1. Overview

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country located in Southeast Europe, at the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula. It is considered the cradle of Western civilisation, being the birthplace of democracy, Western philosophy, Western literature, historiography, political science, major scientific and mathematical principles, theatre, and the Olympic Games. Its rich historical legacy, spanning from ancient civilisations through the Byzantine and Ottoman eras to the modern nation-state, has profoundly shaped its culture and identity.

This article explores the multifaceted aspects of Greece, from its historical evolution and geographical features to its political system, economic structure, societal dynamics, and cultural contributions. It examines the nation's journey through periods of flourishing democratic development, challenges to human rights under authoritarian rule, and ongoing efforts towards social equity and progress. The narrative emphasizes the impact of historical events on the Greek people, the evolution of its democratic institutions, the protection of civil liberties, and the pursuit of social welfare, reflecting a perspective centered on democratic values and human dignity. The article details Greece's geography, its system of government, foreign relations, military, economic sectors including its significant maritime and tourism industries, the societal fabric encompassing demographics, religion, education, and human rights, as well as its contributions to science, technology, and the arts.

2. Name

The native name of the country in Modern Greek is ΕλλάδαElláda (pronounced eh-LAH-thah)Greek, Modern. The corresponding form in Ancient Greek and conservative formal Modern Greek (Katharevousa) is ἙλλάςHellás (Classical: hel-LAS, Modern: eh-LAS)Greek, Modern. This is the source of the English alternative name Hellas, which is mostly found in archaic or poetic contexts today. The Greek adjectival form ελληνικόςellinikos (eh-lee-nee-KOS)Greek, Modern is sometimes also translated as Hellenic and is often rendered in this way in the formal names of Greek institutions, as in the official name of the Greek state, the Hellenic Republic (Ελληνική ΔημοκρατίαEllinikí Dimokratía (eh-lee-nee-KEE dhee-mo-krah-TEE-ah)Greek, Modern).

The English names Greece and Greek are derived, via the Latin GraeciaGREY-shuhLatin and GraecusGREY-kuhsLatin, from the name of the Graeci (ΓραικοίGrai-KOYGreek, Ancient), one of the first ancient Greek tribes to settle Magna Graecia in southern Italy. In Indonesian, the term "Yunani" originates from Arabic اليُونَانal-YūnānArabic, which itself was absorbed from Persian Yunân, referring to Ionia, a region on the western coast of Anatolia historically part of Greece. Similarly, Middle Eastern languages such as Turkish (Yunanistan) and Hebrew (Yaván) also derive their names for Greece from Ionia. The Japanese term for Greece, ギリシャGHEE-ree-shahJapanese, comes from the Portuguese "Grécia". The Chinese name, 希臘XīlàChinese, is a phonetic transcription of the ancient Greek "Ἑλλάς" (Hellas).

3. History

The history of Greece spans millennia, from early prehistoric settlements and the rise of significant Aegean civilisations to the classical era that laid foundational aspects of Western culture, followed by periods under Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman rule. The modern Greek state emerged in the 19th century after a war of independence, navigating through periods of expansion, devastating world wars, civil war, authoritarian dictatorships, and eventually, the establishment of a democratic republic. This historical trajectory has profoundly influenced Greek society, its political development, and the ongoing struggles for human rights and democratic progress.

3.1. Prehistory and Aegean Civilisations

The Apidima Cave in Mani, southern Greece, contains what some suggest are the oldest remains of early modern humans outside of Africa, dated to 200,000 years ago, though other interpretations suggest these are archaic humans. All three stages of the Stone Age are represented in Greece, exemplified by sites like the Franchthi Cave. Neolithic settlements in Greece, dating from the 7th millennium BC, are the oldest in Europe, as Greece was a key route for the spread of farming from the Near East.

Greece is home to the first advanced civilisations in Europe. The earliest was the Cycladic culture, which flourished on the Aegean islands from around 3200 BC, producing distinctive marble figurines. From around 3100 BC to 1100 BC, Crete was the center of the Minoan civilization, known for its vibrant art, religious figurines, and monumental palaces like Knossos. The Minoans used undeciphered scripts known as Linear A and Cretan hieroglyphs. On the mainland, the Mycenaean civilisation developed around 1750 BC, lasting until around 1100 BC. The Mycenaeans were militarily advanced, built large fortifications with Cyclopean masonry, worshipped numerous deities, and used Linear B to write the earliest attested form of the Greek language, known as Mycenaean Greek. These early civilisations laid crucial groundwork for subsequent developments in the region, establishing complex societal structures, artistic traditions, and early forms of administration and writing that influenced the later Greek world.

3.2. Ancient Greece

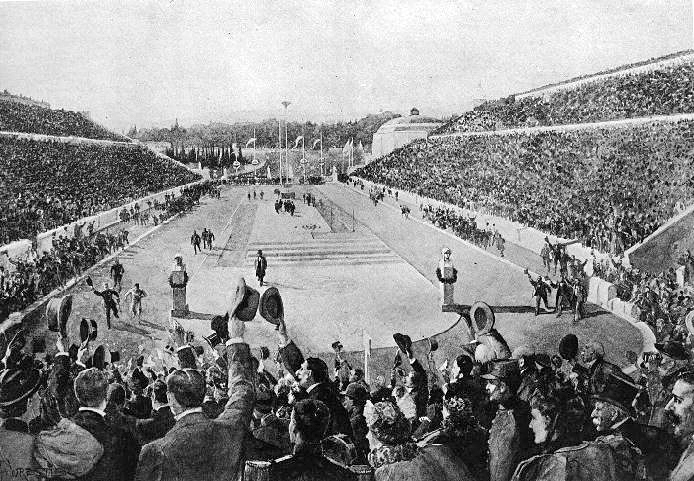

The collapse of the Mycenaean civilisation ushered in the Greek Dark Ages, a period lacking written records, traditionally ending in 776 BC with the first Olympic Games. The epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, attributed to Homer and composed in the 7th or 8th centuries BC, became foundational texts of Western literature, shaping beliefs about the Olympian gods. Ancient Greek religion, however, lacked a rigid priestly class or dogma, encompassing diverse practices like the cult of Dionysus and mystery cults.

During this era, independent city-states, known as poleis (singular polis), emerged across the Greek peninsula and spread through colonization to the Black Sea, Magna Graecia (southern Italy), and Anatolia. These poleis achieved great prosperity, leading to the cultural boom of classical Greece, characterized by advancements in architecture, drama, science, mathematics, and philosophy. A pivotal development was the establishment of the world's first democratic system of government in Athens by Cleisthenes in 508 BC, which, despite its limitations (excluding women, slaves, and foreigners), laid crucial groundwork for later democratic thought.

By 500 BC, the Persian Empire controlled Greek city-states in Asia Minor and Macedonia. The Ionian Revolt against Persian rule failed, leading to Persian invasions of mainland Greece. The first invasion was repelled at the Battle of Marathon (490 BC). In response, Greek city-states formed the Hellenic League in 481 BC, led by Sparta. The second Persian invasion of Greece (480-479 BC) was decisively defeated at Salamis and Plataea, leading to Persian withdrawal from Europe. The Greek victories marked a crucial moment, ushering in the Golden Age of Athens, a period of peace and cultural flourishing that laid many foundations of Western civilisation, including significant advancements in democratic practices and philosophical inquiry.

However, the lack of political unity led to frequent conflicts between Greek states. The devastating Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) between Athens and Sparta resulted in the demise of the Athenian Empire and the rise of Spartan, then Theban, hegemony. Weakened by internal strife, the Greek poleis were subjugated by the rising power of the kingdom of Macedon under Philip II, who formed the League of Corinth. After Philip's assassination in 336 BC, his son Alexander the Great led a Panhellenic campaign against the Persian Empire, conquering vast territories from the eastern Mediterranean to northwestern India before his death in 323 BC.

Alexander's empire fragmented upon his death, initiating the Hellenistic period. His generals, the Diadochi, established large kingdoms like the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt and the Seleucid dynasty in Syria, Mesopotamia, and Iran. Greek settlers in new poleis like Alexandria and Antioch spread Koine Greek and Greek culture (Hellenization), while also adopting Eastern deities. This era saw Greek science, technology, and mathematics reach their peak. Many Greek poleis formed federations (koina or sympoliteiai) to maintain autonomy from the Antigonid kings of Macedon. The Hellenistic period represented a significant diffusion of Greek culture and political systems, though often imposed through conquest, setting the stage for interactions with the rising Roman power.

3.3. Roman and Byzantine Eras

From around 200 BC, the Roman Republic became increasingly involved in Greek affairs, engaging in a series of Macedonian Wars. Macedon's defeat at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC marked the end of Antigonid power. In 146 BC, Macedonia was annexed as a Roman province, and the rest of Greece became a Roman protectorate. The process culminated in 27 BC when Emperor Augustus annexed the remaining Greek territories, constituting them as the senatorial province of Achaea. Despite their military superiority, the Romans deeply admired and were heavily influenced by Greek culture, leading to a Greco-Roman cultural synthesis. This period saw changes in governance as Greek city-states lost their political independence, though many retained a degree of local autonomy and cultural vibrancy.

Greek-speaking communities in the Hellenized East were instrumental in the spread of Christianity in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. The New Testament was written in Greek, and early Christian leaders were often Greek-speaking. However, paganism persisted in Greece, with ancient religious practices continuing until outlawed by Emperor Theodosius I in 391-392 AD. The last recorded Olympic Games were held in 393 AD. The closure of the Neoplatonic Academy of Athens by Emperor Justinian in 529 AD is often considered the end of antiquity, impacting philosophical freedom, though some academic activity may have continued.

The Roman Empire in the east, following the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, is known as the Byzantine Empire. With its capital in Constantinople, its language and culture were predominantly Greek, and its religion was primarily Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The Empire's Balkan territories, including Greece, suffered from barbarian invasions by Goths, Huns, and later Slavs in the 7th century, leading to a decline in imperial authority in the Greek peninsula. However, the view of widespread decline is contested, as many cities showed institutional continuity and prosperity between the 4th and 6th centuries.

Until the 8th century, much of modern Greece was under the jurisdiction of the See of Rome. Byzantine Emperor Leo III shifted this to the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Byzantine recovery of lost provinces began in the 8th century, and most of the Greek peninsula came under imperial control again, facilitated by an influx of Greeks from Sicily and Asia Minor. During the 11th and 12th centuries, stability led to economic growth in the Greek peninsula. The Greek Orthodox Church played a vital role in shaping Greek identity and spreading Greek ideas throughout the Orthodox world. This era solidified the Greek cultural and religious framework that would endure for centuries.

Following the Fourth Crusade and the fall of Constantinople to the Latins in 1204, mainland Greece was fragmented between the Greek Despotate of Epirus and French rule (the Frankokratia). The re-establishment of the imperial capital in Constantinople in 1261 saw the empire recover much of the Greek peninsula, though islands often remained under Genoese and Venetian control. The Palaiologos dynasty (1261-1453) witnessed a resurgence of Greek patriotism and a renewed interest in ancient Greece. However, in the 14th century, much of the Greek peninsula was lost to Serbs and then to the Ottoman Empire. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, and the subsequent conquest of mainland Greece by 1460, marked the end of Byzantine rule and the beginning of a new period of foreign domination, significantly altering the political and social landscape for the Greek-speaking populations.

3.4. Ottoman and Venetian Rule

By the end of the 15th century, most of mainland Greece and the Aegean islands were under Ottoman control. However, Cyprus and Crete remained Venetian possessions until 1571 and 1669, respectively. The Venetian Republic also maintained control of the Ionian Islands until 1797. While some Greeks, particularly Phanariots in Constantinople, achieved positions of power within the Ottoman administration, much of the Greek population suffered economic hardship due to heavy taxation and policies that effectively turned rural Greeks into serfs. This period largely cut Greece off from major European historical developments like the Renaissance, impacting its societal trajectory.

The Greek Orthodox Church, under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, was considered by the Ottomans as the ruling authority for the Orthodox Christian population of the Empire. While non-Muslims were not forced to convert to Islam, Christians faced discrimination, which, combined with harsh local Ottoman authorities, led to some conversions, often superficial. The nature of Ottoman administration varied but was often arbitrary and harsh. Some cities had governors appointed by the Sultan, while others, like Athens, were self-governed municipalities. Mountainous regions and many islands remained effectively autonomous.

The 16th and 17th centuries are often regarded as a "dark age" in Greek history. Despite this, Greeks participated in several uprisings against Ottoman rule, including the Battle of Lepanto (1571), the Morean War (1684-1699), and the Russian-instigated Orlov Revolt (1770). These revolts were brutally suppressed by the Ottomans. Many Greeks were conscripted into the Ottoman military, particularly the navy, while the Ecumenical Patriarchate generally remained loyal to the Empire. The long period of Ottoman rule profoundly shaped Greek society, fostering a strong sense of religious and cultural identity that would later fuel the fight for independence, even as it imposed significant burdens on the population.

3.5. Modern Greece

The era of modern Greece begins with the struggle for independence in the early 19th century, leading to the formation of a new nation-state. This period is characterized by territorial expansion, involvement in major European conflicts, internal political strife including civil war and dictatorship, and eventual democratization. The development of the modern Greek state has been a complex process, marked by both progress in democratic institutions and human rights, and significant challenges to the welfare and liberties of its citizens.

3.5.1. Greek War of Independence and the Kingdom

In the 18th century, Greek merchants gained prominence in Ottoman trade, establishing communities across the Mediterranean and Europe. Their wealth funded educational activities, exposing younger generations to Western ideas and fostering the Modern Greek Enlightenment, which cultivated a notion of a Greek nation among Westernized elites. The secret society Filiki Eteria, formed in 1814, played a crucial role in mobilizing various strata of Greek Orthodox society for the cause of liberal nationalism.

The first revolt began on March 6, 1821, in the Danubian Principalities but was suppressed. This spurred the Greeks of the Peloponnese, and on March 17, the Maniots declared war on the Ottomans. By October 1821, Greeks had captured Tripolitsa. Revolts also occurred in Crete, Macedonia, and Central Greece but were put down. Massacres committed by Turkish and Egyptian forces in 1822 and 1824 galvanized Western European public opinion in favor of the Greeks, highlighting the human rights abuses of the conflict. The Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II secured aid from Mehmet Ali of Egypt, whose son Ibrahim Pasha led an army that controlled most of the Peloponnese by late 1825.

The intervention of three Great Powers-France, Russia, and the United Kingdom-was decisive. Their allied fleet destroyed the Ottoman-Egyptian fleet at the Battle of Navarino (1827). By 1828, the Greeks had captured Central Greece. The nascent First Hellenic Republic was recognized under the London Protocol in 1830.

In 1827, Ioannis Kapodistrias became the first governor of the First Hellenic Republic, establishing state institutions. His assassination in 1831 led the Great Powers to install Bavarian Prince Otto von Wittelsbach as monarch in 1832. Otto's reign was despotic, with Greece initially ruled by a Bavarian oligarchy. An uprising in 1843 forced Otto to grant a constitution and a representative assembly, a step towards democratic governance. Despite its absolutism, Otto's reign was instrumental in developing core Greek administrative and educational institutions. Reforms included education, maritime communications, civil administration, and the legal code. The capital moved from Nafplio to Athens. The Church of Greece was established as the national church, reinforcing the link between Greek identity and Orthodoxy, though this also involved a de-Byzantinification and de-Ottomanisation of historical narratives.

Otto was deposed in 1862 due to his authoritarian rule, heavy taxation, and a failed attempt to annex Crete. He was replaced by Prince Wilhelm of Denmark, who became George I. Britain gifted the Ionian Islands to Greece upon his coronation. A new Constitution in 1864 transitioned Greece from a constitutional monarchy to a more democratic crowned republic. In 1875, the principle of requiring a parliamentary majority for government formation was introduced, curbing monarchical power. However, corruption and high spending (e.g., Corinth Canal) led to public insolvency in 1893. The desire to liberate Hellenic lands under Ottoman rule remained strong, fueled by events like the Cretan Revolt (1866-1869). In 1897, Greece declared war on the Ottomans but was defeated. Through Great Power intervention, Greece lost little territory, and Crete became an autonomous state. Fiscal policy came under International Financial Control. The government sponsored the Macedonian Struggle, a guerrilla campaign in Ottoman-ruled Macedonia, aiming to counter Bulgarian influence, which ended with the Young Turk Revolution in 1908. This period was marked by a slow, often externally influenced, development of state institutions and democratic norms, alongside significant social and economic challenges.

3.5.2. Expansion, World Wars, and National Schism

Amidst dissatisfaction with the perceived inertia of national aspirations, military officers organized the Goudi coup in 1909 and called upon Cretan politician Eleftherios Venizelos. After winning two elections and becoming prime minister in 1910, Venizelos initiated significant fiscal, social, and constitutional reforms, reorganized the military, and led Greece through the Balkan Wars as a member of the Balkan League. By 1913, Greece's territory and population had nearly doubled, annexing Crete, Epirus, and Macedonia.

The struggle between King Constantine I (pro-German) and Venizelos (pro-Entente) over foreign policy on the eve of World War I led to the National Schism, deeply dividing the country and its political landscape. For parts of the war, Greece had two governments: a royalist one in Athens and a Venizelist one in Thessaloniki. They united in 1917 when Greece officially entered the war on the side of the Entente.

After WWI, Greece attempted expansion into Asia Minor, a region with a large native Greek population. This campaign, the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922), ended in a catastrophic defeat for Greece, contributing to the flight of Ottoman Greeks from Asia Minor. These events occurred during the Greek genocide (1914-1922), where Ottoman and Turkish actions led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Asia Minor Greeks, alongside Assyrians and Armenians. The subsequent population exchange between Greece and Turkey, mandated by the Treaty of Lausanne, made the Greek exodus permanent and expanded. Over 1.5 million propertyless Greek refugees from Turkey, many unable to speak Greek, had to be integrated into Greek society, dramatically increasing the population by more than a quarter and posing immense social and economic challenges, deeply affecting human rights and living conditions for the displaced.

Following these disastrous events, the monarchy was abolished via a referendum in 1924, and the Second Hellenic Republic was declared. However, in 1935, royalist general-turned-politician Georgios Kondylis seized power in a coup, abolished the republic, and held a rigged referendum restoring King George II to the throne. This period was marked by profound political instability and social upheaval, with lasting consequences for democratic development.

3.5.3. Civil War, Dictatorship, and Democratization

An agreement between Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas and King George II in 1936 installed Metaxas as head of a dictatorship known as the 4th of August Regime, initiating a period of authoritarian rule that, with interruptions, would last until 1974. Greece remained on good terms with Britain.

In October 1940, Fascist Italy demanded Greece's surrender, but Metaxas refused (Ohi Day). In the ensuing Greco-Italian War, Greece repelled Italian forces into Albania. This initial success was praised, but Greece fell to German forces during the Battle of Greece. The Axis occupation saw Nazis administering Athens and Thessaloniki, while other regions were given to Italy and Bulgaria. The occupation was devastating: over 100,000 civilians died of starvation in the winter of 1941-42, tens of thousands more died in reprisals by Nazis and collaborators, the economy was ruined, and most Greek Jews were deported and murdered. The Greek Resistance was one of Europe's most effective. German occupiers committed widespread atrocities, mass executions, and destruction of towns and villages, leaving almost 1 million Greeks homeless. Around 21,000 Greeks were executed by Germans, 40,000 by Bulgarians, and 9,000 by Italians.

Following liberation, Greece annexed the Dodecanese Islands from Italy and regained Western Thrace from Bulgaria. However, the country descended into a bitter Greek Civil War (1946-1949) between communist forces and the anti-communist Greek government, which ended with the latter's victory. The conflict, an early struggle of the Cold War, caused further economic devastation, population displacement, and severe political polarization that suppressed democratic voices and curtailed civil liberties for decades.

Although the post-war era was marked by social strife and the marginalization of the left, Greece experienced rapid economic growth (the Greek economic miracle), partly fueled by the U.S. Marshall Plan. In 1952, Greece joined NATO.

King Constantine II's dismissal of George Papandreou's centrist government in 1965 (Apostasia of 1965) prompted political turbulence, culminating in a coup on April 21, 1967, by the Greek junta, led by Georgios Papadopoulos. This military dictatorship suspended civil rights, intensified political repression, and human rights abuses, including torture, were rampant. Economic growth continued but plateaued by 1972. The brutal suppression of the Athens Polytechnic uprising in November 1973 triggered a counter-coup that established Brigadier Dimitrios Ioannidis as the new strongman. On July 20, 1974, Turkey invaded Cyprus in response to a Greek-backed Cypriot coup. This crisis led to the collapse of the junta and the restoration of democracy through Metapolitefsi, a critical turning point for the re-establishment of democratic institutions and civil rights in Greece.

3.5.4. Third Hellenic Republic

Former prime minister Konstantinos Karamanlis was invited back from self-exile, and the first multiparty elections since 1964 were held on the anniversary of the Polytechnic uprising. A democratic and republican constitution was promulgated in 1975 following a referendum that abolished the monarchy, marking a definitive shift towards a more stable democratic framework.

Andreas Papandreou, son of George Papandreou, founded the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), which, along with Karamanlis's conservative New Democracy party, dominated Greek politics for the next four decades. Greece rejoined NATO's integrated military structure in 1980. In 1981, Greece became the tenth member of the European Communities (now the European Union), ushering in a period of sustained growth and societal modernization. Investments in industry and infrastructure, EU funds, and revenues from tourism, shipping, and the service sector raised living standards. Andreas Papandreou's election in 1981 led to significant social reforms in the 1980s, including the recognition of civil marriage, abolition of the dowry system, and changes in education and foreign policy. However, his tenure was also associated with issues of corruption, high inflation, and budget deficits that contributed to later economic problems.

Greece adopted the euro in 2001 and successfully hosted the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens. However, in 2010, the country was severely hit by the Great Recession and the related European sovereign debt crisis. As a eurozone member, Greece could not devalue its currency to regain competitiveness. The subsequent austerity measures imposed as part of bailout packages led to widespread social unrest, a significant drop in living standards, and a rise in unemployment, particularly impacting vulnerable groups and straining social cohesion.

The 2012 elections saw a major political shift, with new parties emerging from the collapse of PASOK and New Democracy. In 2015, Alexis Tsipras of the left-wing SYRIZA party was elected prime minister, the first outside the two traditional main parties. The debt crisis officially ended around 2018 with the conclusion of bailout mechanisms and a return to growth. Simultaneously, Tsipras and North Macedonian leader Zoran Zaev signed the Prespa Agreement, resolving the long-standing Macedonia naming dispute, which eased North Macedonia's path to EU and NATO membership and was seen as a step towards regional stability.

In 2019, Kyriakos Mitsotakis of New Democracy became prime minister. In 2020, Katerina Sakellaropoulou was elected as Greece's first female President. A significant social advancement occurred in February 2024 when Greece became the first Orthodox Christian country to legalize same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples, reflecting progress in LGBTQ+ rights and social liberalization. The Third Hellenic Republic continues to navigate contemporary challenges, including economic recovery, social integration, and strengthening its democratic institutions while upholding human rights.

4. Geography

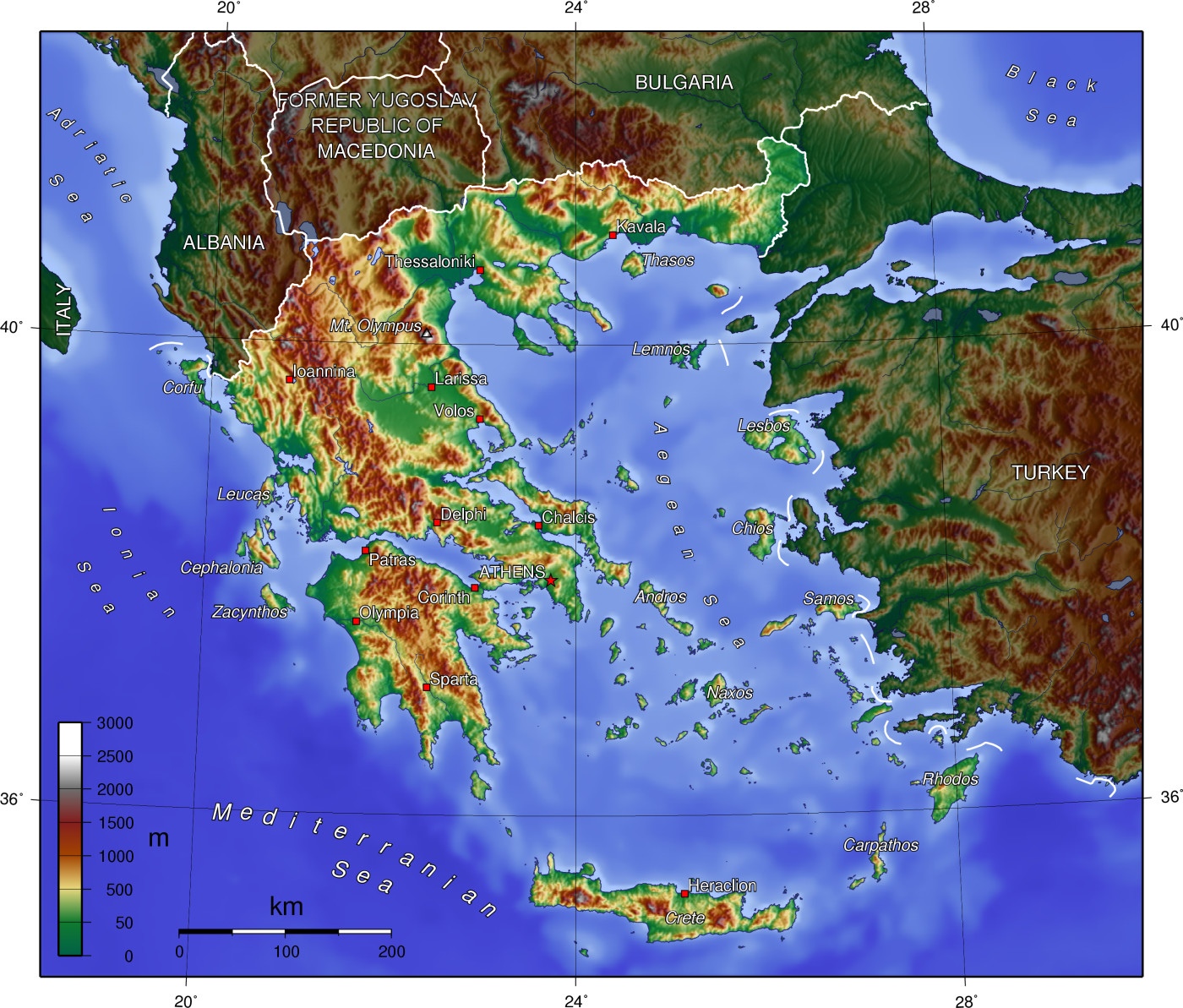

Greece is located in Southern and Southeast Europe, consisting of a mountainous, peninsular mainland jutting out into the sea at the southern end of the Balkans, ending at the Peloponnese peninsula. It is strategically located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to the east. The Aegean Sea lies to the east of the mainland, the Ionian Sea to the west, and the Sea of Crete and the Mediterranean Sea to the south. The country has the 11th longest national coastline in the world, 8.5 K mile (13.68 K km), featuring thousands of islands. Greece comprises nine traditional geographic regions. Approximately 80% of Greece consists of mountains or hills, making it one of the most mountainous countries in Europe. Environmental concerns, including deforestation, soil erosion, and water pollution, are significant, alongside the impacts of climate change such as increased risk of wildfires and desertification.

4.1. Topography and Hydrography

The Greek landscape is predominantly mountainous. Mount Olympus, the mythical abode of the Greek Gods, is the highest peak at 9.6 K ft (2.92 K m). Western Greece is characterized by a number of lakes and wetlands and is dominated by the Pindus mountain range, a continuation of the Dinaric Alps, reaching 8.7 K ft (2.64 K m) at Mount Smolikas. The Pindus range historically formed a significant barrier to east-west travel and its extensions cross through the Peloponnese, ending in Crete. The Vikos Gorge, part of the Vikos-Aoos National Park, is listed as one of the deepest gorges in the world. Another notable formation is the Meteora rock pillars, upon which medieval Greek Orthodox monasteries are built, demonstrating human adaptation to the challenging topography.

Northeastern Greece features the Rhodope range, an area covered with vast, ancient forests, including the Dadia Forest. Extensive plains are primarily located in Thessaly, Central Macedonia, and Thrace, constituting key economic regions due to their arable land. The network of rivers in Greece includes the Aliakmon, Pinios, Evros, Nestos, and Strymonas rivers in the north, and the Achelous in the west. Lakes such as Trichonida, Volvi, and Vegoritida are important freshwater bodies. The topography has heavily influenced settlement patterns, communication routes, and agricultural development throughout Greek history.

4.2. Climate

The climate of Greece is primarily Mediterranean (Köppen: Csa), featuring mild to cool, wet winters and hot, dry summers. This climate occurs at most coastal locations, including Athens, the Cyclades, the Dodecanese, Crete, the Peloponnese, the Ionian Islands, and parts of mainland Greece. The Pindus mountain range significantly affects the climate, with areas to its west being considerably wetter on average than areas to its east due to a rain shadow effect. This can lead to some coastal areas in the south falling into the hot semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSh) category, such as parts of the Athens Riviera and some Cyclades islands. Some northern areas like Thessaloniki and Larissa can feature a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSk).

The mountainous areas of northwestern Greece and higher elevations feature an Alpine climate (Köppen: D, E) with heavy winter snowfalls. Inland parts of northern Greece (Central Macedonia, lower Western Macedonia), Eastern Macedonia and Thrace often have a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa) with cold, damp winters and hot, moderately dry summers with occasional thunderstorms. Snowfall occurs annually in the mountains and northern areas, and brief snowy periods are possible even in low-lying southern areas. Climate change is an increasing concern, with projections indicating hotter summers, more frequent heatwaves, and altered precipitation patterns, which could exacerbate issues like water scarcity and wildfires, impacting agriculture, tourism, and overall societal well-being.

4.3. Islands

Greece features a vast number of islands, estimated between 1,200 and 6,000 depending on the definition, with 227 of them inhabited. These islands are integral to Greece's geography, culture, and economy. Crete is the largest and most populous island, possessing a distinct history and culture. Euboea, separated from the mainland by the narrow Euripus Strait, is the second largest. Other major islands include Lesbos and Rhodes.

The Greek islands are traditionally grouped into several clusters:

- The Argo-Saronic Islands are located in the Saronic Gulf near Athens (e.g., Aegina, Hydra, Poros, Spetses).

- The Cyclades form a large, dense group in the central Aegean Sea (e.g., Mykonos, Santorini, Naxos, Paros). They are renowned for their distinctive white-washed architecture and vibrant tourism.

- The North Aegean islands are a looser grouping off the west coast of Turkey (e.g., Lesbos, Chios, Samos, Lemnos, Thasos).

- The Dodecanese are another loose collection in the southeastern Aegean, between Crete and Turkey (e.g., Rhodes, Kos, Patmos, Karpathos). They have a rich history reflecting diverse cultural influences.

- The Sporades are a small, tight group off the coast of northeast Euboea (e.g., Skiathos, Skopelos, Alonissos).

- The Ionian Islands are located to the west of the mainland in the Ionian Sea (e.g., Corfu, Kefalonia, Zakynthos, Lefkada, Ithaca). They have a distinct cultural heritage influenced by Venetian rule.

These islands contribute significantly to Greece's tourism industry, maritime activities, and agricultural production (e.g., olives, wine). They also face challenges such as water scarcity, infrastructure development, and environmental protection, particularly in the context of climate change and tourism pressures. Their unique cultural and economic aspects reflect centuries of adaptation to island environments and maritime connections.

4.4. Biodiversity

Phytogeographically, Greece belongs to the Boreal Kingdom and is shared between the East Mediterranean province of the Mediterranean Region and the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature and the European Environment Agency, Greece's territory can be subdivided into six ecoregions: the Illyrian deciduous forests, Pindus Mountains mixed forests, Balkan mixed forests, Rhodope montane mixed forests, Aegean and Western Turkey sclerophyllous and mixed forests, and Crete Mediterranean forests. In 2018, Greece had a Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.6/10, ranking it 70th globally out of 172 countries.

Greece boasts rich biodiversity due to its varied climate and topography. Its flora includes thousands of plant species, many of which are endemic. The country is known for its olive groves, vineyards, and diverse wildflowers. Forests, though impacted by human activity and wildfires, cover significant areas, particularly in the northern and mountainous regions. Notable national parks include Olympus National Park, Pindus National Park, Prespa National Park, and Samariá Gorge National Park on Crete, all established to protect unique ecosystems and species.

The fauna of Greece includes rare marine species such as the Mediterranean monk seal (one of the most endangered mammals in Europe) and the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta), which nests on Greek beaches. Its dense forests are home to endangered mammals like the brown bear, the Eurasian lynx, the roe deer, and the wild goat or kri-kri (endemic to Crete). Birdlife is also diverse, with Greece being an important stopover for migratory birds.

Ecological conservation efforts are ongoing, with numerous areas designated as Natura 2000 sites under EU law. However, biodiversity faces threats from habitat loss due to urbanization and tourism development, pollution, unsustainable agricultural practices, and the impacts of climate change, such as prolonged droughts and increased fire risk. In a positive step for marine conservation, Greece became the first country in the European Union in 2024 to ban bottom trawling in all its marine protected areas, aiming to safeguard its marine biodiversity. Addressing these environmental issues is crucial for the long-term ecological health and sustainable development of the country.

5. Politics

Greece is a parliamentary republic with a political system defined by its Constitution, which was enacted in 1975 after the fall of the military dictatorship and has been amended four times since. The constitution establishes a separation of powers into executive, legislative, and judicial branches and guarantees extensive civil liberties and social rights, which were further reinforced in 2001. The system promotes democratic processes, including multi-party elections, and aims to uphold the rule of law, though challenges related to political corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency persist. Public participation, while moderate compared to some OECD countries, is a feature of its democratic life, with citizens actively engaging in political discourse and elections.

5.1. System of Government and Constitution

Greece's form of government is a parliamentary republic. The Constitution, first adopted in 1975 and subsequently revised, is the supreme law of the land. It outlines the fundamental principles of the state, including popular sovereignty, the rule of law, social justice, and the protection of human rights. The Constitution has evolved to reflect societal changes and strengthen democratic institutions, for instance, with amendments enhancing civil liberties and social rights (2001) and modifying the powers of the presidency (1986). Key human rights guarantees enshrined in the Constitution include freedom of speech, assembly, religion, and the press, as well as protections against discrimination and arbitrary detention. The system ensures a multi-party democracy where power is derived from the people through elections.

5.2. President

The President of Greece is the head of state. The President is elected by the Hellenic Parliament for a five-year term and can be re-elected once. While the office is largely ceremonial, particularly after the 1986 constitutional amendment which transferred significant executive powers to the Prime Minister, the President retains certain formal powers. These include promulgating laws passed by Parliament, representing the state in international relations, appointing the Prime Minister, and formally appointing and dismissing other members of the Cabinet upon the Prime Minister's recommendation. The President also has the power to declare a state of emergency under specific constitutional provisions and acts as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, though this role is mostly symbolic. The President is expected to be a unifying figure, standing above partisan politics and safeguarding the democratic framework of the country.

5.3. Executive

The executive power in Greece is exercised by the Government, which consists of the Cabinet headed by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the political party that can obtain a vote of confidence from the Parliament. The Prime Minister is the most powerful political figure in the country, responsible for the general policy of the state and for coordinating the work of the government ministers.

The Cabinet is composed of ministers who are appointed by the President upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister. Ministers are usually Members of Parliament and are responsible for specific government departments (ministries). The Cabinet as a collective body makes key policy decisions, drafts legislation to be submitted to Parliament, and implements laws passed by the legislature. The government is accountable to the Parliament; it must maintain the confidence of the Parliament to remain in power. If a motion of no confidence passes, the government must resign. Key policy-making processes involve consultation within the Cabinet, engagement with parliamentary committees, and, increasingly, alignment with European Union directives and regulations.

5.4. Legislature

The Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των ΕλλήνωνVoo-LEE ton eh-LEE-nonGreek, Modern) is the unicameral legislature of Greece. It consists of 300 members, known as Members of Parliament (MPs), who are elected for a four-year term through direct elections. The electoral system is a form of "reinforced" proportional representation, which often includes a majority bonus system favoring the party that wins a plurality of the popular vote, aiming to facilitate the formation of stable single-party or coalition governments. Parliamentary elections are held every four years, but the President can proclaim early elections on the cabinet's proposal or if a motion of no confidence passes. The current voting age is 17.

The Parliament's main functions include legislating (passing laws), overseeing the government's actions (parliamentary scrutiny), approving the state budget, and electing the President of the Republic. It plays a crucial role in representing the populace, as MPs are elected from various constituencies across the country. Legislative processes involve the introduction of bills by the government or MPs, debate in parliamentary committees and the plenary session, and voting. The Parliament is central to Greece's democratic framework, ensuring accountability and debate on national issues.

5.5. Judiciary

The Greek judicial system is independent of the executive and legislative branches, a principle enshrined in the Constitution to uphold the rule of law and protect human rights. The system is composed of civil courts, which handle civil and penal cases, and administrative courts, which resolve disputes between citizens and state authorities.

There are three Supreme Courts:

- The Court of Cassation (Άρειος ΠάγοςAH-ree-os PAH-ghosGreek, Modern) is the highest court for civil and criminal matters.

- The Council of State (Συμβούλιο της Επικρατείαςseem-VOO-lee-o tees eh-pee-krah-TEE-asGreek, Modern) is the supreme administrative court, hearing cases against administrative acts and having a role in ensuring the constitutionality of laws.

- The Court of Audit (Ελεγκτικό Συνέδριοeh-leg-tee-KO see-NEH-three-oGreek, Modern) is responsible for auditing public expenditures and overseeing public finances.

Judges are appointed for life after a probationary period and are subject to specific constitutional guarantees to ensure their independence. The judiciary plays a critical role in interpreting laws, administering justice, and ensuring that governmental actions comply with the Constitution and legal statutes, thereby safeguarding the rights of individuals and the principles of a democratic society.

5.6. Political Parties

After the restoration of democracy in 1974-1975, the Greek party system was largely dominated by two major parties: the liberal-conservative New Democracy (ND) and the social-democratic Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK). These two parties alternated in power for several decades, shaping the political landscape of post-junta Greece.

The Greek government-debt crisis that began in 2009 led to a significant decline in popularity for both ND and PASOK, as they were often blamed for the economic mismanagement that contributed to the crisis and for implementing harsh austerity measures. This resulted in a fragmentation of the party system and the rise of new political forces. The parliamentary elections of May 2012 marked a turning point, with the left-wing SYRIZA (Coalition of the Radical Left) emerging as the second-largest party, overtaking PASOK as the main party of the centre-left.

SYRIZA, led by Alexis Tsipras, came to power in January 2015, initially opposing austerity but later agreeing to a third bailout package. After a period of SYRIZA governance, New Democracy, under Kyriakos Mitsotakis, returned to power following the 2019 election and secured a parliamentary majority in the June 2023 election.

Other parties currently or recently represented in the Hellenic Parliament include the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), a historically significant party with a consistent voter base; Greek Solution, a nationalist right-wing party; New Left, a splinter group from SYRIZA; Spartans, a far-right party; Niki (Victory), a socially conservative, religious Orthodox party; and Course of Freedom, a left-wing populist party. The rise and fall of parties like the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn (which was declared a criminal organization) also marked this period of political volatility, highlighting challenges to democratic norms and human rights. The party system continues to evolve, reflecting ongoing social and economic pressures.

6. Administrative Divisions

Since the Kallikratis Programme reform entered into effect on January 1, 2011, Greece has consisted of 13 regions (περιφέρειεςpe-ree-FEH-ree-esGreek, Modern), which are the main administrative units. These regions are further subdivided into a total of 332 (as of 2019, following the Kleisthenis I Programme) municipalities (δήμοιDHEE-meeGreek, Modern). The 54 old prefectures and prefecture-level administrations have been largely retained as regional units (περιφερειακές ενότητεςpe-ree-fe-ree-ah-KES eh-NO-tee-tesGreek, Modern) within the regions, primarily for administrative and electoral purposes.

Additionally, seven decentralised administrations group one to three regions for administrative purposes on a regional basis, overseeing certain state functions at a more localized level.

A special administrative status is held by Mount Athos (Άγιο ΌροςAH-yee-o O-rosGreek, Modern, "Holy Mountain"), an autonomous monastic state under Greek sovereignty. It is located on a peninsula bordering the region of Central Macedonia and is governed by its own unique spiritual and administrative system, primarily inhabited by Orthodox monks.

The regions are:

| No. | Region | Capital | Area | Population (2021) | GDP (billion EUR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attica | Athens | 1.5 K mile2 (3.81 K km2) | 3,814,064 | 84.00 B EUR |

| 2 | Central Greece | Lamia | 6.0 K mile2 (15.55 K km2) | 508,254 | 8.00 B EUR |

| 3 | Central Macedonia | Thessaloniki | 7.3 K mile2 (18.81 K km2) | 1,795,669 | 24.00 B EUR |

| 4 | Crete | Heraklion | 3.2 K mile2 (8.26 K km2) | 624,408 | 9.00 B EUR |

| 5 | East Macedonia and Thrace | Komotini | 5.5 K mile2 (14.16 K km2) | 562,201 | 7.00 B EUR |

| 6 | Epirus | Ioannina | 3.6 K mile2 (9.20 K km2) | 319,991 | 4.00 B EUR |

| 7 | Ionian Islands | Corfu | 0.9 K mile2 (2.31 K km2) | 204,532 | 3.00 B EUR |

| 8 | North Aegean | Mytilene | 1.5 K mile2 (3.84 K km2) | 194,943 | 2.00 B EUR |

| 9 | Peloponnese | Tripoli | 6.0 K mile2 (15.49 K km2) | 539,535 | 8.00 B EUR |

| 10 | South Aegean | Ermoupoli | 2.0 K mile2 (5.29 K km2) | 327,820 | 6.00 B EUR |

| 11 | Thessaly | Larissa | 5.4 K mile2 (14.03 K km2) | 688,255 | 9.00 B EUR |

| 12 | West Greece | Patras | 4.4 K mile2 (11.35 K km2) | 648,220 | 8.00 B EUR |

| 13 | West Macedonia | Kozani | 3.6 K mile2 (9.45 K km2) | 254,595 | 4.00 B EUR |

| (14) | Mount Athos (Autonomous Monastic State) | Karyes | 151 mile2 (390 km2) | 1,746 | - |

7. Foreign Relations

Greece's foreign policy is conducted through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and its head, the Minister for Foreign Affairs. The ministry aims to represent Greece before other states and international organizations, safeguard state and citizen interests abroad, promote Greek culture, foster relations with the Greek diaspora, and encourage international cooperation. Due to its geostrategic location at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa, Greece has historically played a significant role in regional affairs, leveraging this to develop policies promoting peace and stability in the Balkans, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. This has accorded the country a middle power status. Greece's foreign policy emphasizes adherence to international law, democratic principles, and human rights.

7.1. Key Bilateral Relations

Greece maintains complex and historically significant relationships with its neighbors and key global partners.

- Turkey: Relations are marked by long-standing disputes, primarily the Aegean dispute concerning maritime boundaries, continental shelf rights, airspace, and the status of certain islands, as well as the Cyprus problem stemming from the 1974 Turkish invasion and subsequent occupation of Northern Cyprus. Despite tensions, there are ongoing dialogues and areas of cooperation, such as trade and tourism. Greece generally supports Turkey's EU accession process, contingent on Ankara meeting membership criteria, including respect for international law and good neighborly relations.

- North Macedonia: Relations significantly improved following the signing of the Prespa Agreement in 2018, which resolved the Macedonia naming dispute. This agreement unblocked North Macedonia's path to NATO and EU membership and is considered a major diplomatic achievement for regional stability and cooperation, though it faced domestic opposition in both countries.

- Cyprus: Greece maintains a "special relationship" with the Republic of Cyprus, based on shared language, culture, and history. Greece has consistently supported Cyprus in efforts to find a just and viable solution to the Cyprus problem, advocating for a bizonal, bicommunal federation in line with UN resolutions, and condemning the continued Turkish military presence.

- United States: Greece and the U.S. have a strong strategic partnership, particularly within the NATO framework. Relations cover defense cooperation, counter-terrorism, and economic ties. The U.S. has military facilities in Greece, such as at Souda Bay, Crete.

- EU Member States: As an EU member, Greece has close political and economic ties with other member states, particularly France, Germany, and Italy. These relationships are crucial for economic policy, regional development, and foreign policy coordination within the EU.

- Albania: Relations with Albania are generally good but have faced challenges concerning the rights of the Greek minority in Albania and maritime border delimitation.

- Israel: Relations have strengthened significantly in recent years, particularly in energy cooperation, defense, and tourism.

- Armenia: Greece has historically close ties with Armenia, partly due to shared historical experiences and a significant Armenian diaspora in Greece.

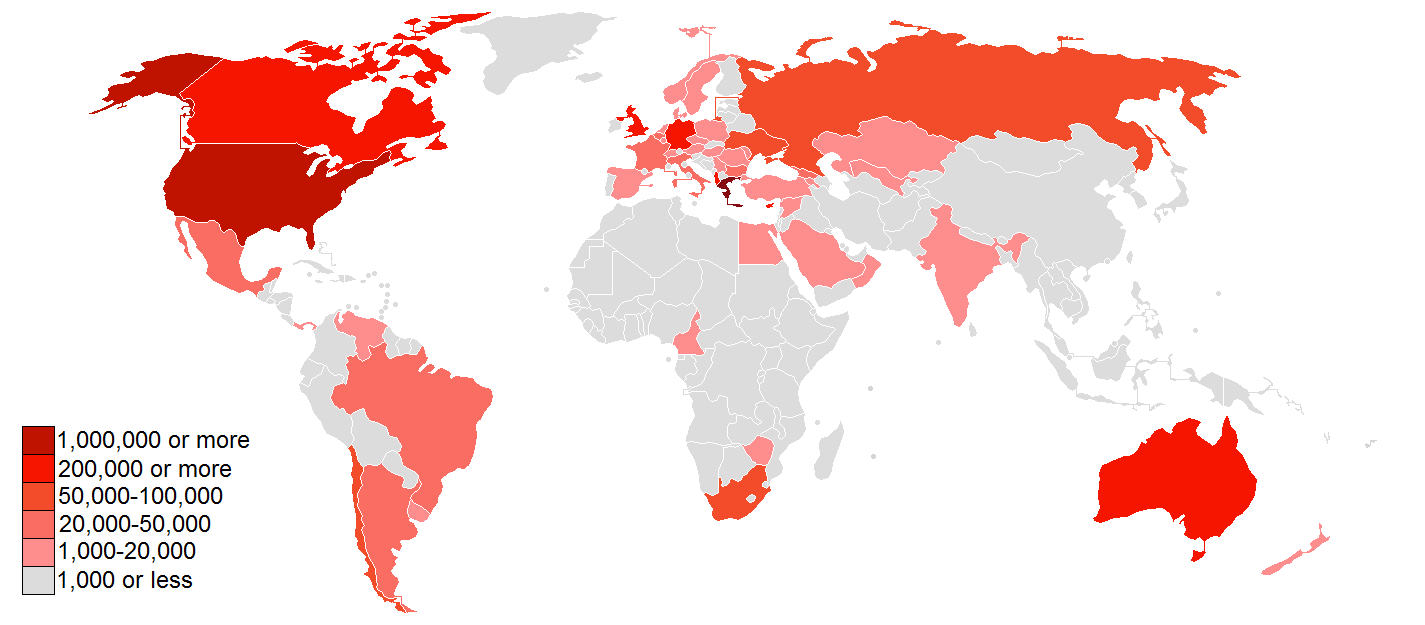

- Australia and Canada: Strong ties due to large Greek diaspora communities in these countries.

Greece's foreign policy strives to balance its national interests with its commitments to international law and multilateral cooperation, often navigating complex regional dynamics with a focus on diplomatic solutions and stability.

7.2. International Organisation Membership

Greece is an active member of numerous international organizations, reflecting its commitment to multilateralism and international cooperation. Key memberships include:

- United Nations (UN)**: Greece is a founding member of the UN (1945) and participates actively in its various agencies and programs, contributing to peacekeeping operations, human rights initiatives, and sustainable development goals.

- European Union (EU)**: Greece joined the European Communities (now EU) in 1981. EU membership has profoundly shaped Greece's economy, political system, and societal standards. It benefits from EU structural funds and participates in the single market and common policies. Greece adopted the euro in 2001.

- NATO**: Greece joined NATO in 1952. Membership is a cornerstone of its defense and security policy. Greece participates in NATO missions and exercises, contributing to collective defense and regional stability, particularly in Southeastern Europe and the Mediterranean.

- Council of Europe (CoE)**: A member since 1949, Greece is committed to the CoE's principles of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. It is a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)**: Greece is a founding member (1961), participating in economic analysis and policy coordination among developed countries.

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)**: Greece is actively involved in the OSCE's efforts to promote security, democracy, and human rights across its vast region.

- World Trade Organization (WTO)**: As a member, Greece adheres to global trade rules and participates in multilateral trade negotiations.

Through these memberships, Greece seeks to advance its national interests, contribute to global governance, and promote its values on the international stage, often playing a role in bridging different regions and perspectives.

8. Military

The Hellenic Armed Forces are overseen by the Hellenic National Defence General Staff (Γενικό Επιτελείο Εθνικής ΆμυναςYe-nee-KO eh-pee-te-LEE-o eth-nee-KEES AHMP-neesGreek, Modern - ΓΕΕΘΑ), with civilian authority vested in the Ministry of National Defence. The President of Greece is the nominal commander-in-chief, but effective command lies with the government, particularly the Prime Minister and the Minister of National Defence, ensuring democratic oversight. The armed forces consist of three branches: the Hellenic Army (Ελληνικός ΣτρατόςEh-lee-nee-KOS strah-TOSGreek, Modern, ES), the Hellenic Navy (Ελληνικό Πολεμικό ΝαυτικόEh-lee-nee-KO po-le-mee-KO naf-tee-KOGreek, Modern, EPN), and the Hellenic Air Force (Ελληνική Πολεμική ΑεροπορίαEh-lee-nee-KEE po-le-mee-KEE ah-e-ro-po-REE-ahGreek, Modern, EPA).

Greece maintains the Hellenic Coast Guard for law enforcement at sea, search and rescue operations, and port security. Though it can support the navy during wartime, it primarily operates under the authority of the Ministry of Shipping and Island Policy.

As of recent estimates, Greek active military personnel total around 142,700, with approximately 221,350 in reserve. Mandatory military service is in effect for males aged 19 to 45, generally for a period of one year. Additionally, Greek males between 18 and 60 living in strategically sensitive areas may be required to serve part-time in the National Guard.

As a member of NATO since 1952, the Greek military participates in alliance exercises and deployments, contributing to collective security. Greece's defense policy is heavily influenced by its geopolitical position and regional dynamics, particularly its relations with Turkey. The country maintains a relatively high level of defense spending, consistently meeting or exceeding NATO's target of 2% of GDP. Major equipment includes modern fighter jets (like the F-16 and Rafale), main battle tanks (like the Leopard 2), and a capable naval fleet including frigates and submarines. The military's role extends to disaster relief and national security operations within Greece.

9. Economy

The Greek economy is a developed, high-income economy. As of 2023, it was the 54th largest globally by purchasing power parity (PPP) at approximately 417.00 B USD and the 15th largest within the 27-member European Union. Per capita income stands at around 40.00 K USD. The economy is primarily service-based (around 85%), with industry contributing about 12% and agriculture 3%. Key sectors include tourism, which attracted 33 million international tourists in 2023 (making Greece the 9th most visited country globally), and merchant shipping, where Greece commands the world's largest fleet (around 18% of global capacity).

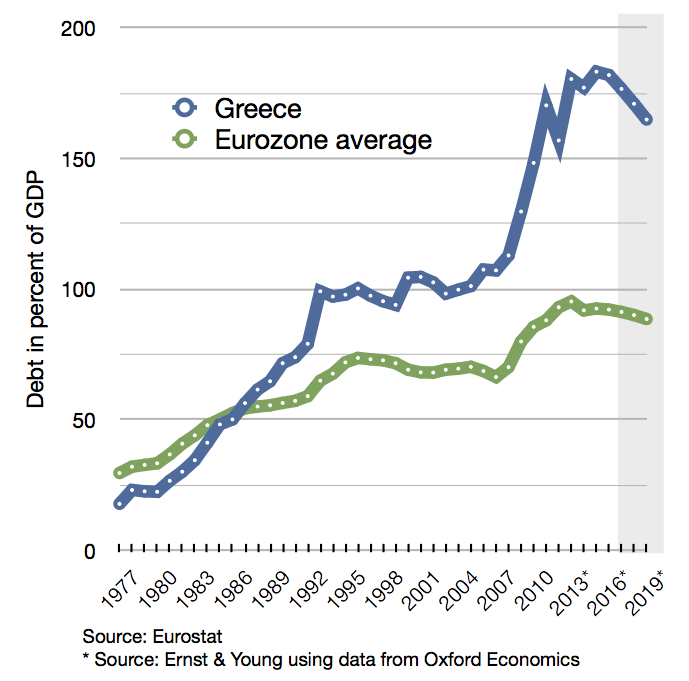

Historically, Greece experienced a period of rapid growth known as the Greek economic miracle from the 1950s through the 1970s. It joined the European Communities (now EU) in 1981 and adopted the euro in 2001. However, the economy was severely impacted by the Greek government-debt crisis starting in the late 2000s, triggered by the global Great Recession and revelations of understated budget deficits. This led to years of austerity, economic contraction (GDP fell by about 25% between 2009 and 2015), high unemployment (13% in 2021, with youth unemployment at 33%), and significant social hardship. Bailout programs from the EU and IMF ended around 2018, and the economy has since shown signs of recovery and growth, projected at nearly 3% in 2024.

Greece is a founding member of the OECD and the BSEC. Challenges remain, including high public debt, structural reforms, and ensuring sustainable and equitable development. Labor rights and social equity are ongoing concerns, particularly in the aftermath of the crisis.

9.1. Macroeconomic Trends

Greece's macroeconomic trends have been characterized by periods of strong growth followed by significant crisis and subsequent recovery efforts. After the post-WWII "economic miracle," growth continued with EU accession in 1981, fueled by EU funds, tourism, and shipping. However, underlying structural issues, including persistent budget deficits and a large public sector, became apparent.

The adoption of the euro in 2001 initially brought low interest rates and credit-fueled growth but also removed the option of currency devaluation to manage competitiveness. The global financial crisis of 2008 exposed these vulnerabilities, leading to the severe Greek government-debt crisis from 2009. Key macroeconomic indicators during this period showed a sharp decline in GDP (contracting by about 25% cumulatively), a surge in unemployment (peaking around 28%, with youth unemployment exceeding 50%), high inflation initially followed by deflationary pressures, and a dramatic increase in public debt-to-GDP ratio (exceeding 180%).

Austerity measures implemented under bailout agreements led to significant cuts in public spending, wage and pension reductions, and tax increases, which had profound social implications, increasing poverty and inequality. Since the end of the bailout programs around 2018, Greece has seen a return to positive GDP growth, a gradual reduction in unemployment, and efforts to improve its fiscal balance. Inflation rates have fluctuated, influenced by domestic and international factors. Per capita income, which had fallen sharply, has begun to recover. The focus of current economic policy is on sustainable growth, attracting investment, reducing public debt, and addressing social disparities exacerbated by the crisis.

9.2. Major Sectors

The Greek economy is predominantly service-oriented, with key contributions from tourism and shipping, alongside a smaller industrial and agricultural base.

- Service sector: This is the largest component of the Greek economy, accounting for approximately 85% of GDP.

- Tourism: A vital pillar, contributing significantly to GDP (around 21% in 2018 when direct and indirect impacts are considered) and employment. Greece is a major global tourist destination, renowned for its historical sites, beaches, and islands.

- Shipping (Maritime Industry): Greece has the largest merchant fleet in the world, representing about 18% of global capacity. This sector is a major source of foreign exchange and employment. Labor conditions in shipping are regulated by international and national laws, though enforcement can be a challenge. Environmental concerns related to shipping emissions are also increasingly addressed.

- Other services include retail, finance, telecommunications, and public administration.

- Industry: Accounts for about 12% of GDP.

- Manufacturing: Includes food and beverage processing, textiles, chemicals, metal products, and cement. The sector has faced challenges from international competition and the economic crisis.

- Construction: Was a significant driver of growth, especially before the 2008 crisis and during preparations for the 2004 Olympics. It has since contracted but remains important for infrastructure development.

- Mining and Quarrying: Greece has resources like lignite, bauxite, marble, and industrial minerals. Environmental regulations and impacts are key considerations.

- Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing: Contributes about 3% of GDP but remains socially important, particularly in rural areas. This sector faces challenges related to land fragmentation, an aging workforce, and environmental sustainability.

Labor rights across sectors have been under pressure, particularly during the austerity years, with concerns about wage levels, job security, and collective bargaining. Environmental aspects are increasingly important, with efforts towards sustainable practices in tourism, shipping, and industry, driven by EU regulations and national policies.

9.3. Agriculture

Agriculture in Greece, including forestry and fishing, contributes approximately 3.8% of the national GDP and employs about 12% of the labor force, making it a significant sector, especially for rural economies and employment. The country's diverse climate and topography allow for a variety of agricultural products.

Key agricultural products include:

- Olives and Olive Oil**: Greece is one of the world's largest producers and exporters of olive oil, a cornerstone of its agricultural identity and cuisine.

- Fruits and Vegetables**: A wide range is cultivated, including tomatoes, cucumbers, oranges, lemons, peaches, and watermelons. Figs are also a notable product.

- Cotton**: Greece is the largest cotton producer in the European Union.

- Tobacco**: Historically an important cash crop, though production has declined.

- Grains**: Wheat and maize are grown, but Greece is a net importer of grains.

- Pistachios and Almonds**: Greece is a significant EU producer of pistachios and almonds.

- Wine**: Viticulture is widespread, with many indigenous grape varieties producing distinctive wines.

- Dairy products**: Feta cheese is a famous Greek dairy product with Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status.

- Fisheries and Aquaculture**: With its long coastline and many islands, fishing is important, and aquaculture (fish farming) has grown significantly.

The structure of Greek farming is characterized by small, often family-owned farms, which can lead to challenges in terms of efficiency and modernization. The EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has been a major influence, providing subsidies and support but also driving structural changes. Issues related to rural development include an aging farming population, the need for investment in modern techniques, water management (especially in the face of climate change), and promoting sustainable farming practices to protect biodiversity and soil health. Organic farming is a growing niche.

9.4. Maritime Industry

The maritime industry has been a cornerstone of the Greek economy and culture since antiquity. Today, Greece controls the largest merchant fleet in the world, accounting for approximately 18% of global deadweight tonnage and about 50% of the EU's fleet. The Greek-owned fleet ranks first globally in tankers and dry bulk carriers, and is also significant in container ships. This industry is a vital source of foreign exchange, contributing around 5% to the GDP and employing about 160,000 people.

The modern Greek maritime industry was largely re-established after World War II, with Greek shipowners acquiring surplus ships sold by the U.S. government through the Ship Sales Act. Influential shipping magnates like Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos played a key role in its expansion during the mid-20th century. Piraeus, the port of Athens, is one of the largest passenger ports in Europe and a major container hub, significantly expanded through foreign investment in recent years.

The industry encompasses not only ship ownership and operation but also related services such as shipbuilding, ship repair (with several major shipyards around Piraeus), marine insurance, and financial services. Greece has also become a leader in the construction and maintenance of luxury yachts.

Labor conditions in the maritime sector are governed by international conventions (e.g., Maritime Labour Convention) and national laws. Challenges include ensuring fair wages, safety standards, and addressing the demanding nature of seafaring work. Environmental regulations are increasingly stringent, with a focus on reducing emissions (sulfur cap, decarbonization efforts), preventing pollution from ships (e.g., ballast water management), and promoting greener shipping technologies, in line with International Maritime Organization (IMO) and EU targets. The industry's global nature means it is highly susceptible to international trade fluctuations and geopolitical events.

9.5. Tourism

Tourism in Greece is a vital sector of the national economy and one of its most important industries, contributing significantly to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) - estimated at around 21% in 2018 when direct and indirect effects are considered - and providing substantial employment. In 2023, Greece attracted approximately 33 million international tourists, making it the 9th most visited country in the world.

The country's appeal lies in its rich cultural heritage, numerous archaeological sites, diverse landscapes, extensive coastline, and hundreds of islands with beautiful beaches. Major destinations include:

- Historical Sites**: Athens (with the Acropolis and Parthenon), Olympia (birthplace of the Olympic Games), Delphi, Mycenae, Epidaurus, Knossos (Crete), and medieval towns like Rhodes and Mystras.

- Islands**: The Cyclades (e.g., Santorini, Mykonos, Paros, Naxos), Crete, the Dodecanese (e.g., Rhodes, Kos), the Ionian Islands (e.g., Corfu, Zakynthos, Kefalonia), and others, each offering unique experiences.

- Mainland Destinations**: Regions like the Peloponnese, Halkidiki, and Epirus offer diverse attractions from beaches to mountains and traditional villages.

The majority of visitors come from other European countries, with the United Kingdom and Germany being key source markets. The most visited region is typically Central Macedonia, followed by Attica (Athens) and the South Aegean islands.

The Greek government and tourism industry focus on extending the tourist season, diversifying the tourism product (e.g., promoting cultural, religious, medical, and eco-tourism), and improving infrastructure. Policies increasingly emphasize sustainable tourism to mitigate environmental impact, preserve cultural heritage, and ensure benefits for local communities. Challenges include managing overtourism in popular spots, water scarcity, waste management, and adapting to climate change. The industry's revenue is crucial for foreign exchange earnings and overall economic stability. Greece has 19 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, which are major attractions.

9.6. Energy

Greece's energy sector has been undergoing a significant transition, moving away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources, in line with EU targets and environmental considerations.

- Energy Production and Consumption**: Historically, Greece relied heavily on imported fossil fuels (oil and natural gas) and domestically mined lignite (a type of brown coal) for electricity generation. Lignite, while abundant, is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, and Greece is phasing out its use.

- Electricity Generation**: The state-owned Public Power Corporation (PPC, or ΔΕΗ - DEI) has traditionally dominated electricity production, supplying about 75% of electricity in 2021. However, the market has been liberalized, with independent power producers playing an increasing role.

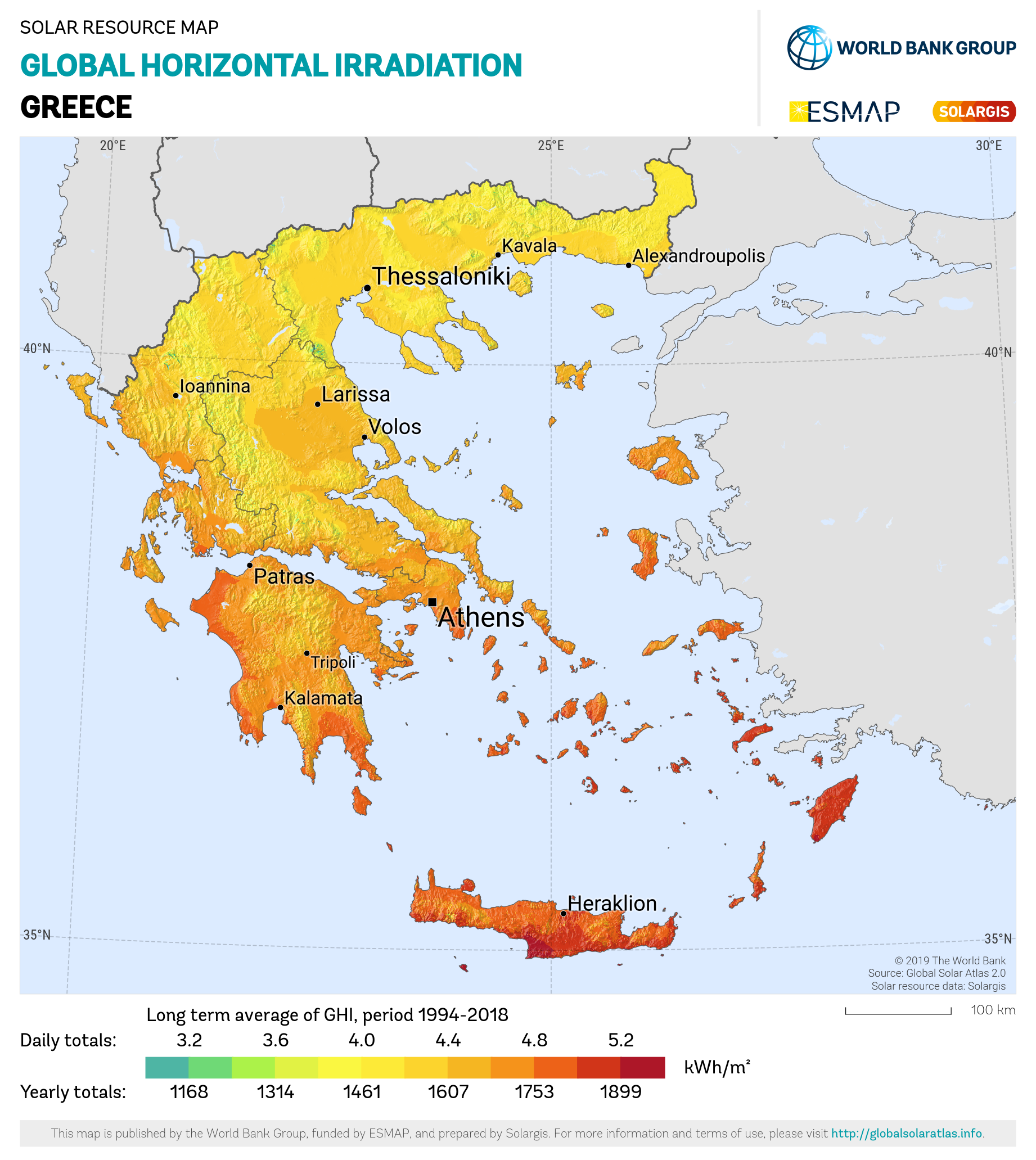

- Renewable Energy Sources (RES)**: Greece has made substantial progress in RES. In 2022, renewables accounted for 46% of Greece's electricity generation, a significant increase from 11% in 2011. Wind power contributed 22%, solar power (photovoltaics) 14%, and hydropower 9%. The country has high potential for solar and wind energy.

- Natural Gas**: Plays a crucial role, accounting for 38% of electricity generation in 2022. Greece imports natural gas, partly via pipelines and LNG terminals, and is developing into a regional gas hub.

- Energy Policy**: Focuses on enhancing energy security, diversifying sources, promoting energy efficiency, and meeting climate goals. This includes expanding interconnections with neighboring countries, upgrading the electricity grid to accommodate more renewables, and promoting energy storage solutions. Greece does not have any nuclear power plants.

- Environmental Considerations**: The shift to renewables is driven by the need to reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change. The phase-out of lignite plants is a key component of this strategy, though it presents socio-economic challenges for regions dependent on mining. Sustainable energy development aims to balance energy needs with environmental protection.

The energy sector is critical for economic development, and its transformation towards a greener and more sustainable model is a national priority, involving significant investment and policy efforts.

9.7. Government Debt Crisis and Economic Reforms

The Greek government-debt crisis, which began in late 2009, was a period of profound economic and social turmoil for Greece. Its causes were multifaceted, including years of high structural budget deficits, significant tax evasion, inaccurate reporting of official economic statistics (which were revealed to be considerably worse than previously stated), and the impact of the global Great Recession of 2007-2008. The crisis was exacerbated by Greece's membership in the Eurozone, which meant it could not devalue its currency to regain competitiveness.

As Greece's borrowing costs soared and a sovereign default loomed, the country received three international bailout packages from the "Troika" - the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) - starting in May 2010. These bailouts, totaling hundreds of billions of euros, came with stringent conditions requiring harsh austerity measures. These included deep cuts in public spending (salaries, pensions), tax increases, and structural reforms aimed at liberalizing the economy, privatizing state assets, and improving fiscal management.

The societal impacts of the crisis and austerity were severe:

- A prolonged and deep recession, with GDP contracting by approximately 25% between 2009 and 2015.

- A surge in unemployment, reaching over 27% at its peak, with youth unemployment exceeding 50%.

- Significant declines in wages and pensions, leading to a sharp drop in living standards and an increase in poverty and social exclusion, particularly affecting vulnerable groups.

- Widespread social unrest, including numerous protests and strikes against austerity policies.

- A political upheaval, with the traditional two-party system collapsing and new political forces emerging.

Economic reforms focused on fiscal consolidation, improving tax collection, reforming the public administration, liberalizing labor markets, and privatizing state-owned enterprises. While Greece achieved a primary budget surplus (budget balance before debt interest payments) in 2013 and returned to modest growth in 2014, the path to recovery was long and arduous. The IMF later admitted that it had underestimated the negative impact of austerity on economic growth.

The bailout programs officially ended in August 2018, though Greece remained under enhanced surveillance by European institutions. The economy has since shown signs of recovery, with growth returning and unemployment gradually declining. However, high public debt remains a challenge, and the social scars of the crisis continue to affect Greek society. The crisis highlighted systemic weaknesses in both the Greek economy and the architecture of the Eurozone, leading to broader debates about fiscal governance and solidarity within the EU.

10. Society

Greek society is a blend of ancient traditions and modern European influences. It has undergone significant transformations in recent decades, marked by demographic shifts, urbanization, and evolving social norms. The Greek Orthodox Church maintains a strong influence on cultural life, though society is becoming increasingly secular. Family ties remain central. Contemporary Greece faces challenges related to economic recovery, social cohesion, the integration of migrants, and addressing human rights issues, particularly for minorities and vulnerable groups. There is an ongoing public discourse on national identity, modernization, and Greece's role in Europe and the world.

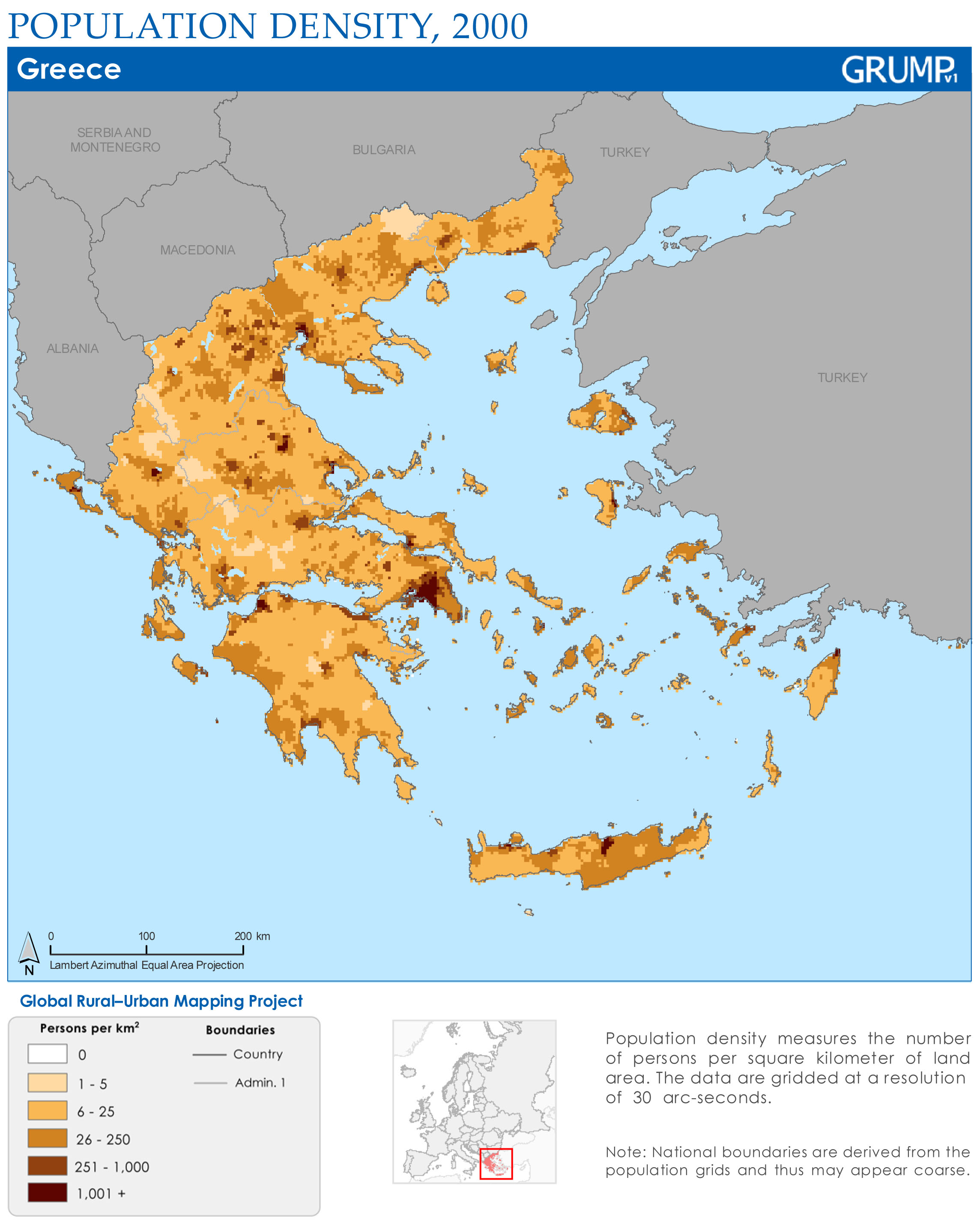

10.1. Demographics

As of 2022, Eurostat estimated the population of Greece at approximately 10.6 million. Greek society has experienced significant demographic shifts in recent decades, aligning with broader European trends of declining fertility rates and an aging population. The birth rate in 2016 was 8.5 per 1,000 inhabitants, a substantial decrease from 14.5 per 1,000 in 1981. Conversely, the mortality rate increased from 8.9 per 1,000 in 1981 to 11.2 per 1,000 in 2016.

The total fertility rate of around 1.4 children per woman is well below the replacement rate of 2.1 and is among the lowest in the world. This has contributed to Greece having one of the oldest populations globally, with a median age of 44.2 years. In 2001, 17% of the population was 65 years or older; by 2016, this proportion had risen to 21%. During the same period, the proportion of those aged 14 and younger declined from 15% to slightly below 14%.

Marriage rates have also declined, from nearly 71 per 1,000 inhabitants in 1981 to 51 in 2004, while divorce rates have increased. These trends have resulted in smaller and older average households. The economic crisis that began in the late 2000s exacerbated these demographic challenges, leading to the emigration of an estimated 350,000 to 450,000 Greeks, predominantly young adults, seeking better economic opportunities abroad. This "brain drain" poses a further challenge to the country's long-term demographic and economic outlook. An aging population also places increasing strain on social security and healthcare systems.

10.1.1. Major Cities

Almost two-thirds of the Greek population lives in urban areas. The largest and most influential metropolitan centers are:

- Athens**: The capital city, with a metropolitan population of approximately 3.74 million people according to the 2021 census. Athens is the historical, cultural, political, and economic heart of Greece, home to iconic landmarks like the Acropolis and a vibrant modern urban life.

- Thessaloniki**: The second-largest city and the capital of the Central Macedonia region, with a metropolitan population of around 1.09 million (2021). Thessaloniki is a major port, industrial center, and cultural hub, often referred to as symprotévousa (co-capital). It has a rich history spanning Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods.

Other prominent cities with urban populations exceeding 100,000 inhabitants include:

- Patras**: Located in the Peloponnese, it is a major port and university city. (Pop. approx. 177,000 in the city proper, 2021)

- Heraklion**: The largest city and administrative capital of Crete, a significant port and tourist destination. (Pop. approx. 163,000 in the city proper, 2021)

- Larissa**: A major agricultural and commercial center in the Thessaly region. (Pop. approx. 148,000 in the city proper, 2021)

- Piraeus**: Part of the Athens urban agglomeration and one of Europe's largest passenger ports. (Pop. approx. 168,000 in the city proper, 2021)

- Volos**: A port city in Thessaly, located at the foot of Mount Pelion. (Pop. approx. 85,000 in the city proper, 2021)

- Ioannina**: The largest city in the Epirus region, situated by Lake Pamvotida. (Pop. approx. 65,000 in the city proper, 2021)

- Chania**: A historic port city on the island of Crete. (Pop. approx. 54,000 in the city proper, 2021)

- Chalcis**: The chief town of the island of Euboea, known for the Euripus Strait. (Pop. approx. 59,000 in the city proper, 2021)

Urbanization trends have led to challenges in major cities, including traffic congestion, housing availability, and environmental pressures. However, cities also serve as centers for innovation, education, and cultural dynamism, driving much of the country's economic activity and social development. Social infrastructure in these urban centers varies, with ongoing efforts to improve public services and quality of life.

10.2. Languages

Greek is the official language of Greece and is spoken by the vast majority of the population. Modern Greek evolved from Koine Greek, which itself developed from Ancient Greek dialects, primarily Attic Greek. The Greek language has a documented history spanning over 3,400 years, making it one of the oldest attested Indo-European languages. Standard Modern Greek, based largely on southern dialects, is used in education, administration, and media.

Several distinct Greek dialects and linguistic varieties exist:

- Pontic Greek**: Spoken by Greeks originating from the Pontus region of Asia Minor, many of whom resettled in Greece after the Greek genocide and the 1919-1922 population exchange.

- Cappadocian Greek**: Also brought by refugees from Asia Minor, it is now highly endangered and spoken by very few.

- Tsakonian**: A distinct Greek language derived from Doric Greek (unlike most Modern Greek dialects which come from Koine/Attic), still spoken in a few villages in the southeastern Peloponnese.

- Sarakatsanika**: An archaic dialect spoken by the Sarakatsani, traditionally transhumant shepherds in northern Greece.

Minority languages are also present in Greece:

- Turkish**: Spoken by the Muslim minority in Thrace, which constitutes approximately 0.95% of the national population.

- Bulgarian (Pomak dialect)**: Spoken by the Pomaks, part of the Muslim minority in Thrace.

- Romani**: Spoken by Roma communities (both Christian and Muslim) throughout the country. The Council of Europe estimates around 265,000 Roma live in Greece.

- Arvanitika**: An Albanian dialect spoken by the Arvanites, a group mostly located in rural areas around Attica and other parts of Greece. Most Arvanites identify ethnically as Greek and are bilingual. The language is endangered.

- Aromanian (Vlach)** and **Megleno-Romanian**: Eastern Romance languages spoken by small communities of Aromanians and Megleno-Romanians, primarily in mountainous regions of northern and central Greece. These languages are also endangered.

- Slavic dialects/Macedonian**: Spoken by some groups near the northern borders, particularly in Greek Macedonia. The speakers' ethnic identification varies, with many identifying as Greek.

- Ladino (Judeo-Spanish)**: Traditionally spoken by the Sephardic Jewish community, now maintained by a very small number of speakers.

The Greek state officially recognizes only Greek as the national language. The status and rights of minority language speakers have been a subject of discussion and, at times, contention, particularly concerning education and public use. Assimilation into the Greek-speaking majority has significantly reduced the number of speakers of many traditional minority languages over the 20th and 21st centuries.

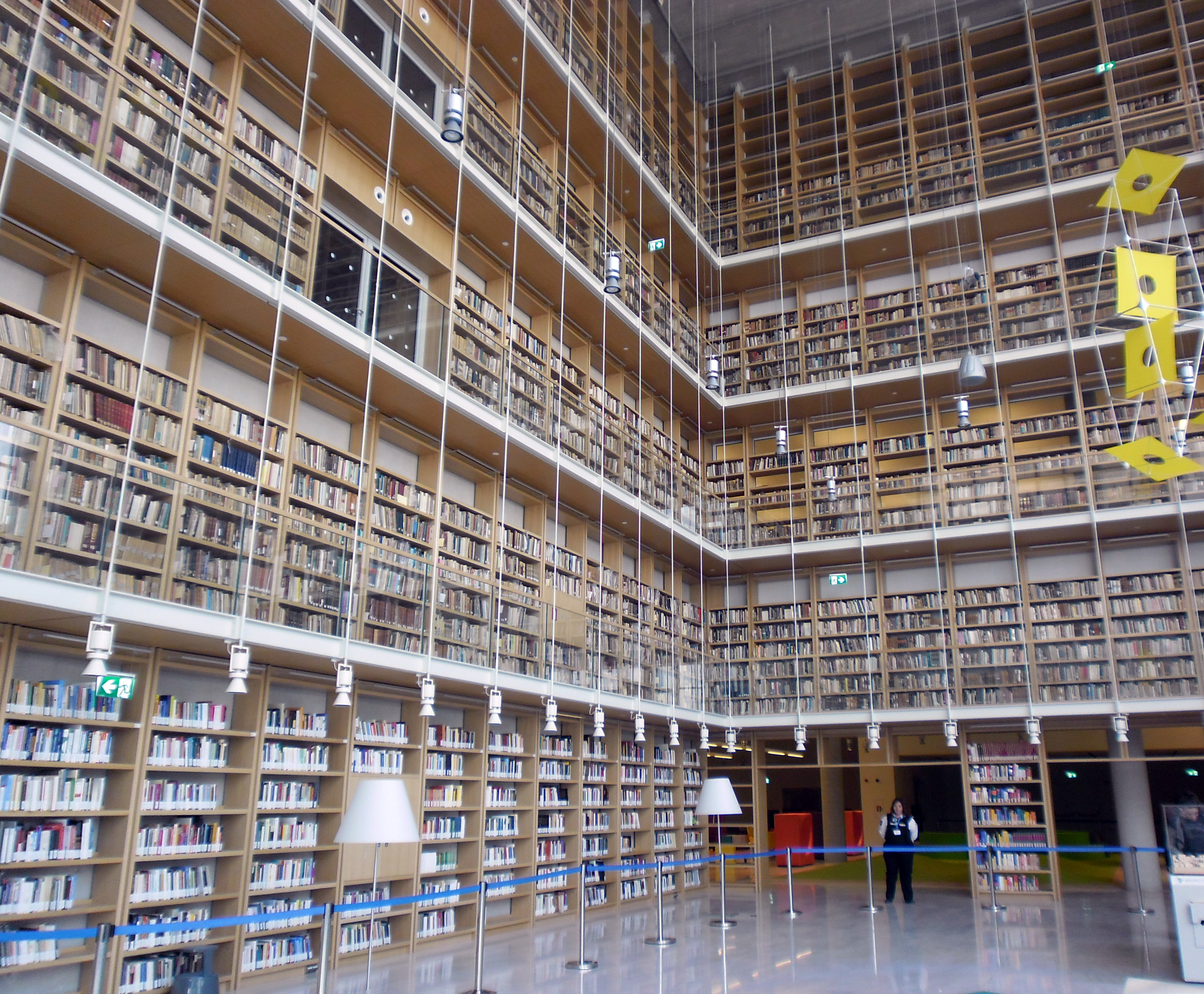

10.3. Religion