1. Overview

The Republic of Benin is a country located in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, and Burkina Faso and Niger to the north. Its southern coastline lies on the Bight of Benin, part of the Gulf of Guinea. The constitutional capital is Porto-Novo, while the seat of government and largest city is Cotonou. Benin covers an area of approximately 43 K mile2 (112.62 K km2) and has a population estimated at over 11 million people, predominantly living in the southern coastal areas.

Historically, the region of present-day Benin was home to prominent kingdoms, most notably the Kingdom of Dahomey, which flourished from the 17th to the 19th century and was significantly involved in the Atlantic slave trade, a deeply problematic aspect of its past that had devastating consequences for countless individuals and communities. France colonized the area in the late 19th century, incorporating it into French West Africa as French Dahomey. Benin achieved full independence on August 1, 1960. The post-independence period was marked by political instability, including several military coups and periods of authoritarian rule which suppressed democratic development and human rights. A Marxist-Leninist state, the People's Republic of Benin, existed from 1975 until 1990. In 1991, the country transitioned to a multi-party democracy. However, in recent years, there have been concerns about democratic backsliding and the erosion of human rights under the current administration, which contrasts with its earlier reputation as a model of democratic development in Africa and raises questions about its commitment to social progress.

Benin's political system is a presidential republic with a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The official language is French, though numerous indigenous languages are widely spoken. The economy is heavily reliant on agriculture, particularly cotton and palm oil production, and regional trade, with the Port of Cotonou serving as a key economic hub. Socially and culturally, Benin is diverse, with multiple ethnic groups, including the Fon, Yoruba, and Bariba. Christianity and Islam are the dominant religions, alongside the deeply rooted traditional Vodun beliefs, which originated in the region. This article explores Benin's geography, history, political system, economy, demographics, and culture, with a perspective that emphasizes social progress, human rights, and democratic development.

2. Etymology

The name "Benin" has historical roots in the region, though not directly from the territory of the modern republic. During French colonial rule and after achieving independence on August 1, 1960, the country was known as the Republic of Dahomey. This name was derived from the Kingdom of Dahomey, the most prominent pre-colonial state in the southern part of the country, primarily inhabited by the Fon.

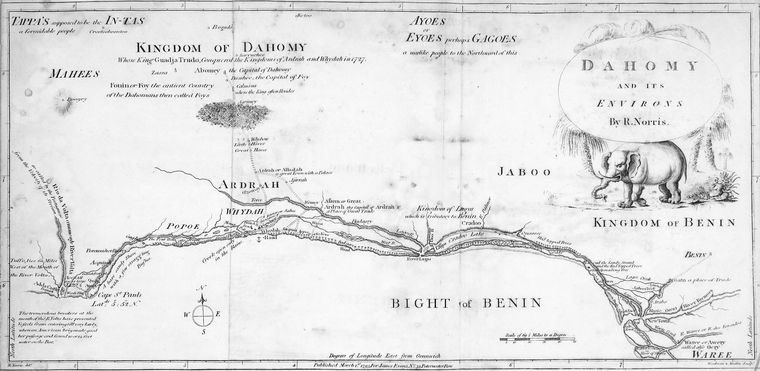

On November 30, 1975, following a military coup led by Mathieu Kérékou that established a Marxist-Leninist government, the country was renamed the People's Republic of Benin. The name "Benin" was chosen to be more inclusive of all ethnic groups within the country, as "Dahomey" was primarily associated with the Fon. The new name was taken from the Bight of Benin, the body of water along the country's southern coast. The Bight of Benin itself was named by Europeans after the historic Kingdom of Benin, a powerful empire located in what is now southwestern Nigeria, not within the borders of modern Benin. When the country abandoned Marxism-Leninism in 1990, it retained the name Benin, becoming the Republic of Benin.

3. History

The history of Benin spans from powerful pre-colonial kingdoms, through French colonial rule that imposed significant hardships, to a post-independence era marked by political transformations and ongoing efforts towards genuine democratic development and respect for human rights.

3.1. Pre-colonial era

Prior to European colonization, the area of present-day Benin was home to several distinct societies and political entities. Along the coast, city-states were primarily inhabited by the Aja ethnic group, with significant populations of Yoruba and Gbe-speaking peoples. Inland, tribal regions were composed of groups such as the Bariba, Mahi, Gedevi, and Kabye. The Oyo Empire, a powerful military force located mainly to the east of Benin (in modern-day Nigeria), exerted influence through raids and by exacting tribute from coastal kingdoms and inland tribes.

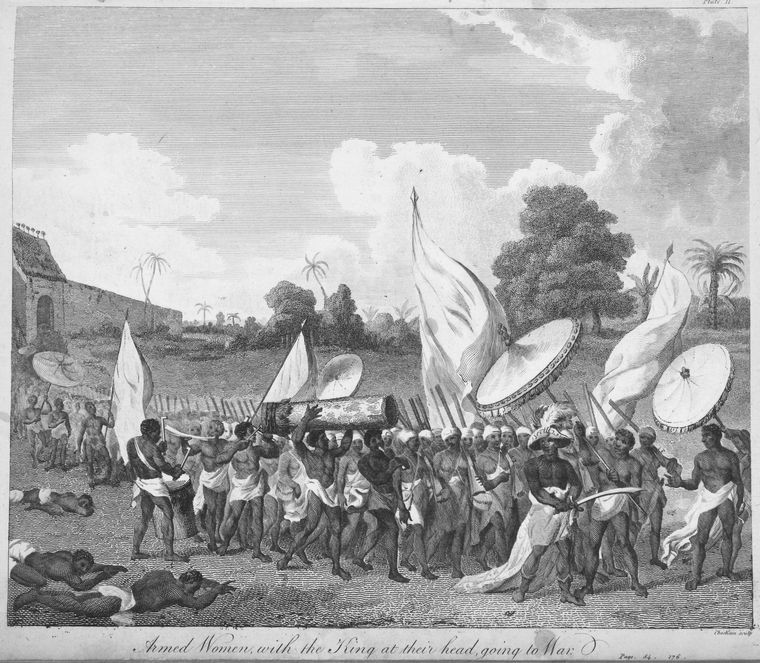

The political landscape shifted significantly in the 17th and 18th centuries with the rise of the Kingdom of Dahomey. Founded by the Fon people on the Abomey plateau around 1600, Dahomey expanded its territory by conquering neighboring areas. By 1727, under King Agaja, Dahomey had conquered the key coastal cities of Allada and Ouidah (Whydah). While Dahomey became a tributary state to the Oyo Empire, it maintained a rivalry with the Oyo-allied city-state of Porto-Novo, though direct attacks were generally avoided. The kingdom developed a highly centralized and militaristic state. Younger people were often apprenticed to older soldiers, learning military customs until they were old enough to join the army. Dahomey was particularly noted for its elite corps of female soldiers, known as the Ahosi (king's wives) or Mino ("our mothers" in Fongbe), and referred to by Europeans as the "Dahomean Amazons". This military prowess earned Dahomey the nickname "Black Sparta" from European observers like Sir Richard Burton.

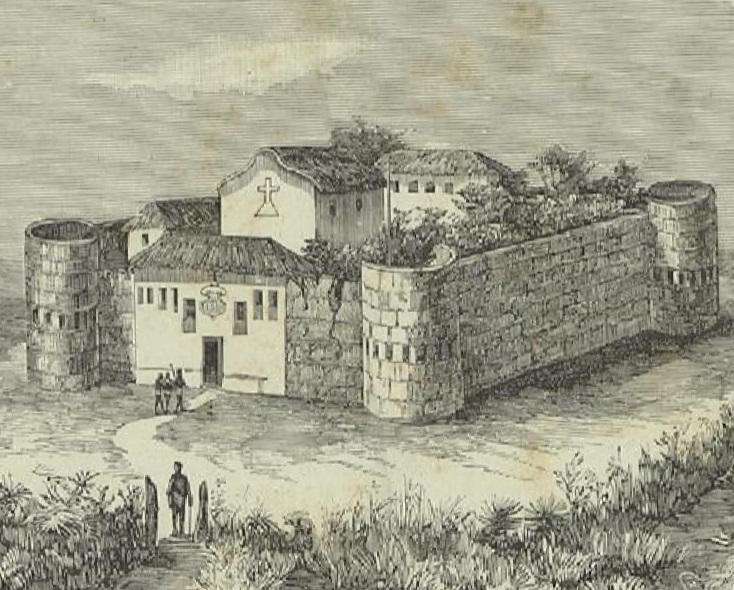

The Kingdom of Dahomey became heavily involved in the Atlantic slave trade. The kings of Dahomey sold war captives to European traders, primarily Portuguese and Dutch, operating from coastal forts like São João Baptista de Ajudá in Ouidah. This trade was a major source of revenue, used to acquire firearms and other European goods, which further fueled Dahomey's military expansion and its role in perpetuating the inhumane slave trade. By around 1750, the King of Dahomey was reportedly earning an estimated 250.00 K GBP per year from selling African captives. The region became known as the Slave Coast of West Africa due to the sheer volume of people trafficked. Dahomey also practiced ritual human sacrifice, particularly during the Annual Customs of Dahomey, where a portion of war captives were killed, reflecting the brutal nature of the era. The scale of slave exports from the area was immense, with an estimated 102,000 people per decade in the 1780s.

The banning of the transatlantic slave trade by Britain in 1808, followed by other European powers, significantly impacted Dahomey's economy, forcing a shift away from its primary reliance on human trafficking. Slave exports declined to 24,000 per decade by the 1860s, with the last slave ship reportedly departing for Brazil in 1885. In response to this decline, King Ghezo (reigned 1818-1858) diversified the economy by promoting the production of palm oil for export. By 1856, British companies were exporting approximately 2,500 tons of palm oil valued at 112.50 K GBP. Despite these efforts, the kingdom's power began to wane in the mid-19th century. Europeans also sought other goods, such as intricately carved ivory items like salt cellars, spoons, and hunting horns, produced by Beninese artisans for the exotic goods market. The Portuguese had the longest European presence, starting in 1680 and only ceding the Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá in 1961, a year after Benin's independence.

3.2. French colonial rule

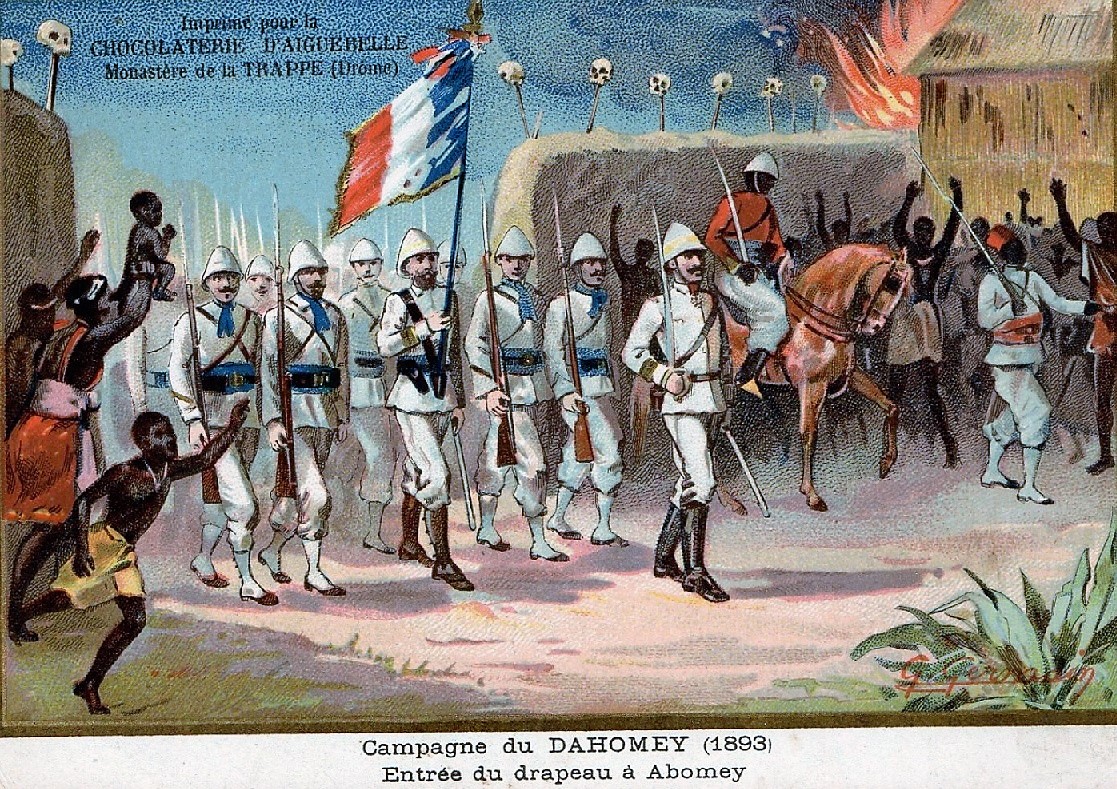

By the mid-19th century, the Kingdom of Dahomey had begun to weaken and lose its status as the dominant regional power. France increasingly asserted its influence in the area, leading to conflicts with Dahomey. Following the First Franco-Dahomean War (1890) and the Second Franco-Dahomean War (1892-1894), French forces defeated Dahomey. King Béhanzin, the last independent ruler of Dahomey, was exiled, and France formally established control over the territory. In 1894, the area was declared a French protectorate, and by 1899, it was incorporated into the larger colonial federation of French West Africa as the colony of French Dahomey.

French colonial administration aimed to exploit the territory for economic benefit, though Dahomey was initially perceived as lacking significant agricultural or mineral resources for large-scale capitalist development. France treated Dahomey as a reserve, pending future discoveries. Colonial policies included the imposition of taxes, forced labor for infrastructure projects like roads and railways, and the promotion of cash crops, primarily palm oil and later cotton, for export. These policies often disrupted traditional social structures and agricultural practices, leading to hardship for the local population and a denial of their self-determination. The French administration also outlawed the capture and sale of slaves. Former slaveowners sought to maintain control over labor by redefining relationships as those between landowners, tenants, and lineage members, leading to struggles over land and labor control between 1895 and 1920.

Education was introduced, but access was limited, primarily aimed at creating a small class of African auxiliaries for the colonial administration rather than empowering the general populace. French became the language of administration and education, impacting local languages and cultural practices. Early forms of resistance and nationalist sentiment began to emerge in response to colonial policies, particularly concerning labor rights, taxation, and lack of political representation, driven by a desire for freedom and self-rule.

After World War II, political reforms in France led to increased political participation for Africans in the colonies. In 1946, Dahomey gained representation in the French National Assembly and a local territorial assembly was established. In 1958, under the leadership of figures like Hubert Maga, Dahomey became an autonomous republic within the French Community, paving the way for full independence. France granted full independence to the Republic of Dahomey on August 1, 1960, a date now celebrated as Independence Day in Benin. Hubert Maga became the first president of the independent nation.

3.3. Post-independence

Following independence from France on August 1, 1960, the Republic of Dahomey (renamed Benin in 1975) experienced a turbulent political history characterized by a series of military coups, changes in government, and ideological shifts before eventually transitioning to a multi-party democracy. The early period was marked by political instability that hindered social progress and the establishment of robust democratic institutions.

The initial years were dominated by regional and ethnic rivalries among three key political figures: Hubert Maga from the north (representing primarily the Bariba), Sourou Migan Apithy from the southeast (representing the Yoruba), and Justin Ahomadégbé from the south-central region (representing the Fon). This power struggle led to chronic instability. After violent clashes marred the 1970 elections, these three leaders agreed to form a Presidential Council, a rotating triumvirate.

This fragile arrangement was overthrown on October 26, 1972, when Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) Mathieu Kérékou seized power in a military coup. Kérékou initially declared that the country would not copy foreign ideologies. However, on November 30, 1974, he announced the adoption of Marxism-Leninism as the state ideology, and on November 30, 1975, the country was renamed the People's Republic of Benin. Under Kérékou, the Military Council of the Revolution (CMR) nationalized key sectors of the economy, including the petroleum industry and banks, and implemented socialist policies. Opposition activities were banned, and human rights were curtailed. The state established close ties with China, North Korea, and Libya. The regime's phases included a nationalist period (1972-1974), a socialist phase (1974-1982), and a later phase involving an opening to Western countries and economic liberalization (1982-1990). Kérékou's government attempted educational reforms and campaigns against "feudal forces," but foreign investment dried up, and the economy stagnated. By the late 1980s, Benin faced severe economic difficulties, including an inability to pay civil servants' salaries and a collapsed banking system, leading to widespread riots in 1989 as popular discontent grew.

Facing mounting pressure from pro-democracy movements, Kérékou renounced Marxism-Leninism in 1989. A National Conference was convened in February 1990, which stripped Kérékou of most of his powers, released political prisoners, and established a transitional government led by Nicéphore Soglo as Prime Minister. A new constitution establishing a multi-party democratic system was adopted, and on March 1, 1990, the country's name was officially changed to the Republic of Benin, marking a significant step towards democratic governance.

In the 1991 presidential election, Kérékou was defeated by Soglo, marking a peaceful transfer of power and making Kérékou the first incumbent president on mainland Africa to lose power through an election, a positive development for democracy in the region. Soglo's presidency focused on economic reforms and democratic consolidation. However, Kérékou returned to power after winning the 1996 presidential election. He was re-elected in 2001 amidst claims of irregularities by opponents. In 1999, Kérékou issued a national apology for the significant role Africans had played in the Atlantic slave trade.

Adhering to constitutional term limits, Kérékou did not run in the 2006 election. Thomas Boni Yayi won the election and assumed office in April 2006. Boni Yayi was re-elected in 2011, becoming the first president since 1991 to win in the first round.

In the March 2016 presidential elections, businessman Patrice Talon defeated former Prime Minister Lionel Zinsou. Talon was sworn in on April 6, 2016, promising constitutional reforms, including limiting presidents to a single five-year term, though this proposal was later rejected by parliament. Talon was re-elected in April 2021 with over 86.3% of the vote. However, his tenure has been marked by increasing concerns over democratic backsliding and an erosion of human rights. Changes to electoral laws led to the exclusion of major opposition parties from parliamentary and presidential elections, resulting in a parliament largely controlled by Talon's supporters and drawing condemnation from international observers and human rights organizations. Protests against these changes have sometimes been met with force, further undermining democratic principles.

In February 2022, Benin experienced its largest terrorist attack, the W National Park massacre, highlighting growing security challenges from extremist groups in the Sahel region. Also in February 2022, President Talon inaugurated an exhibition of 26 sacred art pieces returned by France, which had been looted by colonial forces 129 years prior, marking a significant moment in the restitution of African cultural heritage.

4. Geography

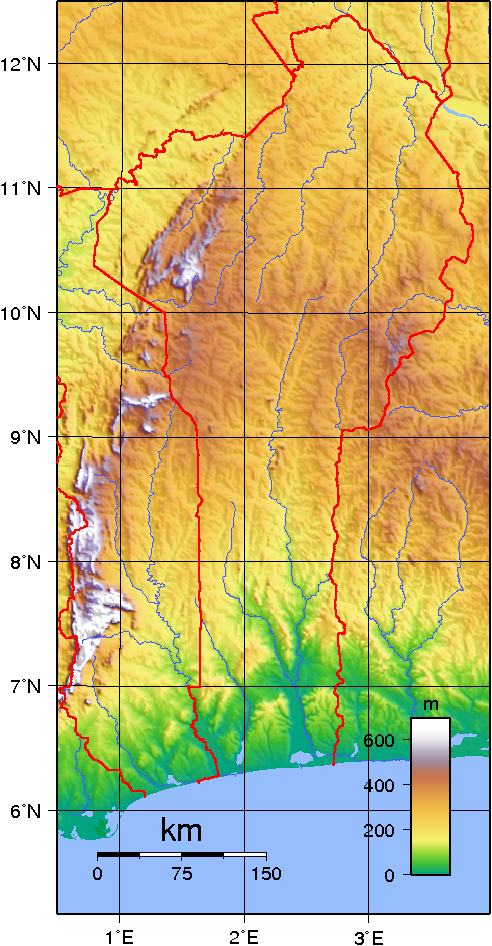

Benin is a West African nation characterized by a relatively narrow north-south strip of land. It features diverse topography, a tropical climate, and notable wildlife reserves, all of which contribute to its unique environmental profile.

4.1. Topography

Benin can be divided into four main topographical regions from south to north.

The first is a low-lying, sandy coastal plain, which is at most 6.2 mile (10 km) wide. This plain has a maximum elevation of 33 ft (10 m) and is characterized by marshes, lakes, and lagoons that connect to the Atlantic Ocean. This region is where a majority of the population and major cities like Cotonou and Porto-Novo are located, making it vulnerable to sea level rise due to climate change.

Behind the coastal plain lie the plateaus of southern Benin, with altitudes ranging from 66 ft (20 m) to 656 ft (200 m). These plateaus are covered by the Guinean forest-savanna mosaic and are dissected by valleys running north to south, formed by rivers such as the Couffo, Zou, and Ouémé Rivers.

Further north, an area of flatter land extends around the cities of Nikki and Savè. This region is dotted with rocky hills, and its altitude can reach up to 1312 ft (400 m).

The northwestern part of Benin is characterized by the Atakora Mountains (also known as the Togo Mountains), which extend along the border with Togo. This range contains Benin's highest point, Mont Sokbaro, at 2159 ft (658 m). The central part of the country features a watershed, with rivers south of it flowing into the Atlantic Ocean and those to the north feeding into the Niger River system.

Benin's total land area is 43 K mile2 (112.62 K km2). The country stretches about 404 mile (650 km) from the Niger River in the north to the Atlantic Ocean in the south. While its coastline is 75 mile (121 km) long, its widest point measures about 202 mile (325 km).

4.2. Climate

Benin has a tropical climate, characterized by heat and humidity, particularly in the south, while the north is drier. The country lies between latitudes 6°N and 13°N, and longitudes 0°E and 4°E.

Southern Benin generally experiences an equatorial climate with two rainy seasons (April to late July and September to November) and two dry seasons. The principal rainy season is from April to late July, with a shorter, less intense rainy period from late September to November. The main dry season runs from December to April, with a shorter, cooler dry season from late July to early September. Annual rainfall in the coastal area averages around 0.1 K in (1.30 K mm). Temperatures and humidity are consistently high along the coast. In Cotonou, the average maximum temperature is 87.8 °F (31 °C), and the minimum is 75.2 °F (24 °C).

Moving northwards, the climate transitions to a tropical savanna climate. Here, there is typically one rainy season (usually May to September) and one long dry season. Variations in temperature become more pronounced further north, towards the Sahel region. From December to March, the Harmattan, a dry, dusty wind from the Sahara Desert, blows across the country. During this period, grasses dry up, vegetation often turns reddish-brown, and a veil of fine dust can obscure the sky, causing overcast conditions. This is also the season when farmers traditionally burn brush in the fields.

The country is vulnerable to climate change, with projections indicating that northern areas may experience increased desertification, while coastal regions face risks from rising sea levels.

4.3. Wildlife

Benin possesses a variety of ecosystems, including fields, mangroves, and remnants of larger sacred forests. In much of the country, the savanna is characterized by thorny scrub and dotted with baobab trees. Some forests line the banks of rivers. Four terrestrial ecoregions lie within Benin's borders: Eastern Guinean forests, Nigerian lowland forests, Guinean forest-savanna mosaic, and West Sudanian savanna. The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.86/10, ranking it 93rd globally out of 172 countries. In 2020, forest cover was around 28% of the total land area, equivalent to 3,135,150 hectares, a decrease from 4,835,150 hectares in 1990. Naturally regenerating forests covered 3,112,150 hectares in 2020, with planted forests covering 23,000 hectares.

Benin is home to significant wildlife populations, particularly in its northern national parks. The W National Park (Parc National du W), located in the north and extending into Niger and Burkina Faso, and the Pendjari National Park are major conservation areas. These parks host populations of elephants, lions, antelopes, hippos, and various monkey species. The W-Arli-Pendjari complex, which includes Pendjari National Park along with Burkina Faso's Arli National Park and the W National Park, is considered one of the most important strongholds for lions in West Africa, with an estimated 246-466 lions. Historically, Benin was also a habitat for the endangered African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), though this species is now thought to be locally extinct. Conservation efforts are ongoing to protect Benin's biodiversity, particularly in the face of poaching and habitat loss.

5. Politics

Benin's political system is a presidential representative democratic republic, operating under a multi-party system. The current political framework is derived from the Constitution of 1990, which marked the country's transition to democracy. This transition was initially hailed as a model for Africa, but recent years have seen developments that raise concerns about democratic erosion and human rights.

5.1. Government

The President of Benin serves as both head of state and head of government. The president is elected by popular vote for a five-year term and is eligible for a second term. Constitutional provisions limit presidential candidates to a maximum of two terms and an age limit of 70 years. The president appoints the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The executive power is exercised by the government.

Legislative power is vested in the unicameral National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale). It consists of 83 members who are elected for four-year terms through a system of proportional representation. The National Assembly has the power to pass laws and oversee the actions of the executive branch.

The judiciary is officially independent of the executive and legislative branches. The highest courts are the Constitutional Court, which rules on constitutional matters and electoral disputes, and the Supreme Court, which is the highest court of appeal for administrative and judicial matters. However, concerns have been raised about the judiciary's practical independence, particularly with the Constitutional Court being headed by a former personal lawyer of the current president, Patrice Talon, which can undermine public trust in the impartiality of justice.

5.2. Democracy and human rights

Benin made a significant transition to democracy in 1991, ending a period of military and one-party rule. For many years, it was regarded as a beacon of democratic stability in West Africa, successfully holding multiple free and fair elections and witnessing peaceful transfers of power. The country was ranked 18th out of 52 African countries in the 2014 Ibrahim Index of African Governance, scoring well in Safety & Rule of Law and Participation & Human Rights.

However, since President Patrice Talon took office in 2016, there has been a noticeable erosion of democratic norms and human rights. In 2018, the government introduced new rules for fielding political candidates and increased the cost of registration. The electoral commission, largely composed of Talon's allies, barred all major opposition parties from participating in the 2019 parliamentary elections. This resulted in a parliament composed entirely of Talon's supporters. Subsequently, this parliament amended electoral laws to require presidential candidates to obtain the approval of at least 10% of Benin's MPs and mayors. Given that parliament and most mayoral offices are controlled by Talon's allies, this effectively gives the president significant control over who can run for the presidency, raising serious concerns about fairness and political pluralism.

These changes have drawn strong condemnation from domestic opposition groups and international observers. Freedom House reported a decline in Benin's freedom scores, and the United States government partially terminated development assistance through the Millennium Challenge Corporation, citing concerns about the decline in democratic governance. Protests against these electoral changes and the exclusion of opposition figures have, at times, been met with force by security services, leading to casualties and arrests of political activists and journalists. Reporters Without Borders' Press Freedom Index showed Benin falling from 53rd in 2007 to 78th in 2016, and further to 113th in subsequent years under Talon's presidency, indicating a worrying trend for freedom of expression. Corruption remains a concern, though Benin has been rated in the middle range in some international indices.

Despite these challenges, civil society organizations continue to operate, advocating for democratic freedoms and the rights of citizens, including minorities and vulnerable groups. The human rights situation, particularly regarding freedom of expression, assembly, and political participation, remains a key area of focus for both domestic and international scrutiny.

5.3. Military

The Benin Armed Forces (Forces Armées BéninoisesFABFrench) are responsible for the territorial defense of Benin and participate in international peacekeeping operations. The military is composed of the Army (l'Armée de TerreFrench), the Navy (la Marine NationaleFrench), the Air Force (la Force AérienneFrench), and the National Gendarmerie (la Gendarmerie NationaleFrench), which primarily handles internal security and policing in rural areas.

The President of Benin is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The total active military personnel is relatively small, estimated to be around 4,500 to 5,000 troops. The defense budget is modest, reflecting the country's economic constraints. Primary equipment is largely sourced from France, Russia, and China, and often consists of older or refurbished materiel.

Domestically, the military's roles include border security, counter-terrorism (increasingly important given the spillover of instability from the Sahel region), and disaster relief. Internationally, Benin has contributed troops to United Nations and African Union peacekeeping missions in various African countries, including Ivory Coast, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Mali.

In recent years, the northern regions of Benin, particularly areas bordering Burkina Faso and Niger, have faced increasing threats from extremist groups linked to Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. This has led to an increased military presence and operations in these areas, as well as incidents such as the W National Park massacre in February 2022, which resulted in casualties among park rangers and soldiers.

5.4. Administrative divisions

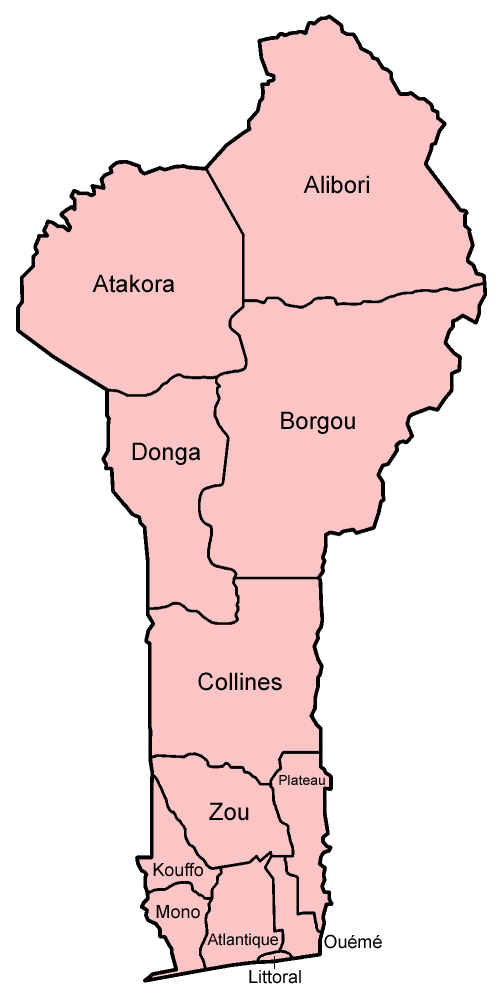

Benin is divided into twelve departments (départementsdépartementsFrench) which serve as the primary administrative units. These departments are further subdivided into 77 communes. The current twelve-department structure was established in 1999 when the previous six departments were each split into two.

The twelve departments are:

- Alibori (Capital: Kandi)

- Atakora (Capital: Natitingou)

- Atlantique (Capital: Allada; though Ouidah is also significant)

- Borgou (Capital: Parakou)

- Collines (Capital: Dassa-Zoumé; though Savalou is also significant)

- Kouffo (CouffoCouffoFrench; Capital: Aplahoué)

- Donga (Capital: Djougou)

- Littoral (Comprises the city of Cotonou)

- Mono (Capital: Lokossa)

- Ouémé (Capital: Porto-Novo)

- Plateau (Capital: Pobè; though Sakété is also significant)

- Zou (Capital: Abomey)

Each department is headed by a Prefect, appointed by the central government. The communes have elected mayors and councils, forming the basis of local governance.

5.5. Major cities

Benin has several important urban centers, primarily concentrated in the southern part of the country.

- Cotonou: Located in the Littoral Department, Cotonou is the largest city, economic capital, and seat of government. With a population of approximately 679,012 (2013 census) in the city proper and a larger metropolitan area, it hosts the country's main port, international airport, and most government ministries and foreign embassies. It is a major hub for trade and commerce.

- Porto-Novo: The official capital of Benin, located in the Ouémé Department. Its population was about 264,320 in 2013. While it holds constitutional capital status, many governmental functions are based in Cotonou. Porto-Novo is an important historical and cultural center, known for its Afro-Brazilian architecture and the Grand Mosque of Porto-Novo.

- Parakou: The largest city in northern Benin and the capital of the Borgou Department, with a population of around 255,478 (2013). Parakou is a significant transportation and trade hub, situated at the end of the railway line from Cotonou and on major road networks connecting to Niger and Nigeria. It is a center for the cotton industry.

- Djougou: A major city in northwestern Benin and the capital of the Donga Department, with a population of about 94,773 (2013). It is an important market town and cultural center for the region.

- Godomey: Located in the Atlantique Department, near Cotonou, Godomey is a rapidly growing urban area with a population of approximately 253,262 (2013), effectively forming part of the Cotonou metropolitan conurbation.

- Abomey-Calavi: Also in the Atlantique Department and part of the greater Cotonou area, Abomey-Calavi had a population of about 117,824 (2013). It is home to the main campus of the University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin's largest public university.

- Bohicon: An important commercial town in the Zou Department, with a population of around 93,744 (2013). It is located near the historic city of Abomey.

- Abomey: The historic capital of the Kingdom of Dahomey, located in the Zou Department, with a population of about 67,885 (2013). It is renowned for the Royal Palaces of Abomey, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Other significant towns include Kandi, Natitingou, Lokossa, and Ouidah, each serving as administrative or cultural centers for their respective regions.

6. Foreign relations

Benin pursues a foreign policy that emphasizes regional cooperation, strong ties with Western nations, particularly its former colonial power, France, and active participation in international organizations. The country generally maintains a non-aligned stance but has been a vocal advocate for democratic principles and human rights on the international stage, although its own recent domestic trends have complicated this image. Benin aims to attract foreign investment and development aid to support its economic growth.

6.1. Relations with France

Benin maintains close and multifaceted relations with France, its former colonial ruler. These ties span political, economic, cultural, and military domains. France is a significant trading partner, a major source of development aid, and provides military assistance and training to the Beninese armed forces. Cultural exchange is robust, with French being the official language of Benin and many Beninese students pursuing higher education in France. A significant recent development has been the restitution of cultural artifacts looted during the colonial era. In 2021, France returned 26 royal treasures, including statues and thrones from the Royal Palaces of Abomey, to Benin. This move has been hailed as a landmark step in addressing colonial legacies and has further shaped the bilateral relationship.

6.2. Relations with neighboring countries

Benin places a high priority on maintaining good relations with its neighboring countries:

- Nigeria: Nigeria is Benin's largest neighbor and most significant trading partner. The extensive border is porous, facilitating substantial formal and informal trade, including the re-export of goods through Benin to Nigeria. This economic interdependence also means Benin is susceptible to Nigerian economic policies, such as border closures, which can severely impact its economy. Both countries cooperate on security matters, particularly concerning cross-border crime and, more recently, the threat of terrorism spilling over from the Sahel.

- Togo: Benin shares close cultural and historical ties with Togo to its west. Relations are generally amicable, with cooperation on border management and regional issues within ECOWAS.

- Niger: Benin provides Niger, a landlocked country, with a crucial maritime outlet through the Port of Cotonou and the connecting road and rail networks. This transit trade is vital for both economies. The two countries share a border along the Niger River and collaborate within the Niger Basin Authority. A past border dispute over Lété Island in the Niger River was resolved peacefully by the International Court of Justice in 2005, with the island awarded to Niger.

- Burkina Faso: Benin also shares a northern border with Burkina Faso. Relations are generally stable, with cooperation on regional security becoming increasingly important due to the growing threat of extremist groups operating in the Sahel region, which affects both nations.

Benin actively participates in regional security initiatives to combat piracy in the Gulf of Guinea and terrorism in the Sahel-Sahara region.

7. Economy

Benin's economy is primarily based on agriculture, especially cotton, and regional trade, with significant reliance on Nigeria. Classified as a Least Developed Country, it faces challenges such as widespread poverty despite consistent GDP growth, which averaged around 5% in recent years (5.1% in 2008, 5.7% in 2009, and approximately 5.6% in 2017). The national currency is the CFA franc, pegged to the Euro. The government aims to diversify by attracting foreign investment, promoting tourism, and developing new industries. Key sectors like transportation and energy are crucial for its economic development, alongside ongoing efforts in science and technology. Benin is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA). The informal economy is substantial, and issues like child labor and forced labor persist.

7.1. Main sectors

- Agriculture: This sector is the backbone of Benin's economy, employing a large portion of the workforce and contributing significantly to GDP. Cotton is the principal cash crop and a major export, accounting for about 40% of GDP and roughly 80% of official export receipts at certain times. Other important agricultural products include palm oil (from oil palm), cashew nuts, shea butter, maize (corn), cassava, yams, beans, and rice. Subsistence farming is prevalent.

- Manufacturing: The manufacturing sector is relatively small and primarily involves the processing of agricultural products, such as cotton ginning, palm oil extraction, and food processing. There is also some production of textiles and construction materials.

- Services: The services sector contributes the largest share to Benin's GDP. This is largely due to its geographical location, which enables significant trade, transportation, and transit activities. The Port of Cotonou is a vital hub, serving not only Benin but also landlocked neighboring countries like Niger. Tourism is also considered a sector with growth potential. Telecommunications has been a growing part of the services sector.

7.2. Transportation

Benin's transportation infrastructure is crucial for its role as a transit country for regional trade.

- Roads: Benin has a total of approximately 4.2 K mile (6.79 K km) of highways, of which about 0.8 K mile (1.36 K km) are paved. This includes around 10 expressways. Paved highways connect Benin to its neighboring countries: Nigeria to the east, Togo, Ghana, and Ivory Coast to the west (as part of the Trans-West African Coastal Highway), and Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali to the north/north-west. Unpaved roads constitute the majority, at around 3.4 K mile (5.43 K km).

- Railways: Rail transport in Benin consists of about 359 mile (578 km) of single-track, 1,000 mm metre-gauge railway. The primary line runs from Cotonou to Parakou in the north, which is important for transporting goods to and from landlocked Niger. There have been plans and some construction work on international lines to connect Benin with Niger and Nigeria, with further outline plans for connections to Togo and Burkina Faso. Benin is a participant in the AfricaRail project.

- Ports: The Port of Cotonou is the country's only major seaport and is a critical gateway for international trade for Benin and neighboring landlocked countries. Efforts are ongoing to expand and modernize its facilities.

- Aviation: Cadjehoun Airport in Cotonou is Benin's primary international airport. It offers direct flights to several African cities including Accra, Niamey, Monrovia, Lagos, Ouagadougou, Lomé, and Douala, as well as international connections to cities like Paris, Brussels, and Istanbul.

- Waterways: Inland waterways are of limited significance for transport.

Challenges in the transport sector include the condition of unpaved roads, particularly during the rainy season, and the need for further investment in modernizing rail and port infrastructure.

7.3. Science and technology

Benin has been working to develop its science and technology sector as a means of fostering economic growth and innovation, though it faces significant challenges related to funding, infrastructure, and human resources.

7.3.1. National policy framework

The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research is responsible for implementing science policy. The National Directorate of Scientific and Technological Research handles planning and coordination. Advisory roles are played by the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research and the National Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters. Financial support is channeled through Benin's National Fund for Scientific Research and Technological Innovation. Technology transfer and the dissemination of research results are managed by the Benin Agency for the Promotion of Research Results and Technological Innovation.

The regulatory framework for science and innovation has evolved since the initial science policy was prepared in 2006. Key updates and complementary texts include:

- A manual for monitoring and evaluating research structures and organizations (2013).

- A manual on selecting research programs and projects and applying for competitive grants from the National Fund for Scientific Research and Technological Innovation (2013).

- A draft act for funding scientific research and innovation and a draft code of ethics for scientific research and innovation (submitted to the Supreme Court in 2014).

- A strategic plan for scientific research and innovation (under development as of 2015).

Benin has also sought to integrate science into broader policy documents such as "Benin Development Strategies 2025: Benin 2025 Alafia" (2000), the "Growth Strategy for Poverty Reduction 2011-2016" (2011), and the "Development Plan for Higher Education and Scientific Research 2013-2017" (2014). As of 2015, Benin's priority areas for scientific research included health, education, construction and building materials, transportation and trade, culture, tourism and handicrafts, cotton/textiles, food, energy, and climate change.

Challenges facing research and development in Benin include an unfavorable organizational framework for research (weak governance, lack of cooperation between research structures, absence of an official document on researcher status), inadequate use of human resources and lack of motivational policies for researchers, and a mismatch between research and development needs. Benin was ranked 119th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

7.3.2. Human and financial investment in research

In 2007, Benin had approximately 1,000 researchers (in headcounts), corresponding to about 115 researchers per million inhabitants. Main research institutions include the Centre for Scientific and Technical Research, the National Institute of Agricultural Research, the National Institute for Training and Research in Education, the Office of Geological and Mining Research, and the Centre for Entomological Research. The University of Abomey-Calavi was selected by the World Bank in 2014 for its Centres of Excellence project due to its expertise in applied mathematics, receiving a 8.00 M USD loan.

Data on Benin's overall investment in research and development (as a percentage of GDP) is often unavailable. In 2013, the government allocated 2.5% of GDP to public health. In 2010, government expenditure on agricultural development was less than 5% of GDP, below the African Union's Maputo Declaration target of 10%.

7.3.3. Research output

According to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded), Benin had the third-highest publication intensity for scientific journals in West Africa in 2014, with 25.5 scientific articles per million inhabitants. This was higher than Senegal (23.2) and Ghana (21.9), but lower than The Gambia (65.0) and Cape Verde (49.6). The volume of publications from Benin in this database tripled between 2005 (86 articles) and 2014 (270 articles). Between 2008 and 2014, Benin's main international scientific collaborators were based in France, the United States, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Germany.

7.4. Energy

Benin faces significant challenges in its energy sector, characterized by insufficient domestic production, reliance on imports, and limited access to electricity for a large portion of its population.

The main sources of energy in Benin include thermal power (generated from imported fossil fuels) and some hydroelectric power, though the latter's potential is not fully exploited. A substantial portion of Benin's electricity is imported, primarily from Nigeria and Ghana. This reliance on imports makes the country vulnerable to supply disruptions and price fluctuations in neighboring countries.

Electricity generation and supply within Benin are often inadequate to meet demand, leading to frequent power outages that adversely affect economic activity and daily life. Access to electricity is a major issue, particularly in rural areas. It is estimated that a significant majority of the population, perhaps up to two-thirds, lacks access to reliable electricity.

The government has recognized the need to improve the energy sector and has outlined plans to increase domestic power production. These plans include developing new thermal power plants, exploring renewable energy sources such as solar power, and potentially investing further in hydroelectric projects. Efforts are also being made to attract private sector investment in independent power production to reduce dependency on imports and improve the stability of the national grid. The West African Gas Pipeline project, involving Nigeria, Benin, Togo, and Ghana, aims to supply natural gas for power generation, which could help improve Benin's energy security if fully realized.

8. Demographics

Benin has a rapidly growing population with a young age structure, diverse ethnic composition, and a variety of languages and religions, reflecting a complex social fabric.

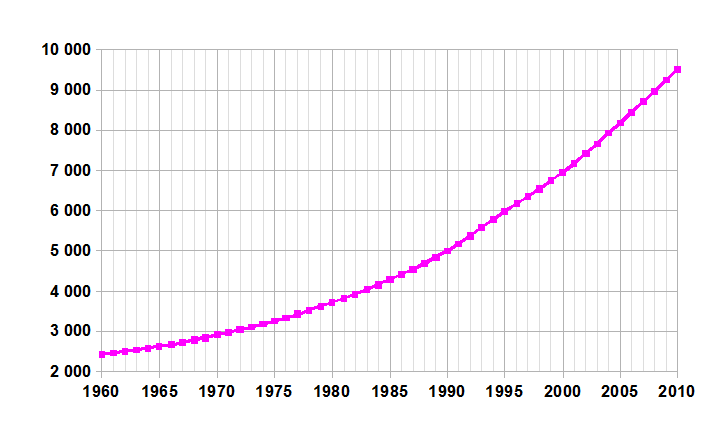

8.1. Population

The population of Benin was estimated to be approximately 11.49 million in 2018, with earlier census data from 2013 indicating around 10 million. The United Nations estimated the population in 2021 to be approximately 13 million. The population growth rate is high. The majority of Benin's inhabitants live in the southern part of the country, particularly in the coastal plains and urban centers like Cotonou and Porto-Novo.

The age structure is predominantly young. Life expectancy at birth is around 62 years (as of 2015-2020 estimates). The urban-rural distribution shows significant urbanization, though a large portion of the population still resides in rural areas and relies on agriculture.

Historical population figures:

- 1950: 2.2 million

- 2000: 6.8 million

8.2. Ethnic groups

Benin is home to about 42 distinct African ethnic groups. These groups migrated to the area at different times and have maintained their unique cultural characteristics. Inter-ethnic relations are generally peaceful, though regional and ethnic affiliations have historically played a role in politics.

The major ethnic groups include:

- Fon: The largest ethnic group, constituting about 38.4% of the population (2013 census). They are primarily located in the south-central region, around Abomey (the historic capital of the Kingdom of Dahomey) and extending towards the coast.

- Adja & Mina: Comprising around 15.1% of the population. The Adja are concentrated in the southwestern Kouffo and Mono departments, having historical links to Togo. The Mina are also found in this coastal region.

- Yoruba: Making up about 12% of the population, the Yoruba are concentrated in the southeast, particularly in and around Porto-Novo and along the Nigerian border. They migrated from what is now Nigeria, beginning in the 12th century.

- Bariba: Constituting about 9.6% of the population, the Bariba are the dominant group in the northeastern Borgou and Alibori departments.

- Fula (Peul or Fulani): Amounting to about 8.6%, the Fula are traditionally pastoralists found throughout West Africa, with significant communities in northeastern Benin.

- Ottamari (or Betammaribe/Somba): About 6.1% of the population, known for their distinctive two-story fortified houses (Tata Somba), primarily inhabiting the Atakora Mountains in the northwest.

- Yoa-Lokpa: Around 4.3% of the population, located in central and northern regions.

- Dendi: Making up about 2.9%, the Dendi are found in the north-central area, particularly along the Niger River. They are descendants of Songhai traders and came from Mali in the 16th century.

- Other groups include the Xueda on the coast.

There is also a small European population (around 5,500), largely consisting of personnel from embassies, foreign aid missions, NGOs, and missionary groups. Recent migrations have brought an increase in nationals from neighboring African countries like Nigeria, Togo, and Mali. A community of Lebanese and Indian origin is also involved in trade and commerce.

8.3. Languages

The official language of Benin is French, a legacy of its colonial period. French is used in government, administration, education (especially at secondary and tertiary levels), and the media.

However, Benin is a multilingual country with over 50 indigenous languages spoken. Some of the most widely spoken indigenous languages include:

- Fon (FɔngbèFɔngbèFon): Spoken by about 24% of the population as a first language, primarily by the Fon people in the south and central regions. It serves as a lingua franca in these areas.

- Yoruba: Widely spoken in the southeast, particularly in Porto-Novo and along the Nigerian border.

- Bariba: Spoken in the northeast.

- Dendi: Spoken in the north, especially along the Niger River, and serves as a trade language.

- Other significant languages include Adja, Mina, Ditammari (of the Ottamari/Betammaribe), Yom, and various Gur and Kwa languages.

Local languages are often used as the medium of instruction in the early years of elementary school, with French being introduced progressively. Beninese languages are generally transcribed using a phonetic alphabet, with a separate letter for each phoneme, rather than relying heavily on diacritics (as in French) or digraphs (as in English for certain sounds). For instance, consonants like /ŋ/ (English 'ng' in 'sing') and /ʃ/ (English 'sh') might be represented by unique letters. Digraphs are used for labial-velar consonants like kp and gb (common in West African languages, e.g., in Fɔngbè). Tone is often marked with diacritics.

The government promotes the development of national languages for communication, as stipulated in the constitution, which guarantees communities the freedom to use their native spoken and written languages.

8.4. Religion

Benin is characterized by a diversity of religious beliefs, with Christianity and Islam being prominent alongside deeply ingrained traditional African religions, most notably Vodun. Religious tolerance is generally high.

Estimates of religious affiliation vary slightly between different surveys and censuses:

- According to the 2013 census:

- Christianity: 48.5% (including Roman Catholic 25.5%, Celestial Church of Christ 6.7%, Methodist 3.4%, and other Christian denominations 12.9%)

- Islam: 27.7%

- Vodun: 11.6%

- Other local traditional religions: 2.6%

- Other religions: 2.6%

- No religious affiliation: 5.8%

- A 2020 CIA World Factbook estimate suggests:

- Christianity: 52.2%

- Islam: 24.6%

- Animist (including Vodun): 17.9% (This figure seems to combine Vodun with other traditional beliefs)

- Others / None: 5.3%

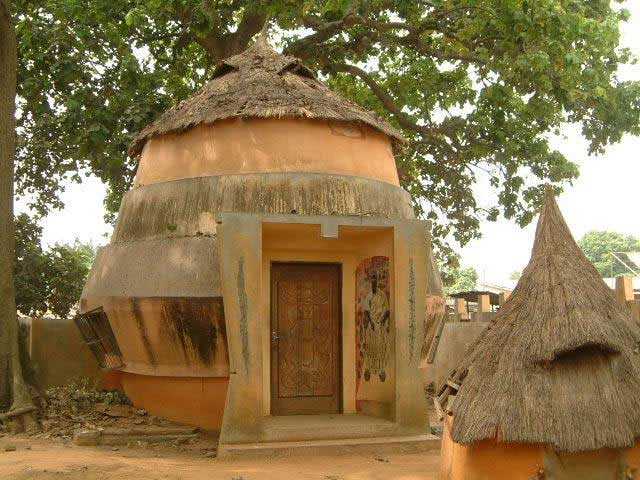

A Vodun temple in Benin. Vodun is an officially recognized religion and an integral part of Beninese culture. Christianity is most prevalent in the southern and central regions of Benin, as well as among the Ottamari people in the Atakora department. Roman Catholicism has the largest following among Christian denominations. African Initiated Churches, such as the Celestial Church of Christ, also have a substantial presence.

Islam was introduced primarily by Songhai and Hausa merchants and is predominantly practiced in the northern departments of Alibori, Borgou, and Donga, as well as among some Yoruba communities who also practice Christianity. The Ahmadiyya Islamic movement also has a presence.

Traditional religions remain influential. Vodun (often anglicized as Voodoo) originated in this region among the Fon, Ewe, and Yoruba peoples and is a complex system of beliefs involving a supreme creator, numerous deities (vodun or orisha), spirits of nature, and ancestor veneration. The city of Ouidah, on the central coast, is considered the spiritual center of Beninese Vodun. Many Beninese who identify as Christian or Muslim may also incorporate elements of Vodun or other traditional beliefs into their practices (syncretism). Vodun was officially recognized as a religion in Benin in 1992, and January 10th is celebrated annually as National Vodun Day, a public holiday. Other traditional beliefs include local animistic religions in the Atakora region and Orisha veneration among the Yoruba and Tado peoples.

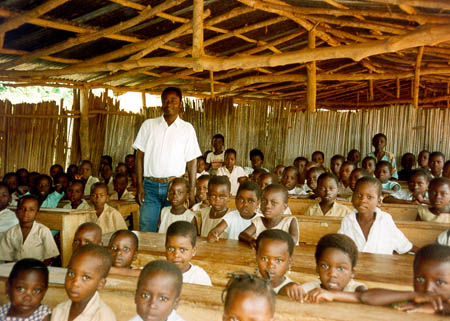

8.5. Education

Benin's education system has made progress, particularly in primary education, but still faces challenges regarding access, quality, and literacy rates. The system is structured into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels.

The literacy rate was estimated at 38.4% in 2015 (49.9% for males and 27.3% for females), indicating a significant gender gap and overall low literacy. The government has been working to improve these figures.

Primary education (elementary school) lasts for six years and is, by law, compulsory. Benin has achieved near universal primary education enrollment, with significant improvements following the abolition of school fees. According to UNESCO Institute for Statistics, in 2013, about half of the children (54%) were enrolled in secondary education. Secondary education is typically divided into a junior cycle (four years) and a senior cycle (three years). French is the language of instruction, especially from the later years of primary school onwards, and is the sole language of instruction at the secondary and tertiary levels. Local languages may be used in early primary education.

Higher education is provided by universities and other tertiary institutions. The main public universities are the University of Abomey-Calavi (formerly National University of Benin) and the University of Parakou. Student enrollment in tertiary education more than doubled between 2006 (50,225 students) and 2011 (110,181 students), encompassing bachelor's, master's, Ph.D. programs, and non-degree post-secondary diplomas.

The government has shown commitment to education, devoting more than 4% of GDP to the sector since 2009 (4.4% in 2015). Within this, about 0.97% of GDP was allocated to tertiary education in 2015. Key challenges in the education sector include disparities in access and quality between urban and rural areas, gender disparities in enrollment and completion rates (especially at higher levels), a shortage of qualified teachers, and inadequate infrastructure and resources. Ensuring access to education for vulnerable groups remains a policy focus.

The たけし小学校Takeshi Shōgakkō (Takeshi Elementary School)Japanese and たけし日本語学校Takeshi Nihongo Gakkō (Takeshi Japanese Language School)Japanese were established in Benin by Zomahoun Rufin, a Beninese national who became a television personality in Japan and later Benin's ambassador to Japan, with support from Japanese entertainer Beat Takeshi. These institutions aim to provide educational opportunities and Japanese language instruction.

8.6. Health

Benin faces significant public health challenges, although improvements have been made in recent decades. The country's health indicators reflect those of many developing nations in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Key health indicators include an infant mortality rate that, while declining, remains high (around 57 deaths per 1,000 live births as of 2017-2020 estimates). Maternal mortality is also a serious concern, with a rate of 397 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2017, though this has shown a downward trend. Life expectancy is approximately 62 years.

Common diseases include malaria, which is endemic and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among children under five. HIV/AIDS is also present, with an adult prevalence rate estimated at around 0.9% to 1.13% (2013-2020 estimates); efforts are ongoing to control its spread and provide treatment. Other prevalent health issues include respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, and malnutrition.

Access to medical services is limited, particularly in rural areas. In the 1980s, less than 30% of the population had access to primary healthcare. The Bamako Initiative, introduced in the late 1980s and early 1990s, aimed to revitalize primary healthcare through community-based reforms, leading to more efficient and equitable service provision. Government expenditure on health was about 2.5% of GDP in 2013. There is a mix of public and private healthcare providers, and traditional medicine also plays a significant role.

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is practiced in some communities, with UNICEF reporting in 2013 that 13% of women had undergone FGM, though rates vary by region and ethnic group.

Benin has participated in international health cooperation, including efforts to combat epidemics like Ebola in West Africa, by sending volunteer health professionals. The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) program has conducted surveys in Benin since 1996, providing valuable data on health trends.

In the 2024 Global Hunger Index, Benin ranked 99th out of 127 countries, indicating ongoing challenges with food security and nutrition.

8.7. Public safety

The general security situation in Benin has traditionally been relatively stable compared to some other countries in the region, but it faces challenges from crime and, more recently, the threat of terrorism spilling over from the Sahel.

Common types of crime include petty theft, street robbery, and burglary, particularly in urban areas like Cotonou. Armed robbery can occur, especially on highways and in residential areas after dark. Credit card and ATM fraud targeting foreigners have also been reported. Drug trafficking has become an increasing concern, with Benin sometimes used as a transit point for narcotics moving from South America to Europe and North America. Cannabis is cultivated in some central parts of the country.

The government, through the national police and gendarmerie, is responsible for maintaining public order. However, resources for law enforcement can be limited. Corruption within law enforcement and the judicial system remains an issue, although Benin has shown some improvement in corruption perception indices over time.

In recent years, the northern border regions of Benin, particularly those adjoining Burkina Faso and Niger, have experienced an increase in attacks by extremist groups affiliated with Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. These attacks have targeted security forces and civilians, leading to heightened security measures in these areas. The W National Park massacre in February 2022, which resulted in the deaths of park rangers, soldiers, and a French instructor, was a significant incident highlighting this growing threat.

Travel advisories from various foreign governments often caution visitors about crime levels in urban areas and, increasingly, security risks in northern border regions. General safety precautions, such as avoiding travel at night in certain areas and securing valuables, are typically recommended for travelers. Human trafficking, particularly of children for forced labor and sexual exploitation, is a serious problem that the government is working to combat, though challenges in enforcement and victim support remain.

8.8. Mass media

Benin has a relatively diverse media landscape, which experienced significant liberalization following the democratic transition in the early 1990s.

Newspapers: Numerous daily and weekly newspapers are published, primarily in French. Prominent titles include La Nation (state-owned), Le Matinal, Fraternité, and various independent publications. These offer a range of perspectives, though financial sustainability can be a challenge for private outlets.

Television and Radio: The state-run Office de Radiodiffusion et Télévision du Bénin (ORTB) operates national television and radio channels. Alongside ORTB, there are many private television and radio stations, particularly FM radio stations, which are a popular source of news and entertainment, broadcasting in French and local languages.

Internet Media: Internet penetration has been growing, leading to an increase in online news portals, blogs, and social media use for information dissemination and discussion.

Press Freedom: For many years, Benin was considered to have one of the freer media environments in West Africa. However, since 2016, under President Patrice Talon's administration, there have been growing concerns about restrictions on press freedom. Reporters Without Borders' World Press Freedom Index has shown a decline in Benin's ranking. Incidents of arrests, harassment of journalists critical of the government, and the shutting down of media outlets have been reported. New media laws and regulatory bodies have also been subjects of debate regarding their impact on media independence.

The media plays a significant role in Beninese society, providing information, facilitating public debate, and holding authorities accountable, though its ability to do so freely has faced increasing pressure.

9. Culture

Benin possesses a rich and diverse cultural heritage, deeply influenced by its pre-colonial kingdoms, colonial history, and vibrant ethnic mosaic. Traditional beliefs and practices, particularly Vodun, continue to play a significant role in contemporary Beninese society.

9.1. Arts

Benin is renowned for its traditional arts. Sculpture, particularly bronze work (though historically more associated with the nearby Kingdom of Benin in Nigeria, some traditions existed), wood carvings, and pottery are significant. Mask-making is an important part of various traditional ceremonies and rituals. Textiles are also a key art form, with intricate weaving and dyeing techniques used to create colorful fabrics, such as the Kanvo cloth.

The Royal Palaces of Abomey, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, feature bas-reliefs that narrate the history and mythology of the Kingdom of Dahomey. Contemporary Beninese artists are also gaining international recognition.

The Biennale Benin, an international contemporary art exhibition, was established in 2010 (initially as "Regard Benin" and becoming a biennial in 2012), showcasing both local and international artists and further promoting Benin's art scene. The country is also known for the historic restitution of 26 royal artifacts from France in 2021, which were looted during the colonial era. These items are now central to Benin's efforts to reclaim and display its cultural heritage.

9.2. Literature

Beninese literature has strong roots in oral traditions, including epic poems, proverbs, and folktales, which were passed down through generations. With colonization, French became the dominant language of written literature.

Félix Couchoro is considered a pioneer, having written the first Beninese novel, L'Esclave (The Slave), published in 1929. Post-independence, a number of notable writers have emerged, exploring themes of colonialism, identity, social change, and political issues. Prominent authors include Olympe Bhêly-Quénum, Jean Pliya, Paulin J. Hountondji (also a philosopher), and Florent Couao-Zotti. Contemporary Beninese literature continues to thrive, with new voices contributing to Francophone African literature.

9.3. Music

Benin has a vibrant and diverse musical landscape, blending traditional rhythms with modern influences. Traditional music varies among ethnic groups, often featuring drums, xylophones, and vocal performances linked to ceremonies, storytelling, and daily life. Vodun ceremonies, in particular, have distinctive musical traditions.

In the post-independence era, native folk music was combined with genres like Ghanaian highlife, French cabaret, American rock, funk, and soul, as well as Congolese rumba. Angélique Kidjo, an internationally acclaimed singer-songwriter, is Benin's most famous musical export, known for her eclectic mix of West African traditions, pop, jazz, and world music.

Other notable musicians and groups include Orchestre Poly-Rythmo de Cotonou, a legendary band active since the 1960s, known for its unique blend of Afrobeat, funk, Sato, and Vodun rhythms. Ignacio Blazio Osho, Pédro Gnonnas y sus Panchos, Les Volcans, and Picoby Band d'Abomey were influential in the post-independence music scene. Nel Oliver developed "Afro-akpala-funk." More recently, artists like Lionel Loueke (jazz guitarist) and the Gangbé Brass Band (fusing traditional Vodun music with jazz and brass band sounds) have gained international recognition. Reggae and hip hop are also popular among younger generations. Music festivals and cultural events play a role in promoting Beninese music.

9.4. Cinema

The film industry in Benin is relatively small but has produced notable works. Early pioneers include Pascal Abikanlou, who directed numerous documentaries and feature films from the 1960s, often focusing on Beninese life and culture. François Sourou Okioh, active from the 1980s, is another significant director, screenwriter, and producer, with over 100 documentaries and television films to his credit.

Beninese filmmakers have often explored themes of tradition, modernity, social issues, and history. Productions may face funding and distribution challenges common in many African film industries. Beninese films and directors have participated in various African and international film festivals, contributing to the broader landscape of African cinema.

9.5. Cuisine

Beninese cuisine features fresh ingredients and a variety of flavorful sauces. Staples vary by region.

In southern Benin, maize (corn) is a primary staple. It is often ground into a flour to prepare a dough or porridge (known as pâte or akassa), which is commonly served with peanut-based or tomato-based sauces. Fish and chicken are common protein sources, along with beef, goat, and occasionally bush rat (agouti).

In northern Benin, yams are a major staple, often pounded into a paste (igname pilée) or boiled, and served with various sauces. Beef and pork are more commonly consumed in the north, often fried in palm or peanut oil or cooked in stews. Cheese, particularly a type of Fulani cheese, is also used in some northern dishes.

Other common foods across the country include rice, beans, couscous, and various vegetables. Fruits such as mangoes, oranges, avocados, bananas, kiwi fruit, and pineapples are widely available and consumed.

Meals are often described as being generous with vegetable fats, with palm oil and peanut oil being the primary cooking oils. Frying is a common meat preparation method. Smoked fish is also widely used.

Street food is popular, with items like akara (fried bean cakes, similar to Brazilian acarajé), grilled meats, and various snacks readily available. "Chicken on the spit" (rotisserie chicken) is a popular preparation. Palm roots are sometimes soaked and tenderized for use in dishes. Many households use traditional outdoor mud stoves for cooking.

9.6. Sports

The most popular sport in Benin is association football (soccer). The Benin national football team, nicknamed "Les Écureuils" (The Squirrels), competes in international competitions. While they have not yet qualified for the FIFA World Cup, they have participated in the Africa Cup of Nations on several occasions, with their best performance being a quarter-final appearance in the 2019 edition. The domestic football league is the Benin Premier League. Notable Beninese footballers include Stéphane Sessègnon.

Other sports played in Benin include basketball, athletics (track and field), volleyball, handball, and tennis. Golf, cycling, baseball, and softball are also practiced, though with smaller followings. Teqball was introduced in the early 21st century. Benin participates in the Olympic Games and other international sporting events. Traditional wrestling forms also exist in various communities.

9.7. Public holidays

Benin observes a mix of national, religious, and traditional holidays. Major public holidays include:

| Date | English Name | French Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| January 1 | New Year's Day | Jour de l'An | |

| January 10 | Vodun Day (Traditional Religions Day) | Fête du Vodoun | Celebrates traditional Vodun beliefs. |

| Moveable | Eid al-Adha | Tabaski (Aïd el-Kebir) | Islamic festival; date varies according to the lunar calendar. |

| Moveable | Easter Monday | Lundi de Pâques | Christian holiday; date varies. |

| May 1 | Labour Day | Fête du Travail | |

| Moveable | Ascension Day | Ascension | Christian holiday; date varies. |

| Moveable | Whit Monday (Pentecost Monday) | Lundi de Pentecôte | Christian holiday; date varies. |

| Moveable | Mawlid (Prophet Muhammad's Birthday) | Maouloud | Islamic festival; date varies. |

| August 1 | Independence Day | Fête Nationale / Fête de l'Indépendance | Commemorates independence from France in 1960. |

| August 15 | Assumption of Mary | Assomption | Christian holiday. |

| Moveable | Eid al-Fitr (End of Ramadan) | Korité (Aïd el-Fitr) | Islamic festival; date varies. |

| November 1 | All Saints' Day | Toussaint | Christian holiday. |

| December 25 | Christmas Day | Noël | Christian holiday. |

Dates for Islamic holidays are determined by lunar sightings and may vary.

9.8. World Heritage sites

Benin is home to sites recognized by UNESCO for their outstanding universal value.

- Royal Palaces of Abomey: Inscribed as a Cultural World Heritage site in 1985, these palaces were the capital of the powerful Kingdom of Dahomey from the mid-17th to the late 19th century. The site consists of a group of earthen palaces built by successive Fon kings. They are a significant testimony to the history, culture, and artistic traditions of the kingdom, particularly known for their bas-reliefs depicting historical events and royal symbols.

- W-Arly-Pendjari Complex: This is a transnational Natural World Heritage site, shared with Niger and Burkina Faso. Benin's Pendjari National Park and part of W National Park are included in this complex. It was inscribed for its significant biodiversity, representing a continuum of Sudano-Sahelian savanna ecosystems. The complex is a crucial habitat for West African wildlife, including elephants, lions, cheetahs, African wild dogs, and a wide variety of ungulates and bird species. The site was an extension of Niger's W National Park (inscribed 1996) to include areas in Benin and Burkina Faso in 2017.