1. Overview

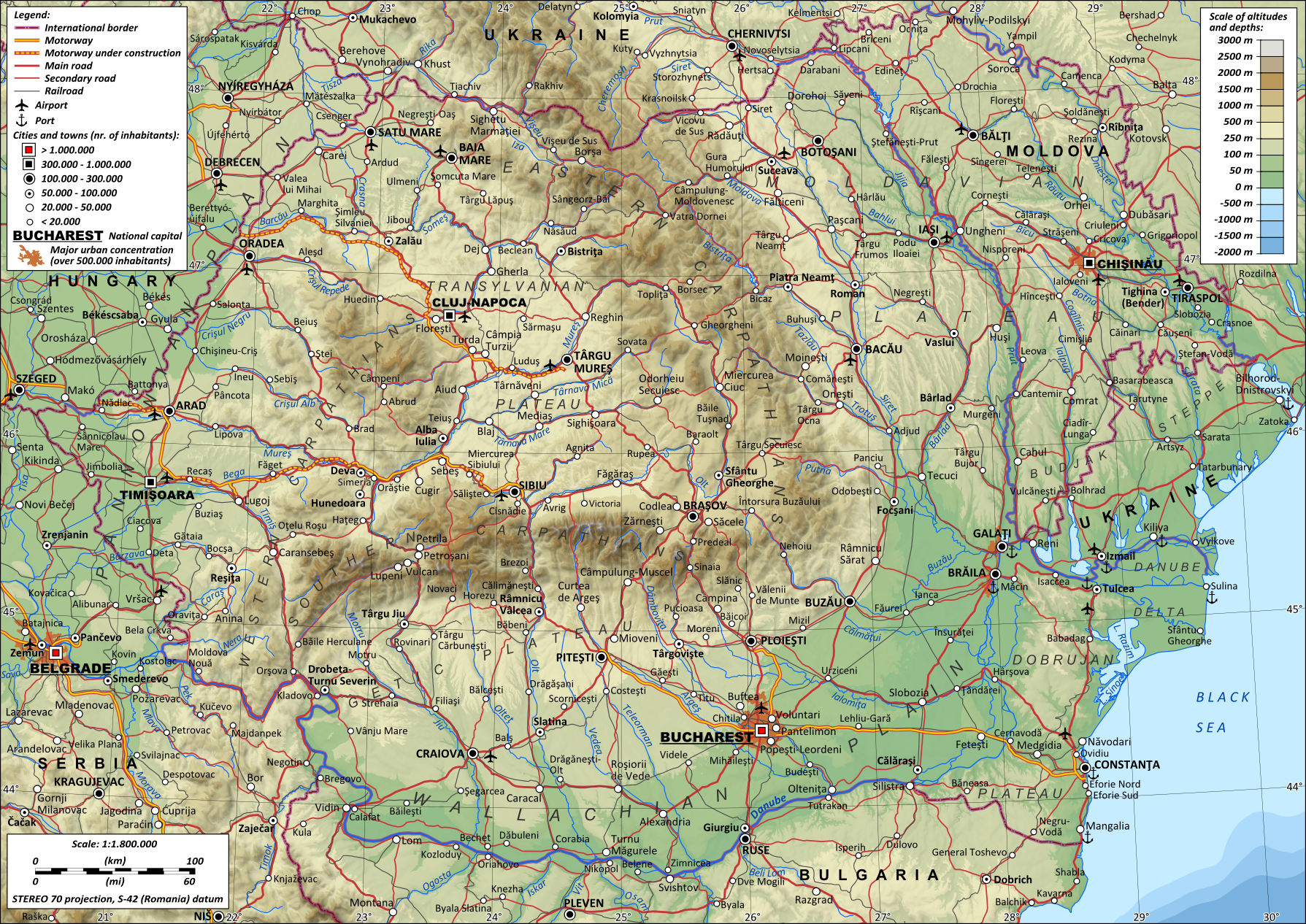

Romania, officially the Republic of Romania, is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to the east, and the Black Sea to the southeast. With an area of 92 K mile2 (238.40 K km2), Romania is the twelfth-largest country in Europe and the sixth-most populous member state of the European Union, with a population of approximately 19 million people. Its capital and largest city is Bucharest, with other major urban centers including Cluj-Napoca, Timișoara, Iași, Constanța, Craiova, and Brașov.

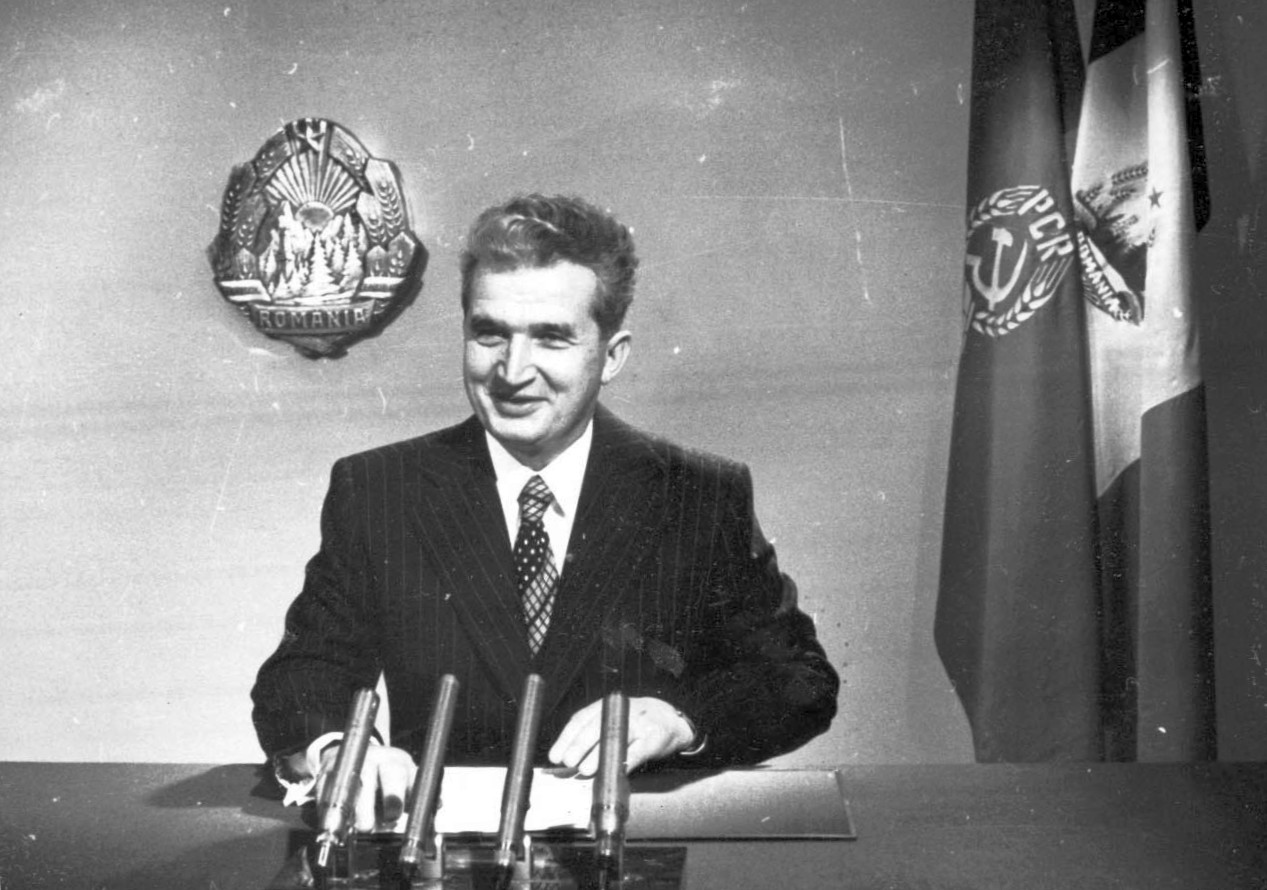

The history of Romania is marked by a long struggle for unity and independence, evolving from ancient Dacian kingdoms and Roman colonization through medieval principalities vying for autonomy against larger empires. The modern Romanian state was formed in 1859 through the unification of Moldavia and Wallachia, gaining independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1877. The "Great Unification" of 1918 saw Transylvania, Bessarabia, and Bukovina join the Kingdom, creating Greater Romania. World War II brought territorial losses and a shift to the Allied side, followed by Soviet occupation and the establishment of a communist regime. This period was characterized by significant repression, particularly under the increasingly oppressive dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu, whose rule severely impacted human rights and democratic values. The Romanian Revolution of 1989 marked a pivotal moment, overthrowing communism and initiating a challenging transition towards democracy and a market economy.

Since 1989, Romania has embarked on a path of democratic development and European integration, joining NATO in 2004 and the European Union in 2007. These accessions have anchored its foreign policy and spurred significant domestic reforms, though challenges related to corruption, social justice, and the protection of minority rights persist. The country's political system is a semi-presidential republic with a multi-party system, striving to uphold the rule of law and democratic principles. Economically, Romania has transitioned to a high-income market economy, with significant growth in recent decades, particularly in the services and industrial sectors, including automotive manufacturing and information technology. However, it continues to address social disparities and work towards sustainable development and improved living standards for all its citizens, including its diverse ethnic minorities. Romanian culture, rich in traditions, arts, and a distinct Romance language, reflects its complex history and its place within the broader European heritage.

2. Etymology

The name "Romania" originates from the local ethnonym for Romanians, românromânRomanian, which in turn is derived from the Latin word romanusromanusLatin, meaning "Roman" or "of Rome". This self-identification reflects the Romanization of the region and the Daco-Romans, the ancestors of the Romanian people, following the Roman conquest of Dacia.

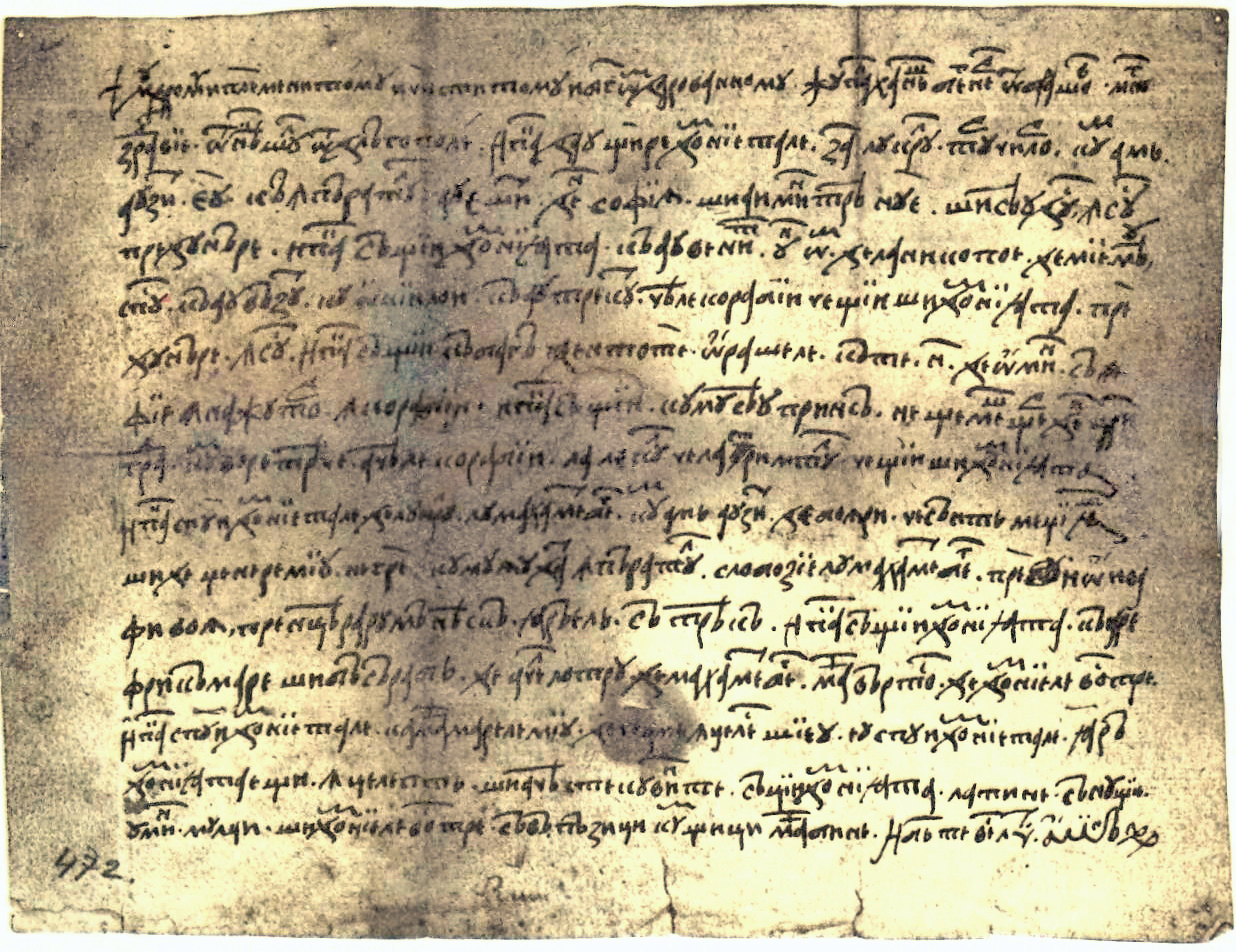

The ethnonym românromânRomanian as a term for Romanians was first attested in the 16th century by Italian humanists traveling through Transylvania, Moldavia, and Wallachia. The oldest known surviving document written in the Romanian language that can be precisely dated is a 1521 letter known as "The Letter of Neacșu from Câmpulung". This document is notable for containing the first documented occurrence of a Romanian-related name for a country: Wallachia is mentioned as Țara RumâneascăThe Romanian LandRomanian (literally "The Romanian Land" or "The Romanian Country"). Historically, two spellings, românromânRomanian and rumânrumânRomanian, were used interchangeably. However, by the late 17th century, socio-linguistic developments led to a semantic differentiation: rumânrumânRomanian came to mean "bondsman" or "serf," while românromânRomanian retained the original ethno-linguistic meaning. After the abolition of serfdom in Wallachia (1746) and Moldavia (1749), the term rumânrumânRomanian gradually fell out of use.

Some scholars suggest that the earliest evidence of the name "Romanian" in a European text may be found in the 13th-century Nibelungenlied, a Middle High German epic poem. It mentions "Duke Ramunch of the land of the Vlachs / with seven hundred warriors he runs to meet her / like wild birds, he was seen galloping." In this context, "Ramunch" might be a transliteration of "Romanian," representing a symbolic leader of the Romanians (Vlachs).

The name "România" as a common designation for the homeland of all Romanians began to be used in the early 19th century. It became the official name of the state formed by the union of Wallachia and Moldavia on January 24, 1862, initially as the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, and has been used continuously since then.

3. History

Romania's history is characterized by the development of distinct peoples and principalities in a strategically important region of Europe, their struggles against larger empires, movements towards national unification, and a turbulent 20th century involving world wars, communist dictatorship, and a transition to democracy.

3.1. Ancient Dacia and Roman Era

Human settlement in the territory of modern Romania dates back to the Lower Paleolithic. The oldest Homo sapiens remains in Europe, dated to approximately 42,000 years ago, were discovered in the Peștera cu Oase ("Cave with Bones") in southwestern Romania. Written records first mention the peoples of this region in the 5th century BC, when Herodotus described the Getae tribes. The Dacians, closely related to or a part of the Getae, were Thracian tribes inhabiting Dacia, an area encompassing much of present-day Romania, Moldova, and northern Bulgaria. According to Strabo, the Getae and Dacians spoke the same Thracian language.

The first centralized Dacian Kingdom was established around 82 BC under the rule of King Burebista, who was assisted by the high priest Deceneus. Burebista unified the Dacian tribes and expanded his kingdom significantly. However, he was assassinated in 44 BC, and his kingdom fragmented into several smaller states. The core of the Dacian state remained in the Șureanu Mountains, where successive rulers like Deceneus, Comosicus, and Coryllus held power. The Dacian state reached its peak of development under King Decebalus (reigned 87-106 AD).

The expanding Roman Empire came into conflict with the Dacians. After Dacia attacked the Roman province of Moesia in 87 AD, Emperor Trajan launched two major campaigns, known as Trajan's Dacian Wars (101-102 AD and 105-106 AD). Decebalus was defeated, and a significant part of Dacia was conquered and transformed into the Roman province of Roman Dacia in 106 AD. The region was rich in resources, particularly gold and silver, which attracted Roman colonists. This period led to intense Romanization, as Roman culture, administration, and, crucially, Vulgar Latin were introduced. Vulgar Latin spoken in Dacia formed the basis for the development of the Romanian language.

However, continuous pressure from migratory tribes, such as the Goths and Carpians, and the empire's overstretched resources led the Romans to withdraw their administration and legions from Dacia between 271 and 275 AD under Emperor Aurelian. Dacia was the first major province to be formally abandoned by the Roman Empire, although a Romanized population remained.

3.2. Medieval Principalities and Phanariot Era

Following the Roman withdrawal, the territory of present-day Romania became a pathway and often a temporary settlement for various migratory peoples. These included the Goths (3rd-4th centuries), Huns (4th century), Gepids (5th century), Avars (6th century), and Slavs (beginning in the 7th century), who had a lasting linguistic and cultural impact. Later came the Magyars (9th century), Pechenegs, Cumans, Uzes, and Alans (10th-12th centuries), and the Tatars (13th century). Despite these migrations, a Daco-Roman population persisted, gradually evolving into the Romanian people.

By the 13th century, small Romanian political entities known as knezate and voivodeships are attested south of the Carpathian Mountains. Amidst weakening Hungarian royal pressure and diminishing Tatar dominance, two major autonomous feudal states emerged:

- Wallachia (Țara RomâneascăThe Romanian LandRomanian - "The Romanian Land"), founded traditionally by Basarab I around 1310.

- Moldavia (MoldovaMoldovaRomanian), founded traditionally by Bogdan I around 1359.

Transylvania, historically inhabited by Romanians, Dacians, and later various Germanic tribes, came under Hungarian rule from the 11th century and was governed by voivodes within the Kingdom of Hungary. After the Battle of Mohács in 1526, which led to the collapse of the medieval Hungarian Kingdom, Transylvania became a self-governing principality under Ottoman suzerainty, later passing to Habsburg control.

Notable medieval Romanian rulers who played significant roles in defending their lands and shaping their identity include Mircea the Elder, Vlad the Impaler (the historical figure who inspired the Dracula legend), Michael the Brave (Mihai Viteazul), and Constantin Brâncoveanu in Wallachia; and Alexander the Good, Stephen the Great (Ștefan cel Mare), Petru Rareș, and Dimitrie Cantemir in Moldavia. John Hunyadi (Iancu de Hunedoara), of Romanian origin, was a key figure in the defense of Hungary and Transylvania against the Ottomans.

From the late 15th century, both Wallachia and Moldavia increasingly fell under the influence of the powerful Ottoman Empire, eventually becoming vassal states. They retained internal autonomy but paid tribute and were subject to Ottoman foreign policy. At the turn of the 17th century (1600-1601), Michael the Brave, Prince of Wallachia, briefly united Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania under his rule, an event later seen as a precursor to modern Romania.

The 18th century marked the beginning of the Phanariot era in Wallachia (from 1716) and Moldavia (from 1711). The Ottoman Sultans, distrustful of native Romanian princes after some had allied with Russia or the Habsburgs, began appointing rulers from prominent Greek families residing in the Phanar district of Constantinople. This period was often characterized by heavy taxation, corruption, and political instability, although some Phanariot rulers also introduced Enlightenment-era reforms. Transylvania, after being under Habsburg rule, was fully incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary following the Ausgleich of 1867, losing its remaining political autonomy.

3.3. Early Modern Period and National Awakening

The early modern period in the Romanian lands was marked by continued Ottoman suzerainty over Wallachia and Moldavia, and Habsburg rule in Transylvania, alongside growing national consciousness and the first steps towards modernization and self-determination.

After the collapse of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary in 1541, the Principality of Transylvania emerged, nominally under Ottoman suzerainty but often acting with considerable autonomy. The Protestant Reformation had a significant impact in Transylvania, with Calvinism, Lutheranism, and Unitarianism being officially recognized alongside Roman Catholicism by the Diet of Torda in 1568. The Orthodox faith of the Romanian majority, however, remained merely tolerated.

In 1594, the princes of Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldavia joined the Holy League against the Ottoman Empire. Michael the Brave (Mihai Viteazul), Prince of Wallachia, famously united the three principalities under his rule in May 1600. Although his union was short-lived, as neighboring powers forced him to abdicate in September of the same year, Michael became a potent symbol of Romanian unity for 19th-century nationalists. Despite continued Ottoman tribute, capable princes like Gabriel Bethlen of Transylvania, Matei Basarab of Wallachia, and Vasile Lupu of Moldavia managed to strengthen their principalities' autonomy and foster cultural development.

The Great Turkish War saw the Holy League expel Ottoman forces from Central Europe between 1684 and 1699, leading to the integration of the Principality of Transylvania into the Habsburg Monarchy. The Habsburgs promoted a church union in 1699, persuading some Orthodox Romanian clergy to unite with the Roman Catholic Church, forming the Romanian Church United with Rome (Greek Catholic). This union reinforced Romanian intellectuals' awareness of their Roman heritage. The Orthodox Church was officially restored in Transylvania only after popular revolts in 1744 and 1759. The establishment of the Transylvanian Military Frontier also caused unrest, particularly among the Székelys in 1764 (known as the Siculicidium).

The Phanariot era began in Moldavia in 1711 and Wallachia in 1716 after Princes Dimitrie Cantemir and Constantin Brâncoveanu, respectively, were deposed for allying with Russia and the Habsburgs against the Ottomans. Phanariot rule was characterized by heavy taxation and political instability, weakening the principalities. Neighboring empires capitalized on this: the Habsburg Monarchy annexed Bukovina (northwestern Moldavia) in 1775, and the Russian Empire seized Bessarabia (eastern Moldavia) in 1812.

In Transylvania, despite a 1733 census showing Romanians as the most numerous ethnic group, they continued to be marginalized politically. Bishop Inocențiu Micu-Klein's demands for recognition of Romanians as a fourth privileged "nation" led to his exile. In 1791, Uniate and Orthodox Romanian leaders jointly submitted the Supplex Libellus Valachorum, a petition for political and civil rights, to Emperor Leopold II, but it was rejected.

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) allowed Russia to act as a protector of Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire, increasing Russian influence in the Danubian Principalities (Wallachia and Moldavia). The Greek War of Independence inspired Tudor Vladimirescu, a Wallachian lesser nobleman, to lead an anti-Ottoman and anti-Phanariot revolt in 1821. Although Vladimirescu was eventually murdered, his revolt contributed to the end of Phanariot rule and the restoration of native Romanian princes. The Treaty of Adrianople (1829), following a Russo-Turkish war, further strengthened the autonomy of the Danubian Principalities, though they remained under Ottoman suzerainty and increasing Russian protectorship.

The Revolutions of 1848 swept through Moldavia and Wallachia, led by figures like Mihail Kogălniceanu and Nicolae Bălcescu. Revolutionaries demanded reforms such as the emancipation of peasants, broader civil rights, and the union of the two principalities. The Wallachian revolutionaries adopted the blue, yellow, and red tricolour as the national flag. However, Russian and Ottoman forces crushed these uprisings. In Transylvania, most Romanians, under leaders like Avram Iancu and Bishop Andrei Șaguna, supported the Habsburg imperial government against the Hungarian revolutionaries who sought to unite Transylvania with Hungary without recognizing Romanian rights. Șaguna proposed unifying the Romanians of the Habsburg Monarchy into a separate duchy, but this was refused. These events, despite their failure, fueled the growing national awakening and desire for self-determination among Romanians.

3.4. Unification and Kingdom of Romania

The mid-19th to early 20th century was a transformative period for the Romanian lands, marked by the unification of Moldavia and Wallachia, the achievement of full independence, and the establishment of the Kingdom of Romania, culminating in the creation of Greater Romania after World War I. This era laid the groundwork for modern Romania, navigating complex geopolitical currents and fostering national development.

3.4.1. Union of Principalities and Pre-World War I

The modern Romanian state emerged from the union of the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859. This "Little Union" was achieved through the election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as prince of both principalities, a move tacitly accepted by the Great Powers through the Paris Convention of 1858. Cuza's reign (1859-1866) was pivotal; he implemented a series of sweeping reforms that laid the foundations for a modern state, including land reform, secularization of monastic estates, adoption of new civil and penal codes, and establishment of a national education system. However, his authoritarian tendencies and the opposition from conservative landowners and some liberal factions led to his forced abdication in 1866 by a broad coalition known as the "Monstrous coalition".

To consolidate the union and provide stability, Romanian political leaders sought a foreign prince. They chose Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, who became Prince Carol I in May 1866. He adopted a new liberal constitution, one of the most advanced in Southeastern Europe at the time. Under Carol I, Romania pursued full independence from the Ottoman Empire. This was achieved through Romania's participation on the Russian side in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878. Romanian troops fought bravely, particularly at the Siege of Pleven. Romania's independence was formally proclaimed on May 10, 1877, and internationally recognized by the Treaty of Berlin (1878). As part of the treaty's arrangements, Romania ceded southern Bessarabia to Russia but gained Northern Dobruja, including the port of Constanța.

On March 14, 1881 (May 10 by the Old Style calendar, a date of great significance), Romania was proclaimed a kingdom, and Prince Carol I was crowned King. His long reign (1866-1914) was characterized by political stability, economic development, and modernization of infrastructure. In 1913, Romania participated in the Second Balkan War against Bulgaria, and as a result, acquired Southern Dobruja (the Quadrilateral) under the Treaty of Bucharest. King Carol I died in 1914, and was succeeded by his nephew, Ferdinand I.

3.4.2. World War I and the Great Unification

When World War I erupted in August 1914, Romania initially declared neutrality, despite King Carol I's Hohenzollern ties to the Central Powers and public opinion largely favoring the Entente. After two years of diplomatic maneuvering and promises of territorial gains (particularly Transylvania from Austria-Hungary), Romania joined the Entente Powers in August 1916 and declared war on Austria-Hungary.

The Romanian military campaign began with an offensive into Transylvania but quickly turned disastrous. Central Powers forces (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire) launched a counter-offensive, occupying Wallachia, including Bucharest, by the end of 1916. The Romanian government, royal family, and remnants of the army retreated to Moldavia, establishing a provisional capital at Iași. Despite significant losses and hardship, the Romanian army, reorganized with French assistance, managed to halt the Central Powers' advance in Moldavia in the summer of 1917, notably at the battles of Mărășești, Mărăști, and Oituz. However, the Russian Revolution and Russia's subsequent withdrawal from the war left Romania isolated, forcing it to sign the punitive Treaty of Bucharest with the Central Powers in May 1918. Romania re-entered the war on the Entente side on November 10, 1918, just a day before the armistice with Germany.

The end of World War I saw the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires. This created an opportunity for the realization of Romanian national aspirations.

- Bessarabia, formerly part of the Russian Empire, proclaimed its union with Romania on April 9, 1918 (March 27 Old Style).

- Bukovina, formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, proclaimed its union with Romania on November 28, 1918.

- Transylvania, along with parts of Banat, Crișana, and Maramureș, formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, proclaimed its union with Romania on December 1, 1918, at the Great National Assembly in Alba Iulia. This date, December 1, is now Romania's National Day.

These unions, often referred to as the "Great Union" (Marea UnireMarea UnireRomanian), led to the formation of Greater Romania (România MareRomânia MareRomanian), which encompassed most territories with a Romanian ethnic majority. The Treaty of Trianon (1920) with Hungary and the Treaty of Saint-Germain (1919) with Austria internationally recognized most of these territorial changes. On October 15, 1922, King Ferdinand I and Queen Marie were symbolically crowned as sovereigns of all Romanians in a grand ceremony at Alba Iulia.

3.4.3. Interwar Period

The Interwar period (1919-1939) in Greater Romania was a time of democratic experimentation, cultural flourishing, and economic development, but also significant political instability, social tensions, and the rise of extremist movements. The new democratic constitution of 1923 granted universal male suffrage and aimed to integrate the newly acquired territories and diverse populations. Land reforms were implemented, breaking up large estates and distributing land to peasants, though not always to their complete satisfaction.

Politically, the era was dominated by the National Liberal Party (PNL) and the National Peasants' Party (PNȚ). However, governments were often short-lived, and the political scene was fragmented. Carol II, who returned from exile in 1930 and usurped the throne from his young son Michael I, played an increasingly assertive and manipulative role in politics. Influenced by his entourage, often referred to as the "Royal Camarilla," he undermined the democratic system, culminating in the establishment of a royal dictatorship in 1938 and the banning of political parties.

Despite being pro-Western, particularly Anglophile, Carol II attempted to appease rising far-right and antisemitic forces. He appointed nationalist governments, including one led by Octavian Goga and another by Patriarch Miron Cristea, which enacted antisemitic legislation. The Iron Guard (Garda de FierGarda de FierRomanian), a fascist and ultranationalist movement, gained considerable influence, engaging in political violence and assassinations.

Economically, Romania made progress in industrialization, particularly in the oil sector, but remained largely agrarian. The Great Depression hit the country hard, exacerbating social inequalities and fueling political extremism. Culturally, this period was vibrant, with notable achievements in literature, art, and science. However, the democratic fabric of Greater Romania proved fragile, unable to withstand internal divisions and the growing pressures of international fascism and revisionism.

3.4.4. World War II

Romania's involvement in World War II was marked by shifting alliances, significant territorial losses and regains, participation in major military campaigns, and ultimately, the onset of Soviet influence.

As international tensions rose in the late 1930s, Romania found itself in a precarious geopolitical position. Following the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which contained secret protocols assigning Romania's eastern territories to the Soviet sphere of influence, Romania faced immense pressure. In June 1940, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum, forcing Romania to cede Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and the Hertsa region to the USSR.

King Carol II, attempting to secure an alliance with Nazi Germany to counter further threats, appointed a pro-Axis government under Ion Gigurtu. Gigurtu declared that Romania would pursue a Nazi-aligned, antisemitic, and fascist-totalitarian policy. However, this did not prevent further territorial losses. Under Axis pressure, Romania was compelled to:

- Cede Northern Transylvania, including the city of Cluj and significant natural resources, to Hungary through the Second Vienna Award arbitrated by Germany and Italy on August 30, 1940.

- Cede Southern Dobruja (the Quadrilateral) to Bulgaria through the Treaty of Craiova on September 7, 1940.

These substantial territorial losses, achieved without a fight, led to widespread public discontent and protests. In response, King Carol II suspended the 1938 Constitution and appointed General Ion Antonescu as Prime Minister with full powers on September 4, 1940. Supported by the Iron Guard, Antonescu forced Carol II to abdicate in favor of his young son, Michael I, on September 6. Antonescu then declared himself "Conducător" (Leader) of the state and established a military dictatorship, initially in partnership with the Iron Guard. In January 1941, Antonescu suppressed a violent rebellion by the Iron Guard and consolidated his sole control.

In June 1941, Romania joined Nazi Germany and the other Axis powers in the invasion of the Soviet Union, aiming to recover Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. Romanian forces participated in heavy fighting on the Eastern Front, including the Siege of Odessa and the Battle of Stalingrad. Romania also became a crucial supplier of oil to Germany. The Antonescu regime was responsible for the persecution and murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews and Roma in Romanian-controlled territories, particularly in Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Transnistria.

As the tide of the war turned against the Axis powers, particularly after the defeat at Stalingrad, opposition to Antonescu's regime grew within Romania. On August 23, 1944, with Soviet forces advancing into Romanian territory, King Michael I, supported by a coalition of political parties, staged a coup d'état. Antonescu was arrested, and Romania switched sides, declaring war on Germany and joining the Allies of World War II. The Romanian army then fought alongside the Soviet Red Army against German and Hungarian forces in Transylvania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Austria until the end of the war in Europe.

Despite its significant contribution to the Allied victory in the final year of the war, Romania was treated as a defeated enemy nation at the Paris Peace Conference of 1947. The treaties confirmed the return of Northern Transylvania to Romania but also reaffirmed the Soviet annexation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. Southern Dobruja remained with Bulgaria. The immediate post-war period saw the increasing dominance of the Romanian Communist Party, backed by the Soviet occupying forces.

3.5. Socialist Republic of Romania

Following World War II and under Soviet occupation, Romania transitioned into a communist state, a period that profoundly shaped its social, economic, and political landscape for over four decades.

The Romanian Communist Party (initially the Romanian Workers' Party), though small before the war, rapidly consolidated power with Soviet backing. In 1947, King Michael I was forced to abdicate, and the Romanian People's Republic was proclaimed on December 30. The regime implemented Stalinist policies, including the nationalization of industry, banking, and transportation, and the forced collectivization of agriculture. Political opposition was ruthlessly suppressed through the Securitate, the powerful secret police force. Thousands of perceived enemies of the state-politicians from historical parties, intellectuals, clergy, military officers, and ordinary citizens-were imprisoned, sent to labor camps, or executed. This period was characterized by severe human rights abuses and a lack of democratic freedoms.

In the early 1960s, under the leadership of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Romania began to assert a degree of independence from the Soviet Union in its foreign policy. This included establishing diplomatic and economic ties with Western countries and taking a neutral stance in the Sino-Soviet split. Domestically, however, repressive policies continued.

After Gheorghiu-Dej's death in 1965, Nicolae Ceaușescu became the General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party. Initially, he continued the policy of relative foreign policy independence, famously condemning the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, which earned him temporary popularity both at home and in the West. In 1965, the country's name was changed to the Socialist Republic of Romania. Ceaușescu became President of the State Council in 1967 and President of the Republic in 1974.

Over his long rule, Ceaușescu's regime became increasingly authoritarian and personalistic, centered around a pervasive cult of personality for himself and his wife, Elena Ceaușescu. In the 1970s, Romania pursued ambitious industrialization projects financed by Western loans. However, poor economic management and the global oil crises led to a severe debt crisis in the early 1980s. To repay the foreign debt, Ceaușescu imposed drastic austerity measures, leading to severe shortages of food, heating, electricity, and basic necessities for the population. This caused immense hardship and a sharp decline in living standards.

Socially, the regime implemented policies aimed at increasing the population, such as banning abortion and contraception (Decree 770), which had devastating consequences for women's health and led to a large number of children ending up in state-run orphanages under horrific conditions. Grandiose construction projects, like the Palace of the Parliament in Bucharest, involved the demolition of historic neighborhoods and further strained the economy. Human rights were systematically violated, with pervasive surveillance, censorship, and suppression of any form of dissent. The impact on democratic values was profound, creating a society characterized by fear and conformity. By the late 1980s, Ceaușescu's Romania was one of the most isolated and oppressive regimes in the Eastern Bloc.

3.6. Romania since 1989

The period since 1989 in Romania has been defined by the dramatic overthrow of the communist dictatorship, a challenging transition to democracy and a market economy, and efforts towards European integration, marked by both significant progress and persistent societal issues.

The Romanian Revolution began in mid-December 1989 in Timișoara with protests against the government's attempt to evict Hungarian Reformed pastor László Tőkés. These protests quickly escalated into a nationwide uprising against Nicolae Ceaușescu's regime. After days of violent clashes and mass demonstrations, Ceaușescu and his wife Elena fled Bucharest on December 22 but were captured, summarily tried, and executed on December 25, 1989. An interim government, the National Salvation Front (FSN), led by Ion Iliescu, a former high-ranking communist official, took power.

The FSN government reversed many of the Ceaușescu regime's most oppressive policies. The first free multi-party elections were held in May 1990, which Iliescu won decisively, and the FSN gained a large majority in Parliament. Petre Roman became Prime Minister. However, the early post-revolutionary period was tumultuous, marked by social unrest, including the Golaniad protests in Bucharest and violent interventions by miners (the Mineriads), which were seen by many as undemocratic. The September 1991 Mineriad led to Roman's resignation, and Theodor Stolojan became Prime Minister.

Throughout the 1990s, Romania struggled with economic reforms, high inflation, and political instability. The FSN split into several factions, most notably the Social Democratic Party (PSD) and the Democratic Party (PD). Ion Iliescu served as president for most of this period (1990-1996 and 2000-2004), with a centrist coalition led by Emil Constantinescu holding power from 1996 to 2000.

The 2000s saw Romania accelerate its integration efforts with Western institutions. Traian Băsescu was elected president in 2004 and re-elected in 2009. Romania joined NATO in March 2004 and the European Union on January 1, 2007. EU membership spurred further reforms, particularly in the judiciary and in combating corruption, though progress has been uneven. The economy experienced a period of high growth in the mid-2000s, sometimes referred to as the "Tiger of Eastern Europe," but was hit hard by the Great Recession in 2008-2009, requiring an IMF-led bailout.

Corruption has remained a significant challenge. The National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA) was established in 2002 and gained prominence for prosecuting high-level officials. However, attempts by ruling parties to weaken anti-corruption legislation and judicial independence led to massive street protests, notably in 2015 after the Colectiv nightclub fire (leading to Prime Minister Victor Ponta's resignation) and during 2017-2019 against the PSD-ALDE government's judicial reforms.

Klaus Iohannis was elected president in November 2014, defeating Victor Ponta, and was re-elected in a landslide in 2019. His presidency has often focused on strengthening the rule of law and maintaining a pro-Western orientation. The post-1989 era also saw significant deindustrialization as many state-owned enterprises from the communist period were closed or privatized, often controversially.

Contemporary Romania continues to navigate the complexities of democratic consolidation, economic development, and social justice. Efforts to improve governance, strengthen institutions, uphold human rights, and ensure the rights of minorities, including the Roma population, are ongoing. The country plays an active role in NATO and the EU, contributing to regional stability and international cooperation.

4. Geography

Romania is the largest country in Southeastern Europe and the twelfth-largest in Europe, with a total area of 92 K mile2 (238.40 K km2). It is situated in the northern part of the Balkan Peninsula, at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. The country lies between latitudes 43° and 49° North and longitudes 20° and 30° East. Its diverse terrain is distributed roughly equally among mountains, hills, and plains. Romania borders Ukraine to the north and east, Moldova to the east, the Black Sea to the southeast, Bulgaria to the south, Serbia to the southwest, and Hungary to the west. The Danube River forms a significant portion of Romania's southern border with Serbia and Bulgaria and flows into the Black Sea, creating the Danube Delta.

4.1. Topography

Romania's landscape is dominated by the Carpathian Mountains, which form an arc through the center of the country. There are 14 mountain ranges reaching altitudes above 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m), with the highest point being Moldoveanu Peak at 8.3 K ft (2.54 K m) in the Făgăraș Mountains. The Carpathians are divided into three main ranges: the Eastern Carpathians, the Southern Carpathians (or Transylvanian Alps), and the Western Carpathians.

These mountains encircle the Transylvanian Plateau in the central and western part of the country. To the east and south of the Carpathians lie large plains: the Moldavian Plateau to the east, and the Wallachian Plain (or Romanian Plain) to the south, which extends to the Danube River. The westernmost part of Romania includes a portion of the Pannonian Plain.

A significant geographical feature is the Danube Delta, located where the Danube River empties into the Black Sea. It is Europe's second-largest and best-preserved river delta, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and a crucial biosphere reserve. With an area of approximately 2.2 K mile2 (5.80 K km2), it is the largest continuous marshland in Europe and is characterized by a network of channels, lakes, reed beds, and islands.

4.2. Climate

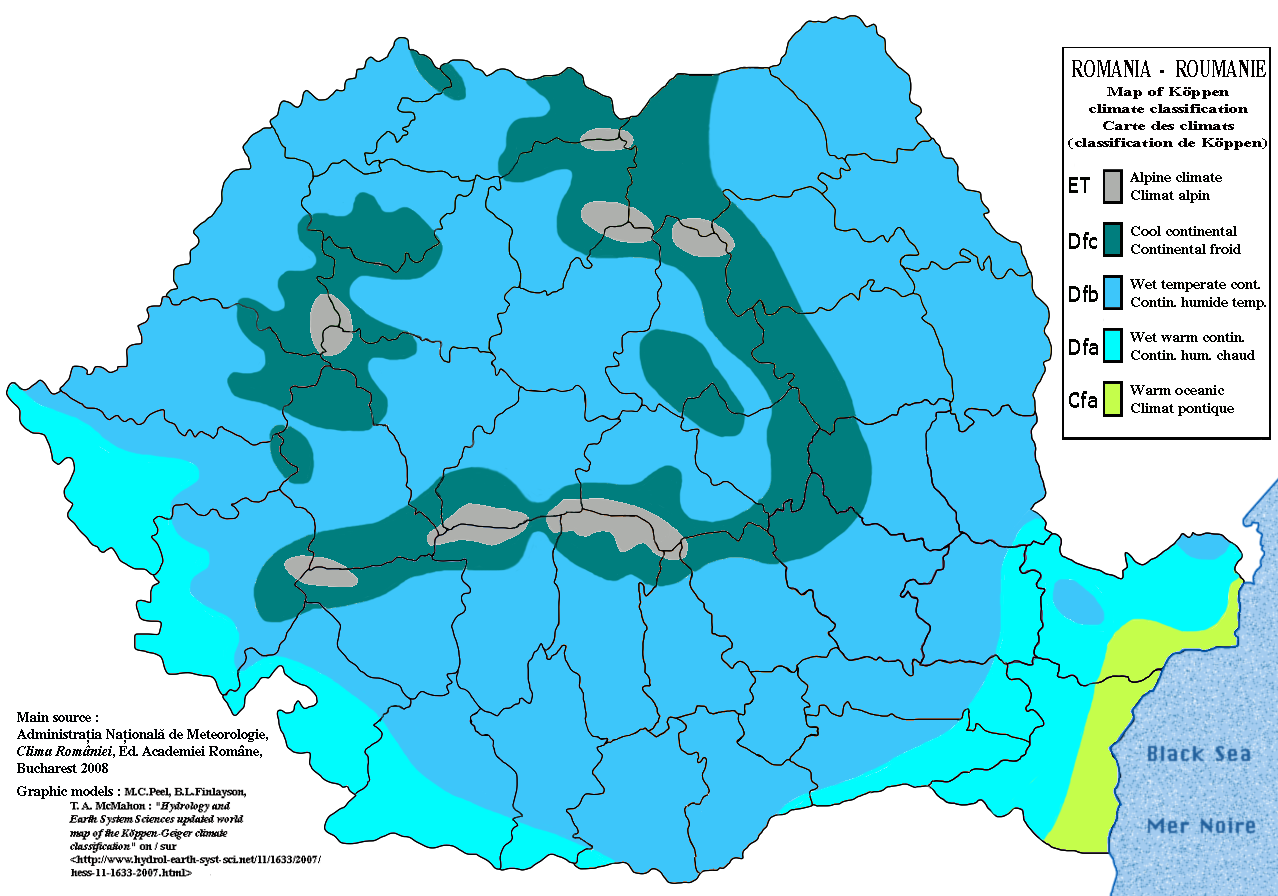

Romania has a climate that is primarily continental, characterized by four distinct seasons. Its position on the southeastern portion of the European continent and its distance from the open sea are major influences.

The average annual temperature is 51.8 °F (11 °C) in the south and 46.4 °F (8 °C) in the north. Summers are generally warm to hot, with average maximum temperatures in Bucharest reaching around 82.4 °F (28 °C). Temperatures exceeding 95 °F (35 °C) are common in the lower-lying areas, particularly in the Wallachian Plain. Winters are cold, with average maximum temperatures often below 35.6 °F (2 °C), and much lower in the mountainous regions. The lowest recorded temperature was -37.3 °F (-38.5 °C) in Bod in 1942, and the highest was 112.1 °F (44.5 °C) at Ion Sion in 1951.

Precipitation varies across the country. The highest western mountains receive over 30 in (750 mm) annually, while in Bucharest, the average is approximately 22 in (570 mm). The Danube Delta is the driest region, with annual precipitation around 15 in (370 mm).

Regional climate variations exist:

- Western Romania, particularly the Banat region, experiences a milder climate with some Mediterranean influences.

- Eastern Romania has a more pronounced continental climate.

- Dobruja, the region between the lower Danube and the Black Sea, is influenced by the maritime climate of the Black Sea, resulting in milder winters and cooler summers compared to the inland plains.

The Carpathian Mountains also play a significant role in moderating the climate, with distinct alpine conditions at higher altitudes.

4.3. Ecosystems and Natural Environment

Romania boasts a rich biodiversity and a variety of ecosystems, thanks to its diverse topography and climate. Approximately 47% of the country's land area is covered by natural and semi-natural ecosystems. Romania has one of the largest areas of undisturbed forest in Europe, covering about 27% of its territory. The country's Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score was 5.95/10 in 2019, ranking it 90th globally out of 172 countries.

There are six main terrestrial ecoregions in Romania: Balkan mixed forests, Central European mixed forests, East European forest steppe, Pannonian mixed forests, Carpathian montane conifer forests, and Pontic steppe.

Romania has a significant network of protected areas, covering almost 3.9 K mile2 (10.00 K km2) (about 5% of the total area). This includes 13 national parks and three biosphere reserves: the Danube Delta, Retezat National Park, and Rodna Mountains National Park. The Danube Delta is particularly noteworthy, supporting 1,688 different plant species alone and serving as a vital habitat for migratory birds.

The country's flora is diverse, with approximately 3,700 plant species identified. Of these, 23 have been declared natural monuments, 74 are considered extinct, 39 endangered, 171 vulnerable, and 1,253 rare. The fauna of Romania is equally rich, comprising 33,792 species of animals, of which 33,085 are invertebrates and 707 are vertebrates. Romania is home to almost 400 unique species of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Notably, it hosts about 50% of Europe's (excluding Russia) brown bear population and 20% of its wolves, primarily in the Carpathian Mountains.

Environmental challenges include deforestation, soil erosion, and water and air pollution in some industrial areas. Conservation efforts are ongoing, often supported by EU initiatives, to protect Romania's valuable natural heritage.

5. Politics

Romania is a unitary semi-presidential representative democratic republic. The Constitution of Romania, originally adopted in 1991 and revised in 2003 to align with EU standards, serves as the fundamental law of the country. It establishes a multi-party system and a framework for governance based on the principles of democracy, separation of powers, and the rule of law, though the practical application of these principles has faced challenges, particularly concerning judicial independence and corruption.

5.1. Government Structure

The Romanian government is structured with distinct executive, legislative, and judicial branches, designed to provide checks and balances, although the interplay between the President and the Prime Minister can sometimes lead to political cohabitation or tension.

The executive branch is led by the President of Romania and the Prime Minister.

- The President is the head of state, directly elected by popular vote for a maximum of two five-year terms. The President represents Romania in international affairs, safeguards the constitutional order, acts as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and mediates between state powers and between the state and society. The President nominates the Prime Minister, promulgates laws, and can call for referendums. The official residence of the President is the Cotroceni Palace.

- The Prime Minister is the head of government. The Prime Minister is appointed by the President, usually from the party or coalition holding a majority in Parliament, and must be confirmed by a vote of confidence from the Parliament. The Prime Minister, along with the Cabinet (Council of Ministers), is responsible for implementing domestic and foreign policies and managing public administration. The Prime Minister and the Government are accountable to Parliament. The seat of the government is Victoria Palace.

The legislative branch is the Parliament (Parlamentul RomânieiParlamentul RomânieiRomanian), which is bicameral, consisting of:

- The Chamber of Deputies (Camera DeputațilorCamera DeputațilorRomanian), the lower house.

- The Senate (SenatulSenatulRomanian), the upper house.

Members of both chambers are elected every four years through a system based on proportional representation in multi-member constituencies. The Parliament enacts laws, approves the state budget, and oversees the government's activities. The Parliament resides in the Palace of the Parliament.

Democratic processes, including regular elections and the functioning of political parties, are central to Romania's governance. However, issues such as political clientelism, legislative instability, and attempts to undermine judicial independence have been recurring concerns impacting the quality of democracy.

5.2. Judiciary

The judiciary is, according to the Constitution, independent of the other branches of government. The judicial system is based on civil law, influenced by the French model, and has an inquisitorial nature.

The structure of the judicial system includes:

- The High Court of Cassation and Justice (Înalta Curte de Casație și JustițieÎnalta Curte de Casație și JustițieRomanian), which is the supreme court of Romania. It ensures the uniform interpretation and application of law by all other courts.

- Courts of Appeal (curți de apelcurți de apelRomanian)

- Tribunals (tribunaletribunaleRomanian) - county-level courts

- Local courts or first-instance courts (judecătoriijudecătoriiRomanian)

The Constitutional Court (Curtea ConstituționalăCurtea ConstituționalăRomanian) stands apart from the regular judicial system. It is responsible for adjudicating the constitutionality of laws before their promulgation and resolving constitutional conflicts between public authorities.

Since Romania's accession to the European Union in 2007, significant emphasis has been placed on judicial reform, strengthening the rule of law, and combating corruption. The EU's Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM) was established to monitor progress in these areas. While some progress has been made, including the prosecution of high-level corruption cases by the National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA), concerns about political interference in the judiciary, the effectiveness of reforms, and the independence of judges remain. Public protests have often erupted in response to perceived threats to judicial independence.

6. Administrative Divisions

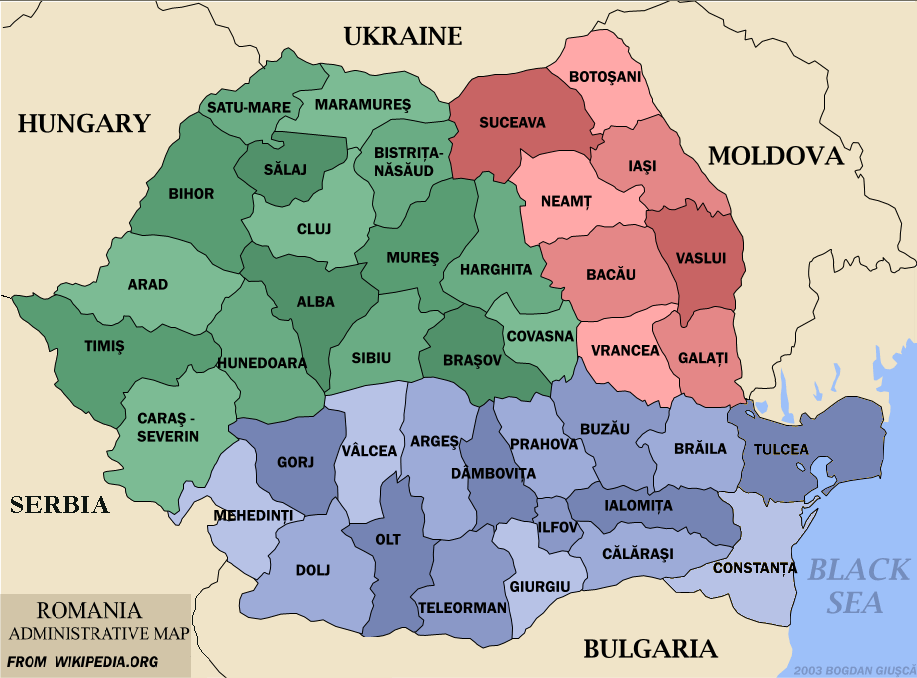

Romania is a unitary state administratively organized into counties (județejudețeRomanian), cities (which include municipalities - municipiimunicipiiRomanian, and towns - orașeorașeRomanian), and communes (comunecomuneRomanian). This structure forms the basis for local governance and public administration across the country.

Romania is divided into 41 counties (județejudețeRomanian, singular: județ) and the municipality of Bucharest, which has a special status comparable to that of a county. Each county is administered by a county council (consiliu județeanconsiliu județeanRomanian), responsible for local affairs and headed by a president elected from its members, and a prefect, who is appointed by the central government to represent it at the county level and oversee the legality of local administrative acts. The prefect cannot be a member of any political party.

Counties are further subdivided into:

- Cities: These are urban localities. Larger, more economically and socially significant cities are designated as municipalities (municipiimunicipiiRomanian), which have greater administrative powers. Smaller urban localities are designated as towns (orașeorașeRomanian). As of recent data, there are 103 municipalities and 217 towns.

- Communes (comunecomuneRomanian): These are rural localities, typically consisting of one or more villages. There are 2,861 communes in Romania.

Each city (municipality or town) and commune has its own mayor (primarprimarRomanian) and a local council (consiliu localconsiliu localRomanian), elected by direct vote, responsible for local governance within their jurisdictions. The municipality of Bucharest is unique; it is divided into six administrative sectors (sectoaresectoareRomanian), each with its own mayor and local council, in addition to the General Mayor of Bucharest and the General Council of Bucharest.

For statistical and development purposes, Romania is also divided into larger regions based on the EU's Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS):

- NUTS-1 level**: 4 macroregions (macroregiunimacroregiuniRomanian)

- NUTS-2 level**: 8 development regions (regiuni de dezvoltareregiuni de dezvoltareRomanian)

- NUTS-3 level**: The 41 counties and the municipality of Bucharest.

The NUTS-1 and NUTS-2 regions do not have administrative capacity themselves but are used for coordinating regional development projects and for statistical reporting to the EU.

| Development region | Area (km2) | Population (2021) | Most populous urban centre (including metropolitan area where applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nord-Vest (North-West) | 34,152 | 2,521,793 | Cluj-Napoca (approx. 411,000 in metro area) |

| Centru (Centre) | 34,097 | 2,271,067 | Brașov (approx. 370,000 in metro area) |

| Nord-Est (North-East) | 36,853 | 3,226,436 | Iași (approx. 382,000 in metro area) |

| Sud-Est (South-East) | 35,774 | 2,367,987 | Constanța (approx. 426,000 in metro area) |

| Sud - Muntenia (South-Muntenia) | 34,469 | 2,864,339 | Ploiești (approx. 276,000 in metro area) |

| București - Ilfov | 1,803 | 2,259,665 | Bucharest (approx. 2,272,000 in metro area) |

| Sud-Vest Oltenia (South-West Oltenia) | 29,207 | 1,873,607 | Craiova (approx. 357,000 in metro area) |

| Vest (West) | 32,042 | 1,668,921 | Timișoara (approx. 385,000 in metro area) |

6.1. Major Cities

Romania has several major urban centers that are significant for their demographic size, economic activity, cultural heritage, and educational institutions.

- Bucharest (BucureștiBucureștiRomanian): The capital and largest city of Romania, Bucharest is the country's primary political, economic, and cultural center. With a city proper population of over 1.7 million (2021 census) and a metropolitan area population approaching 2.2 million, it is one of the largest cities in Southeastern Europe. Bucharest is known for its wide boulevards, Belle Époque architecture, and significant landmarks like the Palace of the Parliament.

- Cluj-Napoca: Often considered the historical capital of Transylvania, Cluj-Napoca is a major academic, cultural, and business hub. It has a large student population and a vibrant IT sector. Its rich history is reflected in its diverse architecture and numerous museums.

- Timișoara: Located in western Romania (Banat region), Timișoara is a multicultural city known for its Baroque architecture and its pivotal role in the 1989 Romanian Revolution. It is an important industrial and technological center.

- Iași: The historical capital of Moldavia, Iași is a significant cultural and educational center in northeastern Romania. It is home to the oldest university in Romania and numerous historical monuments and monasteries.

- Constanța: Romania's largest seaport on the Black Sea coast, Constanța is an ancient city (formerly Tomis) with a rich history dating back to Greek and Roman times. It is a key commercial and tourist hub.

- Craiova: A major city in the Oltenia region of southwestern Romania, Craiova is an important industrial, commercial, and cultural center.

- Brașov: Situated in central Romania in the Transylvania region, Brașov is a popular tourist destination known for its medieval old town, proximity to mountain resorts, and landmarks like the Black Church.

- Galați: A port city on the Danube River in eastern Romania, Galați is an industrial center with a significant shipyard and steel plant.

- Ploiești: Located north of Bucharest, Ploiești is a major center for Romania's oil and gas industry.

- Oradea: Situated in northwestern Romania near the Hungarian border, Oradea is known for its Art Nouveau architecture and thermal baths.

These cities, along with others like Sibiu, Arad, Pitești, and Bacău, contribute significantly to Romania's national identity and development. Many have established metropolitan areas to better coordinate regional development and services.

7. Foreign Relations

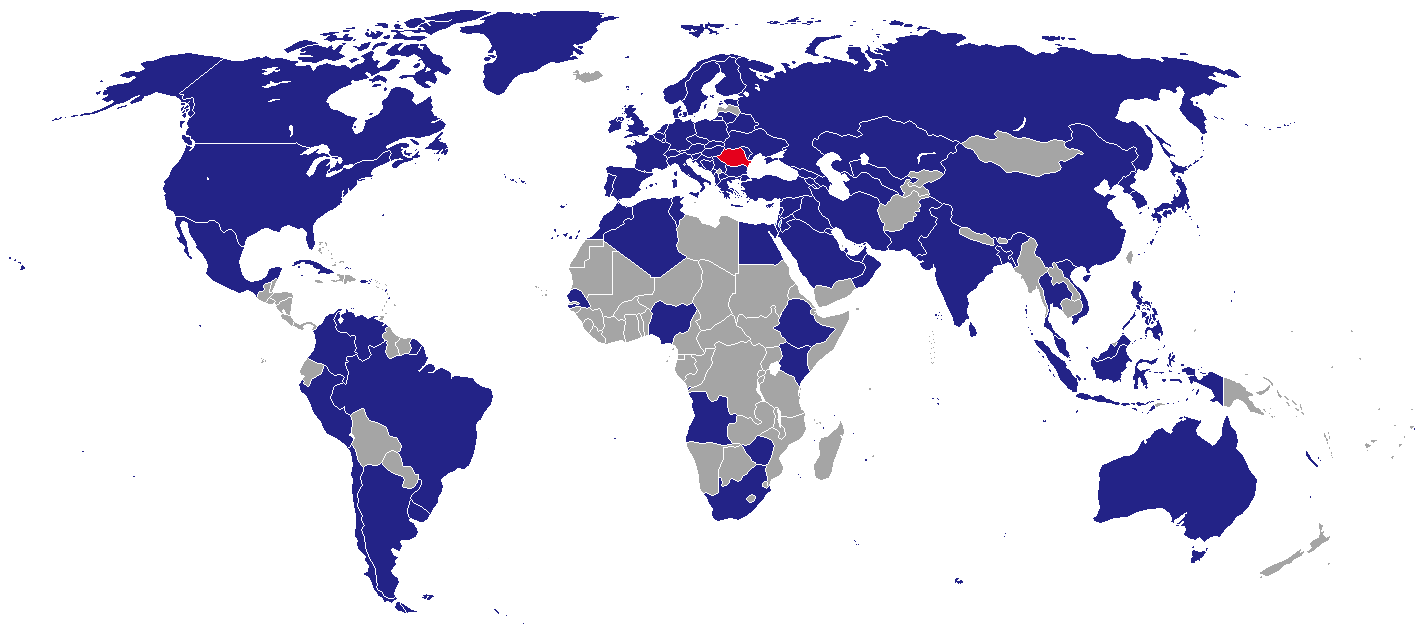

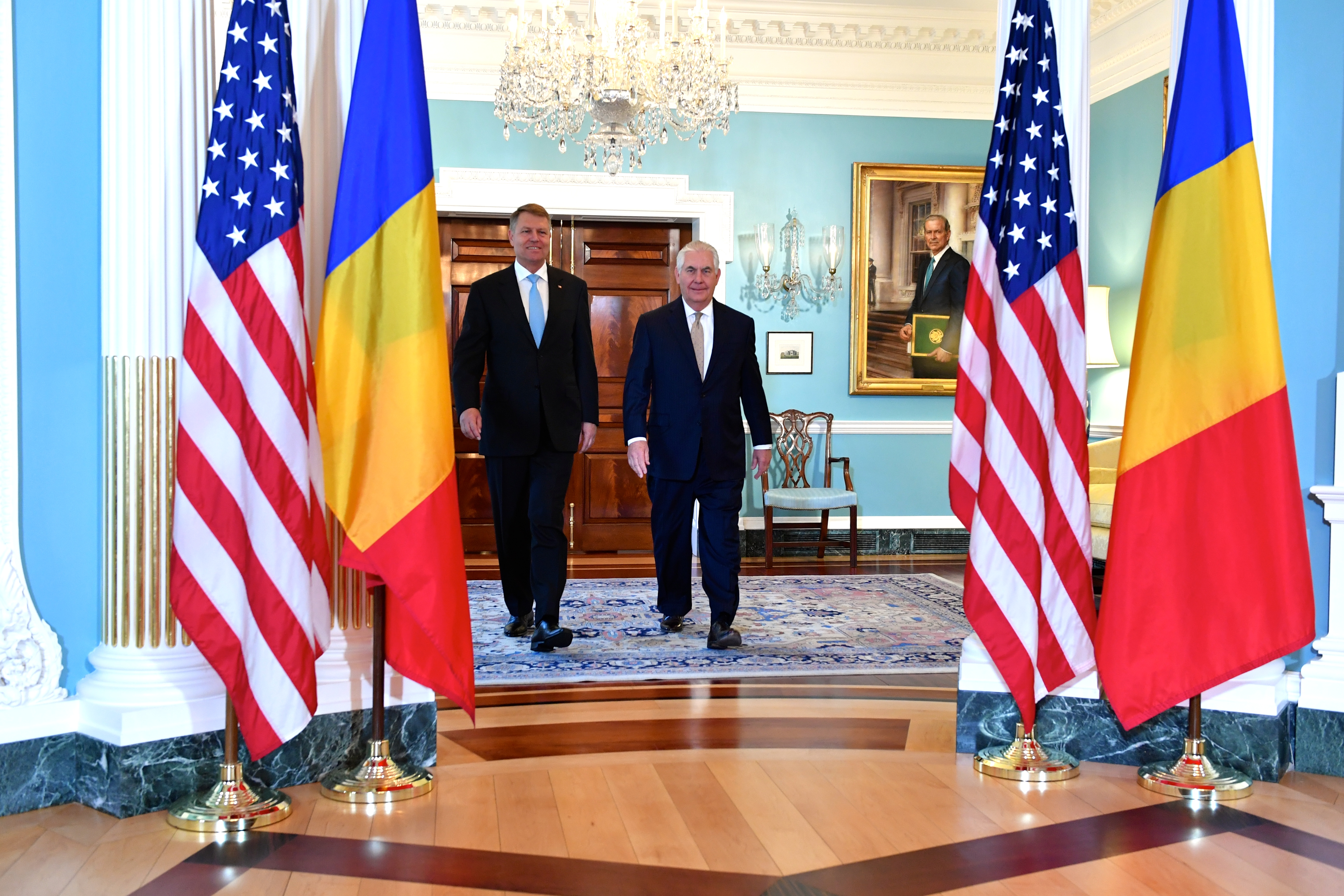

Since the fall of communism in December 1989, Romania has pursued a foreign policy focused on strengthening ties with Western Europe and the United States, Euro-Atlantic integration, and promoting regional stability. Key objectives include ensuring national security, fostering economic development through international partnerships, and upholding democratic values and human rights on the global stage.

A cornerstone of Romania's foreign policy has been its integration into Euro-Atlantic structures. Romania joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on March 29, 2004, significantly enhancing its security framework. It has actively participated in NATO missions and hosted the 2008 Bucharest summit. Romania also became a full member of the European Union (EU) on January 1, 2007. EU membership has profoundly influenced its domestic policies, driving reforms in areas such as the judiciary, public administration, and the economy, and has provided access to significant development funds. Romania joined the Schengen Area with its air and sea borders on March 31, 2024, and became a full member, including land borders, on January 1, 2025, after Austria lifted its veto.

Romania is an active member of the United Nations (UN) since 1955 and participates in various other international organizations, including the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Council of Europe (CoE), the World Trade Organization (WTO) (as a founding member), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC). Romania is recognized as a middle power due to its military capabilities and active diplomatic engagement.

Bilateral relations with the United States are a key component of Romania's foreign policy, defined as a Strategic Partnership. This includes close military cooperation, with Romania hosting U.S. military facilities, such as the Aegis Ashore missile defense site at Deveselu. Romania has consistently supported U.S. and NATO initiatives, including increasing its defense spending.

Relations with neighboring countries are generally positive. Romania has a special relationship with the Republic of Moldova due to shared language, culture, and history. Romania strongly supports Moldova's European integration aspirations and has been a vocal advocate for its sovereignty and territorial integrity. Relations with Hungary are complex due to historical issues and the presence of a significant Hungarian minority in Romania, but both countries cooperate as EU and NATO members. Romania aims to foster good relations with Ukraine, Serbia, and Bulgaria, focusing on cross-border cooperation, economic ties, and regional security.

Romania has also expressed support for the European aspirations of other countries in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, such as Georgia. It has consistently advocated for the enlargement of NATO and the EU to include democratic nations in the region. The country's foreign policy emphasizes multilateralism, international law, and engagement on global issues such as counter-terrorism, non-proliferation, climate change, and the promotion of human rights and international cooperation.

8. Military

The Romanian Armed Forces (Forțele Armate RomâneForțele Armate RomâneRomanian) consist of three main branches: the Land Forces (Forțele TerestreForțele TerestreRomanian), the Air Force (Forțele AerieneForțele AerieneRomanian), and the Naval Forces (Forțele NavaleForțele NavaleRomanian). They are led by a Commander-in-chief (Chief of the General Staff), who operates under the supervision of the Ministry of National Defence. The President of Romania serves as the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces during wartime.

As of recent estimates, the Romanian Armed Forces consist of approximately 71,500 active military personnel and around 55,000 reservists. Active personnel are distributed with roughly 35,800 in the Land Forces, 10,700 in the Air Force, 6,600 in the Naval Forces, and the remainder in other joint fields and support structures. Conscription was abolished in 2007, and Romania transitioned to an all-volunteer professional military.

Romania's defense spending has increased in line with its NATO commitments. In 2023, defense expenditure accounted for approximately 2.44% of the country's total national GDP, amounting to around 8.48 B USD. Significant funds, projected at around 9.00 B USD by 2026, are allocated for the modernization of equipment and acquisition of new military hardware.

The Romanian Air Force operates a mix of aircraft, including F-16AM/BM MLU Fighting Falcon multirole fighters (acquired from Portugal and Norway). It also utilizes C-27J Spartan and C-130 Hercules military transport aircraft, as well as domestically produced IAR 330 Puma and IAR 316 Alouette III helicopters. A procurement program for F-35 Lightning II fifth-generation fighters is currently underway.

The Romanian Naval Forces operate primarily in the Black Sea. Their fleet includes three frigates (two of which are ex-British Royal Navy Type 22 frigates, the Regele Ferdinand and Regina Maria), several corvettes, missile boats, and support vessels. The River Flotilla operates on the Danube River with Mihail Kogălniceanu-class and Smârdan-class river monitors.

Romania has been an active participant in international military cooperation and peacekeeping missions. It contributed troops to the NATO-led mission in Afghanistan from 2002, with a peak deployment of 1,600 troops, concluding its combat mission in 2014. Romanian forces also participated in the coalition operations in Iraq, terminating their mission in 2009. The frigate Regele Ferdinand participated in the 2011 NATO naval operations off Libya.

As a NATO member, Romania hosts allied forces and participates regularly in joint exercises. The Aegis Ashore missile defense system, part of NATO's ballistic missile shield, is operational at the Deveselu base since 2016. In 2024, construction work began on expanding the Mihail Kogălniceanu Air Base, which is set to become the largest NATO air base in Europe.

9. Economy

Romania has a high-income economy and has experienced significant economic transformation since the end of communism in 1989 and its accession to the European Union in 2007. As of 2024, Romania's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in purchasing power parity (PPP) was estimated at around 894.00 B USD, with a GDP per capita (PPP) of approximately 47.20 K USD. According to Eurostat, Romania's GDP per capita (PPS) reached 77% of the EU average in 2022, a substantial increase from 44% in 2007, highlighting one of the fastest convergence rates within the EU.

The Bucharest Stock Exchange (BVB) is the country's main stock exchange. In 2024, it had a market capitalization of about 74.00 B USD and a trading volume of 7.20 B USD, with 86 companies listed. In September 2020, FTSE Russell upgraded the BVB from a frontier market to a secondary emerging market status.

Following the 1989 revolution, Romania underwent a difficult decade of economic instability and decline, partly due to an obsolete industrial base and slow structural reforms. However, from 2000 onwards, the economy stabilized and entered a period of high growth, low unemployment, and declining inflation. This growth was interrupted by the Great Recession in 2008-2009, which necessitated an IMF-led bailout package of 20.00 B EUR and led to a contraction in GDP. The economy has since recovered and resumed a path of strong growth.

Romania's main exports include vehicles (notably cars produced by Dacia and Ford), software and IT services, clothing and textiles, industrial machinery, electrical and electronic equipment, metallurgical products, raw materials, military equipment, pharmaceuticals, fine chemicals, and agricultural products such as fruits, vegetables, and flowers. Trade is predominantly centered on EU member states, with Germany, Italy, and France being its largest trading partners.

After extensive privatization and reforms in the late 1990s and 2000s, government intervention in the Romanian economy is relatively moderate. In 2005, Romania introduced a flat tax system of 16% for both personal income and corporate profit, which was among the lowest rates in the EU at the time (though the system has seen modifications since). The economy is primarily based on services, which accounted for 56.2% of GDP in 2017, followed by industry (30%) and agriculture (4.4%). Despite its relatively small share of GDP, agriculture still employs a significant portion of the workforce (around 25.8%), one of the highest rates in Europe.

Romania has attracted increasing amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI) since 1989, with the FDI stock reaching 83.80 B EUR in June 2019. However, its outward FDI stock remains comparatively low among EU nations.

The official currency is the Romanian leu (RON), which was redenominated in 2005 (1 new leu = 10,000 old lei). Romania is committed to adopting the Euro and currently targets 2029 for its adoption.

9.1. Economic Structure and Major Industries

Romania's economy has a diversified structure, with services being the largest contributor to GDP, followed by industry and agriculture. The country has several major industries that are significant both domestically and for export.

Services: This sector accounts for over half of Romania's GDP and employment. Key service industries include:

- Information Technology (IT) and Software Development: Romania has a rapidly growing IT sector, with a strong pool of skilled professionals. Cities like Bucharest, Cluj-Napoca, and Iași are major IT hubs, hosting numerous local and international tech companies. The country is known for software development, cybersecurity, and IT outsourcing.

- Retail and Wholesale Trade: This sector has expanded significantly with increased consumer spending and the entry of international retail chains.

- Finance and Banking: The banking sector is largely privatized and includes major European banking groups.

- Tourism: A growing contributor to the economy (covered in a separate section).

- Transportation and Logistics: Benefiting from Romania's strategic location.

Industry: Accounting for around 30% of GDP, Romania's industrial sector includes:

- Automotive Manufacturing: This is a flagship industry, with major plants operated by Dacia (owned by Renault) and Ford. Romania is a significant vehicle and automotive parts exporter.

- Oil and Gas: Romania has a long history of oil production and possesses refining capacities. OMV Petrom is a major player. While production of traditional reserves has declined, there is ongoing exploration for new sources, including offshore Black Sea gas.

- Manufacturing: Besides automotive, this includes machinery, electrical and electronic equipment, and metal products.

- Textiles and Clothing: A traditional industry that remains an important employer and exporter, though facing competition.

- Energy Production: Diverse sources including hydro, nuclear (Cernavodă plant), coal, and increasingly, renewables like wind and solar.

- Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals.

Agriculture: While its share of GDP has decreased to around 4-5%, agriculture remains important, employing a substantial part of the population. Romania has significant agricultural potential due to its fertile land. Key products include cereals (wheat, corn), oilseeds (sunflower, rapeseed), vegetables, fruits, and livestock. Challenges include land fragmentation and the need for modernization.

Considerations of labor rights and environmental sustainability are increasingly important across all sectors. EU membership has brought stricter regulations and standards in these areas. Trade unions are active, advocating for workers' rights, while environmental concerns related to industrial pollution, deforestation, and sustainable resource management are part of the national discourse.

9.2. Infrastructure

Romania's infrastructure has undergone significant development and modernization, particularly since its accession to the European Union, though challenges remain in certain areas.

Transportation Network:

- Roads: According to the National Institute of Statistics (INS), Romania's total road network was estimated at 53 K mile (86.08 K km) in 2015. This includes national roads, county roads, and communal roads. The development of motorways (autostrăziautostrăziRomanian) and expressways has been a priority, with EU funds contributing significantly. Key corridors, such as those part of the Pan-European transport network, are being upgraded.

- Railways: Romania has one of the largest railway networks in Europe, estimated by the World Bank at 14 K mile (22.30 K km) of track. The state-owned Căile Ferate Române (CFR) is the main operator. After a period of decline post-1989, efforts are underway to modernize railway lines and rolling stock, particularly on major European corridors. Rail transport accounts for a significant portion of passenger and freight movement. The Bucharest Metro, opened in 1979, is the country's only underground railway system, serving the capital with a network of 50 mile (80.01 km) and carrying hundreds of thousands of passengers daily.

- Airports: Romania has sixteen international commercial airports. The largest is Henri Coandă International Airport in Bucharest (Otopeni), which handled over 12.8 million passengers in 2017. Other important international airports are located in Cluj-Napoca, Timișoara, Iași, and Sibiu.

- Ports: The Port of Constanța on the Black Sea is the largest port in Romania and one of the most important in the region, serving as a key gateway for trade. Danube river ports also play a role in freight transport.

Energy Infrastructure:

- Electricity: Romania has a diverse electricity generation mix. In 2015, sources included hydropower (around 30%), nuclear power (from the Cernavodă Nuclear Power Plant, around 18%), coal (around 28%), and hydrocarbons (around 14%), with a growing share from renewable sources like wind and solar. Romania is a net exporter of electrical energy.

- Oil and Natural Gas: Romania has a long history of oil and gas production and possesses significant refining capacity. While traditional onshore production has declined, there is active exploration and development of new resources, particularly offshore natural gas reserves in the Black Sea. The country has one ofthe largest reserves of crude oil and shale gas in Europe, contributing to its relative energy independence within the EU.

- Renewable Sources: Investment in renewable energy, particularly wind power in Dobruja and solar power, has increased, supported by EU targets and national schemes.

Telecommunications Infrastructure:

- Internet: Romania has a well-developed internet infrastructure, with widespread broadband access. As of June 2014, there were almost 18.3 million internet connections. The country is often cited for having some of the fastest average internet speeds globally, particularly for fixed broadband. Cities like Timișoara have ranked among the highest in the world for internet download speeds.

- Mobile Telephony: Mobile phone penetration is high, with extensive 4G and growing 5G network coverage.

Overall, while significant progress has been made, continued investment is needed to further modernize Romania's infrastructure to meet EU standards and support sustained economic growth.

9.3. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing sector in the Romanian economy, contributing approximately 5% to the GDP and employing a substantial number of people. The country's diverse attractions, ranging from natural landscapes and historical sites to rich cultural heritage, draw millions of visitors annually. In 2016, Romania received 9.33 million foreign tourists, with a steady increase in numbers observed in the years prior and following. A majority of foreign visitors, over 60% as of 2007, come from other EU countries.

Key tourist attractions and destinations include:

- Natural Landscapes:

- The Danube Delta: A UNESCO World Heritage site, offering unique biodiversity, birdwatching opportunities, and boat tours.

- The Carpathian Mountains: Providing opportunities for hiking, skiing, and exploring scenic routes like the Transfăgărășan and Transalpina highways. Popular skiing resorts include those in Valea Prahovei (e.g., Sinaia, Bușteni, Predeal) and Poiana Brașov.

- National Parks and Protected Areas: Such as Retezat National Park, Piatra Craiului National Park, and the Apuseni Mountains with their caves (e.g., Scărișoara Ice Cave).

The Danube Delta is home to a rich array of wildlife, including large colonies of pelicans.

A beach in Mamaia, one of Romania's popular Black Sea resorts, known for its summer tourism. - Historical and Cultural Sites:

- Medieval Cities and Towns in Transylvania: Including Sibiu (a former European Capital of Culture), Brașov, Sighișoara (a UNESCO World Heritage site and the birthplace of Vlad Țepeș), Cluj-Napoca, and Alba Iulia. These cities boast well-preserved medieval architecture, fortified churches, and vibrant cultural scenes.

- Castles and Fortifications: Bran Castle (often associated with the Dracula legend), Peleș Castle (a stunning royal palace in Sinaia), Pelișor Castle, Corvin Castle (a Gothic masterpiece in Hunedoara), and numerous other fortresses and citadels.

- Painted Monasteries of Northern Moldavia: UNESCO World Heritage sites like Voroneț, Sucevița, and Moldovița, famous for their exterior frescoes.

- Wooden churches of Maramureș: UNESCO World Heritage sites showcasing unique timber architecture in the Maramureș region.

- Villages with fortified churches in Transylvania: UNESCO World Heritage sites representing the Saxon heritage of the region.

- Sculptural Ensemble of Constantin Brâncuși at Târgu Jiu: A significant outdoor monument by the internationally renowned sculptor.

- Black Sea Resorts: Popular summer destinations like Mamaia, Vama Veche, Costinești, and Eforie Nord, offering beaches, nightlife, and spas.

- Rural Tourism and Agrotourism: Growing in popularity, this focuses on authentic experiences of Romanian village life, traditions, folklore, and cuisine. Regions like Maramureș, Bukovina, and parts of Transylvania are well-known for this. The Via Transilvanica, a long-distance hiking and cycling trail, further promotes rural and slow tourism.

The tourism industry attracted 400.00 M EUR in investments in 2005, and in 2014, Romania had 32,500 companies active in the hotel and restaurant industry, with a total turnover of 2.60 B EUR. The government and private sector continue to invest in developing tourism infrastructure and promoting Romania as a diverse and attractive travel destination.

9.4. Science and Technology

Romania has a notable history of contributions to science and technology, with several Romanian researchers and inventors achieving international recognition.

Historically, prominent figures include:

- Traian Vuia: An aviation pioneer who designed, built, and tested one of the first monoplanes capable of taking off under its own power in 1906.

- Aurel Vlaicu: Another aviation pioneer who built and flew some of the earliest successful aircraft in Romania.

- Henri Coandă: Discovered the Coandă effect related to fluid dynamics and built an early jet-propelled aircraft.

- Victor Babeș: A physician and bacteriologist who made significant contributions to the study of rabies, leprosy, and diphtheria, discovering more than 50 types of bacteria.

- Nicolae Paulescu: A physiologist and professor of medicine credited by some Romanians with the discovery of an early form of insulin (which he called "pancreine"), demonstrating its effect on lowering blood sugar in diabetic dogs.

- George Emil Palade: A cell biologist who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1974 for his discoveries concerning the functional organization of the cell, particularly ribosomes and the endoplasmic reticulum.

- Lazăr Edeleanu: A chemist who was the first to synthesize amphetamine and invented a process for refining petroleum using selective solvents.

- Other notable figures include mathematician Spiru Haret, physicist and inventor Ștefan Odobleja (a pioneer of cybernetics), and engineer Anghel Saligny (designer of the Cernavodă Bridge).

In the post-communist era (1990s and 2000s), the development of research and development (R&D) in Romania was hampered by factors such as low funding, corruption, and a significant "brain drain" of scientists and engineers. Romania's R&D spending as a percentage of GDP has historically been among the lowest in the European Union, standing at roughly 0.5% in 2016 and 2017, substantially below the EU average.

However, there have been efforts to revitalize the sector. In the early 2010s, the situation for science in Romania was described as "rapidly improving," albeit from a low base. In January 2011, the Romanian Parliament passed a law aimed at enforcing stricter quality control on universities and introducing tougher rules for funding evaluation and peer review. Romania was ranked 48th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

Romania has increased its participation in international scientific collaborations. It became a member of the European Space Agency (ESA) in 2011 and a full member of CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in 2016. However, in 2018, Romania temporarily lost its voting rights in the ESA due to unpaid membership contributions, highlighting ongoing funding challenges.

A significant recent development is Romania's hosting of a major component of the Extreme Light Infrastructure (ELI) project, specifically the ELI-Nuclear Physics (ELI-NP) facility in Măgurele. This facility is designed to be the world's most powerful laser system. In early 2012, Romania launched its first satellite, Goliat, from the Guiana Space Centre in French Guiana. Starting in December 2014, Romania became a co-owner of the International Space Station through its ESA membership.

10. Society

Romanian society is a blend of historical traditions and modern European influences, characterized by its demographic trends, ethnic diversity, linguistic landscape, religious practices, and evolving social systems such as education and healthcare.

10.1. Demographics

According to the 2021 Romanian census, the population of Romania was 19,053,815. Like many countries in the region, Romania's population has been gradually declining due to a combination of sub-replacement fertility rates and a negative net migration rate. The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2018 was estimated at 1.36 children born per woman, significantly below the replacement rate of 2.1 and among the lowest globally. This contrasts with a TFR of 5.82 in 1912. In 2014, 31.2% of births were to unmarried women.

The birth rate (9.49 per 1,000 population in 2012) is lower than the death rate (11.84 per 1,000 in 2012), resulting in a natural population decrease. This, combined with emigration, contributes to an aging population. The median age in 2018 was 41.6 years, one of the oldest in the world, with approximately 16.8% of the total population aged 65 years and over. Life expectancy in 2015 was estimated at 74.92 years (71.46 years for males and 78.59 years for females).

The Romanian diaspora is significant, with an estimated 12 million Romanians and individuals with Romanian ancestry living abroad. After the Romanian Revolution of 1989, many Romanians emigrated to other European countries (notably Italy and Spain), North America, or Australia, seeking better economic opportunities. As of 2009, there were also approximately 133,000 immigrants living in Romania, primarily from Moldova and China.

10.2. Ethnic Groups

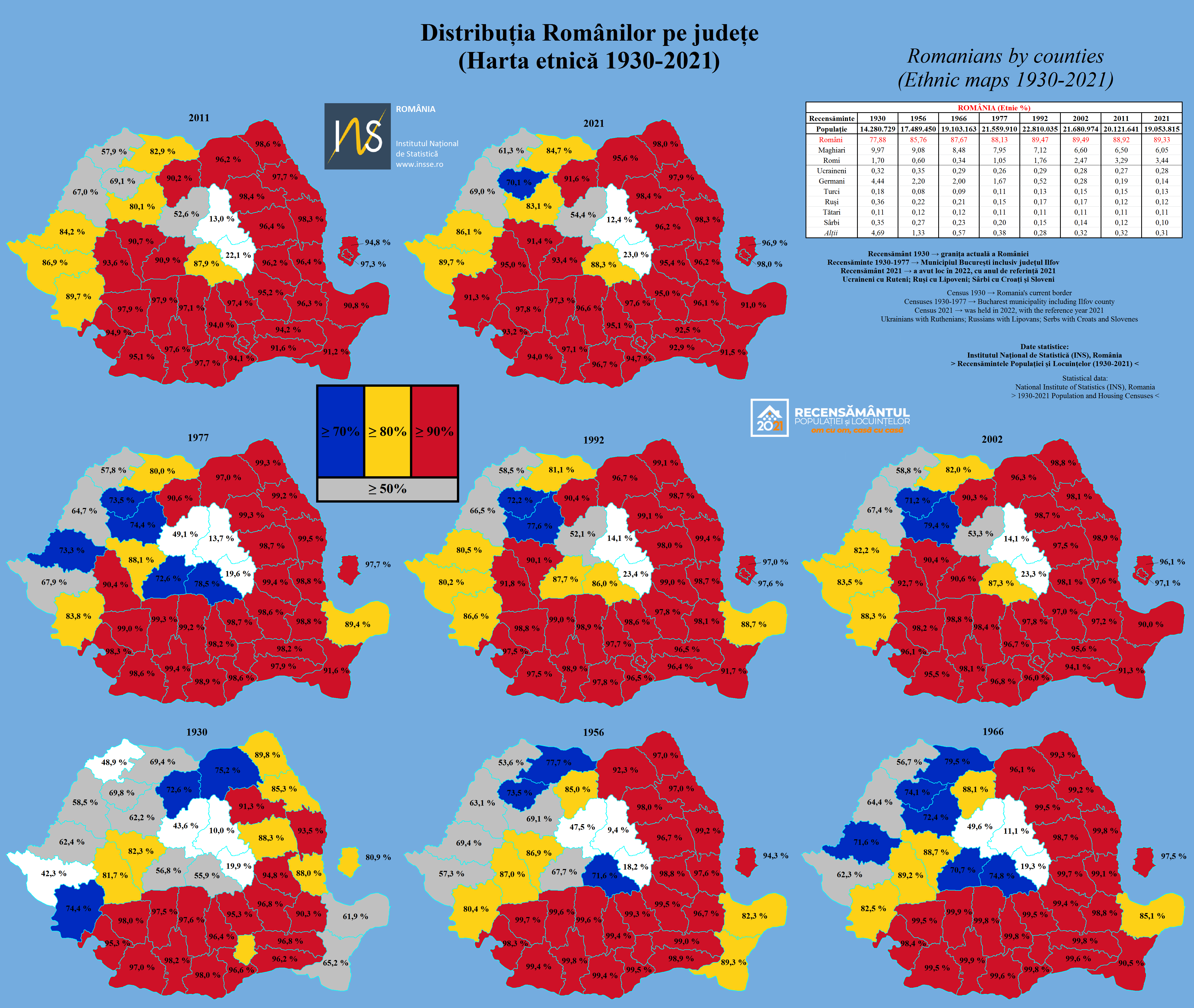

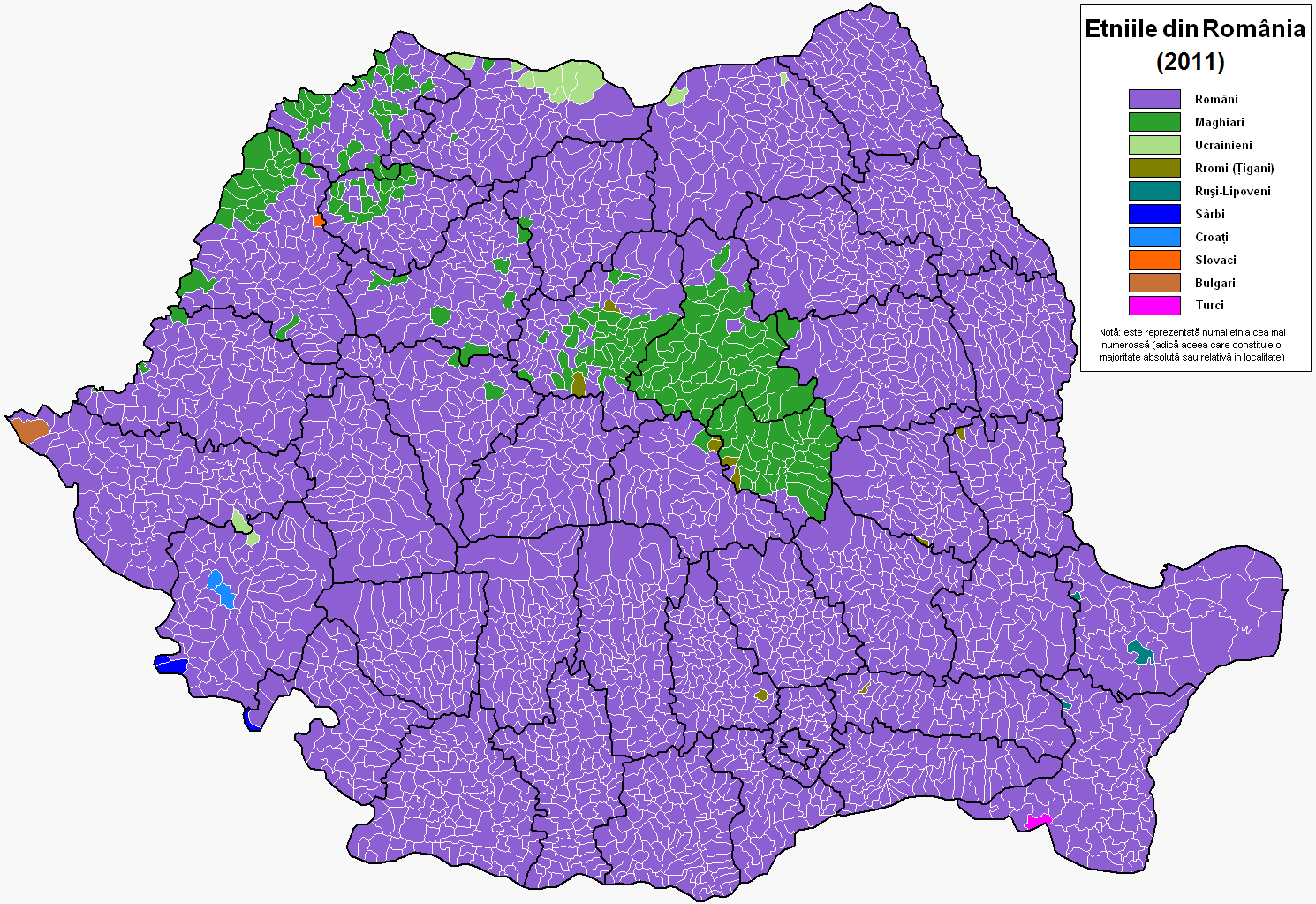

Romania is an ethnically diverse country, though ethnic Romanians constitute the vast majority. According to the 2021 census:

- Romanians make up 89.33% of the population.

- Hungarians are the largest ethnic minority, forming 6.05% of the population. They are concentrated mainly in Transylvania, particularly in the counties of Harghita and Covasna, where they form local majorities.

- Roma constitute 3.44% of the population according to the census. However, it is widely acknowledged that the actual number of Roma is higher, as many may not declare their ethnicity due to social stigma or lack of identification documents. The Council of Europe, for instance, estimates the Roma population to be around 8.32%. Other sources suggest figures ranging from 1 to 2.5 million.

Other recognized minorities include Ukrainians (concentrated near the northern border), Germans (whose numbers have significantly decreased from over 745,000 in 1930 to about 36,000 today due to emigration), Turks and Tatars (mainly in Dobruja), Lipovans (Old Believer Russians), Aromanians, Serbs, Slovaks, Bulgarians, Croats, Greeks, Russians, Jews (once a much larger community), Czechs, Poles, and Italians.

The Romanian constitution and laws guarantee rights for ethnic minorities, including the right to use their mother tongue in administration and education in localities where they form a significant part of the population (typically over 20%), and representation in Parliament. However, minority groups, particularly the Roma, continue to face social and economic challenges, including discrimination and marginalization. Efforts towards better integration and upholding the rights of all vulnerable groups are ongoing, often supported by EU frameworks and civil society organizations.

10.3. Languages

The official language of Romania is Romanian (Limba românăLimba românăRomanian). It is a Romance language belonging to the Eastern Romance branch of the Italic languages within the Indo-European family. Romanian evolved from Vulgar Latin spoken in the Roman province of Dacia and surrounding areas, with influences from Slavic languages, Greek, Turkish, and Hungarian. It exhibits a notable degree of similarity to Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian, and shares many features with other Romance languages like Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Catalan. The Romanian alphabet uses the standard 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, plus five additional letters with diacritics: ă, â, î, ș, and ț, totaling 31 letters.

According to the 2021 census, Romanian is spoken as a first language by 91.55% of the population. Hungarian is the largest minority language, spoken by 6.28% of the population, primarily in Transylvania. Vlax Romani is spoken by 1.20% of the population, though many Roma also speak Romanian or Hungarian. Other minority languages spoken in Romania include Ukrainian (approximately 40,861 native speakers, concentrated near the border), Turkish (around 17,101 speakers), German (around 15,943 speakers), and Russian (around 14,414 speakers), along with languages of other smaller ethnic groups.

The Romanian Constitution guarantees linguistic rights for minorities. In localities where an ethnic minority constitutes over 20% of the population, that minority's language can be used in public administration, the justice system, and education alongside Romanian. Foreign citizens and stateless persons also have access to justice and education in their own language where feasible.

The main foreign languages taught in Romanian schools are English and French. According to a 2012 Eurobarometer survey, 31% of Romanians could speak English, 17% could speak French, and 7% could speak Italian and German each. Romania is a member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, and in 2010, an estimated 4.75 million people in the country could speak French.

10.4. Religion

Romania is a secular state with no official state religion, and freedom of religion is guaranteed by the constitution. The overwhelming majority of the population identifies as Christian.

According to the 2021 census:

- Eastern Orthodox Christians** constitute 73.60% of respondents. The vast majority of these (73.42% of the total population) belong to the autonomous Romanian Orthodox Church (Biserica Ortodoxă RomânăBiserica Ortodoxă RomânăRomanian). This church is in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox churches and is led by a Patriarch. It is the third-largest Eastern Orthodox Church in the world by number of adherents and is unique in that it functions within a predominantly Latin-based culture and uses a Romance liturgical language. Its canonical jurisdiction covers Romania and Moldova.

- Protestant** denominations make up 6.22% of the population. This includes various groups such as Reformed (Calvinist), Pentecostal, Baptist, and Seventh-day Adventist.

- Roman Catholics** account for 3.89% of the population.

- Greek Catholics** (Romanian Church United with Rome, Uniate) represent 0.61%. This church was suppressed during the communist era but re-emerged after 1989.

From the remaining population, 128,291 people (0.67%) belong to other Christian denominations or other religions. This includes:

- Muslims**: Numbering 58,347 in the 2021 census, predominantly of Turkish and Tatar ethnicity, concentrated mainly in the Dobruja region.