1. Overview

The Republic of Moldova (Republica Moldovareˈpublika molˈdovaRomanian) is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, situated on the northeastern corner of the Balkans within the Black Sea Basin. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The country spans a total area of 13 K mile2 (33.84 K km2) and has an estimated population of approximately 2.42 million people as of January 2024. The capital and largest city is Chișinău. The Dniester river forms a significant part of its eastern border with Ukraine, with the unrecognized breakaway state of Transnistria lying on its eastern bank.

Historically, most of Moldova's territory was part of the Principality of Moldavia from the 14th century. In 1812, its eastern half, known as Bessarabia, was annexed by the Russian Empire. Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, Bessarabia briefly became the Moldavian Democratic Republic before uniting with the Kingdom of Romania in 1918. In 1940, as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Romania was forced to cede Bessarabia to the Soviet Union, leading to the creation of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR). During the Soviet era, Moldova underwent significant industrialization, collectivization, and Russification policies, which had profound social and human rights implications.

Moldova declared independence from the Soviet Union on August 27, 1991. The early years of independence were marked by the Transnistria War in 1992, which resulted in the de facto separation of the Transnistria region. Moldova adopted its current constitution in 1994, establishing a unitary parliamentary republic. The country has since navigated a complex political landscape, often balancing pro-Western and pro-Russian influences, while pursuing democratic development and reforms. In recent years, particularly since 2020 under the presidency of Maia Sandu, Moldova has intensified its efforts towards European Union integration, gaining EU candidate status in June 2022. The Russo-Ukrainian War has presented significant challenges to Moldova, including a refugee crisis and heightened security concerns, further shaping its foreign policy and domestic priorities towards strengthening democracy and human rights.

Economically, Moldova is an emerging upper-middle-income economy, though it remains one of the poorer countries in Europe. Its economy has traditionally been reliant on agriculture, particularly its renowned wine industry, and remittances from Moldovans working abroad. The service sector now dominates its GDP, with a growing Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector. Socioculturally, Moldova's identity is primarily rooted in its Romanian heritage, with significant influences from Slavic and other regional cultures, as well as legacies from the Soviet period. The official language is Romanian.

2. Etymology

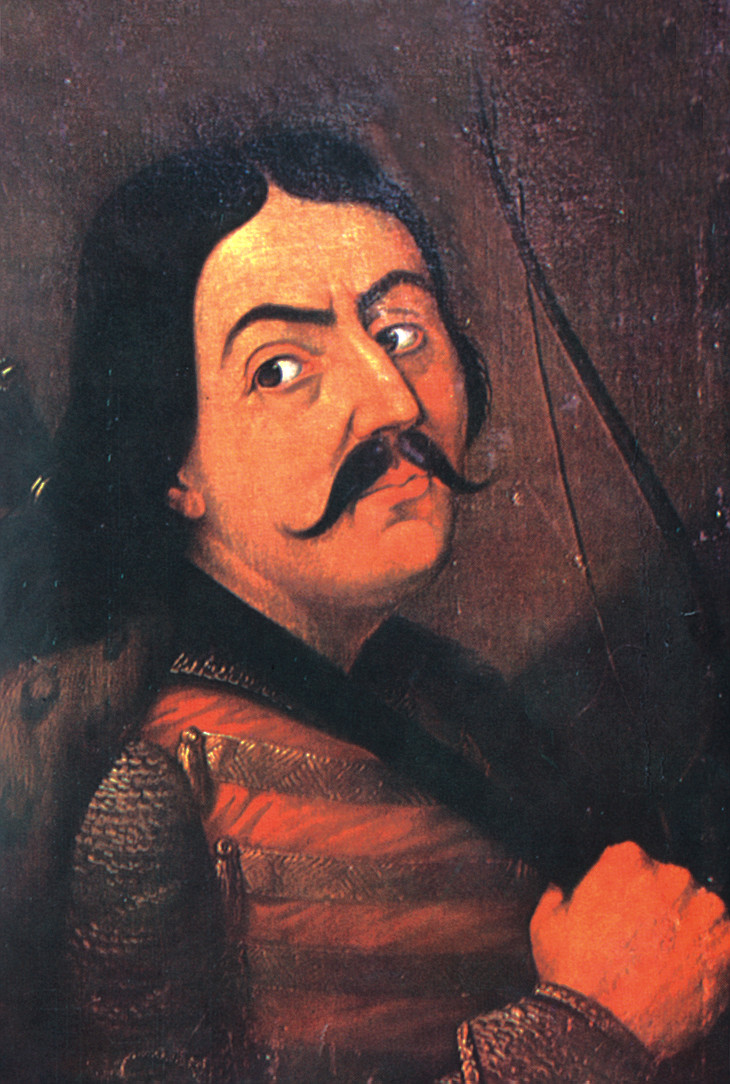

The name Moldova is derived from the Moldova River (MoldauˈmɔldaʊGerman). The valley of this river served as a political centre at the time of the foundation of the Principality of Moldavia in 1359. The origin of the river's name remains unclear. According to a legend recounted by Moldavian chroniclers Dimitrie Cantemir and Grigore Ureche, Prince Dragoș, a Vlach voivode considered the founder of the Principality of Moldavia, named the river after hunting an aurochs. Following the chase, the prince's exhausted hound, Molda (or Seva), drowned in the river. The dog's name was then given to the river and subsequently extended to the principality.

For a short period in the 1990s, at the founding of the Commonwealth of Independent States, the name of the current Republic of Moldova was also spelled Moldavia. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country began to officially use the Romanian name, MoldovamolˈdovaRomanian. Officially, the name Republic of Moldova is designated by the United Nations.

3. History

The history of Moldova encompasses prehistoric cultures, ancient and medieval empires, periods of foreign rule, and modern independence, reflecting its position as a crossroads between major European powers. The following sections detail the major historical periods from early civilizations through its Soviet past to contemporary developments, with a focus on democratic evolution, human rights, and social equity.

3.1. Prehistory, Antiquity, and Middle Ages

Evidence of human habitation in the territory of present-day Moldova dates back 800,000-1.2 million years. Significant developments in agriculture, pottery, and settlement occurred during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. The region was a center of the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, which flourished from approximately 5500 to 2750 BC and was characterized by advanced farming, livestock rearing, hunting, and distinctive pottery.

In antiquity, Moldova's geographical location made it a frequent route for invasions and migrations. The Dacians were the primary inhabitants of the region. Between the 1st and 7th centuries AD, southern Moldova experienced periods of control by the Roman Empire and later the Byzantine Empire. The region was successively invaded by groups such as the Scythians, Goths, Huns, Avars, Magyars, Pechenegs, and Cumans.

The medieval Principality of Moldavia emerged in the 1350s, with Prince Dragoș traditionally considered its founder. The principality became the precursor to modern Moldova and part of modern Romania. It reached its zenith under rulers like Stephen the Great (Ștefan cel Mare, reigned 1457-1504), who fought numerous battles to defend its sovereignty against larger neighboring powers. However, from 1538, the Principality of Moldavia became a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, retaining internal autonomy but paying tribute and ceding foreign policy control to the Ottomans. This status persisted, with varying degrees of Ottoman influence, until the 19th century.

3.2. Russian Imperial and Romanian Periods

In 1812, following the Russo-Turkish War of 1806-1812 and the Treaty of Bucharest, the eastern half of the Principality of Moldavia, situated between the Prut and Dniester rivers and known as Bessarabia, was annexed by the Russian Empire. This marked the beginning of significant Russian influence and rule in the region. Initially, Russia granted Bessarabia a degree of autonomy as the "Oblast of Moldavia and Bessarabia," but this was curtailed in 1828, and a policy of Russification was gradually implemented.

In 1856, following the Crimean War, southern Bessarabia (including the districts of Cahul, Bolhrad, and Izmail) was returned to the Principality of Moldavia. Three years later, in 1859, Moldavia united with Wallachia to form the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, the basis of modern Romania. However, Russian rule was restored over the whole of Bessarabia in 1878 following the Congress of Berlin.

During the Russian Revolution of 1917, Bessarabia briefly became an autonomous state, the Moldavian Democratic Republic (Republica Democratică Moldovenească), within the Russian Republic. On February 6 [O.S. January 24] 1918, it declared full independence from Russia. Later that year, on April 9 [O.S. March 27] 1918, the parliament of the Moldavian Democratic Republic, known as Sfatul Țării (Council of the Land), voted for unification with the Kingdom of Romania. This decision was disputed by Soviet Russia. In 1924, the Soviet Union established the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR) on partially Moldovan-inhabited territories east of the Dniester River, within the Ukrainian SSR, as a way to maintain its claim over Bessarabia.

3.3. Soviet Era

In June 1940, as a consequence of the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Romania received an ultimatum from the Soviet Union and was compelled to cede Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. These territories were subsequently occupied by Soviet forces. On August 2, 1940, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR) was established, primarily from most of Bessarabia and a strip of land from the former MASSR east of the Dniester River. Parts of southern Bessarabia (Budjak) and Northern Bukovina were incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR.

During World War II, in June 1941, Romania, as an ally of Axis Germany, joined the invasion of the Soviet Union and reoccupied Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, also administering the Transnistria territory between the Dniester and Southern Bug rivers. This period saw brutal actions, including the persecution and massacre of Jewish and Roma populations. In August 1944, Soviet forces re-conquered the region during the Jassy-Kishinev Offensive.

Under Soviet rule, the MSSR underwent profound transformations. Collectivization of agriculture was enforced, often brutally, leading to widespread peasant resistance and hardship, including a devastating famine in 1946-1947 that claimed tens of thousands of lives, which some Moldovans view as an artificial famine. Industrialization efforts focused on food processing and light industry. A systematic policy of Russification was implemented: the Moldovan language, written in the Latin script, was forcibly switched to the Cyrillic script and declared distinct from Romanian; Russian was promoted as the language of interethnic communication and official business; and Russian and Ukrainian populations were encouraged to settle in urban and industrial areas, altering the region's demographic composition.

Cultural life was heavily controlled, with an emphasis on Soviet ideology and the suppression of Romanian national identity. Many Moldovan intellectuals, clergy, and "kulaks" (wealthier peasants) faced persecution, deportation to Siberia and Kazakhstan, or execution, particularly during the Stalinist era. These policies aimed to integrate Moldova firmly into the Soviet system and sever its historical and cultural ties with Romania, leading to long-lasting social and human rights implications. Resistance to Soviet rule, though often covert, persisted throughout this period.

3.4. Independence and Modern Era

As the dissolution of the Soviet Union was underway, driven by Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of Glasnost and Perestroika, national movements gained strength in Moldova. In 1989, large demonstrations led to the adoption of Romanian (then referred to as Moldovan) as the official language and the return to the Latin script. On June 23, 1990, the MSSR declared its sovereignty.

On August 27, 1991, following the failed Soviet coup attempt in Moscow, the Moldavian SSR declared full independence and officially changed its name to the Republic of Moldova. Mircea Snegur became the country's first president. However, independence was immediately challenged by the Transnistria region on the eastern bank of the Dniester River, where a Russian-speaking majority, fearing unification with Romania and backed by elements of the Soviet 14th Army, had declared its own "Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic" in September 1990. This led to the Transnistria War in 1992, a brief but violent conflict that ended with a ceasefire brokered by Russia. The conflict left Transnistria as a de facto independent entity, unrecognized internationally, with Russian troops remaining stationed there as "peacekeepers," a situation that continues to complicate Moldova's sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Moldova adopted a new constitution in 1994, establishing a parliamentary republic. The country became a member of the United Nations in March 1992 and joined the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in December 1991, though it later signaled intentions to reduce its participation. The post-independence period was characterized by significant political and economic transition. The shift from a centrally planned economy to a market economy was difficult, leading to economic hardship, high emigration, and social challenges. Moldova struggled with political instability, with frequent changes in government and a persistent divide between pro-Western and pro-Russian political forces. Corruption and weaknesses in the rule of law also hampered democratic development.

Successive governments pursued varying foreign policy orientations. While some advocated for closer ties with Romania and the West, others, like the Party of Communists under President Vladimir Voronin (2001-2009), initially maintained closer relations with Russia before also pivoting towards European integration. Moldova signed a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with the European Union in 1994 and later became part of the European Neighbourhood Policy.

3.4.1. Post-2020 Developments

The political landscape in Moldova saw a significant shift with the election of Maia Sandu as president in November 2020. Sandu, leader of the pro-European Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), campaigned on an anti-corruption and reform platform, defeating the incumbent pro-Russian president Igor Dodon. Her victory was followed by a decisive win for PAS in the snap parliamentary elections of July 2021, giving her party a strong mandate to pursue its reform agenda. President Sandu was re-elected in the November 2024 presidential election with 55% of the vote in the run-off.

The Sandu administration has prioritized democratic reforms, strengthening the rule of law, combating corruption, and advancing European integration. Key challenges include judicial reform, tackling entrenched oligarchic interests, and addressing social issues such as poverty and emigration. Economically, Moldova continues to face difficulties, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and rising energy prices.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has had a profound impact on Moldova. The country, sharing a long border with Ukraine, received a large influx of Ukrainian refugees, placing significant strain on its resources. The war also heightened security concerns, given the presence of Russian troops in Transnistria and instances of missiles violating Moldovan airspace. Moldova strongly condemned the invasion and aligned itself with international sanctions against Russia.

In response to the changed geopolitical landscape, Moldova, alongside Ukraine and Georgia, formally applied for EU membership in March 2022. In June 2022, the European Council granted Moldova candidate status, a landmark step in its European aspirations. Accession talks with the EU officially began on December 13, 2023. The government has also expressed openness to reconsidering Moldova's constitutional neutrality in favor of closer cooperation with NATO. Addressing hybrid threats, including disinformation campaigns and attempts to destabilize the country, allegedly orchestrated by Russia, has become a key focus for the government. A referendum on EU membership held in autumn 2024 saw a narrow majority vote in favor, amidst allegations of external interference.

4. Politics

The Republic of Moldova is a unitary parliamentary republic with a representative democratic framework. Its governance is based on the Constitution of Moldova, adopted in 1994, which provides for a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, and guarantees fundamental human rights and freedoms. The political system is characterized by a multi-party system.

4.1. Government

The President is the head of state, elected by popular vote for a four-year term and eligible for a second term. The president represents the country internationally, promulgates laws, can nominate the prime minister, and is the supreme commander of the armed forces. Between 2001 and 2015, the president was elected by the Parliament, but a 2016 Constitutional Court ruling reverted the election method to direct popular vote. Maia Sandu has been the President since December 2020, and Igor Grosu is the President of the Parliament.

The Prime Minister is the head of government. The President appoints the Prime Minister after consulting the parliamentary majority. The Prime Minister, along with the Cabinet (government), is responsible for implementing domestic and foreign policy and is accountable to the Parliament. Dorin Recean has been the Prime Minister since February 2023.

Legislative authority is vested in the unicameral Parliament (Parlamentul Republicii Moldovaparlaˈmentul reˈpublitʃij molˈdovaRomanian). It consists of 101 members elected for a four-year term through proportional representation from party lists in a single national constituency. The Parliament enacts laws, approves the budget, oversees the government, and can initiate procedures to amend the constitution or dismiss the President.

The judiciary is constitutionally independent. The court system includes courts of first instance, courts of appeal, and the Supreme Court of Justice. The Constitutional Court is separate from the regular judiciary and ensures the constitutionality of laws and government decrees. It consists of six judges appointed for six-year terms (two by the President, two by Parliament, and two by the Superior Council of Magistracy).

The 2021 parliamentary elections were deemed well-administered and competitive by international observers like the OSCE, with fundamental freedoms largely respected. The Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) won a majority, enabling it to form a single-party government. Amending the Constitution requires a parliamentary majority of at least two-thirds, and revisions affecting state sovereignty, independence, or unity must be approved by a referendum.

4.2. Foreign Relations

Moldova's foreign policy since independence has been shaped by its geographical location between Romania and Ukraine, its historical ties to both Russia and the West, and its constitutional neutrality. Key priorities include European integration, maintaining sovereignty and territorial integrity (particularly concerning the Transnistria issue), and fostering stable relations with regional and global partners.

Moldova is a member of numerous international organizations, including the United Nations (since 1992), the Council of Europe (since 1995), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the World Trade Organization (WTO, since 2001), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). It participates in NATO's Partnership for Peace program (since 1994) but is not seeking full NATO membership, adhering to its constitutional neutrality. Moldova is also a member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (since 1996), the GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development, and the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC). While an initial signatory to the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Moldova has significantly reduced its participation and has initiated procedures for withdrawal from various CIS agreements, especially following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The resolution of the Transnistria conflict remains a central foreign policy challenge. Moldova advocates for a peaceful settlement that respects its territorial integrity, with a special status for Transnistria within Moldova. It participates in the "5+2" negotiation format (Moldova, Transnistria, OSCE, Russia, Ukraine, with the EU and US as observers), though talks have stalled. Moldova has consistently called for the withdrawal of Russian troops and munitions from Transnistria.

A major foreign policy goal is accession to the European Union. Moldova signed an Association Agreement with the EU, including a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), in 2014, which fully entered into force in 2016. The country was granted EU candidate status in June 2022, and accession negotiations were formally launched in December 2023. This pro-European trajectory has been strongly pursued by the government of President Maia Sandu.

Moldova maintains strong historical and cultural ties with Romania, with which it shares a common language and history. Romania has been a staunch supporter of Moldova's European integration and has provided significant economic and political assistance.

4.2.1. Relations with Russia

Moldova's relationship with the Russian Federation is complex and multifaceted, marked by historical ties, economic dependencies, and significant political tensions, primarily centered around the unresolved Transnistria conflict and Moldova's geopolitical orientation.

Historically, the territory of modern Moldova was part of the Russian Empire (as Bessarabia) and later the Soviet Union (as the Moldavian SSR). This legacy has left linguistic, cultural, and political imprints. After Moldova's independence in 1991, Russia became a key player in the region, particularly due to its support for the breakaway region of Transnistria, where Russian troops have been stationed since the 1992 war, officially as peacekeepers but viewed by Moldova as an occupying force. The presence of these troops and a large Soviet-era ammunition depot in Cobasna remain major points of contention, with Moldova consistently calling for their unconditional withdrawal.

Economically, Moldova has historically been dependent on Russia for energy supplies, particularly natural gas. This dependency has been used by Russia as leverage, with gas prices and supply becoming political tools. However, in recent years, Moldova has made significant efforts to diversify its energy sources and reduce reliance on Russia, increasingly connecting to European energy networks. Trade relations have also been subject to Russian restrictions, particularly on Moldovan agricultural products like wine, often coinciding with Moldova's pro-European moves.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 further strained relations. Moldova strongly condemned the aggression, aligned with EU sanctions against Russia, and faced direct consequences such as missile overflights and an influx of Ukrainian refugees. Moldovan authorities have accused Russia of conducting hybrid warfare, including disinformation campaigns, cyberattacks, and attempts to destabilize the country by supporting pro-Russian political groups and protests. In response, Moldova has suspended broadcasting licenses of several pro-Russian TV channels, expelled Russian diplomatic staff, and enhanced its security cooperation with Western partners.

Despite these tensions, Russia remains an important factor in Moldovan politics, with some political forces advocating for closer ties with Moscow. The Russian Orthodox Church also maintains significant influence in Moldova through the Moldovan Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate).

4.2.2. Relations with the European Union

Relations between Moldova and the European Union (EU) have significantly deepened over the years, culminating in Moldova's current status as an EU candidate country. The pursuit of EU integration is a key strategic priority for the Moldovan government, reflecting aspirations for democratic consolidation, economic development, and enhanced security.

The formal relationship began with a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement signed in 1994, which came into force in 1998. Moldova later joined the European Neighbourhood Policy in 2004 and the Eastern Partnership initiative in 2009, designed to strengthen political and economic ties with the EU's eastern neighbors.

A pivotal moment was the signing of the Association Agreement in June 2014, which includes a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA). This agreement, fully provisionally applied since September 2014 and fully in force since July 2016, aims to align Moldova's political, trade, and regulatory systems with EU standards. It has led to increased trade with the EU, which is now Moldova's largest trading partner, and facilitated visa-free travel for Moldovan citizens to the Schengen Area since April 2014.

The journey towards EU membership accelerated following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Moldova officially applied for EU membership on March 3, 2022. On June 23, 2022, the European Council granted Moldova candidate status, a historic decision recognizing its European aspirations and progress in reforms. Formal accession negotiations were launched on December 13, 2023.

The EU supports Moldova's reform efforts in areas such as judicial reform, anti-corruption measures, public administration, economic development, and strengthening the rule of law and human rights. Financial and technical assistance is provided through various EU instruments, including the European Peace Facility for security sector modernization. The EU has also provided significant support to Moldova in managing the refugee crisis resulting from the war in Ukraine and in addressing energy security challenges. The EU's High Representative Josep Borrell has stated that Moldova's EU accession path is not dependent on a resolution of the Transnistria conflict.

Moldova has set 2030 as a target date for EU accession. The path requires comprehensive reforms and alignment with the EU's acquis communautaire. A referendum on EU membership was held in Autumn 2024, with a narrow majority voting in favor. On June 27, 2023, Moldova signed a comprehensive free trade agreement with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

4.3. Security

Moldova's national security framework is shaped by its constitutional neutrality, the unresolved Transnistria conflict, regional instability, and emerging hybrid threats. The country's security strategy focuses on maintaining sovereignty and territorial integrity, modernizing its defense capabilities within its neutral status, and strengthening resilience against both conventional and unconventional threats.

The primary security challenge remains the Transnistria conflict and the presence of Russian military forces and a large ammunition depot in the breakaway region. This situation poses a direct threat to Moldova's territorial integrity and stability, particularly in light of increased geopolitical tensions following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Moldova advocates for a peaceful resolution of the conflict and the complete withdrawal of Russian troops.

Moldova faces significant hybrid threats, including disinformation campaigns, cyberattacks, energy blackmail, and foreign interference aimed at destabilizing the country and undermining its pro-European course. The Security and Intelligence Service of Moldova (SIS) is the primary agency responsible for countering these threats. In February 2023, Moldova passed a law criminalizing separatism and actions aimed at undermining state sovereignty.

To enhance its security, Moldova cooperates with various international partners. It has been a member of NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) program since 1994, participating in joint exercises and training. While not seeking NATO membership, cooperation has deepened, focusing on defense reform, interoperability, and capacity building. The European Union also plays a crucial role in Moldova's security. The European Union Partnership Mission in Moldova (EUPM Moldova), launched in May 2023 under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), aims to enhance the resilience of Moldova's security sector, particularly in crisis management and countering hybrid threats. The EU also provides financial support for modernizing the Moldovan armed forces through the European Peace Facility.

Moldova participates in security initiatives within the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which is involved in the Transnistria settlement process. The country is also working to strengthen its border security, with assistance from the European Union Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM).

4.4. Military

The Armed Forces of the Republic of Moldova (Forțele Armate ale Republicii Moldovaˈfortsele arˈmate ale reˈpublitʃij molˈdovaRomanian) consist of the National Army (which includes ground and air components) and the Trupele de Carabinieri (Carabineer Troops), under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Moldova's defense policy is based on its constitutional neutrality, which prohibits the stationing of foreign military bases on its territory.

The National Army is relatively small, with a standing force of around 6,500 active personnel and a reserve force. Conscription is in place, with male citizens required to serve a 12-month term, though there are discussions about transitioning to a fully professional army. The defense budget has historically been low, constituting a small percentage of the GDP (around 0.4%), but has seen increases in recent years due to heightened regional security concerns.

The main components of the National Army are:

- Ground Forces Command**: Comprising several motorized infantry brigades, an artillery brigade, and specialized units.

- Air Force Command**: Primarily equipped with transport aircraft and helicopters; it does not possess combat jets.

Moldova has accepted all relevant arms control obligations of the former Soviet Union, ratifying the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe in 1992 and acceding to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1994. The country does not possess nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons.

Since 1994, Moldova has been a participant in NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) program, engaging in joint training exercises and defense reform initiatives. While maintaining neutrality, Moldova has deepened its cooperation with NATO and the European Union to modernize its armed forces and enhance interoperability. The EU, through the European Peace Facility, has provided significant financial assistance for non-lethal equipment, medical supplies, and cyber defense capabilities. In October 2022, Defense Minister Anatolie Nosatii stated that about 90% of the country's military equipment was outdated, primarily of Soviet origin. Efforts are underway to replace aging Soviet-era equipment with modern systems. Poland has also provided military equipment to Moldova.

Moldovan troops have participated in international peacekeeping missions, including those led by the United Nations in countries like Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire, Sudan, and Georgia, as well as NATO-led operations in Kosovo (KFOR).

The presence of Russian troops in the breakaway region of Transnistria remains a significant security concern and is considered by Moldova to be contrary to its neutrality and sovereignty.

4.5. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Moldova has seen developments and challenges, particularly in the context of its democratic transition and European integration efforts. The Constitution of Moldova guarantees fundamental human rights, and the country is a party to major international human rights treaties.

According to organizations like Freedom House, Moldova is rated as "partly free." While it has a competitive electoral environment and generally respects freedoms of assembly, speech, and religion, significant challenges remain. These include pervasive corruption, undue influence of economic interests on politics, and deficiencies in the justice system and the rule of law, which hamper democratic governance. Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index has shown some improvement for Moldova in recent years. Reporters Without Borders has noted an improvement in Moldova's Press Freedom Index, but cautions that the media landscape remains diverse yet highly polarized, often influenced by oligarchs and political interests.

Key human rights issues identified by Amnesty International and the U.S. State Department include:

- Rule of Law and Judicial Independence**: While reforms are underway, the judiciary still faces challenges related to independence, efficiency, and corruption. Slow progress in investigating and prosecuting officials for human rights abuses and corruption is a concern.

- Torture and Ill-Treatment**: Instances of torture and other ill-treatment in detention facilities continue to be reported, with impunity for past violations by law enforcement remaining an issue.

- Freedom of Assembly and Speech**: Generally respected, but new "temporary" restrictions on public assemblies have been introduced at times. The media environment faces challenges from polarization and disinformation.

- Rights of Minorities**: Ethnic minorities are generally protected by law, but issues related to language use and representation persist. The Gagauz and Transnistria regions present specific contexts for minority rights.

- LGBTQ+ Rights**: While Pride parades have been held with increasing freedom, LGBTQ+ individuals still face harassment, discrimination, and violence. Societal acceptance remains limited.

- Violence Against Women**: Moldova ratified the Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women, a positive step. However, domestic violence remains a serious problem.

- Human Trafficking**: Moldova has historically been a source country for human trafficking, though efforts are being made to combat it.

- Situation in Transnistria**: The human rights situation in the breakaway region of Transnistria is of particular concern, with reports of restrictions on freedom of expression, assembly, and the media, as well as politically motivated prosecutions.

The Moldovan government, particularly under President Maia Sandu, has expressed a commitment to strengthening human rights and the rule of law as part of its European integration agenda. The European Union actively monitors the human rights situation and supports reforms through various programs. The OSCE/ODIHR and the Venice Commission provide recommendations for legal and institutional reforms. Recent legislative changes include amendments to the Criminal Code on hate crime.

4.6. Administrative Divisions

Moldova is administratively divided into districts (raioaneraˈjoaneRomanian, singular: raionraˈjonRomanian), municipalities (municipiimu.niˈtʃi.pijRomanian), and two autonomous regions: Gagauzia (GăgăuziaɡəɡəˈuziaRomanian) and the Administrative-Territorial Units of the Left Bank of the Dniester (effectively, the breakaway region of Transnistria).

As of the current administrative structure, Moldova has:

- 32 Districts**: These are the primary second-level administrative units. Each district is governed by a district council and a president elected by the council.

- Municipalities**: There are 13 localities with municipality status, including the capital, Chișinău, as well as Bălți, Comrat, Bender (Tighina), and Tiraspol. Municipalities have a greater degree of administrative and budgetary autonomy compared to other towns and villages.

- Autonomous Territorial Unit with Special Status Gagauzia**: Located in the south, Gagauzia has a significant Gagauz population. It enjoys a high degree of autonomy, with its own governor (Başkanbaʃˈkangag), legislative assembly (Halk Topluşu), and official languages (Gagauz, Romanian, and Russian). Its capital is Comrat.

- Autonomous Territorial Unit with Special Status Transnistria**: This refers to the territory on the left (eastern) bank of the Dniester River. While legally part of Moldova, it has been under the de facto control of the separatist authorities of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR) since the 1992 Transnistria War. The central Moldovan government does not exercise control over this region. Its main city is Tiraspol. The status of Bender, located on the right bank but controlled by Transnistrian authorities, is also part of this unresolved issue.

Moldova has a total of 66 cities (towns) and 916 communes. Additionally, around 700 villages are too small to have separate administrations and are administratively part of either cities or communes, making a total of 1,682 localities, two of which are uninhabited.

The largest cities in Moldova by population are:

- Chișinău: Approximately 695,400 inhabitants in the city proper.

- Tiraspol: Approximately 129,500 inhabitants (located in Transnistria).

- Bălți: Approximately 102,457 inhabitants.

- Bender (Tighina): Approximately 91,000 inhabitants (controlled by Transnistria).

Other notable towns include Ungheni, Cahul, Soroca, Orhei, and Comrat.

4.7. Law Enforcement and Emergency Services

Law enforcement in Moldova is primarily the responsibility of the General Police Inspectorate (Inspectoratul General al Polițieiinspektoraˈtul dʒeneˈral al poliˈtsiejRomanian), which operates under the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MAI). The police are tasked with maintaining public order, preventing and investigating crimes, traffic control, and ensuring internal security. Civilian authorities maintain effective control over the security forces. The Moldovan Police are divided into state and municipal organizations, often collaborating closely. A specialized unit, the Special Forces Brigade "Fulger" ("Lightning"), deals with organized crime, serious violent crime, and hostage situations.

Other key agencies under the MAI include the Border Police Department, responsible for border security and management (it was a military branch until 2012), and the General Inspectorate for Emergency Situations, which handles emergency response including firefighting, search and rescue, and civil protection.

The Security and Intelligence Service of Moldova (SIS) is the country's main intelligence agency, tasked with ensuring national security by conducting intelligence and counter-intelligence operations to identify and counteract threats to Moldova's independence, sovereignty, and constitutional order.

The judicial process for criminal matters involves investigation by the police and prosecutors, followed by trial in courts. Challenges in the law enforcement and judicial sectors include corruption, the need for improved professionalism and resources, and ensuring adherence to human rights standards in policing and detention. International law requires that police use of firearms be lawful only when necessary to confront an imminent threat of death or serious injury.

Emergency medical services are part of the national healthcare system, providing pre-hospital care and ambulance services. Moldova has a universal healthcare system funded through a mandatory health insurance scheme. Main hospitals are concentrated in Chișinău, such as Medpark International Hospital, with general hospitals also located in other major towns like Bălți, Cahul, and Călărași. Casa Mărioarei, founded in 2002, is a notable domestic violence shelter in Chișinău providing comprehensive support to women.

5. Geography

Moldova is a landlocked country located in Eastern Europe, on the northeastern corner of the Balkans within the Black Sea Basin. It lies between latitudes 45° and 49° N, and mostly between longitudes 26° and 30° E. The country is situated east of the Carpathian Mountains. The total land area is 13 K mile2 (33.84 K km2), of which approximately 182 mile2 (472 km2) is water (1.4% of the total area including Transnistria).

Moldova is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The total length of its national boundaries is 0.9 K mile (1.39 K km), with 583 mile (939 km) shared with Ukraine and 280 mile (450 km) with Romania. The Prut river forms the entire western border with Romania, while the Dniester river (NistruˈnistruRomanian) delineates a significant part of its eastern border with Ukraine, separating the main territory from the breakaway region of Transnistria.

Although landlocked, Moldova gained a 1476 ft (450 m) frontage on the Danube River in 1999 through a territorial exchange with Ukraine. This access is at the confluence of the Prut and Danube rivers, allowing the village of Giurgiulești to develop into the river port, providing Moldova with access to international waters via the Danube and the Black Sea. At its closest point, Moldova is separated from the Dniester Liman, an estuary of the Black Sea, by only 1.9 mile (3 km) of Ukrainian territory.

5.1. Topography and Hydrography

Most of Moldova consists of a hilly plain, with elevations gradually rising from the south towards the north. The country's hills are part of the Moldavian Plateau, which geologically originates from the Carpathian Mountains. The highest point in Moldova is Bălănești Hill (Dealul Bălăneștiˈdealul bələˈneʃtʲRomanian), with an elevation of 1411 ft (430 m) above sea level, located in the Codru hills region in the central part of the country. The term "Codri" (plural of CodruˈkodruRomanian) means "forests" and refers to the forested upland area.

Subdivisions of the Moldavian Plateau in Moldova include:

- The Dniester Hills (Northern Moldavian Hills and Dniester Ridge) in the north and east.

- The Moldavian Plain (Middle Prut Valley and Bălți Steppe) in the north and central-west.

- The Central Moldavian Plateau, which includes the Ciuluc-Soloneț Hills, Cornești Hills (Codri Massive), Lower Dniester Hills, Lower Prut Valley, and Tigheci Hills.

In the south, the country features a small flatland known as the Bugeac Plain (or Budjak Steppe). The territory of Moldova east of the Dniester River (Transnistria) is split between parts of the Podolian Plateau and parts of the Eurasian Steppe.

Moldova's soil is exceptionally fertile, with chernozem (black earth) covering about three-quarters of its land area, making it highly suitable for agriculture.

The country's two main rivers are the Dniester and the Prut. The Dniester, rising in Ukraine, flows southward through eastern Moldova, forming the de facto boundary with Transnistria for much of its course, before re-entering Ukraine and emptying into the Black Sea. The Prut River rises in the Ukrainian Carpathians and flows south along Moldova's entire western border with Romania, eventually joining the Danube River at Giurgiulești. Other significant rivers include the Răut (a tributary of the Dniester) and the Bîc (on which Chișinău is situated, also a Dniester tributary). There are numerous smaller rivers and natural lakes, though most are small.

5.2. Climate

Moldova has a moderately continental climate, influenced by its proximity to the Black Sea to the south and the Atlantic Ocean from the west. This results in warm, long summers and relatively mild, dry winters, with spring and autumn being transitional seasons.

Summers are generally warm, with average daily temperatures in July around 68 °F (20 °C) to 71.6 °F (22 °C). Daytime highs can often exceed 86 °F (30 °C). Winters are milder than in more continental regions of Eastern Europe, with average January temperatures around 26.6 °F (-3 °C) to 23 °F (-5 °C). Snowfall occurs but is not usually persistent throughout the winter, especially in the south.

Annual precipitation ranges from about 16 in (400 mm) in the south (Bugeac Plain) to 24 in (600 mm) in the north and in the higher elevations of the Codri hills. Rainfall is irregular, and Moldova can experience periods of drought, particularly detrimental to its agricultural sector. The heaviest rainfall typically occurs in early summer (June) and again in October. Heavy showers and thunderstorms are common during the summer months. Due to the hilly terrain, intense summer rains can sometimes cause soil erosion and river silting.

Extreme weather phenomena, such as heatwaves, droughts, and occasional severe winters or floods, can occur. The highest temperature ever recorded in Moldova was 106.7 °F (41.5 °C) on July 21, 2007, in Camenca. The lowest temperature ever recorded was -31.9 °F (-35.5 °C) on January 20, 1963, in Brătușeni, Edineț District.

| Location | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chișinău | 27/17 | 81/63 | 1/-4 | 33/24 |

| Tiraspol | 27/15 | 81/60 | 1/-6 | 33/21 |

| Bălți | 26/14 | 79/58 | 0/-7 | 31/18 |

5.3. Biodiversity and Environment

Phytogeographically, Moldova is situated at the intersection of three major ecoregions: the Central European mixed forests to the northwest, the East European forest steppe covering most of the country, and the Pontic steppe in the south and southeast. This location contributes to a diverse range of flora and fauna, although human activity has significantly altered the natural landscape.

Forests currently cover approximately 11-12% of Moldova's territory, a decrease from historical levels due to deforestation for agriculture. The most common tree species include oak, hornbeam, linden, maple, and ash. The Codru region in central Moldova is the most densely forested area and hosts the Codru Reserve, one of the country's oldest protected areas, established to preserve typical forest ecosystems. Other significant protected areas include Orhei National Park (a cultural, natural, and landscape reserve), the Lower Prut Scientific Reserve (a Ramsar site important for wetland birds), Plaiul Fagului Scientific Reserve, Pădurea Domnească Scientific Reserve (home to European bison), and Iagorlîc Scientific Reserve (protecting Dniester River ecosystems).

Moldova's fauna includes mammals such as roe deer, wild boar, foxes, hares, badgers, and various rodents. Red deer and European bison (wisent) have been reintroduced in some areas. The wisent, extinct in Moldova since the 18th century, was reintroduced in 2005 in Pădurea Domnească with individuals from Białowieża Forest in Poland. The country is home to over 280 species of birds, including migratory species. Rivers and lakes support diverse fish populations. The Saiga antelope, once common in the steppe regions, became extinct in Moldova by the late 18th century due to hunting and habitat loss.

| Name | Location | Established | Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codru Reserve | Strășeni | 1971 | 13 K acre (5.18 K ha) |

| Iagorlîc | Dubăsari | 1988 | 2066 acre (836 ha) |

| Lower Prut | Cahul | 1991 | 4.2 K acre (1.69 K ha) |

| Plaiul Fagului | Ungheni | 1992 | 14 K acre (5.64 K ha) |

| Pădurea Domnească | Glodeni | 1993 | 15 K acre (6.03 K ha) |

Environmental issues in Moldova are significant. The Soviet era saw intensive agricultural practices and industrial development with little regard for environmental protection, leading to soil pollution from excessive pesticide and fertilizer use, and water pollution. Soil erosion is a major problem, exacerbated by deforestation and unsustainable farming practices on hilly terrain. Water resources are also under pressure from pollution and over-extraction. Climate change is expected to increase the frequency of droughts and extreme weather events, further stressing Moldova's environment and agriculture. Conservation efforts are underway, supported by national policies and international cooperation, focusing on increasing forest cover, protecting biodiversity, promoting sustainable agriculture, and managing water resources. The Ecological Movement of Moldova, a non-governmental organization, plays a role in environmental advocacy and restoration efforts. Moldova had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 2.2/10, ranking it 158th globally out of 172 countries.

6. Economy

Moldova's economy is an emerging upper-middle income economy that has undergone a significant transition from a centrally planned system to a market-oriented one since its independence in 1991. Key characteristics include a strong agricultural base, a growing service sector, and a heavy reliance on remittances. The country faces challenges related to poverty, emigration, energy security, and the need for structural reforms to improve productivity and competitiveness, all while striving for sustainable development and social equity.

6.1. Economic Overview

Moldova's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was approximately 18.06 B USD (nominal) and 45.41 B USD (PPP) in 2024, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). GDP per capita (PPP) was around 18.52 K USD. Despite consistent growth over the past two decades, Moldova remains one of the poorest countries in Europe by official per capita income. The economy is dominated by the service sector, which accounts for over 60% of GDP, followed by industry and agriculture.

Recent economic trends have been impacted by several factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in neighboring Ukraine, and the ensuing energy crisis. After a strong rebound in 2021 with 13.9% GDP growth, the economy contracted by 5.9% in 2022 due to these shocks. Inflation surged to 28.7% in 2022, primarily driven by high energy prices. Unemployment has remained relatively low, around 2-3%. The World Bank and IMF project modest growth for the subsequent years, contingent on regional stability and continued reforms.

A significant feature of Moldova's economy is its high dependence on remittances from Moldovans working abroad, which historically constituted a large share of GDP (around 15-25%). These inflows support consumption but also highlight the challenges of emigration and a shrinking labor force. Poverty levels have declined over time but remain a concern, particularly in rural areas. The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, was 25.7 in 2021, indicating relatively low inequality compared to some other countries. Moldova's Human Development Index (HDI) was 0.763 in 2022 (ranking 86th), which is one of the lowest in Europe.

Key economic challenges include the need for structural reforms to boost productivity, improve the business environment, strengthen governance and the rule of law, combat corruption, and enhance energy security. The government, with support from international partners like the EU, IMF, and World Bank, is pursuing reforms aimed at addressing these issues and fostering sustainable and inclusive growth.

| Year | GDP (Billions in US dollars) |

|---|---|

| 2017 | 9.52 B USD |

| 2018 | 11.25 B USD |

| 2019 | 11.74 B USD |

| 2020 | 11.53 B USD |

| 2021 | 13.69 B USD |

| 2022 | 14.51 B USD |

| Year | Imports (Billions in US dollars) |

|---|---|

| 2017 | 5.37 B USD |

| 2018 | 6.39 B USD |

| 2019 | 6.61 B USD |

| 2020 | 5.92 B USD |

| 2021 | 7.91 B USD |

| 2022 | 10.91 B USD |

| Year | Exports (Billions in US dollars) |

|---|---|

| 2017 | 3.12 B USD |

| 2018 | 3.45 B USD |

| 2019 | 3.66 B USD |

| 2020 | 3.22 B USD |

| 2021 | 4.20 B USD |

| 2022 | 5.98 B USD |

6.2. Major Sectors

Moldova's economy is characterized by a prominent agricultural sector, a significant and historically important wine industry, and a rapidly developing Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector. These sectors play crucial roles in employment, exports, and overall economic growth.

6.2.1. Agriculture

Agriculture has traditionally been a cornerstone of the Moldovan economy, benefiting from fertile chernozem soils and a favorable climate. It accounts for around 10-12% of GDP and a significant share of employment, particularly in rural areas.

Main agricultural products include grains (wheat, maize, barley), sunflower seeds (for oil), sugar beets, fruits (apples, plums, cherries, grapes), and vegetables. Livestock farming, including cattle, pigs, and poultry, also contributes to the sector. Moldova's agricultural land occupies a large portion of its total area, with arable land being the dominant land use.

Challenges facing the agricultural sector include:

- Climate Change**: Increased frequency of droughts, floods, and hailstorms pose significant risks to crop yields.

- Modernization**: The need for investment in modern farming techniques, irrigation systems, and post-harvest infrastructure to improve productivity and reduce losses.

- Land Fragmentation**: Small land holdings can hinder economies of scale and efficiency.

- Market Access**: While the DCFTA with the EU has opened up new markets, farmers may face challenges in meeting EU standards and competing internationally.

- Access to Finance**: Limited access to credit for small and medium-sized agricultural enterprises.

Efforts are underway to promote sustainable agriculture, improve irrigation, support diversification, and enhance the competitiveness of Moldovan agricultural products on both domestic and international markets. The development of organic agriculture is also a growing area of focus.

6.2.2. Wine Industry

Viticulture and winemaking have a long and rich tradition in Moldova, dating back thousands of years. The wine industry is a source of national pride and a significant contributor to the economy, accounting for about 3% of GDP and 8% of total exports. Moldova is among the top 20 wine-producing countries in the world by volume.

The country has several historical wine regions, including Valul lui Traian (southwest), Ștefan Vodă (southeast), and Codru (center), each with specific microclimates suitable for different grape varieties. Key indigenous grape varieties include Fetească Albă, Fetească Regală, Fetească Neagră, and Rară Neagră, alongside international varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay, and Sauvignon Blanc.

Moldova is famous for its large underground wine cellars, some ofwhich are among the largest in the world. Mileștii Mici holds the Guinness World Record for the largest wine collection (by number of bottles), with cellars stretching for about 124 mile (200 km). Cricova is another renowned winery with extensive underground cellars that attract tourists. Castel Mimi, a 19th-century chateau, has been restored and functions as a winery, museum, and tourist complex.

Historically, Russia was a major export market for Moldovan wine. However, Russian bans on Moldovan wine imports (in 2006 and 2013), often seen as politically motivated, prompted the industry to diversify its export markets. The European Union is now the primary destination for Moldovan wine exports, facilitated by the DCFTA. Efforts continue to promote Moldovan wines internationally and improve quality standards. The "Wine of Moldova" national brand aims to raise the profile of Moldovan wines globally.

6.2.3. Tourism

Tourism in Moldova is a developing sector with considerable potential, though it remains one of the least visited countries in Europe. The country offers a variety of attractions, including its natural landscapes, rich cultural heritage, historical sites, and, notably, its wine culture.

Key attractions for tourists include:

- Wine Tourism**: Moldova's numerous wineries and vast underground cellars, such as Cricova and Mileștii Mici, offer tours and tastings. The annual National Wine Day in October is a major event.

- Cultural and Historical Sites**: These include medieval monasteries like Orheiul Vechi (an archaeological complex with cave monasteries), Căpriana, and Hâncu, as well as fortresses like the Soroca Fort. Chișinău, the capital, offers museums, parks, and examples of 19th-century and Soviet-era architecture. The St वाइब्रिस् Arch and the Nativity Cathedral are landmarks in Chișinău.

- Rural and Eco-Tourism**: The picturesque countryside, with rolling hills, forests, and traditional villages, offers opportunities for hiking, cycling, and experiencing rural life.

- Gastronomy**: Traditional Moldovan cuisine and local products are also part of the tourist experience.

Despite an increase in visitor numbers before the COVID-19 pandemic and a surprising uptick in the first quarter of 2022 (largely non-resident visitors, potentially related to the Ukraine crisis), overall tourist arrivals are modest. The Moldovan government, through its "Moldova Travel" brand, is working to promote the country as a tourist destination, focusing on its authenticity, hospitality, and unique offerings.

Challenges for tourism development include infrastructure limitations (particularly outside Chișinău), marketing and promotion, and regional instability. Efforts are being made to improve tourism infrastructure, develop new tourism products, and enhance service quality. Chișinău International Airport provides international air connections.

6.3. Energy

Moldova's energy sector is characterized by a high dependence on imported energy sources, historically primarily from Russia, particularly for natural gas. This dependency has posed significant challenges to the country's energy security and economic stability, especially in times of geopolitical tension and volatile energy prices.

Key aspects of Moldova's energy sector include:

- Import Dependence**: Moldova imports almost all of its natural gas and a significant portion of its electricity. For many years, Gazprom of Russia was the sole supplier of natural gas. Electricity has been largely sourced from the Cuciurgan power plant located in the breakaway region of Transnistria (which itself relies on Russian gas) and from Ukraine.

- Energy Security Concerns**: The reliance on a single supplier for gas and the geopolitical situation surrounding Transnistria and Ukraine have made Moldova vulnerable to supply disruptions and price manipulation. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent energy crisis in Europe severely impacted Moldova, leading to soaring energy costs and supply uncertainties.

- Diversification Efforts**: In response to these challenges, Moldova has actively pursued diversification of its energy supply routes and sources. This includes connecting its electricity grid to the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E) via Romania, allowing for electricity imports from the European market. Efforts are also underway to secure alternative gas supplies, including through reverse flows from Europe via the Trans-Balkan pipeline and by participating in the EU's joint gas purchasing platform.

- Renewable Energy**: Moldova has potential for renewable energy, particularly solar, wind, and biomass. The government is promoting investment in renewables to increase domestic energy production and reduce import dependency. However, the share of renewables in the energy mix is still relatively small.

- Energy Efficiency**: Improving energy efficiency in buildings, industry, and transport is another key priority to reduce overall energy consumption and costs.

- Infrastructure**: Modernizing energy infrastructure, including electricity grids and gas pipelines, is crucial for improving efficiency and reliability.

The energy crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine prompted Moldova to accelerate its efforts to enhance energy security, with significant support from international partners, including the EU, the US, and international financial institutions. These efforts focus on securing alternative supplies, increasing domestic generation (especially renewables), and improving energy efficiency.

6.4. Transport and Infrastructure

Moldova's transportation network comprises road, rail, air, and limited waterway transport. The state of its infrastructure is varied, with ongoing efforts to modernize and align with European standards, supported by international financing.

- Roads**: The road network is the primary mode of transport for passengers and freight, totaling approximately 7.9 K mile (12.73 K km) of roads, of which about 6.8 K mile (10.94 K km) are paved. However, many roads, particularly outside major routes, require significant rehabilitation and maintenance. Investments are being made to upgrade key national roads and improve connectivity with neighboring countries and European transport corridors.

- Railways**: The railway system, operated by the state-owned company Calea Ferată din Moldova (CFM), spans about 0.7 K mile (1.14 K km) of track. The network primarily uses the broad gauge common in former Soviet countries, which necessitates bogie changes or transshipment for freight and passenger traffic with Romania (which uses standard gauge). Rail transport plays a role in freight, particularly for bulk goods, and offers international passenger connections to cities like Bucharest, Kyiv, and Odesa (though services have been affected by regional conflicts). Modernization of rolling stock and railway infrastructure is a priority.

- Air Transport**: Chișinău International Airport (KIV) is the country's main international airport and the primary gateway for air travel. It offers direct flights to numerous European destinations, as well as connections to the Middle East. The airport has undergone modernization to handle increasing passenger traffic.

- Water Transport**: Moldova has limited access to navigable waterways. The Port of Giurgiulești on the Danube River, near its confluence with the Prut, is Moldova's only port accessible to small seagoing vessels. It provides access to the Black Sea and international shipping routes and handles a variety of cargo, including grain, oil products, and general goods. Shipping on the Prut and Dniester rivers is modest.

- Telecommunications**: Moldova has a relatively well-developed telecommunications infrastructure, particularly for internet access. The country boasts high internet speeds and good coverage, especially in urban areas, with extensive fiber-optic networks. Gigabit-speed internet is widely available. Mobile phone penetration is high, with extensive 3G and 4G coverage. The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector is a growing part of the economy. Efforts are ongoing to improve rural connectivity and digital literacy. Starlink became available in Moldova in August 2022.

Infrastructure development, including transport and energy networks, is crucial for Moldova's economic growth and integration with European markets. Significant investments are being made, often with the support of the EU and international financial institutions, to upgrade infrastructure and enhance its resilience.

6.5. Banking and Finance

Moldova's financial system is centered around its banking sector, with the National Bank of Moldova (NBM) serving as the central bank and regulatory authority. The NBM is responsible for monetary policy, licensing and supervising commercial banks, managing foreign exchange reserves, and ensuring financial stability. It is accountable to the Parliament of Moldova.

The banking sector comprises a number of commercial banks, both locally owned and with foreign capital. In the past, the sector faced significant challenges, including a major bank fraud scandal in 2014-2015 (the "theft of the billion"), which involved the collapse of three major banks and had severe economic and political repercussions. This event highlighted weaknesses in governance, regulation, and supervision.

Since then, significant reforms have been undertaken to strengthen the banking sector, improve transparency, and align with international standards, often in cooperation with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. These reforms have included:

- Improving bank shareholder transparency and fitness.

- Strengthening corporate governance in banks.

- Enhancing the NBM's supervisory and regulatory powers.

- Improving anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing (AML/CFT) frameworks.

These measures have led to increased stability and resilience in the banking sector. The presence of reputable European banking groups has also contributed to improved practices and confidence.

Other components of the financial system include non-bank credit organizations, insurance companies, and a nascent capital market. The Moldova Stock Exchange is small and relatively illiquid. The government and the NBM are working to further develop the financial markets and improve access to finance for businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Ensuring financial stability, combating financial crime, and maintaining a sound regulatory environment are ongoing priorities for Moldova, especially in the context of its European integration aspirations.

7. Demographics

Moldova's demographic landscape is characterized by population decline due to high emigration and low fertility rates, an aging population, and a diverse ethnic composition. The primary sources for demographic data are the National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova and national censuses, the most recent of which (excluding Transnistria) was conducted in 2014, with the next census completed in 2024 (preliminary results published January 2025).

7.1. Population Trends

As of January 2024, the estimated population of Moldova (excluding Transnistria) was approximately 2.423 million. The preliminary results of the 2024 census indicated a usually resident population of 2.401 million (excluding Transnistria), a 13.9% decrease from the 2.789 million recorded in the 2014 census.

The country has experienced a significant population decline since independence, driven by several factors:

- High Emigration**: A large number of Moldovans have emigrated, primarily for economic reasons, to countries like Russia, Italy, Romania, and other EU nations. This "brain drain" and labor migration have substantial economic and social impacts.

- Low Fertility Rates**: The total fertility rate (TFR) has been below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman for many years. In 2022, the TFR was 1.69 children per woman.

- Natural Decrease**: Since 2018, the number of deaths has consistently exceeded the number of live births, contributing to natural population decline.

Population density was approximately 82.8 inhabitants per square kilometer in 2022. Life expectancy at birth in 2022 was around 71.5 years (67.2 years for males and 75.7 years for females). The population is aging, with an increasing proportion of elderly people (60 years and over).

Urbanization is gradually increasing, with 43.4% of the population living in urban areas as of 2022, according to CIA World Factbook estimates; the 2024 census preliminary results indicate a 7.9% increase in urban population proportion over the decade. The capital, Chișinău, and its metropolitan area host about a third of the country's population.

7.2. Ethnic Groups

Moldova is a multi-ethnic country. According to the 2014 census (which excluded Transnistria), the ethnic composition was as follows:

- Moldovans (self-declared): 75.1%

- Romanians (self-declared): 7.0%

- Ukrainians: 6.6%

- Gagauz: 4.6%

- Russians: 4.1%

- Bulgarians: 1.9%

- Roma (Gypsies): 0.3%

- Others: 0.5% (including Poles, Belarusians, Jews, Germans)

The issue of self-identification as "Moldovan" or "Romanian" is a sensitive and politically charged topic, reflecting the ongoing controversy over ethnic and linguistic identity. Many scholars and a significant portion of the population consider Moldovans to be ethnic Romanians. The 2024 census preliminary results (January 2025) showed that 49.2% declared their ethnicity as Moldovan, and 31.3% as Romanian.

The Gagauz, a Turkic-speaking Orthodox Christian people, are concentrated in the autonomous region of Gagauzia in the south. Ukrainians and Russians are significant minorities, residing mainly in urban areas and in the north and east of the country, including Transnistria. Inter-ethnic relations are generally peaceful, but issues related to minority rights, language use, and political representation can arise.

7.3. Languages

The official language of the Republic of Moldova is Romanian. This was constitutionally affirmed in March 2023, when the Parliament amended Article 13 of the Constitution to state "Romanian language" instead of "Moldovan language functioning on the basis of the Latin script," aligning the Constitution with a 2013 Constitutional Court ruling that the Declaration of Independence (which names Romanian as the official language) takes precedence.

The Moldovan language vs. Romanian language debate has historical and political roots, stemming from Soviet-era policies that promoted "Moldovan" as a distinct language written in the Cyrillic alphabet to differentiate it from Romanian and weaken ties with Romania. Linguistically, standard "Moldovan" is identical to standard Romanian, and both use the Latin script since 1989.

According to the 2014 census (where respondents could choose "Moldovan" or "Romanian" for their mother tongue):

- Declared "Moldovan" as mother tongue: 56.7%

- Declared "Romanian" as mother tongue: 23.5%

- Combined, those declaring Romanian/Moldovan as their mother tongue constituted 80.2%.

The 2024 census preliminary results showed "Moldovan" as mother tongue for 49.2% and "Romanian" for 31.3%. Mother tongue speakers in Moldova, based on the 2014 census (excluding Transnistria), were distributed as follows:

- Romanian (declared as "Moldovan" or "Romanian"): 80.2%

- Russian: 9.7%

- Gagauz: 4.2%

- Ukrainian: 3.9%

Russian holds the status of a "language of inter-ethnic communication" and remains widely spoken and understood, particularly by older generations and in urban areas. It is a mother tongue for 9.7% (2014 census). In the autonomous region of Gagauzia, Gagauz (a Turkic language), Romanian, and Russian are official languages. Ukrainian and Bulgarian are spoken by their respective minority communities. The state supports education in minority languages.

7.4. Religion

The dominant religion in Moldova is Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The Constitution provides for freedom of religion and the separation of church and state, while acknowledging the "exceptional importance" of Eastern Orthodoxy in the nation's history and culture.

According to the 2014 census (excluding Transnistria), over 90% of the population identified as Eastern Orthodox Christians. Within Moldovan Orthodoxy, there are two main jurisdictions:

- The Moldovan Orthodox Church, which is autonomous but under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). This is the larger of the two, to which the majority of Orthodox believers (around 80-90%) adhere.

- The Metropolis of Bessarabia, which is autonomous but under the jurisdiction of the Romanian Orthodox Church. This jurisdiction was reactivated after Moldova's independence and represents a smaller portion of Orthodox believers (around 10-20%).

The co-existence of these two patriarchates reflects broader geopolitical and cultural alignments within the country.

Other religious groups in Moldova include:

- Protestants: Various denominations, including Baptists, Pentecostals, and Seventh-day Adventists, collectively form the largest religious minority, numbering several tens of thousands.

- Old Believers: A traditional Orthodox Christian community.

- Roman Catholics: A smaller community, historically present in the region.

- Judaism: The Jewish community, once large and influential, particularly in Bessarabia, significantly diminished due to the Holocaust and emigration during and after the Soviet era. Today, several thousand Jews reside in Moldova, primarily in Chișinău.

- Islam: A small but growing community, mainly composed of immigrants and some converts. The Islamic League of Moldova is a registered NGO.

Religious freedom is generally respected, although some smaller religious groups have reported difficulties with registration or societal discrimination. The authorities in the breakaway region of Transnistria estimate that about 80% of its population belongs to the Moldovan Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate).

7.5. Education

Moldova's education system is structured into pre-school, primary, secondary (gymnasium and lyceum), vocational/technical, and higher education. Education is compulsory up to the 9th grade (gymnasium). The language of instruction is predominantly Romanian, with provisions for education in minority languages such as Russian, Ukrainian, Gagauz, and Bulgarian in areas with significant minority populations.

As of the 2022/23 academic year, Moldova had 1,218 primary and secondary schools, 90 vocational schools, and 21 public higher education institutions, along with 12 private higher education institutions. The total number of pupils and students was around 437,000. The literacy rate for the population aged 15 and over is very high, estimated at 99.6%.

Higher education is offered by universities, academies, and institutes. The main public higher education institutions are located in Chișinău, including:

- Moldova State University (Universitatea de Stat din Moldova, USM), founded in 1946.

- Technical University of Moldova (Universitatea Tehnică a Moldovei, UTM), founded in 1964.

- Academy of Economic Studies of Moldova (Academia de Studii Economice a Moldovei, ASEM), founded in 1991.

- Nicolae Testemițanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy (Universitatea de Stat de Medicină și Farmacie "Nicolae Testemițanu"), founded in 1945.

- Ion Creangă State Pedagogical University of Chișinău (Universitatea Pedagogică de Stat "Ion Creangă"), founded in 1940.

The Academy of Sciences of Moldova, founded in 1961, is the main scientific research institution.

Women have a strong presence in higher education, accounting for 59.1% of students and 70.1% of foreign students in doctoral programs. A higher percentage of employed women (32.3%) have higher education compared to men (24.5%).

Challenges in the education sector include the need to modernize curricula and teaching methods, address teacher shortages (especially in rural areas), improve infrastructure, and ensure equitable access to quality education. Emigration of qualified professionals, including educators, is also a concern. Reforms are ongoing, often with the support of international partners like the EU and World Bank, aimed at aligning the education system with European standards and improving its relevance to labor market needs. Romania provides a significant number of scholarships for Moldovan students to study in Romanian high schools and universities.

7.6. Health

Moldova has a universal healthcare system based on mandatory health insurance, aiming to provide access to medical services for all citizens. The system is managed by the National Health Insurance Company. Healthcare services are delivered through a network of public and private facilities, including primary care centers, hospitals, and specialized clinics.

Key health indicators as of 2022:

- Life expectancy at birth: approximately 71.5 years (67.2 for males, 75.7 for females).

- Infant mortality rate: 9.0 deaths per 1,000 live births.

- Total fertility rate: 1.69 children per woman.

- Crude birth rate: 10.6 per 1,000 inhabitants.

- Crude death rate: 14.2 per 1,000 inhabitants.

The leading causes of death are non-communicable diseases, primarily:

- Diseases of the circulatory system (e.g., ischemic heart disease, stroke): accounted for 58% of deaths in 2022.

- Malignant neoplasms (cancer): 15.8% of deaths.

- Diseases of the digestive system: 7.5% of deaths.

- External causes (accidents, injuries): 4.8% of deaths.

Moldova spends around 6% of its GDP on healthcare. Per 10,000 inhabitants, there were 48.4 doctors and 91 units of paramedical staff in 2022. There are 86 hospitals and numerous pharmacies across the country.

Challenges in the healthcare sector include:

- Underfunding and the need for modernization of medical infrastructure and equipment.

- Shortages of medical personnel, particularly in rural areas, partly due to emigration.

- High rates of certain risk factors, such as smoking and alcohol consumption. Moldova has one ofthe highest rates of alcohol consumption per capita globally, though this has reportedly decreased somewhat in recent years.

- Ensuring equitable access to quality healthcare services across all regions.

Public health initiatives focus on preventing non-communicable diseases, improving maternal and child health, and strengthening primary healthcare. Reforms aim to improve efficiency, quality of care, and financial sustainability of the healthcare system. The retirement age was gradually increased, set to reach 63 years by 2028, as part of reforms linked to an IMF assistance program.

7.7. Emigration and Diaspora

Emigration is a significant and defining demographic and socio-economic phenomenon in Moldova. Since independence in 1991, a large proportion of the population has left the country, primarily seeking better economic opportunities abroad. Estimates suggest that between 1.2 to 2 million Moldovan citizens (which could be over a quarter to a third of the de jure population) live and work abroad, forming a substantial Moldovan diaspora.

The primary destination countries for Moldovan emigrants have traditionally included Russia, Italy, Romania, Ukraine, Portugal, Spain, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Israel, Canada, and the United States.

Economic Impact:

- Remittances**: Remittances sent home by the diaspora are a crucial component of Moldova's economy, significantly contributing to household incomes and consumption, and historically accounting for a large percentage of the country's GDP (sometimes up to 25-30%). While these inflows help alleviate poverty, they also make the economy vulnerable to economic conditions in host countries.

- Labor Market**: Large-scale emigration has led to a shrinking labor force and shortages in various sectors within Moldova, posing challenges for economic development. It also results in a "brain drain" of skilled professionals.

Social and Demographic Impact:

- Population Decline**: Emigration is a primary driver of Moldova's ongoing population decline, alongside low fertility rates.

- Family Separation**: Long-term labor migration often leads to family separation, with social consequences for children and the elderly left behind.

- Aging Population**: The departure of young and working-age individuals contributes to the aging of the population remaining in Moldova.

Government Policies:

The Moldovan government has recognized the importance of engaging with its diaspora. Policies and programs have been developed to:

- Encourage the return of migrants, particularly skilled professionals.

- Facilitate diaspora investment in the Moldovan economy.

- Protect the rights and interests of Moldovan citizens abroad.

- Maintain cultural and linguistic ties with diaspora communities.

The diaspora also plays an increasingly active role in Moldovan politics, with overseas voters significantly influencing election outcomes, such as in the 2020 presidential election and the 2021 parliamentary elections. The war in Ukraine and Moldova's EU accession path have reportedly influenced some diaspora members to return or become more involved in the country's development.

7.8. Regional Differences and Tensions