1. Overview

Djibouti, officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is bordered by Eritrea in the north, Ethiopia in the west and south, and Somalia in the southeast. The remainder of the border is formed by the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden at the east. Djibouti occupies a total area of 9.0 K mile2 (23.20 K km2). The country's strategic location near the world's busiest shipping lanes and the Bab-el-Mandeb strait, which controls access to the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, makes it a significant geopolitical point. It serves as a key refueling and transshipment center, and is the principal maritime port for imports to and exports from neighboring Ethiopia. Djibouti is home to various foreign military bases, reflecting its international importance.

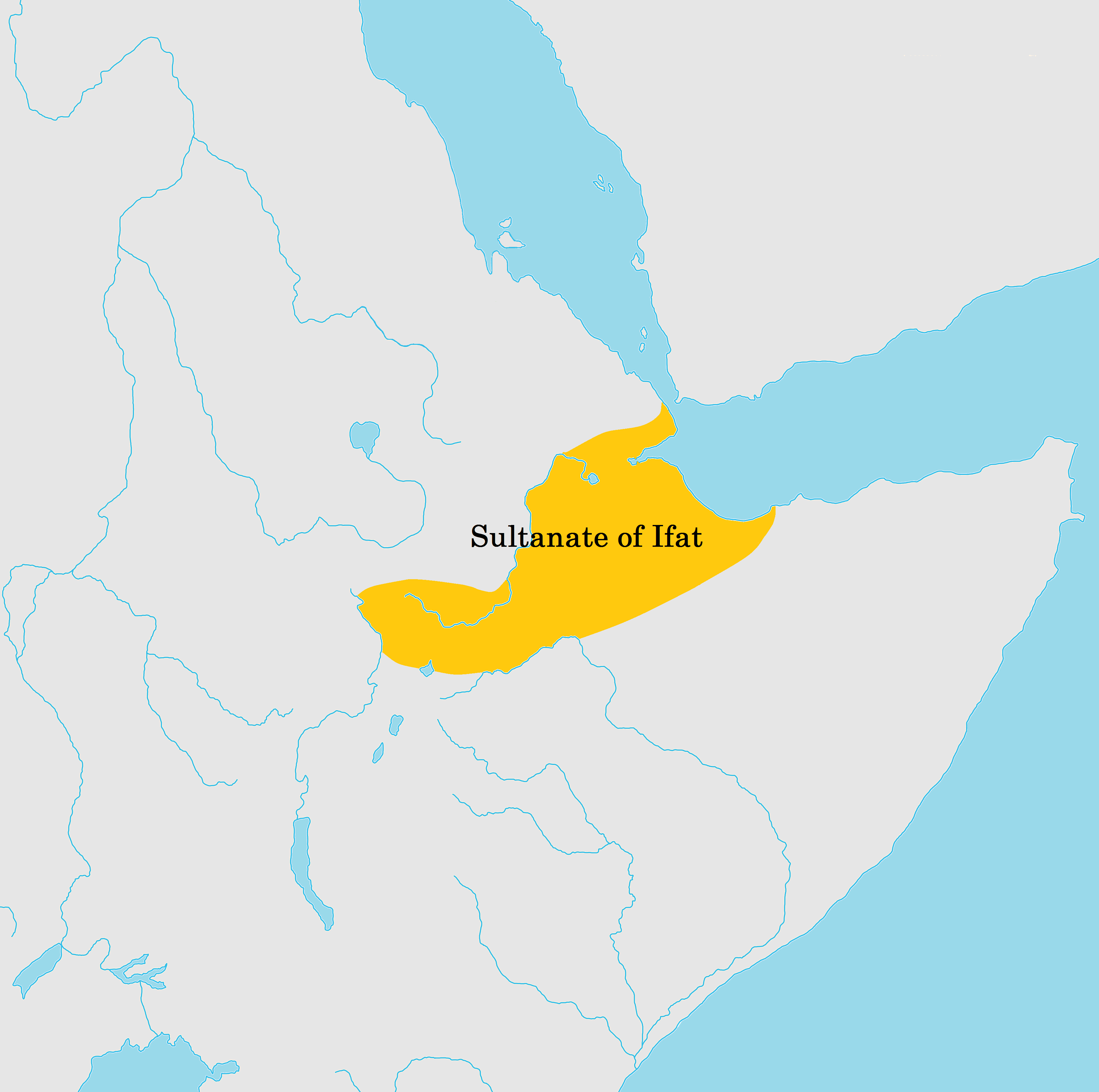

The nation has a diverse population, with the Somalis (primarily the Issa clan) and the Afar being the two largest ethnic groups. Islam is the predominant religion, and French and Arabic are the official languages, while Somali and Afar are widely spoken national languages. Historically, the region was part of the ancient Land of Punt and later saw the rise of influential Islamic sultanates like Ifat and Adal. It became a French colony in the late 19th century, known as French Somaliland and later the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas, before gaining independence in 1977.

Post-independence, Djibouti has navigated challenges including a civil war in the early 1990s, which concluded with a power-sharing agreement. The political landscape has been dominated by President Ismaïl Omar Guelleh since 1999. Economically, Djibouti relies heavily on its port services and the presence of foreign military installations. The government is pursuing development strategies focused on expanding its logistics and trade infrastructure, while also addressing social issues such as high unemployment, poverty, and access to essential services like healthcare and education. Human rights concerns, including political freedoms and the rights of women and minorities, remain pertinent topics in the country's development. Djibouti's culture is a blend of Somali, Afar, Arab, and French influences, evident in its traditions, music, literature, and cuisine.

2. Name and Etymology

Djibouti is officially known as the Republic of Djibouti. In local languages, it is known as YibuutiYibuutiAfar or GabuutiGabuutiAfar in Afar and JabuutiJabuutiSomali in Somali. The country's name is derived from its capital, the City of Djibouti.

The etymology of the name "Djibouti" is disputed, with several theories and legends about its origin, varying by ethnicity. One theory suggests it comes from the Afar word gaboutigaboutiAfar, meaning "plate," possibly referring to the geographical features of the area. Another theory connects it to the Afar word gaboodgaboodAfar, meaning "upland" or "plateau." A different legend suggests the name means "the dhow has arrived," referencing the importance of dhow sailing ships in the region's trade. Another proposed etymology links Djibouti to "Land of Tehuti" or "Land of Thoth," after the ancient Egyptian moon god (DjehutiDjehutiEgyptian (Ancient) or DjehutyDjehutyEgyptian (Ancient)).

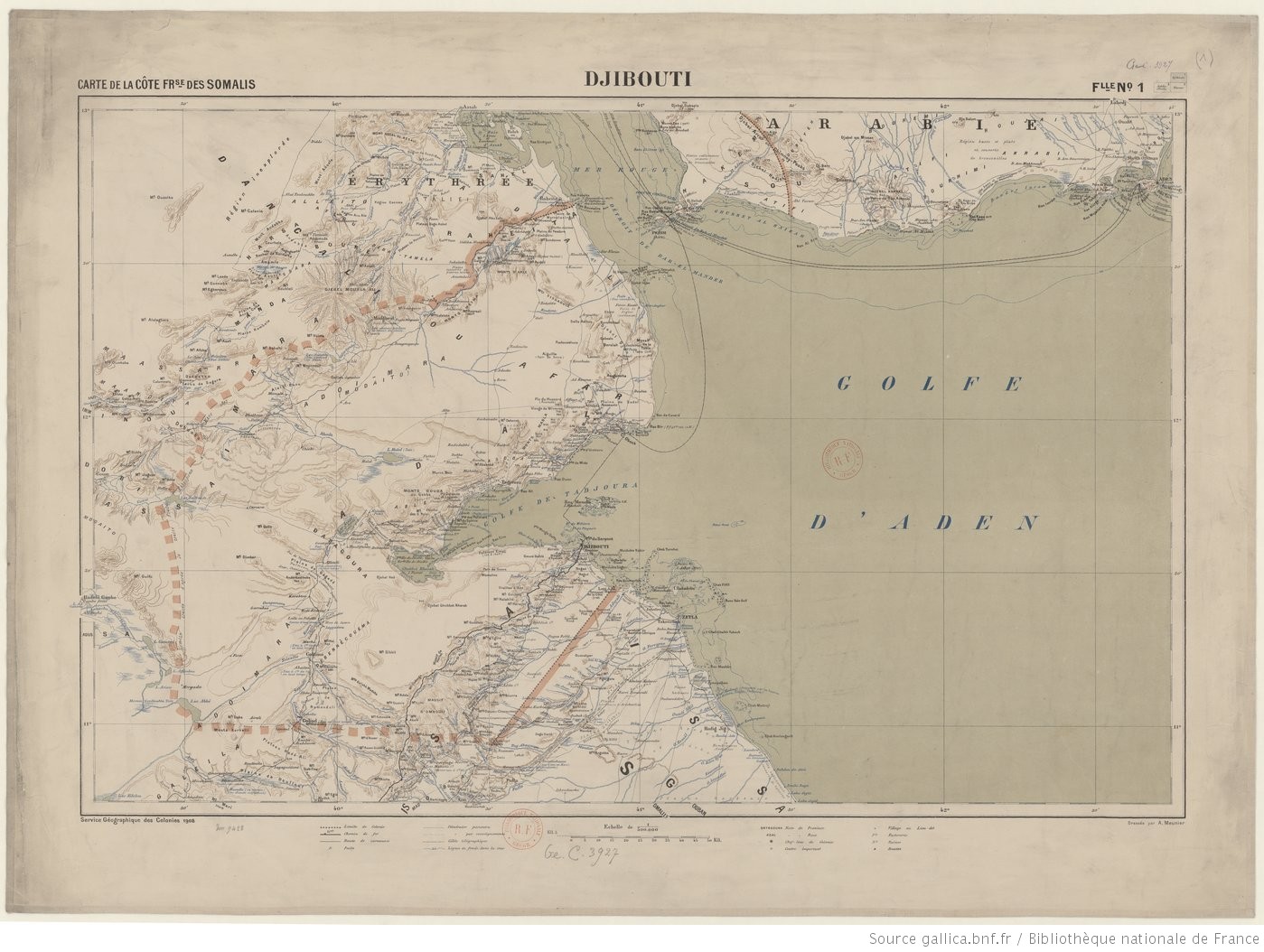

Historically, under French administration, the territory north of the Gulf of Tadjoura was called Obock from 1862 until 1894. From 1896 to 1967 (though some sources say 1897 to 1967), the area was known as French Somaliland (Côte française des SomalisFrench Coast of the SomalisFrench). From 1967 until its independence in 1977, it was called the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas (Territoire français des Afars et des IssasFrench Territory of the Afars and IssasFrench).

3. History

This section chronicles the major historical events and developments in the territory of present-day Djibouti, from early human inhabitation through ancient civilizations, the spread of Islam and medieval sultanates, colonial rule under France, to its independence and contemporary challenges as the Republic of Djibouti, with a focus on social impacts and the experiences of its diverse communities.

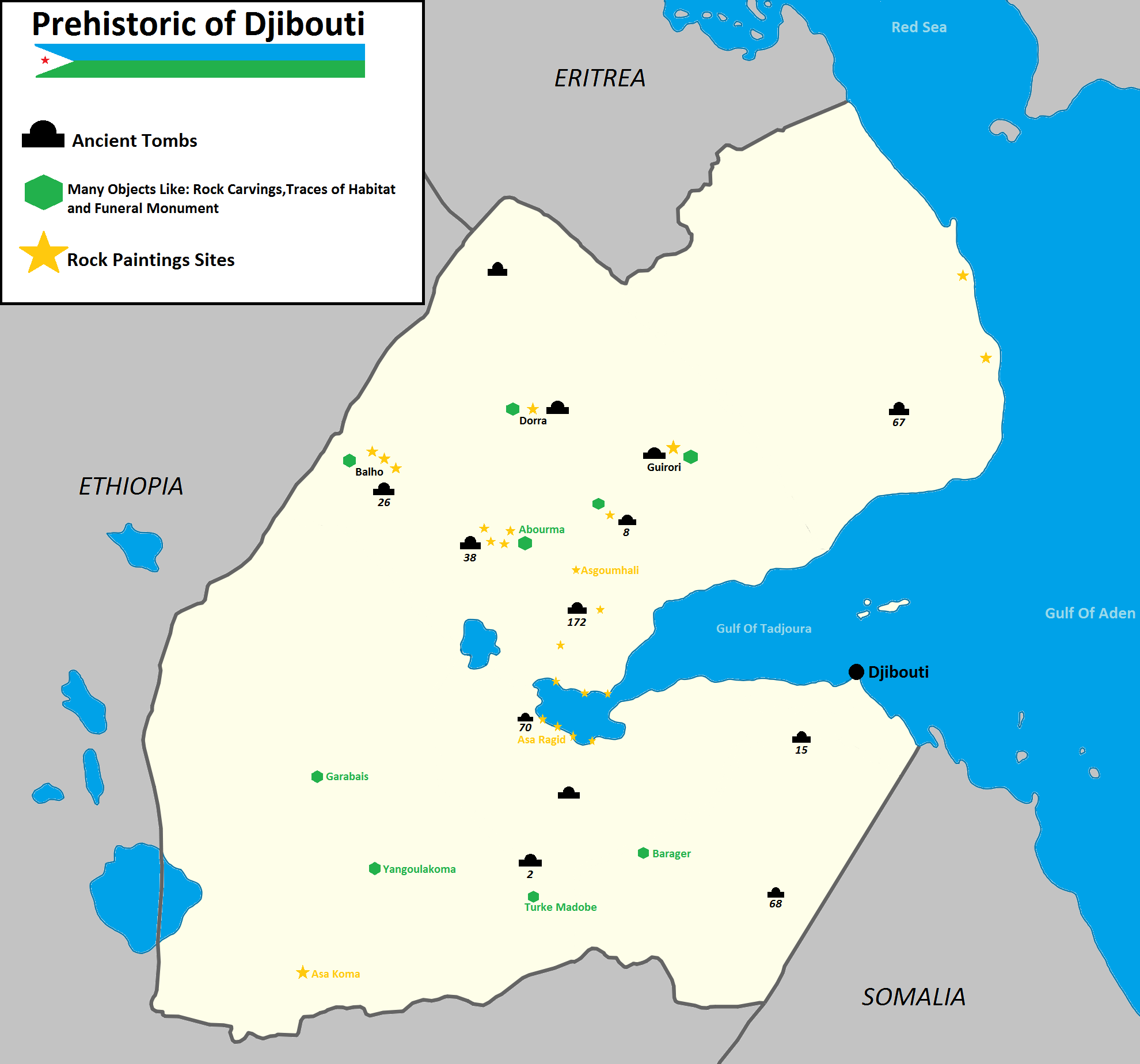

3.1. Prehistory

The Bab-el-Mandeb region, where Djibouti is located, has often been considered a primary crossing point for early hominins following a southern coastal route from East Africa to South and Southeast Asia. The Djibouti area has been inhabited since the Neolithic period. According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during this period, possibly from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley or the Near East. Other scholars suggest the Afroasiatic family developed in situ in the Horn of Africa, with its speakers subsequently dispersing from there.

Archaeological findings include cut stones dated to about 3 million years ago collected in the area of Lake Abbe. In the Gobaad plain, located between Dikhil and Lake Abbe, remains of the extinct elephant Palaeoloxodon recki were discovered, visibly butchered using basalt tools found nearby; these remains date to approximately 1.4 million years BCE. Other similar sites, likely the work of Homo ergaster, have also been identified. An Acheulean site, dated from 800,000 to 400,000 years BCE, where stone was cut, was excavated in the 1990s in Gombourta, between Damerdjog and Loyada, about 9.3 mile (15 km) south of Djibouti City. A Homo erectus jaw found in Gobaad has been dated to 100,000 BCE. On Devil's Island (Île du DiableDevil's IslandFrench), tools dating back 6,000 years, used to open shells, have been found. In the area at the bottom of Goubet (Dankalélo, not far from Devil's Island), circular stone structures and fragments of painted pottery have also been discovered. A fragmentary maxilla, attributed to an older form of Homo sapiens and dated to circa 250,000 years ago, was reported from the valley of the Dagadlé Wadi.

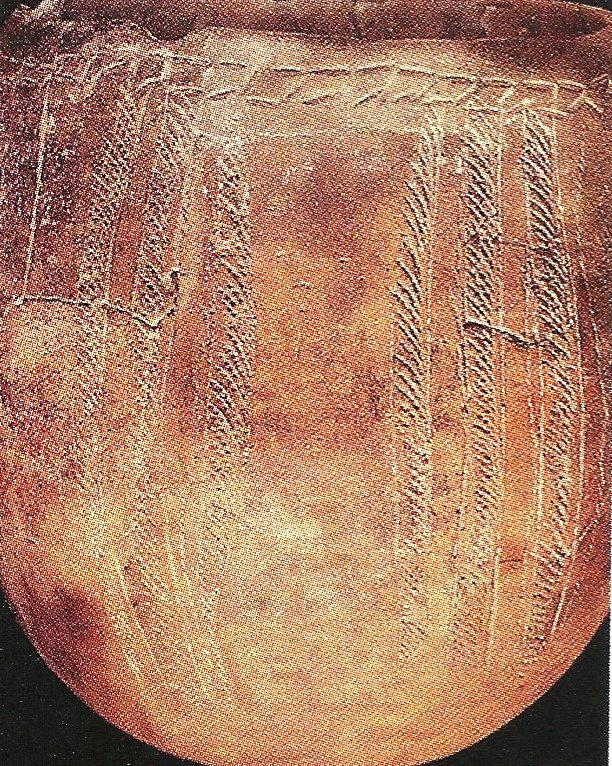

Pottery predating the mid-2nd millennium BCE has been found at Asa Koma, an inland lake area on the Gobaad Plain. The site's ware is characterized by punctate and incised geometric designs, which bear a similarity to the Sabir culture phase 1 ceramics from Ma'layba in Southern Arabia. Long-horned humpless cattle bones discovered at Asa Koma suggest that domesticated cattle were present by around 3,500 years ago. Rock art depicting what appear to be antelopes and a giraffe are also found at Dorra and Balho. The site of Handoga, dated to the fourth millennium BCE, has yielded obsidian microliths and plain ceramics used by early nomadic pastoralists with domesticated cattle.

The site of Wakrita, a small Neolithic establishment on a wadi in the tectonic depression of Gobaad, yielded abundant ceramics during 2004 excavations. These findings helped define a Neolithic cultural facies of this region, also identified at the nearby site of Asa Koma. Faunal remains from Wakrita confirm the importance of fishing in Neolithic settlements near Lake Abbé, as well as bovine husbandry and, for the first time in this area, evidence for caprine herding practices. Radiocarbon dating places this occupation at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE, similar to Asa Koma. These two sites represent the oldest evidence of herding in the region.

Up to 4000 BCE, the region benefited from a climate very different from today, possibly resembling a Mediterranean climate. Water resources were numerous, with lakes in Gobaad, and Lakes Assal and Abbé being larger. Humans lived by gathering, fishing, and hunting. The region was populated by rich fauna including felines, buffaloes, elephants, and rhinos, as evidenced by cave paintings at Balho. In the 3rd and 2nd millennia BCE, some nomads settled around the lakes, practicing fishing and cattle breeding. The burial of an 18-year-old woman from this period, along with hunted animal bones, bone tools, and small jewels, has been unearthed. By about 1500 BCE, the climate began to change, with freshwater sources becoming scarcer. Engravings show dromedaries, some ridden by armed warriors, indicating a shift back to nomadic life. Stone tumuli of various shapes, sheltering graves from this period, have been found throughout the territory.

3.2. Antiquity (Land of Punt)

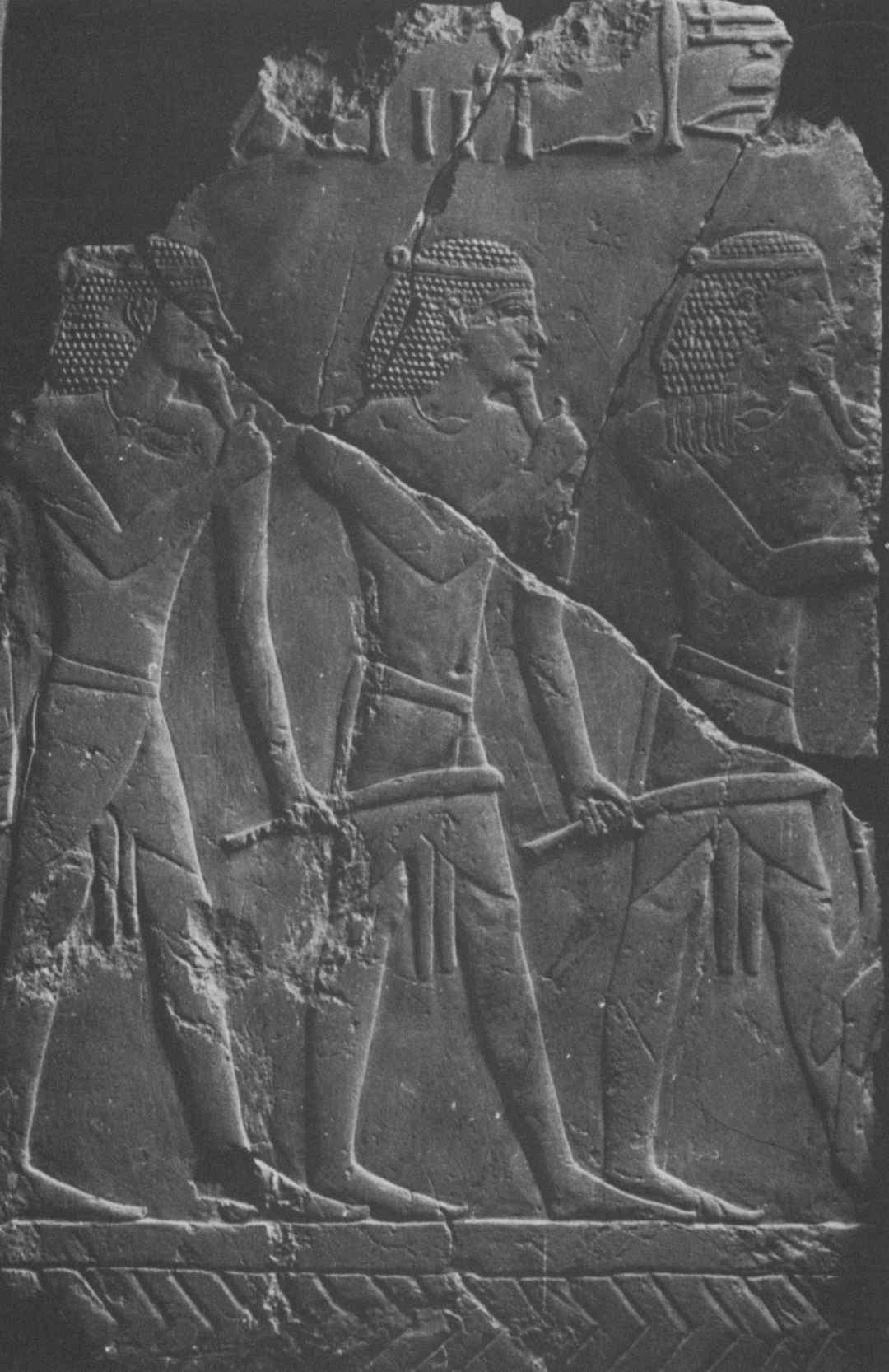

Djibouti, along with northern Ethiopia, Somaliland, Eritrea, and the Red Sea coast of Sudan, is considered the most likely location of the territory known to the Ancient Egyptians as Punt (or Ta Netjeru, meaning "God's Land"). The first mention of Punt dates to the 25th century BCE. The Puntites were a nation of people who had close relations with Ancient Egypt during the reigns of Pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty and Queen Hatshepsut of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

The earliest recorded ancient Egyptian expedition to Punt was organized by Pharaoh Sahure, returning with cargoes of antyue (likely myrrh or frankincense) and Puntites. Gold from Punt is recorded as having been in Egypt as early as the time of Pharaoh Khufu of the Fourth Dynasty. Subsequently, more expeditions to Punt occurred during the Sixth, Eleventh, Twelfth, and Eighteenth dynasties. In the Twelfth Dynasty, trade with Punt was celebrated in popular literature in the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor.

During the reign of Mentuhotep III (11th dynasty, c. 2000 BCE), an officer named Hannu organized voyages to Punt. Trading missions of the 12th dynasty pharaohs Senusret I, Amenemhat II, and Amenemhat IV also successfully navigated to and from Punt.

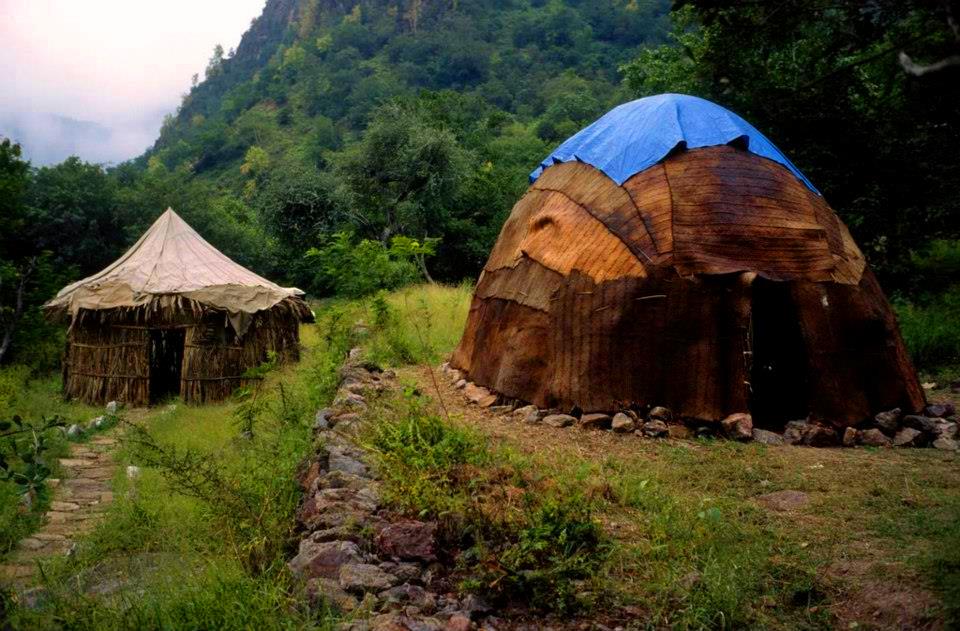

In the Eighteenth Dynasty, Hatshepsut built a Red Sea fleet to facilitate trade between the head of the Gulf of Aqaba and points south, as far as Punt. She personally led the most famous ancient Egyptian expedition to Punt. Her artists depicted much about the royals, inhabitants, habitations, and variety of trees on the island, revealing it as the "Land of the Gods." Traders returned with gold, ivory, ebony, incense, aromatic resins, animal skins, live animals, eye-makeup cosmetics, fragrant woods, and cinnamon. Ships regularly crossed the Red Sea to obtain bitumen, copper, carved amulets, naphtha, and other goods. According to the temple murals at Deir el-Bahari, the Land of Punt was ruled at that time by King Parahu and Queen Ati.

3.3. Introduction of Islam and the Middle Ages (Ifat and Adal Sultanates)

Islam was introduced to the Horn of Africa region early on, shortly after the hijra, when a group of persecuted Muslims sought refuge across the Red Sea. Zeila (now in Somaliland, but historically influential in the Djibouti region) became an early center of Islam. The two-mihrab Masjid al-Qiblatayn in Zeila dates to the 7th century and is one of the oldest mosques in Africa.

The Ifat Sultanate, founded by the Walashma dynasty, emerged in the 13th century, centered initially in eastern Shewa. Sultan Umar Walasma conquered the Sultanate of Shewa and expanded Ifat's influence. By 1288, Sultan Wali Asma had imposed rule over Zeila, Hubat, and other Muslim states. Al-Umari, a 14th-century Arab historian, listed Adal as one of the founding regions of the Ifat Sultanate.

The Adal (also Awdal, Adl, or Adel) was centered around Zeila and was established by local Somali clans in the early 9th century. In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi, an Arab Muslim scholar, described Adal as a small, wealthy kingdom with Zeila as its headquarters. Adal was often in conflict with the Christian Abyssinian Empire.

In 1320, conflict began between the Christian monarch Amda Seyon I of Ethiopia and Muslim Ifat leaders, precipitated by the Mamluk ruler Al-Nasir Muhammad's persecution of Copts in Egypt. Sabr ad-Din I of Ifat rebelled, aiming to become emperor of a Muslim Ethiopia. Amda Seyon I eventually defeated Ifat.

Sultan Sa'ad ad-Din II of Ifat continued to attack Abyssinia but was eventually defeated and killed near Zeila around 1403 or 1410 by Ethiopian forces under Emperor Dawit I or Yeshaq I. His descendants fled to Yemen but returned in 1415. Sabr ad-Din III, Sa'ad ad-Din II's eldest son, re-established the Adal Sultanate, moving its capital to Dakkar. Adal then became a center of Muslim resistance against the expanding Christian Abyssinian kingdom, controlling large parts of modern-day Djibouti, Somaliland, Eritrea, and Ethiopia.

The Djibouti-Loyada area features anthropomorphic and phallic stelae, associated with graves. These are of uncertain age, some adorned with a T-shaped symbol. Similar structures are found in Tiya, Ethiopia. Local residents identify these as Yegragn Dingay or "Gran's stone," referencing Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmad "Gurey" or "Gran"), a 16th-century ruler of Adal.

Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, with an army of Afar, Harari (Harla), and Somalis, launched the Ethiopian-Adal War (Futuh Al-Habash) between 1529 and 1543, bringing three-quarters of Christian Abyssinia under Muslim control. His forces came close to extinguishing the ancient Ethiopian kingdom. However, with Portuguese assistance, the Ethiopians defeated Adal at the Battle of Wayna Daga in 1543, where Imam Ahmad was killed. This defeat marked a turning point, allowing the Oromo people to migrate into new territories.

3.4. Early Modern Era (Imamate of Aussa and Ottoman Influence)

Following the decline of the Adal Sultanate, Nur ibn Mujahid became the Emir of Harar in 1550, fortifying the city. He defeated and killed Ethiopian Emperor Gelawdewos in 1559 but later suffered defeats against the Oromo. After Nur's death in 1567, Adal's power waned. Power struggles ensued, and Imam Muhammad Gasa moved the capital to Aussa in 1576, founding the Imamate of Aussa. This Imamate gradually declined over the next century, eventually falling to the Afar people who established the Sultanate of Aussa. The collapse of Adal led to the formation of smaller successor states such as Aussa, Tadjoura, and Rahayto.

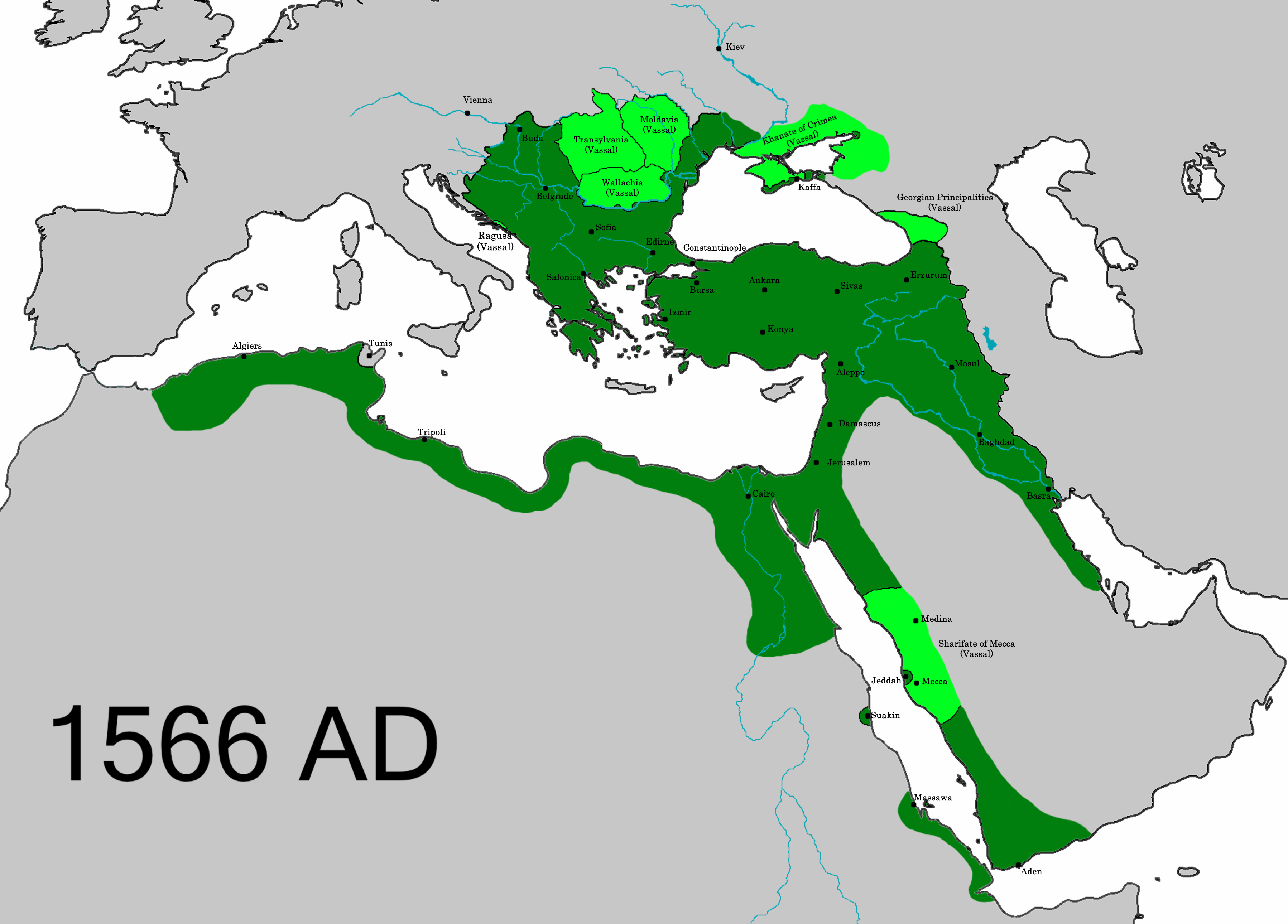

During the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire extended its influence into the Red Sea region. After conquering Mamluk Egypt in 1517, the Ottomans established the Habesh Eyalet, which included parts of the Eritrean and Somali coasts. They occupied Zeila and established a customs house and patrols in the Bab-el-Mandeb. While Ottoman direct control over the interior regions like Djibouti was limited, their presence influenced trade and politics in the coastal areas. By the 17th century, as Ottoman power waned, Zeila and Tadjoura fell under the influence of rulers from Mocha and Sana'a in Yemen. Zeila was often governed by an Emir who paid tribute. Tadjoura, though claiming independence, was also considered subordinate to Zeila, with its sultan receiving an annual stipend. This arrangement continued until Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt extended control over the region in the 19th century, before the arrival of European colonial powers.

3.5. French Colonization (1862-1977)

The period of French colonization significantly shaped modern Djibouti. This era is generally divided into the initial establishment of French Somaliland and its later re-designation as the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas, leading up to independence.

3.5.1. French Somaliland

French interest in the Horn of Africa grew with the construction of the Suez Canal, which began in 1859. The French sought a coaling station for steamships to rival the British port of Aden. In 1862, France signed a treaty with Raieta Dini Ahmet, an Afar sultan, purchasing the territory of Obock. On March 26, 1885, the French signed another treaty with the Issa Somalis, establishing a protectorate over their lands. Between 1883 and 1887, various treaties with local Somali and Afar sultans consolidated French control. An attempt by Russian adventurer Nikolay Achinov to establish a settlement at Sagallo in 1889 was quickly thwarted by French forces.

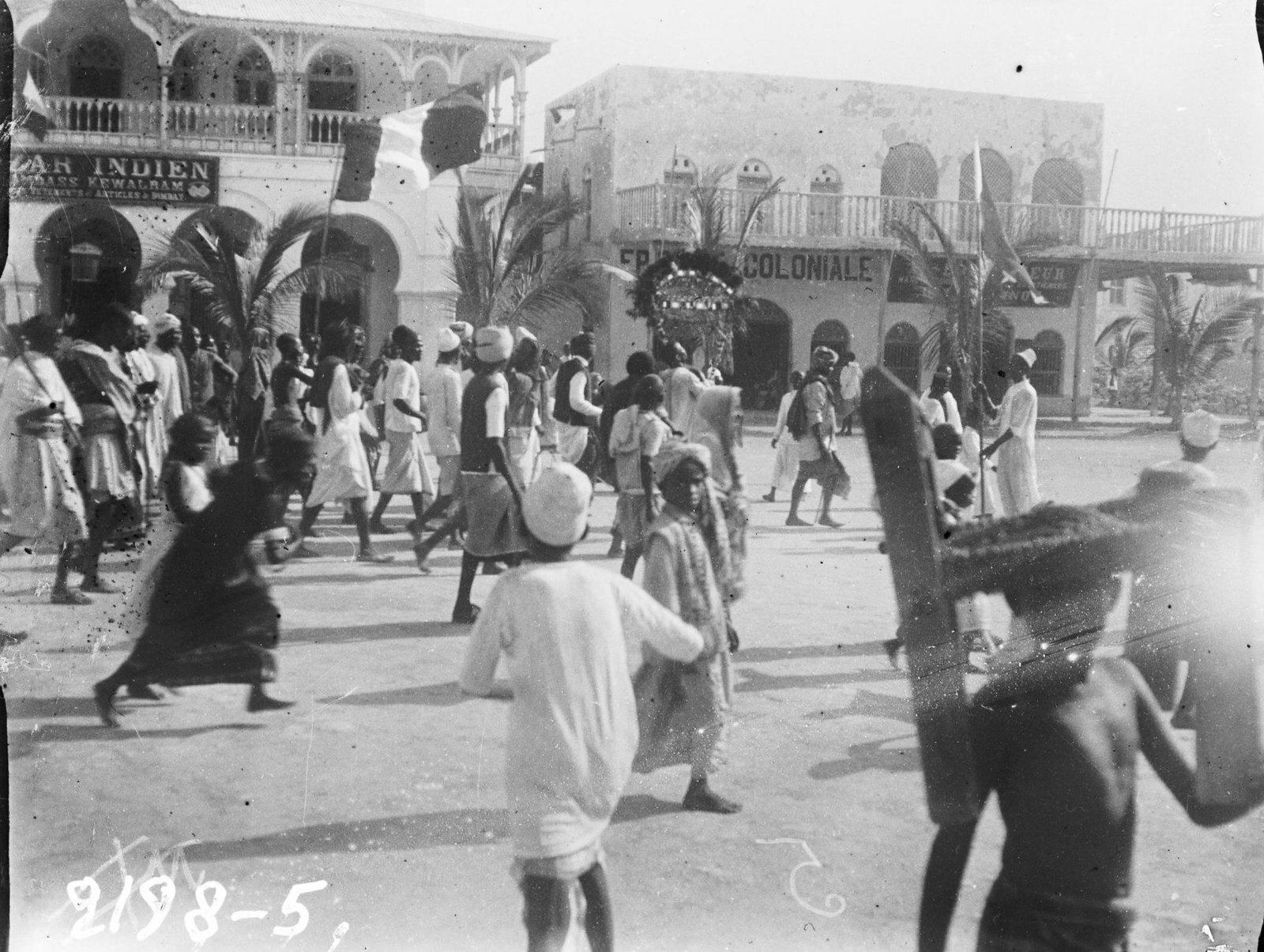

In 1894, Léonce Lagarde established a permanent French administration in the city of Djibouti and named the region French Somaliland (Côte française des SomalisFrench Coast of the SomalisFrench). The capital was moved from Obock to Djibouti city in 1896. The construction of the Imperial Ethiopian Railway (later Djibouti-Ethiopia Railway) from Djibouti city west into Ethiopia began in 1894. It reached Dire Dawa in 1902 and Addis Ababa in 1917. This railway turned the port of Djibouti into a crucial outlet for Ethiopian trade, particularly for coffee and other goods from southern Ethiopia and the Ogaden, quickly surpassing the caravan-based trade at Zeila (then in British Somaliland). Djibouti city grew rapidly, becoming a boomtown of 15,000 people.

During World War I, the 6th Somali Marching Battalion, formed in Madagascar in 1916 with recruits from French Somaliland, was renamed the 1st Battalion of Somali Tirailleurs. They fought in Europe, notably at Fort Douaumont in 1916 and Chemin des Dames in 1917, earning numerous citations. Of the 2,434 riflemen deployed, 517 were killed and 1,200 wounded.

After Italy's invasion of Ethiopia in the mid-1930s, border skirmishes occurred between French Somaliland and Italian East Africa. In June 1940, during World War II, after the Fall of France, the colony was ruled by the pro-Axis Vichy regime. British and Commonwealth forces blockaded the port of Djibouti City. After the defeat of Italian forces in East Africa in 1941, the Vichy administration in French Somaliland remained isolated but held out for over a year. In 1942, about 4,000 British troops occupied the city, and French Somaliland joined the Free French Forces. A local battalion from French Somaliland participated in the Liberation of France in 1944.

In 1947, French Somaliland became an overseas territory of France. Post-World War II, as decolonization swept Africa, the future of French Somaliland became a subject of debate. In a 1958 referendum, the territory voted to remain associated with France. This outcome was partly due to a combined "yes" vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident French, while many Somalis, led by Mahmoud Harbi (Vice President of the Government Council), favored independence and union with a Greater Somalia. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later under suspicious circumstances. Allegations of vote rigging were widespread.

3.5.2. French Territory of the Afars and the Issas

In 1966, France rejected a United Nations recommendation to grant French Somaliland independence. In August of that year, an official visit by French President Charles de Gaulle was met with demonstrations and rioting, reflecting growing pro-independence sentiment, particularly among the Somali population. In response, de Gaulle ordered another referendum.

A second referendum was held in 1967. The results again favored continued association with France, though looser than before. Voting was divided along ethnic lines: the Afars largely opted to remain with France, while the Somalis generally voted for independence with the aim of eventual unification with Somalia. Reports of vote rigging by French authorities marred this referendum as well. Shortly after, French Somaliland was renamed the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas (Territoire français des Afars et des IssasFrench Territory of the Afars and IssasFrench). The announcement of the results sparked civil unrest and several deaths, and France increased its military presence.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the struggle for independence intensified, led by groups like the Front de Libération de la Côte des Somalis (FLCS, Front for the Liberation of the Somali Coast). The FLCS waged an armed struggle, often launching cross-border operations from Somalia and Ethiopia, targeting French personnel. The FLCS was recognized as a national liberation movement by the Organization of African Unity (OAU). In March 1975, the FLCS kidnapped the French Ambassador to Somalia, Jean Guery, exchanging him for two imprisoned FLCS members. The FLCS's demands evolved, sometimes calling for integration into a "Greater Somalia" and at other times for simple independence. By 1975, the FLCS and the African People's League for the Independence (LPAI) opted for the path of independence, causing tensions with Somalia.

In February 1976, an FLCS operation involving the hijacking of a school bus carrying French children (the Loyada incident) further highlighted the difficulties of maintaining French colonial presence. The likelihood of a third referendum favoring France had diminished. The cost of maintaining the colony, France's last outpost on the continent, also pressured France to reconsider its position. These factors, combined with growing international and local pressure, paved the way for Djibouti's independence.

3.6. Republic of Djibouti (Post-Independence)

A third independence referendum was held on 8 May 1977. Unlike previous referendums in 1958 and 1967 that rejected full independence, this vote overwhelmingly supported disengagement from France. A landslide 98.8% of the electorate voted for independence. On 27 June 1977, the Republic of Djibouti was officially proclaimed, marking Djibouti's independence. Hassan Gouled Aptidon, an Issa Somali politician who had campaigned for a "yes" vote in the 1958 referendum to remain with France but later became a key figure in the independence movement, became the nation's first president, serving from 1977 to 1999.

In its first year, Djibouti joined the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union), the Arab League, and the United Nations. In 1986, it became a founding member of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a regional development organization headquartered in Djibouti City. During the Ogaden War (1977-1978) between Somalia and Ethiopia, some influential Issa politicians envisioned a "Greater Djibouti" or "Issa-land," with borders extending from the Red Sea to Dire Dawa in Ethiopia. However, this idea did not materialize as Somali forces were ultimately defeated.

President Aptidon established a one-party state under his People's Rally for Progress (RPP) party. While he appointed Afars to positions such as Prime Minister, the government was largely dominated by the Issa Somalis. This led to growing resentment among the Afar community.

3.6.1. Djiboutian Civil War

In the early 1990s, tensions over government representation and perceived Issa dominance erupted into the Djiboutian Civil War (1991-1994, with sporadic conflict until 2001). The war was primarily fought between the RPP-led government and the Afar-based Front for the Restoration of Unity and Democracy (FRUD). The conflict was mainly concentrated in the north, where the Afar population is predominant. The war had a severe impact on the affected communities, leading to displacement, loss of life, and human rights abuses.

President Aptidon responded by introducing a multi-party system and direct presidential elections in 1992, but opposition parties often boycotted these, alleging unfair conditions. Aptidon was re-elected in 1993. In 1994, a peace agreement was signed between the government and a moderate faction of FRUD, leading to a power-sharing arrangement where FRUD members joined the government. However, a radical faction of FRUD continued the insurgency.

In 1999, Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, President Aptidon's nephew and chosen successor, became president. A final peace accord was signed with the remaining FRUD faction in 2001, officially ending the civil war. The agreements aimed to address some of the Afar community's grievances regarding political representation and resource distribution, though concerns about equitable power-sharing and human rights have persisted. The war highlighted deep ethnic divisions and the challenges of nation-building in a multi-ethnic state.

President Guelleh has remained in power since 1999, winning successive elections. Constitutional changes in 2010 removed term limits, allowing him to run for further terms. His rule has been characterized by stability but also criticized by human rights organizations and opposition groups for restrictions on political freedoms and a lack of democratic development. In April 2021, Ismaïl Omar Guelleh was re-elected for his fifth term.

4. Geography

This section provides a comprehensive description of Djibouti's physical environment, including its strategic location, diverse habitats, distinctive climate patterns, and unique biodiversity, as well as conservation efforts and environmental challenges.

4.1. Location and Habitat

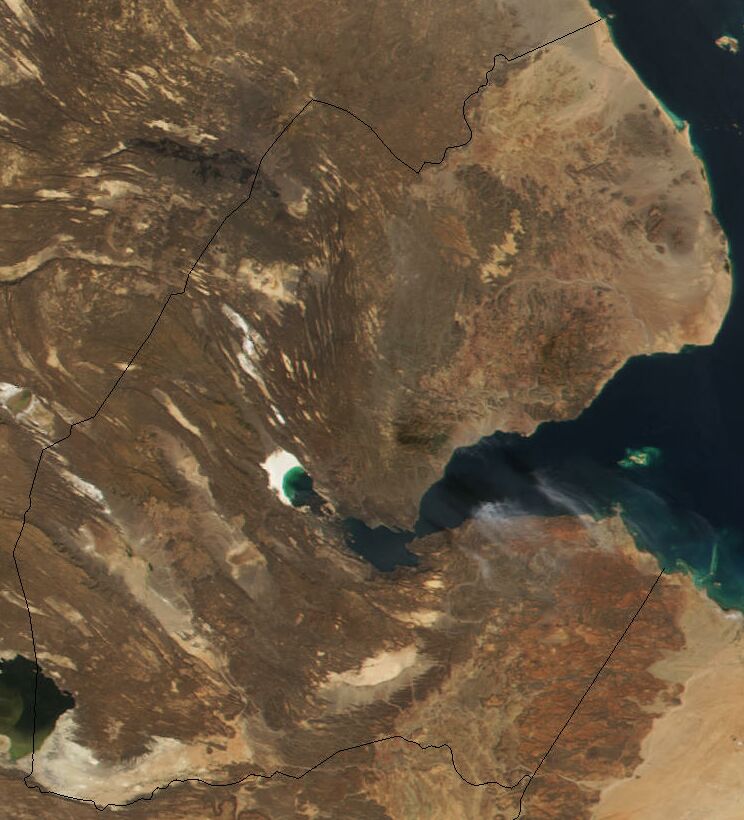

Djibouti is situated in the Horn of Africa, on the Gulf of Aden and the Bab-el-Mandeb strait, at the southern entrance to the Red Sea. It lies between latitudes 11° and 14°N and longitudes 41° and 44°E. This location is at the northernmost point of the Great Rift Valley. It is in Djibouti that the rift between the African Plate and the Somali Plate meets the Arabian Plate, forming a geologic tripoint. The tectonic interaction at this tripoint has created unique geological features, including Lake Assal, which is the lowest point in Africa and the third-lowest depression on Earth not covered by water (after the Dead Sea and the Sea of Galilee).

The country's coastline stretches for approximately 195 mile (314 km). The terrain mainly consists of plateaus, plains, and highlands. Djibouti has a total area of 9.0 K mile2 (23.20 K km2). Its land borders extend for 357 mile (575 km), shared with Eritrea (78 mile (125 km)) to the north, Ethiopia (242 mile (390 km)) to the west and south, and Somaliland (37 mile (60 km)) to the southeast. Djibouti is the southernmost country on the Arabian Plate.

Djibouti has eight mountain ranges with peaks exceeding 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m). The Mousa Ali range, located on the border with Ethiopia and Eritrea, is the country's highest, with its tallest peak reaching an elevation of 6.7 K ft (2.03 K m). The Grand Bara desert covers parts of southern Djibouti in the Arta, Ali Sabieh, and Dikhil regions, mostly at elevations below 1.70 K ft.

Most of Djibouti is part of the Ethiopian xeric grasslands and shrublands ecoregion. An eastern strip along the Red Sea coast belongs to the Eritrean coastal desert ecoregion.

4.2. Climate

Djibouti's climate is predominantly hot and arid. It is significantly warmer and has less seasonal variation than the world average. Mean daily maximum temperatures range from 89.6 °F (32 °C) to 105.8 °F (41 °C), except at high elevations. In Djibouti City, average afternoon highs range from 82.4 °F (28 °C) to 93.2 °F (34 °C) in April. At Airolaf, which is at an elevation between 5.1 K ft (1.54 K m) and 5.2 K ft (1.60 K m), the maximum temperature is around 86 °F (30 °C) in summer, with winter minimums around 48.2 °F (9 °C). In upland areas between 1640 ft (500 m) and 2625 ft (800 m), temperatures are comparable to coastal areas but cooler during the hottest months of June to August. December and January are the coolest months, with average low temperatures sometimes falling to 59 °F (15 °C).

Djibouti generally experiences either a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh) or a hot desert climate (Köppen BWh), though temperatures are moderated at the highest elevations. Annual rainfall is scarce; on the eastern seaboard, it is less than 5 in, while in the central highlands, precipitation is about 8 in to 16 in. The hinterland is significantly less humid than the coastal regions.

| Location | July (°C) (High/Low) | January (°C) (High/Low) |

|---|---|---|

| Djibouti City | 41/31 | 28/21 |

| Ali Sabieh | 36/25 | 26/15 |

| Tadjoura | 41/31 | 29/22 |

| Dikhil | 38/27 | 27/17 |

| Obock | 41/30 | 28/22 |

| Arta | 36/25 | 25/15 |

| Randa | 34/23 | 23/13 |

| Holhol | 38/28 | 26/17 |

| Ali Adde | 38/27 | 26/16 |

| Airolaf | 31/18 | 22/9 |

4.3. Wildlife

Djibouti's flora and fauna inhabit a harsh landscape, with forests accounting for less than one percent of the country's total area. Wildlife is spread across three main regions: the northern mountain region, the volcanic plateaus in the southern and central parts, and the coastal region.

The most significant biodiversity is found in the northern part of the country, particularly in the ecosystem of the Day Forest National Park. Located in the Goda Mountains at an average altitude of 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m) (highest peak 5.8 K ft (1.78 K m)), this park covers an area of 1.4 mile2 (3.5 km2) of Juniperus procera forest, with many trees reaching 66 ft (20 m) in height. This forest is the primary habitat of the critically endangered and endemic Djibouti francolin (Pternistis ochropectus) and the recently noted colubrine snake Platyceps afarensis. It also contains many species of woody and herbaceous plants, including boxwood and olive trees, accounting for about 60% of the total identified plant species in the country.

Djibouti is home to over 820 species of plants, 493 species of invertebrates, 455 species of fish, 40 species of reptiles, three species of amphibians, 360 species of birds, and 66 species of mammals. The country's wildlife is part of the Horn of Africa biodiversity hotspot and the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden coral reef hotspot.

Mammals include several antelope species, such as Soemmerring's gazelle and Pelzeln's gazelle. Due to a hunting ban imposed since the early 1970s, these species are now relatively well conserved. Other characteristic mammals include Grevy's zebra, hamadryas baboon, and Hunter's antelope. The warthog, a vulnerable species, is also found in the Day Forest National Park. Coastal waters are home to dugongs. Green turtles and hawksbill turtles inhabit the coastal waters where they also nest. The Northeast African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii) is thought to be extinct in Djibouti.

Conservation efforts are underway, but environmental challenges such as desertification, deforestation, and water scarcity pose significant threats to Djibouti's biodiversity.

5. Politics

This section examines Djibouti's political system, including its governmental structure, foreign policy, military organization, human rights record, and administrative framework, with an emphasis on democratic development, political participation, and the social impact of its international relations.

5.1. Governance

Djibouti is a unitary presidential republic. The constitution, adopted in 1992 and amended in 2010, establishes the framework for governance. Executive power rests with the President, who is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The president is elected by popular vote for a five-year term; prior to 2010, the term was six years, and a constitutional amendment in that year removed term limits. The current president, Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, has been in office since 1999. The president appoints the Prime Minister, currently Abdoulkader Kamil Mohamed, who heads the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The cabinet is responsible to and presided over by the president.

Legislative power is vested in the unicameral National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale). It consists of 65 members elected every five years through a party-list proportional representation system in multi-seat constituencies. Although the constitution provides for the creation of a Senate, it has not yet been established.

The political system has been characterized as a dominant-party system. The People's Rally for Progress (RPP), led by President Guelleh, has been the ruling party since independence, typically as part of the Union for a Presidential Majority (UMP) coalition, which holds a supermajority of seats in the National Assembly. Opposition parties are legally permitted, but their activities are often restricted. The main opposition coalition, the Union for National Salvation (USN), has participated in elections but has also boycotted them at times, citing government control of the media, repression of opposition candidates, and lack of a fair electoral process. Concerns about democratic development and political participation persist, with critics pointing to limited political pluralism and restrictions on freedoms of expression and assembly. The government is largely dominated by the Somali Issa Dir clan.

The judiciary consists of courts of first instance, a High Court of Appeal, and a Supreme Court. The legal system is a blend of French civil law, Sharia (Islamic law), and customary law (Xeer) of the Somali and Afar peoples. The independence of the judiciary has been a subject of concern for human rights organizations.

In early 2011, Djibouti experienced a series of protests inspired by the Arab Spring, calling for political reforms and an end to President Guelleh's long tenure. However, these protests were suppressed by security forces.

5.2. Foreign Relations

Djibouti's foreign relations are managed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. Its foreign policy is heavily influenced by its strategic geographic location at the crossroads of major shipping lanes and its proximity to volatile regions in the Horn of Africa and the Middle East. Djibouti maintains close ties with France, its former colonial power, and the United States, both of which have significant military presences in the country. Relations with neighboring Ethiopia are crucial, as Djibouti's ports serve as Ethiopia's primary maritime outlet. It also has important relationships with Somalia, China, Japan, and Arab states, particularly those in the Arabian Peninsula.

Djibouti is an active member of several international and regional organizations, including the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU), the Arab League, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), whose headquarters are in Djibouti City. It plays a role in regional mediation and peacekeeping efforts, particularly concerning Somalia. Djibouti has been a member of The Forum of Small States (FOSS) since its founding in 1992.

The country's policy of hosting foreign military bases (see #Foreign Military Presence) is a central element of its foreign and economic policy, providing substantial revenue and security partnerships. However, this has also raised questions about sovereignty and the potential for entanglement in international rivalries. The social and economic impacts of these foreign relations on Djibouti's population are complex, bringing economic benefits but also contributing to issues like increased cost of living in certain areas and social tensions. Djibouti's relationship with Eritrea has been historically tense, marked by border disputes, such as the 2008 border conflict.

In recent years, relations with China have significantly deepened, involving large-scale infrastructure investments by China and the establishment of a Chinese military base. Relations with Turkey have also been strengthened.

5.3. Military

The Djibouti Armed Forces (DAF) are responsible for the national defense of Djibouti. They consist of the Djiboutian National Army (which includes the small Djiboutian Navy and the Djiboutian Air Force) and the National Gendarmerie. As of 2011, the manpower available for military service was estimated at 170,386 males and 221,411 females aged 16 to 49. Djibouti's annual military expenditure was over 36.00 M USD as of 2011.

After independence, Djibouti's military initially consisted of two regiments largely commanded by French officers. In the early 2000s, the DAF sought to modernize and restructure its forces into smaller, more mobile units. The primary roles of the DAF include border security, internal security, and participation in regional security initiatives.

The DAF's first major engagement was the Djiboutian Civil War (1991-2001) against the Front for the Restoration of Unity and Democracy (FRUD). The government forces, with support from France, eventually prevailed, leading to peace agreements.

Djibouti has been an active participant in regional peace processes, notably hosting the Arta conference for Somali reconciliation in 2000. Djiboutian forces have participated in peacekeeping missions, including deployments to Somalia (as part of AMISOM) and Sudan. The military has been improving its training, command structures, and capabilities, often in collaboration with foreign partners whose forces are based in the country.

5.3.1. Foreign Military Presence

Djibouti's strategic location near the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait has made it a highly sought-after location for foreign military bases. This presence is a significant aspect of Djibouti's economy and foreign policy.

- France: French forces have remained in Djibouti since independence under various defense agreements. The current treaty, signed in 2011 and effective since 2014, reaffirms France's commitment to Djibouti's independence and territorial integrity. Historically, the 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion (13 DBLE) formed the core of the French garrison until its relocation to the UAE in 2011. France maintains a significant military presence for regional operations and training.

- United States: Camp Lemonnier, formerly a French base, was leased to the United States Central Command in September 2002 and is now the primary base of operations for Combined Joint Task Force - Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA). The lease was renewed in 2014 for 20 years. It is the only permanent U.S. military base in Africa and is crucial for counter-terrorism operations and regional security. The U.S. pays approximately 63.00 M USD annually for the lease.

- China: China established its first overseas military base, the Chinese PLA Support Base, in Djibouti in 2017. Officially described as a logistics facility to support anti-piracy, peacekeeping, and humanitarian missions, its presence has significant geopolitical implications. China pays approximately 20.00 M USD annually for its base.

- Japan: Japan established its first post-World War II overseas military base in Djibouti in 2011, primarily to support anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. The Japan Self-Defense Force operates naval air patrols from this facility. Japan pays about 30.00 M USD annually.

- Italy: Italy also maintains a military support base, the Italian National Support Military Base (BMIS "Amedeo Guillet"), to support its anti-piracy and regional stability operations.

- Other countries: Forces from other nations, including Spain and Germany, have also operated from Djibouti, often as part of EU or NATO missions.

The hosting of these bases is a major source of revenue for Djibouti, with lease payments contributing significantly to its GDP (over 5% in 2017). However, this extensive foreign military presence raises complex socio-political questions regarding national sovereignty, local economic impacts (such as inflation in housing and goods), social interactions between foreign troops and the local population, and Djibouti's delicate balancing act in its foreign relations.

5.4. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Djibouti is a matter of concern for international observers and local activists. While the constitution provides for certain fundamental rights, their practical application is often limited, reflecting a social liberal concern for individual liberties and vulnerable groups.

Key human rights issues include:

- Freedoms of Expression, Assembly, and Association: These freedoms are significantly restricted. The government maintains control over most media outlets, and journalists critical of the authorities often face harassment, intimidation, and arrest. Public demonstrations are rare and frequently suppressed. Opposition parties and civil society organizations face obstacles in their operations.

- Political Freedoms: The political space is largely dominated by the ruling party, and meaningful political opposition is limited. Elections have been criticized for lacking fairness and transparency. Arbitrary arrests and detentions of opposition figures and activists have been reported.

- Prison Conditions: Prison conditions are often harsh and life-threatening, characterized by overcrowding, poor sanitation, inadequate food and medical care.

- Arbitrary Detention and Due Process: Reports of arbitrary detention by security forces persist. Access to legal counsel and fair trial standards are not always upheld. Impunity for abuses committed by security forces is a problem.

- Women's Rights: While women have some legal protections, they face discrimination in various aspects of life. Female genital mutilation (FGM) is widespread, affecting an estimated 93.1% of women and girls, despite being legally proscribed in 1994. The procedure is deeply ingrained in local culture. Domestic violence against women remains a serious issue, with inadequate government action for prosecution and accountability.

- Rights of Minorities and Vulnerable Groups: Ethnic tensions, particularly between the Afar and Issa communities, continue to be a factor, though large-scale conflict has subsided. The rights of refugees and migrants are also a concern, given Djibouti's position as a transit country.

- Corruption: Significant acts of corruption by officials are reported, often with impunity, undermining good governance and equitable resource distribution.

The government of Djibouti has stated its commitment to improving human rights, but progress has been slow. International human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as the U.S. State Department, regularly report on these issues. The 2011 Freedom House report ranked Djibouti as "Not Free."

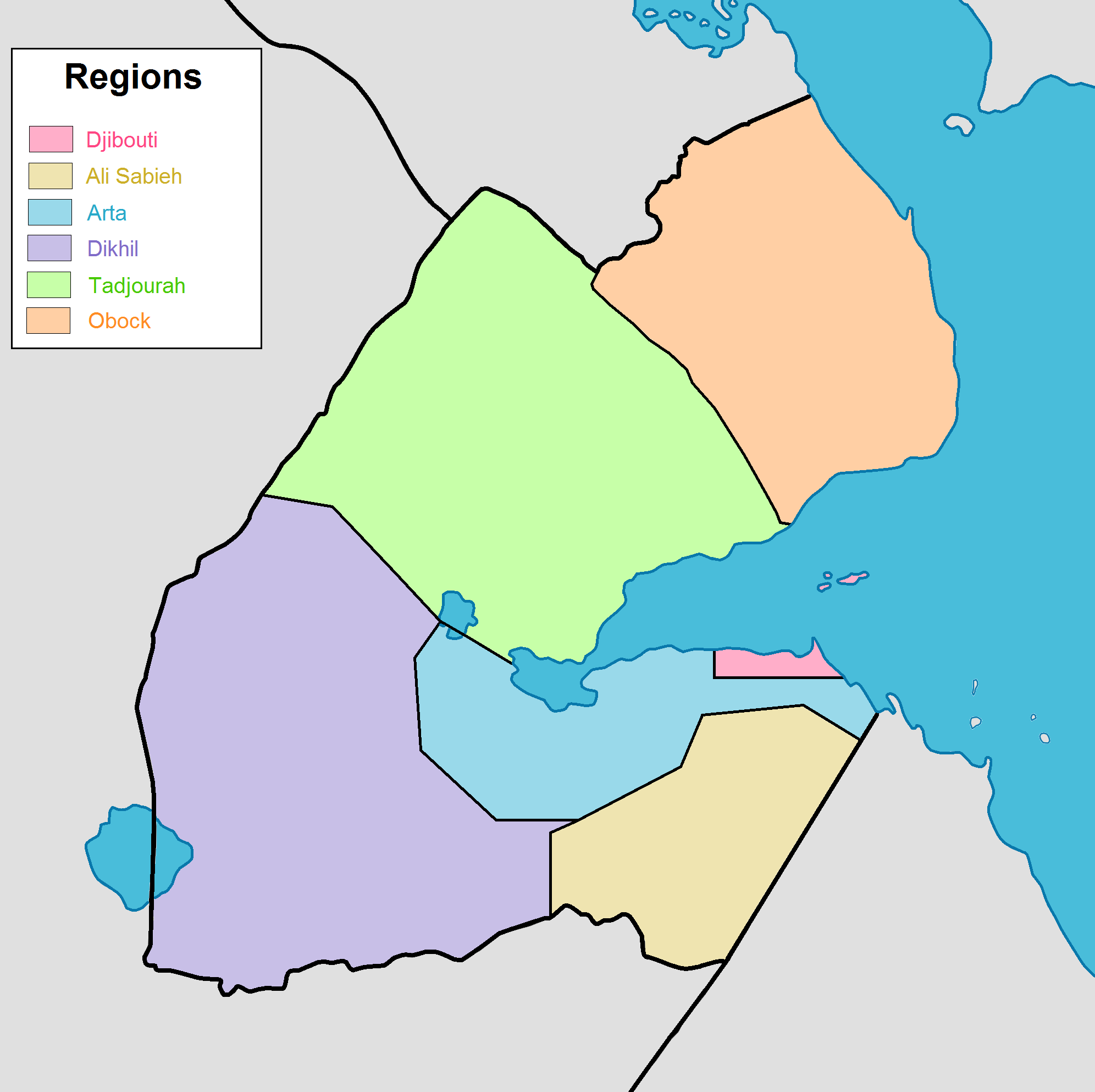

5.5. Administrative Divisions

Djibouti is divided into six administrative regions. The capital, Djibouti City, is treated as one of these regions. The regions are further subdivided into twenty sub-prefectures.

The six regions are:

| Region | Area (km2) | Population (2009 Census) | Population (2024 Census) | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali Sabieh (إقليم علي صبيحIqlīm 'Alī ŞabīḩArabic) | 0.8 K mile2 (2.20 K km2) | 86,949 | 76,414 | Ali Sabieh |

| Arta (إقليم عرتاIqlīm 'ArtāArabic) | 0.7 K mile2 (1.80 K km2) | 42,380 | 48,922 | Arta |

| Dikhil (إقليم دخيلIqlīm DikhīlArabic) | 2.8 K mile2 (7.20 K km2) | 88,948 | 66,196 | Dikhil |

| Djibouti (city) (إقليم جيبوتيIqlīm JībūtīArabic) | 77 mile2 (200 km2) | 475,322 | 776,966 | Djibouti City |

| Obock (إقليم أوبوكIqlīm AubūkArabic) | 1.8 K mile2 (4.70 K km2) | 37,856 | 37,666 | Obock |

| Tadjourah (إقليم تاجورةIqlīm TājūrahArabic) | 2.7 K mile2 (7.10 K km2) | 86,704 | 50,645 | Tadjoura |

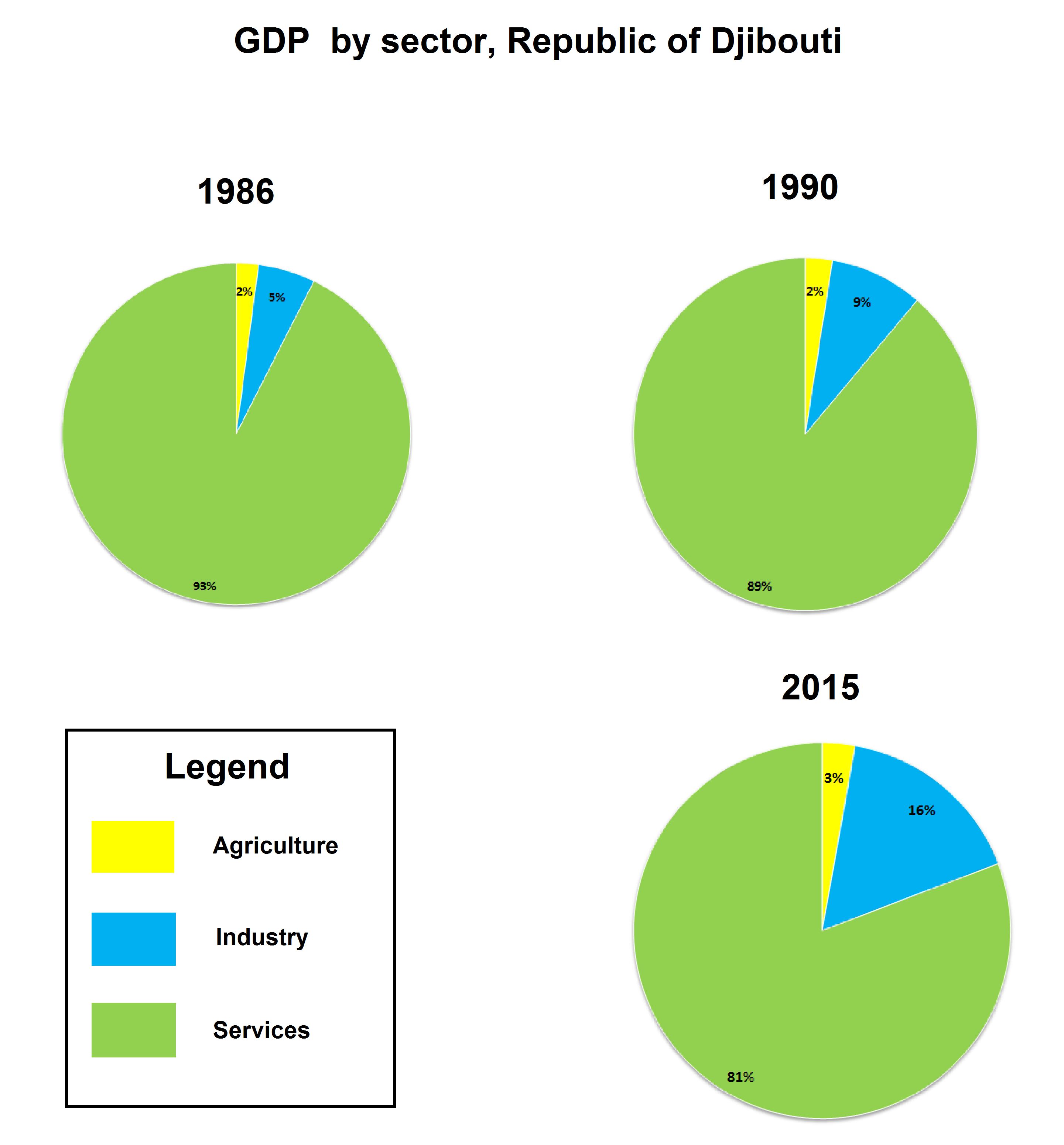

6. Economy

This section analyzes the structure of Djibouti's economy, its key sectors including services, trade, transport, media, tourism, and energy, and addresses challenges like employment, income distribution, and sustainable development from a social liberal perspective.

6.1. Overview

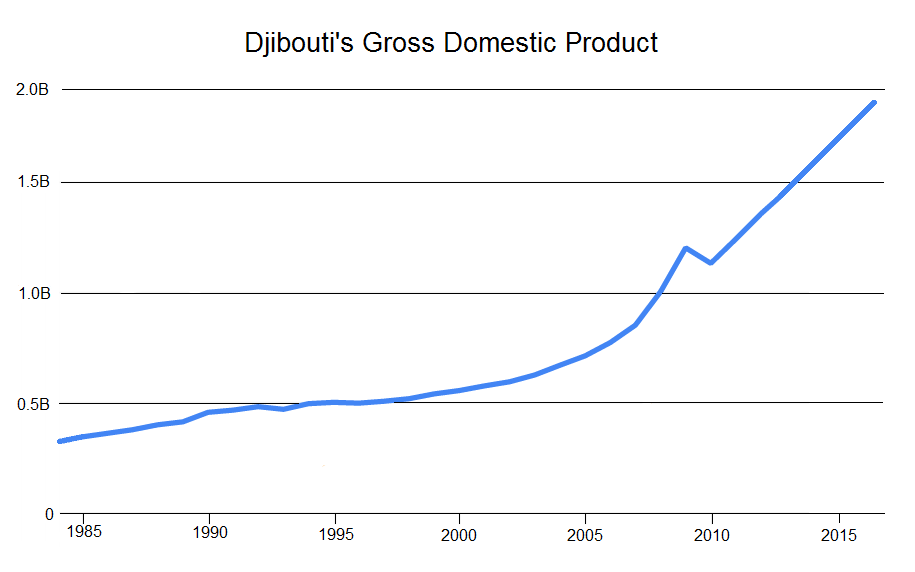

Djibouti's economy is largely concentrated in the service sector, capitalizing on its strategic location as a Red Sea transit point and its free trade policies. Commercial activities revolve around the Port of Djibouti and related logistics. Limited rainfall severely restricts agriculture, making the country heavily reliant on food imports. In 2013, Djibouti's GDP (purchasing power parity) was estimated at 2.50 B USD, with a real growth rate of 5% annually. Per capita income was around 2.87 K USD (PPP). The services sector constituted approximately 79.7% of GDP, followed by industry at 17.3%, and agriculture at a mere 3%. More recent estimates indicate GDP growth has remained relatively stable, driven by port activities and foreign investment in infrastructure.

A significant challenge for Djibouti is its high unemployment rate, estimated at around 60% in urban areas, disproportionately affecting youth. Income distribution is highly unequal, and poverty remains widespread despite the revenue generated from port services and foreign military bases. Sustainable development is hampered by environmental constraints, particularly water scarcity and vulnerability to climate change. The government has outlined development plans, such as the "Strategy of Accelerated Growth and Promotion of Employment" (SCAPE) and "Vision Djibouti 2035," aiming to transform the country into a regional trade and logistics hub, diversify the economy, and improve social indicators. However, reliance on foreign loans for large infrastructure projects has led to a high public debt-to-GDP ratio, raising concerns about debt sustainability. From a social liberal perspective, ensuring that economic growth translates into improved living standards for the majority of the population, job creation, reduced inequality, and enhanced social safety nets are critical priorities.

The Djiboutian franc (DJF) is the national currency, pegged to the U.S. dollar, which provides monetary stability and low inflation but can affect export competitiveness. Djibouti was ranked the 177th safest investment destination in the March 2011 Euromoney Country Risk rankings. The government has introduced policies to improve the investment climate, including tax incentives.

6.2. Transport

Djibouti's transport infrastructure is critical to its economy, primarily due to its role as a regional trade and logistics hub, especially for landlocked Ethiopia.

- Ports: The Port of Djibouti is the cornerstone of the economy. Historically, it handled the bulk of the nation's trade and about 70% of Ethiopia's maritime cargo. In 2018, it was estimated that 95% of Ethiopian transit cargo passed through Djiboutian ports. The original Port of Djibouti includes facilities for general cargo, bulk goods, and livestock. To expand capacity, the Doraleh Container Terminal (DCT) was developed in collaboration with DP World. This modern terminal, with a capacity to handle 1.5 million TEUs annually, significantly boosted transit capabilities. Other specialized ports include the Port of Tadjourah (mainly for potash), the Damerjog Port (livestock), and the Port of Goubet (salt). The ports also serve as international refueling and transshipment centers.

- Railways: The historic metre-gauge Ethio-Djibouti Railway was largely replaced by the new electrified standard gauge Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, which began commercial operations in January 2018. This railway is crucial for freight transport between Ethiopia and the Port of Doraleh, aiming to reduce transit times and costs.

- Airports: Djibouti-Ambouli International Airport in Djibouti City is the country's only international airport, serving intercontinental routes with scheduled and chartered flights. Air Djibouti is the national flag carrier.

- Roads: The Djiboutian highway system connects major towns and links to Ethiopia. The main corridor to Ethiopia is vital for truck-based freight. However, the condition of some roads can be a challenge.

- Ferries: Car ferries operate across the Gulf of Tadjoura, connecting Djibouti City with Tadjoura.

Djibouti is part of China's 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, further underscoring its strategic importance in global trade routes.

6.3. Media and Telecommunications

The media and telecommunications landscape in Djibouti is largely controlled by the state. The Ministry of Communication oversees telecommunications.

- Telecommunications: Djibouti Telecom is the sole provider of telecommunication services, including fixed-line, mobile, and internet services. The network primarily uses microwave radio relay, with fiber-optic cable in the capital and wireless local loop systems in rural areas. Mobile cellular coverage is concentrated in and around Djibouti City. As of 2015, there were approximately 23,000 telephone main lines and 312,000 mobile/cellular lines. Djibouti is connected to international submarine communications cables like SEA-ME-WE 3. It also has satellite earth stations.

- Media: Radiodiffusion Télévision de Djibouti (RTD) is the state-owned national broadcaster, operating the sole terrestrial TV station and two domestic radio networks. Licensing and operation of broadcast media are regulated by the government, which leads to limited media freedom. The main print newspapers are also government-owned, including the French-language daily La Nation, the English weekly Djibouti Post, and the Arabic weekly Al-Qarn. The state news agency is Agence Djiboutienne d'Information (ADI). Independent news websites often operate from abroad due to restrictions within the country (e.g., La Voix de Djibouti based in Belgium). Movie theaters, like the Odeon Cinema in the capital, also exist.

- Internet: As of 2015, internet users comprised around 99,000 individuals. The internet country top-level domain is .dj. Access to information can be limited by state control and infrastructure constraints.

Freedom of the press is severely restricted, and Djibouti consistently ranks low in international press freedom indices.

6.4. Tourism

Tourism in Djibouti is a small but growing sector of the economy. The country attracts fewer than 80,000 arrivals per year, a significant portion of whom are family and friends of military personnel stationed at the foreign bases, or business travelers. The government has expressed interest in developing tourism, particularly ecotourism and adventure tourism, leveraging Djibouti's unique geological landscapes and marine biodiversity.

Key attractions include:

- Lake Assal: Africa's lowest point, a saline lake with dramatic salt flats and volcanic scenery.

- Lake Abbe: Known for its unique limestone chimneys and flamingo populations.

- Day Forest National Park: A remnant forest in the Goda Mountains, home to endemic species like the Djibouti Francolin.

- Moucha and Maskali Islands: Popular for diving, snorkeling, and whale shark watching (seasonal).

- The Gulf of Tadjoura: Offers opportunities for marine activities.

- Arta Plage: A coastal area popular for recreation.

Challenges to tourism development include limited infrastructure outside the capital, high costs for private tours, and a lack of international marketing. The reopening of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway in 2018 has improved land access for regional tourists. The impact of tourism development on the environment and local communities requires careful management to ensure sustainability.

6.5. Energy

Djibouti's energy sector is characterized by a high dependence on imported fossil fuels and a growing focus on developing domestic renewable energy sources.

- Current Capacity: Djibouti has an installed electrical power generating capacity of approximately 126 MW, primarily from thermal plants running on fuel oil and diesel. In 2002, electrical power output was 232 GWh, with consumption at 216 GWh.

- Energy Access and Demand: Per capita annual electricity consumption was about 330 kWh in 2015. A significant portion of the population (around 45% in 2015) lacks access to electricity. There is substantial unmet demand in the power sector, and electricity costs are high.

- Import Dependence: Djibouti imports a significant portion of its electricity from Ethiopia via an interconnection line; this hydropower import satisfies around 65% of Djibouti's demand and is crucial for its energy supply.

- Renewable Energy Development: The government is actively pursuing renewable energy projects to reduce reliance on imported fuels, lower energy costs, and decrease carbon emissions.

- Geothermal Energy: Djibouti has significant geothermal potential due to its location in the Rift Valley. Several sites have been identified, with development efforts, supported by international partners like Japan, underway near Lake Assal. A 56 MW geothermal power plant project has been planned.

- Solar Energy: Solar power is also being developed, with projects like the photovoltaic power station in Grand Bara planned with a capacity of 50 MW.

- Wind Energy: There is also potential for wind energy generation.

Developing these renewable resources is expected to address recurring electricity shortages, reduce costly oil imports, support economic growth, and lower the national debt burden by reducing energy import bills.

7. Demographics

This section details the demographic characteristics of Djibouti's population, including its ethnic composition, languages spoken, religious affiliations, health indicators, educational system, and major urban centers, while considering issues of social cohesion and access to services.

7.1. Population

Djibouti has a population of approximately 1,066,809 inhabitants according to the census held on 20 May 2024. Earlier estimates indicated a population of around 884,017 in 2018 and 869,099 in 2015. The population grew rapidly during the latter half of the 20th century, increasing from about 69,589 in 1955.

Approximately 76% of local residents are urban dwellers, with a large concentration in the capital, Djibouti City. The remainder are primarily pastoralists. Djibouti's location makes it a hub for regional migration, and it hosts a number of immigrants and refugees from neighboring states like Somalia, Ethiopia, and Yemen. There has been a significant influx of migrants from Yemen, particularly due to conflict there.

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 62,001 |

| 1955 | 69,589 |

| 1960 | 83,636 |

| 1965 | 114,963 |

| 1970 | 159,659 |

| 1977 | 277,750 |

| 1980 | 358,960 |

| 1985 | 425,613 |

| 1990 | 590,398 |

| 1995 | 630,388 |

| 2000 | 717,584 |

| 2005 | 784,256 |

| 2010 | 850,146 |

| 2015 | 869,099 |

| 2018 | 884,017 |

| 2024 | 1,066,809 |

| Source: World Bank (to 2018); 2024 Census by Institut National de la Statistique de Djibouti (INSTAD). | |

7.2. Ethnic Groups

Djibouti is a multi-ethnic country. The two largest ethnic groups are the Somalis (approximately 60% of the population) and the Afar (approximately 35%).

- The Somali component is mainly composed of the Issa sub-clan of the Dir, who are the majority Somali group (around 33% of the total population according to some older estimates). Other Somali clans present include the Gadabuursi (also a Dir sub-clan, estimated between 15-20%) and the Isaaq (estimated between 13.3-20%). The Issa traditionally inhabit the southern parts of the country, including the capital.

- The Afar (or Danakil) traditionally inhabit the northern and western regions.

The remaining 5% of the population consists primarily of Yemeni Arabs, Ethiopians (of various ethnic backgrounds), and Europeans (mainly French and Italians).

Relations between the Issa and Afar have historically been complex and have at times led to political tensions and conflict, notably the civil war in the 1990s. Issues of political representation, resource allocation, and power-sharing between these two main groups are crucial for national stability and social cohesion. The government structure attempts to balance these ethnic interests, though Somalis, particularly the Issa clan, have historically held dominant political positions.

7.3. Languages

Djibouti is a multilingual nation. The main languages spoken are:

- Somali: Spoken as a first language by about 60% of the population, primarily by the Issa and other Somali clans. The Northern Somali dialect is common.

- Afar: Spoken as a first language by about 35% of the population, primarily by the Afar ethnic group.

Both Somali and Afar are Cushitic languages belonging to the larger Afroasiatic family. They are considered national languages. The approximate distribution of first languages spoken is: Somali (60%), Afar (35%), and Arabic (Ta'izzi-Adeni dialect, 2%). Other languages make up the remainder.

The two official languages of Djibouti are:

- French: Inherited from the colonial period, French serves as a statutory national language and is the primary language of instruction in schools and is widely used in government and business. Around 17,000 Djiboutians speak it as a first language.

- Arabic: Modern Standard Arabic is an official language and is important for religious purposes. Colloquially, about 59,000 local residents speak the Ta'izzi-Adeni Arabic dialect, also known as Djibouti Arabic.

Immigrant languages include Omani Arabic (spoken by around 38,900 people), Amharic (around 1,400 speakers), and Greek (around 1,000 speakers).

7.4. Religion

The population of Djibouti is predominantly Muslim. Islam is the state religion and is observed by around 98% of the nation's population (approximately 891,000 as of 2022 estimates, older sources state 94% Muslim). Islam entered the region very early, with persecuted Muslims seeking refuge in the Horn of Africa during the time of the Prophet Muhammad.

Most Djiboutian Muslims adhere to Sunni Islam, following the Shafi'i school of jurisprudence. Sufi orders also have a presence. According to a Pew Research Center estimate, religious affiliation among Muslims in Djibouti is approximately: Sunni (87%), Non-denominational Muslims (8%), Other Muslim (3%), and Shia (2%). The constitution of Djibouti guarantees freedom of religious practice for all citizens, although it establishes Islam as the state religion. While Muslims have the legal right to convert or marry someone of another faith, societal pressure against conversion from Islam can be strong.

The remaining population, approximately 2-6% depending on the source, is primarily Christian. The Diocese of Djibouti estimated around 7,000 Catholics in 2006. There are also small communities of other Christian denominations. During the early colonial era (around 1900), the Christian population was very small, mainly consisting of individuals associated with Catholic missions.

7.5. Health

Djibouti faces significant public health challenges, common to many developing countries in arid regions.

- Life Expectancy: Life expectancy at birth is around 64.7 years (estimates vary slightly by source and year).

- Maternal and Child Health: Maternal mortality rates remain high, though efforts have been made to reduce them. The rate was 300 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2010. The under-5 mortality rate is also a concern, at 95 per 1,000 births according to some older data, with neonatal mortality accounting for a significant portion.

- Healthcare Access and Infrastructure: Access to healthcare services is limited, particularly in rural areas. There is a shortage of healthcare professionals, with about 18 doctors per 100,000 persons according to older data. The main hospital facilities are concentrated in Djibouti City.

- Prevalent Health Issues: Common health problems include infectious diseases such as respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, and malaria (though less prevalent than in more humid regions). Malnutrition is also a concern, especially among children.

- Female Genital Mutilation (FGM): FGM is a major public health issue, with an estimated 93.1% of Djiboutian women and girls having undergone the procedure. Although legally proscribed in 1994, it remains widely practiced due to deep-rooted cultural norms. FGM has severe health consequences, including infections, chronic pain, childbirth complications, and psychological trauma.

- Male Circumcision: Approximately 94% of Djibouti's male population has undergone circumcision, consistent with Islamic practice.

The government, with support from international organizations, is working to improve the health system, including infrastructure, human resources, and access to essential medicines and services.

7.6. Education

Education is a priority for the government of Djibouti, which allocated 20.5% of its annual budget to scholastic instruction as of 2009. The education system has undergone reforms to improve access and quality.

- Structure: The Djiboutian educational system was initially based on the French colonial model. Reforms in the late 1990s and early 2000s aimed to make it more suitable for local needs. The current system generally consists of five years of primary school, four years of middle school, and three or four years of high school. Education is compulsory for 9 years (primary and middle school). A Certificate of Fundamental Education is required for admission to secondary school.

- Literacy and Enrollment: The literacy rate was estimated at 70% as of 2012. School enrollment, attendance, and retention rates have shown improvement, though regional disparities exist. For example, between 2004-05 and 2007-08, net primary school enrollment for girls rose by 18.6% and for boys by 8.0%. Middle school net enrollment rose by 72.4% for girls and 52.2% for boys during the same period. Secondary level net enrollment increases were 49.8% for girls and 56.1% for boys. More recent data from 2016 indicated an overall school enrollment rate of about 80% for both genders.

- Challenges: Challenges include ensuring access to quality education for all, particularly in rural and nomadic communities, reducing dropout rates, improving teacher training, and aligning education with labor market needs to address high youth unemployment.

- Higher Education: The University of Djibouti, established in 2006, is the main institution of higher learning. Vocational training is also being emphasized to provide practical skills.

- Language of Instruction: French is the primary language of instruction.

The government has focused on developing institutional infrastructure, such as building new classrooms and supplying textbooks, and on training qualified instructors.

7.7. Largest Cities

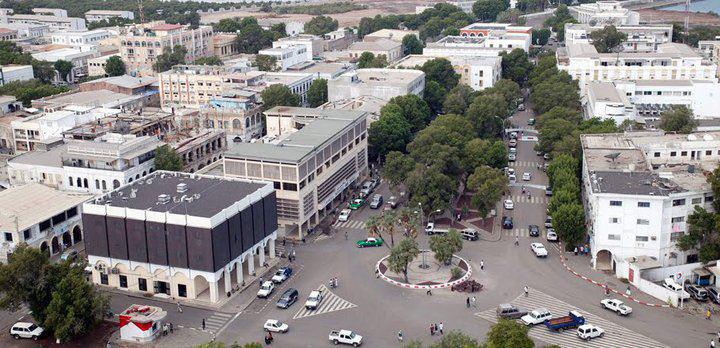

Djibouti City is by far the largest urban center, concentrating a significant majority of the country's population and economic activity. Other towns serve as regional administrative and commercial centers.

| Rank | City | Region | Population (Census Year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Djibouti City | Djibouti | 776,966 (2024) (475,322 in 2009) |

| 2 | Ali Sabieh | Ali Sabieh | 37,939 (2009) |

| 3 | Dikhil | Dikhil | 24,886 (2009) |

| 4 | Tadjoura | Tadjourah | 14,820 (2009) |

| 5 | Arta | Arta | 13,260 (2009) |

| 6 | Obock | Obock | 11,706 (2009) |

| 7 | Ali Adde | Ali Sabieh | 3,500 (2009) |

| 8 | Holhol | Ali Sabieh | 3,000 (2009) |

| 9 | Airolaf | Tadjourah | 1,023 (2009) |

| 10 | Randa | Tadjourah | 1,023 (2009) |

| Source: 2009 Census; Djibouti City also includes 2024 Census data. | |||

8. Culture

Djiboutian culture is a rich tapestry woven from the traditions of its main ethnic groups, the Somalis and the Afar, with influences from Arab, Ethiopian, and French cultures due to historical connections and its strategic location. Much of Djibouti's original art and history is preserved and transmitted orally, especially through song and poetry.

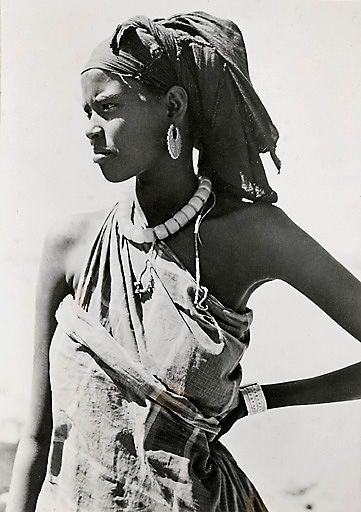

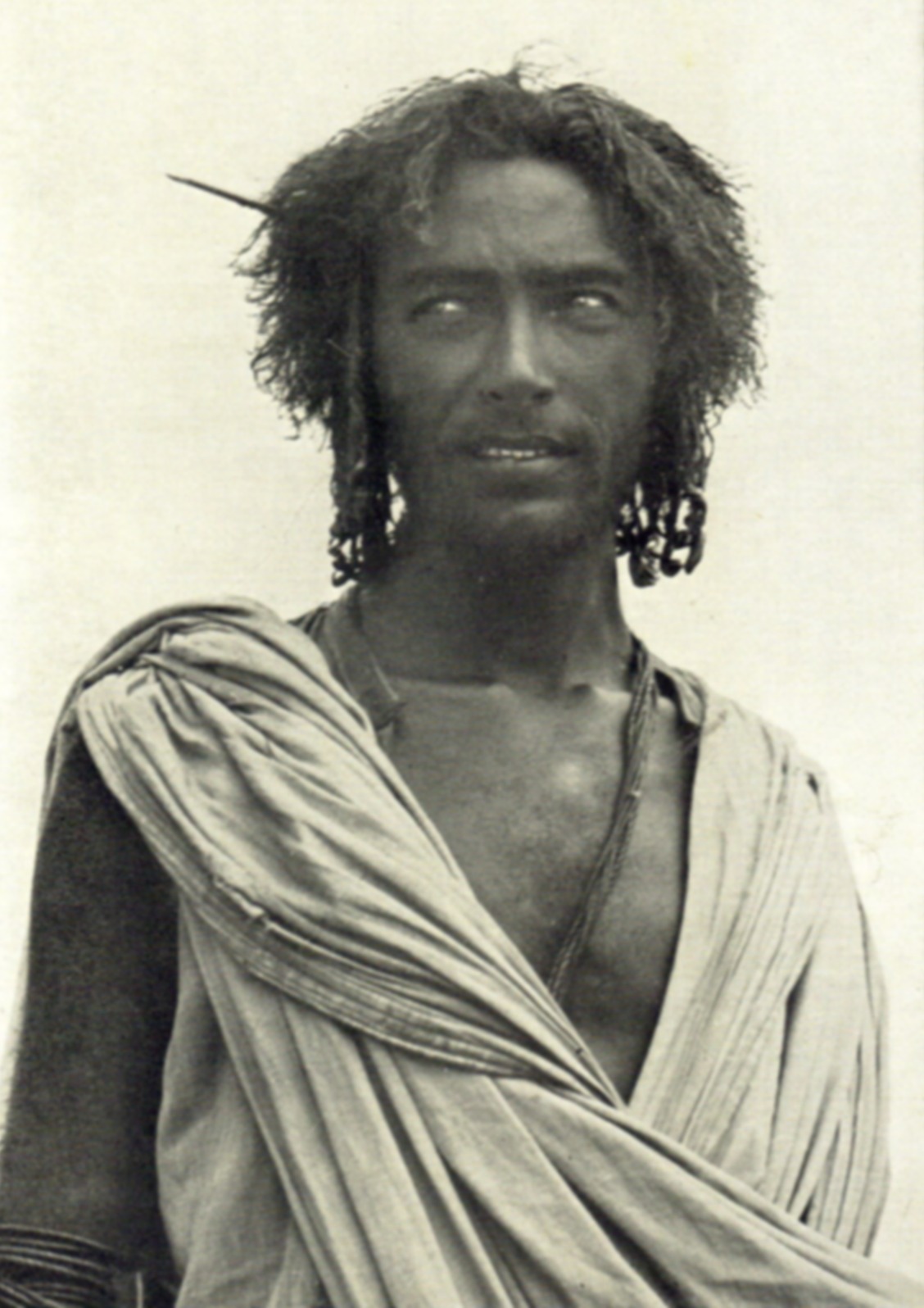

8.1. Attire, Music, and Literature

Attire: Traditional Djiboutian clothing reflects the hot and arid climate. Men, when not in Western attire, often wear the macawiismacawiisSomali, a sarong-like garment worn around the waist. Nomadic men may wear a loosely wrapped white cotton robe called a tobe, resembling a Roman toga. Women typically wear the dirac, a long, light, diaphanous voile dress made of cotton or polyester, worn over a full-length half-slip and a bra. Married women often wear head-scarves known as shash and cover their upper body with a shawl called garbasaar. Traditional Arabian attire like the male jellabiya and female jilbāb is also common. For festivals, women may adorn themselves with specialized jewelry and head-dresses similar to those of Berber tribes.

Music:

Somali music, a significant part of Djiboutian culture, has a rich heritage centered on traditional folklore. Most Somali songs are pentatonic. Somali songs are typically collaborations between lyricists (midhomidhoSomali), songwriters (laxanlaxanSomali), and singers (codkacodkaSomali, "voice"). Balwo is a popular Somali musical style in Djibouti, often centered on themes of love.

Traditional Afar music resembles the folk music of other Horn of Africa regions like Ethiopia and contains elements of Arabic music. Afar oral literature is quite musical, with songs for weddings, war, praise, and boasting. The oud is a common instrument.

Literature:

Djibouti has a long tradition of poetry. Somali verse forms are well-developed and include the gabaygabaySomali (epic poem, often exceeding 100 lines and considered a mark of poetic achievement), jiiftojiiftoSomali, geeraargeeraarSomali, wiglowigloSomali, buraanburburaanburSomali (often composed by women), beercadebeercadeSomali, afareyafareySomali, and guurawguurawSomali. Poems traditionally revolve around themes like elegy (baroorodiiqbaroorodiiqSomali), praise (amaanamaanSomali), romance (jacayljacaylSomali), diatribe (guhaadinguhaadinSomali), gloating (digashodigashoSomali), and guidance (guubaaboguubaaboSomali). Memorizers and reciters (hafidayaalhafidayaalSomali) traditionally propagated this art form.

The Afar people are familiar with the ginnili, a warrior-poet and diviner, and possess a rich oral tradition of folk stories and an extensive repertoire of battle songs.

Djibouti also has a tradition of Islamic literature. A notable historical work is the medieval Futuh Al-Habash by Shihāb al-Dīn, chronicling the Adal Sultanate's 16th-century conquest of Abyssinia. In recent years, Djiboutian politicians and intellectuals have also authored memoirs and reflections on the country. Abdourahman Waberi is a prominent contemporary Djiboutian novelist.

Local buildings often show Islamic, Ottoman, and French architectural influences, featuring plasterwork, motifs, and calligraphy.

8.2. Sport

Football is the most popular sport in Djibouti. The country's football federation became a member of FIFA in 1994. The national team has participated in qualifying rounds for the Africa Cup of Nations and the FIFA World Cup. In November 2007, the team achieved its first World Cup qualifying win by defeating the Somali national squad 1-0.

Other sports practiced include athletics (track and field), basketball, and volleyball. Djibouti has participated in the Olympic Games since 1984, primarily competing in athletics. Runner Hussein Ahmed Salah won Djibouti's only Olympic medal, a bronze in the marathon at the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Ayanleh Souleiman is a notable middle-distance runner.

The World Archery Federation has supported the Djibouti Archery Federation, with plans for an international archery training center in Arta to promote the sport in East Africa and the Red Sea area.

8.3. Cuisine

Djiboutian cuisine is a blend of Somali, Afar, Yemeni, and French cuisine, with additional influences from South Asian (especially Indian) and Middle Eastern culinary traditions. Dishes are often prepared with a variety of spices, ranging from saffron to cinnamon.

Common dishes include:

- Skudahkharis: A national dish, typically a hearty stew made with rice, lamb or goat, and a blend of spices.

- Fah-fah or Soupe Djiboutienne: A spicy boiled beef soup.

- Yetakelt wet: A spicy mixed vegetable stew, showing Ethiopian influence.

- Grilled Yemeni fish: Often opened in half and cooked in tandoor-style ovens, a local delicacy.

- Laxoox or Canjeero: A spongy, pancake-like bread similar to Ethiopian injera, often eaten with stews or curries.

- Sambusa (samosa): Fried pastries filled with spiced meat or vegetables, a popular snack.

- Dates and bananas are common fruits.

Xalwo (pronounced "halwo") is a popular sweet confection made from sugar, corn starch, cardamom powder, nutmeg powder, and ghee, often eaten during festive occasions like Eid celebrations or wedding receptions. Peanuts are sometimes added for texture and flavor.

After meals, homes are traditionally perfumed using incense (uunsiuunsiSomali) or frankincense (lubaanlubaanSomali), burned in an incense burner called a dabqaad. Coffee (bun) and tea (shaah) are popular beverages. French bread (baguettes) is also commonly consumed, a legacy of the colonial period.