1. Overview

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe, bordering Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and the Adriatic Sea to the southwest. It is a parliamentary democratic republic and a member of the European Union, the Eurozone, the Schengen Area, NATO, and numerous other international organizations. The nation's geography is diverse, featuring Alpine mountain ranges, including the Julian Alps with Mount Triglav as its highest peak, extensive forests covering over half its territory, the Karst Plateau known for its cave systems, and a short but significant Adriatic coastline. Historically, the lands of present-day Slovenia have been at the crossroads of Slavic, Germanic, and Romance cultures and languages, experiencing rule by various empires including the Roman Empire, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Habsburg Monarchy.

The Slovene people established early Slavic political entities like Carantania and later endured periods of foreign domination, fostering a distinct national identity through language and culture, particularly during the national revival of the 19th century. After World War I, Slovenia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. World War II brought occupation, partition, and a strong partisan resistance movement. Post-war, Slovenia was a socialist republic within Yugoslavia, characterized by a unique model of workers' self-management and participation in the Non-Aligned Movement, while also experiencing developments towards greater democratic expression. The late 1980s saw the "Slovenian Spring," a period of democratization leading to a referendum and the declaration of independence in 1991, followed by the Ten-Day War.

Slovenia has a developed, high-income economy, with significant industries in manufacturing (automotive, pharmaceuticals), services, and tourism. The country prioritizes social justice, human rights, environmental protection, and sustainable development. Its political system is based on the separation of powers, with a multi-party democracy. Slovenia's culture is rich, reflected in its literature, arts, music, architecture, and cuisine, with a strong emphasis on preserving its heritage and natural beauty. The nation also has a vibrant sporting tradition. This article explores these facets of Slovenia, emphasizing its path to sovereignty, its commitment to democratic values, social equity, and its role in the international community from a center-left, social liberalism perspective.

2. Etymology

The name Slovenia (SlovenijaSloveniyaSlovenian) etymologically means 'Land of the Slovenes'. The origin of the name "Slav" itself remains uncertain, though several theories exist. One common theory suggests it derives from the Proto-Slavic root *slovo ("word", "speech"), implying "people who speak (the same language)" or "people who can understand each other." This would contrast with the Slavic term for Germans, *němьcь, from *němъ ("mute", "mumbling"), meaning "silent people" or those whose speech was incomprehensible. Another theory links "Slav" to the Proto-Slavic *slava ("glory", "fame"). Both *slovo and *slava are thought to originate from the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱlew- ("to be spoken of, glory"), which is also the root of the Greek word κλέος (kléos - "fame") and the Latin word clueo ("to be called"). The suffix -en in "Slovene" (SlovenecSlovenetsSlovenian) forms a demonym. The term "Slovenes" as an ethnonym for the inhabitants is connected to the historical self-designation slověne used by early Slavic groups.

The official name of the state has evolved through different political periods in the 20th century:

- 1945-1946: Federal Slovenia (Federalna SlovenijaFederálna SloveníyaSlovenian), as a constituent unit of Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

- 1946-1963: People's Republic of Slovenia (Ljudska republika SlovenijaLyúdska repúblika SloveníyaSlovenian), as part of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia.

- 1963-1990: Socialist Republic of Slovenia (Socialistična republika SlovenijaSocialístična repúblika SloveníyaSlovenian), as part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

- 1990-present: Republic of Slovenia (Republika SlovenijaRepúblika SloveníyaSlovenian), which became an independent state in 1991.

3. History

The history of the Slovene lands and people spans from prehistoric settlements through various periods of foreign rule, national awakening, involvement in major European conflicts, and culminates in the establishment of an independent democratic state. This historical narrative is marked by significant social, political, and cultural transformations, reflecting both internal developments and broader European trends.

3.1. Prehistory and Early Settlements

The territory of present-day Slovenia has a rich archaeological record indicating human presence from the Paleolithic era through the Iron Age, followed by the arrival and settlement of Slavic tribes. This period laid the groundwork for subsequent cultural and political developments in the region.

3.1.1. Prehistoric Era

The lands of present-day Slovenia have been inhabited since prehistoric times, with evidence of human presence dating back around 250,000 years. One of the most significant Paleolithic findings is the Divje Babe flute, discovered in 1995 in the Divje Babe cave near Cerkno. This pierced cave bear femur, dated to approximately 43,100 ± 700 years BP, is considered by some researchers to be a flute made by Neanderthals, potentially making it the oldest known musical instrument in the world. During the 1920s and 1930s, archaeologist Srečko Brodar unearthed artifacts belonging to Cro-Magnons in Potok Cave, including pierced bones, bone points, and a needle, indicating advanced tool-making capabilities.

The Neolithic period and Chalcolithic period saw the development of early farming communities. In 2002, remnants of pile dwellings over 4,500 years old were discovered in the Ljubljana Marsh (Ljubljansko barjeLjubljansko báryeSlovenian). These settlements, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, provide insight into the lives of these early agricultural societies. Among the discoveries at this site was the Ljubljana Marshes Wheel, the oldest wooden wheel yet found, dating to approximately 3350-3100 BCE. This find indicates that wheeled transport appeared almost contemporaneously in Mesopotamia and Europe, challenging earlier notions of its singular origin.

During the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, the Urnfield culture flourished in the region. The subsequent Hallstatt culture (early Iron Age, roughly 800-450 BCE) left significant archaeological remains, particularly in southeastern Slovenia. The town of Novo Mesto, often referred to as the "Town of Situlas," is famous for its numerous richly decorated bronze situlae (bucket-like vessels), which depict scenes of daily life, rituals, and warfare, showcasing sophisticated metalworking skills and artistic expression of the Hallstatt elites.

3.1.2. Roman Era

Beginning in the 1st century BCE, the territory of present-day Slovenia was gradually incorporated into the Roman Empire. It was divided between the region of Venetia et Histria (Region X of Roman Italy) and the provinces of Pannonia and Noricum. The Romans established important urban centers and military posts, transforming the landscape and society. Key settlements included:

- Emona (modern Ljubljana): A strategically important colony founded around 14 CE, Emona became a significant administrative, commercial, and military hub. It featured typical Roman urban planning with a forum, temples, baths, and defensive walls.

- Poetovio (modern Ptuj): Located on the Drava River, Poetovio was a major military base for legions stationed on the Danube frontier and later developed into a flourishing commercial city, particularly known for its Mithraic shrines.

- Celeia (modern Celje): An important Roman town that gained municipal rights under Emperor Claudius, Celeia was known for its wealth, derived from local resources and trade.

The Romans constructed an extensive network of roads across Slovene territory, facilitating trade, military movements, and communication between Italy, Pannonia, and the Balkans. These roads, such as the Amber Road branch, integrated the region into the wider Roman economic and cultural sphere. Roman rule brought Latin language, Roman law, and aspects of Roman culture, although indigenous Celtic and Illyrian traditions persisted, especially in rural areas. In the 5th and 6th centuries, as the Western Roman Empire declined, the region faced invasions by Huns, Ostrogoths, Lombards, and other Germanic tribes during their incursions into Italy. To protect the Italian heartland, a defensive system of fortifications and walls known as Claustra Alpium Iuliarum was established in the mountainous western part of Slovenia. A crucial battle in Roman history, the Battle of the Frigidus, was fought in the Vipava Valley in 394 CE between Emperor Theodosius I and the usurper Eugenius, significantly impacting the political and religious landscape of the late Empire.

3.1.3. Slavic Settlement

The Migration Period saw significant demographic shifts in the Eastern Alps. Following the westward departure of the Lombards (the last major Germanic tribe to control parts of the area) in 568 CE, Slavic tribes, ancestors of the modern Slovenes, began migrating into the region. This migration, occurring primarily during the late 6th and early 7th centuries, was partly driven by pressure from the Avars, a nomadic group that had established a powerful khaganate in the Pannonian Basin.

The Slavic settlers populated the Eastern Alps, gradually assimilating or displacing the remaining Romano-Celtic and Germanic populations. They established agricultural communities and developed their own social and political structures. One of the earliest known Slavic political entities in this area was the Duchy of Carantania (KarantanijaKarantánijaSlovenian), which emerged in the 7th century in what is now southern Austria and northeastern Slovenia. Carantania is notable for its unique ritual of installing dukes, which involved popular participation and was conducted in the Slovene language. From 623 to 624 or possibly 626 onwards, King Samo united the Alpine and Western Slavs against the Avars and Germanic peoples, establishing what is referred to as Samo's Kingdom. After its disintegration following Samo's death in 658 or 659, the ancestors of the Slovenes located in present-day Carinthia formed the independent duchy of Carantania, and also Carniola (later the Duchy of Carniola). Other parts of present-day Slovenia were again ruled by Avars before Charlemagne's victory over them in 803. The early Slavic society was largely tribal, with local chieftains (župans) playing important roles. Over time, more cohesive political structures began to form, laying the foundation for the medieval Slovene lands.

3.2. Middle Ages

The Middle Ages were a formative period for the Slovene lands, characterized by the consolidation of Slavic identity, Christianization, feudalization, and incorporation into larger Germanic empires, primarily the Holy Roman Empire. The social impact of feudalism and gradual Germanization significantly shaped the region.

The Carantanians, one of the ancestral groups of the modern Slovenes, particularly the Carinthian Slovenes, were among the first Slavic peoples to accept Christianity. This process began in the 8th century, largely through the efforts of Irish missionaries, such as Modestus, known as the "Apostle of Carantanians", and later under the influence of the Archbishopric of Salzburg and the Patriarchate of Aquileia. The Conversio Bagoariorum et Carantanorum, a Latin text from around 870, describes this Christianization process, though it is seen by some historians as emphasizing the role of Salzburg.

In the mid-8th century, Carantania became a vassal duchy under the rule of the Bavarians. By the late 8th century, both Carantania and Carniola, another early Slovene principality, were incorporated into the Carolingian Empire under Charlemagne. Following an anti-Frankish rebellion led by Liudewit, a Pannonian Slavic duke, in the early 9th century, the Franks removed the native Carantanian princes and replaced them with their own border dukes (margraves). This marked the firm establishment of the Frankish feudal system in Slovene territories. Society became increasingly stratified, with a landed nobility (largely Germanic) and a peasant population (largely Slovene) subject to feudal obligations.

After the Magyar invasions of the 10th century were repelled, particularly after Emperor Otto I's victory at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955, the Slovene-inhabited territories were reorganized into several border marches within the Holy Roman Empire. Carantania was elevated to the Duchy of Carinthia in 976. Other important historical provinces that developed over the High Middle Ages (11th-14th centuries) included Carniola, Styria, Gorizia, Trieste, and parts of Istria. The consolidation of these lands was led by various powerful feudal families, such as the Dukes of Spanheim, the Counts of Gorizia, and the Counts of Celje.

The Counts of Celje (Celjski grofjeTsélyski grofjeSlovenian) were a particularly influential native noble family, rising to prominence in the 14th and 15th centuries. They acquired vast estates and, in 1436, were elevated to Princes of the Holy Roman Empire, becoming significant political players in Central Europe and rivals to the Habsburgs. However, the dynasty died out in 1456 with the assassination of Ulrich II, Count of Celje, and their extensive possessions were subsequently inherited by the Habsburgs.

By the 15th century, most of the Slovene-inhabited lands had come under the rule of the House of Habsburg. These territories (Carniola, Styria, Carinthia, Gorizia) retained a degree of autonomy as hereditary lands of the Habsburg monarchy. A parallel process throughout the Middle Ages was the gradual Germanization of the northern and western Slovene ethnic territories, particularly in Carinthia and Styria, which reduced the extent of Slovene-speaking areas. By the 15th century, the Slovene ethnic territory had largely been reduced to its present size. Socially, feudalism entrenched a system where Slovene peasants were often subservient to German-speaking lords, contributing to social tensions that would occasionally erupt in revolts. The Turkish raids began to affect the Slovene lands from the late 15th century, causing economic disruption and demographic setbacks.

3.3. Early Modern Period (Austrian Rule and Napoleonic Interlude)

The Early Modern Period in the Slovene lands, roughly from the 16th to the early 19th century, was predominantly characterized by Austrian Habsburg rule. This era witnessed significant socio-economic changes, religious upheavals, peasant revolts, the persistent threat of Ottoman incursions, and a brief but impactful interlude of French administration under Napoleon.

The 16th century was marked by the Protestant Reformation, which found fertile ground among Slovenes. Figures like Primož Trubar, Adam Bohorič, and Jurij Dalmatin played a crucial role in codifying the Slovene language and producing the first printed books in Slovene, including a translation of the Bible. This laid the foundation for Slovene literary culture and contributed to a nascent national consciousness. However, the Counter-Reformation, vigorously pursued by the Habsburgs and the Catholic Church from the late 16th century onwards, largely suppressed Protestantism in the Slovene lands, with the exception of Prekmurje, which was under Hungarian rule and had a more tolerant religious environment.

Socio-economically, feudal obligations continued to be a source of hardship for the peasantry, leading to several major peasant revolts. The Slovene peasant revolt of 1515 was a large-scale uprising, and the Croatian-Slovenian peasant revolt of 1572-1573 also had significant participation from Slovene peasants. These revolts, though brutally suppressed, reflected deep-seated social discontent. The ongoing Ottoman-Habsburg wars also impacted the region, with frequent raids (akın) leading to devastation, depopulation in border areas, and increased military burdens (e.g., the Military Frontier).

The Habsburgs continued to consolidate their administrative control, although the historical provinces retained some distinct rights and institutions (Estates). Enlightenment ideas began to penetrate the Slovene lands in the 18th century, influencing intellectuals like Anton Tomaž Linhart and Valentin Vodnik, who contributed to historical and linguistic studies, further fostering Slovene cultural identity.

A significant disruption to Austrian rule came with the Napoleonic Wars. After the Treaty of Schönbrunn in 1809, large parts of Slovene-inhabited territory (Carniola, western Carinthia, Gorizia, Trieste, Istria, and parts of Croatia) were incorporated into the French-administered Illyrian Provinces (1809-1813), with Ljubljana (then Laibach) as the capital. French rule brought reforms, including the abolition of certain feudal privileges, legal modernization (introduction of the Napoleonic Code in some areas), and, importantly, the introduction of Slovene as a language of instruction in some primary and secondary schools. Although short-lived, the French interlude had a profound impact on Slovene national consciousness. It weakened old feudal structures, introduced ideas of modern statehood and liberalism, and the use of Slovene in education and administration boosted the language's prestige and contributed to the burgeoning sense of national identity and early democratic ideas. After Napoleon's defeat, the Slovene lands were returned to Austrian rule by the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

3.4. National Revival and World War I

The 19th century was a period of profound national awakening for the Slovenes, characterized by the flourishing of Slovene language and culture, the development of political movements advocating for greater autonomy within Austria-Hungary, and culminating in the devastating impact of World War I. This era laid the groundwork for modern Slovene nationhood.

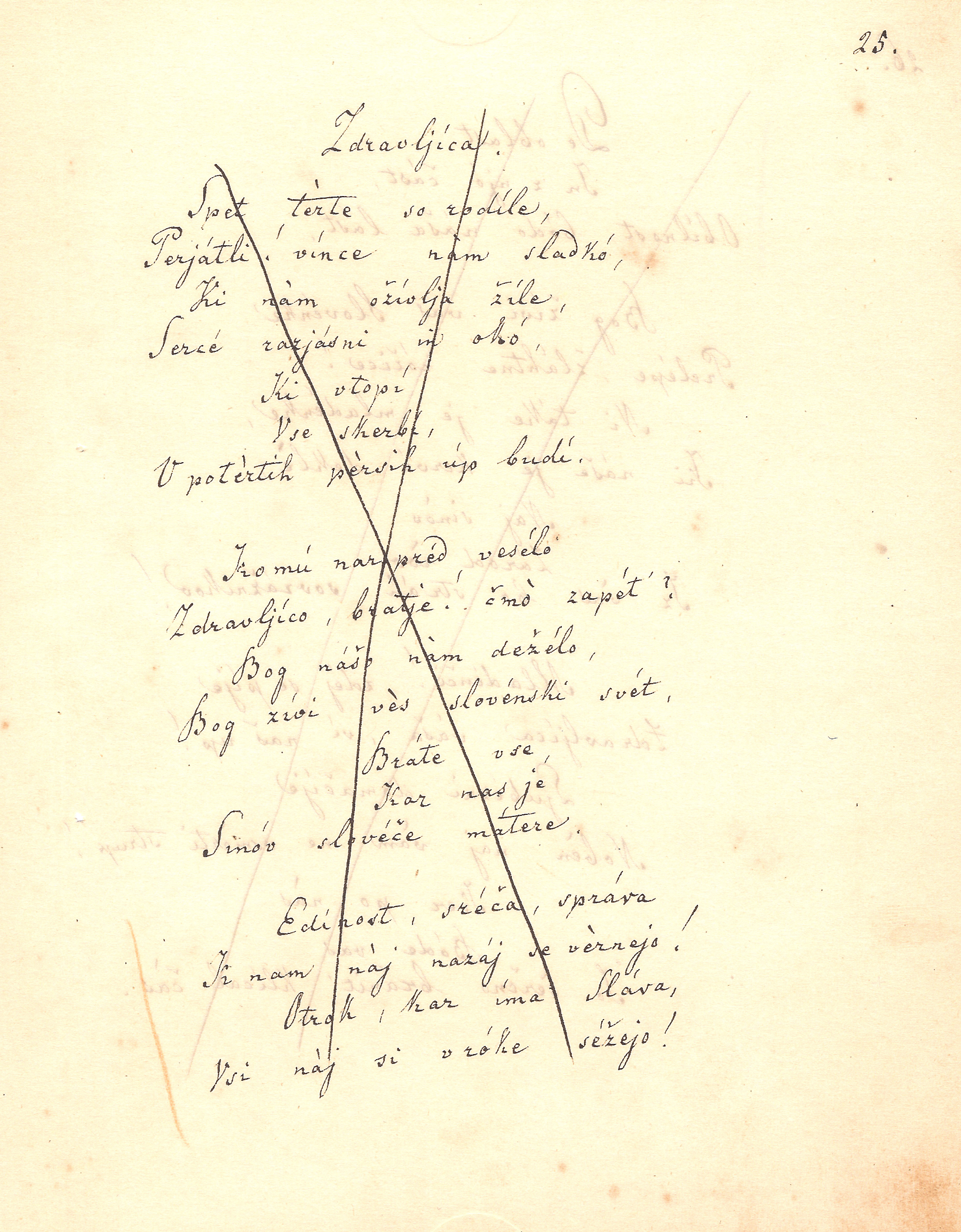

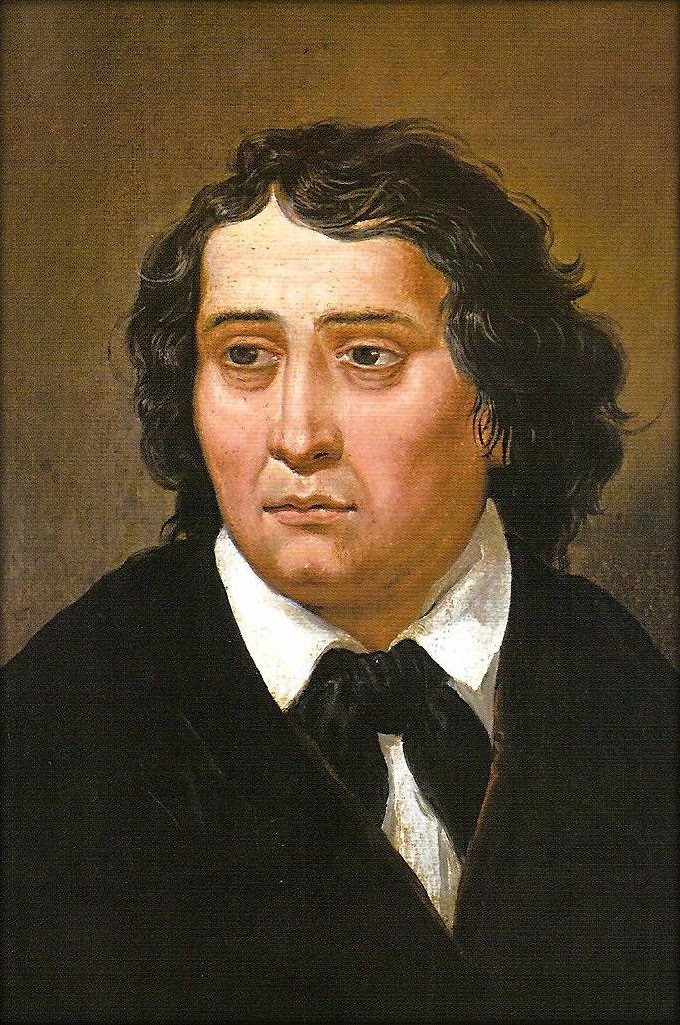

The Romantic nationalism that swept across Europe in the early 19th century deeply influenced Slovene intellectuals. The poet France Prešeren (1800-1849) became a central figure, whose works elevated Slovene to a sophisticated literary language and expressed aspirations for national self-determination. The Revolutions of 1848 saw the first explicit political program for a United Slovenia (Zedinjena SlovenijaZedinjêna SloveníjaSlovenian), demanding the unification of all Slovene-inhabited lands into an autonomous administrative unit within the Austrian Empire, with Slovene as an official language. Although this demand was not met, it became a cornerstone of Slovene political aspirations for decades.

Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, Slovene cultural and political life intensified. Reading societies (čitalnice), cultural associations, and newspapers in Slovene proliferated. Political organization evolved, with various factions (liberal, Catholic-conservative) advocating for Slovene rights. Figures like Janez Bleiweis and Fran Levstik were prominent in cultural and political spheres. The idea of Yugoslavism, promoting unity among South Slavs, also gained traction as a response to Pan-Germanism and Italian irredentism. Industrialization began to take hold, albeit slowly, leading to some social changes and limited urbanization. Emigration, primarily to the United States, also became significant due to limited economic opportunities, with around 300,000 Slovenes emigrating between 1880 and 1910. Despite this, literacy rates were exceptionally high.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 had a catastrophic impact on the Slovene population. Slovene men were conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian Army in large numbers, suffering heavy casualties on various fronts, particularly the Italian Front. When Italy joined the Entente Powers in 1915, a new front opened along the Soča (Isonzo) River, in western Slovene territory. The twelve Battles of the Isonzo (1915-1917) were among the bloodiest engagements of the war, fought in harsh mountainous terrain and resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths, including over 30,000 Slovene soldiers.

The war also brought immense suffering to civilians. Hundreds of thousands of Slovenes from the Austrian Littoral (especially the Princely County of Gorizia and Gradisca) were displaced and became refugees, resettled in camps in Austria and Italy. Those in Italian camps often faced harsh conditions, with thousands dying from malnutrition and disease. The war led to economic hardship, food shortages, and the destruction of entire areas of the Slovene Littoral. The political landscape was also transformed. The Declaration of May (1917) by South Slavic deputies in the Viennese parliament, including Slovene representatives, called for the unification of South Slavs within the Habsburg Monarchy. As the war ended and Austria-Hungary collapsed in October 1918, Slovenes, along with Croats and Serbs, declared the formation of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. This short-lived state soon merged with the Kingdom of Serbia to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in December 1918, marking a new chapter but also bringing new challenges, including territorial disputes and the assimilationist pressures on Slovene minorities left outside the new kingdom's borders, particularly in Italy.

3.5. Interwar Period (Kingdom of Yugoslavia)

Following World War I and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Slovenia became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes on December 1, 1918, which was renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. This period was marked by industrial development, complex political dynamics within the centralized kingdom, and challenging socio-economic conditions for Slovenes, including those who found themselves under foreign rule.

Slovenia entered the new kingdom as its most economically developed and industrialized part. Its industries, inherited from Austria-Hungary, continued to expand, particularly in manufacturing, mining, and textiles. Compared to other parts of Yugoslavia, Slovenia had higher literacy rates and a more developed infrastructure. However, economic policies were often dictated by Belgrade, leading to Slovene perceptions of economic exploitation and insufficient investment in their region. Despite this, Slovenia experienced rapid economic growth in the 1920s, followed by a relatively successful adjustment to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Politically, Slovenes, led primarily by the conservative Slovene People's Party (SLS) under Anton Korošec, sought to preserve Slovene autonomy and cultural identity within the highly centralized Vidovdan Constitution. Korošec briefly served as Prime Minister of Yugoslavia, the only non-Serb to do so in the interwar period. However, the kingdom was dominated by Serbian political elites, leading to tensions and a lack of genuine power-sharing. The 6 January Dictatorship proclaimed by King Alexander I in 1929 further curtailed political freedoms and suppressed national identities.

A significant issue was the fate of Slovene ethnic minorities. The Treaty of Rapallo (1920) assigned a large Slovene-inhabited territory (the Julian March, including Trieste, Gorizia, and parts of Istria) to Italy, where approximately 327,000 Slovenes faced harsh Italianization policies under Mussolini's Fascist regime. Slovene language was banned in public life and education, names were Italianized, and cultural institutions were suppressed. This led to mass emigration of Slovenes from these areas to Yugoslavia and South America. Those who remained organized resistance, both passive and armed, most notably through the TIGR anti-fascist organization. Similarly, Slovenes in Austrian Carinthia (following the 1920 plebiscite which left southern Carinthia with Austria) and in Prekmurje under Hungarian rule (until the Treaty of Trianon awarded most of it to Yugoslavia) also faced assimilationist pressures.

Within Slovenia, social and cultural life continued to develop. Ljubljana grew as a cultural and academic center, with the establishment of the University of Ljubljana in 1919 being a landmark achievement. However, social inequalities persisted, and the rise of fascism in neighboring Italy and Nazism in Germany cast a growing shadow. Anti-fascist movements began to gain traction among Slovene intellectuals and youth, often linked with communist or left-leaning ideologies, in response to both external threats and internal political dissatisfaction. The period was thus a complex mix of progress and increasing vulnerability, setting the stage for the turmoil of World War II.

3.6. World War II

World War II brought devastating consequences for Slovenia, which was uniquely trisected and annexed by Axis powers following the invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941. The conflict was characterized by brutal occupation, widespread civilian suffering, a determined partisan resistance movement, collaboration, and profound socio-political transformations that paved the way for Slovenia's inclusion in socialist Yugoslavia.

The partition divided Slovenia as follows:

- Nazi Germany** annexed Lower Styria, Upper Carniola, and parts of Lower Carniola and Slovene Carinthia. Their policy aimed at rapid Germanisation and ethnic cleansing. Tens of thousands of Slovenes were expelled to Serbia, the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), or German labor camps. Slovene language was banned in public and schools, and Slovene cultural institutions were destroyed. Around 46,000 Slovenes were expelled to Germany, with children often separated from parents.

- Fascist Italy** annexed Lower Carniola (including Ljubljana, which became the capital of the Italian-administered Province of Ljubljana), Inner Carniola, and parts of the Slovene Littoral (which Italy had already annexed after WWI). Italian occupation was initially less brutal than German, but repression escalated significantly with the rise of partisan resistance.

- Hungary** annexed Prekmurje in the east, implementing policies of Magyarization.

In response to the occupation, the Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation (Osvobodilna fronta slovenskega narodaOsvobodílna frónta slovénskega národaSlovenian, or OF) was established on April 26, 1941. It was a coalition of diverse political groups, though increasingly dominated by the Communist Party of Slovenia. The OF organized the Slovene Partisans, who became a highly effective component of the larger Yugoslav Partisans led by Josip Broz Tito. The Partisans engaged in guerrilla warfare against the occupiers and their collaborators.

The occupation authorities responded with extreme violence. The Italians deported some 25,000 Slovenes (7.5% of the population in their zone) to concentration camps, such as Rab and Gonars, where many perished. German reprisals against civilians were equally savage, including mass executions and the burning of villages.

The war also saw the emergence of collaborationist forces. The Slovene Home Guard (Slovensko domobranstvoSlovénsko domobránstvoSlovenian) was an anti-communist militia, formed primarily from conservative Catholic circles, that collaborated with German forces after Italy's capitulation in September 1943 (when Germany occupied the Italian zone). They fought against the Partisans, motivated by anti-communism and fear of revolutionary violence. This led to a bitter and tragic civil conflict within the broader war.

Civilian suffering was immense. Approximately 8% of the Slovene population (around 97,000 people) died during World War II due to combat, executions, concentration camps, or war-related hardship. The small Jewish community, primarily in Prekmurje, was largely annihilated in the Holocaust. The German-speaking minority was mostly expelled or killed in the war's aftermath.

As the war ended in 1945, Yugoslavia was liberated by the Partisans. Slovenia, as Federal Slovenia, became a constituent republic of the new socialist Yugoslavia. The immediate post-war period was marked by summary executions of thousands of captured Home Guard members and other perceived political opponents, notably at sites like the Kočevski Rog and Tezno, and the Foibe massacres in Istria. These events remain a painful and controversial part of Slovenia's history, reflecting the deep divisions and human rights violations of the era. The war fundamentally reshaped Slovenia's political landscape, society, and its place within Yugoslavia.

3.7. Socialist Era (SFR Yugoslavia)

Following World War II, Slovenia became the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, one of the six constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) established in 1945. This era, lasting until 1991, was characterized by a unique socialist model, significant economic development, a degree of political autonomy, active participation in the Non-Aligned Movement, and evolving social and cultural life under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito.

Initially, Yugoslavia, including Slovenia, was closely aligned with the Eastern Bloc. However, the Tito-Stalin split in 1948 led Yugoslavia to pursue its own path to socialism, known as Titoism. A key feature of this was workers' self-management, an economic system developed largely by Slovene Marxist theoretician Edvard Kardelj. This system aimed to give workers greater control over their enterprises, distinguishing Yugoslav socialism from the Soviet model. While it brought some economic decentralization and innovation, it also faced challenges of inefficiency and regional disparities. Suspected opponents of this policy, both within and outside the Communist party, faced persecution in the early years, with thousands sent to political prisons like Goli Otok.

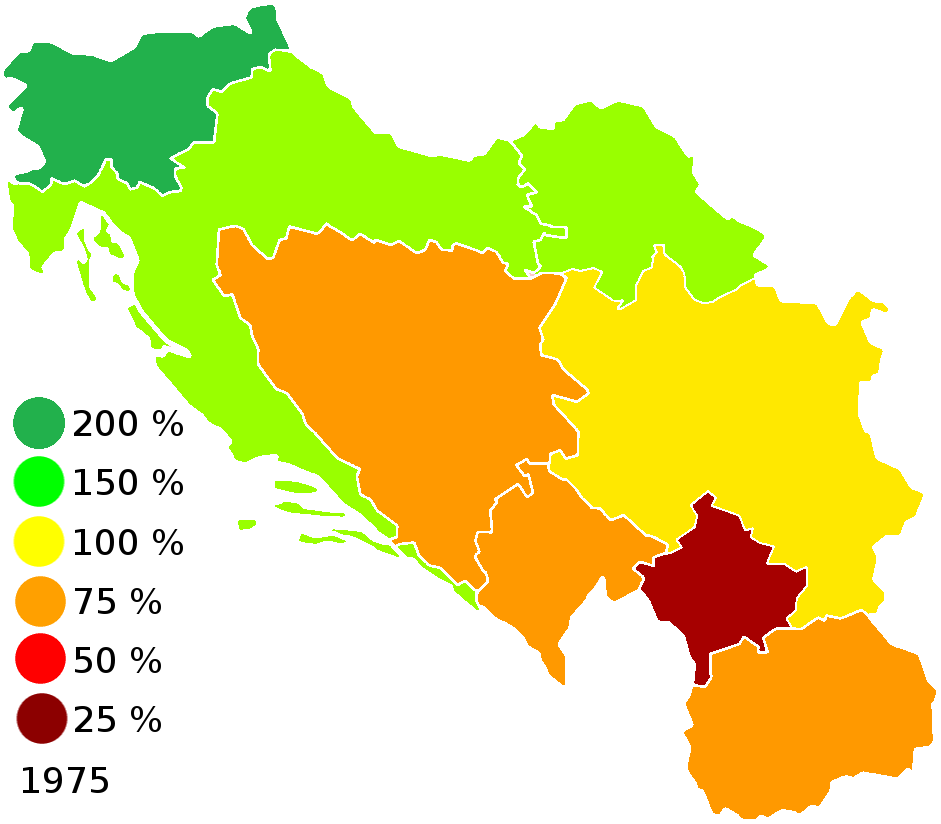

Slovenia, already one of the more industrialized parts of pre-war Yugoslavia, experienced significant economic development during the socialist era. It became the most prosperous republic in Yugoslavia, with a GDP per capita consistently well above the Yugoslav average (e.g., 2.5 times the average by the 1960s). Its economy was export-oriented, with strong ties to Western European markets. This relative prosperity contributed to a higher standard of living compared to other Eastern Bloc countries.

Politically, while the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (and its Slovene branch) maintained a monopoly on power, Slovenia enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy within the federal structure, particularly after the constitutional reforms of 1974. This allowed for some local decision-making and fostered a sense of distinct Slovene identity. Yugoslav citizens, including Slovenes, enjoyed greater freedom of travel compared to other socialist countries, with many working in Western Europe, which helped alleviate domestic unemployment and provided valuable remittances.

In international affairs, Yugoslavia, with Slovenia's participation, was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. This policy of neutrality between the Western and Eastern Blocs provided Yugoslavia with a unique international standing during the Cold War.

Social and cultural life in Slovenia during this period saw both constraints and openings. While overt political dissent was suppressed, there was a degree of cultural liberalization, especially from the late 1950s. Slovene language and culture were officially supported, and institutions like the University of Ljubljana and the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts played important roles. However, aspects of democratic development and human rights remained limited within the one-party socialist system. Freedom of speech and association were curtailed, and political opposition was not tolerated.

Following Tito's death in 1980, economic and political strains within Yugoslavia intensified. Slovenia, feeling economically burdened by the less developed republics and increasingly dissatisfied with the federal system's inefficiencies and Serbian nationalist tendencies, began to push for greater political pluralism and sovereignty. Intellectual and literary circles became more vocal in their critiques of the regime, setting the stage for the democratization process of the late 1980s.

3.8. Democratization and Independence

The late 1980s in Slovenia were marked by a period of intense political and social ferment known as the "Slovenian Spring." This popular movement, driven by demands for democracy, greater sovereignty, and human rights, culminated in Slovenia's independence from Yugoslavia in 1991.

The seeds of change were sown throughout the 1980s, following the death of Josip Broz Tito. Economic stagnation, rising inflation, and inter-republican tensions within Yugoslavia created an environment ripe for reform. In Slovenia, intellectual circles, cultural magazines like Nova revija, and emerging civil society groups became increasingly vocal in their criticism of the communist regime and the federal system. In 1987, the 57th issue of Nova revija published the "Contributions for the Slovenian National Program," which openly discussed Slovene sovereignty and democratic reforms.

The JBTZ trial in 1988, where four individuals (Janez Janša, Ivan Borštner, David Tasić, and Franci Zavrl) were court-martialed by the Yugoslav military for allegedly leaking military secrets, became a major catalyst. The trial, conducted in Serbo-Croatian instead of Slovene, sparked mass protests and unified diverse opposition groups under the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights, led by Igor Bavčar. This popular movement pushed the Slovene communist leadership, then under Milan Kučan, towards embracing democratic reforms.

In September 1989, the Slovene Assembly passed constitutional amendments that asserted Slovenia's right to secession, introduced parliamentary democracy, and legalized political parties. This effectively ended the monopoly of the League of Communists. On March 7, 1990, the official name of the state was changed from the "Socialist Republic of Slovenia" to the "Republic of Slovenia."

In April 1990, Slovenia held its first multi-party elections since before World War II. The Democratic Opposition of Slovenia (DEMOS), a coalition of new center-right and democratic parties led by Jože Pučnik, emerged victorious, forming the first democratically elected government. Lojze Peterle of the Slovene Christian Democrats became Prime Minister, while Milan Kučan, running as an independent (formerly a reformist communist leader), was elected President.

The new government swiftly moved towards independence. On December 23, 1990, a referendum on independence was held, with an overwhelming 88.5% of voters (with a 93.2% turnout) supporting a sovereign and independent Slovenia. Following this mandate, on June 25, 1991, the Slovene Assembly formally declared the independence of Slovenia.

The Yugoslav federal authorities, particularly the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) dominated by Serbs, responded with military force. On June 27, 1991, JNA units moved to seize Slovenia's border crossings and airport, initiating the Ten-Day War (Desetdnevna vojnaDesetdnêvna vôjnaSlovenian). The Slovene Territorial Defence (Teritorialna obramba Republike SlovenijeTeritoriálna obramba Repúblike SloveníjeSlovenian) and police forces, well-prepared and enjoying widespread popular support, mounted effective resistance. The conflict was relatively short and low-intensity compared to later Yugoslav wars, resulting in several dozen casualties. International mediation, primarily by the European Community, led to the Brioni Agreement on July 7, 1991, which brokered a ceasefire and a three-month moratorium on Slovenia's independence declaration. By the end of October 1991, the last JNA soldiers had withdrawn from Slovene territory.

In December 1991, a new Constitution was adopted, solidifying the country's democratic framework and commitment to human rights. International recognition followed, with key European countries and the European Community recognizing Slovenia in January 1992. Slovenia was admitted to the United Nations on May 22, 1992. The transition to independence was a testament to the popular will for self-determination and democracy, achieved with relatively little bloodshed compared to other parts of the disintegrating Yugoslavia, and set Slovenia on a path towards European integration.

4. Geography

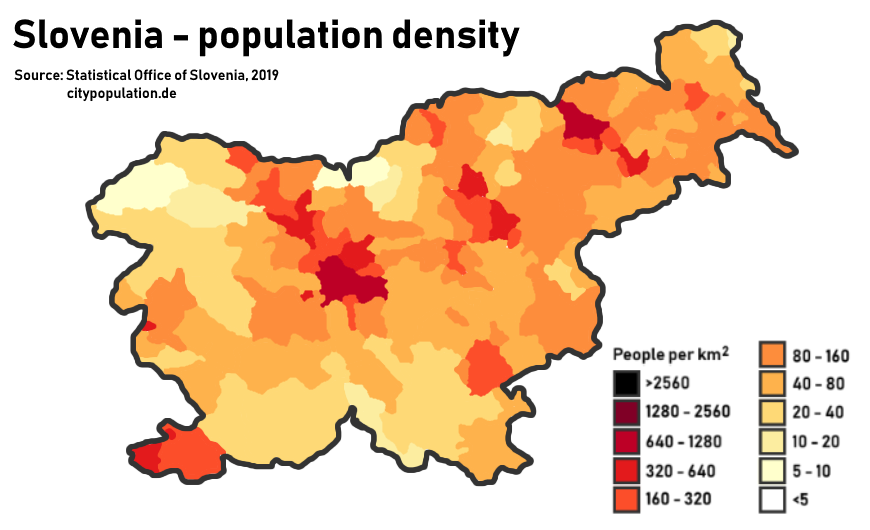

Slovenia is a country located in Central Europe, at the crossroads of major European cultural and trade routes. Its geography is characterized by remarkable diversity for a relatively small country, encompassing Alpine mountains, the Pannonian Plain, the Dinaric Alps, and a short coastline on the Adriatic Sea. This section details its topography, geology, climate, water resources, biodiversity, and environmental aspects, reflecting its commitment to sustainable development.

4.1. Topography and Geology

Slovenia's diverse terrain is a result of its position at the meeting point of four major European physiographic units:

- The Alps dominate northern Slovenia along its border with Austria and Italy. This includes the Julian Alps (Julijske AlpeJúlijske ÁlpēSlovenian) in the northwest, home to Slovenia's highest peak, Mount Triglav (9.4 K ft (2.86 K m)), and the Triglav National Park. Other Alpine ranges are the Kamnik-Savinja Alps (Kamniško-Savinjske AlpeKamniško-Savinjske ÁlpēSlovenian) to the east of the Julian Alps, and the Karawanks (KaravankeKaravánkeSlovenian) forming a long natural border with Austria. The Pohorje massif, a pre-Alpine range, is also significant.

- The Dinaric Alps (Dinarsko gorstvoDinársko gorstvóSlovenian) extend into southern and southeastern Slovenia from Croatia. This region is characterized by limestone plateaus, extensive forests, and karst phenomena.

- The Pannonian Plain (Panonska nižinaPanónska nižinaSlovenian) stretches across northeastern Slovenia, towards the Hungarian and Croatian borders. This area features rolling hills and flatlands, important for agriculture.

- The Mediterranean Littoral in the southwest gives Slovenia a short coastline of approximately 29 mile (47 km) on the Adriatic Sea, part of the Gulf of Trieste.

The Karst Plateau (KrasKrasSlovenian), located in southwestern Slovenia between Ljubljana and the Mediterranean, is a limestone region that has given its name to karst topography worldwide. It is characterized by underground rivers, gorges, sinkholes (dolines), and extensive cave systems, such as the Postojna Cave and the Škocjan Caves (a UNESCO World Heritage Site).

Geologically, Slovenia is situated in a seismically active zone due to its position on the small Adriatic Plate, which is squeezed between the Eurasian Plate to the north and the African Plate to the south. This tectonic activity results in occasional earthquakes. The country's bedrock varies, with limestone and dolomite being prevalent in the Dinaric and Alpine regions, leading to the formation of karst landscapes. Other areas feature different sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous rocks.

About 90% of Slovenia's land surface is 656 ft (200 m) or more above sea level, with an average elevation of 1827 ft (557 m).

4.2. Climate

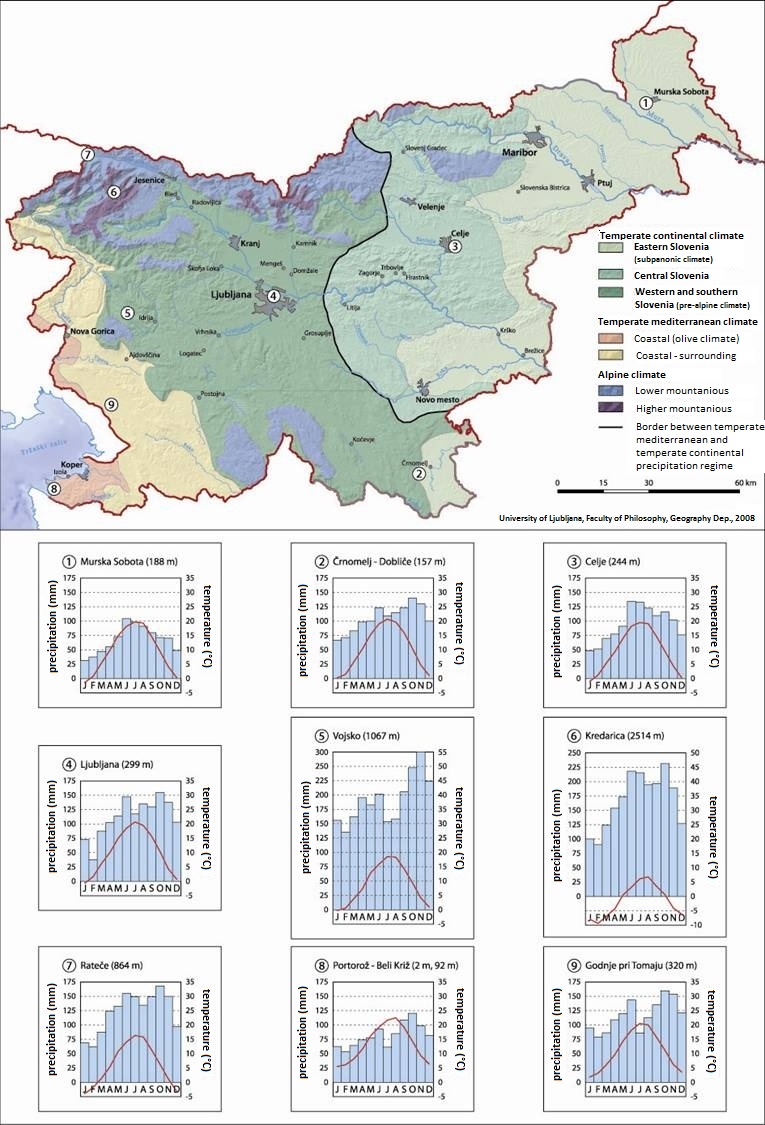

Slovenia's climate is diverse due to its varied topography and the confluence of different climatic influences. Three main climate types can be distinguished:

- Continental Climate: Prevails in most of the interior and northeast of the country, particularly in the Pannonian Plain. It is characterized by warm to hot summers and cold winters, with significant temperature differences between seasons. Ljubljana experiences this type of climate.

- Sub-Mediterranean Climate: Found in the Slovene Littoral along the Adriatic coast and extending inland along the Vipava Valley and parts of the Goriška region. This climate features mild, wet winters and hot, sunny summers. The influence of the Adriatic Sea moderates temperatures.

- Alpine Climate: Dominates the high mountain regions of the Julian Alps, Kamnik-Savinja Alps, and Karawanks. It is characterized by short, cool summers and long, cold, snowy winters. Above the tree line, conditions are harsh.

Precipitation patterns vary significantly across the country. The western and northwestern mountainous regions, exposed to moist air from the Mediterranean and Atlantic, receive the highest amounts, with some areas exceeding 0.1 K in (3.50 K mm) annually. The eastern regions in the Pannonian Plain are drier, typically receiving 31 in (800 mm) to 0.0 K in (1.00 K mm) of precipitation per year. Snowfall is common in winter, especially in the Alpine and continental regions, with significant snow cover lasting for several months in higher elevations. Record snow cover in Ljubljana was 57 in (146 cm) in 1952.

Winds are generally moderate due to the sheltering effect of the Alps. However, specific local winds are notable:

- The Bora (burjabúryaSlovenian) is a cold, gusty, and often strong katabatic wind that blows from the northeast towards the Adriatic Sea, particularly affecting the Vipava Valley and the Karst region.

- The Jugo (jugoyúgoSlovenian or široko) is a warm, humid southeasterly wind originating from the Mediterranean, often bringing rain.

- The Foehn is a warm, dry wind that can occur on the leeward side of mountain ranges.

Due to climate change, Slovenia is experiencing rising temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, and an increase in extreme weather events, posing challenges for agriculture, water resources, and ecosystems.

4.3. Water Resources

Slovenia is a water-rich country, with a dense network of rivers, numerous lakes, and significant groundwater resources. Approximately 81% of its territory (6.3 K mile2 (16.42 K km2)) belongs to the Black Sea drainage basin, while the remaining 19% (1.5 K mile2 (3.85 K km2)) drains into the Adriatic Sea.

Rivers: The main rivers draining into the Black Sea (via the Danube) are:

- The Sava: The longest river flowing through Slovenia, originating from two headwaters, the Sava Dolinka and the Sava Bohinjka (which flows from Lake Bohinj). It flows eastward through central Slovenia, past Ljubljana (indirectly, via its tributary the Ljubljanica), and into Croatia. Many important Slovenian rivers are tributaries of the Sava, including the Ljubljanica, Kamnik Bistrica, Savinja, and Krka.

- The Drava: Enters Slovenia from Austria in the north and flows eastward through cities like Maribor and Ptuj before continuing into Croatia.

- The Mura: Forms part of the border with Austria and Hungary in the northeast before joining the Drava in Croatia.

- The Kolpa (KolpaKólpaSlovenian): Forms a significant part of the southern border with Croatia and is a tributary of the Sava.

The main river draining into the Adriatic Sea is the Soča (known as Isonzo in Italian). Famous for its emerald-green waters, it originates in the Julian Alps and flows southward through western Slovenia before entering Italy and emptying into the Gulf of Trieste. Other smaller rivers in the Littoral also flow into the Adriatic.

Lakes: Slovenia has several natural and artificial lakes.

- Lake Bled (Blejsko jezeroBléjsko jézeroSlovenian): An iconic glacial lake in the Julian Alps, famous for its island church and medieval castle.

- Lake Bohinj (Bohinjsko jezeroBohínjsko jézeroSlovenian): The largest permanent natural lake in Slovenia, also of glacial origin, located in Triglav National Park.

- Lake Cerknica (Cerkniško jezeroCerkníško jézeroSlovenian): An intermittent lake, one of the largest in Europe, located in the Karst region. Its size varies dramatically with rainfall and underground water levels.

- The Triglav Lakes Valley (Dolina Triglavskih jezerDolina Triglavskih jézerSlovenian) contains a series of smaller glacial lakes.

- Numerous artificial lakes have been created for hydroelectric power, such as those on the Drava River.

Groundwater: Karst regions have extensive groundwater systems, feeding springs and underground rivers. Groundwater is a crucial source of drinking water for much of the population.

Water quality in Slovenia is generally considered high, partly because many rivers originate in mountainous, sparsely populated areas. However, challenges exist related to water pollution from agriculture, industry, and urban areas, as well as the need for sustainable water management in the face of climate change and increasing demand. The country is actively involved in water protection and management initiatives, including the implementation of EU water directives.

4.4. Biodiversity

Slovenia boasts exceptional biodiversity for its size, a result of its varied geography, climate, and the confluence of several biogeographical regions (Alpine, Pannonian, Dinaric, and Mediterranean). The country is home to a rich array of flora, fauna, and fungi, with many endemic and protected species. Approximately 1% of the world's known organisms can be found on just 0.004% of the Earth's surface area that Slovenia occupies. Slovenia has four terrestrial ecoregions: Dinaric Mountains mixed forests, Pannonian mixed forests, Alps conifer and mixed forests, and Illyrian deciduous forests. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.78/10, ranking it 140th globally out of 172 countries.

National efforts for conservation are significant, with a substantial portion of its territory protected. Triglav National Park is the largest and most prominent protected area. Slovenia has an extensive network of Natura 2000 sites, covering about 36% of its land area, one of the highest percentages in the European Union. These sites are crucial for the conservation of habitats and species of European importance. Slovenia signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity and has developed a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.

4.4.1. Fauna

Slovenia is home to a diverse range of animal species.

Mammals: There are 75 recorded mammal species. Large carnivores include a stable population of brown bears (estimated at around 450), Eurasian lynx (reintroduced and a subject of ongoing conservation efforts), and wolves (around 40-60 individuals). Other notable mammals include the Alpine ibex and chamois in mountainous regions, various species of deer (red deer, roe deer), wild boar, European jackal, European wildcat, red fox, martens, hedgehogs, and the edible dormouse, which is traditionally hunted in some areas.

Birds: Over 390 bird species have been recorded. Birds of prey like the golden eagle, short-toed snake eagle, various hawks, and owls (e.g., tawny owl, long-eared owl, Eurasian eagle-owl) inhabit diverse habitats. Forests are home to black woodpeckers and European green woodpeckers, while wetlands and open areas support species like the white stork (nesting mainly in Prekmurje).

Reptiles and Amphibians: Slovenia has a variety of snakes, including venomous vipers (e.g., common European adder) and non-venomous species like the grass snake. Lizards are also common. Amphibians are particularly diverse due to the abundant water bodies. The most famous is the olm (Proteus anguinus), a blind aquatic salamander endemic to the subterranean waters of the Dinaric Karst. It is a symbol of Slovenian natural heritage and can be found in caves like Postojna.

Fish: Freshwater fish include the endemic marble trout (Salmo marmoratus) in the Soča River basin, subject to conservation programs. Other species include grayling, huchen (Danube salmon), and wels catfish. The northern Adriatic Sea waters host species like the bottlenose dolphin.

Invertebrates: Slovenia has an exceptionally rich invertebrate fauna, especially in its cave systems, with many endemic species of insects and other cave-dwellers. The Carniolan honey bee (Apis mellifera carnica) is a native subspecies, prized for its gentle nature and productivity.

Wildlife management includes regulated hunting and conservation programs aimed at protecting endangered species and their habitats, often in collaboration with neighboring countries.

4.4.2. Flora

Slovenia's plant life is exceptionally diverse, with over 3,000 vascular plant species. Forests cover 58.3% of the territory, making it one of Europe's most forested countries.

- Forests: The dominant tree species vary by region. In the interior, Central European mixed forests are common, primarily featuring European beech (Fagus sylvatica) and oak species (e.g., Quercus robur, Quercus petraea). In mountainous areas, coniferous forests of Norway spruce (Picea abies), European silver fir (Abies alba), and European larch (Larix decidua) are prevalent, along with mountain pine species. The Karst Plateau has forests adapted to its limestone bedrock, including various pine species. The small-leaved lime (Tilia cordata) is considered a national symbol. Remnants of primeval forests are preserved, notably in the Kočevje region. The tree line is typically between 5.6 K ft (1.70 K m) and 5.9 K ft (1.80 K m).

- Alpine Flora: The Alpine regions boast a rich variety of mountain flowers, including endemic and protected species such as Daphne blagayana, various gentians (e.g., Gentiana clusii, Gentiana froelichii), Primula auricula (auricula), edelweiss (Leontopodium nivale subsp. alpinum), the lady's slipper orchid (Cypripedium calceolus), the snake's head fritillary (Fritillaria meleagris), and Pulsatilla grandis.

- Other Vegetation Zones: The sub-Mediterranean region in the southwest supports thermo-xerophilic vegetation, including species adapted to warmer, drier conditions. Wetlands, grasslands, and heathlands also host specific plant communities.

- Endemic Plants: Slovenia has a number of endemic plant species, reflecting its unique ecological niches.

- Ethnobotany: Many plants have traditional uses. Of 59 known species of ethnobotanical importance, some, like Aconitum napellus, Cannabis sativa, and Taxus baccata, have restricted use due to toxicity or legal regulations.

4.4.3. Fungi

Slovenia has a rich mycoflora, with over 2,400 fungal species recorded. This figure does not include lichen-forming fungi, so the actual number of species is considerably higher, with many still undiscovered. Fungi play a crucial ecological role in decomposition and symbiotic relationships (mycorrhizae) with plants, particularly in Slovenia's extensive forests. Mushroom foraging is a popular traditional activity.

4.5. Protected Areas and Environmental Issues

Slovenia has a strong commitment to environmental protection and biodiversity conservation, reflected in its extensive network of protected areas and active participation in international conservation efforts.

Protected Areas Network:

- Triglav National Park (Triglavski narodni parkTríglavski národni párkSlovenian): The only national park in Slovenia, covering a large part of the Julian Alps, including Mount Triglav. It is one of the oldest national parks in Europe, established to protect its unique Alpine ecosystems, biodiversity, and cultural landscapes.

- Regional Parks: These include areas like Škocjan Caves Regional Park (also a UNESCO World Heritage site), Kozjansko Regional Park, and Notranjska Regional Park. They aim to balance conservation with sustainable local development.

- Nature Parks and Reserves: Numerous smaller nature parks, reserves, and natural monuments protect specific habitats, species, or geological features. Examples include the Strunjan Nature Park on the coast and the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park, important for salt production heritage and birdlife.

- Natura 2000 Sites: As an EU member, Slovenia has designated a significant portion of its territory (approximately 36%) as Natura 2000 sites. This network aims to ensure the long-term survival of Europe's most valuable and threatened species and habitats. Slovenia's contribution to this network is among the largest in the EU by percentage of land area.

Environmental Issues and Policies:

Despite strong conservation efforts, Slovenia faces several environmental challenges:

- Pollution: Air pollution from traffic and industry (historically, e.g., from thermal power plants), water pollution from agriculture (nitrates, pesticides) and insufficiently treated wastewater in some areas, and soil contamination are concerns.

- Waste Management: Improving waste reduction, recycling rates, and the management of hazardous waste remain ongoing tasks, in line with EU targets.

- Climate Change: Slovenia is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns leading to more frequent droughts and floods, and impacts on Alpine ecosystems (e.g., glacier retreat, changes in species distribution).

- Habitat Fragmentation: Infrastructure development (roads, railways) can lead to habitat fragmentation, affecting wildlife movement and biodiversity.

Slovenia has adopted various policies and strategies to address these issues, focusing on sustainable development. These include promoting renewable energy sources, improving energy efficiency, sustainable transport, organic farming, and implementing EU environmental directives. The country's Environmental Performance Index often ranks it as a "strong performer" in environmental protection efforts. Public awareness and the activity of environmental NGOs also play a role in advocating for environmental protection.

5. Government and Politics

Slovenia is a parliamentary democratic republic with a multi-party system. Its political framework is defined by the Constitution of Slovenia, adopted in 1991, which establishes the principles of separation of powers, rule of law, and protection of human rights. The country's political system emphasizes democratic processes, citizen participation, and accountability, aligning with a center-left/social liberalism perspective that underscores social justice and human rights.

5.1. Political System

Slovenia operates as a parliamentary democracy. The core principles enshrined in its constitution include:

- Popular Sovereignty**: Power derives from the people, exercised directly (e.g., through referendums) and indirectly (through elected representatives).

- Rule of Law**: All state actions are subject to and constrained by law.

- Separation of Powers**: Legislative, executive, and judicial powers are distinct and balanced.

- Multi-party System**: A pluralistic political landscape with numerous political parties competing in elections.

- Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms**: The constitution guarantees a wide range of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights.

Mechanisms for citizen participation include elections, referendums (legislative, consultative, and constitutional), and the right to popular initiative. Democratic accountability is ensured through parliamentary oversight of the government, an independent judiciary, the Human Rights Ombudsman, and an active civil society.

5.2. Executive Branch

The executive branch is composed of the President of the Republic and the Government (Prime Minister and ministers).

- The President of the Republic is the head of state. The president is elected by direct popular vote for a five-year term and can serve a maximum of two consecutive terms. The role is largely ceremonial and representative, but the president also serves as the commander-in-chief of the Slovenian Armed Forces, calls parliamentary elections, promulgates laws, and appoints certain state officials. The current president is Nataša Pirc Musar.

- The Government (Vlada Republike SlovenijeVláda Repúblike SloveníjeSlovenian) holds the main executive authority and is responsible for implementing laws and policies. It is headed by the Prime Minister, who is typically the leader of the party or coalition that commands a majority in the National Assembly. The Prime Minister and the cabinet of ministers are elected by and accountable to the National Assembly. The current Prime Minister is Robert Golob.

5.3. Legislative Branch

The Parliament of Slovenia is bicameral, though with an asymmetric structure where the lower house holds significantly more power:

- The National Assembly (Državni zborDržavni zborSlovenian) is the main legislative body. It consists of 90 members elected for a four-year term. 88 members are elected through a system of proportional representation. Two additional members are elected by the autochthonous Hungarian and Italian ethnic minorities, respectively, to represent their specific interests. The National Assembly passes laws, adopts the state budget, elects the Prime Minister, and exercises oversight over the government.

- The National Council (Državni svetDržavni svêtSlovenian) is the upper house, representing social, economic, professional, and local interest groups. It has 40 members, elected indirectly for five-year terms. Its powers are primarily advisory and include proposing laws to the National Assembly, requesting reconsideration of laws passed by the Assembly (suspensive veto), and calling for legislative referendums.

5.4. Judiciary

The Slovenian judicial system is based on the principle of judicial independence and the rule of law. It is structured as follows:

- Constitutional Court**: Composed of nine judges elected for nine-year terms by the National Assembly upon nomination by the President. It is the highest body for the protection of constitutionality, legality, and human rights. It reviews the constitutionality of laws and regulations and adjudicates on constitutional complaints regarding violations of human rights by state authorities.

- Regular Courts**: The system includes local courts (first instance for minor cases), district courts (first instance for more serious cases), higher courts (appellate courts), and the Supreme Court (Vrhovno sodiščeVrhôvno sodîščeSlovenian), which is the highest court of appeal for civil, criminal, and commercial matters.

- Specialized Courts**: These include labor and social courts, and an administrative court.

Judges are appointed by the National Assembly upon the proposal of the Judicial Council, an independent body responsible for ensuring judicial autonomy and quality. The system aims to protect citizens' rights and ensure access to justice.

5.5. Political Parties and Elections

Slovenia has a vibrant multi-party system. Major political parties represent a spectrum of ideologies, from left to right. Some prominent parties include (but are not limited to, as the landscape can change): Freedom Movement (GS), Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS), Social Democrats (SD), New Slovenia - Christian Democrats (NSi), and The Left (Levica).

Elections for the National Assembly are held every four years under a proportional representation system, which often results in coalition governments as no single party typically wins an absolute majority. Recent election results have shown shifts in political support, reflecting the dynamic nature of Slovenian politics. Presidential elections are held every five years. The electoral system is designed to ensure broad representation and political pluralism.

5.6. Military

The Slovenian Armed Forces (Slovenska vojskaSlovénska vôjskaSlovenian) are responsible for the military defense of the country and for fulfilling Slovenia's international military commitments. Conscription was abolished in 2003, and the military is now a fully professional force. The President of the Republic is the Commander-in-Chief.

Slovenia has been a member of NATO since 2004. Its armed forces have undergone significant transformation to meet NATO standards and participate in international operations. They contribute to peacekeeping missions and security operations under NATO, EU, and UN auspices (e.g., in Kosovo, Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina). Military spending was approximately 0.91% of GDP in 2016. The focus is on maintaining a smaller, well-trained, and deployable force capable of contributing to collective defense and international stability.

5.7. Foreign Relations

Slovenia pursues an active foreign policy focused on strengthening its position within the European Union and NATO, fostering good neighborly relations, and contributing to international peace, security, and development. Key foreign policy objectives include:

- Commitment to multilateralism and international law.

- Active participation in the EU, including holding the Presidency of the Council of the EU (most recently in the second half of 2021).

- Strong transatlantic relations through NATO.

- Promotion of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law globally.

- Regional cooperation, particularly in the Western Balkans, supporting the region's Euro-Atlantic integration.

- Economic diplomacy to promote Slovenian trade and investment.

Slovenia maintains bilateral relations with countries worldwide, with a particular focus on its neighbors (Italy, Austria, Hungary, Croatia) and key partners in Europe and beyond. It is an active member of the United Nations (UN), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Council of Europe, and other international bodies. Slovenia's foreign policy often reflects a commitment to humanitarian concerns, international development aid, and addressing global challenges like climate change. It generally supports balanced discussions on international issues, advocating for diplomatic solutions and respect for international norms.

5.8. Human Rights

The Constitution of Slovenia guarantees a broad range of human rights and fundamental freedoms. Slovenia is a party to major international human rights treaties. The state of human rights is generally good, though some challenges and areas for improvement are noted by domestic and international monitoring bodies.

- Civil and Political Liberties**: Freedoms of expression, assembly, association, and the media are generally respected.

- Minority Rights**: The autochthonous Hungarian and Italian minorities have constitutionally guaranteed rights, including representation in the National Assembly, education in their languages, and cultural autonomy in their respective areas. The Roma community also has a special status, but faces challenges regarding social inclusion, housing, education, and employment, with ongoing efforts to address these issues.

- Gender Equality**: Slovenia has made progress in gender equality, with legal frameworks in place to combat discrimination. However, issues such as the gender pay gap and underrepresentation of women in certain leadership positions persist.

- LGBTQ+ Rights**: Slovenia has made significant strides in LGBTQ+ rights. Same-sex marriage was legalized in 2022 following a Constitutional Court ruling. Anti-discrimination laws cover sexual orientation and gender identity, though societal prejudice can still be a concern.

- Rights of Vulnerable Groups**: Efforts are made to protect the rights of children, the elderly, persons with disabilities, and asylum seekers/refugees, though challenges in implementation and resource allocation can arise. For example, issues regarding the integration of refugees and asylum seekers, and conditions in reception centers have been raised.

- Justice System**: Access to justice and the efficiency of the judiciary are important aspects of human rights protection.

The Human Rights Ombudsman is an independent institution that monitors the observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms. Civil society organizations play a vital role in advocating for human rights, raising awareness, and providing support to victims of violations. Slovenia's commitment to human rights is also reflected in its foreign policy.

6. Administrative Divisions

Slovenia's administrative structure is primarily based on municipalities as the fundamental units of local self-government. The country does not have formally constituted administrative regions with significant political power, although statistical regions are used for planning and EU cohesion policy purposes, and traditional regions hold cultural significance.

6.1. Municipalities (Občine)

Slovenia is officially divided into 212 municipalities (občineôbčineSlovenian). Twelve of these have the status of urban municipalities (mestne občineméstne ôbčineSlovenian), which grants them some additional responsibilities, particularly in urban planning and services. Municipalities are the sole bodies of local self-government and are responsible for a wide range of local public affairs, including:

- Local planning and development

- Local infrastructure (roads, water supply, sewage)

- Primary education and pre-school care

- Primary healthcare

- Social welfare services

- Culture and sports facilities

- Public order and civil protection at the local level

Each municipality is headed by a mayor (županžupanSlovenian), who is directly elected by popular vote for a four-year term. The municipal council (občinski svetobčínski svétSlovenian) is the legislative body of the municipality, also elected for a four-year term. The method of election for the council varies: most use proportional representation, while smaller municipalities may use a plurality voting system. Urban municipalities have councils referred to as town or city councils. Each municipality also has a Head of the Municipal Administration (načelnik občinske upravenačélnik občinske upráveSlovenian), appointed by the mayor, responsible for the day-to-day functioning of the local administration.

The system of municipalities aims to ensure local autonomy and enable citizens to participate in decisions affecting their communities. However, the large number of relatively small municipalities has sometimes been cited as a challenge for efficient service delivery and regional coordination.

6.2. Statistical Regions

For statistical, planning, and EU cohesion policy purposes, Slovenia is divided into 12 statistical regions (statistične regijestatistíčne régijeSlovenian). These regions correspond to the NUTS-3 level of the European Union. They do not have administrative functions or directly elected bodies; they are primarily used for collecting and analyzing statistical data, for regional development planning, and for the allocation of EU structural funds.

The 12 statistical regions are:

1. Pomurska (Mura)

2. Podravska (Drava)

3. Koroška (Carinthia)

4. Savinjska (Savinja)

5. Zasavska (Central Sava)

6. Posavska (Lower Sava; formerly Spodnjeposavska)

7. Jugovzhodna Slovenija (Southeast Slovenia)

8. Osrednjeslovenska (Central Slovenia)

9. Gorenjska (Upper Carniola)

10. Primorsko-notranjska (Littoral-Inner Carniola; formerly Notranjsko-kraška)

11. Goriška (Gorizia)

12. Obalno-kraška (Coastal-Karst)

These 12 statistical regions are further grouped into two macroregions (NUTS-2 level) for EU purposes:

- Eastern Slovenia (Vzhodna SlovenijaVzhódna SloveníjaSlovenian - SI01): Comprising Pomurska, Podravska, Koroška, Savinjska, Zasavska, Posavska, Jugovzhodna Slovenija, and Primorsko-notranjska.

- Western Slovenia (Zahodna SlovenijaZahódna SloveníjaSlovenian - SI02): Comprising Osrednjeslovenska, Gorenjska, Goriška, and Obalno-kraška.

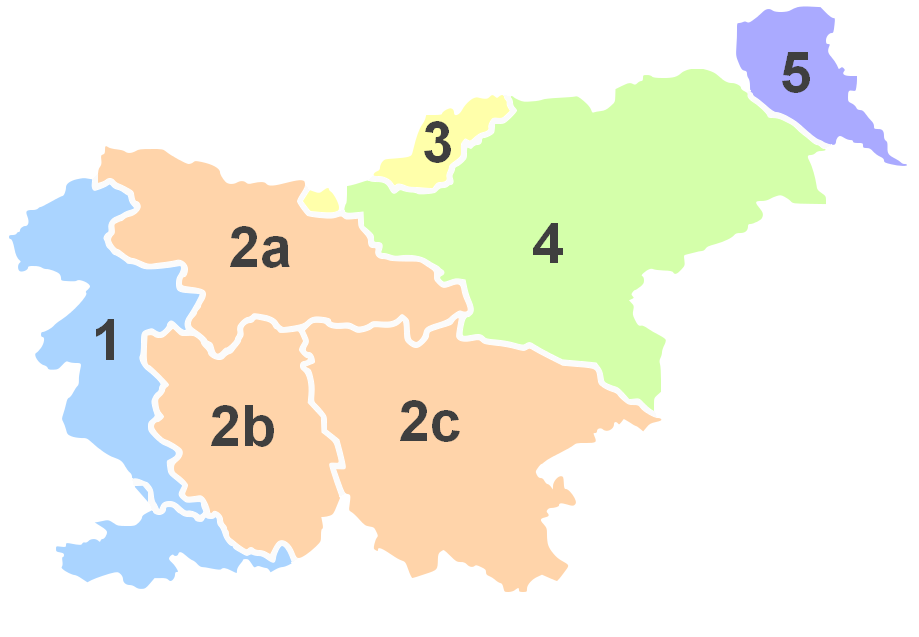

6.3. Traditional Regions

In addition to official administrative and statistical divisions, Slovenia is also commonly understood through its informal traditional regions (pokrajinepokrájineSlovenian). These regions are based on the historical Habsburg crown lands and have strong cultural and historical identities, often more deeply ingrained in popular consciousness than the statistical regions. The main traditional regions are:

- Upper Carniola (GorenjskaGorénjskaSlovenian): The Alpine northwest, including Kranj and Bled.

- Lower Carniola (DolenjskaDolénjskaSlovenian): The southeast, known for its rolling hills and Novo Mesto.

- Inner Carniola (NotranjskaNótranjskaSlovenian): The southwest interior, characterized by karst landscapes, including Postojna.

- Styria (ŠtajerskaŠtájerskaSlovenian), more precisely Lower Styria: The northeast, with Maribor as its main center, known for wine production.

- Littoral (PrimorskaPrimórskaSlovenian): The western region, bordering Italy and the Adriatic Sea, encompassing areas like Gorizia, the Vipava Valley, the Karst Plateau, and Slovenian Istria (Koper, Piran).

- Carinthia (KoroškaKoróškaSlovenian): A smaller region in the north, bordering Austria.

- Prekmurje: The far northeastern region, bordering Hungary, with a distinct cultural identity and Hungarian minority.

Ljubljana, the capital, was historically the administrative seat of Carniola and is generally considered part of Upper Carniola or a central region bridging several traditional areas. There have been ongoing discussions and proposals to establish formal administrative regions with greater powers, but no consensus has yet been reached.

7. Economy

Slovenia possesses a developed, high-income economy that has undergone significant transformation since its independence in 1991. It is characterized by a strong export orientation, a skilled workforce, and well-developed infrastructure. The country is a member of the Eurozone and the OECD. Economic policy often considers aspects of social equity, labor rights, and sustainable development, in line with a center-left/social liberalism perspective.

7.1. Economic Overview and Growth

Following independence, Slovenia pursued a gradual transition from a socialist self-management economy to a market-based system. It was the wealthiest republic in former Yugoslavia and managed the transition relatively successfully. Early economic growth was robust, allowing Slovenia to be the first of the 2004 EU accession countries to adopt the euro in 2007.

The Slovene economy is heavily reliant on foreign trade, particularly with other EU countries, making it susceptible to global economic conditions. Germany, Italy, and Austria are key trading partners. Exports account for a significant portion of the country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

GDP growth was strong in the mid-2000s (averaging nearly 5% annually in 2004-06, and almost 7% in 2007), often fueled by debt, especially in the construction sector. However, the Great Recession (2008-2009) and the subsequent European sovereign debt crisis severely impacted Slovenia. The economy experienced a significant contraction (GDP shrank by 8% in 2009), a rise in unemployment, and banking sector problems due to bad loans. Austerity measures were implemented, and the government undertook bank bailouts and privatizations to stabilize the economy.

Economic recovery began around 2014, with growth rates improving (e.g., 2.5% in 2016, 5% in 2017). The COVID-19 pandemic caused another contraction in 2020, but the economy has since shown resilience.

Key economic indicators include:

- GDP**: Moderately growing in recent years (pre-COVID).

- Inflation**: Generally managed within Eurozone targets.

- Employment**: Unemployment rates have fluctuated, rising after the 2008 crisis but declining during recovery periods. Youth unemployment and long-term unemployment remain challenges.

- National Debt**: Increased significantly due to crisis-related spending and bailouts, though efforts are made to manage it.

Social aspects of economic policy are important. Slovenia has one of the lowest Gini coefficients (a measure of income inequality) in the EU, indicating a relatively equitable distribution of income. Policies aim to support social welfare, reduce poverty, and ensure access to public services. The rapidly aging population presents a long-term challenge for public finances and the labor market.

7.2. Major Industries

Slovenia has a diversified industrial base and a significant service sector.

- Manufacturing**: This remains a cornerstone of the economy, contributing significantly to GDP and exports. Key manufacturing sub-sectors include:

- Automotive: Production of car parts and assembly (e.g., Revoz, a subsidiary of Renault).

- Pharmaceuticals: Major companies like Krka and Lek (a subsidiary of Novartis) are significant international players.

- Electrical and Electronic Equipment: Including home appliances (e.g., Gorenje).

- Machinery and Metal Products.

- Services**: This is the largest sector, employing the majority of the workforce. It includes:

- Finance and Banking.

- Information Technology (IT) and Telecommunications.

- Retail and Wholesale Trade.

- Logistics and Transport (leveraging Slovenia's strategic location).

- Tourism (see separate section).

Labor rights and working conditions are generally protected by law and collective agreements, though debates continue regarding labor market flexibility and wage levels. Trade unions have a significant presence.

7.3. Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries

The primary sector (agriculture, forestry, fisheries) contributes a smaller percentage to GDP but is important for rural employment, food security, and landscape preservation.

- Agriculture**: Main agricultural products include wine (Slovenia has several distinct wine regions), hops (a traditional export), cereals, potatoes, fruits, and dairy products. Farms are often small-scale and family-owned. There is a growing emphasis on organic farming and sustainable agricultural practices.

- Forestry**: With over half of its territory covered by forests, forestry is an important sector. Sustainable forest management is practiced, with timber production balanced by conservation needs. Wood processing industries also contribute to the economy.

- Fisheries**: Slovenia has a small marine fishing sector in the Adriatic and some freshwater aquaculture.

7.4. Energy

Slovenia's energy mix includes nuclear power, hydroelectric power, thermal power (from coal, mainly lignite), and a growing share of renewable energy sources (solar, biomass). In 2018, net energy production was 12,262 GWh, while consumption was 14,501 GWh, indicating some import dependency.

- The Krško Nuclear Power Plant, co-owned with Croatia, provides a significant portion of Slovenia's electricity (Slovenia's share is 50%).

- Hydroelectric power plants are numerous, particularly on the Drava and Sava rivers. New plants like HE Krško, HE Brežice, and HE Mokrice have been added.

- Thermal power plants, such as the Šoštanj Thermal Power Plant (which uses domestic lignite), contribute to base-load electricity but also face environmental scrutiny due to emissions. A new 600 MW block at Šoštanj became operational in 2014.

- Renewable energy sources (excluding large hydro) are being promoted to meet EU targets. This includes investments in solar photovoltaics (295 MWp installed by end of 2018), biogas power plants (31.4 MW by end of 2018), and wind power, though development can be slowed by land use and environmental considerations.

Energy policy focuses on energy efficiency, increasing the share of renewables, ensuring security of supply, and addressing the environmental impacts of energy production, including the transition away from coal.

7.5. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing industry in Slovenia, contributing substantially to the economy and employment. The country offers a diverse range of attractions, appealing to various types of tourists. Slovenia has been recognized for its efforts in sustainable tourism, and was declared the world's first "Green Country" by the Netherlands-based organization Green Destinations in 2016.

Key attractions and types of tourism include:

- Alpine Tourism**: The Julian Alps, Kamnik-Savinja Alps, and Karawanks attract hikers, mountaineers, skiers, and nature lovers. Lake Bled with its island church, Lake Bohinj, and the Soča Valley (known for water sports like kayaking and rafting) are major destinations. Triglav National Park is central to this.

- Coastal Tourism**: The short Adriatic coast features historic towns like Piran (with Venetian Gothic architecture) and Izola, as well as the resort town of Portorož, known for its beaches, spas, and casinos.

- Karst Tourism**: The Karst Plateau offers unique experiences, with world-renowned caves such as Postojna Cave (famous for its cave train and olms) and the UNESCO-listed Škocjan Caves.

- Spa and Wellness Tourism**: Slovenia has a long tradition of thermal spas. Towns like Rogaška Slatina, Radenci, Čatež ob Savi, Dobrna, and Moravske Toplice are popular for health and wellness tourism.

- Cultural Tourism**: Cities like Ljubljana (with its Baroque and Art Nouveau architecture, and works by Jože Plečnik), Maribor, Ptuj (Slovenia's oldest town), and Škofja Loka offer historical and cultural experiences. Numerous castles, such as Predjama Castle, and museums attract visitors.

- Rural and Eco-Tourism**: Farm stays, hiking and cycling trails in rural areas, and nature-based tourism are increasingly popular, aligning with the country's focus on sustainability.

- Wine Tourism**: Slovenia's wine regions (Podravje, Posavje, Primorska) offer wine tasting and vineyard tours. Maribor is home to the world's oldest productive grapevine.

- Congress and Gambling Tourism**: Ljubljana and other cities host international conferences. Casinos, particularly in Nova Gorica (e.g., Perla Casino) and Portorož, attract visitors.

Most foreign tourists come from European markets such as Italy, Austria, Germany, Croatia, Belgium, the Netherlands, Serbia, Russia, and Ukraine, followed by the UK and Ireland. The tourism industry is focused on promoting Slovenia as a green, active, and healthy destination.

7.6. Transport

Slovenia's strategic location at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe makes its transport infrastructure vital for both domestic needs and international transit. The country is situated on important Pan-European corridors, notably Corridor V (linking the North Adriatic with Central and Eastern Europe) and Corridor X (connecting Central Europe with the Balkans).

7.6.1. Road Transport

Road transport is the dominant mode for both freight (around 80%) and passenger travel in Slovenia. Private car ownership is high, and public road passenger transport has seen a relative decline.