1. Overview

Solomon Islands is an island nation located in Melanesia, part of Oceania, in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, east of Papua New Guinea. Comprising six major islands and over 900 smaller ones, its geography is characterized by mountainous volcanic islands, tropical rainforests, and extensive coral reefs. The capital, Honiara, is situated on the largest island, Guadalcanal.

The islands have a long history of human habitation, dating back at least 30,000 years, with significant cultural contributions from later Lapita migrants. European contact began in 1568 with Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña. The islands later became a British protectorate and were a significant theatre of conflict during World War II, particularly the Guadalcanal campaign. Solomon Islands achieved self-government in 1976 and full independence in 1978, establishing a constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth of Nations.

Post-independence, Solomon Islands has faced political instability, including significant ethnic conflict between 1998 and 2003, which necessitated international intervention through the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI). The country's political system is a parliamentary democracy, though it has experienced challenges related to governance and national unity. Recent geopolitical shifts, including the switch in diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China in 2019, have significant domestic and international implications.

Socio-economically, Solomon Islands is classified as a least developed country, with a large portion of its population engaged in subsistence agriculture and fishing. Key economic sectors include forestry, fisheries, and agriculture, though the nation grapples with issues of sustainable development and reliance on foreign aid. Human development indicators highlight ongoing challenges in education, healthcare, water and sanitation, and gender equality. Cultural heritage is rich and diverse, with numerous indigenous languages and traditions, including the significant 'Wantok' (one talk/kinship) system and 'Kastom' (customary law and practices). The nation is also highly vulnerable to natural disasters and the impacts of climate change, including sea level rise. This article examines these aspects through a lens emphasizing human development, social justice, and democratic values.

2. Name

In 1568, the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña was the first European to visit the Solomon Islands archipelago. He did not name the archipelago at that time, only certain individual islands. However, following reports of his voyage, others began referring to the islands as Islas SalomónSolomon IslandsSpanish. This name was likely inspired by the optimistic, though mistaken, belief that these islands were the source of the legendary wealth of the biblical King Solomon, specifically the fabled city of Ophir.

During most of the colonial period, the territory's official name was the "British Solomon Islands Protectorate". This changed in 1975 when the name was officially shortened to "The Solomon Islands." Upon achieving independence in 1978, the country adopted the name "Solomon Islands" as defined in its Constitution. As a Commonwealth realm, this is its formal title.

The definite article, "the," is not part of the country's official name since independence. However, it is still commonly used in colloquial references, both within and outside the country, and often appears in historical contexts referring to the area pre-independence. Informally, the islands are often referred to simply as "the Solomons."

3. History

The history of Solomon Islands spans from ancient human settlement to its modern status as an independent nation, marked by European discovery, colonial rule, intense wartime experiences, and a challenging path to national cohesion and development.

3.1. Prehistory

The Solomon Islands were first settled by people migrating from the Bismarck Islands and New Guinea during the Pleistocene era, between 30,000 and 28,800 BC. Archaeological evidence for this early settlement has been found at Kilu Cave on Buka Island, which is now part of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville in Papua New Guinea. During this period, sea levels were lower, and Buka and Bougainville were physically connected to the southern Solomons, forming a single landmass sometimes referred to as "Greater Bougainville." The extent to which these early settlers spread southwards is unclear, as no other archaeological sites from this specific period have been discovered further south in the archipelago.

As the Ice Age ended and sea levels rose between 4000 and 3500 BC, the Greater Bougainville landmass fragmented into the numerous islands seen today. Later evidence of human settlements, dating to between 4500 and 2500 BC, has been found at Poha Cave and Vatuluma Posovi Cave on Guadalcanal. The ethnic identity of these early peoples is not definitively known, but it is thought that the speakers of the Central Solomon languages-a unique language family unrelated to other languages in the Solomons-may be descendants of these initial settlers.

A significant subsequent wave of migration occurred between 1200 and 800 BC with the arrival of the Austronesian Lapita people from the Bismarcks. They are recognized by their characteristic ceramic pottery. Evidence of Lapita presence has been found throughout the Solomon archipelago, including the Santa Cruz Islands in the southeast, with different islands being settled at various times. Linguistic and genetic studies suggest that the Lapita people initially "leap-frogged" the already inhabited main Solomon Islands and settled first in the Santa Cruz group. Later, back-migrations brought their culture to the main islands.

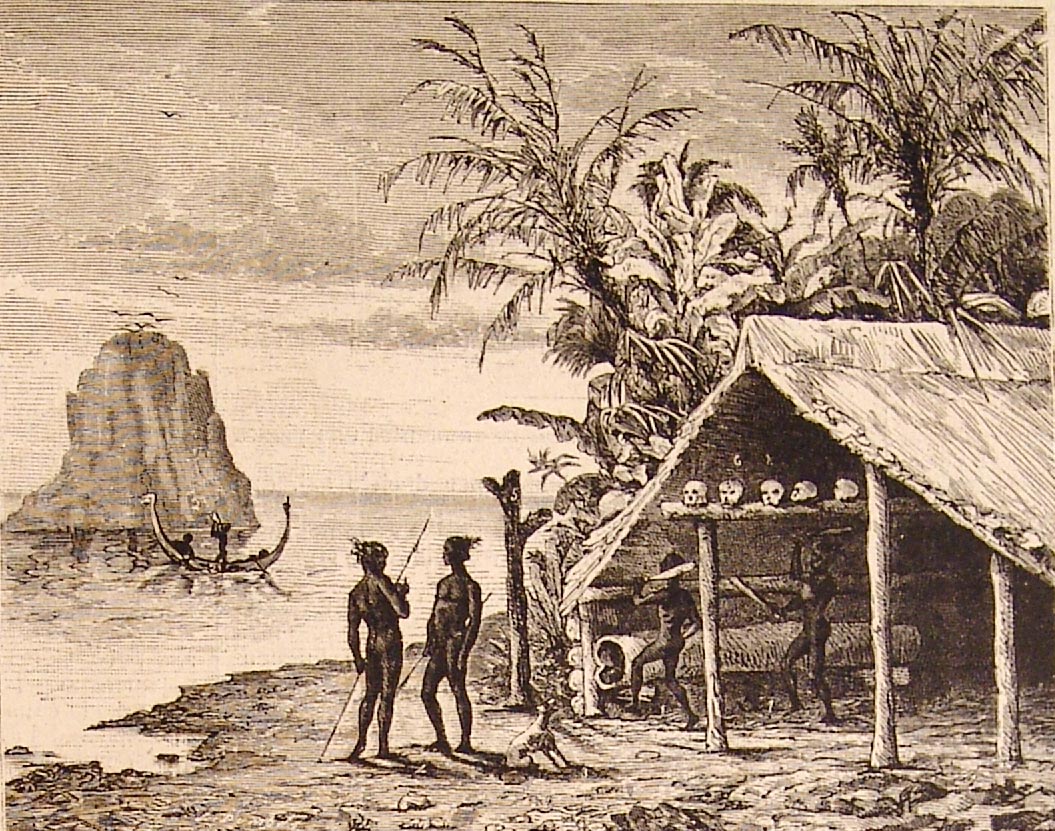

These Lapita migrants mixed with the existing indigenous populations. Over time, their languages became dominant, and most of the 60 to 70 languages spoken in Solomon Islands today belong to the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian language family. Communities generally existed in small villages, practicing subsistence agriculture, though extensive inter-island trade networks were also established. Numerous ancient burial sites and other evidence of permanent settlements from the period AD 1000-1500 have been found throughout the islands. A prominent example is the Roviana cultural complex, centered on the islands off the southern coast of New Georgia, where a large number of megalithic shrines and other structures were built in the 13th century. Before the arrival of Europeans, the people of Solomon Islands were known for practices such as headhunting and, in some instances, cannibalism.

3.2. Arrival of Europeans (1568-1886)

The first European to visit the islands was the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira, who sailed from Peru in 1568. He landed on Santa Isabel on February 7 and subsequently explored several other islands, including Makira, Guadalcanal, and Malaita. Initial relations with the indigenous Solomon Islanders were cordial but often deteriorated over time due to misunderstandings and conflicts. Consequently, Mendaña returned to Peru in August 1568.

Mendaña made a second voyage to the Solomons in 1595 with a larger crew, aiming to colonize the islands. They landed on Nendö in the Santa Cruz Islands and established a small settlement at Gracioso Bay. However, the settlement failed due to poor relations with the native peoples and epidemics of disease among the Spanish, which caused numerous deaths, including Mendaña himself in October 1595. The new commander, Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, decided to abandon the settlement and sailed north to the Spanish territory of the Philippines. Queirós later returned to the region in 1606, sighting Tikopia and Taumako, though this voyage was primarily focused on Vanuatu in search of the mythical Terra Australis.

Except for Abel Tasman's sighting of the remote Ontong Java Atoll in 1648, no European sailed to the Solomons again until 1767, when the British explorer Philip Carteret passed by the Santa Cruz Islands, Malaita, and further north, Bougainville and the Bismarck Islands. French explorers also reached the Solomons: Louis Antoine de Bougainville named Choiseul in 1768, and Jean-François de Surville explored the islands in 1769. In 1788, John Shortland, captaining a supply ship for Britain's new Australian colony at Botany Bay, sighted the Treasury and Shortland Islands. In the same year, the French explorer Jean-François de La Pérouse was shipwrecked on Vanikoro. A rescue expedition led by Bruni d'Entrecasteaux sailed to Vanikoro but found no trace of La Pérouse. His fate was not confirmed until 1826, when the English merchant Peter Dillon visited Tikopia and discovered items belonging to La Pérouse in the possession of the local people. This was later confirmed by the voyage of Jules Dumont d'Urville in 1828.

Some of the earliest regular foreign visitors to the islands were whaling vessels from Britain, the United States, and Australia, starting in the late 18th century. They came for food, wood, and water, establishing trading relationships with the Solomon Islanders and later recruiting islanders as crewmen. Relations between the islanders and visiting seamen were not always peaceful, and bloodshed sometimes occurred. The increased European contact led to the spread of diseases to which local populations had no immunity, and a shift in the balance of power between coastal groups (who gained access to European weapons and technology) and inland groups.

In the second half of the 19th century, more traders arrived seeking turtleshells, sea cucumbers, copra, and sandalwood, occasionally establishing semi-permanent trading stations. However, initial attempts at long-term settlement, such as Benjamin Boyd's colony on Guadalcanal in 1851, were unsuccessful.

Beginning in the 1840s and accelerating in the 1860s, islanders were recruited, often forcibly kidnapped, as laborers for colonies in Australia, Fiji, and Samoa in a practice known as "blackbirding". Conditions for these workers were frequently poor and exploitative, leading to resentment and, at times, violent attacks by islanders against Europeans who appeared on their shores. The blackbirding trade was documented by writers like Joe Melvin and Jack London.

Christian missionaries also began visiting the Solomons from the 1840s. An early attempt by French Catholics under Jean-Baptiste Epalle to establish a mission on Santa Isabel in 1845 was abandoned after Epalle was killed by islanders. Anglican missionaries arrived from the 1850s, followed by other denominations, gradually gaining a large number of converts.

3.3. Colonial period (1886-1978)

The colonial period in Solomon Islands was marked by the division of influence between European powers, the establishment of British rule, significant socio-economic changes, and the profound impact of World War II, ultimately leading to the path towards independence.

3.3.1. Protectorate establishment and early rule

In 1884, the Germany annexed northeast New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago. By 1886, Germany extended its rule over the North Solomon Islands, which included Bougainville, Buka, Choiseul, Santa Isabel, the Shortlands, and Ontong Java atoll. In the same year, Germany and Britain confirmed this arrangement, with the British gaining a "sphere of influence" over the southern Solomons. Germany paid little attention to these islands, with German authorities based in New Guinea not even visiting the area until 1888.

The German presence, combined with pressure from missionaries to curb the abuses of blackbirding (coercive labor recruitment), prompted the British to declare a protectorate over the southern Solomons in March 1893. This protectorate initially encompassed New Georgia, Malaita, Guadalcanal, Makira, Mono Island, and the central Nggela Islands.

In April 1896, colonial official Charles Morris Woodford was appointed as the British Acting Deputy Commissioner, and he was confirmed in his position the following year. The Colonial Office appointed Woodford as the Resident Commissioner in the Solomon Islands on February 17, 1897. His directives included controlling blackbirding and stopping the illegal trade in firearms. Woodford established an administrative headquarters on the small island of Tulagi, proclaiming it the protectorate capital in 1896. Between 1898 and 1899, the Rennell and Bellona Islands, Sikaiana, the Santa Cruz Islands, and outlying islands such as Anuta, Fataka (likely Fatutaka), Temotu (referring to the province, not a single island), and Tikopia were added to the protectorate.

In 1900, under the terms of the Tripartite Convention of 1899, Germany ceded its claims in the Northern Solomons (except Buka and Bougainville, which became part of German New Guinea) to Britain. This transfer brought the Shortlands, Choiseul, Santa Isabel, and Ontong Java into the British Solomon Islands Protectorate.

Woodford's administration was underfunded and struggled to maintain law and order in the remote colony. From the late 1890s to the early 1900s, numerous European merchants and colonists were killed by islanders. The British response often involved deploying Royal Navy warships to launch punitive expeditions against the villages deemed responsible. Arthur Mahaffy was appointed Deputy Commissioner in January 1898, based in Gizo. His duties included suppressing headhunting in New Georgia and neighboring islands.

The British colonial government attempted to encourage the establishment of plantations by colonists; however, by 1902, only about 80 European colonists resided in the islands. Economic development efforts had mixed results, though Levers Pacific Plantations Ltd., a subsidiary of Lever Brothers, managed to establish a profitable copra plantation industry that employed many islanders. Small-scale mining and logging industries were also developed. However, the colony remained largely a backwater, with education, medical, and other social services primarily administered by missionaries. Violence continued, notably with the murder of colonial administrator William R. Bell by Basiana of the Kwaio people on Malaita in 1927, as Bell attempted to enforce an unpopular head tax. Several Kwaio were killed in a retaliatory raid, and Basiana and his accomplices were executed. This event highlighted the tensions and resistance to colonial rule, as well as the often brutal methods used to enforce it, impacting the human rights and autonomy of the local populations.

3.3.2. World War II

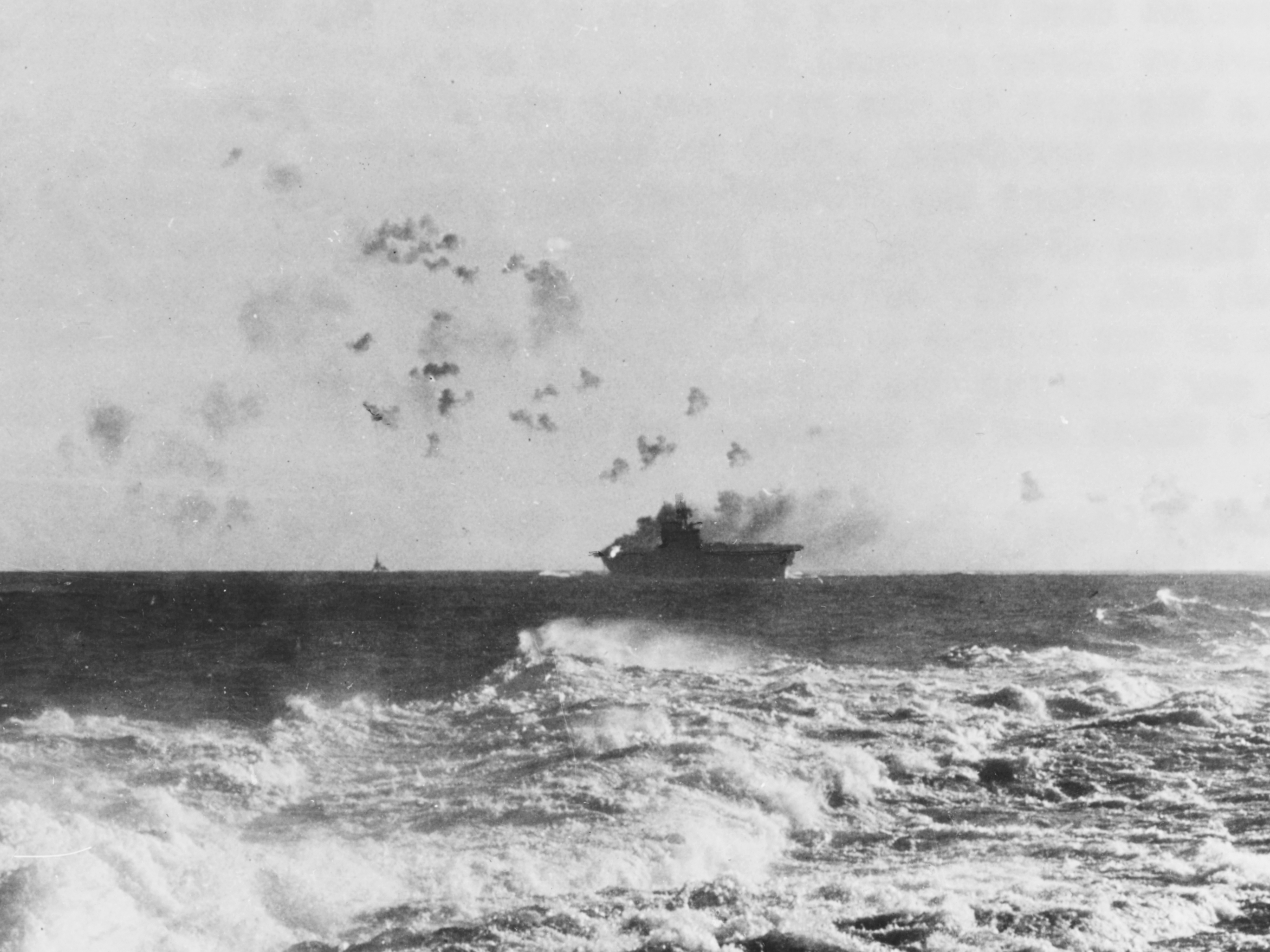

From 1942 until the end of 1943, the Solomon Islands became a major battleground in the Pacific War, witnessing fierce land, sea, and air battles between the Allied forces (primarily the United States and British Imperial forces) and the Empire of Japan.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Japan sought to secure its southern flank by invading Southeast Asia and New Guinea. In May 1942, as part of Operation Mo, Japanese forces occupied Tulagi and most of the western Solomon Islands, including Guadalcanal, where they began constructing an airfield. The British administration had already relocated to Auki on Malaita, and most of the European population had been evacuated to Australia.

The Allies launched a counter-invasion of Guadalcanal in August 1942, which marked a turning point in the Pacific War. This was followed by the New Georgia campaign in 1943. These campaigns effectively halted and then began to reverse the Japanese advance in the Pacific. The fighting was intense and resulted in significant casualties on all sides, with hundreds of thousands of Allied, Japanese, and civilian deaths, as well as immense destruction across the islands. The Solomon Islands Campaign cost the Allies approximately 7,100 men, 29 ships, and 615 aircraft, while the Japanese lost around 31,000 men, 38 ships, and 683 aircraft.

Coastwatchers, including Solomon Islanders, played a crucial role in providing intelligence on Japanese movements and rescuing Allied servicemen. U.S. Admiral William Halsey, commander of Allied forces during the Battle for Guadalcanal, famously stated, "The coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal and Guadalcanal saved the South Pacific." Approximately 3,200 Solomon Islanders served in the Solomon Islands Labour Corps, and around 6,000 enlisted in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force. Their exposure to American forces and the wider world brought significant social and political transformations. The Americans extensively developed Honiara, which became the capital in 1952, replacing Tulagi. The Solomons Pijin was also heavily influenced by interactions between Americans and the island inhabitants.

Islanders Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana became famous for finding the shipwrecked John F. Kennedy and his crew of the PT-109. They suggested writing a rescue message on a coconut and delivered it by paddling a dugout canoe. This coconut was later kept on Kennedy's desk when he became President of the United States.

The war had a profound impact on the Solomon Islanders. It disrupted traditional life, caused widespread displacement, and exposed islanders to new ideas and technologies. The shared experience of resisting Japanese occupation and working alongside Allied forces fostered a sense of common identity and political awareness among some Solomon Islanders, which would contribute to post-war political movements and the eventual drive for independence. The devastation of the war also left a lasting legacy on the landscape and the collective memory of the people.

3.3.3. Post-war and independence process

The aftermath of World War II brought significant political and social changes to the Solomon Islands, leading to the rise of indigenous movements and a gradual process towards self-government and eventual independence.

In 1943-44, Aliki Nono'ohimae, a chief from Malaita, founded the Maasina Rule movement (also known as the Native Council Movement, literally "Brotherhood Rule"). He was later joined by another chief, Hoasihau. The movement's aims were to improve the economic well-being of native Solomon Islanders, achieve greater autonomy, and act as a liaison between the islanders and the colonial administration. Maasina Rule gained particular popularity among ex-Labour Corps members, and its numbers swelled after the war, spreading to other islands. The British administration, alarmed by the movement's growth, launched "Operation De-Louse" in 1947-48 and arrested most of the Maasina leaders. In response, Malaitans organized a campaign of civil disobedience, which led to mass arrests.

In 1950, a new Resident Commissioner, Henry Gregory-Smith, arrived and released the leaders of the movement, although the civil disobedience campaign continued. In 1952, the new High Commissioner (later Governor) Robert Stanley met with leaders of Maasina Rule and agreed to the creation of an island council for Malaita, a key demand of the movement. This marked a step towards greater local participation in governance. In late 1952, Stanley formally moved the capital of the territory from Tulagi to Honiara, utilizing the infrastructure left by the Americans. During the early 1950s, the British and Australian governments discussed the possibility of transferring sovereignty of the islands to Australia. However, the Australians were reluctant to accept the financial burden of administering the territory, and the idea was shelved.

As the wave of decolonisation swept across the colonial world, and Britain was no longer willing or able to bear the financial burdens of its empire, the colonial authorities began to prepare the Solomons for self-governance. Appointed Executive and Legislative Councils were established in 1960. A degree of elected Solomon Islander representation was introduced in 1964 and extended in 1967. A new constitution was drawn up in 1970, merging the two councils into a single Governing Council, though the British Governor still retained extensive powers. Dissatisfaction with this arrangement led to the creation of a new constitution in 1974, which reduced many of the Governor's remaining powers and created the post of Chief Minister, first held by Solomon Mamaloni. This was a significant step towards self-determination.

Full self-government for the territory was achieved in 1976, a year after neighboring Papua New Guinea gained independence from Australia. During this period, discontent grew in the Western islands, with many fearing marginalization in a future state potentially dominated by Honiara or Malaita. This led to the formation of the Western Breakaway Movement, reflecting underlying regional tensions and aspirations for local autonomy.

A conference held in London in 1977 agreed that the Solomons would gain full independence the following year. Under the terms of the Solomon Islands Act 1978, the country was annexed to Her Majesty's dominions and granted independence on July 7, 1978. The first prime minister was Sir Peter Kenilorea of the Solomon Islands United Party (SIUP). Elizabeth II became the Queen of Solomon Islands, represented locally by a Governor General. The achievement of independence was a culmination of years of political aspiration and negotiation, though the new nation faced significant challenges in forging national unity and sustainable development.

3.4. Independence era (1978-present)

Since achieving independence, Solomon Islands has navigated a complex path of political development, economic challenges, ethnic tensions, and evolving foreign relations, reflecting the difficulties of nation-building in a diverse and geographically fragmented country.

3.4.1. Early political situation and economic development efforts

Following independence in 1978, Sir Peter Kenilorea became the first Prime Minister. He won the 1980 Solomon Islands general election and continued to serve until 1981, when he was replaced by Solomon Mamaloni of the People's Alliance Party (PAP) after a vote of no confidence. Mamaloni's government established the Central Bank and the national airline, and advocated for greater autonomy for individual islands within the country. These early years were focused on establishing national institutions and formulating development plans.

Kenilorea returned to power after winning the 1984 election, but his second term lasted only two years before he was replaced by Ezekiel Alebua following allegations of misuse of French aid money. This highlighted early challenges with governance and corruption. In 1986, Solomon Islands co-founded the Melanesian Spearhead Group, aimed at fostering cooperation and trade among Melanesian countries.

Solomon Mamaloni and the PAP returned to power after the 1989 election. Mamaloni dominated Solomon Islands politics from the early to mid-1990s, with a brief interruption by the premiership of Francis Billy Hilly. Mamaloni made unsuccessful efforts to make the Solomons a republic. His tenure was also marked by the spillover effects of the conflict in neighboring Bougainville, which began in 1988 and caused many refugees to flee to the Solomons. Tensions arose with Papua New Guinea as PNG forces frequently entered Solomons territory in pursuit of rebels. Relations improved after the conflict ended in 1998.

Economically, the country faced significant challenges. The national financial situation deteriorated, with much of the budget reliant on the logging industry, often conducted at an unsustainable rate. Mamaloni's creation of a 'discretionary fund' for use by politicians fostered an environment conducive to fraud and corruption, undermining efforts towards equitable development and democratic accountability. Public discontent with his rule led to a split in the PAP, and Mamaloni lost the 1993 election to Billy Hilly. However, Hilly was later sacked by the Governor-General after a number of defections caused him to lose his majority, allowing Mamaloni to return to power in 1994, where he remained until 1997. Excessive logging, government corruption, and unsustainable levels of public spending continued to grow. Public discontent led to Mamaloni losing the 1997 election.

The new prime minister, Bartholomew Ulufa'alu of the Solomon Islands Liberal Party, attempted to enact economic reforms. However, his premiership soon became engulfed in a serious ethnic conflict known as "The Tensions," which would have devastating consequences for the nation's stability and development. These early post-independence years were thus characterized by fluctuating political leadership, persistent economic vulnerabilities, and emerging social divisions that would later erupt into open conflict.

3.4.2. Ethnic conflict (1998-2003)

The period from 1998 to 2003 in Solomon Islands was dominated by severe ethnic conflict, commonly referred to as "the Tensions." This civil unrest was primarily characterized by fighting between the Isatabu Freedom Movement (IFM), also known as the Guadalcanal Revolutionary Army, representing indigenous Guale interests, and the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF), along with the Marau Eagle Force, representing Malaitan settlers.

For many years, people from the densely populated island of Malaita had been migrating to Honiara and other parts of Guadalcanal, attracted by greater economic opportunities, particularly in the capital and surrounding agricultural areas. This influx led to increasing tensions with the indigenous Guale inhabitants of Guadalcanal over land ownership, resource access, and cultural differences.

In late 1998, the IFM was formed and began a campaign of intimidation and violence against Malaitan settlers on Guadalcanal, aiming to drive them out. Thousands of Malaitans were forced to flee their homes, either returning to Malaita or seeking refuge in Honiara. In response, the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF) was established in mid-1999 to protect Malaitan interests and retaliate against the IFM.

The conflict escalated rapidly. Prime Minister Bartholomew Ulufa'alu declared a four-month state of emergency in late 1999 and requested assistance from Australia and New Zealand, but his appeal was rejected at that time. Law and order on Guadalcanal collapsed. The police force, ethnically divided and poorly equipped, was unable to assert authority, and many of its weapons depots were raided by the militias. By this point, the MEF effectively controlled Honiara, while the IFM controlled much of rural Guadalcanal.

On June 5, 2000, Ulufa'alu, himself a Malaitan, was kidnapped by the MEF, who felt he was not doing enough to protect Malaitan interests. Ulufa'alu subsequently resigned in exchange for his release. Manasseh Sogavare, who had earlier been Finance Minister in Ulufa'alu's government but had joined the opposition, was controversially elected as prime minister. Several MPs, thought to be supporters of his opponent, were unable to attend parliament for the crucial vote.

The Townsville Peace Agreement was signed on October 15, 2000, by the MEF, elements of the IFM, and the Solomon Islands Government. This was followed by the Marau Peace Agreement in February 2001, involving the Marau Eagle Force. However, a key Guale militant leader, Harold Keke, refused to sign the agreement, leading to a split within the Guale groups. Subsequently, Guale signatories to the agreement, led by Andrew Te'e, joined with the Malaitan-dominated police to form the 'Joint Operations Force.' The conflict then shifted to the remote Weathercoast region of southern Guadalcanal as the Joint Operations unsuccessfully attempted to capture Keke and his group.

The humanitarian impact of the conflict was severe. Communities were displaced, lives were lost, and human rights abuses were widespread. The economy collapsed, and the government became bankrupt by early 2001. The conflict exposed deep-seated ethnic grievances and the fragility of national unity. In April 2003, seven Christian brothers of the Melanesian Brotherhood, including Brother Robin Lindsay, were killed on the Weather Coast of Guadalcanal by Harold Keke's group while on a peace mission. This event further highlighted the brutality of the conflict and the risks faced by those attempting to mediate.

New elections in December 2001 brought Allan Kemakeza to power. However, law and order continued to deteriorate. Violence persisted on the Weathercoast, while militants in Honiara increasingly turned to crime, extortion, and banditry. The Department of Finance was often surrounded by armed men when funding was due. In December 2002, Finance Minister Laurie Chan resigned after being forced at gunpoint to sign a cheque for militants. Conflict also broke out in Western Province between locals and Malaitan settlers. The pervasive atmosphere of lawlessness and ineffective policing prompted a formal request by the Solomon Islands Government for outside help, a request unanimously supported in Parliament, leading to the RAMSI intervention. An estimated 200 people were killed during the Tensions.

3.4.3. Post-conflict era and RAMSI's role

Following the period of intense ethnic conflict, Solomon Islands entered a post-conflict era heavily shaped by the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI). RAMSI, an Australian-led international intervention, arrived in July 2003 at the formal request of the Solomon Islands Government, which was struggling with a breakdown of law and order, a collapsed economy, and ineffective state institutions. The mission, known locally as "Operation Helpem Fren" (Help a Friend), comprised a sizeable international security contingent of 2,200 police and troops from Australia, New Zealand, and about 15 other Pacific nations.

RAMSI's initial and primary objective was to restore law and order. This was achieved relatively quickly. Violence largely ceased, and key militant leaders, including Harold Keke, surrendered or were apprehended. A significant number of weapons were collected through an amnesty program. The improved security situation allowed for the beginning of broader peace-building and state-building efforts.

RAMSI's mandate extended beyond security to include strengthening government institutions, improving economic management, and promoting good governance. Key areas of focus included:

- Rebuilding the Police Force:** The Royal Solomon Islands Police Force (RSIPF) had been severely compromised during the conflict. RAMSI undertook extensive efforts to retrain, re-equip, and reform the RSIPF, aiming to restore public trust and its capacity to maintain order independently.

- Strengthening Governance and Rule of Law:** This involved support for the judiciary, correctional services, and public administration. Efforts were made to combat corruption and improve transparency and accountability within government.

- Economic Recovery and Reform:** RAMSI assisted in stabilizing government finances, reforming public financial management, and creating an environment conducive to economic recovery and development. This included support for key sectors like agriculture and efforts to diversify the economy.

- National Reconciliation:** While RAMSI's role was primarily in security and institutional capacity building, the improved stability provided a platform for national reconciliation efforts. In 2008, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established to examine the causes and consequences of the Tensions and to help heal the wounds of the conflict. Its aim was to provide a forum for victims and perpetrators to share their stories and to make recommendations for preventing future conflict, thereby addressing social justice concerns.

The political landscape during this period remained volatile. Sir Allan Kemakeza remained Prime Minister until the 2006 elections. His successor, Snyder Rini, faced immediate protests and riots in Honiara, particularly in Chinatown, fueled by allegations of corruption and influence from Chinese businessmen. This led to Rini's resignation and the election of Manasseh Sogavare as Prime Minister. Sogavare's relationship with RAMSI, particularly Australia, was often strained. He was ousted in a no-confidence vote in 2007 and replaced by Derek Sikua.

RAMSI's presence gradually scaled down as stability improved and local capacity increased. The military component of RAMSI departed in 2013, and the policing and broader governance support mission concluded in June 2017, marking the end of a 14-year intervention.

RAMSI is generally credited with successfully restoring peace and stability, preventing a complete state collapse, and laying foundations for recovery. However, its long-term impact on sustainable governance, economic development, and national unity remains a subject of ongoing discussion. The underlying issues that fueled the Tensions, including land disputes, ethnic identity, unequal development, and corruption, continue to pose challenges for Solomon Islands. The post-RAMSI era requires the nation to consolidate the gains made and to address these persistent issues to ensure lasting peace and equitable development for its people.

3.4.4. Recent developments and foreign relations

In recent years, Solomon Islands has experienced significant political shifts, most notably in its foreign policy, alongside ongoing domestic challenges. Manasseh Sogavare returned to the prime ministership after the 2019 election, an event that sparked some rioting in Honiara, reflecting underlying political tensions.

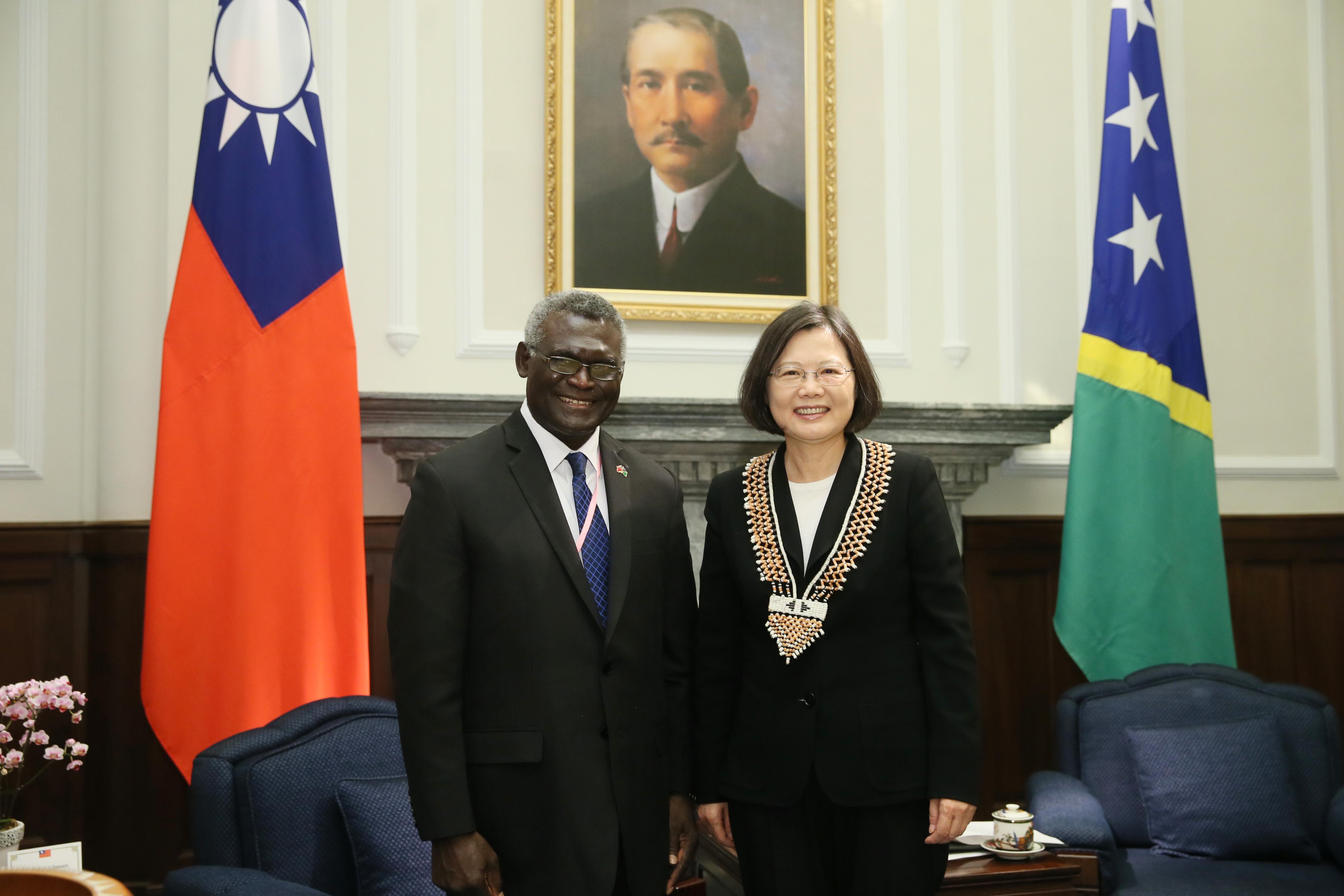

A pivotal development occurred in September 2019 when Prime Minister Sogavare's government announced the decision to switch diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People's Republic of China (PRC). This ended 36 years of official ties with Taiwan. The decision was controversial domestically, with some provinces, notably Malaita Province under then-Premier Daniel Suidani, expressing strong opposition and a desire to maintain links with Taiwan and Western partners. This highlighted internal divisions regarding the country's foreign policy direction and concerns about China's growing influence. The switch had immediate international implications, with the United States and Australia expressing concerns about regional stability and China's strategic ambitions in the Pacific.

The relationship with China rapidly deepened. In March 2022, Solomon Islands signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on policing cooperation with China. This was followed by a more comprehensive security agreement in April 2022. Leaked drafts of the security pact indicated it could allow for the deployment of Chinese military and police personnel to Solomon Islands to assist in maintaining social order, and potentially permit Chinese naval vessels to make port calls. This agreement caused significant alarm among traditional partners like Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, who feared it could lead to a permanent Chinese military presence in the region and destabilize regional security. Prime Minister Sogavare defended the pact as necessary for internal security and asserted it would not undermine regional peace.

Domestic unrest continued to be a feature. In November 2021, major riots and unrest broke out in Honiara, partly fueled by economic grievances, political dissatisfaction with Sogavare's government, and opposition to the switch to China. The Solomon Islands Government requested assistance from Australia under their 2017 Bilateral Security Treaty, leading to the deployment of Australian Federal Police and Defence Forces. Further protests occurred in February 2023 after the Premier of Malaita Province, Daniel Suidani, a vocal critic of the China switch, was removed from office through a vote of no confidence.

In terms of other foreign relations, Solomon Islands remains a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, and the Pacific Islands Forum. It has continued to advocate on issues of concern to Pacific Island nations, such as climate change. The country has also been vocal on human rights issues in West Papua, often joining other Pacific nations in calling for UN attention to the situation there, reflecting a commitment to regional human rights concerns.

On the policy front, in November 2019, Solomon Islands launched a national ocean governance policy aimed at the sustainable development and use of its ocean resources for the benefit of its people.

The May 2024 general election saw Jeremiah Manele elected as the new Prime Minister, succeeding Manasseh Sogavare. This change in leadership may herald shifts in both domestic policy and foreign relations, although the underlying challenges of economic development, national unity, and navigating geopolitical interests remain. The nation continues to grapple with social issues such as access to healthcare and education, gender inequality, and the impacts of natural disasters, all of which require sustained attention and resources for the betterment of its citizens.

4. Politics

Solomon Islands operates as a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government, based on the Westminster system. The country's political landscape is characterized by a multi-party system, though political parties tend to be fluid and coalition governments are common, often leading to political instability.

The following sections detail the structure of the government and key political aspects, considering democratic development and governance challenges.

4.1. Government structure

The King of Solomon Islands, currently Charles III, is the head of state. The King is represented in the country by a Governor-General, who is appointed for a five-year term on the advice of the Parliament. The Governor-General's role is largely ceremonial, acting on the advice of the government.

The head of government is the Prime Minister, who is elected by and from the members of the unicameral National Parliament. The Prime Minister heads the Cabinet, which is the executive arm of the government. Cabinet ministers are appointed by the Governor-General on the advice of the Prime Minister from among the members of Parliament. Each ministry is headed by a cabinet member, assisted by a permanent secretary, who is a career public servant responsible for the ministry's staff and operations.

The National Parliament consists of 50 members, elected for four-year terms through universal suffrage for citizens over the age of 21. Representation is based on single-member constituencies. Parliament can be dissolved by a majority vote of its members before the completion of its term, leading to early elections.

Political parties in Solomon Islands are numerous but often lack strong ideological bases or widespread grassroots support. As a result, parliamentary coalitions are frequently formed based on personal loyalties and short-term interests, leading to frequent votes of no confidence and changes in government. This political fluidity poses a significant challenge to stable governance, long-term policy planning, and democratic consolidation.

Efforts to strengthen democratic institutions and improve governance are ongoing, often with the support of international partners. However, issues such as corruption, regionalism, and the influence of logging and other commercial interests on political decision-making remain persistent challenges to democratic development and social equity. Land ownership is reserved for Solomon Islanders, and disputes over land are common and can be politically sensitive.

4.2. Judiciary

The judicial system of Solomon Islands is based on the English common law system, with elements of local customary law also recognized, particularly in civil matters and land disputes at the local level. The Constitution of Solomon Islands provides for the independence of the judiciary.

The court system is hierarchical:

1. **Magistrates' Courts:** These are the courts of first instance for most criminal and civil cases. They handle summary offenses and less serious indictable offenses, as well as civil claims up to a certain monetary limit.

2. **High Court:** The High Court has unlimited original jurisdiction in both civil and criminal matters. It also hears appeals from the Magistrates' Courts. The Chief Justice is the head of the High Court.

3. **Court of Appeal:** This is the highest court in Solomon Islands and hears appeals from the High Court on matters of law and fact. Its decisions are final. The President of the Court of Appeal heads this court. Justices of Appeal are often drawn from senior judges from other Commonwealth countries.

The Governor-General appoints the Chief Justice of the High Court on the advice of the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. Other judges (Justices of the High Court and Justices of Appeal) are appointed by the Governor-General on the advice of a Judicial and Legal Services Commission.

Ensuring the rule of law and access to justice for all citizens remains a challenge, particularly in rural and remote areas. The judiciary has faced issues related to resource constraints, capacity limitations, and the need to effectively integrate customary law with the formal legal system. International assistance, including through RAMSI and other programs, has aimed to strengthen the capacity and independence of the judiciary and improve the overall administration of justice.

Justice Edwin Goldsbrough served as President of the Court of Appeal for Solomon Islands from March 2014, having previously served as a Judge of the High Court (2006-2011) and later as Chief Justice of the Turks and Caicos Islands. Sir Albert Palmer is a notable figure who has served as Chief Justice.

4.3. Foreign relations

Solomon Islands maintains diplomatic relations with numerous countries and is a member of several key international and regional organizations, including the United Nations (UN), Interpol, the Commonwealth of Nations, the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), the Pacific Community (SPC), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) Group of States (through the Lomé Convention and subsequent agreements).

A significant shift in its foreign policy occurred in September 2019 when Solomon Islands terminated diplomatic relations with the Republic of China (Taiwan) and established official ties with the People's Republic of China (PRC). This decision ended 36 years of relations with Taiwan and was met with mixed reactions domestically and internationally. It has led to increased engagement with China, including economic assistance and a controversial security pact signed in 2022, which allows for Chinese security forces to be deployed to Solomon Islands to quell unrest. This pact has raised concerns among traditional partners like Australia, New Zealand, and the United States about China's growing influence in the Pacific region and potential implications for regional security.

Australia has historically been a major partner and aid donor, particularly evident during the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) from 2003 to 2017. Relations with Papua New Guinea (PNG) have been complex, particularly due to the influx of refugees from the Bougainville conflict and cross-border issues. However, a 1998 peace accord on Bougainville and a 2004 agreement on border operations have helped to normalize relations.

Solomon Islands has consistently advocated for the human rights of people in West Papua. In international forums like the UN Human Rights Council and the UN General Assembly, Solomon Islands, often alongside other Pacific nations like Vanuatu and Tuvalu, has raised concerns about alleged human rights violations in the Indonesian-administered region and called for UN investigations. This stance reflects a broader Pacific concern for self-determination and human rights in Melanesia, though it has been met with strong objections from Indonesia.

Foreign aid from various sources, including Australia, New Zealand, China, Japan, and multilateral organizations, plays a crucial role in the country's budget and development efforts. The diverse impacts of this aid and the increasing geopolitical competition in the Pacific region continue to shape Solomon Islands' foreign policy and its efforts to maintain sovereignty while addressing pressing national development needs. The nation seeks to balance its relationships to maximize benefits for its people while navigating the complexities of international diplomacy.

4.4. Military

Solomon Islands has not maintained a regular military force since its independence in 1978. During World War II, the locally recruited British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force was part of the Allied forces and participated in fighting in the Solomons.

Post-independence, defense and security have primarily been the responsibility of the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force (RSIPF). Various paramilitary elements within the RSIPF were disbanded and disarmed in 2003 following the intervention of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI). RAMSI itself included a small military detachment, headed by an Australian commander, which assisted the police element of RAMSI in maintaining internal and external security.

The RSIPF is responsible for a range of security functions, including maintaining law and order, border protection, and maritime surveillance. The force operates two Guardian-class patrol boats (such as the former Pacific-class patrol boats RSIPV Auki and RSIPV Lata), which constitute the country's de facto navy, primarily used for maritime surveillance within its extensive Exclusive Economic Zone.

The police budget has faced strains, particularly following the civil unrest in the late 1990s and early 2000s. For instance, after Cyclone Zoe struck the islands of Tikopia and Anuta in December 2002, Australia provided financial assistance (50.00 K AUD) for fuel and supplies for the patrol boat Lata to deliver relief.

In the long term, the RSIPF is expected to fully resume all defense-related roles. The police force is headed by a Commissioner, appointed by the Governor-General and responsible to the Minister of Police, National Security & Correctional Services.

The security agreement signed with China in 2022 has introduced a new dimension to the country's security landscape, allowing Solomon Islands to request Chinese police and military personnel to assist in maintaining social order, disaster response, and other areas. This development has sparked debate both domestically and internationally regarding its implications for Solomon Islands' sovereignty and regional security dynamics.

4.5. Human rights

The status of human rights in Solomon Islands presents a mixed picture, with constitutional protections in place but significant challenges remaining in practice, particularly concerning social and economic rights, gender equality, and access to justice. The country has ratified several international human rights treaties, but implementation and enforcement face obstacles due to resource constraints, cultural factors, and weak institutional capacity. Solomon Islands does not have a national human rights institution compliant with the Paris Principles.

Key human rights issues include:

- Access to Basic Services:** Many Solomon Islanders, especially in rural and remote areas, lack adequate access to quality education, healthcare, safe drinking water, and sanitation facilities. These deficiencies disproportionately affect vulnerable groups, including women, children, and people with disabilities, and impede overall human development.

- Gender Equality and Domestic Violence:** Gender inequality is pervasive, and domestic violence and sexual violence against women and girls are alarmingly high. Reports indicate that a significant majority of women have experienced physical or sexual abuse by a partner. Cultural norms, traditional practices like bride price (which can be misinterpreted as conferring ownership), and economic disparities contribute to the vulnerability of women. While the Family Protection Act 2014 was a significant legislative step to address domestic violence, effective implementation, access to support services for survivors, and changing societal attitudes remain critical challenges.

- Rights of Minorities and Vulnerable Groups:** While the population is predominantly Melanesian, Polynesian and Micronesian minorities exist. Ensuring their full participation and protection from discrimination is important. People with disabilities face significant barriers in accessing education, employment, and public services.

- LGBT Rights:** Homosexual acts between consenting adult males are criminalized under the penal code, punishable by up to 14 years of imprisonment. This legal framework contributes to discrimination and stigma against LGBT individuals, hindering their ability to live openly and access services without fear. There is limited public discussion or advocacy for LGBT rights within the country.

- Access to Justice:** The justice system faces challenges, including delays, limited resources, and difficulties in reaching remote populations. Integrating customary law with the formal legal system in a manner that upholds human rights standards is an ongoing process.

- Corruption and Governance:** Corruption can undermine human rights by diverting resources from essential public services and weakening the rule of law. Strengthening transparency, accountability, and good governance is crucial for the protection of human rights.

Efforts by the government, civil society organizations, and international partners are underway to address these human rights issues. These include legal reforms, awareness campaigns, capacity building for state institutions, and programs aimed at improving access to services and promoting social justice. However, sustained commitment and resources are needed to achieve meaningful progress in upholding the human rights of all Solomon Islanders.

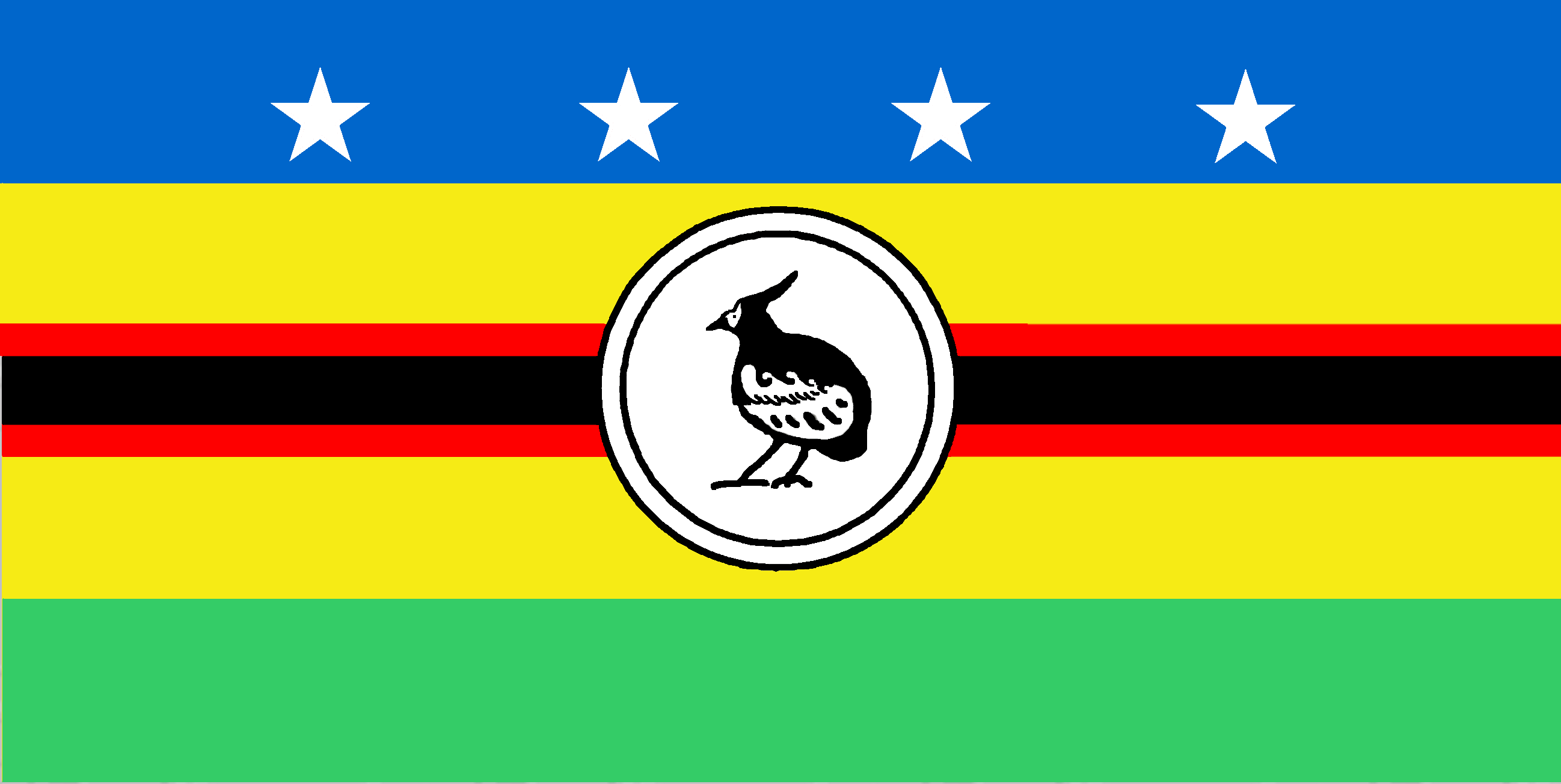

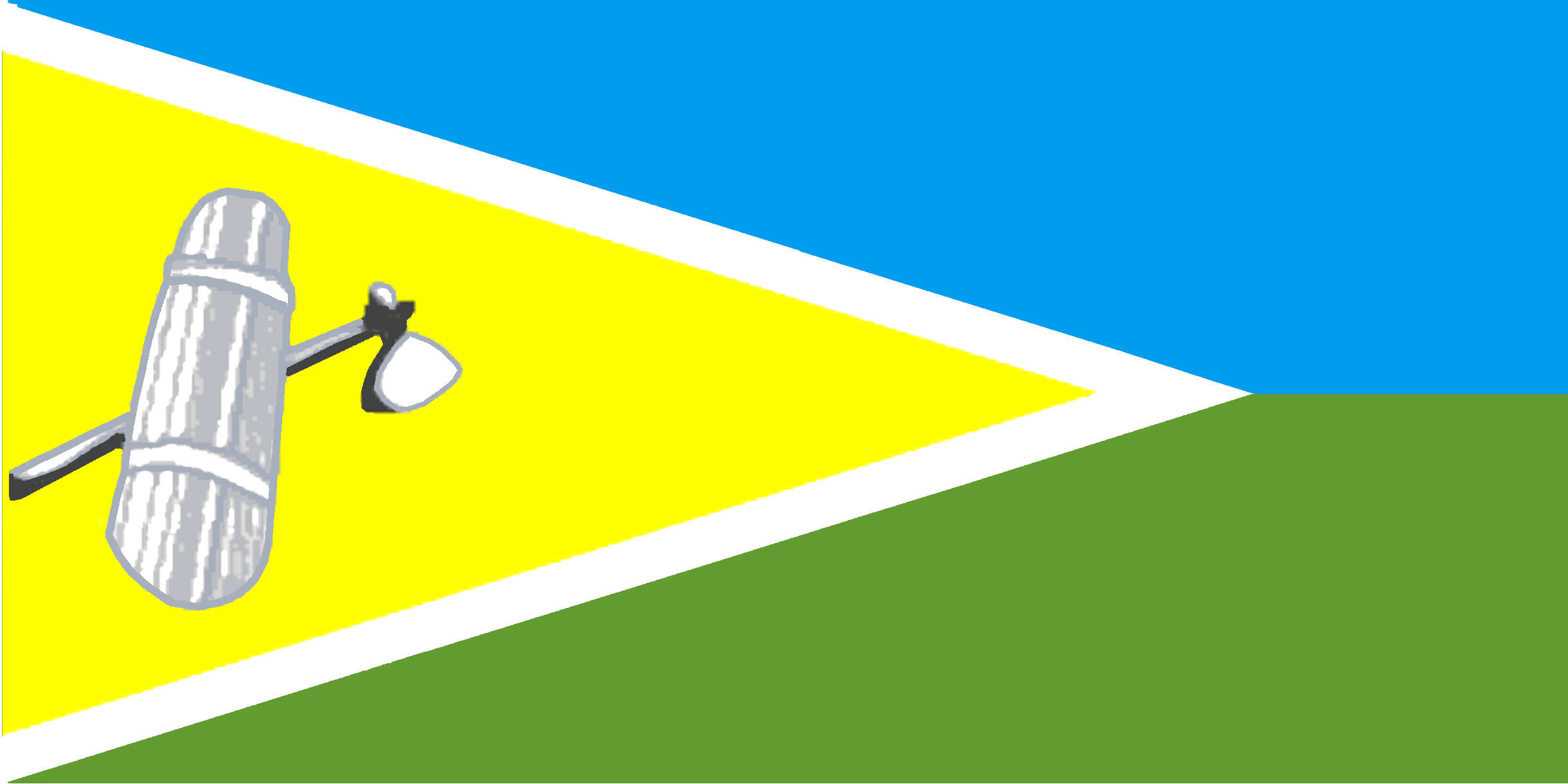

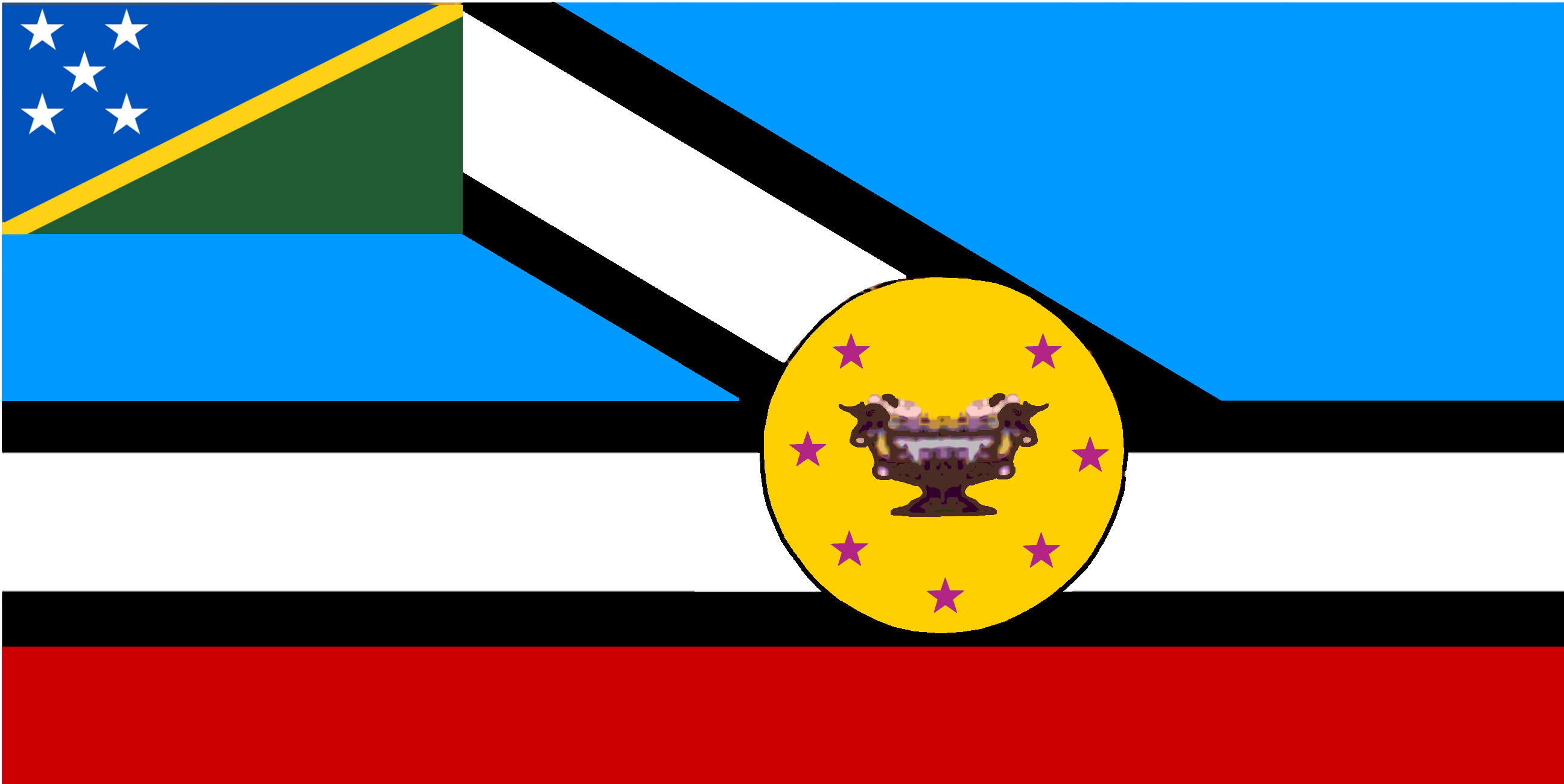

5. Administrative divisions

Solomon Islands is divided into nine provinces and one capital territory for local government purposes. Each of the nine provinces is administered by an elected provincial assembly, headed by a Premier. The capital, Honiara, is administered by the Honiara Town Council, headed by a Mayor.

The administrative divisions are as follows:

| # | Province | Capital | Premier (example, may vary) | Area (km2) | Population (1999 Census) | Population (2009 Census) | Population (2019 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Central Province | Tulagi | Stanely Manetiva | 615 | 21,577 | 26,051 | 30,318 |

| 2 | Choiseul Province | Taro Island | Harrison Benjamin | 3,837 | 20,008 | 26,372 | 30,775 |

| 3 | Guadalcanal ProvinceA | Honiara | Willie Atu (example, Francis Sade more recent) | 5,336 | 60,275 | 107,090 (figure appears to include Honiara in some sources or is for a broader definition) / 93,613 (excluding Honiara) | 154,022 |

| 4 | Isabel Province | Buala | Lesley Kikolo | 4,136 | 20,421 | 26,158 | 31,420 |

| 5 | Makira-Ulawa Province | Kirakira | Julian Maka'a | 3,188 | 31,006 | 40,419 | 51,587 |

| 6 | Malaita Province | Auki | Martin Fini (example, Daniel Suidani was prominent) | 4,225 | 122,620 | 157,405 (figure may be for a broader definition) / 137,596 | 172,740 |

| 7 | Rennell and Bellona Province | Tigoa | Japhet Tuhanuku | 671 | 2,377 | 3,041 | 4,100 |

| 8 | Temotu Province | Lata | Clay Forau | 895 | 18,912 | 21,362 | 25,701 |

| 9 | Western Province | Gizo | Billy Veo (example, David Gina more recent) | 5,475 | 62,739 | 76,649 | 94,106 |

| - | Capital Territory | Honiara | Eddie Siapu (Mayor) | 22 | 49,107 | 73,910 (figure appears to be for broader Honiara) / 64,609 | 129,569 |

| Solomon Islands | Honiara | - | 28,400 (approx. total land area) / 30,407 (sum of provinces in some tables) | 409,042 | 515,870 (2009 census total) / 558,457 (used in some sources for 2009) | 720,956 (2019 census total, may slightly differ from sum due to rounding or specific definitions) / 721,455 (2019 census total from en source) |

A Excluding the Capital Territory of Honiara.

Note: Premier names are examples and subject to change with elections. Population figures can vary slightly between sources due to different calculation methods or inclusion criteria for Honiara within Guadalcanal Province figures. The 2019 Census total population was 721,455.

6. Geography

Solomon Islands is an archipelagic nation in Melanesia, characterized by its numerous islands, volcanic origins, tropical climate, and rich biodiversity, facing significant environmental challenges including vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change.

6.1. Topography and islands

Solomon Islands lies east of Papua New Guinea and consists of six major islands and over 992 smaller islands, cays, and atolls. The main island group forms part of the larger Solomon Islands archipelago, which also includes Bougainville (politically part of Papua New Guinea). The major islands of the nation of Solomon Islands include Guadalcanal (the largest and location of the capital, Honiara), Malaita, Santa Isabel, Makira (formerly San Cristobal), Choiseul, and the New Georgia Islands. Other significant island groups and islands include the Shortland Islands, the Russell Islands, the Florida Islands (Nggela Islands), Tulagi, Maramasike, Ulawa, Owaraha (Santa Ana), Sikaiana, Rennell Island, Bellona Island, and the Santa Cruz Islands. Outlying islands such as Tikopia, Anuta, and Fatutaka are also part of the country.

The islands are predominantly mountainous and of volcanic origin, with several active and dormant volcanoes. The highest peak is Mount Popomanaseu on Guadalcanal, reaching 7.6 K ft (2.33 K m) (sources vary, some state 2,440m). The terrain is rugged, often covered in dense tropical rainforest. The distance between the westernmost and easternmost islands is approximately 0.9 K mile (1.50 K km) (or 0.9 K mile (1.45 K km)). The Santa Cruz Islands, including Tikopia, are particularly isolated, situated north of Vanuatu and more than 124 mile (200 km) from the other main islands.

Soil quality varies, ranging from rich volcanic soils on some of the larger islands to relatively infertile limestone on others. The volcanic islands often feature narrow coastal plains.

6.2. Climate

Solomon Islands has a tropical oceanic climate, characterized by high humidity and warm temperatures throughout the year. The mean temperature is around 79.7 °F (26.5 °C) (or 80.6 °F (27 °C)), with minimal seasonal variation.

Rainfall is abundant, with an annual average of about 0.1 K in (3.05 K mm), though this can vary significantly by location and altitude. The period from November to April is generally the wetter season, influenced by northwesterly winds, and is also when tropical cyclones are more likely to occur. June through August tends to be slightly cooler and drier.

The country is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including sea level rise, increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, and threats to its marine and terrestrial ecosystems. According to the WorldRiskReport 2021, Solomon Islands ranks second among countries with the highest disaster risk worldwide. In 2023, Solomon Islands, along with other vulnerable Pacific island states, launched the "Port Vila Call for a Just Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific," advocating for a phase-out of fossil fuels and a transition to renewable energy.

6.3. Ecology

Solomon Islands boasts rich and diverse terrestrial and marine ecosystems, but these are under increasing pressure from human activities and climate change.

The Solomon Islands archipelago is part of two distinct terrestrial ecoregions. Most of the islands belong to the Solomon Islands rain forests ecoregion, which also includes Bougainville and Buka. These forests are characterized by high biodiversity but have come under significant pressure from commercial logging. The Santa Cruz Islands are part of the Vanuatu rain forests ecoregion, shared with the neighboring archipelago of Vanuatu. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.19/10, ranking it 48th globally out of 172 countries. More than 230 varieties of orchids and other tropical flowers are found in Solomon Islands.

The islands contain several active and dormant volcanoes, such as Tinakula and Kavachi (an active submarine volcano).

6.3.1. Forests and biodiversity

Tropical rainforests cover a significant portion of Solomon Islands, harboring a wealth of flora and fauna, including many endemic species of birds, insects, and plants. The isolation of the islands has contributed to this unique biodiversity. However, deforestation due to unsustainable logging practices poses a major threat to these forests and their inhabitants. Mining activities also contribute to habitat destruction and environmental degradation.

Conservation efforts are underway, often involving local communities and international organizations, but face challenges due to economic pressures and limited resources. For example, on the southern side of Vangunu Island, local communities have been advocating for the protection of forests around Zaira, which provide habitat for vulnerable animal species, against logging and mining interests. Ensuring ecological sustainability and fair labor practices in resource extraction industries is a critical concern for the long-term well-being of both the environment and the people.

6.3.2. Coral reefs

Solomon Islands is located within the Coral Triangle, an area recognized for its exceptionally high marine biodiversity. The country's coral reefs are among the most diverse in the world. A 2004 marine biodiversity survey found 474 species of corals, including nine potentially new to science, ranking its coral diversity second only to the Raja Ampat Islands in Indonesia.

These reefs support a vast array of marine life, including numerous fish species, and are crucial for coastal protection and local livelihoods, particularly for fishing communities. However, coral reefs in Solomon Islands face significant threats from climate change (leading to coral bleaching and ocean acidification), unsustainable fishing practices (such as dynamite fishing and overfishing), pollution from land-based activities (e.g., logging and agriculture runoff), and damage from crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks.

Protection initiatives, including the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) and community-based resource management programs, are being implemented to conserve these vital ecosystems.

6.4. Natural disasters

Solomon Islands is highly susceptible to a range of natural disasters due to its geographical location in the Pacific Ring of Fire and its tropical climate. These disasters pose significant risks to human life, infrastructure, and the economy, exacerbating existing vulnerabilities.

- Earthquakes:** The islands experience frequent seismic activity. Major earthquakes can cause significant damage to buildings and infrastructure, trigger landslides, and generate tsunamis. For example, in April 2007, an Mw 8.1 earthquake and subsequent tsunami primarily affected Western Province and Choiseul Province, resulting in at least 52 deaths, destroying over 900 homes, and displacing thousands. The land upthrust from this quake extended the shoreline of Ranongga Island by up to 230 ft (70 m). Another significant event was the February 2013 Mw 8.0 earthquake in the Santa Cruz Islands, which also generated a tsunami, causing fatalities and widespread destruction.

- Tsunamis:** Generated by local or distant earthquakes, tsunamis pose a severe threat to coastal communities, which form the majority of settlements in Solomon Islands.

- Tropical cyclones:** The country lies within the cyclone belt and is affected by cyclones, particularly between November and April. These can bring destructive winds, heavy rainfall, storm surges, and widespread flooding, causing extensive damage to crops, housing, and infrastructure, and disrupting essential services.

- Flooding and Landslides:** Heavy rainfall, often associated with cyclones or prolonged wet seasons, can lead to severe flooding, especially in low-lying coastal areas and river valleys. The mountainous terrain also makes many areas prone to landslides.

- Volcanic Eruptions:** Several active volcanoes, such as Tinakula and the submarine volcano Kavachi, pose a risk of eruption, which could lead to ashfall, pyroclastic flows, and localized tsunamis.

The national disaster response system involves government agencies, provincial authorities, non-governmental organizations, and international partners. Efforts focus on disaster preparedness, early warning systems, emergency response, and post-disaster recovery and reconstruction. However, logistical challenges due to the scattered nature of the islands and limited resources can hamper effective disaster management. Climate change adaptation measures are also critical to reducing vulnerability to climate-related disasters.

6.5. Water and sanitation

Access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation facilities remains a significant challenge in Solomon Islands, particularly in rural and remote areas, and has profound implications for public health and overall human development.

While the islands generally have sources of fresh water, these are often not easily accessible, consistently available, or safe for consumption without treatment. Piped water systems are largely confined to urban centers like Honiara, and even there, supply can be intermittent and quality variable. Rural communities often rely on rainwater harvesting, wells, springs, or surface water sources, which can be contaminated, especially during floods or droughts.

Sanitation coverage is also low. According to a UNICEF report, many communities, including poorer urban areas, lack access to adequate sanitation facilities (e.g., improved latrines or toilets). A significant percentage of schools reportedly lack access to safe water and sanitation.

The consequences of inadequate water and sanitation are severe:

- Health Issues:** Contaminated water and poor sanitation are major contributors to waterborne diseases such as diarrhea, cholera, and typhoid fever, which are leading causes of illness and mortality, especially among children. Skin diseases and eye infections are also common.

- Impact on Education:** Lack of safe water and sanitation in schools affects student health and attendance, particularly for girls.

- Economic Burden:** Illness due to poor water and sanitation leads to loss of productivity and increased healthcare costs for families and the nation.

Efforts to improve water and sanitation are underway, involving the government, NGOs, and international development partners like the World Bank and the European Union. Programs such as the Solomon Islands Second Rural Development Program (active 2014-2020) have aimed to deliver infrastructure, including water supply systems (like rain catchment and storage systems in villages such as Bolava, Western Province) and sanitation facilities, to rural areas.

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals related to clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) requires sustained investment, community participation, capacity building for local water management, and attention to hygiene promotion. Addressing these challenges is crucial for improving the health, well-being, and resilience of the Solomon Islands population.

7. Economy

The economy of Solomon Islands is characterized by its reliance on natural resources, a large subsistence sector, and significant dependence on foreign aid. It faces challenges common to Small Island Developing States, including a narrow economic base, vulnerability to external shocks, and geographical dispersion. Efforts towards equitable development are ongoing but are hampered by various structural and governance issues.

7.1. Economic structure and current status

Solomon Islands is classified as a Least Developed Country (LDC). In 2017, its GDP per capita was approximately 600 USD (though other sources give slightly higher figures like $2,145 PPP in 2017). A large majority of the labor force, estimated at over 75%, is engaged in subsistence agriculture and fishing, producing food primarily for their own consumption.

The formal economy is heavily reliant on a few key sectors:

- Forestry:** Timber has historically been a major export, but unsustainable logging practices have led to resource depletion and environmental concerns. Efforts are being made towards more sustainable forest management, but illegal logging and weak governance remain challenges. The distribution of benefits from logging has also been a contentious issue.

- Agriculture:** Cash crops include copra, cocoa, and palm oil.

- Fisheries:** Tuna is a significant marine resource, and fishing (both domestic and through licensing foreign fleets) contributes to export earnings.

- Mining:** Gold mining has occurred (e.g., Gold Ridge on Guadalcanal), and there are undeveloped deposits of other minerals like lead, zinc, and nickel. Mining operations have often been controversial due to environmental and social impacts.

The country imports most manufactured goods and petroleum products. Only a small percentage of land (around 3.9%) is used for agriculture, while a large proportion (around 78.1%) is covered by forests.

The Solomon Islands Government faced insolvency in 2002, prior to the RAMSI intervention. RAMSI (2003-2017) played a crucial role in stabilizing the economy, reforming public finances, and improving economic governance. However, the country continues to rely heavily on foreign aid from donors such as Australia, New Zealand, China (increasingly), Japan, and the European Union.

Challenges to equitable economic development include:

- Geographical fragmentation:** High transportation and communication costs.

- Limited infrastructure:** Inadequate roads, ports, and energy supply.

- Vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change.**

- Governance issues:** Corruption and political instability can deter investment and misdirect resources.

- Land tenure disputes:** Complex customary land ownership systems can complicate large-scale development projects.

Efforts are focused on diversifying the economy, promoting sustainable resource management, improving infrastructure, strengthening governance, and enhancing human capital to achieve more inclusive and equitable growth.

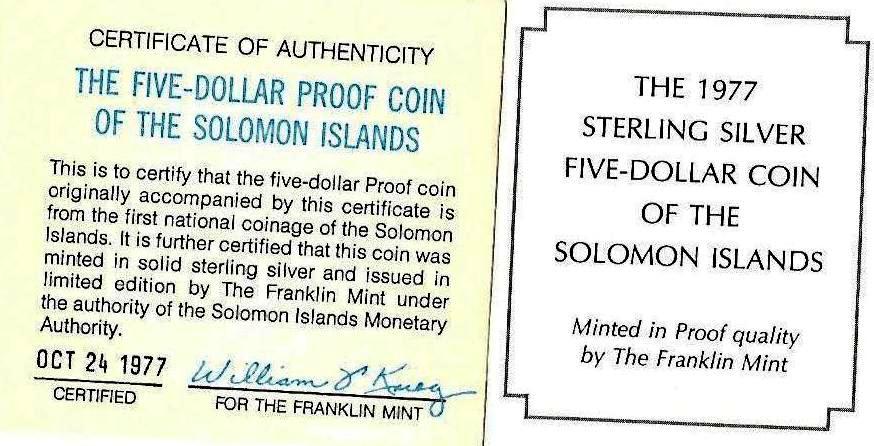

7.2. Currency

The official currency of Solomon Islands is the Solomon Islands dollar (SBD), which has the ISO 4217 code SBD. It was introduced in 1977, replacing the Australian dollar at par. The symbol for the Solomon Islands dollar is typically "SI$", although the "SI" prefix may be omitted if there is no confusion with other currencies that also use the dollar sign "$". The Solomon Islands dollar is subdivided into 100 cents.

In addition to the official currency, traditional forms of currency, notably shell money, still hold cultural and ceremonial importance in certain provinces. Shell money, which consists of small, polished shell disks drilled and strung together, is particularly manufactured in areas like the Langa Langa Lagoon in Malaita Province and on Guadalcanal. While primarily used for traditional purposes such as bride price payments and ceremonial exchanges, in some remote parts of the country, shell money may still be used for trade. It can sometimes be bought at markets like the Honiara Central Market.

In very remote areas, the barter system, exchanging goods and services directly without the use of any form of money, may also occur.

7.3. Main industries

The economy of Solomon Islands is largely based on its natural resources, with primary industries playing a central role. These sectors face challenges related to sustainability, global commodity price fluctuations, and the need for equitable benefit-sharing.

7.3.1. Agriculture

Agriculture is the mainstay of the Solomon Islands economy, engaging the vast majority of the population, primarily at a subsistence level.

- Subsistence Crops:** Key staple crops grown for local consumption include taro (45,901 tons in 2017), yams (44,940 tons in 2017), sweet potatoes, cassava, and bananas (313 tons in 2017). Rice is also grown (2,789 tons in 2017), but the country is not self-sufficient.

- Cash Crops:**

- Coconuts/Copra:** Coconuts are widely grown, and copra (dried coconut flesh) is a traditional export. In 2017, 317,682 tons of coconuts were harvested, making the country the 18th largest producer globally. Copra accounted for 24% of exports in one assessment.

- Palm Oil:** Large-scale oil palm plantations exist, primarily on Guadalcanal (e.g., near Tetere) and Russell Islands. In 2017, 285,721 tons of palm oil were produced, ranking Solomon Islands 24th globally. This industry provides employment but has also faced scrutiny over land use and environmental impacts.

- Cocoa:** Cocoa beans are grown, mainly on Guadalcanal, Makira, and Malaita. In 2017, 4,940 tons were harvested (27th globally).

- Other:** Tobacco (118 tons in 2017) and various spices (217 tons in 2017) are also cultivated.

Challenges in the agricultural sector include the old age of many coconut and cacao trees, which hampers productivity, limited access to markets and finance for smallholders, vulnerability to pests and diseases, and the impacts of climate change. Promoting sustainable agricultural practices and improving value chains are key development goals.

7.3.2. Forestry and timber exports

Forestry has historically been a dominant sector in the Solomon Islands economy and a major source of export revenue. However, it has also been fraught with issues related to unsustainable practices and governance.

- Economic Importance:** Timber, particularly round logs, has been the country's primary export product for many years. Rough wood constituted two-thirds of the country's exports in 2022, valued at over 2.50 B SBD (approximately 308.00 M USD).

- Unsustainable Logging:** The rate of logging has often far exceeded sustainable levels, leading to rapid deforestation, soil erosion, loss of biodiversity, and damage to water catchments. This has raised significant environmental concerns both domestically and internationally.

- Governance and Regulation:** The forestry sector has been plagued by issues of weak governance, corruption, lack of transparency in concession allocation, and insufficient enforcement of regulations. This has often resulted in foreign logging companies extracting resources with limited benefits accruing to local communities or the national treasury. There have been reports of companies failing to adhere to environmental standards or fair labor practices.

- Policies for Sustainable Management:** There is a growing recognition of the need for sustainable forest management. Efforts are being made, often with international support, to improve forest governance, strengthen monitoring and enforcement, promote reforestation and community-based forest management, and explore downstream processing to add value to timber products locally. However, balancing economic needs with environmental protection and ensuring equitable benefit-sharing for resource owners remain significant challenges.

The long-term viability of the forestry sector depends on a shift towards more sustainable practices and better governance to ensure that forest resources contribute to the country's development in an environmentally and socially responsible manner.

7.3.3. Fisheries

The fisheries sector is a vital component of the Solomon Islands economy, providing food security, livelihoods, and significant export revenue. The country has a large Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) rich in marine resources, particularly tuna.

- Major Marine Resources:** Tuna (skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye) is the primary commercial fish species. Other coastal fisheries resources are important for local consumption and smaller-scale commercial activities.

- Economic Contribution:** The fishing industry, both industrial and artisanal, makes a substantial contribution to the GDP and export earnings. Licensing fees from foreign fishing fleets operating in Solomon Islands' waters are also a key source of government revenue.

- Domestic and International Fishing Activities:**

- Industrial Tuna Fishery:** This is dominated by foreign fleets (e.g., from Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and China) operating under access agreements, as well as some locally-based operations. Onshore processing facilities, such as canneries (e.g., Solomon Taiyo Ltd. in Noro, Western Province, which operated as a Japanese joint venture before local management took over after ethnic tensions), add value to some of the catch. Solomon Taiyo Ltd. temporarily closed in mid-2000 due to ethnic disturbances but later reopened.

- Artisanal and Subsistence Fisheries:** Coastal communities heavily rely on fishing for food and income. These fisheries target a variety of reef fish, shellfish, and other marine organisms.

- Resource Management:** Sustainable management of fisheries resources is crucial. Challenges include combating illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, overfishing of certain stocks, and the impacts of climate change on marine ecosystems. Solomon Islands participates in regional fisheries management organizations like the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) to manage highly migratory tuna stocks. Efforts are also underway to strengthen national fisheries management capacity, improve monitoring and surveillance, and promote community-based resource management for coastal fisheries.

The development of sustainable and locally beneficial fisheries is a key priority for ensuring long-term economic and food security for Solomon Islands.

7.3.4. Mining

Mining has the potential to be a significant contributor to the Solomon Islands economy, given the presence of various mineral resources. However, the sector has also been associated with considerable social and environmental challenges, and its development has been sporadic.

- Mineral Resources:** The islands are known to possess deposits of several minerals, including:

- Gold:** The Gold Ridge mine on Guadalcanal is the most prominent gold mining operation. It commenced in 1998 but has experienced several closures and changes in ownership due to factors like ethnic tensions (leading to a closure in 2000 and again after riots in 2006), disputes with landowners, and operational difficulties. Negotiations for its reopening have occurred periodically.

- Nickel:** Significant nickel laterite deposits exist, particularly in Isabel Province and Choiseul Province. There has been interest from international mining companies in developing these resources.

- Bauxite:** The Rennell Island bauxite mine operated on Rennell Island from approximately 2011 to 2021. This operation drew considerable criticism for serious ecological damage, including multiple spills that affected the unique ecosystem of Lake Tegano (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), and for disputes over royalties and benefits to local communities.

- Other Minerals:** Deposits of lead, zinc, copper, and phosphate have also been identified.

- Economic, Social, and Environmental Impacts:**

- Economic Potential:** Mining can generate substantial export revenue, government income (through royalties and taxes), and employment.

- Social Impacts:** Mining projects often involve complex negotiations with customary landowners, and disputes over land access, benefit-sharing, and resettlement can arise. The influx of workers and changes to local economies can also create social tensions. Ensuring that local communities genuinely benefit from mining operations and that their rights are respected is a major challenge.

- Environmental Impacts:** Mining activities, if not properly managed, can cause significant environmental damage, including deforestation, soil erosion, water pollution (from mine tailings and chemical runoff), and loss of biodiversity. The case of the Rennell Island bauxite mine highlights the severe environmental consequences that can occur.

Effective regulation, transparent governance, robust environmental impact assessments, and meaningful community engagement are crucial for ensuring that any mining development in Solomon Islands is conducted responsibly and contributes positively to sustainable and equitable national development.

7.3.5. Tourism

Tourism has significant potential as an economic driver for Solomon Islands, owing to its rich natural beauty, diverse cultures, and unique historical sites, particularly those related to World War II. However, the industry remains relatively underdeveloped compared to other Pacific Island destinations, constrained by several factors.

- Tourism Resources:**

- Diving and Snorkeling:** The country boasts pristine coral reefs and abundant marine life, making it an attractive destination for divers and snorkelers. Famous dive sites include those around the Russell Islands, New Georgia Islands, and Marovo Lagoon.

- World War II History:** Guadalcanal and other islands were sites of major battles, and numerous wrecks (ships and aircraft) attract history enthusiasts and wreck divers.

- Cultural Tourism:** The diverse Melanesian, Polynesian, and Micronesian cultures offer opportunities for authentic cultural experiences, including village stays, traditional craft displays, and festivals.

- Nature and Eco-tourism:** Rainforest trekking, bird watching, and exploring volcanic landscapes are potential attractions.

- Current Tourist Numbers:** Solomon Islands receives a relatively small number of international tourists. In 2017, there were 26,000 visitors, making it one of the least frequently visited countries globally. In 2019, this number increased slightly to 28,900 before dropping significantly to 4,400 in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The government has expressed ambitions to increase these numbers, for example, aiming for 30,000 by the end of 2019 and 60,000 per year by 2025 (pre-pandemic targets).

- Potential for Development:** There is considerable untapped potential for tourism growth, which could provide employment, generate foreign exchange, and support local economies.

- Constraints:**

- Infrastructure Limitations:** Limited international and domestic air access, underdeveloped road networks, and a shortage of quality tourist accommodation (especially outside Honiara) are major impediments.