1. Overview

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country located in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa. It possesses an extensive coastline on the Red Sea and is bordered by Sudan to the west, Ethiopia to the south, and Djibouti to the southeast. Its capital and largest city is Asmara. The nation encompasses a total area of approximately 45 K mile2 (117.60 K km2) and includes the Dahlak Archipelago and several of the Hanish Islands. Eritrea is a multi-ethnic country with nine recognized ethnic groups, each with its own language. Tigrinya and Arabic are the most widely spoken, while Tigrinya, Arabic, and English serve as working languages.

Historically, the region was home to ancient civilizations, including the Land of Punt and the Kingdom of Aksum. It experienced various forms of foreign influence, including Ottoman, Egyptian, and eventually Italian colonization in 1890, which established its modern borders. After Italian rule and a period of British administration following World War II, Eritrea was federated with Ethiopia in 1952 and subsequently annexed in 1962. This led to a protracted 30-year Eritrean War of Independence, which concluded with de facto independence in 1991 and de jure independence in 1993 following a referendum.

Since independence, Eritrea has been governed by the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), with Isaias Afwerki as president. The country is a unitary one-party presidential republic, and national legislative and presidential elections have never been held. The political system has faced significant international criticism for its human rights record, particularly concerning indefinite national service, restrictions on freedoms of speech, press, and religion, and the lack of democratic processes, leading to large-scale emigration. The post-independence period has also been marked by conflict, notably the Eritrean-Ethiopian War (1998-2000) and, more recently, involvement in the Tigray War.

Eritrea's economy is largely based on subsistence agriculture, with mining emerging as a significant sector. The country faces developmental challenges, including those related to its political isolation and the socio-economic impact of prolonged national service. Culturally, Eritrea is diverse, with rich traditions in music, dance, cuisine, and a notable architectural heritage in Asmara, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of Eritrea, with a particular focus on its social development, human rights situation, and democratic progress (or lack thereof) from a perspective that emphasizes these aspects.

2. Etymology

The name Eritrea is derived from the ancient Greek name for the Red Sea, the Erythraean Sea (Ἐρυθρὰ ΘάλασσαErythra ThalassaGreek, Ancient). This, in turn, was based on the Greek adjective ἐρυθρόςerythrosGreek, Ancient, meaning "red". The name was formally adopted in 1890 with the formation of Italian Eritrea (Colonia EritreaItalian Colony of EritreaItalian). The name persisted through the subsequent British administration and Ethiopian rule and was reaffirmed by the 1993 independence referendum and the 1997 constitution (though the latter has not been implemented).

3. History

Eritrea's history spans from early human presence and ancient kingdoms to Italian colonization, a lengthy war for independence, and subsequent post-independence developments, including significant conflicts and ongoing political challenges. The following sections detail these periods, examining the formation of the modern state and the societal impacts of these historical events.

3.1. Prehistory

Human remains found in Eritrea have been dated to 1 million years old, and anthropological research indicates that the area may contain significant records related to the evolution of humans. One notable find is Madam Buya, a hominid fossil discovered by Italian anthropologists in Eritrea. Dated to 1 million years old, it is considered one of the oldest hominid fossils representing a possible link between the earlier Homo erectus and an archaic Homo sapiens. This find is significant for understanding human evolutionary stages. The Danakil Depression region in Eritrea is believed to have been a major site for human evolution and may hold further traces of this transition.

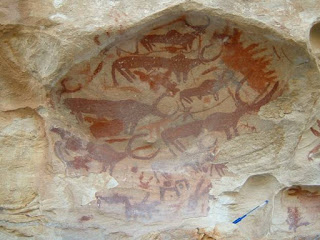

During the last interglacial period, the Red Sea coast of Eritrea was occupied by early anatomically modern humans. This area is thought to have been on the route out of Africa used by early humans to colonize other parts of the Old World. In 1999, an Eritrean research team, along with Canadian, American, Dutch, and French scientists, discovered a Paleolithic site near the Gulf of Zula, south of Massawa. This site contained stone and obsidian tools dated to over 125,000 years old, believed to have been used by early humans for harvesting marine resources like clams and oysters. Archaeological findings, including tools from the Barka Valley dating back to 8,000 BC, provide further evidence of early human settlement. Rock art sites, such as those in Deka Arbaa, with depictions of domesticated cattle, suggest long-term human occupation and pastoral activities.

3.2. Antiquity

The ancient period in Eritrea saw the rise and fall of several influential kingdoms and cultures that shaped its early societal and economic structures. These include early cultures like the Land of Punt and the Gash Group, the kingdom of D'mt, and the powerful Kingdom of Aksum, which became a major trading empire.

3.2.1. Early Cultures and Polities (Punt, Gash Group, Ona Culture)

Around 2000 BC, parts of Eritrea were likely part of the Land of Punt, a kingdom first mentioned in Egyptian records dating to the 25th century BC. Punt was known for producing and exporting gold, aromatic resins like frankincense and myrrh, blackwood (ebony), ivory, and wild animals. Ancient Egyptian records detail trade expeditions to Punt, notably a well-documented mission during the reign of Queen Hatshepsut around 1469 BC, which aimed to re-establish trade routes.

Excavations in and near Agordat in central Eritrea yielded remains of an ancient pre-Aksumite civilization known as the Gash Group. Ceramics discovered at these sites have been dated to between 2500 BC and 1500 BC. This culture is considered contemporaneous with the Kerma culture in Nubia.

In the greater Asmara area, excavations at Sembel revealed evidence of the Ona Culture, an ancient pre-Aksumite urban civilization. The Ona are believed to have been among the oldest pastoral and agricultural communities in East Africa. Artifacts from Ona sites, including evidence of trade with Pharaonic Egypt (such as items from the time of Amenhotep II), have been dated to between 800 BC and 400 BC, contemporaneous with other pre-Aksumite settlements in the Eritrean and Ethiopian highlands.

3.2.2. Kingdom of Dʿmt

The Kingdom of Dʿmt (ዳሞትDʿmtGeez) existed from approximately the 10th to the 5th centuries BC in what is now Eritrea and northern Ethiopia. While the major temple complex at Yeha (in modern Ethiopia) is often considered its capital, significant Dʿmt cities in southern Eritrea included Matara and Qohaito. Qohaito is often identified with the town of Koloe mentioned in the 1st-century AD Greek travelogue, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.

The Dʿmt kingdom developed irrigation schemes, used plows, cultivated millet, and produced iron tools and weapons. Its culture shows influences from the Sabaean Kingdom in Southern Arabia, particularly in architecture and religious practices. After the fall of Dʿmt in the 5th century BC, the plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms. This period, often referred to as the pre-Aksumite era, lasted until the rise of the Kingdom of Aksum in the 1st century AD, which eventually reunified the region.

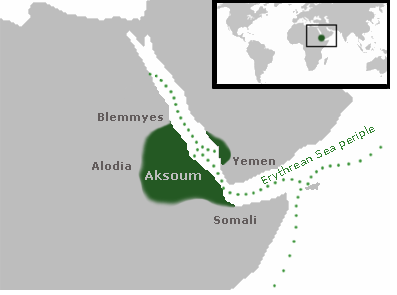

3.2.3. Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum was a major trading empire centered in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, flourishing from approximately 100 AD to 940 AD. It grew from proto-Aksumite Iron Age cultures around the 4th century BC, achieving prominence by the 1st century AD. The kingdom's influence extended across the Red Sea to parts of the Arabian Peninsula. The port city of Adulis on the Eritrean coast was a crucial hub for Aksum's extensive trade network, connecting it with Egypt, the Roman Empire, India, and beyond. Ivory was a key export.

Aksumite rulers facilitated trade by minting their own currency. The kingdom erected large stelae, such as the famous Obelisk of Aksum, which served religious purposes in pre-Christian times. Around the middle of the 4th century AD, under King Ezana (fl. 320-360 AD), Aksum adopted Christianity. This marked a significant cultural shift, and Eritrea became one of the earliest regions in Africa to embrace the new faith. The Debre Sina monastery, built in the 4th century, is one of the oldest monasteries in Africa. Debre Libanos monastery, founded in the late 5th or early 6th century, also became an important religious center.

In the 7th century, early Muslims fleeing persecution in Mecca sought refuge in the Aksumite kingdom, an event known as the First Hijrah. They are said to have built the Mosque of the Companions in Massawa, considered by some to be the first mosque in Africa. The decline of Aksum began in the 7th century due to the rise of Islamic power in the Red Sea, which disrupted its trade routes, and environmental degradation.

3.3. Medieval Period (Medri Bahri)

After the decline of the Aksumite Kingdom, the Eritrean highlands came under the domain of the Christian Zagwe dynasty and later fell within the sphere of influence of the Solomonid Ethiopian Empire. The region was initially known as Ma'ikele Bahri ("between the seas/rivers," i.e., the land between the Red Sea and the Mareb River). For a period, the coastal domain of Ma'ikele Bahri was under the Adal Sultanate during the reign of Sultan Badlay ibn Sa'ad ad-Din.

Later, the Ethiopian Emperor Zara Yaqob reconquered the area and reorganized the administration of the coastal highlands into the Christian province of Medri Bahri ("Sea Land" in Tigrinya). This kingdom, ruled by a governor titled the Bahr Negash (King of the Sea), had its capital at Debarwa. The main provinces of Medri Bahri were Hamasien, Serae, and Akele Guzai. Medri Bahri maintained a complex relationship with the Ethiopian Empire, sometimes acting as a vassal state and at other times asserting greater autonomy.

The Portuguese explorer Francisco Álvares, who visited the region in 1520, provided early Western documentation of Medri Bahri and its relationship with the Ethiopian interior. Massawa served as a key port, facilitating contact between the Portuguese and their Ethiopian allies during conflicts such as the Ethiopian-Adal War. In 1541, Cristóvão da Gama landed troops at Massawa for a military campaign that eventually defeated the Adal Sultanate.

3.4. Ottoman and Egyptian Influence

Starting in the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire began to exert influence over the Eritrean coast. In 1557, the Ottomans conquered Massawa and parts of the coastal lowlands, establishing the Habesh Eyalet (Ottoman Abyssinia). Massawa initially served as its capital, though administrative control later shifted to Jeddah. The Ottomans attempted to expand into the Eritrean highlands but faced resistance from the Bahr Negash and local forces. In 1578, with the help of Bahr Negash Yisehaq (who had switched allegiances), they made further inroads, but Ethiopian Emperor Sarsa Dengel launched punitive expeditions, and by 1589, the Ottomans were largely confined to the coast. They retained control over the seaboard, including Massawa and other ports, for several centuries, though their direct rule over the interior was limited.

In the 1730s, the Afar leader Kedafu established the Mudaito Dynasty, which came to include the southern Denkel lowlands of Eritrea, incorporating this area into the Sultanate of Aussa.

In the 19th century, Egyptian influence grew in the region. In May 1865, under the Khedivate of Egypt, much of the coastal lowlands previously under Ottoman sway came under Egyptian administration. This lasted until the Egyptians withdrew in February 1885, paving the way for Italian colonial expansion.

3.5. Italian Colonization (Italian Eritrea)

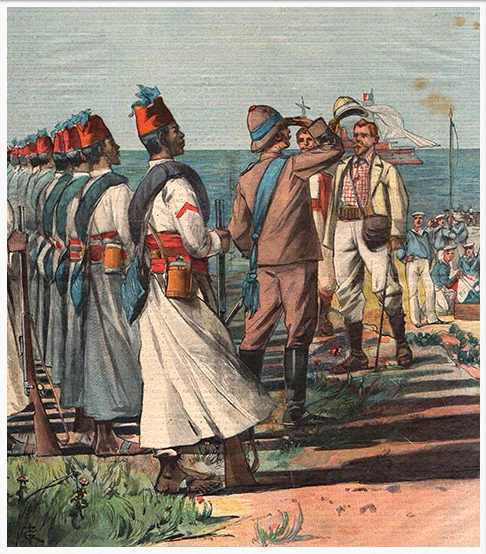

The boundaries of present-day Eritrea were largely established during the Scramble for Africa. In 1869, an Italian missionary, Giuseppe Sapeto, purchased land around the Bay of Assab on behalf of the Rubattino Shipping Company, establishing a coaling station. In 1882, the Italian government formally took possession of Assab. Following the Egyptian withdrawal in 1885, Italy expanded its control to include Massawa and much of the Eritrean coastal lowlands.

In the power vacuum following the death of Ethiopian Emperor Yohannes IV in 1889, Italian General Oreste Baratieri occupied the Eritrean highlands. On January 1, 1890, Italy proclaimed the establishment of Italian Eritrea (Colonia Eritrea). The Treaty of Wuchale, signed in 1889 with Menelik II of Shewa (later Emperor of Ethiopia), recognized Italian control over parts of the Eritrean highlands in exchange for financial aid and access to arms.

The Italian colonial administration launched significant development projects. The Eritrean Railway was built, connecting Massawa to Asmara by 1911. The Asmara-Massawa Cableway, once the longest in the world, was also constructed. Asmara underwent extensive urban development, particularly during the 1930s under Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime, which envisioned Eritrea as an industrial hub for Italian East Africa. The city became renowned for its modernist architecture, with styles like Art Deco, Futurism, and Rationalism transforming its landscape; this architectural heritage later earned Asmara UNESCO World Heritage Site status in 2017. Key buildings from this era include the Fiat Tagliero Building and Cinema Impero.

However, Italian colonization also involved economic exploitation and social segregation. Eritreans were largely employed in manual labor and public service, particularly in the police and public works. Thousands of Eritreans, known as Ascari, were conscripted into the Italian colonial army and served in various campaigns, including the Italo-Turkish War and the First and Second Italo-Abyssinian Wars. While some infrastructure was developed and factories were established (producing items like buttons, pasta, and construction materials), the primary benefits accrued to the Italian colonizers. Land was often expropriated for Italian settlers, and discriminatory policies were implemented, limiting opportunities for Eritreans. The social impact of Italian rule was profound, creating a stratified society and laying some of the groundwork for future nationalist sentiments. Bahta Hagos emerged as an early leader of resistance against Italian and Ethiopian encroachment.

3.6. British Administration

During World War II, Italian rule in Eritrea ended after the Battle of Keren in 1941, where British and Commonwealth forces defeated the Italians. Eritrea was subsequently placed under British Military Administration (BMA) from 1941 to 1952.

The British administration dismantled some Italian industrial infrastructure, such as the Asmara-Massawa Cableway, selling parts as war reparations or for scrap. Economically, the early years of British rule saw a continuation of wartime production to support Allied efforts, but post-war, the Eritrean economy faced recession as war factories closed and Italian repatriation began. The BMA undertook some economic restructuring, but development was limited by the uncertain future of the territory.

Politically, the British period was marked by debates and uncertainty regarding Eritrea's future. The Allied Powers could not agree on its status. The British initially proposed partitioning Eritrea, with parts going to Sudan (then under Anglo-Egyptian rule) and parts to Ethiopia. Various Eritrean political groups emerged, advocating different solutions: some favored independence, others union with Ethiopia, and some supported partition. The United Nations became involved, sending a Commission of Enquiry in 1950 to ascertain the wishes of the Eritrean people and recommend a course of action. This ultimately led to the UN decision to federate Eritrea with Ethiopia.

3.7. Federation with and Annexation by Ethiopia

Following the UN General Assembly's adoption of Resolution 390A(V) in December 1950, Eritrea was federated with Ethiopia in 1952. The resolution, heavily influenced by the strategic interests of powers like the United States who sought to reward Ethiopia for its wartime support and secure access to Red Sea ports, called for a loose federal structure under the sovereignty of the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie.

Under the federation, Eritrea was to have its own autonomous government, including an elected parliament, a separate judicial system, its own flag, and control over domestic affairs such as police, local administration, and taxation. The federal government (effectively the Ethiopian imperial government) would control foreign affairs, defense, finance, and transportation.

However, from the outset, the Ethiopian government worked to undermine Eritrean autonomy. Emperor Haile Selassie viewed Eritrean self-rule as a threat to Ethiopian unity and gradually eroded the federal arrangement. Eritrean political parties were suppressed, freedom of the press was curtailed, and the use of Eritrean languages (Tigrinya and Arabic) in official contexts was discouraged in favor of Amharic. Economic policies favored Ethiopian interests.

This systematic dismantling of Eritrean autonomy culminated in 1962 when the Ethiopian government unilaterally dissolved the Eritrean parliament and formally annexed Eritrea, declaring it the 14th province of Ethiopia. This act of annexation was a direct violation of the UN resolution and ignited widespread Eritrean resistance, leading directly to the Eritrean War of Independence.

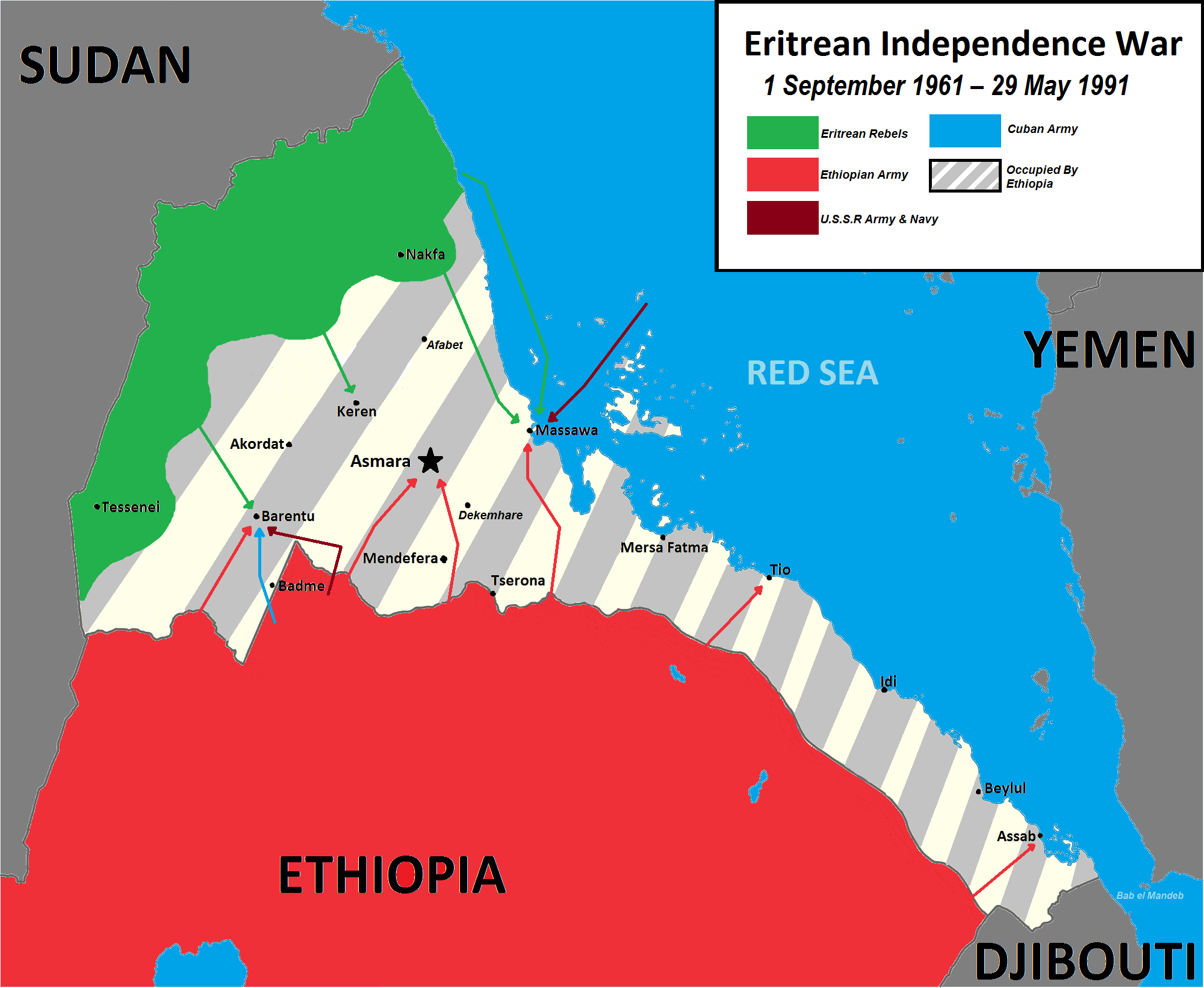

3.8. War of Independence

The Eritrean War of Independence was a 30-year armed struggle (1961-1991) waged by Eritrean liberation movements against successive Ethiopian governments. The war began in response to Ethiopia's increasing encroachment on Eritrean autonomy and its eventual annexation of Eritrea in 1962.

The first shots of the war were fired on September 1, 1961, by Hamid Idris Awate, leader of the nascent Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF). The ELF, initially a diverse coalition, launched guerrilla attacks against Ethiopian forces. Over time, internal divisions within the ELF, partly based on religious and regional lines, led to the formation of rival factions.

In the early 1970s, a more ideologically driven and militarily effective group, the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF), emerged from splits within the ELF. The EPLF, largely Marxist-inspired, emphasized national unity, social reform (including gender equality and land reform in liberated areas), and self-reliance. For a period, the ELF and EPLF fought each other in bitter civil wars (Eritrean Civil Wars) alongside their struggle against Ethiopia.

The war intensified following the 1974 Ethiopian revolution, which overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie and brought the Derg military junta, led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, to power. The Derg, backed by the Soviet Union and its allies, launched massive military offensives against Eritrean forces. Despite being heavily outnumbered and outgunned, the EPLF, under leaders like Isaias Afwerki, proved resilient, employing effective guerrilla tactics and establishing sophisticated underground networks and social services in areas under its control.

Key phases of the war included major battles for Eritrean towns and strategic positions. The human cost was immense, with hundreds of thousands of casualties, widespread displacement of civilians, and significant destruction of infrastructure. Eritrean civilians suffered greatly under Ethiopian occupation, facing repression, mass killings, and famine, exacerbated by drought and conflict.

The tide turned in the late 1980s as Soviet support for the Derg regime waned. The EPLF, in coordination with Ethiopian rebel groups (notably the Tigray People's Liberation Front, TPLF), launched decisive offensives. In May 1991, EPLF forces captured Asmara and other key Eritrean cities, achieving de facto independence. Simultaneously, the EPRDF (a coalition including the TPLF) overthrew the Derg regime in Addis Ababa.

Following a UN-supervised referendum in April 1993, in which Eritreans overwhelmingly voted for sovereignty, Eritrea officially declared its independence on May 24, 1993, and gained international recognition. The EPLF transformed itself into the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) and formed the first government of independent Eritrea.

3.9. Post-Independence Era

The period following Eritrea's de jure independence in 1993 has been characterized by initial nation-building efforts, subsequent political consolidation under the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) led by President Isaias Afwerki, and significant internal and external challenges, including wars and severe human rights issues.

Upon independence, Eritrea faced the monumental task of rebuilding a war-torn country. The PFDJ-led government focused on national reconstruction, infrastructure development, and fostering a sense of national unity. A new constitution was drafted and ratified in 1997, envisioning a multi-party democracy, but it has never been implemented. National elections have been repeatedly postponed and have never been held.

The initial post-independence years saw relative stability and some economic progress. However, the political space gradually narrowed. The PFDJ became the sole legal political party, and dissent was increasingly suppressed. Hopes for a democratic transition faded as the government centralized power.

3.9.1. Eritrean-Ethiopian War (1998-2000)

Relations with Ethiopia, initially cooperative, deteriorated rapidly over border disputes, economic disagreements (including issues related to the new Eritrean currency, the Nakfa), and political tensions. In May 1998, these tensions erupted into a full-scale Eritrean-Ethiopian War over contested border areas, particularly around the town of Badme.

The war was characterized by brutal trench warfare and heavy artillery bombardments, reminiscent of World War I, resulting in tens of thousands of casualties on both sides (estimates vary, but some suggest up to 70,000 or more combined). The conflict caused massive displacement of civilians and had a devastating humanitarian impact, exacerbating food insecurity in the region. Both countries, already impoverished, diverted vast resources to the war effort. From a human rights perspective, the war led to mass expulsions of each other's nationals and widespread suffering among border communities.

The war ended in June 2000 with the signing of the Algiers Agreement, brokered by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the United Nations, and the United States. The agreement called for a cessation of hostilities, the deployment of a UN peacekeeping mission (UNMEE), and the establishment of an independent Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC) to demarcate the border.

3.9.2. Border Demarcation and Stalemate

The Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC) delivered its ruling in April 2002, awarding disputed territories, including Badme, to Eritrea. However, Ethiopia initially rejected parts of the ruling and refused to withdraw its forces from Badme, leading to a protracted stalemate. Eritrea, in turn, insisted on the full implementation of the EEBC's decision.

This "no war, no peace" situation dominated Eritrean politics and society for nearly two decades. The unresolved border became a justification for the Eritrean government to maintain a highly militarized state, including the controversial policy of indefinite national service. Tensions remained high, with periodic skirmishes and accusations from both sides of supporting opposition groups in the other's territory. The protracted stalemate contributed significantly to Eritrea's increasing international isolation and its deteriorating human rights situation.

3.9.3. 2018 Peace Agreement with Ethiopia

A significant breakthrough occurred in 2018. Following the rise of Abiy Ahmed as Prime Minister of Ethiopia, who announced Ethiopia's willingness to fully implement the Algiers Agreement and the EEBC ruling, a rapid rapprochement took place. On July 9, 2018, President Isaias Afwerki and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed signed a historic joint declaration in Asmara, formally ending the state of war between the two countries.

This agreement led to the normalization of diplomatic relations, the reopening of borders and embassies, the resumption of direct flights, and renewed economic and social ties. The peace deal was widely hailed internationally and generated considerable optimism for regional stability and development. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was awarded the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

3.9.4. Involvement in the Tigray War

Despite the 2018 peace agreement, new regional dynamics emerged. In November 2020, conflict erupted in Ethiopia's Tigray Region between the Ethiopian federal government and the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), the former dominant party in Ethiopian politics and a historical adversary of both the Eritrean government and Abiy Ahmed's administration.

Eritrean forces intervened militarily in the Tigray War on the side of the Ethiopian federal government and allied Amhara regional forces. Eritrea's motivations were complex, including long-standing enmity with the TPLF and perceived strategic interests. Eritrean troops were heavily involved in combat operations across Tigray.

Eritrea's involvement in the Tigray War has been accompanied by widespread and credible allegations of serious human rights violations committed by Eritrean soldiers, including massacres of civilians, widespread looting, destruction of infrastructure (including health facilities and refugee camps), and sexual violence. These abuses have been documented by international human rights organizations, media reports, and survivor testimonies, leading to international condemnation and calls for the withdrawal of Eritrean forces and accountability for atrocities. The conflict has caused a devastating humanitarian crisis in Tigray, with famine-like conditions and massive displacement. The Eritrean government initially denied its forces' presence but later acknowledged their involvement. The human cost and the impact on civilian populations in Tigray have been severe, raising significant concerns from a human rights and social justice perspective.

4. Geography

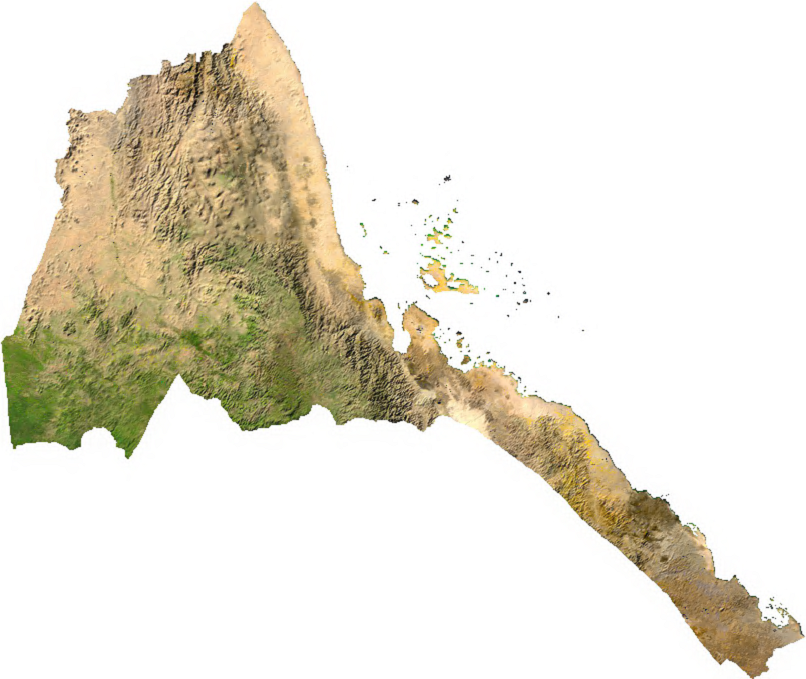

Eritrea's geography is diverse, encompassing coastal plains, highlands, and arid depressions, which contribute to varied climates and ecosystems.

The country's location in the Horn of Africa along the Red Sea gives it strategic importance and a unique natural environment.

4.1. Topography and Geology

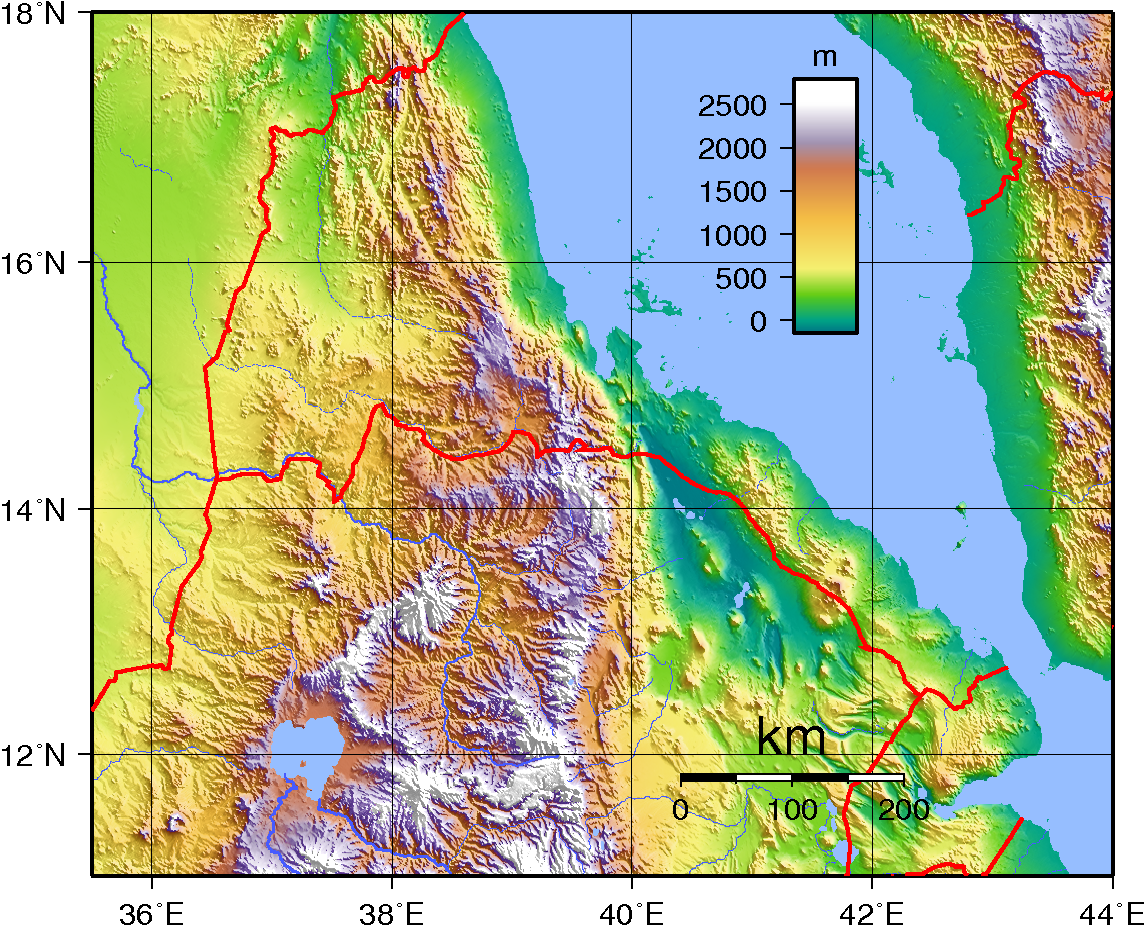

Eritrea is located in Eastern Africa, bordered by Sudan to the west, Ethiopia to the south, Djibouti to the southeast, and the Red Sea to the east and northeast. The country lies between latitudes 12° and 18°N, and longitudes 36° and 44°E.

The topography of Eritrea is highly varied. A branch of the East African Rift virtually bisects the country, influencing its geology and landforms. The central part of the country is dominated by the Eritrean Highlands, an extension of the Ethiopian Highlands, with elevations reaching up to 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m). The highest point in Eritrea is Emba Soira, at 9.9 K ft (3.02 K m) above sea level, located in this central highland region.

To the east of the highlands, there is a steep escarpment that drops sharply to the coastal plains along the Red Sea. These coastal lowlands are generally narrow in the west and widen towards the east. The southeastern part of Eritrea includes a portion of the Danakil Depression (also known as the Afar Triangle or Afar Depression), one of the lowest and hottest places on Earth, with areas below sea level. This region is geologically active and is considered a triple junction where three tectonic plates (the African, Arabian, and Somali plates) are pulling away from each other. Volcanic activity occurs in this southeastern region, with the Nabro Volcano having erupted in 2011.

The western lowlands slope more gradually from the highlands towards the Sudanese border. Major rivers include the Atbara (known as Tekezé in its upper reaches), which flows into Sudan to join the Nile, and the Barka River, which also flows into Sudan and sometimes reaches the Red Sea during flood seasons. The Mareb River (or Gash River) forms part of the border with Ethiopia.

The Dahlak Archipelago, consisting of over 120 islands, and several of the Hanish Islands in the Red Sea are also part of Eritrean territory.

4.2. Climate

Eritrea's climate varies significantly due to its diverse topography and geographical location. It can be broadly divided into three major climatic zones:

1. Temperate Highlands: The central highlands, including Asmara (altitude around 7.5 K ft (2.30 K m)), experience a temperate or mild subtropical highland climate. Temperatures are generally moderate throughout the year. The hottest month is usually May, with temperatures around 86 °F (30 °C), while the coolest months are December to February, where night temperatures can drop significantly. This region receives the majority of the country's rainfall, primarily during the main rainy season from June to September, with a smaller rainy season from March to April. Filfil, in a sub-tropical rainforest microclimate on the eastern escarpment, receives over 0.0 K in (1.10 K mm) of rainfall annually.

2. Arid Coastal Plains and Lowlands: The Red Sea coastal plains and the western lowlands are characterized by an arid or semi-arid climate. This zone experiences high temperatures year-round, especially during the summer months (June to September), when temperatures can exceed 104 °F (40 °C). Rainfall is scarce and erratic. The coastal area around Massawa is known for its high humidity combined with high temperatures.

3. Danakil Depression: The southeastern Danakil Depression is one of the hottest and driest places on Earth, with hyper-arid conditions.

Rainfall patterns are highly variable across the country. Local variability in rainfall and reduced precipitation can lead to soil erosion, floods, droughts, land degradation, and desertification, posing significant challenges to agriculture and water resources.

4.3. Biodiversity

Eritrea possesses a diverse range of flora and fauna, reflecting its varied topography and climate zones, from montane forests to arid shrublands and rich marine ecosystems. The country has recorded 126 mammal species, 560 bird species, 90 reptile species, and 19 amphibian species. Over 700 plant species, including marine plants and seagrass, have been identified.

Flora: Vegetation varies from sub-tropical rainforests like those at Filfil Solomona in the highlands to acacia savannas in the western lowlands and xeric shrublands along the coast. Mangrove forests are found along parts of the Red Sea coast.

Fauna: Mammals commonly seen include the Abyssinian hare, African wildcat, black-backed jackal, African golden wolf, genet, ground squirrel, pale fox, Soemmerring's gazelle, and warthog. Dorcas gazelle are found in coastal plains and Gash-Barka. Lions are reported to inhabit the mountains of Gash-Barka. Dik-diks are also present. The critically endangered African wild ass can be found in the Danakil region. Other wildlife includes bushbuck, duikers, greater kudu, klipspringer, African leopards, oryx, and crocodiles. The spotted hyena is widespread. A small population of African bush elephants, thought to have been victims of the independence war, was rediscovered in 2001 near the Gash River; these are the most northerly of East African elephants. The endangered African wild dog was previously found but is now considered extirpated.

Marine Life: The Eritrean Red Sea coast and the Dahlak Archipelago boast rich marine biodiversity. Common species include dolphins, dugongs, whale sharks, marine turtles, marlin, swordfish, and manta rays. Over 500 fish species have been recorded. The Dahlak Archipelago is a particularly important area for coral reefs and marine life.

National Parks and Conservation: Eritrea has established several protected areas, including the Dahlak Marine National Park, Nakfa Wildlife Reserve, Gash-Setit Wildlife Refuge, Semenawi Bahri National Park, and Yob Wildlife Reserve. In 2006, Eritrea announced its intention to turn its entire coast into an environmentally protected zone. However, conservation efforts face challenges from land degradation, deforestation, overgrazing, soil erosion, and the impacts of climate change, such as increased drought frequency. These environmental issues also pose a threat to the livelihoods of communities dependent on natural resources. The expected costs for Eritrea to adapt to and mitigate the consequences of climate change are projected to be substantial.

5. Government and Politics

Eritrea's political system is characterized by a single-party rule under the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), with limited political freedoms and significant human rights concerns. The following sections delve into the structure of its government, the state of elections, and the pressing issues of human rights and media freedom.

5.1. Political System

Eritrea is a unitary one-party presidential republic operating under what many international observers and human rights organizations describe as a totalitarian dictatorship. The People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), which evolved from the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) that led the country to independence, is the only legally permitted political party.

The current president, Isaias Afwerki, has been in office since Eritrea's official independence in 1993. He serves as both head of state and head of government. The Constitution of 1997, which provides for a multi-party system and democratic elections, was ratified but has never been implemented. Consequently, the country operates without a functioning constitution to limit executive power or guarantee fundamental rights.

Power is highly centralized in the hands of the president and a small circle within the PFDJ. There is no independent judiciary or legislature to provide checks and balances on the executive branch. Decision-making processes are opaque, and there is little public accountability. The political environment is marked by a lack of political pluralism, suppression of dissent, and severe restrictions on civil liberties. President Isaias Afwerki has publicly expressed disdain for "Western-style" democracy, stating in a 2008 interview that Eritrea might wait decades before holding elections.

5.2. National Assembly

The National Assembly (Hagerawi Baito) is nominally the country's legislature. It has 150 seats. Following independence in 1993, 75 members were PFDJ central committee members, and the remaining 75 were representatives elected from the 6th congress of the EPLF or appointed. However, the National Assembly has not convened since January 2002.

In practice, the National Assembly does not function as an independent legislative body. Legislative power is effectively wielded by the executive branch. The absence of legislative elections and the dormancy of the Assembly mean that there is no popular representation or legislative oversight of government actions.

5.3. Elections

National legislative and presidential elections have never been held since Eritrea gained independence in 1993. Elections were periodically scheduled but subsequently cancelled or postponed indefinitely, often citing national security concerns related to the unresolved border conflict with Ethiopia (prior to the 2018 peace agreement) or other reasons.

Local or regional elections were held in 2003-2004 and again in 2010-2011, but these were not considered free or fair by international standards and did not involve multi-party competition. The lack of national elections means that citizens have not had the opportunity to choose their leaders or hold them accountable through the ballot box, a fundamental aspect of democratic governance. This absence of electoral processes contributes to Eritrea's characterization as an authoritarian state.

5.4. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Eritrea is widely reported by international organizations like Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) as among the worst in the world. The government of Eritrea, however, dismisses these allegations as politically motivated.

Key human rights concerns include:

- Indefinite National Service: All Eritreans, male and female, are subject to mandatory national service, which officially lasts 18 months but is often extended indefinitely, sometimes for decades. Conscripts are subjected to forced labor, harsh conditions, meager pay, and abuse, including torture and sexual violence. This system is a primary driver of the large-scale emigration of Eritreans.

- Restrictions on Freedoms: There are severe restrictions on the freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and association. Criticism of the government is not tolerated.

- Arbitrary Detentions and Enforced Disappearances: Thousands of political prisoners, including former government officials (such as the G-15, arrested in 2001 for calling for democratic reforms), journalists, and individuals perceived as opponents of the regime, are detained incommunicado without charge or trial, often in harsh and life-threatening conditions. Enforced disappearances are common.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment: Torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment are reportedly widespread in detention facilities.

- Freedom of Religion: Only four religious denominations are officially recognized: the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Sunni Islam, the Eritrean Catholic Church, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Members of unrecognized faiths, such as Jehovah's Witnesses and various Protestant groups, face persecution, including arrest, detention, and harassment.

- Restrictions on Movement: Citizens require exit visas to leave the country, which are often denied, leading many to flee illegally. Internal movement can also be restricted.

- Lack of Rule of Law: The judicial system is not independent and fails to provide due process or fair trials. The 1997 constitution, which includes a bill of rights, has never been implemented.

- LGBT Rights: Same-sex sexual activity is illegal and punishable by imprisonment.

These systemic human rights violations have led to a continuous outflow of Eritrean refugees and asylum seekers. A UNHRC Commission of Inquiry concluded in 2016 that crimes against humanity, including enslavement, imprisonment, enforced disappearances, torture, persecution, rape, murder, and other inhumane acts, have been committed in Eritrea since 1991.

5.5. Media Freedom

Media freedom in Eritrea is virtually non-existent. The country consistently ranks at or near the bottom of global press freedom indices. Reporters Without Borders has frequently described Eritrea as one of the world's worst countries for journalists.

Key aspects of media control include:

- State Monopoly on Media: All domestic media outlets are state-owned and controlled by the Ministry of Information. There are no privately owned or independent newspapers, radio stations, or television channels. State media outlets primarily serve as propaganda tools for the government, relaying official narratives and suppressing critical viewpoints.

- Ban on Independent Media: Independent media were banned in September 2001. Simultaneously, numerous journalists were arrested and imprisoned without trial. Many of these journalists remain in detention, and some are reported to have died in custody.

- Censorship: Strict censorship is enforced, and access to information from external sources is limited. Internet penetration is low, and access is often monitored.

- No Foreign Correspondents: Few, if any, independent foreign correspondents are based in Asmara, making it difficult to obtain unbiased information from within the country.

- Imprisonment of Journalists: Eritrea is one of the world's leading jailers of journalists relative to its population. Journalists are often detained in harsh conditions without due process. The journalist Dawit Isaak, a Swedish-Eritrean citizen, has been imprisoned without trial since 2001, becoming a symbol of the dire state of press freedom. He was awarded the Edelstam Prize in 2024.

The lack of media freedom means that Eritrean citizens have little access to diverse sources of information and are unable to freely express their opinions or hold their government accountable.

6. Administrative Divisions

Eritrea is divided into regions (Zobas) and further into districts (sub-zobas) for administrative purposes. These divisions play a role in local governance and resource management.

6.1. Regions and Districts

1. Northern Red Sea, 2. Anseba, 3. Gash-Barka, 4. Central (Maekel), 5. Southern (Debub), 6. Southern Red Sea

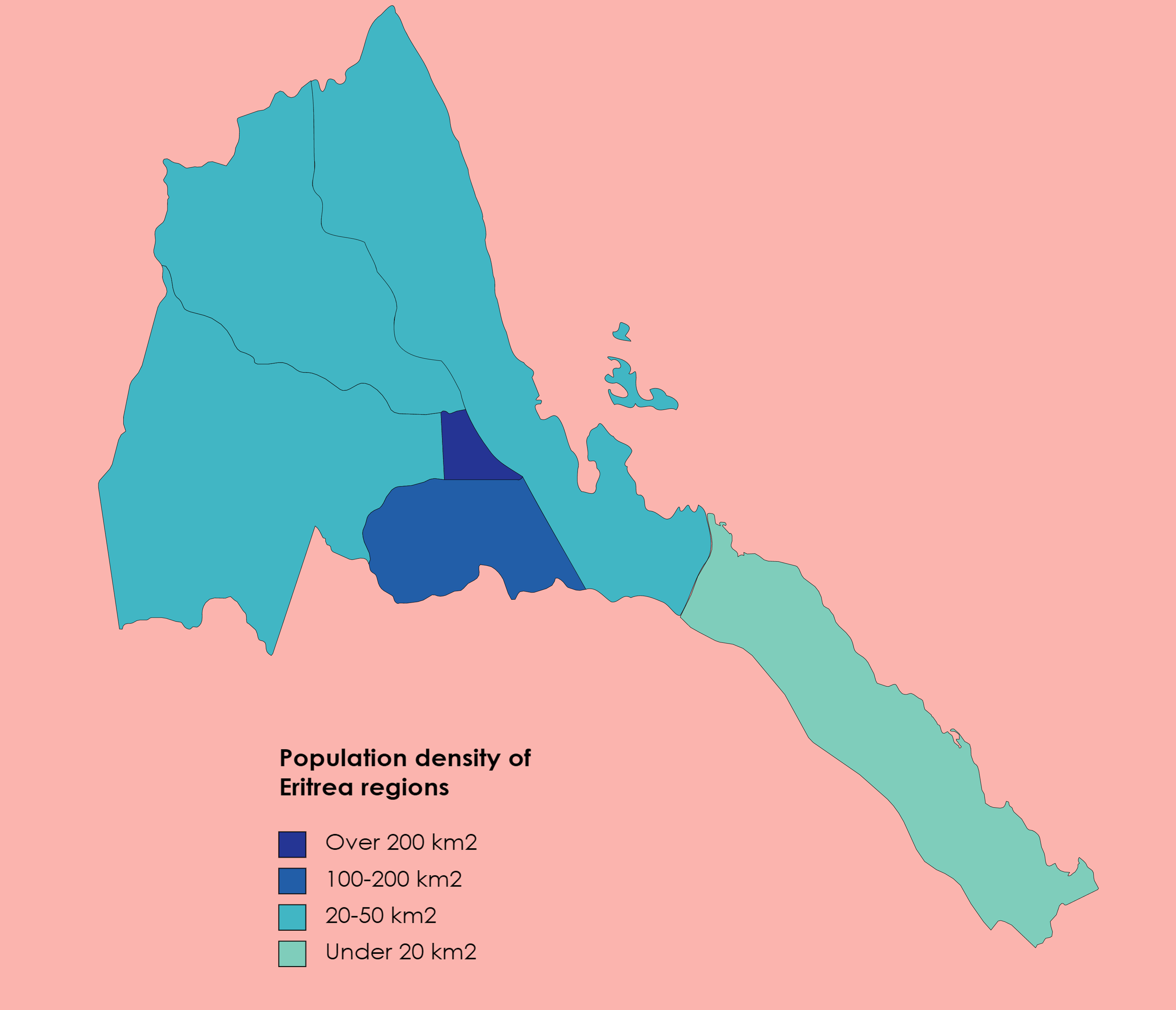

Eritrea is divided into six administrative regions (singular: Zoba, plural: Zobat). These regions were established in 1996, replacing the ten provinces that existed at the time of independence. The boundaries of the new regions were designed to be based on water catchment basins, aiming to facilitate resource management and, in theory, reduce historical inter-provincial conflicts.

The six regions are:

| Region Name | Area (km2) | Capital |

|---|---|---|

| Maekel (Central) | 0.5 K mile2 (1.30 K km2) | Asmara |

| Anseba | 9.0 K mile2 (23.20 K km2) | Keren |

| Gash-Barka | 13 K mile2 (33.20 K km2) | Barentu |

| Debub (Southern) | 3.1 K mile2 (8.00 K km2) | Mendefera |

| Semienawi Keyih Bahri (Northern Red Sea) | 11 K mile2 (27.80 K km2) | Massawa |

| Debubawi Keyih Bahri (Southern Red Sea) | 11 K mile2 (27.60 K km2) | Assab |

Each region is further subdivided into districts (singular: sub-zoba, plural: sub-zobat). There are a total of 58 districts across the six regions. Regional and district administrators are appointed by the central government.

6.2. Major Cities

Eritrea has several urban centers, with Asmara being the largest and most prominent.

- Asmara: The capital and largest city, located in the Maekel (Central) Region, with an approximate population of 963,000. It is renowned for its well-preserved early 20th-century modernist architecture, a legacy of Italian colonization, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Asmara is the political, economic, and cultural heart of Eritrea.

- Massawa (Mitsiwa): A historic port city on the Red Sea coast in the Northern Red Sea Region, with a population of approximately 54,090. It has a rich history, having been controlled by various powers, including the Ottomans and Egyptians, before becoming a key port for Italian Eritrea. Massawa suffered significant damage during the War of Independence but remains an important maritime hub.

- Assab (Aseb): A port city in the Southern Red Sea Region, near the border with Djibouti, with a population of approximately 28,000. It was the first territory acquired by the Italians in Eritrea and has strategic importance due to its location near the Bab-el-Mandeb strait.

- Keren: The second-largest city and the capital of the Anseba Region, with a population of approximately 120,000. It is a significant agricultural and commercial center, known for its historical sites, including the site of the crucial Battle of Keren in World War II.

- Mendefera (Adi Ugri): The capital of the Debub (Southern) Region, an important market town with historical significance and a population of approximately 53,000.

- Barentu: The capital of the Gash-Barka Region, a major agricultural area in western Eritrea, with a population of approximately 15,891.

- Agordat (Akordat): A town in the Gash-Barka Region, historically significant as a trading post and site of early archaeological finds (Gash Group), with a population of approximately 8,857.

- Dekemhare: A town in the Debub Region, known for its Italian colonial-era industrial and agricultural developments, with a population of approximately 120,000.

- Adi Keyh: A town in the Debub Region, near several archaeological sites, with a population of approximately 13,061.

- Edd: A town in the Debubawi Keyih Bahri region with a population of approximately 11,259.

Urbanization is gradually increasing, but a large portion of the population still resides in rural areas.

7. Foreign Relations

Eritrea's foreign relations since independence have often been characterized by a focus on sovereignty, self-reliance, and, at times, significant tensions with neighboring countries and the wider international community. The country is a member of the United Nations (admitted on May 28, 1993), the African Union (AU), and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), although its participation in these bodies has fluctuated. Eritrea also holds observer status in the Arab League.

Its foreign policy has been shaped by its long struggle for independence and perceived threats to its security. This has led to a highly militarized state and a foreign policy stance that is often assertive and resistant to external pressure. The Eritrean government has frequently accused external actors of interference in its internal affairs and of supporting opposition groups.

7.1. Relations with Ethiopia

The relationship between Eritrea and Ethiopia is central to Eritrean foreign policy and has been marked by periods of close alliance, devastating conflict, and, more recently, a complex rapprochement.

- War of Independence and Early Relations: The EPLF (now PFDJ) fought alongside Ethiopian rebel groups, particularly the TPLF, to overthrow the Derg regime. After Eritrea's independence in 1993, relations were initially cooperative.

- Eritrean-Ethiopian War (1998-2000): Disputes over the border, economic issues, and political rivalries led to a brutal war that caused tens of thousands of deaths and widespread displacement. The Algiers Agreement (2000) ended hostilities and established the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC) to demarcate the border.

- Stalemate and "No War, No Peace": Ethiopia's refusal to fully implement the EEBC's 2002 ruling, which awarded Badme to Eritrea, led to a nearly two-decade-long stalemate. This period was characterized by high military tension, mutual accusations, and support for proxy forces.

- 2018 Peace Agreement: A dramatic shift occurred in 2018 when Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed accepted the EEBC ruling. A peace agreement was signed, normalizing relations, reopening borders, and restoring diplomatic ties. This was initially hailed as a landmark achievement for regional peace.

- Tigray War Involvement: Starting in late 2020, Eritrean forces intervened in Ethiopia's Tigray War alongside the Ethiopian federal government against the TPLF. This intervention has been marked by extensive allegations of human rights abuses by Eritrean troops, drawing international condemnation. The war significantly altered regional dynamics and the nature of the Eritrean-Ethiopian relationship, moving from formal peace to a de facto military alliance against a common enemy (TPLF), though the long-term implications remain complex. The human cost of this involvement for civilians in Tigray has been immense, highlighting severe humanitarian and human rights concerns.

7.2. Relations with Neighboring Countries

- Sudan: Relations with Sudan have been historically mixed, with periods of cooperation and tension. Both countries have accused each other of supporting rebel groups at different times. Cross-border trade and refugee flows are significant factors.

- Djibouti: Eritrea and Djibouti have had a strained relationship, primarily due to a border dispute over the Doumeira Islands and the Ras Doumeira peninsula. This led to armed clashes in 2008. Qatar mediated the dispute for a time, but relations remain cool.

- Yemen: Eritrea and Yemen fought a brief conflict in 1995 over the Hanish Islands in the Red Sea. The dispute was resolved through international arbitration, which awarded most of the islands to Yemen, though Eritrea received some. Relations have since been largely stable.

7.3. Relations with Other Countries and International Organizations

- United States: Relations with the U.S. have been complex and often strained. While there was some cooperation in counter-terrorism efforts post-9/11, the U.S. has been highly critical of Eritrea's human rights record and lack of democracy. Eritrea, in turn, has accused the U.S. of interference. Sanctions have been imposed on Eritrea at various times, including in relation to its involvement in the Tigray War. In 2019, the U.S. removed Eritrea from a "Counterterror Non-Cooperation List," and a U.S. congressional delegation visited for the first time in 14 years, signaling a potential thaw that was later complicated by the Tigray conflict.

- China: Eritrea has increasingly cultivated ties with China, particularly in economic and diplomatic spheres, as part of China's broader engagement in Africa.

- Russia: Relations with Russia have also strengthened, with Eritrea being one of the few countries to vote against UN resolutions condemning Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine. President Afwerki visited Moscow in 2023.

- European Union: The EU has been a significant development partner but has also been critical of Eritrea's human rights situation, leading to periods of strained relations.

- United Nations: Eritrea is a UN member, but its relationship with UN bodies, particularly the Human Rights Council, has been contentious due to critical reports on its human rights record.

- African Union: Eritrea's participation in the AU has been inconsistent. It withdrew its representative for a period, protesting the AU's handling of the Ethiopia-Eritrea border issue, but has since re-engaged to some extent.

- Arab League: Eritrea holds observer status. Its location on the Red Sea and historical ties with the Arab world inform this relationship.

- United Arab Emirates: In recent years, the UAE established a military presence in Assab, reportedly used in the context of the Yemen conflict. The UAE also played a role in brokering the 2018 peace deal between Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Eritrea's foreign policy often prioritizes what it perceives as its national sovereignty and security, sometimes leading to isolation but also to pragmatic engagements with various global and regional actors.

8. Military

The Eritrean military, known as the Eritrean Defence Forces (EDF), is a significant institution in the country, deeply intertwined with its political and social fabric, primarily through the system of national service. It is considered one of the largest militaries in Africa relative to its population.

8.1. Eritrean Defence Forces (EDF)

The Eritrean Defence Forces (EDF) are the official armed forces of the State of Eritrea. The EDF consists of three main branches:

- Eritrean Army: The largest branch, responsible for ground operations.

- Eritrean Navy: Operates along Eritrea's extensive Red Sea coastline and around its islands.

- Eritrean Air Force: Provides air support and defense capabilities.

The EDF's primary mandate is to defend the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Eritrea. Given the country's history of conflict, particularly the long War of Independence and the subsequent Eritrean-Ethiopian War, the military maintains a high state of readiness. Its capabilities have been developed through these conflicts and, in recent years, through its involvement in the Tigray War. The exact size and equipment of the EDF are not always transparent, but it is known to be a substantial force. In 2012, the government also formed the People's Militia (Hizbawi Serawit) to provide additional military training to civilians and assist in development work, effectively expanding the pool of individuals with military training.

8.2. National Service (Conscription)

National service is a cornerstone of Eritrean state policy and has profound social, economic, and human rights implications. It was formally instituted in 1995 through the National Service Proclamation No. 82/1995.

- Mandate and Duration: Officially, all Eritrean citizens, both male and female, aged 18 to 40 (or 50 in some interpretations or during crises) are required to perform 18 months of national service. This includes approximately six months of military training, often at the Sawa military training center, followed by 12 months of deployment in military or civilian roles, such as agriculture, construction, teaching, or civil administration. Students typically complete their final year of secondary education (12th grade) at Sawa, combined with military training.

- Indefinite Extension: Since the 1998-2000 Eritrean-Ethiopian War, the 18-month legal limit has been largely disregarded. National service has been extended indefinitely for many conscripts, often lasting for many years, sometimes decades. Release from service is often arbitrary and depends on the decision of commanders. A 2014 study of escaped conscripts found the average service duration to be 6.5 years, with some serving over 12 years.

- Conditions and Impact: Conscripts often endure harsh living and working conditions, meager pay (insufficient to support themselves or their families), and severe disciplinary measures. There are widespread reports of forced labor, physical abuse, torture, and sexual harassment and violence, particularly against female conscripts.

- Human Rights Concerns: The indefinite nature of national service and the associated abuses are considered by the UN and human rights organizations to constitute a form of enslavement or forced labor. The system severely restricts individual freedoms, educational and career opportunities, and family life.

- Driver of Emigration: The indefinite national service is a primary reason why tens of thousands of Eritreans, particularly youth, flee the country each year, often undertaking perilous journeys to seek asylum elsewhere.

- Conscientious Objection: The right to conscientious objection to military service is not recognized. Failure to enlist or refusal to perform military service is punishable by imprisonment.

The Eritrean government justifies the prolonged national service by citing national security needs (historically the threat from Ethiopia) and the necessity of national development. However, critics argue it is a tool of social control and a means of providing cheap labor for state-run enterprises and military activities, severely undermining the human rights and future prospects of a generation of Eritreans.

9. Economy

Eritrea's economy is largely underdeveloped and centrally planned, with the government playing a dominant role. It has faced significant challenges due to past conflicts, international isolation, limited foreign investment, and the impact of the indefinite national service program on labor availability and human capital. The country has pursued a policy of "self-reliance," which has often meant limiting engagement with international financial institutions and foreign aid.

9.1. Macroeconomic Overview

Eritrea's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was estimated by the IMF in 2020 at around 2.10 B USD (nominal) or 6.40 B USD (on a PPP basis). Economic growth has been volatile, influenced by factors such as mining output, agricultural performance, and regional conflicts. For instance, between 2016 and 2019, GDP growth reportedly ranged from 7.6% to 10.2%, partly driven by the mining sector. However, events like the COVID-19 pandemic and global economic shocks (e.g., the war in Ukraine) have impacted growth, with a projected GDP growth of 2.8% for 2023.

Inflation has been a persistent issue. The national currency is the Nakfa (ERN). The government maintains strict control over foreign exchange, and there is a significant disparity between the official exchange rate and black market rates. Remittances from the Eritrean diaspora are a crucial source of foreign currency, estimated to account for around 12% of GDP in 2020.

The government's emphasis on self-reliance has led to a command economy with significant state ownership and control over key sectors. This, combined with the country's political situation, has deterred foreign investment and limited private sector development. Eritrea is considered one of the Least Developed Countries.

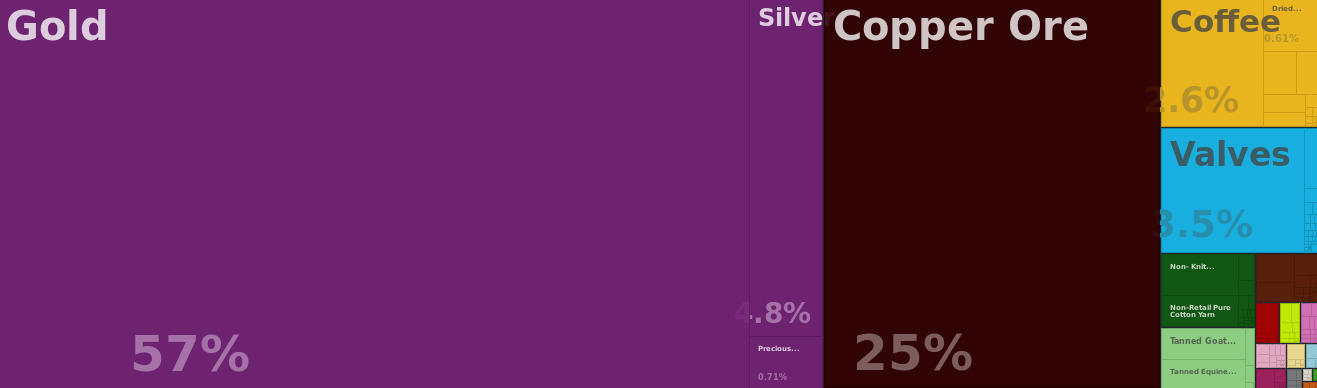

9.2. Mining

The mining sector has become a significant component of Eritrea's economy, accounting for about 20% of GDP in 2021. The country possesses mineral resources including gold, copper, zinc, silver, and potash.

The Bisha Mine, initially operated by Canadian company Nevsun Resources (later acquired by China's Zijin Mining), has been a major source of revenue, producing gold, silver, copper, and zinc. Production at Bisha commenced in the early 2010s and provided a substantial boost to the economy.

The Colluli Potash Project, located in the Danakil Depression, is another significant mining development, focused on one of the world's largest and shallowest potash deposits. It is being developed by Australian and Eritrean interests.

While mining offers economic opportunities, there have been concerns regarding labor conditions, environmental impact, and the transparency of revenue management. Allegations of forced labor linked to the national service system have been raised in connection with some mining operations, leading to legal challenges against international companies involved. The social impact on local communities, including displacement and benefit sharing, also requires careful management.

9.3. Agriculture

Agriculture remains a vital sector in Eritrea, employing a large portion of the population (around 70-80%), though its contribution to GDP (around 20% in 2021) is less dominant than its employment figures suggest. Much of the agriculture is subsistence-based.

Main crops include sorghum, millet, barley, wheat, legumes, vegetables, fruits, sesame, and flaxseed. Livestock rearing (cattle, sheep, goats, and camels) is also important, particularly in pastoral and agro-pastoral communities.

Challenges facing the agricultural sector are numerous:

- Drought and Climate Variability: Eritrea is prone to recurrent droughts and erratic rainfall, severely impacting crop yields and food security.

- Land Degradation: Soil erosion, deforestation, and overgrazing contribute to land degradation, reducing agricultural productivity.

- Limited Technology and Inputs: Access to modern farming techniques, irrigation, fertilizers, and improved seeds is limited.

- Labor Shortages: The indefinite national service program draws significant labor away from rural areas, affecting agricultural production.

- Food Security: Eritrea frequently faces food shortages and relies on imports and, at times, food aid (though the government has often restricted external aid).

The government has invested in water infrastructure, including the construction of numerous dams and micro-dams (such as the Gerset Dam), to improve water availability for irrigation and combat drought. However, achieving sustainable food security remains a major challenge, deeply affecting the livelihoods of farming communities and overall social development.

9.4. Manufacturing

The manufacturing sector in Eritrea is relatively small and underdeveloped. It includes industries established during the Italian colonial era and some newer enterprises. Key manufacturing activities include:

- Food processing (e.g., pasta, beverages)

- Textiles and garments

- Leather products

- Cement and construction materials

- Salt production

Many factories operate below capacity due to shortages of raw materials, foreign exchange, skilled labor, and outdated technology. The sector's contribution to GDP and employment is limited. The dominance of state-owned enterprises and lack of private investment also hinder its growth.

9.5. Energy

Eritrea's energy sector faces significant challenges, with limited domestic production and heavy reliance on imported fuels.

- Electricity Generation and Access: Electricity access is low, particularly in rural areas. Generation capacity is insufficient and often unreliable, primarily based on aging diesel-powered thermal plants. The main power plant is located near Massawa.

- Reliance on Imported Fuels: Eritrea imports almost all of its petroleum products, making the economy vulnerable to global oil price fluctuations and foreign exchange shortages. Annual petroleum consumption was estimated at 370,000 tons in 2001. The Eritrean Petroleum Corporation manages fuel purchases.

- Renewable Energy Potential: Eritrea has considerable potential for renewable energy, including solar, wind, and geothermal sources. The government has expressed interest in developing these resources. Solar power manufacturing has seen some growth. The coastal areas and highlands offer good potential for wind energy, and the East African Rift Valley presents geothermal possibilities. However, large-scale development of renewables has been slow due to financial and technical constraints.

Improving energy infrastructure and increasing access to reliable and affordable energy are critical for Eritrea's economic and social development.

9.6. Tourism

Eritrea possesses significant tourism potential due to its diverse natural attractions, rich cultural heritage, and unique historical sites. However, the tourism industry remains largely underdeveloped, affected by the country's political situation, past conflicts, and limited infrastructure.

Attractions:

- Asmara: The capital city is a major draw, famous for its well-preserved early 20th-century modernist architecture, which earned it UNESCO World Heritage status. Its Italian colonial-era buildings, tree-lined avenues, and vibrant café culture offer a unique urban experience.

- Dahlak Archipelago: A group of islands in the Red Sea, known for their pristine coral reefs, diverse marine life, and opportunities for diving, snorkeling, and fishing.

- Danakil Depression: While partly in Ethiopia, the Eritrean section offers dramatic landscapes, volcanic formations, and extreme environments.

- Coastal Areas: The Red Sea coast provides beaches and opportunities for water sports.

- Historical and Archaeological Sites: Sites like Qohaito, Matara, and Adulis offer glimpses into Eritrea's ancient past.

- Eritrean Railway: The historic narrow-gauge railway, with its scenic route from Massawa to Asmara, is a potential tourist attraction, though services are limited.

Current Status and Challenges:

Tourism contributed about 2% to Eritrea's economy before 1997, but revenue declined significantly after the 1998-2000 war. In 2006, it accounted for less than 1% of GDP. Visitor numbers have seen some increase in recent years, with around 142,000 annual visitors reported in 2016, many of whom are from the Eritrean diaspora.

Factors affecting tourism growth include:

- Political climate and international image.

- Strict visa policies and travel restrictions.

- Limited international flight connections (the national carrier, Eritrean Airlines, has had inconsistent service).

- Underdeveloped tourism infrastructure (hotels, transport).

Despite these challenges, Eritrea has been featured in travel publications like National Geographic and Lonely Planet for its unique offerings. The government has expressed intentions to develop the tourism sector, including a "2020 Eritrea Tourism Development Plan," though progress has been slow. Enhanced tourism could offer economic benefits but requires significant investment and a more open political environment.

9.7. Infrastructure

Eritrea's infrastructure, including transportation and communication systems, has seen some development since independence but still faces significant challenges. Much of it was damaged during the wars and requires modernization and expansion.

Roads: The road network is the primary mode of transportation. Highways are classified as primary (P), secondary (S), and tertiary (T). Primary roads, connecting major cities, are generally asphalted. Secondary roads connect district capitals and are often single-layered asphalt. Tertiary roads, serving local areas, are typically improved earth roads and can become impassable during wet seasons. A significant project was the construction of a coastal highway connecting Massawa with Assab. The government has invested in road construction and rehabilitation, often utilizing labor from the national service program (e.g., through the Wefri Warsay Yika'alo program). Driving is on the right.

Railways: The historic Eritrean Railway is a narrow-gauge (950 mm) line built by the Italians between 1887 and 1932, connecting the port of Massawa with Asmara and extending to Agordat. It was badly damaged during World War II and later conflicts, with final closure in 1978. After independence, a rebuilding effort commenced, and the section from Massawa to Asmara was reopened in 2003. Services are sporadic, often using vintage steam locomotives, primarily for tourist groups and special excursions due to the age of the rolling stock.

Ports: Eritrea has two main ports on the Red Sea:

- Massawa: The primary port, handling most of the country's cargo.

- Assab: Located further south, historically important, and has seen renewed strategic interest, including use by foreign military forces (e.g., UAE).

Both ports require modernization to handle increased traffic efficiently.

Airports:

- Asmara International Airport (ASM) is the main international gateway.

- Massawa International Airport (MSW) and Assab International Airport (ASA) also exist but handle limited traffic.

Eritrean Airlines is the national carrier, but its services have been inconsistent.

Communications: Telecommunications infrastructure is underdeveloped. Internet penetration is among the lowest in the world, and access is often slow, expensive, and monitored by the state. Mobile phone services are available but limited. The country's cctld is .er, and the calling code is +291.

Improving infrastructure is crucial for economic development, trade, and providing basic services, but progress is hampered by financial constraints and the political environment.

10. Society

Eritrea's society is a complex tapestry of diverse ethnic groups, languages, and religions, shaped by a long history and the profound impacts of war, political governance, and migration. The following sections explore key demographic and social aspects, including population trends, ethnic and linguistic diversity, religious practices, and human development indicators in education and health, often viewed through the lens of social progress and human rights.

10.1. Population Statistics

Sources on Eritrea's current population vary, with estimates ranging from as low as 3.5 million (UN, 2024) to as high as 6.4 million (US Census Bureau, 2025). The Eritrean government has never conducted an official census. According to UN data for 2020, approximately 41.1% of the population was below the age of 15, 54.3% were between 15 and 65 years of age, and 4.5% were 65 or older.

Life expectancy at birth has shown improvement, increasing from around 39.1 years in 1960 to approximately 66.44 years in 2020. Population density is relatively low, with significant variations between the more densely populated highlands and the sparsely inhabited lowlands and coastal areas.

A critical demographic feature is the significant outflow of refugees and emigrants. Since the late 1990s, and particularly in the 21st century, hundreds of thousands of Eritreans have fled the country. This emigration is largely attributed to the indefinite national service program, severe human rights violations, lack of political and economic opportunities, and the authoritarian nature of the government. At the end of 2018, the UNHCR estimated that about 507,300 Eritreans were refugees. This large-scale emigration represents a substantial loss of human capital and has significant social and economic consequences for the country, despite remittances from the diaspora being an important source of foreign exchange.

10.2. Ethnic Groups

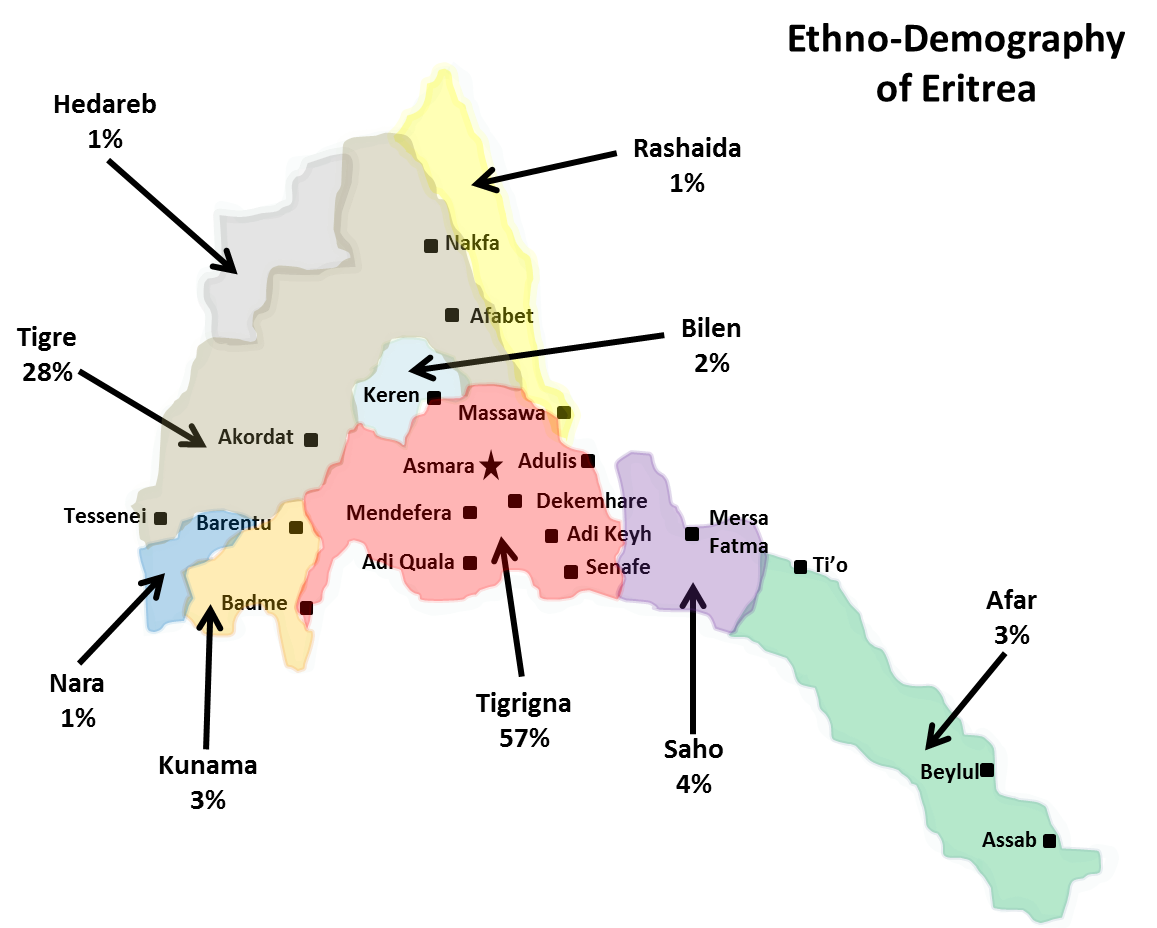

Eritrea officially recognizes nine main ethnic groups, each with distinct languages, cultural traditions, and geographical distributions. The government promotes a policy of national unity and equality among these groups. However, the dominance of the Tigrinya language and culture in government and public life has sometimes led to concerns among minority groups regarding their cultural and linguistic rights and representation.

The recognized ethnic groups are:

1. Tigrinya: The largest ethnic group, making up approximately 50-55% of the population. They primarily inhabit the central highlands (Maekel and Debub regions) and are predominantly Orthodox Christians, with a Catholic minority. Their language is Tigrinya.

2. Tigre: The second-largest group, constituting around 30% of the population. They mainly live in the western lowlands, northern highlands, and coastal areas. Most Tigre people are Sunni Muslims. Their language is Tigre.

3. Saho: Primarily pastoralists and agriculturalists, living in the southeastern highlands and coastal plains. They make up about 4% of the population and are mostly Sunni Muslims. Their language is Saho.

4. Afar (Danakil): Predominantly pastoralists inhabiting the arid Danakil Depression in the Southern Red Sea Region, also extending into Ethiopia and Djibouti. They constitute about 4% of the population and are Sunni Muslims. Their language is Afar.

5. Kunama: One of the Nilo-Saharan speaking groups, residing in the Gash-Barka region near the Ethiopian border. They are traditionally agriculturalists and make up about 2-4% of the population. Their traditional religion is dominant, with some converting to Christianity or Islam. Their language is Kunama.

6. Bilen (Bilin): Live primarily around the city of Keren in the Anseba region. They are about 2-3% of the population and are agriculturalists. They are religiously mixed, with both Christians (mostly Catholic) and Sunni Muslims. Their language is Bilen.

7. Beja (Hedareb): A Cushitic-speaking group, mainly pastoralists, living in the northwestern lowlands along the Sudanese border. They comprise about 2% of the population and are Sunni Muslims. The Hedareb are considered a subgroup of the Beja.

8. Nara (Baria): A Nilo-Saharan speaking group, primarily agriculturalists, living in the Gash-Barka region. They are about 1.5-2% of the population and are predominantly Sunni Muslims. Their language is Nara.

9. Rashaida: An Arabic-speaking nomadic group who migrated from the Arabian Peninsula in the 19th century. They inhabit the northern coastal lowlands and constitute about 1-2% of the population. They are Sunni Muslims.

In addition, there are small communities of Italian Eritreans, descendants of Italian colonizers, mainly in Asmara, and some individuals of Ethiopian Tigrayan origin. The rights and social standing of minority groups, particularly concerning language use in education and administration, and political representation, remain areas that require ongoing attention to ensure genuine equality and social cohesion.

10.3. Languages

Eritrea is a multilingual country with no single official language. The 1997 Constitution (which is not implemented) establishes the "equality of all Eritrean languages." There are nine national languages corresponding to the nine officially recognized ethnic groups: Tigrinya, Tigre, Afar, Beja (specifically its Hedareb dialect), Bilen, Kunama, Nara, and Saho. Arabic is also considered a national language, particularly associated with the Rashaida people and as a language of religious practice for Muslims.

Working Languages: Tigrinya, Arabic, and English serve as the de facto working languages of the government and for commerce.

- Tigrinya** is the most widely spoken language, particularly in the highlands and in government administration.

- Arabic** is used in commerce, by Arabic-speaking communities, and as a liturgical language for Muslims. It also has historical significance in education.

- English** is the primary language of instruction in higher education and is used in many technical fields and international communication.

Most Eritrean languages belong to the Afroasiatic language family, specifically the Semitic branch (e.g., Tigrinya, Tigre, Dahlik) or the Cushitic branch (e.g., Afar, Beja, Bilen, Saho). The Kunama and Nara languages belong to the Nilo-Saharan family. Dahlik, spoken in the Dahlak Archipelago, is a recently recognized Semitic language distinct from Tigre.

Language Policy: The government's policy promotes the use of mother tongues in primary education (grades 1-5/6). The Asmara Declaration on African Languages and Literatures (2000) emphasized the importance of developing and using African languages in all domains. However, the practical implementation of multilingual education faces challenges, including resource limitations and the dominance of Tigrinya and English in higher levels of education and public life. The status and development of minority languages remain important for cultural preservation and social equity.

Italian, the former colonial language, has no official status but is still spoken by some older Eritreans, in some commercial contexts, and was taught at the Italian government-operated school in Asmara (Scuola Italiana di Asmara) until its closure in 2020. A pidgin form, Eritrean Italian, also developed.

10.4. Religion

Religion is a significant aspect of Eritrean society, with Christianity and Islam being the two main faiths. Estimates of adherents vary:

- The Pew Research Center (2020 data) estimated that 62.9% of the population adhered to Christianity, 36.6% to Islam, and 0.4% to traditional African religions, with the remainder being other faiths or unaffiliated.

- The U.S. Department of State (2019 data) estimated that Christians and Muslims each constituted about 49% of the population, with the remaining 2% observing other religions, including traditional faiths and animism.

- The World Religion Database (2020) reported 47% Christian and 51% Muslim.

Christianity in Eritrea primarily consists of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, an Oriental Orthodox church that is the largest Christian denomination. There are also significant communities of the Eritrean Catholic Church (an Eastern Catholic Church in full communion with Rome) and various Protestant denominations, notably the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Eritrea. Christianity has ancient roots in Eritrea, dating back to the Kingdom of Aksum in the 4th century. The Debre Sina monastery is one of the oldest in Africa.

Islam in Eritrea is predominantly Sunni Islam. Muslims are concentrated mainly in the lowlands (western and eastern) and coastal areas, as well as among certain highland communities. Islam also has a long history in Eritrea, with the First Hijrah (migration of Prophet Muhammad's companions) leading to early Muslim settlements, including the Mosque of the Companions in Massawa.

Freedom of Religion: Since May 2002, the Eritrean government officially recognizes only four religious institutions:

1. The Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church

2. Sunni Islam

3. The Eritrean Catholic Church

4. The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Eritrea (affiliated with the Lutheran World Federation)

All other religious groups are required to register with the government, a process that is often difficult and, for many, has not resulted in approval. Groups not officially recognized, including Jehovah's Witnesses, Pentecostal and other Evangelical Christians, Baháʼís, and Seventh-day Adventists, face severe restrictions and persecution. This includes arbitrary arrest, detention without trial (sometimes for many years in harsh conditions), torture, and harassment. Members of these groups may be denied ration cards, work permits, and other civil rights. Jehovah's Witnesses, for example, were stripped of their citizenship in 1994 for their refusal to participate in military service and political processes on grounds of conscience.

The government's policy is officially aimed at preventing religious extremism, but it has been widely criticized by international human rights organizations and foreign governments as a severe violation of freedom of religion or belief. Eritrea has been designated as a "Country of Particular Concern" (CPC) by the U.S. State Department for its record on religious freedom. A small Jewish community historically existed in Asmara, but it has largely dwindled.

10.5. Urbanization

Urbanization in Eritrea is a gradual process, with a significant portion of the

population still residing in rural areas and engaged in agriculture and

pastoralism. However, cities and towns play crucial roles as administrative,

commercial, and cultural centers.

Patterns of Urbanization:

- The capital city, Asmara, is the largest urban center and primate city, accounting for a substantial share of the urban population. Its growth was significantly shaped during the Italian colonial period.

- Other major towns include port cities like Massawa and Assab, and regional capitals such as Keren and Mendefera.

- Urban growth has been influenced by factors such as rural-to-urban migration (though less pronounced than in some African countries due to restrictions and national service), historical development, and economic activities.

Characteristics of Major Cities: (Details integrated into the "Major Cities" subsection under "Administrative Divisions")

Urban Development Challenges:

- Infrastructure**: Many urban areas face challenges related to aging infrastructure, including housing, water supply, sanitation, and transportation.