1. Overview

Spain, officially the Kingdom of Spain, is a sovereign state located in Southwestern Europe, with territories in North Africa. It occupies most of the Iberian Peninsula and also includes the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea, the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean, and the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla in Africa. Spain is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy and a developed country with a high quality of life. It is a member of the European Union, the United Nations, NATO, and numerous other international organizations.

This article explores Spain's rich history, diverse geography, complex political system, dynamic economy, multifaceted society, and vibrant culture. It traces Spain's journey from prehistoric settlements through Roman and Visigothic rule, the centuries of Muslim presence and the Reconquista, the rise and fall of a global empire, the tumultuous 20th century marked by civil war and dictatorship, and its subsequent transition to a modern democracy. The narrative emphasizes Spain's democratic development, social progress, cultural diversity, and its ongoing efforts to address contemporary challenges related to human rights, social cohesion, and economic equity from a center-left, social liberal perspective. The country's geography is characterized by high plateaus, mountain ranges, and extensive coastlines, supporting a wide array of climates and ecosystems. Spanish society is marked by linguistic and ethnic diversity, with a strong emphasis on regional autonomy within a unified state. The Spanish economy, a major player in Europe, is examined through its key sectors, infrastructure, and scientific advancements, alongside its social impacts. Finally, Spain's cultural contributions, from art and architecture to literature, music, and cuisine, are highlighted, underscoring its significant global influence.

2. Etymology

The name Spain in English, and Españaehs-PAHN-yahSpanish in Spanish, originates from the Roman name Hispaniahiss-PAHN-ee-ahLatin, which was used to refer to the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces during the Roman Empire. The precise etymological origin of "Hispania" is uncertain, with several theories proposed.

One prominent theory links it to the Phoenicians, who were active traders and colonizers in the region. They are thought to have called the peninsula i-shphan-imee-shfan-EEMPhoenician. This Phoenician term has been variously interpreted. One interpretation is "Land of Rabbits" or "Island of Rabbits." This is supported by Roman coins minted in the region during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, which depict a female figure with a rabbit at her feet. The Greek geographer Strabo also referred to it as the "land of the rabbits." It is possible the Phoenicians mistook the native hyrax for a rabbit, as "shphan" actually means hyrax. Another interpretation of i-shphan-imee-shfan-EEMPhoenician is "Land of Metals" or "edge," referring to its location at the western end of the Mediterranean.

Philologists Jesús Luis Cunchillos and José Ángel Zamora of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) proposed that the Phoenician name translates to "land where metals are forged" or "island of metalworking." They argue that the root of "span" is the Phoenician word spyspee (to forge metals)Phoenician, meaning "to forge metals." Thus, i-spn-yaee-spen-YAH (the land where metals are forged)Phoenician would mean "the land where metals are forged," alluding to the peninsula's rich gold mines and metallurgical activities known to the Phoenicians. This theory is considered highly credible by some scholars.

Another theory suggests that "Hispania" derives from the Basque word Ezpannaez-PAN-nah (edge or border)Basque, meaning "edge" or "border," again referencing the Iberian Peninsula's geographical position as the southwestern corner of Europe.

A Renaissance-era scholar, Antonio de Nebrija, proposed that "Hispania" evolved from the Iberian word Hispalishiss-PAH-lis (city of the western world)xib (modern Seville), which he interpreted as "city of the western world."

The name "España" itself became a common vernacular term for the region. Even after the unification of the crowns of Castile and Aragon in 1492, the monarch was a common sovereign of a united kingdom often termed the "Catholic Monarchy" or "Spanish Monarchy," with separate courts and governments for constituent kingdoms. It wasn't until 1707, with the Nueva Planta decrees, that the composite monarchy was abolished in favor of a centralized state, though "Spain" wasn't formally adopted as the sole official name then. The title "King of Spain" officially appeared with Joseph Bonaparte's accession in 1808. The 1978 Constitution does not define a singular formal name but uses Españaehs-PAHN-yahSpanish, Estado españoles-TAH-doh es-pah-NYOL (Spanish State)Spanish, and Nación españolanah-see-OHN es-pah-NYO-lah (Spanish Nation)Spanish. Reino de EspañaRAY-noh deh es-PAHN-yah (Kingdom of Spain)Spanish is commonly used in official and international contexts.

3. History

The history of Spain is rich and complex, marked by various cultures, conquests, a global empire, and significant political transformations. This section details the major periods from its earliest inhabitants to its current democratic state, emphasizing democratic development, social progress, and cultural diversity.

3.1. Prehistory and Pre-Roman Peoples

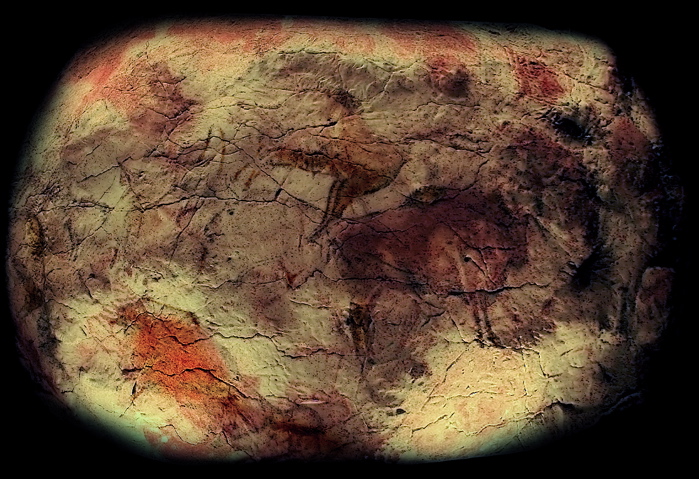

Archaeological research, notably at the Atapuerca sites, indicates that the Iberian Peninsula was populated by hominids as early as 1.2 or 1.3 million years ago. Among the discoveries at Atapuerca are fossils of Homo antecessor, considered one of the earliest known hominin species in Europe. Modern humans (Cro-Magnon) first arrived in Iberia, likely migrating on foot from the north across the Pyrenees, approximately 35,000 years ago. The most famous artefacts from these prehistoric human settlements are the vivid cave paintings in the Altamira cave in Cantabria, northern Iberia. These paintings, created by Cro-Magnon artists, date from between 35,600 and 13,500 BCE. Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that the Iberian Peninsula served as one of several major refugia from which northern Europe was repopulated following the end of the last ice age.

During the Iron Age, before the Roman conquest, the Iberian Peninsula was inhabited by several distinct groups. The two largest were the Iberians and the Celts. The Iberians primarily inhabited the Mediterranean side of the peninsula, from the northeast to the southwest. The Celts occupied much of the interior and the Atlantic coastal regions in the north and northwest. In areas where these two cultures met and mingled, particularly in the interior, a mixed Celtiberian culture emerged.

Other distinct pre-Roman peoples included the Basques, who occupied the western area of the Pyrenees mountain range and adjacent areas. In the southwest, in what is now Andalusia, the Phoenician-influenced Tartessian civilization flourished, possibly dating back to around 1100 BCE. The Lusitanians and Vettones were prominent tribes in the central-western parts of the peninsula.

Starting from around the 9th century BCE, Phoenicians established trading cities along the coast, such as Gadir (modern Cádiz), near Tartessos. Later, from around the 6th century BCE, Greeks founded trading outposts and colonies in the east, such as Emporion (modern Empúries). Eventually, Phoenician-Carthaginians expanded their influence, moving inland towards the Meseta; however, due to the bellicose nature of the inland tribes, Carthaginian settlements were largely confined to the coasts of the Iberian Peninsula before the arrival of the Romans.

3.2. Roman Hispania and the Visigothic Kingdom

During the Second Punic War, the expanding Roman Republic began its conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, capturing Carthaginian trading colonies along the Mediterranean coast between 210 and 205 BCE. Although it took the Romans nearly two centuries to complete the subjugation of the entire peninsula, often facing fierce resistance from local tribes, they subsequently retained control of the territory, known as Hispania, for over six centuries. Roman rule was consolidated and maintained through the imposition of law, the Latin language, and the construction of an extensive network of Roman roads.

The diverse cultures of the pre-Roman populations were gradually Romanized (Latinized) at varying rates across different parts of the peninsula. Local leaders and elites were often integrated into the Roman aristocratic class. The Roman system of large agricultural estates, or latifundia, was superimposed on existing Iberian landholding systems. Hispania served as a vital granary for the Roman market, and its ports exported significant quantities of gold, wool, olive oil, and wine. Agricultural production was enhanced through the introduction of advanced irrigation projects, some of which remarkably remain in use. Several prominent figures of the Roman Empire were born in Hispania, including the Emperors Hadrian, Trajan, and Theodosius I, as well as the philosopher Seneca, and poets Martial, Quintilian, and Lucan. The Aqueduct of Segovia, estimated to have been built in the late 1st century CE, stands as a monumental example of Roman engineering.

Christianity was introduced into Hispania during the 1st century CE and gained popularity in the cities by the 2nd century. Most of Spain's present languages (which evolved from Vulgar Latin), its religion, and the foundations of its legal system originate from this period of Romanization and Christianization. Starting around 170 CE, the southern province of Baetica experienced incursions from Mauri tribes from North Africa.

The weakening of the Western Roman Empire's authority over Hispania began after 409 CE, with the influx of Germanic tribes such as the Suebi and Vandals, along with the Sarmatian Alans. The Suebi established a kingdom in northwestern Iberia (Gallaecia), while the Vandals settled in the south by 420 CE before crossing into North Africa in 429 CE. As the Western Roman Empire disintegrated, the socio-economic base of Hispania became simplified. However, the successor regimes established by these Germanic groups, particularly the Visigoths who arrived later and established the Visigothic Kingdom (c. 415-711 CE), maintained many of the institutions and laws of the late Roman Empire, including Christianity (though initially often in its Arian form before King Reccared I converted to Chalcedonian Christianity at the Third Council of Toledo in 589 CE). The Visigoths eventually extended their rule over most of the peninsula, establishing their capital at Toledo. For a period, the Byzantine Empire established an occidental province, Spania, in the south during the 6th century, with the aim of reviving Roman rule throughout Iberia, but this territory was eventually reabsorbed by the Visigothic Kingdom. The Visigothic era saw the influential work of scholars like Isidore of Seville, whose writings helped preserve classical knowledge.

3.3. Muslim Rule and Reconquista

From 711 to 718, as part of the expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate, which had recently conquered North Africa from the Byzantine Empire, nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula was rapidly conquered by Muslim armies composed mainly of Arabs and Berbers from across the Strait of Gibraltar. This conquest led to the collapse of the Visigothic Kingdom. Only a small area in the mountainous north of the peninsula, notably the Kingdom of Asturias, managed to resist the initial invasion and maintain Christian rule. The conquered territory became known as Al-Andalus.

Under Muslim rule, Christians and Jews were considered dhimmi (protected peoples) or "People of the Book," allowed to practice their religions but subject to a special tax (jizya) and certain social and legal restrictions. Conversion to Islam occurred gradually, and by the end of the 10th century, the muladíes (Muslims of ethnic Iberian origin) are believed to have formed the majority of the population of Al-Andalus. Córdoba, the capital of Al-Andalus, particularly under the Caliphate of Córdoba (929-1031), became one of the largest, wealthiest, and most culturally sophisticated cities in Europe, a major center for learning, trade, and the arts. Islamic civilization in Iberia saw significant advancements in agriculture, science, philosophy, and architecture, with iconic structures like the Mezquita of Córdoba and later the Alhambra in Granada.

The period of Muslim rule was not monolithic. After the initial Umayyad Emirate and subsequent Caliphate, Al-Andalus fragmented into numerous petty kingdoms known as taifas in the 11th century. This disunity allowed the northern Christian kingdoms - Asturias (later León), Castile, Aragon, Navarre, and Portugal - to gradually expand southward in a centuries-long process known as the Reconquista (Reconquest). The Christian kingdoms sometimes fought amongst themselves but also formed alliances against the Muslim states. The capture of the strategic city of Toledo by Castile in 1085 marked a significant shift in the balance of power.

The arrival of North African Islamic dynasties, the Almoravids (late 11th-mid 12th century) and later the Almohads (mid 12th-mid 13th century), temporarily reunified Muslim Iberia and, with a stricter interpretation of Islam, reversed some Christian gains. However, the decisive Christian victory at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 crippled Almohad power, leading to the swift conquest of most remaining Muslim territories in the following decades. By the mid-13th century, only the Nasrid Emirate of Granada in the far south remained as the last Muslim-ruled polity, largely as a tributary state to Castile. The Reconquista culminated in 1492 when the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, conquered Granada, ending nearly eight centuries of Muslim presence in Iberia.

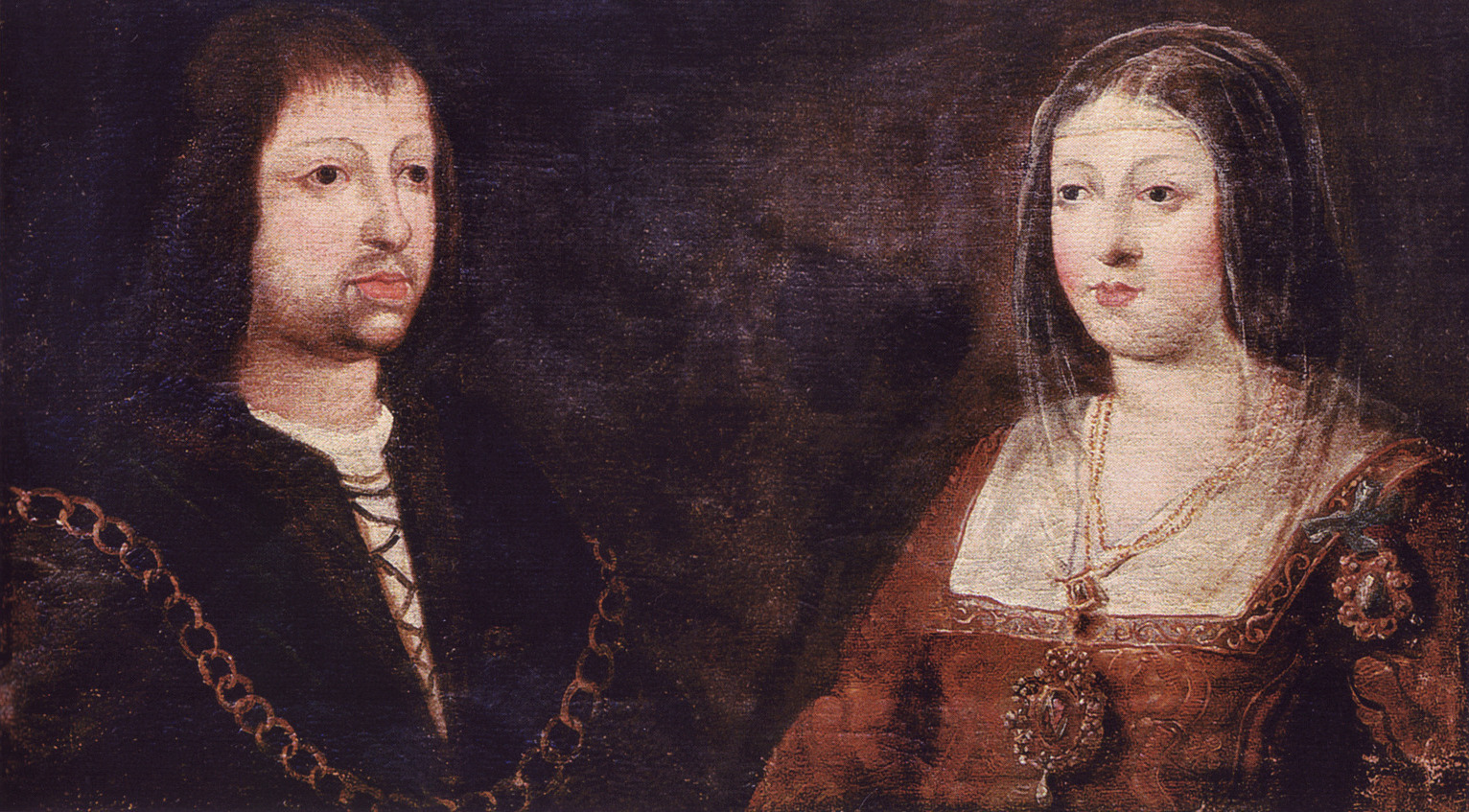

3.4. Spanish Empire

The dynastic union of the Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon through the marriage of Isabella I and Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1469, and their joint rule from 1479, is often considered the de facto unification of Spain as a nation-state, although each kingdom retained its distinct laws, institutions, and languages for centuries. The Catholic Monarchs pursued policies of religious uniformity and political centralization. In 1492, a pivotal year, they completed the Reconquista with the fall of Granada. They also issued the Alhambra Decree, forcing Jews to convert to Catholicism or face expulsion; as many as 200,000 Jews were expelled. Muslims in Granada were initially granted religious tolerance under the Treaty of Granada, but this was revoked a few years later, leading to forced conversions (creating the Moriscos) and eventual expulsions, notably after the War of the Alpujarras (1568-1571), with over 300,000 Moriscos expelled by the early 17th century. These expulsions had significant demographic and economic consequences.

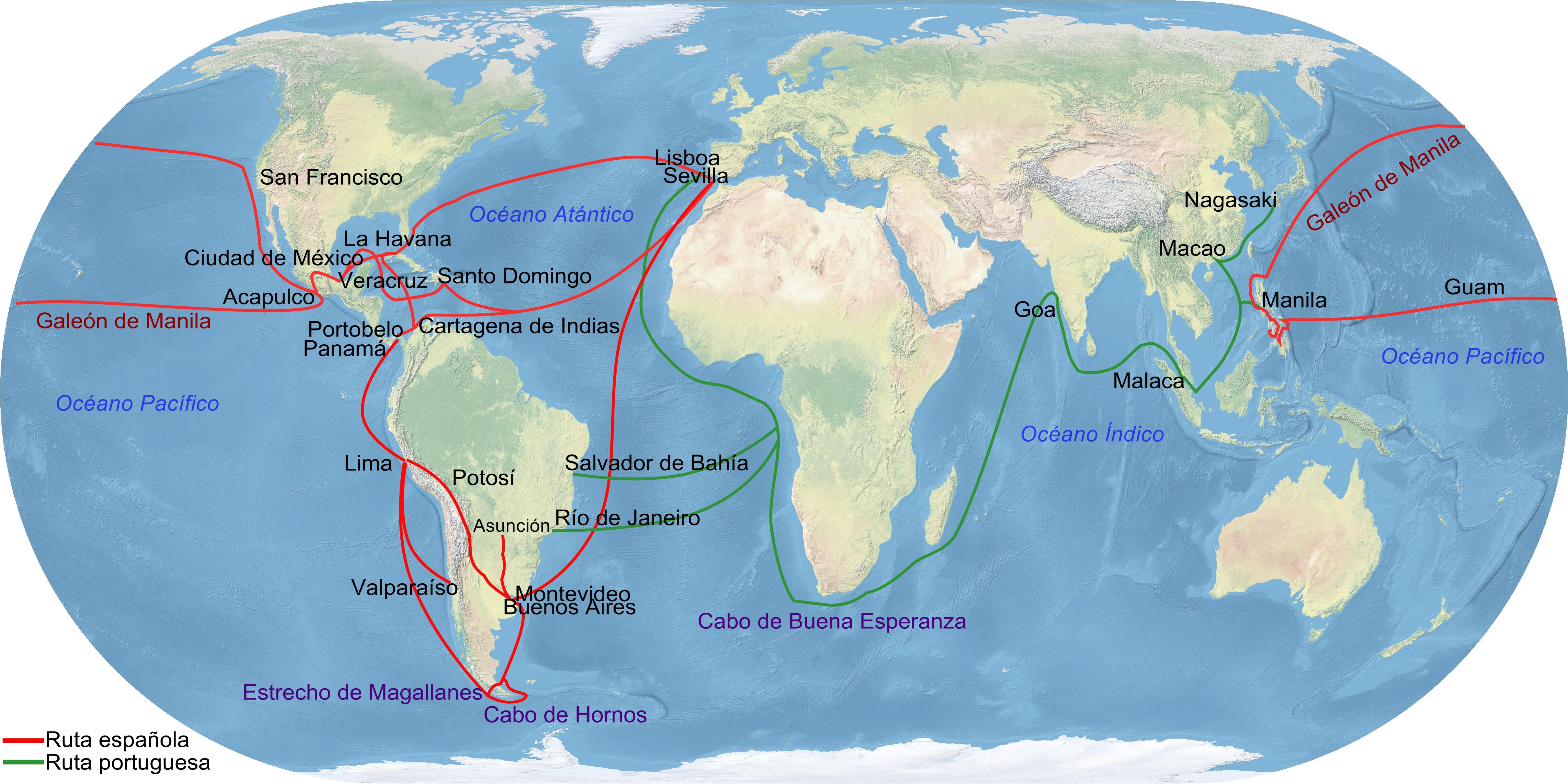

The year 1492 also marked the first voyage of Christopher Columbus to the Americas, funded by Isabella I. This initiated the Age of Discovery and the Spanish colonization of the Americas, leading to the formation of one of the largest empires in history. Spanish conquistadores like Hernán Cortés (conquering the Aztec Empire) and Francisco Pizarro (conquering the Inca Empire) established vast territories for the Spanish Crown. The Spanish Empire expanded across the Americas, parts of Asia (notably the Philippines), and Africa, and also held significant territories in Europe through Habsburg inheritance. Habsburg Spain, particularly under Charles I (Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor) (1516-1556) and Philip II (1556-1598), was a leading world power. This period, known as the Spanish Golden Age (Siglo de Oro), saw immense wealth flow from the American mines (especially silver from Potosí and Zacatecas), fueling a global trading system and supporting Spain's numerous European wars, including the Italian Wars, conflicts with the Ottoman Empire (e.g., Battle of Lepanto, 1571), the Dutch Revolt, and wars with France and England (e.g., the Spanish Armada's defeat in 1588, though the Anglo-Spanish War continued with mixed outcomes).

The empire's expansion brought immense wealth but also challenges. The influx of American silver contributed to inflation (the Price revolution). The Protestant Reformation embroiled Spain in costly religious wars across Europe. Intellectual life flourished, with the School of Salamanca debating international law, just war theory, and early concepts of human rights in the context of colonization. Art and literature thrived with figures like El Greco, Diego Velázquez, Miguel de Cervantes, and Lope de Vega.

The 17th century saw a gradual decline in Spanish power. Continuous warfare, plagues (like the Great Plague of Seville), internal revolts (e.g., in Catalonia and Portugal), and economic mismanagement took their toll. Spain recognized the independence of the Dutch Republic in 1648 (Peace of Westphalia) and lost Portugal in 1640 (formally recognized in 1668). Despite these setbacks, Spain maintained its vast overseas empire.

3.4.1. 18th Century

The death of Charles II without an heir in 1700 led to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). This conflict ended with the Treaty of Utrecht, which confirmed Philip V, a grandson of Louis XIV of France, as King of Spain, establishing the Bourbon dynasty in Spain. However, Spain lost its European possessions outside Iberia (e.g., territories in Italy and the Netherlands) to Austria and Savoy, and ceded Gibraltar and Menorca to Great Britain.

Under the Bourbons, Spain underwent significant administrative and political reforms, known as the Bourbon Reforms. The Nueva Planta decrees (early 18th century) abolished most of the traditional autonomous institutions and laws (fueros) of the constituent kingdoms of the Crown of Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Majorca), centralizing power in Madrid and imposing Castilian administrative and legal models. This aimed to create a more unified and efficient state. The 18th century also saw some economic recovery and population growth. Enlightenment ideas influenced a segment of the elite and the monarchy, leading to reforms in education, science, and infrastructure under rulers like Charles III (1759-1788). Spain participated in conflicts like the Seven Years' War and the American Revolutionary War (siding with the American colonists against Britain).

3.5. Decline of the Empire and Emergence of the Modern State

The 19th century was a period of profound crisis and transformation for Spain, marked by the gradual decline of its imperial power, domestic political instability, and the struggle to modernize. The century began with the Napoleonic Wars. In 1793, Spain joined the First Coalition against revolutionary France, but was defeated. Later, allied with Napoleonic France, Spain suffered a devastating naval defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805). In 1807, Napoleon's troops entered Spain, ostensibly to invade Portugal, but instead occupied Spain. This led to the abdication of Charles IV and Ferdinand VII, and Napoleon installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte as King of Spain in 1808.

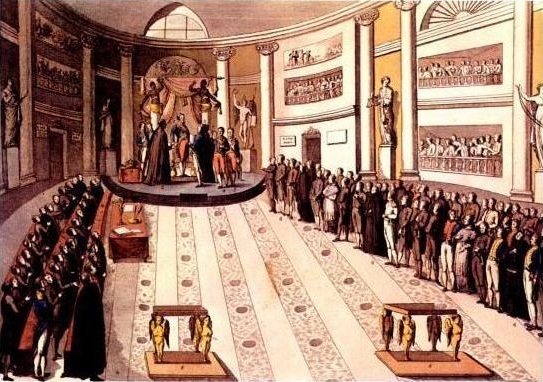

The French occupation sparked the Peninsular War (1808-1814), known in Spain as the War of Independence. Widespread popular uprisings, brutal guerrilla warfare, and the intervention of British and Portuguese forces under the Duke of Wellington eventually led to the expulsion of the French and the restoration of Ferdinand VII in 1814. During the war, the Cortes of Cádiz, a revolutionary body, drafted the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812 (La Pepa), which established a constitutional monarchy and popular sovereignty. However, upon his return, Ferdinand VII abolished the constitution and restored absolutism, leading to decades of conflict between liberals and absolutists.

The turmoil in Spain during the Napoleonic Wars provided an opportunity for its American colonies to seek independence. Starting in 1809, a series of Spanish American wars of independence led to the loss of most of Spain's empire in the Americas by 1826, with only Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines remaining. This loss of empire severely impacted Spain's economy and international standing.

The reign of Ferdinand VII was followed by the Carlist Wars, a series of civil wars fought over the succession and the nature of the Spanish state, pitting the absolutist and traditionalist Carlists (supporters of Don Carlos, Ferdinand VII's brother) against the liberals who supported Isabella II, Ferdinand's daughter. Liberalism eventually prevailed, but Spanish politics remained highly unstable, with frequent military interventions (pronunciamientos), changes in government, and several constitutions. The 19th century saw attempts at economic modernization, including early industrialization in regions like Catalonia and the Basque Country, and the development of railways, but Spain lagged behind other Western European nations. Social tensions grew with the rise of new ideologies like anarchism and socialism.

The Glorious Revolution of 1868 overthrew Isabella II, leading to the Sexenio Democrático (Democratic Sexennium, 1868-1874), a period of experimentation that included a short-lived parliamentary monarchy under Amadeo I and the First Spanish Republic (1873-1874). This turbulent era ended with the Bourbon Restoration in 1874, which brought Alfonso XII to the throne and established a constitutional monarchy based on a two-party system (Conservatives and Liberals) that, while providing some stability, was often characterized by political corruption (caciquismo).

The late 19th century saw the loss of Spain's remaining major colonies. The Cuban War of Independence and the Philippine Revolution, followed by U.S. intervention in the Spanish-American War of 1898, resulted in Spain ceding Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to the United States. This "Disaster of '98" (El Desastre del 98) profoundly impacted Spanish society and intellectual life, fueling calls for national regeneration (Regeneracionismo) and critical analysis from the Generation of '98.

3.6. 20th Century: Republic, Civil War, and Francoist Dictatorship

The early 20th century in Spain was marked by increasing social unrest, political polarization, and economic challenges, despite periods of industrial growth, particularly in Catalonia and the Basque Country. Spain remained neutral during World War I. Heavy losses in colonial wars in Morocco, such as the Battle of Annual (1921) during the Rif War, discredited the government and further undermined the monarchy of Alfonso XIII. Labor movements, including socialist and anarchist factions like the PSOE (founded 1879), UGT (1888), and the anarcho-syndicalist CNT (1910), gained strength. Regionalist and nationalist movements in Catalonia (Lliga Regionalista, 1901) and the Basque Country (PNV, 1895) also grew.

The political system of the Restoration, weakened by corruption and repression (e.g., the Tragic Week in Barcelona, 1909), collapsed with the military coup of General Miguel Primo de Rivera in 1923, who established a dictatorship with royal support. Primo de Rivera's regime lasted until 1930. Following his resignation and a brief period of instability, municipal elections in April 1931 showed overwhelming support for republican parties in major cities. King Alfonso XIII went into exile, and the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed on April 14, 1931.

The Second Republic (1931-1939) was a period of significant democratic reforms and social upheaval. A new, progressive constitution was adopted, granting women's suffrage, separating church and state, and allowing for regional autonomy. Governments led by figures like Manuel Azaña initiated agrarian reform, military restructuring, and educational improvements. However, the Republic faced immense challenges: deep political divisions between left and right, economic hardship exacerbated by the Great Depression, and resistance from conservative elements including the Church, landowners, and parts of the military. Political violence, including church burnings, attempted coups (like Sanjurjo's in 1932), and the Revolution of 1934 (notably the Asturian miners' strike), marked this era.

The victory of the left-wing Popular Front in the February 1936 elections further polarized the country. On July 17-18, 1936, a military uprising against the Republican government, initiated by conservative generals including Francisco Franco, began in Spanish Morocco and spread to parts of mainland Spain. The coup's partial success led to the devastating Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). The Republicans, supported by the Soviet Union, Mexico, and international volunteers, fought against the Nationalists (or rebels), who received crucial military aid from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Western democracies like Britain and France adopted a policy of non-intervention, which largely harmed the Republic. The war was characterized by extreme brutality on both sides, including massacres, political assassinations, and widespread human rights abuses like the bombing of Guernica. It claimed over 500,000 lives and forced up to half a million Spaniards into exile.

On April 1, 1939, the Nationalist forces led by General Franco emerged victorious, establishing an authoritarian Francoist dictatorship that lasted until his death in 1975. The Franco regime was characterized by authoritarianism, intense repression of political opponents (with thousands imprisoned in Francoist concentration camps or executed), promotion of a unitary national identity, National Catholicism (where the Catholic Church held significant power), and suppression of regional languages and cultures. The only legal political organization was the FET y de las JONS (later known as the Movimiento Nacional). During World War II, Spain remained officially neutral but sympathetic to the Axis Powers, even sending the volunteer Blue Division to fight alongside Germany on the Eastern Front.

Post-war, Spain faced international isolation and was excluded from the United Nations until 1955. However, the Cold War made Spain strategically important to the United States, leading to pacts that allowed U.S. military bases in exchange for economic and military aid. From the late 1950s, technocratic reforms led to the Spanish miracle (1959-1974), a period of unprecedented economic growth driven by industrialization, internal migration from rural areas to cities like Madrid, Barcelona, and the Basque Country, and the development of mass tourism. This economic development brought significant social changes, but political freedoms remained severely restricted, and human rights abuses continued.

3.7. Restoration of Democracy and Contemporary Spain

Following General Franco's death in November 1975, Prince Juan Carlos de Borbón was proclaimed King of Spain, as designated by Franco. However, instead of continuing the authoritarian regime, King Juan Carlos I played a pivotal role in dismantling the Francoist state and ushering in the transition to democracy (La Transición). He appointed Adolfo Suárez as Prime Minister in 1976, who, along with other political figures and broad societal consensus, spearheaded reforms. The Spanish 1977 Amnesty Law pardoned political prisoners and also granted immunity to officials of the Franco regime, a controversial aspect that has been debated for its impact on historical memory and accountability for past human rights abuses.

Key milestones in the transition included the legalization of political parties (including the Communist Party), the first democratic elections in 1977, and the drafting of a new constitution, which was approved by a referendum in December 1978. The 1978 Constitution established Spain as a parliamentary constitutional monarchy, guaranteeing fundamental rights and freedoms, and creating a decentralized state based on autonomous communities, recognizing Spain's regional diversity.

The transition was not without challenges. On February 23, 1981, a military coup attempt (known as 23-F) sought to restore authoritarian rule by seizing the Cortes. King Juan Carlos I's decisive condemnation of the coup on national television was crucial in its failure, reaffirming Spain's commitment to democracy. The Basque separatist group ETA continued its violent campaign for independence throughout this period and beyond, posing a significant challenge to democratic stability until its dissolution in May 2018.

The PSOE, led by Felipe González, won the 1982 general election, marking a significant consolidation of democracy. Under González (1982-1996), Spain joined the European Economic Community (EEC, later the EU) in 1986 and NATO (after a referendum in 1986 affirmed earlier entry in 1982). Integration into Europe brought significant economic modernization, investment, and social change. Spain hosted the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona and Expo '92 in Seville, showcasing its transformation. Culturally, this era saw a flourishing of freedom of expression, exemplified by movements like La Movida Madrileña.

The conservative Partido Popular (PP), led by José María Aznar, came to power in 1996. Spain adopted the euro in 1999 (physical currency in 2002) and experienced strong economic growth in the early 2000s, partly fueled by a construction boom. Aznar's government supported the Iraq War, a decision that was highly unpopular domestically. The 2004 Madrid train bombings on March 11, 2004, carried out by an Islamist terrorist group inspired by Al-Qaeda, killed 191 people just days before the general election. The handling of the attacks became a major political issue, and the PSOE, led by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, won the election.

Zapatero's government (2004-2011) withdrew Spanish troops from Iraq, legalized same-sex marriage (2005), enacted further gender equality laws, and attempted negotiations with ETA, which announced a permanent ceasefire in 2010. The bursting of the Spanish property bubble in 2008 triggered a severe economic crisis, leading to high unemployment (especially youth unemployment), austerity measures, and social unrest, including the 15-M Movement (Indignados).

Mariano Rajoy's PP government (2011-2018) implemented further austerity measures to address the crisis. On June 19, 2014, King Juan Carlos I abdicated in favor of his son, who became King Felipe VI. The Catalan independence movement intensified, culminating in a disputed referendum in October 2017 and a unilateral declaration of independence, which was not recognized internationally and led to the Spanish government imposing direct rule on Catalonia for a period.

In June 2018, Pedro Sánchez of the PSOE became Prime Minister after a vote of no confidence against Rajoy. Spain formed its first coalition government since the restoration of democracy after the November 2019 general election, between PSOE and Unidas Podemos. Contemporary Spain faces ongoing challenges including managing regional nationalisms, addressing economic disparities, ensuring the sustainability of its welfare state, combating corruption, and upholding human rights and democratic accountability. The COVID-19 pandemic starting in 2020 posed significant health and economic challenges, leading to a drop in life expectancy and requiring substantial recovery efforts, partly supported by the Next Generation EU package. In March 2021, Spain legalized active euthanasia. Following the 2023 general election, Pedro Sánchez formed another coalition government, this time with Sumar. An institutional crisis surrounding the General Council of the Judiciary's mandate renewal, ongoing from 2018, was resolved in 2024. In 2024, Salvador Illa became the first non-separatist regional president of Catalonia in over a decade, signaling a potential normalization of relations.

4. Geography

Spain's diverse geography encompasses mountainous regions, extensive coastlines, arid plains, and fertile river valleys, as well as island archipelagos. This section outlines its key physical features, climate zones, and unique island territories.

4.1. Topography, Mountains, and Rivers

Mainland Spain is a predominantly mountainous country, dominated by high plateaus and extensive mountain chains. The largest physiographic unit is the Meseta Central (Inner Plateau), a vast plateau in the heart of peninsular Spain. It is divided into two sub-plateaus (Submeseta Norte and Submeseta Sur) by the Sistema Central mountain range, which includes peaks like Pico Almanzor (8.5 K ft (2.59 K m)).

Major mountain ranges radiate from or surround the Meseta. To the north, the Pyrenees form a natural border with France and Andorra, with peaks like Aneto (11 K ft (3.40 K m)). West of the Pyrenees, along the northern coast, lie the Cantabrian Mountains, which include the Picos de Europa. The Sistema Ibérico (Iberian System) extends from the Cantabrian Mountains southeastwards, bordering the Meseta to the northeast and east. In the south, the Baetic System (Sistema Bético) runs parallel to the Mediterranean coast and includes the Sierra Nevada, home to mainland Spain's highest peak, Mulhacén (11 K ft (3.48 K m)). The Sierra Morena forms the southern rim of the Meseta. The highest point in all of Spanish territory is Teide (12 K ft (3.72 K m)), an active volcano on the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands; it is the third largest volcano in the world from its base.

Spain has several major rivers, many of which originate in the mountainous interior and flow across the Meseta. The longest river on the Iberian Peninsula is the Tagus (Tajo), which flows westward through Spain and Portugal to the Atlantic. Other significant rivers include the Ebro, which flows southeast into the Mediterranean; the Douro (Duero), Guadiana, and Guadalquivir, all of which flow west or southwest to the Atlantic. The Guadalquivir valley in Andalusia forms a large, fertile alluvial plain. Other important rivers are the Júcar, Segura, and Turia flowing into the Mediterranean, and the Minho (Miño) in the northwest flowing into the Atlantic. Coastal plains are found along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts, with the largest being that of the Guadalquivir.

Spain is a transcontinental country, situated between latitudes 27°N and 44° N, and longitudes 19° W and 5° E. Its Atlantic coast faces west and north (Bay of Biscay). Its Mediterranean coast runs from the Strait of Gibraltar eastward. Spain shares land borders with Portugal (the 0.8 K mile (1.21 K km) Portugal-Spain border, the longest uninterrupted border within the EU), France, Andorra, Gibraltar (a British Overseas Territory), and Morocco (at Ceuta, Melilla, and Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera). The town of Llívia is a Spanish exclave entirely surrounded by French territory.

4.2. Climate

Spain exhibits a wide variety of climates due to its large size, varied topography, and influence from both the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Three main climatic zones can be distinguished:

- The Mediterranean climate is predominant in much of the country. It is characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters (Köppen Csa). This climate prevails along the Mediterranean coast, in the Balearic Islands, and in large parts of Andalusia and the interior. A variation with warm, rather than hot, dry summers and cooler winters (Köppen Csb) is found in parts of Galicia and inland areas at higher altitudes, such as western Castile and León and northeastern Castile-La Mancha.

- The Oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb) is found in the northern quarter of the country, encompassing Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque Country, and northern Navarre. This region, often called "Green Spain," experiences mild, rainy winters and warm, relatively cool and moist summers, with less pronounced seasonal drought. Highland areas along the Iberian System and in the Pyrenean valleys also experience this type of climate, sometimes with humid subtropical variants (Cfa).

- The Semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk, BSh) is prevalent in the southeastern quarter of the country, particularly in the Region of Murcia, southern and central-eastern Valencia, and eastern Andalusia (e.g., Almería, which contains Europe's only true desert climate, BWh, BWk). It is also found in the Ebro Valley (southern Navarre, central Aragon, western Catalonia) and parts of Castile-La Mancha, Madrid, and Extremadura. These areas have very hot summers, mild winters, and scarce, irregular rainfall, with a dry season extending beyond summer.

Apart from these main types, other sub-types exist:

- Alpine climate occurs in high mountain areas like the Pyrenees, Sierra Nevada, Cantabrian Range, Central System, and Iberian System.

- Continental climate influences (hot summers, cold winters, Dfc, Dfb / Dsc, Dsb) are found in interior high-altitude areas of these mountain ranges.

- The Canary Islands generally have a subtropical climate, with mild temperatures year-round. Coastal low-lying areas experience conditions akin to a tropical climate due to average temperatures above 64.4 °F (18 °C) in their coolest month, though aridity leads to classification as arid or semi-arid according to AEMET (Spanish State Meteorological Agency).

Spain is significantly affected by climate change, experiencing more frequent and intense heat waves and droughts, particularly in the south and east. Water resources are under increasing stress. In response, Spain is promoting a transition to renewable energy sources, especially solar and wind power.

4.3. Islands

Spain's territory includes several significant island groups and smaller islets:

- The Balearic Islands (Illes BalearsBalearic IslandsCatalan, Islas BalearesBalearic IslandsSpanish) are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The four largest islands are Majorca (Mallorca), Menorca (Minorca), Ibiza (Eivissa), and Formentera. They form an autonomous community and are a major tourist destination.

- The Canary Islands (Islas CanariasCanary IslandsSpanish) are an archipelago located in the Atlantic Ocean, off the northwestern coast of Africa (Morocco and Western Sahara). The seven main islands are Tenerife, Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria, Lanzarote, La Palma, La Gomera, and El Hierro. They form another autonomous community and are known for their volcanic landscapes and distinct climate. Mount Teide on Tenerife is Spain's highest peak.

- Plazas de soberanía (Places of Sovereignty) are a series of small Spanish territories located on or off the Mediterranean coast of Morocco. These include the uninhabited islands of Chafarinas Islands, Peñón de Alhucemas, and the peninsula of Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera. The cities of Ceuta and Melilla, also on the North African coast, are autonomous cities with a status between a municipality and an autonomous community.

- Alboran Island (Isla de AlboránAlboran IslandSpanish) is a small volcanic island in the Alboran Sea, part of the western Mediterranean, situated between Spain and Morocco. It is administered by the municipality of Almería.

- Pheasant Island (Isla de los FaisanesPheasant IslandSpanish, Île des FaisansPheasant IslandFrench) in the Bidasoa river is a unique condominium, with sovereignty alternating between Spain and France every six months.

Spain has 11 major islands with their own governing bodies: Tenerife, Gran Canaria, Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, La Palma, La Gomera, and El Hierro in the Canary Islands (governed by cabildos insulares); and Majorca, Ibiza, Menorca, and Formentera in the Balearic Islands (governed by consells insulars). Ibiza and Formentera together form the Pityusic Islands. These islands are specifically mentioned in the Spanish Constitution regarding their senatorial representation.

4.4. Fauna and Flora

Spain boasts a high level of biodiversity, a result of its geographical position between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, and between Africa and Eurasia, as well as its great variety of habitats and biotopes stemming from diverse climates and distinct regions. The country includes different phytogeographic regions, each with its own floral characteristics shaped by climate, topography, soil type, fire, and biotic factors. Spain has the largest number of plant species in Europe, with approximately 7,600 vascular plants. In 2019, Spain had a Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.23/10, ranking it 130th globally out of 172 countries. There are an estimated 17.8 billion trees in Spain, with an average of 284 million more growing each year.

Notable fauna includes species that are rare or extinct elsewhere in Europe. The Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus) and the Cantabrian brown bear (Ursus arctos pyrenaicus) survive in the Cantabrian Mountains and parts of the Pyrenees. The critically endangered Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) is endemic to the peninsula and is the subject of intensive conservation efforts. The Spanish ibex (Capra pyrenaica) is found in mountainous areas. Spain is a crucial migratory route and wintering ground for birds from Northern Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa. Birdlife is exceptionally rich, with species like the Spanish imperial eagle, Cinereous vulture, and numerous waterfowl. The Canary Islands have many endemic species due to their isolation, including unique lizards, birds (like the blue chaffinch), and insects.

Spanish flora is also highly diverse. The Mediterranean region is characterized by sclerophyllous vegetation like holm oak (Quercus ilex), cork oak (Quercus suber), olive trees, and various shrubs. The more humid Atlantic region ("Green Spain") features deciduous forests of oak (Quercus robur, Quercus petraea), beech (Fagus sylvatica), and chestnut. Mountainous areas host alpine and subalpine flora, including pine forests (Pinus sylvestris, Pinus nigra) and juniper. Semi-arid regions in the southeast have unique flora adapted to drought conditions. The Canary Islands possess a remarkable endemic flora, including the Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis) and the iconic dragon tree (Dracaena draco). Spain has numerous national parks and protected natural spaces, such as Doñana National Park, Picos de Europa National Park, and Teide National Park, dedicated to conserving its rich biodiversity and ecological balance.

5. Politics

Spain is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy. The Spanish Constitution of 1978 establishes a democratic framework based on the separation of powers, a multi-party system, and a high degree of regional autonomy. The political system aims to ensure democratic development, accountability, and respect for human rights.

5.1. Government and Governance

The Spanish state is structured around key institutions whose roles and functions are defined by the Constitution. This framework ensures a balance of power and representation for its citizens within a democratic system.

5.1.1. The Crown

King Felipe VI described the role of the Crown in 2014, stating, "The independence of the Crown, its political neutrality and its wish to embrace and reconcile the different ideological standpoints enable it to contribute to the stability of our political system, facilitating a balance with the other constitutional and territorial bodies, promoting the orderly functioning of the State and providing a channel for cohesion among Spaniards."

The Crown (La Corona) is the head of state. The current monarch is King Felipe VI. The King's role is primarily symbolic and ceremonial. According to the Constitution, the King "arbitrates and moderates the regular functioning of the institutions," acts as the highest representative of the Spanish State in international relations, and exercises the functions expressly conferred on him by the Constitution and the laws. The King is the commander-in-chief of the Spanish Armed Forces. However, the monarch has limited political powers and does not make policy decisions, which are the responsibility of the elected government. All acts of the King must be countersigned by the Prime Minister or other competent ministers. This ensures that political responsibility lies with the government, not the monarch, upholding the democratic principle of accountability. The Crown plays a vital role in ensuring the stability and continuity of the state and promoting national unity.

5.1.2. Cortes Generales (Parliament)

Legislative power is vested in the Cortes Generales (Cortes GeneralesKor-tes Khe-ne-RA-les (General Courts)Spanish), the bicameral Spanish Parliament. It consists of:

- The Congress of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados): This is the lower house and holds primary legislative power. It currently has 350 members (deputies) elected by universal suffrage through a system of proportional representation (using the D'Hondt method) in multi-member constituencies corresponding to Spain's provinces. The Congress of Deputies invests the Prime Minister, can pass a motion of no confidence in the government, and has the final say on most legislation.

- The Senate (Senado): This is the upper house and is conceived as a chamber of territorial representation. It currently has 259 senators. Most senators (208 in the 2023 election) are directly elected by popular vote in provincial constituencies (using a limited voting system), while the remaining are appointed by the legislatures of the autonomous communities. The Senate can amend or veto legislation passed by the Congress, but the Congress can override the Senate's veto by an absolute majority vote (or a simple majority after two months). It also plays a key role in authorizing measures affecting autonomous communities, such as the application of Article 155 of the Constitution (direct rule).

Both houses share legislative initiative with the government and the autonomous communities (in certain cases). The electoral term for both houses is typically four years, unless dissolved earlier. The Parliament is responsible for passing laws, approving the national budget, and overseeing the actions of the government, ensuring democratic accountability.

5.1.3. Government (Executive)

Executive power is exercised by the Government (Gobierno de España), also known as the Council of Ministers (Consejo de Ministros). It is led by the Prime Minister (Presidente del Gobierno), who is nominated by the King after consultations with political parties represented in the Congress of Deputies, and then must receive a vote of confidence from the Congress. Once invested, the Prime Minister is formally appointed by the King. The Prime Minister then appoints the other ministers who form the cabinet.

The Government directs domestic and foreign policy, civil and military administration, and the defense of the State. It is politically accountable to the Congress of Deputies. If the Government loses the confidence of the Congress (e.g., through a successful motion of no confidence or failure to pass a vote of confidence), it must resign. The Prime Minister can also propose the dissolution of the Cortes Generales and call for new elections.

5.2. Administrative Divisions

Spain is a highly decentralized unitary state. Its territorial organization is based on the principle of autonomy for its nationalities and regions, as recognized in the 1978 Constitution.

5.2.1. Autonomous Communities

The first-level administrative divisions are the 17 autonomous communities (comunidades autónomaskoh-moo-nee-DAH-des ow-TOH-no-mas (autonomous communities)Spanish) and 2 autonomous cities (Ceuta and Melilla, located in North Africa). Each autonomous community has its own Statute of Autonomy, which functions as its basic institutional law, defining its name, territory, institutions of self-government (a legislative assembly, a regional president, and a governing council), and the powers (competencies) it assumes.

The process of devolution of powers from the central state to the autonomous communities has been extensive, covering areas such as education, healthcare, social services, culture, urban planning, and environmental protection. The level of autonomy and the specific competencies vary among communities, leading to an "asymmetrical" model of decentralization. Some communities, often referred to as "historic nationalities" (like the Basque Country, Catalonia, and Galicia), have broader powers, including their own police forces (e.g., Ertzaintza in the Basque Country, Mossos d'Esquadra in Catalonia). The Basque Country and Navarre also have unique fiscal regimes (concierto económico and convenio, respectively) granting them significant financial autonomy. This system aims to accommodate regional diversity and promote self-governance while maintaining the unity of the Spanish state.

5.2.2. Provinces and Municipalities

Autonomous communities are typically composed of one or more provinces (provinciaspro-VEEN-thee-as (provinces)Spanish). There are 50 provinces in total. Provinces serve as territorial building blocks for the autonomous communities and as districts for central government administration and elections. Some autonomous communities (Asturias, Cantabria, La Rioja, Madrid, Murcia, Navarre, and the Balearic Islands) consist of a single province, in which case the institutions of the province are effectively merged with those of the autonomous community.

The basic local government units are municipalities (municipiosmoo-nee-THEE-pee-os (municipalities)Spanish). The constitution guarantees their autonomy to manage their own local affairs. They are governed by elected town or city councils (ayuntamientos).

5.3. Foreign Relations

Spain's foreign policy priorities since its transition to democracy have focused on integration into Europe, strengthening ties with Ibero-America (Latin America and the Iberian Peninsula), and playing an active role in international organizations. Spain is a committed member of the European Union (since 1986) and NATO (since 1982). It participates actively in EU decision-making and common foreign and security policy initiatives. Spain is also a member of the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the OECD, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Union for the Mediterranean, whose headquarters are in Barcelona. Spain is a permanent guest of the G20.

Spain maintains special historical, cultural, and linguistic ties with Ibero-America, promoting cooperation through the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI) and the Ibero-American Summits. It has a significant development aid program focused on this region and on North Africa. Its foreign policy emphasizes multilateralism, international law, human rights, and international cooperation for development and peace.

Territorial disputes include the claim over Gibraltar, a British Overseas Territory located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula. Spain calls for negotiations with the UK regarding its sovereignty, a position supported by UN resolutions, while the UK maintains that the Gibraltarians' right to self-determination is paramount. Morocco claims the Spanish autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla and several smaller Spanish islets (plazas de soberanía) off the North African coast. Spain asserts these territories are integral parts of Spain. Portugal does not recognize Spanish sovereignty over Olivenza, a town on the Spanish-Portuguese border. Spain also disputes Portugal's claim to an Exclusive Economic Zone around the Savage Islands.

5.4. Military

The Spanish Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas EspañolasFWER-thas ar-MA-thas es-pah-NYO-las (Spanish Armed Forces)Spanish) are responsible for guaranteeing the sovereignty and independence of Spain, defending its territorial integrity and the constitutional order. The King is the commander-in-chief, but operational command and policy are directed by the civilian government through the Minister of Defence. The highest-ranking military officer is the Chief of the Defence Staff (JEMAD).

The Armed Forces are divided into three branches:

- Army (Ejército de Tierraeh-KHER-thee-toh de tee-EH-rra (Army of Land)Spanish)

- Navy (Armadaar-MA-thah (Navy)Spanish)

- Air and Space Force (Ejército del Aire y del Espacioeh-KHER-thee-toh del EYE-reh ee del es-PA-thee-oh (Army of the Air and Space)Spanish)

Spain abolished conscription in 2001 and has a fully professional military. In 2017, active personnel numbered around 121,900, with 4,770 in reserve. The Civil Guard (Guardia CivilGWAR-dee-ah thee-VEEL (Civil Guard)Spanish), a gendarmerie force with both civil and military functions, numbers around 77,000 and comes under the control of the Ministry of Defence in times of national emergency or war, though it normally operates under the Ministry of the Interior for most policing duties.

Spain is an active member of NATO and participates in numerous international peacekeeping and security missions under UN, EU, or NATO mandates (e.g., in Lebanon, Mali, Iraq, and the Horn of Africa). The defense budget has faced constraints, particularly after the 2008 economic crisis, but the country maintains modern and capable armed forces. Spain has a significant domestic defense industry and participates in multinational defense projects like the Eurofighter Typhoon and the Airbus A400M Atlas. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Spain is the 23rd most peaceful country in the world.

5.5. Human Rights

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 guarantees a broad range of human rights and fundamental freedoms, stating in its preamble the will to "protect all Spaniards and all the peoples of Spain in the exercise of human rights, their cultures and traditions, languages and institutions." Spain is a signatory to major international human rights treaties. Overall, Spain has a good human rights record, and is considered a country with a high degree of civil liberties and political rights.

Key areas and issues concerning human rights in Spain include:

- Civil Liberties: Freedom of speech, assembly, and association are generally well-respected. However, controversial "gag laws" (like the 2015 Public Security Law) have faced criticism from human rights organizations and parts of civil society for potentially restricting these freedoms and imposing hefty fines for certain forms of protest.

- Gender Equality: Spain has made significant strides in gender equality. The 2007 Gender Equality Act aimed to promote equality in political and economic life. Violence against women, particularly domestic violence, remains a serious concern, though the government has implemented comprehensive laws and measures to combat it (e.g., the 2004 Organic Law on Integrated Protection Measures against Gender Violence). Spain has a relatively high representation of women in parliament.

- LGBT Rights: Spain is considered one of the most progressive countries in the world regarding LGBT rights. Same-sex marriage was legalized in 2005, and comprehensive anti-discrimination laws are in place. Public acceptance of homosexuality is very high. Laws facilitating legal gender recognition for transgender people have also been enacted.

- Minority Rights: The rights of ethnic and linguistic minorities, such as Catalans, Basques, and Galicians, are largely protected through the system of autonomous communities, which allows for the co-official status of regional languages and cultural promotion. The Roma community (Gitanos), estimated at around 750,000 to 1 million people, historically faced and continues to experience discrimination and social exclusion, although efforts are made to improve their integration in areas like education, housing, and employment.

- Immigrant Rights: Spain has a large immigrant population. While legal frameworks exist to protect their rights, immigrants, particularly undocumented ones and asylum seekers, can face challenges related to detention conditions, access to services, and integration. There have been concerns about treatment at the borders of Ceuta and Melilla.

- Historical Memory and Accountability: Addressing the legacy of the Spanish Civil War and the Francoist dictatorship remains a sensitive issue. The Historical Memory Law (2007) and subsequent legislation aim to recognize victims, remove Francoist symbols, and facilitate the exhumation of mass graves. However, debates continue regarding the extent of accountability for crimes committed during that era, partly due to the 1977 Amnesty Law.

- Police Conduct and Detention: While generally professional, there have been reports and concerns from organizations like Amnesty International regarding alleged police abuses, lengthy investigations into such abuses, and conditions in some detention facilities.

Spain's commitment to human rights is reflected in its democratic institutions, an active civil society, and adherence to European and international human rights mechanisms. However, ongoing vigilance and efforts are required to address remaining challenges and ensure full protection for all individuals.

6. Economy

Spain has a developed mixed economy, the fifteenth-largest in the world by nominal GDP and the fourth-largest in the Eurozone. It is characterized by a significant services sector, a robust tourism industry, and strong manufacturing, particularly in automotive and renewable energy. The Spanish economy has undergone significant transformation, especially since its integration into the European Union, but has also faced periods of crisis and challenges related to unemployment and social equity.

6.1. Economic Structure and Trends

Historically, Spain's industrialization occurred later and more unevenly than in other major Western European countries, primarily concentrated in Catalonia (textiles) and the Basque Country (iron and steel). The Spanish Civil War and subsequent autarkic policies under Franco hindered economic development until the Spanish miracle of the 1960s and early 1970s, a period of rapid industrialization and growth fueled by foreign investment, tourism, and remittances from emigrant workers.

Since its transition to democracy and accession to the European Economic Community (now EU) in 1986, Spain has further liberalized and modernized its economy. It adopted the euro in 1999. The economy experienced a significant boom in the early 2000s, largely driven by construction and real estate. However, the bursting of the property bubble in 2008 led to a severe recession, a banking crisis, and a surge in unemployment, particularly among young people. Spain received a bailout for its banking sector and implemented austerity measures.

The Spanish economy has since recovered, showing strong growth in the mid-to-late 2010s, outperforming many Eurozone peers. Key economic indicators include:

- GDP: Approximately 1.83 T USD (nominal, 2025 estimate), 2.77 T USD (PPP, 2025 estimate).

- Unemployment: Historically high, it peaked at over 26% during the crisis but had fallen to around 10.61% by early 2025. Youth unemployment remains a significant challenge.

- Inflation: Subject to fluctuations, influenced by energy prices and EU monetary policy.

- Public Debt: Increased significantly after the 2008 crisis, remaining a concern for fiscal sustainability.

- Gini Coefficient: Around 31.2 (2024), indicating moderate income inequality within the EU context.

- Human Development Index (HDI): 0.911 (2022), ranking 27th globally, reflecting high living standards.

Economic policies have focused on fiscal consolidation, labor market reforms (often controversial for their impact on job security and wages), and promoting competitiveness. The impact of these policies on social welfare, income distribution, and regional disparities remains a subject of ongoing debate. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a severe economic shock in 2020, but recovery has been supported by EU funds like Next Generation EU. As of 2024, Spain was noted as the fastest-growing major advanced economy.

6.2. Major Industries

Spain's economy is diversified, with services accounting for the largest share of GDP and employment.

- Services: This sector is dominant, encompassing tourism (see below), retail, banking (Banco Santander, BBVA), telecommunications (Telefónica), and business services.

- Manufacturing: Spain has a strong manufacturing base. The automotive industry is a major exporter and employer, with plants from numerous international brands. In 2023, Spain was the 8th largest automobile producer globally and 2nd in Europe, producing 2.45 million vehicles. Other important manufacturing sub-sectors include chemicals, pharmaceuticals, machinery, and food processing.

- Agriculture: While its share of GDP has declined, agriculture remains important, particularly in regions like Andalusia and Murcia. Spain is a leading global producer of olive oil, wine, fruits (especially citrus), and vegetables. Fishing is also significant. Modernization and irrigation have boosted productivity, but challenges include water scarcity and EU Common Agricultural Policy reforms.

- Construction: Historically a major driver of economic growth, the construction sector experienced a severe downturn after the 2008 property bubble burst. It has since seen a partial recovery, focusing more on infrastructure and renovation.

- Renewable Energy: Spain is a global leader in renewable energy, particularly wind and solar power (see Energy section). Companies like Iberdrola are major international players.

Considerations for labor rights and environmental sustainability are increasingly integrated into industrial policies, though challenges remain.

6.2.1. Tourism

Tourism is a cornerstone of the Spanish economy. In 2024, Spain was the second most visited country in the world (after France), receiving 94 million international tourists, who spent approximately 126.00 B EUR. The sector contributed 12.3% to Spain's GDP in 2023. The headquarters of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) are in Madrid.

Main tourist attractions include:

- Coastal destinations: The Mediterranean coast (Costa del Sol, Costa Brava, Costa Blanca) and the Balearic and Canary Islands are famous for their beaches and resorts.

- Cultural tourism: Historic cities like Madrid, Barcelona, Seville, Granada, Toledo, and Santiago de Compostela attract millions with their rich artistic and architectural heritage. Spain has 50 UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- Rural and nature tourism: Growing in popularity, focusing on national parks, mountains, and traditional villages. Castile and León is a leader in rural tourism.

Challenges for the tourism sector include:

- Sustainability: Managing the environmental impact of mass tourism, particularly water consumption and coastal development.

- Over-tourism: Some popular destinations like Barcelona and Palma de Mallorca face issues of overcrowding, rising housing costs for locals, and pressure on public services.

- Seasonality and diversification: Efforts are underway to reduce reliance on summer beach tourism and promote year-round attractions and alternative forms of tourism.

- Labor conditions: Ensuring fair wages and working conditions in a sector often characterized by seasonal and precarious employment.

6.2.2. Energy

Spain's energy mix has been evolving, with a significant push towards renewable sources. Historically reliant on imported fossil fuels, the country has made substantial investments in clean energy.

- Renewable Energy: Spain is a world leader in renewable energy, particularly wind power (one of the largest producers in Europe) and solar power (both photovoltaic and concentrated solar power). In 2010, wind turbines generated 16.4% of Spain's electricity, and on some days, wind power has covered over half of the mainland's electricity demand. Hydroelectric power and biomass also contribute. The government aims for a carbon-neutral economy by 2050.

- Fossil Fuels: Oil and natural gas are largely imported. Coal production has declined significantly due to environmental concerns and EU policies, with remaining coal power plants being phased out or converted.

- Nuclear Power: Spain has several operational nuclear reactors (8 as of the early 2010s), which contribute a significant portion of its electricity (around 19% in 2010). There is ongoing public and political debate about the future of nuclear energy, with plans for a gradual phase-out.

- Energy Security and Transition: Spain's energy policy focuses on reducing dependence on imported fuels, increasing energy efficiency, and promoting a green transition. This involves developing interconnections with France and Portugal, investing in smart grids, and supporting research in new energy technologies like green hydrogen. Environmental impact and the social costs of the energy transition are key considerations.

6.3. Foreign Trade

Spain has an open economy with strong trade links, primarily within the European Union, which is its largest trading partner.

- Main Export Partners: France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, United Kingdom.

- Main Import Partners: Germany, France, China, Italy, United States.

- Key Traded Goods and Services:

- Exports: Motor vehicles and parts, machinery, chemical products, pharmaceuticals, food products (fruits, vegetables, olive oil, wine), tourism services.

- Imports: Fuels (oil and gas), machinery and electrical equipment, chemical products, vehicles, consumer goods.

- Trade Balance: Spain historically had a trade deficit, but this has improved in recent years, with periods of trade surplus, particularly due to strong export performance and a recovery in tourism.

- Trade Agreements: As an EU member, Spain benefits from the EU single market and participates in EU trade agreements with third countries.

6.4. Transport

Spain has a well-developed and modern transportation infrastructure.

- High-Speed Rail (AVE): Spain boasts one of the world's most extensive high-speed rail networks (Alta Velocidad Española - AVE), connecting major cities like Madrid, Barcelona, Seville, Valencia, and Málaga with trains operating at speeds up to 205 mph (330 km/h). As of early 2025, the network spanned 2.5 K mile (3.97 K km), the longest in Europe and second longest globally after China. The AVE is known for its speed, punctuality (often cited as second only to Japan's Shinkansen), and contribution to regional development.

- Highways: An extensive network of toll-free dual carriageways (autovías) and toll motorways (autopistas) connects all major cities and regions. The road system is largely centralized, with radial highways emanating from Madrid.

- Airports: Spain has 47 public airports. Madrid-Barajas Airport is the busiest, serving 60 million passengers in 2023 (15th busiest globally, 3rd in the EU). Barcelona-El Prat Airport is also a major hub (50 million passengers in 2023, 30th busiest globally). Other key airports are located in Palma de Mallorca, Málaga, Gran Canaria, and Alicante.

- Ports: Spain has numerous important seaports, facilitating freight and passenger traffic. Major ports include Algeciras (one of the busiest in Europe for container traffic), Valencia, Barcelona, Bilbao, and Las Palmas.

- Public Transport: Major cities have efficient public transport systems, including metro networks (Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Bilbao, etc.), trams, and bus services.

- Electric cars: Spain has initiatives to promote electric vehicles to save energy and improve efficiency, aiming for one million electric cars by 2014 as part of earlier government plans.

Transportation policy considers accessibility, regional development, integration with European networks, and environmental impact, including efforts to promote sustainable transport modes.

6.5. Science and Technology

Spain has made significant strides in science and technology, though investment in research and development (R&D) as a percentage of GDP has traditionally been lower than the EU average.

- CSIC (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas): This is the leading public agency dedicated to scientific research in Spain and one of the largest in Europe. It ranked as the 5th top governmental scientific institution worldwide in the 2018 SCImago Institutions Rankings.

- R&D Investment: While public R&D funding exists, private sector investment in R&D has been comparatively low, though efforts are being made to stimulate it. Higher education institutions perform a significant portion (around 60%) of basic research.

- Key Areas of Advancement: Spain has strengths in areas such as renewable energy technologies, biotechnology, medicine, astrophysics (with world-class observatories like the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory in La Palma, home to the Gran Telescopio Canarias), materials science, and information technology.

- Innovation: Spain was ranked 28th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024. There is a growing startup ecosystem, particularly in cities like Barcelona and Madrid.

- International Collaboration: Spanish researchers and institutions actively participate in international research programs, including those funded by the EU (e.g., Horizon Europe).

Challenges include bridging the gap between research output and commercialization, increasing private R&D investment, and retaining scientific talent. The social applications and ethical implications of technological progress are also areas of increasing focus.

7. Society and Demographics

Spanish society is a blend of historical traditions and modern European influences, characterized by regional diversity, evolving demographics, and a comprehensive welfare system. The emphasis from a social liberal perspective is on diversity, social inclusion, and the well-being of its population.

7.1. Population

As of January 2025, Spain had a population of approximately 49,077,984 people, according to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Spain's population density is around 97/km2 (251.2 per sq mi), which is lower than that of most Western European countries. Population distribution is uneven, with concentrations along the coasts and around major urban centers like Madrid, while large areas of the interior are sparsely populated.

Spain's population grew significantly during the demographic boom of the 1960s and early 1970s. However, the total fertility rate (TFR) plunged in the 1980s and has remained low. In 2023, the TFR was 1.12 children per woman, one of the lowest in the world and well below the replacement rate of 2.1. This has contributed to an aging population, with an average age of 43.1 years (as of 2021). Life expectancy is high, though it experienced a temporary drop due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Demographic challenges include population aging, low fertility, and rural depopulation (often referred to as "Empty Spain" or España vaciada).

7.1.1. Urbanisation and Major Cities

Spain is a highly urbanized country. The process of urbanization accelerated in the mid-20th century with industrialization and internal migration from rural areas to cities.

The largest metropolitan areas are:

- Madrid: The capital and largest city, a major political, economic, and cultural center. (Population of municipality: approx. 3.3 million; Metropolitan area: approx. 6.7 million)

- Barcelona: The second-largest city, capital of Catalonia, a global hub for tourism, commerce, and culture. (Population of municipality: approx. 1.6 million; Metropolitan area: approx. 5.5 million)

- Valencia: A major port city and capital of the Valencian Community. (Metropolitan area: approx. 1.5-2.3 million)

- Seville: The largest city in Andalusia and a significant historical and cultural center. (Metropolitan area: approx. 1.3-1.5 million)

Other major urban areas include Zaragoza, Málaga, Murcia, Palma de Mallorca, Las Palmas, Bilbao, and Alicante. These cities are centers of economic activity, education, and cultural life, but also face challenges related to housing affordability, transportation, and social integration in diverse urban populations.

7.1.2. Immigration

Immigration has significantly shaped Spain's demographic landscape, particularly since the late 1990s. As of January 2025, foreign residents accounted for 13.9% (6.8 million) of the population, with the total foreign-born population being 19.11% (9.3 million).

- Origins of Immigrants: Historically, major sources of immigration include Latin America (due to linguistic and cultural ties), Morocco, other North African countries, and Romania and other Eastern European countries. There are also significant communities from the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and China. More recently, there has been an increase in immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

- Impact of Economic Cycles: Immigration boomed during Spain's economic expansion in the early 2000s. The 2008 financial crisis led to a decrease in new arrivals and an increase in emigration, including some foreign residents returning to their home countries. However, immigration levels have since recovered.

- Policies and Integration: Spanish immigration policy has evolved, with periods of regularization for undocumented immigrants and efforts to manage flows and promote integration. Challenges include combating irregular immigration, ensuring access to services for immigrants, addressing social exclusion, and promoting intercultural understanding. The rights of immigrants and asylum seekers, particularly regarding detention conditions and border management at Ceuta and Melilla, are areas of human rights concern.

Immigration has contributed to cultural diversity and economic dynamism but also presents social and political challenges related to integration, resource allocation, and public perception.

7.2. Ethnic Groups

Spain is a diverse country with a population primarily composed of Spaniards, who themselves encompass various regional identities. The concept of "Spanish people" is often seen as an overarching identity that includes distinct historical nationalities and regions.

- Regional Identities: Strong regional identities exist, particularly among Castilians, Catalans, Galicians, and Basques, each with their own distinct cultural traditions, and in many cases, languages. Other regions like Andalusia, Asturias, Aragon, and the Canary Islands also have pronounced regional identities. The 1978 Constitution recognizes these "nationalities and regions" and grants them significant autonomy.

- Roma Community (Gitanos): Spain has one of Europe's largest Roma populations, estimated between 750,000 and 1 million. The Roma have a long history in Spain (since the 15th century) and have made significant cultural contributions, especially to music (e.g., Flamenco). However, they have historically faced and continue to experience significant discrimination and socio-economic marginalization, despite government efforts to promote their inclusion in education, employment, and housing.

- Other Minority Groups: Immigrant communities from various parts of the world (Latin America, Africa, Asia, other European countries) contribute to Spain's ethnic and cultural mosaic. The integration of these groups, respect for their cultural rights, and combating discrimination are ongoing societal concerns.

The emphasis from a social liberal perspective is on recognizing and valuing this diversity, ensuring equal rights and opportunities for all ethnic and cultural groups, and promoting an inclusive national identity that respects regional specificities.

7.3. Languages

Spain is a multilingual state with a rich linguistic diversity.

- Spanish (Castilian) (españoles-pah-NYOLSpanish or castellanokas-teh-LYAH-noSpanish): It is the official language throughout the entire country, as established by the Constitution. All Spaniards have the duty to know it and the right to use it. Spanish is a global language, the second-most spoken native language worldwide.

- Co-official Regional Languages: The Constitution also recognizes that "the other Spanish languages" can be co-official in their respective autonomous communities, in accordance with their Statutes of Autonomy. These include:

- Catalan (catalàkə-tə-LAHCatalan): Co-official in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, and the Valencian Community (where it is officially known and historically referred to as Valencian, valenciàvə-len-see-AHCatalan). Approximately 17% of the Spanish population speak Catalan/Valencian.

- Galician (galegoɡaˈleɣoGalician): Co-official in Galicia. Spoken by about 7% of the population.

- Basque (euskaraews-KAH-ɾaBasque): Co-official in the Basque Autonomous Community and parts of Navarre. Basque is a language isolate, unrelated to any other known living language. Spoken by about 2% of the population.

- Aranese (aranésaɾaˈnesOccitan (post 1500)): A variety of Occitan, co-official in the Val d'Aran in Catalonia.

- Recognized but Non-Official Languages: Some other regional languages have a degree of official recognition and protection in their respective territories, though not full co-official status. These include:

- Asturian (asturianuas-tu-ɾiˈa-nuAsturian or bable): Recognized and protected in Asturias.

- Aragonese (aragonésaɾaɣoˈnesAragonese): Recognized and protected in Aragon.

- Other Languages: Immigrant communities speak a wide variety of languages. Moroccan Arabic, Romanian, and English are among the most common foreign languages. Caló, the language of the Spanish Roma, has influenced Spanish slang but has few fluent speakers. Spanish Sign Language is also recognized.

Linguistic diversity is a significant aspect of Spain's cultural heritage. The promotion and protection of regional languages, alongside Castilian Spanish, are important for cultural rights and regional identity, though language policy can sometimes be a source of political debate.

7.4. Religion

According to a February 2025 survey by the Spanish Centre for Sociological Research (CIS), religious self-definition was as follows: 19.1% practicing Catholic, 35.7% non-practicing Catholic (total 54.8% Catholic), 3.7% believer in another religion, 10.7% agnostic, 13.0% indifferent or non-believer, and 15.5% atheist, with 2.2% not answering.

Roman Catholicism has historically been the dominant religion in Spain and played a significant role in the country's history and culture. However, Spanish society has become increasingly secularized, especially since the transition to democracy.

- Roman Catholicism: While Catholicism remains the largest religious affiliation, regular church attendance has declined significantly.