1. Overview

Chad, officially the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon to the southwest, Nigeria to the southwest (at Lake Chad), and Niger to the west. With a total area of approximately NaN Q mile2 (NaN Q km2), Chad is the fifth-largest country in Africa. The nation's geography is diverse, featuring the Sahara Desert in the north, an arid Sahelian belt in the center, and a more fertile Sudanian Savanna zone in the south. Lake Chad, from which the country derives its name, is a significant wetland, though its size has fluctuated dramatically.

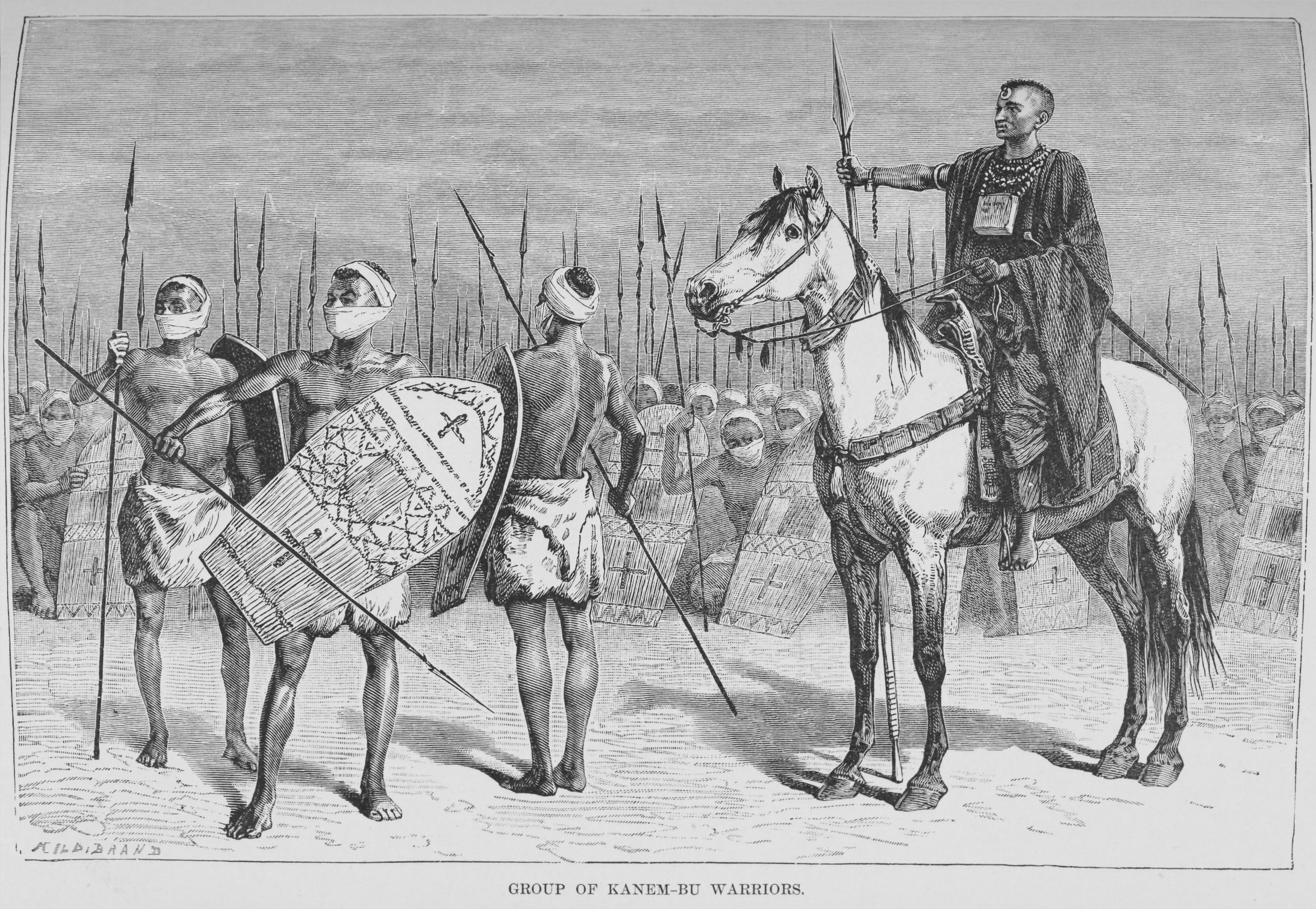

Chad's history is marked by the rise and fall of ancient civilizations and empires, such as the Sao civilisation, the Kanem-Bornu Empire, the Sultanate of Bagirmi, and the Wadai Empire, which controlled trans-Saharan trade routes. French colonization began in the early 20th century, incorporating Chad into French Equatorial Africa. Independence was achieved in 1960 under President François Tombalbaye, but the post-independence era has been characterized by significant political instability, recurrent civil wars, and authoritarian rule. Tensions between the Muslim north and the predominantly Christian and animist south have fueled many conflicts. The dictatorships of Hissène Habré and Idriss Déby were marked by widespread human rights abuses and persistent democratic deficits. Following Idriss Déby's death in 2021, a Transitional Military Council led by his son, Mahamat Déby, assumed power, facing ongoing challenges in transitioning to civilian democratic rule.

The country is home to over 200 distinct ethnic and linguistic groups. French and Arabic are the official languages, with Chadian Arabic serving as a lingua franca. Islam and Christianity are the predominant religions. Chad's economy has historically relied on agriculture, particularly cotton, and livestock. Since 2003, crude oil has become the primary source of export earnings, though the benefits have not significantly alleviated widespread poverty or promoted equitable development. Chad consistently ranks among the lowest in the Human Development Index and faces severe challenges related to poverty, corruption, inadequate infrastructure, and human rights. The nation's socio-political landscape continues to be shaped by efforts towards democratic development, respect for human rights, and the pursuit of sustainable and equitable progress, often amidst internal and regional conflicts.

2. History

The history of Chad encompasses ancient human settlements, the rise and fall of powerful Sahelian empires, French colonization, and a turbulent post-independence period marked by political instability, civil wars, and authoritarian governance, all of which have profoundly shaped Chadian society and its path towards democratic development.

2.1. Early History and Pre-Colonial States

In the 7th millennium BC, ecological conditions in the northern half of Chadian territory favored human settlement, and its population increased considerably. Some of the most important African archaeological sites are found in Chad, mainly in the Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Region; some date to earlier than 2000 BC. The discovery of the skull of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, dating back approximately 7 million years, highlights the region's deep human prehistory.

For more than 2,000 years, the Chadian Basin has been inhabited by agricultural and sedentary people. The region became a crossroads of civilizations. The earliest of these was the legendary Sao civilisation, known from artifacts and oral histories. The Sao eventually fell to the Kanem Empire, the first and longest-lasting of the empires that developed in Chad's Sahelian strip by the end of the 1st millennium AD. The Kanem Empire, founded in the 9th century near Lake Chad, became a dominant force through its control of trans-Saharan trade routes, primarily exporting ivory and slaves. The empire embraced Islam in the 11th century. In the 14th century, internal strife led to the relocation of its capital to Bornu, southwest of Lake Chad, eventually becoming the Kanem-Bornu Empire. Under rulers like Idris Alooma in the late 16th century, the empire regained its strength and influence, which lasted until the 19th century.

Two other significant states in the region, the Sultanate of Bagirmi (southeast of Lake Chad) and the Wadai Empire (east of Lake Chad), emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries respectively. These states, also Muslim, based their power on controlling trans-Saharan trade routes and often raided southern non-Muslim populations for slaves. In Kanem, about a third of the population were slaves. These empires and kingdoms maintained a complex web of rivalries and alliances until the arrival of European colonial powers. The spread of Islam was a significant cultural and political development during this period, shaping the identities and structures of these pre-colonial states.

2.2. French Colonial Period (1900-1960)

French colonial expansion led to the creation of the Territoire Militaire des Pays et Protectorats du TchadMilitary Territory of the Lands and Protectorates of ChadFrench in 1900, following events like the Battle of Kousséri. By 1920, France had secured full control of the colony and incorporated it as part of French Equatorial Africa. French rule in Chad was characterized by an absence of policies to unify the territory and sluggish modernization compared to other French colonies. The French primarily viewed the colony as an unimportant source of untrained labor and raw cotton; France introduced large-scale cotton production in 1929. This focus on cotton cultivation led to the formation of a precarious underclass of poorly-paid rural workers, a decrease in food production, and even famines in some areas. Tensions between farmers and elites, exacerbated by colonial policies, culminated in events such as the 1952 Bébalem massacre by colonial authorities.

The colonial administration in Chad was critically understaffed and had to rely on less competent French civil servants. Only the Sara of the south were governed effectively; French presence in the Islamic north and east was nominal. The educational system was deeply affected by this neglect, leading to disparities in development between the regions. Rice was also introduced as a crop in wetland areas.

During World War II, Chad became the first French colony to rally to Free France under the leadership of its governor, Félix Éboué. After the war, France granted Chad the status of an overseas territory, and its inhabitants gained the right to elect representatives to the French National Assembly and a Chadian territorial assembly. The largest political party was the Chadian Progressive Party (Parti Progressiste TchadienChadian Progressive PartyFrench, PPT), based in the southern half of the colony, which had benefited more from colonial education and administrative attention. As independence movements grew across Africa, Chad was granted autonomy within the French Community in 1958. On August 11, 1960, Chad achieved full independence, with the PPT's leader, François Tombalbaye, an ethnic Sara from the south, as its first president.

2.3. Post-Independence Era

Chad's post-independence history has been defined by persistent political instability, recurrent civil wars, numerous coup attempts, and significant regime changes. The deep-seated ethnic and regional tensions, particularly between the northern Muslim populations and the southern Christian and animist groups, often favored by the colonial and early post-colonial administrations, have fueled these conflicts, hindering democratic development and sustainable peace.

2.3.1. Tombalbaye Presidency and First Civil War (1960-1979)

François Tombalbaye, Chad's first president, quickly consolidated power. Two years after independence, in 1962, he banned opposition parties and established a one-party system under his Chadian Progressive Party (PPT). Tombalbaye's autocratic rule and insensitive mismanagement exacerbated inter-ethnic tensions. His policies heavily favored the southern Sara ethnic group, leading to widespread resentment, particularly among the Muslim populations in the north and east. This discontent culminated in the first Chadian Civil War, which began in 1965 with the formation of the National Liberation Front of Chad (Front de Libération Nationale du TchadNational Liberation Front of ChadFrench). FROLINAT, a coalition of northern Muslim rebel groups, received support from Libya. The war devastated the country and deepened regional divides, impacting various ethnic and social groups, with many civilians caught in the crossfire or displaced.

Tombalbaye's regime became increasingly repressive. Despite French military assistance, his government struggled to contain the insurgency. In 1975, Tombalbaye was overthrown and killed in a military coup led by General Noël Milarew Odingar, who was soon replaced by another southerner, General Félix Malloum. However, the change in leadership did not end the civil war. Malloum's government also failed to quell the rebellion. In 1978, in an attempt to broaden his government's base, Malloum appointed Hissène Habré, a prominent FROLINAT leader, as Prime Minister. This power-sharing arrangement was short-lived. By 1979, the rebel factions, though internally divided, managed to conquer the capital, N'Djamena, leading to the collapse of central authority and Malloum's ousting. The country descended into a period of anarchy as various armed factions, many originating from the northern rebellion, contended for power, marking the end of southern political hegemony for a time.

2.3.2. Habré Dictatorship and Conflicts (1979-1990)

Following the collapse of Félix Malloum's government in 1979, Chad was plunged into further chaos as various rebel factions vied for control. Hissène Habré, leader of the Armed Forces of the North (FAN), initially formed a precarious coalition government with Goukouni Oueddei, who became president. However, this alliance soon broke down, and by 1980, intense fighting erupted between their forces. Goukouni, with significant military support from Libya under Muammar Gaddafi, managed to oust Habré from N'Djamena by the end of 1980. Libya's intervention was driven by Gaddafi's expansionist ambitions, including a desire to annex the Aouzou Strip, a mineral-rich territory in northern Chad, which Libya had occupied since 1973.

Habré, however, regrouped and, with support from the United States and France (who were wary of Libyan expansionism), launched a counter-offensive. In June 1982, Habré's forces recaptured N'Djamena, forcing Goukouni Oueddei to flee. Habré then consolidated his power, establishing an eight-year dictatorship characterized by extreme brutality and widespread human rights abuses. His regime systematically targeted perceived political opponents and rival ethnic groups, particularly the Sara and other southern groups, as well as dissenting northern factions like the Zaghawa. Thousands of people are estimated to have been killed, tortured, or "disappeared" under his rule, with his security forces, notably the Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS), responsible for these atrocities.

The conflict with Libya continued throughout Habré's rule, escalating into the Chadian-Libyan conflict. Libyan forces, allied with Goukouni's GUNT (Transitional Government of National Unity) rebels, occupied northern Chad. With substantial French military intervention (such as Operation Manta and Operation Épervier) and US logistical support, Chadian forces, under Habré, managed to repel the Libyans in a series of victories, culminating in the "Toyota War" of 1987. This conflict saw Chadian forces, utilizing agile pickup trucks mounted with anti-tank missiles, inflict heavy losses on the more heavily armored Libyan army, forcing their withdrawal from most of Chad, though Libya continued to occupy the Aouzou Strip. A ceasefire was declared in 1988.

Despite his military successes against Libya, Habré's regime was marked by severe political repression and a climate of fear. He favored his own Daza (Toubou) ethnic group and alienated many former allies. His authoritarianism and human rights record eventually led to his downfall. In December 1990, Idriss Déby, Habré's Zaghawa former army chief who had fallen out with him and fled to Sudan, launched a Libyan-backed rebellion and successfully overthrew Habré. Habré fled into exile in Senegal. Years later, after a long campaign by victims and human rights organizations, Habré was tried by a special African Union-backed court in Senegal. In May 2016, he was convicted of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and torture, including rape and sexual slavery, and sentenced to life in prison, marking a landmark case for international justice in Africa.

2.3.3. Déby Era and Second Civil War (1990-2021)

Idriss Déby seized power in December 1990 after overthrowing Hissène Habré. He initially promised a transition to democracy and introduced a multi-party system. A new constitution was approved by referendum in 1996, and Déby won the subsequent presidential election, followed by another victory in 2001. However, his long tenure, lasting over three decades, was characterized by the consolidation of authoritarian rule under his Patriotic Salvation Movement (MPS) party. While opposition parties were allowed to exist, they faced significant restrictions and harassment, and elections were frequently criticized by observers as neither free nor fair. In 2005, Déby controversially amended the constitution to remove presidential term limits, allowing him to remain in power indefinitely, a move that sparked uproar among civil society and opposition groups.

The exploitation of oil began in Chad in 2003, with the completion of the Chad-Cameroon pipeline. This brought hopes of economic prosperity, but critics argued that oil revenues were not equitably distributed, often fueling corruption and military spending rather than significantly improving the lives of ordinary Chadians or addressing widespread poverty. The management of oil wealth remained a contentious issue, with concerns about transparency and its impact on governance.

Déby's rule was challenged by numerous rebellions and coup attempts. The second Chadian Civil War erupted in 2005, partly fueled by the spillover effects of the Darfur crisis in neighboring Sudan. Chad accused Sudan of backing Chadian rebels, while Sudan accused Chad of supporting Darfuri insurgents. This period saw intense fighting, with rebel forces launching major assaults on N'Djamena in 2006 and 2008, which were repelled by government forces, often with French military support. An agreement with Sudan in 2010 helped to reduce the intensity of this conflict.

Chad also faced significant security threats from extremist groups like Boko Haram, particularly in the Lake Chad region, leading to increased military engagement and displacement of populations. Déby positioned Chad as a key security partner for Western powers, particularly France, in counter-terrorism efforts in the Sahel.

Throughout the Déby era, human rights concerns persisted. Reports of arbitrary arrests, restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly, and impunity for security forces were common. Democratic deficits remained significant, with power concentrated in the hands of the president and his allies, often from his Zaghawa ethnic group. Despite these issues, Déby managed to maintain power through a combination of military strength, political maneuvering, and international alliances. His rule came to an abrupt end in April 2021 when he was reportedly killed during clashes with rebels from the Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT) in northern Chad, shortly after being declared the winner of a presidential election that extended his rule for a sixth term.

2.3.4. Military Transitional Government (2021-present)

Following the death of President Idriss Déby on April 20, 2021, during clashes with FACT rebels in northern Chad, a Transitional Military Council (CMT) immediately seized power. The council was led by Idriss Déby's son, General Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno, a four-star general. The CMT dissolved the National Assembly and suspended the constitution, announcing an 18-month transitional period intended to lead to "free and democratic" elections.

The takeover was met with mixed reactions both domestically and internationally. While some international partners, notably France, expressed support for the CMT as a means of ensuring stability in a volatile region, opposition parties and civil society groups in Chad condemned it as a coup d'état and a dynastic succession. Protests calling for a swift return to civilian rule and a more inclusive transition process erupted in N'Djamena and other cities, sometimes met with violent crackdowns by security forces, leading to casualties and arrests. These events highlighted ongoing concerns about human rights and the restriction of political freedoms.

The CMT appointed a civilian transitional government headed by Albert Pahimi Padacké as Prime Minister, but real power remained with Mahamat Déby and the military council. A "national dialogue" was initiated, ostensibly to pave the way for a new constitution and elections. However, this process was criticized by some opposition figures and rebel groups for a lack of inclusivity. In October 2022, the national dialogue concluded by extending the transition period by an additional two years, allowing Mahamat Déby to remain as interim president and to be eligible to run in future elections, contrary to earlier pledges by the African Union. This extension triggered further protests and condemnation from opposition and civil society groups, who accused the CMT of perpetuating military rule and delaying the democratic process.

The transitional government faces numerous challenges, including continued threats from rebel groups, socio-economic difficulties, pressure from international partners to ensure a credible transition to civilian rule, and managing complex regional security dynamics, including the situations in Libya, Sudan, and the Sahel region. The path towards democratic elections and stable civilian governance remains uncertain, with significant concerns about the military's continued dominance in politics and the protection of fundamental human rights and democratic principles. On May 23, 2024, Mahamat Idriss Déby was sworn in as President of Chad following a disputed presidential election held on May 6, 2024, which officially ended the period of military rule but was criticized by opponents as lacking fairness and transparency.

3. Geography

Chad is a large, landlocked country in north-central Africa, characterized by distinct geographical zones ranging from desert in the north to savanna in the south. Its diverse topography, climate patterns, and water systems define its environment and influence human settlement and economic activities.

3.1. Topography and Regions

Chad covers an area of 0.5 M mile2 (1.28 M km2), making it the world's twentieth-largest country. It lies between latitudes 7° and 24°N, and longitudes 13° and 24°E. The dominant physical structure is a wide basin, the Chad Basin, which is bounded to the north and east by the Ennedi Plateau and the Tibesti Mountains. The Tibesti Mountains in the north are of volcanic origin and include Emi Koussi, a dormant volcano that reaches 11 K ft (3.41 K m) above sea level, the highest point in Chad and the Sahara. The northern third of the country lies within the Sahara Desert, characterized by vast arid plains, dune fields, and rocky plateaus like the Ennedi, known for its unique sandstone formations.

Central Chad forms part of the Sahelian belt, an arid to semi-arid transitional zone between the Sahara to the north and the more fertile savannas to the south. This region is characterized by grasslands and thorny scrub.

Southern Chad features the Sudanian Savanna zone, which is more fertile and receives higher rainfall. This region consists of savanna plains and woodlands, drained by the country's major rivers, the Chari and Logone, and their tributaries. These rivers flow from the southeast into Lake Chad.

Lake Chad, after which the country is named, is located in the far west of the country, on the border with Niger, Nigeria, and Cameroon. It is the remains of an immense lake that occupied 127 K mile2 (330.00 K km2) of the Chad Basin approximately 7,000 years ago. Although in the 21st century it covers a much smaller area, currently around 6.9 K mile2 (17.81 K km2), its surface area is subject to heavy seasonal fluctuations and has shrunk considerably over recent decades due to climate change and increased water usage. Despite this, it remains Africa's second-largest wetland.

3.2. Climate

Chad has a diverse climate largely determined by its latitude. Each year, a tropical weather system known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) crosses Chad from south to north, bringing a wet season.

- The northern Saharan region experiences a desert climate with extremely low rainfall, typically under 2.0 in (50 mm) annually. Temperatures are high during the day and can drop significantly at night. Vegetation is sparse, limited to occasional oases.

- The central Sahelian region has a semi-arid climate. Annual precipitation varies from 12 in (300 mm) to 24 in (600 mm), occurring mainly between June and September. This region experiences a distinct dry season and is prone to drought.

- The southern Sudanian savanna zone has a tropical savanna climate. Yearly rainfall in this belt is over 35 in (900 mm), concentrated between May and October. This region supports more extensive agriculture and denser vegetation.

The country also experiences the Harmattan, a hot, dry wind from the northeast, particularly during the dry season (November to March), which can carry significant amounts of dust.

3.3. Wildlife and Conservation

Chad's flora and fauna correspond to its three climatic zones. In the Saharan region, flora is limited to date-palm groves of oases. Palms and acacia trees grow in the Sahelian region. The southern, or Sudanic, zone consists of broad grasslands or prairies suitable for grazing. As of 2002, there were at least 134 species of mammals, 509 species of birds (354 resident and 155 migrant species), and over 1,600 species of plants throughout the country.

Chad is home to a variety of wildlife, including elephants, lions, buffalo, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses (though critically endangered or locally extinct in many areas), giraffes, antelopes, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, and many species of snakes. However, most large carnivore populations have been drastically reduced since the early 20th century due to habitat loss and poaching. Zakouma National Park in southeastern Chad is one of the country's most important protected areas and has been a focus of significant conservation efforts, particularly for its elephant population, which suffered heavily from poaching but has seen some recovery. The Ennedi Plateau is notable for its unique desert ecosystems and is home to a relict population of the West African crocodile, one of the last known colonies in the Sahara.

Challenges to wildlife conservation in Chad are numerous, including poaching for ivory and bushmeat, habitat degradation due to agricultural expansion and livestock grazing, deforestation, and the impacts of climate change. Political instability and limited resources have often hampered effective conservation enforcement.

Forest cover in Chad is around 3% of the total land area, equivalent to 11 M acre (4.31 M ha) in 2020, down from 17 M acre (6.73 M ha) in 1990. Extensive deforestation has resulted in the loss of trees such as acacias, baobab, dates, and palm trees. This has also caused loss of natural habitat for wild animals.

National and international organizations are involved in conservation efforts. These include anti-poaching patrols, community-based conservation programs, and efforts to reforest degraded areas. For example, the Food and Agriculture Organization has worked to improve relations between farmers, agro-pastoralists, and pastoralists in and around protected areas to promote sustainable development. Replanting efforts, such as planting acacia trees (which produce gum arabic), aim to combat desertification and provide economic benefits to local communities. However, the scale of the challenges requires sustained and increased commitment to protect Chad's biodiversity and ensure the ecological balance of its varied ecosystems, considering the impact on local communities who depend on these natural resources. Chad had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.18/10, ranking it 83rd globally out of 172 countries.

4. Government and Politics

Chad's political system has historically been characterized by a strong executive branch, frequent instability, and challenges to democratic development. The country is a republic, but its democratic institutions have often been undermined by authoritarian rule, military interventions, and civil unrest. The human rights situation remains a significant concern.

4.1. Government Structure

Chad's government structure is based on a presidential system, though its functioning has been significantly impacted by periods of military rule and constitutional changes.

The Executive Branch is headed by the President, who is the head of state and, under most constitutional arrangements, also the head of government. The president has historically wielded extensive powers, including appointing the Prime Minister (when the office exists) and cabinet members, and exercising considerable influence over the judiciary, military, and provincial administrations. Presidential terms and limits have been subject to constitutional amendments, often reflecting the political aims of the incumbent.

The Legislative Branch is constitutionally vested in the National Assembly, a unicameral body whose members are typically elected for multi-year terms. The Assembly is responsible for enacting legislation, approving the national budget, and overseeing the executive. However, its independence and effectiveness have often been curtailed by presidential dominance and, at times, suspension during military takeovers. Following the death of President Idriss Déby in April 2021 and the subsequent military takeover, the National Assembly was dissolved, and a transitional legislative body was later appointed by the military council.

The Judicial Branch is based on French civil law and Chadian customary law, where the latter does not conflict with public order or constitutional guarantees. The system includes a Supreme Court, courts of appeal, criminal courts, and magistrate courts. A Constitutional Council has the power to review the constitutionality of laws, treaties, and international agreements. Despite constitutional provisions for judicial independence, the judiciary has often been influenced by the executive branch, particularly in the appointment of key judicial officials.

The interrelations between these branches have frequently been imbalanced, with the executive branch, particularly the presidency, dominating the political landscape.

4.2. Political Landscape

Chad's political landscape has been marked by a history of one-party rule, military regimes, and a constrained multi-party system. After Idriss Déby seized power in 1990, opposition parties were legalized in 1992. Since then, numerous political parties have registered, but the Patriotic Salvation Movement (MPS), founded by Déby, remained the dominant political force for three decades.

Presidential and legislative elections have been held periodically, but they have often been marred by irregularities, boycotts by opposition parties, and accusations of fraud, raising serious questions about their fairness and credibility. The opposition has frequently accused the ruling party of using state resources and security forces to maintain its grip on power, thereby limiting genuine political competition and democratic development.

Following Idriss Déby's death in 2021 and the military takeover led by his son, Mahamat Déby, the established political order was disrupted. The military council promised a transition to civilian rule, but the process has faced criticism for its length, lack of inclusivity, and the military's continued influence. The disputed 2024 presidential election, which saw Mahamat Déby officially declared the winner, highlighted the ongoing challenges to achieving a stable and broadly accepted democratic political landscape. Political stability remains fragile, with the potential for renewed conflict and resistance to the current authorities.

4.3. Domestic Political Issues and Challenges

Chad has faced a multitude of persistent domestic political issues and challenges that have hindered its democratic development and overall stability.

- Long-term Rule and Succession: The extended presidencies of figures like François Tombalbaye, Hissène Habré, and particularly Idriss Déby (who ruled for over 30 years) have entrenched authoritarian tendencies and limited political pluralism. The succession of Mahamat Déby after his father's death in 2021 raised concerns about dynastic rule and further delayed democratic transition.

- Coup Attempts and Rebel Activities: Chad has a long history of coup d'états and armed rebellions. Various rebel groups, often based in neighboring countries and sometimes receiving external support, have repeatedly challenged the central government, leading to internal conflicts and instability, particularly in the northern and eastern regions. These insurgencies have diverted resources from development and contributed to humanitarian crises.

- Challenges to Democratic Development: Genuine democratic development has been impeded by a weak rule of law, restrictions on fundamental freedoms (such as freedom of speech, assembly, and the press), harassment of opposition figures and human rights defenders, and a political environment that often favors the incumbent. The development of a vibrant and independent civil society has also faced obstacles.

- Governance Issues and Corruption: Corruption is pervasive at all levels of government and remains a major obstacle to good governance and socio-economic progress. Lack of transparency and accountability, particularly in the management of natural resource revenues (such as oil), has led to the misallocation of funds and public disillusionment. Chad consistently ranks poorly on international corruption indices.

- Civil Liberties and Political Freedoms: The state of civil liberties and political freedoms is a significant concern. Security forces have often been implicated in human rights abuses, including arbitrary arrests, extrajudicial killings, and torture, with perpetrators frequently enjoying impunity. Restrictions on media and the activities of non-governmental organizations further limit public discourse and accountability. These issues disproportionately affect marginalized social groups and those perceived as critical of the government.

Addressing these deeply rooted political issues is crucial for Chad to move towards greater stability, democratic governance, and respect for human rights, which are essential for the equitable development and well-being of its diverse population.

4.4. Administrative Divisions

Chad's system of local governance has undergone reforms aimed at decentralization, although implementation has been slow and uneven. Since 2012, the country has been divided into 23 regions (régionsregionsFrench). This structure replaced the previous system of 14 prefectures as part of a decentralization process initiated in 2003.

Each region is headed by a governor, who is appointed by the president. The regions are further subdivided into departments (départementsdepartmentsFrench), currently numbering 61. Prefects administer these departments.

The departments are, in turn, divided into sub-prefectures (sous-préfecturessub-prefecturesFrench), which are composed of cantons. There are 200 sub-prefectures and 446 cantons.

The constitution provides for decentralized government to compel local populations to play an active role in their own development. To this end, the constitution declares that each administrative subdivision should be governed by elected local assemblies. However, local elections have been infrequent and often postponed, meaning that many local administrative positions are filled by appointment rather than by democratic vote. This has limited the extent of genuine local autonomy and participation in governance. The cantons are scheduled to be replaced by communautés ruralesrural communitiesFrench (rural communities), but the legal and regulatory framework for this transition has not yet been fully completed.

The regions are:

- Batha

- Chari-Baguirmi

- Hadjer-Lamis

- Wadi Fira

- Bahr el Gazel

- Borkou

- Ennedi-Est

- Ennedi-Ouest

- Guéra

- Kanem

- Lac

- Logone Occidental

- Logone Oriental

- Mandoul

- Mayo-Kebbi Est

- Mayo-Kebbi Ouest

- Moyen-Chari

- Ouaddaï

- Salamat

- Sila

- Tandjilé

- Tibesti

- N'Djamena (capital city, special status)

5. Foreign Relations

Chad's foreign policy has been largely shaped by its geographical position in a volatile region, its history of internal conflicts often intertwined with those of its neighbors, and its economic and security needs. It has maintained complex relationships with neighboring countries and has been an active, though sometimes controversial, player in regional security efforts, while also engaging with major global powers and international organizations.

5.1. Relations with Neighboring Countries

Chad shares borders with six countries, and its relations with them have often been fraught with challenges.

- Libya: Relations with Libya have historically been turbulent, marked by Libyan military interventions in Chad's civil wars and the dispute over the Aouzou Strip, which was resolved in Chad's favor by the International Court of Justice in 1994. Under Muammar Gaddafi, Libya frequently supported Chadian rebel groups. The instability in Libya following Gaddafi's overthrow in 2011 has continued to pose security challenges for Chad, with arms proliferation and the movement of militant groups across their shared border.

- Sudan: The relationship with Sudan has been particularly volatile, especially due to the Darfur conflict that began in 2003. Chad hosted hundreds of thousands of Sudanese refugees, and both countries accused each other of supporting rebel groups operating against their respective governments. This led to direct military confrontations and a proxy war. Relations improved somewhat after a 2010 agreement, but the long border remains a source of tension and insecurity, affecting local populations and humanitarian efforts.

- Central African Republic (CAR): Chad has frequently intervened in the CAR's internal conflicts, sometimes supporting different factions. Instability in the CAR has led to refugee flows into southern Chad and cross-border security incidents. Chadian forces have participated in regional peacekeeping missions in the CAR, though their role has sometimes been controversial.

- Cameroon: Cameroon is a vital partner for landlocked Chad, as the Chad-Cameroon pipeline transports Chadian oil to the Cameroonian port of Kribi for export. Relations are generally stable, driven by economic interdependence. Both countries also cooperate on security issues in the Lake Chad Basin.

- Nigeria: Relations with Nigeria are significant, particularly concerning the security situation in the Lake Chad Basin, where the Boko Haram insurgency has affected both countries. Chad has been an active participant in the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) to combat Boko Haram, often deploying troops into Nigerian territory. The humanitarian crisis resulting from the conflict, including large numbers of refugees and internally displaced persons, is a shared concern.

- Niger: Chad and Niger also share concerns about security in the Sahel and Lake Chad regions, including threats from Boko Haram and other extremist groups. They cooperate within regional security frameworks like the G5 Sahel.

Cross-border issues such as refugee crises, arms trafficking, and the movement of armed groups have significantly impacted populations in these border regions, often exacerbating humanitarian needs and requiring international assistance.

5.2. Relations with Major Powers and International Organizations

Chad has cultivated relationships with several major global powers and participates actively in international and regional organizations.

- France: As the former colonial power, France has maintained strong political, economic, and military ties with Chad. France has frequently provided military support to Chadian governments, including interventions to repel rebel attacks and assistance in counter-terrorism operations in the Sahel (e.g., Operation Barkhane). This close relationship has been criticized by some as propping up authoritarian regimes in exchange for regional stability and French influence. However, in 2024, Chad ended its military cooperation agreement with France, and by early 2025, the French military handed over its last base, ending its decades-long military presence.

- United States: The U.S. has engaged with Chad primarily on security and counter-terrorism issues, viewing Chad as an important partner in the fight against extremist groups in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin. The U.S. has provided military training and assistance. However, concerns about human rights and democratic governance in Chad have also been part of the bilateral dialogue.

- China: China's influence in Chad has grown, particularly in the economic sphere. Chinese companies are involved in infrastructure projects and the oil sector. Chad switched its diplomatic recognition from Taiwan (ROC) to the People's Republic of China in 2006 to foster these ties.

- United Arab Emirates: The UAE has increased its engagement with Chad, particularly in providing humanitarian aid and development assistance. In 2023, the UAE opened a coordination office for foreign aid in Amdjarass to support efforts for Chadian citizens and Sudanese refugees.

- International Organizations: Chad is a member of the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), and the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC). It has been an active participant in AU-led peacekeeping missions and regional security initiatives like the G5 Sahel Joint Force and the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) against Boko Haram. Chad's role in these bodies often reflects its security concerns and its efforts to garner international support for addressing regional instability and its own development challenges. However, its human rights record and democratic deficits have sometimes drawn criticism from these organizations. In 2019, Chad re-established diplomatic relations with Israel after a break since 1972, driven partly by shared security concerns, particularly regarding Islamic extremism.

6. Military

The Chadian National Army (Armée Nationale TchadienneChadian National ArmyFrench, ANT) plays a significant role in both domestic security and regional stability operations. It has been shaped by decades of internal conflict and external threats, making it one of the more battle-hardened forces in the Sahel region.

6.1. Structure and Capabilities

As of 2024, Chad's armed forces were estimated to have approximately 33,250 active military personnel. This includes:

- Ground Forces: Around 27,500 personnel. Organized into seven military regions and twelve battalions, including armored, infantry, artillery, and logistical units.

- Air Force: Around 350 personnel, operating a modest fleet of aircraft, including combat jets, helicopters, and transport planes.

- General Directorate of the Security Services of State Institutions (DGSSIE): Approximately 5,400 personnel, primarily responsible for protecting government institutions and high-ranking officials.

In addition, there are paramilitary forces:

- National Gendarmerie: Around 4,500 personnel, responsible for law enforcement in rural areas and supporting the military.

- National and Nomadic Guard (GNNT): Around 7,400 personnel, tasked with border security, particularly in desert regions, and maintaining order among nomadic populations.

The Chadian military's equipment is largely of Soviet/Russian, French, and Chinese origin, with some more modern acquisitions. The defense budget has historically consumed a significant portion of the national revenue, particularly during periods of conflict or when oil revenues were higher. The CIA World Factbook estimated military spending at 4.2% of GDP in 2006, during a civil war, but this figure dropped to around 2.0% by 2011 according to the World Bank, after the conflict subsided. The actual expenditure often fluctuates based on perceived security threats.

6.2. Domestic and International Role

The Chadian military has a prominent domestic role, often involved in maintaining internal security, responding to rebellions, and managing border security. Its experience in desert warfare has been a key characteristic. However, its involvement in domestic security has sometimes led to concerns about human rights abuses by security forces, including excessive force, arbitrary arrests, and impunity.

Internationally, Chad has been a significant contributor to regional security efforts. It has played a leading role in:

- Counter-terrorism operations**: Particularly against Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin as part of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), and against Al-Qaeda and Islamic State-affiliated groups in the Sahel as part of the G5 Sahel Joint Force. Chadian troops are often considered among the most effective and experienced in these theaters.

- Peacekeeping missions**: Chad contributed troops to the MINUSMA (UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali) until the mission's dissolution. In 2023, its last year, 1,449 Chadian soldiers were deployed there.

France was a long-standing key security partner, providing training, logistical support, and direct military intervention at times. However, this military cooperation agreement ended in 2024. The Chadian military faces challenges including resource constraints, the need for modernization, and addressing human rights concerns within its operations to build trust with civilian populations. Its effectiveness in regional operations has often come at a high cost in terms of personnel and resources, impacting domestic priorities.

7. Economy

Chad's economy is characterized by its reliance on agriculture and, more recently, oil, alongside significant structural challenges including widespread poverty, inequality, limited infrastructure, and vulnerability to external shocks. Efforts towards equitable and sustainable development have been hampered by political instability, corruption, and environmental factors.

7.1. Overview and Structure

Chad is one of the poorest countries in the world, with the United Nations' Human Development Index consistently ranking it very low (seventh poorest in some assessments). A large majority of the population, estimated at over 75-80%, lives below the poverty line. In 2018, 4.2 out of 10 people lived below the national poverty line. While the poverty rate declined from 55% in 2003 to 47% in 2011, the absolute number of poor people increased from 4.7 million in 2011 to 6.5 million in 2019. The GDP (purchasing power parity) per capita was estimated as 1.65 K USD in 2009.

The economy is predominantly based on agriculture and livestock raising, which employ the vast majority of the workforce and are largely for subsistence. Since 2003, crude oil has become the dominant export, significantly impacting national revenue but also making the economy highly vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices. The country is part of the Bank of Central African States (BEAC), uses the Central African CFA franc as its currency, and is a member of the Customs and Economic Union of Central Africa (UDEAC) and the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).

Challenges to economic development include its landlocked position, poor infrastructure, arid climate in much of the country, high levels of corruption, and a history of political instability and conflict. Uneven inclusion in the global political economy as a site for colonial resource extraction (primarily cotton and crude oil), a global economic system that has not encouraged Chadian industrialization, and the failure to adequately support local agricultural production have contributed to persistent poverty and food insecurity.

7.2. Major Sectors

Chad's economy is heavily reliant on a few key sectors, with limited diversification.

7.2.1. Oil Industry

Since production began in 2003 from oil fields near Doba in southern Chad, crude oil has become the cornerstone of the Chadian economy and its primary source of export earnings, replacing cotton. The Chad-Cameroon pipeline, extending 0.7 K mile (1.07 K km) to the Cameroonian port of Kribi, facilitates these exports. At its peak, daily production reached significant levels (e.g., 100,000 barrels per day).

Oil revenues initially brought hopes for substantial economic development and poverty reduction. The World Bank, which partly financed the pipeline, initially insisted that a significant portion of oil revenues be allocated to development projects and poverty reduction programs through a revenue management law. However, the Chadian government later amended these laws to allocate more funds to security and other expenditures, leading to disputes with the World Bank and concerns among civil society about transparency and accountability.

The oil industry faces challenges including:

- Resource Management and Transparency:** Ensuring that oil wealth translates into broad-based development has been a major hurdle. Issues of corruption and a lack of transparency in how revenues are managed and spent have been persistent.

- Equitable Distribution of Wealth:** The benefits of oil extraction have not been evenly distributed, with limited impact on reducing widespread poverty or improving social services for the majority of the population.

- Social and Environmental Consequences:** Oil extraction can lead to localized environmental degradation and social disruption if not managed responsibly. Conflicts over land and compensation for affected communities have also occurred.

- Vulnerability to Price Shocks:** Heavy reliance on oil makes Chad's economy highly susceptible to fluctuations in global oil prices, impacting government revenue and overall economic stability.

Despite these challenges, oil remains critical to Chad's public finances and export earnings.

7.2.2. Agriculture and Livestock

Agriculture and livestock herding are the traditional mainstays of the Chadian economy, employing over 80% of the population, mostly at a subsistence level.

- Crops:** The main food crops include sorghum, millet, and, in some areas, maize and rice. Groundnuts and cassava are also cultivated. Cotton has historically been the most important cash crop, particularly in the southern regions, and was the primary export before the advent of oil. However, its production and export volumes have faced challenges from fluctuating world prices and internal organizational issues within the sector (e.g., Cotontchad).

- Livestock:** Chad has substantial livestock resources, including cattle, sheep, goats, and camels. Traditional pastoralism is a way of life for many, particularly in the Sahelian and northern regions. Livestock and livestock products (meat, hides) are significant exports, mainly to neighboring countries.

Challenges in this sector include:

- Food Security:** Despite agricultural activity, Chad frequently faces food insecurity due to drought, variable rainfall, pest infestations, and limited access to modern farming techniques and inputs.

- Land Use Conflicts:** Competition for land and water resources between farmers and pastoralists is a common source of conflict, particularly as climate change and population pressure exacerbate resource scarcity.

- Agricultural Development Policies:** Efforts to modernize the agricultural sector and improve productivity have had limited success. There is a need for policies that support smallholder farmers, improve infrastructure (irrigation, storage, transport), and promote sustainable land management practices.

- Labor Rights and Environmental Sustainability:** Issues related to fair labor practices in commercial agriculture and the environmental impact of farming and grazing (e.g., deforestation, soil degradation) require attention.

Gum arabic, collected from acacia trees, is another traditional export product.

7.3. Trade and Investment

Chad's trade is dominated by the export of crude oil, which accounts for the vast majority of its export earnings. Other exports include livestock, cotton, and gum arabic. Its main imports consist of machinery and transport equipment, industrial goods, foodstuffs, and textiles.

Key trading partners for exports have traditionally included the United States and China (for oil), and neighboring countries for livestock. Imports primarily come from countries like France, Cameroon, China, and Nigeria.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows have been heavily concentrated in the oil sector. The overall investment climate is challenging due to political instability, corruption, weak legal frameworks, poor infrastructure, and a shortage of skilled labor. Attracting diversified investment beyond the extractive industries remains a significant hurdle. Opportunities exist in agriculture, renewable energy, and infrastructure development, but realizing this potential requires substantial improvements in governance and the business environment.

7.4. Economic Challenges and Development

Chad faces profound economic challenges that hinder its path towards sustainable development and poverty reduction. Promoting social equity within this context is a critical imperative.

- Chronic Poverty and Inequality:** Widespread poverty affects a large majority of the population, with significant disparities between urban and rural areas, and between different regions. Access to basic services like healthcare, education, clean water, and sanitation is severely limited for many. Inequality in income and opportunity remains high.

- High Unemployment Rates:** Formal sector employment is scarce, and underemployment is rampant, particularly among youth. The economy's limited diversification restricts job creation.

- Fragile Infrastructure:** Inadequate infrastructure - including roads, energy supply, and telecommunications - significantly increases the cost of doing business, hampers internal trade and connectivity, and impedes access to markets and services.

- Heavy Reliance on Foreign Aid:** Despite oil revenues, Chad remains heavily dependent on foreign aid and loans from international financial institutions and donor countries to fund development projects and humanitarian assistance. Debt sustainability can also be a concern.

- Vulnerability to External Shocks:** The economy is highly vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices, climatic shocks (droughts, floods) affecting agriculture, and regional instability impacting trade and security.

- Need for Sustainable Growth and Diversification:** Long-term development requires diversifying the economy away from over-reliance on oil and subsistence agriculture. Investing in human capital (education and health), promoting private sector development in non-extractive industries, and improving agricultural productivity are crucial.

- Poverty Reduction Strategies and Social Equity:** Effective poverty reduction strategies must focus on inclusive growth, ensuring that the benefits of economic activity reach the poorest and most vulnerable segments of society. This includes targeted social protection programs, investments in rural development, and measures to address gender inequality and empower women. Good governance, transparency, and the fight against corruption are essential preconditions for achieving these goals.

The long history of conflict and political instability has further exacerbated these economic challenges, diverting resources and undermining efforts to build a resilient and equitable economy.

7.5. Infrastructure

Chad's infrastructure is underdeveloped and presents a major constraint to economic growth and social development. Significant investment and improvement are needed across all sectors.

7.5.1. Transport

Chad's landlocked position and vast territory make transportation infrastructure crucial, yet it remains severely limited.

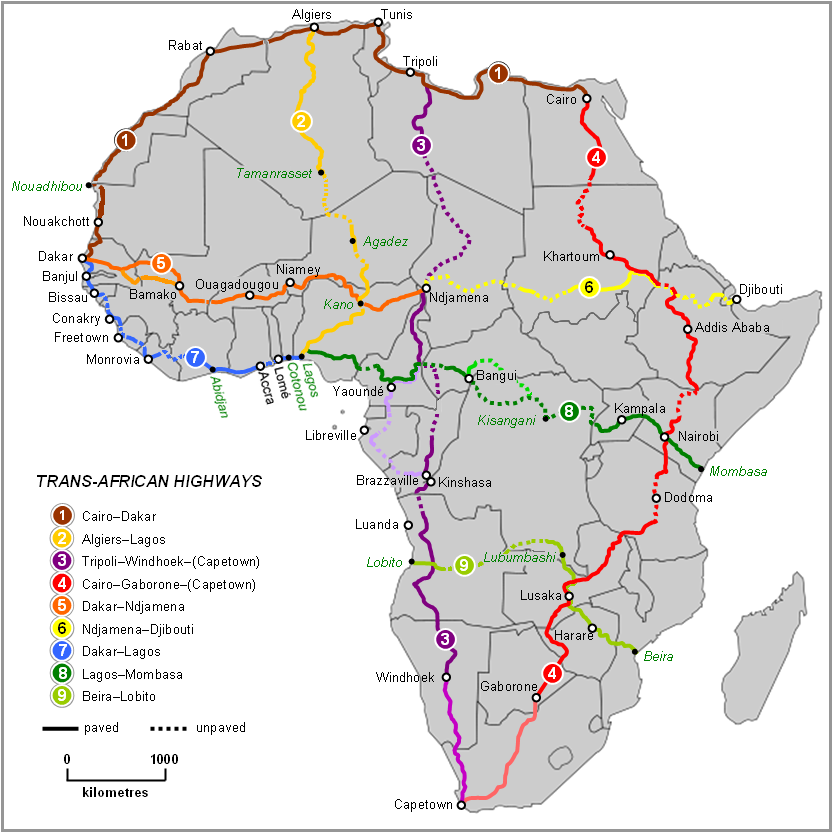

- Road Network:** The road network is sparse. In 1987, Chad had only 19 mile (30 km) of paved roads. While rehabilitation projects improved this to 342 mile (550 km) by 2004, the majority of roads remain unpaved and are often unusable during the rainy season, isolating many regions for several months of the year. This poor connectivity hinders internal trade, access to markets and services, and humanitarian efforts. Three trans-African automobile routes pass through Chad: the Tripoli-Cape Town Highway, the Dakar-Ndjamena Highway, and the Ndjamena-Djibouti Highway, but their Chadian sections are often in poor condition.

- Railways:** Chad has historically lacked a railway system. Plans have been announced for railway lines connecting N'Djamena to Sudan and Cameroon, with an agreement signed with a Chinese company in 2011 and construction reportedly starting in 2016, but progress has been slow and uncertain. Railways would significantly reduce transport costs for exports and imports, which currently rely heavily on Cameroon's rail system to reach the seaport of Douala.

- Air Transport:** As of 2013, Chad had an estimated 59 airports, but only 9 had paved runways. N'Djamena International Airport is the main international gateway, providing flights to Paris and several African cities. Air transport is vital for connecting remote areas but is too expensive for most of the population and for bulk cargo.

The state of transport infrastructure significantly impacts economic development by increasing costs, limiting market access, and isolating communities, thereby hindering social connectivity and equitable progress.

7.5.2. Energy

Access to modern energy services in Chad is extremely limited, posing a significant barrier to economic development and improved living standards.

- Power Generation and Access to Electricity:** The national power utility, the Chad Water and Electric Society (STEE), has struggled with mismanagement and inadequate capacity. It primarily serves the capital, N'Djamena, providing power to only about 15% of its citizens, and national electricity access covers a mere 1.5% of the total population. Power outages are frequent even in connected areas. The high cost of electricity further limits its use.

- Reliance on Biomass:** The vast majority of Chadians, especially in rural areas, rely on traditional biomass fuels such as wood and animal manure for cooking and heating. This reliance contributes to deforestation, indoor air pollution, and health problems, particularly for women and children.

- Oil Sector:** While Chad is an oil-exporting country, this has not translated into widespread energy security for its population.

- Development of Renewable Energy Sources:** Chad has significant potential for renewable energy, particularly solar power due to its abundant sunshine. However, the development of renewable energy sources is still in its nascent stages. Investing in renewables could help improve energy access, reduce reliance on biomass and expensive imported fuels for generators, and mitigate environmental impacts.

Addressing the energy deficit through investment in generation capacity (including renewables), grid expansion, and improved management of the sector is crucial for social and economic progress, industrial development, and environmental sustainability.

7.5.3. Telecommunications

Chad's telecommunications infrastructure is among the least developed in the world, though mobile services have seen some growth.

- Fixed-Line Telephony:** Fixed-line telephone services, provided by the state-owned company SotelTchad, are extremely limited. In 2000, there were only 14 fixed telephone lines per 10,000 inhabitants, one of the lowest densities globally. This situation has not significantly improved due to the high cost and limited reach of fixed infrastructure.

- Mobile Telephony:** Mobile phone penetration has increased but remains relatively low compared to other African countries. In September 2010, the mobile phone penetration rate was estimated at 24.3%. While this has likely grown, affordability and network coverage, especially in rural areas, remain challenges. Mobile services are primarily offered by private operators.

- Internet Connectivity:** Internet access is very limited and expensive. Chad consistently ranks at or near the bottom of global indices for network readiness and internet penetration. The lack of reliable electricity and terrestrial fiber optic infrastructure further hinders internet development. In September 2013, the government announced plans to seek partners for fiber optic technology, but widespread, affordable access is yet to be achieved.

The poor state of telecommunications infrastructure impedes business development, access to information, education, financial services, and overall social and economic integration. Improving connectivity is vital for Chad's development in the digital age.

8. Society

Chadian society is characterized by its rich ethnic and linguistic diversity, a young and rapidly growing population, and significant challenges in education, health, and human rights. Religious adherence, primarily to Islam and Christianity, also plays a vital role in social life.

8.1. Population

Chad's national statistical agency, INSEED, projected the country's 2015 population to be around 13.67 million, with approximately 3.2 million living in urban areas and 10.4 million in rural areas. The agency assessed the population as of mid-2017 at 15.77 million. By 2020, estimates placed the population at over 16 million. The population growth rate is high.

The country's population is very young, with an estimated 47% under the age of 15. The birth rate is high (estimated at 42.35 births per 1,000 people in some reports), while the mortality rate is also high, contributing to a life expectancy that is among the lowest in the world (around 52 years).

Population distribution is uneven. Density is extremely low in the Saharan Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Region (around 0.1 persons per square kilometer) but much higher in the southern Logone Occidental Region (around 52.4 persons per square kilometer). About half of the nation's population lives in the southern fifth of its territory. Urban life is concentrated in the capital, N'Djamena, which is the largest city with over 1.5 million inhabitants in 2017. Other major urban centers include Moundou, Sarh, Abéché, and Doba, which are considerably smaller but are experiencing rapid population growth and economic activity.

Chad also hosts a significant number of refugees, primarily from Sudan (due to the Darfur conflict) and the Central African Republic, placing additional strain on resources and services in host communities, particularly in the east and south.

The largest cities and towns by population (based on 2009 census data, with N'Djamena's figure being more recent) include:

| Rank | City | Population (2009 Census) | Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | N'Djamena | 951,418 | N'Djamena |

| 2. | Moundou | 137,251 | Logone Occidental |

| 3. | Abéché | 97,963 | Ouaddaï |

| 4. | Sarh | 97,224 | Moyen-Chari |

| 5. | Kélo | 57,859 | Tandjilé |

| 6. | Am Timan | 52,270 | Salamat |

| 7. | Doba | 49,647 | Logone Oriental |

| 8. | Pala | 49,461 | Mayo-Kebbi Ouest |

| 9. | Bongor | 44,578 | Mayo-Kebbi Est |

| 10. | Goz Beïda | 41,248 | Sila |

In the 2024 Global Hunger Index, Chad ranked 125th out of 127 countries, with a score indicating an alarming level of hunger.

8.2. Ethnic Groups

Chad is home to over 200 distinct ethnic groups, each with its own unique cultural characteristics, languages, and traditions. This ethnic diversity creates a complex social fabric. The colonial administration and subsequent independent governments have attempted to foster a national identity, but for most Chadians, local or regional affiliations often remain more influential than national identity, outside the immediate family.

The peoples of Chad carry significant ancestry from Eastern, Central, Western, and Northern Africa.

Broadly, ethnic groups can be classified according to the geographical region in which they live and their traditional lifestyles:

- Southern Groups:** Predominantly sedentary agriculturalists, many of whom are Christian or practice traditional animist religions. The largest single ethnic group in Chad is the Sara (estimated at 27.7% of the population in some older surveys), who live mainly in the fertile southern regions. Other southern groups include the Moundang.

- Sahelian and Northern Groups:** This region is inhabited by a mix of sedentary agriculturalists, semi-nomadic pastoralists, and nomadic groups, who are predominantly Muslim. The Arabs (often referred to as Baggara if cattle herders) constitute the second-largest ethnic grouping (around 12.3%). Other significant groups include the Toubou (comprising Teda and Daza subgroups) who are nomadic pastoralists in the northern Saharan regions; the Zaghawa, primarily in the east, straddling the border with Sudan; the Kanembu around Lake Chad; and the Maba (Ouaddaïan) in the east. Hausa and Fulani (Fulbe) groups are also present, often involved in trade and pastoralism.

Inter-ethnic relations have sometimes been strained, exacerbated by competition for resources (land and water), political manipulation, and historical grievances. Issues of social inclusion, representation in government, and the rights of minority groups are ongoing concerns for achieving national unity and equitable development.

8.3. Languages

Chad is a linguistically diverse nation with French and Arabic as its official languages. Beyond these, over 120 indigenous languages and dialects are spoken across the country, reflecting its rich ethnic tapestry.

- Official Languages:** French, inherited from the colonial period, is widely used in administration, education, and formal sectors. Standard Arabic is also an official language, important for religious and cultural purposes, particularly among Muslim populations.

- Chadian Arabic**: This dialect of Arabic has evolved as a widely spoken lingua franca throughout much of the country, facilitating communication and trade among different ethnic groups. It differs significantly from Modern Standard Arabic and incorporates elements from local languages.

- Indigenous Languages:** These belong to several major African language families:

- Nilo-Saharan: Includes languages like Kanuri (spoken by the Kanembu), Dazaga and Tedaga (spoken by the Toubou), Sara (a cluster of related languages like Ngambay, Sar, and Mbay spoken by the Sara people in the south), and Maban (spoken by the Maba/Ouaddaïan people).

- Afro-Asiatic: Primarily represented by various dialects of Arabic, including Chadian Arabic. The Chadic languages branch, to which Hausa belongs, also has some presence.

- Niger-Congo: A few languages from this family are spoken in the south.

The multiplicity of languages underscores the cultural diversity of Chad. While French and Chadian Arabic serve as unifying mediums of communication, the preservation and promotion of indigenous languages are important for maintaining cultural heritage.

8.4. Religion

Chad is a religiously diverse country. According to various estimates (including Pew Research in 2010 and other surveys), Islam is the majority religion, practiced by approximately 52-58% of the population. Christianity is followed by about 39-44% of Chadians. A smaller proportion adheres to traditional animist beliefs (around 1-4%), and some report no religious affiliation.

- Islam:** Muslims are largely concentrated in the northern, central, and eastern regions of Chad. The vast majority of Chadian Muslims are Sunni, often adhering to the Maliki school of jurisprudence. Sufism is also influential, with the Tijaniyyah order being prominent (followed by about 35% of Chadian Muslims in some surveys). Islam in Chad often incorporates local customs and traditions. A small minority (5-10%) may follow more fundamentalist interpretations, sometimes associated with Salafi influences.

- Christianity:** Christians are primarily found in southern Chad and the Guéra Region. Roman Catholics represent the largest Christian denomination (around 20-22%), while Protestants (including various evangelical groups, such as the Nigeria-based "Winners' Chapel") constitute a significant portion (around 17-20%). Christianity arrived in Chad with French and American missionaries and, like Chadian Islam, sometimes syncretizes aspects of pre-Christian religious beliefs.

- Traditional Animist Beliefs:** These encompass a variety of ancestor and place-oriented indigenous religions, with practices highly specific to particular ethnic groups. While their distinct adherence has declined, elements of animist beliefs often persist alongside Islam and Christianity.

- Other Religions:** Small communities of the Baháʼí Faith and Jehovah's Witnesses are also present, introduced after independence.

The constitution of Chad provides for a secular state and guarantees religious freedom. Generally, different religious communities coexist peacefully, although historical and political tensions have sometimes had religious undertones, particularly between the predominantly Muslim north and the largely Christian/animist south. Foreign missionaries representing both Christian and Islamic groups operate in the country. Saudi Arabian funding has supported social and educational projects and mosque construction.

8.5. Education

Chad's education system faces considerable challenges due to a dispersed population, limited resources, cultural factors, and a history of instability. These challenges have resulted in low literacy rates and constrained access to quality education for many Chadians.

- Structure:** The education system generally follows a structure of primary, secondary, and higher education.

- Literacy Rates:** Chad has one of the lowest literacy rates in Sub-Saharan Africa. Estimates vary, but literacy for adults has been reported around 33-40%, with significant disparities between men and women (e.g., 35.4% for men and 18.2% for women in a 2021 estimate).

- Access and Enrollment:** Although primary education is compulsory, enrollment and completion rates are low. In 2013, school attendance for children aged 5-14 was reported as low as 39%. Only about 68% of boys attend primary school, and the figure for girls is often lower due to cultural norms, early marriage, and domestic responsibilities. Child labor also impacts school attendance, with a 2013 report indicating 53% of children aged 5-14 were working.

- Quality of Education:** The quality of education is hampered by a shortage of qualified teachers, inadequate school infrastructure (classrooms, teaching materials), and large class sizes. Curricula may not always be relevant to local needs.

- Higher Education:** Higher education is limited. The primary institution is the University of N'Djamena. There are a few other specialized institutions. Access to higher education is restricted for most of the population.

- Disparities:** Significant disparities in educational access and attainment exist based on gender, geographic location (urban vs. rural, north vs. south), and socio-economic status. Girls, children in rural and nomadic communities, and those from impoverished families are particularly disadvantaged.

- Government Policies:** The Chadian government has expressed commitment to improving education, but efforts are constrained by budget limitations and the scale of the challenges. International organizations and NGOs play a role in supporting educational initiatives.

Addressing these educational challenges is crucial for Chad's human capital development, economic progress, and the promotion of social equity. Improving access to quality education, particularly for girls and marginalized groups, and enhancing literacy are key priorities.

8.6. Health

Chad faces severe public health challenges, reflected in some of the world's poorest health indicators. Access to medical services is extremely limited, particularly in rural areas, and the healthcare system is under-resourced and poorly equipped to meet the needs of the population.

- Key Health Indicators:**

- Life expectancy at birth is very low, often cited as one of the lowest globally (around 52-54 years).

- Infant mortality rates and under-five mortality rates are exceptionally high.

- Maternal mortality rates are also among the highest in the world (e.g., a 6.49% lifetime risk of maternal death has been reported, the world's highest).

- Access to Medical Services:** There is a critical shortage of healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses, midwives), medical facilities, and essential medicines. Most health infrastructure is concentrated in N'Djamena and a few other urban centers, leaving rural populations largely underserved. Financial barriers and long distances to health facilities further limit access for many.

- Prevalent Diseases and Endemic Health Issues:**

- Infectious diseases are widespread, including malaria, respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases (often due to poor sanitation and unsafe water), tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS (though prevalence is lower than in some other African regions).

- Malnutrition is a major problem, especially among children, contributing significantly to child mortality and stunting.

- Neglected tropical diseases are also prevalent.

- Outbreaks of diseases like measles and meningitis occur periodically.

- National Challenges in Improving Public Health:**

- Underfunding:** The health sector is chronically underfunded.

- Weak Health System:** Lack of infrastructure, equipment, and skilled personnel.

- Poor Sanitation and Hygiene:** Limited access to clean water and sanitation facilities contributes to the spread of waterborne diseases.

- Cultural Factors and Health-Seeking Behavior:** Traditional beliefs and practices can sometimes influence health-seeking behavior.

- Impact on Vulnerable Groups:** Women, children, refugees, internally displaced persons, and impoverished communities are particularly vulnerable to poor health outcomes. The ongoing humanitarian crises in and around Chad exacerbate these vulnerabilities.

Improving public health in Chad requires sustained investment in strengthening the healthcare system, expanding access to primary healthcare services, addressing malnutrition, improving water and sanitation, and implementing targeted interventions for major diseases and vulnerable populations. International aid plays a crucial role in supporting health initiatives.

8.7. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Chad is a matter of serious concern and has been consistently poor for decades. Authoritarian governance, prolonged periods of conflict, weak rule of law, and impunity for security forces have contributed to a climate where fundamental rights are frequently violated.

- Political Freedoms and Civil Liberties:**

- Freedom of expression, assembly, and association are severely restricted. Critics of the government, journalists, human rights defenders, and opposition activists often face harassment, intimidation, arbitrary arrest, and detention.

- Peaceful protests are frequently met with excessive force by security forces, sometimes resulting in injuries and fatalities.

- Media outlets face censorship and pressure from authorities.

- Due Process and Conditions of Detention:**

- Arbitrary arrests and detentions are common. Detainees are often held for extended periods without charge or trial.

- The judicial system is weak and subject to executive influence, undermining the right to a fair trial.

- Conditions in prisons and detention centers are harsh and often life-threatening, characterized by overcrowding, poor sanitation, inadequate food and medical care, and torture or other ill-treatment.

- Rights of Women and Children:**

- Violence against women, including domestic violence and sexual violence (particularly in conflict-affected areas), is widespread.

- Female genital mutilation is practiced in many communities despite being prohibited by law. Early and forced marriage is also a concern.

- Women face discrimination in law and practice, limiting their access to education, employment, and political participation.

- Child labor, including its worst forms, and child trafficking persist. Children have also been recruited by armed groups in past conflicts.

- Situation of Ethnic Minorities and Other Vulnerable Groups:**

- Ethnic discrimination and tensions have been recurrent issues, sometimes fueled by political dynamics. Certain ethnic groups have reported marginalization and targeting by state security forces or rival communities.

- Refugees and internally displaced persons face precarious living conditions and protection challenges.

- Impunity:** A culture of impunity for human rights violations committed by security forces and government officials is a major problem. Investigations into abuses are rare, and perpetrators are seldom brought to justice, which perpetuates cycles of violence and mistrust.

- Role of Civil Society and International Scrutiny:**

- Local human rights organizations operate under difficult conditions but play a vital role in documenting abuses and advocating for reform.

- International human rights groups and UN bodies regularly report on the human rights situation in Chad, calling for accountability and improvements.

Addressing these deep-seated human rights issues requires comprehensive reforms, including strengthening the judiciary, ensuring accountability for perpetrators of abuse, protecting fundamental freedoms, and promoting a culture of respect for human rights across all sectors of society. This is essential for fostering democratic development, social justice, and lasting peace in Chad.

9. Culture

Chad possesses a rich and diverse cultural heritage, stemming from its multitude of ethnic groups, languages, and historical influences. Chadian culture is expressed through its traditional lifestyles, arts, cuisine, music, and sports. The Chadian government has made efforts to promote national traditions, including through institutions like the Chad National Museum and the Chad Cultural Centre.

9.1. Cuisine

Millet is the staple food in much of Chad. It is often ground into flour and used to make balls of paste (alyshalyshArabic) in the north, biyabiyaFrench in the south) that are typically dipped in various sauces made from meat, fish, or vegetables like okra. Sorghum is another important grain. In the south, cassava and rice are also consumed.

Fish is popular, especially around Lake Chad and the rivers. It is commonly prepared and sold either as salanga (sun-dried and lightly smoked smaller fish like Alestes and Hydrocynus) or as banda (larger smoked fish). Meat, particularly goat, sheep, and beef (in areas where cattle are raised), is also part of the diet, though often reserved for special occasions by poorer families. Fried grasshoppers are a local delicacy in some areas.

Popular traditional beverages include carcaje, a sweet red tea extracted from hibiscus leaves, and millet beer, known as billi-billi when brewed from red millet and coshate when from white millet. Alcoholic beverages are more common in the south than in the predominantly Muslim north.

9.2. Music and Performing Arts

The music of Chad is diverse, reflecting its ethnic variety. Traditional instruments include:

- The kinde, a type of bow harp.

- The kakaki, a long tin horn often associated with royalty in Sahelian cultures.

- The hu hu, a stringed instrument that uses calabash gourds as resonators.

- Various types of drums, whistles, balafons (xylophones), and flutes.

Specific instruments and musical styles are often linked to particular ethnic groups. For example, the Sara people often use whistles, balafons, harps, and kodjo drums, while the Kanembu combine drum rhythms with flute-like instruments.

Traditional dances and songs are integral to ceremonies, festivals, and social gatherings, varying significantly from one ethnic group to another.

Modern Chadian music has seen some development. The group Chari Jazz, formed in 1964, is considered a pioneer. Later groups like African Melody and International Challal attempted to blend modern styles with traditional Chadian music. Groups such as Tibesti have often focused on traditional sai, a style of music from southern Chad. While modern music faced initial resistance, interest grew in the 1990s, leading to wider distribution. However, piracy and lack of legal protection for artists' rights remain challenges for the music industry.

9.3. Literature

Like in other Sahelian countries, literature in Chad has been affected by economic, political, and social challenges. Many Chadian authors have written from exile or expatriate status, and their works often explore themes of political oppression, historical discourse, social issues, and cultural identity.

Since 1962, around 20 Chadian authors have produced some 60 works of fiction. Notable Chadian writers include: