1. Overview

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country located in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia, at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. It is a unitary, multi-party, democratic nation-state with an ancient and rich cultural heritage, deeply influenced by its history as the first nation to adopt Christianity as its state religion in 301 AD. This article traces Armenia's journey from its prehistoric origins and ancient kingdoms through periods of foreign domination, national awakening, the devastating Armenian Genocide, Soviet rule, and its path to modern independence. It emphasizes Armenia's democratic development, the ongoing struggle for human rights, the profound impact of historical and recent conflicts on its people, particularly minorities and vulnerable groups, and the socio-economic challenges and achievements that shape the well-being of its populace. The narrative focuses on the resilience of the Armenian people, their cultural contributions, and their continuous efforts to build a sovereign, democratic, and socially just society amidst regional complexities and geopolitical shifts.

2. Etymology

The native Armenian name for the country was originally ՀայքHayk'Armenian. The contemporary name, ՀայաստանHayastanArmenian, became popular in the Middle Ages with the addition of the Persian suffix "-stan" (meaning "place" or "land"). However, the origins of "Hayastan" trace back to earlier dates and were first attested in circa 5th-century works by Armenian historians such as Agathangelos, Faustus of Byzantium, Ghazar Parpetsi, Koryun, and Sebeos.

Traditionally, the name "Hayk'" and "Hayastan" are derived from Hayk (ՀայկArmenian), the legendary patriarch of the Armenians and a great-great-grandson of Noah. According to the 5th-century AD author Movses Khorenatsi (Moses of Chorene), Hayk defeated the Babylonian king Bel (identified by some with Nimrod) in 2492 BC and established his nation in the Ararat region. The further origin of the name "Hay" is uncertain. It has been postulated that "Hay" comes from one of the two confederated, Hittite vassal states - Hayasa-Azzi (1600-1200 BC).

The exonym "Armenia" is attested in the Old Persian Behistun Inscription (515 BC) as the Old Persian Armina (𐎠𐎼𐎷𐎡𐎴ArminaPersian, Old). The Ancient Greek terms ἈρμενίαArmeníaGreek, Ancient and ἈρμένιοιArménioiGreek, Ancient (Armenians) were first mentioned by Hecataeus of Miletus (circa 550 BC - circa 476 BC). Xenophon, a Greek general, described aspects of Armenian village life around 401 BC.

Some scholars have linked "Armenia" with the Early Bronze Age state of Armani (Armanum, Armi) or the Late Bronze Age state of Arme (Shupria). These connections remain inconclusive. It is possible that "Armenia" originates in Armini, Urartian for "inhabitant of Arme" or "Armean country." The Arme tribe of Urartian texts may have been the Urumu, who in the 12th century BC attempted to invade Assyria.

According to Moses of Chorene and Michael Chamchian, "Armenia" derives from the name of Aram, a lineal descendant of Hayk. The Hebrew Bible's Table of Nations lists Aram as the son of Shem. The Book of Jubilees attests that the land of Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates to the north of the Chaldees, including the mountains of Asshur and the land of 'Arara', came forth for Aram. The historian Flavius Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews states that Ul, a son of Aram, founded Armenia. In Malay, Armenians are referred to as Lamender, a term believed to have originated from a Betawi (Jakarta) corruption of the Portuguese word "Armario" through sound shifts.

3. History

The history of Armenia encompasses its development from prehistoric settlements in the Armenian Highlands, through ancient kingdoms, medieval states under various empires, periods of foreign rule, national awakenings, devastating conflicts including the Armenian Genocide, its incorporation into the Soviet Union, and its emergence as an independent republic in the late 20th century, facing ongoing challenges and transformations.

3.1. Prehistory

The Armenian Highlands show evidence of human presence from the Lower Paleolithic period, with Acheulean tools found near obsidian outcrops dating back over 1 million years. The Nor Geghi 1 Stone Age site in the Hrazdan River valley, with artifacts dated to 325,000 years ago, suggests that human technological innovation, such as Levallois technology, may have occurred intermittently across the Old World rather than spreading from a single origin.

The region was home to numerous Bronze Age cultures. Early Bronze Age settlements, part of the Kura-Araxes culture, have been found throughout Armenia, including Shengavit (near modern Yerevan), Harich, Karaz, and Garni. The Shengavit settlement, flourishing in the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE, was a significant urban center. Archaeological findings from this period include evidence of early metallurgy, sophisticated pottery, and agricultural practices. The Trialeti-Vanadzor culture, succeeding the Kura-Araxes, is known for its rich burial mounds containing elaborate gold and silver artifacts.

Discoveries in Armenia have included some of the world's oldest known artifacts, such as the Areni-1 shoe (c. 3500 BC), a 5,900-year-old skirt found in the Areni-1 cave, and the Areni-1 winery (c. 4100 BC), the earliest known wine-making facility, indicating advanced societal development. Petroglyphs found on Mount Ughtasar and elsewhere depict scenes of hunting, animals, and human figures, dating back possibly to the 12th millennium BC, though more commonly associated with the Bronze Age. The Zorats Karer (also known as Karahunj) megalithic complex, dating to the Middle Bronze Age or earlier, consists of hundreds of standing stones, some with circular holes, suggesting potential astronomical or ritualistic functions.

During the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, confederations of tribes such as Hayasa-Azzi and Nairi emerged in the Armenian Highlands. These entities are considered by some scholars to be among the precursors to the later Armenian state and people.

3.2. Antiquity

The ancient history of Armenia is marked by the rise and fall of powerful kingdoms, interactions with major empires, and the pivotal adoption of Christianity. The Armenian Highlands served as a cradle for these developments.

The first major state in the region was Urartu (known as Ararat or Biainili in its own language), which emerged in the 9th century BC and flourished until the early 6th century BC. Centered around Lake Van, Urartu developed a sophisticated culture with impressive fortresses (like Erebuni in modern Yerevan, founded in 782 BC by King Argishti I), irrigation systems, and a unique cuneiform script. Urartu frequently clashed with the Assyrian Empire.

Following the decline of Urartu, the region came under the influence of the Median Empire and subsequently the Achaemenid Empire. Armenia was organized as a satrapy within the Achaemenid Empire, mentioned in the Behistun Inscription of Darius I (c. 515 BC). The Orontid Dynasty (Yervanduni) ruled Armenia, first as satraps and later as independent kings after the collapse of the Achaemenid Empire following Alexander the Great's conquests in the 4th century BC. Armenia then fell under the influence of the Seleucid Empire.

Around 190 BC, Artaxias I, an Orontid general, founded the Artaxiad dynasty (Artashesian), establishing a fully sovereign Kingdom of Armenia. This kingdom reached its zenith under Tigranes the Great (r. 95-55 BC), who expanded its borders from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean Sea, creating a vast empire that briefly became the most powerful state east of the Roman Republic. Tigranes built a new capital, Tigranocerta. However, his expansion brought him into conflict with Rome, and after defeats by Roman generals Lucullus and Pompey, Armenia became a Roman client state.

The following centuries saw Armenia as a buffer state contended by the Roman (later Byzantine) and Parthian (later Sasanian Persian) empires. The Arsacid dynasty (Arshakuni), a branch of the Parthian Arsacids, was established on the Armenian throne in the 1st century AD under Tiridates I of Armenia. Despite periods of independence and autonomy, Armenia was often subject to the influence or direct rule of these larger powers. The pagan Garni Temple, likely built in the 1st century AD during the reign of Tiridates I, stands as a unique example of Greco-Roman architecture in the region.

A pivotal event in Armenian history was the adoption of Christianity as the state religion. According to tradition, this occurred in 301 AD when King Tiridates III of Armenia, converted by Gregory the Illuminator (Grigor Lusavorich), declared Christianity the official religion. This made Armenia the first nation to do so, an act that had profound and lasting consequences for Armenian identity, culture, and political orientation, often setting it apart from its Zoroastrian Persian and later Islamic neighbors. The Etchmiadzin Cathedral, traditionally founded in 303 AD, became the spiritual center of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

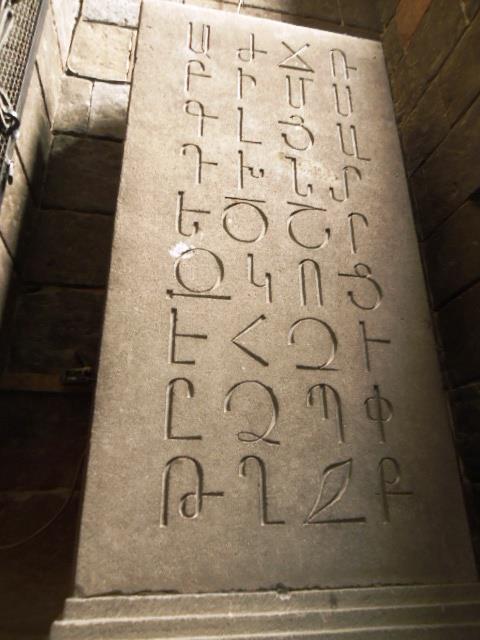

In the early 5th century, around 428 AD, the Arsacid Kingdom of Armenia was abolished, and its territory was divided between the Byzantine Empire (Western Armenia) and the Sasanian Empire (Eastern Armenia, known as Persarmenia), which was administered as a marzpanate (province). Despite political division, Armenians maintained a strong sense of cultural unity, significantly bolstered by the invention of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop Mashtots around 405 AD. This invention facilitated the translation of the Bible and other religious and literary works into Armenian, ushering in a golden age of Armenian literature and preserving national identity. The Battle of Avarayr in 451 AD, though a military defeat for the Armenians led by Vardan Mamikonian against the Sasanians who sought to reimpose Zoroastrianism, is remembered as a moral victory that ultimately secured Armenia's right to practice Christianity.

3.3. Middle Ages

The Middle Ages in Armenia were characterized by periods of restored sovereignty alternating with domination by powerful neighboring empires, significant cultural achievements, and the eventual loss of statehood on the Armenian Highlands, leading to the rise of a new Armenian kingdom in Cilicia.

Following the division of Armenia between the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires in the 5th century, Eastern Armenia remained under Persian rule until the Arab conquests of the 7th century. In the mid-7th century, the Rashidun Caliphate conquered Sasanian Persia and subsequently Armenia. The region became an autonomous principality known as Arminiya within the Umayyad Caliphate and later the Abbasid Caliphate. It was ruled by an Armenian prince (ostikan), recognized by both the Caliph and often the Byzantine Emperor, with its center at Dvin. Despite Arab rule, Armenians largely retained their Christian faith and cultural identity, and the Armenian nobility played a significant role in the administration of the region.

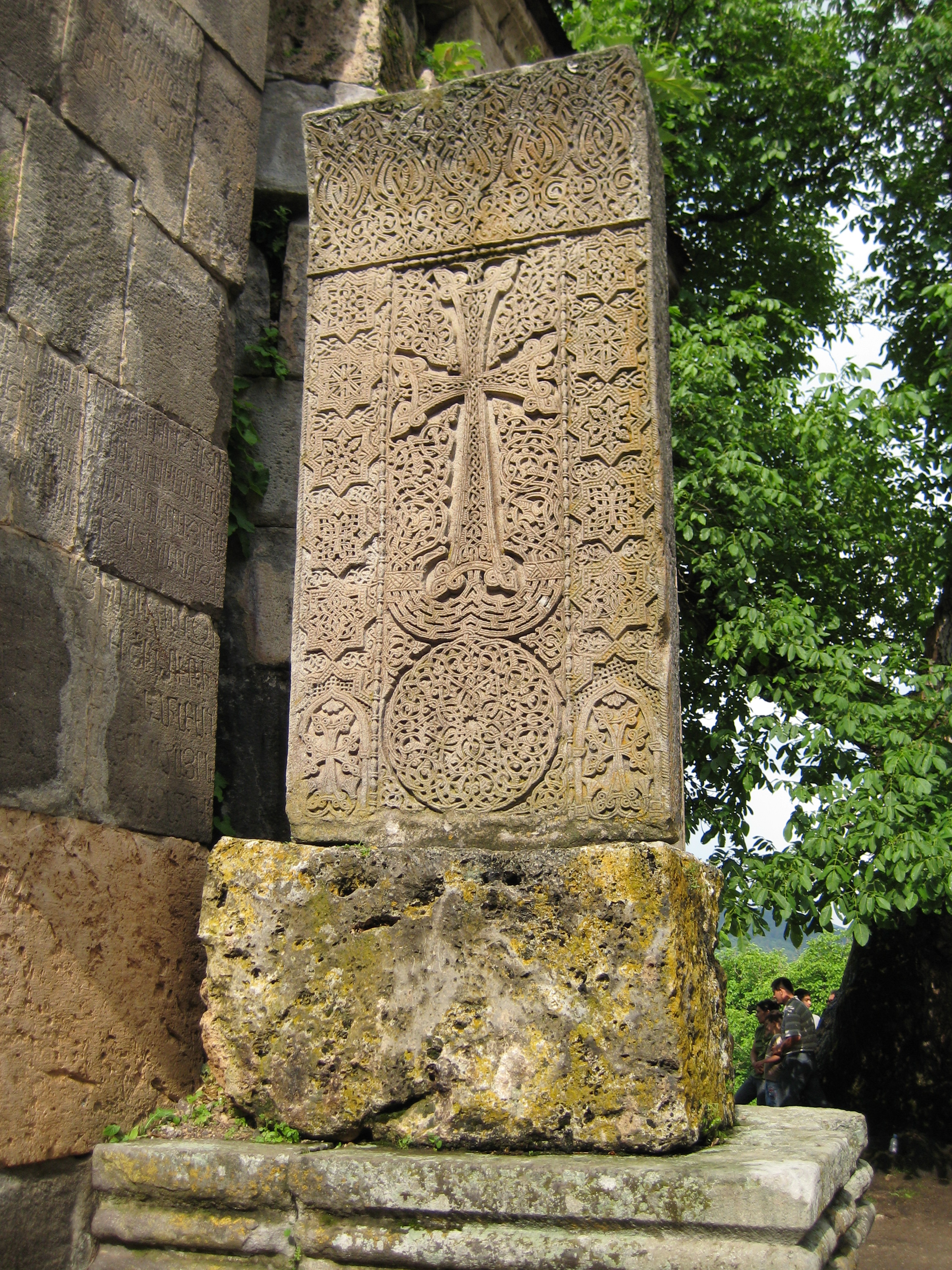

In the 9th century, as the Abbasid Caliphate weakened, Armenian noble families, particularly the Bagratunis (Bagratids), gained increasing power. In 884/885 AD, Ashot I Bagratuni was recognized as King of Armenia by both the Caliph and the Byzantine Emperor, restoring the Armenian Kingdom. The Bagratid era, centered in cities like Ani (its capital from 961 AD), is considered a golden age of Armenian culture, architecture, and learning. Ani, known as the "city of a thousand and one churches," became a major urban center. However, the kingdom was often plagued by internal divisions and pressure from external powers. Several regions, such as Vaspurakan (under the Artsrunis), Syunik, and Artsakh, formed independent or semi-independent kingdoms while nominally recognizing Bagratid supremacy.

The Bagratid Kingdom eventually succumbed to Byzantine pressure and Seljuk Turk invasions. In 1045, Ani was annexed by the Byzantine Empire. Byzantine rule was short-lived, as the Seljuks, under Alp Arslan, defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, opening Anatolia and Armenia to Turkic settlement. This defeat had devastating consequences for both Byzantium and Armenia, leading to widespread destruction and displacement of the Armenian population.

In response to the Seljuk invasions, many Armenians migrated southwards to the Taurus Mountains and the Mediterranean coast, where they established new principalities. One of these, founded by Ruben I, Prince of Armenia, evolved into the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (also known as Lesser Armenia). Officially declared a kingdom in 1198 under Leo I (Levon I), Cilician Armenia, with its capital at Sis, became an important commercial and cultural center. It maintained close ties with the European Crusaders and served as a bastion of Christianity in the East. The seat of the Catholicos (head of the Armenian Church) was transferred to Cilicia during this period. Cilician Armenia flourished for several centuries, adopting Western European feudal structures and legal codes, but eventually fell to the Egyptian Mamluks in 1375.

Back in the Armenian Highlands, following the decline of Seljuk power, parts of northern and eastern Armenia experienced a revival under the Zakarids (Mkhargrdzeli), Armenian princes who served the Georgian Kingdom in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. This period, known as Zakarid Armenia, saw a resurgence of Armenian culture and monastic life. However, this revival was cut short by the Mongol invasions in the 1230s. Armenia became part of the Mongol Empire and later suffered further devastation from the campaigns of Timur (Tamerlane) in the late 14th century. These invasions led to a significant decline in the region's prosperity and population, and a further dispersal of Armenians. The Orbelian Dynasty maintained a degree of local autonomy in Syunik, while the House of Hasan-Jalalyan ruled the Kingdom of Artsakh in Nagorno-Karabakh.

3.4. Early Modern Era

The Early Modern Era for Armenia, spanning from the 16th to the early 19th centuries, was predominantly characterized by foreign domination, as the traditional Armenian homeland became a battleground and a divided territory between the Ottoman Empire and successive Persian empires (Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar). This period profoundly impacted the socio-cultural and demographic landscape of the Armenian people.

From the early 16th century, after the decline of local Turcoman dynasties like the Kara Koyunlu and Ag Qoyunlu, the Armenian Highlands were contested between the expanding Ottoman Empire to the west and the Safavid Empire of Iran to the east. The Ottoman-Safavid Wars frequently ravaged Armenian lands. The Peace of Amasya in 1555 formally divided historic Armenia: Western Armenia came under Ottoman rule, while Eastern Armenia (including regions like Yerevan and Karabakh) fell under Persian control. This division was largely reaffirmed by the Treaty of Zuhab in 1639 and remained, with some territorial shifts, until the Russian conquests of the 19th century.

Under Ottoman rule, Western Armenians were part of the millet system, which granted religious minorities a degree of autonomy in their internal affairs, particularly in religious and cultural matters, under the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. While Armenians initially played significant roles in Ottoman commerce, crafts, and administration, their status as non-Muslims (dhimmi) subjected them to legal and social disabilities, including higher taxes and restrictions. Conditions varied over time and by region, but generally deteriorated in later centuries, particularly with the weakening of central Ottoman authority and the rise of local Kurdish chieftains.

In Eastern Armenia, under Persian rule, Armenians also experienced periods of both relative tolerance and severe persecution. Shah Abbas I (r. 1588-1629) of the Safavid dynasty implemented a "scorched earth" policy during his wars with the Ottomans. In 1604-1605, he ordered the forced resettlement of a large Armenian population from the Ararat valley and Nakhichevan to Persia, primarily to Isfahan, where they established the New Julfa quarter. This was done to depopulate the border regions against Ottoman advances and to bring skilled Armenian merchants and artisans into Persia to boost its economy. While New Julfa became a thriving center of Armenian culture and international trade, the forced deportations were a traumatic event, causing immense suffering and loss of life. Eastern Armenia was often administered as a province (khanate), such as the Erivan Khanate.

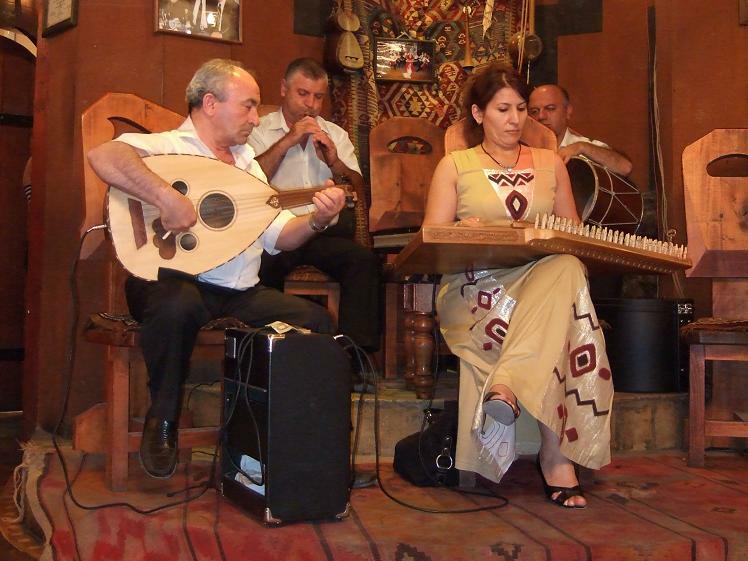

Throughout this period, the Armenian Church played a crucial role in preserving Armenian identity, language, and culture in both Ottoman and Persian Armenia. Monasteries remained centers of learning and manuscript production. The Armenian diaspora, which had begun in earlier centuries, continued to grow, with significant communities emerging in various parts of Europe, Asia, and later, the Americas. These diaspora communities often maintained strong ties with their homeland and contributed to Armenian cultural and intellectual life.

The socio-economic conditions for many Armenians, particularly peasants, were often harsh under both empires, subject to heavy taxation, feudal exploitation, and insecurity due to wars and local conflicts. Despite these challenges, Armenian merchants and craftsmen continued to play vital roles in regional and international trade networks.

3.5. Modern Era

The Modern Era for Armenia, stretching from the 19th century to the early 20th century, was marked by continued foreign rule, a significant national awakening, devastating conflicts including the Armenian Genocide, and the first, albeit brief, period of modern independent statehood.

3.5.1. Russian and Ottoman Rule and National Awakening

In the early 19th century, the geopolitical landscape of the Armenian homeland shifted dramatically. Following the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813) and the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828), Qajar Iran was forced to cede Eastern Armenia (including the Erivan Khanate and Karabakh Khanate) to the Russian Empire under the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828). This part of Armenia became known as Russian Armenia. Under Russian rule, conditions for Eastern Armenians were somewhat more stable compared to those under Ottoman or Persian rule, though they were still subject to Tsarist autocracy and Russification policies. The establishment of the Armenian Oblast in 1828 was an early administrative form.

Meanwhile, Western Armenia remained under Ottoman rule. The 19th century saw a decline in the Ottoman Empire's power and increasing discontent among its Christian minorities. While some reforms (Tanzimat) were introduced, the situation for Western Armenians often remained precarious, marked by discrimination, heavy taxation, and lack of security. In response to worsening conditions and inspired by nationalist movements elsewhere in Europe, an Armenian national awakening (Zartonk) began in both Russian and Ottoman Armenia. This cultural and intellectual movement sought to revive Armenian language, literature, and historical consciousness. Armenian schools, newspapers, and cultural societies were established. Political consciousness also grew, with calls for reforms, autonomy, and eventually, liberation from foreign rule.

In the Ottoman Empire, Armenian demands for reforms and protection led to increased repression. Sultan Abdul Hamid II responded to Armenian activism and rebellions (such as the Sasun rebellion of 1894) with brutal force, organizing the Hamidian massacres between 1894 and 1896, which resulted in the deaths of an estimated 80,000 to 300,000 Armenians. These massacres earned Abdul Hamid II the epithet "Red Sultan" or "Bloody Sultan" and foreshadowed the larger-scale atrocities to come. Armenian revolutionary parties, such as the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun) and the Hnchakian Party, were formed during this period, advocating for self-defense and Armenian rights, sometimes through armed resistance (fedayi groups).

The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 initially raised hopes among Armenians for equality and reform within the Ottoman Empire. However, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which came to power, soon adopted a more nationalist and authoritarian agenda. The Adana massacre of 1909, in which 20,000-30,000 Armenians were killed, was a grim indicator of continuing anti-Armenian sentiment. As World War I approached, the Armenian reform package of 1914 was an attempt to address Armenian grievances, but its implementation was cut short by the outbreak of the war.

3.5.2. World War I and Armenian Genocide

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 set the stage for one of the darkest chapters in Armenian history: the Armenian Genocide. The Ottoman Empire, under the rule of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), commonly known as the Young Turks, allied with the Central Powers. The war provided the CUP with a pretext to implement its ultranationalist policies aimed at Turkifying the empire and eliminating non-Turkish elements, particularly the Armenians, whom they viewed with suspicion as a potential pro-Russian fifth column, especially as the Russian Empire (an Entente Power) bordered Ottoman Armenia and had Armenian volunteer units within its army.

The genocide began on April 24, 1915, a date now commemorated as Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day. On that day, several hundred Armenian intellectuals, community leaders, clergy, and professionals were arrested in Constantinople (Istanbul) and other major cities, then deported and mostly killed. This act was designed to decapitate the Armenian community and remove its leadership.

Following these arrests, the Ottoman government, under the pretext of wartime necessity, initiated the systematic extermination of its Armenian population. The Tehcir Law (Law of Deportation) of May 29, 1915, provided a veneer of legality for the forced displacement of Armenians from their ancestral lands in Western Armenia and other parts of Anatolia. The genocide was carried out in two main phases:

1. The massacre of able-bodied Armenian men: Armenian men serving in the Ottoman army were disarmed, transferred to labor battalions, and then systematically killed. Civilian men were also rounded up and executed.

2. The deportation of women, children, the elderly, and the infirm: These groups were forced on death marches into the Syrian Desert (primarily around Deir ez-Zor). Driven by military escorts, they were deprived of food, water, and shelter, and subjected to robbery, rape, torture, and mass killings by Ottoman gendarmes, soldiers, and irregular Kurdish or Turkish bands. Many perished from starvation, disease, and exhaustion. Concentration camps were established where survivors faced further atrocities.

There were instances of Armenian resistance, such as the defense of Van, Musa Dagh, and Urfa, but these were largely isolated and ultimately overwhelmed.

The systematic nature of the killings, the direct involvement of state organs, and the clear intent to destroy the Armenian population as a group lead most Western historians and many countries to recognize these events as genocide. Estimates of the number of Armenians killed range from 600,000 (an early estimate by Arnold J. Toynbee for 1915-1916 only) to over 1.5 million, with the most common figure cited being around 1 to 1.5 million. The genocide resulted in the near-total annihilation of the Armenian presence in their historic homeland in Western Armenia, the destruction of countless churches, monasteries, schools, and cultural heritage sites, and the creation of a vast Armenian diaspora.

International reactions at the time included condemnations from Allied powers (Britain, France, Russia) who warned the Ottoman government that they would hold it responsible for these "crimes against humanity." Foreign diplomats, missionaries, and aid workers (like Henry Morgenthau Sr., the US Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire) witnessed and documented the atrocities.

The long-term consequences for survivors and the diaspora have been profound, shaping Armenian identity, memory, and political aspirations. The denial of the genocide by successive Turkish governments remains a major point of contention and a barrier to reconciliation. For the Armenian people, the pursuit of recognition, justice, and remembrance of the genocide is a central and deeply felt issue, impacting their efforts towards democratic development and human rights advocacy, as the trauma of this event underscores the vulnerability of minorities and the importance of international accountability.

3.5.3. First Republic of Armenia (1918-1920)

The collapse of the Russian Empire following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent Russian Civil War created a power vacuum in the Caucasus. Eastern Armenia, along with Georgia and Azerbaijan, initially formed the short-lived Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic in February 1918. However, internal divisions and external pressures, particularly from the advancing Ottoman army, led to its dissolution in May 1918.

On May 28, 1918, the Armenian National Council declared the independence of the First Republic of Armenia (also known as the Democratic Republic of Armenia) in Tiflis (Tbilisi), with its capital later established in Yerevan. Aram Manukian was a key figure in its establishment. The new republic faced immense challenges from its inception. It was born amidst war, territorial disputes with its neighbors (Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the Ottoman Empire/Turkey), and a massive humanitarian crisis caused by the influx of hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing the Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Armenia. These refugees brought disease and starvation, overwhelming the fledgling state's resources.

Militarily, the nascent republic had to fight for its survival. The Battle of Sardarabad, Battle of Karakilisa, and Battle of Bash Abaran in May 1918, where Armenian forces, including regular army units and volunteer militias, successfully halted the Ottoman advance into Eastern Armenia, were crucial for the establishment of the state. The Treaty of Batum (June 1918) forced Armenia to cede significant territories to the Ottoman Empire, but the republic survived.

The government of the First Republic, dominated by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun), attempted to build state institutions, establish a parliamentary system, and gain international recognition. It introduced reforms in education and land distribution. Women were granted suffrage. However, the political landscape was fractured, and the government struggled with internal dissent and uprisings by Muslim populations in some regions.

The Entente Powers, particularly the United States, Britain, and France, provided some humanitarian aid and political support. The Treaty of Sèvres (August 10, 1920), signed between the Allies and the defeated Ottoman Empire, recognized Armenia's independence and proposed to assign it significant territories in Western Armenia (often referred to as "Wilsonian Armenia" as U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was tasked with drawing the borders). However, this treaty was never ratified by the Ottoman parliament and was rejected by the Turkish National Movement led by Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk).

In late 1920, the First Republic faced a two-front assault. Turkish nationalist forces under Kâzım Karabekir invaded from the west, leading to the Turkish-Armenian War. Simultaneously, the Soviet Eleventh Army invaded from the east, aiming to establish Soviet rule in the Caucasus. Defeated by the Turks and facing internal pressure from Armenian Bolsheviks, the government of the First Republic was forced to sign the Treaty of Alexandropol (December 2, 1920), ceding Kars and other territories to Turkey and renouncing the Treaty of Sèvres. On the same day, Soviet forces entered Yerevan, and the Armenian government agreed to transfer power to a Soviet-backed Revolutionary Committee. The First Republic of Armenia ceased to exist after only two and a half years.

Despite its short existence, the First Republic was a crucial experience in modern Armenian statehood, providing a symbol of independence and self-governance that would be revived decades later. Its legacy continues to influence Armenian national consciousness and political thought, particularly concerning democratic ideals and territorial integrity. The humanitarian catastrophe it inherited from the Genocide, and its own struggles with war and displacement, highlighted the vulnerability of the Armenian people and the urgent need for stable statehood and international support.

3.6. Soviet Era

The Soviet era in Armenia spanned from late 1920 to 1991, a period of profound transformation that included nation-building within a totalitarian framework, industrialization, cultural developments, political repression, and ultimately, a movement towards independence. This era significantly shaped modern Armenian society, its economy, and its national consciousness, with lasting impacts on human rights and democratic aspirations.

3.6.1. Formation and Early Soviet Period

Following the invasion by the Soviet 11th Red Army in November-December 1920, the First Republic of Armenia was overthrown, and the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (Armenian SSR) was proclaimed on December 2, 1920. Initially, there was a brief anti-Bolshevik February Uprising in 1921, which established the Republic of Mountainous Armenia in southern Armenia under Garegin Nzhdeh, but it was suppressed by the Red Army by July 1921.

On March 4, 1922, Armenia, along with Georgia and Azerbaijan, was incorporated into the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (TSFSR), which became one of the founding republics of the Soviet Union in December 1922. The Treaty of Kars (October 1921) between Turkey and the Soviet republics of the Caucasus (including Armenia) finalized Armenia's western borders, ceding Kars and Ardahan to Turkey, a loss deeply resented by Armenians. Joseph Stalin's decision as Commissar for Nationalities to assign Nagorno-Karabakh (an Armenian-populated region) and Nakhichevan to the Azerbaijan SSR, despite their historical ties to Armenia, sowed the seeds for future conflict and remains a point of major grievance, impacting the rights and security of Armenians in those regions.

The TSFSR was dissolved in 1936, and Armenia became a full constituent republic of the USSR as the Armenian SSR. The early Soviet period saw efforts at nation-building, including the promotion of Armenian language and culture, albeit within Soviet ideological constraints. Yerevan was extensively reconstructed and became a modern capital. However, this period was also marked by Stalin's Great Purge in the 1930s, which saw the execution or exile of many Armenian intellectuals, political figures, and clergy, severely impacting Armenian civil society and human rights. The Armenian Apostolic Church faced intense persecution, with many churches closed or destroyed and clergy repressed.

Economic policies focused on rapid industrialization and collectivization of agriculture. While industrial output grew, collectivization was often brutal and led to famine and peasant resistance, disrupting traditional rural life and negatively impacting the well-being of the agricultural populace.

3.6.2. World War II

Armenia was not a direct theater of combat in World War II, but Armenians participated significantly in the Soviet war effort against Nazi Germany. An estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Armenians served in the Red Army, and about half of them, approximately 175,000, perished. Six special Armenian military divisions were formed, with the 89th "Tamanyan" Division famously fighting its way to Berlin. Many Armenians also distinguished themselves as commanders, such as Marshal Ivan Bagramyan and Admiral Ivan Isakov. On the home front, Armenia contributed to war production. The war effort placed a heavy burden on the Armenian economy and society, but it also fostered a sense of Soviet patriotism among some, while others harbored hopes that the war might lead to changes in Soviet policy or even the recovery of lost territories.

3.6.3. Post-Stalin Period and Thaw

After Stalin's death in 1953, the period known as the Khrushchev Thaw brought a degree of liberalization to the Soviet Union, including Armenia. Political repression eased somewhat, and there was a resurgence of Armenian national consciousness and cultural activity. The Armenian Apostolic Church experienced a partial revival under Catholicos Vazgen I, who assumed office in 1955.

A significant event during this period was the mass demonstrations in Yerevan on April 24, 1965, the 50th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. Thousands of Armenians openly commemorated the genocide and demanded its official recognition by the Soviet government and the international community, as well as the return of lost Armenian territories. These demonstrations were unprecedented in the Soviet Union at the time and marked a turning point in the public expression of Armenian national grievances. In response, the Soviet authorities permitted the construction of the Tsitsernakaberd genocide memorial complex in Yerevan, completed in 1967. This period saw a flowering of Armenian literature, arts, and sciences, though still within the confines of Soviet censorship. Concerns about environmental degradation from Soviet-era industries also began to emerge.

3.6.4. Gorbachev Era and Independence Movement

The late 1980s, under Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of Glasnost (openness) and Perestroika (restructuring), created new opportunities for political expression and mobilization across the Soviet Union. In Armenia, this period was dominated by the Karabakh movement. Starting in 1988, mass demonstrations erupted in Yerevan and Stepanakert (the capital of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) within Azerbaijan SSR), demanding the unification of the predominantly Armenian-populated NKAO with Armenia. The NKAO regional soviet had voted to secede from Azerbaijan and join Armenia, a move supported by Armenians but rejected by Azerbaijani and central Soviet authorities.

The Karabakh movement became a powerful force for Armenian national consolidation and a direct challenge to Soviet authority. It was met with anti-Armenian pogroms in Sumgait (February 1988) and later in Baku (January 1990) within Azerbaijan, leading to hundreds of deaths and the flight of hundreds of thousands of Armenians from Azerbaijan. These events, along with the devastating 1988 Armenian earthquake on December 7, 1988, which killed over 25,000 people and left hundreds of thousands homeless, further fueled disillusionment with Soviet rule and strengthened the desire for independence. The earthquake highlighted the inadequacies of the Soviet system in disaster response and reconstruction, increasing reliance on international aid and diaspora support.

The Pan-Armenian National Movement emerged as the leading political force advocating for democratic reforms and self-determination. On August 23, 1990, the Armenian Supreme Soviet adopted a Declaration of Sovereignty, asserting the supremacy of Armenian laws over Soviet laws and signaling a move towards full independence. Armenia boycotted the March 1991 all-Union referendum on the preservation of the USSR. Following the failed August 1991 coup attempt in Moscow, which fatally weakened central Soviet power, Armenia held a referendum on September 21, 1991, in which over 99% of voters approved secession from the Soviet Union. Independence was formally declared on September 23, 1991. The Soviet Union officially ceased to exist on December 26, 1991.

3.7. Independent Armenia (1991-present)

The period following Armenia's declaration of independence in 1991 has been characterized by efforts to build a democratic state and a market economy, while grappling with regional conflicts, geopolitical challenges, and socio-economic transformations. The pursuit of human rights, democratic development, and ensuring the well-being of its citizens, including those displaced by conflict, has been central to this era.

3.7.1. First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-1994)

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, which had begun in 1988 with Armenian demands for the unification of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) with Armenia, escalated into a full-scale war following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the declarations of independence by Armenia and Azerbaijan. Nagorno-Karabakh, with a majority ethnic Armenian population, declared its own independence as the Republic of Artsakh, which was not internationally recognized.

The First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-1994) was a brutal conflict resulting in tens of thousands of casualties and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people on both sides. Armenian forces, with support from Armenia, gained control not only of most of Nagorno-Karabakh but also several surrounding Azerbaijani-majority districts, creating a buffer zone. The war had devastating social and economic consequences for Armenia, which faced an economic blockade imposed by Azerbaijan and its ally Turkey, severe energy shortages, and the burden of absorbing refugees from Azerbaijan and Artsakh. The humanitarian impact was profound, with widespread suffering among the affected populations. A Russian-brokered ceasefire was signed in May 1994 (Bishkek Protocol), freezing the conflict but leaving Nagorno-Karabakh's status unresolved. The OSCE Minsk Group was established to mediate a peaceful settlement, but decades of negotiations failed to produce a lasting solution. This unresolved conflict deeply affected Armenia's foreign policy, security, and economic development, and the rights of displaced persons remained a pressing issue.

3.7.2. Early 21st Century Developments (2000s-2010s)

The first two decades of the 21st century in Armenia were marked by political consolidation, economic struggles and reforms, and ongoing foreign policy challenges. Levon Ter-Petrosyan served as the first president until his resignation in 1998, followed by Robert Kocharyan (1998-2008) and Serzh Sargsyan (2008-2018). The political landscape was often characterized by a strong executive, contested elections, and concerns about democratic backsliding, corruption, and the independence of the judiciary. The 1999 Armenian parliament shooting, in which the Prime Minister, Parliament Speaker, and other officials were assassinated, was a major political trauma.

Economically, Armenia transitioned to a market economy, but faced challenges including high unemployment, poverty, and the continued impact of regional blockades. The country relied significantly on remittances from its large diaspora and on foreign aid. Some sectors, like IT and tourism, showed growth. Armenia joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2003. In terms of foreign policy, Armenia sought to balance its strategic alliance with Russia (including membership in the CSTO and hosting a Russian military base) with efforts to deepen ties with Western countries and institutions, including the European Union (through the Eastern Partnership) and NATO (through the Partnership for Peace program). Relations with Turkey remained frozen due to Turkey's denial of the Armenian Genocide and its support for Azerbaijan. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict continued to dominate Armenia's security agenda. Social issues included emigration, demographic challenges, and the need to strengthen social safety nets and protect vulnerable groups.

3.7.3. 2018 Velvet Revolution and Aftermath

In April-May 2018, Armenia experienced a series of widespread, peaceful anti-government protests known as the Velvet Revolution. The protests were initially triggered by Serzh Sargsyan's attempt to retain power as Prime Minister after serving two terms as President, following constitutional changes that shifted power from the presidency to the parliament. Led by opposition MP Nikol Pashinyan, the movement quickly grew, fueled by popular discontent over corruption, cronyism, economic stagnation, and a perceived lack of democratic accountability.

The revolution was characterized by civil disobedience, marches, and strikes, largely centered in Yerevan but with support across the country. The protests were notable for their peaceful nature and the significant participation of youth. Under immense public pressure, Serzh Sargsyan resigned on April 23, 2018. Nikol Pashinyan was elected Prime Minister by the National Assembly on May 8, 2018.

The Velvet Revolution was widely hailed as a victory for democratic development and popular sovereignty in Armenia. Pashinyan's government promised sweeping reforms aimed at tackling corruption, strengthening the rule of law and judicial independence, improving human rights protections, and fostering economic development. Early parliamentary elections in December 2018 resulted in a landslide victory for Pashinyan's My Step Alliance. The revolution raised hopes for a more democratic and accountable Armenia, with a renewed focus on citizens' rights and well-being. However, the new government faced significant challenges in implementing its reform agenda and addressing long-standing socio-economic problems and the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The impact on human rights was initially positive, with increased media freedom and space for civil society, but challenges remained, particularly concerning judicial reform and addressing past injustices.

3.7.4. 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War

On September 27, 2020, a full-scale war erupted in Nagorno-Karabakh, significantly more intense than previous clashes. Azerbaijan, with open military support from Turkey and the reported use of foreign mercenaries, launched a major offensive against Armenian forces in Artsakh and Armenia proper. The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war lasted for 44 days and involved heavy artillery, drone warfare, and significant casualties on both sides, including civilians.

Armenian forces suffered substantial setbacks, and Azerbaijani forces made significant territorial gains, including capturing the strategically important city of Shusha. The war ended on November 10, 2020, with a trilateral ceasefire agreement brokered by Russia, signed by the leaders of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia.

The terms of the agreement were deeply unfavorable to the Armenian side. Armenia agreed to withdraw from the Azerbaijani districts surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh that it had controlled since the first war. Parts of Nagorno-Karabakh itself, including Shusha, also came under Azerbaijani control. A Russian peacekeeping force of nearly 2,000 troops was deployed to the region, including along the Lachin corridor, which was to remain the sole land link between Armenia and the parts of Nagorno-Karabakh still under Armenian control.

The war had devastating political, social, and humanitarian repercussions for Armenia. It resulted in thousands of deaths, many more wounded, and the displacement of tens of thousands of ethnic Armenians from Artsakh. The territorial losses and the perceived national humiliation led to a severe political crisis in Armenia, with widespread protests demanding Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan's resignation. The war exposed Armenia's military vulnerabilities and the limitations of its security alliances. The humanitarian crisis for the displaced population, many of whom fled to Armenia, became a major challenge, requiring urgent aid and long-term solutions. The conflict also raised serious concerns about the protection of Armenian cultural heritage in the territories that came under Azerbaijani control and the future security and rights of the Armenian population remaining in Artsakh.

3.7.5. 2023 Azerbaijani Offensive and Displacement from Nagorno-Karabakh

Following the 2020 war, tensions remained high. Azerbaijan gradually increased pressure on the remaining Armenian-populated areas of Nagorno-Karabakh. This culminated in a blockade of the Lachin corridor by Azerbaijan, starting in December 2022, which severely restricted the flow of food, medicine, fuel, and other essential supplies into Nagorno-Karabakh, leading to a worsening humanitarian crisis for its approximately 120,000 ethnic Armenian inhabitants. International calls for Azerbaijan to lift the blockade, including orders from the International Court of Justice, were largely unheeded.

On September 19, 2023, Azerbaijan launched a large-scale military offensive against Nagorno-Karabakh. The Artsakh Defence Army, significantly outnumbered and outgunned, was unable to withstand the assault. After just one day of fighting, with reports of civilian casualties and infrastructure damage, the authorities of the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh agreed to a ceasefire on September 20, under terms dictated by Azerbaijan. These terms included the disbandment of Artsakh's military forces and the start of negotiations for the "reintegration" of Nagorno-Karabakh into Azerbaijan.

The offensive and the subsequent capitulation led to a mass exodus of the ethnic Armenian population from Nagorno-Karabakh. Fearing for their safety and facing an uncertain future under Azerbaijani rule, over 100,000 ethnic Armenians - virtually the entire Armenian population of the region - fled to Armenia within a week. This rapid displacement created a major humanitarian crisis for Armenia, which had to accommodate and provide for the influx of refugees. On September 28, 2023, the President of the Republic of Artsakh, Samvel Shahramanyan, signed a decree to dissolve all state institutions by January 1, 2024, effectively ending the three-decade existence of the self-proclaimed republic.

The events of September 2023 were widely condemned internationally, with many observers and human rights organizations describing them as ethnic cleansing. The offensive and the subsequent displacement of over 100,000 people had profound domestic implications for Armenia, exacerbating political tensions and placing a immense strain on its resources. Internationally, it raised questions about the effectiveness of Russian peacekeeping efforts, the role of international diplomacy in conflict resolution, and the future of regional stability. The humanitarian crisis and the long-term integration of the displaced population from Nagorno-Karabakh became paramount challenges for Armenia, significantly impacting its socio-economic well-being and testing its democratic institutions.

4. Geography

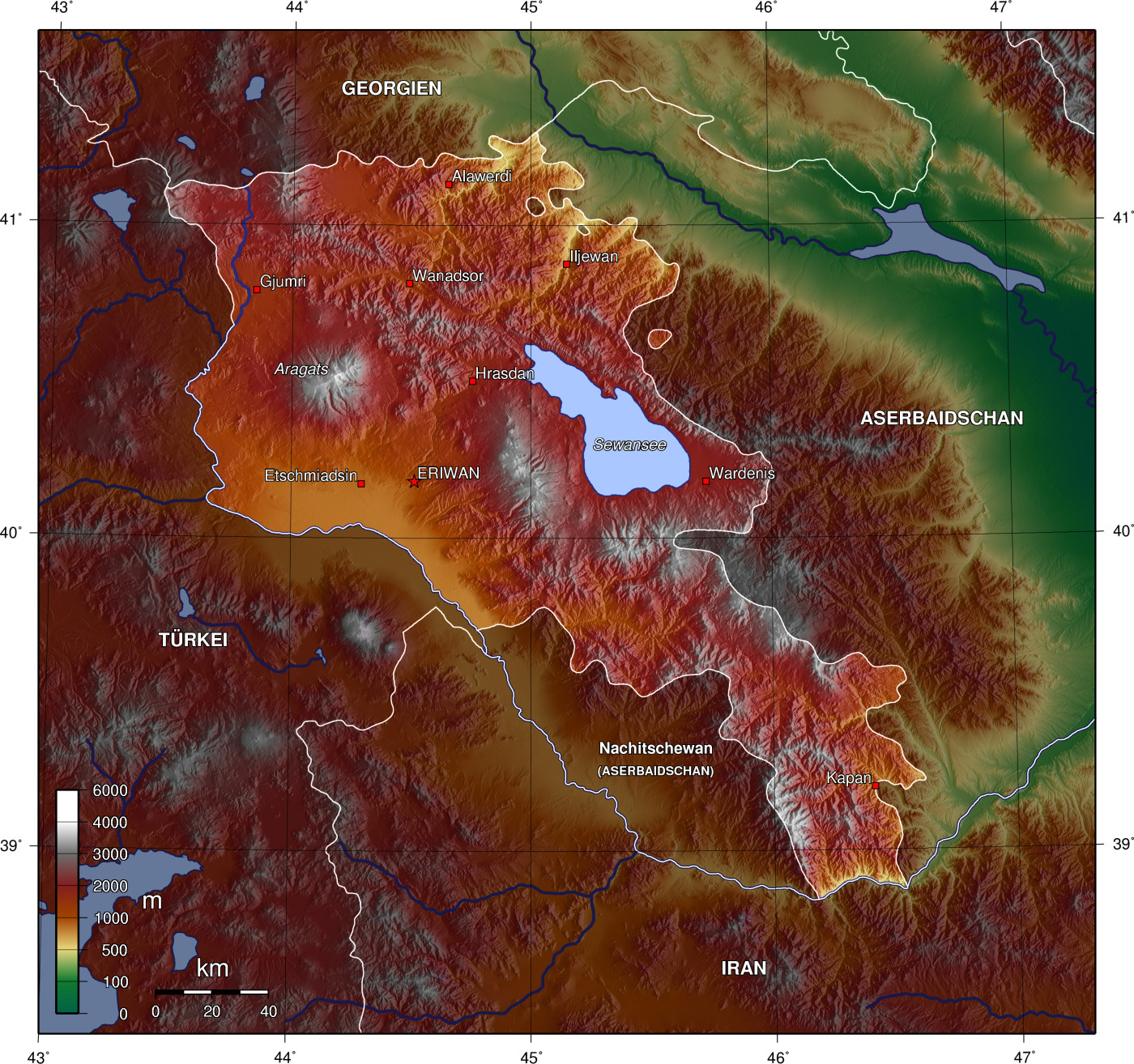

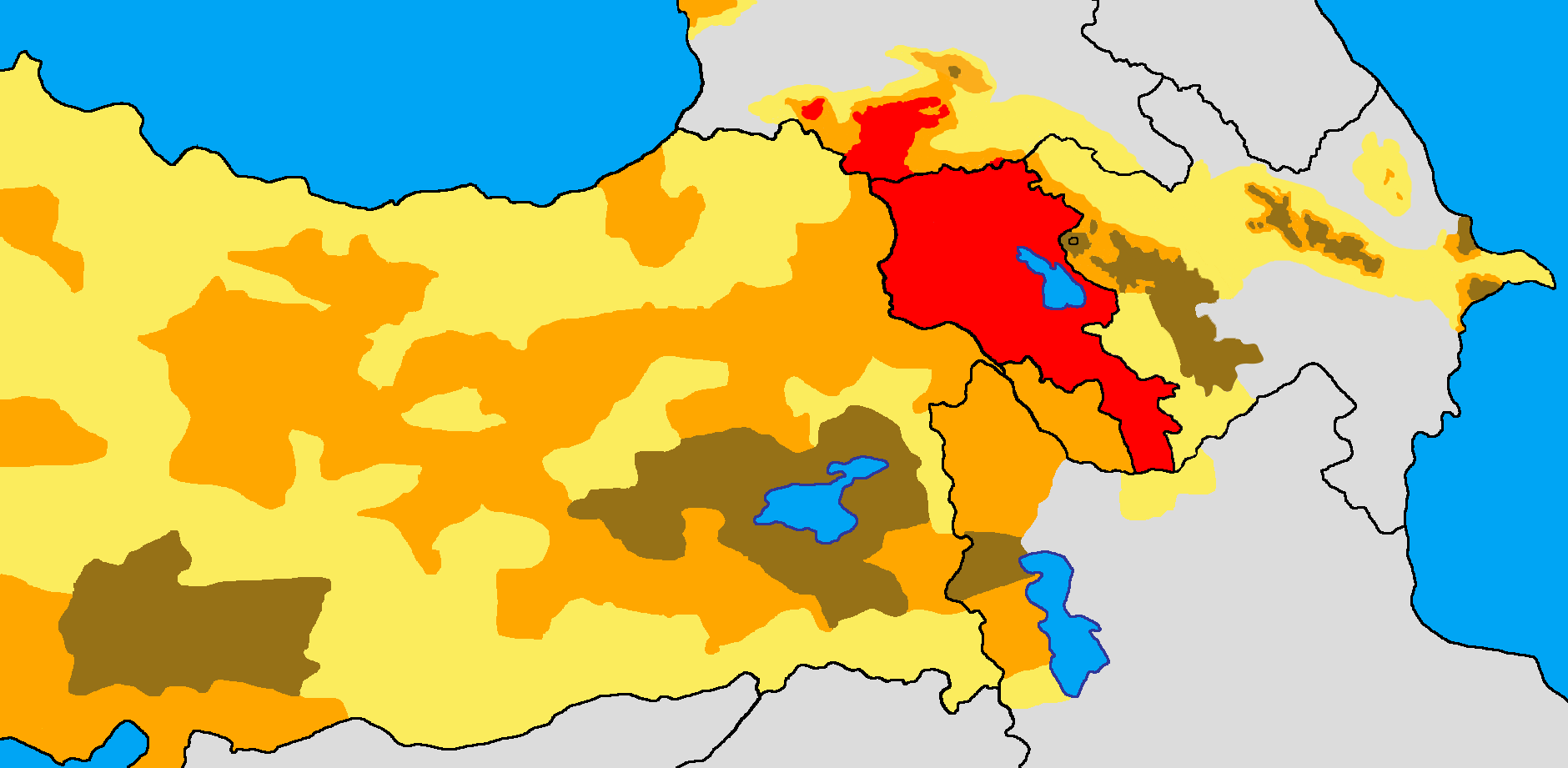

Armenia is a landlocked country situated in the Armenian Highlands, part of the South Caucasus region of West Asia. It is bordered by Georgia to the north, Azerbaijan to the east, Iran to the south, and Turkey to the west. The Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhichevan also borders Armenia to the south.

The country's geography has played a significant role in its history, culture, and economy, contributing to both its resilience and its vulnerability.

4.1. Topography

Armenia's terrain is predominantly mountainous, characterized by a complex network of ranges, volcanic plateaus, and deep river gorges. Approximately 90% of the country lies at an altitude of 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m) or more above sea level. The average elevation is around 5.9 K ft (1.80 K m). The highest point is Mount Aragats, an extinct volcano with four peaks, the northernmost reaching 13 K ft (4.09 K m). The lowest point, at 1230 ft (375 m), is in the Debed River valley in the north.

The Lesser Caucasus mountain range extends across northern and eastern Armenia, forming a significant part of its landscape. The Ararat Plain, a fertile lowland area, stretches across the southwestern part of the country, along the border with Turkey, and is home to the capital, Yerevan. Historically, Mount Ararat, though now located in Turkey, is a powerful national symbol for Armenians and is visible from much of Armenia.

Principal rivers include the Aras River (Araks), which forms a large part of the border with Iran and Turkey; the Hrazdan River, which flows through Yerevan and into the Aras; the Debed River in the north; and the Vorotan River in the south.

Lake Sevan (Սևանա լիճSevana lichArmenian) is the largest lake in Armenia and one of the largest high-altitude freshwater lakes in the world. Located in the eastern part of the country at an elevation of about 6.2 K ft (1.90 K m), it is of immense ecological, economic, and cultural importance. Its water levels have fluctuated due to human intervention, primarily for irrigation and hydroelectric power, leading to environmental concerns.

The mountainous terrain makes transportation and agriculture challenging in many areas but also provides stunning natural scenery and resources for mining and hydroelectric power. Armenia is also located in a seismically active zone and has experienced destructive earthquakes, most notably the 1988 Spitak earthquake.

4.2. Climate

Armenia has a highland continental climate, characterized by distinct seasons with significant variations in temperature and precipitation due to its topography and elevation. Generally, summers are dry and sunny, while winters are cold and snowy.

- Summers** (June to mid-September) are typically hot and dry, especially in the Ararat Plain and lower-lying areas, where temperatures can range from 71.6 °F (22 °C) to 96.8 °F (36 °C), occasionally exceeding 104 °F (40 °C). Humidity is generally low, making high temperatures more tolerable. Higher elevations experience cooler summers.

- Winters** (mid-November to March) are cold, particularly in mountainous regions, with abundant snowfall. Temperatures in Yerevan and the Ararat Plain can range from 14 °F (-10 °C) to 23 °F (-5 °C), but can drop much lower in higher altitudes. Mountain passes may become snowbound.

- Spring** (April to May) is generally short, with mild temperatures and increasing precipitation.

- Autumn** (mid-September to mid-November) is long and often considered the most pleasant season, with mild, sunny weather and colorful foliage.

Precipitation varies significantly across the country. The Ararat Plain is relatively arid, receiving about 7.9 in (200 mm) to 9.8 in (250 mm) of rainfall annually. Mountainous regions, especially in the north and southeast, receive more precipitation, ranging from 20 in (500 mm) to 31 in (800 mm) or more, often as snow in winter.

The country experiences a high number of sunny days per year, particularly in the Ararat Plain. Regional climatic differences are pronounced: the southern regions generally have a drier and warmer climate, while the northern, forested regions are cooler and more humid. The climate of Lake Sevan has its own microclimate, with cooler summers and colder winters than the surrounding areas.

4.3. Environment

Armenia faces a range of environmental issues, many of which are linked to its Soviet past, economic development pressures, and geographical characteristics. Efforts towards environmental conservation and sustainable development are underway, involving government policies and civil society initiatives.

Key environmental challenges include:

- Deforestation**: Historically, Armenia had more extensive forest cover. Deforestation occurred due to logging for fuel and construction, particularly during the energy crisis of the 1990s following independence. Reforestation efforts are ongoing, but illegal logging remains a concern. Current forest cover is around 11-12% of the total land area.

- Water pollution**: Rivers and Lake Sevan have suffered from pollution due to untreated or inadequately treated municipal wastewater, industrial discharges (especially from mining), and agricultural runoff (pesticides and fertilizers). This impacts water quality, biodiversity, and human health. Lake Sevan, in particular, has faced ecological challenges due to water level fluctuations and pollution, though efforts are being made to restore its ecosystem.

- Air pollution**: Urban areas, particularly Yerevan, experience air pollution primarily from vehicle emissions and industrial activities. Dust from construction and open mines can also contribute to poor air quality.

- Waste Management**: Waste management is underdeveloped. Most solid waste is disposed of in landfills that often do not meet modern environmental standards. There is limited waste sorting, recycling, and proper disposal of hazardous waste. Plans for modern waste processing facilities are being developed.

- Soil degradation and Erosion**: Unsustainable agricultural practices, overgrazing, and deforestation have led to soil erosion and degradation in some areas, impacting agricultural productivity and biodiversity.

- Mining Impacts**: Armenia has a significant mining sector (copper, molybdenum, gold), which is a major contributor to its economy but also a source of environmental concern. Issues include water and soil pollution from mine tailings and wastewater, habitat destruction, and air pollution. Balancing economic benefits with environmental protection in the mining sector is a critical challenge, with significant social impact on local communities often bearing the brunt of environmental degradation.

- Biodiversity loss**: Armenia is part of the Caucasus biodiversity hotspot, with a rich variety of flora and fauna, including many endemic species. Habitat loss and degradation, pollution, poaching, and climate change pose threats to this biodiversity.

- Protected Areas and Conservation Efforts:**

Armenia has established several protected areas, including national parks, state reserves, and sanctuaries, to conserve its unique ecosystems and species. Notable protected areas include Dilijan National Park, Sevan National Park, Khosrov Forest State Reserve, and Shikahogh State Reserve. These areas aim to protect forests, wetlands, alpine meadows, and diverse wildlife.

Government policies and legislation for environmental protection are in place, and Armenia is a signatory to various international environmental conventions. Civil society organizations and environmental activists play an important role in raising awareness, advocating for stronger environmental governance, and monitoring environmental issues. There is a growing focus on sustainable development, renewable energy (Armenia has potential for solar, wind, and hydropower), and green economy initiatives. Addressing the social impact of environmental degradation, particularly on vulnerable communities dependent on natural resources, is also an increasing concern. The Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant remains an environmental and safety concern, with ongoing discussions about its future and potential replacements.

In the Environmental Performance Index (EPI), Armenia's ranking has varied, highlighting ongoing challenges in areas like air quality and ecosystem vitality.

5. Government and Politics

Armenia is a parliamentary republic with a multi-party system. The country's political system has undergone significant transformations since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, most notably with constitutional changes in 2015 that transitioned it from a semi-presidential system to a parliamentary republic, a shift fully implemented after the 2018 Velvet Revolution. The framework of governance is based on the principles of separation of powers, democratic elections, and the rule of law, though challenges related to corruption, judicial independence, and electoral integrity have been noted by observers.

5.1. Governance Structure

The current Constitution of Armenia, adopted via a referendum in 2015 and amended subsequently, defines the structure of governance:

- The President:** The President of Armenia is the head of state. Under the parliamentary system, the President's role is largely ceremonial and representational. The President is elected by the National Assembly for a single seven-year term and is not eligible for re-election. The President's functions include signing laws passed by the National Assembly, appointing and dismissing ambassadors upon the Prime Minister's recommendation, awarding honors, and representing the state in international relations. The President is also the guarantor of the Constitution and is expected to be impartial.

- The Prime Minister:** The Prime Minister of Armenia is the head of government and holds executive power. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the political party or coalition that commands a majority in the National Assembly. They are appointed by the President based on the parliamentary majority. The Prime Minister forms the government (the Cabinet), directs its activities, and is responsible for implementing domestic and foreign policy. The Prime Minister is accountable to the National Assembly.

- The National Assembly (Azgayin Zhoghov):** The National Assembly is the unicameral legislature of Armenia. It is the supreme representative body of the people. Its members (deputies) are elected for five-year terms through a proportional representation system. The National Assembly enacts laws, approves the state budget, oversees the government, ratifies international treaties, and can declare war or a state of emergency. It also elects the President, the Human Rights Defender (Ombudsman), and members of key independent bodies. The minimum number of seats is 101, but can be higher due to mechanisms ensuring a stable majority and representation for national minorities.

- The Cabinet (Government):** The Cabinet, headed by the Prime Minister, consists of ministers responsible for various sectors of public administration. Ministers are appointed and dismissed by the President upon the Prime Minister's recommendation. The Government implements laws and manages the day-to-day affairs of the state.

- The Judiciary:** The judicial system is headed by the Court of Cassation (the highest court of appeal for most matters) and the Constitutional Court (which reviews the constitutionality of laws and other legal acts). The system also includes courts of first instance and appellate courts. Judicial reform aimed at ensuring independence and combating corruption has been a key priority, particularly after the 2018 revolution.

Armenia has universal suffrage for citizens aged 18 and above. The Fragile States Index has consistently ranked Armenia relatively well compared to its neighbors, though challenges remain.

5.2. Political Parties

Armenia has a multi-party system, with numerous political parties representing a range of ideologies and interests. The political landscape has been dynamic, particularly since the 2018 Velvet Revolution, which disrupted the long-standing dominance of the Republican Party of Armenia.

Major political parties and their general ideological leanings include:

- Civil Contract**: Led by Nikol Pashinyan, this party came to power following the 2018 Velvet Revolution. It generally positions itself as centrist, pro-reform, and anti-corruption, advocating for democratic development, rule of law, and social justice. It has formed the My Step Alliance and later run independently, securing majorities in parliamentary elections.

- Republican Party of Armenia (RPA)**: Formerly the dominant ruling party for nearly two decades before 2018, led by former Presidents Robert Kocharyan (though not formally a member for all his tenure) and Serzh Sargsyan. It is a conservative, nationalist party. Its influence significantly declined after the Velvet Revolution but it remains a key opposition force.

- Prosperous Armenia (BHK)**: Founded by businessman Gagik Tsarukyan, this party is generally considered centrist or center-right, with a populist appeal. It has been both a coalition partner with the RPA and an opposition party at different times.

- Bright Armenia**: A liberal, pro-European party that emerged as a significant opposition force after the 2018 revolution, advocating for closer ties with the EU and democratic reforms.

- Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF or Dashnaktsutyun)**: One of the oldest Armenian political parties, founded in 1890. It is a socialist and nationalist party with a strong presence in the Armenian diaspora. It has been part of governing coalitions and in opposition at various times.

- Armenia Alliance (Hayastan Dashink)**: An opposition bloc formed for the 2021 elections, led by former President Robert Kocharyan, largely comprising conservative and nationalist elements critical of the Pashinyan government.

- I Have Honor Alliance (Pativ Unem Dashink)**: Another opposition bloc, associated with former President Serzh Sargsyan and the Republican Party, also critical of the post-revolution government.

Numerous smaller parties also exist, often forming alliances for elections. Electoral performance has seen shifts, with the post-2018 period favoring parties associated with the Velvet Revolution, though the political scene remains competitive and sometimes polarized. The influence of political parties on democratic processes includes participation in elections, parliamentary work, policy debate, and public mobilization. Challenges include party financing transparency, internal party democracy, and the personalization of politics around key leaders.

5.3. Judiciary

The judiciary of Armenia is structured as a three-tiered system, with the Constitution of Armenia guaranteeing its independence and separation from the legislative and executive branches. However, ensuring genuine judicial independence, efficiency, and public trust has been a persistent challenge, with reforms being a key focus, especially after the 2018 Velvet Revolution.

The main components of the Armenian judicial system are:

- Courts of First Instance:** These are general jurisdiction courts that handle civil, criminal, and administrative cases at the initial level. They are located throughout the country. There are also specialized first-instance courts, such as the Administrative Court and the Bankruptcy Court.

- Courts of Appeal:** There are separate appellate courts for civil, criminal, and administrative matters. These courts review decisions made by the courts of first instance.

- Court of Cassation**: This is the highest court of appeal in Armenia for most civil, criminal, and administrative cases (except for constitutional matters). Its primary role is to ensure the uniform application of law and to correct fundamental errors of law made by lower courts. It does not typically re-examine facts but focuses on legal interpretation.

- Constitutional Court**: This is a specialized court responsible for interpreting the Constitution and determining the constitutionality of laws, decrees, international treaties, and other legal acts. It also resolves disputes related to election results and referendums, and can provide opinions on matters of constitutional importance. It consists of nine judges.

- Judicial Independence and Reforms:**

Historically, the Armenian judiciary has faced criticism regarding its independence from political influence, particularly from the executive branch. Corruption within the judiciary has also been a significant concern. Public trust in the judicial system has often been low.

Following the 2018 Velvet Revolution, judicial reform became a top priority for the new government. Key objectives of these reforms include:

- Strengthening judicial independence and impartiality.

- Combating corruption within the judiciary.

- Improving the efficiency and transparency of court proceedings.

- Enhancing the professionalism and accountability of judges.

- Ensuring fair trials and access to justice for all citizens.

Reforms have involved legislative changes, vetting processes for judges (transitional justice mechanisms), improvements in judicial training, and efforts to increase court funding and resources. The establishment and functioning of the Supreme Judicial Council, responsible for judicial appointments, discipline, and administration, has also been a focus of reform.

Challenges remain in fully implementing these reforms and overcoming entrenched issues. International organizations and domestic civil society groups continue to monitor the progress of judicial reform in Armenia, emphasizing its critical importance for democratic development and the rule of law.

5.4. Human Rights and Freedoms

The state of human rights in Armenia has seen notable developments since its independence, particularly following the 2018 Velvet Revolution, which brought a renewed focus on democratic principles and fundamental freedoms. While progress has been made in several areas, challenges persist, and ongoing efforts are needed to fully align with international human rights standards. Reports from international organizations like Freedom House, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the Council of Europe provide regular assessments.

- Key Areas of Human Rights:**

- Freedom of Speech and Press:** The media landscape in Armenia is diverse, with numerous television and radio stations, newspapers, and online outlets. Following the 2018 revolution, there was a significant improvement in press freedom, with reduced government pressure and increased space for critical reporting. Armenia's ranking in international press freedom indices improved. However, challenges remain, including concerns about media ownership transparency, instances of pressure or violence against journalists, and the spread of disinformation, particularly online. Defamation laws have sometimes been used in ways that could stifle free expression.

- Freedom of Assembly:** The right to peaceful assembly is generally respected, and Armenia has a vibrant tradition of public protest. The 2018 Velvet Revolution itself was a testament to the power of peaceful assembly. While demonstrations are usually permitted, there have been instances of excessive force used by law enforcement in the past, and isolated incidents continue to be monitored.

- Electoral Integrity:** Armenia has held regular presidential and parliamentary elections. While earlier elections were often criticized by international observers for irregularities, including vote-buying and pressure on voters, more recent elections, particularly those after 2018, have been assessed more positively as being generally free and fair, reflecting an improvement in democratic processes. However, issues related to campaign finance and the use of administrative resources still draw attention.

- Minority Rights:** Armenia is ethnically quite homogeneous, but it has small minority populations, including Yazidis, Russians, Assyrians, Kurds, and others. The Constitution guarantees rights for national minorities, including the preservation of their traditions and language. The Yazidi community is the largest minority. Challenges include ensuring full social and economic integration, adequate representation, and protection against discrimination. The rights of religious minorities are generally respected, though the Armenian Apostolic Church holds a dominant position in society.

- LGBT Rights:** LGBT rights remain a sensitive issue in Armenia's socially conservative society. While homosexual acts are legal, LGBT individuals often face discrimination, harassment, and social stigma. There is limited legal protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Public discourse on LGBT issues is often negative, and pride events have faced strong opposition.

- Corruption:** Corruption has historically been a significant problem in Armenia, affecting various sectors, including the judiciary, public administration, and healthcare. The post-2018 government made combating corruption a key priority, launching investigations and implementing anti-corruption strategies. Progress has been made, but systemic corruption remains a challenge, impacting human rights by undermining the rule of law and equal access to public services.

- Judicial Independence and Fair Trial:** Ensuring an independent and impartial judiciary is crucial for the protection of human rights. As mentioned, judicial reform is ongoing, aiming to address issues of political influence, corruption, and inefficiency within the courts, and to guarantee the right to a fair trial.

- Rights of Vulnerable Groups:** Protecting the rights of vulnerable groups, including women, children, persons with disabilities, and displaced persons (particularly those affected by the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict), is an ongoing concern. Issues include domestic violence, gender inequality, access to education and employment for persons with disabilities, and providing adequate support and durable solutions for refugees and internally displaced persons. The mass displacement of over 100,000 ethnic Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023 created a major humanitarian crisis and highlighted the urgent need to protect the rights of displaced populations.

Progress in democratic development includes strengthening parliamentary oversight, improving electoral processes, and increasing civic participation. However, regional conflicts and security challenges can put pressure on human rights and democratic institutions. Armenia is a member of the Council of Europe and is party to numerous international human rights treaties, and its human rights record is subject to monitoring by international bodies.

6. Foreign Relations

Armenia's foreign relations are shaped by its geopolitical location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, its history, security concerns, economic needs, and its large diaspora. Since independence in 1991, Armenia has pursued a multi-vector foreign policy, often described as "complementarity," aiming to balance relations with major global and regional powers. Key priorities include ensuring national security, resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict (historically), fostering economic development, and maintaining ties with the Armenian diaspora.

6.1. Overview

Armenia's primary foreign policy objectives include safeguarding its sovereignty and territorial integrity, achieving a just and lasting resolution to conflicts affecting its interests, promoting economic growth through international cooperation, and supporting Armenian communities abroad.

Armenia is a member of numerous international organizations, which reflects its engagement on multiple fronts:

- United Nations (UN)** and its specialized agencies.

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)**, which has played a key role in the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process through the Minsk Group.

- Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO)**, a Russia-led military alliance. However, Armenia's participation has been "frozen" since early 2024 amid strained relations with Russia and dissatisfaction with the CSTO's response to security challenges.

- Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU)**, an economic union with Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

- Council of Europe**, reflecting its commitment to European standards of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law.

- Eastern Partnership** with the European Union, aimed at deepening political and economic ties. Armenia signed a Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with the EU, which came into force in 2021.

- World Trade Organization (WTO)**.

- Organisation internationale de la Francophonie**, reflecting its cultural and historical ties with France.

Armenia has generally sought to maintain a strategic partnership with Russia while also developing closer relations with Western countries (notably the United States and France, both home to large Armenian diasporas) and the European Union. Its relationship with neighboring Iran is pragmatic, driven by economic and energy interests, especially given the closed borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan.

6.2. Relations with Neighboring Countries

Armenia's relations with its immediate neighbors are complex and vary significantly.

- Georgia:** Relations with Georgia are generally positive and cooperative. Georgia provides a vital transit route for Armenia's trade and energy supplies. There are shared interests in regional stability and economic development, though occasional minor issues arise.

- Iran:** Armenia has maintained good relations with Iran, driven by mutual economic interests and Iran's role as an alternative route to the outside world for landlocked Armenia, especially given the blockades by Turkey and Azerbaijan. Cooperation exists in energy, trade, and transport.

- Azerbaijan:** Relations with Azerbaijan have been dominated by the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict for over three decades, leading to two major wars (1988-1994 and 2020) and numerous clashes. There are no diplomatic relations, and the border is closed. The conflict has resulted in immense human suffering, displacement, and deep-seated animosity.

- Turkey:** Relations with Turkey are also fraught. Turkey closed its border with Armenia in 1993 in solidarity with Azerbaijan during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War and has refused to establish diplomatic relations. A key stumbling block is Turkey's denial of the Armenian Genocide. Attempts at normalization, such as the Zurich Protocols in 2009, have failed.

6.2.1. Relations with Azerbaijan

The relationship with Azerbaijan has been overwhelmingly defined by the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. This conflict, rooted in historical claims and ethnic demography, erupted in the late 1980s when the Armenian-majority Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast sought to secede from Soviet Azerbaijan and unite with Armenia.

- First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-1994):** Resulted in Armenian forces taking control of Nagorno-Karabakh and several surrounding Azerbaijani districts. A ceasefire in 1994 left a legacy of unresolved status, displaced populations (hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis from Armenia and the occupied territories, and hundreds of thousands of Armenians from Azerbaijan), and a heavily militarized "line of contact."

- Negotiations and Stalemate:** Decades of peace negotiations mediated by the OSCE Minsk Group (co-chaired by Russia, the US, and France) failed to achieve a breakthrough. Sporadic clashes continued along the line of contact.

- 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War:** A 44-day war in which Azerbaijan, with Turkish support, retook significant territories, including parts of Nagorno-Karabakh. A Russian-brokered ceasefire agreement on November 10, 2020, led to the deployment of Russian peacekeepers and further territorial concessions by Armenia. The humanitarian consequences included thousands killed and tens of thousands of Armenians displaced.

- Post-2020 Tensions and 2023 Offensive:** Tensions persisted, with Azerbaijan increasing pressure. In September 2023, Azerbaijan launched a military offensive that led to the rapid collapse of Artsakh's defenses and the mass displacement of over 100,000 ethnic Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, effectively ending the Armenian presence in the region and dissolving the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh.

The conflict has had profound humanitarian consequences, including refugees, internally displaced persons, loss of life, and deep psychological trauma for affected populations on both sides. The issue of return for displaced persons, cultural heritage protection, and border delimitation remain critical challenges in any future peace process.

6.2.2. Relations with Turkey

Armenia's relationship with Turkey is deeply troubled and complex, characterized by a lack of formal diplomatic relations and a closed border since 1993. Key issues include:

- Non-recognition of the Armenian Genocide:** Turkey's official denial of the systematic extermination of 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottoman Empire in 1915-1923 is the primary obstacle. Armenia and its diaspora actively campaign for international recognition of the genocide, which Turkey vehemently opposes, claiming the events were a tragic consequence of wartime conditions and inter-communal conflict, not a deliberate state-sponsored extermination. This historical wound deeply impacts Armenian national identity and foreign policy.

- Closed Border and Lack of Diplomatic Ties:** Turkey closed its border with Armenia in 1993 in support of Azerbaijan during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. Despite some attempts at normalization, notably the Zurich Protocols signed in 2009 under Swiss and US mediation, the process stalled and ultimately failed, partly due to Turkish preconditions linking normalization with progress on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and Armenian diaspora activities.

- Regional Stability and Geopolitics:** The closed border and lack of relations hinder regional economic cooperation and contribute to Armenia's relative isolation. Turkey's strong alliance with Azerbaijan further complicates the regional dynamics for Armenia.

- Human Rights Concerns:** For Armenia, Turkey's denial of the genocide is seen as a continuation of injustice and a human rights issue. The lack of accountability for past atrocities and ongoing restrictions on freedom of expression within Turkey regarding the genocide are also major concerns.

Occasional high-level contacts and "football diplomacy" have occurred, but a fundamental breakthrough remains elusive. The normalization of relations with Turkey is a significant foreign policy challenge for Armenia, with implications for its economic development, security, and regional integration.

6.3. Relations with Russia

Historically, Russia has been Armenia's closest strategic, military, and economic partner since independence. This relationship is rooted in historical ties, shared security concerns, and economic interdependence.

- Military and Security Cooperation:** Armenia is a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a Russia-led military alliance. Russia maintains the Russian 102nd Military Base in Gyumri, Armenia, which has been seen as a key element of Armenia's security architecture, particularly as a deterrent. Russian border guards also patrolled Armenia's borders with Turkey and Iran (though Armenia requested their withdrawal from Yerevan's Zvartnots airport in 2024).

- Economic Ties:** Russia is Armenia's largest trading partner and a major source of investment and remittances. Armenia is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), and its energy sector, including the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant, has been heavily reliant on Russian fuel and technical assistance.