1. Overview

Transnistria, officially the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), is a breakaway state located in Eastern Europe, situated on a narrow strip of land between the Dniester river and the eastern Moldovan border with Ukraine. While it declared independence in 1990 and maintains de facto sovereignty with its own government, parliament, military, currency (Transnistrian ruble), and constitution, it is not recognized by any United Nations member state and is internationally considered part of Moldova. The region's capital and largest city is Tiraspol. Its inhabitants are known as Transnistrians or Pridnestrovians. This article explores Transnistria's complex history from ancient settlements through its Soviet past, the secession from Moldova leading to the Transnistria War, and its subsequent political, social, and economic development. It emphasizes the human rights situation, democratic processes (or lack thereof), and the significant social impacts of its unresolved political status, particularly in light of ongoing regional dynamics, including the influence of Russia and the impact of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The narrative adopts a center-left/social liberalism perspective, critically examining the challenges to democratic development and human rights within the territory while factually presenting its political and historical context.

2. Toponymy

The name "Transnistria" is an adaptation of the Romanian colloquial term for the region, meaning "beyond the Dniester River". This term first gained political currency in 1989 through Leonida Lari, a member of the Popular Front of Moldova, who used it in an election slogan expressing a desire to expel non-Romanian populations from the region. Other English variations include "Trans-Dniester", "Transdniester", or "Transdniestria".

The authorities of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR) refer to their state by its official name:

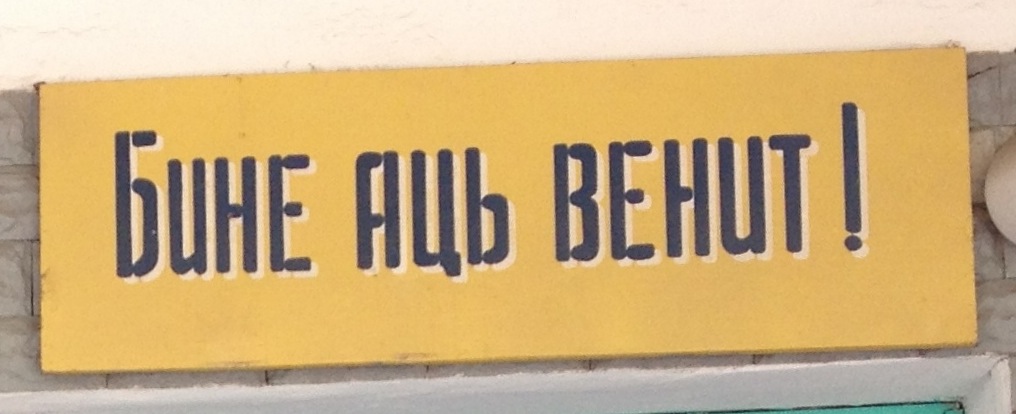

- Приднестровская Молдавская РеспубликаPridnestrovskaya Moldavskaya RespublikaRussian (PMR) in Russian

- Република Молдовеняскэ НистрянэRepublica Moldovenească NistreanăRomanian (RMN) in Moldovan (using the Cyrillic script)

- Придністровська Молдавська РеспублікаPrydnistrovs'ka Moldavs'ka RespublikaUkrainian (PMR) in Ukrainian

The short form preferred by the PMR authorities is Pridnestrovie (ПриднестровьеPridnestrov'yeRussian; НистренияNistreniaRomanian; Придністров'яPrydnistroviaUkrainian), which literally means "[land] by the Dniester".

The Moldovan government officially refers to the region as Unitățile Administrativ-Teritoriale din stînga NistruluiAdministrative-Territorial Units of the Left Bank of the DniesterRomanian, or more simply as Stînga NistruluiLeft Bank of the DniesterRomanian.

In September 2024, the Supreme Council of Transnistria passed a law banning the use of the term "Transnistria" within the region, imposing fines or imprisonment for its public use. This highlights the sensitivity and political charge associated with the region's name.

3. History

The history of the region now known as Transnistria is marked by centuries of shifting political control, demographic changes, and conflicts, culminating in its current status as an unrecognized breakaway state. This section traces its development from ancient times through its incorporation into various empires, the Soviet era, its secession from Moldova, and the ongoing consequences of that separation.

3.1. Early history

The territory of Transnistria has been inhabited since ancient times. Archaeological evidence points to the presence of various cultures, including the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, Scythians, and Sarmatians. Around 600 BC, Greek colonists founded the city of ΤύραςTyrasGreek, Ancient near the mouth of the Dniester River (present-day Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi in Ukraine).

During the Roman period, the region was on the periphery of the Roman Empire but experienced its cultural and economic influence. In the 4th century AD, the Goths conquered Tyras and Olbia, with Gothic tribes settling on both sides of the Dniester, later known as Visigoths and Ostrogoths. The Huns subsequently overran the area.

In the early Middle Ages, various Turkic and Slavic tribes, including the Ulichs and Tivertsi, migrated through or settled in the region. The Primary Chronicle mentions Romanian-speaking populations (Vlachs) in the area by the 10th century. For a period, the region fell under the influence of Kievan Rus'.

From the 14th century, parts of the region were controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and later the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The southern part of Transnistria, closer to the Black Sea, came under the influence of the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire. The Principality of Moldavia, established in the mid-14th century, extended its territory to the Dniester by the late 14th century but generally did not control the lands to its east (Transnistria).

3.2. Russian Empire

The gradual incorporation of Transnistria into the Russian Empire began in the late 18th century. Following the Russo-Turkish War of 1787-1792, the southern part of Transnistria was ceded by the Ottoman Empire to Russia under the Treaty of Jassy (1792). The northern part was acquired by Russia following the Second Partition of Poland in 1793.

The Russian administration named the region "New Moldavia" and encouraged large-scale colonization to populate the sparsely inhabited lands. This policy aimed to secure the western border of the empire. Many Russians, Ukrainians, and Moldovans (Romanians), as well as Germans and Bulgarians, were settled in the area. Moldovan peasants were offered tax-free land to encourage their migration. Cities like Tiraspol (founded in 1792 by Alexander Suvorov) and Dubăsari were established or developed during this period as strategic and administrative centers.

With the Russian annexation of Bessarabia in 1812, Transnistria ceased to be a border region. It was integrated into various governorates of the Russian Empire, primarily the Kherson Governorate and Podolia Governorate. Throughout the 19th century, the region underwent significant socio-economic development, with agriculture being the mainstay, alongside the growth of trade and small industries. The demographic composition continued to diversify, with a significant Slavic presence alongside the Romanian/Moldovan population. Russification policies, common throughout the empire, also impacted the region, particularly in administration and education.

3.3. Soviet era

The Soviet era brought profound administrative, socio-economic, and cultural transformations to Transnistria, shaping its distinct identity within the broader Moldovan context. This period saw the region's industrialization, collectivization of agriculture, and shifting political boundaries, as well as efforts towards Russification that significantly influenced its demographic and linguistic makeup.

3.3.1. Moldavian ASSR

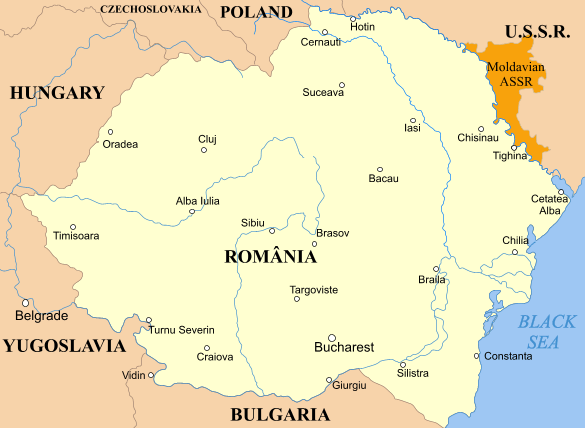

In 1924, the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR) was established within the Ukrainian SSR. Its creation was a geopolitical move by the Soviet Union partly aimed at staking a claim to Bessarabia, which had become part of Romania after World War I. The MASSR included the territory of present-day Transnistria (approximately 1.6 K mile2 (4.10 K km2)) and an additional area of about 1.6 K mile2 (4.20 K km2) to its northeast around the city of Balta (then the capital, later moved to Tiraspol in 1929).

The MASSR's population was ethnically diverse. According to official figures at the time, Ukrainians constituted a plurality, followed by Moldovans/Romanians, Russians, and Jews. The Soviet authorities promoted a distinct Moldovan identity and language, written in the Cyrillic script, separate from Romanian, although linguistically they are largely the same. This policy aimed to counter Romanian influence and legitimize Soviet claims over Bessarabia. Romanian-language schools using Latin script were initially allowed but later suppressed in favor of the Cyrillic-based "Moldovan language."

During the 1920s and 1930s, the MASSR experienced Soviet policies of industrialization and agricultural collectivization. Tiraspol and other towns saw some industrial development. However, the period was also marked by political repression, including the Great Purge of the 1930s, which affected local cadres and ordinary citizens. In 1927, peasant and worker uprisings against Soviet authorities in Tiraspol and other cities were suppressed by military force. Thousands of Romanian-speaking Transnistrians fled to Romania during this period to escape Soviet rule.

3.3.2. World War II and Moldavian SSR

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union paved the way for significant territorial changes in Eastern Europe. In June 1940, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum to Romania, demanding the cession of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. Romania complied, and on August 2, 1940, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR created the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR). The MSSR was formed by merging the western part of the MASSR (roughly corresponding to present-day Transnistria) with the bulk of Bessarabia. The eastern part of the MASSR, including Balta, remained within the Ukrainian SSR, as did the strategically important Black Sea coast and Danube estuary (Bujak) from southern Bessarabia.

In June 1941, Axis forces, including Romania allied with Germany, invaded the Soviet Union. Romanian troops, as part of Operation Barbarossa, reoccupied Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina and advanced eastward across the Dniester. The territory between the Dniester and the Southern Bug rivers, including Transnistria and parts of Ukraine with the city of Odesa as its administrative center, was organized into the Transnistria Governorate, administered by Romania from 1941 to 1944. This expanded Transnistria had an area of 15 K mile2 (39.73 K km2) and a population of 2.3 million. The Romanian administration implemented policies of Romanianization.

During the Romanian occupation, the Transnistria Governorate became a site of the Holocaust. Between 150,000 and 250,000 Jews (Ukrainian and Romanian) and Romani people were deported to ghettos and concentration camps in Transnistria, where the majority were murdered by Romanian and German forces or died from disease, starvation, and exposure.

In 1944, the Red Army reconquered the region during the Jassy-Kishinev Offensive. Soviet control was re-established, and Transnistria once again became part of the Moldavian SSR. The post-war period saw continued Soviet policies, including further industrialization concentrated in Transnistria, Russification, and political consolidation. Soviet authorities executed, exiled, or imprisoned many inhabitants accused of collaboration with the Romanian occupiers. A campaign against wealthy peasant families (kulaks) led to deportations to Kazakhstan and Siberia, notably during "Operation South" on July 6-7, 1949, which saw over 11,342 families deported. These policies further altered the demographic and socio-political landscape of the region, reinforcing its distinct characteristics compared to the rest of Moldova.

3.4. Secession

The late 1980s, under Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness), saw a rise in national movements across the Soviet Union. In the Moldavian SSR, this manifested as a resurgence of Moldovan (Romanian) nationalism, with calls for greater cultural and political autonomy. The Popular Front of Moldova (PFM), formed in 1988, became the leading force advocating for these changes.

Key demands of the PFM included declaring Moldovan (Romanian) as the sole state language, returning to the Latin alphabet (from the Soviet-imposed Cyrillic script), and recognizing the shared ethnic and linguistic identity of Moldovans and Romanians. Some radical factions within the PFM also expressed anti-minority sentiments, particularly targeting the Slavic (Russian and Ukrainian) and Gagauz populations, who were perceived as agents of Russification.

On August 31, 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the Moldavian SSR adopted laws that made Moldovan the official language, mandated the return to the Latin script, and acknowledged the Moldovan-Romanian linguistic unity. Russian was retained for secondary purposes. These changes caused alarm among the non-Moldovan-speaking populations, especially in Transnistria, where Russians and Ukrainians formed a significant portion of the population, and Russian was the primary language of interethnic communication. Many feared linguistic discrimination, loss of cultural identity, and potential unification with Romania, which was a goal for some PFM members.

In response, counter-mobilization occurred in Transnistria and Gagauzia. The Yedinstvo (Unity) Movement, representing Slavic interests, advocated for equal status for Russian and Moldovan. Tensions escalated. In Transnistria, local leaders, many of whom were Soviet-era factory directors and officials, began to organize resistance to the Moldovan nationalist agenda. They saw the changes as a threat to their political and economic power, as well as to the rights of the Russian-speaking population.

In early 1990, the PFM won the first multi-party parliamentary elections in the Moldavian SSR. As the new government began implementing its policies, separatist sentiments in Transnistria intensified. Strikes and protests were organized in Transnistrian cities. On September 2, 1990, the Second Extraordinary Congress of Peoples' Deputies of All Levels of Pridnestrovie, an ad hoc assembly, proclaimed the creation of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (PMSSR) as a Soviet republic, with the intention of remaining within the USSR if Moldova seceded or united with Romania. This declaration was based on local referendums organized by separatist leaders, the legitimacy of which was not recognized by Chișinău or Moscow. Human rights concerns for minorities in Moldova were cited by Transnistrian leaders as a justification for secession, although critics argued that these concerns were manipulated to serve separatist goals and maintain the old Soviet power structures.

Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev declared the PMSSR's proclamation illegal and void by a presidential decree on December 22, 1990, citing the restriction of civil rights of ethnic minorities by Moldova as a cause of the dispute but affirming Moldova's territorial integrity. However, the central Soviet government, weakened by internal crises, took no effective action to disband the separatist structures. The PMSSR authorities gradually consolidated control over the region, establishing their own administrative and security bodies.

Following the failed 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt in August 1991, Moldova declared its independence from the Soviet Union on August 27, 1991. Shortly thereafter, on August 25, 1991, the PMSSR declared its independence from the USSR. On November 5, 1991, the PMSSR was renamed the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), abandoning Soviet socialist ideology in its name, though retaining many Soviet-era symbols. The stage was set for a direct military confrontation.

3.5. Transnistria War

The Transnistria War was an armed conflict that took place between March and July 1992, pitting forces of the newly independent Republic of Moldova against separatists from Transnistria, who were supported by elements of the Russian 14th Guards Army stationed in the region and Cossack and other volunteers from Russia and Ukraine.

Causes: The primary cause was Transnistria's desire to secede from Moldova. This was fueled by fears among the predominantly Russian-speaking population of Transnistria regarding Moldovan nationalism, potential unification with Romania, and language laws that promoted Moldovan (Romanian) at the expense of Russian. Transnistrian elites, many from the old Soviet industrial and political apparatus, also sought to maintain their influence and prevent integration into a Moldova they perceived as hostile to their interests. Moldova, on the other hand, was determined to maintain its territorial integrity.

Main Events:

Armed clashes had occurred sporadically since November 1990, particularly in and around Dubăsari. The conflict escalated into open warfare on March 2, 1992, when Moldova, now a UN member, initiated concerted military action to assert control over the breakaway region.

Fighting centered on several key areas:

- The city of Dubăsari on the eastern bank of the Dniester.

- The city of Bender (Tighina) on the western bank, which became a major flashpoint.

- Villages along the Dniester River.

The Moldovan forces, newly formed and poorly equipped, faced well-organized Transnistrian militias (the Republican Guard) and paramilitary units. Crucially, elements of the Russian 14th Guards Army, stationed in Transnistria since the Soviet era and commanded by General Alexander Lebed, intervened on the side of the separatists. While officially neutral, the 14th Army provided weapons, ammunition, and, in some instances, direct fire support and personnel to the Transnistrian forces. This intervention was a decisive factor in the conflict. The heaviest fighting occurred in June 1992 in Bender, where Moldovan forces initially made gains but were pushed back after intense urban combat and intervention by 14th Army tanks.

Belligerents:

- Moldova: Moldovan Army, police, and volunteer units.

- Transnistria (PMR): Transnistrian Republican Guard, local militias, Cossack volunteers from Russia and Ukraine, and individual volunteers from other regions. Critically, they received substantial material and personnel support from the Russian 14th Guards Army.

Outcome and Ceasefire:

The war ended with a ceasefire agreement signed on July 21, 1992, in Moscow by Moldovan President Mircea Snegur and Russian President Boris Yeltsin, with Transnistrian leader Igor Smirnov also involved. The agreement established:

- A demilitarized security zone along the Dniester River.

- A tripartite peacekeeping force composed of Russian, Moldovan, and Transnistrian contingents to monitor the ceasefire.

The ceasefire effectively froze the conflict, leaving Transnistria outside Moldovan government control but unrecognized internationally.

Consequences:

- Casualties: Estimates vary, but approximately 700-1,000 people were killed on both sides, including civilians. Thousands were wounded.

- Displacement: Tens of thousands of people were displaced from their homes, becoming refugees or internally displaced persons.

- Impact on Civilians and Inter-ethnic Relations: The war deepened ethnic divisions and mistrust between the Moldovan-speaking population and the Russian-speaking communities in Transnistria. Civilian populations suffered from shelling, displacement, and human rights abuses committed by various forces. The war solidified the de facto separation of Transnistria and created long-lasting political and social scars. For Moldova, it meant the loss of control over a significant portion of its internationally recognized territory and a persistent source of instability. For Transnistria, it cemented its self-proclaimed independence but led to international isolation and economic difficulties, heavily reliant on Russian support.

3.6. Post-war period

Following the 1992 ceasefire, Transnistria solidified its de facto independence, establishing its own government, currency, military, and borders, though remaining internationally unrecognized. The post-war period has been characterized by a "frozen conflict," political stagnation, economic challenges, human rights concerns, and ongoing, largely unsuccessful, international mediation efforts aimed at resolving its status.

Political Developments and Mediation:

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) has been the primary international body facilitating negotiations. On May 8, 1997, Moldovan President Petru Lucinschi and Transnistrian leader Igor Smirnov signed the "Memorandum on the Principles of Normalization of Relations between the Republic of Moldova and Transnistria" (Primakov Memorandum). This document aimed to establish legal and state relations, but its vague terms were interpreted differently by each side and failed to produce a breakthrough.

In November 2003, Russia proposed the "Kozak memorandum", brokered by Dmitry Kozak, then an aide to Russian President Vladimir Putin. It suggested an asymmetric federal Moldovan state where Transnistria would have significant autonomy and veto power over constitutional changes. While initially supported by Moldovan President Vladimir Voronin and Transnistria (as it allowed for a continued Russian military presence for 20 years), Voronin ultimately refused to sign it due to strong domestic opposition and pressure from Western organizations like the OSCE and the United States, who were concerned about the extent of Russian influence and the lack of genuine democratic concessions.

The "5+2 format" for negotiations was established in 2005, involving Moldova and Transnistria as parties; Russia, Ukraine, and the OSCE as mediators; and the European Union and the United States as observers. Talks in this format resumed in Vienna in February 2011 and continued sporadically, yielding minor agreements on practical issues (like freedom of movement or recognition of diplomas) but no resolution to the core political status. By 2023, Moldova had largely ceased referring to the 5+2 format in diplomatic discussions, signaling its perceived ineffectiveness, especially after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Socio-Economic Changes and Internal Conflicts:

Transnistria's economy, heavily industrialized during the Soviet era, faced significant challenges post-secession. It became reliant on Russian subsidies, particularly cheap gas, and was often accused of involvement in illicit activities such as smuggling and arms trafficking, allegations its authorities deny. The Sheriff conglomerate emerged as a dominant economic and political force, controlling large sectors of the economy and influencing politics.

Internal political life has been dominated by a small group of elites, with limited political pluralism and media freedom. Human rights organizations have consistently reported concerns regarding freedom of speech, assembly, the rights of Romanian-speaking Moldovans (particularly concerning Romanian-language schools using the Latin script), and due process.

After Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014, Transnistrian authorities renewed calls to join the Russian Federation, reflecting a long-standing aspiration among a significant part of its population and leadership.

3.6.1. 2006 independence referendum

On September 17, 2006, the Transnistrian authorities organized a referendum on independence and potential future integration with Russia. This was the fourth such referendum held in the region since its declaration of independence.

Context: The referendum was held amidst ongoing deadlocked negotiations with Moldova and a desire by the Transnistrian leadership to demonstrate popular support for its separatist stance and strengthen its negotiating position, particularly in seeking closer ties with Russia. It followed shortly after Montenegro's independence, which Transnistrian officials cited as a precedent.

Process and Questions: Voters were asked two questions:

1. Do you support the course towards independence for the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic and its subsequent free association with the Russian Federation?

2. Do you consider it possible to renounce the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic's independent status and subsequently become part of the Republic of Moldova?

Results: According to the Transnistrian Central Election Commission:

- On the first question (independence and association with Russia): 97.2% voted in favor.

- On the second question (reintegration with Moldova): 94.9% voted against (meaning 3.4% were in favor of reintegration, with some invalid ballots).

Turnout was reported at 78.6%.

International Reactions: The referendum was widely condemned and not recognized by the international community, including Moldova, the European Union, the United States, the OSCE, Ukraine, and Romania. They considered it illegitimate, lacking democratic standards, and unhelpful to the conflict resolution process. Russia, while not officially recognizing the referendum's outcome as legally binding for international recognition, expressed that the will of the Transnistrian people should be taken into account. The Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Moldova reported irregularities, including coerced voting and inflated turnout figures, questioning the fairness of the process.

Implications:

- Regional Stability: The referendum did not alter the de facto situation but reinforced the political stalemate. It highlighted the deep divisions and the limited prospects for Moldova's territorial reunification under terms acceptable to both sides.

- Democratic Processes: The lack of international observation and the controlled political environment in Transnistria led to significant doubts about the referendum's democratic legitimacy. It was seen by critics as a tool for the Transnistrian leadership to consolidate power rather than a genuine expression of free will.

- International Standing: The referendum further isolated Transnistria internationally, as no country (other than the similarly unrecognized states of Abkhazia and South Ossetia) acknowledged its results. It did, however, serve to signal Transnistria's strong pro-Russian orientation.

3.6.2. Impact of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

The full-scale 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine commencing in February 2022 has had significant and multifaceted impacts on Transnistria's political, economic, security, and international standing.

Political and Security Impact:

- Increased Geopolitical Scrutiny: Transnistria, hosting Russian troops and a large Soviet-era ammunition depot at Cobasna, immediately became a focal point of concern. There were fears that Russia might use Transnistria as a staging ground to open a new front against southwestern Ukraine, particularly towards Odesa. Ukrainian officials accused Russia of planning "false flag" operations in Transnistria to justify such an escalation.

- Series of Incidents: In April 2022, a series of unexplained explosions and incidents occurred in Transnistria, targeting the Ministry of State Security building in Tiraspol, military units, and old Soviet-era radio towers broadcasting Russian programs near Maiac. Transnistrian authorities blamed external forces (implying Ukraine), while Ukraine and Moldova suggested these were provocations aimed at destabilizing the region or drawing Transnistria into the war. Transnistria declared a "red" level terrorist alert and increased security measures.

- Neutrality Stance and Russian Pressure: The Transnistrian leadership officially declared neutrality in the conflict, denying any intention to assist Russia's attack on Ukraine. However, the region remains heavily dependent on Russia, and there were concerns about potential pressure from Moscow to become involved. The presence of the Operational Group of Russian Forces (OGRF) in Transnistria continued to be a source of tension.

- Moldovan Response: Moldova condemned the Russian invasion and reinforced its own security while maintaining a neutral stance. The war accelerated Moldova's bid for European Union membership. On March 15, 2022, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution defining Transnistria as a territory under military occupation by Russia.

Economic Impact:

- Border Closure and Trade Disruption: Ukraine sealed its border with Transnistria, which had been a crucial route for Transnistrian trade, particularly imports and exports not passing through Moldovan-controlled territory. This forced Transnistria to rely almost entirely on Moldova for its external trade, increasing Chișinău's leverage.

- Increased Dependence on Moldova and EU: With Ukrainian markets and transit routes closed, Transnistrian businesses had to reorient towards or through Moldova, complying with Moldovan and EU regulations for trade, especially under the DCFTA that Moldova has with the EU. This led to an intensification of dialogue with Chișinău on economic matters.

- Energy Concerns: Transnistria's economy, particularly its large industrial plants like the Moldavskaya GRES power plant, relies heavily on free or heavily discounted Russian natural gas transiting through Ukraine. The war raised concerns about the future of this gas supply. The Cuciurgan power station, which supplies electricity to both Transnistria and Moldova, became a critical point of leverage. The expiration of the Russian gas transit deal via Ukraine at the end of 2024 led to a severe energy crisis in early 2025, with Transnistria refusing to buy gas at market rates from Moldova and Russia not rerouting supplies.

- Calls for Russian Assistance: In February 2024, the Transnistrian Supreme Council appealed to Russia for economic assistance, accusing Moldova of committing "genocide" through economic pressure (referring to new Moldovan customs duties on Transnistrian imports/exports). This rhetoric, coupled with pro-Russian protests in Moldova, further strained relations.

Humanitarian Aspects:

- Refugee Influx: Transnistria, like Moldova, received a significant number of refugees fleeing Ukraine. Both Transnistrian authorities and civil society provided assistance, though the scale was smaller compared to Moldova proper. This created a complex situation where a pro-Russian region was aiding victims of Russian aggression.

International Standing:

- The war further isolated Transnistria and highlighted its vulnerability. While its leadership tried to maintain a delicate balance, its dependence on Russia became even more pronounced. The conflict also diminished the viability of existing negotiation formats like the 5+2, as Ukraine, a mediator, was now at war with Russia, another mediator.

The long-term consequences for Transnistria are still unfolding but include increased economic hardship, heightened security risks, and a more complex geopolitical environment.

4. Geography

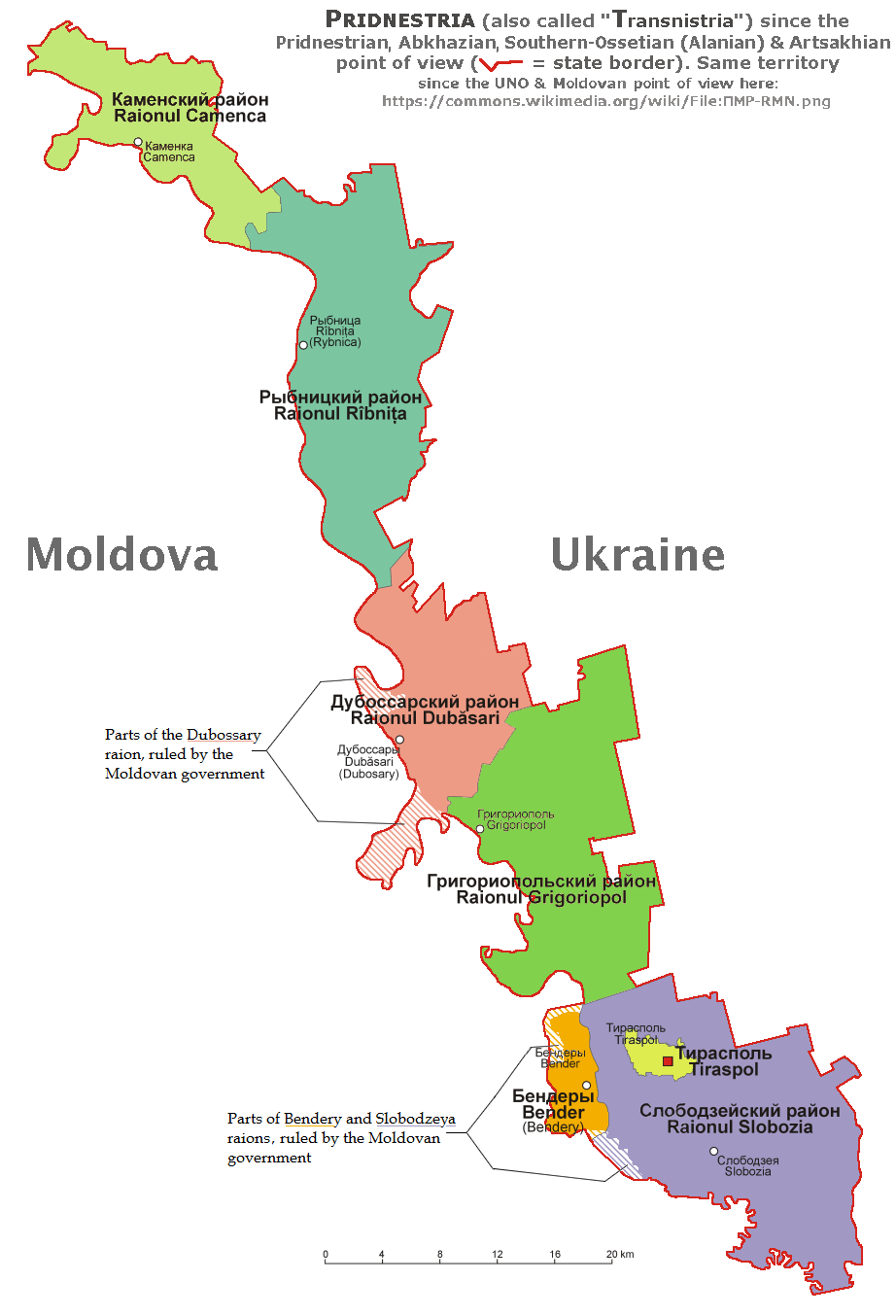

Transnistria is a landlocked territory in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Moldova to the west (the region of Bessarabia, for approximately 255 mile (411 km)) and by Ukraine to the east (for approximately 252 mile (405 km)). The territory largely corresponds to the left (eastern) bank of the Dniester River, which forms a natural boundary along most of its de facto border with Moldova proper. Transnistria's total area is approximately 1.6 K mile2 (4.16 K km2).

The topography is predominantly a hilly plain, part of the larger East European Plain. The land gently slopes from northwest to southeast. The average elevation is around 492 ft (150 m) above sea level. The highest point is often cited as being near the village of Pervomaisc in the north, though specific elevations are modest.

The Dniester River is the defining geographical feature and the primary water source. It flows from north to south along Transnistria's western edge before entering Ukraine and eventually emptying into the Black Sea. Several smaller rivers and streams, tributaries of the Dniester, cross the territory.

The climate is moderately continental, characterized by warm, dry summers and relatively mild winters, though cold spells with snow can occur. Average January temperatures range from 24.8 °F (-4 °C) to 28.4 °F (-2 °C), and July temperatures average 68 °F (20 °C) to 71.6 °F (22 °C). Annual precipitation is moderate, typically between 16 in (400 mm) and 22 in (550 mm), with more rainfall during the summer months. Droughts can occasionally affect agriculture.

Transnistria's natural resources are limited. The fertile chernozem (black earth) soil is its most significant natural asset, supporting agriculture. There are deposits of construction materials like limestone, sand, and gravel. The region lacks significant deposits of fossil fuels or metallic ores.

Environmental issues include soil erosion, water pollution in the Dniester River from industrial and agricultural runoff, and issues related to waste management. The large Soviet-era ammunition dump at Cobasna poses a potential environmental and security risk.

Border Issues:

The territory controlled by the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR) mostly, but not entirely, coincides with the left bank of the Dniester.

- Moldovan-controlled areas on the left bank**: Six communes (Cocieri, Molovata Nouă, Corjova, Pîrîta, Coșnița, and Doroțcaia) remain under Moldovan government control as part of the Dubăsari District. These are situated north and south of the city of Dubăsari, which is under PMR control. The village of Roghi (part of Molovata Nouă commune) is also PMR-controlled, while Moldova controls the other nine villages of these six communes.

- PMR-controlled areas on the right (western) bank**: The city of Bender (Tighina) and four communes to its east and south (Proteagailovca, Gîsca, Chițcani, and Cremenciug) are controlled by the PMR.

These territorial arrangements create a complex border situation with enclaves and exclaves, leading to a security zone monitored by the Joint Control Commission. The main transportation route, the M4 highway from Tiraspol to Rîbnița, passes through some Moldovan-controlled land corridors (e.g., Doroțcaia, Cocieri, Roghi, Vasilievca), which has been a source of tension.

5. Government and politics

Transnistria operates as a de facto independent state with its own system of government, though it lacks international recognition. Its political structure is that of a semi-presidential republic with a powerful executive branch. The political landscape has been characterized by a strong presidential system, limited political pluralism, and significant influence from economic groups, notably the Sheriff conglomerate. Democratic development has been hampered by its unresolved status, external influences, and internal controls.

5.1. Political system

Transnistria's political system is defined by its 1995 constitution (with subsequent amendments). It features a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, though in practice, the presidency has historically wielded significant authority.

- Executive Branch**:

- The President is the head of state and is directly elected for a five-year term, with a two-consecutive-term limit. The President appoints the Prime Minister and government ministers (with parliamentary approval for the Prime Minister), is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and has significant decree powers. The current President is Vadim Krasnoselsky, first elected in 2016 and re-elected in 2021.

- The Government (Cabinet of Ministers), headed by the Prime Minister, is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the state. The Prime Minister is accountable to both the President and the legislature. The current Prime Minister is Aleksandr Rozenberg.

- Legislative Branch**:

- The Supreme Council (Верховный СоветVerkhovny SovetRussian) is the unicameral legislature. It currently consists of 33 members (previously 43) elected for five-year terms from single-mandate constituencies.

- The Supreme Council's powers include adopting laws, approving the budget, ratifying treaties, and overseeing the government. It can also impeach the president.

- Major political parties or movements include Renewal (Obnovlenie), which has been the dominant force in the Supreme Council for many years and is associated with the Sheriff conglomerate, and the Transnistrian Communist Party. Opposition parties exist but have limited influence.

- Judicial Branch**:

- The judicial system includes a Constitutional Court, a Supreme Court, an Arbitration Court (for economic disputes), and lower-level courts. Judges are appointed, and the judiciary's independence has been questioned by external observers. The legal system is largely based on Soviet and Russian models.

Electoral Processes and Democratic Principles:

Transnistria holds regular presidential and parliamentary elections. However, these elections are not recognized by international organizations like the OSCE or the Council of Europe, nor by individual countries, due to the unresolved status of the region and concerns about the fairness and freedom of the electoral environment.

Criticisms often point to:- Limited media freedom and state control over major media outlets.

- Restrictions on opposition activities and civil society.

- The dominant role of the Sheriff conglomerate in the economy and politics, leading to an uneven playing field.

- Historically, the political regime was described as "super-presidentialism" before constitutional reforms in 2011 aimed at slightly increasing parliamentary powers.

While elections have seen some competition and even changes in leadership (e.g., Igor Smirnov's defeat in 2011), the overall adherence to democratic principles is considered weak by international standards. Reports from organizations like Freedom House consistently rate Transnistria as "not free" in terms of political rights and civil liberties.

5.2. Political status

Transnistria's political status is highly contested. It declared independence from Moldova on September 2, 1990, and has since functioned as a de facto independent state. It possesses all the attributes of statehood, including a defined territory, a permanent population, its own government, the capacity to enter into relations with other entities (albeit limited), a constitution, military, police, currency (Transnistrian ruble), and flag.

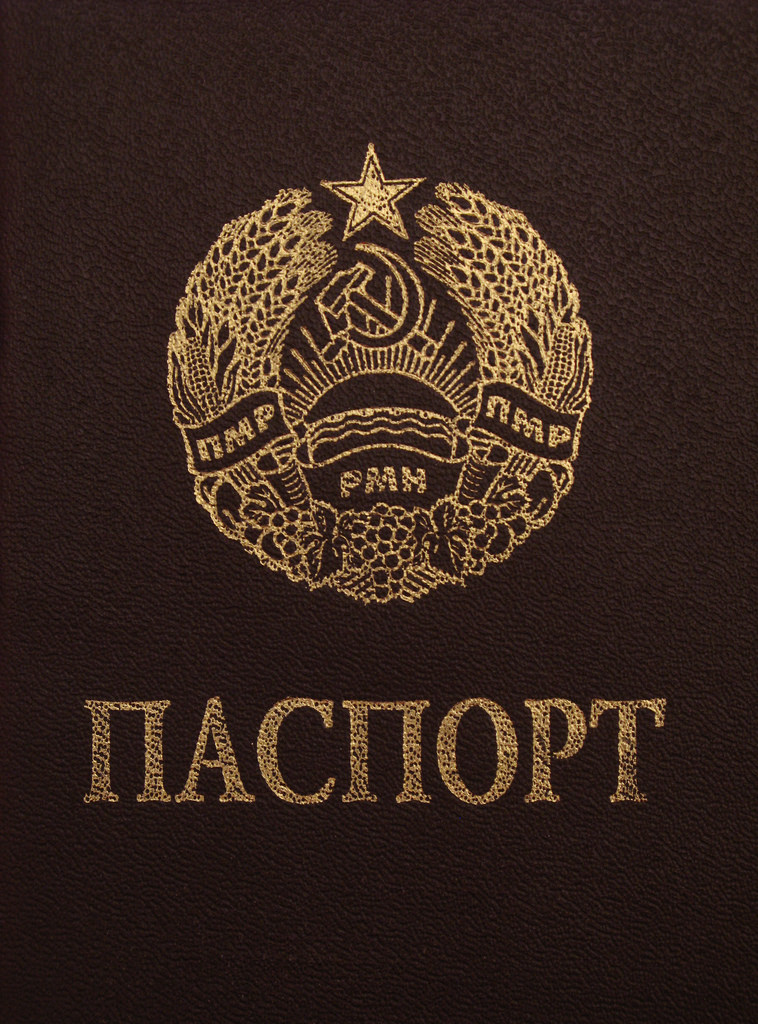

However, Transnistria lacks international recognition from any UN member state. It is recognized only by three other post-Soviet breakaway states that themselves have limited or no UN recognition: Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and (until its dissolution in 2023) Artsakh. These entities form the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations.

Internationally, Transnistria is considered legally part of the Republic of Moldova. The United Nations, the European Union, the OSCE, and all individual UN member states affirm Moldova's territorial integrity. Moldova itself designates the region as the Administrative-Territorial Units of the Left Bank of the Dniester (Unitățile Administrativ-Teritoriale din stînga NistruluiAdministrative-Territorial Units of the Left Bank of the DniesterRomanian). In 2005, the Moldovan parliament passed Law No. 173-XVI "On the Basic Provisions of the Special Legal Status of the Localities on the Left Bank of the Dniester (Transnistria)". This law offers a special autonomous status within Moldova, but it was drafted without Transnistrian participation and has been rejected by the Transnistrian authorities, who insist on full independence or, as an alternative, eventual unification with Russia.

The stance of the international community generally supports a peaceful resolution of the conflict based on Moldova's sovereignty and territorial integrity, with a special status for Transnistria. The 5+2 format (Moldova, Transnistria, OSCE, Russia, Ukraine + EU, US as observers) was the main negotiation platform, but it has been largely stalled, especially since the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In March 2022, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution defining the territory as being under military occupation by Russia. This reflects growing international concern over Russia's influence and military presence in the region.

The unresolved status has significant implications for human rights, as residents of Transnistria often have limited access to justice mechanisms recognized internationally and can face challenges with travel and recognition of documents issued by Transnistrian authorities. Many residents hold multiple citizenships (Moldovan, Russian, Ukrainian, and sometimes Romanian) to navigate these difficulties.

5.3. Foreign relations

Transnistria's foreign relations are severely constrained by its lack of international recognition. As an unrecognized state, it cannot formally establish diplomatic relations with UN member states. Its foreign policy primarily focuses on seeking international recognition, maintaining its de facto independence, and cultivating relationships with key actors, particularly Russia, and other unrecognized states.

- Russia**: This is Transnistria's most crucial relationship. Russia provides significant political, economic, military, and humanitarian support.

- Political Support: While not officially recognizing Transnistria's independence, Russia has acted as a patron and protector, advocating for a "special status" for Transnistria and playing a key role in the conflict settlement process (often seen by Moldova and Western countries as favoring Transnistrian interests). Transnistrian leaders frequently appeal to Moscow for closer integration or even annexation.

- Economic Support: Russia supplies natural gas to Transnistria at heavily discounted prices or effectively free (as Transnistria accumulates debt to Gazprom that Moldova proper is expected to cover but which is unlikely to be paid by Tiraspol). Russian pensions are also paid to many residents.

- Military Support: The Operational Group of Russian Forces (OGRF) remains stationed in Transnistria, ostensibly as peacekeepers following the 1992 war and to guard the Cobasna ammunition depot. This presence is a major point of contention with Moldova and the West, who call for its withdrawal.

- The local impact of Russian support is profound, ensuring Transnistria's economic survival and security but also fostering dependence and hindering democratic development by propping up a static regime.

- Moldova**: Relations are complex and generally adversarial, characterized by ongoing negotiations over Transnistria's status.

- Moldova considers Transnistria an integral part of its territory and seeks reintegration, offering broad autonomy. Transnistria demands sovereignty or equal status in any confederation.

- Practical cooperation exists on some issues like trade (especially after Ukraine closed its border segment with Transnistria in 2022, forcing Transnistrian goods to transit through Moldova), customs, and occasionally law enforcement, but these are often fraught with political tension.

- The impact on the local population includes difficulties with freedom of movement, recognition of documents, and economic uncertainty.

- Ukraine**: Historically, Ukraine maintained a more neutral stance, acting as a mediator and allowing significant cross-border trade.

- After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, relations deteriorated sharply. Ukraine sealed its border with Transnistria, viewing the Russian military presence there as a security threat. This significantly impacted Transnistria's economy and increased its reliance on Moldova. Ukrainian officials have expressed concerns about Transnistria being used as a base for Russian operations.

- Other Unrecognized/Partially Recognized States**: Transnistria maintains close ties with Abkhazia and South Ossetia (and formerly Artsakh). These entities have mutually recognized each other's independence and cooperate within the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations. These relationships provide mutual political support but have little practical impact on their international isolation.

- European Union and United States**: The EU and US are observers in the 5+2 negotiation format and support Moldova's territorial integrity. They have imposed sanctions on Transnistrian officials in the past and advocate for a peaceful resolution, respect for human rights, and democratic reforms in Transnistria. The EU's Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM) aims to help Moldova and Ukraine manage their common border, including the Transnistrian segment, and to curb illicit trade.

The lack of recognition severely impacts Transnistria's ability to engage in formal international trade, receive international aid directly, or participate in international organizations, affecting the socio-economic well-being of its population and contributing to regional instability.

5.4. Border customs dispute

The border customs dispute refers to ongoing issues surrounding the control and regulation of trade across Transnistria's de facto borders with Moldova and Ukraine. This has been a significant source of economic and political tension.

Historically, Transnistria controlled its own customs procedures along its segment of the Moldovan-Ukrainian border, leading to accusations from Moldova and international observers of smuggling and illicit trade, which Transnistrian authorities denied.

A major point of contention arose on March 3, 2006, when Ukraine, in agreement with Moldova and with the support of the EU Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM), implemented new customs regulations. These rules required that all goods transiting from Transnistria through Ukraine to external markets (and vice versa for imports) must have official Moldovan customs documents. Effectively, Transnistrian companies had to register with Moldovan authorities in Chișinău to legally export or import goods.

Reactions and Impacts:

- Transnistria and Russia** decried this as an "economic blockade," arguing it infringed on Transnistria's economic autonomy and was designed to pressure it politically. Transnistria responded by temporarily blocking Moldovan and Ukrainian transport at its borders.

- Moldova, Ukraine, the EU, and the US** supported the move, stating it was aimed at ensuring transparency, combating smuggling, and reasserting Moldova's sovereignty over its customs territory.

- Economic Impact on Transnistria**: In the immediate aftermath, Transnistrian exports reportedly declined significantly as businesses struggled to adapt or refused to comply. Transnistria declared a "humanitarian catastrophe," though Moldova dismissed this as misinformation. Over time, many Transnistrian businesses did register in Chișinău to access EU markets, especially under Moldova's DCFTA with the EU.

- Political Impact**: The customs regime became a key bargaining chip in negotiations. It increased Moldova's leverage over Transnistria but also deepened resentment in Tiraspol.

- Social Impact**: The economic difficulties resulting from trade disruptions and new regulations affected employment and living standards for the population in Transnistria.

The situation evolved further after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Ukraine sealed its border with Transnistria, meaning all Transnistrian trade had to transit through Moldovan-controlled territory. This gave Moldova almost complete control over Transnistria's external trade flows.

In early 2024, Moldova implemented changes to its customs code, requiring companies in Transnistria to pay customs duties to the Moldovan budget for imports and exports, similar to any other Moldovan economic agent. This ended a long-standing preferential treatment where Transnistrian businesses largely did not contribute to Moldova's state budget. Transnistrian authorities strongly protested this move, again labeling it as economic pressure and appealing to Russia for assistance.

The customs dispute underscores the economic dimension of the unresolved political conflict and its direct impact on businesses and the daily lives of people in Transnistria.

5.5. Law

Transnistria's legal system is based on its 1995 Constitution, with subsequent amendments. It claims to operate as a rule-of-law state with a separation of powers, but its unrecognized status and political environment raise significant concerns about the independence of the judiciary and the consistent application of law, particularly concerning human rights.

The legal framework is heavily influenced by Soviet and Russian law. The main branches of law include:

- Constitutional Law**: Defines the structure of the state, the rights and freedoms of citizens, and the powers of state bodies. The Constitution proclaims Transnistria as a sovereign, democratic, legal, and secular state. Key constitutional acts establish the Supreme Court, Arbitration Court, Constitutional Court, and the overall judicial and governmental system. It also covers citizenship, special legal regimes, and the status of government officials.

- Civil Law**: Regulates property rights, contracts, and other private relations. A Civil Code, similar to those in other post-Soviet states, is in place.

- Criminal Law**: Defines crimes and punishments. A Criminal Code and a Code of Criminal Procedure are in force. Concerns have been raised by international observers about due process, fair trial standards, and conditions in detention facilities.

- Administrative Law**: Governs the activities of state administrative bodies and the relationship between citizens and the state.

- Economic and Taxation Law**: Regulates business activities, investment, and taxation. This area includes laws on budget, finance, and privatization.

- Family Law**: Governs marriage, divorce, and parental rights.

- Labor Law**: Regulates employment relations.

- Military and Defence Law**: Covers the organization and functioning of the armed forces and defence sector.

- Laws on social protection, healthcare, education, culture, media, and political rights.**

Judicial Institutions:

- Constitutional Court**: Reviews the constitutionality of laws and official acts.

- Supreme Court**: The highest court of appeal for civil, criminal, and administrative cases.

- Arbitration Court**: Handles economic and commercial disputes.

- City and Raion (District) Courts**: Courts of first instance.

Protection of Fundamental Rights:

The Transnistrian Constitution nominally guarantees a range of fundamental human rights, including freedom of speech, assembly, religion, and the press, as well as the right to a fair trial. However, numerous reports by international human rights organizations (such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch) and governmental bodies (e.g., U.S. State Department) have documented significant shortcomings in the protection of these rights.

Commonly cited issues include:

- Restrictions on freedom of expression and media, with state control over major news outlets.

- Limitations on freedom of assembly and association for opposition groups and critical NGOs.

- Problems with due process, arbitrary arrest and detention, and lack of judicial independence.

- Discrimination against Moldovan/Romanian speakers, particularly regarding education in the Romanian language with the Latin alphabet (see #Romanian-language schools issue).

- Harassment of minority religious groups.

Because Transnistria is not recognized, its residents have limited access to international human rights protection mechanisms. While some cases have been brought before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), these typically involve holding Russia or Moldova responsible due to their influence or de jure sovereignty over the territory.

In June 2016, Transnistria enacted a law criminalizing public criticism of the Russian military mission or presenting "false" interpretations of its role, with penalties including imprisonment. This law has been widely condemned as a severe restriction on freedom of speech.

5.6. Symbols

Transnistria has its own state symbols, reflecting its distinct identity and Soviet legacy. The state flag is a horizontal triband of red-green-red, with a golden hammer and sickle in the canton of the top red band. A plain version of the flag without the hammer and sickle is used for non-governmental (civil) purposes. In 2017, a second flag, a tricolor of white-blue-red closely resembling the flag of Russia but with a 1:2 ratio, was adopted for co-official use alongside the state flag.

The state emblem is a modified version of the emblem of the former Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, retaining elements such as the hammer and sickle, a red star, and agricultural symbols (wheat, corn, grapes, fruits) framed by sun rays over the Dniester River. A scroll bears the state's name in Russian, Moldovan (Cyrillic script), and Ukrainian.

The national anthem is "Мы славим тебя, ПриднестровьеMy slavim tebya, PridnestrovieRussian", which translates to "We Sing the Praises of Transnistria".

6. Military

Transnistria maintains its own armed forces and security apparatus, which play a crucial role in upholding its de facto independence. Additionally, the presence of Russian military forces in the region is a significant factor in its security landscape and a major point of contention in the conflict resolution process.

6.1. Transnistrian armed forces

The Armed Forces of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic were officially created on September 6, 1991. They consist of:

- Land Forces**: These form the core of the military and are organized into several motorized infantry brigades, typically stationed in major towns like Tiraspol, Bender, Rîbnița, and Dubăsari. Estimates of active personnel vary, often cited as being between 4,500 and 7,500 soldiers. The military also has a reserve component, potentially allowing for mobilization of up to 15,000-25,000 additional personnel.

- Air Force Component**: This is very limited, primarily consisting of a few transport and utility helicopters (e.g., Mi-8, Mi-2) and possibly some older fixed-wing aircraft like An-2 or An-26. They do not possess significant combat air capabilities.

- Other Security Structures**: These include the Ministry of State Security (MGB), border guards, and internal troops, which supplement the regular military.

Equipment: The Transnistrian military primarily uses Soviet-era equipment. This includes:

- Tanks (e.g., T-64)

- Armoured personnel carriers (APCs) and infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs)

- Artillery pieces (field guns, howitzers)

- Anti-aircraft systems

- Anti-tank weapons

Specific numbers vary by source and over time, but reports from the mid-2000s indicated around 18 tanks, over 100 armored vehicles, and dozens of artillery pieces. Much of this equipment likely originated from the stocks of the former Soviet 14th Army.

Conscription: Transnistria employs a system of conscription, requiring male citizens to serve in the military, typically for one year. This provides a pool of trained reservists.

Operational Capabilities: The Transnistrian armed forces are primarily geared towards defense and maintaining internal security. While not comparable to larger national armies, they proved capable during the 1992 war (with significant Russian support) of resisting Moldovan forces. Their continued existence is a key element of Transnistria's de facto statehood.

6.2. Russian military presence

A significant Russian military presence has been maintained in Transnistria since the collapse of the Soviet Union, evolving from the former Soviet 14th Guards Army. This presence has two main components:

1. **Peacekeeping Force**: Following the July 1992 ceasefire agreement that ended the Transnistria War, a tripartite peacekeeping force was established. This includes Russian, Moldovan, and Transnistrian contingents operating under the Joint Control Commission (JCC). The Russian contingent is the largest and most influential part of this force.

2. **Operational Group of Russian Forces (OGRF)**: This is the successor to the 14th Army. Its official tasks include participating in the peacekeeping mission and guarding the massive Cobasna ammunition depot, which stores tens of thousands of tons of Soviet-era munitions. The OGRF's size has been reduced over the years but is estimated to be around 1,200-1,500 troops.

Background and Legal Basis:

- The initial presence of the 14th Army was a legacy of Soviet military deployments.

- The 1992 ceasefire agreement legitimized a Russian peacekeeping role.

- At the 1999 OSCE Istanbul Summit, Russia committed to withdrawing its troops and munitions from Transnistria. While some equipment and ammunition were removed in the early 2000s, the process stalled, and a full withdrawal has not occurred. Russia argues that the remaining troops are legitimate peacekeepers and guards for the Cobasna depot, and will remain until a political settlement is reached.

Controversies and International Stance:

- Moldova considers the continued presence of the OGRF (beyond the agreed peacekeeping contingent) a violation of its sovereignty and an illegal occupation, demanding its unconditional withdrawal. This position is supported by many Western countries and international organizations like NATO.

- The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe declared Transnistria a "zone of Russian occupation" in March 2022.

- The Cobasna depot is a major concern due to the risk of accidental explosion or illicit proliferation of weapons.

- The Russian military presence is seen as a key factor enabling Transnistria's de facto independence and giving Russia significant leverage in the region.

Impact of the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine:

- The invasion heightened concerns that Russia might use its forces in Transnistria to open a new front against Ukraine or to destabilize Moldova.

- Ukraine sealed its border with Transnistria, making resupply and rotation of Russian forces more difficult, as they traditionally transited through Ukrainian territory or Chișinău International Airport (which became more restrictive).

- The Transnistrian authorities have denied any plans to involve their forces or the Russian contingent in the Ukraine war.

The Russian military presence remains a core issue in the Transnistria conflict, deeply intertwined with regional security and the prospects for a political settlement.

6.3. Arms control and disarmament

Arms control and disarmament in Transnistria primarily revolve around two key issues: the vast Soviet-era ammunition stockpiles, particularly at the Cobasna depot, and persistent allegations of illicit arms trafficking originating from or transiting through the region.

Soviet-era Ammunition Stockpiles (Cobasna Depot):

- Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Russian 14th Army left behind an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 tons of weapons, ammunition, and military equipment in Transnistria, with the largest concentration at Cobasna, near the Ukrainian border. This is often described as one of the largest, if not the largest, ammunition dumps in Eastern Europe.

- International Commitments**: At the 1999 OSCE Istanbul Summit, Russia committed to withdrawing or destroying these stockpiles. Some progress was made in the early 2000s:

- In 2000-2001, Russia withdrew 141 self-propelled artillery pieces and other armored vehicles, and locally destroyed 108 T-64 tanks and 139 other pieces of equipment limited by the CFE Treaty.

- In 2002-2003, further armored vehicles were destroyed, and significant quantities of ammunition were transported back to Russia (e.g., 1,153 tons in 2001, 2,405 tons in 2002, and 16,573 tons in 2003, according to OSCE data).

- Stalemate**: The process stalled after March 2004. A large quantity of ammunition (estimated around 20,000 tons) remains. Russia cites logistical difficulties, the need for Transnistrian consent, and the unresolved political status as reasons for the delay.

- Security and Environmental Risks**: The aging ammunition at Cobasna poses a significant risk of accidental explosion, which could have catastrophic humanitarian and environmental consequences. There are also concerns about the security of the depot and potential for proliferation.

- OSCE Involvement**: The OSCE has been involved in monitoring and verification efforts and has repeatedly called for the completion of the withdrawal process. Transnistrian authorities have, at times, allowed OSCE inspections.

Allegations of Illicit Arms Trafficking:

- Transnistria has frequently been accused of being a hub for illicit arms trafficking, particularly in small arms and light weapons (SALW), originating from its own production facilities (a legacy of Soviet industry) or from the vast stockpiles.

- Denials and Evidence**: Transnistrian authorities consistently deny involvement in arms manufacturing for export or trafficking.

- International bodies and experts have offered mixed assessments. While the potential exists, concrete, large-scale evidence of ongoing state-sponsored trafficking has often been elusive.

- An OSCE mission spokesman, Claus Neukirch, stated in the mid-2000s that there was no convincing evidence of widespread arms sales from Transnistria.

- A 2007 UN-backed report by SEESAC (South Eastern and Eastern Europe Clearinghouse for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons) suggested that past evidence of illicit production and trafficking might have been exaggerated, though some trafficking of light weapons likely occurred before 2001. The report noted that historically low transparency reinforced negative perceptions.

- EU and OSCE officials in 2005 stated there was no evidence Transnistria "has ever trafficked arms or nuclear material," attributing some alarm to Moldovan efforts to pressure Transnistria.

- The lack of transparency and full access for international monitors has made definitive assessments difficult. The primary concern is often less about large-scale, state-directed trafficking and more about the potential for smaller-scale leakage from stockpiles or corruption-facilitated deals.

International efforts continue to push for transparency, complete removal or destruction of the Cobasna stockpiles, and robust arms control measures to enhance regional security.

- International Commitments**: At the 1999 OSCE Istanbul Summit, Russia committed to withdrawing or destroying these stockpiles. Some progress was made in the early 2000s:

7. Administrative divisions

Transnistria is subdivided into five districts (raions) and two municipalities (cities with republican status). These administrative units are listed below, generally from north to south. Russian names and transliterations are provided, as Russian is a primary language of administration.

- Municipalities (Cities of republican significance)**:

1. Tiraspol (ТираспольTiraspol'Russian) - The capital city. It is geographically surrounded by but administratively distinct from Slobozia District.

2. Bender (БендерыBenderyRussian; also known as TighinaTighinaRomanian) - Situated on the western bank of the Dniester, in historical Bessarabia, and geographically outside the main Transnistrian strip. It is controlled by PMR authorities who consider it part of their administrative organization, though Moldova views it as a separate municipality.

- Districts (Raions)**:

1. Camenca District (Каменский районKamenskiy rayonRussian)

- Administrative center: Camenca (КаменкаKamenkaRussian)

- Key characteristics: Northernmost district, largely agricultural.

2. Rîbnița District (Рыбницкий районRybnitskiy rayonRussian)

- Administrative center: Rîbnița (РыбницаRybnitsaRussian)

- Key characteristics: Contains the large Moldova Steel Works, significant Ukrainian population.

3. Dubăsari District (Дубоссарский районDubossarskiy rayonRussian)

- Administrative center: Dubăsari (ДубоссарыDubossaryRussian)

- Key characteristics: Site of a major hydroelectric power station. Some parts of the de jure Dubăsari district of Moldova located on the eastern bank are controlled by Moldova, not the PMR.

4. Grigoriopol District (Григориопольский районGrigoriopol'skiy rayonRussian)

- Administrative center: Grigoriopol (ГригориопольGrigoriopol'Russian)

- Key characteristics: Significant Moldovan population, agricultural area.

5. Slobozia District (Слободзейский районSlobodzeyskiy rayonRussian)

- Administrative center: Slobozia (СлободзеяSlobodzeyaRussian)

- Key characteristics: Southernmost district, agricultural, surrounds Tiraspol. Contains the Cuciurgan power station in Dnestrovsc.

Each district is further subdivided into towns and communes (which may consist of one or more villages).

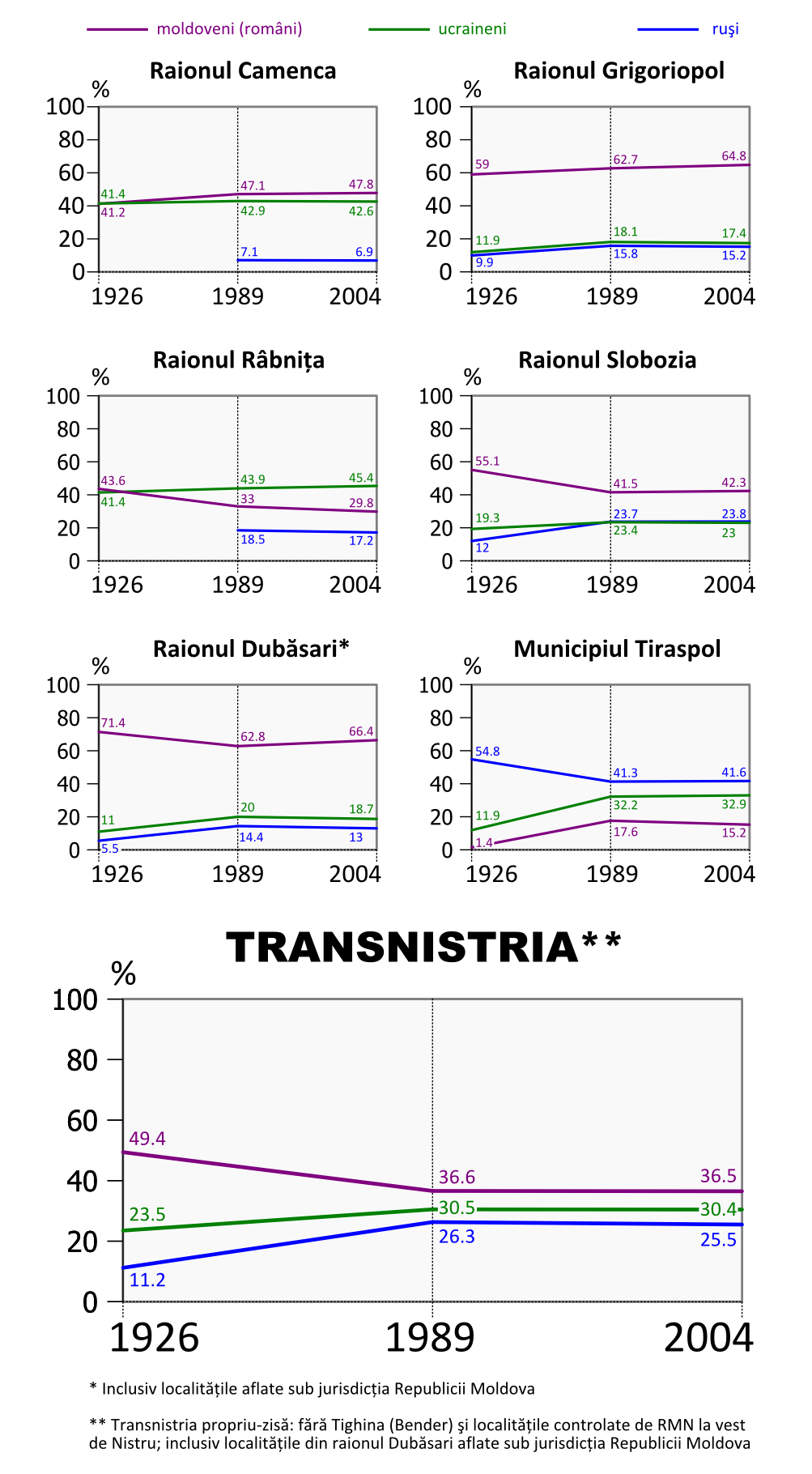

The following table provides an overview based on available census data, primarily from the 2004 Transnistrian census for ethnic composition and the 2015 census for population and area, highlighting key demographic and economic features. Note that data reliability can be a concern.

| Name | Capital | Area (km²) | Population (2015 Census) | Ethnic composition (2004 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camenca District (Каменский районKamenskiy rayonRussian) | Camenca (CamencaKamencaRomanian; КаменкаKamenkaRussian; Кам'янкаKam'yankaUkrainian) | 168 mile2 (436 km2) | 21,000 | 47.82% Moldovans, 42.55% Ukrainians, 6.89% Russians, 2.74% others |

| Rîbnița District (Рыбницкий районRybnitskiy rayonRussian) | Rîbnița (RîbnițaRîbnițaRomanian; РыбницаRybnitsaRussian; РибницяRybnytsyaUkrainian) | 328 mile2 (850 km2) | 69,000 | 29.90% Moldovans, 45.41% Ukrainians, 17.22% Russians, 7.47% others |

| Dubăsari District (Дубоссарский районDubossarskiy rayonRussian) | Dubăsari (DubăsariDubăsariRomanian; ДубоссарыDubossaryRussian; ДубоссариDubossaryUkrainian) | 147 mile2 (381 km2) | 31,000 | 50.15% Moldovans, 28.29% Ukrainians, 19.03% Russians, 2.53% others |

| Grigoriopol District (Григориопольский районGrigoriopol'skiy rayonRussian) | Grigoriopol (GrigoriopolGrigoriopolRomanian; ГригориопольGrigoriopol'Russian; ГригоріопольHryhoriopol'Ukrainian) | 317 mile2 (822 km2) | 40,000 | 64.83% Moldovans, 15.28% Ukrainians, 17.36% Russians, 2.26% others |

| Slobozia District (Слободзейский районSlobodzeyskiy rayonRussian) | Slobozia (SloboziaSloboziaRomanian; СлободзеяSlobodzeyaRussian; СлободзеяSlobodzeyaUkrainian) | 337 mile2 (873 km2) | 84,000 | 41.51% Moldovans, 21.71% Ukrainians, 26.51% Russians, 10.27% others |

| City of Tiraspol (ТираспольTiraspol'Russian) | Tiraspol (TiraspolTiraspolRomanian; ТираспольTiraspol'Russian; ТираспольTyraspol'Ukrainian) | 79 mile2 (205 km2) | 129,000 | 18.41% Moldovans, 32.31% Ukrainians, 41.44% Russians, 7.82% others |

| City of Bender (БендерыBenderyRussian) | Bender (TighinaTighinaRomanian; БендерыBenderyRussian; БендериBenderyUkrainian) | 37 mile2 (97 km2) | 91,000 | 25.03% Moldovans, 17.98% Ukrainians, 43.35% Russians, 13.64% others |

8. Economy

Transnistria's economy is a mixed economy that evolved from a heavily industrialized segment of the Moldavian SSR. Since its de facto secession, it has faced challenges due to its unrecognized status, limited access to international markets, and dependence on external support, primarily from Russia. The economy is characterized by a significant state influence, a few large industrial enterprises, and a substantial shadow economy component according to some observers. Issues of social equity, labor conditions, and environmental sustainability are pertinent concerns.

8.1. Economic history

During the Soviet era, Transnistria was developed as an industrial hub within the largely agricultural Moldavian SSR. In 1990, it accounted for about 40% of Moldova's GDP and 90% of its electricity production, despite having only 17% of its population. Key industries included steel production, machine building, textiles, and power generation.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and the 1992 war, Transnistria initially attempted to maintain a Soviet-style planned economy. However, by the late 1990s and early 2000s, it underwent a process of privatisation, often non-transparent, which led to the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few individuals and groups. The Sheriff conglomerate emerged as the dominant economic player, with interests spanning retail, telecommunications, fuel distribution, media, banking, and the KVINT distillery.

The region's economy has been heavily reliant on Russian support, including direct financial aid and, crucially, the provision of natural gas at heavily subsidized prices or effectively free of charge, as Transnistria accumulates debt to Gazprom that is unlikely to be repaid by Tiraspol authorities. This subsidised energy has been vital for its heavy industries and for generating electricity, some of which is exported to Moldova proper.

Periodic economic crises have occurred, often linked to external factors such as changes in customs regimes with Moldova and Ukraine (e.g., 2006 customs crisis) or regional geopolitical shifts. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine severely impacted Transnistria's economy by cutting off its direct trade routes through Ukraine, increasing its dependence on Moldova for transit.

Social consequences of these economic shifts include periods of high unemployment, wage arrears, and emigration of the working-age population.

8.2. Macroeconomics

Reliable and internationally verified macroeconomic data for Transnistria is often difficult to obtain due to its unrecognized status. Data is primarily provided by Transnistrian authorities.

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP)**: According to Transnistrian authorities, the GDP in 2007 was approximately 799.00 M USD. By 2012, it was estimated at around 1.00 B USD. The Pridnestrovian Republican Bank reported a GDP of 1.20 B USD for 2021.

- GDP per capita**: In 2007, it was around 1.50 K USD, reportedly rising to 2.14 K USD, which was cited as higher than Moldova's at the time. For 2021, the nominal GDP per capita was reported as 2.58 K USD.

- Inflation**: Has been variable, sometimes experiencing high rates. For example, in 2007, the inflation rate was reported at 19.3%.

- Public Debt**: Transnistria has accumulated significant external debt, primarily to Russia for gas supplies. In 2004, total debts were reported at 1.20 B USD. By March 2007, the debt to Gazprom alone for natural gas had reportedly increased to 1.30 B USD, and this figure has continued to grow substantially over the years, reaching several billion US dollars.

- Employment and Poverty**: Unemployment and underemployment have been persistent issues. Poverty levels are a concern, though precise, comparable data is scarce. Many rely on pensions (some subsidized by Russia) and remittances from relatives working abroad.

- Budget**: The government budget often runs a deficit, which has historically been covered by external aid, revenues from state enterprises, or privatization proceeds. For example, the 2007 budget was 246.00 M USD with an estimated deficit of 100.00 M USD. The 2008 budget was 331.00 M USD with an 80.00 M USD deficit.

- Currency**: Transnistria issues its own currency, the Transnistrian ruble (PRB), through the Transnistrian Republican Bank. It is not convertible outside Transnistria. Its exchange rate is managed by the central bank.

The economic situation worsened significantly in the first half of 2023, with imports rising to 1.32 B USD and exports falling to 346.00 M USD, resulting in a trade deficit of 970.00 M USD. This deficit was largely financed by the non-payment for Russian natural gas. The energy crisis in early 2025, following the halt of Russian gas transit via Ukraine, severely impacted the economy, with general gas supplies cut and planned power outages.

8.3. External trade

Transnistria's external trade patterns have shifted over time, influenced by its political status, regional agreements, and geopolitical events.

Historical Patterns:

In the early 2000s, over 50% of Transnistria's exports went to CIS countries, primarily Russia, but also Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova (which Transnistrian authorities consider a foreign trading partner). Main non-CIS markets included Italy, Egypt, Greece, Romania, and Germany. The CIS accounted for over 60% of imports, with the EU contributing about 23%. Key imports included non-precious metals, food products, and electricity.

Impact of Moldova-EU DCFTA:

After Moldova signed an Association Agreement and a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) with the European Union in 2014, Transnistrian companies, by registering in Chișinău, gained tariff-free access to EU markets. This led to a significant reorientation of trade:

- In 2015, 27% of Transnistria's 189.00 M USD exports went to the EU, while exports to Russia fell to 7.7%. This trend continued, with the EU becoming a major export destination.

- In 2020, the Transnistrian Customs reported exports of 633.10 M USD and imports of 1.05 B USD.

Impact of the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine:

- The closure of the Ukrainian border with Transnistria in March 2022 forced all Transnistrian trade to transit through Moldovan-controlled territory. This increased Moldova's control over Transnistrian trade and required Transnistrian businesses to comply more fully with Moldovan and EU standards.

- Trade data for the first half of 2023 showed:

- Exports: 48% to the rest of Moldova, over 33% to the EU, and 9% to Russia.

- Imports: 68% from Russia (largely gas), 14% from the EU, and 7% from Moldova.

Customs Regulations and Disputes:

- The 2006 joint Moldova-Ukraine customs regime required Transnistrian companies to register with Moldovan authorities for legal trade.

- In 2024, Moldova began requiring Transnistrian companies to pay customs duties to the Moldovan budget, ending a long-standing preferential treatment. This was met with strong protests from Tiraspol.

Main Export and Import Products:

- Exports**: Metals and metal products (primarily from Moldova Steel Works), electricity (from Cuciurgan power station), textiles (from Tirotex), machinery, food products, and alcoholic beverages (e.g., Kvint brandy).

- Imports**: Natural gas, raw materials for industry, consumer goods, food products.

The region's trade remains vulnerable to political developments and its unresolved status, which complicates access to international finance and markets. The dependence on Russian gas and the need to transit goods through Moldova are key economic realities.

8.4. Main economic sectors

Transnistria's economy is characterized by a few dominant industrial sectors, a legacy of Soviet-era planning, alongside agriculture and a growing service sector. Labor practices, workers' rights, and environmental impacts vary across these sectors and have been subjects of concern.

1. **Steel Production**:

- The Moldova Steel Works (MMZ) in Rîbnița is the flagship industrial enterprise and a major contributor to Transnistria's exports and budget revenue (reportedly accounting for about 60% of budget revenue at certain times). It was formerly part of the Russian Metalloinvest holding.

- The plant produces steel billets and wire rod, primarily for export.

- Labor conditions at such heavy industrial sites are typical of older Soviet-era plants, with ongoing needs for modernization and safety improvements. Environmental impact, particularly air emissions, is a concern for the local area.

2. **Electricity Generation**:

- The Moldavskaya GRES (Cuciurgan power station) in Dnestrovsc is one of the largest thermal power plants in Eastern Europe. It is owned by the Russian company Inter RAO.

- It primarily runs on natural gas supplied by Russia (historically at heavily subsidized rates). It also has the capability to use coal and fuel oil.

- The plant supplies electricity to Transnistria, Moldova proper (a significant portion of Moldova's needs), and sometimes for export.

- This sector is critical for the regional economy and also a point of energy leverage. Environmental concerns relate to emissions from burning fossil fuels. The halt of Russian gas transit via Ukraine in early 2025 forced the plant to rely more on coal, exacerbating these concerns and impacting output.

3. **Textiles and Light Manufacturing**:

- Tirotex in Tiraspol is one of Europe's largest textile companies, specializing in cotton fabrics and garments. It is a major employer.

- Other light manufacturing includes footwear, apparel, and some food processing.

- Labor conditions in the textile sector, often employing a large female workforce, can be subject to issues typical of the global garment industry, such as low wages and intensive work, though specific independent assessments are limited.

4. **Alcoholic Beverages**:

- The KVINT distillery in Tiraspol is renowned for its brandies (cognac-style), wines, and vodka. It is a significant exporter and a well-known Transnistrian brand.

- The company has a long history and contributes to the local agricultural economy through grape sourcing.

5. **Agriculture**:

- The fertile chernozem soils support the cultivation of grains (wheat, corn), sunflowers, sugar beets, fruits, and vegetables.

- Land ownership and farming structures have transitioned from Soviet collective farms, with a mix of larger agricultural enterprises and smaller private farms.

- Environmental concerns include soil degradation and water pollution from agricultural runoff.

6. **Other Sectors**:

- Machine-building and metalworking**: A legacy of Soviet industry, producing various types of machinery and equipment, though often facing challenges with modernization and market access.

- Construction**: Driven by local demand and some investment projects.

- Trade and Services**: Retail, transportation, and other services form a growing part of the economy, largely dominated by local conglomerates like Sheriff.

Labor Practices and Workers' Rights:

Trade unions exist, but their independence and effectiveness in advocating for workers' rights in a politically controlled environment are questionable. Issues such as timely wage payments, workplace safety, and the right to organize and bargain collectively are areas where robust, independent oversight is often lacking due to Transnistria's isolation.

Environmental Impact: