1. Overview

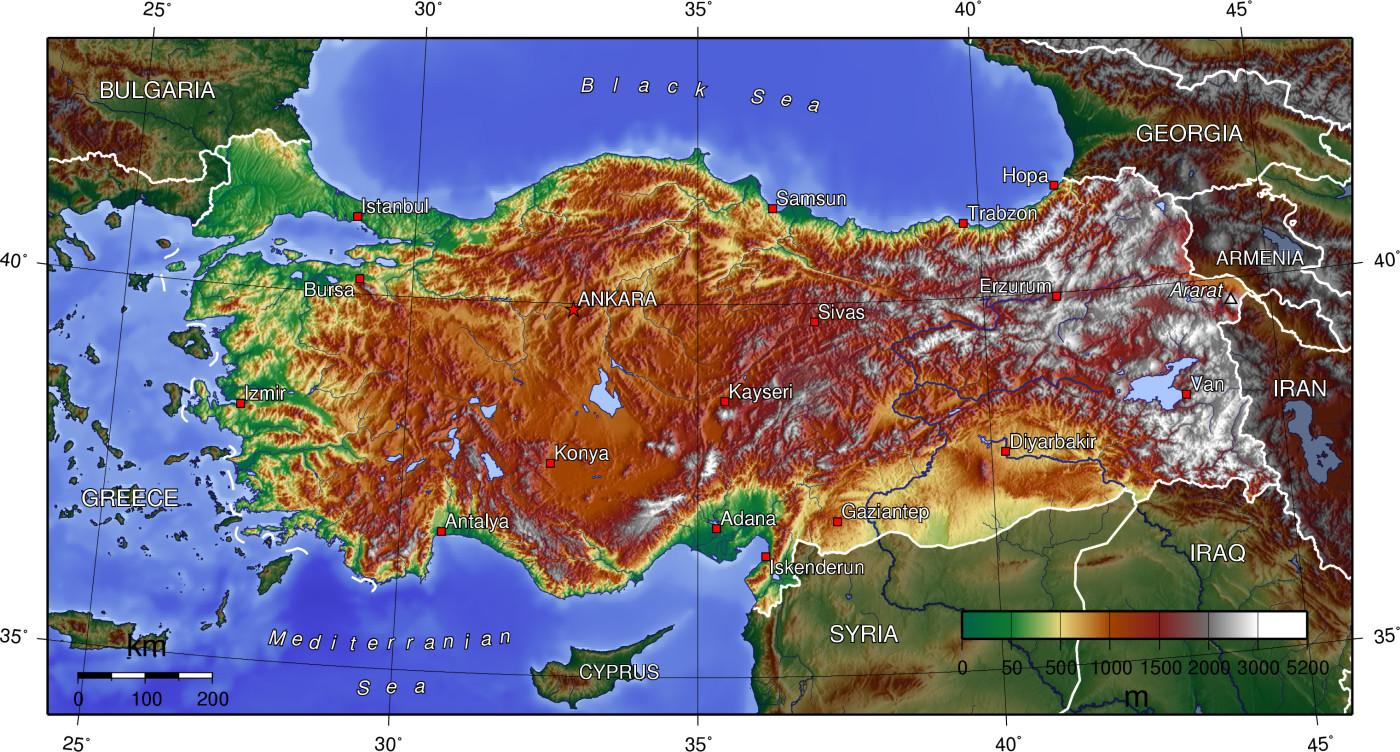

The Republic of Türkiye is a transcontinental country located primarily on the Anatolian Peninsula in West Asia, with a smaller portion on the Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe. It shares borders with eight countries: Greece and Bulgaria to the northwest; Georgia to the northeast; Armenia, the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan, and Iran to the east; and Iraq and Syria to the south. The Black Sea lies to its north, the Mediterranean Sea to its south, and the Aegean Sea to its west. The Bosphorus, Sea of Marmara, and Dardanelles straits separate its European and Asian territories and are vital international waterways. Ankara is the capital, while Istanbul is the largest city and main cultural and commercial hub.

Historically, the region of modern-day Türkiye has been a cradle of civilizations, including ancient Anatolian peoples, Greek colonies, and the Roman and Byzantine Empires. The arrival of Turkic peoples in the 11th century, followed by the rise of the Seljuk and later the Ottoman Empire, profoundly shaped the area's identity. The Ottoman Empire, at its zenith, was a global power spanning three continents. Its decline and defeat in World War I led to its dissolution and the subsequent Turkish War of Independence. The modern Republic of Türkiye was founded in 1923 by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who implemented sweeping reforms to establish a secular, unitary, and constitutional republic.

Türkiye's contemporary history includes periods of multi-party democracy interspersed with military coups, ongoing efforts to join the European Union, and significant geopolitical involvement in regional and international affairs. The country has a diverse economy, with major sectors including manufacturing, services, and agriculture, and is recognized as an emerging market and a regional power.

Türkiye's complex identity is that of a nation striving for modernization while grappling with its Ottoman past and diverse internal dynamics. Its path has been marked by significant social reforms, yet persistent challenges related to democratic consolidation, human rights, and the rights of minorities, particularly the Kurdish population, remain. The nation plays a pivotal, often complex, role in regional and international geopolitics, balancing its secular foundations established by Atatürk with evolving societal and political currents, including renewed assertions of religious identity in public life and debates over the direction of its democratic institutions.

2. Etymology

The name "Türkiye" in Turkish (TürkiyeTur-kiyehTurkish) is derived from the ethnonym Türk combined with the abstract suffix -iye, meaning "land of the Turks" or "belonging to the Turks". This suffix is related to the Arabic -iyya and the medieval Latin -ia in Turchia. The term Türk or Türük as an endonym is first recorded in the Orkhon inscriptions of the Göktürks (Celestial Turks) in Central Asia around the 8th century CE. The Chinese recorded the name Tu-kin as early as 177 BCE for inhabitants south of the Altai Mountains.

In European texts, Turchia began to be used for Anatolia by the end of the 12th century. The word Türk in Turkic languages may mean "strong, strength, ripe" or "flourishing, in full strength". As an ethnonym, its precise origin remains unknown. The earliest mention of Türk (𐱅𐰇𐰺𐰜türüqotk or 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰚türk/törkotk) in Turkic languages comes from the Second Turkic Khaganate.

In Byzantine sources from the 10th century, the name Tourkia (ΤουρκίαTourkiaGreek, Ancient) was used to define two medieval states: Hungary (Western Tourkia) and Khazaria (Eastern Tourkia). The Mamluk Sultanate, with its Turkic ruling elite, was called the "State of the Turks" (Dawlat al-TurkState of the TurksArabic, Dawlat al-AtrākState of the TurksArabic, or Dawlat al-TurkiyyaState of the TurksArabic). Turkestan, also meaning "land of the Turks," historically referred to a region in Central Asia.

Middle English usage of Turkye or Turkeye is found in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Book of the Duchess (written 1369-1372) to refer to Anatolia or the Ottoman Empire. The modern English spelling Turkey dates back to at least 1719. The name Turkey was used in international treaties referring to the Ottoman Empire. With the Treaty of Alexandropol, the name Türkiye entered international documents for the first time. In the treaty signed with Afghanistan in 1921, the expression Devlet-i Âliyye-i TürkiyyeSublime Turkish StateTurkish, Ottoman ("Sublime Turkish State") was used, likened to the Ottoman Empire's own name.

In December 2021, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan issued a circular calling for the expanded official use of Türkiye in English and other languages, stating that Türkiye "represents and expresses the culture, civilization, and values of the Turkish nation in the best way." This change was also partly motivated by the desire to dissociate the country's name from the bird of the same name in English and its negative connotations (meaning "a failure" or "a silly person"). In May 2022, the Turkish government formally requested the United Nations and other international organizations to adopt Türkiye as the official English name. The UN agreed and implemented the change shortly thereafter. Consequently, official documents and communications now use "Republic of Türkiye" and "Türkiye".

3. History

The history of Türkiye is a rich tapestry woven from millennia of human settlement, the rise and fall of empires, and the birth of a modern nation-state. This section outlines the major historical periods, from the earliest human presence in Anatolia through ancient civilizations, the Seljuk and Ottoman eras, and the formation and development of the Republic of Türkiye, highlighting key events and their lasting impacts, particularly concerning social and democratic evolution.

3.1. Prehistory and ancient Anatolia

Present-day Türkiye has been inhabited by modern humans since the Upper Paleolithic period and contains some of the world's oldest Neolithic sites. Göbekli Tepe, dating back nearly 12,000 years (around 10,000 BCE), is recognized as one of the oldest known man-made religious structures. Parts of Anatolia are within the Fertile Crescent, a cradle of early agriculture. Other significant Anatolian Neolithic sites include Çatalhöyük (c. 7500 BCE to 5700 BCE) and Alaca Höyük. Neolithic Anatolian farmers were genetically distinct from those in Iran and the Jordan Valley and began migrating into Europe around 9,000 years ago, contributing to the spread of agriculture. The earliest layers of Troy date back to around 4500 BCE.

Historical records in Anatolia begin with cuneiform clay tablets from approximately 2000 BCE, found in modern-day Kültepe, belonging to an Assyrian trade colony. The languages spoken in Anatolia at this time included Hattian (an indigenous language with no known modern connections), Hurrian (spoken in northern Syria), and the Indo-European languages of Hittite, Luwian, and Palaic, which form the Anatolian subgroup and are among the oldest written Indo-European languages.

The Hattians were gradually assimilated by the Hittites, who established a large kingdom in Central Anatolia with its capital at Hattusa (c. 1700-1200 BCE). The Hittite kingdom co-existed with the Palaians and Luwians. As the Hittite kingdom disintegrated around 1200 BCE, further waves of Indo-European peoples, including the Thracians in Turkish Thrace, migrated from southeastern Europe. The historicity of the Trojan War is debated, though Late Bronze Age layers of Troy align with Homer's Iliad.

Around 750 BCE, Phrygia was established, with centers in Gordium and modern-day Kayseri. The Phrygians spoke an Indo-European language closer to Greek than to Anatolian languages. They shared Anatolia with Neo-Hittite states (where Luwian was likely predominant) and Urartu (whose capital was near Lake Van and whose people spoke a non-Indo-European language). Both Urartu and Phrygia fell in the 7th century BCE, replaced by the Carians, Lycians, and Lydians, cultures seen as a reassertion of ancient indigenous Anatolian traditions.

Before 1200 BCE, Greek-speaking settlements like Miletus existed in Anatolia. Around 1000 BCE, Greeks began migrating more extensively to the west coast of Anatolia, establishing important cities such as Miletus, Ephesus, Halicarnassus, Smyrna (modern İzmir), and Byzantium (modern Istanbul, founded by colonists from Megara in the 7th century BCE). These settlements, grouped as Aeolis, Ionia, and Doris, were crucial in shaping Archaic Greek civilization, excelling in trade, science, and philosophy, with figures like Thales and Anaximander founding the Ionian School of philosophy.

In 547 BCE, Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire conquered Anatolia. The Armenian province in the east became part of this empire. While Greek city-states on the Aegean coast regained independence after the Greco-Persian Wars, much of the interior remained under Persian rule. Two of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus and the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, were located in Anatolia.

Alexander the Great's victories in 334 BCE (Battle of the Granicus) and 333 BCE (Battle of Issus) led to the collapse of the Achaemenid Empire, and Anatolia became part of the Macedonian Empire. This accelerated cultural homogenization and Hellenization in the Anatolian interior, though not without resistance. After Alexander's death, the Seleucid Empire ruled large parts of Anatolia, while native Anatolian states and the Kingdom of Armenia emerged. In the 3rd century BCE, Celts invaded central Anatolia, establishing themselves as the Galatians.

The Roman Republic intervened in Anatolia in the 2nd century BCE, eventually annexing the Kingdom of Pergamon as the province of Asia. Roman influence grew, and after conflicts like the Mithridatic Wars with the Kingdom of Pontus, Rome solidified its control by the 1st century BCE, annexing parts of Pontus and Bithynia and turning other Anatolian states into Roman satellites. This period also saw several Roman-Parthian Wars.

Early Christianity found fertile ground in Anatolia, largely due to the efforts of Saint Paul, whose letters from Anatolia form some of the oldest Christian literature. Ecumenical councils, such as the First Council of Nicaea (Iznik) in 325 CE, held under Roman authority, were pivotal in shaping Christian doctrine.

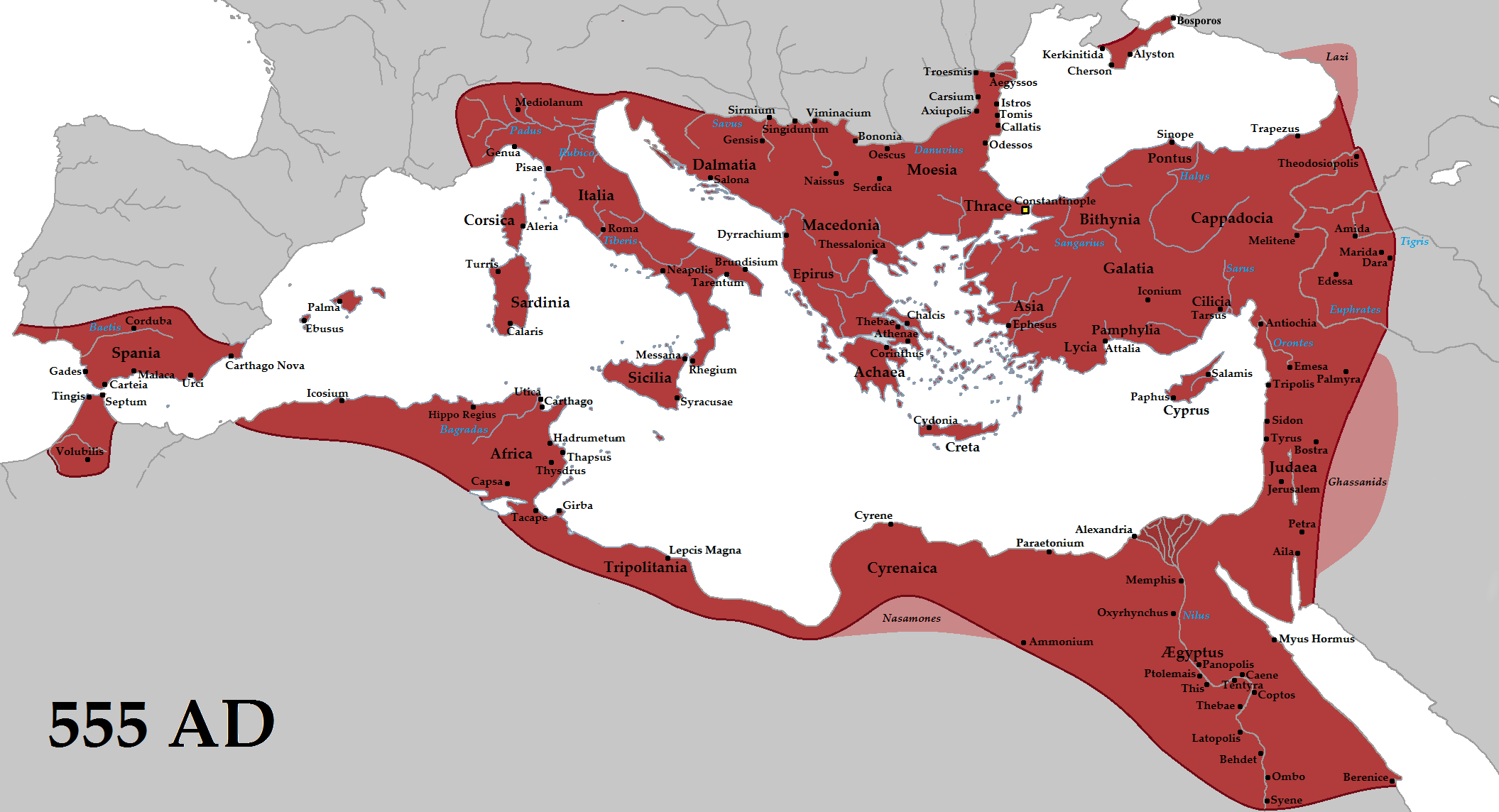

When the Roman Empire was formally divided in 395 CE, Constantinople (formerly Byzantium) became the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the Byzantine Empire. This empire, a continuation of Roman traditions but increasingly Greek in language and Christian in religion, controlled most of Anatolia until the Late Middle Ages. During the early Byzantine period, coastal Anatolia was largely Greek-speaking, while the interior, though heavily Hellenized, hosted diverse groups including Goths, Celts, Persians, and Jews. Over time, indigenous Anatolian languages became extinct due to Hellenization. The Byzantine Empire remained a dominant economic, cultural, and military force in the Mediterranean world for much of its existence, until its fall to the Ottomans in 1453.

3.2. Seljuks and the Ottoman Empire

This period covers the migration of Turkic peoples into Anatolia, the rise of the Seljuk Empire and the Sultanate of Rum, and the subsequent emergence and expansion of the Ottoman Empire, including its golden age, eventual decline, and the socio-political upheavals of its final years, culminating in genocides against Christian minorities.

The Proto-Turkic language is believed to have originated in Central-East Asia. Early Turkic-speaking groups were diverse, potentially including hunter-gatherers, farmers, and later, nomadic pastoralists. They exhibited a range of physical appearances and genetic origins due to long-term contact with neighboring peoples such as Iranian peoples, Mongolic peoples, Tocharians, Uralic peoples, and Yeniseian peoples. In the 9th and 10th centuries CE, the Oghuz Turks lived on the Caspian and Aral Sea steppes. Pressured by groups like the Kipchaks, they migrated into the Iranian Plateau and Transoxiana, mixing with Iranic-speaking groups and converting to Islam. These Oghuz Turks were also known as Turkmens or Turkomans.

The ruling Seljuk dynasty originated from the Kınık branch of the Oghuz Turks. In 1040, the Seljuks defeated the Ghaznavids at the Battle of Dandanaqan, establishing the Seljuk Empire in Greater Khorasan. They captured Baghdad, the Abbasid Caliphate's capital, in 1055. The Seljuk period is characterized by a blend of Turkish, Persian, and Islamic influences, with Khorasani traditions playing a significant role in art, culture, and politics.

In the latter half of the 11th century, Seljuk Turks began penetrating medieval Armenia and Anatolia. At that time, Anatolia was a diverse, largely Greek-speaking region that had been Hellenized. The Seljuks defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, a pivotal event that accelerated the Turkification process in Anatolia. This process involved Turkic migrations, intermarriages, and conversions to Islam, gradually transforming the region over several centuries. Sufi mystical orders, like the Mevlevi Order, played a role in the Islamization of Anatolia's diverse population. The Seljuks established the Sultanate of Rum in Anatolia, alongside other Turkish principalities (beyliks) like the Danishmendids. Seljuk expansion was one of the triggers for the Crusades. A second significant wave of Turkic migration occurred in the 13th century as people fled the Mongol invasions. The Sultanate of Rum was defeated by the Mongols at the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243 and disintegrated by the early 14th century, replaced by various Turkish beyliks.

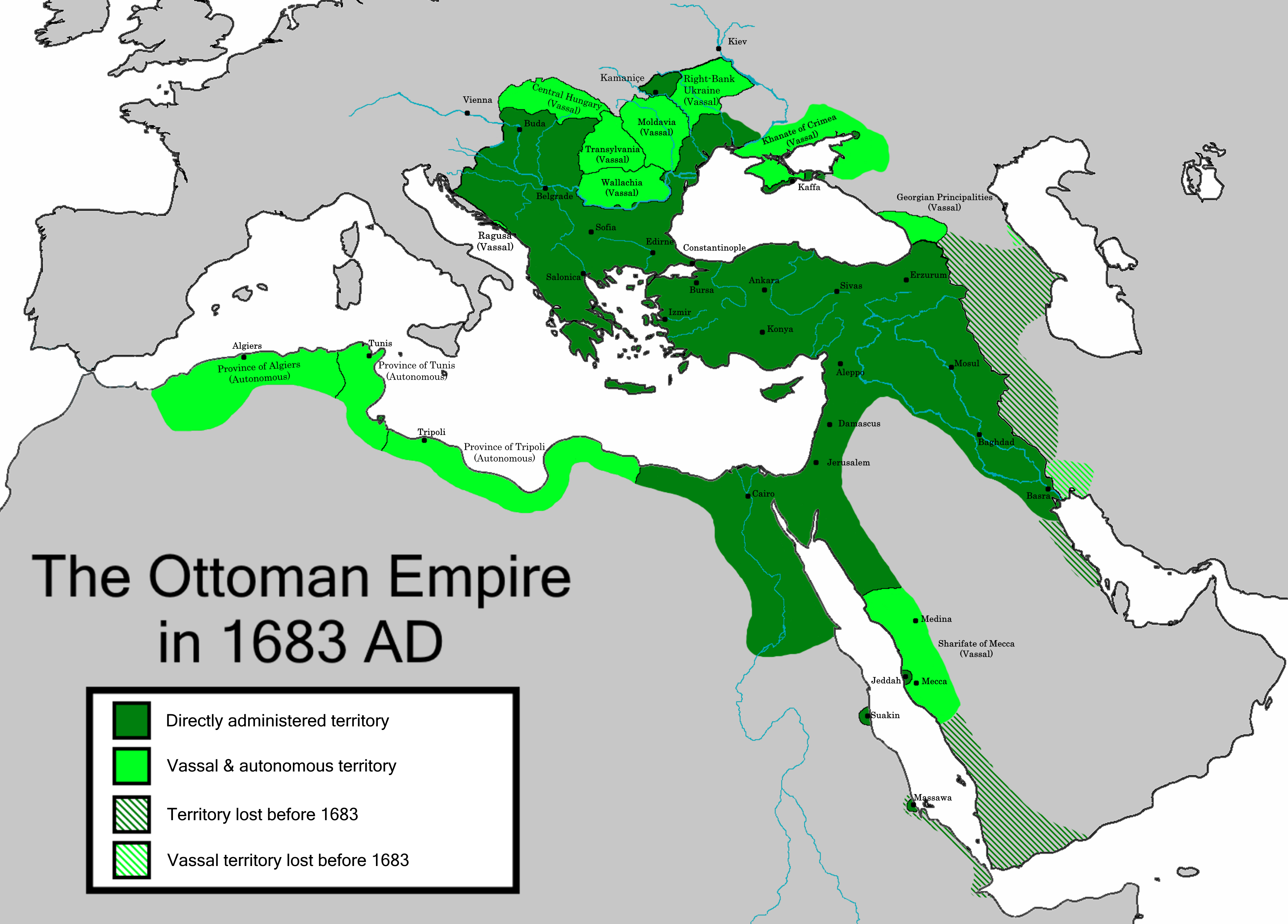

The Ottoman Beylik, centered around Söğüt, was founded by Osman I in the early 14th century. According to Ottoman chroniclers, Osman descended from the Kayı tribe of Oghuz Turks. The Ottomans began annexing neighboring Turkish beyliks in Anatolia and expanded into the Balkans. On May 29, 1453, Mehmed II conquered Constantinople (modern Istanbul), ending the Byzantine Empire. Selim I later united Anatolia under Ottoman rule. Turkification continued as Ottomans intermingled with indigenous populations in Anatolia and the Balkans. The Ottoman Empire became a global power during the reigns of Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Sephardic Jews migrated to the Ottoman Empire following their expulsion from Spain.

From the second half of the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire began to decline. The Tanzimat reforms, initiated by Mahmud II in 1839, aimed to modernize the Ottoman state. The Ottoman constitution of 1876 was the first among Muslim states but was short-lived. As the empire shrank, nationalist sentiment rose among its diverse subject peoples, leading to increased ethnic tensions. The Ottoman economic crisis of 1875 led to uprisings in Balkan provinces, culminating in the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878). The Hamidian massacres of Armenians in the 1890s claimed up to 300,000 lives. Ottoman territories in Europe (Rumelia) were largely lost in the First Balkan War (1912-1913), though some territory, like Edirne, was recovered in the Second Balkan War (1913).

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, persecution of Muslims during the Ottoman contraction and in the Russian Empire resulted in an estimated 5 million deaths, including Turks. Between five to nine million Muslim refugees (Muhacirs), including Turks, Circassians (survivors of the Circassian genocide), and Crimean Tatars, migrated to modern-day Türkiye from the Balkans, Caucasus, Crimea, and Mediterranean islands, shifting the empire's demographic center to Anatolia.

Following the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état, the Three Pashas took control. The Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated. During the war, the Ottoman government committed genocides against its Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian subjects. The Armenian genocide involved the deportation of Armenians to Syria, resulting in an estimated 600,000 to over 1.5 million deaths. The Turkish government has consistently denied these events constituted genocide, stating Armenians were "relocated" from a war zone. Genocidal campaigns also targeted the Greek and Assyrian minorities. These atrocities represent a dark chapter in the empire's final years, marked by widespread human suffering and the destruction of ancient Christian communities in Anatolia. The Armistice of Mudros in 1918 was followed by the Allied Powers' attempt to partition the Ottoman Empire through the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920. Between 1912 and 1924, there was also large-scale loss of life among ethnic Turks and Kurds. A population exchange between Greece and Turkey was agreed upon during the Lausanne Treaty negotiations. Türkiye's population declined by around 20%, from approximately 17 million to 13 million, between roughly 1913 and 1924.

3.3. Republic of Türkiye

This section details the period from the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, through the Turkish War of Independence led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, to the establishment and evolution of the modern Republic of Türkiye, including its reforms, geopolitical positioning, internal conflicts like the Kurdish issue, and contemporary political developments under leaders such as Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, with a focus on democratic processes and human rights concerns.

The occupation of Istanbul (1918) and İzmir (1919) by the Allies of World War I after World War I spurred the Turkish National Movement. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, a military commander distinguished during the Gallipoli campaign, the Turkish War of Independence (1919-1923) was waged to revoke the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920).

The Turkish Provisional Government in Ankara, declared the legitimate government on April 23, 1920, engaged in armed and diplomatic struggles. By 1923, Armenian, Greek, French, and British forces had been expelled. The military and diplomatic successes led to the Armistice of Mudanya on October 11, 1922. On November 1, 1922, the Turkish Parliament in Ankara formally abolished the Sultanate, ending 623 years of Ottoman monarchical rule.

The Treaty of Lausanne of July 24, 1923, which superseded the Treaty of Sèvres, led to international recognition of the sovereignty of the new Turkish state as the successor to the Ottoman Empire. On October 4, 1923, the Allied occupation ended with the withdrawal of the last Allied troops from Istanbul. The Turkish Republic was officially proclaimed on October 29, 1923, in Ankara, the new capital. The Lausanne Convention stipulated a population exchange between Greece and Turkey, aiming to create more ethnically homogeneous states, though this involved significant displacement and hardship. Türkiye emerged as a more homogenous nation state.

Mustafa Kemal became the republic's first president and initiated numerous reforms aimed at transforming the old religion-based, multi-communal Ottoman monarchy into a Turkish nation-state governed as a parliamentary republic under a secular constitution. Key reforms included the adoption of secularism, the language reform (replacing the Arabic script with a Latin-based alphabet), legal reforms based on European models, and the granting of women's suffrage (nationally in 1934). The Surname Law of 1934 required all citizens to adopt a hereditary surname; the Parliament bestowed upon Kemal the honorific surname "Atatürk" (Father Turk). These reforms, while modernizing, caused discontent among some Kurdish and Zaza tribes, leading to the Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925 and the Dersim rebellion in 1937, which were suppressed by the state, highlighting early tensions regarding minority rights and central authority.

İsmet İnönü became the second president after Atatürk's death in 1938. In 1939, the Republic of Hatay voted to join Türkiye. Türkiye remained neutral during most of World War II but joined the Allies on February 23, 1945. Later that year, Türkiye became a charter member of the United Nations. In 1950, it became a member of the Council of Europe. After participating in the Korean War as part of UN forces, Türkiye joined NATO in 1952, becoming a key Cold War ally against Soviet expansion.

Türkiye's transition to a democratic multi-party system was complicated by military coups or interventions in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997. Prominent political leaders who achieved multiple election victories between 1960 and the end of the 20th century included Süleyman Demirel, Bülent Ecevit, and Turgut Özal. The Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), designated a terrorist organization by Türkiye, the United States, and the European Union, began a campaign of attacks in the 1980s, leading to a long and violent conflict primarily in southeastern Türkiye, known as the Kurdish issue. Tansu Çiller became Türkiye's first female prime minister in 1993. Türkiye applied for full membership of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1987, joined the European Union Customs Union in 1995, and started accession negotiations with the European Union in 2005. The Customs Union significantly impacted the Turkish manufacturing sector.

In 2014, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan won Türkiye's first direct presidential election. On July 15, 2016, an unsuccessful coup attempt sought to oust the government. The government accused the Gülen movement of orchestrating the coup, leading to widespread purges and arrests. As of 2024, thousands remain imprisoned in connection to the coup attempt. A constitutional referendum in 2017 replaced the parliamentary republic with an executive presidential system, abolishing the office of prime minister and transferring its powers to the president. The referendum was controversial, with opposition parties claiming irregularities, particularly regarding the Supreme Electoral Council's decision to accept unstamped ballots. These changes, along with increasing restrictions on freedom of speech, press, and assembly, have led to growing concerns both domestically and internationally about democratic backsliding and the erosion of human rights in Türkiye under Erdoğan's leadership.

4. Geography

Türkiye is a transcontinental country with a diverse range of geographical features, climates, and ecosystems. This section explores its topography and geology, including its position on active fault lines, its varied regional climates and vulnerability to climate change, and its rich biodiversity across several important hotspots.

4.1. Topography and geology

Türkiye covers an area of 303 K mile2 (783.56 K km2). It bridges Western Asia and Southeastern Europe, with the Turkish Straits (Bosphorus, Sea of Marmara, Dardanelles) separating the two. The Asian part, Anatolia, constitutes 97% of its surface, while East Thrace, the European part, covers 3% and holds about 10% of the population. The country is bordered by the Aegean Sea to the west, the Black Sea to the north, and the Mediterranean Sea to the south.

Türkiye is characterized by a high central plateau, the Anatolian Plateau, which becomes increasingly rugged eastward. Major mountain ranges include the Pontic Mountains and Köroğlu Mountains to the north, and the Taurus Mountains to the south. The Turkish Lakes Region in southwestern Anatolia contains large lakes such as Lake Beyşehir and Lake Eğirdir. Eastern Türkiye, often referred to as the Eastern Anatolian plateau or Armenian plateau, is mountainous and includes Mount Ararat, Türkiye's highest point at 17 K ft (5.14 K m), and Lake Van, the country's largest lake. Major rivers like the Euphrates, Tigris, and Aras originate in this region. The Southeastern Anatolia Region includes the northern plains of Upper Mesopotamia.

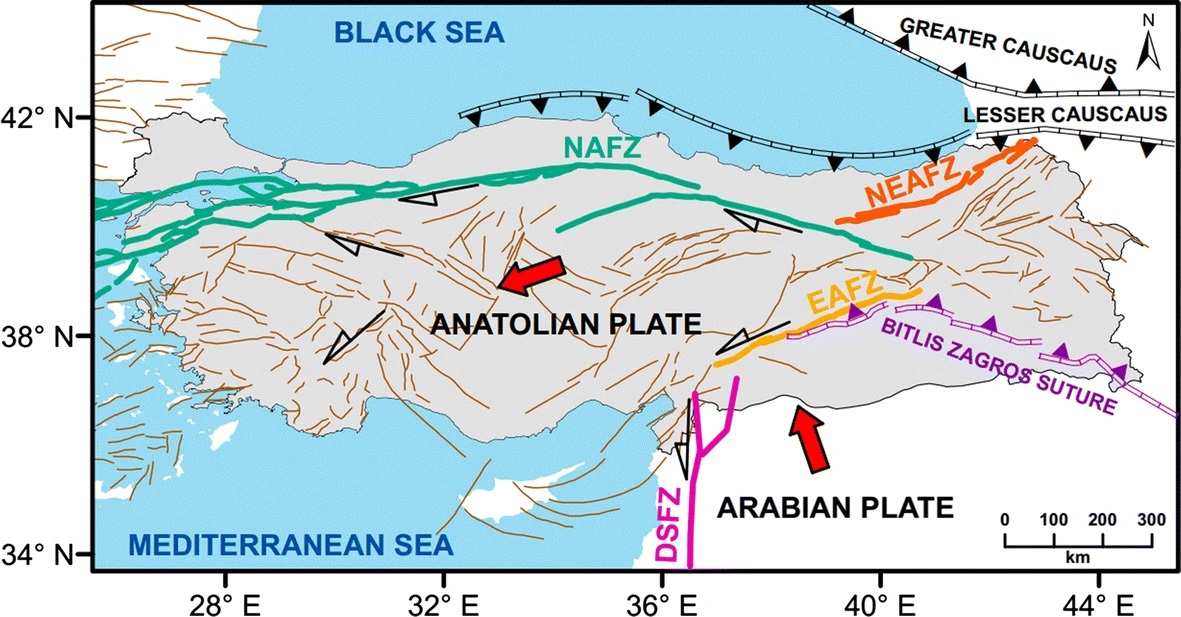

Geologically, Türkiye is located in a highly active seismic zone. The Anatolian Plate is bordered by the North Anatolian Fault zone to the north, the East Anatolian Fault zone and Bitlis-Zagros collision zone to the east, the Hellenic and Cyprus subduction zones to the south, and the Aegean extensional zone to the west. This complex tectonic setting results in frequent earthquakes. Approximately 70% of the population lives in areas with high or second-highest seismic risk. Major earthquakes, such as the 1999 İzmit and Düzce earthquakes along the North Anatolian Fault, and the devastating 2023 Turkey-Syria earthquakes in the southeast, highlight the country's vulnerability. Earthquake preparedness and building standards are critical issues, though often compared unfavorably with other seismically active developed nations like Chile.

4.2. Climate

Türkiye exhibits diverse regional climates.

The coastal areas bordering the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas have a temperate Mediterranean climate, characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters.

The coastal areas along the Black Sea experience a temperate oceanic climate, with warm, wet summers and cool to cold, wet winters. The Turkish Black Sea coast, particularly its eastern part, receives the highest precipitation in the country, averaging 0.1 K in (2.20 K mm) annually, and is the only region with high precipitation throughout the year.

The coastal areas around the Sea of Marmara, connecting the Aegean and Black Seas, have a transitional climate between Mediterranean and oceanic, featuring warm to hot, moderately dry summers and cool to cold, wet winters.

Snowfall occurs on the coastal areas of the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea almost every winter, though it usually melts within a few days. Snow is rare along the Aegean coast and very rare along the Mediterranean coast.

The Anatolian plateau inland experiences a continental climate with sharply contrasting seasons, as mountains near the coast prevent Mediterranean influences from extending far. Winters on the plateau are severe, especially in northeastern Anatolia, where temperatures can drop to -22 °F (-30 °C) to -40 °F (-40 °C), and snow may cover the ground for at least 120 days, or year-round on the highest mountain summits. In central Anatolia, temperatures can fall below -4 °F (-20 °C).

Türkiye is highly vulnerable to climate change due to a combination of socioeconomic, climatic, and geographic factors. It faces risks in nine out of ten climate vulnerability dimensions, significantly higher than the OECD median. The country aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2053. Achieving these climate goals will require substantial investments but is projected to yield net economic benefits, primarily through reduced fuel imports and improved public health from lower air pollution. Inclusive and rapid growth is considered essential for reducing this vulnerability.

4.3. Biodiversity

Türkiye's location at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa, combined with its varied habitats, has resulted in considerable species diversity. The country is home to three of the world's 36 biodiversity hotspots: the Mediterranean, Caucasus, and Irano-Anatolian hotspots.

The forests of Turkey include species like the Turkey oak, oriental plane, and the Turkish pine, which is predominantly found in Turkey and other eastern Mediterranean countries. Anatolia is also the native region for several wild species of tulip; these flowers were first introduced to Western Europe from the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century.

Türkiye has 40 national parks, 189 nature parks, 31 nature preserve areas, 80 wildlife protection areas, and 109 nature monuments. Notable examples include Gallipoli Peninsula Historical National Park, Mount Nemrut National Park, Ancient Troy National Park, Ölüdeniz Nature Park, and Polonezköy Nature Park.

The Northern Anatolian conifer and deciduous forests ecoregion covers most of the Pontic Mountains in northern Turkey, while the Caucasus mixed forests extend across the eastern end of the range. These regions are home to Eurasian wildlife such as the Eurasian sparrowhawk, golden eagle, eastern imperial eagle, lesser spotted eagle, Caucasian black grouse, red-fronted serin, and wallcreeper.

The Anatolian leopard is still found in very small numbers in the northeastern and southeastern regions. Other felids include the Eurasian lynx, European wildcat, and caracal. The Caspian tiger, now extinct, lived in easternmost Turkey until the latter half of the 20th century. Renowned domestic animals from Ankara include the Angora cat, Angora rabbit, and Angora goat. The Van cat is from Van Province. National dog breeds include the Kangal Shepherd Dog, Malaklı, and Akbash.

5. Government and Politics

Türkiye is a presidential republic with a multi-party system, operating under a constitution that emphasizes secularism and the rule of law. This section examines Türkiye's governmental structure, its political landscape including parties and elections, its legal system, foreign relations with a focus on NATO and EU aspirations, its military, and the state of human rights, all considered from a perspective that prioritizes democratic development and social liberalism.

5.1. Government structure

Türkiye is a presidential republic characterized by a multi-party system. The current Constitution of Turkey was adopted in 1982, though it has undergone significant amendments, most notably in 2017 which transitioned the country from a parliamentary to a presidential system.

The government comprises three branches:

1. **Legislative Branch:** The Grand National Assembly of Turkey (Türkiye Büyük Millet MeclisiTBMM (Grand National Assembly of Turkey)Turkish) is the unicameral parliament. It consists of 600 members elected for five-year terms through a party-list proportional representation system, with an electoral threshold (currently 7%) for parties to gain representation. The parliament's duties include enacting, amending, and repealing laws; supervising the Council of Ministers (though its direct oversight role has changed with the presidential system); authorizing the budget; and declaring war.

2. **Executive Branch:** The President of Turkey is the head of state and head of government, holding significant executive powers. The President is directly elected for a five-year term and can serve a maximum of two terms, unless early elections are called by parliament during the second term. The President appoints ministers, issues decrees, represents Türkiye in foreign relations, and is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The office of the Prime Minister was abolished in 2017.

3. **Judicial Branch:** The judiciary is, in principle, independent. Key judicial institutions include the Constitutional Court (which reviews the constitutionality of laws and can hear individual applications regarding human rights violations), the Court of Cassation (the final court of appeal for criminal and civil cases), and the Council of State (the highest administrative court). The Constitutional Court is composed of 15 members, elected for single 12-year terms, and they must retire at age 65.

The principle of separation of powers is enshrined in the constitution, but its practical application has been a subject of debate, particularly following the 2017 constitutional changes which concentrated more power in the executive presidency. Concerns have been raised by domestic and international observers about the erosion of checks and balances and increased political influence over the judiciary, contributing to what is often described as democratic backsliding or a competitive authoritarian system.

5.2. Political parties and elections

Türkiye operates under a multi-party system, although the political landscape has seen periods of dominance by certain parties or coalitions. Elections are held for the presidency, parliament, and local government positions (municipality mayors, district mayors, council members, and muhtars). Referendums are also held occasionally. Universal suffrage for both sexes has been in place since 1934 (for national elections), and all Turkish citizens aged 18 and over have the right to vote and stand as candidates. Voter turnout in Türkiye is generally high, often exceeding 80%.

Historically, Turkish politics has been characterized by a spectrum of parties ranging from secularist-Kemalist to conservative-nationalist and Islamist.

- The Republican People's Party (Cumhuriyet Halk PartisiCHP (Republican People's Party)Turkish), founded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, is the oldest political party and traditionally represents secularist, social democratic, and Kemalist ideologies. It is currently the main opposition party.

- The Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma PartisiAKP (Justice and Development Party)Turkish or AK Parti), founded in 2001, has been the dominant political force since 2002. It has roots in political Islam but officially describes itself as conservative democratic. Under its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who served as Prime Minister and is now President, the AKP has overseen significant economic growth but also faced criticism for authoritarian tendencies and undermining democratic institutions.

- The Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket PartisiMHP (Nationalist Movement Party)Turkish) is a far-right party espousing Turkish nationalism. It has often formed alliances or provided support to right-wing governments.

- The Peoples' Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik PartisiHDP (Peoples' Democratic Party)Turkish), now often represented by successor parties like the Peoples' Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party) due to legal challenges, is a left-wing party focusing on minority rights (particularly Kurdish rights), democratic freedoms, and social justice. It has faced intense pressure from the state, including arrests of its leaders and attempts to ban it.

Other significant parties include the Good Party (İyi PartiİYİ Parti (Good Party)Turkish), a nationalist, secularist party that split from the MHP. The electoral system for parliamentary elections employs a party-list proportional representation method with a national electoral threshold of 7% (lowered from 10% in 2022). Parties can form electoral alliances to overcome this threshold. Independent candidates are not subject to this threshold. The Constitutional Court has the power to strip political parties of public financing or ban them altogether if they are deemed anti-secular or linked to terrorism, a power that has been used controversially, particularly against pro-Kurdish parties.

The last parliamentary and presidential elections were held in 2023. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was re-elected President. The political climate remains polarized, with ongoing debates about the direction of the country, democratic norms, and human rights.

5.3. Law

Türkiye's legal system is based on the civil law tradition, largely influenced by European legal systems following the establishment of the Republic. It replaced the Sharia-derived Ottoman law.

- The Civil Code, adopted in 1926, was primarily based on the Swiss Civil Code of 1907 and the Swiss Code of Obligations of 1911. It underwent significant revisions in 2002 but retains much of its original foundation.

- The Criminal Code, originally based on the Italian Criminal Code, was replaced in 2005 by a new code with principles similar to the German Penal Code and German law generally.

- Administrative law is based on the French equivalent.

- Procedural law generally shows influences from Swiss, German, and French legal systems.

Islamic principles do not play a formal part in the modern legal system, reflecting the country's constitutional secularism. The court structure includes:

- Constitutional Court** (Anayasa MahkemesiAnayasa Mahkemesi (Constitutional Court)Turkish): Reviews the constitutionality of laws and governmental decrees, and hears individual applications concerning human rights violations.

- Court of Cassation** (YargıtayYargitay (Court of Cassation)Turkish): The highest court of appeal for civil and criminal cases.

- Council of State** (DanıştayDanıştay (Council of State)Turkish): The highest administrative court and court of appeal for administrative cases.

- Court of Jurisdictional Disputes** (Uyuşmazlık MahkemesiUyuşmazlık Mahkemesi (Court of Jurisdictional Disputes)Turkish): Resolves disputes between civil, administrative, and military courts regarding jurisdiction.

Law enforcement in Turkey is primarily carried out by several agencies under the Ministry of Internal Affairs:

- The **General Directorate of Security** (Emniyet Genel MüdürlüğüEmniyet Genel Müdürlüğü (General Directorate of Security)Turkish): The main civilian police force responsible for urban areas.

- The **Gendarmerie General Command** (Jandarma Genel KomutanlığıJandarma Genel Komutanlığı (Gendarmerie General Command)Turkish): A military force with law enforcement responsibilities in rural areas and border security, though its internal security role has been increasingly civilianized.

- The **Coast Guard Command** (Sahil Güvenlik KomutanlığıSahil Güvenlik Komutanlığı (Coast Guard Command)Turkish): Responsible for maritime law enforcement.

In recent years, particularly since the 2013 Gezi Park protests and the 2016 coup attempt, the independence and impartiality of the Turkish judiciary have been increasingly questioned by domestic and international institutions, human rights organizations, and legal professionals. Concerns include political interference in the appointment and promotion of judges and prosecutors, mass dismissals of judicial personnel, and the use of the legal system to suppress dissent and critical voices. These developments have raised serious concerns about the rule of law and the protection of fundamental rights in Türkiye.

5.4. Foreign relations

Türkiye's foreign policy is shaped by its geostrategic location at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Historically, its foreign policy goal has been to pursue national interests, focusing on economic growth and security from internal and external threats. After the Republic's establishment, Atatürk and İnönü followed a principle of "Peace at Home, Peace in the World" until the Cold War.

A cornerstone of Turkish foreign policy has been its alignment with the West. Facing threats from the Soviet Union, Türkiye joined NATO in 1952 and has been a key member, hosting important military installations. It remains an early and significant member of the Council of Europe. Türkiye has been an EU candidate country since 1999, and accession talks began in 2005, though they have largely stalled due to concerns over democratic backsliding, human rights, and disputes with EU member states like Cyprus and Greece. Türkiye is part of the EU Customs Union since 1995.

Türkiye plays an active role in various international organizations, including as a founding member of the OECD, G20, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). It also fosters close ties with Turkic-speaking countries in Central Asia and the Caucasus through the Organization of Turkic States and the International Organization of Turkic Culture (TURKSOY). Relations with Azerbaijan are particularly strong, often described as "one nation, two states."

Relations with neighboring regions are complex:

- Middle East:** Following the Arab Spring, relations with countries like the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt became strained, but have seen some improvement in recent years. The Syrian civil war led to a breakdown in relations with Syria, with Türkiye supporting opposition groups and conducting military operations in northern Syria to counter perceived threats from Kurdish groups (YPG/PKK) and ISIS. These operations have drawn international criticism for their impact on civilians and regional stability. Relations with Israel, once strong, deteriorated significantly after the Gaza flotilla raid in 2010 and have remained tense, particularly due to Türkiye's strong support for the Palestinian cause and criticism of Israeli policies. Trade with Israel was halted by Türkiye in 2024 amid the Israel-Hamas war.

- Greece and Cyprus:** Long-standing disputes exist with Greece over maritime boundaries in the Aegean Sea, airspace, and the militarization of islands. The Cyprus issue remains a major point of contention, with Türkiye being the only country to recognize the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) and maintaining a military presence there since its 1974 invasion. This issue significantly impacts Türkiye's EU accession bid and relations with Greece and the EU.

- Russia:** Relations with Russia are multifaceted, involving cooperation in energy (e.g., TurkStream pipeline) and tourism, but also competition and divergence on regional conflicts like Syria and Libya. Türkiye's purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defense system strained relations with NATO allies, particularly the US.

- Armenia:** Relations remain frozen due to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict (where Türkiye supports Azerbaijan) and Türkiye's refusal to recognize the Armenian genocide.

Human rights implications of foreign policy are often highlighted, particularly concerning Türkiye's military interventions, its stance on refugee issues, and its relations with countries with poor human rights records. The country has hosted millions of refugees, primarily from Syria, facing significant social and economic challenges.

5.5. Military

The Turkish Armed Forces (Türk Silahlı KuvvetleriTürk Silahlı Kuvvetleri (Turkish Armed Forces)Turkish) are responsible for the defense of Türkiye against foreign threats. The President is the Commander-in-Chief. The TSK consists of the Land Forces (Army), Naval Forces (Navy), and Air Force, which typically report to the Minister of National Defence. The Gendarmerie General Command (Jandarma Genel KomutanlığıJandarma Genel Komutanlığı (Gendarmerie General Command)Turkish) and the Coast Guard Command (Sahil Güvenlik KomutanlığıSahil Güvenlik Komutanlığı (Coast Guard Command)Turkish) are law enforcement agencies with military status, operating under the Ministry of the Interior during peacetime but can be subordinated to the Army and Navy respectively during wartime.

Türkiye has the second-largest standing military force in NATO, after the United States, with an estimated strength of around 890,700 active and reserve personnel as of early 2022. Military service is compulsory for most male citizens, typically for 6-12 months, although options for shorter service with payment exist. Türkiye does not recognize conscientious objection to military service and does not offer a civilian alternative, a stance criticized by human rights organizations.

As part of NATO's nuclear sharing policy, Türkiye hosts United States B61 nuclear bombs at the Incirlik Air Base. The Turkish Armed Forces maintain a significant military presence abroad, with bases or deployments in Albania, Iraq (primarily for operations against the PKK), Qatar, and Somalia. Türkiye has maintained a force of approximately 36,000 troops in Northern Cyprus since 1974.

Türkiye has participated in international missions under the UN and NATO since the Korean War, including peacekeeping in Somalia and the former Yugoslavia, and operations in Afghanistan (ISAF). It remains active in Kosovo Force (KFOR), Eurocorps, and EU Battlegroups. Türkiye has also provided training and assistance to Peshmerga forces in Iraqi Kurdistan and the Somali Armed Forces.

The Turkish defense industry has seen significant development in recent years, with a focus on indigenous production of military hardware, including drones (like the Baykar Bayraktar TB2), armored vehicles, naval vessels, and missile systems. Companies like Aselsan, Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI), and Roketsan are prominent players. The development of the TAI TF Kaan fifth-generation fighter jet and unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) like the Baykar Bayraktar Kızılelma reflects this ambition for greater self-sufficiency and technological advancement in defense.

5.6. Human rights

The Constitution of Turkey guarantees fundamental human rights and freedoms, including adherence to the rule of law. However, the actual human rights situation in Türkiye has been a subject of significant concern for domestic and international human rights organizations, the Council of Europe, and the European Union.

Key areas of concern include:

- Freedom of Speech and Expression:** Restrictions on freedom of speech and the press are widespread. Journalists, academics, activists, and ordinary citizens face prosecution and imprisonment for criticizing the government or expressing dissenting views, often under vaguely worded anti-terror laws or articles criminalizing "insulting the Turkish nation" or the president. Media censorship and self-censorship are prevalent. Türkiye consistently ranks low in global press freedom indices.

- Kurdish Issue and Minority Rights:** The long-standing Kurdish issue remains a major source of human rights violations. While some legal changes were made in the 2000s regarding the public use of the Kurdish language, including the establishment of a Kurdish-language national TV channel (TRT Kurdî), broader political and cultural rights for Kurds are limited. Pro-Kurdish political parties and activists face intense pressure, arrests, and legal persecution. Anti-terror operations in the southeast have often resulted in civilian casualties and displacement, with allegations of disproportionate force and impunity for security forces. Other unrecognized ethnic and religious minorities, such as Alevis and Roma, also face discrimination and challenges in practicing their culture and religion freely.

- Democratic Backsliding and Rule of Law:** Since the 2013 Gezi Park protests and particularly after the 2016 coup attempt, there has been a significant erosion of democratic institutions and the rule of law. The government's response to the coup attempt included mass purges of civil servants, academics, judges, and prosecutors, often with limited due process. The judiciary's independence has been severely undermined, with concerns about political influence over courts. States of emergency have been used to curtail fundamental freedoms. The 2017 constitutional changes concentrating power in the presidency further weakened checks and balances.

- Freedoms of Assembly and Association:** The right to peaceful assembly is often restricted, with protests frequently met with excessive force by police. Civil society organizations, particularly those working on human rights, face increasing pressure and obstacles.

- LGBT Rights:** While same-sex acts have never been criminalized under the Republic, LGBT individuals face widespread discrimination, harassment, and violence. Istanbul Pride marches, once a significant event, have been banned by authorities since 2015, citing security concerns, though these bans have been widely criticized as discriminatory. There is a lack of legal protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

- Vulnerable Groups:** Women continue to face challenges regarding gender equality and violence. Domestic violence remains a serious problem. While sentences for violence against women were strengthened in the past, enforcement and a holistic approach to prevention are often lacking. Refugees and asylum seekers, particularly the large Syrian population, face precarious living conditions and challenges in accessing rights and services.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has issued numerous judgments against Türkiye for violations of the European Convention on Human Rights. Türkiye's failure to implement some key ECHR judgments has been a point of contention with the Council of Europe. The European Commission's annual reports on Türkiye consistently highlight deficiencies in human rights, the rule of law, and democratic standards as major obstacles to its EU accession. The Turkish government often rejects such criticisms as biased or politically motivated.

6. Administrative divisions

Türkiye is a unitary state with a centralized administrative system. The country is divided into 81 provinces (ilil (province)Turkish). Each province is administered by a governor (valivali (governor)Turkish) appointed by the central government. Provinces serve as the primary level of sub-national administration.

Provinces are further subdivided into districts (ilçeilçe (district)Turkish). There are 923 districts in total. Each district typically has a district governor (kaymakamkaymakam (district governor)Turkish), also appointed by the central government, and may include a district capital town and surrounding villages.

Local administration is handled by municipalities (belediyebelediye (municipality)Turkish).

- Metropolitan Municipalities** (büyükşehir belediyesibüyükşehir belediyesi (metropolitan municipality)Turkish): In larger urban areas, a two-tier municipal system exists. As of recent reforms, there are 30 metropolitan municipalities, including major cities like Istanbul, Ankara, and İzmir. These municipalities have jurisdiction over the entire provincial area (in most cases) and are responsible for city-wide services such as urban planning, transportation, water, and sewage. They are headed by an elected metropolitan mayor. Within metropolitan municipalities, there are also district municipalities (ilçe belediyesiilçe belediyesi (district municipality)Turkish), each with its own elected mayor and council, responsible for more local services within their specific district.

- Provincial and District Municipalities:** In provinces that are not metropolitan municipalities, there are provincial municipalities (for the central city of the province) and district municipalities, each with elected mayors and councils.

- Town Municipalities** (belde belediyesibelde belediyesi (town municipality)Turkish): Smaller settlements with sufficient population can also form municipalities.

- Villages** (köyköy (village)Turkish): The smallest administrative units are villages, which are administered by a village headman (muhtarmuhtar (village headman)Turkish) and a council of elders, both elected by village residents. Muhtars also exist in urban neighborhoods.

For statistical and planning purposes, Türkiye is also informally categorized into seven geographical regions: Marmara, Aegean, Black Sea, Central Anatolia, Eastern Anatolia, Southeastern Anatolia, and Mediterranean. However, these regions do not have any administrative function.

The distribution of major cities largely follows population density, with Istanbul being the most populous city by a significant margin, followed by the capital Ankara, and then İzmir, Bursa, and Antalya. The metropolitan municipality system aims to provide more integrated and efficient governance for these large urban agglomerations.

7. Economy

Türkiye possesses a dynamic and diversified economy, classified as an emerging market and an upper-middle-income country. This section explores its overall economic structure and status, key industrial sectors, critical infrastructure in energy and transport, and developments in science and technology, with consideration for social equity and environmental sustainability.

7.1. Economic structure and status

Türkiye is an emerging market and an upper-middle-income country. It is a founding member of the OECD and the G20. By GDP, Türkiye's economy is the world's 17th-largest by nominal GDP and 12th-largest by Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)-adjusted GDP, according to International Monetary Fund estimates for 2024. Its GDP per capita by PPP was estimated at $40,283, while its nominal GDP per capita was $15,666 in the same year.

The economic structure is dominated by the services sector, which accounts for the majority of GDP (around 64% in 2009). The industry sector contributes over 30%, while agriculture accounts for about 7%. Despite its smaller share of GDP, agriculture remains significant for employment in certain regions.

Türkiye has experienced periods of rapid economic growth, particularly in the early 2000s, but has also faced challenges such as high inflation, currency volatility, and current account deficits. Potential growth is often hampered by structural issues, including slow productivity growth and macroeconomic obstacles. Foreign direct investment (FDI) peaked in 2007 at $22.05 billion and was $13.09 billion in 2022.

Social equity concerns persist. While poverty rates have declined (the share of population below the $6.85/day international poverty threshold fell from 20% in 2007 to 7.6% in 2021), income inequality remains an issue. In 2021, an estimated 47% of total disposable income was received by the top 20% of income earners, while the lowest 20% received only 6%. The national at-risk-of-poverty rate was 13.9% in 2023. In 2021, 34% of the population were at risk of poverty or social exclusion according to Eurostat definitions. Unemployment stood at 10.4% in 2022.

7.2. Major industries

Türkiye has a diversified industrial base. Key manufacturing sectors include:

- Automotive:** Türkiye is a significant automotive manufacturer and exporter, ranking 13th globally in motor vehicle production. Major international brands have production facilities in Türkiye, and domestic companies like Togg (electric vehicles), TEMSA, Otokar, and BMC are prominent.

- Electronics and Home Appliances:** Companies like Arçelik (owner of Beko) and Vestel are major global producers of consumer electronics and household appliances.

- Textiles and Apparel:** A traditional strength, Türkiye is the fifth largest exporter of textiles globally.

- Construction:** The Turkish construction industry is internationally active, with Turkish contractors ranking second globally in the number of firms in the top 250 international contractors list in 2022.

- Steel and Mining:** Türkiye ranks 8th in crude steel production. It also has significant mining operations for various minerals.

- Food Processing:** A large domestic market and agricultural output support a substantial food processing industry.

- Defense Industry:** A rapidly growing sector with increasing indigenous capabilities in aerospace, land systems, and naval platforms (see Science and Technology).

The **tourism industry** is a vital component of the Turkish economy, accounting for about 8% of GDP. In 2022, Türkiye ranked fifth globally in international tourist arrivals with 50.5 million foreign tourists. Istanbul was the most visited city in the world in 2023, and Antalya ranked fourth. The country boasts 21 UNESCO World Heritage Sites and 519 Blue Flag beaches (third most globally).

7.3. Infrastructure

Türkiye has been heavily investing in its infrastructure, including energy and transportation networks, to support economic growth and its role as a regional hub.

7.3.1. Energy

Türkiye is the 16th largest electricity producer globally. Its energy generation capacity has significantly increased, with renewable energy production tripling in the past decade. In 2019, renewables accounted for 43.8% of its electricity generation, with hydroelectricity being a major component (29.2% in 2019). Türkiye is also the fourth-largest producer of geothermal power. The country's first nuclear power station, Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, is under construction and aims to diversify the energy mix.

Despite progress in renewables, fossil fuels still dominate total final energy consumption (73%). Coal remains a significant part of the energy system and a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. While the government has invested in a low-carbon energy transition and aims for net-zero emissions by 2053, fossil fuels were still subsidized as of 2017. Energy security is a top priority due to heavy reliance on imported gas and oil, primarily from Russia, West Asia, and Central Asia. Domestic gas production began in 2023 from the Sakarya gas field in the Black Sea, expected to supply about 30% of domestic needs when fully operational.

Türkiye aims to be a regional energy transportation hub, with several key pipelines traversing the country, including the Blue Stream, TurkStream, and Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. These pipelines transport oil and gas from Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia towards European markets. The environmental impact of energy sources like coal and the social implications of energy policies, including displacement for large dam projects, are ongoing concerns.

7.3.2. Transport

Türkiye has made substantial investments in its transportation network.

- Roads:** As of 2023, Türkiye had 2.3 K mile (3.73 K km) of controlled-access highways (motorways) and 18 K mile (29.37 K km) of divided highways.

- Bridges and Tunnels:** Multiple major bridges and tunnels connect its Asian and European sides, including the Çanakkale 1915 Bridge over the Dardanelles (the world's longest suspension bridge), and the Marmaray rail tunnel and Eurasia Tunnel road tunnel under the Bosphorus in Istanbul. The Osman Gazi Bridge spans the Gulf of İzmit.

- Railways:** Turkish State Railways (TCDD) operates conventional and high-speed rail (YHT) lines. The YHT network is expanding, with key routes including Ankara-Istanbul, Ankara-Konya, and Ankara-Sivas. The Istanbul Metro is the largest subway network, with around 704 million annual riders in 2019.

- Aviation:** There are 115 airports in Türkiye as of 2024. Istanbul Airport is one of the world's top 10 busiest airports. Turkish Airlines is the national flag carrier and a major international airline.

- Maritime Transport:** With extensive coastlines, maritime transport is crucial for trade. Major ports are located in Istanbul, İzmir, Mersin, and İzmit.

Türkiye aims to leverage its strategic location to become a major transportation and logistics hub connecting Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. It is part of various international transport corridors, including the Middle Corridor. In 2024, Türkiye, Iraq, UAE, and Qatar signed an agreement for the Development Road project, aiming to link Iraqi port facilities to Türkiye via road and rail.

7.4. Science and technology

Türkiye has been increasing its investment and focus on science and technology (S&T) to foster innovation and economic development.

- R&D Investment:** Spending on research and development (R&D) as a share of GDP rose from 0.47% in 2000 to 1.40% in 2021.

- Innovation Rankings:** In the 2024 Global Innovation Index, Türkiye ranked 37th in the world and 3rd among upper-middle-income countries. It ranks 16th globally in terms of scientific and technical journal article output and 35th in the Nature Index.

- Patents:** The Turkish Patent and Trademark Office ranks 21st worldwide in overall patent applications and 3rd in industrial design applications. Turkish residents rank 21st globally for overall patent applications filed in all patent offices.

- Major Institutions:** The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (Türkiye Bilimsel ve Teknolojik Araştırma KurumuTÜBİTAK (Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey)Turkish) is a key agency for funding and conducting research. Universities also play a significant role in S&T development.

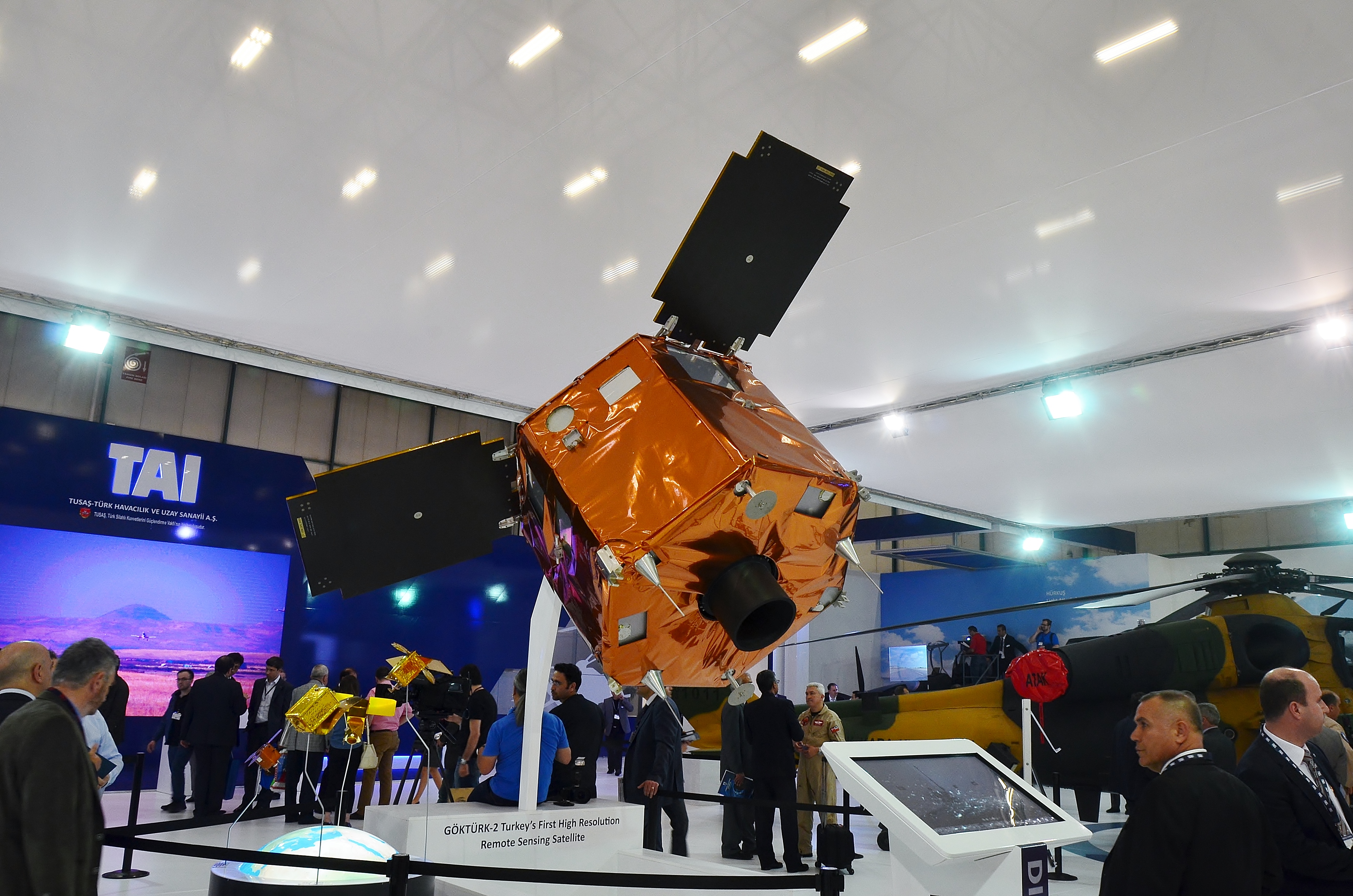

- Space Program:** The Turkish space program aims to develop a national satellite launch system and enhance capabilities in space exploration, astronomy, and satellite communication. The Turkish Space Systems, Integration and Test Center was built under the Göktürk Program. Türkiye's first domestically manufactured communications satellite, Türksat 6A, was launched in 2024.

- Defense Technology:** Türkiye is considered a significant power in unmanned aerial vehicles (UCAVs). The defense industry has grown substantially, with companies like Aselsan, Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI), Roketsan, and ASFAT ranking among the top 100 defense companies globally. These companies invest heavily in R&D. Aselsan is also involved in quantum technology research.

- Other Initiatives:** An electron accelerator called TARLA, part of a planned particle accelerator center, became operational in 2024. Türkiye also plans to establish the Turkish Antarctic Research Station on Horseshoe Island.

While progress has been made, challenges remain in translating R&D into commercial innovation and increasing the overall technological intensity of the economy.

8. Demographics

This section covers Türkiye's population statistics, ethnic and linguistic composition (including the status of Turks, Kurds, and other minorities), recent immigration trends with a focus on refugees, the religious landscape emphasizing secularism and the majority Muslim population, the education system, and the national health sector, paying attention to issues affecting minorities and social welfare.

8.1. Population

According to the Address-Based Population Recording System, Türkiye's population was 85,372,377 in 2023 (excluding Syrians under temporary protection). Approximately 93% of the population lived in urban areas (province and district centers).

The age structure in 2023 was:

- 0-14 years: 21.4%

- 15-64 years: 68.3%

- 65 years and older: 10.2%

Türkiye's population more than quadrupled between 1950 (20.9 million) and 2020 (83.6 million). However, the population growth rate slowed to 0.1% in 2023. The total fertility rate in 2023 was 1.51 children per woman, which is below the replacement rate of 2.10. This marks a significant demographic shift towards lower fertility. Despite this, a 2018 health survey indicated an ideal family size of 2.8 children per woman (3 for married women), suggesting a potential gap between desired and actual fertility.

8.2. Ethnicity and language

Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a Turk as anyone who is a citizen of Türkiye, a civic definition rather than an ethnic one. However, the majority of the population identifies as ethnically Turkish. It is estimated that there are at least 47 ethnic groups in Türkiye. Reliable data on the precise ethnic mix is limited as official censuses after 1965 do not include statistics on ethnicity.

- Turks:** Ethnic Turks are estimated to constitute 70-75% of the population according to The World Factbook. Surveys by KONDA Research and Consultancy estimated this figure at 76% in 2006 and 77% of adult citizens self-identifying as ethnically Turkish in 2021.

- Kurds:** Kurds are the largest ethnic minority, with estimates of their population share ranging from 12% to 20% or more. A 2021 KONDA survey found 19% of adult citizens identified as ethnic Kurds. Kurds form a majority in several provinces in southeastern and eastern Anatolia (e.g., Ağrı, Batman, Diyarbakır, Hakkari, Mardin, Şırnak, Van) and a significant minority in others. Due to internal migration, large Kurdish diaspora communities exist in major western cities; Istanbul is estimated to have the largest Kurdish population of any city in the world (around 3 million). Some individuals may identify with multiple ethnic identities, such as both Turk and Kurd, and interethnic marriages are not uncommon.

- Other Minorities:** Non-Kurdish ethnic minorities are estimated by The World Factbook to be 7-12% of the population. A 2021 KONDA survey found 4% of adult citizens identified as non-Turk or non-Kurd.

- Officially recognized minorities under the Treaty of Lausanne are non-Muslims: Armenians, Greeks, and Jews. Bulgarians were also historically recognized, though their community is now very small. In 2013, a court ruling suggested that Assyrians and the Syriac language should also be covered by Lausanne's minority provisions.

- Other unrecognized ethnic groups include Arabs, Zazas, Circassians, Laz, Albanians, Bosniaks, Georgians, Pomaks, and Roma.

The official language is Turkish, the most widely spoken Turkic language. It is spoken as a first language by 85% to 90% of the population.

- Kurdish (primarily Kurmanji and Zaza/Dimli) is the largest minority language group, spoken as a first language by an estimated 13% of the population (KONDA 2006).

- Other minority languages include Arabic, Caucasian languages (e.g., Circassian, Laz, Georgian), and Gagauz. Several languages in Turkey are endangered.

The linguistic rights of officially recognized minorities (Armenian, Greek, Hebrew, Bulgarian, and more recently Syriac through court interpretation) are de jure protected, allowing for education in these languages to some extent. However, the broader issue of language rights for unrecognized minorities, particularly Kurdish, remains a sensitive political topic. While public use and teaching of Kurdish have seen some legal changes, including the establishment of the Kurdish-language TV channel TRT Kurdî, full linguistic rights in education and public administration are still debated and limited.

8.3. Immigration

Excluding Syrians under temporary protection, there were 1,570,543 foreign citizens residing in Türkiye in 2023.

Historically, Türkiye has experienced various waves of migration. Millions of Kurds fled to Türkiye and Kurdish areas of Iran during the Gulf War in 1991. More recently, Türkiye's migrant crisis in the 2010s and early 2020s, largely driven by the Syrian civil war, has resulted in the influx of millions of refugees and immigrants, making Türkiye the host of the largest refugee population in the world for several years.

- Syrian Refugees:** This is the largest group. In November 2020, there were 3.6 million Syrian refugees in Türkiye, including other ethnic groups from Syria such as Syrian Kurds and Syrian Turkmen. By August 2023, this number was estimated to be around 3.3 million. The Turkish government, through the Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (AFAD), manages the refugee crisis. By November 2023, approximately 238,000 Syrians had been granted Turkish citizenship. The presence of such a large refugee population has significant social, economic, and political implications, and public sentiment towards refugees has become increasingly negative amid economic difficulties.

- Ukrainian Refugees:** Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, approximately 96,000 Ukrainian refugees sought refuge in Türkiye as of May 2023.

- Russian Migrants:** In 2022, nearly 100,000 Russian citizens migrated to Türkiye, an increase of over 218% from 2021, partly due to the geopolitical situation following the invasion of Ukraine.

- Other Migrants and Asylum Seekers:** Türkiye is also a transit and destination country for migrants and asylum seekers from other countries, including Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and African nations.

The humanitarian aspects of managing such large displaced populations are significant, involving issues of shelter, healthcare, education, employment, and social integration, as well as challenges related to border security and international cooperation.

8.4. Religion

Türkiye is constitutionally a secular state with no official state religion. The constitution provides for freedom of religion and conscience. Islam is the predominant religion.

- Muslims:** According to the CIA World Factbook, Muslims constitute 99.8% of the population, the vast majority being Sunni (primarily following the Hanafi school of jurisprudence). A 2006 KONDA survey estimated Muslims at 99.4%.

- Alevis:** Alevis form a significant Islamic minority, distinct from Sunnism, with estimates of their population share ranging from 5% (KONDA 2006) or 4% (KONDA 2021 adult citizens survey) to as high as 10-40% according to Minority Rights Group International. Their distinct religious practices and requests for official recognition of their places of worship (cemevis) are ongoing issues.

- A 2021 KONDA survey found 88% of adult citizens identified as Sunni.

- Non-Muslims:** Non-Muslims constitute a very small percentage of the population, estimated at 0.2% by the World Factbook or 0.18% (KONDA 2006 for non-Islam religions). Historically, the non-Muslim population was much larger (19.1% in 1914) but drastically decreased due to events like the late Ottoman genocides, the population exchange with Greece, and emigration.

- Christians:** Estimates range from 180,000 to 320,000. This includes Armenians (mostly Armenian Apostolic), Assyrians/Syriacs (various denominations including Syriac Orthodox, Chaldean Catholic), Bulgarian Orthodox, Roman Catholics, Greeks (mostly Greek Orthodox), and Protestants. There are 439 churches and synagogues in Türkiye. The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople is based in Istanbul and holds a historic primacy in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

- Jews:** Türkiye has the largest Jewish community among Muslim-majority countries, though their numbers have also declined due to emigration.

- Irreligion/No Religion:** The non-religious population is growing. A 2006 KONDA survey estimated 0.47% as having no religion. By 2021, a KONDA survey found that the share of adult citizens identifying as unbelievers increased from 2% in 2011 to 6%. A 2020 Gezici Araştırma poll found that 28.5% of Generation Z in Türkiye identify as irreligious.

The Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet İşleri BaşkanlığıDiyanet İşleri Başkanlığı (Directorate of Religious Affairs)Turkish) is a state institution that primarily serves the Sunni Muslim majority, managing mosques and employing imams. The secular framework of the state means that religious law is not part of the legal system, but religion plays a significant role in society and politics. Issues such as the status of Alevi places of worship, the reopening of the Halki Greek Orthodox seminary, and property rights of religious minorities remain points of discussion regarding religious freedom.

8.5. Education

Türkiye's education system is overseen by the Ministry of National Education for pre-tertiary levels and the Council of Higher Education (Yükseköğretim KuruluYÖK (Council of Higher Education)Turkish) for universities. The system has seen significant expansion and reforms aimed at improving access and quality, though challenges remain.

- Structure:** Compulsory education lasts 12 years and is free at public schools. It is divided into:

- Primary School (ilkokulilkokul (primary school)Turkish): 4 years

- Middle School (ortaokulortaokul (middle school)Turkish): 4 years

- High School (liselise (high school)Turkish): 4 years

- Pre-primary education (kindergarten, anaokuluanaokulu (kindergarten)Turkish) is expanding but not yet universal.

- Access and Attainment:** Türkiye has made significant progress in increasing education access over the past two decades. From 2011 to 2021, there was a large increase in educational attainment for 25-34 year-olds at upper secondary or tertiary levels, and the number of pre-school institutions quadrupled.

- Quality and PISA Results:** PISA results suggest improvements in education quality, but Türkiye still lags behind the OECD average. Significant disparities exist in student outcomes between different schools and between rural and urban areas.

- Higher Education:** There are 208 universities in Turkey (both public and private foundation universities). Admission to universities is based on a centralized national examination system (YKS), managed by the Measuring, Selection and Placement Center (ÖSYM). Since 2016, the president of Türkiye directly appoints all rectors of state and private universities, a move that has raised concerns about university autonomy.

- Top-ranking universities according to Times Higher Education (2024) include Koç University, Middle East Technical University, Sabancı University, and Istanbul Technical University. The Academic Ranking of World Universities (Shanghai Ranking) lists Istanbul University, University of Health Sciences, and Hacettepe University among the top.

- Türkiye is a member of the Erasmus+ Programme, facilitating student and academic exchanges with European countries. It has become a hub for international students, with 795,962 foreign students in 2016. The government-funded Türkiye Scholarships program attracts numerous international applicants.

- Challenges:**

- Quality Disparities:** Ensuring equitable quality across all schools and regions.

- Pre-primary Access:** Expanding access to early childhood education.

- Education for Refugees:** Providing education for a large number of refugee children, primarily Syrians, presents significant challenges in terms of resources, language barriers, and integration.

- Curriculum Debates:** Contentious debates sometimes arise regarding the curriculum, particularly concerning the balance between secular and religious education, and the teaching of evolution versus creationism.

8.6. Health

Healthcare in Türkiye is administered by the Ministry of Health and features a universal public healthcare system.

- Universal Health Insurance:** Since 2003, Türkiye has implemented a universal health insurance system (Genel Sağlık SigortasıGSS (Universal Health Insurance)Turkish), funded primarily by a tax surcharge on employers (currently 5%). Public-sector funding covers approximately 75.2% of health expenditures.

- Healthcare Expenditure:** Despite universal healthcare, Türkiye's total expenditure on health as a share of GDP was 6.3% in 2018, which was the lowest among OECD countries (average 9.3%).

- Infrastructure:** The country has numerous public and private hospitals. Since 2013, the government has planned and constructed several large hospital complexes known as "city hospitals" (şehir hastanelerişehir hastaneleri (city hospitals)Turkish), often through public-private partnerships. These modern facilities aim to increase capacity and service quality, though their financing models and impact on existing public hospitals have been debated.

- Health Indicators:**

- Average life expectancy is 78.6 years (75.9 for males, 81.3 for females), slightly below the EU average of 81 years.

- Major health issues include high rates of obesity (29.5% of adults with BMI ≥ 30), and health problems related to air pollution, which is a significant cause of premature death.

- Medical Tourism:** Türkiye has become one of the top 10 destinations for medical tourism, attracting patients for procedures ranging from cosmetic surgery to complex treatments, due to relatively lower costs and modern facilities.

The healthcare system has undergone significant transformation, aiming to improve access and quality, but challenges remain in ensuring equitable service delivery across all regions and addressing public health concerns like non-communicable diseases and environmental health risks.

9. Culture

The culture of Türkiye is a rich amalgamation of diverse influences, reflecting its historical position as a bridge between East and West. This section introduces various cultural elements, including its literature, performing and visual arts, music, distinctive architectural heritage, world-renowned cuisine, popular sports, and dynamic media landscape, all of which contribute to Türkiye's unique cultural identity.

9.1. Literature, theatre, and visual arts

Turkish literature spans over a thousand years, evolving from oral traditions and epic poetry to sophisticated court literature and modern narrative forms.

- Ottoman Literature:** Seljuk and Ottoman periods produced numerous literary and poetic works. Turkic tales like the Book of Dede Korkut represent the oral narrative tradition. The 11th-century Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk contains early Turkish linguistic information and poetry. Yunus Emre, influenced by Rumi, was a pivotal figure in Anatolian Turkish poetry. Ottoman Divan poetry was characterized by refined diction, complex vocabulary, and themes of Sufi mysticism and romanticism.

- Modern Turkish Literature:** Beginning in the 19th century, Ottoman literature was increasingly influenced by Western genres like the novel and journalism. Aşk-ı Memnu by Halid Ziya Uşaklıgil is considered the "first truly refined Turkish novel." Fatma Aliye Topuz was the first female Turkish novelist. After the Republic's establishment in 1923, Atatürk's language and alphabet reforms reshaped Turkish literature. It began to reflect socioeconomic conditions with greater variety. The "Village Novel" genre emerged in the mid-1950s, depicting rural poverty, exemplified by Yaşar Kemal's Memed, My Hawk (Türkiye's first Nobel Prize in Literature nominee in 1973). Orhan Pamuk won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, bringing contemporary Turkish literature to global prominence.

Turkish theatre encompasses four major traditions:

- Folk Theatre:** Ancient traditions surviving in rural communities.

- Popular Theatre:** Includes live actor plays, puppet shows, shadow plays (like Karagöz and Hacivat), and storytelling performances.

- Court Theatre:** A refined version of popular theatre.

- Western Theatre:** Introduced in the 19th century, it became more established with the founding of the Republic, which saw the formation of a state conservatory and the State Theatre Company.

Turkish visual arts can be broadly categorized as "decorative" and "fine" arts.

- Fine Arts:** Modern Turkish painting and sculpture have gained international recognition. Contemporary art is showcased in galleries like Istanbul Modern and events like the Istanbul Biennial. Photography, fashion design, and graphic arts are also vibrant fields.

- Traditional Arts:** There has been a resurgence in traditional Ottoman-era arts, including ceramics, carpets, calligraphy, and paper marbling (ebru). These art forms are highly regarded in the Islamic world.

9.2. Music and dance

Turkish music is diverse, broadly categorized into:

- Turkish folk music**: Reflects the varied cultural heritage of Türkiye's regions.

- Turkish art music (Türk sanat müziği)**: Developed in Ottoman courts, with intricate melodies and rhythmic structures.

- Popular Music**: Includes genres like Turkish pop, which has produced international stars such as Ajda Pekkan, Sezen Aksu, and Tarkan; Arabesque, a melancholic genre influenced by Arabic music; and Anatolian rock, a fusion of rock music with Turkish folk influences, pioneered by artists like Barış Manço and Cem Karaca.

Internationally acclaimed Turkish jazz and blues musicians include Ahmet Ertegun, founder of Atlantic Records, and Nükhet Ruacan.