1. Overview

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria (Република БългарияRepublika BŭlgariyaBulgarian), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans, bordered by Romania to the north (largely along the Danube River), Serbia and North Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, and the Black Sea to the east. Covering an area of 43 K mile2 (110.99 K km2), Bulgaria is Europe's sixteenth-largest country. Its capital and largest city is Sofia; other major urban centers include Plovdiv, Varna, and Burgas.

The nation's history is marked by the rise and fall of powerful empires, periods of foreign domination, and a persistent struggle for national identity and self-determination, significantly shaping its social fabric and democratic aspirations. Prehistoric cultures like the Karanovo and Varna cultures flourished in these lands, leaving behind remarkable artifacts, including the world's oldest gold jewelry, which offer insights into early European social structures. The ancient Thracians, known for their metallurgical skills and distinct cultural practices, were later followed by Roman and Byzantine rule, which brought Christianity and new administrative systems but also periods of conflict. The arrival of Slavs and Bulgars led to the formation of the First and Second Bulgarian Empires, which became major cultural and political centers in medieval Europe, most notably through the development and dissemination of the Cyrillic script, a cornerstone of Slavic literacy.

Nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule profoundly impacted Bulgarian society, leading to the suppression of its institutions and culture, alongside periods of resistance and a burgeoning National Revival in the 19th century that emphasized enlightenment ideals and self-governance. The establishment of the modern Bulgarian state in 1878, following the Russo-Turkish War, was a pivotal moment, though territorial disputes and involvement in major 20th-century conflicts, including both World Wars, brought significant socio-political upheaval and human cost. The subsequent Communist era (1946-1989) saw rapid industrialization and initial improvements in living standards for some, but also severe political repression, suppression of human rights, particularly for minorities like the Turkish population during forced assimilation campaigns, and economic centralization under Soviet influence.

The transition to democracy after 1989 has been a complex period, characterized by the adoption of a market economy, accession to NATO and the European Union, and efforts to build democratic institutions. However, Bulgaria continues to face challenges related to political instability, corruption, judicial inefficiency, and economic disparities, which impact social cohesion and public trust. Environmental concerns, including air and water pollution from industrial activities, also pose significant risks to public health and natural heritage, despite conservation efforts and a rich biodiversity. Culturally, Bulgaria preserves a vibrant heritage of folk traditions, music, literature, and arts, alongside its numerous UNESCO World Heritage Sites that attest to its long and complex history. The demographic situation is marked by a declining population due to emigration and low birth rates, presenting further social and economic challenges for the nation's future development and the welfare of its citizens.

2. Etymology

The name Bulgaria is derived from the Bulgars, a tribe of Turkic origin that founded the First Bulgarian Empire. Their name is not completely understood and is difficult to trace back earlier than the 4th century AD. However, it is possibly derived from the Proto-Turkic word bulģha, meaning "to mix", "shake", or "stir", and its derivative bulgak, meaning "revolt" or "disorder". The meaning may be further extended to "rebel", "incite", or "produce a state of disorder", and thus, in the derivative, the "disturbers". Tribal groups in Inner Asia with phonologically similar names, such as the Buluoji (a component of the "Five Barbarians" groups during the 4th century), were frequently described in similar terms, as both a "mixed race" and "troublemakers". In Japanese, Bulgaria is also known by the Kanji transcription 勃牙利 (勃牙利BotugariJapanese), often shortened to 勃 (勃Bots[u]Japanese).

3. History

The history of Bulgaria spans from early human settlements in prehistory through antiquity, the rise and fall of powerful Bulgarian empires during the Middle Ages, nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule, the emergence of a modern independent state, a period under communist governance, and its contemporary transition to democracy within the European Union. These periods have been characterized by significant cultural achievements, struggles for sovereignty, and profound social and political transformations that continue to shape the nation.

3.1. Prehistory and Antiquity

The lands of modern-day Bulgaria have been inhabited since prehistoric times. Neanderthal remains dating to around 150,000 years ago, or the Middle Paleolithic, represent some of the earliest traces of human activity. Remains of Homo sapiens found in Bulgaria are dated to approximately 47,000 years BP, making them the earliest evidence of modern humans in Europe.

The Neolithic Karanovo culture emerged around 6,500 BC and was one of several societies in the region that thrived on agriculture. The Chalcolithic Varna culture (fifth millennium BC) is credited with inventing gold metallurgy. The associated Varna Necropolis contains the oldest golden jewellery in the world, with an approximate age of over 6,000 years (radiocarbon dated between 4,600 BC and 4,200 BC). This treasure has been invaluable for understanding social hierarchy and stratification in the earliest European societies. Other significant prehistoric cultures in the region include the Hamangia culture and Vinča culture (6th to 3rd century BC) and the Bronze Age Ezero culture.

The Thracians, one of the three primary ancestral groups of modern Bulgarians, appeared on the Balkan Peninsula sometime before the 12th century BC. They excelled in metallurgy and contributed the Orphean and Dionysian cults to Greek culture, but largely remained tribal and stateless. The Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered parts of present-day Bulgaria, particularly eastern Bulgaria, in the 6th century BC and retained control over the region until 479 BC. This invasion acted as a catalyst for Thracian unity, leading the bulk of their tribes to unite under king Teres I to form the Odrysian kingdom in the 470s BC. This kingdom was subsequently weakened and vassalized by Philip II of Macedon in 341 BC, attacked by Celts (who established a capital at Tylis) in the 3rd century BC, and finally became a province of the Roman Empire (Thracia) in AD 45.

By the end of the 1st century AD, Roman governance was established over the entire Balkan Peninsula. Christianity began spreading in the region around the 4th century. The Gothic Bible-the first book in a Germanic language-was created by the Gothic bishop Ulfilas in what is today northern Bulgaria around 381 AD. After the fall of Rome in 476, the region came under Byzantine control. However, the Byzantines were often engaged in prolonged warfare against Persia and could not adequately defend their Balkan territories from barbarian incursions. This enabled the Slavs to enter the Balkan Peninsula, primarily through an area between the Danube River and the Balkan Mountains known as Moesia. Gradually, the interior of the peninsula became a country of the South Slavs, who lived under a form of democracy. The Slavs assimilated the partially Hellenised, Romanised, and Gothicised Thracian population in the rural areas, forming a key component of the future Bulgarian ethnicity.

3.2. First Bulgarian Empire

Not long after the Slavic incursion into the Balkans, Moesia was invaded by the Bulgars, a Turkic people, under Khan Asparuh. Their horde was a remnant of Old Great Bulgaria, a tribal confederacy situated north of the Black Sea in what is now Ukraine and southern Russia, which had been subjugated by the Khazars. Asparukh attacked Byzantine territories in Moesia and conquered the Slavic tribes there in 680 AD. A peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire was signed in 681 AD, marking the foundation of the First Bulgarian Empire. The capital was established at Pliska, south of the Danube. The minority Bulgars formed a close-knit ruling caste, and together with the more numerous Slavs, laid the foundation for the Bulgarian state and people. Asparukh's brother, Kuber, also settled with a group of Bulgars in Macedonia.

Succeeding rulers strengthened the Bulgarian state throughout the 8th and 9th centuries. Khan Tervel (700/701-718/721) played a crucial role in defeating a large Arab army during the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople, thereby helping to halt a major Arab advance into Europe. Khan Krum (circa 803-814) expanded the empire's territory significantly and introduced a written code of law applicable to both Slavs and Bulgars. He famously defeated the Byzantine emperor Nicephorus I at the Battle of Pliska in 811, where Nicephorus I was killed.

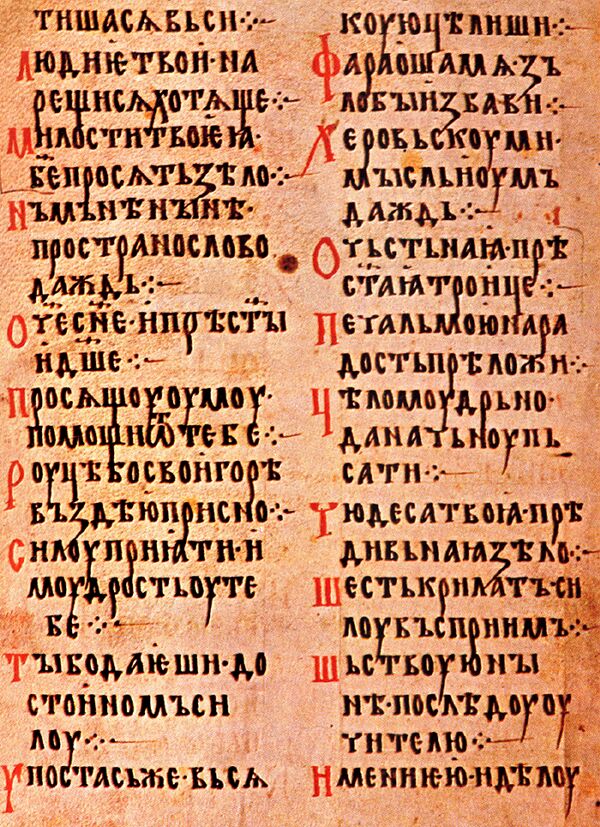

A pivotal moment in Bulgarian history was the reign of Boris I (852-889), who abolished paganism (including the traditional Tengrism of the Bulgars) in favour of Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 864 AD. The conversion was followed by Byzantine recognition of the Bulgarian church and the adoption of the Cyrillic script, which was developed at the Preslav Literary School and the Ohrid Literary School. This script, along with the Old Church Slavonic language (also known as Old Bulgarian), became the lingua franca of the Slavic Orthodox world. The common language, religion, and script strengthened central authority and gradually fused the Slavs and Bulgars into a unified people speaking a single Slavic language.

A golden age for the First Bulgarian Empire began during the 34-year rule of Emperor Simeon I the Great (893-927), who oversaw the largest territorial expansion of the state. Simeon I also sought military supremacy over the Byzantine Empire, demonstrated by the decisive Bulgarian victory at the Battle of Achelous (917), one of the bloodiest battles of the Middle Ages. During his reign, Bulgaria became one of the three major powers in Europe, alongside the Byzantine Empire and the Carolingian Empire. The literature produced in Old Bulgarian, centered in Preslav, soon spread north and became a cornerstone of culture in Eastern Europe.

After Simeon's death, Bulgaria was weakened by wars with Magyars and Pechenegs and the spread of Bogomilism, a dualistic religious movement. Consecutive Rus' and Byzantine invasions led to the seizure of Preslav by the Byzantine army in 971 and the capture of Emperor Boris II. The empire briefly recovered under Samuel (997-1014), who managed to conquer Serbia, Bosnia, and Duklja. However, this resurgence ended when Byzantine emperor Basil II ("the Bulgar-Slayer") decisively defeated the Bulgarian army at the Battle of Klyuch in 1014. After this battle, Basil II is said to have blinded 15,000 Bulgarian prisoners of war. Samuel died shortly after the battle, and by 1018, the Byzantines had conquered the entirety of the First Bulgarian Empire.

After the conquest, Basil II sought to prevent revolts by retaining the rule of local nobility, integrating them into the Byzantine bureaucracy and aristocracy as archons or strategoi. He also relieved their lands of the obligation to pay taxes in gold, allowing tax in kind instead. The Bulgarian Patriarchate was reduced to an archbishopric but retained its autocephalous status and its dioceses.

3.3. Byzantine Rule and Second Bulgarian Empire

Byzantine domestic policies changed after Basil II's death, and a series of unsuccessful rebellions broke out, the largest being led by Peter Delyan (1040-1041), who proclaimed himself emperor, and later by Constantine Bodin (also known as Peter III) in 1072. The Byzantine Empire's authority declined after a catastrophic military defeat at Manzikert against Seljuk invaders in 1071 and was further disturbed by the Crusades. These factors prevented Byzantine attempts at Hellenisation and created fertile ground for further revolt.

In 1185, nobles of the Asen dynasty, Ivan Asen I and Peter IV, organized a major uprising and succeeded in re-establishing the Bulgarian state. This marked the beginning of the Second Bulgarian Empire, with its capital at Tarnovo (now Veliko Tarnovo).

Kaloyan, the third of the Asen monarchs (reigned 1197-1207), extended his dominion to Belgrade and Ohrid. He acknowledged the spiritual supremacy of the Pope and received a royal crown from a papal legate, although Bulgaria remained firmly Eastern Orthodox. Kaloyan famously defeated the forces of the Latin Empire at the Battle of Adrianople (1205).

The empire reached its zenith under Ivan Asen II (1218-1241), when its borders expanded to include Albania, parts of Serbia, Epirus, Macedonia, and much of Thrace. Commerce and culture flourished, with the Tarnovo Artistic School producing significant works of art and the first coins being minted by Bulgarian rulers. Ivan Asen II's rule was also marked by a shift away from Rome in religious matters, reasserting the independence of the Bulgarian Church.

The Asen dynasty became extinct in 1257. Internal conflicts and incessant Byzantine and Hungarian attacks followed, enabling the Mongols to establish suzerainty over the weakened Bulgarian state in the late 13th century. In 1277, a swineherd named Ivaylo led a great peasant revolt that briefly expelled the Mongols from Bulgaria and made him emperor. However, he was overthrown in 1280 by the boyars (feudal landlords), whose factional conflicts caused the Second Bulgarian Empire to disintegrate into small feudal dominions by the 14th century. These fragmented rump states-two tsardoms at Vidin and Tarnovo, and the Despotate of Dobrudzha-became easy prey for a new threat arriving from the Southeast: the Ottoman Turks. During the rule of Emperor Ivan Alexander (1331-1371), the Bulgarian Empire entered a period of cultural renaissance, sometimes referred to as the "Second Golden Age of Bulgarian culture".

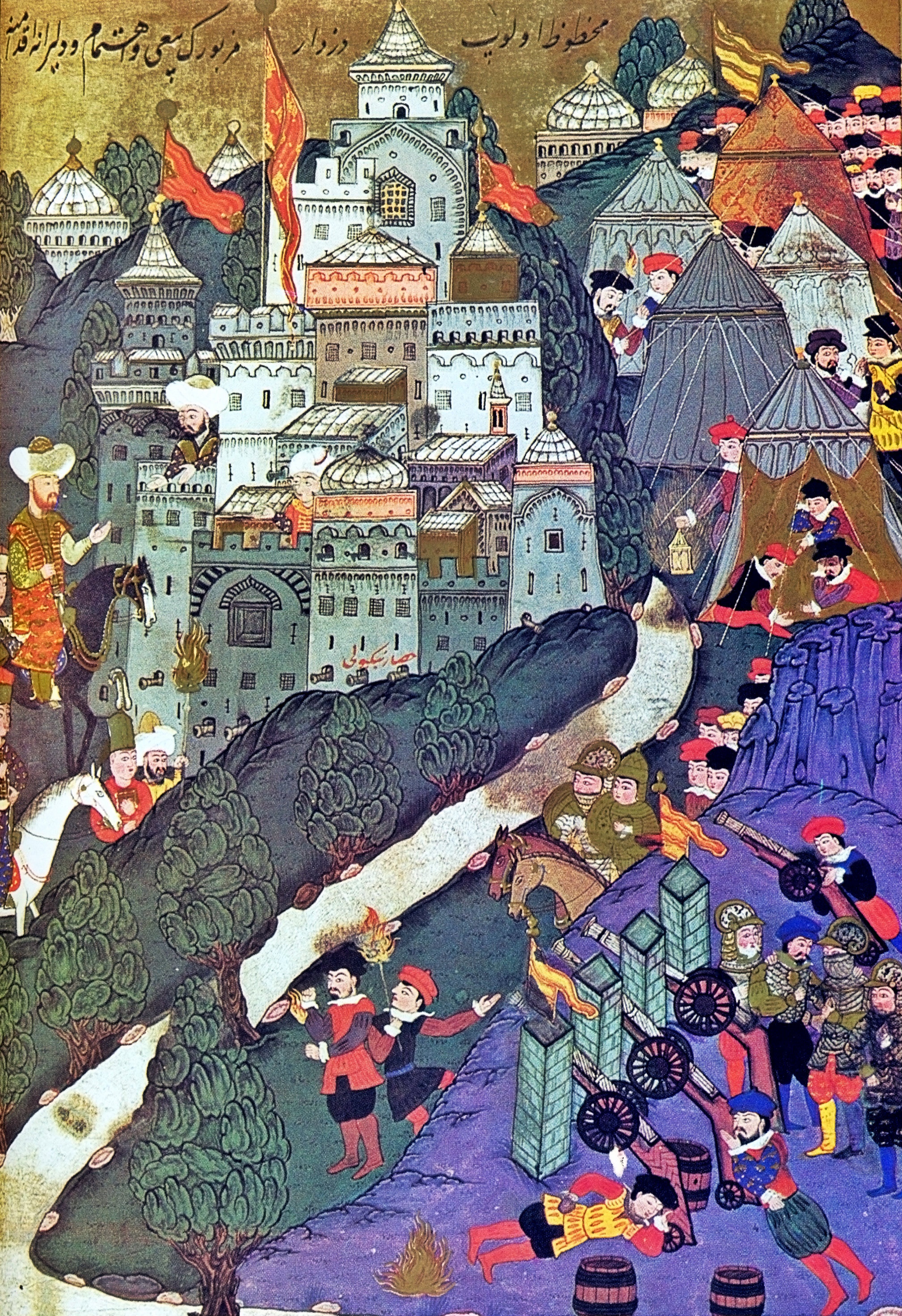

3.4. Ottoman Rule

The Ottomans were initially employed as mercenaries by the Byzantines in the 1340s but soon became invaders in their own right. Sultan Murad I took Adrianople (Edirne) from the Byzantines in 1362, which became the Ottoman capital. Sofia fell in 1382, followed by Shumen in 1388. The Ottomans completed their conquest of Bulgarian lands in 1393 when Tarnovo was sacked after a three-month siege. The Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, where a Crusader army was defeated, brought about the fall of the Vidin Tsardom, the last independent Bulgarian entity. Sozopol was the last Bulgarian settlement to fall, in 1453. This marked the beginning of nearly five centuries of Ottoman governance, a period that profoundly impacted Bulgarian society, economy, and culture.

Under Ottoman rule, the Bulgarian nobility was largely eliminated-its members either perished, fled, or accepted Islam and Turkification-and the peasantry was enserfed to Ottoman masters. Much of the educated clergy also fled to other countries. Bulgarians were subjected to heavy taxes, including the Devshirme (blood tax), a levy of young boys who were converted to Islam and trained for Ottoman military or civil service. Bulgarian culture was suppressed, and the population experienced partial Islamisation. The Ottoman authorities established a religious administrative community called the Rum Millet, which governed all Orthodox Christians regardless of their ethnicity. Most of the local population gradually lost its distinct national consciousness over the centuries, often identifying primarily by their Christian faith rather than as Bulgarians. However, the clergy remaining in some isolated monasteries, along with the militant Catholic community in the northwest of the country, helped keep the ethnic identity alive, enabling its survival in remote rural areas. The traditional hajduk (outlaw) bands also represented a form of resistance to Ottoman authority.

As Ottoman power began to wane from the 17th century onwards, Habsburg Austria and Russia increasingly saw Bulgarian Christians as potential allies. The Austrians backed several uprisings, including the First Tarnovo Uprising in 1598, the Second in 1686, the Chiprovtsi Uprising in 1688, and finally Karposh's rebellion in 1689. The Russian Empire also asserted itself as a protector of Christians in Ottoman lands, notably with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774.

The Western European Enlightenment in the 18th century influenced the initiation of a national awakening in Bulgaria. This movement restored national consciousness and provided an ideological basis for the liberation struggle. Key figures of this revival included Paisius of Hilendar, who wrote Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya (Slavonic-Bulgarian History) in 1762, and revolutionaries like Vasil Levski, Georgi Rakovski, Lyuben Karavelov, and Hristo Botev. The struggle culminated in the April Uprising of 1876, the largest and best-organized revolt. Although Ottoman authorities brutally suppressed the rebellion, killing up to 30,000 Bulgarians, the massacres (often referred to as the "Bulgarian Horrors") prompted the Great Powers to take action. They convened the Constantinople Conference in 1876 to propose reforms, but their decisions were rejected by the Ottomans. This diplomatic failure allowed the Russian Empire to seek a military solution without risking confrontation with other Great Powers, as had happened in the Crimean War. In 1877, Russia declared war on the Ottomans. With the crucial help of Bulgarian volunteers (Opalchentsi), particularly during the heroic defense of Shipka Pass, the Russian army defeated the Ottomans.

3.5. Third Bulgarian State (Modern and Contemporary History)

The period from 1878 marks the re-establishment of a Bulgarian state, its evolution through kingdom, communist rule, and the transition to a democratic republic, characterized by struggles for national unification, involvement in major European conflicts, significant socio-economic transformations, and ongoing efforts to strengthen democratic institutions and human rights.

3.5.1. Independence and Kingdom Era (1878-1946)

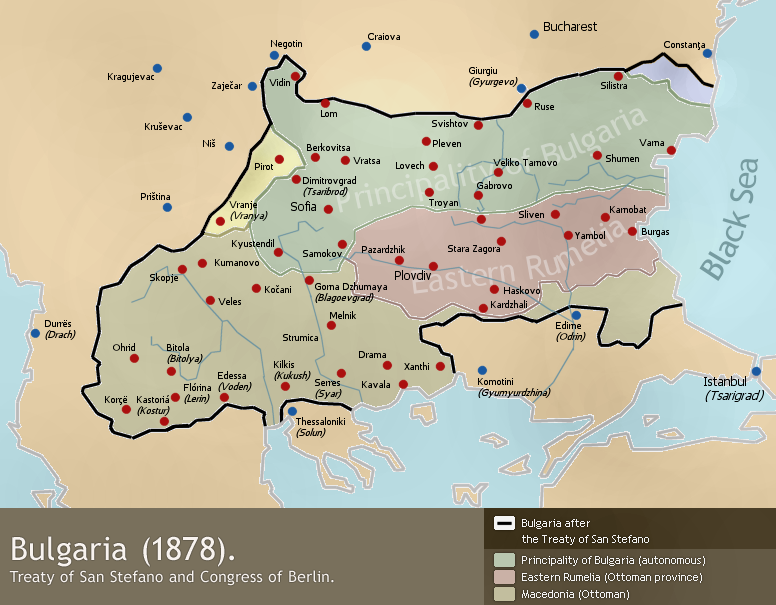

The Russo-Turkish War concluded with the Treaty of San Stefano on 3 March 1878, signed by Russia and the Ottoman Empire. It proposed an autonomous Bulgarian principality spanning Moesia, Macedonia, and Thrace, roughly corresponding to the territories of the Second Bulgarian Empire. This day is now a public holiday called National Liberation Day. However, the other Great Powers immediately rejected the treaty, fearing that such a large country in the Balkans might threaten their interests and expand Russian influence. It was superseded by the Treaty of Berlin, signed on 13 July 1878. This treaty provided for a much smaller state, the Principality of Bulgaria, comprising only Moesia and the region of Sofia, and an autonomous Ottoman province of Eastern Rumelia to its south. Large populations of ethnic Bulgarians, particularly in Macedonia and Thrace, were left outside the new country. This outcome significantly contributed to Bulgaria's irredentist sentiments and militaristic foreign policy during the first half of the 20th century. Alexander of Battenberg became the first prince.

The Bulgarian principality, still nominally under Ottoman suzerainty, won a war against Serbia in 1885 and successfully incorporated Eastern Rumelia, effectively unifying a large part of the Bulgarian-populated lands. On 5 October 1908 (22 September O.S.), Prince Ferdinand I proclaimed Bulgaria a fully independent state, elevating it to the status of a Kingdom. In the years following independence, Bulgaria increasingly militarized and was often referred to as "the Balkan Prussia".

Bulgaria became involved in three consecutive conflicts between 1912 and 1918. The First Balkan War (1912-1913), allied with Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro, was successful against the Ottoman Empire. However, disputes over the division of Macedonia led to the Second Balkan War (1913), in which Bulgaria fought against its former allies and Romania and was disastrously defeated, losing territory. In World War I, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers, hoping to reclaim lost territories. Despite fielding a large army (over a quarter of its population, totaling 1,200,000 soldiers) and achieving several decisive victories, such as at Doiran and Monastir, Bulgaria found itself on the losing side and capitulated in 1918. The war resulted in significant territorial losses (Western Outlands to Serbia, Western Thrace to Greece), a total of 87,500 soldiers killed, and a wave of over 253,000 refugees from the lost territories immigrating to Bulgaria between 1912 and 1929, placing additional strain on the already ruined national economy.

The resulting political unrest led to the establishment of a royal authoritarian dictatorship by Tsar Boris III (reigned 1918-1943). In 1925, the Incident at Petrich, nicknamed "the War of the Stray Dog," occurred when Greece invaded Bulgaria after a border incident. The conflict was settled by the League of Nations, resulting in a Bulgarian diplomatic victory and Greece being ordered to pay 45.00 K GBP to Bulgaria.

Bulgaria entered World War II in 1941 as a member of the Axis Powers, having been promised the return of territories in Macedonia and Thrace. However, it declined to participate in Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union, with whom it maintained diplomatic relations. A significant aspect of Bulgaria's WWII history was the rescue of its Jewish population (around 50,000 people) from deportation to Nazi concentration camps within Bulgaria proper, largely due to public outcry and efforts by parliamentarians, clergy, and intellectuals. However, the Bulgarian authorities, under German pressure, did participate in the deportation of almost 12,000 Jews from the occupied territories of Greek Thrace and Yugoslav Macedonia to camps like Treblinka.

The sudden death of Tsar Boris III in mid-1943 pushed the country into political turmoil as the war turned against Germany, and the communist guerrilla movement gained momentum. The government of Bogdan Filov subsequently failed to achieve peace with the Allies. Bulgaria did not comply with Soviet demands to expel German forces from its territory, resulting in a declaration of war and an invasion by the USSR in September 1944. The communist-dominated Fatherland Front seized power in a coup on 9 September 1944, ended Bulgaria's participation in the Axis, and joined the Allied side until the war ended. Bulgaria suffered little war damage, and the Soviet Union demanded no reparations. However, all wartime territorial gains, with the notable exception of Southern Dobrudzha (which had been regained from Romania in 1940), were lost.

3.5.2. Communist Era (1946-1989)

The left-wing coup d'état of 9 September 1944 led to the abolition of the monarchy and the executions of an estimated 1,000 to 3,000 dissidents, alleged war criminals, and members of the former royal elite. Following a referendum in 1946, a one-party people's republic was instituted, marking the formal end of the Tsardom.

Bulgaria fell firmly into the Soviet sphere of influence under the leadership of Georgi Dimitrov (1946-1949), who established a repressive, rapidly industrializing Stalinist state. The country became a loyal member of the Eastern Bloc and Comecon. By the mid-1950s, under Todor Zhivkov (who led the Communist Party from 1954 and the state until 1989), standards of living rose significantly for many, and political repression eased to some extent compared to the immediate post-war years. The Soviet-style planned economy saw some experimental market-oriented policies emerging. Compared to wartime levels, national GDP increased five-fold, and per capita GDP quadrupled by the 1980s, although severe debt spikes occurred in 1960, 1977, and 1980.

Lyudmila Zhivkova, Todor Zhivkov's daughter and Minister of Culture, bolstered national pride by promoting Bulgarian heritage, culture, and arts worldwide during the 1970s. However, the Zhivkov regime also engaged in severe human rights abuses. Facing declining birth rates among the ethnic Bulgarian majority, Zhivkov's government in 1984 initiated a brutal forced assimilation campaign against the minority ethnic Turks, known as the "Revival Process." This campaign forced ethnic Turks to adopt Slavic names, closed their mosques, and suppressed their language and cultural identity. These policies resulted in significant unrest, violence, and the emigration (often forced) of some 300,000 ethnic Turks to Turkey in 1989, causing a major humanitarian crisis and economic disruption, particularly in agriculture due to the loss of labor.

3.5.3. Post-1989 Transition to Democracy

The Communist Party was forced to give up its political monopoly on 10 November 1989, under the influence of the Revolutions of 1989 sweeping across Eastern Europe. Todor Zhivkov resigned, and Bulgaria embarked on a transition to a parliamentary democracy. The first free elections in June 1990 were won by the Communist Party, which had rebranded itself as the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP). A new constitution was adopted in July 1991, providing for a relatively weak elected president and a prime minister accountable to the legislature.

The initial transition period was marked by economic hardship, high inflation, and rising unemployment, as the country struggled to adapt to a market economy and the loss of COMECON markets. The average quality of life and economic performance remained lower than under communism well into the early 2000s, leading to significant emigration, a "brain drain" of young and educated Bulgarians.

After 2001, economic, political, and geopolitical conditions improved. Bulgaria achieved high Human Development status in 2003. It became a member of NATO in 2004 and participated in the War in Afghanistan. After several years of reforms, Bulgaria joined the European Union and the single market on 1 January 2007, despite ongoing EU concerns over government corruption and organized crime. Bulgaria hosted the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in 2018.

Bulgarian politics since 1989 has been characterized by a pattern of unstable governments and recurring political crises. Boyko Borisov, leader of the centre-right, pro-EU party GERB, served three terms as prime minister between 2009 and 2021. His tenures were marked by some infrastructure development but also by persistent allegations of corruption and erosion of democratic norms. Nationwide protests in 2013 over low living standards and corruption led to his government's resignation. After a series of snap elections and short-lived governments, Borisov returned to power. His last cabinet faced large-scale mass protests in 2020 triggered by further corruption revelations and concerns about media freedom. A series of parliamentary elections between April 2021 and April 2023 (five in total) failed to produce stable governing coalitions, highlighting deep political fragmentation. In June 2023, a coalition government was formed between We Continue the Change (PP-DB) and GERB, led by Nikolai Denkov, with an agreement for a rotational prime ministership.

Organizations like Freedom House have reported a continuing deterioration of democratic governance in Bulgaria after 2009, citing reduced media independence, stalled judicial reforms, abuse of authority at the highest level, and increased dependence of local administrations on the central government. While still listed as "Free," Bulgaria is categorized as a semi-consolidated democracy with deteriorating scores. The Democracy Index defines it as a "flawed democracy." Corruption remains a significant challenge, impacting public trust, economic development, and the country's full integration into EU mechanisms like the Schengen Area (though Bulgaria joined Schengen by air and sea in March 2024).

4. Geography

Bulgaria is located in Southeastern Europe, on the eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula. It features diverse topography, including plains, mountain ranges, and a Black Sea coastline, which influence its varied climate and rich biodiversity. Environmental challenges, particularly air and water pollution, alongside conservation efforts, are significant aspects of its geography.

4.1. Topography and Natural Resources

Bulgaria covers an area of 43 K mile2 (110.99 K km2) and is the sixteenth-largest country in Europe. Its land borders with its five neighboring countries (Romania, Serbia, North Macedonia, Greece, and Turkey) run a total length of 1.1 K mile (1.81 K km), and its coastline along the Black Sea is 220 mile (354 km) long. Bulgaria's geographic coordinates are approximately 43° N latitude and 25° E longitude.

The most notable topographical features are the Danubian Plain to the north, the Balkan Mountains (Stara Planina) running laterally through the middle of the country from west to east, the Thracian Plain (Maritsa Basin) to the south of the Balkan Mountains, and the Rila-Rhodope massif in the southwest. The southern edge of the Danubian Plain slopes upward into the foothills of the Balkans, while the Danube River defines most of the border with Romania. The Thracian Plain is roughly triangular, beginning southeast of Sofia and broadening as it reaches the Black Sea coast. It is one of the most fertile regions.

The mountainous southwest of Bulgaria has two distinct alpine-type ranges-Rila and Pirin-which border the lower but more extensive Rhodope Mountains to the east. Other notable medium-altitude mountains include Vitosha near Sofia, Osogovo, and Belasitsa. Musala, in the Rila Mountains, at 9.6 K ft (2.93 K m), is the highest point in both Bulgaria and the entire Balkan Peninsula. The Black Sea coast forms the country's lowest point. Plains occupy about one-third of the territory, while plateaus and hills occupy 41%.

Most rivers in Bulgaria are relatively short and have low water levels. The longest river located solely in Bulgarian territory is the Iskar, with a length of 229 mile (368 km). The Struma and the Maritsa are two other major rivers, primarily flowing southwards.

Bulgaria possesses deposits of coal (lignite), iron ore, copper, lead, zinc, and manganese. Smaller reserves of gold, silver, and other minerals are also found. These natural resources have historically supported the country's mining and industrial sectors. However, their extraction often carries significant environmental costs, including habitat disruption and pollution, which can impact local communities and ecosystems. Fertile soils in the Danubian and Thracian plains are crucial for agriculture, supporting rural livelihoods and food production, though intensive farming practices can lead to soil degradation and water pollution if not managed sustainably.

4.2. Climate

Bulgaria has a varied and changeable climate, which results from its position at the meeting point of the Mediterranean, Oceanic, and Continental air masses, combined with the barrier effect of its mountains.

Northern Bulgaria generally averages 1.8 °F (1 °C) cooler and registers about 7.9 in (200 mm) more precipitation annually than the regions south of the Balkan Mountains. Temperature amplitudes vary significantly in different areas. The lowest recorded temperature is -36.94 °F (-38.3 °C), while the highest is 113.36 °F (45.2 °C). Precipitation averages about 25 in (630 mm) per year and varies from 20 in (500 mm) in Dobrudja (northeast) to more than 0.1 K in (2.50 K mm) in the mountains. Continental air masses bring significant amounts of snowfall during winter, particularly in the mountainous regions and the Danubian Plain.

Considering its relatively small area, Bulgaria has a variable and complex climate. The country occupies the southernmost part of the continental climatic zone, with small areas in the south falling within the Mediterranean climatic zone. The continental influence is predominant, stronger during the winter, producing abundant snowfall. The Mediterranean influence increases during the second half of summer, producing hot and dry weather.

Bulgaria is subdivided into five climatic zones:

- Continental zone: Danubian Plain, Pre-Balkan regions, and the higher valleys of the Transitional geomorphological region.

- Transitional zone: Upper Thracian Plain, most of the Struma and Mesta river valleys, and the lower Sub-Balkan valleys.

- Continental-Mediterranean zone: The southernmost areas of the Struma and Mesta valleys, the eastern Rhodope Mountains, Sakar, and Strandzha mountains.

- Black Sea zone: Along the coastline, extending about 19 mile (30 km) to 25 mile (40 km) inland, characterized by milder winters and cooler summers than the interior.

- Alpine zone: In the mountains above 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m) altitude (central Balkan Mountains, Rila, Pirin, Vitosha, western Rhodope Mountains, etc.), featuring short, cool summers and long, snowy winters.

Climate change is an emerging concern, with potential impacts on agriculture, water resources, and the frequency of extreme weather events, which could affect social well-being and economic stability.

4.3. Biodiversity and Environment

The interaction of climatic, hydrological, geological, and topographical conditions has produced a relatively wide variety of plant and animal species. Bulgaria's biodiversity is one of the richest in Europe and is conserved in three national parks (Rila, Pirin, and Central Balkan), 11 nature parks, 10 biosphere reserves recognized by UNESCO, and 565 protected areas.

Approximately 93 of the 233 mammal species of Europe are found in Bulgaria, along with 49% of butterfly species and 30% of vascular plant species. Overall, an estimated 41,493 plant and animal species are present. Larger mammals with sizable populations include deer (around 106,000 individuals), wild boar (around 89,000), golden jackal (around 47,000), and red fox (around 32,000). Partridges number some 328,000 individuals, making them the most widespread gamebird. A third of all nesting birds in Bulgaria can be found in Rila National Park, which also hosts Arctic and alpine species at high altitudes. The brown bear, Eurasian lynx, and European mink are among the rarer, protected mammals.

Bulgarian flora includes more than 3,800 vascular plant species, of which 170 are endemic (found only in Bulgaria) and 150 are considered endangered. A checklist of larger fungi in Bulgaria by the Institute of Botany identifies more than 1,500 species. Forest cover is around 36% of the total land area, equivalent to 3,893,000 hectares (ha) in 2020, an increase from 3,327,000 hectares in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 3,116,000 ha, and planted forest covered 777,000 ha. Of the naturally regenerating forest, 18% was reported to be primary forest (consisting of native tree species with no clearly visible indications of human activity), and around 18% of the forest area was found within protected areas. For the year 2015, 88% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership and 12% under private ownership. Some of the world's oldest trees, like Baikushev's pine and the Granit Oak, are found in Bulgaria.

In 1998, the Bulgarian government adopted the National Biological Diversity Conservation Strategy, a comprehensive program seeking the preservation of local ecosystems, protection of endangered species, and conservation of genetic resources. Bulgaria has some of the largest Natura 2000 areas in Europe, covering 33.8% of its territory, which aims to protect valuable habitats and species. The country also achieved its Kyoto Protocol objective of reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 30% from 1990 to 2009.

Despite these conservation efforts, Bulgaria faces significant environmental challenges. The country ranked 37th in the 2024 Environmental Performance Index but scored low on air quality. Particulate matter levels are among the highest in Europe, especially in urban areas affected by automobile traffic and coal-based power stations. The lignite-fired Maritsa Iztok-2 power station, for example, is cited as causing some of the highest damage to health and the environment in the European Union. Pesticide use in agriculture and antiquated industrial sewage systems contribute to extensive soil and water pollution. Deforestation, partly due to illegal logging, remains a concern. Water quality began to improve in 1998 and has maintained a trend of moderate improvement, with over 75% of surface rivers meeting European standards for good quality. These environmental issues directly impact social well-being through health problems, degradation of natural resources essential for livelihoods (e.g., clean water, fertile soil), and loss of aesthetic and recreational values. Addressing these challenges is crucial for sustainable development and improving the quality of life for Bulgarian citizens.

5. Politics

Bulgaria is a parliamentary democracy operating under a constitution adopted in 1991. The political system features a separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, and upholds universal suffrage. However, the country has faced challenges related to political stability, corruption, and the efficiency of its democratic institutions.

5.1. Government Structure and Constitution

Bulgaria is a parliamentary democracy where the prime minister is the head of government and holds the most powerful executive position. The political system has three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. Universal suffrage is granted to all citizens aged at least 18 years. The Constitution, adopted in July 1991, outlines the fundamental principles of the Republic, the rights and duties of citizens, and the roles of key state institutions. It also provides for mechanisms of direct democracy, namely petitions and national referendums. Elections are supervised by an independent Central Election Commission, which includes members from all major political parties. Parties must register with the commission before participating in a national election. Normally, the prime minister-elect is the leader of the party that receives the most votes in parliamentary elections, although this is not always the case due to coalition politics.

The president serves as the head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The president is directly elected for a five-year term and can serve a maximum of two terms. While the president's domestic power is more limited compared to the prime minister, they have the authority to return a bill to the National Assembly for further debate. However, the parliament can override the presidential veto by a simple majority vote. The current president is Rumen Radev, first elected in 2016 and re-elected in 2021.

Bulgaria has experienced a pattern of unstable governments since its transition to democracy. Boyko Borisov, leader of the centre-right, pro-EU party GERB, served three non-consecutive terms as prime minister between 2009 and 2021. His tenures were marked by protests against low living standards and corruption. A series of snap elections occurred frequently. For instance, in February 2013, Borisov's government resigned after nationwide protests. Subsequent elections led to a government led by Plamen Oresharski, which also resigned in July 2014 amid large-scale protests. Borisov returned to power, but his third government, a coalition with the far-right United Patriots, also faced challenges. His last cabinet saw a notable decrease in press freedom and a number of corruption revelations that triggered yet another wave of mass protests in 2020.

The political landscape remained fragmented, leading to five parliamentary elections between April 2021 and April 2023. In June 2023, a coalition government was formed by We Continue the Change (PP-DB) and GERB, with Nikolai Denkov (PP-DB) as Prime Minister, based on an agreement for a rotational prime ministership with Mariya Gabriel (GERB). However, this coalition collapsed in March 2024, leading to the appointment of a caretaker government led by Dimitar Glavchev and new snap elections.

International observers, such as Freedom House, have reported a continuing deterioration of democratic governance in Bulgaria after 2009, citing issues like reduced media independence, stalled reforms, abuse of authority, and increased central government control over local administrations. While Bulgaria is still listed as "Free" by Freedom House, its political system is designated as a semi-consolidated democracy with deteriorating scores. The Democracy Index has classified it as a "flawed democracy." Public trust in democratic institutions has been affected, with a 2018 survey by the Institute for Economics and Peace reporting that less than 15% of respondents considered elections to be fair. Democratic accountability remains a key challenge, with corruption and the rule of law being persistent concerns for both citizens and international partners.

5.2. Legislature (National Assembly)

The National Assembly (Народно събраниеNarodno SabranieBulgarian) is Bulgaria's unicameral parliament. It consists of 240 deputies who are elected for four-year terms through direct popular vote under a system of proportional representation. Political parties or coalitions must achieve a minimum of 4% of the national vote to gain seats in the Assembly.

The National Assembly holds significant powers, including the authority to enact laws, approve the national budget, schedule presidential elections, select and dismiss the prime minister and other ministers, declare war, authorize the deployment of troops abroad, and ratify international treaties and agreements. It is the primary legislative body responsible for shaping the legal framework of the country and exercising oversight over the executive branch, contributing to democratic accountability.

5.3. Executive

The executive branch in Bulgaria is primarily embodied by the President and the Council of Ministers (the Cabinet).

The President is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Directly elected for a five-year term, the President can serve a maximum of two terms. Key functions include representing Bulgaria in international relations, appointing and dismissing certain high-ranking officials (often in consultation with other bodies), and having the power to veto legislation passed by the National Assembly, though this veto can be overridden by a parliamentary majority. The President also chairs the National Security Advisory Council. As of early 2024, Rumen Radev is the President.

The Council of Ministers (Cabinet) is the principal body of executive power and is headed by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the largest party or coalition in the National Assembly and is appointed by the President after parliamentary elections. The Cabinet is responsible for implementing laws, managing state administration, and conducting the day-to-day governance of the country. It is accountable to the National Assembly. Due to recent political instability, Bulgaria has seen several changes in government; as of mid-2024, Dimitar Glavchev was leading a caretaker government pending new elections.

5.4. Judiciary and Legal System

Bulgaria has a civil law legal system, where laws enacted by the Parliament are the primary source of law. The judiciary is constitutionally independent but has faced significant challenges regarding efficiency, transparency, and corruption, which have been points of concern for both domestic and international observers, including the European Union.

The judicial system is overseen by the Ministry of Justice in administrative terms, but judicial power is exercised by the courts. The court hierarchy includes regional courts, district courts, and courts of appeal. The highest courts are the Supreme Court of Cassation, which is the final court of appeal for criminal and civil cases, and the Supreme Administrative Court, which deals with the legality of administrative acts. There is also a Constitutional Court (composed of 12 judges with 9-year terms, appointed/elected from different branches) responsible for interpreting the Constitution and ruling on the constitutionality of laws.

The Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) is a key body responsible for the self-management of the judiciary, including the appointment, promotion, demotion, and dismissal of judges, prosecutors, and investigators. It is intended to safeguard judicial independence.

Despite reforms, the Bulgarian legal system is often cited by organizations like the European Commission as needing further improvements to combat corruption effectively, ensure judicial independence, and enhance the rule of law. Public trust in the judiciary has been relatively low due to perceived inefficiencies and corruption scandals. Law enforcement is primarily carried out by agencies under the Ministry of the Interior, including the General Directorate of National Police (GDNP), which combats general crime and maintains public order. The GDNP has approximately 26,578 police officers. The most common criminal cases are transport-related, followed by theft and drug-related crime; homicide rates are relatively low. The Ministry of the Interior also heads the Border Police Service and the National Gendarmerie, a specialized branch for anti-terrorist activity, crisis management, and riot control. Counterintelligence and national security are the responsibility of the State Agency for National Security (SANS).

5.5. Major Political Parties

Bulgaria operates under a multi-party system, which has often led to coalition governments and periods of political instability. The main political parties influencing national politics, based on recent election results and parliamentary representation, include:

- GERB (Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria): A centre-right, pro-European party, which has been a dominant force in Bulgarian politics for over a decade, led by former Prime Minister Boyko Borisov.

- We Continue the Change (PP): A centrist, anti-corruption party that emerged prominently in the 2021 elections. It often forms alliances with Democratic Bulgaria (DB).

- Revival (Vazrazhdane): A far-right, nationalist, and Eurosceptic party that has gained increasing support in recent years.

- Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS): Traditionally represents the interests of the Turkish minority in Bulgaria, and often plays a kingmaker role in coalition formations.

- BSP for Bulgaria (an electoral coalition led by the Bulgarian Socialist Party): The successor to the former Bulgarian Communist Party, it is a centre-left, social democratic party.

- Democratic Bulgaria (DB): A centre-right, pro-European, and reformist electoral alliance focused on judicial reform and anti-corruption.

- There Is Such a People (ITN): A populist party founded by entertainer Slavi Trifonov, which saw a surge in support in 2021 but has since seen its influence wane.

The fragmented political landscape often requires complex coalition negotiations, and ideological differences between parties can make stable governance challenging. Public dissatisfaction with corruption and the political establishment has also contributed to the rise of new political formations and protest movements.

5.6. Administrative Divisions

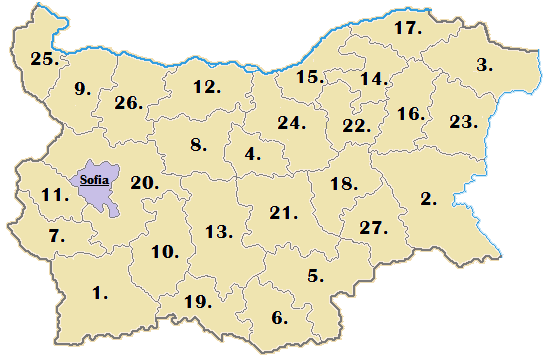

Bulgaria is a unitary state. Since the 1880s, the number of territorial management units has varied. Between 1987 and 1999, the administrative structure consisted of nine provinces (областиoblastiBulgarian, singular oblast). A new administrative structure was adopted in 1999 in parallel with the decentralization of the economic system.

This structure includes 27 provinces and a metropolitan capital province, the Sofia City (Sofia-grad). All provinces take their names from their respective capital cities. The provinces are further subdivided into 265 municipalities (общиниobshtiniBulgarian, singular obshtina). These municipalities are run by mayors, who are elected for four-year terms, and by directly elected municipal councils. The municipalities are the basic units of local self-government.

Bulgaria is a highly centralised state where the Council of Ministers (the national government) directly appoints regional governors for each of the 28 provinces. These governors are responsible for implementing national policies at the regional level and coordinating the activities of central government bodies. Provinces and municipalities are heavily dependent on the central government for funding. The capital city of Sofia, as Sofia City Province, also functions as a municipality (Stolichna Obshtina). Large cities like Sofia, Plovdiv, and Varna are further divided into districts (райониrayoniBulgarian) with elected district mayors.

The 28 provinces are:

- Blagoevgrad

- Burgas

- Dobrich

- Gabrovo

- Haskovo

- Kardzhali

- Kyustendil

- Lovech

- Montana

- Pazardzhik

- Pernik

- Pleven

- Plovdiv

- Razgrad

- Ruse

- Shumen

- Silistra

- Sliven

- Smolyan

- Sofia City

- Sofia Province (surrounds Sofia City)

- Stara Zagora

- Targovishte

- Varna

- Veliko Tarnovo

- Vidin

- Vratsa

- Yambol

5.7. Military

The Bulgarian Armed Forces are the military of Bulgaria and are composed of the Land Forces, Navy, and Air Force. As of 2021, the Armed Forces have approximately 36,950 active troops, supplemented by around 3,000 reservists. Military service is voluntary, as conscription was abolished in 2008.

The Land Forces consist of two mechanized brigades and eight independent regiments and battalions. The Air Force operates around 106 aircraft and various air defense systems across six air bases. The Navy operates a variety of ships, helicopters, and coastal defense weapons, primarily focused on the Black Sea.

Bulgaria's military inventory has historically consisted mainly of Soviet-era equipment, such as MiG-29 and Su-25 jets, S-300PT air defense systems, and SS-21 Scarab short-range ballistic missiles. However, as a NATO member since 2004, Bulgaria has been in the process of modernizing its armed forces to meet NATO standards. This includes the acquisition of new equipment such as F-16 Block 70 fighter jets, new multi-purpose corvettes, US-built Stryker armored vehicles, new 155 mm self-propelled howitzers, new 3D early-warning radars, and new surface-to-air missile systems.

Bulgaria's national defense policy is oriented towards collective defense within the NATO framework and participation in international peacekeeping and security operations. The country has contributed troops to various NATO, EU, and UN missions, including in Afghanistan and Kosovo. The US-Bulgarian Defence Cooperation Agreement, signed in April 2006, allows for the cooperative use of several Bulgarian military facilities (Bezmer Air Base, Graf Ignatievo Air Base, the Novo Selo Range, and a logistics center in Aytos) by the United States and Bulgarian militaries. These joint facilities support training and operational activities within the NATO alliance. Military expenditure in 2009 was around $1.19 billion, and has fluctuated since, generally aiming to meet NATO's guideline of 2% of GDP. Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Bulgaria has provided assistance to Ukraine and has taken steps to reduce its reliance on Russian military equipment and energy.

6. Foreign Relations

Bulgaria's foreign policy since 1989 has been strongly oriented towards Euro-Atlantic integration, focusing on its membership in the European Union and NATO, while navigating complex historical and contemporary relationships with regional and global powers, including Russia. The country aims to be a stabilizing factor in the Balkans and an active participant in international security and cooperation, though its foreign policy stances are sometimes influenced by domestic political considerations and public opinion shaped by historical ties.

6.1. Relations with the European Union

Membership in the European Union has been a cornerstone of Bulgarian foreign policy since the fall of communism. Aspirations to join European communities existed even during the late communist era under Todor Zhivkov by 1987. Bulgaria officially signed the EU Treaty of Accession on 25 April 2005, and became a full member of the European Union on 1 January 2007, alongside Romania.

As an EU member state, Bulgaria participates in the European Single Market and aligns its legislation with EU acquis. It has benefited from EU structural and cohesion funds aimed at infrastructure development, economic modernization, and institutional reform. However, Bulgaria's progress in areas such as judicial reform, combating corruption, and tackling organized crime has been subject to ongoing monitoring by the European Commission under the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM), which concluded in 2019, though concerns remain. Bulgaria partially joined the Schengen Area (for air and sea borders) in March 2024, with efforts ongoing for full accession including land borders. The country hosted the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2018. Bulgaria also engages in tripartite economic and diplomatic collaboration with fellow EU members Romania and Greece.

6.2. Relations with NATO

Integration into NATO was another key foreign policy objective for Bulgaria post-1989. Bulgaria joined NATO on 29 March 2004. As a member, Bulgaria participates in collective defense planning and operations, contributing to international security. The country has deployed troops in NATO-led missions, notably in Afghanistan.

The US-Bulgarian Defence Cooperation Agreement, signed in April 2006, allows for the joint use of several Bulgarian military facilities by the United States military, enhancing interoperability and regional security. These facilities include the Bezmer Air Base, Graf Ignatievo Air Base, the Novo Selo Range, and a logistics center in Aytos. Despite active international defense collaborations, Bulgaria generally ranks as a peaceful country in global indices.

6.3. Relations with Russia

Bulgaria and Russia share deep historical, cultural, and linguistic ties, stemming from Russia's role in Bulgaria's liberation from Ottoman rule in 1878 and shared Slavic Orthodox heritage. During the Communist era, Bulgaria was one of the Soviet Union's closest allies.

However, contemporary relations have become more complex, particularly following Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. As an EU and NATO member, Bulgaria has aligned with Western sanctions against Russia. Bulgaria has provided humanitarian and military assistance to Ukraine and has taken steps to reduce its significant historical energy dependence on Russia, including halting imports of Russian oil and gas in 2023 after Gazprom unilaterally stopped gas exports to Bulgaria. This shift has occurred amidst internal political debates reflecting divided public opinion, with some segments of society maintaining pro-Russian sentiments.

6.4. Relations with Neighboring Countries

Bulgaria seeks to maintain stable and cooperative relations with its Balkan neighbors: Romania, Serbia, North Macedonia, Greece, and Turkey.

- Romania: Relations are generally good, with cooperation within the EU and NATO frameworks. The Danube River forms a large part of their shared border.

- Serbia: Relations are stable, with ongoing economic and cultural exchanges.

- North Macedonia: Relations are complex due to historical, linguistic, and identity issues. Bulgaria was the first country to recognize North Macedonia's independence but has at times blocked its EU accession talks over disputes concerning shared history and language, and the rights of people identifying as Bulgarian in North Macedonia.

- Greece: Relations are strong, with close cooperation in trade, tourism, energy, and defense, particularly within the EU and NATO.

- Turkey: Relations are multifaceted, influenced by historical ties, the presence of a significant Turkish minority in Bulgaria, and shared interests in regional stability and economic cooperation, as well as challenges related to migration and security.

Bulgaria actively participates in regional cooperation initiatives in Southeastern Europe, aiming to promote stability, economic development, and good neighborly relations.

6.5. Relations with Other Key Nations

- United States: Relations are strong, particularly in defense and security cooperation through NATO and the bilateral Defence Cooperation Agreement. The US is a significant investor and partner in democratic and institutional reforms.

- China: Bulgaria maintains good diplomatic and economic ties with China, focusing on trade and investment, though these are balanced within the broader EU policy towards China.

- Vietnam: Bulgaria has historically good relations with Vietnam, stemming from cooperation during the Cold War era, particularly in education, with many Vietnamese having studied in Bulgaria.

Bulgaria became a member of the United Nations in 1955 and has served as a non-permanent member of the Security Council three times, most recently from 2002 to 2003. It was also among the founding nations of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in 1975.

7. Economy

Bulgaria possesses an open, high-income range market economy, where the private sector accounts for more than 70% of its GDP. The country has undergone significant economic transformation since the end of communism, marked by periods of growth, crisis, and ongoing efforts towards convergence with EU standards, while grappling with issues like income inequality and corruption.

7.1. Economic Structure and Trends

From a largely agricultural country with a predominantly rural population in 1948, Bulgaria had transformed into an industrial economy by the 1980s, with scientific and technological research prioritized in budgetary expenditure. The loss of COMECON markets in 1990 and the subsequent "shock therapy" applied to the planned system caused a steep decline in industrial and agricultural production, ultimately followed by an economic collapse and hyperinflation in 1997. The economy largely recovered during a period of rapid growth in the early 2000s, spurred by reforms and the prospect of EU membership. However, the average salary, at 2,072 Bulgarian leva (approximately 1.14 K USD) per month as of late 2023, remains the lowest in the EU, highlighting significant income disparities.

A balanced budget was achieved in 2003, and the country began running a surplus the following year. In 2017, expenditures amounted to 21.15 B USD and revenues were 21.67 B USD. Most government spending on institutions is earmarked for security (defense, interior, justice), while ministries responsible for the environment, tourism, and energy often receive less funding. Taxes form the bulk of government revenue, around 30% of GDP. Bulgaria has some of the lowest corporate income tax rates in the EU, with a flat 10% rate. The tax system is two-tier: VAT, excise duties, corporate and personal income tax are national, whereas real estate, inheritance, and vehicle taxes are levied by local authorities.

Strong economic performance in the early 2000s reduced government debt from 79.6% of GDP in 1998 to 14.1% in 2008. It has since increased but remained relatively low, at 22.6% of GDP by 2022, the second lowest in the EU. The Yugozapaden planning area, which includes the capital city Sofia and the surrounding Sofia Province, is the most developed region, with a per capita gross domestic product (PPP) of 29.82 K USD in 2018. Sofia alone generates 42% of the national GDP despite hosting only 22% of the population. In 2019, Bulgaria's GDP per capita (in PPS) stood at 53% of the EU average, and the cost of living was 52.8% of the EU average. The national PPP GDP was estimated at 143.10 B USD in 2016, with a per capita value of 20.12 K USD. Economic growth statistics take into account illegal transactions from the informal economy, which is reported to be one of the largest in the EU as a percentage of economic output. The Bulgarian National Bank issues the national currency, the lev (BGN), which is pegged to the euro at a rate of 1.95583 levа per euro. Bulgaria aims to adopt the Euro, but the timeline has been subject to delays.

After several consecutive years of high growth, repercussions of the financial crisis of 2007-2008 resulted in a 3.6% contraction of GDP in 2009 and increased unemployment. Positive growth was restored in 2010, but intercompany debt became a significant issue, exceeding 59.00 B USD in 2010 (meaning 60% of all Bulgarian companies were mutually indebted) and rising to 97.00 B USD (227% of GDP) by 2012. The government implemented strict austerity measures with IMF and EU encouragement, which yielded some positive fiscal results. However, the social consequences of these measures, such as increased income inequality and accelerated outward migration, have been described as "catastrophic" by the International Trade Union Confederation.

Siphoning of public funds due to corruption, particularly involving families and relatives of politicians from incumbent parties, has resulted in fiscal and welfare losses to society. Bulgaria consistently ranks poorly in the Corruption Perceptions Index (71st in one recent report) and experiences some of the worst levels of corruption in the European Union, a phenomenon that remains a source of profound public discontent. Along with organized crime, corruption has, at times, resulted in the rejection of the country's full Schengen Area application and has deterred foreign investment. Government officials have reportedly engaged in embezzlement, influence trading, government procurement violations, and bribery with relative impunity. Government procurement, in particular, is a critical area for corruption risk, with an estimated 10.00 B BGN (approximately 5.99 B USD) of state budget and European cohesion funds spent on public tenders each year; nearly 14.00 B BGN (approximately 8.38 B USD) were spent on public contracts in 2017 alone. A large share of these contracts are often awarded to a few politically connected companies amid widespread irregularities, procedure violations, and tailor-made award criteria. Despite repeated criticism from the European Commission, EU institutions have sometimes been seen as refraining from stronger measures against Bulgaria due to its support for Brussels on other issues, unlike countries such as Poland or Hungary. These issues of corruption directly affect social equity by diverting resources that could be used for public services and welfare, and undermine trust in democratic institutions.

7.2. Major Industries

Bulgaria's labor force is approximately 3.36 million people. As of recent estimates, 6.8% are employed in agriculture, 26.6% in industry, and 66.6% in the services sector.

Key industrial activities include the extraction of metals and minerals, production of chemicals, machine building (including components for vehicles), steel manufacturing, biotechnology, tobacco processing, food processing, and petroleum refining. The mining sector alone employs around 24,000 people directly and supports about 120,000 jobs in related industries, contributing approximately 5% to the country's GDP. Bulgaria is Europe's fifth-largest coal producer (mainly lignite). Local deposits of coal, iron ore, copper, and lead are vital for the manufacturing and energy sectors. The Kremikovtzi complex near Sofia was historically a major metallurgical center, though it has faced restructuring. Pernik and Debelt are other areas with metallurgical activities.

The development of these industries, particularly mining and heavy manufacturing, has significant environmental impacts, including air and water pollution, and land degradation, which require careful management and investment in cleaner technologies. Labor conditions in some industrial sectors have also been a concern, with issues related to wages and workplace safety. The services sector, including ICT, tourism, and retail, has become increasingly important for economic growth and employment.

7.3. Trade

Bulgaria's economy is highly open, with trade playing a crucial role. As a member of the European Union, its primary trading partners are other EU member states, particularly Germany, Italy, Romania, and Greece. Outside the EU, Bulgaria's main export destinations include Turkey, China, and Serbia. The largest import partners from outside the EU are Russia (historically for energy), Turkey, and China.

Bulgaria's main export commodities include manufactured goods (such as clothing and footwear), machinery and equipment, chemicals, fuel products (refined petroleum), base metals (copper, iron, steel), and food products (including grains, dairy, and processed foods). Two-thirds of its food and agricultural exports go to OECD countries.

Imports primarily consist of machinery and transport equipment, fuels and raw materials, chemicals, and manufactured goods. Bulgaria's foreign trade policy is aligned with that of the EU, benefiting from the European Single Market but also facing competition from other member states. Efforts to diversify export markets and improve the competitiveness of Bulgarian goods are ongoing.

7.4. Science and Technology

Bulgaria has a tradition of scientific and technological development, though it faces challenges related to funding and brain drain. Spending on research and development (R&D) amounts to approximately 0.78% of GDP, with the bulk of public R&D funding allocated to the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS). Private businesses accounted for more than 73% of R&D expenditures and employed 42% of Bulgaria's 22,000 researchers in 2015. In the Bloomberg Innovation Index of 2015, Bulgaria ranked 39th out of 50 countries, scoring highest in education (24th) but lower in value-added manufacturing (48th). In the Global Innovation Index 2024, Bulgaria was ranked 38th. Chronic government underinvestment in research since 1990 has forced many professionals in science and engineering to leave Bulgaria.

Despite funding challenges, research in chemistry, materials science, and physics remains relatively strong. Bulgaria actively participates in Antarctic research through the St. Kliment Ohridski Base on Livingston Island in Western Antarctica.

The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector is a significant and growing part of the Bulgarian economy, generating about 3% of economic output and employing between 40,000 and 51,000 software engineers. During the Soviet era, Bulgaria played a key role in COMECON computing technology production and was sometimes referred to as a "Communist Silicon Valley". The government's push for IT skills in schools also, paradoxically, made Bulgaria a notable source of computer viruses in the 1980s and 90s. The country is a regional leader in high-performance computing, operating Avitohol, formerly the most powerful supercomputer in Southeast Europe, and is set to host one of the eight petascale EuroHPC supercomputers.

Bulgaria has made numerous contributions to space exploration. These include two scientific satellites, more than 200 payloads and 300 experiments in Earth orbit, as well as two cosmonauts since 1971 (Georgi Ivanov in 1979 and Aleksandr Aleksandrov in 1988). Bulgaria was the first country to grow wheat in space with its Svet greenhouses on the Mir space station. It was involved in the development of the Granat gamma-ray observatory and the Vega program (modeling trajectories and guidance algorithms for Vega probes). Bulgarian instruments have been used in the exploration of Mars; a spectrometer took the first high-quality spectroscopic images of Mars's moon Phobos with the Phobos 2 probe. Cosmic radiation en route to and around Mars has been mapped by Liulin-ML dosimeters on the ExoMars TGO. Variants of these instruments have also been fitted on the International Space Station and the Chandrayaan-1 lunar probe. The SpaceIL lunar mission Beresheet was also equipped with a Bulgarian-manufactured imaging payload. Bulgaria's first geostationary communications satellite, BulgariaSat-1, was launched by SpaceX in 2017.

7.5. Infrastructure

Bulgaria's infrastructure, encompassing transportation, energy, and telecommunications, has seen development and modernization efforts, particularly since its EU accession, though challenges remain.

Telecommunications: Telephone services are widely available, with a central digital trunk line connecting most regions. Vivacom (formerly BTC) serves more than 90% of fixed lines and is one of the three major mobile service operators, alongside A1 (formerly Mtel) and Yettel (formerly Telenor). Internet penetration stood at 69.2% of the population aged 16-74 and 78.9% of households in 2020, with ongoing efforts to expand broadband access.

Energy: Bulgaria's strategic geographic location and a relatively well-developed energy sector make it a key European energy center, despite its lack of significant fossil fuel deposits. In recent years, thermal power plants (mainly lignite-fired) generated approximately 48.9% of electricity, followed by nuclear power from the Kozloduy reactors (around 34.8%), and renewable sources (around 16.3%, including hydro, solar, and wind). Equipment for a second nuclear power station at Belene has been acquired, but the project's fate remains uncertain due to financial and political considerations. Bulgaria's installed electricity generation capacity amounts to roughly 12,668 MW, allowing the country to exceed domestic demand and export energy at times. The country is working to diversify its energy sources and reduce reliance on Russian gas, partly by developing interconnectors with neighboring countries.

Transportation:

- Roads: The national road network has a total length of approximately 12 K mile (19.51 K km), of which about 12 K mile (19.23 K km) are paved. Efforts are underway to expand and upgrade the motorway network, which includes key routes like the Trakia (A1), Hemus (A2), Struma (A3), and Maritsa (A4) motorways. As of recent data, around 441 km of motorways were operational, with more under construction or planned.

- Railways: Railroads are a major mode of freight transportation, although highways carry a progressively larger share. Bulgaria has approximately 3.9 K mile (6.24 K km) of railway track (around 4,294 km of main lines), with over 60% electrified. Rail links are available to Romania, Turkey, Greece, and Serbia, and express trains serve direct routes to cities like Kyiv, Minsk, Moscow, and Saint Petersburg, though international services have been impacted by geopolitical events. Modernization of key railway lines, such as Plovdiv-Burgas and Sofia-Vidin, is ongoing with EU funding.

- Airports: Sofia is the country's main air travel hub. Other international airports are located in Varna, Burgas, and Plovdiv. Smaller airports like Gorna Oryahovitsa and Rousse serve limited traffic.

- Ports: Varna and Burgas are the principal maritime trade ports on the Black Sea. River ports on the Danube, such as Ruse and Lom, also handle freight.

Infrastructure development is crucial for economic growth, regional connectivity, and social equity, but projects can sometimes be affected by corruption and administrative delays.

7.6. Tourism

Tourism is a significant contributor to the Bulgarian economy, leveraging the country's diverse offerings, including its Black Sea coast, mountain resorts, cultural heritage, and spa facilities. In 2008, Bulgaria was visited by 8.9 million tourists, and while numbers fluctuate, the sector has generally grown. Pre-pandemic, in 2019, international tourist arrivals reached nearly 9.3 million.

Key tourist destinations include:

- Black Sea Resorts: Albena, Golden Sands, Sunny Beach, Sozopol, and Nesebar are popular for their beaches, nightlife, and family-friendly amenities.

- Ski Areas/Winter Resorts: Bansko, Pamporovo, and Borovets in the Rila, Pirin, and Rhodope mountains offer skiing, snowboarding, and other winter sports.

- Cultural Heritage Sites: Cities like Sofia (the capital, with numerous museums and churches), Plovdiv (one of Europe's oldest cities, European Capital of Culture 2019, with a Roman theatre and charming Old Town), and Veliko Tarnovo (the medieval capital, with Tsarevets Fortress) are major attractions. The Rila Monastery, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is a significant spiritual and cultural landmark. Other UNESCO sites include Thracian tombs, Orthodox churches, and ancient cities.

- Rural and Eco-Tourism: Villages like Arbanasi and Bozhentsi preserve traditional Bulgarian architecture and ethnographic traditions. National parks and protected areas offer opportunities for hiking, wildlife observation, and nature-based tourism.

- Spa and Wellness Tourism: Bulgaria has numerous mineral springs, leading to the development of spa resorts in towns like Velingrad, Hisarya, and Sandanski.

The majority of international visitors traditionally come from neighboring countries such as Romania, Greece, and Turkey, as well as from Germany, the United Kingdom, Russia, Poland, Serbia, and the Netherlands. The government promotes tourism through initiatives like the 100 Tourist Sites of Bulgaria system, which encourages visits to important cultural and natural landmarks. The tourism industry provides significant employment and foreign currency earnings but also faces challenges related to seasonality, infrastructure development in some areas, and the need for sustainable practices to protect natural and cultural resources. The COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted the sector, with ongoing recovery efforts.

8. Demographics

Bulgaria's demographic landscape is characterized by a declining population, an aging populace, and diverse ethnic and religious compositions. These trends present significant social and economic challenges, including pressures on social welfare systems and the labor market, alongside ongoing efforts to ensure minority rights and social integration.

8.1. Population Statistics and Urbanization

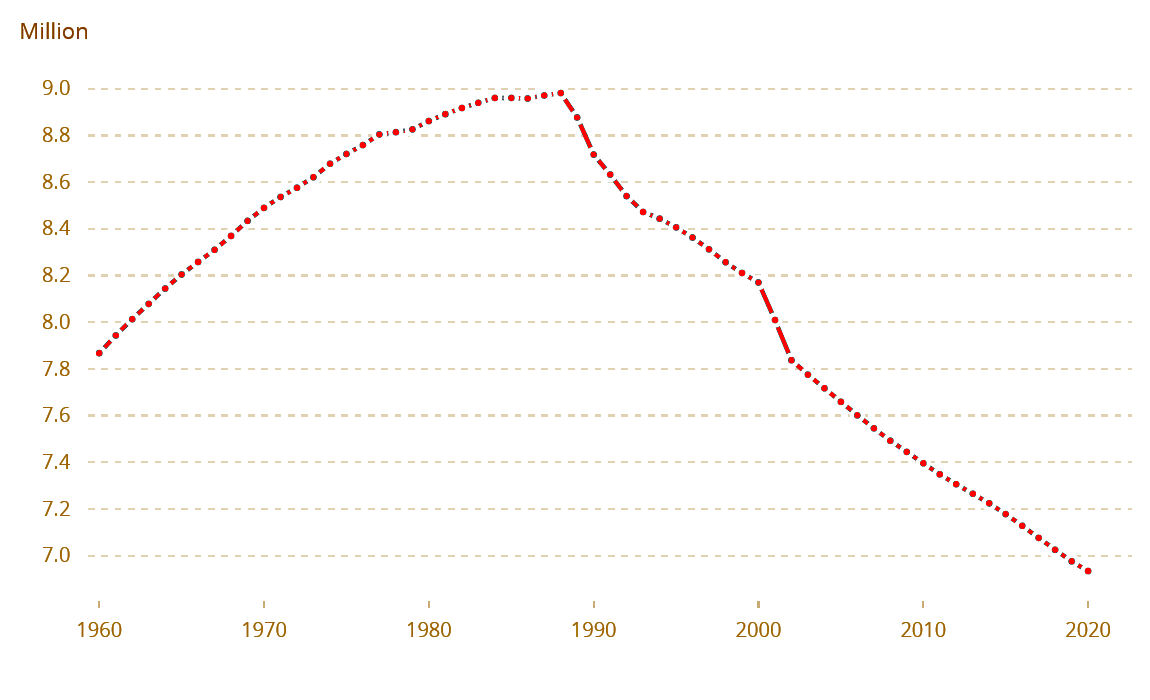

According to the government's official estimate for 2022, the population of Bulgaria was 6,447,710, a decrease from the 6,519,789 recorded in the 2021 census. This continues a trend of population decline that began in the late 1980s. In 1985, Bulgaria recorded its peak population of approximately 8.95 million. The majority of the population, 72.5% according to the 2011 census, resides in urban areas.

As of 2019, the largest urban centers were:

- Sofia (capital): 1,241,675 people

- Plovdiv: 346,893 people

- Varna: 336,505 people

- Burgas: 202,434 people

- Ruse: 142,902 people

Bulgaria is experiencing a significant demographic crisis, characterized by negative population growth since 1989. This is attributed to the post-Cold War economic collapse, which caused a long-lasting emigration wave (an estimated 937,000 to 1,200,000 people, mostly young adults, had left by 2005), coupled with low birth rates. The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2024 was estimated at 1.59 children per woman. While this is an increase from 1.56 in 2018 and well above the all-time low of 1.1 in 1997, it remains below the replacement rate of 2.1 and considerably below the historical high of 5.83 children per woman in 1905. A notable social trend is that the majority of children are born to unmarried women.

Consequently, Bulgaria has one of the oldest populations in the world, with an average age of 43 years. A third of all households consist of only one person, and 75.5% of families do not have children under the age of 16. The country's birth rates are among the lowest globally, while its death rates are among the highest. This demographic situation poses serious challenges for the labor market, social security systems, and healthcare provision.

Despite these demographic challenges, Bulgaria scores relatively high in gender equality, ranking 18th in the 2018 Global Gender Gap Report. Women's suffrage was enabled in 1937. Women today have equal political rights, high workforce participation, and legally mandated equal pay. In 2021, one market research agency ranked Bulgaria as the best European country for women to work. Bulgaria has the highest ratio of female ICT researchers in the EU and the second-highest ratio of females in the technology sector (44.6% of the workforce), a legacy partly attributed to policies during the Socialist era that encouraged female participation in technical fields.

| City | Province | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Sofia | Sofia-Capital | 1,196,806 |

| Plovdiv | Plovdiv | 325,485 |

| Varna | Varna | 314,607 |

| Burgas | Burgas | 188,114 |

| Ruse | Ruse | 122,116 |

| Stara Zagora | Stara Zagora | 121,207 |

| Pleven | Pleven | 89,030 |

| Sliven | Sliven | 78,627 |

| Dobrich | Dobrich | 70,411 |

| Shumen | Shumen | 67,300 |

8.2. Ethnic Composition

According to the 2021 census, Bulgarians are the main ethnic group, constituting 84.57% of the population (or 84.6% of those who declared an ethnicity). The two largest minorities are Turks (8.40% or 8.4% of declared) and Roma (4.41% or 4.4% of declared). Approximately 40 smaller minorities account for 1.31% (or 1.3% of declared), and another 1.31% (or 1.3% of declared) did not self-identify with an ethnic group. Other minorities include Russians, Armenians, Vlachs (Romanians), Sarakatsani (Greeks), Ukrainians, Jews, and Tatars.

The Roma minority is often believed to be underestimated in official census data due to factors such as social stigma and self-identification with other groups; some estimates suggest the Roma population may represent up to 10-11% of the total population, or around 750,000 people. The Turkish minority is concentrated mainly in the Kardzhali, Shumen, Silistra, Razgrad, and Targovishte provinces. Roma communities are present throughout the country but often face significant socio-economic disadvantages, discrimination, and challenges in accessing education, healthcare, and employment, which are critical issues for social integration and minority rights.