sustainability and adequacy of these benefits are ongoing challenges given the economic structure.

The overall labor environment is heavily regulated, with limited space for independent labor activism.

10. Society and Demographics

Belarusian society and its demographic profile have been shaped by its historical experiences, including wars, migrations, and Soviet-era policies, as well as more recent trends common in Eastern Europe. This section covers key demographic characteristics, ethnic composition, language use, religious landscape, and aspects of its education, health, and public safety systems.

10.1. Population

According to the 2019 census, the total population of Belarus was 9.41 million. The country has experienced a negative population growth rate and a negative natural growth rate for several years, similar to many other Eastern European nations. In 2007, for instance, the population declined by 0.41%, and the total fertility rate was 1.22, well below the replacement rate. However, its net migration rate has sometimes been slightly positive.

- Population Density:** Approximately 50 people per square kilometer (127 per sq mi).

- Urbanization:** About 79.6% (as of 2021) of the population lives in urban areas. Minsk, the capital, is the largest city with over 2 million residents (1.99 million in 2019). Other major cities include Gomel, Mogilev, Vitebsk, Grodno, and Brest.

- Age Structure:** The population is aging. As of 2015, 69.9% were aged 14-64, 15.5% were under 14, and 14.6% were 65 or older. The median age was estimated to rise significantly by 2050.

- Sex Ratio:** There are about 0.87 males per female.

- Life Expectancy:** Average life expectancy is around 72.15 years (66.53 for men and 78.1 for women, as of 2007 estimates).

- Ethnic Composition (2019 Census):**

- Belarusians: 84.9%

- Russians: 7.5%

- Poles: 3.1%

- Ukrainians: 1.7%

- Others (including Jews, Armenians, Tatars, Roma, Azerbaijanis, and Lithuanians): 2.8%

The status of minorities, particularly the Polish minority, has at times been a subject of political discussion and concern regarding cultural and educational rights.

10.2. Languages

Belarus has two official languages: Belarusian and Russian.

- Russian:** Following a 1995 referendum, Russian was elevated to an official language alongside Belarusian. It is the dominant language in most aspects of public life, including government, business, media, and urban communication. According to the 2009 census, 70% of the population described Russian as the language normally spoken at home. Most Belarusians are fluent in Russian. After the election of Alexander Lukashenko, many schools in major cities increasingly taught in Russian rather than Belarusian, and the circulation of Belarusian-language literature significantly decreased between 1990 and 2020.

- Belarusian:** Belarusian is an East Slavic language closely related to Russian and Ukrainian. While 53% of the population described Belarusian as their "mother tongue" in the 2009 census, only 23% reported speaking it normally at home. There have been ongoing efforts by cultural activists and some state initiatives to promote its use, but it faces challenges from the prevalence of Russian. Historically, its use was suppressed during periods of Russification under the Russian Empire and, to some extent, during the Soviet era.

- Trasyanka**: This is a sociolect or mixed language that combines elements of Belarusian and Russian. It is commonly spoken in rural areas and by some urban dwellers, reflecting the language contact and shift.

- Minority Languages:** Other languages spoken by minority groups include Polish (particularly in western regions near the Polish border), Ukrainian, and Eastern Yiddish (historically significant, though the Jewish population is now much smaller).

The language situation is complex, with diglossia (the coexistence of two languages or dialects within a community, often with different social functions) being a prominent feature. While Belarusian holds symbolic importance as the national language, Russian is more prevalent in practical daily use for a majority of the

population.

10.3. Religion

According to a November 2011 census by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Belarus, 58.9% of Belarusians adhered to some form of religion. Among these, the vast majority belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church.

- Eastern Orthodoxy**: This is the dominant religion, with an estimated 82% of religious adherents (or about 48.3% of the total population) belonging to the Belarusian Orthodox Church, which is an exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). There is also a small, largely émigré-based Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church which is not recognized by the state or the Moscow Patriarchate.

- Roman Catholicism**: This is the second-largest denomination, practiced by about 7.1% of the total population (or a larger percentage of religious adherents). It is most prevalent in the western regions of Belarus, particularly around Grodno, and has historical ties to the country's Polish and Lithuanian minorities, as well as ethnic Belarusians.

- Irreligion**: A significant portion of the population, around 41.1% in 2011, identified as not religious, a legacy of Soviet-era atheistic policies.

- Other Religions (3.3% of total population):**

- Protestantism: Various denominations exist, including Lutherans, Baptists, Pentecostals, and Calvinists.

- Greek Catholicism (Uniate): A historically significant church that maintains Eastern rites but is in communion with Rome. It has a small following today.

- Judaism: Belarus was once a major center of European Jewry, with Jews constituting about 10% of the population before World War II. The Holocaust, emigration, and Soviet policies drastically reduced this number. Today, the Jewish community is very small (less than 1% of the population).

- Islam: Primarily practiced by the Lipka Tatars, an ethnic minority with a long history in Belarus, and more recent immigrant communities. The Lipka Tatar community numbers over 15,000.

- Neo-paganism (Rodnovery): A small number of adherents follow modern pagan beliefs based on ancient Slavic traditions.

Article 16 of the Constitution of Belarus states that Belarus has no official religion and grants freedom of worship. However, it also stipulates that religious organizations whose activities are deemed harmful to the government or social order can be prohibited. The government's relationship with religious organizations, particularly non-Orthodox ones, has sometimes been subject to scrutiny regarding registration, property rights, and religious freedom. President Lukashenko has stated that Orthodox and Catholic believers are the "two main confessions in our country."

10.4. Education

The Belarusian education system is largely state-controlled and follows a structure inherited from the Soviet era, though with some reforms since independence. Education is compulsory through basic secondary education.

- Structure:** The system generally includes:

- Preschool Education:** Kindergartens and nurseries.

- General Secondary Education:** Typically 11 years, divided into primary (grades 1-4), basic secondary (grades 5-9), and upper secondary (grades 10-11). Completion of basic secondary education (9 grades) is mandatory. After 9th grade, students can continue to upper secondary school for a general education diploma, or enter vocational-technical schools or specialized secondary colleges (technikums).

- Vocational-Technical Education:** Provides training for skilled trades.

- Specialized Secondary Education (Colleges/Technikums):** Offers mid-level professional qualifications.

- Higher Education:** Provided by universities, academies, and institutes. Admission is typically based on centralized testing and school performance. Degrees include Bachelor's, Specialist (a traditional 5-year degree), Master's, and doctoral levels (Kandidat Nauk and Doktor Nauk).

- Major Institutions:**

- Belarusian State University (BSU) in Minsk is the leading and largest university.

- Other significant universities include the Belarusian National Technical University (BNTU), Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radioelectronics (BSUIR), Minsk State Linguistic University, and regional universities in Brest, Gomel, Grodno, Mogilev, and Vitebsk.

- The National Academy of Sciences of Belarus plays a key role in research and postgraduate education.

- Languages of Instruction:** While both Belarusian and Russian are official languages, Russian is the predominant language of instruction, especially in higher education and urban schools. There are schools and classes that use Belarusian, but their numbers have fluctuated.

- Government Policies and Trends:** The government heavily subsidizes education, and literacy rates are very high (over 99% for those aged 15 and older). Current trends include efforts to align with international standards like the Bologna Process (though full implementation faces challenges), development of IT education, and maintaining state control over curriculum and ideology in education. There have been criticisms regarding academic freedom and political interference in universities.

10.5. Health and Welfare

Belarus has a state-funded public healthcare system that aims to provide universal access to medical services. The system is largely centralized and inherited its structure from the Soviet Semashko model.

- Healthcare System:**

- Services are provided through a network of polyclinics (for outpatient care), hospitals, specialized medical centers, and rural health posts (feldsher-midwife stations).

- Medical care is generally free at the point of service for citizens, though informal payments and a growing private sector exist for some services.

- The Ministry of Health oversees the system.

- Key Health Indicators:**

- Life expectancy: Around 72-74 years (lower for men, higher for women).

- Infant mortality rates are relatively low for the region.

- Major health challenges include cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and lifestyle-related conditions. The long-term health consequences of the Chernobyl disaster (e.g., thyroid cancer, particularly in the past) remain a concern in affected regions.

- Accessibility and Quality:** While access to basic care is widespread, the quality of services can vary, particularly between urban and rural areas and in terms of access to advanced medical technologies and pharmaceuticals. There can be shortages of certain medications or long waiting times for specialized procedures.

- Social Security and Welfare System:** Belarus has a comprehensive social security system that includes:

- Pensions:** Old-age, disability, and survivor pensions. The retirement age has been gradually increasing.

- Family Support:** Maternity benefits, child allowances, and support for large families.

- Unemployment Benefits:** Provided, though official unemployment rates are kept low.

- Social Assistance:** Support for vulnerable groups, including people with disabilities and low-income households.

The system is funded through social security contributions and general state revenues. The government often emphasizes its commitment to social protection as a key aspect of its "socially-oriented market economy."

10.6. Public Order and Safety

Belarus generally has a low reported rate of violent crime compared to many Western countries, but this is within the context of a highly controlled state.

- Crime Trends:** Petty crimes like theft can occur, particularly in urban areas and tourist spots. Organized crime is present but not as visibly disruptive as in some other post-Soviet states.

- Law Enforcement Agencies:**

- The Militsiya (police) is the primary law enforcement body, operating under the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD). It is responsible for general policing, public order, and criminal investigations.

- The State Security Committee (KGB) is the main intelligence and security agency, retaining its Soviet-era name. It deals with national security threats, counter-intelligence, and has been implicated in the suppression of political dissent.

- Other bodies include the Internal Troops (also under MVD, used for public order and security) and the Presidential Security Service.

- Significant Public Safety Issues:**

- Traffic Safety:** Road accidents are a concern.

- Authoritarian Control:** While contributing to low street crime, the extensive state control and surveillance raise concerns about civil liberties and potential for abuse of power by law enforcement.

- Suppression of Protests:** Law enforcement agencies have been heavily involved in suppressing public protests, often using excessive force and arbitrary detentions, particularly evident during the 2020-2021 protests.

- Government Policies:** The government maintains a strong emphasis on public order and state security, often at the expense of individual freedoms. The judicial system and law enforcement are seen as instruments of state control. Belarus is the only country in Europe that still uses the death penalty.

11. Transport