1. Overview

Tuvalu is a Polynesian island nation located in Oceania, midway between Hawaii and Australia. Comprising nine low-lying coral atolls and reef islands, it is one of the smallest and most remote nations in the world. With a population of just over 11,000, it is the second-least populous sovereign state globally. Tuvalu's unique geography, characterized by its extremely low elevation, makes it exceptionally vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, particularly sea level rise, which poses an existential threat to its land, people, and culture. This article explores Tuvalu's history from its initial settlement by Polynesians through colonization and independence, its distinct societal structures, and its contemporary challenges, focusing on the profound social and human rights implications of environmental change and the nation's efforts to advocate for global climate justice and secure its future. The perspective adopted emphasizes environmental justice, the human impacts of climate change, and the resilience and agency of the Tuvaluan people in the face of adversity.

2. History

The history of Tuvalu spans from its initial settlement by Polynesians thousands of years ago, through European contact, colonial administration, and its journey to independence and contemporary nationhood. This section details these key periods, highlighting the resilience of Tuvaluan society and the significant impacts of external forces, including labor exploitation and the Second World War, as well as the nation's path to self-determination and its ongoing struggles, particularly with climate change.

2.1. Prehistory

The origins of the people of Tuvalu are linked to the broader Polynesian migration across the Pacific, which began approximately 3,000 years ago. It is believed that Polynesians, skilled in Polynesian navigation using outrigger canoes and double-hulled canoes, voyaged from Samoa and Tonga to settle the Tuvaluan atolls. These islands then may have served as a stepping stone for further migrations into the Polynesian outliers in Melanesia and Micronesia. Oral traditions vary among the islands; for instance, the founding ancestors of Niutao, Funafuti, and Vaitupu are said to be from Samoa, while those of Nanumea are described as originating from Tonga.

Eight of Tuvalu's nine islands were traditionally inhabited, which is the origin of the name "Tuvalu," meaning "eight standing together" in the Tuvaluan language. Archaeological evidence, such as possible human-made fires in the Caves of Nanumanga, suggests human occupation of the islands for thousands of years.

An important creation myth is the story of te Pusi mo te Ali (the Eel and the Flounder), who are said to have created the islands. Te Ali (the flounder) is believed to be the origin of the flat atolls, and te Pusi (the eel) is the model for the vital coconut palms.

2.2. Early European Contact and Naming

The first European sighting of Tuvalu occurred on January 16, 1568, when Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira sailed past Nui during his expedition in search of Terra Australis. He charted it as Isla de Jesús (Island of Jesus). Mendaña made contact with the islanders but was unable to land. On his second voyage in 1595, he passed Niulakita, naming it La Solitaria (The Solitary One).

Captain John Byron passed through the islands in 1764 during his circumnavigation, charting the atolls as Lagoon Islands. In 1781, Spanish naval officer Francisco Mourelle de la Rúa, captaining the frigate La Princesa, sighted Nanumea and charted it as San Augustin. He also sighted Niutao, which he named El Gran Cocal (The Great Coconut Plantation).

In May 1819, Captain Arent Schuyler de Peyster of the American-owned but British-flagged brigantine Rebecca sighted Nukufetau and Funafuti. He named Funafuti "Ellice's Island" after Edward Ellice, a British politician and the owner of the Rebecca's cargo. Later, English hydrographer Alexander George Findlay applied the name "Ellice Islands" to the entire nine-island group. Russian explorer Mikhail Lazarev visited Nukufetau in 1820. In 1824, Louis-Isidore Duperrey, captain of La Coquille, sailed past Nanumanga. A Dutch expedition in 1825 found Nui and named its main island, Fenua Tapu, Nederlandsch Eiland (Dutch Island).

2.3. 19th Century: Traders, Missionaries, and Blackbirding

From the 1820s, whalers began to frequent the Pacific, though Tuvalu was visited less often due to landing difficulties. Captain George Barrett of the American whaler Independence II is identified as the first whaler in Tuvaluan waters, bartering for coconuts in Nukulaelae in 1821 and also visiting Niulakita. He established a shore camp on Sakalua islet of Nukufetau for processing whale blubber.

European traders became active in Tuvalu from the mid-19th century. John O'Brien was the first European to settle, becoming a trader on Funafuti in the 1850s and marrying Salai, the daughter of Funafuti's paramount chief. Louis Becke traded on Nanumanga and later Nukufetau. By the 1890s, traders like Edmund Duffy (Nanumea), Jack Buckland (Niutao), Harry Nitz (Vaitupu), Alfred Restieaux and Emile Fenisot (Nukufetau), and Martin Kleis (Nui) were present. However, by 1909, resident European traders representing large companies had largely disappeared, replaced by supercargos on trading ships dealing directly with islanders, though some like Fred Whibley, Restieaux, and Kleis remained until their deaths.

Christianity was introduced to Tuvalu in 1861 when Elekana, a deacon from a Congregational church in Manihiki, Cook Islands, drifted to Nukulaelae after a storm. He began preaching and was later trained at a London Missionary Society (LMS) college in Samoa. In 1865, Rev. A.W. Murray of the LMS became the first European missionary to arrive. By 1878, Protestantism was well established, with preachers on each island, predominantly Samoans, who significantly influenced the Tuvaluan language and music.

The period also saw the devastating impact of blackbirding. Between 1862 and 1863, Peruvian ships seeking labor for Peru forcibly recruited or impressed workers from Polynesia. On Funafuti and Nukulaelae, some resident traders facilitated this exploitation. Rev. Murray reported that in 1863, about 170 people were taken from Funafuti and 250 from Nukulaelae. Nukulaelae's population, recorded at 300 in 1861, was reduced to fewer than 100 after these raids, highlighting the severe human cost of this practice.

2.4. Colonial Administration

In the late 19th century, the Ellice Islands came under Great Britain's sphere of influence. Between 9 and 16 October 1892, Captain Herbert Gibson of HMS Curacoa declared each of the Ellice Islands a British protectorate. The islands were administered as part of the British Western Pacific Territories (BWPT) by a Resident Commissioner based in the Gilbert Islands.

In 1916, the administration of the BWPT ended, and the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony (GEIC) was established. This administrative arrangement continued until 1975. During this period, significant social and administrative changes occurred. The colonial government introduced Western systems of governance, education, and law, often alongside or supplanting traditional structures. The influence of Samoan pastors, who were instrumental in establishing the Church of Tuvalu, also shaped Tuvaluan society and language.

2.5. Second World War

During the Second World War, the Ellice Islands, as a British colony, were aligned with the Allies. The Japanese occupied nearby Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati). The strategic importance of the Ellice Islands grew, leading to the United States Marine Corps landing on Funafuti on 2 October 1942, and subsequently on Nanumea and Nukufetau in August 1943.

Funafuti became a significant Allied base, used for preparing seaborne attacks on the Japanese-held Gilbert Islands. The local Tuvaluan population played a crucial role, assisting American forces in building airfields on Funafuti (which became Funafuti International Airport), Nanumea (Nanumea Airfield), and Nukufetau (Nukufetau Airfield), and in unloading supplies. On Funafuti, islanders relocated to smaller islets to allow for the construction of the airfield and Naval Base Funafuti on Fongafale. The US Navy's Seabees (Naval Construction Battalions) built a seaplane ramp and a compacted coral runway. USN PT boats and seaplanes were based at Funafuti from November 1942 to May 1944.

The atolls served as staging posts for the Battle of Tarawa and the Battle of Makin in November 1943. The war had lasting effects on Tuvaluan society. The construction projects, particularly the airfield on Funafuti, altered the landscape and impacted freshwater aquifers through the creation of borrow pits. The influx of military personnel and resources also brought significant social and economic changes, exposing islanders to new goods, ideas, and a cash economy, which had long-term consequences for traditional ways of life.

2.6. Path to Independence

Following World War II, the global movement towards decolonization, supported by the United Nations, paved the way for self-determination in Britain's Pacific colonies. In 1974, ministerial government was introduced to the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony.

A crucial step towards independence was the 1974 referendum, where the predominantly Polynesian population of the Ellice Islands voted overwhelmingly to separate from the predominantly Micronesian Gilbert Islands. This decision reflected cultural and administrative differences and a desire for greater self-governance.

The separation occurred in two stages. The Tuvaluan Order 1975, effective 1 October 1975, recognized Tuvalu as a separate British colony with its own government. On 1 January 1976, separate administrations were formally established. Elections for the House of Assembly of the Colony of Tuvalu were held on 27 August 1977, and Toaripi Lauti became Chief Minister on 1 October 1977.

2.7. Post-Independence Era

Tuvalu achieved full independence as a sovereign state within the Commonwealth on 1 October 1978, with Toaripi Lauti as its first Prime Minister. It adopted a constitutional monarchy with the British monarch (currently King Charles III) as King of Tuvalu, represented by a Governor-General. The date of independence is celebrated annually as a public holiday.

On 5 September 2000, Tuvalu became the 189th member of the United Nations. As an independent nation, Tuvalu has faced significant political, economic, and social challenges. Its small size, remoteness, limited natural resources, and dependence on foreign aid have shaped its development. A critical and overarching challenge is climate change and sea level rise, which threaten the very existence of the nation.

In response to this existential threat, Tuvalu has become a vocal advocate for climate action on the international stage. Domestically, it has pursued various adaptation measures. On 15 November 2022, Tuvalu announced plans to create a digital replica of itself in the metaverse to preserve its cultural heritage as sea levels rise.

A significant recent development is the Falepili Union treaty signed with Australia on 10 November 2023. "Falepili" signifies traditional values of good neighborliness, care, and mutual respect. The treaty addresses climate change and security, with Australia committing to increased contributions to the Tuvalu Trust Fund and the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project. Critically, it also provides a pathway for up to 280 Tuvaluan citizens per year to migrate to Australia, offering a form of climate-related mobility.

3. Geography

This section details Tuvalu's geographical setting, including its constituent islands, landforms, and prevailing climatic conditions, emphasizing the nation's extreme vulnerability due to its low elevation.

3.1. Topography and Islands

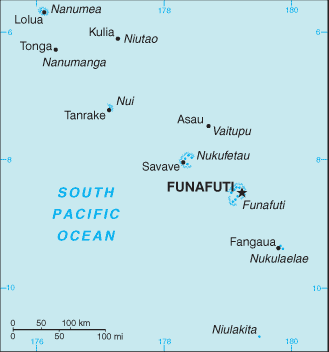

Tuvalu is a volcanic archipelago located in Polynesia, consisting of three reef islands (Nanumanga, Niutao, and Niulakita) and six true atolls (Funafuti, Nanumea, Nui, Nukufetau, Nukulaelae, and Vaitupu). These islands are spread out between the latitude of 5° and 10° south and between the longitude of 176° and 180° east, west of the International Date Line.

The total land area is only about 10 mile2 (26 km2), making it the fourth smallest country in the world. The islands are low-lying with poor soil. The highest elevation in Tuvalu is 15 ft (4.6 m) above sea level on Niulakita. This extremely low elevation makes the islands highly susceptible to seawater flooding, especially during cyclones, storm surges, and king tides.

Funafuti is the largest atoll and serves as the capital. It comprises numerous islets around a central lagoon, known as Te Namo, which is approximately 16 mile (25.1 km) long (north-south) and 11 mile (18.4 km) wide (west-east). The atolls typically feature an annular reef rim surrounding a lagoon, with natural reef channels providing access to the open sea.

The exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Tuvalu covers an oceanic area of approximately 347 K mile2 (900.00 K km2). The predominant vegetation type is cultivated coconut woodland, covering 43% of the land, while native broadleaf forest is limited to 4.1%. Tuvalu is part of the Western Polynesian tropical moist forests terrestrial ecoregion.

3.2. Climate

Tuvalu has a tropical maritime climate, characterized by consistently high temperatures and humidity throughout the year. It experiences two distinct seasons: a wet season from November to April and a dry season from May to October. The period from November to April, known as Tau-o-lalo, is marked by westerly gales and heavy rainfall. From May to October, tropical temperatures are moderated by easterly winds.

Annual rainfall is substantial, typically ranging between 7.9 in (200 mm) and 16 in (400 mm) per month. The country is influenced by El Niño and La Niña phenomena. El Niño conditions tend to increase the likelihood of tropical storms and cyclones, while La Niña conditions can lead to drought.

The average daily temperature ranges from 82.58 °F (28.1 °C) to 83.12 °F (28.4 °C).

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 92.84 °F (33.8 °C) | 93.91999999999999 °F (34.4 °C) | 93.91999999999999 °F (34.4 °C) | 91.76 °F (33.2 °C) | 93.02 °F (33.9 °C) | 93.02 °F (33.9 °C) | 91.03999999999999 °F (32.8 °C) | 91.22 °F (32.9 °C) | 91.03999999999999 °F (32.8 °C) | 93.91999999999999 °F (34.4 °C) | 93.02 °F (33.9 °C) | 93.02 °F (33.9 °C) | 93.91999999999999 °F (34.4 °C) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 87.26 °F (30.7 °C) | 87.44 °F (30.8 °C) | 87.08000000000001 °F (30.6 °C) | 87.8 °F (31 °C) | 87.61999999999999 °F (30.9 °C) | 87.08000000000001 °F (30.6 °C) | 86.72 °F (30.4 °C) | 86.72 °F (30.4 °C) | 87.26 °F (30.7 °C) | 87.8 °F (31 °C) | 88.16 °F (31.2 °C) | 87.8 °F (31 °C) | 87.44 °F (30.8 °C) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 82.75999999999999 °F (28.2 °C) | 82.58 °F (28.1 °C) | 82.58 °F (28.1 °C) | 82.75999999999999 °F (28.2 °C) | 83.12 °F (28.4 °C) | 82.94 °F (28.3 °C) | 82.58 °F (28.1 °C) | 82.58 °F (28.1 °C) | 82.75999999999999 °F (28.2 °C) | 82.75999999999999 °F (28.2 °C) | 83.12 °F (28.4 °C) | 82.94 °F (28.3 °C) | 82.75999999999999 °F (28.2 °C) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 77.9 °F (25.5 °C) | 77.54 °F (25.3 °C) | 77.72 °F (25.4 °C) | 78.25999999999999 °F (25.7 °C) | 78.44 °F (25.8 °C) | 78.62 °F (25.9 °C) | 78.25999999999999 °F (25.7 °C) | 78.44 °F (25.8 °C) | 78.44 °F (25.8 °C) | 78.25999999999999 °F (25.7 °C) | 78.44 °F (25.8 °C) | 78.25999999999999 °F (25.7 °C) | 78.44 °F (25.8 °C) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 71.6 °F (22 °C) | 71.96 °F (22.2 °C) | 73.04 °F (22.8 °C) | 73.4 °F (23 °C) | 68.9 °F (20.5 °C) | 73.4 °F (23 °C) | 69.8 °F (21 °C) | 60.980000000000004 °F (16.1 °C) | 68 °F (20 °C) | 69.8 °F (21 °C) | 73.04 °F (22.8 °C) | 73.04 °F (22.8 °C) | 60.980000000000004 °F (16.1 °C) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 16 in (413.7 mm) | 14 in (360.6 mm) | 13 in (324.3 mm) | 10 in (255.8 mm) | 10 in (259.8 mm) | 8.5 in (216.6 mm) | 10.0 in (253.1 mm) | 11 in (275.9 mm) | 8.6 in (217.5 mm) | 10 in (266.5 mm) | 11 in (275.9 mm) | 16 in (393.9 mm) | 0.1 K in (3.51 K mm) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 20 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 223 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 82 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 81 | 82 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 179.8 | 161.0 | 186.0 | 201.0 | 195.3 | 201.0 | 195.3 | 220.1 | 210.0 | 232.5 | 189.0 | 176.7 | 2,347.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 5.8 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 6.4 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst | |||||||||||||

4. Climate Change and Environmental Issues

Tuvalu faces severe and multifaceted environmental challenges, predominantly driven by climate change. Its low-lying atolls are acutely vulnerable to sea level rise, increased storm intensity, and other climate-related impacts, which threaten the nation's territory, resources, culture, and very existence. This section explores these critical issues, emphasizing the human cost and the pursuit of environmental justice.

4.1. Sea Level Rise and Impacts

Global warming is causing sea levels to rise, and Tuvalu is on the front line of this crisis. The sea level at the Funafuti tide gauge has reportedly risen at approximately 0.2 in (3.9 mm) per year, which is about twice the global average. Some studies in 2018 indicated a net increase in the land area of Tuvalu's islets over four decades, suggesting sediment accretion from increased wave energy across reef surfaces. However, Tuvaluan leaders have contested these findings, emphasizing that such changes do not equate to habitable land gain and overlook critical issues like saltwater intrusion into freshwater aquifers, which contaminates drinking water sources and damages agriculture (especially pulaka cultivation in pits).

The direct impacts of sea level rise are already being felt:

- Coastal Inundation: Low-lying areas, including parts of the capital Funafuti and the airport, regularly experience flooding during king tides (unusually high tides) and storm surges. Seawater can be seen bubbling up through the porous coral rock during high tides.

- Damage to Agriculture: Saltwater intrusion renders land unsuitable for traditional crops like pulaka and taro, impacting food security.

- Infrastructure Damage: Roads, homes, and other essential infrastructure are frequently damaged by coastal flooding.

- Effects on Daily Life: The constant threat of inundation and the degradation of resources significantly impact the well-being and livelihoods of Tuvaluans.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that a sea level rise of 7.9 in (20 cm) to 16 in (40 cm) within the next 100 years could render Tuvalu uninhabitable. This stark reality underscores the urgency of global climate action and local adaptation efforts.

4.2. Cyclones and King Tides

Tuvalu is vulnerable to tropical cyclones, which can cause widespread devastation due to the islands' low elevation and lack of natural defenses. The impact of cyclones is often exacerbated when they coincide with high tides or king tides.

Historically, Tuvalu experienced an average of three cyclones per decade between the 1940s and 1970s, increasing to eight in the 1980s. Notable cyclones include:

- A cyclone in 1883 recorded by trader George Westbrook on Funafuti.

- A cyclone in 1886 that struck Nukulaelae.

- A severe cyclone in 1894.

- Cyclone Bebe (October 1972): An early-season storm that submerged Funafuti, destroyed 90% of structures, contaminated freshwater sources, and resulted in six deaths.

- Cyclone Meli (1979): Devastated Funafuti's Tepuka Vili Vili islet, stripping its vegetation and sand.

- Cyclone Ofa (1990): Caused major damage to vegetation and crops across most islands.

- Cyclone Pam (March 2015): Generated waves of 9.8 ft (3 m) to 16 ft (5 m), causing extensive damage to homes, crops, and infrastructure, particularly on Nui, Nukufetau, and Nanumanga. A state of emergency was declared, and freshwater sources were contaminated. Vasafua islet in the Funafuti Conservation Area was reduced to a sandbar.

- Cyclone Tino (January 2020): Impacted the whole of Tuvalu with its associated convergence zone.

King tides, or perigean spring tides, regularly cause coastal flooding, especially in low-lying areas like Funafuti. The highest recorded peak tide by the Tuvalu Meteorological Service was 11 ft (3.4 m) (February 2006 and February 2015). These events, compounded by historical sea level rise and storm surges, increasingly inundate land, damage infrastructure, and contaminate freshwater resources, highlighting the daily reality of climate change impacts for Tuvaluans. A warning system using the Iridium satellite network was introduced in 2016 to improve disaster preparedness on outer islands.

4.3. Other Major Environmental Challenges

Beyond sea level rise and cyclones, Tuvalu faces several other significant environmental problems:

- World War II Borrow Pits: The construction of Funafuti International Airport during WWII involved excavating coral material, creating large borrow pits. These pits disrupted the freshwater lens, increased saltwater intrusion, and became stagnant water bodies, posing health risks. A remediation project in 2014-2015, funded by New Zealand, filled 10 of these pits with sand from the lagoon, increasing usable land on Fongafale by 8%.

- Coastal Erosion: Alterations to the reef and shoreline on Funafuti during WWII, including pier construction and channel excavation, changed wave patterns, leading to reduced sand accumulation and increased coastal erosion. Attempts to stabilize the shoreline have had limited success.

- Coral Reef Bleaching and Degradation: Rising ocean temperatures, particularly during El Niño events (e.g., 1998-2001, which bleached an average of 70% of Acropora spp. corals in Funafuti), have caused significant coral bleaching and degradation. This impacts marine biodiversity, fisheries, and the natural coastal defenses provided by healthy reefs. Reef restoration projects and research into coral rebuilding using foraminifera are underway, supported by organizations like the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

- Waste Management: With a growing population and reliance on imported goods, waste management is a major challenge, particularly for plastic waste. Inadequate sanitation systems can lead to pollution of groundwater and coastal waters. The Waste Operations and Services Act (2009) and Environment Protection (Litter and Waste Control) Regulation (2013) provide frameworks for improved waste management, including projects for organic waste composting and controlling non-biodegradable material imports.

4.4. Water Resources and Sanitation

Freshwater is a scarce and precious resource in Tuvalu. The primary source is rainwater harvesting, with households and communities relying on collection and storage systems. However, the effectiveness of these systems can be diminished by poor maintenance of roofs, gutters, and pipes. Sustainable groundwater supplies are only found on Nukufetau, Vaitupu, and Nanumea.

During droughts, particularly those associated with La Niña events (such as the 2011 Tuvalu drought), water scarcity becomes acute. To supplement rainwater, desalination plants operate, especially on Funafuti. A 85 yd3 (65 m3) desalination plant on Funafuti aims to produce around 52 yd3 (40 m3) per day, but continuous demand often necessitates constant operation. Water delivery from these plants is subsidized by the government.

International aid programs, from countries like Australia and the European Union, have focused on improving water storage capacity and infrastructure. In 2012, Tuvalu developed a National Water Resources Policy under the Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) Project and the Pacific Adaptation to Climate Change (PACC) Project, aiming for a target of 50 to 100 liters of water per person per day.

Sanitation is another challenge. Leaking septic tanks on Funafuti can contaminate the freshwater lens and coastal waters. Efforts are being made, with support from the Pacific Community (SPC), to implement composting toilets, which reduce water use and improve waste treatment. Public health is closely linked to water and sanitation quality, with concerns about waterborne diseases if resources are contaminated or scarce.

4.5. Climate Change Adaptation and International Cooperation

Tuvalu has been proactive in developing national strategies to adapt to climate change and in advocating for global action. Key domestic initiatives include:

- National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA): Launched in 2007, NAPA identified urgent and immediate adaptation needs across various sectors, including coastal protection, water resources, agriculture, health, and fisheries. It outlined seven priority adaptation projects.

- Te Kakeega III and Te Kete: These national strategies for sustainable development (Te Kakeega III for 2016-2020, and Te Kete for 2021-2030) integrate climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction into broader development planning.

- Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project (TCAP): Launched in 2017 with support from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), TCAP is a major initiative to enhance coastal resilience. A significant component involves land reclamation on Funafuti, creating a raised platform of approximately 7.8 hectares designed to remain above sea level rise and storm waves beyond 2100. Work on this began in December 2022. TCAP also includes capital works on the outer islands of Nanumea and Nanumanga to reduce coastal damage.

Internationally, Tuvalu is a prominent voice in climate negotiations, often "punching above its weight." It is an active member of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF). Tuvalu has consistently called for more ambitious global emissions reduction targets and greater financial and technical support for vulnerable nations.

The Falepili Union treaty with Australia, signed in 2023, is a landmark bilateral agreement. It includes Australian commitments to support Tuvalu's climate adaptation efforts and, significantly, provides a special visa pathway for Tuvaluans to migrate to Australia due to climate-related pressures, offering a critical avenue for climate-related mobility while aiming to allow Tuvaluans to "live with dignity."

In 2023, Tuvalu, along with other vulnerable Pacific island nations, launched the "Port Vila Call for a Just Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific," advocating for the phase-out of fossil fuels, a just transition to renewable energy, and strengthening environmental law, including the introduction of the crime of ecocide.

4.6. National Identity and Future in a Changing Climate

Climate change poses a profound threat not only to Tuvalu's physical territory but also to its national sovereignty, culture, and identity. The prospect of displacement and the potential loss of ancestral lands raise complex legal and ethical questions about statehood and the rights of climate-vulnerable populations.

Tuvaluan leaders and citizens have expressed a strong desire to remain in their homeland if possible, emphasizing the deep connection between land, culture, and identity. Evacuation is often viewed as a last resort.

To address the threat of cultural loss, Tuvalu launched the 'Future Now' project, which includes the 'digital nation' initiative announced in November 2022 by Foreign Minister Simon Kofe. This innovative plan aims to create a digital replica of Tuvalu - its islands, landmarks, and cultural practices - to preserve its heritage and maintain a sense of national identity even if the physical islands become uninhabitable. This project also seeks to ensure Tuvalu can continue to function as a state and maintain its maritime boundaries and resources under international law, regardless of the physical impacts of sea level rise. The 2023 amendments to the Constitution of Tuvalu enshrined the country's statehood as permanent, irrespective of territorial changes due to climate change.

These efforts reflect Tuvalu's determination to shape its own future, preserve its unique heritage, and advocate for global solidarity in addressing the climate crisis, highlighting the disproportionate burden faced by small island developing states.

5. Government

This section explains Tuvalu's political framework, governmental structure, judicial system, defence and law enforcement mechanisms, and local governance, noting the influence of its constitutional monarchy and traditional systems.

5.1. Political System and Parliament

Tuvalu is a parliamentary democracy and a Commonwealth realm, with King Charles III as the King of Tuvalu, who is the Head of State. The King is represented by a Governor-General, appointed on the advice of the Prime Minister. Referendums in 1986 and 2008 to transition to a republic were unsuccessful, retaining the monarchy.

The Constitution of Tuvalu is the supreme law. The most recent amendments, passed as the Constitution of Tuvalu Act 2023, came into effect on 1 October 2023, reinforcing cultural values, addressing climate change, and recognizing traditional governance structures.

The legislature is the unicameral Parliament of Tuvalu (Palamene o Tuvalu), formerly the House of Assembly. It consists of 16 members elected every four years through universal suffrage. There are no formal political parties; election campaigns are typically based on personal and family ties, and individual reputations. Parliament meets in the Vaiaku maneapa.

The Prime Minister, who is the head of government, is elected by the members of Parliament. The Cabinet ministers are appointed by the Governor-General on the advice of the Prime Minister.

5.2. Legal System

The legal system is based on English common law, supplemented by Acts of the Tuvaluan Parliament and customary law, particularly concerning land tenure. The Constitution of Tuvalu guarantees fundamental rights and freedoms and includes a Bill of Rights.

The court system comprises:

- Island Courts and Lands Courts: There are eight Island Courts and associated Lands Courts. Appeals regarding land disputes go to the Lands Courts Appeal Panel.

- Magistrates Court: Hears appeals from Island Courts and the Lands Courts Appeal Panel, and has jurisdiction over civil cases involving up to 10.00 K AUD.

- High Court: The superior court with unlimited original jurisdiction to interpret Tuvaluan law and hear appeals from lower courts.

- Court of Appeal: Hears appeals from the High Court.

- Privy Council (His Majesty in Council): The final court of appeal, located in London.

The land tenure system is largely based on kaitasi (extended family ownership). Tuvalu is a state party to key human rights treaties, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). The Tuvalu National Council for Women is an umbrella organization for women's rights groups. Male homosexuality remains illegal.

Historically, women's representation in the judiciary was limited, but the first female Island Court magistrate was appointed in the 1980s, and by 2007, there were seven female magistrates in Island Courts.

5.3. Defence and Law Enforcement

Tuvalu has no regular military and spends no money on defence. National security and law enforcement are the responsibility of the Tuvalu Police Force, headquartered in Funafuti. The police force includes a maritime surveillance unit, customs, prisons, and immigration services. Police officers wear British-style uniforms.

For maritime surveillance and fisheries patrol within its extensive exclusive economic zone (EEZ), Tuvalu has relied on patrol boats provided by Australia. The Pacific-class patrol boat HMTSS Te Mataili served from 1994 to 2019. It was replaced by the Guardian-class patrol boat HMTSS Te Mataili II in 2019. After Te Mataili II was severely damaged by cyclones, Australia provided a replacement, HMTSS Te Mataili III, in October 2024. ("HMTSS" stands for His/Her Majesty's Tuvaluan State Ship).

In May 2023, Tuvalu signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Sea Shepherd Global to combat Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing. Sea Shepherd provides the vessel Allankay to support patrols by Tuvaluan police officers.

Crime in Tuvalu is generally not a significant social problem, attributed to an effective criminal justice system, the influence of the Falekaupule (traditional island councils), and the central role of religious institutions.

5.4. Administrative Divisions and Local Governance

Tuvalu consists of nine main island/atoll districts. Eight of these are self-governing, while Niulakita is administered by Niutao. Each inhabited island forms a local government district. The districts are:

- Funafuti (capital, population approx. 6,320 in 2017)

- Nanumanga (population approx. 491)

- Nanumea (population approx. 512)

- Niutao (population approx. 582, administers Niulakita)

- Nui (population approx. 610)

- Nukufetau (population approx. 597)

- Nukulaelae (population approx. 300)

- Vaitupu (population approx. 1,061)

- Niulakita (population approx. 34)

Local governance is characterized by the Falekaupule, the traditional assembly of elders on each island. The Falekaupule system holds significant cultural and decision-making authority. Since the Falekaupule Act of 1997, their powers and functions are formally recognized and often shared with the pule o kaupule (elected village president). Each island also has its own high-chief (ulu-aliki) and several sub-chiefs (aliki), who exercise informal authority at the local level, with chiefs often chosen based on ancestry. The 2023 constitutional amendments further recognized the Falekaupule as the traditional governing authorities.

Tuvalu has ISO 3166-2 codes defined for one town council (Funafuti) and seven island councils.

6. Foreign Relations

This section describes Tuvalu's fundamental foreign policy objectives, its key bilateral relationships, and its engagement in international organizations and multilateral cooperation, with a strong focus on climate change advocacy and sustainable development.

6.1. Foreign Policy Priorities

Tuvalu's foreign policy is primarily driven by its vulnerability to climate change and its status as a small island developing state. Key priorities include:

- Climate Change Advocacy: Urging robust global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, seeking international support for adaptation and mitigation measures, and highlighting the existential threat posed by sea level rise. Tuvalu is a leading voice in forums like the UN and AOSIS.

- Marine Resource Management: Sustainably managing its extensive exclusive economic zone (EEZ), particularly its tuna fisheries, and combating illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

- Sustainable Development: Pursuing economic development that is environmentally sustainable and improves the quality of life for its citizens, often relying on partnerships and foreign aid.

- Securing International Partnerships and Aid: Building and maintaining strong relationships with donor countries and international organizations to support its development and climate resilience goals.

- Preserving Sovereignty and Culture: Ensuring Tuvalu's continued existence as a nation-state and preserving its unique cultural heritage in the face of climate change threats.

6.2. Bilateral Relations

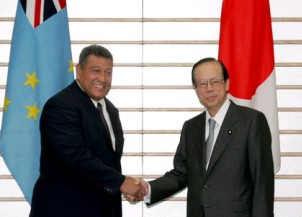

Tuvalu maintains diplomatic relations with numerous countries, with some partnerships being particularly significant.

6.2.1. Australia

Australia is a key partner for Tuvalu. The relationship was formalized and deepened by the Falepili Union treaty signed on 10 November 2023. This comprehensive treaty covers:

- Security: Cooperation on traditional security threats, major natural disasters, and health pandemics.

- Climate Change Response: Australian support for Tuvalu's adaptation efforts, including contributions to the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project (TCAP) and the Tuvalu Trust Fund.

- Migration Pathway: A special visa pathway allowing up to 280 Tuvaluan citizens per year to migrate to Australia, providing a crucial avenue for climate-related mobility.

- Economic Development Support: Ongoing development assistance.

Australia has maintained a High Commission in Tuvalu since 2018.

6.2.2. New Zealand

New Zealand has a long-standing and close relationship with Tuvalu. Key aspects of the partnership include:

- Development Aid: Consistent provision of development assistance across various sectors.

- Seasonal Worker Programs: The Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) scheme allows Tuvaluans to work seasonally in New Zealand's horticulture and viticulture industries, providing important remittance income.

- Pacific Access Category (PAC) Ballot: An annual quota allowing a certain number of Tuvaluans to gain residency in New Zealand.

- Disaster Relief Cooperation: New Zealand frequently provides support following natural disasters.

6.2.3. Taiwan (Republic of China)

Tuvalu is one of the few countries that maintain official diplomatic relations with the Republic of China (ROC), commonly known as Taiwan, rather than the People's Republic of China. This relationship is highly significant for Tuvalu.

- Key Partnership: Taiwan is a crucial partner, providing substantial economic and technical assistance, including in areas like agriculture, healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

- Mutual Visits: High-level visits between officials of both countries occur regularly.

- Diplomatic Support: Tuvalu has consistently supported Taiwan's participation in international organizations.

Despite pressure from the People's Republic of China, Tuvalu has affirmed its commitment to its relationship with Taiwan. Taiwan maintains an embassy in Funafuti.

6.2.4. Other Key Partners

- Japan: Provides development assistance, particularly in infrastructure (e.g., inter-island ferries) and fisheries.

- South Korea: Offers development aid and cooperation.

- United States: Engages through treaties like the South Pacific Tuna Treaty and provides some development assistance. A Treaty of Friendship signed in 1983 saw the US renounce prior territorial claims to four Tuvaluan islands.

- United Kingdom: The former colonial power, maintains ties and contributes to the Tuvalu Trust Fund.

- European Union: Provides development aid and engages through agreements like the Cotonou Agreement. The first enhanced High Level Political Dialogue between Tuvalu and the EU under the Cotonou Agreement was held in Funafuti in 2017.

6.3. Multilateral Cooperation and International Organizations

Tuvalu actively participates in numerous international and regional organizations:

- United Nations (UN): Became the 189th member in 2000. Tuvalu uses the UN platform extensively for climate change advocacy.

- Commonwealth of Nations: A member since independence in 1978.

- Pacific Islands Forum (PIF): A key regional body for political and economic cooperation.

- Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS): A coalition of small island and low-lying coastal countries, where Tuvalu plays a leading role in climate negotiations, advocating for ambitious emissions reductions and support for vulnerable nations.

- Pacific Community (SPC): Participates in the work of the SPC.

- Nauru Agreement and Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC): Involved in regional fisheries management.

- World Bank and Asian Development Bank (ADB): Member of both, receiving financial and technical assistance.

- Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF): Joined in 2016.

- Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER Plus): Signed in 2017 and ratified in 2022, aimed at reducing trade barriers.

Tuvalu's engagement in these forums is crucial for amplifying its voice on global issues, particularly climate change, and for securing the resources needed for its sustainable development and survival. Under the Majuro Declaration (2013), Tuvalu committed to achieving 100% renewable energy generation, primarily through solar PV.

7. Economy

This section provides an overview of Tuvalu's economic structure, main industries, financial status, reliance on external aid, and efforts towards sustainable development, acknowledging its unique challenges as a small, remote, and climate-vulnerable island nation.

7.1. Economic Structure and Performance

Tuvalu's economy is small and vulnerable, heavily reliant on external factors. It is designated a Least Developed Country (LDC) by the United Nations due to its limited economic development potential, lack of exploitable resources, small size, and susceptibility to external shocks. Its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is among the smallest of any sovereign nation.

Economic performance has been modest and often volatile. From 1996 to 2002, Tuvalu experienced relatively strong growth, but this slowed thereafter. The economy contracted during the global financial crisis and faced challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, with real GDP growth falling from 13.8% in 2019 to -4.3% in 2020, recovering to 1.8% in 2021. Inflation rose to 11.5% in 2022 due to drought and rising global food prices but was projected to fall.

Key economic challenges include:

- Geographical isolation and distance from major markets.

- Small domestic market and limited economies of scale.

- Dependence on imported goods, including food and fuel, making it vulnerable to price shocks.

- Environmental vulnerability, particularly to climate change impacts, which impose significant economic costs.

The national development strategy, Te Kete - National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2021-2030, guides government efforts towards economic resilience and improved living standards.

7.2. Key Revenue Sources

Tuvalu's government revenue relies on a few key sources:

- Fisheries Licensing: A significant portion of national income comes from selling licenses for foreign vessels to fish in Tuvalu's vast exclusive economic zone (EEZ), primarily for tuna. Revenue from the US South Pacific Tuna Treaty and other agreements is crucial.

- Leasing of the ".tv" country-code top-level domain (ccTLD): The ".tv" domain is commercially valuable. Initially managed by Verisign, an agreement in 2023 with GoDaddy outsourced its marketing, sales, and branding to the Tuvalu Telecommunications Corporation. This provides a substantial and unique income stream.

- Tuvalu Trust Fund (TTF): Established in 1987 with contributions from Australia, New Zealand, and the UK (and later Japan and South Korea), the TTF is a sovereign wealth fund. Earnings from the fund are used to finance government budget deficits and development projects. Its value was approximately 190.00 M AUD in 2022, though it is subject to global market volatility.

- Remittances: Money sent home by Tuvaluans working overseas, particularly seafarers employed on international merchant ships and seasonal workers in New Zealand and Australia, is a vital source of income for many families. Approximately 15% of adult males work as seamen.

- Philatelic Sales: The Tuvalu Philatelic Bureau generates income from the sale of postage stamps to collectors.

- Foreign Aid and Grants: Tuvalu remains heavily dependent on foreign aid from partners like Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Taiwan, the EU, and international financial institutions.

- Tuvalu Ship Registry: Provides some income.

7.3. Tourism

Tourism in Tuvalu is very limited due to its remoteness, infrequent flights, and lack of developed tourist infrastructure. Visitor numbers are low; for example, 1,684 in 2010 and around 2,000 in 2016. Many visitors are on business, development officials, or technical consultants, rather than traditional tourists.

The main island of Funafuti is the primary destination, as it hosts the country's only international airport and hotel facilities. Ecotourism is a potential area for development, with attractions like the Funafuti Conservation Area, which covers 12.74 mile2 of ocean, reef, lagoon, and uninhabited islets, offering opportunities for diving, snorkeling, and experiencing pristine marine environments.

However, there are generally no organized tours, tour operators, or cruise ship visits. Access to outer islands is via government-operated passenger-cargo ships, with basic guesthouse accommodation sometimes available. The focus is on authentic, small-scale experiences.

7.4. Transport Infrastructure

Transport infrastructure in Tuvalu is limited and faces challenges due to the country's geography and resource constraints.

- Air Transport: The sole airport is Funafuti International Airport (FUN). Fiji Airways operates services between Suva (and sometimes Nadi) in Fiji and Funafuti, typically a few times a week, using ATR 72-600 aircraft. This is the primary international link.

- Sea Transport: Inter-island transport relies on government-operated passenger-cargo ships, such as the Nivaga III and Manú Folau (both donated by Japan). These vessels provide essential links to the outer islands, usually making round trips every three to four weeks. They also occasionally travel to Suva, Fiji. In 2020, a landing barge, Moeiteava, was acquired to transport dangerous goods and building materials to outer islands. The Tuvalu Fisheries Department operates vessels like Manaui and Tala Moana for research, FAD deployment, and patrols. Landing on some islands is difficult due to reef structures, requiring transfer to smaller boats. Projects are underway, with support from Australia and the ADB, to improve boat harbor facilities on Niutao and Nui.

- Roads: There are approximately 5.0 mile (8 km) of roads. The streets of Funafuti were paved in 2002, but roads on other islands are generally unpaved. Tuvalu has no railways.

Connectivity remains a significant challenge for both internal and external transport.

7.5. Telecommunications and Media

Telecommunications in Tuvalu rely heavily on satellite technology for telephone, television, and internet access.

- Tuvalu Telecommunications Corporation (TTC): This state-owned enterprise is the primary provider of telecommunications services. It offers fixed-line telephone services on each island and mobile phone services on Funafuti, Vaitupu, and Nukulaelae. TTC also distributes the Sky Pacific satellite television service from Fiji.

- Internet: Internet access has historically been limited and expensive. In July 2020, Tuvalu signed an agreement with Kacific Broadband Satellites to improve internet connectivity via VSAT satellite receivers, aiming to provide 400-600 Mbit/s capacity to schools, clinics, government agencies, businesses, and Wi-Fi hotspots, as well as maritime antennae for inter-island ferries. By 2022, Kacific and Agility Beyond Space (ABS) satellites provided a combined capacity of 510 Mbit/s. There were 5,915 active broadband users in 2022.

- Media: The Tuvalu Media Department (formerly Tuvalu Media Corporation) of the government operates Radio Tuvalu, the national broadcaster, transmitting from Funafuti. Upgraded AM broadcast equipment, funded by Japan in 2011, allows its signal to reach all nine islands. Fenui - news from Tuvalu is a digital publication of the Tuvalu Media Department, distributed via email and Facebook, covering government activities and local events. There are no daily newspapers.

The ".tv" domain, managed by the Tuvalu Telecommunications Corporation's .tv unit in partnership with GoDaddy, remains a crucial asset for the country's telecommunications revenue.

8. Society

This section covers Tuvalu's demographic characteristics, languages, predominant religions, healthcare system, and educational framework, reflecting the unique Polynesian culture and the influences of modern challenges.

8.1. Demographics

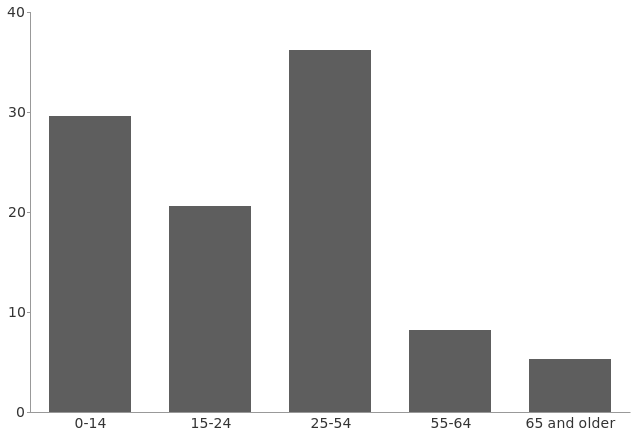

Tuvalu is one of the least populous countries in the world. The population was 9,561 at the 2002 census, 10,645 at the 2017 census, and estimated at 11,342 in 2020.

The population is predominantly of Polynesian ethnicity. Approximately 5.6% of the population are Micronesians, mainly of Gilbertese-speaking descent, particularly concentrated on Nui.

Key demographic indicators (2018 estimates):

- Life expectancy: 70.2 years for women, 65.6 years for men.

- Population growth rate: 0.86%.

- Net migration rate: -6.6 migrants/1,000 population, indicating some emigration.

A significant portion of the population, nearly two-thirds, resides on the main atoll of Funafuti, which is the capital and administrative center. This concentration leads to issues of overcrowding and pressure on resources on Funafuti.

Migration is an important aspect of Tuvaluan demographics. Historically, some Tuvaluans from Vaitupu migrated to Kioa island in Fiji between 1947 and 1983, and were granted Fijian citizenship in 2005. In recent years, New Zealand and Australia have been primary destinations for migration and seasonal work, facilitated by schemes like New Zealand's Pacific Access Category (PAC) and Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) program, and Australia's Pacific Seasonal Worker Program. The 2023 Falepili Union treaty with Australia includes a pathway for 280 Tuvaluans to migrate to Australia annually due to climate-related mobility. Despite the threat of sea level rise, many Tuvaluans express a strong preference to remain in their homeland due to cultural ties and identity.

8.2. Languages

The official languages of Tuvalu are Tuvaluan and English.

- Tuvaluan (Te Gana Tuvalu): A Polynesian language belonging to the Ellicean group, closely related to languages spoken in Polynesian outliers in Micronesia and Melanesia. It is spoken by virtually the entire population. The language has borrowed some vocabulary from Samoan, due to the influence of Samoan Christian missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There are distinct dialects of Tuvaluan spoken on different islands. Worldwide, there are about 13,000 Tuvaluan speakers.

- English: While an official language, English is not commonly spoken in daily life. It is used in some official contexts and in education, but parliamentary proceedings and most official functions are conducted in Tuvaluan.

- Gilbertese: A Micronesian language, very similar to the language of Kiribati, is spoken on the island of Nui by its inhabitants of Gilbertese descent.

Radio Tuvalu broadcasts programming primarily in the Tuvaluan language.

8.3. Religion

Christianity is the dominant religion in Tuvalu. The Church of Tuvalu (Te Ekalesia Kelisiano Tuvalu), a Protestant church in the Calvinist tradition (Congregational), is the state church. Approximately 97% of the population (as of 2012) adheres to the Church of Tuvalu. While it is the state church, this status primarily grants it "the privilege of performing special services on major national events." The introduction of Christianity in the 19th century, largely by Samoan missionaries of the London Missionary Society, led to the decline of traditional animistic beliefs and the worship of ancestral spirits and deities.

The Constitution of Tuvalu guarantees freedom of religion. Other Christian denominations present include:

- Roman Catholicism: Served by the Mission Sui Iuris of Funafuti.

- Seventh-day Adventism: Accounts for about 2.8% of the population.

- Tuvalu Brethren Church: Has around 500 members (approx. 4.5%).

The largest non-Christian religion is the Baháʼí Faith, constituting about 2.0% of the population, with communities on Nanumea and Funafuti. There is also a small Ahmadiyya Muslim community of about 50 members (0.4%).

Religious institutions play a central role in Tuvaluan community life and social cohesion.

8.4. Health and Healthcare

Healthcare services in Tuvalu are primarily provided by the government. The Princess Margaret Hospital on Funafuti is the country's only hospital and the main medical facility. It also coordinates health clinics located on the outer islands.

Major health issues in Tuvalu include a high prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which are the leading causes of death. These include:

- Heart disease

- Diabetes

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Obesity

- Cerebrovascular disease

In 2016, cardiac diseases were the majority cause of death. The lifestyle changes associated with increased reliance on imported processed foods and reduced physical activity contribute to these health problems.

Medical personnel and facilities are limited. Tuvalu relies on overseas medical aid and referrals for specialized treatments. The country faces challenges in maintaining adequate medical supplies and retaining skilled healthcare professionals. Public health initiatives focus on NCD prevention, maternal and child health, and managing the impacts of environmental factors like water quality and sanitation.

8.5. Education System

Education in Tuvalu is free and compulsory for children between the ages of 6 and 15. The adult literacy rate is high, at 99.0% (2002).

- Primary Education: Each island has a primary school. Nauti School on Funafuti is the largest, accounting for about 45% of total primary school enrolment. The teacher-pupil ratio is generally favorable, around 1:18, except at Nauti School (1:27).

- Secondary Education:

- Motufoua Secondary School, located on Vaitupu, is the government secondary school. Students board at the school during term time. It offers the Fiji Junior Certificate (FJC), Tuvaluan Certificate, and the Pacific Senior Secondary Certificate (PSSC).

- Fetuvalu Secondary School, a day school on Funafuti operated by the Church of Tuvalu, offers the Cambridge syllabus.

- Post-Secondary and Vocational Training:

- Students who pass the PSSC can undertake the Augmented Foundation Programme, funded by the government, at the University of the South Pacific (USP) Tuvalu Campus in Funafuti. This program is a prerequisite for tertiary education abroad.

- The Tuvalu Maritime Training Institute (TMTI) on Amatuku islet, Funafuti, trains marine cadets for employment on merchant ships, a key source of remittances.

- Community Training Centres (CTCs) within primary schools offer vocational training in areas like carpentry, gardening, sewing, and cooking for students who do not proceed to secondary school.

- Other institutions include the Tuvalu Atoll Science Technology Training Institute (TASTII) and the Australian Pacific Training Coalition (APTC).

The Tuvaluan Employment Ordinance of 1966 sets the minimum age for paid employment at 14 years.

9. Culture

Tuvaluan culture is deeply rooted in its Polynesian heritage, characterized by strong community bonds, traditional arts, music, dance, and a way of life adapted to its atoll environment. This section introduces Tuvalu's traditional lifestyle, artistic expressions, community values, and contemporary cultural practices.

9.1. Traditional Architecture

Traditional Tuvaluan buildings were constructed using locally sourced materials, reflecting an intimate knowledge of the environment. Key materials included:

- Timber from native broadleaf forest trees such as pouka (Hernandia peltata), ngia or ingia bush (Pemphis acidula), miro (Thespesia populnea), and tonga (Rhizophora mucronata).

- Fibre from coconut (for sennit rope), ferra (native fig, Ficus aspem), and fala (screw pine or Pandanus) for thatching and weaving.

Structures were traditionally built without nails, instead being lashed together with plaited sennit rope handmade from dried coconut fibre.

The most important traditional building is the Falekaupule (or maneapa), the community meeting house. This central structure serves as a venue for discussions on important matters, decision-making by elders, wedding celebrations, feasts, and performances of traditional music and dance like the fatele. Traditional homes (fale) were also constructed using similar materials and techniques, designed for ventilation and resilience.

Following European contact, imported materials like iron products, nails, and corrugated roofing began to be used. Modern buildings increasingly use imported timber and concrete. Church and community buildings are often coated with a white paint called lase, made by burning dead coral with firewood to create a powder that is mixed with water.

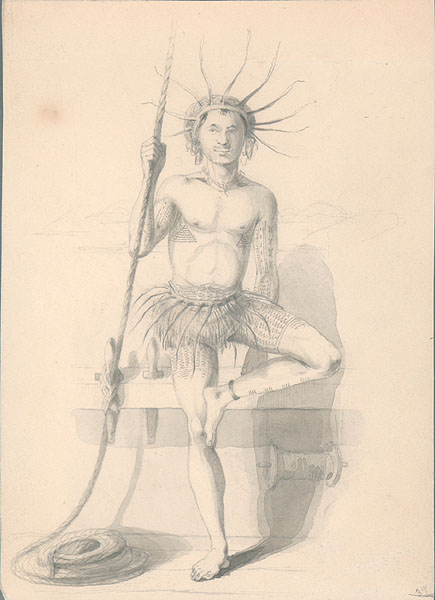

9.2. Arts and Crafts

Tuvaluan artistic traditions are prominently expressed through handicrafts, primarily created by women. These crafts are not only functional but also carry significant cultural value. Key forms include:

- Weaving: Women are skilled in weaving mats (papa or epa), fans, baskets, and other household items using pandanus leaves and other plant fibres. These items often feature intricate patterns.

- Clothing Adornments: Traditional clothing includes skirts (titi or tidi), tops (teuga saka), headbands (fau o aliki or kahoa), armbands, and wristbands. These are often made from natural fibres and decorated with shells, seeds, and flowers, and are integral to dance performances.

- Shell and Seed Jewelry: Cowrie shells (pule), other types of shells, and seeds are used to create beautiful necklaces, earrings, and other jewelry.

- Kolose (Crochet): Crochet is a highly developed art form among Tuvaluan women, who create intricate patterns for clothing, bedspreads, and decorative items. This skill is often passed down through generations.

- Canoe and Fish Hook Design: The material culture of Tuvalu also includes the traditional design elements in utilitarian objects like outrigger canoes and fish hooks, which were historically made from traditional materials like wood, shell, and bone.

In 2015, an exhibition in Funafuti titled "Kope ote olaga" (possessions of life) showcased various Tuvaluan cultural artifacts, with some artworks addressing the theme of climate change.

9.3. Music and Dance

Music and dance are integral to Tuvaluan culture, serving as forms of storytelling, entertainment, and social cohesion. Traditional music often features group singing with harmonies, accompanied by percussion.

Key traditional dance forms include:

- Fatele: This is the most common and well-known Tuvaluan dance. It is a group dance performed by both men and women, often in rows, with energetic movements and singing. The fatele tells stories, commemorates events, or honors individuals. It is performed at community gatherings, celebrations (like weddings and Independence Day), and to welcome important visitors. The tempo often starts slow and gradually increases.

- Fakaseasea: A slower, more graceful dance, often performed by women, emphasizing fluid hand and arm movements.

- Fakanau: A traditional sitting dance, often involving intricate hand movements and storytelling.

Traditional musical instruments are primarily percussive and include:

- Pate: A wooden slit drum, beaten with sticks to provide rhythm.

- Empty kerosene tins or wooden boxes are also used as makeshift drums.

- Hand clapping (pati) is a common accompaniment.

Samoan missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries influenced Tuvaluan music, particularly church hymns. However, traditional Tuvaluan musical styles, characterized by their unique rhythms and vocal arrangements, remain vibrant. The Tuvaluan style has been described as a "musical microcosm of Polynesia, where contemporary and older styles co-exist."

9.4. Cuisine and Food Culture

Traditional Tuvaluan cuisine is based on the staples available from its atoll environment, heavily featuring coconut and seafood.

Key traditional foods include:

- Pulaka (swamp taro or ''Cyrtosperma merkusii''): A root crop grown in specially prepared pits dug below the freshwater lens. It is a primary source of carbohydrates and a culturally significant food, often reserved for special occasions.

- Taro (''Colocasia esculenta''): Another important root crop.

- Bananas and Breadfruit: Supplemental carbohydrate sources.

- Coconut: Used extensively - the flesh is eaten, coconut milk and cream are used in cooking, and the juice (''pi'') is a refreshing drink. Coconut toddy (''kaleve''), made from fermented coconut sap, is a traditional beverage.

- Seafood: A wide variety of fish from the lagoon and ocean is consumed, including flying fish (''সিস]], ''hahave''), which are caught using nets and spotlights. Coconut crab (''ūpē'') and other shellfish are also important.

- Seabirds: Traditionally, seabirds like the black noddy (''taketake'') and white tern (''akiaki'') were hunted for food.

Pork is typically eaten at feasts (''fateles'') and special celebrations. Traditional cooking methods often involve baking in earth ovens (''umu'') or boiling. Coconut cream is a common ingredient for enhancing the flavor of dishes.

With increased reliance on imported goods, processed foods have become more common, contributing to health issues like diabetes and obesity. Efforts are made to promote traditional, healthier diets. A 1,560-square-meter pond was built on Vaitupu in 1996 to support aquaculture.

9.5. Community Life and Heritage

Community life in Tuvalu is characterized by strong kinship ties, communal values, and traditional governance systems.

- Falekaupule System: The Falekaupule (island council or meeting house) is the cornerstone of traditional decision-making and community governance on each island. It comprises elders and respected community members who deliberate on local matters, manage resources, and resolve disputes according to traditional customs (aganu). The Falekaupule building itself is the central meeting place for community events.

- Family and Kinship: The social structure is based on extended families (kaitasi). Land tenure is largely communal or family-based. Strong obligations of mutual support and sharing exist within kinship groups.

- Communal Work (Salanga): Each family traditionally has specific tasks or responsibilities (salanga) to perform for the community, such as fishing, house building, or defense. Skills are passed down through generations.

- Resource Sharing: Traditions of communal work and sharing resources are deeply ingrained. For example, a large fish catch might be shared among the community.

- Intangible Cultural Heritage: This includes a rich body of oral folklore, mythology, traditional songs, dances (like the fatele), and knowledge related to navigation, fishing, and agriculture. The story of te Pusi mo te Ali (the Eel and the Flounder) is an important creation myth.

- Fusi: Most islands have community-owned shops (fusi) similar to convenience stores, where canned foods and other goods can be purchased. These often offer better prices for local produce.

The traditional community system, while adapting to modern influences, continues to play a vital role in Tuvaluan society, fostering social cohesion and resilience. There are no dedicated museums, but the creation of a Tuvalu National Cultural Centre and Museum is part of the government's strategic plan.

9.6. Traditional Canoeing

Traditional outrigger canoes, known as paopao (a term borrowed from Samoan for a small fishing canoe made from a single log), were essential to Tuvaluan life for fishing, inter-islet travel, and occasionally longer voyages. The largest could carry four to six adults.

Construction involved skilled craftsmanship using local timber, with hulls often carved from a single log. Parts were lashed together with sennit rope made from coconut fibre.

Key features and types:

- Reef-type or Paddled Canoes: Developed on islands like Vaitupu and Nanumea, these were designed to be carried over reefs and primarily paddled rather than sailed.

- Nui Sailing Canoes: Canoes from Nui were distinct, featuring an indirect outrigger attachment and a double-ended hull (no distinct bow or stern). They were designed for sailing within the Nui lagoon and had longer outrigger booms for greater stability under sail.

Traditional navigation skills, relying on knowledge of stars, currents, and wave patterns, were highly developed and crucial for survival and inter-island communication. While the use of modern boats has increased, traditional canoe building and sailing skills are still valued as part of Tuvalu's cultural heritage.

9.7. Sports and Leisure

Sport and leisure activities in Tuvalu blend traditional games with modern sports.

- Kilikiti: A traditional Tuvaluan sport similar to cricket, played with unique rules and often involving entire villages. It is a highly social and competitive game.

- Te ano: A popular traditional ball game specific to Tuvalu. It is played with two round balls, about 4.7 in (12 cm) in diameter, made from pandanus leaves. Teams volley the hard balls at great speed, trying to prevent them from hitting the ground. It is similar to volleyball but played with distinct rules and great energy.

- Traditional Sports (Historical): In the late 19th century, activities like foot racing, lance throwing, quarterstaff fencing, and folk wrestling were common, though some were discouraged by Christian missionaries.

- Modern Sports: Popular modern sports include football (soccer), futsal, volleyball, handball, basketball, and rugby sevens. Tuvalu has national sports organizations for athletics, badminton, tennis, table tennis, football, basketball, rugby union, weightlifting, and powerlifting.

Tuvalu participates in regional and international sporting events:

- Pacific Games: Tuvalu first participated in 1978. Telupe Iosefa won Tuvalu's first-ever Pacific Games gold medal in powerlifting (120kg male division) at the 2015 Games.

- Pacific Mini Games: Tuau Lapua Lapua won Tuvalu's first international gold medal in weightlifting (62kg male snatch) at the 2013 Pacific Mini Games.

- Commonwealth Games: Tuvalu first participated in 1998. Athletes have competed in weightlifting, table tennis, shooting, and athletics.

- Olympic Games: The Tuvalu Association of Sports and National Olympic Committee (TASNOC) was recognized in 2007. Tuvalu first competed at the 2008 Beijing Olympics in weightlifting and athletics (100m sprints). They have participated in subsequent Summer Olympics, typically with small delegations in athletics. Etimoni Timuani was the sole representative at the 2016 Rio Olympics (100m). Karalo Maibuca and Matie Stanley represented Tuvalu at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics (held in 2021) in the 100m events. Karalo Maibuca and Temalini Manatoa represented Tuvalu in athletics at the 2024 Summer Olympics.

- World Championships in Athletics: Tuvaluan athletes have participated in the 100m sprints since 2009.

The Tuvalu National Football Association is an associate member of the Oceania Football Confederation (OFC) and seeks full FIFA membership. The Tuvalu Sports Ground in Funafuti is the main venue for football. The national futsal team competes in the OFC Futsal Nations Cup.

A major local sporting event is the "Independence Day Sports Festival" held annually on 1 October. The Tuvalu Games, held yearly since 2008, are also an important national sporting competition.