1. Early Life and Background

Louis Mountbatten's early life was shaped by his royal lineage and a significant family name change during a period of intense national sentiment.

1.1. Birth and Family

Mountbatten was born Prince Louis of Battenberg on 25 June 1900 at Frogmore House in Home Park, Windsor, Berkshire. He was the youngest child and second son of Prince Louis of Battenberg and his wife, Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine. His maternal grandparents were Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse, and Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, who was a daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. His paternal grandparents were Prince Alexander of Hesse and by Rhine and Julia, Princess of Battenberg. The marriage of his paternal grandparents was considered morganatic because his grandmother was not of royal lineage. Consequently, he and his father were styled "Serene Highness" rather than "Grand Ducal Highness," were not eligible for the title Princes of Hesse, and were given the less exalted Battenberg title.

Mountbatten's elder siblings were Princess Alice of Battenberg (mother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh), Princess Louise of Battenberg (later Queen Louise of Sweden), and Prince George of Battenberg (later George Mountbatten, 2nd Marquess of Milford Haven). He was baptized in the large drawing room of Frogmore House on 17 July 1900 by the Dean of Windsor, Philip Eliot. His godparents included Queen Victoria (his maternal great-grandmother), Nicholas II of Russia (his maternal uncle through marriage and paternal second cousin, represented by the child's father), and Prince Francis Joseph of Battenberg (his paternal uncle, represented by Lord Edward Clinton). He wore the original 1841 royal christening gown at the ceremony.

1.2. Childhood and Education

Mountbatten, nicknamed "Dickie" by family and friends (a change from "Nicky" suggested by Queen Victoria to avoid confusion with the many Nickys in the Russian Imperial Family, especially Nicholas II), was educated at home for the first 10 years of his life. He was then sent to Lockers Park School in Hertfordshire and subsequently to the Royal Naval College, Osborne, in May 1913. After his naval service in World War I, he briefly attended Christ's College, Cambridge, for two terms starting in October 1919, where he studied English literature, including works by John Milton and Lord Byron. This program was designed to augment the education of junior officers whose schooling had been curtailed by the war. He was elected for a term to the Standing Committee of the Cambridge Union Society and was suspected of sympathy for the Labour Party, which was then emerging as a potential party of government.

Mountbatten's mother's younger sister was Russian Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. In his childhood, he visited the Imperial Court of Russia in St Petersburg and became intimate with the Russian Imperial Family. He harbored romantic feelings towards his maternal first cousin Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, whose photograph he kept at his bedside for the rest of his life.

1.3. Name Change

Mountbatten adopted his surname as a direct result of World War I. From 1914 to 1918, Britain and its allies were at war with the Central Powers, led by the German Empire. To appease British nationalist sentiment and distance the monarchy from its German roots, King George V issued a royal proclamation in 1917, changing the name of the British royal house to the House of Windsor. The King's British relatives with German names and titles followed suit. Mountbatten's father adopted the surname Mountbatten, an anglicization of Battenberg. The elder Mountbatten was subsequently created Marquess of Milford Haven. This change meant that in June 1917, Mountbatten acquired the courtesy title appropriate to a younger son of a marquess, becoming known as Lord Louis Mountbatten (or Lord Louis for short) until he was created a peer in his own right in 1946.

3. Viceroy and Governor-General of India

Mountbatten's tenure in India was dominated by the complex and ultimately tragic process of the Partition of India.

3.1. Appointment as Viceroy and Mandate

Mountbatten's experience in the region and his perceived Labour sympathies at that time, along with his wife's longstanding friendship and collaboration with V. K. Krishna Menon, led to Menon proposing Mountbatten as a viceregal candidate acceptable to the Indian National Congress in clandestine meetings with Sir Stafford Cripps and Clement Attlee. Attlee advised King George VI to appoint Mountbatten Viceroy of India on 20 February 1947, charged with overseeing the transition of British India to independence no later than 30 June 1948. Mountbatten's instructions were to avoid partition and preserve a united India as a result of the transfer of power, but he was authorized to adapt to a changing situation to ensure Britain's prompt withdrawal with minimal reputational damage. The mandate also included observing pledges to the princes and Muslims, securing agreement to the Cabinet Mission plan without coercing any parties, keeping the Indian army undivided, and retaining India within the Commonwealth.

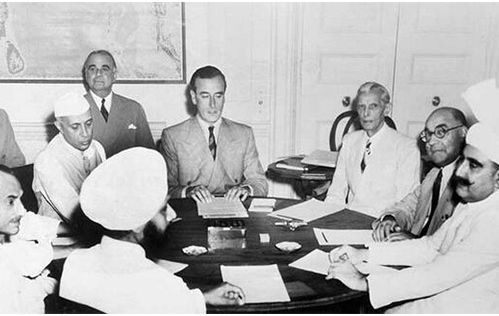

3.2. Partition of India

Mountbatten arrived in India on 22 March 1947. His arrival coincided with large-scale communal riots in Delhi, Bombay, and the Rawalpindi. Mountbatten concluded that the situation was too volatile to wait even a year before granting independence to India. Although his advisers favored a gradual transfer of independence, Mountbatten decided the only way forward was a quick and orderly transfer of power before the end of 1947. In his view, any longer would mean civil war. He also hurried the process as he desired to return to the Royal Navy.

Mountbatten was fond of Congress leader Jawaharlal Nehru and his liberal outlook for the country. Through the efforts of their close mutual friend, Krishna Menon, Mountbatten developed a certain depth of feeling and intimacy with Nehru, which was shared by his wife, Edwina. He felt differently about the Muslim League leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah, but was aware of his power, stating, "If it could be said that any single man held the future of India in the palm of his hand in 1947, that man was Mohammad Ali Jinnah." During his meeting with Jinnah on 5 April 1947, Mountbatten tried to persuade him of a united India, citing the difficult task of dividing the mixed states of Punjab and Bengal, but the Muslim leader was unyielding in his goal of establishing a separate Muslim state called Pakistan.

Given the British government's recommendations to grant independence quickly, Mountbatten concluded that a united India was an unachievable goal and resigned himself to a plan for partition, creating the independent nations of India and Pakistan. Mountbatten set the date for the transfer of power from the British to the Indians, arguing that a fixed timeline would convince Indians of his and the British government's sincerity in working towards swift and efficient independence, excluding all possibilities of stalling the process.

Among the Indian leaders, Mahatma Gandhi emphatically insisted on maintaining a united India and for a while successfully rallied people to this goal. During his meeting with Mountbatten, Gandhi asked Mountbatten to invite Jinnah to form a new central government, but Mountbatten never conveyed Gandhi's ideas to Jinnah. When Mountbatten's timeline offered the prospect of attaining independence soon, sentiments took a different turn. Given Mountbatten's determination, Nehru and Sardar Patel's inability to deal with the Muslim League, and Jinnah's obstinacy, all Indian party leaders (except Gandhi) acquiesced to Jinnah's plan to divide India, which in turn eased Mountbatten's task. Mountbatten also developed a strong relationship with the Indian princes, who ruled those portions of India not directly under British rule. His intervention was decisive in persuading the vast majority of them to see advantages in opting to join the Indian Union. While the integration of the princely states can be viewed as one of the positive aspects of his legacy, the refusal of Hyderabad, Jammu and Kashmir, and Junagadh to join one of the dominions led to future wars between Pakistan and India.

Mountbatten brought forward the date of the partition from June 1948 to 15 August 1947. The uncertainty of the borders caused Muslims and Hindus to move towards areas where they felt they would be in the majority. Hindus and Muslims were thoroughly terrified, and the Muslim movement from the East was balanced by the similar movement of Hindus from the West. A boundary committee chaired by Sir Cyril Radcliffe was charged with drawing boundaries for the new nations. With a mandate to leave as many Hindus and Sikhs in India and as many Muslims in Pakistan as possible, Radcliffe produced a map that split the two countries along the Punjab and Bengal borders. This left 14 M people on the "wrong" side of the border, and many of them fled to "safety" on the other side when the new lines were announced, leading to widespread violence and displacement.

3.3. First Governor-General of India

When India and Pakistan attained independence at midnight of 14-15 August 1947, Mountbatten was alone in his study at the Viceroy's house, reflecting that for a few more minutes, he was the most powerful man on Earth. At 12 AM, as a last act of showmanship, he created Joan Falkiner, the Australian wife of the Nawab of Palanpur, a highness, an act that was apparently one of his favorite duties and which was annulled at the stroke of midnight.

Notwithstanding the self-promotion of his own part in Indian independence-notably in the television series The Life and Times of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Mountbatten of Burma, produced by his son-in-law Lord Brabourne, and Freedom at Midnight by Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins (of which he was the main quoted source)-his record is seen as very mixed. One common view, held by critics such as John Kenneth Galbraith, is that he hastened the process of independence unduly and recklessly, foreseeing vast disruption and loss of life and not wanting this to occur on his watch, but thereby actually helping it to occur (albeit indirectly), especially in Punjab and Bengal. However, another view is that the British were forced to expedite the partition process to avoid involvement in a potential civil war, with law and order having already broken down and Britain having limited resources after the Second World War. According to historian Lawrence James, Mountbatten was left with no other option but to withdraw quickly, as the alternative would have been involvement in a protracted and difficult civil war.

The creation of Pakistan was never emotionally accepted by many British leaders, including Mountbatten. He clearly expressed his lack of support and faith in the Muslim League's idea of Pakistan. Jinnah refused Mountbatten's offer to serve as Governor-General of Pakistan. When Mountbatten was asked if he would have sabotaged the creation of Pakistan had he known that Jinnah was dying of tuberculosis, he replied, "Most probably."

Mountbatten became the first Governor-General of independent India on 15 August 1947 at the request of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Life magazine noted on his reception in India that, "The people gathered in the streets to cheer Mountbatten as no European had ever been cheered before." During his reign as governor-general until 21 June 1948, he played a significant role in the political integration of India and persuaded many princely states to join India. On Mountbatten's advice, India took the issue of Kashmir to the newly formed United Nations in January 1948. Accounts differ on the future Mountbatten desired for Kashmir. Pakistani accounts suggest that Mountbatten favored the accession of Kashmir to India, citing his close relationship to Nehru. Mountbatten's own account states that he simply wanted Maharaja Hari Singh to make up his mind. The viceroy made several attempts to mediate between the Congress leaders, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and Hari Singh on issues relating to the accession of Kashmir, though he was largely unsuccessful in resolving the conflict. After the tribal invasion of Kashmir, it was on his suggestion that India moved to secure the accession of Kashmir from Hari Singh before sending in military forces for his defense.

After his tenure as governor-general concluded, Mountbatten continued to enjoy close relations with Nehru and the post-Independence Indian leadership, and was welcomed as a former governor-general of India on subsequent visits to the country, including during an official trip in March 1956. The Pakistani government, by contrast, lacked a positive view of Mountbatten for his perceived hostile attitude towards Pakistan and deemed him persona non grata, barring him from transiting their airspace during the same visit.

4. Later Career and Public Service

Following his significant role in India, Mountbatten continued to serve in high-ranking naval and public service positions.

4.2. First Sea Lord

Mountbatten served his final posting at the Admiralty as First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff from April 1955 to July 1959, a position his father had held some forty years prior. This was the first time in Royal Naval history that a father and son had both attained such high office. He was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on 22 October 1956.

During the Suez Crisis of 1956, Mountbatten strongly advised his old friend Prime Minister Anthony Eden against the Conservative government's plans to seize the Suez Canal in conjunction with France and Israel. He argued that such a move would destabilize the Middle East, undermine the authority of the United Nations, divide the Commonwealth, and diminish Britain's global standing. His advice was not taken. Eden insisted that Mountbatten not resign, and instead, he worked hard to prepare the Royal Navy for war with characteristic professionalism and thoroughness.

Despite his military rank, Mountbatten was initially ignorant of the physics involved in a nuclear explosion and had to be reassured that the fission reactions from the Bikini Atoll tests would not spread through the oceans and destroy the planet. As Mountbatten became more familiar with this new form of weaponry, he increasingly opposed its use in combat. Yet, he realized the potential for nuclear energy, especially with regard to submarines. Mountbatten expressed his feelings towards the use of nuclear weapons in combat in his article "A Military Commander Surveys The Nuclear Arms Race," published shortly after his death in International Security in Winter 1979-1980.

4.3. Chief of the Defence Staff

After leaving the Admiralty, Mountbatten took the position of Chief of the Defence Staff. He served in this post for six years, during which he was able to consolidate the three service departments of the military branch into a single Ministry of Defence. Ian Jacob, co-author of the 1963 Report on the Central Organisation of Defence that served as the basis of these reforms, described Mountbatten as "universally mistrusted in spite of his great qualities." Upon their election in October 1964, the Wilson ministry had to decide whether to renew his appointment the following July. The Defence Secretary, Denis Healey, interviewed the forty most senior officials in the Ministry of Defence; only one, Sir Kenneth Strong, a personal friend of Mountbatten, recommended his reappointment. Healey recalled, "When I told Dickie of my decision not to reappoint him, he slapped his thigh and roared with delight; but his eyes told a different story."

4.4. Other Public Offices

Mountbatten was appointed Colonel of The Life Guards and Gold Stick in Waiting on 29 January 1965, and Life Colonel Commandant of the Royal Marines the same year. He was Governor of the Isle of Wight from 20 July 1965 and then the first Lord Lieutenant of the Isle of Wight from 1 April 1974.

Mountbatten was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and received an honorary doctorate from Heriot-Watt University in 1968. In 1969, Mountbatten tried unsuccessfully to persuade his second cousin, the Spanish pretender Infante Juan, Count of Barcelona, to ease the eventual accession of his son, Juan Carlos, to the Spanish throne by signing a declaration of abdication while in exile. The next year, Mountbatten attended an official White House dinner during which he had a 20-minute conversation with Richard Nixon and Secretary of State William P. Rogers, later writing, "I was able to talk to the President a bit about both Tino [Constantine II of Greece] and Juanito [Juan Carlos of Spain] to try and put over their respective points of view about Greece and Spain, and how I felt the US could help them." In January 1971, Nixon hosted Juan Carlos and his wife Sofia (sister of the exiled King Constantine) during a visit to Washington, and later that year, The Washington Post published an article alleging that Nixon's administration was seeking to persuade Franco to retire in favor of the young Bourbon prince.

From 1967 until 1978, Mountbatten was president of the United World Colleges Organisation, then represented by a single college: Atlantic College in South Wales. Mountbatten supported the United World Colleges and encouraged heads of state, politicians, and personalities worldwide to share his interest. Under his presidency and personal involvement, the United World College of South East Asia was established in Singapore in 1971, followed by the United World College of the Pacific in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1974. In 1978, Mountbatten passed the presidency of the college to his great-nephew, Charles, Prince of Wales.

Mountbatten also helped launch the International Baccalaureate; in 1971, he presented the first IB diplomas in the Greek Theatre of the International School of Geneva, Switzerland. In 1975, Mountbatten finally visited the Soviet Union, leading the delegation from the UK as personal representative of Queen Elizabeth II at the celebrations to mark the 30th anniversary of Victory Day in the Second World War in Moscow.

5. Personal Life

Mountbatten's personal life was characterized by a complex marriage, various relationships, and later, serious allegations, alongside his role as a mentor and his diverse leisure interests.

5.1. Marriage and Family

Mountbatten was married on 18 July 1922 to Edwina Cynthia Annette Ashley, daughter of Wilfred William Ashley, later 1st Baron Mount Temple, and a grandson of the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. She was the favorite granddaughter of the Edwardian magnate Sir Ernest Cassel and the principal heir to his fortune. The couple spent heavily on households, luxuries, and entertainment. Their honeymoon tour of European royal courts and North America included a visit to Niagara Falls (because "all honeymooners went there"). During their honeymoon in California, the newlyweds starred in a silent home movie by Charlie Chaplin called Nice And Friendly, which was not shown in cinemas.

Mountbatten admitted: "Edwina and I spent all our married lives getting into other people's beds." He maintained an affair for several years with Yola Letellier, the wife of Henri Letellier, publisher of Le Journal and mayor of Deauville (1925-28). Yola Letellier's life story was the inspiration for Colette's novel Gigi.

After Edwina died in 1960, Mountbatten was involved in relationships with young women, according to his daughter Patricia, his secretary John Barratt, his valet Bill Evans, and William Stadiem, an employee of Madame Claude. He had a long-running affair with American actress Shirley MacLaine, whom he met in the 1960s.

Lord and Lady Mountbatten had two daughters: Patricia Knatchbull (14 February 1924 - 13 June 2017), sometime lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth II, and Lady Pamela Hicks (born 19 April 1929), who accompanied them to India in 1947-1948 and was also sometime lady-in-waiting to the Queen. Since Mountbatten had no sons when he was created Viscount Mountbatten of Burma, of Romsey in the County of Southampton on 27 August 1946, and then Earl Mountbatten of Burma and Baron Romsey, in the County of Southampton on 18 October 1947, the Letters Patent were drafted such that in the event he left no sons or male issue, the titles could pass to his daughters, in order of seniority of birth.

5.2. Relationships and Controversies

Mountbatten's personal life has been subject to various allegations and controversies, particularly concerning his sexual conduct. In 2019, Ron Perks, Mountbatten's driver in Malta in 1948, alleged that he used to visit the Red House, an upmarket gay brothel in Rabat frequented by naval officers. Andrew Lownie, a fellow of the Royal Historical Society, wrote that the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) maintained files regarding Mountbatten's alleged homosexuality. Lownie also interviewed several young men who claimed to have been in a relationship with Mountbatten. However, John Barratt, Mountbatten's personal and private secretary for 20 years, stated that Mountbatten was not homosexual and that such a fact could not have been hidden from him.

In 2019, files became public showing that the FBI knew in the 1940s of allegations that Mountbatten was homosexual and a paedophile. The FBI file on Mountbatten, begun after he took on the role of Supreme Allied Commander in Southeast Asia in 1944, describes Mountbatten and his wife Edwina as "persons of extremely low morals," and contains a claim by American author Elizabeth, Baroness Decies, that Mountbatten was known to be a homosexual and had "a perversion for young boys." Norman Nield, Mountbatten's driver from 1942 to 1943, told the tabloid New Zealand Truth that he transported young boys aged 8 to 12 who had been procured for the Admiral to Mountbatten's official residence and was paid to keep quiet. Robin Bryans also claimed to the Irish magazine Now that Mountbatten and Anthony Blunt, among others, were part of a ring that engaged in homosexual orgies and procured boys in their first year at public schools such as the Portora Royal School in Enniskillen. Former residents of the Kincora Boys' Home in Belfast have asserted that they were trafficked to Mountbatten at Classiebawn Castle, his residence in Mullaghmore, County Sligo. These claims were dismissed by the Historical Institution Abuse (HIA) Inquiry, which stated that the article making the original allegations "did not give any basis for the assertions that any of these people [Mountbatten and others] were connected with Kincora."

In October 2022, Arthur Smyth, a former resident of Kincora, waived his anonymity to make allegations of child abuse against Mountbatten. The allegations are part of a civil case against state authorities responsible for the care of children in Kincora. Smyth claims that he was raped twice by Mountbatten in encounters facilitated by the house father of Kincora.

5.3. Mentorship of Prince Charles

Mountbatten was a strong influence in the upbringing of his great-nephew, the future King Charles III, and later served as a mentor-"Honorary Grandfather" and "Honorary Grandson," they fondly called each other. However, according to biographies by Jonathan Dimbleby and Philip Ziegler, the results may have been mixed. Mountbatten from time to time strongly upbraided the Prince for showing tendencies towards the idle pleasure-seeking dilettantism of his predecessor as Prince of Wales, King Edward VIII, whom Mountbatten had known well in their youth. Yet he also encouraged the Prince to enjoy the bachelor life while he could, and then to marry a young and inexperienced girl to ensure a stable married life.

Mountbatten's qualification for offering advice to this particular heir to the throne was unique. It was he who had arranged the visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to Dartmouth Royal Naval College on 22 July 1939, taking care to include the young Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret in the invitation, but assigning his nephew, Cadet Prince Philip of Greece, to keep them amused while their parents toured the facility. This was the first recorded meeting of Charles's future parents. A few months later, Mountbatten's efforts nearly came to naught when he received a letter from his sister Alice in Athens informing him that Philip was visiting her and had agreed to repatriate permanently to Greece. Within days, Philip received a command from his cousin and sovereign, King George II of Greece, to resume his naval career in Britain, which, though given without explanation, the young prince obeyed.

In 1974, Mountbatten began corresponding with Charles about a potential marriage to his granddaughter, Amanda Knatchbull, who was also Charles's second cousin. It was about this time he also recommended that the 25-year-old prince get on with "sowing some wild oats." Charles dutifully wrote to Amanda's mother (who was also his godmother and his father's first cousin), Lady Brabourne, about his interest. Her answer was supportive, but advised him that she thought her daughter was still rather young to be courted. In February 1975, Charles visited New Delhi to play polo and was shown around Rashtrapati Bhavan, the former Viceroy's House, by Mountbatten.

Four years later, Mountbatten secured an invitation for himself and Amanda to accompany Charles on his planned 1980 tour of India. Their fathers promptly objected. Prince Philip thought that the Indian public's reception would more likely reflect their response to the uncle than to the nephew. Lord Brabourne counseled that the intense scrutiny of the press would be more likely to drive Mountbatten's godson and granddaughter apart than together. Charles was rescheduled to tour India alone, but Mountbatten did not live to the planned date of departure. When Charles finally did propose marriage to Amanda later in 1979, the circumstances had changed, and she refused him.

5.4. Leisure Interests

Mountbatten was passionate about genealogy, an interest he shared with other European royalty and nobility; according to Ziegler, he spent a great deal of his leisure time studying his links with European royal houses. From 1957 until his death, Lord Mountbatten was Patron of the Cambridge University Heraldic and Genealogical Society. He was equally passionate about orders, decorations, military ranks, and uniforms, though he considered this interest a sign of vanity and constantly tried to distance himself from it, with limited success. Over the course of his career, he consistently attempted to secure as many orders and decorations as possible. Particular about details of dress, Mountbatten took an interest in fashion design, introducing trouser zips, a tail-coat with broad, high lapels, and a "buttonless waistcoat" that could be pulled on over the head. In 1949, having by then relinquished the office of Governor-General of India but retaining a keen interest in Indian affairs, he designed new flags, insignia, and uniform details for the Indian Armed Forces ahead of the transition from British dominion to republic; many of his designs were implemented and remain in use.

Like many members of the royal family, Mountbatten was an aficionado of polo. He introduced the sport to the Royal Navy in the 1920s and wrote a book on the subject. He received US patent 1,993,334 in 1931 for a polo stick. He also served as Commodore of Emsworth Sailing Club in Hampshire from 1931. He was a long-serving Patron of the Society for Nautical Research (1951-1979). Apart from official documents, Mountbatten was not much of a reader, though he liked P. G. Wodehouse's books. He enjoyed the cinema; his favorite stars were Fred Astaire, Rita Hayworth, Grace Kelly, and Shirley MacLaine. In general, however, he had a limited interest in the arts.

6. Assassination

Lord Mountbatten's life ended tragically in an assassination by the Provisional Irish Republican Army.

6.1. The Incident

Mountbatten usually holidayed at his summer home, Classiebawn Castle, on the Mullaghmore Peninsula in County Sligo, in the north-west of Ireland. The village was only 12 mile from the border with County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland and near an area known to be used as a cross-border refuge by IRA members. In 1978, the IRA had allegedly attempted to shoot Mountbatten as he was aboard his boat, but poor weather had prevented the sniper from taking his shot.

On 27 August 1979, Mountbatten went lobster-potting and tuna fishing in his 30 ft wooden boat, Shadow V, which had been moored in the harbor at Mullaghmore. IRA member Thomas McMahon had slipped onto the unguarded boat the previous night and attached a radio-controlled bomb weighing 50 lb (50 lb). When Mountbatten and his party had taken the boat just a few hundred yards from the shore, the bomb was detonated. The boat was destroyed by the force of the blast, and Mountbatten's legs were almost blown off. Mountbatten, then aged 79, was pulled alive from the water by nearby fishermen, but died from his injuries before being brought to shore.

6.2. Victims

Also aboard the boat were his elder daughter Patricia, Lady Brabourne; her husband Lord Brabourne; their twin sons Nicholas and Timothy Knatchbull; Lord Brabourne's mother Doreen, Dowager Lady Brabourne; and Paul Maxwell, a young crew member from Enniskillen in County Fermanagh. Nicholas (aged 14) and Paul (aged 15) were killed by the blast, and the others were seriously injured. Doreen, Dowager Lady Brabourne (aged 83), died from her injuries the following day.

6.3. Aftermath

The attack triggered outrage and condemnation around the world. Queen Elizabeth II received messages of condolence from leaders including US President Jimmy Carter and Pope John Paul II. Carter expressed his "profound sadness" at the death. The Irish American community was disgusted with the attack, especially since many American soldiers served under Mountbatten during World War II. Jim Rooney, son of Pittsburgh Steelers president Dan M. Rooney (who co-founded The Ireland Funds in 1976), recalled that: "Mountbatten's murder shocked many Irish-Americans, my parents included, because they remembered him for the role he played in defeating the Axis. 'It was quite sad because being in America, you were familiar with Lord Mountbatten because of World War II,' my mother recalled. 'It was a very sad time.' But my father didn't give in to despair. 'That didn't slow down [my father] one bit. It more or less gave him more energy,' my mother said."

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said: "His death leaves a gap that can never be filled. The British people give thanks for his life and grieve at his passing." George Colley, the Tánaiste (Deputy head of the Government of Ireland), said: "No effort will be spared to bring those responsible to justice. It is understood that subversives have claimed responsibility for the explosion. Assuming that police investigations substantiate the claim, I know that the Irish people will join me in condemning this heartless and terrible outrage."

The IRA issued a statement afterward, saying: "The IRA claim responsibility for the execution of Lord Louis Mountbatten. This operation is one of the discriminate ways we can bring to the attention of the English people the continuing occupation of our country. The death of Mountbatten and the tributes paid to him will be seen in sharp contrast to the apathy of the British Government and the English people to the deaths of over three hundred British soldiers, and the deaths of Irish men, women, and children at the hands of their forces."

Six weeks later, Sinn Féin vice-president Gerry Adams said of Mountbatten's death: "The IRA gave clear reasons for the execution. I think it is unfortunate that anyone has to be killed, but the furor created by Mountbatten's death showed up the hypocritical attitude of the media establishment. As a member of the House of Lords, Mountbatten was an emotional figure in both British and Irish politics. What the IRA did to him is what Mountbatten had been doing all his life to other people; and with his war record I don't think he could have objected to dying in what was clearly a war situation. He knew the danger involved in coming to this country. In my opinion, the IRA achieved its objective: people started paying attention to what was happening in Ireland." In 2015, Adams reaffirmed his stance, stating, "I stand over what I said then. I'm not one of those people that engages in revisionism. Thankfully the war is over."

Indian prime minister Charan Singh remarked: "Here in India, he will be remembered as a Viceroy and a Governor General who at the time of India's Independence gave us abundantly of his wisdom and goodwill. It was in recognition of our affection for him, respect for his impartiality and regard for his concern for India's freedom that the entire nation readily accepted Lord Mountbatten as the first Governor General of Independent India. His drive and vigor helped in the difficult period after our Independence." In India, a week of national mourning was declared over Mountbatten's death. Burma also announced a 3-day period of mourning.

On the day of the bombing, the IRA also ambushed and killed eighteen British soldiers at the gates of Narrow Water Castle, just outside Warrenpoint, in County Down in Northern Ireland, sixteen of them from the Parachute Regiment, in what became known as the Warrenpoint ambush. It was the deadliest attack on the British Army during the Troubles.

6.3.1. Funeral

On 5 September 1979, Mountbatten received a ceremonial funeral at Westminster Abbey, which was attended by Queen Elizabeth II, the royal family, and members of European royal houses. Watched by thousands of people, the funeral procession, which started at Wellington Barracks, included representatives of all three British Armed Services, and military contingents from Burma, India, the United States (represented by 70 sailors of the US Navy and 50 US Marines), France (represented by the French Navy), and Canada. His coffin was drawn on a gun carriage by 118 Royal Navy ratings. Mountbatten's funeral was the first major royal funeral to be held in the Abbey since the 18th century. During the televised service, his great-nephew Charles read the lesson from Psalm 107. In an address, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Donald Coggan, highlighted his various achievements and his "lifelong devotion to the Royal Navy." After the public ceremonies, which he had planned himself, Mountbatten was buried in Romsey Abbey. As part of the funeral arrangements, his body had been embalmed by Desmond Henley.

6.3.2. Aftermath

Two hours before the bomb detonated, Thomas McMahon had been arrested at a Garda checkpoint between Longford and Granard on suspicion of driving a stolen vehicle. He was tried for the assassinations in Ireland and convicted on 23 November 1979 based on forensic evidence supplied by James O'Donovan that showed flecks of paint from the boat and traces of nitroglycerine on his clothes. He was released in 1998 under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement.

On hearing of Mountbatten's death, the then Master of the Queen's Music, Malcolm Williamson, wrote the Lament in Memory of Lord Mountbatten of Burma for violin and string orchestra. The 11-minute work was given its first performance on 5 May 1980 by the Scottish Baroque Ensemble, conducted by Leonard Friedman. On his death, his estate was valued for probate purposes at 2.20 M GBP.

7. Legacy and Assessment

Mountbatten's legacy is complex, encompassing both significant achievements and considerable criticisms, particularly regarding his role in the Partition of India and aspects of his personal conduct.

7.1. Career Assessments

Mountbatten's faults, according to his biographer Philip Ziegler, like everything else about him, "were on the grandest scale. His vanity though child-like, was monstrous, his ambition unbridled... He sought to rewrite history with cavalier indifference to the facts to magnify his own achievements." However, Ziegler concludes that Mountbatten's virtues outweighed his defects: "He was generous and loyal... He was warm-hearted, predisposed to like everyone he met, quick-tempered but never bearing grudges... His tolerance was extraordinary; his readiness to respect and listen to the views of others was remarkable throughout his life." Ziegler argues he was truly a great man, and despite being an executor of a policy rather than an initiator, he came to be known as its creator. "What he could do with superlative aplomb was to identify the object at which he was aiming, and force it through to its conclusion. A powerful, analytic mind of crystalline clarity, a superabundance of energy, great persuasive powers, endless resilience in the face of setback or disaster rendered him the most formidable of operators. He was infinitely resourceful, quick in his reactions, always ready to cut his losses and start again... He was an executor of policy rather than an initiator; but whatever the policy, he espoused it with such energy and enthusiasm, made it so completely his own, that it became identified with him and, in the eyes of the outside world as well as his own, his creation."

Others were not so conflicted. Field Marshal Sir Gerald Templer, the former Chief of the Imperial General Staff, once told him, "You are so crooked, Dickie, that if you swallowed a nail, you would shit a corkscrew."

Mountbatten supported the burgeoning nationalist movements that grew up in the shadow of Japanese occupation. His priority was to maintain practical, stable government, but driving him was an idealism in which he believed every people should be allowed to control their own destiny. Critics said he was too ready to overlook their faults, and especially their subordination to communist control. Ziegler says that in Malaya, where the main resistance to the Japanese came from Chinese who were under considerable communist influence, "Mountbatten proved to have been naïve in his assessment... He erred, however, not because he was 'soft on Communism'... but from an over-readiness to assume the best of those with whom he had dealings." Furthermore, Ziegler argues, he was following a practical policy based on the assumption that it would take a long and bloody struggle to drive the Japanese out, and he needed the support of all the anti-Japanese elements, most of which were either nationalists or communists.

7.2. Impact of the Partition of India

Mountbatten's role in the Partition of India remains a subject of intense historical debate and criticism. While he aimed to facilitate a swift and orderly transfer of power, his decision to accelerate the partition date to 15 August 1947 is widely criticized for contributing to the immense human suffering that followed. The rapid drawing of borders by the Radcliffe Line, dividing the Punjab and Bengal regions, led to the displacement of an estimated 14 M people and widespread communal violence, massacres, and forced migrations. Critics, including economist John Kenneth Galbraith, argue that his haste, driven in part by a desire to avoid the chaos occurring on his watch and to return to his naval career, inadvertently exacerbated the very disruption he sought to prevent.

Conversely, some historians argue that given the breakdown of law and order and Britain's limited resources after World War II, Mountbatten had little choice but to expedite the process to avoid deeper involvement in a potential civil war. However, his personal bias against the creation of Pakistan and his close relationship with Nehru are often cited as factors that may have influenced his decisions, leading to a partition that was not emotionally accepted by many British leaders, including Mountbatten himself. His reported willingness to "sabotage" the creation of Pakistan had he known of Jinnah's impending death further highlights the controversial nature of his actions. The unresolved issues of princely states like Hyderabad, Jammu and Kashmir, and Junagadh following partition also contributed to future conflicts between India and Pakistan, leaving a lasting and often painful legacy on the subcontinent.

7.3. Criticisms and Controversies

Beyond the Partition, Mountbatten faced other significant criticisms and controversies throughout his career. The Dieppe Raid of 1942, which he largely planned and promoted, was a catastrophic failure with almost 60% casualties, predominantly Canadian troops. This led to enduring animosity from Canadian veterans and historians who questioned the necessity of such a costly "lesson" for future amphibious landings.

Later in his life, Mountbatten was implicated in alleged plots against the Labour government of Harold Wilson. Peter Wright, in his 1987 book Spycatcher, claimed that Mountbatten attended a private meeting in May 1968 where press baron Cecil King urged him to lead a government of national salvation to overthrow Wilson's crisis-stricken government, an idea dismissed as "rank treachery" by Solly Zuckerman. While Mountbatten was reluctant to act, Andrew Lownie suggested that it took the intervention of Queen Elizabeth II to dissuade him. A 2006 BBC documentary, The Plot Against Harold Wilson, further alleged another plot involving Mountbatten to oust Wilson during his second term (1974-1976), involving right-wing military figures and elements within MI5. While the first official history of MI5, The Defence of the Realm (2009), confirmed the existence of a plot against Wilson, it clarified that it was not official and centered on a small group of discontented officers.

Furthermore, allegations concerning Mountbatten's personal conduct, particularly regarding homosexuality and pedophilia, have emerged. These claims, detailed in the "Relationships and Controversies" section, include accounts from former drivers and residents of the Kincora Boys' Home. While some claims have been dismissed by official inquiries, others, such as Arthur Smyth's allegations of child abuse, are part of ongoing civil cases, casting a shadow over his public image.

7.4. Influence in Specific Fields

Mountbatten's influence extended across military strategy, naval technology, international relations, and even the British monarchy. In military strategy, his leadership at Combined Operations led to innovations like PLUTO, Mulberry harbour, and the development of tank-landing ships, crucial for Allied amphibious assaults. His early recognition of the threat posed by air power, as demonstrated by his accurate prediction of the Pearl Harbor attack, showcased his strategic foresight.

In naval technology, his interest in gadgetry and technological development was evident in his involvement with the Institution of Electrical Engineers and his proposals for projects like Project Habakkuk. His later opposition to the use of nuclear weapons in combat, alongside his recognition of nuclear energy's potential for submarines, highlights his evolving understanding of modern warfare.

In international relations, his role as Viceroy of India was a defining moment in the history of the British Empire and the subcontinent. Despite the criticisms of the Partition, his efforts to persuade princely states to accede to India were significant for the political integration of the newly independent nation. His later service as Chairman of the NATO Military Committee also underscored his continued involvement in global security.

Within the British monarchy and political landscape, Mountbatten's mentorship of King Charles III was profound, shaping the future monarch's upbringing and personal views. His close ties to the royal family, combined with his high military and political offices, made him a powerful figure, as evidenced by his alleged involvement in plots against the government, even if ultimately unsuccessful.

8. Commemoration

Mountbatten's legacy is also honored through various institutions and memorials.

8.1. Enduring Influence

Mountbatten's commitment to intercultural understanding led to the development of the Mountbatten Institute in 1984, with his elder daughter as patron. This institute provides young adults with opportunities to enhance their intercultural appreciation and experience by spending time abroad. The IET annually awards the Mountbatten Medal for outstanding contributions to the promotion of electronics or information technology and their application.

8.2. Memorials and Honorees

Canada's capital city of Ottawa named Mountbatten Avenue in his memory. Java Street in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, was renamed Jalan Mountbatten after the Second World War; it was renamed again to Jalan Tun Perak in 1981. The Mountbatten estate in Singapore and Mountbatten MRT station were named after him. Mountbatten's personal papers, comprising approximately 250,000 papers and 50,000 photographs, are preserved in the University of Southampton Library.

9. Awards and Decorations

| Country | Date | Appointment | Ribbon | Post-nominal letters | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1911 | King George V Coronation Medal |  | |||

| 1918 | British War Medal |  | |||

| 1918 | Victory Medal |  | |||

| 1920 | Member of the Royal Victorian Order |  | MVO | Promoted to KCVO in 1922 | |

| 1922 | Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order |  | KCVO | Promoted to GCVO in 1937 | |

| Kingdom of Spain | 1922 | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic |  | gcYC | |

| Kingdom of Egypt | 1922 | Order of the Nile, Fourth Class |  | ||

| Romania | 1924 | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown |  | ||

| 1929 | Commander of the Order of St John |  | Promoted to KStJ in 1940 | ||

| 1935 | King George V Silver Jubilee Medal |  | |||

| 1937 | King George VI Coronation Medal |  | |||

| 1937 | Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order |  | GCVO | ||

| Romania | 1937 | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Romania |  | ||

| 1940 | Knight of Justice of the Order of St John |  | |||

| 1941 | Companion of the Distinguished Service Order |  | DSO | ||

| Kingdom of Greece | 1941 | War Cross |  | ||

| 1943 | Companion of the Order of the Bath |  | CB | Promoted to KCB in 1945 | |

| 1943 | Chief Commander of the Legion of Merit |  | |||

| 1945 | Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath |  | KCB | Promoted to GCB in 1955 | |

| 1945 | 1939-45 Star |  | |||

| 1945 | Atlantic Star |  | |||

| 1945 | Africa Star |  | |||

| 1945 | Burma Star |  | |||

| 1945 | Italy Star |  | |||

| 1945 | Defence Medal |  | |||

| 1945 | War Medal 1939-1945 |  | |||

| 1945 | Special Grand Cordon of the Order of the Cloud and Banner |  | |||

| 1945 | Distinguished Service Medal | ||||

| 1945 | Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal |  | |||

| 1946 | Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter |  | KG | ||

| Kingdom of Greece | 1946 | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of George I |  | ||

| 21 January 1946 | Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of the White Elephant |  | PCh (KCE) | ||

Kingdom of Nepal | 10 May 1946 | Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of Nepal |  | ||

| 3 June 1946 | Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour |  | |||

| 3 June 1946 | 1939-1945 War Cross |  | |||

| India | 1947 | Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India |  | GCSI | As Viceroy and Governor-General of India, who was the ex officio Grand Master of the order. |

| India | 1947 | Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire |  | GCIE | As Viceroy and Governor-General of India, who was the ex officio Grand Master of the order. |

| 1948 | Indian Independence Medal |  | |||

Kingdom of the Netherlands | 1948 | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion |  | ||

| Portuguese Republic | 1951 | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Aviz |  | GCA | |

| 1952 | Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal |  | |||

| 1952 | Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim |  | RSerafO | ||

| 1955 | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath |  | GCB | ||

| Union of Burma | 1956 | Grand Commander of the Order of Thiri Thudhamma |  | ||

Kingdom of Denmark | 1962 | Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog |  | ||

| 1965 | Member of the Order of Merit |  | OM | Military Division | |

| Ethiopian Empire | 1965 | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Seal of Solomon |  | S.K. | |

| 1972 | Order of the Distinguished Rule of Izzuddin |  | |||

Kingdom of Nepal | 24 February 1975 | King Birendra Coronation Medal |  | ||

| 1977 | Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal |  | |||

| Naval General Service Medal |  |

He was appointed personal aide-de-camp by Edward VIII, George VI, and Elizabeth II, and therefore bore the unusual distinction of being allowed to wear three royal cyphers on his epaulettes.

10. Arms and Ancestry

10.1. Coat of Arms

Mountbatten's coat of arms, reflecting his lineage and honors, consists of:

- Escutcheon: Within the Garter, Quarterly, 1st and 4th, Hesse with a bordure compony argent and gules; 2nd and 3rd, Battenberg; charged at the honor point with an inescutcheon of the British Royal arms with a label of three points argent, the center point charged with a rose gules and each of the others with an ermine spot sable (representing his grandmother, Princess Alice).

- Crest: Crests of Hesse modified and Battenberg.

- Helm: Helms of Hesse modified and Battenberg.

- Supporters: Two Lions queue fourchée and crowned all or.

- Motto: In honour bound

- Orders: The Order of the Garter ribbon, with the motto Honi soit qui mal y pense (Shame be to him who thinks evil of it).

10.2. Ancestry

Louis Mountbatten's ancestry connects him to several European royal houses, particularly through his maternal line to Queen Victoria.

His immediate parents were Prince Louis of Battenberg and Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine.

His paternal grandparents were Prince Alexander of Hesse and by Rhine and Julia, Princess of Battenberg.

His maternal grandparents were Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and Princess Alice of the United Kingdom.

Through his maternal grandmother, Princess Alice, he was a great-grandson of Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

His paternal great-grandparents included Louis II, Grand Duke of Hesse and Princess Wilhelmine of Baden, and Count John Maurice Hauke and Sophie Lafontaine.

His maternal great-grandparents included Prince Charles of Hesse and by Rhine and Princess Elisabeth of Prussia, and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom.