1. Overview

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an archipelagic nation within the Lucayan Archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean. It comprises over 700 islands, cays, and islets, with New Providence Island hosting the capital, Nassau. Geographically, it is characterized by low-lying limestone formations, extensive Bahama Banks, and a tropical savannah climate vulnerable to hurricanes and climate change impacts such as sea-level rise.

Historically, the islands were first inhabited by the Lucayan people, a branch of the Taíno. Christopher Columbus's arrival in 1492 marked the beginning of European contact, leading to the decimation of the indigenous population through enslavement and disease. British colonization began in the 17th century, and the islands became a Crown Colony in 1718. The Bahamas served as a haven for pirates, a resettlement site for American Loyalists and their enslaved people, and later, a refuge for liberated Africans after the abolition of the slave trade and slavery. The nation achieved independence from the United Kingdom on July 10, 1973, and has since developed as a parliamentary constitutional monarchy.

The Bahamian government operates under a Westminster system, with a bicameral Parliament. The political landscape is largely a two-party system. The economy is heavily reliant on tourism and offshore financial services, the latter of which has drawn international scrutiny regarding tax transparency. Challenges include economic diversification, social equity, immigration (particularly from Haiti), and environmental protection. Bahamian society is predominantly Afro-Bahamian, with English as the official language and a vibrant Christian religious life. The culture is a rich blend of African, British, and American influences, most famously expressed in the Junkanoo festival. The nation is committed to social progress, democratic development, and addressing human rights issues, including those affecting minorities and vulnerable groups, while navigating the complexities of its economic model and environmental challenges.

2. Etymology and Naming

The name Bahamas is widely believed to be derived from the Lucayan Taíno term Bahamatnq, meaning 'large upper middle island', which was the indigenous name for Grand Bahama. Another prominent theory suggests the name originates from the Spanish baja marSpanish, meaning 'shallow sea' or 'low tide', reflecting the shallow waters surrounding the islands. However, scholars like Wolfgang Ahrens argue that the "baja mar" explanation is likely a folk etymology. An alternative origin might be Guanahanítnq, a local Lucayan name for one of the islands, though its meaning is unclear.

The name "Bahama" was first recorded on the Turin Map of 1523, initially referring specifically to Grand Bahama. By 1670, the term was used in English to encompass the entire island group. Toponymist Isaac Taylor proposed that the name derived from Bimani (present-day Bimini), which Spanish explorers in Haiti associated with Palombe, a mythical land mentioned in John Mandeville's Travels as possessing a fountain of youth.

The Bahamas is one of only two countries, the other being The Gambia, whose official English name begins with the definite article "The". This usage likely arose because "The Bahamas" refers to the archipelago as a geographical feature, which typically takes a definite article in English. The official full name of the country is the Commonwealth of The Bahamas.

3. History

The history of The Bahamas spans from its earliest human inhabitation by indigenous peoples through European colonization, piracy, slavery, emancipation, and finally, to its emergence as an independent nation in the 20th century, navigating modern challenges and developments. This historical trajectory has profoundly shaped Bahamian society, its demographic composition, and its cultural identity, with ongoing implications for social justice and democratic governance.

3.1. Early Inhabitants and European Contact

The first inhabitants of the islands now known as The Bahamas were the Taíno people, an Arawakan-speaking group who migrated from mainland South America to Hispaniola and Cuba. Around the 7th to 11th centuries AD (estimations vary between 700s-1000s AD), they moved into the southern Bahamian islands, developing a distinct culture and becoming known as the Lucayan people. At the time of European arrival, an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 Lucayans populated the archipelago.

On October 12, 1492, Christopher Columbus made his first landfall in the New World on a Bahamian island he named San Salvador. The Lucayans called this island Guanahanítnq. While there is general agreement that the landing occurred within The Bahamas, the precise island remains a subject of scholarly debate, with San Salvador Island (formerly Watling's Island) and Samana Cay being the primary candidates. Columbus claimed the islands for the Crown of Castile and engaged in trade with the Lucayans.

The arrival of Europeans was catastrophic for the Lucayan people. The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) theoretically placed The Bahamas within the Spanish sphere of influence. Though the Spanish made little effort to settle the islands, they ruthlessly exploited the Lucayan population. Many Lucayans were forcibly taken to Hispaniola and other Spanish colonies as enslaved laborers. The brutal conditions of enslavement, combined with exposure to European diseases such as smallpox, to which they had no immunity, led to a rapid and drastic decline in their numbers. Within approximately two decades, the Lucayan population was decimated through forced labor, disease, warfare, emigration, and intermarriage. By 1513, the Bahama islands were largely depopulated, remaining mostly deserted until the mid-17th century. This period represents a profound human tragedy and the erasure of an entire indigenous society.

3.2. British Colonization and the Era of Piracy

English interest in The Bahamas dates back to 1629, but permanent European settlement began in 1648-1650. A group of English Puritans from Bermuda, led by Captain William Sayle and known as the Eleutheran Adventurers, sought greater religious freedom and established a settlement on an island they named Eleuthera (from the Greek word for "free"). They later settled New Providence, initially calling it Sayle's Island. Life for these early settlers was arduous, and many, including Sayle, returned to Bermuda. The remaining colonists often relied on salvaging goods from shipwrecks to survive.

In 1670, King Charles II granted the islands to the Lords Proprietors of the Carolinas. They administered the islands from New Providence, which became the capital, Charles Town (later renamed Nassau). However, proprietary rule was weak, and The Bahamas became a notorious haven for piracy during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, with infamous figures like Blackbeard (Edward Teach) using the islands as a base. The era was marked by instability, with frequent attacks from Spanish and French forces. In 1684, the Spanish privateer Juan de Alcon raided Charles Town, and in 1703, a joint Franco-Spanish expedition briefly occupied Nassau during the War of the Spanish Succession.

To end the "Republic of Pirates" and establish orderly government, Britain declared The Bahamas a crown colony in 1718. Woodes Rogers, a former privateer, was appointed as the first Royal Governor. Rogers successfully suppressed piracy, offering pardons to those who surrendered and hunting down those who resisted. In 1720, the Spanish attacked Nassau again during the War of the Quadruple Alliance. A significant step towards self-governance occurred in 1729 with the establishment of a local House of Assembly, granting colonists a degree of representation, although real power remained with the British-appointed governor.

During the American Revolutionary War, the islands became a target. In 1776, US Marines under Commodore Esek Hopkins briefly occupied Nassau. In 1782, a Spanish fleet captured Nassau without resistance. However, the Treaty of Paris (1783) returned The Bahamas to British control in exchange for East Florida. Following American independence, between 1783 and 1785, approximately 7,300 American Loyalists and their enslaved people migrated to The Bahamas, primarily from New York, Florida, and the Carolinas. These Loyalists, including prominent figures, received land grants and established plantations, significantly altering the demographic and economic landscape. The influx of enslaved Africans and their descendants made them the majority population from this period onward, laying the groundwork for the social and racial dynamics that would characterize Bahamian society. The plantation economy, reliant on enslaved labor, brought new economic activity but also entrenched the brutal system of slavery, with significant human rights implications.

3.3. 19th Century Developments

The 19th century in The Bahamas was marked by transformative events, primarily the abolition of the slave trade and then slavery itself, leading to profound social and economic shifts.

In 1807, the United Kingdom passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, making it illegal to transport enslaved Africans in British ships or to British colonies. The Royal Navy actively patrolled the Atlantic, intercepting illegal slave ships, and thousands of liberated Africans, known as "Liberated Africans," were resettled in The Bahamas, particularly on New Providence and other islands. This added a new dimension to the Afro-Bahamian population.

In 1818, a ruling from the Home Office in London stated that any enslaved person brought to The Bahamas from outside the British West Indies would be manumitted (freed). This policy led to the freedom of nearly 300 enslaved people owned by U.S. nationals on ships that wrecked or sought refuge in Bahamian ports between 1830 and 1835. Notable instances involved the American slave ships Comet (wrecked off Abaco in 1830) and Encomium (wrecked off Abaco in 1834). When these ships were brought into Nassau, British colonial officials freed the enslaved individuals aboard, despite protests from the American owners. The United Kingdom eventually paid an indemnity to the United States for these cases in 1855.

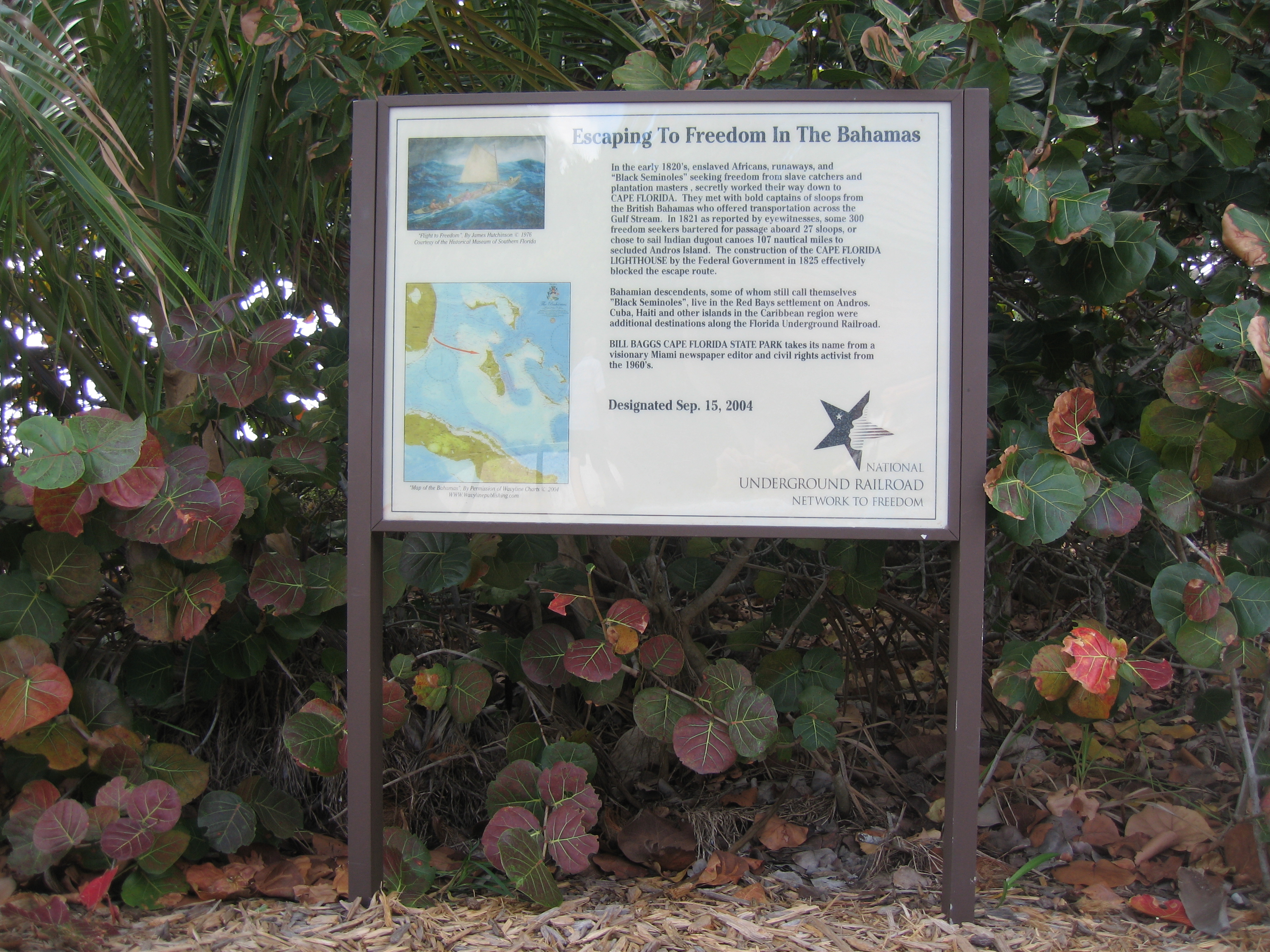

During the Seminole Wars in Florida in the 1820s, hundreds of enslaved African Americans and Black Seminoles escaped from Cape Florida to The Bahamas, often aided by Bahamians. Many settled on Andros Island, particularly in Red Bays, where their descendants continue to preserve some African Seminole traditions. This further solidified The Bahamas' reputation as a haven for those escaping slavery.

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 abolished slavery throughout most of the British Empire, coming into effect on August 1, 1834. This act had a monumental impact on Bahamian society. Following abolition, Bahamian officials continued to free enslaved Americans who arrived in Bahamian territory. This included 78 individuals from the Enterprise (which diverted to Bermuda in 1835, where they were freed based on similar principles) and 38 from the Hermosa (wrecked off Abaco in 1840).

The most significant incident was the Creole in 1841. Enslaved people aboard the American brig Creole, which was transporting 135 enslaved individuals from Virginia to New Orleans, revolted and forced the ship to Nassau. Bahamian officials, adhering to British law, freed the 128 enslaved people who chose to remain in The Bahamas. This event, considered one of the most successful slave revolts in U.S. history, further strained relations between the United States and the United Kingdom over the issue of slavery.

The transition from a slave society to a free society was a complex process. While formal freedom was granted, ex-slaves often faced economic hardship and social discrimination. Many turned to subsistence farming, fishing, and sponging. The development of a peasantry and a free labor economy reshaped the islands' social structure.

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), The Bahamas briefly prospered as a center for blockade runners supplying the Confederacy. This period brought temporary economic relief but was short-lived. The latter part of the 19th century saw continued economic challenges and the gradual development of new industries like sponging and pineapple cultivation, alongside the ongoing importance of maritime activities.

3.4. Path to Independence

The early 20th century was a period of economic hardship for many Bahamians, with a stagnant economy and widespread poverty. Most relied on subsistence agriculture, fishing, and the declining sponging industry. Global events, however, began to impact the islands. The Prohibition era in the United States (1920-1933) turned The Bahamas into a significant center for liquor smuggling, bringing a temporary and illicit economic boom.

The Great Depression further exacerbated economic difficulties. During World War II, The Bahamas hosted a Royal Air Force base and a U.S. naval facility. A significant wartime development was the "Project," an agreement allowing Bahamian laborers to work in the United States, which provided some economic relief.

From August 1940 to March 1945, the Duke of Windsor, formerly King Edward VIII, served as Governor of The Bahamas, accompanied by his wife, Wallis Simpson. His tenure was controversial. While he undertook some efforts to alleviate poverty and opened the local parliament in October 1940, he was also criticized for his perceived disdain for the local population and his associations, such as a visit to the "Out Islands" on the yacht of Axel Wenner-Gren, a Swedish industrialist suspected of Nazi sympathies. A key event during his governorship was the Burma Road Riots in June 1942, stemming from disputes over low wages for Bahamian workers at a U.S. airbase construction project. The Duke's response, while restoring order, was seen by some as heavy-handed and dismissive of the workers' legitimate grievances. This event highlighted underlying social tensions and a growing desire for political change.

The post-World War II era saw the rise of modern political consciousness and organization. The first political parties emerged in the 1950s, largely along racial and economic lines. The United Bahamian Party (UBP), representing the interests of the white merchant elite (often called the "Bay Street Boys"), initially dominated politics. In opposition, the Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) was formed in 1953, primarily representing the Black Bahamian majority and advocating for greater social justice and political rights.

A pivotal moment was the 1956 resolution in the House of Assembly to end racial discrimination in public places, pushed by the PLP. The 1958 general strike further galvanized the movement for majority rule. In 1958, the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park, the first marine protected area in The Bahamas and the world, was established, marking an early recognition of environmental concerns.

Constitutional advancements followed. A new constitution in 1964 granted The Bahamas internal self-government. Sir Roland Symonette of the UBP became the first Premier. However, the PLP, led by Lynden Pindling, continued to push for majority rule. In the landmark 1967 general election, the PLP and the UBP each won 18 seats. With the support of a Labour Party member and an independent, Lynden Pindling became the first Black Premier of the colony. In 1968, the title of the head of government was changed to Prime Minister.

In 1968, Pindling announced that The Bahamas would seek full independence. A new constitution adopted that year granted the colony increased control over its own affairs. In 1971, a faction of disaffected PLP members merged with remnants of the UBP to form the Free National Movement (FNM), which became the main opposition party.

A constitutional conference was held in London in December 1972. On June 20, 1973, the United Kingdom Government issued an Order in Council granting independence. On July 10, 1973, The Bahamas became a fully independent nation within the Commonwealth of Nations, with Lynden Pindling as its first Prime Minister. Prince Charles (now King Charles III) delivered the official independence documents. Sir Milo Butler was appointed the first Bahamian Governor-General, representing Queen Elizabeth II as head of state. This transition to independence was a culmination of decades of struggle for democratic rights, majority rule, and self-determination, marking a significant step in social and political progress for the Bahamian people.

3.5. Post-Independence Era

Following independence on July 10, 1973, The Bahamas, under the leadership of Prime Minister Sir Lynden Pindling and his Progressive Liberal Party (PLP), embarked on nation-building. The country quickly joined international bodies, becoming a member of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank on August 22, 1973, and the United Nations on September 18, 1973.

The first two decades of independence were politically dominated by the PLP, which won successive elections. This period saw significant economic growth, primarily fueled by the established twin pillars of tourism and offshore finance. The standard of living for many Bahamians rose considerably. However, Pindling's long tenure was also marked by persistent allegations of corruption, connections with international drug traffickers (as The Bahamas became a major transshipment point for cocaine en route to the US), and financial impropriety within the government. These issues became central to political discourse and international relations, particularly with the United States.

The burgeoning economy also made The Bahamas an attractive destination for migrants, most notably from Haiti. This influx led to complex social, economic, and political challenges related to illegal immigration, straining social services and leading to debates about national identity, labor, and human rights, particularly concerning the treatment of the Haitian community and Bahamians of Haitian descent.

In the 1992 general election, after 25 years in power, Lynden Pindling and the PLP were defeated by the Free National Movement (FNM), led by Hubert Ingraham. Ingraham's government focused on economic liberalization, privatization of some state-owned enterprises, and addressing corruption. The FNM won re-election in 1997.

The PLP, under the leadership of Perry Christie, returned to power in the 2002 election. The subsequent years saw alternations in power: Ingraham and the FNM governed from 2007 to 2012, followed by Christie and the PLP again from 2012 to 2017. In 2017, amid concerns about economic stagnation and governance, the FNM, led by Dr. Hubert Minnis, was re-elected, making Minnis the fourth prime minister since independence.

A major challenge during this period was the impact of Hurricane Dorian in September 2019. This Category 5 hurricane devastated the Abaco Islands and parts of Grand Bahama, causing at least 7.00 B USD in damages, claiming over 70 lives (with hundreds remaining missing), and displacing thousands. The disaster highlighted the nation's vulnerability to climate change and intense hurricanes, testing its disaster response capabilities and requiring significant international aid. The recovery and rebuilding efforts have had long-term social and economic consequences, emphasizing the need for climate resilience and support for affected communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which reached The Bahamas in March 2020, delivered another severe blow to the economy, particularly the tourism sector. The government implemented public health measures and economic support programs, but the pandemic led to a deep recession and exacerbated existing social inequalities.

In a snap election held in September 2021, against the backdrop of economic struggles and the ongoing pandemic response, the PLP, led by Philip "Brave" Davis, defeated the FNM. Davis was sworn in as the fifth Prime Minister of The Bahamas. His government has faced the tasks of economic recovery, addressing the social impacts of recent crises, and navigating issues of fiscal stability, crime, and continued calls for greater transparency and good governance. Discussions around constitutional reform, including the possibility of transitioning to a republic, have also continued.

Throughout the post-independence era, The Bahamas has grappled with balancing economic development with social equity, managing its natural resources sustainably, and asserting its identity on the international stage, all while addressing the specific vulnerabilities of a small island developing state.

4. Geography

The Bahamas is an archipelago located in the Atlantic Ocean, characterized by its extensive chain of islands, cays, and islets, its unique geological formations, and a climate that is both a draw for tourism and a source of environmental vulnerability.

4.1. Topography and Island Composition

The Bahamas consists of an archipelago of more than 700 islands and approximately 2,400 cays and islets, spread out over some 500 mile in the Atlantic Ocean. The total land area is approximately 5.4 K mile2 (13.88 K km2) (or 3.9 K mile2 (10.01 K km2) excluding uninhabited rocks and some cays). It is located north of Cuba and Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), northwest of the Turks and Caicos Islands, southeast of the U.S. state of Florida, and east of the Florida Keys. The islands lie between latitudes 20° and 28°N, and longitudes 72° and 80°W, straddling the Tropic of Cancer. The Royal Bahamas Defence Force describes the nation's territory as encompassing 180.00 K mile2 of ocean space.

Of these islands, only about 30 are inhabited. The most populous island is New Providence, where the capital city, Nassau, is located. Other major islands include Grand Bahama (home to the second-largest city, Freeport), Andros (the largest island by land area), Eleuthera, Cat Island, Long Island, San Salvador Island, Acklins, Crooked Island, Exuma, and Great Abaco.

The islands are generally low and flat, formed primarily from coral reefs and limestone. The topography features low, rounded ridges that usually rise no more than 49 ft (15 m) to 66 ft (20 m) above sea level. The highest point in the country is Mount Alvernia (formerly Como Hill) on Cat Island, which has an elevation of 210 ft (64 m). The landmass of The Bahamas is believed to have begun forming around 200 million years ago with the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea. The Pleistocene Ice Age significantly influenced the archipelago's current formation, particularly the vast, shallow underwater platforms known as the Bahama Banks (e.g., Great Bahama Bank and Little Bahama Bank). During periods of lower sea levels in ice ages, these banks were exposed as large landmasses.

4.2. Climate

The Bahamas has a predominantly tropical savannah climate (Köppen classification Aw), characterized by a hot, wet summer season and a warm, dry winter season. The climate is significantly influenced by the warm tropical Gulf Stream current, especially in winter, as well as the islands' low latitude and low elevation, resulting in a generally warm and winterless climate.

Seasonal rainfall tends to follow the sun, making summer the wettest season. There is only about a 13 °F (7 °C) difference in mean temperature between the warmest month (typically July/August) and the coolest month (typically January/February). Average daily temperatures range from 69.8 °F (21 °C) in winter to 80.6 °F (27 °C) in summer. While generally warm, incursions of cold air from the North American mainland can occasionally cause temperatures to drop below 50 °F (10 °C) for brief periods, though frost or freezing temperatures have never been officially recorded. Snowfall is exceptionally rare; a notable instance occurred in Freeport on January 19, 1977, when snow mixed with rain was observed briefly. The Bahamas enjoys abundant sunshine, averaging over 3,000 hours annually, or about 340 sunny days per year.

Tropical storms and hurricanes pose a significant threat, particularly from June to November. Notable hurricanes that have impacted The Bahamas include Hurricane Andrew (1992), which struck the northern islands; Hurricane Floyd (1999), which affected eastern parts; Hurricane Frances (2004) and Hurricane Jeanne (2004), which caused widespread damage; and Hurricane Wilma (2005). Hurricane Dorian in 2019 was one of the most powerful, devastating the northwestern islands of Abaco and Grand Bahama as a Category 5 storm with sustained winds of 185 mph and gusts up to 220 mph.

Climate Change Impacts: The Bahamas is highly vulnerable to climate change. Temperatures have risen by approximately 0.9 °F (0.5 °C) since 1960, with warming occurring more rapidly in warmer seasons. A 2 °C global temperature increase above pre-industrial levels could make extreme hurricane rainfall four to five times more likely in The Bahamas. With at least 80% of its land area below 33 ft (10 m) in elevation, the country faces severe risks from sea level rise, threatening coastal infrastructure, freshwater resources, and ecosystems. Climate change may also alter disease transmission patterns. While The Bahamas' greenhouse gas emissions are relatively small (2.94 million tonnes in 2023), it is heavily reliant on imported fossil fuels. The government aims to generate 30% of its energy from solar power by 2033 and has pledged to reduce emissions by 30% by 2030, contingent on international support, reflecting a commitment to environmental justice and sustainable development despite its vulnerabilities.

4.3. Geology

The geology of The Bahamas is dominated by limestone platforms, known as the Bahama Banks, which have been accumulating for millions of years. It is generally believed that the Bahamas platform began to form around 200 million years ago when the supercontinent Pangaea started to break apart. The limestone that comprises the Banks has been accumulating since at least the Cretaceous period, and possibly as early as the Jurassic. Today, the total thickness of limestone under the Great Bahama Bank is over 2.8 mile (4.5 km). As this limestone was deposited in shallow water, the immense thickness indicates that the entire platform has been slowly subsiding under its own weight at a rate of roughly 1.4 in (3.6 cm) per 1,000 years.

The Bahamas is part of the Lucayan Archipelago, which also includes the Turks and Caicos Islands, the Mouchoir Bank, the Silver Bank, and the Navidad Bank. The broader Bahamas Platform, encompassing Southern Florida, Northern Cuba, the Turks and Caicos, and the Blake Plateau, formed about 150 million years ago. The 4.0 mile (6.4 km) thick limestones that predominate date back to the Cretaceous and were deposited in shallow seas on a stretched and thinned portion of the North American continental crust.

Around 80 million years ago, the area was flooded by the Gulf Stream. This event led to the drowning of the Blake Plateau and the separation of the Bahamas from Cuba and Florida, as well as the fragmentation of the southeastern Bahamas into separate banks, including the Cay Sal Bank, and the Little and Great Bahama Banks. Sedimentation from the "carbonate factory" of each bank, or atoll, continues today at a rate of about 0.8 in (20 mm) per millennium. Coral reefs form the "retaining walls" of these atolls, within which oolites and pellets accumulate.

Coral growth was more prolific during the Tertiary period until the onset of the ice ages, hence Tertiary deposits are more abundant below a depth of 118 ft (36 m). An ancient extinct reef exists about half a kilometer seaward of the present one, 98 ft (30 m) below current sea level. Oolites form when oceanic water, rich in calcium carbonate, penetrates the shallow banks, where increased temperature (by about 5.4 °F (3 °C)) and salinity (by 0.5 per cent) promote their precipitation. Cemented ooids are known as grapestone. Giant stromatolites are found off the Exuma Cays.

Fluctuations in sea level during the ice ages caused periods when the banks were exposed. During these times, wind-blown oolite formed extensive sand dunes with characteristic cross-bedding. Overlapping dunes created oolitic ridges, which were rapidly lithified by rainwater, forming eolianite. Most islands feature ridges ranging from 98 ft (30 m) to 148 ft (45 m) in height, although Cat Island has a ridge reaching 197 ft (60 m). The land between these ridges often hosts lakes and swamps.

The solution weathering of the limestone results in a distinctive "Bahamian Karst" topography. This includes features such as potholes, blue holes (like Dean's Blue Hole), sinkholes, beachrock formations (such as the debated Bimini Road), limestone crusts, and extensive cave systems (both dry and sea caves), formed in the absence of surface rivers. Several blue holes are aligned along the South Andros Fault line. Tidal flats and tidal creeks are common, but more dramatic drainage patterns are found in submarine troughs and canyons like the Great Bahama Canyon, which show evidence of turbidity currents and turbidite deposition.

The stratigraphy of the islands primarily consists of the Middle Pleistocene Owl's Hole Formation, overlain by the Late Pleistocene Grotto Beach Formation, and then the Holocene Rice Bay Formation. These units are not always stacked sequentially but can be found laterally. The Owl's Hole and Grotto Beach formations are often capped by a terra rossa paleosol, unless eroded. The Grotto Beach Formation is the most widespread.

4.4. Ecology and Conservation

The Bahamas possesses distinct terrestrial ecoregions, including Bahamian dry forests (tropical dry broadleaf forests), Bahamian pine mosaic (dominated by Caribbean pine), and Bahamian mangroves. The country's biodiversity is rich, particularly its marine life, which thrives in the clear waters of the Bahama Banks and around its numerous coral reefs. Forest cover in The Bahamas was approximately 51% of the total land area in 2020, equivalent to 509,860 hectares. This figure has remained largely unchanged since 1990. The forests are primarily naturally regenerating, with no significant area of planted forest. Reports indicate that 0% of this forest is primary forest (native tree species with no clear signs of human activity), and a very small percentage (around 0%) of the forest area was found within formally protected areas as of 2020. In 2015, it was reported that 80% of the forest area was under public ownership, while 20% was privately owned. The Bahamas had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.35 out of 10, ranking it 44th globally out of 172 countries.

Conservation efforts are crucial for The Bahamas, given its ecological sensitivity and economic reliance on its natural environment, particularly for tourism. The establishment of the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park in 1958 was a pioneering step, creating one of the world's first marine protected areas. Since then, The Bahamas has expanded its network of national parks and protected areas to conserve its marine and terrestrial biodiversity, including coral reefs, mangrove ecosystems, pine forests, and critical habitats for endangered species like the Bahama parrot, rock iguanas, and sea turtles.

These conservation initiatives are not only vital for ecological health but also hold significant social importance. Healthy marine ecosystems support fisheries, a key source of livelihood and food security for many Bahamians. Mangroves and coral reefs provide natural coastal protection against storm surges and erosion, which is increasingly critical in the face of climate change and rising sea levels. Ecotourism and responsible enjoyment of natural areas also offer sustainable economic opportunities. However, challenges remain, including threats from coastal development, pollution, overfishing, invasive species, and the impacts of climate change (such as coral bleaching and increased hurricane intensity). Balancing economic development with environmental stewardship and ensuring that local communities benefit from conservation efforts are ongoing priorities for the nation, reflecting a growing awareness of environmental justice and the need for sustainable practices.

5. Government and Politics

The Bahamas operates as a parliamentary constitutional monarchy, with a political and legal framework largely derived from the Westminster system of the United Kingdom. Its governance structure emphasizes democratic processes, constitutional safeguards for human rights, and a dynamic political landscape.

5.1. Governmental Structure

The Bahamas is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy and an independent Commonwealth realm. Charles III is the King of The Bahamas and serves as the head of state. The King is represented in The Bahamas by a Governor-General, who is appointed on the advice of the Bahamian Prime Minister. The current Governor-General is Her Excellency Cynthia A. Pratt.

The Prime Minister is the head of government. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the party that commands a majority of seats in the House of Assembly. The current Prime Minister is The Honourable Philip "Brave" Davis MP. Executive power is exercised by the Cabinet, which is composed of the Prime Minister and other ministers selected by the Prime Minister from among the members of Parliament. The Cabinet is responsible to Parliament.

The legislative power is vested in a bicameral Parliament, which consists of:

- The House of Assembly (the lower house): It has 38 members (the number can vary slightly based on electoral boundaries), elected for a five-year term from single-member districts through universal adult suffrage.

- The Senate (the upper house): It has 16 members appointed by the Governor-General. Nine senators are appointed on the advice of the Prime Minister, four on the advice of the Leader of His Majesty's Loyal Opposition, and three on the advice of the Prime Minister after consultation with the Leader of the Opposition. The Senate primarily functions as a chamber of review.

The Prime Minister may dissolve Parliament and call a general election at any time within the five-year term. Constitutional safeguards are in place to protect fundamental rights and freedoms, including freedom of speech, press, worship, movement, and association. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature, and its jurisprudence is based on English common law. The court system includes Magistrates' Courts, the Supreme Court, and the Court of Appeal. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London serves as the highest court of appeal for The Bahamas. Democratic processes, including regular free and fair elections, are central to the Bahamian political system, and constitutional safeguards are intended to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms.

5.2. Political Landscape and Culture

The Bahamas has a well-established two-party system, which has dominated its political landscape since before independence. The two major political parties are:

- The Progressive Liberal Party (PLP): A centre-left party, historically associated with the movement for majority rule and independence.

- The Free National Movement (FNM): A centre-right party, formed in 1971.

These two parties have consistently alternated in power. Several smaller political parties have emerged over the years, such as the Bahamas Democratic Movement, the Coalition for Democratic Reform, the Bahamian Nationalist Party, and the Democratic National Alliance (DNA), but they have generally struggled to win significant representation in Parliament.

Contemporary political issues include economic management, unemployment, crime, immigration, and environmental concerns. There is also an ongoing discussion about constitutional reform, including the possibility of The Bahamas becoming a republic and replacing the monarch with a Bahamian president as head of state. This debate gained some traction following the death of Queen Elizabeth II, with opinion polls suggesting growing support for such a change. Electoral processes are generally considered free and fair, contributing to a stable democratic culture. Voter turnout is typically high.

5.3. Foreign Relations

The Bahamas maintains strong bilateral relationships with the United States and the United Kingdom. It has an embassy in Washington, D.C., and a High Commission in London. The U.S. is a key partner in trade, tourism, and security, particularly in areas like counter-narcotics and disaster relief. For instance, after Hurricane Dorian in 2019, the U.S. embassy provided significant aid, including 3.60 M USD for shelters, medical evacuation boats, and construction materials.

The Bahamas is an active member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), participating in regional cooperation on economic, security, and social issues, though it is not part of the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME). It is also a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, the Organization of American States (OAS), and various other international organizations.

The country's foreign policy generally aligns with promoting democratic values, human rights, and international cooperation, particularly on issues relevant to small island developing states, such as climate change, sustainable development, and financial regulation. It also engages with international partners on issues such as combating illegal drug trafficking and illegal immigration.

5.4. Defence Force

The military of The Bahamas is the Royal Bahamas Defence Force (RBDF). Established on March 31, 1980, the RBDF is primarily a naval force, encompassing a Commando Squadron (a land unit) and an Air Wing. Its mandate, under the Defence Act, is to defend The Bahamas, protect its territorial integrity, patrol its extensive waters, provide assistance and relief in times of disaster (such as hurricanes), maintain order in conjunction with law enforcement agencies, and carry out other duties as determined by the National Security Council.

The RBDF's key responsibilities include combating drug smuggling, illegal immigration, poaching of marine resources, and providing assistance to mariners in distress. It plays a crucial role in search and rescue operations within Bahamian waters. The Defence Force is also a member of the CARICOM's Regional Security Task Force, contributing to regional security efforts.

As of recent reports, the RBDF has a fleet of approximately 26 coastal and inshore patrol craft, along with several aircraft for surveillance and transport. Its personnel strength is over 1,100, including officers and enlisted members, with women serving in various capacities. Service in the RBDF is voluntary.

5.5. Administrative Divisions

The Bahamas has a system of local government for the Family Islands (the islands outside of New Providence). New Providence, where approximately 70% of the national population resides and the capital city of Nassau is located, is directly administered by the central government.

The "Local Government Act" of 1996 established the framework for this system, creating Family Island administrators, local government districts, local district councillors, and local town committees. The primary goal of this act is to empower elected local leaders to manage the affairs of their respective districts with a degree of autonomy from the central government, fostering local participation in governance and development.

There are a total of 32 districts. Elections for local government officials are held every five years. These elections determine the composition of district councils and town committees, with approximately 110 councillors and 281 town committee members elected to represent the various communities. Each councillor or town committee member is responsible for the appropriate use of public funds for the maintenance and development of their constituency.

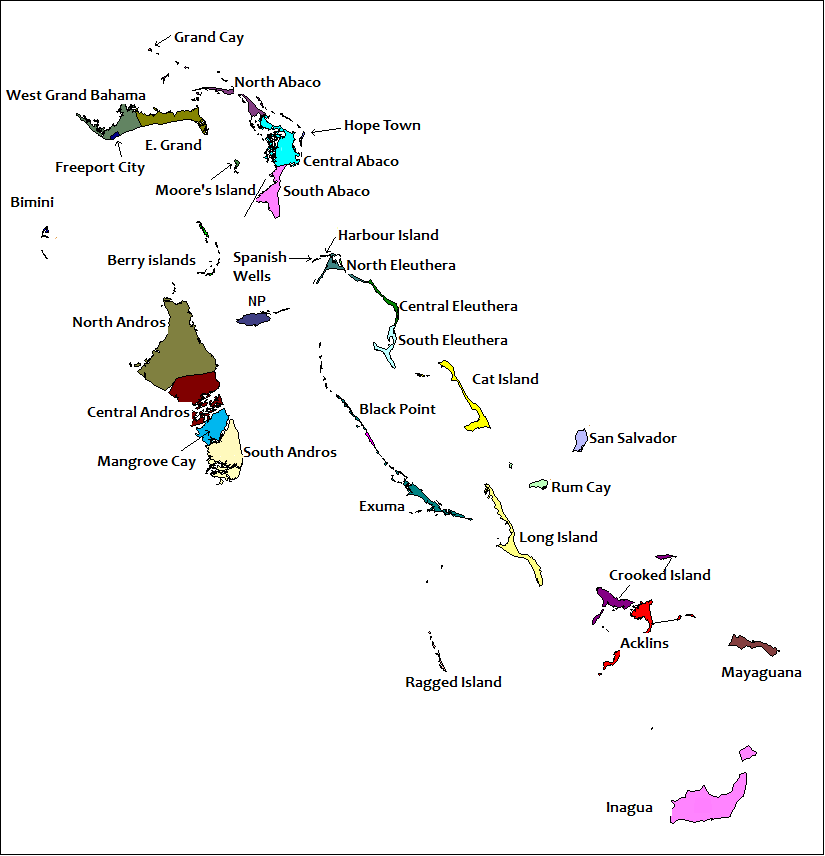

The districts (excluding New Providence) are:

- Acklins

- Berry Islands

- Bimini

- Black Point, Exuma

- Cat Island

- Central Abaco

- Central Andros

- Central Eleuthera

- City of Freeport, Grand Bahama

- Crooked Island

- East Grand Bahama

- Exuma (main district, distinct from Black Point)

- Grand Cay, Abaco

- Harbour Island, Eleuthera

- Hope Town, Abaco

- Inagua

- Long Island

- Mangrove Cay, Andros

- Mayaguana

- Moore's Island, Abaco

- North Abaco

- North Andros

- North Eleuthera

- Ragged Island

- Rum Cay

- San Salvador

- South Abaco

- South Andros

- South Eleuthera

- Spanish Wells, Eleuthera

- West Grand Bahama

6. Economy

The Bahamian economy is primarily driven by tourism and offshore financial services, with a focus on maintaining its status as a high-income developing country. The government actively works to balance economic growth with social welfare and sustainable development, though challenges related to diversification and international financial regulations persist.

6.1. Economic Sectors and Industries

The Bahamas is recognized as one of the wealthiest countries in the Americas in terms of GDP per capita. Its currency, the Bahamian dollar (BSD), is maintained at a one-to-one peg with the US dollar.

The economy is heavily reliant on tourism, which is the dominant sector. Tourism accounts for approximately 70% of the Bahamian GDP and provides employment for about half of the country's workforce, directly or indirectly. The islands' proximity to the United States, favorable climate, beaches, and clear waters attract millions of visitors annually. In 2012, for example, The Bahamas received 5.8 million visitors, with over 70% arriving via cruise ships. The socio-economic impacts of tourism are profound, driving infrastructure development, service industries, and overall economic activity. However, this reliance also makes the economy vulnerable to external shocks like global recessions, natural disasters, and pandemics, as seen with Hurricane Dorian and the COVID-19 pandemic. Ensuring sustainable tourism practices and equitable benefit distribution are ongoing concerns, alongside upholding labor rights within the sector.

The second most important economic sector is offshore international financial services, which contributes around 15-20% of the GDP. The Bahamas has established itself as a significant international financial center, offering services such as private banking, wealth management, and company registration. This sector also provides high-value employment, though its scale of direct employment is smaller than tourism.

6.2. Taxation and Offshore Financial Services

The Bahamas operates with a highly competitive tax regime, often classified as a tax haven. The government derives its revenue primarily from import tariffs, Value Added Tax (VAT, introduced in 2015 to broaden the tax base), license fees, property tax, and stamp duty. Notably, there is no income tax, corporate tax, capital gains tax, or wealth tax. Payroll taxes are levied to fund social insurance benefits, with contributions from both employees (e.g., 3.9%) and employers (e.g., 5.9%). In 2010, overall tax revenue as a percentage of GDP was 17.2%.

The offshore financial sector has faced international scrutiny regarding tax transparency and anti-money laundering regulations. Events like the "Panama Papers" and subsequent leaks (sometimes referred to broadly as "Bahamas Papers" or similar, due to Bahamian entities being listed) revealed The Bahamas as a jurisdiction with a large number of registered offshore entities. The country has since taken steps to comply with international standards for financial transparency and information exchange set by organizations like the OECD. These efforts aim to maintain its reputation as a legitimate financial center while addressing concerns about tax avoidance and evasion. The social implications involve balancing the economic benefits of the sector with the need for domestic revenue generation and addressing international pressures for greater regulatory oversight. Some estimates suggest The Bahamas holds trillions of dollars in private and corporate wealth within its offshore structures.

6.3. Agriculture, Fisheries, and Manufacturing

Agriculture, fisheries, and manufacturing constitute a smaller segment of the Bahamian economy, collectively representing about 5-7% of the total GDP. The country relies heavily on food imports, with an estimated 80% of its food supply being imported.

Agriculture is limited by infertile soil and a lack of freshwater on many islands. Major crops include onions, okra, tomatoes, oranges, grapefruit, cucumbers, sugar cane, lemons, limes, and sweet potatoes. There are ongoing efforts to support local production, promote food security, and reduce import dependency, including initiatives in sustainable farming and aquaculture.

Fisheries are an important traditional industry, focusing on spiny lobster (crawfish), conch, and various finfish. The sector provides local employment and contributes to export earnings, particularly from crawfish. Sustainable fisheries management is critical to protect marine resources from overexploitation.

Manufacturing is small-scale, focusing on items like processed foods, beverages (notably rum), handicrafts for the tourist market, and some light industrial products.

6.4. Transport Infrastructure

The Bahamas has approximately 1.0 K mile (1.62 K km) of paved roads, primarily on the more populated islands. Inter-island transport is crucial and is conducted mainly by sea (ferries, mail boats) and air. The country has a total of 61 airports and airstrips.

The main international airports are:

- Lynden Pindling International Airport (NAS) on New Providence, the primary gateway to the country.

- Grand Bahama International Airport (FPO) in Freeport, Grand Bahama.

- Leonard M. Thompson International Airport (MHH) on Abaco Island.

Ports and harbors are essential for both international trade (container shipping, fuel imports) and domestic transport. Nassau Harbour is a major cruise ship port. The transport network is vital for economic activity, especially tourism, and for ensuring social connectivity, including access to services and goods for communities on the Family Islands. Maintaining and upgrading infrastructure, particularly in the face of hurricane threats and the needs of remote communities, is an ongoing priority.

7. Demographics and Society

The demographics and societal structure of The Bahamas reflect its unique history, characterized by migration, slavery, and the development of a distinct national identity. The nation strives to address issues of social equity, integration, and the well-being of all its residents, including minority and vulnerable groups.

7.1. Population Demographics

The population of The Bahamas was approximately 400,516 according to a 2022 estimate.

Key demographic indicators from around 2010 show:

- Age Structure**: Approximately 25.9% of the population was 14 years old or under, 67.2% were between 15 and 64, and 6.9% were 65 or older.

- Population Growth Rate**: Around 0.925% (2010).

- Birth Rate**: Approximately 17.81 births per 1,000 population.

- Death Rate**: Approximately 9.35 deaths per 1,000 population.

- Net Migration Rate**: Approximately -2.13 migrants per 1,000 population, though this can fluctuate significantly due to illegal immigration patterns.

- Infant Mortality Rate**: Approximately 23.21 deaths per 1,000 live births.

- Life Expectancy at Birth**: Around 69.87 years (73.49 years for females, 66.32 years for males).

- Total Fertility Rate**: About 2.0 children born per woman (2010).

The most populous island is New Providence, where the capital city of Nassau is located, home to roughly 70% of the total population. The second most populous island is Grand Bahama, where the city of Freeport is situated. The remaining population is dispersed among the Family Islands. Population distribution and density vary significantly across the archipelago. Social implications of these demographics include pressures on urban infrastructure in Nassau, the need for equitable service delivery to the Family Islands, and planning for an aging population.

7.2. Ethnic Groups and National Identity

The ethnic composition of The Bahamas is a direct result of its historical development:

- Afro-Bahamians: Constitute the vast majority, around 90.6% of the population according to the 2010 census. Their ancestry primarily traces back to West Africans brought to the islands as enslaved people during the colonial era, as well as Liberated Africans freed from slave ships by the British Royal Navy in the 19th century. The first Africans arrived with the Eleutheran Adventurers from Bermuda, some as freed individuals.

- White Bahamians: Make up about 4.7% of the population. They are mainly descendants of early English Puritan settlers who arrived in the mid-17th century and American Loyalists who fled the American Revolution in the late 18th century, bringing their enslaved people with them. Many Southern Loyalists settled on Abaco, which historically had a higher proportion of European descendants. The term "Conchy Joe" is sometimes used colloquially to refer to Bahamians of Anglo descent.

- Mixed Race: Individuals of mixed African and European ancestry accounted for about 2.1% in the 2010 census.

- Haitian Community: There is a significant population of Haitians and Bahamians of Haitian descent, estimated to be around 80,000 or more (which would represent about 20-25% of the total population if considered as a distinct group, though census figures may categorize them within Afro-Bahamians). Many are undocumented immigrants or face challenges with legal status. This community has made substantial cultural and economic contributions but also faces issues of discrimination, integration, and access to rights and services. The Bahamian government has periodically undertaken efforts to repatriate undocumented Haitian migrants, which has sometimes drawn criticism from human rights organizations.

- Other Groups: Smaller minorities include Greek Bahamians (descendants of Greek laborers who came in the early 20th century for the sponging industry, comprising less than 2% but maintaining a distinct culture), Asians, and individuals of Spanish or Portuguese origin.

National identity is strongly rooted in the shared history of overcoming slavery and colonialism, and the achievement of independence. Issues of race, colorism, and national belonging can be complex, particularly in relation to the Haitian community. Efforts towards anti-discrimination and promoting the rights of all minority groups are important aspects of social development, reflecting the country's commitment to democratic ideals and human rights. In 1722, when the first official census was taken, 74% of the population was European or native British, and 26% was African or mixed, highlighting the dramatic demographic shift over three centuries.

7.3. Languages

The official language of The Bahamas is English. It is used in government, education, business, and the media.

Many Bahamians also speak an English-based creole language known as Bahamian Creole (often referred to simply as "dialect" or "Bahamianese"). Bahamian Creole exhibits variations across different islands and social groups and is an important part of the national cultural identity. The term "Bahamianese" was notably promoted by Bahamian writer and actor Laurente Gibbs.

Haitian Creole, a French-based creole language, is widely spoken by the Haitian community and Bahamians of Haitian descent, who constitute a significant portion of the population (estimated around 25%). It is often referred to simply as "Creole" to distinguish it from Bahamian English/Creole.

Small immigrant communities may also use other languages such as Spanish or Portuguese.

7.4. Religion

The Bahamas is a predominantly Christian country, with a strong religious presence in daily life and culture. Protestant denominations collectively form the largest religious group, accounting for more than 80% of the population according to some classifications, or over 70% based on 2010 data.

The major Christian denominations include:

- Baptists: Representing about 35% of the population, forming the largest single denomination.

- Anglicans: Constituting about 15% of the population, with historical ties to the Church of England.

- Roman Catholics: Making up a significant community of about 14.5%.

- Pentecostals: Around 8%.

- Church of God: About 5%.

- Seventh-day Adventists: About 5%.

- Methodists: Around 4%.

- Other Christian groups, including Brethren and Assemblies of God, also have a presence.

There is a small Jewish community in The Bahamas, with roots tracing back to early European expeditions (Luis De Torres, an interpreter for Columbus, is believed by some to have been a converso or secretly Jewish). Today, the community numbers around 200-300 individuals.

A small Muslim community also exists, estimated at around 300 people. While some enslaved and free Africans in the colonial era may have had Muslim backgrounds, Islam was largely absent until a revival in the 1970s.

Other faiths and spiritual practices include the Baháʼí Faith, Hinduism, and Rastafarianism. Traditional African-based folk magic and spiritual practices like Obeah are also found, particularly in the Family Islands, though Obeah is officially illegal. The constitution guarantees freedom of religion, and religious tolerance is generally practiced. About 3.1% of the population identified as unaffiliated in 2010.

7.5. Education System

The education system in The Bahamas aims to provide accessible schooling from primary to tertiary levels, viewing education as a key means of social advancement and national development. The literacy rate for the adult population was estimated at 95% according to 2011 figures.

Education is compulsory for children between the ages of 5 and 16. The public education system is managed by the Ministry of Education and includes primary schools, junior high schools, and senior high schools. There are also numerous private and denominational schools.

The University of the Bahamas (UB) is the national tertiary education institution. Chartered on November 10, 2016, it evolved from the College of The Bahamas (established in 1974). UB offers a range of undergraduate (associate and baccalaureate) and graduate (masters) degrees. It has three main campuses (Oakes Field and Grosvenor Close in Nassau, and UB-North in Grand Bahama) and several teaching and research centers throughout the archipelago.

Other tertiary institutions include the Bahamas Technical and Vocational Institute (BTVI) and various offshore medical schools and specialized colleges. Efforts are ongoing to improve educational standards, expand access to higher education and vocational training, and align the education system with the country's economic and social development needs. Ensuring equitable access to quality education, particularly for students in the Family Islands and from disadvantaged backgrounds, remains a priority.

7.6. Public Health

The Bahamas has a mixed public and private healthcare system, striving to provide accessible and quality medical services to its population. The Ministry of Health oversees the public health sector, which includes government-operated hospitals, clinics, and community health services. The two main public hospitals are the Princess Margaret Hospital in Nassau and the Rand Memorial Hospital in Freeport. There are also several community clinics throughout New Providence and the Family Islands, which are crucial for providing primary care, especially in more remote areas.

Private healthcare facilities, including doctors' offices, specialized clinics, and one major private hospital (Doctors Hospital in Nassau), offer alternative and often more specialized services, primarily to those with health insurance or the ability to pay out-of-pocket. National health insurance, in the form of the National Health Insurance (NHI) Bahamas program, was introduced in phases starting in 2016, aiming to improve access to affordable healthcare for all legal residents.

Major health concerns in The Bahamas include non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer, which are leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Lifestyle factors like diet and physical inactivity contribute to these issues. Communicable diseases, including HIV/AIDS and occasional outbreaks of mosquito-borne illnesses like dengue fever, also require ongoing public health attention.

The COVID-19 pandemic posed significant challenges to the Bahamian public health system. The government implemented measures such as border closures, lockdowns, testing, contact tracing, and a vaccination program to manage the spread of the virus and treat affected individuals. The pandemic strained healthcare resources and highlighted the need for continued investment in public health infrastructure, emergency preparedness, and equitable access to care, particularly for vulnerable populations and those in the Family Islands. Ensuring adequate healthcare staffing, modernizing facilities, and addressing health disparities remain key objectives.

8. Culture

The culture of The Bahamas is a vibrant tapestry woven from African, British, and American influences, reflecting its history of migration, colonization, and proximity to the United States. This blend is expressed through unique traditions, arts, cuisine, music, and national symbols, with ongoing efforts to preserve and promote its rich African and indigenous (Lucayan, though largely erased) heritage.

8.1. Traditional Culture, Festivals, and Folklore

Junkanoo is arguably the most iconic Bahamian cultural expression. It is a traditional Afro-Bahamian street parade characterized by "rushing" (a rhythmic, shuffling dance), vibrant music played on goatskin drums, cowbells, horns, and whistles, and elaborate, colorful costumes made of crepe paper and cardboard. Major Junkanoo parades are held in Nassau (and some other settlements) on Boxing Day (December 26) and New Year's Day. Junkanoo is also featured during other celebrations like Emancipation Day. Its origins are debated but are strongly linked to the cultural expressions of enslaved Africans.

Regattas are important social and sporting events in many Family Island settlements. These typically involve several days of sailing races featuring traditional, locally-built work boats, accompanied by onshore festivities with music, food, and crafts.

Storytelling is a significant oral tradition, with folk tales often featuring animal characters and moral lessons, reflecting West African influences.

Folklore includes mythical creatures and legends such as the lusca (a sea monster) and the chickcharney (a bird-like creature said to inhabit the forests of Andros Island), Pretty Molly on Exuma, and tales of the Lost City of Atlantis sometimes associated with Bimini.

Obeah, a form of African-based folk magic or spiritual practice, is present in The Bahamas, particularly in some Family Islands. While its practice is officially illegal and punishable by law, it remains a part of the cultural undercurrent for some.

The preservation of African heritage is evident in many aspects of Bahamian culture, from music and dance to storytelling and social customs. While the Lucayan indigenous culture was largely eradicated, archaeological efforts and cultural memory initiatives attempt to acknowledge this foundational element of Bahamian history.

8.2. Cuisine

Bahamian cuisine is a flavorful blend of Caribbean, African, and European influences, heavily featuring fresh local seafood and tropical fruits.

Key ingredients and dishes include:

- Seafood**: Conch is a staple, prepared in numerous ways (conch salad, cracked conch, conch fritters, conch chowder). Grouper, snapper, lobster (crawfish), and crab are also popular.

- Side Dishes**: Peas 'n' rice (pigeon peas and rice), baked macaroni and cheese, potato salad, and coleslaw are common accompaniments. Johnnycake (a type of cornbread) is also traditional.

- Soups**: Conch chowder and pea soup with dumplings are hearty favorites.

- Fruits**: Tropical fruits like guava (used in "duff," a dessert), pineapple, mango, papaya, and soursop are widely available.

- Beverages**: Switcha (a lemonade-like drink made with native limes) and Sky Juice (coconut water mixed with gin and condensed milk) are popular local drinks. Rum is also a significant part of the culinary landscape.

Many settlements host food-related festivals celebrating local specialties, such as the "Pineapple Fest" in Gregory Town, Eleuthera, and the "Crab Fest" on Andros Island. These festivals showcase local culinary traditions and ingredients.

8.3. Music and Performing Arts

Music and dance are integral to Bahamian cultural expression.

- Junkanoo music, with its distinctive polyrhythms from drums, cowbells, and horns, is the most prominent.

- Rake-and-scrape is a traditional Bahamian folk music form, characterized by the use of a carpenter's saw (scraped with a nail or screwdriver), a goatskin drum (often a "goombay" drum), and an accordion or guitar. It is often played at social gatherings and dances.

- Goombay music combines African rhythms with European melodies and is often associated with storytelling and social commentary. Well-known musicians like Blake Alphonso Higgs (Blind Blake) were prominent in this genre.

- Calypso and Soca music, originating from Trinidad and Tobago, are also popular and have influenced local artists.

- Gospel and hymns are deeply ingrained, with local variations like the uniquely rhyming spirituals performed by artists such as Joseph Spence.

- Contemporary Bahamian musicians blend these traditional forms with reggae, R&B, and other international genres. The group Baha Men gained international fame with their song "Who Let the Dogs Out?", which won a Grammy Award. Ronnie Butler was another highly influential contemporary musician.

Literature in The Bahamas includes a growing body of poetry, short stories, plays, and novels. Common themes explore Bahamian identity, history, social change, the beauty of the islands, and the complexities of post-colonial life. Notable writers include Susan Wallace, Marion Bethel, Percival Miller, Robert Johnson, Raymond Brown, O.M. Smith, William Johnson, Eddie Minnis, and Winston Saunders.

8.4. Sports

Sport plays a significant role in Bahamian culture, with both traditional British-influenced sports and those popular in the United States having a strong following.

- Cricket is historically considered the national sport, having been played in The Bahamas since 1846, making it the oldest organized sport in the country. The Bahamas Cricket Association was formed in 1936. While its popularity has declined since the 1970s, it is still played by locals and immigrants, particularly from other Caribbean nations.

- Athletics (Track and Field) is arguably the most successful sport for Bahamians on the international stage. The country has a strong tradition in sprints and jumps, producing numerous Olympic and World Championship medalists. It is a very popular spectator sport.

- Basketball is extremely popular, influenced by proximity to the United States. Several Bahamians have played in the NBA.

- Baseball also enjoys popularity, with a number of Bahamians having played in MLB.

- American football has gained considerable traction, with local leagues for various age groups.

- Soccer is popular, especially at the high school level, and is governed by the Bahamas Football Association. Efforts have been made to promote the sport, including exhibition matches with international clubs like Tottenham Hotspur.

- Sailing and Regattas are deeply rooted in the maritime heritage of the islands. The Bahamas has achieved Olympic success in sailing.

- Other popular sports include swimming, tennis, and boxing, where Bahamians have also seen international success. Growing sports include golf, rugby league, rugby union, beach soccer, and netball.

The Bahamas first participated in the Olympic Games in 1952 and has competed in every Summer Olympics since, except for the boycotted 1980 Games. The nation has never participated in the Winter Olympics. Bahamian athletes have won a total of sixteen Olympic medals, all in athletics and sailing. The Bahamas holds the distinction of winning more Olympic medals per capita than any other country with a population under one million.

The country has hosted several international sporting events, including the first three editions of the IAAF World Relays, the 2017 FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup (the first senior FIFA tournament staged in the Caribbean), the 2017 Commonwealth Youth Games, the annual Bahamas Bowl (NCAA college American football), and the Battle 4 Atlantis (NCAA college basketball tournament).

8.5. National Symbols

The national symbols of The Bahamas represent the nation's sovereignty, natural environment, history, and aspirations.

- National Flag: Adopted on July 10, 1973. The design features a black equilateral triangle on the hoist side, symbolizing the strength, vigor, and unity of the Bahamian people. The background consists of three horizontal stripes: aquamarine (representing the clear waters surrounding the islands) at the top and bottom, and a gold stripe in the center (representing the sun and rich land resources).

- Coat of Arms: The central element is a shield depicting the Santa María of Christopher Columbus sailing beneath the sun, symbolizing the discovery of the islands. The shield is supported by a marlin (representing marine life and the fishing industry) and a flamingo (the national bird, representing wildlife and the islands' unique ecology). The flamingo stands on land, and the marlin in the sea, indicating the geography. Above the shield is a conch shell (representing diverse marine life) atop a helmet. The national motto, "Forward, Upward, Onward, Together", is displayed on a banner below the shield.

- National Anthem: "March On, Bahamaland", with lyrics by Timothy Gibson and music by Timothy Gibson. It was adopted in 1973.

- National Song: "God Bless Our Sunny Clime" is also recognized as a national song.

- National Flower: The Yellow Elder (Tecoma stans). It was chosen by a popular vote of garden club members in the 1970s because it is endemic to the islands, blooms throughout the year, and was not already the national flower of another country at the time (though it is now also the national flower of the United States Virgin Islands).

- National Bird: The Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber).

- National Fish: The Blue Marlin (Makaira nigricans).

- National Tree: The Lignum vitae (Guaiacum sanctum).

- Pledge of Allegiance: A pledge recited by Bahamians, particularly schoolchildren, expressing loyalty to the nation.

These symbols are widely used in official capacities and serve as unifying elements of Bahamian national identity and heritage.

8.6. Media

The media landscape in The Bahamas includes several privately owned newspapers, numerous radio stations, and television broadcasting services. Freedom of the press is generally respected.

Major daily newspapers include The Nassau Guardian, The Tribune, and The Bahama Journal. There are also several weekly publications. Radio is a popular medium, with a variety of stations offering news, music, and talk shows. The Broadcasting Corporation of The Bahamas (BCB), also known as ZNS (Zephyr Nassau Sunshine), is a government-owned entity that operates radio and television services. Several private television stations also operate.

Access to cable television and internet services is widespread, particularly in New Providence and Grand Bahama, providing Bahamians with a range of local and international media content.