1. Overview

Bhutan (འབྲུག་ཡུལ་Druk YulDzongkha; pronounced boo-TAHN), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan (འབྲུག་རྒྱལ་ཁབ་Druk Gyal KhapDzongkha), is a landlocked country in South Asia, located in the Eastern Himalayas. It is bordered by China to the north and India to the south, east, and west. The Indian state of Sikkim separates Bhutan from Nepal. With a population of over 727,145 (2022 census) and an area of 15 K mile2 (38.39 K km2), Bhutan is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democratic system. The King is the head of state, and the Prime Minister is the head of government. Vajrayana Buddhism is the state religion, and the Je Khenpo is the head of this religious tradition.

The country's landscape ranges from lush subtropical plains in the south to the Himalayan mountains in the north, where peaks exceed 23 K ft (7.00 K m) above sea level. Gangkhar Puensum is Bhutan's highest peak and the world's highest unclimbed mountain. The wildlife of Bhutan is renowned for its diversity, including species like the Himalayan takin (the national animal) and the golden langur. The capital and largest city is Thimphu.

Historically, Bhutan, like neighboring Tibet, was influenced by Buddhism originating from the Indian subcontinent. The Vajrayana school of Buddhism spread to Bhutan in the first millennium. In the 17th century, Ngawang Namgyal unified Bhutan's valleys, establishing a distinct Bhutanese identity, repelling Tibetan invasions, codifying the Tsa Yig legal system, and creating a dual system of theocratic and civil administration. Though historically maintaining close ties with Great Britain, Bhutan was never colonized. The Wangchuck dynasty established a hereditary monarchy in 1907. Bhutan maintained its sovereignty through treaties with British India and later, independent India, which guided its foreign policy while preserving internal autonomy.

Bhutan joined the United Nations in 1971 and has since developed relations with numerous countries. The 2008 Constitution marked a significant transition to a parliamentary democracy. Bhutan is a founding member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and is recognized for its commitment to Gross National Happiness (GNH) over Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a measure of development, emphasizing sustainable development, cultural preservation, environmental conservation, and good governance. The nation is also celebrated for its environmental policies, being the only country in the world with negative carbon emissions, largely due to its extensive forest cover. However, it faces challenges such as the Lhotshampa refugee issue, which has raised human rights concerns, and the impacts of climate change on its glaciers.

2. Etymology

The precise etymology of "Bhutan" is not definitively known, though it is widely believed to derive from the Tibetan endonym "Böd," referring to Tibet. One prominent theory suggests it is a transcription of the Sanskrit term Bhoṭa-anta (भोट-अन्तBhoṭa-antaSanskrit), meaning "end of Tibet," which likely came through the Nepali Bhuṭān (भुटानBhuṭānNepali). This name reflects Bhutan's geographical position at the southern extremity of the Tibetan plateau and its cultural sphere. Another Sanskrit-based theory proposes the origin from Bhu-Uttan (भू-उत्थानBhu-UttanSanskrit), meaning "High Land," alluding to its mountainous terrain.

Since the 17th century, Bhutan's official name in Dzongkha, the national language, has been Druk Yul (འབྲུག་ཡུལ་Druk YulDzongkha). This name translates to "Land of the Drukpa Lineage" or, more poetically, "Land of the Thunder Dragon." This refers to the Drukpa Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, which is the state religion. The term "Bhutan" primarily appears in English-language official correspondence. Derived from Druk Yul are titles such as Druk Gyalpo ("Dragon King") for the Kings of Bhutan, and the endonym Drukpa for the Bhutanese people, meaning "Dragon people."

Historically, various names similar to Bhutan, such as Bohtan, Buhtan, Bottanthis, Bottan, and Bottanter, began appearing in European records around the 1580s. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier's 1676 work, Six Voyages, is noted as the first to record the name Boutan. However, these early European references often conflated Bhutan with the Kingdom of Tibet. The clear distinction between the two regions emerged later, notably following the 1774 expedition of Scottish explorer George Bogle. Recognizing the cultural and political differences, Bogle's report to the East India Company formally proposed calling the Druk Desi's kingdom "Boutan" and the Panchen Lama's realm "Tibet." The EIC's surveyor general, James Rennell, subsequently anglicized the French "Boutan" to "Bootan" and helped popularize the distinction. The first instance of a separate Kingdom of Bhutan appearing on a Western map was under its local name, "Broukpa."

Other historical names for Bhutan include Lho Mon (ལྷོ་མོནLho MonDzongkha, "Dark Southland" or "Southern Darkness," possibly referring to the Monpa people), Monyul ("Dark Land"), Lho Tsendenjong (ལྷོ་ཙན་དན་ལྗོངས།Lho TsendenjongDzongkha, "Southland of the Sandalwood" or "Southland of the Cypress"), Lhomen Khazhi (ལྷོ་མོན་ཁ་བཞི་Lhomen KhazhiDzongkha, "Southland of the Four Approaches"), and Lho Menjong (ལྷོ་སྨན་ལྗོངས།Lho MenjongDzongkha, "Southland of the Medicinal Herbs").

3. History

The history of Bhutan spans from early human settlements and the introduction of Buddhism to the formation of a unified state and its modern transition to a constitutional monarchy, focusing on its unique cultural development and challenges related to sovereignty and human rights.

3.1. Early History and Medieval Period

Archaeological evidence, including stone tools, weapons, elephant remains, and remnants of large stone structures, indicates that Bhutan was inhabited as early as 2000 BC. However, no written records from this period exist. Historians have theorized that a state known as Lhomon (literally "southern darkness") or Monyul ("Dark Land," possibly a reference to the Monpa people, an indigenous group in Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh, India) may have existed between 500 BC and AD 600. Names such as Lhomon Tsendenjong ("Sandalwood Country") and Lhomon Khashi or Southern Mon ("country of four approaches") appear in ancient Bhutanese and Tibetan chronicles.

Buddhism was first introduced to Bhutan in the mid-7th century AD. The Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo (reigned 627-649), a convert to Buddhism who expanded the Tibetan Empire into Sikkim and Bhutan, ordered the construction of two important Buddhist temples: Jambay Lhakhang in Bumthang in central Bhutan and Kyichu Lhakhang in the Paro Valley. The serious propagation of Buddhism began in 746 AD under King Sindhu Rāja (also known as Künjom, Sendha Gyab, or Chakhar Gyalpo), an exiled Indian king who had established a government in Bumthang at Chakhar Gutho Palace. The arrival of Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) in the 8th century further solidified Buddhism's presence, integrating it with local Bon practices. Over time, various Buddhist subsects emerged, often patronized by different regional powers and Mongol warlords, especially after the decline of the Yuan dynasty in the 14th century. This period saw these subsects vying for political and religious supremacy, eventually leading to the ascendancy of the Drukpa Lineage by the 16th century. Much of Bhutan's early history remains unclear because most records were destroyed in a fire that ravaged the ancient capital, Punakha, in 1827.

3.2. Formation of a Unified State (Zhabdrung Era)

Until the early 17th century, Bhutan existed as a patchwork of minor warring fiefdoms. The unification of the region into a single state was achieved by Ngawang Namgyal (1594-1651), a Tibetan lama and military leader who fled religious persecution in Tibet in 1616. He established himself as the Zhabdrung Rinpoche, the temporal and spiritual ruler of Bhutan. To defend the newly unified country against intermittent Tibetan incursions and to consolidate his power, Ngawang Namgyal constructed a network of impregnable dzongs (fortresses). These dzongs served as centers of religious and civil administration and many remain active today. He also promulgated the Tsa Yig, a code of law that brought local lords under centralized control, establishing a dual system of government, with the Je Khenpo overseeing religious matters and the Druk Desi managing secular affairs.

The earliest Western record of Bhutan comes from Portuguese Jesuits Estêvão Cacella and João Cabral, who visited in 1627 on their way to Tibet. They met Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, presented him with firearms, gunpowder, and a telescope, and offered their services in the war against Tibet, but the Zhabdrung declined. Cacella's detailed letter from Chagri Monastery provides a rare contemporary account of the Zhabdrung.

When Ngawang Namgyal died in 1651, his death was kept secret for 54 years to prevent instability. After a period of consolidation, Bhutan experienced internal conflict. In 1711, Bhutan went to war against the Raja of the kingdom of Koch Bihar to its south. During the ensuing chaos, Tibetans unsuccessfully attacked Bhutan in 1714. During the 17th century, Bhutan controlled large parts of northeast India, Sikkim, and Nepal, and wielded significant influence in Cooch Behar State.

3.3. Establishment of the Monarchy and Modernization (Wangchuck Dynasty)

In the 18th century, Bhutanese forces invaded and occupied the kingdom of Koch Bihar. In 1772, the Maharaja of Koch Bihar appealed to the British East India Company, which helped oust the Bhutanese and subsequently attacked Bhutan itself in 1774. A peace treaty was signed, with Bhutan agreeing to retreat to its pre-1730 borders. However, peace was tenuous, and border skirmishes with the British continued for the next century, culminating in the Duar War (1864-65) over control of the Bengal Duars. After Bhutan's defeat, the Treaty of Sinchula was signed, ceding the Duars to British India in exchange for an annual payment of 50.00 K INR. This treaty ended hostilities between British India and Bhutan.

During the 1870s, power struggles between the rival valleys of Paro and Trongsa led to civil war. This conflict eventually led to the ascendancy of Ugyen Wangchuck, the penlop (governor) of Trongsa. From his power base in central Bhutan, Ugyen Wangchuck defeated his political enemies and united the country after several civil wars and rebellions between 1882 and 1885.

In 1907, a pivotal year, Ugyen Wangchuck was unanimously chosen as the hereditary king by an assembly of leading Buddhist monks, government officials, and heads of important families, with a strong petition from Gongzim Ugyen Dorji. John Claude White, the British Political Agent in Bhutan, photographed the coronation ceremony. The British government promptly recognized the new monarchy. In 1910, Bhutan signed the Treaty of Punakha, a subsidiary alliance that granted Britain control over Bhutan's foreign affairs in exchange for internal autonomy and an increased annual subsidy. This arrangement effectively made Bhutan an Indian princely state in terms of foreign relations, though it had little real impact on Bhutan's traditional reticence and its relations with Tibet.

After the Union of India gained independence from the United Kingdom on August 15, 1947, Bhutan was one of the first countries to recognize India's independence. On August 8, 1949, a new treaty was signed with independent India, similar to the 1910 treaty, where India assumed the role of guiding Bhutan's foreign policy while respecting its sovereignty. Early modernization efforts began under the Wangchuck dynasty, focusing on infrastructure, education, and healthcare, leading to gradual societal changes.

3.4. Democratization and Modern Era

The path towards democratization began under King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, who, in 1953, established the country's first legislature, a 130-member National Assembly, to promote a more democratic form of governance. He also set up a Royal Advisory Council in 1965 and formed a Cabinet in 1968. Bhutan was admitted to the United Nations in 1971, after three years as an observer.

His son, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, ascended to the throne in July 1972 at the age of sixteen. He continued the modernization process and introduced significant political reforms. In 1998, he transferred most of his administrative powers to the Council of Cabinet Ministers and allowed for the impeachment of the King by a two-thirds majority of the National Assembly. In 1999, the government lifted the ban on television and the internet, making Bhutan one of the last countries to introduce these technologies. The King emphasized that while these were critical for modernization and Gross National Happiness, their misuse could erode traditional Bhutanese values.

A defining aspect of this era was the "One Nation, One People" policy (Driglam Namzhag) initiated in the late 1980s, which aimed to promote a unified national identity based on Drukpa traditions. This included enforcing a national dress code (the gho for men and kira for women) and promoting Dzongkha as the national language. The teaching of Nepali in schools in southern Bhutan was discontinued. These policies, coupled with a 1988 census in southern Bhutan aimed at identifying illegal immigrants, led to significant unrest among the Lhotshampa (Nepali-speaking) community. Protests for civil and cultural rights escalated, and the government's response included arrests and detentions. Between 80,000 and 100,000 Lhotshampas were reported to have been forcefully evicted or fled Bhutan in the early 1990s, becoming refugees in camps in Nepal. This Lhotshampa issue became a major human rights concern, with reports of widespread violence and arbitrary deportations. Since 2008, many Western countries have resettled a majority of these refugees.

In early 2005, a new constitution was presented. In December 2005, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck announced his intention to abdicate in 2008 in favor of his son. He unexpectedly abdicated on December 9, 2006. This was followed by the first national parliamentary elections, with National Council (upper house) elections in December 2007 and National Assembly (lower house) elections in March 2008. This marked Bhutan's formal transition to a constitutional monarchy.

On November 6, 2008, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck was crowned as the fifth King of Bhutan. The People's Democratic Party (PDP), led by Tshering Tobgay, came to power in the 2013 elections. In the 2018 elections, Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT) won, and Lotay Tshering became Prime Minister. Tshering Tobgay returned to power as Prime Minister after the 2024 election.

Contemporary Bhutan continues to develop its democratic institutions while facing challenges such as economic development, youth unemployment, and environmental sustainability. In July 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Bhutan achieved a high vaccination rate. On December 13, 2023, Bhutan was officially delisted as a least developed country.

4. Geography

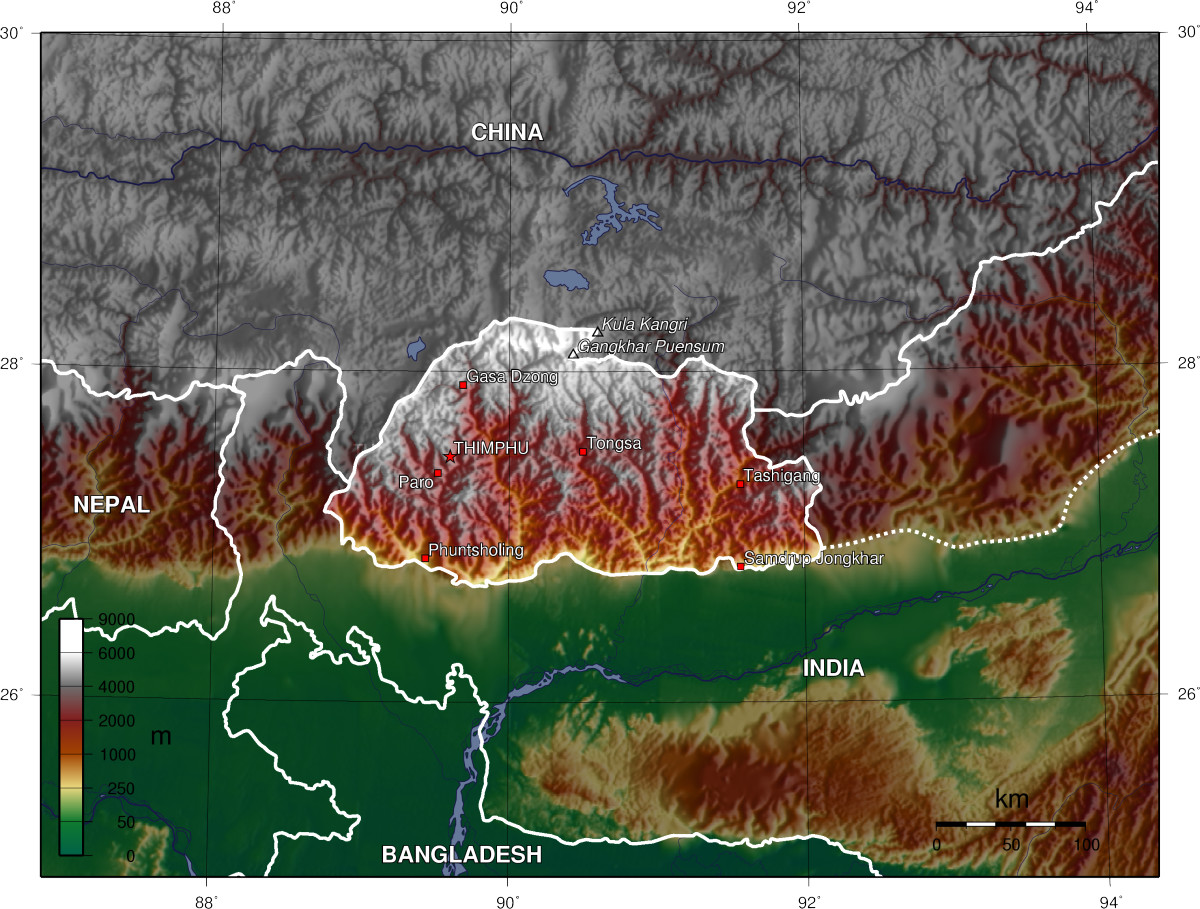

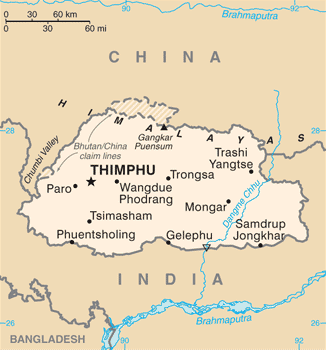

Bhutan is a landlocked country situated on the southern slopes of the eastern Himalayas. It is located between latitudes 26°N and 29°N, and longitudes 88°E and 93°E. The country is bordered by the Tibet Autonomous Region of China to the north, and the Indian states of Sikkim to the west, West Bengal and Assam to the south, and Arunachal Pradesh to the east. Bhutan's total land area is approximately 15 K mile2 (38.39 K km2). The terrain consists predominantly of steep and high mountains, making it the most mountainous country in the world with 98.8% of its land covered by mountains. These mountains are crisscrossed by a network of swift rivers that carve deep valleys before flowing into the Indian plains. This geographical diversity, combined with varied climatic conditions, contributes to Bhutan's remarkable range of biodiversity and ecosystems.

4.1. Topography and Climate

Bhutan's topography is characterized by extreme variations in altitude. Elevation rises dramatically from about 656 ft (200 m) in the southern foothills to over 23 K ft (7.00 K m) in the northern peaks. The northern region of Bhutan forms an arc of Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows, culminating in glaciated mountain peaks. Many peaks in this region exceed 23 K ft (7.00 K m) above sea level.

The highest point is Gangkhar Puensum, which stands at 25 K ft (7.57 K m) and holds the distinction of being the highest unclimbed mountain in the world. The lowest point, at 322 ft (98 m), is located in the valley of the Drangme Chhu river where it crosses the border into India. The alpine valleys in the north, fed by snow-melt rivers, provide pasture for livestock tended by a sparse population of migratory shepherds.

The Black Mountains in central Bhutan form a crucial watershed between two major river systems: the Mo Chhu and the Drangme Chhu. Peaks in the Black Mountains range from 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m) to 16 K ft (4.92 K m) above sea level. Fast-flowing rivers have carved deep gorges in the lower mountain areas. The forests in this central region consist of Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests at higher elevations and Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests at lower elevations. These woodlands are the primary source of Bhutan's forest products. The main rivers of Bhutan, including the Torsa, Raidāk, Sankosh, and Manas, flow through this region. The central highlands are where most of the population resides.

In the south, the Sivalik Hills are covered with dense Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests, alluvial lowland river valleys, and mountains reaching up to about 4.9 K ft (1.50 K m) above sea level. These foothills descend into the subtropical Duars Plain. The Duars, a name meaning "doors" or "gates" in several local languages, refer to the strategic mountain passes. While most of the Duars plain lies in India, a strip approximately 6.2 mile (10 km) to 9.3 mile (15 km) wide extends into Bhutan. The Bhutan Duars are divided into northern and southern Duars. The northern Duars, adjacent to the Himalayan foothills, have rugged, sloping terrain and dry, porous soil with dense vegetation and abundant wildlife. The southern Duars feature moderately fertile soil, heavy savanna grass, dense mixed jungle, and freshwater springs. Mountain rivers, fed by snowmelt or monsoon rains, eventually flow into the Brahmaputra River in India.

Bhutan's climate varies significantly with elevation. It ranges from subtropical in the south to temperate in the highlands, and polar-type conditions with year-round snow in the north. The country experiences five distinct seasons: summer, monsoon, autumn, winter, and spring. Western Bhutan receives the heaviest monsoon rains. Southern Bhutan has hot, humid summers and cool winters. Central and eastern Bhutan are temperate and drier than the west, with warm summers and cool winters.

4.2. Biodiversity and Environment

Bhutan is part of the Eastern Himalayas global biodiversity hotspot and is recognized as one of the world's 234 globally outstanding ecoregions. The country signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on June 11, 1992, and became a party to the convention on August 25, 1995. It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, with the most recent revision submitted in 2010.

4.2.1. Flora

Bhutan boasts a rich diversity of plant life, with over 5,400 species recorded, including unique species like Pedicularis cacuminidenta. As of 2020, forest cover is approximately 71% of the total land area, equivalent to 2,725,080 hectares. This is an increase from 2,506,720 hectares in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 2,704,260 hectares, while planted forest covered 20,820 hectares. About 15% of the naturally regenerating forest is primary forest, and around 41% of the forest area lies within protected areas. All forest area was reported to be under public ownership in 2015. Fungi are a key component of Bhutanese ecosystems, with mycorrhizal species supporting tree growth and decomposer species playing a vital role in nutrient cycling.

4.2.2. Fauna

Bhutan is home to a rich primate life, including rare species such as the golden langur. A variant of the Assamese macaque, potentially a new species named Macaca munzala, has also been recorded. The tropical lowland and hardwood forests in the south host Bengal tigers, clouded leopards, hispid hares, and sloth bears. Temperate zones with mixed conifer, broadleaf, and pine forests are inhabited by grey langurs, tigers, goral, and serow. Fruit-bearing trees and bamboo provide habitat for the Himalayan black bear, red panda, squirrels, sambar, wild pigs, and barking deer. The alpine habitats of the northern Himalayan range are home to the snow leopard, blue sheep, Himalayan marmot, Tibetan wolf, antelope, Himalayan musk deer, and the takin, Bhutan's national animal. The endangered wild water buffalo is found in southern Bhutan in small numbers.

Over 770 species of birds have been recorded in Bhutan. The globally endangered white-winged duck was added to Bhutan's bird list in 2006. A 2010 BBC documentary, Lost Land of the Tiger, featured an expedition that claimed the first footage of tigers living at 13 K ft (4.00 K m) in the high Himalayas, including evidence suggesting breeding at this elevation. Camera traps also recorded other rare forest creatures like dholes (Indian wild dogs), Asian elephants, leopards, and leopard cats.

4.2.3. Conservation

Bhutan is recognized as a model for proactive conservation initiatives and has received international acclaim for its commitment to maintaining biodiversity. Key policies include maintaining at least 60% of its land area under forest cover, designating over 40% of its territory as national parks, reserves, and other protected areas, and identifying an additional 9% of land as biodiversity corridors linking these protected areas. This network of biological corridors allows animals to migrate freely throughout the country. Environmental conservation is a core component of Bhutan's development strategy, the "middle path," and is integrated into overall development planning, supported by law. The country's constitution includes multiple sections on environmental standards.

4.2.4. Environmental Issues

While Bhutan's natural heritage remains largely intact, the government acknowledges ongoing challenges. Nearly 56.3% of Bhutanese are involved in agriculture, forestry, or conservation. The country has net negative greenhouse gas emissions, as its small pollution output is absorbed by its extensive forests. Bhutan produces about 2.20 M t of carbon dioxide annually, while its forests (covering 72% of the country) act as a carbon sink, absorbing over four million tons of carbon dioxide each year. Bhutan had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.85/10, ranking it 16th globally out of 172 countries.

Bhutan has progressive environmental policies, leading the head of the UNFCCC to call it an "inspiration and role model." Electric cars are promoted, and the country relies heavily on hydroelectric power, minimizing greenhouse gas emissions from energy production.

However, the overlap of protected lands with populated areas has led to human-wildlife conflict, with wildlife damaging crops and killing livestock. Bhutan has implemented measures such as an insurance scheme, solar-powered alarm fences, watchtowers, searchlights, and providing fodder and salt licks away from human settlements. The high market value of the Ophiocordyceps sinensis fungus (caterpillar fungus) has led to unsustainable harvesting, which is difficult to regulate.

Bhutan enforced a plastic ban from April 1, 2019, replacing plastic bags with alternatives made of jute and other biodegradable materials. A significant environmental concern is the melting of glaciers due to climate change.

5. Politics

Bhutan is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary form of government. The country's political system transitioned to a democracy in 2008, viewed as an evolution of its social contract with the monarchy established in 1907. The Democracy Index classified Bhutan as a hybrid regime in 2019. Since 2008, minorities have seen increasing representation in government, including in the cabinet, parliament, and local government.

5.1. Government Structure and Constitution

The Druk Gyalpo (Dragon King) is the head of state. The current monarch is Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. The Constitution of Bhutan, adopted in 2008, establishes the framework for governance. It enshrines the philosophy of Gross National Happiness (GNH) as a guiding principle for development, balancing material well-being with spiritual, cultural, and environmental health. The King plays a symbolic role, representing unity and stability, while executive power is vested in the elected government. The constitution also allows for the impeachment of the King by a two-thirds majority of the Parliament.

5.2. Legislature (Parliament)

The Parliament is bicameral, consisting of the National Council (upper house) and the National Assembly (lower house).

The National Council has 25 members: 20 are elected from each of the 20 dzongkhags (districts), and 5 are appointed by the King. It serves as a house of review, providing checks and balances on the legislative process.

The National Assembly has 47 members, elected from constituencies across the country through a two-round system. In the first round, political parties compete, and the two parties with the highest number of votes proceed to the second round, where candidates from these two parties contest in individual constituencies. The party that wins the majority of seats in the second round forms the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the National Assembly. The political system grants universal suffrage.

The first general elections for the National Assembly were held on March 24, 2008. The Bhutan Peace and Prosperity Party (DPT), led by Jigme Thinley, won 45 out of 47 seats, and Jigme Thinley served as Prime Minister from 2008 to 2013. The People's Democratic Party (PDP) came to power in the 2013 elections, winning 32 seats, with Tshering Tobgay as Prime Minister from 2013 to 2018. In the 2018 election, Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT) won, and Lotay Tshering became Prime Minister. Tshering Tobgay returned to power as Prime Minister after the 2024 election, with the PDP gaining 30 seats; he assumed office on January 28, 2024.

5.3. Executive Branch

Executive power is exercised by the Lhengye Zhungtshog (Council of Ministers), led by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is the head of government and is appointed from the party that wins the majority in the National Assembly elections. The ministers are appointed by the King upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister. Major ministries oversee various sectors such as finance, foreign affairs, home and cultural affairs, health, education, and economic affairs.

5.4. Judiciary

The judicial power is vested in the courts of Bhutan. The legal system originates from the semi-theocratic Tsa Yig code and was influenced by English common law during the 20th century. The court system includes the Supreme Court, the High Court, Dzongkhag Courts, and Dungkhag Courts. The Chief Justice is the administrative head of the judiciary and is appointed by the King upon the recommendation of the National Judicial Commission. Judicial independence is a key principle, with mechanisms in place for the appointment and removal of judges to ensure impartiality.

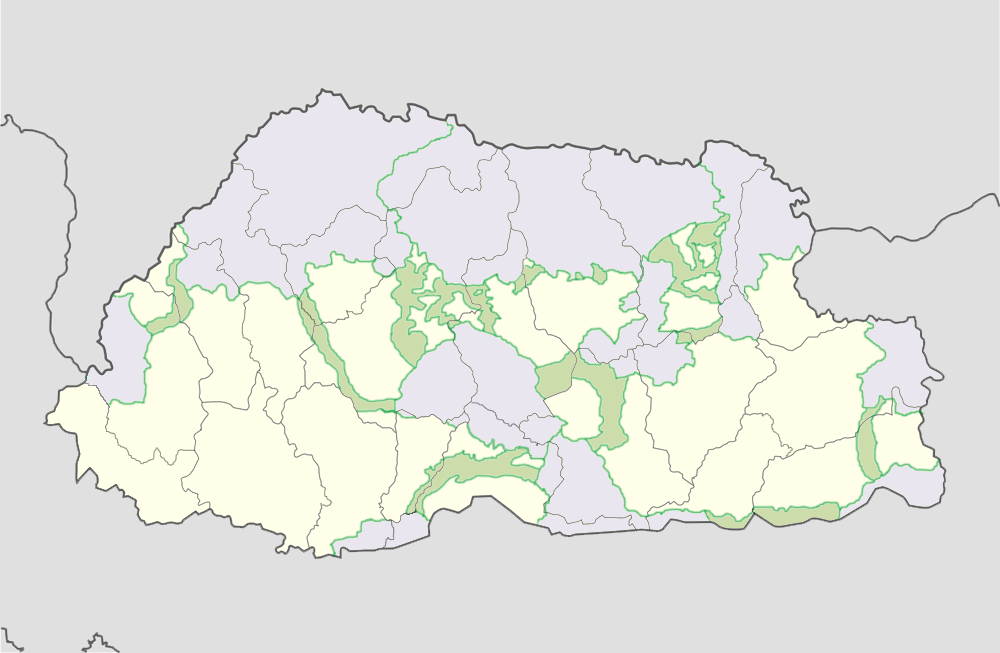

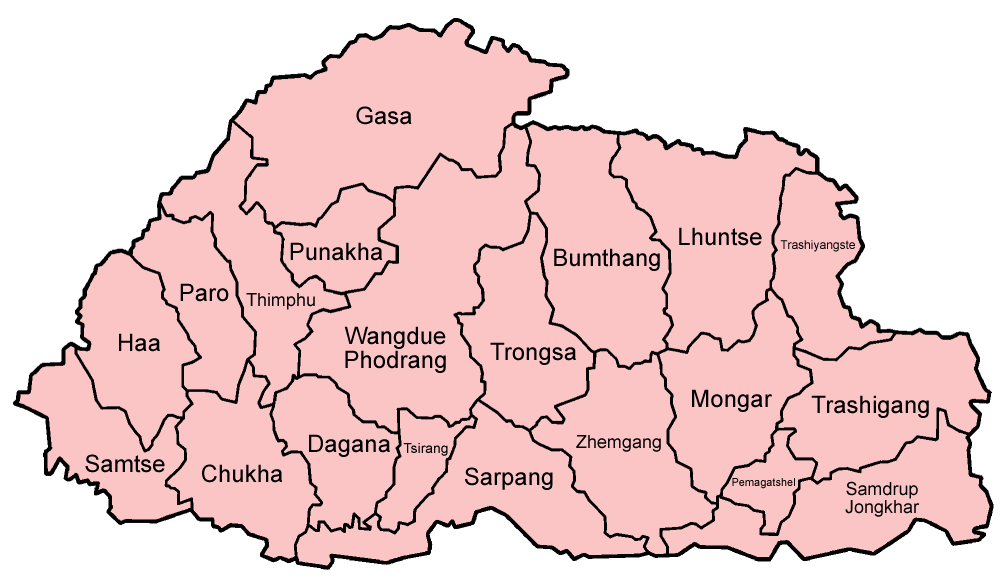

5.5. Administrative Divisions

Bhutan is divided into twenty dzongkhags (districts), each administered by a Dzongdag (governor) appointed by the central government. Each dzongkhag has a Dzongkhag Tshogdu (District Council), which is the highest decision-making body at the district level.

Dzongkhags are further subdivided into gewogs (blocks of villages), totaling 205 gewogs. Each gewog is administered by a Gup (headman), who is elected by the local people, and a Gewog Tshogde (Block Development Committee). Some larger dzongkhags may also have dungkhags (sub-districts) as an intermediary administrative level between the dzongkhag and gewogs.

Major urban centers are designated as thromdes (municipalities), which have their own elected Thrompons (mayors) and Thromde Tshogdes (Municipal Councils). The basis of electoral constituencies is the chiwog, a subdivision of gewogs.

| Dzongkhags (Districts) of the Kingdom of Bhutan | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| District | Dzongkha name | District | Dzongkha name |

| 1. Bumthang | བུམ་ཐང་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 11. Samdrup Jongkhar | བསམ་གྲུབ་ལྗོངས་མཁར་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

| 2. Chukha | ཆུ་ཁ་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 12. Samtse | བསམ་རྩེ་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

| 3. Dagana | དར་དཀར་ན་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 13. Sarpang | གསར་སྤང་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

| 4. Gasa | མགར་ས་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 14. Thimphu | ཐིམ་ཕུ་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

| 5. Haa | ཧཱ་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 15. Trashigang | བཀྲ་ཤིས་སྒང་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

| 6. Lhuntse | ལྷུན་རྩེ་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 16. Trashiyangtse | བཀྲ་ཤིས་གཡང་རྩེ་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

| 7. Mongar | མོང་སྒར་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 17. Trongsa | ཀྲོང་གསར་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

| 8. Paro | སྤ་རོ་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 18. Tsirang | རྩི་རང་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

| 9. Pemagatshel | པད་མ་དགའ་ཚལ་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 19. Wangdue Phodrang | དབང་འདུས་ཕོ་བྲང་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

| 10. Punakha | སྤུ་ན་ཁ་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha | 20. Zhemgang | གཞམས་སྒང་རྫོང་ཁག་Dzongkha |

6. Foreign Relations

Bhutan follows a foreign policy based on non-alignment and the principles of peaceful coexistence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity. Historically, Bhutan maintained a policy of isolation, but since joining the United Nations in 1971, it has gradually expanded its diplomatic ties. As of 2020, Bhutan has formal diplomatic relations with 53 countries and the European Union. It has missions in India, Bangladesh, Thailand, Kuwait, and Belgium, and two UN missions in New York and Geneva. However, it does not have formal diplomatic relations with any of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, including China. Bhutan is a founding member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and is also a member of the BIMSTEC, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Group of 77. The country opposed the Russian annexation of Crimea in United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262.

6.1. Relations with India

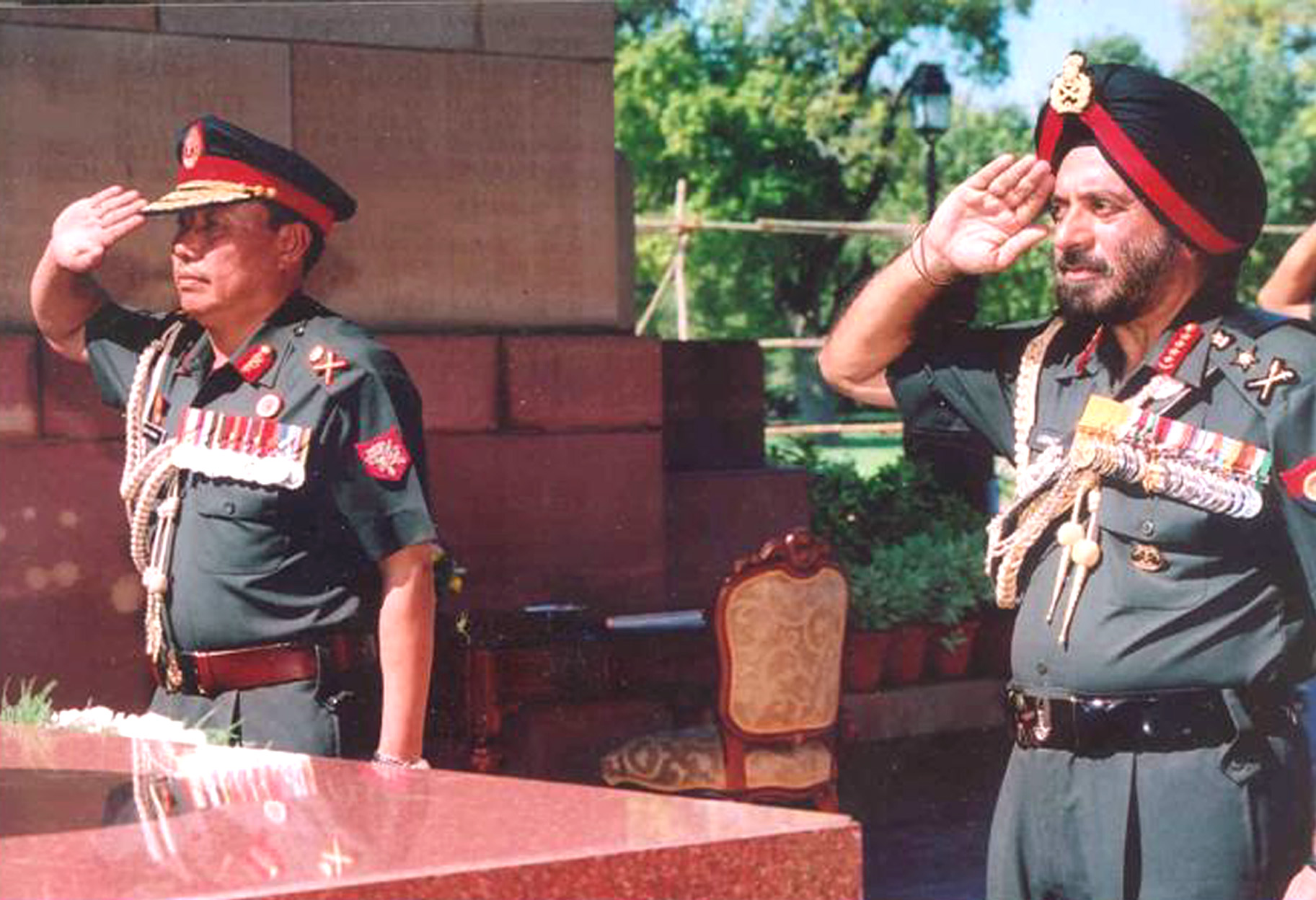

Bhutan and India share a "special relationship" characterized by close political, economic, strategic, and military ties. This relationship is rooted in the 1949 Treaty of Friendship, which was updated in 2007. The revised treaty replaced the provision that India would guide Bhutan's foreign policy with a commitment to cooperate closely on issues relating to their national interests, affirming Bhutan's sovereignty. India is Bhutan's largest trading partner and a major source of development aid and investment, particularly in the hydropower sector. Indian and Bhutanese citizens can travel to each other's countries without a passport or visa, using national identity cards, and Bhutanese citizens can work in India without legal restrictions. The Indian Military Training Team (IMTRAT) is permanently based in Bhutan to train the Royal Bhutan Army.

6.2. Relations with China and Border Issues

Bhutan does not have formal diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China. The border between Bhutan and China, approximately 292 mile (470 km) long, is not fully demarcated and has been a subject of dispute. Several areas, particularly in the north and west, are claimed by both countries. Since 1984, Bhutan and China have held numerous rounds of border talks to resolve these disputes. In 2021, the two countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding on a "Three-Step Roadmap" to expedite negotiations. Despite the lack of formal ties, there have been unofficial exchanges and visits at various levels. Bhutan has also established honorary consulates in the Chinese Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau.

Border incidents have occurred, such as in 2005 when Chinese soldiers reportedly crossed into disputed territories and began building infrastructure. More recently, tensions arose in 2017 over Chinese road construction in the disputed Doklam plateau, an area near the tri-junction of Bhutan, China, and India, which also involved Indian troops due to India's security concerns and treaty obligations with Bhutan. From a perspective that emphasizes Bhutan's sovereignty and the well-being of its people, the border issues with China represent a significant challenge to its territorial integrity and security, requiring careful diplomatic navigation.

6.3. Relations with Other Countries and International Organizations

Bhutan has been gradually expanding its diplomatic outreach. It has warm relations with Japan, which is a significant development aid partner, particularly in agriculture and infrastructure. Japan has also assisted Bhutan with early warning systems for glacial lake outburst floods. Bhutan was one of the first countries to recognize Bangladesh's independence in 1971, and the two nations share strong political and diplomatic ties, signing a preferential trade agreement in 2020.

While Bhutan does not have formal diplomatic relations with the United States or the United Kingdom, it maintains informal contact through their respective embassies in New Delhi and through Bhutan's permanent mission to the UN. The UK has an honorary consul in Thimphu. Bhutan established diplomatic relations with Israel on December 12, 2020.

Bhutan actively participates in various international organizations, including the UN and its specialized agencies like UNESCO and the WHO, the Non-Aligned Movement, and the Climate Vulnerable Forum. Its engagement reflects a commitment to global cooperation on issues such as climate change, sustainable development, and cultural preservation.

7. Military

The Royal Bhutan Army (RBA) is Bhutan's military service. It includes the Royal Bodyguard (RBG), an elite force responsible for the security of the King and the royal family, and the Royal Bhutan Police (RBP), which handles law enforcement. Membership in the RBA is voluntary, with a minimum recruitment age of 18. The standing army is estimated to number around 16,000 personnel and is trained by the Indian Army, specifically through the Indian Military Training Team (IMTRAT) stationed in Bhutan. The annual military budget is approximately 13.70 M USD, or about 1.8% of the GDP. According to the Global Firepower survey, Bhutan's armed forces are considered among the weakest globally in terms of power index.

As a landlocked country, Bhutan has no navy. It also does not have an air force or army aviation corps. For air assistance, the RBA relies on the Eastern Air Command of the Indian Air Force.

The primary mission of the RBA is to defend Bhutan's sovereignty and territorial integrity, maintain internal security, and assist in disaster relief operations. In 2003, the RBA conducted Operation All Clear, its first major military operation, to flush out Indian insurgent groups (such as ULFA, NDFB, and KLO) that had established camps in southern Bhutan. This operation was undertaken in coordination with the Indian military and was considered successful in removing the militant presence.

8. Economy

Bhutan's economy is one of the world's smallest but has experienced rapid growth in recent decades, driven significantly by its hydropower sector and strong ties with India. The national currency is the ngultrum (BTN), which is pegged at par with the Indian rupee (INR). The Indian rupee is also widely accepted as legal tender. The country's economic philosophy is guided by the principle of Gross National Happiness (GNH), which seeks to balance material well-being with cultural preservation, environmental protection, and good governance.

8.1. Economic Structure and Key Indicators

Bhutan's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis was approximately 10.97 B USD in 2023, with a nominal GDP of around 2.69 B USD. The GDP per capita (PPP) was about 14.30 K USD, while the nominal per capita GDP stood at approximately 3.50 K USD. The economy saw significant growth in the mid-2000s, with rates of 8% in 2005 and 14% in 2006, and a peak of 22.4% in 2007, largely due to the commissioning of the Tala Hydroelectric Power Station.

Key economic indicators include an inflation rate estimated at around 3% in 2003. The Gini coefficient, measuring income inequality, was 28.5 in 2022, indicating a decrease in inequality. Bhutan's Human Development Index (HDI) was 0.681 in 2022, ranking it 125th globally. Unemployment rates, particularly among youth, remain a concern. Bhutan officially graduated from the Least Developed Country (LDC) category on December 13, 2023. Access to biocapacity in Bhutan is high, with 5.0 global hectares per person in 2016, significantly above the world average, indicating a biocapacity reserve.

8.2. Major Industries

Bhutan's economy is primarily based on agriculture and forestry, tourism, and the export of hydroelectric power.

8.2.1. Agriculture and Forestry

Agriculture provides the main livelihood for about 55.4% of the population, largely consisting of subsistence farming and animal husbandry. Major crops include rice (especially Bhutanese red rice, a significant export), maize, potatoes, buckwheat, barley, root crops, apples, and citrus fruits at lower elevations. Dairy products, from both yaks and cows, are also important.

Forestry is another key component, with forest cover around 71% of the total land area. The government aims for Bhutan to become the first country with 100% organic farming, though this goal has proven challenging, with only 1% of agricultural land certified organic as of 2023. Fishing in Bhutan is mainly centered on trout and carp. The environmental and social impacts of these sectors, such as sustainable land use and community benefits, are increasingly considered under the GNH framework.

8.2.2. Tourism

Tourism in Bhutan operates under a "High Value, Low Volume" (or "High Value, Low Impact") policy, aimed at minimizing the cultural and environmental impact of tourism while maximizing revenue. In 2014, Bhutan received 133,480 foreign visitors. The industry employs around 21,000 people and accounts for about 1.8% of GDP. Tourists (except citizens of India, Bangladesh, and Maldives) are required to pay a daily Sustainable Development Fee (SDF), which was 200 USD per person per day after being reduced from a higher rate in 2023 (previously, it was US$65 before a hike to US$200, then further reduced). Indian nationals pay an SDF of 1.20 K INR per day.

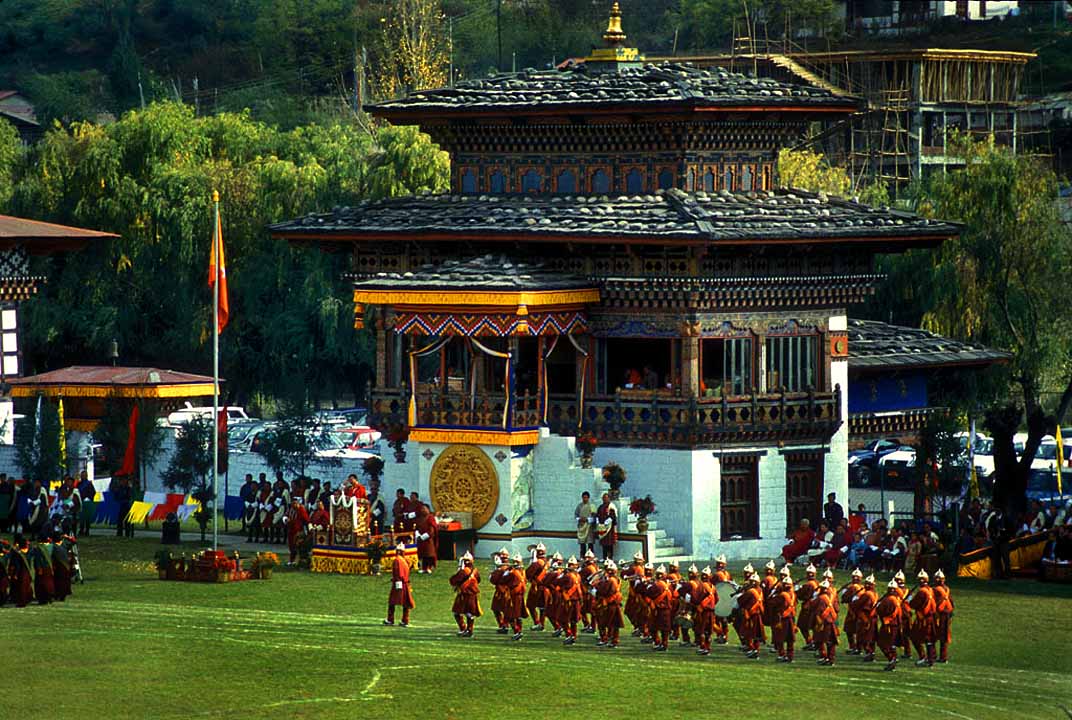

Major tourist attractions include its pristine landscapes, unique dzongs (fortress-monasteries), vibrant Buddhist culture, and festivals like Tshechu. Popular destinations include Thimphu, Paro (site of the international airport), and Punakha. The policy aims to ensure sustainable development and direct benefits to local communities, though it makes Bhutan a relatively expensive travel destination. Bhutan has eight tentative sites for UNESCO World Heritage inclusion and one element, the "Mask dance of the drums from Drametse," on the Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

8.2.3. Hydropower and Energy

Hydropower is Bhutan's largest export and a cornerstone of its economy, utilizing the country's abundant water resources from Himalayan rivers. As of 2015, Bhutan generated about 2,000 MW of hydropower and has a potential to generate up to 30,000 MW. The majority of this electricity is exported to India, providing a significant source of revenue. Major power plants include the Tala Hydroelectric Power Station (1,020 MW), Chukha (336 MW), and Kurichhu (60 MW). India, Austria, and the Asian Development Bank have provided assistance in developing these projects. Future projects are being planned with Bangladesh.

While hydropower is a clean energy source, large-scale projects can have environmental and social impacts, such as effects on river ecosystems and displacement of communities. These aspects are considered within Bhutan's GNH framework. Besides hydropower, Bhutan also has significant potential for other renewable energy sources like solar (around 12,000 MW capacity) and wind (around 760 MW capacity). Its vast forest cover also offers immense bioenergy potential.

8.2.4. Mining

Bhutan has deposits of various minerals, including coal, dolomite, gypsum, and limestone, which are commercially produced. The country also has proven reserves of beryl, copper, graphite, lead, mica, pyrite, tin, tungsten, and zinc. However, many of these mineral deposits remain largely untapped due to the government's preference for environmental conservation and the challenging mountainous terrain which makes extraction difficult and costly. The economic and environmental implications of mining are carefully weighed against the principles of Gross National Happiness.

8.2.5. Other Industries and Finance

The manufacturing sector in Bhutan is nascent, with most production coming from cottage industries. Key manufacturing activities include the production of ferroalloy, cement, metal poles, iron and non-alloy steel products, processed graphite, copper conductors, alcoholic and carbonated beverages, processed fruits, carpets, and wood products. Handicrafts, particularly weaving and religious art, are important small-scale industries.

The financial sector includes five commercial banks, with the Bank of Bhutan and the Bhutan National Bank being the largest. Other banks are the Bhutan Development Bank, T-Bank, and Druk Punjab National Bank. Non-banking financial institutions include the Royal Insurance Corporation of Bhutan, National Pension and Provident Fund (NPPF), and Bhutan Insurance Limited (BIL). The Royal Monetary Authority of Bhutan (RMA) serves as the central bank, and the Royal Securities Exchange of Bhutan is the main stock exchange. The SAARC Development Fund is based in Thimphu.

Bhutan has also explored emerging technologies, including cryptocurrency. The country has engaged in Bitcoin mining, leveraging its hydropower resources. As of November 2024, Bhutan reportedly held over 1.00 B USD worth of Bitcoin and aims to expand its mining capacity in partnership with international tech companies.

8.3. Transport

Bhutan's transport infrastructure is heavily influenced by its mountainous terrain, which makes construction and maintenance challenging and expensive.

The primary mode of transport is by road. The Lateral Road is Bhutan's main east-west corridor, connecting major towns like Phuentsholing in the southwest to Trashigang in the east, passing through Wangdue Phodrang and Trongsa. Spurs connect to the capital Thimphu, Paro, and Punakha. Bhutanese roads are known for safety concerns due to pavement conditions, sheer drops, hairpin turns, adverse weather, and landslides. Since 2014, road widening, particularly for the north-east-west highway from Trashigang to Dochula, has been a priority to improve travel time and efficiency, and to encourage tourism in the eastern regions.

Bhutan has no railways within its territory. However, an agreement exists with India to link southern Bhutan to the Indian Railways network by constructing an 11 mile (18 km)-long, 0.1 K in (1.68 K mm) broad-gauge rail line between Hasimara in West Bengal (India) and Gelephu in Bhutan. The planned Gelephu Green City is also intended to be linked by railway to the Indian state of Assam.

Paro Airport is the only international airport in Bhutan. The national carrier, Drukair, operates flights from Paro to regional destinations. Drukair also operates domestic flights connecting Paro Airport with Bathpalathang Airport in Jakar (Bumthang Dzongkhag), Gelephu Airport in Gelephu (Sarpang Dzongkhag), and Yongphulla Airport in Trashigang Dzongkhag on a weekly basis.

9. Society

Bhutanese society is characterized by its strong Buddhist traditions, unique cultural identity, and a focus on community well-being as encapsulated in the Gross National Happiness philosophy. It is undergoing a gradual modernization while striving to preserve its heritage.

9.1. Population Composition

As of a 2022 census, Bhutan had a population of 727,145 people. The population density is relatively low due to the mountainous terrain. Key demographic features include a median age of 24.8 years, indicating a youthful population. The sex ratio is approximately 1,070 males for every 1,000 females. Life expectancy at birth was 70.2 years in 2016 (69.9 for males and 70.5 for females). The literacy rate was around 66% as of recent estimates, with ongoing efforts to improve education access across the country. Population figures have been subject to revisions; a 2005 national census reported a population of 672,425, which was lower than some previous estimates.

9.2. Ethnic Groups

Bhutanese society is multi-ethnic. The primary ethnic groups are:

- The Ngalops (also called Ngalongs or "Western Bhutanese"): Descendants of Tibetan migrants who arrived in Bhutan from the 9th century onwards, they primarily inhabit the western and central parts of Bhutan. They introduced Tibetan Buddhism to the country and their culture is closely related to that of Tibet. The Ngalops are politically and culturally dominant, as the monarchy and many government leaders belong to this group. Dzongkha, the national language, is their native tongue.

- The Sharchops ("Eastern Bhutanese"): Considered the aboriginal inhabitants of eastern Bhutan, they are of Indo-Mongoloid origin. Their language, Tshangla (Sharchopkha), is distinct from Dzongkha. While they are the largest single ethnic group, the Ngalops have historically held more political influence. They traditionally follow the Nyingmapa school of Buddhism.

- The Lhotshampa ("Southerners"): This heterogeneous group, primarily of Nepalese ancestry, settled in the southern foothills of Bhutan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They are predominantly Hindu and speak Nepali. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, tensions arose over issues of national identity and citizenship policies, leading to the displacement of a significant number of Lhotshampas, who became refugees in Nepal. This remains a sensitive issue concerning human rights and inter-ethnic relations.

Other minority groups include indigenous communities like the Brokpas, Layaps, and Doyas, each with distinct cultures and languages. Intermarriage between groups, particularly Ngalops and Sharchops, has increased with improved transportation and communication.

9.3. Languages

The national language of Bhutan is Dzongkha, a Sino-Tibetan language spoken natively by the Ngalops in western Bhutan. It is written using the Tibetan script (locally called Chhokey). Dzongkha is taught as the national language in schools, and its use is promoted by the government to foster national unity.

English is widely spoken and serves as the medium of instruction in most schools and is commonly used in government and business.

Tshangla (or Sharchopkha) is the language of the Sharchops in eastern Bhutan and is spoken by a large number of people. It is a Tibeto-Burman language but not easily classified with Dzongkha.

Nepali, an Indo-Aryan language, is spoken by the Lhotshampa community in southern Bhutan. Historically, Nepali was taught in schools in the south, but this was discontinued in the late 1980s as part of national language policies.

Ethnologue lists 24 languages spoken in Bhutan, almost all belonging to the Tibeto-Burman family. Other minority languages include Khengkha (central Bhutan), Bumthangkha (central Bhutan), Dzalakha (east), Chocangacakha (east), Brokpakha (east), and Lhopkha (southwest). Many of these languages are not well-documented. The linguistic diversity reflects the country's varied ethnic makeup and geographical isolation of different communities.

9.4. Religion

According to 2020 data from the Pew Research Center, the religious composition of Bhutan was approximately: Buddhism (74.7%), Hinduism (22.6%), Bon (1.9%), Christianity (0.5%), and other religions (0.3%).

The state religion of Bhutan is Vajrayana Buddhism, specifically the Drukpa Kagyu school, which is followed by an estimated 75% of the population. Buddhism deeply influences the country's culture, traditions, laws, and daily life. The Je Khenpo is the chief religious hierarch and head of the monastic body. Monasteries (dzongs and lhakhangs) are central to community life.

Hinduism is the second-largest religion, practiced by about 22.6% of the population, primarily the Lhotshampa community in southern Bhutan.

Bon, an indigenous animistic and shamanistic belief system that predates Buddhism in the Himalayas, is practiced by a small minority (around 1.9%), often syncretized with Buddhist practices.

Christianity and Islam are practiced by very small minorities (less than 1% combined).

The Constitution of Bhutan guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. However, proselytism by non-Buddhist religions is restricted by law. Religious institutions and personalities play a significant role in society, and the government actively promotes the preservation of Bhutan's spiritual heritage. There have been concerns raised by international organizations regarding the rights of religious minorities, particularly in the context of restrictions on public practice and construction of non-Buddhist places of worship.

9.5. Education

Bhutan's education system has undergone significant development since the mid-20th century. Historically, education was primarily monastic, focusing on Buddhist philosophy and scriptures. Secular education was introduced in the 1960s with the establishment of modern schools.

The government provides free primary education. English is the medium of instruction in most schools, while Dzongkha is taught as the national language. The literacy rate has improved considerably, though challenges remain, particularly in remote areas due to the mountainous terrain.

Higher education institutions include the Royal University of Bhutan (RUB), a decentralized university with several constituent colleges spread across the country, offering programs in various fields. The Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan (KGUMSB) focuses on health sciences.

The first Five-Year Plan provided for a central education authority, established in 1961. The Asian Development Bank has supported staff training, development, and infrastructure. Teachers from India, particularly from Kerala, have historically played a significant role, especially in remote areas. In 2018 and 2019, Bhutan honored retired Indian teachers for their contributions. Currently, there are still Indian teachers placed in schools across Bhutan.

Current educational challenges include improving the quality of education, reducing dropout rates, enhancing vocational training to address youth unemployment, and ensuring equitable access for all children, including those in remote regions and those with disabilities.

9.6. Health and Welfare

Bhutan has made significant strides in improving healthcare, guided by the principle of providing free and universal access to basic health services as mandated by the Constitution. The national healthcare system is primarily government-funded and includes a network of hospitals, Basic Health Units (BHUs), and outreach clinics.

Key health indicators have shown considerable improvement. Life expectancy has increased, and infant and maternal mortality rates have significantly declined. Immunization coverage is high. Traditional Bhutanese medicine (Sowa Rigpa) is integrated into the national healthcare system and is practiced alongside modern medicine, with traditional medicine units available in many hospitals.

Major health challenges include non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension, diabetes, and cancer, which are on the rise due to changing lifestyles. Communicable diseases like tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS also remain public health concerns, though control programs are in place. Mental health is an emerging area of focus.

Social welfare programs are developing. The government provides support for vulnerable groups, and the concept of community solidarity plays a strong role in social support. The National Pension and Provident Fund (NPPF) provides retirement benefits for formal sector employees.

9.7. Status of Women

The status of women in Bhutan is characterized by a mix of traditional matrilineal customs in some communities and patriarchal influences in others, alongside ongoing efforts towards gender equality. Traditionally, in some Bhutanese communities, inheritance, particularly of land and property, can pass through the female line, with daughters often inheriting the parental home. This is partly due to the belief that daughters will care for aging parents.

However, decision-making power within the household may still rest with men. Love marriages are becoming more common, especially in urban areas, though arranged marriages persist in rural regions. Polygamy is legally accepted but uncommon, often historically used to keep property within a family unit. The previous king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, had four wives who are sisters. The current king, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, is in a monogamous marriage.

Women's participation in the workforce is relatively high for the region, but they are often concentrated in agriculture and lower-paid or insecure jobs. The gender pay gap persists. Female literacy rates and educational attainment have improved significantly.

In politics, women's representation has been traditionally low, but there is a gradual increase in women holding leadership positions. Bhutan elected its first female Dzongda (District Administrator) in 2012 and its first female minister, Dorji Choden, in 2013. The National Commission for Women and Children (NCWC), established in 2004, works to promote and protect the rights of women and children and advocate for gender equality.

Access to reproductive health services has improved, leading to a significant drop in maternal mortality rates and an increase in contraceptive use. However, challenges such as domestic violence and the need for greater economic empowerment for women remain.

9.8. Major Cities

Bhutan is predominantly rural, but urbanization is gradually increasing. The major urban centers serve as administrative, commercial, and cultural hubs.

- Thimphu: The capital and largest city of Bhutan, located in the western part of the country. It is the political, economic, and cultural heart of Bhutan. Thimphu is unique as one ofthe few world capitals without traffic lights (intersections are managed by police officers). Major landmarks include the Tashichho Dzong (the seat of government), the National Memorial Chorten, and numerous monasteries. Population: Approximately 114,551 (2017 Census).

- Phuentsholing: Located in southern Bhutan, on the border with India, Phuentsholing is the main commercial hub and a major gateway for trade with India. It has a more tropical climate and a bustling atmosphere compared to other Bhutanese towns. Population: Approximately 27,658 (2017 Census).

- Paro: Situated in a fertile valley in western Bhutan, Paro is home to Paro Airport, the country's only international airport. It is known for its historical sites, including the iconic Taktsang Monastery (Tiger's Nest), Rinpung Dzong, and the National Museum of Bhutan. Population: Approximately 11,448 (2017 Census).

- Punakha: The former capital of Bhutan until 1955, Punakha is located at the confluence of the Pho Chhu and Mo Chhu rivers. It is renowned for the majestic Punakha Dzong, one of the most beautiful and historically significant dzongs in the country, which serves as the winter residence of the Je Khenpo and the central monastic body. Population: Approximately 6,262 (2017 Census).

- Gelephu: A town in southern Bhutan (Sarpang District), located near the Indian border. It is developing as another commercial center and has a domestic airport. Population: Approximately 9,858 (2017 Census).

- Jakar: The administrative headquarters of Bumthang District in central Bhutan, often referred to as the cultural heartland of the country. It is known for its numerous ancient temples and monasteries, including Jambay Lhakhang and Kurjey Lhakhang. Population: Approximately 6,243 (2017 Census).

- Samdrup Jongkhar: Located in southeastern Bhutan, bordering the Indian state of Assam. It is an important commercial town and entry/exit point for eastern Bhutan. Population: Approximately 9,325 (2017 Census).

- Mongar: The main town of eastern Bhutan, serving as a commercial and administrative center for the region. Population figures vary but it is a key urban area in the east.

- Trashigang: The administrative headquarters of Trashigang District, the most populous district in the country, located in eastern Bhutan. It is an important market town.

10. Culture

Bhutan possesses a rich and unique cultural heritage that has remained largely intact due to its historical isolation from the rest of the world until the mid-20th century. This distinct culture, deeply steeped in Vajrayana Buddhism, is a primary attraction for tourists and a cornerstone of the nation's identity. The government actively promotes the preservation of traditions through policies guided by the philosophy of Gross National Happiness. Bhutan is often referred to as "The Last Shangri-La" due to its unspoiled natural environment and cultural heritage. The societal structure has traditional feudal elements, and social status can be indicated by attire. In Bhutanese families, inheritance patterns can be matrilineal, with daughters sometimes inheriting the parental home, though this varies. While love marriages are common in urban areas, arranged marriages persist in rural regions. Polygamy is legally accepted but rare.

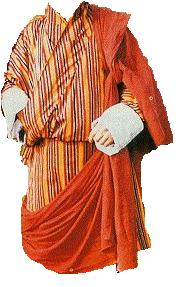

10.1. Traditional Dress

The national dress is an important aspect of Bhutanese identity. For men, it is the gho, a knee-length robe tied at the waist by a cloth belt known as the kera. For women, the national dress is the kira, an ankle-length dress made from a rectangular piece of cloth. It is clipped at the shoulders with two identical brooches called koma and tied at the waist with a kera. Underneath the kira, women wear a long-sleeved blouse called a wonju. A long-sleeved, jacket-like garment known as a toego is worn over the kira. The sleeves of the wonju and tego are folded together at the cuffs, inside out.

The textures, colors, and decorations of the garments often signify social status and class. Bhutanese law requires all government employees to wear the national dress at work, and all citizens are expected to wear it when visiting schools, government offices, and during formal occasions and festivals. Colorful scarves, known as kabney for men and rachu for women, are also important indicators of social standing and are worn on formal occasions. The color of the kabney signifies the wearer's rank or status; for instance, a saffron kabney is worn by the King and the Je Khenpo, while ordinary citizens wear white kabneys. The "Bura Maap" (Red Scarf), accompanied by the title of Dasho, is one of the highest honors a Bhutanese civilian can receive from the King for outstanding service to the nation.

10.2. Architecture

Bhutanese architecture is distinctive and traditional, characterized by the use of rammed earth, wattle and daub construction, stone masonry, and intricate woodwork, especially around windows and roofs. A unique feature is that traditional architecture uses no nails or iron bars in construction.

The most iconic architectural form is the dzong, a type of castle-fortress. Since ancient times, dzongs have served as the religious, military, administrative, and social centers of their districts. They typically house administrative offices, a monastery, and temples. Other traditional structures include lhakhangs (temples) and rural houses, which often feature brightly painted wooden window frames, small arched windows, and sloping roofs. Bhutanese law mandates that all buildings, including new constructions, adhere to traditional architectural styles to preserve the country's aesthetic and cultural heritage. The University of Texas at El Paso in the United States has notably adopted Bhutanese architectural styles for its campus buildings.

10.3. Cuisine

Bhutanese cuisine prominently features chili peppers, which are considered a vegetable rather than just a spice. The national dish is ema datshi, a spicy stew made with chili peppers and locally produced cheese. Rice, particularly red rice (a medium-grain variety that is nutty in flavor and slightly sticky when cooked), is a staple, along with buckwheat and increasingly, maize.

The diet also includes pork, beef, yak meat, chicken, and lamb. Soups and stews made from meat and dried vegetables, generously spiced with chilies and cheese, are common. Dairy foods, especially butter and cheese from yaks and cows, are widely consumed; much of the milk produced is turned into these products.

Popular beverages include suja (butter tea, made with tea leaves, yak butter, and salt), black tea, and locally brewed alcoholic drinks such as ara (a traditional spirit distilled from rice, maize, millet, or wheat) and beer.

10.4. Arts and Performances

Traditional Bhutanese arts, known as Zorig Chusum (the thirteen traditional crafts), are highly valued and include thangka painting (religious scroll paintings), sculpture, woodworking, calligraphy, paper-making, bronze casting, embroidery, and weaving. These arts are deeply intertwined with Buddhist philosophy and iconography.

Bhutanese music includes traditional genres like zhungdra (classical folk music) and boedra (a more courtly style), as well as modern rigsar, which emerged in the early 1990s and incorporates electronic keyboards and influences from Indian popular music.

Masked dances, known as Cham, are a significant part of religious festivals (Tshechus). Dancers wearing colorful wooden or composite face masks and elaborate costumes depict deities, demons, animals, and historical figures, often re-enacting religious stories and moral tales. These dances are usually accompanied by traditional music played on instruments like cymbals, drums, and horns. They are performed by both monks and laypeople and serve as a form of religious instruction and meditation.

10.5. Sports

The national sport of Bhutan is archery (Datshe). It is an integral part of Bhutanese culture and is played with unique rules and traditions. Competitions are held regularly in most villages and are social events, often involving entire communities with food, drink, singing, and dancing. Unlike Olympic archery, Bhutanese archery targets are small and placed at a distance of over 328 ft (100 m). Teams shoot from one end of the field to the other, and distracting opponents with jeers and jokes is common.

Another popular traditional sport is khuru (darts), where players throw heavy wooden darts with a 3.9 in (10 cm) nail point at a small, paperback-sized target placed 33 ft (10 m) to 66 ft (20 m) away. Digor is another traditional sport resembling shot put and horseshoe throwing.

Football (soccer) has gained significant popularity, especially among the youth. In 2002, Bhutan's national football team played Montserrat in a match famously dubbed "The Other Final", held on the same day as the FIFA World Cup final; Bhutan won 4-0. Cricket has also become popular, largely due to television broadcasts from India. The Bhutan national cricket team is an affiliate member of the International Cricket Council. Taekwondo is also practiced, with Bhutanese athletes participating in international competitions.

10.6. Public Holidays and Festivals

Bhutan observes numerous public holidays, many of which are linked to traditional, seasonal, secular, or religious events. These include the winter solstice (around January 1st, varying with the lunar calendar), Losar (Tibetan New Year, in February or March), the King's Birthday, the Coronation Anniversary of the King, the official end of the monsoon season (Blessed Rainy Day, around September 22nd), and National Day (December 17th, commemorating the establishment of the monarchy in 1907).

Religious festivals, particularly Tshechus, are major cultural events held annually in various regions and dzongs. Tshechus are dedicated to Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava) and feature elaborate masked dances (Cham dances), religious rituals, and social gatherings. These festivals typically last for several days and attract large crowds, providing opportunities for spiritual merit, community bonding, and the display of traditional arts and crafts. Hindu festivals like Dashain are also celebrated, particularly by the Lhotshampa community.

11. Human Rights

Bhutan's human rights record has seen improvements with its transition to democracy, but several issues remain, particularly concerning minority rights, freedom of expression, and the treatment of refugees. The government's commitment to Gross National Happiness includes good governance, which implicitly involves upholding human rights, yet challenges persist in practice. Freedom House rates Bhutan as "Partly Free."

The Constitution of Bhutan guarantees fundamental rights, including freedom of speech, religion, and assembly. However, there are laws that can restrict these freedoms, such as provisions against proselytism by religions other than Buddhism and laws related to national security and social harmony. Media freedom is developing, with private media outlets operating alongside state-run media, but self-censorship can be a factor.

Bhutan's parliament decriminalized homosexuality in 2020 by amending the penal code, a significant step for LGBT rights.

The status of women in Bhutan is evolving, with increased participation in education and the workforce. However, women remain underrepresented in political leadership and certain economic sectors. The government has established the National Commission for Women and Children to address gender equality and child protection issues.

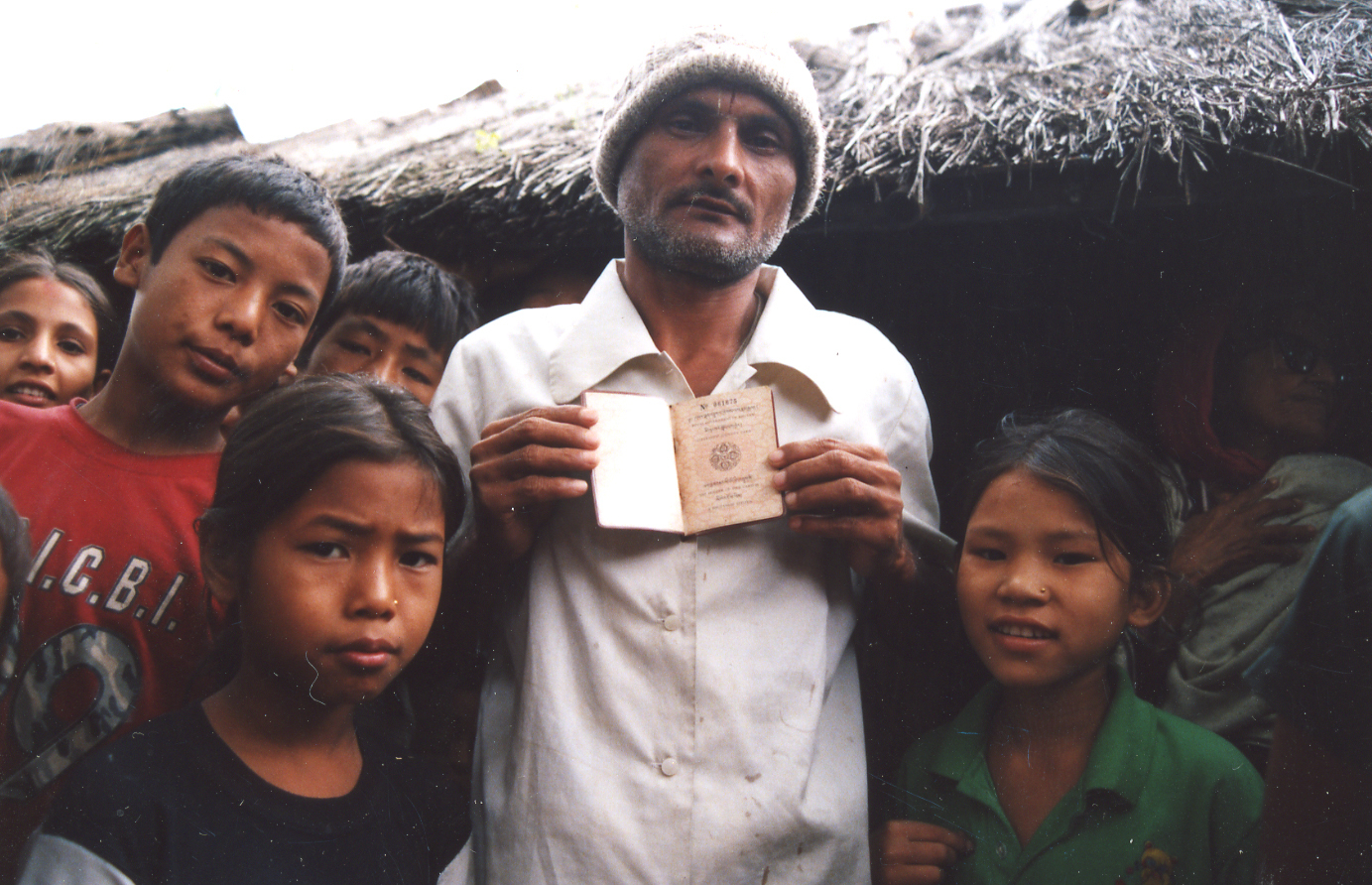

The most significant human rights concern for Bhutan has been the Lhotshampa issue and the resulting refugee crisis.

11.1. Lhotshampa Issue and Refugees

The Lhotshampa (meaning "southerners" in Dzongkha) are Bhutanese citizens of Nepali origin who predominantly inhabit the southern foothills of Bhutan. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Bhutanese government implemented "One Nation, One People" policies aimed at strengthening a national identity based on Ngalop Drukpa culture and the Dzongkha language. These policies included the enforcement of a national dress code (Driglam Namzhag), the promotion of Dzongkha as the sole national language (discontinuing Nepali in schools), and stricter citizenship laws, particularly the 1985 Citizenship Act. A census conducted in 1988 in southern Bhutan was used to identify individuals deemed to be illegal immigrants.

These policies led to widespread discontent and protests among the Lhotshampa community, who felt their cultural identity and civil rights were being suppressed. The government viewed these protests as a threat to national unity and security, fearing a repeat of events in Sikkim where Nepali immigration had significantly altered the demographics and political landscape. The situation escalated, with reports of human rights violations by Bhutanese security forces, including arbitrary arrests, detentions, torture, and forced evictions. Some Lhotshampas were also accused of engaging in violent activities.

As a result, tens of thousands of Lhotshampas (estimates range from 80,000 to over 100,000, approximately one-sixth of Bhutan's population at the time) fled or were expelled from Bhutan, becoming refugees in eastern Nepal. They were housed in refugee camps managed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) for nearly two decades. Bilateral talks between Bhutan and Nepal to resolve the refugee crisis failed to achieve repatriation for most.

From a human rights and social justice perspective, the Lhotshampa issue represents a period of significant suffering and displacement. International human rights organizations criticized Bhutan for ethnic discrimination and the denial of citizenship rights. The Bhutanese government has maintained that those who left were either illegal immigrants or had voluntarily emigrated.

Starting in 2007, a third-country resettlement program was initiated, with countries like the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and several European nations accepting the majority of the Lhotshampa refugees from the camps in Nepal. While resettlement has provided a solution for many, issues related to family reunification, the right to return for those wishing to, and reconciliation remain. The Lhotshampa issue continues to be a sensitive topic in Bhutan and affects its international image regarding human rights and the treatment of minorities. Within Bhutan, discussions around this period are often muted, but it remains a critical point in the nation's modern history and its journey towards democratic development and social inclusion.