1. Overview

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country situated at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, on the Adriatic Sea. It is bordered by Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro to the southeast, and shares a maritime border with Italy. The capital and largest city is Zagreb. Croatia's diverse geography includes a long Adriatic coastline with over a thousand islands, the Dinaric Alps, and the Pannonian Basin.

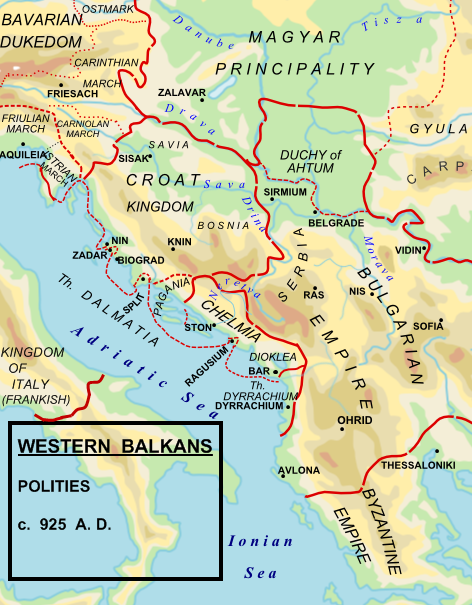

The Croats arrived in the area in the late 6th century and organized the state into two duchies by the 7th century. Croatia was first internationally recognized in 879 and became a kingdom in 925. After a period of personal union with Hungary and later Habsburg rule, Croatia faced Ottoman incursions. The 20th century saw Croatia as part of various Yugoslav states. The Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a Nazi-installed puppet state during World War II, was marked by the Ustaše regime's atrocities and a significant anti-fascist Partisan resistance. Following World War II, Croatia became a constituent republic of Socialist Yugoslavia. Growing national aspirations, notably during the Croatian Spring, eventually led to the declaration of independence in 1991. The ensuing Croatian War of Independence resulted in a sovereign Croatia but also significant human suffering and displacement.

Modern Croatia is a parliamentary republic and a developed country with a high-income economy. Key sectors include services, industry (notably shipbuilding, food processing, and pharmaceuticals), and agriculture, with tourism being a major source of revenue. The country has made significant strides in democratic development, joining NATO in 2009, the European Union in 2013, and the Eurozone and Schengen Area in 2023. Challenges include addressing wartime legacies, combating corruption, and ensuring social equity and minority rights. Croatian culture is a rich blend of Central European and Mediterranean influences, reflected in its arts, literature, music, and traditions. The protection of human rights, including those of ethnic minorities (such as Serbs, Bosniaks, and Roma), gender equality, and LGBTQ+ rights, remains an important aspect of its social liberal development.

2. Etymology

The name "Croatia" derives from Medieval Latin CroātiaCroatiaLatin, which itself is a derivation of the North-West Slavic *Xərwate*Xərwatezlw. This term evolved through liquid metathesis from the Common Slavic period form *Xorvat, which is proposed to come from the Proto-Slavic *Xъrvátъ. This Proto-Slavic term might originate from a 3rd-century Scytho-Sarmatian form attested in the Tanais Tablets as ΧοροάθοςKhoroáthosGreek, Ancient. Alternate transliterations of this name or related terms found in the tablets include Khoróatos and Khoroúathos. The origin of this ethnonym is uncertain, but it is most likely from the Proto-Ossetian / Alanian *xurvæt- or *xurvāt-, meaning "one who guards" or "protector." The native Croatian name for the country is HrvatskaHřvatskaCroatian. In the Arebica script (a version of Perso-Arabic script used for Bosnian and Croatian), it can be written as حرواتسقاḤrwātsqāArabic.

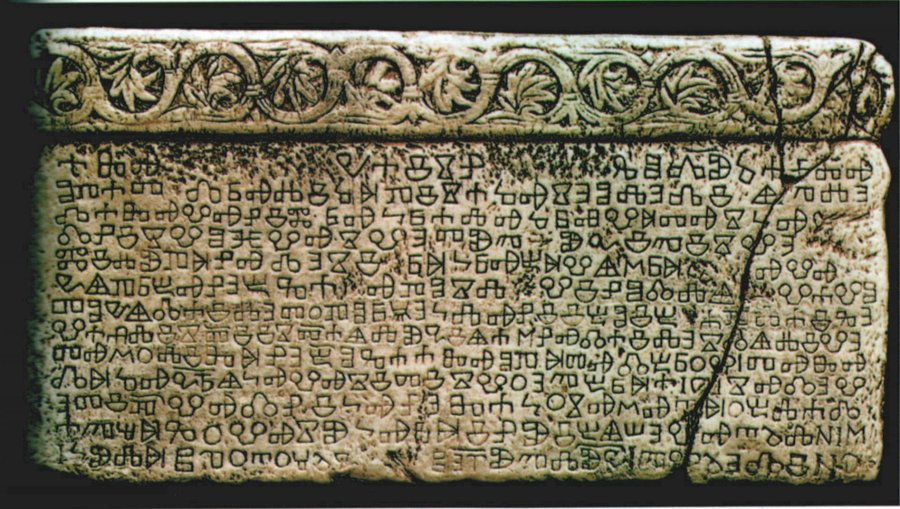

The oldest preserved record of the Croatian ethnonym's native variation, *xъrvatъ, is found on the Baška tablet in the style zvъnъmirъ kralъ xrъvatъskъ ("Zvonimir, Croatian king"). The Latin variation Croatorum is archaeologically confirmed on a church inscription found in Bijaći near Trogir, dated to the late 8th or early 9th century. The presumably oldest stone inscription with the fully preserved ethnonym is the 9th-century Branimir inscription found near Benkovac, where Duke Branimir is styled Dux Cruatorvm (Duke of Croats), likely dated between 879 and 892, during his rule. The Latin term ChroatorumChroatorum (of the Croats)Latin is attributed to a charter of Duke Trpimir I of Croatia, dated to 852 in a 1568 copy of a lost original, but it is not certain if the original was indeed older than the Branimir inscription.

3. History

The history of Croatia spans from ancient human settlements through periods of Roman rule, medieval kingdoms, unions with neighboring powers, 20th-century Yugoslav states, and finally, to modern independence. Key themes include the development of Croatian identity, struggles for sovereignty, and the impact of major European conflicts and political shifts on its people and territory, including significant human rights challenges and democratic transitions.

3.1. Prehistory and Antiquity

The area known as Croatia today was inhabited throughout the prehistoric period. Neanderthal fossils dating to the Middle Palaeolithic period were unearthed in northern Croatia, with the Krapina site being the most prominent. Remnants of Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures have been found in all regions of the country. The largest proportion of these sites is in the river valleys of northern Croatia, with the most significant cultures being Starčevo, Vučedol, and Baden. The Iron Age hosted the early Illyrian Hallstatt culture and the Celtic La Tène culture.

The region of modern-day Croatia was later settled by Illyrians and Liburnians. The first Greek colonies were established on the islands of Hvar (by Dionysius I of Syracuse), Korčula, and Vis. In 9 AD, the territory of today's Croatia became part of the Roman Empire. The Roman Emperor Diocletian, who was native to the region, had a large palace built in Split, to which he retired after abdicating in AD 305. During the 5th century, Julius Nepos, the last de jure Western Roman Emperor, ruled a small realm from this palace after fleeing Italy in 475. The Roman period left a lasting legacy in terms of infrastructure, language (Latin's influence on local dialects), and early Christianization.

3.2. Middle Ages

The Roman period ended with invasions by the Avars and Croats in the late 6th and first half of the 7th century, leading to the destruction of almost all Roman towns. Roman survivors retreated to more defensible sites on the coast, islands, and mountains. The city of Dubrovnik was founded by such survivors from Epidaurum.

The ethnogenesis of the Croats is a subject of some debate. The most accepted theory, the Slavic theory, proposes the migration of White Croats from White Croatia during the Migration Period. Conversely, the Iranian theory suggests a Sarmatian-Alanic origin for the Proto-Croats, based on the Tanais Tablets which contain Ancient Greek inscriptions of names like Khoroúathos, interpreted as anthroponyms related to the Croatian ethnonym. According to the work De Administrando Imperio by the 10th-century Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII, the Croats settled in the Roman province of Dalmatia in the first half of the 7th century after defeating the Avars. Recent archaeological data generally supports the settlement of Slavs/Croats in the late 6th and early 7th centuries.

By the 7th century, the Croats had organized the territory into two duchies: the Duchy of Croatia (also known as Littoral Croatia or Dalmatian Croatia) in the south, and the Duchy of Pannonian Croatia in the north. These duchies became Frankish vassals in the late 8th century but eventually gained independence. The Christianisation of the Croats began in the 7th century, possibly during the time of archon Porga of Croatia, initially likely encompassing only the elite, and was largely completed by the 9th century.

The first native Croatian ruler recognized by the Pope was Duke Branimir, whom Pope John VIII addressed as dux Croatorum (Duke of Croats) in 879. Tomislav became the first king by 925, elevating Croatia to the status of a kingdom. He successfully defended against Hungarian and Bulgarian invasions. The medieval Croatian kingdom reached its peak in the 11th century during the reigns of Petar Krešimir IV (1058-1074) and Dmitar Zvonimir (1075-1089).

Following the death of Stjepan II in 1091, which ended the Trpimirović dynasty, a succession crisis ensued. Ladislaus I of Hungary, brother-in-law of Dmitar Zvonimir, claimed the Croatian crown. This led to a war and eventually, in 1102, Croatia entered into a personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary under King Coloman. Under this union, Croatia retained its own institutions, including the Sabor (parliament) and a Ban (viceroy), and was not simply absorbed into Hungary.

3.3. Union with Hungary and Habsburg Rule

For the next four centuries, the Kingdom of Croatia was ruled by the Sabor (parliament) and a Ban (viceroy) appointed by the Hungarian king. This period saw the rise of influential noble families such as the Frankopans and Šubićs. An increasing threat of Ottoman conquest and a struggle against the Republic of Venice for control of coastal areas characterized this era. The Venetians controlled most of Dalmatia by 1428, with the exception of the city-state of Dubrovnik (Ragusa), which maintained its independence.

Ottoman conquests led to the 1493 Battle of Krbava field and the 1526 Battle of Mohács, both ending in decisive Ottoman victories. King Louis II died at Mohács. In 1527, faced with Ottoman expansion, the Croatian Parliament met in Cetin and elected Ferdinand I of the House of Habsburg as the new ruler of Croatia, on the condition that he protect Croatia against the Ottoman Empire while respecting its political rights. This decision marked the beginning of Habsburg rule over Croatia, which would last until 1918.

Following the Ottoman victories, Croatia was split into civilian and military territories in 1538. The military territories became known as the Croatian Military Frontier and were under direct Habsburg control, serving as a buffer zone against the Ottomans. Ottoman advances continued until the 1593 Battle of Sisak, the first decisive Ottoman defeat, which stabilized the borders. During the Great Turkish War (1683-1698), Slavonia was regained, but western Bosnia, which had been part of Croatia before the Ottoman conquest, remained outside Croatian control. The present-day border between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina is largely a remnant of this outcome. Dalmatia, the southern part of the border, was similarly defined by Venetian and Ottoman wars.

The Ottoman wars drove significant demographic changes. During the 16th century, Croats from western and northern Bosnia, Lika, Krbava, and other areas migrated towards Austria and present-day Burgenland in Austria. To replace the fleeing population and garrison the Military Frontier, the Habsburgs encouraged Orthodox Serbs, Vlachs, and others from Bosnia and Serbia to settle in these depopulated areas, granting them land in exchange for military service. This resettlement had long-term impacts on the ethnic composition of these regions.

The Croatian Parliament supported King Charles III's Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 and signed their own Pragmatic Sanction in 1712. Subsequently, the emperor pledged to respect all privileges and political rights of the Kingdom of Croatia. Queen Maria Theresa made significant contributions to Croatian affairs, such as introducing compulsory education.

Between 1797 and 1809, the First French Empire under Napoleon increasingly occupied the eastern Adriatic coastline and its hinterland, ending the Venetian and Ragusan republics and establishing the Illyrian Provinces. In response, the British Royal Navy blockaded the Adriatic Sea, leading to the Battle of Vis in 1811. The Illyrian Provinces were captured by the Austrians in 1813 and absorbed by the Austrian Empire following the Congress of Vienna in 1815. This led to the formation of the Kingdom of Dalmatia and the restoration of the Croatian Littoral to the Kingdom of Croatia, though Dalmatia remained administered separately from Vienna.

The 1830s and 1840s featured romantic nationalism that inspired the Croatian National Revival (Ilirski pokret). This political and cultural campaign advocated for the unity of South Slavs within the Habsburg Empire. Its primary focus was establishing a standard Croatian language as a counterweight to Hungarian influence and promoting Croatian literature and culture. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, Croatia sided with Austria. Ban Josip Jelačić helped defeat the Hungarians in 1849 and subsequently ushered in a period of Germanisation policy.

By the 1860s, the failure of this absolutist policy became apparent, leading to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (Ausgleich), which created the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. The treaty left Croatia's status to be resolved with Hungary, which was achieved through the Croatian-Hungarian Settlement (Nagodba) of 1868. This agreement united the kingdoms of Croatia and Slavonia into the autonomous Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia within the Hungarian part of the Empire. The Kingdom of Dalmatia remained under de facto Austrian control, while Rijeka (Fiume) retained its status of corpus separatum, a special autonomous body under direct Hungarian administration, introduced in 1779. The Nagodba granted Croatia autonomy in internal affairs, justice, and education, but finances and defense remained under joint control, often leading to tensions with Hungarian authorities over the extent of autonomy.

After Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina following the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, the Military Frontier was gradually abolished. The Croatian and Slavonian sectors of the Frontier were returned to Croatia in 1881, under the provisions of the Croatian-Hungarian Settlement. Renewed efforts to reform Austria-Hungary, including proposals for federalisation with Croatia as a federal unit (such as trialism), were ultimately stopped by the outbreak of World War I. Social and political impacts on the Croatian people during this long period included fluctuating degrees of autonomy, economic development often tied to imperial interests, linguistic and cultural pressures, and the slow fostering of a modern national consciousness.

3.4. The World Wars and Yugoslavia

This period covers Croatia's complex journey through two World Wars, its incorporation into different Yugoslav states, the traumatic experience of the NDH regime, the anti-fascist struggle, and its existence as a socialist republic, culminating in the events that led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia. Social impacts, human rights issues, and democratic (or anti-democratic) developments are central to understanding this era.

On 29 October 1918, as Austria-Hungary collapsed at the end of World War I, the Croatian Parliament (Sabor) declared independence and decided to join the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs. This state, however, was short-lived and, under pressure from Italian territorial claims and lacking international recognition, entered into a union with the Kingdom of Serbia on 1 December 1918, to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. The Croatian Parliament never ratified this union, and many Croats viewed it as a loss of sovereignty, with power centralized in Belgrade under a Serbian monarchy. The 1921 constitution established a unitary state, abolishing historical administrative divisions and effectively ending Croatian autonomy, which was a source of significant political tension.

The most widely supported Croatian political party, the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS) led by Stjepan Radić, opposed the centralist constitution and advocated for federalism and greater Croatian rights. The political situation deteriorated when Radić was assassinated in the Yugoslav Parliament in 1928 by a Serbian nationalist politician. This event led King Alexander I to establish the 6 January Dictatorship in 1929, further suppressing political dissent. The dictatorship formally ended in 1931, but the unitary system remained. The HSS, now led by Vladko Maček, continued to advocate for federalization. This eventually resulted in the Cvetković-Maček Agreement of August 1939, which created an autonomous Banovina of Croatia. The Yugoslav government retained control of defense, internal security, foreign affairs, trade, and transport, while other matters were left to the Croatian Sabor and a crown-appointed Ban. This was a significant step towards recognizing Croatian autonomy, but it came too late to fully resolve underlying tensions, and World War II soon engulfed the region.

In April 1941, Yugoslavia was occupied by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Following the invasion, a German-Italian installed puppet state, the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), was established. It encompassed most of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the region of Syrmia. Parts of Dalmatia were annexed by Italy, and Hungary annexed the northern Croatian regions of Baranja and Međimurje. The NDH regime was led by Ante Pavelić and the ultranationalist Ustaše, a movement that had been a fringe group in pre-war Croatia. With German and Italian military and political support, the Ustaše regime introduced racial laws and launched a brutal campaign of genocide against Serbs, as well as the Holocaust against Jews and the genocide of Roma. Many were imprisoned and systematically murdered in concentration camps, the largest and most notorious being the Jasenovac complex. Anti-fascist Croats were also targeted by the regime. Simultaneously, Italian concentration camps such as Rab and Gonars were established in Italian-occupied territories, primarily interning Slovenes and Croats. The Yugoslav Royalist and Serbian nationalist Chetniks, while notionally opposing the Axis, also committed atrocities against Croats and Bosniaks, sometimes aided by Italy. Nazi German forces committed numerous war crimes and reprisals against civilians in retaliation for Partisan actions, such as in the villages of Kamešnica and Lipa in 1944.

A resistance movement quickly emerged. On 22 June 1941, the 1st Sisak Partisan Detachment was formed near Sisak, recognized as one of the first armed anti-fascist resistance units in occupied Europe. This marked the beginning of the Yugoslav Partisan movement, a communist-led, multi-ethnic anti-fascist force led by Josip Broz Tito (himself of Croat-Slovene origin). Croats were the second-largest ethnic group contributing to the Partisan movement, after Serbs, and in per capita terms, their contribution was proportionate to their population within Yugoslavia. By May 1944, Croats made up 30% of the Partisans' ethnic composition. The movement grew rapidly and gained recognition from the Allies at the Tehran Conference in December 1943. With Allied support and Soviet assistance in the 1944 Belgrade Offensive, the Partisans gained control of Yugoslavia by May 1945. Members of the NDH armed forces, other Axis collaborators, and some civilians retreated towards Austria but were largely captured and many were killed in the post-war reprisals and death marches. Ethnic Germans in Croatia also faced persecution and internment. Estimates of total casualties in Croatia during WWII and its aftermath vary, but demographer Vladimir Žerjavić estimated around 295,000 deaths from the territory of SR Croatia (excluding areas ceded from Italy), including 125-137,000 Serbs, 118-124,000 Croats, 16-17,000 Jews, and 15,000 Roma.

After World War II, Croatia became a single-party socialist federal unit, the Socialist Republic of Croatia, within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), ruled by the League of Communists. While having a degree of autonomy, political and economic power remained centralized. In 1967, Croatian authors and linguists published the Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Standard Language, demanding equal treatment for the Croatian language, distinct from Serbo-Croatian. This declaration contributed to a national movement seeking greater civil rights, economic reforms to address perceived inequalities in the distribution of wealth within Yugoslavia, and further decentralization, culminating in the Croatian Spring (Hrvatsko proljeće) of 1971. This popular movement was suppressed by the Yugoslav leadership, who viewed it as a resurgence of dangerous nationalism. However, the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution did grant increased autonomy to the federal units, fulfilling some of the goals of the Croatian Spring and, ironically, providing a legal basis for the eventual independence of the constituent republics.

Following Tito's death in 1980, the political and economic situation in Yugoslavia deteriorated. National tensions were fanned by the 1986 SANU Memorandum (a Serbian nationalist document) and the 1989 anti-bureaucratic revolutions in Vojvodina, Kosovo, and Montenegro, which were seen as consolidating Serbian power under Slobodan Milošević. In January 1990, the League of Communists of Yugoslavia fragmented along national lines, with the Croatian and Slovene delegations walking out of the 14th Congress. In the same year, the first multi-party elections were held in Croatia. The victory of Franjo Tuđman's Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), a party advocating for greater Croatian sovereignty, further exacerbated nationalist tensions. Some Serbs in Croatia, fearing a repeat of WWII-era persecution and encouraged by Serbian nationalist rhetoric from Belgrade, left the Sabor and declared the autonomy of the unrecognized Republic of Serbian Krajina, expressing their intent to remain in Yugoslavia or achieve independence from Croatia if Croatia seceded. This set the stage for conflict.

3.5. War of Independence and Modern Croatia

As tensions rose, Croatia declared independence on 25 June 1991, following a referendum where the overwhelming majority voted for sovereignty. However, the full implementation of the declaration was delayed by a three-month moratorium requested by the European Community, only coming into effect on 8 October 1991. In the meantime, tensions escalated into the overt war as the Serbian-controlled Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and various Serb paramilitary groups, supported by Serbia, attacked Croatia. By the end of 1991, a high-intensity conflict fought along a wide front reduced Croatia's control to about two-thirds of its territory. Serb paramilitary groups and the JNA engaged in a campaign of killing, terror, and expulsion of Croats and other non-Serbs in the occupied territories, leading to thousands of civilian deaths and the displacement of hundreds of thousands. Notable atrocities included the Vukovar massacre and the shelling of Dubrovnik. Serbs living in Croatian towns, especially those near the front lines, also faced discrimination and violence. Some Croatian Serbs in Eastern and Western Slavonia and parts of the Krajina were forced to flee or were expelled by Croatian forces, though on a more restricted scale and in lesser numbers during this phase. The Croatian government publicly deplored these practices and sought to stop them. The war caused immense suffering, with estimates of around 20,000 deaths.

On 15 January 1992, Croatia gained diplomatic recognition from the European Economic Community members, followed by the United Nations. The war effectively ended in August 1995 with two major Croatian military offensives: Operation Flash in May and Operation Storm in August. Operation Storm led to a decisive Croatian victory and the collapse of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina. This event is commemorated annually on 5 August as Victory and Homeland Thanksgiving Day and the Day of Croatian Defenders. However, the offensive also resulted in the exodus of approximately 150,000-200,000 Croatian Serbs who fled the region, and hundreds of mainly elderly Serb civilians were killed in the aftermath. The return of Serb refugees has been a slow and challenging process, with about half having returned since. Their abandoned homes were subsequently settled by Croat refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina. The remaining occupied areas in Eastern Slavonia, Baranja, and Western Syrmia were peacefully reintegrated into Croatia following the Erdut Agreement of November 1995, with the UNTAES mission concluding in January 1998.

After the war, Croatia faced the challenges of post-war reconstruction, the return of refugees and displaced persons, establishing robust democratic institutions, protecting human rights, and fostering social and economic development. The 2000s were characterized by democratization, economic growth, structural and social reforms. However, issues such as unemployment, corruption, and the inefficiency of public administration persisted. In November 2000 and March 2001, the Parliament amended the Constitution (first adopted on 22 December 1990), changing its bicameral structure back to its historic unicameral form and reducing presidential powers, strengthening the parliamentary system.

Croatia joined the Partnership for Peace on 25 May 2000, and became a member of the World Trade Organization on 30 November 2000. On 29 October 2001, Croatia signed a Stabilisation and Association Agreement with the European Union, submitted a formal application for EU membership in 2003, was granted candidate country status in 2004, and began accession negotiations in 2005. Although the Croatian economy enjoyed a significant boom in the early 2000s, the financial crisis in 2008 forced the government to cut spending, provoking public outcry. A wave of anti-government protests in 2011 reflected general dissatisfaction with the political and economic situation, particularly concerning corruption scandals.

Croatia served a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council for the 2008-2009 term. On 1 April 2009, Croatia joined NATO. On 30 June 2011, Croatia successfully completed EU accession negotiations. The country signed the Accession Treaty on 9 December 2011, and a referendum on 22 January 2012 saw Croatian citizens vote in favor of EU membership. Croatia officially joined the European Union on 1 July 2013.

Croatia was affected by the 2015 European migrant crisis when Hungary's closure of its border with Serbia pushed over 700,000 refugees and migrants to pass through Croatia on their way to other EU countries. Andrej Plenković became Prime Minister in October 2016, and Zoran Milanović was elected President in January 2020. On 25 January 2022, the OECD Council decided to open accession negotiations with Croatia, with full membership anticipated in 2025. On 1 January 2023, Croatia adopted the euro as its official currency, replacing the kuna, and simultaneously became the 27th member of the border-free Schengen Area, marking its full EU integration. The country continues to work on strengthening its democratic institutions, rule of law, and addressing social and economic disparities.

4. Geography

Croatia's geography is marked by its extensive Adriatic coastline, numerous islands, mountainous regions, and fertile plains. This diversity contributes to varied climates and rich biodiversity.

4.1. Topography and Borders

Croatia is situated in Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro to the southeast, and shares a maritime border with Italy to the west. It lies mostly between latitudes 42° and 47° N and longitudes 13° and 20° E. Part of the territory in the extreme south surrounding Dubrovnik is a practical exclave connected to the rest of the mainland by territorial waters but separated on land by a short coastline strip belonging to Bosnia and Herzegovina around Neum. The Pelješac Bridge, opened in 2022, now connects this exclave with mainland Croatia, bypassing Bosnian territory.

The territory covers 22 K mile2 (56.59 K km2), consisting of 22 K mile2 (56.41 K km2) of land and 49 mile2 (128 km2) of water. It is the world's 127th largest country. Elevation ranges from the mountains of the Dinaric Alps, with the highest point being the Dinara peak at 6.0 K ft (1.83 K m) near the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina in the south, to the shore of the Adriatic Sea which makes up its entire southwest border. Insular Croatia consists of over a thousand islands and islets varying in size, 48 of which are permanently inhabited. The largest islands are Cres and Krk, each having an area of around 156 mile2 (405 km2).

The hilly northern parts of Hrvatsko Zagorje and the flat plains of Slavonia in the east, which is part of the Pannonian Basin, are traversed by major rivers such as the Danube, Drava, Kupa, and the Sava. The Danube, Europe's second-longest river, runs through the city of Vukovar in the extreme east and forms part of the border with the Vojvodina region of Serbia. The central and southern regions near the Adriatic coastline and islands consist of low mountains and forested highlands. Natural resources found in quantities significant enough for production include oil, coal, bauxite, low-grade iron ore, calcium, gypsum, natural asphalt, silica, mica, clays, salt, and hydropower. Karst topography makes up about half of Croatia and is especially prominent in the Dinaric Alps and coastal regions. Croatia hosts many deep caves, with 49 deeper than 820 ft (250 m), 14 deeper than 1640 ft (500 m), and three deeper than 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m). Croatia's most famous lakes are the Plitvice Lakes, a system of 16 terraced lakes connected by waterfalls over dolomite and limestone cascades.

4.2. Climate

Most of Croatia has a moderately warm and rainy continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb), particularly in the interior. The Adriatic coast enjoys a Mediterranean climate (Csa). There is also a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) in some coastal areas and a warm-summer humid continental climate (Dfb) in the mountainous interior.

Mean monthly temperature ranges between 26.6 °F (-3 °C) in January and 64.4 °F (18 °C) in July for inland areas. Coastal areas are milder, with January mean temperatures from 41 °F (5 °C) to 50 °F (10 °C) and July means from 71.6 °F (22 °C) to 78.8 °F (26 °C). The coldest parts of the country are Lika and Gorski Kotar, featuring a snowy, forested climate (Dfc, Dfb) at elevations above 3.9 K ft (1.20 K m). The warmest areas are at the Adriatic coast and especially in its immediate hinterland, characterized by a Mediterranean climate, as the sea moderates temperature highs. Consequently, temperature peaks are more pronounced in continental areas. The lowest temperature of -31.9 °F (-35.5 °C) was recorded on 3 February 1919 in Čakovec, and the highest temperature of 109.03999999999999 °F (42.8 °C) was recorded on 4 August 1981 in Ploče.

Mean annual precipitation ranges between 24 in (600 mm) and 0.1 K in (3.50 K mm) depending on geographic region and climate type. The least precipitation is recorded in the outer islands (e.g., Biševo, Lastovo, Svetac, Vis) and the eastern parts of Slavonia. However, in the latter case, rain occurs mostly during the growing season. The maximum precipitation levels are observed on the windward slopes of the Dinaric Alps, such as in Gorski Kotar (e.g., Risnjak and Snježnik mountains).

Prevailing winds in the interior are light to moderate northeast or southwest. In the coastal area, prevailing winds are determined by local features. Higher wind velocities are more often recorded in cooler months along the coast, generally as the cool northeasterly Bura or less frequently as the warm southerly Jugo (Sirocco). The sunniest parts of the country are the outer islands, Hvar and Korčula, where more than 2,700 hours of sunshine are recorded per year, followed by the middle and southern Adriatic Sea area in general, and the northern Adriatic coast, all with more than 2,000 hours of sunshine per year.

4.3. Biodiversity and Protected Areas

Croatia can be subdivided into ecoregions based on climate and geomorphology and is one of the richest countries in Europe in terms of biodiversity. Croatia has four types of biogeographical regions: the Mediterranean along the coast and in its immediate hinterland, the Alpine in most of Lika and Gorski Kotar, the Pannonian along the Drava and Danube rivers, and the Continental in the remaining areas. The country contains three terrestrial ecoregions: Dinaric Mountains mixed forests, Pannonian mixed forests, and Illyrian deciduous forests.

The most significant habitats are karst habitats, which include submerged karst systems like the Zrmanja and Krka river canyons and their tufa barriers, as well as underground habitats. Karst geology harbors approximately 7,000 caves and pits, some of which are the habitat of the only known aquatic cave vertebrate-the olm. Forests are abundant, covering 6.2 M acre (2.49 M ha) or 44% of Croatian land area. Other habitat types include wetlands, grasslands, bogs, fens, scrub habitats, and diverse coastal and marine habitats.

In terms of phytogeography, Croatia is part of the Boreal Kingdom and is situated within the Illyrian and Central European provinces of the Circumboreal Region, as well as the Adriatic province of the Mediterranean Region. The World Wide Fund for Nature divides Croatia among three ecoregions: Pannonian mixed forests, Dinaric Mountains mixed forests, and Illyrian deciduous forests.

Croatia hosts an estimated 37,000 known plant and animal species, though the actual number is believed to be between 50,000 and 100,000. More than a thousand species are endemic, especially in the Velebit and Biokovo mountains, Adriatic islands, and karst rivers. National legislation protects 1,131 species. The most serious threats to biodiversity are habitat loss and degradation, as well as invasive alien species, notably the Caulerpa taxifolia alga, which is regularly monitored and removed to protect benthic habitats. Croatia also has numerous indigenous cultivated plant strains and domesticated animal breeds, including five breeds of horses, five of cattle, eight of sheep, two of pigs, and one poultry breed. Nine of these indigenous breeds are endangered or critically endangered.

Croatia has 444 protected areas, encompassing 9% of the country. These include eight national parks, two strict reserves, and ten nature parks. The most famous protected area and the oldest national park in Croatia is Plitvice Lakes National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Velebit Nature Park is part of the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme. Strict and special reserves, as well as national and nature parks, are managed and protected by the central government, while other protected areas are managed by counties. In 2005, the National Ecological Network was established as the first step in preparation for EU accession and joining the Natura 2000 network, underscoring Croatia's commitment to conservation.

5. Politics and Government

Croatia is a unitary, democratic parliamentary republic. The separation of powers is a fundamental principle, with distinct legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The country's political development since independence has focused on strengthening democratic institutions, human rights, and integration into Euro-Atlantic structures.

5.1. Governmental Structure

The President of the Republic (Predsjednik RepublikePresident of the RepublicCroatian) is the head of state, directly elected for a five-year term and limited by the Constitution to a maximum of two terms. The President is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, has the procedural duty of appointing the Prime Minister with the consent of the Parliament, and holds some influence in foreign policy, representing the country abroad.

The Government (VladaGovernmentCroatian) is headed by the Prime Minister, who typically has several deputy prime ministers and ministers in charge of particular sectors (e.g., 16 ministers and four deputy prime ministers in past configurations). As the executive branch, the Government is responsible for proposing legislation and a budget, enforcing laws, and guiding the country's foreign and internal policies. The Government is seated at Banski dvori in Zagreb and is accountable to the Croatian Parliament.

The Parliament (SaborParliamentCroatian) is a unicameral legislative body. The number of Sabor members can vary from 100 to 160. They are elected by popular vote to serve four-year terms. The Sabor enacts laws, adopts the state budget, declares war and peace, amends the Constitution, and oversees the work of the Government. Legislative sessions take place from 15 January to 15 July, and from 15 September to 15 December annually. The two largest political parties have historically been the center-right Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) and the center-left Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP), though other parties also play significant roles in coalition governments.

5.2. Law and Judicial System

Croatia has a civil law legal system, where law primarily arises from written statutes, and judges act as implementers rather than creators of law. Its development has been largely influenced by German and Austrian legal systems. Croatian law is divided into two principal areas: private law and public law. Before its accession to the European Union, Croatian legislation was fully harmonized with the Community acquis.

The main national courts are the Constitutional Court, which oversees the constitutionality of laws and protects human rights and fundamental freedoms, and the Supreme Court, which is the highest court of appeal ensuring uniform application of laws. There are also specialized courts such as Administrative Courts, Commercial Courts, County Courts (second instance for municipal courts and first instance for more serious crimes), Misdemeanor Courts, and Municipal Courts (first instance courts). Cases are typically decided by a single professional judge in the first instance, while appeals are deliberated in mixed tribunals of professional judges. Lay magistrates also participate in some trials.

The State's Attorney Office (Državno odvjetništvo Republike HrvatskeState's Attorney Office of the Republic of CroatiaCroatian, DORH) is the judicial body composed of public prosecutors empowered to instigate the prosecution of perpetrators of offenses. Judicial reforms aimed at improving efficiency, reducing backlogs, and strengthening the rule of law have been an ongoing process, particularly in the context of EU accession and post-accession monitoring.

Law enforcement agencies are organized under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior, which primarily consists of the national police force. Croatia's security service is the Security and Intelligence Agency (SOA).

5.3. Human Rights

The state of human rights in Croatia is an area of ongoing development and scrutiny, reflecting the country's transition to a stable democracy. The Constitution of Croatia guarantees a range of fundamental human rights and freedoms, including freedom of speech, assembly, religion, and the press, as well as the right to a fair trial.

Key areas of focus for human rights include:

- Minority Rights: Croatia officially recognizes 22 national minorities. The Constitutional Act on the Rights of National Minorities provides for their cultural autonomy, representation in government, and use of minority languages and scripts in certain municipalities. However, challenges remain, particularly for the Serb and Roma minorities, concerning issues like full implementation of property return and reconstruction for war-affected individuals, access to employment, education in minority languages, and combating societal discrimination and hate speech.

- Gender Equality: Gender equality is legally guaranteed, and Croatia has made progress in areas like female political representation, though disparities persist in employment, pay, and representation in leadership positions. Domestic violence and violence against women remain serious concerns, with ongoing efforts to strengthen support services and legal protections.

- LGBTQ+ Rights: Croatia has made significant progress in LGBTQ+ rights. Same-sex couples have been able to register for "life partnerships" since 2014, granting them most of the same rights as married heterosexual couples, except for joint adoption. However, societal acceptance varies, and LGBTQ+ individuals can still face discrimination and prejudice. Zagreb Pride is an annual event that has grown in visibility.

- Freedom of the Press and Speech: While generally free, journalists sometimes face political pressure, threats, or lawsuits (SLAPPs - Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) when investigating corruption or sensitive topics. The independence of public media is also a subject of ongoing discussion.

- Refugee and Migrant Rights: As a country on the EU's external border, Croatia has faced challenges related to the treatment of asylum seekers and migrants, with reports from human rights organizations alleging pushbacks and violations of rights at the border. The government generally denies systemic wrongdoing.

- Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Efforts are underway to improve accessibility and inclusion for persons with disabilities, but challenges remain in areas like physical accessibility, employment, and access to specialized services.

- War Crimes and Transitional Justice: Processing war crimes from the 1990s remains an important issue. While progress has been made, some cases remain unresolved, and ensuring accountability for all perpetrators and justice for victims is a continued focus.

Institutions like the Ombudsman and specialized ombudspersons (e.g., for children, gender equality, persons with disabilities) play a role in monitoring and advocating for human rights. Civil society organizations are also very active in these areas. From a social liberal perspective, continued efforts are needed to strengthen the rule of law, combat all forms of discrimination, ensure the effective protection of vulnerable groups, and foster a culture of tolerance and respect for human rights.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Croatia has established diplomatic relations with 194 countries. As of 2019, it supported 57 embassies, 30 consulates, and eight permanent diplomatic missions abroad. Numerous foreign embassies and consulates operate in Croatia, alongside offices of international organizations such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), International Organization for Migration (IOM), Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), World Bank, World Health Organization (WHO), International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and UNICEF.

The stated aims of Croatian foreign policy include enhancing relations with neighboring countries, developing international cooperation, and promoting the Croatian economy and Croatia itself. A key strategic goal achieved was membership in the European Union (since 1 July 2013) and NATO (since 1 April 2009). Croatia also joined the Eurozone and the Schengen Area on 1 January 2023, marking its full integration into the EU. Croatia is actively pursuing membership in the OECD.

Croatia has generally good relations with its neighbors, though some unresolved border issues persist with Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Montenegro stemming from the breakup of Yugoslavia. The country participates in regional initiatives and plays a constructive role in Southeast Europe, supporting the Euro-Atlantic integration of other countries in the region. Croatia has also been an active participant in international peacekeeping missions.

Croatia maintains intensive contacts with the Croatian diaspora worldwide, supporting cultural, sports, and economic initiatives. It also works to guarantee the rights of Croatian minorities in various host countries.

5.5. Military

The Croatian Armed Forces (CAF) consist of three branches: the Croatian Army (Hrvatska kopnena vojskaCroatian ArmyCroatian, HKoV), the Croatian Navy (Hrvatska ratna mornaricaCroatian NavyCroatian, HRM), and the Croatian Air Force (Hrvatsko ratno zrakoplovstvoCroatian Air ForceCroatian, HRZ). Additionally, there are the Education and Training Command and Support Command. The CAF is headed by the General Staff, which reports to the Minister of Defence, who in turn reports to the President of the Republic. According to the constitution, the President is the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. In case of an immediate threat during wartime, the President issues orders directly to the General Staff.

Following the Croatian War of Independence (1991-1995), defence spending and the size of the CAF began a constant decline. As of 2019, military spending was estimated at 1.68% of the country's GDP. In 2005, the budget fell below the NATO-required 2% of GDP, down from a record high of 11.1% in 1994 during the war. Traditionally relying on conscripts, the CAF underwent significant reforms focused on downsizing, restructuring, and professionalization in the years before accession to NATO in April 2009. According to a presidential decree issued in 2006, the CAF aimed for around 18,100 active-duty military personnel, 3,000 civilians, and 2,000 voluntary conscripts in peacetime.

Until 2008, military service was obligatory for men at age 18, with conscripts serving six-month tours of duty (reduced in 2001 from nine months). Conscientious objectors could opt for eight months of civilian service. Compulsory conscription was abolished in January 2008. However, in light of changing security dynamics in Europe, particularly following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, discussions about reintroducing some form of compulsory military service or training emerged, with plans for a reintroduction of a shorter, two-month active duty period mooted for 2025.

As of 2019, the Croatian military had personnel stationed in foreign countries as part of United Nations-led international peacekeeping forces and NATO-led missions, including ISAF in Afghanistan and KFOR in Kosovo. Croatia has a military-industrial sector that exports military equipment. Croatian-made weapons and vehicles used by the CAF include the standard sidearm HS2000 pistol (globally known as the Springfield XD) manufactured by HS Produkt and the M-84D battle tank (an upgraded version of the Yugoslav M-84, itself a version of the Soviet T-72) designed by the Đuro Đaković factory. Uniforms and helmets worn by CAF soldiers are also locally produced and marketed internationally. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Croatia is ranked as the 15th most peaceful country in the world.

6. Administrative Divisions

Croatia is a unitary state divided into 20 counties (županijecountiesCroatian, singular: županija) and the capital city of Zagreb, which has the dual authority and legal status of both a county and a city. This structure of local government plays a key role in regional administration and development.

Croatia was first divided into counties in the Middle Ages. The traditional division was abolished in the 1920s when the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia) introduced oblasts and then banovinas. Communist-ruled Croatia, as part of post-World War II Yugoslavia, abolished earlier divisions and introduced municipalities. Counties were reintroduced in 1992 legislation, following Croatia's independence, though their territories were significantly altered relative to pre-1920s subdivisions. The county borders have been revised in some instances, with the last major revision in 2006.

The counties are the primary level of local self-government and state administration. They are responsible for a range of functions delegated by the central government, including education, healthcare, spatial and urban planning, economic development, transport infrastructure, and culture, to the extent not managed centrally or by lower-level units. Each county has an assembly (županijska skupštinacounty assemblyCroatian) as its representative body, elected by popular vote, and a county prefect (županprefectCroatian) who is the head of the executive. The City of Zagreb, as the capital, has a special status that combines the functions of a city and a county, managed by the City Assembly and the Mayor.

The counties are further subdivided into cities (gradovicitiesCroatian, singular: grad) and municipalities (općinemunicipalitiesCroatian, singular: općina). As of the last revisions, there are 127 cities and 429 municipalities. Cities typically encompass larger urban centers, while municipalities usually cover rural areas or smaller towns. These units form the basic level of local self-government, responsible for local services, utilities, and community development.

For statistical purposes, Croatia is also divided according to the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) system.

- NUTS 1: The entire country.

- NUTS 2: Croatia is divided into four NUTS 2 regions (since a 2021 revision): Pannonian Croatia, Adriatic Croatia, City of Zagreb, and Northern Croatia. (Previously, there were two: Continental Croatia and Adriatic Croatia).

- NUTS 3: This level corresponds to the 20 counties and the City of Zagreb.

The Local Administrative Unit (LAU) divisions are two-tiered. LAU 1 divisions also match the counties and the City of Zagreb (same as NUTS 3), while LAU 2 subdivisions correspond to the cities and municipalities.

The counties of Croatia are:

| County | Croatian Name | County Seat | Area (km2) | Population (2021 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjelovar-Bilogora County | Bjelovarsko-bilogorska županijaBjelovarsko-bilogorska županijaCroatian | Bjelovar | 1.0 K mile2 (2.64 K km2) | 101,879 |

| Brod-Posavina County | Brodsko-posavska županijaBrodsko-posavska županijaCroatian | Slavonski Brod | 0.8 K mile2 (2.03 K km2) | 130,267 |

| Dubrovnik-Neretva County | Dubrovačko-neretvanska županijaDubrovačko-neretvanska županijaCroatian | Dubrovnik | 0.7 K mile2 (1.78 K km2) | 115,564 |

| Istria County | Istarska županijaIstarska županijaCroatian | Pazin | 1.1 K mile2 (2.81 K km2) | 195,237 |

| Karlovac County | Karlovačka županijaKarlovačka županijaCroatian | Karlovac | 1.4 K mile2 (3.63 K km2) | 112,195 |

| Koprivnica-Križevci County | Koprivničko-križevačka županijaKoprivničko-križevačka županijaCroatian | Koprivnica | 0.7 K mile2 (1.75 K km2) | 101,221 |

| Krapina-Zagorje County | Krapinsko-zagorska županijaKrapinsko-zagorska županijaCroatian | Krapina | 0.5 K mile2 (1.23 K km2) | 120,702 |

| Lika-Senj County | Ličko-senjska županijaLičko-senjska županijaCroatian | Gospić | 2.1 K mile2 (5.35 K km2) | 42,748 |

| Međimurje County | Međimurska županijaMeđimurska županijaCroatian | Čakovec | 281 mile2 (729 km2) | 105,250 |

| Osijek-Baranja County | Osječko-baranjska županijaOsječko-baranjska županijaCroatian | Osijek | 1.6 K mile2 (4.16 K km2) | 258,026 |

| Požega-Slavonia County | Požeško-slavonska županijaPožeško-slavonska županijaCroatian | Požega | 0.7 K mile2 (1.82 K km2) | 64,084 |

| Primorje-Gorski Kotar County | Primorsko-goranska županijaPrimorsko-goranska županijaCroatian | Rijeka | 1.4 K mile2 (3.59 K km2) | 265,419 |

| Šibenik-Knin County | Šibensko-kninska županijaŠibensko-kninska županijaCroatian | Šibenik | 1.2 K mile2 (2.98 K km2) | 96,381 |

| Sisak-Moslavina County | Sisačko-moslavačka županijaSisačko-moslavačka županijaCroatian | Sisak | 1.7 K mile2 (4.47 K km2) | 139,603 |

| Split-Dalmatia County | Splitsko-dalmatinska županijaSplitsko-dalmatinska županijaCroatian | Split | 1.8 K mile2 (4.54 K km2) | 423,407 |

| Varaždin County | Varaždinska županijaVaraždinska županijaCroatian | Varaždin | 0.5 K mile2 (1.26 K km2) | 159,487 |

| Virovitica-Podravina County | Virovitičko-podravska županijaVirovitičko-podravska županijaCroatian | Virovitica | 0.8 K mile2 (2.02 K km2) | 70,368 |

| Vukovar-Syrmia County | Vukovarsko-srijemska županijaVukovarsko-srijemska županijaCroatian | Vukovar | 0.9 K mile2 (2.45 K km2) | 143,113 |

| Zadar County | Zadarska županijaZadarska županijaCroatian | Zadar | 1.4 K mile2 (3.65 K km2) | 159,766 |

| Zagreb County | Zagrebačka županijaZagrebačka županijaCroatian | Zagreb | 1.2 K mile2 (3.06 K km2) | 301,206 |

| City of Zagreb | Grad ZagrebGrad ZagrebCroatian | Zagreb | 247 mile2 (641 km2) | 767,131 |

7. Economy

The Croatian economy is classified as a high-income, developed market economy. Since its independence, it has undergone significant transition, particularly with its accession to the European Union, the Eurozone, and the Schengen Area. The economy is characterized by a dominant service sector, followed by industry and agriculture. Efforts towards sustainable development, social equity, and combating corruption are ongoing aspects of its economic policy.

7.1. Overview and Key Sectors

Croatia's nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was projected by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to reach $88.08 billion in 2024, with a GDP per capita of $22,966. In terms of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), the GDP was projected at $175.269 billion, or $45,702 per capita. According to Eurostat, Croatian GDP per capita in PPS stood at 76% of the EU average in 2023, with real GDP growth for that year being 2.8%. The average net salary in April 2024 was approximately 1.33 K EUR per month. The unemployment rate has seen a significant decrease, dropping to 5.6% in April 2024.

The Croatian economy is dominated by the service sector, which accounts for approximately 70% of GDP. Key industries within this sector include tourism, retail, and financial services. The industrial sector contributes around 26% of GDP, with important branches including shipbuilding (a long-standing tradition, though facing restructuring), food processing, pharmaceuticals (notably Pliva), information technology (a growing sector with companies like Rimac Automobili and Infobip), biochemicals, and the timber industry. Agriculture accounts for a smaller share of GDP (around 3-4%) but remains important for rural employment and food production, with main products including grains, fruits, vegetables, and wine.

Croatia's main trading partners are other European Union countries, particularly Germany, Italy, and Slovenia. Since joining the EU, Croatia has benefited from access to the single market and EU funds for development projects. However, the economy also faces challenges, including regional disparities, demographic decline (emigration and an aging population), and the need for further structural reforms to improve competitiveness and administrative efficiency. Efforts to combat corruption and ensure social welfare are key priorities, with a focus on sustainable development and social equity to ensure that economic growth benefits all segments of the population. The Croatian state still controls significant parts of the economy, with government expenditures accounting for a substantial portion of GDP.

7.2. Tourism

Tourism is a dominant component of the Croatian service sector and a cornerstone of the national economy, accounting for up to 20% of the country's GDP. In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism income was estimated at 10.50 B EUR. The industry has a significant positive impact throughout the economy, boosting retail business, fostering the development of related services, and creating seasonal employment. Foreign visitor spending plays a crucial role in reducing the country's trade imbalance.

The tourist industry has grown rapidly, especially since Croatia's independence, attracting more than 17 million visitors annually in the years leading up to 2019. The main source markets for tourists include Germany, Slovenia, Austria, Italy, the United Kingdom, Czechia, Poland, Hungary, France, and the Netherlands, along with domestic tourists. The average tourist stay was around 4.7 days in 2019.

Much of Croatia's tourism is concentrated along its extensive Adriatic coastline and numerous islands. Opatija was one of the earliest holiday resorts, gaining popularity in the mid-19th century and becoming a significant European health resort by the 1890s. Today, numerous resorts cater to both mass tourism and various niche markets. Major tourist destinations include historic cities like Dubrovnik, Split, Zadar, Pula, and Rovinj, as well as islands such as Hvar, Brač, Korčula, and Vis.

Types of tourism are diverse:

- Coastal and Island Tourism: Centered on beaches, crystal-clear waters, and scenic beauty. Croatia has unpolluted marine areas, numerous nature reserves, and over 100 Blue Flag beaches. In 2022, the European Environmental Agency ranked Croatia first in Europe for swimming water quality.

- Nautical Tourism: A significant segment, supported by numerous marinas with over 16,000 berths, attracting yachters and sailors.

- Cultural Tourism: Relies on the appeal of medieval coastal cities, Roman ruins (like the Pula Arena and Diocletian's Palace in Split), and numerous cultural events taking place during the summer, such as the Dubrovnik Summer Festival. Croatia has several UNESCO World Heritage Sites that are major attractions.

- Naturism: Croatia has a long tradition of naturism and was one of the first European countries to develop commercial naturist resorts.

- Inland Tourism: Growing in importance, offering agrotourism, mountain resorts (e.g., in Gorski Kotar), and spas (e.g., in Hrvatsko Zagorje). Zagreb, the capital, is a significant destination in its own right, rivaling major coastal cities and resorts with its cultural offerings, historical sites, and vibrant atmosphere.

The socio-economic impacts of tourism are substantial, providing employment and driving regional development. However, there are also concerns about environmental sustainability, particularly regarding over-tourism in popular destinations, strain on infrastructure, and the need for responsible development to protect natural and cultural heritage. In 2023, Croatia was ranked highly as a solo travel destination and noted as a popular honeymoon destination.

7.3. Infrastructure

Croatia has significantly invested in its infrastructure since the 2000s, particularly in transport and energy networks, to support economic growth, tourism, and European integration.

7.3.1. Transport

The motorway network was largely built in the late 1990s and the 2000s. As of December 2020, Croatia had completed 0.8 K mile (1.31 K km) of motorways, connecting Zagreb to other regions and following various European routes and four Pan-European corridors. The busiest motorways are the A1, connecting Zagreb to Split and extending towards Dubrovnik, and the A3, passing east-west through northwest Croatia and Slavonia. A widespread network of state roads acts as motorway feeder roads while connecting major settlements. The Croatian motorway network is recognized for its high quality and safety levels, confirmed by programs like EuroTAP and EuroTest. A major recent infrastructure project is the Pelješac Bridge, opened in July 2022. This 1.5 mile (2.4 km)-long bridge connects the Pelješac peninsula with the Croatian mainland, bypassing a short strip of Bosnian territory and thus providing a direct land link to the Dubrovnik region. The project was co-financed by the European Union.

Croatia has an extensive rail network spanning 1.6 K mile (2.60 K km), including 611 mile (984 km) of electrified railways and 158 mile (254 km) of double-track railways (as of 2017). The most significant railways are within the Pan-European transport corridors Vb (Rijeka to Budapest) and X (Ljubljana to Belgrade), both via Zagreb. Croatian Railways (Hrvatske željezniceCroatian RailwaysCroatian, HŽ) operates all rail services. The rail network requires further modernization to improve speed and efficiency.

There are several international airports in Croatia, including in Zagreb (Franjo Tuđman Airport, the largest and busiest), Split, Dubrovnik, Zadar, Pula, Rijeka (on Krk island), and Osijek. Croatia Airlines is the national flag carrier. Croatia complies with International Civil Aviation Organization aviation safety standards.

The busiest cargo seaport is the Port of Rijeka. The busiest passenger ports are Split and Zadar, primarily due to ferry traffic. Numerous minor ports serve ferries connecting the many islands to the mainland and coastal cities, with ferry lines also operating to several cities in Italy. Jadrolinija is the main state-owned ferry operator. The largest river port is Vukovar, located on the Danube, representing the nation's outlet to the Pan-European transport corridor VII.

7.3.2. Energy

Croatia has 379 mile (610 km) of crude oil pipelines connecting the Rijeka oil terminal with refineries in Rijeka and Sisak, as well as several transshipment terminals. The system, operated by Jadranski naftovod (JANAF), has a capacity of 20 million t per year. The natural gas transportation system comprises 1.3 K mile (2.11 K km) of trunk and regional pipelines and associated structures, connecting production rigs, the Okoli natural gas storage facility, end-users, and distribution systems, operated by Plinacro.

Croatia plays an important role in regional energy security. The floating liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminal off Krk island commenced operations on January 1, 2021. This facility positions Croatia as a regional energy hub and contributes to the diversification of Europe's energy supply, particularly for Central and Southeastern Europe.

In 2010, Croatian domestic energy production covered 85% of nationwide natural gas demand and 19% of oil demand. In 2016, Croatia's primary energy production involved natural gas (24.8%), hydropower (28.3%), crude oil (13.6%), fuelwood (27.6%), and heat pumps and other renewable energy sources (5.7%). In 2017, net total electrical power production reached 11,543 GWh, while it imported 12,157 GWh, or about 40% of its electric power needs. A significant portion of these imports comes from the Krško Nuclear Power Plant in Slovenia, of which Croatia's national electricity company, Hrvatska elektroprivreda (HEP), is a 50% owner, providing approximately 15% of Croatia's electricity. There is a growing emphasis on renewable energy sources, particularly wind and solar power, to increase energy independence and meet climate goals.

8. Demographics

Croatia's demographic landscape is characterized by a relatively small population for its size, an aging trend, negative natural population growth, and significant emigration, particularly since joining the EU. Ethnic Croats form the majority, with several recognized national minorities.

8.1. Population Statistics and Trends

As of the 2021 census, Croatia had a population of 3.87 million. This represents a significant decrease of nearly 10% from the 2011 census figure of 4.28 million. The country ranks around 127th by population globally. Its population density in 2018 was approximately 72.9 inhabitants per square kilometer, making it one of the more sparsely populated European countries.

The overall life expectancy at birth was 76.3 years in 2018. The total fertility rate (TFR) is low, around 1.41 children per mother, which is well below the replacement rate of 2.1. This TFR has remained considerably below its historical high of 6.18 children per woman in 1885. Croatia's death rate has continuously exceeded its birth rate since 1998, resulting in a negative natural population growth. Consequently, Croatia has one of the world's older populations, with an average age of 43.3 years.

The population rose steadily from 2.1 million in 1857 until 1991, when it peaked at 4.7 million, with exceptions for censuses following the World Wars (1921 and 1948). The demographic transition was completed in the 1970s.

The population decrease in recent decades has been exacerbated by emigration, particularly after Croatia's accession to the EU in 2013, which allowed for easier movement of labor to other EU countries. The Croatian government has been pressured to increase permit quotas for foreign workers to address labor shortages, reaching a high of 68,100 in 2019. The government is also trying to entice emigrants to return.

The Croatian War of Independence (1991-1995) also significantly impacted demographics, displacing large numbers of people and increasing emigration. In 1991, over 400,000 Croats were removed from their homes or fled violence in predominantly Serb-occupied areas. During the final days of the war in 1995 (Operation Storm), about 150,000-200,000 Serbs fled the Krajina region. Post-war, many territories abandoned during the war were settled by Croat refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina, while some displaced persons, including Serbs, returned to their homes, though the process has been slow and faced challenges.

| Rank | City | County | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zagreb | City of Zagreb | 790,017 |

| 2 | Split | Split-Dalmatia | 178,102 |

| 3 | Rijeka | Primorje-Gorski Kotar | 128,624 |

| 4 | Osijek | Osijek-Baranja | 108,048 |

| 5 | Zadar | Zadar | 75,062 |

| 6 | Pula | Istria | 57,460 |

| 7 | Slavonski Brod | Brod-Posavina | 59,141 |

| 8 | Karlovac | Karlovac | 55,705 |

| 9 | Varaždin | Varaždin | 46,946 |

| 10 | Šibenik | Šibenik-Knin | 46,332 |

8.2. Ethnic Groups and Minorities

According to the 2021 census, the majority of inhabitants are Croats (91.6%). The largest national minority are Serbs, constituting 3.2% of the population. Other recognized minorities include Bosniaks (0.62%), Roma (0.46%), Italians (0.36%), Albanians (0.36%), Hungarians (0.27%), Czechs (0.20%), Slovenes (0.20%), Slovaks (0.10%), Macedonians (0.09%), Germans (0.09%), and Montenegrins (0.08%). Other ethnic groups make up 1.56% of the population. There is a significant Croatian diaspora, with estimates of around 4 million Croats and their descendants living abroad.

Croatia has a legal framework for protecting minority rights, including the Constitutional Act on the Rights of National Minorities. This act guarantees cultural autonomy, representation in state and local government, the right to education in their own language and script, and the official use of minority languages in areas where minorities constitute a significant portion of the population. The social integration of minorities, particularly Serbs and Roma, remains an ongoing process, with challenges related to discrimination, access to resources, and full reconciliation after the 1990s war. The government is committed to improving the situation, often under the scrutiny of international human rights organizations and EU bodies.

| Ethnic Group | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Croats | 91.6% |

| Serbs | 3.2% |

| Bosniaks | 0.62% |

| Roma | 0.46% |

| Italians | 0.36% |

| Albanians | 0.36% |

| Hungarians | 0.27% |

| Czechs | 0.20% |

| Slovenes | 0.20% |

| Slovaks | 0.10% |

| Macedonians | 0.09% |

| Germans | 0.09% |

| Montenegrins | 0.08% |

| Other/Undeclared/Unknown | 1.56% |

8.3. Languages

The official language of Croatia is Croatian, a South Slavic language written using the Latin alphabet. It has been one of the official languages of the European Union since Croatia's accession in 2013. According to the 2011 census, 95.6% of citizens declared Croatian as their native language.

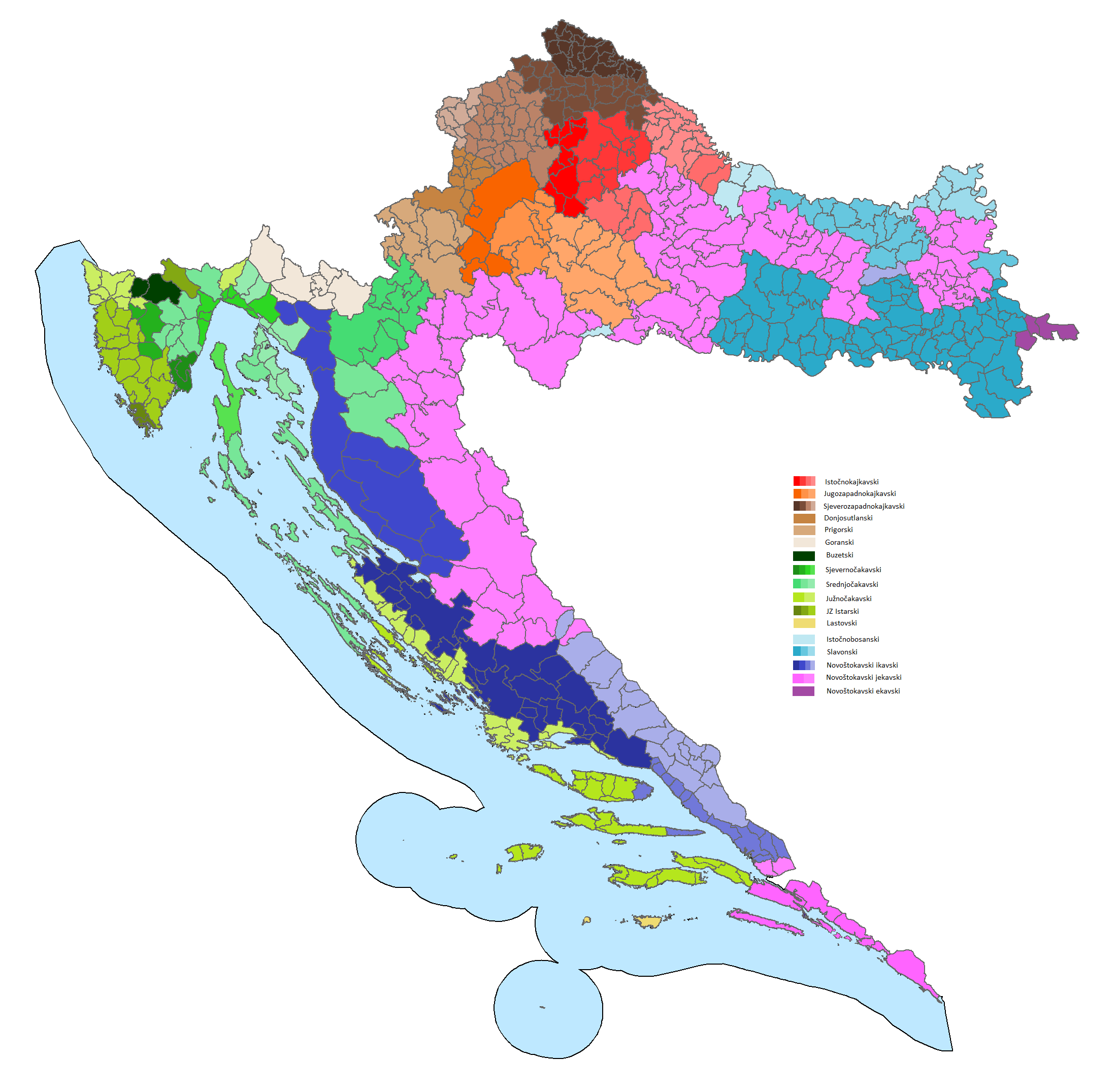

Croatian has three main dialect groups, which are largely mutually intelligible but possess distinct phonological, accentual, and lexical features:

- Shtokavian: The most widespread dialect, forming the basis for standard Croatian, standard Serbian, standard Bosnian, and standard Montenegrin. It is spoken in most of Slavonia, Baranja, Lika, Kordun, most of Dalmatia, and by Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- Chakavian: Spoken along the Adriatic coast, in Istria, the Kvarner Gulf islands, and parts of Dalmatia and Lika. It is considered the oldest Croatian dialect and preserves some archaic Slavic features.

- Kajkavian: Spoken in northwestern Croatia, including the capital Zagreb and the Hrvatsko Zagorje region. It shares many features with neighboring Slovene dialects and Hungarian.

Minority languages are in official use in local government units where more than a third of the population consists of national minorities or where specific local enabling legislation applies. According to the 2011 census, Serbian was declared as a native language by 1.2% of the population. Other recognized minority languages with official status in certain municipalities include Czech, Hungarian, Italian, and Slovak. Additional recognized minority languages, though not necessarily with official local status everywhere, include Albanian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, German, Hebrew, Macedonian, Montenegrin, Polish, Romanian, Istro-Romanian (an endangered Eastern Romance language spoken in Istria), Romani, Russian, Rusyn, Slovene, Turkish, and Ukrainian.

A 2011 survey revealed that 78% of Croats claim knowledge of at least one foreign language. According to a 2005 European Commission survey, 49% of Croats spoke English as a second language, 34% spoke German, 14% spoke Italian (especially in Istria and coastal regions), 10% spoke French, 4% spoke Russian, and 2% spoke Spanish. The country is part of various language-based international associations, most notably the European Union Language community.

8.4. Religion

Croatia has no official state religion. The Constitution guarantees freedom of religion and equality for all religious communities before the law, and they are considered separate from the state.

According to the 2011 census, the religious landscape of Croatia is dominated by Christianity:

- Roman Catholicism: 86.28% of the population. The Catholic Church plays a significant role in Croatian society and culture.

- Eastern Orthodoxy: 4.44% of the population, primarily adherents of the Serbian Orthodox Church, largely corresponding to the Serb minority.

- Islam: 1.47% of the population, mainly Bosniaks and some Albanians and Roma.

- Protestantism: 0.34%, including various denominations such as Lutherans, Calvinists, Baptists, and Pentecostals.

- Other Christians: 0.30%.

- Non-religious, Atheists, Agnostics, Undeclared, or Other: 7.61% (4.57% described themselves as non-religious or atheists, 2.17% undeclared, and others).

In a 2010 Eurostat Eurobarometer Poll, 69% of the Croatian population responded that "they believe there is a God." A 2009 Gallup poll found that 70% answered yes to the question "Is religion an important part of your daily life?" However, actual regular attendance at religious services is lower, with a Pew Research Center survey from 2017 indicating that around 24% of the population attends religious services regularly. Religious education is offered in public schools as an optional subject, in cooperation with religious communities. The relationship between the state and major religious communities, particularly the Catholic Church, is regulated by concordats and agreements that address issues like funding, property, and education.

| Religion | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Roman Catholicism | 86.28% |

| Eastern Orthodox Christianity | 4.44% |

| Islam | 1.47% |

| Protestantism | 0.34% |

| Other Christians | 0.30% |

| Non-religious / Atheist | 4.57% |

| Undeclared / Unknown | 2.17% |

| Other | 0.43% |

8.5. Education

Education in Croatia is predominantly public and largely free at the primary and secondary levels. The system aims to provide accessible and quality education, contributing to social mobility and democratic development. Literacy in Croatia is high, standing at 99.2%.

Primary education starts at the age of six or seven and consists of eight grades. It is compulsory. In 2007, a law was passed to increase free, though non-compulsory, education until 18 years of age. Secondary education is provided by gymnasiums (general secondary schools preparing for university) and vocational schools (providing specific job skills and qualifications). As of 2019, there were 2,103 elementary schools and 738 schools providing various forms of secondary education. Primary and secondary education are also available in the languages of recognized minorities in Croatia, with classes held in Czech, Hungarian, Italian, Serbian, German, and Slovak where there is sufficient demand. There are also specialized music and art schools, as well as schools for disabled children and youth, and adult education centers.

A nationwide state leaving exam (državna maturastate exit examCroatian) was introduced for secondary education students in the 2009-2010 school year. It comprises three compulsory subjects (Croatian language, mathematics, and a foreign language) and optional subjects, and is a prerequisite for enrollment in higher education institutions.

Croatia has eight public universities: the University of Zagreb, University of Split, University of Rijeka, University of Osijek, University of Zadar, University of Dubrovnik, University of Pula, and University North. There are also private universities and numerous public and private polytechnics and colleges of applied sciences. The University of Zadar, originally founded in 1396 and re-established in 2002, is the oldest university in Croatia. The University of Zagreb, founded in 1669, is the oldest continuously operating university in Southeast Europe. In total, there are over 130 institutions of higher education in Croatia, attended by more than 160,000 students.

Scientific research and development are pursued by companies, government institutions, and non-profit organizations. Among the scientific institutes, the largest is the Ruđer Bošković Institute in Zagreb. The Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnostiCroatian Academy of Sciences and ArtsCroatian, HAZU) in Zagreb is a learned society promoting language, culture, arts, and science since its inception in 1866 (originally as the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts). Croatia was ranked 43rd in the Global Innovation Index in 2024. The European Investment Bank has supported digital infrastructure and equipment for primary and secondary schools in Croatia to aid in the integration of technology in teaching and administration.

8.6. Healthcare

Croatia has a universal health care system, the roots of which can be traced back to the Hungarian-Croatian Parliament Act of 1891, which provided a form of mandatory insurance for factory workers and craftsmen. The current system aims to provide comprehensive healthcare coverage to all citizens.

The population is covered by a basic health insurance plan provided by statute through the Croatian Health Insurance Fund (Hrvatski zavod za zdravstveno osiguranjeCroatian, HZZO), and there is also optional (supplementary and additional) health insurance available. In 2017, annual healthcare-related expenditures reached 22.20 B HRK. Healthcare expenditures comprised a small percentage from private health insurance, with public spending forming the bulk. In 2017, Croatia spent around 6.6% of its GDP on healthcare.

In 2020, Croatia ranked 41st in the world in life expectancy with 76.0 years for men and 82.0 years for women. It had a low infant mortality rate of 3.4 per 1,000 live births.

There are hundreds of healthcare institutions in Croatia, including 75 hospitals and 13 clinics with approximately 23,049 beds (as of 2018 data). These institutions care for more than 700,000 patients per year and employ thousands of medical doctors, including specialists. There is a total of nearly 70,000 health workers. Emergency medical services are provided through a network of emergency units in health centers.

The principal causes of death in 2016 were cardiovascular disease (39.7% for men and 50.1% for women), followed by tumors (32.5% for men and 23.4% for women). Public health challenges include managing chronic diseases, addressing lifestyle risk factors such as smoking (in 2016, an estimated 37.0% of Croatians were smokers), and obesity (in 2016, 24.40% of the adult population was obese). The healthcare system faces ongoing challenges related to funding, efficiency, and ensuring equitable access to services across all regions, particularly in rural and island areas.

9. Culture

Croatian culture is a vibrant tapestry woven from diverse historical and geographical influences, primarily Central European and Mediterranean, with Balkan elements also present. This unique blend is evident in its arts, literature, music, architecture, traditions, and cuisine. The Croatian government, through the Ministry of Culture, actively works to preserve the nation's rich cultural and natural heritage.

9.1. Overview

Positioned at a historical crossroads, Croatia has absorbed cultural influences from the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, Venice, the Habsburg Monarchy (Austria-Hungary), and the Ottoman Empire, all of which have left indelible marks. The Illyrian movement in the 19th century was a crucial period for national cultural awakening, fostering the Croatian language, literature, and a sense of national identity.

Croatia boasts a significant intangible cultural heritage, with 15 elements inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, ranking it high globally. These include traditions like klapa multipart singing of Dalmatia, the Sinjska alka knights' tournament, lace-making, and gingerbread crafting from Northern Croatia. A notable global cultural contribution from Croatia is the necktie, derived from the cravat originally worn by 17th-century Croatian mercenaries in France. Cultural institutions such as museums, theaters, and libraries play a vital role in preserving and promoting Croatian culture.

9.2. Arts and Architecture

Croatian architecture reflects its diverse historical influences. Austrian and Hungarian styles are evident in public spaces and buildings in the northern and central regions, particularly in cities like Zagreb, Osijek (Tvrđa district), Varaždin, and Karlovac, which feature Baroque urban planning. Along the coasts of Dalmatia and Istria, Venetian and Italian Renaissance influences are prominent. The subsequent influence of Art Nouveau is also visible in early 20th-century architecture.

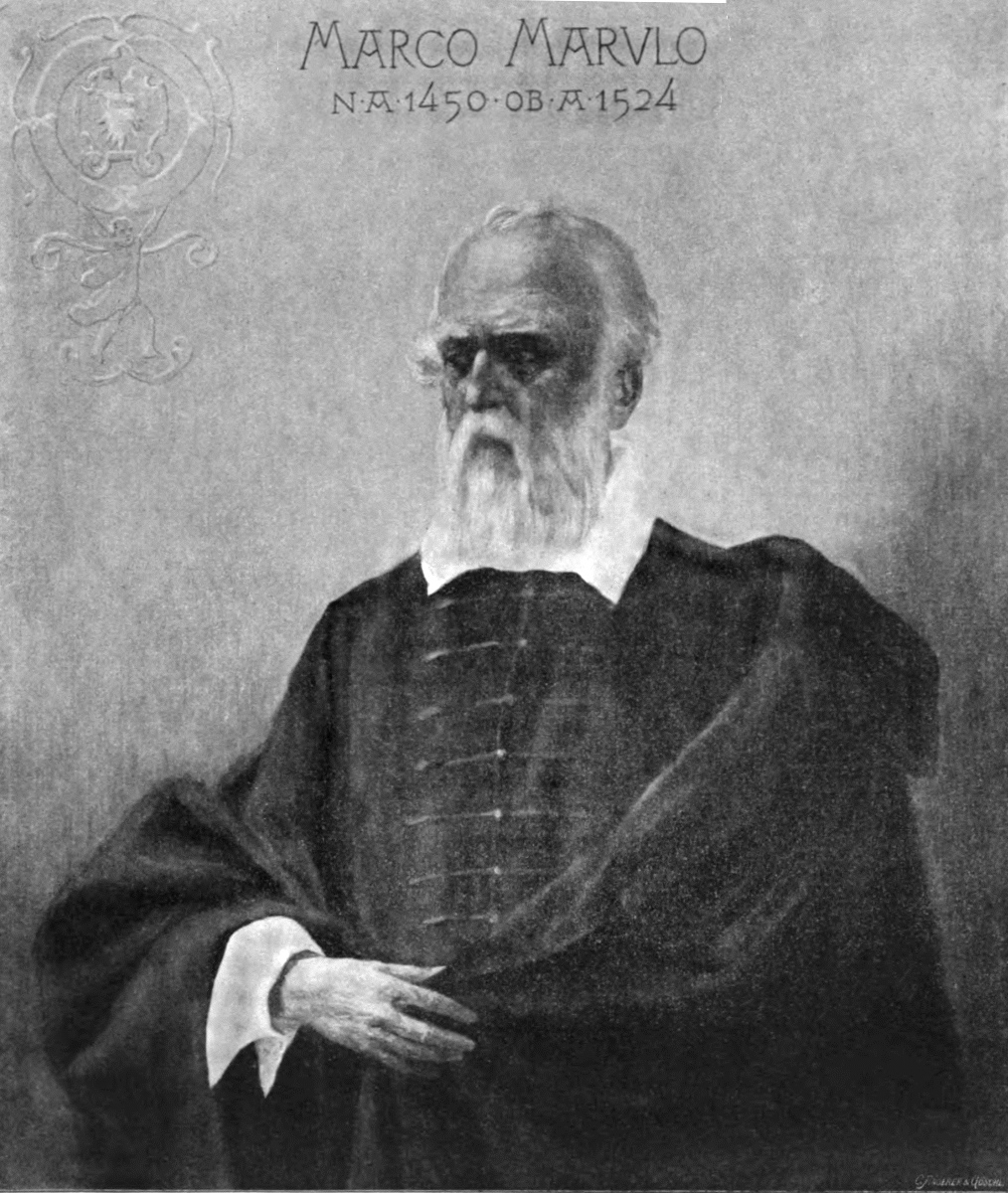

The oldest preserved examples of Croatian architecture are 9th-century pre-Romanesque churches, such as the Church of St. Donatus in Zadar. Romanesque art is notably represented by the stone portal of the Trogir Cathedral, created by Master Radovan. The Renaissance had its greatest impact on the Adriatic coast, with works by artists like Giorgio da Sebenico (Juraj Dalmatinac) and Nicolas of Florence (Nikola Firentinac), exemplified by the Cathedral of St. James in Šibenik, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Art flourished during the Baroque and Rococo periods as Ottoman influence waned.