1. Overview

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country located at the center of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia. It is bordered to the north by Myanmar and Laos, to the east by Laos and Cambodia, to the south by the Gulf of Thailand and Malaysia, and to the west by the Andaman Sea. Its maritime boundaries include Vietnam in the Gulf of Thailand to the southeast, and Indonesia and India on the Andaman Sea to the southwest. Bangkok is the nation's capital and largest city.

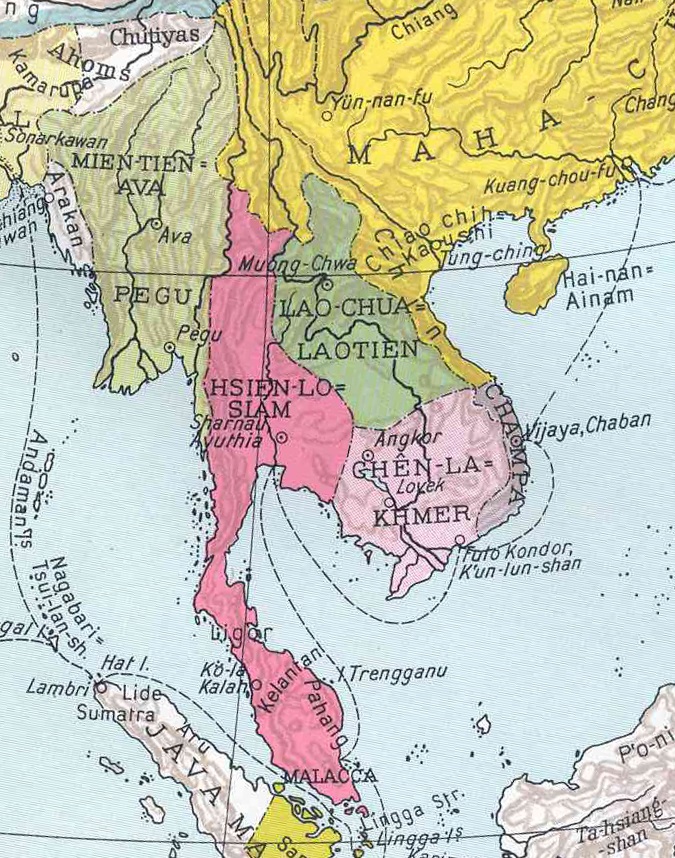

The country's history is marked by the migration of Tai peoples from southwestern China, the rise and fall of influential Indianised kingdoms such as the Mon, Khmer, and Malay states, and the subsequent emergence of Thai kingdoms like Sukhothai, Lan Na, and Ayutthaya. Ayutthaya became a major regional power, engaging in trade and diplomacy with European nations from the 16th century. Despite significant external pressures during the era of Western imperialism, Thailand is notable for being the only Southeast Asian nation to avoid direct colonization, though it was forced to cede territory and accept unequal treaties. A pivotal moment was the 1932 revolution, which transformed the absolute monarchy into a constitutional monarchy. Thailand's modern history has been characterized by periods of democratic governance interspersed with military coups and political instability, reflecting an ongoing struggle for democratic development and human rights. Recent decades have seen significant political conflicts, pro-democracy movements challenging established powers, and calls for reform.

Geographically, Thailand features mountainous northern highlands, the northeastern Khorat Plateau, fertile central plains dominated by the Chao Phraya River, and a southern peninsular region. The climate is tropical monsoon, with distinct rainy, dry, and cool seasons. The nation possesses rich biodiversity, though it faces environmental challenges such as deforestation and pollution, which have significant social and ecological impacts.

Thailand's government operates as a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system. However, the military has historically exerted considerable political influence, and lèse-majesté laws have been criticized for their impact on freedom of expression and democratic processes. The economy is newly industrialized and heavily export-dependent, with manufacturing, agriculture (especially rice), and tourism being key sectors. Issues of income inequality, poverty, and labor rights, particularly within the large informal economy and for migrant workers, remain significant social concerns. Infrastructure development in transportation, energy, and telecommunications is ongoing, though challenges in equitable access and internet freedom persist.

Thai society is predominantly Buddhist, with Islam as the largest minority religion, concentrated in the south. The official language is Thai. The population is diverse, comprising the majority Thai people and various ethnic minorities, including Chinese-Thai, Malay-Thai, and numerous hill tribes, whose social standing and rights are important considerations. Education and healthcare systems have seen improvements, but disparities and quality issues continue to be addressed.

Thai culture, rich in traditions and customs like the wai greeting, is deeply influenced by Buddhism and historical interactions with neighboring cultures. Traditional arts, architecture (notably wats or temples), literature such as the Ramakien, classical music, and dance forms like Khon are integral to its heritage. Thai cuisine is globally renowned.

2. Etymology

Thailand was known to outsiders as Siam (สยามSayam (sajǎːm)Thai) before 1939, and this name was officially used until that year. The name Siam was also briefly reinstated between 1945 and 1949. The origin of the name "Siam" is debated. It may have originated from Sanskrit श्याम (śyāma, meaning 'dark') or from the Mon language word ရာမည (rhmañña, meaning 'stranger'), possibly sharing the same root as "Shan" and "Assam". Another theory suggests the name derives from the Chinese term "Xian" (暹) used to refer to the region. Ancient Khmer inscriptions also used "Siam" to refer to people in the Chao Phraya River valley. The signature of King Mongkut (Rama IV, r. 1851-1868) read SPPM Mongkut Rex Siamensium (Mongkut, King of the Siamese), and its use in the Bowring Treaty gave "Siam" official international status.

The word Thai (ไทยThaiThai) itself holds significant meaning. According to George Cœdès, "Thai" means 'free man' in the Thai language, differentiating the Thai from other groups within Thai society who might have been considered serfs. However, Chit Phumisak argued that Thai (ไทThaiThai) simply means 'people' or 'human being', noting its use in some rural areas instead of the common Thai word khon (คนkhonThai) for people. Michel Ferlus proposed that the ethnonyms Thai-Tai evolved from the etymon *k(ə)ri: ('human being').

Thais often refer to their country using the polite form prathet Thai (ประเทศไทยPrathet ThaiThai), or the more colloquial mueang Thai (เมืองไทยMueang ThaiThai). The term mueang archaically referred to a city-state and is commonly used for a city or town. The formal name Ratcha Anachak Thai (ราชอาณาจักรไทยRatcha Anachak ThaiThai) translates to 'Kingdom of Thailand' or 'Kingdom of the Thai'. Its components are: ratcha (from Sanskrit राजन्rājanSanskrit, 'king, royal, realm'); ana- (from Pali āṇā, 'authority, command, power', itself from Sanskrit आज्ञाājñāSanskrit); and -chak (from Sanskrit चक्रcakraSanskrit, 'wheel', a symbol of power and rule).

The Thai National Anthem, written in the 1930s, refers to the nation as prathet Thai. The first line, ประเทศไทยรวมเลือดเนื้อชาติเชื้อไทยprathet thai ruam lueat nuea chat chuea thaiThai, translates to 'Thailand is founded on blood and flesh'. The change from "Siam" to "Thailand" in 1939 under the government of Plaek Phibunsongkhram was part of a nationalist campaign, emphasizing the land belonging to the Thai people.

3. History

The history of Thailand encompasses early human settlements, the rise and fall of various kingdoms and empires, interactions with foreign powers, and the nation's transformation into a modern constitutional monarchy. This historical narrative includes periods of significant cultural achievement, intense conflict, colonial pressures, and ongoing struggles for political stability and democratic governance.

3.1. Prehistory and Early States

Evidence of continuous human habitation in present-day Thailand dates back at least 20,000 years. The earliest evidence of rice cultivation is dated at 2,000 BCE. Bronze appeared around 1,250-1,000 BCE, with the site of Ban Chiang in northeast Thailand recognized as one of the earliest known centers of copper and bronze production in Southeast Asia. Iron appeared around 500 BCE. The region that is now Thailand also participated in the Maritime Jade Road trading network, which existed for 3,000 years, from 2000 BCE to 1000 CE.

The Kingdom of Funan, flourishing from the 2nd century BCE, was an early and powerful Southeast Asian kingdom with significant Indian cultural influence. Subsequently, the Mon people established principalities such as Dvaravati (6th-11th centuries) in central Thailand and the Hariphunchai kingdom (7th-13th centuries) in the north. These Mon kingdoms were significant centers of Buddhism and art.

The Khmer Empire, centered in Angkor, rose in the 9th century and exerted considerable influence over large parts of what is now Thailand for several centuries. Many Khmer temples and artifacts are found throughout Thailand. Concurrently, Srivijaya, a maritime empire based on Sumatra, and other Malay states like Tambralinga (a Malay state controlling trade through the Malacca Strait, rising in the 10th century), also influenced the southern regions of present-day Thailand. These early states were part of a broader network of Indianized kingdoms in Southeast Asia, deeply influenced by Indian culture, religion (Hinduism and Buddhism), and political ideas.

The Tai peoples, characterized by common linguistic roots, began migrating from southwestern China into mainland Southeast Asia, including present-day Thailand, from approximately the 6th to 11th centuries. They gradually settled in areas already occupied by Mon and Khmer populations, leading to cultural intermixing. The earliest historical mentions of Syam (Siam) individuals appear in 11th-century Cham epigraphy as slaves or prisoners of war, and in 12th-century bas-reliefs at Angkor Wat depicting warriors identified as Syam. However, the precise ethnicity and origins of these early Syam groups remain a subject of scholarly discussion.

3.2. Sukhothai Kingdom

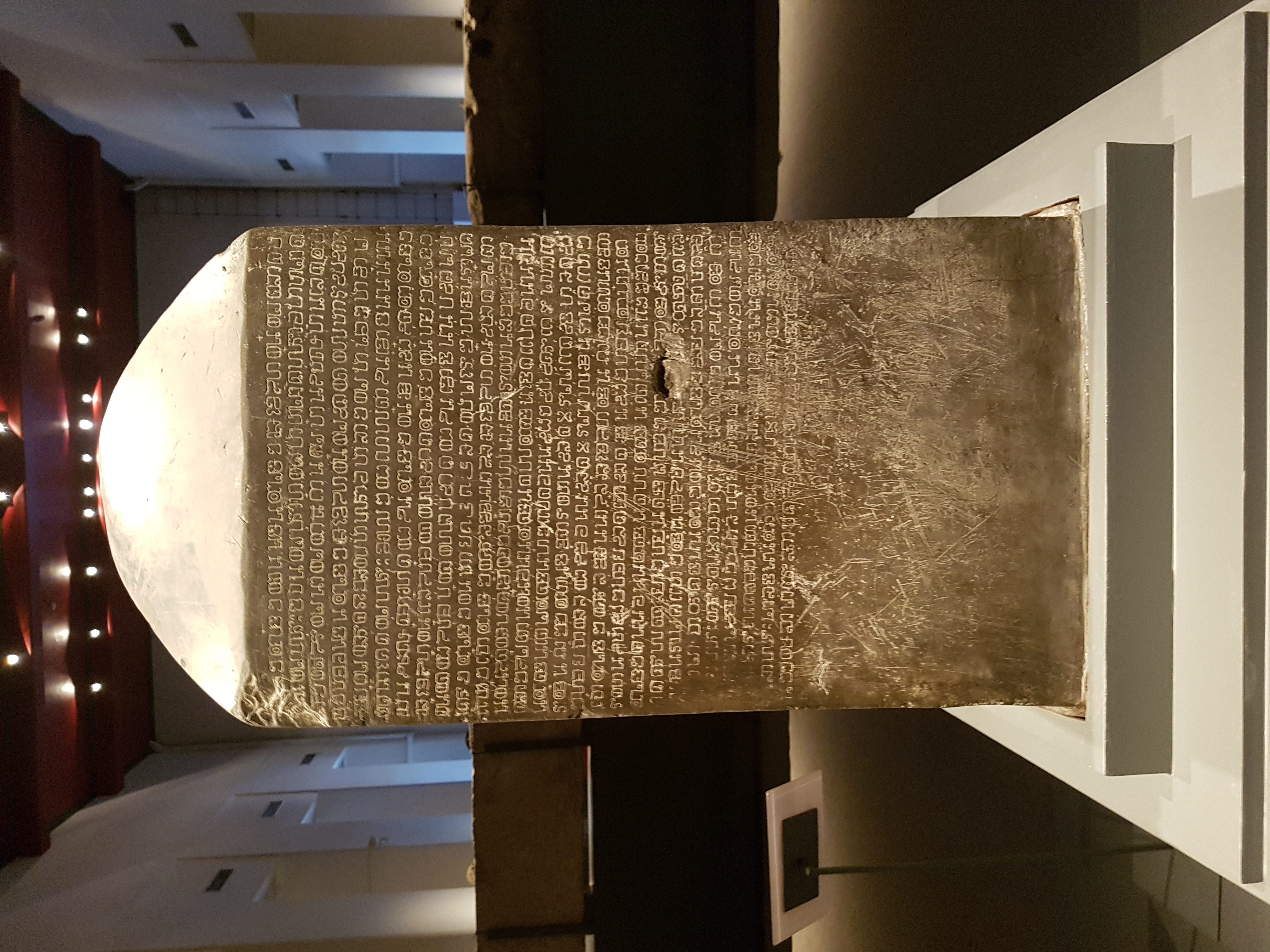

The Sukhothai Kingdom (1238-1438) is traditionally considered the first major Thai kingdom. It was established in the upper Chao Phraya River valley when local Tai rulers, Pho Khun Bang Klang Hao and Pho Khun Pha Mueang, declared independence from the declining Khmer Empire around 1238. Si Inthrathit became the first king of Sukhothai.

The kingdom reached its zenith under King Ram Khamhaeng (reigned c. 1279-1298). During his rule, Sukhothai expanded its influence significantly, though this was often through a network of local lords who swore fealty rather than direct control. Ram Khamhaeng is credited with the creation of the Thai script in 1283, based on Mon and Khmer scripts, a pivotal development in Thai cultural identity. The Ram Khamhaeng Inscription, allegedly from this period, describes a prosperous and paternalistic kingdom. Sukhothai was also known for its production of high-quality ceramics (Sangkhalok ware), which were an important export.

Theravada Buddhism was adopted and flourished during the Sukhothai period, particularly under King Maha Thammaracha I (Lithai, reigned 1347-1368), who was a devout Buddhist scholar and author of the Traiphum Phra Ruang, a significant work of Thai Buddhist cosmology. The art and architecture of Sukhothai, characterized by elegant Buddha images and distinctive stupa designs, represent a golden age of Thai culture.

However, after Ram Khamhaeng's death, Sukhothai gradually weakened due to internal succession disputes and the rising power of the Ayutthaya Kingdom to its south. By 1378, Sukhothai became a vassal state of Ayutthaya and was eventually fully incorporated into it in the 15th century, with its capital moved to Phitsanulok around 1430.

3.3. Ayutthaya Kingdom

The Ayutthaya Kingdom (1351-1767) was founded by King Uthong (Ramathibodi I) in 1351 on an island in the Chao Phraya River. It rose from the earlier Lavo Kingdom and Suvarnabhumi, strategically located for trade. Ayutthaya rapidly grew into a powerful state, supplanting the Khmer Empire and Sukhothai as the dominant force in the region. By the end of the 15th century, Ayutthaya had invaded the Khmer Empire multiple times, sacking its capital Angkor and incorporating Sukhothai as a vassal state.

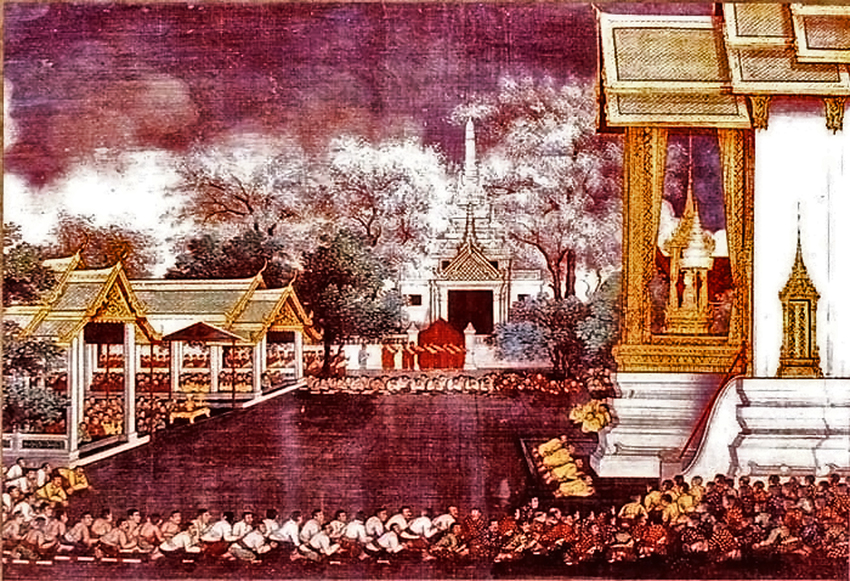

Ayutthaya's political system was a mandala system, a patchwork of self-governing principalities and tributary provinces owing allegiance to the Ayutthayan king. King Borommatrailokkanat (reigned 1448-1488) implemented significant bureaucratic reforms, centralizing power and establishing the sakdina system, a social hierarchy that defined an individual's status and obligations, including corvée labor for commoners. These reforms shaped Thai administration for centuries.

Ayutthaya became a major international trading hub. Early European contact began in 1511 with a Portuguese diplomatic mission led by Duarte Fernandes. The Portuguese, followed by the Dutch, English, French, and Spanish, established trading posts and engaged in commerce. The kingdom prospered particularly during the reign of King Narai (1656-1688), who cultivated diplomatic ties with European powers, notably King Louis XIV of France. Ayutthaya was considered an Asian great power, comparable to China and India. However, growing French influence led to a nationalist backlash, culminating in the Siamese revolution of 1688, which curtailed Western influence for a period.

The kingdom faced constant rivalry with the Burmese Taungoo dynasty. Wars in the 16th century, particularly during the reigns of Burmese kings Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung, led to the capture of Ayutthaya in 1569, making it a Burmese vassal for a short period until King Naresuan declared independence in 1584 and restored Ayutthaya's power.

The 18th century brought a "golden age" of art, literature, and learning. However, the last fifty years of the kingdom were marked by bloody succession crises and internal weakening. In 1765, Burmese armies under the new Konbaung dynasty invaded from the north and west. After a brutal 14-month siege, the capital city fell and was systematically destroyed in April 1767, ending the Ayutthaya Kingdom. The destruction was immense, with countless artistic treasures, literary works, and historical records lost.

3.4. Thonburi Kingdom

Following the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767, Siam was fragmented, with various local leaders declaring themselves rulers. Among them was Taksin, a skilled military leader of Sino-Thai heritage, who had served as a governor in Ayutthaya. Escaping the Burmese siege with a contingent of followers, Taksin established a base at Chanthaburi on the eastern coast. He rapidly raised an army and navy.

Within seven months of Ayutthaya's destruction, Taksin sailed up the Chao Phraya River, defeated the Burmese garrison at a fort in Thonburi (on the west bank of the Chao Phraya, opposite present-day Bangkok), and recaptured Ayutthaya. Recognizing the extensive damage to Ayutthaya and its vulnerability, Taksin decided to establish his new capital at Thonburi in the same year, 1767. He was crowned Taksin the Great and began the task of reunifying the fractured Siamese territories.

Taksin's reign (1767-1782) was characterized by constant warfare to subdue rival warlords and repel renewed Burmese invasions. He successfully drove the Burmese out of Lan Na (northern Thailand) in 1775 and captured Vientiane in 1778, extending Siamese influence over Laotian kingdoms. He also intervened in Cambodian affairs, attempting to install pro-Siamese rulers.

Despite his military successes in reunifying the kingdom and restoring Siamese independence, Taksin's later years were marked by increasing paranoia and religious zeal, leading some to believe he had become insane. This, coupled with strains from continuous warfare and economic hardship, contributed to discontent among officials. In 1782, a coup d'état was launched by a group of high-ranking officials. Taksin was deposed and, according to some accounts, executed along with some of his sons. General Chao Phraya Chakri, a long-time companion and one of Taksin's most important military commanders, returned from a campaign in Cambodia, assumed control, and established the Chakri dynasty, becoming King Rama I. This marked the end of the brief but crucial Thonburi Kingdom.

3.5. Rattanakosin Kingdom (Chakri Dynasty)

The Rattanakosin Kingdom, founded by King Rama I (Phutthayotfa Chulalok) in 1782, marked the beginning of the current Chakri dynasty. Rama I moved the capital from Thonburi across the Chao Phraya River to Bangkok, which he established as the new administrative and cultural center. His reign (1782-1809) focused on consolidating the kingdom, successfully defending against Burmese attacks (notably the Nine Armies' War), ending Burmese incursions, and re-establishing Siamese suzerainty over large parts of Laos and Cambodia. He also oversaw the compilation of new legal codes and the revival of Thai culture after the destruction of Ayutthaya.

During the 19th century, Siam faced increasing pressure from Western colonial powers. In 1826, after the British victory in the First Anglo-Burmese War, Siam signed the Burney Treaty with Britain, followed by a treaty with the United States in 1833. These treaties initiated a period of engagement with the West. The Lao rebellion led by Anouvong of Vientiane was suppressed, resulting in the destruction of Vientiane and forced resettlement of Lao populations. Siam also fought several wars with Vietnam (the Siamese-Vietnamese wars) for dominance over Cambodia, ultimately regaining hegemony.

The reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV, 1851-1868) was pivotal in navigating the threat of Western imperialism. Recognizing the need for modernization, he initiated reforms and engaged in diplomacy. In 1855, he signed the Bowring Treaty with Britain, an unequal treaty that opened Siam to Western trade and limited its fiscal and judicial autonomy. Similar treaties followed with other Western powers. While these treaties curtailed Siamese sovereignty, they also spurred economic development and prevented outright colonization. Mongkut also promoted Western science and education.

King Chulalongkorn (Rama V, 1868-1910) is renowned for his extensive modernization reforms. He abolished slavery and the corvée labor system, centralized the administration, established a modern bureaucracy with ministries (krom), reformed the legal and judicial systems, and developed infrastructure such as railways and telegraph lines. He successfully maintained Siam's independence by skillfully playing off British and French interests and by ceding territories to both colonial powers (parts of Laos, Cambodia, and the Malay states). The Franco-Siamese War of 1893 resulted in significant territorial losses to France. Despite these concessions, Siam remained the only Southeast Asian nation to avoid direct colonization, partly because Britain and France agreed in 1896 to maintain the Chao Phraya valley as a buffer state. Chulalongkorn's reforms laid the foundation for modern Thailand and his efforts to preserve independence earned him great reverence. The Palace Revolt of 1912, a failed attempt by Western-educated military officers to overthrow the monarchy during the reign of King Vajiravudh (Rama VI, 1910-1925), highlighted growing desires for political change. Rama VI promoted Thai nationalism and, during World War I, sided with the Allies, which helped Siam renegotiate some of the unequal treaties and gain international standing.

3.6. Constitutional Monarchy and Modern Era

The era of constitutional monarchy in Thailand began with the bloodless revolution of 1932, which transformed the country from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional one. This period has been marked by political turbulence, including military coups, periods of democratic rule, involvement in major global conflicts, significant economic development, and profound social changes. The struggle for stable democratic governance and respect for human rights has been a persistent theme.

3.6.1. World War II and Cold War Period

The revolution of 1932, led by a group of military officers and civil servants known as Khana Ratsadon (People's Party), ended centuries of absolute monarchy. King Prajadhipok (Rama VII) was forced to accept a constitution. Discontent fueled by the Great Depression and internal political disputes contributed to the revolution. In 1933, a royalist counter-rebellion failed. King Prajadhipok later abdicated in 1935, and the young Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII), then studying in Switzerland, was chosen as his successor.

In the late 1930s, Plaek Phibunsongkhram (Phibun) rose to power, becoming prime minister in 1938. His government promoted Thai nationalism, changing the country's name from Siam to Thailand in 1939. During World War II, following the Japanese invasion in December 1941, Phibun's government allied with Japan. Thailand declared war on the Allies, though the Thai ambassador to the United States, Seni Pramoj, refused to deliver the declaration, forming the Free Thai Movement (Seri Thai) abroad. This movement, with significant support within Thailand, including from regent Pridi Banomyong, worked covertly against the Japanese occupation. Thailand regained some territories lost earlier to France with Japanese assistance. After Japan's defeat, Thailand's association with the Free Thai Movement helped it avoid being treated as a defeated enemy by the Allies, although it had to return the territories gained during the war.

King Ananda Mahidol died in 1946 under mysterious circumstances, and his younger brother, Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX), ascended to the throne. The post-war period saw the rise of military influence in politics. During the Cold War, Thailand became a key ally of the United States in Southeast Asia, joining the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) in 1954 and playing an active role in anti-communist efforts. It allowed the U.S. to use its territory for airbases during the Vietnam War. A military coup in 1957 led by Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat further entrenched military rule and revived the monarchy's historically influential role in politics. This era also saw significant economic development and modernization, but also suppression of political dissent. A communist insurgency was active, particularly in rural areas, from the 1960s until the early 1980s. The student-led uprising of October 1973 overthrew the military dictatorship of Thanom Kittikachorn, leading to a brief period of parliamentary democracy.

3.6.2. Contemporary History (since 1973)

Thailand's contemporary history, beginning with the democratic uprising of 1973, has been characterized by a volatile political landscape, alternating between periods of democratic rule and military coups, and marked by significant social and political conflicts. The 1973 uprising, which overthrew the military junta of Thanom Kittikachorn, ushered in a brief period of democracy. However, this was short-lived, ending with the Thammasat University massacre in 1976 and a subsequent military coup. This event led to a crackdown on leftist movements and fueled the communist insurgency.

The late 1970s and 1980s saw a gradual return to a "semi-democracy" under Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda. This period witnessed economic growth but also continued military influence and limited political freedoms. The communist insurgency largely subsided by the mid-1980s.

The 1990s brought further democratic reforms, culminating in the promulgation of the 1997 "People's Constitution," which was considered the most democratic in Thai history. However, the 1997 Asian financial crisis severely impacted the Thai economy.

The 2000s were dominated by the political rise and fall of Thaksin Shinawatra, who became prime minister in 2001. His populist policies gained him strong rural support but also led to accusations of corruption and authoritarianism, creating deep political divisions. This polarization manifested in large-scale street protests by rival groups: the "Yellow Shirts" (People's Alliance for Democracy, PAD), largely anti-Thaksin, and the "Red Shirts" (United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship, UDD), who supported him. Thaksin was overthrown in a military coup in 2006.

Despite a return to civilian rule, political instability continued. Pro-Thaksin parties won subsequent elections, leading to further protests and political crises, including violent crackdowns on Red Shirt protesters in 2010. In 2011, Thaksin's sister, Yingluck Shinawatra, became prime minister. Her government also faced intense opposition, culminating in another military coup in 2014 led by General Prayut Chan-o-cha.

The junta, known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), ruled Thailand for five years, overseeing the drafting of a new constitution (promulgated in 2017) which critics argue was designed to entrench military influence in politics. King Bhumibol Adulyadej died in 2016 after a 70-year reign and was succeeded by his son, King Vajiralongkorn (Rama X). A general election was held in 2019, resulting in Prayut Chan-o-cha continuing as prime minister under the new constitutional framework, which included a military-appointed Senate.

In 2020-2021, large-scale pro-democracy protests re-emerged, led mainly by students and youth. These protests called for Prayut's resignation, constitutional reforms, and, unprecedentedly, reforms to the monarchy. The government responded with arrests and the use of lèse-majesté laws. The COVID-19 pandemic also significantly impacted the country's economy and society during this period.

The 2023 general election saw a surprise victory for the reformist Move Forward Party (MFP). However, its leader, Pita Limjaroenrat, was blocked from becoming prime minister by the military-appointed Senate and conservative lawmakers. Subsequently, a coalition government was formed by the Pheu Thai Party, with Srettha Thavisin becoming prime minister. This period highlighted the ongoing tensions between popular democratic aspirations and the established conservative and military power structures, raising continued concerns about democratic development and human rights in Thailand. Srettha Thavisin was later dismissed by the Constitutional Court of Thailand on August 14, 2024, due to alleged ethics violations related to a cabinet appointment, further underscoring the judiciary's significant role in Thai politics. Paetongtarn Shinawatra, daughter of Thaksin Shinawatra, became the new prime minister.

4. Geography

Thailand is located in the center of mainland Southeast Asia. It has a total area of 198 K mile2 (513.12 K km2), making it the 50th-largest country in the world. The country is bordered by Myanmar to the north and west, Laos to the north and east, Cambodia to the southeast, and Malaysia to the south. The Gulf of Thailand lies to the south and east, while the Andaman Sea is to the southwest. Thailand also shares maritime borders with Vietnam in the Gulf of Thailand and with Indonesia and India in the Andaman Sea. Bangkok is the capital and largest city. The country's geography is diverse, featuring mountainous regions, fertile plains, and a long coastline.

4.1. Topography

Thailand's topography can be divided into several distinct regions:

The North is a mountainous area characterized by the Thai highlands, a series of parallel mountain ranges extending from the Daen Lao Range in the north. The highest peak in Thailand, Doi Inthanon, at 8.4 K ft (2.56 K m), is located in the Thanon Thong Chai Range in this region. These mountains are incised by steep river valleys and are heavily forested, forming the headwaters of several major rivers, including tributaries of the Chao Phraya.

The Northeast (Isan) consists mainly of the Khorat Plateau, a large, relatively flat upland area bordered to the east by the Mekong River, which forms a natural boundary with Laos. The Mun and Chi rivers are major tributaries of the Mekong in this region. The soil in the Khorat Plateau is often sandy and less fertile, and the region experiences more arid conditions compared to other parts of the country.

The Central Plains are dominated by the fertile alluvial plain of the Chao Phraya River and its tributaries, such as the Ping, Wang, Yom, and Nan rivers. This region is the agricultural heartland of Thailand, particularly for rice cultivation. The plains are mostly flat and low-lying, extending southwards to the Gulf of Thailand. Bangkok, the capital city, is located in this region on the banks of the Chao Phraya River.

The East features short mountain ranges alternating with small basins of short rivers that drain into the Gulf of Thailand. This region has a mix of agricultural land and coastal areas, with popular beach resorts like Pattaya and islands such as Ko Samet and Ko Chang.

The South consists of the narrow Kra Isthmus, which widens into the Malay Peninsula. This region has a long coastline on both the Andaman Sea to the west and the Gulf of Thailand to the east. The topography includes a central mountain range that runs down the peninsula, coastal plains, and numerous islands, such as Phuket, Ko Samui, and the Phi Phi Islands, which are major tourist destinations. This region is important for rubber and palm oil cultivation, as well as fishing and tourism.

The Chao Phraya River and the Mekong River are crucial watercourses for rural Thailand, supporting agriculture through irrigation and serving as transportation routes. The Gulf of Thailand covers approximately 124 K mile2 (320.00 K km2) and is fed by the Chao Phraya, Mae Klong, Bang Pakong, and Tapi rivers. Its clear, shallow waters along the coasts of the southern region and the Kra Isthmus are important for tourism. The eastern shore of the Gulf of Thailand hosts the country's premier deepwater port at Sattahip and its busiest commercial port, Laem Chabang.

4.2. Climate

Thailand has a tropical monsoon climate, influenced by seasonal monsoon winds. Most of the country is classified under the Köppen climate classification as having a tropical savanna climate (Aw). The southern peninsular region and the eastern tip of the country experience a tropical monsoon climate (Am), while some parts of the far south have a tropical rainforest climate (Af).

The climate is generally characterized by three seasons:

1. The Rainy Season (southwest monsoon): Occurs from mid-May to mid-October. Warm, moist air from the Indian Ocean brings abundant rainfall across most of the country. August and September are typically the wettest months. This season can sometimes lead to flooding, especially in low-lying areas. The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and tropical cyclones also contribute to rainfall during this period.

2. The Cool/Dry Season (northeast monsoon): Lasts from mid-October to mid-February. Cool, dry air from mainland China moves over most of Thailand, resulting in lower humidity, milder temperatures, and generally clear skies. This is often considered the most pleasant time of year in many parts of the country. However, the southern part of Thailand, particularly the east coast of the peninsula, can experience heavy rainfall during this period due to the northeast monsoon picking up moisture over the Gulf of Thailand.

3. The Hot/Dry Season: Runs from mid-February to mid-May, before the onset of the southwest monsoon. This season is characterized by high temperatures and humidity, especially in April and May, which are often the hottest months. Temperatures can reach up to 104 °F (40 °C) in inland areas.

Regional variations exist. The northern and northeastern regions experience more pronounced temperature differences between the cool and hot seasons, with cooler winters (temperatures can occasionally drop significantly in mountainous areas) and very hot summers. The central plains also experience high temperatures during the hot season. Southern Thailand, being a peninsula, has a more maritime climate with less diurnal and seasonal temperature variation. It generally receives more rainfall throughout the year, with distinct rainy periods on its west and east coasts due to the differing monsoon patterns. The west coast (Andaman Sea) typically receives more rain during the southwest monsoon (May-October), while the east coast (Gulf of Thailand) receives more rain during the northeast monsoon (October-January).

Mean annual rainfall across the country ranges from 0.0 K in (1.20 K mm) to 0.1 K in (1.60 K mm), though some areas, like Ranong on the west coast and Trat in the east, can receive over 0.2 K in (4.50 K mm) annually. Thailand is also vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including rising sea levels, particularly in the Bangkok area, and an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events.

4.3. Biodiversity and Environment

Thailand boasts rich biodiversity, with a wide array of flora and fauna reflective of its tropical location and varied ecosystems, which range from mountainous forests to coastal mangroves and coral reefs. The country is home to numerous species of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, as well as a vast diversity of plant life. It is part of the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot.

To protect its natural heritage, Thailand has established an extensive network of protected areas. These include 156 national parks, 58 wildlife sanctuaries, 67 non-hunting areas, and 120 forest parks, covering almost 31% of the kingdom's territory. These areas are administered by the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) under the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MNRE). Notable national parks include Khao Yai National Park (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), Doi Inthanon National Park, and numerous marine national parks like Similan Islands and Ang Thong.

Despite these conservation efforts, Thailand faces significant environmental challenges. Deforestation has been a major issue, driven by agricultural expansion, logging (though commercial logging is now largely banned), and infrastructure development. While forest cover has seen some recovery in recent years due to reforestation programs, pressures remain. Air pollution, particularly PM2.5 particulate matter, is a serious problem in major cities like Bangkok and Chiang Mai, especially during the dry season, caused by vehicle emissions, industrial activity, agricultural burning, and transboundary haze. Water pollution from industrial, agricultural, and domestic sources affects rivers and coastal areas. Coastal erosion and damage to coral reefs from tourism, overfishing, and climate change are also concerns.

The illegal wildlife trade poses a threat to many species. Elephants, the national symbol of Thailand, have seen their wild populations decline drastically from historical numbers due to habitat loss and poaching for ivory and, more recently, meat. Young elephants are sometimes captured for the tourism industry, raising concerns about animal welfare. Tigers, leopards, and other large cats are hunted for their pelts and body parts, despite being protected. The Chatuchak Weekend Market in Bangkok has been identified in the past as a hub for the sale of endangered species.

Conservation efforts include stricter law enforcement, community-based conservation initiatives, habitat restoration projects, and public awareness campaigns. However, balancing economic development with environmental protection remains a critical challenge, with social impacts often falling disproportionately on rural and vulnerable communities who depend directly on natural resources. Climate change is expected to exacerbate many of these environmental pressures. Thailand's performance in the global Environmental Performance Index (EPI) has been mediocre, with particular weaknesses in air quality and the climate and energy sector due to high CO2 emissions per kWh produced.

5. Politics and Government

Thailand operates under a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system. However, the nation's political history since the abolition of absolute monarchy in 1932 has been marked by frequent military interventions, numerous constitutions, and periods of instability. This has led to a complex political environment where democratic institutions often coexist with significant influence from the military and traditional elites. The role of the monarchy, while constitutionally limited, remains highly influential and is protected by strict lèse-majesté laws, which have drawn criticism for their impact on freedom of expression and democratic processes.

5.1. Government System

The current Constitution of Thailand (promulgated in 2017) outlines a system of government with three branches:

- The Executive Branch is headed by the Prime Minister, who is the head of government. The Prime Minister is typically the leader of the majority party or coalition in the House of Representatives and is formally appointed by the King. The Prime Minister appoints a Cabinet of up to 35 ministers. The current Prime Minister is Paetongtarn Shinawatra.

- The Legislative Branch is the National Assembly (Ratthasapha), which is bicameral. It consists of:

- The House of Representatives (Sapha Phuthaen Ratsadon), the lower house, with 500 members elected through a mixed-member apportionment system (400 from single-member constituencies and 100 from party lists). Members serve a four-year term.

- The Senate (Wutthasapha), the upper house, with 200 members chosen through an indirect election process involving various professional and social groups, for a five-year term. Under the 2017 constitution's transitional provisions, the first Senate (2019-2024) consisted of 250 members entirely appointed by the military junta. This appointed Senate played a crucial role in prime ministerial selection, contributing to concerns about military influence.

- The Judicial Branch is composed of several court systems, including the Courts of Justice (handling criminal and civil cases), Administrative Courts, and the Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court has significant power, including the ability to dissolve political parties and rule on the constitutionality of laws and actions of political figures. The judiciary is constitutionally independent, but its rulings, particularly from the Constitutional Court, have often been politically controversial and perceived by critics as favoring conservative interests and undermining democratic processes.

The Monarchy is a central institution in Thailand. The King is the Head of State, a hereditary monarch. The current King is Vajiralongkorn (Rama X). Constitutionally, the King exercises power through the three branches of government and is "enthroned in a position of revered worship" and "shall not be violated." The monarchy is protected by stringent lèse-majesté laws, which criminalize criticism of the King, Queen, Heir-apparent, or Regent, carrying severe penalties. These laws have been widely criticized by human rights organizations and pro-democracy activists for suppressing freedom of expression and being used to silence political dissent, particularly during periods of political unrest and military rule. The King also holds significant symbolic and, at times, informal political influence, often intervening or being perceived to intervene during political crises.

Despite the framework of a parliamentary democracy, Thailand's political system has been described by some analysts as a "hybrid regime" or a "constitutional dictatorship" due to the structural advantages granted to the military and conservative establishment by the constitution, frequent military coups (Thailand has experienced more coups than any other country in modern history), and the judiciary's role in shaping political outcomes.

5.2. Major Political Parties and Elections

Thailand has a multi-party system, though historically, political parties have often been short-lived, centered around prominent personalities, or subject to dissolution by military juntas or court orders. The political landscape has been highly polarized since the early 2000s, largely revolving around the figure of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and his supporters versus a conservative, royalist, and military-aligned establishment.

Key political parties include:

- The Pheu Thai Party: A major populist party with strong support in the north and northeast, linked to Thaksin Shinawatra. It has won several elections but has also seen its governments overthrown by coups or judicial decisions.

- The Move Forward Party (MFP): A progressive, reformist party that gained significant popularity, especially among younger voters, in the 2023 election. It advocates for democratic reforms, including changes to the lèse-majesté law and military reforms. Its predecessor, the Future Forward Party, was dissolved by the Constitutional Court in 2020, and the MFP itself was dissolved by the Constitutional Court in August 2024.

- The Democrat Party: Thailand's oldest political party, generally considered conservative and royalist, with support bases primarily in Bangkok and southern Thailand.

- The Palang Pracharath Party (PPRP): Formed with links to the military junta that took power in 2014, it was the vehicle for Prayut Chan-o-cha to continue as prime minister after the 2019 election.

- The United Thai Nation Party: Another pro-military party, which became Prayut Chan-o-cha's party for the 2023 election.

- The Bhumjaithai Party: A significant medium-sized party often playing a kingmaker role in coalition governments, with a strong base in certain regions and a focus on practical policies, notably the decriminalization of cannabis.

Elections in Thailand have often been contentious. The electoral system for the House of Representatives uses a mixed-member apportionment system. The Senate, under the 2017 constitution, is not directly elected by popular vote. The military's historical intervention in politics through coups d'état (the most recent being in 2006 and 2014) has repeatedly disrupted democratic processes. Challenges to stable democratic governance include the influence of unelected bodies, judicial activism, restrictions on civil liberties, and the deep-rooted power of the military and conservative elites. Human rights concerns persist, particularly regarding freedom of expression, assembly, and the use of lèse-majesté laws against activists and critics.

5.3. Administrative Divisions

Thailand is a unitary state. Its administrative services are divided into three levels: central, provincial, and local.

Thailand is composed of 76 provinces (จังหวัดchangwatThai). The capital city, Bangkok, is a special administrative area at the provincial level and is often counted as the 77th province. Pattaya is another specially governed district with a degree of autonomy.

Each province is administered by a governor, who is appointed by the central government's Ministry of Interior. Provinces are divided into districts (อำเภอamphoeThai), and Bangkok is divided into 50 districts (เขตkhetThai). As of 2010, there were 878 districts nationwide. Districts are further subdivided into sub-districts (ตำบลtambonThai) and then into villages (หมู่บ้านmubanThai).

Local government is organized into various forms, including provincial administrative organizations (PAOs), municipalities (thesaban), and sub-district administrative organizations (SAOs or TAOs). While there are elected local councils and executives, local autonomy is often constrained by the centralized administrative structure and budget allocations from the central government.

For broader geographical, statistical, and sometimes planning purposes, Thailand's provinces are often grouped into regions. Common regional groupings include:

- North

- Northeast (Isan)

- Central

- East

- West

- South

These regional divisions are not formal administrative units but are widely used.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Thailand's foreign policy has traditionally been characterized by pragmatism and flexibility, often described as "bamboo bending with the wind," adapting to shifts in regional and global power dynamics to safeguard its independence and national interests. Historically, Siam skillfully navigated the pressures of Western colonialism by balancing relations between Britain and France.

Thailand is a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and plays an active role in the organization, prioritizing regional cooperation in economic, political, security, and socio-cultural matters. It maintains close ties with its ASEAN neighbors, though border disputes, such as the conflict with Cambodia over the Preah Vihear Temple area, have occasionally flared up.

During the Cold War, Thailand was a key ally of the United States in Southeast Asia, joining SEATO and allowing U.S. forces to use its territory during the Vietnam War. It remains a major non-NATO ally of the U.S. However, in recent decades, particularly after the 2014 military coup which strained relations with Western democracies, Thailand has increasingly strengthened its ties with China. This includes enhanced economic cooperation, infrastructure projects under China's Belt and Road Initiative, and closer military-to-military relations. This shift reflects a broader trend in the region and Thailand's efforts to balance its relationships with major powers.

Thailand also maintains important relationships with other major global and regional players, including Japan (a major trading partner and investor), India, and the European Union. It participates actively in various international organizations, including the United Nations, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and forums such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the East Asia Summit.

Human rights considerations have sometimes influenced Thailand's foreign relations. Concerns raised by international bodies and other countries regarding human rights abuses, restrictions on democracy, and the treatment of refugees and migrant workers have occasionally led to diplomatic tensions. For example, the handling of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar has drawn international scrutiny. During the 2023 Israel-Hamas war, Thailand initially condemned the attack on Israel but later adopted a neutral stance, focused on the safety and repatriation of its numerous migrant workers in Israel. The country's approach to foreign policy often seeks to balance its strategic alliances, economic imperatives, and its image on the international stage, while navigating complex domestic political dynamics.

5.5. Military

The Royal Thai Armed Forces (กองทัพไทยKong Thap ThaiThai) are the military forces of the Kingdom of Thailand. They consist of the Royal Thai Army (กองทัพบกไทย), the Royal Thai Navy (กองทัพเรือไทย), and the Royal Thai Air Force (กองทัพอากาศไทย). It also incorporates various paramilitary forces. The King is the nominal Head of the Thai Armed Forces (จอมทัพไทยChom Thap ThaiThai). The armed forces are managed by the Ministry of Defence, headed by the Minister of Defence (a cabinet member), and commanded by the Royal Thai Armed Forces Headquarters.

The Thai Armed Forces have a combined active-duty manpower of around 306,000 personnel, with an additional 245,000 active reserve personnel. The annual defense budget has seen significant increases, accounting for approximately 1.4% of GDP in 2016.

A key characteristic of the Thai military is its significant and recurrent political influence. Thailand has experienced numerous coups d'état throughout its modern history, with the military frequently overthrowing civilian governments. The most recent coups occurred in 2006 and 2014. The military has often justified its interventions by citing political instability, corruption, or threats to the monarchy. The 2017 Constitution, drafted under military oversight, contains provisions that critics argue are designed to ensure continued military influence in politics, such as a military-appointed Senate during its initial term.

Conscription is in place for males over the age of 21. Men are subject to a lottery system; those who draw a red card serve in the military for up to two years, while those who draw a black card are exempt. The length of service can vary based on education level and voluntary enlistment. The conscription system has faced criticism regarding its fairness, necessity, and allegations of mistreatment of conscripts, including claims that conscripts are used as personal servants for senior officers or face institutionalized abuse. Amnesty International has reported on such abuses.

The military is also involved in internal security operations, particularly in the southern border provinces where a long-running separatist insurgency persists. The Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) is a powerful military-dominated agency with a broad mandate covering national security, and it has been criticized for its lack of transparency and alleged human rights abuses. The military also plays a role in disaster relief and some development projects. Corruption and nepotism within the military are also frequently reported concerns.

6. Economy

Thailand's economy is classified as a newly industrialised economy. It is the second-largest economy in Southeast Asia after Indonesia and the 23rd-largest in the world by PPP (as of recent estimates). The economy is heavily export-dependent, with exports accounting for more than two-thirds of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Key export sectors include automotive, electronics, machinery, agricultural products (notably rice, rubber, and sugar), and processed foods. Tourism is also a vital contributor to the Thai economy. The country faces ongoing challenges related to income inequality, reliance on global economic conditions, and the social impacts of its economic policies on various segments of the population.

6.1. Economic Structure and Key Indicators

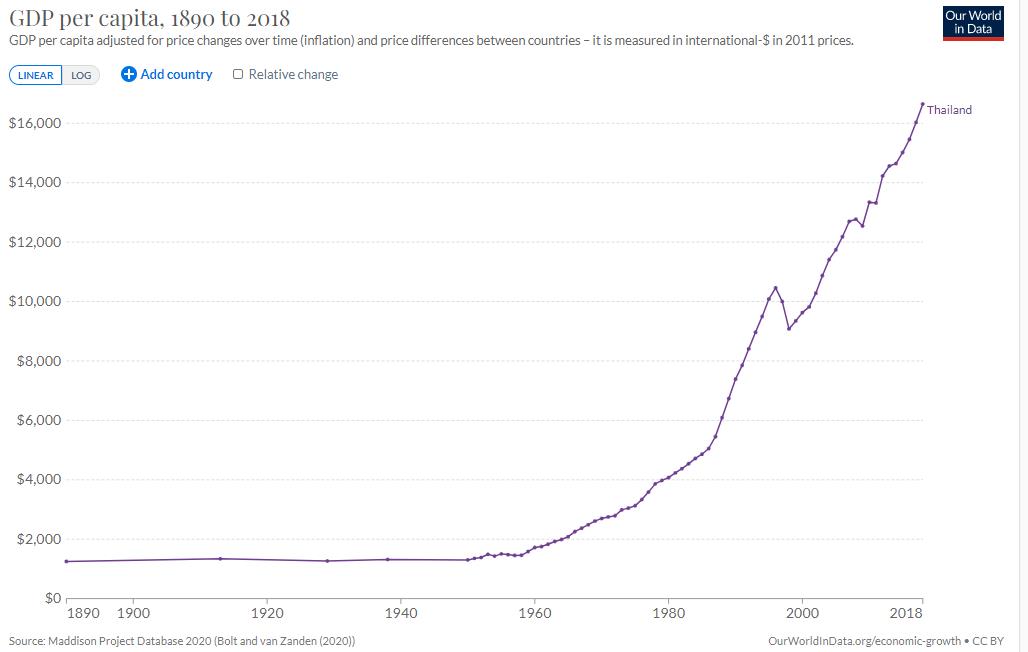

Thailand's nominal GDP was approximately 14.53 T THB in 2016. The economy has experienced periods of rapid growth, particularly from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, but was significantly affected by the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Since then, growth has been more moderate, often impacted by political instability, global economic downturns, and natural disasters like the 2004 tsunami and major floods. In 2017, GDP growth was around 3.9%.

Key economic indicators include:

- Inflation:** Headline inflation was 0.7% in 2017, with core inflation at 0.6%.

- Employment:** The employment-to-population ratio was 68.0% in 2017. Unemployment has traditionally been low, reported at 1.2% in 2017, partly due to a large informal sector. However, underemployment and vulnerable employment are significant issues.

- Public Debt:** Total public debt was approximately 6.37 T THB in December 2017. The COVID-19 pandemic led to increased public spending, prompting authorities to raise the public debt ceiling.

- Currency:** The official currency is the Thai baht (THB).

The economic structure is diversified, with significant contributions from manufacturing, services (including tourism and finance), and agriculture. However, there are concerns about low productivity in some sectors, challenges in education and skill development, high household debt, and the need for structural reforms to sustain long-term growth. Social implications of economic policies, such as the impact of trade liberalization on local industries or the effects of large-scale development projects on communities and the environment, are important considerations.

| Nominal GDP | 14.53 T THB (2016) |

|---|---|

| GDP growth | 3.9% (2017) |

| Headline inflation | 0.7% (2017) |

| Core inflation | 0.6% (2017) |

| Employment rate | 68.0% (2017) |

| Unemployment | 1.2% (2017) |

| Total public debt | 6.37 T THB (Dec 2017) |

| Poverty rate | 8.61% (2016) |

| Net household worth | 20.34 T THB (2010) |

6.2. Major Industries

Thailand's economy is driven by several key industries that contribute significantly to its GDP, employment, and exports. These sectors reflect a mix of traditional strengths and modern industrial development, each with its own social and labor implications.

6.2.1. Agriculture and Natural Resources

Agriculture has historically been a cornerstone of the Thai economy, employing around 49% of the labor force, though this share has decreased from 70% in 1980 with industrialization. Rice is the most important crop, and Thailand is one of the world's leading exporters of rice, particularly jasmine rice. Other major agricultural products include rubber, tapioca, sugarcane, fruits (such as durian, mango, and longan), and fishery products. Forestry and mining of natural resources like tin (historically) and gypsum also contribute, though to a lesser extent now.

The agricultural sector faces challenges such as fluctuating commodity prices, climate change impacts, debt among farmers, and an aging rural population. The social impact on rural communities is significant, as many depend on agriculture for their livelihoods. Issues of land rights, access to water and credit, and fair prices for produce are critical for these communities. Labor in the agricultural and fisheries sectors, particularly involving migrant workers, has also raised concerns regarding working conditions and exploitation.

6.2.2. Manufacturing and Exports

Manufacturing is a major driver of the Thai economy and its exports. Key manufacturing sectors include:

- Automotive:** Thailand is a major automotive production hub in Southeast Asia, often referred to as the "Detroit of Asia." It hosts numerous international car and auto parts manufacturers. The industry produces vehicles for both domestic consumption and export.

- Electronics and Electrical Appliances:** This sector is another significant exporter, producing items such as hard disk drives, integrated circuits, computer components, and various consumer electronics and appliances.

- Textiles and Garments:** While facing increased competition from lower-cost countries, this sector remains an important employer.

- Food Processing:** Leveraging its strong agricultural base, Thailand is a major exporter of processed foods, including canned tuna, shrimp, and processed fruits.

The manufacturing sector relies heavily on export markets. Labor rights and working conditions within these industries, especially in factories employing low-skilled or migrant labor, are ongoing concerns for human rights advocates. Issues include wages, workplace safety, and the right to organize.

6.2.3. Tourism

Tourism is a critical component of the Thai economy, contributing significantly to GDP and foreign exchange earnings. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Thailand was one of the most visited countries globally, attracting millions of international tourists annually. Major tourist destinations include Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Phuket, Pattaya, Ko Samui, and numerous historical sites and national parks.

The industry encompasses various segments, including cultural tourism, beach resorts, ecotourism, and medical tourism, with Thailand being a leading destination for procedures like cosmetic surgery and sex reassignment surgery.

The social impacts of tourism are diverse. While it creates employment and income, it can also lead to environmental degradation in popular areas, strain local resources, and contribute to cultural commodification. Concerns about exploitative practices in some parts of the tourism sector, including the sex industry (which, while officially illegal, is a visible part of the tourism landscape in some areas), persist. The environmental impact includes coastal erosion, damage to coral reefs, and waste management issues in heavily touristed areas. Ensuring sustainable tourism practices that benefit local communities and protect the environment is a key challenge.

6.2.4. Informal Economy

The informal economy plays a substantial role in Thailand, encompassing a wide range of activities not captured in official statistics. This includes street vendors, motorcycle taxi drivers, domestic workers, small-scale agricultural producers selling directly to consumers, and various forms of informal labor in construction, manufacturing, and services. It is estimated that informal workers comprise a majority (around 62.6% in 2012) of the Thai workforce.

The informal sector provides livelihoods for millions, particularly for those with limited education or skills, rural migrants to urban areas, and other vulnerable groups. Street food, a hallmark of Thai culture, is a prominent part of this sector. While the informal economy offers flexibility and entrepreneurial opportunities, workers within it often lack social security, legal protection, access to credit, and formal employment benefits. They may face precarious working conditions, low and unstable incomes, and limited access to healthcare or unemployment support.

The socioeconomic impact of the informal economy is significant. It contributes to poverty reduction and provides essential goods and services at affordable prices. However, its unregulated nature can also lead to issues such as tax evasion, unfair competition for formal businesses, and challenges in urban planning and public space management. Government policies have often struggled to effectively integrate or support the informal sector, with crackdowns on street vendors in some areas contrasting with efforts to promote certain aspects like street food tourism. For vulnerable groups, including women and migrants who are disproportionately represented in some informal sectors, the lack of formal protections can exacerbate their precarity.

6.3. Income Distribution and Poverty

Despite significant economic development, Thailand continues to grapple with issues of income inequality and poverty. While overall poverty rates have declined over the past decades, disparities persist between urban and rural areas, different regions, and various social groups.

In 2016, Thailand's poverty rate was reported at 8.61%. However, if "near poor" individuals are included, the figure rises significantly, indicating a substantial portion of the population remains vulnerable to falling back into poverty. The Northeast region (Isan) and parts of the South have traditionally experienced higher poverty rates compared to the Central region and Bangkok.

Income inequality is a major concern. Credit Suisse reported in 2014 that Thailand was one of the world's most unequal countries, with the top 10% richest holding a disproportionately large share of the nation's wealth (79% of assets, with the top 1% holding 58%). The 50 richest Thai families were reported to have a total net worth accounting for around 30% of GDP. This concentration of wealth highlights structural issues within the economy and society.

Factors contributing to inequality include unequal access to education and economic opportunities, disparities in land ownership, and a wage structure that often favors skilled labor in urban centers over agricultural or informal sector workers. Household debt is also a significant problem for many Thais, particularly those with lower incomes, reaching 89.2% of GDP in the first quarter of 2023, with an average debt per household around 500.00 K THB.

Social equity and the well-being of marginalized populations, including ethnic minorities, migrant workers, and those in the informal sector, are key challenges. Government policies aimed at poverty reduction and social welfare, such as universal healthcare coverage and various subsidy programs, have had some positive impacts, but addressing the root causes of inequality requires more comprehensive structural reforms. The political instability and frequent changes in government have sometimes hindered consistent long-term strategies for tackling these deep-seated social issues.

6.4. Science and Technology

Thailand has made efforts to advance its science and technology (S&T) capabilities to support economic development and improve competitiveness. The Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation is the primary government body overseeing these efforts. In 2019, Thailand devoted approximately 1.1% of its GDP to research and development (R&D), with over 166,788 R&D personnel. Thailand ranked 41st in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

Major research areas include biotechnology, nanotechnology, electronics and information technology, agriculture, and health sciences. The government has promoted S&T through various policies and initiatives, such as establishing science parks, research institutes, and providing funding for R&D projects. The "Thailand 4.0" economic model, introduced by the government, aims to transform Thailand into a value-based and innovation-driven economy, emphasizing S&T in sectors like smart electronics, next-generation automotive, affluent medical and wellness tourism, agriculture and biotechnology, and food for the future.

Despite these efforts, Thailand faces challenges in S&T development. These include a shortage of highly skilled S&T personnel, relatively low private sector investment in R&D compared to some other newly industrialized economies, and a gap between research output and commercialization. The quality of S&T education, particularly at the higher education level, and the ability to translate research into practical applications and innovations that benefit society broadly are ongoing concerns.

Access to technology and the social benefits derived from it are not always evenly distributed. There is a digital divide between urban and rural areas, and between different socioeconomic groups. While mobile phone and internet penetration are relatively high, access to high-speed broadband and advanced digital skills can be limited for some segments of the population. Government policies related to S&T also need to consider ethical implications, environmental sustainability, and ensuring that technological advancements contribute to inclusive growth and social well-being, rather than exacerbating existing inequalities.

7. Infrastructure

Thailand has been continually developing its infrastructure to support economic growth, facilitate trade and tourism, and improve the quality of life for its citizens. Major investments have been made in transportation, energy, and telecommunications networks, although challenges in terms of coverage, quality, and sustainability remain.

7.1. Transportation

Thailand's transportation infrastructure is relatively well-developed, especially in and around major urban centers and economic corridors. This includes extensive road networks, a national railway system, numerous airports, and significant maritime ports.

7.1.1. Road Transport

Road transport is the dominant mode of transportation in Thailand. The country has an extensive network of highways and national roads, totaling around 242 K mile (390.00 K km). Major arterial routes connect Bangkok with all regions of the country. Many two-lane highways have been upgraded to four-lane divided highways to improve capacity and safety. The Bangkok Metropolitan Region features a system of expressways and tollways to alleviate traffic congestion.

Vehicle ownership is high, with over 37 million registered vehicles, including more than 20 million motorcycles. Traffic congestion is a severe problem in Bangkok and other major cities. Characteristic modes of local road transport include tuk-tuks (three-wheeled motorized rickshaws), songthaews (converted pickup trucks with benches for passengers), motorcycle taxis, and regular taxis. Public bus services are widespread in cities and for intercity travel. Road safety remains a significant concern, with Thailand having one of the highest road fatality rates in the world.

7.1.2. Rail Transport

The State Railway of Thailand (SRT) operates the national rail network, which consists of approximately 2.8 K mile (4.51 K km) of track, mostly meter gauge and single-track, though some sections around Bangkok are double or triple-tracked. Krung Thep Aphiwat Central Terminal and Bangkok (Hua Lamphong) station are the main hubs. The rail system connects major cities and extends to the borders with Malaysia, Laos, and Cambodia. The railway has faced criticism for being outdated, slow, and inefficient, but efforts are underway to modernize the network, including double-tracking projects and the development of high-speed rail lines, often with international cooperation, particularly from China and Japan.

Urban rail transport in Bangkok has expanded significantly to combat traffic congestion. Systems include the BTS Skytrain (elevated), the MRT (underground and elevated), the SRT Red Lines (commuter rail), and the Airport Rail Link connecting the city center to Suvarnabhumi Airport.

7.1.3. Air Transport

Thailand has a well-developed air transport infrastructure, crucial for its large tourism industry and international connectivity. There are over 100 airports in the country, with Suvarnabhumi Airport (BKK) in Bangkok being the main international gateway and one of the busiest airports in Asia. Don Mueang International Airport (DMK), also in Bangkok, primarily serves low-cost carriers and domestic flights. Other major international airports include those in Chiang Mai, Phuket, Krabi, and Hat Yai.

Major airlines include the national carrier Thai Airways International, as well as several private and low-cost carriers such as Bangkok Airways, Thai AirAsia, Nok Air, and Thai Lion Air.

7.1.4. Water Transport

Historically, water transport was vital in Thailand, particularly along the Chao Phraya River and its extensive network of canals (khlongs), earning Bangkok the nickname "Venice of the East." While many canals have been filled in for road construction, river and canal transport remains important in Bangkok for commuting and tourism, with services like the Chao Phraya Express Boat and longtail boats.

Maritime transport is crucial for international trade. Laem Chabang is the country's largest deep-sea port, located on the Eastern Seaboard, handling the majority of containerized cargo. Other significant ports include Bangkok Port (Klong Toey Port) and ports in the southern region.

7.2. Energy

Thailand's energy sector relies heavily on fossil fuels, with natural gas being the primary source for electricity generation (around 75% in 2014), followed by coal (around 20%). The remainder comes from biomass, hydroelectricity, and biogas. Thailand is a net importer of oil and natural gas, despite having some domestic production.

The government has been promoting renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and biomass to diversify the energy mix and reduce reliance on imports and fossil fuels. The Alternative Energy Development Plan aims to significantly increase the share of renewables in power generation.

Energy policies also focus on energy efficiency and conservation. Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) is the main state-owned power utility. Challenges in the energy sector include ensuring energy security, managing the environmental impact of power generation (especially from coal), and balancing energy costs for consumers and businesses. The development of new power plants, particularly coal-fired and nuclear (which has been discussed but not implemented), often faces public opposition due to environmental and safety concerns.

7.3. Telecommunications

Thailand has a relatively developed telecommunications infrastructure.

- Telephone:** Fixed-line telephone penetration has declined with the rise of mobile phones.

- Mobile Communications:** Mobile phone penetration is very high, with more subscribers than the total population, indicating many individuals own multiple SIM cards. 5G networks are being rolled out. Major mobile operators include AIS, TrueMove H, and DTAC.

- Internet:** Internet penetration has grown significantly, with a large number of users accessing the internet primarily through mobile devices. Broadband internet access is widely available in urban areas, but disparities in access and speed persist in rural regions. The government has initiatives to expand internet access nationwide.

- Censorship and Control:** The Thai government exercises significant control over internet content. Censorship of websites deemed to violate lèse-majesté laws, threaten national security, or contain pornographic material is common. The Computer Crime Act has been criticized for its broad provisions, which are often used to stifle dissent and freedom of expression online. Social media platforms are widely used but are also subject to monitoring and content removal requests from authorities. This has raised concerns among human rights groups about digital rights and freedom of information.

8. Demographics

Thailand's population was estimated at around 71.7 million as of 2023. The country has undergone significant demographic changes, including a dramatic decline in population growth due to successful family planning programs, and is now facing the challenges of an aging population. The population is largely rural but with increasing urbanization, especially towards Bangkok.

8.1. Population Statistics

- Total Population:** Approximately 71.7 million (2023 estimate). The first census in 1909 recorded a population of 8.2 million.

- Population Growth Rate:** Has fallen significantly from over 3.1% in 1960 to around 0.4% or lower in recent years. Thailand has one of the lowest fertility rates in Southeast Asia.

- Sex Ratio:** Slightly more males than females, with a ratio of approximately 1.05 males per female.

- Age Structure:** The population is aging rapidly. In 2022, the average Thai household size was 3 people, down from 5.7 in 1970. More than 20% of the population is aged over 60, and this proportion is projected to increase significantly in the coming decades. This demographic shift poses challenges for the workforce, healthcare system, and social welfare programs.

- Urbanization:** Approximately 44.2% of the population lived in urban areas as of 2010, a slow increase from 29.4% in 1990. Bangkok is a primate city, overwhelmingly larger and more economically dominant than any other urban center in the country.

The dramatic decline in fertility rates was largely a result of government-sponsored family planning programs initiated in the 1970s. While successful in controlling population growth, this has led to the current demographic challenge of an aging society with a shrinking workforce. Social consequences include increased burden on the healthcare system, pension schemes, and the need for policies to support the elderly and encourage higher fertility or manage labor shortages through migration.

8.2. Ethnic Groups

Thailand is an ethnically diverse country, though the majority of the population identifies as Thai.

- Majority Thai:** Thai people (Siamese, Central Thai, Isan people/Lao, Northern Thai/Khon Mueang, Southern Thai/Pak Tai) constitute the largest ethnic group, making up around 75-86% of the population according to various estimates. The concept of "Thai" ethnicity itself has been shaped by historical processes of assimilation and nation-building.

- Chinese-Thai:** People of Chinese descent form a significant minority, estimated at around 14% of the population. Many Thais have some Chinese ancestry. Chinese-Thais are well-integrated into Thai society and have historically played a prominent role in commerce and politics.

- Malay-Thai:** Primarily concentrated in the southernmost provinces bordering Malaysia (Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat, and parts of Songkhla), Malay-Thais constitute about 2-3% of the population. They are predominantly Muslim and speak a dialect of Malay. This region has experienced a long-running separatist insurgency.

- Khmer-Thai:** Found mainly in provinces bordering Cambodia, particularly in the lower Northeast.

- Mon:** Descendants of the Dvaravati kingdom, with communities in various parts of Thailand.

- Hill Tribes:** Various ethnic groups inhabiting the mountainous regions of northern and western Thailand. These include the Karen, Hmong, Akha, Lisu, Lahu, Yao (Mien), and others. Many hill tribe communities maintain distinct languages and cultural traditions. They have historically faced challenges related to citizenship, land rights, poverty, and access to state services.

- Other groups:** Include Vietnamese, Lao, Burmese, Indians, and others. Thailand also hosts a large population of migrant workers, primarily from neighboring countries like Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia.

The Royal Thai Government officially recognized 62 ethnic communities in a 2011 report. The social standing and cultural characteristics of these groups vary. While assimilation into the dominant Thai culture has been a historical trend, there is increasing recognition of multiculturalism. However, ethnic minorities, particularly hill tribes and some Malay-Thais, have faced discrimination and challenges in exercising their rights and accessing opportunities. Issues of citizenship, land tenure, and political representation remain pertinent for many minority communities.

8.3. Language

The official language of Thailand is Thai (ภาษาไทยPhasa ThaiThai), a Kra-Dai language. It is the principal language of education, government, media, and is spoken throughout the country. Standard Thai is based on the dialect of the central Thai people (historically Siamese) and is written in the Thai alphabet, an abugida script derived from the Old Khmer script, which itself has roots in the Pallava script of Southern India.

Thailand is linguistically diverse, with numerous regional dialects and minority languages. The Royal Thai Government officially recognized 62 languages in 2011.

- Regional Dialects of Thai:**

- Northern Thai (คำเมืองKham MueangThai or Phasa Nuea) is spoken in the northern region.

- Isan (ภาษาอีสานPhasa IsanThai) is spoken in the northeastern region and is essentially a dialect of the Lao language.

- Southern Thai (ภาษาใต้Phasa TaiThai or Pak Tai) is spoken in the southern region.

These dialects can differ significantly from Standard Thai in terms of vocabulary, pronunciation, and sometimes grammar, but are generally mutually intelligible to varying degrees.

- Minority Languages:**

- Chinese dialects:** Varieties of Chinese, particularly Teochew, are spoken by the Thai Chinese population.

- Malay (Yawi/Jawi):** Spoken by the Malay Muslim population in the southernmost provinces.

- Khmer:** Spoken in areas bordering Cambodia.

- Mon:** Spoken by descendants of the Mon people.

- Hill tribe languages:** A variety of languages spoken by ethnic groups in mountainous areas, belonging to different language families:

- Austroasiatic languages: such as Mlabri, Lawa.

- Sino-Tibetan languages: such as Karen dialects, Akha.

- Hmong-Mien languages: such as Hmong.

- Other Tai languages: such as Phu Thai, Saek, Shan.

- Austronesian languages:** such as Cham, Moken, and Urak Lawoi' (spoken by sea nomadic groups).

English is widely taught as a foreign language in schools and is used in commerce, tourism, and higher education, but English proficiency among the general population remains relatively low.

8.4. Religion

The predominant religion in Thailand is Theravada Buddhism. According to 2018 estimates, it is practiced by approximately 93.46% of the population and is deeply integrated into Thai identity and culture. Buddhism in Thailand is characterized by its emphasis on merit-making, monastic life, and the observance of Buddhist holidays and rituals. Temples (wats) are central to community life, serving not only as places of worship but also as community centers and, historically, educational institutions. Thai Buddhism incorporates elements from Hinduism, animism, and ancestor worship. The King of Thailand is constitutionally required to be a Buddhist and is considered the upholder of all religions.

Islam is the second-largest religion, comprising about 5.37% of the population. The majority of Thai Muslims are Sunni Muslims and are concentrated in the southernmost provinces bordering Malaysia, namely Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat, and parts of Songkhla and Satun. Most of these are ethnically Malay. There are also Muslim communities in other parts of Thailand, including Bangkok.

Christianity is practiced by about 1.13% of the population, including both Protestants and Roman Catholics. Christian missionaries have been active in Thailand for centuries.

Hinduism and Sikhism are practiced by small Indian communities, primarily in urban areas. There is also a small Jewish community with a history dating back to the 17th century. Other religions, or those unspecified, account for the remaining 0.04%.

The Thai constitution guarantees freedom of religion, and the government generally respects this right. However, there have been occasional calls from some nationalist groups to declare Buddhism the official state religion, reflecting concerns about the perceived decline of Buddhism's influence and the ongoing insurgency in the Muslim-majority southern provinces. Religious life is vibrant, with numerous festivals and ceremonies observed throughout the year. While Buddhism holds a dominant cultural position, religious tolerance is generally practiced. Some laws, such as restrictions on alcohol sales on major Buddhist holidays, reflect Buddhist traditions.

8.5. Education

Thailand's education system is overseen by the Ministry of Education. Education is compulsory for nine years (from primary school up to the lower secondary level, typically age 14), and the government provides free basic education for twelve years (up to upper secondary level, age 17). The youth literacy rate was 98.1% in 2015.

The education system consists of:

- Early Childhood Education:** Kindergartens and pre-schools.

- Basic Education:**

- Primary School (Prathom): 6 years

- Lower Secondary School (Matthayom 1-3): 3 years

- Upper Secondary School (Matthayom 4-6): 3 years (divided into general/academic and vocational streams)

- Higher Education:** Includes universities, colleges, and vocational/technical institutes. There are numerous public and private universities. Chulalongkorn University and Mahidol University are among the top-ranking universities.

- International schools:** Thailand has a large number of international schools, primarily catering to expatriate children and affluent Thais, often offering curricula from other countries (e.g., British, American, IB).

Despite progress, the Thai education system faces several challenges:

- Quality and Standards:** Concerns persist about the quality of education, particularly in public schools. Standardized test scores (like PISA) have often been below average for OECD countries. The curriculum has been criticized for emphasizing rote learning over critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

- Disparities:** Significant disparities in educational quality and access exist between urban and rural areas, and between different socioeconomic groups. Students in remote areas and from disadvantaged backgrounds often have fewer opportunities. Ethnic minority children, particularly those in hill tribe communities, may face language barriers (as instruction is in Thai) and cultural insensitivity.

- Teacher Quality and Development:** Improving teacher training, professional development, and motivation is a key challenge.

- Vocational Education:** While vocational education is available, it sometimes suffers from a perception of lower status compared to academic tracks, despite the need for skilled labor in various industries.