1. Overview

The Argentine Republic is a vast country located in the southern part of South America, characterized by its rich and diverse geography, a complex history marked by periods of prosperity and turmoil, a vibrant political landscape that has transitioned to democracy after periods of instability, a significant economy with strong agricultural and industrial sectors, a society shaped by waves of immigration, and a deeply influential culture with European roots and unique local expressions. This article explores Argentina through a center-left/social liberalism perspective, emphasizing the social impacts of historical and economic events, the ongoing struggle for human rights, and the nation's journey toward democratic development and social equity. Argentina's territory encompasses a wide range of climates and terrains, from the tropical north to the subantarctic south, from the towering Andes Mountains to the fertile Pampas plains. Historically, Argentina has experienced indigenous civilizations, Spanish colonization, a fight for independence, periods of civil war, significant European immigration that shaped its demographic and cultural makeup, and alternating periods of democratic rule and military dictatorships. The legacy of these periods, particularly the human rights violations during the last military dictatorship and subsequent economic crises, continues to influence contemporary Argentine politics and society. The nation's economy, while possessing rich natural resources and a diversified industrial base, has faced recurrent challenges of inflation and debt. Argentine society is predominantly urban, with a strong European heritage, particularly Italian and Spanish, but also with notable indigenous and mestizo communities. Culturally, Argentina is renowned for tango, its literary figures like Jorge Luis Borges, its passionate football (soccer) tradition, and its unique culinary offerings. The country continues to navigate challenges related to social justice, economic stability, and the strengthening of its democratic institutions, reflecting a dynamic interplay of its historical legacies and contemporary aspirations.

2. Etymology

The name 'Argentina' derives from the Latin word argentum, meaning 'silver'. The association of the region with silver dates back to the early European explorers. When Spanish colonizers first sailed into the Río de la Plata (literally "River of Silver"), survivors of an expedition led by Juan Díaz de Solís were given silver gifts by indigenous peoples. News of the legendary Sierra del Plata ("Silver Mountains") reached Spain around 1524. Consequently, the Spanish named the river explored by Solís as Río de la Plata.

The term 'Argentina' to describe the region was found on a Venetian map in 1536. In English, the name 'Argentina' comes from the Spanish language; however, the naming itself is not Spanish, but Italian. 'Argentina' (masculine 'argentino') means in Italian '(made) of silver, silver coloured'. The name was likely first given by Venetian and Genoese navigators, such as John Cabot. In Spanish and Portuguese, the words for 'silver' are plata and prata respectively, and '(made) of silver' is plateado and prateado, although argento for 'silver' and argentado for 'covered in silver' exist in Spanish.

The first written use of the name in Spanish can be traced to La Argentina, a 1602 poem by Martín del Barco Centenera describing the region and its conquest. Although "Argentina" was already in common usage by the 18th century, the country was formally named "Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata" by the Spanish Empire, and "United Provinces of the Río de la Plata" after independence.

The 1826 constitution included the first use of the name "Argentine Republic" in legal documents. The name "Argentine Confederation" was also commonly used and was formalized in the 1853 Constitution. In 1860, a presidential decree settled the country's name as "Argentine Republic", and that year's constitutional amendment ruled all names used since 1810 as legally valid. These historical names, including United Provinces of the Río de la Plata and Argentine Confederation, remain official names for the country according to the current constitution. In English, the country was traditionally called "the Argentine", mimicking the typical Spanish usage la Argentina, but this fell out of fashion during the mid-to-late 20th century, and the country is now referred to simply as "Argentina".

3. History

Argentina's history is a complex tapestry woven from indigenous cultures, Spanish colonization, a protracted struggle for independence and national unity, waves of European immigration, periods of economic prosperity and crisis, and a turbulent political journey marked by democratic aspirations, authoritarian rule, and a persistent quest for social justice and human rights.

3.1. Pre-Columbian era

The earliest traces of human life in the area now known as Argentina date back to the Paleolithic period, approximately 13,000 years Before Present, with further evidence from the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods. Until European colonization, Argentina was relatively sparsely populated by a wide array of diverse indigenous cultures with different social organizations. These cultures can be broadly divided into three main groups.

The first group consisted of basic hunters and food gatherers who had not developed pottery, such as the Selk'nam and Yaghan in the extreme south (Tierra del Fuego). The second group comprised more advanced hunters and food gatherers, including the Puelche, Querandí, and Serranos in the centre-east, and the Tehuelche in the south. Many of these groups, particularly the Tehuelche, were later conquered or significantly influenced by the Mapuche people spreading from Chile. In the north, the Kom (Toba) and Wichi peoples also belonged to this category of advanced hunters and gatherers.

The third group included farmers who practiced pottery. Among these were the Charrúa, Minuane, and Guaraní in the northeast, who engaged in slash-and-burn agriculture and had a semi-sedentary existence. The Diaguita people in the northwest represented an advanced sedentary trading culture, which was eventually conquered and incorporated into the Inca Empire around 1480. Other agricultural groups included the Toconoté and Hênîa and Kâmîare in the country's centre, and the Huarpe in the centre-west, a culture that raised llamas and was strongly influenced by the Incas. The Inca Empire's expansion into the northwest of present-day Argentina brought parts of the region into its administrative province of Collasuyu. These indigenous societies possessed varied social structures, belief systems, and levels of technological development, all of which were profoundly impacted by the subsequent European arrival.

3.2. Colonial era

European presence in the region began with the 1502 voyage of Amerigo Vespucci. Spanish navigators Juan Díaz de Solís and Sebastian Cabot visited the territory that is now Argentina in 1516 and 1526, respectively. In 1536, Pedro de Mendoza founded the small settlement of Buenos Aires, but it was abandoned in 1541 due to conflicts with indigenous populations and lack of resources.

Further colonization efforts originated from Paraguay (establishing the Governorate of the Río de la Plata), Peru, and Chile. Francisco de Aguirre founded Santiago del Estero in 1553, which is considered Argentina's oldest continuously inhabited city. Other settlements followed: Londres (1558), Mendoza (1561), San Juan (1562), and San Miguel de Tucumán (1565). Juan de Garay founded Santa Fe in 1573, and in the same year, Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera established Córdoba. Garay re-founded Buenos Aires in 1580, establishing it as a permanent port. San Luis was established in 1596.

The Spanish Empire initially subordinated the economic potential of the Argentine territory to the immediate wealth derived from the silver and gold mines in Bolivia (then Upper Peru) and Peru. Consequently, the region became part of the Viceroyalty of Peru. In 1776, the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata was created with Buenos Aires as its capital. This administrative reorganization aimed to better defend the region from Portuguese and British ambitions and to control the burgeoning (and often illicit) trade through Buenos Aires. Colonial society was hierarchical, with Spanish-born peninsulares at the top, followed by Criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the Americas), mestizos (mixed European and indigenous), indigenous peoples, and enslaved Africans. The indigenous populations suffered significantly from disease, forced labor (such as the mita and encomienda systems), and loss of land, leading to demographic decline and cultural disruption. The socio-economic structure was largely based on agriculture, livestock raising (particularly cattle and horses which thrived on the Pampas), and trade, though manufacturing was limited.

In 1806 and 1807, Buenos Aires successfully repelled two British invasions. These victories, achieved largely by local militias without significant aid from Spain, fostered a sense of local pride and capability, fueling ideas of self-governance. The ideas of the Age of Enlightenment and the example of the American Revolution and French Revolution generated criticism of the absolutist monarchy that ruled the country. The overthrow of King Ferdinand VII by Napoleon during the Peninsular War created a power vacuum and great concern throughout Spanish America, setting the stage for independence movements.

3.3. Independence and civil wars

The quest for independence in Argentina began in earnest with the May Revolution of 1810 in Buenos Aires. This event, triggered by the news of Spain's weakening control due to the Napoleonic Wars, led to the ousting of the Spanish viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros and the establishment of the Primera Junta, the first autonomous government formed by local Criollos. This marked the beginning of the Argentine War of Independence (1810-1825).

The early years were marked by military campaigns to secure the territory of the former Viceroyalty. While the Junta successfully crushed a royalist counter-revolution in Córdoba, its forces faced difficulties in Upper Peru (modern-day Bolivia), Paraguay, and the Banda Oriental (modern-day Uruguay), regions that would eventually become independent states. Figures like Manuel Belgrano played crucial roles in these early military and political efforts.

A formal Declaration of Independence was made on July 9, 1816, at the Congress of Tucumán, proclaiming the sovereignty of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (later renamed Argentina). General José de San Martín emerged as the foremost military leader of the independence movement. Recognizing that Argentine independence would not be secure as long as Spanish royalists held power in neighboring regions, San Martín conceived a daring plan to cross the Andes Mountains. In 1817, he led his Army of the Andes into Chile, securing its independence with victories at Chacabuco and Maipú, in cooperation with Chilean patriot Bernardo O'Higgins. San Martín then launched a naval expedition to Peru, the main Spanish stronghold in South America, proclaiming its independence in 1821.

Internally, the newly independent territory was plagued by conflict between two main political factions: the Unitarians (Centralists) and the Federalists. Unitarians, based primarily in Buenos Aires, advocated for a strong central government. Federalists, representing the interests of the provinces, favored greater regional autonomy. This ideological divide led to a series of protracted and bloody Argentine Civil Wars that lasted for much of the 19th century, until 1880.

The period saw a succession of governments and attempts at constitutional organization. A centralist constitution enacted in 1819 was soon abrogated by federalist forces. In 1826, another centralist constitution was adopted, and Bernardino Rivadavia became the first president of Argentina. However, provincial resistance forced his resignation and the discarding of the constitution. The civil wars resumed, with caudillos (regional strongmen) playing significant roles. From 1831, the Argentine Confederation was formed, largely dominated by the powerful governor of Buenos Aires Province, Juan Manuel de Rosas. Rosas, a Federalist, ruled as a virtual dictator until 1852, maintaining a semblance of order through authoritarian means but also fostering a sense of Argentine nationalism. His regime faced internal opposition and foreign blockades (French, and later Anglo-French) but managed to prevent further territorial loss. However, his trade restriction policies angered interior provinces and other caudillos. In 1852, Justo José de Urquiza, governor of Entre Ríos, allied with other disgruntled elements and Brazil, defeated Rosas at the Battle of Caseros. Urquiza then convened a constitutional assembly that enacted the federal Constitution of 1853, which, with amendments, remains Argentina's constitution today. Buenos Aires, however, seceded from the Confederation, leading to further conflict until it was defeated and forcibly rejoined in 1859.

3.4. Rise of the modern nation

The latter half of the 19th century marked Argentina's consolidation as a modern nation-state. After the Battle of Pavón in 1861, where Bartolomé Mitre of Buenos Aires defeated Urquiza, Buenos Aires's predominance was secured, and Mitre was elected the first president of a reunified Argentina in 1862. His presidency, along with those of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (1868-1874) and Nicolás Avellaneda (1874-1880), laid the foundations of the modern Argentine state. This period saw the establishment of national institutions, expansion of education, and initial efforts towards infrastructure development. Sarmiento, in particular, championed public education, believing it crucial for national progress.

Starting with Julio Argentino Roca's first presidency (1880-1886), a period known as the Conservative Republic began, dominated by the National Autonomist Party (PAN). This era, lasting until 1916, was characterized by liberal economic policies, political control by a landed oligarchy, and significant social and economic transformation. A massive wave of European immigration, primarily from Italy and Spain, but also from other parts of Europe, reshaped Argentine society and demography. Between 1870 and 1910, Argentina's population grew fivefold, and its economy expanded fifteen-fold, driven by agricultural exports (wheat, beef) facilitated by the expansion of railways and new technologies like refrigerated shipping. By 1908, Argentina was considered one of the world's wealthiest nations per capita. This economic boom, however, was largely based on an export-oriented agricultural model dependent on foreign capital (mainly British) and markets, and industrialization, while occurring, lagged behind agricultural development.

This era also witnessed the brutal Conquest of the Desert (1878-1884), a military campaign led by General Roca aimed at subduing indigenous peoples in the Pampas and Patagonia and incorporating their lands into the national territory. This campaign resulted in the deaths of thousands of indigenous people, the displacement of many others, and the distribution of vast tracts of land to large landowners and military officers. This conquest effectively ended indigenous resistance in these regions and opened them up for agricultural exploitation, but at a devastating human cost to indigenous communities, who were often viewed as obstacles to "civilization" and progress. The government considered indigenous peoples as inferior, denying them the same rights as Criollos and Europeans. Similar campaigns, known as the Conquest of Chaco, extended into the late 19th century to incorporate the northern territories.

Social changes were profound. The influx of immigrants created a more diverse and urbanized society. Buenos Aires grew into a major cosmopolitan city, often called the "Paris of South America." However, this period also saw the rise of social tensions, including the emergence of a working class, often composed of immigrants, who began to organize and demand better conditions and rights. Anarchist and socialist ideas gained traction among workers.

Politically, the oligarchic rule of the PAN faced increasing challenges. The Radical Civic Union (UCR), founded in 1891, emerged as a major opposition force, advocating for political reform and an end to electoral fraud. In 1912, President Roque Sáenz Peña enacted the Sáenz Peña Law, which established universal, secret, and compulsory male suffrage. This landmark reform paved the way for the UCR's Hipólito Yrigoyen to win the 1916 presidential election, marking the end of the Conservative Republic and the beginning of a new political era. Yrigoyen's first presidency (1916-1922) saw social and economic reforms, including support for small farms and businesses. Argentina remained neutral during World War I. However, Yrigoyen's second administration (1928-1930) faced an economic crisis precipitated by the Great Depression, leading to his overthrow by a military coup in 1930. This coup marked the beginning of a period known as the "Infamous Decade" and ushered in an era of political instability and recurrent military interventions in Argentine politics.

3.5. Peronist years

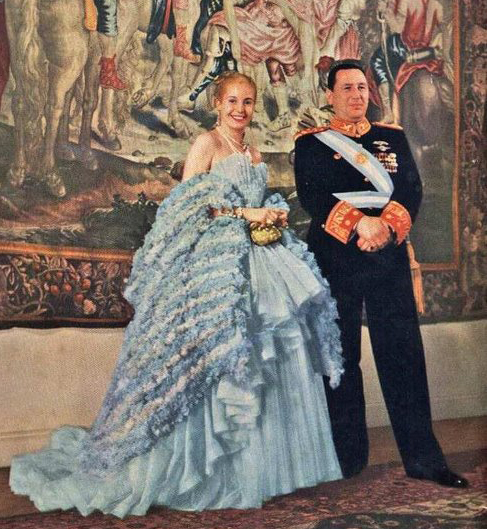

The period from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s, and its enduring legacy, is defined by the rise and influence of Juan Perón and Peronism. Following the military coup of 1930 and the "Infamous Decade" of conservative rule marked by electoral fraud and economic hardship for many, another military coup in 1943 (the Revolution of '43) brought a group of nationalist officers to power. Among them was Colonel Juan Perón, who, as Secretary of Labor and Welfare, cultivated strong support among the working class by enacting pro-labor reforms.

Perón's growing popularity and power led to his brief arrest in 1945, but massive demonstrations by workers secured his release. He went on to win the 1946 presidential election by a landslide, campaigning on a platform of social justice, economic independence, and national sovereignty. His ideology, Peronism (or Justicialismo), combined elements of nationalism, corporatism, and social welfare.

During his first two presidencies (1946-1952, 1952-1955), Perón implemented significant changes. His government nationalized strategic industries and services (including railways, telecommunications, and the central bank), expanded social security benefits, improved wages and working conditions, and strengthened labor unions, which became a key pillar of his support. Women's suffrage was enacted in 1947, largely due to the efforts of his influential wife, Eva Perón ("Evita"). Evita played a critical role in mobilizing support for Perón, especially among the poor (the descamisados, or "shirtless ones") and women, through her charitable Eva Perón Foundation and her powerful oratory. Her early death from cancer in 1952 was a significant blow to the regime and a moment of national mourning.

Perón's policies aimed to reduce foreign economic influence and promote industrialization through import substitution. While these policies initially led to economic growth and improved living standards for many, by the early 1950s, the economy began to face difficulties, including inflation and declining export revenues, partly due to government expenditures and protectionist measures.

The Peronist years also involved significant political polarization and suppression of dissent. The government exerted control over the media, universities, and the judiciary. Opposition figures and critics faced harassment, imprisonment, or exile. Perón fired over 2,000 university professors and faculty members perceived as disloyal. He sought to bring most trade unions under his control, sometimes resorting to violence against dissenting labor leaders like Cipriano Reyes.

Increasing economic problems, authoritarian tendencies, and conflict with the Catholic Church eroded some of Perón's support. In June 1955, the Navy bombed the Plaza de Mayo in an attempted coup, resulting in hundreds of civilian casualties. Perón survived, but in September 1955, a military uprising known as the Revolución Libertadora ("Liberating Revolution") successfully ousted him. He went into exile in Spain, but Peronism remained a potent political force in Argentina, and its legacy, including the emphasis on labor rights, social welfare, and national industry, continued to shape Argentine society and politics for decades to come, even during periods when the Peronist party was banned.

3.6. Revolución Libertadora and military interventions

Following Juan Perón's ousting in September 1955 by the military coup known as the Revolución Libertadora, Argentina entered a prolonged period of political instability characterized by weak civilian governments, military interventions, and the proscription of Peronism. The "Revolución Libertadora" itself was led by figures like General Pedro Eugenio Aramburu, who took over the presidency and implemented policies aimed at "de-Peronizing" the country, banning the Peronist party and symbols, and reversing many of Perón's social and economic measures. This period deepened political divisions and often involved repression against Peronist supporters.

In the 1958 general election, held with Peronism banned, Arturo Frondizi of the Intransigent Radical Civic Union (UCRI) won the presidency. Frondizi attempted to foster economic development through foreign investment, particularly in the oil and industrial sectors. He also sought a rapprochement with Peronists, lifting the ban on their party, which proved controversial with the military and conservative sectors. His efforts to navigate between Peronist demands and military pressures ultimately failed, and he was overthrown by another military coup in 1962.

Amidst the ensuing political turmoil, Senate leader José María Guido assumed the presidency, effectively a puppet of the military. Elections were annulled, and Peronism was once again proscribed. In the 1963 election, Arturo Illia of the People's Radical Civic Union (UCRP) was elected. Illia's government pursued moderate nationalist economic policies and respected democratic norms, leading to a period of relative prosperity and social peace. However, his administration was viewed as slow and indecisive by powerful economic interests and the military, who were also wary of growing Peronist influence in labor unions and provincial elections.

In June 1966, General Juan Carlos Onganía led another military coup, terming it the Argentine Revolution. This was a different kind of military intervention; Onganía envisioned a long-term authoritarian state, suspending political activities, dissolving Congress, and intervening in universities. His regime aimed to modernize the economy and impose social order, but it faced growing opposition, including student protests (like the infamous "Night of the Long Batons") and labor unrest, such as the Cordobazo uprising in 1969. These events highlighted the deep-seated social conflicts and the impossibility of governing Argentina without addressing the Peronist question. The Onganía regime and subsequent military governments under Generals Roberto M. Levingston and Alejandro Agustín Lanusse struggled with internal divisions, economic problems, and escalating political violence from both left-wing and right-wing extremist groups. This period of military interventions significantly undermined democratic institutions and set the stage for further political upheaval.

3.7. Perón's return and death

By the early 1970s, Argentina was in a state of profound political and social turmoil. The military government, then led by General Alejandro Agustín Lanusse, faced increasing pressure for a return to democracy and an inability to quell escalating political violence from various guerrilla groups, most notably the Peronist Montoneros and the Marxist People's Revolutionary Army (ERP). In an attempt to find a political solution, Lanusse allowed for elections in March 1973.

Juan Perón, still in exile in Spain, was barred from running himself, but his designated candidate, Héctor José Cámpora, a left-leaning Peronist, won a decisive victory under the slogan "Cámpora to government, Perón to power." Cámpora took office on May 25, 1973. One of his first actions was to grant amnesty to political prisoners, including many guerrilla members. This, along with a surge in social conflicts, strikes, and factory occupations, characterized his brief tenure.

Perón made his triumphant return to Argentina on June 20, 1973. His arrival was marred by the Ezeiza Massacre, a violent confrontation at the airport between right-wing and left-wing Peronist factions awaiting him, which resulted in numerous deaths and injuries and signaled the deep divisions within the Peronist movement.

Amidst this escalating crisis, Cámpora and Vice President Vicente Solano Lima resigned in July 1973, paving the way for new elections. This time, Juan Perón was the Justicialist Party nominee, with his third wife, Isabel Perón (María Estela Martínez de Perón), as his running mate. Perón won the September 1973 election overwhelmingly.

Perón's third term was marked by an attempt to restore order and navigate the intense conflicts within his own movement and in the country at large. He increasingly sided with the conservative and right-wing elements of Peronism, distancing himself from and eventually expelling the Montoneros from the party. Political violence continued to escalate, with actions by left-wing guerrillas and the emergence of the right-wing death squad, the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (Triple A), which operated with state backing to target leftists and dissidents.

However, Perón's health was failing. After a series of heart attacks and signs of pneumonia, Juan Perón died on July 1, 1974, at the age of 78. His death plunged Argentina into further uncertainty and grief. As per the constitution, he was succeeded by his wife and vice president, Isabel Perón. Her presidency was fraught with immense challenges, including a deteriorating economy, rampant inflation, escalating political violence, and a lack of strong political leadership. Her government proved unable to control the situation, leading to a constitutional crisis and paving the way for the military coup of 1976.

3.8. National Reorganization Process (Military Dictatorship)

The period from 1976 to 1983 in Argentina is known as the National Reorganization Process (Proceso de Reorganización Nacional), a military dictatorship established after a coup d'état on March 24, 1976, overthrew President Isabel Perón. This era was characterized by systematic state terrorism and egregious human rights violations, infamously known as the Dirty War (Guerra Sucia).

The coup was led by a military junta comprising the heads of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, with Army General Jorge Rafael Videla initially assuming the presidency. The junta dissolved Congress, banned political parties and trade unions, imposed strict censorship, and suspended constitutional rights. The regime's stated aims were to combat left-wing subversion, restore order, and restructure the economy.

The "Dirty War" involved the widespread persecution, abduction, torture, and murder of anyone perceived as a political opponent or "subversive." This included left-wing activists, militants, guerrilla members (like the Montoneros and ERP), trade unionists, students, journalists, intellectuals, artists, priests, and even their families or associates. Thousands of people became desaparecidos (the disappeared) - secretly arrested, detained in clandestine detention centers, tortured, and ultimately killed, their bodies often disposed of in unmarked graves or dropped into the sea. Estimates of the number of disappeared range from 15,000 to 30,000 people. The regime also engaged in the systematic theft of babies born to captive mothers, who were then given to families associated with the military or police.

This campaign of terror was part of the broader Operation Condor, a coordinated effort by right-wing dictatorships in the Southern Cone of South America (including Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Brazil) to eliminate political opponents across borders, often with the knowledge and support of the United States. Argentina received technical support and military aid from the U.S. government during several administrations.

The dictatorship implemented neoliberal economic policies, leading to deindustrialization, increased foreign debt, and growing social inequality, although inflation was initially brought under control. These policies, championed by Economy Minister José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, benefited financial speculators and agro-exporters but harmed local industries and the working class.

Despite the brutal repression, resistance emerged. The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo began their courageous public protests, demanding to know the whereabouts of their disappeared children and grandchildren, becoming powerful symbols of defiance and the fight for human rights.

The regime's power began to wane due to economic problems, international condemnation of its human rights record, and internal divisions within the military. In a desperate attempt to rally nationalist sentiment and divert attention from domestic issues, the junta, then led by General Leopoldo Galtieri, launched an invasion of the British-held Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) on April 2, 1982. The ensuing Falklands War resulted in a swift and humiliating defeat for Argentina by June 1982. This defeat discredited the military, led to Galtieri's downfall, and accelerated the transition back to democracy. Street riots in Buenos Aires followed, and the military leadership, under General Reynaldo Bignone, began to organize the return to civilian rule, although not before passing a self-amnesty law, which was later repealed. The period of the National Reorganization Process left a deep scar on Argentine society, with lasting consequences for its political culture, social fabric, and the ongoing struggle for justice and remembrance for the victims of state terrorism.

3.9. Return to democracy and contemporary era

Argentina's return to democracy began with the 1983 elections, won by Raúl Alfonsín of the Radical Civic Union (UCR). Alfonsín's presidency (1983-1989) was marked by efforts to consolidate democratic institutions and address the human rights violations of the preceding military dictatorship. The landmark Trial of the Juntas in 1985 convicted several top military leaders for their roles in the Dirty War. However, under intense military pressure, Alfonsín's government later passed the Full Stop Law (1986) and the Due Obedience Law (1987), which effectively halted further prosecutions of lower-ranking officers. His administration also faced severe economic challenges, including hyperinflation and a large foreign debt, leading to social unrest and his early resignation in 1989.

Carlos Menem of the Justicialist Party (Peronist) won the 1989 election and served two terms (1989-1999) after a constitutional amendment in 1994 allowed for re-election. Menem implemented sweeping neoliberal economic reforms, including privatization of state-owned companies, deregulation, and a fixed exchange rate pegging the Argentine peso to the US dollar (the Convertibility Plan). These policies initially curbed hyperinflation and spurred economic growth in the early 1990s. Menem also pardoned the military officers convicted during Alfonsín's term, a controversial move aimed at national reconciliation but criticized by human rights groups. However, by the mid-1990s, the economic model began to show strains, with rising unemployment, increasing foreign debt, and growing social inequality.

Fernando de la Rúa of the UCR-led Alianza coalition won the 1999 elections. His government inherited a worsening economic situation and maintained Menem's fixed exchange rate policy, which became increasingly unsustainable. A severe recession, coupled with massive capital flight, led to restrictive measures on bank withdrawals (the corralito). This triggered widespread social unrest and the December 2001 riots, forcing De la Rúa to resign. Argentina experienced a period of acute political instability, with five presidents in two weeks. Congress eventually appointed Eduardo Duhalde as interim president. Duhalde's government abandoned the currency convertibility plan, leading to a sharp devaluation of the peso and a severe banking crisis, which wiped out the savings of many Argentines. By late 2002, the economy began a slow recovery.

In the 2003 election, Néstor Kirchner, a left-leaning Peronist, became president. Kirchner's presidency (2003-2007) marked a shift away from neoliberal policies. His administration oversaw a period of strong economic growth, renegotiated Argentina's defaulted foreign debt with a significant discount, paid off the country's debt to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and pursued a more assertive foreign policy. Crucially, Kirchner prioritized human rights, annulling the Full Stop and Due Obedience laws, which were subsequently declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. This reopened prosecutions against those responsible for crimes committed during the dictatorship.

Néstor Kirchner chose not to seek re-election, and his wife, Senator Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, won the 2007 presidential election, becoming the first woman elected president of Argentina. She was re-elected in 2011. Her presidencies (2007-2015) continued many of her husband's policies, including social programs, state intervention in the economy (such as the nationalization of the oil company YPF and private pension funds), and a focus on human rights trials. Her tenure also saw increased polarization, conflicts with agricultural sectors and media groups, and, in later years, economic challenges including high inflation and stagnating growth. Despite these challenges, efforts towards justice for past human rights abuses continued, and social movements, particularly around gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights, gained prominence.

In the 2015 election, Mauricio Macri, candidate of the center-right Cambiemos coalition, defeated the Peronist candidate, ending twelve years of Kirchnerismo. Macri's presidency (2015-2019) implemented market-oriented reforms, settled disputes with holdout creditors, and sought to reintegrate Argentina into global financial markets. However, his administration struggled with persistent inflation, recession, and rising foreign debt, leading to a significant loan package from the IMF in 2018. Social discontent grew due to austerity measures and economic hardship.

Alberto Fernández, representing a united Peronist front (Frente de Todos) with Cristina Fernández de Kirchner as his vice-presidential candidate, won the 2019 presidential election. His term (2019-2023) was immediately confronted by the COVID-19 pandemic and its severe economic consequences, exacerbating existing problems of debt, inflation, and poverty. His government renegotiated debt with private creditors and the IMF, and implemented social assistance programs, but faced ongoing economic instability and political divisions. In the 2021 midterm legislative elections, the ruling coalition lost its majority in Congress.

The 2023 general election saw a dramatic shift with the victory of Javier Milei, a libertarian economist and political outsider representing the La Libertad Avanza coalition. Milei campaigned on a platform of radical economic liberalization, including dollarization, drastic cuts in public spending, and the closure of the central bank. His presidency, beginning in December 2023, signaled a significant departure from previous political and economic paradigms, promising profound changes to Argentine society. The contemporary era continues to be shaped by efforts to achieve sustainable economic development, strengthen democratic institutions, address social inequalities, and reconcile with a complex past, particularly concerning human rights and justice.

4. Geography

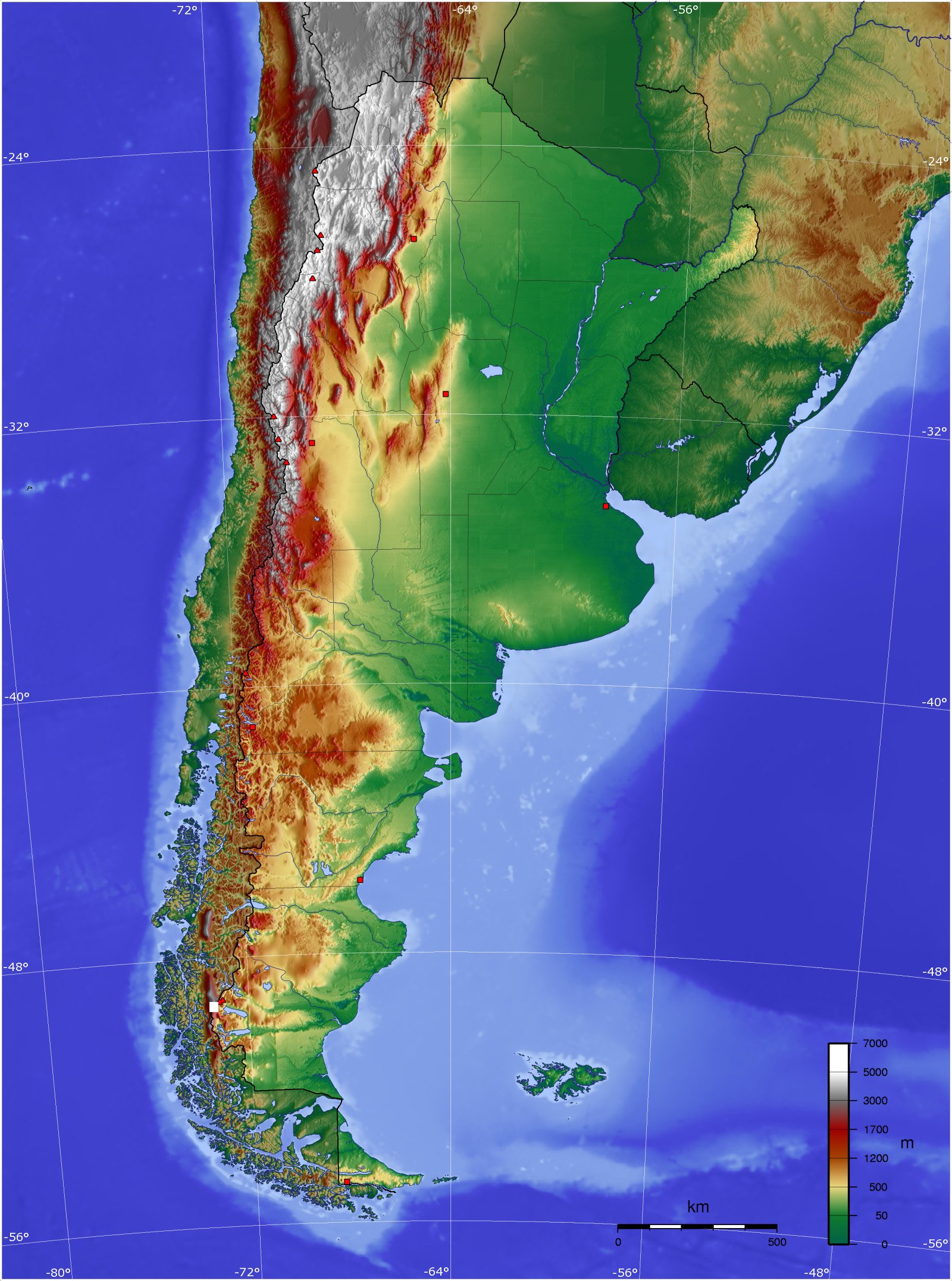

Argentina is located in the southern part of South America, covering a mainland surface area of 1.1 M mile2 (2.78 M km2). It is the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourth-largest in the Americas, and the eighth-largest in the world. The country shares land borders with Chile across the Andes to the west; Bolivia and Paraguay to the north; Brazil to the northeast; Uruguay and the South Atlantic Ocean to the east; and the Drake Passage to the south. The overall land border length is 5.8 K mile (9.38 K km), and its coastal border over the Río de la Plata and South Atlantic Ocean is 3.2 K mile (5.12 K km) long. Argentina's highest point is Aconcagua in Mendoza Province, at 23 K ft (6.96 K m) above sea level, which is also the highest point in both the Southern and Western Hemispheres. The lowest point is Laguna del Carbón in Santa Cruz Province, at -344.5 ft (-105 m) below sea level, also the lowest point in both hemispheres and the seventh lowest on Earth. The country's major regional divisions include the Pampas plains, the mountainous Andes region, the arid Patagonia region, the subtropical Mesopotamia, and the Gran Chaco.

4.1. Topography and regions

Argentina's topography is highly diverse, featuring vast plains, high mountains, and extensive plateaus, which define its distinct geographical regions and influence resource distribution and social development.

The Andes Mountains: This formidable mountain range forms the western backbone of Argentina, stretching along its border with Chile. It is home to Aconcagua, the highest peak outside of Asia. The Andean region is characterized by rugged terrain, high plateaus (like the Puna de Atacama), and intermontane valleys. This region is rich in mineral resources, including copper, gold, silver, and lithium. Historically, indigenous cultures like the Diaguita thrived here before Inca and Spanish colonization. The availability of water from snowmelt supports agriculture, particularly viticulture in regions like Mendoza and San Juan, making Argentina a major wine producer. However, the mountainous terrain also presents challenges for transportation and communication, and some Andean communities remain relatively isolated.

The Pampas: Located in the central-eastern part of the country, the Pampas are vast, fertile plains that constitute Argentina's agricultural heartland. This region is divided into the Humid Pampa (to the east, with higher rainfall) and the Dry Pampa (to the west, more arid). The deep, rich soils (mollisols) make the Humid Pampa exceptionally productive for crops like wheat, maize (corn), soybeans, and sunflowers, as well as for cattle ranching, which is central to Argentina's culinary identity and export economy. The Pampas are heavily populated and host major cities, including Buenos Aires, Rosario, and Córdoba. The concentration of economic activity and population in this region has historically led to disparities with other parts of the country. Intensive agriculture has also led to environmental concerns such as soil degradation.

Patagonia: Occupying the southern third of Argentina, Patagonia is a vast, sparsely populated region characterized by arid plateaus, strong winds, and a cooler climate. It stretches from the Colorado River in the north to Tierra del Fuego in the south. The Patagonian Steppe dominates much of the interior, supporting extensive sheep farming. The Andean foothills in western Patagonia feature forests, lakes (like Nahuel Huapi Lake), and glaciers, making it a significant area for tourism. The region is rich in energy resources, including petroleum and natural gas, particularly in provinces like Neuquén and Chubut. The Valdes Peninsula is a notable UNESCO World Heritage Site for marine wildlife. Resource extraction has social implications, including debates about environmental impact and benefits for local communities.

Gran Chaco: Located in the north, the Gran Chaco is a hot, semi-arid lowland region shared with Paraguay, Bolivia, and Brazil. It is characterized by scrub forests, grasslands, and wetlands. Traditionally, it has been an area of subsistence agriculture, forestry (especially for tannin from the quebracho tree), and cattle ranching. The region faces challenges such as deforestation, poverty, and limited access to infrastructure and services for its inhabitants, including indigenous communities like the Wichi and Qom.

Mesopotamia: Situated between the Paraná and Uruguay rivers in the northeast, this region (comprising the provinces of Misiones, Corrientes, and Entre Ríos) has a subtropical climate with abundant rainfall. It features rolling hills, forests, and wetlands like the Iberá Wetlands. Key economic activities include agriculture (citrus fruits, rice, yerba mate, tea), forestry, and cattle ranching. The magnificent Iguazu Falls, a major tourist attraction and World Heritage Site, are located in Misiones Province.

Cuyo: Located in west-central Argentina, at the foothills of the Andes, the Cuyo region (comprising Mendoza, San Juan, and San Luis) is characterized by an arid to semi-arid climate. Irrigation from Andean rivers has transformed parts of this region into fertile oases, making it the primary wine-producing area of Argentina. Olive oil production and fruit cultivation are also important. Mining is another significant economic activity.

The distribution of natural resources across these regions has historically shaped Argentina's economic development patterns and, at times, contributed to regional inequalities and political tensions.

4.2. Hydrography

Argentina's hydrography is characterized by several major river systems, extensive lakes, and significant wetland areas, all of which play crucial roles in the country's environment, economy, and population distribution.

The most important river system is the Río de la Plata Basin, which drains a vast area of southeastern South America. Its main tributaries within or bordering Argentina are:

- The Paraná River: This is Argentina's longest and most significant river, forming part of its borders with Paraguay and Brazil before flowing south through the country. It is a major waterway for navigation and supports significant hydroelectric power generation (e.g., the Yacyretá Dam, shared with Paraguay). The Paraná Delta, near its confluence with the Uruguay River, is an extensive wetland ecosystem.

- The Uruguay River: This river forms Argentina's eastern border with Brazil and Uruguay. It is also important for navigation and hydroelectricity (e.g., the Salto Grande Dam, shared with Uruguay). The Paraná and Uruguay rivers join to form the Río de la Plata, a vast estuary that opens into the Atlantic Ocean and on whose shores lies Buenos Aires. The Río de la Plata is vital for shipping and is a densely populated area.

- The Paraguay River: A major tributary of the Paraná, it forms part of Argentina's border with Paraguay.

- The Pilcomayo River and Bermejo River: These are important tributaries flowing from the Andes into the Paraguay River system, often carrying significant sediment loads.

Other significant rivers include:

- The Salado River (Buenos Aires Province) (Río Salado del Sur): Flows through the Pampas and into the Río de la Plata estuary. Another Salado River (Río Salado del Norte or Juramento) flows from the Andes into the Paraná.

- The Colorado River and the Río Negro: These are the most important rivers in northern Patagonia, originating in the Andes and flowing east to the Atlantic. They are crucial for irrigation in their arid to semi-arid basins.

- The Santa Cruz River: Located in southern Patagonia, it flows from Lake Argentino to the Atlantic.

Argentina possesses numerous lakes, particularly in the Patagonian Andes. These glacial lakes are known for their scenic beauty and include:

- Lake Argentino and Viedma Lake: The largest lakes in Argentina, located in Santa Cruz Province, fed by glaciers like the Perito Moreno Glacier.

- Nahuel Huapi Lake: Located in the northern Patagonian Andes near Bariloche.

- Lake Buenos Aires (shared with Chile, where it's called General Carrera Lake) and Lake San Martín (shared with Chile as O'Higgins Lake).

- Mar Chiquita: A large endorheic salt lake in Córdoba Province.

Wetlands are also a significant feature, with the Iberá Wetlands in Corrientes Province being one of the largest freshwater wetland ecosystems in the world, supporting rich biodiversity.

The country's water resources are vital for agriculture (irrigation), hydroelectric power, industrial and domestic water supply, and transportation. However, challenges such as water pollution in urban and industrial areas, and the impact of climate change on water availability (particularly from Andean snowmelt) are growing concerns. The distribution of water resources also influences population patterns, with major settlements often located along rivers or in irrigated areas.

4.3. Biodiversity

Argentina is recognized as one of the most megadiverse countries, hosting a vast array of ecosystems and a rich variety of flora and fauna due to its extensive latitudinal range, diverse topography, and varied climates. The country encompasses 15 continental zones, 2 marine zones, and the Antarctic region within its territory.

Ecosystems:

- Pampas grasslands:** Originally vast temperate grasslands, much of which has been converted to agriculture. Remnant areas support native grasses and associated wildlife.

- Andean region:** Ranges from high-altitude deserts (Puna) with specialized flora and fauna (like vicuñas and condors) to temperate forests on the lower slopes, particularly in Patagonia (Nothofagus or southern beech forests).

- Patagonian Steppe:** Arid and semi-arid shrublands and grasslands adapted to harsh, windy conditions.

- Gran Chaco:** A mix of dry forests, savannas, and wetlands with unique species like the Chacoan peccary.

- Mesopotamian wetlands and grasslands:** Includes the extensive Iberá Wetlands, a haven for capybaras, caimans, and numerous bird species.

- Subtropical rainforests:** Found in the northeast (Misiones Province, e.g., Iguazu National Park) with high biodiversity, including jaguars, toucans, and monkeys.

- Monte desert:** An arid region in the west, characterized by xerophytic shrubs.

- Marine ecosystems:** The Argentine Sea, part of the South Atlantic, is highly productive, supporting important fisheries and marine mammals like southern right whales, sea lions, and penguins. The Valdes Peninsula is a key breeding ground for marine wildlife.

Flora: Argentina has over 9,300 catalogued species of vascular plants. Notable native trees include the ombú (a tree-like herb iconic to the Pampas), various species of Nothofagus in Patagonian forests, the quebracho tree (important for tannin) in the Chaco, and diverse subtropical species in the northeast. Cacti are prominent in arid and semi-arid regions.

Fauna: The country is home to approximately 375 mammal species, over 1,000 bird species, 338 reptilian species, and 162 amphibian species.

- Mammals: Jaguar, puma, Andean mountain cat, guanaco, vicuña, huemul, capybara, giant anteater, various species of armadillo, maned wolf, and marine mammals like the southern right whale and orcas.

- Birds: Andean condor (one of the largest flying birds), Rufous hornero (national bird), rheas (ñandú), Magellanic penguin, flamingos, toucans, and numerous passerines and waterfowl.

- Reptiles and Amphibians: Various snakes (including boa constrictors and vipers), lizards (like the tegu), caimans, turtles, and a diverse range of frogs and toads.

Conservation and National Parks: Argentina has a network of national parks and protected areas covering a significant portion of its territory, aimed at conserving its biodiversity and natural landscapes. The National Parks Administration (Administración de Parques Nacionales) manages these areas. Some of the most well-known national parks include Iguazu National Park, Los Glaciares National Park (home to the Perito Moreno Glacier), Nahuel Huapi National Park, and Tierra del Fuego National Park. Argentina had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.21/10, ranking it 47th globally out of 172 countries.

Impact of Human Activity: Human activities, particularly agriculture, deforestation, urbanization, and resource extraction, have put considerable pressure on Argentina's biodiversity. Habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution, and the introduction of invasive species are significant threats. Climate change is also expected to further impact ecosystems and species distribution. Conservation efforts focus on expanding protected areas, sustainable resource management, and raising public awareness, though challenges remain in balancing economic development with environmental protection. The historical expansion of agriculture in the Pampas, for example, led to the decimation of much of the original grassland ecosystem.

4.4. Climate

Argentina's vast territory encompasses an exceptional diversity of climates, ranging from subtropical in the north to subantarctic and polar in the far south, and from humid conditions in the east to arid and semi-arid in the west and Patagonia. The primary determinants of its climate are its wide latitudinal span, the influence of the Andes Mountains, and its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. Generally, four main climate types can be identified: warm humid subtropical, moderate humid subtropical, arid (desert and steppe), and cold.

- North (Subtropical): The northeastern part of Argentina, including Mesopotamia and parts of the Gran Chaco, experiences a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa, Cwa). Summers are hot and humid, with abundant rainfall, while winters are mild and relatively dry. Misiones Province, with its rainforests, has high year-round precipitation. The northwestern Andean foothills also have subtropical highland climates with a pronounced dry season in winter.

- Central (Temperate): The Pampas region, including Buenos Aires and Córdoba, generally has a temperate climate. The eastern Pampas have a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) with hot, humid summers and mild winters. Rainfall is generally well-distributed throughout the year, though summer thunderstorms are common. The western Pampas transition to a semi-arid climate (BSk) with less rainfall.

- West (Arid and Semi-Arid): The Cuyo region (Mendoza, San Juan) and large parts of the Andean northwest have arid (desert climate, BWk) or semi-arid (steppe, BSk) climates. These areas are characterized by low rainfall, high solar radiation, and significant diurnal temperature variations. Irrigation from Andean rivers is crucial for agriculture in these regions. The Puna high plateau in the northwest has a cold desert or cold steppe climate due to its altitude.

- South (Patagonia - Arid and Cold): Most of Patagonia experiences a cold desert climate (BWk) or cold semi-arid climate (BSk). It is generally dry due to the rain shadow effect of the Andes, and is characterized by strong westerly winds. Summers are mild to warm, while winters can be cold with snowfall, especially in the west and at higher elevations. Southern Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego have a subpolar oceanic climate (Cfc) or even a tundra climate (ET) in the southernmost tips and higher Andes, with cool summers and cold, snowy winters. The Southern Patagonian Ice Field is a testament to the cold conditions in this region.

Significant Meteorological Phenomena:

- Pampero winds: Cool, dry winds blowing from the southwest across the Pampas and Patagonia, often following a cold front and bringing a sharp drop in temperature and sometimes dust storms.

- Sudestada winds: Persistent southeasterly winds, common in late autumn and winter along the central coast and in the Río de la Plata estuary. They usually moderate cold temperatures but bring heavy rains, rough seas, and coastal flooding.

- Zonda wind: A hot, dry foehn wind that affects Cuyo and the central Pampas, descending from the Andes. It can cause rapid temperature increases, low humidity, and strong gusts, sometimes fueling wildfires.

Mean annual temperatures range from 41 °F (5 °C) in the far south to 77 °F (25 °C) in the north. Average annual precipitation varies from less than 5.9 in (150 mm) in the driest parts of Patagonia to over 0.1 K in (2.00 K mm) in the westernmost parts of Patagonia and the northeastern rainforests.

Climate change is an increasing concern, with predictions of significant effects on precipitation patterns, temperatures, and the frequency of extreme weather events, impacting agriculture, water resources, and biodiversity. The highest increases in precipitation (from 1960-2010) have occurred in the eastern parts of the country, leading to more variability and a higher risk of prolonged droughts in some northern regions.

4.5. Environmental issues

Argentina faces several significant environmental challenges stemming from its economic activities, land use patterns, and the impacts of climate change. These issues affect its diverse ecosystems, natural resources, and the well-being of its population.

Deforestation: This is a major concern, particularly in the Gran Chaco region and the subtropical rainforests of the northeast. The primary drivers of deforestation are the expansion of the agricultural frontier for soybean cultivation and cattle ranching, as well as unsustainable logging. Deforestation leads to loss of biodiversity, soil erosion, disruption of hydrological cycles, and contributes to climate change. Indigenous communities and small farmers are often disproportionately affected by land clearing.

Soil Degradation and Desertification: Intensive agricultural practices, overgrazing, and deforestation have led to soil degradation in many parts of the country, especially in the Pampas and semi-arid regions. Soil erosion by wind and water, loss of organic matter, and salinization reduce agricultural productivity and can lead to desertification, particularly in vulnerable areas like Patagonia and parts of the Cuyo and Northwest regions.

Water Pollution: Rivers and water bodies near urban centers and industrial areas suffer from pollution due to untreated domestic sewage, industrial effluents, and agricultural runoff (pesticides and fertilizers). The Matanza-Riachuelo River in Buenos Aires is one of the most polluted rivers in the world, posing serious health risks to nearby populations. Mining activities, particularly in the Andean region, can also lead to water contamination from heavy metals and chemicals if not properly managed.

Air Pollution: Urban areas, especially Greater Buenos Aires, experience air pollution primarily from vehicle emissions and industrial activities. This contributes to respiratory problems and other health issues.

Waste Management: Inadequate waste management, particularly in rapidly growing urban areas, is a significant problem. Many municipalities lack proper sanitary landfills, leading to open dumpsites that contaminate soil and water and pose public health risks. Efforts to promote recycling and sustainable waste management are underway but face challenges.

Impacts of Climate Change: Argentina is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including changes in precipitation patterns (more intense rainfall in some areas, prolonged droughts in others), rising temperatures, glacial retreat in the Andes (affecting water supply), and increased frequency of extreme weather events. These changes threaten agriculture, water resources, biodiversity, and human settlements.

Loss of Biodiversity: Habitat destruction and fragmentation due to agricultural expansion, deforestation, and urbanization, as well as pollution and overexploitation of resources, are leading to a loss of biodiversity. Several native species are threatened or endangered.

National and Local Responses: Argentina has environmental laws and institutions at both national and provincial levels. The country is a signatory to various international environmental agreements. Efforts to address these issues include the creation of protected areas, programs for sustainable agriculture and forestry, initiatives to control pollution, and policies to promote renewable energy. However, enforcement of environmental regulations can be challenging, and balancing economic development with environmental protection remains a constant tension. Social movements and non-governmental organizations play an active role in advocating for environmental conservation and justice. The debate around large-scale mining projects, particularly concerning water use and potential contamination, often highlights these conflicts.

5. Politics

Argentina experienced significant political turmoil and democratic reversals in the 20th century. Between 1930 and 1976, the armed forces overthrew six governments. The country alternated periods of democracy (1912-1930, 1946-1955, and 1973-1976) with periods of restricted democracy and military rule. Following a transition that began in 1983, full-scale democracy was re-established.

5.1. Government

Argentina is a federal constitutional republic and a representative democracy. The government operates under a system of separation of powers with checks and balances defined by the Constitution of Argentina, the country's supreme legal document, which was first adopted in 1853 and significantly amended in 1994. The seat of government is the city of Buenos Aires, designated by the National Congress. Suffrage is universal, equal, secret, and mandatory for citizens aged 18 to 70 (optional for those aged 16-17 and over 70).

The federal government is composed of three branches:

Executive Branch:

The President is both the head of state and head of government. The President is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, can veto legislative bills (subject to Congressional override), and appoints Cabinet ministers and other federal officials. The President and Vice President are elected by direct popular vote for a four-year term and may be re-elected for one consecutive term.

Legislative Branch:

The National Congress (Congreso Nacional) is bicameral, consisting of:

- The Senate (Senado): Composed of 72 members, with three senators representing each of the 23 provinces and three for the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. Senators are elected by direct popular vote for six-year terms, with one-third of the Senate renewed every two years.

- The Chamber of Deputies (Cámara de Diputados): Composed of 257 members, elected by direct popular vote using a system of proportional representation for four-year terms. Half of the Chamber is renewed every two years. Seats are apportioned among the provinces according to their population.

The Congress makes federal laws, declares war, approves treaties, and has the power of the purse and of impeachment. At least one-third of the candidates on party lists for congressional elections must be women, promoting gender representation.

Judicial Branch:

The Judicial branch includes the Supreme Court of Justice (Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación) and lower federal courts. The judiciary interprets laws and can overturn those it finds unconstitutional through judicial review. It is independent of the executive and legislative branches. The Supreme Court has five members (though the number has varied historically) appointed by the President with the Senate's approval, who serve for life during good behavior. Lower federal court judges are proposed by the Council of Magistracy (an independent body composed of representatives from various legal and political sectors) and appointed by the President with Senate approval.

Argentina's political system has historically been characterized by strong presidentialism and the significant influence of political parties, most notably the Justicialist Party (Peronist) and the Radical Civic Union (UCR). The country has a multi-party system, though Peronism has often been the dominant force. Recent decades have seen the emergence of new political coalitions and figures, reflecting evolving social and economic concerns. Democratic participation is generally high, but the system has faced challenges related to political polarization, corruption, and economic instability.

5.2. Human rights

The state of human rights in Argentina is deeply intertwined with its history, particularly the legacy of the last military dictatorship (1976-1983) and the subsequent efforts to achieve justice, truth, and memory. Contemporary challenges also persist, including issues related to police brutality, prison conditions, and the rights of minorities and vulnerable groups.

Legacy of the Dictatorship (Dirty War): The "Dirty War" saw systematic state-sponsored terrorism, including the forced disappearance of an estimated 15,000 to 30,000 people, torture, extrajudicial killings, and the theft of babies born in captivity. The return to democracy in 1983 brought efforts to prosecute those responsible. The Trial of the Juntas in 1985 was a landmark event, convicting top military leaders. However, subsequent laws (Full Stop and Due Obedience) halted further prosecutions until they were annulled in the 2000s under President Néstor Kirchner and later declared unconstitutional. This allowed for the resumption of trials, and hundreds of former officials have since been convicted for crimes against humanity. Human rights organizations like the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo have been instrumental in the fight for justice and in locating disappeared individuals and stolen grandchildren. The struggle for memory and against impunity remains a central theme in Argentine society.

Contemporary Challenges:

- Police Brutality and Prison Conditions:** Reports of police brutality, excessive use of force, and torture in detention persist. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, and violence are significant problems in many Argentine prisons.

- Judicial System:** While independent, the judiciary has faced criticism for delays, inefficiency, and occasional political influence, which can impede access to justice.

- Freedom of Expression and Press:** Generally respected, but there have been periods of tension between the government and certain media outlets, leading to concerns about media concentration and potential pressure on journalists.

- Corruption:** Corruption remains a significant problem, affecting public trust in institutions and diverting resources.

- Violence Against Women:** Femicide and gender-based violence are serious issues, prompting large-scale social movements like Ni una menos ("Not one [woman] less") demanding state action and cultural change.

- Rights of Indigenous Peoples:** Indigenous communities continue to face challenges related to land rights, access to basic services (health, education), discrimination, and consultation regarding development projects affecting their territories. While legal frameworks exist to protect indigenous rights, implementation often falls short.

- LGBTQ+ Rights:** Argentina has made significant progress in LGBTQ+ rights. It was the first country in Latin America to legalize same-sex marriage (in 2010) and has comprehensive gender identity laws allowing transgender individuals to change their legal gender without requiring surgery or judicial approval. However, discrimination and violence against LGBTQ+ individuals, particularly transgender people, still occur.

- Migrants and Refugees:** Argentina has a history of immigration and generally maintains an open policy, but migrants and refugees can face discrimination and difficulties accessing services.

- Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights:** Poverty and inequality remain significant challenges, impacting access to adequate housing, healthcare, and education for a substantial portion of the population, particularly affecting children and marginalized groups.

The Argentine state has various institutions dedicated to human rights, and civil society organizations are very active in monitoring, advocating, and providing legal assistance. The emphasis on human rights is a strong component of Argentina's democratic identity, shaped by the traumatic experiences of the past.

5.3. Administrative divisions

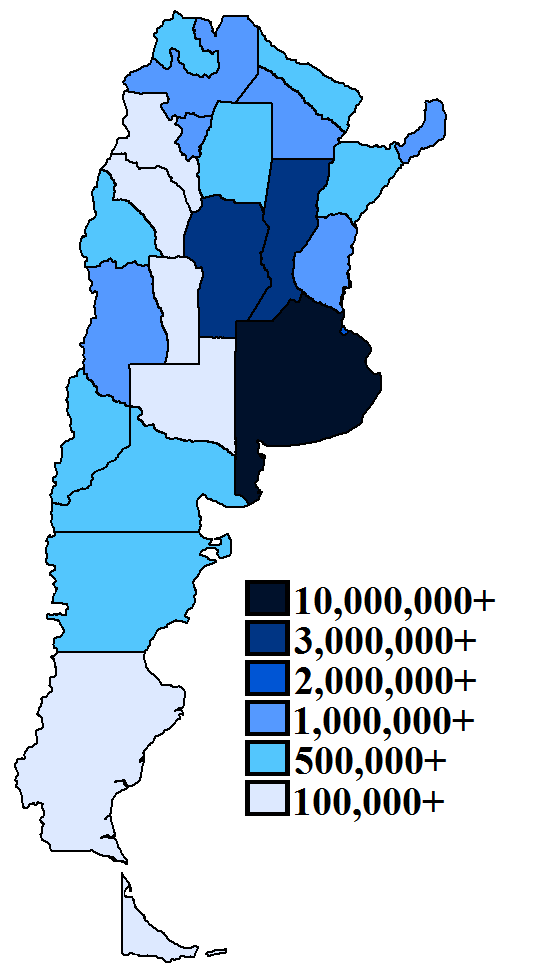

Argentina is a federation composed of twenty-three provinces (provincias) and one autonomous city (Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), which serves as the federal capital. This federal structure is enshrined in the Constitution of Argentina.

Each province has its own constitution, which must align with the national constitution, and enjoys a significant degree of autonomy. Provinces have their own executive, legislative, and judicial branches. They elect their own governors and provincial legislatures. Provincial governments are responsible for local matters such as education (shared with the federal government), healthcare, local policing, and managing their natural resources.

The provinces are:

# Buenos Aires Province (capital: La Plata)

# Catamarca (capital: San Fernando del Valle de Catamarca)

# Chaco (capital: Resistencia)

# Chubut (capital: Rawson)

# Córdoba (capital: Córdoba)

# Corrientes (capital: Corrientes)

# Entre Ríos (capital: Paraná)

# Formosa (capital: Formosa)

# Jujuy (capital: San Salvador de Jujuy)

# La Pampa (capital: Santa Rosa)

# La Rioja (capital: La Rioja)

# Mendoza (capital: Mendoza)

# Misiones (capital: Posadas)

# Neuquén (capital: Neuquén)

# Río Negro (capital: Viedma)

# Salta (capital: Salta)

# San Juan (capital: San Juan)

# San Luis (capital: San Luis)

# Santa Cruz (capital: Río Gallegos)

# Santa Fe (capital: Santa Fe)

# Santiago del Estero (capital: Santiago del Estero)

# Tierra del Fuego, Antarctica and South Atlantic Islands (capital: Ushuaia) - This province nominally includes Argentine Antarctica and the disputed Falkland Islands (Malvinas) and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

# Tucumán (capital: San Miguel de Tucumán)

The Autonomous City of Buenos Aires is a special federal district. While it functions like a province with its own elected Head of Government (Mayor) and legislature, it is distinct as the nation's capital.

Provinces are further divided for administrative purposes. Most provinces are subdivided into departments (departamentos), which are then typically divided into municipalities (municipios) or communes. An exception is Buenos Aires Province, which is divided into partidos, which function similarly to departments or counties and are themselves municipalities. The City of Buenos Aires is divided into communes (comunas).

The relationship between the federal government and the provinces can sometimes be a source of political tension, particularly concerning revenue sharing and resource control.

5.4. Foreign relations

Argentina's foreign policy is managed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Worship and is directed by the President. Historically, Argentina has strived to maintain an independent foreign policy, balancing relationships with global powers while prioritizing regional integration in Latin America. It holds the status of a middle power and is a regional power in the Southern Cone.

Key aspects of Argentina's foreign relations include:

- Regional Integration:** Argentina is a founding member of Mercosur (Southern Common Market), along with Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay (Venezuela's membership is currently suspended). Mercosur is a primary focus of its foreign policy, aiming to promote free trade, economic cooperation, and political coordination among its members. Argentina also actively participates in other regional organizations such as the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) and the Organization of American States (OAS).

- Relations with Neighboring Countries:** Relations with Brazil are crucial, as they are the two largest economies in South America and key partners in Mercosur. Historically, there was rivalry, but cooperation has deepened significantly. Relations with Chile have improved markedly since the resolution of border disputes, particularly the Beagle Channel dispute mediated by the Vatican in 1984.

- Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Dispute:** Argentina maintains its sovereignty claim over the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), as well as South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands and the surrounding maritime areas, which are administered by the United Kingdom as Overseas Territories. This dispute led to the Falklands War in 1982. Argentina continues to pursue its claim through diplomatic means in international forums like the United Nations.

- Antarctic Claims:** Argentina claims a sector of Antarctica (known as Argentine Antarctica), which overlaps with claims by Chile and the United Kingdom. These claims are subject to the provisions of the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, of which Argentina is an original signatory. The Antarctic Treaty freezes territorial claims and promotes scientific cooperation. Argentina maintains several permanent bases in Antarctica, with the Orcadas Base being the oldest continuously inhabited station in Antarctica (since 1904).

- Relations with Global Powers:** Argentina has historically had strong ties with European countries, particularly Spain and Italy, due to immigration and cultural links. Relations with the United States have varied, ranging from close alignment (e.g., being designated a Major non-NATO ally in 1998) to periods of tension, often related to economic policies or differing stances on international issues. In recent years, Argentina has also sought to strengthen ties with other global players, including China, which has become a major trading partner and source of investment.

- International Organizations:** Argentina is a founding member of the United Nations and participates actively in its various agencies and peacekeeping operations. It is a member of the G-15 and the G20. Argentina is also a member of the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI). It has been an OECD candidate country since January 2022.

- Human Rights in Foreign Policy:** Argentina often emphasizes human rights in its foreign policy, influenced by its own history. It is a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and has supported international efforts to combat impunity for crimes against humanity.

Argentina's foreign policy aims to promote its national interests, foster regional stability and development, and contribute to a multilateral global order. Economic considerations, including trade, investment, and debt negotiations, often play a significant role in shaping its international relationships.

5.5. Armed forces

The Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic (Fuerzas Armadas de la República Argentina) are under the civilian control of the President of Argentina, who is the commander-in-chief, and the Ministry of Defense. A strict legal framework separates national defense from internal security systems. The National Defence System is an exclusive responsibility of the federal government.

The Argentine Armed Forces consist of three main branches:

- Argentine Army** (Ejército Argentino)

- Argentine Navy** (Armada de la República Argentina)

- Argentine Air Force** (Fuerza Aérea Argentina)

The primary role of the armed forces is to guarantee the sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity of Argentina, and to protect the lives and liberty of its inhabitants against external military aggression. Secondary missions include participation in multinational peacekeeping operations under the United Nations framework, internal support missions (e.g., disaster relief), assisting friendly countries, and contributing to sub-regional defense systems.

Historically, the Argentine military played a significant and often disruptive role in politics, staging numerous coups d'état throughout the 20th century. Following the return to democracy in 1983 and the trials for human rights abuses committed during the last dictatorship, significant efforts were made to subordinate the military to civilian authority. This included budget cuts, restructuring, and a redefinition of their role to focus on external defense rather than internal security or political intervention. Conscription was abolished in 1994, and the armed forces are now an all-volunteer force. Enlistment age is between 18 and 24 years old.

Argentina's defense industry once had significant capabilities, including research facilities, shipyards, and aircraft factories. However, real military expenditures declined steadily after the defeat in the Falklands War in 1982. The defense budget has remained relatively low as a percentage of GDP compared to regional averages, leading to an erosion of military capabilities due to underfunding for training, maintenance, and modernization of equipment. The accidental loss of the submarine ARA San Juan in 2017 highlighted some of these challenges.

Despite these limitations, Argentina has participated in numerous UN peacekeeping missions, including in Haiti, Cyprus, Western Sahara, and the Middle East. It was the only South American country to send warships and cargo planes to the Gulf War in 1991 under a UN mandate.

The Interior Security System is distinct from the national defense system and is jointly administered by federal and provincial governments. Federal security forces include the Federal Police, the Naval Prefecture (coast guard duties), the National Gendarmerie (border guard and rural security tasks), and the Airport Security Police. Provincial police forces are responsible for law enforcement within their respective jurisdictions. The historical role of the armed forces in internal repression during dictatorships has led to a strong societal and legal emphasis on keeping military and internal security functions separate under democratic rule.

6. Economy

Argentina possesses rich natural resources, a highly literate population, a diversified industrial base, and an export-oriented agricultural sector. It is Latin America's third-largest economy and the second-largest in South America. However, its economic history has been marked by periods of high growth followed by severe recessions, high inflation, and debt crises.

The country has a "very high" rating on the Human Development Index and a considerable internal market size. As a middle emerging economy, it is a member of the G20. Argentina ranks 66th by nominal GDP per capita.

6.1. Main industries

Argentina's economy is characterized by a diverse range of industries, with agriculture and livestock historically forming its backbone, complemented by significant manufacturing and mining sectors. Labor conditions and environmental impacts vary across these sectors and remain important areas of social concern.

Agriculture and Livestock: This sector is a cornerstone of the Argentine economy and a major source of export revenue.

- Crops:** The fertile Pampas region is ideal for grain and oilseed production. Argentina is a leading global producer and exporter of soybeans and soy products (oil, meal), maize (corn), wheat, sunflower seeds and oil, and barley. It is also a significant producer of sorghum, lemons, pears, and grapes (primarily for wine). Yerba mate cultivation is extensive, with Argentina being the world's largest producer due to high domestic consumption.

- Livestock:** Cattle ranching is iconic, and Argentine beef is renowned worldwide for its quality. Argentina is a major beef producer and exporter. Sheep farming is prevalent in Patagonia, primarily for wool and meat. The country is also among the world's top producers of honey.

- Labor Conditions:** Agricultural labor, particularly for seasonal and migrant workers, can involve precarious conditions, low wages, and informal employment. Efforts to improve labor rights and formalize employment exist but face ongoing challenges.

- Environmental Impact:** The expansion of agriculture, especially soy cultivation, has led to deforestation (particularly in the Gran Chaco), soil degradation, and increased use of agrochemicals, raising concerns about biodiversity loss and water pollution.

Manufacturing: Manufacturing accounted for 20.3% of GDP in 2012, making it the largest single sector. It is well-integrated with the agricultural sector, with about half of industrial exports having rural origins.

- Food Processing:** This is a major sub-sector, including meatpacking, dairy production, flour milling, beverage production, and fruit and vegetable processing.

- Automotive:** Argentina has a significant automotive industry, producing vehicles and auto parts, with major international companies operating plants in the country, primarily in Córdoba and Greater Buenos Aires.

- Textiles and Leather:** Historically important, this sector produces clothing, footwear, and leather goods.

- Chemicals and Petrochemicals:** Includes the production of basic chemicals, pharmaceuticals, fertilizers, and biodiesel (leveraging its soy production).

- Metallurgy and Machinery:** Production of steel, aluminium, iron, industrial machinery, and agricultural equipment.

- Other Industries:** Home appliances, furniture, plastics, tires, glass, cement, and print media.

- Wine Industry:** Argentina is one of the top five wine-producing countries globally, famous for Malbec and Torrontés varieties.

- Labor Conditions:** Manufacturing jobs are often unionized, providing better wages and benefits than in some other sectors, but the industry is susceptible to economic downturns affecting employment.

- Environmental Impact:** Industrial activities can contribute to air and water pollution if not properly regulated. Energy consumption by industry is also a factor.

Mining: The mining industry has been growing in importance.

- Minerals:** Argentina is a significant producer of lithium (ranking among the top global producers, with vast reserves in the "Lithium Triangle" in the Andes), gold, silver, copper, and boron.