1. Overview

The Dominican Republic, a nation located on the eastern five-eighths of the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, is a country characterized by a rich and complex tapestry of geography, history, governance, economy, demographics, and culture. It shares a land border with Haiti to the west and maritime borders with Puerto Rico to the east. With an area of approximately 19 K mile2 (48.67 K km2) and a population of around 11.4 million people, it is the second-largest Caribbean nation by both area (after Cuba) and population (after Haiti). The capital city, Santo Domingo, is the first permanent European settlement in the Americas and a significant urban center.

Geographically, the Dominican Republic is diverse, featuring rugged mountain ranges, including Pico Duarte, the Caribbean's highest peak, fertile valleys like the Cibao, and extensive coastlines along the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. Lake Enriquillo is the largest lake and lowest point in the Caribbean. The climate is predominantly tropical, with variations due to topography and exposure to hurricanes. This environment supports a rich biodiversity, though it faces challenges such as deforestation and pollution.

Historically, the island was inhabited by the Taíno people before Christopher Columbus's arrival in 1492. Spanish colonization led to the decimation of the Taíno population and the establishment of the first European institutions in the New World, alongside the brutal introduction of African slavery. The nation's path to sovereignty was marked by ephemeral independence, Haitian occupation, a war of independence in 1844, re-annexation by Spain, and a restoration war. The 20th century was dominated by the long and oppressive dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, followed by periods of political instability, civil war, US interventions, and a gradual, though often challenged, transition towards a more democratic system. Social equity and human rights have been significant concerns throughout its history, particularly concerning the treatment of marginalized groups and the impacts of authoritarian rule.

The government is a representative democratic republic with a presidential system and a bicameral legislature. Politics have been characterized by the influence of several major parties and ongoing efforts to strengthen democratic institutions and combat corruption. The Dominican Republic's foreign relations are notably complex with neighboring Haiti, marked by migration issues and historical tensions, and significantly intertwined with the United States.

Economically, the Dominican Republic has experienced substantial growth, transitioning from an agriculture-based economy to one driven by services, tourism, manufacturing, and mining. However, this development has often been accompanied by social inequalities, labor rights concerns, and environmental impacts. The Dominican peso is the national currency. Tourism is a vital sector, attracting visitors to its beaches, historical sites, and natural attractions.

The population is predominantly of mixed European, African, and indigenous Taíno ancestry. Dominican Spanish is the official language, and Roman Catholicism is the dominant religion. The nation grapples with complex issues of racial and national identity, particularly in relation to Haitian immigrants and Dominicans of Haitian descent, facing challenges of discrimination and statelessness. Emigration, especially to the United States and Spain, has created a significant diaspora that contributes to the national economy through remittances. Education and healthcare systems face ongoing challenges in providing equitable access and quality services.

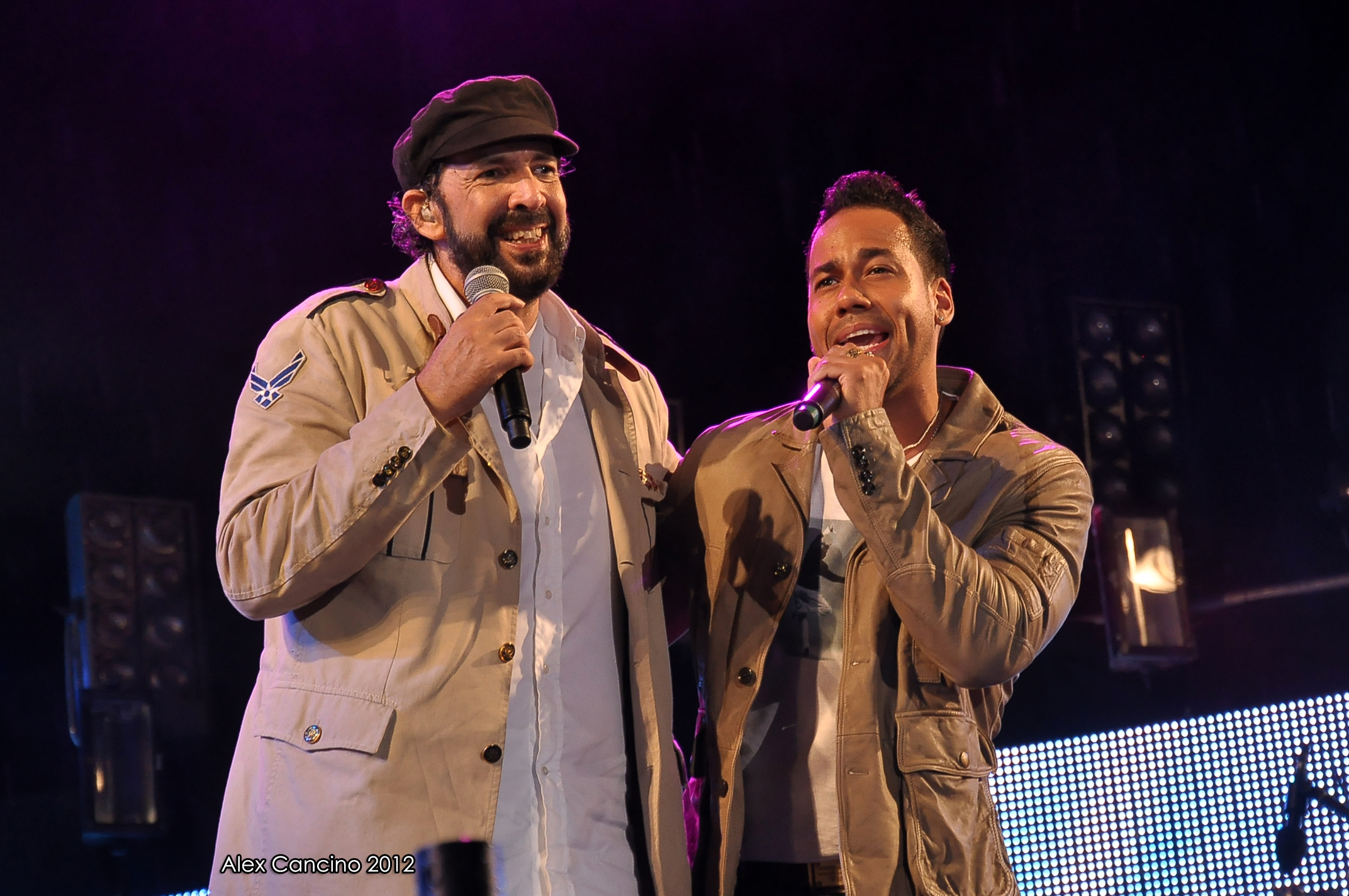

Culturally, the Dominican Republic is a vibrant fusion of Taíno, African, and Spanish European influences, evident in its music (Merengue and Bachata), dance, cuisine, visual arts, literature, and architecture. Baseball is the national sport and a significant source of national pride. The nation's symbols reflect its history and natural heritage.

2. Etymology

The name "Dominican Republic" and "Santo Domingo" have historical roots connected to Saint Dominic and the Dominican Order. Christopher Columbus named the island "La Española" upon his arrival. His brother, Bartholomew Columbus, founded the city of Santo Domingo on Sunday, August 4, 1496. The city was named in honor of the sanctity of Sunday and also in honor of their father, Domenico Colombo, and Saint Dominic de Guzmán, the founder of the Dominican Order and patron saint of astronomers.

The Dominican Order established a house of high studies in Santo Domingo, which later became the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo, considered the first university in the New World. For much of its colonial history, the territory was known simply as Santo DomingoSpanish. This name was commonly used in English as well until the early 20th century. The inhabitants of the colony were called "Dominicans" (DominicanosSpanish), the adjectival form of "Domingo."

When the eastern part of Hispaniola declared independence from Haiti on February 27, 1844, the revolutionaries named their newly independent country "La República Dominicana" (The Dominican Republic), drawing directly from the name of their capital city and the identity of its people.

In the National Anthem of the Dominican Republic (Himno Nacional de la República DominicanaSpanish), the poetic term "Quisqueyans" (QuisqueyanosSpanish) is often used instead of "Dominicans." The word "Quisqueya" is purported to derive from a Taíno word meaning "mother of all lands" or "great thing" and is frequently used in songs and literature as another name for the country. The country's name in English is sometimes shortened to "the D.R.," though this abbreviation is less common in Spanish (where "la R.D." might be seen).

3. History

The history of the Dominican Republic is a narrative of indigenous cultures, European colonization, struggles for independence, periods of foreign occupation and intervention, authoritarian rule, and the ongoing development of a democratic society. From the Taíno chiefdoms to modern-day challenges, the nation's past has profoundly shaped its present identity, social structures, and political landscape, with recurring themes of resistance, social inequity, and the pursuit of sovereignty and human rights.

3.1. Pre-Columbian era

The island of Hispaniola, like other islands in the Caribbean, was first settled around 6,000 years ago by hunter-gatherer peoples who likely originated from Central America or northern South America. The Arawakan-speaking ancestors of the Taíno people migrated from the Guianas region of South America, moving into the Caribbean islands during the 1st millennium BC. They reached Hispaniola by approximately 600 AD to 650 AD, gradually displacing or assimilating earlier inhabitants.

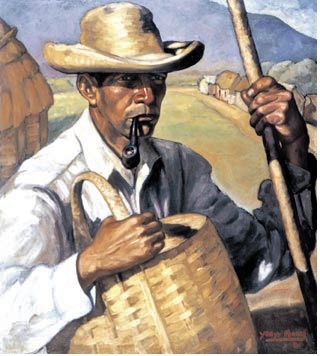

The Taíno developed a sophisticated society based on agriculture, fishing, hunting, and gathering. Their agricultural practices included the cultivation of crops such as cassava (yuca), sweet potatoes (batata), maize (corn), beans, peanuts, and tobacco. They also cultivated pineapples and other fruits. They were skilled in pottery, weaving cotton, and carving wood and stone. The Taíno lived in villages led by caciques (chiefs), and their society was organized into a hierarchical structure of chiefdoms. By the time of European contact in 1492, Hispaniola was divided into five major chiefdoms: Marién, Maguá, Maguana, Jaragua, and Higüey. The Taíno name for the entire island was either Ayiti (meaning "mountainous land") or Quisqueya (meaning "mother of all lands" or "great thing").

Estimates of Hispaniola's Taíno population in 1492 vary widely, ranging from tens of thousands to as high as two million. Without accurate contemporary records, precise figures are impossible to determine. The Taíno had a rich spiritual life, with a belief system centered around deities called zemís. Their culture included ceremonial ball games called batú, music, dance, and oral storytelling traditions. The Pomier Caves, located north of San Cristóbal, contain an extensive collection of Taíno rock art, some dating back 2,000 years, offering insights into their worldview and artistic expression.

3.2. European colonization

Christopher Columbus, sailing for the Spanish Crown, landed on the island of Hispaniola on December 5, 1492, during his first voyage to the Americas. He named it La Española (The Spanish Island) due to its perceived resemblance to the Spanish landscape and climate. In 1493, during his second voyage, Columbus established La Isabela, the first formal European settlement, near present-day Puerto Plata. In 1496, his brother, Bartholomew Columbus, founded the city of Santo Domingo on the southern coast, which became the first permanent European city in the Americas and the seat of Spanish colonial administration in the New World.

The arrival of Europeans marked a catastrophic turning point for the indigenous Taíno population. Initially, relations were sometimes amicable, but Spanish demands for gold and labor quickly led to conflict and subjugation. The Spanish implemented the encomienda system, a grant of indigenous labor and tribute to Spanish colonists, which often resulted in brutal exploitation. Taíno resistance, led by caciques such as Caonabo, Anacaona, Guacanagaríx, Guamá, Hatuey, and Enriquillo, was met with overwhelming Spanish military force. Enriquillo's rebellion in the Bahoruco mountains (1519-1533) was notable for securing a temporary autonomous enclave for his people.

However, the primary cause of the Taíno's rapid decline was the introduction of Old World diseases to which they had no immunity. Epidemics of smallpox (the first recorded in 1507), measles, influenza, and other diseases decimated their numbers within a few decades. Combined with forced labor in gold mines and plantations, massacres, and societal disruption, the Taíno population collapsed. Estimates suggest that from a pre-contact population potentially in the hundreds of thousands or even millions, only a few thousand remained by the mid-16th century.

To replace the dwindling Taíno labor force, the Spanish began importing enslaved Africans as early as 1503. The cultivation of sugarcane, introduced from the Canary Islands, led to the establishment of the first sugar mill in the Americas in Hispaniola in 1516, further fueling the demand for enslaved African labor. This marked the beginning of a brutal system of chattel slavery that would profoundly shape the demographic and social fabric of the island.

Santo Domingo became the administrative and judicial hub of the Spanish Empire in the Americas for several decades, home to the first cathedral, university (Universidad Santo Tomás de Aquino), monastery, and fortress in the New World. However, as Spain conquered vast territories on the mainland (Mexico and Peru) rich in silver and gold, Hispaniola's importance diminished. The island became increasingly depopulated as colonists sought fortunes elsewhere.

By the late 17th century, French buccaneers and settlers had established a presence on the western part of Hispaniola, which Spain had largely neglected. The Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 formally ceded the western third of the island to France, which became the prosperous colony of Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), heavily reliant on sugar plantations and a vast enslaved African population. The eastern Spanish colony of Santo Domingo remained less developed and sparsely populated. By 1789, Santo Domingo's population was around 125,000, a stark contrast to Saint-Domingue's nearly half a million, 90% of whom were enslaved. The Treaty of Aranjuez in 1777 further delineated the border between the two colonies.

During the French Revolutionary Wars, Spain ceded its colony of Santo Domingo to France under the Peace of Basel in 1795. French control over the eastern part of the island was tenuous. The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) in Saint-Domingue, led by figures like Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, culminated in Haiti's independence on January 1, 1804. Louverture had briefly occupied Santo Domingo in 1801, abolishing slavery. In 1809, with British assistance, Spanish creoles in Santo Domingo revolted against French rule in the War of Reconquista, restoring Spanish sovereignty over the eastern part of the island, a period known as España Boba (Foolish Spain) due to its neglect and economic stagnation.

Despite the Taíno's numerical decline, their genetic and cultural legacy persisted through intermarriage and cultural exchange. Census records from 1514 indicated that 40% of Spanish men in Santo Domingo were married to Taíno women. Aspects of Taíno language, cuisine, and traditions were integrated into the evolving Dominican culture.

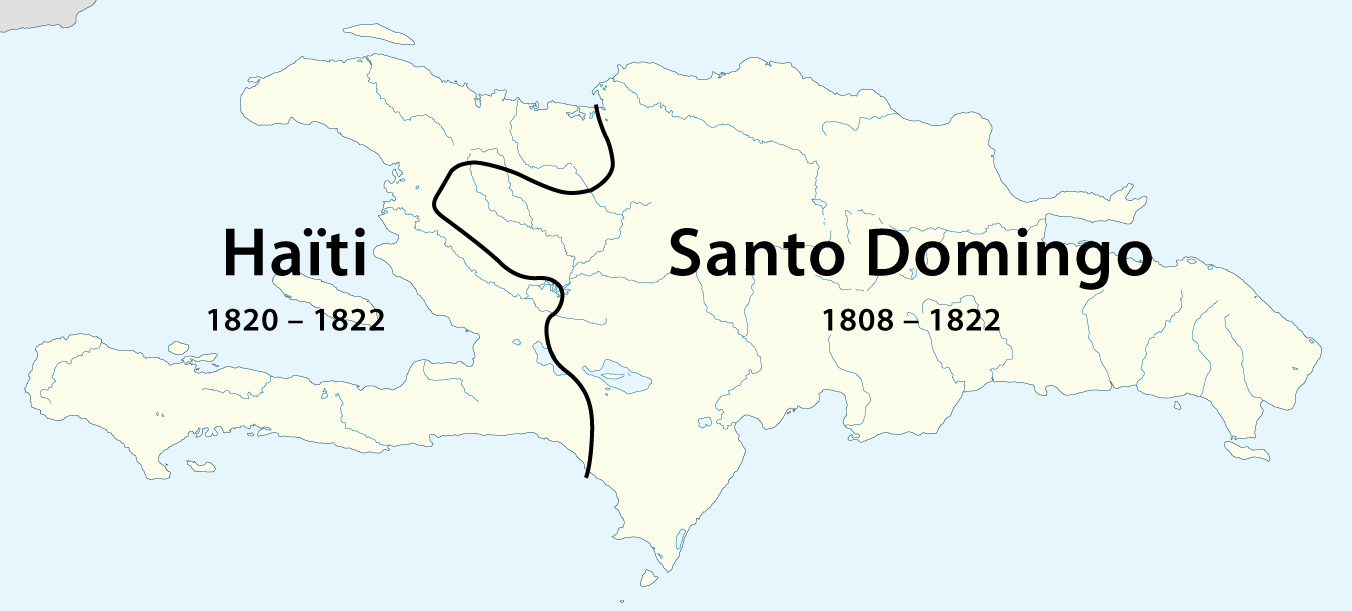

3.3. Ephemeral independence (Spanish Haiti) and Haitian unification

After more than a decade of Spanish neglect and economic hardship during the España Boba period, coupled with several failed independence plots (such as the 1812 revolt led by freedmen José Leocadio, Pedro de Seda, and Pedro Henríquez), a movement for independence from Spain gained momentum among the criollo elite in Santo Domingo. On November 30, 1821, José Núñez de Cáceres, a prominent lawyer and former Lieutenant-Governor, led a group of criollos to declare independence from the Spanish crown. This newly proclaimed state was named the Republic of Spanish Haiti (Estado Independiente de Haití EspañolSpanish). This period is often referred to as the "Ephemeral Independence" due to its brief duration.

Núñez de Cáceres envisioned the Republic of Spanish Haiti joining Simón Bolívar's Gran Colombia, seeking its protection and integration into a larger Latin American federation. However, the new republic was fragile, facing internal divisions and lacking broad popular support or external recognition.

Meanwhile, in neighboring Haiti, President Jean-Pierre Boyer saw an opportunity to unify the entire island of Hispaniola under Haitian rule. Boyer argued that a divided island was vulnerable to European recolonization and that unification was necessary for the security and prosperity of both peoples. On February 9, 1822, just nine weeks after the declaration of Spanish Haiti's independence, Haitian forces led by Boyer marched into Santo Domingo without significant opposition. Núñez de Cáceres, lacking the military means to resist, handed over the keys to the city.

This marked the beginning of a 22-year period (1822-1844) during which the entire island of Hispaniola was unified under Haitian rule. Boyer abolished slavery in the eastern part, which had been re-established to some extent under Spanish rule after its initial abolition by Toussaint Louverture. He also implemented land reforms, aiming to break up large estates and distribute land to former slaves and landless peasants, though these reforms had limited success and often clashed with existing land tenure systems (terrenos comuneros). The Haitian government imposed French as the official language and sought to assimilate the eastern population.

The Haitian occupation, referred to by Dominicans as the "Haitian occupation of Santo Domingo" (Ocupación haitiana de Santo DomingoSpanish), faced growing resentment in the former Spanish colony. Dominicans, who identified with Spanish language, Catholic traditions, and their distinct criollo culture, resisted Haitian efforts at assimilation. Economic policies, such as heavy taxation to pay Haiti's indemnity to France (for lost property, including slaves), and the conscription of Dominicans into the Haitian army, further fueled discontent. Boyer's Code Rural aimed to tie peasants to the land to boost agricultural production, which was unpopular. The closure of the university, expropriation of church properties, and perceived cultural suppression contributed to an increasing desire for self-determination among Dominicans. This period laid the groundwork for the Dominican War of Independence.

3.4. Dominican War of Independence and the First Republic (1844-1861)

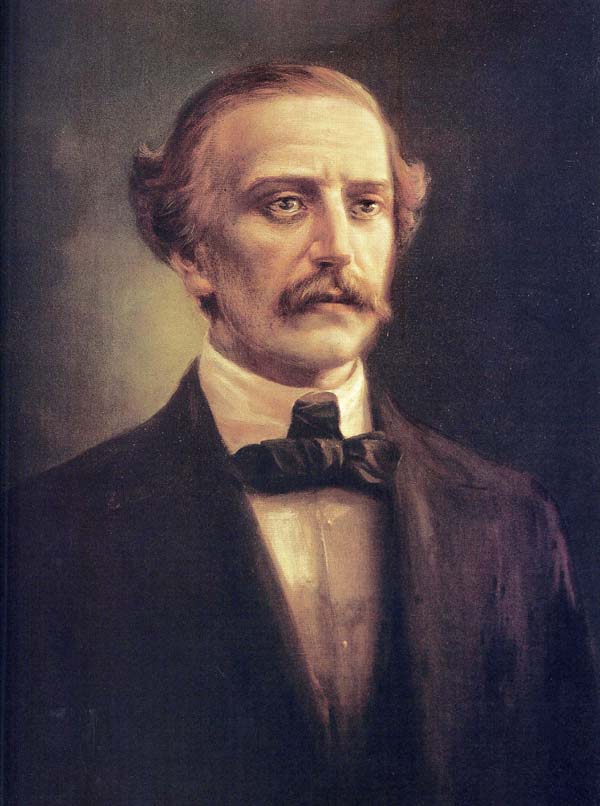

The 22-year Haitian rule over the eastern part of Hispaniola (1822-1844) fostered growing discontent among the Dominican population, who resented cultural assimilation efforts, economic policies, and military conscription. This dissatisfaction culminated in a movement for independence. In 1838, Juan Pablo Duarte, a young intellectual inspired by liberal and nationalist ideals, along with Matías Ramón Mella and Francisco del Rosario Sánchez, founded a secret society called La Trinitaria (The Trinity). Its goal was to achieve the complete independence of Santo Domingo, free from both Haitian and any other foreign domination. Duarte, Mella, and Sánchez are revered as the Founding Fathers of the Dominican Republic.

After years of clandestine organizing, and capitalizing on political instability in Haiti following the overthrow of President Boyer in 1843, La Trinitaria seized the opportune moment. On February 27, 1844, members of La Trinitaria, led by Sánchez after Duarte's exile, proclaimed independence from Haiti. The declaration was made at the Puerta del Conde in Santo Domingo, marked by Mella firing a symbolic trabucazo (blunderbuss shot). This act ignited the Dominican War of Independence.

The nascent republic faced immediate military challenges from Haiti, which launched several invasions to reclaim its territory. Dominican forces, often outnumbered, successfully defended their new nation in a series of crucial battles. Key military leadership was provided by figures like General Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle rancher from El Seibo, and General Antonio Duvergé. Notable early victories included the Battle of Azua (March 19, 1844), the Battle of Santiago (March 30, 1844), and the naval Battle of Tortuguero (April 15, 1844). These victories were crucial in consolidating Dominican independence. Subsequent Haitian invasions in 1845, 1849 (Battle of Las Carreras), and 1855-1856 were also repelled, though the threat remained a constant factor in Dominican politics.

The First Dominican Republic (1844-1861) was characterized by significant political instability, caudillismo (rule by strongmen), economic difficulties, and frequent changes in government. The first Constitution of the Dominican Republic was adopted on November 6, 1844. However, Article 210 of this constitution granted extraordinary powers to President Santana, effectively allowing for authoritarian rule during the war. The political landscape was dominated by two rival caudillos: Pedro Santana and Buenaventura Báez. Both men held the presidency multiple times, often ousting each other through coups or political maneuvering. Their rivalry shaped the era, and both, at different times, pursued plans to annex the Dominican Republic to a stronger foreign power as a means of ensuring stability and protection against Haiti. Santana favored annexation by Spain, while Báez explored annexation by the United States or France.

The population of the Dominican Republic in 1845 was estimated to be around 230,000, composed of whites, blacks, and a large mulatto (mixed-race) majority. The economy remained largely agrarian, with cattle ranching in the south and tobacco cultivation in the fertile Cibao valley in the north. Economic development was hampered by constant warfare, political turmoil, and lack of infrastructure. The period was marked by factionalism, internal revolts, and the exile of political opponents, including the founding father Juan Pablo Duarte, who was sidelined by Santana's more conservative and militaristic faction. Despite the establishment of republican institutions, democratic practices were weak, and power was concentrated in the hands of a few influential figures. The persistent threat from Haiti and internal power struggles led many to believe that the young republic could not survive on its own, paving the way for the controversial decision to seek re-annexation by Spain.

3.5. Spanish annexation and the Restoration War (1861-1865)

The political and economic instability that plagued the First Dominican Republic, combined with the persistent threat of Haitian invasions, led President Pedro Santana to seek a drastic solution. Fearful that the nation could not sustain its independence, and believing that association with a European power would bring stability and economic benefits, Santana negotiated the re-annexation of the Dominican Republic to Spain. On March 18, 1861, the Dominican Republic was officially proclaimed a province of Spain, and Santana became its Governor-General. Spain, which had not fully come to terms with the loss of its American colonies decades earlier, welcomed the opportunity to reassert its presence in the Caribbean.

The Spanish administration, however, quickly proved unpopular. Many Dominicans, who had fought for independence less than two decades earlier, felt betrayed by Santana's decision. The Spanish authorities implemented policies that alienated various sectors of Dominican society. These included the imposition of tariffs that harmed local commerce, the appointment of Spanish officials to key positions (often perceived as arrogant and discriminatory), attempts to enforce stricter Catholic religious practices which clashed with local folk traditions, and the segregation of Dominican troops under Spanish command. Furthermore, the Spanish faced economic difficulties, with a depreciating currency and inability to pay their troops regularly. The hoped-for stability and prosperity did not materialize.

Discontent grew rapidly, leading to numerous uprisings. The most significant resistance movement began on August 16, 1863, with the Grito de Capotillo, a proclamation of rebellion in the northern town of Capotillo Hill, near Dajabón. This event marked the beginning of the Dominican Restoration War (Guerra de la RestauraciónSpanish). Leaders such as Gregorio Luperón, Santiago Rodríguez Masagó, and Benito Monción emerged as key figures in the nationalist struggle. Haitian President Fabre Geffrard, fearing the re-establishment of a European power on Hispaniola that might threaten Haiti's own sovereignty, provided covert support, including arms and refuge, to the Dominican restorationists.

The war was a brutal and costly guerrilla conflict. Dominican forces, though often poorly equipped, utilized their knowledge of the terrain to their advantage against the larger and better-armed Spanish army, which was also bolstered by Cuban and Puerto Rican volunteers and some Dominican loyalists. The Spanish faced significant logistical challenges and suffered heavy casualties not only from combat but also from tropical diseases like yellow fever. Key battles and sieges took place across the country. By mid-September 1863, Spanish forces in Santiago were forced to retreat to Puerto Plata, which was then bombarded by Dominican forces, causing significant destruction. Fighting was intense in both the north and south. The capture of Azua by Spanish forces was a costly endeavor.

By 1865, Dominican forces had confined Spanish troops largely to coastal cities, particularly Santo Domingo. The war became increasingly untenable for Spain, both militarily and financially. Faced with mounting losses (estimated at over 10,000 Spanish soldiers killed or wounded, plus thousands more from disease, and significant Dominican casualties on both sides), and growing domestic opposition to the colonial venture, the Spanish Crown decided to withdraw. On March 3, 1865, Queen Isabella II of Spain signed the decree annulling the annexation. The last Spanish troops departed in July 1865, and Dominican independence was restored.

The Restoration War is a pivotal event in Dominican history, celebrated as a testament to national resilience and the struggle for self-determination. It reinforced Dominican national identity and demonstrated a clear rejection of foreign domination. However, the war also left the country economically devastated and politically fractured, setting the stage for further instability in the ensuing Second Republic.

3.6. Second Republic and instability (1865-1916)

Following the victory in the Restoration War and the departure of Spanish forces in 1865, the Dominican Republic entered its Second Republic period. However, the hard-won independence did not usher in an era of stability. Instead, the country plunged back into intense political turmoil, characterized by frequent changes in government, military revolts, factionalism, and economic difficulties. The patterns of caudillismo that marked the First Republic re-emerged, with various regional strongmen and political factions vying for power.

The presidency changed hands rapidly, often through coups and uprisings. Figures like Buenaventura Báez returned to power, alternating with other leaders. Báez, during his subsequent terms, revived his earlier ambitions of annexing the country to the United States. He negotiated a treaty of annexation with the administration of U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, who sought a naval base in Samaná Bay and a potential site for resettling newly freed African Americans. The treaty, however, was defeated in the United States Senate in 1870, partly due to the efforts of Senator Charles Sumner, who opposed annexation on moral and anti-imperialist grounds.

The period saw continued economic struggles. The national debt, already substantial, grew further as successive governments borrowed heavily, often under unfavorable terms from foreign creditors. Infrastructure remained underdeveloped, and the economy, largely based on agriculture (tobacco, sugar, coffee, cocoa) and timber, was vulnerable to price fluctuations and lacked diversification.

A brief period of relative peace and economic progress occurred during the 1880s under the authoritarian rule of General Ulises Heureaux, nicknamed "Lilís," who came to power in 1882 and dominated Dominican politics until his assassination in 1899. Heureaux maintained control through a combination of political maneuvering, repression, and a network of spies and informants. While his regime brought some modernization, particularly to the sugar industry which attracted foreign investment and immigrant labor (including from the Middle East - Lebanese, Syrians, and Palestinians), it was also marked by extreme corruption and financial recklessness. Heureaux amassed a huge personal fortune and plunged the nation deep into debt with European and American financiers, often using the funds for personal gain and to maintain his repressive police state. By the end of his rule, the country was effectively bankrupt.

Heureaux's assassination in 1899 led to another period of intense political chaos. Short-lived governments rose and fell, often overthrown by regional caudillos. The country's dire financial situation, with overwhelming foreign debt, prompted European powers (France, Germany, Italy) to threaten military intervention to collect on their loans. This situation alarmed the United States, which was increasingly asserting its influence in the Caribbean, particularly after the Spanish-American War and with an interest in protecting the future Panama Canal.

President Theodore Roosevelt articulated the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, asserting the right of the United States to intervene in Latin American countries to prevent European intervention and to stabilize their finances. In 1905, the U.S. brokered an agreement whereby it took control of Dominican customs collections, the primary source of government revenue. Under this arrangement (formalized in a 1907 treaty), a portion of the customs revenue was used to service the Dominican Republic's foreign debt, managed by U.S. officials. While this averted immediate European intervention and brought some fiscal order, it also represented a significant loss of Dominican sovereignty and deepened U.S. involvement in the country's affairs.

Political instability continued. President Ramón Cáceres, who had been instrumental in Heureaux's assassination and had himself served as president, was assassinated in 1911. This event triggered several years of civil war and political deadlock. U.S. mediation efforts by the administrations of William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson provided only temporary respites. In 1914, an ultimatum from Wilson forced Dominican factions to choose a president, leading to the election of Juan Isidro Jimenes Pereyra. However, internal power struggles persisted, particularly with his own Secretary of War, Desiderio Arias. When Jimenes resigned in May 1916 amid political crisis and a U.S. offer of military aid against Arias, President Wilson ordered the U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic, marking the end of the tumultuous Second Republic.

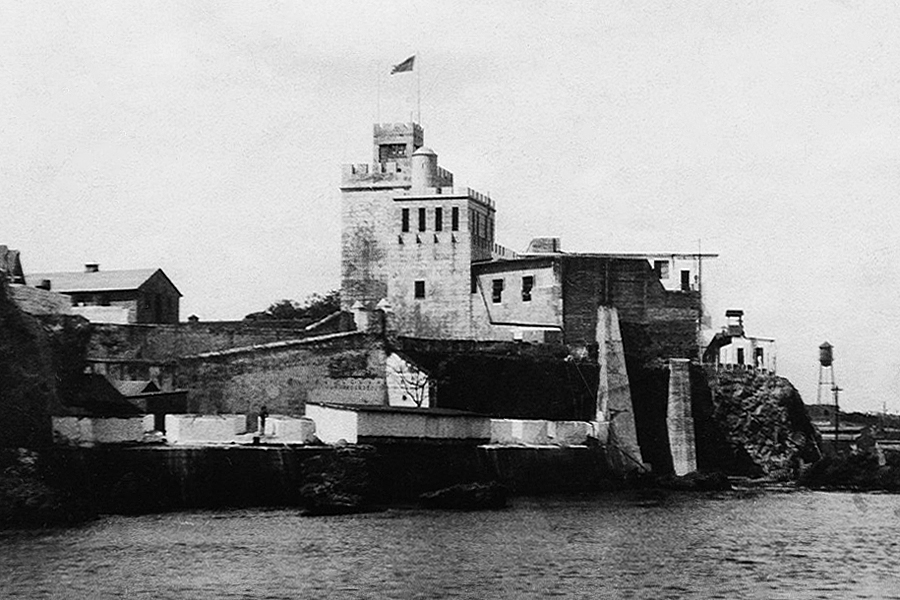

3.7. United States occupation (1916-1924)

Citing political instability, the threat of civil war, and the potential for European powers to exploit the situation to collect debts (which could challenge the Monroe Doctrine), U.S. President Woodrow Wilson ordered the United States occupation of the Dominican Republic. U.S. Marines landed on May 16, 1916. President Juan Isidro Jimenes Pereyra had resigned on May 7, refusing U.S. military aid against his political rival, Secretary of War Desiderio Arias. The U.S. forces quickly seized Santo Domingo and other key ports. General Arias initially retreated to his stronghold in Santiago but eventually surrendered in July after facing superior U.S. weaponry, including machine guns, which Dominican forces encountered for the first time.

On November 29, 1916, the United States formally established a military government under Vice Admiral Harry Shepard Knapp. This government suspended the Dominican Congress and ruled by decree. While the U.S. occupation was widely repudiated by many Dominicans and met with armed resistance in some areas, particularly in the eastern region by guerrilla fighters known as gavilleros, organized national resistance largely ceased for a period.

The occupation regime implemented a number of changes and projects:

1. Pacification and Disarmament: The U.S. military disarmed the population and suppressed local militias and political factions, aiming to end the chronic civil unrest.

2. Infrastructure Development: Significant investments were made in infrastructure. Roads and bridges were built, creating a network that connected previously isolated regions of the country. Public works, sanitation projects, and improvements to ports were also undertaken.

3. Fiscal Reform and Debt Management: The U.S. continued to manage Dominican customs and finances, aiming to stabilize the economy and ensure debt repayment. The nation's debt was reduced.

4. Creation of the Guardia Nacional: A key objective was the establishment of a professional, apolitical national police force, the Guardia Nacional Dominicana (Dominican National Guard), later the basis for the Dominican Army. This force was trained and equipped by the U.S. Marines. Ironically, Rafael Trujillo, who would later become a long-reigning dictator, rose through the ranks of this U.S.-trained force.

5. Education and Public Health: Some efforts were made to improve education and public health systems. Between 1918 and 1920, over three hundred schools were established.

Despite these material improvements, the occupation was a period of foreign domination that engendered deep resentment among Dominicans. Nationalist sentiments grew, and there were widespread calls for the restoration of Dominican sovereignty. Critics pointed to abuses by occupying forces, censorship, and the suppression of civil liberties. The U.S. government faced increasing pressure both domestically and internationally to end the occupation.

Negotiations for U.S. withdrawal began, culminating in the Hughes-Peynado Plan. The U.S. government's rule officially ended in October 1922. Elections were held in March 1924, and Horacio Vásquez, a former president, was inaugurated on July 13, 1924. The last U.S. forces departed in September of that year.

The consequences of the U.S. occupation were mixed. While it brought a temporary halt to civil strife and led to some infrastructure and administrative modernization, it also fostered anti-American sentiment and, crucially, created the Guardia Nacional, the institution from which Trujillo would launch his dictatorial takeover just six years after the U.S. departure. The occupation profoundly influenced U.S.-Dominican relations and Dominican political development for decades to come.

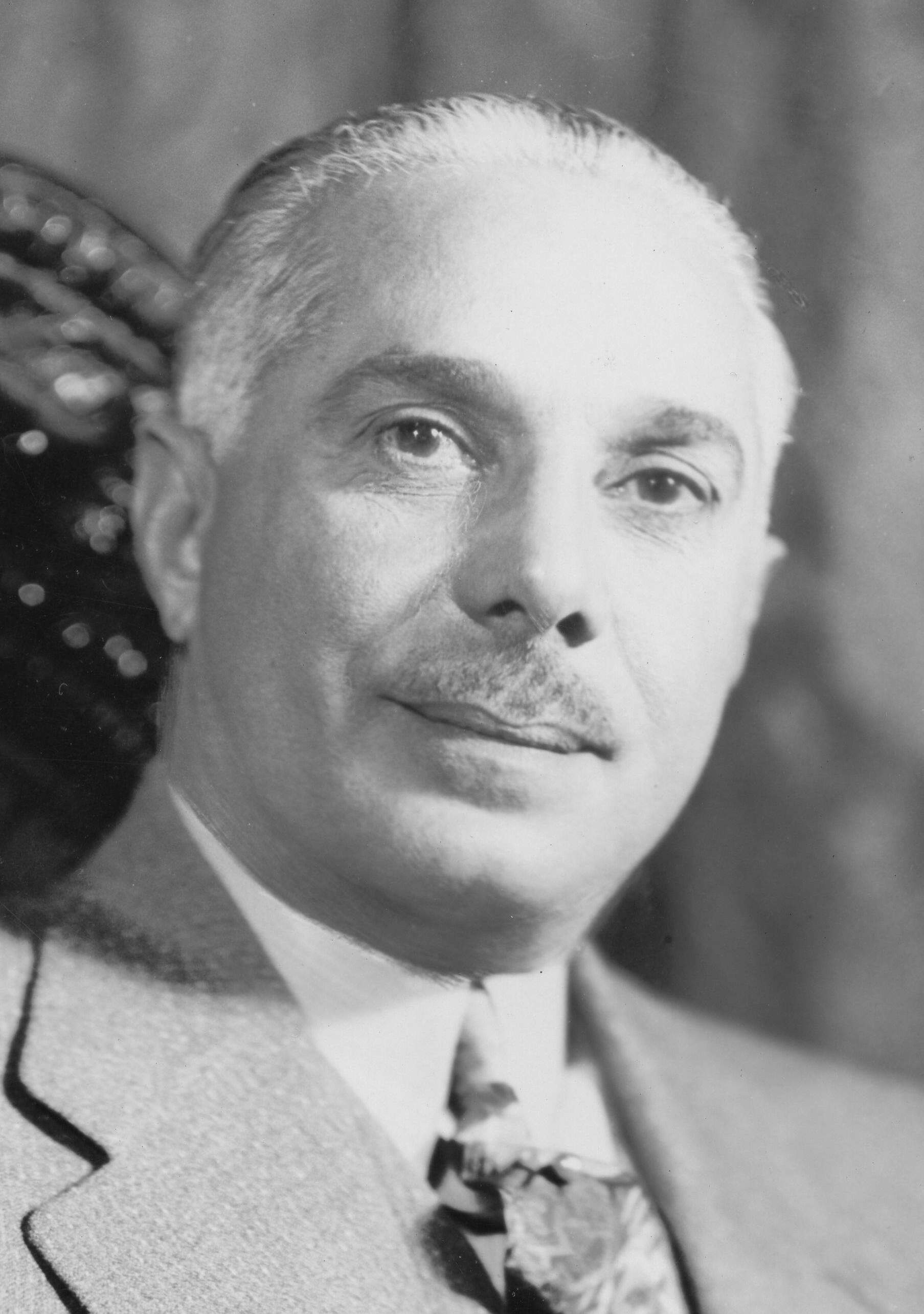

3.8. The Trujillo Era (1930-1961)

The period from 1930 to 1961 in the Dominican Republic was dominated by the iron-fisted dictatorship of General Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina, one of the longest and most absolute tyrannies in Latin American history. Trujillo, who had risen through the ranks of the U.S.-trained Guardia Nacional, seized power in February 1930 through a military revolt against President Horacio Vásquez, exploiting political instability. He officially became president after a fraudulent election.

Trujillo consolidated his power rapidly, especially after the devastating 1930 San Zenon hurricane hit Santo Domingo in September, killing thousands. He used the disaster as a pretext to assume emergency powers and eliminate opponents. His regime was characterized by:

1. Absolute Political Repression: All political opposition was brutally suppressed. Trujillo established a totalitarian state with a pervasive secret police force (the Military Intelligence Service, or SIM). Dissidents were imprisoned, tortured, exiled, or assassinated. Freedom of speech, press, and assembly were non-existent. His control extended to all aspects of Dominican life. Several Dominicans involved in anti-Trujillo activities were assassinated even in New York City.

2. Personality Cult and Propaganda: Trujillo cultivated an extreme personality cult. The capital city, Santo Domingo, was renamed Ciudad Trujillo in 1936. Provinces, mountains (Pico Duarte became Pico Trujillo), streets, and public buildings were named after him and his family members. Propaganda portrayed him as a benefactor and savior of the nation. Slogans like "Dios en el cielo, Trujillo en la tierra" (God in Heaven, Trujillo on Earth) were common.

3. Economic Control and Corruption: Trujillo and his family amassed an immense personal fortune by monopolizing key sectors of the economy. They controlled vast landholdings, industries (sugar, salt, rice, meat, tobacco, cement, shoes, paint, and insurance), and commercial enterprises. While there was some economic growth and infrastructure development (hospitals, schools, roads, harbors), a significant portion of the nation's wealth was siphoned off by the Trujillo clan. He made the country debt-free in 1947, a point of national pride he heavily promoted.

4. Social Control and Terror: The regime maintained power through fear and intimidation. The SIM was notorious for its brutality. The populace lived under constant surveillance.

5. Human Rights Abuses: The Trujillo era was marked by widespread human rights violations. One of the most horrific events was the Parsley Massacre (El Corte) in October 1937. Under Trujillo's orders, Dominican troops slaughtered an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 Haitians living in the border regions, as well as Dominicans of Haitian descent, often using machetes. This atrocity was part of Trujillo's policy of antihaitianismo and his ambition to "whiten" the Dominican population.

6. Foreign Policy and International Relations: Trujillo initially maintained close ties with the United States, positioning himself as an anti-communist ally during the Cold War. During World War II, he symbolically sided with the Allies and offered refuge to some European Jews fleeing Nazi persecution, settling them in Sosúa (though this was also seen as part of his "whitening" policy). However, his regime's brutality and meddling in the affairs of other Latin American countries eventually led to international condemnation. His arsenal at San Cristóbal produced rifles, machine guns, and ammunition. He even formed a Foreign Legion to attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro in Cuba, which failed.

The beginning of the end for Trujillo's regime came with his increasingly brazen international actions. In 1960, his agents attempted to assassinate Venezuelan President Rómulo Betancourt, a vocal critic. This act led the Organization of American States (OAS) to impose diplomatic and economic sanctions on the Dominican Republic. The United States, under President Dwight D. Eisenhower and later John F. Kennedy, also turned against Trujillo, viewing him as a liability.

On May 30, 1961, Rafael Trujillo was ambushed and assassinated by a group of Dominican dissidents, some of whom had connections to individuals within the U.S. government, though the extent of direct CIA involvement remains debated. His death ended 31 years of oppressive rule but plunged the country into a period of political uncertainty and transition. The Trujillo era left a deep and lasting scar on Dominican society, impacting its political culture, social structures, and collective memory.

3.9. Post-Trujillo period and democratization (1961-present)

The assassination of Rafael Trujillo on May 30, 1961, marked the end of a 31-year dictatorship and ushered in a turbulent period of political transition, civil conflict, and a gradual, often challenging, path towards democratization and socio-economic development. This era has been characterized by efforts to establish stable democratic institutions, address deep-seated social inequalities, and navigate complex international relations.

3.9.1. Transition, 1965 Civil War, and U.S. intervention (1961-1966)

Following Trujillo's assassination, his son, Ramfis Trujillo, initially maintained de facto control. However, under internal and external pressure, particularly from the United States, the Trujillo family was forced to leave the country by late 1961. Joaquín Balaguer, Trujillo's last puppet president, remained in office and oversaw the initial transition. The Organization of American States (OAS) lifted its sanctions in January 1962.

In December 1962, the Dominican Republic held its first free elections in over three decades. Juan Bosch, a writer and leader of the social-democratic Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD), won the presidency and took office in February 1963. Bosch initiated a program of reforms, including a new liberal constitution that provided for land reform, civil liberties, and secular education. These reforms, however, alienated conservative elements, including the military, the economic elite, and the Catholic Church hierarchy, who viewed Bosch as too leftist and feared a potential communist influence, particularly in the context of the Cold War and the recent Cuban Revolution.

In September 1963, after only seven months in office, Bosch was overthrown in a military coup led by Colonel Elías Wessin y Wessin. A civilian triumvirate, led by Donald Reid Cabral, was installed, but it lacked popular legitimacy and struggled to govern effectively.

On April 24, 1965, a group of younger, reformist military officers and civilian supporters of Bosch, known as the "Constitutionalists," launched a rebellion to restore Bosch to power and reinstate the 1963 constitution. This uprising quickly escalated into the Dominican Civil War of 1965, pitting the Constitutionalists, led by Colonel Francisco Caamaño, against a conservative military faction known as the "Loyalists," led by General Wessin y Wessin and General Antonio Imbert Barrera. The Constitutionalists gained control of much of Santo Domingo and armed civilian militias.

Fearing a "second Cuba" and citing the need to protect American lives, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, on April 28, 1965, ordered a U.S. military intervention. Over 20,000 U.S. troops, primarily Marines and the 82nd Airborne Division, were deployed. The intervention was later legitimized by the OAS, which formed an Inter-American Peace Force (IAPF), though it was largely dominated by U.S. forces. The U.S. intervention effectively halted the Constitutionalist advance and led to a stalemate. The intervention was highly controversial, criticized both domestically and internationally as an infringement on Dominican sovereignty and an overreaction driven by Cold War anxieties. It had a profound impact on the nation's trajectory, sidelining the popular Constitutionalist movement and paving the way for a more conservative political outcome. The civil war resulted in thousands of deaths and widespread destruction. After lengthy negotiations, an interim government under Héctor García-Godoy was established to organize new elections.

3.9.2. The Balaguer years (1966-1978 and 1986-1996)

Joaquín Balaguer, who had served as Trujillo's last puppet president and returned from exile, won the U.S.-supervised presidential election of 1966, defeating Juan Bosch. This marked the beginning of Balaguer's "Twelve Years" (1966-1978). His rule during this period was characterized by:

- Authoritarianism and Repression**: While maintaining the facade of democracy, Balaguer's government engaged in systematic repression of political opponents, particularly those associated with the left and Bosch's PRD. Security forces and paramilitary groups were implicated in disappearances, assassinations, and suppression of dissent. Human rights abuses were common.

- Infrastructure Development**: Balaguer undertook ambitious public works projects, including the construction of highways, dams, housing complexes, sports facilities, and cultural institutions like the Columbus Lighthouse. These projects provided employment and were often used to bolster his popular support, but were also criticized for corruption and cronyism.

- Economic Policies**: His economic policies favored foreign investment and large landowners. While there was some economic growth, particularly in tourism and export agriculture, wealth distribution remained highly unequal.

- Political Control**: Balaguer skillfully manipulated the political system, co-opting opponents and maintaining a tight grip on power through his Social Christian Reformist Party (PRSC).

In 1978, facing mounting domestic and international pressure for greater democratization, Balaguer allowed a relatively free election. Antonio Guzmán Fernández of the PRD won, marking the first peaceful transfer of power from an incumbent to an opposition candidate in Dominican history. Guzmán's presidency (1978-1982) saw some political liberalization, but he died by suicide shortly before his term ended. Salvador Jorge Blanco, also of the PRD, served as president from 1982 to 1986, a period marked by economic crisis, austerity measures imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and social unrest, including deadly riots in 1984 (the poblada).

Balaguer returned to power in 1986 and served two more consecutive terms (1986-1990 and 1990-1994). His later presidencies continued to emphasize infrastructure projects. The 1990 and 1994 elections were marred by accusations of fraud and irregularities, particularly the 1994 contest against PRD candidate José Francisco Peña Gómez. International pressure led Balaguer to agree to shorten his term and hold new elections in 1996, in which he did not run. Balaguer's long and complex legacy includes periods of economic growth and modernization alongside authoritarian practices, political violence, and the perpetuation of social inequalities.

3.9.3. Democratic governance and contemporary challenges (1978-1986 and 1996-present)

The period from 1978 onwards marked a more sustained, though still evolving, phase of democratic governance in the Dominican Republic. The PRD presidencies of Antonio Guzmán Fernández (1978-1982) and Salvador Jorge Blanco (1982-1986) represented a break from Balaguer's long rule and an attempt at political liberalization. However, this era was also characterized by economic difficulties, including rising foreign debt and social unrest due to IMF-imposed austerity measures.

The 1996 presidential election saw Leonel Fernández of the Dominican Liberation Party (PLD) - founded by Juan Bosch after he left the PRD - achieve victory. This was the PLD's first presidential win. Fernández's first term (1996-2000) focused on economic modernization, privatization of state enterprises, and attracting foreign investment. His administration oversaw significant GDP growth, relatively stable inflation, and initiatives to improve the judicial system and infrastructure.

In 2000, Hipólito Mejía of the PRD won the presidency. His term (2000-2004) was marked by a severe banking crisis in 2003, triggered by the fraudulent collapse of Baninter, the country's second-largest private commercial bank. The crisis led to a sharp economic recession, high inflation, and a costly government bailout, eroding public trust and Mejía's popularity. Under Mejía, the Dominican Republic also participated in the US-led coalition in the 2003 Iraq War.

Leonel Fernández returned to power for two consecutive terms (2004-2008 and 2008-2012). During these administrations, the Dominican Republic experienced strong economic growth, driven by tourism, remittances from Dominicans abroad, foreign direct investment, and sectors like telecommunications and construction. Fernández's governments invested in infrastructure, including the Santo Domingo Metro, and pursued technological modernization. However, his administrations also faced persistent accusations of corruption and criticism regarding the equitable distribution of economic benefits.

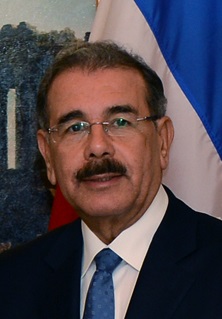

Danilo Medina, also of the PLD, was elected president in 2012 and re-elected in 2016. Medina continued many of Fernández's economic policies, and the country maintained relatively high growth rates. His administration implemented social programs, including literacy campaigns and initiatives to support small and medium-sized enterprises. However, concerns over rising crime rates, government corruption (including scandals like the Odebrecht bribery scandal), and a perceived weak justice system became prominent issues.

The 2020 general election, held amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and following significant protests against the PLD government and perceived electoral irregularities in municipal elections, marked a significant political shift. Luis Abinader of the Modern Revolutionary Party (PRM), an opposition party formed by a split from the PRD, won the presidency, ending 16 years of PLD rule. Abinader took office in August 2020, facing challenges related to the pandemic's economic and social impact, as well as long-standing issues of corruption, institutional reform, and relations with Haiti. His administration has emphasized transparency, economic recovery, and a tough stance on illegal immigration. In May 2024, President Abinader won a second term in office, with his policies towards Haitian migration being a popular factor among voters.

Contemporary challenges for the Dominican Republic include strengthening democratic institutions, ensuring the rule of law, combating corruption, addressing social inequality and poverty, improving public services like education and healthcare, managing environmental issues, and navigating the complex and often fraught relationship with neighboring Haiti, particularly concerning migration, border security, and human rights. The country continues to strive for sustainable and equitable development within a democratic framework.

4. Geography

The Dominican Republic is located on the eastern five-eighths of Hispaniola, the second-largest island in the Greater Antilles archipelago, situated in the Caribbean Sea. It shares the island with Haiti, which occupies the western three-eighths. The land border between the two countries is approximately 234 mile (376 km) long. The Dominican Republic's total land area is reported as 19 K mile2 (48.67 K km2) (or 19 K mile2 (48.44 K km2) according to some sources). To its north lies the Atlantic Ocean, and to its south is the Caribbean Sea. Eastward, across the Mona Passage, is Puerto Rico, while to the north and northwest are The Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands. The country lies near active fault lines in the Caribbean, making it susceptible to earthquakes.

The geography of the Dominican Republic is characterized by a diverse and rugged topography, featuring extensive mountain ranges, fertile valleys, coastal plains, and numerous rivers and lakes.

4.1. Topography

The Dominican Republic is a mountainous country with several major cordilleras (mountain ranges) that traverse its territory, generally running in an east-west direction.

- Cordillera Central (Central Mountain Range): This is the largest and highest mountain range in the Dominican Republic and indeed in the entire West Indies. It extends from the Haitian border eastward into the center of the country. It is home to the four highest peaks in the Caribbean: Pico Duarte (10 K ft (3.10 K m), the highest point), La Pelona (10 K ft (3.09 K m)), La Rucilla (10 K ft (3.05 K m)), and Pico Yaque (9.1 K ft (2.76 K m)). This range is the source of many of the country's major rivers.

- Cordillera Septentrional (Northern Mountain Range): This range runs parallel to the Atlantic coast in the north, extending from near Monte Cristi in the northwest to the Samaná Peninsula in the east. It is lower in elevation compared to the Cordillera Central.

- Cordillera Oriental (Eastern Mountain Range): Located in the eastern part of the country, this is a lower and less extensive range compared to the Cordillera Central and Septentrional.

- Sierra de Neiba: Situated in the southwest, south of the Cordillera Central, this range runs along the Haitian border.

- Sierra de Bahoruco: This range is located further south in the southwestern corner of the country, forming a continuation of Haiti's Massif de la Selle.

Between these mountain ranges lie several important valleys and plains:

- Cibao Valley: This is the largest and most fertile valley, located between the Cordillera Central and the Cordillera Septentrional. It is a major agricultural region and home to important cities like Santiago de los Caballeros and La Vega.

- San Juan Valley: A semi-arid valley south of the Cordillera Central.

- Neiba Valley (Hoya de Enriquillo): Located between the Sierra de Neiba and the Sierra de Bahoruco, this is an arid, desert-like rift valley. It contains Lake Enriquillo, a large saltwater lake that is the lowest point in the Caribbean, at approximately 148 ft (45 m) below sea level.

- Coastal Plains: The Llano Costero del Caribe (Caribbean Coastal Plain) is the largest plain, stretching east of Santo Domingo and traditionally an important area for sugarcane cultivation. The Plena de Azua is another arid plain in Azua Province. Smaller coastal plains exist along the northern coast and in the Pedernales Peninsula.

The country has numerous rivers, many originating in the Cordillera Central. The four major rivers are:

- Yaque del Norte: The longest and most important river, draining the Cibao Valley and flowing northwest into Monte Cristi Bay.

- Yuna River: Drains the eastern part of the Cibao (Vega Real) and empties into Samaná Bay in the northeast.

- Yaque del Sur: Drains the San Juan Valley and flows south into the Caribbean Sea.

- Artibonito: The longest river on Hispaniola, originating in the Cordillera Central and flowing westward into Haiti.

Besides Lake Enriquillo, other notable lakes include Laguna Redonda and Laguna Limón in the east. There are also many small offshore islands and cays, the largest being Saona Island to the southeast and Beata Island to the southwest. Catalina Island is another notable offshore island. Further offshore to the north are the largely submerged Navidad Bank, Silver Bank, and Mouchoir Bank, which are ecologically important marine areas.

4.2. Climate

The Dominican Republic has a predominantly tropical climate, characterized by warm temperatures year-round and distinct wet and dry seasons. However, the country's diverse topography, with its high mountain ranges and deep valleys, leads to considerable regional variations in climate.

- Temperature: The annual average temperature is around 77 °F (25 °C) to 78.8 °F (26 °C) in lowland and coastal areas. In the higher elevations of the Cordillera Central, temperatures are much cooler, averaging around 64.4 °F (18 °C), and can even drop to near freezing or below in the highest peaks, with rare instances of snowfall on Pico Duarte. Coastal areas generally experience average temperatures around 82.4 °F (28 °C). August is typically the hottest month, while January and February are the coolest.

- Rainfall: Rainfall patterns vary significantly across the country. The wet season generally runs from May through November for most of the country, with May often being the wettest month. Along the northern coast, the wet season can extend from November through January due to the influence of northeasterly trade winds. The average annual rainfall nationwide is about 0.1 K in (1.50 K mm). However, the Cordillera Oriental in the northeast can receive over 0.1 K in (2.74 K mm) annually, making it one of the wettest regions. In contrast, the arid Neiba Valley in the southwest and parts of the northwestern coast (like Monte Cristi) are much drier, with annual rainfall as low as 14 in (350 mm) in some areas. The southern coast generally receives less rainfall than the northern and eastern regions.

- Tropical cyclones (Hurricanes): The Dominican Republic is located in the Atlantic hurricane belt and is susceptible to hurricanes, particularly from June to October, which is the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season. Hurricanes can bring strong winds, heavy rainfall, storm surges, and cause significant damage and loss of life. The southern coast is impacted more frequently than the northern coast. Notable hurricanes that have affected the country include Hurricane David (1979), Hurricane Georges (1998), and more recently, Hurricane Fiona (2022).

The diverse microclimates support a wide range of ecosystems, from tropical rainforests in wetter areas to dry forests and even desert-like conditions in the most arid regions.

4.3. Biodiversity

The Dominican Republic boasts a rich and diverse array of flora and fauna, reflecting its varied topography, microclimates, and island geography. It is considered a biodiversity hotspot within the Caribbean. The country is home to five terrestrial ecoregions: Hispaniolan moist forests, Hispaniolan dry forests, Hispaniolan pine forests, Enriquillo wetlands, and Greater Antilles mangroves.

- Flora: The vegetation varies greatly from region to region.

- Moist Forests**: Found in the wetter mountain slopes and lowlands, these forests are characterized by lush vegetation, tall trees, ferns, orchids, and bromeliads. The Cordillera Central and parts of the Samaná Peninsula host significant areas of moist forest.

- Dry Forests**: Predominant in the southwestern regions (like the Neiba Valley and parts of Azua) and some northwestern areas, these forests feature drought-tolerant species such as cacti, thorny shrubs, and deciduous trees.

- Pine Forests**: Hispaniolan pine (Pinus occidentalis) forests are found at higher elevations in the Cordillera Central and Sierra de Bahoruco. These unique ecosystems are adapted to cooler temperatures and poorer soils.

- Mangroves**: Extensive mangrove forests line many coastal areas, particularly around estuaries and protected bays like Samaná Bay and Monte Cristi. They are vital ecosystems for marine life and coastal protection.

- Endemic Species**: Hispaniola has a high level of plant endemism. Notable endemic plants include the Bayahibe rose (Leuenbergeria quisqueyana), which is the national flower, and the West Indian mahogany (Swietenia mahagoni), the national tree. Many species of orchids and palms are also endemic.

- Fauna: The native terrestrial fauna is characterized by a high degree of endemism, typical of island ecosystems.

- Mammals**: Native land mammals are few and mostly consist of bats (which make up 90% of native terrestrial mammal species) and rodents like the Hispaniolan hutia (Plagiodontia aedium) and the Hispaniolan solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus), an endangered insectivore. The Antillean manatee can be found in coastal waters.

- Birds**: The avifauna is diverse, with over 300 bird species recorded, including about 32 endemics to Hispaniola. Notable endemic birds include the Palmchat (Dulus dominicus), the national bird, the Hispaniolan parakeet, Hispaniolan trogon, Hispaniolan woodpecker, and the endangered Ridgway's hawk. The island is also an important stopover for migratory birds.

- Reptiles and Amphibians**: The Dominican Republic has a rich herpetofauna. This includes various species of anole lizards, geckos, snakes (none of which are dangerously venomous to humans), and the endangered rhinoceros iguana. The American crocodile has a significant population in Lake Enriquillo. Endemic frogs, including several species of the genus Eleutherodactylus, are also prominent.

- Invertebrates**: A vast array of insects, spiders, and land snails exists, many of which are endemic. Butterflies, such as the mariposa (Hispaniolan kite swallowtail), are notable.

- Marine Life**: The surrounding waters of the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea support diverse marine ecosystems, including coral reefs, seagrass beds, and open ocean habitats. These are home to numerous species of fish, corals, marine mammals (like humpback whales, which breed in Samaná Bay), sea turtles, and crustaceans.

Conservation efforts are underway to protect this biodiversity, with numerous national parks and protected areas established. However, habitats face threats from deforestation, agricultural expansion, urban development, pollution, and invasive species.

4.4. Environmental issues

The Dominican Republic faces several significant environmental challenges that threaten its rich biodiversity, natural resources, and the well-being of its population. These issues are often interconnected and exacerbated by economic pressures, population growth, and sometimes weak enforcement of environmental regulations.

- Deforestation: This is one of the most critical environmental problems. Forests are cleared for agriculture (both commercial and subsistence), cattle ranching, charcoal production (especially along the Haitian border due to demand from Haiti), and illegal logging. Deforestation leads to soil erosion, loss of biodiversity, disruption of water cycles, and increased vulnerability to landslides and flooding. While there have been reforestation efforts and some stabilization in forest cover in recent years, pressures remain high, particularly on primary forests.

- Water Pollution: Contamination of rivers, lakes, and coastal waters is a serious concern. Sources of pollution include untreated or inadequately treated sewage from urban areas, agricultural runoff (pesticides and fertilizers), industrial discharges, and waste from mining operations (such as cyanide and heavy metals from gold mining). This pollution affects drinking water quality, harms aquatic ecosystems, and can impact human health and industries like fishing and tourism.

- Soil Erosion and Land Degradation: Deforestation, improper agricultural practices on steep slopes, and overgrazing contribute to significant soil erosion. This reduces soil fertility, leading to decreased agricultural productivity and desertification in some areas. Siltation from eroded soil also damages rivers and coastal ecosystems like coral reefs.

- Solid Waste Management: Inadequate collection and disposal of solid waste are prevalent problems, particularly in urban areas and tourist zones. Open dumpsites are common, leading to land and water pollution, air pollution from burning waste, and public health risks. Lack of recycling infrastructure and public awareness contribute to the issue.

- Coastal and Marine Degradation: Coastal ecosystems, including coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass beds, are under threat from pollution (sediment, nutrients, chemicals), overfishing, coastal development (hotels, marinas), and the impacts of climate change (coral bleaching, sea-level rise). Destructive fishing practices like dynamite fishing and trawling also cause damage.

- Loss of Biodiversity: Habitat destruction and degradation, pollution, overexploitation of resources (e.g., overfishing, illegal hunting), and the introduction of invasive species threaten the country's unique flora and fauna, many of which are endemic.

- Mining Impacts: While mining (gold, nickel, bauxite) contributes to the economy, it can have severe environmental consequences if not managed properly. These include deforestation, soil erosion, water contamination from acid mine drainage and chemical spills, and social conflicts over land use and environmental damage.

- Climate Change Vulnerability: As a small island developing state, the Dominican Republic is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including more intense hurricanes, sea-level rise (threatening coastal communities and infrastructure), changes in rainfall patterns (affecting water availability and agriculture), and increased temperatures (impacting health and ecosystems).

Conservation Efforts:

The Dominican government, often in collaboration with NGOs and international organizations, has undertaken various conservation initiatives. These include the establishment of a network of national parks and protected areas (such as Jaragua National Park, Los Haitises National Park, and Valle Nuevo National Park), reforestation programs, efforts to improve waste management, and the promotion of sustainable tourism practices. Environmental laws and regulations exist, but enforcement can be a challenge. Public awareness and participation in environmental protection are growing but require further strengthening. Addressing these environmental issues is crucial for the long-term sustainable development of the Dominican Republic and the preservation of its natural heritage, which also impacts social equity as marginalized communities often bear the brunt of environmental degradation.

5. Government and politics

The Dominican Republic is a representative democracy operating as a democratic republic. The political system is structured around a separation ofpowers among three branches: the executive, legislative, and judicial. The country has a multi-party system, and its governance framework is defined by the Constitution. The path towards stable democratic governance has been marked by periods of authoritarianism and political instability, and contemporary politics continue to grapple with challenges such as corruption and the need for institutional strengthening, impacting social equity and human rights.

5.1. Political system

The Dominican Republic's political system is based on the principles of a representative democratic republic. The Constitution serves as the supreme law of the land, outlining the structure of government, the rights and duties of citizens, and the separation of powers.

- Executive Branch: The President is the head of state, head of government, and commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces. The president is elected by direct popular vote for a four-year term and can be re-elected. The current constitution allows for a maximum of two consecutive terms, after which a president must sit out a term before being eligible to run again (though this has been subject to constitutional changes in the past). The president appoints the Cabinet (Council of Ministers) and is responsible for executing laws passed by the legislature and conducting foreign policy. The Vice President is elected on the same ticket as the president.

- Legislative Branch: The national legislature is a bicameral Congress (Congreso NacionalSpanish), composed of:

- The Senate (SenadoSpanish): It has 32 members, one elected from each of the 31 provinces and one from the National District (Santo Domingo), for four-year terms.

- The Chamber of Deputies (Cámara de DiputadosSpanish): It has 190 members (as of recent reforms, the number can fluctuate slightly based on population), elected through a system of proportional representation from the provinces and the National District, also for four-year terms. Some seats are reserved for minority party representation and for Dominicans living abroad.

Congress is responsible for drafting and passing laws, approving the national budget, ratifying treaties, and overseeing the executive branch.

- Judicial Branch: The judiciary is headed by the Supreme Court of Justice (Suprema Corte de JusticiaSpanish), whose 16 judges are appointed by the National Council of the Magistracy. The judicial system also includes courts of appeal, courts of first instance, and justices of the peace. The Constitutional Tribunal, separate from the Supreme Court, is responsible for interpreting the constitution and ruling on the constitutionality of laws. Efforts have been made to strengthen judicial independence and combat corruption within the judiciary, though challenges remain.

- Electoral System: Elections for president, vice president, and congressional representatives are held every four years. Municipal elections for mayors and local councils are also held. Since 2016, presidential, congressional, and municipal elections have been held concurrently. The Central Electoral Board (Junta Central ElectoralSpanish, JCE) is responsible for organizing and overseeing elections. While international observers have generally deemed recent elections as free and fair, issues related to campaign financing, use of state resources, and occasional irregularities have been noted.

- Political Parties: The Dominican Republic has a multi-party system, though a few major parties have historically dominated the political landscape. Key parties include:

- The Dominican Liberation Party (Partido de la Liberación DominicanaSpanish, PLD): A center-left party founded by Juan Bosch, it was in power for 16 consecutive years from 2004 to 2020.

- The Modern Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario ModernoSpanish, PRM): A center-left party formed from a major split within the PRD, it came to power in 2020 with President Luis Abinader.

- The Dominican Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario DominicanoSpanish, PRD): Historically a major social-democratic party, its influence has declined after several internal divisions.

- The Social Christian Reformist Party (Partido Reformista Social CristianoSpanish, PRSC): A conservative party historically associated with Joaquín Balaguer.

- Other smaller parties also participate in the political process, often forming alliances.

Challenges to the political system include institutional weakness, corruption, clientelism, high levels of public distrust in political institutions, and issues related to citizen security and drug trafficking. Ensuring social equity and upholding human rights remain ongoing concerns within the political discourse.

5.2. Administrative divisions

The Dominican Republic is administratively divided into provinces and one National District, which encompasses the capital city, Santo Domingo. These divisions form the basis for local governance and the organization of public services.

- Provinces (ProvinciasSpanish): There are 31 provinces. Each province is headed by a Governor (Gobernador CivilSpanish) who is appointed by the President of the Republic and acts as the representative of the executive branch in that province. The provinces serve as the primary first-level administrative subdivisions. Provincial capitals are typically the main urban centers and host regional offices of the central government.

- National District (Distrito NacionalSpanish): The capital city, Santo Domingo de Guzmán, is contained within the National District. It functions similarly to a province but has a distinct administrative status. It is governed by a Mayor (AlcaldeSpanish or Síndico) and a Municipal Council (Ayuntamiento del Distrito NacionalSpanish), who are elected by popular vote. Unlike provinces, the National District does not have an appointed Governor. The National District was created in 1936. Prior to this, the area was part of the old Santo Domingo Province. In 2001, the Santo Domingo Province was created from the territory surrounding the National District, effectively splitting the metropolitan area into the centrally located National District and the surrounding, more populous Santo Domingo Province.

- Municipalities (MunicipiosSpanish): The provinces are further subdivided into municipalities. These are the second-level political and administrative units. Each municipality is governed by an elected Mayor and a Municipal Council (ayuntamientoSpanish). There are 158 municipalities as of recent counts.

- Municipal Districts (Distritos MunicipalesSpanish): Some municipalities are further divided into municipal districts, which are created to provide more localized governance for specific communities within a larger municipality. These are also headed by an elected director and a council.

Local governments (municipalities and municipal districts) are responsible for local services such as urban planning, waste collection, maintenance of local roads and parks, public markets, and local public safety. Elections for mayors and municipal councils are held every four years, concurrently with presidential and congressional elections.

The provinces are:

| Province | Capital city |

|---|---|

| Azua | Azua de Compostela |

| Baoruco | Neiba |

| Barahona | Santa Cruz de Barahona |

| Dajabón | Dajabón |

| Duarte | San Francisco de Macorís |

| El Seibo | Santa Cruz de El Seibo |

| Elías Piña | Comendador |

| Espaillat | Moca |

| Hato Mayor | Hato Mayor del Rey |

| Hermanas Mirabal | Salcedo |

| Independencia | Jimaní |

| La Altagracia | Salvaleón de Higüey |

| La Romana | La Romana |

| La Vega | Concepción de La Vega |

| María Trinidad Sánchez | Nagua |

| Monseñor Nouel | Bonao |

| Province | Capital city |

|---|---|

| Monte Cristi | Monte Cristi |

| Monte Plata | Monte Plata |

| Pedernales | Pedernales |

| Peravia | Baní |

| Puerto Plata | San Felipe de Puerto Plata |

| Samaná | Samaná |

| San Cristóbal | San Cristóbal |

| San José de Ocoa | San José de Ocoa |

| San Juan | San Juan de la Maguana |

| San Pedro de Macorís | San Pedro de Macorís |

| Sánchez Ramírez | Cotuí |

| Santiago | Santiago de los Caballeros |

| Santiago Rodríguez | San Ignacio de Sabaneta |

| Santo Domingo | Santo Domingo Este |

| Valverde | Mao |

5.3. Foreign relations

The Dominican Republic maintains diplomatic relations with numerous countries worldwide and is a member of various international organizations, including the United Nations (UN), the Organization of American States (OAS), the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), and the Central American Integration System (SICA) as an associate member. Its foreign policy is primarily aimed at promoting economic development, attracting foreign investment, ensuring national security, and managing its complex relationship with neighboring Haiti. The country has historically maintained close ties with the United States and European nations, particularly Spain. It has a free trade agreement with the United States and Central American countries (CAFTA-DR) and an Economic Partnership Agreement with the European Union through CARIFORUM. The Dominican Republic is also a regular member of the Organisation Internationale de la FrancophonieFrench. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, the Dominican Republic ranks as the 97th most peaceful country globally.

5.3.1. Relations with Haiti

The relationship between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, which share the island of Hispaniola, is profoundly complex, often strained, and deeply rooted in historical, social, economic, and environmental factors. It is arguably the most critical bilateral relationship for both nations.

Historical Context: The historical legacy of colonial division (Spanish Santo Domingo and French Saint-Domingue), the Haitian Revolution, Haiti's 22-year occupation of Santo Domingo (1822-1844), and subsequent border conflicts and invasions have left a lasting impact on mutual perceptions and national identities. The 1937 Parsley Massacre, where thousands of Haitians were killed in the Dominican Republic under Trujillo's orders, remains a dark chapter and a source of Haitian distrust.

Migration: This is the most dominant and contentious issue. Due to severe poverty, political instability, and environmental degradation in Haiti, hundreds of thousands of Haitians have migrated to the Dominican Republic, many undocumented, seeking economic opportunities, primarily in agriculture (sugarcane, coffee, bananas), construction, and domestic service. This large-scale migration places significant pressure on Dominican social services, labor markets, and infrastructure.

Human Rights Concerns: The treatment of Haitian migrants and Dominicans of Haitian descent has been a consistent source of concern for human rights organizations. Issues include:

- Statelessness**: A 2013 Dominican Constitutional Court ruling (TC/0168/13) retroactively denied Dominican citizenship to individuals born in the country to undocumented foreign parents, primarily affecting Dominicans of Haitian descent. This decision rendered tens of thousands stateless, sparking international condemnation. Subsequent legislation aimed to regularize some individuals, but challenges and complexities persist.

- Discrimination and Xenophobia**: Anti-Haitian sentiment (antihaitianismo) is prevalent in some sectors of Dominican society, often fueled by historical animosities, racial prejudice, and economic anxieties. Haitians and those perceived as Haitian often face discrimination in access to employment, education, healthcare, and justice.

- Deportations**: The Dominican Republic regularly deports undocumented Haitians. These deportations have often been criticized for lacking due process, leading to family separations, and sometimes involving the expulsion of individuals who may have a right to Dominican nationality or refugee status. Mass deportations and the construction of a border wall have intensified in recent years.

- Labor Exploitation**: Haitian migrants, particularly in the agricultural sector, are often subjected to exploitative labor conditions, low wages, and poor living standards.

Border Issues: The approximately 234 mile (376 km) border is porous and difficult to control. It is a conduit for irregular migration, smuggling of goods (including charcoal from Dominican forests to Haiti), and trafficking of persons and illicit substances. The Dominican government has increased border security measures, including the construction of a border fence/wall.

Socio-Economic Impacts: While Haitian labor is crucial for certain sectors of the Dominican economy, the social and economic impacts of migration are debated. Some Dominicans blame Haitians for increased crime, overburdening public services, and depressing wages, though these claims are often disputed or lack comprehensive evidence. Conversely, remittances sent by Haitians in the Dominican Republic are a significant income source for Haiti. The Dominican Republic also incurs substantial costs providing healthcare and other services to Haitian nationals, including a large number of Haitian women who cross the border for childbirth due to inadequate facilities in Haiti.

Bilateral Cooperation and Tensions: Despite the tensions, there are areas of cooperation, particularly in trade (Haiti is a major market for Dominican goods) and disaster response (e.g., Dominican aid after the 2010 Haiti earthquake). However, diplomatic relations can be volatile, often impacted by migration policies and incidents.

From a social liberal perspective, addressing the Dominican-Haitian relationship requires a focus on human rights, non-discrimination, due process for migrants and asylum seekers, and pathways to regularize status for long-term residents and those born in the Dominican Republic. It also involves acknowledging the economic contributions of Haitian labor while ensuring fair labor practices and combating exploitation. International cooperation and support for sustainable development in Haiti are also seen as crucial to addressing the root causes of migration.

5.3.2. Relations with the United States

The relationship between the Dominican Republic and the United States is multifaceted, encompassing significant political, economic, social, and historical dimensions. It is one of the most important foreign relationships for the Dominican Republic.

Historical Interventions and Influence: The U.S. has a long history of intervention and influence in Dominican affairs. This includes:

- The Roosevelt Corollary and U.S. customs receivership (early 20th century).

- The first U.S. occupation (1916-1924), which, while bringing some infrastructure development, was seen as an infringement on sovereignty and inadvertently helped create the conditions for Trujillo's rise.

- Support for the Trujillo dictatorship for much of its duration due to his anti-communist stance during the Cold War, followed by a break with Trujillo towards the end of his regime.

- The 1965 military intervention during the Dominican Civil War, aimed at preventing a perceived "second Cuba" and heavily influencing the political outcome. This intervention remains a sensitive topic, viewed by many Dominicans as a violation of national sovereignty that suppressed a popular democratic movement.

This history of intervention has created a complex legacy, with some Dominicans viewing the U.S. with suspicion, while others see it as a crucial partner.

Economic Ties: The U.S. is the Dominican Republic's most important trading partner.

- Trade**: The Dominican Republic is part of the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) with the United States, which has significantly shaped trade relations. The U.S. is a major market for Dominican exports (textiles, agricultural products, medical devices) and a primary source of its imports.

- Investment**: The U.S. is a leading source of foreign direct investment in the Dominican Republic, particularly in tourism, free trade zones, and telecommunications.