1. Overview

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country located in the heart of Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south, the Republic of the Congo to the southwest, and Cameroon to the west. The nation's capital and largest city is Bangui. Covering a land area of approximately 239 K mile2 (620.00 K km2), the Central African Republic had an estimated population of around 5.3 million as of 2024. The country is characterized by its diverse ethnic composition, with over 80 distinct groups, and has been plagued by a civil war since 2012.

Formerly a French colony known as Ubangi-Shari, the Central African Republic gained independence in 1960. Its post-independence history has been marked by significant political instability, including a series of autocratic leaders, military coups, and periods of intense internal conflict. The regime of Jean-Bédel Bokassa, who declared himself Emperor of the Central African Empire from 1976 to 1979, was particularly notorious for its extravagance and human rights abuses. Attempts at democratic governance in the 1990s were short-lived, and the country has since experienced recurrent cycles of violence and humanitarian crises, deeply impacting its social fabric and hindering development.

Geographically, the CAR consists mainly of Sudano-Guinean savannas, with an equatorial forest zone in the south and a Sahelo-Sudanian zone in the north. The Ubangi River and Chari River are its principal waterways. Despite possessing significant natural resources, including diamonds, gold, uranium, timber, and hydropower potential, the Central African Republic remains one of the poorest and least developed countries in the world. Persistent conflict, weak governance, and corruption have severely undermined its economic potential and led to dire humanitarian conditions, with widespread poverty, food insecurity, and limited access to basic services such as healthcare and education. The ongoing civil war has exacerbated these challenges, leading to mass displacement and severe human rights violations committed by various armed factions. The nation's political system is a presidential republic, but the government's control over its territory is often contested by rebel groups. International actors, including France and more recently Russia, have played significant roles in the country's security and political landscape, with interventions and influence that have complex implications for sovereignty and human rights. The cultural tapestry of the CAR is rich, reflecting its diverse ethnic makeup through various traditional customs, languages, music, and arts.

2. Etymology

The name "Central African Republic" directly reflects the country's geographical position in the central part of the African continent and its republican form of government. This name was favored by Barthélemy Boganda, the nation's first prime minister, who reportedly envisioned a larger union of countries in Central Africa and preferred it over the colonial designation "Ubangi-Shari."

During the French colonial era, the territory was known as Ubangi-Shari (Oubangui-ChariOubangui-ShariFrench). This name was derived from two major rivers that flow through the region: the Ubangi River and the Chari River, which served as important waterways.

For a brief period, from 1976 to 1979, under the rule of Jean-Bédel Bokassa, the country was renamed the Central African Empire when Bokassa declared himself Emperor. Following his overthrow in 1979, the name reverted to the Central African Republic.

3. History

This section chronicles the major historical events and developmental stages of the Central African Republic, from its earliest societies through the periods of external incursions, French colonization, independence, and the subsequent decades marked by political instability, autocratic rule, and persistent civil conflict, with a focus on the social and human rights impacts of these developments.

3.1. Early history and indigenous societies

The land that is now the Central African Republic has been inhabited for at least 10,000 years. Around 10,000 years ago, desertification in the Sahara region forced hunter-gatherer societies southward into the Sahel regions of what is now northern Central Africa, where some groups settled. The Neolithic Revolution brought farming to the area. Initially, white yam cultivation progressed to millet and sorghum. Before 3000 BCE, the domestication of the African oil palm improved nutrition and allowed for population expansion. This agricultural revolution, along with a "Fish-stew Revolution" involving fishing and the use of boats, facilitated the transport of goods, often in ceramic pots.

The Bouar megaliths in the western region of the country indicate an advanced level of habitation dating back to the very late Neolithic Era (circa 3500-2700 BCE). Ironwork developed in the region around 1000 BCE.

Over time, various indigenous societies formed. The Ubangian-speaking peoples settled along the Ubangi River in what is now the central and east-central Central African Republic. Some Bantu peoples migrated from the southwest of Cameroon. The arrival of bananas in the region during the first millennium BCE added an important source of carbohydrates to the diet and was also used in the production of alcoholic beverages. The production of copper, salt, dried fish, and textiles dominated economic trade in the Central African region. These early societies had complex social structures and engaged in regional trade and cultural exchange.

3.2. 16th to 19th centuries: External incursions and the slave trade

From the 16th and 17th centuries, the region began to experience significant external incursions, primarily related to the slave trade. Slave traders, expanding the Saharan and Nile River slave routes, raided communities in the area. Captives were enslaved and transported to the Mediterranean coast, Europe, Arabia, the Western Hemisphere, or to slave ports and factories along the West and North African coasts, as well as south along the Ubangi and Congo rivers. This trade had a devastating impact on local societies, leading to depopulation, social disruption, and increased conflict.

During the 18th century, the Bandia-Nzakara Azande peoples established the Bangassou Kingdom along the Ubangi River. In the mid-19th century, the Bobangi people became major slave traders, selling captives to the Americas by using the Ubangi River to reach the coast. By 1875, the Sudanese sultan Rabih az-Zubayr governed Upper-Oubangui, which included the present-day Central African Republic, further integrating the region into larger political and economic networks driven by slave raiding and trade. These external pressures profoundly shaped the demographic and political landscape of the area leading up to European colonization.

3.3. French colonial period (Ubangi-Shari)

The European invasion of Central African territory commenced in the late 19th century as part of the Scramble for Africa. Europeans, primarily the French, Germans, and Belgians, arrived in the area around 1885. France seized and colonized the territory, establishing Ubangi-Shari in 1894. In 1910, Ubangi-Shari became part of French Equatorial Africa, administered from Brazzaville. In 1911, under the Treaty of Fez, France ceded a nearly 116 K mile2 (300.00 K km2) portion of the Sangha and Lobaye basins to the German Empire, which in turn ceded a smaller area in present-day Chad to France. After World War I, France re-annexed the territory.

French colonial rule in Ubangi-Shari was characterized by severe economic exploitation and human rights abuses. Modeled on King Leopold II's Congo Free State, concessions were granted to private companies that ruthlessly stripped the region's assets. These companies forced local populations into forced labor to harvest rubber, coffee, and other commodities without pay, often holding families hostage until quotas were met. This system led to widespread suffering and depopulation. The French also introduced mandatory cotton cultivation in the 1920s and 1930s. A network of roads was built, often using forced labor, such as for the Congo-Ocean Railway, where an estimated 17,000 Ubangian workers perished from industrial accidents and diseases like malaria by its completion in 1934. Attempts were made to combat sleeping sickness, and Protestant missions were established.

Local resistance to French rule was significant. The Kongo-Wara rebellion (War of the Hoe Handle) broke out in Western Ubangi-Shari in 1928 and continued for several years, representing one of the largest anti-colonial rebellions in Africa during the interwar period. The extent of this insurrection was often concealed by French authorities. French colonization in Ubangi-Shari is widely considered to have been among the most brutal within the French colonial empire.

During World War II, in September 1940, pro-Gaullist French officers took control of Ubangi-Shari, and General Leclerc established his headquarters for the Free French Forces in Bangui. In 1946, Barthélemy Boganda was elected to the French National Assembly, becoming the first representative from Ubangi-Shari. Boganda advocated against racism and the colonial regime. Disheartened by the French political system, he returned to Ubangi-Shari and founded the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (MESAN) in 1950, laying the groundwork for the country's path to independence.

3.4. Post-independence era (1960-present)

The Central African Republic has faced significant political transformations, major tumultuous events, and profound societal changes from its independence in 1960 to the current period, marked by a recurring cycle of autocratic rule, military coups, and civil conflict, severely impacting its democratic development and human rights.

3.4.1. Dacko's first republic and the Bokassa regime (1960-1979)

In the 1957 Ubangi-Shari Territorial Assembly election, Barthélemy Boganda's Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (MESAN) won decisively, leading to his election as president of the Grand Council of French Equatorial Africa and vice-president of the Ubangi-Shari Government Council. On December 1, 1958, he declared the establishment of the Central African Republic, which gained autonomy within the French Community, with Boganda as its first prime minister. After Boganda's death in a plane crash in March 1959, his cousin, David Dacko, took control of MESAN.

The Central African Republic formally received independence from France on August 13, 1960, and Dacko became its first president. Dacko quickly consolidated power, suppressing political rivals like Abel Goumba and, by November 1962, declared MESAN the sole legal party, establishing a one-party state. His rule became increasingly autocratic.

On December 31, 1965, Dacko was overthrown in the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état by Colonel Jean-Bédel Bokassa, his cousin and the army's chief of staff. Bokassa suspended the constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, and established a military dictatorship. In 1972, he declared himself President for Life. On December 4, 1976, Bokassa proclaimed the Central African Empire, naming himself Emperor Bokassa I. A year later, he held an extravagant and costly coronation ceremony, which drew international condemnation and severely strained the nation's finances.

Bokassa's rule was characterized by brutality, corruption, and gross human rights abuses. In April 1979, student protests against a decree requiring the purchase of school uniforms from a company owned by one of Bokassa's wives were violently suppressed, resulting in the deaths of approximately 100 children and teenagers. Bokassa was reportedly personally involved in some of these killings. This atrocity, coupled with his tyrannical regime, led to his downfall. In September 1979, France intervened militarily through Operation Caban, ousting Bokassa and restoring David Dacko to power. The country's name was reverted to the Central African Republic.

3.4.2. Dacko's second republic and Kolingba's military rule (1979-1993)

Following the overthrow of Jean-Bédel Bokassa in September 1979 with French support, David Dacko was restored as president. His second tenure began with attempts to stabilize the country and introduce political reforms, including a new constitution and the re-establishment of a multi-party system. In March 1981, Dacko won a contested presidential election against opponents like Ange-Félix Patassé. However, his victory was met with widespread protests and accusations of electoral fraud, leading Dacko to declare a state of emergency and once again consolidate power, moving towards autocratic rule.

The political and economic situation remained precarious, and on September 1, 1981, Dacko was overthrown for a second time in a bloodless military coup led by General André Kolingba, the army chief of staff. Kolingba suspended the constitution, banned political activity, and established the Military Committee for National Recovery (CMRN) to govern the country. His rule was initially marked by efforts to address corruption and restore order, but it also suppressed political dissent.

In 1985, Kolingba dissolved the CMRN and created a new political party, the Rassemblement Démocratique Centrafricain (RDC), as the sole legal party. A new constitution was adopted by referendum in 1986, officially returning the country to civilian rule, though Kolingba remained president. Semi-free parliamentary elections were held in 1987 and 1988, but key opposition figures like Abel Goumba and Ange-Félix Patassé were barred from participating.

By the early 1990s, influenced by the wave of democratization across Africa and international pressure, particularly from France and the United States, Kolingba reluctantly agreed to political reforms. A pro-democracy movement gained momentum, forcing Kolingba to legalize opposition parties in 1991 and agree to hold multi-party elections in October 1992. However, he attempted to suspend the election results citing irregularities. Renewed pressure from international donors (GIBAFOR) led to the establishment of a Provisional National Political Council (CNPPR) and a Mixed Electoral Commission to oversee new elections. This period of military governance under Kolingba significantly delayed democratic development and was characterized by limited political freedoms and economic stagnation.

3.4.3. Patassé's democratic government and political instability (1993-2003)

Following intense domestic and international pressure, multi-party presidential elections were held in 1993. Ange-Félix Patassé of the Movement for the Liberation of the Central African People (MLPC) won in the second round with 53% of the vote, defeating Abel Goumba. Patassé's MLPC gained a plurality but not an absolute majority in the National Assembly, requiring coalition partners to govern. Patassé's presidency marked an attempt at democratic governance after years of military rule.

However, his government faced immense challenges. Patassé's administration was accused of favoring his own ethnic group, the Gbaya, and marginalizing others, particularly the Yakoma, who had been prominent under Kolingba. This led to increased ethnic tensions. The government struggled with severe economic problems, including a large national debt and difficulties in paying salaries to civil servants and soldiers, a persistent issue that fueled discontent.

From 1996 to 1997, the country was rocked by three successive army mutinies, largely driven by unpaid wages and ethnic grievances within the military. These mutinies resulted in widespread destruction of property, particularly in Bangui, and further heightened ethnic divisions. The social consequences were severe, with increased insecurity and displacement. International intervention was required to quell the unrest. The Bangui Agreements, signed in January 1997, provided for the deployment of an inter-African military mission, the Mission Interafricaine de Surveillance des Accords de Bangui (MISAB), which was later replaced by a United Nations peacekeeping force, the MINURCA, in April 1998.

Despite the ongoing instability, parliamentary elections were held in 1998, with Kolingba's RDC winning 20 out of 109 seats. In 1999, Patassé won a second presidential term amidst allegations of electoral irregularities and widespread public anger over corruption and poor governance.

Political instability continued. On May 28, 2001, an unsuccessful coup attempt was launched by elements of the military. Patassé managed to retain power with the help of troops from Libya and Jean-Pierre Bemba's Congolese rebel forces. The aftermath saw repressive measures against suspected opponents. Patassé grew suspicious of his army chief of staff, General François Bozizé, whom he accused of involvement in another coup plot. This led Bozizé to flee to Chad in 2002 with loyal troops, setting the stage for further conflict. Patassé's era, while starting with democratic hopes, ultimately succumbed to deep-seated political divisions, economic mismanagement, and persistent military insubordination, leading to significant social suffering and a failure to consolidate democratic institutions.

3.4.4. Bozizé regime and the Bush War (2003-2013)

On March 15, 2003, while President Ange-Félix Patassé was out of the country, General François Bozizé launched a coup d'état with troops that had been based in Chad. Bozizé's forces quickly seized Bangui, and Patassé was overthrown. Bozizé suspended the constitution, dissolved the parliament, and declared himself president. He initially established a transitional government that included some opposition figures, with Abel Goumba appointed as prime minister and later vice-president. A National Transition Council was formed to draft a new constitution, which was approved by referendum in December 2004.

Bozizé won the presidential election held in May 2005, which was criticized by some for irregularities and the exclusion of Patassé. Despite his electoral victory, Bozizé's regime faced immediate challenges from various rebel groups, particularly in the northern and eastern parts of the country. This led to the Central African Republic Bush War, which officially began in 2004. The war involved several rebel factions, including the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (UFDR) led by Michel Djotodia, fighting against government forces (FACA).

The conflict was characterized by widespread human rights abuses committed by both government forces and rebel groups, including attacks on civilians, looting, displacement, and sexual violence. The humanitarian impact was severe, with hundreds of thousands of people displaced and access to basic services severely disrupted. The government struggled to maintain control over large swathes of territory.

In an effort to end the conflict, several peace agreements were signed. A peace deal was reached in Sirte, Libya, in February 2007, and the Birao Peace Agreement was signed in April 2007 with the UFDR. These agreements called for a ceasefire, disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of rebel fighters, and the inclusion of rebel representatives in the government. However, implementation was weak, and fighting continued intermittently. Another peace agreement, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, was signed in Libreville, Gabon, in June 2008, involving multiple rebel groups, but it also failed to bring lasting peace.

Bozizé was re-elected in the 2011 presidential election, which was marred by allegations of fraud and irregularities from the opposition. Despite these electoral mandates, his government's authority remained fragile, and discontent simmered due to corruption, poor governance, and the unresolved grievances of various armed groups. The Bush War, while officially ending with peace accords, laid the groundwork for the larger and more devastating civil war that would erupt in 2012. The period was marked by significant humanitarian suffering and a failure to address the root causes of conflict, including regional marginalization and competition for resources.

3.4.5. Séléka rebellion and transitional government (2013-2016)

In December 2012, the Séléka (meaning "alliance" in Sango) rebel coalition, a loose alliance of predominantly Muslim armed groups from the north and east, launched a major offensive against President François Bozizé's government. They accused Bozizé of failing to honor peace agreements signed between 2007 and 2011. Séléka forces rapidly advanced, capturing several key towns. A short-lived ceasefire and power-sharing deal, the Libreville Agreement, was signed in January 2013, which saw Nicolas Tiangaye, an opposition figure, appointed as prime minister.

However, the agreement collapsed, and Séléka resumed its offensive in March 2013, culminating in the capture of the capital, Bangui, on March 24, 2013. President Bozizé fled the country. Séléka leader Michel Djotodia declared himself president, becoming the country's first Muslim head of state. He suspended the constitution and dissolved the government and parliament, establishing a transitional government.

The Séléka takeover plunged the country into chaos. Séléka fighters, many of whom were foreign mercenaries from Chad and Sudan, engaged in widespread looting, extrajudicial killings, rape, and other human rights abuses, primarily targeting the non-Muslim population. In response, local self-defense groups known as Anti-balaka (meaning "anti-machete" or "anti-bullet" in Sango), initially formed to protect communities from bandits and Séléka abuses, emerged. The Anti-balaka, composed mainly of Christians and animists, began retaliatory attacks against Muslim civilians, whom they associated with Séléka. This led to a brutal cycle of inter-communal violence and sectarian killings, pushing the country to the brink of genocide.

The humanitarian crisis escalated dramatically. Hundreds of thousands were displaced, many seeking refuge in makeshift camps or religious sites. Access to food, water, and healthcare became critically limited. In September 2013, Djotodia formally disbanded Séléka, but many fighters refused to disarm and continued their rampage as "ex-Séléka." The transitional government proved unable to control its own forces or establish security.

International responses intensified. France launched Operation Sangaris in December 2013, deploying troops to stabilize Bangui and disarm militias. An African Union-led peacekeeping mission, the International Support Mission to the Central African Republic (MISCA), was also deployed. Despite these efforts, violence continued. Due to mounting international pressure and his inability to halt the atrocities, Djotodia and Prime Minister Tiangaye resigned in January 2014 during a regional summit in Chad.

Catherine Samba-Panza, the mayor of Bangui, was elected as interim president by the National Transitional Council, becoming the country's first female head of state. Her administration faced the immense task of restoring security, facilitating humanitarian aid, and organizing elections. In September 2014, the UN peacekeeping mission, MINUSCA, took over from MISCA, with a larger mandate to protect civilians and support the political transition. Despite a ceasefire agreement signed in Brazzaville in July 2014, fighting persisted, and the country remained de facto partitioned, with ex-Séléka factions controlling the northeast and Anti-balaka militias dominant in the southwest. The period was marked by extreme violence against civilians, particularly Muslims who were targeted and displaced en masse, and a profound breakdown of state authority, impacting all social groups and devastating human rights.

3.4.6. Touadéra presidency and ongoing civil conflict (2016-present)

Presidential and parliamentary elections were held in late 2015 and early 2016, despite ongoing insecurity in many parts of the country. Faustin-Archange Touadéra, a former prime minister under François Bozizé, won the presidential election in the second round in February 2016 and was sworn in on March 30, 2016. His election raised hopes for a return to stability and constitutional order.

However, Touadéra's presidency has been dominated by the continuation of the civil war. Despite the official end of the Séléka-Anti-balaka conflict phase, numerous armed groups, often evolving from these larger coalitions or based on ethnic and regional lines, continued to control vast swathes of territory, estimated at up to 80% of the country outside the capital, Bangui. These groups engaged in fighting amongst themselves and against government forces, perpetuating violence against civilians, including killings, displacement, and sexual violence. Control over natural resources, particularly diamonds, gold, and livestock, became a major driver of conflict.

Several peace initiatives were attempted. The African Union led efforts, resulting in the "African Initiative for Peace and Reconciliation in the Central African Republic," which culminated in a peace agreement signed in Khartoum in February 2019 between the government and 14 major armed groups. This agreement included provisions for power-sharing and the integration of rebel leaders into government positions. However, its implementation has been fraught with challenges, and violence has persisted.

A significant development during Touadéra's tenure has been the increasing influence of Russia. Starting around 2018, Russia deployed military instructors and private military contractors, notably from the Wagner Group, to support the Central African Armed Forces (FACA) and provide security for President Touadéra. This Russian involvement has been credited by the government with helping to recapture some territory from rebel groups. However, it has also raised serious concerns regarding national sovereignty, the exploitation of natural resources (such as diamonds and gold) by Russian entities, and numerous allegations of human rights abuses committed by Russian mercenaries, including summary executions, torture, and indiscriminate attacks against civilians. The UN and various human rights organizations have documented these abuses.

The general elections in December 2020 were held amidst significant insecurity. A new rebel coalition, the Coalition of Patriots for Change (CPC), formed by groups opposing Touadéra and including elements loyal to former president Bozizé (whose candidacy was rejected), launched an offensive to disrupt the elections and marched on Bangui. Government forces, backed by Russian mercenaries and Rwandan troops, repelled the attack. Touadéra was declared the winner of the presidential election, though turnout was low, and voting could not take place in many rebel-held areas.

The human rights situation remains dire. Civilians continue to bear the brunt of the conflict, facing displacement, food insecurity, and lack of access to basic services. Armed groups and, increasingly, state-allied forces, have been implicated in serious violations of international humanitarian law. Efforts towards justice and accountability, including through the Special Criminal Court (a hybrid court established to try war crimes and crimes against humanity), have been slow and face numerous obstacles. Democratic governance remains fragile, with the government's authority limited outside Bangui, and the country heavily reliant on international aid and peacekeeping forces (MINUSCA). The ongoing conflict and the complex role of foreign actors continue to pose significant challenges to achieving lasting peace, security, and respect for human rights in the Central African Republic. In 2023, a controversial constitutional referendum was passed, allowing President Touadéra to seek a third term and extending presidential term limits, raising concerns about democratic backsliding.

4. Geography

The Central African Republic is a landlocked nation situated within the interior of the African continent, characterized by its diverse physical features, tropical climate, and significant, though threatened, biodiversity.

4.1. Topography and hydrology

The Central African Republic lies between latitudes 2° and 11°N, and longitudes 14° and 28°E. Much of the country consists of a vast, flat or rolling plateau savanna, with an average elevation of around 1640 ft (500 m) above sea level. This plateau forms part of the watershed separating the Congo River basin to the south and the Chad basin to the north.

In the northeast, the Fertit Hills (also known as the Bongo Massif) rise, and there are scattered hills in the southwestern regions. The northwest features the Yade Massif, a granite plateau with an average altitude of 3.7 K ft (1.14 K m), which includes Mount Ngaoui (4.6 K ft (1.41 K m)), the country's highest point, located on the border with Cameroon. The Central African Republic is also known for the Bangui Magnetic Anomaly, one of the largest crustal magnetic anomalies on Earth.

The country's hydrology is dominated by two major river systems. Approximately two-thirds of the country lies within the Ubangi River basin, which flows into the Congo River. The Mbomou River and the Uele River merge to form the Ubangi, which constitutes a significant portion of the southern border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Sangha River, another Congo tributary, flows through some of the western regions. The remaining third of the country, primarily in the north, lies within the basin of the Chari River, which flows northward into Lake Chad. The eastern border roughly follows the edge of the Nile River watershed. These rivers are crucial for transportation, agriculture, and local livelihoods.

The country contains six terrestrial ecoregions: Northeastern Congolian lowland forests, Northwestern Congolian lowland forests, Western Congolian swamp forests, East Sudanian savanna, Northern Congolian forest-savanna mosaic, and Sahelian Acacia savanna.

4.2. Climate

The Central African Republic generally experiences a tropical climate, characterized by high temperatures and distinct wet and dry seasons. The length of these seasons varies from north to south.

In the southern regions, closer to the equator, the climate is more equatorial, with a longer wet season typically lasting from May to October. The northern regions have a shorter wet season, usually from June to September. During the wet season, rainstorms are frequent, often occurring daily, and early morning fog is common. Annual precipitation is highest in the upper Ubangi region, reaching approximately 0.1 K in (1.80 K mm) (71 in).

The dry season is influenced by the Harmattan, a hot, dry, and dusty trade wind blowing from the Sahara Desert, particularly affecting the northern parts of the country from roughly November/December to February/May. Temperatures can be very high during this period. The southern regions experience a less severe dry season.

Regional variations exist: the northern areas are hot and humid from February to May before the rains. The extreme northeast of the country has a steppe climate and is prone to desertification, while the southern regions, though generally humid, can also be affected by land degradation. Average temperatures across the country typically range from 77 °F (25 °C) to 86 °F (30 °C), with less diurnal and seasonal variation in the south compared to the north.

4.3. Biodiversity and environmental issues

The Central African Republic possesses a rich biodiversity, housed within its diverse ecosystems that range from dense equatorial forests in the south to savanna grasslands in the central and northern regions. The southwestern area is home to the Dzanga-Sangha Complex of Protected Areas, part of the larger Sangha Trinational UNESCO World Heritage Site (shared with Cameroon and the Republic of Congo). This region is noted for its significant populations of forest elephants, western lowland gorillas, chimpanzees, and bongos.

In the north, the Manovo-Gounda St. Floris National Park, another UNESCO World Heritage site (currently listed as in danger), is known for its extensive savannas and diverse wildlife, which historically included leopards, lions, cheetahs, black rhinos, and numerous ungulate species. The Bamingui-Bangoran National Park is located in the northeast.

Forest cover in 2020 was around 36% of the total land area, equivalent to 22.3 million hectares, down from 23.2 million hectares in 1990. Most of this is naturally regenerating forest, with a small portion being primary forest. The country had a high Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 9.28/10 in 2018, ranking it seventh globally.

However, the nation's biodiversity and natural resources face severe threats. Deforestation is a significant issue, driven by unsustainable logging (both legal and illegal), expansion of agriculture, and fuelwood collection. The deforestation rate was reported to have increased by 71% in 2021. Poaching for ivory, bushmeat, and other animal products has decimated wildlife populations, particularly affecting elephants and rhinos. This has been exacerbated by decades of armed conflict and weak governance, which hinder conservation efforts and facilitate illicit activities. Armed groups often engage in poaching and illegal resource extraction (e.g., diamonds, gold) within protected areas to fund their activities.

The ongoing civil conflict has had a devastating impact on the environment. Displacement of populations puts pressure on natural resources in new areas, and the breakdown of law and order allows for uncontrolled exploitation. National parks and protected areas have been particularly affected by the presence of armed groups and poachers, often from neighboring countries like Sudan. There are also concerns about the environmental impact of unregulated mining activities. Addressing these environmental issues is crucial for the long-term well-being of both the ecosystems and the people of the Central African Republic.

5. Government and politics

The Central African Republic's political system is formally a presidential republic with a multi-party system. However, its history has been marked by extreme instability, including coups, rebellions, and prolonged civil conflicts, which have severely undermined democratic institutions, the rule of law, and human rights. The government's authority is often limited outside the capital, Bangui, with large parts of the country controlled by various armed groups.

5.1. Government structure

The current constitution, adopted by referendum in 2023 (replacing the 2016 constitution), outlines a presidential republic with a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. However, in practice, power is heavily concentrated in the executive, and the independence of the other branches is often compromised.

5.1.1. Executive branch

The President is the head of state and holds significant executive powers. Under the 2023 constitution, the president is elected by popular vote for a seven-year term (changed from five years) and can be re-elected. The president appoints the Prime Minister, who is the head of government, as well as other members of the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The Council of Ministers is responsible for implementing laws and overseeing government operations. The 2023 constitution also reintroduced the post of Vice President, appointed by the President. President Faustin-Archange Touadéra has been in office since March 2016.

5.1.2. Legislative branch

The legislative power is vested in a unicameral National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale). Members of the National Assembly are elected by popular vote for a five-year term using a two-round system. The National Assembly's primary functions include drafting and passing laws, approving the national budget, and overseeing the actions of the executive branch. However, its effectiveness has been hampered by political instability and the overarching influence of the executive.

5.1.3. Judicial branch

The judicial system is based on French civil law. The judiciary is nominally independent, but it suffers from underfunding, corruption, lack of qualified personnel, and political interference. It consists of several levels of courts. The Supreme Court (Cour Suprême) is the highest court for most civil and criminal matters. The Constitutional Court is responsible for reviewing the constitutionality of laws, treaties, and electoral disputes. Judges for these high courts are typically appointed by the president. The overall state of the rule of law is extremely weak, particularly outside Bangui, where traditional justice systems or the dictates of armed groups often prevail. Impunity for serious crimes, including human rights abuses, is a pervasive problem.

5.2. Political parties and armed groups

The Central African Republic has a multi-party system, but political parties are often weak, personality-driven, and ethnically or regionally based. Major political parties include:

- National Convergence "Kwa Na Kwa" (KNK): Formerly associated with François Bozizé.

- Movement for the Liberation of the Central African People (MLPC): Party of former president Ange-Félix Patassé.

- United Hearts Movement (MCU): Party of the current president Faustin-Archange Touadéra.

- Central African Democratic Rally (RDC): Party of former president André Kolingba.

- Union for Central African Renewal (URCA): Led by Anicet-Georges Dologuélé.

Numerous opposition parties exist, but their influence is often limited. The political landscape is heavily fragmented and dominated by the ongoing presence and activities of various rebel factions and armed militias. These groups, which emerged from the Séléka and Anti-balaka coalitions or formed along ethnic/regional lines, control significant portions of the country's territory, especially in the provinces. They engage in illicit activities such as controlling mines, imposing illegal taxes, and trafficking resources. Some key armed groups include:

- Various ex-Séléka factions such as the Popular Front for the Rebirth of Central Africa (FPRC), the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (UPC), and the Movement of Central African Liberators for Justice (MLCJ).

- Anti-balaka affiliated groups.

- The Coalition of Patriots for Change (CPC), an alliance of several rebel groups formed in late 2020 to oppose President Touadéra, which includes supporters of François Bozizé.

These armed groups significantly influence the political and security situation, often engaging in clashes with government forces (FACA), allied foreign mercenaries (like the Wagner Group), UN peacekeepers (MINUSCA), and each other, with devastating consequences for the civilian population. Peace agreements have been signed, notably the 2019 Khartoum Agreement, but their implementation has been largely unsuccessful.

5.3. Human rights

The human rights situation in the Central African Republic is dire and has been consistently poor for decades, exacerbated by recurrent armed conflicts, weak rule of law, and widespread impunity. Abuses are committed by state security forces, allied foreign mercenaries (such as the Russian Wagner Group), and various non-state armed groups.

Civilians bear the brunt of the violence. Common abuses include:

- Unlawful killings:** Extrajudicial executions and massacres of civilians by all parties to the conflict are frequent.

- Torture and ill-treatment:** Suspects, detainees, and civilians are often subjected to torture, beatings, and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment by both state actors and armed groups.

- Sexual and gender-based violence:** Rape and other forms of sexual violence are widespread, used as a weapon of war by armed groups and also perpetrated by state forces and their allies. Women and girls are disproportionately affected, facing immense trauma and limited access to justice or support services.

- Arbitrary arrest and detention:** Security forces often conduct arbitrary arrests and detentions, with detainees held for prolonged periods without charge or trial in harsh and life-threatening prison conditions.

- Displacement:** Millions have been internally displaced or forced to become refugees in neighboring countries due to violence and insecurity.

- Restrictions on freedoms:** Freedom of speech, press, assembly, and movement are severely restricted. Journalists, human rights defenders, and critics of the government or armed groups face intimidation, harassment, and violence.

- Child rights violations:** Children are victims of violence, recruitment as child soldiers by armed groups, abduction, and lack of access to education and healthcare. Child marriage is prevalent, with approximately 68% of girls married before 18.

- Rights of minorities and vulnerable groups:** Indigenous Pygmy peoples (such as the Aka) face discrimination and marginalization. Accusations of witchcraft, often targeting children and elderly women, can lead to violence and ostracism. Witchcraft remains a criminal offense.

- Impunity:** A culture of impunity for serious human rights violations is deeply entrenched. Efforts to ensure accountability, including through national courts and the Special Criminal Court (a hybrid tribunal), have made limited progress.

International bodies, including the United Nations (notably MINUSCA and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights), the African Union, and numerous non-governmental organizations, play a crucial role in monitoring the human rights situation, providing humanitarian assistance, and advocating for accountability and protection of civilians. However, the scale of the crisis and the ongoing insecurity pose immense challenges to these efforts. The country consistently ranks among the lowest in the world on the Human Development Index.

5.4. Recent political situation and challenges

The Central African Republic continues to grapple with a protracted and complex political and security crisis. The government of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, re-elected in December 2020 amidst controversy and violence, struggles to assert control over the entire national territory. Large areas, particularly in the provinces, remain under the influence or direct control of numerous armed rebel groups, which often fight for control of resources like diamonds, gold, and livestock, as well as for political influence.

The 2019 Khartoum peace agreement between the government and 14 major armed groups has largely failed to bring lasting peace, with frequent violations and continued fighting. The formation of the Coalition of Patriots for Change (CPC) in late 2020, aimed at overthrowing Touadéra, further destabilized the country, leading to renewed offensives and a siege on the capital, Bangui, which was repelled with the help of Rwandan troops and Russian private military contractors.

Key challenges include:

- Ongoing Civil Conflict:** Sporadic but intense fighting continues between government forces (FACA) and their allies (Rwandan soldiers, Russian mercenaries) against various rebel factions. This violence results in civilian deaths, mass displacement, and a severe humanitarian crisis.

- Weak Governance and State Authority:** The state's capacity to provide basic services, security, and justice is extremely limited outside Bangui. Corruption is rampant and undermines public trust and development efforts.

- Humanitarian Crisis:** Millions of Central Africans require humanitarian assistance due to conflict-induced displacement, food insecurity, and lack of access to healthcare and clean water.

- Foreign Influence:** The role of foreign actors is a significant factor. While France, the former colonial power, has reduced its direct military presence, Russia has emerged as a key security partner, providing military support and training. However, the presence of Russian mercenaries (Wagner Group) has been linked to serious human rights abuses and concerns over the exploitation of natural resources and national sovereignty. The UN peacekeeping mission, MINUSCA, continues its efforts but faces significant challenges.

- Democratic Development:** Democratic institutions are fragile. A controversial constitutional referendum in 2023, which removed presidential term limits and extended term lengths, raised concerns about democratic backsliding and the consolidation of power by President Touadéra. Opposition parties face restrictions, and the space for civil society and independent media is shrinking.

- Economic Recovery:** The economy is devastated by conflict and instability. Efforts towards economic recovery are hampered by insecurity, lack of infrastructure, and poor governance. The country remains heavily reliant on foreign aid.

- Peace and Reconciliation:** Deep-seated ethnic and religious tensions, exacerbated by the conflict, make national reconciliation a difficult and long-term process. Justice and accountability for past and ongoing atrocities remain elusive for many victims.

Addressing these multifaceted challenges requires sustained international support, genuine political will from national actors to engage in inclusive dialogue and reform, a commitment to human rights and the rule of law, and efforts to tackle the root causes of the conflict, including poverty, marginalization, and competition over resources.

6. Administrative divisions

The Central African Republic is divided into a hierarchical system of administrative units for governance and public administration. As of a reorganization in 2020/2021, the country is divided into 20 prefectures (préfecturesprefecturesFrench). Previously, there were 14 prefectures, 2 economic prefectures, and the autonomous commune of Bangui. The capital city, Bangui, is an autonomous commune (commune autonomeautonomous communeFrench) with prefecture-level status.

The 20 prefectures are:

# Bamingui-Bangoran (Capital: Ndélé)

# Bangui (Autonomous Commune)

# Basse-Kotto (Capital: Mobaye)

# Haute-Kotto (Capital: Bria)

# Haut-Mbomou (Capital: Obo)

# Kémo (Capital: Sibut)

# Lim-Pendé (Capital: Paoua) (Created from Ouham-Pendé)

# Lobaye (Capital: Mbaïki)

# Mambéré (Capital: Carnot) (Created from Mambéré-Kadéï)

# Mambéré-Kadéï (Capital: Berbérati)

# Mbomou (Capital: Bangassou)

# Nana-Grébizi (Economic Prefecture, Capital: Kaga-Bandoro)

# Nana-Mambéré (Capital: Bouar)

# Ombella-M'Poko (Capital: Bimbo)

# Ouaka (Capital: Bambari)

# Ouham (Capital: Bossangoa)

# Ouham-Fafa (Capital: Batangafo) (Created from Ouham)

# Ouham-Pendé (Capital: Bozoum)

# Sangha-Mbaéré (Economic Prefecture, Capital: Nola)

# Vakaga (Capital: Birao)

The prefectures are further subdivided into 84 sub-prefectures (sous-préfecturessub-prefecturesFrench), which are the next tier of local administration. Below the sub-prefectures are communes. This administrative structure is often challenged by the reality of limited state control in many rural areas due to ongoing conflict and the presence of armed groups.

6.1. Major cities

The Central African Republic is predominantly rural, but it has several urban centers that serve as administrative, economic, and social hubs. The capital city, Bangui, is by far the largest and most important urban area.

Key cities include (population figures are estimates and can vary due to displacement):

- Bangui**: The capital and largest city, located on the Ubangi River in the southwest. It is the political, economic, and cultural center of the country. Population estimates for the metropolitan area vary but are generally over 800,000.

- Bimbo**: Located near Bangui in the Ombella-M'Poko prefecture, it is effectively a suburb of the capital and one of the most populous cities after Bangui. Its population was around 124,176 according to the 2003 census.

- Berbérati**: The capital of the Mambéré-Kadéï prefecture in the southwest, near the border with Cameroon. It is an important center for the diamond mining industry. Population was around 76,918 (2003 census).

- Carnot**: Also in Mambéré-Kadéï, known for diamond mining activities. Population was around 45,421 (2003 census).

- Bambari**: Capital of the Ouaka prefecture in the central part of the country. It has been significantly affected by conflict. Population was around 41,356 (2003 census).

- Bouar**: Capital of the Nana-Mambéré prefecture in the west. It is historically an important trading town and military post. Population was around 40,353 (2003 census).

- Bossangoa**: Capital of the Ouham prefecture in the northwest. It is a significant agricultural center. Population was around 36,478 (2003 census).

- Bria**: Capital of the Haute-Kotto prefecture in the east-central region. It is located in a diamond-rich area and has experienced considerable conflict. Population was around 35,204 (2003 census).

- Bangassou**: Capital of the Mbomou prefecture in the south, on the Mbomou River bordering the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Population was around 31,553 (2003 census).

- Nola**: Capital of the Sangha-Mbaéré economic prefecture in the southwest, in a forested region known for logging. Population was around 29,181 (2003 census).

- Kaga-Bandoro**: Capital of the Nana-Grébizi economic prefecture, north of Bangui. Population was around 24,661 (2003 census).

Many of these cities have experienced significant population fluctuations due to internal displacement caused by ongoing conflicts. They often host large numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and are centers for humanitarian operations.

7. Military and security

The military and security apparatus of the Central African Republic is multifaceted, involving national forces, international peacekeeping missions, and various foreign military actors. The sector is chronically under-resourced, poorly trained, and has been deeply affected by decades of political instability and civil war, often implicated in human rights abuses.

The Central African Armed Forces (FACA) are the official national military. They consist of a ground army (which includes a small air component) and a gendarmerie. The FACA has historically been weak, poorly equipped, and often ethnically divided, with its capacity to ensure national security severely limited. Efforts to reform and rebuild the FACA have been ongoing with international support, but progress is slow due to persistent conflict and lack of resources. The FACA has been accused of human rights violations in its operations against rebel groups.

The National Police is responsible for civilian law enforcement, primarily in urban areas. Like the FACA, it suffers from inadequate training, equipment, and corruption.

The Gendarmerie is a paramilitary force with policing responsibilities, particularly in rural areas, and also plays a role in state security.

Due to the ongoing civil war and the limited capacity of national security forces, international peacekeeping forces have played a crucial role. The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) was established in 2014 with a mandate to protect civilians, support the political process, facilitate humanitarian assistance, and promote human rights. MINUSCA is one of the UN's largest peacekeeping operations but faces significant challenges due to the complex security environment and attacks against its personnel.

Foreign military actors also have a significant presence and impact:

- France**: As the former colonial power, France has historically intervened militarily (e.g., Operation Sangaris 2013-2016). While its direct military footprint has reduced, it continues to provide some support and maintain political influence.

- Russia**: Since around 2018, Russia has become a key security partner for the CAR government. This includes the deployment of official military instructors and, more controversially, private military contractors (PMC) like the Wagner Group. These forces have provided training to FACA, engaged in combat operations against rebel groups, and offered close protection to President Touadéra. However, their presence has been linked to widespread and serious human rights abuses, including extrajudicial killings, torture, and indiscriminate attacks, as well as the exploitation of the CAR's natural resources.

- Rwanda**: Rwanda has contributed a significant contingent of troops to MINUSCA and also provides bilateral security support to the CAR government.

The overall security situation remains volatile. Large parts of the country are controlled by various armed rebel groups who challenge state authority. The proliferation of weapons and the activities of these groups, along with criminality and banditry, pose a constant threat to civilians. The security sector's impact on human rights and civilian protection is a major concern, with both state-affiliated forces and rebel groups frequently implicated in abuses. Establishing a professional, accountable, and effective national security apparatus that respects human rights is a critical long-term challenge for the Central African Republic.

8. Foreign relations

The Central African Republic's foreign policy is heavily influenced by its historical ties, its dependence on foreign aid and security assistance, and its geographical position in a volatile region. The country is a member of the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, and the Non-Aligned Movement. Due to persistent internal conflict and weak governance, its foreign relations often revolve around seeking international support for peace, security, and humanitarian assistance.

8.1. Relations with key countries

Bilateral relationships with certain nations significantly shape the CAR's international standing and internal dynamics.

8.1.1. Relations with France

France, the former colonial power, has historically maintained strong political, economic, and military ties with the Central African Republic. French influence has been pervasive since independence, with France often intervening militarily to support or remove regimes (e.g., ousting Bokassa, Operation Sangaris). Paris has been a major provider of development aid and budget support. However, in recent years, particularly with the rise of Russian influence, France's direct role has somewhat diminished, though it remains an important partner, especially within the European Union and UN Security Council frameworks. The relationship is complex, sometimes perceived as neo-colonial by Central Africans, yet also seen as a vital source of support.

8.1.2. Relations with Russia

Since approximately 2018, Russia has rapidly expanded its political and military influence in the CAR. This includes providing military training, weapons, and the deployment of Russian military instructors and private military contractors (like the Wagner Group) who have been instrumental in bolstering President Touadéra's security and combating rebel groups. This partnership has granted Russia access to the CAR's natural resources (diamonds, gold) and a strategic foothold in Central Africa. However, it has drawn significant international criticism due to numerous credible reports of serious human rights abuses committed by Russian mercenaries, including summary executions, torture, and looting. This growing Russian presence has implications for the CAR's national sovereignty, the transparency of resource management, and the overall human rights situation, and has also shifted geopolitical dynamics in the region, often at the expense of traditional Western partners. Western ambassadors have described the CAR as becoming a "vassal state" of the Kremlin.

8.1.3. Relations with neighboring countries

The CAR's relations with its neighbors are crucial due to shared borders, cross-border ethnic ties, refugee flows, and regional security dynamics.

- Chad**: Historically, Chad has played a significant, sometimes interventionist, role in CAR politics. Chadian mercenaries have been involved in CAR conflicts, and political relations have fluctuated. Border security and the movement of armed groups are ongoing concerns.

- Sudan** and **South Sudan**: The porous eastern borders with Sudan and South Sudan have facilitated the movement of armed groups, refugees, and illicit trade. Conflicts in these neighboring countries often spill over into the CAR.

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)** and **Republic of the Congo**: These southern neighbors share the Ubangi River border. Refugee flows occur in both directions depending on regional stability. Both Congos have participated in regional peacekeeping efforts.

- Cameroon**: Cameroon serves as a vital economic lifeline for the landlocked CAR, with the main import/export corridor running through its territory to the port of Douala. Border security and refugee movements are also key aspects of their relations.

Regional instability often has a direct impact on the CAR, and vice-versa.

8.1.4. Relations with other significant countries

- United States**: The U.S. provides humanitarian aid and has supported peace and security initiatives, including UN peacekeeping operations. It has expressed concerns about human rights abuses and Russian influence in the CAR.

- China**: China's engagement has been growing, primarily focused on economic interests, including infrastructure projects and resource extraction, though less prominently than in some other African nations.

- European Union**: The EU collectively is a major humanitarian and development aid donor and supports efforts for peace, security sector reform, and good governance.

8.2. Engagement with international organizations and aid

The Central African Republic is heavily reliant on international organizations and foreign aid for its survival and development. It actively participates in the United Nations, where its internal crisis is a frequent subject of discussion and action by the UN Security Council. The MINUSCA is a large UN peacekeeping operation deployed in the country.

The African Union (AU) plays a significant role in mediation efforts, peace initiatives (like the African Initiative for Peace and Reconciliation), and has deployed peacekeeping forces in the past. The CAR is also a member of regional bodies like the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), which works on regional integration and conflict resolution.

International aid, both humanitarian and developmental, is critical. Numerous NGOs and UN agencies (e.g., UNHCR, WFP, UNICEF) provide essential services such as food, shelter, healthcare, and protection that the government is often unable to deliver. In 2019, over US$100 million in foreign aid was spent, mostly on humanitarian assistance. The UN Peacebuilding Commission has also been engaged in supporting peacebuilding efforts. However, the scale of the needs often outstrips available resources, and insecurity hampers aid delivery.

8.3. Humanitarian crisis and international response

The Central African Republic has been mired in one ofthe world's most severe and protracted humanitarian crises, primarily driven by decades of armed conflict, political instability, and widespread human rights violations. The civilian population, particularly women, children, and other vulnerable groups, bears the heaviest burden.

Key humanitarian challenges include:

- Displacement:** Millions of people have been forcibly displaced from their homes. Many are internally displaced persons (IDPs), living in precarious conditions in camps or host communities, while hundreds of thousands have sought refuge in neighboring countries like Cameroon, Chad, and the DRC.

- Food Insecurity:** Widespread insecurity disrupts agricultural activities, markets, and livelihoods, leading to acute food shortages and high rates of malnutrition, especially among children. The country consistently ranks among the worst on the Global Hunger Index.

- Health Crisis:** The healthcare system is largely dysfunctional, particularly outside Bangui. Access to basic medical care, clean water, and sanitation is extremely limited. Outbreaks of preventable diseases like measles and malaria are common, and maternal and infant mortality rates are among the highest in the world.

- Protection Concerns:** Civilians face constant threats of violence, including killings, sexual and gender-based violence, abductions, and forced recruitment by armed groups. Lack of security and impunity for perpetrators exacerbate these issues.

- Limited Access:** Humanitarian access to affected populations is often hampered by insecurity, attacks on aid workers, poor infrastructure, and bureaucratic impediments.

The international response involves a large-scale effort coordinated by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and implemented by numerous UN agencies (e.g., UNHCR, WFP, UNICEF, WHO), international NGOs, and local partners. This response focuses on providing life-saving assistance such as food aid, shelter, medical care, water and sanitation, and protection services. The UN peacekeeping mission, MINUSCA, also plays a role in protecting civilians and facilitating humanitarian access.

Despite these efforts, the humanitarian needs remain immense and are chronically underfunded. Sustained conflict, weak governance, and the impact of climate change continue to drive the crisis, requiring long-term solutions that go beyond emergency aid to address the root causes of instability and promote sustainable development and peace.

9. Economy

The economy of the Central African Republic is underdeveloped and among the poorest in the world, severely hampered by decades of political instability, armed conflict, corruption, and weak infrastructure. It is heavily reliant on subsistence agriculture, forestry, and mining, with a large informal sector.

9.1. Economic structure and main sectors

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is extremely low, often listed as around 400 USD per year, making it one of the lowest globally. This figure often overlooks the significant unregistered sales of food, locally produced alcoholic beverages, diamonds, ivory, bushmeat, and traditional medicines. The official currency is the Central African CFA franc (XAF), which is pegged to the Euro and shared with other Central African states. In April 2022, Bitcoin was briefly adopted as legal tender alongside the CFA franc, but this status was repealed.

9.1.1. Agriculture and forestry

Agriculture is the backbone of the economy, employing the majority of the population, primarily at a subsistence level.

- Food Crops:** Key staple food crops include cassava, yams, peanuts, maize, sorghum, millet, sesame, and plantains. Production is mainly for local consumption, though surplus is sold in local markets. The annual production of cassava, the main staple, ranges between 200,000 and 300,000 tonnes. Food security is a chronic issue, exacerbated by conflict and climate change, leading to widespread hunger and malnutrition.

- Cash Crops:** Exported cash crops include cotton and coffee. Cotton production ranges from 25,000 to 45,000 tonnes a year. However, the contribution of these crops to export earnings has declined due to instability and lack of investment.

- Forestry:** The country has significant forestry resources, particularly in the southern rainforest belt, with commercially valuable timber species such as Ayous, Sapelli, and Sipo. Timber is a key export, accounting for a substantial portion of official export revenues (e.g., 39.9% in 2013, 19.0% in 2015). However, the sector is plagued by illegal logging and unsustainable practices. The social impact of resource management often involves displacement and conflict over land use. Livestock development is hindered by the presence of the tsetse fly.

9.1.2. Mining (diamonds, gold, etc.)

The Central African Republic is rich in mineral resources, but their exploitation has often fueled conflict and provided limited benefit to the general population.

- Diamonds:** Diamonds are the most important export, traditionally accounting for 40-55% of export revenues. However, a significant portion (estimated at 30-50%) is smuggled out of the country. The CAR has been subject to the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme due to concerns about conflict minerals. While some regions have been cleared for export, many diamond-producing areas remain under the control of armed groups.

- Gold:** Gold is also mined, often artisanally and informally, and is another source of revenue for armed groups.

- Uranium:** The country has uranium reserves (e.g., at Bakouma), but exploitation has been limited due to instability and lack of investment.

Issues in the mining sector include harsh labor conditions (including child labor), severe environmental degradation from unregulated mining, and the inequitable distribution of benefits, with local communities rarely seeing improvements in their living standards.

9.2. Economic conditions and challenges

The Central African Republic faces profound economic challenges:

- Poverty and Inequality:** Extremely high poverty rates persist, with a large majority of the population living below the poverty line. Income inequality is stark.

- Low Per Capita GDP:** The country has one of the lowest GDP per capita figures in the world. Real GDP growth is slightly above 3% in good years but can plummet during conflict.

- Foreign Debt:** The CAR has a significant foreign debt burden, though it has received debt relief in the past.

- Corruption:** Endemic corruption at all levels of government diverts public resources and deters investment.

- Political Instability and Conflict:** This is the primary impediment to economic development. Conflict disrupts production, trade, and investment, destroys infrastructure, and displaces populations.

- Dependence on Foreign Aid:** The country is heavily reliant on international aid for basic services and budget support.

- Landlocked Status:** Being landlocked increases transportation costs and complicates trade.

Strategies for sustainable economic development and poverty reduction focus on restoring security, improving governance, investing in human capital (health and education), developing infrastructure, diversifying the economy, and ensuring more transparent and equitable management of natural resources. However, progress is severely constrained by the ongoing crisis. The CAR is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA). In the World Bank's Doing Business reports, it consistently ranks very low in terms of ease of doing business.

9.3. Infrastructure

The state of infrastructure in the Central African Republic is extremely poor and represents a major obstacle to economic development and public welfare. Decades of neglect, conflict, and lack of investment have left most essential infrastructure dilapidated or non-existent, particularly outside the capital.

9.3.1. Transportation and communications

- Road Network:** The road network is rudimentary. Bangui is the main transport hub, with eight primary roads connecting it to other major towns and neighboring countries (Cameroon, Chad, South Sudan). However, most roads are unpaved and in very poor condition. Only toll roads and some urban streets are paved. During the rainy season (July-October), many roads become impassable, isolating large parts of the country. Two trans-African automobile routes, the Tripoli-Cape Town Highway and the Lagos-Mombasa Highway, notionally pass through the CAR.

- River Transport:** The Ubangi River is a crucial waterway, navigable for most of the year between Bangui and Brazzaville (Republic of Congo). From Brazzaville, goods can be transported by rail to the Atlantic port of Pointe-Noire. The river port at Bangui handles the majority of the country's international trade, with a cargo handling capacity of 350.00 K t, 1148 ft (350 m) of wharfs, and 258 K ft2 (24.00 K m2) of warehousing space.

- Air Travel:** Bangui M'Poko International Airport is the only international airport. It offers limited direct flights to regional capitals and Paris. There are a few other domestic airfields, but services are unreliable.

- Railways:** There are no railways in the Central African Republic. Plans to connect Bangui to the Transcameroon Railway have existed since at least 2002 but have not materialized.

- Telecommunications:** Telecommunications infrastructure is very limited. Socatel is the leading provider for internet and mobile phone access. Mobile phone penetration has increased but remains low compared to other countries. Internet access is scarce and expensive, largely confined to Bangui. The Ministry of Posts, Telecommunications, and New Technologies is the primary regulator. The International Telecommunication Union provides support for infrastructure improvement.

9.3.2. Energy

Access to electricity is extremely limited, with an estimated 15.6% of the total population having access (34.6% in urban areas, 1.5% in rural areas as of 2023). The primary source of electricity is hydroelectricity, with power plants like the Boali Falls facility. However, generation capacity is insufficient and unreliable, leading to frequent power outages even in Bangui. Many businesses and affluent households rely on private generators. The lack of reliable energy severely constrains economic activity and quality of life. Expansion of hydropower potential and exploration of other renewable sources are priorities but require significant investment and stability. Most of the population relies on traditional biomass (wood, charcoal) for cooking.

10. Society

The social fabric of the Central African Republic has been severely frayed by decades of political instability, armed conflict, and chronic poverty. Widespread insecurity, a breakdown in public order, and extreme levels of poverty and hunger define the daily lives of many Central Africans. Civil society organizations, though often operating under difficult circumstances, play a crucial role in addressing societal needs.

10.1. Public order and security

The state of law and order in the Central African Republic is extremely fragile, particularly outside the capital, Bangui. Decades of coups, rebellions, and ongoing civil war have led to a near-total breakdown of state authority in many regions. Government security forces (FACA, police, gendarmerie) are often weak, poorly equipped, underpaid, and lack the capacity to provide security for the population. They have also been implicated in human rights abuses.

Large parts of the country are controlled or influenced by numerous armed groups, including ex-Séléka factions, Anti-balaka militias, and other rebel movements. These groups often engage in violence against civilians, including killings, looting, extortion, and sexual violence. Banditry and criminality are also rampant. The widespread insecurity has led to massive internal displacement, with millions forced to flee their homes. Civilian life is characterized by constant fear and vulnerability.

International efforts, notably the MINUSCA peacekeeping mission and bilateral support from countries like Rwanda and Russia (including the controversial Wagner Group), aim to restore security and protect civilians. However, the scale of the challenge is immense. Government efforts to re-establish state authority and public order in conflict-affected areas are ongoing but face significant obstacles due to the proliferation of arms, the entrenchment of armed groups, and deep-seated grievances. The impact on vulnerable populations, such as women, children, and ethnic minorities, is particularly severe, further damaging social cohesion.

10.2. Poverty and hunger

Poverty in the Central African Republic is pervasive and extreme, with the vast majority of the population living below the international poverty line. The country consistently ranks at or near the bottom of global human development indices. Chronic food shortages and malnutrition are widespread, affecting a significant portion of the population, especially children. The Global Hunger Index regularly classifies the CAR as having an alarming level of hunger.

Several socio-economic factors contribute to this dire situation:

- Conflict and Insecurity:** Ongoing violence disrupts agricultural production, displaces farmers, destroys markets, and prevents access to land. This is the primary driver of food insecurity.

- Weak Economy:** Lack of economic opportunities, unemployment, and low wages limit people's ability to purchase food and other essential goods.

- Poor Infrastructure:** Inadequate roads and transportation systems make it difficult to move food from areas of surplus to areas of deficit, leading to localized shortages and high prices.

- Climate Change and Environmental Degradation:** Changing weather patterns, droughts, and floods can negatively impact crop yields. Deforestation and land degradation further reduce agricultural productivity.

- Limited Access to Basic Services:** Poor access to healthcare, clean water, and sanitation contributes to high rates of disease, which can worsen malnutrition.

National and international responses, including emergency food aid from organizations like the World Food Programme (WFP) and FAO, as well as programs aimed at improving agricultural productivity and resilience, are crucial for alleviating suffering. However, these efforts are often hampered by insecurity and insufficient funding. Addressing the root causes of poverty and hunger requires long-term strategies focused on peacebuilding, economic development, good governance, and investment in human capital.

11. Demographics

The Central African Republic's population is characterized by its ethnic diversity, rapid growth rate despite high mortality, and the profound impact of ongoing conflict on its distribution and well-being.

11.1. Population statistics

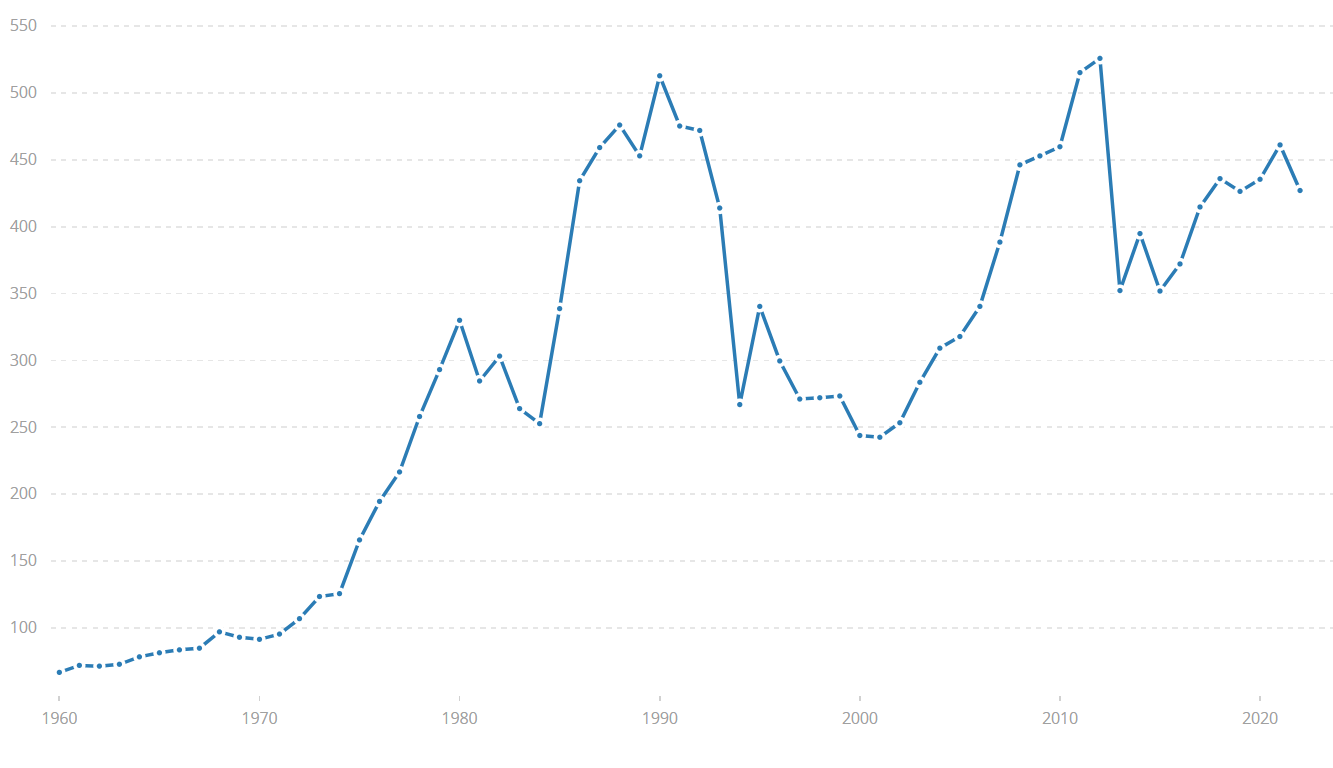

The population of the Central African Republic has nearly quadrupled since independence in 1960, when it was approximately 1.23 million. As of 2024, UN estimates place the population at around 5.3 million. The country has a high population growth rate, driven by high fertility rates, though this is somewhat offset by high mortality rates, including one of the highest infant and child mortality rates globally.

Life expectancy at birth is very low, around 53 years (2021 estimate), among the lowest in the world. The urbanization rate is relatively low, with more than half the population (around 58% in 2023) still living in rural areas, though conflict has driven many to urban centers like Bangui or displacement camps. The population is very young, with a large proportion of children under 15 years old (around 40.4% in 2020), indicative of a youthful age structure. The gender structure is roughly balanced. The ongoing civil war has led to significant internal displacement and refugee outflows, making precise demographic figures difficult to ascertain.

11.2. Ethnic groups

The Central African Republic is home to over 80 distinct ethnic groups, each with its own language and cultural traditions. The largest ethnic groups include:

- Gbaya (or Baya)**: Traditionally inhabiting the western and central parts of the country, they are one of the largest groups, estimated at around 29-33% of the population.

- Banda**: Predominantly found in the central and eastern regions, they constitute another major group, estimated at around 23-27%.

- Mand(j)ia**: Located in the central regions, making up around 13%.

- Sara**: Primarily in the north, near the Chadian border, accounting for about 10%.

Inter-ethnic relations have historically been complex but generally peaceful at the local level. However, political manipulation and the dynamics of armed conflict have often exacerbated ethnic tensions, particularly since the 2013 crisis. Certain groups have been targeted or have aligned with specific armed factions, leading to communal violence and displacement. Peacebuilding efforts often focus on fostering inter-ethnic dialogue and reconciliation.

11.3. Languages

The Central African Republic has two official languages:

- French**: The language of administration, formal education, and international communication, inherited from the colonial period.

- Sango** (also spelled Sangho): A Ngbandi-based creole language that evolved as an inter-ethnic lingua franca along the Ubangi River. It is widely spoken by the majority of the population across different ethnic groups and serves as a national language of unity. The CAR is one of the few African countries to have an indigenous language as an official language.

In addition to French and Sango, each of the over 80 ethnic groups speaks its own indigenous language. These languages belong to various African language families, primarily Ubangian (part of the Niger-Congo family) and Bongo-Bagirmi (part of the Nilo-Saharan family). The linguistic diversity is a key aspect of the country's cultural heritage.

11.4. Religion

The Central African Republic is a religiously diverse nation, with Christianity being the predominant faith, followed by Islam and traditional indigenous beliefs. Religious affiliation often coexists with adherence to traditional practices.

According to estimates (which can vary, the 2003 census being the last official detailed count):

- Christianity**: Approximately 80-90% of the population identifies as Christian.

- Protestant**: This is the largest Christian denomination, accounting for roughly 50-60% of the population. Various denominations are present, including Baptists, Lutherans, and Pentecostal groups, many established through missionary work.

- Roman Catholic**: Catholics make up a significant portion, around 25-30% of the population. The Catholic Church has a structured presence with dioceses across the country.

- Islam**: Muslims constitute about 9-15% of the population. They are predominantly Sunni and are concentrated mainly in the northern and eastern regions, with historical trading links to Sahelian and Sudanese Islamic centers.