1. Etymology

The name of Fiji's main island, Viti Levu, served as the origin of the name "Fiji." The common English pronunciation is based on the pronunciation used by Fiji's island neighbors in Tonga. An official account of the emergence of the name states that Fijians first impressed themselves on European consciousness through the writings of the members of the expeditions of Captain James Cook who met them in Tonga. They were described as formidable warriors and ferocious cannibals, builders of the finest vessels in the Pacific, but not great sailors. They inspired awe amongst the Tongans, and all their Manufactures, especially bark cloth and clubs, were highly valued and much in demand. They called their home Viti, but the Tongans called it Fisi, and it was by this foreign pronunciation, Fiji, first promulgated by Captain James Cook, that these islands are now known.

"Feejee," the Anglicised spelling of the Tongan pronunciation, was used in accounts and other writings by missionaries and travelers visiting Fiji until the late 19th century. The Fijian name for Fiji is VitiVitiFijian.

2. History

The history of Fiji is a complex narrative of settlement, cultural development, external contact, colonial imposition, and the challenges of nation-building in a post-colonial, multi-ethnic society. It details periods of indigenous societal flourishing, the profound impacts of European arrival and colonization-including indentured labor systems that reshaped its demographics-and a turbulent path since independence marked by political instability and efforts toward democratic governance and social cohesion.

2.1. Early Settlement and Indigenous Societies

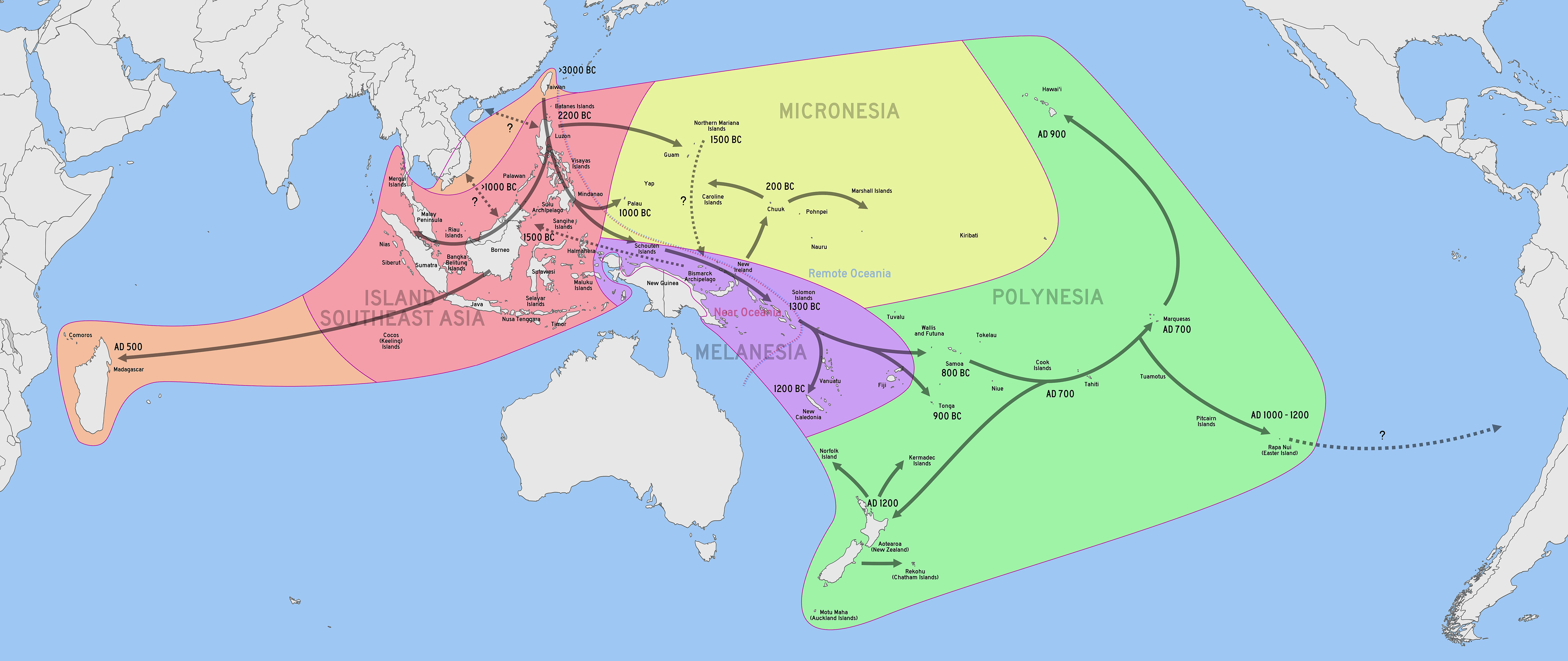

Pottery art from Fijian towns indicates that Fiji was settled by Austronesian peoples by at least 3500 to 1000 BC, with Melanesians following around a thousand years later. There are ongoing academic discussions about the specific dates and patterns of human migration. It is believed that either the Lapita people or the ancestors of the Polynesians settled the islands first. After the Melanesians arrived, the earlier culture may have influenced the new one, and archaeological evidence suggests that some migrants moved on to Samoa, Tonga, and even Hawai'i. Archaeological evidence from Moturiki Island shows signs of human settlement beginning at least by 600 BC, possibly as far back as 900 BC. While some aspects of Fijian culture are similar to Melanesian cultures of the western Pacific, Fijian culture also has strong connections to older Polynesian cultures. Trade between Fiji and neighboring archipelagos existed long before Europeans made contact.

In the 10th century, the Tu'i Tonga Empire was established in Tonga, and Fiji came within its sphere of influence, bringing Polynesian customs and language. This empire began to decline in the 13th century.

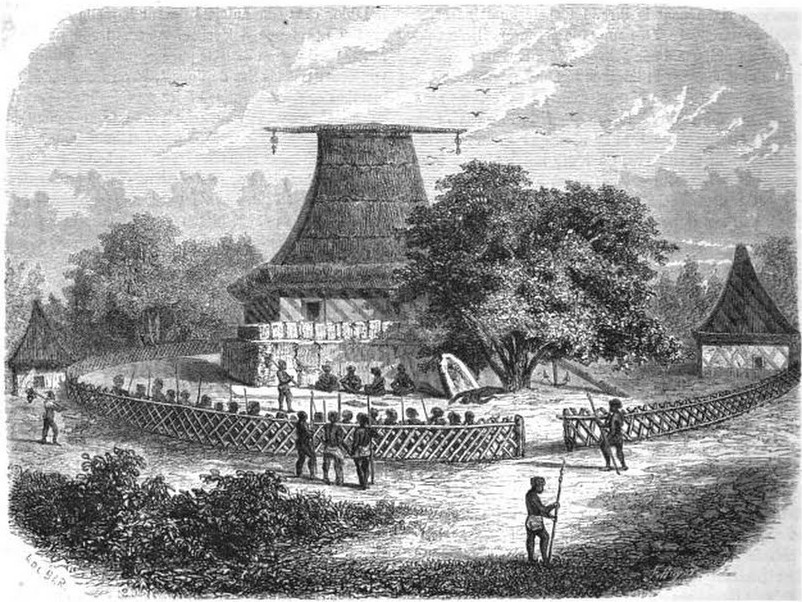

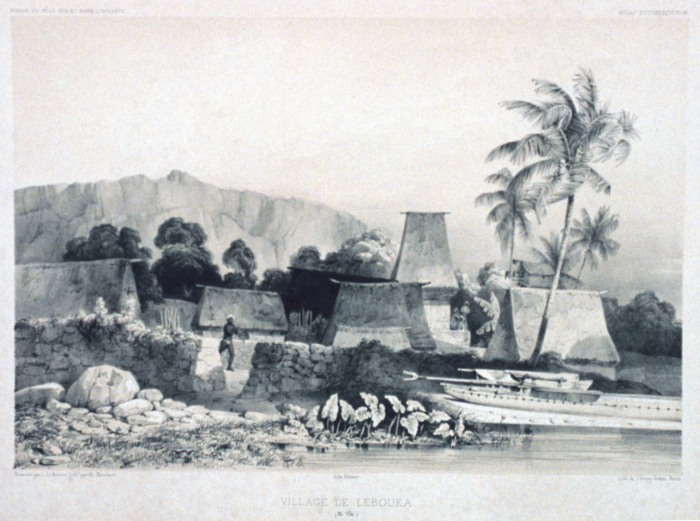

Fiji has long had permanent settlements, but its peoples also have a history of mobility. Over centuries, unique Fijian cultural practices developed. Fijians constructed large, elegant watercraft with rigged sails called druadruaFijian, exporting some to Tonga. They developed a distinctive style of village architecture, including communal and individual burebureFijian and valevaleFijian housing, and advanced systems of ramparts and moats around important settlements. Pigs were domesticated, and agriculture, such as banana plantations, existed from an early stage. Villages were supplied with water via constructed wooden aqueducts. Fijian societies were led by chiefs, elders, and notable warriors. Spiritual leaders, often called betebeteFijian, were also important cultural figures. The production and consumption of yaqonayaqona (kava)Fijian (kava) was part of their ceremonial and community rites. Fijians developed a monetary system where polished sperm whale teeth, called tambuatambuaFijian, became an active currency. A form of writing existed, visible in petroglyphs. They also developed a refined masimasi (tapa cloth)Fijian (tapa cloth) textile industry, used for sails and clothing like the malomaloFijian and likulikuFijian.

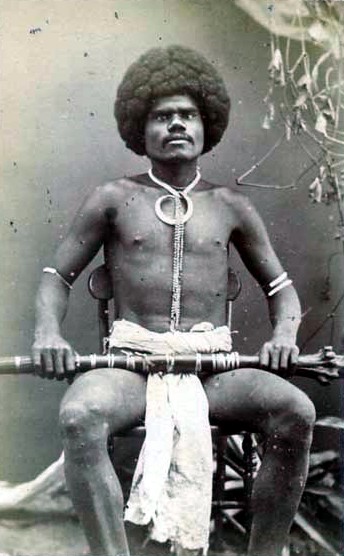

Warfare was an important part of pre-colonial Fijian life, with distinctive weapons, especially war clubs, which were broadly divided into two-handed clubs and specialized throwing clubs called ulaulaFijian.

European colonists and missionaries in the late 19th century often pointed to the practice of cannibalism in Fiji as a moral justification for colonization, labeling many native customs as primitive. Some 19th-century accounts, later perpetuated by authors like Deryck Scarr, described mass human sacrifice and extensive cannibalism. Colonial-era Fiji was sometimes known as "the Cannibal Isles." Modern archaeological research, including studies by Degusta, Cochrane, and Jones, has confirmed that Fijians did practice cannibalism, evidenced by burnt or cut human skeletons. However, these studies suggest that cannibalistic practices were likely more intermittent and ritualistic, possibly nonviolent in some contexts, rather than as widespread or purely savage as some colonial accounts implied. The colonial narrative around cannibalism served to legitimize European control and often exaggerated or decontextualized the practice, contributing to a view of Fiji as a "paradise wasted on savage cannibals."

2.2. European Contact and Early Interactions

Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first known European visitor to Fiji, sighting the northern island of Vanua Levu and the North Taveuni archipelago in 1643 while searching for the Great Southern Continent. In 1774, British navigator James Cook visited one of the southern Lau islands. However, it was not until 1789 that the islands were charted when William Bligh, captain of HMS Bounty, passed Ovalau and sailed between Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. The Bligh Water strait is named after him, and the islands were briefly known as the "Bligh Islands."

The first Europeans to maintain substantial contact were sandalwood merchants, whalers, and bêche-de-mer traders. The first whaling vessel, the Ann and Hope, visited in 1799, followed by many others in the 19th century, seeking water, food, firewood, and later, crew. Some Europeans were accepted by locals and allowed to reside in Fiji. Notable among these was Charles Savage, a shipwrecked sailor who lived among Fijians.

By the 1820s, Levuka was established as the first European-style town on Ovalau. The lucrative bêche-de-mer market in China led British and American merchants to set up processing stations, utilizing local Fijians for labor. Fijian workers were often given firearms and ammunition in exchange, and by the late 1820s, many chiefs possessed muskets. Some chiefs used these new weapons to forcibly obtain more destructive weaponry; in 1834, men from Viwa and Bau captured the French ship L'amiable Josephine and used its cannon against enemies on the Rewa River.

Christian missionaries, like David Cargill, arrived in the 1830s from recently converted regions like Tonga and Tahiti. By 1840, the European settlement at Levuka had grown, with former whaler David Whippey as a notable resident. The religious conversion of Fijians was gradual. Captain Charles Wilkes of the United States Exploring Expedition observed that "all the chiefs seemed to look upon Christianity as a change in which they had much to lose and little to gain." Christianized Fijians were pressured to cut their hair, adopt the sulusuluFijian (a skirt-like garment from Tonga), and change marriage and funeral traditions, a process of enforced cultural change called lotulotuFijian.

Cultural conflicts intensified. In one notable incident, Wilkes led a punitive expedition against the people of Malolo. He ordered an attack with rockets, which acted as incendiary devices, burning the village with occupants trapped inside. Wilkes noted the "shouts of men were intermingled with the cries and shrieks of the women and children" as they burned. He demanded the survivors "sue for mercy" or "expect to be exterminated." Around 57 to 87 Maloloan people were killed, a stark example of the violent impact of early European military actions on indigenous communities and a violation of their human rights.

2.3. Cakobau Era and Unification Attempts

The 1840s in Fiji were marked by conflict as various clans attempted to assert dominance. Ratu Seru Epenisa Cakobau of Bau Island emerged as a powerful warlord, building on the influence of his father, Ratu Tanoa Visawaqa, the VunivaluVunivaluFijian (paramount chief) of Bau, who had subdued much of western Fiji. Cakobau became so dominant that he expelled Europeans from Levuka for five years over a dispute involving their supply of weapons to his enemies. In the early 1850s, Cakobau declared war on all Christians. His plans were thwarted by support for the missionaries from converted Tongans and the presence of a British warship. The Tongan Prince Enele Maʻafu, a Christian, had established himself on Lakeba in 1848, forcibly converting locals to Methodism. Cakobau and other western Fijian chiefs viewed Maʻafu as a threat.

Cakobau's influence began to wane as his heavy taxation led other chiefs, who saw him as first among equals, to defect. The United States also became involved, threatening intervention following incidents involving their consul, John Brown Williams. In 1849, Williams's trading store was looted after an accidental fire during a Fourth of July celebration. In 1853, the European settlement of Levuka was burned down. Williams blamed Cakobau for both incidents, and the U.S. representative sought retaliation. A naval blockade around Bau pressured Cakobau. On April 30, 1854, Cakobau offered his sorosoroFijian (supplication) and converted to Christianity in the lotulotuFijian ceremony. Traditional Fijian temples in Bau were destroyed, and sacred nokonokonokonokoFijian (Casuarina equisetifolia) trees were cut down. Cakobau and his men were then compelled to join the Tongans, backed by Americans and British, to subjugate remaining chiefs who resisted conversion. Leaders like Qaraniqio of Rewa and Ratu Mara of Kaba were defeated. After these wars, most of Fiji, except for interior highland areas (Kai Colo), was forced to abandon many traditional systems and became subject to Western interests. Cakobau was retained as a largely symbolic figure, allowed the self-proclaimed title of Tui VitiTui VitiFijian (King of Fiji), but overarching control shifted to foreign powers.

The rising price of cotton during the American Civil War (1861-1865) attracted hundreds of settlers from Australia and the United States to Fiji in the 1860s, seeking land to grow cotton. With no functioning government, planters often acquired land through violent or fraudulent means, exchanging weapons or alcohol with Fijians who may not have been true owners. This led to problematic competing land claims. In 1865, settlers proposed a confederacy of the seven main native kingdoms. Cakobau was elected its first president.

As white planters pushed into the hilly interior of Viti Levu, they confronted the Kai Colo, a general term for various inland clans who lived traditionally, were not Christianized, and were not under Cakobau's rule. In 1867, missionary Thomas Baker was killed by Kai Colo in the Sigatoka River headwaters. Acting British consul John Bates Thurston demanded Cakobau lead a force to suppress the Kai Colo. Cakobau's campaign into the mountains resulted in a humiliating loss, with 61 of his fighters killed. Settlers also conflicted with the eastern Kai Colo (Wainimala). Thurston called for Royal Navy assistance. Commander Rowley Lambert and HMS Challenger conducted a punitive mission, shelling and burning the village of Deoka, resulting in over 40 Wainimala deaths. These actions demonstrate the brutal force used to extend control over indigenous populations resisting encroachment.

2.4. Colonial Era (1874-1970)

This period marked Fiji's incorporation into the British Empire, bringing profound administrative, social, and economic transformations, including the devastating measles epidemic, the introduction of Indian indentured labor which reshaped Fiji's demographics, and various forms of indigenous resistance against colonial authority, alongside Fiji's involvement in global conflicts.

2.4.1. Cession to Britain and Establishment of Colonial Rule

After the collapse of the earlier confederacy, Enele Maʻafu established a stable administration in the Lau Islands. Other foreign powers, like the United States, considered annexing Fiji, a prospect unappealing to many British settlers from Australia. Britain initially refused annexation. In June 1871, George Austin Woods, an ex-Royal Navy lieutenant, influenced Cakobau to form a new governing administration, establishing the Kingdom of Fiji with Cakobau as monarch (Tui VitiTui VitiFijian). Most Fijian chiefs, including Ma'afu, agreed to participate in this constitutional monarchy. However, many settlers, accustomed to coercive dealings with indigenous populations in Australia, formed aggressive, racially motivated groups like the British Subjects Mutual Protection Society and even a Ku Klux Klan chapter. Cakobau's appointment of respected individuals like Charles St Julian, Robert Sherson Swanston, and John Bates Thurston helped establish some authority.

Increased white settlement intensified land acquisition conflicts with the Kai Colo. In 1871, the killing of two settlers near the Ba River prompted a large punitive expedition of about 400 armed white farmers, imported laborers, and coastal Fijians. A battle near Cubu resulted in casualties on both sides and the village's destruction. The Kai Colo retaliated with raids in the Ba district. Similarly, on the upper Rewa River, the settler squad Rewa Rifles burned villages and shot many Kai Colo.

The Cakobau government, while not approving of vigilante justice, sought Kai Colo subjugation. Robert S. Swanston, Minister for Native Affairs, organized the King's Troops (or Native Regiment), comprising Fijian volunteers and prisoners, led by white officers James Harding and W. Fitzgerald, similar to Australia's Native Police. This force was distrusted by many white planters.

In early 1873, the killing of the Burns family by a Kai Colo raid in the Ba River area led the Cakobau government to deploy King's Troopers. Local whites initially resisted their posting. To assert authority and prove the Native Regiment's worth, an augmented force massacred about 170 Kai Colo people at Na Korowaiwai. Upon returning, they were met by white settlers who still saw them as a threat. Intervention by Captain William Cox Chapman of HMS Dido prevented a skirmish, detaining settlers' leaders and establishing the Cakobau government's authority to crush the Kai Colo.

From March to October 1873, a force of about 200 King's Troops, with around 1,000 coastal Fijian and white auxiliaries, campaigned through Viti Levu's highlands. Majors Fitzgerald and H.C. Thurston led a two-pronged attack. The Kai Colo were defeated at Na Culi, with dynamite and fire used to flush them from caves. Many were killed, and leader Ratu Dradra surrendered with about 2,000 prisoners. Resistance continued around Nibutautau but was crushed. Villages were burned, more Kai Colo killed, and many prisoners taken. About 1,000 prisoners (men, women, and children) were sent to Levuka; some were hanged, and the rest sold into slavery on plantations, a severe human rights violation.

Despite military victories, the Cakobau government faced legitimacy and economic problems, with tax refusal and a collapsed cotton price. John Bates Thurston, at Cakobau's request, approached the British government with another offer to cede the islands. The new Conservative British government under Benjamin Disraeli was more sympathetic to annexation. The murder of Bishop John Patteson of the Melanesian Mission at Nukapu and the massacre of over 150 Fijians by the crew of the brig Carl provoked public outrage and influenced British opinion. Two British commissioners investigated annexation. After vacillation between Cakobau and Ma'afu, Cakobau made a final offer on March 21, 1874, which Britain accepted. On September 23, Sir Hercules Robinson, future Governor of Fiji, arrived. Cakobau renounced his Tui VitiTui VitiFijian title, retaining VunivaluVunivaluFijian. The formal cession occurred on October 10, 1874, with the signing of the Deed of Cession by Cakobau, Ma'afu, and senior chiefs, establishing the Colony of Fiji and 96 years of British rule.

2.4.2. Impact of Colonization and Indigenous Resistance

To celebrate annexation, Hercules Robinson took Cakobau and his sons to Sydney, where a measles outbreak occurred. All three contracted the disease. Upon returning to Fiji, colonial administrators, despite extensive knowledge of infectious diseases' devastating effects on unexposed populations, did not quarantine the ship. The resulting 1875-76 measles epidemic killed over 40,000 Fijians, about one-third of the population. While some Fijians allege this was deliberate, historians find no evidence; the disease spread before the new British governor and medical officers arrived, and no quarantine rules existed under the outgoing regime. This catastrophic event severely impacted indigenous society and highlighted the devastating, if unintended, consequences of colonial contact.

Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon replaced Robinson as Governor in June 1875 and immediately faced an insurgency by the Qalimari and Kai Colo. In early 1875, colonial administrator Edgar Leopold Layard met highland clans at Navuso to formalize their subjugation. Layard's delegation inadvertently spread measles to the highlanders, causing mass deaths and fueling anger against the British. An uprising ensued along the Sigatoka River and in the highlands. Gordon was tasked with quashing this rebellion, termed the "Little War."

The suppression involved two military campaigns. Arthur John Lewis Gordon (Governor Gordon's cousin) led against the Qalimari, and Louis Knollys against the Kai Colo. Governor Gordon invoked martial law, granting them absolute power. The old Native Regiment soldiers, supported by about 1,500 Christian Fijian volunteers, conducted the campaigns. The New Zealand Government provided weapons, including Snider rifles.

The Sigatoka River campaign used a scorched earth policy: villages were burned, fields ransacked. After capturing fortified towns like Koroivatuma, Bukutia, and Matanavatu, the Qalimari surrendered. 827 prisoners, including leader Mudu, were taken. Women and children were dispersed; of the men, 15 were sentenced to death at Sigatoka. Governor Gordon, present but leaving judicial responsibility to his relative, noted his "feet were literally stained with the blood that I had shed." Four were hanged, ten (including Mudu) shot; one escaped.

The northern campaign against the Kai Colo involved clearing rebels from large caves. Knollys' forces killed or wounded many men, women, and children. Survivors were imprisoned. Chief medical officer William MacGregor participated in killing and tending to wounded Kai Colo. After the caves were taken, leader Bisiki was captured. Trials, mostly at Nasaucoko under Le Hunte, resulted in 32 men hanged or shot, including Bisiki.

By October 1876, the "Little War" ended. Remaining insurgents were exiled with hard labor. Some non-combatants returned to rebuild villages, but many highland areas remained depopulated by Gordon's order. Gordon built Fort Canarvon to maintain British control and renamed the Native Regiment the Armed Native Constabulary. He introduced a system of appointed chiefs (RokoRokoFijian and BuliBuliFijian) and village constables, establishing a Great Council of Chiefs under his authority as Supreme Chief. This body existed until suspension in 2007 and abolition in 2012. Gordon also extinguished individual Fijian land ownership, transferring control to colonial authorities, a policy with long-lasting negative consequences for indigenous land rights and economic autonomy.

2.4.3. Indentured Labor and Blackbirding

Governor Gordon decided in 1878 to import indentured laborers from India to work on sugarcane fields, which had replaced cotton plantations. The first 463 Indians arrived on May 14, 1879, the beginning of some 61,000 who would come before the scheme ended in 1916. The system involved a five-year contract, after which workers could return to India at their own expense. A second five-year term offered government-paid return or settlement in Fiji. The vast majority chose to stay, profoundly altering Fiji's demographic landscape and creating a multi-ethnic society with inherent tensions. The Queensland Act, regulating indentured labor there, was also applied in Fiji. This system was often exploitative, with harsh working conditions and limited rights for laborers, contributing to long-term social and economic disparities.

The blackbirding era began in Fiji in 1865, with the first New Hebridean and Solomon Islands laborers transported to work on cotton plantations. The American Civil War had cut off US cotton supplies. European planters flocked to Fiji but found natives unwilling to work on their terms, so they sought labor from other Melanesian islands. On July 5, 1865, Ben Pease received the first license to provide 40 laborers from the New Hebrides.

British and Queensland governments attempted to regulate this labor recruitment. Melanesian laborers were to be recruited for three years, paid three pounds annually, given basic clothing, and access to company stores. However, many were recruited by deceit, often lured aboard ships with gifts and then confined. In 1875, Fiji's chief medical officer, Sir William MacGregor, reported a mortality rate of 540 per 1,000 laborers. Contracts required captains to return laborers to their villages, but many were dropped off at the first sighted island. British warships enforced the Pacific Islanders Protection Act 1872, but few culprits were prosecuted.

[[File:Seizure of blackbirder Daphne.jpg|thumb|The seizure of the blackbirding vessel Daphne, illustrating attempts to regulate the coercive labor trade.}}

A notorious incident was the 1871 voyage of the brig Carl, organized by Dr. James Patrick Murray to recruit laborers for Fijian plantations. Murray's men posed as missionaries; when islanders were enticed to a "religious service," they were forcibly taken. Murray shot about 60 islanders during the voyage but was never tried, receiving immunity for testifying against his crew. The Carl's captain, Joseph Armstrong, was sentenced to death. This practice represented a severe violation of human rights.

In addition to blackbirded labor from other islands, thousands of indigenous Fijians were sold into slavery on plantations. As the settler-backed Cakobau government, and later the British colonial government, subjugated areas, prisoners of war were regularly sold at auction to planters. This provided revenue and dispersed rebels. For example, the Lovoni people of Ovalau, after defeat in 1871, were rounded up and sold at £6 per head. Two thousand Lovoni men, women, and children were sold into five years of slavery. After the Kai Colo wars in 1873, thousands from Viti Levu's hill tribes were sold into slavery. Warnings from the Royal Navy were largely unenforced, and British consul Edward Bernard Marsh often ignored this labor trade. These practices constituted systematic human rights abuses under colonial watch.

2.4.4. Tuka Rebellions and Social Change

With British colonial authorities controlling most aspects of indigenous Fijian social life, charismatic individuals preaching dissent and a return to pre-colonial culture gained followings. These movements, called TukaTukaFijian ("those who stand up"), represented significant indigenous resistance. The first was led by Ndoongumoy (Navosavakandua, "he who speaks only once"). He told followers that returning to traditional ways and deities like Degei and Rokola would transform their condition, making whites and their puppet chiefs subservient. Previously exiled in 1878, Navosavakandua was quickly arrested and exiled again to Rotuma, dying soon after his 10-year sentence.

Other Tuka organizations emerged. The colonial administration ruthlessly suppressed leaders and followers; Sailose was banished to an asylum for 12 years. In 1891, entire village populations sympathetic to Tuka ideology were deported. Three years later in Vanua Levu's highlands, where locals re-engaged in traditional religion, Governor Thurston ordered the Armed Native Constabulary to destroy towns and religious relics. Leaders were jailed, villagers exiled or forced into government-run communities.

In 1914, Apolosi Nawai founded Viti Kabani, a co-operative to monopolize agriculture and boycott European planters. The British and their proxy Council of Chiefs could not prevent its rise and again sent the Armed Native Constabulary. Apolosi and his followers were arrested in 1915; the company collapsed in 1917. For the next 30 years, Apolosi was re-arrested, jailed, and exiled, viewed as a threat until his death in 1946. These rebellions and their brutal suppression highlight the ongoing struggle for autonomy and cultural preservation against colonial oppression.

2.4.5. World Wars and Path to Independence

Fiji was peripherally involved in World War I. A notable incident was in September 1917 when Count Felix von Luckner arrived at Wakaya Island after his raider, SMS Seeadler, ran aground in the Cook Islands. Von Luckner, not realizing local police were unarmed, unwittingly surrendered. Colonial authorities, citing unwillingness to exploit Fijians, did not permit them to enlist. However, Ratu Lala Sukuna, a great-grandson of Cakobau, joined the French Foreign Legion and received France's Croix de Guerre. After a law degree at Oxford University, he returned in 1921 as a war hero and Fiji's first university graduate, becoming a powerful chief and forging institutions for the future Fijian nation.

By World War II, Britain reversed its policy, and thousands of Fijians volunteered for the Fiji Infantry Regiment, commanded by Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau, another great-grandson of Cakobau. The regiment was attached to New Zealand and Australian units. Fiji's central location made it an Allied training base. An airstrip at Nadi (later an international airport) was built, and gun emplacements lined the coast. Fijians gained a reputation for bravery in the Solomon Islands campaign. Corporal Sefanaia Sukanaivalu was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for bravery in the Battle of Bougainville.

A constitutional conference in London in July 1965 discussed changes for responsible government. Indo-Fijians, led by A. D. Patel, demanded immediate full self-government, a fully elected legislature by universal suffrage on a common voters' roll. Ethnic Fijian delegates vigorously rejected this, fearing loss of control over native land and resources if an Indo-Fijian dominated government came to power. Britain, however, was determined to bring Fiji to self-government and independence. Fijian chiefs decided to negotiate.

Compromises led to a cabinet system in 1967, with Ratu Kamisese Mara as the first Chief Minister. Ongoing negotiations between Mara and Sidiq Koya (who led the mainly Indo-Fijian National Federation Party after Patel's death in 1969) led to a second constitutional conference in London in April 1970. Fiji's Legislative Council agreed on a compromise electoral formula and a timetable for independence within the Commonwealth. The Legislative Council would be replaced by a bicameral Parliament: a Senate dominated by Fijian chiefs and a popularly elected House of Representatives. In the 52-member House, Native Fijians and Indo-Fijians were each allocated 22 seats (12 communal, 10 national). Another 8 seats were for "general electors" (Europeans, Chinese, Banaban Islanders, other minorities; 3 communal, 5 national). This system, while enabling independence, embedded ethnic divisions into the political structure, which would contribute to future instability and challenges to democratic development and minority rights. Fiji became independent on October 10, 1970.

2.5. Independent Fiji (1970-Present)

Fiji's journey since independence has been characterized by the establishment of democratic institutions, significant socio-economic development, and recurrent political crises, including multiple coups d'état. These events have profoundly affected ethnic relations, human rights, and the nation's democratic trajectory, often leading to international scrutiny and periods of isolation.

2.5.1. Early Post-Independence Period

Following independence on October 10, 1970, Fiji established democratic institutions based on the Westminster model, with Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara of the Alliance Party as its first Prime Minister. The initial political landscape was dominated by the Alliance Party, which drew support mainly from indigenous Fijians and general electors, and the National Federation Party (NFP), largely supported by Indo-Fijians. Early nation-building efforts focused on developing the economy, particularly the sugar and tourism industries, and establishing Fiji's place in the international community, including joining the United Nations and the Commonwealth of Nations. However, the ethnically-based electoral system, a compromise from the colonial era, continued to be a source of underlying tension and political division, impacting social cohesion and the rights of minority groups.

2.5.2. 1987 Coups d'état

Democratic rule was interrupted by two military coups in 1987, led by Lieutenant Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka. The coups were precipitated by the victory of a multiracial coalition government led by Dr. Timoci Bavadra, which was perceived by some indigenous Fijian nationalists as a threat to their political dominance and control over land. The first coup in May overthrew Bavadra's government. After a period of negotiation and attempts to restore constitutional rule, Rabuka staged a second coup in September.

The immediate aftermath saw the abrogation of the 1970 constitution, the declaration of Fiji as a republic (replacing the Queen of Fiji as head of state with a President), and Fiji's departure from the Commonwealth. The coups had a severe impact on ethnic relations, particularly worsening the sense of insecurity among Indo-Fijians, leading to significant emigration of skilled professionals and business people from this community. This exodus had detrimental effects on the economy. The coups also marked a serious setback for democratic governance and human rights in Fiji, drawing international condemnation and ushering in a period of political instability and racially discriminatory policies aimed at entrenching indigenous Fijian political supremacy.

2.5.3. Constitutional Developments and Ethnic Tensions (1990s)

Following the 1987 coups, a new constitution was promulgated in 1990. This constitution was highly controversial as it institutionalized ethnic Fijian political dominance, guaranteeing them a majority in Parliament and reserving key government positions for indigenous Fijians. This move further exacerbated ethnic tensions and was criticized both domestically by groups like the Group Against Racial Discrimination (GARD) and internationally for its discriminatory nature and impact on the rights of Indo-Fijians and other minorities.

Sitiveni Rabuka, leader of the 1987 coups, became Prime Minister following elections held under this constitution in 1992. Amid ongoing political tensions and international pressure, Rabuka's government established a Constitutional Review Commission in 1995. This led to the adoption of a new, more equitable constitution in 1997. The 1997 Constitution removed many of the overtly discriminatory provisions of the 1990 document, introduced a more inclusive electoral system, and included a Bill of Rights. It was supported by most leaders of both the indigenous Fijian and Indo-Fijian communities and led to Fiji's readmission to the Commonwealth of Nations. Despite these positive constitutional developments, underlying ethnic tensions and distrust persisted, and the period saw continued efforts towards national reconciliation, though with limited success in fully bridging the divides.

2.5.4. 2000 Coup d'état

In May 2000, Fiji experienced another coup, this time led by civilian nationalist George Speight. Speight and a group of armed supporters stormed Parliament, taking Prime Minister Mahendra Chaudhry - Fiji's first Indo-Fijian Prime Minister elected in 1999 under the 1997 Constitution - and most of his cabinet hostage for 56 days. The coup was ostensibly aimed at restoring indigenous Fijian political supremacy, which Speight and his supporters felt was threatened by Chaudhry's government.

The crisis led to widespread lawlessness, racial violence targeting Indo-Fijians, and economic devastation. The military, led by Commodore Frank Bainimarama, eventually intervened, abrogating the 1997 Constitution and assuming executive authority after President Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara resigned (or was possibly forced to resign). Speight was eventually arrested. An interim civilian government headed by Laisenia Qarase was installed.

The 2000 coup severely damaged Fiji's democratic institutions, led to its suspension from the Commonwealth again, and had a devastating impact on international relations and social cohesion. It highlighted the fragility of multiracial democracy in Fiji and the deep-seated ethnic fissures that continued to plague the nation, with significant negative consequences for human rights and the rule of law. General elections were held in 2001, which Laisenia Qarase's Soqosoqo Duavata ni Lewenivanua (SDL) party won.

2.5.5. 2006 Coup d'état and Subsequent Political Climate

On December 5, 2006, Commodore Frank Bainimarama, Commander of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF), led a military coup, overthrowing the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase. This was Fiji's fourth coup in two decades. Tensions had been building between Bainimarama and Qarase's government over several issues, including controversial bills like the Reconciliation, Tolerance, and Unity Bill, which Bainimarama argued would grant amnesty to those involved in the 2000 coup. Bainimarama cited corruption and racially discriminatory policies by Qarase's government as reasons for the takeover.

Following the coup, Bainimarama dismissed Qarase, dissolved Parliament, and assumed presidential powers before appointing himself interim Prime Minister. President Ratu Josefa Iloilo, who initially appeared to oppose the coup, later endorsed Bainimarama's actions. In April 2009, after the Court of Appeal ruled the 2006 coup illegal, President Iloilo abrogated the 1997 Constitution, dismissed the judiciary, and reappointed Bainimarama as Prime Minister under a "New Legal Order," imposing Public Emergency Regulations that curtailed civil liberties, including freedom of speech and assembly, and led to media censorship.

Fiji was suspended from the Pacific Islands Forum in 2009 and fully suspended from the Commonwealth of Nations again for failing to return to democracy. The prolonged period of military-backed rule saw significant pressure from international partners like Australia and New Zealand for a return to democratic processes. The regime argued that it needed time to implement reforms, including a new non-racial electoral system and a new constitution, to overcome the country's "coup culture." This period was marked by concerns about human rights abuses and restrictions on democratic freedoms. Elections were eventually promised for 2014.

2.5.6. Contemporary Politics (2014 onwards)

Fiji held general elections on September 17, 2014, under a new constitution promulgated in 2013 and a new electoral system. Frank Bainimarama's FijiFirst party won a decisive victory, securing 32 of the 50 seats in Parliament, and Bainimarama became the democratically elected Prime Minister. International observers deemed the election credible, marking a return to parliamentary democracy. Fiji's suspension from the Commonwealth was lifted following these elections.

The FijiFirst party maintained its majority in the 2018 general election, though with a reduced margin, winning 27 out of 51 seats. Bainimarama continued as Prime Minister. In October 2021, Ratu Wiliame Katonivere was elected President by the Parliament.

The December 2022 general election resulted in a hung parliament. After negotiations, a coalition government was formed by the People's Alliance party led by Sitiveni Rabuka, the National Federation Party, and the Social Democratic Liberal Party (SODELPA). Sitiveni Rabuka became Prime Minister on December 24, 2022, ending FijiFirst's eight-year rule.

Contemporary Fiji continues to face challenges related to democratic development, including ensuring robust checks and balances, protecting human rights (such as freedom of expression and media freedom), addressing social justice issues like poverty and inequality, and fostering national unity in a multi-ethnic society. The legacy of past coups and ethnic divisions still influences the political landscape.

3. Geography

This section details Fiji's tropical marine climate, its varied rainfall patterns, and vulnerability to cyclones and climate change. It also covers the nation's distinct ecoregions and biodiversity, including endemic species and marine ecosystems, along with ongoing conservation efforts and challenges.

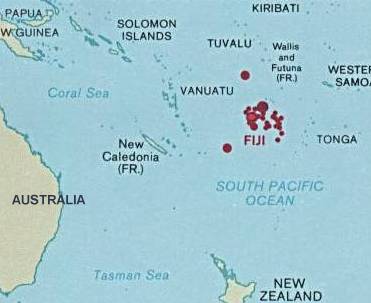

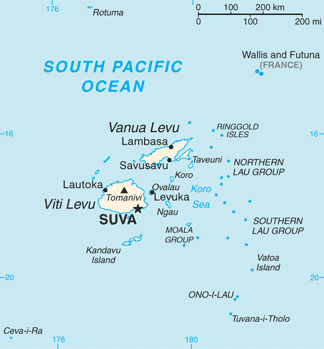

Fiji lies approximately 3.2 K mile (5.10 K km) southwest of Hawaii and roughly 2.0 K mile (3.15 K km) from Sydney, Australia. Fiji is the hub of the Southwest Pacific, midway between Vanuatu and Tonga. The archipelago is located between 176° 53′ east and 178° 12′ west longitude. The 180° meridian runs through Taveuni, but the International Date Line is bent to give uniform time (UTC+12) to all of the Fiji group.

With the exception of Rotuma, the Fiji group lies between 15° 42′ and 20° 02′ south latitude. Rotuma is located 220 nautical miles (approximately 253 mile (407 km)) north of the group, 360 nautical miles (approximately 414 mile (667 km)) from Suva, at 12° 30′ south of the equator.

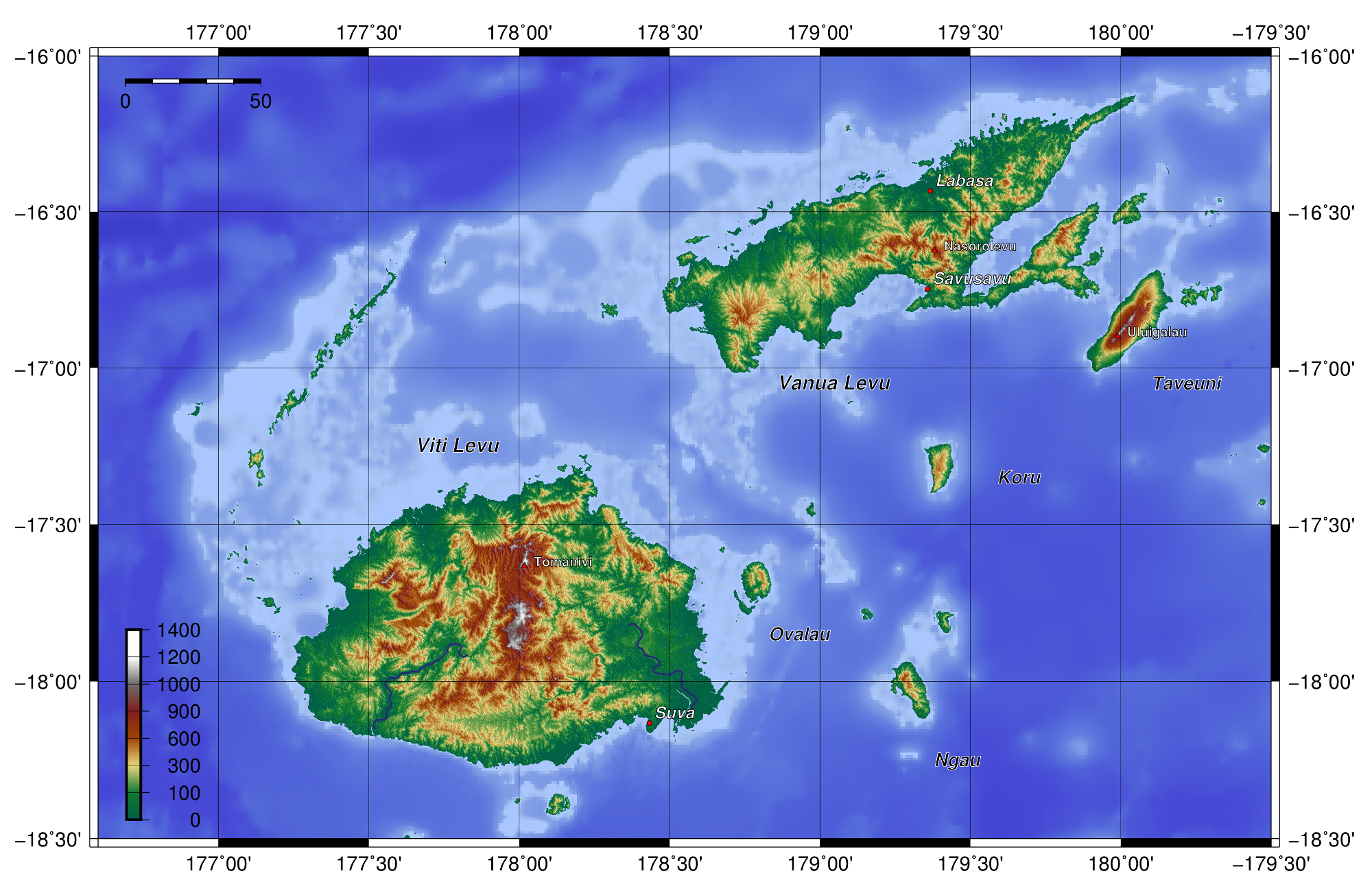

Fiji covers a total area of some 75 K mile2 (194.00 K km2), of which around 10% is land. This land area is distributed across 332 islands (of which 106 are inhabited) and 522 smaller islets. The two most important islands are Viti Levu and Vanua Levu, which account for about three-quarters of the total land area of the country. The islands are mountainous, with peaks up to 4.3 K ft (1.32 K m), and covered with thick tropical forests. The majority of Fiji's islands were formed by volcanic activity starting around 150 million years ago. Some geothermal activity still occurs today on the islands of Vanua Levu and Taveuni. The geothermal systems on Viti Levu are non-volcanic in origin and have low-temperature surface discharges (of between roughly 95 °F (35 °C) and 140 °F (60 °C)).

The highest point is Mount Tomanivi on Viti Levu. Viti Levu hosts the capital city of Suva and is home to nearly three-quarters of the population. Other important towns include Nadi (the location of the international airport), and Lautoka, Fiji's second largest city with large sugar cane mills and a seaport.

The main towns on Vanua Levu are Labasa and Savusavu. Other islands and island groups include Taveuni and Kadavu (the third and fourth largest islands, respectively), the Mamanuca Group (just off Nadi) and Yasawa Group, which are popular tourist destinations, the Lomaiviti Group, off Suva, and the remote Lau Group. Rotuma has special administrative status in Fiji. Ceva-i-Ra, an uninhabited reef, is located about 250 nautical miles (approximately 288 mile (463 km)) southwest of the main archipelago.

3.1. Climate

The climate in Fiji is tropical marine and warm year-round with minimal extremes. The warm season is from November to April, and the cooler season lasts from May to October. Temperatures in the cool season average 71.6 °F (22 °C). Rainfall is variable, with the warm season experiencing heavier rainfall, especially inland. For the larger islands, rainfall is heavier on the southeast portions of the islands than on the northwest portions, with consequences for agriculture in those areas. Winds are moderate, though cyclones occur about once annually (10-12 times per decade).

Climate change in Fiji is an exceptionally pressing issue. As an island nation, Fiji is particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and extreme weather. These changes, along with temperature rise, will displace Fijian communities and disrupt the national economy - tourism, agriculture, and fisheries, the largest contributors to the nation's GDP, will be severely impacted, causing increases in poverty and food insecurity. As a party to both the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Climate Agreement, Fiji hopes to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. This goal, along with national policies, aims to mitigate the impacts of climate change. The governments of Fiji and other at-risk island states (including Niue, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Tonga, and Vanuatu) launched the "Port Vila Call for a Just Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific," calling for the phase-out of fossil fuels, a 'rapid and just transition' to renewable energy, and strengthening environmental law, including introducing the crime of ecocide.

3.2. Ecology and Biodiversity

Fiji contains two ecoregions: Fiji tropical moist forests and Fiji tropical dry forests. It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.35/10, ranking it 24th globally out of 172 countries. The country is home to a variety of endemic species, including several types of iguanas. The birdlife is considered the richest in Western Polynesia, with several endemic species, some of which also inhabit neighboring Tonga and Samoa. Fiji's marine environment boasts extensive coral reefs, which are vital for biodiversity and support local livelihoods but are threatened by climate change and pollution. Conservation efforts are underway to protect these unique ecosystems, managed by government agencies and non-governmental organizations, focusing on sustainable resource management, protected areas, and community-based conservation initiatives. Challenges include habitat loss, invasive species, overfishing, and the impacts of climate change such as coral bleaching.

4. Government and Politics

Politics in Fiji normally take place in the framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic wherein the Prime Minister is the head of government and the President is the Head of State, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Parliament of Fiji. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature, although its independence has been tested during periods of political upheaval.

The 2013 Constitution established a unicameral Parliament of 55 members (previously 51, increased from 50), elected for a four-year term through an open list proportional representation system with the entire country as a single constituency. The voting age is 18.

A general election took place on 17 September 2014. Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama's FijiFirst party won with 59.2% of the vote, and the election was deemed credible by international observers. In the 2018 election, FijiFirst won again with 50.02% of the total votes, securing 27 of the 51 seats. The Social Democratic Liberal Party (SODELPA) came in second with 39.85%. The 2022 election saw FijiFirst lose its parliamentary majority. Sitiveni Rabuka of the People's Alliance party, with the backing of SODELPA and the National Federation Party, became Fiji's new Prime Minister, succeeding Frank Bainimarama. This transition marked a significant shift in Fiji's political landscape, highlighting the ongoing evolution of its democratic processes.

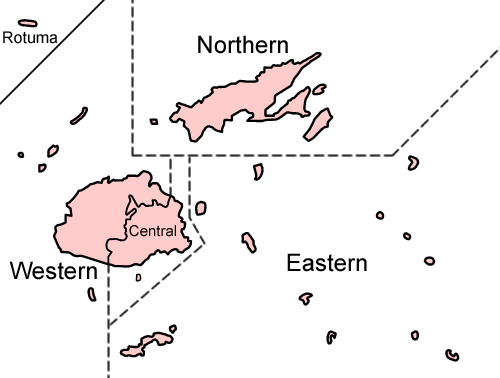

4.1. Administrative Divisions

Fiji is divided into four major divisions, which are further divided into 14 provinces. These divisions serve as the primary administrative units for local governance. They are:

- Central Division: Comprising 5 provinces: Naitasiri, Namosi, Rewa, Serua, and Tailevu. The capital, Suva, is located in Rewa Province.

- Northern Division: Comprising 3 provinces: Bua, Cakaudrove, and Macuata. The main town is Labasa.

- Eastern Division: Comprising 3 provinces: Kadavu, Lau, and Lomaiviti. The main town is Levuka on Ovalau, Fiji's former capital.

- Western Division: Comprising 3 provinces: Ba, Nadroga-Navosa, and Ra. This division includes major towns like Lautoka and Nadi.

The island of Rotuma, located about 311 mile (500 km) north of the main archipelago, holds a special status as a dependency. While officially part of the Eastern Division for statistical purposes, it has its own council and a degree of autonomy in local matters due to its distinct cultural and linguistic heritage.

Fiji was also traditionally divided into three confederacies or matanitumatanituFijian: Kubuna, Burebasaga, and Tovata. While these are not formal political or administrative divisions today, they remain significant in the social and traditional chiefly structures of the indigenous Fijian (iTaukeiiTaukeiFijian) people. The Great Council of Chiefs, a body that historically played an influential role in Fijian politics, particularly concerning indigenous affairs, drew its membership from these traditional structures until its abolition in 2012 (it was later reinstated in 2023).

| Confederacy | Paramount Chief (Title) |

|---|---|

| Kubuna | Vunivalu of Bau (Vacant for extended periods, historically highly influential) |

| Burebasaga | Roko Tui Dreketi (Currently Ro Teimumu Vuikaba Kepa) |

| Tovata | Tui Cakau (Currently Ratu Naiqama Tawake Lalabalavu) |

4.2. Armed Forces and Law Enforcement

The military of Fiji consists of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF), which has a total manpower of approximately 3,500 active soldiers and 6,000 reservists. The RFMF includes a Navy unit of about 300 personnel. The land force comprises the Fiji Infantry Regiment (organized into regular and territorial force light infantry battalions), the Fiji Engineer Regiment, a Logistic Support Unit, and a Force Training Group. Fiji does not have an air force.

Relative to its size, Fiji maintains fairly large armed forces and has been a significant contributor to UN peacekeeping missions in various parts of the world, including deployments in the Golan Heights (UNDOF), Iraq (UNAMI), Sinai (MFO), Lebanon (UNIFIL), Israel (UNTSO), Yemen (UNMHA), and South Sudan (UNMISS). A considerable number of former military personnel have also served in the lucrative private security sector, notably in Iraq following the 2003 U.S-led invasion.

The RFMF has played a prominent and often controversial role in Fiji's domestic politics, having been involved in multiple coups d'état (1987, 2000, 2006). This involvement has significantly impacted Fiji's democratic development and human rights situation, leading to periods of international isolation and criticism. Efforts towards security sector reform and ensuring the military's subservience to civilian democratic control remain ongoing challenges.

Law enforcement is primarily the responsibility of the Fiji Police Force. The Fiji Corrections Service manages the nation's prisons. Both entities operate under the broader justice system, which has faced challenges during periods of political instability.

- Military Equipment (Army):**

- Naval Vessels:**

5. Foreign Relations

Fiji's foreign policy has traditionally focused on its relationships with other Pacific Island nations, as well as with key regional powers like Australia and New Zealand, and increasingly with global actors such as China. As a prominent island nation in the Pacific, Fiji plays an active role in regional organizations, including the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), of which Suva hosts the secretariat, and the Melanesian Spearhead Group.

Fiji is a member of the United Nations and participates in various UN agencies and peacekeeping operations. It is also a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, though its membership has been suspended at times following coups, reflecting international concern over democratic governance and human rights.

The country's foreign relations have been significantly impacted by its domestic political instability. Following the coups of 1987, 2000, and 2006, Fiji faced sanctions and strained relations with traditional partners who pushed for a swift return to democracy and adherence to human rights standards. This led Fiji to diversify its foreign policy, notably strengthening ties with non-traditional partners as part of its "Look North Policy."

Fiji is a strong advocate for climate action on the international stage, given its vulnerability to climate change impacts. It played a significant role in global climate negotiations, including presiding over COP23 (the 2017 UN Climate Change Conference).

5.1. Relations with Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand are Fiji's closest developed neighbors and historically its most significant partners in terms of trade, investment, tourism, development aid, and security cooperation. The relationship is deeply rooted, with strong people-to-people links, including large Fijian diasporas in both countries.

However, the relationship has experienced periods of significant tension, particularly following Fiji's military coups. Both Australia and New Zealand have been strong proponents of democratic governance and human rights in Fiji, leading them to impose sanctions (such as travel bans on regime members and suspension of non-humanitarian aid and military cooperation) after the 2000 and 2006 coups. These actions were met with resistance from Fiji's interim governments, which accused Australia and New Zealand of interference in Fiji's internal affairs. During these periods, Fiji sought to strengthen ties with other nations, notably China.

Since Fiji's return to parliamentary democracy in 2014, relations have largely normalized, with a resumption of full diplomatic ties, development assistance, and security cooperation. Both Australia and New Zealand are major sources of tourists for Fiji and play crucial roles in supporting Fiji's economy and development, particularly in areas like disaster relief, education, health, and institutional strengthening. Despite the improvement, underlying sensitivities can occasionally surface, reflecting the complex history and differing perspectives on regional leadership and governance.

5.2. Relations with China

Fiji's relationship with the People's Republic of China (PRC) has grown significantly, especially since the early 2000s and particularly following the 2006 coup when Fiji faced strained relations with traditional partners like Australia and New Zealand. China offered diplomatic and economic support without the same level of criticism regarding Fiji's domestic political situation, aligning with China's foreign policy principle of non-interference.

This engagement has manifested in increased Chinese development assistance, investment, and concessional loans for infrastructure projects, such as roads, government buildings (including the Suva Government complex refurbishment and the Navua Hospital), and hydroelectric power plants. China has also provided military and police training and equipment. For Fiji, this provided an alternative source of support during periods of Western sanctions and isolation.

The growing relationship has also been viewed within the broader context of China's increasing influence in the Pacific region, leading to strategic competition among major powers. While Fiji has benefited from Chinese aid and investment, concerns have been raised by some observers and within Fiji regarding debt sustainability, the terms of loans, the environmental and social impacts of some projects, and the potential implications for Fiji's sovereignty and long-term strategic alignment.

Fiji has generally adhered to the One-China policy. The relationship also involves cultural exchange programs and an increasing number of Chinese tourists visiting Fiji, facilitated by improved air links before the COVID-19 pandemic. The dynamic of Fiji-China relations continues to evolve as Fiji balances its traditional partnerships with new geopolitical realities.

5.3. Relations with other Pacific Island Nations

Fiji plays a significant leadership role among Pacific Island nations due to its relatively larger economy, population, and central location, which makes Suva a hub for many regional organizations and diplomatic missions. It is an active member of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), the premier regional political grouping, and hosts the PIF Secretariat in Suva. Fiji also plays a key role in the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), a sub-regional organization promoting economic and political cooperation among Melanesian countries.

Fiji's relations with its Pacific neighbors are generally cooperative, focusing on shared challenges such as climate change, maritime security, sustainable development, and fisheries management. It participates in various regional initiatives aimed at addressing these issues.

However, Fiji's domestic political instability, particularly the coups, has at times strained its relations within the region. Fiji's suspension from the PIF in 2009 following the abrogation of its constitution was a significant moment, though it was readmitted in 2014 after holding democratic elections.

Fiji often advocates for a stronger collective voice for Pacific Island Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in international forums, particularly on issues of climate change and ocean governance, where the existential threats are acutely felt across the region. It also provides development assistance and technical expertise to some smaller island nations.

5.4. Territorial Disputes

Fiji is involved in a territorial dispute concerning the Minerva Reefs (Ongo TelekiOngo TelekiFijian), located approximately 400 kilometers southwest of Tonga and south of Fiji. Both Fiji and Tonga lay claim to these two submerged atolls, which are visible only at low tide.

The dispute has historical roots. In 1972, the short-lived Republic of Minerva, a micronation project initiated by American businessman Michael Oliver, attempted to claim the reefs by building artificial islands. Tonga responded by sending troops, annexing the reefs, and asserting its sovereignty, an action largely recognized by other Pacific nations at the time, including Fiji through the Pacific Islands Forum.

However, Fiji later revived its claim. In 2005, Fiji lodged a submission with the International Seabed Authority regarding its continental shelf, which included the Minerva Reefs, reigniting the dispute. Tensions flared periodically, for example, in 2011 when Fijian naval vessels reportedly damaged Tongan navigational beacons on the reefs.

From Fiji's perspective, exercising de facto control involves asserting its maritime rights in the area based on its interpretation of international law and geographical proximity. However, Tonga maintains its historical claim. The dispute remains unresolved, though both nations generally seek peaceful means of addressing such issues within the framework of regional diplomacy. The reefs are primarily of interest due to potential marine resources and their strategic location within the exclusive economic zones of the claimants.

6. Economy

This section outlines Fiji's key economic industries, including the vital tourism sector, the historically significant sugar industry, and contributions from agriculture, forestry, and fisheries. It also examines Fiji's trade and investment landscape, transport infrastructure, and developments in science and technology.

Fiji, endowed with forest, mineral, and fish resources, possesses one of the most developed economies among the Pacific island nations, though a significant subsistence sector persists. The introduction of credit unions in the 1950s by Marion M. Ganey brought some progress to this sector. Key natural resources include timber, fish, gold, copper, potential offshore oil, and hydropower. Fiji experienced rapid growth in the 1960s and 1970s but saw stagnation in the 1980s. The coups of 1987 caused further economic contraction.

Economic liberalization following the coups spurred a boom in the garment industry and steady growth despite uncertainty in the sugar industry regarding land tenure. The expiration of leases for sugarcane farmers, coupled with reduced farm and factory efficiency, led to a decline in sugar production, despite EU subsidies. Fiji's gold mining industry is centered in Vatukoula.

Urbanization and expansion in the service sector have contributed to recent GDP growth. Sugar exports and a rapidly growing tourist industry - with tourist numbers reaching 430,800 in 2003 and increasing subsequently - are major sources of foreign exchange. Fiji is highly dependent on tourism for revenue. Sugar processing constitutes one-third of industrial activity. Long-term economic challenges include low investment and uncertain property rights. Political instability, particularly the coups, has historically had severe negative impacts on the economy, leading to periods of recession and slow recovery. Efforts towards sustainable development and social equity are ongoing.

The South Pacific Stock Exchange (SPSE), based in Suva, is the only licensed securities exchange in Fiji and aims to become a regional exchange.

6.1. Key Industries

Fiji's economy is driven by several key industries, with tourism being the most prominent. The sugar industry, historically a mainstay, continues to be significant, alongside agriculture, forestry, and fisheries which contribute to both domestic consumption and export earnings.

6.1.1. Tourism

Tourism is a cornerstone of Fiji's economy, serving as its largest foreign exchange earner and a major source of employment. Popular regions for tourists include Nadi (the main international gateway), the Coral Coast on Viti Levu, Denarau Island (an integrated resort complex), and the Mamanuca Islands and Yasawa Islands groups, known for their white sandy beaches, clear waters, and vibrant coral reefs. Scuba diving is a common tourist activity.

The main attractions are the tropical weather, beautiful beaches, and picturesque islands. Fiji offers a range of accommodations, from budget resorts to world-class five-star hotels like the Laucala Island Resort. Official statistics from 2012 showed that 75% of visitors came for holidays, with honeymoons and romantic getaways being very popular. Family-friendly resorts with facilities for children are also common. Attractions on the mainland (Viti Levu) include the Thurston Gardens in Suva, Sigatoka Sand Dunes, and Colo-I-Suva Forest Park.

The largest sources of international visitors are Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. The Fiji Bureau of Statistics provides data on visitor arrivals:

| Country | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 367,020 | 365,660 | 365,689 | 360,370 | 367,273 |

| New Zealand | 205,998 | 198,718 | 184,595 | 163,836 | 138,537 |

| United States | 96,968 | 86,075 | 81,198 | 69,628 | 67,831 |

| China | 47,027 | 49,271 | 48,796 | 49,083 | 40,174 |

| United Kingdom | 16,856 | 16,297 | 16,925 | 16,712 | 16,716 |

| Canada | 13,269 | 13,220 | 12,421 | 11,780 | 11,709 |

| Japan | 14,868 | 11,903 | 6,350 | 6,274 | 6,092 |

| South Korea | 6,806 | 8,176 | 8,871 | 8,071 | 6,700 |

| Total | 894,389 | 870,309 | 842,884 | 792,320 | 754,835 |

Fiji has also served as a location for Hollywood movies like Mr. Robinson Crusoe (1932), The Blue Lagoon (1980), Return to the Blue Lagoon (1991), Cast Away (2000), and Anacondas: The Hunt for the Blood Orchid (2004). The U.S. reality TV show Survivor has filmed many seasons in the Mamanuca Islands since 2016.

The tourism industry, while beneficial, also presents challenges, including environmental impacts on fragile ecosystems, the need for sustainable practices, and ensuring that economic benefits are equitably distributed to local communities. The COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted the industry, highlighting its vulnerability to global shocks.

6.1.2. Sugar Industry

The sugar industry has historically been a vital part of Fiji's economy, though its significance has declined in recent decades. Introduced during the colonial era, sugarcane cultivation led to the arrival of Indian indentured laborers, profoundly shaping Fiji's demographic and social landscape. For many years, sugar was Fiji's primary export and a major employer, particularly in rural areas of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu.

The industry has faced numerous challenges, including the expiration of land leases under the Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Act (ALTA), which created uncertainty for predominantly Indo-Fijian tenant farmers and affected productivity. The loss of preferential market access to the European Union under the Sugar Protocol also impacted export revenues. Other issues include aging infrastructure, inefficiencies in mills, declining global sugar prices, and the impacts of climate change, such as cyclones and droughts.

Efforts have been made to restructure and revitalize the industry, focusing on improving efficiency, diversification, and supporting affected farming communities. Despite its reduced dominance, the sugar industry continues to provide livelihoods for a significant portion of the rural population and contributes to export earnings. The socio-economic well-being of those dependent on the sugar sector remains a key concern for policymakers, intertwining with issues of land rights, ethnic relations, and rural development.

6.1.3. Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries

Beyond sugar, Fiji's primary sector includes diverse agricultural activities, forestry, and fisheries, all contributing to the national economy, food security, and employment.

Agriculture: Besides sugarcane, other important crops include copra (dried coconut kernel), ginger, taro (dalodalo (taro)Fijian), cassava (taviokatavioka (cassava)Fijian), kava (yaqonayaqona (kava)Fijian), fruits (like pineapple and papaya), and vegetables. These are grown for both domestic consumption and export. The government promotes agricultural diversification to reduce reliance on sugar and enhance food security. Challenges include susceptibility to natural disasters, limited access to markets for smallholders, and the need for improved farming techniques and infrastructure.

Forestry: Fiji has significant forest resources, including native forests and pine plantations. The timber industry, particularly the harvesting of mahogany and pine, contributes to export earnings. Sustainable forest management is a key concern to prevent deforestation and ensure long-term viability. Community-based forestry initiatives aim to involve local landowners in managing and benefiting from forest resources.

Fisheries: The fisheries sector is crucial for both coastal communities (subsistence and artisanal fishing) and the national economy (commercial fishing, primarily tuna). Fiji's extensive Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) supports a valuable tuna industry, with exports to international markets. Aquaculture, particularly prawn and tilapia farming, is also being developed. Key challenges include overfishing of some coastal species, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, and the impacts of climate change on marine ecosystems and fish stocks. Effective resource management, conservation of marine biodiversity, and ensuring equitable benefit-sharing with local communities are priorities.

6.2. Trade and Investment

Fiji's economy is open, with international trade playing a crucial role. Key export commodities include bottled water (such as Fiji Water), sugar, fish (primarily tuna), timber, gold, and garments. Major import items include manufactured goods, machinery, petroleum products, food, and chemicals.

Fiji's primary export markets historically include Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In recent years, there has been an effort to diversify export destinations, including markets in Asia. Similarly, major import sources are Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, China, and the United States.

Fiji is a member of several regional trade agreements, such as the Melanesian Spearhead Group Trade Agreement (MSGTA) and has been involved in negotiations for broader Pacific trade pacts like PACER Plus. These agreements aim to enhance regional economic integration and market access.

The Fijian government actively seeks to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) through various incentives and by promoting sectors like tourism, manufacturing, agriculture, and information technology. Investment Fiji is the national investment promotion agency. Challenges to attracting and retaining FDI have included political instability in the past, issues related to land tenure, infrastructure limitations, and the business regulatory environment. Efforts are ongoing to improve the investment climate and streamline processes for investors.

6.3. Transport Infrastructure

Fiji's transport infrastructure is crucial for its archipelagic geography, connecting its islands and linking the nation to international routes, supporting tourism, trade, and daily life.

Airports: Nadi International Airport (NAN) on Viti Levu is Fiji's main international gateway, handling most international flights and serving as a hub for Fiji Airways, the national airline. Nausori International Airport (SUV), near Suva, serves as a secondary international airport and a domestic hub. There are also several smaller domestic airports on other islands, such as Labasa Airport on Vanua Levu, facilitating inter-island travel. Airports Fiji Limited (AFL) operates 15 public airports.

Seaports: The main seaports are Suva (Port of Suva) and Lautoka, both on Viti Levu. These ports handle international cargo and cruise ships. Inter-island shipping services are vital for transporting passengers and goods between the islands. Roll-on/roll-off ferries, like those operated by Patterson Brothers Shipping Company, connect Viti Levu with Vanua Levu and other smaller islands.

Roads: Viti Levu has a relatively extensive road network, including the Queen's Road and King's Road that circumnavigate the island, connecting major towns and coastal areas. Vanua Levu also has a main road system. Roads in more remote areas and on smaller islands can be less developed. Public buses are a common and affordable mode of transport on the larger islands, serving both urban and rural routes. Taxis are also widely available. The Land Transport Authority (LTA) regulates bus fares, routes, and licenses for public service vehicles.

Railways: Fiji has a narrow-gauge railway system, primarily used for transporting sugarcane from farms to mills during the harvest season, particularly in western Viti Levu and on Vanua Levu. These are not generally used for passenger transport, though some limited tourist train services have operated in the past.

Challenges in transport infrastructure include maintaining and upgrading aging facilities, improving connectivity to remote islands, ensuring resilience to natural disasters (like cyclones that frequently damage roads and jetties), and securing funding for development projects.

6.4. Science and Technology

Fiji's efforts in science and technology (S&T) focus on areas crucial to its development, such as agriculture, health, renewable energy, and climate change adaptation. Gross domestic expenditure on research and development (GERD) was cited at 0.15% of GDP in 2012, with private-sector R&D being negligible. Government investment tends to favor agriculture, which accounted for nearly 60% of government R&D expenditure in 2012.

In health, the Fijian Ministry of Health seeks to develop local research capacity, launching the Fiji Journal of Public Health in 2012 and establishing guidelines for training and technology access.

Renewable energy is a key focus for diversification. While large-scale hydropower projects exist, there is potential to expand solar, wind, geothermal, and ocean-based energy. The University of Fiji established a Centre of Renewable Energy in 2014, assisted by the EU-funded Renewable Energy in Pacific Island Countries Developing Skills and Capacity (EPIC) program. This program developed master's degrees in renewable energy management at the University of Fiji and the University of Papua New Guinea.

In 2020, the Regional Pacific Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) Hub Office was launched in Fiji to support climate change mitigation and adaptation. This highlights the importance of S&T in addressing climate challenges.

Despite these initiatives, challenges remain, including limited funding for R&D, a shortage of skilled S&T personnel, and the need for greater integration of S&T into national development planning. Pacific authors on the frontlines of climate change also remain underrepresented in scientific literature regarding disaster impacts and climate resilience strategies.

7. Society

Fijian society is a multicultural tapestry woven from the traditions of its indigenous iTaukei people, the descendants of Indian indentured laborers (Indo-Fijians), Rotumans, and smaller communities of Europeans, Chinese, and other Pacific Islanders. This diversity is reflected in its languages, religions, social structures, and daily life, though it has also been a source of political and social tension throughout Fiji's history.

7.1. Demographics

The major urban centers in Fiji, along with their provinces and populations (based on recent estimates), include:

| City | Province | Population Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Suva | Rewa | 88,271 |

| Nadi | Ba | 71,048 |

| Nausori | Tailevu | 57,882 |

| Lautoka | Ba | 52,220 |

| Labasa | Macuata | 27,949 |

| Lami | Rewa | 20,529 |

| Nakasi | Naitasiri | 18,919 |

| Ba | Ba | 18,526 |

| Sigatoka | Nadroga-Navosa | 9,622 |

| Navua | Serua | 5,812 |

Population figures are approximate and can vary based on census data and estimation methods.

The 2017 census found that the population of Fiji was 884,887, an increase from 837,271 in the 2007 census. The population density in 2007 was 45.8 inhabitants per square kilometer. The life expectancy in Fiji was approximately 72.1 years around that period. Since the 1930s, Fiji's population has increased at an average rate of 1.1% per year. The median age of the population in 2017 was 29.9 years, and the gender ratio was 1.03 males per 1 female.

Approximately 87% of the total population lives on the two major islands, Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. About three-quarters of Fijians live on Viti Levu's coasts, either in the capital city of Suva, or in smaller urban centers such as Nadi or Lautoka. The interior of Viti Levu is sparsely inhabited due to its terrain.

Fiji's score on the 2024 Global Hunger Index (GHI) is 10.2, indicating a moderate level of hunger. Population growth is mainly observed on Viti Levu, while Vanua Levu, particularly Macuata Province, has seen population decline due to the termination of sugarcane field contracts. In 2007, 39% of the population was under 20 years old, suggesting continued population growth in the following decade.

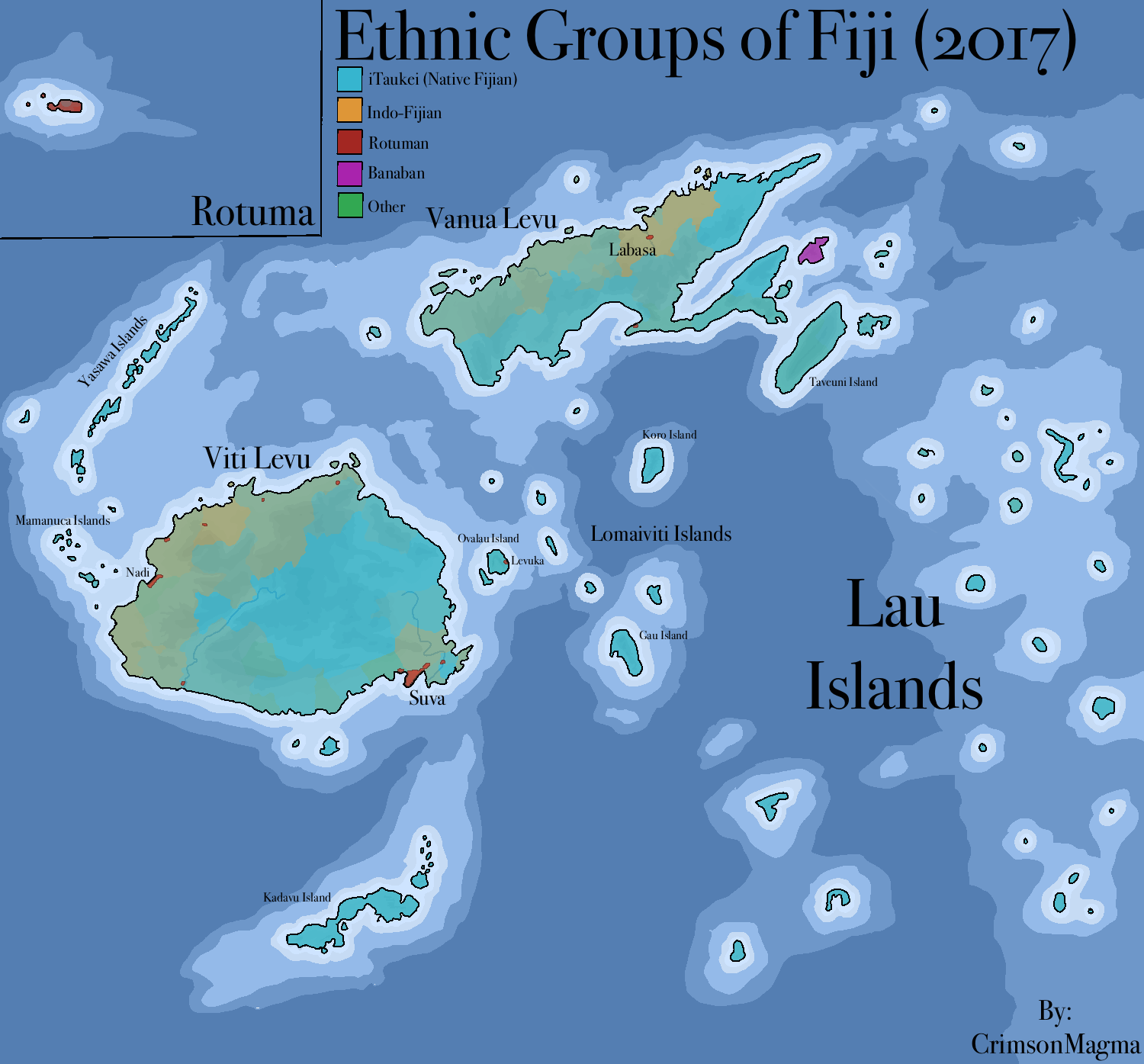

7.2. Ethnic Groups

The population of Fiji is predominantly composed of indigenous Fijians (iTaukeiiTaukeiFijian), who accounted for 56.8% in the 2007 census and 54.3% in later estimates. They are primarily of Melanesian origin, though many also have Polynesian ancestry. The second major ethnic group is Indo-Fijians, descendants of Indian contract laborers brought to the islands by British colonial authorities in the 19th century. They constituted 37.5% of the population in 2007 (later estimated at 38.1%). The percentage of Indo-Fijians has declined significantly over the past few decades due to emigration, often prompted by political instability, discriminatory policies, and concerns about their security and future, particularly after the coups of 1987 and 2000 which saw reprisals against them.

About 1.2% of the population are Rotuman, indigenous to Rotuma Island, whose culture shares more similarities with Polynesian societies like Tonga or Samoa than with the rest of Fiji. There are also small but economically significant groups of Europeans, Chinese, and other Pacific Islander minorities, collectively making up about 4.5% of the population. Approximately 3,000 people (0.3%) living in Fiji are from Australia.

Relationships between ethnic Fijians and Indo-Fijians have often been strained, particularly in the political arena, and these tensions have dominated Fijian politics for generations. This has led to challenges in national unity and has impacted social cohesion and the rights of minority groups.

Within indigenous Fijian communities, the concept of family and community (vanuavanuaFijian) is paramount. Extended family members often adopt specific titles and roles. Kinship is traditionally determined through lineage to a particular spiritual leader, forming clans (yavusayavusaFijian or matanitumatanituFijian) based on customary ties. Within these are smaller collectives known as matagalimatagaliFijian (clan subdivisions) and tokatokatokatokaFijian or yavusa lailaiyavusa lailaiFijian (extended family units, sometimes referred to as mbitombitoFijian in some sources, though tokatokatokatokaFijian is more common). Descent is traditionally patrilineal, with status derived from the father's side.

7.3. Demonym and National Identity

The term for a citizen of Fiji has been a subject of discussion and change, reflecting the complexities of national identity in a multi-ethnic society. The 2013 Constitution refers to all citizens of Fiji as "Fijians." This was a significant change aimed at fostering a common national identity.

Historically, and in some contexts still today, the term "Fijian" was often used to refer specifically to indigenous Fijians (iTaukeiiTaukeiFijian). Previous constitutions, like the 1997 one, might have used terms like "Fiji Islanders" for all citizens, while reserving "Fijian" for the indigenous community in certain legal or customary contexts.

In August 2008, a proposal under the People's Charter for Change, Peace and Progress recommended that all citizens, regardless of ethnicity, be called "Fijians." It suggested changing the English name for indigenous Fijians from "Fijians" to "iTaukeiiTaukeiFijian," their endonym. This proposal was controversial. Deposed Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase argued that "Fijian" belonged exclusively to indigenous Fijians. The Methodist Church, to which a large majority of indigenous Fijians belong, also strongly opposed the change, calling it "daylight robbery."

Military leader and interim Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, a key proponent of the inclusive "Fijian" demonym, stated in 2009: "I know we all have our different ethnicities, our different cultures... However, at the same time we are all Fijians. We are all equal citizens." In May 2010, then-Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum reiterated this stance, which again met with protest from some indigenous groups who argued that the term "Fijian" also referred to a legal standing with specific rights for iTaukeiiTaukeiFijian.

The adoption of "Fijian" as an inclusive national demonym in the 2013 Constitution represents an official effort to promote multiculturalism and national unity, though discussions around ethnic identity and its relationship with national identity continue.

7.4. Languages

Fiji has three official languages as stipulated by the 1997 constitution and maintained in the 2013 Constitution: English, Fijian (also known as iTaukeiiTaukeiFijian or Bau Fijian), and Fiji Hindi (often referred to as Hindustani in older contexts).

English, a legacy of British colonial rule, was the sole official language until 1997. It is widely used in government, business, education, the judiciary, and as a lingua franca between different ethnic groups.

Fijian (Vosa VakavitiVosa VakavitiFijian) is an Austronesian language from the Malayo-Polynesian family. It is spoken as a first language by indigenous Fijians (over 350,000 native speakers) and as a second language by many others (around 200,000). There are numerous dialects across the islands, broadly classified into Eastern and Western Fijian. Missionaries in the 1840s chose an eastern dialect, specifically the speech of Bau Island (the seat of Cakobau's power), as the standard for written Fijian.

Fiji Hindi (फ़िजी बातFiji Baathif or Fijian Hindustani) is the language spoken by most Fijian citizens of Indian descent. It is derived mainly from the Awadhi and Bhojpuri varieties of Hindi, brought by indentured laborers primarily from eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. It has also borrowed extensively from Fijian and English, developing unique features that distinguish it from the Hindi spoken in India.

Other languages spoken in Fiji include Rotuman on Rotuma Island (more closely related to Polynesian languages), various other Fijian dialects, and languages of smaller migrant communities such as Gujarati, Telugu, Tamil, and Chinese.

The Fijian alphabet has some unique phonetic values. For instance, "c" is pronounced as a voiced "th" sound ([ð]), "b" and "d" are prenasalized ([mb], [nd]), "q" is pronounced like a prenasalized "g" ([ŋg]), and "g" is pronounced as "ng" ([ŋ]) as in "singer."

A simple comparison of greetings:

| English | hello/hi | good morning | goodbye |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fijian | BulaBoo-lahFijian | YadraYahn-drahFijian | MoceMo-theyFijian |

| Fiji Hindi | नमस्तेNamastehif (general) राम रामRam Ramhif (for Hindus) असलमु अलैकुमAs-salamu alaykumhif (for Muslims) | सुप्रभातSuprabhathif | अलविदाAlavidāhif |

7.5. Religion

Fiji is a multi-religious country, with Christianity being the most widely practiced faith, followed by Hinduism and Islam, primarily among the Indo-Fijian community. The constitution provides for freedom of religion.

According to the 2007 census:

- Christians comprised 64.4% of the population.

- Methodists were the largest Christian group, accounting for 34.6% of the total population (and 54% of all Christians), making Fiji one of the countries with the highest proportion of Methodists globally. The Methodist Church of Fiji and Rotuma is the main Methodist body.