1. Overview

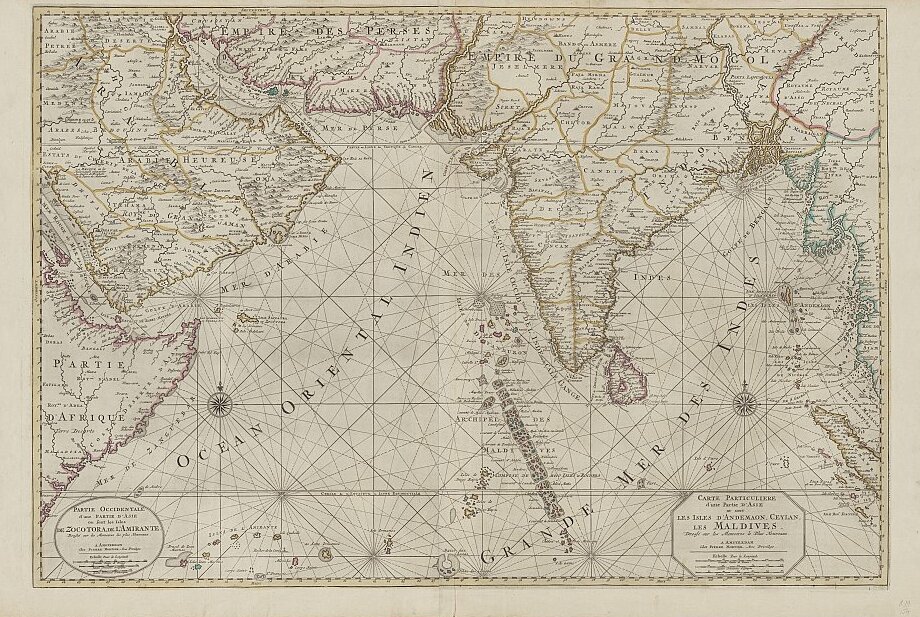

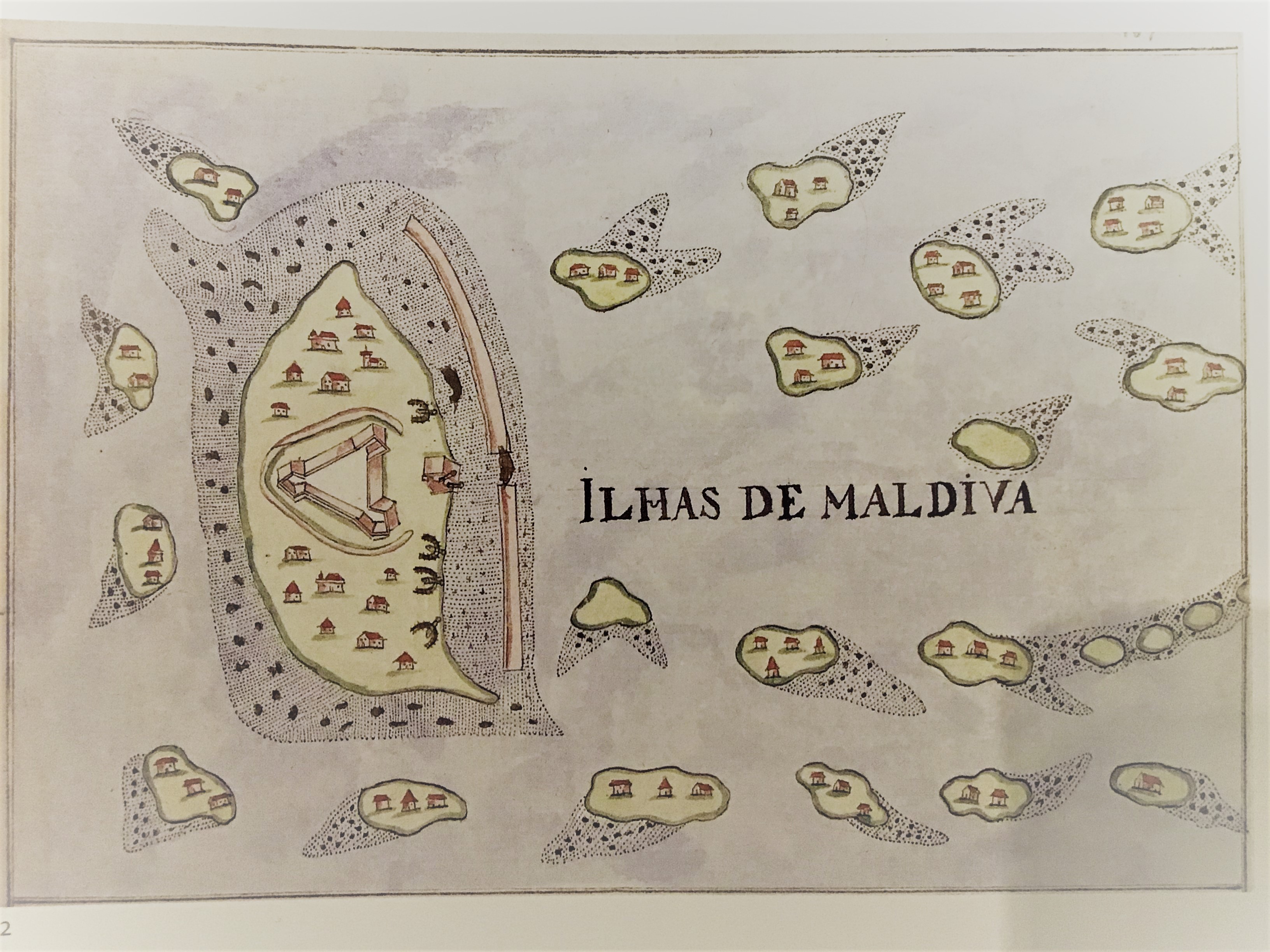

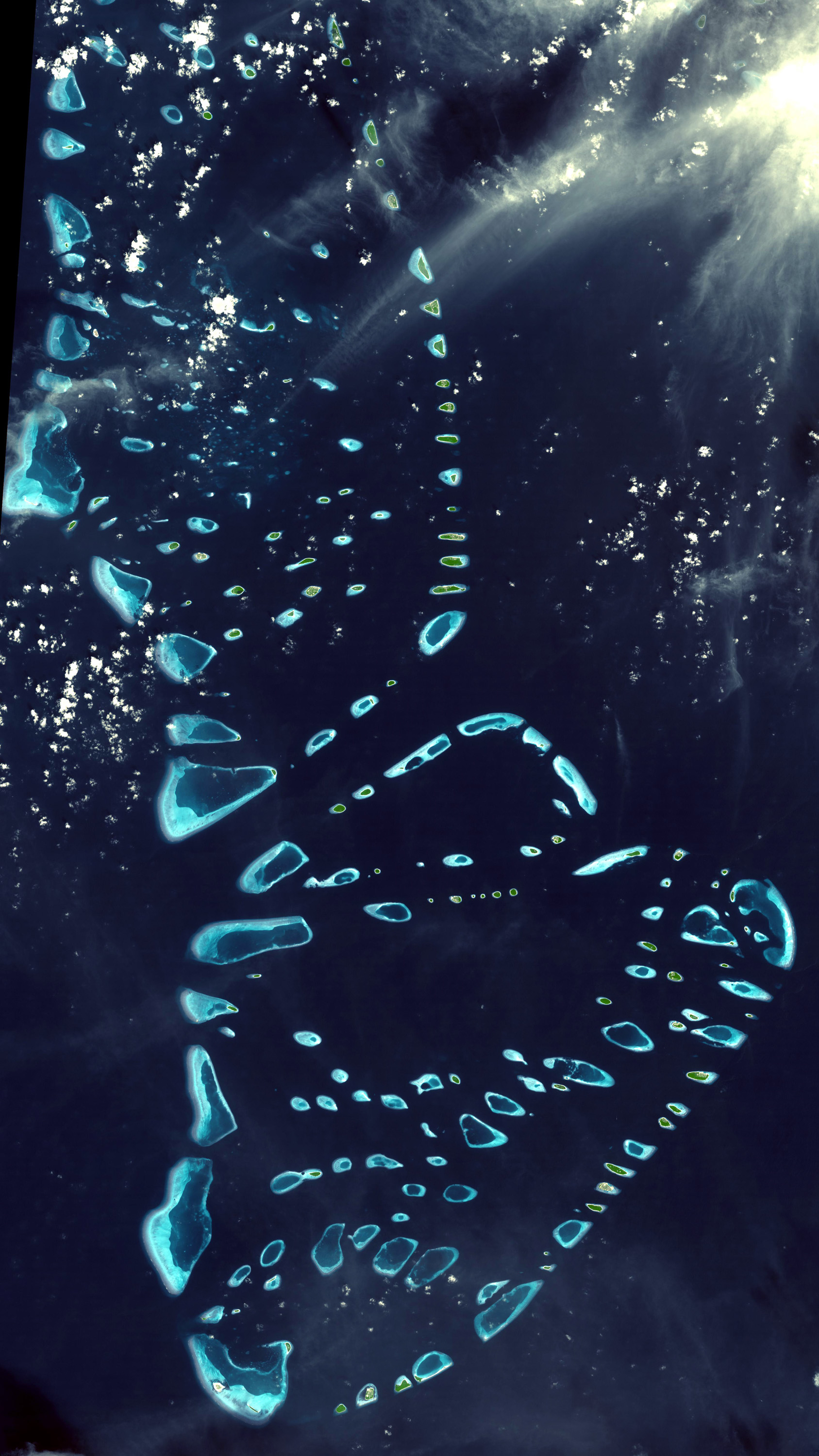

The Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives, is an archipelagic state located in South Asia, situated in the Indian Ocean. It lies southwest of Sri Lanka and India, about 466 mile (750 km) from the Asian continent's mainland. The nation comprises a chain of 26 atolls, stretching from Ihavandhippolhu Atoll in the north to Addu Atoll in the south, encompassing 1,192 coral islands. With a land area of only 115 mile2 (298 km2) spread over roughly 35 K mile2 (90.00 K km2) of sea, it is one of the world's most geographically dispersed sovereign states and Asia's smallest country by land area. Its population of approximately 515,132 (2022 census) makes it the second least populous country in Asia. The capital and most populous city is Malé.

The Maldives is renowned for its unique geography, characterized by low-lying coral islands with an average ground-level elevation of 4.9 ft (1.5 m) above sea level, making it the world's lowest-lying country and exceptionally vulnerable to sea level rise due to climate change. This environmental challenge poses an existential threat to the nation and significantly impacts its social equity and development.

Historically, the Maldives has a rich past, with evidence of settlement dating back over 2,500 years. The islands transitioned from Buddhism to Islam in the 12th century, becoming a sultanate that developed strong commercial and cultural ties. European colonial influence began in the 16th century, with the Maldives eventually becoming a British protectorate in 1887. Independence from the United Kingdom was achieved in 1965, and a presidential republic was established in 1968. The subsequent decades have been marked by political instability, efforts toward democratic reform, and environmental challenges.

The Maldivian economy is heavily reliant on tourism and fisheries. While tourism has driven significant economic growth, leading to a "high" Human Development Index rating and a higher per capita income than other SAARC nations, issues of income inequality, labor rights, and the environmental sustainability of economic activities remain pertinent.

The nation's political system is a presidential republic. Recent decades have seen significant political transformations, including a shift towards multi-party democracy. However, challenges to democratic development, human rights, and good governance persist. Islam is the state religion, and its principles influence the legal system, which also incorporates secular laws. The human rights situation, particularly concerning freedom of religion, expression, and the rights of minorities and vulnerable groups, is a subject of ongoing domestic and international attention.

The Maldives actively participates in international forums, advocating for climate action and human rights. It is a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC).

2. Etymology

The origin of the name "Maldives" is subject to several theories, reflecting the diverse linguistic and cultural influences on the archipelago over centuries.

According to Maldivian legends, the first settlers of the islands were people known as the Dheyvis. The earliest kingdom was known as the Kingdom of Dheeva Maari (দীবামাড়ি রাজ্যDheeva Maari KingdomBengali). Historical records from the 3rd century BCE, when emissaries visited the islands, note that the Maldives was known as Dheeva Mahal. Between around 1100 and 1166, the Maldives was also referred to as Diva Kudha, and the Laccadive archipelago, then part of the Maldives, was called Diva Kanbar by the scholar al-Biruni.

The name Maldives may derive from the Sanskrit term मालाmālāSanskrit (meaning "garland" or "necklace") and द्वीपdvīpaSanskrit (meaning "island"), potentially as मालाद्वीपmālādvīpaSanskrit ("garland of islands"). This interpretation is supported by Jan Hogendorn, a professor of economics, and reflects the visual appearance of the atolls as a chain or garland of islands. Similarly, in Sinhala, the term මාල දිවයිනMaala DivainaSinhala also means "Necklace Islands." The Maldivian people are called Dhivehin. The word Dheeb or Deeb (an archaic Dhivehi word related to the Sanskrit dvīpa) means "island," and Dhives (or Dhivehin) means "islanders."

In other South Indian languages, similar formations exist: in Tamil, "Garland of Islands" can be translated as மாலைத்தீவுMālaitīvuTamil; in Malayalam, it is മാലദ്വീപ്MaladweepuMalayalam; and in Kannada, it is ಮಾಲೆದ್ವೀޕMaaledweepaKannada. However, none of these specific names are found in early literature. Classical Sanskrit texts dating to the Vedic period mention the "Hundred Thousand Islands" (लक्षद्वीपLakshadweepaSanskrit), a generic name which would have included not only the Maldives but also the Laccadives, Aminidivi Islands, Minicoy, and the Chagos Archipelago.

The ancient Sri Lankan chronicle, the Mahavamsa, mentions an island designated as Mahiladiva ("Island of Women", महिलादिभMahilādibhaPali) in Pali, which might be an erroneous translation of the Sanskrit term for "garland."

Medieval Arab Muslim travelers, such as Ibn Battuta, referred to the islands as محل ديبيةMaḥal DībīyātArabic. This name likely originated from the Arabic word محلmaḥalArabic ("palace"), which is how the Berber traveler might have interpreted the name of Malé, having passed through Muslim North India where Perso-Arabic words were introduced into the local vocabulary. This Arabic name, Maḥal Dībīyāt, is currently inscribed on the scroll in the Maldivian state emblem. The classical Persian/Arabic name for the Maldives is ديبجاتDibajatArabic.

During the colonial period, the Dutch referred to the islands as Maldivische EilandenMaldivian IslandsDutch, while the British anglicized the local name first to the "Maldive Islands" and later simply to "Maldives."

Garcia de Orta, in a conversational book published in 1563, wrote: "I must tell you that I have heard it said that the natives do not call it Maldiva but Nalediva. In the Malabar language, nale means four, and diva means island. So that in that language, the word signifies 'four islands', while we, corrupting the name, call it Maldiva."

The local name for the Maldives in the Dhivehi language is ދިވެހިރާއްޖެDhivehi RaajjeDivehi, meaning "Kingdom of the Dhivehi people" or "Kingdom of Islands."

3. History

The history of the Maldives spans over 2,500 years, marked by early settlements, the influence of major religions, periods of colonial rule, and the journey towards independence and a modern republic. These historical developments have profoundly shaped its society, culture, and political systems.

3.1. Ancient history and early settlement

The Maldives already had established kingdoms by the 6th-5th century BCE. According to historical evidence and legends, the country possesses an established history exceeding 2,500 years. The first settlers of the Maldives are believed to be people known as Dheyvis, who, according to the 17th-century Arabic text Kitāb fi āthār Mīdhu al-qādimah (On the Ancient Ruins of Meedhoo) by Allama Ahmed Shihabuddine, came from Kalibangan in India. The exact time of their arrival is unknown but predates the kingdom of Emperor Ashoka (269-232 BCE). Shihabuddine's account aligns well with the recorded history of South Asia and the Maldivian copperplate document known as Loamaafaanu.

The Mahāvaṃsa, a Sri Lankan chronicle dating to 300 BCE, records people from Sri Lanka emigrating to the Maldives. Assuming that cowrie shells originated from the Maldives, historians speculate that people may have inhabited the Maldives during the Indus Valley civilisation (3300-1300 BCE). Several artifacts also indicate the presence of Hinduism in the country before the Islamic period.

The ancient history of the Maldives is recounted through copperplates, ancient scripts carved on coral artifacts, traditions, language, and the diverse ethnicities of Maldivians. The Maapanansa, copper plates recording the history of the first Kings of the Maldives from the Solar Dynasty, were lost early on. A 4th-century notice by Ammianus Marcellinus (362 CE) mentions gifts sent to the Roman emperor Julian by a deputation from the nation of Divi, a name similar to Dheyvi, the first settlers.

The earliest Maldivians did not leave significant archaeological artifacts. Their buildings were likely constructed from wood, palm fronds, and other perishable materials, which would have decayed quickly in the tropical climate. Moreover, chiefs or headmen did not reside in elaborate stone palaces, nor did their religion necessitate the construction of large temples.

Comparative studies of Maldivian oral, linguistic, and cultural traditions confirm that the first settlers were from the southern shores of the neighboring Indian subcontinent. This includes the Giraavaru people, who are mentioned in ancient legends and local folklore regarding the establishment of the capital and kingly rule in Malé. A strong underlying layer of Dravidian and North Indian cultures persists in Maldivian society, with a clear Elu (an ancient Prakrit language) substratum in the language, which also appears in place names, kinship terms, poetry, dance, and religious beliefs. The North Indian cultural elements were largely brought by the original Sinhalese settlers from Sri Lanka. Seafaring cultures from the Malabar Coast and the Pandyan kingdom also led to the settlement of the islands by Tamil and Malabar seafarers. The Maldivian islands are mentioned in ancient Tamil Sangam literature as "Munneer Pazhantheevam," or "Old Islands of Three Seas."

3.2. Buddhist period

The Buddhist period, spanning approximately 1,400 years, is of foundational importance in Maldivian history, though often briefly mentioned in historical accounts. It was during this era that Maldivian culture developed and flourished, aspects of which survive to this day. The Maldivian language, early Maldivian scripts, architecture, ruling institutions, customs, and manners originated when the Maldives was a Buddhist kingdom.

Buddhism likely spread to the Maldives in the 3rd century BCE, around the time of Emperor Ashoka's expansion, and it became the dominant religion of the Maldivian people until the 12th century CE. Archaeological evidence from an ancient Buddhist monastery on Kaashidhoo Island has been dated to between 205 and 560 AD, based on radiocarbon dating of shell deposits found in the foundations of stupas and other structures within the monastery. The ancient Maldivian Kings promoted Buddhism, and the earliest Maldivian writings and artistic achievements, in the form of highly developed sculpture and architecture, stem from this period. Nearly all archaeological remains in the Maldives are from Buddhist stupas and monasteries, and all artifacts found to date display characteristic Buddhist iconography. Buddhist (and Hindu) temples were typically mandala-shaped, oriented according to the four cardinal directions with the main gate facing east. Local historian Hassan Ahmed Maniku, in a provisional list published in 1990, counted as many as 59 islands with Buddhist archaeological sites.

3.3. Islamic period and Sultanates

The prominence of Arab traders in the Indian Ocean by the 12th century may partly explain the conversion of the last Buddhist king of the Maldives, Dhovemi, to Islam in the year 1153 (or 1193, according to some sources). Adopting the Muslim title of Sultan Muhammad al-Adil, he initiated a series of six Islamic dynasties that lasted until 1932 when the sultanate became elective. The formal title of the sultan up to 1965 was, Sultan of Land and Sea, Lord of the twelve-thousand islands and Sultan of the Maldives, which came with the style of Highness.

The conversion is traditionally attributed to Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari, a Moroccan (or Berber) traveler. According to the account told to Ibn Battuta, a mosque was built with the inscription: 'The Sultan Ahmad Shanurazah accepted Islam at the hand of Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari.' Some scholars suggest Ibn Battuta might have misread Maldivian texts or favored a North African narrative. Other accounts suggest he may have been from the Persian town of Tabriz, identifying him as Abdul Barakat Yusuf Shams ud-Dīn at-Tabrīzī, locally known as Tabrīzugefānu. This interpretation is supported by local historical chronicles like the Raadavalhi and Taarikh. The similarity in Arabic script between "al-Barbari" (البربري) and "al-Tabrizi" (التبريزي) could have led to this confusion, as early Arabic script lacked the diacritical dots that distinguish consonants like 'B' and 'T'. The venerated tomb of this scholar now stands on the grounds of Medhu Ziyaaraiy, near the Hukuru Miskiy in Malé, one of the oldest surviving mosques in the Maldives, originally built in 1153 and reconstructed in 1658.

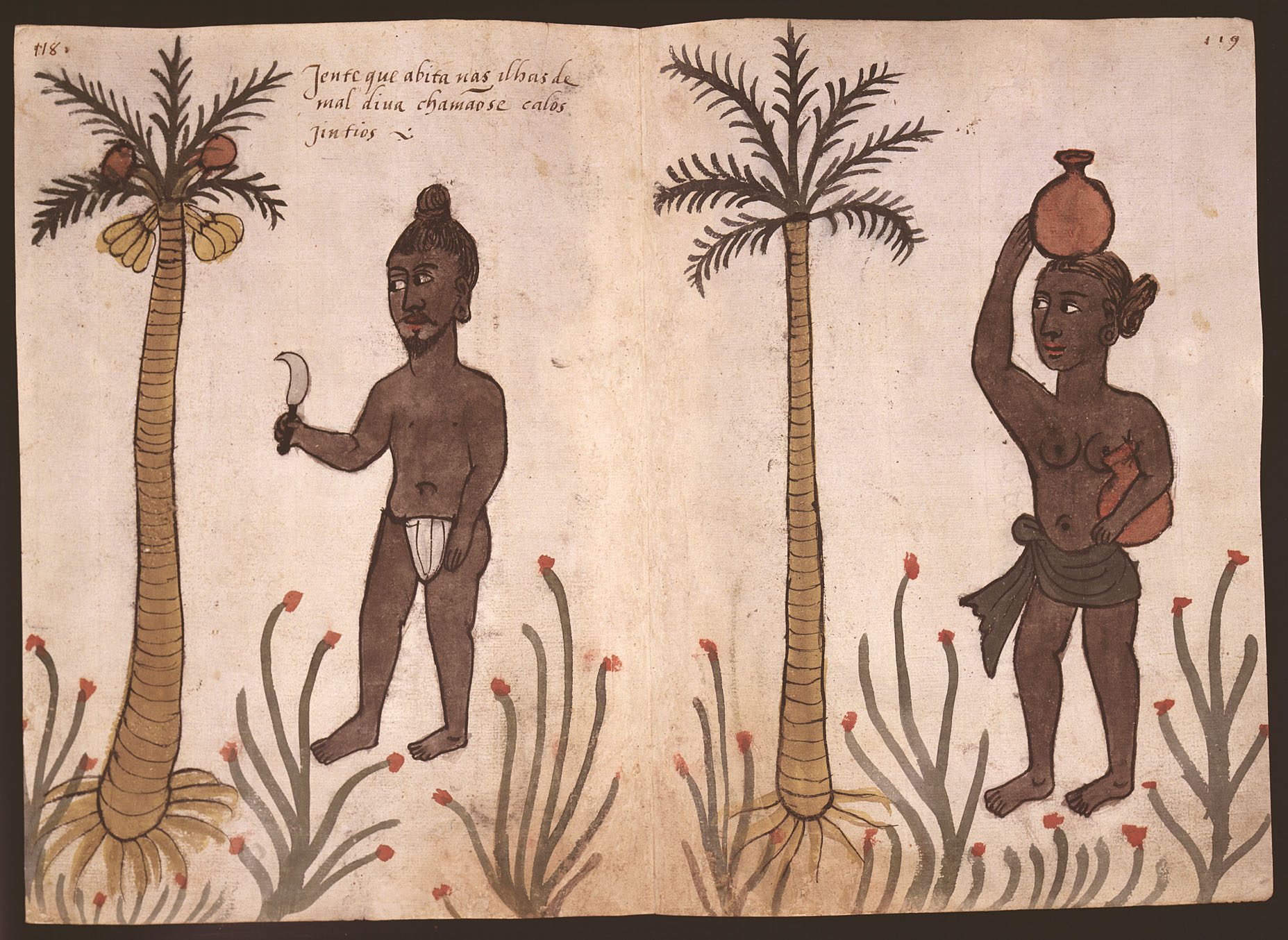

Following the Islamic concept of Jahiliyyah (ignorance) before Islam, Maldivian history books often consider the introduction of Islam in the late 12th century as the cornerstone of the country's history. Nevertheless, the cultural influence of Buddhism persisted, a reality directly experienced by Ibn Battuta during his nine-month stay between 1341 and 1345, when he served as a chief judge and married into the royal family of Sultan Omar I. He became embroiled in local politics and left when his strict judgments in the relatively laissez-faire island kingdom began to clash with its rulers. In particular, he was angered by local women going about with no clothing above the waist-a cultural norm in the region at the time but seen as a violation of Middle Eastern Islamic rules of modesty-and the locals taking no notice of his complaints.

Compared to other areas of South Asia, the Maldives' conversion to Islam occurred relatively late, with the kingdom remaining Buddhist for another 500 years after neighboring regions had converted. Arabic became the primary language of administration (instead of Persian or Urdu), and the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence was introduced, both hinting at direct contact with the core of the Arab world. Middle Eastern seafarers, who began to dominate Indian Ocean trade routes in the 10th century, found the Maldives an important link, being the first landfall for traders from Basra sailing to Southeast Asia. Trade primarily involved cowrie shells-widely used as currency throughout Asia and parts of the East African coast-and coir fiber. The Bengal Sultanate, where cowrie shells were legal tender, was a principal trading partner, making the Bengal-Maldives cowry shell trade the largest shell currency network in history. Coir, the fiber from dried coconut husks, was another essential Maldivian export, used for stitching and rigging dhows across the Indian Ocean, and was traded to Sindh, China, Yemen, and the Persian Gulf.

3.4. Colonial period and Protectorate

In 1558, the Portuguese established a small garrison with a ViadorViadorPortuguese (overseer of a trading post), known in Dhivehi as Viyazoaru, in the Maldives, administered from their main colony in Goa. Their attempts to forcefully impose Christianity under threat of death provoked a local revolt led by Muhammad Thakurufaanu al-Auzam, his two brothers, and Dhuvaafaru Dhandahele. Fifteen years later, they successfully drove the Portuguese out of the Maldives. This event is commemorated as National Day (Qaumee Dhuvas), celebrated on the 1st of Rabi' al-Awwal, the third month of the Hijri calendar.

In the mid-17th century, the Dutch, who had replaced the Portuguese as the dominant power in Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), established hegemony over Maldivian affairs without direct involvement in local matters, which continued to be governed according to centuries-old Islamic customs.

The British expelled the Dutch from Ceylon in 1796 and subsequently included the Maldives as a British protectorate. The status of the Maldives as a British protectorate was officially recorded in an 1887 agreement. In this agreement, Sultan Muhammad Mueenuddeen II accepted British influence over Maldivian external relations and defense while retaining home rule. Internal affairs continued to be regulated by traditional Muslim institutions in exchange for an annual tribute. The islands' status was akin to other British protectorates in the Indian Ocean region, such as Zanzibar and the Trucial States.

During the British period, the Sultan's powers were largely taken over by the Chief Minister, much to the chagrin of the British Governor-General, who continued to deal with the often ineffectual Sultan. Consequently, Britain encouraged the development of a constitutional monarchy, and the first Constitution was proclaimed in 1932. However, these new arrangements favored neither the aging Sultan nor the Chief Minister but rather a new generation of British-educated reformists. As a result, angry mobs were incited against the Constitution, which was publicly torn up. This period highlighted the tensions between traditional rule and emerging modern political aspirations, with British influence often acting as a catalyst for change, though not always in a manner that satisfied local factions. The local autonomy was preserved in internal matters, but foreign policy and defense were firmly under British control, impacting the Maldives' interactions with the wider world and limiting its independent geopolitical role. Socially, while Islamic customs remained dominant, the exposure to British administration and education began to introduce new ideas, particularly among the elite.

The Maldives remained a British crown protectorate until 1953 when the sultanate was suspended and the First Republic was declared under the short-lived presidency of Mohamed Amin Didi. While serving as prime minister during the 1940s, Didi nationalized the fish export industry. As president, he is remembered as a reformer of the education system and an advocate for women's rights. However, his progressive policies faced opposition from conservative elements in Malé, who eventually ousted his government. During a riot over food shortages, Didi was beaten by a mob and died on a nearby island. This period underscored the deep societal divisions and the challenges in implementing reforms against entrenched traditional interests, with significant implications for human rights and social progress.

Beginning in the 1950s, the political history of the Maldives was largely influenced by the British military presence on the islands. In 1954, the restoration of the sultanate perpetuated the traditional rule. Two years later, the United Kingdom obtained permission to re-establish its wartime RAF Gan airfield in the southernmost Addu Atoll, employing hundreds of locals. This presence brought economic benefits to the southern atolls but also became a point of contention. In 1957, the new prime minister, Ibrahim Nasir, called for a review of the agreement. Nasir's stance was challenged in 1959 by a local secessionist movement in the three southernmost atolls, which benefited economically from the British presence on Gan. This group cut ties with the Maldivian government and formed an independent state, the United Suvadive Republic, with Abdullah Afeef as president and Hithadhoo as its capital. The secession was short-lived; one year later, the Suvadive Republic was dismantled after Nasir sent gunboats from Malé with government police, and Abdullah Afeef went into exile. This episode highlighted internal tensions regarding development, autonomy, and the influence of foreign powers, with significant impact on the affected communities.

Meanwhile, in 1960, the Maldives allowed the United Kingdom to continue using both the Gan and Hithadhoo facilities for thirty years, with a payment of £750,000 from 1960 to 1965 for the Maldives' economic development. The base was eventually closed in 1976 as part of the larger British withdrawal of permanently stationed forces 'East of Suez'. The closure of the base had economic repercussions, particularly for the southern atolls that had become reliant on employment and trade related to the British presence.

3.5. Independence and establishment of the Republic

As the British Empire faced increasing challenges in maintaining its colonial hold across Asia, with indigenous populations demanding freedom, an agreement was signed on 26 July 1965. Representing the Sultan, Ibrahim Nasir Rannabandeyri Kilegefan, then Prime Minister, and on behalf of the British government, Sir Michael Walker, British Ambassador-designate to the Maldive Islands, formalized the end of British authority over the defense and external affairs of the Maldives. The islands thus achieved independence, with the ceremony taking place at the British High Commissioner's Residence in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Following independence, the sultanate continued for another three years under Sultan Sir Muhammad Fareed Didi, who declared himself King.

On 15 November 1967, a vote was taken in the parliament to decide whether the Maldives should continue as a constitutional monarchy or become a republic. Of the 44 members of parliament, 40 voted in favor of a republic. Subsequently, on 15 March 1968, a national referendum was held on the question, and an overwhelming 93.34% of participants voted in favor of establishing a republic. The republic was officially declared on 11 November 1968, thus ending the 853-year-old monarchy. Ibrahim Nasir became the first president of the Second Republic. Since the King had held little real power, this transition was largely seen as a cosmetic change and required few alterations in the structures of government.

The early years of the republic saw the development of tourism, which began to emerge in the archipelago at the beginning of the 1970s. The first tourist resort in the Maldives, Kurumba Maldives, welcomed its first guests on 3 October 1972. This marked a turning point for the Maldivian economy. The first accurate census was conducted in December 1977, showing a population of 142,832 people.

Political infighting during the 1970s between Nasir's faction and other political figures led to the 1975 arrest and exile of elected prime minister Ahmed Zaki to a remote atoll. Economic decline followed the closure of the British airfield at Gan and the collapse of the market for dried fish, an important export. With support for his administration faltering, Nasir fled to Singapore in 1978, allegedly with millions of dollars from the treasury.

Maumoon Abdul Gayoom began his 30-year tenure as president in 1978, winning six consecutive elections without opposition. His election was initially seen as ushering in a period of political stability and economic development, with Gayoom prioritizing the development of poorer islands. Tourism flourished, and increased foreign contact spurred development. However, Gayoom's rule became increasingly controversial. Critics described him as an autocrat who quelled dissent by limiting freedoms, including freedom of speech and assembly, and by practicing political favoritism. This period saw a consolidation of power and limited progress in democratic reforms, with human rights concerns frequently raised by international observers.

A series of coup attempts (in 1980, 1983, and 1988) by Nasir supporters and business interests sought to topple the government. While the first two attempts met with little success, the 1988 coup attempt involved a mercenary force of approximately 80 members of the PLOTE. They seized the airport and caused Maumoon to flee from house to house until the intervention of 1,600 Indian troops, airlifted into Malé, restored order. This event, known as Operation Cactus, highlighted the nation's vulnerability and the geopolitical interests in the region. The coup attempt was headed by Ibrahim Lutfee, a businessman, and Sikka Ahmed Ismail Manik. The attackers were defeated by the then National Security Services of Maldives. The Indian Air Force airlifted a parachute battalion group from Agra, flying them over 1.2 K mile (2.00 K km) to the Maldives. By the time Indian armed forces reached Malé, the mercenary forces had already left on the hijacked ship MV Progress Light. Indian paratroopers landed at Hulhulé, secured the airfield, and restored government rule within hours. The Indian Navy also assisted in capturing the freighter and rescuing hostages. The aftermath of the coup attempt saw a further tightening of political control and a continued lack of space for opposition voices, impacting democratic development.

3.6. 21st century

The 21st century in the Maldives has been characterized by significant political upheaval, democratic movements, social changes, and the profound impact of natural disasters, all while grappling with progress and setbacks in human rights and democratic governance.

The Maldives were devastated by a tsunami on 26 December 2004, following the Indian Ocean earthquake. The disaster highlighted the nation's extreme vulnerability to environmental catastrophes. Only nine islands reportedly escaped any flooding. Fifty-seven islands faced serious damage to critical infrastructure, fourteen islands had to be totally evacuated, and six islands were destroyed. A further twenty-one resort islands were forced to close due to tsunami damage. The total damage was estimated at more than 400.00 M USD, or some 62% of the GDP. Tragically, 102 Maldivians and 6 foreigners reportedly died in the tsunami. The destructive impact of the waves on the low-lying islands was somewhat mitigated by the absence of a continental shelf or land mass upon which the waves could gain height; the tallest waves were reported to be 14 ft high. The aftermath of the tsunami required massive relief and reconstruction efforts, testing the government's capacity and exposing social vulnerabilities. The distribution of aid and long-term recovery plans became critical issues, with implications for social equity.

During the later part of Maumoon Gayoom's rule, independent political movements emerged, challenging the ruling Dhivehi Rayyithunge Party (DRP) and demanding democratic reform. Dissident journalist and activist Mohamed Nasheed founded the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) in 2003 and pressured Maumoon into allowing gradual political reforms. In 2008, a new constitution was approved, and the first direct multi-party presidential elections were held. Mohamed Nasheed won in the second round, marking a historic shift in Maldivian politics. His administration faced numerous challenges, including the substantial debt left by the previous government, the economic downturn following the 2004 tsunami, overspending through the overprinting of the local currency (the rufiyaa), unemployment, corruption, and increasing drug use. Nasheed's government introduced taxation on goods for the first time, reduced import duties, and implemented social welfare programs such as universal health insurance (Aasandha) and benefits for the elderly, single parents, and those with special needs. These reforms aimed to improve social equity but were implemented amidst a challenging economic and political landscape.

Social and political unrest grew in late 2011, fueled by opposition campaigns often framed around the protection of Islam. Nasheed controversially resigned from office in February 2012 following protests and a mutiny by a significant number of police and army personnel. His vice-president, Mohamed Waheed Hassan Manik, was sworn in as president. Nasheed and his supporters claimed his resignation was forced under duress, labeling it a coup d'état. This event plunged the country into a prolonged political crisis, undermining democratic institutions and raising concerns about human rights and the rule of law. Nasheed was later arrested, convicted of terrorism in a trial widely seen by international observers and human rights organizations as flawed and politically motivated, and sentenced to 13 years in prison. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention called for Nasheed's immediate release.

The presidential election in late 2013 was highly contested. Former president Nasheed won the most votes in the first round, but the Supreme Court annulled the results despite positive assessments from international election observers. In the re-run vote, Abdulla Yameen, the half-brother of former president Maumoon Gayoom, assumed the presidency. Yameen's presidency was marked by a crackdown on dissent, restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly, and allegations of corruption and authoritarianism. He survived an alleged assassination attempt in late 2015. His Vice President, Mohamed Jameel Ahmed, was removed from office after a no-confidence motion, amid allegations of conspiring with opposition parties. Another Vice President, Ahmed Adeeb, was later arrested along with 17 supporters for "public order offences," and the government instituted a broader crackdown. A state of emergency was declared ahead of a planned anti-government rally, and the People's Majlis accelerated Adeeb's removal. This period saw a significant erosion of democratic norms and human rights.

In the 2018 election, Ibrahim Mohamed Solih of the MDP won a surprise victory, and was sworn in as the Maldives' new president in November 2018. His presidency promised a return to democratic reforms and a focus on human rights. Ahmed Adeeb was freed by courts in Malé in July 2019 after his conviction was overruled but was placed under a travel ban; he later attempted to flee the country but was apprehended. Former president Abdulla Yameen was sentenced to five years in prison in November 2019 for money laundering. The High Court upheld the sentence in January 2021, but the Supreme Court overturned Yameen's conviction in November 2021.

In the 2023 election, People's National Congress (PNC) candidate Mohamed Muizzu won the second-round runoff, defeating incumbent president Ibrahim Solih with 54% of the vote. Muizzu was sworn in as the eighth President on 17 October 2023. His election campaign included a pledge to remove foreign (specifically Indian) troops from Maldivian soil, signaling a potential shift in foreign policy. Muizzu is widely seen as pro-China, potentially impacting relations with India and the broader geopolitical dynamics of the region. In April 2024, ex-President Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom was freed from his 11-year conviction, and the High Court ordered a new trial, adding another layer to the country's complex political narrative and ongoing struggles with justice and accountability. These frequent shifts in political power and judicial outcomes reflect the challenges in consolidating democratic institutions and ensuring impartial justice.

4. Geography

The Maldives' geography is unique and profoundly influences its environment, society, and economy. Its low-lying atoll-based topography makes it exceptionally vulnerable to climate change, particularly sea level rise, which poses significant social and environmental challenges.

4.1. Topography and islands

The Maldives consists of 1,192 coral islands grouped in a double chain of 26 atolls. These atolls stretch along a length of 541 mile (871 km) from north to south and 81 mile (130 km) from east to west, spread over roughly 35 K mile2 (90.00 K km2) of ocean. However, only 115 mile2 (298 km2) of this area is dry land, making the Maldives one of the world's most geographically dispersed countries. It lies between latitudes 1°S and 8°N, and longitudes 72° and 74°E.

The atolls are composed of live coral reefs and sandbars, situated atop a submarine ridge 597 mile (960 km) long that rises abruptly from the depths of the Indian Ocean and runs north to south. Only near the southern end of this natural coral barricade do two open passages permit safe ship navigation from one side of the Indian Ocean to the other through Maldivian territorial waters. For administrative purposes, the Maldivian government has organized these atolls into 21 administrative divisions.

The largest island in the Maldives is Gan, which belongs to Laamu Atoll (also known as Hahdhummathi Maldives). In Addu Atoll, the westernmost islands are connected by roads built over the reef, collectively called Link Road, with a total length of 8.7 mile (14 km). Approximately 200 of the islands are inhabited. The unique topography, with its numerous small, dispersed islands, presents challenges for infrastructure development, service delivery, and national cohesion, but also forms the basis of its famed tourism industry.

The Maldives is the lowest-lying country in the world. Its maximum natural ground level is only 7.9 ft (2.4 m) above sea level, with an average elevation of just 4.9 ft (1.5 m). Some sources state the highest point, Mount Villingili, as 17 ft (5.1 m). In areas where construction has occurred, the ground level has been artificially raised by several meters. More than 80 percent of the country's land is composed of coral islands that rise less than one meter above sea level. This extreme low elevation makes the Maldives acutely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

4.2. Climate

The Maldives has a tropical monsoon climate (Am under the Köppen climate classification), significantly affected by the large landmass of South Asia to the north. Due to the country's extremely low elevation, the temperature is consistently hot and often humid. The presence of the Asian landmass causes differential heating of land and water, which, in turn, sets off a rush of moisture-rich air from the Indian Ocean over South Asia, resulting in the southwest monsoon.

Two distinct seasons dominate Maldives' weather:

1. The dry season is associated with the winter northeastern monsoon, typically occurring from November to April.

2. The rainy season is associated with the southwest monsoon, which brings strong winds and storms, usually from May to October.

The shift from the dry northeast monsoon to the moist southwest monsoon occurs during April and May. During this period, the southwest winds contribute to the formation of the southwest monsoon, which reaches the Maldives at the beginning of June and lasts until the end of November. However, the weather patterns of the Maldives do not always conform strictly to the monsoon patterns of South Asia.

Annual rainfall averages 100 in (254 cm) in the north and 150 in (381 cm) in the south. The monsoonal influence is greater in the northern Maldives, while the south is more influenced by equatorial currents.

The average high temperature is 88.7 °F (31.5 °C) and the average low temperature is 79.52 °F (26.4 °C).

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average high °C (°F) | 86.53999999999999 °F (30.3 °C) | 87.26 °F (30.7 °C) | 88.52 °F (31.4 °C) | 88.88000000000001 °F (31.6 °C) | 88.16 °F (31.2 °C) | 87.08000000000001 °F (30.6 °C) | 86.9 °F (30.5 °C) | 86.72 °F (30.4 °C) | 86.36 °F (30.2 °C) | 86.36 °F (30.2 °C) | 86.18 °F (30.1 °C) | 86.18 °F (30.1 °C) | 87.26 °F (30.7 °C) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 82.4 °F (28 °C) | 82.94 °F (28.3 °C) | 84.02 °F (28.9 °C) | 84.56 °F (29.2 °C) | 83.84 °F (28.8 °C) | 82.94 °F (28.3 °C) | 82.75999999999999 °F (28.2 °C) | 82.4 °F (28 °C) | 82.04 °F (27.8 °C) | 82.04 °F (27.8 °C) | 81.86 °F (27.7 °C) | 82.04 °F (27.8 °C) | 82.75999999999999 °F (28.2 °C) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 78.25999999999999 °F (25.7 °C) | 78.62 °F (25.9 °C) | 79.52 °F (26.4 °C) | 80.24000000000001 °F (26.8 °C) | 79.34 °F (26.3 °C) | 78.8 °F (26 °C) | 78.44 °F (25.8 °C) | 77.9 °F (25.5 °C) | 77.54 °F (25.3 °C) | 77.72 °F (25.4 °C) | 77.36 °F (25.2 °C) | 77.72 °F (25.4 °C) | 78.44 °F (25.8 °C) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 4.5 in (114.2 mm) | 1.5 in (38.1 mm) | 2.9 in (73.9 mm) | 4.8 in (122.5 mm) | 8.6 in (218.9 mm) | 6.6 in (167.3 mm) | 5.9 in (149.9 mm) | 6.9 in (175.5 mm) | 7.8 in (199 mm) | 7.6 in (194.2 mm) | 9.1 in (231.1 mm) | 8.5 in (216.8 mm) | 0.1 K in (1.90 K mm) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.0 in (1 mm)) | 6 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 12 | 131 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 248.4 | 257.8 | 279.6 | 246.8 | 223.2 | 202.3 | 226.6 | 211.5 | 200.4 | 234.8 | 226.1 | 220.7 | 2778.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78.0 | 77.0 | 76.9 | 78.1 | 80.8 | 80.7 | 79.1 | 80.5 | 81.0 | 81.7 | 82.2 | 80.9 | 79.7 |

4.3. Sea level rise and environmental issues

The Maldives faces a critical existential threat from sea level rise due to global warming. In 1988, Maldivian authorities warned that sea-level rise could "completely cover this Indian Ocean nation of 1,196 small islands within the next 30 years." The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its 2007 report predicted that the upper limit of sea-level rise would be 23 in (59 cm) by 2100, potentially rendering most of the republic's 200 inhabited islands uninhabitable. According to researchers from the University of Southampton, the Maldives is the third most endangered island nation due to flooding from climate change as a percentage of its population.

This vulnerability has driven successive Maldivian governments to become vocal advocates for international climate action. In 2008, then-President Mohamed Nasheed announced plans to investigate purchasing new land in India, Sri Lanka, and Australia, funded by tourism revenue, as a contingency for potential climate refugees. He stated, "We do not want to leave the Maldives, but we also do not want to be climate refugees living in tents for decades." At the 2009 International Climate Talks, Nasheed emphasized that transitioning away from fossil fuels was not only morally right but also in the Maldives' economic self-interest. He famously hosted the "world's first underwater cabinet meeting" in 2009 to raise awareness. In 2012, he warned, "If carbon emissions continue at the rate they are climbing today, my country will be underwater in seven years." His predecessor, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, also voiced concerns over rising sea levels.

The threat of sea level rise has profound implications for social equity, as displacement would disproportionately affect vulnerable populations and could lead to loss of cultural heritage and national identity. National responses have included investments in coastal protection measures, such as seawalls, and exploring land reclamation projects like Hulhumalé, an artificial island designed to accommodate a significant portion of the population. However, a 2020 study by the University of Plymouth suggested that while natural processes like tidal sediment movement could help some low-lying islands adapt by increasing their elevation, man-made structures like seawalls might compromise this natural adaptability, making island drowning inevitable in such cases.

Other major environmental problems include waste management and sand theft. While tourist resorts are often kept pristine, waste disposal is a significant challenge. Much of the waste from Malé and nearby resorts is disposed of at Thilafushi, an industrial island built on a reclaimed lagoon. This practice has led to Thilafushi becoming a large, polluting landfill, raising concerns about its environmental and health impacts, which disproportionately affect workers and nearby communities. The Maldives has 31 protected areas administered by the Ministry of Climate Change, Environment and Energy, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), aimed at conserving its fragile ecosystems.

4.4. Marine ecosystem

The Maldives boasts a rich and diverse marine ecosystem, encompassing deep sea, shallow coast, and extensive coral reef systems, along with fringing mangroves, wetlands, and dry land habitats. The coral reefs are formed by 187 species of coral and are central to the nation's biodiversity and economy. This region of the Indian Ocean is home to approximately 1,100 species of fish, 5 species of sea turtle, 21 species of whales and dolphins, 400 species of mollusk, and 83 species of echinoderm. The marine environment also supports a variety of crustaceans, including 120 copepod species, 15 amphipod species, over 145 crab species, and 48 shrimp species.

Among the many marine families represented are pufferfish, fusiliers, jackfish, lionfish, oriental sweetlips, reef sharks, groupers, eels, snappers, bannerfish, batfish, humphead wrasse, spotted eagle rays, scorpionfish, lobsters, nudibranchs, angelfish, butterflyfish, squirrelfish, soldierfish, glassfish, surgeonfish, unicornfish, triggerfish, Napoleon wrasse, and barracuda. These coral reefs are vibrant ecosystems supporting a wide array of marine life, from planktonic organisms to the majestic whale shark.

The marine ecosystem, particularly its coral reefs, is vital for the Maldivian economy and society. It underpins the lucrative tourism industry, attracting divers and snorkelers from around the world, and supports the traditional fishing industry, a key source of livelihood and protein for the local population. Sponges found in Maldivian waters have also gained importance, with five species displaying anti-tumor and anti-cancer properties.

However, these ecosystems are fragile and under threat. In 1998, a significant El Niño event caused sea-temperature warming of as much as 9.0 °F (5 °C), leading to widespread coral bleaching that killed an estimated two-thirds of the nation's coral reefs. Efforts to induce reef regrowth included placing electrified cones at depths of 20 ft to 60 ft to provide a substrate for larval coral attachment, which reportedly resulted in corals regenerating at five times the normal rate. Despite these efforts, the coral reefs experienced another severe bleaching incident in 2016, with up to 95% of coral around some islands dying. Surface water temperatures reached a high of 87.8 °F (31 °C) in May 2016. The recurring bleaching events, driven by rising sea temperatures linked to climate change, pose a severe threat to the marine biodiversity and the livelihoods dependent on it, demanding urgent conservation and climate mitigation measures. Recent scientific studies also suggest that faunistic composition can vary greatly between neighboring atolls, especially in terms of benthic fauna, possibly due to differences in fishing pressure, including poaching.

4.5. Wildlife

The wildlife of the Maldives includes the flora and fauna of its islands, reefs, and surrounding ocean. The unique geographical isolation and tropical climate have fostered a distinct biodiversity, although terrestrial habitats are limited by the small size and low elevation of the islands. Recent scientific studies suggest that faunal distribution can vary significantly between atolls, possibly influenced by factors like fishing pressure and poaching.

Terrestrial habitats face considerable threats from extensive development encroaching on limited land resources. Previously uninhabited islands are now at risk, with many natural environments crucial for indigenous species being severely endangered or destroyed. Coral reef habitats have also been damaged by land reclamation for artificial islands and coastal development, which can alter currents and affect coral growth. Mangroves thrive in brackish or muddy regions, with the archipelago hosting fourteen species, including the fern Acrostichum aureum.

The waters surrounding the Maldives are exceptionally rich in marine life, boasting a vibrant tapestry of corals and over 2,000 species of fish. This includes colorful reef fish, blacktip reef sharks, moray eels, and a diverse range of rays like manta rays, stingrays, and eagle rays. The magnificent whale shark is also found in Maldivian waters. These waters harbor rare species of both biological and commercial significance, with tuna fisheries being a longstanding traditional resource. In the limited freshwater habitats such as ponds and marshes, freshwater fish like the milkfish (Chanos chanos) and various smaller species thrive. The introduction of tilapia in the 1970s by a UN agency has further diversified the aquatic life.

Due to the islands' diminutive size, land-dwelling reptiles are scarce. The few species include a type of gecko, the oriental garden lizard (Calotes versicolor), the white-spotted supple skink (Riopa albopunctata), the Indian wolf snake (Lycodon aulicus), and the brahminy blind snake (Ramphotyphlops braminus). In contrast, the surrounding seas host a more diverse reptilian fauna. Maldivian beaches serve as nesting grounds for the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), the hawksbill turtle, and the leatherback turtle. Saltwater crocodiles have occasionally been reported to reach the islands and inhabit marshy regions.

The avifauna of the Maldives is mainly restricted to pelagic birds due to the archipelago's oceanic location. Most bird species are Eurasian migratory birds, with only a few typically associated with the Indian subcontinent. Some, like the frigatebird, are seasonal. Birds such as the grey heron and the moorhen dwell in marshes and island bush. White terns are occasionally found on the southern islands due to their rich habitats. The biodiversity of the Maldives is crucial for its ecological balance and national heritage, and conservation efforts are vital to protect its unique wildlife from threats posed by development and climate change.

5. Government and politics

The Maldives is a presidential constitutional republic with a multi-party system. The government is structured around the separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, though the president holds extensive influence. The nation's political landscape has seen significant evolution, particularly in its pursuit of democratic development, which continues to face challenges related to governance, accountability, and human rights.

5.1. Governance structure

The President of the Maldives is the head of state and head of government, and also serves as the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. The president heads the executive branch and appoints the cabinet, whose members must be approved by the People's Majlis (the unicameral parliament). Both the President and the members of the People's Majlis serve five-year terms. The current president, serving since 17 November 2023, is Mohamed Muizzu.

The People's Majlis is the legislative authority. The total number of members is determined by atoll populations. The 2024 parliamentary election resulted in the People's National Congress (PNC) winning a super-majority of 66 out of 93 seats, with its allies taking an additional nine seats, giving the president the backing of 75 legislators, enough to change the constitution.

The republican constitution came into force in 1968 and was subsequently amended in 1970, 1972, and 1975. On 27 November 1997, it was replaced by another constitution assented to by then-President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, which came into force on 1 January 1998. The current Constitution of the Maldives was ratified by President Maumoon on 7 August 2008 and came into effect immediately. This new constitution introduced significant reforms, including a judiciary to be run by an independent commission, and independent commissions to oversee elections and combat corruption. It also aimed to reduce the executive powers vested in the president and strengthen the parliament.

Despite these reforms, the path to democratic consolidation has been challenging. In 2018, the ruling Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM-Y)'s tensions with opposition parties and a subsequent crackdown were termed an "assault on democracy" by the UN Human Rights chief. The effectiveness of democratic institutions, political stability, and good governance remain ongoing concerns, with frequent shifts in political alliances and power dynamics. The Order of the Distinguished Rule of Izzuddin is the Maldives' highest civilian honor, bestowed by the president.

The April 2019 parliamentary election saw the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) of then-President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih win a landslide victory, securing 65 out of 87 seats. This was the first time a single party had achieved such a high number of seats in Maldivian parliamentary history, reflecting a strong public mandate for democratic reform and accountability at the time. However, the subsequent 2023 presidential election and the 2024 parliamentary election saw a shift in power, indicating the fluid nature of Maldivian politics.

5.2. Law

The Maldivian legal system is based on a combination of Islamic law (Shari'ah) and English common law, with Islamic Shari'ah being the primary source, particularly for family and criminal law. According to the Constitution of the Maldives, "the judges are independent, and subject only to the Constitution and the law. When deciding matters on which the Constitution or the law is silent, judges must consider Islamic Shari'ah."

Islam is the official religion of the Maldives, and the open practice of any other religion is forbidden and restricted. The 2008 constitution states that the republic "is based on the principles of Islam" and that "no law contrary to any principle of Islam can be applied." Non-Muslims are prohibited from becoming citizens, and adherence to Sunni Islam is a requirement for citizenship. This legal framework has significant implications for civil liberties, particularly freedom of religion. The requirement to adhere to a particular religion and the prohibition of public worship for other faiths is contrary to Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which the Maldives is a party. However, the Maldives made a reservation when acceding to the Covenant, stating that "The application of the principles set out in Article 18 of the Covenant shall be without prejudice to the Constitution of the Republic of Maldives."

A new penal code came into effect on 16 July 2015, replacing the 1968 law. It was intended as the first modern, comprehensive penal code to incorporate major tenets and principles of Islamic law alongside modern criminal justice standards. However, the application of certain Shari'ah-prescribed punishments, such as flogging, has drawn international criticism, particularly concerning women's rights and due process.

Same-sex relations are illegal in the Maldives and are punishable under the law. This affects the rights and freedoms of LGBTQ+ individuals. While tourist resorts often operate with a degree of leniency concerning certain social norms, the legal framework for Maldivian citizens remains strict. Access to justice, particularly for minorities and vulnerable groups, can be challenging, and the independence and capacity of the judiciary have been areas of concern and reform efforts.

5.3. Military

The Maldives National Defence Force (MNDF) is the combined security organization responsible for defending the security and sovereignty of the Maldives. Its primary task is to attend to all internal and external security needs, including the protection of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the maintenance of peace and security.

The MNDF comprises several component branches:

- Coast Guard: Plays a vital role in maritime security, surveillance of Maldivian waters, protection against poaching and foreign intrusion in the EEZ, and responding to maritime distress calls, including search and rescue operations. Patrol boats are stationed at various MNDF Regional Headquarters.

- Marine Corps: Provides land-based defense capabilities.

- Special Forces: Handles specialized security operations.

- Service Corps

- Defence Intelligence Service

- Military Police

- Corps of Engineers

- Special Protection Group (responsible for protecting high-level officials)

- Medical Corps

- Adjutant General's Corps

- Air Corps

- Fire and Rescue Service

Given that almost 99% of the country is covered by sea and the remaining 1% land is scattered over a vast area (497 mile (800 km) × 75 mile (120 km)), with the largest island being no more than 3.1 mile2 (8 km2), maritime security is a paramount concern. The MNDF's task of maintaining surveillance over Maldivian waters is immense, both logistically and economically.

The Maldives has historically maintained a non-aligned stance but cooperates with international partners on security matters. For instance, it has an arrangement with India for cooperation on radar coverage to enhance maritime domain awareness. The MNDF also participates in international disaster relief and humanitarian aid efforts, reflecting its role beyond traditional defense. Its involvement in maintaining national sovereignty was notably demonstrated during the 1988 coup attempt, which was thwarted with the assistance of Indian forces.

In 2019, the Maldives signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, underscoring its commitment to global disarmament efforts. The military's role also extends to internal security and disaster response, making it a key institution in the country's overall national security framework.

5.4. Human rights

The human rights situation in the Maldives is a complex and often contentious issue, with progress in some areas and persistent challenges in others. While the country has made strides towards democratic governance, concerns remain regarding fundamental freedoms, the rights of vulnerable groups, and the overall protection of human rights, often highlighted by international organizations and local civil society.

Freedom of Religion: Islam is the state religion, and the constitution stipulates that all citizens must be Muslims. The open practice of any religion other than Islam is prohibited for citizens. This restriction significantly curtails freedom of religion and belief, and non-Muslims cannot become citizens. While tourists and foreign workers are generally allowed to practice their religions in private, the legal framework for Maldivian citizens remains restrictive.

Freedom of Expression and Assembly: Freedom of expression and assembly has seen fluctuations depending on the political climate. While the 2008 constitution provides for these freedoms, governments have at times imposed restrictions, particularly during periods of political unrest. Journalists and activists have faced harassment, intimidation, and legal action. The Evidence Act, which came into effect in January 2023, grants courts the authority to compel journalists to reveal their confidential sources, which is seen as a threat to press freedom. The Maldives Media Council (MMC) and the Maldives Journalists Association (MJA) act as watchdogs, but the environment for media freedom remains challenging.

Women's Rights: While women in the Maldives have relatively high literacy rates and participate in public life, they face discrimination and challenges. Gender-based violence, including domestic violence, is a significant concern. Women are underrepresented in political and decision-making positions. The application of certain interpretations of Sharia law, such as flogging for extramarital sex, disproportionately affects women and has drawn international condemnation. Efforts to strengthen legal protections and support services for women are ongoing but require more robust implementation.

LGBTQ+ Rights: Same-sex sexual conduct is criminalized in the Maldives, and LGBTQ+ individuals face legal discrimination and social stigma. There are no legal protections for LGBTQ+ people, and public discussion of LGBTQ+ issues is highly restricted.

Labor Rights: A large expatriate workforce, primarily from South Asian countries, forms a significant part of the Maldivian labor force, particularly in construction and tourism. Many migrant workers face exploitative conditions, including low wages, poor living conditions, withholding of passports, and debt bondage. Human trafficking and forced labor are serious concerns. While the government has taken some steps to address these issues, enforcement of labor laws and protection for migrant workers remain inadequate.

Justice System and Rule of Law: Concerns about the independence and impartiality of the judiciary, due process, and access to justice persist. Political interference in the judiciary has been alleged, particularly in high-profile cases. Prison conditions and treatment of detainees have also been subjects of criticism.

International human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as the U.S. State Department and Freedom House, regularly report on the human rights situation in the Maldives. While the country has engaged with international human rights mechanisms, including becoming a party to key human rights treaties (with reservations on certain articles, particularly related to religious freedom), the full implementation of these standards and the fostering of a culture of human rights respect and accountability remain critical challenges for democratic development and social equity.

6. Foreign relations

The Maldives pursues a foreign policy centered on safeguarding its sovereignty, territorial integrity, and Islamic identity, while also actively engaging with the international community on issues of mutual concern, particularly climate change, human rights, and economic development. Historically, it has maintained a non-aligned stance, though its strategic location in the Indian Ocean has increasingly drawn the attention of regional and global powers.

6.1. Relations with major countries

The Maldives has traditionally maintained close ties with its South Asian neighbors, India and Sri Lanka.

India: Relations with India have historically been strong, encompassing political, economic, defense, and cultural cooperation. India has been a significant development partner and provided crucial assistance, including during the 1988 coup attempt and the 2004 tsunami. However, the relationship has experienced fluctuations depending on the Maldivian government in power. Administrations perceived as pro-India have deepened security and economic ties, while those leaning towards other powers have sometimes led to strains. The presence of Indian military personnel in the Maldives for operating gifted aircraft and helicopters for surveillance and rescue has become a sensitive political issue, with some Maldivian political factions advocating for their removal, citing sovereignty concerns. India remains a key trading partner and a source of tourism and investment.

Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka is another important neighbor with longstanding historical, cultural, and economic links. Many Maldivians travel to Sri Lanka for education, healthcare, and commerce.

China: Relations with China have significantly expanded in the 21st century, particularly under administrations seeking to diversify foreign partnerships and attract infrastructure investment. China has funded and built major projects in the Maldives, including the Sinamalé Bridge connecting Malé to Hulhulé and Hulhumalé, as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. This growing engagement has led to concerns about debt sustainability and geopolitical implications, particularly in the context of Sino-Indian rivalry in the Indian Ocean region. Governments perceived as pro-China have strengthened these ties, while others have sought to rebalance foreign policy.

The Maldives also engages with other key countries in Asia, the Middle East, and Europe for trade, investment, and development assistance. As an Islamic nation, it maintains close ties with countries in the Muslim world.

Strategic interests, economic dependencies, and human rights considerations often influence these bilateral relationships. The Maldives has, at times, faced international scrutiny regarding its human rights record, which can affect its diplomatic engagements. The nation's stance on issues like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict also shapes its foreign relations; for instance, in June 2024, the Maldivian government decided to ban Israeli passport holders from entering the country in response to the war in Gaza.

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and subsequent Western sanctions on Russian oligarchs, many sought refuge for their mega-yachts in the Maldives, partly due to the absence of an extradition treaty with the United States and other sanctioning countries.

6.2. Participation in international organizations

The Maldives is an active member of several international and regional organizations:

- United Nations (UN): The Maldives joined the UN in 1965 and actively participates in its various agencies and forums. It has been a prominent voice on climate change, advocating for the interests of small island developing states (SIDS).

- Commonwealth of Nations: The Maldives joined the Commonwealth in 1982. It withdrew in October 2016, protesting allegations of human rights abuses and failing democracy. Following a change in government and evidence of democratic reforms, it rejoined the Commonwealth on 1 February 2020.

- South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC): The Maldives is a founding member of SAARC and has hosted its summits. It engages in regional cooperation on economic, social, and cultural issues.

- Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC): As a Muslim-majority nation, the Maldives is an active member of the OIC, participating in initiatives related to the Islamic world.

- Non-Aligned Movement (NAM): The Maldives adheres to the principles of non-alignment, though its foreign policy is also pragmatic, balancing relationships with major powers.

- Indian Ocean Commission (IOC): Since 1996, the Maldives has been an official progress monitor (observer) of the IOC and has expressed interest in closer ties, reflecting its identity as a small island state focused on economic development and environmental preservation.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO): The Maldives is a Dialogue Partner of the SCO.

Through these platforms, the Maldives champions causes such as climate justice, sustainable development, maritime security, and human rights (though its domestic record sometimes faces criticism). Its foreign policy aims to navigate a complex geopolitical environment while securing its national interests and contributing to global and regional stability.

7. Administrative divisions

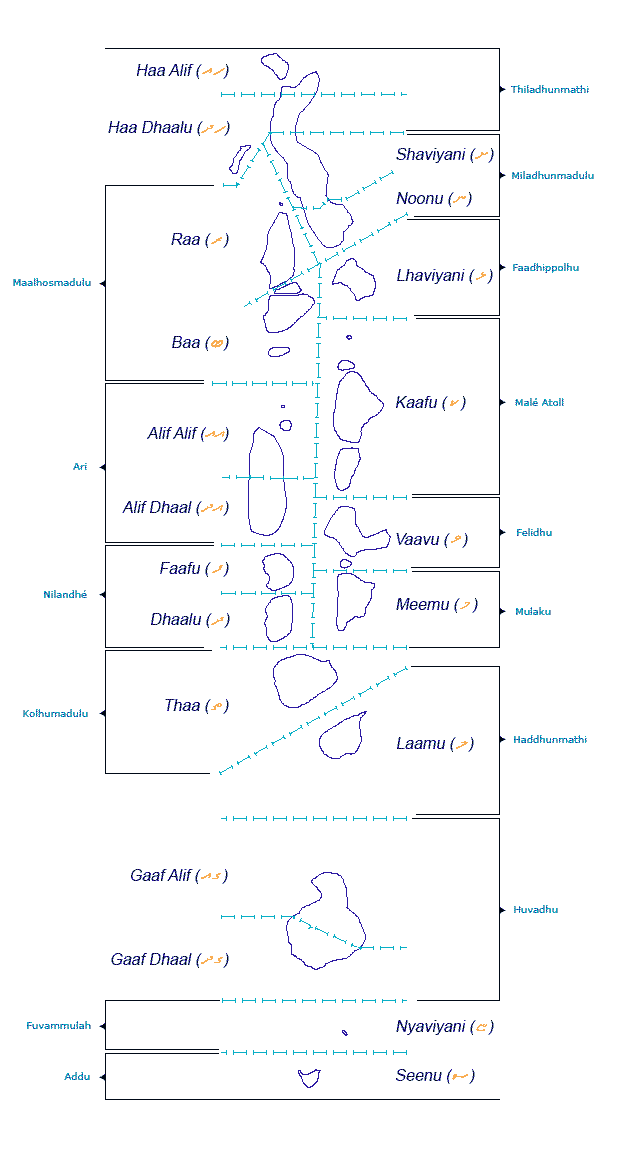

The Maldives is divided into administrative units for governance purposes. The country comprises twenty-six natural atolls and a few island groups on isolated reefs. These natural atolls have been administratively organized into twenty-one divisions: 17 administrative atolls and the cities of Malé, Addu, Fuvahmulah, Thinadhoo, and Kulhudhuffushi.

Each administrative atoll is governed by an elected Atoll Council, and individual inhabited islands are administered by an elected Island Council. This system of local governance aims to decentralize power and promote local participation in development and decision-making, although the effectiveness and autonomy of these councils can vary.

In addition to a geographical name, every administrative division is identified by Maldivian code letters (e.g., "Haa Alif" for Thiladhunmathi Uthuruburi or North Thiladhunmathi Atoll) and a Latin code letter. The Maldivian code letter corresponds to the traditional Maldivian name of the atoll, while the Latin code letter is often a more convenient abbreviation. Since some islands in different atolls share the same name, this code is quoted before the island's name for administrative clarity (e.g., Baa Funadhoo, Kaafu Funadhoo, Gaafu-Alifu Funadhoo). The long geographical names of atolls also lead to the frequent use of these code letters in official communications and even website names.

The introduction of these code-letter names has sometimes caused confusion, especially among foreigners, who might mistake the code letter for a new name that has replaced the geographical one. However, in formal geographical, historical, or cultural contexts, the traditional Dhivehi names are typically used.

This administrative structure facilitates the governance of a geographically dispersed nation, addressing the unique challenges posed by its archipelago geography.

8. Economy

The Maldivian economy has undergone significant transformation, moving from a traditional reliance on fisheries to a service-oriented economy dominated by tourism. While this shift has brought considerable economic growth and improved living standards for some, it also presents challenges related to income inequality, labor rights, environmental sustainability, and vulnerability to external shocks. The government continues to pursue economic reforms and diversification efforts.

Historically, the Maldives was known for providing enormous quantities of cowrie shells, which served as an international currency in early ages. From the 2nd century CE, Arab traders referred to the islands as the 'Money Isles.' Monetaria moneta cowries from the Maldives were used for centuries as currency in parts of Africa and Asia, with large amounts introduced into Africa by Western nations during the slave trade. The cowry shell is now the symbol of the Maldives Monetary Authority.

In the early 1970s and 1980s, the Maldives was one of the world's 20 poorest countries, with a population of around 100,000. The economy was largely dependent on fisheries and trading local goods such as coir rope, ambergris (Maavaharu), and coco de mer (Tavakkaashi) with neighboring countries and East Asian nations.

The Maldivian government initiated a largely successful economic reform program in the 1980s, lifting import quotas and providing more opportunities for the private sector. This period coincided with the nascent development of the tourism sector, which would become a crucial driver of the nation's economy.

Agriculture and manufacturing play lesser roles due to the limited availability of cultivable land and a shortage of domestic labor. However, some agricultural products like coconuts and certain fruits are grown, and small-scale manufacturing includes boat building and handicrafts.

8.1. Tourism

Tourism is the cornerstone of the Maldivian economy, accounting for approximately 28% of the GDP and more than 60% of the country's foreign exchange receipts. Over 90% of government tax revenue is derived from import duties and tourism-related taxes. The development of tourism, which began in the early 1970s, has fostered the overall growth of the country's economy, creating direct and indirect employment and income generation opportunities in related industries.

The first tourist resorts, Bandos Island Resort and Kurumba Village (now Kurumba Maldives), opened in 1972, transforming the Maldivian economy from its dependence on fisheries. In just over three decades, tourism became the main source of income. By 2008, 89 resorts offered over 17,000 beds and hosted over 600,000 tourists annually. In 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, over 1.7 million visitors came to the islands. The number of resorts increased from 2 in 1972 to 159 by 2020, along with 13 hotels and 638 guesthouses, indicating a diversification in accommodation types.

The Maldives is renowned for its luxury resorts, pristine beaches, clear waters, and abundant marine life, making it a popular destination for honeymoons, scuba diving, and relaxation. The "one island, one resort" concept, where a resort typically occupies an entire uninhabited island, has been a hallmark of Maldivian tourism, offering exclusivity and minimizing direct impact on local inhabited islands. However, recent trends have seen the growth of guesthouses on inhabited islands, allowing tourists to experience local culture and providing more direct economic benefits to local communities.

The socio-economic impacts of tourism are multifaceted. While it has driven economic growth and improved infrastructure on some islands, concerns exist regarding:

- Labor Conditions: A significant portion of the tourism workforce consists of expatriate labor. Issues related to wages, working conditions, and workers' rights have been raised. Ensuring fair labor practices and opportunities for Maldivian nationals in the industry is an ongoing challenge.

- Benefit Distribution: Questions about the equitable distribution of tourism revenue and its benefits to the wider population persist. While the sector generates substantial wealth, addressing income inequality and ensuring that local communities share in the prosperity is crucial for social equity.

- Environmental Impact: The tourism industry is heavily reliant on the health of the marine environment. Coastal development, waste generation from resorts, and the carbon footprint of international travel pose environmental challenges. Sustainable tourism practices, marine conservation, and responsible waste management are vital for the long-term viability of the industry and the protection of the Maldives' natural heritage.

The country has six heritage Maldivian coral mosques listed as UNESCO tentative sites, which could potentially diversify its tourism attractions beyond beaches and marine activities.

Visitors to the Maldives generally do not need to apply for a visa pre-arrival, regardless of their country of origin, provided they have a valid passport, proof of onward travel, and sufficient funds. Most visitors arrive at Velana International Airport, located on Hulhulé Island adjacent to Malé.

8.1.1. Tourist demographics and trends

The Maldives attracts tourists from around the globe. Historically, European countries like Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom were major source markets. In recent years, there has been significant growth in arrivals from Asian countries, particularly China and India. Other important markets include Russia, the United States, and countries in the Middle East.

Tourism trends have been influenced by global economic conditions, travel preferences, and events such as the 2004 tsunami and the COVID-19 pandemic. The industry has shown resilience and adaptability, with efforts to diversify source markets and tourism products. The Maldivian government and tourism industry stakeholders continuously work on marketing and promotion campaigns to maintain the country's appeal as a premier tourist destination.

Revenue from tourism is a critical component of the Maldivian economy. Statistics on tourist arrivals, occupancy rates, and tourism-related earnings are closely monitored by the Ministry of Tourism and are key indicators of the nation's economic health. The shift towards guesthouse tourism on inhabited islands represents a trend towards more diverse and potentially more locally integrated tourism experiences, though it also requires careful management to ensure sustainability and minimize negative social impacts.

8.2. Fishing industry

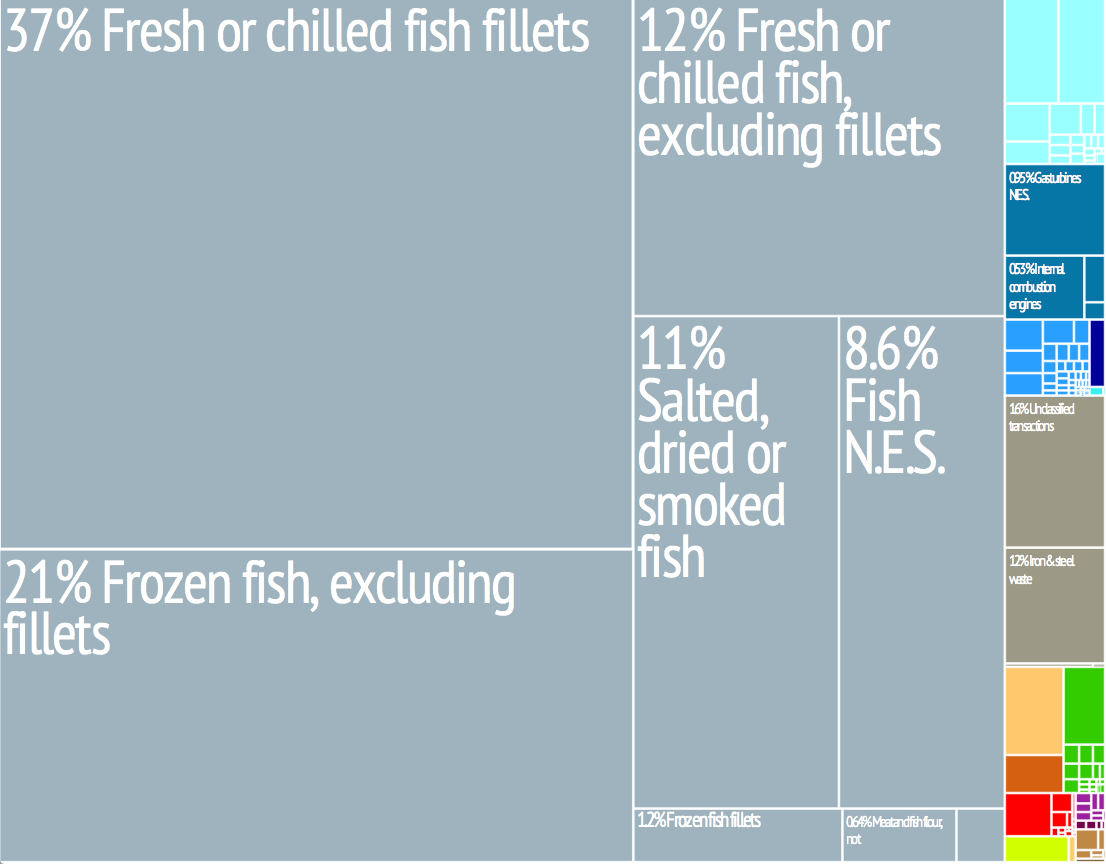

For many centuries, the Maldivian economy was entirely dependent on fishing and other marine products. Fishing remains a vital sector, the main traditional occupation, and a significant contributor to the economy, second only to tourism in foreign exchange earnings. The government continues to prioritize the fisheries sector, focusing on sustainability and the well-being of fishing communities.

The mechanization of the traditional fishing boat, the dhoni, in 1974 was a major milestone in the development of the industry. A fish canning plant was installed on Felivaru in 1977, as a joint venture with a Japanese firm. In 1979, a Fisheries Advisory Board was established to advise the government on policy guidelines for the overall development of the fisheries sector.

Manpower development programs began in the early 1980s, and fisheries education was incorporated into the school curriculum. The introduction of fish aggregating devices (FADs) and navigational aids at various strategic points helped improve catch efficiency. Moreover, the opening up of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the Maldives for fisheries further enhanced the growth of the sector.

As of 2010, fisheries contributed over 15% of the country's GDP and employed about 30% of the country's workforce. The primary catch is tuna, particularly skipjack tuna and yellowfin tuna. Maldivian tuna is caught using traditional pole-and-line methods, which are considered environmentally sustainable and dolphin-friendly, a key selling point in international markets. Other fish caught include reef fish and other oceanic species.

The industry encompasses catching, processing, and exporting fish. Products include fresh, frozen, canned, dried, and salted fish. Japan, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and European countries are significant export markets for Maldivian fish products. Around 90% of total fishery product exports from Maldives consist of fresh, dried, frozen, salted, and canned tuna.

Ensuring the sustainability of fish stocks is crucial. The Maldives has been an advocate for sustainable fishing practices and has implemented measures to manage its fisheries resources. The socio-economic conditions of fishing communities are also a focus, with efforts to improve livelihoods and ensure that benefits from the industry are shared equitably. Challenges include fluctuating international fish prices, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing by foreign vessels, and the impacts of climate change on marine ecosystems and fish stocks.

8.3. Other industries

While tourism and fisheries are the dominant sectors, the Maldivian economy includes other industries, though their contribution is comparatively smaller.

Agriculture: Due to limited arable land and infertile soil, agriculture is not a major economic activity. However, some crops are cultivated, primarily for local consumption. These include coconuts (a significant traditional crop used for food, oil, and coir fiber), bananas, breadfruit, papayas, mangoes, taro, sweet potatoes, and onions. Most food items, especially staples like rice and flour, need to be imported, which contributes to food security concerns. There are ongoing efforts to promote small-scale farming and home gardening to enhance local food production.

Manufacturing: The manufacturing sector is small and primarily caters to local needs and the tourism industry. Key activities include:

- Boat building: The construction and repair of traditional dhonis and other vessels is an important skill and industry.

- Handicrafts: Production of traditional crafts like lacquer work (laajehun), woven mats, and items made from coconut wood and shells, often sold as souvenirs to tourists.

- Food processing: This mainly involves fish canning and processing of other local produce.

- Other small-scale manufacturing includes production of PVC pipes, soap, furniture, and some food products.

Construction: The construction sector has seen growth, driven by tourism development (resort construction and renovation) and public infrastructure projects, including housing, harbors, and coastal protection. The demand for construction materials, most of which are imported, and labor (often expatriate) is significant. Environmental considerations, such as the impact of dredging and reclamation for construction, are important in this sector.

These other industries, while not as prominent as tourism and fisheries, play a role in providing employment and contributing to the domestic economy. Diversifying the economic base remains a long-term goal for the Maldives to reduce its vulnerability to external shocks affecting its main industries. Social and environmental considerations, such as labor conditions in construction and sustainable sourcing of materials, are relevant to these sectors as well.

9. Society

Maldivian society is a unique blend of traditional customs and modern influences, shaped by its Islamic faith, island environment, and increasing interconnectedness with the global community. Key aspects include its demographics, religious practices, languages, and systems of education and healthcare, with ongoing attention to social welfare and equity.

9.1. Demographics

The population of the Maldives was approximately 341,356 according to the 2014 census, comprising 339,761 resident Maldivians and a significant number of resident foreigners. The 2022 census recorded a population of 515,132. The population doubled by 1978, and the population growth rate peaked at 3.4% in 1985. By the 2006 census, the population had reached 298,968, though the growth rate had declined to 1.9% by 2000. Life expectancy at birth rose from 46 years in 1978 to approximately 77 years by 2011 and over 79 years more recently. Infant mortality has significantly declined, from 127 per 1,000 live births in 1977 to around 12 per 1,000. Adult literacy is high, at 99%.

The largest ethnic group is the Dhivehin, native to the historic region of the Maldive Islands, which includes the present-day Republic of Maldives and the island of Minicoy in Lakshadweep, India. They share a common culture and speak the Dhivehi language. They are principally an Indo-Aryan people, with genetic traces from Middle Eastern, South Asian, Austronesian, and African populations. In the past, there was also a small Tamil population known as the Giraavaru people, who were native to Giraavaru island but have now been largely absorbed into the broader Maldivian society after their island was evacuated in 1968 due to severe erosion.

Social stratification exists but is not rigid, with rank based on factors like occupation, wealth, Islamic virtue, and family ties. Historically, there was a distinction between noble (bēfulhu) and common people, with the social elite concentrated in Malé. Contemporary social issues include addressing disparities between the capital, Malé, and the outer atolls in terms of access to services and economic opportunities.

There is a significant expatriate worker population, estimated to be around 281,000 as of May 2021, with a large proportion (estimated 63,000) being undocumented. The largest groups of foreign workers are from Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and the Philippines, primarily employed in construction, tourism, and domestic service. The status and rights of these migrant workers are critical social and human rights concerns, including issues of exploitation and access to services. The high population density in Malé and some other islands also presents social and infrastructural challenges.

9.2. Religion

Islam is the state religion of the Maldives, and adherence to Sunni Islam is a legal requirement for citizenship according to the 2008 Constitution. The historical conversion of the Maldives from Buddhism to Islam occurred in the mid-12th century, traditionally attributed to the Moroccan (or Persian/Tabrizi) scholar Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari. His venerated tomb is located at Medhu Ziyaaraiy in Malé.