1. Overview

North Macedonia is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, situated in the northern part of the larger geographical region of Macedonia. It is bordered by Kosovo and Serbia to the north, Bulgaria to the east, Greece to the south, and Albania to the west. The capital and largest city, Skopje, is home to a significant portion of its approximately 1.83 million inhabitants. The country's geography is characterized by mountainous terrain, deep basins and valleys, and significant rivers like the Vardar, as well as large natural lakes such as Ohrid, Prespa, and Dojran.

The history of the region dates back to ancient Paeonia, followed by incorporation into the Kingdom of Macedon and later the Roman and Byzantine Empires. Slavic tribes settled in the area from the 6th century, leading to periods under the Bulgarian and Serbian Empires before five centuries of Ottoman rule. The early 20th century saw the Balkan Wars and the region's incorporation into Serbia, followed by periods of Bulgarian rule during both World Wars. After World War II, it became the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, a constituent republic of Yugoslavia. It declared independence peacefully in 1991. A significant naming dispute with Greece was resolved in 2019 with the adoption of the name "Republic of North Macedonia." The country experienced an internal conflict with ethnic Albanian insurgents in 2001, resolved by the Ohrid Agreement, which aimed to improve inter-ethnic relations and minority rights. North Macedonia became a member of NATO in 2020 and is a candidate for European Union membership, a path that involves ongoing reforms focused on democratic development and human rights.

North Macedonia is a parliamentary republic. Its political system has evolved significantly since independence, with a focus on multi-party democracy and addressing inter-ethnic relations. The economy is an open, developing one, having transitioned from a socialist system. Major sectors include manufacturing, agriculture, and services, with tourism, particularly around Lake Ohrid, being an important contributor. The country's infrastructure, including transport and telecommunications, has been undergoing modernization.

The population is ethnically diverse, with Macedonians being the majority, and a large Albanian minority, alongside Turks, Roma, Serbs, and others. Macedonian is the official language, with Albanian also holding official status at the state level. Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Islam are the predominant religions. Culturally, North Macedonia boasts a rich heritage in arts, architecture, music, and literature, influenced by its Byzantine, Slavic, and Ottoman past. It is known for its medieval frescoes, traditional music, and distinct cuisine. The nation actively participates in international sports, with football and handball being popular.

2. Names and Etymology

The naming of North Macedonia has been a subject of significant historical and political discussion, primarily revolving around the term "Macedonia" and its implications. The resolution of the naming dispute with Greece led to the country's current official name.

2.1. Etymology and Historical Names

The name "Macedonia" derives from the Greek word ΜακεδονίαMakedoníaGreek, Ancient, which referred to the ancient kingdom of Macedon and later the geographical region of Macedonia. The ancient Macedonians were called ΜακεδόνεςMakedónesGreek, Ancient. This term is believed to ultimately derive from the ancient Greek adjective Makednos (μακεδνόςmakednósGreek, Ancient), meaning 'tall' or 'taper'. This adjective shares the same root as μακρόςmakrósGreek, Ancient, meaning 'long', 'tall', or 'high' in ancient Greek. Thus, the name "Macedonia" is thought to have originally meant 'highland' or 'land of the tall people', possibly describing the physical characteristics of the ancient inhabitants or the mountainous nature of their homeland. Linguist Robert S. P. Beekes suggested that both terms are of Pre-Greek substrate origin and cannot be explained through Indo-European morphology, although linguist Filip De Decker found Beekes's arguments insufficiently supported.

During the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, the name "Macedonia" as a geographical denomination was largely forgotten, apart from its use for the Byzantine theme of Macedonia, which was located in a different area (modern Thrace). The name was revived in the early 19th century, primarily through the efforts of Greek and Bulgarian nationalist movements. For educated Greeks, "Macedonia" was the historical Greek land of kings Philip II and Alexander the Great. Bulgarian nationalists also accepted "Macedonia" as a regional denomination, considering it one of the "historic" Bulgarian lands. By the mid-19th century, with the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire, the term "Macedonia" re-entered popular consciousness to describe the broader geographical region. In the early 20th century, the region became a contested national cause among Bulgarian, Greek, and Serbian nationalists.

During the interwar period, the use of the name "Macedonia" was prohibited in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia due to policies of Serbianisation aimed at the local Slavic-speaking population. The name "Macedonia" was officially adopted for the first time at the end of World War II by the newly established Socialist Republic of Macedonia, which became one of the six constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

2.2. Naming Dispute and the Prespa Agreement

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia and the declaration of independence in 1991, the country adopted the constitutional name "Republic of Macedonia." This immediately led to a major dispute with Greece. Greece objected to the use of the name "Macedonia" without a geographical qualifier, arguing that it implied territorial claims on its own northern region of Macedonia and an appropriation of ancient Hellenic history and symbols, such as the Vergina Sun (used on the republic's first flag) and figures like Alexander the Great. Greece also opposed the use of the term "Macedonian" for the country's largest ethnic group and its language, as ethnic Greeks also identify as Macedonians in a regional Hellenic context. The dispute had significant international implications, with Greece imposing an economic embargo in 1994-1995 and blocking Macedonia's accession to NATO and the European Union.

As a result of the dispute, the country was admitted to the United Nations in 1993 under the provisional name "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" (abbreviated as "FYROM" or "FYR Macedonia"). This name was used by many international organizations, although numerous countries recognized it by its constitutional name, "Republic of Macedonia."

Years of negotiations, mediated by the UN envoy Matthew Nimetz, eventually led to a breakthrough. On June 17, 2018, the Prespa Agreement was signed by the foreign ministers of Macedonia and Greece. This agreement stipulated that the country would change its name to the "Republic of North Macedonia." In return, Greece would lift its objections to North Macedonia's NATO and EU membership aspirations. The agreement also addressed issues of identity, acknowledging the Macedonian language (of Slavic origin) and clarifying that the term "Macedonian" for citizens of North Macedonia refers to their citizenship and is distinct from ancient Hellenic civilization. Both countries agreed to remove irredentist content from textbooks and maps.

A non-binding referendum on the Prespa Agreement was held in Macedonia on September 30, 2018. While over 90% of voters supported the agreement, turnout was only around 37%, below the 50% threshold required for it to be constitutionally valid, largely due to boycotts. Despite this, the Macedonian parliament proceeded with constitutional changes. On January 11, 2019, the parliament approved the constitutional amendment to change the country's name. The Greek Parliament ratified the Prespa Agreement and the Protocol on the Accession of North Macedonia to NATO on January 25 and February 8, 2019, respectively. The name change to "Republic of North Macedonia" officially came into effect on February 12, 2019. Despite the official renaming, the country is still often unofficially referred to as "Macedonia" by many of its citizens and local media.

3. History

The history of North Macedonia encompasses ancient civilizations, medieval empires, centuries of Ottoman rule, national awakening, its role within Yugoslavia, and its journey as an independent nation, marked by significant social and political transformations.

3.1. Early History

The region of present-day North Macedonia roughly corresponds to the ancient kingdom of Paeonia. The Paeonians were a people of Thracian or Thraco-Illyrian origin. The northwest was inhabited by the Dardani, an Illyrian tribe, while the southwest was inhabited by tribes like the Enchelei, Pelagones, and Lyncestae, generally regarded as Molossian tribes of the northwestern Greek group. The headwaters of the Axios river (Vardar) are mentioned by Homer as the home of Paeonian allies of Troy.

In the late 6th century BC, the Persian Achaemenid Empire under Darius the Great subjugated the Paeonians, incorporating the area into its vast territories. After the Persian defeat in the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 479 BC, the Persians eventually withdrew from their European holdings.

In 356 BC, Philip II of Macedon absorbed the regions of Upper Macedonia (Lynkestis and Pelagonia) and the southern part of Paeonia (Deuriopus) into the Kingdom of Macedonia. His son, Alexander the Great, conquered the remainder of the region and incorporated it into his empire, reaching as far north as Scupi (modern Skopje), though Scupi and its surroundings largely remained part of Dardania. After Alexander's death, Celtic armies raided the southern regions.

The Roman Republic conquered the region in the 2nd century BC and established the province of Macedonia in 146 BC. Under Diocletian, the province was subdivided. Most of modern North Macedonia fell within Macedonia Salutaris (or Macedonia Secunda), with Stobi as its capital. The Scupi area became part of the Province of Moesia. While Greek remained dominant in the eastern Roman Empire, particularly south of the Jireček Line, Latin also spread to some extent in Macedonia. Early societal structures involved tribal kingdoms and interactions often characterized by conflict and alliance with neighboring powers like the Macedonians and later the Romans.

3.2. Medieval Period

Beginning in the late 6th century AD, Slavic tribes, often led by Avars, settled in the Balkan region, including North Macedonia. These Slavic groups, such as the Draguvite, Sagudate, and Strymonoi, established communities, sometimes merging with the local populations. Around 680 AD, a Bulgar leader named Kuber settled with a diverse group of followers, including Bulgars, Byzantines, Slavs, and Germanic peoples, in the region of Pelagonia.

During the reign of Presian I of Bulgaria in the 9th century, Bulgarian control extended over the Slavic tribes in and around Macedonia. The Slavic tribes in the region converted to Christianity around the 9th century during the reign of Tsar Boris I of Bulgaria. The Ohrid Literary School, established in Ohrid in 886 by Saint Clement of Ohrid under Boris I, became a major cultural center of the First Bulgarian Empire, alongside the Preslav Literary School, playing a crucial role in spreading the Cyrillic script.

After Sviatoslav's invasion of Bulgaria, the Byzantines took control of East Bulgaria. Samuil was proclaimed Tsar of a revived Bulgarian Empire, moving his capital first to Skopje and then to Ohrid, which had been a cultural and military center. However, after decades of conflict, the Byzantine Emperor Basil II decisively defeated Samuil's armies in 1014. By 1018, the Byzantines had restored control over the Balkans, and modern-day North Macedonia was incorporated into a new province called Bulgaria. The autocephalous Bulgarian Patriarchate was downgraded to the Archbishopric of Ohrid, under the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.

By the late 12th century, Byzantine decline saw the region contested by various political entities, including a brief Norman occupation in the 1080s. In the early 13th century, a revived Second Bulgarian Empire gained control of the region. However, plagued by political difficulties, the empire did not last, and the region came once again under Byzantine control in the early 14th century. Subsequently, in the 14th century, it became part of the expanding Serbian Empire under Tsar Stefan Dušan, who made Skopje his capital. Following Dušan's death, power struggles among nobles led to the fragmentation of the Serbian Empire, coinciding with the Ottoman Turks' advance into Europe.

3.3. Ottoman Rule

The Kingdom of Prilep, one of the successor states to the Serbian Empire, was conquered by the Ottomans at the end of the 14th century. Gradually, all of the central Balkans, including the territory of modern North Macedonia, fell under Ottoman domination for five centuries. The region was part of the Eyalet of Rumelia. The name Rumelia (RumeliRumeliTurkish) means "Land of the Romans" in Turkish, referring to the lands conquered from the Byzantine Empire. Over time, Rumelia Eyalet was reduced in size, and by the 19th century, the territory of Macedonia was part of the vilayets of Manastir (Bitola), Kosova (Skopje), and Selanik (Thessaloniki).

Ottoman rule brought significant social, cultural, and economic changes. A system of millets allowed religious communities some autonomy. However, the Christian population faced various forms of discrimination and economic hardship. Resistance movements emerged, notably the Karposh Uprising in 1689.

With the Bulgarian National Revival in the 19th century, many reformers, including the Miladinov brothers, Rayko Zhinzifov, Yoakim Karchovski, and Kiril Peychinovich, came from this region. The bishoprics of Skopje, Debar, Bitola, Ohrid, Veles, and Strumica voted to join the Bulgarian Exarchate after its establishment in 1870, reflecting a desire for ecclesiastical independence from the Greek-dominated Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and an assertion of Slavic/Bulgarian identity.

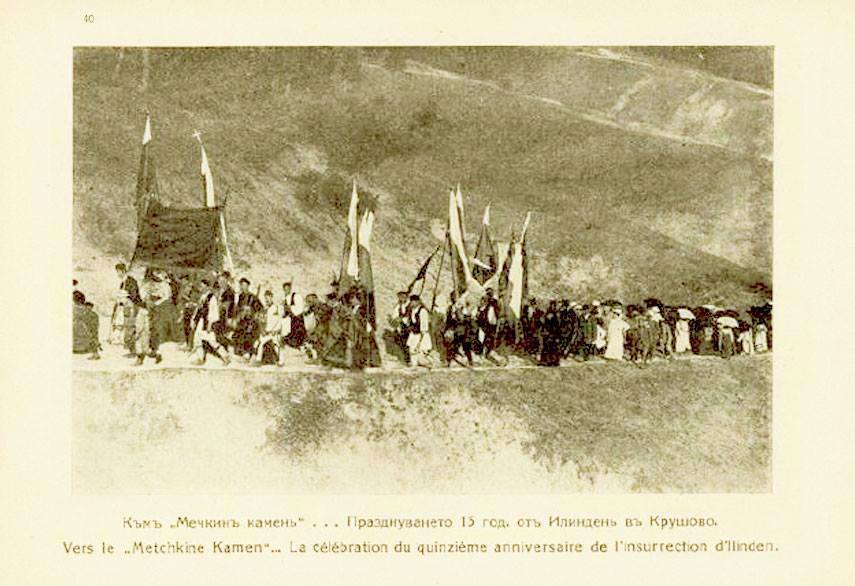

In the late 19th century, several movements aimed at establishing an autonomous Macedonia emerged. The earliest was the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees, later becoming the Secret Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (SMARO), and in 1905, the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO). While initially focused on Bulgarians, membership later extended to all inhabitants of European Turkey. The majority of its members were Macedonian Bulgarians. In 1903, IMRO organized the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising against Ottoman rule. Despite initial successes, including the formation of the short-lived Kruševo Republic under Nikola Karev, the uprising was brutally suppressed, resulting in significant loss of life. The Ilinden Uprising is considered a cornerstone in the development of Macedonian national consciousness and statehood, and its leaders are celebrated as national heroes.

3.4. Early 20th Century and World Wars

This period was marked by significant political upheavals, conflicts, and profound impacts on the population of the region.

3.4.1. Balkan Wars and Serbian Rule

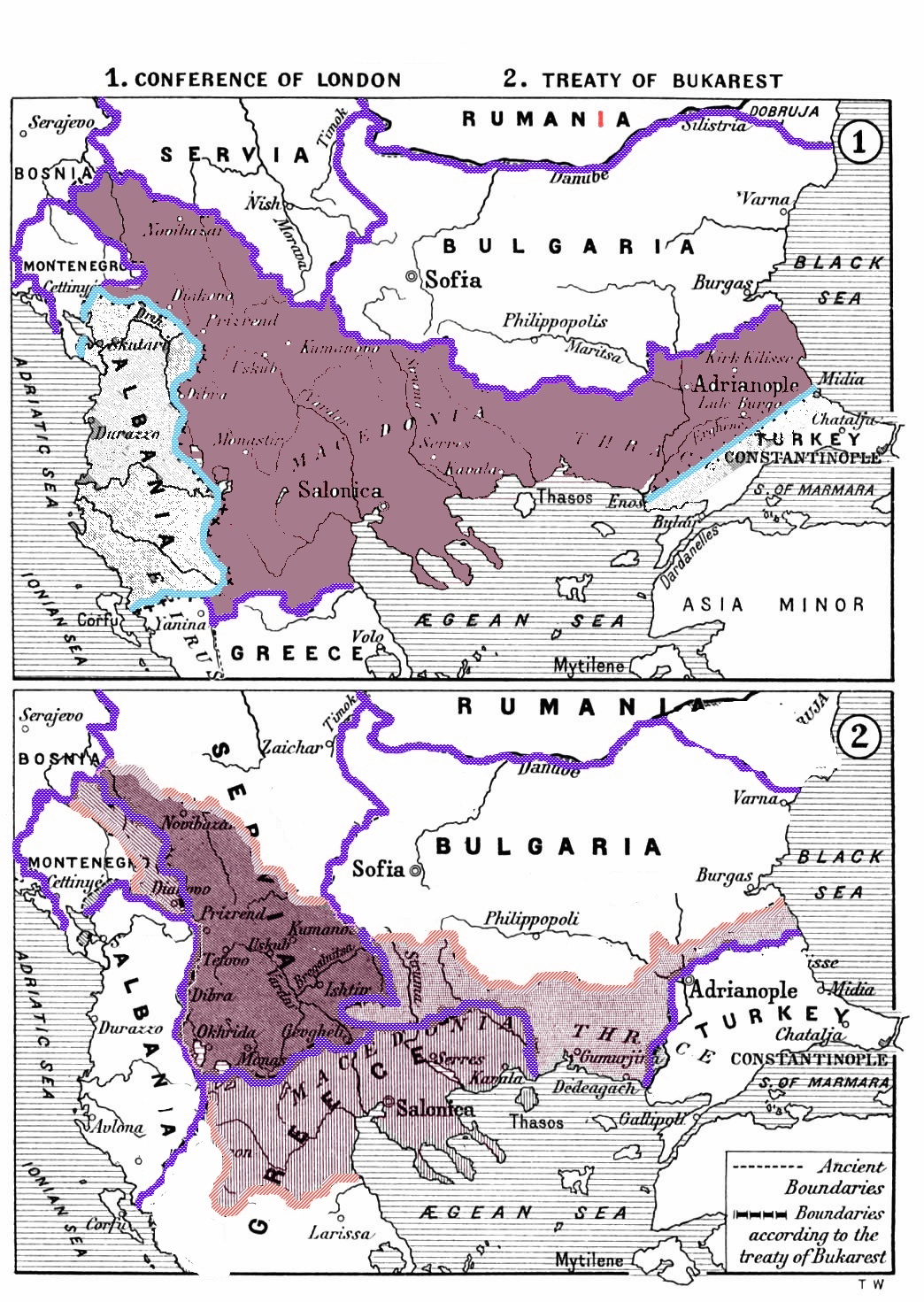

Following the two Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, most of its European territories were divided among Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia. The territory that would become North Macedonia was annexed by the Kingdom of Serbia according to the Treaty of Bucharest (1913), with the Strumica region initially going to Bulgaria but later passed to Serbia after World War I.

Under Serbian rule, an anti-Bulgarian campaign was implemented. Bulgarian schools and churches were closed, Exarchist clergy and teachers were expelled, and the use of Macedonian dialects and standard Bulgarian was proscribed. This led to the Ohrid-Debar uprising in 1913, organized by IMRO and local Albanians against Serbian rule. The uprising, which saw the temporary capture of towns like Gostivar, Struga, and Ohrid, was suppressed by the Serbian army, resulting in casualties and refugees fleeing to Bulgaria and Albania. The socio-political conditions under Serbian administration were characterized by efforts to assimilate the local Slavic population, often referred to as "Southern Serbs."

3.4.2. World War I

During World War I, most of present-day North Macedonia was occupied by Bulgaria after Serbia was invaded by the Central Powers in late 1915. The region was administered as the "Military Inspection Area of Macedonia." Bulgarian authorities initiated a policy of Bulgarisation, promoting the Bulgarian language, changing Serbian-sounding names, and replacing Serbian clergy and teachers with Bulgarians. Serbian books were destroyed. IMRO served as gendarmerie, enforcing this policy. Adult males were sent to labor camps or conscripted into the Bulgarian Army, and Serbian intellectuals were deported or executed. This occupation aimed to create pure Bulgarian territories by denationalizing the non-Bulgarian Slavic population. The impact on the local population was severe, with wartime hardships compounded by oppressive occupation policies.

3.4.3. Kingdom of Yugoslavia

After Bulgaria's capitulation and the end of World War I, the area returned to Serbian control as part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929). Anti-Bulgarian measures were reintroduced, including the expulsion of Bulgarian teachers and clergy and the dissolution of Bulgarian organizations. The Strumica region was annexed to Serbian Macedonia in 1919 under the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine.

The Serbian government pursued a policy of forced Serbianisation, which included systematic suppression of Bulgarian activists, altering family surnames, internal colonization (settling Serbian families in the region), exploitation of workers, and intense propaganda. Some 50,000 Serbian army and gendarmerie personnel were stationed in the area. By 1940, around 280 Serbian colonies were established. The region was administratively organized as the Vardar Banovina.

During the interwar period, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) promoted the concept of an Independent Macedonia. Its leaders advocated for the independence of the Macedonian territory split between Serbia and Greece. In 1924, the Communist International (Comintern) suggested a platform of a "United Macedonia", but this was rejected by Bulgarian and Greek communists. IMRO, along with the Macedonian Youth Secret Revolutionary Organization, conducted an insurgent war in Vardar Macedonia. In 1934, IMRO member Vlado Chernozemski assassinated King Alexander I of Yugoslavia.

Macedonist ideas, supported by the Comintern, grew in Yugoslav Vardar Macedonia and among the left diaspora in Bulgaria. In 1934, a Comintern resolution provided directions for recognizing a separate Macedonian nation and language for the first time.

3.4.4. World War II

During World War II, Yugoslavia was occupied by the Axis powers from 1941 to 1945. The Vardar Banovina was divided between Bulgaria and Italian-occupied Albania. Bulgarian Action Committees, often formed by former IMRO members, were established to prepare the region for Bulgarian administration. The leader of Vardar Macedonian communists, Metodi Shatorov, switched allegiance from the Yugoslav to the Bulgarian Communist Party and initially resisted military action against the Bulgarian Army.

Under German pressure, Bulgarian authorities were responsible for the deportation of over 7,000 Jews from Skopje and Bitola to Nazi concentration camps. This brutal occupation encouraged many in Vardar Macedonia to support Josip Broz Tito's Communist Partisan resistance movement after 1943, leading to the National Liberation War of Macedonia.

Following the Bulgarian coup d'état of 1944, Bulgarian troops, surrounded by German forces, fought their way back to Bulgaria's old borders. The new pro-Soviet Bulgarian government mobilized its army, which re-entered occupied Yugoslavia in October 1944 to block German forces withdrawing from Greece.

The foundations for a Macedonian state were laid during this period, notably with the Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) in 1944, which proclaimed the People's Republic of Macedonia. The human cost of the war and occupation was significant, but the resistance efforts played a crucial role in shaping the post-war political landscape.

3.5. Socialist Yugoslavia and Independence

This era saw the formalization of Macedonian statehood within a federal structure and its eventual emergence as a sovereign nation.

3.5.1. Socialist Republic of Macedonia

In December 1944, the Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) proclaimed the People's Republic of Macedonia as part of the People's Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. ASNOM remained an acting government until the end of the war. This marked a significant step in the codification of a distinct Macedonian national identity and state. The Macedonian language was codified by linguists of ASNOM, based on the phonetic alphabet of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić and the principles of Krste Misirkov.

As one ofthe six republics of the Yugoslav federation, the People's Republic of Macedonia (renamed the Socialist Republic of Macedonia in 1963, along with the federation's renaming to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) experienced considerable political, social, and economic development. National institutions were established, and the Macedonian language and culture were promoted. During the Greek Civil War (1946-1949), Macedonian communist insurgents supported the Greek communists, and many refugees fled from Greece to the Socialist Republic of Macedonia.

Compelled by the Soviet Union with a view towards creating a large South Slav Federation, in 1946, the new Bulgarian Communist government under Georgi Dimitrov agreed to give Bulgarian Macedonia to a United Macedonia. With the Bled Agreement in 1947, Bulgaria formally confirmed the envisioned unification, but postponed this until after the formation of the future Federation. This was the first time Bulgaria accepted the existence of a separate Macedonian ethnicity and language. However, after the Tito-Stalin split in 1948, the idea of a large South Slav Federation collapsed, Pirin Macedonia remained part of Bulgaria, and the Bulgarian Communist Party later revised its view on the Macedonian nation and language.

3.5.2. Declaration of Independence

North Macedonia officially celebrates September 8, 1991, as Independence Day (Ден на независностаDen na nezavisnostaMacedonian), following the referendum endorsing independence from Yugoslavia. The anniversary of the start of the Ilinden Uprising (August 2) is also officially celebrated as Day of the Republic.

The republic peacefully seceded from Yugoslavia, changing its official name to the "Republic of Macedonia." Robert Badinter, head of the Arbitration Commission of the Peace Conference on Yugoslavia, recommended EC recognition in January 1992. On January 15, 1992, Bulgaria was the first country to recognize its independence.

Macedonia remained at peace through the Yugoslav Wars of the early 1990s. Minor border adjustments with Yugoslavia were agreed upon. However, the new state faced immediate challenges, including international recognition (particularly due to the naming dispute with Greece) and internal cohesion. The Kosovo War in 1999 seriously destabilized the country, as an estimated 360,000 ethnic Albanian refugees from Kosovo sought refuge there. Though they departed shortly after the war, tensions rose, and Albanian nationalists on both sides of the border took up arms soon after, seeking autonomy or independence for Albanian-populated areas of Macedonia.

3.6. 21st Century

The 21st century has been marked by efforts to consolidate democracy, address inter-ethnic relations, and pursue international integration.

3.6.1. 2001 Albanian Insurgency

A conflict, known as the 2001 insurgency in Macedonia, took place between government forces and ethnic Albanian insurgents, primarily represented by the National Liberation Army (NLA), mostly in the north and west of the country, from February to August 2001. The insurgency was rooted in grievances among some ethnic Albanians regarding their status, rights, and representation within the state. The NLA, which had links to veterans of the Kosovo Liberation Army, sought greater autonomy or improved rights for Albanians.

The conflict ended with the intervention of a NATO ceasefire monitoring force and the signing of the Ohrid Agreement in August 2001. This agreement was a crucial turning point. Under its terms, the government agreed to devolve greater political power and cultural recognition to the Albanian minority. This included provisions for the official use of the Albanian language in municipalities where Albanians constituted a significant portion of the population, increased representation of Albanians in public institutions, and constitutional amendments recognizing Albanian identity. The Albanian side, in turn, agreed to abandon separatist demands, fully recognize all Macedonian institutions, and the NLA was to disarm and hand over its weapons to a NATO force.

The Ohrid Agreement significantly impacted inter-ethnic relations and minority rights, aiming to create a more inclusive and stable multi-ethnic state. However, implementation has been an ongoing process, and inter-ethnic tensions have occasionally flared, as seen in incidents in 2012 and armed confrontations with militant groups in 2007 and the 2015. In April 2017, protesters, reportedly mostly from the conservative VMRO-DPMNE party, stormed the Macedonian Parliament following the election of Talat Xhaferi, an ethnic Albanian and former NLA commander, as Speaker of the Assembly, highlighting lingering divisions.

3.6.2. "Antiquisation" Policy and Political Changes

Upon coming to power in 2006, and especially after the country's non-invitation to NATO in 2008 due to the Greek veto, the VMRO-DPMNE government led by Nikola Gruevski pursued a policy of "Antiquisation" (АнтиквизацијаAntikvizatzijaMacedonian). This policy involved the promotion of an identity rooted in ancient Macedonia, exemplified by the erection of statues of Alexander the Great and Philip II of Macedon in Skopje and other cities, and the renaming of public infrastructure like airports and highways after these ancient figures. The large-scale urban renewal project "Skopje 2014" was a centerpiece of this policy.

The motivations behind Antiquisation were complex, including attempts to build a strong national identity, assert historical continuity, and potentially put pressure on Greece in the naming dispute. However, the policy was highly controversial. Domestically, it faced criticism for its cost, its perceived nationalist and divisive nature, and its aesthetic impact on Skopje. Internationally, it exacerbated the dispute with Greece, which saw it as a provocation and appropriation of Hellenic heritage, further stalling the country's EU and NATO applications. EU diplomats also expressed concerns.

Following the Prespa Agreement and political changes after 2016, the new SDSM-led government began to reverse some aspects of the Antiquisation policy as a gesture of goodwill towards Greece and as part of the implementation of the agreement. This included renaming the main airport and highway. The Prespa Agreement itself requires both countries to acknowledge that their respective understandings of the terms "Macedonia" and "Macedonian" refer to different historical contexts and cultural heritages.

3.6.3. European Union and NATO Membership

North Macedonia's path towards NATO and European Union membership has been a central foreign policy goal since independence, but it faced significant hurdles, primarily the naming dispute with Greece and, later, historical issues raised by Bulgaria.

In August 2017, the then-Republic of Macedonia signed a friendship treaty with Bulgaria, aiming to improve bilateral relations and address historical disagreements, including interpretations of shared history and national figures.

The Prespa Agreement with Greece in June 2018, which resolved the naming dispute, was a major breakthrough. It led to Greece lifting its veto on North Macedonia's NATO and EU aspirations. Consequently, NATO invited Macedonia to start accession talks in July 2018, and on February 6, 2019, the accession protocol was signed in Brussels. North Macedonia officially became the 30th member of NATO on March 27, 2020.

The EU path has been more complex. Following the Prespa Agreement, the European Union approved the start of accession talks in June 2018, contingent on the deal's implementation. In March 2020, EU leaders formally gave approval for North Macedonia (and Albania) to begin membership talks. However, in November 2020, Bulgaria vetoed the EU's negotiation framework for North Macedonia, effectively blocking the official start of accession talks. Bulgaria cited concerns over the implementation of the 2017 friendship treaty, alleged hate speech, minority claims, and what it termed an "ongoing nation-building process" in North Macedonia based on historical negationism of Bulgarian identity, culture, and legacy in the wider region of Macedonia. This veto drew condemnation from intellectuals in both states and criticism from international observers.

In July 2022, following a French proposal to resolve the deadlock with Bulgaria (which involved North Macedonia amending its constitution to recognize a Bulgarian minority, among other conditions), the Assembly of North Macedonia passed the proposal, allowing accession talks with the EU to officially begin. However, the 2023 European Commission Progress Report cited unfulfilled constitutional changes (specifically, the inclusion of Bulgarians in the constitution) as a primary reason for blocking further progress. The EU's intentions regarding accession remain somewhat unclear, influenced by geopolitical dynamics and the desire to counter Russian and Chinese influence in the Western Balkans. In September 2024, the EU announced the separation of Albania's accession path from North Macedonia's due to the ongoing disputes between North Macedonia and Bulgaria, allowing Albania to proceed with opening negotiation chapters independently.

4. Geography

North Macedonia is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, defined by its mountainous terrain, river valleys, and large lakes. It is characterized by a central valley formed by the Vardar river, framed by mountain ranges along its borders.

4.1. Topography and Hydrology

North Macedonia covers a total area of 9.8 K mile2 (25.44 K km2). The terrain is mostly rugged, situated between the Šar Mountains in the northwest and Osogovo mountains in the east, which frame the valley of the Vardar river. The country features numerous mountain ranges. The Šar Mountains and the West Vardar/Pelagonia group of mountains (including Baba Mountain, Nidže, Kožuf, and Jakupica), part of the Dinaric range, are younger and higher. The Osogovo-Belasica mountain chain, part of the Rhodope range, consists of older mountains. The highest peak is Mount Korab on the Albanian border, at 9.1 K ft (2.76 K m).

The country is rich in water resources, with over 1,100 large sources of water. The main river is the Vardar, which flows south through the country and into the Aegean Sea in Greece. Its valley is crucial for the country's economy and communication. Other significant rivers include the Black Drin, which flows from Lake Ohrid towards the Adriatic Sea, and the Binačka Morava, which flows towards the Black Sea basin.

North Macedonia has three large natural lakes: Lake Ohrid, Lake Prespa, and Dojran Lake, all located on its southern borders and shared with neighboring countries (Albania and Greece). Lake Ohrid is one of the oldest and deepest lakes in Europe, renowned for its unique biodiversity and considered a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The region is seismically active and has experienced destructive earthquakes, most notably the 1963 Skopje earthquake. There are also around fifty smaller ponds and glacial lakes. The country has nine spa towns and resorts: Banište, Banja Bansko, Istibanja, Katlanovo, Kežovica, Kosovrasti, Banja Kočani, Kumanovski Banji, and Negorci.

4.2. Climate

North Macedonia has a transitional climate from Mediterranean to continental. Summers are generally warm and dry, while winters are moderately cold and snowy. Temperatures can range from -4 °F (-20 °C) in winter to over 104 °F (40 °C) in summer.

There are three main climatic zones:

- Mildly continental climate in the north.

- Temperate Mediterranean climate in the south, particularly along the valleys of the Vardar and Strumica rivers (in regions like Gevgelija, Valandovo, Dojran, Strumica, and Radoviš). The warmest regions are Demir Kapija and Gevgelija.

- Mountain climate in high-altitude areas, characterized by long, snowy winters and short, cool summers.

Average annual precipitation varies from 0.1 K in (1.70 K mm) in the western mountainous areas to 20 in (500 mm) in the eastern areas and the Vardar valley. The diverse climate and irrigation allow for the cultivation of various crops, including wheat, corn, potatoes, poppies, peanuts, and rice.

4.3. Biodiversity

North Macedonia possesses a rich biodiversity. The flora includes around 210 families, 920 genera, and approximately 3,700 plant species. Flowering plants are the most abundant (around 3,200 species), followed by mosses (350 species) and ferns (42). Phytogeographically, North Macedonia belongs to the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Digital Map of European Ecological Regions by the European Environment Agency, its territory can be subdivided into four terrestrial ecoregions: Pindus Mountains mixed forests, Balkan mixed forests, Rodope montane mixed forests, and Aegean and Western Turkey sclerophyllous and mixed forests. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.42/10, ranking it 40th globally out of 172 countries.

The native forest fauna is diverse, including bears, wild boars, wolves, foxes, squirrels, chamois, and deer. The rare Balkan lynx is found in the mountains of western Macedonia. Forest birds include the blackcap, grouse, black grouse, Eastern imperial eagle, and forest owl. Endemic species and ecosystem health are important aspects of the country's natural heritage.

Conservation efforts are centered around its national parks. North Macedonia has four national parks:

| Name | Established | Size | Map | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mavrovo | 1948 | 282 mile2 (731 km2) |  | |

| Galičica | 1958 | 88 mile2 (227 km2) |  | |

| Pelister | 1948 | 48 mile2 (125 km2) |  | |

| Šar Mountains | 2021 | 94 mile2 (244 km2) |  |

5. Politics

North Macedonia is a parliamentary republic with a multi-party system. The political landscape focuses on democratic development, inter-ethnic relations, and European integration.

|  |

| Gordana Siljanovska-Davkova, President | Hristijan Mickoski, Prime Minister |

5.1. Government Structure

North Macedonia is a parliamentary democracy. The Constitution of North Macedonia, adopted in 1991 and subsequently amended, establishes the framework for government.

The President is the head of state, elected by popular vote for a five-year term, and can serve a maximum of two terms. The president's role is largely ceremonial, representing the country internationally, acting as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and heading the State Security Council. Gordana Siljanovska-Davkova assumed office as president on May 12, 2024, becoming the country's first female president.

The Prime Minister is the head of government and holds the real executive power. The prime minister is typically the leader of the majority party or coalition in the Assembly and is appointed by the president. The government, composed of ministers chosen by the prime minister, is responsible to the Assembly. Hristijan Mickoski became Prime Minister in June 2024.

The Assembly (СобраниеSobranieMacedonian) is the unicameral legislature, composed of 120 members elected every four years through a proportional representation system. The Assembly enacts laws, approves the budget, elects and dismisses the government, and oversees its work. The current president of Parliament is Jovan Mitreski since January 2024.

The Judiciary is independent. The court system is headed by the Supreme Court, with a Constitutional Court responsible for ensuring the constitutionality of laws and protecting fundamental rights. Judges are appointed by the Assembly upon proposal by the Republican Judicial Council.

5.2. Political Parties and Elections

North Macedonia has a multi-party system with two major political blocs, historically led by the center-right VMRO-DPMNE and the center-left Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM). Ethnic Albanian political parties, such as the Democratic Union for Integration (DUI) and the Alliance for Albanians, play a significant role in coalition-building and representing the interests of the Albanian minority. The Ohrid Agreement (2001) established power-sharing mechanisms that often require coalition governments to include representatives from major ethnic Albanian parties.

Elections are generally held every four years for parliamentary seats and every five years for the presidency. The political landscape has seen shifts in power between the major blocs. The early parliamentary elections on July 15, 2020, resulted in a narrow victory for the SDSM-led coalition. Zoran Zaev served as prime minister until his resignation in late 2021, after which Dimitar Kovačevski (SDSM) became prime minister in January 2022. Stevo Pendarovski (SDSM-backed) served as president from 2019 to 2024. Following the 2024 parliamentary and presidential elections, VMRO-DPMNE secured a significant victory, leading to Hristijan Mickoski becoming Prime Minister and Gordana Siljanovska-Davkova becoming President.

5.3. Foreign Relations

North Macedonia's foreign policy priorities include full integration into European and Euro-Atlantic structures, maintaining good neighborly relations, and promoting regional cooperation.

The country became a member of the United Nations on April 8, 1993, initially under the provisional reference "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" due to the naming dispute with Greece. This dispute was resolved with the Prespa Agreement in 2018, leading to the adoption of the name "Republic of North Macedonia" in February 2019. This paved the way for North Macedonia to become the 30th member of NATO on March 27, 2020.

North Macedonia was officially recognized as an EU candidate state in 2005. Accession talks formally began in July 2022, but progress has been complicated by bilateral issues, initially with Greece and subsequently with Bulgaria over historical and identity-related matters. Bulgaria's veto in November 2020 stalled the process, citing concerns over the implementation of a 2017 friendship treaty and interpretations of shared history.

North Macedonia is a member of various international organizations, including the Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), World Trade Organization (WTO), Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA), and La Francophonie. It maintains diplomatic relations with numerous countries and actively participates in regional initiatives like the Southeast European Cooperative Initiative (SECI). Relations with neighboring countries are crucial, with ongoing efforts to resolve historical and cultural issues, particularly with Bulgaria. The country's foreign policy aims to balance its Euro-Atlantic aspirations with the complexities of Balkan regional politics.

5.4. Military

The Army of the Republic of North Macedonia (ARSM) is the national military force. It is led by the General Staff. Its structure includes the Operations Command (comprising the Mechanized Infantry Brigade, the Air Brigade, the Special Operations Regiment, and several independent battalions), the Training and Doctrine Command (which also oversees the Military Reserve Force), and the Logistics Base. An Honor Guard Battalion is directly subordinated to the General Staff.

As of 2022, the ARSM had approximately 8,000 active personnel and 4,850 reservists, with a military budget of around US$235 million. Conscription was ended in 2007, and the military has since been a fully professional volunteer force.

As a NATO member since March 2020, North Macedonia participates in collective defense and security cooperation. The ARSM has contributed troops to international peacekeeping missions led by NATO, the EU, or the UN, including deployments in Afghanistan (ISAF/Resolute Support), Bosnia and Herzegovina (EUFOR Althea), Iraq, Kosovo (KFOR), and Lebanon (UNIFIL). These contributions highlight its commitment to international security and its role as a NATO ally.

The Ministry of Defence is responsible for developing the country's defense strategy, assessing threats and risks, and managing the defense system, including training, readiness, equipment, and the defense budget.

5.5. Human Rights

North Macedonia is a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights, the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, and the Convention against Torture. The Constitution guarantees basic human rights to all citizens.

Despite these legal frameworks, human rights organizations have periodically raised concerns. Reports from the early 2000s by organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch highlighted issues such as suspected extrajudicial executions, threats and intimidation against human rights activists and opposition journalists, and allegations of torture by police.

More recent assessments by international bodies and NGOs continue to monitor areas such as:

- Freedom of Speech and Media Freedom: Challenges include political interference in media, lack of transparency in media ownership, and occasional intimidation or pressure on journalists.

- Minority Rights: The Ohrid Agreement (2001) significantly improved the rights of the ethnic Albanian minority, particularly in language use and representation in public institutions. However, challenges remain in full implementation and in addressing the rights of other smaller minorities, such as the Roma, who often face discrimination and socio-economic marginalization.

- Democratic Development and Rule of Law: Judicial independence and efficiency, corruption, and political influence over state institutions are areas of ongoing concern and focus for reforms, especially in the context of EU accession.

- Rights of Vulnerable Groups: This includes issues related to LGBT rights, gender equality, and protection against domestic violence. While some progress has been made, societal discrimination and inadequate implementation of laws remain challenges.

- Prison Conditions and Treatment of Detainees: Overcrowding and poor conditions in prisons have been noted as concerns.

The government has undertaken various reforms and initiatives aimed at addressing these human rights concerns, often in line with recommendations from international organizations and as part of its EU accession process. The effectiveness and full implementation of these reforms are crucial for the country's democratic development and social justice.

6. Administrative Divisions

North Macedonia is divided into 80 municipalities (општиниopshtiniMacedonian; singular: општинаopshtinaMacedonian) following a reorganization in August 2004, which reduced the number from the previous 123 municipalities established in 1996. Ten of these municipalities constitute the City of Skopje, which is a distinct unit of local self-government and the country's capital. Municipalities are the basic units of local self-government, responsible for a range of local services and development. Neighboring municipalities may establish co-operative arrangements.

For statistical and planning purposes, these municipalities are grouped into eight statistical regions. These regions do not have administrative powers of their own but are used for legal and statistical data collection and analysis.

The statistical regions are:

- Eastern (Источен регион, Istochen region)

- Northeastern (Североисточен регион, Severoistochen region)

- Pelagonia (Пелагониски регион, Pelagoniski region)

- Polog (Полошки регион, Poloshki region)

- Skopje (Скопски регион, Skopski region)

- Southeastern (Југоисточен регион, Jugoistochen region)

- Southwestern (Југозападен регион, Jugozapaden region)

- Vardar (Вардарски регион, Vardarski region)

7. Economy

North Macedonia has undergone significant economic reforms since its independence, transitioning towards an open market economy. Its economic development has been influenced by regional instability, international sanctions on former Yugoslavia, the Greek trade embargo in the 1990s, and the 2001 internal conflict, but has shown resilience and growth in recent years, with a focus on attracting foreign investment and integrating into European markets. Social aspects such as labor rights, environmental protection, and social equity are increasingly considered in its economic policies.

7.1. Economic Performance and Policies

Since gaining independence, North Macedonia has worked to establish a stable macroeconomic environment. Key economic indicators include GDP, inflation, and unemployment. GDP growth has been steady, albeit sometimes slow, with periods of more robust expansion. For instance, GDP grew by 3.1% in 2005 and was projected for higher growth in subsequent years before being affected by global and regional economic shifts. The World Bank ranked it as the fourth "best reformatory state" in 2009.

The government has largely succeeded in controlling inflation, maintaining low rates (e.g., 3% in 2006, 2% in 2007). A major policy initiative was the introduction of a flat tax system (12% in 2007, lowered to 10% in 2008) aimed at simplifying the tax code and attracting foreign investment. Fiscal reforms have focused on fiscal discipline and reducing public debt.

Unemployment has been a persistent challenge, historically high (e.g., 37.2% in 2005). However, through employment measures and foreign direct investment (FDI) attraction, the rate has seen a significant decrease, falling to 27.3% by the first quarter of 2015 and further in subsequent years. Poverty rates have also been a concern, though efforts are made to address them through social programs. The country is classified as an upper-middle-income economy by the World Bank. The grey market is estimated to be a considerable portion of the GDP, close to 20%. PPS GDP per capita stood at 36% of the EU average in 2017. Corruption and a relatively ineffective legal system are acknowledged restraints on economic development.

7.2. Major Sectors

The economy of North Macedonia is diversified across primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors.

- Primary Sector (Agriculture): Agriculture accounted for 9.6% of GDP in 2013. Key agricultural products include grapes (for wine production), tobacco, vegetables (tomatoes, peppers), fruits, and dairy. The varied climate supports diverse cultivation. The sector faces challenges such as land fragmentation and the need for modernization, but it remains vital for rural employment and exports. Environmental sustainability in agriculture is a growing concern.

- Secondary Sector (Industry and Construction): Manufacturing, including mining and construction, constituted the largest part of GDP at 21.4% in 2013. Key industries include food processing, beverages, textiles, chemicals, iron, steel, cement, energy, and pharmaceuticals. The country has attracted FDI in the automotive components industry, with companies like Johnson Controls, Van Hool, Johnson Matthey, Lear Corporation, Visteon, Kostal, Gentherm, Dräxlmaier Group, Kromberg & Schubert, Marquardt Group, and Amphenol establishing local subsidiaries. Mining, particularly of lead, zinc, and copper, also contributes. Construction has seen periods of growth, partly driven by public infrastructure projects and private investment. Labor rights and environmental standards within industrial operations are areas of focus.

- Tertiary Sector (Services): The services sector, including trade, transportation, accommodation, finance, and IT, is the largest contributor to the economy, representing 18.2% of GDP (for trade, transport, accommodation) in 2013 and growing. The IT market has shown significant growth. The financial sector is developing, and tourism is an increasingly important service industry. Social equity in access to services and employment opportunities is a relevant consideration.

7.3. Trade

North Macedonia has an open economy, with trade accounting for over 90% of GDP in some years. The collapse of the Yugoslav internal market and subsequent regional conflicts significantly impacted its trade patterns.

Its main export commodities include chemicals and related products, machinery and transport equipment, manufactured goods (especially textiles and clothing), iron, steel, and agricultural products (wine, tobacco, fresh produce).

Major import commodities are manufactured goods, machinery and transport equipment, mineral fuels and lubricants, and chemicals.

The European Union is by far the largest trading partner, accounting for 68.8% of foreign trade in 2014. Key EU partners include Germany, Greece, Italy, and Bulgaria. Trade with Western Balkan countries also forms a significant portion (almost 12% in 2014). North Macedonia is a member of CEFTA, which promotes regional trade. Efforts to integrate into global markets include WTO membership. The country has benefited from trade preferences with the EU.

7.4. Tourism

Tourism plays a significant role in North Macedonia's economy, accounting for 6.7% of its GDP in 2016, with an annual income of approximately 616.00 M EUR that year. The number of foreign visitors has generally been on the rise, with a 14.6% increase in 2011 and 1,184,963 tourist arrivals in 2019 (757,593 foreign).

Key attractions include:

- Lake Ohrid**: A UNESCO World Heritage site, renowned for its natural beauty, ancient churches, monasteries (like St. John at Kaneo), and historical town of Ohrid. It is a major center for cultural and lake tourism.

- Skopje**: The capital city, offering historical sites like the Old Bazaar, Kale Fortress, Stone Bridge, alongside modern architecture and museums. The "Skopje 2014" project, though controversial, added numerous monuments and buildings.

- National Parks**: Mavrovo, Galičica, and Pelister offer opportunities for hiking, skiing, and observing nature.

- Cultural Heritage**: Ancient archaeological sites (e.g., Stobi, Heraclea Lyncestis), Byzantine-era monasteries with well-preserved frescoes, and Ottoman-era architecture.

- Wine Tourism**: The Tikveš wine region is becoming increasingly popular.

- Rural and Ecotourism**: Growing interest in experiencing traditional village life and untouched natural landscapes.

Tourists primarily come from Turkey, neighboring Serbia, Greece, and Bulgaria, as well as Poland and other Western European countries. Skopje and the southwestern region (especially Ohrid) receive the bulk of tourists.

The government aims to promote sustainable tourism practices that benefit local communities and preserve the country's natural and cultural heritage. Challenges include improving infrastructure and diversifying the tourism offerings.

8. Infrastructure

North Macedonia has been working to develop and modernize its essential infrastructure, including transportation networks, education systems, and telecommunications, to support economic growth and social development.

8.1. Transport

Being a landlocked country in the central Balkans, North Macedonia's transport network is crucial for domestic connectivity and as a transit route for goods moving between Greece, the rest of the Balkans, and Central/Eastern Europe.

- Roads**: As of 2019, there were approximately 6.6 K mile (10.59 K km) of roads, with about 3.7 K mile (6.00 K km) paved. The main road corridor is the north-south Corridor X, which includes the E75 highway connecting Serbia with Greece via Skopje and Veles. Corridor VIII, an east-west route connecting the Adriatic Sea (Albania) with the Black Sea (Bulgaria) via North Macedonia, is also under development.

- Railways**: As of 2019, the total length of the railway network was 573 mile (922 km), operated by Makedonski Železnici (Macedonian Railways). The most important line runs along Corridor X (border with Serbia-Kumanovo-Skopje-Veles-Gevgelija-border with Greece). Efforts have been made to develop the rail link along Corridor VIII, including a line to Bulgaria (Beljakovci-border with Bulgaria) to establish a direct Skopje-Sofia connection. Skopje is the main railway hub, with Veles and Kumanovo as other important junctions.

- Air Transport**: There are two international airports: Skopje International Airport (formerly Alexander the Great Airport) and Ohrid St. Paul the Apostle Airport. These airports provide connections to various European cities.

- Water Transport**: Limited to lake traffic on Lake Ohrid and Lake Prespa, primarily for tourist purposes.

North Macedonia Post is the state-owned company for postal services, established in 1992.

The country has faced challenges due to the collapse of the Yugoslav internal market and regional conflicts, which affected its traditional export routes. High transit costs through Serbia have been an issue.

8.2. Education

The education system in North Macedonia is structured into primary, secondary, and higher education. Compulsory education lasts for nine years (primary and lower secondary).

- Primary and Secondary Education**: Primary education starts at age six. Secondary education includes general secondary schools (gymnasiums) and vocational schools. The Ministry of Education and Sciences oversees the system. Efforts have been made to modernize curricula and improve teaching standards.

- Higher Education**: There are several state universities, including:

- Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje (founded in 1949)

- St. Clement of Ohrid University of Bitola

- Goce Delčev University of Štip

- State University of Tetova (primarily teaching in Albanian)

- University of Information Science and Technology "St. Paul The Apostle" in Ohrid.

There are also a number of private university institutions, such as the European University, Slavic University in Sveti Nikole, and the South East European University (SEEU) in Tetovo, which also offers multilingual education.

Access to education and its quality are important for social development. North Macedonia participates in international educational cooperation programs. The country was ranked 58th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) supported the "Macedonia Connects" project, which aimed to make North Macedonia one of the first all-broadband wireless countries. Many schools are connected to the internet. The national library is the National and University Library "St. Kliment of Ohrid" in Skopje.

8.3. Telecommunications and Media

The telecommunications sector in North Macedonia has undergone liberalization and modernization.

- Telecommunications**: The fixed-line telephone market was traditionally dominated by Makedonski Telekom (part of Deutsche Telekom group), but alternative operators have emerged. Mobile telephony has high penetration rates, with several operators competing in the market. Internet penetration has increased significantly, with broadband services widely available. The "Macedonia Connects" project aimed to provide nationwide wireless internet access, and an ISP, On.net, created a MESH Network for Wi-Fi in major cities.

- Media Landscape**: North Macedonia has a diverse media landscape with numerous television and radio stations (public and private) and print and online media outlets.

- Public Broadcaster**: Macedonian Radio Television (MRT), founded in 1993 by the Assembly, operates several TV channels and radio stations.

- Private Media**: There are many private TV channels, including national broadcasters like Sitel, Kanal 5, Telma, Alfa TV, and Alsat-M (which broadcasts in Albanian and Macedonian). Popular newspapers include Nova Makedonija (the oldest, founded in 1944), Utrinski vesnik, Dnevnik (ДневникDnevnikMacedonian), Vest, and Večer, as well as magazines like Fokus and Tea Moderna.

- Freedom of the Press**: Freedom of the press is constitutionally guaranteed, but challenges remain. Issues reported by media freedom organizations include political influence, lack of transparency in media ownership, financial pressures on media outlets, and occasional threats or attacks against journalists. The media environment can be polarized, reflecting political divisions. Efforts to align media legislation with EU standards are ongoing.

9. Society

The social fabric of North Macedonia is characterized by its ethnic and religious diversity, demographic trends shaped by history and migration, and ongoing efforts to foster social cohesion and address the needs of various communities, including minorities and vulnerable groups.

9.1. Population and Ethnic Groups

According to the 2021 census, North Macedonia had a population of 1,836,713. The population density was 72.2 persons per km2, and the average age was 40.08 years. There were 598,632 households, with an average of 3.06 members per household. The gender balance was 50.4% female and 49.6% male.

The country is ethnically diverse. According to the 2021 census, the largest ethnic group are the Macedonians, constituting 58.44% of the population for whom ethnicity was declared. Albanians are the second-largest group at 24.30%. Other ethnic groups include Turks (3.86%), Roma (2.53%), Serbs (1.30%), Bosniaks (0.87%), Aromanians (including Megleno-Romanians, 0.47%), and others (1.03%). For approximately 7.20% of the population, ethnicity data was taken from administrative sources or was not declared. Unofficial estimates sometimes suggest higher numbers for Turks and a significantly larger Roma population, possibly up to 260,000 for the latter.

Demographic trends include emigration, particularly among younger people seeking better economic opportunities abroad, and varying birth rates among different ethnic groups. Social integration and inter-ethnic relations are key societal issues, with the Ohrid Agreement (2001) providing a framework for power-sharing and minority rights.

9.2. Religion

Religious freedom is constitutionally guaranteed. According to the 2021 census, Eastern Orthodoxy is the predominant religion, adhered to by 46.1% of the population. The vast majority belong to the Macedonian Orthodox Church - Ohrid Archbishopric (MOC-OA). The MOC-OA declared autocephaly in 1967, which was not recognized by other Orthodox churches for decades. In 2022, its canonical status was restored by the Serbian Orthodox Church and recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, followed by other Orthodox churches. There is also a small presence of the Orthodox Ohrid Archbishopric, an autonomous archbishopric linked to the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Islam is the second-largest religion, with Muslims constituting 32.2% of the population (2021 census). Most Muslims are ethnic Albanians, Turks, Roma, or Bosniaks; there is also a small community of Macedonian Muslims (Torbeši). North Macedonia has one of the highest proportions of Muslims in Europe.

Catholicism accounts for 0.4% of the population. This includes adherents of the Macedonian Greek Catholic Church (an Eastern Catholic church in communion with Rome, using a Byzantine Rite and Macedonian in liturgy, with approximately 11,000 adherents) and Roman Catholics.

Other Christian denominations, including various Protestant groups like Methodists and Baptists, make up around 13.9% (2021 census; this figure may include those identifying broadly as Christian or other smaller groups). The late President Boris Trajkovski was a Methodist.

A small percentage of the population adheres to other faiths or is unaffiliated/atheist (0.1% identified as None/Agnostic/Atheist, while 7.3% were Others/Not Stated/Unknown in the 2021 census). The historical Jewish community, largely Sephardic, was almost entirely destroyed during the Holocaust; today, it numbers around 200 people, mostly in Skopje.

As of the end of 2011, there were 1,842 churches and 580 mosques in the country. Both Orthodox and Islamic communities have secondary religious schools, and there is an Orthodox theological college in Skopje. Interfaith relations are generally peaceful, though societal divisions can sometimes align with religious affiliations.

9.3. Languages

North Macedonia has a diverse linguistic landscape reflecting its ethnic composition.

- Macedonian**: The national and official language across the entire territory and in international relations. It is a South Slavic language, belonging to the Eastern South Slavic branch, and is spoken as a mother tongue by the majority of the population (declared by 1,344,815 citizens in the 2002 census). It is closely related to and mutually intelligible with standard Bulgarian.

- Albanian**: Since 2019, Albanian is a co-official language at the state level (excluding defense, central police, and monetary policy). It is spoken by a significant minority (declared by 507,989 citizens in 2002) and is an official language in municipalities where at least 20% of the population are Albanian speakers.

- Other Minority Languages**: Several other languages are spoken by minority communities and have official status in specific municipalities where their speakers meet the 20% threshold. These include:

- Turkish**: Spoken by the Turkish minority (declared by 71,757 citizens in 2002). Balkan Gagauz Turkish is also present.

- Romani**: Spoken by the Roma community (declared by 38,528 citizens in 2002).

- Serbian**: Spoken by the Serbian minority (declared by 24,773 citizens in 2002).

- Bosnian**: Spoken by the Bosniak minority (declared by 8,560 citizens in 2002).

- Aromanian** (including Megleno-Romanian): Spoken by the Aromanian community (declared by 6,884 citizens in 2002).

The Macedonian Sign Language is the primary language of the deaf community. Language policy aims to protect and promote the use of minority languages in education, media, and public life, in line with the Constitution and the Ohrid Agreement. Language plays a significant role in cultural identity and inter-ethnic relations.

9.4. Major Cities

The urban landscape of North Macedonia is centered around its capital, Skopje, with several other cities playing important roles regionally.

- Skopje**: The capital and largest city, with a population of 526,502 (within the 10 municipalities that form the City of Skopje, 2021 census). It is the political, economic, cultural, and educational center of the country. Skopje has a diverse population and a rich history, with landmarks like the Stone Bridge, Kale Fortress, the Old Bazaar, and numerous modern buildings from the "Skopje 2014" project.

- Bitola**: The second-largest city (69,287 inhabitants, 2021), located in the Pelagonia region of southwestern North Macedonia. Historically known as Monastir, it was an important administrative and cultural center during the Ottoman era, often called the "city of consuls." It boasts elegant 19th-century architecture and the ancient ruins of Heraclea Lyncestis.

- Kumanovo**: The third-largest city (75,051 inhabitants, 2021), located in the northeastern part of the country. It is an industrial and commercial center with a mixed ethnic population.

- Prilep**: Located in the Pelagonia region (63,308 inhabitants, 2021), known for its tobacco industry and the medieval Marko's Towers fortress.

- Tetovo**: A major urban center in the Polog region (63,176 inhabitants, 2021), with a large ethnic Albanian population. It is home to the State University of Tetova and the Šarena Džamija (Painted Mosque).

- Ohrid**: A historic city (38,818 inhabitants, 2021) on the shores of Lake Ohrid, a UNESCO World Heritage site. It is a major tourist destination, known for its ancient churches, monasteries, and rich cultural heritage.

- Veles**: An industrial city (40,664 inhabitants, 2021) on the Vardar River in central North Macedonia.

- Štip**: A center in eastern North Macedonia (42,000 inhabitants, 2021), known for its textile industry and home to Goce Delčev University of Štip.

- Strumica**: A significant agricultural and commercial center in southeastern North Macedonia (33,825 inhabitants, 2021).

- Gostivar**: Another important city in the Polog region (32,814 inhabitants, 2021), with a significant Albanian population.

These cities are hubs of economic activity, cultural life, and social interaction, reflecting the diverse character of North Macedonia. Urbanization trends and the social dynamics within these centers are important aspects of the country's development.

10. Culture

North Macedonia possesses a rich and diverse cultural heritage, shaped by centuries of interaction between various civilizations, including ancient Macedonian, Roman, Byzantine, Slavic, and Ottoman influences. This heritage is expressed in its arts, architecture, music, literature, cuisine, sports, and national symbols.

10.1. Arts and Architecture

North Macedonia is renowned for its medieval Byzantine fresco paintings, particularly from the 11th to 16th centuries. Thousands of square meters of frescoes are preserved in churches and monasteries across the country, many of which are considered masterworks of the Macedonian school of ecclesiastical painting. Notable examples can be found in Ohrid (e.g., Church of St. Sophia, Church of St. Clement and Panteleimon) and Nerezi (Church of St. Panteleimon).

Icon painting also flourished, with the Ohrid collection being particularly valuable.

Architectural styles reflect the country's diverse history. Ancient sites like Stobi and Heraclea Lyncestis showcase Roman and early Christian architecture. Byzantine-style churches and monasteries are abundant. Ottoman-era architecture is prominent in old bazaars (like Skopje's Old Bazaar), mosques (e.g., Šarena Džamija in Tetovo), and public buildings. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw the introduction of Neoclassical and other European styles, particularly in Bitola. The "Skopje 2014" project controversially reshaped the capital's center with numerous statues, new buildings in classical and baroque styles, and facades. Contemporary art forms, including painting, sculpture, and graphic arts, are actively pursued.

10.2. Music and Literature

Macedonian music is characterized by its complex rhythms and traditional folk melodies, often played on instruments like the gajda (bagpipe), kaval (flute), tambura (lute), and tapan (drum). Folk dances, such as the oro, are an integral part of cultural celebrations. Byzantine church music has had a strong influence on traditional music. Contemporary music scenes encompass various genres, including pop, rock, jazz, and electronic music. The Skopje Jazz Festival is a notable annual event.

Macedonian literature developed with the codification of the Macedonian language in the mid-20th century. Key figures in modern Macedonian literature include poets like Kočo Racin and Blaže Koneski (who also played a crucial role in standardizing the language), and prose writers such as Slavko Janevski and Živko Čingo. The Struga Poetry Evenings, an internationally acclaimed poetry festival held annually in Struga, attracts poets from around the world.

10.3. Cuisine

The cuisine of North Macedonia is representative of Balkan culinary traditions, with strong Mediterranean (particularly Greek) and Middle Eastern (Ottoman) influences, as well as elements from Italian, German, and other Eastern European cuisines. The country's relatively warm climate provides excellent conditions for a variety of vegetables, herbs, and fruits.

Characteristic dishes include:

- Tavče gravče**: Baked beans, often considered the national dish.

- Ajvar**: A relish made primarily from red bell peppers, with eggplant, garlic, and chili pepper.

- Šopska salad**: A cold salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, raw or roasted peppers, and sirene cheese.

- Stuffed peppers** (Полнети пиперкиPolneti piperkiMacedonian)

- Pastrmajlija**: A type of oval-shaped bread pie with meat.

- Kebabs** and various grilled meats.

Local alcoholic beverages include rakija (a fruit brandy) and various wines. Mastika is considered a national drink.

10.4. Sports

Popular sports in North Macedonia include football, handball, and basketball.

- Football**: The North Macedonia national football team is controlled by the Football Federation of Macedonia. Their home stadium is the Toše Proeski Arena in Skopje. In November 2003, Darko Pančev, winner of the 1991 European Golden Shoe, was selected as North Macedonia's Golden Player by UEFA. The national team qualified for its first major tournament, UEFA Euro 2020 (held in 2021).

- Handball**: Handball is a very popular team sport. The men's national team has appeared in multiple European and World championships, with a best finish of fifth at the 2012 European Championship. Macedonian clubs have also achieved European success; RK Vardar won the EHF Champions League in 2017 and 2019, and Kometal Gjorče Petrov Skopje won the EHF Women's Champions League in 2002. North Macedonia co-hosted the 2008 European Women's Handball Championship.

- Basketball**: The men's national basketball team achieved its best result by finishing 4th at EuroBasket 2011. Pero Antić was the first Macedonian basketball player in the NBA.

The Ohrid Swimming Marathon is an annual event held on Lake Ohrid. Winter sports, particularly skiing, are popular in mountain resorts. North Macedonia participates in the Olympic Games, organized by the Olympic Committee of North Macedonia. Magomed Ibragimov won the country's first Olympic medal (bronze in freestyle wrestling) at the 2000 Summer Olympics.

10.5. Cinema

The history of filmmaking in the country dates back over 110 years, with the first film produced on its territory made in 1895 by Janaki and Milton Manaki in Bitola.

Macedonian cinema has depicted the history, culture, and everyday life of its people. The first Macedonian feature film was Frosina (1952), directed by Vojislav Nanović. The first feature film in color was Miss Stone (1958).

The most internationally acclaimed Macedonian film is Before the Rain (1994), directed by Milcho Manchevski, which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Manchevski also directed Dust (2001) and Shadows (2007).

More recently, the documentary Honeyland (2019), directed by Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov, received Academy Award nominations for Best International Feature Film and Best Documentary Feature, making it the first non-fictional film to be nominated in both categories.

10.6. Public Holidays

The main public holidays in North Macedonia reflect significant historical, cultural, and religious events. These include:

| Date | English name | Macedonian name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| January 1-2 | New Year's Day | Нова Година, Nova Godina | |

| January 7 | Christmas Day (Orthodox) | Прв ден Божиќ, Prv den Božik | Observed according to the Julian calendar. |

| Moveable | Good Friday (Orthodox) | Велики Петок, Veliki Petok | Date varies according to the Orthodox Paschal cycle. |

| Moveable | Easter Sunday (Orthodox) | Прв ден Велигден, Prv den Veligden | |

| Moveable | Easter Monday (Orthodox) | Втор ден Велигден, Vtor den Veligden | |

| May 1 | Labour Day | Ден на трудот, Den na trudot | |

| May 24 | Saints Cyril and Methodius Day | Св. Кирил и Методиј, Ден на сèсловенските просветители, Sv. Kiril i Metodij, Den na sèslovenskite prosvetiteli | Day of the All-Slavic Educators. |

| August 2 | Republic Day / Ilinden | Ден на Републиката, Den na Republikata | Commemorates the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising of 1903 and the First Session of ASNOM in 1944, establishing the Macedonian state. |

| September 8 | Independence Day | Ден на независноста, Den na nezavisnosta | Commemorates the 1991 referendum for independence from Yugoslavia. |

| October 11 | Day of People's Uprising | Ден на востанието, Den na vostanieto | Commemorates the beginning of the anti-fascist struggle in World War II in 1941. |

| October 23 | Day of the Macedonian Revolutionary Struggle | Ден на македонската револуционерна борба,Den na makedonskata revolucionarna borba | Commemorates the founding of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) in 1893. |

| Moveable (1 Shawwal) | Eid al-Fitr | Рамазан Бајрам, Ramazan Bajram | End of Ramadan, date varies according to the Islamic lunar calendar. A holiday for Muslim citizens. |

| December 8 | Saint Clement of Ohrid Day | Св. Климент Охридски, Sv. Kliment Ohridski | Commemorates St. Clement of Ohrid, a prominent medieval scholar and patron saint. |

In addition to these, there are other holidays observed by specific ethnic or religious communities, which may be non-working days for members of those communities.

10.7. National Symbols

The national symbols of North Macedonia represent its identity, history, and sovereignty.

- Flag**: The current flag, adopted on October 5, 1995, features a golden-yellow sun with eight broadening rays extending to the edges of a red field. This design replaced an earlier flag (used 1992-1995) which featured the Vergina Sun, a symbol claimed by Greece as part of its Hellenic heritage, leading to the flag change as part of an interim accord with Greece. The sun symbol represents the "new sun of Liberty" referred to in the national anthem.

- Coat of Arms**: The current coat of arms was adopted on July 27, 1946, by the People's Assembly of the People's Republic of Macedonia and retained after independence, with minor revisions in 2009 that removed the five-pointed red star. It is based on the emblem of the SFR Yugoslavia. The emblem features a garland of wheat sheaves, tobacco leaves, and poppy seed heads, tied with a ribbon decorated with traditional Macedonian folk embroidery. In the center is a landscape with a mountain (Mount Korab), a river (Vardar), a lake (Lake Ohrid), and the rising sun. These elements are intended to represent "the richness of our country, our struggle, and our freedom." There have been proposals to replace it with a more traditional heraldic coat of arms, but no consensus has been reached.

- National Anthem**: "Denes nad Makedonija" (Today Over Macedonia) was adopted as the national anthem in 1992. The lyrics were written by Vlado Maleski in the 1940s, and the music was composed by Todor Skalovski. The anthem refers to the struggle for freedom and mentions historical figures of the Macedonian revolutionary movement such as Gotse Delchev, Pitu Guli, Dame Gruev, and Yane Sandanski.