1. Overview

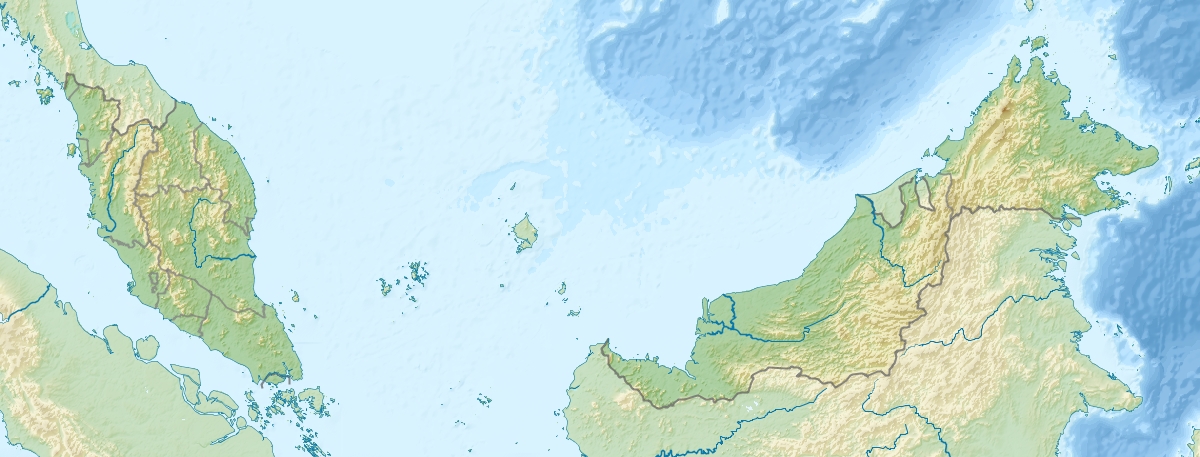

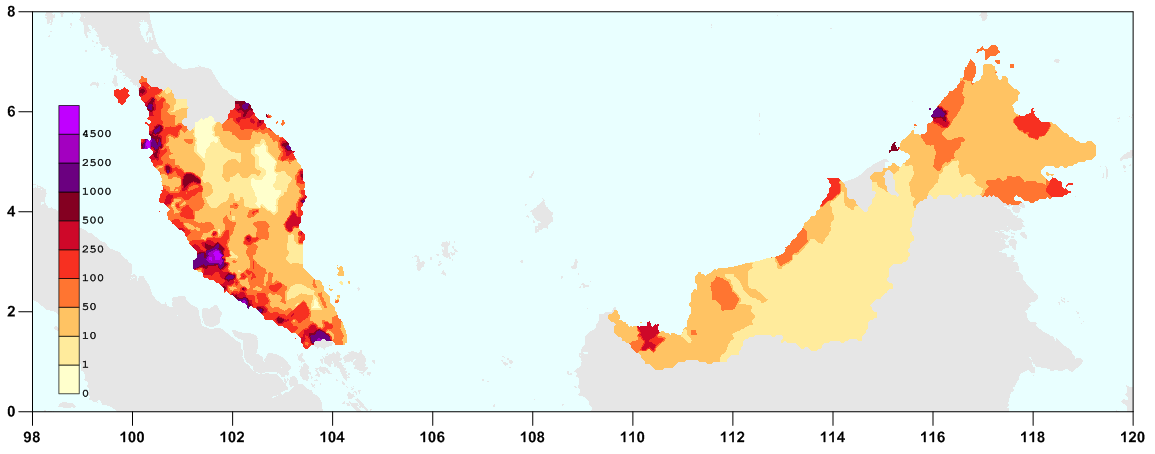

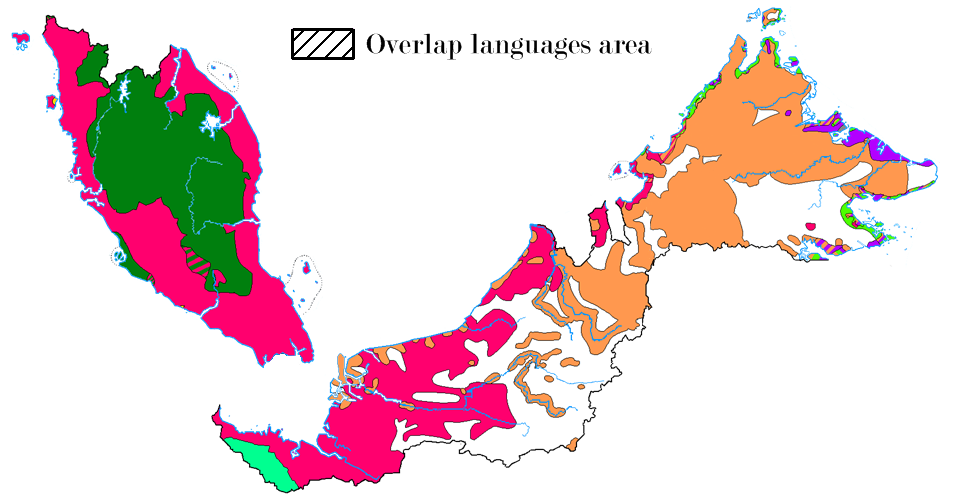

Malaysia is a federal constitutional monarchy located in Southeast Asia. It consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, geographically separated by the South China Sea into two main regions: Peninsular Malaysia (West Malaysia) and East Malaysia (Malaysian Borneo). Peninsular Malaysia shares a land border with Thailand to the north and maritime borders with Singapore to the south, Vietnam to the northeast, and Indonesia to the west. East Malaysia, on the island of Borneo, shares land borders with Brunei and Indonesia, and maritime borders with the Philippines and Vietnam. The country's capital is Kuala Lumpur, which is also its largest city and the seat of the legislative branch. The federal administrative capital is Putrajaya, home to the executive and judicial branches. With a population exceeding 34 million, Malaysia is a multicultural and multiethnic nation. The majority of the population is ethnically Malay, with significant minorities of Chinese and Indians, alongside diverse indigenous groups, particularly in East Malaysia. Islam is the official religion, but the constitution guarantees freedom of religion for non-Muslims. The official language is Malaysian Malay, with English widely used as a second language.

Historically, the region was home to various Malay kingdoms influenced by Indian and Chinese trade and culture. European colonial powers, primarily the British, began establishing control in the 18th century, leading to the formation of British Malaya. Following Japanese occupation during World War II, nationalist sentiments grew, culminating in the independence of the Federation of Malaya in 1957. In 1963, Malaya united with North Borneo (now Sabah), Sarawak, and Singapore to form Malaysia; Singapore later separated in 1965. Post-independence, Malaysia's politics have been significantly shaped by its ethnic composition, leading to policies like the New Economic Policy (NEP) aimed at addressing socio-economic disparities, particularly benefiting the Bumiputera (Malays and other indigenous peoples). While this policy contributed to the rise of a Malay middle class, its impact on social equity and inter-ethnic relations remains a subject of debate, with concerns about its discriminatory aspects and its effectiveness in genuinely uplifting the most vulnerable.

Malaysia's government is modeled on the Westminster parliamentary system. The economy, once reliant on primary commodities like tin and rubber, has diversified into manufacturing, services, and tourism. Significant economic growth occurred, especially under Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, though this period also saw concerns regarding democratic space and human rights. Recent political history includes the 1MDB scandal, which led to a historic change in government in 2018, followed by further political crises. Issues of human rights, including freedom of expression, the rights of minorities (ethnic, religious, LGBT), the death penalty, and the treatment of migrant workers and refugees, are ongoing concerns actively discussed by civil society and international observers, reflecting the challenges in balancing development with democratic principles and social justice. The country's rich biodiversity faces threats from deforestation and development, prompting conservation efforts aimed at sustainable practices. Malaysia's foreign policy emphasizes neutrality and regional cooperation, particularly within ASEAN, while navigating complex geopolitical issues, including territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

2. Etymology

The name "Malaysia" is a combination of the word "Malays" and the Latin-Greek suffix "-ia"/"-ία", which can be translated as 'land of the Malays'. The term "Melayu" (Malay) itself is thought to have originated from various sources. One theory suggests it comes from the Sanskrit word "Malayadvipa", meaning "land of mountains," a term used by ancient Indian traders to refer to the Malay Peninsula. Another theory proposes a Tamil origin, from "malai" (mountain) and "ur" (city or land). The 7th-century Chinese monk Yijing's account also mentions "Malayu" in reference to a kingdom in Sumatra, likely Srivijaya or a related entity.

The term "Malaysia" in a broader geographical sense, referring to the Malay Archipelago, was proposed in the 19th century. French navigator Jules Dumont d'Urville, in 1831, suggested "Malaisia" (along with "Micronesia" and "Melanesia") to the Société de Géographie in Paris to distinguish the island groups of the Pacific. He described "Malaisia" as "an area commonly known as the East Indies." In 1850, English ethnologist George Samuel Windsor Earl, writing in the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, proposed naming the islands of Southeast Asia as "Melayunesia" or "Indunesia", favoring the former. The name Malaysia gained some usage to label what is now the Malay Archipelago.

Before European colonization, the Malay Peninsula was known indigenously as Tanah Melayu ('Malay Land'). The German scholar Johann Friedrich Blumenbach used the term "Malay race" in his racial classification system for the indigenous peoples of maritime Southeast Asia. The name "Federation of Malaya" was chosen for the entity that gained independence in 1957, in preference to other potential names like "Langkasuka" (an ancient kingdom in the northern Malay Peninsula) or "Malaysia" itself. The name "Malaysia" was officially adopted in 1963 when the Federation of Malaya united with Singapore, North Borneo (present-day Sabah), and Sarawak to form the new federation. One theory suggests the "si" in Malaysia was chosen to represent the inclusion of Singapore, North Borneo (Sabah), and Sarawak. Interestingly, politicians in the Philippines had also contemplated renaming their state "Malaysia" before the modern country adopted the name.

In Malay, the official name of the country as it appears on some official documents, including the oath of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, is Persekutuan MalaysiaFederation of MalaysiaMalay. However, "Malaysia" is predominantly used officially, including in the Malaysia Agreement 1963 and the Federal Constitution.

3. History

The history of Malaysia is a complex tapestry woven from indigenous cultures, migrations, trade, colonial influences, and the formation of a modern nation-state. It encompasses ancient kingdoms, the rise of powerful sultanates, centuries of European colonial domination, the struggle for independence, and the challenges and achievements of a multi-ethnic, post-colonial nation. The narrative includes significant impacts on indigenous populations, the development of social structures, and evolving ethnic relations.

3.1. Prehistory and Early Kingdoms

Evidence of modern human habitation in Malaysia dates back approximately 40,000 years. The earliest inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula are believed to be the Negrito peoples. Archaeological findings, such as stone tools in Kota Tampan, Perak, and human skulls in Niah Caves, Sarawak, attest to early human presence. These early communities were likely hunter-gatherers. Around 2000 BC to 1000 AD, areas of Malaysia participated in the Maritime Jade Road, a prehistoric trade network.

By the first century AD, traders and settlers from India and China began arriving, establishing trading ports and coastal towns. This interaction led to significant Indian and Chinese cultural influences on the local populations, who adopted Hinduism and Buddhism. Sanskrit inscriptions dating as early as the fourth or fifth century have been found. Several early kingdoms emerged, including the kingdom of Langkasuka in the northern Malay Peninsula around the second century AD, which lasted until about the 15th century. Other notable early riverine and coastal states included Kedaram (ancient Kedah), Beruas, and Gangga Negara in Perak, and Pan Pan in Kelantan. These early states were often part of larger regional networks and empires. Between the 7th and 13th centuries, much of the southern Malay Peninsula was under the influence or direct control of the maritime Srivijayan empire, based in Sumatra. Following Srivijaya's decline, the Majapahit empire, based in Java, extended its influence over most of the peninsula and the Malay Archipelago. The arrival and establishment of these early kingdoms and their interactions with larger empires undoubtedly impacted the indigenous populations, often leading to displacement, assimilation, or changes in their traditional ways of life.

3.2. Malacca Sultanate

In the early 15th century, Parameswara, a prince believed to be from Palembang and linked to the old Srivijayan court, founded the Malacca Sultanate. Fleeing from Majapahit attacks, he initially sought refuge in Temasek (present-day Singapore) before establishing a new settlement at the mouth of the Bertam River, which grew into the city of Malacca. According to the Malay Annals (Sejarah Melayu), Parameswara was inspired to found the city after witnessing a mousedeer outwit a hunting dog under a Melaka tree, taking it as a good omen.

The Malacca Sultanate rapidly rose to prominence as a major international trading emporium. Its strategic location along the Strait of Malacca, a key maritime route between India and China, attracted traders from across Asia, including Arabs, Persians, Indians, Chinese, and Southeast Asians. Malacca became a vital hub for the spice trade and other valuable commodities.

The reign of Parameswara and his successors saw the consolidation of power and the expansion of Malacca's influence. A significant development during this period was the conversion of Parameswara (who later took the title Iskandar Shah) to Islam, likely influenced by his marriage to a princess from Pasai or through interactions with Muslim traders. The adoption of Islam by the Malaccan court led to its spread throughout the Malay Peninsula and the wider Malay Archipelago, with Malacca becoming a key center for Islamic learning and dissemination in the region. The Sultanate developed a sophisticated administrative system and a code of laws, such as the Hukum Kanun Melaka (Laws of Malacca) and the Undang-Undang Laut Melaka (Maritime Laws of Malacca).

Key rulers following Parameswara, such as Sultan Muzaffar Shah, Sultan Mansur Shah, and Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah, further expanded Malacca's territory and influence, which at its peak extended over much of the Malay Peninsula and parts of Sumatra. The prosperity and cosmopolitan nature of Malacca during this era are well-documented in historical accounts. However, its dominance came to an end in 1511 when it was conquered by a Portuguese fleet led by Afonso de Albuquerque.

3.3. European Colonial Rule

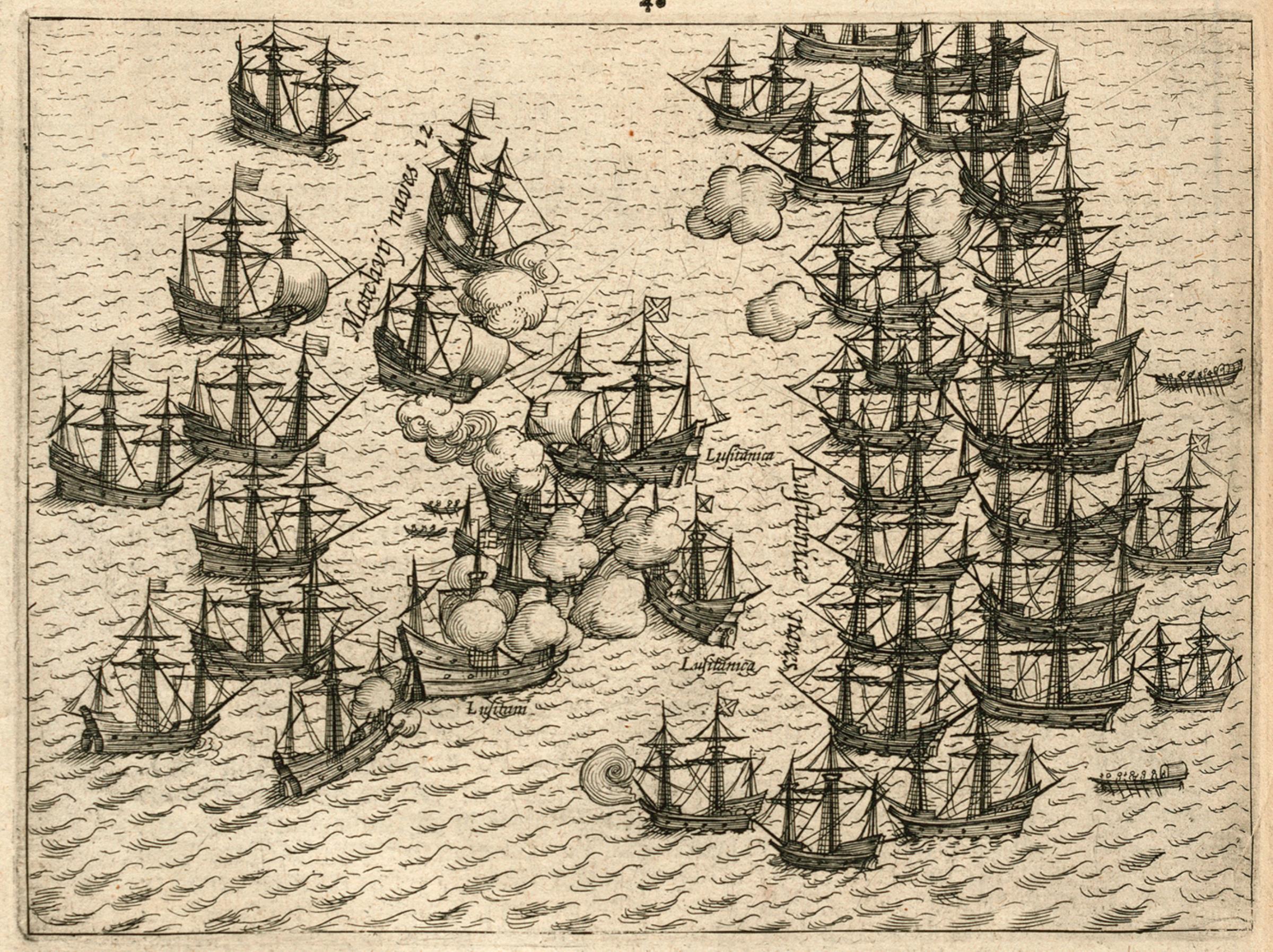

European colonial intervention in the Malay region began with the Portuguese conquest of the Malacca Sultanate in 1511. Malacca became a strategic Portuguese outpost for controlling the spice trade. However, Portuguese influence was largely confined to Malacca itself, facing challenges from other regional powers like the Johor Sultanate (successor to Malacca) and Aceh. The Portuguese presence lasted for over a century until 1641 when Malacca was captured by the Dutch, who were allied with Johor. Dutch Malacca then became part of the Dutch colonial network, though its prominence as a trade center declined relative to other Dutch-controlled ports like Batavia (Jakarta).

British involvement in the Malay Peninsula began in the late 18th century. In 1786, the British East India Company acquired Penang Island from the Sultan of Kedah, establishing George Town as a trading post. In 1819, Stamford Raffles founded Singapore for the British, which rapidly grew into a major port. Following the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, which demarcated British and Dutch spheres of influence in the archipelago, Malacca was transferred to British control in exchange for Bencoolen (Bengkulu) in Sumatra. In 1826, Penang, Malacca, and Singapore were consolidated into the Straits Settlements, a Crown Colony directly administered by Britain. Labuan Island was added to the Straits Settlements later.

Throughout the 19th century, British influence extended into the Malay states of the peninsula. Internal conflicts within these states and the lucrative tin mining industry attracted British intervention. Through a series of treaties, beginning with the Pangkor Treaty of 1874 with Perak, the British installed Residents or Advisors in several states. Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, and Pahang became the Federated Malay States (FMS) in 1895, with a centralized British administration under a Resident-General in Kuala Lumpur. While the Malay Sultans retained their sovereign titles, actual power increasingly rested with the British officials. The remaining five states - Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu - became known as the Unfederated Malay States (UMS). They maintained greater autonomy but also accepted British advisors and came under British protection, largely through treaties in the early 20th century, such as the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 which transferred suzerainty over the northern states from Siam to Britain.

In Borneo, James Brooke, an English adventurer, was granted territory in Sarawak by the Sultan of Brunei in 1841 and established the Brooke dynasty of "White Rajahs", ruling Sarawak as a private kingdom until it became a British Crown Colony in 1946. North Borneo (present-day Sabah) came under the control of the British North Borneo Company in the late 19th century after cessions from the Sultans of Brunei and Sulu, and became a British protectorate, later a Crown Colony.

Colonial rule brought significant social and economic changes. The British developed infrastructure like railways and ports to support the extraction of resources, primarily tin and rubber. Large-scale immigration of Chinese and Indian laborers was encouraged to work in the mines and plantations. This led to the formation of a multi-ethnic society but also laid the groundwork for future ethnic tensions. The economic policies were primarily geared towards benefiting the colonial power, and indigenous populations often found themselves marginalized or their traditional livelihoods disrupted. While some elites benefited from collaboration, the broader social and economic impact on the local populace was complex, often involving exploitation and the imposition of foreign systems of governance and law, which had profound and lasting effects on Malaysian society.

3.4. World War II and Japanese Occupation

During World War II, the Malay Peninsula and British Borneo became a key theater of conflict in Southeast Asia. On December 8, 1941, shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Imperial Japanese Army launched its invasion of Malaya, landing at Kota Bharu. British, Australian, and Indian forces stationed in Malaya were ill-prepared and quickly overwhelmed by the Japanese advance down the peninsula. Singapore, considered a British fortress, fell to the Japanese on February 15, 1942. North Borneo and Sarawak were also occupied by Japanese forces.

The Japanese occupation lasted for over three years, until Japan's surrender in August 1945. This period was marked by significant hardship for the local population. The Japanese administration was often brutal, particularly towards the Chinese community, who were targeted due to the ongoing Second Sino-Japanese War. Shortages of food and essential goods were common, leading to widespread suffering. The occupation also disrupted the colonial economy, which was reoriented to serve Japan's war effort.

The Japanese occupation had a profound impact on ethnic relations and the growth of nationalism in Malaya. The Japanese policy of favoring Malays and Indians over the Chinese in some administrative roles exacerbated existing ethnic tensions. However, the defeat of the British, a major European colonial power, by an Asian power shattered the myth of European invincibility and fueled aspirations for independence among various local groups. Resistance movements emerged, including the predominantly Chinese Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), which was aligned with the Malayan Communist Party (MCP). The experience of the occupation and the subsequent struggle for liberation played a crucial role in shaping the post-war political landscape and the push towards self-governance and independence. The shared suffering under occupation also, in some instances, fostered a sense of common Malayan identity, although ethnic divisions remained significant.

3.5. Path to Independence

Following the end of World War II and the Japanese surrender in 1945, British colonial rule was restored in Malaya. However, the war had significantly weakened British prestige and fueled nationalist sentiments across the region. The British initially proposed the Malayan Union in 1946, a plan to unify all the Malay states on the peninsula (excluding Singapore) into a single Crown Colony with equal citizenship rights for all races. This proposal met with strong opposition from the Malay community, led by figures like Onn Jaafar and the newly formed United Malays National Organisation (UMNO). They feared the erosion of the Malay Rulers' sovereignty and the potential loss of Malay special rights. The widespread protests forced the British to abandon the Malayan Union.

In its place, the Federation of Malaya was established on February 1, 1948. This new arrangement restored the positions of the Malay Rulers and provided more safeguards for Malay special status, while still maintaining British oversight. Singapore remained a separate Crown Colony.

The post-war period was also marked by the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960), an armed insurgency launched by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), whose members were predominantly Chinese. The MCP sought to establish a communist state in Malaya. The British, with Commonwealth forces (including troops from Australia and New Zealand), responded with a protracted counter-insurgency campaign. This conflict involved guerrilla warfare, resettlement of rural populations (primarily Chinese squatters into "New Villages" to deny support to the communists), and significant military and intelligence operations. The Emergency further complicated ethnic relations but also spurred the British to accelerate the move towards self-government as a means to counter communist appeal.

The independence movement gained momentum throughout the 1950s. Key political parties emerged, representing different ethnic communities, notably UMNO (Malays), the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), and the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC). These three parties formed the Alliance Party, a multi-ethnic coalition led by Tunku Abdul Rahman of UMNO. The Alliance advocated for a negotiated path to independence. In 1955, the Federation held its first federal elections, which the Alliance Party won decisively. This victory paved the way for negotiations with the British government.

On August 31, 1957, the Federation of Malaya achieved independence (Merdeka) within the Commonwealth of Nations. Tunku Abdul Rahman became the first Prime Minister. The independence was achieved peacefully through constitutional means, but the legacy of colonial ethnic stratification and the recent Emergency left significant challenges for the newly independent nation, particularly concerning national unity and socio-economic disparities. The rights of minorities and the definition of national identity were central issues in the newly independent federation.

3.6. Formation of Malaysia and Early Challenges

Following the independence of the Federation of Malaya in 1957, discussions began about a larger federation that would include Malaya, Singapore, and the British Borneo territories of North Borneo (later Sabah), Sarawak, and Brunei. The proposal, championed by Malayan Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, aimed to create a more politically and economically stable entity, and also to counterbalance the ethnic Chinese majority in Singapore by incorporating the indigenous populations of Borneo.

After negotiations and a UN-ascertainment mission (the Cobbold Commission) to gauge public opinion in Borneo, the Federation of Malaysia was officially formed on September 16, 1963. It comprised the Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Sabah, and Sarawak. Brunei, which had initially shown interest, opted out due to disagreements over the Sultan's status and oil revenues.

The formation of Malaysia was met with immediate external challenges. Indonesia, under President Sukarno, launched a policy of "Konfrontasi" (Confrontation), viewing Malaysia as a neo-colonial creation of the British and a threat to Indonesian interests. This involved military incursions into Borneo, commando raids on Peninsular Malaysia, and diplomatic hostility. The Confrontation lasted until 1966 when relations were normalized after a change in Indonesian leadership. The Philippines also had a territorial claim over North Borneo (Sabah), which added to regional tensions.

Internally, the new federation faced significant challenges, particularly concerning ethnic relations and the integration of Singapore. Singapore, with its predominantly Chinese population and dynamic leader Lee Kuan Yew, had different political and economic priorities from the federal government in Kuala Lumpur, which was dominated by Malay political interests. Tensions arose over issues of economic policy, language, education, and the political influence of Singapore within the federation. Lee Kuan Yew's People's Action Party (PAP) advocated for a "Malaysian Malaysia," emphasizing equal rights for all races, which was seen as a challenge to the Malay-centric policies of the federal government.

These tensions culminated in Singapore's separation from Malaysia on August 9, 1965. The separation was mutually agreed upon by both governments as a way to resolve irreconcilable differences, though it was a painful and emotional event for leaders on both sides.

Within Malaysia, ethnic tensions persisted. The most significant early internal crisis was the 13 May 1969 race riots in Kuala Lumpur. These riots, primarily between Malays and Chinese, erupted after the general election of that year, which saw opposition parties (largely supported by non-Malays) make significant gains. The riots resulted in numerous deaths and extensive property damage, leading to the declaration of a state of emergency and the suspension of Parliament. This event had a profound impact on Malaysian politics and society, highlighting the fragility of inter-ethnic harmony and leading to major policy shifts aimed at addressing ethnic imbalances. The incident underscored the challenges of nation-building in a multi-ethnic society and the deep-seated socio-economic disparities that fueled communal unrest.

3.7. Modern Malaysia

Following the 13 May 1969 race riots, Malaysian politics and society underwent significant transformations. The government, under Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak, implemented the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1971. The NEP had two main objectives: to eradicate poverty irrespective of race and to restructure society to eliminate the identification of race with economic function. In practice, this led to extensive affirmative action programs favoring the Bumiputera (Malays and other indigenous peoples) in areas such as education, employment, business ownership, and public sector jobs. The NEP aimed to increase Bumiputera participation in the modern economy and reduce socio-economic disparities. While it contributed to the growth of a Malay middle class and reduced absolute poverty, the NEP also faced criticism for creating new forms of inequality, fostering a culture of dependency, and being implemented in ways that sometimes led to cronyism and inefficiency. Its impact on inter-ethnic relations was complex, sometimes viewed as divisive by non-Bumiputera communities who felt their opportunities were curtailed. The NEP officially ended in 1990 but was succeeded by similar policies like the National Development Policy (NDP) and later, the National Vision Policy (NVP), which continued to prioritize Bumiputera advancement.

Under the long premiership of Mahathir Mohamad (1981-2003), Malaysia experienced rapid economic growth and industrialization. His administration pursued ambitious development projects, including the Petronas Towers, the North-South Expressway, the Multimedia Super Corridor, and the new federal administrative capital of Putrajaya. This era, often associated with the "Look East Policy" (emulating Japan and South Korea), saw Malaysia transition from a commodity-based economy to one more reliant on manufacturing and exports, particularly electronics. However, Mahathir's tenure was also marked by a concentration of power in the executive, a weakening of judicial independence, and crackdowns on dissent, which raised concerns about democratic development and human rights. The Internal Security Act (ISA), allowing for detention without trial, was used against political opponents and activists.

The Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 severely impacted Malaysia. Mahathir controversially rejected IMF bailout packages and imposed capital controls, which were credited by some with helping Malaysia recover more quickly, though criticized by others. The post-Mahathir era saw Abdullah Ahmad Badawi (2003-2009) and then Najib Razak (2009-2018) as Prime Ministers. Najib's premiership was overshadowed by the 1MDB scandal, a massive financial fraud involving billions of dollars allegedly siphoned from a state investment fund, with funds traced to Najib's personal accounts. The scandal triggered widespread public anger and international investigations.

The 2018 general election resulted in a historic defeat for the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition, which had ruled Malaysia since independence. The Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition, led by a returning Mahathir Mohamad (who had allied with his former rival Anwar Ibrahim), came to power on a platform of reform and anti-corruption. However, this government was short-lived, collapsing in early 2020 due to internal defections, leading to a period of political instability known as the 2020-22 Malaysian political crisis. This crisis saw several changes in government, with Muhyiddin Yassin and then Ismail Sabri Yaakob becoming Prime Ministers. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated economic and social challenges during this period.

The 2022 general election resulted in a hung parliament, with no single coalition securing a majority. Anwar Ibrahim eventually became Prime Minister, leading a unity government. Modern Malaysia continues to grapple with issues of democratic consolidation, ethnic and religious relations, economic equity, corruption, and the balance between development and environmental sustainability. Civil society remains active in advocating for human rights, good governance, and social justice, reflecting an ongoing evolution in the nation's political and social landscape.

4. Geography

Malaysia is located in Southeast Asia. The country consists of two main geographical regions: Peninsular Malaysia (or West Malaysia) and East Malaysia (or Malaysian Borneo). These two regions are separated by approximately 398 mile (640 km) of the South China Sea. Peninsular Malaysia occupies the southern part of the Malay Peninsula and shares a land border with Thailand to the north. To its south, it is connected to Singapore by a causeway and a bridge. Its western coast faces the Strait of Malacca, and its eastern coast faces the South China Sea. East Malaysia is situated on the northern part of the island of Borneo. It shares land borders with Indonesia (Kalimantan) to the south and Brunei to the north (Brunei is almost entirely enclaved within the Malaysian state of Sarawak). East Malaysia also has maritime borders with the Philippines and Vietnam. Tanjung Piai in the state of Johor is the southernmost point of continental Eurasia.

4.1. Topography

The topography of Malaysia is varied, featuring coastal plains, hills, and high mountain ranges.

Peninsular Malaysia is characterized by a central mountain range, the Titiwangsa Mountains (Banjaran Titiwangsa), which runs from north to south and effectively divides the peninsula into its eastern and western coastal regions. The highest peak in this range is Mount Korbu at 7.2 K ft (2.18 K m). Flanking these highlands are fertile coastal plains, which are wider on the western side of the peninsula where most of the population and agricultural activity are concentrated. Major rivers in Peninsular Malaysia include the Pahang River (the longest), the Perak River, and the Kelantan River. The coastline is extensive, with numerous islands, such as Penang, Langkawi, and the Perhentian Islands.

East Malaysia (Malaysian Borneo) is generally more rugged and mountainous than the peninsula. It is dominated by several mountain ranges, including the Crocker Range in Sabah, which is home to Mount Kinabalu, the highest peak in Malaysia and Southeast Asia, at 13 K ft (4.10 K m). Other significant ranges include the Trusmadi Range and the Witti Range in Sabah, and the Iran Mountains and Hose Mountains in Sarawak. East Malaysia also features extensive lowlands and river systems. The longest river in Malaysia, the Rajang River, is located in Sarawak, along with other major rivers like the Baram River and the Lupar River. Sabah's main rivers include the Kinabatangan River and the Padas River. The coastlines of Sabah and Sarawak are dotted with numerous islands, including Labuan, Sipadan, and the Tunku Abdul Rahman Park islands. Extensive cave systems, such as those in Gunung Mulu National Park (a UNESCO World Heritage site), are also a notable feature of Sarawak's topography.

4.2. Climate

Malaysia has an equatorial climate, characterized by high temperatures, high humidity, and abundant rainfall throughout the year. Its location near the equator means that there is little variation in daylight hours or temperature from month to month.

The average annual temperature in the lowlands is typically between 71.6 °F (22 °C) and 89.6 °F (32 °C), although temperatures can be significantly cooler in highland areas like the Cameron Highlands and Genting Highlands. Humidity is consistently high, usually ranging from 70% to 90%.

Rainfall is plentiful across the country, with annual averages often exceeding 0.1 K in (2.50 K mm). However, rainfall patterns are significantly influenced by the monsoon system. There are two main monsoon seasons:

1. The Southwest Monsoon, which typically occurs from late May to September. This monsoon brings moist air from the Indian Ocean, resulting in heavier rainfall on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia and in Sabah.

2. The Northeast Monsoon, which usually lasts from November to March. This monsoon brings heavy rainfall, particularly to the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia and to Sarawak and Sabah. The east coast states of Kelantan, Terengganu, and Pahang, as well as parts of Borneo, often experience severe flooding during this period.

There are also inter-monsoon periods, usually in April and October, which can bring convective thunderstorms, often in the afternoons. While Malaysia does not experience typhoons directly, the tail-end effects of typhoons in the South China Sea or the Philippines can sometimes bring strong winds and heavy rain to northern Borneo. The consistent warmth and moisture support Malaysia's lush tropical rainforests and rich biodiversity.

4.3. Biodiversity and Conservation

Malaysia is recognized as one of the world's 17 megadiverse countries, possessing an exceptionally high level of biodiversity and a significant number of endemic species. Its tropical rainforests, believed to be among the oldest on Earth (some dating back 130 million years), are home to a vast array of flora and fauna. About two-thirds of Malaysia was covered in forest as of 2007.

The country is estimated to contain 20% of the world's animal species. There are about 210 mammal species, including iconic animals like the Malayan tiger (a critically endangered subspecies), Asian elephant, orangutan (found in Borneo), Malayan tapir, and various species of monkeys and gibbons. Over 620 bird species have been recorded in Peninsular Malaysia alone, with many more in East Malaysia, including numerous endemic species in the Bornean mountains. Malaysia also hosts around 250 reptile species (including about 150 snake species and 80 lizard species) and about 150 frog species. The insect diversity is immense, with thousands of species.

Malaysia's marine biodiversity is also remarkable. Its waters, particularly around islands like Sipadan (often cited as one of the world's top diving spots), are part of the Coral Triangle, a global hotspot for marine biodiversity, with around 600 coral species and 1,200 fish species. The Exclusive economic zone of Malaysia covers an area 1.5 times larger than its land area. Mangrove forests, covering over 0.6 K mile2 (1.43 K km2), and peat swamp forests are also important ecosystems.

The plant life is equally rich, with an estimated 8,500 species of vascular plants in Peninsular Malaysia and another 15,000 in East Malaysia. The forests are dominated by dipterocarps. East Malaysian forests are particularly diverse, with some areas having up to 240 different tree species per hectare. Malaysia is also home to the Rafflesia, which produces the world's largest flower, some species reaching up to 3.3 ft (1 m) in diameter. Nearly 4,000 species of fungi have been recorded.

However, this rich biodiversity faces significant threats. Deforestation due to logging, agricultural expansion (especially for palm oil plantations), and infrastructure development is a major concern, leading to habitat loss and fragmentation. Over 80% of Sarawak's rainforest has been impacted by logging, and over 60% of the peninsula's forests have been cleared. This has endangered many species and worsened environmental problems like soil erosion and flooding. Wildlife trafficking and illegal fishing (including destructive methods like dynamite fishing) also pose serious threats to both terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Pollution from industrial and agricultural sources further degrades habitats.

Conservation efforts are underway, but their effectiveness is often debated in the context of economic development priorities. The Malaysian government signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity in 1993 and has established numerous national parks and protected areas, such as Taman Negara, Gunung Mulu National Park, and Kinabalu National Park (both UNESCO World Heritage Sites). There are 28 national parks, with 23 in East Malaysia and five in the peninsula. Efforts to promote sustainable development and ecotourism are being pursued, and the federal government has aimed to reduce logging rates. Addressing the conflict between economic growth and environmental protection remains a critical challenge, with civil society groups and environmental organizations advocating for stronger enforcement of environmental laws and more sustainable land-use policies to protect Malaysia's invaluable natural heritage.

5. Government and Politics

Malaysia operates as a federal constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. The political system is closely modeled on the Westminster system, a legacy of British colonial rule. The country's governance structure involves a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, though in practice, the executive has historically held significant influence. Politics in Malaysia are characterized by a multi-ethnic society where ethnic considerations often play a significant role in party alignments and policy-making.

5.1. Government Structure

Malaysia is a federation comprising 13 states and three federal territories. The Constitution of Malaysia is the supreme law of the land and outlines the structure of the government. It establishes a parliamentary system with a bicameral Parliament at the federal level. The principle of separation of powers divides governmental authority into three branches:

1. **Legislative Branch (Perundangan):** This branch is responsible for making laws. At the federal level, it consists of the Parliament of Malaysia, which comprises the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (King), the Dewan Negara (Senate or Upper House), and the Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives or Lower House).

2. **Executive Branch (Eksekutif):** This branch is responsible for implementing and enforcing laws. It is led by the Prime Minister and the Cabinet. The Prime Minister is appointed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong from among the members of the Dewan Rakyat who, in the King's judgment, is likely to command the confidence of the majority of the members of that House.

3. **Judicial Branch (Kehakiman):** This branch is responsible for interpreting laws and administering justice. It is headed by the Federal Court, the highest court in the country. The judiciary is theoretically independent, though its autonomy has faced challenges at times.

Each of the 13 states also has its own constitution and government structure, typically consisting of a State Legislative Assembly (Dewan Undangan Negeri) and a state executive council led by a Chief Minister (Menteri Besar in states with hereditary rulers, or Ketua Menteri in other states).

5.2. Head of State

The head of state of Malaysia is the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, often referred to as the King. Malaysia has a unique system of elective monarchy where the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is elected for a five-year term. The election is conducted by the Conference of Rulers (Majlis Raja-Raja), which comprises the nine hereditary rulers (Sultans or equivalent titles) of the Malay states (Perlis, Kedah, Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Johor, Pahang, Terengganu, and Kelantan). The governors (Yang di-Pertua Negeri) of the other four states (Penang, Malacca, Sabah, and Sarawak) are members of the Conference of Rulers but do not participate in the election of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong.

By informal agreement, the position of Yang di-Pertuan Agong is rotated among the nine hereditary rulers, generally based on seniority of their reign. The current Yang di-Pertuan Agong is Ibrahim Iskandar of Johor, who ascended to the federal throne on January 31, 2024.

The Yang di-Pertuan Agong's role is largely ceremonial and symbolic, similar to that of a constitutional monarch in other parliamentary democracies. Constitutional powers include:

- Appointing the Prime Minister, based on who commands the confidence of the majority in the Dewan Rakyat.

- Appointing Cabinet ministers and deputy ministers on the advice of the Prime Minister.

- Giving royal assent to bills passed by Parliament before they become law (though this power is limited).

- Dissolving Parliament on the advice of the Prime Minister, leading to general elections.

- Acting as the Supreme Commander of the Malaysian Armed Forces.

- Serving as the head of Islam in his own state, Penang, Malacca, Sabah, Sarawak, and the Federal Territories.

- The power to grant pardons, reprieves, and respites for offences tried in federal courts and in the Federal Territories.

While the King acts on the advice of the Prime Minister and the Cabinet in most matters, there are certain discretionary powers, such as the appointment of the Prime Minister and the withholding of consent to dissolve Parliament. Constitutional amendments in 1993 and 1994 somewhat curtailed some of the monarch's powers and immunities, aiming to balance the monarch's traditional role with modern democratic governance.

5.3. Executive Branch

The executive branch of the Malaysian government is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the country and the implementation of laws passed by the legislature. Executive power is vested in the Cabinet, which is led by the Prime Minister.

The **Prime Minister** is the head of government. According to the constitution, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong appoints as Prime Minister a member of the Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) who, in the King's judgment, is likely to command the confidence of the majority of the members of that House. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the political party or coalition that holds the majority of seats in the Dewan Rakyat. The current Prime Minister is Anwar Ibrahim.

The **Cabinet** is appointed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong on the advice of the Prime Minister. Cabinet ministers are chosen from among the members of both houses of Parliament (Dewan Rakyat and Dewan Negara). The Cabinet is collectively responsible to Parliament. It formulates government policies and directs the activities of the various government ministries and agencies.

Major government ministries cover a wide range of portfolios, including finance, home affairs, defense, education, health, foreign affairs, trade and industry, and others. Each ministry is headed by a minister, often assisted by one or more deputy ministers. The civil service, known as the Public Service of Malaysia, is responsible for carrying out the administrative functions of the government. Putrajaya serves as the federal administrative capital, where most government ministries and agencies are located.

The executive branch has historically been powerful in Malaysia. The Prime Minister, as the leader of the majority party or coalition, exercises significant influence over government policy and legislative agenda. Challenges to executive dominance and calls for greater accountability and transparency have been features of Malaysia's political discourse, particularly concerning issues of good governance and human rights.

5.4. Legislative Branch

The legislative branch of the Malaysian federal government is the Parliament of Malaysia. It is a bicameral body, meaning it consists of two houses:

1. **Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives):** This is the lower house and is the primary legislative chamber. It currently has 222 members, known as Members of Parliament (MPs), who are directly elected by the people through general elections. Elections are held at least once every five years, based on a first-past-the-post system in single-member constituencies. The Dewan Rakyat is where most government bills are introduced and debated. To become law, a bill must usually be passed by the Dewan Rakyat and then the Dewan Negara, before receiving Royal Assent from the Yang di-Pertuan Agong. The party or coalition with the majority of seats in the Dewan Rakyat forms the federal government, and its leader becomes the Prime Minister.

2. **Dewan Negara (Senate):** This is the upper house. It currently has 70 members, known as Senators. Senators serve three-year terms, and their terms can be renewed once. The composition of the Dewan Negara is as follows:

- 26 Senators are elected by the 13 State Legislative Assemblies, with each state electing two Senators.

- 44 Senators are appointed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong on the advice of the Prime Minister. These appointed Senators are intended to represent various professional fields, minority groups, or individuals who have distinguished service or achieved distinction in public life.

The Dewan Negara acts as a house of review. It can debate bills passed by the Dewan Rakyat and propose amendments. However, its power to block legislation is limited; it can only delay bills for a certain period. If the Dewan Negara rejects a bill or fails to pass it within a specified time, the Dewan Rakyat can bypass the Dewan Negara and present the bill directly to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong for Royal Assent (except for constitutional amendments, which require specific majorities in both houses).

The **legislative process** typically begins with a bill being introduced in the Dewan Rakyat (though some bills can originate in the Dewan Negara, except for money bills which must start in the Dewan Rakyat). The bill goes through several readings and committee stages in both houses. If passed by both houses (or by the Dewan Rakyat under certain circumstances if the Dewan Negara objects), it is presented to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong for Royal Assent. Once Royal Assent is given, the bill becomes an Act of Parliament and is gazetted as law.

Parliament's functions include:

- Making and amending federal laws.

- Approving the federal budget and new taxes.

- Scrutinizing the actions of the government through debates, question time, and parliamentary committees.

- Serving as a forum for public discussion and debate on national issues.

The effectiveness of Parliament as a check on executive power has been a subject of discussion, with concerns sometimes raised about executive dominance, particularly when the ruling coalition holds a large majority. Efforts to strengthen parliamentary oversight and empower parliamentary committees are ongoing aspects of Malaysia's democratic development.

5.5. Judicial Branch

The judicial branch in Malaysia is responsible for the administration of justice and the interpretation of laws. The Malaysian legal system is primarily based on English common law, a legacy of British colonial rule, but it also incorporates local customs and Islamic law for Muslims in personal matters.

The hierarchy of courts in Malaysia is as follows:

1. **Federal Court of Malaysia (Mahkamah Persekutuan):** This is the highest court in Malaysia and the final court of appeal. It hears appeals from the Court of Appeal, and also has original jurisdiction in certain constitutional matters and disputes between states or between the federal government and a state. It is headed by the Chief Justice of Malaysia.

2. **Court of Appeal of Malaysia (Mahkamah Rayuan):** This court hears appeals from the High Courts on both civil and criminal matters. It is headed by the President of the Court of Appeal.

3. **High Courts of Malaysia (Mahkamah Tinggi):** There are two High Courts with co-ordinate jurisdiction: the High Court in Malaya (for Peninsular Malaysia) and the High Court in Sabah and Sarawak (for East Malaysia). They have general supervisory and revisionary jurisdiction over all subordinate courts and hear appeals from them. They also have original jurisdiction in more serious civil and criminal cases, such as those involving amounts exceeding certain limits or offences punishable by death.

4. **Subordinate Courts:** These include:

- Sessions Courts (Mahkamah Sesyen):** They have jurisdiction over most criminal offences except those punishable by death, and can hear civil cases where the amount in dispute does not exceed RM1 million (unless agreed otherwise by parties).

- Magistrates' Courts (Mahkamah Majistret):** They deal with minor civil and criminal cases. First Class Magistrates have wider jurisdiction than Second Class Magistrates.

- Courts for Children:** These courts deal with offences committed by minors (persons under 18 years of age).

Parallel to the civil court system, there is a system of **Syariah Courts (Mahkamah Syariah)** which have jurisdiction over Muslims only, in matters of Islamic personal law and certain religious offences. These matters include marriage, divorce, inheritance, apostasy, and custody. The Syariah Courts have their own hierarchy, with Syariah Subordinate Courts, Syariah High Courts, and Syariah Courts of Appeal at the state level. The Federal Court does not hear appeals from the Syariah Courts, as they are considered separate jurisdictions. The relationship and occasional conflicts between the civil and Syariah court systems have been a source of legal and social debate, particularly in cases involving religious conversion or family law disputes affecting both Muslims and non-Muslims.

The independence of the judiciary is a constitutional principle, but it has faced periods of challenge and public scrutiny, particularly regarding the appointment process for judges and concerns about executive influence. Efforts to strengthen judicial independence and ensure public confidence in the justice system are crucial for Malaysia's democratic health and the rule of law.

5.6. Political Parties and Elections

Malaysia has a multi-party system, although historically, one coalition, Barisan Nasional (BN; National Front), dominated federal politics from independence until 2018. Elections are a central feature of Malaysian democracy, determining the composition of the Dewan Rakyat (federal House of Representatives) and the State Legislative Assemblies.

- Major Political Parties and Coalitions:**

- Pakatan Harapan (PH; Alliance of Hope):** A major political coalition that formed the federal government after the 2018 general election, marking the first change of federal government in Malaysia's history. Key component parties include the People's Justice Party (PKR), Democratic Action Party (DAP), and National Trust Party (AMANAH). PH advocates for reforms, good governance, and social justice.

- Barisan Nasional (BN; National Front):** Formerly the long-ruling coalition, dominated by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO). Other component parties include the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC). BN generally represents more conservative and Malay-centric interests.

- Perikatan Nasional (PN; National Alliance):** A coalition that emerged following the political crisis of 2020, initially forming the government. Key parties include Bersatu (Malaysian United Indigenous Party) and the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS). PN often emphasizes Malay-Muslim unity and conservative values.

- Electoral System:**

Federal parliamentary elections are held at least once every five years to elect members of the Dewan Rakyat. Malaysia uses a first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system in single-member constituencies. The candidate who receives the most votes in a constituency wins the seat. This system has sometimes been criticized for not accurately reflecting the overall popular vote share of parties (i.e., a party can win a majority of seats without winning a majority of the popular vote).

State elections for State Legislative Assemblies are usually held concurrently with federal elections, although states have the autonomy to dissolve their assemblies at different times (Sarawak, for instance, often holds its elections separately).

The Election Commission (Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya Malaysia) is responsible for conducting elections. The fairness and integrity of the electoral process have often been subjects of public debate and scrutiny, with concerns raised about issues such as gerrymandering, malapportionment (unequal constituency sizes), the use of government resources by incumbent parties, and media bias. Reforms to the electoral system and processes have been a key demand of opposition parties and civil society groups aiming to enhance democratic fairness and transparency. The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18 in 2019.

- Outcomes of Major Elections:**

These developments highlight a more competitive and dynamic political environment in Malaysia, though challenges related to democratic processes, institutional reform, and political stability persist.

5.7. Ethnicity in Politics

Ethnicity is a deeply significant and often defining factor in Malaysian politics. The country's multi-ethnic composition, primarily consisting of Malays, Chinese, and Indians, alongside various indigenous groups (collectively termed Bumiputera along with Malays), has profoundly shaped its political landscape, party structures, and public policies since independence.

- Ethnic-Based Political Parties:**

Many of Malaysia's major political parties were initially formed along ethnic lines or have a primary support base within a specific ethnic community.

- The United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) has historically been the dominant party representing Malay interests.

- The Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC) were formed to represent the Chinese and Indian communities, respectively, and were long-term partners with UMNO in the Barisan Nasional coalition.

- The Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) primarily appeals to conservative Malay-Muslim voters.

- The Democratic Action Party (DAP), while officially multiracial, draws significant support from the Chinese community and advocates for secularism and social democracy.

- Parties in East Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak) often represent the interests of specific indigenous ethnic groups in those states.

While some newer parties and coalitions, like Pakatan Harapan, have strived for a more multiracial platform, ethnic considerations continue to influence voter behavior and political strategies.

- The Bumiputera Policy:**

A central element of ethnicity in Malaysian politics is the Bumiputera policy, which encompasses a range of affirmative action measures designed to improve the socio-economic standing of Malays and other indigenous peoples. This policy was formally institutionalized through the New Economic Policy (NEP) (1971-1990) following the 13 May 1969 race riots, and has been continued in various forms under subsequent national development plans.

The Bumiputera policy provides preferential treatment in areas such as:

- Public sector employment and promotions.

- Admission to public universities and allocation of scholarships.

- Ownership of equity in businesses and licensing.

- Access to housing and other economic opportunities.

The rationale for these policies is rooted in addressing historical economic imbalances, where Bumiputeras were perceived to be economically disadvantaged compared to other ethnic groups, particularly the Chinese. Proponents argue that these policies have been crucial for social stability and for creating a Malay middle class.

However, the Bumiputera policy has been a source of significant political debate and social tension. Critics, including many non-Bumiputeras and some reform-minded Malays, argue that:

- It is discriminatory and undermines principles of meritocracy and equal opportunity.

- It has sometimes led to cronyism, inefficiency, and the enrichment of a connected elite rather than broadly benefiting the Bumiputera masses.

- It may perpetuate ethnic divisions and hinder national unity.

- Its long-term continuation is questioned, with calls for a more needs-based, rather than race-based, approach to affirmative action that focuses on uplifting all Malaysians from disadvantaged backgrounds, regardless of ethnicity.

- Ethnic Relations and Equity:**

The emphasis on ethnic identity in politics has led to a delicate balance in managing inter-ethnic relations. Issues of language, religion (Islam as the official religion), and cultural rights are often intertwined with ethnic politics. Political discourse frequently revolves around the protection of various community rights and the perceived threats to them.

Achieving genuine ethnic equity and fostering a truly inclusive national identity, where all citizens feel a sense of belonging and equal stake in the nation's progress, remains an ongoing challenge. Debates about the future of the Bumiputera policy, the promotion of a "Bangsa Malaysia" (Malaysian Nation) identity that transcends ethnic lines, and ensuring fair treatment for all communities are central to Malaysia's continued political and social development. Ongoing political discourse includes calls for policies that address socio-economic disparities based on need rather than race, and that strengthen democratic institutions to protect the rights of all citizens, reflecting aspirations for a more equitable and inclusive society.

5.8. Administrative Divisions

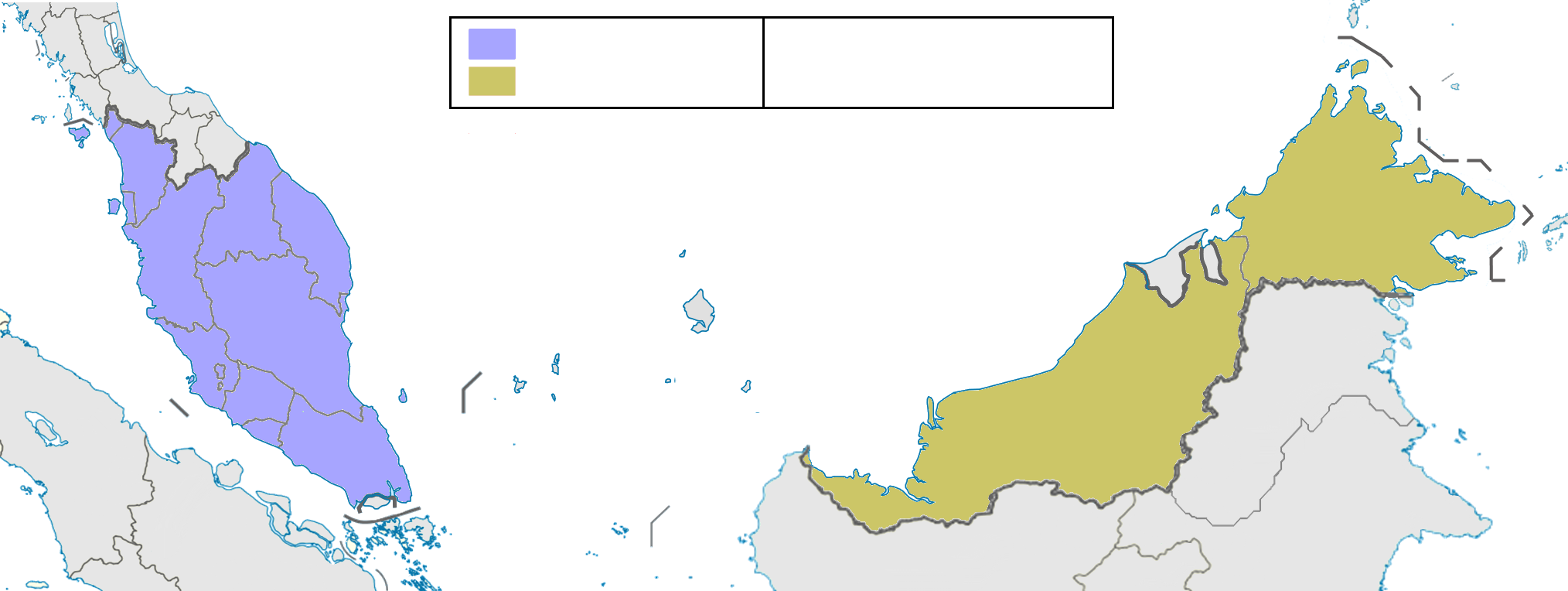

Malaysia is a federation composed of 13 states (negeri) and three federal territories (Wilayah Persekutuan). These are geographically divided between Peninsular Malaysia (West Malaysia) and East Malaysia (on the island of Borneo).

- Peninsular Malaysia** consists of 11 states and two federal territories:

- States:**

1. Johor (State capital: Johor Bahru) - Located at the southern tip of the peninsula, known for its economic links with Singapore and agricultural produce.

2. Kedah (State capital: Alor Setar) - A northern state, known as the "rice bowl" of Malaysia, with a rich history.

3. Kelantan (State capital: Kota Bharu) - A conservative state on the northeast coast, known for its unique Malay culture and traditions.

4. Malacca (Melaka) (State capital: Malacca City) - A historic state with a rich colonial past, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

5. Negeri Sembilan (State capital: Seremban) - Known for its Minangkabau traditions and unique adat perpatih (matrilineal customary law).

6. Pahang (State capital: Kuantan) - The largest state in Peninsular Malaysia, rich in natural resources and home to Taman Negara (National Park).

7. Penang (State capital: George Town) - An island state with a vibrant multicultural heritage, another UNESCO World Heritage site, and a major electronics manufacturing hub.

8. Perak (State capital: Ipoh) - Known for its tin mining history, limestone hills, and colonial architecture.

9. Perlis (State capital: Kangar) - The smallest state in Malaysia, located in the north, bordering Thailand.

10. Selangor (State capital: Shah Alam) - The most populous and developed state, surrounding Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya.

11. Terengganu (State capital: Kuala Terengganu) - An east coast state known for its beaches, islands, and traditional Malay culture.- Federal Territories:**

1. Kuala Lumpur - The national capital and largest city, a major commercial and cultural center.

2. Putrajaya - The federal administrative capital, home to most government ministries.- East Malaysia** consists of two states and one federal territory:

- States:**

1. Sabah (State capital: Kota Kinabalu) - Known for Mount Kinabalu, rich biodiversity, and diverse indigenous cultures.

2. Sarawak (State capital: Kuching) - The largest state by area, known for its rainforests, extensive river systems, and diverse indigenous communities.- Federal Territory:**

1. Labuan (Capital: Victoria) - An island off the coast of Sabah, an offshore financial center.

- Local Governance:**

Each state has its own constitution and a unicameral State Legislative Assembly (Dewan Undangan Negeri), whose members are elected. State governments are led by a Chief Minister (Menteri Besar in states with hereditary rulers, or Ketua Menteri in other states). The federal territories are governed directly by the federal government through the Ministry of Federal Territories. Below the state level, local government is administered by local authorities such as city councils (Majlis Bandaraya), municipal councils (Majlis Perbandaran), and district councils (Majlis Daerah), which are responsible for local services and development. Sabah and Sarawak have a greater degree of autonomy compared to the peninsular states, particularly in matters of immigration, land, and local government. This autonomy is a legacy of the terms under which they joined the federation in 1963.

5.9. Foreign Relations

Malaysia's foreign policy is officially based on the principle of neutrality, maintaining peaceful relations with all countries, and prioritizing the security and stability of Southeast Asia. It is a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and actively participates in numerous international organizations, including the United Nations (UN), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), and the Commonwealth of Nations.

Key aspects of Malaysia's foreign relations include:

- ASEAN Centrality:** Malaysia plays a significant role in ASEAN, advocating for regional integration, economic cooperation, and a collective voice on regional and international issues. It has chaired ASEAN multiple times and hosted key summits like the first East Asia Summit in 2005.

- Relations with Major Powers:** Malaysia maintains pragmatic relations with major global powers, including the United States, China, and Japan. It balances its economic ties with China, its largest trading partner, with security cooperation with the United States and other Western countries. The relationship with China involves significant trade and investment, but also complexities related to the South China Sea disputes.

- Islamic World:** As a majority-Muslim country, Malaysia actively engages with the Islamic world through the OIC and bilateral relations. It often seeks to project an image of a moderate and progressive Islamic nation and has spoken out on issues affecting Muslim communities globally, such as the Palestinian cause. Malaysia does not have diplomatic relations with Israel.

- Territorial Disputes:** Malaysia is a claimant state in the South China Sea disputes, with overlapping claims with China, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Brunei over certain islands and maritime features, primarily in the Spratly Islands area. While historically pursuing a quieter diplomacy compared to some other claimants, Malaysia has become more assertive in condemning encroachments into its territorial waters and airspace. It has also resolved some border issues, such as maritime boundary delimitations with Indonesia and an agreement with Brunei ending mutual land claims in 2009. The Philippines maintains a dormant claim to eastern Sabah.

- Human Rights and International Law:** Malaysia's stance on international human rights has sometimes been a point of contention. While engaging with UN human rights mechanisms, its domestic policies on issues like freedom of speech, assembly, and treatment of refugees and migrant workers have drawn criticism from international human rights organizations. From a social liberalism perspective, there is a need for Malaysia's foreign policy to more consistently champion human rights and international humanitarian law, not only in rhetoric but also in its bilateral and multilateral engagements, and to ensure its domestic practices align with these principles. Malaysia has signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

- Bilateral Relations:** Malaysia maintains close ties with its immediate neighbors, though relations can sometimes be complex due to historical, economic, or border issues. For instance, relations with Singapore are multifaceted, involving close economic interdependence alongside occasional diplomatic disagreements. Ties with Indonesia are generally strong, based on shared cultural and linguistic heritage, but have also seen disputes over maritime boundaries and treatment of migrant workers.

Malaysia's foreign policy aims to safeguard its national sovereignty and economic interests while contributing to regional peace and stability. The perspectives of affected parties in territorial disputes, such as local fishing communities, and the human rights implications of its foreign policy decisions, are important considerations for a balanced and just approach to international relations.

5.10. Military

The Malaysian Armed Forces (Angkatan Tentera Malaysia, ATM) are responsible for the defense of Malaysia's sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as supporting national interests and contributing to international peacekeeping efforts. The ATM consists of three main branches:

1. **Malaysian Army (Tentera Darat Malaysia, TDM):** The land-based force, responsible for ground operations, border security, and internal security assistance.

2. **Royal Malaysian Navy (Tentera Laut Diraja Malaysia, TLDM):** Responsible for maritime security, protecting Malaysia's extensive coastlines, territorial waters, and strategic sea lanes like the Strait of Malacca.

3. **Royal Malaysian Air Force (Tentera Udara Diraja Malaysia, TUDM):** Responsible for air defense, air superiority, and air support operations.

Malaysia does not have conscription; military service is voluntary, and the required age is 18. In terms of defense spending, the military utilizes approximately 1.5% of the country's GDP, and it employs around 1.23% of Malaysia's workforce.

- Key Defense Policies and Cooperation:**

The Malaysian Armed Forces are undergoing modernization efforts to enhance their capabilities in areas such as maritime surveillance, cybersecurity, and response to non-traditional security threats, reflecting the evolving security landscape in Southeast Asia.

5.11. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Malaysia presents a mixed picture, with constitutional guarantees often challenged by restrictive laws and practices. From a center-left/social liberalism perspective, several areas raise significant concerns regarding the protection of fundamental liberties and the rights of vulnerable groups.

- Freedom of Expression, Assembly, and Association:**

- Rights of Minorities:**

- Ethnic and Religious Minorities:** While Islam is the official religion, and Malays/Bumiputera enjoy special privileges under affirmative action policies, concerns exist about the rights and treatment of ethnic and religious minorities. Issues include perceived discrimination in public sector employment and education, restrictions on the building of non-Muslim places of worship, and controversies surrounding religious conversion (particularly out of Islam, which is legally complex and often prohibited for Muslims). The use of the word "Allah" by non-Muslims has also been a contentious issue.

- LGBT Rights:** Homosexuality is illegal in Malaysia under both secular law (Section 377 of the Penal Code, criminalizing "carnal intercourse against the order of nature") and, for Muslims, under Syariah law. LGBT individuals face significant discrimination, social stigma, and the threat of legal punishment, including caning and imprisonment. There have been instances of raids on LGBT gatherings and public shaming. Efforts by LGBT activists to advocate for rights and challenge discriminatory laws face strong opposition from conservative religious and political groups. Vigilante actions and hate speech against the LGBT community are serious concerns. The sodomy trials of Anwar Ibrahim were widely seen by human rights groups as politically motivated.

- Death Penalty:**

- Migrant Workers and Refugees:**

- Government Policies and Civil Society Efforts:**

Improving the human rights record requires comprehensive legal and institutional reforms, greater political will to uphold fundamental freedoms, and a commitment to ensuring equality and non-discrimination for all individuals in Malaysia.

6. Economy

Malaysia's economy is characterized as a relatively open, state-oriented, and newly industrialized market economy. It has experienced significant growth and structural transformation since independence, evolving from a primary commodity producer to a more diversified economy with substantial manufacturing and service sectors. The government has played an active role in economic development through various national plans and policies.

6.1. Economic Development and Structure

Post-independence, Malaysia's economy was heavily reliant on the export of raw materials, particularly rubber and tin. To address socio-economic imbalances and promote broader development, the government launched the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1971, following the 13 May 1969 race riots. The NEP's twin goals were to eradicate poverty irrespective of race and to restructure society to reduce the identification of race with economic function, aiming to increase Bumiputera (Malays and other indigenous peoples) participation in the economy. The NEP led to significant state intervention, including the establishment of state-owned enterprises and affirmative action programs. While it contributed to poverty reduction and the creation of a Malay middle class, its impact on overall social equity and its potential for fostering cronyism and ethnic divisions have been subjects of ongoing debate. Critics argue that the race-based approach may not have effectively reached the most marginalized Bumiputeras and could have hindered meritocracy.

From the 1980s, under Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia pursued rapid industrialization, shifting from an agriculture-based economy to one increasingly focused on manufacturing (especially electronics) and, later, services. The "Look East Policy," emulating the development models of Japan and South Korea, was a hallmark of this era. National development strategies like "Wawasan 2020" (Vision 2020), launched in 1991, aimed for Malaysia to achieve fully developed country status by the year 2020. This period saw significant infrastructure development and economic growth.

The Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 posed a major challenge, but Malaysia, under Mahathir, controversially implemented capital controls and pegged the ringgit, avoiding an IMF bailout, which some analysts argue helped in its recovery. The economy has since diversified further, with the service sector becoming the largest contributor to GDP.

However, achieving equitable development and addressing social and environmental impacts remain key challenges. While absolute poverty has declined, concerns about relative poverty, income inequality (both inter-ethnic and intra-ethnic), and the environmental consequences of rapid development (such as deforestation for palm oil plantations) persist. Sustainable development and inclusive growth are crucial considerations for Malaysia's future economic path. The goal of Wawasan 2020 was not fully met, and subsequent development plans continue to address these complex issues.

6.2. Main Industries

Malaysia's economy is diversified across several key industrial sectors, reflecting its transition from a commodity-based to a more industrialized and service-oriented nation.

- Manufacturing:** This has been a cornerstone of Malaysia's economic growth for decades.

- Electronics and Electrical Products (E&E):** Malaysia is a major global hub for the assembly and testing of semiconductors and other electronic components. It plays a significant role in the global electronics supply chain. Penang is a notable center for this industry.

- Automotive:** Malaysia has a domestic automotive industry, with national car manufacturers like Proton and Perodua. It also hosts assembly plants for international car brands.

- Other manufacturing sub-sectors include chemicals, machinery and equipment, petroleum products, and processed food.

- Agriculture:** While its share of GDP has declined, agriculture remains important, particularly for rural employment and exports.

- Palm Oil:** Malaysia is one of the world's largest producers and exporters of palm oil. This industry is a major foreign exchange earner but also faces scrutiny over environmental sustainability and deforestation.

- Rubber:** Historically a dominant commodity, rubber production continues, though on a smaller scale compared to palm oil. Malaysia is still a significant producer of natural rubber and rubber products like gloves.

- Other agricultural products include cocoa, pepper, timber, and fruits. Fisheries and aquaculture are also significant.

- Mining and Quarrying:**

- Petroleum and Natural Gas:** Malaysia is a net exporter of oil and natural gas, primarily sourced from offshore fields in the South China Sea (off Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah, and Sarawak). Petronas, the national oil and gas company, is a major contributor to government revenue and a global energy player.

- Tin mining, once a pillar of the economy, has declined significantly.

- Services:** This is now the largest sector of the Malaysian economy.

- Tourism:** Tourism is a significant contributor to GDP and employment, attracting visitors with its diverse cultural heritage, natural attractions (rainforests, beaches, islands), and modern cities. Medical tourism has also been a growing niche.

- Finance and Banking:** Kuala Lumpur is a regional financial center. Malaysia has a well-developed banking system, including a significant Islamic finance sector, where it is a global leader.

- Wholesale and Retail Trade:** A large and dynamic sector catering to domestic consumption.

- Telecommunications and Information Technology:** The Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) initiative has aimed to foster the growth of the IT and digital economy.

- Transportation and Logistics:** Driven by Malaysia's role as a trading nation and its strategic location.

The government continues to promote diversification and value-addition across these sectors, with an emphasis on moving towards higher-technology industries, knowledge-based services, and sustainable practices.

6.3. Trade

Trade plays a vital role in Malaysia's economy, reflecting its open and export-oriented nature. The country is strategically located along major shipping routes, particularly the Strait of Malacca.

- Major Export Items:**

Malaysia's exports are diverse, covering manufactured goods, commodities, and agricultural products. Key export categories include:

1. **Electrical and Electronic (E&E) Products:** This is consistently the largest export category, encompassing semiconductors, integrated circuits, consumer electronics, and telecommunications equipment.

2. **Petroleum and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG):** Crude oil, refined petroleum products, and LNG are major foreign exchange earners, managed by the national oil company, Petronas.

3. **Palm Oil and Palm Oil-based Products:** Malaysia is one of the world's top exporters of palm oil and related products used in food, oleochemicals, and biofuels.

4. **Chemicals and Chemical Products:** Including plastics, resins, and various industrial chemicals.

5. **Machinery, Equipment, and Parts:** Reflecting the growth of the manufacturing sector.

6. **Rubber Products:** Particularly medical gloves, for which Malaysia is a leading global supplier, as well as tires and other rubber goods.

7. **Manufactured Goods:** Including optical and scientific equipment, wood products, and textiles.

- Major Import Items:**

Imports consist largely of intermediate goods for the manufacturing sector, capital goods, and consumer products. Key import categories include:

1. **Electrical and Electronic (E&E) Products:** Intermediate components and parts for assembly in Malaysia's E&E industry.

2. **Machinery and Transport Equipment:** Industrial machinery, vehicles, and parts needed for various sectors.

3. **Chemicals and Chemical Products:** Raw materials and processed chemicals.

4. **Petroleum Products:** While an exporter of crude oil, Malaysia also imports certain refined petroleum products.

5. **Manufactured Goods:** A variety of finished and semi-finished goods.

6. **Food:** Malaysia is a net importer of certain food items to meet domestic demand.

- Major Trading Partners:**

Malaysia's main trading partners include:

- China (often the largest trading partner for both exports and imports)

- Singapore (a key trading and transshipment hub)

- United States

- Japan

- European Union (EU) countries

- Other ASEAN countries (e.g., Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia)

- Balance of Trade:**

Malaysia has generally maintained a trade surplus (exports exceeding imports) over the years, which contributes positively to its balance of payments. The performance of its external trade is closely linked to global economic conditions, commodity prices, and demand in its key export markets. The government actively promotes trade through various agencies and participates in regional trade agreements like the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) and broader pacts such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

6.4. Infrastructure

Malaysia has developed a relatively extensive and modern infrastructure network, particularly in Peninsular Malaysia, which has been a key factor in its economic development. However, disparities exist between the peninsula and East Malaysia.

- Transportation:**

- Roads:** Malaysia has a well-developed road network, especially in the peninsula, totaling over 148 K mile (238.82 K km) as of 2016. The North-South Expressway is a major toll highway that spans the length of Peninsular Malaysia, from the Thai border to Singapore. Other expressways connect major urban centers. The road network in Sabah and Sarawak is less developed and faces challenges due to terrain and vast distances, though efforts to improve it, such as the Pan-Borneo Highway project, are ongoing.

- Railways:** Keretapi Tanah Melayu Berhad (KTMB) operates the main railway lines in Peninsular Malaysia, including intercity services and commuter trains in the Klang Valley. The Electric Train Service (ETS) provides faster intercity travel on electrified double-tracked sections. In East Malaysia, the Sabah State Railway operates a limited line. Urban rail transit systems, including LRT (Light Rail Transit), MRT (Mass Rapid Transit), and monorail lines, serve Kuala Lumpur and the surrounding Klang Valley.

- Ports:** Malaysia has several major seaports. Port Klang, near Kuala Lumpur, and the Port of Tanjung Pelepas in Johor are among the busiest container ports in the world, leveraging Malaysia's strategic position on global shipping routes. Other important ports include Penang Port, Johor Port (Pasir Gudang), Kuantan Port, and Bintulu Port.

- Airports:** There are numerous airports across the country, including 6 international airports. Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) in Sepang is the main international gateway and a major regional hub. Other significant international airports are located in Penang, Kota Kinabalu, Kuching, Langkawi, and Senai (Johor Bahru). Domestic air travel is crucial for connecting Peninsular Malaysia with Sabah and Sarawak.

- Telecommunications:**

- Energy:**

- Water and Sanitation:**

Ongoing infrastructure development focuses on upgrading existing facilities, expanding networks to underserved areas (particularly in East Malaysia), improving urban public transport to reduce traffic congestion, and incorporating sustainable and environmentally friendly practices. However, large infrastructure projects sometimes face scrutiny regarding their environmental impact, cost-effectiveness, and benefit distribution.

6.5. Socio-economic Disparities