1. Overview

Albania, officially the Republic of Albania, is a country located in Southeast Europe on the Balkan Peninsula. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, North Macedonia to the east, and Greece to the south and southeast. Albania has a coastline on the Adriatic Sea to the west and the Ionian Sea to the southwest, with Italy situated less than 45 mile (72 km) away across the Strait of Otranto. The country covers an area of 11 K mile2 (28.75 K km2) and has a population of approximately 2.4 million people as of 2023. Its capital and largest city is Tirana.

Historically, the lands of present-day Albania were inhabited by Illyrian and Epirote tribes, with Greek colonies established along the coast. The region was later annexed by Rome and became part of the Byzantine Empire. The first autonomous Albanian principality, Arbanon, emerged in the 12th century. From the 15th century, Albania came under Ottoman rule for nearly five centuries, a period that significantly shaped its cultural and religious landscape, leading to a large Muslim population alongside Christian communities. Albania declared independence in 1912 following the Balkan Wars. The 20th century was marked by periods of monarchy, foreign occupation during both World Wars, and a long, isolating communist dictatorship under Enver Hoxha. Hoxha's regime, characterized by extreme Stalinist policies, led to severe human rights abuses, religious persecution, and international isolation, though it also saw some modernization in education and infrastructure.

The fall of communism in 1991 ushered in a period of democratic transition, but also significant economic hardship and social unrest, most notably the 1997 civil unrest triggered by the collapse of pyramid schemes. Since then, Albania has pursued integration into Euro-Atlantic structures, becoming a member of NATO in 2009 and an official candidate for European Union membership since 2014. The country is a developing nation with an upper-middle-income economy, primarily driven by the services sector, particularly tourism, and manufacturing. Albania is a parliamentary constitutional republic with a commitment to democratic principles, human rights, and social justice, though challenges related to corruption, judicial reform, and media freedom persist. From a center-left/social liberal perspective, Albania's journey involves ongoing efforts to strengthen democratic institutions, ensure social equity, protect human rights, and address the legacy of its authoritarian past while navigating the complexities of a market economy and global integration.

2. Etymology

The name "Albania" is the medieval Latin term for the country. It is believed to be derived from the name of the Illyrian tribe known as the Albani, who were noted by the Greco-Egyptian geographer Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. Ptolemy's map identified a city named Albanopolis, located northeast of Durrës. The name may have continued through a medieval settlement called Albanon or Arbanon, though the exact continuity between Albanopolis and Arbanon is a subject of scholarly discussion. Another theory suggests that "Albania" might originate from the Proto-Indo-European word *albh*, meaning "white", possibly referring to the white, snow-capped mountains or the limestone rock prevalent in the country, similar to the origin of names like Albion or the Alps.

The first undisputed historical mention of Albanians comes from the Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates, who, in his 11th-century work, referred to the Albanoi as having participated in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043, and the Arbanitai as subjects of the Duke of Dyrrachium (Durrës). During the Middle Ages, the inhabitants called their land ArbëriArbëriAlbanian or ArbëniArbëniAlbanian and referred to themselves as ArbëreshëArbëreshëAlbanian or ArbëneshëArbëneshëAlbanian.

The native name for the country is ShqipëriShqipëriAlbanian (indefinite form) or ShqipëriaShqipëria [ʃcipəˈɾi(a)]Albanian (definite form). This name began to appear in the 14th century but only started to replace the older Arbëria and Arbëresh among Albanian speakers in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Alternative Gheg Albanian forms include ShqipniShqipniAlbanian, ShqipniaShqipniaAlbanian, ShqypniShqypniAlbanian, or ShqypniaShqypniaAlbanian. The terms Shqipëri and Shqiptarë (Albanians) are popularly interpreted as "Land of the Eagles" and "Children of the Eagles" respectively, derived from the Albanian word shqiponjëshqiponjë (eagle)Albanian. This symbolism is reflected in the double-headed eagle on the flag of Albania, a motif historically associated with Byzantine and various Albanian noble families.

3. History

The history of Albania chronicles the development of the Albanian lands and people from ancient settlements through periods of foreign rule, national awakening, independence, a tumultuous 20th century including a harsh communist regime, and its subsequent transition to democracy and efforts towards European integration. This historical narrative focuses on major political, social, and cultural transformations, with particular attention to their impact on the Albanian populace, democratic development, and human rights.

3.1. Prehistory

Archaeological findings indicate that Albania was inhabited during the Paleolithic and Mesolithic periods. Mesolithic sites have been found near the Adriatic coast and in caves, such as a cave near Xarrë where flint and jasper objects along with fossilized animal bones were discovered. At Mount Dajt, bone and stone tools similar to those of the Aurignacian culture have been found.

The Neolithic era in Albania began around 7000 BC, evidenced by findings that indicate the domestication of sheep and goats and small-scale agriculture. Some Neolithic populations may have descended from local Mesolithic groups, as seen in the Konispol cave where Mesolithic strata coexist with Pre-Pottery Neolithic finds. The Cardium pottery culture appeared in coastal Albania and across the Adriatic after 6500 BC, while inland settlements participated in the development of the Starčevo culture. Albanian bitumen mines at Selenicë show early evidence of bitumen exploitation in Europe, dating to the Late Neolithic (from 5000 BC). Local communities used it for ceramic decoration, waterproofing, and as an adhesive. Selenicë bitumen circulated to eastern Albania from the early 5th millennium BC and was exported overseas to southern Italy by the Neolithic and Bronze Ages.

The Indo-Europeanization of Albania began after 2800 BC. Early Bronze Age tumuli (burial mounds) near later Apollonia date to 2679±174 calBC. These mounds belong to the southern expression of the Adriatic-Ljubljana culture, which moved southwards from the northern Balkans. Similar mounds were built by the same community in Montenegro (Rakića Kuće) and northern Albania (Shtoj). The first archaeogenetic evidence related to Indo-Europeanization in Albania comes from a man with predominantly Yamnaya ancestry buried in a tumulus in northeastern Albania, dating to 2663-2472 calBC. During the Middle Bronze Age, Cetina culture sites and finds appeared in Albania, having moved southwards from the Cetina valley in Dalmatia. In Albania, Cetina finds are concentrated around southern Lake Shkodër and appear in tumulus cemeteries like Shkrel and Shtoj, hillforts like Gajtan (Shkodër), cave sites like Blaz, Nezir, and Keputa (central Albania), and lake basin sites like Sovjan (southeastern Albania).

3.2. Antiquity

The territory of modern Albania was historically inhabited by various Indo-European peoples, including numerous Illyrian and Epirote tribes. The region known as Illyria corresponded roughly to the area east of the Adriatic Sea, extending south to the mouth of the Vjosë river. The first historical account of Illyrian groups comes from the Periplus of the Euxine Sea, a Greek text from the 4th century BC. Bryges were present in central Albania, while the south was inhabited by the Epirote Chaonians, whose capital was at Phoenice. Several important Greek colonies, such as Apollonia, Epidamnos (later Dyrrachium, modern Durrës), and Amantia, were established by Greek city-states on the coast, starting in the 7th century BC. These colonies became significant centers of trade and culture, influencing the local Illyrian populations.

The Illyrian Taulantii were a powerful tribe among the earliest recorded in the area. Their ruler, Glaucias, allied with Cleitus, the Dardanian ruler, to fight against Alexander the Great at the Battle of Pelium in 335 BC. Later, Cassander of Macedon captured Apollonia in 314 BC. Glaucias subsequently besieged Apollonia and captured Epidamnos.

The Illyrian Ardiaei tribe, centered in modern Montenegro, came to rule much of northern Albania. Their kingdom reached its peak under King Agron. After Agron's death in 230 BC, his wife, Queen Teuta, assumed control and expanded operations southward into the Ionian Sea. Roman concerns over Illyrian piracy and raids on Roman ships led to the First Illyrian War in 229 BC, which ended in Illyrian defeat in 227 BC. Gentius, who became king in 181 BC, clashed with the Romans in 168 BC during the Third Illyrian War. This conflict resulted in the Roman conquest of the region by 167 BC. The Romans subsequently divided Illyria into three administrative divisions, effectively ending Illyrian independence and incorporating the territory into the Roman Republic. Roman rule brought significant changes, including the construction of roads like the Via Egnatia, urbanization, and the spread of Latin culture, although Illyrian language and customs persisted, particularly in inland areas.

3.3. Middle Ages

After the division of the Roman Empire in 395 AD, the territory of modern Albania became part of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire). During the 6th and 7th centuries, Slavic tribes migrated into the Balkans, crossing the Danube and settling in large parts of the region, leading to significant demographic and cultural shifts. The Illyrians were last mentioned in historical records in the 7th century. The Great Schism of 1054 between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism had a lasting impact on Albania, with the north increasingly aligning with Catholicism and the south with Orthodoxy.

In 1190, the first known Albanian autonomous entity, the Principality of Arbanon, was established in the mountainous region around Krujë, with Progon of Kruja as its ruler. His sons, Gjin and Dhimitër, succeeded him. After Dhimitër's death, Arbanon came under the rule of the Albanian-Greek lord Gregory Kamonas and later Golem of Kruja. Arbanon, considered a precursor to a unified Albanian state, maintained a semi-autonomous status, often as a western extremity of the Byzantine sphere under the Doukai of Epirus or the Laskarids of Nicaea. The principality was dissolved in the 13th century.

The first undisputed mention of Albanians in historical records dates to 1079 or 1080, in a work by the Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates, who referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople. By this time, Albanians were largely Christianized.

In 1272, Charles of Anjou established the Kingdom of Albania after conquering territories from the Despotate of Epirus. This kingdom extended from Durrës (Dyrrhachium) along the Adriatic coast down to Butrint. It represented a significant Catholic political structure in the Balkans, supported by Helen of Anjou, Charles's cousin, who facilitated the construction of numerous Catholic churches and monasteries, primarily in northern Albania.

During the 14th century, the Serbian Empire under Stefan Dušan expanded to include most of Albania, except Durrës. Following the fragmentation of the Serbian Empire, several Albanian principalities emerged or reasserted themselves. These included the Principality of Albania (under the Thopia family), the Principality of Kastrioti, the Lordship of Berat (under the Muzaka family), the Principality of Dukagjini, and the Despotate of Arta in the south. These principalities often engaged in complex alliances and rivalries with each other and with external powers like Venice, Naples, and the declining Byzantine Empire. The Venetian Republic also established control over key coastal towns, forming Albania Veneta. This period of fragmented rule and shifting allegiances set the stage for the Ottoman invasions in the late 14th and early 15th centuries.

3.4. Ottoman Rule

The Ottoman Empire began its expansion into the Balkans in the late 14th century, reaching the Albanian coast in 1385. They established garrisons in southern Albania by 1415 and had occupied most of the country by 1431. This conquest led many Albanians to flee to Western Europe, particularly to Calabria, Naples, Ragusa, and Sicily; others sought refuge in the mountainous regions of Albania. As Christians, Albanians were initially considered an inferior class (Rayah) under Ottoman rule and were subjected to heavy taxes, including the Devşirme system, which involved the conscription of Christian boys for the Janissary corps. The Ottoman conquest also initiated a gradual process of Islamisation and the construction of mosques.

The most significant resistance to Ottoman rule was led by Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg. After serving in the Ottoman army, Skanderbeg deserted and united several Albanian principalities through the League of Lezhë in 1444. He became the Lord of Albania and successfully repelled numerous major Ottoman invasions for 25 years, defeating armies led by Sultans Murad II and Mehmed II. Skanderbeg's resistance is credited with delaying Ottoman expansion into Western Europe, giving Italian principalities more time to prepare. However, despite support from Naples and the Papacy, broader European aid was limited. Skanderbeg's victories, while remarkable, could not permanently halt the Ottoman advance due to insufficient manpower and resources. After his death in 1468, organized resistance gradually weakened, and Shkodër, the last major stronghold, fell in 1479, marking the full incorporation of Albania into the Ottoman Empire for nearly five centuries.

Under Ottoman rule, Albanian towns were organized into four principal sanjaks. The Ottomans fostered trade, and Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Spain settled in cities like Vlorë, which became a trading hub for European goods. The process of Islamization accelerated from the 17th century onwards. Islam offered opportunities for social and political advancement within the Ottoman Empire. While some scholars cite diverse motives for conversion, the suppression of Catholicism contributed to conversions among Catholic Albanians in the 17th century, followed by Orthodox Albanians in the 18th century.

Many Muslim Albanians achieved prominent positions in the Ottoman military and bureaucracy, contributing culturally to the broader Muslim world. Over two dozen Albanians served as Grand Viziers. Notable figures included members of the influential Köprülü family, Zagan Pasha, Muhammad Ali of Egypt (who later founded a dynasty in Egypt), and Ali Pasha of Tepelena, a powerful autonomous ruler in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Additionally, Ottoman Sultans Bayezid II and Mehmed III had mothers of Albanian origin. Despite the opportunities, Ottoman rule also brought periods of hardship and exploitation, and local resentments occasionally flared into rebellions, though none achieved the scale of Skanderbeg's uprising until the national awakening movements of the 19th century.

3.5. Rilindja (National Awakening)

The Albanian National Awakening, or Rilindja Kombëtare, was a period of burgeoning national consciousness that began in the late 18th century and intensified throughout the 19th century. This movement aimed to foster a sense of Albanian national identity, promote the Albanian language and culture, and ultimately achieve political autonomy or independence from the Ottoman Empire. It was influenced by the broader Romanticism and Enlightenment principles sweeping across Europe. Prior to this, Ottoman authorities generally suppressed expressions of distinct national unity among Albanians.

A key moment in the Rilindja was the formation of the League of Prizren in 1878. This organization emerged in response to the Treaty of San Stefano, which followed the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878) and proposed ceding Albanian-populated territories to neighboring Slavic and Greek states. The League, initially supported by Ottoman authorities concerned with maintaining the empire's territorial integrity and leveraging Muslim solidarity, aimed to protect Albanian lands. Its early manifesto, the Kararname, signed by 47 Muslim deputies, proclaimed the willingness of Albanians from northern Albania, Epirus, and Bosnia to defend Ottoman territory against Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro.

However, under the leadership of figures like Abdyl Frashëri, the League's objectives evolved. It began advocating for Albanian autonomy within the Ottoman Empire, calling for the unification of the four vilayets with significant Albanian populations (Kosovo, Shkodër, Monastir, and Ioannina) into a single Albanian Vilayet. The League used military force to resist the ceding of areas like Plav and Gusinje to Montenegro, achieving some successes in battles such as the Battle of Novšiće. As the League's autonomist ambitions grew, Ottoman support waned, and the Sultan eventually sent troops to suppress the movement. The League was defeated by 1881.

Despite its military defeat, the League of Prizren was crucial in crystallizing Albanian national aspirations. The Rilindja continued through cultural and educational efforts. Figures like Naum Veqilharxhi, who created an original Albanian alphabet, and Sami Frashëri, who advocated for Albanian language education and cultural development, played vital roles. The establishment of Albanian-language schools, newspapers, and literary works helped to standardize the language and disseminate nationalist ideas. The movement laid the groundwork for Albania's eventual declaration of independence in the early 20th century.

3.6. Independence and State Formation

Albania declared independence from the Ottoman Empire on November 28, 1912, during the First Balkan War. This historic declaration was made in Vlorë by an assembly of Albanian leaders, led by Ismail Qemali, who formed a provisional government. The Senate was established on December 4, 1912. The Conference of London, convened by the Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Russia), recognized Albania's sovereignty. However, the Treaty of London, signed on May 30, 1913, delineated Albania's borders in a way that left a significant portion of Albanian-populated territories, notably Kosovo and parts of modern-day North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Greece, outside the new state. This division had profound and lasting consequences for the region.

The International Commission of Control (ICC) was established on October 15, 1913, headquartered in Vlorë, to oversee the administration of the newly formed Principality of Albania until its political institutions were fully established. The International Gendarmerie was created as its first law enforcement agency. Prince Wilhelm of Wied, a German nobleman, was selected by the Great Powers to be the first monarch of the principality. He arrived in Durrës, the provisional capital, on March 7, 1914, and appointed Turhan Pasha Përmeti to form the first Albanian cabinet.

The new state faced immediate challenges. In November 1913, pro-Ottoman forces offered the Albanian throne to Ahmed Izzet Pasha, an Ottoman war minister of Albanian origin. Many pro-Ottoman peasants viewed the new regime as a tool of Christian Great Powers and local landowners. In February 1914, the local Greek population in Gjirokastër proclaimed the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus, opposing incorporation into Albania, though this entity was short-lived and the southern provinces were eventually integrated by 1921. Simultaneously, a revolt of Albanian peasants, led by Muslim clerics and centered around Essad Pasha Toptani (who proclaimed himself a savior of Albania and Islam), erupted against Prince Wilhelm's rule. To counter the revolt, Prince Wilhelm appointed Prênk Bibë Doda, a Mirdita Catholic leader, as foreign minister to gain the support of northern Catholic volunteers. Isa Boletini and his men, mostly from Kosovo, also joined the International Gendarmerie. Despite these efforts, the rebels gained control of much of Central Albania by August 1914. With the outbreak of World War I and internal instability, Prince Wilhelm's regime collapsed, and he departed Albania on September 3, 1914, leaving the country in a state of near anarchy.

During World War I, Albania became a battleground for various occupying forces, including Austria-Hungary, Italy, France, Serbia, and Greece, each vying for influence and territory. The war further fragmented the country and exacerbated its political instability.

3.7. Interwar Period

The interwar period in Albania (1920-1939) was characterized by persistent economic and social difficulties, political instability, and increasing foreign intervention, particularly from Italy. After World War I, Albania lacked a recognized government and stable borders, making it vulnerable to its neighbors. Greece, Italy, and Yugoslavia all sought to expand their influence. The Congress of Durrës in 1918 sought protection at the Paris Peace Conference, but its efforts were largely rebuffed, further complicating Albania's international standing. Territorial tensions escalated, with Yugoslavia (particularly Serbia) aiming for control of northern Albania and Greece seeking dominance in the south. In 1919, Serbian forces launched attacks on Albanian inhabitants in areas like Gusinje and Plav, resulting in massacres and large-scale displacement.

Political life was turbulent. Fan Noli, an idealist Harvard-educated bishop, became Prime Minister in 1924 after the "June Revolution" overthrew the conservative government. Noli envisioned a Western-style constitutional government, land reform to abolish feudalism, countering Italian influence, and improving infrastructure, education, and healthcare. However, his government faced internal opposition and struggled to secure foreign aid. His decision to establish diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union, an adversary of the Serbian elite, led to accusations of Bolshevism and increased pressure from Italy and Yugoslavia.

Noli's government was short-lived. Ahmet Zogu, a powerful northern chieftain who had previously been Minister of Interior and Prime Minister, returned to power with Yugoslav and White Russian émigré support in December 1924, ousting Noli. Zogu initially served as President of the First Albanian Republic, proclaimed in January 1925. His rule became increasingly authoritarian. In 1928, Zogu declared Albania a monarchy and proclaimed himself King Zog I, establishing the Albanian Kingdom. He dissolved the Senate and established a unicameral National Assembly, while retaining significant personal power.

King Zog's reign saw some modernization efforts, including attempts at legal reform, road construction, and education expansion. However, Albania remained largely agrarian and one of Europe's poorest countries. Crucially, Zog's regime became heavily reliant on Fascist Italy under Benito Mussolini. Italy provided loans and economic assistance but in return gained increasing control over Albania's economy and foreign policy through a series of treaties, effectively turning Albania into an Italian protectorate. This growing Italian influence culminated in the Italian invasion of Albania on April 7, 1939, which brought an end to Zog's rule and the interwar period of Albanian independence. King Zog fled into exile.

3.8. World War II

World War II began for Albania with the Italian invasion on April 7, 1939. Benito Mussolini's forces quickly overran the country, forcing King Zog I into exile. Albania was transformed into an Italian protectorate and later formally annexed, with Italian King Victor Emmanuel III declared King of Albania. The Italians established a fascist puppet government. Following Italy's Axis invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece in 1941, territories with significant Albanian populations, including Kosovo, western parts of North Macedonia, and areas in Montenegro and Greece (Chameria), were incorporated into a "Greater Albania" under Italian control. This expansion, while fulfilling some nationalist aspirations, was part of Italy's imperial ambitions.

Resistance to Italian occupation began to organize. Two main groups emerged: the nationalist and republican Balli Kombëtar (National Front) and the communist-led National Liberation Movement (Lëvizja Nacional-Çlirimtare, LNÇ), later known as the Partisans, headed by Enver Hoxha. Initially, both groups fought the Italians, but ideological differences and differing views on post-war Albania soon led to conflict between them.

After Italy's surrender to the Allies in September 1943, Nazi Germany swiftly occupied Albania to prevent an Allied landing and secure its Balkan flank. The German occupation (1943-1944) was harsh, involving forced labor, economic exploitation, and repression. Some elements of Balli Kombëtar collaborated with the Germans, forming a "neutral" government in Tirana, primarily to counter the growing strength of the communist Partisans. The LNÇ, receiving some material support from the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), intensified its guerrilla warfare against both the Germans and collaborating Albanian forces.

The Partisans, under Enver Hoxha's leadership, proved to be the more effective and ruthless fighting force. By late 1944, as German forces retreated from the Balkans, the Partisans managed to liberate Albania without direct intervention from major Allied armies, although Soviet advances in the region contributed to the German withdrawal. Albania was one of the few European countries to largely liberate itself. The LNÇ declared the formation of a provisional democratic government in Berat in October 1944, with Enver Hoxha as Prime Minister. By November 29, 1944 (celebrated as Albania's Liberation Day), the last German troops had been expelled. The war left Albania devastated, with significant loss of life, destroyed infrastructure, and a deeply divided society. The communist Partisans, having emerged victorious from the internal power struggle, were poised to establish a new regime.

3.9. Communist Era

Following liberation from Axis occupation in November 1944, the Communist Party of Albania (later renamed the Party of Labour of Albania), led by Enver Hoxha, consolidated power and established the People's Republic of Albania (proclaimed in January 1946). Hoxha's regime was a hardline Marxist-Leninist dictatorship that lasted for over four decades, profoundly shaping Albanian society.

Consolidation of Power and Repression: The regime immediately initiated purges of political opponents, collaborators, and pre-war elites. "War crimes trials" were often used to eliminate rivals. A pervasive security apparatus, the Sigurimi, was established, instilling widespread fear through surveillance, informants, and brutal repression. Human rights abuses were systematic and widespread, including arbitrary arrests, imprisonment in harsh labor camps (such as Spaç Prison), torture, and executions. Freedom of speech, press, assembly, and movement were severely curtailed. Private property was abolished through nationalization and collectivization of agriculture.

Socio-Economic Policies: Hoxha pursued radical socio-economic transformation. Land reforms distributed land to peasants, followed by forced collectivization. A Soviet-style centrally planned economy was implemented, prioritizing heavy industry and electrification. While the regime claimed successes in modernization, such as increased literacy rates (through aggressive campaigns), improved healthcare access (though basic), and industrial development (often inefficient and environmentally damaging), these came at an immense human cost and led to chronic shortages of consumer goods and low living standards. A notable, and visually enduring, aspect of Hoxha's paranoia was the construction of hundreds of thousands of concrete bunkers across the country to defend against perceived foreign invasion.

Extreme Isolationism: Albania's foreign policy under Hoxha was characterized by a series of alliances followed by bitter breaks. Initially aligned with Yugoslavia, Hoxha broke with Tito in 1948 after the Tito-Stalin split, fearing Yugoslav domination. Albania then became a close ally of the Soviet Union. However, after Nikita Khrushchev's de-Stalinization speech in 1956, Hoxha denounced Soviet "revisionism," leading to a rupture in relations by 1961. Albania subsequently aligned itself with the People's Republic of China, receiving substantial aid. But when China began rapprochement with the United States in the 1970s, Hoxha condemned Chinese policies as well, leading to a break in 1978. This left Albania almost completely isolated, priding itself as the world's only true Marxist-Leninist state.

Religious Persecution: The regime was virulently anti-religious. In 1967, Albania was declared the world's first constitutionally atheist state. All religious institutions - mosques, churches, and tekkes - were closed, destroyed, or repurposed. Clergy of all faiths (Muslim, Orthodox, Catholic, Bektashi) were persecuted, imprisoned, or executed. Religious practices were banned, and citizens were forced to renounce their faith. This systematic religious persecution aimed to eradicate religion from public and private life, replacing it with socialist ideology and a cult of personality around Hoxha.

Legacy: Enver Hoxha died in 1985, succeeded by Ramiz Alia. While Alia initiated some cautious reforms, the core oppressive structures of the regime remained. By the late 1980s, Albania was one of the poorest and most repressed countries in Europe. The communist era left a legacy of profound social trauma, economic backwardness, environmental degradation, and a deep-seated distrust of authority, alongside claims of achieving national unity and modernization in certain sectors. The systematic denial of individual freedoms and democratic development under Hoxha's rule remains a critical aspect of Albania's 20th-century history.

3.10. Fall of Communism and Fourth Republic

The fall of communism in Albania began in the late 1980s and early 1990s, influenced by broader changes in Eastern Europe and growing internal dissent. Student protests in December 1990 forced Ramiz Alia's regime to concede to multi-party elections. The first multi-party elections were held in March 1991, which the ruling Party of Labour (soon renamed the Socialist Party) won. However, widespread strikes and continued unrest led to the formation of a "government of national stability" that included opposition parties. New elections in March 1992 resulted in a decisive victory for the newly formed Democratic Party, led by Sali Berisha, who became president. This marked the formal end of communist rule and the establishment of the Fourth Republic.

The transition to democracy and a market economy was fraught with difficulties. The early 1990s saw economic collapse, high unemployment, and social instability. A major crisis erupted in 1997 due to the collapse of large-scale pyramid schemes, in which a significant portion of the population had invested their savings, often with government tacit approval or encouragement. The schemes' failure led to widespread protests that quickly escalated into the 1997 civil unrest, also known as the Albanian Rebellion. Government authority disintegrated, armories were looted, and the country descended into near anarchy. The crisis caused an estimated 2,000 deaths and prompted international intervention (Operation Alba, a UN-authorized multinational force led by Italy) to restore order and facilitate humanitarian aid. The unrest led to the resignation of President Berisha and early elections, which brought the Socialist Party back to power.

Since 1997, Albania has worked towards democratic consolidation and economic reform. Political life has often been characterized by intense rivalry between the Democratic Party and the Socialist Party. Economic reforms focused on privatization, attracting foreign investment, and developing key sectors like tourism and energy. The country pursued integration into Euro-Atlantic institutions, joining NATO in 2009 and being granted European Union candidate status in 2014. Accession negotiations with the EU officially began in 2020.

Challenges have included combating corruption, strengthening the rule of law and judicial independence, tackling organized crime, and addressing issues of social equity and high emigration rates. Significant events in the contemporary period include the 2019 Albania earthquake, which caused widespread damage and casualties, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Political reforms, such as a major judicial reform initiated in the mid-2010s with EU and US support, aim to address systemic problems but have faced political obstacles and slow implementation. The country continues to navigate the complexities of building robust democratic institutions and a sustainable market economy while striving for full European integration. There have been ongoing efforts to address the legacy of the communist past, including issues of property restitution and lustration, though these have been contentious.

In September 2024, plans were reported for the creation of the Sovereign State of the Bektashi Order, a sovereign microstate for the Bektashi Order within Tirana, aimed at promoting religious tolerance and further raising the profile of this Sufi order historically significant in Albania.

4. Geography and Environment

Albania is characterized by its diverse physical geography, including rugged mountains, fertile plains, and an extensive coastline. The country experiences varied climatic conditions and possesses rich biodiversity, though it also faces significant environmental challenges that necessitate conservation efforts.

4.1. Geography

Albania is located in Southeast Europe, on the western part of the Balkan Peninsula. It has a total area of 11 K mile2 (28.75 K km2). The country shares land borders with Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, North Macedonia to the east, and Greece to the south and southeast. To the west, Albania is bordered by the Adriatic Sea, and to the southwest by the Ionian Sea. The coastline stretches for approximately 296 mile (476 km).

Albania's topography is predominantly mountainous, with about 70% of its territory consisting of mountains and hills. The average elevation is 2323 ft (708 m) above sea level. Major mountain ranges include the Albanian Alps (also known as the Accursed Mountains) in the north, which are an extension of the Dinaric Alps; the Korab Mountains in the east, which include Albania's highest peak, Mount Korab (9.1 K ft (2.76 K m)); the Skanderbeg Mountains in the central part; the Pindus Mountains extending into the southeast; and the Ceraunian Mountains along the southwestern Ionian coast.

Between these mountain ranges lie fertile lowland plains, particularly along the Adriatic coast. The most extensive plains are the Myzeqe plain in the west-central region and the coastal plains around Durrës and Shkodër.

Albania is rich in water resources. Major rivers include the Drin (the longest river, flowing through the north), the Vjosë, the Shkumbin, the Seman, and the Mat. Many of these rivers originate in the eastern mountains and flow westward into the Adriatic or Ionian Seas. The country is also home to three large and deep tectonic lakes of international importance:

- Lake Shkodër (Lake Scutari): The largest lake in the Balkan Peninsula, shared with Montenegro.

- Lake Ohrid: One of the oldest and deepest lakes in Europe, shared with North Macedonia, renowned for its unique biodiversity and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Lake Prespa: Comprising the Great Prespa Lake (shared with North Macedonia and Greece) and Little Prespa Lake (shared with Greece).

The westernmost point of Albania is Sazan Island in the Adriatic Sea, and its easternmost point is near Vërnik.

4.2. Climate

Albania has a diverse climate due to its varied topography and latitudinal range. It generally experiences a Mediterranean climate along the coast and a more continental climate inland.

- Coastal Lowlands: Characterized by a Mediterranean climate with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. Average temperatures in these regions range from about 44.6 °F (7 °C) in winter to 75.2 °F (24 °C) in summer. The southern coastal areas, particularly along the Albanian Riviera, tend to be warmer.

- Inland and Mountainous Regions: Experience a continental climate. Winters are colder, especially at higher altitudes, with frequent snowfall. Summers can be warm in the valleys but cooler in the mountains. The Albanian Alps in the north and the Korab Mountains in the east are the coldest areas, with winter temperatures often dropping below freezing. The Northern Mountain Range, particularly the Albanian Alps, is one ofthe most humid regions in Europe, receiving significant rainfall, sometimes exceeding 0.1 K in (3.10 K mm) annually. Four small glaciers were discovered in these mountains in 2009 at a relatively low altitude of around 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m).

Precipitation varies significantly across the country, generally higher in mountainous areas and during the winter months. The average annual precipitation is about 0.1 K in (1.49 K mm), but it can range from 24 in (600 mm) in some areas to over 0.1 K in (3.00 K mm) in others. The highest recorded temperature was 111.02 °F (43.9 °C) in Kuçovë on July 18, 1973, and the lowest was -20.200000000000003 °F (-29 °C) in Shtyllë, Librazhd, on January 9, 2017. The country has four distinct seasons. According to the Köppen climate classification, Albania includes Mediterranean, subtropical, oceanic, continental, and subarctic climate types.

4.3. Biodiversity

Albania is considered a biodiversity hotspot due to its geographical location at the crossroads of various biogeographical regions and its diverse climatic, geological, and hydrological conditions. The country possesses an exceptionally rich and varied flora and fauna.

Approximately 3,500 different species of vascular plants can be found in Albania, reflecting Mediterranean and Eurasian influences. At least 300 local plant species are used in traditional herbal medicine. Forests cover around 29% of Albania's total land area (approximately 788,900 hectares in 2020). Dominant tree species include fir, oak, beech, and pine. A significant portion of these forests are naturally regenerating, with about 11% reported as primary forest.

Albania's fauna is also diverse. The remote mountains and hills provide habitats for a wide variety of animals, including endangered species like the Balkan lynx and the brown bear. Other notable mammals include the wildcat, grey wolf, red fox, and golden jackal. The golden eagle, the national animal, and the Egyptian vulture are among the prominent bird species. The country's wetlands, estuaries, and lakes are crucial for birdlife, including the greater flamingo, pygmy cormorant, and the rare Dalmatian pelican. The coastal waters and shores are nesting grounds for the Mediterranean monk seal, loggerhead sea turtle, and green sea turtle.

In terms of phytogeography, Albania is part of the Boreal Kingdom, specifically within the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal and Mediterranean Regions. Its territory can be subdivided into four terrestrial ecoregions of the Palearctic realm:

- Illyrian deciduous forests: Covering much of the coastal and lowland areas.

- Balkan mixed forests: Found in the northeastern parts.

- Pindus Mountains mixed forests: Covering the southeastern mountains.

- Dinaric Mountains mixed forests: In the far northern mountainous regions (Albanian Alps).

4.4. Environmental Issues and Conservation

Albania faces several significant environmental challenges. Deforestation has been a historic issue, though forest cover has slightly increased since 1990. Water and air pollution are concerns, particularly in urban areas and near industrial sites, stemming from inadequate waste management, industrial discharges, and vehicle emissions. Waste management itself remains a major challenge, with insufficient infrastructure for collection, recycling, and proper disposal. Climate change is projected to exacerbate existing problems, leading to increased risks of floods, droughts, rising sea levels impacting coastal areas, and effects on agriculture and biodiversity. Albania is considered one of the European countries most vulnerable to natural disasters. In 2023, Albania emitted 7.67 million tonnes of greenhouse gases, equivalent to 2.73 tonnes per person, a relatively low figure. The country has pledged a 20.9% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 and aims for net-zero emissions by 2050.

Conservation efforts have been underway to protect Albania's rich biodiversity and natural landscapes. The country has established numerous protected areas, which include:

- National Parks: There are 12 national parks, such as Butrint National Park (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), Llogara National Park, Theth National Park, Valbonë Valley National Park (these two now part of the larger Albanian Alps National Park), Divjakë-Karavasta National Park (home to the Karavasta Lagoon, a Ramsar site), Prespa National Park, Shebenik-Jabllanicë National Park, and Europe's first wild river national park, Vjosa National Park, established to protect the Vjosa River and its tributaries. Other mountain parks include Dajti, Lurë-Dejë Mountain, and Tomorr Mountain. These parks cover a significant portion of the country and aim to preserve ecosystems, wildlife, and cultural heritage.

- Ramsar Sites: Albania has designated four wetlands as Wetlands of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention: Lake Shkodër and Buna River, Lake Butrint, Karavasta Lagoon, and the Albanian part of Lake Prespa.

- Biosphere Reserves: The Ohrid-Prespa Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, shared with North Macedonia, is part of UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere Programme.

- Other Protected Areas: Numerous other types of conservation reserves exist, contributing to a network covering a substantial percentage of the country's territory.

Albania is a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and has developed a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. It also collaborates with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The Gashi River and Rrajca regions are part of the transnational UNESCO World Heritage site of Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe. Despite these efforts, effective management and enforcement in protected areas remain challenging due to limited resources and developmental pressures. Albania's Environmental Performance Index (EPI) score indicates moderate and improving performance, ranking 62nd out of 180 countries in 2022, though this is a decrease from its highest rank of 15th in 2012.

5. Politics

Albania is a sovereign parliamentary constitutional republic. Its political system operates under a constitution adopted in 1998, which emphasizes the separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, and guarantees fundamental human rights and a multi-party democratic system.

5.1. Government

The structure of the Albanian government is as follows:

- The President: The President is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the military. The role is largely ceremonial, with powers including representing the unity of the people, appointing the Prime Minister (based on parliamentary majority), and certain duties related to foreign affairs and national security. The President is elected by the Parliament for a five-year term and can serve a maximum of two terms.

- The Prime Minister: The Prime Minister is the head of government and holds the most executive power. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the majority party or coalition in Parliament and is responsible for forming the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The cabinet, led by the Prime Minister, directs the country's internal and foreign policies and is accountable to Parliament.

- The Parliament (Kuvendi): The Kuvendi i Shqipërisë is the unicameral legislature of Albania. It consists of 140 members elected for a four-year term through a system of proportional representation with regional multi-member constituencies. The Parliament enacts laws, approves the budget, ratifies international treaties, elects the President, and oversees the government.

- The Judiciary: The judiciary is independent. The legal system is based on civil law, codified and influenced by the Napoleonic Code. The court system includes the Supreme Court (the highest court of appeal for most cases), the Constitutional Court (which interprets the constitution and reviews the constitutionality of laws), Courts of Appeal, and district courts. There are also specialized administrative courts. Judicial reform has been a major focus, particularly in the context of EU integration efforts, aiming to improve independence, efficiency, and combat corruption within the judiciary.

Law enforcement is primarily the responsibility of the Albanian State Police.

5.2. Political Parties

Albania has a multi-party system. Since the fall of communism, the political landscape has been dominated by two main parties:

- The Socialist Party (Partia Socialiste, PS): Successor to the former communist Party of Labour, it has evolved into a centre-left, social-democratic party.

- The Democratic Party (Partia Demokratike, PD): Founded during the anti-communist protests, it is a centre-right, conservative party.

Other significant parties that have played roles in coalition governments or as opposition include the Socialist Movement for Integration (Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim, LSI), which split from the Socialist Party and has often acted as a kingmaker, and smaller parties representing various ideological positions or minority interests. Political discourse is often highly polarized.

5.3. Elections

Parliamentary elections are held every four years. Local elections for mayors and municipal councils are also held regularly. The electoral system for parliamentary elections has undergone several changes but generally uses a form of proportional representation. Electoral processes have often been contentious, with allegations of irregularities. International observers from organizations like the OSCE/ODIHR monitor elections and have noted progress over time but also persistent challenges in areas such as campaign finance, media bias, and vote buying. Electoral reform remains an ongoing topic of political discussion aimed at strengthening democratic consolidation.

5.4. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Albania is guaranteed by the constitution and various international conventions to which Albania is a signatory. However, challenges persist. Key areas of concern often highlighted by domestic and international human rights organizations include:

- Freedom of Speech and the Press: While media is pluralistic, concerns exist regarding media ownership concentration, political influence, intimidation of journalists, and self-censorship.

- Judicial Independence and Corruption: Corruption remains a significant problem affecting various levels of government and society, including the judiciary. Efforts to reform the justice system, including a vetting process for judges and prosecutors, aim to address these issues but face political resistance and slow implementation. Judicial independence is often undermined by political pressure.

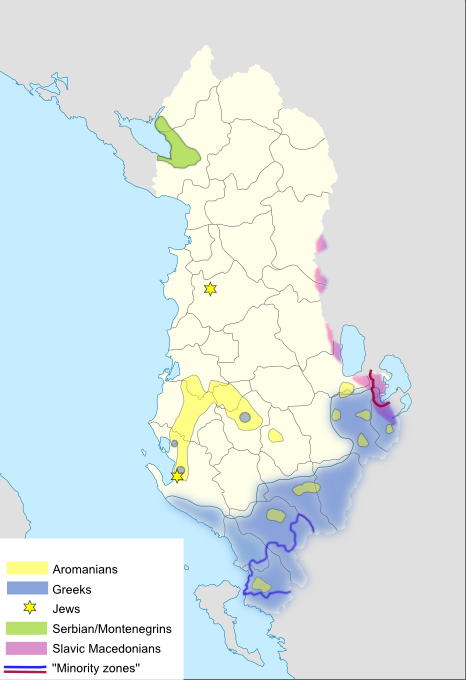

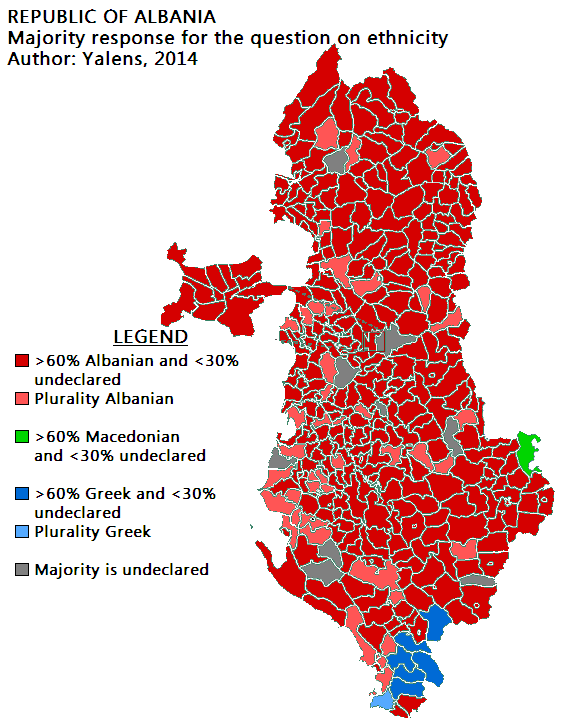

- Minority Rights: Albania officially recognizes several national minorities (e.g., Greek, Macedonian, Montenegrin) and cultural minorities (e.g., Aromanian, Roma, Balkan Egyptian). Issues related to the full implementation of minority rights, including language use, education, political representation, and combating discrimination against Roma and Egyptian communities, are ongoing concerns.

- LGBT Rights: While homosexuality was decriminalized in 1995 and anti-discrimination laws covering sexual orientation and gender identity are in place, societal discrimination and prejudice against LGBT individuals persist. Pride events are held, but often with significant security presence.

- Domestic Violence and Women's Rights: Domestic violence remains a serious issue, though legal frameworks and support services have improved. Gender inequality, particularly in political and economic participation, is also a concern. Nearly 60% of women in rural areas report suffering physical or psychological violence, and nearly 8% are victims of sexual violence. Protection orders are often violated. The Commissioner for Protection from Discrimination has raised concerns about family registration laws that can discriminate against women, as heads of households (overwhelmingly men) can change family residency without their partners' permission.

- Property Rights: Issues related to property restitution and compensation for properties confiscated during the communist era remain largely unresolved and are a source of social tension and legal disputes.

Successive governments have committed to improving the human rights situation, often in response to requirements for EU integration. Civil society organizations play an important role in monitoring and advocating for human rights.

6. Foreign Relations

Albania's foreign policy has undergone a significant transformation since the end of its communist-era isolation. The country actively pursues integration into Euro-Atlantic structures, regional cooperation, and the protection of the rights of Albanians living abroad.

6.1. General Foreign Policy

Key foreign policy objectives for Albania include:

- Euro-Atlantic Integration**: This has been a cornerstone of Albanian foreign policy. Albania became a member of NATO in 2009 and is an official candidate for European Union membership, with accession negotiations formally opened in 2020. Aligning its legislation and institutions with EU standards is a primary domestic and foreign policy goal.

- Regional Stability and Cooperation**: Albania actively participates in regional initiatives in the Balkans aimed at fostering peace, stability, and economic development. It maintains generally good relations with its neighbors, though historical issues and minority rights can sometimes cause friction.

- Engagement with the Albanian Diaspora**: The large Albanian diaspora in countries like Italy, Greece, the United States, and elsewhere is considered an important asset. The government seeks to maintain strong ties with diaspora communities and encourage their involvement in Albania's development.

- Support for Kosovo**: Albania was one of the first countries to recognize Kosovo's independence in 2008 and strongly advocates for its international recognition and integration into international organizations.

- International Partnerships**: Albania maintains strong bilateral relations with key international partners, notably the United States and major European powers. It is a member of the United Nations (since 1955), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Council of Europe, and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), reflecting its diverse diplomatic engagements.

6.2. Bilateral Relations

- Neighboring Balkan Countries**:

- Kosovo: Relations are exceptionally close and fraternal, based on shared ethnicity, culture, and strategic interests. Albania strongly supports Kosovo's sovereignty and development.

- North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia: Albania maintains diplomatic relations and engages in regional cooperation. Issues related to Albanian minorities in these countries are sometimes part of the bilateral agenda.

- Greece: Relations have historically been complex, influenced by the Greek minority in Albania, the Cham Albanian issue (concerning Albanians expelled from Greece after World War II), maritime border delimitations, and economic ties (many Albanians work in Greece). Despite occasional tensions, cooperation exists in various fields.

- Italy**: As a close neighbor across the Adriatic, Italy is a major trading partner, investor, and a strong supporter of Albania's EU integration. Historical ties are deep, and Italian culture has a significant influence in Albania.

- United States**: The United States is considered a key strategic partner. The U.S. has strongly supported Albania's democratic transition, its NATO membership, and its EU aspirations.

- Turkey**: Relations with Turkey are also strong, rooted in historical ties from the Ottoman era and contemporary strategic and economic cooperation. Turkey is a significant investor in Albania.

- European Powers**: Besides Italy, Albania cultivates close ties with other major EU members like Germany and France, which are important for its EU accession process and economic development.

Albania has condemned Russia's invasion of Ukraine and aligned itself with EU sanctions against Russia. The country served as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council for the 2022-2023 term.

6.3. European Union Integration

Albania's path towards European Union membership is a central strategic goal.

- Application**: Albania formally applied for EU membership on April 28, 2009.

- Candidate Status**: It was granted official EU candidate status on June 24, 2014.

- Accession Negotiations**: After several delays, the EU officially launched accession negotiations with Albania (and North Macedonia) in March 2020. The first Intergovernmental Conference, marking the formal start of talks, took place in July 2022.

The accession process requires Albania to implement comprehensive reforms across various areas, known as chapters, including the rule of law, judicial independence, fight against corruption and organized crime, public administration reform, economic criteria, and alignment with the EU's common foreign and security policy. Progress is regularly monitored by the European Commission, and the pace of negotiations depends on Albania's ability to meet the required benchmarks. EU integration is seen as a driver for modernization and democratic consolidation in Albania.

7. Military

The Albanian Armed Forces (Forcat e Armatosura të Shqipërisë, AAF) are responsible for the defense of the independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity of Albania. They also participate in humanitarian, combat, non-combat, and peace support operations. The President of Albania is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In peacetime, executive authority is exercised through the Prime Minister and the Minister of Defence.

The AAF consists of three main branches:

- Land Force (Forca Tokësore)**

- Air Force (Forca Ajrore)**

- Naval Force (Forca Detare)**

It also includes a Joint Forces Command and a Support Command.

Since the fall of communism, Albania has significantly reformed its military. Conscription was abolished in 2010, and the AAF transitioned to an all-volunteer professional force. The legal minimum age for service is 19. The size of the active military has been considerably reduced from its Cold War levels (from around 65,000 in 1988 to approximately 14,500 by 2009, with further restructuring since).

A key strategic goal achieved by Albania was membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Albania joined NATO on April 1, 2009. NATO membership has driven modernization efforts, including upgrading equipment, improving training standards to meet NATO interoperability requirements, and participating in NATO-led missions and operations. Albanian forces have participated in international peacekeeping and security operations in various parts of the world, including Afghanistan (as part of ISAF and Resolute Support Mission), Iraq, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo (KFOR), and NATO's Operation Active Endeavour in the Mediterranean.

Military spending has fluctuated. It was around 1.5% of GDP in the mid-1990s, peaked at around 2% at the time of NATO accession in 2009, and has since generally remained around 1.5% to 1.7% of GDP, with commitments to reach the NATO guideline of 2% of GDP. Modernization efforts focus on acquiring NATO-compatible equipment, enhancing cyber defense capabilities, and developing specialized units. Albania is also planning to host a NATO airbase in Kuçovë and a naval base in Porto Romano (near Durrës), reflecting its strategic importance in the region.

8. Administrative Divisions

Albania is a unitary state with a system of local governance. The primary administrative divisions are the 12 counties (qarqeqarqe (counties)Albanian, singular: qarkqark (county)Albanian). These were re-established on July 31, 2000, superseding the previous 36 districts (rrethë). The counties are responsible for regional coordination and implementing national policies at a regional level.

The 12 counties are:

1. Berat

2. Dibër

3. Durrës

4. Elbasan

5. Fier

6. Gjirokastër

7. Korçë

8. Kukës

9. Lezhë

10. Shkodër

11. Tirana

12. Vlorë

Each county is further subdivided into municipalities (bashkibashki (municipalities)Albanian, singular: bashkiabashkia (municipality)Albanian). Following a major administrative-territorial reform implemented in 2015, the number of municipalities was reduced from 373 (including urban municipalities and rural communes) to 61. These municipalities are the first level of local self-government and are responsible for local services such as urban planning, waste management, local infrastructure, social services, and local law enforcement to some extent. Mayors and municipal councils are directly elected.

The municipalities are themselves composed of administrative units (njësi administrativenjësi administrative (administrative units)Albanian), which often correspond to former communes or city neighborhoods. There are 373 such administrative units. Below this level are villages (fshatrafshatra (villages)Albanian) and city neighborhoods (lagjelagje (neighborhoods)Albanian). There are approximately 2,980 villages in Albania.

The largest county by population is Tirana County, with over 900,000 people (as of 2020 estimates), while the smallest is Gjirokastër County with around 60,000 people. The largest county by area is Korçë County (1.4 K mile2 (3.71 K km2)), and the smallest is Durrës County (296 mile2 (766 km2)).

| Emblem | County | Capital | Area | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berat | Berat | 0.7 K mile2 (1.80 K km2) | 122,003 | 0.782 | |

| Dibër | Peshkopi | 1.0 K mile2 (2.59 K km2) | 115,857 | 0.754 | |

| Durrës | Durrës | 296 mile2 (766 km2) | 290,697 | 0.802 | |

| Elbasan | Elbasan | 1.2 K mile2 (3.20 K km2) | 270,074 | 0.784 | |

| Fier | Fier | 0.7 K mile2 (1.89 K km2) | 289,889 | 0.767 | |

| Gjirokastër | Gjirokastër | 1.1 K mile2 (2.88 K km2) | 59,381 | 0.794 | |

| Korçë | Korçë | 1.4 K mile2 (3.71 K km2) | 204,831 | 0.790 | |

| Kukës | Kukës | 0.9 K mile2 (2.37 K km2) | 75,428 | 0.749 | |

| Lezhë | Lezhë | 0.6 K mile2 (1.62 K km2) | 122,700 | 0.769 | |

| Shkodër | Shkodër | 1.4 K mile2 (3.56 K km2) | 200,007 | 0.784 | |

| Tirana | Tirana | 0.6 K mile2 (1.65 K km2) | 906,166 | 0.820 | |

| Vlorë | Vlorë | 1.0 K mile2 (2.71 K km2) | 188,922 | 0.802 |

9. Economy

Albania's economy has undergone a significant transformation from a centrally planned system during the communist era to an open market-based economy. It is classified as a developing, upper-middle-income economy by the World Bank. The transition has involved extensive privatization, liberalization, and efforts to attract foreign investment, although challenges such as corruption, informal economy, and brain drain persist.

9.1. Overview

Following the collapse of communism in 1991, Albania embarked on market-oriented reforms. Early years were marked by economic instability, culminating in the 1997 crisis due to the collapse of pyramid schemes. Since then, the economy has generally seen periods of growth, driven by remittances from Albanians working abroad, foreign direct investment (FDI), and the development of the services sector.

Key economic indicators include:

- GDP: The Gross Domestic Product has grown, though per capita income remains lower than the EU average. In 2012, Albania's GDP per capita was 30% of the EU average, while GDP (PPP) per capita was 35%. Forbes reported GDP growth at 2.8% as of December 2016. The IMF predicted 2.6% growth for Albania in 2010 and 3.2% in 2011.

- Unemployment: Unemployment rates have been a persistent challenge, although they have seen some decline. In 2016, the unemployment rate was estimated at 14.7%, one of the lower rates in the Balkans at that time.

- Main Trading Partners: Albania's largest trading partners are predominantly EU countries, especially Italy and Greece. Other important partners include China, Spain, Kosovo, and the United States.

- Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): FDI has increased, particularly in sectors like energy, infrastructure, and tourism. The government has implemented reforms to improve the business climate.

- Currency: The official currency is the Lek (ALL).

- Inflation: Generally kept under control by the Bank of Albania.

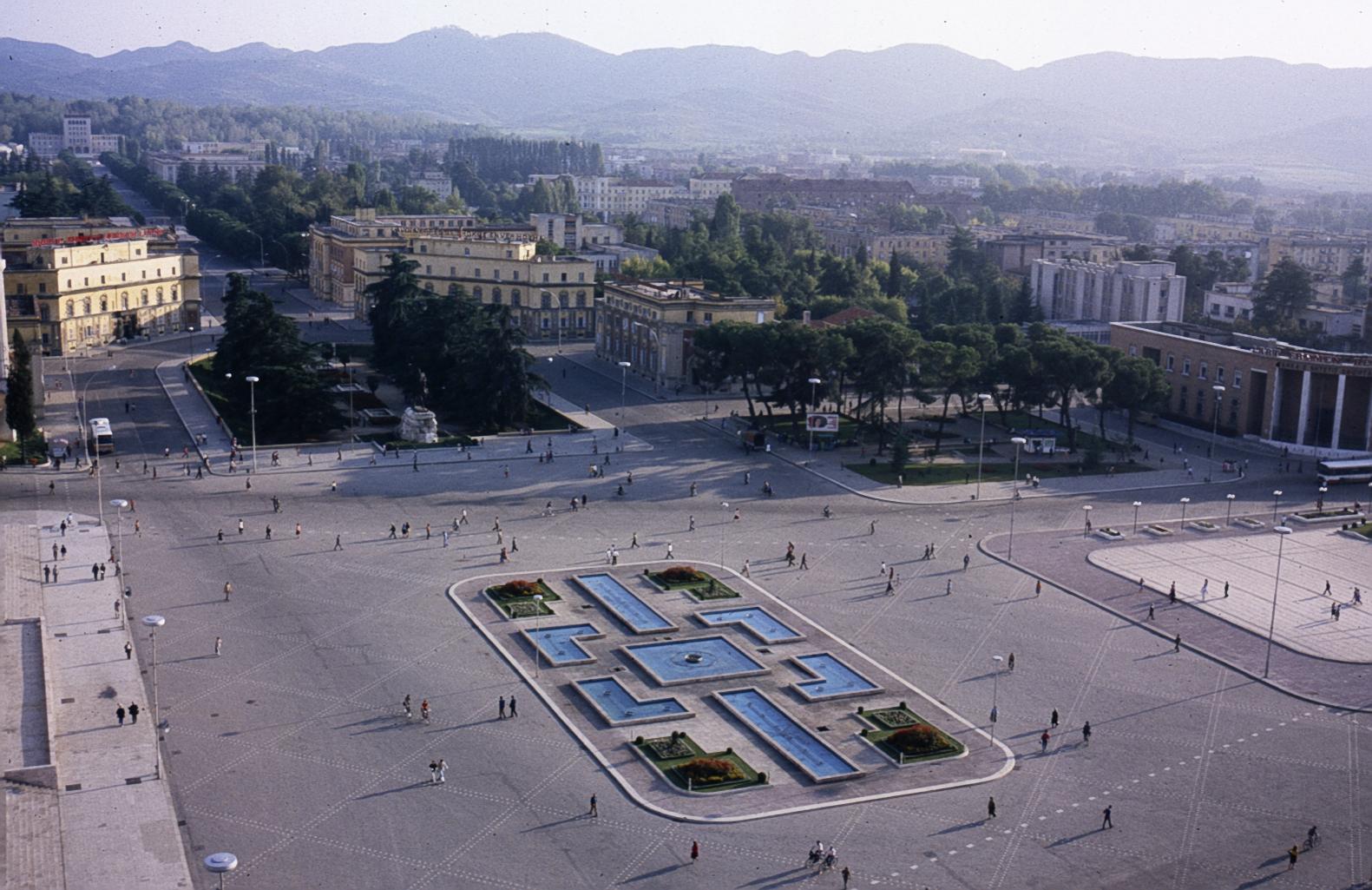

The cities of Tirana and Durrës are the economic and financial centers of the country, hosting major domestic and international companies. Key companies include the state-owned energy distribution company OSHEE, steel producer Kurum, oil companies like Kastrati, Albpetrol, and the former ARMO, the mineral company AlbChrome, the investment firm BALFIN Group, and telecommunications companies like One Albania and Vodafone Albania.

9.2. Primary Sector

Agriculture remains a significant sector in the Albanian economy, employing a large portion of the population (around 41%) and utilizing about 24.31% of the land. Farming is typically based on small to medium-sized family-owned units. Albania is known for its early farming sites in Europe.

- Main Crops: Wheat, maize, potatoes, tomatoes, olives, grapes, citrus fruits (oranges, lemons), figs, apples, peaches, cherries, plums, and strawberries. Albania is also a significant producer of sugar beets and tobacco.

- Aromatic and Medicinal Plants: The country is a notable global producer of salvia (sage), rosemary, and yellow gentian.

- Livestock and Dairy: Livestock farming (sheep, goats, cattle) and the production of dairy products and honey are also important.

- Fishing: With its Adriatic and Ionian coastlines, Albania has potential in the fishing industry, though it remains relatively underdeveloped. Common catches include carp, trout, sea bream, mussels, and crustaceans.

- Viticulture: Albania has a long history of winemaking, dating back thousands of years. In 2009, the nation produced an estimated 17,500 tonnes of wine.

Farmers receive support through the EU's Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) funds to improve agricultural standards. Challenges in this sector include land fragmentation, outdated technology, and limited access to credit and markets.

9.3. Secondary Sector

The secondary sector (industry) has diversified since the fall of communism.

- Manufacturing: Key manufacturing industries include textiles and footwear (often through outward processing arrangements with Italian companies), food processing, and construction materials like cement. The Antea Cement plant in Fushë-Krujë is a major industrial investment. The textile industry had an annual growth of 5.3% and a turnover of around 1.50 B EUR as of 2016.

- Mining: Albania has significant mineral resources. It is a leading global producer and exporter of chromium. It also produces copper, nickel, iron ore, and coal. The Batra mine, Bulqizë mine, and Thekna mine are among the notable active mines.

- Energy Production: This is covered in more detail under the "Energy" subsection, but it forms part of the secondary sector.

- Oil and Gas: Albania has the second-largest onshore oil deposits in the Balkans (after Romania) and significant oil reserves in Europe, primarily in the Patos-Marinza field. Albpetrol is the state-owned company overseeing petroleum agreements.

The industrial sector faces challenges such as the need for technological upgrades and improved infrastructure.

9.4. Tertiary Sector

The tertiary (services) sector is the largest and fastest-growing component of the Albanian economy, contributing about 65% of GDP and employing around 36% of the workforce.

- Tourism: Tourism is a major growth area and a significant source of revenue and employment. It directly accounted for 8.4% of GDP in 2016, with indirect contributions pushing the proportion to 26%. The country received approximately 4.74 million visitors in 2016. Albania offers diverse attractions, including its Adriatic and Ionian coastlines (the Albanian Riviera), historical sites (like Butrint, Berat, Gjirokastër), and mountainous regions (Albanian Alps). Lonely Planet named Albania a top travel destination in 2011, and The New York Times ranked it as the 4th global tourist destination in 2014.

- Banking and Finance: The banking sector has largely been privatized and is relatively stable, overseen by the Bank of Albania.

- Telecommunications: The telecommunications industry has developed rapidly through privatization and investment. Major providers include Vodafone Albania and One Albania (formerly Telekom Albania and Eagle Mobile).

- Retail and Other Services: Retail, real estate, transport, and business services also contribute significantly to the tertiary sector.

The development of infrastructure, particularly in transport and energy, is crucial for the continued growth of the services sector, especially tourism.

9.5. Transport

Transportation in Albania has seen significant development since the early 2000s, with major investments in road infrastructure, air travel, and port facilities. The Ministry of Infrastructure and Energy, along with entities like the Albanian Road Authority (ARRSH) and the Albanian Civil Aviation Authority (AAC), manage the sector.

- Airports: The Tirana International Airport Nënë Tereza is the main international gateway, serving as the hub for the national carrier, Air Albania. In 2019, it handled over 3.3 million passengers, with connections to numerous European cities and destinations in Asia and Africa. Plans are in place to develop more airports, particularly in southern Albania (e.g., Vlorë, Sarandë, Gjirokastër) to support tourism.

- Roads: The network of highways and motorways has been extensively upgraded.

- The A1 Motorway (Autostrada 1, also known as Rruga e Kombit or "Nation's Road") connects Durrës on the Adriatic coast with Pristina in Kosovo, and is planned to link to the Pan-European Corridor X in Serbia.

- The A2 Motorway (Autostrada 2) is part of the Adriatic-Ionian Corridor and Pan-European Corridor VIII, connecting Fier with Vlorë.

- The A3 Motorway (Autostrada 3) connects Tirana with Elbasan and is part of Pan-European Corridor VIII.

When completed, these corridors will provide Albania with an estimated 472 mile (759 km) of highways linking it with neighboring countries.

- Ports: The Port of Durrës is the busiest and largest seaport, followed by the Port of Vlorë, Port of Shëngjin, and Port of Sarandë. Durrës is a major passenger port on the Adriatic, handling about 1.5 million passengers annually (as of 2014), with ferry services connecting Albania to Italy, Greece, and Croatia.

- Railways: The rail network, administered by Hekurudha Shqiptare (Albanian Railways), was extensively promoted during the communist era but has since declined with the rise of private car ownership and bus transport. Plans are underway for a new railway line connecting Tirana and its airport to Durrës, which is considered an important economic development project due to the high population density in this corridor.

Challenges in the transport sector include the need for continued investment in maintenance and expansion, especially for rural roads and the railway network.

9.6. Science and Technology

Following the fall of communism in 1991, Albania experienced a significant brain drain, with approximately 50% of professors and scientists from universities and research institutions leaving the country between 1991 and 2005. In 2009, the government approved a National Strategy for Science, Technology, and Innovation (2009-2015), aiming to triple public spending on research and development (R&D) to 0.6% of GDP and increase foreign funding for R&D, including from EU framework programs. Albania was ranked 84th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

The telecommunications sector is one of the fastest-growing in Albania. Key mobile and internet providers include Vodafone Albania and One Albania (formed from the merger of Albtelecom and Eagle, and later Telekom Albania). As of 2018, there were approximately 2.7 million active mobile users and almost 1.8 million active broadband subscribers.

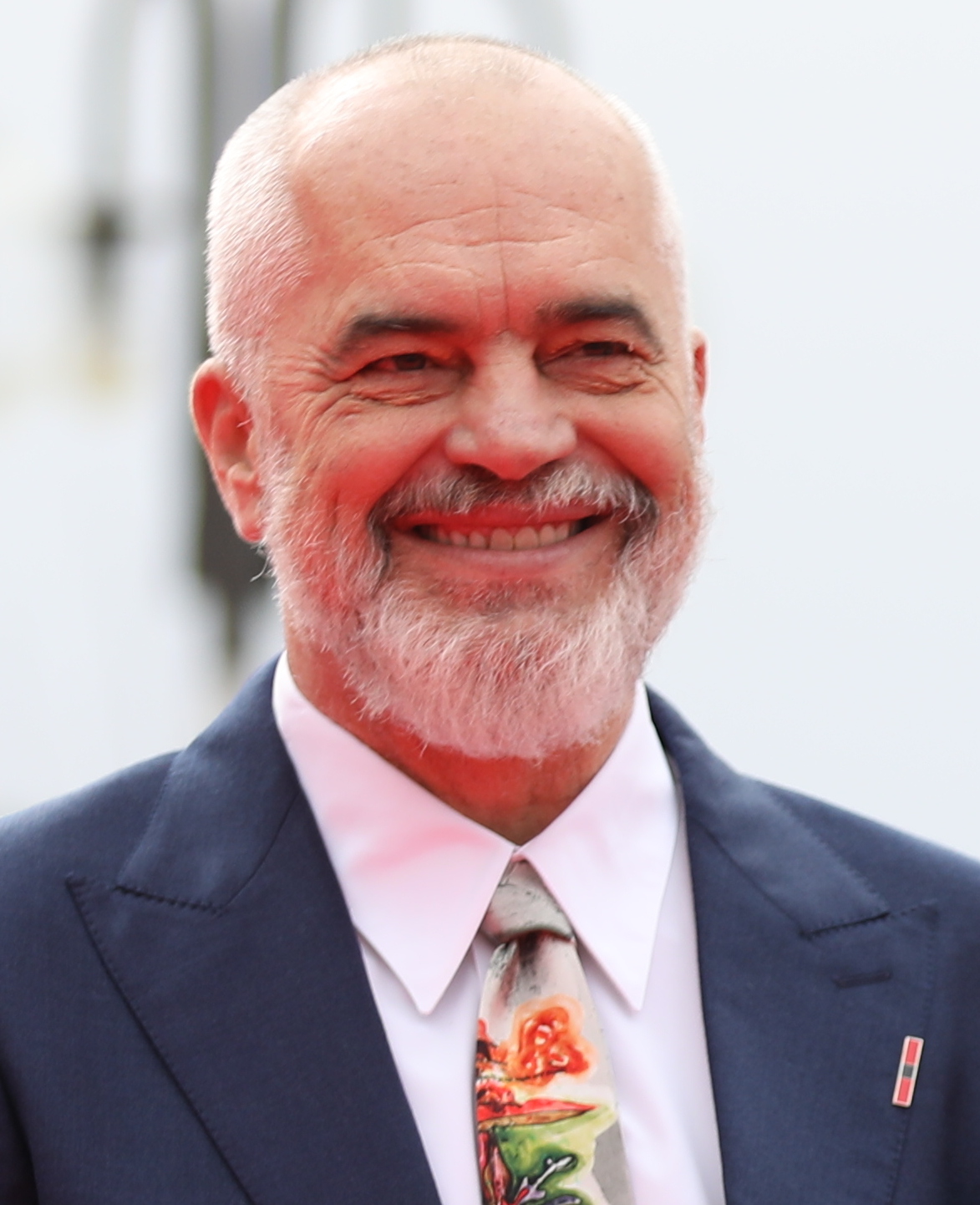

In January 2023, Albania launched its first two satellites, Albania 1 and Albania 2, into orbit, a milestone for monitoring its territory and identifying illegal activities. Albanian-American engineer Mira Murati, Chief Technology Officer of OpenAI, has played a significant role in the development of AI services like ChatGPT, Codex, and DALL-E. In December 2023, Prime Minister Edi Rama announced plans for collaboration between the Albanian government and ChatGPT, facilitated by discussions with Murati, aiming to streamline the alignment of Albanian laws with EU regulations.

9.7. Energy

Albania possesses a variety of energy resources, including oil, gas, coal, and significant potential for renewable energy sources like hydropower, solar, and wind. The country ranked 21st globally in the World Economic Forum's 2023 Energy Transition Index.

- Hydropower: Albania's electricity generation is overwhelmingly dependent on hydroelectricity, ranking fifth globally in terms of the percentage of electricity produced from hydro sources (nearly 100%). Major hydroelectric power stations are located on the Drin River in the north (Fierza, Koman, Skavica, Vau i Dejës) and the Devoll River in the south (Banjë, Moglicë). This reliance on hydropower makes the energy supply vulnerable to hydrological conditions and climate change impacts like droughts and floods.

- Oil and Gas: Albania has considerable oil deposits, with the 10th-largest proven oil reserves in Europe. The main deposits are located along the Adriatic coast and the Myzeqe Plain. The Patos-Marinza field is the largest onshore oil field in Europe. The Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), part of the Southern Gas Corridor, traverses 134 mile (215 km) of Albanian territory, bringing natural gas from Azerbaijan to Europe.

- Renewable Energy Development: Besides hydropower, Albania is working to develop other renewable energy sources, particularly solar and wind, to diversify its energy mix and enhance energy security.

- Water Resources: Albania has abundant freshwater resources from lakes, rivers, springs, and groundwater aquifers, with one of the highest per capita availability rates in Europe. As of 2015, about 93% of the population had access to improved sanitation.

National energy policy focuses on ensuring energy security, diversifying sources, increasing efficiency, and integrating with regional energy markets, often in line with EU directives.

10. Society

This section examines the demographic composition, social structures, and key societal aspects of Albania, including its ethnic makeup, languages, religious landscape, education system, healthcare, and media environment.

10.1. Demographics

According to the 2023 census conducted by the Instituti i Statistikave (INSTAT), the population of Albania was 2,402,113. This represents a notable decline from the 2,821,977 recorded in the 2011 census. The population decrease began after the fall of the communist regime in 1991 and is attributed to a combination of declining fertility rates and significant emigration. Albania has one of the highest rates of out-migration relative to its population in the world, with estimates suggesting up to a third of those born within its borders now live abroad. The birth rate in 2022 was 20% lower than in 2021, largely due to the emigration of people of childbearing age. Population projections indicate a continued shrinking trend for the next decade.

The population density is approximately 83.6 inhabitants per square kilometer, with uneven distribution. The counties of Tirana and Durrës are the most densely populated, accounting for about 41% of the total population (32% in Tirana, 9% in Durrës). Peripheral and rural counties like Gjirokastër and Kukës have much lower population densities, each contributing around 3% to the total population.

Urbanisation has been rapid since 1991. The proportion of the urban population increased from 47% in 2001 to 65% in 2023. The Tirana-Durrës agglomeration along the western coastal lowlands is the primary center of population growth due to internal migration from rural and peripheral areas, leading to regional imbalances.

Life expectancy at birth in Albania is 77.8 years (as of recent estimates), ranking 37th globally. Key demographic trends include an aging population, decreasing household size, and ongoing urbanization.

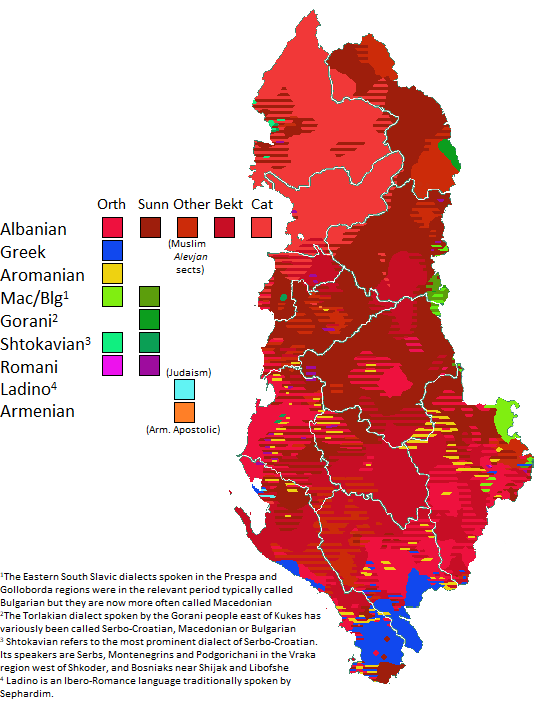

10.2. Ethnic Groups and Minorities

Albania is a relatively ethnically homogeneous country. According to the 2023 census, the ethnic composition was:

- Albanians: 2,186,917 (91.04%)

- Greeks: 23,485 (0.98%)

- Macedonians: 2,281 (0.09%)

- Montenegrins: 511 (0.02%)

- Aromanians (Vlachs): 2,459 (0.1%)

- Roma: 9,813 (0.4%)

- Balkan Egyptians: 12,375 (0.5%)

- Bosnians: 2,963 (0.12%)

- Serbs: 584 (0.02%)

- Bulgarians: 7,057 (0.29%)

- Mixed ethnicities: 770 (0.03%)

- Other ethnicities: 3,798 (0.15%)

- Unspecified ethnicity: 134,451 (5.60%)

National minorities officially recognized include Greeks, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs, Aromanians, Roma, and Balkan Egyptians. Bulgarians were officially recognized as a minority in 2017. Jewish and Gorani peoples are also considered minority groups.

Minority groups have often disputed official census figures, claiming larger numbers. For instance, the Greek government has estimated the ethnic Greek population to be around 300,000, significantly higher than census figures. The US State Department and other international observers have noted that the 2011 census data on minorities may have been affected by boycotts and concerns over self-identification procedures. The rights and integration of minorities, particularly the Roma and Balkan Egyptian communities who often face socio-economic marginalization and discrimination, remain important social and political issues.

10.3. Languages

The official language of Albania is Albanian (ShqipShqip (Albanian)Albanian). It is an Indo-European language forming its own distinct branch. Albanian has two main dialects:

- Gheg: Spoken in the northern part of Albania and by Albanians in Kosovo, Montenegro, and parts of North Macedonia and Serbia.

- Tosk: Spoken in southern Albania. Standard Albanian is largely based on the Tosk dialect, a decision formalized during the communist era.

The Shkumbin river is traditionally considered the geographical dividing line between the two dialects.

Minority languages spoken in Albania include Greek (primarily in the south, by the Greek minority), Macedonian (official in Pustec Municipality), Aromanian, Romani, Serbian, Bosnian, and Bulgarian.

Due to historical factors, migration, and education, knowledge of foreign languages is widespread. English is the most commonly spoken foreign language, particularly among younger generations (around 40% proficiency). Italian is also widely understood and spoken (around 27.8%), reflecting close ties and media influence. Greek is spoken by a significant portion of the population (around 22.9%), especially in the south and among those who have worked in Greece. There is also growing interest in German and Turkish due to economic and cultural links.

The 2011 census reported that 98.8% of the population declared Albanian as their mother tongue.

10.4. Religion

Albania is a constitutionally secular country with no official religion, guaranteeing freedom of religion, belief, and conscience. The religious landscape is diverse. According to the 2023 census:

- Islam: 50.67%

- Sunni Muslims: 45.86%

- Bektashi Muslims: 4.81%

- Christianity: 15.0%

- Roman Catholics: 8.38%

- Eastern Orthodox: 7.22%

- Evangelical Christians: 0.4%

- Believers without denomination: 13.82%

- Atheists: 3.55%

- Undeclared: 15.76%

- Other religions: 0.15%

Historically, Albania has been a crossroads of religions. Christianity arrived in the 1st century AD. Following the Great Schism, northern Albania leaned towards Catholicism and the south towards Orthodoxy. Islam was introduced during the Ottoman rule from the 15th century onwards and became the majority religion. The Bektashi Order, a Sufi Islamic order, has a significant historical presence and its world headquarters are in Tirana.

During the communist regime under Enver Hoxha, all religious observance was brutally suppressed. In 1967, Albania was declared the world's first officially atheist state. Religious institutions were closed, clergy were persecuted, and religious property was confiscated. Religious freedom was restored after the fall of communism in 1990.

Today, Albania is characterized by a high degree of religious tolerance and interfaith harmony. While many citizens identify with a particular religion, levels of religious observance are generally considered moderate, and society is largely secular. Religious identity often coexists with a strong national identity. Some smaller religious communities include various Protestant denominations and a small Jewish community.

10.5. Education