1. Overview

Montenegro, a country in Southeastern Europe on the Balkan Peninsula, possesses a rich tapestry of geography, history, culture, and political development. Geographically, it is characterized by rugged mountains, a stunning Adriatic coastline, and significant biodiversity. Its history stretches from Illyrian and Roman times through various medieval principalities like Duklja and Zeta, periods of Ottoman and Venetian influence, the unique Prince-Bishopric, and its eventual emergence as a kingdom. The 20th century saw Montenegro integrated into Yugoslavia, endure World War II, and become a socialist republic. Following the Yugoslav breakup, it formed a union with Serbia before achieving full independence in 2006. Culturally, Montenegro reflects a blend of Orthodox, Ottoman, Slavic, and Mediterranean influences, evident in its traditions, arts, and cuisine. Politically, it is a parliamentary republic navigating the complexities of democratic consolidation, European Union accession, and addressing challenges such as corruption and social justice. Economically, Montenegro is transitioning to a market-based system, with tourism playing a crucial role alongside services and industry. This article examines these facets from a perspective that emphasizes social justice, democratic development, and human rights, critically assessing historical events and the impact of political figures on the nation's progress.

2. Etymology

The name "Montenegro" is of Venetian origin and translates to "Black Mountain." This name is a calque of the Montenegrin phrase Crna GoraTsrna GoraMontenegrin (Црна ГораTsrna GoraMontenegrin in Cyrillic, transliterated as Tsrna Gora), which also means "Black Mountain." The designation is believed to derive from the appearance of Mount Lovćen when it was densely covered with evergreen forests. The term Crna GoraTsrna GoraMontenegrin was first recorded in edicts issued by Stefan Uroš I to the Serbian Orthodox Zeta Episcopate seat at Vranjina island in Lake Skadar. By the 15th century, it came to denote the majority of contemporary Montenegro, especially after the fall of the Serbian Despotate in 1459.

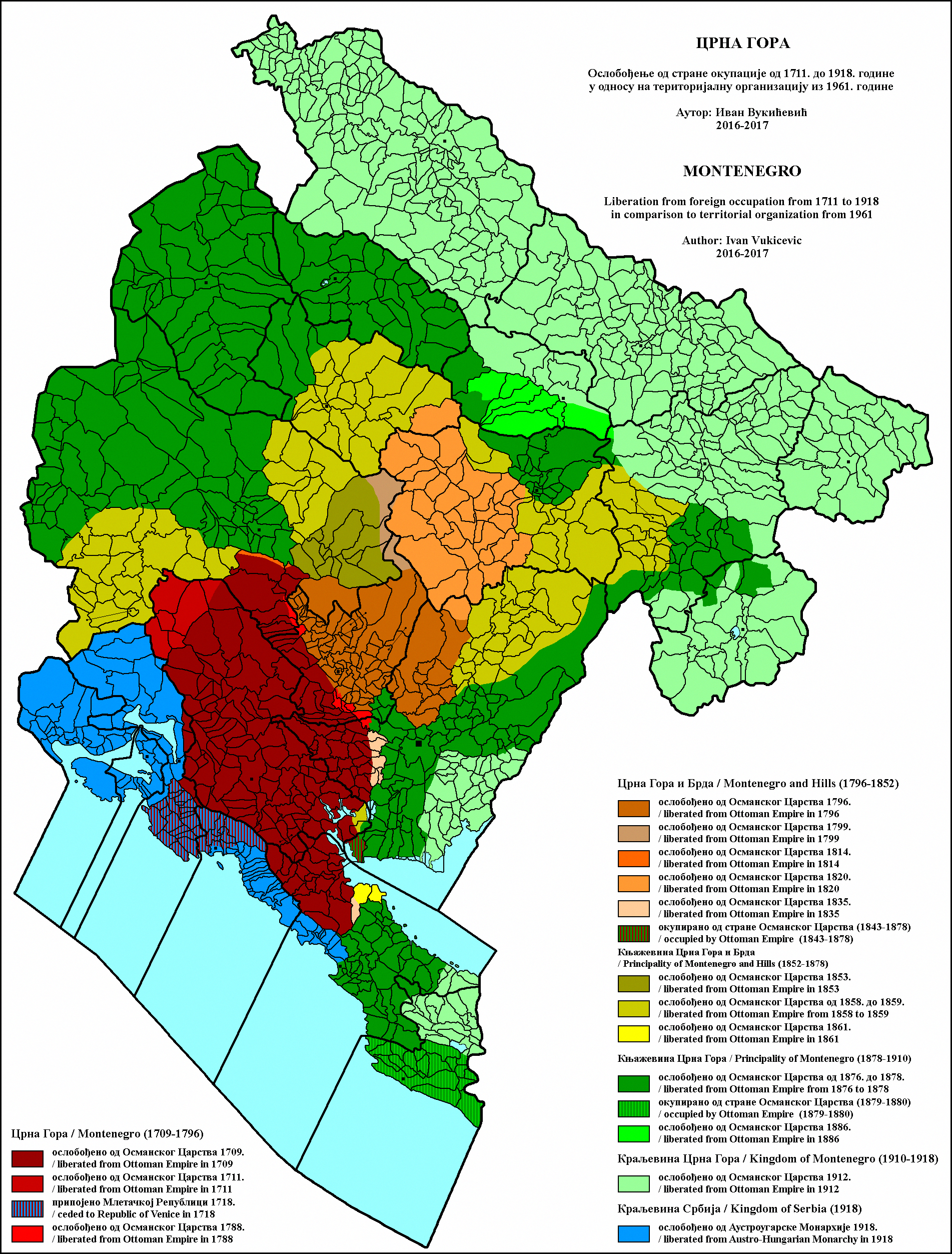

Originally, "Crna Gora" referred to a smaller strip of land under the rule of the Paštrovići tribe. However, the name expanded to encompass the wider mountainous region following the rise to power of the Crnojević dynasty in Upper Zeta. By the 19th century, this independent region became known as Stara Crna GoraStara Tsrna GoraMontenegrin ("Old Montenegro") to distinguish it from adjacent Ottoman-occupied Montenegrin territory called BrdaBrdaMontenegrin ("the Highlands"). Montenegro's territory expanded several times up to the 20th century through wars against the Ottoman Empire, annexing Old Herzegovina and parts of Metohija and southern Raška. Its borders have seen little change since then, apart from losing Metohija and gaining the Bay of Kotor.

In other languages, the country's name also often reflects the "Black Mountain" meaning. For example, in Albanian, it is known as Mali i ZiMali i ZiAlbanian, and in Turkish as KaradağKaradagTurkish. During its time within Yugoslavia, after World War II, it was known as the Federal State of Montenegro (Savezna država Crne GoreSavezna drjava Tsrne GoreMontenegrin / Савезна држава Црне ГореSavezna drjava Tsrne GoreMontenegrin in Cyrillic) from 1943, then the People's Republic of Montenegro (Narodna Republika Crna GoraNarodna Republika Tsrna GoraMontenegrin / Народна Република Црна ГораNarodna Republika Tsrna GoraMontenegrin in Cyrillic) from 1945, and the Socialist Republic of Montenegro (Socijalistička Republika Crna GoraSotsialistichka Republika Tsrna GoraMontenegrin / Социјалистичка Република Црна ГораSotsialistichka Republika Tsrna GoraMontenegrin in Cyrillic) from 1963. With the breakup of Yugoslavia, it became the Republic of Montenegro (Republika Crna GoraRepublika Tsrna GoraMontenegrin / Република Црна ГораRepublika Tsrna GoraMontenegrin in Cyrillic) on 27 April 1992. Since 22 October 2007, following its independence, the country is officially known simply as Montenegro.

3. History

The history of Montenegro spans from ancient settlements through medieval states, periods of foreign domination, the emergence of a unique theocratic and later secular principality, its transformation into a kingdom, its incorporation into Yugoslavia, and its eventual path to renewed independence in the 21st century. This historical journey has been marked by struggles for autonomy, complex regional dynamics, and significant socio-political transformations, including challenges related to democratic development and human rights.

3.1. Antiquity

The region of modern-day Montenegro was part of Illyria in ancient times and was primarily inhabited by Illyrians, an Indo-European speaking people. Various Illyrian tribes resided in the area. The Illyrian kingdom eventually came into conflict with the expanding Roman Republic. Following the Illyro-Roman Wars, the Romans conquered the region.

The territory was incorporated into the Roman administrative system, initially as part of the province of Illyricum. Later, through administrative reorganizations, it became part of the provinces of Dalmatia and, subsequently, Praevalitana. Praevalitana, established during the reign of Emperor Diocletian, covered much of the territory of contemporary Montenegro. Roman rule brought significant changes, including the development of roads, urbanization in some areas, and the gradual spread of Roman culture and Latin. Cities like Doclea (Duklja) emerged as important Roman centers in the region.

3.2. Arrival of the Slavs and Middle Ages

During the 6th and 7th centuries CE, Slavs began migrating into the Balkan Peninsula, settling in the territories of present-day Montenegro. This led to the gradual assimilation of the previous Romanized and Illyrian populations and the formation of new political entities. Three principalities emerged on this territory: Duklja, roughly corresponding to the southern half; Travunia, to the west; and parts of Rascia (Principality of Serbia (early medieval)), to the north.

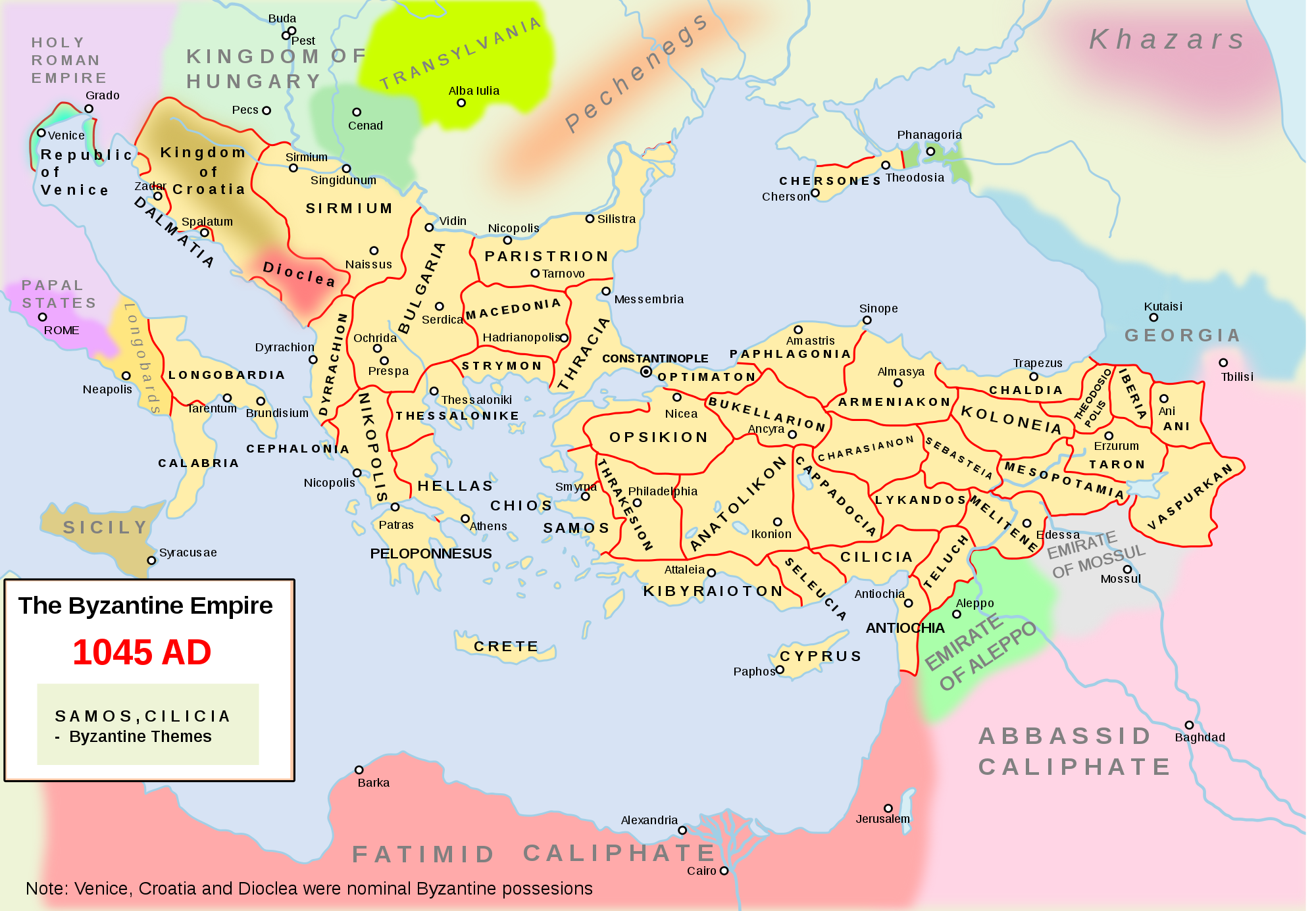

Duklja, initially a vassal state of the Byzantine Empire, gained its independence in 1042 under the leadership of Stefan Vojislav. Under his son, Mihailo I (ruled 1046-1081), Duklja expanded its territory and was recognized as a kingdom by Pope Gregory VII in 1077. His grandson, Constantine Bodin (ruled 1081-1101), further extended Duklja's influence, incorporating neighboring Rascia and Bosnia. However, after Bodin's death, internal strife and succession struggles weakened the kingdom, leading to its decline in the early 12th century.

By 1186, the territory of modern Montenegro became part of the state ruled by Stefan Nemanja and the Nemanjić dynasty for the next two centuries. The name Zeta increasingly replaced Duklja to refer to the region. After the collapse of the Serbian Empire in the mid-14th century, local noble families rose to prominence. The Balšić dynasty became the sovereigns of Zeta, ruling from the late 14th century. They were followed by the Crnojević dynasty in the 15th century. It was during the Crnojević rule that the name Crna Gora (Montenegro) began to be more frequently used for the region.

In 1421, Zeta was briefly annexed to the Serbian Despotate. However, after 1455, the Crnojević family re-established sovereign rule, making Zeta the last free monarchy in the Balkans before the Ottoman advance. Ivan Crnojević moved his capital from Žabljak Crnojevića to Cetinje due to Ottoman pressure. Zeta, under the Crnojevićs, resisted Ottoman incursions for a time but was eventually overcome. In 1496, most of Zeta fell to the Ottomans and was annexed to the sanjak of Shkodër. For a brief period, between 1514 and 1528, Montenegro existed as a separate autonomous sanjak within the Ottoman Empire, known as the Sanjak of Montenegro. The region of Old Herzegovina also became part of the Ottoman Sanjak of Herzegovina.

3.3. Ottoman and Venetian Domination

From the late 14th century, and more significantly after the fall of the Crnojević state in 1496, large parts of Montenegrin territory came under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans organized the conquered lands into administrative units called sanjaks. Montenegrin territories were initially part of the Sanjak of Shkodër and later, for a period, formed the autonomous Sanjak of Montenegro (1514-1528). Ottoman rule brought significant socio-political and religious changes, including the introduction of Islam, although many Montenegrin clans in the rugged mountainous interior retained a degree of autonomy and their Eastern Orthodox Christian faith.

Simultaneously, the Republic of Venice established its presence along the Adriatic coast. From 1392, Venice controlled numerous parts of the territory, including strategic coastal towns like Kotor (Cattaro), Budva (Budua), and others. These areas became part of Venetian Albania (Albania Veneta), centered around the Bay of Kotor. Venetian rule lasted for centuries, significantly influencing the culture, architecture, and maritime traditions of the coastal region. The Venetians introduced governors who often interfered in Montenegrin politics, and their control extended over these coastal territories until the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797.

Life under Ottoman rule was characterized by frequent resistance from Montenegrin clans. The mountainous terrain provided a natural defense, allowing local chieftains to maintain a degree of autonomy. In the 16th century, Montenegro developed a unique form of autonomy within the Ottoman Empire, permitting Montenegrin clans freedom from certain restrictions. However, discontent with Ottoman rule persisted, leading to repeated rebellions throughout the 17th century. These culminated in the Montenegrin participation and Ottoman defeat in the Great Turkish War (1683-1699), which weakened Ottoman control in the region and laid the groundwork for greater Montenegrin autonomy.

3.4. Prince-Bishopric and Principality of Montenegro

Following the decline of Ottoman central authority and inspired by successful resistance, Montenegro developed a unique form of governance. In 1516, after the last Crnojević ruler, Đurađ Crnojević, abdicated, power transitioned to the Metropolitans (bishops) of Cetinje. This marked the beginning of the Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro, a theocratic state where the spiritual leader also held temporal power. The office of the Prince-Bishop (vladika) became hereditary within the Petrović-Njegoš dynasty from 1697, with power passing from uncle to nephew, as bishops were celibate.

The Petrović-Njegoš dynasty played a crucial role in unifying Montenegrin tribes and leading the struggle against Ottoman rule. Notable prince-bishops include Danilo I Petrović-Njegoš, Petar I Petrović-Njegoš, and Petar II Petrović-Njegoš. Petar I (ruled 1782-1830) was a key figure in strengthening state institutions, codifying laws, and uniting the disparate Montenegrin clans. He achieved significant military victories against the Ottomans and laid the foundation for a more centralized state. His nephew, Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (ruled 1830-1851), was a celebrated poet and philosopher, best known for his epic poem The Mountain Wreath. He continued efforts to modernize the state and assert its independence. During this period, people from Montenegro were often described as Orthodox Serbs.

In 1852, Danilo II Petrović-Njegoš decided to secularize the state. He renounced his ecclesiastical title, married, and proclaimed Montenegro a secular principality, with himself as Prince (Knjaz) Danilo I. This move ended the theocratic rule and marked a significant step towards a modern state. Danilo I introduced further reforms, including a new legal code (Danilo's Code, 1855) and continued the fight for full independence. In 1858, Montenegrin forces achieved a major victory over the Ottomans at the Battle of Grahovac, led by Grand Duke Mirko Petrović-Njegoš, Danilo's elder brother. This victory significantly enhanced Montenegro's international standing and led to the formal demarcation of its borders with the Ottoman Empire, effectively recognizing its de facto independence.

3.5. Kingdom of Montenegro

Under Prince Nicholas I (ruled 1860-1918), the Principality of Montenegro continued its struggle for territorial expansion and full international recognition. Montenegro participated in the Montenegrin-Ottoman War (1876-1878), fighting alongside Serbia and Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Key victories, such as the Battle of Vučji Do, contributed to the Ottoman defeat in the wider Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878). As a result, the Congress of Berlin in 1878 formally recognized Montenegro's independence and significantly expanded its territory.

Nicholas I's long reign saw the modernization of the Montenegrin state, including the introduction of its first constitution in 1905. This constitution established a parliamentary monarchy, although Nicholas retained considerable power. Diplomatic relations were established with the Ottoman Empire, leading to a period of relative peace, with minor border skirmishes, until the deposition of Abdul Hamid II in 1909.

In 1910, on the 50th anniversary of his reign, Prince Nicholas I proclaimed Montenegro a kingdom, and he assumed the title of King. The newly established kingdom participated in the Balkan Wars (1912-1913). In the First Balkan War, Montenegro allied with Serbia, Greece, and Bulgaria against the Ottoman Empire, achieving further territorial gains, including cities like Peć, Đakovica, and parts of the Sandžak region. A common border with Serbia was established. However, the Great Powers awarded the strategic city of Shkodër to the newly created state of Albania, despite its capture by Montenegrin forces.

During World War I (1914-1918), Montenegro joined the Allied Powers, siding with Serbia against Austria-Hungary and the Central Powers. The Montenegrin army, though small, offered significant resistance. In the Battle of Mojkovac in January 1916, Montenegrin forces achieved a notable tactical victory against superior Austro-Hungarian forces, allowing the Serbian army to retreat through Albania. However, Montenegro was subsequently occupied by Austria-Hungary from 1916 to October 1918. King Nicholas I and his government went into exile in Bordeaux, France. The war had devastating consequences for Montenegro, leading to significant loss of life and economic hardship.

3.6. Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Following the end of World War I and the collapse of Austria-Hungary, the political landscape of the Balkans was significantly altered. In Montenegro, a controversial Podgorica Assembly was convened in November 1918, which voted to depose King Nicholas I (still in exile) and unite Montenegro with the Kingdom of Serbia. Shortly thereafter, on December 1, 1918, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was proclaimed, which included Montenegro. This decision was contentious, with supporters of King Nicholas and Montenegrin independence (the "Greens") opposing the union, leading to the Christmas Uprising in January 1919, which was suppressed by Serbian forces and supporters of the union (the "Whites").

Within the new Yugoslav kingdom, Montenegro initially lost its distinct administrative status. In 1922, it formally became the Oblast of Cetinje, with the addition of coastal areas around Budva and the Bay of Kotor. A further administrative restructuring in 1929 established the Zeta Banovina (or Zeta Province) as one of nine banovinas in the renamed Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The Zeta Banovina was significantly larger than historical Montenegro, encompassing present-day Montenegro as well as parts of Serbia (including Raška and Metohija), Croatia (around Dubrovnik), and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Cetinje served as its administrative center.

King Alexander I, Nicholas's grandson and the monarch of Yugoslavia, dominated the government. The period of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was marked by political centralization and efforts to create a unified Yugoslav identity, which often clashed with regional and national sentiments, including those in Montenegro. Economic development was uneven, and Montenegro remained one ofthe poorer regions of the kingdom.

3.7. World War II and Socialist Yugoslavia

In April 1941, during World War II, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded and occupied by the Axis powers, including Nazi Germany and the Kingdom of Italy. Montenegro was occupied by Italian forces, who established a puppet state, the Italian Governorate of Montenegro, nominally restoring the monarchy under Italian protection. Some Montenegrin nationalists collaborated with the Italians, hoping to achieve greater autonomy or independence.

However, resistance to the occupation quickly emerged. On July 13, 1941, a large-scale uprising, led primarily by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) and former Royal Yugoslav Army officers, broke out across Montenegro. This was one of the first and largest organized revolts in occupied Europe. Although initially successful in liberating large parts of the territory, the uprising was brutally suppressed by a massive Italian counter-offensive.

The resistance movement subsequently split into two main factions: the communist-led Yugoslav Partisans and the royalist, Serbian nationalist Chetniks. These groups initially cooperated in some areas but soon turned against each other in a bitter civil war, alongside fighting the occupiers. Montenegrin Partisans, including notable figures like Milovan Đilas, Peko Dapčević, and Svetozar Vukmanović-Tempo, played a significant role in the broader Yugoslav liberation struggle. Chetnik forces in Montenegro, some of whom collaborated with the Italian and later German occupiers against the Partisans, also engaged in the conflict. After Italy's capitulation in September 1943, German forces occupied Montenegro, leading to continued fierce fighting. The Partisans eventually liberated Montenegro in December 1944.

Following World War II, Montenegro became one of the six constituent republics of the newly established Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), led by Josip Broz Tito. It was initially named the People's Republic of Montenegro and later, in 1963, the Socialist Republic of Montenegro. Its capital, Podgorica, was renamed Titograd in honor of Tito. Within the socialist federation, Montenegro experienced significant socio-economic development. Infrastructure was rebuilt and expanded, including the construction of the Belgrade-Bar railway. Industrialization efforts were undertaken, and educational institutions, such as the University of Montenegro, were established. The 1974 Yugoslav Constitution granted the republics, including Montenegro, greater autonomy, reinforcing its status as a distinct political entity within the federation. However, political life was dominated by the League of Communists, and dissent was often suppressed, reflecting the authoritarian nature of the one-party state.

3.8. Montenegro within FR Yugoslavia and Serbia and Montenegro

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, which saw Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia declare independence, Montenegro chose to remain in a federation with Serbia. In a referendum held in March 1992, 95.96% of voters opted to stay in Yugoslavia, on a turnout of 66%. This result was influenced by the political climate and was boycotted by several opposition parties and minority groups who favored independence or were wary of Serbian dominance under Slobodan Milošević. On April 27, 1992, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) was proclaimed, consisting of the Republic of Serbia and the Republic of Montenegro.

During the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, particularly the Croatian War of Independence and the Bosnian War, Montenegrin forces, as part of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and later the Army of Yugoslavia (VJ), were involved in military operations. Notably, Montenegrin units participated in the Siege of Dubrovnik (1991-1992), an action widely condemned internationally. This involvement led to accusations of war crimes and human rights violations. Montenegrin General Pavle Strugar was later convicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for his role in the shelling of Dubrovnik. There were also instances of Montenegrin police arresting Bosnian Muslim refugees and handing them over to Bosnian Serb forces, where they faced torture and execution, such as in the Foča region. These events cast a shadow on Montenegro's role during the conflicts and raised serious questions about accountability and human rights.

By the mid-1990s, political dynamics within Montenegro began to shift. Milo Đukanović, who became Prime Minister in 1991 and later President of Montenegro, initially aligned with Milošević but started to distance himself and Montenegro from Serbian policies, particularly after the Dayton Agreement in 1995. Đukanović's government sought greater economic autonomy, adopting the German Deutsche Mark (and later the Euro) as its de facto currency, bypassing the Yugoslav Dinar. Tensions between the Montenegrin leadership and the federal government in Belgrade grew. During the NATO bombing of FRY in 1999 over the Kosovo War, targets in Montenegro were also hit, though less extensively than in Serbia.

In 2002, under mediation from the European Union, Serbia and Montenegro agreed to transform the FRY into a looser state union. This led to the creation of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro in February 2003. The Constitutional Charter of the State Union allowed either republic to hold an independence referendum after a period of three years. The relationship within the State Union remained strained, with Montenegro continuing to pursue policies that emphasized its distinct identity and sovereignty.

3.9. Independence and Recent History

The path to renewed independence culminated in the independence referendum held on May 21, 2006. The European Union had set a threshold requiring a 55% affirmative vote from a turnout of at least 50%. The referendum saw a high turnout of 86.5%, with 55.5% of voters choosing independence, narrowly surpassing the EU's condition by about 2,300 votes. International observers, including a mission from the OSCE/ODIHR, assessed the referendum process as generally compliant with international standards. On June 3, 2006, the Montenegrin Parliament formally declared independence. Serbia acknowledged the result, and Montenegro became an independent state, recognized internationally. On June 28, 2006, Montenegro joined the United Nations as its 192nd member state.

Post-independence Montenegrin politics were dominated for a long period by Milo Đukanović and his Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS). Đukanović served multiple terms as Prime Minister and President. While credited with leading Montenegro to independence and towards Euro-Atlantic integration, his rule was also marked by accusations of authoritarianism, cronyism, state capture, and links to organized crime. Investigative journalists' networks, such as the OCCRP, highlighted issues of corruption, naming Đukanović "Person of the Year in Organized Crime" in 2015. These concerns led to street demonstrations and calls for his removal. The long period of DPS rule contributed to regional disparities and social inequalities, with high unemployment in the north and a significant portion of the population living below the poverty line. The Law on the Status of the Descendants of the Petrović Njegoš Dynasty was passed in 2011, rehabilitating the Royal House and recognizing limited symbolic roles.

A significant event in recent history was the alleged coup d'état attempt on the day of the parliamentary elections in October 2016, reportedly aimed at preventing Montenegro's NATO accession and assassinating then-Prime Minister Đukanović. Montenegrin authorities arrested a group of Serbian and Montenegrin citizens, and later implicated Russian nationalists and intelligence operatives. Fourteen people, including two Russian nationals and two Montenegrin opposition leaders, Andrija Mandić and Milan Knežević, were indicted and subsequently convicted, though these verdicts were later overturned by an appellate court and a retrial was ordered.

Montenegro formally joined NATO on June 5, 2017, a move seen as a key foreign policy achievement but one that was opposed by Russia and parts of the Montenegrin opposition. The country has also been an official candidate for European Union membership since 2010, with accession negotiations starting in 2012. The goal of EU accession has been a driving force for reforms, though progress has been affected by concerns over the rule of law, corruption, and media freedom. Freedom House, in 2020, categorized Montenegro as a hybrid regime rather than a full democracy due to these declining standards.

In late 2019, the adoption of a controversial Law on Freedom of Religion sparked widespread and prolonged protests, primarily led by the Serbian Orthodox Church and its supporters, who feared the law would lead to the confiscation of church property. These protests significantly impacted the political landscape and contributed to the defeat of the DPS in the parliamentary elections of August 2020. This marked the first time in three decades that the DPS did not win a majority, leading to a new coalition government led by Zdravko Krivokapić. This government, however, proved unstable and was ousted in a no-confidence vote in February 2022. A minority government led by Dritan Abazović took office in April 2022 but also lost a confidence vote in August 2022, leading to a period of political instability.

In the presidential election of April 2023, Jakov Milatović of the newly formed Europe Now! movement defeated incumbent Milo Đukanović. Snap parliamentary elections in June 2023 saw Europe Now! emerge as the largest party, and Milojko Spajić became Prime Minister in October 2023, leading a new coalition government. Recent developments include ongoing efforts to accelerate EU accession, address rule of law issues, and navigate complex regional relations. In June 2024, the Montenegrin Parliament adopted a resolution acknowledging atrocities at the Jasenovac concentration camp during World War II, a move viewed by some as a response to Montenegro's earlier support for a UN resolution on the Srebrenica genocide, leading to diplomatic tensions with Croatia.

4. Geography

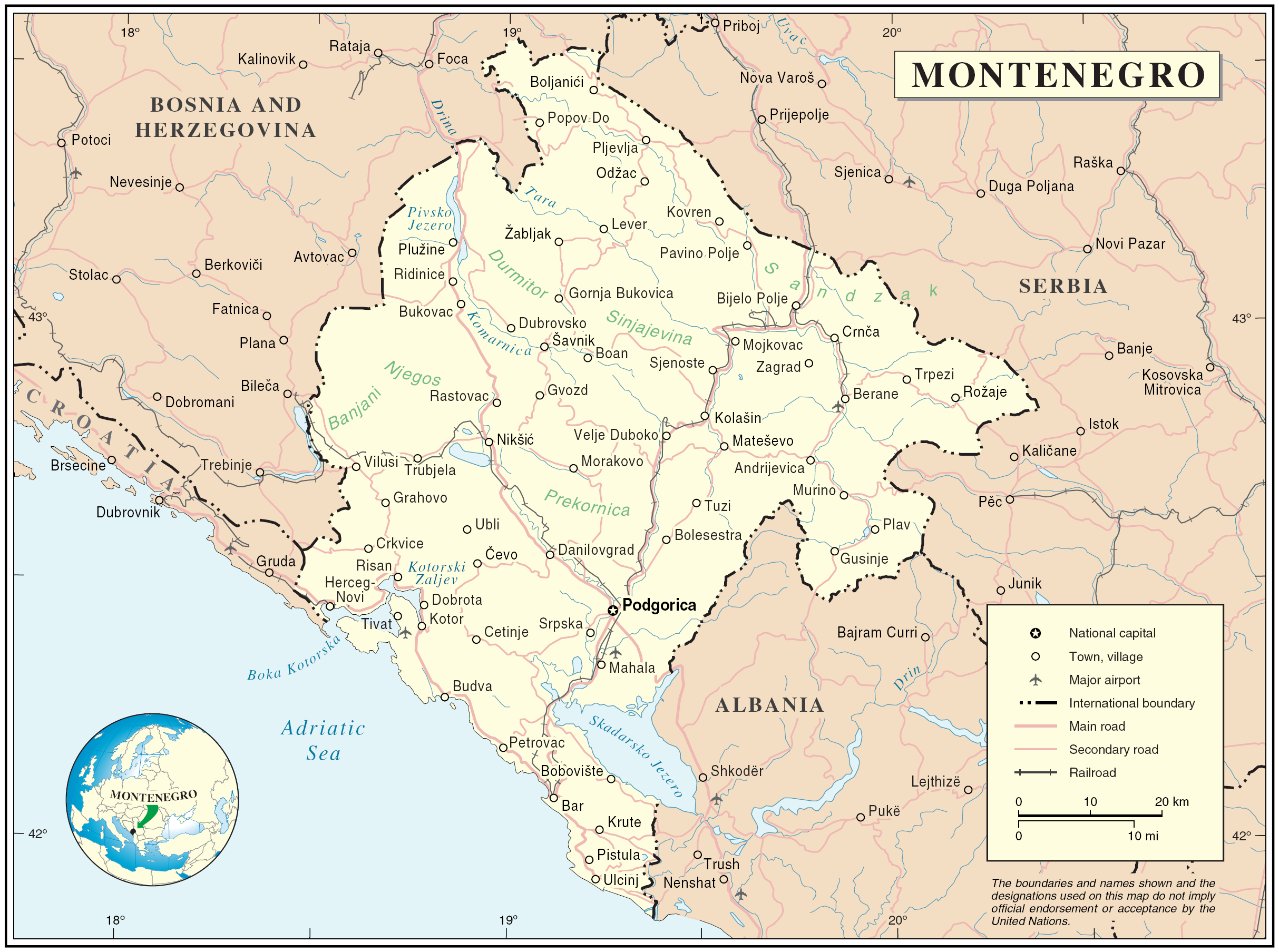

Montenegro is located in Southeastern Europe, on the Balkan Peninsula. It is bordered by Croatia to the west, Bosnia and Herzegovina to the northwest, Serbia to the northeast, Kosovo to the east, and Albania to the southeast. To the southwest, it has a coastline on the Adriatic Sea. The country lies between latitudes 41° and 44°N, and longitudes 18° and 21°E.

Montenegro's terrain is highly varied. It features high mountain peaks along its borders, particularly in the north and east, which are part of the Dinaric Alps. These mountains include some of the most rugged landscapes in Europe, with many peaks exceeding 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m). The highest peak is Zla Kolata in the Prokletije range, at 8.3 K ft (2.53 K m), followed by Bobotov Kuk in the Durmitor massif, at 8.3 K ft (2.52 K m). The country also encompasses a significant portion of the karst topography characteristic of the western Balkan Peninsula. This limestone terrain features caves, sinkholes, and underground rivers.

The coastal region consists of a narrow plain, varying in width from 0.9 mile (1.5 km) to 3.7 mile (6 km). This plain is abruptly interrupted in the north where Mount Lovćen and Mount Orjen dramatically descend into the Bay of Kotor, a large, fjord-like bay (ria) that is one of the most distinctive geographical features of the Mediterranean. The Bay of Kotor is surrounded by high mountains, creating a stunning natural harbor.

Inland, the Zeta River valley, at an elevation of around 1640 ft (500 m), forms a lower-lying segment. Major rivers include the Tara River, known for its deep canyon (the deepest in Europe), the Lim River, the Piva River, and the Morača River. Lake Skadar (Skadarsko Jezero), located on the border with Albania, is the largest lake in the Balkan Peninsula. Montenegro's climate is diverse: the coast has a Mediterranean climate with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, while the inland regions, particularly at higher altitudes, experience a continental climate with cold, snowy winters and warm summers. Due to the hyper-humid climate on their western sides, the Montenegrin mountain ranges were among the most ice-eroded parts of the Balkan Peninsula during the last glacial period. Over 0.8 K mile2 (2.00 K km2) of Montenegro's territory lies within the Danube catchment area, making it a member of the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River.

4.1. Biodiversity

Montenegro is recognized as a European and global biodiversity hotspot due to its diverse geological base, varied landscapes, climate, soil types, and its strategic position on the Balkan Peninsula and the Adriatic Sea. The country boasts a high number of species per unit area, with an index of 0.837, reportedly the highest in Europe.

The country's rich flora includes an estimated 7,000-8,000 species of vascular plants, with over 1,200 species of freshwater algae and 300 species of marine algae. There are also 589 species of moss and around 2,000 species of fungi. The fauna is equally diverse, with estimates suggesting 16,000-20,000 species of insects. Montenegro's waters are home to 407 species of marine fish and numerous freshwater fish species. The country also hosts 56 species of reptiles and 18 species of amphibians. Its avian diversity is significant, with 333 species of regularly visiting birds. Mammalian diversity is also high.

Montenegro can be divided into two main biogeographic regions: the Mediterranean Biogeographic Region along the coast and the Alpine Biogeographic Region in the mountainous interior. It is also home to three terrestrial ecoregions: Balkan mixed forests, Dinaric Mountains mixed forests, and Illyrian deciduous forests. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.41/10, ranking it 73rd globally out of 172 countries.

Conservation efforts are centered around its system of protected areas. Montenegro has five national parks:

- Durmitor National Park (established 1952, area 151 mile2 (390 km2)), a UNESCO World Heritage Site, known for its dramatic mountains, glacial lakes, and the Tara River Canyon.

- Biogradska Gora National Park (established 1952, area 21 mile2 (54 km2)), home to one of the last three large virgin forests in Europe.

- Lovćen National Park (established 1952, area 25 mile2 (64 km2)), encompassing Mount Lovćen, a symbol of Montenegrin identity.

- Lake Skadar National Park (established 1983, area 154 mile2 (400 km2)), protecting the largest lake in the Balkans and a vital wetland habitat.

- Prokletije National Park (established 2009, area 64 mile2 (166 km2)), covering the rugged Prokletije (Accursed) Mountains.

In total, protected areas cover 9.05% of Montenegro's territory. Despite these efforts, environmental challenges persist, including illegal construction, deforestation, water pollution, and the impacts of climate change, which require ongoing attention to ensure the preservation of Montenegro's unique natural heritage.

5. Politics

Montenegro is a parliamentary representative democratic republic. Its political system is defined by the Constitution of Montenegro, which was adopted in 2007. The constitution establishes Montenegro as a "civic, democratic, ecological state of social justice, based on the rule of law." The country operates under a multi-party system. The separation of powers is enshrined, with distinct executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government.

The President of Montenegro is the head of state, elected for a five-year term through direct popular vote. The President's role is largely ceremonial but includes representing the country abroad, promulgating laws, calling parliamentary elections, proposing candidates for Prime Minister and Constitutional Court justices to the Parliament, granting amnesty, and conferring decorations. The official residence of the President is in Cetinje. The current president is Jakov Milatović, who assumed office in May 2023.

The Government of Montenegro exercises executive power and is led by the Prime Minister of Montenegro. The Prime Minister is the most powerful political office in the country. The Prime Minister and cabinet ministers are responsible to the Parliament. Governments in Montenegro since its independence have typically been coalition governments. The main government offices are located in Podgorica. The current Prime Minister is Milojko Spajić, who took office in October 2023.

The Parliament of Montenegro (Skupština Crne Gore) is the country's unicameral legislature. It is composed of 81 members (deputies) elected for a four-year term through proportional representation using the D'Hondt method. The Parliament passes laws, ratifies treaties, appoints the Prime Minister and ministers, appoints judges, adopts the budget, and can pass a motion of no confidence in the government.

Recent political trends have seen shifts in power. The Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), led by Milo Đukanović, which had dominated Montenegrin politics for three decades, lost its majority in the 2020 parliamentary election. This led to a period of new coalition governments. The 2023 election resulted in the Europe Now! movement becoming the largest party. Challenges to democratic governance include concerns about rule of law, corruption, state capture, and media freedom. Organizations like Freedom House have previously categorized Montenegro as a hybrid regime, though it is generally considered a "flawed democracy" by the Economist Democracy Index. Ongoing efforts focus on strengthening democratic institutions and meeting the requirements for European Union membership.

5.1. Administrative divisions

Montenegro is administratively divided into twenty-five municipalities (opštinaopshtinaMontenegrin, plural: opštineopshtineMontenegrin). Each municipality can contain multiple cities, towns, and villages. The municipalities are the basic units of local self-government. The capital, Podgorica, has a special status as the Capital City, and it is further subdivided into urban municipalities (Golubovci and Tuzi were formerly urban municipalities within Podgorica but have since become independent municipalities). Cetinje also has a special status as the Old Royal Capital.

Historically, the territory was divided into nahije, and during the early Socialist Republic of Montenegro, it was divided into counties (srez). The current municipal structure has evolved over time, with some municipalities being created more recently through the division of larger ones (e.g., Petnjica, Gusinje, Tuzi, Zeta).

The municipalities are:

- Andrijevica

- Bar

- Berane

- Bijelo Polje

- Budva

- Cetinje (Old Royal Capital)

- Danilovgrad

- Gusinje

- Herceg Novi

- Kolašin

- Kotor

- Mojkovac

- Nikšić

- Petnjica

- Plav

- Plužine

- Pljevlja

- Podgorica (Capital City)

- Rožaje

- Šavnik

- Tivat

- Tuzi

- Ulcinj

- Žabljak

- Zeta

For statistical purposes, Montenegro is also divided into three statistical regions: the Northern Region, the Central Region, and the Coastal Region. These regions do not have an administrative function. Other organizations, such as the Football Association of Montenegro, may use different regional divisions.

Northern Region

| Municipality | Area (km2) | Population (2023 prelim.) |

|---|---|---|

| Andrijevica | 283 | 3,978 |

| Berane | 544 | 25,162 |

| Bijelo Polje | 924 | 39,710 |

| Gusinje | 157 | 4,662 |

| Kolašin | 897 | 6,765 |

| Mojkovac | 367 | 6,824 |

| Petnjica | 173 | 5,552 |

| Plav | 328 | 9,081 |

| Plužine | 854 | 2,232 |

| Pljevlja | 1,346 | 24,542 |

| Rožaje | 432 | 25,247 |

| Šavnik | 553 | 1,588 |

| Žabljak | 445 | 3,002 |

Central Region

| Municipality | Area (km2) | Population (2023 prelim.) |

|---|---|---|

| Cetinje | 899 | 14,465 |

| Danilovgrad | 501 | 18,832 |

| Nikšić | 2,065 | 66,725 |

| Podgorica | 1,399 | 204,877 (including Tuzi and Zeta at time of some historic data, but more recently they are separate. Podgorica proper approx. 179,505) |

| Tuzi | 236 | 13,142 (formerly part of Podgorica) |

| Zeta | 153 | 16,231 (formerly part of Podgorica, municipality of Golubovci) |

Coastal Region

| Municipality | Area (km2) | Population (2023 prelim.) |

|---|---|---|

| Bar | 598 | 46,171 |

| Budva | 122 | 26,667 |

| Herceg Novi | 235 | 30,597 |

| Kotor | 335 | 22,899 |

| Tivat | 46 | 16,340 |

| Ulcinj | 255 | 21,395 |

(Note: Population figures are from the 2023 preliminary census results, and area figures can vary slightly between sources. Some population figures for Podgorica in older tables might include former sub-municipalities.)

5.2. Foreign relations

Montenegro's foreign policy is primarily focused on Euro-Atlantic integration and maintaining good neighborly relations. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs defines and implements these priorities in cooperation with other state institutions. A key strategic goal since independence has been membership in the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Montenegro officially became the 29th member of NATO on June 5, 2017. This membership is considered a significant step for the country's security and international standing, though it was met with opposition from Russia and some domestic political factions. As a NATO member, Montenegro participates in collective defense activities and international missions.

Regarding the European Union, Montenegro applied for membership in December 2008 and was granted candidate status in December 2010. Accession negotiations began in June 2012. The process of joining the EU involves aligning Montenegro's laws and institutions with EU standards (the acquis communautaire). Progress has been made in various areas, but challenges remain, particularly concerning the rule of law, judicial reform, combating corruption and organized crime, and ensuring media freedom. The EU provides financial and technical assistance to support these reforms. The government aims to accelerate the accession process, with some officials expressing hopes of joining by the late 2020s.

Montenegro is a member of the United Nations (since June 2006), the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA). It is also a founding member of the Union for the Mediterranean.

The country maintains diplomatic relations with numerous countries worldwide. It prioritizes strong ties with its Balkan neighbors, participating in regional cooperation initiatives to promote stability and economic development. Relations with Serbia are complex due to shared history and close cultural ties but have also seen periods of tension, particularly around issues of national identity and church property. Montenegro recognized Kosovo's independence in 2008, a decision that strained relations with Serbia at the time but is consistent with its pro-Western foreign policy orientation. Relations with Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Albania are generally good, though occasional disputes, such as border demarcation or differing interpretations of historical events (like the recent Jasenovac resolution controversy with Croatia), can arise. Montenegro strives to play a constructive role in the Western Balkans, supporting regional integration and reconciliation efforts, while carefully balancing its relationships with major global powers like the United States, EU member states, Russia, and China, considering their impact on regional stability and adherence to human rights principles.

5.3. Law

Montenegro's legal system is based on civil law traditions and is framed by its Constitution, adopted in 2007. The Constitution proclaims Montenegro as a civic, democratic, ecological, and social justice state, founded on the rule of law. It guarantees a range of human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The judicial system is structured with several levels of courts. The Supreme Court of Montenegro is the highest court of general jurisdiction, ensuring uniform application of laws. Below it are High Courts, which handle more serious criminal and civil cases and act as appellate courts for Basic Courts. Basic Courts are the courts of first instance for most minor civil and criminal matters. There is also an Appellate Court and Administrative Courts, which deal with disputes involving public administration. The Constitutional Court is a separate body responsible for safeguarding the Constitution, reviewing the constitutionality of laws and other legal acts, and deciding on constitutional complaints regarding human rights violations. Judges are appointed by the Judicial Council, an independent body, and serve until the age of 67. The President of Montenegro appoints judges upon the recommendation of the Judicial Council.

Key areas of law are codified, including criminal law, civil procedure, and commercial law. Significant efforts have been made to harmonize Montenegrin legislation with EU law as part of the accession process. This includes reforms in areas such as judicial independence, efficiency of the justice system, and the fight against corruption and organized crime.

Regarding human rights, the Constitution guarantees a wide array of protections, including the right to life, freedom of expression, assembly, and religion. The Protector of Human Rights and Freedoms (Ombudsman) is an independent institution tasked with protecting and promoting human rights. Montenegro has laws prohibiting discrimination on various grounds, including sexual orientation and gender identity. Same-sex life partnerships have been legally recognized since July 2021, granting registered same-sex couples rights similar to marriage in many areas, though not adoption. LGBT rights have seen gradual improvement, with Pride parades being held in Podgorica, though societal acceptance can still be a challenge.

Minority rights are also constitutionally protected, with provisions for the representation of minorities in political life and the preservation of their cultural and linguistic identities. However, challenges remain in fully implementing these protections and ensuring social justice for all segments of society. Issues such as domestic violence, rights of persons with disabilities, and the situation of the Roma community continue to require attention. The country has a relatively low homicide rate. Abortion is legal on request during the first ten weeks of pregnancy.

5.4. Law enforcement and Security

Law enforcement in Montenegro is primarily the responsibility of agencies under the Ministry of Interior. The main national police force is the Police Directorate (Uprava policije), which is responsible for maintaining public order, crime prevention and investigation, border control, traffic safety, and other general policing duties.

In addition to the national police, municipal police (Komunalna policija) operate at the local level. Their responsibilities include enforcing municipal regulations, maintaining communal order (e.g., noise control, parking violations), and assisting the national police.

The National Security Agency (ANB) is the country's main intelligence and security agency, responsible for counterintelligence, counter-terrorism, and protecting national security interests.

Specialized units within the Police Directorate handle specific tasks. For example, the Special Anti-Terrorist Unit (SAJ) and the Special Police Unit (PJP) are trained for high-risk operations, combating organized crime, and counter-terrorism. Border police are responsible for securing Montenegro's state borders. Interpol Montenegro facilitates international police cooperation.

Montenegro has signed agreements with international bodies to enhance its law enforcement capabilities. For instance, an agreement with the EU allows Frontex (the European Border and Coast Guard Agency) personnel to operate in Montenegro to support local border police, particularly on non-EU borders.

Emergency services, including medical services, firefighting, and search and rescue, are coordinated by the Directorate for Emergency Situations within the Ministry of Interior. Emergency medical services are provided by local health institutions under the oversight of the Ministry of Health. The focus of law enforcement and security agencies is on maintaining public order, ensuring internal security, upholding the rule of law, and combating various forms of crime, including organized crime, which remains a significant challenge in the region.

5.5. Military

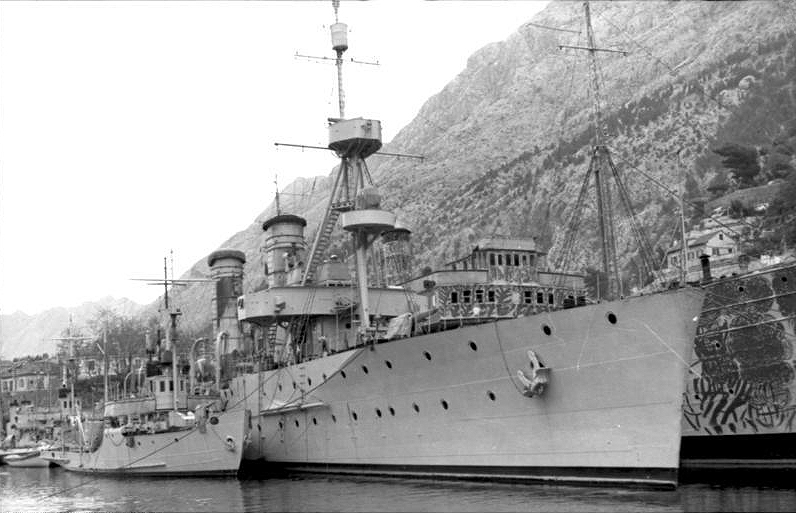

The Armed Forces of Montenegro (Vojska Crne Gore) are responsible for the country's defense. The military consists of three main professional service branches: the Montenegrin Ground Army, the Montenegrin Navy, and the Montenegrin Air Force. The armed forces are managed by the Ministry of Defence and operate under the command of the Chief of the General Staff. The President of Montenegro is the Commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

Since its independence in 2006, Montenegro has pursued a policy of Euro-Atlantic integration for its security. A major milestone was achieved on June 5, 2017, when Montenegro became the 29th member of NATO. NATO membership is a cornerstone of Montenegro's defense policy, providing collective security guarantees and opportunities for military cooperation and modernization.

The Montenegrin military is a relatively small, professional force. Conscription was abolished in 2006. The focus has been on developing niche capabilities and contributing to international peacekeeping and security operations. Montenegro has participated in various NATO-led missions, such as the Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan, and UN peacekeeping operations. It is also a member of the Adriatic Charter, an association formed by Albania, Croatia, North Macedonia, the United States, and Montenegro to aid their attempts to join NATO.

The primary roles of the Armed Forces of Montenegro include:

- Defending the independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity of Montenegro.

- Contributing to international peace and security through participation in international missions and operations.

- Providing support to civil authorities in case of natural disasters and other emergencies.

Modernization efforts aim to bring the military's equipment and training in line with NATO standards. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Montenegro is ranked as the 35th most peaceful country in the world.

6. Economy

Montenegro's economy is classified as an upper-middle-income economy that is largely service-based. It is in a late stage of transition to a market economy. Since regaining independence, the country has focused on macroeconomic stability, privatization, and attracting foreign investment, particularly in tourism and energy.

The GDP (nominal) of Montenegro was approximately 7.06 B USD in 2023, with a GDP per capita of around NaN Q USD. In terms of purchasing power parity (PPP), the GDP was about 17.43 B USD, and GDP per capita (PPP) was around NaN Q USD in 2023. According to Eurostat data, Montenegrin GDP per capita (in PPS) stood at 48% of the EU average in 2018. The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, was 29.4 in 2023. The country's Human Development Index (HDI) was 0.844 in 2022, ranking it 50th globally and placing it in the "very high human development" category.

Montenegro unilaterally adopted the Euro (€) as its currency in 2002 (initially the Deutsche Mark in 1999) and continues to use it, although it is not a member of the Eurozone. The Central Bank of Montenegro does not issue Euros and is not part of the Eurosystem; its role is primarily supervisory and regulatory.

Key sectors of the Montenegrin economy include:

- Tourism:** This is a vital and rapidly growing sector, contributing significantly to GDP and employment. Montenegro's Adriatic coast, with towns like Budva, Kotor, and Herceg Novi, and its mountainous regions like Durmitor and Prokletije, are major attractions.

- Services:** Beyond tourism, the service sector includes trade, real estate, telecommunications, and financial services.

- Agriculture:** While its share of GDP has declined, agriculture remains important, particularly in rural areas. Products include olives, grapes (for wine), citrus fruits, tobacco, and livestock.

- Industry:** Major industries include aluminum production (KAP smelter in Podgorica, though its future has been uncertain), steel, and food processing.

Montenegro is a member of the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). It has a free trade agreement with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). The country actively seeks foreign direct investment (FDI), which has played a role in sectors like tourism, real estate, and energy.

Economic challenges include a relatively high public debt, unemployment (particularly among youth and in the northern region), a significant trade deficit, and regional economic disparities. Efforts to improve the business environment, combat the informal economy, and strengthen the rule of law are ongoing, partly driven by the EU accession process. The government has focused on infrastructure development, including transport and energy projects, often financed through international loans, which has contributed to rising public debt. Ensuring social equity and environmental sustainability alongside economic growth are important considerations for long-term development. Montenegro was ranked 65th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

6.1. Infrastructure

Montenegro's infrastructure, particularly in transport and energy, has been a focus of development efforts, aiming to support economic growth, tourism, and regional connectivity. However, challenges remain in bringing it up to Western European standards.

- Transportation:**

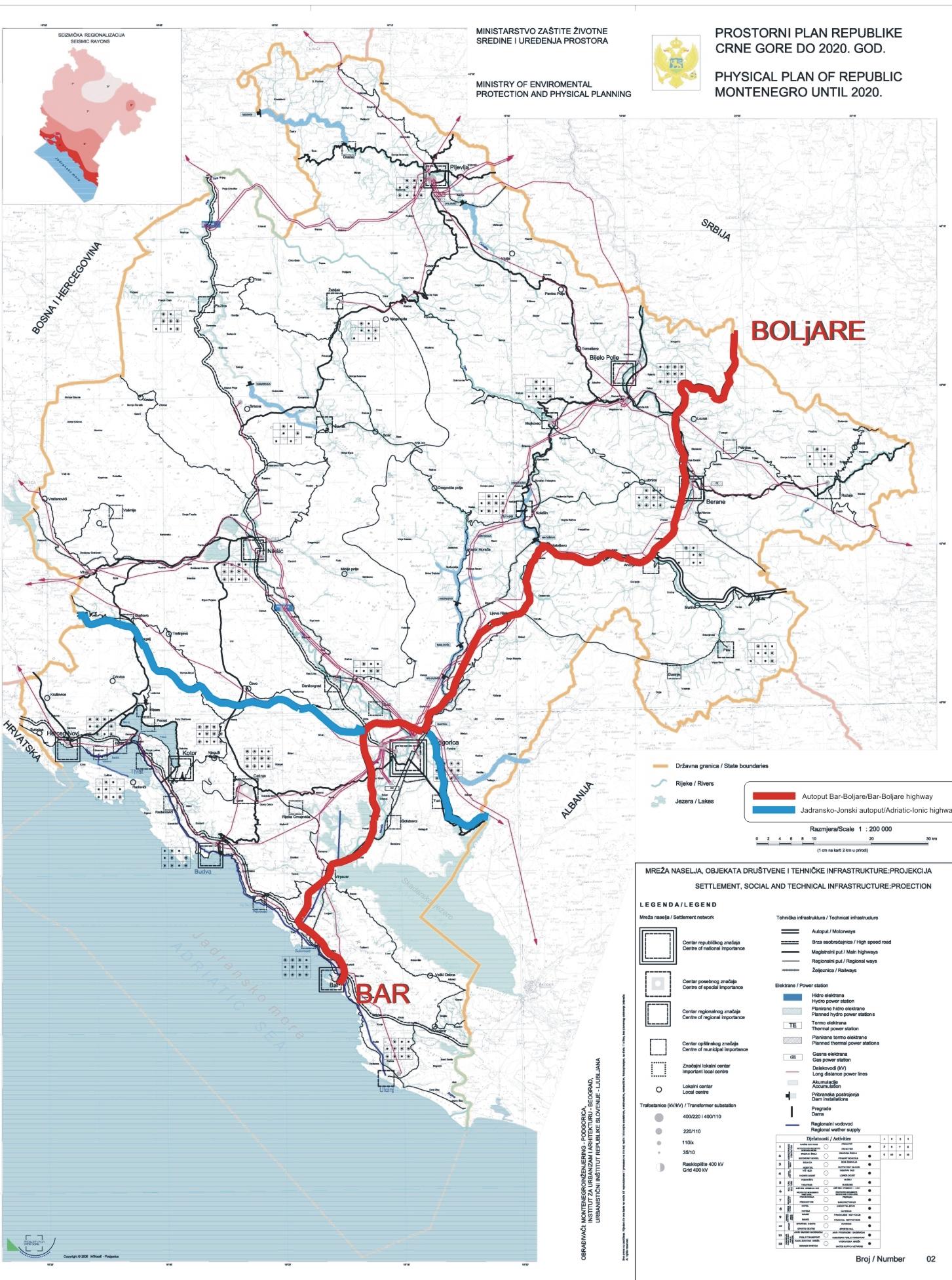

- Roads:** The road network is the primary mode of transport. Montenegro has a network of national and regional roads. A major ongoing project is the construction of the Bar-Boljare motorway (part of the international E65/E80 corridor), which aims to connect the Port of Bar on the Adriatic coast with the Serbian border in the north. The first section of this motorway, from Smokovac (near Podgorica) to Mateševo, opened in 2022. This project is significant for improving north-south connectivity but has also been a source of substantial public debt due to Chinese loans. Other roads are being upgraded, but mountainous terrain makes construction costly and challenging.

- Railways:** The backbone of the Montenegrin rail network is the Belgrade-Bar railway, which provides an international link to Serbia. This line is important for both passenger and freight transport, especially for the Port of Bar. There is also the Nikšić-Podgorica railway, which was upgraded and electrified for passenger traffic. A line from Podgorica to the Albanian border, the Podgorica-Shkodër railway, exists but has limited use for freight and no regular passenger service.

- Airports:** Montenegro has two international airports: Podgorica Airport (TGD) and Tivat Airport (TIV). Podgorica Airport serves the capital and inland areas, while Tivat Airport primarily serves the coastal region and is crucial for tourism.

- Ports:** The Port of Bar is the country's main seaport, handling various types of cargo. It is a key logistical hub, and its development is linked to improvements in road and rail infrastructure. Smaller ports and marinas along the coast cater to tourism and local needs. An LNG terminal at Bar has been planned to receive gas imports as of 2023.

- Energy:**

Montenegro's energy sector relies on a mix of hydropower and thermal power (coal). The country has significant hydropower potential due to its mountainous terrain and rivers. The Piva Hydroelectric Power Plant is a major facility. The Pljevlja Thermal Power Plant, fueled by local lignite, is another key electricity producer but also a source of significant pollution. Montenegro aims to increase the share of renewable energy sources (wind, solar) in its energy mix, in line with EU targets and environmental concerns. Projects like the Možura wind farm have been developed. Improving energy efficiency and interconnectivity with neighboring countries are also priorities.

- Telecommunications:**

The telecommunications sector in Montenegro is relatively developed, with several mobile network operators and internet service providers offering modern services, including widespread mobile broadband coverage. Fiber optic networks are being expanded to improve high-speed internet access.

Overall, infrastructure development is crucial for Montenegro's economic prospects, but it requires careful planning to ensure financial sustainability and minimize environmental impact, especially given the country's ecological significance and reliance on tourism.

6.2. Tourism

Tourism is a cornerstone of Montenegro's economy, contributing a significant share to its GDP and employment. The country offers a diverse range of attractions, from its Adriatic coastline to its rugged mountains and national parks. In 2022, Montenegro recorded 2.1 million visitor arrivals, who spent 12.4 million overnight stays. The majority of foreign visitors traditionally come from neighboring countries like Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo, as well as from Russia and other European nations.

- Major Attractions and Types of Tourism:**

- Coastal Tourism:** The Montenegrin Adriatic coast, approximately 183 mile (295 km) long, features 45 mile (72 km) of beaches. Popular coastal destinations include:

- Budva**: Known as the "metropolis of tourism," famous for its lively nightlife, beaches (like Jaz Beach, Mogren Beach, Bečići Beach), and historic Old Town.

- Kotor**: A UNESCO World Heritage Site, renowned for its medieval Old Town, ancient walls, and stunning location on the Bay of Kotor.

- Herceg Novi**: A coastal town at the entrance of the Bay of Kotor, known for its fortresses and pleasant climate.

- Sveti Stefan**: An iconic fortified island village, now an exclusive resort, which has graced the covers of international travel magazines.

- Ulcinj**: Located in the south, famous for Velika Plaža (Long Beach), a 8.1 mile (13 km) sandy beach, and Ada Bojana, a river island popular for naturism and kitesurfing.

- Perast**: A picturesque baroque town in the Bay of Kotor, with nearby islets like Our Lady of the Rocks.

- Mountain and Nature Tourism:** Montenegro's mountainous interior offers opportunities for hiking, mountaineering, skiing, and exploring pristine nature.

- Durmitor National Park**: Another UNESCO World Heritage Site, featuring dramatic peaks (like Bobotov Kuk), glacial lakes (like the Black Lake), and the deep Tara River Canyon, popular for rafting.

- Prokletije National Park**: Known as the "Accursed Mountains," offering wild, alpine landscapes for adventurous travelers.

- Biogradska Gora National Park**: Home to one of Europe's last virgin forests and Lake Biograd.

- Lovćen National Park**: Centered around Mount Lovćen, a historically significant site with the mausoleum of Petar II Petrović-Njegoš.

- Lake Skadar National Park**: The largest lake in the Balkans, a haven for birdwatching and boat trips.

- Cultural and Historical Tourism:** Montenegro's rich history is reflected in its numerous monasteries (like Ostrog Monastery, a major pilgrimage site, and Cetinje Monastery), archaeological sites, and traditional villages.

- Adventure Tourism:** Activities like white-water rafting, canyoning, paragliding, and mountain biking are increasingly popular.

- Impact and Development:**

The tourism sector has seen significant foreign investment, particularly in hotels and resorts. The government has promoted Montenegro as a high-end tourist destination. Publications like National Geographic Traveler have featured Montenegro as a prime travel spot. The New York Times has also highlighted regions like the Ulcinj South Coast.

However, the rapid growth of tourism also presents challenges, including the need for sustainable development, environmental protection (especially along the coast and in national parks), managing infrastructure capacity, and ensuring that local communities benefit. Issues like illegal construction and the strain on water and waste management systems are concerns. Efforts are being made to diversify the tourism offer, promote year-round tourism, and develop rural and eco-tourism to alleviate pressure on coastal areas and distribute economic benefits more widely. - Coastal Tourism:** The Montenegrin Adriatic coast, approximately 183 mile (295 km) long, features 45 mile (72 km) of beaches. Popular coastal destinations include:

7. Demographics and Society

Montenegro is a multiethnic and multicultural country with a relatively small population. Its demographic trends and social fabric have been shaped by its history, geography, and political developments. Understanding these aspects is crucial for appreciating the country's contemporary social dynamics and challenges related to social justice and equality.

7.1. Ethnic groups

Montenegro is a multiethnic state with no single ethnic group forming an absolute majority. According to the preliminary results of the 2023 census, the main ethnic groups are:

- Montenegrins**: Approximately 41.1% of the population identify as Montenegrin.

- Serbs**: Approximately 32.9% identify as Serb. The distinction between Montenegrins and Serbs can be complex, as many share common linguistic, cultural, and religious (Eastern Orthodox) heritage. Self-identification can fluctuate based on political and social contexts.

- Bosniaks**: Constituting around 9.4% of the population, Bosniaks are a significant minority group, predominantly Muslim, concentrated mainly in the northern Sandžak region.

- Albanians**: Making up about 5.0% of the population, Albanians are concentrated primarily in municipalities along the border with Albania and Kosovo, such as Ulcinj, Tuzi, and parts of Plav and Rožaje. They are predominantly Muslim, with a Catholic minority.

- Russians**: Comprising around 2.0% of the population, this group has seen an increase in recent years.

- Croats**: A smaller minority, historically concentrated in the Bay of Kotor region, primarily Catholic.

- Roma**: The Roma community faces significant socio-economic challenges and issues of discrimination.

- Others**: Various other smaller ethnic groups also reside in Montenegro.

The historical presence of these groups varies. Montenegrins and Serbs have deep historical roots in the region. Bosniaks are descendants of Slavic Muslims from the Ottoman era. Albanians have inhabited their respective areas for centuries. Inter-ethnic relations are generally peaceful, but historical grievances and political exploitation of ethnic identity can sometimes lead to tensions. The Montenegrin constitution guarantees rights for minority groups, including representation in political institutions and the use of minority languages in official contexts in areas where they form a significant part of the population. Ensuring full equality, combating discrimination, and fostering a truly multicultural society remain ongoing tasks for promoting social justice.

7.2. Languages

The linguistic landscape of Montenegro is diverse, reflecting its multiethnic composition.

- Official Language:** The Constitution of Montenegro designates Montenegrin as the official language. Montenegrin is a standardized form of the Shtokavian dialect of Serbo-Croatian.

- Languages in Official Use:** Serbian, Bosnian, Albanian, and Croatian are also recognized as languages in official use. This means they can be used in administrative and educational contexts in municipalities where speakers of these languages constitute a significant portion of the population.

According to the 2023 preliminary census data on mother tongue:

- A plurality of the population, 43.18%, declared Serbian as their native language.

- 34.52% declared Montenegrin as their native language.

- Significant numbers also speak Bosnian (6.98%), Albanian (5.25%), and Russian (2.36%).

Montenegrin, Serbian, Bosnian, and Croatian are largely mutually intelligible. The debate over the Montenegrin language and its distinction from Serbian has been a politically sensitive issue, intertwined with questions of national identity.

- Alphabets:** Both the Latin and Cyrillic alphabets are recognized as equal under the constitution. In practice, the Latin script is more widely used in official communications, media, and daily life, although Cyrillic is still used, particularly by those who identify more closely with Serbian cultural heritage and by the Serbian Orthodox Church. Language policies aim to protect and promote the linguistic rights of all communities.

7.3. Religion

Montenegro is a multi-religious country with a long history of co-existence between its main religious communities. Religious freedom is guaranteed by the constitution.

- Eastern Orthodoxy**: This is the predominant religion, with approximately 71.1% of the population adhering to it (2023 preliminary census). Most Orthodox Christians in Montenegro belong to the Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC), specifically its Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral and the Eparchy of Budimlja and Nikšić. The SOC is the largest and historically most influential religious institution in the country.

A smaller, canonically unrecognized Montenegrin Orthodox Church (MOC) was established in 1993 by supporters of Montenegrin autocephaly. It claims to be the successor of an earlier independent Montenegrin church and is followed by a minority of those identifying as Orthodox Montenegrins. The MOC is not in communion with other canonical Orthodox churches and has not been recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. The status and property of religious communities, particularly the SOC, have been sources of significant political and social tension, culminating in the controversial 2019 law on religious freedom and the subsequent protests.

- Islam**: Muslims constitute the second-largest religious group, making up about 19.9% of the population (2023 preliminary census). Most Muslims in Montenegro are Sunni. They primarily include ethnic Bosniaks, Albanians, and a smaller group who identify as Muslims by nationality. Islam has a long history in Montenegro, dating back to the Ottoman era. In 2012, a protocol recognized Islam as an official religion, ensuring rights such as the provision of halal food in public institutions and the right for Muslim women to wear headscarves in schools and public institutions.

- Catholicism**: Catholics represent about 3.2% of the population (2023 preliminary census). They are mainly ethnic Albanians (in coastal areas and near the Albanian border) and Croats (primarily in the Bay of Kotor region). The Catholic Church in Montenegro is organized into the Archdiocese of Bar (headed by the Primate of Serbia, a historical title) and the Diocese of Kotor.

- Other Religions and Irreligion**: Smaller religious communities and individuals identifying as having no religion (around 2.7%) or not stating their religion (around 2.2%) also exist.

Historically, Montenegro has generally maintained religious tolerance, though the Yugoslav Wars did cause some inter-religious tensions in the broader region. Religious institutions are separate from the state, but religion often plays a significant role in public life and national identity.

7.4. Education

The Montenegrin education system is structured in several levels, with efforts ongoing to modernize and align it with European standards, particularly in the context of the EU accession process.

- Preschool Education:** Optional for children up to the age of 6.

- Primary Education (Osnovna škola):** Compulsory and free, lasting for nine years, typically for children aged 6 to 15. It is divided into three cycles.

- Secondary Education (Srednja škola):** After primary school, students can enroll in various types of secondary schools, typically lasting for three or four years:

- Gymnasium (Gimnazija):** Four-year general academic education, preparing students for higher education.

- Vocational Schools (Stručna škola):** Offer three or four-year programs providing vocational qualifications for various trades and professions, as well as access to higher education (for four-year programs).

- Higher Education:** Provided by universities, faculties, art academies, and colleges of applied sciences.

- The University of Montenegro is the oldest and largest public higher education institution, with its main campus in Podgorica and faculties in other cities.

- There are also private universities and independent faculties.

- Higher education follows the Bologna Process principles, with a three-cycle system (Bachelor, Master, PhD).

The language of instruction is predominantly Montenegrin. In areas with significant minority populations, education is also provided in Albanian and, to a lesser extent, other recognized minority languages.

Challenges in the Montenegrin education system include ensuring equitable access to quality education, particularly in rural and less developed regions; modernizing curricula and teaching methods; improving infrastructure; and addressing issues such as teacher training and matching educational outcomes with labor market needs. Reforms aim to enhance the quality, relevance, and inclusivity of the education system.

7.5. Health

Montenegro's healthcare system is predominantly public, with a network of primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare facilities. The Ministry of Health is responsible for overall health policy and regulation. The Health Insurance Fund (Fond za zdravstveno osiguranje) manages the compulsory health insurance scheme, which covers most of the population.

- Primary Healthcare:** Delivered through local health centers (Dom zdravlja) located in municipalities. These centers provide general practitioner services, pediatric care, women's health services, dental care, and emergency outpatient services.

- Secondary Healthcare:** Provided by general hospitals located in larger towns, offering specialized medical services and inpatient care.

- Tertiary Healthcare:** The Clinical Centre of Montenegro (Klinički centar Crne Gore) in Podgorica is the main tertiary healthcare institution, providing highly specialized diagnostics, treatment, and medical research. There are also specialized hospitals, such as the hospital for lung diseases in Brezovik.

Private healthcare practices and clinics also exist, offering a range of services, particularly in dentistry, specialist consultations, and diagnostics.

Major health concerns in Montenegro include cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and respiratory diseases, which are common causes of mortality. Lifestyle factors such as smoking, diet, and physical inactivity contribute to these non-communicable diseases. Public health initiatives focus on prevention, health promotion, and screening programs.

Challenges in the healthcare system include:

- Funding and Resources:** Ensuring adequate and sustainable funding for the public healthcare system.

- Infrastructure and Equipment:** Modernizing medical equipment and facilities.

- Human Resources:** Addressing shortages of certain medical specialists and retaining healthcare professionals.

- Access to Services:** Ensuring equitable access to healthcare, especially for vulnerable populations and those in remote areas.

- Waiting Lists:** Reducing waiting times for certain specialist examinations and procedures.

Reforms in the healthcare sector aim to improve the quality, efficiency, and accessibility of services, strengthen primary healthcare, optimize hospital network management, and enhance public health programs. Aligning with EU standards in healthcare is also a priority.

8. Culture

Montenegrin culture is a rich mosaic shaped by a confluence of historical and geographical influences. Its position at the crossroads of civilizations has resulted in a unique blend of Orthodox, Ottoman, Slavic, Venetian, and broader Mediterranean cultural elements. This diversity is reflected in its traditions, arts, architecture, folklore, and societal values.

- Traditions and Folklore:**

Montenegrin traditions are deeply rooted in its clan-based history and its long struggle for survival and independence. Epic poetry, celebrating heroic deeds and historical events, has played a significant role in preserving cultural memory and shaping national identity. The ethical ideal of Čojstvo i Junaštvo (Humaneness and Gallantry) is a cornerstone of traditional Montenegrin values, emphasizing bravery, honor, integrity, and the protection of others. Traditional music often features the gusle, a single-stringed instrument used to accompany epic poems. Folk dances, such as the Oro (eagle dance), are vibrant expressions of cultural heritage, often performed at celebrations.

- Arts:**

- Literature:** Montenegrin literature includes a strong tradition of epic poetry. Petar II Petrović-Njegoš is the most celebrated Montenegrin writer, whose epic poem The Mountain Wreath (Gorski vijenac) is considered a masterpiece of South Slavic literature. Modern Montenegrin literature encompasses various genres and themes.

- Visual Arts:** Early Montenegrin art was heavily influenced by Byzantine traditions, particularly in frescoes and icons found in medieval monasteries like Morača, Piva, and Savina. Coastal regions show Venetian and Renaissance influences. Modern and contemporary Montenegrin artists have explored various styles and mediums.

- Music:** Traditional music is diverse, with regional variations. In addition to epic songs accompanied by the gusle, there are lyrical folk songs and instrumental music. Modern Montenegrin music spans popular genres, rock, and classical music.

- Architecture:** Montenegrin architecture reflects its varied history. Coastal towns like Kotor, Perast, and Budva showcase Venetian and Mediterranean styles, with stone houses, palaces, and fortifications. Inland, Ottoman influences are visible in some older structures. Monasteries often combine Byzantine and local architectural elements. Modern architecture is present in urban centers.

- World Heritage and Cultural Sites:**

Montenegro has several significant cultural and historical sites. The Natural and Culturo-Historical Region of Kotor is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized for its well-preserved medieval town and its harmonious integration with the natural landscape of the bay. The Durmitor National Park is also a World Heritage Site, valued for its natural beauty and biodiversity, but also holding cultural significance. Medieval monasteries throughout the country, such as Ostrog, Cetinje, Morača, and Piva, are important cultural and religious centers, many containing valuable frescoes and artifacts. The Stećci Medieval Tombstone Graveyards, a transnational UNESCO site, includes locations in Montenegro. The traditional Boka Navy of Kotor, a historic maritime confraternity, is inscribed on UNESCO's list of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

The National Museum of Montenegro, located in Cetinje, houses extensive collections related to Montenegrin history, art, and ethnography. Cultural events, festivals, and local celebrations play an important role in contemporary cultural life.8.1. Media

The media landscape in Montenegro includes a mix of public and private outlets across television, radio, print, and online platforms. The Constitution of Montenegro guarantees freedom of speech and freedom of the media.

- Public Broadcaster:** Radio and Television of Montenegro (RTCG) is the national public service broadcaster, operating television channels (TVCG 1, TVCG 2, TVCG Parlament) and radio stations (Radio Montenegro). It is funded through a combination of state budget allocations and other revenues.

- Private Media:** There are several private television stations (e.g., Vijesti TV, Prva TV, Nova M) and numerous local TV and radio stations. The print media market includes daily newspapers such as Vijesti, Dan, and Pobjeda (formerly state-owned, now privatized but with historical ties), as well as weekly magazines and specialized publications. Online media has become increasingly influential, with numerous news portals and websites.

- Media Freedom and Pluralism:**

The state of media freedom in Montenegro has been a subject of concern for domestic and international organizations. While the legal framework generally supports media freedom, challenges persist in practice. These include:

- Political Influence:** Concerns about political pressure and influence on media outlets, particularly the public broadcaster and media considered sympathetic to the government of the day.

- Safety of Journalists:** Cases of threats, intimidation, and physical attacks against journalists have been reported, some of which remain unresolved. This creates a chilling effect and hinders investigative journalism.

- Economic Pressures:** The small market size and economic vulnerabilities can make media outlets susceptible to financial pressures and influence from advertisers or political actors.

- Defamation and Regulation:** While defamation has been decriminalized, civil lawsuits can still be used to pressure journalists. The regulatory framework for media is evolving, with ongoing efforts to align it with European standards.

- Disinformation and Propaganda:** Like many countries, Montenegro faces challenges related to the spread of disinformation, particularly through online platforms and media outlets with external influences.

Organizations such as the European Commission, Reporters Without Borders, and Freedom House regularly monitor and report on the media situation in Montenegro. Improving media freedom, ensuring the safety of journalists, strengthening the independence of the public broadcaster, and promoting media pluralism are key areas for reform, especially in the context of Montenegro's EU accession process. Efforts are needed to foster a media environment where journalists can work freely and critically, contributing to democratic accountability and informed public discourse.

8.2. Sport

Exterior of the Morača Sports Center in Podgorica. Sport plays a significant role in Montenegrin society, with several team and individual sports enjoying popularity and achieving international success.

- Popular Team Sports:**

- Water Polo:** Often considered the national sport, water polo is extremely popular. The Montenegro men's national water polo team is highly successful, having won the 2008 Men's European Water Polo Championship and the 2009 FINA World League. They have also been consistent contenders in Olympic Games and World Championships. Montenegrin club Primorac Kotor won the LEN Euroleague in 2009.

- Football (Soccer):** Football is the most widely played sport. The Montenegrin First League is the top national football competition. The Montenegro national football team, established after independence in 2006, has competed in qualifications for the FIFA World Cup and UEFA European Championship, reaching the playoffs for UEFA Euro 2012. Notable Montenegrin footballers include Dejan Savićević, Predrag Mijatović, Mirko Vučinić, and Stevan Jovetić.

- Basketball:** Basketball is also very popular. The Montenegro national basketball team has participated in several EuroBasket tournaments. Montenegrin clubs compete in regional leagues like the Adriatic League.

- Handball:** Women's handball has brought Montenegro significant international success. The Montenegro women's national handball team won the silver medal at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, which was Montenegro's first-ever Olympic medal. They also won the 2012 European Women's Handball Championship. The club ŽRK Budućnost is one of Europe's top women's handball clubs, having won the EHF Champions League multiple times. Montenegro co-hosted the 2022 European Women's Handball Championship.

- Individual Sports:**

Individual sports such as boxing, tennis, swimming, judo, karate, athletics, table tennis, and chess are also practiced. Montenegrin athletes have achieved success in various individual disciplines at European and world levels.

Montenegro participates in the Olympic Games as an independent nation since 2008 (having previously competed as part of Yugoslavia and Serbia and Montenegro). The Montenegrin Olympic Committee oversees the country's participation in the Olympics and promotes sports development. Sports infrastructure includes stadiums, sports halls (like the Morača Sports Center in Podgorica), and swimming pools, although further investment is often needed, particularly at the local level.

8.3. Cuisine

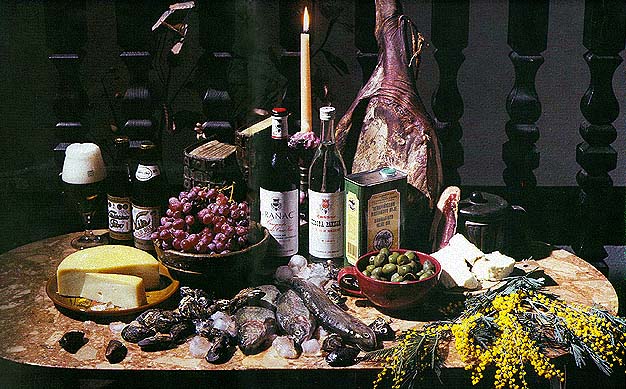

Various foods from Montenegro. Montenegrin cuisine is a reflection of its diverse geography, history, and cultural influences. It combines elements of Mediterranean, Balkan, Turkish, Hungarian, and Central European culinary traditions. Dishes vary significantly between the coastal region, the central plains, and the northern highlands.

- Coastal Cuisine:**

The cuisine of the Adriatic coast is typically Mediterranean, characterized by the use of fresh seafood, olive oil, vegetables, and herbs. Italian influences are prominent.

- Seafood:** Grilled fish (riba na žaru), squid (lignje), octopus (hobotnica), and shellfish (školjke) are common. Brodet (fish stew) is a popular dish.

- Olive Oil:** Locally produced olive oil is a staple ingredient.

- Vegetables:** Fresh salads, grilled vegetables, and dishes like blitva (chard) with potatoes are widely consumed.