1. Overview

Tajikistan, officially the Republic of Tajikistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. It is characterized by its predominantly mountainous terrain, with the Pamir Mountains covering over 90% of its territory, influencing its geography, climate, and culture. Historically, the region has been a crossroads of civilizations, from ancient Bactrian and Sogdian cultures through the Samanid Empire, which played a vital role in shaping Tajik identity, to periods under Russian and Soviet rule. Tajikistan declared independence in 1991 following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, an event quickly followed by a devastating civil war that lasted from 1992 to 1997.

The post-war era has seen efforts towards political stabilization under President Emomali Rahmon, who has been in power since 1994. However, his long-term rule is widely viewed as authoritarian, with significant concerns regarding human rights, suppression of political opposition, and limitations on freedom of the press and freedom of religion. These issues cast a shadow on the country's democratic development.

Economically, Tajikistan is one of the poorest countries in the former Soviet bloc, heavily reliant on remittances from migrant workers (primarily in Russia), agriculture (notably cotton), and aluminum production. Drug trafficking from neighboring Afghanistan also presents a significant challenge. The country faces social issues related to poverty, access to education and healthcare, and the rights of ethnic minorities and women. Tajik culture, with deep roots in Persian traditions, is expressed through its language (Tajik, a dialect of Persian), literature, music, and festivals like Nowruz. This article explores these aspects, focusing on the social impacts of historical and contemporary developments and the ongoing challenges related to human rights and democratic progress, reflecting a center-left, social liberalism perspective.

2. Etymology

The name Tajikistan means "Land of the Tajiks." The suffix "-stan" is Persian for "place of" or "country," and Tajik is the name of the primary ethnic group.

The term "Tajik" itself is believed to derive ultimately from the Middle Persian Tāzīk, which was the Turkic interpretation of the Arabic ethnonym Ṭayyi'. This term denoted a large Qahtanite Arab tribe that migrated to the Transoxiana region of Central Asia in the 7th century AD.

Before 1991, Tajikistan was commonly spelled as Tadjikistan or Tadzhikistan in English. This variation arose from the transliteration of its Russian name, ТаджикистанTadzhikistanRussian. In Russian, the phoneme /dʒ/ (as in "judge") is represented by the digraph джdzhRussian, as there is no single letter for this sound. Tadzhikistan remains an alternative spelling found in English literature derived from Russian sources. The spelling "Tadjikistan" is also seen, influenced by French transliteration. In the Perso-Arabic script, Tajikistan is written as تاجیکستانTājīkestānPersian.

The Library of Congress's 1997 Country Study of Tajikistan noted the difficulty in definitively stating the origins of the word "Tajik" due to its entanglement in 20th-century political disputes regarding whether Turkic or Iranic peoples were the original inhabitants of Central Asia. However, scholarly consensus suggests that contemporary Tajiks are descendants of the Eastern Iranic inhabitants of the region, particularly the Sogdians and Bactrians, and possibly other groups.

Historian Richard Nelson Frye highlighted the complexity of the Tajiks' historical origins, stating in 1996 that various factors contributed to the evolution of the peoples whose remnants are the Tajiks. He emphasized that the peoples of Central Asia, whether Iranic or Turkic-speaking, share a common culture, religion, social values, and traditions, with language being the primary differentiator.

The Encyclopædia Britannica describes the Tajiks as direct descendants of Iranic peoples whose continuous presence in Central Asia and northern Afghanistan dates back to the middle of the first millennium BC. Their ancestors formed the core of the ancient populations of Khwarazm (Khorezm) and Bactria, which were part of Transoxiana (Sogdiana). Over time, the Eastern Iranic dialect used by ancient Tajiks evolved into the modern Tajiki Persian.

A popular domestic theory in Tajikistan suggests that "Tajik" relates to the Persian word تاجtājPersian, meaning "crown." In this interpretation, "Tajikistan" would mean "land of the crowned people," though this is not the scholarly consensus on the etymology.

3. History

The history of Tajikistan encompasses ancient civilizations, periods under various empires, Russian and Soviet domination, and the challenges of post-Soviet independence, including a devastating civil war and the subsequent establishment of a government whose commitment to democratic principles and human rights remains a significant concern.

This section covers the major historical periods from ancient times to the present day, focusing on the socio-political developments and their impact on the Tajik people.

3.1. Ancient and Early Medieval Period

Cultures in the region of present-day Tajikistan date back to at least the fourth millennium BC. Notable prehistoric cultures include the Bronze Age Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC, also known as the Oxus civilization) and the Andronovo culture. The pro-urban site of Sarazm, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, stands as a testament to early settlements in the area.

Around 500 BC, most of what is now Tajikistan became part of the Achaemenid Empire. Some historians suggest that in the 7th and 6th centuries BC, parts of the region, including territories in the Zeravshan Valley, were associated with the Kambojas before Achaemenid rule.

Following Alexander the Great's conquest of the Achaemenid Empire in the 4th century BC, the region became part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander's empire. Northern Tajikistan, including the cities of Khujand and Panjakent, was part of Sogdia, a collection of city-states. Around 150 BC, Sogdia was overrun by Scythian and Yuezhi nomadic tribes. The Silk Road passed through this region, and after the expedition of Chinese explorer Zhang Qian during the reign of Emperor Wudi (141 BC-87 BC), commercial relations between the Han Empire and Sogdiana flourished. Sogdians played a significant role in facilitating trade and were also known as farmers, carpet weavers, glassmakers, and woodcarvers.

The Kushan Empire, formed by Yuezhi tribes, took control of the region in the first century AD and ruled until the fourth century AD. During this period, Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Manichaeism were practiced in the region. Subsequently, the Hephthalite Empire, another group of nomadic tribes, moved into the area.

In the 7th century AD, Arab armies began the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana, leading to the gradual Islamization of the region by the 8th century. Despite resistance, Islam eventually became the dominant religion, profoundly shaping the cultural and social fabric of the area that would become Tajikistan.

3.2. Samanid Empire

The Samanid Empire (819-999 AD) marked a significant period in the history of the Tajik people and is often considered a golden age for Persian culture and identity in Central Asia. The Samanids, an Iranian dynasty of Sogdian origin, restored Persian control over the region after Arab rule and played a crucial role in the development of Tajik national consciousness. Their empire was centered in Khorasan and Transoxiana, and at its zenith, encompassed modern-day Afghanistan, large parts of Iran, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and parts of Kazakhstan and Pakistan.

The Samanid state was founded by four brothers: Nuh, Ahmad, Yahya, and Ilyas, each ruling territories under Abbasid suzerainty. In 892, Ismail Samani (ruled 892-907) united the Samanid state under a single ruler, effectively ending the feudal system previously used by the Samanids. It was under Ismail Samani that the Samanids achieved de facto independence from Abbasid authority, though they continued to formally recognize the Caliph.

The Samanids were patrons of Persian language and literature, science, and art. Their capital, Bukhara, along with Samarkand, became major cultural centers of the Islamic world. Figures like Rudaki, often considered the father of Persian poetry, and Avicenna (Ibn Sina), a renowned philosopher and physician, flourished during or shortly after the Samanid era, laying foundations for a rich intellectual heritage. The Samanids promoted the use of New Persian (which developed into modern Tajik and Dari) written in the Arabic script as the language of administration and literature, contributing significantly to its standardization and spread.

This period is viewed by modern Tajiks as a cornerstone of their national identity, with Ismail Samani revered as a national hero. The currency of Tajikistan, the somoni, is named after him, and the highest mountain in Tajikistan is Ismoil Somoni Peak. The Samanid legacy emphasizes the deep historical and cultural connections of Tajiks to Persian civilization and their role in the Islamic Golden Age.

The decline of the Samanid Empire began in the late 10th century due to internal strife and pressure from rising Turkic powers.

3.3. Late Medieval and Early Modern Period

Following the decline of the Samanid Empire at the end of the 10th century, the territory of modern Tajikistan experienced centuries of rule by various Turkic and Mongol dynasties, significantly altering the political and ethnic landscape of Central Asia while Persian culture and language continued to exert influence.

The Kara-Khanid Khanate, a Turkic confederation, conquered Transoxiana, including Samanid territories, around 999 AD and ruled until 1211. Their arrival marked a definitive shift from Iranian to Turkic predominance in Central Asia, although the Kara-Khanids gradually assimilated into the Perso-Arab Muslim culture of the region.

In the early 13th century, the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan swept through Central Asia. The Mongols invaded the Khwarazmian Empire, which had controlled the region, sacking major cities like Bukhara and Samarkand, leading to widespread destruction and loss of life. This conquest brought the region under Mongol rule, which significantly impacted its social and political structures.

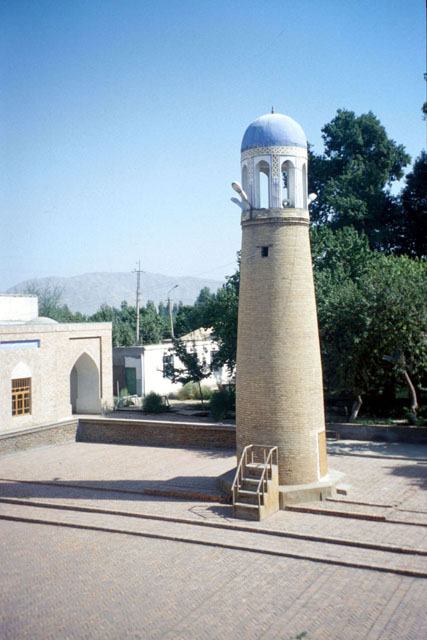

After the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire, the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) founded the Timurid Empire in the late 14th century. Centered in Samarkand, Timur's empire included much of modern Tajikistan. The Timurid period, particularly under Timur's successors like Ulugh Beg, saw a flourishing of arts, architecture, and science, known as the Timurid Renaissance. Magnificent mosques, madrasahs, and observatories were built, reflecting a blend of Persian and Turkic cultural traditions.

By the 16th century, the region that would become Tajikistan fell under the rule of the Khanate of Bukhara, established by the Shaybanids, an Uzbek dynasty. The Khanate of Bukhara, and later the Emirate of Bukhara which succeeded it in the 18th century, controlled much of Transoxiana for several centuries. During this period, Tajik populations were primarily agriculturalists and artisans living in oasis towns and mountain valleys, often under Uzbek political domination. The Khanate of Kokand, another Uzbek state, also controlled parts of what is now northern Tajikistan. Persian remained an important language of culture and administration, but Turkic languages gained increasing prominence in political life. Society remained largely feudal, with local khans and emirs exercising considerable power, often leading to internal conflicts and instability. These conditions persisted until the Russian conquest in the 19th century.

3.4. Russian Imperial Era

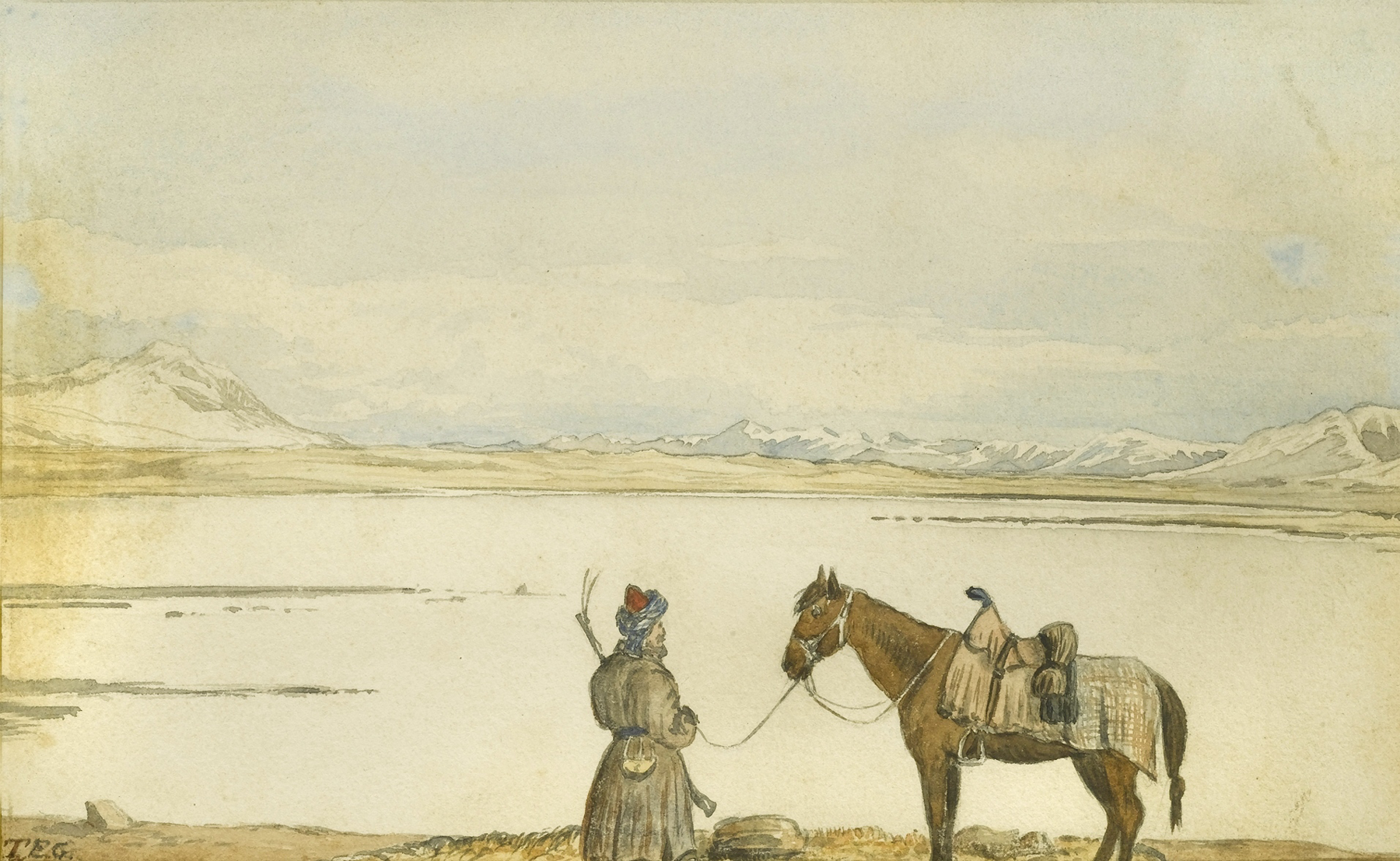

The 19th century marked a pivotal period for Central Asia, including the territories of modern Tajikistan, as the Russian Empire expanded its influence and control over the region, a process intertwined with the geopolitical rivalry known as "The Great Game" between Russia and the British Empire.

The Russian conquest of Turkestan occurred primarily between 1864 and 1885. The lands inhabited by Tajiks, which were largely under the Emirate of Bukhara and the Khanate of Kokand, gradually fell under Russian sway. While the Khanate of Kokand was directly annexed by Russia, the Emirate of Bukhara became a Russian protectorate in 1868, retaining nominal autonomy in internal affairs but ceding control over foreign policy and defense to Russia. Eastern Bukhara, which included much of present-day southern and central Tajikistan, remained part of this protectorate.

Russia's interest in the region was multifaceted. Economically, access to cotton was a major driver. Russian authorities encouraged and later, during the Soviet era, enforced the cultivation of cotton, often at the expense of food crops, to supply Russian textile industries. This policy had long-term social and ecological consequences for the region.

The imposition of Russian rule brought some changes to the traditional society. While Russian influence was initially limited in many remote Tajik areas, particularly in the mountains, the period saw the beginnings of modern infrastructure, such as telegraph lines and some new roads, although these primarily served Russian administrative and military needs.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Jadidist movement emerged among Central Asian intellectuals, including some Tajiks. Jadidism advocated for the modernization of Islamic education and society, promoting literacy, science, and national identity. While Jadidists were generally pro-modernization and not necessarily anti-Russian, their reformist ideas and emphasis on local culture were sometimes viewed with suspicion by the Tsarist authorities, who were wary of any movement that could challenge their control or foster pan-Turkic or pan-Islamic sentiments.

Resistance to Russian rule did occur, though often localized. For instance, uprisings against the Khanate of Kokand between 1910 and 1913 required Russian military intervention. In July 1916, widespread discontent over a Tsarist decree for the conscription of Central Asians for labor duties during World War I led to the Central Asian Revolt. In Khujand, demonstrators attacked Russian soldiers, leading to violent clashes. Although Russian troops suppressed the revolt in Khujand, unrest continued in various parts of Tajikistan, reflecting underlying tensions against colonial rule and its exactions on the local population. The Russian Imperial era laid the groundwork for the profound transformations that would occur under Soviet rule.

3.5. Soviet Period

The Soviet period, spanning from the aftermath of the Russian Revolution to 1991, dramatically reshaped the political, social, economic, and cultural landscape of Tajikistan.

Following the revolution, Central Asia became a battleground. The Basmachi movement, a guerrilla uprising composed of various local groups, including Tajiks, fought against Bolshevik armies in an attempt to resist Soviet control and maintain independence. The Bolsheviks ultimately prevailed after a brutal four-year war (roughly 1918-1922, with some resistance continuing later), during which villages were burned and the population faced severe repression. This conflict had a devastating impact on the local population and economy.

In 1924, as part of the Soviet national delimitation policy in Central Asia, the Tajik Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Tajik ASSR) was created as a part of the Uzbek SSR. This was a significant moment in the formation of a modern Tajik national identity, though the drawing of borders was contentious. Notably, the historically Persian-speaking cities of Samarkand and Bukhara, with large Tajik populations, were included in the Uzbek SSR, a decision that remains a point of sensitivity for some Tajiks. In 1929, the Tajik ASSR was upgraded to a full constituent republic, the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic (Tajik SSR).

The Soviet era brought about radical socio-economic changes. Between 1927 and 1934, the Soviet government implemented agricultural collectivization and a massive expansion of cotton production, particularly in the southern regions. This policy involved dispossessing wealthier peasants (kulaks) and forcing others onto collective farms (kolkhozes). Collectivization was met with resistance, leading to violence, destruction of livestock, and the revival of the Basmachi movement in some areas. Forced resettlement of populations also occurred. Combined with agricultural mismanagement, these policies contributed to famines in Central Asia, including Tajikistan.

Simultaneously, an anti-religious campaign was launched. Islamic practices, as well as other religions, were suppressed. Many mosques, madrasas, and religious courts were closed, and religious leaders were persecuted. This secularization drive aimed to replace religious identity with Soviet ideology, though Islamic traditions persisted, often practiced covertly.

The 1930s were marked by Stalin's purges. Two major rounds of purges (1927-1934 and 1937-1938) resulted in the expulsion and execution of thousands from all levels of the Communist Party of Tajikistan, including many early Tajik nationalist intellectuals and political figures. Ethnic Russians were often sent to replace those purged, leading to Russian domination in party and administrative positions for much of the Soviet period. The proportion of Russians in Tajikistan's population grew from less than 1% in 1926 to 13% by 1959.

During World War II, Tajiks were conscripted into the Red Army. Around 260,000 Tajik citizens fought against Nazi Germany and its allies. Estimates of Tajik casualties range from 60,000 to 120,000, a significant loss for a small republic. The war also saw increased industrialization efforts geared towards the war effort.

In the post-war period, efforts were made to expand agriculture and industry. The Virgin Lands Campaign under Nikita Khrushchev in the late 1950s also impacted Tajikistan, aiming to increase agricultural output. However, Tajikistan generally lagged behind other Soviet republics in terms of living standards, education, and industrial development. By the 1980s, it had the lowest household saving rate, the lowest percentage of households in top income groups, and the lowest rate of university graduates per capita in the USSR.

Despite Soviet development, which included expanded irrigation, some industrial growth, and significant improvements in literacy and healthcare access, Tajikistan remained one of the poorest and most traditional republics. Bobojon Ghafurov, First Secretary of the Communist Party of Tajikistan from 1946 to 1956, was one of the few Tajik politicians of major significance outside the republic during this era.

By the 1980s, with the advent of Glasnost and Perestroika under Mikhail Gorbachev, Tajik nationalist sentiments resurfaced, and calls for increased rights and autonomy grew. Real disturbances, however, did not occur until the Dushanbe riots of February 1990, fueled by socio-economic grievances and nationalist tensions. The following year, as the Soviet Union disintegrated, Tajikistan declared its independence on September 9, 1991.

3.6. Post-Independence

The period following Tajikistan's declaration of independence on September 9, 1991, was marked by profound political instability, a devastating civil war, and subsequent efforts towards nation-building and economic recovery under an increasingly authoritarian government. This era highlights the challenges of transitioning from Soviet rule and the deep societal divisions that emerged.

3.6.1. Declaration of Independence and Civil War

Tajikistan declared independence amidst the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The initial post-Soviet government, led by former communist elites, faced immediate challenges from a coalition of nationalist, democratic, and Islamist groups. These tensions, rooted in regional clan loyalties, ideological differences, and economic disparities exacerbated by the Soviet collapse, rapidly escalated.

In February 1990, riots and strikes in Dushanbe and other cities, initially sparked by housing shortages and youth unemployment, took on a political character. Nationalist and democratic opposition groups, along with supporters of independence and Islamist factions, joined the protests, demanding democratic reforms and greater sovereignty. The Soviet leadership deployed Internal Troops to quell the unrest.

The Tajikistani Civil War erupted in May 1992 and lasted until June 1997. The conflict pitted the government forces, dominated by figures from the Khujand and Kulob regions and supported by Russia and Uzbekistan, against the United Tajik Opposition (UTO). The UTO was a diverse coalition comprising liberal democratic reformers and Islamist groups, with strongholds in the Gharm and Gorno-Badakhshan regions.

The war was characterized by extreme brutality, widespread human rights abuses, and significant civilian displacement. Estimates suggest that over 100,000 people were killed, and around 1.2 million became refugees, either internally displaced or fleeing to neighboring countries, particularly Afghanistan. The conflict caused immense economic devastation and social trauma, deeply affecting the country's development trajectory.

Emomali Rahmon (then Rahmonov) came to power in November 1992, replacing President Rahmon Nabiyev, who was forced to resign at gunpoint in September 1992. Rahmon, originally from the Kulob region, consolidated his power with Russian military backing. International reactions to the war were mixed, with Russia playing a key role in both supporting the government and eventually brokering peace. The United Nations also became involved in mediation efforts.

The war officially ended with the signing of the General Agreement on Peace and National Accord in Moscow in June 1997. This agreement, brokered by the UN and with significant Russian and Iranian involvement, provided for the UTO's integration into the government, guaranteeing them 30% of ministerial positions, and paved the way for disarmament and the return of refugees. The successful conclusion of the peace agreement was seen as a notable UN peacekeeping achievement, though the implementation faced numerous challenges.

3.6.2. Post-Civil War and 21st Century

Following the end of the Tajikistani Civil War in 1997, Tajikistan embarked on a path of political stabilization and economic reconstruction, but this period has also been characterized by the consolidation of power under President Emomali Rahmon and persistent concerns about human rights and democratic development.

The peace agreement led to the formation of a coalition government, but President Rahmon gradually marginalized former UTO members and strengthened his grip on power. A presidential election was held in November 1999, which Rahmon won with 98% of the vote amidst criticism from opposition parties and international observers who deemed it unfair. Subsequent elections, including the 2006, 2013, and 2020 presidential elections, have consistently returned Rahmon to office with overwhelming majorities. These elections have been widely criticized by international bodies like the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) for lacking genuine competition, failing to meet democratic standards, and being marred by irregularities. Opposition parties often boycotted these elections or faced significant obstacles to participation.

Rahmon's rule has become increasingly authoritarian. Constitutional amendments have extended presidential terms and, in 2016, a referendum removed term limits for Rahmon, effectively allowing him to be president for life, and lowered the age of presidential candidacy, potentially paving the way for his son, Rustam Emomali, to succeed him. The title "Leader of the Nation" was bestowed upon Rahmon, granting him lifelong immunity from prosecution.

The political landscape is dominated by the ruling People's Democratic Party of Tajikistan. Opposition parties face severe restrictions. The Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), once a significant opposition force and part of the post-war government, was banned in 2015 after being declared a terrorist organization by the government, a move widely seen as politically motivated to eliminate dissent. Many of its leaders and members were imprisoned or forced into exile.

Human rights in Tajikistan have deteriorated significantly in the 21st century. Freedom of the press is severely curtailed, with independent media outlets facing harassment, censorship, and closure. Access to websites, including social media and news sites, is often blocked. Freedom of religion is also restricted, with the government tightly controlling religious institutions and practices, particularly Islamic ones, under the pretext of combating extremism. There have been crackdowns on unregistered religious groups, restrictions on religious education for youth, and campaigns against visible signs of Islamic piety like beards and hijabs. The treatment of political opposition figures, human rights defenders, and lawyers has been harsh, with reports of arbitrary detention, torture, and unfair trials.

Economically, Tajikistan has seen some growth, largely driven by remittances from migrant workers (mainly in Russia), foreign aid, and exports of aluminum and cotton. However, it remains one of the poorest countries in the former Soviet Union, with high unemployment and widespread poverty. Corruption is a major challenge, hindering economic development and social progress. The country is also heavily reliant on Russia both economically and for security.

Security concerns, particularly related to the unstable situation in neighboring Afghanistan and the threat of Islamic extremism, have been a prominent feature of the 21st century. In 2010, there were clashes between government forces and militants in the Rasht Valley. Colonel Gulmurod Khalimov, commander of the OMON special police unit, defected to the Islamic State in 2015, highlighting internal security vulnerabilities. Following the Taliban's takeover of Afghanistan in 2021, Tajikistan has expressed concerns about border security and potential spillover effects, and allegedly supported anti-Taliban resistance groups.

Border tensions with Kyrgyzstan have also escalated, leading to armed clashes, notably the 2021 and 2022 border conflicts, which resulted in casualties on both sides and highlighted unresolved border demarcation issues.

Despite some economic recovery and relative stability after the civil war, Tajikistan in the 21st century faces significant challenges in terms of democratic governance, human rights, economic diversification, and regional security. The long-term rule of President Rahmon has brought stability at the cost of political pluralism and fundamental freedoms, a trend that continues to draw criticism from the international community.

4. Geography

Tajikistan is a landlocked country located in the heart of Central Asia, characterized by its predominantly mountainous terrain. This section outlines its geographical features, including its topography, climate, hydrology, and ecosystems.

Tajikistan is the smallest nation in Central Asia by area, covering approximately 55 K mile2 (142.60 K km2). It lies mostly between latitudes 36° and 41° N, and longitudes 67° and 75° E. The country is bordered by Afghanistan to the south, Uzbekistan to the west, Kyrgyzstan to the north, and China to the east. A narrow strip of Afghan territory, the Wakhan Corridor, separates Tajikistan from Pakistan. Over 90% of Tajikistan's territory is covered by mountains of the Pamir, Alay, and Tian Shan ranges, with more than half the country situated at elevations exceeding 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m) above sea level.

4.1. Topography

Tajikistan's topography is dominated by some of the highest mountain ranges in the world. The Pamir Mountains, often referred to as the "Roof of the World," cover much of the eastern part of the country, particularly within the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province (GBAO). This region is home to several peaks exceeding 23 K ft (7.00 K m), including Ismoil Somoni Peak (formerly Communism Peak) at 25 K ft (7.50 K m), the highest point in Tajikistan and the former Soviet Union, and Lenin Peak (now Ibn Sina Peak) at 23 K ft (7.13 K m), located on the border with Kyrgyzstan in the Trans-Alay Range. Other significant peaks include Peak Korzhenevskaya (23 K ft (7.11 K m)) and Independence Peak (formerly Revolution Peak) at 23 K ft (6.97 K m)).

The Academy of Sciences Range and the Peter I Range are other major mountain systems within the Pamirs. The western part of the country features extensions of the Alay and Gissar ranges.

Areas of lower land are found in the north, within the southwestern part of the Fergana Valley (shared with Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan), and in the southern river valleys of the Kofarnihon and Vakhsh, which flow into the Amu Darya. The capital city, Dushanbe, is situated in the Gissar Valley on the southern slopes above the Kofarnihon River, at an elevation of around 2625 ft (800 m). Plains and lowlands are limited, constituting less than 10% of the country's total area, and are crucial for agriculture and settlement.

The mountainous terrain presents significant challenges for transportation, agriculture, and infrastructure development but also provides stunning natural beauty and valuable water resources. The country is also located in an active seismic zone, making it prone to earthquakes.

The following table lists some of the major peaks in Tajikistan:

| Mountain | Height | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Ismoil Somoni Peak (Highest) | 25 K ft (7.50 K m) | North-western edge of Gorno-Badakhshan (GBAO), south of the Kyrgyzstan border |

| Ibn Sina Peak (Lenin Peak) | 23 K ft (7.13 K m) | Northern border in the Trans-Alay Range, north-east of Ismoil Somoni Peak |

| Peak Korzhenevskaya | 23 K ft (7.11 K m) | North of Ismoil Somoni Peak, on the south bank of Muksu River |

| Independence Peak (Revolution Peak) | 23 K ft (6.97 K m) | Central Gorno-Badakhshan, south-east of Ismoil Somoni Peak |

| Academy of Sciences Range (highest point) | 22 K ft (6.79 K m) | North-western Gorno-Badakhshan, stretches in the north-south direction |

| Karl Marx Peak | 22 K ft (6.73 K m) | GBAO, near the border with Afghanistan in the northern ridge of the Shakhdara Range |

| Garmo Peak | 22 K ft (6.59 K m) | Northwestern Gorno-Badakhshan, in the Academy of Sciences Range |

| Mayakovskiy Peak | 20 K ft (6.10 K m) | Extreme south-west of GBAO, near the border with Afghanistan |

| Concord Peak | 18 K ft (5.47 K m) | Southern border in the northern ridge of the Wakhan Range |

| Kyzylart Pass (mountain pass) | 14 K ft (4.28 K m) | Northern border in the Trans-Alay Range |

4.2. Climate

Tajikistan's climate is predominantly continental, characterized by significant seasonal temperature variations, aridity in some regions, and considerable influence from its mountainous topography and high altitudes.

The lowlands, such as the southwestern valleys and parts of the Fergana Valley in the north, experience hot summers and mild winters. Summer temperatures in these areas can often exceed 104 °F (40 °C), while winter temperatures generally hover around freezing, though they can occasionally drop lower. These regions receive relatively low precipitation, typically concentrated in the winter and spring months.

In contrast, the mountainous regions, particularly the Pamirs, have a much harsher climate. At higher elevations, summers are short and cool, while winters are long, extremely cold, and snowy. Temperatures in the eastern Pamirs can plummet to below -40 °F (-40 °C) in winter. This highland climate is classified as alpine or high-altitude desert climate, with very low precipitation, often less than 3.9 in (100 mm) annually in some parts of the eastern Pamirs.

Altitude is the primary determinant of temperature and precipitation patterns across the country. Generally, temperature decreases and precipitation increases with rising elevation up to a certain point, beyond which precipitation may decrease again in very high, arid plateaus like the eastern Pamirs. The southern slopes of mountain ranges tend to receive more moisture from prevailing westerly and southwesterly air currents.

Seasonal weather patterns involve dry, hot summers and cooler, wetter winters and springs in the lower elevations. The Pamir region experiences a more prolonged winter with heavy snowfall, which feeds the country's extensive glacier systems. Dust storms can occur in the lowland plains, particularly during dry periods. The diverse climate supports a range of ecosystems but also poses challenges for agriculture, which is heavily reliant on irrigation in the arid lowlands.

4.3. Hydrology

Tajikistan possesses abundant water resources, primarily originating from its vast mountain glacier systems and snowmelt. These resources are crucial for the country's agriculture, hydropower generation, and for downstream countries in Central Asia.

Rivers: The country has over 900 rivers longer than 6.2 mile (10 km). The two main river systems are the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya.

The Amu Darya (ancient Oxus) is one of Central Asia's major rivers. Its main headwaters, the Panj River and the Vakhsh River, originate in Tajikistan's mountains. The Panj River forms a significant portion of Tajikistan's southern border with Afghanistan. The Vakhsh River, known for its hydropower potential, flows through central Tajikistan before joining the Panj to form the Amu Darya. Other important tributaries to the Amu Darya system in Tajikistan include the Kofarnihon and the Zeravshan River. The Zeravshan River, historically significant for cities like Samarkand and Bukhara (in Uzbekistan), rises in the Zeravshan Glacier in Tajikistan but largely flows westward into Uzbekistan, diminishing before reaching the Amu Darya.

The Syr Darya (ancient Jaxartes), another major Central Asian river, has some of its headwaters in northern Tajikistan, within the Fergana Valley.

Lakes: Tajikistan has numerous lakes, many of which are of glacial or tectonic origin.

- Karakul: Located in the eastern Pamirs, this is a large, brackish, endorheic lake formed in a meteorite impact crater, situated at an altitude of nearly 13 K ft (4.00 K m).

- Sarez Lake: A deep lake in the Pamirs, formed in 1911 after a massive earthquake caused a landslide (the Usoy Dam) that dammed the Murghab River. There are concerns about the stability of this natural dam.

- Iskanderkul: A scenic alpine lake of glacial origin located in the Fann Mountains in northwestern Tajikistan.

- Zorkul: A freshwater lake in the Pamirs on the border with Afghanistan, part of the Zorkul Nature Reserve.

- Artificial reservoirs created by dams, such as the Nurek Reservoir on the Vakhsh River and the Kayrakkum Reservoir (also known as the "Tajik Sea") on the Syr Darya in the north, are important for irrigation and hydropower.

Glaciers: Tajikistan is home to thousands of glaciers, concentrated in the Pamir and Alay mountains. The Fedchenko Glacier, stretching for over 43 mile (70 km), is one of the longest non-polar glaciers in the world. These glaciers are vital as they are the primary source of runoff for many of Central Asia's rivers, feeding into the Aral Sea basin. However, climate change is causing these glaciers to retreat, posing a long-term threat to water security in the region.

The country's hydrological resources are fundamental to its economy, particularly for hydropower, which is a major source of energy, and for irrigated agriculture, which is the mainstay of the rural population. Water management and transboundary water sharing with neighboring countries are significant political and environmental issues.

4.4. Ecosystems and Conservation

Tajikistan's diverse topography and climate support a range of ecosystems, from arid deserts and semi-deserts in the lowlands to temperate woodlands, alpine meadows, and high-altitude cold deserts in the mountains. The country is part of the Mountains of Central Asia biodiversity hotspot.

Ecoregions:

Tajikistan contains five major terrestrial ecoregions:

- Alai-Western Tian Shan steppe: Characterized by grasslands and shrublands in the foothills and lower mountain slopes of the north and west.

- Gissaro-Alai open woodlands: Found at mid-altitudes in western Tajikistan, these ecosystems feature open forests of juniper, pistachio, almond, and maple, interspersed with steppes and meadows. They are rich in biodiversity, including many fruit and nut tree ancestors.

- Pamir alpine desert and tundra: Dominates the high-altitude Pamir Plateau in the east. This ecoregion is characterized by sparse vegetation adapted to cold, arid conditions, including cushion plants, grasses, and sedges.

- Badghyz and Karabil semi-desert: A small area in the extreme southwest, featuring arid landscapes.

- Paropamisus xeric woodlands: Also in the southwest, with dry woodlands and shrublands.

Riparian forests, known as tugai, occur along river valleys, supporting unique flora and fauna.

Flora and Fauna:

Tajikistan is home to a rich diversity of plant and animal species, many of which are endemic or rare.

- Flora:** The country boasts over 5,000 species of vascular plants. The Gissaro-Alai region is particularly rich in wild relatives of cultivated plants, including apples, pears, walnuts, and tulips. Juniper forests (archa) are a characteristic feature of many mountain slopes.

- Fauna:** Notable mammal species include the snow leopard (a flagship species for conservation), Marco Polo sheep (argali), Siberian ibex, markhor, Eurasian lynx, brown bear, and various smaller mammals. Birdlife is also diverse, with species like the Himalayan snowcock, lammergeier (bearded vulture), and various raptors.

Environmental Issues:

Tajikistan faces several significant environmental challenges:

- Soil Degradation:** Overgrazing, deforestation (for fuel and timber), and unsustainable agricultural practices have led to soil erosion and desertification, particularly in lowland and foothill areas. Salinization of irrigated lands is also a problem.

- Water Resource Depletion and Pollution:** While water-rich overall, inefficient irrigation systems lead to water loss. Pollution from agricultural runoff (pesticides, fertilizers) and industrial/municipal waste affects water quality. The shrinking of glaciers due to climate change poses a long-term threat to water availability.

- Loss of Biodiversity:** Habitat degradation, poaching, and unsustainable resource use threaten many plant and animal species. Snow leopards, Marco Polo sheep, and other iconic species are vulnerable.

- Climate Change:** Tajikistan is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including increased frequency of extreme weather events (droughts, floods, mudflows), accelerated glacier melt, and shifts in ecosystems.

Conservation Efforts:

The government of Tajikistan has undertaken efforts to conserve its biodiversity and natural resources, often with international support.

- Protected Areas:** A network of protected areas has been established, including national parks, nature reserves (zapovedniks), and заказники (special purpose reserves). Tajik National Park (Mountains of the Pamirs), a UNESCO World Heritage Site, covers a vast area of the Pamir Mountains and is crucial for the conservation of high-altitude ecosystems and species like the snow leopard. Other important protected areas include the Tigrovaya Balka Nature Reserve (preserving unique tugai ecosystems) and the Zorkul Nature Reserve.

- Legislation and Policies:** National strategies and laws for environmental protection and biodiversity conservation have been adopted.

- International Cooperation:** Tajikistan is a signatory to various international environmental conventions, including the Convention on Biological Diversity, CITES, and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. It collaborates with international organizations like WWF, UNDP, and GEF on conservation projects.

Despite these efforts, challenges remain in effectively implementing conservation measures due to limited financial resources, institutional capacity, and pressures from economic development and poverty. Balancing conservation needs with the livelihoods of local communities is a key ongoing task.

5. Politics

Tajikistan's political system is a presidential republic, though in practice, it functions as an authoritarian state under the long-standing rule of President Emomali Rahmon. This section explores the governmental structure, key political institutions, major political issues, and the human rights situation, analyzed from a center-left/social liberalism perspective that emphasizes democratic development and social impact.

After gaining independence in 1991, Tajikistan was plunged into a devastating civil war (1992-1997) between various factions, often distinguished by regional and clan loyalties, and supported by external actors including Russia, Iran, and Afghanistan. Russia backed the pro-government faction and deployed troops to guard the Tajik-Afghan border. The war ended with a peace agreement in 1997, which initially promised power-sharing. However, President Emomali Rahmon, who came to power in 1992, gradually consolidated his authority, leading to the current political landscape characterized by limited political pluralism and significant human rights concerns.

5.1. Government Structure

The Constitution of Tajikistan establishes a government based on the principle of separation of powers, with executive, legislative, and judicial branches. However, in practice, the executive branch, led by the President, holds overwhelming power and influence over the other branches.

- Executive Branch:** The President is the head of state and holds supreme executive authority. The President appoints the Prime Minister and members of the government (Cabinet of Ministers), who are responsible for implementing laws and policies. The executive branch wields considerable control over all aspects of governance and public life.

- Legislative Branch:** The legislature is the bicameral Supreme Assembly (Majlisi Oli). It consists of the National Assembly (Majlisi Milli - upper house) and the Assembly of Representatives (Majlisi Namoyandagon - lower house). While constitutionally tasked with lawmaking and oversight, the parliament is largely dominated by the President's party and lacks genuine independence, often rubber-stamping executive decisions.

- Judicial Branch:** The judiciary comprises the Supreme Court, Constitutional Court, Supreme Economic Court, and lower courts. Judges are formally independent, but the judicial system is widely seen as lacking independence, suffering from corruption, and being susceptible to political influence from the executive branch. This significantly undermines the rule of law and access to fair trials.

5.2. President

The President of Tajikistan is the head of state and holds the most powerful position in the country. According to the constitution, the President is elected by direct popular vote. However, presidential elections have consistently been criticized by international observers as lacking genuine competition and failing to meet democratic standards.

Emomali Rahmon has been President since November 1994 (initially as Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, effectively head of state, then formally as President). His rule has been characterized by the systematic consolidation of power and the suppression of political opposition.

- Powers:** The President has extensive powers, including appointing and dismissing the Prime Minister and government members, commanding the armed forces, representing the country internationally, and issuing decrees with the force of law. The President also has significant influence over the legislative and judicial branches.

- Elections and Term Limits:** Constitutional amendments have progressively strengthened Rahmon's position. A 2003 referendum extended presidential terms, and a 2016 referendum removed term limits specifically for Emomali Rahmon, granting him the title "Founder of Peace and National Unity - Leader of the Nation" and allowing him to run for office indefinitely. The same referendum lowered the minimum age for presidential candidates, a move seen by many as paving the way for his son, Rustam Emomali, to succeed him.

- Impact on Democracy and Human Rights:** Rahmon's long-term rule has led to a significant erosion of democratic institutions and human rights. Political opposition has been marginalized or eliminated, freedom of expression and the media are severely restricted, and civil society faces increasing pressure. The concentration of power in the hands of the President and his family, along with widespread corruption, has hindered socio-economic development and good governance. Domestic and international assessments consistently rank Tajikistan low in terms of political freedoms, civil liberties, and democratic accountability. While Rahmon is credited by some for bringing stability after the civil war, this has come at the expense of fundamental democratic principles and human rights, creating an environment of fear and self-censorship.

5.3. Parliament

The Supreme Assembly (Majlisi Oli) is the bicameral parliament of Tajikistan. It is responsible for legislative functions, but its independence and effectiveness are severely limited by the dominance of the executive branch.

- Composition:**

- National Assembly (Majlisi Milli):** The upper house has 33 members. Twenty-five members are indirectly elected by local majlises (councils) from the provinces, GBAO, Dushanbe, and towns/districts of republican subordination. The remaining eight members are appointed by the President. Former presidents are ex-officio lifetime members. The term of office is five years.

- Assembly of Representatives (Majlisi Namoyandagon):** The lower house has 63 members who are directly elected for five-year terms. Forty-one members are elected from single-mandate constituencies using a first-past-the-post system, and twenty-two members are elected through a proportional representation system from a single national constituency based on party lists.

- Functions:** The primary functions of the Supreme Assembly include adopting and amending laws, approving the state budget, ratifying international treaties, and overseeing the activities of the government. The National Assembly has specific powers, such as electing and recalling judges of higher courts (upon presidential proposal) and approving presidential decrees on certain matters. The Assembly of Representatives is the main law-making body.

- Legislative Process:** Bills can be introduced by deputies, the President, the government, and other designated bodies. For a bill to become law, it generally needs to be approved by both houses and signed by the President. The President has veto power, which can be overridden by a two-thirds majority in both houses, though this rarely occurs in practice.

- Electoral System and Political Reality:** Parliamentary elections, like presidential elections, have been consistently criticized by international observers (such as the OSCE) for failing to meet democratic standards. Issues cited include a restrictive political environment, lack of genuine political competition, media bias in favor of the ruling party, irregularities in vote counting, and pressure on voters and opposition candidates. The ruling People's Democratic Party of Tajikistan, led by President Rahmon, consistently dominates the Assembly of Representatives, ensuring that the legislature largely serves to legitimize presidential policies rather than acting as an independent check on executive power. This lack of genuine parliamentary opposition significantly undermines democratic accountability and public trust in political institutions.

5.4. Major Political Parties

Tajikistan's political landscape is characterized by the dominance of the ruling People's Democratic Party of Tajikistan (PDPT) and severe restrictions on opposition parties. While the constitution allows for a multi-party system, the actual political space for genuine competition and dissent is extremely limited.

- People's Democratic Party of Tajikistan (PDPT):** This is the ruling party, chaired by President Emomali Rahmon. It was founded in 1994 and has consistently held a vast majority in parliament since the end of the civil war. The PDPT's platform officially supports national unity, stability, and socio-economic development, but it largely functions as the political vehicle for President Rahmon's administration and lacks a distinct ideology beyond supporting the incumbent. Its extensive administrative resources and control over state media give it an overwhelming advantage in elections.

- Communist Party of Tajikistan (CPT):** The successor to the Soviet-era Communist Party, the CPT was once a significant political force. While it still exists and participates in elections, its influence has waned considerably. It generally adopts a pro-government stance on most issues.

- Agrarian Party of Tajikistan (APT):** Established in 2005, the Agrarian Party primarily focuses on agricultural issues and rural development. It is generally considered loyal to the government.

- Party of Economic Reforms (PER):** Founded in 2005, this party advocates for market-oriented economic reforms. It also tends to align with the government's positions.

- Socialist Party of Tajikistan (SPT):** This party has a socialist platform but holds limited influence and is often seen as pro-government.

- Democratic Party of Tajikistan (DPT):** The DPT has a history of opposition but has faced internal splits and government pressure, significantly weakening its impact.

- Social Democratic Party of Tajikistan (SDPT):** Led by Rahmatillo Zoyirov, the SDPT is one of the few parties that has consistently attempted to offer a critical opposition voice. However, it has faced significant harassment, has been denied registration for elections at times, and holds no seats in parliament. Its activities are severely constrained.

- Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) (Banned):** Formerly the only legally registered religious party in Central Asia and a key component of the United Tajik Opposition during the civil war, the IRPT played a role in the post-war coalition government. However, it faced increasing government pressure over the years. In 2015, the party was officially banned and declared a terrorist organization by the Tajik authorities, a move widely condemned by international human rights organizations as politically motivated to eliminate the main opposition force. Many of its leaders and members were arrested, imprisoned, or forced into exile.

The suppression of genuine opposition parties, particularly the IRPT, has created an environment where meaningful political competition is virtually non-existent. The electoral influence of parties other than the PDPT is minimal, and the parliament largely consists of pro-government deputies. This situation raises serious concerns about political pluralism, freedom of association, and the overall health of democracy in Tajikistan.

5.5. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Tajikistan is a matter of grave concern, characterized by widespread abuses and a systematic crackdown on fundamental freedoms by the authoritarian government of President Emomali Rahmon. International human rights organizations and Western governments have consistently criticized the Tajik authorities for their poor record.

- Freedom of the Press and Expression:** Freedom of the press is severely restricted. Independent media outlets face harassment, politically motivated tax inspections, and closure. Journalists often practice self-censorship due to fear of reprisals. Access to online news sources, social media platforms, and websites critical of the government is frequently blocked. Defamation remains a criminal offense, and laws are used to silence critical voices. Public criticism of the president or government policies is not tolerated.

- Freedom of Religion:** While the constitution provides for freedom of religion, the government imposes significant restrictions on religious practices, particularly those related to Islam. A 2009 religion law requires religious communities to register with the state and places stringent controls on religious education, the construction of places of worship, and the import of religious literature. Unregistered religious activity is prohibited. There have been campaigns against wearing hijabs and beards, promoted as measures against "alien" cultural influences and extremism. Minors are effectively barred from public religious practice. Minority religious groups also face difficulties with registration and harassment.

- Treatment of Political Opposition:** Political opposition is systematically suppressed. The banning of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) in 2015 and the subsequent imprisonment or exile of its leadership and members effectively eliminated the main opposition force. Other opposition figures, activists, and perceived critics of the government face harassment, arbitrary detention, politically motivated charges, and unfair trials. Torture and ill-treatment of detainees, particularly those accused of security-related offenses or belonging to banned groups, are reported to be widespread and often go unpunished.

- Freedom of Assembly and Association:** The rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association are severely curtailed. Unauthorized public gatherings are prohibited, and organizers and participants of unsanctioned protests face arrest and prosecution. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), especially those working on human rights and good governance, operate under restrictive laws and face pressure from authorities.

- Due Process and Rule of Law:** The judiciary lacks independence and is subject to executive influence. Fair trial standards are often not met, particularly in politically sensitive cases. Corruption within the justice system is rampant.

- Other Issues:** Domestic violence against women remains a serious problem, with inadequate protection and support services. There are concerns about forced labor, particularly in the cotton sector, although the government has taken some steps to address this. LGBT individuals face discrimination and social stigma.

- International Scrutiny:** The Tajik government's human rights record is regularly criticized by the United Nations human rights bodies, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and international NGOs like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. While Tajik officials often dismiss these criticisms or attribute restrictive measures to national security concerns and the fight against extremism, the overall trend points to a deepening authoritarianism and a disregard for international human rights obligations. The situation reflects a stark contrast between constitutional guarantees and the reality on the ground, severely impacting the lives and freedoms of Tajik citizens. In July 2019, Tajikistan was one of the UN ambassadors from 37 countries that signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region.

6. Military

The Armed Forces of the Republic of Tajikistan consist of the Ground Forces, Mobile Forces (paratroopers and special forces), Air and Air Defense Forces, and the National Guard. There are also internal security troops under the Ministry of Internal Affairs and border troops under the State Committee for National Security.

- Organizational Structure and Troop Strength:** The total active military personnel is estimated to be around 15,000-20,000, though exact figures can vary. The Ground Forces form the largest component. The Mobile Forces are considered a more elite and combat-ready component. The Air Force is small and operates primarily Soviet-era aircraft and helicopters. Conscription is the primary method of recruitment, typically for two-year terms, although issues with draft evasion and hazing (dedovshchina) are reported.

- Major Equipment:** Much of the military equipment is of Soviet origin, including tanks (T-72, T-62), armored personnel carriers (BMP, BTR series), artillery pieces, and various aircraft (e.g., Mi-8/Mi-17 helicopters, Su-25 attack aircraft). Modernization efforts have been slow and often reliant on assistance from Russia and other partners.

- Defense Policy:** Tajikistan's defense policy is primarily focused on border security (especially the long and porous border with Afghanistan), counter-terrorism, and maintaining internal stability. The country faces threats from drug trafficking, potential spillover of Islamist extremism from Afghanistan, and unresolved border issues with Kyrgyzstan. Tajikistan is a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a military alliance of several post-Soviet states led by Russia. This membership is a cornerstone of its security policy, providing a security guarantee and access to military assistance and training from Russia.

- Military Relations with Neighboring Countries and Major Powers:**

- Russia:** Russia is Tajikistan's most important military and security partner. Russia maintains a significant military presence in Tajikistan, primarily at the 201st Military Base, which is Russia's largest military installation abroad. This base plays a crucial role in regional security and provides a deterrent against external threats. Russia also provides Tajikistan with military equipment, training, and financial assistance.

- China:** China has increased its security cooperation with Tajikistan, particularly concerning border security and counter-terrorism, driven by concerns about instability in Afghanistan and potential threats to its Xinjiang region. China has provided financial aid for border infrastructure and reportedly has a security presence in the Gorno-Badakhshan region near the Afghan border.

- Afghanistan:** The border with Afghanistan is a major security concern. Tajikistan has generally supported efforts to stabilize Afghanistan and has cooperated with international forces on counter-narcotics and counter-terrorism efforts. Following the Taliban's return to power in Afghanistan in 2021, Tajikistan has expressed strong concerns and has been cautious in its engagement with the new Afghan authorities.

- Kyrgyzstan:** Relations with Kyrgyzstan have been strained by unresolved border demarcation issues, leading to periodic clashes between border guards and local communities, some of which have escalated into serious armed confrontations (e.g., in 2021 and 2022).

- United States and NATO:** The U.S. and NATO have provided assistance to Tajikistan, particularly in areas like border security, counter-narcotics, and counter-terrorism training, especially after the 9/11 attacks and during the NATO mission in Afghanistan. French troops were stationed at Dushanbe Airport in support of air operations for the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). The U.S. also periodically conducts joint training missions.

- India:** India has historical ties with Tajikistan and has invested in military infrastructure, notably refurbishing the Ayni Air Base near Dushanbe, though its current operational use by India is limited.

The Tajik military faces challenges related to funding, outdated equipment, training standards, and corruption. Its capacity to independently address major external threats is limited, making its reliance on Russia and other partners crucial for national security.

7. Foreign Relations

Tajikistan's foreign policy is shaped by its geographical location, economic vulnerabilities, security concerns, and historical ties, particularly from the Soviet era. The country aims to maintain a multi-vector foreign policy, balancing relations with major powers and regional actors, while prioritizing national security and attracting foreign investment.

- Fundamental Foreign Policy:** Key objectives include safeguarding sovereignty and territorial integrity, ensuring regional stability (especially concerning Afghanistan), combating terrorism and drug trafficking, and promoting economic development through international cooperation. Tajikistan officially pursues a policy of "open doors," seeking friendly relations with all countries.

- Activities in Major International Organizations:**

- United Nations (UN):** Tajikistan is an active member of the UN and its specialized agencies.

- Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS):** It participates in the CIS, maintaining political, economic, and security ties with other former Soviet republics.

- Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO):** Membership in this Russian-led military alliance is a cornerstone of Tajikistan's security policy.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO):** Tajikistan is a founding member of the SCO, which focuses on regional security, counter-terrorism, and economic cooperation among its members (China, Russia, India, Pakistan, Iran, and Central Asian states).

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE):** Tajikistan participates in the OSCE, engaging in discussions on security, economic, environmental, and human rights issues.

- Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC):** As a Muslim-majority country, Tajikistan is a member of the OIC, fostering ties with the Islamic world.

- Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO):** It is a member of the ECO, which promotes economic, technical, and cultural cooperation among its member states in Central and South Asia and the Middle East.

- World Trade Organization (WTO):** Tajikistan became a WTO member in 2013, aiming to integrate further into the global economy.

- Relationships with Neighboring Countries:**

- Afghanistan:** The long and often porous border with Afghanistan is a primary security concern due to drug trafficking, potential militant infiltration, and refugee flows. Tajikistan has generally supported international efforts to stabilize Afghanistan and has been critical of the Taliban regime.

- Uzbekistan:** Relations were strained for many years due to border disputes, water management issues, and Uzbekistan's concerns about security and Islamist influence from Tajikistan. However, relations have significantly improved since Shavkat Mirziyoyev became President of Uzbekistan, leading to reopened borders, resumed flights, and increased cooperation.

- Kyrgyzstan:** Relations are complicated by undemarcated borders, leading to frequent disputes over land and water resources, which have at times escalated into violent clashes between border communities and security forces.

- China:** China is an increasingly important economic and security partner. It is a major investor in Tajik infrastructure and has provided assistance for border security.

7.1. Relations with Major Countries

Tajikistan seeks to maintain balanced relationships with global powers, navigating their respective interests in Central Asia.

7.1.1. Relations with Russia

Russia is Tajikistan's most crucial strategic, economic, and security partner. This deep relationship is rooted in historical ties from the Soviet era and shared security concerns.

- Security Cooperation:** Tajikistan hosts Russia's 201st Military Base, Moscow's largest military installation abroad, which is vital for regional stability and Tajikistan's defense. Tajikistan is a member of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Russia provides military aid, equipment, and training to Tajik forces and plays a key role in guarding the Tajik-Afghan border.

- Economic Ties:** Russia is a major trading partner and a primary destination for Tajik labor migrants. Remittances from these migrants constitute a significant portion of Tajikistan's GDP.

- Political Support:** Russia generally supports President Rahmon's government, viewing it as a bulwark against instability and extremism in the region. However, tensions can arise, such as President Rahmon's 2022 public call for Russia to treat Central Asian nations with more respect and not as former Soviet vassals.

7.1.2. Relations with China

China's influence in Tajikistan has grown substantially, primarily through economic engagement.

- Economic Investment:** China is a major investor in Tajikistan, particularly in infrastructure projects like roads, tunnels, and power plants, often through loans and grants as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. This has led to Tajikistan accruing significant debt to China.

- Trade:** China is a key trading partner.

- Security Cooperation:** Beijing is concerned about security along its border with Tajikistan and potential spillover from Afghanistan affecting its Xinjiang region. China has provided assistance for Tajik border security and is reported to have a security presence in eastern Tajikistan.

7.1.3. Relations with the United States

The United States has engaged with Tajikistan primarily on security issues, particularly after the 9/11 attacks and in the context of operations in Afghanistan.

- Security Assistance:** The U.S. has provided aid for border security, counter-narcotics efforts, and counter-terrorism training. U.S. and French forces used Tajik airbases for logistical support during the Afghanistan war.

- Democracy and Human Rights:** The U.S. has also voiced concerns about the human rights situation and lack of democratic progress in Tajikistan, though these concerns are often balanced against security cooperation priorities.

- Economic and Development Aid:** The U.S. provides development assistance in areas like economic growth, health, and education.

7.1.4. Relations with Iran

Iran shares deep historical, cultural, and linguistic ties with Tajikistan, as both are Persian-speaking nations.

- Cultural and Economic Cooperation:** Iran has invested in Tajik infrastructure, such as the Sangtuda-2 hydroelectric power plant. Cultural exchange programs exist.

- Political Relations:** Relations have sometimes been complex. Iran played a role in mediating the Tajik civil war. However, Tajikistan has occasionally accused Iran of supporting Islamist opposition elements, and relations have seen periods of coolness, partly due to Tajikistan's closer alignment with Sunni Arab states financially and religiously distinct Iran.

7.1.5. Relations with South Korea

Diplomatic relations between the Republic of Tajikistan and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) were established on April 27, 1992. Since then, the two countries have gradually developed their bilateral ties.

- Diplomatic Representation:** South Korea has an embassy in Dushanbe, and Tajikistan has an embassy in Seoul.

- Economic Cooperation:** Trade volume between the two countries is modest but has potential for growth. Areas of cooperation include energy, technology, and small and medium-sized enterprises. South Korean companies have shown some interest in Tajikistan's natural resources and infrastructure projects. The Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) has implemented development projects in Tajikistan focusing on areas like vocational training, healthcare, and public administration.

- Cultural Exchange:** Cultural exchanges have taken place, including visits by art troupes, academic exchanges, and participation in cultural festivals. There is an interest in Korean culture (K-pop, dramas) among Tajik youth. Educational cooperation includes scholarships for Tajik students to study in South Korea.

- High-Level Visits and Political Dialogue:** There have been occasional high-level visits and consultations between officials from both countries to discuss bilateral cooperation and regional issues.

- Major Issues:** Key areas for further development include increasing trade and investment, enhancing technical cooperation, and expanding people-to-people exchanges. Like many developing nations, Tajikistan seeks to attract South Korean investment and expertise in various sectors. South Korea, as part of its engagement with Central Asia, views Tajikistan as a partner in a strategically important region.

8. Administrative Divisions

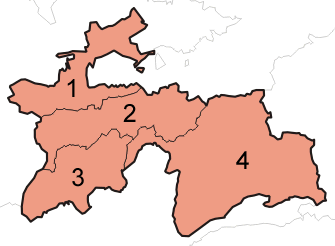

Tajikistan is divided into several primary administrative units. These divisions reflect the country's diverse geography and historical development. The main administrative units are:

- Two **Provinces** (вилоятviloyatTajik):

- Sughd**: Located in the northwest, encompassing the fertile Fergana Valley region. Its capital is Khujand (formerly Leninabad), a major industrial and cultural center. Sughd is historically significant and relatively more industrialized and densely populated compared to other regions.

- Khatlon**: Situated in the southwest, Khatlon is the most populous province and a key agricultural region, known for cotton cultivation. Its capital is Bokhtar (formerly Qurghonteppa).

- One **Autonomous Province**:

- Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province (GBAO)** (Вилояти Мухтори Кӯҳистони БадахшонViloyati Mukhtori Kūhistoni BadakhshonTajik): Covering the vast, mountainous eastern part of the country, including the Pamir Mountains. Its capital is Khorugh. GBAO is sparsely populated, geographically isolated, and home to various Pamiri peoples who speak distinct Eastern Iranian languages and predominantly follow Ismaili Shia Islam, distinguishing them from the Sunni Tajik majority. It has a special autonomous status due to its unique cultural and geographical characteristics.

- The **Districts of Republican Subordination** (RRP; Ноҳияҳои тобеи ҷумҳурӣNohiyahoi tobei jumhurīTajik; Russian: Районы республиканского подчинения, Raiony respublikanskogo podchineniya): This is a collection of districts in the central part of the country that are directly administered by the central government rather than being part of a province. This area includes the Gissar Valley and was formerly known as Karotegin Province. Major towns include Vahdat, Hisor, and Tursunzoda.

- The **Capital City**:

- Dushanbe**: The capital and largest city of Tajikistan. Dushanbe has the status of an independent administrative unit, equivalent to a province. It is the political, economic, and cultural heart of the country.

Each province and GBAO is further subdivided into **districts** (ноҳияnohiyaTajik, plural: nohiyaho; also known as raions from Russian). Districts, in turn, are subdivided into **jamoats** (ҷамоатjamoatTajik), which are village-level self-governing units or rural municipalities, and then into **villages** (деҳаdehaTajik or qyshloq). As of 2006, there were 58 districts and 367 jamoats in Tajikistan. Major cities within these divisions often have special administrative status.

Division ISO 3166-2 Map No. (on image) Capital Area (km2) Population (2019 Estimate) Sughd TJ-SU 1 Khujand 9.8 K mile2 (25.40 K km2) 2,658,400 Districts of Republican Subordination TJ-RR 2 Dushanbe (administration centered here) 11 K mile2 (28.60 K km2) 2,122,000 Khatlon TJ-KT 3 Bokhtar 9.6 K mile2 (24.80 K km2) 3,274,900 Gorno-Badakhshan TJ-GB 4 Khorugh 25 K mile2 (64.20 K km2) 226,900 Dushanbe (Capital City) TJ-DU (not numbered on map, central) Dushanbe 48 mile2 (124.6 km2) 846,400

9. Economy

Tajikistan's economy is characterized as a transitional economy that has faced significant challenges since independence, including the aftermath of a civil war, reliance on a few key commodities, and high levels of poverty and unemployment. It is one of the poorest countries in the former Soviet Union. The government's economic policies aim for growth and poverty reduction, but progress is often hampered by structural weaknesses, corruption, and external vulnerabilities.

9.1. Economic Structure

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP):** Tajikistan has a relatively small GDP. According to World Bank data, its GDP expanded at an average rate of 9.6% between 2000 and 2007, showing recovery after the civil war. However, growth has been volatile and dependent on external factors.

- Per Capita Income:** Per capita income remains low, placing Tajikistan among low-income countries. A significant portion of the population lives below the national poverty line. According to some estimates, about 47% of the population lived on less than 1.25 USD per day in earlier years, though poverty rates have reportedly declined. Malnutrition remains a concern, with the World Food Programme estimating a 30% rate in 2023.

- Composition of Major Industries:** The economy relies heavily on services (largely trade and state services), agriculture, and industry (dominated by aluminum production and mining).

- Foreign Trade:** Key exports include aluminum, cotton, electricity, fruits, and vegetable oils. Imports consist mainly of petroleum products, machinery, foodstuffs, and chemicals. Major trading partners include Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan.

- Remittances:** A critical feature of Tajikistan's economy is its heavy dependence on remittances from migrant workers, primarily those working in Russia. In 2019, remittances accounted for nearly 29% of GDP, one of the highest rates globally. These inflows are vital for household incomes and poverty reduction but make the economy highly vulnerable to economic conditions in Russia and exchange rate fluctuations. The 2014-2015 Russian economic downturn significantly impacted these remittances.

- Foreign Aid and Debt:** International assistance has been an essential source of support for development and rehabilitation programs. The country has also accumulated significant external debt, particularly to China, raising concerns about debt sustainability.

- Challenges:** Key economic challenges include widespread corruption, a weak business environment, lack of economic diversification, underdeveloped infrastructure (especially in transport and energy distribution), high unemployment and underemployment, and vulnerability to climate change impacts on agriculture and water resources.

9.2. Major Industries

Tajikistan's industrial sector is relatively underdeveloped and concentrated in a few areas.

9.2.1. Agriculture

Agriculture is a vital sector, employing a large portion of the workforce and contributing significantly to rural livelihoods, though its share of GDP has declined.

- Major Agricultural Products:**

- Cotton:** Historically the most important cash crop, accounting for a large share of agricultural output and export revenue. Cotton production supports a significant percentage of the rural population and uses a substantial portion of irrigated arable land. However, its production has faced challenges related to pricing, debt, and the need for diversification.

- Grains:** Wheat is the primary grain crop, mainly for domestic consumption.

- Fruits and Vegetables:** Tajikistan produces a variety of fruits (apricots, grapes, apples, pomegranates) and vegetables (onions, potatoes, tomatoes), some ofwhich are exported.

- Agricultural Technology and Policies:** Agricultural technology is often outdated, and productivity is hampered by small farm sizes, limited access to credit and modern inputs, and water management issues. Government policies have aimed to reform the agricultural sector, including land reform and efforts to diversify away from cotton monoculture.

- Social and Environmental Impact:** Cotton cultivation has historically been associated with issues like forced labor (though officially banned), farmer debt, and environmental problems such as soil degradation, salinization from irrigation, and water pollution from pesticides and fertilizers. The social impact on farming communities, particularly concerning income security and land rights, remains a critical issue. Water scarcity and the effects of climate change are growing concerns for the agricultural sector.

9.2.2. Mining and Industry

Tajikistan is rich in mineral resources, but the mining sector's development has been constrained by difficult terrain, underdeveloped infrastructure, and lack of investment.

- Major Mineral Resources:**

- Aluminum:** The country has a major aluminum smelter, the Tajik Aluminium Company (TALCO) in Tursunzoda, which is one of the largest in the world. It relies on imported alumina (raw material) and vast amounts of electricity from domestic hydropower plants. Aluminum is a key export commodity.

- Gold:** Tajikistan has gold deposits, and mining operations are carried out by both state-owned and foreign-invested companies.

- Silver, Antimony, Mercury, Lead, Zinc, Coal:** These and other minerals are also present and mined to varying extents. Coal is used for domestic energy and industrial purposes.

- Development of Related Industries:** Besides aluminum smelting, industrial activity includes food processing, textiles, and construction materials. However, the manufacturing sector is generally small and not well diversified.

- Labor Conditions and Environmental Concerns:** Labor conditions in the mining and heavy industry sectors can be challenging, with concerns about occupational health and safety. Environmental impacts from mining activities, such as land degradation, water pollution from tailings, and air pollution from smelters, are significant concerns that require better regulation and mitigation efforts. The energy-intensive nature of aluminum production also places a large demand on the country's electricity resources.

9.2.3. Energy

Energy is a critical sector for Tajikistan, with a strong reliance on hydropower.

- Hydropower Dominance:** Tajikistan has immense hydropower potential due to its mountainous terrain and numerous rivers. Hydropower accounts for the vast majority of electricity generation.

- Major Power Generation Facilities:**

- Nurek Dam:** Located on the Vakhsh River, it is one of the tallest dams in the world and the country's primary electricity source.