1. Overview

Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosna i HercegovinaBosna i HercegovinaBosnian; Босна и ХерцеговинаBosna i HercegovinaSerbian), sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, abbreviated BiH (БиХBiHSerbian), is a country located in Southeast Europe, on the Balkan Peninsula. Geographically, it is bordered by Croatia to the north, west, and south; Serbia to the east; and Montenegro to the southeast. It possesses a very short coastline of approximately 12 mile (20 km) along the Adriatic Sea centered around the town of Neum. The nation's history is marked by its position as a cultural crossroads, experiencing periods under Roman, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian rule, each leaving a significant imprint on its cultural and social fabric. Key historical periods include the medieval Kingdom of Bosnia, nearly four centuries of Ottoman governance which introduced Islam to a significant portion of the population, and Austro-Hungarian administration which brought modernization efforts. The 20th century saw Bosnia and Herzegovina become part of various Yugoslav states, endure the devastation of World War II with widespread persecution and resistance, and later experience relative peace and industrial development as a constituent republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s led to the brutal Bosnian War (1992-1995), characterized by severe human rights abuses, ethnic cleansing, and the Srebrenica genocide. The Dayton Agreement ended the war, establishing a complex political structure.

The country's political system is a parliamentary representative democracy with a decentralized federal structure. It comprises two primary autonomous entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (largely Bosniak and Croat inhabited) and Republika Srpska (largely Serb inhabited), along with the self-governing Brčko District. A tripartite Presidency, representing the three main constituent peoples (Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats), serves as the collective head of state. This power-sharing mechanism, designed to ensure representation, has often faced challenges related to political gridlock and reform efforts. The Office of the High Representative plays a significant role in overseeing civilian peace implementation.

The ethnic composition is primarily made up of Bosniaks (largely Muslim), Serbs (largely Orthodox Christian), and Croats (largely Roman Catholic), with smaller minorities. Bosnian, Serbian, and Croatian are the official languages and are mutually intelligible. Culturally, Bosnia and Herzegovina boasts a rich heritage evident in its diverse architecture (from Ottoman-era mosques and bridges like Stari Most to Austro-Hungarian buildings), literature (including Nobel laureate Ivo Andrić), vibrant traditional music such as Sevdalinka, and a resilient film industry. The country is a developing country working to transition its economy and continues to aspire towards European Union and NATO membership, having received EU candidate status in December 2022. This article emphasizes social impacts, human rights, and democratic development, reflecting a center-left/social liberalism perspective.

2. Etymology

The name "Bosnia" is widely believed to have originated from the Bosna river, which flows through the heartland of the region. The first preserved and widely acknowledged mention of a form of "Bosnia" appears in De Administrando Imperio, a politico-geographical handbook written by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII between 948 and 952 AD. In this work, he describes the "small land" (χωρίονchorionGreek, Modern) of "Bosona" (ΒοσώναBosonaGreek, Modern) where the Serbs were said to dwell. According to philologist Anton Mayer, the name Bosna could derive from the Illyrian term *"Bass-an-as," which itself might stem from the Proto-Indo-European root *bʰegʷ-*, meaning "the running water." The English medievalist William Miller suggested that Slavic settlers in Bosnia adapted the Latin designation "Basante" for the river to their own idiom, calling the stream Bosna and themselves Bosniaks.

The name "Herzegovina" translates to "herzog's land" or "duke's domain," with "herzog" deriving from the German word for "duke." This name originates from the title of Stjepan Vukčić Kosača, a powerful 15th-century Bosnian magnate who declared himself "Herceg [Herzog] of Hum and the Coast" in 1448. Hum, formerly known as Zachlumia, was an early medieval principality that had been incorporated into the Bosnian Banate in the first half of the 14th century. When the Ottomans took control of the region, they referred to it as the Sanjak of Herzegovina (Hersek SancağıHersek SanjakTurkish). This sanjak was initially part of the Bosnia Eyalet. In the 1830s, a short-lived Herzegovina Eyalet was formed, which re-emerged in the 1850s. Following this, the combined administrative region became commonly known as Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Upon the initial proclamation of independence in 1992, the country's official name was the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, following the 1995 Dayton Agreement and the new constitution that accompanied it, the official name was changed to simply Bosnia and Herzegovina. The country is often informally referred to as Bosnia and abbreviated as BiH (БиХBiHSerbian).

3. History

The history of Bosnia and Herzegovina spans from ancient settlements and medieval kingdoms like the Banate and Kingdom of Bosnia, through nearly four centuries of Ottoman rule that introduced Islam and shaped much of its cultural heritage, followed by Austro-Hungarian administration which brought modernization. The 20th century saw its inclusion in various Yugoslav states, the devastation of World War II, and subsequently the brutal Bosnian War (1992-1995) after Yugoslavia's dissolution, which concluded with the Dayton Agreement establishing its current complex political structure.

3.1. Early history

The region of Bosnia and Herzegovina has been inhabited by humans since at least the Upper Paleolithic period. One of the oldest known cave paintings was discovered in Badanj Cave. During the Neolithic age, permanent human settlements were established, belonging to notable cultures such as the Butmir (c. 6230 BCE-c. 4900 BCE), Kakanj, and Vučedol cultures, primarily along the Bosna river. The Bronze Age saw the rise of the Illyrians, an ethnic group with a distinct culture and art form, who began to organize themselves across a wide area that includes modern-day Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Albania.

From the 8th century BCE, Illyrian tribes evolved into kingdoms. The earliest recorded Illyrian kingdom was that of the Enchele in the 8th century BCE. The Autariatae under Pleurias (337 BCE) were also considered a kingdom. The Kingdom of the Ardiaei, originally a tribe from the Neretva valley region, began around 230 BCE and ended in 167 BCE. Notable Illyrian kingdoms and dynasties include those of Bardylis of the Dardani and Agron of the Ardiaei, who created the last and best-known Illyrian kingdom, extending his rule over various tribes.

During the 7th century BCE, iron began to replace bronze, though jewelry and art objects continued to be made from bronze. Illyrian tribes, influenced by the Hallstatt culture to the north, formed distinct regional centers. Parts of Central Bosnia were inhabited by the Daesitiates tribe, commonly associated with the Central Bosnian cultural group, while the Iron Age Glasinac-Mati culture is linked with the Autariatae tribe. The cult of the dead played a significant role, evident in their elaborate burials and ceremonies. Northern regions practiced cremation and burial in shallow graves, while in the south, the dead were interred in large stone or earth tumuli (known locally as gromile), some in Herzegovina reaching monumental sizes (over 164 ft (50 m) wide and 164 ft (50 m) high). The Japodian tribes were known for their affinity for decoration, including heavy necklaces of glass paste and large bronze fibulae, spiral bracelets, diadems, and bronze foil helmets.

The first Celtic invasion was recorded in the 4th century BCE. They introduced the potter's wheel, new types of fibulae, and different bronze and iron belts. Their influence in Bosnia and Herzegovina was relatively minor as they mainly passed through on their way to Greece. Celtic migrations displaced many Illyrian tribes, though some Celtic and Illyrian tribes intermingled. While concrete historical evidence from this period is scarce, it appears the region was populated by various peoples speaking distinct languages. In the Neretva Delta, the Illyrian Daors tribe showed significant Hellenistic influences. Their capital, Daorson, near Stolac, was surrounded by 5-meter-high megalithic stonewalls in the 4th century BCE, and they produced unique bronze coins and sculptures.

Conflict between the Illyrians and Romans began in 229 BCE, but Rome only completed its annexation of the region in 9 AD. The Roman campaign against Illyricum, known as the Bellum Batonianum (Bellum BatonianumBatonian WarLatin; 6-9 AD), was one of Rome's most challenging battles since the Punic Wars, as described by the Roman historian Suetonius. The revolt, spanning four years, arose from an attempt to recruit Illyrians and ended with their subjugation. During the Roman period, Latin-speaking settlers from across the Roman Empire settled among the Illyrians, and Roman soldiers were encouraged to retire in the region.

Following the split of the Roman Empire between 337 and 395 AD, the provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia became part of the Western Roman Empire. The Ostrogoths conquered the region in 455 AD. It subsequently changed hands between the Alans and the Huns. By the 6th century, Emperor Justinian I had reconquered the area for the Byzantine Empire.

3.1.1. Arrival of Slavs and Early Medieval Period

Early Slavs raided and settled in the Western Balkans, including Bosnia, during the 6th and early 7th centuries as part of the Migration Period. These groups were composed of small tribal units originating from a Slavic confederation known to the Byzantines as the Sclaveni. Concurrently, the related Antes colonized the eastern parts of the Balkans. Historical sources, such as Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus' De Administrando Imperio (written between 948 and 952), mention a "small land" (χωρίονchorionGreek, Modern) called "Bosona" (ΒοσώναBosonaGreek, Modern) where Serbs dwelled. This is one of the earliest preserved mentions of a form of the name "Bosnia." The interpretation of this passage has been a subject of scholarly debate, particularly concerning the early ethnic and political affiliations of the region. Some scholars interpret this as Bosnia being a distinct territory, albeit one dependent on Serbs at that time under Prince Časlav.

The De Administrando Imperio also describes a second, later migration of "Serbs" and "Croats" during the second quarter of the 7th century. The exact identity and numbers of these groups are debated by scholars. These "Serb" and "Croat" tribes came to predominate in neighboring regions. Croats are described as settling in an area roughly corresponding to modern Croatia and possibly including most of Bosnia proper, except for the eastern strip of the Drina valley. Serbs are described as settling in an area corresponding to modern southwestern Serbia (later known as Raška), gradually extending their rule into the territories of Duklja and Hum (Herzegovina).

Initial Christianization occurred under the influence of the Byzantine Empire. Early political entities began to emerge in the region, though their exact nature and extent are often unclear from the limited historical sources. Bosnia, at times, found itself under the influence or temporary rule of neighboring powers like Serbia or Croatia, but it gradually developed its own distinct identity and institutions.

3.2. Middle Ages

During the High Middle Ages, the region of Bosnia became a contested area between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Byzantine Empire. Following shifts in power between these two entities in the early 12th century, Bosnia found itself largely outside the direct control of either, leading to the emergence of the Banate of Bosnia, ruled by local bans. The first Bosnian ban known by name was Ban Borić. He was followed by Ban Kulin (reigned 1180-1204), whose rule is often considered a period of stability and prosperity. Ban Kulin's era also marked the beginning of a significant controversy involving the Bosnian Church, an indigenous Christian church considered heretical by both the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. In response to Hungarian attempts to use this religious issue as a pretext to assert sovereignty over Bosnia, Kulin held a council of local church leaders in 1203 at Bilino Polje, where they formally renounced heresy and embraced Catholicism. Despite this, Hungarian ambitions towards Bosnia persisted long after Kulin's death, only waning after an unsuccessful invasion in 1254. During this medieval period, the inhabitants of Bosnia were often referred to as Dobri Bošnjani ("Good Bosnians"). While names like "Serb" and "Croat" appeared in peripheral areas, they were not commonly used for the population within Bosnia proper.

Bosnian history from the mid-13th century until the early 14th century was characterized by a power struggle between the Šubić and Kotromanić noble families. This conflict largely ended in 1322 when Stephen II Kotromanić became Ban. By the time of his death in 1353, Stephen II had successfully expanded Bosnian territory to the north and west, and also annexed Zahumlje (Hum) and parts of Dalmatia. He was succeeded by his nephew, Tvrtko I Kotromanić. After a prolonged struggle with internal nobility and inter-family strife, Tvrtko I consolidated full control over the country by 1367.

In 1377, Bosnia was elevated to a kingdom with the coronation of Tvrtko I as the first Bosnian King. The coronation took place in Mile, near Visoko, in the Bosnian heartland. Under King Tvrtko I, the Kingdom of Bosnia reached its zenith, expanding its territory further and playing a significant role in regional politics. However, following Tvrtko I's death in 1391, Bosnia entered a long period of decline. The Ottoman Empire had begun its conquest of Europe and posed an increasing threat to the Balkan Peninsula throughout the first half of the 15th century. After decades of political and social instability, internal divisions among the nobility, and increasing Ottoman pressure, the Kingdom of Bosnia ceased to exist in 1463 after its conquest by the Ottoman Empire. Herzegovina, under the rule of the Kosača family, fell to the Ottomans a few decades later, by 1482.

Medieval Bosnian society was feudal, with a distinct nobility. The Bosnian Church, with its unique practices, remained a significant religious institution alongside Catholicism and, to a lesser extent, Orthodoxy in peripheral regions. There was a general awareness among some medieval Bosnian nobles of a shared state with Serbia and common ethnic roots, but this awareness diminished over time due to differing political and social developments, though it was maintained longer in Herzegovina and parts of Bosnia that had been part of the Serbian state.

3.3. Ottoman Empire

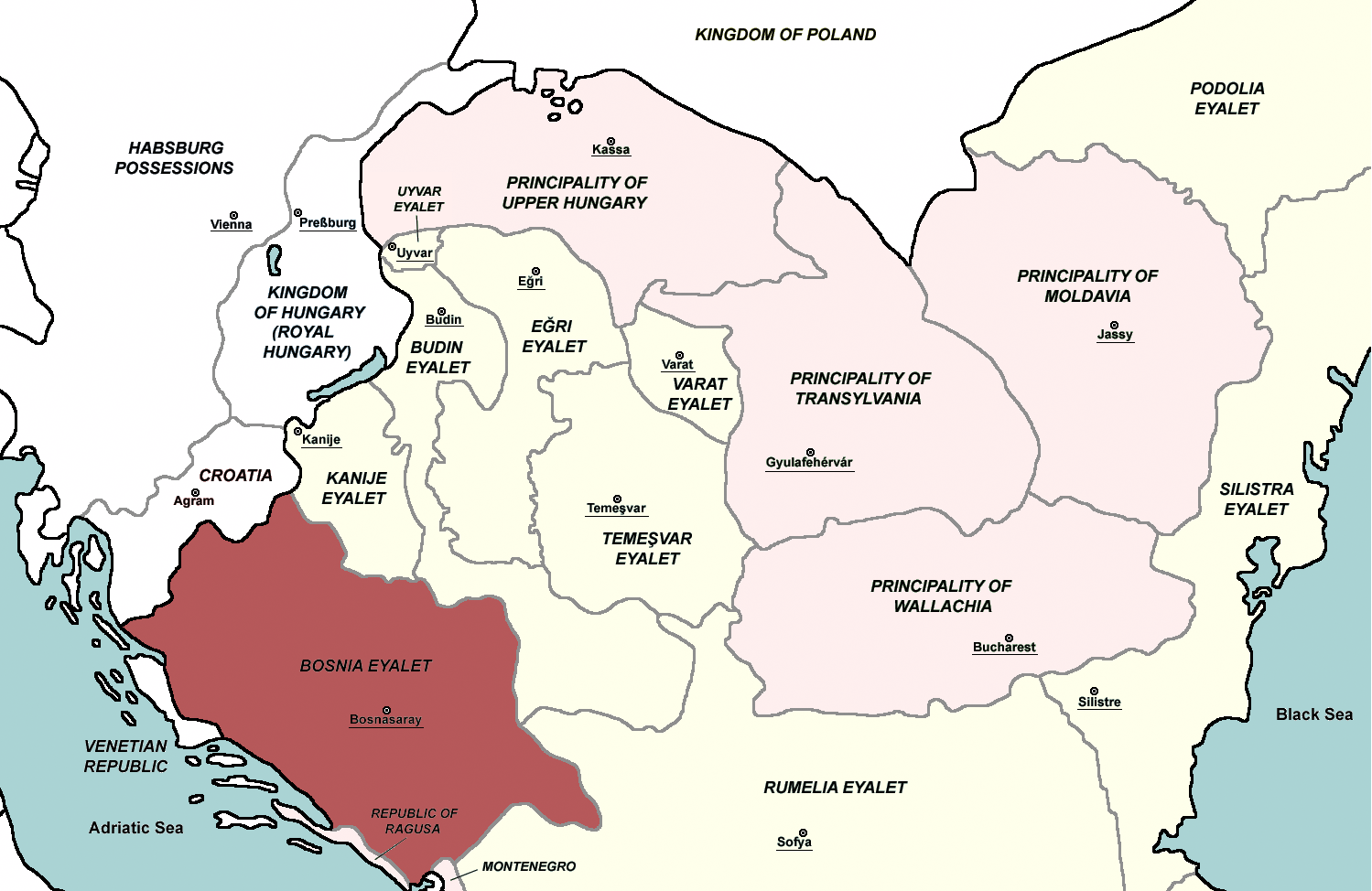

The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia in 1463, followed by Herzegovina in 1482, marked a new era in the country's history, introducing profound changes in its political, social, and cultural landscape. The Ottomans incorporated Bosnia as an integral province, initially as the Sanjak of Bosnia, which was later elevated to the Bosnia Eyalet (Pashalik). This administrative unit largely preserved Bosnia's historical name and territorial integrity, a unique case among the conquered Balkan states.

3.3.1. Integration and Administration

Under Ottoman rule, a new landholding system, known as the timar system, was introduced, and administrative units were reorganized. Society became more complex, with differentiation based on class and religious affiliation. Cities like Sarajevo and Mostar were established or significantly developed, becoming regional centers of trade, urban culture, and Islamic learning. Ottoman governors and local benefactors financed the construction of numerous architectural works, including mosques like the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque in Sarajevo, bridges such as the Stari Most in Mostar, madrasas (Islamic schools), and public baths. Sarajevo, for instance, received its first library, a school of Sufi philosophy, and a clock tower (Sahat Kula).

A significant portion of the local Slavic-speaking population gradually converted to Islam. This process was complex and occurred over centuries, influenced by factors such as the absence of strong, unified Christian church organizations prior to the conquest (the indigenous Bosnian Church eventually disappeared, its members likely converting to Islam or other Christian denominations), the social and economic advantages offered to Muslims within the Ottoman system, and continuous rivalry between the Orthodox and Catholic churches. The Ottomans often referred to Christians generally as kristianlar, while distinguishing between Orthodox and Catholics when necessary, or using terms like gebir or kafir (unbeliever) for non-Muslims. The Bosnian Franciscans, representing the Catholic population, were protected by official imperial decrees (ahdname), although in practice, their status often depended on the arbitrary rule of local elites.

The Ottoman period also saw demographic shifts. While many Catholics fled to neighboring Catholic lands, particularly in the early Ottoman period, an Orthodox Christian population grew in Bosnia, partly due to Ottoman policies that sometimes favored the Serbian Orthodox Church over the Catholic Church, and the migration of Orthodox Vlachs and Serbs from Serbia and other regions into Bosnia. By the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Muslims are considered to have become the largest ethno-religious group. The Albanian Catholic priest Pjetër Mazreku reported in 1624 that Bosnia and Herzegovina had approximately 450,000 Muslims, 150,000 Catholics, and 75,000 Eastern Orthodox Christians.

Several Bosnian Muslims played influential roles in the Ottoman Empire's cultural and political history. These included admirals like Matrakçı Nasuh; generals such as Isa-Beg Ishaković, Gazi Husrev-beg, Telli Hasan Pasha, and Sarı Süleyman Pasha; administrators like Ferhad Pasha Sokolović and Osman Gradaščević; and Grand Viziers such as the influential Sokollu Mehmed Pasha and Damat Ibrahim Pasha. Bosnian scholars, Sufi mystics, and poets also contributed to Ottoman culture, writing in Turkish, Arabic, and Persian.

3.3.2. Revolts and Decline

By the late 17th century, the Ottoman Empire's military fortunes began to wane. The Great Turkish War concluded with the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, which once again made Bosnia the empire's westernmost province, now bordering the expanding Habsburg Monarchy and Venetian Republic. The 18th century was marked by further military failures for the Ottomans, numerous local revolts within Bosnia often led by disgruntled local lords (ayans), and several outbreaks of plague.

The Ottoman central government's efforts at modernization in the 19th century, known as the Tanzimat reforms, were met with significant resistance in Bosnia. Local aristocrats and janissaries stood to lose much of their traditional power and privileges. This, combined with frustrations over territorial concessions in the northeast and the plight of Slavic Muslim refugees arriving from the Sanjak of Smederevo (Serbia), culminated in a major revolt led by Husein Gradaščević in 1831. Gradaščević, known as the "Dragon of Bosnia," sought an autonomous Bosnia Eyalet, free from the direct authoritarian rule of Sultan Mahmud II. The revolt was eventually suppressed by 1832, with the reluctant assistance of figures like Ali Pasha Rizvanbegović. Related rebellions continued sporadically until 1850, but the overall situation in the province continued to deteriorate.

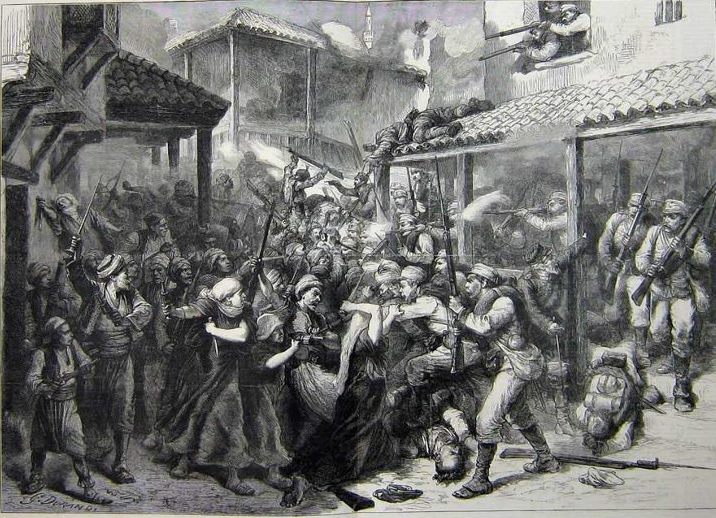

New nationalist movements began to appear in Bosnia by the mid-19th century. Following Serbia's de facto independence from the Ottoman Empire, Serbian and Croatian nationalism gained traction in Bosnia, with proponents making irredentist claims to Bosnian territory. Agrarian unrest, fueled by economic hardship and oppressive taxation, eventually sparked the Herzegovina Uprising in 1875. This widespread peasant rebellion rapidly spread and drew in several Balkan states and the Great Powers, leading to the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878) and ultimately the Congress of Berlin and the Treaty of Berlin in 1878. This treaty placed Bosnia and Herzegovina under Austro-Hungarian occupation and administration, though it formally remained Ottoman territory.

3.4. Austria-Hungary

Following the Congress of Berlin in 1878, Austria-Hungary obtained the mandate to occupy and administer Bosnia and Herzegovina, although it officially remained under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire. The Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister, Gyula Andrássy, also secured the right to station garrisons in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, an Ottoman administrative unit that separated Serbia from Montenegro. Austro-Hungarian troops began their occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in August 1878, facing some armed resistance but establishing control relatively quickly.

Although Austro-Hungarian officials managed to reach an agreement with many Bosnians, tensions persisted, and a mass emigration of some Bosnians, particularly Muslims, occurred. However, a state of relative stability was soon achieved, allowing Austro-Hungarian authorities to embark on a number of social and administrative reforms. Their aim was to transform Bosnia and Herzegovina into a "model" colony, modernizing its infrastructure, economy, and administration. This period saw significant industrialization, the development of railways, the expansion of cities like Sarajevo, and the introduction of new legal and educational systems. The Habsburg rule also attempted to foster a distinct Bosnian or Bosniak identity to counter the growing South Slav nationalism, particularly Serb and Croat claims to the region.

3.4.1. Annexation and Political Developments

Austria-Hungary began planning the formal annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but international complexities delayed this until the Bosnian Crisis of 1908. Several external factors influenced this decision. A bloody coup in Serbia in 1903 brought a radical anti-Austrian government to power in Belgrade. Then, in 1908, the Young Turk Revolution in the Ottoman Empire raised concerns in Vienna that the new Ottoman government might seek the outright return of Bosnia and Herzegovina or grant it autonomy, undermining Austro-Hungarian influence. These factors pushed the Austro-Hungarian government to seek a permanent resolution.

Taking advantage of the turmoil in the Ottoman Empire, Austro-Hungarian diplomacy secured provisional Russian approval for changing the status of Bosnia and Herzegovina in exchange for Austrian support for Russian naval access to the Dardanelles. On October 6, 1908, Austria-Hungary proclaimed the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This act caused a major international crisis, deeply angering Serbia (which had aspirations to unite South Slavs, including those in Bosnia) and its patron, Russia. Despite international objections, Russia and Serbia were compelled to accept the annexation in March 1909, though the crisis significantly damaged Austro-Russian relations and heightened South Slav nationalist sentiments against Habsburg rule. Austro-Hungarian troops also withdrew from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar at this time as a conciliatory gesture.

In 1910, Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph proclaimed the first constitution for Bosnia, which led to the relaxation of earlier laws, the holding of elections, and the formation of the Bosnian Diet (Sabor). This allowed for the growth of new political life, although the Diet had limited powers and franchise was restricted. Nationalist movements among Serbs, Croats, and Muslims continued to develop and express their political aspirations.

3.4.2. World War I

On June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb student and member of the revolutionary movement Young Bosnia (Mlada Bosna), assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarajevo. This event, known as the Sarajevo assassination, provided the spark that ignited World War I. Austria-Hungary, with German backing, issued an ultimatum to Serbia, leading to a cascade of alliances being activated and plunging Europe into war.

During World War I, many Bosnians, particularly from the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry (Bošnjak) regiments of the Austro-Hungarian Army, served on various fronts. These regiments were known for their loyalty and fighting prowess. The Bosnian Muslim population, per capita, suffered significant losses serving in the Austro-Hungarian military. The war also exacerbated inter-ethnic tensions within Bosnia and Herzegovina. Austro-Hungarian authorities established an auxiliary militia known as the Schutzkorps, predominantly recruited from the Bosnian Muslim population. The Schutzkorps were tasked with hunting down rebel Serbs (Chetniks and Komitadji) and became known for their persecution of Serbs, particularly in Serb-populated areas of eastern Bosnia, partly in retaliation for Serbian Chetnik attacks against the Muslim population in 1914. Austro-Hungarian authorities arrested around 5,500 citizens of Serb ethnicity in Bosnia and Herzegovina; between 700 and 2,200 died in prison, and 460 were executed. Approximately 5,200 Serb families were forcibly expelled from the region. Despite these internal conflicts and the wider war, Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole managed to escape the direct devastation of major battles on its soil, unlike Serbia or Galicia. The war ended with the collapse of Austria-Hungary in 1918.

3.5. Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Following the end of World War I and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bosnia and Herzegovina became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes on December 1, 1918. This new South Slav state was soon renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. Political life in Bosnia and Herzegovina during this period was marked by two major trends: social and economic unrest related to land reform and property redistribution, and the formation of several political parties that frequently changed coalitions and alliances with parties in other Yugoslav regions.

The dominant ideological conflict within the Yugoslav state was between Croatian regionalism and Serbian centralism. This conflict was approached differently by Bosnia and Herzegovina's major ethnic groups-Bosniaks (then commonly referred to as Muslims), Serbs, and Croats-and was largely dependent on the overall political atmosphere. The land reforms enacted by the new kingdom had a significant impact on Bosnian Muslims, who, according to the 1910 Austro-Hungarian census, owned a substantial portion of the land (91.1% of property, with Orthodox Serbs owning 6.0% and Croat Catholics 2.6%). Following the reforms, Bosnian Muslims were dispossessed of a total of 1,175,305 hectares of agricultural and forest land, leading to considerable economic hardship and social displacement for many. This process often benefited Serb settlers and fueled resentment.

Although the initial administrative division of the country into 33 oblasts (provinces) in 1922 largely erased traditional geographic entities from the map, the efforts of Bosnian politicians, such as Mehmed Spaho of the Yugoslav Muslim Organization (JMO), ensured that the six oblasts carved out from Bosnia and Herzegovina corresponded roughly to the six sanjaks from Ottoman times. This maintained a semblance of the country's traditional boundaries as a whole.

3.5.1. Administrative Changes and Ethnic Tensions

The establishment of a royal dictatorship by King Alexander I in 1929 brought about a more drastic redrawing of administrative regions into nine large banovinas (banates). These banovinas were deliberately designed to avoid historical and ethnic lines, effectively removing any trace of a distinct Bosnian entity. Parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina were incorporated into different banovinas, such as the Vrbas Banovina, Drina Banovina, Littoral Banovina, and Zeta Banovina, often with the aim of diluting ethnic concentrations and promoting a unified Yugoslav identity, though in practice, this often exacerbated Serbo-Croat tensions.

Serbo-Croat tensions over the structuring of the Yugoslav state continued throughout the interwar period. The concept of a separate Bosnian division received little or no consideration from the dominant Serb and Croat political elites in Belgrade and Zagreb, respectively. These tensions culminated in the Cvetković-Maček Agreement of August 1939. This agreement, aimed at resolving the "Croatian question," created an autonomous Banovina of Croatia, which incorporated significant parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina with Croat populations, effectively leading to a partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina between Croatia and what remained under Serbian influence. This arrangement caused alarm among Bosnian Muslims, who felt their interests were being disregarded. However, the rising threat of Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany soon forced Yugoslav politicians to shift their attention. Following a period of attempted appeasement, the signing of the Tripartite Pact, and a coup d'état that overthrew the pro-Axis government, Yugoslavia was invaded by Germany and its allies on April 6, 1941.

3.6. World War II

Following the Axis invasion and occupation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in April 1941, all of Bosnia and Herzegovina was incorporated into the Nazi puppet state known as the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), led by the fascist Ustaše movement under Ante Pavelić. The NDH regime immediately embarked on a brutal campaign of extermination against Serbs, Jews, and Roma, as well as dissident Croats and, later, Josip Broz Tito's Partisans. Numerous death camps were established, where systematic massacres occurred. The Ustaše regime systematically and brutally massacred Serbs in villages, particularly in the countryside. The scale of this violence was immense; approximately every sixth Serb living in Bosnia and Herzegovina became a victim of massacre, and an estimated 209,000 Serbs (16.9% of Bosnia's Serb population) were killed on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war. This horrific experience left a profound and lasting trauma in the collective memory of Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Ustaše regime recognized both Catholicism and Islam as national religions but viewed the Eastern Orthodox Church, a symbol of Serb identity, as its greatest foe. Although Croats formed the largest ethnic group within the Ustaše, the Vice President of the NDH and leader of the Yugoslav Muslim Organization, Džafer Kulenović, was a Muslim, and Muslims constituted nearly 12% of the Ustaše military and civil service. A percentage of Muslims also served in Nazi Waffen-SS Handschar Division, which was involved in massacres of Serbs in northwest and eastern Bosnia, notably in Vlasenica. In response to the Ustaše persecutions, a group of 108 prominent Sarajevan Muslims signed the Resolution of Sarajevo Muslims on October 12, 1941, condemning the persecution of Serbs, distinguishing between Muslims who participated in such acts and the Muslim population as a whole, highlighting persecutions of Muslims by Serbs as well, and requesting security for all citizens.

3.6.1. Occupation and Resistance Movements

In response to the Ustaše atrocities, many Serbs took up arms and joined the Chetniks, a Serb nationalist and royalist movement aiming to establish an ethnically homogeneous 'Greater Serbia' within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The Chetniks, in turn, pursued a genocidal campaign against ethnic Muslims and Croats, as well as persecuting communist Serbs and other sympathizers. Muslim populations in Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Sandžak were primary targets, with systematic massacres of captured Muslim villagers. Of the approximately 75,000 Muslims who died in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war, around 30,000 (mostly civilians) were killed by the Chetniks. Massacres against Croats by Chetniks were smaller in scale but similar in action; between 64,000 and 79,000 Bosnian Croats were killed between April 1941 and May 1945, with about 18,000 killed by Chetniks.

Starting in 1941, Yugoslav communists under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito organized their own multi-ethnic resistance group, the Partisans, who fought against Axis forces, the Ustaše, and the Chetniks. The Partisans aimed to liberate Yugoslavia and establish a socialist federal state. Bosnia and Herzegovina became a central battleground for all warring factions, with its population bearing the brunt of the fighting and atrocities. During the course of World War II in Yugoslavia, statistics show that 64.1% of all Bosnian Partisans were Serbs, 23% were Muslims, and 8.8% Croats, reflecting the diverse appeal of the Partisan movement against occupation and inter-ethnic violence.

3.6.2. Establishment of the Socialist Republic

On November 29, 1943, the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ), with Tito at its helm, held its second session in Jajce, Bosnia and Herzegovina. At this historic conference, Bosnia and Herzegovina was re-established as a republic with its Habsburg-era borders within the future Yugoslav federation. This decision recognized Bosnia and Herzegovina's distinct historical identity and multi-ethnic character.

Military successes eventually prompted the Allies to shift their support from the Chetniks to the Partisans, particularly after the successful Maclean Mission. However, Tito largely relied on his own forces. All major military offensives by the antifascist movement of Yugoslavia against the Nazis and their local collaborators were conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The human and material losses during the war were immense. More than 300,000 people died in Bosnia and Herzegovina in World War II, representing over 10% of its population. At the end of the war, the establishment of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), with the constitution of 1946, officially made Bosnia and Herzegovina one of the six constituent republics in the new state.

3.7. Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

Following World War II, Bosnia and Herzegovina became one ofthe six constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) from 1945 until 1992. Due to its central geographic position within the federation and its rich natural resources, post-war Bosnia was strategically selected as a base for the development of the military defense industry. This led to a large concentration of arms factories and military personnel in Bosnia, a factor that would become significant during the war that followed the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

3.7.1. Political and Economic Development

For a large part of its existence within Yugoslavia, Bosnia and Herzegovina experienced a period of relative peace and considerable prosperity. There was high employment, a strong industrial base with an export-oriented economy, a good education system, and social and medical security for its citizens. Several international corporations operated in Bosnia, including Volkswagen (through the TAS car factory in Sarajevo, from 1972), Coca-Cola (from 1975), SKF of Sweden (from 1967), and Marlboro (a tobacco factory in Sarajevo), alongside Holiday Inn hotels. A major highlight of this era was Sarajevo hosting the 1984 Winter Olympics, which brought international recognition and investment to the republic.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Bosnia was often considered a political backwater within Yugoslavia. However, in the 1970s, a strong Bosnian political elite emerged, partly fueled by Tito's leadership in the Non-Aligned Movement and the significant number of Bosnians serving in Yugoslavia's diplomatic corps. Politicians such as Džemal Bijedić (who served as Prime Minister of Yugoslavia), Branko Mikulić (also a Yugoslav Prime Minister and later President of the Presidency of Yugoslavia), and Hamdija Pozderac (a key figure in Bosnian politics) worked within the Socialist system to reinforce and protect the sovereignty and distinctiveness of Bosnia and Herzegovina within the federation. Their efforts, including the recognition of Muslims (Bosniaks) as a distinct nation in the Yugoslav context, proved crucial during the turbulent period following Tito's death in 1980 and are today considered by some as early steps towards eventual Bosnian independence.

3.7.2. Seeds of Dissolution

The death of Josip Broz Tito in 1980 marked a turning point for Yugoslavia. The central authority began to weaken, and long-suppressed ethnic nationalism started to rise throughout the federation. Economic difficulties in the 1980s, including high inflation and foreign debt, further exacerbated political tensions. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, while inter-ethnic relations had been largely harmonious, the increasingly nationalistic climate began to take its toll. The fall of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 and the start of the breakup of Yugoslavia saw the doctrine of "brotherhood and unity" lose its potency. This created an opportunity for nationalist elements within Bosnian society, representing Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats, to spread their influence and advocate for differing visions of the republic's future, setting the stage for the federation's violent disintegration in the early 1990s.

3.8. Bosnian War

The Bosnian War (1992-1995) was an international armed conflict that took place in Bosnia and Herzegovina following its declaration of independence from Yugoslavia. It involved complex and shifting alliances between the country's main ethnic groups: Bosniaks (Muslims), Serbs, and Croats, fueled by political, ethnic, and religious nationalisms. The war was characterized by widespread ethnic cleansing, war crimes, including the Srebrenica genocide, the protracted Siege of Sarajevo, and immense human suffering. International intervention eventually led to the Dayton Agreement, which ended the war but established a highly complex and decentralized political structure for the country. This section will specifically address the humanitarian issues, the impact on civilians, and the roles of different ethnic groups and political factions, reflecting a perspective that emphasizes human rights and the devastating social consequences of the conflict.

3.8.1. Path to Independence and Outbreak of War

On November 18, 1990, the first multi-party parliamentary elections were held in Bosnia and Herzegovina. These elections saw communist power replaced by a coalition of three ethnically based parties: the Bosniak Party of Democratic Action (SDA) led by Alija Izetbegović, the Serb Democratic Party (SDS) led by Radovan Karadžić, and the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ BiH) led by Stjepan Kljuić. Following Slovenia's and Croatia's declarations of independence from Yugoslavia in June 1991, a significant political split developed among the residents of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The issue was whether to remain within a rump Yugoslavia (overwhelmingly favored by Serbs) or seek independence (overwhelmingly favored by Bosniaks and Croats).

The Serb members of parliament, mainly from the SDS, abandoned the central parliament in Sarajevo and formed the Assembly of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina on October 24, 1991. This effectively ended the three-ethnic coalition. This assembly established the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (later Republika Srpska) on January 9, 1992, in parts of Bosnian territory. Similarly, on November 18, 1991, the HDZ BiH proclaimed the existence of the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia as a separate political, cultural, economic, and territorial whole, with the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) as its military branch. The Bosnian government declared Herzeg-Bosnia illegal.

A declaration of sovereignty by Bosnia and Herzegovina on October 15, 1991, was followed by a referendum for independence held on February 29 and March 1, 1992. The referendum was largely boycotted by Bosnian Serbs at the instigation of the SDS. The turnout was 63.4%, with 99.7% of voters choosing independence. Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on March 3, 1992, and received international recognition on April 6, 1992, from the European Community and the United States. The country was admitted as a member state of the United Nations on May 22, 1992.

Even before international recognition, tensions escalated. Bosnian Serb militias, supported by the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and paramilitary forces from Serbia, began to mobilize and seize territory. The newly independent Bosnian government forces were poorly equipped and unprepared for the war that swiftly followed the declaration of independence. Widespread hostilities broke out across the country.

3.8.2. Course of the War and Ethnic Cleansing

The war quickly escalated with Bosnian Serb forces, later reformed as the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) under the command of General Ratko Mladić, launching offensives and rapidly gaining control of large swathes of Bosnian territory. These offensives were armed and equipped from JNA stockpiles and received extensive support from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro). The VRS advances were accompanied by systematic ethnic cleansing of Bosniak and Bosnian Croat populations from areas under Serb control. This involved mass killings, forced displacement, the establishment of concentration camps (such as Omarska, Keraterm, and Trnopolje), torture, rape as a weapon of war, and the destruction of cultural and religious heritage. The Siege of Sarajevo, which lasted for nearly four years (April 1992 to February 1996), became a symbol of the war's brutality, with the city's civilian population subjected to constant shelling and sniper fire, resulting in over 11,000 deaths.

The most notorious act of ethnic cleansing was the Srebrenica massacre in July 1995, where VRS forces systematically executed more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys after overrunning the UN-declared "safe area." This event was later ruled to have been a genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Bosniak and Bosnian Croat forces also committed war crimes and atrocities against civilians from different ethnic groups, though on a smaller scale than those committed by Serb forces. These included killings, mistreatment of prisoners in camps like Čelebići, and destruction of property. Much of the Croat-perpetrated atrocities occurred during the Croat-Bosniak War (1992-1994), a sub-conflict within the larger Bosnian War that pitted the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH), loyal to the Sarajevo government, against the HVO, the military arm of Herzeg-Bosnia which was backed by Croatia. This conflict saw intense fighting in central Bosnia and Herzegovina, notably in areas like Mostar, where the historic Stari Most (Old Bridge) was destroyed by HVO shelling in 1993. The Bosniak-Croat conflict ended in March 1994 with the signing of the Washington Agreement, brokered by the United States, which led to the creation of a joint Bosniak-Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This re-established an alliance against the Serb forces.

The humanitarian impact of the war was catastrophic. Millions were displaced, becoming refugees or internally displaced persons. The deliberate targeting of civilians, systematic rape, and the establishment of concentration camps caused immense trauma and fundamentally altered the demographic landscape of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

3.8.3. International Intervention and Dayton Agreement

The international community's response to the Bosnian War was initially hesitant and often criticized as ineffective. The United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed with a mandate primarily focused on humanitarian aid delivery and monitoring ceasefires, but it lacked the resources and authority to effectively stop the fighting or protect civilians in many instances, particularly in the UN "safe areas" like Srebrenica and Žepa.

Growing international outrage over atrocities, particularly the Srebrenica genocide and the Markale market massacres in Sarajevo, eventually led to more robust NATO intervention. NATO conducted airstrikes against Bosnian Serb positions in 1995 (Operation Deliberate Force), which, combined with successful ground offensives by the unified Bosniak-Croat forces (ARBiH and HVO) and the Croatian Army (Operation Storm and Operation Mistral 2), significantly weakened the VRS.

These developments paved the way for peace negotiations. Under the auspices of the United States, peace talks were held in Dayton, Ohio, involving the presidents of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Alija Izetbegović), Croatia (Franjo Tuđman), and Serbia (Slobodan Milošević, representing the Bosnian Serbs). The Dayton Agreement was initialed on November 21, 1995, and formally signed in Paris on December 14, 1995.

The Dayton Agreement ended the war and preserved Bosnia and Herzegovina as a single state within its internationally recognized borders. However, it established a complex internal political structure, dividing the country into two largely autonomous entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (covering 51% of the territory) and Republika Srpska (covering 49%). A central government with limited powers was created, along with intricate power-sharing mechanisms designed to protect the interests of the three constituent peoples. The agreement also provided for the deployment of a NATO-led peacekeeping force, the Implementation Force (IFOR), later succeeded by the Stabilisation Force (SFOR) and then the EU-led EUFOR Althea, to oversee military aspects of the peace accord. The Office of the High Representative (OHR) was established to oversee the civilian implementation of the agreement.

While the Dayton Agreement succeeded in stopping the bloodshed, its constitutional framework has been criticized for entrenching ethnic divisions and creating a dysfunctional political system prone to gridlock, hindering post-war reconciliation and democratic development.

3.9. Recent history

The post-Dayton period in Bosnia and Herzegovina, from 1995 to the present, has been characterized by the immense challenges of state-building under a complex constitutional framework, socio-economic recovery from a devastating war, and persistent ethnic tensions. The Dayton Agreement established a political structure dividing the country into two main entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska, plus the Brčko District, with power-sharing mechanisms designed to ensure representation for Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats. However, this system has often led to political gridlock and hindered effective governance and reform.

The Office of the High Representative (OHR), created to oversee the civilian implementation of the Dayton Agreement, has played a significant, and at times controversial, role, possessing "Bonn Powers" to impose laws and dismiss officials. While crucial in the early post-war years for maintaining stability and pushing through essential reforms, the OHR's extensive powers have also raised questions about the country's full sovereignty and democratic maturity.

Socio-economic recovery has been slow, hampered by war damage, high unemployment, corruption, and a complex administrative environment. Privatization processes have often been problematic, leading to job losses and public discontent. In February 2014, widespread social unrest and protests, dubbed the "Bosnian Spring," erupted, starting in Tuzla and spreading to other cities. These protests were driven by frustration over high unemployment, government corruption, and political inertia, marking the largest outbreak of public anger since the war.

Persistent ethnic tensions and nationalist rhetoric continue to challenge national reconciliation and political reform. Efforts towards further constitutional reform to create a more functional state have largely stalled due to disagreements among ethnic political leaders. Corruption remains a significant problem, undermining public trust and economic development.

Despite these challenges, Bosnia and Herzegovina has made some progress. The country has maintained peace, and its armed forces were unified in 2005. It has pursued aspirations towards European Union and NATO membership. Bosnia and Herzegovina initiated the Stabilisation and Association Process with the EU in 2007 and formally applied for EU membership in 2016. It was granted EU candidate status in December 2022, a significant milestone. The country has also been part of NATO's Membership Action Plan (MAP) since 2010, though progress towards full NATO membership has been complicated by internal political divisions, particularly from Republika Srpska.

Human rights and reconciliation efforts remain ongoing concerns. Prosecuting war crimes through domestic courts and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has been a crucial part of addressing the legacy of the war, but many victims still await justice and full acknowledgment of their suffering. Issues such as segregated education systems ("Two schools under one roof") highlight the ongoing challenges in building a truly integrated and inclusive society. Reports from international bodies, such as a late 2021 report by Christian Schmidt of the OHR, have warned of intensified political and ethnic tensions that could potentially threaten the country's stability and territorial integrity. The path towards full democratic consolidation, sustainable economic prosperity, and lasting reconciliation remains complex.

4. Geography

Bosnia and Herzegovina is situated in Southeast Europe, specifically on the western part of the Balkan Peninsula. It is bordered by Croatia to the north, west, and south (a border length of 579 mile (932 km)), Serbia to the east (188 mile (302 km)), and Montenegro to the southeast (140 mile (225 km)). The country is almost entirely landlocked, except for a very short stretch of coastline on the Adriatic Sea, approximately 12 mile (20 km) long, centered around the town of Neum. This narrow coastal access effectively splits the Croatian mainland from its southernmost Dubrovnik region. Bosnia and Herzegovina lies between latitudes 42° and 46° N, and longitudes 15° and 20° E. The country's name is derived from its two historical regions: Bosnia, which forms the larger northern and central part, and Herzegovina, the smaller southern region, whose precise boundary has never been formally defined.

4.1. Topography and Climate

The country's terrain is predominantly mountainous, dominated by the central Dinaric Alps. These mountains generally run in a southeast-northwest direction and tend to increase in elevation towards the south. The highest point in Bosnia and Herzegovina is Maglić, at 7.8 K ft (2.39 K m), located on the border with Montenegro. Other major mountains include Volujak, Zelengora, Lelija, Lebršnik, Orjen, Kozara, Grmeč, Čvrsnica, Prenj, Vran, Vranica, Velež, Vlašić, Cincar, Romanija, Jahorina, Bjelašnica, Treskavica, and Trebević. The geological composition of the Dinaric chain in Bosnia primarily consists of limestone (including Mesozoic limestone), with deposits of iron, coal, zinc, manganese, bauxite, lead, and salt found in some areas, particularly in central and northern Bosnia.

The northwestern part of Bosnia is moderately hilly, while the northeastern parts, particularly along the Sava River in the Posavina region, are predominantly flat and form part of the fertile Pannonian Basin, extending into neighboring Croatia and Serbia. This area is heavily farmed. Herzegovina, the smaller, southern region, is mostly mountainous with dominant karst topography, characterized by underground rivers, sinkholes, and caves.

The climate varies across the country. Bosnia generally has a moderate continental climate, with hot summers and cold, snowy winters. Herzegovina experiences a Mediterranean climate, with milder, wetter winters and hot, dry summers. The short Adriatic coastline around Neum also shares this Mediterranean climate.

4.2. Biodiversity

Bosnia and Herzegovina possesses a rich biodiversity, owing to its varied topography, climate, and geographical position. Phytogeographically, the country belongs to the Boreal Kingdom and is shared between the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region and the Adriatic province of the Mediterranean Region. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina can be subdivided into four main ecoregions: Balkan mixed forests, Dinaric Mountains mixed forests, Pannonian mixed forests, and Illyrian deciduous forests.

The country has a significant forest cover, with nearly 50% of its land area being forested. Most forest areas are concentrated in the central, eastern, and western parts of Bosnia. In 2020, forest cover was estimated at 2,187,910 hectares (ha), a slight decrease from 2,210,000 ha in 1990. As of 2015, approximately 74% of the forest area was under public ownership, and 26% was privately owned. Bosnia and Herzegovina had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.99/10, ranking it 89th globally out of 172 countries.

The diverse habitats support a wide range of endemic flora and fauna. The country has established several national parks and protected areas to conserve its natural heritage. Notable national parks include:

- Sutjeska National Park, the oldest national park, home to Maglić (the country's highest peak) and the Perućica primeval forest, one of the last remaining old-growth forests in Europe.

- Kozara National Park, known for its dense forests and memorial complex dedicated to World War II battles.

- Una National Park, protecting the upper course of the Una River and its tributaries, renowned for its waterfalls (like Štrbački buk), rapids, and biodiversity.

- Drina National Park, established more recently to protect the Drina River canyon and its surrounding ecosystems in Republika Srpska.

Challenges to biodiversity include habitat loss, illegal logging, pollution, and the impacts of climate change. Conservation efforts are ongoing, often supported by international organizations, but face difficulties due to complex administrative structures and limited resources.

4.3. Major Rivers and Cities

Bosnia and Herzegovina is rich in water resources, with numerous rivers and tributaries carving through its mountainous landscape. The major rivers include:

- The Sava river is the largest river by volume passing through the country and forms its northern natural border with Croatia. It drains approximately 76% of the country's territory into the Danube and then the Black Sea. Bosnia and Herzegovina is a member of the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR).

- The Una, Sana, and Vrbas are significant right tributaries of the Sava, located in the northwestern region of Bosanska Krajina. They are known for their natural beauty and recreational opportunities, such as rafting.

- The Bosna river, from which the country partly derives its name, is the longest river fully contained within Bosnia and Herzegovina. It flows through central Bosnia, from its source near Sarajevo northward to the Sava.

- The Drina river flows through the eastern part of Bosnia, forming a large part of the natural border with Serbia. It is known for its dramatic canyons and hydroelectric potential.

- The Neretva river is the major river of Herzegovina and the only large river in the country that flows south, emptying into the Adriatic Sea through Croatia. It is famous for the city of Mostar and its historic bridge.

The country's main urban centers, which are also significant economic and cultural hubs, include:

- Sarajevo: The capital and largest city, located in the Bosna river valley, surrounded by mountains. It is the political, cultural, and economic heart of the country.

- Banja Luka: The second-largest city and the de facto capital of the Republika Srpska entity, situated in the northwestern Bosanska Krajina region on the Vrbas river.

- Tuzla: A major industrial city in the northeastern part of Bosnia, known for its salt deposits and coal mining.

- Zenica: An industrial city in central Bosnia on the Bosna river, historically a center for steel production.

- Mostar: The largest city in the Herzegovina region and its historical capital, located on the Neretva river, famous for the Stari Most (Old Bridge).

Other notable cities include Prijedor, Bijeljina, Doboj, and Brčko.

5. Politics

The political system of Bosnia and Herzegovina is exceptionally complex, largely a result of the Dayton Agreement signed in 1995 to end the Bosnian War. This agreement established a decentralized federal structure designed to balance the interests of the country's three "constituent peoples" - Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats. While intended to ensure representation and prevent renewed conflict, this structure has often led to political gridlock, hindering reforms and democratic consolidation. The country operates as a parliamentary representative democracy.

5.1. Government Structure

The central government institutions of Bosnia and Herzegovina include:

- The Presidency: This is the collective head of state, composed of three members: one Bosniak and one Croat elected from the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and one Serb elected from Republika Srpska. The Chairmanship of the Presidency rotates among the three members every eight months during their four-year term. Each member has veto power over decisions if they are deemed destructive to a vital national interest of their constituent people.

- The Council of Ministers: This acts as the country's government (executive branch). The Chair of the Council of Ministers is nominated by the Presidency and approved by the Parliamentary Assembly. The Chair then appoints other ministers (e.g., Foreign Minister, Minister of Foreign Trade), who also require parliamentary approval. The distribution of ministerial posts also reflects ethnic quotas.

- The Parliamentary Assembly: This is the bicameral legislature of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- The House of Peoples (upper house) has 15 delegates. Two-thirds (5 Bosniaks and 5 Croats) are selected by the House of Peoples of the Federation, and one-third (5 Serbs) are selected by the National Assembly of Republika Srpska. It has significant powers to block legislation if it is deemed harmful to the vital national interests of one of the constituent peoples.

- The House of Representatives (lower house) is composed of 42 members elected directly by the people under a system of proportional representation. Two-thirds of the members (28) are elected from the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and one-third (14) from Republika Srpska.

The electoral system is based on the two entities, with voters in the Federation electing Bosniak and Croat members of the Presidency and their representatives to the House of Representatives, while voters in Republika Srpska elect the Serb member of the Presidency and their representatives. This system has been criticized for discriminating against citizens who do not identify with one of the three constituent peoples or who reside in an entity where they are a minority for certain electoral contests (e.g., the Sejdić and Finci case at the European Court of Human Rights).

The Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina is the supreme arbiter of legal matters and has the final say on constitutional issues. It is composed of nine members: four are selected by the House of Representatives of the Federation, two by the National Assembly of Republika Srpska, and three international judges are selected by the President of the European Court of Human Rights after consultation with the Presidency. These international judges cannot be citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina or any neighboring country.

5.2. Administrative Divisions

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a highly decentralized state. Its internal political structure is primarily composed of:

- Two main Entities:

- The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH): Covering approximately 51% of the country's territory, it is predominantly inhabited by Bosniaks and Croats.

- Republika Srpska (RS): Covering approximately 49% of the territory, it is predominantly inhabited by Serbs.

Each entity has its own constitution, president, parliament, government, police force, and largely separate administrative systems, retaining significant powers.

- The Brčko District: Located in the northeast of the country, it was created in 2000 as a self-governing administrative unit under the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is officially part of both entities but is governed by neither, functioning under a decentralized system of local government supervised by an international supervisor. For election purposes, Brčko District voters can choose to participate in either the Federation or Republika Srpska elections for state-level offices. It has been praised for maintaining a multiethnic population and a degree of prosperity.

The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is further subdivided into ten Cantons (kantoni), each with its own government and legislature. Some cantons are ethnically mixed (e.g., Bosniak-Croat majority) and have special laws to ensure power-sharing and equality, while others have a clear majority of one group. Republika Srpska is not divided into cantons but is centralized, with direct administration over its municipalities.

Both entities and the Brčko District are further divided into Municipalities (općine/opštine). The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided into 79 municipalities, and Republika Srpska into 64. Municipalities have their own local governments and are typically based on the most significant city or town in their territory.

The country also has four officially designated Cities: Sarajevo, Banja Luka, Mostar, and East Sarajevo. The cities of Banja Luka and Mostar correspond to their respective municipalities. Sarajevo and East Sarajevo consist of several municipalities. Cities have their own city government with powers between those of municipalities and cantons (or the entity in the case of RS).

This complex administrative structure, with multiple layers of government and ethnic quotas, contributes to the country's political challenges, including high administrative costs and difficulties in policy coordination and implementation.

5.3. International Supervision and Challenges

The civilian implementation of the Dayton Agreement is supervised by the Office of the High Representative (OHR), an ad hoc international institution. The High Representative is selected by the Peace Implementation Council (PIC), an international body. The High Representative holds the highest political authority in the country and has historically wielded significant powers, known as the "Bonn Powers." These powers allow the High Representative to impose laws, amend constitutions, and dismiss elected and non-elected officials who are deemed to be obstructing the peace process or violating the Dayton Agreement. Due to these vast powers, the position has sometimes been compared to that of a viceroy. While the use of Bonn Powers has decreased in recent years, the OHR remains a key institution. The international supervision is intended to end when the country is deemed politically and democratically stable and self-sustaining.

Bosnia and Herzegovina faces numerous ongoing challenges in its state-building process:

- National Reconciliation: Overcoming the legacy of the 1990s war and fostering trust among the constituent peoples remains a profound challenge. Nationalist rhetoric and differing interpretations of the past continue to hinder genuine reconciliation.

- Political Reform: The complex Dayton constitutional structure is often cited as a source of political gridlock and inefficiency. Efforts to reform the constitution to create a more functional and less ethnically divided state have largely failed due to a lack of consensus among political leaders. The European Court of Human Rights has issued several rulings (e.g., Sejdić-Finci) finding parts of the constitution discriminatory, but implementation of these rulings has been slow.

- Corruption: Corruption is a severe and pervasive problem at all levels of government and society, undermining democratic institutions, hindering economic development, and eroding public trust.

- Achieving Full Sovereignty: The continued presence and powers of the OHR are seen by some as an impediment to the country's full sovereignty, while others view it as necessary for stability.

- Functional Democratic Consolidation: Building strong, independent democratic institutions, ensuring the rule of law, and fostering an active civil society are ongoing processes. Political interference in the judiciary and media remains a concern.

Despite these challenges, the country has made progress in areas such as defense reform (unification of armed forces) and has advanced on its path towards European integration.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Bosnia and Herzegovina's foreign policy is primarily focused on regional cooperation, integration into Euro-Atlantic structures (European Union and NATO), and maintaining balanced relations with global powers. The country is a member of the United Nations (UN), the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA). It was also a founding member of the Union for the Mediterranean.

Relations with its immediate neighbors-Croatia, Serbia, and Montenegro-are crucial and have generally been stable since the signing of the Dayton Agreement, though occasional political tensions arise, often related to historical issues, border demarcation, or the status of constituent peoples. The implementation of the Dayton Agreement has guided efforts towards regional stabilization among the successor states of the former Yugoslavia.

5.4.1. European Union and NATO Aspirations

Integration into the European Union (EU) is a primary strategic foreign policy objective for Bosnia and Herzegovina. The country initiated the Stabilisation and Association Process (SAP) with the EU in 2007, which is a framework for countries in the Western Balkans on their path to membership. A Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) was signed in 2008 and fully entered into force in 2015. Bosnia and Herzegovina formally applied for EU membership in February 2016. In December 2022, the European Council granted Bosnia and Herzegovina EU candidate status, a significant step in its integration journey. Accession talks are set to begin following the implementation of further reforms. The EU integration process requires extensive political, economic, and legal reforms, including strengthening the rule of law, fighting corruption, and improving public administration.

Bosnia and Herzegovina also aspires to join NATO. It became a member of NATO's Partnership for Peace program in 2006. In April 2010, NATO foreign ministers invited Bosnia and Herzegovina to join the Membership Action Plan (MAP), the final step before full membership. However, activation of the MAP was conditioned on the resolution of issues related to the registration of immovable defense property to the state. In December 2018, NATO foreign ministers endorsed Bosnia and Herzegovina's submission of its first Annual National Programme under the MAP, effectively activating it. Progress towards full NATO membership remains a subject of internal political debate, with Republika Srpska expressing reservations largely influenced by Serbia's policy of military neutrality and close ties with Russia.

These integration processes are seen as crucial for the country's long-term stability, democratic development, security, and economic prosperity. They also carry social implications, potentially fostering greater inter-ethnic cooperation and aligning the country with European norms and values.

5.5. Military

The Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Oružane snage Bosne i Hercegovine, OSBiH) were unified into a single professional military entity in 2005. This significant reform involved the merger of the two formerly separate entity armies: the Army of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (VFBiH), which itself was a combination of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO), and the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS). The Ministry of Defence of Bosnia and Herzegovina was established in 2004 to provide civilian command and control over the unified armed forces.

The OSBiH consists of:

- Bosnian Ground Forces (Kopnena vojska)**: This is the largest component, responsible for land-based operations. As of recent estimates, the Ground Forces have around 7,200 active personnel and 5,000 reserve personnel. They are equipped with a mix of weaponry, vehicles, and military equipment of American, Yugoslavian, Soviet, and European origin.

- Air Force and Air Defense (Zračne snage i protivzračna odbrana)**: This branch has approximately 1,500 personnel and operates a variety of aircraft, primarily helicopters for transport and support roles, as well as radar systems and surface-to-air missile (SAM) batteries for air defense. They utilize MANPADS, anti-aircraft cannons, and radar systems.

The OSBiH operates under the command of the Presidency (as Commander-in-Chief) through the Ministry of Defence. A key reform has been the adoption of standardized uniforms, such as MARPAT-style uniforms, particularly for personnel serving in international missions. Domestic production programs aim to ensure army units are equipped with appropriate ammunition.

Since 2007, the OSBiH has participated in various international peacekeeping and security missions, including deployments with the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan, as well as missions in Iraq and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These deployments have been commended by international partners.

The unification of the armed forces is considered one of the most successful post-Dayton reforms, contributing to the country's stability and its aspirations for NATO membership. The military continues to undergo modernization and professionalization efforts, often with assistance from NATO allies.

6. Economy

Bosnia and Herzegovina's economy is a transitional one, moving from a system significantly shaped by its socialist past within Yugoslavia and heavily impacted by the devastating Bosnian War (1992-1995), towards a market-oriented system. It is classified as a developing country with an upper-middle-income economy. The post-war recovery has been substantial, but the country still faces significant economic challenges related to its complex political structure, corruption, and high unemployment.

6.1. Economic Overview and Challenges

The Bosnian War inflicted enormous material damage, estimated at around €200 billion, and caused massive disruption to production, trade, and human capital. The subsequent recovery has been supported by international aid and remittances, but rebuilding infrastructure and institutions has been a long process.

Key economic indicators show a mixed picture:

- GDP: The economy has grown since the war, but remains modest compared to EU averages. According to Eurostat data, Bosnia and Herzegovina's PPS GDP per capita stood at 29% of the EU average in 2010. The World Bank predicted 3.4% growth in 2019 before the global pandemic.

- Currency: The national currency is the Convertible Mark (BAM or KM), which is pegged to the Euro under a currency board arrangement, ensuring monetary stability.

- Inflation: Annual inflation has generally been low.

- National Debt: While the national debt has seen periods of reduction, managing public finances within the complex entity structure remains a challenge. As of June 30, 2018, public debt was about €6.04 billion (34.92% of GDP).

- Unemployment: High unemployment, especially among youth, is a persistent and severe challenge. In 2017, the unemployment rate was 20.5%, though some predictions indicated a falling trend prior to recent global economic shifts.

- Trade Deficit: The country consistently runs a large trade deficit, importing significantly more than it exports.

- Corruption: Widespread corruption is a major impediment to economic development, deterring foreign investment and hindering fair competition.

- Informal (Grey) Economy: A significant informal economy, estimated by some to be around 25.5% of GDP, poses challenges for tax collection and official economic statistics.

Social equity and sustainable development are important considerations. The country has a relatively high income equality ranking compared to some nations but faces disparities between urban and rural areas and across entities. The brain drain, with skilled young people emigrating, is also a concern.

6.2. Main Industries

The economy of Bosnia and Herzegovina is diversified, with key sectors including:

- Industry: This has traditionally been a strong sector, a legacy from the Yugoslav era when Bosnia and Herzegovina was a center for heavy industry and military production. Key industrial branches include:

- Metals: Production of aluminium (e.g., Aluminij Mostar), steel, and other metal processing.

- Defense Industry: A long tradition of arms and military equipment manufacturing continues with companies like "Zrak" d.d. Sarajevo, PD "Igman" Konjic, and Ginex d.d. Goražde.

- Manufacturing: This includes wood processing and furniture production (utilizing the country's abundant forests), textiles, and automotive components (e.g., car seats).

- Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals.

- Agriculture: Conducted mainly on privately owned farms, agriculture produces grains (like wheat), fruits, vegetables, and livestock (beef, lamb). Fresh food has traditionally been an export. Northern Posavina is a particularly fertile agricultural region.

- Energy Sector:

- Coal: Significant coal reserves are used for thermal power generation.

- Hydroelectric Power: The country has substantial hydroelectric potential due to its numerous rivers (e.g., Neretva, Drina, Vrbas). Companies like Elektroprivreda BiH are major players. There have been discussions and plans for further development, including nuclear energy considerations in Tuzla, though these face environmental and public debate.

- Mining: Besides coal, deposits include iron ore, bauxite, lead, zinc, and manganese.

- Tourism: A rapidly growing sector (see details under Tourism).

- Service Sector: This includes trade, banking (with both domestic and international banks like Addiko Bank, Bosna Bank International), telecommunications, and IT.

Labor rights and environmental issues are important social aspects related to these industries. The transition from state-owned enterprises to private ownership has often been complex, affecting employment and working conditions. Environmental standards and their enforcement are developing, particularly concerning heavy industry and energy production.

6.3. Tourism

Tourism in Bosnia and Herzegovina has been a rapidly growing sector in the post-war era, with the World Tourism Organization once projecting it to have one of the highest tourism growth rates globally between 1995 and 2020. The country offers a diverse range of attractions, blending rich history, cultural heritage, and stunning natural landscapes.

Key attractions and tourism trends include:

- Historical and Cultural Tourism**:

- Sarajevo: The capital city, known for its unique blend of Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian architecture, historic Baščaršija (old bazaar), religious sites (mosques, churches, synagogues), and museums. It hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics and has been recognized by publications like Lonely Planet and travel blog Foxnomad as a top city to visit.

- Mostar: Famous for its iconic Stari Most (Old Bridge), a UNESCO World Heritage site, and its charming Old Town.

- Višegrad: Home to the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge, another UNESCO site, immortalized in Ivo Andrić's novel "The Bridge on the Drina."

- Medieval fortresses, Stećci (medieval tombstones, also UNESCO listed), and traditional villages like Počitelj.

- Religious Pilgrimage**:

- Međugorje: A small town that has become one of the most popular pilgrimage sites for Catholics worldwide due to reported apparitions of the Virgin Mary since 1981. It attracts over a million visitors annually, and pilgrimages have been officially authorized by the Vatican since 2019.

St. James Church in Medjugorje, a major center for Catholic pilgrimage. - Nature and Adventure Tourism**:

- Ski Resorts**: The mountains that hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics, such as Bjelašnica, Jahorina, and Igman, are popular skiing destinations.

- Ecotourism and Hiking**: Bosnia and Herzegovina is one of the last undiscovered natural regions of the southern Alps, with vast tracts of wild and untouched nature. The central Dinaric Alps are favored by hikers and mountaineers. National Geographic named it the best mountain biking adventure destination for 2012.

- Whitewater Rafting**: This has become a national pastime, with popular rivers including the Vrbas, Tara (which has the deepest river canyon in Europe), Drina, Neretva, and Una. The Vrbas and Tara rivers hosted the 2009 World Rafting Championship.

- National Parks**: Sutjeska National Park (with Perućica primeval forest), Kozara National Park, and Una National Park offer pristine nature and outdoor activities.

Tourist arrivals have shown significant growth. In 2017, 1,307,319 tourists visited, an increase of 13.7% from the previous year, with 2,677,125 overnight stays. In 2018, tourist numbers rose to 1,883,772 (a 44.1% increase) with 3,843,484 overnight stays. A majority of tourists (around 71-72%) come from foreign countries. The HuffPost named Bosnia and Herzegovina the "9th Greatest Adventure in the World for 2013," highlighting its clean water and air, untouched forests, and wildlife.