1. Overview

Papua New Guinea, officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is an Oceanian country occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and numerous offshore islands in Melanesia, a region of the southwestern Pacific Ocean north of Australia. Its capital, Port Moresby, is located on its southern coast. The nation's history is marked by early human settlement over 40,000 years ago, the independent development of agriculture, and a complex colonial past involving German, British, and Australian administration before achieving independence in 1975. Governed as a Commonwealth realm with a parliamentary constitutional monarchy, Papua New Guinea faces challenges in democratic development, human rights, and social justice. The economy is rich in natural resources, particularly minerals and timber, but development is hampered by rugged terrain, infrastructure deficits, and issues related to land tenure and equitable benefit sharing. The country is one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse in the world, with over 850 indigenous languages and a population predominantly living in traditional rural communities. This article explores Papua New Guinea through a lens of social liberalism, emphasizing social justice, human rights, sustainable development, and the equitable distribution of the nation's wealth and opportunities, while respecting its profound cultural heritage and addressing the challenges of environmental protection and social equity.

2. Etymology

The name 'Papua New Guinea' is a combination of two distinct historical appellations reflecting the island's colonial past. The term 'Papua' is derived from a local term of uncertain origin, possibly the Malay word pepuahfrizzy-hairedMalay, used to describe the characteristic hair of Melanesian peoples. The Portuguese captain and geographer António Galvão, writing about the islands of New Guinea, noted, "The people of all these islands are blacke, and have their haire frisled, whom the people of Maluco do call Papuas."

'New Guinea' (Nueva GuineaNew GuineaSpanish) was the name given to the island in 1545 by the Spanish explorer Yñigo Ortiz de Retez. He observed a resemblance between the indigenous peoples of the island and those he had previously seen along the Guinea coast of West Africa. The name 'Guinea' itself is etymologically derived from the Portuguese word GuinéGuineaPortuguese, which historically referred to the "land of the blacks," a term used by European explorers in reference to the dark skin of the inhabitants of that African region. The dual name became official as the country integrated its northern (formerly German New Guinea, later the Territory of New Guinea) and southern (formerly British New Guinea, later the Territory of Papua) administrative regions under Australian rule, eventually leading to the independent nation of Papua New Guinea. In Tok Pisin, a lingua franca of the country, the official name is Independen Stet bilong Papua NiuginiIndependent State of Papua New GuineaTok Pisin, commonly shortened to Papua NiuginiPapua New GuineaTok Pisin.

3. History

The history of Papua New Guinea is characterized by ancient human settlement, diverse cultural development, European colonial division, and a journey towards modern nationhood, significantly influenced by its interactions with global powers and internal dynamics, particularly concerning land, resources, and autonomy.

3.1. Prehistory

Archaeological evidence indicates that humans first arrived on the island of New Guinea between 42,000 and 50,000 years ago. These early inhabitants were descendants of migrants who originated in Africa and journeyed through Southeast Asia, reaching the ancient landmass of Sahul, which connected present-day Australia and New Guinea during periods of lower sea levels. Sea level rise isolated New Guinea approximately 10,000 years ago. Genetic studies suggest that Aboriginal Australians and Papuans diverged genetically around 37,000 years before present. Furthermore, research by evolutionary geneticist Svante Pääbo revealed that the genomes of New Guinean people share between 4% and 7% with the Denisovans, indicating interbreeding between the ancestors of Papuans and these archaic hominins in Asia.

Agriculture was independently developed in the New Guinea highlands around 7,000 BC, making it one of the few areas in the world where plant domestication occurred without external influence. A significant migration of Austronesian-speaking peoples to the coastal regions of New Guinea took place around 500 BC (or 2,500 years ago according to some sources). This migration is associated with the introduction of pottery, pigs, and specific fishing techniques.

In the 18th century, traders brought the sweet potato to New Guinea from the Maluku Islands, where it had been introduced by the Portuguese from South America. The higher crop yields from sweet potatoes radically transformed traditional agriculture and societies, largely supplanting the previous staple, taro, and leading to a significant population increase in the highlands.

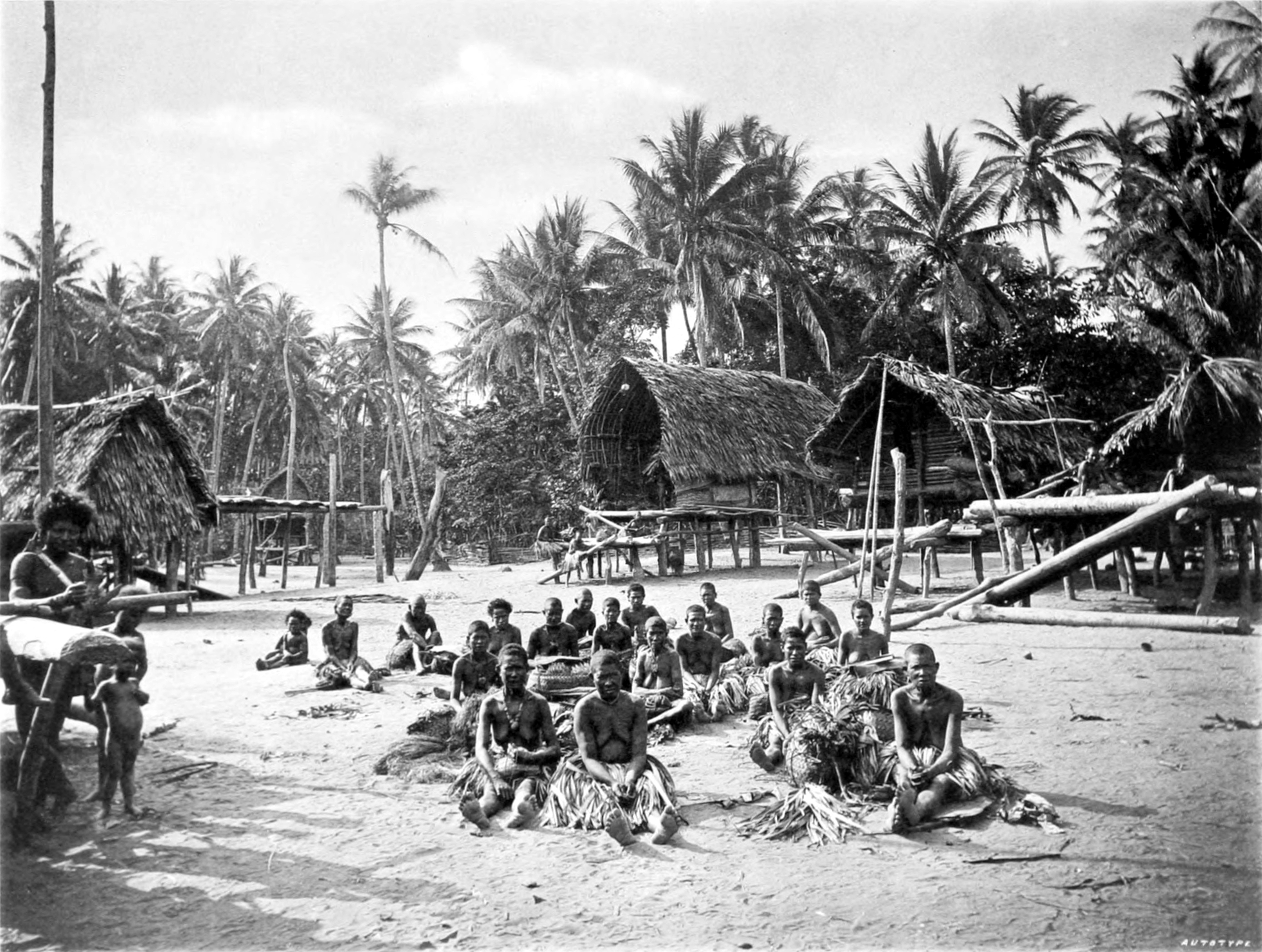

Historically, practices such as headhunting and cannibalism were part of ritual warfare and spiritual beliefs in many parts of the country, aimed at taking in enemy spirits or powers. While these practices were practically eradicated by the late 20th century, their historical prevalence is documented. For instance, in 1901, missionary Harry Moore Dauncey found 10,000 skulls in longhouses on Goaribari Island in the Gulf of Papua. Early forms of currency also existed, with shell money being made in Talasea on New Britain as early as 5,000 years ago, considered among the oldest forms of shell currency.

3.2. European Encounters and Colonialism

European knowledge of New Guinea remained limited until the 19th century, although Portuguese and Spanish explorers, such as Dom Jorge de Menezes (circa 1526-27) and Yñigo Ortiz de Retez (1545), had encountered the island in the 16th century. De Menezes is credited with naming the main island "Papua," while Retez named it "New Guinea." Long before European arrival, traders from Southeast Asia had been visiting New Guinea for at least 5,000 years, primarily to collect bird-of-paradise plumes.

Christianity was first introduced to New Guinea on September 15, 1847, when a group of Marist missionaries arrived on Woodlark Island and established their first mission on Umboi Island. They were forced to withdraw but, on October 8, 1852, the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions re-established the mission on Woodlark Island, facing challenges from disease and local resistance.

The colonial division of the eastern half of New Guinea began in 1884. The German Empire took control of the northern part, establishing German New Guinea. Concurrently, Great Britain established a protectorate over the southern part. In 1888, the British protectorate, along with adjacent islands, was formally annexed as British New Guinea. In 1902, administrative authority over British New Guinea was effectively transferred to the newly formed Commonwealth of Australia. The Papua Act 1905 officially renamed the area the Territory of Papua, with Australian administration becoming formal in 1906. This period marked the beginning of a complex administrative history that would shape the future nation, with different colonial powers imposing their systems and often disregarding indigenous structures and rights, laying groundwork for future social and political challenges.

3.3. Australian Rule and Independence

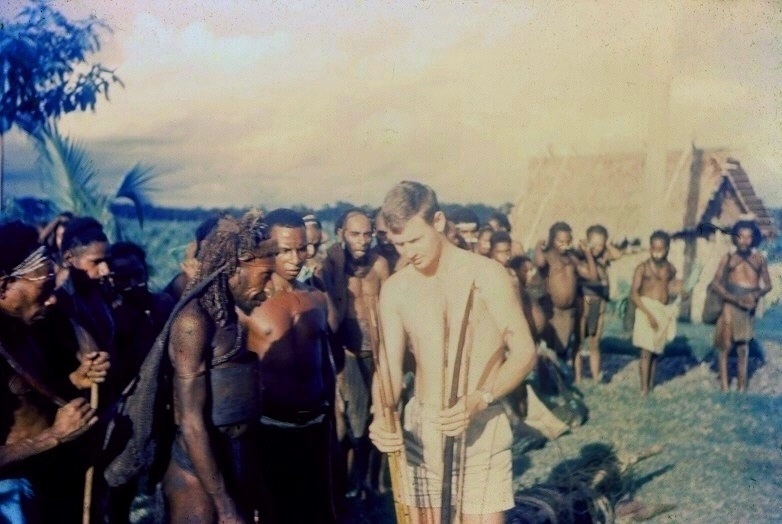

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Australian forces captured German New Guinea and occupied it throughout the war. After Germany's defeat, the League of Nations authorized Australia to administer this area as a mandate territory, which became the Territory of New Guinea. In contrast, the Territory of Papua (formerly British New Guinea) remained legally a British possession but was administered as an external territory of the Australian Commonwealth. This difference in legal status meant that until 1949, Papua and New Guinea had entirely separate administrations, both controlled by Australia. These distinct administrative paths contributed to the complexity of organizing the country's post-independence legal system. During the 1930s, Australian explorers ventured into the highland valleys, encountering populations estimated at over a million people who had previously had little contact with the outside world.

The New Guinea campaign during World War II (1942-1945) was a major theatre of conflict between Japan and the Allies. Approximately 216,000 Japanese, Australian, and U.S. servicemen died during the campaign. The island became a critical battleground, with significant engagements such as the Kokoda Track campaign. The war had a profound impact on the local population, who were often caught in the crossfire or conscripted as laborers and carriers, infamously described in a Japanese saying as "Java's paradise, Burma's hell, New Guinea from which you can't return even if you die." After World War II and the Allied victory, the two territories of Papua and New Guinea were administratively combined into the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, often referred to simply as "Papua New Guinea."

Post-World War II, Australia continued to administer the combined territories. In 1951, a 28-member Legislative Council was instituted, though largely dominated by Australian administrative members, with only three seats allocated to Papua New Guineans. Sir Donald Cleland, an Australian soldier, became the first administrator of this council. In 1964, the Council was replaced by the 64-member House of Assembly of Papua and New Guinea, which for the first time had a majority of Papua New Guinean members. The Assembly's membership increased to 84 in 1967 and to 100 by 1971.

Debate over Australian administration grew both within Papua New Guinea and in Australia. The Bougainville independence movement gained traction, fueled by grievances over the exploitative practices of the Australian mining company Rio Tinto at the Panguna mine. Indigenous landowners demanded fair compensation and protested against the environmental degradation caused by the mine. Australian Opposition Leader Gough Whitlam visited Papua New Guinea in 1970 and 1971 amidst calls for independence by groups like the Tolai people in the Gazelle Peninsula. Whitlam advocated for self-governance for the Territory as early as 1972.

In the 1972 Papua New Guinean general election, Michael Somare was elected as the first Papua New Guinean Chief Minister. In December of the same year, Whitlam was elected Prime Minister of Australia. The Whitlam Government instituted self-governance under Somare's leadership in late 1973. Over the next two years, arguments for full independence intensified. The Whitlam Government passed the Papua New Guinea Independence Act 1975 in September 1975, designating September 16, 1975, as the date of independence. Gough Whitlam and then-Prince Charles attended the independence ceremony, with Somare continuing as the country's first Prime Minister. This peaceful transition to independence marked a significant moment, though the legacy of colonial resource exploitation and imposed political structures would continue to pose challenges for the new nation in terms of social justice and equitable development.

3.4. Bougainville Conflict

A secessionist revolt on Bougainville Island in 1975-76 led to a significant modification of the draft Constitution of Papua New Guinea, granting Bougainville and the other eighteen districts quasi-federal status as provinces. However, tensions remained, particularly concerning the Panguna mine, which was a major source of revenue for Papua New Guinea (generating up to 40% of the national budget) but also a source of severe environmental damage and social disruption for the local Bougainvillean population. The indigenous people felt they bore the adverse environmental consequences of mining-including contamination of land, water, and air-without receiving a fair share of the profits or adequate respect for their land rights.

These grievances culminated in a renewed and far more devastating uprising on Bougainville which began in 1988, led by figures such as Francis Ona and the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA). The conflict, which lasted until 1997 (with a formal peace agreement in 2001), claimed an estimated 20,000 lives and caused widespread human suffering and displacement. The Papua New Guinean government's attempts to suppress the rebellion, including a controversial attempt to hire mercenaries in 1997 (the Sandline affair), further complicated the situation and drew international criticism.

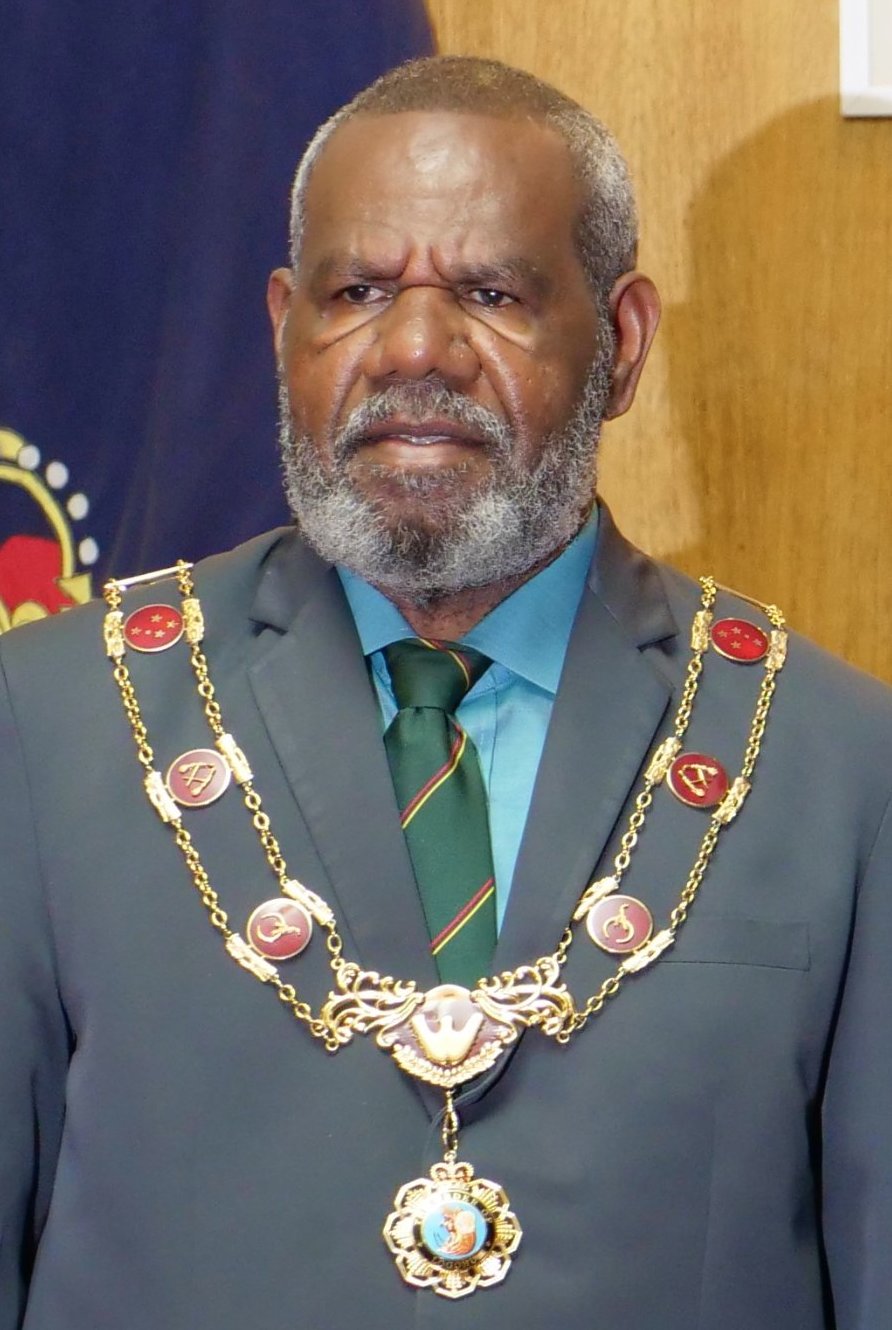

A peace agreement was eventually negotiated, leading to the establishment of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville. Joseph Kabui, a former BRA leader, was elected as the first president of the autonomous region in 2005 and served until his death in 2008. He was succeeded by his deputy John Tabinaman as acting president, followed by James Tanis who won an election in December 2008. John Momis won the 2010 elections.

As part of the peace settlement, a non-binding independence referendum was held between November 23 and December 7, 2019. The referendum offered a choice between greater autonomy within Papua New Guinea and full independence for Bougainville. The result was an overwhelming vote (98.31%) in favor of independence. Following the referendum, negotiations commenced between the Bougainville government, under President Ishmael Toroama (elected in 2020), and the national Papua New Guinean government, led by Prime Minister James Marape, on a pathway to Bougainville's potential independence. In July 2021, an agreement was reached for Bougainville to achieve full independence by 2027, subject to ratification by the Papua New Guinean National Parliament. The Bougainville conflict highlights critical issues of resource governance, indigenous rights, environmental justice, and the right to self-determination, aspects central to a social justice perspective on Papua New Guinea's history.

4. Geography

Papua New Guinea's geography is characterized by its diverse and often rugged terrain, extensive coastlines, numerous islands, and rich but vulnerable ecosystems. This section details its physical location, varied topography, climate, and significant natural features.

4.1. Topography and Geology

Papua New Guinea, with an area of 179 K mile2 (462.84 K km2), is the world's 54th-largest country and the third-largest island country. It is part of the Australasian realm. The mainland of the country is the eastern half of the island of New Guinea, where the largest towns, including the capital Port Moresby and Lae, are located. Other major islands within Papua New Guinea include New Ireland, New Britain, Manus, and Bougainville.

A dominant feature of the country's topography is the New Guinea Highlands, a spine of mountains that runs the length of the island of New Guinea. This mountainous interior forms a populous highlands region, mostly covered with tropical rainforest. The Papuan Peninsula, also known as the 'Bird's Tail', extends to the southeast. Dense rainforests are also found in the lowland and coastal areas, along with very large wetland areas surrounding major river systems like the Sepik and Fly. Other significant rivers include the Ramu, Markham, Musa, Purari, Kikori, Turama, and Wawoi. The highest peak in Papua New Guinea is Mount Wilhelm, at 15 K ft (4.51 K m). The country is surrounded by extensive coral reefs, which are ecologically significant but face threats from climate change and human activities.

Papua New Guinea is situated on the Pacific Ring of Fire, at the point of collision of several tectonic plates. Geologically, the island of New Guinea is a northern extension of the Indo-Australian Plate, forming part of a single landmass called Australia-New Guinea (also known as Sahul or Meganesia). It is connected to the Australian segment by a shallow continental shelf across the Torres Strait, which in former ages lay exposed as a land bridge, particularly during ice ages when sea levels were lower. The collision of the Indo-Australian Plate with the Eurasian Plate pushed up the Himalayas, the Indonesian islands, and New Guinea's Central Range. The Central Range is much younger and higher than the mountains of Australia, and its highest elevations are home to rare equatorial glaciers, although these are rapidly receding. The rugged terrain has made the development of transportation infrastructure exceptionally difficult, with air travel often being the only practical means of connecting remote areas. The country has numerous active volcanoes, and eruptions are frequent.

The land border between Papua New Guinea and Indonesia was confirmed by a treaty with Australia before independence in 1974. It largely follows the 141st meridian east in the north, then deviates to follow the thalweg of the Fly River for a segment, before returning to a meridian line further south. The maritime boundary with Australia was confirmed by a treaty in 1978, and with the Solomon Islands by a treaty in 1989.

4.2. Climate

The climate of Papua New Guinea is predominantly tropical, characterized by high temperatures and humidity throughout the year, but it varies significantly with altitude and region. The lowland and coastal areas typically experience mean maximum temperatures between 86 °F (30 °C) and 89.6 °F (32 °C), with mean minimum temperatures around 73.4 °F (23 °C) to 75.2 °F (24 °C).

In the highlands, at elevations above 6.9 K ft (2.10 K m), conditions are considerably cooler. Night frosts are common in these areas, while daytime temperatures generally exceed 71.6 °F (22 °C) regardless of the season. Some of the most elevated parts of the mainland can even experience snowfall, a rare phenomenon for equatorial regions.

Rainfall is generally high across the country, influenced by monsoon winds. Most regions have distinct wet and dry seasons, although the timing varies. The primary wet season for most of the country is from December to March, while the dry season typically runs from May to October. However, areas like Lae and Alotau experience their wettest period between May and October. April and November are often transitional months with unpredictable weather. The high rainfall contributes to the lush vegetation and large river systems but also poses challenges such as flooding and landslides.

4.3. Biodiversity and Ecoregions

Papua New Guinea is recognized as one of the world's 17 megadiverse countries, possessing an extraordinary richness of biological diversity. Many species of birds and mammals found on New Guinea have close genetic links with corresponding species in Australia, reflecting their shared geological history as part of the supercontinent of Gondwana. A notable common feature is the presence of several species of marsupial mammals, including various kangaroos and possums, which are not found elsewhere outside the Australasian realm. The country is believed to be home to many undocumented species of plants and animals.

Many of the other islands within Papua New Guinean territory, such as New Britain, New Ireland, Bougainville, the Admiralty Islands, the Trobriand Islands, and the Louisiade Archipelago, were never linked to New Guinea by land bridges. Consequently, they have developed their own distinct flora and fauna, often lacking many of the land mammals and flightless birds common to New Guinea and Australia.

New Guinea is part of the humid tropics, and many Indomalayan rainforest plants have spread across the narrow straits from Asia, mixing with the older Australian and Antarctic floras. This has resulted in New Guinea being identified as the world's most floristically diverse island, with 13,634 known species of vascular plants. The country's Antarctic flora heritage includes coniferous podocarps and Araucaria pines, as well as the broad-leafed southern beech (Nothofagus).

Papua New Guinea includes a variety of terrestrial ecoregions:

- Admiralty Islands lowland rain forests: Forested islands north of the mainland, home to a distinct flora.

- Central Range montane rain forests: The mountainous spine of New Guinea.

- Huon Peninsula montane rain forests: A distinct montane ecoregion.

- Louisiade Archipelago rain forests: Forests of the Louisiade island group.

- New Britain-New Ireland lowland rain forests: Lowland forests of these major islands.

- New Britain-New Ireland montane rain forests: Montane forests of these islands.

- New Guinea mangroves: Extensive mangrove ecosystems along the coasts.

- Northern New Guinea lowland rain and freshwater swamp forests: Diverse lowland and swamp forests.

- Northern New Guinea montane rain forests: Montane forests in the northern ranges.

- Solomon Islands rain forests: Includes Bougainville Island and Buka Island.

- Southeastern Papuan rain forests: Forests of the southeastern peninsula.

- Southern New Guinea freshwater swamp forests: Extensive swamp forests in the south.

- Southern New Guinea lowland rain forests: Lowland forests of the southern plains.

- Trobriand Islands rain forests: Forests of the Trobriand group.

- Trans-Fly savanna and grasslands: Savanna and grassland ecosystems in the southwest.

- Central Range sub-alpine grasslands: High-altitude grasslands.

Conservation challenges are significant. Nearly one-quarter of Papua New Guinea's rainforests were damaged or destroyed between 1972 and 2002, primarily due to logging, agricultural expansion, and mining activities. Deforestation and illegal logging remain serious concerns, threatening endemic species and the livelihoods of communities dependent on forest resources. The country had a Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.84/10 in 2020, ranking it 17th globally out of 172 countries, indicating that large tracts of forest still maintain high ecological integrity, but these are under increasing pressure. Efforts towards sustainable forestry and biodiversity conservation are crucial for protecting this unique natural heritage for future generations and ensuring that development benefits local communities equitably.

4.4. Earthquakes and Natural Disasters

Papua New Guinea's location on the Pacific Ring of Fire, at the collision point of several tectonic plates, makes it highly susceptible to a range of natural disasters. Earthquakes are frequent and can be severe, sometimes triggering devastating tsunamis and landslides. Active volcanoes are numerous, and eruptions pose an ongoing threat to nearby communities and the environment.

Notable seismic events include:

- On July 17, 1998, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck north of Aitape, triggering a 15-meter-high (50-foot) tsunami that killed over 2,180 people, making it one of the worst natural disasters in the country's history.

- In September 2002, a magnitude 7.6 earthquake off the coast of Wewak, Sandaun Province, resulted in six deaths and left 3,000 people homeless.

- From March to April 2018, a series of earthquakes, the largest being a magnitude 7.5 event on February 25, struck Hela Province and the Southern Highlands Province. These quakes caused widespread landslides, extensive damage to infrastructure, and the deaths of approximately 200 people. International aid was provided by nations from Oceania and Southeast Asia.

- On September 11, 2022, another severe earthquake struck, killing at least seven people and causing significant damage in major cities like Lae and Madang, with tremors felt as far as Port Moresby.

- On May 24, 2024, a catastrophic landslide occurred in the village of Kaokalam in Enga Province, approximately 373 mile (600 km) northwest of Port Moresby. The landslide buried an estimated 2,000 people alive and caused major destruction to buildings, food gardens, and critical infrastructure, impacting the economic lifeline of the country. This event is considered one of the deadliest landslides of the 21st century.

These recurrent natural disasters pose significant challenges to the safety and livelihoods of the population, requiring robust disaster preparedness, response mechanisms, and sustainable land-use planning to mitigate their impact, particularly in vulnerable communities. Ensuring adequate support and resources for affected populations, as well as investing in resilient infrastructure, are critical aspects of social justice and sustainable development in this disaster-prone nation.

5. Government and Politics

Papua New Guinea operates as a Commonwealth realm with a parliamentary constitutional monarchy. This section details the structure of its government, legal framework, administrative divisions, foreign policy, military, and critical issues related to crime and human rights, with a focus on democratic development, accountability, and social justice.

5.1. Government Structure

Charles III

since

9 September 2022

Bob Dadae

since

28 February 2017

The Head of State is Charles III, who is the King of Papua New Guinea. The monarch's representative is the Governor-General of Papua New Guinea, currently Sir Bob Dadae. Uniquely among Commonwealth realms (along with the Solomon Islands), the Governor-General is elected by the unicameral National Parliament, although still formally appointed by the monarch in accordance with the parliamentary vote.

The national constitution provides for the executive to be responsible to parliament, which represents the Papua New Guinean people. The Prime Minister, currently James Marape, is elected by the National Parliament. Other ministers are appointed by the Governor-General on the Prime Minister's advice and form the National Executive Council, which acts as the country's cabinet.

The National Parliament has 111 seats. Of these, 22 are occupied by the governors of the 20 provinces and the National Capital District. Candidates for members of parliament are voted upon when the Prime Minister asks the Governor-General to call a national election, which must occur at a maximum of five years after the previous national election.

In the early years of independence, the instability of the party system led to frequent votes of no confidence in parliament, resulting in frequent changes of government. To address this, successive governments have passed legislation preventing such votes sooner than 18 months after a national election and within 12 months of the next election. In 2012, initial steps were taken to extend this period to 30 months. While this has arguably resulted in greater stability, it has also raised concerns about reducing the accountability of the executive branch.

Elections in Papua New Guinea attract numerous candidates. After independence in 1975, members were elected by the first-past-the-post voting system, with winners often gaining less than 15% of the vote. Electoral reforms in 2001 introduced the Limited Preferential Vote system (LPV), a version of the alternative vote, first used in the 2007 general election.

Under a 2002 amendment, the leader of the party winning the largest number of seats in the election is invited by the Governor-General to form the government, if they can muster the necessary majority in parliament. The process of forming coalitions often involves considerable negotiation. Peter O'Neill became Prime Minister after the July 2012 election. In May 2019, O'Neill resigned and was replaced by James Marape. Following the 2022 general election, which was criticized by observers for inadequate preparation and instances of abuse and violence, James Marape's Pangu Pati secured the most seats, enabling him to continue as Prime Minister. The 2022 election saw two women elected to Parliament, including Rufina Peter, who also became Governor of Central Province, marking a small but important step for female representation in a political landscape often dominated by men. The 2011-2012 period saw a significant constitutional crisis between the parliament-elected Prime Minister Peter O'Neill and Sir Michael Somare, whom the Supreme Court deemed to retain office, highlighting tensions between the legislature and judiciary.

5.2. Law

The unicameral National Parliament enacts legislation in a manner similar to other Commonwealth realms using the Westminster system of government. The cabinet collectively agrees on government policy, and then the relevant minister introduces bills to Parliament. Backbench members of parliament can also introduce bills. Parliament debates bills, and they become enacted laws when the Speaker certifies that Parliament has passed them; there is no Royal Assent by the Governor-General in the final stage of enactment.

All ordinary statutes enacted by Parliament must be consistent with the Constitution. The courts have jurisdiction to rule on the constitutionality of statutes. Unusually among developing countries, the judicial branch of government in Papua New Guinea has maintained a remarkable degree of independence, and successive executive governments have generally respected its authority.

The "underlying law," which is Papua New Guinea's common law, consists of principles and rules of common law and equity in English common law as it stood on September 16, 1975 (the date of independence), and thereafter the decisions of Papua New Guinea's own courts. The Constitution and, more recently, the Underlying Law Act, direct the courts to take note of the "custom" of traditional communities. They are tasked with determining which customs are common to the whole country and may be declared part of the underlying law. In practice, this has proven difficult and has been largely neglected. Many statutes are adapted from overseas jurisdictions, primarily Australia and England. Advocacy in the courts follows the adversarial pattern of other common-law countries.

The national court system, used in towns and cities, is supported by a village court system in the more remote areas. The law underpinning the village courts is 'customary law,' reflecting the diverse traditional legal practices of the nation's many communities. The effective integration of customary law with the formal legal system remains a challenge, particularly in ensuring access to justice and protection of human rights for all citizens, especially vulnerable groups.

5.3. Administrative Divisions

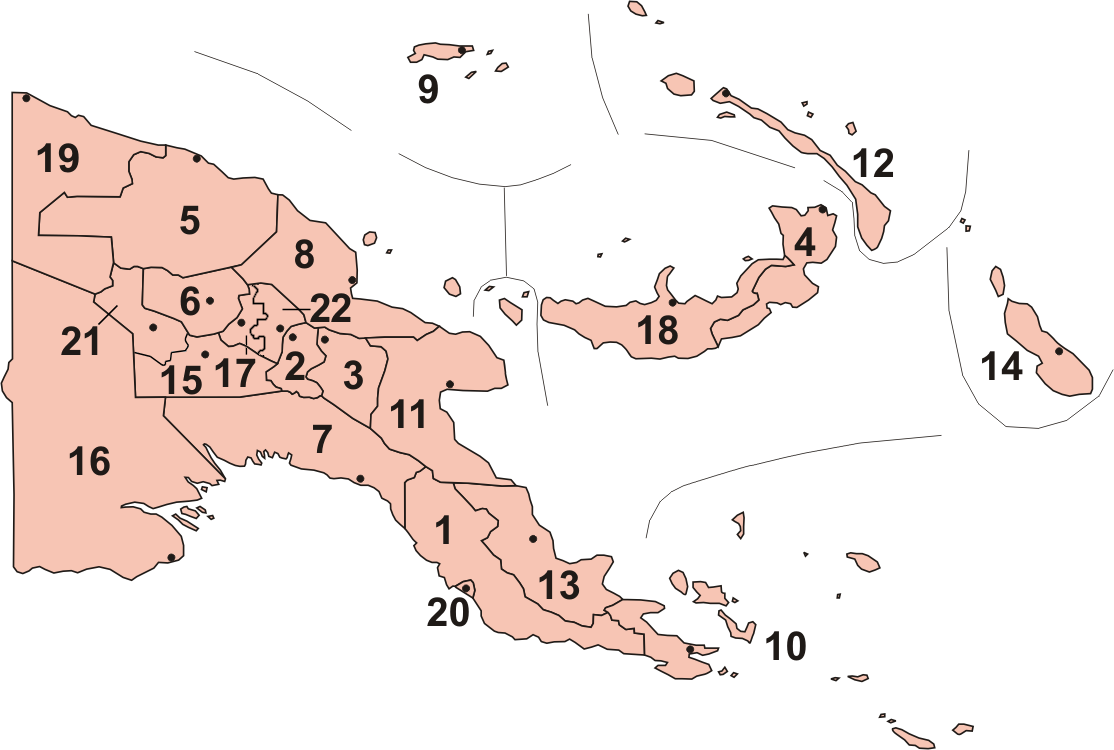

Papua New Guinea is divided into four regions: the Southern Region (Papua), the Highlands Region, the Momase Region (north coast), and the Islands Region. While these regions are not the primary administrative divisions, they are quite significant in many aspects of government, commercial, sporting, and other activities.

The nation has 22 province-level divisions. These consist of twenty provinces, the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, and the National Capital District (Port Moresby). Each province is divided into one or more districts, which in turn are divided into one or more Local-Level Government areas (LLGs).

Provinces are the primary administrative divisions of the country. Provincial governments are branches of the national government, as Papua New Guinea is not a federation of provinces. The province-level divisions are as follows:

# Central

# Chimbu (Simbu)

# Eastern Highlands

# East New Britain

# East Sepik

# Enga

# Gulf

# Madang

# Manus

# Milne Bay

# Morobe

# New Ireland

# Northern (Oro Province)

# Bougainville (autonomous region)

# Southern Highlands

# Western Province (Fly)

# Western Highlands

# West New Britain

# West Sepik (Sandaun)

# National Capital District

# Hela

# Jiwaka

In 2009, Parliament approved the creation of two additional provinces: Hela Province, consisting of part of the existing Southern Highlands Province, and Jiwaka Province, formed by dividing Western Highlands Province. Hela and Jiwaka officially became separate provinces on May 17, 2012. This division was partly driven by the administrative needs related to the large liquefied natural gas (LNG) project situated in these areas, raising questions about equitable resource distribution and local governance capacity.

The Autonomous Region of Bougainville held a non-binding independence referendum in December 2019, where an overwhelming 97.7% of voters favored independence from Papua New Guinea. Negotiations on the future political status of Bougainville are ongoing between the autonomous government and the national government, with a target of achieving full independence by 2027, pending ratification by the National Parliament. This process highlights the complexities of self-determination and national unity within Papua New Guinea's diverse administrative structure.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Papua New Guinea maintains an active role in regional and international affairs. It is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, the Pacific Community (SPC), the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), and the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG). The country was accorded observer status within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1976, which was later upgraded to special observer status in 1981. Papua New Guinea has also filed an application for full ASEAN membership, though its geographical location outside Southeast Asia has been a point of discussion. Additionally, it is a member of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and an ACP country, associated with the European Union. Since its founding in 1992, Papua New Guinea has been a member of the Forum of Small States (FOSS).

A key aspect of Papua New Guinea's foreign policy is its relationship with Australia, its former colonial administrator and largest aid donor. The relationship is generally close, though sometimes strained by specific incidents or policy differences. In recent years, China has also emerged as a significant partner, providing development assistance and loans, particularly for infrastructure projects. This has led to discussions about debt sustainability and geopolitical influence in the region.

Papua New Guinea's relationship with its western neighbor, Indonesia, is complex, particularly concerning the status of Western New Guinea (Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua). While the Papua New Guinean government has officially supported Indonesia's sovereignty over the territory, there is considerable public sympathy within Papua New Guinea for the West Papuan self-determination movement, fueled by reports of human rights violations committed by Indonesian security forces. This issue remains a sensitive point in bilateral relations and for regional stability. From a social justice perspective, Papua New Guinea's stance on international human rights issues, including its response to the West Papua situation and its engagement with global human rights mechanisms, is an important area of scrutiny. The country's role in promoting regional stability often involves balancing its national interests with broader concerns for human rights and democratic principles in the Pacific.

5.5. Military

The Papua New Guinea Defence Force (PNGDF) is the military organization responsible for the defence of Papua New Guinea. It consists of three main elements: the Land Element, the Air Element, and the Maritime Element.

The Land Element is the largest component and includes the Royal Pacific Islands Regiment (which has two infantry battalions), a special forces unit, an engineer battalion, and several smaller units primarily dealing with signals, health, and training, including a military academy.

The Air Element consists of one aircraft squadron, which primarily provides transport support for the other military wings and for government operations.

The Maritime Element is responsible for patrolling Papua New Guinea's extensive exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Its fleet has historically included Pacific-class patrol boats and ex-Australian Balikpapan-class landing craft, one of which is used as a training ship. More recently, Australia has been supplying new Guardian-class patrol boats to replace the aging Pacific-class vessels. The main tasks of the Maritime Element are to conduct maritime surveillance, patrol inshore waters, enforce fisheries laws, and transport the Land Element.

The primary roles of the PNGDF are to ensure national security, defend against external threats, assist in maintaining internal security when called upon by the civil authorities, and participate in disaster relief operations and nation-building tasks. The PNGDF also contributes to regional security initiatives and peacekeeping operations.

Challenges facing the PNGDF include chronic underfunding, which affects operational readiness, equipment maintenance, and personnel welfare. The vast and rugged terrain of the country, coupled with its extensive maritime borders, makes effective surveillance and control difficult. Modernizing the force and ensuring its capacity to meet contemporary security challenges, including transnational crime and illegal fishing, while upholding human rights and accountability, are ongoing priorities.

5.6. Crime and Human Rights

Papua New Guinea faces significant challenges related to crime and human rights, impacting social justice and the well-being of its citizens, particularly vulnerable groups.

High rates of violence against women and children are a severe problem, with Papua New Guinea often cited as one of the most dangerous places for women globally. A 2013 study in The Lancet found that 27% of men on Bougainville Island reported having raped a non-partner, while 14.1% reported committing gang rape. UNICEF has reported that nearly half of reported rape victims are under 15 years old, and 13% are under 7. ChildFund Australia noted that 50% of those seeking medical help after rape are under 16. The Family Protection Act (2013) and the Lukautim Pikinini (Child Welfare) Act (2015) were passed to address these issues, but implementation and enforcement remain challenging.

Sorcery accusation-related violence (SARV) is another grave human rights concern. Until its repeal in 2013, the 1971 Sorcery Act criminalized the practice of "black magic." Despite the repeal, accusations of sorcery frequently lead to brutal attacks and killings, with an estimated 50-150 alleged "witches," predominantly women, killed each year. A Sorcery and Witchcraft Accusation Related National Action Plan (SNAP) was approved in 2015, but funding and application have been deficient.

LGBT rights are not protected, and homosexual acts remain criminalized by law, contributing to discrimination and violence against LGBT individuals.

Tribal violence has long been a feature of life in the highlands regions, but it has been exacerbated by the increased availability of modern firearms. These weapons are believed to be sourced from smuggling operations across the border with Indonesia and from losses from government armories. Clashes have become deadlier, with traditional rules of engagement often disregarded. Village massacres have occurred, such as the killing of 69 villagers in an attack in Enga Province in February 2024, the largest such incident since the Bougainville conflict. The Human Rights Measurement Initiative gave Papua New Guinea a score of 5.6 out of 10 for safety from the state in 2023, indicating significant concerns.

The Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary (RPNGC), the national police force, has been troubled by issues of infighting, political interference, corruption, and brutality. It has been recognized since independence that the national police force alone cannot maintain law and order across the country, necessitating effective local-level policing systems like the village court magisterial service. A 2004 RPNGC Administrative Review highlighted weaknesses and poor working conditions. In September 2020, then-Minister for Police Bryan Jared Kramer publicly accused elements within the RPNGC of widespread corruption, including involvement in organized crime, drug and firearm smuggling, and misuse of funds. Then-Commissioner for Police David Manning acknowledged the presence of "criminals in uniform" within the force. These issues severely undermine public trust and the rule of law, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities and hindering efforts towards social justice. Addressing these systemic problems is crucial for protecting human rights and ensuring the safety and security of all Papua New Guineans.

6. Economy

Papua New Guinea's economy is characterized by its rich endowment of natural resources, a large subsistence agriculture sector, and significant challenges related to infrastructure, governance, and equitable development. This section analyzes its economic landscape with a focus on sustainable growth, social equity, and environmental protection.

6.1. Overview of Economic Structure

Papua New Guinea is classified as a developing economy by the International Monetary Fund. The economy is heavily reliant on its natural resources, particularly minerals (such as gold, copper, and silver) and energy resources (oil and liquefied natural gas - LNG), which account for the majority of export earnings. Agriculture, both for subsistence and cash crops, provides a livelihood for approximately 85% of the population and contributes significantly to the GDP.

The country's rugged terrain, including high mountain ranges, dense forests, and numerous islands, poses substantial challenges to infrastructure development, particularly transportation and communication networks. This, combined with issues like law and order problems in some areas and the complexities of the customary land tenure system, can hinder outside investment and domestic development. Years of deficient investment in education, health, and access to finance also constrain local entrepreneurial capacity.

Despite its resource wealth, Papua New Guinea faces significant disparities in wealth distribution. A large portion of the population lives in rural areas and engages in subsistence agriculture, remaining relatively independent of the cash economy. The HDI remains low, and poverty is widespread.

In recent years, economic growth has been driven by strong commodity prices and major resource extraction projects, especially in the LNG sector. However, this reliance on commodities also makes the economy vulnerable to global price fluctuations and the "Dutch disease," where a boom in the resource sector can negatively impact other sectors like agriculture and manufacturing. Former Prime Minister Sir Mekere Morauta initiated reforms to restore integrity to state institutions, stabilize the kina (the national currency) and the national budget, and privatize public enterprises where appropriate. Successive governments have aimed to attract international support, including from the IMF and the World Bank, for development assistance.

As of 2019, Papua New Guinea's real GDP growth rate was 3.8%, with an inflation rate of 4.3%. Long-term national plans like Vision 2050 emphasize the need for a more diverse and sustainable economy, moving away from over-reliance on resource extraction and promoting industries that provide broader employment and equitable benefits. The establishment of a sovereign wealth fund is one measure taken to manage resource revenues and stabilize government finances. However, achieving sustainable and equitable economic development requires ongoing reforms to improve governance, tackle corruption, enhance service delivery, and empower local communities and businesses.

6.2. Major Sectors

Papua New Guinea's economy is comprised of primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors, with the primary sector, particularly resource extraction and agriculture, being dominant.

6.2.1. Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries

Agriculture is the backbone of the livelihood for about 85% of Papua New Guinea's population, predominantly through subsistence farming. Traditional food crops include taro, yam, sweet potato, and sago. Major cash crops for export include palm oil (which has become the main agricultural export, largely from estates and with extensive outgrower output), coffee (primarily grown in the Highlands provinces by smallholders), cocoa and coconut oil/copra (from coastal areas, also largely by smallholders), tea (produced on estates), and rubber. The expansion of cash crops, particularly palm oil, has raised concerns about deforestation, land rights, and the impact on local food security and traditional agricultural systems.

The forestry industry is another significant contributor to the economy, but it is also associated with serious sustainability concerns. Deforestation due to commercial logging, often involving illegal logging practices, threatens Papua New Guinea's rich biodiversity and the customary lands of indigenous communities. Ensuring sustainable forest management, equitable benefit sharing with landowners, and effective regulation are critical challenges.

The fisheries sector is also important, with Papua New Guinea's waters being rich in marine resources, particularly tuna. A large portion of the world's major tuna stocks are found in its exclusive economic zone. While the sector offers significant economic potential, there are concerns about overfishing, the impact of industrial fishing on local small-scale fishers and coastal communities, and ensuring that the benefits from this resource contribute to national development and food security. Sustainable management of fisheries resources is vital for both economic and ecological reasons.

6.2.2. Mining and Energy

The mining and energy sectors are the primary drivers of Papua New Guinea's export economy, contributing the largest share of foreign exchange earnings. The country is rich in mineral resources, including gold, copper, and silver, and energy resources such as oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Major mining projects include the Ok Tedi Mine (copper and gold), the Porgera Gold Mine, and the Lihir Gold Mine. These large-scale operations have historically been significant contributors to GDP and government revenue. However, they have also been associated with severe environmental and social impacts, including riverine tailings disposal (as at Ok Tedi), land disputes with customary landowners, concerns about labor conditions, and the equitable distribution of benefits to affected communities. The legacy of these projects underscores the critical need for responsible mining practices, robust environmental regulation, and meaningful engagement with local communities to ensure their rights are protected and they receive fair compensation and development opportunities.

The energy sector has seen substantial growth with the development of LNG projects. The PNG LNG project, operated by ExxonMobil in a joint venture with companies like Oil Search and Santos, is one ofthe largest private-sector investments in the country's history. It involves gas production and processing facilities in Hela, Southern Highlands, and Western Provinces, with liquefaction and storage facilities near Port Moresby. A second major LNG project, Papua LNG, is being developed by TotalEnergies. While these projects promise significant economic returns, they also raise concerns about environmental impact, land use, the displacement of communities, and ensuring that the wealth generated translates into broad-based development and improved living standards for the population, rather than exacerbating inequalities or leading to "Dutch disease." The governance of resource revenues and their investment in sustainable development and social services is a key challenge. The discovery of oil fields like the Iagifu/Hedinia field in 1986 has also contributed to the energy sector.

The development of these sectors must be balanced with the principles of social justice, human rights, and environmental sustainability, ensuring that indigenous landowners are treated as genuine partners, their informed consent is obtained, and they share equitably in the benefits derived from their customary lands.

6.3. Science and Technology

Papua New Guinea's development in science and technology (S&T) is guided by national strategies such as National Vision 2050, adopted in 2009. This vision led to the establishment of the Research, Science and Technology Council, which emphasizes sustainable development through S&T. Medium-term priorities include emerging industrial technology for downstream processing, infrastructure technology for economic corridors, knowledge-based technology, science and engineering education, and a target of investing 5% of GDP in research and development (R&D) by 2050. However, actual investment in R&D has been very low, recorded at 0.03% of GDP in 2016. In 2016, women accounted for 33.2% of researchers in the country.

In terms of scientific output, Papua New Guinea had the largest number of publications among Pacific Island states in 2014 according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science, with many focusing on immunology, genetics, biotechnology, and microbiology. Collaboration with international scientists, particularly from Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Switzerland, is common. By 2019, according to the Scopus database, Papua New Guinea was second to Fiji in publication numbers among Pacific Island states, with health sciences accounting for nearly half of its output.

Forestry, an important economic resource, generally utilizes low and semi-intensive technological inputs, limiting product diversification. The lack of automated machinery and adequately trained local technical personnel hinders the adoption of advanced technologies.

Renewable energy sources represent about two-thirds of the total electricity supply, with hydropower being significant. There is considerable potential to expand other renewable options such as solar, wind, geothermal, and ocean-based energy. The European Union funded the Renewable Energy in Pacific Island Countries Developing Skills and Capacity (EPIC) programme (2013-2017), which helped establish a Master's programme in renewable energy management and a Centre of Renewable Energy at the University of Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea is also a beneficiary of a broader EU-Pacific Islands Forum programme on Adapting to Climate Change and Sustainable Energy.

Challenges in S&T include limited funding, a small pool of skilled researchers and technicians, and difficulties in adopting and disseminating technology, especially in remote rural areas. For S&T to contribute effectively to equitable benefit and sustainable development, there needs to be increased investment in education and R&D, better infrastructure, and policies that promote innovation and technology transfer in a manner that empowers local communities and protects the environment.

6.4. Land Tenure

Land tenure in Papua New Guinea is predominantly based on customary systems, which has profound cultural significance and complex impacts on economic development, resource projects, and social stability. Approximately 97% of the total land area is held under customary land title, meaning it is owned by indigenous clans or kinship groups according to their traditional laws and customs. The remaining 3% is alienated land, which is either held privately under state lease (typically for 99 years) or is government land. Freehold title is virtually non-existent and can only be held by Papua New Guinean citizens; any existing freeholds are automatically converted to state leases upon transfer.

Customary land ownership is deeply intertwined with identity, social structure, and livelihood for the majority of Papua New Guineans. The precise nature of customary tenure varies significantly between different cultural groups. While often portrayed as communal ownership by clans, closer studies usually show that specific rights to use and manage land portions are often held by individual heads of extended families and their descendants. Customary land cannot be devised by will; it is inherited according to the customs of the deceased's community.

The predominance of customary land tenure presents both opportunities and challenges for economic development. On one hand, it provides a strong basis for community cohesion and local control over resources. On the other hand, identifying the legitimate landowners for development projects (such as mining, forestry, or agriculture) can be complex and lead to disputes if not handled with due diligence and respect for local protocols. The issue of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) from customary landowners is critical.

Historically, there have been significant issues with "land grabs," where large tracts of customary land have been acquired, often through the misuse of provisions like Special Agricultural and Business Leases (SABLs). These leases, purportedly for agricultural projects, have in many cases served as a backdoor mechanism for large-scale logging, circumventing the stricter requirements of the Forest Act and often failing to secure genuine landowner approval or provide fair compensation and benefits. A Commission of Inquiry into SABLs was established in mid-2011, highlighting the systemic problems in land administration and resource governance.

The Lands Act and the Land Group Incorporation Act were amended in 2010 with the intention of improving the management of state land, providing mechanisms for dispute resolution over land, and enabling customary landowners to better access finance and form partnerships for developing portions of their land. These reforms aim to allow for more specific identification of customary landowners and require their explicit authorization for land arrangements.

Ensuring fair compensation, equitable benefit sharing, and the protection of landowner rights in the context of resource development projects are central to achieving social justice and sustainable development. This requires transparent and accountable land administration systems, respect for customary law, and genuine partnership with indigenous communities. The discovery of gold, traced back to 1852 in pottery from Redscar Bay, marked the beginning of resource interest that continues to shape land use and tenure dynamics.

6.5. Transport

Transportation infrastructure in Papua New Guinea is severely constrained by its extremely rugged and mountainous terrain, dense rainforests, and numerous islands. This has historically isolated many communities and continues to pose significant challenges for economic development, service delivery, and national integration.

Air transport is the most critical mode of transportation for connecting different parts of the country. Aeroplanes played a key role in opening up the interior during the colonial period and remain essential for most inter-urban travel and the movement of high-density or high-value freight. The capital, Port Moresby, has no road links to any of Papua New Guinea's other major towns, such as Lae or Mount Hagen. Many remote villages and communities are accessible only by light aircraft or by foot. Jacksons International Airport in Port Moresby is the country's main international airport and domestic hub. In addition to two international airfields, Papua New Guinea has approximately 578 airstrips, the vast majority of which are unpaved and can only accommodate small aircraft. The national airline is Air Niugini. Fuel shortages can occasionally ground airlines, highlighting the vulnerability of this vital transport link.

The road network is limited and largely fragmented. As of recent estimates, there are about 5.8 K mile (9.35 K km) of roads, with more than half being unpaved. The longest highway in the country, the Highlands Highway, stretches for about 435 mile (700 km), connecting the port city of Lae on the north coast with major towns in the Highlands region, such as Goroka, Mount Hagen, and Tari. However, road conditions are often poor, and maintenance is a constant challenge due to the terrain and frequent landslides. The limited road network severely impacts access to markets, schools, healthcare, and other essential services for a large portion of the rural population.

Maritime transport is crucial for connecting the coastal areas and the numerous islands. The country has several important ports, with Port Moresby and Lae being the largest and handling most international shipping. Coastal shipping and smaller vessels play a vital role in inter-island trade and transport.

There are no railways in Papua New Guinea. The development of a comprehensive and resilient transportation network remains a major priority for the government, but the associated costs and engineering challenges are immense. Improving transport infrastructure is essential for fostering economic growth, reducing regional disparities, and enhancing the quality of life for its citizens.

7. Demographics

Papua New Guinea's demographic landscape is characterized by extreme diversity, a predominantly rural population, and significant challenges in providing social services and ensuring equity across its varied communities.

7.1. Population

Papua New Guinea is one of the most heterogeneous nations in the world. As of 2020, the estimated population was around 8.95 million inhabitants, though a December 2022 report by the United Nations, based on satellite imagery and ground-truthing, suggested a new population estimate closer to 17 million, nearly double the country's official estimate at the time. This would make Papua New Guinea the most populous Pacific island country.

There are hundreds of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to Papua New Guinea. The majority of these groups are classified as Papuans, whose ancestors arrived in the New Guinea region tens of thousands of years ago. The other major indigenous groups are Austronesians, whose ancestors arrived in the region less than four thousand years ago, primarily settling in coastal and island areas. This diverse ethnic composition, with numerous small, often isolated communities, contributes to the country's rich cultural tapestry but also presents challenges for national unity, social cohesion, and equitable resource allocation. The age structure is generally young, typical of a developing country with high birth rates.

7.2. Urbanization

Papua New Guinea has one of the lowest levels of urbanization in the world. According to CIA World Factbook data from 2018, only 13.2% of the population lived in urban areas, second lowest globally only to Burundi. The vast majority of the population (over 85%) lives in rural areas, often in traditional, customary communities, relying on subsistence agriculture.

The primary factors contributing to this low urbanization rate are the country's rugged geography, which makes internal migration and the development of large urban centers difficult, and the strong attachment to customary land and traditional ways of life. The urbanization rate, measured as the projected change in urban population, was 2.51% between 2015 and 2020.

The largest urban centers are:

- Port Moresby (National Capital District): The capital city and largest urban area.

- Lae (Morobe Province): A major industrial center and port city.

- Mount Hagen (Western Highlands Province): The largest urban center in the Highlands region.

- Kokopo (East New Britain Province): Became the provincial capital after Rabaul was largely destroyed by volcanic eruptions.

- Popondetta (Oro Province)

- Madang (Madang Province)

- Arawa (Autonomous Region of Bougainville)

- Mendi (Southern Highlands Province)

- Kimbe (West New Britain Province)

- Goroka (Eastern Highlands Province)

Urban areas, particularly Port Moresby and Lae, face significant challenges, including the growth of informal settlements (squatter settlements) due to rural-urban migration, high unemployment rates, crime, and inadequate access to basic services such as housing, clean water, sanitation, and healthcare. Addressing these urban challenges while supporting sustainable rural development is a key priority for equitable national progress.

7.3. Immigration

Immigration to Papua New Guinea has historically been limited but has involved various groups contributing to the country's social and economic fabric. Before independence in 1975, there were around 40,000 to 50,000 expatriates, mostly from Australia (administrators, business people, missionaries) and China (traders, laborers). Most of these individuals had departed by the early 21st century, though a smaller expatriate community remains. According to World Bank data from 2015, international migrants constituted about 0.3% of Papua New Guinea's population.

The Chinese community, though small, has a long history in Papua New Guinea, with many establishing businesses. However, this has sometimes led to social tensions. In May 2009, anti-Chinese rioting involving tens of thousands of people broke out, sparked by a fight at a Chinese-owned nickel factory and fueled by native resentment against perceived Chinese dominance in small business sectors.

Other immigrant groups include Indonesians, Filipinos, and smaller numbers of Europeans (other than Australians), Polynesians, and Micronesians. There is an existing collaboration between Papua New Guinea and African countries through forums like the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) Group of States, and a small community of Africans live and work in the country.

Social integration of immigrant communities and their impact on local communities and economies are ongoing considerations. Issues can arise concerning business competition, employment opportunities, and cultural differences. Ensuring fair treatment and non-discrimination for all residents, while addressing any legitimate concerns of the local population regarding economic participation and social impact, is important from a social justice standpoint.

7.4. Languages

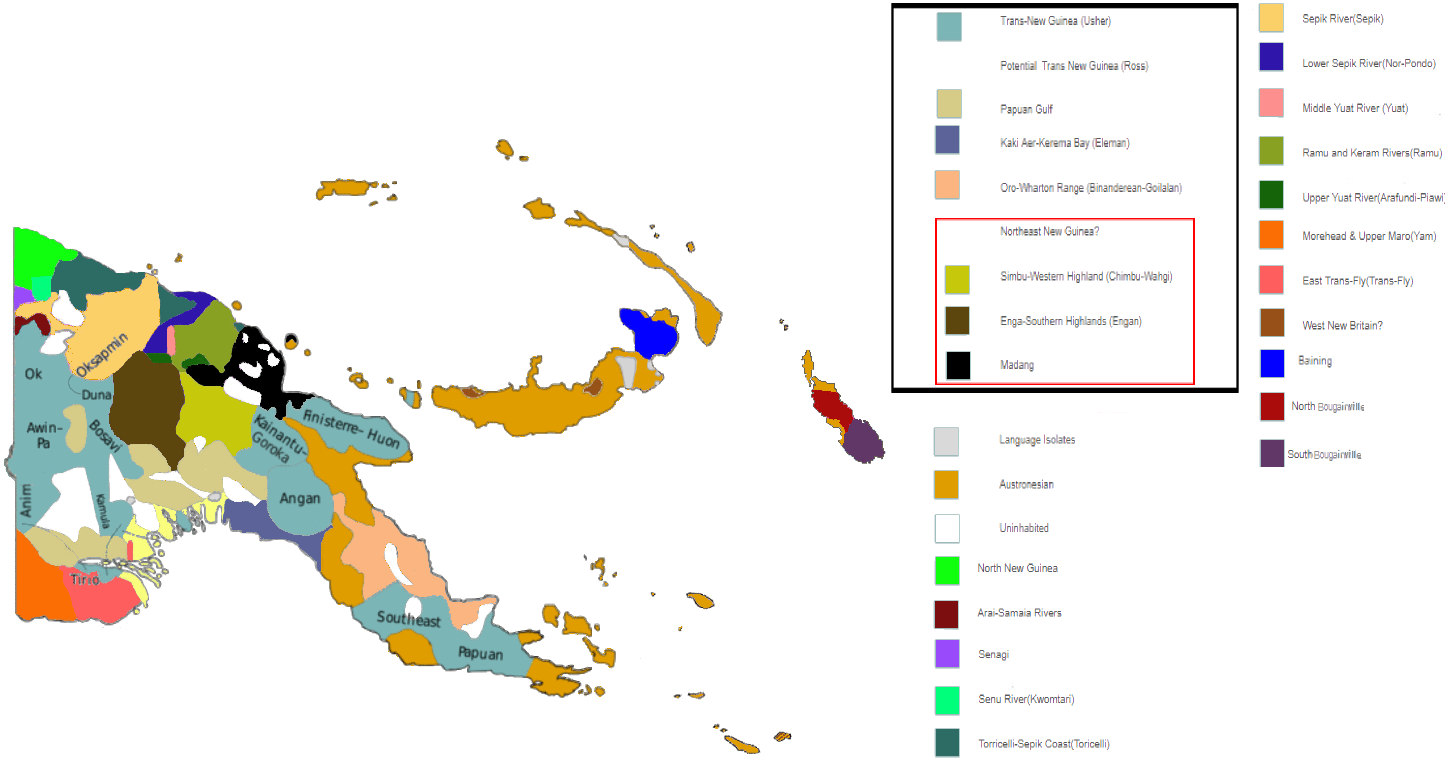

Papua New Guinea is renowned as one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world, with over 820 distinct indigenous languages, representing approximately 12% of the world's total. Most of these languages have fewer than 1,000 speakers, and with an average of only around 7,000 speakers per language, Papua New Guinea has a greater density of languages than any other nation on Earth except Vanuatu. The most widely spoken indigenous language is Enga, with about 200,000 speakers, followed by languages like Melpa and Huli.

The indigenous languages are broadly classified into two large groups: Austronesian languages and non-Austronesian languages (collectively referred to as Papuan languages). Austronesian languages, numbering around 16% of the total, are mostly found in coastal and island regions and include languages like Motu, Kuanua, and Halia. The Papuan languages, constituting the vast majority (around 84%), are incredibly diverse and are generally grouped into about 13 phyla, though their interrelationships are complex and often unclear. The largest group among these is the Trans-New Guinea phylum. The extreme linguistic diversity is attributed to the country's rugged geography, which historically isolated communities.

There are four official languages in Papua New Guinea:

- English: The language of government, the education system, and formal business. However, it is not widely spoken by the general population as a first language.

- Tok Pisin: An English-based creole language that serves as the primary lingua franca throughout much ofthe country, particularly in the northern mainland, the Highlands, the islands, and in urban centers like Port Moresby. Much of the debate in Parliament is conducted in Tok Pisin, and it is widely used in media and public information campaigns. The national weekly newspaper, Wantok, is published in Tok Pisin.

- Hiri Motu: A Motu-based pidgin, historically used as a trade language in the southern coastal region of Papua. Its use has declined somewhat with the spread of Tok Pisin and English, but it remains an official language.

- Papua New Guinean Sign Language: Recognized as an official language in 2015, to support the deaf community.

The linguistic richness of Papua New Guinea is a significant cultural heritage, but many languages are endangered due to the small number of speakers and the increasing influence of lingua francas and English. Language preservation efforts are crucial for maintaining this unique aspect of global diversity and ensuring the cultural continuity of its many communities.

7.5. Religion

The Constitution of Papua New Guinea guarantees religious freedom, and the government and judiciary generally uphold this right. The 2011 census found that 95.6% of citizens identified as Christian. However, religious syncretism is high, with many citizens combining their Christian faith with traditional indigenous beliefs and practices. Virtually no respondents in the census identified as non-religious.

According to the 2011 census, the religious affiliations of the citizen population were as follows:

- Roman Catholic: 26%

- Evangelical Lutheran: 18.4%

- Seventh-day Adventist: 12.9%

- Pentecostal: 10.4%

- United Church: 10.3%

- Evangelical Alliance: 5.9%

- Anglican: 3.2%

- Baptist: 2.8%

- Salvation Army: 0.4%

- Kwato Church: 0.2%

- Other Christian: 5.1%

- Non-Christian: 1.4%

- Not stated: 3.1%

The majority of Christians in Papua New Guinea are Protestant, constituting roughly 70% of the total Christian population if combining the denominations listed.

Minority faiths include the Baháʼí Faith, with the first Baháʼí arriving in 1954. The community grew, leading to the election of a National Spiritual Assembly in 1969, and as of 2020, there were over 30,000 Baháʼís. Construction of the first Baháʼí House of Worship in Papua New Guinea began in Port Moresby in 2018, with a design inspired by a woven basket, a common cultural feature, and the traditional Haus Tambaran (Spirit House). Islam is practiced by a small community of approximately 5,000 people, the majority belonging to the Sunni group. The Papua New Guinea Council of Churches has noted the activity of both Muslim and Confucian missionaries.

Traditional indigenous religions are often animist, involving beliefs in spirits inhabiting the natural world and often elements of veneration of the dead. Given the extreme heterogeneity of Melanesian societies, these beliefs and practices vary widely. A prevalent belief in many traditional communities is in masalai, or spirits (often considered evil), which are sometimes blamed for misfortune, illness, and death. The practice of puripuri (often translated as sorcery or witchcraft) is also a part of some traditional belief systems, though accusations of harmful sorcery can lead to severe social problems and violence, as discussed in the Human Rights section. The interplay between introduced religions and enduring traditional beliefs creates a complex and dynamic religious landscape in Papua New Guinea.

7.6. Education

Papua New Guinea's education system faces significant challenges in terms of access, quality, and equity, particularly for remote populations and girls. A large proportion of the adult population is illiterate, with women being disproportionately affected.

Education is provided by both government and church institutions. Church-run schools, such as the approximately 500 schools operated by the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea, play a substantial role in the education sector. The system generally includes elementary, primary, secondary, and tertiary levels.

Papua New Guinea has six universities and other tertiary institutions. The two founding universities are:

- The University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG), based in the National Capital District.

- The Papua New Guinea University of Technology (Unitech), based near Lae in Morobe Province.

Four other universities, formerly colleges, have since gained university status:

- The University of Goroka in Eastern Highlands Province.

- Divine Word University (run by the Catholic Church's Divine Word Missionaries) in Madang Province.

- The University of Natural Resources and Environment (formerly Vudal University) in East New Britain Province.

- Pacific Adventist University (run by the Seventh-day Adventist Church) in the National Capital District.

Despite these institutions, access to higher education is limited. Challenges across the education system include shortages of qualified teachers, inadequate school infrastructure and resources (especially in rural areas), high dropout rates, and financial barriers for many families. The Human Rights Measurement Initiative reported that, based on its level of income, Papua New Guinea is achieving 68.5% of what should be possible for the right to education.

Improving education is critical for social mobility, empowering citizens (especially women and marginalized groups) to participate more fully in democratic processes, and for developing the human capital needed for sustainable national development. Efforts to enhance educational outcomes often focus on increasing enrollment and retention rates, improving teacher training, making education more relevant to local contexts, and addressing gender and geographical disparities in access and quality.

7.7. Health

Papua New Guinea faces significant public health challenges, reflected in key health indicators and the accessibility and quality of healthcare services, particularly for its large rural and vulnerable populations.

As of 2019, life expectancy at birth was approximately 63 years for men and 67 for women. Government expenditure on health in 2014 accounted for 9.5% of total government spending, with total health expenditure equating to 4.3% of GDP. The number of physicians was low, at around five per 100,000 people in the early 2000s, indicating a severe shortage of healthcare professionals.

The maternal mortality rate was 250 per 100,000 live births in 2010, a significant concern though an improvement from earlier figures (311.9 in 2008 and 476.3 in 1990). The under-5 mortality rate was 69 per 1,000 live births, with neonatal mortality accounting for 37% of these deaths. There was approximately 1 midwife per 1,000 live births, and the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women was 1 in 94, highlighting deficiencies in maternal and child health services.

Prevalent diseases include malaria, tuberculosis (TB), and HIV/AIDS. Papua New Guinea has one of the highest incidences of HIV/AIDS in the Pacific region. Other communicable diseases, as well as growing rates of non-communicable diseases, also strain the healthcare system.

Access to healthcare services is a major challenge, especially for the 85% of the population living in rural and remote areas. Rugged terrain, limited transportation infrastructure, and inadequate funding contribute to poorly equipped health facilities and shortages of medical supplies and personnel in many parts of the country.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative finds that Papua New Guinea is achieving 71.9% of what should be possible for the right to health, based on its level of income. Addressing these health disparities and improving overall public health requires sustained investment in primary healthcare, strengthening health systems, improving access to clean water and sanitation, and tackling the social determinants of health, including poverty and education. Public health campaigns also need to address issues like family planning and awareness of preventable diseases, ensuring services are culturally appropriate and reach the most vulnerable populations.

8. Culture

Papua New Guinea's culture is extraordinarily rich and diverse, stemming from its more than one thousand distinct ethnic groups. This cultural mosaic is a defining characteristic of the nation, and its preservation is of immense importance.

8.1. Traditional Societies and Customs

Traditional societies in Papua New Guinea are typically village-based, with a strong reliance on subsistence farming. In some areas, people also hunt and collect wild plants (such as yam roots and karuka nuts) to supplement their diets. Those who become skilled at hunting, farming, and fishing often earn great respect within their communities.

Social structures vary widely, but a key element in many societies is the 'Wantok' system (from Tok Pisin "wan tok" meaning "one language" or "one people"). This refers to a strong sense of kinship, mutual support, and obligation among people who share a common language, village, or clan. While the Wantok system provides vital social safety nets, it can also present challenges in modern contexts, such as contributing to nepotism or straining individual resources.

Customs related to rituals, ceremonies, marriage, conflict resolution, and daily life are diverse. "Sing-sings" are significant cultural events, particularly in the Highlands, where people engage in colorful local rituals. Participants paint themselves and dress elaborately with feathers, pearls, and animal skins to represent birds, trees, or mountain spirits. Sometimes, important events, such as legendary battles, are enacted at these musical festivals.

Marriage customs vary greatly. In some cultures, the groom's family must provide a bride price to the bride's family, which can consist of traditional items like golden-edged clam shells, shell money, pigs, cassowaries, or cash. In other regions, it is the bride's family who traditionally pays a dowry, while in others, neither practice is prevalent.

Traditional conflict resolution mechanisms exist within communities, though inter-tribal warfare was historically common and, in some remote areas, sporadic violence still occurs. Gender roles are often clearly defined, and in many traditional societies, women have faced systemic disadvantages and lower status, though their roles in agriculture and family life are crucial. Addressing gender inequality and violence against women within both traditional and modern contexts remains a significant challenge for social justice.

Papua New Guinea possesses one UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Kuk Early Agricultural Site, which was inscribed in 2008 for its archaeological evidence of independent agricultural development dating back thousands of years. However, despite its vast array of intangible cultural heritage elements, the country has not yet had any elements inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

8.2. Arts and Music

The artistic expressions of Papua New Guinea are as diverse as its cultures. Traditional arts are deeply connected to spiritual beliefs, social structures, and daily life. Wood carving is a prominent art form, particularly renowned in the Sepik River region, where intricate carvings often depict ancestral figures, spirits, animals, and plants, adorning houses, canoes, and ceremonial objects. Masks are another significant artistic expression, used in dances, rituals, and ceremonies, varying widely in style and meaning across different groups.

Pottery, weaving (especially of bilum bags by women), and body adornment (including elaborate headdresses, body paint, and jewelry made from shells, feathers, and other natural materials) are also important traditional arts.

Musical traditions are equally diverse, with a vast array of instruments, songs, and ceremonial dances. Traditional instruments include various types of drums (such as the kundu hourglass drum), flutes, panpipes, and slit gongs. Songs and dances often accompany rituals, tell stories, mark important life events, or celebrate harvests. The "sing-sing" gatherings are vibrant displays of music, dance, and costume. The preservation and promotion of these rich artistic and musical traditions are vital for cultural identity and continuity.

8.3. Sport

Sport plays an important part in Papua New Guinean culture, with rugby league being by far the most popular sport and often described as the national passion. In a nation where communities can be geographically isolated and many people live at a minimal subsistence level, the enthusiasm for rugby league has been described by some as a modern replacement for traditional tribal rivalries, channeling local pride and competitive spirit. Many Papua New Guineans who represent their country, the Kumuls, or play in overseas professional leagues become national celebrities. The annual Australian State of Origin series is also fervently followed in Papua New Guinea, and the support can be so passionate that violent clashes supporting different teams have unfortunately occurred over the years. The Kumuls usually play an annual match against the Australian Prime Minister's XIII, typically in Port Moresby.

While not as dominant as rugby league, Australian rules football also has a significant following, and the national team (the Mosquitos) has achieved international success, often ranked second globally after Australia.

Other popular sports include association football (soccer), netball (particularly among women), rugby union, basketball, and, in eastern Papua, cricket. These sports contribute to national identity, provide recreational opportunities, and can serve as avenues for personal development and community engagement.

8.4. Media

The media landscape in Papua New Guinea includes a mix of state-owned and private outlets across print, broadcast, and digital platforms. Major newspapers include the The National and the Post-Courier, both English-language dailies. The Wantok is a significant Tok Pisin weekly.

Radio is a crucial medium for reaching the diverse and often remote population. The National Broadcasting Corporation (NBC PNG) is the state-owned public broadcaster, operating national and provincial radio services. There are also numerous commercial and community radio stations.

Television broadcasters include the state-owned NBC TV (formerly Kundu 2) and the private commercial station EMTV. Access to television is more limited in rural areas compared to radio.

The use of the internet and mobile technology has been growing, though access and affordability remain challenges, particularly outside urban centers. Digicel PNG is a major provider of mobile and internet services. Social media platforms are increasingly used for communication and information sharing.