1. Overview

The State of Palestine is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia, claiming sovereignty over the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip. These territories have been under Israeli occupation since the 1967 Six-Day War. The political and humanitarian situation in Palestine is profoundly shaped by this ongoing occupation, the historical displacement of Palestinians, and the protracted Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This article examines Palestine's history, political structures, socio-economic conditions, and cultural identity, with a critical focus on the impact of the conflict on human rights, democratic development, social justice, and the rights of vulnerable populations, including refugees. Despite significant challenges, including restrictions on movement, settlement expansion, and recurrent hostilities, Palestinians continue to assert their right to self-determination and strive for statehood and a just resolution to the conflict. The international community remains divided on full recognition, though Palestine holds non-member observer state status at the United Nations. The ongoing conflict, particularly events like the Nakba, the occupation, the blockade of Gaza, and recent wars, has had devastating consequences for the Palestinian people, leading to significant loss of life, displacement, and a persistent humanitarian crisis that underscores the urgent need for a sustainable peace grounded in international law and respect for human rights.

2. Etymology

The term "Palestine" originates from ancient Greek, ΠαλαιστίνηPalaistinēGreek, Ancient, which itself is derived from a Semitic toponym likely related to the Philistines, a people mentioned in the Hebrew Bible who inhabited the coastal region in the late second millennium BCE. The Latin term is Palæstina. Historically, "Palestine" has been used to refer to the region at the southeastern corner of the Mediterranean Sea, adjacent to Syria. In the 5th century BCE, the Greek historian Herodotus, in his work The Histories, described a "district of Syria, called Palaistine" where Phoenicians interacted with other maritime peoples. The Roman Emperor Hadrian, in the 2nd century CE, renamed the province of Judaea to Syria Palaestina, a move interpreted by some scholars as an attempt to erase Jewish historical connections to the land following the Bar Kokhba revolt. This name continued to be used through various empires.

3. Terminology

This article uses the terms "Palestine", "State of Palestine", and "occupied Palestinian territory" (oPt or OPT) interchangeably depending on the context. The "State of Palestine" refers to the state declared by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1988 and recognized by a majority of UN member states. The term "occupied Palestinian territory" specifically refers as a whole to the geographical areas of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip, which have been occupied by Israel since 1967.

The name "Palestine" can also be commonly interpreted as the entire territory of the former British Mandate for Palestine, which today includes both Israel and the Palestinian territories. This broader geographical "Palestine (region)" should be distinguished from the State of Palestine. Other homonymous uses for the term include references to the Palestinian National Authority (the interim self-governing body), the Palestine Liberation Organization (the internationally recognized representative of the Palestinian people), and various historical proposals for a Palestinian state. Depending on the context, Palestine may be referred to as a country or a state, and its authorities can generally be identified as the Government of Palestine.

4. History

The history of Palestine is a long and complex narrative, marked by the presence of numerous civilizations, empires, and significant religious developments. This section chronicles the major historical events from ancient times to the present, focusing on the emergence of Palestinian national identity and the enduring Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Particular attention is given to the causes, progression, and consequences of these events, especially concerning their impact on human rights, social justice, and the experiences of affected populations and victims.

4.1. From Prehistory to the Ottoman Era

The region of Palestine, situated at a continental crossroads between Asia and Africa, has been inhabited since prehistoric times and has been ruled by various empires, experiencing significant demographic changes. It served as a vital land bridge for armies and merchants traveling between the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia, as well as from North Africa, China, and India.

The land is considered the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity. According to Jewish tradition, the patriarch Abraham received a divine promise of the land for his descendants. After a period in Egypt, the Israelites, led by Moses, are said to have returned and conquered Canaan, eventually establishing the United Kingdom of Israel and building the First Temple in Jerusalem. Following the kingdom's division and eventual conquests by empires such as the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which destroyed the First Temple, and later the Achaemenid Empire (Persian) and Macedonian (Hellenistic) empires, the region came under Roman rule. It was during Roman rule, in the 1st century CE, that Jesus of Nazareth lived and preached, leading to the birth of Christianity. Initially persecuted, Christianity spread widely and became the state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century.

For Islam, which emerged in the 7th century CE, Palestine also holds profound religious significance. Jerusalem is home to the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock on the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif), considered the third holiest site in Islam, associated with the Prophet Muhammad's Night Journey and Ascension.

In the 7th century, the Rashidun Caliphate conquered Palestine from the Byzantine Empire, marking the beginning of a long period of Islamic rule and the gradual Arabization and Islamization of the local population. European Crusaders in the 11th to 13th centuries sought to reclaim the Holy Land from Muslim control, establishing Crusader states, but these were eventually defeated, notably by Saladin of the Ayyubid Sultanate in the late 12th century. From the early 16th century until the end of World War I, Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire. Under the Ottomans, the millet system allowed religious communities a degree of autonomy.

4.2. Rise of Palestinian Nationalism

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of various nationalist movements within its territories, including Arab nationalism. Palestinian Arab elites, particularly urban notable families who had worked within the Ottoman bureaucracy, played a significant role in the burgeoning Pan-Arab movements. These movements arose partly in response to the emergence of the Young Turks movement and the subsequent weakening of Ottoman power, especially during World War I.

Simultaneously, the Zionist movement emerged in Europe, aiming to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. This movement led to increased Jewish immigration to Palestine and the purchase of land, which began to create tensions with the local Arab population. Abdul Hamid II, the last effective sultan of the Ottoman Empire, opposed the Zionist movement's efforts in Palestine.

The end of Ottoman rule in Palestine coincided with the conclusion of World War I. The failure of Emir Faisal's efforts to establish a Greater Syria (encompassing Palestine) in the face of British and French colonial claims also shaped the aspirations of Palestinian elites for local autonomy and self-determination. The rise of Zionism acted as a strong catalyst for the development of a distinct Palestinian national consciousness, as the local Arab population increasingly perceived the Zionist project as a threat to their land, rights, and identity.

4.3. British Mandate

The defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I led to the dismantling of its rule over Palestine. In 1917, British forces led by General Allenby captured Jerusalem, marking the end of Ottoman control. In 1920, the League of Nations granted Britain the Mandate for Palestine, entrusting it with the administration of the region. The Mandate, formally approved in 1922, incorporated the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which supported the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, while also stipulating that nothing should be done to prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities.

Throughout the British Mandate period (1920-1948), Palestine experienced significant political and social upheaval. Jewish immigration increased substantially, leading to demographic shifts and growing competition for land and resources. This fueled intercommunal conflict between Arabs and Jews. Tensions escalated, resulting in violent clashes and riots across Palestine as early as 1920. In 1929, violent riots erupted over disputes concerning Jewish immigration and access to the Western Wall in Jerusalem.

Arab nationalist groups, led by figures like Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, and organized under bodies such as the Arab Higher Committee, increasingly demanded an end to Jewish immigration, restrictions on land sales to Jews, and the establishment of an independent Arab state. The Arab Revolt (1936-1939) was a major uprising against British rule and Jewish immigration. The British responded by deploying significant military forces and implementing stringent security measures to quell the revolt, leading to substantial casualties and widespread arrests among the Palestinian Arab population.

In an attempt to address the escalating tensions, the British government issued the White Paper of 1939, which imposed severe restrictions on Jewish immigration and land purchases, and envisioned an independent Palestinian state (with a shared Arab-Jewish government) within ten years. This policy was met with strong opposition from the Zionist movement, which viewed it as a betrayal of the Balfour Declaration and their aspirations for a Jewish state. Zionist organizations, including the Jewish Agency and the Histadrut, organized strikes and protests against the White Paper.

During the late 1930s and 1940s, several Zionist militant groups, including the Irgun and Lehi (Stern Gang), carried out acts of violence against British military and civilian targets, as well as Arab civilians, in their campaign for an independent Jewish state. Notable incidents included the King David Hotel bombing in Jerusalem in 1946, orchestrated by the Irgun, which resulted in 91 deaths. Figures like Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir, who later became Israeli Prime Ministers, were leaders in these militant organizations.

During World War II, Palestine served as a strategically important location for British military operations. The Holocaust in Europe further intensified Zionist demands for a Jewish state in Palestine as a refuge for Jewish survivors. The Exodus 1947 incident, where a ship carrying Jewish Holocaust survivors was intercepted by the British navy and the refugees deported back to Europe, highlighted the plight of Jewish refugees and the growing international pressure on Britain.

By 1947, unable to resolve the conflict, Britain announced its intention to terminate the Mandate and referred the question of Palestine to the United Nations. The UN proposed a partition plan (Resolution 181 (II)) that recommended the creation of separate Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem placed under a special international regime. The plan was accepted by Jewish leaders but rejected by Arab leaders and states, who opposed the division of Palestine and the creation of a Jewish state on what they considered Arab land. The rejection of the partition plan by the Palestinian Arab leadership and neighboring Arab states set the stage for the 1948 war.

4.4. 1948 Palestine War and Nakba

Following the United Nations' 1947 Partition Plan (Resolution 181 (II)), which proposed the division of Mandatory Palestine into separate Arab and Jewish states with Jerusalem as an international city, tensions escalated into the 1947-1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine. The Jewish leadership accepted the plan, while Palestinian Arab leaders and Arab states rejected it, arguing it was unjust and violated the rights of the Arab majority.

On May 14, 1948, on the eve of the British Mandate's expiration, David Ben-Gurion declared the establishment of the State of Israel. The following day, neighboring Arab states-Egypt, Transjordan (now Jordan), Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq-intervened militarily, leading to the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

The war resulted in a decisive Israeli victory. Israel expanded its territory beyond the UN partition plan's allocated borders, capturing about 78% of Mandatory Palestine. The remaining territories, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip, came under the administration of Transjordan and Egypt, respectively. Transjordan subsequently annexed the West Bank in 1950, a move recognized only by the United Kingdom and Pakistan, while Egypt administered the Gaza Strip through the All-Palestine Government until it was effectively dissolved in 1959.

For Palestinians, the 1948 war and its aftermath are known as the Nakba (النكبةan-NakbahArabic, meaning "catastrophe"). During the war, approximately 700,000 to 750,000 Palestinian Arabs-about half of the Arab population of Mandatory Palestine-were expelled or fled from their homes in the territory that became Israel. Hundreds of Palestinian villages and towns were depopulated and subsequently destroyed or resettled by Jews. The causes of the exodus are debated, with historians pointing to a combination of factors, including direct expulsions by Israeli forces, fear of massacres (such as the Deir Yassin massacre), the psychological impact of warfare, and calls by Arab leaders for civilians to temporarily evacuate.

The Nakba had a devastating and lasting impact on Palestinian society, leading to a major refugee crisis. The displaced Palestinians sought refuge in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and neighboring Arab countries like Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Egypt. Most of these refugees and their descendants remain in refugee camps or in exile, with their demand for the Palestinian right of return to their homes and properties in what is now Israel becoming a central and unresolved issue in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The denial of this right is viewed by Palestinians as a continuous injustice and a violation of international law. The Nakba also led to the fragmentation of Palestinian society and the loss of a cohesive political entity on their homeland, profoundly shaping Palestinian national identity and political aspirations for self-determination and redress.

4.5. Israeli Occupation and PLO Activity (Post-1967)

In June 1967, the Six-Day War erupted between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (Egypt, Jordan, and Syria). Israel launched a preemptive strike and achieved a swift and decisive victory. As a result, Israel occupied the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan, the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, and the Golan Heights from Syria. This marked the beginning of the Israeli military occupation of Palestinian territories, profoundly altering the lives of millions of Palestinians and the dynamics of the conflict.

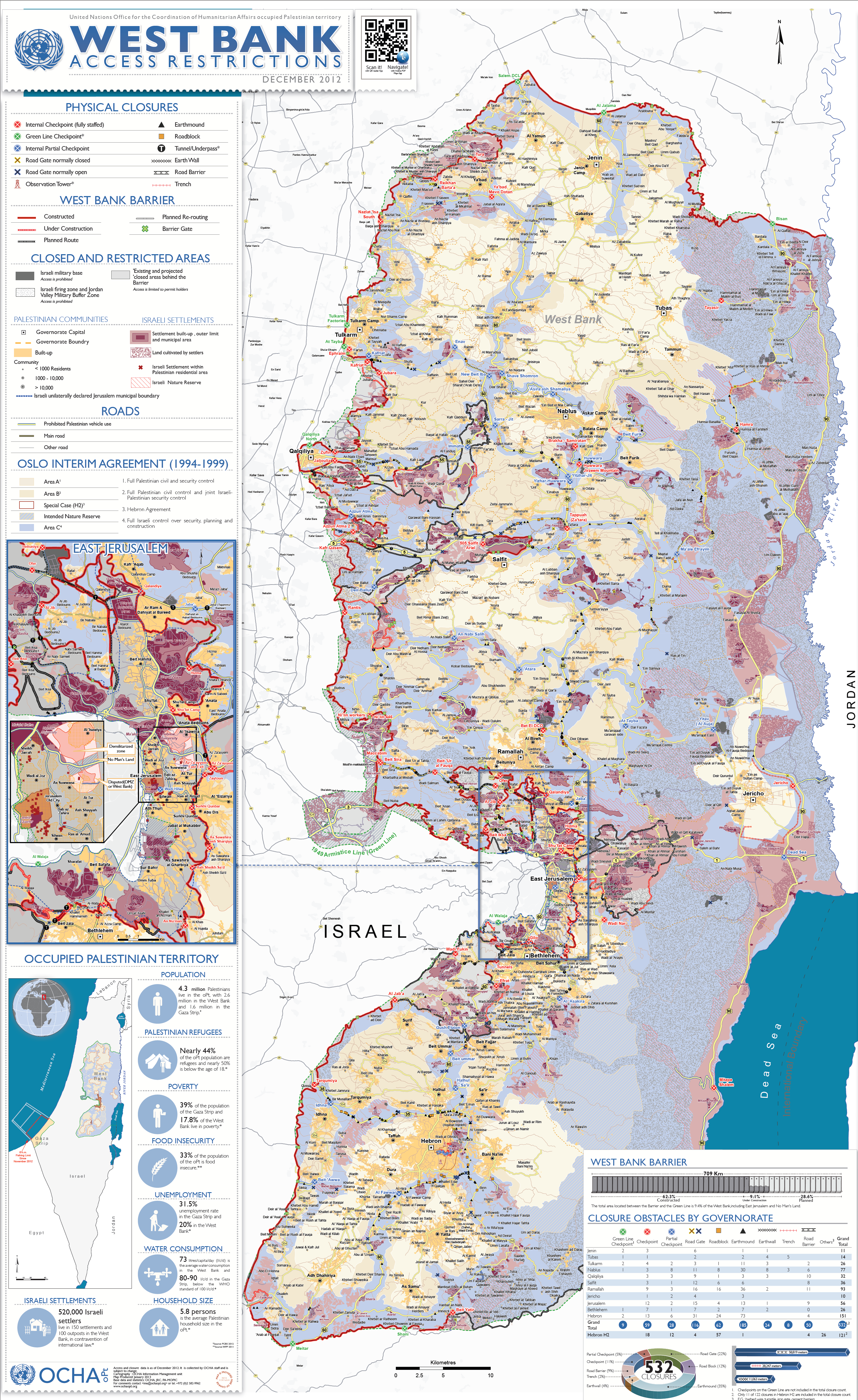

The occupation brought the entire Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza Strip under Israeli military rule. Israel established a military administration to govern these territories, imposing restrictions on movement, political activity, and economic life. The occupation had severe socio-political consequences for Palestinians, including land confiscation for the construction of Israeli settlements (which are considered illegal under international law), house demolitions, arrests and detentions, and limitations on access to resources such as water and land. These measures were widely condemned as violations of international humanitarian law, particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention.

In response to the 1967 occupation and the perceived failure of Arab states to liberate Palestine, Palestinian nationalism and resistance movements gained prominence. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), established in 1964, emerged as the main umbrella organization representing Palestinians. Initially based in Jordan, the PLO, under the leadership of Yasser Arafat from 1969, escalated its armed struggle against Israel. After being expelled from Jordan in 1970-1971 (an event known as Black September), the PLO relocated its headquarters to Lebanon.

The PLO engaged in various forms of resistance, including guerrilla warfare and international diplomacy, to achieve Palestinian self-determination and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state. The PLO's activities and Palestinian resistance under occupation were often met with harsh Israeli countermeasures, leading to cycles of violence. The human rights implications of the occupation became a major concern, with numerous reports by international organizations detailing abuses such as collective punishment, restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly, and the impact of settlements on Palestinian daily life. The international community, through numerous UN resolutions, repeatedly called for Israel's withdrawal from the occupied territories and affirmed the Palestinians' right to self-determination, but these calls largely went unheeded. The occupation solidified the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a central issue in Middle Eastern politics and international affairs.

4.6. Uprising, Declaration, and Peace Process

The late 1980s and early 1990s were a transformative period for the Palestinian struggle. In December 1987, the First Intifada (انتفاضةIntifāḍahArabic, "uprising" or "shaking off") erupted in the Gaza Strip and quickly spread to the West Bank. It was a largely spontaneous, grassroots Palestinian uprising against the Israeli occupation, characterized by widespread protests, strikes, boycotts of Israeli goods, civil disobedience (such as tax refusal), and stone-throwing by youths. The Intifada demonstrated the depth of Palestinian popular resistance and the unsustainability of the occupation. Israel's response, which included mass arrests, curfews, deportations, and the use of lethal force, drew international criticism and highlighted the human rights situation in the occupied territories. The Intifada significantly raised the international profile of the Palestinian cause and put pressure on Israel and the international community to find a political solution.

On November 15, 1988, amidst the First Intifada, the Palestinian National Council (PNC), the PLO's legislative body, convened in Algiers and issued the Palestinian Declaration of Independence. This declaration proclaimed the establishment of the State of Palestine on Palestinian territory, with Jerusalem as its capital, based on UN Resolution 181 (the 1947 Partition Plan) and "the historical right of the Palestinian Arab people to their homeland." Crucially, the declaration implicitly recognized Israel by accepting UN resolutions that formed the basis for a two-state solution. Many countries quickly recognized the State of Palestine. Following the declaration, the UN General Assembly acknowledged the proclamation and decided to use the designation "Palestine" instead of "Palestine Liberation Organization" in the UN system.

The First Intifada and the changing geopolitical landscape following the end of the Cold War and the Gulf War (1990-1991) created new dynamics for peace. The Madrid Conference in October 1991 was the first time Israeli, Palestinian (as part of a joint Jordanian-Palestinian delegation), and other Arab representatives met for direct peace negotiations. While the Madrid Conference itself did not achieve a breakthrough, it paved the way for secret bilateral talks between Israel and the PLO in Norway.

These secret talks led to the historic signing of the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, commonly known as the Oslo I Accord, on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993. The Oslo Accords marked a turning point, with Israel and the PLO formally recognizing each other. The accords established a framework for a five-year interim period of Palestinian self-government in parts of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, leading to a permanent settlement based on UN Security Council Resolution 242 and 338. The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) was established in 1994 to administer these areas. Yasser Arafat returned from exile to head the PNA.

The Oslo Accords generated significant hope for democratic development and state-building among Palestinians and was seen by many internationally as a pathway to a two-state solution. However, the process faced numerous challenges from the outset. Key issues such as Jerusalem, Israeli settlements, refugees, borders, and security were deferred to "final status" negotiations. Opposition from hardliners on both sides, continued Israeli settlement expansion, and acts of violence, including suicide bombings by Palestinian militant groups like Hamas and Islamic Jihad, and attacks by Israeli extremists like the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre in 1994, undermined trust and the peace process. Despite these difficulties, state-building efforts commenced, with the establishment of Palestinian institutions and the holding of elections in 1996. The social impact of this period was mixed, with initial optimism gradually giving way to frustration as the promised improvements in daily life and progress towards full sovereignty failed to materialize for many Palestinians.

4.7. Second Intifada and Political Divisions

The Camp David Summit in July 2000, mediated by U.S. President Bill Clinton between Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, failed to reach a final status agreement. The failure was attributed to disagreements over core issues, including the status of Jerusalem, Israeli settlements, borders, and the Palestinian refugee issue. Both sides blamed each other for the collapse of the talks.

In September 2000, a provocative visit by then-Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif) in Jerusalem, a site holy to both Muslims and Jews, ignited widespread Palestinian protests. These protests quickly escalated into the Second Intifada, also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada. This uprising was characterized by a higher level of violence than the first, involving armed confrontations, suicide bombings by Palestinian militant groups against Israeli civilians, and large-scale Israeli military operations, including incursions into Palestinian cities, targeted assassinations, and widespread destruction of infrastructure.

The Second Intifada, which lasted roughly from 2000 to 2005, had devastating consequences. Thousands of people, overwhelmingly Palestinians but also many Israelis, were killed, and many more were injured. The violence severely impacted civilians on both sides, leading to a deep humanitarian crisis in the Palestinian territories, exacerbated by Israeli closures, curfews, and the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier. The barrier, which Israel stated was for security, was built largely inside the West Bank, annexing Palestinian land and severely restricting Palestinian movement and access to resources, drawing international condemnation as a violation of international law. The International Court of Justice issued an advisory opinion in 2004 deeming the barrier illegal where it deviated from the Green Line.

The human rights situation deteriorated significantly during this period. Events like the Battle of Jenin and the Siege of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem drew international attention. The Israeli military reoccupied areas previously under Palestinian Authority control. Yasser Arafat was confined by Israeli forces to his Ramallah headquarters (the Muqata'a) for much of this period until shortly before his death in November 2004.

Following Arafat's death, Mahmoud Abbas was elected President of the Palestinian Authority in January 2005. In 2005, Israel unilaterally disengaged from the Gaza Strip, withdrawing its settlements and military forces, though it maintained control over Gaza's borders, airspace, and coastline, leading many to argue that the occupation continued in a different form.

The Second Intifada also contributed to a major political schism within Palestinian society. In the 2006 legislative elections, Hamas, an Islamist militant group, won a majority, defeating the long-dominant Fatah party. This led to a political standoff and power struggle between Fatah and Hamas. Tensions escalated into the Battle of Gaza in June 2007, resulting in Hamas violently taking control of the Gaza Strip. This de facto division of Palestinian governance-with Hamas ruling Gaza and the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority administering parts of the West Bank-has persisted, severely weakening the Palestinian national movement, hindering efforts for a unified negotiating position, and exacerbating the humanitarian and political challenges faced by Palestinians in both territories. The Gaza Strip, under Hamas control, has since faced a severe blockade imposed by Israel and Egypt, leading to a dire socio-economic situation.

4.8. Continued Conflict and Current Situation

Since the late 2000s, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has remained entrenched, marked by recurrent violence, stalled peace efforts, and a deteriorating humanitarian situation, particularly in the Gaza Strip. The political division between the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and the Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip has persisted, complicating Palestinian governance and national aspirations.

The Blockade of the Gaza Strip, imposed by Israel and Egypt since Hamas took control in 2007, has had a devastating impact on Gaza's 2 million residents. Restrictions on the movement of people and goods have crippled the economy, led to high rates of unemployment and poverty, and severely limited access to essential services like healthcare, clean water, and electricity. International organizations have repeatedly described the situation as a man-made humanitarian crisis.

Recurrent conflicts between Israel and Hamas in Gaza have caused widespread destruction and loss of life. Major escalations occurred in 2008-2009 (Cast Lead), 2012 (Pillar of Defense), 2014 (Protective Edge), and 2021 (Guardian of the Walls). These conflicts involved Israeli airstrikes and ground incursions into Gaza, and rocket fire from Hamas and other militant groups into Israel. Civilians, particularly in densely populated Gaza, have borne the brunt of the violence, with significant concerns raised about violations of international humanitarian law by all parties.

In the West Bank, Israeli settlement expansion in occupied territory, including East Jerusalem, has continued and accelerated, despite being widely regarded as illegal under international law and a major obstacle to a two-state solution. These settlements, now housing hundreds of thousands of Israelis, fragment Palestinian land, restrict Palestinian movement, and lead to the confiscation of Palestinian property and resources. Israeli settler violence against Palestinians and their property has also been a persistent issue, often occurring with impunity. Access restrictions, including checkpoints, the separation barrier (much of which is built inside the West Bank), and permit systems, severely impede Palestinian daily life, economic activity, and access to services like education and healthcare.

The 2023 Israel-Hamas war marked a catastrophic escalation. On October 7, 2023, Hamas-led militants launched a large-scale attack on southern Israel, killing approximately 1,200 Israelis and foreign nationals, mostly civilians, and taking around 250 hostages. Israel responded with an extensive military campaign in the Gaza Strip, involving intense aerial bombardment and a ground invasion. The war has resulted in an unprecedented humanitarian crisis in Gaza. As of mid-2024, tens of thousands of Palestinians, a large percentage of whom are women and children, have been killed, and the vast majority of Gaza's population has been displaced. Much of Gaza's infrastructure, including homes, hospitals, schools, and water systems, has been destroyed or severely damaged. There are widespread reports of famine-like conditions, a collapse of the healthcare system, and severe shortages of food, water, medicine, and fuel.

The scale of death and destruction in Gaza has led to accusations of war crimes and genocide against Israel at the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court. Human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as several UN experts, have stated that Israel's actions in Gaza amount to genocide or crimes against humanity, such as extermination. The war has also seen a surge in violence and restrictions in the West Bank, with increased Israeli military raids, settler attacks, and Palestinian casualties.

The current political and social landscape is dire. The peace process has been moribund for years, and the prospects for a two-state solution appear increasingly remote due to settlement expansion and political intransigence. The international community remains divided, though there has been growing international pressure on Israel regarding its conduct in the war and increasing calls for a ceasefire and a sustainable political resolution that addresses the root causes of the conflict, upholds international law, and ensures justice and security for both Palestinians and Israelis. The human rights of Palestinians, including their right to self-determination, freedom from occupation, and a life of dignity, remain at the forefront of international concern.

5. Geography

The territories claimed by the State of Palestine, namely the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, are located in the Southern Levant region of the Middle East. These territories are part of the larger historical region of Palestine, which is also considered part of the Fertile Crescent. The West Bank and Gaza Strip are geographically non-contiguous, separated by Israeli territory. Together, their land area is approximately 2.3 K mile2 (6.02 K km2), which would rank as the 163rd largest country by land area. Palestine shares maritime borders with Israel, Egypt, and Cyprus.

The Gaza Strip is a coastal enclave bordering the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Egypt to the south, and Israel to the north and east. It is a relatively flat and sandy area.

The West Bank is a landlocked territory bordered by Jordan to the east and Israel to the north, south, and west. Topographically, the West Bank is largely mountainous. It can be divided into several regions, including the northern Samarian Hills (Jibal Nablus), the central Jerusalem Mountains (Jibal al-Quds), and the southern Hebron Hills (part of the Judean Hills). The highest point in the West Bank is Mount Nabi Yunis, located in the Hebron Governorate, at an elevation of 3.4 K ft (1.03 K m). Hebron was historically one of the highest cities in the Middle East. Jerusalem itself is situated on a plateau in the central highlands, surrounded by valleys. The region also includes fertile valleys such as parts of the Jordan Valley.

Significant water bodies are associated with the region. The Jordan River flows southward, forming part of Palestine's eastern border (for the West Bank) and passing through the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias, not part of Palestinian-administered territory) before emptying into the Dead Sea. The Dead Sea, bordering the eastern West Bank, is the Earth's lowest point on land. The nearby city of Jericho is considered the lowest city in the world. Many seasonal streams, known as wadis, traverse the landscape, providing water for agriculture and supporting local ecosystems, especially in rural areas around Jerusalem. Olive cultivation is a prominent feature of Palestinian agriculture, with an estimated 45% of cultivated land dedicated to olive trees. The Al-Badawi olive tree in the village of Al-Walaja near Bethlehem is reputed to be one of the oldest and largest olive trees in the world.

Environmentally, Palestine faces several challenges. The Gaza Strip suffers from desertification, salinization of freshwater resources, inadequate sewage treatment leading to waterborne diseases, soil degradation, and the depletion and contamination of its coastal aquifer. The West Bank faces similar issues, although freshwater is more plentiful; however, access is often restricted by the Israeli occupation and the unequal distribution of shared water resources. Three terrestrial ecoregions are present: Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests, Arabian Desert, and Mesopotamian shrub desert.

5.1. Climate

The climate of Palestine varies across its regions and with altitude. The West Bank generally experiences a Mediterranean climate, characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. Higher elevation areas tend to be cooler than the coastal plains. The eastern parts of the West Bank, including the Judean Desert and the western shoreline of the Dead Sea, have a dry and hot desert climate.

The Gaza Strip has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSh), with mild winters and dry, hot summers. Spring typically arrives in March-April. The hottest months are July and August, with average high temperatures around 91.4 °F (33 °C). The coldest month is January, with average temperatures around 44.6 °F (7 °C). Rainfall is scarce and primarily occurs between November and March, with an annual precipitation rate of approximately 4.6 in (116 mm) (4.57 inches) in Gaza City. Jericho, being in the Jordan Valley and well below sea level, experiences very hot summers and mild winters. Jerusalem has warm, dry summers and cool, wet winters, occasionally experiencing snowfall.

5.2. Biodiversity

Palestine's biodiversity reflects its varied geography and climate, encompassing Mediterranean, Irano-Turanian, and Saharo-Arabian biogeographical zones. The region hosts a range of flora and fauna, although many habitats and species face significant pressures.

While Palestine does not have an extensive system of officially recognized national parks equivalent to international standards, largely due to the political situation and occupation, there are several areas designated as nature reserves or protected zones, particularly in the West Bank, where conservation efforts are underway. Wadi Qelt, near Jericho, is a notable desert valley with unique plant and animal life, rugged landscapes, natural springs, and historical sites like the St. George Monastery. Efforts have been made to protect its biodiversity. The Judaean Desert is home to species adapted to arid conditions, including the "Judaean Camel," though camels are domesticated.

Environmental challenges significantly impact biodiversity. These include habitat loss due to urbanization and agricultural expansion, water scarcity and pollution, overgrazing, and the effects of the Israeli occupation. Restrictions on access to land and resources, the construction of the separation barrier, and the expansion of Israeli settlements have fragmented habitats and hindered conservation efforts. For example, Israeli national parks have been established in Area C of the West Bank, which is under Israeli military and civil control, a practice considered problematic under international law by Palestinians as it involves land not under their jurisdiction for such purposes.

The Qalqilya Zoo in the West Bank is the only currently active zoo in the Palestinian territories. The Gaza Zoo faced severe challenges and closures due to the blockade and conflict. The sustainable management of natural resources and the protection of biodiversity are critical issues for Palestine, intertwined with the broader political and human rights context.

6. Government and Politics

The State of Palestine operates under a semi-presidential republic framework, although its sovereignty and governing capacity are severely constrained by the ongoing Israeli occupation. The political landscape is complex, involving institutions associated with both the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). The 1988 Declaration of Independence serves as the founding document for the State of Palestine. The Palestine Basic Law, amended in 2003 and 2005, functions as an interim constitution for the PNA.

The PLO, internationally recognized as the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people," is the umbrella organization for various Palestinian political factions. The President of the State of Palestine is the head of state, a position currently held by Mahmoud Abbas. The President is typically the Chairman of the PLO Executive Committee and is formally appointed by the Palestinian Central Council (a body within the PLO). The Palestinian National Council (PNC) is the legislative body of the PLO, acting as a parliament-in-exile. The PLO Executive Committee performs the functions of a government-in-exile and manages Palestine's extensive foreign relations network.

The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) was established in 1994 as an interim administrative body following the Oslo Accords. It exercises limited self-rule in designated areas of the West Bank (Areas A and B) and, until 2007, in the Gaza Strip. The PNA has a President (the same individual as the President of the State of Palestine), a Prime Minister (currently Mohammad Mustafa, appointed in March 2024 after Mohammad Shtayyeh's resignation), and a Cabinet. The Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) is the PNA's elected parliament. However, the PLC has been largely inactive since 2007 due to internal Palestinian political divisions and Israeli restrictions. The last general elections were held in 2006.

A major challenge to Palestinian governance is the political schism between Fatah, the dominant party in the PLO and PNA, which largely governs the West Bank, and Hamas, an Islamist militant and political organization that won the 2006 PLC elections and has controlled the Gaza Strip since violently ousting Fatah-aligned PNA forces in 2007. This division has resulted in two de facto separate administrations, hindering unified Palestinian governance and efforts towards statehood and democratic development. Yahya Sinwar was the leader of the Hamas government in the Gaza Strip until his death in October 2024.

The proclaimed capital of Palestine is East Jerusalem, which remains under Israeli occupation and annexation (not recognized internationally). The administrative center of the PNA is in Ramallah. Some government buildings, including a planned parliament building, were constructed in Abu Dis, a suburb of Jerusalem, but political circumstances and Israeli restrictions have prevented their full utilization.

Democratic development in Palestine faces significant obstacles. These include the Israeli occupation, which limits the PNA's authority and restricts Palestinian political life (e.g., freedom of movement, assembly, and the ability to hold nationwide elections). Internal Palestinian divisions, corruption, and criticisms of authoritarian tendencies within both the PNA and Hamas administrations also pose challenges. Human rights organizations have reported concerns regarding freedom of expression, press freedom, and the treatment of political dissidents in both the West Bank and Gaza. The lack of regular elections since 2006 has further eroded democratic legitimacy and accountability.

6.1. Administrative Divisions

The State of Palestine is administratively divided into sixteen governorates (محافظةmuḥāfaẓahArabic). Eleven of these governorates are located in the West Bank, and five are in the Gaza Strip.

West Bank Governorates:

- Jenin

- Tubas

- Tulkarm

- Nablus

- Qalqilya

- Salfit

- Ramallah and al-Bireh

- Jericho (includes Al-Aghwar, the Jordan Valley area)

- Jerusalem (includes PNA-administered areas and Israeli-occupied East Jerusalem, which Palestine claims as its capital)

- Bethlehem

- Hebron

Gaza Strip Governorates:

- North Gaza

- Gaza

- Deir al-Balah

- Khan Yunis

- Rafah

The Oslo II Accord (1995) further divided the West Bank into three administrative areas with differing levels of Palestinian and Israeli control, significantly impacting governance, Palestinian sovereignty, and daily life:

- Area A: Comprises approximately 18% of the West Bank and includes major Palestinian cities. The Palestinian Authority (PA) has full civil and security control in Area A.

- Area B: Constitutes about 22% of the West Bank, mainly Palestinian rural areas. The PA has civil control, while Israel retains overriding security control.

- Area C: Represents around 60% of the West Bank and is the largest contiguous area. It includes most Israeli settlements, buffer zones, military areas, and a significant portion of Palestinian agricultural land and natural resources. Israel retains full civil and security control in Area C. Palestinian development and construction in Area C are heavily restricted by Israeli authorities.

This division, intended as an interim arrangement, has become a long-term reality, fragmenting Palestinian territory, hindering economic development, and impeding the contiguity of a future Palestinian state. East Jerusalem was not included in these area classifications and was effectively annexed by Israel, a move not recognized by the international community. The Gaza Strip, following Israeli disengagement in 2005 and Hamas's takeover in 2007, is under Hamas administration but remains subject to an Israeli (and Egyptian) blockade, severely impacting its governance and humanitarian situation.

| Name | Area (km2) | Population (Est.) | Density (per km2) | Muhafazah (District Capital) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jenin | 583 | 311,231 | 533.8 | Jenin |

| Tubas | 402 | 64,719 | 161.0 | Tubas |

| Tulkarm | 246 | 182,053 | 740.0 | Tulkarm |

| Nablus | 605 | 380,961 | 629.7 | Nablus |

| Qalqilya | 166 | 110,800 | 667.5 | Qalqilya |

| Salfit | 204 | 70,727 | 346.7 | Salfit |

| Ramallah & Al-Bireh | 855 | 348,110 | 407.1 | Ramallah |

| Jericho & Al Aghwar | 593 | 52,154 | 87.9 | Jericho |

| Jerusalem | 345 | 419,108 | 1214.8 | Jerusalem (proclaimed, status disputed) |

| Bethlehem | 659 | 216,114 | 327.9 | Bethlehem |

| Hebron | 997 | 706,508 | 708.6 | Hebron |

| North Gaza | 61 | 362,772 | 5947.1 | Jabalia |

| Gaza | 74 | 625,824 | 8457.1 | Gaza City |

| Deir Al-Balah | 58 | 264,455 | 4559.6 | Deir al-Balah |

| Khan Yunis | 108 | 341,393 | 3161.0 | Khan Yunis |

| Rafah | 64 | 225,538 | 3524.0 | Rafah |

Population data are estimates and may vary; official census data can be difficult to obtain uniformly across all territories due to the political situation. Jerusalem Governorate data includes populations in areas claimed by Palestine but under Israeli administration.

6.2. Law and Security

The legal framework of Palestine is complex, drawing from Ottoman law, British Mandate regulations, Jordanian law (in the West Bank), Egyptian law (in Gaza), Israeli military orders, and laws enacted by the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) and Presidential decrees. The Palestine Basic Law, amended in 2003 and 2005, serves as an interim constitution for the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) and outlines the powers of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

The judicial system includes first instance courts, courts of appeal, and a High Court/Court of Cassation. There are also specialized courts, such as military courts and, in Gaza, courts applying principles influenced by Hamas's interpretation of Islamic law. However, the judiciary's independence and effectiveness are hampered by several factors, including the Israeli occupation, internal political divisions between the West Bank and Gaza, lack of resources, and political interference.

The Palestinian Security Services (PSS) are the official security forces of the PNA, established under the Oslo Accords. Their primary mandate is to maintain internal security, law and order in areas under PNA control (primarily Area A of the West Bank), and cooperate with Israel on security matters as stipulated by the accords. The PSS include several branches:

- The Civil Police Force: Responsible for regular policing and law enforcement.

- The National Security Forces: A gendarmerie-type force, responsible for broader security tasks and border control (where applicable).

- The Preventive Security Service: An internal intelligence agency focused on internal threats.

- The General Intelligence Service: Focused on external intelligence.

The functioning of the PSS is heavily constrained by the Israeli occupation. Israeli forces frequently conduct operations in PNA-controlled areas, undermining PNA authority and the rule of law. Movement restrictions also impede the PSS's ability to operate effectively. The PSS have faced criticism from human rights organizations for issues such as arbitrary detention, torture and ill-treatment of detainees, and suppression of dissent, particularly against political opponents or critics of the PNA.

In the Gaza Strip, Hamas maintains its own security forces and legal system, separate from the PNA. These forces, including the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades (Hamas's armed wing) and various police and internal security units, are responsible for security and law enforcement in Gaza. Hamas's governance in Gaza has also faced human rights scrutiny, including concerns about due process, freedom of expression, and the application of capital punishment.

The overarching challenge to law and security in Palestine is the Israeli occupation itself. Israeli military law applies to Palestinians in Area C of the West Bank, and Israeli military courts have a conviction rate for Palestinians exceeding 99%. Israeli settlements in the West Bank have their own civilian legal system (Israeli law applies to settlers), creating a dual legal system that discriminates against Palestinians. Issues like administrative detention (detention without charge or trial) by Israel, land confiscation, home demolitions, and lack of accountability for settler violence further erode the rule of law and security for Palestinians. The internal Palestinian political divide also complicates security coordination and the consistent application of law across Palestinian territories.

6.3. Human Rights

The human rights situation in the State of Palestine is deeply concerning and complex, shaped significantly by the prolonged Israeli occupation, internal Palestinian governance issues, and ongoing conflict. Numerous international and local human rights organizations, as well as UN bodies, regularly document a wide range of violations.

Violations related to the Israeli Occupation:

- Right to Life and Security of Person: Israeli military operations in the West Bank and Gaza Strip have resulted in significant Palestinian casualties, including civilians. Concerns persist over excessive use of force by Israeli security forces, particularly in policing demonstrations and during military incursions. The 2023 Israel-Hamas war led to an unprecedented number of civilian deaths in Gaza.

- Freedom of Movement: Palestinians face severe restrictions on their freedom of movement due to Israeli checkpoints, the Separation Barrier (much of which is built inside the West Bank), road closures, and a complex permit system. These restrictions impede access to work, education, healthcare, and family life. The blockade of Gaza by Israel and Egypt constitutes a form of collective punishment and severely restricts movement.

- Right to Property and Adequate Housing: Israeli settlement expansion in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, often involves the confiscation of Palestinian land and is illegal under international law. Demolitions of Palestinian homes and structures, often on the grounds of lacking Israeli-issued building permits (which are notoriously difficult for Palestinians to obtain, especially in Area C and East Jerusalem), lead to forced displacement.

- Settler Violence: Attacks by Israeli settlers against Palestinians and their property (including olive groves, livestock, and homes) are a persistent problem, particularly in the West Bank. Israeli authorities have often been criticized for failing to prevent settler attacks and for not adequately investigating and prosecuting perpetrators, leading to a climate of impunity.

- Arbitrary Detention and Due Process: Thousands of Palestinians are held in Israeli prisons, many under administrative detention (without charge or trial). Concerns exist regarding fair trial standards in Israeli military courts, which try Palestinians from the occupied territories, and allegations of torture and ill-treatment in detention are common.

- Access to Resources: Palestinians face discrimination in accessing natural resources, particularly water, with a disproportionate share of shared water resources being allocated to Israeli settlements and within Israel.

Violations by Palestinian Authorities (PNA in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza):

- Freedom of Expression, Assembly, and Association: Both the PNA and Hamas authorities have been criticized for restricting these freedoms. Journalists, human rights defenders, and political opponents have faced harassment, intimidation, arbitrary arrest, and detention.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment: Allegations of torture and ill-treatment of detainees in Palestinian custody persist in both the West Bank and Gaza.

- Due Process and Fair Trials: Concerns exist regarding the independence of the judiciary and fair trial standards in Palestinian courts. In Gaza, Hamas authorities have carried out executions, sometimes after summary trials, drawing international condemnation.

- Women's Rights: While Palestinian law includes some protections, women continue to face discrimination in law and practice, and issues like domestic violence remain a concern.

- Rights of Minorities and Vulnerable Groups: While Palestine is largely ethnically and religiously homogenous (Palestinian Arab, majority Sunni Muslim), minority groups such as Christians and Bedouins may face specific challenges. LGBT individuals face legal discrimination and social stigma. Persons with disabilities also face challenges in accessing their rights.

The ongoing conflict and lack of accountability for violations by all parties contribute to a cycle of violence and impunity, undermining respect for human rights and international law. The internal Palestinian political split also impacts the human rights situation, sometimes leading to abuses by one authority against supporters of the other. International bodies, including the International Criminal Court, have initiated investigations into alleged war crimes committed in the Palestinian territories.

7. Security Forces

The official security apparatus of the State of Palestine is primarily represented by the Palestinian Security Services (PSS), which operate under the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) in the areas of the West Bank where it has administrative and/or security control (Areas A and B, as defined by the Oslo Accords). The PSS were established following the Oslo Accords in the mid-1990s with the mandate to maintain internal security, public order, and cooperate on security matters with Israel. Their structure includes several branches:

- Civil Police Force:** Responsible for day-to-day policing, traffic control, and criminal investigations in PNA-controlled areas.

- National Security Forces (NSF):** A gendarmerie-like force, tasked with broader internal security, counter-terrorism (as defined by the PNA), and formerly border control functions.

- Preventive Security Service (PSS):** An internal intelligence agency focusing on preventing threats to PNA stability and internal security.

- General Intelligence Service (Mukhabarat):** The primary external intelligence agency.

- Presidential Guard:** Responsible for protecting the President and other high-ranking officials and institutions.

The capabilities and operations of the PSS are significantly constrained by the Israeli occupation. Israeli forces frequently conduct raids and arrests even within PNA-controlled Area A, undermining PSS authority. The PSS also face challenges related to funding, equipment, and training. They have received assistance, including training and equipment, from various international partners, notably the United States and European Union countries, often aimed at professionalization and counter-terrorism capacity building. However, this assistance has also been criticized by some Palestinians for prioritizing Israeli security concerns over Palestinian rights and for bolstering what they see as an unaccountable security apparatus. Human rights organizations have documented abuses by PSS personnel, including arbitrary arrests, detention of political opponents, and allegations of torture and ill-treatment of detainees.

In the Gaza Strip, which has been under the de facto control of Hamas since 2007, a separate set of security forces operates. These include:

- Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades:** The armed wing of Hamas, which functions as a quasi-military force. It is primarily focused on armed conflict with Israel but also plays a role in internal security and control within Gaza.

- Hamas-run Police and Internal Security Forces:** Hamas maintains its own police force for civil policing and various internal security agencies responsible for maintaining its authority in Gaza.

Other armed Palestinian factions, such as the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) and its Al-Quds Brigades, also operate, particularly in Gaza, and sometimes coordinate with Hamas forces. These groups are not part of the official PNA security structure and often have differing ideologies and objectives.

The Palestine Liberation Army (PLA), historically the official military wing of the PLO, was established in the 1960s. While it still nominally exists, its role has become largely symbolic, with most of its units stationed outside Palestine in countries like Syria and Jordan, and it does not play a significant operational role in the current security landscape of the West Bank or Gaza.

The divided security landscape, with separate and often rival forces in the West Bank and Gaza, reflects the broader political schism. Accountability for actions by all security forces and armed groups remains a significant challenge, contributing to ongoing human rights concerns.

8. Foreign Relations

The foreign relations of the State of Palestine are conducted by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which is internationally recognized as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. The PLO, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), maintains an extensive network of diplomatic missions (embassies and representative offices) in countries that recognize the State of Palestine or the PLO.

Key foreign policy objectives for Palestine include:

- Achieving full international recognition of Palestinian statehood based on the 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital.

- Ending the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories.

- Securing a just and lasting solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, including the issue of Palestinian refugees based on UN Resolution 194 (right of return).

- Gaining full membership in the United Nations and other international organizations.

- Mobilizing international political, economic, and humanitarian support for the Palestinian people and for Palestinian state-building efforts.

Palestine is a full member of the Arab League, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), and the Union for the Mediterranean. It also holds observer status or membership in numerous UN agencies and other international bodies. The support of Arab and Islamic countries has been a cornerstone of Palestinian diplomacy. Countries like Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia have historically played significant roles in regional peace efforts and in supporting the Palestinian cause. Iran has provided support, particularly military and financial, to Palestinian militant groups like Hamas and Islamic Jihad, often as part of its "Axis of Resistance" in the region. Qatar has also been a key financial supporter of Gaza and has hosted Hamas political leaders, while Turkey has expressed strong support for the Palestinian cause and Hamas.

Relations with Western powers are complex. While many European countries provide significant financial aid to the PNA and support a two-state solution, most have not formally recognized the State of Palestine, often citing the need for a negotiated settlement with Israel first. However, some European nations, such as Sweden (in 2014), and more recently Spain, Ireland, Norway, and Slovenia (in 2024), have recognized Palestine, reflecting a growing international momentum influenced by the perceived stalemate in the peace process and the humanitarian situation. The United States has historically been Israel's strongest ally and has often used its veto power in the UN Security Council to block resolutions critical of Israel or supportive of Palestinian statehood outside a negotiated framework. The US provides security assistance to the PNA and has played a primary role in mediating peace talks, though these efforts have been largely unsuccessful in recent years.

India was one of the first non-Arab countries to recognize Palestine in 1988 and has historically maintained strong support, though it has also developed closer ties with Israel since the 1990s. Many countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America have recognized Palestine and express solidarity with its cause. Countries like South Africa and Ireland, drawing on their own historical experiences with colonialism or conflict, have been particularly vocal advocates for Palestinian rights.

The ongoing 2023 Israel-Hamas war has significantly impacted Palestine's foreign relations, leading to increased international scrutiny of Israeli actions, heightened calls for a ceasefire and humanitarian aid, and a renewed push by some countries for Palestinian state recognition as a step towards peace. Diplomatic efforts are often focused on addressing the immediate humanitarian crisis, seeking accountability for alleged war crimes, and trying to revive a political track for a long-term solution. The socio-economic and political situation in Palestine is heavily influenced by these international dynamics, including the flow of foreign aid, international pressure (or lack thereof) on Israel, and the broader geopolitical shifts in the Middle East.

9. International Recognition and Status

The international legal and political status of the State of Palestine is a complex and evolving issue. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) declared the establishment of the State of Palestine on November 15, 1988. As of mid-2024, 146 out of 193 United Nations (UN) member states have formally recognized the State of Palestine. This recognition is largely based on the 1967 borders (the Green Line), with East Jerusalem as its capital.

Key aspects of Palestine's international status:

- UN Status:** In 1974, the PLO was granted observer status at the UN as a "non-state entity." Following the 1988 declaration of independence, the UN General Assembly acknowledged the proclamation and began using the designation "Palestine." A significant development occurred on November 29, 2012, when the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 67/19, upgrading Palestine's status to that of a non-member observer State. This was a de facto recognition of Palestinian statehood by the General Assembly and granted Palestine enhanced participation rights, though not voting rights, in UN proceedings. This status is similar to that held by the Holy See.

- Efforts for Full UN Membership:** Palestine has sought full UN membership, which requires a recommendation from the UN Security Council followed by a two-thirds majority vote in the General Assembly. However, these efforts have been consistently blocked by the United States, a permanent member of the Security Council with veto power, which maintains that Palestinian statehood should be achieved through direct negotiations with Israel. In April 2024, a Security Council resolution to recommend full UN membership for Palestine was vetoed by the US. In May 2024, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution (ES-10/23) determining that the State of Palestine is qualified for membership and recommending that the Security Council reconsider the matter favorably. This resolution also granted Palestine additional rights and privileges of participation in UN sessions and work, short of full voting rights.

- Membership in International Organizations:** Palestine is a full member of numerous international organizations, including the Arab League, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), UNESCO (since 2011), the International Criminal Court (ICC) (since 2015), and G77. Membership in the ICC allows Palestine to bring cases of alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed on its territory to the court, which has opened an investigation into the situation in Palestine.

- Bilateral Relations:** Palestine maintains diplomatic relations with the countries that recognize it, operating embassies and missions abroad.

- Challenges to Effective Sovereignty:** Despite widespread international recognition and its upgraded UN status, Palestine's effective sovereignty is severely limited by the ongoing Israeli occupation of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the blockade of the Gaza Strip. Israel maintains control over Palestine's borders (except the Gaza-Egypt border at Rafah, which is also heavily restricted), airspace, territorial waters (for Gaza), security, and many aspects of civil administration, particularly in Area C of the West Bank and East Jerusalem. The internal Palestinian political split between the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza also complicates the exercise of unified and effective sovereignty.

The international discourse on Palestine's status often revolves around the principles of self-determination, the illegality of Israeli settlements, the status of Jerusalem, the rights of Palestinian refugees, and the framework for a two-state solution. The recognition of Palestine by more states, particularly Western nations, is seen by supporters as a way to advance the peace process by affirming Palestinian rights and creating a more level playing field for negotiations. Opponents, including Israel and the US, argue that unilateral recognition undermines direct negotiations. The implications of Palestine's evolving international status are significant for international law, human rights accountability, and the prospects for a just and lasting resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

10. Economy

The economy of the State of Palestine is significantly impacted by the ongoing Israeli occupation, political instability, and internal divisions. It is generally characterized as a developing economy, heavily reliant on foreign aid, remittances from Palestinians working abroad, and limited local industries. The World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) classify it as a lower-middle-income economy. In 2023, prior to the major escalation of conflict in Gaza, the estimated GDP was around $19-20 billion USD, with a per capita income of approximately $4,500-$5,000 USD. However, these figures mask significant disparities between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and the devastating economic consequences of the 2023-2024 Gaza war.

The Israeli occupation imposes severe restrictions that stifle economic development. These include:

- Restrictions on Movement and Access:** Checkpoints, the separation barrier, road closures, and permit systems severely hinder the movement of people and goods within the West Bank, between the West Bank and Gaza, and with the outside world. This increases transportation costs, disrupts supply chains, and limits access to markets. The "back-to-back" system, forcing goods to be unloaded and reloaded at crossings, adds significant costs.

- Control over Area C:** Area C, constituting over 60% of the West Bank and under full Israeli civil and security control, contains most of Palestine's agricultural land, water resources, and areas with potential for tourism and industrial development. Palestinian access to and development in Area C is heavily restricted by Israel. The World Bank estimates that if Palestinians had unrestricted access to Area C, it could boost Palestinian GDP by as much as 35%.

- Blockade of the Gaza Strip:** Since 2007, the Israeli and Egyptian blockade has crippled Gaza's economy, leading to de-development, extreme poverty, and one of the highest unemployment rates in the world. Exports are severely limited, and imports of essential goods, including construction materials and raw materials for industry, are restricted.

- Resource Exploitation:** Israel's control and exploitation of Palestinian natural resources, such as water from West Bank aquifers and minerals from the Dead Sea, without benefit to the Palestinian economy, represent a significant economic loss.

- Dependence on Israel:** The Palestinian economy is highly dependent on Israel for trade, employment (for Palestinians working in Israel or settlements), and essential services like electricity and water. This dependence creates vulnerabilities.

Key economic sectors include:

- Services:** This is the largest sector, encompassing public administration, trade, and tourism.

- Agriculture:** Historically important, but facing challenges from land confiscation, water scarcity, and restricted access to markets.

- Manufacturing:** Small-scale, primarily producing for the local market, constrained by restrictions on imports of raw materials and exports of finished goods.

- Construction:** Important for employment, but heavily reliant on donor funding and Israeli permits for materials, especially in Gaza.

- Tourism:** Significant potential, particularly religious and historical tourism, but hampered by political instability and access restrictions.

Unemployment is chronically high, especially among youth and in Gaza. Poverty rates are also high, with a significant portion of the population relying on humanitarian assistance. The Palestinian Authority (PA) faces persistent fiscal challenges, with expenditures often exceeding revenues, leading to reliance on international donor aid to fund its budget and public services. This aid dependence makes the economy vulnerable to political pressures and donor fatigue.

The ongoing conflict, particularly the 2023 Israel-Hamas war, has had catastrophic economic consequences, especially in Gaza, where widespread destruction of infrastructure, businesses, and agricultural land has occurred. The World Bank and UN have reported near-total collapse of Gaza's economy, with massive increases in poverty and unemployment. The West Bank economy has also suffered due to increased restrictions, loss of labor in Israel, and reduced trade. Efforts towards sustainable economic development, poverty reduction, and social equity are contingent upon a resolution of the conflict, an end to the occupation, and the lifting of restrictions that currently suffocate Palestinian economic potential.

10.1. Agriculture

Agriculture has historically been a cornerstone of the Palestinian economy and cultural heritage. However, the sector faces immense challenges primarily due to the Israeli occupation, in addition to climate change and water scarcity. Key agricultural products include olives and olive oil (which are of significant cultural and economic importance), fruits (such as grapes, figs, citrus), vegetables, and livestock.

Major challenges and their impact on food security and rural livelihoods:

- Land Confiscation and Access Restrictions:** A significant portion of Palestinian agricultural land, particularly in the West Bank's Area C (under full Israeli control), has been confiscated for the construction of Israeli settlements, bypass roads, military zones, or declared "state land." The Separation Barrier has also isolated large tracts of Palestinian farmland, making it difficult for farmers to access their lands. These actions reduce the land available for Palestinian agriculture and undermine the livelihoods of rural communities.

- Water Access:** Israel controls most of the water resources in the West Bank, including the Mountain Aquifer. Palestinians face severe restrictions on drilling new wells or rehabilitating existing ones, while Israeli settlements receive a disproportionately larger share of water. This water scarcity critically limits irrigation and crop yields for Palestinian farmers. In the Gaza Strip, the coastal aquifer, the main source of water, is severely depleted and contaminated by saltwater intrusion and sewage, rendering much of it unfit for agriculture or human consumption.

- Impact of Israeli Settlements:** The expansion of Israeli settlements often leads to the destruction of Palestinian agricultural land, uprooting of olive trees, and damage to irrigation networks. Settlers have also been involved in attacks on Palestinian farmers and their crops, often with impunity.

- Restrictions on Movement and Trade:** Israeli checkpoints and other movement restrictions hinder farmers' ability to transport their produce to markets, both domestically and for export. This leads to spoilage, increased costs, and reduced competitiveness. The blockade of Gaza severely limits the import of agricultural inputs (like fertilizers and seeds) and the export of agricultural products.

- Food Security:** These challenges collectively undermine Palestinian food security. Reduced agricultural production, coupled with high poverty and unemployment rates, makes many Palestinian households reliant on food aid. The ability of Palestine to produce enough food to feed its population is severely compromised.

- Rural Livelihoods:** Agriculture is a traditional source of income and employment for many Palestinian families, particularly in rural areas. The decline of the agricultural sector due to the occupation contributes to rural poverty, displacement, and increased dependence on alternative, often precarious, livelihoods.

Despite these obstacles, Palestinian farmers demonstrate resilience, employing traditional farming practices alongside modern techniques where possible. The olive sector, in particular, remains a vital part of the economy and a symbol of Palestinian rootedness to the land. International organizations and NGOs provide some support for agricultural development, but a fundamental improvement in the sector requires an end to the occupation and the restrictions it imposes.

10.2. Water Supply and Sanitation

Water supply and sanitation in the Palestinian territories are critical issues, characterized by severe water scarcity, unequal distribution of shared resources, and inadequate infrastructure, largely due

to the Israeli occupation and, in Gaza, the ongoing blockade and recurrent conflicts.

- West Bank:**

- Water Resources:** The primary sources of freshwater for the West Bank are the Mountain Aquifer (shared with Israel) and the Jordan River. However, under agreements stemming from the Oslo Accords, which Palestinians argue are inequitable, Israel controls the vast majority of these shared water resources.

- Restricted Access and Control:** Israel retains control over all water extraction, development, and infrastructure projects in the West Bank, particularly in Area C. Palestinians require Israeli permits to drill new wells, rehabilitate old ones, or build water infrastructure, and these permits are often denied or significantly delayed. This severely limits the Palestinians' ability to meet their water needs.

- Unequal Distribution:** Per capita water consumption for Palestinians in the West Bank is significantly lower than that for Israelis and for Israeli settlers in the West Bank, often falling below the minimum recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). Settlers typically have access to a continuous and ample water supply, while many Palestinian communities face chronic water shortages, especially during summer months, and rely on expensive tankered water.

- Sanitation:** Sewage infrastructure is underdeveloped in many parts of the West Bank. Untreated or inadequately treated wastewater from Palestinian communities and Israeli settlements often pollutes groundwater and surface water sources, posing public health and environmental risks. The development of wastewater treatment plants by Palestinians is also subject to Israeli approval and restrictions.

- Gaza Strip:**

- Coastal Aquifer Crisis:** The Gaza Strip relies almost entirely on the Coastal Aquifer for its freshwater needs. However, years of over-extraction (due to the high population density and lack of alternative sources) and contamination from seawater intrusion and sewage infiltration have rendered over 95% of the aquifer's water unfit for human consumption according to WHO standards.

- Blockade Impact:** The Israeli (and Egyptian) blockade imposed since 2007 has severely hampered efforts to improve water and sanitation infrastructure. Restrictions on the entry of essential materials (pipes, pumps, construction materials, fuel for operating facilities) have delayed or prevented the construction and repair of water wells, desalination plants, and wastewater treatment facilities.

- Energy Crisis:** Chronic electricity shortages in Gaza, exacerbated by the blockade and damage to power infrastructure during conflicts, cripple the operation of water pumps, desalination plants, and sewage treatment plants, further worsening the water and sanitation crisis.

- Wastewater Pollution:** Most sewage in Gaza is discharged untreated or partially treated into the Mediterranean Sea, causing severe marine pollution and posing health risks to the population who rely on the sea for fishing and recreation.

- Humanitarian Impact:** The dire water and sanitation situation in Gaza has led to a public health crisis, with high rates of waterborne diseases, particularly among children. Access to safe drinking water is a daily struggle for most Gazans. The 2023 Israel-Hamas war caused catastrophic damage to already fragile water and sanitation systems, leading to widespread disease outbreaks.

- Overall Challenges:**

10.3. Manufacturing

The manufacturing sector in Palestine, while having potential, operates under significant constraints primarily due to the Israeli occupation, restrictions on movement and trade, and limited access to resources and markets. It contributes a relatively small but important share to the Palestinian GDP and employment.

Key manufacturing sub-sectors include:

- Stone and Marble:** Palestine, particularly the West Bank, is rich in high-quality stone and marble (e.g., "Jerusalem stone"). This is one of the most significant export-oriented manufacturing industries. However, quarrying operations often face difficulties related to Israeli permits, access to land (especially in Area C), and environmental concerns.

- Food Processing:** This includes the production of olive oil, dairy products, beverages, and processed foods, largely for the domestic market but with some export potential.

- Textiles and Garments:** This sector, once more prominent, has faced increased competition and challenges related to importing raw materials and exporting finished goods.

- Furniture and Wood Products:** Primarily serves the local market.

- Pharmaceuticals:** A small but growing sector with some companies producing generic drugs.

- Construction Materials:** Includes cement products (though cement itself is largely imported), tiles, and other materials for the construction industry.

- Plastics and Chemicals:** Produces a range of goods for local consumption.

- Challenges and Limiting Factors:**

- Restrictions on Movement and Access:** Israeli checkpoints, the separation barrier, and road closures severely impede the transport of raw materials to factories and finished goods to markets (both domestic and international). This increases costs and delivery times, reducing competitiveness.

- Trade Restrictions:** Palestinian manufacturers face difficulties exporting their goods due to Israeli control over borders and complex customs procedures. Access to international markets is limited.

- Limited Access to Raw Materials and Technology:** Restrictions on imports can make it difficult and expensive to obtain necessary raw materials, machinery, and technology.

- Infrastructure Deficiencies:** Inadequate and unreliable electricity supply (especially in Gaza), water shortages, and underdeveloped industrial zones hinder manufacturing operations.

- Israeli Competition and Policies:** Palestinian industries often struggle to compete with Israeli products, which have easier access to the Palestinian market. Israeli policies can also favor Israeli industries over Palestinian ones.

- Gaza Blockade:** The manufacturing sector in Gaza has been particularly devastated by the Israeli blockade, which restricts the entry of raw materials and the exit of finished goods, leading to the closure of many factories and massive unemployment. Recurrent conflicts have also destroyed industrial infrastructure.

- Investment Climate:** Political instability, the occupation, and lack of legal certainty deter both local and foreign investment in the manufacturing sector.