1. Overview

New Zealand, known in Māori as AotearoaLand of the long white cloudMaori, is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It comprises two main landmasses-the North Island (Te Ika-a-MāuiThe fish of MāuiMaori) and the South Island (Te WaipounamuThe waters of greenstoneMaori)-and over 700 smaller islands. Geographically, it is notable for its varied topography, including the Southern Alps and volcanic plateaus, a result of tectonic uplift and volcanic activity. Historically, New Zealand was one of the last major landmasses settled by humans, with Polynesians arriving and developing a distinct Māori culture between 1280 and 1350 CE. European contact began in 1642, leading to British colonisation and the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, a document whose interpretation continues to shape Crown-Māori relations.

Politically, New Zealand is a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy, with Charles III as its head of state, represented by a Governor-General. The nation's capital is Wellington, while Auckland is its most populous city. Economically, it is a developed country with a market economy, historically reliant on agriculture but now diversified, with a significant service sector and tourism industry. Socially, New Zealand is committed to social justice and human rights, though challenges related to economic inequality and structural discrimination, particularly affecting Māori and Pasifika peoples, persist. Culturally, New Zealand is a blend of Māori, European, and more recent immigrant influences, reflected in its languages, arts, and societal values. This article explores these aspects from a center-left perspective, emphasizing democratic development, human rights, and the well-being of all its communities, especially minorities and vulnerable groups.

2. Etymology

The name "New Zealand" originated with Dutch cartographers. In 1642, Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to sight the islands, naming them Staten Land, believing they were part of a landmass off the southern tip of South America. After Hendrik Brouwer proved in 1643 that the South American land was an island, Dutch cartographers renamed Tasman's discovery Nova ZeelandiaNova ZeelandiaLatin, after the Dutch province of Zeeland. This was later anglicised to "New Zealand" by British explorer Captain James Cook, who extensively mapped the coastline in 1769. In the Māori language, the name was rendered as Nu Tireni or Nu Tirani.

AotearoaLand of the long white cloudMaori is the most widely known and accepted Māori name for New Zealand. Its precise origin is subject to various traditions, with some attributing it to the explorer Kupe. Originally, AotearoaAotearoaMaori may have referred only to the North Island. Before European arrival, Māori did not have a single, universally accepted name for the entire archipelago. Traditional names for the main islands include Te Ika-a-MāuiThe fish of MāuiMaori for the North Island, and Te WaipounamuThe waters of greenstoneMaori or Te Waka o AorakiThe canoe of AorakiMaori for the South Island.

Early European maps sometimes labelled the islands as North, Middle (for the South Island), and South (for Stewart Island). By the early 20th century, "North Island" and "South Island" became the common English names. In 2013, the New Zealand Geographic Board formalised these names alongside their Māori equivalents: North Island or Te Ika-a-MāuiThe fish of MāuiMaori, and South Island or Te WaipounamuThe waters of greenstoneMaori. The combined form "Aotearoa New Zealand" is increasingly used in both official and unofficial contexts to reflect the nation's bicultural heritage, although "Aotearoa" alone as the official name is a subject of ongoing discussion and advocacy, particularly by the Māori Party.

3. History

New Zealand's history is marked by several distinct periods: the initial Polynesian settlement and development of Māori society, European arrival and subsequent colonisation, the conflicts and accommodations between Māori and Pākehā (Europeans), its evolution as a British dominion towards full independence, and its development as a modern nation facing contemporary challenges. This history is central to understanding New Zealand's bicultural foundation and its ongoing efforts towards social justice and reconciliation.

3.1. Polynesian settlement and Māori culture

New Zealand was one of the last major landmasses to be settled by humans. The first settlers were Polynesians who arrived in ocean-going wakacanoesMaori in several waves between approximately 1280 and 1350 CE. Radiocarbon dating, evidence of deforestation, and mitochondrial DNA variability within Māori populations support this timeframe. These settlers originated from East Polynesia, concluding a long series of voyages across the Pacific. According to many Māori oral traditions, the mythical explorer Kupe was the first to discover the islands. Over centuries, these Polynesian settlers developed a distinct culture and society, becoming known as the Māori.

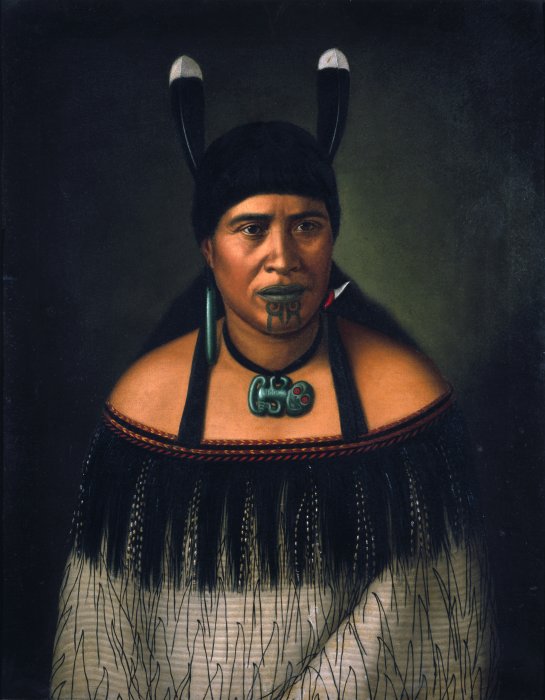

Māori society was tribal, organised into iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes or clans), which were the main political and social units. Leadership was provided by rangatira (chiefs) and tohunga (priests or skilled experts), whose positions often depended on lineage, skill, and community approval. Māori developed a rich oral culture, including intricate mythologies, genealogies (whakapapagenealogiesMaori), and art forms such as carving (whakairocarvingMaori), weaving (rarangaweavingMaori), and tattooing (tā mokotattooingMaori). Their spiritual life was deeply connected to the natural world, with concepts like tapusacred/forbiddenMaori and manaspiritual power/authorityMaori playing crucial roles. They adapted their Polynesian agricultural practices to New Zealand's temperate climate, cultivating crops like kūmarasweet potatoMaori, taro, and yams, and relied on hunting (notably the now-extinct moa), fishing, and gathering native plants. Some Māori later migrated to the Chatham Islands, where they developed the distinct Moriori culture.

3.2. European arrival and early interactions

The first European to sight New Zealand was Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642. During a tense encounter in what is now Golden Bay, four of Tasman's crew were killed, and at least one Māori was hit by canister shot. Tasman named the land Staten Landt. Europeans did not return until 1769, when British explorer Captain James Cook arrived on the Endeavour. Cook and his crew, including the Tahitian navigator Tupaia who could communicate with Māori, extensively mapped the coastline and made detailed observations of the land and its people.

Following Cook, New Zealand was visited by increasing numbers of European and North American whalers, sealers, and traders. These early interactions were complex, involving both cooperation and conflict. Māori engaged in trade, exchanging resources like timber, flax (harakekeflaxMaori), and provisions for European goods such as metal tools, cloth, and, significantly, muskets. The introduction of potatoes and muskets had a profound impact on Māori society. Potatoes provided a reliable food surplus, supporting larger populations and enabling longer military campaigns. Muskets, acquired by some tribes earlier than others, led to a period of intense intertribal warfare known as the Musket Wars (roughly 1801-1840). These conflicts resulted in significant loss of life, estimated at 30,000-40,000 Māori, and major shifts in tribal territories and power dynamics.

Christian missionaries, primarily from Britain, began to arrive in the early 19th century, starting with Samuel Marsden of the Church Missionary Society in 1814. They established mission stations, introduced literacy in Māori, and gradually converted a large portion of the Māori population to Christianity. However, the arrival of Europeans also brought devastating diseases to which Māori had no immunity, such as measles, influenza, and tuberculosis, leading to a significant decline in the Māori population throughout the 19th century.

3.3. Treaty of Waitangi and colonisation

By the 1830s, increasing European settlement, lawlessness, and concerns about potential French annexation prompted the British government to consider formal intervention in New Zealand. In 1832, James Busby was appointed as the British Resident, a consular-type role with limited authority. In 1835, following a rumour of a French attempt to claim sovereignty, Busby helped a confederation of northern Māori chiefs, known as the United Tribes of New Zealand, to declare the Independence of New Zealand, seeking British protection.

The British government, influenced by humanitarian concerns and the lobbying of the New Zealand Company (which was planning large-scale colonisation), dispatched Captain William Hobson to negotiate a treaty with Māori chiefs. The Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o WaitangiThe Treaty of WaitangiMaori) was first signed on 6 February 1840, at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands, by Hobson on behalf of the British Crown and numerous Māori chiefs. Copies of the treaty were then taken around the country for further signatures.

The Treaty exists in English and Māori versions, and significant differences in wording and interpretation between the two have been a source of contention ever since. In the English version, Māori chiefs ceded "sovereignty" to the British Crown. In the Māori version, chiefs granted kāwanatangagovernorshipMaori to the Crown, while retaining tino rangatiratangaabsolute sovereigntyMaori over their lands, villages, and taongatreasuresMaori. The treaty also guaranteed Māori the rights and privileges of British subjects and affirmed Crown pre-emption over land sales.

Despite the differing interpretations, the Treaty paved the way for British colonisation. Hobson proclaimed British sovereignty over New Zealand on 21 May 1840. New Zealand initially became a dependency of the Colony of New South Wales and then a separate Crown Colony in 1841. Organised settlement, largely driven by the New Zealand Company and other associations, brought thousands of British immigrants to New Zealand, leading to increased pressure for land and resources, which often conflicted with Māori interests and understandings of the Treaty.

3.3.1. New Zealand Wars and land confiscations

Disputes over land ownership and sovereignty, exacerbated by cultural misunderstandings and violations of the Treaty of Waitangi, led to a series of armed conflicts between Māori and colonial forces (including British imperial troops and local militia) from the 1840s to the 1870s. These conflicts are collectively known as the New Zealand Wars (or the Land Wars; Māori: Nga Pakanga o AotearoaThe Wars of AotearoaMaori).

Major conflicts included the Northern War (1845-46) in the Bay of Islands, the Taranaki Wars (starting in the early 1860s), and the Waikato War (1863-64). Māori tribes, though often outnumbered and outgunned, demonstrated sophisticated military tactics, including the use of fortified pāfortified villagesMaori. Figures like Hōne Heke, Te Kooti, and Tītokowaru became prominent leaders of Māori resistance. The colonial government, determined to assert its authority and acquire land for settlement, responded with military force.

A significant and devastating consequence of the wars was the large-scale confiscation (raupatuconfiscationMaori) of Māori land by the colonial government, particularly in the Waikato, Taranaki, and Bay of Plenty regions. Millions of acres were taken, often from tribes deemed to be "in rebellion," though sometimes from neutral or even pro-government tribes. This land was then made available for European settlement. The confiscations, along with ongoing land purchases (often through dubious means), severely undermined Māori economic and social structures, leading to widespread poverty, displacement, and deep-seated grievances that continue to be addressed in contemporary New Zealand through the Treaty settlement process. The wars and confiscations had a profound and lasting negative impact on Māori autonomy, culture, and well-being.

3.4. Dominion and path to independence

New Zealand gained a representative government with the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852, which established a General Assembly (Parliament) and provincial councils. The first Parliament met in 1854. By 1856, the colony achieved responsible government, meaning ministers became accountable to Parliament rather than the Governor, for most domestic matters except "native policy," which remained under Crown control until the mid-1860s. In 1865, the capital was moved from Auckland to the more centrally located Wellington.

New Zealand chose not to join the Federation of Australia in 1901, preferring to forge its own national identity. In 1907, New Zealand was granted Dominion status within the British Empire, signifying its effective self-government. New Zealanders participated significantly in World War I on the side of Britain and the Allies. The Gallipoli Campaign in 1915, despite its military failure, became a foundational moment in New Zealand's national consciousness and the ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) tradition. The war exacted a heavy toll, with a high per capita casualty rate.

The path to full legal independence was gradual. The Balfour Declaration of 1926 recognised the Dominions as autonomous communities within the British Empire. This was formalised by the Statute of Westminster 1931, which, once adopted by a Dominion's parliament, would remove most of the British Parliament's authority to legislate for that Dominion. New Zealand was initially reluctant to adopt the Statute, valuing its close ties to Britain. However, it eventually passed the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1947, marking full statutory independence. The monarch remained the head of state, represented by the Governor-General. Final legislative links with Britain were severed with the Constitution Act 1986, and the right of appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London was abolished in 2003, replaced by the Supreme Court of New Zealand.

3.5. 20th century

The 20th century saw New Zealand transform socially, economically, and politically. The early part of the century was marked by the Liberal Government's social reforms (1891-1912), which included old-age pensions and industrial arbitration. World War I (1914-1918) had a profound impact, fostering a sense of national identity but also causing significant loss of life.

The Great Depression of the 1930s hit New Zealand hard, leading to widespread unemployment and hardship. This period saw the election of the first Labour Government in 1935, led by Michael Joseph Savage. This government introduced a comprehensive welfare state, including social security benefits, state housing, and a free public health system, shaping New Zealand's social fabric for decades.

New Zealand again made a significant contribution to the Allied effort in World War II (1939-1945), with forces serving in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific. Post-war, New Zealand experienced a period of prosperity, driven by strong agricultural exports to Britain. This era also saw significant Māori urbanization, as many Māori moved from rural areas to cities in search of work and opportunities. This migration, however, often led to new challenges, including inadequate housing, employment discrimination, and the erosion of traditional support systems.

From the 1960s, Māori assertiveness grew, leading to a Māori protest movement that challenged Eurocentrism, advocated for the recognition of Māori culture and language, and demanded that the Crown honour its obligations under the Treaty of Waitangi. Key events included the 1975 Māori land march (Te Roopu o te MatakiteThe group of the clear-sightedMaori) and occupations of land such as Bastion Point. In 1975, the Waitangi Tribunal was established to investigate alleged breaches of the Treaty, and in 1985 its jurisdiction was extended to cover historical grievances dating back to 1840.

The latter part of the 20th century brought significant economic changes. Britain's entry into the European Economic Community in 1973 reduced New Zealand's access to its traditional primary export market. This, combined with oil shocks, led to economic difficulties. From 1984, the Fourth Labour Government implemented radical free-market reforms known as Rogernomics (after Finance Minister Roger Douglas), which transformed the economy from a protected, regulated system to one of the most liberalised in the OECD. These reforms included floating the dollar, removing subsidies, privatising state assets, and reducing trade barriers. While credited by some with modernising the economy, these reforms also led to increased social inequality and unemployment in the short term, disproportionately affecting Māori and other vulnerable groups.

3.6. 21st century

Contemporary New Zealand continues to grapple with the legacies of its past while navigating new global and domestic challenges. Economic policy has generally remained market-oriented, with a focus on international trade, particularly with Australia and Asia. The dairy industry has become a major export earner, alongside tourism, wine, and horticulture. However, issues of economic inequality, housing affordability, and child poverty remain significant social concerns, prompting ongoing debate about the role of government and the fairness of the economic system.

Crown-Māori relations have seen continued development, with the Treaty settlement process addressing historical injustices through apologies, financial redress, and the return of culturally significant lands. Efforts to revitalise the Māori language (te reo Māorithe Māori languageMaori) and integrate Māori culture (te ao Māorithe Māori worldMaori) into national life have gained momentum, reflected in education, media, and public discourse. However, disparities in health, education, and justice outcomes for Māori persist, highlighting ongoing systemic challenges.

Socially, New Zealand has become increasingly diverse due to immigration, particularly from Asia and the Pacific Islands, leading to a more multicultural society. Issues of biculturalism and multiculturalism continue to be debated. The country has a strong record on human rights and LGBTQ+ rights, having legalised same-sex marriage in 2013.

In international affairs, New Zealand maintains an independent foreign policy, characterised by its anti-nuclear stance, commitment to multilateralism, and active role in the Pacific region. It has contributed to international peacekeeping efforts and engages in global discussions on climate change, trade, and human rights. Key events in the 21st century include the 2011 Christchurch earthquake, which caused widespread devastation and loss of life, and the 2019 Christchurch mosque shootings, a terrorist attack that prompted national mourning and new gun control legislation. The COVID-19 pandemic also had a significant impact, leading to border closures and economic disruption but also showcasing a strong public health response. New Zealand continues to evolve, balancing its unique heritage with the demands of a changing world, with ongoing emphasis from a center-left perspective on social equity, environmental sustainability, and democratic values.

4. Geography and environment

New Zealand's unique geography and environment are defining features of the nation, characterized by its isolation, diverse landforms shaped by tectonic and volcanic activity, a predominantly temperate maritime climate, and exceptionally rich and often endemic biodiversity. Environmental challenges and conservation efforts are significant, reflecting a growing awareness of the need to protect its natural heritage and address the social impacts of environmental policies.

4.1. Physical geography

New Zealand is an island country located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, near the centre of the water hemisphere. Its physical geography is diverse, encompassing rugged mountain ranges, expansive plains, volcanic plateaus, and an extensive coastline.

4.1.1. Islands and terrain

New Zealand consists of two main islands, the North Island (Te Ika-a-MāuiThe fish of MāuiMaori) and the South Island (Te WaipounamuThe waters of greenstoneMaori), separated by the Cook Strait, which is 14 mile (22 km) wide at its narrowest point. There are also over 700 smaller islands, including Stewart Island (across Foveaux Strait), the Chatham Islands, Great Barrier Island (in the Hauraki Gulf), D'Urville Island (in the Marlborough Sounds), and Waiheke Island. The country is long and narrow, stretching over 1.0 K mile (1.60 K km) along its north-north-east axis with a maximum width of 249 mile (400 km). It has a total land area of approximately 103 K mile2 (268.00 K km2) and a coastline of about 9.3 K mile (15.00 K km).

The South Island is the larger of the two main islands and is dominated by the Southern Alps, a mountain range that runs almost its entire length. This range includes Aoraki / Mount Cook, New Zealand's highest peak at 12 K ft (3.72 K m), and 17 other peaks exceeding 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m). The southwestern corner of the South Island features Fiordland, an area of steep mountains, deep fiords, and extensive glaciation. The eastern side of the Southern Alps includes the Canterbury Plains, the country's largest area of flat land.

The North Island is less mountainous than the South but is characterized by significant volcanic activity. The North Island Volcanic Plateau in the central North Island features active and dormant volcanoes, including Mount Ruapehu (9.2 K ft (2.80 K m)), the North Island's highest point. This region also contains Lake Taupō, New Zealand's largest lake, which is a caldera formed by a massive supervolcanic eruption. The North Island also has rolling hill country, fertile plains, and a deeply indented coastline with many harbours.

4.1.2. Geology and tectonics

New Zealand's geology is complex and dynamic, primarily due to its location on the boundary of two major tectonic plates: the Pacific Plate and the Indo-Australian Plate. The country is part of Zealandia, a largely submerged microcontinent that broke away from the supercontinent Gondwana around 80 million years ago.

The interaction between these plates is responsible for much of New Zealand's topography and its high levels of geological activity. Along the South Island, the plates slide past each other along the Alpine Fault, a major strike-slip fault. The immense pressure from this collision has uplifted the Southern Alps. In the North Island, the Pacific Plate is subducting beneath the Indo-Australian Plate, creating the Hikurangi Trough offshore and fueling the volcanic activity of the Taupō Volcanic Zone. This zone is one of "the world's most active volcanic and geothermal an geothermal areas".

Consequently, New Zealand experiences frequent earthquakes and has numerous active and dormant volcanoes. Notable volcanic features include the geothermal areas of Rotorua and Taupō, and volcanic peaks such as Mount Taranaki, Mount Ruapehu, Mount Ngauruhoe, and Mount Tongariro. Geothermal energy is a significant renewable energy source for the country. The dynamic tectonic setting also contributes to ongoing land uplift and subsidence in various parts of the country.

4.2. Climate

New Zealand has a predominantly temperate maritime climate (Köppen: Cfb), characterized by mild temperatures, high rainfall in many areas, and abundant sunshine. The climate is strongly influenced by the surrounding oceans and prevailing westerly winds. Mean annual temperatures range from about 50 °F (10 °C) in the south to 60.8 °F (16 °C) in the north. Extreme temperatures are rare, though historical highs have reached 108.32 °F (42.4 °C) in Rangiora, Canterbury, and lows have fallen to -14.079999999999998 °F (-25.6 °C) in Ranfurly, Otago.

Regional climatic variations are significant. The West Coast of the South Island is the wettest part of the country, receiving very high annual rainfall due to the orographic effect of the Southern Alps on the prevailing westerlies. In contrast, areas to the east of the mountains, such as Central Otago and the Mackenzie Basin, are much drier and experience a semi-arid or continental climate with greater temperature extremes. Northland, in the far north of the North Island, has a near-subtropical climate.

Most of New Zealand receives ample sunshine, with major cities like Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch averaging over 2,000 hours per year. The sunniest areas are in the northern and northeastern parts of the South Island, such as Nelson and Marlborough, which can receive over 2,400 hours. Snowfall is common in mountain areas and in the southern and eastern parts of the South Island during winter (June to October).

| Location | January high °C (°F) | January low °C (°F) | July high °C (°F) | July low °C (°F) | Annual rainfall mm (in) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auckland | 73.4 °F (23 °C) | 59 °F (15 °C) | 59 °F (15 °C) | 46.4 °F (8 °C) | 0.0 K in (1.21 K mm) |

| Wellington | 68 °F (20 °C) | 57.2 °F (14 °C) | 51.8 °F (11 °C) | 42.8 °F (6 °C) | 0.0 K in (1.21 K mm) |

| Hokitika | 68 °F (20 °C) | 53.6 °F (12 °C) | 53.6 °F (12 °C) | 37.4 °F (3 °C) | 0.1 K in (2.90 K mm) |

| Christchurch | 73.4 °F (23 °C) | 53.6 °F (12 °C) | 51.8 °F (11 °C) | 35.6 °F (2 °C) | 24 in (618 mm) |

| Alexandra | 77 °F (25 °C) | 51.8 °F (11 °C) | 46.4 °F (8 °C) | 28.4 °F (-2 °C) | 14 in (359 mm) |

4.3. Biodiversity

New Zealand's biodiversity is renowned for its high level of endemism, a result of its long geographic isolation (around 80 million years) after separating from the supercontinent Gondwana. This isolation allowed unique flora and fauna to evolve. Before human arrival, New Zealand's ecosystems were dominated by birds, with very few native land mammals (only three species of bats, one now extinct, and a unique, mouse-sized mammal discovered from fossils). This absence of mammalian predators led to the evolution of many flightless bird species, such as the kiwi, kākāpō, takahē, and the extinct moa.

The arrival of Polynesians around 1280-1350 CE, and later Europeans, brought about significant changes. Humans introduced mammalian predators like rats (kiorePolynesian ratMaori), stoats, ferrets, and possums, which devastated native bird populations. Hunting and habitat destruction also led to the extinction of many species, including the giant moa and its predator, the Haast's eagle.

4.3.1. Flora and fauna

New Zealand's native flora is diverse and unique. About 82% of its indigenous vascular plants are endemic. Forests are primarily of two types: broadleaf-podocarp forests, characterized by trees like kauri, rimu, and totara, and beech forests dominated by southern beech species in cooler, higher-altitude areas. Other notable native plants include the flowering pōhutukawa (often called the New Zealand Christmas tree), tree ferns (pongatree fernsMaori), and various species of flax (harakekeflaxMaori).

The native fauna is equally distinctive. Iconic birds include the kiwi (a national symbol), the critically endangered kākāpō (the world's only flightless parrot), the kea (an alpine parrot known for its intelligence), the tūī, and the korimako/bellbird. Reptiles include the ancient tuatara (often called a "living fossil"), skinks, and geckos. Native frogs of the ancient Leiopelmatidae family exist, and there is a rich diversity of invertebrates, including the giant wētā. Marine life is abundant, with nearly half the world's cetacean species (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) found in New Zealand waters, along with numerous fur seals and penguins (more penguin species are found here than in any other country).

4.3.2. Conservation efforts

New Zealand has a strong history of conservation efforts, driven by public awareness and government initiatives. The Department of Conservation (DOC) is the primary government agency responsible for protecting natural and historic heritage. Key strategies include the establishment of national parks (13 in total), forest parks, and marine reserves.

Pioneering methods have been developed for pest control (targeting introduced predators like stoats, rats, and possums) and the restoration of threatened species. Island sanctuaries, free of introduced predators, have been crucial for the recovery of endangered birds like the kākāpō and takahe. Wildlife translocation, captive breeding programs (like for the kiwi), and ecological restoration projects are actively pursued. The "Predator Free 2050" initiative aims to eradicate key introduced predators to protect native wildlife. Despite successes, many species remain threatened, and ongoing efforts are critical to address habitat loss, invasive species, and the impacts of climate change. The social and economic implications of conservation, particularly for rural communities and iwi (Māori tribes) with connections to conserved lands, are also important considerations.

4.4. Environmental issues

New Zealand faces several significant environmental issues, largely stemming from human activity since settlement. Deforestation has been extensive; before human arrival, about 80% of the land was forested, but this was reduced to around 23% by the late 20th century due to clearing for agriculture and logging. While some reforestation has occurred, primarily with exotic plantation forests, the loss of native forest habitat remains a concern.

Water pollution, particularly in lowland rivers and lakes, is a major issue, largely driven by agricultural intensification, especially dairy farming. Runoff containing nitrates, phosphates, and sediment from farmland impacts water quality and aquatic ecosystems. Urban stormwater and wastewater discharges also contribute to pollution.

Climate change presents significant challenges, including rising sea levels, increased frequency of extreme weather events, and impacts on agriculture and biodiversity. New Zealand has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but agriculture, a major source of methane and nitrous oxide, poses a particular challenge for mitigation efforts.

Other environmental concerns include soil erosion, the impact of invasive species on native ecosystems, and pressures from urban development and tourism. Government policies, such as the Resource Management Act 1991, aim to promote sustainable management of natural resources, but balancing economic development with environmental protection remains a complex task. Public awareness and engagement in environmental issues are generally high, with numerous community groups and non-governmental organizations actively involved in conservation and advocacy. The social impacts of environmental policies, such as restrictions on land use or water abstraction, are often debated, highlighting the need for equitable solutions that consider diverse community interests.

5. Government and politics

New Zealand operates as a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy. Its political system is based on the Westminster system, although it has unique features, notably its mixed-member proportional representation (MMP) electoral system. The country has a strong tradition of democratic principles, human rights, and a commitment to the rule of law, though challenges in achieving full social equity persist.

5.1. System of government

New Zealand's system of government is characterized by the separation of powers among the executive, legislature, and judiciary, although the executive is drawn from and accountable to the legislature. It does not have a single codified constitution; instead, its constitutional framework is derived from a mix of statutes (like the Constitution Act 1986 and the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990), Treaty of Waitangi principles, court decisions, and constitutional conventions.

5.1.1. Monarchy and Governor-General

King of New Zealand

The Head of State is the King of New Zealand, currently Charles III. The King's functions are largely ceremonial and are exercised in New Zealand by the Governor-General, who is appointed by the King on the advice of the Prime Minister. The current Governor-General is Dame Cindy Kiro. The Governor-General acts on the advice of ministers, except in rare circumstances involving reserve powers, such as dissolving Parliament or appointing a Prime Minister after an election. The powers of the monarch and Governor-General are constrained by constitutional convention and law.

5.1.2. Parliament and legislature

Legislative power is vested in the New Zealand Parliament, which is unicameral and consists of the King (represented by the Governor-General) and the House of Representatives. Parliament has parliamentary sovereignty, meaning it has the ultimate authority to make and unmake laws. The House of Representatives typically has 120 Members of Parliament (MPs), though this number can vary slightly due to overhang seats under the MMP system. MPs are elected for a three-year term. Parliament's functions include making laws, scrutinising the government, and representing the people.

5.1.3. Prime Minister and Cabinet

Executive power is exercised by the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, who are collectively known as the Government. The Prime Minister is the head of government and is typically the leader of the political party or coalition of parties that commands a majority in the House of Representatives. The Prime Minister advises the Governor-General on the appointment of ministers. The current Prime Minister is Christopher Luxon.

The Cabinet is the central decision-making body of government. It consists of the Prime Minister and senior ministers. Cabinet operates on the principle of collective responsibility, meaning all ministers must publicly support Cabinet decisions or resign. Ministers are responsible for specific government departments and policy areas.

5.2. Elections and political parties

New Zealand holds general elections at least every three years. Since 1996, elections have been conducted using the mixed-member proportional (MMP) electoral system. Under MMP, voters cast two votes: one for a local electorate MP and one for a political party. Electorate MPs are elected through a first-past-the-post system in single-member constituencies. There are currently 72 electorates, including seven Māori electorates reserved for voters of Māori descent who choose to be on the Māori electoral roll. The remaining seats (typically 48, to make a total of 120) are filled from party lists to ensure that the overall composition of Parliament reflects each party's share of the party vote, provided the party meets a threshold (either winning an electorate seat or gaining 5% of the party vote).

The MMP system has led to multi-party governments and increased representation for smaller parties. Major political parties include the centre-right National Party and the centre-left Labour Party. Other significant parties represented in Parliament have included the Green Party, ACT Party, NZ First, and Te Pāti Māori (Māori Party).

5.3. Judiciary and legal system

The judiciary is independent of the executive and legislature. The court system is hierarchical, with the Supreme Court as the final court of appeal. Below it are the Court of Appeal, the High Court (which has general jurisdiction and deals with serious criminal cases and major civil disputes), and District Courts (which handle the majority of criminal and civil cases). There are also specialist courts, such as the Employment Court, the Environment Court, and the Māori Land Court.

Judges are appointed by the Governor-General on the advice of the Attorney-General. Judicial independence is a cornerstone of the legal system, ensuring that judges can make decisions without political interference. New Zealand law is derived from common law, statute law enacted by Parliament, and principles of the Treaty of Waitangi.

6. Administrative divisions

New Zealand's administrative structure includes local government authorities responsible for regional and district-level governance, as well as constitutional arrangements with associated territories within the wider Realm of New Zealand.

6.1. Local government

Local government in New Zealand operates under a two-tier system established by reforms in 1989. There are 11 regional councils and 67 territorial authorities. The provinces that existed in early colonial New Zealand were abolished in 1876 in favour of a more centralised system, though regional identity often persists in cultural and sporting contexts.

Regional councils are primarily responsible for environmental and resource management within their region, including water quality, air quality, pest control, flood protection, and regional transport planning. They implement the provisions of the Resource Management Act 1991.

Territorial authorities consist of 13 city councils, 53 district councils, and the Chatham Islands Council. They are responsible for a wide range of local services and infrastructure, including local roads, water supply, sewerage and stormwater systems, waste management, parks and recreation facilities, libraries, building consents, and local land use planning.

Five territorial authorities (Auckland Council, Nelson City Council, Gisborne District Council, Tasman District Council, and Marlborough District Council) are unitary authorities, meaning they perform the functions of both a regional council and a territorial authority. The Chatham Islands Council also functions largely as a unitary authority. Local government bodies are democratically elected, typically every three years, but voter turnout in local elections has historically been lower than in general elections, a concern for democratic participation.

6.2. Realm of New Zealand and external territories

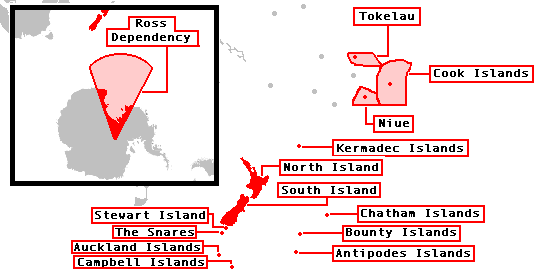

The Realm of New Zealand is the entire area over which the King of New Zealand is sovereign. It comprises New Zealand itself, Tokelau, the Ross Dependency (New Zealand's territorial claim in Antarctica), and the self-governing states of the Cook Islands and Niue.

The Cook Islands and Niue are in a state of free association with New Zealand. This means they are fully self-governing in their internal affairs, but their citizens are New Zealand citizens. New Zealand retains responsibility, in consultation with their governments, for their external affairs and defence if requested. The New Zealand Parliament cannot legislate for these countries without their consent.

Tokelau is a non-self-governing territory administered by New Zealand. While it has moved towards greater self-government, with referendums on self-government in free association held in 2006 and 2007 (both narrowly failing to reach the required two-thirds majority), it remains a dependent territory. Its people are New Zealand citizens.

The Ross Dependency is New Zealand's territorial claim in Antarctica, established in 1923. This claim, like other Antarctic claims, is subject to the provisions of the Antarctic Treaty System, which effectively suspends sovereignty claims and promotes scientific cooperation. New Zealand operates Scott Base, a research facility in the Ross Dependency.

7. Foreign relations

New Zealand's foreign policy is characterized by its commitment to multilateralism, international law, peace, and human rights, alongside a historically independent stance, particularly evident in its anti-nuclear policy. The nation actively participates in global and regional affairs, balancing its relationships with key partners while promoting its values and interests on the international stage.

7.1. Overview and policy

New Zealand's foreign policy objectives are shaped by its geographical isolation, its status as a small, developed nation heavily reliant on international trade, and its bicultural heritage. Key priorities include maintaining international peace and security, promoting sustainable development, advancing free and fair trade, protecting human rights, and addressing global challenges like climate change. Historically, New Zealand's foreign policy was closely aligned with the United Kingdom. Following World War II, it developed closer ties with the United States and Australia, notably through the ANZUS treaty. However, its anti-nuclear policy, adopted in the 1980s, led to a suspension of US security obligations under ANZUS and marked a significant assertion of an independent foreign policy. New Zealand remains committed to disarmament and arms control. It strongly supports the United Nations and other multilateral institutions as crucial forums for addressing global issues. The country is also known for its contributions to international development assistance, particularly in the Pacific region.

7.2. Key bilateral relationships

New Zealand maintains important relationships with a range of countries across the globe.

7.2.1. Australia

The relationship with Australia is New Zealand's closest and most comprehensive. Often referred to as the Trans-Tasman relationship, it is underpinned by strong historical, cultural, economic, and political ties. The Closer Economic Relations (CER) agreement has created a largely seamless single market, and the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement allows citizens of each country to live and work freely in the other. The two countries cooperate closely on defence, security, and foreign policy matters, though they maintain distinct national interests. A significant number of New Zealanders live in Australia, and vice-versa, contributing to deep people-to-people links.

7.2.2. Pacific Islands

New Zealand has a special responsibility and deep engagement with the Pacific Island nations. This relationship is rooted in shared Polynesian heritage, geographical proximity, and historical connections. New Zealand is a major provider of development aid to the region, focusing on sustainable economic development, governance, health, and education. It plays an active role in regional cooperation through organisations like the Pacific Islands Forum. Many Pasifika people have migrated to New Zealand, forming a significant and vibrant part of New Zealand society. The constitutional relationships with the Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau are a unique aspect of its Pacific engagement.

7.2.3. United Kingdom and Europe

Historical ties with the United Kingdom remain important, stemming from New Zealand's colonial past and shared Commonwealth membership. While the UK's entry into the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1973 significantly altered trade patterns, cultural, political, and people-to-people links endure. New Zealand also maintains strong relationships with other European nations, engaging on issues such as trade, climate change, and international security. A free trade agreement with the European Union was signed in 2023.

7.2.4. United States

The relationship with the United States is multifaceted, encompassing trade, security cooperation, and cultural exchange. While the ANZUS alliance obligations were suspended by the US due to New Zealand's non-nuclear policy, cooperation in areas like intelligence sharing (through the Five Eyes alliance), counter-terrorism, and regional security has continued. The Wellington Declaration (2010) and Washington Declaration (2012) signaled a strengthening of the strategic partnership. New Zealand is designated as a Major non-NATO ally of the United States.

7.2.5. Asia

New Zealand has increasingly focused on strengthening its engagement with Asia, recognizing the region's growing economic and strategic importance. China has become New Zealand's largest trading partner, and a free trade agreement was signed in 2008. Relationships with other key Asian nations, including Japan, South Korea, and countries in Southeast Asia (particularly through ASEAN), are also significant, focusing on trade, investment, tourism, and diplomatic cooperation.

7.3. International organisations

New Zealand is a strong advocate for multilateralism and an active member of numerous international organisations. It was a founding member of the United Nations and continues to play a constructive role in its various agencies and initiatives, including peacekeeping operations. New Zealand is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, and the World Trade Organization (WTO). It also participates in regional forums such as the Pacific Islands Forum and the East Asia Summit. New Zealand's engagement in these organisations reflects its commitment to international cooperation, global governance, and addressing shared challenges.

7.4. Non-nuclear policy

New Zealand's anti-nuclear policy is a cornerstone of its national identity and foreign policy. Adopted in the mid-1980s and formalised in the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987, the policy prohibits nuclear weapons and nuclear-powered vessels from New Zealand territory, including its waters. This stance arose from strong public opposition to nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific and concerns about nuclear proliferation.

The policy led to a significant diplomatic rift with the United States, resulting in the US suspending its security obligations to New Zealand under the ANZUS treaty. Despite this, the non-nuclear policy has widespread domestic support and is seen as a fundamental expression of New Zealand's values and its commitment to peace and disarmament. It has shaped New Zealand's independent voice in international affairs and its advocacy for nuclear disarmament on the global stage.

8. Military

The New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) is responsible for the nation's security and contributes to international peace and stability. It comprises three services: the New Zealand Army, the Royal New Zealand Navy, and the Royal New Zealand Air Force, and operates under a framework that emphasizes professionalism, adaptability, and a commitment to democratic values and human rights in its operations.

8.1. New Zealand Defence Force

The New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF; Te Ope Kātua o AotearoaThe New Zealand Defence ForceMaori) is a modern, professional military force. Its primary roles include protecting New Zealand's sovereignty and national interests, contributing to regional security, and participating in international peacekeeping and humanitarian assistance operations. Given New Zealand's geographical isolation and limited direct threats, its defence needs are often described as modest, but its military has a history of global engagement.

The New Zealand Army (Ngāti TūmatauengaTribe of the God of WarMaori) is a light infantry force capable of a range of operations, from disaster relief to combat.

The Royal New Zealand Navy (Te Taua Moana o AotearoaThe Sea Warriors of New ZealandMaori) operates frigates, offshore and inshore patrol vessels, and support ships, focusing on maritime security, resource protection in New Zealand's extensive Exclusive Economic Zone, and regional presence.

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF; Te Tauaarangi o AotearoaThe New Zealand Warriors of the SkyMaori) provides air patrol, transport, and search and rescue capabilities, operating maritime patrol aircraft, transport aircraft, and helicopters. It no longer maintains a combat air wing.

The NZDF is characterized by its professionalism, adaptability, and integration of Māori culture, including the use of the haka and Māori design elements. It often works closely with Australian forces and other international partners.

8.2. Historical engagements and peacekeeping

New Zealand has a long history of military engagement, often alongside allies. It made significant contributions to both World War I and World War II. Key World War I campaigns included Gallipoli, which became a defining moment for New Zealand's national identity, and the Western Front. In World War II, New Zealand forces served with distinction in North Africa (e.g., El Alamein), Italy (e.g., Cassino), Greece, Crete, and the Pacific. The Māori Battalion earned a formidable reputation during World War II.

Post-World War II, New Zealand participated in the Korean War, the Malayan Emergency, the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation, and the Vietnam War. More recently, it has contributed to operations in the Gulf War, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

New Zealand has a strong record of contributing to international peacekeeping and peace support operations. It has deployed personnel to numerous UN and multinational missions in regions such as the Balkans (Bosnia and Herzegovina), East Timor, the Solomon Islands, Bougainville, Cyprus, Somalia, the Sinai, and various missions in Africa and the Middle East. These contributions reflect New Zealand's commitment to international peace and security and its role as a responsible global citizen.

9. Economy

New Zealand has a developed market economy that has undergone significant transformation, moving from a protected, agriculturally based system to a more diversified and liberalised free-trade economy. While agriculture remains important, the service sector now dominates. The nation faces ongoing economic challenges related to productivity, international competitiveness, and ensuring social equity in the distribution of economic benefits.

9.1. Overview and economic history

New Zealand is classified as an advanced market economy. It ranks highly on international measures of human development and economic freedom. Its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is comparable to that of many Western European nations. The national currency is the New Zealand dollar (NZD), often informally called the "Kiwi dollar."

Historically, New Zealand's economy was built on the export of agricultural products, primarily wool, meat, and dairy, largely to the United Kingdom. This reliance on a narrow range of commodities and markets made the economy vulnerable. The first shipment of refrigerated meat in 1882 was a pivotal event, opening up large-scale agricultural exports. For much of the mid-20th century, New Zealand enjoyed high living standards. However, Britain's entry into the European Economic Community in 1973, coupled with the oil shocks of the 1970s, led to a severe economic downturn and a period of re-evaluation.

9.1.1. Economic reforms (Rogernomics)

From 1984, the Fourth Labour Government implemented a series of radical and rapid economic reforms, commonly known as "Rogernomics" (after then-Finance Minister Roger Douglas). These reforms aimed to transform New Zealand from a highly regulated, protectionist economy into a more open, market-driven one. Key measures included:

- Floating the New Zealand dollar.

- Removing extensive subsidies, particularly in agriculture.

- Reducing import tariffs and other trade barriers.

- Privatising many state-owned enterprises (e.g., telecommunications, banking, airlines, railways).

- Deregulating financial markets.

- Reforming the tax system, including introducing a comprehensive Goods and Services Tax (GST).

- Labour market deregulation.

These reforms were continued, albeit sometimes at a slower pace, by subsequent governments. Proponents argue that Rogernomics modernized the New Zealand economy, made it more efficient and competitive, and controlled inflation. Critics, however, point to the significant social costs associated with the reforms, including a sharp rise in unemployment in the short to medium term, increased income inequality, and a decline in social cohesion. The long-term effects of Rogernomics on economic performance and social equity remain a subject of ongoing debate and analysis, with a center-left perspective often highlighting the negative social consequences and the need for policies that mitigate inequality and support vulnerable communities.

9.2. Major sectors

The New Zealand economy is composed of primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors, with the service sector being the largest contributor to GDP and employment.

9.2.1. Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

Agriculture remains a cornerstone of the New Zealand economy and a major export earner. Key agricultural industries include:

- Dairy farming**: New Zealand is one of the world's largest exporters of dairy products, with Fonterra being a dominant global player.

- Sheep and beef farming**: Historically significant, meat and wool continue to be important exports.

- Horticulture**: New Zealand is a major producer and exporter of kiwifruit (with Zespri as a leading brand), apples, and wine (particularly Sauvignon Blanc from Marlborough).

- Forestry**: Plantation forests, primarily of exotic radiata pine, support a significant timber and wood products industry.

- Fishing and aquaculture**: New Zealand has a substantial fishing industry, with its extensive Exclusive Economic Zone yielding various fish species and shellfish. Aquaculture, including salmon and mussels, is also important.

The primary sector faces challenges related to environmental sustainability, climate change impacts, and international market volatility. There is a growing focus on sustainable farming practices and adding value to primary products.

9.2.2. Manufacturing and industry

The manufacturing sector in New Zealand is diverse, though it has faced increased competition from imports following economic liberalization. Key manufacturing activities include:

- Food processing**: This is the largest component of the manufacturing sector, adding value to agricultural and horticultural products (e.g., dairy processing, meat processing, winemaking).

Industrial activities are often concentrated in and around major urban centres.

9.2.3. Tourism

Tourism is a major contributor to the New Zealand economy, a significant source of foreign exchange earnings, and a large employer. The country's diverse natural landscapes, including mountains, fiords, beaches, forests, and geothermal areas, are major attractions. Adventure tourism (e.g., bungy jumping, white-water rafting, skiing) is particularly well-known. Cultural tourism, focusing on Māori culture and heritage, is also growing. Major international visitor markets include Australia, China, the United States, and the United Kingdom. The industry has faced challenges, such as the impact of global events like the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the need for resilience and sustainable tourism practices.

9.2.4. Service sector

The service sector is the largest part of the New Zealand economy, accounting for the majority of GDP and employment. It encompasses a wide range of activities, including:

- Finance, insurance, and business services.

- Retail and wholesale trade.

- Education (including international education).

- Healthcare and social assistance.

- Information technology (IT) and telecommunications.

- Hospitality and food services.

- Government administration and public services.

- Transport and logistics.

- Creative industries.

The growth of the service sector reflects the evolution of New Zealand into a modern, developed economy.

9.3. Trade

New Zealand has a small domestic market and is heavily reliant on international trade. Exports account for a significant portion of its GDP. The country has a long history of advocating for free trade and has numerous free trade agreements in place.

Main export commodities include dairy products, meat, wood and wood products, fruit (especially kiwifruit and apples), wine, and fish. Key import categories include machinery and equipment, vehicles, petroleum products, electronics, and textiles.

New Zealand's main trading partners are:

- China (largest overall trading partner)

- Australia (historically the closest economic partner)

- United States

- European Union

- Japan

- Other Asian countries (e.g., South Korea, Singapore)

The country actively participates in international trade organisations like the World Trade Organization (WTO) and regional economic forums such as Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). Diversifying export markets and products, and moving up the value chain, are ongoing economic priorities.

9.4. Infrastructure

New Zealand's infrastructure is essential for its economic activity and quality of life, encompassing energy, transport, and communications networks.

9.4.1. Energy

New Zealand's energy supply comes from a mix of sources, with a high proportion of renewable energy, particularly in electricity generation.

- Electricity**: Over 80% of New Zealand's electricity is generated from renewable sources. Hydroelectricity is the largest contributor, with major schemes on rivers like the Waikato, Waitaki, and Clutha. Geothermal energy, primarily from the Taupō Volcanic Zone, is another significant renewable source. Wind power is also growing. Natural gas and coal make up the remainder of electricity generation. State-owned Transpower operates the national electricity transmission grid.

- Other energy**: Petroleum products (petrol, diesel, aviation fuel) are largely imported and are essential for transport. Natural gas is used for electricity generation, industrial processes, and domestic heating/cooking. Coal is used for some industrial purposes and electricity generation.

The government has targets to increase the share of renewable energy and improve energy efficiency to address climate change.

9.4.2. Transport

New Zealand's transport network connects its geographically dispersed population and facilitates trade.

- Roads**: The road network is extensive, with over 58 K mile (94.00 K km) of roads. Private car ownership is high, and road transport is the dominant mode for passengers and freight. State highways are managed by Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency.

- Rail**: The rail network, operated by state-owned KiwiRail, primarily serves freight transport, though there are some long-distance passenger services and urban commuter rail in Auckland and Wellington.

- Air**: Air travel is crucial for international connectivity and domestic travel between major centres. Auckland Airport is the main international gateway. Air New Zealand is the national airline.

- Sea**: Ports handle the vast majority of New Zealand's international trade. Inter-island ferries (between the North and South Islands) are vital for passengers and freight.

Challenges include maintaining and upgrading aging infrastructure, reducing transport emissions, and improving public transport options in urban areas.

9.4.3. Communications

Telecommunications infrastructure is well-developed.

- Internet and Broadband**: Internet penetration is high. The government has invested significantly in ultra-fast broadband (UFB) fibre-optic networks to improve connectivity across the country. Mobile networks (4G and 5G) are also widely available.

- Postal Services**: New Zealand Post provides postal services throughout the country.

The telecommunications market was deregulated in the late 1980s and 1990s, leading to competition among providers. Chorus owns and operates much of the fixed-line network infrastructure, while companies like Spark, One NZ (formerly Vodafone NZ), and 2degrees are major retail service providers.

9.5. Science and technology

New Zealand has a growing science and technology sector, with a focus on areas that leverage its natural advantages and address national challenges. Early indigenous contributions included Māori tohungaskilled expertsMaori accumulating knowledge of agricultural practices and herbal remedies. European scientific exploration began with voyages like those of James Cook and Charles Darwin.

Crown Research Institutes (CRIs) are government-owned companies that undertake scientific research in areas such as agriculture, environmental science, and industrial technology. Universities also play a significant role in research and development (R&D). Government policy aims to foster innovation, increase R&D investment (which has historically been lower than in many other OECD countries), and build a "knowledge economy."

Key areas of research and innovation include:

- Agricultural technology (AgriTech)

- Biotechnology and life sciences

- Food science and technology

- Environmental science and conservation technology

- Information and communications technology (ICT), including software development and digital media

- Renewable energy technology

- Aerospace, with companies like Rocket Lab gaining international recognition for small satellite launches.

The New Zealand Space Agency was established in 2016. Challenges include scaling up innovative businesses and retaining skilled talent.

9.6. Economic inequality and poverty

Despite being a developed nation with a generally high standard of living, New Zealand faces persistent issues of economic inequality and poverty. These issues have been exacerbated at times by economic reforms and global economic trends.

- Income and Wealth Disparity**: There is a significant gap between high-income earners and those on lower incomes. Wealth is also unevenly distributed, with a concentration at the top.

- Poverty**: Poverty, particularly child poverty, is a major social concern. Certain groups are disproportionately affected, including Māori, Pasifika peoples, sole-parent families, and people with disabilities.

- Housing Affordability**: A major driver of inequality and hardship is the high cost of housing, especially in major cities like Auckland. This affects renters and aspiring homeowners, contributing to housing insecurity and homelessness for some.

Successive governments have implemented various measures to address these issues, including changes to the tax and benefit system (e.g., Working for Families tax credits), increases to the minimum wage, and initiatives to increase the supply of affordable housing. However, the scale of the problem means that economic inequality and poverty remain key challenges for social justice and the well-being of vulnerable groups. A center-left perspective typically advocates for stronger government intervention, progressive taxation, robust social safety nets, and targeted support for disadvantaged communities to reduce these disparities.

10. Demographics

New Zealand's population is diverse and has undergone significant changes in its ethnic composition and distribution over time. Demographic trends reflect patterns of immigration, natural increase, and internal migration.

10.1. Population

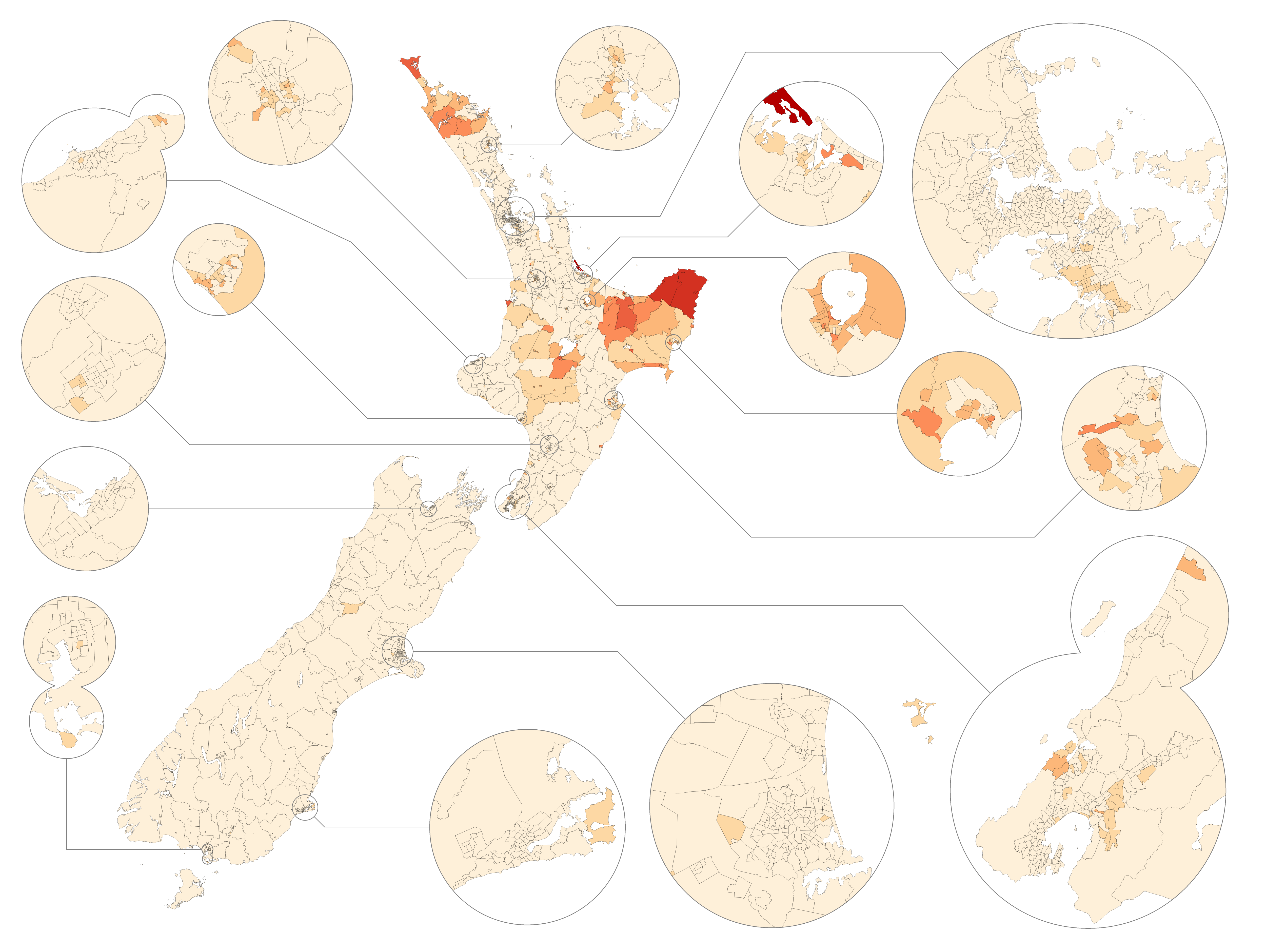

As of June 2024, New Zealand's estimated resident population is approximately 5.39 million. The population has grown steadily, driven by both natural increase (births minus deaths) and net migration. The 2023 census enumerated a resident population of 4,993,923.

The population is not evenly distributed. The North Island is home to roughly three-quarters of the population, with the Auckland region alone accounting for over a third of the total. This reflects a long-term "drift to the north." New Zealand is a highly urbanised country, with about 87% of the population living in urban areas.

Key demographic indicators include:

- Population Growth Rate**: Has varied, influenced by migration levels.

- Population Density**: Relatively low overall, but higher in urban centres.

- Age Structure**: The population is aging, though at a slower rate than some other developed countries. The median age was 37.4 years at the 2018 census.

- Life Expectancy**: High, at around 80.0 years for males and 83.5 years for females (2017-2019).

- Fertility Rate**: The total fertility rate was 1.6 children per woman in 2020, which is below replacement level but relatively high for a developed country.

| Rank | Urban Area | Region | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Auckland | Auckland | 1,478,800 |

| 2 | Christchurch | Canterbury | 384,800 |

| 3 | Wellington | Wellington | 215,200 |

| 4 | Hamilton | Waikato | 185,300 |

| 5 | Tauranga | Bay of Plenty | 161,800 |

| 6 | Lower Hutt | Wellington | 113,000 |

| 7 | Dunedin | Otago | 106,200 |

| 8 | Palmerston North | Manawatū-Whanganui | 82,500 |

| 9 | Napier | Hawke's Bay | 67,500 |

| 10 | Hibiscus Coast | Auckland | 63,400 |

| 11 | Porirua | Wellington | 62,400 |

| 12 | New Plymouth | Taranaki | 59,600 |

| 13 | Rotorua | Bay of Plenty | 58,900 |

| 14 | Whangārei | Northland | 56,900 |

| 15 | Nelson | Nelson | 51,900 |

| 16 | Hastings | Hawke's Bay | 51,500 |

| 17 | Invercargill | Southland | 51,000 |

| 18 | Upper Hutt | Wellington | 45,400 |

| 19 | Whanganui | Manawatū-Whanganui | 42,800 |

| 20 | Gisborne | Gisborne | 38,200 |

10.2. Ethnicity and immigration

New Zealand is an ethnically diverse nation. The 2023 census reported the following major ethnic groupings (people can identify with more than one ethnicity):

- European: 67.8%

- Māori: 17.8%

- Asian: 17.3%

- Pacific peoples (Pasifika): 8.9%

- Middle Eastern/Latin American/African (MELAA): 1.5%

- Other (including "New Zealander"): 1.2%

The ethnic makeup of New Zealand has changed significantly over time. In 1961, Europeans constituted 92% of the population, and Māori 7%. The growth in Asian and Pasifika populations, particularly since the late 20th century due to changes in immigration policy, has contributed to increasing multiculturalism. Immigration continues to be a significant factor in New Zealand's demographic and social landscape. While the United Kingdom was historically the main source of immigrants, recent decades have seen more arrivals from Asia (notably China and India), the Pacific Islands, and South Africa.

10.2.1. Māori population

The indigenous Māori are the second-largest ethnic group. The Māori population has experienced significant demographic recovery since its decline in the 19th century. Māori are a youthful population compared to other ethnic groups in New Zealand. While Māori culture and language are integral to New Zealand's identity, Māori continue to face socio-economic disparities in areas such as health, education, employment, and income. Addressing these disparities and supporting Māori self-determination (tino rangatiratangaself-determinationMaori) are key priorities for achieving social equity. The majority of the Māori population lives in the North Island, particularly in urban areas, though strong connections to ancestral lands (whenuaancestral landsMaori) and tribal affiliations (iwitribesMaori and hapūsub-tribesMaori) remain vital.

10.2.2. Pākehā (European New Zealanders)

Pākehā, or New Zealanders of European descent, form the largest ethnic group. This group is itself diverse, with ancestries primarily from the British Isles (England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland), but also including descendants of settlers from other European countries such as the Netherlands, Germany, and Scandinavia. The term "Pākehā" is a Māori word, and its usage and meaning can be complex and sometimes debated. Pākehā culture has significantly shaped New Zealand's institutions, language, and societal norms, while also evolving in response to the New Zealand environment and interaction with Māori and other cultures.

10.2.3. Asian New Zealanders

New Zealanders of Asian descent are a rapidly growing and diverse group, encompassing people with origins from East Asia (e.g., China, Korea, Japan), South Asia (e.g., India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan), and Southeast Asia (e.g., Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam). Immigration from Asian countries increased significantly from the late 1980s. Asian New Zealanders have made substantial contributions to New Zealand's economy, culture, and society, and are concentrated largely in Auckland.

10.2.4. Pasifika New Zealanders

Pasifika peoples (or Pacific peoples) are New Zealanders with heritage from various Pacific Island nations, including Samoa, Tonga, Cook Islands, Fiji, Niue, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. Significant migration from the Pacific Islands to New Zealand began in the post-World War II era, driven by economic opportunities and historical ties (especially for countries within the Realm of New Zealand). Pasifika communities have enriched New Zealand's cultural diversity, particularly in areas like music, dance, art, and sport. However, they also face socio-economic challenges, including disparities in health, housing, and income, which are areas of focus for social equity initiatives. Auckland is home to the largest Polynesian population of any city in the world.

10.2.5. Immigration trends

Immigration has been a defining feature of New Zealand's history and continues to shape its society. Early European immigration was predominantly from the British Isles. Restrictive policies, similar to the White Australia policy, historically limited non-European immigration. These policies were gradually relaxed from the mid-20th century, particularly from the 1970s and 1980s, leading to increased arrivals from Asia and the Pacific Islands.

Current immigration policy aims to attract skilled migrants, investors, and entrepreneurs, while also fulfilling family reunification and humanitarian commitments (e.g., refugee quotas). Net migration levels fluctuate depending on economic conditions and policy settings, and have a significant impact on population growth, labour supply, and demand for services. The social and economic integration of immigrants, and the balance between skilled migration and addressing domestic labour shortages, are ongoing policy considerations.

10.3. Languages

New Zealand has three official languages: English, Māori (te reo Māorithe Māori languageMaori), and New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL). English is the most commonly spoken language, used by over 95% of the population. New Zealand English is a distinct dialect with unique pronunciations and vocabulary, similar in some respects to Australian English.

The Māori language is the ancestral language of the indigenous Māori people. After a period of decline due to colonisation and policies that discouraged its use, te reo Māorithe Māori languageMaori has undergone a significant revitalisation effort since the late 20th century. It was made an official language in 1987. Initiatives to promote its use include Māori-medium education (kōhanga reolanguage nestsMaori, and kura kaupapa MāoriMāori immersion schoolsMaori), broadcasting (e.g., Māori Television), and increased visibility in public life. According to the 2018 census, about 4% of the population (and over 20% of Māori) can hold a conversation in Māori.

New Zealand Sign Language became an official language in 2006. It is the main language of New Zealand's Deaf community and is unique to the country.

Besides the official languages, many other languages are spoken by immigrant communities, reflecting New Zealand's multicultural makeup. The most common of these, according to the 2018 census, include Samoan, Northern Chinese (including Mandarin), Hindi, and French.

10.4. Religion

New Zealand is a secular state with no official religion, and freedom of religion is guaranteed. The religious landscape is diverse. According to the 2018 census, the largest religious affiliation is Christianity (37.0%), though the proportion of Christians has been declining. The main Christian denominations include Anglican, Roman Catholic, and Presbyterian.

A significant and growing proportion of the population (48.5% in 2018) reported having no religion. This makes New Zealand one of the most secular countries in the world.

Other religions present in New Zealand include Hinduism (2.6%), Islam (1.3%), Buddhism (1.1%), and Sikhism (0.9%), largely reflecting patterns of immigration. Traditional Māori spiritual beliefs also continue to be an important part of Māori culture, sometimes practiced alongside Christianity or other faiths. The Rātana and Ringatū faiths are indigenous Christian-Māori movements. The Auckland Region exhibits the greatest religious diversity.

11. Society

New Zealand society is shaped by its bicultural heritage, multicultural influences, and a commitment to social welfare, though it faces ongoing challenges related to equity and social issues. The well-being of its citizens, particularly vulnerable groups, is a key consideration in social policy.

11.1. Education

Education is compulsory for children aged 6 to 16, though most start school at age 5. The system comprises early childhood education, primary and secondary schooling, and tertiary education. State (public) schools are free for New Zealand citizens and permanent residents up to the age of 19. The curriculum aims to be inclusive and culturally responsive, acknowledging the Treaty of Waitangi.

New Zealand has a high adult literacy rate (99%). Tertiary education includes universities (eight public universities), Te Pūkenga (New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology, formed by merging polytechnics and institutes of technology), wānanga (Māori tertiary institutions), and private training establishments. While the education system generally performs well in international comparisons (e.g., PISA), disparities in achievement persist, particularly for Māori and Pasifika students, and students from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Addressing these inequities is an ongoing focus.

11.2. Health

New Zealand has a publicly funded healthcare system that aims to provide universal access to medical services. Public health indicators are generally good, with high life expectancy.

11.2.1. Healthcare system

The healthcare system is primarily funded through general taxation. Te Whatu Ora - Health New Zealand is the national entity responsible for planning and delivering health services, working alongside Te Aka Whai Ora - Māori Health Authority, which aims to improve health outcomes for Māori and ensure the health system is responsive to Māori needs. District Health Boards (DHBs) were disestablished in 2022.

Most essential health services are free or subsidised, including hospital care and visits to general practitioners (GPs) for children. Adults usually pay a co-payment for GP visits, though this can be subsidised for low-income individuals. Prescription medications are also subsidised through Pharmac, the national drug-buying agency. Challenges for the health system include managing an aging population, addressing health inequities (particularly for Māori and Pasifika), improving mental health services, and managing healthcare costs.

11.2.2. Social welfare

New Zealand has a comprehensive social welfare system designed to provide financial and social support to individuals and families in need. Key components include:

- Unemployment benefits

- Sickness and disability benefits

- Support for sole parents

- New Zealand Superannuation (a universal pension for those aged 65 and over)

- Family support, including Working for Families tax credits and paid parental leave.

- Housing support, such as accommodation supplements.

The Ministry of Social Development is the main government agency responsible for administering welfare benefits and services. While the system aims to provide a safety net, the adequacy of benefit levels and the impact of welfare policies on poverty and inequality are ongoing subjects of public and political debate. Ensuring the system effectively supports vulnerable populations and promotes social inclusion is a key concern from a social justice perspective.

11.3. Social issues

New Zealand faces a range of contemporary social issues that impact the well-being of its citizens and require ongoing attention and policy responses. A center-left perspective often emphasizes the need for collective responsibility and government intervention to address these challenges and support vulnerable groups.

11.3.1. Housing

Housing affordability and availability are major social issues. Rapidly rising house prices, particularly in Auckland and other major centres, have made homeownership unattainable for many and have increased rental costs. This contributes to housing insecurity, overcrowding, and homelessness. Government responses have included initiatives to increase housing supply, provide social housing, and offer support for first-home buyers, but the problem remains complex and deeply entrenched. The quality of housing, particularly insulation and heating, is also a concern, impacting health outcomes.

11.3.2. Crime and justice

Crime rates and the functioning of the criminal justice system are ongoing social concerns. While New Zealand is generally considered a safe country, issues such as family violence, youth offending, and property crime persist. There is a significant overrepresentation of Māori in the criminal justice system, both as offenders and victims, reflecting systemic inequalities and historical injustices. Efforts towards restorative justice and rehabilitation are increasingly emphasized alongside punitive measures. Addressing the root causes of crime, such as poverty, inequality, and lack of opportunity, and reducing reoffending are key priorities. Ensuring fairness and equity within the justice system, particularly for Māori and other minority groups, is a critical aspect of social justice.

11.3.3. Gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights

New Zealand has a strong record on gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights. It was the first country to grant women the right to vote in 1893. Same-sex marriage was legalised in 2013, and there are legal protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. However, challenges remain, including the gender pay gap, underrepresentation of women in leadership positions, and issues of family violence and sexual harassment, which disproportionately affect women. For LGBTQ+ individuals, while legal recognition is strong, issues of social acceptance, mental health disparities, and access to inclusive services continue to require attention. Promoting genuine equality and ensuring the safety and well-being of all individuals, regardless of gender or sexual orientation, is a key focus from a human rights perspective.

12. Culture