1. Overview

The Kingdom of Tonga is a Polynesian sovereign state and archipelago comprising 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Located in the South Pacific Ocean, Tonga has a unique history as the only Pacific island nation to have continuously retained its monarchy and avoided formal colonization, though it was a British protectorate from 1900 to 1970. The nation's history is marked by the powerful Tuʻi Tonga Empire, a significant maritime power in the Pacific, and a gradual transition towards a constitutional monarchy with increasing democratic representation in recent decades. This transition has included significant political reforms and social movements aimed at enhancing civil liberties and human rights.

Tonga's geography is characterized by volcanic and coral islands, including the deep Tonga Trench, and it faces significant environmental challenges such as volcanic activity, tsunamis (notably the devastating 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai eruption and tsunami), and the impacts of climate change, including sea level rise and increased storm intensity. The Tongan economy relies heavily on remittances from its large diaspora, agriculture (particularly squash, coconuts, and vanilla), and tourism. It confronts economic challenges common to small island developing states, including vulnerability to external shocks and the need for sustainable development that addresses income inequality and supports labor rights.

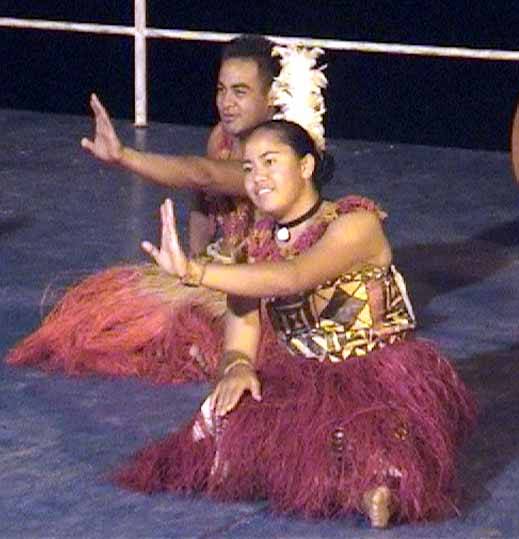

Tongan society is deeply rooted in Polynesian traditions and Christianity, which significantly influences daily life and law. The nation has made strides in education and health, but faces issues such as high rates of obesity and non-communicable diseases. Culturally, Tonga is known for its traditional social structures, intricate arts and crafts like ngatu (tapa cloth), vibrant music and dance forms such as the Lakalaka (a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage), and the central role of kava in social and ceremonial life. The article explores these facets, emphasizing Tonga's journey of social and political development, its cultural richness, and its resilience in the face of contemporary challenges, all from a perspective that underscores social impacts, human rights, and democratic progress.

2. Etymology

The name "Tonga" originates from the Tongan language tongaˈtoŋaTonga (Tonga Islands), which means "southwards" or "south." This naming reflects the archipelago's geographical position as the southernmost group of islands in central Polynesia. The term tongaˈtoŋaTonga (Tonga Islands) itself is derived from fakatongain a southerly mannerTonga (Tonga Islands), meaning "in a southerly manner." This geographical descriptor was significant in the context of early Polynesian navigation and settlement patterns across the vast Pacific Ocean.

The word tongaˈtoŋaTonga (Tonga Islands) is cognate with the Hawaiian language word konaleeward / southwestHawaiian, which means "leeward" or "southwest," and is the origin of the name for the Kona District in Hawaii. This linguistic connection highlights the shared Austronesian roots and migratory paths of Polynesian peoples.

Tonga became known to Western explorers as the "Friendly Islands." This name was bestowed by Captain James Cook during his first visit in 1773, prompted by the seemingly congenial reception he received from the Tongan people. Cook arrived during the annual ʻinasiannual harvest festivalTonga (Tonga Islands) festival, a significant cultural event involving the presentation of the first fruits of the harvest to the Tuʻi Tonga, the paramount chief or monarch of the islands. Cook was invited to participate in these festivities. However, according to accounts by William Mariner, an English sailor who lived in Tonga for several years in the early 19th century, some Tongan political leaders had plotted to attack and kill Cook and his crew during this visit. The plan was reportedly abandoned because the chiefs could not agree on a strategy for the attack. This historical anecdote adds a layer of irony to the "Friendly Islands" moniker, revealing underlying political complexities beneath the surface of initial European encounters.

3. History

Tonga's history spans millennia, from its initial settlement by the Lapita people to its emergence as a powerful maritime empire, encounters with Europeans, unification under a monarchy, a period as a British protectorate, and its journey as an independent nation in the modern era. Key themes include the evolution of its unique social and political structures, the impact of Christianity, the resilience of its indigenous governance, and ongoing efforts towards democratic reform and sustainable development.

3.1. Prehistory and Lapita Culture

The first inhabitants of Tonga are believed to be people associated with the Lapita culture, an Austronesian-speaking group that migrated from Island Melanesia. Archaeological evidence suggests that these settlers arrived in Tonga sometime between 1500 and 1000 BC. Thorium dating of artifacts found in Nukuleka, on the main island of Tongatapu, indicates that this site, considered the earliest known settlement in Tonga, was inhabited by 888 BC (± 8 years). These early Polynesians were skilled navigators and agriculturalists, bringing with them taro, yam, bananas, coconuts, and domesticated animals such as pigs, dogs, and chickens.

Over centuries, these settlers developed a distinct Tongan identity, language, and culture. Early Tongan society was characterized by a complex hierarchical structure, with powerful chiefs and a system of land tenure. Archaeological findings from this period include distinctive Lapita pottery, tools made from stone and shell, and evidence of early agricultural practices. The Lapita people gradually expanded throughout the Tongan archipelago, establishing settlements on various islands. Tonga's pre-contact history was primarily transmitted through rich oral traditions, including myths, legends, and genealogies, which were passed down from generation to generation and later recorded after European contact. According to Tongan mythology, the demigod Maui fished the islands of Tongatapu, the Haʻapai group, and Vavaʻu from the ocean, forming the core of what is now Tonga.

3.2. Tuʻi Tonga Empire

By the 10th century AD, Tonga had emerged as a significant regional power, leading to the establishment of the Tuʻi Tonga Empire. The empire's influence, at its zenith between the 12th and 15th centuries, extended over a vast area of the Pacific, making it a formidable maritime thalassocracy. The first Tongan king, ʻAhoʻeitu, is traditionally credited with founding the Tuʻi Tonga dynasty around 950 AD, consolidating power and laying the groundwork for imperial expansion.

The Tuʻi Tonga Empire was characterized by a centralized political system headed by the Tuʻi Tonga, who held both sacred and secular authority. The capital was located at Muʻa on Tongatapu, which became a major political and ceremonial center. The empire's reach extended from parts of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, and Fiji in the west, to Samoa, Niue, and even as far as parts of modern-day French Polynesia in the east. This influence was maintained through a combination of military might, strategic marriages, trade networks, and cultural prestige. Conquered territories often paid tribute to the Tuʻi Tonga.

The social structure of the empire was highly stratified, with a complex system of chiefs, nobles, and commoners. The Tuʻi Tonga was considered semi-divine, and a sophisticated system of rituals and ceremonies reinforced his authority. Over time, the immense power of the Tuʻi Tonga led to internal pressures. To manage the growing administrative and secular burdens, the Tuʻi Tonga later delegated some temporal powers, leading to the creation of collateral chiefly lines, such as the Tuʻi Haʻatakalaua in the 15th century and later the Tuʻi Kanokupolu in the 17th century. These lines gradually gained more political influence.

The decline of the Tuʻi Tonga Empire began in the 13th century, notably with the Samoan revolution which challenged Tongan dominance in that region. Internal strife, civil wars (particularly in the 15th and 17th centuries), and the rising power of collateral chiefly lines further weakened the central authority of the Tuʻi Tonga. Despite its eventual decline, the legacy of the Tuʻi Tonga Empire shaped the political and cultural landscape of Tonga and the wider Pacific region for centuries. Its economic, ethnic, and cultural influence remained significant even after its political power waned.

3.3. Early European Contact and Unification (c. 1616 - 1875)

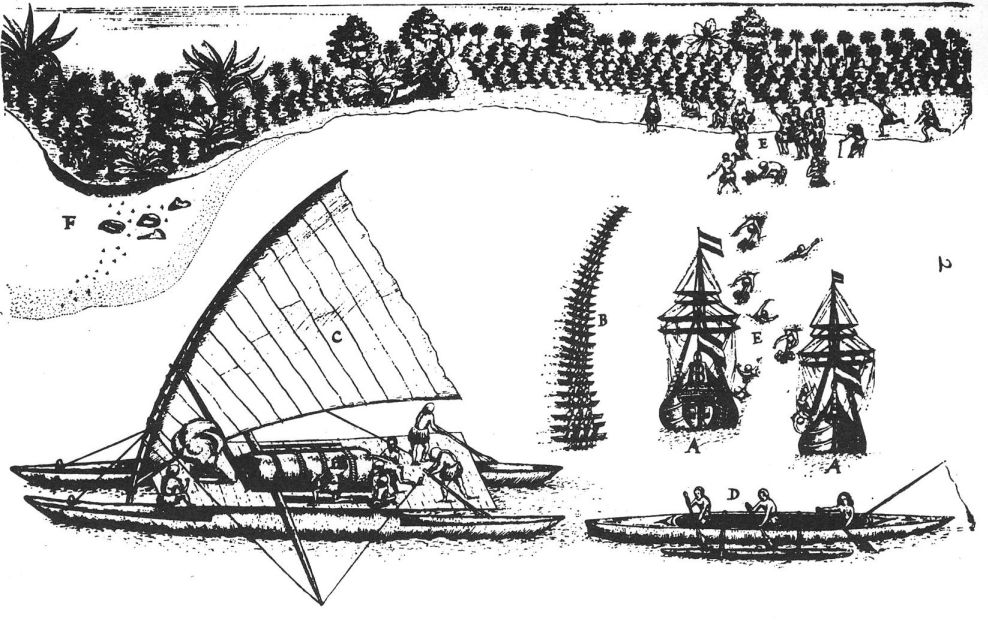

The first documented European contact with Tonga occurred in 1616 when the Dutch vessel Eendracht, captained by Willem Schouten and with Jacob Le Maire, made a brief visit to the northern islands, including Niuatoputapu, for trade. In 1643, another Dutch explorer, Abel Tasman, visited Tongatapu and the Haʻapai group. These early encounters were fleeting and had limited immediate impact on Tongan society.

More significant European contact began in the late 18th century. Captain James Cook of the British Royal Navy visited Tonga on three separate voyages in 1773, 1774, and 1777. Cook famously named Tonga the "Friendly Islands" due to the apparently warm reception he received, although later accounts suggest there were undercurrents of suspicion and even plots against him by some chiefs. Cook's voyages brought Tonga to wider European attention and were followed by other explorers, including the Spanish Navy explorers Francisco Mourelle de la Rúa in 1781 and Alessandro Malaspina in 1793.

The early 19th century saw the arrival of Christianity missionaries. The first London Missionary Society missionaries arrived in 1797 but had little success. Wesleyan Methodist missionaries, beginning with Reverend Walter Lawry in 1822, were more influential, particularly through their conversion of powerful chiefs. The introduction of Christianity led to profound social and cultural changes, gradually displacing traditional religious beliefs and practices. Whaling vessels also became regular visitors from the late 18th century (the first recorded being the Ann and Hope in 1799) through the 19th century, seeking supplies and sometimes recruiting Tongan men as crew. The United States Exploring Expedition visited Tonga in 1840.

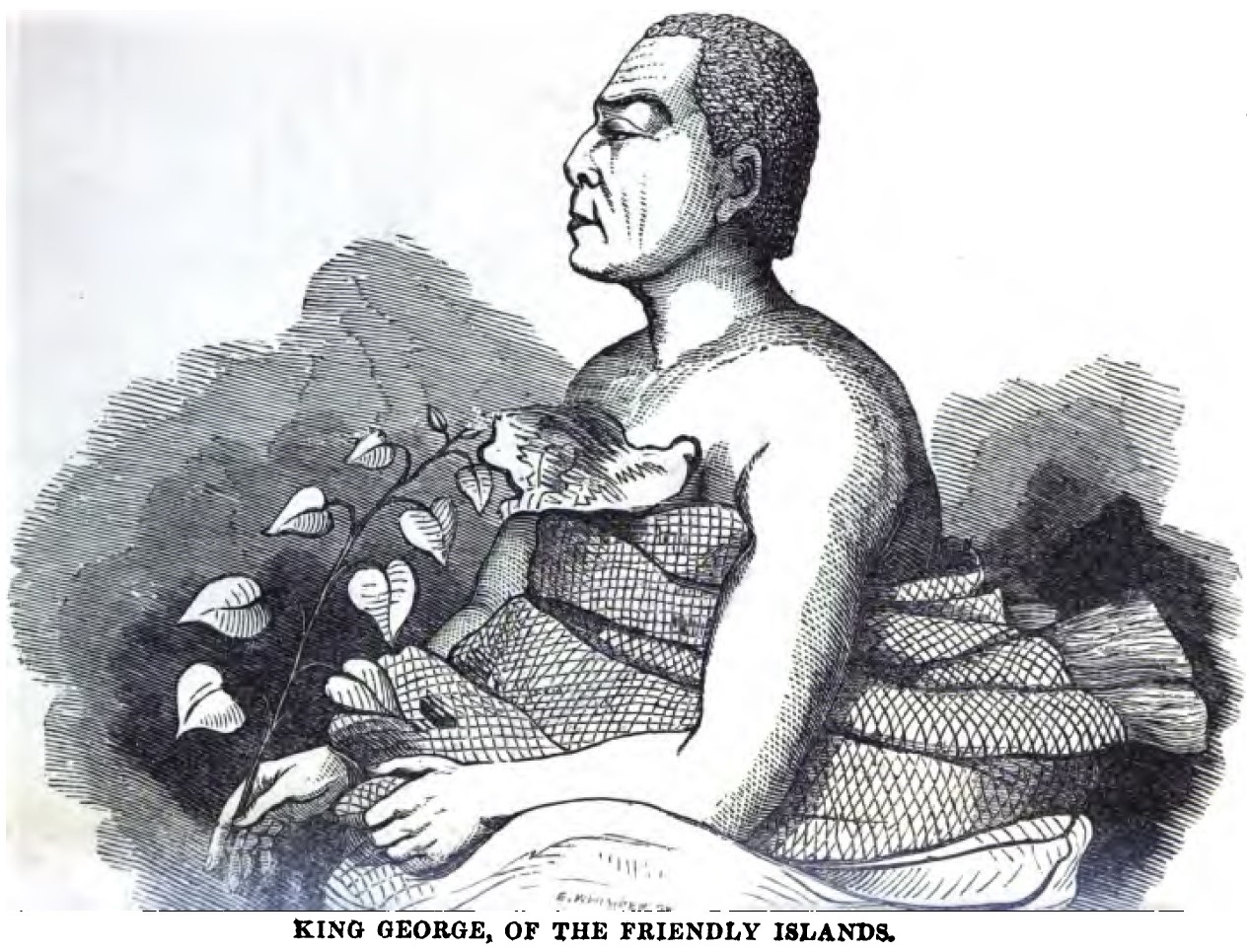

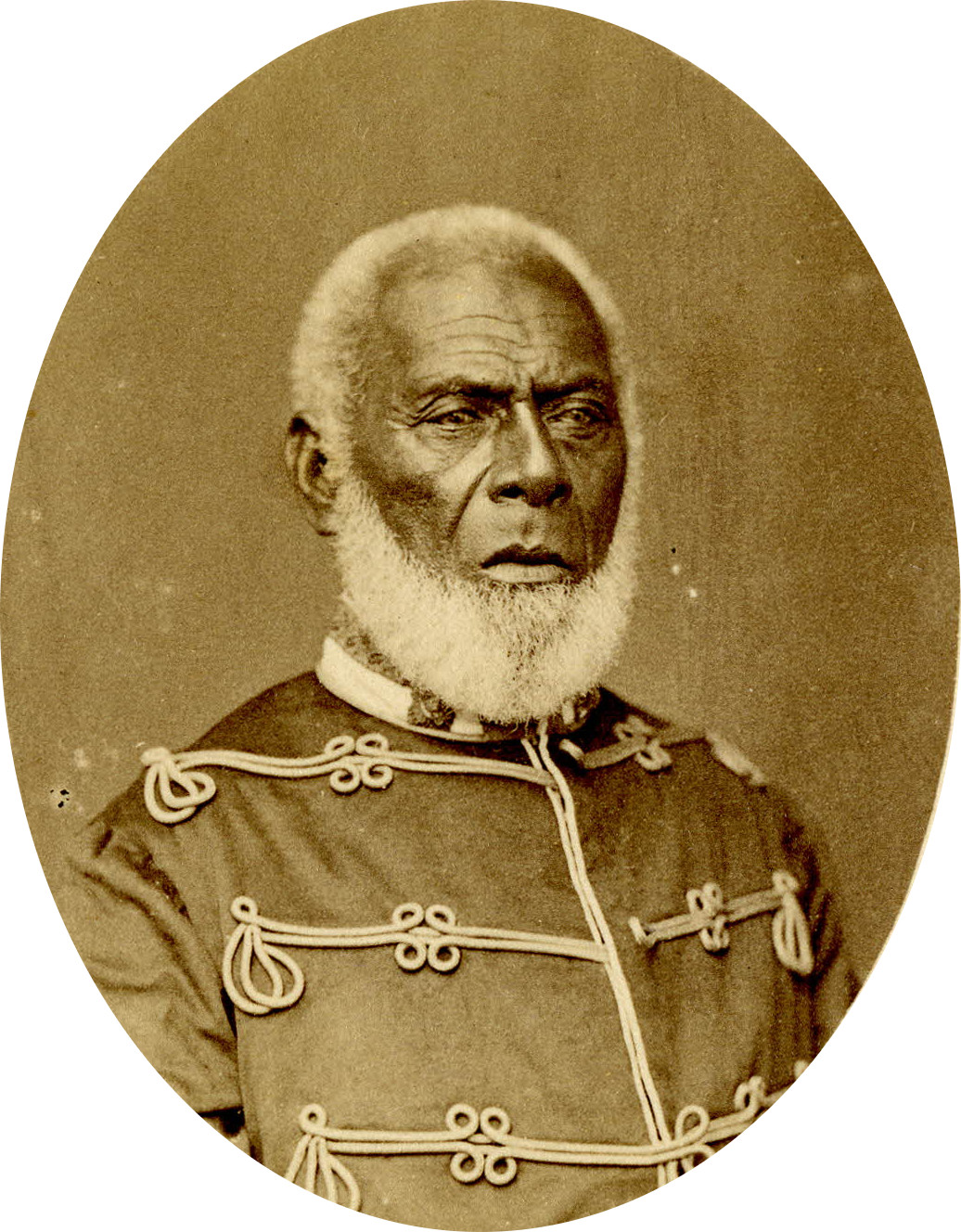

Internally, Tonga was experiencing a period of political upheaval and civil war among rival chiefly factions. This tumultuous period paved the way for the rise of Tāufaʻāhau, an ambitious young warrior, strategist, and orator from the Tuʻi Kanokupolu line. Baptized as Siaosi (George) by Methodist missionaries in 1831, Tāufaʻāhau strategically consolidated power through warfare and alliances. By 1845, he had effectively united the Tongan islands under his rule, becoming King George Tupou I.

With the assistance of missionary Shirley Waldemar Baker, King George Tupou I embarked on a series of major reforms to modernize Tonga and centralize power. In 1875, he promulgated Tonga's first written constitution, establishing a constitutional monarchy based on the Western model. This constitution formally adopted a Western royal style, emancipated commoners (serfs), enshrined a code of law and a system of land tenure (which prevented the sale of land to foreigners, a key factor in Tonga retaining its sovereignty), guaranteed freedom of the press, and limited the traditional powers of the chiefs. These reforms laid the foundation for the modern Tongan state.

3.4. Kingdom of Tonga and British Protectorate (1875 - 1970)

Following the unification of Tonga and the promulgation of the 1875 constitution under King George Tupou I, Tonga embarked on its journey as a constitutional monarchy. This period was marked by efforts to maintain internal stability and sovereignty amidst increasing European colonial pressures in the Pacific. The constitution established a framework for governance that included a monarch, a legislative assembly, a judiciary, and a system of land tenure designed to protect Tongan ownership.

Despite these efforts, internal rivalries and external influences continued. After the death of George Tupou I in 1893, his great-grandson George Tupou II ascended to the throne. Facing attempts by European settlers and rival Tongan chiefs to oust him, and amidst growing geopolitical competition among colonial powers, Tonga entered into a Treaty of Friendship with Great Britain on 18 May 1900. This treaty established Tonga as a British protectorate, formally known as the British Protected State of Tonga.

Under the protectorate status, Tonga retained its monarchy and a significant degree of internal autonomy. The Tongan government continued to manage its domestic affairs, but its foreign affairs were handled by Britain. A British Consul (from 1901 to 1970) was stationed in Tonga as Britain's representative, but unlike many other Pacific islands, Tonga never had a resident British governor, nor did it relinquish its sovereignty directly to the British Crown. The Tongan monarchy, with its uninterrupted line of hereditary rulers from one family, remained a central institution. This unique status allowed Tonga to avoid direct colonization, a distinction it holds among Pacific nations.

Social changes continued during this period, influenced by Christianity, increased contact with the outside world, and the policies of the Tongan government. Education and healthcare systems saw development, often with the involvement of missionary organizations. The 1918 flu pandemic had a devastating impact, brought by a ship from New Zealand, killing approximately 1,800 Tongans, which represented about 8% of the population at the time. Throughout the protectorate, Tongan leaders, notably Queen Sālote Tupou III (reigned 1918-1965), skillfully navigated the relationship with Britain, safeguarding Tongan interests and paving the way for eventual full independence. Queen Sālote was instrumental in making arrangements for the termination of the protectorate status before her death in 1965.

3.5. Independence and Modern Tonga (1970 - present)

Tonga regained its full sovereignty and independence from Great Britain on June 4, 1970, terminating the protectorate status that had been in place since 1900. This transition was managed under arrangements set in motion by Queen Sālote Tupou III before her death and was overseen by her son, King Tāufaʻāhau Tupou IV (reigned 1965-2006). Upon independence, Tonga joined the Commonwealth of Nations, atypically as a nation with its own indigenous monarch rather than recognizing the British monarch as Head of State, a status shared with countries like Malaysia, Lesotho, and Eswatini. Tonga later became a member of the United Nations in September 1999.

The post-independence era has been characterized by efforts to modernize the economy, develop infrastructure, and navigate its place in the regional and international community. However, a significant theme has been the ongoing political development and the push for greater democracy.

3.5.1. Political Reforms and Pro-Democracy Movement

For much of its modern history, Tonga's political system, though a constitutional monarchy, vested considerable power in the monarch and the traditional nobility. The Legislative Assembly (Fale Alea) had a limited number of representatives elected by commoners, with nobles and royal appointees holding significant influence. This structure led to the emergence of a pro-democracy movement in the late 20th century, advocating for greater popular representation, transparency, and accountability in government.

Key figures like ʻAkilisi Pōhiva became prominent in this movement, challenging the existing political order and calling for constitutional reforms. The movement gained momentum through the 1990s and 2000s, often facing resistance from the monarchy and established elites. Demands included increasing the number of popularly elected representatives in Parliament and reducing the king's direct political powers.

Public pressure and a series of events, including periods of civil unrest, gradually led to significant political reforms. In 2008, King George Tupou V (reigned 2006-2012) announced that he would relinquish most of his executive powers and allow the Prime Minister to be chosen by the elected members of Parliament. Constitutional changes were enacted, paving the way for the 2010 general election, which was the first where a majority of parliamentary seats were contested by popular vote. This marked a significant shift towards a more democratic system, transforming Tonga from a near-absolute monarchy to a semi-constitutional monarchy where the monarch retains influence but day-to-day governance is largely in the hands of elected officials. The transition has involved ongoing debates about the balance of power, the role of the monarchy, freedom of the press, and the protection of civil liberties. These reforms have been crucial in shaping Tonga's contemporary political landscape and its efforts to strengthen democratic institutions and human rights.

3.5.2. 2006 Nukuʻalofa Riots

The 2006 Nukuʻalofa riots, which occurred on November 16, 2006, in Tonga's capital, Nukuʻalofa, were a significant event in the country's modern history, deeply connected to the ongoing pro-democracy movement and frustrations over the pace of political reforms. The riots were triggered by delays in the implementation of promised democratic changes, particularly the slow progress towards a more representative parliament.

Pro-democracy activists and their supporters had been anticipating significant reforms, but when it appeared that the parliament would adjourn for the year without making substantial advancements, tensions escalated. Demonstrations turned violent, leading to widespread looting, arson, and destruction of property, primarily targeting businesses, government offices, and properties associated with the royal family or elite. A significant portion of Nukuʻalofa's downtown business district was destroyed by fires.

The riots resulted in several deaths (reports vary, but at least six people were killed) and numerous injuries. The Tongan government declared a state of emergency, and Tongan Security Forces, with assistance from troops deployed from New Zealand and Australia under a joint task force, worked to restore order.

The socio-political consequences of the riots were profound. They highlighted the deep-seated desire for democratic change among a significant portion of the Tongan population and put immense pressure on the monarchy and government to accelerate reforms. While the destruction set back the economy, the events ultimately contributed to King George Tupou V's decision in 2008 to cede many of his executive powers and to the subsequent constitutional changes that led to the more democratic elections in 2010. The riots remain a stark reminder of the challenges faced during Tonga's transition towards a more democratic system of governance and underscored the importance of addressing public grievances regarding representation and political participation.

3.5.3. 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai Eruption and Tsunami

On January 15, 2022, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai submarine volcano, located about 40 mile (65 km) north of Tonga's main island, Tongatapu, experienced a massive and violent eruption. The eruption was one of the largest volcanic events recorded globally in decades, sending a colossal plume of ash, gas, and steam tens of kilometers into the atmosphere and generating powerful atmospheric shockwaves that were detected around the world.

The eruption triggered tsunami waves that inundated coastal areas across the Tongan archipelago, including the capital, Nukuʻalofa, and several outlying islands. Waves reached heights of up to 49 ft (15 m) in some areas, causing widespread destruction to homes, infrastructure, and agricultural lands. The impact was particularly severe on low-lying islands like Mango, Fonoifua, and Nomuka in the Haʻapai group, where entire villages were destroyed. Four fatalities were confirmed in Tonga as a direct result of the tsunami, and many more were displaced. The tsunami also caused deaths and damage in other Pacific Rim countries, including two drownings in Peru due to abnormal waves.

The immediate aftermath saw Tonga largely cut off from the rest of the world. The eruption severed the nation's single submarine communications cable, disrupting internet and international phone services for several weeks. Ashfall contaminated water supplies and agricultural land, posing significant health risks and threatening food security. The Fuaʻamotu International Airport was forced to close temporarily due to ash on the runway, hindering initial relief efforts.

The humanitarian response involved both domestic efforts and significant international aid from countries like Australia, New Zealand, Japan, China, and international organizations. Relief operations focused on providing clean water, food, shelter, and medical supplies, as well as restoring communications and clearing ash.

The long-term environmental consequences include damage to coral reefs, coastal erosion, and potential impacts on marine ecosystems from volcanic deposits and altered water chemistry. Socially and economically, the event caused significant trauma, displacement, and economic disruption, particularly affecting the agriculture and fisheries sectors, which are vital to Tongan livelihoods. The recovery and rebuilding process is expected to be a long-term endeavor, highlighting Tonga's vulnerability to natural disasters and the critical need for climate resilience and disaster preparedness.

4. Geography

Tonga is an archipelago located in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the southern Pacific Ocean. It lies directly south of Samoa, about two-thirds of the way from Hawaii to New Zealand. The country is surrounded by Fiji and Wallis and Futuna (France) to the northwest, Samoa to the northeast, Niue (its nearest foreign territory) to the east, and the Kermadec Islands (New Zealand) to the southwest. Tonga is approximately 1.1 K mile (1.80 K km) from New Zealand's North Island.

The nation consists of 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. These islands are scattered over an area of approximately 270 K mile2 (700.00 K km2) of ocean, stretching about 497 mile (800 km) in a north-south line. The total land area is about 290 mile2 (750 km2). The islands are primarily divided into three main groups:

- Tongatapu**: The southernmost and largest island group, home to the capital city, Nukuʻalofa, and more than 70% of the country's population. Tongatapu island itself covers 99 mile2 (257 km2).

- Vavaʻu**: A group of hilly islands in the north, known for its deep harbor and as a popular destination for yachting and whale watching.

- Haʻapai**: A central group of low-lying coral islands and a few volcanic islands.

The geography of Tonga influences its climate, biodiversity, and susceptibility to natural hazards, playing a crucial role in the life and culture of its people.

4.1. Topography and Islands

The Tongan archipelago comprises a diverse range of islands, primarily of two geological types: volcanic islands and coral islands (limestone-based). The islands are generally aligned in two parallel chains running roughly north-south.

- The western chain consists of volcanic islands, some of which are active volcanoes. These islands are typically higher and more rugged. Examples include Kao, which is the highest point in Tonga at 3.4 K ft (1.03 K m), and Tofua, which has an active caldera. Other volcanic islands include Late, Fonualei, and the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai volcanic complex.

- The eastern chain consists mainly of low-lying coral atolls and uplifted coral limestone islands. These islands were formed by the accumulation of coral growth on subsiding volcanic bases or through tectonic uplift. Tongatapu, the largest island, is a relatively flat, uplifted coral limestone island. The Haʻapai group is predominantly made up of low coral islands, while Vavaʻu features a more complex topography with uplifted limestone forming a network of waterways and sheltered bays. The Niuas group, in the far north, includes both volcanic (e.g., Niuafoʻou) and limestone islands (e.g., Niuatoputapu).

Notable landforms include the numerous small islands (motu) that dot the archipelago, extensive coral reef systems surrounding many islands, and coastal features such as beaches, cliffs, and lagoons. A significant submarine feature associated with Tonga is the Tonga Trench, located to the east of the island chain. It is one of the deepest oceanic trenches in the world, reaching a maximum depth of over 35 K ft (10.80 K m) at the Horizon Deep. This trench is a result of the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the Indo-Australian Plate. The islands are generally characterized by fertile volcanic soils on the volcanic islands and thinner, less fertile soils on the coral islands, though often enriched by volcanic ash deposits.

4.2. Geology and Volcanism

The Tongan islands are situated in a geologically active region along the Pacific Ring of Fire. Their formation and ongoing geological processes are primarily driven by the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the Indo-Australian Plate at the Tonga Trench. This subduction zone is one ofthe most seismically active in the world and is responsible for the chain of volcanoes that form the western part of the Tongan archipelago, known as the Tongan Volcanic Arc.

The islands themselves are diverse in origin. The western islands are predominantly volcanic, formed by magma rising from the subducting Pacific Plate. Some of these volcanoes are active, with notable recent eruptions including Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai (which had a major eruption in 2022), Tofua, and Fonualei. Volcanic activity has also led to the formation of new, ephemeral islands, such as Home Reef, which has emerged and submerged multiple times following eruptions. The volcanic islands are characterized by fertile soils derived from volcanic ash.

The eastern islands are primarily limestone-based, formed from uplifted coral formations or coral growth on older, submerged volcanic edifices. Tongatapu, the largest island, is a prime example of an uplifted coral limestone platform. The Haʻapai group consists mainly of low-lying coral islands and atolls, while Vavaʻu is a complex of uplifted limestone islands.

Due to its location on an active plate boundary, Tonga is prone to significant seismic activity, including earthquakes and associated tsunamis. The convergence rate at the Tonga Trench is among the fastest on Earth, contributing to the high frequency of earthquakes. The geological setting also means Tonga possesses potential for geothermal energy, though this resource is yet to be substantially exploited. The dynamic geology of Tonga continues to shape its landscape and presents ongoing natural hazards for its population.

4.3. Climate

Tonga has a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen: Af), characterized by warm temperatures and high humidity year-round, with a distinct warmer, wetter season and a cooler, drier season.

The warm, rainy season typically runs from December to April. During this period, temperatures often rise above 89.6 °F (32 °C). This is also the main tropical cyclone season, which officially runs from November 1 to April 30, although cyclones can occasionally form outside this window. Tonga is vulnerable to the impacts of these powerful storms, which can bring destructive winds, heavy rainfall, and storm surges.

The cooler, drier season occurs from May to November. Temperatures during this time are milder, rarely exceeding 80.6 °F (27 °C). This period is influenced by the southeast trade winds, which bring more stable weather conditions.

Rainfall varies across the archipelago. The northern islands, being closer to the Equator, generally receive higher rainfall (around 0.1 K in (2.97 K mm) annually) and experience warmer temperatures (average around 80.6 °F (27 °C)) compared to the southern islands like Tongatapu, which receives around 0.1 K in (1.70 K mm) of rain annually with average temperatures around 73.4 °F (23 °C). The wettest period is usually around March, with an average rainfall of about 10 in (263 mm) in Nukuʻalofa. Average daily humidity is consistently high, around 80%.

The highest temperature recorded in Tonga was 95 °F (35 °C) on February 11, 1979, in Vavaʻu. The coldest temperature recorded was 47.66 °F (8.7 °C) on September 8, 1994, in Fuaʻamotu on Tongatapu. Temperatures of 59 °F (15 °C) or lower are more common during the dry season in southern Tonga.

Tonga is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including sea level rise, which threatens low-lying coastal areas and atolls, increased intensity of tropical cyclones, changes in rainfall patterns leading to droughts or flooding, and ocean acidification impacting coral reefs and fisheries. The WorldRiskReport 2021 ranked Tonga as third among countries with the highest disaster risk worldwide, primarily due to its exposure to multiple natural hazards.

| Climate data for Nukuʻalofa (Köppen Af) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32 (90) | 32 (90) | 31 (88) | 30 (86) | 30 (86) | 28 (82) | 28 (82) | 28 (82) | 28 (82) | 29 (84) | 30 (86) | 31 (88) | 32 (90) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.4 (84.9) | 29.9 (85.8) | 29.6 (85.3) | 28.5 (83.3) | 26.8 (80.2) | 25.8 (78.4) | 24.9 (76.8) | 24.8 (76.6) | 25.3 (77.5) | 26.4 (79.5) | 27.6 (81.7) | 28.7 (83.7) | 27.3 (81.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.4 (79.5) | 26.8 (80.2) | 26.6 (79.9) | 25.3 (77.5) | 23.6 (74.5) | 22.7 (72.9) | 21.5 (70.7) | 21.5 (70.7) | 22.0 (71.6) | 23.1 (73.6) | 24.4 (75.9) | 25.6 (78.1) | 24.1 (75.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.4 (74.1) | 23.7 (74.7) | 23.6 (74.5) | 22.1 (71.8) | 20.3 (68.5) | 19.5 (67.1) | 18.1 (64.6) | 18.2 (64.8) | 18.6 (65.5) | 19.7 (67.5) | 21.1 (70.0) | 22.5 (72.5) | 20.9 (69.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 16 (61) | 17 (63) | 15 (59) | 15 (59) | 13 (55) | 11 (52) | 10 (50) | 11 (52) | 11 (52) | 12 (54) | 13 (55) | 16 (61) | 10 (50) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 174 (6.85) | 210 (8.27) | 206 (8.11) | 165 (6.50) | 111 (4.37) | 95 (3.74) | 95 (3.74) | 117 (4.61) | 122 (4.80) | 128 (5.04) | 123 (4.84) | 175 (6.89) | 1,721 (67.76) |

| Average rainy days | 17 | 19 | 19 | 17 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 180 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77 | 78 | 79 | 76 | 78 | 77 | 75 | 75 | 74 | 74 | 73 | 75 | 76 |

| Source: Weatherbase | |||||||||||||

4.4. Ecology and Biodiversity

Tonga is part of the Tongan tropical moist forests terrestrial ecoregion. The country's biodiversity encompasses a range of terrestrial and marine ecosystems, reflecting its tropical island setting.

Terrestrial ecosystems include tropical moist forests, coastal strand vegetation, and scrublands. The original forest cover has been significantly reduced due to land clearing for agriculture and settlement, particularly on the more populated islands like Tongatapu. However, remnants of native forest persist, especially in less accessible areas and on some uninhabited islands. These forests harbor various plant species, including endemic trees and ferns. ʻEua National Park on the island of ʻEua is a key protected area for terrestrial biodiversity, known for its cloud forests and unique plant life.

Tonga's marine biodiversity is rich, centered around its extensive coral reef systems. These reefs support a wide array of fish species, corals, mollusks, crustaceans, and other marine invertebrates. The waters of Tonga are also important migratory routes and breeding grounds for marine mammals, most notably humpback whales, which visit Tongan waters annually (primarily around Vavaʻu and Haʻapai) to breed and calve. Dolphins and sea turtles are also common.

Notable flora includes various species of palms, flowering trees, and ferns. Endemic plant species, though not numerous, are found, particularly on isolated islands or in specialized habitats. Fauna includes a variety of bird species, with 73 species recorded, including two endemics: the Tongan whistler (Pachycephala jacquinoti) found in Vavaʻu, and the Tongan megapode (Megapodius pritchardii), a ground-nesting bird primarily found on Niuafoʻou. Flying foxes (fruit bats) are a distinctive part of Tonga's fauna and hold cultural significance; they are considered sacred and the property of the monarchy, which has afforded them protection and allowed their populations to thrive on many islands. Reptiles include various lizards and geckos, with some endemic species.

Conservation efforts in Tonga aim to protect its natural heritage. These include the establishment of national parks and marine protected areas, community-based resource management programs, and initiatives to combat invasive species. However, Tonga's biodiversity faces threats from habitat loss, over-exploitation of resources (such as overfishing), pollution, invasive species, and the impacts of climate change, including coral bleaching and sea level rise. The devastating 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai eruption and tsunami also had significant impacts on both marine and terrestrial ecosystems, the full extent of which is still being assessed.

5. Politics

Tonga operates as a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government. The nation has undergone significant democratic transitions in recent decades, moving from a system where the monarch held substantial executive power to one where the Prime Minister and Cabinet, responsible to an elected legislature, manage the day-to-day affairs of government. Human rights and the rule of law are important considerations in its political framework, though challenges remain.

5.1. Government and Constitution

The Constitution of Tonga, originally granted in 1875 by King George Tupou I, is the supreme law of the land and has been amended several times, most significantly in 2010 to facilitate greater democracy.

The framework of the Tongan government consists of three branches:

- The Monarch**: The King of Tonga is the Head of State. The current monarch is King Tupou VI. While the King's direct political powers have been reduced, the monarch retains significant ceremonial roles, influence, and certain prerogative powers, including the power to assent to legislation, dissolve Parliament on the advice of the Prime Minister, and appoint judges on the recommendation of judicial bodies. The monarch is also the Commander-in-Chief of His Majesty's Armed Forces. Reverence for the monarch remains a strong element of Tongan culture.

- The Legislative Assembly (Fale Alea)**: Tonga has a unicameral Legislative Assembly (Fale Alea). Following the 2010 reforms, the Assembly consists of 26 members. Seventeen members are People's Representatives, elected by popular vote from multi-member constituencies for a four-year term. Nine members are Nobles' Representatives, elected by and from amongst the 33 hereditary nobles of Tonga. The Speaker of the Assembly is elected by the members from among their number or from outside the Assembly. The Fale Alea is responsible for passing laws, approving the national budget, and holding the government accountable.

- The Executive**: The executive branch is headed by the Prime Minister, who is elected by a majority of the members of the Legislative Assembly and then formally appointed by the King. The Prime Minister is the head of government. The Prime Minister appoints Cabinet ministers, who are primarily chosen from the elected members of the Assembly. The Cabinet is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the government and is collectively responsible to the Fale Alea.

- The Judiciary**: The judiciary is independent of the executive and legislative branches. It comprises the Court of Appeal (the highest appellate court), the Supreme Court, the Magistrates' Courts, and the Land Court. Judges are appointed by the King on the recommendation of the Judicial Appointments and Discipline Panel. The Privy Council, in its judicial capacity, can also hear certain appeals. The constitution provides for the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms.

This structure reflects Tonga's unique blend of traditional authority and modern democratic principles. The transition towards a more democratic system continues to evolve, with ongoing discussions about constitutional roles and governance.

5.2. Political Culture, Human Rights, and Democratization

Tonga's political culture is a complex interplay of traditional Polynesian values, the enduring influence of the monarchy and nobility, and a growing embrace of democratic principles. For much of its history, Tongan society was characterized by a hierarchical structure with deep respect for authority, particularly that of the King and nobles. However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries saw the rise of a significant pro-democracy movement, advocating for greater popular representation, accountability, and transparency. This movement, often facing resistance, was instrumental in pushing for the constitutional and political reforms of 2008-2010, which shifted significant executive power from the monarch to an elected parliament and government.

The process of democratization is ongoing, with challenges including ensuring the full independence of democratic institutions, fostering a vibrant civil society, and managing the relationship between elected representatives and traditional leaders. Political debate can be robust, and issues such as land rights, economic development, and governance remain central to public discourse.

Human rights are protected under the Tongan Constitution, which guarantees fundamental freedoms. However, concerns have been raised by domestic and international observers regarding certain areas:

- Freedom of Speech and Press**: While generally respected, there have been instances of government attempts to control or influence the media. The media landscape includes both state-owned and private outlets.

- Freedom of Assembly**: The right to peaceful assembly is generally upheld, though demonstrations have at times faced restrictions.

- LGBT Rights**: Male same-sex sexual activity remains criminalized under Tongan law, although these laws are reportedly not strictly enforced. There is limited legal recognition or protection for LGBT individuals, and social discrimination can occur. Advocacy for LGBT rights is emerging but faces cultural and religious opposition.

- Women's Rights**: Women participate in many aspects of Tongan life, but underrepresentation in political leadership and issues related to domestic violence are ongoing concerns. Efforts are being made to promote gender equality.

- Accountability and Governance**: Issues of corruption and the need for greater accountability in government have been subjects of public concern and political debate. Strengthening mechanisms for oversight and transparency is a focus of ongoing reform efforts.

Civil society organizations, including churches, NGOs, and community groups, play an important role in Tongan society, often advocating for social issues, human rights, and good governance. The journey towards a more fully realized democracy continues to be a defining feature of Tonga's contemporary political landscape, reflecting a society navigating the balance between its rich traditions and modern democratic aspirations.

5.3. Administrative Divisions

Tonga is divided into five main administrative divisions, which serve as the primary level of sub-national government. These divisions are largely based on the main island groups. Each division is headed by a governor, appointed by the monarch on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. The divisions are:

1. **ʻEua**: This division comprises the island of ʻEua and its surrounding smaller islets. ʻEua is known for its rugged terrain and national park. The main town is ʻOhonua.

2. **Haʻapai**: This division consists of a scattered group of islands in the central part of the archipelago, including low-lying coral islands and some volcanic islands. The administrative center is Pangai on the island of Lifuka.

3. **Niuas**: The northernmost division, comprising the islands of Niuatoputapu, Niuafoʻou, and Tafahi. These are the most remote islands of Tonga. The main settlement on Niuatoputapu is Hihifo.

4. **Tongatapu**: This division includes the main island of Tongatapu, where the capital city Nukuʻalofa is located, along with several nearby smaller islands. It is the most populous and economically important division.

5. **Vavaʻu**: This division encompasses the Vavaʻu island group in the northern part of Tonga, known for its scenic beauty and sheltered harbor. The main town and administrative center is Neiafu.

These divisions are further subdivided into districts (vahe) and villages (kolo). Local governance structures exist at these lower levels, often involving town officers (ʻofisa kolo) and district officers (ʻofisa vahe), who play a role in local administration and community affairs, working under the authority of the central government and the divisional governors.

6. Military

His Majesty's Armed Forces (HMAF), formerly known as the Tonga Defence Services (TDS), is the military organization responsible for the defense of the Kingdom of Tonga. It is one of the smallest militaries in the world but plays a significant role in national security, maritime surveillance, disaster relief, and international peacekeeping. The King of Tonga is the Commander-in-Chief of HMAF.

HMAF consists of several components:

- Land Force (Tongan Royal Army)**: This includes regular infantry units and the Royal Guard. The Royal Guard is responsible for the security of the monarch and ceremonial duties.

- Tongan Maritime Force (Royal Tongan Navy)**: Responsible for maritime surveillance of Tonga's extensive Exclusive Economic Zone, search and rescue operations, fisheries protection, and inter-island transport for government purposes. It operates several patrol boats, some of which have been gifted by international partners like Australia.

- Air Wing**: A small component primarily focused on surveillance and transport, operating limited aircraft.

- Support services**: Including logistics, training, and administrative units.

The primary responsibilities of HMAF include:

- Defending Tonga's sovereignty and territorial integrity.

- Maritime surveillance and enforcement within its EEZ.

- Providing assistance during natural disasters, such as cyclones and tsunamis, through search and rescue, damage assessment, and distribution of aid.

- Supporting civilian authorities and maintaining public order when required.

- Participating in international and regional peacekeeping operations and security cooperation initiatives.

Tonga has a history of contributing personnel to international peacekeeping missions. Tongan soldiers served with the American-led "coalition of the willing" in the Iraq War, deploying contingents in 2004 and later years. They returned home by the end of 2008. HMAF also contributed a significant contingent of troops to the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, working alongside British forces. This deployment concluded in 2014. Additionally, Tonga has contributed troops and police to regional stability operations, such as in Bougainville (Papua New Guinea) and the Australian-led RAMSI in the Solomon Islands.

HMAF maintains close defense ties with countries like Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and the United Kingdom, often participating in joint training exercises and receiving assistance for capacity building and equipment. The military budget is modest, reflecting Tonga's small economy, but HMAF is considered a professional and disciplined force.

7. Foreign Relations

Tonga pursues a foreign policy aimed at maintaining its sovereignty, promoting economic development, and addressing key regional and global issues, particularly climate change. As a small island developing state, Tonga actively engages in multilateral diplomacy and maintains relationships with a range of international partners.

Key diplomatic partners include:

- Australia and New Zealand**: These are Tonga's closest and most significant partners, providing substantial development assistance, security cooperation, and being home to large Tongan diaspora communities.

- United States**: Tonga maintains cordial relations with the U.S., which has historical ties to the region and provides some development aid and security cooperation. The U.S. opened an embassy in Tonga in 2023.

- China (People's Republic of China)**: Relations with China have grown significantly in recent years. China has become a major provider of development assistance and infrastructure financing, including projects like a new royal palace and roads. This has also led to Tonga incurring substantial debt to China, which is a subject of ongoing economic consideration. Tonga adheres to the One China policy.

- Japan**: Japan is another important development partner, providing aid in areas such as infrastructure, fisheries, and disaster relief.

- United Kingdom**: While historical ties remain, the relationship is less central than in the past. The UK closed its High Commission in Nukuʻalofa in 2006 but re-established it in January 2020.

Tonga is an active member of several regional and international organizations:

- Pacific Islands Forum (PIF)**: Tonga is a full member and participates actively in regional decision-making on political, economic, and environmental issues.

- United Nations (UN)**: Tonga joined the UN in 1999 and uses the platform to advocate for issues critical to small island states, such as climate change and sustainable development.

- Commonwealth of Nations**: Tonga has been a member since its independence in 1970.

- Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS)**: Tonga is a member of this coalition, which advocates for the interests of small island nations, particularly in climate change negotiations.

A primary focus of Tonga's foreign policy is addressing the existential threat of climate change. Tonga is highly vulnerable to sea-level rise, increased storm intensity, and ocean acidification. It consistently advocates for stronger global action on climate mitigation and adaptation. In 2023, Tonga joined other vulnerable Pacific island nations in launching the "Port Vila Call for a Just Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific," calling for the phase-out of fossil fuels and a rapid transition to renewable energy. Tonga also has an ongoing maritime dispute with Fiji over the Minerva Reefs. Both nations claim sovereignty over the reefs, which are located between the two countries. Tonga asserted its claim in 1972, and the issue remains a point of contention, though diplomatic discussions have occurred.

The socio-economic impacts of its international ties are significant. Remittances from Tongans living abroad (primarily in New Zealand, Australia, and the US) are a crucial part of the national economy. Foreign aid and development partnerships also play a vital role in supporting infrastructure projects, social services, and economic development initiatives. Tonga's foreign relations are thus shaped by a combination of geopolitical considerations, economic necessities, and a strong commitment to regional cooperation and global advocacy on issues of critical importance to its survival and well-being.

8. Economy

The Tongan economy is characterized by its small scale, a large non-monetary (subsistence) sector, a heavy reliance on remittances from Tongans living abroad, and vulnerability to external shocks and natural disasters. Key sectors include agriculture, fisheries, and tourism. The government plays a significant role in the economy, and efforts are ongoing to promote private sector development and achieve sustainable economic growth while addressing social equity. Labor rights, income inequality, and sustainable development are important considerations within its economic framework.

The Tongan paʻanga (TOP) is the national currency. The National Reserve Bank of Tonga serves as the country's central bank.

Tonga's development plans emphasize diversifying the economy, upgrading agricultural productivity, developing tourism, improving infrastructure, and building resilience to climate change. Challenges include a narrow export base, distance from major markets, high transportation costs, and a susceptibility to volatile commodity prices. The royal family and nobles have historically had significant involvement in parts of the monetary sector. In 2008, Forbes magazine named Tonga the sixth-most corrupt country, though such rankings can be subjective and change over time. The March 2011 Euromoney Country Risk rankings placed Tonga as the 165th-safest investment destination. The country became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on July 27, 2007. The Tonga Chamber of Commerce and Industry, established in 1996, works to represent private sector interests.

8.1. Key Sectors

The Tongan economy is built upon several key sectors, each with its own contributions and societal impacts. These include agriculture and fisheries, which form the backbone of rural livelihoods, tourism, which is a growing source of foreign exchange, and the significant inflow of remittances.

8.1.1. Agriculture and Fisheries

Agriculture and fisheries are fundamental to the Tongan economy, providing the majority of employment, a significant portion of foreign exchange earnings, and essential food security for the population. Rural Tongans largely depend on both plantation (cash crop) and subsistence farming.

Key agricultural products include:

- Squash**: A major export crop, primarily destined for the Japanese market, particularly during the Northern Hemisphere's off-season. The industry began in the late 1980s and has been a vital source of income, though it is subject to price fluctuations and market risks.

- Coconuts**: Coconuts and their products, such as copra (dried coconut kernel) and coconut oil, have historically been important. Desiccated coconut was once a significant industry, but declining world prices and lack of replanting have impacted this sector.

- Vanilla**: Vanilla beans are another important cash crop, cultivated for export.

- Root Crops**: Staple food crops for domestic consumption and some export include taro, yam, cassava, and sweet potato. These form the basis of the traditional Tongan diet.

Livestock production primarily involves pigs and poultry, which are important for local consumption and cultural feasts. Horses are kept for draft purposes, especially by farmers. Cattle raising is increasing, leading to a decline in beef imports. Forestry resources are limited.

The fisheries sector is also crucial. Tonga has a substantial Exclusive Economic Zone rich in marine resources. The sector includes:

- Coastal Fisheries**: Supplying local markets and subsistence needs. This involves reef fish, shellfish, and other coastal marine life.

- Offshore Fisheries**: Primarily targeting tuna (such as albacore, yellowfin, and bigeye) for export. The government licenses both domestic and foreign fishing vessels.

- Aquaculture**: There are efforts to develop aquaculture, particularly for species like seaweed and giant clams.

Sustainability challenges in both agriculture and fisheries are significant. These include overfishing in coastal areas, the impacts of climate change (e.g., on coral reefs and crop yields), soil degradation, and vulnerability to natural disasters. Traditional land tenure systems, where farmers may not have full ownership security, can also affect long-term investment in agricultural improvements. Efforts are underway to promote sustainable farming and fishing practices, improve post-harvest handling, and diversify agricultural exports.

8.1.2. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing sector in the Tongan economy, recognized by the government as having major potential for economic development and foreign exchange earnings. The industry is relatively undeveloped compared to some other Pacific destinations but offers unique attractions.

Key attractions for tourists include:

- Whale watching**: Tonga is renowned as one of the world's premier destinations for swimming with and observing humpback whales. These whales migrate to Tongan waters (particularly around Vavaʻu, Haʻapai, and ʻEua) between July and October to breed and calve. This is a major drawcard for international visitors.

- Cultural Experiences**: Tourists can engage with Tongan culture through village visits, traditional feasts (pola), music and dance performances (like the Lakalaka and Tauʻolunga), and learning about local crafts such as ngatu (tapa cloth) making.

- Beaches and Marine Activities**: Tonga's numerous islands offer pristine beaches, clear waters, and extensive coral reefs, making it suitable for snorkeling, diving, kayaking, sailing, and game fishing. Vavaʻu, with its sheltered harbor, is a particularly popular hub for yachting.

- Natural Beauty**: The diverse island landscapes, from volcanic peaks to lush tropical forests and limestone caves, appeal to eco-tourists and adventurers.

The economic impact of tourism is substantial, contributing to employment, income generation, and supporting local businesses such as hotels, tour operators, and handicraft producers. Community involvement in tourism is encouraged, with efforts to ensure that benefits flow to local communities.

The government and tourism authorities are working towards sustainable tourism development. This includes initiatives to protect the marine environment (especially crucial for whale watching), manage visitor numbers to prevent overcrowding, promote eco-friendly practices, and enhance infrastructure such as airports, roads, and accommodation. Challenges include air access, marketing the destination internationally, and ensuring consistent service quality. Cruise ships frequently stop in Vavaʻu and Nukuʻalofa, contributing to visitor arrivals. Tonga's postage stamps, often featuring colorful and unusual designs (including heart-shaped and banana-shaped stamps), are also popular with philatelists and can be considered a niche tourism-related product. The tourism industry saw a decline in visitors after the onset of the 2008 global economic crisis, with numbers under 90,000 tourists per year for a period, but efforts continue to revitalize and grow this key sector.

8.2. Trade, Remittances, and Aid

Tonga's economy is significantly influenced by its external economic relationships, particularly in the areas of international trade, the flow of remittances from its diaspora, and reliance on foreign aid.

- Trade**: Tonga has a narrow export base, primarily reliant on agricultural products and fish.

- Exports**: Key exports include squash (mainly to Japan), fish (especially tuna), vanilla beans, root crops, and some handicrafts.

- Imports**: Tonga imports a wide range of goods, including food products, fuel, machinery, manufactured goods, and vehicles.

- Trading Partners**: Major export destinations include Japan, the United States, New Zealand, and South Korea. Primary sources of imports are Fiji, New Zealand, China, and the United States.

Tonga faces a persistent trade deficit, with the value of imports significantly exceeding that of exports. Challenges to expanding trade include high transportation costs, distance from major markets, and vulnerability to global price fluctuations for its primary commodities.

- Remittances**: Remittances from Tongans living and working abroad are a critical component of the Tongan economy, often constituting one of the largest sources of foreign exchange and significantly supporting household incomes. The Tongan diaspora is substantial, with large communities in New Zealand, Australia, and the United States. These overseas Tongans regularly send money back to their families in Tonga. Remittances help to alleviate poverty, support consumption, and fund small-scale investments. However, the flow of remittances can be vulnerable to economic conditions in host countries, as seen with declines following the 2008 global economic crisis. The government has recognized the importance of the diaspora and has taken steps such as amending citizenship laws in 2007 to allow Tongans to hold dual citizenship, partly to maintain these vital connections.

- Aid**: Foreign aid (Official Development Assistance) plays a crucial role in Tonga's development, funding infrastructure projects (such as roads, airports, and utilities), social services (like health and education), and capacity-building initiatives. Major aid donors include Australia, New Zealand, Japan, the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, and increasingly, China. Aid effectiveness and the management of aid-funded projects are important considerations for the Tongan government. The reliance on aid also makes Tonga susceptible to the priorities and policies of donor countries and institutions.

These three elements - trade, remittances, and aid - underscore Tonga's interconnectedness with the global economy and the particular vulnerabilities and opportunities faced by a small island developing state.

8.3. Energy

Tonga's energy sector is heavily reliant on imported fossil fuels, primarily diesel, for electricity generation and transportation. This dependence makes the country vulnerable to volatile global oil prices and contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. Energy consumption was projected to reach around 66 gigawatt-hours by 2020.

Electricity is mainly generated by diesel-powered plants operated by Tonga Power Ltd., the state-owned utility. Access to electricity is relatively high on the main island of Tongatapu but can be more limited or reliant on smaller, independent generators on outer islands. The cost of electricity is generally high due to the reliance on imported fuels.

Recognizing the economic and environmental unsustainability of fossil fuel dependence, Tonga has set ambitious goals for transitioning to renewable energy. The Tonga Energy Road Map (TERM) 2010-2020 aimed for a 50% reduction in diesel importation for power generation by 2020, to be achieved through a mix of renewable technologies and energy efficiency measures. As of 2018, Tonga was generating about 10% of its electricity from renewable sources. The country has continued to pursue renewable energy targets beyond 2020.

Key renewable energy initiatives include:

- Solar power**: Solar energy is considered the most promising renewable resource for Tonga. Several solar photovoltaic (PV) projects have been implemented, including grid-connected solar farms and smaller off-grid systems for outer islands and individual households. In 2019, Tonga announced the construction of a 6-megawatt solar farm on Tongatapu, intended to be the second-largest solar plant in the Pacific at the time of its completion.

- Wind power**: Wind power potential has also been explored, though large-scale deployment has been more limited compared to solar.

- Energy Efficiency**: Efforts are also underway to promote energy efficiency in households, businesses, and government operations.

The transition to renewable energy faces challenges, including the high upfront costs of renewable technologies, the need for grid upgrades to accommodate intermittent renewable sources, technical capacity building, and securing sustainable financing. International partners and organizations like the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and the Green Climate Fund have been instrumental in supporting Tonga's renewable energy projects. The Pacific Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (PCREEE) was established in Tonga in 2016 to advise the private sector, provide capacity development, and promote business investment in renewable energy. This center is part of a global network aimed at attracting international investment in the sector.

8.4. Economic Challenges and Social Impact

Tonga faces a range of significant economic challenges common to many Small Island Developing States (SIDS), which have profound social impacts on its population. Efforts towards poverty reduction and equitable development are central to addressing these issues.

Key economic challenges include:

- Small Scale and Remoteness**: The small size of the domestic market and Tonga's geographical isolation lead to high transportation costs, limited economies of scale, and difficulty in competing in global markets.

- Narrow Economic Base**: The economy is heavily reliant on a few sectors, primarily agriculture (especially squash and vanilla), fisheries, tourism, and remittances. This lack of diversification makes it vulnerable to shocks in any one sector (e.g., crop failures, downturns in tourism, or fluctuations in remittance flows).

- Vulnerability to External Shocks**: Tonga is highly susceptible to global economic downturns (which can affect tourism and remittances), fluctuations in commodity prices (for its exports and imported fuel), and the impacts of natural disasters.

- Natural Disasters and Climate Change**: The country is frequently affected by tropical cyclones, volcanic activity (as seen with the 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai eruption), and earthquakes. Climate change exacerbates these risks through sea-level rise, increased storm intensity, and threats to agriculture and fisheries. The costs of disaster recovery and adaptation are substantial.

- National Debt**: Tonga has accumulated significant external debt, partly due to loans for infrastructure projects. Managing this debt sustainably is a major challenge, particularly given its limited revenue-generating capacity. A significant portion of this debt is owed to China.

- Limited Private Sector Development**: While efforts are underway to promote the private sector, it remains relatively small. Challenges include access to finance, a complex regulatory environment, and a shortage of skilled labor in some areas.

- Brain Drain**: The emigration of skilled Tongans seeking better opportunities abroad, while generating remittances, can also lead to a shortage of skilled professionals within the country.

Social impacts of these economic challenges include:

- Poverty and Inequality**: While Tonga has made progress in human development, poverty and income inequality persist. Vulnerable groups, including those in outer islands and those reliant on agriculture, can be particularly affected by economic downturns or disasters.

- Employment**: Limited formal employment opportunities, especially for youth, are a concern. Many Tongans rely on informal sector activities, subsistence agriculture, or seek employment overseas.

- Cost of Living**: Reliance on imported goods, including food and fuel, can lead to a high cost of living, particularly when global prices rise.

- Access to Services**: Providing equitable access to essential services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure across all islands remains a challenge due to geographical dispersion and resource constraints.

The Tongan government, often with support from international partners, implements various strategies to address these challenges. These include efforts to diversify the economy (e.g., by developing niche agricultural products or expanding tourism), invest in resilient infrastructure, promote sustainable resource management, improve fiscal management, and strengthen social safety nets. Poverty reduction programs and initiatives aimed at equitable development are key components of national development plans, seeking to ensure that economic progress benefits all segments of Tongan society.

9. Demographics and Society

Tonga's demographics and societal structure are shaped by its Polynesian heritage, the significant influence of Christianity, a large diaspora, and ongoing processes of modernization. The population is relatively small and homogenous, with strong community and kinship ties. Social well-being and development are key focuses for the nation.

9.1. Population and Ethnic Groups

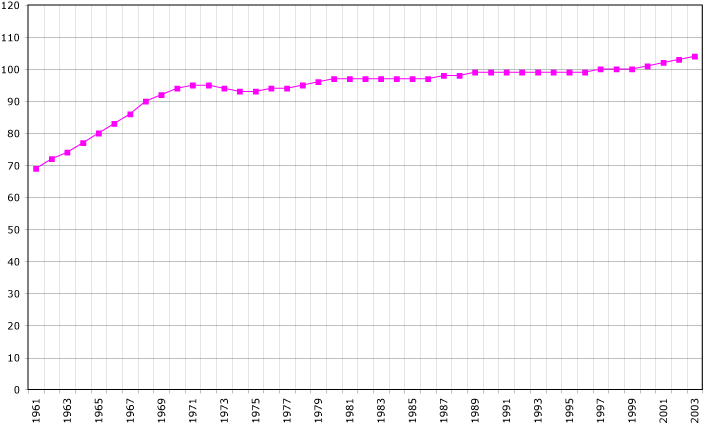

According to the United Nations estimates, Tonga had a population of approximately 104,494 as of 2021. Over 70% of the inhabitants reside on the main island of Tongatapu, particularly in and around the capital, Nukuʻalofa, which is the only significant urban center. While urbanization is increasing, village life remains influential. The population grew from about 32,000 in the 1930s to over 90,000 by 1976, despite emigration.

Ethnically, the population is predominantly Polynesian. According to government sources, Tongans, who are Polynesian with some Melanesian admixture, represent more than 98% of the inhabitants. About 1.5% are of mixed Tongan descent. Other minority groups are very small and include Europeans (mostly British), other Pacific Islanders, and Asians. In 2001, there were an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 ethnic Chinese residents, constituting 3-4% of the population. However, following the 2006 Nukuʻalofa riots, which targeted some Chinese-owned businesses, a number of Chinese residents emigrated, reducing their numbers to around 300 according to some estimates.

Population density varies across the islands, being highest on Tongatapu. Population distribution is also affected by internal migration from outer islands to Tongatapu in search of economic and educational opportunities.

The Tongan diaspora is substantial, with more Tongans living abroad (primarily in New Zealand, Australia, and the United States) than in Tonga itself. In 2018, 82,389 people of Tongan ethnicity lived in New Zealand. As of 2000, 36,840 Tongans lived in the US, and over 8,000 in Australia. This diaspora plays a crucial role in the Tongan economy through remittances and maintains strong ties with relatives in Tonga.

9.2. Languages

The official languages of Tonga are Tongan (lea fakatongaTongan languageTonga (Tonga Islands)) and English.

- Tongan** is an Austronesian language belonging to the Polynesian branch, specifically the Tongic subgroup. It is closely related to Niuean (the language of Niue) and the nearly extinct Niuafoʻouan. It is more distantly related to other Polynesian languages such as Samoan, Hawaiian, Māori, and Tahitian. Tongan is the primary language spoken in everyday life by the vast majority of the population. It is used in homes, communities, and many official settings. There are dialectal variations, particularly between the main island groups.

- English** is widely used in government, business, education, and for international communication. It is taught in schools from an early age, and many Tongans, especially in urban areas and among younger generations, are bilingual. Official documents and media are often available in both Tongan and English.

The literacy rate in Tonga is high. There are no other indigenous languages spoken in Tonga, though languages of immigrant communities (such as Chinese) may be used within those groups. The preservation and promotion of the Tongan language are important cultural priorities.

9.3. Religion

Religion plays a highly significant role in Tongan society, influencing daily life, culture, law, and politics. Christianity is the dominant religion, with the vast majority of the population identifying as Christian. Tonga does not have an official state religion, and the Constitution of Tonga provides for freedom of religion.

The main Christian denominations in Tonga, according to the 2011 census, include:

- Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga (Siasi Uēsiliana Tauʻatāina ʻo Tonga)**: This is the largest denomination, with about 36% of the population (36,592 adherents in 2011). It has historical ties to the monarchy, and Queen Sālote Tupou III established it as the state church in 1928, a status that has since changed, though it retains significant influence. The chief pastor of the Free Wesleyan Church often plays a role in state ceremonies like coronations.

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons)**: This denomination has a substantial presence, with about 18% of the population (18,554 adherents in 2011). Missionaries from the LDS Church first arrived in 1891.

- Roman Catholic Church**: Adhered to by about 15% of the population (15,441 adherents in 2011).

- Free Church of Tonga (Siasi ʻo Tonga Tauʻatāina)**: This denomination accounted for about 12% of the population (11,863 adherents in 2011). It separated from the Free Wesleyan Church in 1928 in opposition to its establishment as a state religion at that time.

The influence of Christianity is pervasive. Sunday is observed as a strict day of rest (Sabbath), as mandated by the Constitution. Most commercial and entertainment activities cease from midnight Saturday to midnight Sunday. Church attendance is generally high, and religious values are deeply ingrained in the social fabric. Religious leaders often hold respected positions in the community.

While Christianity is predominant, other religions are present in much smaller numbers. Islam is a minority religion, with a small Sunni Muslim community and a mosque (Al-Khadeejah Mosque) in Tonga. Religious freedom is generally respected, but the strong Christian ethos of the country can influence social attitudes and public policy.

9.4. Education

Education is highly valued in Tongan society, and the country has achieved relatively high literacy rates and educational attainment levels compared to some other Pacific island nations. The literacy rate is reported to be 98.9%.

- Structure and Policies**:

- Levels of Education**:

- Primary Education**: Focuses on foundational literacy, numeracy, and general subjects.

- Secondary Education**: Offers a broader range of subjects, preparing students for further education or vocational training. Nominal fees may be charged for secondary education in state schools, while mission schools have their own fee structures.

- Higher Education and Vocational Training**: Opportunities for higher education within Tonga are somewhat limited but include:

- Teacher training colleges.

- Nursing and medical training programs.

- A small private university.

- A women's business college.

- Several private agricultural schools.

- The University of the South Pacific (USP) has a campus in Tonga, offering a range of degree and certificate programs.

Many Tongans pursue higher education degrees (including medical and graduate degrees) overseas, often through scholarships funded by foreign governments or institutions, particularly in New Zealand, Australia, and Fiji.

- Opportunities and Challenges**:

- Access**: While primary education is compulsory and largely accessible, access to quality secondary and higher education can be more challenging, especially for students from outer islands or lower-income families.

- Quality**: Maintaining and improving the quality of education, including teacher training, curriculum relevance, and learning resources, is an ongoing focus.

- Brain Drain**: The emigration of educated and skilled Tongans can pose a challenge, although remittances from the diaspora also contribute significantly to the economy.

- Kukū Kaunaka Collection**: Tongan scholars and their academic achievements are held in high esteem. The Kukū Kaunaka Collection, curated at the Institute for Education in Tonga, archives every doctoral and master's dissertation written by any Tongan worldwide, reflecting the value placed on academic knowledge.

Overall, Tonga's education system aims to provide foundational learning for all citizens and pathways for further development, though it faces resource constraints and challenges common to small island developing states.

9.5. Health

Public health in Tonga faces a mix of challenges typical of developing nations and specific issues related to lifestyle and environment in the Pacific islands. The government provides a national healthcare system with services largely free or at minimal cost to citizens.

- Key Health Indicators and Concerns**:

- Life Expectancy**: Life expectancy at birth is around 71 years for males and 74 years for females (estimates vary).

- Infant Mortality**: Infant mortality rates have seen improvement but remain a concern compared to more developed nations.

- Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs)**: Tonga has one of the highest rates of obesity in the world. According to World Health Organization (WHO) data from 2014, Tonga ranked fourth globally in mean body mass index (BMI). In 2011, 90% of the adult population was considered overweight, with over 60% classified as obese. High rates of obesity contribute to a significant burden of NCDs such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. These are major causes of morbidity and mortality. Dietary changes, including increased consumption of imported processed foods (like mutton flaps) and reduced intake of traditional, healthier foods, along with sedentary lifestyles, are contributing factors.

- Infectious Diseases**: While NCDs are the primary concern, Tonga also manages infectious diseases, though major tropical diseases are not as prevalent as in some other regions. Immunization programs are in place.

- COVID-19**: Tonga remained free of COVID-19 for a significant period due to strict border controls. It reported its first case in late October 2021 from an air passenger arriving from New Zealand. The 2022 volcanic eruption and tsunami complicated COVID-19 prevention efforts during the initial international aid response.

- Healthcare System**:

Challenges to the healthcare system include limited financial and human resources, the high cost of medical supplies and equipment (much of which is imported), and the logistical difficulties of providing services across a dispersed archipelago. Addressing the NCD crisis through public health campaigns, promoting healthy lifestyles, and improving access to preventative care are major priorities for Tonga's health sector.

10. Infrastructure

Tonga's infrastructure, encompassing transportation, communications, and other essential services, faces challenges typical of a small, geographically dispersed island nation. Development efforts, often supported by international aid, focus on improving connectivity, resilience, and access to basic services for its population.

10.1. Transport

Tonga's transportation network is vital for connecting its scattered islands and facilitating trade and movement of people.

- Air Transport**:

- Fuaʻamotu International Airport (TBU) on Tongatapu is the main international gateway, serving flights to and from countries like New Zealand, Australia, Fiji, and Samoa. Airlines operating international routes include Air New Zealand, Fiji Airways, and Qantas.

- Domestic air services connect Tongatapu with other island groups like Vavaʻu, Haʻapai, and ʻEua. Lupepauʻu International Airport (VAV) in Vavaʻu also handles some international flights, primarily from Fiji. Domestic air travel is crucial for inter-island connectivity, especially for more distant islands. Real Tonga Airlines was the primary domestic carrier for a period. Challenges include the cost of domestic flights and maintaining regular services to all inhabited islands.

- Maritime Transport**:

- Inter-island shipping is essential for the movement of goods and passengers between Tonga's islands. A fleet of ferries and cargo vessels operates, though services can sometimes be irregular or affected by weather conditions. Safety and reliability of inter-island shipping are ongoing concerns.

- The main international port is the Port of Nukuʻalofa on Tongatapu, which handles most of the country's cargo imports and exports. Other significant ports include Neiafu in Vavaʻu (popular with yachts) and Pangai in Haʻapai.

- Road Systems**:

- Tonga has a network of roads, particularly on the main island of Tongatapu. The total road length is approximately 423 mile (680 km), of which a portion is paved (around 114 mile (184 km)).

- Road conditions vary, with paved roads generally found in urban areas and main routes, while rural and outer island roads may be unpaved and of lower quality.

- Maintenance of the road network is a challenge due to resource constraints and the impact of weather events like heavy rain and cyclones.

- Vehicles drive on the left-hand side of the road. Public transport primarily consists of buses and taxis, especially in Nukuʻalofa.

Challenges in the transport sector include the high cost of fuel, maintaining infrastructure across numerous islands, ensuring safety standards, and building resilience to natural disasters which can damage ports, airports, and roads. Improving inter-island connectivity remains a priority for economic development and access to services for outer island populations.

10.2. Communications and Media

Tonga's communications infrastructure and media landscape have been developing, though challenges related to its geography and economy persist.

- Telecommunications**:

- Telephone Services**: Fixed-line telephone services are available, primarily in urban areas. Mobile phone penetration is relatively high, with services provided by companies like Digicel Tonga and Tonga Communications Corporation (TCC). Mobile networks cover most inhabited islands.

- Internet**: Internet access has been improving, largely through mobile broadband and the Tonga Cable System, a submarine fiber optic cable connecting Tonga to international networks via Fiji. This cable significantly improved internet speeds and reliability compared to previous satellite-based connections. However, the cable was severely damaged during the 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai eruption and tsunami, highlighting the vulnerability of this critical infrastructure; repairs took several weeks. Internet cafes are available in Nukuʻalofa, and access is expanding, though affordability and digital literacy can still be barriers.

- Media Landscape**: