1. Overview

Abkhazia is a disputed territory located in the South Caucasus, on the eastern coast of the Black Sea, at the intersection of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. Geographically, it is characterized by coastal lowlands and the southwestern slopes of the Greater Caucasus Mountains. Historically, the region has ancient roots, having been part of Colchis, the Roman and Byzantine Empires, and later forming the Kingdom of Abkhazia, which subsequently unified with the Kingdom of Georgia. It experienced periods under Ottoman and Russian imperial rule, followed by varying degrees of autonomy and repression during the Soviet era.

The core of the Abkhazia conflict stems from its unresolved political status following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Ethnic tensions between Abkhaz and Georgians escalated into the War in Abkhazia (1992-1993), which resulted in Georgia losing control over most of the territory and the mass displacement and ethnic cleansing of Georgians. Despite a 1994 ceasefire and numerous negotiation attempts, the dispute remains a significant source of instability in the region.

The de facto Republic of Abkhazia declared independence and exercises control over the majority of the territory, with Sukhumi as its capital. However, this independence is recognized by only a few UN member states, including Russia, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria, as well as some other partially recognized states. The Georgian government, along with most of the international community and the United Nations, considers Abkhazia an integral part of Georgia, officially designating it as the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia, with a government-in-exile based in Tbilisi. Many international bodies also refer to Abkhazia as a Russian-occupied territory, particularly following the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, which further entrenched Russian military and political influence.

The conflict has had severe social impacts, including a profound humanitarian crisis involving hundreds of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees, primarily ethnic Georgians. Human rights issues, particularly concerning the rights of returnees, minority rights, and freedom of movement, remain critical concerns. The socio-economic situation in Abkhazia is heavily reliant on Russia, affecting its de facto sovereignty and development. This article explores these multifaceted aspects of Abkhazia from a perspective that emphasizes social justice, human rights, and the experiences of all affected populations.

2. Toponymy

The name Abkhazia has various forms and etymologies across different languages. The Abkhaz people call their land АԥсныApsnyabkhazian. This name is popularly etymologized as "a land of the soul," but its literal meaning is closer to "a country of mortals" or "land of the Abkhazians (mortals)." The term АԥсныApsnyabkhazian possibly first appeared in an Armenian text in the seventh century, perhaps referring to the ancient Apsilae people.

The Russian name АбхазияAbkhaziyaRussian is adapted from the Georgian აფხაზეთიApkhazetiGeorgian. In Mingrelian, a Kartvelian language related to Georgian, Abkhazia is known as აბჟუაAbzhuaxmf or სააფხაზოSaapkhazoxmf.

In early Muslim sources, the term "Abkhazia" was often used to refer to the territory of Georgia more broadly. Historically, as a successor state to Lazica (known as Egrisi in Georgian sources), Abkhazia was sometimes referred to as Egrisi in certain Byzantine-era Georgian and Armenian chronicles.

The Constitution of the de facto Republic of Abkhazia states that the names "Republic of Abkhazia" and "Apsny" are equivalent and interchangeable. The official full name in Abkhaz is Аԥсны АҳәынҭқарраApsny Ahwyntqarraabkhazian, and in Russian, it is Республика АбхазияRespublika AbkhaziyaRussian. Before the 20th century, the region was sometimes referred to in English language sources as "Abhasia."

3. History

The history of Abkhazia spans millennia, encompassing periods of ancient kingdoms, imperial domination, Soviet rule, and post-Soviet conflict leading to its current disputed status. The region has been a crossroads of cultures and powers, profoundly shaping its societal structures and inter-ethnic relations.

3.1. Ancient and Medieval Periods

Between the 9th and 6th centuries BC, the territory of modern Abkhazia was part of the ancient Kingdom of Colchis. Around the 6th century BC, Greek traders established colonies along the Black Sea coast, notably at Pitiunt (modern Pitsunda) and Dioscurias (modern Sukhumi). Classical authors like Arrian, Pliny the Elder, and Strabo described various peoples inhabiting the region, including the Abasgoi (considered ancestors of the Abkhaz) and the Moschoi. In 63 BC, this region was absorbed into the Kingdom of Lazica (also known as Egrisi).

The Roman Empire conquered Lazica in the 1st century AD, though its direct control was largely confined to coastal ports like Dioscurias, where a small Roman outpost existed. The Abasgoi and Apsilae peoples were nominal Roman subjects, with some Abasgoi, such as those in the Ala Prima Abasgorum, serving in the Roman army in places like Egypt. By the 4th century, Lazica regained a degree of independence but remained within the Byzantine Empire's sphere of influence. Anacopia (modern New Athos) became the principality's capital. Christianity spread in the region, and an archbishop's seat was established in Pityus. Stratophilus, the Metropolitan of Pityus, participated in the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. According to Eastern tradition, Simon the Zealot, one of the apostles, died during a missionary trip in Abkhazia and was buried in Nicopsis; his remains were later transferred to Anacopia.

In the mid-6th century AD, the Lazic War erupted between the Byzantine Empire and Sasanian Persia for supremacy over Abkhazia. During this conflict, the Abasgians revolted against Byzantine rule, seeking Sasanian assistance, but the revolt was suppressed by the Byzantine general Bessas. In 736 AD, an Arab incursion led by Marwan II was repelled by Prince Leon I of Abkhazia in alliance with Lazic and Iberian forces. Leon I married the daughter of Mirian of Kakheti, and his successor, Leon II of Abkhazia, utilized this dynastic union to acquire Lazica in the 770s.

Around 778 AD, Prince Leon II, with the help of the Khazars, declared independence from the Byzantine Empire, establishing the Kingdom of Abkhazia and transferring his capital to Kutaisi. During this period, the Georgian language gradually replaced Greek as the language of literacy and culture. The Kingdom of Abkhazia flourished between 850 and 950 AD. In the late 10th and early 11th centuries, through dynastic succession, the Kingdom of Abkhazia unified with eastern Georgian states to form a single Kingdom of Georgia under King Bagrat III.

Within the unified Georgian kingdom, Abkhazia retained a degree of distinctiveness. During the reign of Queen Tamar in the 12th-13th centuries, Georgian chronicles mention Otagho of the House of Sharvashidze (also known as Chachba) as the Eristavi (duke) of Abkhazia. This house would continue to rule Abkhazia as a principality for centuries. In the 1240s, the Mongols invaded and divided Georgia into eight military-administrative sectors (tümens); the territory of contemporary Abkhazia formed part of the tümen administered by Tsotne Dadiani.

3.2. Ottoman Era

In the 16th century, following the fragmentation of the unified Kingdom of Georgia into smaller kingdoms and principalities, the Principality of Abkhazia emerged, nominally a vassal of the Kingdom of Imereti and ruled by the Sharvashidze dynasty. The Ottoman Empire began to exert its influence in the region. The Ottomans first attacked Sukhumi in 1453 and established a garrison there in the 1570s. Throughout the 17th century, Ottoman attacks continued, eventually leading to the imposition of tribute on Abkhazia.

Ottoman influence grew significantly in the 18th century. A fort was constructed in Sukhumi, and the ruling Sharvashidze princes and many other Abkhaz converted to Islam. The Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi, who visited the region in 1641, provided some of the earliest written evidence of the spread of Islam in Abkhazia. He noted the presence of a mosque and described some Abkhazians as "Muslims" hostile to Christians, though perhaps not strictly adhering to the Quran. Islamization was more pronounced among the higher strata of society. For instance, Prince Shervashidze-Chachba was forcibly converted to Islam in 1733 after the Turks destroyed Elyr, an important Abkhaz pilgrimage site near Ochamchira. Despite the conversions and Ottoman presence, conflicts between the Abkhaz and the Turks persisted. Evliya Çelebi also recorded that the Chách, described as the principal tribe of the Abkhazian principality, spoke the Mingrelian language.

By the early 19th century, Abkhazia sought protection from the expanding Russian Empire. In 1801, Prince Kelesh Ahmed-Bey made overtures to Russia, but this was shortly followed by his assassination. In 1810, Russia declared Abkhazia an autonomous principality under its suzerainty.

3.3. Russian Imperial Era

Throughout the early 19th century, the rulers of Abkhazia navigated the rivalry between the Russian and Ottoman Empires. Prince Kelesh Ahmed-Bey initiated relations with Russia in 1803. However, after his assassination in 1808 by his pro-Ottoman son, Aslan-Bey, a brief pro-Ottoman period ensued. On July 2, 1810, Russian marines stormed Sukhum-Kale (Sukhumi) and replaced Aslan-Bey with his Christianized brother, Sefer Ali-Bey (who took the name George). Abkhazia then joined the Russian Empire as an autonomous principality, though Sefer-Bey's rule was largely limited to the areas around Sukhumi and the Bzyb river, with many mountain regions remaining effectively independent.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829 significantly strengthened Russia's position in the Caucasus, further dividing the Abkhaz elite along religious lines. During the Crimean War (1853-1856), Russian forces had to evacuate Abkhazia, and Prince Hamud-Bey Sharvashidze-Chachba (Mikhail), who ruled from 1822 to 1864, appeared to switch allegiance to the Ottomans.

By 1864, Russia had subjugated the highlanders of the Western Caucasus. The autonomy of Abkhazia, which had served as a pro-Russian buffer, was no longer deemed necessary by the Tsarist government. In November 1864, Prince Mikhail was forced to renounce his rights and resettle in Voronezh, Russia, ending the rule of the Sharvashidze dynasty. Abkhazia was incorporated into the Russian Empire as the Sukhum-Kale special military province, which was transformed in 1883 into an okrug (district) within the Kutaisi Governorate.

A significant consequence of Russian annexation was the Muhajirism, the mass emigration of Muslim Abkhaz and other Caucasian Muslims to the Ottoman Empire between 1864 and 1878. It is estimated that as much as 40% of the Abkhaz population left. This exodus left large areas of Abkhazia depopulated, leading to subsequent migrations of Armenians, Georgians (including Mingrelians and Svans), Russians, and others into the vacated territories, altering the region's demographic makeup. Some Georgian historians assert that Georgian tribes had populated parts of Abkhazia since ancient times.

Under Tsarist rule, policies of Russification were implemented. The Abkhaz people were officially branded as "guilty people" following uprisings, and they lacked leadership capable of mounting significant opposition. Russian became the language of education and official prayer. In 1898, the Russian Orthodox Church prohibited teaching and religious services in Georgian in the Sukhumi district, leading to protests from the Georgian population. While a subsequent Holy Synod decree allowed Georgian in Mingrelian parishes and Old Church Slavonic in Abkhaz parishes, this was inconsistently applied. Efforts by figures like Tedo Sakhokia to introduce Abkhaz and Georgian in church services and education were met with official resistance and criminal charges.

3.4. Georgian Democratic Republic (1918-1921)

Following the October Revolution in Russia in 1917, the Transcaucasian Commissariat was established in the South Caucasus, which moved towards independence from Russia. On April 9, 1918, the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic was declared. In Abkhazia, Bolsheviks attempted to seize power in May 1918 and disbanded the local Abkhaz People's Council. The Council requested aid from the Transcaucasian authorities, which dispatched the Georgian People's Guard to defeat the Bolshevik rebels on May 17.

On May 26, 1918, Georgia declared its independence from the Transcaucasian Federation, which soon dissolved. On June 8, 1918, the Abkhaz People's Council signed a treaty with the Georgian National Council, which confirmed Abkhazia's status as an autonomous region within the Georgian Democratic Republic. The Georgian army suppressed another Bolshevik revolt and a Turkish expedition in Abkhazia in 1918. Forces of the Russian White movement, led by General Anton Denikin, laid claim to Abkhazia and briefly captured Gagra, but Georgian forces counter-attacked in April 1919 and retook the city. In May 1920, Bolshevik Russia signed an agreement with Georgia, recognizing Abkhazia as part of Georgia.

In 1919, the first election to the Abkhaz People's Council was held. The Council favored Abkhazia remaining an autonomous region within Georgia. This arrangement lasted until the Red Army invasion of Georgia in February 1921.

3.5. Soviet Era

The Soviet era brought significant political and socio-cultural transformations to Abkhazia, with its status changing multiple times, marked by periods of nominal autonomy, development, and intense repression, profoundly affecting its diverse population.

3.5.1. Abkhaz Socialist Soviet Republic (1921-1931)

In February-March 1921, the Bolshevik Red Army invaded Georgia, ending its brief independence. On March 31, 1921, Abkhazia was declared the Socialist Soviet Republic of Abkhazia (SSR Abkhazia). Its status was ambiguous, initially described as a "treaty republic" associated with the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (Georgian SSR). This arrangement notionally granted Abkhazia a degree of independence while maintaining close ties with Soviet Georgia. During this period, Abkhazia began to experience Soviet-style political and economic restructuring, including land reforms and the establishment of collective farms, alongside efforts to promote Abkhaz culture and language to some extent, though always within the ideological confines of the Soviet state.

3.5.2. Abkhaz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (within Georgian SSR, 1931-1991)

In February 1931, Joseph Stalin downgraded Abkhazia's status, transforming the SSR Abkhazia into the Abkhaz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Abkhaz ASSR), directly incorporated within the Georgian SSR. Despite its nominal autonomy, Abkhazia was subjected to strong direct rule from central Soviet authorities and intense policies of Georgianization, particularly during the 1930s and 1940s under the influence of Stalin and Lavrenty Beria (who was himself of Mingrelian origin and had headed the party organization in Georgia).

During this period, the publication of materials in the Abkhaz language dwindled and was eventually stopped. Abkhaz schools were closed between 1945 and 1946, forcing Abkhaz children to study in the Georgian language. This was part of a wider Soviet educational reform launched in 1938, but in Abkhazia, it had a distinct Georgianizing character. The Abkhaz alphabet was even changed from a Latin-based script to one based on Georgian characters. The Great Purge of 1937-1938 saw the Abkhaz ruling elite decimated. By 1952, over 80% of the 228 top party and government officials and enterprise managers in Abkhazia were ethnic Georgians; only 34 Abkhaz, 7 Russians, and 3 Armenians remained in these positions. The leader of the Georgian Communist Party, Kandid Charkviani, actively supported the Georgianization of Abkhazia. Policies also encouraged the resettlement of ethnic Georgians, primarily from western Georgia, into Abkhazia; about 9,000 peasant households were settled in underpopulated areas between 1947 and 1952. These demographic changes and repressive policies fueled resentment among the Abkhaz population.

After Stalin's death in 1953 and Beria's execution, the policy of repression was eased. The Abkhaz language was reinstated in schools, publications resumed, and Abkhaz individuals were given a greater role in the governance of the autonomous republic. As in most smaller autonomous republics, the Soviet government encouraged the development of culture and particularly literature in the titular language. The Abkhaz ASSR was unique in that its constitution confirmed Abkhaz as one of its official languages. However, demographic shifts continued. By the late Soviet period, despite constituting only about 17.8% of the region's population (while Georgians were 45.7%), ethnic Abkhaz held a disproportionately large number of official posts: 41% of seats in the Abkhazian Supreme Soviet and 67% of republican minister positions were held by ethnic Abkhaz, including the First Secretary of the Communist Party in Abkhazia. These policies, while aimed at addressing past grievances, contributed to growing ethnic tensions with the Georgian population in Abkhazia.

3.6. Dissolution of the USSR and the Georgian-Abkhaz Conflict

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s saw a dramatic escalation of ethnic tensions between Georgians and Abkhaz, ultimately leading to a devastating war and Abkhazia's de facto independence from Georgia. This period was marked by rising nationalism, political maneuvering, and tragic humanitarian consequences.

3.6.1. Background to the Conflict and Declaration of Independence

As the Soviet Union began to disintegrate in the late 1980s under Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of perestroika and glasnost, nationalist sentiments surged in many Soviet republics, including Georgia. Georgians pushed for independence from Moscow, while many Abkhaz feared that an independent Georgia would lead to the erosion or elimination of their autonomy and a renewal of Georgianization policies. The Abkhaz argued for the establishment of Abkhazia as a separate Soviet republic or at least for stronger guarantees of their rights.

In 1988, Abkhaz nationalists, through the popular movement Aidgylara, sent the "Abkhazian Letter" to Gorbachev, outlining their grievances and demanding the reinstatement of Abkhazia's status as a Union Republic, as it had notionally been between 1921 and 1931. They justified this by referring to the Leninist principle of the right of nations to self-determination. Tensions flared into violence on July 16, 1989, in Sukhumi during riots that erupted over the opening of a branch of Tbilisi State University in the city. The clashes resulted in several deaths and numerous injuries before Soviet troops restored order.

In March 1990, Georgia declared its sovereignty and unilaterally nullified treaties concluded by the Soviet government since 1921, moving closer to full independence. When the Soviet Union held a referendum on its preservation in March 1991, Georgia boycotted it. However, 52.3% of Abkhazia's population (comprising almost all of the ethnic non-Georgian population) participated, with an overwhelming 98.6% voting to preserve the Union. Conversely, most ethnic non-Georgians in Abkhazia boycotted Georgia's independence referendum on March 31, 1991, which saw massive support for independence across Georgia. Georgia declared independence on April 9, 1991, under President Zviad Gamsakhurdia. Initially, under Gamsakhurdia, a power-sharing agreement was reached in Abkhazia, granting the Abkhaz a degree of over-representation in the local legislature, which temporarily calmed the situation.

However, Gamsakhurdia's nationalist rule was soon challenged, and he was ousted in a military coup in January 1992. Former Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze returned to lead Georgia. On February 21, 1992, Georgia's ruling Military Council announced it was abolishing the Soviet-era constitution and restoring the 1921 constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia. Many Abkhaz interpreted this as an abolition of their autonomous status, although the 1921 constitution did contain a provision for Abkhazia's autonomy. In response, on July 23, 1992, the Abkhaz faction in the republic's Supreme Council declared the restoration of the 1925 Abkhazian constitution, which defined Abkhazia as a sovereign state, effectively declaring independence from Georgia. This move was boycotted by ethnic Georgian deputies and was not recognized internationally. The Abkhaz leadership began ousting Georgian officials from their posts, a process often accompanied by violence. Meanwhile, Abkhaz leader Vladislav Ardzinba intensified ties with hard-line Russian politicians and military elites, declaring readiness for war with Georgia.

3.6.2. War in Abkhazia (1992-1993)

In August 1992, war broke out when the National Guard of Georgia entered Abkhazia. The stated aims were to protect Georgian-language schools, free captive Georgian officials, and secure the railway line which had been subject to attacks. Abkhaz troops were reported to have fired first. The Abkhaz separatist government retreated from Sukhumi to Gudauta, where a Russian military base was located. UNHCR reported ethnic-based violence against Georgians in Gudauta during this period. Georgian troops, meeting relatively little initial resistance, marched into Sukhumi but subsequently engaged in widespread ethnically based pillage, looting, assault, and murder, according to Human Rights Watch.

The Abkhaz military defeat prompted a hostile response from the self-styled Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus, an umbrella group uniting various movements from the North Caucasus, including Chechens (led by the then little-known Shamil Basayev), Circassians, Abazins, Cossacks, and Ossetians. Hundreds of volunteer paramilitaries and mercenaries from Russia crossed the border, reportedly unimpeded by Russian military forces, to support the Abkhaz separatists. There have been suggestions that Basayev and his battalion received training from the Russian Army.

On September 25, 1992, the Supreme Soviet of Russia passed a resolution condemning Georgia, supporting Abkhazia, calling for the suspension of arms deliveries to Georgia, and advocating for the deployment of a Russian peacekeeping force. In October 1992, Abkhaz and North Caucasian paramilitaries launched a major offensive, capturing Gagra after breaking a ceasefire, and driving Georgian forces out of large parts of northwestern Abkhazia. Shevardnadze's government accused Russia of giving covert military support to the separatists. By the end of 1992, the rebels controlled much of Abkhazia northwest of Sukhumi.

The conflict remained in a stalemate until July 1993, when Abkhaz separatist militias launched an abortive attack on Georgian-held Sukhumi. They surrounded and heavily shelled the capital, where Shevardnadze himself was trapped. A Russian-brokered truce was agreed upon in Sochi at the end of July, but it broke down on September 16, 1993, when Abkhaz forces, with armed support from outside Abkhazia, launched fresh attacks on Sukhumi and Ochamchira. Despite a United Nations Security Council call for an immediate cessation of hostilities and condemnation of the Abkhaz violation of the ceasefire, fighting continued.

After ten days of intense fighting, Sukhumi fell to Abkhaz forces on September 27, 1993. Shevardnadze narrowly escaped. The fall of Sukhumi was followed by the massacre of many remaining ethnic Georgian civilians by Abkhaz, North Caucasian militants, and their allies. The mass killings and destruction continued for two weeks, leaving thousands dead and missing. The Abkhaz forces quickly overran the rest of Abkhazia, with only a small region in eastern Abkhazia, the upper Kodori Valley, remaining under Georgian control until 2008. Gross human rights violations were reported on both sides during the war.

3.6.3. Ethnic Cleansing of Georgians and Humanitarian Issues

Before the 1992-1993 war, ethnic Georgians constituted nearly half of Abkhazia's population (around 45.7% in the 1989 census), while ethnic Abkhaz made up less than one-fifth (around 17.8%). As the war progressed and Abkhaz separatist forces gained control, a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing was implemented against the Georgian civilian population. This campaign aimed to expel and eliminate the Georgian ethnic presence in Abkhazia to consolidate Abkhaz control and alter the region's demographic balance.

Estimates of the number of Georgians killed during the ethnic cleansing vary, with figures commonly cited between 5,000 and 10,000. Hundreds more went missing. Up to 250,000 ethnic Georgians were forcibly expelled from their homes, becoming internally displaced persons (IDPs) within Georgia or refugees in other countries. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) officially recognized the ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia at its summits in Budapest (1994), Lisbon (1996), and Istanbul (1999). The United Nations Security Council, while avoiding the term "ethnic cleansing," repeatedly affirmed the unacceptability of the demographic changes resulting from the conflict and upheld the right of all refugees and IDPs to return to their homes in safety and dignity.

The campaign of violence and expulsion was not limited to Georgians; Russians, Armenians, Greeks, moderate Abkhaz, and other ethnic minorities also suffered. More than 20,000 houses owned by ethnic Georgians were destroyed, and hundreds of schools, kindergartens, churches, hospitals, and historical monuments were pillaged and destroyed. Pogroms against remaining Georgians reportedly continued in some areas even after the main phase of the war ended, into early 1995. The population of Abkhazia plummeted from over 525,000 in 1989 to around 216,000 in the immediate post-war period.

The resulting refugee crisis created a dire humanitarian situation. Between 1994 and 1998, some 40,000 to 60,000 Georgian IDPs spontaneously returned to the Gali District of Abkhazia, which borders Georgia proper. However, many were displaced again during a flare-up of fighting in Gali in 1998. Despite these setbacks, a significant number of Georgians continued to reside in or commute to Gali, primarily for agricultural work. The human rights situation for these returnees remained precarious, with reports of discrimination, restrictions on movement, and limited access to education in their native language. International organizations, including the UN, repeatedly urged the de facto Abkhaz authorities to respect the right of return and international human rights standards, and to allow for international human rights monitoring, but access and cooperation were often limited. The focus on victims and human rights violations is crucial for understanding the long-term impact of the conflict.

3.6.4. Post-war Situation and Involvement in the 2008 South Ossetia War

Following the 1994 Moscow Agreement on Ceasefire and Separation of Forces, an unstable peace settled over Abkhazia. The dispute remained unresolved, with Abkhazia functioning as a de facto independent state but unrecognized internationally. A peacekeeping force from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), largely composed of Russian troops, and the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG) were deployed to monitor the ceasefire line along the Inguri River. Sporadic acts of violence and skirmishes continued throughout the post-war years. Georgia frequently accused Russian peacekeepers of bias, alleging they supplied Abkhaz rebels with arms and financial support, thereby undermining Georgia's territorial integrity. Russia's influence in Abkhazia grew, with the Russian ruble becoming the de facto currency and Russia beginning to issue its passports to Abkhaz residents.

In July 2006, Georgian forces launched a police operation in the upper Kodori Valley, the only part of Abkhazia remaining under Georgian control, against a local militia leader, Emzar Kvitsiani. The operation successfully brought the gorge back under Tbilisi's direct administration, and it was renamed Upper Abkhazia. This move was condemned by Abkhaz and Russian authorities. Tensions escalated further with incidents such as the shooting down of Georgian helicopters over Kodori and, in April 2008, a Russian MiG fighter jet shooting down an unmanned Georgian reconnaissance drone over Abkhazia.

The situation dramatically changed with the outbreak of the 2008 South Ossetia War. On August 9, 2008, as fighting raged in South Ossetia, Abkhaz forces, with Russian support, opened a second front by attacking Georgian forces in the Kodori Valley. An estimated 9,000 Russian soldiers entered Abkhazia, ostensibly to reinforce the existing peacekeeping contingent. Abkhaz forces, backed by Russian air and artillery support, quickly overran the Kodori Valley. By August 12, Georgian forces and civilians had evacuated this last part of Abkhazia under Georgian government control.

On August 26, 2008, Russia formally recognized the independence of Abkhazia (and South Ossetia). This act was widely condemned by the international community as a violation of Georgia's sovereignty and territorial integrity. Following Russia's recognition, the 1994 ceasefire agreement was annulled, and the UNOMIG and OSCE missions were terminated as their mandates became untenable. On August 28, 2008, the Parliament of Georgia passed a resolution declaring Abkhazia a Russian-occupied territory, a position supported by most UN member states. The 2008 war significantly altered the geopolitical landscape, solidifying Abkhazia's separation from Georgia and deepening its dependence on Russia, while further impacting regional stability and the lives of civilians affected by the ongoing displacement.

3.6.5. Political Developments Since the 2008 War

Following Russia's recognition of Abkhazia's independence in August 2008, political life in the de facto republic became increasingly intertwined with Moscow. A series of controversial agreements were signed, leasing or selling key state assets to Russian entities and ceding control over borders and security to Russia. These moves sparked protests in May 2009 from opposition parties and war veteran groups, who argued that such deals undermined Abkhazia's sovereignty and risked exchanging Georgian domination for Russian. Vice President Raul Khajimba resigned in agreement with these criticisms. However, Sergei Bagapsh won the subsequent presidential election in December 2009.

After Bagapsh's death in May 2011, his vice president, Alexander Ankvab, became acting president and won the presidential election in August 2011. Ankvab's presidency faced growing discontent. In the spring of 2014, the opposition, led by Raul Khajimba, issued an ultimatum demanding Ankvab dismiss the government and implement radical reforms. On May 27, 2014, thousands of opposition supporters demonstrated in Sukhumi, and Ankvab's presidential headquarters was stormed, forcing him to flee to Gudauta. This event became known as the Abkhazian Revolution. While the opposition cited poverty and corruption as causes, a key point of contention was President Ankvab's perceived liberal policy towards ethnic Georgians in the Gali District, which opponents claimed could endanger Abkhazia's ethnic Abkhaz identity.

On May 31, 2014, the People's Assembly of Abkhazia declared Ankvab unable to serve and appointed parliamentary speaker Valeri Bganba as acting president, scheduling an early presidential election for August 24, 2014. Ankvab formally resigned, accusing his opponents of acting immorally and violating the constitution. Raul Khajimba was subsequently elected president and took office in September 2014.

In November 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Khajimba signed a "Treaty on Alliance and Strategic Partnership," which further formalized the integration of Abkhazia's military into the Russian armed forces and deepened economic and social ties. The Georgian government denounced this agreement as "a step towards annexation." Abkhazia's de facto independent status remains heavily reliant on Russian political, economic, and military support. Internal political dynamics continue to be shaped by this dependency, alongside social challenges such as economic development, demographic concerns, and the unresolved status of ethnic Georgians. Unrest was reported again in December 2021, highlighting ongoing internal tensions.

4. Legal Status and International Recognition

The legal status of Abkhazia is one of the most contentious issues in the Caucasus region, central to the Abkhaz-Georgian conflict. Abkhazia is considered by most of the international community to be an integral part of Georgia, while the de facto government of Abkhazia asserts its sovereignty as the Republic of Abkhazia.

4.1. Declaration of Independence and International Response

Abkhazia first declared sovereignty in the context of the dissolving Soviet Union. On July 23, 1992, the Abkhaz faction of the region's Supreme Council declared the restoration of the 1925 Abkhaz constitution, effectively asserting independence from Georgia. This declaration was not recognized internationally. Following the 1992-1993 war, which resulted in the expulsion of Georgian forces from most of Abkhazia, the de facto authorities adopted a new constitution on November 26, 1994, and an Act of State Independence on October 12, 1999.

For many years, no UN member state recognized Abkhazia's independence. The international community, including the United Nations and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), consistently reaffirmed Georgia's sovereignty and territorial integrity. The UN Security Council passed numerous resolutions calling for a peaceful settlement of the conflict based on these principles and emphasizing the right of return for all refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs).

The situation changed dramatically after the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. On August 26, 2008, Russia became the first UN member state to recognize Abkhazia's independence (along with South Ossetia's). This was followed by recognitions from:

- Nicaragua (September 5, 2008)

- Venezuela (September 10, 2009)

- Nauru (December 15, 2009) - reportedly in exchange for significant financial aid from Russia.

- Syria (May 29, 2018)

Vanuatu recognized Abkhazia in 2011 but withdrew its recognition in 2013. Tuvalu also recognized Abkhazia in 2011 but withdrew its recognition in 2014. Abkhazia is also recognized by other partially recognized or unrecognized states, namely South Ossetia and Transnistria, with which it forms the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations. The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic also recognized Abkhazia before its dissolution in 2023.

The overwhelming majority of UN member states, including the United States, the European Union, and major international organizations, do not recognize Abkhazia's independence and continue to consider it part of Georgia. They have condemned Russia's recognition and its military presence in Abkhazia as a violation of international law and Georgian sovereignty. Many view Abkhazia as being under Russian occupation. The de facto Abkhaz authorities, however, maintain that Abkhazia is a sovereign state, basing their claim on the right to self-determination and the historical context of their conflict with Georgia. This divergence in legal interpretation and political stance perpetuates the "frozen conflict" status of the region, balancing the de facto authorities' claims against established international legal norms regarding territorial integrity.

4.2. Georgia's Position and Law on Occupied Territories

The Georgian government unequivocally considers Abkhazia an integral part of its sovereign territory. Its official position is that Abkhazia is an autonomous republic within Georgia, and it maintains the Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia as the legitimate government-in-exile, based in Tbilisi. Georgia views the de facto Abkhaz authorities in Sukhumi as an illegitimate separatist regime, supported and controlled by Russia.

Following the 2008 Russo-Georgian War and Russia's recognition of Abkhazia's independence, Georgia intensified its stance. On August 28, 2008, the Parliament of Georgia passed a resolution declaring Abkhazia and South Ossetia as territories occupied by the Russian Federation. This position is shared by many Western countries and international organizations.

In October 2008, President Mikheil Saakashvili signed into law the "Law of Georgia on Occupied Territories." This law defines Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region (South Ossetia) as occupied territories and outlines specific legal and administrative consequences:

- Restrictions on Entry and Movement:** Foreign citizens are generally required to enter these territories only through Georgia proper (i.e., from Zugdidi Municipality for Abkhazia). Unauthorized entry from other directions (primarily Russia) is considered illegal.

- Economic Activity:** The law restricts economic activities in the occupied territories if they require licenses or registration under Georgian law. It also bans air, sea, and railway communications, international transit via these regions, mineral exploration, and certain financial transactions unless authorized by Georgian authorities. These provisions are retroactive to 1990.

- Responsibility:** The law assigns full responsibility to the Russian Federation, as the occupying power, for human rights violations in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and for compensating material and moral damages inflicted on Georgian citizens and others.

- Legitimacy of Structures:** De facto state agencies and officials operating in the occupied territories are considered illegal by Georgia.

- Exceptions:** The law allows for special permits for entry if the trip serves Georgia's state interests, peaceful conflict resolution, de-occupation, or humanitarian purposes.

Georgia has put forward various proposals for conflict resolution over the years, generally offering Abkhazia broad autonomy within a unified Georgian state, potentially including a federal structure, joint free economic zones, and representation in central Georgian authorities, including the post of vice-president with veto rights on Abkhaz-related issues. These proposals have consistently been rejected by the Abkhaz de facto authorities. A key element of Georgia's position is the unconditional and dignified return of all internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees, primarily ethnic Georgians, to their homes in Abkhazia and the restoration of their property rights, a stance supported by numerous UN resolutions.

4.3. Proposals for Accession to the Russian Federation and Controversies

Since the 1992-1993 war, various proposals have emerged regarding Abkhazia's potential accession to the Russian Federation or the Union State (an alliance between Russia and Belarus). These proposals have been met with strong opposition from the Georgian government and have generated considerable controversy both within Abkhazia and internationally, raising concerns about Abkhaz sovereignty and human rights.

Historically, the idea of joining Russia was voiced even before the war. In March 1989, the Abkhaz ethno-nationalist organization Aidgylara issued the Lykhny Appeal, which called for Abkhazia to become part of the Russian SFSR. This appeal is considered by some as a significant early step towards the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict. After the 1992-1993 war, in November 1993, the then-leader of Abkhazia, Vladislav Ardzinba, proposed holding a referendum on joining the Russian Federation. In 2001, Abkhazia's de facto Prime Minister, Anri Jergenia, reiterated this desire, stating that Abkhazia was preparing to join Russia and planned a referendum on the issue.

Following Russia's recognition of Abkhazia's independence in 2008 and the signing of the 2014 "Treaty of Alliance and Strategic Partnership," Abkhazia's integration with Russia has deepened significantly across military, economic, and social spheres. In October 2022, the de facto President of Abkhazia, Aslan Bzhania, declared Abkhazia's readiness to host a Russian naval base and to join the Russia-Belarus Union State. This proposal, however, faced criticism as impractical, partly because Belarus does not recognize Abkhazia as a sovereign state and considers it part of Georgia.

Russian officials have also periodically voiced support for such integration. In August 2023, Dmitry Medvedev, Deputy Chair of the Security Council of Russia, stated there were "good reasons" for Abkhazia and South Ossetia to join Russia, accusing Georgia of "escalating tensions" with its potential NATO membership aspirations. Medvedev had previously made controversial statements suggesting that Georgia could only be united as part of Russia.

These proposals and the ongoing integration process have been strongly condemned by Georgia, which views them as steps towards the de facto annexation of its sovereign territory. Within Abkhazia itself, while there is widespread support for close ties with Russia due to security and economic dependence, the prospect of full accession to the Russian Federation is a more divisive issue. Some Abkhaz express concerns that such a move would lead to the complete loss of their already limited sovereignty and cultural identity, potentially subsuming Abkhazia into the larger Russian state. The human rights implications, particularly for ethnic minorities and those who might oppose deeper integration, are also a significant concern, as increased Russian control could lead to further restrictions on freedoms. International actors largely view these proposals as further undermining Georgia's territorial integrity and regional stability.

4.4. Status-Neutral Passports

The issue of travel documents for residents of Abkhazia is a complex aspect of its disputed status. While Georgia considers all residents of Abkhazia its citizens, many residents identify as Abkhaz citizens and hold de facto Abkhaz passports, which are not recognized for international travel by most countries. A significant portion of the population also holds Russian passports, a result of Russia's "passportization" policy.

In the summer of 2011, the Parliament of Georgia adopted legislative amendments to allow for the issuance of "status-neutral" identification and travel documents to residents of Abkhazia and the former South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast. These documents were designed to facilitate international travel for residents of the disputed territories and allow them to access social benefits available in Georgia. Crucially, these "neutral passports" do not carry any state symbols of Georgia, aiming to be acceptable to residents who do not wish to use Georgian state documents.

The introduction of status-neutral passports received mixed reactions. Several countries, including Japan, the Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, the United States, Bulgaria, Poland, Israel, Estonia, and Romania, announced their recognition of these documents for travel purposes by May 2013. This provided a channel for some Abkhaz residents to travel internationally without relying solely on Russian passports, the widespread use of which was a point of contention for Georgia.

However, the de facto Abkhaz authorities strongly criticized the initiative. Viacheslav Chirikba, then de facto Foreign Minister of Abkhazia, called the introduction of neutral passports "unacceptable," viewing them as an attempt by Georgia to reassert its sovereignty. The de facto President Alexander Ankvab reportedly threatened that international organizations suggesting or accepting these neutral passports would have to leave Abkhazia.

For many residents of Abkhazia, particularly ethnic Georgians and others who did not wish to or could not easily obtain Russian passports, the status-neutral documents offered a potential solution to travel restrictions. However, the political opposition from the de facto Abkhaz government and the practicalities of their issuance and acceptance have limited their widespread adoption and impact. The situation is further complicated by reports that some Abkhazian residents holding Russian passports issued in Abkhazia have faced difficulties obtaining Schengen visas.

5. Politics and Government

The political landscape of Abkhazia is defined by its disputed status. The de facto Republic of Abkhazia operates as an independent state with its own governmental structures, while Georgia maintains that the legitimate government is the Tbilisi-based Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia.

5.1. Republic of Abkhazia (de facto government)

The de facto Republic of Abkhazia operates its own political system and institutions, though its sovereignty is recognized by only a few UN member states and it is heavily reliant on Russia.

5.1.1. Political System and Key Institutions

Abkhazia is a presidential republic. The President of Abkhazia is the head of state and head of the executive branch, elected for a five-year term with a maximum of two terms. Past presidents include Vladislav Ardzinba, Sergei Bagapsh, Alexander Ankvab, and Raul Khajimba. The current de facto president is Aslan Bzhania since April 2020. The executive branch also includes a Prime Minister and a Cabinet of Ministers, appointed by the President.

Legislative power is vested in the unicameral People's Assembly of Abkhazia (Parliament), which consists of 35 members elected for five-year terms from single-seat constituencies. The most recent parliamentary elections were held in March 2022.

The judicial system includes a Supreme Court, lower courts, and an arbitration court. However, the de facto government faces significant challenges to democratic development. These include its limited international recognition, heavy dependence on Russia, and internal political issues. Ethnic minorities, such as Armenians, Russians, and particularly Georgians, are often claimed to be under-represented in the Assembly and government. A major challenge is the exclusion of hundreds of thousands of predominantly ethnic Georgian refugees and IDPs from the political process, as they have been unable to return to their homes since the 1992-1993 war. This exclusion significantly impacts the legitimacy and representativeness of the de facto institutions.

A 2010 study by the University of Colorado Boulder indicated that a vast majority of Abkhazia's then-resident population supported independence, with a smaller number favoring union with the Russian Federation. Support for reunification with Georgia was reported to be very low, even among the remaining ethnic Georgians, many of whom had adjusted to the post-war reality, though their rights and security remained precarious.

5.1.2. Harmonization of Laws with Russia

Following Russia's recognition of Abkhazia's independence in 2008, the de facto republic's reliance on Russia has deepened across all sectors. In November 2014, Abkhazia and the Russian Federation signed a "Treaty of Alliance and Strategic Partnership." This treaty, among other things, called for the creation of a common defence and security space, coordination of foreign policy, and the formation of a common social and economic space.

Building on this treaty, in November 2020, Abkhazia launched a program for the "formation of common social and economic space" with Russia. The explicit aim of this program is to harmonize Abkhaz legislation and administrative systems with Russian standards. This process covers a wide range of areas, including social policy, economic regulations, healthcare, customs, and taxation. By August 2024, Dmitry Volvach, the Russian Deputy Minister of Economic Development, stated that the process of Abkhazia's harmonization of its laws with Russia was "almost complete."

This harmonization process has significant implications for Abkhazia's local governance and de facto sovereignty. While proponents argue it brings economic benefits and administrative efficiencies, critics, both within Abkhazia and internationally, express concerns that it further erodes Abkhazia's autonomy and makes it increasingly a Russian protectorate. The alignment with Russian laws can impact local social policies, potentially sidelining Abkhaz-specific needs or cultural practices. The economic integration, including the use of the Russian ruble and reliance on Russian financial aid (which constitutes about half of Abkhazia's budget), reinforces this dependency. The social impact includes increased Russian cultural influence and the widespread issuance of Russian passports, which has political and demographic consequences.

5.2. Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia (Georgian government-in-exile)

The Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia is the administrative entity that Georgia recognizes as the legal government of Abkhazia. It functions as a government in exile, with its headquarters currently in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. This body is tasked with representing the interests of the region within Georgia's constitutional framework and, crucially, overseeing the affairs of the approximately 250,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs), predominantly ethnic Georgians, who were forced to leave Abkhazia following the 1992-1993 war and the subsequent ethnic cleansing.

During the war, the Georgian faction of the "Council of Ministers of Abkhazia" (the precursor to the current government-in-exile) was forced to leave Sukhumi when Abkhaz separatist forces took control in September 1993. For nearly 13 years, it operated from Tbilisi. Under leaders like Tamaz Nadareishvili, this government-in-exile was known for a hard-line stance, often advocating for a military solution to the conflict.

In July 2006, following a Georgian police operation, the government-in-exile briefly relocated to the upper Kodori Valley in Abkhazia, which was the only part of Abkhazia under Georgian control at the time. This move was intended to assert Georgian sovereignty. However, during the August 2008 war, Abkhaz and Russian forces took control of the Kodori Valley, forcing the government-in-exile to evacuate back to Tbilisi.

The current head of the Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia is Ruslan Abashidze, who assumed office in 2019. The stated roles of this government include facilitating the return of IDPs, preserving Georgian cultural heritage in Abkhazia, participating in peace negotiations (though their direct involvement is often limited by the de facto authorities' refusal to engage with them), and providing humanitarian and social support to the displaced population. It also aims to maintain a legal and political framework for the eventual reintegration of Abkhazia into Georgia.

6. Foreign Relations

Abkhazia's foreign relations are predominantly shaped by its disputed status. The de facto Republic of Abkhazia maintains diplomatic ties with a small number of states that recognize its independence, with Russia being its principal ally and supporter. Georgia, on the other hand, considers Abkhazia its sovereign territory and conducts its foreign policy aimed at restoring its territorial integrity and managing the consequences of the conflict.

6.1. Relations with Russia

The relationship between the de facto Republic of Abkhazia and the Russian Federation is comprehensive and defining for Abkhazia's existence. Following Russia's recognition of Abkhazia's independence on August 26, 2008, formal diplomatic relations were established. Russia provides extensive political, economic, and military support to Abkhazia, which has led to a significant dependency.

Political Support: Russia is Abkhazia's primary international advocate, promoting its case for sovereignty in various forums, although this has not led to widespread international recognition. Bilateral treaties, including the 2014 "Treaty on Alliance and Strategic Partnership," have further integrated Abkhazia's foreign policy and governance structures with Russia's.

Military Cooperation: Russia maintains a significant military presence in Abkhazia, including the 7th Military Base headquartered in Gudauta. Russian border guards also patrol Abkhazia's de facto borders with Georgia proper. This presence is seen by Abkhazia as a security guarantee against Georgia, but by Georgia and much of the international community as an illegal occupation. Joint military exercises are common.

Economic Support: Abkhazia's economy is heavily reliant on Russia. The Russian ruble is the official currency. Russia provides substantial financial aid, which constitutes about half of Abkhazia's budget. Russian investments are prominent, particularly in tourism and infrastructure. Trade is overwhelmingly with Russia. Russia also facilitates Abkhazia's access to energy. This economic integration has socio-economic consequences, including limited diversification and vulnerability to Russian economic shifts.

Passportization: Since the early 2000s, Russia has conducted a policy of "passportization," issuing Russian passports to a large majority of Abkhazia's population. This allows residents to travel internationally (as Abkhaz passports have very limited recognition) and access Russian social benefits, such as pensions. However, it has also been criticized as a means of extending Russian influence and undermining Georgian sovereignty.

Social Implications: The close ties with Russia have significant social implications. While providing a sense of security and economic opportunity for some, it also raises concerns about the erosion of Abkhaz identity and autonomy. Russian language and culture have a strong presence. The dependency on Russia also limits Abkhazia's options for independent development and foreign policy diversification. For many Abkhaz, especially the older generation, Russia is seen as a protector, while younger generations may have more complex views regarding long-term sovereignty.

6.2. Relations with Georgia

Relations between the de facto Republic of Abkhazia and Georgia are characterized by an unresolved conflict, mutual non-recognition, and deep-seated animosity stemming from the 1992-1993 war and its aftermath. Georgia considers Abkhazia its sovereign territory under Russian occupation, while Abkhazia asserts its independence.

Ongoing Conflict and Negotiation Processes: Despite a ceasefire since 1994, the conflict remains "frozen." The primary internationally-mediated negotiation forum was the Geneva International Discussions (GID), co-chaired by the EU, UN, and OSCE, which began after the 2008 war. These talks involve representatives from Abkhazia, Georgia, Russia, South Ossetia, and the United States. However, progress on core political issues has been minimal. The Abkhaz side generally refuses direct political talks with Tbilisi unless their independence is acknowledged, a non-starter for Georgia.

Border Issues: The de facto border along the Inguri River (and the Psou River with Russia) is heavily controlled, primarily by Russian and Abkhaz forces. Georgia considers this an administrative boundary line within its territory, not an international border. Crossings are restricted, significantly impacting local populations, particularly ethnic Georgians in the Gali district who have ties on both sides. Freedom of movement is a major humanitarian concern.

Refugee and IDP Return: The return of hundreds of thousands of predominantly ethnic Georgian IDPs and refugees who were displaced during the 1992-1993 war is a critical and highly contentious issue. Georgia and the international community insist on their unconditional and safe right to return. The Abkhaz de facto authorities have largely resisted large-scale returns, citing security concerns and demographic balance. This issue is a major point of contention and a significant human rights concern, central to any lasting peace settlement.

Main Points of Contention:

- Status:** Abkhazia's demand for recognition of its independence versus Georgia's insistence on its territorial integrity.

- Security:** Concerns from both sides regarding military build-up and potential for renewed hostilities. Abkhazia relies on Russia for security, which Georgia views as occupation.

- IDP/Refugee Return:** As mentioned, a fundamental disagreement with profound human rights implications.

- Property Rights:** The rights of IDPs to their former properties in Abkhazia.

- Language and Cultural Rights:** Particularly for the remaining Georgian population in Abkhazia, especially in the Gali district, concerning education in their native language.

From the perspective of affected populations, the unresolved conflict perpetuates uncertainty, limits opportunities, and infringes on fundamental human rights, including the right to return, property rights, freedom of movement, and access to education and healthcare in one's native language.

6.3. Relations with Other States and International Organizations

Abkhazia's relations with states beyond Russia and Georgia, and with international organizations, are severely limited by its disputed status.

Relations with Recognizing States: Besides Russia, Abkhazia is recognized by Nicaragua, Venezuela, Nauru, and Syria. Diplomatic and economic ties with these countries are generally modest, often symbolic, and heavily facilitated or influenced by Russia. Abkhazia also has mutual recognition with South Ossetia and Transnistria.

International Organizations:

- United Nations (UN):** The UN does not recognize Abkhazia's independence and considers it part of Georgia. Prior to 2009, the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG) monitored the ceasefire. The UN has consistently called for a peaceful resolution respecting Georgia's territorial integrity and the right of return for IDPs. Various UN agencies (UNHCR, UNDP, UNICEF) have been involved in humanitarian aid, human rights monitoring (to a limited extent), and development projects, often facing access challenges.

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE):** The OSCE also upholds Georgia's territorial integrity. It was involved in peacekeeping efforts and human rights monitoring before its mission was discontinued after the 2008 war. The OSCE has repeatedly condemned the ethnic cleansing of Georgians and called for the return of IDPs. Its Parliamentary Assembly has referred to Abkhazia as a Russian-occupied territory.

- European Union (EU):** The EU does not recognize Abkhazia's independence and supports Georgia's territorial integrity. The European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia (EUMM) was established after the 2008 war to monitor the ceasefire lines, but it is denied access to Abkhazia by Russian and de facto Abkhaz authorities. The EU provides humanitarian aid and supports conflict resolution efforts, primarily through the Geneva International Discussions.

- Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs):** Several international NGOs have been active in Abkhazia, focusing on humanitarian aid, demining (e.g., HALO Trust, which declared Abkhazia "mine-free" in 2011), and confidence-building measures. For example, Première Urgence Internationale has implemented food security programs. Access for NGOs can be challenging and politically sensitive.

Overall, Abkhazia remains largely isolated internationally, with its external interactions heavily mediated by its relationship with Russia. International organizations primarily engage on humanitarian grounds and in efforts to facilitate dialogue, while adhering to the principle of Georgia's territorial integrity.

7. Geography and Climate

Abkhazia's diverse geography, ranging from coastal plains to high mountains, and its generally mild climate have significantly influenced its history, culture, and economy.

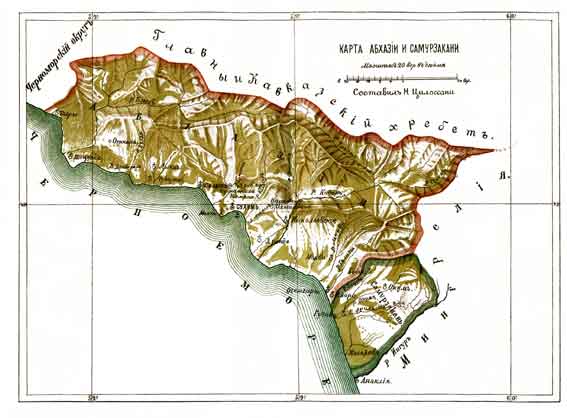

7.1. Topography

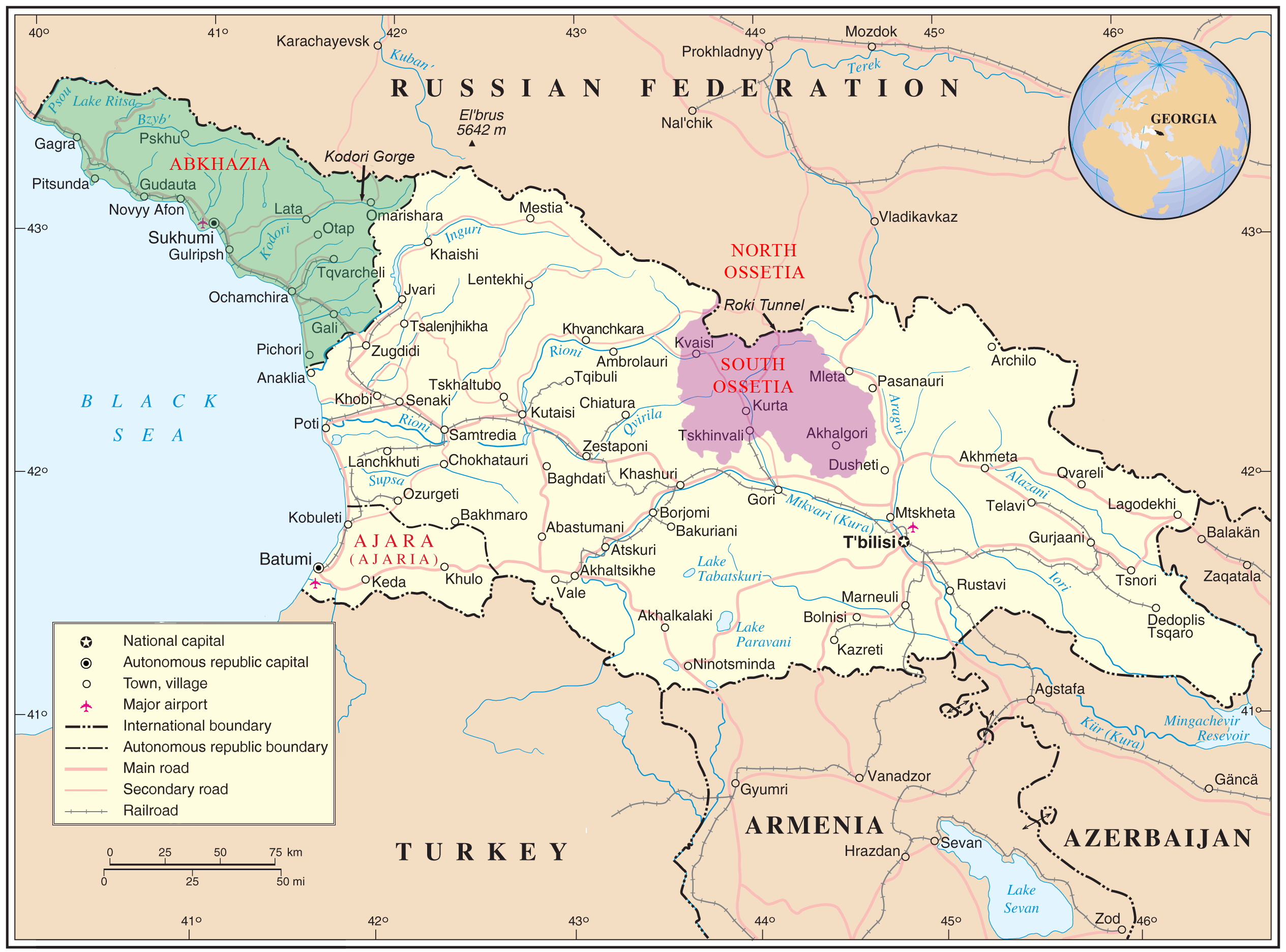

Abkhazia is located on the eastern coast of the Black Sea, covering an area of approximately 3.3 K mile2 (8.67 K km2). Its topography is characterized by a narrow coastal lowland strip along the Black Sea to the south and southwest, which gradually rises to the rugged southwestern slopes of the Greater Caucasus Mountains to the north and northeast. These mountains form a natural border with the Russian Federation.

The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range, with its spurs - the Gagra, Bzyb, and Kodori ranges - divides Abkhazia into a series of deep, well-watered valleys. The highest peaks are found in the northeast and east, with several exceeding 13 K ft (4.00 K m) above sea level. This mountainous terrain covers a significant portion of the territory.

The landscape transitions from coastal forests and citrus plantations in the lowlands to permanent snows and glaciers in the high mountain zones. While the complex topography has limited extensive human development in many areas, the fertile lowlands and valleys are suitable for agriculture. The world's deepest known cave, Veryovkina Cave, with a measured vertical extent of 7.3 K ft (2.21 K m), is located in Abkhazia's western Caucasus mountains. The lowland regions were historically covered by forests of oak, beech, and hornbeam, much of which has since been cleared for agriculture and settlement.

7.2. Climate

Abkhazia's climate is generally mild, largely influenced by its proximity to the Black Sea and the sheltering effect of the Caucasus Mountains, which protect it from cold northern air masses.

The coastal areas experience a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfa). The average annual temperature in most coastal regions is around 59 °F (15 °C). Winters are mild, with average January temperatures remaining above freezing. Summers are warm and humid.

As elevation increases, the climate transitions from maritime mountainous to colder conditions. Higher altitudes experience cooler summers and colder, snowier winters. The windward slopes of the Caucasus Mountains ensure that Abkhazia receives high amounts of precipitation. Annual precipitation varies from 0.0 K in (1.20 K mm) to 0.1 K in (1.40 K mm) along the coast to between 0.1 K in (1.70 K mm) and 0.1 K in (3.50 K mm) in the higher mountainous areas. The mountains receive significant snowfall, contributing to the region's water resources and glaciers. Humidity is generally high, particularly in coastal areas, though it tends to decrease further inland.

7.3. Major Rivers and Lakes

Abkhazia is richly irrigated by numerous small rivers and streams that originate in the Caucasus Mountains and flow into the Black Sea. The most significant rivers include:

- The Psou River: Forms the northwestern border of Abkhazia with Russia.

- The Bzyb River (БзыԥBzyhabkhazian)

- The Ghalidzga River (ЕгрыEgryabkhazian / ღალიძგაGhalidzgaGeorgian)

- The Gumista River (ГәымсҭаGәymstaabkhazian)

- The Kodori River (КәыдрыKәydryabkhazian) - the longest river in Abkhazia.

- The Inguri River (ЕгрыEgryabkhazian / ენგურიEnguriGeorgian): Forms much of the de facto southeastern border between Abkhazia and Georgia proper. The Inguri Dam, a major hydroelectric power station, is located on this river.

The region also hosts several picturesque lakes, particularly in the mountainous areas. The most important and well-known is Lake Ritsa (РиҵаRitsaabkhazian), a deep mountain lake surrounded by forests, which is a popular tourist destination. Other lakes include smaller periglacial and crater lakes found at higher elevations. These water bodies are crucial for local ecosystems, agriculture, and tourism.

8. Administrative Divisions

1) Gagra

2) Gudauta

3) Sukhumi

4) Gulripshi

5) Ochamchira

6) Tkvarcheli

7) Gali

The de facto Republic of Abkhazia is divided into seven districts (араионқәаaraionkwaabkhazian, singular: араионaraionabkhazian), which are equivalent to raions in other post-Soviet states. These districts are generally named after their primary cities or administrative centers:

1. **Gagra District**

2. **Gudauta District**

3. **Sukhumi District**

4. **Gulripshi District** (also spelled Gulrypsh)

5. **Ochamchira District**

6. **Tkvarcheli District** (also spelled Tquarchal)

7. **Gali District**

The current administrative divisions largely follow the structure from the Soviet era, with one significant change: the Tkvarcheli District was created in 1995 from parts of the Ochamchira and Gali districts by the de facto Abkhaz authorities.

Under the de facto government structure, the President of the Republic appoints the heads of these districts from among those elected to the respective district assemblies. There are also elected village assemblies, whose heads are appointed by the district heads.

Georgia's official administrative divisions for Abkhazia (as the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia) are identical to the historical Soviet-era districts, meaning Georgia does not officially recognize the Tkvarcheli District as a separate entity. It considers the territory of the Tkvarcheli District as part of the Ochamchira and Gali districts. The capital city, Sukhumi, also holds a special status.

9. Military

The Abkhazian Armed Forces are the military of the de facto Republic of Abkhazia. Their formation began in early 1992 with the establishment of the ethnically Abkhaz National Guard, which formed the core of the separatist forces during the 1992-1993 war. A significant portion of their initial weaponry reportedly came from the former Russian airborne division base in Gudauta. The Abkhazian military is primarily a ground force but also includes small naval and air units. Its permanent force is estimated to be around 5,000 personnel, but with reservists and paramilitary personnel, this number can reportedly increase to up to 50,000 in times of military conflict. The exact numbers and types of equipment remain difficult to verify independently.

The Abkhazian Land Forces form the main component. The Abkhazian Navy consists of a few small vessels organized into divisions based in Sukhumi, Ochamchire, and Pitsunda; however, Russian coast guard units largely patrol Abkhazia's maritime borders. The Abkhazian Air Force is a small unit with a few fighter aircraft and helicopters.

A crucial aspect of Abkhazia's security situation is the presence of Russian military forces. Following the 2008 Russo-Georgian War and Russia's recognition of Abkhazia's independence, Russia established the 7th Military Base in Abkhazia, with its headquarters in Gudauta. These Russian military units are reportedly subordinate to the Russian 49th Combined Arms Army and include ground forces, air defense assets, and potentially naval support elements. The Russian military presence is seen by the de facto Abkhaz government as a security guarantee against Georgia. However, Georgia and most of the international community consider this presence an illegal military occupation of Georgian territory.

The stationing of Russian troops and the close integration of Abkhazian and Russian military structures (formalized by treaties such as the 2014 "Treaty on Alliance and Strategic Partnership") significantly impact local security. While providing a deterrent against external military threats from Georgia's perspective, it also underscores Abkhazia's profound dependence on Russia and limits its de facto sovereignty. From a human rights perspective, the heavy militarization of the region and the presence of external forces raise concerns about accountability and the rights of local populations, particularly in border areas and zones of past conflict. The lack of international monitoring access further complicates the human rights situation.

10. Economy

Abkhazia's economy is small and heavily reliant on Russia, a dependency that has deepened since the 2008 South Ossetia war and Russia's subsequent recognition of its independence. The region uses the Russian ruble as its currency, and a 2014 bilateral agreement with Russia aims to create a common economic and customs space. Approximately half of Abkhazia's state budget is financed through aid from Russia. While the economy has seen some modest upswing, particularly in tourism, it faces significant challenges due to its unresolved political status, damaged infrastructure, and international isolation.

10.1. Main Industries

The core sectors of Abkhazia's economy are tourism and agriculture.

Tourism: Tourism is a key industry, attracting primarily Russian tourists drawn by its Black Sea beaches, mountainous scenery, and relatively low costs. Popular destinations include Gagra, Pitsunda, and Lake Ritsa. According to Abkhaz authorities, almost a million tourists, mainly from Russia, visited in 2007, and numbers saw an increase after 2008. Russian businesses have invested in Abkhazian tourist infrastructure, with some damaged hotels being restored. However, the sector's sustainability is impacted by political instability and infrastructure limitations.

Agriculture: Abkhazia's subtropical climate is conducive to agriculture. Main agricultural products include citrus fruits (especially tangerines), hazelnuts, tea, tobacco, and wine. While these sectors were significant during the Soviet era, production has declined due to conflict, loss of markets, and underinvestment. Efforts are made to revive these traditional industries, but challenges remain regarding quality control, access to international markets, and sustainable farming practices. Labor rights and social equity within these industries are areas that require attention, particularly given the reliance on seasonal and often vulnerable workers.

Electricity is largely supplied by the Inguri hydroelectric power station, located on the Inguri River, which forms the de facto border with Georgia proper. The power station is operated jointly by Abkhaz and Georgian entities, a rare example of cooperation, though management and distribution often involve political complexities.

10.2. Foreign Trade

Abkhazia's foreign trade is limited due to its unrecognized status and international sanctions (though Russia declared in 2008 it would no longer participate in CIS sanctions).

Its primary trading partner is Russia, accounting for the vast majority of its trade turnover. In the first half of 2012, Russia constituted 64% of Abkhazia's trade.

Turkey is the second most significant trading partner, accounting for 18% in the same period, often through informal channels.

Key export commodities include agricultural products like citrus fruits, hazelnuts, and wine. Imports consist mainly of consumer goods, fuel, and manufactured products, largely sourced from or via Russia. The lack of direct access to global markets severely restricts Abkhazia's trade potential and economic diversification.

10.3. Economic Dependence on Russia

Abkhazia's economic reliance on Russia is profound and multifaceted. This dependence shapes almost every aspect of its economy and has significant socio-economic consequences.

- Financial Aid:** Russia provides substantial direct financial assistance, which reportedly makes up around half of Abkhazia's state budget. This aid is crucial for funding public sector salaries, pensions, and infrastructure projects.

- Investments:** Russian state-owned and private companies are the primary investors in Abkhazia, particularly in tourism, infrastructure (roads, railways), and potentially resource extraction.

- Trade:** As mentioned, Russia is the dominant trading partner, creating a captive market situation.

- Currency and Banking:** The use of the Russian ruble and integration with the Russian banking system further solidify this dependence.

- Energy Supply:** While the Inguri Dam is a joint operation, overall energy security and infrastructure development often rely on Russian support.

The socio-economic consequences of this dependency include limited economic sovereignty, vulnerability to Russian political and economic decisions, and a lack of incentive for internal economic reforms or diversification. While Russian support has provided a degree of stability and some economic recovery, it also perpetuates a patron-client relationship that hinders the development of a self-sustaining and independent economy. Issues like labor rights and social equity can be overshadowed by geopolitical considerations and the need to maintain Russian support.

10.4. Cryptocurrency Mining and Energy Issues

In the late 2010s, Abkhazia experienced a boom in cryptocurrency mining, driven by its relatively low (though often subsidized and unreliably priced) electricity costs. Investors, both local and foreign (often from Russia), set up numerous mining farms, hoping to profit from the global cryptocurrency surge.

However, this unregulated boom quickly led to a severe energy crisis. Abkhazia's aging and dilapidated energy infrastructure, heavily reliant on the Inguri Dam (whose output is shared with Georgia and can fluctuate), was unable to cope with the massive increase in electricity demand from mining operations. This resulted in frequent power outages, overburdened grids, and significant strain on the energy supply for ordinary households and businesses, particularly during winter months.

In response, the de facto Abkhaz government implemented various regulations. Initially, there were attempts to register and tax mining operations. However, as the crisis deepened, authorities resorted to temporary and then more prolonged bans on cryptocurrency mining and the import of mining equipment. For example, in early 2019, facilities were temporarily closed to secure winter power. These bans have been inconsistently enforced and have faced opposition from those who invested in mining.

The environmental impact includes the strain on energy resources, which are primarily hydroelectric but still have infrastructure and maintenance footprints. The social impact has been significant, with public discontent over power shortages and the perception that a select few benefited from mining at the expense of the general population's access to reliable electricity. The situation highlighted the vulnerability of Abkhazia's infrastructure and the challenges of managing new economic activities within a context of limited resources and governance capacity.

11. Society

Abkhazia's society is characterized by its ethnic diversity, the profound demographic shifts resulting from conflict, and ongoing challenges related to nationality, language, and human rights, particularly for minority and vulnerable groups.

11.1. Population

According to the last census conducted by the de facto Abkhaz authorities in 2011, Abkhazia had a population of 240,705. This figure is significantly lower than the pre-war (1989) population of 525,061, reflecting the massive displacement that occurred during and after the 1992-1993 war.

Estimates of Abkhazia's population have varied. The Department of Statistics of Georgia estimated approximately 179,000 in 2003 and 178,000 in 2005. The International Crisis Group estimated the population in 2006 to be between 157,000 and 190,000. The population density is relatively low given its area of approximately 3.3 K mile2 (8.67 K km2).

Trends in population change show a drastic decline following the 1992-1993 war due to the ethnic cleansing and flight of Georgians. Since then, the population has seen some stabilization and slight growth, partly due to the return of some Abkhaz diaspora members and natural increase, but it remains far below pre-war levels. The demographic future is a significant concern for the de facto authorities, given the small size of the titular Abkhaz ethnic group.

11.2. Ethnic Composition

Abkhazia has historically been a multi-ethnic region. The ethnic composition has been dramatically altered by the 1992-1993 war and its aftermath.

According to the 2011 de facto census, the main ethnic groups were:

- Abkhaz:** 50.7%

- Georgians** (mostly Mingrelians): 19.2% (primarily concentrated in the Gali district)

- Armenians:** 17.4%

- Russians:** 9.1%

- Greeks:** 0.6%

Other smaller ethnic groups include Ukrainians, Belarusians, Ossetians, Tatars, Turks, Roma, and Estonians.

This contrasts sharply with the 1989 Soviet census, where Georgians were the largest ethnic group (45.7%), and Abkhaz constituted 17.8%. Armenians were also a significant group (around 14.6%), as were Russians (14.3%). The war led to the mass expulsion of ethnic Georgians and the flight of many Russians and other minorities.

During the Soviet era, particularly under Stalin and Beria, policies of Georgianization and large-scale enforced migration led to an increase in the Georgian, Russian, and Armenian populations relative to the Abkhaz. Greeks were a significant minority in the early 1920s (around 50,000) but were deported to Central Asia in 1945.

More recently, in the wake of the Syrian Civil War, Abkhazia granted refugee status to a few hundred Syrians of Abkhaz, Abazin, and Circassian ancestry, a move seen by some as an attempt by the de facto authorities to bolster the titular ethnic group. Inter-group relations remain complex, with the legacy of ethnic conflict and displacement continuing to affect social cohesion.

11.3. Diaspora

There is a significant Abkhaz diaspora, primarily located in Turkey. This diaspora largely originated from the Muhajirism of the mid-to-late 19th century, when thousands of Abkhaz (along with other North Caucasian peoples like Circassians and Ubykhs) were exiled or emigrated to the Ottoman Empire following the Russian conquest of the Caucasus and subsequent uprisings.

Estimates of the size of the Abkhaz diaspora in Turkey vary widely. Diaspora leaders claim figures as high as one million, while more conservative estimates by Abkhaz scholars range from 150,000 to 500,000. These communities have largely maintained their Abkhaz identity and language to varying degrees over generations. There are also smaller Abkhaz diaspora communities in other countries, including Syria, Jordan, and some Western nations.