1. Overview

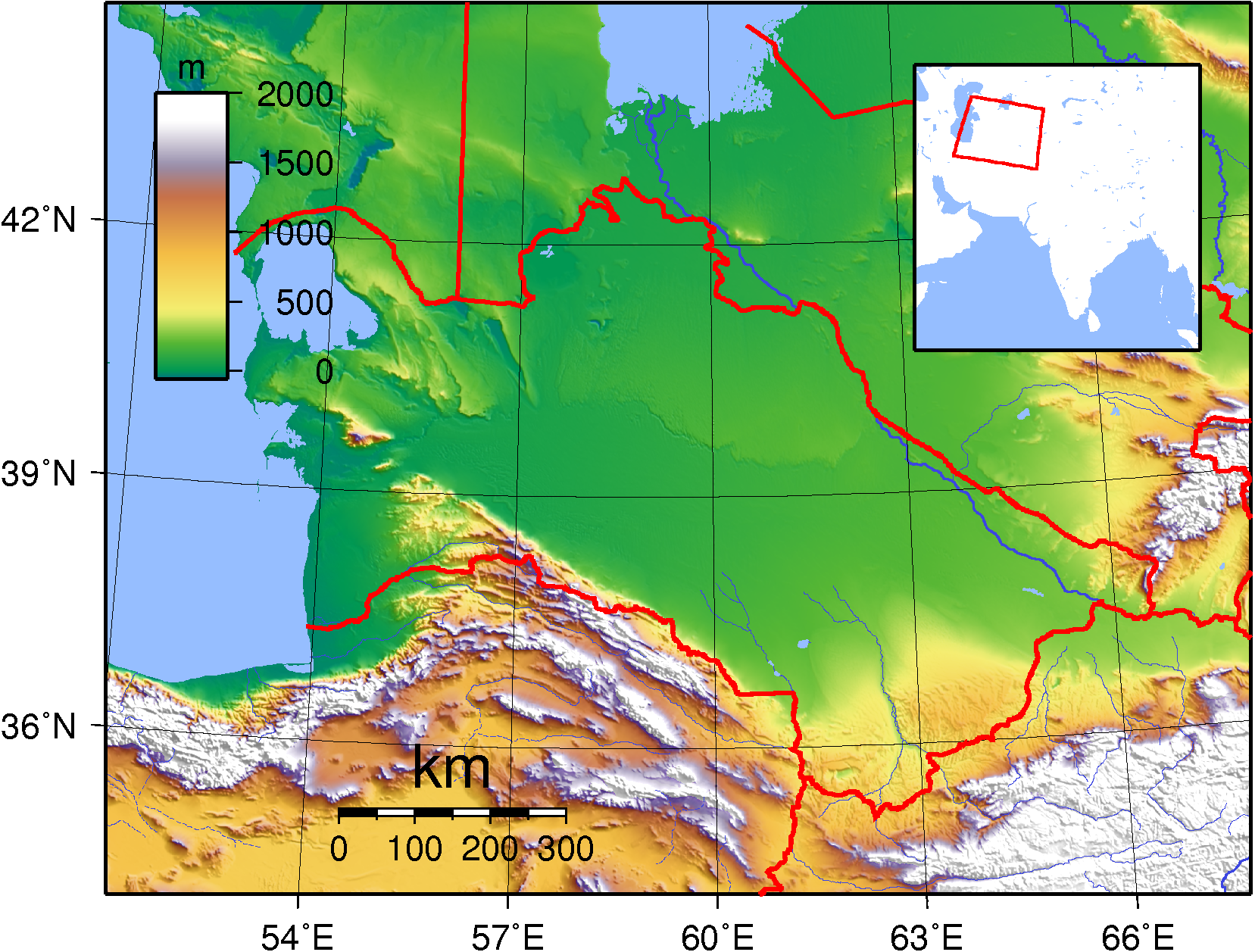

Turkmenistan, officially known as Türkmenistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. It is bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east, and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the south and southwest, and the Caspian Sea to the west. The capital and largest city is Ashgabat. With a population reported by the government to be over 7 million, Turkmenistan is the 35th most-populous country in Asia, though independent estimates suggest a significantly lower figure due to emigration. It is one of the most sparsely populated nations on the Asian continent, with over 80% of its territory covered by the Karakum Desert.

This article explores Turkmenistan's history from ancient civilizations through its Soviet era and tumultuous post-independence period, marked by authoritarian rule and pervasive personality cults under Saparmurat Niyazov, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, and his son Serdar Berdimuhamedow. It delves into the country's geography, characterized by vast deserts and significant mountain ranges, and its rich natural resources, particularly natural gas and oil, which form the backbone of its economy but also raise concerns about revenue management and environmental impact, including substantial methane leakage.

The political system is a presidential republic, though in practice, it functions as a totalitarian state with a single dominant party, severely limited political pluralism, and a judiciary lacking independence. The article examines the dire human rights situation, including restrictions on freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and religion, widespread censorship, the use of forced labor, particularly in the cotton industry, and pervasive corruption. The socio-cultural fabric, including its diverse ethnic groups, the significance of Turkmen tribes, traditional customs, and the state-controlled media and education systems, will also be analyzed. This document adopts a center-left, social liberal perspective, emphasizing the social impacts of government policies, human rights concerns, and the state of democratic development alongside factual information.

2. Etymology

The name "Turkmenistan" (TürkmenistanTurkmen) is derived from two components: the ethnonym Türkmen and the Persian suffix -stan, meaning "land of" or "country of." The name "Türkmen" itself is believed to originate from "Turk" combined with the Sogdian suffix -men, signifying "almost Turk" or "resembling a Turk," possibly referring to their status outside the Turkic dynastic mythological system.

Muslim chroniclers, such as Ibn Kathir, proposed an alternative etymology, suggesting that "Turkmen" derived from the words Türk and iman (إيمانfaith or beliefArabic). This interpretation relates to a large-scale conversion of two hundred thousand households in the region to Islam in the year 971.

The modern name of the state, "Turkmenistan" (TürkmenistanTurkmen / ТүркменистанTurkmen), was officially established by constitutional law on October 27, 1991, following the country's declaration of independence from the Soviet Union. During the Soviet era, a common Russian name for the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic was "Turkmenia" (ТуркменияTurkmeniyaRussian), which was sometimes used in international reports around the time of its independence.

3. History

Turkmenistan's history is characterized by its strategic location as a crossroads of civilizations, experiencing conquests by numerous empires and the migration of various peoples. The region has seen the rise and fall of indigenous cultures, Iranian empires, Turkic migrations, Islamic influence, Mongol invasions, Russian colonization, and Soviet rule, culminating in its current status as an independent nation grappling with a legacy of authoritarianism.

3.1. Ancient and medieval history

The territory of modern Turkmenistan was historically inhabited by Indo-Iranian peoples. The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), also known as the Oxus civilization, flourished in the region from around 2300 BC to 1700 BC. Early agricultural settlements, such as the Anau culture near modern Ashgabat, date back to the Neolithic period.

Written history begins with the region's annexation by the Achaemenid Empire of Ancient Iran (circa 550-330 BC). Under Achaemenid rule, the area was divided into satrapies, including Margiana, Khwarezmia, and Parthia. Alexander the Great conquered the region in the 4th century BC during his campaigns in Central Asia. Following Alexander's death, the area came under the control of the Seleucid Empire. Around this time, the Silk Road began to develop as a major trade route connecting East Asia with the Mediterranean world.

The Parthian Empire (247 BC - 224 AD), originating from the Parni tribe of the Dahae confederation in the region, established its first capital at Nisa, near present-day Ashgabat, now a UNESCO World Heritage site. The Parthians, renowned for their cavalry, became a major power rivaling Rome. After the fall of the Parthians, the region was incorporated into the Sasanian Empire (224-651 AD), another Persian dynasty.

In the 7th century AD, Arab armies conquered the region, introducing Islam and integrating Turkmenistan into the broader Islamic world. The city of Merv (also a UNESCO World Heritage site) became a major center of Islamic learning and culture, serving as the capital of the province of Khorasan under the Abbasid Caliphate, particularly during the reign of Caliph Al-Ma'mun.

Starting in the 8th century, Turkic-speaking Oghuz tribes began migrating from Mongolia into Central Asia. By the 10th century, the term "Turkmen" was applied to Oghuz groups that had accepted Islam and started to occupy present-day Turkmenistan. These Oghuz formed the ethnic basis of the modern Turkmen population. They came under the dominion of the Seljuk Empire (1037-1194), which was founded by Oghuz Turks and had its heartland in Iran and Turkmenistan. Seljuk Turkmen played a significant role in the expansion of Turkic culture as they migrated westward into Azerbaijan and Anatolia.

In the 12th century, the Khwarazmian dynasty, also of Turkic origin, rose to prominence, making Konye-Urgench (another UNESCO World Heritage site) its capital. However, the Khwarzamian Empire was short-lived. In the early 13th century, the region was devastated by the Mongol invasions led by Genghis Khan. The Mongols destroyed cities like Merv and Urgench, leading to a significant decline in the settled population and infrastructure. The area subsequently became part of the Ilkhanate and later the Timurid Empire, founded by Timur (Tamerlane) in the late 14th century.

3.2. Early modern period

From the 16th to the late 19th century, the history of the Turkmen lands was marked by fragmentation and the influence of larger regional powers. After the decline of the Timurid Empire, the region became a contested area between the Khanate of Khiva and the Khanate of Bukhara, both Uzbek-led states, as well as Safavid and later Qajar Persia.

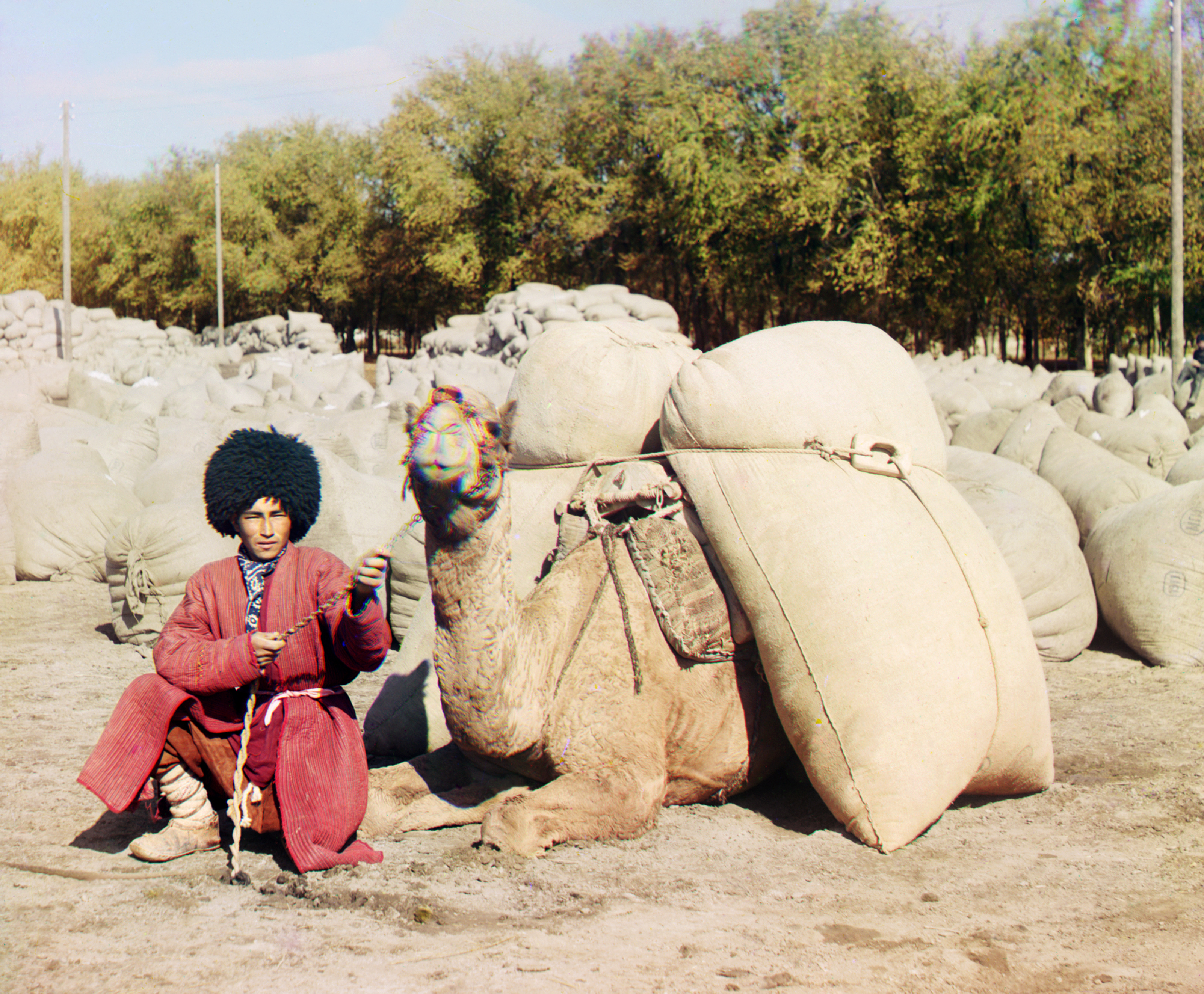

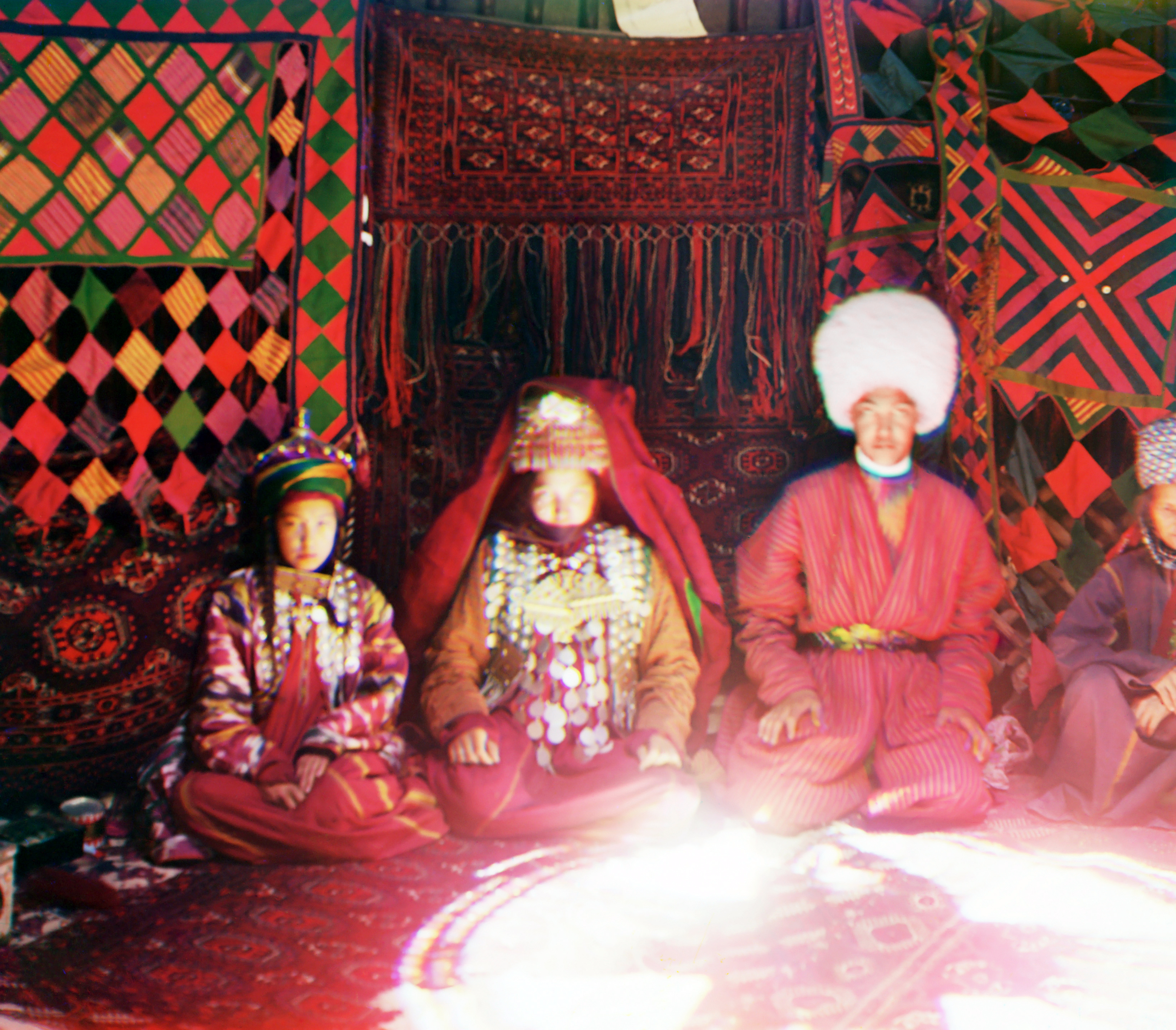

Turkmen tribes, known for their nomadic lifestyle and martial skills, maintained a degree of autonomy, often forming loose confederations. They were frequently involved in raids and conflicts with neighboring sedentary populations and were also recruited as soldiers by the Khivan and Bukharan khanates. Turkmen soldiers formed an important part of the Uzbek militaries during this period. The major Turkmen tribes, including the Teke, Yomut, Ersari, Chowdur, Gokleng, and Saryk, often had complex relationships with each other and with the ruling khanates.

Persian influence remained significant, particularly in the southern regions. Nader Shah, in the 18th century, temporarily reasserted Persian control. However, Turkmen tribal independence often prevailed. The Turkmen were known and feared for their involvement in the Central Asian slave trade, raiding Persian and other settled territories for captives.

In the 19th century, the Yomut Turkmen tribe's raids and rebellions led to their dispersal by Uzbek rulers. However, Turkmen tribes also achieved notable military victories. In 1855, the Teke tribe, led by Gowshut-Khan, defeated an invading army from the Khanate of Khiva under Muhammad Amin Khan. In 1861, they repelled an invading Persian army under Naser al-Din Shah Qajar. By the second half of the 19th century, northern Turkmen tribes were a significant military and political force within the Khanate of Khiva. This period of tribal autonomy and regional power struggles set the stage for the Russian conquest.

3.3. Russian Empire and Soviet era

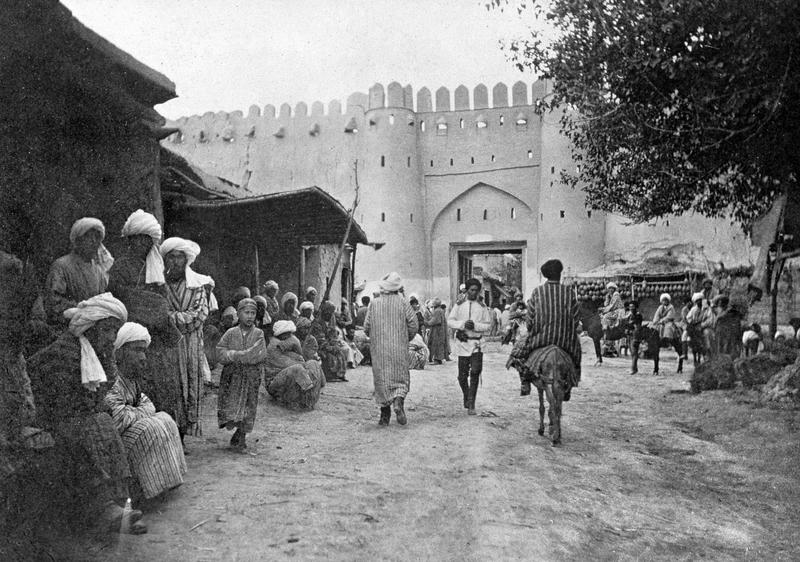

The Russian Empire's expansion into Central Asia reached Turkmen territories in the latter half of the 19th century. Russian forces, advancing from their Caspian Sea base at Krasnovodsk (now Türkmenbaşy), gradually overcame the Uzbek khanates of Khiva and Bukhara, making them protectorates. The Turkmen tribes, particularly the Teke, offered fierce resistance.

In 1879, Russian forces suffered a defeat at the first Battle of Geok Tepe against the Teke Turkmens. However, in 1881, a larger and better-equipped Russian army under General Mikhail Skobelev returned and, after a bloody siege, captured the fortress of Geok Tepe, effectively crushing the last significant Turkmen resistance. This event is remembered for the large number of Turkmen casualties. Shortly thereafter, the region was annexed by the Russian Empire and organized as the Transcaspian Oblast (Закаспийская областьZakaspíyskaya óblastRussian, 'Transcaspian Province'), initially under the Caucasus Viceroyalty and later as part of Russian Turkestan. The Trans-Caspian railway was constructed, connecting the region more closely with European Russia and facilitating Russian settlement and economic exploitation, primarily focused on cotton cultivation.

The Russian Empire's involvement in World War I and the subsequent Russian Revolution of 1917 had a profound impact on the region. In 1916, an anti-conscription revolt, part of the larger Central Asian revolt, swept through Turkmen lands. Following the revolution, Turkmen forces joined other Central Asian peoples in the Basmachi movement, a prolonged and widespread guerrilla resistance against Soviet rule that lasted into the 1920s and, in some areas, the early 1930s.

In 1921, the Transcaspian Oblast was renamed the Turkmen Oblast (Туркменская областьTurkménskaya óblastRussian). As part of the Soviet Union's policy of national delimitation, the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic (Turkmen SSR) was formally established on May 13, 1925, becoming one of the constituent republics of the USSR.

The Soviet era brought radical transformations to Turkmen society. The nomadic lifestyle was largely eradicated through forced collectivization of agriculture in the 1920s and 1930s, which met with significant local resistance. Cotton production was heavily emphasized, often at the expense of food crops and with detrimental environmental consequences, such as the desiccation of the Aral Sea due to irrigation diversions. Traditional social structures were undermined, and a Soviet-educated Turkmen elite emerged. The Turkmen language was initially Latinized, then Cyrillicized. While Soviet policies promoted literacy and some aspects of Turkmen culture (in a Soviet-approved form), political life was tightly controlled by Moscow through the Communist Party of the Turkmen SSR.

On October 6, 1948, a devastating earthquake struck Ashgabat and its surrounding areas, resulting in an estimated death toll exceeding 110,000 people, which amounted to two-thirds of the city's population at the time. The scale of the disaster was largely concealed by Soviet authorities.

For the next half-century, Turkmenistan remained a relatively quiet republic within the Soviet Union, largely isolated from major world events. The liberalization policies of Mikhail Gorbachev's Perestroika in the late 1980s had a limited initial impact compared to other Soviet republics. However, growing national consciousness and concerns about economic exploitation by Moscow led the Supreme Soviet of Turkmenistan to declare sovereignty on August 22, 1990.

3.4. Post-independence

Following the failed August Coup in Moscow, the impetus for full independence grew. Although then-Communist leader Saparmurat Niyazov initially favored preserving the Soviet Union, the rapid disintegration of the USSR forced his hand. A national referendum on independence was held on October 26, 1991, with an overwhelming majority voting in favor. Turkmenistan declared independence on October 27, 1991. The Soviet Union officially ceased to exist on December 26, 1991.

Saparmurat Niyazov, who had been the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Turkmen SSR since 1985, became the first President of independent Turkmenistan. He quickly consolidated power, establishing an authoritarian regime characterized by a pervasive cult of personality. Niyazov adopted the title Türkmenbaşy ("Head of the Turkmens") and his rule was marked by extensive human rights abuses, suppression of dissent, and a lack of democratic processes. A 1994 referendum extended his term, and in 1999, the Mejlis (Parliament) declared him President for Life. His idiosyncratic policies included renaming months and days of the week after himself and his family members, writing the Ruhnama (Book of the Soul) which became mandatory reading, and undertaking grandiose construction projects in Ashgabat while neglecting basic services in rural areas. In 2005, he controversially ordered the closure of all hospitals outside Ashgabat and all rural libraries.

Internationally, Turkmenistan adopted a policy of "permanent neutrality," which was formally recognized by the United Nations in 1995. Niyazov eschewed membership in regional security organizations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and maintained relations with both the Taliban and the Northern Alliance in neighboring Afghanistan during the late 1990s. Following an alleged assassination attempt in November 2002, Niyazov launched a new wave of security crackdowns, purging government officials and further restricting media freedom. Exiled former foreign minister Boris Shikhmuradov was accused of planning the attack and subsequently imprisoned; his fate remains unknown.

Niyazov died suddenly on December 21, 2006. Deputy Prime Minister Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow was named acting president, despite constitutional provisions that should have seen the speaker of parliament take this role. Berdimuhamedow subsequently won a presidential election in February 2007, which was widely criticized by international observers as non-democratic and lacking genuine competition.

Berdimuhamedow initially made some tentative moves to dismantle Niyazov's cult of personality, reversing some of his predecessor's more eccentric policies, such as restoring traditional names for months and days and reopening rural hospitals. He also oversaw constitutional changes, ostensibly to modernize the political system. However, he soon developed his own extensive cult of personality, being referred to as Arkadag ("The Protector"). His rule continued the authoritarian practices of his predecessor, with no significant improvements in human rights or democratic freedoms. Political opposition remained suppressed, media heavily censored, and elections were not free or fair. Berdimuhamedow won subsequent presidential elections in 2012 and 2017 with reported landslide victories amidst a tightly controlled political environment.

In a move seen as establishing a political dynasty, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow's son, Serdar Berdimuhamedow, rapidly rose through government ranks. In March 2022, Serdar Berdimuhamedow won a snap presidential election, described by international observers as neither free nor fair. He was inaugurated on March 19, 2022. While Serdar became president, his father, Gurbanguly, transitioned to the role of Chairman of the Halk Maslahaty (People's Council), a newly empowered upper chamber of parliament (which later became a separate supreme representative body), effectively creating a system of shared, or perhaps dual, power. This transition has not led to any significant political liberalization, and Turkmenistan remains one of the most repressive and isolated countries in the world, facing persistent criticism for its human rights record, lack of democratic processes, and the socio-political impacts of its authoritarian governance.

4. Geography

Turkmenistan is a landlocked country located in Central Asia. It has a total area of 188 K mile2 (488.10 K km2), making it the 52nd largest country in the world. The country's geography is dominated by deserts, plains, and mountain ranges, with significant water resources being scarce.

4.1. Topography

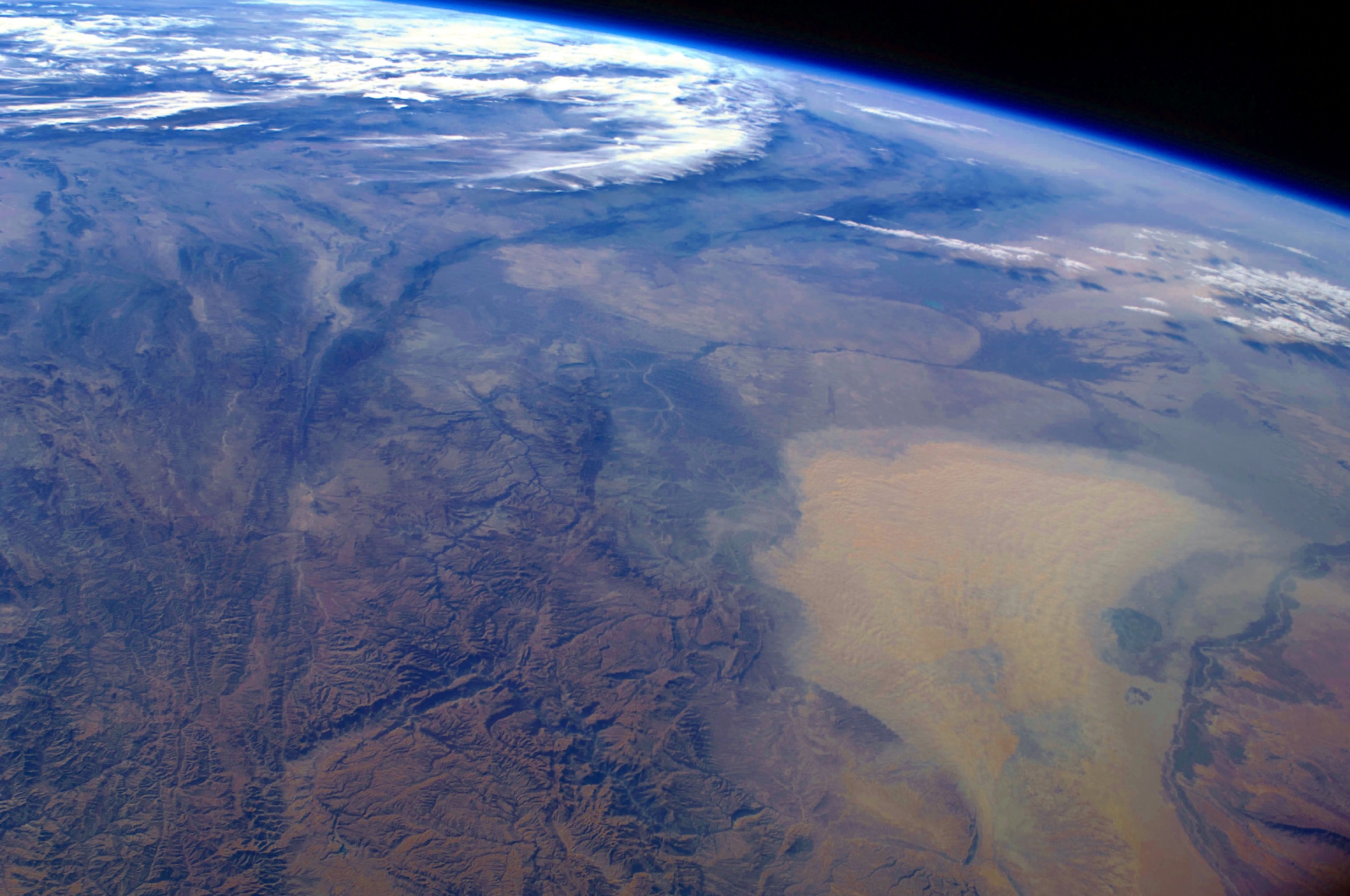

The most prominent topographical feature of Turkmenistan is the Karakum Desert (meaning "Black Sand"), which covers over 80% of the country's territory. This vast desert is part of the larger Turan Depression, a low-lying plain that extends across much of Central Asia. The Karakum is characterized by extensive sand dunes, arid plains, and sparse vegetation.

To the south and southwest, Turkmenistan is bordered by the Kopet Dag mountain range, which forms a natural boundary with Iran. The Kopet Dag range is seismically active and features peaks reaching up to 9.5 K ft (2.91 K m) at Kuh-e Rizeh (Mount Rizeh). This range receives more precipitation than the desert regions and supports a more varied ecosystem.

In the west, near the Caspian Sea, lies the Great Balkhan Range (Uly Balkan Gerşi) in Balkan Province, with its highest point, Mount Arlan (Gora Arlan), reaching 6.2 K ft (1.88 K m). To the east, along the border with Uzbekistan in Lebap Province, is the Köýtendag Range, which includes Turkmenistan's highest peak, Ayrybaba (formerly Peak of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia), at 10 K ft (3.14 K m).

The northern part of the country includes the Ustyurt Plateau, a vast clay and stony desert shared with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Turkmenistan has a coastline of 1.1 K mile (1.75 K km) along the Caspian Sea to the west. The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water and is rich in oil and gas reserves. The Turkmen coast is generally low-lying and includes the Garabogazköl (Kara-Bogaz-Gol), a large, shallow lagoon.

Major rivers include the Amu Darya, which flows along the northeastern border with Uzbekistan and is a vital source of irrigation water. Other important rivers are the Murghab River and the Tejen (Harirud) River, both of which flow from Afghanistan and dissipate in the Karakum Desert, and the Atrek River (Etrek), which flows from Iran and forms part of the southern border before emptying into the Caspian Sea. Tributaries of the Atrek include the Sumbar and Chandyr rivers.

The country includes three main tectonic regions: the Epigersin platform region, the Alpine shrinkage region, and the Epiplatform orogenesis region. The Alpine tectonic region, particularly the Kopet Dag, is prone to earthquakes. Significant earthquakes occurred in 1869, 1893, 1895, 1929, and notably the devastating 1948 Ashgabat earthquake which largely destroyed the capital city.

4.2. Climate

Turkmenistan has a sharply continental and arid desert climate. It is characterized by long, hot, and dry summers, and mild, relatively short, and dry winters, though winters can be cold in the north. Temperature variations between summer and winter, and also between day and night, can be extreme.

Summers, from May to September, are typically very hot, with average daytime temperatures often exceeding 95 °F (35 °C) and frequently reaching 104 °F (40 °C) to 113 °F (45 °C) in the Karakum Desert. The highest temperature ever recorded in Ashgabat was 118.4 °F (48 °C), and an unofficial record of 125.06 °F (51.7 °C) was noted in Kerki, an inland city on the Amu Darya River, in July 1983. The Repetek Biosphere State Reserve recorded 122.18 °F (50.1 °C), the highest official temperature in the former Soviet Union.

Winters are generally mild but can be cold, especially in the northern regions and when cold air masses from Siberia penetrate the area. Average January temperatures range from 23 °F (-5 °C) in the north to 39.2 °F (4 °C) in the south along the Iranian border. Snowfall is infrequent and light, particularly in the southern lowlands.

Precipitation is scarce throughout the country, with most areas receiving less than 7.9 in (200 mm) annually. The Karakum Desert is one of the driest deserts in the world, with some areas averaging only 0.5 in (12 mm) of rain per year. Most precipitation occurs during the late autumn, winter, and early spring months, primarily between October and May. The Kopet Dag mountains receive the highest rainfall, up to 16 in (400 mm) annually in some locations.

The country enjoys a high amount of sunshine, with an average of 235 to 240 sunny days per year. The climate is influenced by its remoteness from oceans, the presence of mountain ranges to the south and southeast that block moist air from the Indian Ocean, and the open plains to the north that allow cold Arctic air incursions in winter. Limited winter and spring rains are primarily due to moist air from the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea moving eastward.

4.3. Water systems

Turkmenistan's water systems are critical for its arid environment, supporting agriculture, industry, and human consumption. The country relies heavily on a few major rivers and extensive canal systems.

The most significant river is the Amu Darya, which forms part of the northern and eastern borders with Uzbekistan. It is the largest river in Central Asia by discharge and is the primary source of water for irrigation and other uses in Turkmenistan. However, its flow has been significantly reduced due to extensive water withdrawal for agriculture upstream and in Turkmenistan itself, contributing to the Aral Sea crisis.

Other important rivers include:

- The Murghab River, which rises in Afghanistan and flows into Turkmenistan, creating an oasis around the city of Mary before its waters are largely consumed by irrigation and dissipate in the Karakum Desert.

- The Tejen River (also known as the Harirud), which also originates in Afghanistan, flows along the border with Iran, and supports the Tejen oasis before disappearing into the desert.

- The Atrek River (Etrek), which rises in Iran and forms part of the border between Turkmenistan and Iran before flowing into the Caspian Sea. Its tributaries within Turkmenistan include the Sumbar and Chandyr rivers.

The most extensive man-made water system is the Karakum Canal (Garagum Canal), one of the longest irrigation and water supply canals in the world. Stretching over 0.9 K mile (1.38 K km), it diverts water from the Amu Darya westward across the Karakum Desert to irrigate large agricultural areas, primarily for cotton and wheat cultivation, and to supply water to cities, including Ashgabat. While vital for agriculture, the canal has been associated with significant water loss through seepage and evaporation, and has contributed to salinization and desertification issues.

Turkmenistan also has a coastline on the Caspian Sea, the world's largest inland body of water. The Caspian Sea provides resources such as fish and, significantly, offshore oil and gas. The Garabogazköl (Kara-Bogaz-Gol) is a large, shallow saline lagoon on the eastern shore of the Caspian, known for its mineral deposits.

Water management is a critical issue for Turkmenistan. The arid climate and reliance on transboundary rivers like the Amu Darya make the country vulnerable to water scarcity and disputes with neighboring countries over water allocation. The government has invested in water infrastructure, including reservoirs and irrigation systems, but challenges related to inefficient water use, deteriorating infrastructure, and environmental degradation persist. Groundwater resources are also utilized but are limited in many areas. The increasing impacts of climate change are expected to further exacerbate water stress in the region.

4.4. Biodiversity and environment

Turkmenistan's biodiversity is adapted to its predominantly arid and desert environments, with distinct flora and fauna found in its various ecoregions. The country faces significant environmental challenges, including desertification, water scarcity, and the impacts of resource extraction.

Flora and Fauna:

The Karakum Desert supports a range of desert-adapted plants such as saxaul trees (Haloxylon), saltworts, and various grasses and shrubs. Animal life includes desert mammals like the goitered gazelle, desert fox, corsac fox, wildcat, and various rodents. Reptiles are abundant, including numerous lizard species (like the desert monitor) and snakes (such as cobras and vipers). Birdlife includes desert warblers, larks, and raptors.

The Kopet Dag mountains in the south host a richer biodiversity due to higher precipitation. These areas feature juniper woodlands, pistachio groves, and diverse herbaceous vegetation. Mammals in this region include urial (wild sheep), wild boar, leopard (rare), and porcupine.

River valleys, particularly along the Amu Darya and Murghab, support riparian woodlands (tugai forests) with poplar, willow, and tamarisk, providing habitats for deer, jackals, and various bird species. The Caspian Sea coast is important for migratory birds and is home to the Caspian seal. The endemic Akhal-Teke horse, known for its speed, endurance, and distinctive metallic sheen, is a national symbol.

Terrestrial Ecoregions:

Turkmenistan encompasses several terrestrial ecoregions, including:

- Alai-Western Tian Shan steppe

- Kopet Dag woodlands and forest steppe

- Badghyz and Karabil semi-desert

- Caspian lowland desert

- Central Asian riparian woodlands

- Central Asian southern desert

- Kopet Dag semi-desert

Protected Areas:

Turkmenistan has a system of protected areas (zapovedniks) aimed at conserving its unique ecosystems and species. Some notable protected areas include:

- Repetek Biosphere State Reserve (Karakum Desert)

- Köýtendag Nature Reserve (mountain ecosystems, dinosaur footprints)

- Sünt-Hasardag Nature Reserve (Kopet Dag, diverse flora)

- Gaplaňgyr Nature Reserve (Ustyurt Plateau)

- Amyderýa Nature Reserve (Amu Darya tugai forests)

- Hazar Nature Reserve (Caspian coast, wetlands for birds)

Environmental Issues:

Turkmenistan faces severe environmental challenges:

- Desertification: Overgrazing, unsustainable agricultural practices, and deforestation for fuel have exacerbated desertification, particularly around oases and the Karakum Canal.

- Water Scarcity and Mismanagement: Inefficient irrigation, particularly from the Karakum Canal, leads to massive water loss, soil salinization, and waterlogging. The diversion of water from the Amu Darya has contributed to the Aral Sea disaster.

- Pollution: Agricultural runoff containing pesticides and fertilizers, as well as industrial pollution from the oil and gas sector, affect water and soil quality.

- Biodiversity Loss: Habitat degradation, poaching, and unsustainable resource use threaten many species.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Turkmenistan has one of the world's highest per capita greenhouse gas emissions, largely due to methane leaks from its extensive natural gas infrastructure (extraction, processing, and transportation). The Darvaza gas crater (often called the "Gates of Hell"), a continuously burning natural gas field, is a significant source of methane emissions. The government has expressed intentions to extinguish it.

- Caspian Sea Issues: Pollution from oil extraction and fluctuating sea levels pose threats to the Caspian ecosystem.

The government's approach to environmental protection has often been criticized for lacking transparency and effective enforcement, with economic priorities frequently overshadowing environmental concerns. The social impacts of environmental degradation, such as on public health and rural livelihoods, are also significant.

5. Administrative divisions

Turkmenistan is divided into five provinces (welayatlarTurkmen, singular: welayat) and one capital city district (şäherTurkmen), Ashgabat, which has the status of a province. The provinces are further subdivided into districts (etraplarTurkmen, singular: etrap), which can be either counties or cities. According to the Constitution of Turkmenistan, some cities may also have the status of a welayat or etrap.

The administrative divisions are as follows:

| Division | ISO 3166-2 | Capital city | Area | Population (2022 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashgabat City | TM-S | Ashgabat | 181 mile2 (470 km2) | 1,030,063 |

| Ahal Province | TM-A | Arkadag | 38 K mile2 (97.16 K km2) | 886,845 |

| Balkan Province | TM-B | Balkanabat | 54 K mile2 (139.27 K km2) | 529,895 |

| Daşoguz Province | TM-D | Daşoguz | 28 K mile2 (73.43 K km2) | 1,550,354 |

| Lebap Province | TM-L | Türkmenabat | 36 K mile2 (93.73 K km2) | 1,447,298 |

| Mary Province | TM-M | Mary | 34 K mile2 (87.15 K km2) | 1,613,386 |

The city of Arkadag, established as the new administrative center of Ahal Province, was officially inaugurated in 2023 and is being developed as a "smart city."

5.1. Major cities

Turkmenistan's urban landscape is dominated by its capital, with several other cities serving as important regional, economic, and cultural centers.

- Ashgabat (AşgabatTurkmen) is the capital and largest city of Turkmenistan, located in a tectonically active oasis at the foothills of the Kopet Dag mountains near the Iranian border. It serves as the country's political, administrative, economic, scientific, and cultural center. Extensively rebuilt after a devastating earthquake in 1948 and further redeveloped with monumental white marble architecture under Niyazov and Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, Ashgabat is known for its numerous parks, fountains, and grand official buildings. Its population according to the 2022 census was 1,030,063. The city has a special administrative status equivalent to a province.

- Türkmenabat (formerly Çärjew) is the second-largest city and the administrative center of Lebap Province in eastern Turkmenistan, situated on the banks of the Amu Darya river. It is a significant industrial and transportation hub, with industries including chemical production, food processing, and textiles. Its population was 1,447,298 for the province in 2022, with the city itself having around 280,000 inhabitants (prior census estimates).

- Daşoguz (formerly Tashauz) is the third-largest city and the administrative center of Daşoguz Province in northern Turkmenistan, near the border with Uzbekistan. It is an important agricultural center, particularly for cotton and grains, and has some light industry. The province's population was 1,550,354 in 2022; the city itself had a population of around 245,000 (prior census estimates). It is a gateway to the nearby UNESCO World Heritage site of Konye-Urgench.

- Mary is the administrative center of Mary Province in southeastern Turkmenistan, located in the Murghab River oasis. It is a major center for natural gas production and cotton cultivation. The city is historically significant as the successor to ancient Merv, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The province's population was 1,613,386 in 2022; the city itself had around 126,000 inhabitants (prior census estimates).

- Balkanabat (formerly Nebit-Dag) is the administrative center of Balkan Province in western Turkmenistan. It is a key center for the country's oil and natural gas industry, with significant reserves located in the surrounding region and offshore in the Caspian Sea. The province's population was 529,895 in 2022; the city itself had around 90,000 inhabitants (prior census estimates).

- Türkmenbaşy (formerly Krasnovodsk) is a major port city on the Caspian Sea in Balkan Province. It is a crucial hub for Turkmenistan's oil exports, with a large oil refinery and the Turkmenbashi International Seaport. It is also a developing tourist destination with the Awaza resort zone located nearby. Its population was around 74,000 (prior census estimates).

- Arkadag is a newly constructed city, designated as the administrative center of Ahal Province in 2022. It is being developed as a "smart city" and is named in honor of former President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, who holds the title of Arkadag ("Protector").

Other notable towns include Serdar (formerly Kyzyl-Arvat), Baýramaly, Tejen, and Magdanly (formerly Gowurdak). The development and population figures of these cities are often influenced by state investment policies, resource extraction activities, and agricultural importance.

6. Government and politics

Turkmenistan is a presidential republic operating under a constitution that formally provides for a separation of powers. However, in practice, the country is a highly centralized, authoritarian state dominated by the executive branch and characterized by a single-party system, a pervasive cult of personality around its leaders, and a severe lack of political freedoms and democratic processes. The political landscape has been shaped by over a century of Russian and Soviet influence, followed by more than three decades of autocratic rule since independence in 1991.

6.1. Government structure

The government of Turkmenistan is structured around three main branches: the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary. However, power is overwhelmingly concentrated in the hands of the President.

The Presidency:

The President of Turkmenistan is both the head of state and head of government. The president is the supreme commander-in-chief of the armed forces and directs both domestic and foreign policy. The president appoints and dismisses the Cabinet of Ministers (who are also deputy chairpersons), heads of regional and local administrations, judges, and other senior officials. Constitutional amendments in 2016 extended the presidential term from five to seven years and removed the upper age limit for presidential candidates.

Since independence, Turkmenistan has had three presidents:

- Saparmurat Niyazov (1991-2006), who was declared President for Life in 1999.

- Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow (2006-2022), who also cultivated an extensive personality cult.

- Serdar Berdimuhamedow (2022-present), son of Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow.

The Cabinet of Ministers:

The Cabinet of Ministers is the chief executive and administrative body. It is headed by the President, who also acts as the Chairman of the Cabinet. Deputy Chairpersons of the Cabinet (equivalent to deputy prime ministers) oversee specific sectors of the economy and government. Ministers are appointed by and accountable to the President.

The Legislature:

The legislature of Turkmenistan has undergone several structural changes.

- From 1992 to 2021, and again from January 2023, the legislature is the unicameral Assembly (MejlisTurkmen). It currently has 125 members elected for five-year terms from single-seat constituencies.

- Between March 2021 and January 2023, a bicameral parliament called the National Council (Milli GeňeşTurkmen) existed, with the Mejlis as the lower house and the newly created People's Council (Halk MaslahatyTurkmen) as the upper house.

- In January 2023, the bicameral system was abolished. The Mejlis reverted to being a unicameral parliament. The Halk Maslahaty was reconstituted as a separate "supreme representative body of people's power" with broad constitutional authority, chaired by former President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, who was also declared the "National Leader of the Turkmen people." This move effectively institutionalized his continued influence.

Despite its formal legislative role, the Mejlis is widely regarded as a rubber-stamp body that does not exercise independent power or provide meaningful checks on the executive.

The Judiciary:

The judicial system is headed by the Supreme Court. Judges at all levels, including the Chairperson of the Supreme Court, are appointed and can be dismissed by the President, often with the nominal consent of the Mejlis. The judiciary lacks independence and is subject to executive control. The Chief Justice is considered part of the executive and sits on the State Security Council.

The overall government structure ensures the President's dominance over all aspects of state power, with limited accountability or democratic oversight.

6.1.1. Legislature

The legislative branch of Turkmenistan has experienced significant changes in its structure, particularly concerning the roles of the Assembly (Mejlis) and the People's Council (Halk Maslahaty).

The Assembly (MejlisTurkmen) is the primary legislative body. As of January 2023, it functions as a unicameral parliament. It consists of 125 members who are elected for five-year terms from single-seat constituencies. The Mejlis is responsible for adopting laws, amending the constitution (though often initiated or heavily influenced by the President), approving the state budget, and ratifying international treaties. However, its de facto power is severely limited, and it generally serves to approve decisions made by the President. International observers have consistently noted that parliamentary elections in Turkmenistan are not free or fair and lack genuine political competition, with candidates often handpicked or approved by the government.

The People's Council (Halk MaslahatyTurkmen, meaning "People's Council") has had a complex history.

- Originally, under President Niyazov, it was a large representative body with supreme authority, often superseding the Mejlis. It was abolished by the 2008 constitution.

- It was revived in 2017 as a separate body.

- From March 2021 to January 2023, it served as the upper house of the bicameral National Council (Milli GeňeşTurkmen).

- In January 2023, the bicameral parliament was dissolved. The Halk Maslahaty was reconstituted again as a separate "supreme representative body of people's power" positioned above the Mejlis, with extensive constitutional authority, including the power to amend the constitution and determine main directions of domestic and foreign policy. Former President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow was appointed its Chairman and officially designated the "National Leader of the Turkmen people," granting him significant ongoing power and influence over state affairs, even after his son became president.

State media has referred to this reformed People's Council as the "supreme organ of government authority." This structure, particularly the role and powers vested in the Halk Maslahaty under Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow's chairmanship, further concentrates power outside the regular democratic framework and undermines the Mejlis's role as an independent legislature. The legislative process is largely a formality, endorsing presidential decrees and policies rather than initiating or scrutinizing legislation independently. This system reinforces the authoritarian nature of the Turkmen government, where true legislative power and decision-making reside with the President and, more recently, the "National Leader."

6.1.2. Judiciary

The judicial system in Turkmenistan is formally structured with a hierarchy of courts, headed by the Supreme Court. Other courts include provincial, district, and city courts, as well as economic courts. The constitution provides for an independent judiciary.

However, in practice, the judiciary is not independent and operates under the firm control of the executive branch, particularly the President. Key aspects highlighting this lack of independence include:

- Appointment and Dismissal of Judges: Under Articles 71 and 100 of the constitution, the President appoints all judges, including the Chairperson (Chief Justice) of the Supreme Court. The President also has the authority to dismiss them, typically with the nominal consent of the Mejlis, which itself is not an independent body. There is no independent judicial council or transparent process for judicial appointments or dismissals.

- Subordination to the Executive: The judiciary is widely seen as subordinate to presidential directives. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court is a member of the State Security Council, an executive body, further blurring the lines of separation of powers.

- Lack of Judicial Review: There is no effective mechanism for judicial review of presidential actions or legislation to ensure constitutional compliance.

- Corruption and Inefficiency: The judiciary is reputed to be affected by corruption and inefficiency. Decisions are often influenced by political considerations or bribery rather than the rule of law.

International human rights organizations and foreign governments, including the U.S. Department of State, have consistently reported on the lack of judicial independence in Turkmenistan. Their reports highlight that the legal system does not provide citizens with fair trials or adequate protection of their rights, particularly in politically sensitive cases. The judiciary often serves as an instrument of state control rather than an impartial arbiter of justice. While many national laws are published, their application is often arbitrary and subservient to the interests of the ruling regime.

6.2. Political parties

Turkmenistan's political system is characterized by the overwhelming dominance of a single party and a severe lack of genuine political pluralism or opposition. While the constitution, particularly after amendments in 2008, formally permits the formation of multiple political parties, the political environment remains tightly controlled by the state.

The Democratic Party of Turkmenistan (DPT) is the ruling party. It is the successor to the Communist Party of the Turkmen SSR. It was headed by President Saparmurat Niyazov until his death and subsequently by President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow. The DPT controls all levels of government and the electoral process.

In August 2012, the Party of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs was established, marking the formal end of the single-party system. In 2014, the Agrarian Party was also registered. Despite the existence of these parties, they are widely viewed as pro-government entities created to give an appearance of multi-party democracy rather than offering genuine political alternatives or opposition. They operate under the direction of the DPT and do not challenge the president's policies. Candidates from these parties participate in elections, but the elections themselves are not considered free or fair by international observers.

Political gatherings and activities are strictly controlled by the government, and any form of independent political opposition is suppressed. Opposition figures are often imprisoned, forced into exile, or face other forms of harassment. There are no true opposition parties represented in the Turkmen parliament or allowed to operate legally within the country. The creation of new parties is subject to restrictive registration processes controlled by the government.

The lack of genuine political competition and the dominance of the DPT and its allied parties mean that there is no meaningful public debate on policy issues, and citizens have no real choice in electing their representatives. This contributes to Turkmenistan's status as one of the world's most authoritarian states.

6.3. Foreign relations

Turkmenistan's foreign policy is officially based on the principle of "permanent neutrality," which was formally recognized by a United Nations General Assembly resolution on December 12, 1995. This neutrality, enshrined in the country's constitution, dictates that Turkmenistan will not participate in military alliances or multinational defense organizations, though it allows for military assistance if requested.

Key aspects of Turkmenistan's foreign relations include:

- Relations with Neighboring Countries: Turkmenistan maintains diplomatic relations with all its neighbors.

- Russia: Relations with Russia remain significant due to historical ties, economic links (particularly in the energy sector, though diminished from Soviet times), and Russia's influence in Central Asia.

- China: China has become a crucial economic partner, primarily as the largest buyer of Turkmen natural gas through the Central Asia-China gas pipeline.

- Iran: Turkmenistan shares a long border and historical ties with Iran. Cooperation exists in trade and energy, though disputes over gas payments have occurred.

- Afghanistan: Turkmenistan shares a border with Afghanistan and has been involved in infrastructure projects like the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India Pipeline (TAPI). It maintains a pragmatic approach to the governments in Kabul due to security and economic interests.

- Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan: Relations with these Central Asian neighbors involve cooperation on water management, energy, and transportation, though historical border and resource issues have occasionally caused friction.

- Relations with Other Key Countries:

- Turkey: Turkmenistan has close linguistic and cultural ties with Turkey, which is a significant trade and investment partner.

- United States and European Union: Relations are often shaped by Western concerns over human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in Turkmenistan. However, engagement continues, particularly on issues of regional security, energy diversification, and counter-terrorism.

- International Organizations: Turkmenistan is a member of the United Nations (UN), Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), and an observer state in the Organisation of Turkic States and Türksoy. It is also a member of financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. Turkmenistan was a founding member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) but later downgraded its status to an associate member in 2005, consistent with its neutrality policy.

Human Rights and Foreign Policy: Turkmenistan's human rights record is a persistent point of contention in its relations with Western countries and international organizations. While the government emphasizes its neutrality and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, it faces international criticism for its own domestic policies.

Energy Diplomacy: A major focus of Turkmenistan's foreign policy is energy diplomacy, aimed at diversifying export routes for its vast natural gas reserves. This includes projects like TAPI and exploring potential pipelines across the Caspian Sea.

Regional Security: Despite its neutrality, Turkmenistan is concerned about regional stability, particularly given its border with Afghanistan. It cooperates on border security and counter-narcotics efforts.

According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Turkmenistan was ranked as the 83rd most peaceful country in the world. However, this assessment primarily reflects the absence of external conflict and internal state-controlled order, rather than a robust civil society or adherence to democratic peace principles.

6.4. Military

The Armed Forces of Turkmenistan (Türkmenistanyň Ýaragly GüýçleriTurkmen), informally known as the Turkmen National Army (Türkmenistanyň Milli goşunTurkmen), are responsible for the national defense of Turkmenistan. Consistent with the country's policy of permanent neutrality, the military's doctrine is primarily defensive. The President of Turkmenistan is the Supreme Commander-in-Chief.

The Armed Forces consist of several branches:

- Ground Forces: This is the largest component of the military, responsible for land-based defense operations. It is equipped primarily with Soviet-era and some Russian-made weaponry, including tanks, armored personnel carriers, artillery, and air defense systems.

- Air Force and Air Defense Forces: This branch operates a mix of combat aircraft, transport aircraft, and helicopters, largely of Soviet/Russian origin. It is also responsible for the country's air defense network.

- Navy: Established after independence, the Turkmen Navy operates on the Caspian Sea. Its primary roles include protecting Turkmenistan's maritime borders, offshore energy infrastructure, and combating smuggling and terrorism. The fleet consists mainly of patrol boats and smaller vessels.

Other independent formations include:

- State Border Service (Border Troops): Responsible for guarding the country's extensive land and maritime borders.

- Internal Troops: Part of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, tasked with maintaining public order, guarding important state facilities, and assisting in disaster relief.

- National Guard: An elite unit primarily responsible for ceremonial duties and protecting high-ranking officials and key government buildings.

Military service is compulsory for adult males. Turkmenistan has gradually sought to modernize its military equipment, often through purchases from Russia, China, Turkey, and other countries. The country also participates in limited military cooperation and training programs with some foreign partners, within the bounds of its neutrality policy. The military's overall capability is focused on border defense and maintaining internal security rather than power projection. The emphasis on neutrality means Turkmenistan does not participate in military alliances.

6.5. Law enforcement and public order

Law enforcement in Turkmenistan is primarily the responsibility of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (Içeri İşler MinistirligiTurkmen) and the Ministry for National Security (Milli Howpsuzlyk MinistirligiTurkmen, MNB). These agencies operate within a highly centralized and authoritarian state structure, where maintaining public order is often intertwined with upholding state control and suppressing dissent.

Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD):

The MVD commands the national police force (polisiýaTurkmen) and the Internal Troops. The police are responsible for general law enforcement duties, including crime prevention and investigation, traffic control, and maintaining public order. The Internal Troops are a gendarmerie-type force tasked with guarding important state facilities, assisting in crowd control, and responding to internal security threats. The MVD's forces are estimated to be around 25,000 personnel.

Ministry for National Security (MNB):

The MNB is the primary intelligence and counterintelligence agency of Turkmenistan. It is the successor to the Soviet-era KGB. The MNB's functions include state security, surveillance of the population, monitoring perceived threats to the regime (including political dissent and independent activism), and counter-terrorism. The MNB is known for its pervasive surveillance and plays a significant role in enforcing the government's tight control over society.

Public Order:

Public order in Turkmenistan is generally maintained through a strong state presence and strict controls. Crime rates reported by the state are often low, but independent verification is difficult. The authorities place significant emphasis on visible security and order, particularly in the capital, Ashgabat.

Implications for Civil Liberties:

Law enforcement agencies in Turkmenistan have been widely criticized by international human rights organizations for their role in upholding an oppressive state apparatus. Concerns include:

- Arbitrary arrest and detention.

- Lack of due process and fair trial standards.

- Use of torture and ill-treatment in detention.

- Suppression of fundamental freedoms, including freedom of speech, assembly, and association.

- Surveillance and harassment of activists, journalists, and perceived critics of the government.

- Corruption within law enforcement agencies.

The legal framework governing law enforcement exists, but its application is often subservient to the political interests of the regime. The lack of an independent judiciary further limits accountability for abuses committed by law enforcement personnel. While these agencies are tasked with maintaining public safety, their operations often prioritize state security and regime stability over the protection of individual civil liberties and human rights.

6.6. Human rights

The human rights situation in Turkmenistan is extremely poor and has been consistently criticized by international organizations, foreign governments, and human rights activists. The country is considered one of the world's most repressive and authoritarian states, with severe restrictions on nearly all fundamental freedoms.

Restrictions on Fundamental Freedoms:

- Freedom of Speech and Press: There is no independent media in Turkmenistan. All media outlets-television, radio, newspapers, and online publications-are state-controlled and serve as propaganda tools for the government. Criticism of the president or government policies is not tolerated. Access to foreign news sources is severely restricted, and independent journalists face harassment, intimidation, and imprisonment. Censorship is pervasive.

- Freedom of Assembly and Association: The government severely restricts freedom of assembly and association. Unauthorized public gatherings are prohibited, and attempts to form independent political parties or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are suppressed.

- Freedom of Religion: While the constitution provides for freedom of religion, religious practice is tightly controlled by the state. All religious groups must register with the government, and unregistered religious activity is illegal. Minority religious groups, including various Christian denominations (such as Protestants and Jehovah's Witnesses) and others, face harassment, raids, confiscation of religious literature, and difficulties in registering. The government appoints Muslim clerics and oversees Islamic institutions. The influence of Saparmurat Niyazov's Ruhnama in religious contexts, once mandated, highlighted state interference.

- Freedom of Movement: Turkmen citizens face significant restrictions on their ability to travel abroad. The government maintains a blacklist of individuals barred from leaving the country, often including activists, relatives of exiled dissidents, and former officials. Internal movement can also be subject to controls.

Political Repression and Lack of Due Process:

- Political dissent is not tolerated. Activists, critics of the government, and their families are subject to surveillance, harassment, imprisonment, and enforced disappearances.

- The justice system lacks independence and is subservient to the executive. Fair trials are not guaranteed, particularly in politically sensitive cases. Arbitrary arrest and detention are common, and torture and ill-treatment of detainees are reported to be systematic.

- Prisons are overcrowded, and conditions are harsh, with inadequate food, water, and medical care. Many individuals have "disappeared" within the prison system, their whereabouts and fate unknown to their families.

Forced Labor:

The Turkmen government has a long-standing practice of mobilizing state employees (including teachers, doctors, and nurses) and, historically, children for the annual cotton harvest under threat of punishment, such as loss of employment. This state-sponsored forced labor has led to international boycotts of Turkmen cotton by numerous global brands. While there have been some recent official acknowledgements and efforts to address the issue under international pressure, concerns about forced labor persist.

Treatment of Ethnic Minorities:

Ethnic minorities, including Russians, Uzbeks, and Baloch, have reported discrimination in areas such as education, employment, and cultural expression. Policies of "Turkmenization" have sometimes marginalized minority languages and cultures. Universities have reportedly been encouraged to reject applicants with non-Turkmen surnames. Teaching the customs and language of the Baloch minority is reportedly forbidden.

Access to Information:

The government heavily controls access to information. The internet is tightly filtered, with many independent news websites, social media platforms (like Facebook and YouTube), and encrypted communication apps blocked. The use of VPNs to bypass censorship is prohibited and actively targeted.

LGBT Rights:

Homosexual acts between men are illegal in Turkmenistan and punishable by imprisonment. There is no legal recognition or protection for LGBT individuals, and societal discrimination is prevalent.

International Scrutiny:

Organizations like Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Reporters Without Borders, and various UN bodies consistently rank Turkmenistan among the worst violators of human rights. The government generally denies access to independent international monitors and human rights investigators. While the death penalty was officially abolished in 2008 (suspended in 1999), the overall human rights situation remains dire with little sign of meaningful improvement.

6.6.1. Restrictions on free and open communication

Turkmenistan imposes severe restrictions on free and open communication, effectively isolating its population from independent sources of information and fostering an environment of pervasive state control over the flow of news and ideas.

Media Censorship and State Control:

All domestic media outlets, including television, radio, newspapers, and news websites, are state-owned and tightly controlled. Content is heavily censored and primarily serves as a tool for government propaganda, glorifying the president and official policies. There is no independent journalism within the country. Foreign journalists are generally denied entry or operate under strict surveillance.

Internet Censorship and Surveillance:

Internet access is limited, expensive, and heavily filtered by the state-controlled telecommunications provider, Turkmentelekom.

- Blocked Websites: A vast number of international news websites, social media platforms (such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram), messaging apps (like WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal), and sites belonging to human rights organizations or exiled opposition groups are routinely blocked.

- VPN Prohibition: The use of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and other circumvention tools to access blocked content is strictly prohibited. Authorities actively work to identify and block VPN services, and individuals caught using them can face interrogation, fines, or other repercussions.

- Surveillance: Internet traffic is monitored by state security services. Citizens are often required to present identification to use internet cafes, and their online activities can be tracked.

Restrictions on Satellite Television:

For many years, satellite dishes provided a crucial window to the outside world for Turkmen citizens, allowing access to foreign television channels. However, the government has intermittently and sometimes aggressively campaigned to remove privately owned satellite dishes, particularly in urban areas, under various pretexts such as urban beautification. While the first national communications satellite, TurkmenSat 1 (TürkmenÄlem 52°E), was launched in 2015, ostensibly to improve domestic telecommunications, the move was also seen as part of an effort to consolidate state control over information by encouraging or forcing a switch to state-controlled cable packages. The primary target of these campaigns has often been access to foreign news, including services like Radio Azatlyk (RFE/RL's Turkmen service).

Impact on Citizens:

These restrictions create an information vacuum, limiting citizens' ability to access diverse perspectives, engage in open discussion, or hold the government accountable. The fear of surveillance and reprisal leads to widespread self-censorship. The lack of access to independent information severely hampers political participation, social development, and the free exchange of ideas, contributing to Turkmenistan's isolation. International bodies consistently rank Turkmenistan at the bottom of global press freedom and internet freedom indices.

6.7. Corruption

Corruption is a pervasive and deeply entrenched problem in Turkmenistan, affecting all levels of government and society. It significantly undermines the country's economic development, distorts public administration, and contributes to the erosion of the rule of law and public trust. Turkmenistan consistently ranks among the countries with the highest perceived levels of corruption in global indices. For example, Transparency International's 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index placed Turkmenistan 169th out of 180 countries.

Manifestations of Corruption:

- Bribery and Extortion: Bribery is reportedly commonplace in interactions with public officials, from accessing basic services like healthcare and education to obtaining licenses, permits, or favorable treatment from law enforcement and the judiciary.

- Nepotism and Cronyism: Appointments to government positions and access to economic opportunities are often based on personal connections, loyalty to the ruling elite, and tribal affiliations rather than merit. State contracts are frequently awarded to companies with close ties to government officials.

- Misappropriation of State Assets: Revenue from Turkmenistan's vast natural gas and oil reserves is largely controlled by the state, and there is a lack of transparency regarding its management and use. Off-budget funds controlled by the president have been a particular concern for anti-corruption watchdogs, with allegations that significant portions of state wealth are diverted for personal enrichment or grandiose projects with little public benefit. The non-governmental organization Crude Accountability has described Turkmenistan's economy as a kleptocracy.

- Corruption in Specific Sectors:

- Law Enforcement and Judiciary: These sectors are widely reputed to be corrupt, with justice often for sale.

- Education: Bribery for university admissions, favorable grades, and even school placements is reportedly widespread. In 2020, the deputy prime minister for education and science, Pürli Agamyradow, was dismissed for failing to control bribery in the education sector.

- Healthcare: Patients may need to pay bribes to receive adequate medical treatment or access to scarce medications.

- Customs and Border Control: These agencies are also susceptible to corruption related to the movement of goods and people.

- Public Procurement: Lack of transparency in government tenders and contracts creates opportunities for illicit enrichment.

Impact of Corruption:

- Economic Stagnation: Corruption diverts resources from productive investments, hinders economic diversification, and discourages foreign investment (outside the energy sector, which operates under specific conditions).

- Social Inequality: It exacerbates social inequality, as those with connections or the ability to pay bribes gain preferential access to resources and opportunities.

- Erosion of Rule of Law: Pervasive corruption undermines the legal system and public institutions.

- Human Rights: Corruption can fuel human rights abuses, for instance, when bribes are demanded to avoid arbitrary detention or secure basic rights. The illegal adoption of abandoned babies has been linked to rampant corruption in the official adoption process, pushing desperate couples towards illicit channels.

Government Efforts and Challenges:

While the Turkmen government periodically announces anti-corruption campaigns and high-profile dismissals or arrests of officials for corruption (such as the 2019 conviction and imprisonment of Interior Minister Isgender Mulikov), these actions are often seen as selective or part of internal power struggles rather than a systematic effort to address the root causes of corruption. There is a lack of independent anti-corruption institutions, a free press to investigate and report on corruption, and a vibrant civil society to demand accountability. The highly centralized and opaque nature of the government makes it difficult to combat corruption effectively.

7. Economy

Turkmenistan's economy is heavily reliant on its vast natural resources, particularly natural gas and oil, which account for the majority of its export revenues and GDP. The state maintains significant control over most economic sectors. Despite its resource wealth, the country faces challenges related to economic diversification, poverty, opaque governance, and a difficult investment climate for entities not directly aligned with state interests.

7.1. Natural resources

Turkmenistan is endowed with significant reserves of hydrocarbons, which are the cornerstone of its economy.

7.1.1. Natural gas and export routes

Turkmenistan possesses the world's fourth or fifth-largest proven reserves of natural gas. The Galkynysh Gas Field (formerly South Yoloten-Osman) is one of the largest gas fields globally, with estimated reserves of around 21.2 trillion cubic meters. Other significant gas fields include Dauletabad and fields in the Amu Darya basin and the Caspian Sea shelf. The state-owned company Türkmengaz controls the extraction, processing, and transportation of natural gas.

Export Routes:

Historically, Turkmenistan's gas exports were primarily directed to or through Russia via the Central Asia-Center pipeline system. After independence, disputes over pricing and transit led Turkmenistan to seek diversification.

- China: Since the inauguration of Line A in 2009, China has become the largest importer of Turkmen gas. Multiple pipelines (Lines A, B, C, and a planned Line D) now connect Turkmenistan to China via Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. In 2019, China purchased over 30 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas from Turkmenistan, and by 2023, Turkmenistan's quota on this system was stated as 40 bcm annually.

- Russia: Gas exports to Russia significantly decreased and were even halted for a period (2016-2019) due to pricing disagreements. While Gazprom resumed purchases in 2019, volumes remain lower than historical levels.

- Iran: The Korpeje-Kordkuy pipeline, opened in 1997, supplied gas to northern Iran. However, exports to Iran (estimated at 12 bcma) ceased in 2017 due to payment disputes.

- TAPI Pipeline: Turkmenistan has long promoted the TAPI pipeline project to export gas to Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. The Turkmen section was reportedly completed in 2019, but progress in the other countries has been slow due to security concerns and financing challenges.

- East-West Pipeline: Completed in 2015, this domestic pipeline connects gas fields in eastern Turkmenistan to the Caspian coast, intended to feed potential future export routes like the proposed Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline to Azerbaijan and Europe, though this project has yet to materialize.

Social and Environmental Impacts:

While natural gas revenue is crucial for the state budget, there are significant concerns about transparency in how these revenues are managed and distributed, with much wealth reportedly controlled by off-budget presidential funds. Environmentally, Turkmenistan's gas industry is a major source of methane leakage, a potent greenhouse gas. Satellite data has revealed massive methane plumes from its oil and gas infrastructure, making Turkmenistan one of the world's top methane emitters. The Darvaza gas crater, continuously burning since 1971, is a visible symbol of these emissions.

7.1.2. Oil

Turkmenistan also possesses substantial oil reserves, primarily located in the western part of the country, both onshore (e.g., Balkanabat, Cheleken Peninsula fields like Goturdepe, Gumdag) and offshore in the Turkmen sector of the Caspian Sea. Estimated reserves are around 700 million tons for the main western fields. Oil production in 2019 was 9.8 million tons.

The state-owned company Türkmennebit (Turkmenoil) is responsible for most onshore oil extraction. Foreign companies, including Eni (Italy), Dragon Oil (UAE), and Petronas (Malaysia), are involved in offshore oil production under production sharing agreements.

Oil is refined at the Türkmenbaşy and Seydi refineries. Exports occur via tankers across the Caspian Sea to ports like Baku (Azerbaijan) and Makhachkala (Russia) for onward transit. In January 2021, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan signed a memorandum of understanding to jointly develop the Dostluk ("friendship") oil and gas field (formerly Kyapaz/Serdar) in a disputed area of the Caspian Sea.

Similar to natural gas, concerns exist regarding the transparency of oil revenue management and its contribution to broader socio-economic development for the Turkmen population. The benefits of this wealth are not always evident in the living standards of ordinary citizens outside the showcase capital.

7.2. Energy

Turkmenistan's energy sector is dominated by electricity generation from its abundant natural gas resources. The country is self-sufficient in electricity and also a net exporter to neighboring countries in Central Asia and to Afghanistan and Iran.

Electricity Generation:

Most electricity is generated by thermal power plants fueled by natural gas. Major power plants are located in Mary (Mary State Power Plant, one of the largest in Central Asia), Ashgabat (including the Ahal power plant built to supply the capital and the Olympic Village), Balkanabat, Büzmeýin, Daşoguz, Türkmenbaşy, Türkmenabat, and Seydi. Recent additions include the Mary-3 combined cycle power plant (1.574 GW, commissioned 2018, primarily for export) and the Zerger power plant in Lebap Province (432 MW, commissioned 2021, also for export).

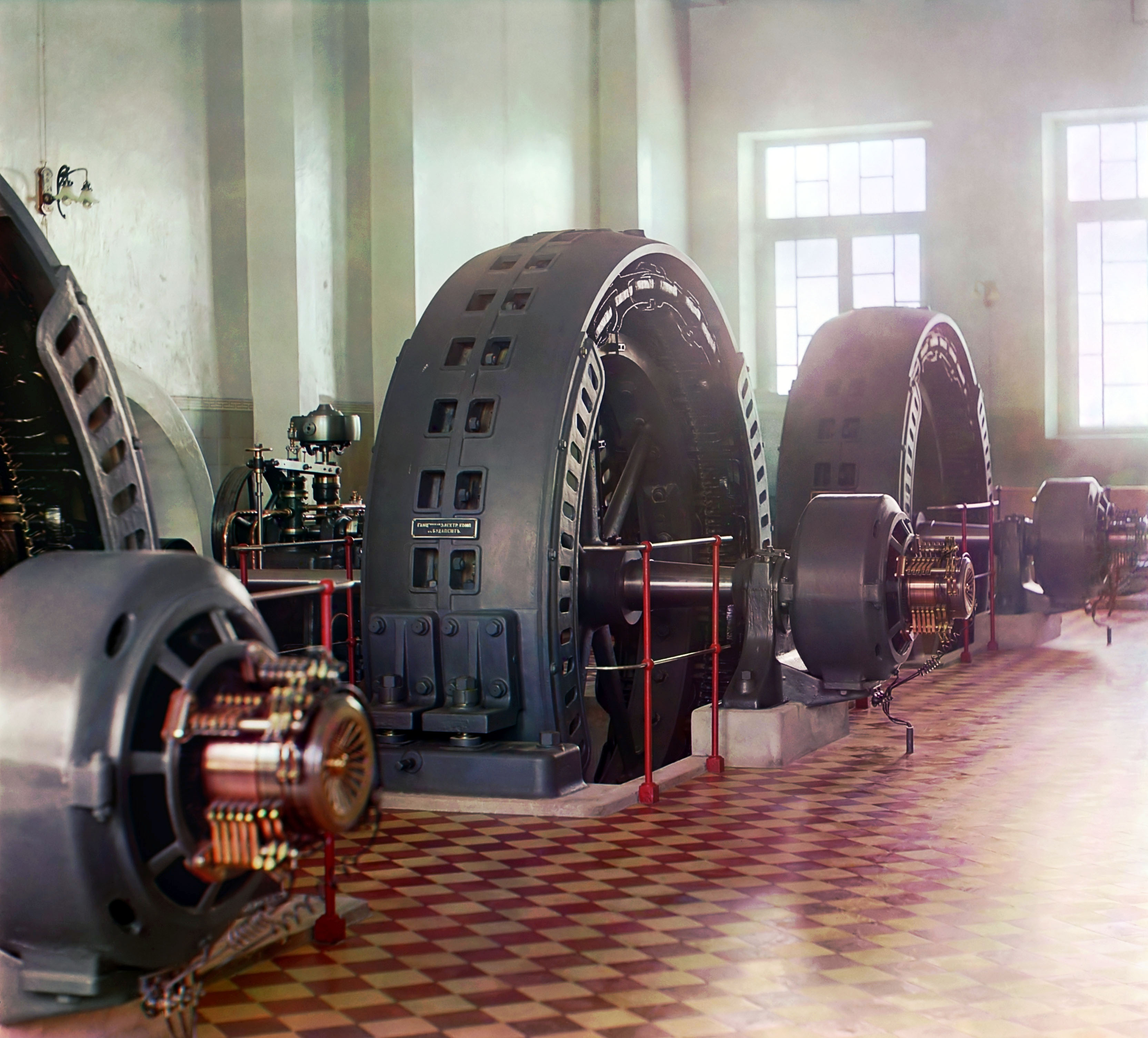

Hydroelectric power plays a smaller role. The historic Hindukush Hydroelectric Station on the Murghab River, originally built in 1913 with a capacity of 1.2 MW, has been modernized and has a current rated capacity of around 350 MW, though its actual output may vary.

Total electricity production in 2019 was reported as 22.52 terawatt-hours (TWh). The state-owned company Türkmenenergo is responsible for the generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity.

National Power Grid and Exports:

Turkmenistan has a national power grid connecting its major generation facilities and consumption centers. It also has interconnections with the power grids of neighboring countries, facilitating electricity exports. Key export markets include Afghanistan, Iran, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. The government aims to further increase electricity exports as a source of revenue.

Impact of Energy Policies on Citizens:

A notable aspect of Turkmenistan's energy policy was the provision of free utilities to its citizens. From 1993 until the end of 2018, citizens received government-provided electricity, water, and natural gas free of charge or heavily subsidized, up to certain quotas. This policy was a cornerstone of the social contract established by President Niyazov and continued by President Berdimuhamedow. However, citing the need for rational resource use and economic sustainability, these subsidies were abolished effective January 1, 2019, and citizens are now required to pay for utilities. This change has had a significant impact on household expenses for the population.

The development of the energy sector, while providing revenue and energy security, also carries environmental implications, primarily related to greenhouse gas emissions from gas-fired power plants.

7.3. Agriculture

Agriculture is a significant sector in Turkmenistan's economy, although its contribution to GDP is smaller than that of the hydrocarbon industry. It employs a substantial portion of the population. The sector is heavily state-controlled, with production targets set by the government, particularly for key crops like cotton and wheat. Due to the arid climate, almost all crop cultivation relies on irrigation.

Main Agricultural Products:

- Cotton: Turkmenistan is a major global cotton producer, ranking among the top ten. Cotton, often referred to as "white gold," is a strategic export commodity. In 2019, 551,000 hectares were planted with cotton. Production in 2020 was reportedly around 1.5 million tons of raw cotton. Historically, raw cotton was exported, but since 2019, the government has shifted focus towards processing cotton domestically into yarn and textiles to add value.

- Wheat: Wheat is the primary food staple, and achieving self-sufficiency in wheat production is a government priority. In 2019, 761,000 hectares were planted with wheat.

- Other crops include rice, fruits (melons, grapes, pomegranates), vegetables, and sesame.

Irrigation:

Given the arid climate, irrigation is essential. The Karakum Canal is the main source of irrigation water, diverting water from the Amu Darya river across vast desert areas. Other rivers like the Murghab and Tejen also support oases and irrigated agriculture. However, inefficient irrigation methods, aging infrastructure, and poor water management contribute to problems like waterlogging, soil salinization, and water loss.

Animal Husbandry:

Livestock breeding is also important, including Karakul sheep (for wool and pelts), cattle, camels, and goats. The Akhal-Teke horse, a renowned breed, is a national symbol and an important part of Turkmen culture.

State Control and Farmers Associations:

After independence, Soviet-era collective (kolkhoz) and state (sovkhoz) farms were transformed into "farmers associations" (daýhan birleşigiTurkmen). However, land largely remains state-owned, and farmers often operate under lease agreements with strict production quotas and fixed procurement prices set by the government. This system limits farmers' autonomy and economic incentives.

Forced Labor in the Cotton Harvest:

A critical and internationally condemned issue in Turkmen agriculture is the systematic use of state-sponsored forced labor in the annual cotton harvest. For many years, public sector employees (teachers, doctors, civil servants), and sometimes students, have been compelled by the government to pick cotton under threat of losing their jobs or other penalties if they refuse. This practice has led to international criticism and boycotts of Turkmen cotton by numerous global apparel brands and retailers. While the government has taken some steps to address these concerns under international pressure, including officially banning child labor and, more recently, making commitments to end adult forced labor, human rights organizations report that coerced mobilization continues, albeit sometimes in less overt forms. This practice has severe human rights implications and impacts the livelihoods and well-being of a significant portion of the population.

The agricultural sector faces challenges including water scarcity, land degradation, outdated technology, and the inefficiencies of a centrally planned system.

7.4. Tourism

Tourism in Turkmenistan is a relatively undeveloped sector, despite the country possessing unique historical, cultural, and natural attractions. The government has expressed ambitions to develop tourism, particularly with the creation of the Awaza tourist zone on the Caspian Sea, but growth has been limited by restrictive visa policies, limited infrastructure outside the capital, and the country's overall political isolation and tight state control. In 2019, Turkmenistan reported 14,438 foreign tourist arrivals.

Key Attractions:

- Ancient Historical Sites (UNESCO World Heritage):

- Ancient Merv: One of the most important oasis cities on the Silk Road, with ruins spanning several millennia.

- Konye-Urgench: The former capital of the Khwarezmian Empire, featuring impressive mausoleums and a minaret.

- Parthian Fortresses of Nisa: The site of one of the earliest capitals of the Parthian Empire.

- Natural Wonders:

- Darvaza Gas Crater (often called the "Gates of Hell"): A large natural gas crater that has been burning continuously since it was lit by Soviet geologists in 1971. It has become an iconic, albeit somewhat controversial, tourist attraction. In January 2022, President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow ordered that the fire be extinguished, citing environmental, health, and economic (gas wastage) reasons, though the method and timeline remain unclear.

- Yangykala Canyon: A dramatic canyon landscape with colorful rock formations.

- Kow-Ata Underground Lake: A subterranean thermal lake.

- Köýtendag Mountains: Featuring dinosaur footprints and diverse landscapes.

- Ashgabat: The capital city, known for its modern white marble architecture, numerous monuments, museums (like the Carpet Museum and National Museum), and the Tolkuchka Bazaar.

- Awaza: A large-scale tourist resort zone developed on the Caspian Sea coast near Türkmenbaşy, featuring luxury hotels, recreational facilities, and an artificial river. Despite massive investment, it has struggled to attract significant numbers of international tourists.

- Cultural Tourism: Opportunities to experience traditional Turkmen culture, including music, carpet weaving, and equestrian traditions centered around the Akhal-Teke horse.

- Health Tourism: Sanatoria in locations like Mollagara, Bayramaly, Ýylysuw, and Archman offer treatments based on local mineral waters and muds.

Visa Policies and State Control:

Obtaining a tourist visa for Turkmenistan is generally a complex process for citizens of most countries. It typically requires an invitation letter (visa support) from a licensed local travel agency, and tourists are often required to be accompanied by a guide. Independent travel is highly restricted. This tight control over the tourism sector, combined with limited flight connections and the country's human rights record, acts as a deterrent for many potential visitors. The government's approach to tourism often prioritizes showcasing state achievements and maintaining control over promoting open access and diverse experiences.

8. Transportation

Turkmenistan's transportation infrastructure, comprising road, rail, air, and maritime networks, has seen development since independence, largely driven by state investment to support its resource-based economy and improve internal connectivity across its vast and sparsely populated territory.

8.1. Automobile transport