1. Overview

The Independent State of Samoa (Malo Saʻoloto Tutoʻatasi o SāmoaMālo Saʻoloto Tutoʻatasi o SāmoaSamoan), commonly known as Samoa (SāmoaSāmoaSamoan), is an island country in the Polynesian region of the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands, Savai'i and Upolu, two smaller inhabited islands, Manono and Apolima, and several smaller, uninhabited islets. The capital and largest city, Apia, is located on Upolu. This article explores Samoa's journey from its early settlement by the Lapita people through periods of colonial rule, its struggle for independence, and its contemporary development as a nation grappling with challenges related to democratic governance, human rights, social equity, and environmental sustainability. The narrative emphasizes the resilience of the Samoan people and their unique culture, Faʻa Sāmoa, in the face of historical and modern pressures, reflecting a perspective concerned with social justice and the well-being of its populace.

2. History

The history of Samoa encompasses its initial settlement, early European encounters, colonial rivalries and partition, periods under German and New Zealand administration, and its path to independence and development as a contemporary nation. This historical trajectory has significantly shaped Samoa's political, social, and cultural landscape, with a particular focus on the Samoan people's quest for self-determination and the impacts of external influences on their society.

2.1. Prehistory and Early European Contact

The Samoan Islands were first discovered and settled by the Lapita people, Austronesian voyagers who originated from Island Melanesia, around 3,500 years ago (between 1500 and 1000 BCE). Archaeological evidence, including ancient human remains found at a Lapita site in Mulifanua on Upolu island, dates the earliest settlement to between roughly 2,900 and 3,500 years ago, with findings published in 1974. Over millennia, these settlers developed a distinct Samoan language and a rich Samoan cultural identity known as Faʻa Sāmoa. Genetic, linguistic, and anthropological research continues to explore Samoan origins, with one theory suggesting they were Austronesians arriving during a final period of eastward Lapita expansion.

Geologically, the Samoan islands were formed during the Miocene period. For the past two million years, the archipelago has experienced volcanic activity related to the Samoa hotspot, likely resulting from a mantle plume. This volcanic origin shaped the islands' topography.

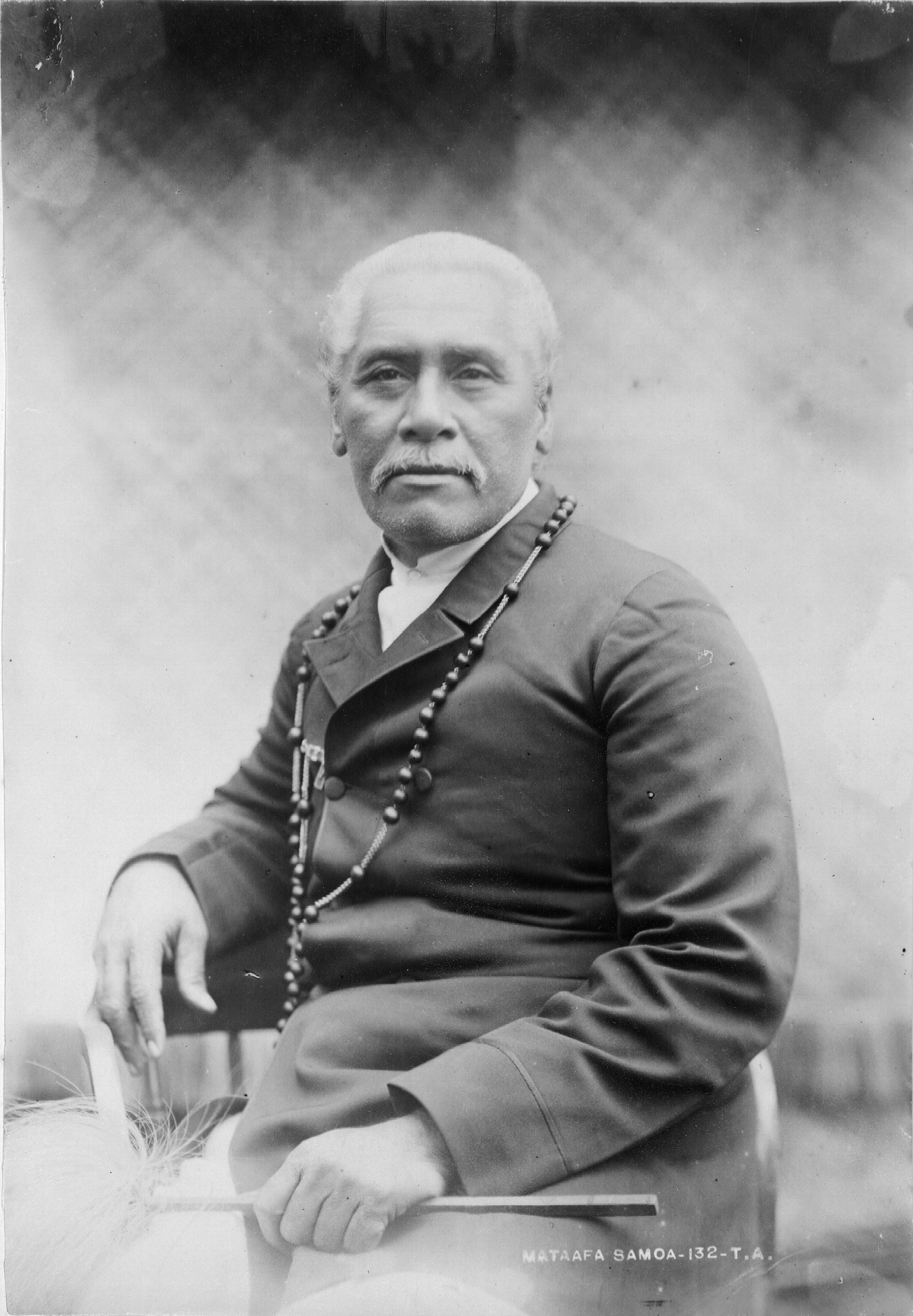

Early Samoan society maintained intimate sociocultural and genetic ties with Fiji and Tonga, supported by archaeological records and oral traditions detailing inter-island voyaging and intermarriage. Prominent figures in Samoan history included the Tui Manu'a chiefly line, Queen Salamasina, King Fonoti of Falefa, and the four paramount chiefly titles (tama a ʻāiga): Malietoa, Tupua Tamasese, Mataʻafa, and Tuimalealiʻifano. The war goddess Nafanua, daughter of Saveasi'uleo (ruler of the spirit realm Pulotu), was a deified figure whose patronage was crucial for rulers.

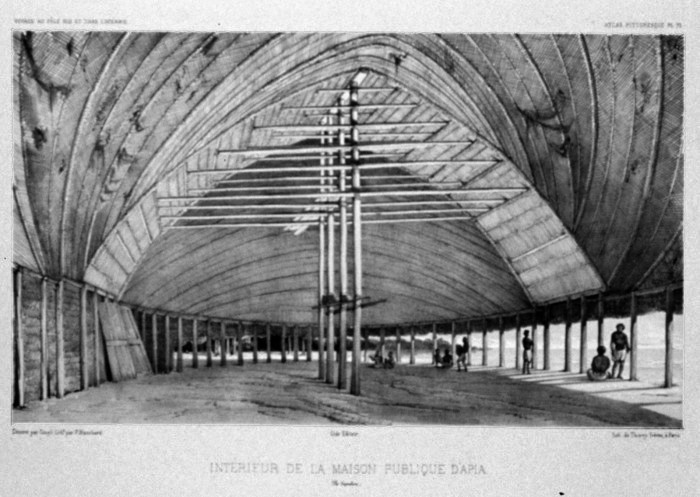

European contact began in the early 18th century. The Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen was the first known non-Polynesian to sight the islands in 1722. He was followed by French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville in 1768, who named them the "Navigator Islands" due to the Samoans' seafaring skills. Contact remained limited until the 1830s, when British missionaries from the London Missionary Society (LMS), whalers, and traders began to arrive, initiating more sustained interaction and subsequent profound changes in Samoan society. John Williams of the LMS arrived in Sapapali'i from the Cook Islands and Tahiti in 1830, marking the formal beginning of Christian missionary work.

2.2. 19th Century: Colonial Rivalry and Partition

The 19th century saw a significant increase in European and American presence in Samoa, driven by commercial interests such as whaling and the copra trade. American trading vessels like the Salem brig Roscoe (1821) and whalers like the Maro (1824) were among the early callers, seeking fresh water, firewood, provisions, and later, local crewmen. The last recorded American whaler visit was the Governor Morton in 1870.

This growing foreign interest led to intense rivalry between Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States, each seeking to exert influence and control over the islands. German firms, particularly on Upolu, monopolized copra and cocoa bean processing. The United States established commercial shipping interests and sought harbor rights in Pago Pago Bay in eastern Samoa, forcing alliances with local chiefs. Britain also deployed troops to protect its business enterprises and consular office.

These colonial powers often interfered in Samoan internal politics, supplying arms and support to various warring Samoan factions, exacerbating existing chiefly rivalries and contributing to an eight-year civil war. The writer Robert Louis Stevenson, who resided in Samoa during his later years, detailed these power struggles and the political machinations in his work A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (1892). He expressed alarm at the Samoans' vulnerability to economic exploitation and urged them to actively use and develop their land to avoid dispossession.

The Samoan crisis reached a critical point in March 1889 when German, British, and American warships converged in Apia harbour, threatening a larger conflict. However, a massive tropical cyclone on March 15, 1889, damaged or destroyed most of the warships, averting immediate large-scale military confrontation between the colonial powers.

Despite the temporary reprieve, the underlying tensions persisted. The Second Samoan Civil War (1898-1899) saw renewed conflict. In March 1899, during the Siege of Apia, Samoan forces loyal to Malietoa Tanumafili I were besieged by rebels supporting Mata'afa Iosefo. American and British warships, including the USS Philadelphia, shelled Apia on March 15, 1899, in support of Tanumafili. After several days of fighting, the rebels were defeated.

Ultimately, the three powers resolved to end the hostilities by partitioning the archipelago. The Tripartite Convention was signed in Washington D.C. on December 2, 1899, with ratifications exchanged on February 16, 1900. Under this agreement:

- The western islands (the larger landmass, including Upolu and Savaiʻi) became a German colony known as German Samoa.

- The eastern islands (including Tutuila and Manu'a) became a territory of the United States, later known as American Samoa.

- The United Kingdom relinquished its claims in Samoa in exchange for Germany ceding its rights in Tonga, all of the Solomon Islands south of Bougainville, and territorial adjustments in West Africa.

The Samoan kingship was abolished by the joint commission in June 1899, marking a significant shift in Samoan political structures under colonial imposition.

2.3. German Samoa (1900-1914)

The German Empire governed the western part of the Samoan archipelago, known as German Samoa, from 1900 to 1914. Wilhelm Solf was appointed as the colony's first governor. The German colonial administration operated on the principle that "there was only one government in the islands." Consequently, there was no Samoan Tupu (king), nor an alii sili (a position similar to a governor). Instead, the colonial government appointed two Fautua (advisors) from the Samoan chiefly class. Traditional Samoan governments like Tumua and Pule (representing Upolu and Savaiʻi respectively) were suppressed, and all decisions regarding land and titles were under the control of the colonial Governor.

German commercial interests continued to expand, particularly on Upolu, where German firms monopolized copra and cocoa bean processing. They introduced large-scale plantation operations and developed new industries, notably cocoa beans and rubber, often relying on imported laborers from China and Melanesia.

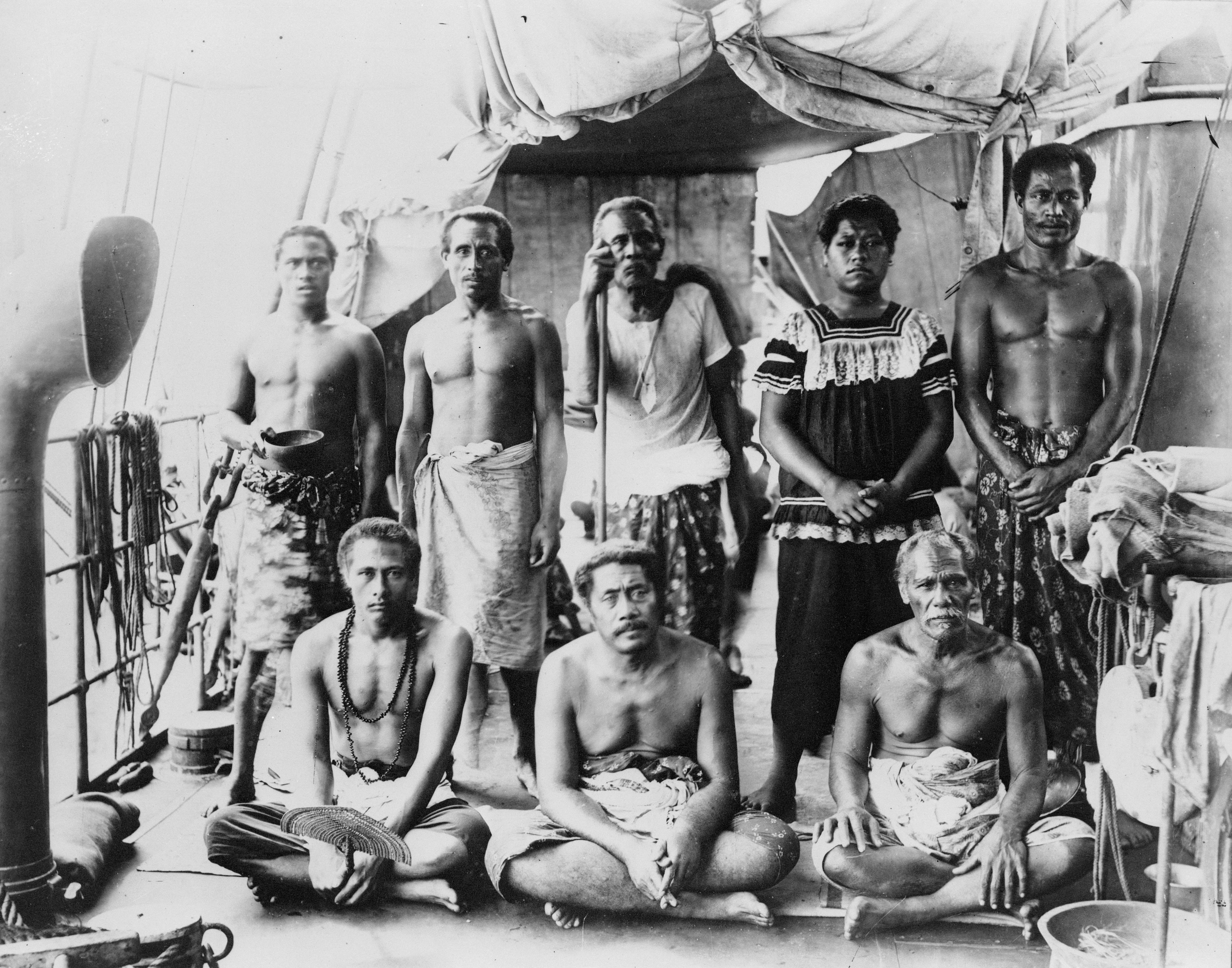

During this period, the indigenous resistance movement, the Mau a Pule, emerged. This non-violent movement, which had its beginnings in the early 1900s on Savai'i, opposed the colonial administration's policies. In 1908, Governor Solf responded to the Mau a Pule's activities by banishing its leader, the orator chief Lauaki Namulau'ulu Mamoe, and other chiefs to Saipan in the German Northern Mariana Islands.

German colonial rule in Samoa ended abruptly in August 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I. Following a request from Great Britain, troops of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force landed unopposed on Upolu on August 29, 1914, and seized control of the colony from the German authorities. This marked the beginning of New Zealand's administration of Western Samoa.

2.4. New Zealand Rule (1914-1961)

From the end of World War I until 1962, New Zealand controlled Western Samoa. Initially, this was an occupation force during the war. After the war, in 1920, New Zealand officially gained control as a League of Nations Class C Mandate, and the territory became known as the Territory of Western Samoa. Following World War II, in 1946, its status was converted to a United Nations Trust Territory under New Zealand administration. Between 1919 and 1962, Samoa was administered by the Department of External Affairs (later renamed the Department of Island Territories) of New Zealand. New Zealand's administration was marked by several critical events that deeply affected the Samoan people and fueled the movement towards independence.

2.4.1. Flu pandemic

A devastating event during early New Zealand rule was the 1918 influenza pandemic. In November 1918, the SS Talune arrived from Auckland and was allowed to berth by the New Zealand administration in breach of quarantine protocols, despite carrying infected passengers. The Spanish flu spread rapidly throughout Western Samoa, which had no prior immunity. The pandemic had a catastrophic impact: approximately one-fifth of the Samoan population died. Estimates suggest 90% of the population was infected, with 30% of adult men, 22% of adult women, and 10% of children perishing. A 1919 Royal Commission of Inquiry confirmed that the epidemic was introduced by the Talune. This tragedy severely undermined Samoan confidence in New Zealand's administrative capacity and competence, leading some Samoans to request a transfer of governance to the Americans or the British. The immense loss of life and perceived negligence had a lasting impact on Samoan attitudes towards New Zealand rule.

2.4.2. Mau movement

The Mau movement (literally "strongly held opinion") was a non-violent popular movement advocating for Samoan independence. It had earlier origins in the Mau a Pule on Savai'i under German rule, led by Lauaki Namulauʻulu Mamoe. The Mau gained widespread support in the 1920s in response to New Zealand's colonial policies, inflation, and the mishandling of the 1918 influenza pandemic.

One of the prominent leaders of the Mau was Olaf Frederick Nelson, a successful merchant of mixed Samoan and Swedish heritage. Nelson was exiled by the New Zealand administration in the late 1920s and early 1930s but continued to support the movement financially and politically.

The Mau's struggle for self-determination culminated in a tragic event known as "Black Saturday." On December 28, 1929, High Chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III, a key leader of the Mau, led a peaceful demonstration in downtown Apia. New Zealand colonial police attempted to arrest one of the demonstrators, leading to a confrontation. The police fired into the crowd, and a Lewis gun was used to disperse the peaceful protestors. Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III was shot from behind and killed while trying to calm his followers. Ten other Samoans died that day, and approximately 50 were injured. This event became a pivotal moment in Samoa's struggle for independence, further solidifying resistance against colonial rule.

In January 1930, the New Zealand authorities banned the Mau. Around 1,500 Mau men retreated to the bush, pursued by marines and seamen from HMS Dunedin and military police, supported by a seaplane. Villages were raided. In March, Mau leaders agreed to disperse after mediation. However, arrests of Mau supporters continued, leading women to take a more prominent role in rallying support and staging demonstrations.

The political climate began to change after the Labour Party won the 1935 general election in New Zealand. A "goodwill mission" to Apia in June 1936 recognized the Mau as a legitimate political organization, and Olaf Nelson was allowed to return from exile. In September 1936, Samoans were allowed to elect members to the advisory Fono of Faipule for the first time, with Mau representatives winning a significant majority of seats. These events marked crucial steps toward self-governance and eventual independence.

2.5. Independence and Contemporary Samoa

After sustained efforts by the Samoan independence movement, the New Zealand Western Samoa Act of 24 November 1961 terminated the Trusteeship Agreement. The Independent State of Western Samoa formally achieved independence on January 1, 1962, becoming the first small-island country in the Pacific to do so. A Treaty of Friendship was signed with New Zealand later that year. Western Samoa joined the Commonwealth of Nations on August 28, 1970, and was admitted to the United Nations on December 15, 1976, requesting to be referred to as the Independent State of Samoa within the UN. Although independence was effective from January 1, Samoa celebrates its Independence Day on June 1 annually.

At independence, Fiamē Mataʻafa Faumuina Mulinuʻu II, one of the four highest-ranking paramount chiefs, became Samoa's first Prime Minister. Tupua Tamasese Meaʻole and Malietoa Tanumafili II became joint Heads of State for life. After Tupua Tamasese Meaʻole's death in 1963, Malietoa Tanumafili II continued as sole Head of State until his death in 2007.

On July 4, 1997, the government amended the constitution to officially change the country's name from Western Samoa to Samoa. This change was met with protests from neighboring American Samoa, which argued that the name change diminished its own identity.

In 2002, New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark formally apologized for New Zealand's role in the 1918 Spanish influenza outbreak and for the Black Saturday killings in 1929, acknowledging the tragic impact these events had on the Samoan people.

Several significant events have marked contemporary Samoa:

- 2009 Road Rule Change**: On September 7, 2009, Samoa switched from right-hand to left-hand driving, aligning with most other Commonwealth countries in the region like Australia and New Zealand, where many Samoans reside. This was primarily to allow for the easier import of more affordable right-hand drive vehicles.

- 2009 Earthquake and Tsunami**: On September 29, 2009, a powerful earthquake and tsunami struck, causing significant damage and loss of life, particularly on the southern coast of Upolu. Over 180 people died in Samoa.

- 2011 International Date Line Shift**: At the end of December 29, 2011, Samoa moved its time zone from UTC-11 to UTC+13, effectively skipping December 30, 2011, and shifting the International Date Line to its east. This was done to facilitate trade with Australia and New Zealand by aligning business days. Samoa also ceased observing daylight saving time in October 2021.

- 2017 State Religion Amendment**: In June 2017, Parliament amended Article 1 of the Samoan Constitution to declare Samoa a Christian nation, stating, "Samoa is a Christian nation founded on God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit".

- 2019 Measles Outbreak**: A severe measles outbreak beginning in September 2019 resulted in the deaths of 83 people, mostly young children, and infected thousands. The government declared a state of emergency and implemented a mandatory vaccination program. This outbreak highlighted vulnerabilities in the public health system and the tragic consequences of low vaccination rates, influenced partly by anti-vaccine misinformation.

- 2021 Constitutional Crisis and Change of Government**: The April 2021 general election led to a historic change in government. The newly formed FAST party, led by Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa, narrowly won, challenging the nearly four-decade rule of the Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP) under Prime Minister Tuilaʻepa Saʻilele Malielegaoi. A prolonged constitutional crisis ensued, involving legal challenges and a period of political deadlock. On May 24, 2021, Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa was sworn in as Samoa's first female Prime Minister in an ad-hoc ceremony outside the locked Parliament building. The Supreme Court eventually upheld the legality of her swearing-in in July 2021, ending Tuilaʻepa's 22-year premiership and ushering in a new political era for Samoa, seen by many as a significant step in its democratic development.

Samoa also signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in 2017, reflecting its commitment to global peace and disarmament.

3. Geography

Samoa's geography is characterized by its volcanic islands, tropical climate, and unique ecosystems in the Polynesian region of the Pacific Ocean.

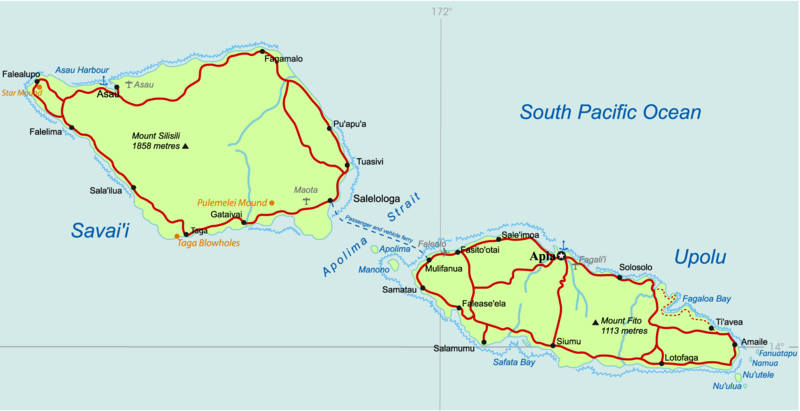

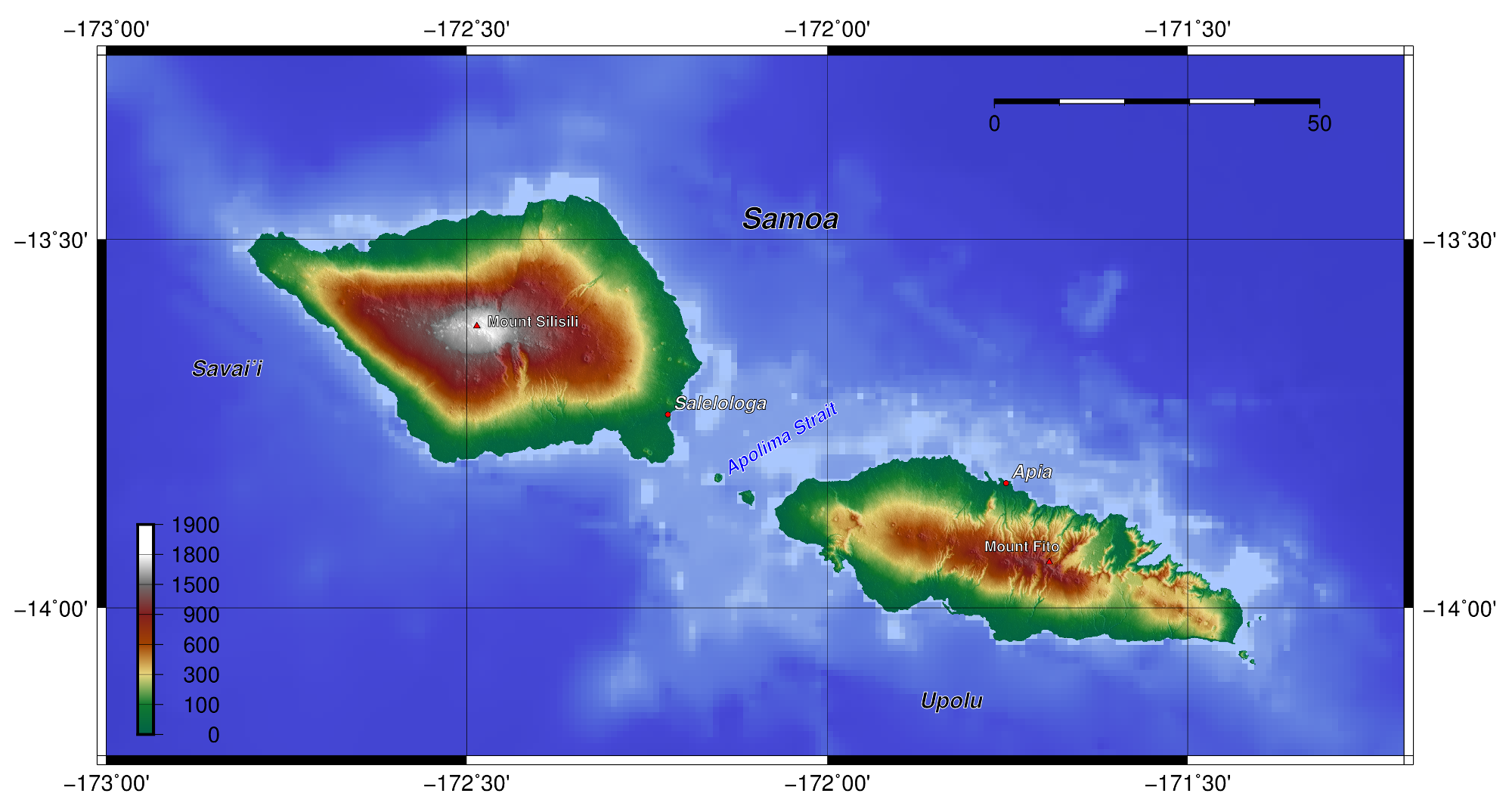

Samoa is located south of the equator, approximately halfway between Hawaii and New Zealand. The total land area is 1.1 K mile2 (2.84 K km2). The country consists of two main islands, Upolu and Savai'i, which together account for 99% of the total land area. Upolu is home to nearly three-quarters of Samoa's population and the capital city, Apia. Savaiʻi is the largest of the Samoan islands and the sixth-largest Polynesian island.

There are eight smaller islets:

- The three islets in the Apolima Strait: Manono, Apolima, and Nuʻulopa.

- The four Aleipata Islands off the eastern end of Upolu: Nuʻutele, Nuʻulua, Namua, and Fanuatapu.

- Nuʻusafeʻe, a tiny islet less than 2.5 acre (1 ha) in area, located about 0.9 mile (1.4 km) off the south coast of Upolu.

The Samoan islands are of volcanic origin, formed by the Samoa hotspot. While all islands have volcanic origins, only Savaiʻi remains volcanically active, with recent eruptions at Mount Matavanu (1905-1911), Mata o le Afi (1902), and Mauga Afi (1725). The highest point in Samoa is Mount Silisili on Savaiʻi, at 6.1 K ft (1.86 K m). The Saleaula lava fields on Savaiʻi, covering 19 mile2 (50 km2), are a result of the Mount Matavanu eruptions. Coastlines feature both coral reefs and steep sea cliffs.

3.1. Climate

Samoa experiences a tropical rainforest climate, classified as an equatorial climate. The average annual temperature is around 79.7 °F (26.5 °C). There is a distinct main rainy season from November to April, although heavy rain can occur in any month. The islands are also susceptible to tropical cyclones.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average high °C | 30.4 | 30.6 | 30.6 | 30.7 | 30.4 | 30.0 | 29.5 | 29.6 | 29.9 | 30.1 | 30.3 | 30.5 | 30.2 |

| Average low °C | 23.9 | 24.2 | 24.0 | 23.8 | 23.4 | 23.2 | 22.6 | 22.8 | 23.1 | 23.4 | 23.6 | 23.8 | 23.5 |

| Average rainfall mm | 19 in (489 mm) | 14 in (368 mm) | 14 in (352.1 mm) | 8.3 in (211.2 mm) | 7.6 in (192.6 mm) | 4.8 in (120.8 mm) | 4.8 in (120.7 mm) | 4.5 in (113.2 mm) | 6.1 in (153.9 mm) | 8.8 in (224.3 mm) | 10 in (261.7 mm) | 14 in (357.5 mm) | 0.1 K in (2.87 K mm) |

3.2. Ecology

Samoa is part of the Samoan tropical moist forests ecoregion. Since human settlement, approximately 80% of the lowland rainforests have been cleared for agriculture and human habitation. Despite this, Samoa's forests still harbor significant biodiversity. About 28% of the plant species and 84% of land bird species found in Samoa are endemic, meaning they are found nowhere else in the world.

The country has several protected areas aimed at conserving its unique natural heritage. These include national parks like O Le Pupu-Puē National Park on Upolu and Togitogiga National Park, as well as marine protected areas. Conservation efforts face challenges from deforestation, invasive species, climate change, and natural disasters. There is a growing emphasis on community-based conservation initiatives and sustainable resource management to protect Samoa's fragile ecosystems and biodiversity, which are crucial for both ecological balance and the well-being of the Samoan people.

4. Government and Politics

Samoa operates as a parliamentary democracy, blending British-style parliamentary conventions with unique Samoan traditional elements, particularly the Faʻamatai chiefly system. The 1960 constitution, which came into force with independence in 1962, provides the framework for its governance. The national modern government is referred to as the Malo.

4.1. Governance Structure

The Samoan governance structure consists of a Head of State, a unicameral legislature, and an executive branch led by a Prime Minister, alongside an independent judiciary.

- Head of State (O le Ao o le Malo): The O le Ao o le Malo is the head of state. Since the office was established, only paramount chiefs have held this position. Initially, two paramount chiefs, Malietoa Tanumafili II and Tupua Tamasese Meaʻole, served jointly for life. After Tupua Tamasese Meaʻole's death in 1963, Malietoa Tanumafili II continued as sole Head of State until his death in 2007. Subsequently, the Head of State is elected by the Legislative Assembly for a five-year term. While the constitution allows any person qualified to be a Member of Parliament to be elected, tradition strongly favors the selection of one of the four tama a ʻāiga (paramount chiefs). The current Head of State is Tuimalealiʻifano Vaʻaletoʻa Sualauvi II, first elected in 2017 and re-elected in 2022.

- Legislature (Fono): The Legislative Assembly of Samoa (Fono) is the unicameral legislature. It consists of 51 members who serve five-year terms. Of these, 49 are matai (chiefly titleholders) elected from territorial constituencies by universal suffrage. The remaining two seats were historically reserved for non-Samoans elected on a separate electoral roll, but this system has been subject to reforms. A constitutional amendment mandates that at least 10% of Members of Parliament must be women, reflecting efforts to improve female representation.

- Executive Branch: The Prime Minister is the head of government. The Prime Minister is chosen by a majority in the Fono and formally appointed by the Head of State. The Prime Minister then selects members of the Cabinet, typically numbering around 12 ministers, who are also appointed by the Head of State and are responsible to the Fono. Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa became Samoa's first female Prime Minister in 2021.

- Judiciary: The judicial system incorporates English common law and local customs. The Supreme Court of Samoa is the highest court of first instance and has appellate jurisdiction. The Court of Appeal of Samoa is the final appellate court. The Chief Justice of Samoa is appointed by the Head of State on the recommendation of the Prime Minister.

4.2. Elections and Political Parties

Samoa holds general elections every five years. Universal suffrage for all citizens aged 21 and over was adopted in 1990. However, to stand for election in the 49 traditional Samoan seats, a candidate must hold a matai (chiefly) title. There are over 25,000 matai in the country, with a small but growing percentage being women.

The main political parties in recent history have been the Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP), which dominated Samoan politics for nearly four decades, and the Faʻatuatua i le Atua Samoa ua Tasi (FAST) party, which came to power after the 2021 general election. The 2021 election was highly contentious, leading to a constitutional crisis that was eventually resolved by the courts, resulting in Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa of FAST becoming Prime Minister. This election marked a significant shift in Samoa's political landscape and was viewed as a test of its democratic institutions.

Prominent women in Samoan politics include the late Laʻulu Fetauimalemau Mataʻafa (wife of Samoa's first Prime Minister), her daughter Prime Minister Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa, scholar and orator-chief Aiono Fanaafi Le Tagaloa, and Matatumua Maimoana.

4.3. Human Rights

The state of human rights in Samoa presents a mixed picture, with ongoing challenges in several areas. From a social liberal perspective, key concerns include:

- Political Representation of Women**: While a constitutional amendment mandates at least 10% female representation in Parliament and Samoa elected its first female Prime Minister in 2021, women remain under-represented in political leadership and decision-making roles overall. Efforts to increase women's participation in the matai system and politics are ongoing but face cultural barriers.

- Domestic Violence**: Domestic violence and violence against women and children are serious issues in Samoa. Despite legislative measures and awareness campaigns, underreporting and lack of effective enforcement remain challenges. Cultural norms can sometimes hinder efforts to address these issues comprehensively.

- Correctional Facilities**: Conditions in prisons and correctional facilities have been a concern, with reports of overcrowding and inadequate resources. Efforts to reform the justice system and improve prison conditions are periodically undertaken.

- LGBT Rights**: Homosexual acts between males are illegal under Samoan law, though enforcement is reportedly rare. Societal discrimination against LGBT individuals persists, influenced by conservative cultural and religious values. There is limited public discussion or advocacy for LGBT rights, and no legal recognition of same-sex relationships. This lack of protection and recognition is a significant concern from a human rights and social equity standpoint.

- Freedom of Religion**: While Samoa is predominantly Christian and constitutionally declared a Christian nation in 2017, the constitution also provides for freedom of religion. However, the emphasis on Christianity can create societal pressure on religious minorities.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) finds that Samoa is fulfilling 88.0% of what it should be fulfilling for the right to education based on the country's level of income. HRMI breaks down the right to education by looking at the rights to both primary education and secondary education. While taking into consideration Samoa's income level, the nation is achieving 97.7% of what should be possible based on its resources (income) for primary education but only 78.3% for secondary education.

Advocacy for stronger human rights protections and greater social equity continues, often led by non-governmental organizations and international partners.

4.4. State Religion

In June 2017, the Samoan Parliament passed an Act to amend Article 1 of the Constitution, formally declaring Samoa a Christian nation. The amended Article 1(1) states: "Samoa is a Christian nation founded on God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit". The preamble to the constitution already described the country as "an independent State based on Christian principles and Samoan custom and traditions."

The background to this amendment involved discussions about national identity and the role of Christianity in Samoan society. Proponents argued it formalized an existing reality, as the vast majority of Samoans identify as Christian and Christian values are deeply embedded in the culture. However, the move also raised concerns among some observers about its potential implications for religious freedom and the rights of religious minorities, despite constitutional guarantees for freedom of religion. The societal implications include a more pronounced official Christian identity for the state, which could influence public discourse and policy, and potentially create a more challenging environment for those of other faiths or no faith, particularly in a society where religion plays a significant public role.

5. Administrative Divisions

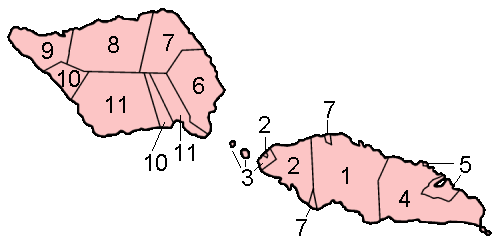

Samoa is comprised of eleven traditional political districts, known as itūmālō. These districts predate European contact and are founded on traditional Samoan custom and usage. Each district has its own constitutional foundation (faʻavae) based on the traditional order of title precedence found in its faʻalupega (ceremonial greetings and chiefly genealogies). The capital village of each district administers and coordinates its affairs and is typically the seat for conferring the district's paramount chiefly titles.

The eleven itūmālō are:

On Upolu:

# Tuamasaga (Capital: Afega; including the faipule (electoral constituency) district of Siumu)

# Aʻana (Capital: Leulumoega)

# Aiga-i-le-Tai (Capital: Mulifanua; including the islands of Manono, Apolima, and Nuʻulopa)

# Atua (Capital: Lufilufi; including the Aleipata Islands and Nuʻusafeʻe Island)

# Vaʻa-o-Fonoti (Capital: Samamea)

On Savaiʻi:

# Faʻasaleleaga (Capital: Safotulafai)

# Gagaʻemauga (Capital: Saleaula; smaller parts of Gagaʻemauga are also on Upolu, specifically the villages of Salamumu, Salamumu-Uta, and Leauvaʻa)

# Gagaʻifomauga (Capital: Safotu)

# Vaisigano (Capital: Asau)

# Satupaʻitea (Capital: Satupaʻitea)

# Palauli (Capital: Vailoa)

For example, the district of Aʻana has its capital at Leulumoega. The paramount tama a ʻāiga (royal lineage) title of Aʻana is Tuimalealiʻifano. The orator group which confers this title, the Faleiva (House of Nine), is based at Leulumoega. Similarly, Ātua has its capital at Lufilufi, with paramount titles like Tupua Tamasese and Mataʻafa, conferred by specific political families and orator groups. Tuamasaga, with its capital at Afega, is associated with the Malietoa title. These traditional structures continue to play a significant role in Samoa's political and social organization.

6. Foreign Relations

Samoa maintains an independent foreign policy, characterized by its active participation in regional and international forums. It is a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, the Pacific Islands Forum, and other international organizations. Samoa's foreign policy prioritizes close relationships with its Pacific neighbors, particularly New Zealand and Australia, as well as engagement with larger powers for development assistance and cooperation on global issues. A key aspect of its foreign relations involves advocating for issues critical to small island developing states, such as climate change, sustainable development, and ocean governance. When discussing Samoa's international engagements, a balanced perspective includes considering the viewpoints of affected parties and any human rights implications arising from these relationships.

6.1. Relations with Key Countries

Samoa has established significant bilateral relationships with several key countries:

- New Zealand: Relations with New Zealand are particularly close, rooted in historical ties (including the period of New Zealand administration) and a Treaty of Friendship signed in 1962. New Zealand is a major development aid partner, a significant source of tourism, and home to a large Samoan diaspora. Cooperation spans economic development, education, health, security, and disaster relief. New Zealand has also formally apologized for colonial-era wrongdoings, which has helped in fostering a more equitable relationship.

- Australia: Australia is another key partner for Samoa, providing substantial development assistance, trade opportunities, and support in areas like governance, education, and security. Like New Zealand, Australia hosts a significant Samoan community.

- United States: Relations with the United States are influenced by the proximity of American Samoa and historical connections. The U.S. provides some development aid and collaborates on regional security issues. The large Samoan-American community also fosters cultural and familial ties.

- China: China has emerged as an increasingly important partner for Samoa, primarily through development assistance, infrastructure projects (often financed by loans), and trade. This relationship has geopolitical significance within the broader context of China's growing influence in the Pacific. Discussions around Chinese aid often involve considerations of debt sustainability and the long-term impacts on Samoa's sovereignty and development, reflecting concerns for ensuring that such engagements benefit the Samoan people equitably and sustainably.

- Other Pacific Island Nations: Samoa plays an active role in regional organizations like the Pacific Islands Forum and maintains close diplomatic ties with other Pacific island nations. These relationships focus on collective advocacy for regional interests, addressing shared challenges like climate change, maritime security, and economic vulnerability, and promoting Pacific solidarity.

- Japan: Japan is a significant aid donor to Samoa, particularly in infrastructure development, fisheries, and education.

Samoa's foreign relations aim to balance its national interests with its commitment to regional stability and international cooperation, often emphasizing partnerships that support its sustainable development goals and respect its sovereignty.

7. Military and Security

Samoa does not have a formal defence structure or regular armed forces. Its national security is primarily focused on domestic law and order, maritime surveillance, and disaster response.

Under the bilateral Treaty of Friendship signed in 1962, New Zealand is required to consider any request for assistance from Samoa. This treaty provides an informal defense guarantee, meaning New Zealand could offer support in the event of an external threat, though the specifics would be subject to consultation.

Domestic law and order are maintained by the Samoa Police Service. Officers of the Samoa Police Service are regularly unarmed but may be armed in exceptional circumstances with ministerial approval. As of 2022, there were between 900 and 1,100 police officers in Samoa. The police service is responsible for general policing, criminal investigations, traffic control, and participates in regional security initiatives. Given Samoa's vast Exclusive Economic Zone, maritime surveillance to combat illegal fishing and transnational crime is a priority, often undertaken with assistance from partners like Australia and New Zealand.

8. Economy

Samoa's economy is that of a developing country, classified as such by the United Nations since 2014. In 2017, its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in purchasing power parity was estimated at 1.13 B USD. The services sector is the largest contributor, accounting for approximately 66% of GDP, followed by the industry (around 23.6%) and agriculture (around 10.4%). The labor force was estimated at 50,700 in the same year. The national currency is the Samoan tālā (WST), issued and regulated by the Central Bank of Samoa.

The economy traditionally relied on agriculture and fishing at the local level. In modern times, key economic drivers include development aid, private family remittances from overseas Samoans (especially from New Zealand, Australia, and the US), agricultural exports, and tourism.

8.1. Key Sectors

The Samoan economy is based on several key sectors:

- Agriculture: This sector employs about two-thirds of the labor force and historically furnished a large portion of exports. Key agricultural products include taro, coconuts (for copra, coconut cream, and oil), cocoa beans, bananas, and noni fruit (for juice). Taro was once the largest export, but a devastating taro leaf blight in the early 1990s significantly reduced its production and export revenue, impacting rural livelihoods. Efforts continue to diversify agricultural output and improve resilience. Small-scale subsistence farming remains vital for food security.

- Fisheries: The fisheries sector is an important source of food and export revenue, particularly tuna. Coastal fisheries are crucial for local communities, while offshore fishing involves both domestic and foreign fleets. Sustainable management of fish stocks is a key concern.

- Tourism: Tourism is a major and growing sector, contributing significantly to GDP (around 25%) and employment. Samoa offers natural beauty, beaches, cultural experiences, and eco-tourism opportunities. The sector is vulnerable to natural disasters and global economic conditions.

- Manufacturing: The manufacturing sector is relatively small, primarily focused on processing agricultural products (e.g., coconut oil, beer) and some light manufacturing. A large automotive wire harness factory (Yazaki Corporation) was a major employer for many years but ceased operations in 2017, leading to significant job losses and highlighting the vulnerability of relying on single large industries.

- Services: This is the largest sector, encompassing retail, wholesale trade, government services, finance, and communications.

8.2. Transport

Samoa's transport infrastructure is essential for its economy and connectivity.

- Air Transport: Faleolo International Airport, located west of Apia on Upolu, is the main international gateway, connecting Samoa with New Zealand, Australia, Fiji, American Samoa, and other Pacific destinations.

- Maritime Transport: Apia is the main port, handling most international cargo. Ferry services operate daily between Mulifanua on Upolu and Salelologa on Savaiʻi, transporting passengers and vehicles. The crossing takes approximately 60-90 minutes. Smaller ports and wharves serve inter-island and local needs.

- Road Networks: Samoa has a network of roads, particularly coastal roads, connecting villages and towns on Upolu and Savaiʻi. The quality of roads varies, with ongoing efforts to upgrade and maintain them. Public transport is primarily provided by brightly decorated local buses and taxis. Samoa switched to left-hand driving in 2009.

- Electricity: Sixty percent of Samoa's electricity comes from renewable sources like hydro, solar, and wind, with diesel generators providing the remainder. The Electric Power Corporation has aimed for 100% renewable energy.

8.3. Development Challenges and Prospects

Samoa faces several economic development challenges:

- Vulnerability to Natural Disasters**: As a small island nation, Samoa is highly susceptible to tropical cyclones, tsunamis (as seen in 2009), and the impacts of climate change (sea-level rise, increased storm intensity), which can devastate infrastructure and key economic sectors like agriculture and tourism.

- Reliance on Foreign Aid and Remittances**: The economy is significantly dependent on development assistance from international partners and remittances from the large Samoan diaspora. While crucial, this reliance can create vulnerabilities.

- Limited Diversification**: The economy has a narrow base, making it susceptible to shocks in key sectors (e.g., the taro blight, closure of the Yazaki factory).

- Geographic Isolation and Small Market Size**: Samoa's remoteness and small domestic market can limit economies of scale and increase transportation costs.

- Debt Sustainability**: Infrastructure projects, often financed by external loans, have raised concerns about public debt levels and long-term sustainability, particularly in relation to loans from China.

Prospects for development focus on:

- Sustainable Tourism**: Developing tourism in an environmentally and culturally sensitive manner.

- Agricultural Diversification and Value Addition**: Promoting new crops, improving productivity, and increasing local processing of agricultural products.

- Renewable Energy**: Expanding renewable energy sources to reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels and mitigate climate change.

- Climate Resilience**: Investing in climate-resilient infrastructure and adaptation measures.

- Human Capital Development**: Improving education and skills training to support economic growth and social equity.

- Good Governance and Fiscal Discipline**: Maintaining sound economic management and transparency.

Efforts towards sustainable economic development must prioritize social equity, ensuring that benefits are widely shared, and environmental protection, safeguarding Samoa's natural resources for future generations.

9. Demographics and Society

This section covers the population composition, distribution, and key social characteristics of Samoa, including vital statistics, ethnic groups, languages, religion, and public services such as health and education.

9.1. Population Statistics

Samoa reported a population of 194,320 in its 2016 census. This figure increased to 205,557 in the 2021 Census. Approximately three-quarters of the population reside on the main island of Upolu, where the capital, Apia, is located. The remaining population primarily lives on Savaiʻi, with smaller communities on Manono and Apolima. Population density and urbanization are centered around Apia. The country experiences significant emigration, with large Samoan diaspora communities in New Zealand, Australia, and the United States, which contributes to substantial remittance inflows.

9.2. Ethnic Groups

The population of Samoa is overwhelmingly of Samoan ethnicity, accounting for approximately 92.6% to 96% of the total. Samoans are a Polynesian people. There is a notable population of Euronesians (people of mixed European and Polynesian descent), constituting about 7% (or 2% for dual Samoan-New Zealander according to some estimates). A small percentage (around 0.4% to 1.9%) comprises other ethnic groups, including Europeans and Asians.

9.3. Languages

The official languages of Samoa are Samoan (Gagana FaʻasāmoaGagana FaʻasāmoaSamoan) and English. Samoan is a Polynesian language and is the predominantly spoken language in everyday life and in most homes. English is widely used in government, business, and education, and is generally understood, especially in urban areas. Including second-language speakers, there are more speakers of Samoan than English. Samoan Sign Language is also used among the deaf community, and efforts have been made to promote its use and teach it to public service members.

9.4. Religion

Religion plays a significant role in Samoan society. Since 2017, Article 1 of the Samoan Constitution states that "Samoa is a Christian nation founded of God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit". The overwhelming majority of the population identifies as Christian.

According to the 2021 Census, the main Christian denominations include:

- Congregational Christian Church of Samoa (CCCS): 27%

- Roman Catholic: 19%

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons): 18%

- Methodist: 12%

- Assemblies of God: 10%

Other Christian denominations and other religions account for the remaining 16%. The former Head of State, Malietoa Tanumafili II, who passed away in 2007, was a follower of the Baháʼí Faith. Samoa hosts one of the nine Baháʼí Houses of Worship in the world, located in Tiapapata, near Apia, which was completed in 1984. Churches are prominent features in Samoan villages, and Sunday is widely observed as a day of rest and worship.

9.5. Health

Samoa's public health system faces challenges common to many Pacific island nations, including combating non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like diabetes and heart disease, which are major health concerns. Access to healthcare services can be limited in rural areas.

The 2019 measles outbreak had a devastating impact, resulting in 83 deaths, primarily among young children, and infecting over 5,700 people (around 2.8% of the population). The outbreak exposed vulnerabilities in the healthcare system, including low vaccination rates at the time, partly attributed to misinformation. The government responded with a state of emergency and a mass vaccination campaign, significantly increasing immunization coverage. This event highlighted the critical importance of public health infrastructure and vaccination programs.

The government continues to work on strengthening healthcare services, improving health education, and addressing NCDs through various policies and initiatives, often with support from international partners like the World Health Organization. Life expectancy and infant mortality rates are generally comparable to other developing nations in the region.

9.6. Education

The Samoan government provides primary and secondary education, with education being compulsory through age 16 and largely tuition-free for the first eight years. The literacy rate in Samoa is high, with a 2012 UNESCO report stating that 99 percent of Samoan adults are literate.

The main tertiary educational institution is the National University of Samoa (NUS), established in 1984 in Apia. Samoa also hosts a campus of the regional University of the South Pacific (USP) at Alafua, specializing in agriculture, and the Oceania University of Medicine, a private medical school.

Educational challenges include ensuring equitable access to quality education, particularly in rural areas, retaining qualified teachers, and aligning the curriculum with the country's development needs. Reforms often focus on improving teacher training, curriculum development, and vocational education to provide skills relevant to the job market. The strong emphasis on education reflects the value Samoan society places on learning and its role in individual and national development.

10. Culture

Samoan culture is rich and deeply ingrained in the daily lives of its people, characterized by ancient traditions, strong community bonds, and vibrant artistic expressions. It is a culture that places high value on family (ʻaiga), community, respect (faʻaaloalo), and service (tautua), all encapsulated within the overarching philosophy of Faʻa Sāmoa (the Samoan Way). The visual arts, music, dance, and oral traditions are all vital components of this living heritage.

The following subsections delve into the specific expressions of Samoan culture, from the foundational principles of Faʻa Sāmoa to its manifestations in mythology, traditional arts, intricate tattooing practices, and vibrant contemporary cultural scene, including literature, film, and cuisine.

10.1. Faʻa Sāmoa (The Samoan Way)

Faʻa Sāmoa, or the traditional Samoan way of life, is the cultural bedrock of Samoan society. It is one of the oldest Polynesian cultures, having developed over 3,000 years and maintained its core tenets despite centuries of European influence. Faʻa Sāmoa encompasses a holistic system of values, social structures, and customs. Key elements include:

- ʻAiga (Family)**: The extended family is the central unit of Samoan society, emphasizing communal living, shared responsibilities, and collective well-being.

- Matai System**: The matai or chiefly system is a cornerstone of Samoan governance and social organization. Matai are titleholders who lead their extended families, manage communal lands, and represent their families in village councils (fono). Titles are bestowed based on lineage, service, and consensus within the ʻaiga.

- Faʻaaloalo (Respect)**: Respect for elders, matai, guests, and established social hierarchies is paramount.

- Tautua (Service)**: Service to one's family, village, and church is a fundamental expectation and a path to earning respect and status.

- Feagaiga (Covenant)**: This refers to the sacred covenant between brothers and sisters, where sisters (feagaiga) hold a position of honor and respect within the family, and brothers (aitu) have a duty of protection and care.

- Va Fealoaʻi (Relationships)**: The importance of maintaining harmonious and respectful relationships between people.

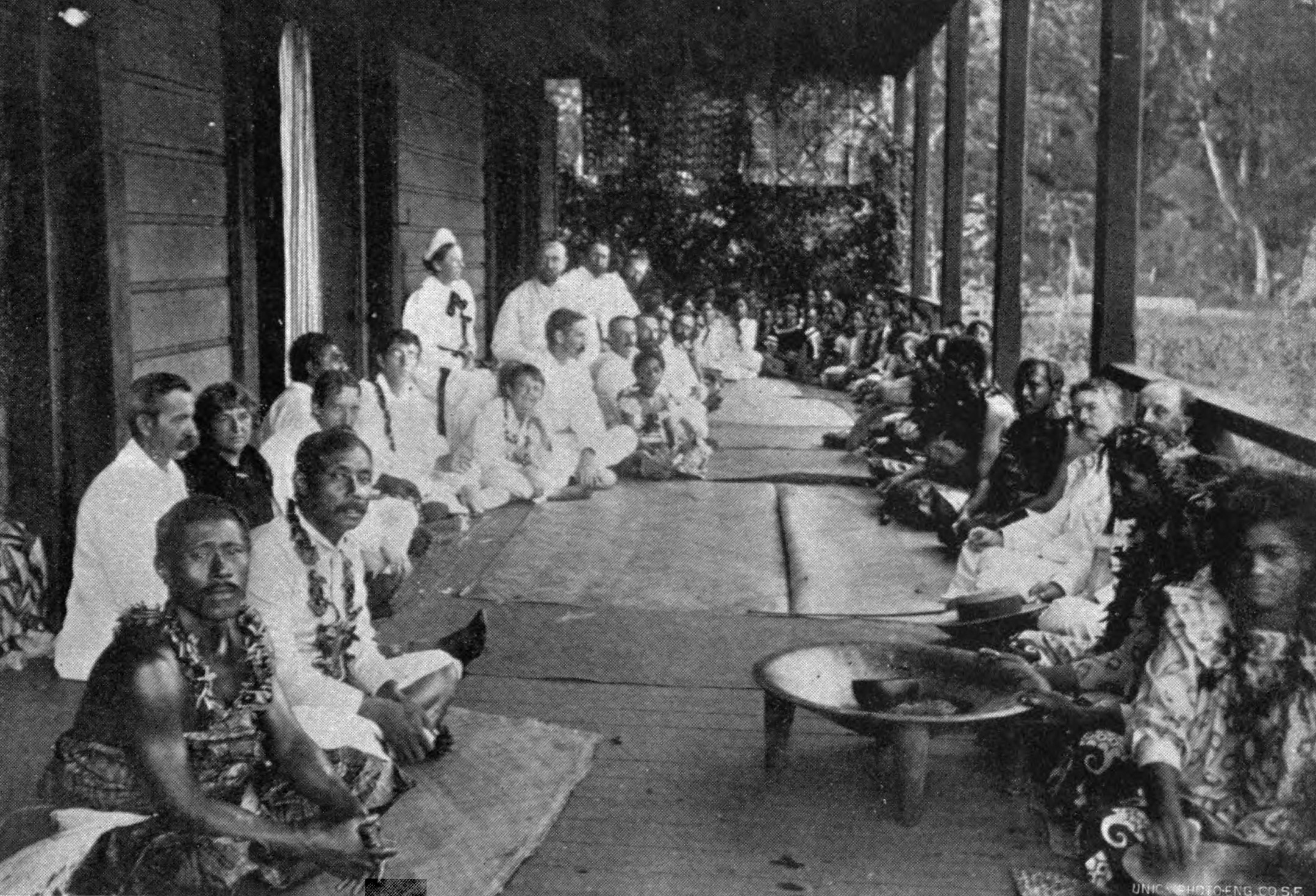

Faʻa Sāmoa continues to influence all aspects of life, including politics, religion, and daily interactions, providing a strong sense of identity and social cohesion. The ʻava ceremony, a solemn ritual involving the preparation and sharing of a beverage made from the kava plant, is highly significant at important occasions, such as the bestowing of matai titles.

10.2. Mythology and Legends

Samoan mythology is rich with creation stories, deities, and legendary figures.

- Tagaloa**: The supreme creator god in many Polynesian mythologies, including Samoan. Various legends attribute the creation of the islands and people to Tagaloa.

- Nafanua**: A revered war goddess, daughter of Saveasi'uleo (ruler of Pulotu, the spirit world). Her patronage was sought by warriors and rulers.

- Sina and the Eel**: A well-known legend that explains the origin of the first coconut tree. It tells the story of a beautiful girl named Sina and an eel who falls in love with her.

- Maui**: The pan-Polynesian demigod Maui also features in some Samoan legends, known for his exploits such as fishing up islands and snaring the sun.

These myths and legends are an integral part of Samoan oral tradition, conveying cultural values, history, and explanations for the natural world.

10.3. Traditional Arts

Samoan traditional arts are diverse and vibrant, reflecting the cultural heritage of the islands.

- Dance (Siva)**: Samoan dance, or siva, is known for its graceful and expressive movements that tell stories.

- The female siva often involves gentle hand and body movements.

- Male dances, such as the faʻataupati (slap dance), are more energetic and rhythmic, where dancers create percussive sounds by slapping different parts of their bodies. This is traditionally performed by men and is said to have originated from slapping insects.

- The sasa is a group dance performed sitting or standing, involving rapid, synchronized movements of the hands and arms in time to the rhythm of wooden slit drums (pate) or rolled mats.

- Music**: Traditional Samoan music features choral singing (often in churches), drumming, and the use of instruments like the pate, fala (rolled mat beaten with sticks), and shell trumpets.

- Crafts**:

- Siapo (Tapa Cloth): Barkcloth made from the paper mulberry tree, decorated with intricate geometric patterns and motifs derived from nature, using natural dyes. Siapo serves both functional and ceremonial purposes.

- ʻIe Toga (Fine Mats): Highly valued ceremonial mats woven by women from pandanus leaves. These mats are considered treasures (measina) and are exchanged at important cultural events such as weddings, funerals, and chiefly title bestowals. Their value is determined by their fineness, softness, and historical significance.

- Carving: Wood carving is used to create tools, weapons, house posts, and other utilitarian and decorative items.

10.4. Tattooing (Peʻa and Malu)

Traditional Samoan tattooing is a highly significant and sacred art form, representing courage, identity, and service. The practice is gender-specific:

- Peʻa**: This is the intricate and extensive tattoo for men, covering the lower body from the waist to the knees. The Peʻa consists of complex geometric patterns applied using traditional handmade tools by a master tattooist (tufuga ta tatau). The process is long, painful, and requires immense bravery. A man who successfully completes the Peʻa is called a sogaʻimiti and earns great respect.

- Malu**: This is the tattoo for women, typically applied to the thighs and knees (sometimes extending to the hands). The Malu features more delicate patterns, often including motifs like the frigate bird (malu). It signifies a woman's role and status within the family and community.

Both Peʻa and Malu are deeply symbolic, connecting individuals to their lineage, culture, and responsibilities within Faʻa Sāmoa. The art of traditional Samoan tattooing has experienced a resurgence and is recognized internationally.

10.5. Contemporary Culture

Samoan contemporary culture blends traditional elements with modern influences, expressed through literature, film, visual arts, and music.

- Literature**:

- Albert Wendt is a prominent Samoan novelist, poet, and academic whose works explore themes of colonialism, cultural identity, and post-colonial life in Samoa and the Pacific. His novels like Sons for the Return Home (1973) and Flying Fox in a Freedom Tree (1974) have been influential.

- Sia Figiel is an acclaimed novelist and poet, known for works like Where We Once Belonged (1996), which won the Commonwealth Writers' Prize.

- Tusiata Avia is a celebrated poet and performer whose work often addresses issues of Pacific identity, colonialism, and gender. Her collection Wild Dogs Under My Skirt has received international recognition.

- Other notable writers include Momoe Malietoa Von Reiche, Dan Taulapapa McMullin, Sapa'u Ruperake Petaia, Eti Sa'aga, and Savea Sano Malifa.

- Film and Theatre**:

- The late John Kneubuhl, born in American Samoa, was an accomplished playwright and screenwriter; his play Think of a Garden (1993) explores Samoa's struggle for independence.

- Sima Urale is a filmmaker whose short film O Tamaiti won Best Short Film at the Venice Film Festival in 1996. Her feature film Apron Strings (2008) also received acclaim.

- Sione's Wedding (2006), co-written by Oscar Kightley, was a popular comedy film.

- The Orator (O Le Tulafale) (2011), written and directed by Tusi Tamasese, was the first feature film entirely in the Samoan language, shot in Samoa with a Samoan cast, and received international critical acclaim.

- Visual Arts**: Contemporary Samoan artists often explore themes of cultural heritage, identity, and contemporary issues. Notable artists include Fatu Feu'u, Johnny Penisula, Shigeyuki Kihara, Michel Tuffery, Lily Laita, Andy Leleisi'uao, and Raymond Sagapolutele. The Tautai Pacific Arts Trust is an important organization supporting Pacific artists.

- Music**: Popular local bands include The Five Stars, Penina o Tiafau, and Punialava'a. Samoan musicians have also achieved success internationally, particularly in New Zealand and Australia, in genres like hip hop (e.g., King Kapisi, Scribe, Dei Hamo, Savage, Tha Feelstyle), reggae, and R&B. The Yandall Sisters had a number one hit in New Zealand in 1974.

- Dance**: Lemi Ponifasio's dance company MAU and Neil Ieremia's Black Grace dance company have gained international recognition for their contemporary Pacific dance performances. Hip hop culture is also popular among Samoan youth, often integrated with traditional dance elements.

10.6. Cuisine

Traditional Samoan cuisine relies heavily on locally sourced ingredients. Staple foods include:

- Root crops: Taro (talo), yam (ufi), and breadfruit (ʻulu) are fundamental.

- Fruits: Bananas (faʻi), coconuts (niu), papaya (esi), mango (mago), and pineapple (fala) are widely consumed.

- Seafood: Fish, octopus (feʻe), crab, and other seafood are important protein sources.

- Meats: Chicken (moa) and pork (puaʻa) are common, especially for feasts.

Coconut cream (peʻepeʻe) is a key ingredient used in many dishes, such as palusami (taro leaves baked with coconut cream, sometimes with onions or meat) and oka iʻa (raw fish marinated in lemon juice, coconut cream, onions, and chili).

Traditional cooking methods include the umu (earth oven), where food is wrapped in banana leaves and cooked over hot stones.

Contemporary dietary habits have seen an increase in imported processed foods, contributing to health challenges like obesity and diabetes. However, there is also a growing appreciation for traditional, healthy Samoan foods.

10.7. Festivals and Public Holidays

Samoa observes a number of national festivals and public holidays, reflecting its cultural and religious heritage.

- Independence Day**: Celebrated on June 1st (though actual independence was gained on January 1st), this is a major national holiday with parades, cultural performances, sports competitions, and official ceremonies.

- Teuila Festival**: Usually held in early September, this is Samoa's largest annual cultural festival, showcasing traditional music, dance (siva), tattooing, craftwork, fautasi (longboat) races, and other cultural events.

- Christian Holidays**: Good Friday, Easter Monday, Christmas Day, and Boxing Day are public holidays and widely observed.

- Mother's Day** and **Father's Day**: Celebrated on the second Sunday of May and August respectively, these are official public holidays reflecting the importance of family.

- Lotu a Tamaiti (Children's Sunday/White Sunday)**: Celebrated on the second Sunday in October, this is a special day dedicated to children. Children lead church services, recite scriptures, perform songs and plays, and are honored with new white clothing and special meals. The following Monday is a public holiday.

- New Year's Day**: January 1st and 2nd are public holidays.

These festivals and holidays are important occasions for community gathering, cultural expression, and religious observance.

11. Sport

Sport is a significant aspect of Samoan life, with several sports enjoying widespread popularity both for participation and spectatorship. The country has also produced athletes who have competed successfully on the international stage.

11.1. Rugby Union

Rugby union is considered the national sport of Samoa. The national team, popularly known as Manu Samoa (named after a famous Samoan warrior), is a highly competitive force in international rugby, often performing strongly against teams from much larger nations.

- History and Achievements**: Manu Samoa has competed in every Rugby World Cup since the 1991 tournament, making notable appearances in the quarter-finals in 1991 and 1995, and reaching the second round (playoffs) in the 1999. They are known for their physical style of play and passionate performances.

- Competitions**: Samoa participates in the Pacific Nations Cup and has previously been part of the Pacific Tri-Nations. They also compete in rugby sevens, with the Samoa Sevens team achieving significant success, including winning the IRB World Sevens Series title in 2009-10 and prestigious tournaments like the Hong Kong Sevens.

- Prominent Players**: Many Samoan players have gained international renown, playing for Manu Samoa and also for professional clubs around the world. Notable players include Pat Lam and Brian Lima. Additionally, numerous players of Samoan descent have represented other national teams, particularly the New Zealand All Blacks.

- Domestic Scene**: Rugby is widely played at club and village level throughout Samoa. The sport is governed by the Samoa Rugby Union.

The success of Manu Samoa is a great source of national pride, and rugby plays a vital role in Samoan identity and community life.

11.2. Other Sports

While rugby union holds a special place, several other sports are popular in Samoa:

- Rugby league**: The Samoa national rugby league team (Toa Samoa) has also achieved international success, notably reaching the final of the 2021 Rugby League World Cup (played in 2022). Many Samoan and Samoan-descended players compete in top professional leagues like the National Rugby League (NRL) in Australia and the Super League in Europe.

- Soccer (Football)**: Soccer is played in Samoa, with a national league and a national team that competes in Oceania Football Confederation (OFC) tournaments.

- Samoan Cricket (Kilikiti)**: Kilikiti is a traditional Samoan form of cricket, distinct from the standard international version. It is a popular community sport, played with unique rules, often involving entire villages, singing, and dancing.

- Netball**: Netball is a popular sport for women and girls in Samoa, with national competitions and a national team that participates in regional and international events.

- Volleyball**: Volleyball is widely played, especially at the village level, both socially and competitively.

- Boxing**: Boxing has a following in Samoa, and the country has produced several professional boxers.

- Professional wrestling**: Samoans have made a significant impact in professional wrestling, with many wrestlers of Samoan heritage achieving international fame in promotions like WWE. The Anoaʻi family is particularly renowned in this field.

- American football**: While not as widely played in Samoa itself, American football is very popular in nearby American Samoa. Many ethnic Samoans (including those from American Samoa and the diaspora) have excelled in the National Football League (NFL) in the United States.

- Sumo wrestling**: Some Samoan wrestlers have achieved high ranks in Japanese sumo wrestling, with Musashimaru (Fiamalu Penitani) reaching the top rank of yokozuna, and Konishiki (Salevaʻa Atisanoʻe) reaching ōzeki.