1. Overview

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country in West Africa, characterized by a predominantly flat topography with significant Sahelian and Sudanic savanna ecoregions. Historically, the region was home to the powerful Mossi Kingdoms from the 11th century until French colonization in the late 19th century. It gained independence as the Republic of Upper Volta in 1960. The nation's history has been marked by political instability, including several coups d'état. A pivotal period was the revolutionary government of Captain Thomas Sankara (1983-1987), who renamed the country Burkina Faso, meaning "Land of Incorruptible People," and initiated ambitious social and economic reforms aimed at national self-sufficiency, women's empowerment, and anti-imperialism. His popular programs significantly impacted social justice and national consciousness but were cut short by his assassination. He was succeeded by Blaise Compaoré, whose 27-year rule ended with a popular uprising in 2014. The subsequent democratic transition has been challenged by renewed instability, including a severe and ongoing jihadist insurgency since the mid-2010s, which has led to a major humanitarian crisis and widespread internal displacement, severely impacting human rights and security. Military coups in 2022 have returned the country to military rule, suspending democratic institutions.

The country's economy is largely based on agriculture, particularly cotton and livestock, and gold mining. It faces significant challenges including poverty, environmental degradation, and inadequate infrastructure. Socially, Burkina Faso is ethnically diverse, with the Mossi people being the largest group. Islam is the majority religion, followed by Christianity and traditional indigenous beliefs. The nation has a rich cultural heritage, particularly in music, cinema (hosting the biennial FESPACO), and traditional arts and crafts. Efforts to improve education and healthcare continue amidst ongoing security and economic challenges, with a strong focus on achieving social progress and equitable development.

2. Etymology

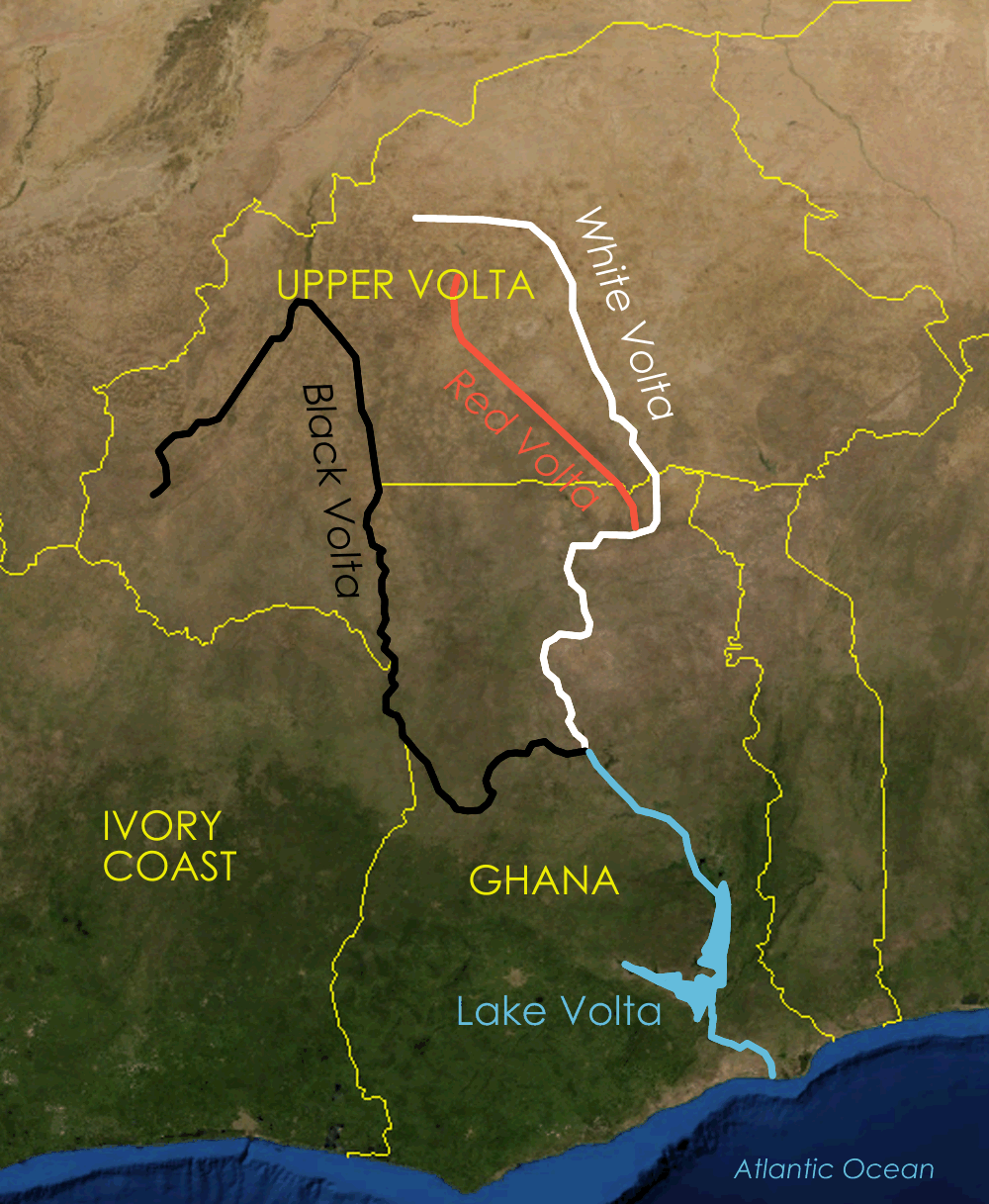

Burkina Faso was formerly known as the Republic of Upper Volta, a name derived from its geographical location on the upper courses of the Volta River. The river system is composed of three main tributaries: the Black Volta (Mouhoun), White Volta (Nakambé), and Red Volta (Nazinon), which were reflected in the colors of the former national flag.

On August 4, 1984, then-President Thomas Sankara initiated the renaming of the country to "Burkina Faso." This name is a composite of words from two of the country's major indigenous languages. "Burkina" originates from the Mooré language and means "upright," "honest," or "incorruptible," signifying the pride and integrity of its people. "Faso" comes from the Dyula language (written in N'Ko script as ߝߊ߬ߛߏ߫fasoDyula) and means "fatherland" or "father's house." Thus, "Burkina Faso" is commonly translated as "Land of Incorruptible People" or "Land of Honest Men." The demonym for its citizens, "Burkinabè," incorporates the suffix "-bè" from the Fula language, meaning "women or men."

3. History

The history of Burkina Faso spans from early human settlements through the rise and fall of powerful indigenous kingdoms, French colonial domination, a turbulent post-independence period marked by revolutionary change and political instability, and contemporary challenges including democratic consolidation and security crises.

3.1. Early History and Mossi Kingdoms

The northwestern part of present-day Burkina Faso was inhabited by hunter-gatherers from approximately 14,000 BCE to 5,000 BCE. Archaeological excavations in 1973 unearthed their tools, including scrapers, chisels, and arrowheads. Agricultural settlements began to appear between 3600 and 2600 BCE, with evidence of relatively permanent structures. The Iron Age Bura culture flourished in the southwest of modern-day Niger and the southeast of contemporary Burkina Faso from the 3rd to the 13th centuries CE. The development of iron working, including smelting and forging for tools and weapons, occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa by 1200 BCE. The oldest evidence of iron smelting in Burkina Faso dates from 800 to 700 BCE and is part of the Ancient Ferrous Metallurgy Sites of Burkina Faso, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

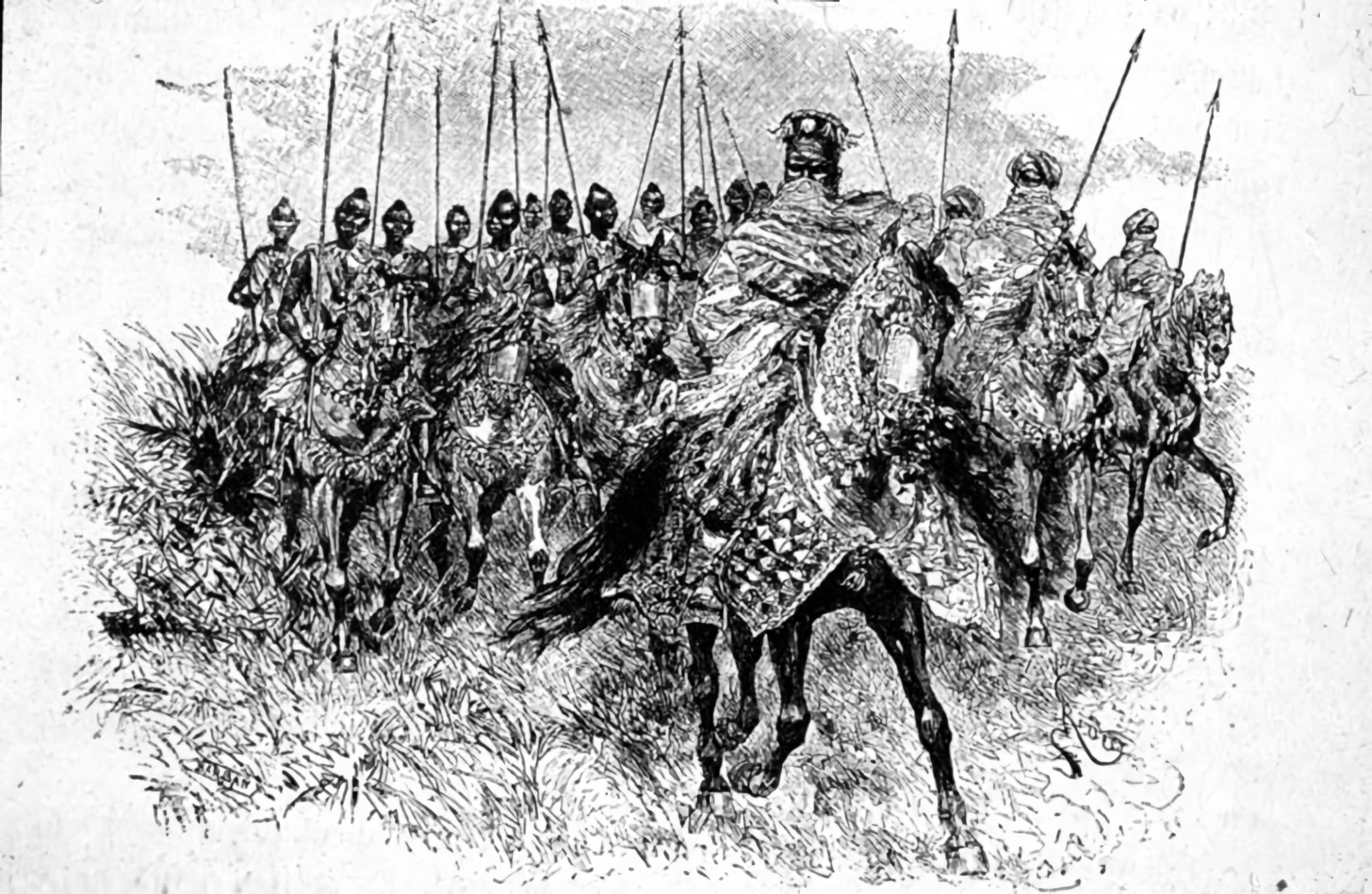

Various ethnic groups, including the Mossi, Fula, and Dioula, arrived in successive waves between the 8th and 15th centuries. The Proto-Mossi arrived in the far eastern part of what is today Burkina Faso sometime between the 8th and 11th centuries. From the 11th century onwards, the Mossi people established several powerful and distinct kingdoms. The most prominent among these were Ouagadougou, Tenkodogo, and Yatenga. These kingdoms developed sophisticated political and social structures and maintained their dominance in the Volta River basin region for centuries. The Mossi kingdoms were characterized by a hierarchical system led by an emperor or king, the Mogho Naba, particularly in Ouagadougou. Their cavalry was renowned and enabled them to raid deep into enemy territories, even contending with larger empires like the Mali Empire. Between 1328 and 1338, Mossi warriors raided Timbuktu. However, they were later defeated by Sonni Ali of the Songhai Empire at the Battle of Kobi in Mali in 1483. The Mossi kingdoms largely resisted Islamization for an extended period, maintaining their traditional beliefs and social order. Other groups like the Samo arrived around the 15th century, and the Dogon inhabited the north and northwest regions until migrating in the 15th or 16th centuries. During the early 16th century, the Songhai Empire conducted numerous slave raids into the area. The 18th century saw the establishment of the Gwiriko Empire at Bobo-Dioulasso, and settlement by groups such as the Dyan, Lobi, and Birifor along the Black Volta. These early societies and kingdoms laid the foundation for the cultural and ethnic makeup of modern Burkina Faso.

3.2. French Colonial Rule

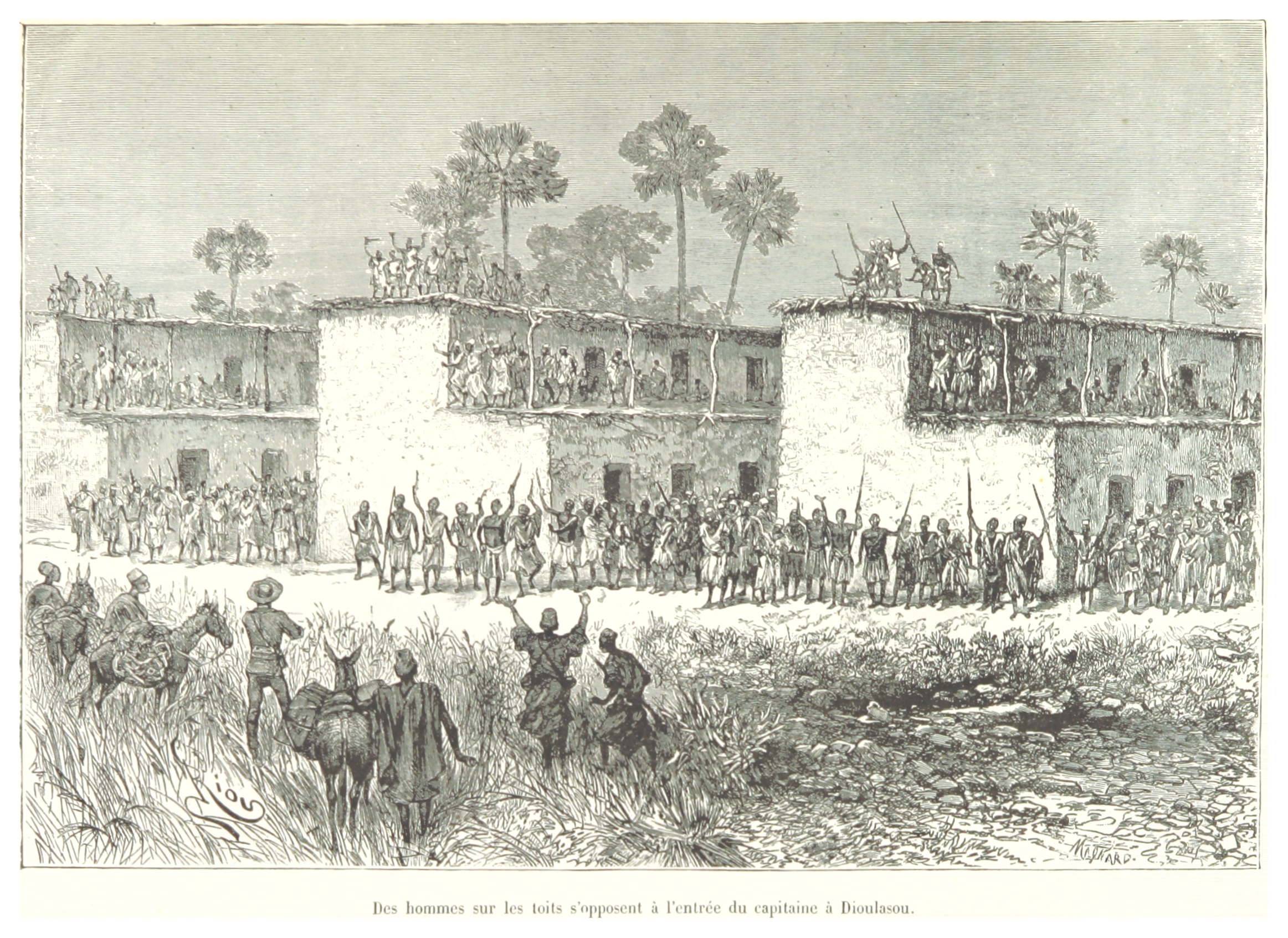

The Scramble for Africa in the late 19th century saw European powers vying for control over the continent. French military incursions into the region of present-day Burkina Faso began in the early 1890s. French officers sometimes fought local peoples and at other times forged alliances and treaties. In 1896, the French military forces conquered Ouagadougou, the capital of the most powerful Mossi Kingdom, and established a protectorate. The eastern and western regions, where resistance from forces loyal to the powerful ruler Samori Ture complicated matters, came under French occupation by 1897. By 1898, most of the territory was nominally conquered, although French control remained uncertain in many areas. The Franco-British Convention of June 14, 1898, established the modern borders of the country.

In 1904, the territories of the Volta River basin were integrated into the Upper Senegal and Niger colony, part of the larger French West Africa federation, with its capital in Bamako. The French colonial administration implemented a system of indirect rule in some areas, utilizing existing traditional leadership structures like the Mossi kingdoms, but ultimate authority rested with the French. French became the language of administration and education.

The indigenous population faced significant discrimination. For instance, African children were often denied basic privileges afforded to children of colonists. Conscripted soldiers from the territory, known as Tirailleurs sénégalais, participated in World War I on European fronts. Between 1915 and 1916, the western districts and the eastern fringe of Mali became the stage for the Volta-Bani War, one of the most significant armed oppositions to colonial government in French West Africa. The French eventually suppressed this movement after suffering defeats and organizing a large expeditionary force.

On March 1, 1919, fearing recurrent uprisings and for economic reasons, the French colonial government separated the territory of present-day Burkina Faso from Upper Senegal and Niger, creating the distinct colony of French Upper Volta (Haute-VoltaHaute-VoltaFrench). François Charles Alexis Édouard Hesling became its first governor. He initiated road construction and promoted cotton cultivation for export, often through coercive means, which ultimately proved unsuccessful.

On September 5, 1932, the colony of French Upper Volta was dismantled, and its territory was divided among the neighboring French colonies of Ivory Coast, French Sudan (present-day Mali), and Niger. The Ivory Coast received the largest share, including most of the population and the cities of Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso.

Following World War II, amid rising anti-colonial sentiment, France reconstituted the colony of Upper Volta on September 4, 1947, within its previous boundaries, as part of the French Union. On December 11, 1958, Upper Volta achieved self-government as the Republic of Upper Volta (République de Haute-VoltaRépublique de Haute-VoltaFrench) within the French Community, a significant step towards full independence. This was spurred by the Loi Cadre (Overseas Reform Act) of 1956, which initiated decentralization and increased self-governance in French overseas territories. Full independence was achieved on August 5, 1960.

3.3. Republic of Upper Volta (1958-1984)

The Republic of Upper Volta was established on December 11, 1958, as a self-governing autonomous republic within the French Community. Full independence from France was attained on August 5, 1960. This period was characterized by initial attempts at nation-building, followed by significant political instability, military coups, and social unrest, culminating in a revolutionary period that led to the country's renaming.

3.3.1. Early Independence and Political Instability (1960-1983)

Maurice Yaméogo, leader of the Voltaic Democratic Union (UDV), became the first president of the independent Republic of Upper Volta. The 1960 constitution provided for a presidential system with a national assembly elected by universal suffrage for five-year terms. However, shortly after coming to power, Yaméogo banned all political parties other than the UDV, establishing a one-party state. His government faced growing discontent due to economic difficulties and authoritarian tendencies. Mass demonstrations and strikes by students, labor unions, and civil servants led to the first military coup on January 3, 1966.

Lieutenant-Colonel Sangoulé Lamizana seized power, suspended the constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, and headed a military government. The army remained in power for four years. Lamizana's rule, which lasted through the 1970s in various military or mixed civil-military governments, coincided with the severe Sahel drought and famine, which had a devastating impact on Upper Volta. A new constitution was ratified in 1970, leading to a brief return to civilian rule, but political infighting persisted. Lamizana was re-elected in open elections in 1978 after another constitution was approved in 1977. However, his government continued to face problems with powerful trade unions.

On November 25, 1980, Colonel Saye Zerbo overthrew President Lamizana in a bloodless coup (1980 coup), establishing the Military Committee of Recovery for National Progress (CMRPN) and abrogating the 1977 constitution. Zerbo's regime also encountered resistance from trade unions and was itself overthrown two years later, on November 7, 1982, by Major Dr. Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo and the Council of Popular Salvation (CSP) in the 1982 coup. The CSP continued to ban political parties but promised a transition to civilian rule and a new constitution.

Infighting soon developed within the CSP between moderate and radical leftist factions. Captain Thomas Sankara, a charismatic leader of the leftist faction, was appointed Prime Minister in January 1983. However, his rising popularity and radical ideas led to his arrest in May 1983 under pressure from conservative elements within the CSP and possibly external influences.

3.3.2. Thomas Sankara and the Revolution (1983-1987)

On August 4, 1983, a military coup (1983 coup) orchestrated by Captain Blaise Compaoré brought his close friend and ally, Captain Thomas Sankara, to power as President. This event marked the beginning of what became known as the "Burkinabè Revolution." Sankara's government, the National Council for the Revolution (CNR), embarked on an ambitious and radical program of social, economic, and political transformation.

His foreign policies centered on anti-imperialism, Pan-Africanism, and non-alignment. Sankara's government rejected foreign aid that came with conditions, pushed for odious debt reduction, nationalized all land and mineral wealth, and sought to avert the influence of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. He fostered relations with other revolutionary governments, including Cuba and Libya.

Domestically, Sankara's policies aimed at self-sufficiency and social justice. Key initiatives included:

- Name Change:** On August 4, 1984, the country's name was changed from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, meaning "Land of Incorruptible People" or "Land of Upright Men," to symbolize a break from the colonial past and foster national pride.

- Social Reforms:** A nationwide literacy campaign was launched. Significant advancements were made in women's rights, including outlawing female genital mutilation (FGM), forced marriage, and polygamy. Women were encouraged to participate in all sectors of society, including government and the military.

- Public Health:** Mass vaccination campaigns were conducted, immunizing over 2.5 million children against meningitis, yellow fever, and measles. Every village was encouraged to build a medical dispensary.

- Land Reform and Agriculture:** Land was redistributed to peasants, and agrarian self-sufficiency was promoted through irrigation projects and support for local agricultural consumption. Cereal production significantly increased.

- Infrastructure Development:** Efforts were made to construct railways and roads, often utilizing community labor (travaux d'intérêt commun).

- Anti-Corruption and Austerity:** Sankara led by example, reducing government waste, selling off the fleet of expensive government cars, and promoting a modest lifestyle for public officials. Popular Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) were established at local levels, intended to involve citizens in governance and revolutionary vigilance, though they were sometimes criticized for overreach.

- Environmental Protection:** Sankara was a pioneer in environmental awareness, launching programs to combat desertification by planting millions of trees (over 10 million in 15 months) and regulating firewood cutting and cattle roaming.

Sankara's charismatic leadership and populist policies gained him widespread support among the Burkinabè people and made him an iconic figure across Africa, often dubbed "Africa's Che Guevara." His emphasis on self-reliance, social justice, and challenging neo-colonial structures resonated deeply. From a perspective valuing popular empowerment and social progress, Sankara's era represented a significant attempt to fundamentally alter the country's trajectory towards greater equity and sovereignty.

However, his revolutionary methods, including the establishment of People's Tribunals and the sometimes heavy-handed actions of the CDRs, alienated some segments of society, including traditional chiefs, some business elites, and elements within the military. His foreign policy also created tensions with some neighboring conservative regimes and former colonial powers.

On October 15, 1987, Thomas Sankara was assassinated along with twelve other officials in a coup d'état organized by his former colleague and second-in-command, Blaise Compaoré. Sankara's death sent shockwaves across Africa and marked the end of the Burkinabè Revolution. His legacy continues to inspire movements for social justice and democratic change in Burkina Faso and beyond. His contributions to challenging corruption, empowering women, and promoting self-determination are viewed positively, though the authoritarian aspects of his rule remain a subject of discussion.

3.4. Burkina Faso (1984-present)

This period begins with the country's renaming by Thomas Sankara and continues through the long rule of Blaise Compaoré, a popular uprising, a fragile democratic transition, and the severe challenges posed by a jihadist insurgency and subsequent military coups.

3.4.1. Blaise Compaoré's Era (1987-2014)

Blaise Compaoré seized power on October 15, 1987, after the assassination of Thomas Sankara. Compaoré immediately began to reverse many of Sankara's revolutionary policies, moving away from socialist-inspired programs and towards economic liberalization, re-engaging with international financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank. He consolidated his power, establishing the Popular Front. While some CDRs mounted armed resistance for several days, they were suppressed by the army.

Compaoré cited deteriorating relations with neighboring countries and France as reasons for the coup, arguing Sankara had jeopardized foreign relations. Following an alleged coup attempt in 1989, Compaoré introduced limited democratic reforms. A new constitution was adopted in 1991, allowing for a multi-party system. Compaoré was subsequently "elected" president in the 1991 presidential election, which was boycotted by major opposition parties. He was re-elected in 1998, 2005, and 2010, often in elections criticized for lacking fairness and transparency.

During his 27-year rule, Compaoré's regime was characterized by a concentration of power and limited political freedoms. While maintaining a facade of democracy, his government was often accused of human rights abuses, suppression of dissent, and corruption. The assassination of investigative journalist Norbert Zongo in 1998, who was probing the death of a chauffeur working for Compaoré's brother, became a symbol of impunity and lack of press freedom, sparking widespread protests.

Economically, Burkina Faso saw some growth, particularly in the gold mining sector, but remained one of the least developed countries, with high poverty rates. Compaoré played a significant role as a mediator in several West African conflicts, including crises in Ivory Coast, Togo, and Mali, which enhanced his regional standing but was sometimes seen as a way to deflect attention from domestic issues.

In 2000, the constitution was amended to reduce the presidential term from seven to five years and to impose a two-term limit. However, a controversial ruling by the constitutional council in 2005 stated that the amendment would not apply to Compaoré's terms served before 2000, allowing him to run again. The 2011 protests, sparked by a schoolboy's death and coupled with military mutinies and strikes, called for Compaoré's resignation and reforms, indicating growing dissatisfaction.

Compaoré's impact on democracy and human rights is largely viewed critically. While he introduced a multi-party system, it was often seen as a managed democracy that did not allow for genuine political competition or accountability. Human rights organizations consistently reported on restrictions on freedom of expression, assembly, and the press, as well as instances of extrajudicial killings and impunity for state security forces. His long tenure stifled democratic development and fostered a climate of fear for opponents and critics.

3.4.2. 2014 Uprising and Transitional Government

In October 2014, Blaise Compaoré attempted to amend the constitution to allow him to run for another presidential term, extending his 27-year rule. This move triggered massive popular protests, known as the 2014 Burkinabè uprising. Starting on October 28, demonstrators, largely led by youth and civil society activists, took to the streets of Ouagadougou and other cities.

On October 30, protests escalated as demonstrators set fire to the parliament building and took over the national television headquarters. The Ouagadougou International Airport was closed, and MPs suspended the vote on the constitutional amendment. The military, initially hesitant, eventually stepped in, dissolving all government institutions and imposing a curfew. On October 31, 2014, faced with overwhelming public opposition and loss of military support, Blaise Compaoré resigned and fled the country, initially to Ivory Coast.

Following Compaoré's departure, there was a brief period of uncertainty as the military vied for control. Lieutenant Colonel Yacouba Isaac Zida, deputy commander of the presidential guard, initially declared himself head of state. However, after pressure from opposition parties, civil society, and international actors (including the African Union and ECOWAS), a transitional charter was negotiated.

In November 2014, a transitional government was established to guide the country to new elections. Michel Kafando, a former diplomat, was appointed as the transitional president. Lt. Col. Zida became the acting Prime Minister and Minister of Defense. The transitional government was tasked with organizing free and fair elections and implementing reforms. This period marked a significant moment of popular mobilization for democratic change in Burkina Faso, demonstrating the public's demand for an end to autocratic rule and a desire for genuine democratic governance.

3.4.3. Democratic Transition and Renewed Instability (2015-2021)

The transitional period faced a significant challenge in September 2015 when members of the elite Regiment of Presidential Security (RSP), a unit loyal to former President Compaoré, staged a coup d'état. They arrested interim President Michel Kafando and Prime Minister Isaac Zida, declaring General Gilbert Diendéré, Compaoré's former chief of staff, as the new head of state. The coup was widely condemned both domestically and internationally. Popular resistance, mediation efforts by ECOWAS, and pressure from the regular army led to the collapse of the coup within a week. On September 23, 2015, Kafando and Zida were reinstated. The RSP was subsequently disbanded.

General elections were held on November 29, 2015. Roch Marc Christian Kaboré of the People's Movement for Progress (MPP) won the presidency in the first round with 53.5% of the vote, marking the country's first democratic transition of power in decades without a president with a military background taking office. Kaboré was sworn in on December 29, 2015.

Kaboré's presidency focused on democratic consolidation, economic development, and addressing social needs. However, his government faced immense challenges, most notably the rapidly deteriorating security situation due to the jihadist insurgency spreading from neighboring Mali. Despite efforts to reform the security sector and engage in regional cooperation, the government struggled to contain the violence.

Kaboré was re-elected in the general election of November 22, 2020, but his party, the MPP, failed to secure an absolute parliamentary majority. The elections were held amidst the escalating security crisis, which prevented voting in some areas. The persistent insecurity, coupled with economic hardship and social grievances, continued to fuel political instability and erode public trust in the government's ability to protect its citizens and provide basic services.

3.4.4. Jihadist Insurgency and Security Crisis (Mid-2010s-present)

Since the mid-2010s, Burkina Faso has been severely affected by the expansion of Islamist extremist groups, including those allied with Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS), operating across the Sahel region. The insurgency, which began in earnest in August 2015, initially targeted northern regions bordering Mali and Niger but rapidly spread to eastern and other parts of the country.

Attacks by groups such as Jama'at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), as well as local groups like Ansarul Islam, have targeted security forces, state symbols, religious leaders, schools, and civilians, including specific targeting of Christians. High-profile attacks, such as the January 2016 attack in Ouagadougou that killed 30 people, and the March 2018 attacks on the French embassy and army headquarters, brought the reality of the threat to the capital.

The violence has led to a devastating humanitarian crisis. By early 2023, over two million people had become internally displaced persons (IDPs), fleeing their homes due to attacks and threats. The conflict has disrupted agriculture, closed thousands of schools and health centers, and exacerbated food insecurity, with millions requiring humanitarian assistance.

The security forces, often under-equipped and overwhelmed, have struggled to contain the insurgency. They have also been implicated in serious human rights abuses, including extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances, particularly targeting members of the Fulani ethnic group, who are often stereotyped as supporting jihadists. Human Rights Watch reported that between mid-2018 and February 2019, jihadists murdered at least 42 people, while military forces killed at least 116 mostly Fulani civilians without trial. The Karma massacre in April 2023, where uniformed men believed to be soldiers killed at least 156 civilians, highlighted the grave concerns. These abuses have fueled inter-communal tensions and potentially driven recruitment into extremist groups.

Affected populations have suffered immensely, facing loss of life, livelihoods, and displacement, with limited access to justice or protection. The government's inability to stem the violence and protect civilians became a major source of public discontent and a key factor leading to the military coups in 2022. International military support, notably from France's Operation Barkhane, proved insufficient to turn the tide. The insurgency has transformed Burkina Faso from a relatively stable country into one of the epicenters of conflict in the Sahel. The 2024 Barsalogho attack in August, reportedly killing hundreds, underscored the ongoing severity of the crisis.

3.4.5. 2022 Coups d'état and Military Rule

The escalating security crisis and the government's perceived inability to effectively counter the jihadist insurgency led to two military coups in 2022.

On January 23-24, 2022, mutinying soldiers, citing the worsening security situation and lack of support for the armed forces, arrested and deposed President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré (January 2022 coup). The coup was led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, who established the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (MPSR) as the ruling junta. The constitution was initially suspended, then restored on January 31, with Damiba appointed as interim president. Both ECOWAS and the African Union suspended Burkina Faso's membership in response to the coup. Damiba pledged to prioritize the fight against insurgents and restore security. A charter was approved in March 2022 allowing for a three-year military-led transition before elections.

However, the security situation continued to deteriorate under Damiba's rule. Discontent within the military grew, particularly among younger officers who felt that Damiba's strategy was failing. On September 30, 2022, a second coup (September 2022 coup) overthrew Damiba. Captain Ibrahim Traoré, a relatively unknown army officer, emerged as the new leader of the MPSR. Traoré justified the coup by citing Damiba's inability to stem the jihadist violence. Damiba resigned and left the country.

Captain Traoré was officially appointed president on October 6, 2022, and Apollinaire Joachim Kyélem de Tambèla was appointed interim Prime Minister. The new military junta also promised to focus on the security crisis. In April 2023, authorities declared a "general mobilization" to combat terrorism. The military government has sought to diversify its international partnerships, notably strengthening ties with Russia while relations with France, the traditional key partner, have significantly deteriorated, leading to the departure of French troops. In January 2024, the junta, alongside those in Mali and Niger, announced their withdrawal from ECOWAS.

The status of political party activities has been curtailed under military rule, and democratic processes are suspended. International responses have included condemnations of the coups and calls for a swift return to constitutional order, though the junta initially stated the 3-year transition plan remained, later extending military rule by five years in May 2024, pushing potential elections to 2029 due to the ongoing security crisis. The human rights situation remains precarious, with concerns over abuses by both state security forces and non-state armed groups in the context of the counter-insurgency operations.

4. Geography

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country located in West Africa. It covers an area of 106 K mile2 (274.22 K km2). It is bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the south, and Ivory Coast to the southwest. The country lies mostly between latitudes 9° and 15° N, and longitudes 6° W and 3° E.

The geography of Burkina Faso is characterized by a relatively flat terrain, with some variations in elevation and distinct climatic zones.

4.1. Topography and Geology

The country consists of two major types of landscape. The larger part of Burkina Faso is a vast peneplain, forming a gently undulating landscape with an average altitude of around 1312 ft (400 m). In some areas, isolated hills, remnants of a Precambrian massif, rise above the plateau. The southwestern region forms a sandstone massif, where the country's highest peak, Ténakourou, is located at an elevation of 2457 ft (749 m). This massif is characterized by sheer cliffs that can reach up to 492 ft (150 m) in height. Overall, the difference between the highest and lowest terrain is no greater than 1969 ft (600 m), making Burkina Faso a relatively flat country. The geological composition is primarily ancient crystalline rocks of the Precambrian era, covered in many areas by lateritic soils.

4.2. Climate

Burkina Faso has a primarily tropical climate with two distinct seasons: a rainy season and a dry season.

- The rainy season typically lasts for about four months, from May/June to September. During this period, the country receives most of its annual rainfall, which varies from north to south.

- The dry season is characterized by the Harmattan, a hot, dry, and dusty wind blowing from the Sahara Desert.

The country can be divided into three main climatic zones:

- Sahelian Zone:** Located in the north, this zone typically receives less than 24 in (600 mm) of rainfall annually. Temperatures are high, ranging from 41 °F (5 °C) to 116.6 °F (47 °C). It is a relatively dry tropical savanna that extends from the Horn of Africa to the Atlantic, bordering the Sahara to its north.

- Sudan-Sahel Zone:** Situated between approximately 11°3′ and 13°5′ north latitude, this is a transitional zone in terms of rainfall and temperature.

- Sudan-Guinea Zone:** Located further south, this zone receives more than 35 in (900 mm) of rain each year and experiences cooler average temperatures.

The climate contributes significantly to food insecurity, with the country experiencing radical climatic variations from severe flooding to extreme drought. These unpredictable climatic shocks make agriculture, the mainstay of the economy, highly vulnerable. The climate also makes crops susceptible to insect attacks, such as locusts and crickets.

4.3. Hydrology

Burkina Faso's former name, Upper Volta, was derived from its three main rivers:

- The Black Volta (or Mouhoun)

- The White Volta (Nakambé)

- The Red Volta (Nazinon)

The Black Volta and the Komoé River (which flows to the southwest) are the only two rivers in the country that flow year-round. The basin of the Niger River also drains approximately 27% of the country's surface. Tributaries of the Niger, such as the Béli, Gorouol, Goudébo, and Dargol, are seasonal streams, flowing for only four to six months a year but can cause significant flooding when they overflow.

The country also contains numerous lakes, with the principal ones being Tingrela, Bam, and Dem. There are also large ponds, such as Oursi, Béli, Yomboli, and Markoye. Water shortages are a frequent problem, particularly in the northern regions of the country.

4.4. Natural Resources and Ecosystems

Burkina Faso possesses several natural resources, including gold, manganese, limestone, marble, phosphates, pumice, and salt. Gold mining has become a particularly important sector of the economy.

The country lies within two major terrestrial ecoregions: the Sahelian Acacia savanna in the north and the West Sudanian savanna further south.

- The Sahelian Acacia savanna is characterized by thorny acacia trees and grasses, adapted to arid conditions.

- The West Sudanian savanna is a tropical savanna with more woodland and taller grasses due to higher rainfall.

Forest cover in Burkina Faso was around 23% of the total land area in 2020, equivalent to 6,216,400 hectares (ha), a decrease from 7,716,600 ha in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 6,039,300 ha, and planted forest covered 177,100 ha. Primary forest (native tree species with no clear signs of human activity) constituted 0% of the naturally regenerating forest. About 16% of the forest area was within protected areas. In 2015, 100% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership.

Representative flora includes various species of acacia, shea trees, baobabs, and tamarinds. The fauna includes elephants (Burkina Faso has a larger elephant population than many West African countries), lions, leopards, buffalo (including the dwarf or red buffalo), cheetahs, caracals, spotted hyenas, and the endangered African wild dog.

Protected areas are crucial for conserving biodiversity. The main national parks and reserves include:

- The W National Park, a transboundary park shared with Benin and Niger, and part of the W-Arly-Pendjari Complex UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- The Arly National Park (Arly Wildlife Reserve) in the east.

- The Léraba-Comoé Classified Forest and Partial Reserve of Wildlife in the west.

- The Mare aux Hippopotames (Lake of Hippopotamuses) in the west, a Ramsar site.

5. Politics and Government

Burkina Faso is officially a semi-presidential republic. However, following military coups in January and September 2022, the constitution has been suspended, and the country is currently under military rule led by the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (MPSR). This section describes the governmental structure as defined by the constitution (when active) and the recent political developments.

5.1. Government Structure and Constitution

The constitution of June 2, 1991 (last significantly revised in 2018, but currently suspended) established a government with a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

- Executive Branch:** The President is the head of state, historically elected by popular vote for a five-year term, renewable once (amendment in 2000 reduced the term from seven years and set a two-term limit). The president appoints the Prime Minister, who is the head of government. The Prime Minister recommends a cabinet for appointment by the president. The 2018 constitutional revision included provisions preventing any individual from serving as president for more than ten years (consecutively or intermittently) and provided a method for impeaching a president.

- Legislative Branch:** The legislature was unicameral, known as the National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale). It historically comprised 111 members (later increased to 127) elected for five-year terms through a system of proportional representation. The National Assembly could be dissolved by the President. An earlier bicameral system with an upper house (Chamber of Representatives) was abolished in 2002.

- Judicial Branch:** The judiciary is nominally independent. The highest court for most matters is the Supreme Court. There is also a Constitutional Council, composed of ten members, responsible for constitutional matters, and an Economic and Social Council with purely consultative roles.

Following the January 2022 coup, the military junta dissolved the parliament and government and initially suspended the constitution. The constitution was briefly restored on January 31, 2022, but was suspended again following the September 2022 coup. In March 2022, the first junta approved a charter for a three-year military-led transition to be followed by elections, a timeline that the second junta initially said it would respect, but in May 2024, military rule was extended for five more years.

5.2. Major Political Parties and Elections

Historically, Burkina Faso operated under a multi-party system. Key political parties included:

- The People's Movement for Progress (MPP): Formed by Roch Marc Christian Kaboré after leaving the CDP, it became the ruling party after the 2015 elections.

- The Congress for Democracy and Progress (CDP): The former ruling party of Blaise Compaoré, it was a dominant force for over two decades.

- The Union for Progress and Reform (UPC): A significant opposition party.

Presidential and legislative elections were held regularly after the 1991 constitution, though often criticized for irregularities and lack of a level playing field, especially during Compaoré's era. The 2015 elections were considered a significant step towards democracy, leading to Kaboré's presidency. He was re-elected in 2020.

Currently, under military rule, the activities of political parties are severely restricted, and electoral processes are suspended.

5.3. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Burkina Faso has long been a concern, exacerbated by political instability and the ongoing security crisis.

Key issues include:

- Freedom of the Press and Expression:** Historically, journalists have faced harassment and violence. The unsolved 1998 assassination of investigative journalist Norbert Zongo remains a symbol of impunity. While private media outlets exist, self-censorship can occur due to fear of reprisal, especially in the current political climate.

- Political Repression:** During Compaoré's rule, opposition activists faced repression. The military coups of 2022 have further curtailed political freedoms and suspended democratic institutions. Freedom of assembly is often restricted.

- Women's and Children's Rights:** Female genital mutilation (FGM) remains prevalent despite being outlawed. Child marriage and child labor, particularly in agriculture and artisanal gold mines, are serious problems. While legal frameworks exist to protect women and children, enforcement is weak.

- Protection of Civilians in Conflict Zones:** The jihadist insurgency has led to widespread abuses against civilians by both extremist groups and state security forces. Extremists have targeted civilians, schools, and health centers. Security forces have been implicated in extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture, particularly targeting communities perceived as sympathetic to insurgents, such as the Fulani. The lack of accountability for these abuses is a major concern. The Karma massacre in 2023, where over 150 civilians were killed by men in military uniform, underscores the severity of this issue.

- Justice System:** The judicial system is often under-resourced, inefficient, and subject to political influence, leading to a culture of impunity.

Governmental bodies and international organizations, including the UN Human Rights Council and various NGOs, monitor the situation and advocate for improvements. However, the ongoing conflict and political instability severely hamper efforts to protect and promote human rights effectively. The current military government has emphasized security over democratic rights, further raising concerns about the protection of fundamental freedoms.

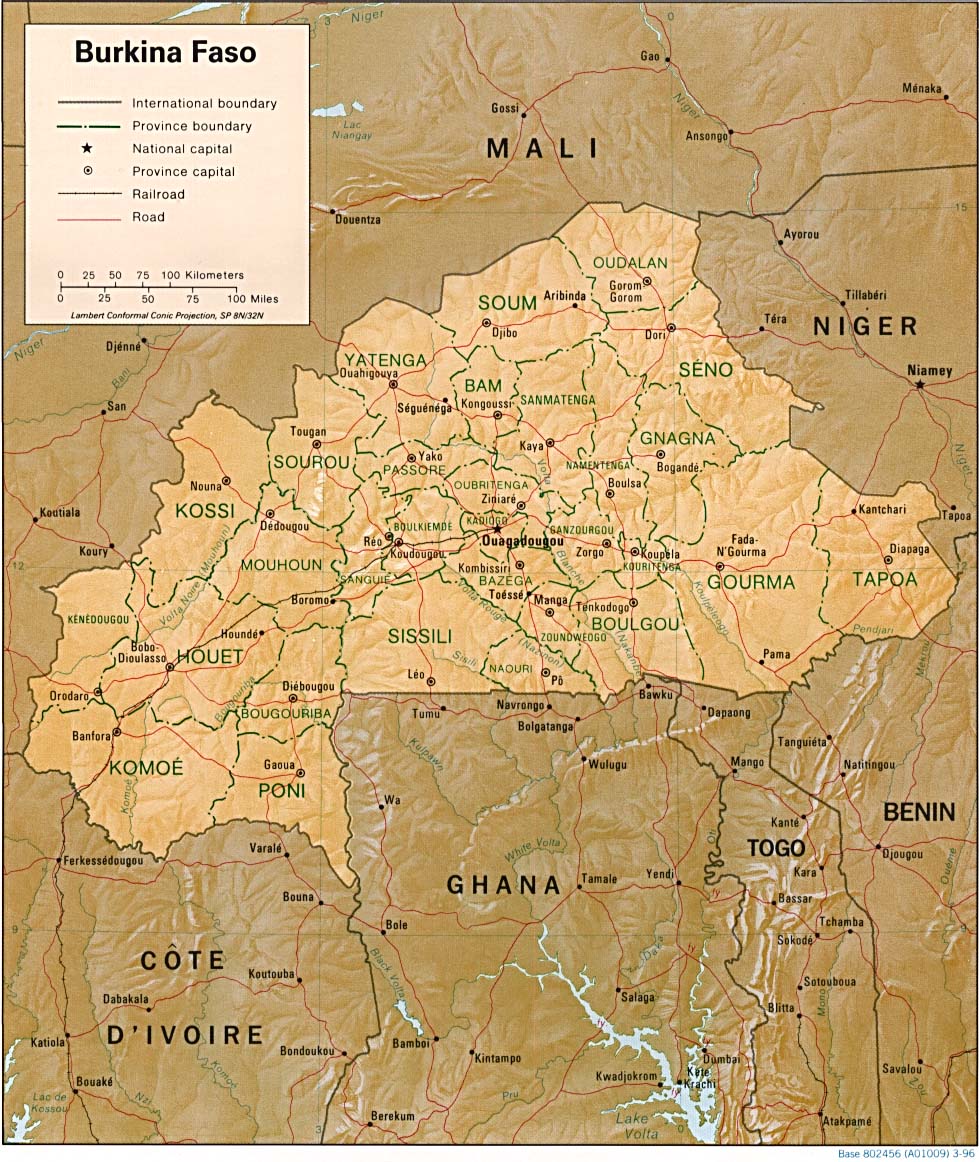

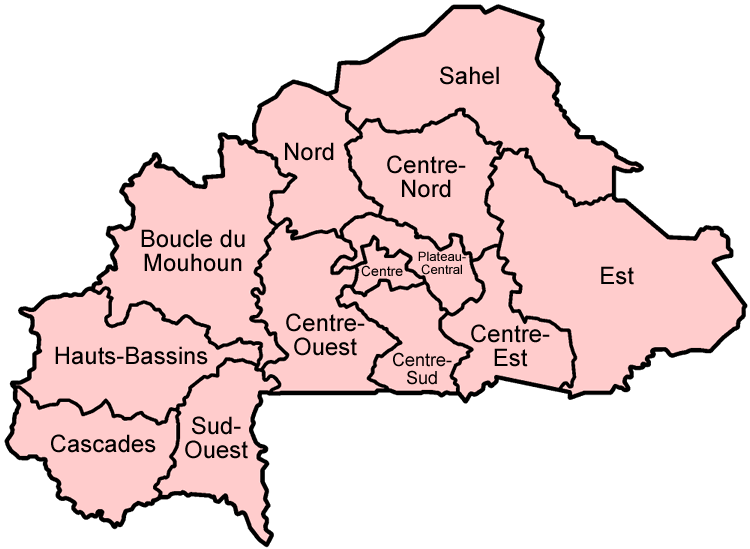

6. Administrative Divisions

Burkina Faso is divided into a hierarchical system of administrative units for governance and development purposes. The structure comprises regions, provinces, and departments.

- Regions:** The country is divided into 13 administrative regions. Each region is administered by a Governor, appointed by the central government. The regions are:

- Boucle du Mouhoun

- Cascades

- Centre (contains the capital, Ouagadougou)

- Centre-Est

- Centre-Nord

- Centre-Ouest

- Centre-Sud

- Est

- Hauts-Bassins (contains the second-largest city, Bobo-Dioulasso)

- Nord

- Plateau-Central

- Sahel

- Sud-Ouest

- Provinces:** These 13 regions are further subdivided into 45 provinces. Each province is headed by a High Commissioner.

- Departments (Communes):** The provinces are divided into 351 departments or communes (municipalities). Of these, there are urban communes (cities) and rural communes. Each department is generally administered by a mayor, though local governance structures have been impacted by the security crisis and military takeovers.

This administrative structure is intended to facilitate decentralization and bring governance closer to the people, although its effectiveness has been challenged by resource constraints and the ongoing security situation in many parts of the country.

The major cities include the capital, Ouagadougou, the economic hub of Bobo-Dioulasso, Koudougou, Ouahigouya, and Banfora.

7. Military and Security Forces

The Burkinabè Armed Forces (Forces Armées Nationales - FAN) are responsible for national defense and security. They have been significantly challenged by the jihadist insurgency since the mid-2010s and have also played a central role in the country's recent political upheavals, including the coups of 2022.

The armed forces consist of:

- Army (Armée de Terre):** The largest branch, responsible for ground operations. It has approximately 6,000 active personnel, though numbers may have increased due to mobilization efforts against insurgents. It is structured into several military regions and specialized units.

- Air Force (Force Aérienne de Burkina Faso - FABF):** A relatively small air arm, operating a limited number of aircraft, including transport planes, helicopters, and a few combat/surveillance aircraft (e.g., some 19 operational aircraft reported previously, though acquisitions like Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones have occurred more recently). Its primary roles are reconnaissance, transport, and limited air support for ground forces.

- National Gendarmerie (Gendarmerie Nationale):** A military force with law enforcement duties, particularly in rural areas and along borders. It operates under the Ministry of Defence (or equivalent under junta rule) and plays a crucial role in internal security and counter-insurgency operations.

- People's Militia (Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland - VDP):** Established to support the army in the fight against insurgents, the VDP (Volontaires pour la Défense de la Patrie) is composed of civilian volunteers who receive basic military training and arms. While intended to bolster security, the VDP has also faced accusations of human rights abuses and contributing to inter-communal tensions.

In addition to the armed forces, other security forces include:

- National Police (Police Nationale):** Responsible for law enforcement in urban areas, operating under the Ministry of Security.

The equipment of the Burkinabè military is generally modest, relying on a mix of older Soviet-era and Western hardware, though recent efforts have been made to acquire more modern equipment to combat the insurgency, including armored vehicles and drones. Training and support have historically been provided by international partners like France and the United States, but these relationships have shifted following the 2022 coups, with increased cooperation with countries like Russia.

The domestic security situation remains extremely challenging. Large swathes of territory, particularly in the north and east, are outside of effective state control, with jihadist groups operating freely. The military has been engaged in continuous counter-insurgency operations, but has struggled to contain the violence. The armed forces themselves have suffered significant casualties. The military coups of 2022 were largely justified by the leaders as a response to the failing security strategy of the civilian government. The current military junta has made security its top priority, implementing measures like "military zones" and large-scale recruitment for the VDP.

8. Foreign Relations

Burkina Faso's foreign policy has historically been guided by principles of non-alignment, though its relationships and alliances have evolved, particularly in response to domestic political changes and regional security dynamics.

- Membership in International Organizations:** Burkina Faso is a member of the United Nations (UN), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and La Francophonie. However, following the military coups in 2022, its membership in the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) was suspended. In January 2024, Burkina Faso, along with Mali and Niger, announced its withdrawal from ECOWAS. It was also a member of the G5 Sahel, a regional cooperation framework focused on development and security, but withdrew in December 2023 along with Niger and Mali, citing concerns that the organization served foreign interests.

- Relations with Neighboring Countries:** Relations with neighboring countries are crucial due to its landlocked status and shared security challenges. It has worked within regional frameworks to address issues like terrorism and cross-border crime. However, the alignment with military juntas in Mali and Niger has created a distinct bloc, sometimes at odds with other ECOWAS members. Historical border disputes, such as the Agacher Strip War with Mali in 1985, were resolved through international arbitration.

- Relations with France:** France, the former colonial power, has historically been a key political, economic, and military partner. However, relations have significantly deteriorated since the 2022 coups. The Burkinabè military government has demanded the withdrawal of French troops (part of Operation Barkhane and Task Force Sabre), terminated military agreements, and expelled the French ambassador, reflecting a broader anti-French sentiment in parts of the Sahel.

- Relations with Other Powers:** The junta has sought to diversify its partnerships, notably strengthening ties with Russia, including reported engagement with Russian security instructors. It has also maintained relations with countries like China (after switching diplomatic recognition from Taiwan in 2018), Turkey, and others.

- Stance on International Issues:** Under Thomas Sankara, Burkina Faso adopted a strong anti-imperialist and Pan-Africanist stance. Subsequent governments were more aligned with Western interests. The current military junta has revived some of Sankara's rhetoric regarding sovereignty and anti-imperialism, particularly in its critique of French influence.

The country's foreign policy is currently heavily influenced by the domestic security crisis and the junta's efforts to consolidate power and secure international support for its counter-insurgency efforts.

9. Economy

Burkina Faso's economy is characterized as low-income and heavily reliant on agriculture and natural resources, particularly gold. It is one of the least developed countries in the world. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was approximately 16.23 B USD in 2022. GDP per capita remains low. Economic development is hampered by factors such as its landlocked position, limited infrastructure, vulnerability to climatic shocks, high population growth, and, more recently, severe insecurity.

9.1. Economic Overview and Trends

The economy is largely agrarian, with about 80% of the population engaged in subsistence farming and livestock rearing. Poverty rates are high, although there had been some reduction prior to the escalation of the security crisis. The country has historically depended on international aid and remittances from Burkinabè working abroad, primarily in Ivory Coast and Ghana.

Recent economic trends have been significantly impacted by the jihadist insurgency, political instability, the COVID-19 pandemic, and global economic pressures. The insurgency has disrupted agricultural production, displaced populations, and deterred investment. Inflation has been a challenge. Government economic development plans, such as the National Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES), have aimed to boost growth and reduce poverty, but their implementation has been severely affected by the ongoing crises. Social equity remains a major concern, with significant disparities in income and access to services. The public deficit and debt have been areas of concern, managed through concessional aid and regional borrowing. Burkina Faso is a member of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU/UEMOA) and uses the West African CFA franc as its currency, which is pegged to the Euro and managed by the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO).

9.2. Major Sectors

The economy is structured around a few key sectors.

9.2.1. Agriculture and Livestock

Agriculture is the backbone of the economy, contributing significantly to GDP (around 32%) and employing the vast majority of the workforce.

- Major Crops:** Key food crops include sorghum, pearl millet, maize, rice, and peanuts. Cotton is the main cash crop and a significant export commodity, although its production has faced challenges from price volatility and competition. Sesame has also become an important export crop.

- Livestock:** Livestock rearing, including cattle, sheep, and goats, is a major economic activity, particularly in the northern and Sahelian regions. It contributes to export earnings and local livelihoods.

The agricultural sector is highly vulnerable to climate change, including irregular rainfall patterns, droughts, and desertification. The ongoing insecurity has further crippled agriculture by displacing farmers, preventing access to fields, and disrupting markets.

9.2.2. Mining

The mining sector, particularly gold mining, has become a crucial driver of economic growth and the primary source of export revenue. Gold accounted for around 78.5% of total exports in 2017 and its share has remained dominant. Burkina Faso is one of Africa's largest gold producers. Several large industrial mines are operated by international companies.

Other mineral resources include manganese, zinc, copper, limestone, and phosphates, though their exploitation is less developed than gold.

Challenges in the mining sector include:

- Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (ASM):** A large number of people are involved in ASM, often in precarious and unsafe conditions. Issues include child labor, environmental degradation (e.g., mercury use), and conflicts with industrial mining operations.

- Security:** Mining operations and personnel have been targeted by armed groups, disrupting production and deterring investment.

- Revenue Management:** Ensuring that mineral wealth translates into broad-based development and benefits local communities remains a challenge, with concerns about transparency and governance in the sector.

9.3. Infrastructure

Inadequate infrastructure is a major constraint on Burkina Faso's economic development.

9.3.1. Transport

- Roads:** The road network is extensive (around 9.3 K mile (15.00 K km) total) but largely unpaved (only about 1.6 K mile (2.50 K km) paved). Poor road conditions, especially during the rainy season, hinder transportation and trade.

- Railways:** A single railway line, the Abidjan-Niger railway, connects Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso with Abidjan in Ivory Coast. It is crucial for freight transport, particularly for a landlocked country, but has faced challenges with aging infrastructure and operational inefficiencies. An extension from Ouagadougou to Kaya exists.

- Aviation:** The main international airport is Ouagadougou Airport. Bobo-Dioulasso Airport also serves some international and domestic flights. Air transport is vital for international connectivity.

9.3.2. Energy

Access to electricity is limited, especially in rural areas. The country relies heavily on imported fossil fuels for power generation and also imports electricity from neighboring countries (Ivory Coast, Ghana).

Efforts are underway to increase domestic generation capacity and diversify the energy mix, with a strong focus on renewable energy, particularly solar power. The Zagtouli solar power plant near Ouagadougou, inaugurated in 2017, was one of the largest in West Africa at the time of its construction, with a capacity of 33 megawatts. Many smaller solar projects are also being developed to improve energy access and reduce import dependency.

9.3.3. Water and Sanitation

Access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation remains a challenge, particularly in rural areas, although progress has been made.

The National Office for Water and Sanitation (ONEA) is the state-owned utility responsible for urban water supply and has been recognized for its relatively good performance in improving access and service quality in cities. According to UNICEF, access to drinking water in rural areas increased from 39% to 76% between 1990 and 2015, and in urban areas from 75% to 97% during the same period.

However, challenges persist in water resource management, ensuring sustainable access, and improving sanitation coverage to reduce waterborne diseases. The security crisis has further complicated efforts to maintain and expand water and sanitation infrastructure in affected regions.

9.4. Science and Technology

Investment in research and development (R&D) in Burkina Faso is relatively low, at around 0.20% of GDP in 2009. However, the number of researchers per million inhabitants (48 in 2010) was higher than the sub-Saharan African average.

The government established the Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation in 2011 to promote science, technology, and innovation (STI). Key policy documents include the National Policy for Scientific and Technical Research (2012) and a National Innovation Strategy (2014). Priorities include improving food security through agricultural and environmental sciences, and developing effective health systems. The International Institute of Water and Environmental Engineering (2iE) in Ouagadougou is a notable centre of excellence.

In 2013, the Science, Technology and Innovation Act established mechanisms for financing research and innovation, such as the National Fund for Research and Innovation for Development. The country was ranked 129th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024. Challenges include insufficient funding, brain drain, and translating research into practical applications for development.

10. Society

Burkina Faso's society is characterized by its youthful demographic profile, ethnic diversity, and significant social challenges related to poverty, health, and education, many of which are exacerbated by the ongoing security crisis.

10.1. Demographics

Burkina Faso has a rapidly growing population, estimated at approximately 23.3 million in 2024. Key demographic indicators include:

- Population Growth Rate:** High, around 2.68% annually (2001 estimate), driven by a high total fertility rate (estimated at 5.93 children per woman in 2014, among the highest globally).

- Age Structure:** Extremely young population, with a median age of around 17 years. A large proportion of the population (around 47.5% in 2005) is under 15 years old.

- Average Life Expectancy:** Relatively low, estimated at around 60 years for males and 61 for females in 2016.

- Urbanization:** While still predominantly rural, the rate of urbanization is increasing, with significant migration to cities like Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso.

Hundreds of thousands of Burkinabè migrate regularly to Ivory Coast and Ghana, mainly for seasonal agricultural work. These migration flows can be affected by regional instability. Modern slavery and trafficking in persons, particularly children, remain concerns.

The largest cities, according to the 2019 Census, are:

| City | Region | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Ouagadougou | Centre | 2,415,266 |

| Bobo-Dioulasso | Hauts-Bassins | 904,920 |

| Koudougou | Centre-Ouest | 160,239 |

| Saaba | Centre | 136,011 |

| Ouahigouya | Nord | 124,587 |

| Kaya | Centre-Nord | 121,970 |

| Banfora | Cascades | 117,452 |

| Pouytenga | Centre-Est | 96,469 |

| Houndé | Hauts-Bassins | 87,151 |

| Fada N'gourma | Est | 73,200 |

10.2. Ethnic Groups

Burkina Faso is home to over 60 distinct ethnic groups, broadly belonging to two major West African cultural groups: the Voltaic and the Mandé.

- Mossi:** The largest ethnic group, constituting about 40-50% of the population. They are predominantly farmers and claim descent from warriors who migrated to the area around the 11th century, establishing powerful kingdoms. Their traditional leader is the Mogho Naba, based in Ouagadougou.

- Fula (Fulani/Peul):** Constituting around 9-10% of the population, they are traditionally pastoralists and are found throughout the Sahel region.

- Gurma (Gourmantché):** Found primarily in the eastern regions, making up about 6-7%.

- Other significant groups:** Include the Bobo, Gurunsi (including Lyele, Nuni, Kasena), Senufo, Lobi, Bissa, Samo, Marka (Dafing), Dyula, and Tuareg.

While generally characterized by ethnic integration and coexistence, the ongoing security crisis has at times strained inter-communal relations, particularly with the stigmatization of some Fulani communities.

10.3. Languages

Burkina Faso is a multilingual country with an estimated 69 languages spoken.

- Official Languages:** As of a constitutional amendment ratified in January 2024, Mooré, Bissa, Dyula, and Fula were elevated to the status of official languages.

- Working Languages:** French, introduced during the colonial period, was formerly the sole official language. Its status was demoted to that of a "working language" alongside English by the January 2024 constitutional amendment. French remains widely used in administration, education, and formal sectors.

- Indigenous Languages:** About 60 languages are indigenous. Mooré is the most widely spoken indigenous language, used by about half the population, particularly in the central region around Ouagadougou. Other widely spoken languages include Fula (Fulfulde), mainly in the north; Dyula (Jula), a Mandé language used as a trade language in the west and southwest; Gourmanché in the east; and Bissa in the south. Other notable languages include Bobo, Samo, Dagara, Lyélé, Nuni, Dafing (Marka), Tamasheq (Tuareg), Kassem, and various Gur languages.

The government officially recognizes these indigenous languages and promotes their use.

10.4. Religion

Burkina Faso is a secular state with religious freedom constitutionally guaranteed, though recent jihadist violence has targeted religious communities. The main religious groups are:

- Islam:** The majority religion, practiced by approximately 63.8% of the population according to the 2019 government census (60.5% in the 2006 census). Most Muslims are Sunni, adhering to the Maliki school of jurisprudence, with a significant number identifying with the Tijaniyyah Sufi order. There is also a small minority of Shia Muslims and some adherents of Ahmadiyya.

- Christianity:** Practiced by about 26.3% of the population (2019 census; 23.2% in 2006). Of these, Roman Catholics form the largest group (20.1%), followed by various Protestant denominations (6.2%).

- Indigenous Traditional Beliefs (Animism):** Followed by approximately 9.0% of the population (2019 census; 15.3% in 2006). These beliefs vary among ethnic groups and often involve reverence for ancestors and nature spirits. In the Sud-Ouest region, animists constitute the largest religious group, at 48.1%.

It is common for individuals to blend elements of Islam or Christianity with traditional indigenous practices. Religious tolerance has generally been a hallmark of Burkinabè society, though this has been challenged by the rise of extremist ideologies.

10.5. Education

The education system in Burkina Faso is structured into primary, secondary, and higher education. French has traditionally been the primary language of instruction, though there are efforts to incorporate national languages.

- Educational Indicators:** Literacy rates remain low, estimated at 21.8% for those 15 and over in 2003 (29.4% male, 15.2% female), although concerted efforts have been made to improve this (e.g., to 25.3% by 2008). School enrollment rates, particularly for girls and in rural areas, are below desired levels.

- Challenges:** The education sector faces numerous challenges, including:

- High costs of schooling (though efforts have been made to make it cheaper, especially for girls).

- Shortage of qualified teachers and adequate school infrastructure.

- Low female enrollment and completion rates, though increasing due to government policies.

- The impact of the security crisis, which has led to the closure of thousands of schools, particularly in conflict-affected regions, depriving hundreds of thousands of children of education.

- Higher Education:** Major institutions of higher education include the University of Ouagadougou (officially Université Joseph Ki-Zerbo), the Polytechnic University of Bobo-Dioulasso, and the University of Koudougou. There are also some small private colleges. The International School of Ouagadougou (ISO) provides an American-based curriculum.

- Reforms and Efforts:** The government has focused on increasing access to education, improving quality, and promoting girls' education through scholarships and fee reductions. National exams are required to progress between educational levels.

Despite these efforts, Burkina Faso was ranked as having the lowest literacy level globally in the 2008 UN Development Program Report. The ongoing conflict poses a severe threat to educational progress.

10.6. Health

Burkina Faso faces significant public health challenges, reflected in key health indicators:

- Life Expectancy:** Average life expectancy was estimated at 60 years for males and 61 for females in 2016.

- Mortality Rates:** The under-five mortality rate was 76 per 1,000 live births in 2018, and the infant mortality rate was also high. The maternal mortality ratio was estimated at 300 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2010.

- Prevalent Diseases:** Major health concerns include malaria (a leading cause of morbidity and mortality), respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, HIV/AIDS (adult prevalence around 1.0% in 2012, with declining rates among pregnant women), and dengue fever (outbreaks occur, e.g., 2016). Meningitis is also a recurrent threat.

- Medical Infrastructure and Personnel:** There is a severe shortage of healthcare facilities, equipment, and qualified medical personnel, especially in rural areas. The physician density was very low, around 0.05 per 1,000 population in 2010.

- Health Expenditure:** Central government spending on health was around 3% of GDP in 2001, and overall health expenditure was 6.5% of GDP in 2011.

- Female Genital Mutilation (FGM):** FGM is a widespread traditional practice, with an estimated 72.5% of girls and women having undergone the procedure (WHO 2005 report), despite being illegal. This poses serious health risks.

- Impact of Security Crisis:** The ongoing insurgency has severely impacted the health sector, with many health facilities closed or inaccessible in conflict zones, and healthcare workers targeted or displaced. This has further limited access to essential health services for vulnerable populations.

Demographic and Health Surveys have been conducted periodically to monitor health trends.

10.7. Food Security

Food security is a chronic and pressing issue in Burkina Faso, deeply intertwined with poverty, climate change, and recently, the escalating conflict. The country consistently ranks low on the Global Hunger Index, indicating serious levels of hunger.

- Malnutrition:** High rates of malnutrition persist, especially among children under five and pregnant or lactating women. Stunted growth due to chronic malnutrition affects a significant portion of children (around one-third from 2008-2012), impacting their physical and cognitive development and educational attainment. Acute malnutrition, including its most severe forms, threatens hundreds of thousands of children annually. Micronutrient deficiencies, such as anemia, are also prevalent.

- Vulnerability of Agriculture:** The agricultural sector, which most people depend on for food and income, is highly vulnerable to:

- Climate Change:** Irregular rainfall, droughts, and floods devastate harvests. Desertification is an ongoing concern.

- Pests and Diseases:** Crop losses due to pests like locusts and crickets are common.

- Insecurity:** The jihadist insurgency has massively disrupted agricultural activities by displacing farmers, preventing access to land, restricting movement, and destroying infrastructure and markets. This has led to a sharp decline in food production in affected areas.

- Access and Affordability:** Even when food is available, poverty limits access for many households. Rising food prices further exacerbate the situation.

- Impact:** Food insecurity contributes to high infant and child mortality rates, reduced productivity, and perpetuates cycles of poverty. It also fuels social tensions and can be a factor in displacement and instability.

- Efforts to Improve Food Security:**

- Government Initiatives:** National programs aim to boost agricultural productivity, support vulnerable households, and build resilience to shocks.

- International Aid:** Organizations like the World Food Programme (WFP), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), UNICEF, and various NGOs provide emergency food assistance, nutrition support (e.g., treatment for acute malnutrition), and implement longer-term food security projects (e.g., promoting sustainable agriculture, improving market access).

- World Bank:** Projects like the Agricultural Productivity and Food Security Project aim to improve the capacity of poor producers and ensure better food availability in rural markets.

Despite these efforts, the scale of food insecurity remains immense, particularly in regions affected by conflict and climate extremes. Over 954,300 people were estimated to need food security support in late 2018, a number that has likely increased significantly due to the worsening crisis.

11. Culture

Burkina Faso possesses a rich and diverse cultural heritage, shaped by its numerous ethnic groups, historical experiences, and artistic traditions.

11.1. Arts and Crafts

Traditional arts and crafts are vibrant and vary among ethnic groups.

- Masks and Sculptures:** Burkina Faso is renowned for its diverse and intricate masks, which play significant roles in ritual ceremonies, festivals (like FESTIMA), and social events. Wooden sculptures, pottery, and bronzes are also important art forms. Different ethnic groups, such as the Bobo, Bwa, Mossi, Lobi, and Gurunsi, have distinct styles and iconographies.

- Textiles:** Weaving is a highly developed craft, producing colorful cotton fabrics, including the famous Faso Dan Fani (woven striped cloth), which has become a national symbol.

- Contemporary Art:** There is a growing contemporary art scene, especially in Ouagadougou.

- SIAO:** The International Art and Craft Fair, Ouagadougou (Salon International de l'Artisanat de OuagadougouSalon International de l'Artisanat de OuagadougouFrench, SIAO) is a major biennial event, one of Africa's most important trade shows for art and handicrafts, attracting artisans and buyers from across the continent and beyond.

The Symposium de sculpture sur granit de Laongo, held near Ouagadougou, features artists creating sculptures on granite outcrops.

11.2. Music

The music of Burkina Faso is highly diverse, reflecting the traditions of its over 60 ethnic groups.

- Traditional Music:** Each ethnic group has its unique musical styles, instruments, and performance practices, often linked to ceremonies, storytelling, and daily life. Common instruments include drums (like the djembe and tama), balafons (a type of xylophone), flutes, and stringed instruments like the kora and n'goni.

- Popular Music:** Contemporary Burkinabè popular music incorporates traditional rhythms and melodies with modern genres like Afrobeat, reggae, hip hop, and coupé-décalé. Artists often sing in French and various national languages. While Burkina Faso has not produced as many internationally renowned musicians as some neighboring countries, several artists have gained regional and international recognition.

11.3. Literature

Burkinabè literature has strong roots in oral tradition, which remains an important form of cultural expression, conveying history, myths, proverbs, and social values.

- Early Written Literature:** During the French colonial period, some efforts were made to document oral traditions. For example, Dim-Dolobsom Ouédraogo published Maximes, pensées et devinettes mossi (Maxims, Thoughts and Riddles of the Mossi) in 1934.

- Post-Independence Writers:** The 1960s saw the emergence of Burkinabè writers like Nazi Boni and Roger Nikiema, whose works were influenced by oral traditions. Playwriting also began to develop during this period.

- Contemporary Literature:** Since the 1970s, Burkinabè literature has grown, with an increasing number of writers publishing novels, poetry, and plays in French and, to a lesser extent, national languages. Themes often explore social issues, political realities, cultural identity, and historical experiences.

- Slam Poetry:** Slam poetry has gained popularity, particularly among youth, as a dynamic form of expression. Artists like Malika Ouattara (Malika la Slameuse) use slam poetry to address social issues, raise awareness (e.g., on blood donation, albinism, COVID-19), and engage audiences.

11.4. Cinema

The cinema of Burkina Faso is one of the most significant and influential in Africa. Ouagadougou is often considered a capital of African cinema due to:

- FESPACO:** The Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (Festival panafricain du cinéma et de la télévision de OuagadougouFestival panafricain du cinéma et de la télévision de OuagadougouFrench, FESPACO), launched in 1969 as a film week, is the largest and most prestigious film festival on the African continent. Held biennially, it showcases films from Africa and the African diaspora, playing a crucial role in promoting African cinema and filmmakers.

- Renowned Filmmakers:** Burkina Faso has produced several internationally acclaimed film directors, including Idrissa Ouédraogo (winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes for Tilai), Gaston Kaboré (winner of the FESPACO Golden Stallion for Wend Kuuni and Buud Yam), and Dani Kouyaté. Their films often explore themes of tradition, modernity, social change, and African identity, and have won numerous international awards.

- FEPACI:** For many years, the headquarters of the Federation of Panafrican Filmmakers (FEPACI) was in Ouagadougou, receiving significant support during Thomas Sankara's presidency.

The country also produces popular television series, such as Les Bobodiouf.

11.5. Media

- State Media:** The principal state-sponsored media outlet is Radiodiffusion Télévision du Burkina (RTB), which operates national television and radio services. RTB broadcasts on medium-wave (AM), several FM frequencies, and maintains a worldwide short-wave news broadcast in French.

- Private Media:** There are numerous privately owned radio stations (sports, cultural, music, religious) and television channels. Several independent newspapers and online news portals also operate.

- Freedom of the Press:** Freedom of the press has faced challenges. The 1998 assassination of investigative journalist Norbert Zongo, who was investigating the death of a chauffeur linked to the president's brother, remains a dark chapter. While the media landscape became more open after the 2014 uprising, journalists can still face pressure and threats, particularly when covering sensitive political or security issues. The current military rule has raised concerns about potential restrictions on media freedom. Sams'K Le Jah, a popular radio reggae host known for critical commentary, received death threats in 2007, and his car was burned.

11.6. Cuisine

Burkinabè cuisine is typical of West African cuisine, based on staple foods such as sorghum, millet, rice, maize, peanuts, potatoes, beans, yams, and okra.

- Staple Dishes:**

- Tô** (or Saghbo in Mooré): A thick porridge or paste made from millet, sorghum, or maize flour, often served with sauces made from vegetables (e.g., okra, baobab leaves), meat, or fish.

- Fufu:** A dough-like food made from pounded yams or cassava, also common.

- Protein Sources:** Chicken, chicken eggs, and freshwater fish are the most common sources of animal protein. Beef and mutton are also consumed.

- Sauces:** Sauces are a key component of meals, often flavored with shea butter (karité), ground peanuts, or spices.

- Vegetables and Legumes:** A variety of local vegetables and legumes are used. Zamnè (Acacia macrostachya), a native legume, can be served as a main dish or in sauces, especially in times of food scarcity.

- Beverages:**

- Banji** or **Palm Wine:** Fermented palm sap.

- Dolo:** A traditional millet beer, brewed locally by women.

- Zoom-koom:** A popular non-alcoholic beverage made from millet flour, water, sugar, ginger, and sometimes tamarind, often described as "grain water."

- Bissap:** A drink made from hibiscus flowers.

Street food is also popular, offering items like grilled meat (brochettes), fried plantains, and various snacks.

11.7. Sports

Various sports are played in Burkina Faso, with football (soccer) being the most popular.

- Football:** Played widely, both professionally and informally. The Burkina Faso national football team is nicknamed "Les Étalons" (The Stallions), a reference to the legendary horse of Princess Yennenga.

- The team has participated in the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) multiple times, with their best performance being runners-up in the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations. They also finished third in 1998 (which they hosted) and 2017.

- The domestic league is the Burkinabé Premier League.

- Basketball:** Another popular sport for both men and women. The men's national team qualified for AfroBasket, the continental championship, for the first time in 2013.

- Cycling:** Cycling enjoys a strong following, with the Tour du Faso being a prominent annual international cycling race.

- Athletics:** Hugues Fabrice Zango made history by winning Burkina Faso's first-ever Olympic medal at the 2020 Summer Olympics (held in 2021), securing a bronze in the men's triple jump. He later won the gold medal at the 2023 World Athletics Championships.

- Other Sports:** Rugby union, handball, tennis, boxing, and martial arts are also practiced. Cricket is emerging, with Cricket Burkina Faso running a 10-club league.

11.8. Festivals and Public Holidays

Burkina Faso celebrates various national public holidays and cultural festivals.

- National Public Holidays:** These include:

- New Year's Day (January 1)

- Anniversary of the 1966 Revolution (January 3)

- International Women's Day (March 8)

- Easter (variable date)

- Labour Day (May 1)

- Ascension Day (variable date)

- Pentecost (variable date)

- Anniversary of the 1983 Revolution (August 4)

- Independence Day (August 5 - marking independence from France in 1960)

- Assumption of Mary (August 15)

- Anniversary of the Rectification (October 15 - marking Compaoré's 1987 coup)

- All Saints' Day (November 1)

- Proclamation of the Republic (December 11 - marking autonomy in 1958)

- Christmas Day (December 25)

- Islamic holidays such as Mawlid (Prophet's Birthday), Eid al-Fitr (end of Ramadan), and Eid al-Adha (Tabaski), which vary according to the lunar calendar.

- Cultural Festivals:**

- FESPACO (Festival Panafricain du Cinéma et de la Télévision de Ouagadougou):** Held biennially (odd years) in Ouagadougou, it is Africa's largest film festival.

- SIAO (Le Salon International de l'Artisanat de Ouagadougou):** A major biennial trade show for African arts and handicrafts, held in Ouagadougou (even years).

- SNC (La Semaine Nationale de la Culture):** A biennial event held in Bobo-Dioulasso, showcasing diverse cultural expressions from across the country, including music, dance, traditional sports, and cuisine.

- FESTIMA (Festival International des Masques et des Arts):** A biennial festival celebrating traditional masks, held in Dédougou. It brings together mask troupes from various ethnic groups in Burkina Faso and neighboring countries.

11.9. World Heritage Sites

Burkina Faso is home to three UNESCO World Heritage Sites:

- Ruins of Loropéni**: Inscribed in 2009, these imposing stone ruins are the best-preserved of ten similar fortresses in the Lobi region. They are believed to be associated with the trans-Saharan gold trade and date back at least 1,000 years. Their precise origins and builders remain a subject of research.