1. Overview

Kiribati, officially the Republic of Kiribati, is an island nation located in the central Pacific Ocean, straddling the equator and the 180th meridian, making it the only country in the world situated in all four hemispheres. Comprising 32 atolls and one raised coral island, Banaba, its land area is small but dispersed over a vast expanse of ocean, granting it one of the largest Exclusive Economic Zones globally. The population of over 119,000 (2020 census) is predominantly I-Kiribati, of Micronesian origin, with a significant concentration on the capital atoll, South Tarawa.

The nation's history is marked by early Austronesian settlement, the development of unique traditional societies, and later influences from Polynesian and Melanesian voyagers. The colonial era began with European contact in the 17th-19th centuries, leading to the establishment of the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony. World War II saw Japanese occupation and significant battles, particularly the Battle of Tarawa. Phosphate mining on Banaba profoundly impacted its environment and people, leading to their eventual relocation. Kiribati achieved independence in 1979, embarking on nation-building amidst significant socio-economic challenges.

Geographically, Kiribati consists of low-lying atolls vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, particularly sea level rise, which poses an existential threat to the nation. This vulnerability has placed Kiribati at the forefront of international climate advocacy. Its tropical marine climate, diverse marine ecosystems, including the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA), and limited terrestrial resources define its environmental context.

Kiribati operates as a parliamentary democratic republic. Its economy relies heavily on fishing license fees, remittances from seafarers, development assistance, and income from its sovereign wealth fund, the Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund (RERF). Key sectors include fisheries, copra production, and a nascent tourism industry. Limited resources, remoteness, and susceptibility to external shocks, including climate change, present ongoing economic challenges.

I-Kiribati culture is rich in traditional music, dance (notably the te mwaie), and social customs centered around the maneaba (community meeting house). Gilbertese and English are the official languages, and Christianity is the predominant religion, though often blended with traditional beliefs. The nation faces significant health challenges, including non-communicable diseases and issues related to water and sanitation, exacerbated by environmental pressures. Education is a priority, with efforts to provide access across its dispersed islands. Kiribati's foreign policy is strongly influenced by its fight for survival against climate change, engaging actively in regional and international forums to advocate for global action and support for adaptation.

2. Etymology and naming

The name Kiribati is the Gilbertese rendition of "Gilberts," derived from the English name for the nation's main archipelago, the Gilbert Islands. The name is pronounced KiribatiKIRR-i-bass /ˌkɪrɪˈbæs/English; in Gilbertese it is Kiribatiki-ri-bas /kiɾibas/Gilbertese, as the digraph -tis soundGilbertese in Gilbertese represents an /s/ sound. The people of Kiribati are known as I-Kiribati, pronounced I-Kiribatiee-KIRR-i-bass /iːˌkɪrɪˈbæs/English.

The Gilbert Islands were named îles GilbertGilbert IslandsFrench around 1820 by Russian admiral Adam Johann von Krusenstern and French captain Louis-Isidore Duperrey. This was in honor of the British captain Thomas Gilbert, who, along with captain John Marshall, sighted some of these islands in 1788 while traversing the "outer passage" route from Port Jackson (now Sydney) to Canton (now Guangzhou). Both von Krusenstern's and Duperrey's maps, published in 1824, were written in French.

In the 19th century, the archipelago, particularly its southern part, was often referred to in English as the Kingsmills. However, the name Gilbert Islands gained increasing usage, appearing in the Western Pacific Order in Council of 1877 and the Pacific Order of 1893. The name Gilbert was already part of the British protectorate's designation since 1892 and was incorporated into the name of the entire Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony (GEIC) from 1916. It was retained even after the Ellice Islands separated to become Tuvalu in 1976.

The spelling KiribatiKiribatiGilbertese for "Gilberts" can be found in Gilbertese language books prepared by missionaries, such as those by the Hawaiian Board of Missionaries in 1895, where it referred to the Gilbertese people and language. The first dictionary entry listing Kiribati as the native name for the country was recorded in 1952 by Ernest Sabatier in his Dictionnaire gilbertin-françaisGilbertese-French DictionaryFrench.

An indigenous name often suggested for the Gilbert Islands proper is TungaruTungaru (indigenous name)Gilbertese. However, when the nation gained independence in 1979, the name Kiribati was chosen by the chief minister, Sir Ieremia Tabai, and his cabinet. The reasons cited were that Kiribati was considered more modern and that it better encompassed the inclusion of outer islands like the Phoenix Islands and Line Islands, which were not traditionally considered part of the Tungaru (or Gilberts) chain.

3. History

The history of Kiribati encompasses early human settlement, the development of distinct cultural and political systems, colonial rule, and the challenges of post-independence nationhood, particularly in the face of climate change. This history has shaped the I-Kiribati people, their society, and their environment.

3.1. Early settlement and traditional society

The islands now known as Kiribati were first settled by Austronesian peoples speaking an Oceanic language between 3000 BC and 1300 AD. These early settlers populated the islands from north to south, including Nui which is now part of Tuvalu. The area was not entirely isolated; subsequent voyages by people from Samoa, Tonga, and Fiji introduced Polynesian and Melanesian cultural aspects. Intermarriage and extensive navigation between the islands led to a significant degree of cultural homogenization over time. Oral traditions suggest that the earliest inhabitants may have been a dark-skinned, frizzy-haired people of short stature, possibly of Melanesian origin. These groups were later visited or joined by taller, fairer-skinned Austronesian seafarers from a place orally described as Matang (likely referring to the west). These groups intermittently clashed and intermingled, eventually forming a more uniform population.

Around AD 1300, a significant migration from Samoa occurred, adding Polynesian ancestry to the Gilbertese population. These Samoans brought with them strong Polynesian linguistic and cultural features, establishing clans based on their traditions which gradually intertwined with the indigenous clans and power structures already present. By the 15th century, distinct systems of governance emerged. The northern islands were primarily under chiefly rule (uea), while the central and southern islands were largely governed by councils of elders (unimwaane). Tabiteuea may have been an exception, known for maintaining a traditionally egalitarian society; its name, derived from Tabu-te-Uea, means "chiefs are forbidden."

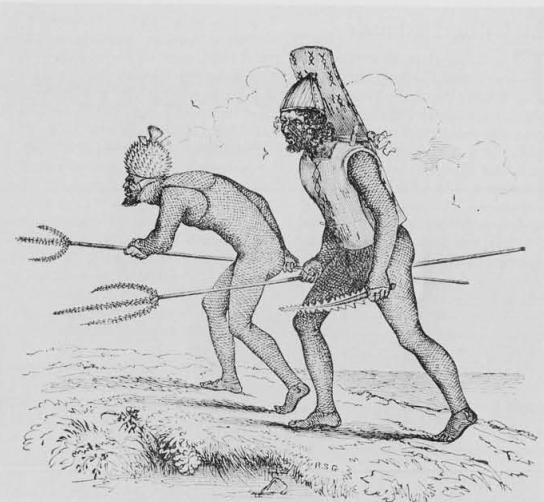

Land acquisition was a primary driver of conflict, leading to civil wars as clans and chiefs fought over resources, often fueled by long-standing feuds. This turmoil continued into the period of European contact. The traditional weaponry of the I-Kiribati included spears, knives, and swords embedded with shark teeth, and armor made from dense coconut fiber. These were often preferred over European firearms due to their sentimental and ancestral value, although some I-Kiribati leaders did utilize European weapons provided through trade. Hand-to-hand combat skills were highly valued. High Chief Tembinok' of Abemama was one of the last expansionist chiefs of this era, despite Abemama historically adhering to the southern tradition of governance by unimwaane. His character and rule were documented by Robert Louis Stevenson in his book In the South Seas. The 90th anniversary of Stevenson's arrival in the Gilbert Islands was chosen for Kiribati's independence celebrations on 12 July 1979.

3.2. Colonial era

European ships made sporadic visits to the islands in the 17th and 18th centuries during circumnavigation attempts or while seeking Pacific trade routes. The 19th century saw increased contact with Europeans, including whalers operating in the "On-The-Line" grounds, traders, and blackbirders. Blackbirding, the coercive recruitment of Kanakas (Pacific Islanders) for labor on plantations in places like Queensland, Samoa, and Central America, had severe social, economic, political, religious, and cultural consequences. Over 9,000 I-Kiribati were taken abroad between 1845 and 1895, many of whom never returned. This exploitation significantly impacted the indigenous population and disrupted traditional structures.

From the 1830s, a small number of Europeans, Chinese, Samoans, and others resided on the islands, including beachcombers, castaways, traders, and missionaries. Dr. Hiram Bingham II of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) arrived on Abaiang in 1857. Roman Catholicism was introduced to Nonouti around 1880 by two I-Kiribati men, Betero and Tiroi, who had converted in Tahiti. Catholic missionaries Father Joseph Leray, Father Edward Bontemps, and Brother Conrad Weber arrived on Nonouti in 1888. Protestant missionaries from the London Missionary Society (LMS) were also active in the southern Gilberts; Rev. Samuel James Whitmee visited Arorae, Tamana, Onotoa, and Beru in 1870, and George Pratt visited in 1872.

In 1886, an Anglo-German agreement partitioned the "unclaimed" central Pacific. Nauru fell into the German sphere of influence, while Ocean Island (Banaba) and the future Gilbert and Ellice Islands came under the British sphere. In 1892, Captain Edward Davis of HMS Royalist declared the Gilbert Islands a British protectorate, with the agreement of local authorities (an uea from the northern Gilberts and atun te boti, or heads of clans, on other islands). The nearby Ellice Islands (now Tuvalu) were also included. The protectorate was administered by a Resident Commissioner, initially based on Makin Islands (1893-95), then Betio, Tarawa (1896-1908), and later Ocean Island (1908-1942). The administration was overseen by the Western Pacific High Commission (WPHC) based in Fiji.

Banaba was annexed to the protectorate in 1900 following the discovery of rich phosphate rock deposits by Albert Fuller Ellis of the Pacific Islands Company. Phosphate mining began shortly thereafter, providing significant revenue through taxes and duties for the WPHC, but at a great cost to the Banaban people and their island. The conduct of William Telfer Campbell, the second Resident Commissioner (1896-1908), was criticized for maladministration, including allegations of forced labor, leading to an inquiry by Arthur Mahaffy in 1909. The operations of the Pacific Phosphate Company on Banaba also drew criticism for their exploitative nature.

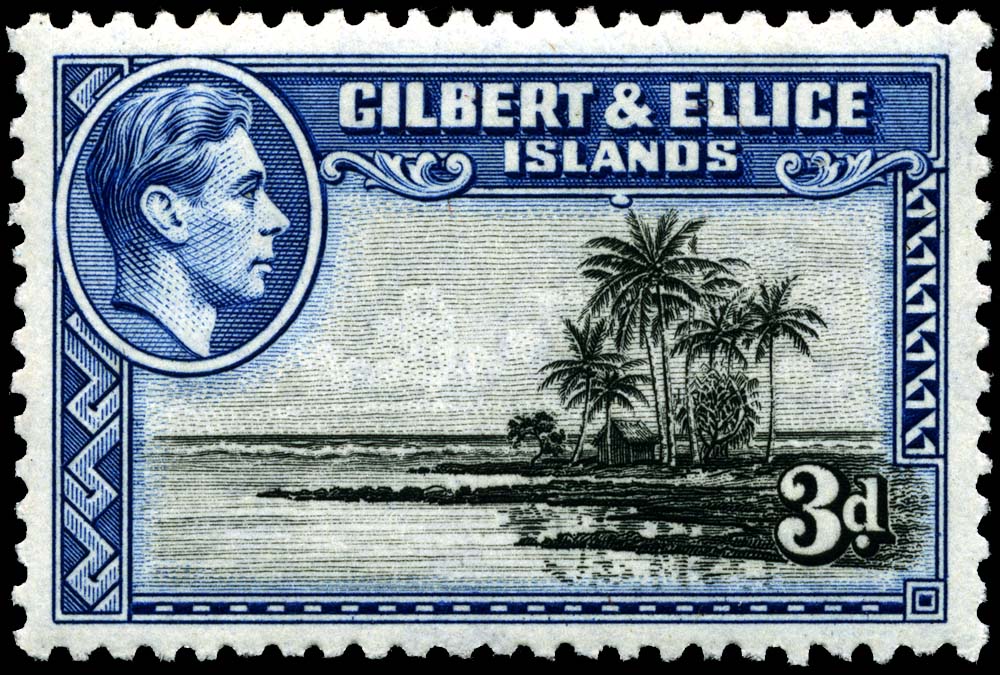

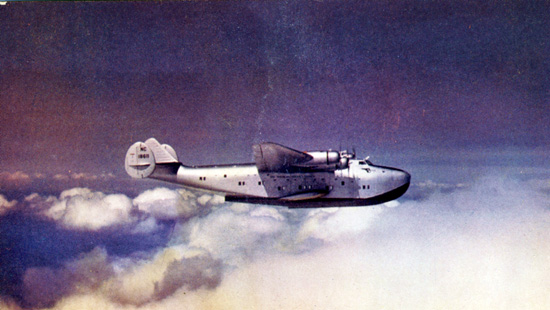

In 1916, the islands became the crown colony of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands (GEIC). The Northern Line Islands, including Christmas Island (Kiritimati), were added to the colony in 1919, and the Phoenix Islands in 1937, partly for the Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme. On 12 July 1940, Pan Am Airways' American Clipper made its first landing on Canton Island during a flight from Honolulu to Auckland. Sir Arthur Grimble served as a cadet administrative officer and later as Resident Commissioner (1926). In 1902, the Pacific Cable Board laid a trans-Pacific telegraph cable connecting Bamfield, British Columbia, to Fanning Island (Tabuaeran) and Fiji, completing part of the All Red Line global telegraph network. The United States also laid claim to some of the northern Line Islands and Phoenix Islands, including Howland, Jarvis, and Baker islands, leading to territorial disputes that were resolved by the Treaty of Tarawa after Kiribati's independence.

During World War II, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Butaritari and Tarawa, along with other northern Gilbert Islands, were occupied by Japan from 1941 to 1943. Betio on Tarawa was developed into a Japanese airfield and supply base. The Battle of Tarawa in November 1943, part of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign, was one of the bloodiest battles in US Marine Corps history, as US forces fought to expel the Japanese. Banaba, the colony's headquarters, was bombed, evacuated, and occupied by Japan in 1942. It was not liberated until 1945, after Japanese forces had massacred all but one of the remaining I-Kiribati on the island. The provisional headquarters of the colony was moved to Funafuti (in the Ellice Islands) from 1942 to 1946, before returning to Tarawa.

After the war, in late 1945, most of the surviving Banabans, who had been dispersed to Kosrae, Nauru, and Tarawa, were relocated by the British government to Rabi Island in Fiji, which had been purchased for this purpose in 1942. This relocation was due to the extensive environmental devastation caused by phosphate mining, which had rendered Banaba largely uninhabitable. The mining continued until the phosphate deposits were exhausted around the time of Kiribati's independence. The impact of mining on Banaba remains a significant and painful legacy for the Banaban people, highlighting the human rights concerns associated with resource extraction and displacement.

On 1 January 1953, the British Western Pacific High Commissioner's office was transferred from Fiji to Honiara in the British Solomon Islands, though the GEIC Resident Commissioner remained in Tarawa. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Christmas Island was used by the United Kingdom and the United States for nuclear weapons testing, including hydrogen bomb tests, further impacting the environment and potentially the health of those present, raising human rights and health concerns for those exposed.

Institutions of internal self-rule were established on Tarawa from around 1967. In 1974, the Polynesian inhabitants of the Ellice Islands voted for separation from the predominantly Micronesian Gilbert Islands due to cultural and political differences. This separation became effective on 1 January 1976, and in 1978, the Ellice Islands became the independent nation of Tuvalu.

3.3. Independence and contemporary Kiribati

The Gilbert Islands achieved independence as the Republic of Kiribati on 12 July 1979. Ieremia Tabai, a figure seen as a defender of the people's interests, became the first President. In September 1979, the United States relinquished all claims to the sparsely inhabited Phoenix and Line Islands in the Treaty of Tarawa (ratified in 1983), which then became part of Kiribati. Although the indigenous Gilbertese name for the Gilbert Islands proper is "Tungaru," the new state chose "Kiribati" to encompass all its territories, including Banaba, the Line Islands, and the Phoenix Islands, some of which had been resettled by I-Kiribati under British and later Kiribati government schemes.

Post-independence Kiribati has faced numerous challenges, including overcrowding on South Tarawa, limited economic resources, and the overarching threat of climate change. In 1988, a resettlement program was announced to move 4,700 residents from the main island group to less populated islands. Teburoro Tito was elected president in 1994. In 1995, Kiribati unilaterally moved the International Date Line eastward to encompass the Line Islands group, ensuring the entire country shared the same day. This move, fulfilling a campaign promise by President Tito, aimed to simplify business and administration across its vast territory and positioned Kiribati as the first country to greet the third millennium, a boon for tourism. Tito was re-elected in 1998. Kiribati became a full member of the United Nations in 1999.

In 2002, a controversial law allowed the government to shut down newspaper publishers, following the launch of Kiribati's first successful non-government-run newspaper, raising concerns about freedom of the press and democratic principles. President Tito was re-elected in 2003 but was removed from office by a no-confidence vote in March 2003, replaced by a Council of State. Anote Tong of the opposition party Boutokaan Te Koaua was elected president in July 2003 and was re-elected in 2007 and 2011.

President Tong became a prominent international voice on climate change, advocating for the human rights of his people threatened by rising sea levels. In June 2008, Kiribati officials asked Australia and New Zealand to accept I-Kiribati citizens as permanent refugees, as the nation is predicted to be one of the first to lose all its land territory to rising sea levels. Tong stated that Kiribati had reached "the point of no return." In early 2012, the Kiribati government purchased the 5.4 K acre (2.20 K ha) Natoavatu Estate on Vanua Levu, Fiji. While initially reported as a potential site for mass relocation, it was later clarified as an investment for food security and potential refuge. In May 2014, the purchase of some 5.5 K acre (5.46 K acre) of land on Vanua Levu was confirmed.

In March 2016, Taneti Maamau was elected president. He was re-elected in June 2020. President Maamau's government shifted diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the People's Republic of China in 2019. In November 2021, the government announced it would consider opening the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) to commercial fishing, a move that drew concern from conservationists regarding environmental protection. A 2022 Kiribati constitutional crisis emerged with the suspension of several senior judges, raising questions about judicial independence and the rule of law.

Kiribati maintained strict border controls during the COVID-19 pandemic, remaining largely virus-free until January 2022 when the first international commercial flight in nearly two years brought in cases. By 2024, over 5,000 cases and 24 deaths had been reported. In January 2023, Kiribati confirmed its intention to rejoin the Pacific Islands Forum, ending a two-year split. The existential threat of climate change continues to dominate Kiribati's national and international agenda, impacting all aspects of life, from housing and food security to cultural integrity and fundamental human rights.

4. Geography

Kiribati's geography is defined by its dispersal across a vast area of the central Pacific Ocean and its composition of low-lying atolls and one raised coral island. This unique geographical context presents both opportunities, such as a large Exclusive Economic Zone, and significant challenges, particularly vulnerability to climate change.

4.1. Island groups and topography

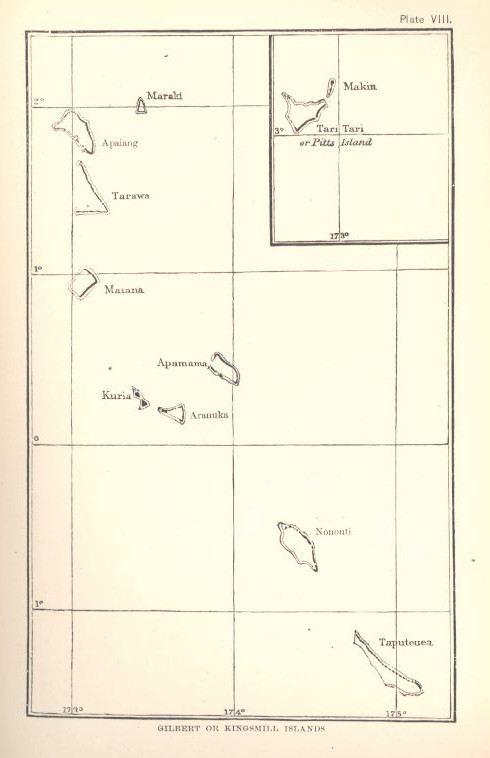

Kiribati consists of 32 atolls and one solitary raised coral island, Banaba. These islands extend into both the Eastern and Western Hemispheres and the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. The nation's extensive Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers three non-contiguous traditional geographic subregions: Banaba (located in a Melanesian-Micronesian transitional area), the Gilbert Islands (Micronesia), and the Line and Phoenix Islands (Polynesia).

The main island groups are:

- Banaba**: An isolated, raised coral island situated between Nauru and the Gilbert Islands. It was once a rich source of phosphate, but intensive mining exhausted these deposits before independence, leaving the island severely degraded.

- Gilbert Islands**: A chain of sixteen atolls located approximately 0.9 K mile (1.50 K km) north of Fiji. This group is the most populous, with the capital, South Tarawa, located here.

- Phoenix Islands**: Eight atolls and coral islands located about 1.1 K mile (1.80 K km) southeast of the Gilberts. Most of this group forms the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA), one of the world's largest marine protected areas. Kanton is the only inhabited island in this group.

- Line Islands**: Eight atolls and one reef, situated approximately 2.1 K mile (3.30 K km) east of the Gilberts. This group includes Kiritimati (Christmas Island), which is the world's largest coral atoll by land area. Due to a 1995 realignment of the International Date Line, the Line Islands were the first area to enter each new year, including the year 2000. Consequently, Caroline Island was renamed Millennium Island.

Apart from Banaba, the land in Kiribati consists of sand and reef rock islets forming atolls, which typically rise only one or two meters above sea level. The soil is generally thin, calcareous, with low water-holding capacity and low organic matter and nutrient content, except for calcium, sodium, and magnesium. This makes large-scale agriculture challenging.

4.2. Climate

Kiribati experiences a tropical marine climate or tropical rainforest climate (Af), characterized by consistently high temperatures and humidity throughout the year. Temperatures are stable, typically close to 86 °F (30 °C). In the capital, Tarawa, the average annual rainfall is approximately 0.1 K in (2.05 K mm), with an average of 172 rainy days per year. The average humidity is around 80%. Daily mean temperatures in Tarawa are consistently around 82.4 °F (28 °C), with average highs around 87.8 °F (31 °C) and lows around 77 °F (25 °C). Sunshine averages about 7 to 8 hours per day.

From April to October, predominant winds are from the northeast. From November to April, western gales can bring more rain. This period, from November to April, is known as te Auu-Meang (the wet season) and is also considered the tropical cyclone (te Angibuaka) season. Although tropical cyclones rarely form or pass directly over Kiribati due to its equatorial location, the country can be affected by distant tropical cyclones, experiencing impacts such as strong winds, high waves, and coastal inundation even when these systems are in their developmental stages (tropical low/disturbance) or before they reach full cyclone strength. For instance, Cyclone Pam in 2015, though centered on Vanuatu, caused significant flooding and coastal damage in Kiribati.

The fair season, known as when Ten Rimwimata (Antares) appears in the sky after sunset, typically lasts from May to November. This period is characterized by gentler winds, calmer currents, and less rain. Towards December, when Nei Auti (Pleiades) replaces Antares in the evening sky, the season of sudden westerly winds and heavier rain returns, traditionally discouraging long-distance inter-island travel by canoe.

Precipitation varies significantly across the islands. For example, the annual average rainfall is around 0.1 K in (3.00 K mm) in the northern Gilbert Islands but only about 20 in (500 mm) in the southern Gilberts and parts of the Phoenix and Line Islands, which lie in the dry belt of the equatorial oceanic climatic zone and can experience prolonged droughts. The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) heavily influences rainfall patterns, and its seasonal shifts, along with phenomena like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), contribute to this variability.

4.3. Environmental issues and climate change

Kiribati faces profound environmental challenges, primarily driven by global climate change. These issues have severe societal, economic, and cultural implications for the nation, whose very existence is threatened by rising sea levels and associated impacts.

4.3.1. Sea level rise and impacts

As a nation composed almost entirely of low-lying atolls, Kiribati is extremely vulnerable to sea level rise. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects significant sea level increases by 2100, which could render much of Kiribati's land uninhabitable. Already, the country is experiencing coastal erosion, land loss (with small uninhabited islets like Tebua Tarawa and Abanuea reportedly disappearing in 1999), and saltwater intrusion into freshwater lenses, which are crucial for drinking water and agriculture. The sea level at Christmas Island rose by 2.0 in (5 cm) between 1972 and 2022.

These impacts have direct socio-economic and humanitarian consequences. Housing is threatened as coastlines erode, forcing communities to relocate inland where space is limited or build seawalls with varying degrees of success. Food security is undermined by saltwater intrusion damaging taro pits (for bwabwai) and reducing arable land, and by impacts on coastal fisheries. The potential for widespread displacement is a major concern, with the government having explored options such as purchasing land in Fiji (the Natoavatu Estate on Vanua Levu) as a long-term security measure, though primarily for food security and investment. This displacement raises significant human rights issues concerning the right to housing, food, water, and a safe environment.

The Pacific decadal oscillation (PDO) and El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events exacerbate these vulnerabilities by influencing sea levels. La Niña periods can cause higher sea levels and more frequent, higher high tides, including king tides, which lead to seawater flooding of low-lying areas. Studies by researchers like Paul Kench and Arthur Webb have shown that some atoll islands can be dynamic, with areas of accretion and erosion. For instance, parts of Betio, Bairiki, and Nanikai on Tarawa Atoll showed increases in land area over several decades. However, these studies also acknowledge that this dynamism does not negate the overall vulnerability to inundation, as the height of the islands has not significantly changed. Gradual sea-level rise might allow coral polyps to build up reefs, but if the rise is too rapid or if ocean acidification damages coral growth, this natural resilience is compromised. The Human Rights Measurement Initiative notes that the climate crisis has moderately worsened human rights conditions in Kiribati, impacting access to food, water, housing, and cultural integrity.

4.3.2. Ecology, biodiversity, and conservation

Kiribati's ecosystems include Central Polynesian tropical moist forests, Eastern Micronesia tropical moist forests, and Western Polynesian tropical moist forests. Due to the young geological age of the atolls and high soil salination, terrestrial flora is relatively limited. The Gilbert Islands have around 83 indigenous and 306 introduced plant species, while the Line and Phoenix Islands have 67 and 283, respectively. None are endemic, and many indigenous species are threatened by human activities like phosphate mining and habitat loss. Common "wild" plants include coconut palms, pandanus trees, and breadfruit trees. The traditional staple crop is bwabwai (giant swamp taro), cultivated in pits dug down to the freshwater lens. Imported crops like Chinese cabbage, pumpkin, tomato, watermelon, and cucumber are also grown.

Land mammals are few and not indigenous, including the Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans), dogs, cats, and pigs. Among the 75 bird species, the Bokikokiko (Acrocephalus aequinoctialis), or Kiritimati Reed Warbler, is endemic to Kiritimati.

The marine environment is far richer, with 600-800 species of inshore and pelagic finfish, around 200 coral species, and about 1,000 shellfish species. Kiribati's coral reefs are vital for coastal protection and fisheries but are threatened by coral bleaching due to rising sea temperatures, ocean acidification, and pollution. Fisheries, particularly for skipjack tuna and yellowfin tuna, are economically crucial but face pressures from overfishing and the impacts of climate change on fish stocks.

Conservation efforts are significant, most notably the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA). Established in 2008 and expanded, PIPA is one of the largest marine protected areas in the world, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its exceptional marine biodiversity and near-pristine ecosystems. However, in 2021, the Kiribati government considered opening parts of PIPA to commercial fishing to generate revenue, raising concerns among conservationists about the long-term sustainability and protection of this critical habitat. Plastic pollution is another key challenge, harming marine biodiversity and the economy. The Environment and Conservation Division (ECD) has been working on national strategies and promoting international cooperation, such as through the Global Plastic Pollution Treaty negotiations.

4.3.3. National adaptation and mitigation efforts

Kiribati has been proactive in developing national strategies to adapt to climate change impacts. The Kiribati Adaptation Program (KAP), initiated in 2003 with support from the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the World Bank, and other partners, has been a cornerstone of these efforts. KAP focuses on reducing vulnerability by raising awareness, assessing and protecting water resources, managing inundation, and mainstreaming climate change considerations into national planning.

Specific adaptation measures include:

- Coastal protection**: Building seawalls, planting mangroves, and protecting public infrastructure from coastal erosion.

- Water resource management**: Improving rainwater harvesting systems, protecting freshwater lenses from salinization, and exploring desalination options.

- Community-based adaptation**: Supporting local communities in developing and implementing adaptation projects tailored to their specific needs.

- Food security**: Diversifying food sources, promoting sustainable land and marine resource management, and investing in agricultural resilience (e.g., the land purchased in Fiji for potential agricultural use).

- Population settlement planning**: Developing strategies to manage population distribution and reduce risks in highly vulnerable areas.

Alongside adaptation, Kiribati is a strong advocate for global mitigation actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, recognizing that adaptation alone cannot secure its future without significant global efforts to curb climate change.

5. Politics and government

Kiribati is a parliamentary democratic republic. The political system operates under the Constitution of Kiribati, promulgated on 12 July 1979, which provides for free and open elections and a separation of powers.

5.1. Constitution and government structure

The Constitution of Kiribati establishes the framework for the nation's governance.

The executive branch is led by the President, known as te Beretitenti, who is both the head of state and head of government. The president is directly elected by the citizens from a list of three or four candidates nominated by and from among the members of the legislature following a general election. The president is limited to serving three four-year terms and remains a member of the assembly. The Cabinet is composed of the President, the Vice-President (appointed by the President from among the ministers), and up to 13 ministers. Ministers are appointed by the President from among the members of Parliament.

The legislative branch is the unicameral Maneaba ni Maungatabu (House of Assembly). It typically consists of 45 members: 44 elected members serving four-year terms, and one nominated representative of the Banaban people residing on Rabi Island in Fiji (to represent the interests of Banaba, formerly Ocean Island). Until 2016, the Attorney General also served as an ex officio member.

The judicial branch is independent of governmental interference. It is made up of the High Court, located in Betio, and the Court of Appeal. The President appoints the presiding judges. The judiciary of Kiribati faced a constitutional crisis in 2022 with the suspension of several senior justices, an event with significant implications for the rule of law and democratic checks and balances.

5.2. Political parties and elections

Political parties in Kiribati exist, but their organization is often informal, with ad hoc opposition groups tending to coalesce around specific issues or personalities rather than rigid ideologies. Alliances can shift, and members of parliament may not always vote strictly along party lines. The main recognizable parties in recent times include the Boutokaan Kiribati Moa Party (BKM, formerly Boutokaan te Koaua) and the Tobwaan Kiribati Party (TKP).

Elections are held for the Maneaba ni Maungatabu (parliamentary elections) and for the President (presidential elections). Universal suffrage is granted at age 18. Parliamentary elections use a two-round system in multi-member constituencies. If no candidate receives an absolute majority in the first round, a second round is held between the top candidates. Following parliamentary elections, the newly elected Maneaba nominates three or four of its members as candidates for the presidential election.

5.3. Administrative divisions

Local government in Kiribati is administered through island councils with elected members. These councils handle local affairs, make their own estimates of revenue and expenditure, and generally operate with a degree of autonomy from the central government, similar in concept to town meetings.

Kiribati is comprised of 21 inhabited islands, each generally having its own council. There are exceptions: Tarawa Atoll is divided into three councils: Betio Town Council (BTC), Teinainano Urban Council (TUC) for the rest of South Tarawa, and Eutan Tarawa Council (ETC) for North Tarawa. Tabiteuea Atoll also has two councils (North and South).

For statistical and some administrative purposes, Kiribati is sometimes divided into geographical groups or districts. The historical districts before independence included Banaba, Tarawa Atoll, Northern Gilbert Islands, Central Gilbert Islands, Southern Gilbert Islands, and Line Islands. More recently, for some administrative functions, the country has been divided into 5 districts: Northern Kiribati, Central Kiribati, Southern Kiribati, South Tarawa, and Line & Phoenix. However, the island councils remain the primary units of local governance.

5.4. Law enforcement and human rights

Law enforcement in Kiribati is the responsibility of the Kiribati Police Service (KPS), which performs all law enforcement and paramilitary duties for the nation. Police posts are located on all inhabited islands. The KPS has one Guardian-class patrol boat, the RKS Teanoai II, primarily used for maritime surveillance and sovereignty patrols within Kiribati's vast EEZ. Kiribati has no military forces; defense assistance, if needed, would likely come from Australia or New Zealand under bilateral agreements. The main prison is Walter Betio Prison in Betio, with another facility in London on Kiritimati.

The legal system is derived from English common law, supplemented by customary law, particularly in matters of land tenure and local disputes. The status of human rights in Kiribati is generally considered fair, but some issues persist. Freedom of speech and the freedom of the press are generally respected, though a 2002 law allowing the government to shut down newspaper publishers raised concerns about potential infringements on these democratic freedoms.

LGBT rights are limited. Male homosexuality is illegal under a colonial-era law, punishable by up to 14 years in prison, though this law is reportedly not actively enforced. Female homosexuality is legal. Discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment is prohibited. Gender equality remains an area for improvement, with traditional customs sometimes impacting women's roles and opportunities.

The impacts of climate change on fundamental human rights, such as the rights to life, housing, water, food, and health, are a growing concern. The Human Rights Measurement Initiative has reported that the climate crisis has worsened human rights conditions in Kiribati, particularly affecting access to essential resources and cultural integrity. This highlights the intersection of environmental challenges and human rights, a critical issue for the nation's future.

6. Foreign relations

Kiribati actively engages with the international community, maintaining close ties with its Pacific neighbors and key development partners. Its foreign policy is significantly shaped by the existential threat of climate change, which drives its advocacy in regional and global forums.

6.1. Bilateral and multilateral relations

Kiribati maintains close relationships with Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, which are major providers of foreign aid. The country also has relations with China and the United States. There are resident diplomatic missions in South Tarawa from Australia (High Commission), New Zealand (High Commission), and the People's Republic of China (Embassy, re-established in 2020 after Kiribati switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan). The United States announced plans in 2022 to open an embassy in Kiribati, and its embassy in Suva, Fiji, is currently accredited to Kiribati.

Kiribati is a member of the United Nations (since 1999), the Commonwealth of Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States. It is also a member of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF). In February 2021, Kiribati, along with Marshall Islands, Nauru, and the Federated States of Micronesia, announced its withdrawal from the PIF following a leadership dispute, but in January 2023, Kiribati confirmed its intention to rejoin the Forum.

In November 1999, Kiribati agreed to lease land on Kiritimati (Christmas Island) to Japan's National Space Development Agency (NASDA) for 20 years for a potential spaceport and downrange tracking station for its proposed HOPE-X reusable unmanned space shuttle. The HOPE-X project was eventually cancelled by Japan in 2003, but a Japanese tracking station has operated on Kiritimati.

The US Peace Corps had a presence in Kiribati from 1973 to 2008, with volunteers involved in infrastructure development, education, and health projects. The program was scaled down and eventually ended due to transportation and medical support challenges. In July 2022, the US announced plans to re-establish a Peace Corps presence in the region, including Kiribati.

6.2. Climate change diplomacy and advocacy

As one of the world's most vulnerable nations to the effects of global warming, climate change is the central pillar of Kiribati's foreign policy. Kiribati has been an active participant in international diplomatic efforts, particularly the UNFCCC Conferences of the Parties (COP). It is a member of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), an intergovernmental organization of low-lying coastal and small island countries that consolidates their voices in global climate negotiations. AOSIS was instrumental in proposing early draft texts for the Kyoto Protocol.

Former President Anote Tong was a prominent international advocate for climate action, repeatedly highlighting the existential threat to his nation and the human rights implications for its people. He attended the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) and signed declarations committing to green economies. In November 2010, Kiribati hosted the Tarawa Climate Change Conference (TCCC), aiming to build consensus among vulnerable states and partner countries ahead of COP16. President Tong famously stated that for I-Kiribati to survive, migration might become necessary and urged proactive preparation. The government's purchase of land in Fiji was partly framed within this long-term security concern.

The case of Ioane Teitiota, an I-Kiribati man who sought "climate change refugee" status in New Zealand, drew international attention in 2013. While his claim was ultimately unsuccessful in New Zealand courts, the New Zealand Supreme Court acknowledged that environmental degradation from climate change could, in principle, create a pathway for protection under refugee conventions, signifying a potential shift in how climate-induced displacement is viewed under international law.

Kiribati signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in 2017, reflecting its history with nuclear testing in the region and its commitment to global peace and disarmament.

7. Economy

Kiribati's economy is characterized by its small scale, limited natural resources, geographical remoteness, and high vulnerability to external shocks, including climate change and global economic fluctuations. It is classified as one of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs).

7.1. Economic overview and challenges

Kiribati's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is among the lowest in Oceania. The economy relies heavily on a few key sources of external revenue:

- Fishing license fees**: Revenue from foreign nations fishing for tuna in Kiribati's vast Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is a primary source of government income.

- Remittances**: Money sent home by I-Kiribati working abroad, especially as seafarers trained at the Marine Training Centre, provides a significant income stream for many families.

- International aid**: Development assistance from partners like Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and multilateral organizations (e.g., World Bank, Asian Development Bank, EU) is crucial for public investment and budget support.

- Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund (RERF)**: This sovereign wealth fund, established in 1956 with earnings from phosphate mining on Banaba, provides income through investments and helps stabilize government finances. Its value was around 400.00 M USD in 2008, though it has fluctuated with global financial conditions and government drawdowns.

Challenges to economic development include:

- Limited natural resources**: Phosphate deposits on Banaba were exhausted by independence. Land-based resources are scarce.

- Remoteness and dispersion**: The vast distances between islands and from major international markets increase transportation costs and hinder trade and tourism.

- Small domestic market**: Limits economies of scale for local businesses.

- Vulnerability to external shocks**: The economy is highly susceptible to climate change impacts (sea level rise, extreme weather), global commodity price fluctuations (especially for food and fuel, as Kiribati is a net importer), and global economic downturns.

- Infrastructure deficits**: Inadequate transport, communication, and energy infrastructure.

- Shortage of skilled labor**: While efforts are made in education and vocational training, a lack of skilled workers can impede development.

Despite these challenges, the economy has shown periods of growth, often linked to large infrastructure projects, fisheries revenue, and RERF performance. Inflation can be volatile due to reliance on imports and the use of the Australian dollar as the domestic currency. The ANZ Bank is a major commercial bank operating in Kiribati.

7.2. Major sectors

The economy of Kiribati is primarily based on services (including government), agriculture, and fisheries.

7.2.1. Fisheries and marine resources

The fisheries sector is paramount to Kiribati's economy. Commercial fishing, particularly for tuna (skipjack and yellowfin), within Kiribati's EEZ generates substantial revenue through licensing agreements with foreign fishing fleets (e.g., from Japan, Taiwan, China, South Korea, and the US). Artisanal (subsistence) fishing is vital for local livelihoods and food security, targeting a variety of reef and pelagic fish.

Aquaculture is a developing area. Seaweed farming (primarily Eucheuma alvarezii and Eucheuma spinosum, introduced from the Philippines in 1977) provides income for outer island communities. The ornamental fish trade, especially for species like the flame angelfish (Centropyge loriculus), is another niche export, with operators based mainly on Kiritimati. Collection of black-lipped pearl oysters (Pinctada margaritifera) and other shellfish also occurs.

Sustainable management of marine resources is a critical issue, given the economic dependence and threats from overfishing and climate change. Kiribati participates in regional fisheries management organizations.

7.2.2. Agriculture and copra production

Subsistence agriculture is widely practiced, focusing on traditional crops adapted to atoll environments. The most important crops include:

- Coconut**: Essential for food, drink, and materials. Copra (dried coconut meat) is a key agricultural export, though its production is subject to price volatility and weather conditions.

- Pandanus (te kaina)**: Fruit is eaten, leaves used for weaving.

- Breadfruit (te mai)**: A staple carbohydrate source.

- Bwabwai (giant swamp taro)**: Cultivated in pits dug to reach the freshwater lens, a culturally important food, especially for feasts.

Challenges for agriculture include poor soil fertility, limited arable land (especially on atolls), freshwater scarcity, and the impacts of climate change (saltwater intrusion, drought).

7.2.3. Tourism

The tourism sector is relatively small but holds potential, particularly for niche markets. Key attractions include:

- Ecotourism**: Leveraging Kiribati's unique atoll environments and marine biodiversity (e.g., PIPA).

- Game fishing**: Kiritimati (Christmas Island) is renowned for bonefishing and other sport fishing.

- Cultural tourism**: Offering insights into I-Kiribati traditions, music, and dance.

- Birdwatching**: Kiritimati is also a significant seabird rookery.

Limitations to tourism development include remoteness, limited international air access, and insufficient infrastructure (accommodation, transport). Sustainability is a key concern, ensuring that tourism development does not harm the fragile environment or local culture.

7.3. Trade and finance

Kiribati is heavily reliant on imports for essential goods, including foodstuffs, fuel, and manufactured items. Its main exports are copra, fish (fresh, frozen, and ornamental), and seaweed. Key trading partners for imports often include Australia, Fiji, and Asian countries, while export markets vary depending on the commodity.

The management of national finances is heavily influenced by the performance of the Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund (RERF). The RERF's investment income helps to cover budget deficits and fund development projects. Sound fiscal management is crucial given the economy's vulnerabilities. Banking services are primarily provided by the ANZ Bank, with efforts ongoing to improve financial inclusion, especially in outer islands.

7.4. Infrastructure

Infrastructure development is a major challenge due to the country's geography and limited resources.

7.4.1. Transport

- Air transport**: Bonriki International Airport (TRW) on South Tarawa is the main international gateway. Cassidy International Airport (CXI) on Kiritimati also serves international flights, primarily connecting to Fiji and sometimes Honolulu. Air Kiribati, the national airline, provides domestic services primarily within the Gilbert Islands. Coral Sun Airways also offered domestic flights. Reaching the Phoenix and Line Islands (other than Kiritimati) by air is difficult.

- Sea transport**: Inter-island shipping is vital for connecting the dispersed islands, transporting people and goods. Port facilities are concentrated in South Tarawa (Betio port) and Kiritimati. Kiribati relies on maritime links for international trade.

7.4.2. Communications and media

Telecommunications infrastructure has been improving but faces challenges due to remoteness.

- Internet and Mobile**: Internet connectivity was historically limited and expensive, relying on satellite. However, projects like the Southern Cross NEXT submarine cable (connecting Kiritimati) and the planned East Micronesian Cable system (connecting Tarawa) aim to significantly improve bandwidth and reduce costs. Satellite services like Starlink have also become available. Mobile phone services are widespread in urban areas like South Tarawa and are expanding. Amalgamated Telecom Holdings Kiribati Limited (ATHKL), formerly Telecom Services Kiribati Ltd (TSKL), is a key provider.

- Radio**: Radio Kiribati, operated by the Broadcasting and Publications Authority (BPA), is the main national broadcaster, reaching most islands via AM and FM (on Tarawa).

- Television**: TV Kiribati Ltd, government-owned, operated from 2004 to mid-2012 but had limited reach.

- Print Media**: Weekly newspapers include the government-published Te Uekara, Te Mauri (Kiribati Protestant Church), and the privately run Kiribati Independent (published from Auckland) and Kiribati Newstar.

8. Demographics

The demographic profile of Kiribati is shaped by its unique geography, cultural history, and socio-economic conditions, with a young and growing population concentrated on a few islands.

8.1. Population, ethnicity, and settlement patterns

According to the November 2020 census, Kiribati had a population of 119,940. The population is youthful, with a significant proportion under the age of 15. Population growth rates have been relatively high.

Population density is extremely high on South Tarawa, the capital and urban center, where more than half the nation's population resides (52.9% in 2015, with the 2024 estimate for South Tarawa being around 69,710). This includes Betio, the largest township. Such concentration leads to challenges in housing, sanitation, water supply, and employment. Historically, people lived mostly in villages with populations between 50 and 3,000 on the outer islands. Internal migration from outer islands to South Tarawa in search of education, employment, and services is a significant trend. About 90% of the population lives in the Gilbert Islands. The Phoenix Islands are largely uninhabited except for Kanton, and only a few of the Line Islands are populated, with Kiritimati being the most significant.

The indigenous people of Kiribati are called I-Kiribati. Ethnically, they are primarily Micronesians, a subgroup of Austronesians, who settled the islands thousands of years ago. Around the 14th century, incursions by Fijians, Samoans, and Tongans introduced some Polynesian and Melanesian influences into the genetic and cultural makeup. However, extensive intermarriage over centuries has led to a population that is reasonably homogeneous in appearance and traditions. The 2020 census showed I-Kiribati as 95.71%, part I-Kiribati 3.76%, Tuvaluan 0.24%, and other ethnicities 1.8%.

8.2. Languages

The official languages of Kiribati are Gilbertese (also known as I-Kiribati or te taetae ni Kiribati) and English. Gilbertese, an Oceanic language of the Malayo-Polynesian subgroup, is spoken by virtually the entire indigenous population and is the primary language of daily life, education (especially at early levels), and domestic media. English is used in government, higher education, and international communication but is not as widely spoken outside of urban centers like Tarawa. Code-switching and the incorporation of English loanwords into Gilbertese are common. For example, kamea (from "come here") is a Gilbertese word for dog, alongside the Oceanic-derived kiri; other loanwords include buun (spoon), moko (smoke), and beeki (pig).

8.3. Religion

Christianity is the predominant religion in Kiribati, introduced by missionaries in the latter half of the 19th century. According to the 2020 census:

- Roman Catholicism is the largest denomination, with 58.9% of the population.

- Protestant churches collectively account for a significant portion:

- Kiribati Uniting Church (formerly part of the Kiribati Protestant Church, KPC) with 21.2%.

- Kiribati Protestant Church (KPC) with 8.4%. (These two together make up 29.6% of major Protestant groups).

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) accounts for 5.6%.

- The Baháʼí Faith has a notable presence at 2.1%.

- The Seventh-day Adventist Church accounts for 2.1%.

Other religious groups, including Pentecostals and Jehovah's Witnesses, make up less than 2% of the population. Religion plays an influential role in Kiribati society, with churches often involved in education and community services. Traditional beliefs and customs may also coexist with Christian practices for some individuals.

8.4. Health

Kiribati faces significant public health challenges, contributing to a relatively low life expectancy at birth, which was approximately 68.46 years overall (around 64.3 for males and 69.5 for females, with some variations in reported figures). The infant mortality rate is also relatively high.

Major health issues include:

- Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)**: Rates of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease are very high, linked to dietary changes (increased consumption of imported processed foods), high smoking rates (Kiribati has one of the world's highest smoking prevalences, with over 50% of adults smoking), and lifestyle factors. Obesity is also a major concern. These NCDs lead to severe complications, including a high rate of amputations.

- Infectious diseases**: While efforts are made to control them, diseases like tuberculosis (365 cases per 100,000 per year reported previously), diarrheal diseases, dysentery, conjunctivitis, and fungal infections are prevalent. These are often linked to issues with sanitation and water quality.

- Sanitation and water quality**: Access to clean drinking water and adequate sanitation is a persistent problem, especially in overcrowded areas like South Tarawa and on outer islands. Freshwater lenses are fragile and susceptible to saltwater intrusion (exacerbated by sea level rise and over-extraction) and contamination from human and animal waste. Only about 66% of the population had access to clean water according to some reports.

- Healthcare services**: Healthcare facilities are concentrated in South Tarawa, with more limited services on outer islands. Access to specialized medical care can be difficult. Kiribati relies on international aid for its health sector, and has benefited from the presence of foreign medical personnel, such as doctors from Cuba, who have reportedly contributed to decreases in infant mortality. Government expenditure on health was around 268 USD per capita (PPP) in 2006. In the period 1990-2007, there were about 23 physicians per 100,000 people.

- Climate change impacts on health**: Rising sea levels, increased frequency of king tides, and potential changes in rainfall patterns directly affect water security, food security, and can increase the risk of vector-borne and waterborne diseases. Displacement and stress related to climate change also have mental health implications.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative found that Kiribati was fulfilling 77.2% of what it should for the right to health based on its income, with better performance for child health (93.8%) than for adult health (92.2%) or reproductive health (45.5%, "very bad" category).

8.5. Education

Education in Kiribati is a priority for the government, though providing quality and accessible education across widely dispersed islands presents significant challenges. The Ministry of Education oversees the system.

- Structure**: The education system generally includes preschool, primary school, junior secondary school, and senior secondary school.

- Primary education is free and compulsory, typically for the first nine years, starting at age six.

- Secondary education is available through government schools such as King George V and Elaine Bernacchi School (KGV/EBS) in Tarawa, Tabiteuea North Senior Secondary School, and Melaengi Tabai Secondary School. Christian churches also operate a significant number of secondary schools (around thirteen).

- Literacy and Enrollment**: Efforts are made to achieve universal primary education, and literacy rates have improved. However, completion rates at secondary and tertiary levels can be affected by various socio-economic factors.

- Curriculum**: The curriculum aims to provide foundational knowledge and skills, with increasing emphasis on subjects relevant to Kiribati's context, including environmental awareness. English and Gilbertese are languages of instruction.

- Tertiary and Vocational Education**:

- The University of the South Pacific (USP) has a campus in Teaoraereke, Tarawa, offering distance and flexible learning programs, as well as preparatory studies for degrees undertaken at other USP campuses in the region (e.g., Fiji).

- Vocational training institutions are crucial for skills development. These include:

- The Marine Training Centre (MTC) in Betio, which trains I-Kiribati seafarers for international employment, a vital source of remittances.

- The Kiribati Institute of Technology (KIT).

- Other institutions like the Kiribati Fisheries Training Centre, Kiribati School of Nursing, Kiribati Police Academy, and Kiribati Teachers College.

- Challenges and Opportunities**: Challenges include a shortage of qualified teachers, limited resources, the logistical difficulties of serving remote outer islands, and ensuring educational quality and relevance. Opportunities for overseas study exist, with students often going to Fiji, Australia, New Zealand, or Cuba (particularly for medical training) through scholarship programs.

9. Culture

The culture of Kiribati is rich and deeply rooted in its unique atoll environment and history. It is characterized by strong community bonds, traditional arts, and social customs that continue to shape daily life, even amidst modern influences.

9.1. Music and dance

Music (te anene) and particularly dance (te mwaie) are highly valued cultural expressions in Kiribati. Traditional Kiribati folk music is often based on chanting or other forms of vocalizing, frequently accompanied by body percussion. In modern public performances, a seated chorus accompanied by a guitar is common.

However, during formal performances of traditional dances like the standing dance (Te Kaimatoa) or the hip dance (Te Buki), a distinctive wooden box drum is used as a percussion instrument. This box is constructed to produce a hollow, reverberating tone when struck by a chorus of men sitting around it. Traditional songs often explore themes of love, competition, religion, children's stories, patriotism, war, and weddings.

Kiribati dance is unique among Pacific island dance forms for its emphasis on the dancer's outstretched arms and sudden, bird-like movements of the head. The frigatebird (Fregata minor), depicted on the Kiribati flag, is a significant symbol, and its movements are often emulated in dance. Most dances are performed in either a standing or sitting position, with movements that are often limited and staggered. Smiling while dancing is generally considered inappropriate in the context of traditional Kiribati dance because its primary purpose is not solely entertainment but also a form of storytelling and a display of the dancer's skill, beauty, and endurance. There are also stick dances (te tirere, pronounced seerere), which accompany legends and semi-historical stories, typically performed only during major festivals. Unique dance styles include the ruoia.

9.2. Cuisine

Traditional Kiribati cuisine is heavily based on the resources available from the ocean and the atolls. Key staples include:

- Seafood**: A wide variety of fish (tuna, reef fish, flying fish), shellfish, and other marine life are central to the diet. Fish is often eaten raw (sashimi-style) with accompaniments like coconut sap, soy sauce, or vinegar-based dressings, sometimes combined with chilies and onions. Coconut crabs and mud crabs are traditionally given to breastfeeding mothers, believed to stimulate high-quality breast milk production.

- Coconut**: Used in numerous forms - the flesh (te ben), coconut water (te moimoto), coconut cream (te anrannano), and fermented sap (te karewe). Te kamaimai is a coconut sap syrup.

- Pandanus fruit (te kaina)**: The fruit is processed into various foods, including te tuae (a dried pandanus cake) and te kabubu (dried pandanus flour).

- Breadfruit (te mai)**: A starchy staple when in season.

- Bwabwai (giant swamp taro)**: A culturally important root crop cultivated in pits dug down to the freshwater lens. It is often reserved for special occasions and feasts.

Traditional food preparation methods include baking in earth ovens, boiling, and roasting. The diet was historically low in easily cultivated starch-based carbohydrates due to the challenging atoll environment. After World War II, rice became a daily staple in many households and remains so today. The increasing availability of imported processed foods has led to dietary shifts and associated health challenges, such as non-communicable diseases.

9.3. Sport

Several sports are popular in Kiribati, both modern and traditional. Football (soccer) is the most popular sport. The Kiribati Islands Football Federation (KIFF) is an associate member of the Oceania Football Confederation (OFC) but not of FIFA. It is, however, a member of ConIFA. The Kiribati national team has participated in the Pacific Games. The Bairiki National Stadium in South Tarawa, with a capacity of around 2,500, is the main venue. The Betio Soccer Field also hosts local teams. Volleyball is another widely played team sport. Traditional games and sports also continue to be part of community life.

Kiribati has participated in international sporting events such as the Commonwealth Games (since 1998) and the Olympic Games (since 2004). The nation sent three competitors (two sprinters and a weightlifter) to its first Olympics in Athens. Kiribati achieved its first-ever Commonwealth Games medal at the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, when weightlifter David Katoatau won gold in the 105 kg category. Katoatau gained further international recognition for his "dancing weightlifter" persona, used to raise awareness about the threat of climate change to his country.

9.4. Social customs and traditions

Traditional I-Kiribati society is organized around strong kinship ties and community structures. The maneaba (community meeting house) is the central institution in village life, serving as a venue for social gatherings, discussions, decision-making, dispute resolution, ceremonies, and cultural performances. Each maneaba has its own traditions and protocols.

Kinship systems are complex and play a vital role in social organization, land tenure, and resource access. Respect for elders (unimwaane) is a core value. Traditional values also emphasize hospitality, sharing, and communal cooperation. Storytelling, oral traditions, and knowledge of navigation and fishing are highly regarded skills passed down through generations. While modern influences are present, many traditional customs and values continue to shape social interactions and community life in Kiribati.

9.5. Public holidays

Kiribati observes several national and public holidays, reflecting important historical, cultural, and religious events. Major public holidays include:

- New Year's Day (January 1)

- Good Friday

- Easter Monday

- Health Day (often in April)

- Independence Day (July 12, often celebrated over several days with festivities)

- Youth Day (often in August)

- Christmas Day (December 25)

- Boxing Day (December 26)

The dates for some holidays, particularly those related to Easter, vary each year. Independence Day is the most significant national holiday, commemorating Kiribati's sovereignty achieved in 1979.