1. Early Life and Education

Muhammad Ali Jinnah's early life was rooted in a merchant family in Karachi, British India, and his formative educational experiences in both India and England significantly shaped his worldview and laid the foundation for his future political career.

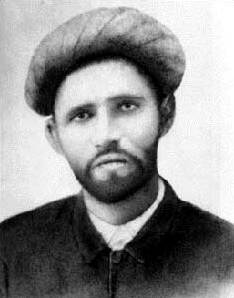

1.1. Birth and Family

Jinnah was born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai, likely in 1876, though his birthday is officially celebrated on December 25, 1876. Early school records suggest an October 20, 1875, birthdate, but the official date has been widely accepted. He was born to Jinnahbhai Poonja and Mithibai in a rented apartment at Wazir Mansion in Karachi, then part of the Bombay Presidency of British India, now in Sindh, Pakistan. His paternal grandfather hailed from Gondal State in the Kathiawar peninsula, now in Gujarat, India. Jinnah's family were Khojas, following Nizari Isma'ili Shia Islam tradition from Gujarat, though he later adopted Twelver Shia teachings. Some relatives and witnesses claimed he converted to Sunni Islam later in life. His family's ancestry is also traced to Rajputs from Sahiwal in Punjab who moved to Kathiawar after becoming Khojas, and his grandfather's family also had a Bhatia caste background.

Jinnah's father, Jinnahbhai Poonja, was a wealthy Gujarati merchant and textile weaver from Paneli village in Gondal. His mother was from the nearby village of Dhaffa. They had moved to Karachi in 1875, drawn by the city's economic boom after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which significantly shortened shipping routes to Europe compared to Bombay. Jinnah was the second of seven children and had three brothers and three sisters, including his younger sister Fatima Jinnah, who would become his lifelong companion and close political advisor. Despite his Gujarati heritage, Jinnah was not fluent in Gujarati or Urdu, preferring English as his primary language throughout his life. Little is known about his other siblings, their settlements, or their contact with him as his legal and political career advanced.

1.2. Childhood and Early Education

As a boy, Jinnah resided briefly in Bombay with an aunt, where he may have attended the Gokal Das Tej Primary School and later the Cathedral and John Connon School. In Karachi, he studied at the Sindh Madressatul Islam and the Christian Missionary Society High School. He successfully matriculated from Bombay University at the high school level at the age of 16.

Numerous anecdotes circulated about his boyhood, particularly after his death, depicting him as a diligent student who supposedly spent his spare time observing court proceedings or studying by streetlights. His official biographer, Hector Bolitho, documented a story where the young Jinnah encouraged other children to play cricket instead of marbles, urging them to maintain cleanliness and aspire to greater things.

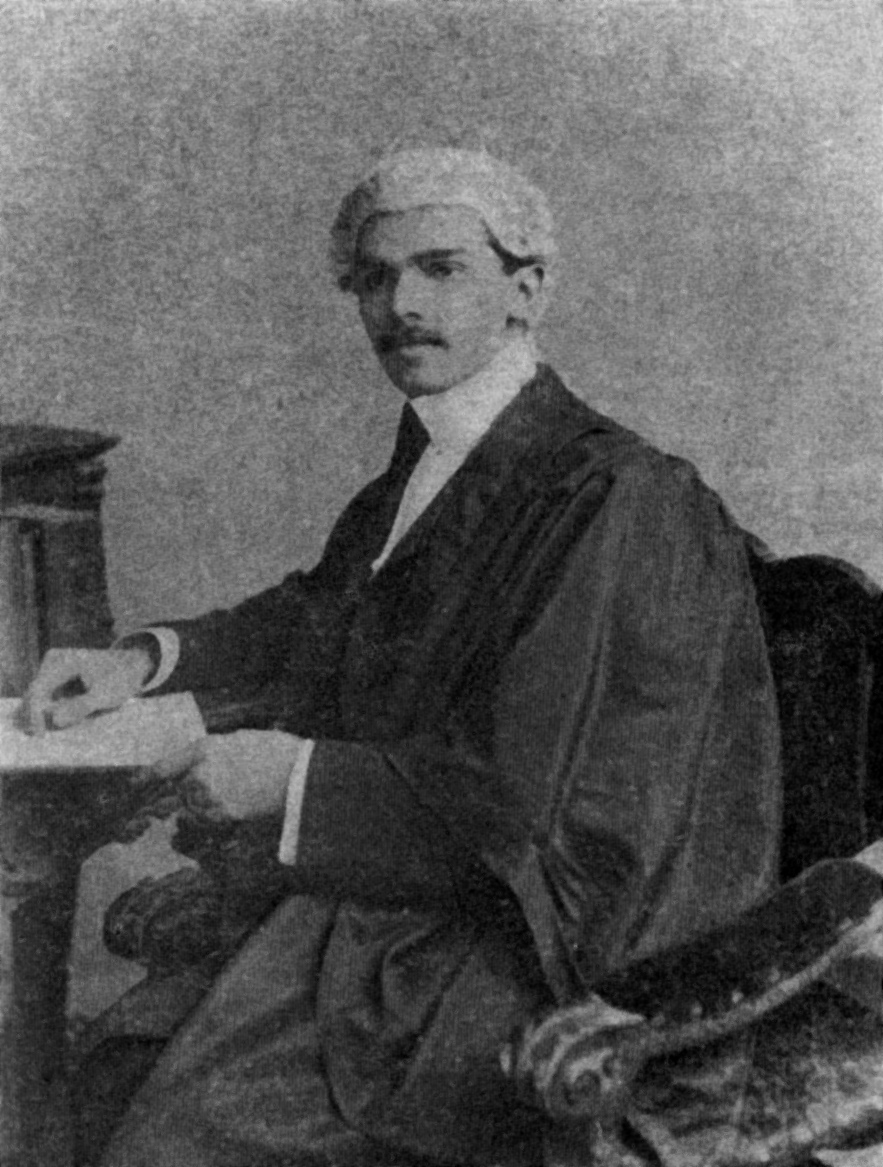

1.3. Education in England

In 1892, at the age of 16, Jinnah accepted an apprenticeship offer from Sir Frederick Leigh Croft's firm, Graham's Shipping and Trading Company, in London. This opportunity came despite opposition from his mother, who arranged his marriage to his cousin, Emibai Jinnah, two years his junior, from their ancestral village of Paneli, just before his departure. Both his mother and first wife passed away during his time in England. One reason for sending him abroad was a legal proceeding against his father that threatened the family's property with sequestration. In 1893, the Jinnahbhai family moved to Bombay.

Soon after arriving in London, Jinnah abandoned the business apprenticeship to pursue law, much to his father's dismay, who had provided him with enough funds for three years. He joined Lincoln's Inn, reportedly choosing it because the names of the world's great lawgivers, including Muhammad, were inscribed above its main entrance. However, biographer Stanley Wolpert notes that no such inscription exists there, only a mural depicting Muhammad among other lawgivers, suggesting Jinnah might have later altered the story to avoid mentioning an image that could offend many Muslims. His legal education followed the pupillage system, where he learned from established barristers and studied lawbooks. During this period, he officially shortened his name to Muhammad Ali Jinnah. In 1895, at age 19, he became the youngest British Indian to be called to the bar in England. Though he initially returned to Karachi, he soon relocated to Bombay.

While a student in England, Jinnah, like many other future Indian independence leaders, was deeply influenced by 19th-century British classical liberalism. His intellectual inspirations included figures like Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, Herbert Spencer, and Auguste Comte. This exposure to progressive politics and the idea of a democratic nation profoundly shaped his political education. He became a fervent admirer of Parsi British Indian political leaders such as Dadabhai Naoroji and Sir Pherozeshah Mehta. Jinnah witnessed Naoroji's historic maiden speech in the House of Commons from the visitor's gallery, an event that deeply resonated with him.

The Western world also influenced Jinnah's personal preferences, especially his sartorial choices. He embraced Western-style clothing, meticulously dressed in public throughout his life. He reportedly owned over 200 suits, worn with starched shirts and detachable collars, and as a barrister, prided himself on never wearing the same silk tie twice. Even in his final days, he insisted on being formally dressed. In later years, he often wore a Karakul hat, which became known as the "Jinnah cap". Dissatisfied with law for a brief period, Jinnah pursued a stage career with a Shakespearean company but abandoned it after receiving a stern letter from his father.

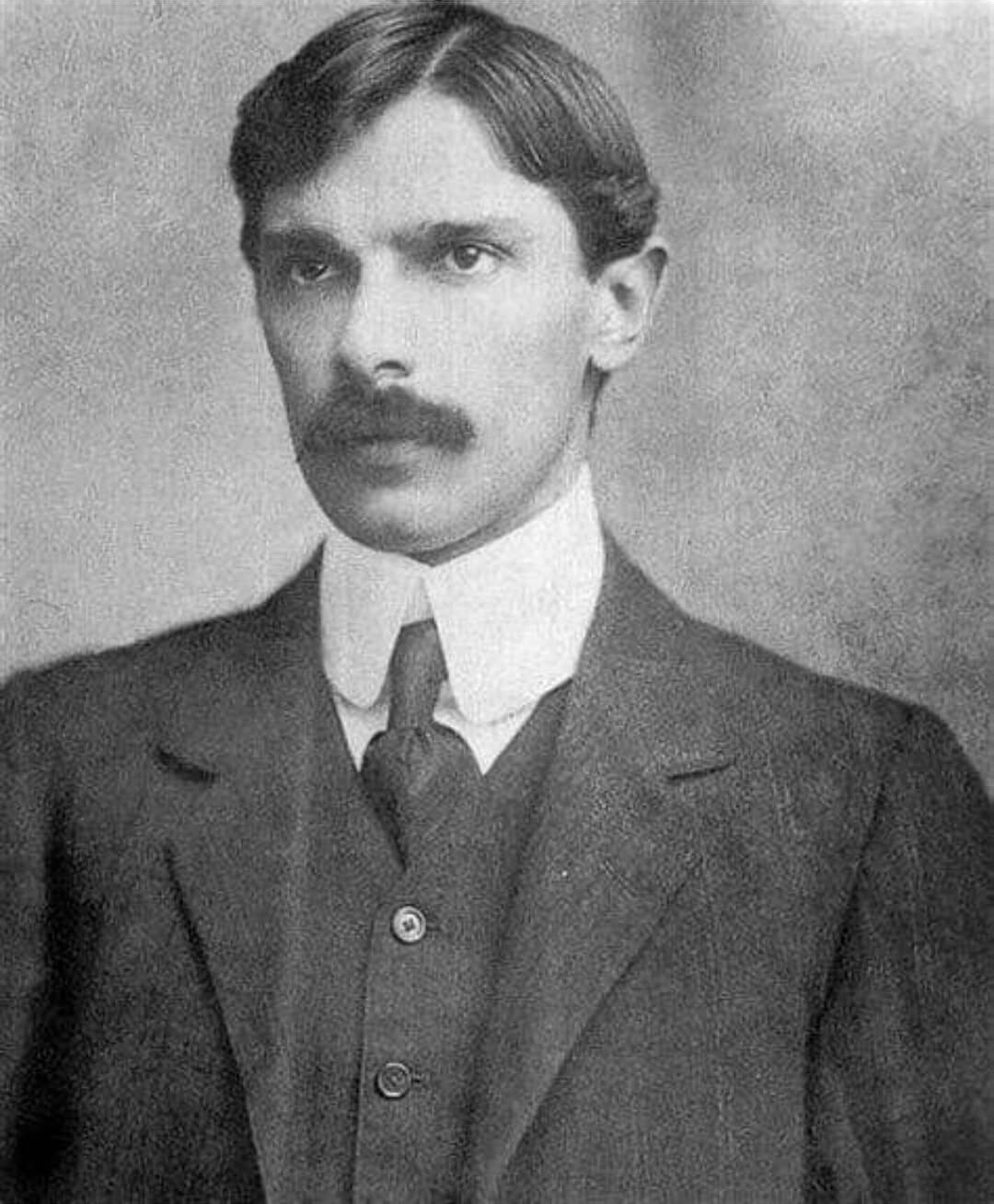

2. Legal and Early Political Career

Jinnah's professional beginnings as a barrister quickly established his reputation for legal acumen, and his early engagement with Indian politics reflected a moderate approach, initially championing Hindu-Muslim unity.

2.1. Barrister

At the age of 20, Jinnah commenced his legal practice in Bombay, being the sole Muslim barrister in the city. English became his principal language. His initial three years, from 1897 to 1900, yielded few clients. His career took a significant turn when John Molesworth MacPherson, the acting Advocate General of Bombay, invited Jinnah to work from his chambers. In 1900, Jinnah secured an interim position as a Bombay presidency magistrate for six months. Despite being offered a permanent position with a salary of 1.50 K INR per month, Jinnah politely declined, stating his ambition to earn 1.50 K INR a day-a goal he eventually achieved. However, as Governor-General of Pakistan, he notably fixed his own salary at 1 INR per month.

Jinnah gained prominence for his skillful handling of the 1908 "Caucus Case", a controversy surrounding alleged rigging of Bombay municipal elections by Europeans to prevent Sir Pherozeshah Mehta from entering the council. Jinnah's successful advocacy for Mehta, a renowned barrister, significantly enhanced his reputation for legal logic. In 1908, when his factional rival in the Indian National Congress, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, was arrested for sedition, Jinnah unsuccessfully attempted to secure his bail but later achieved an acquittal for Tilak on similar charges in 1916.

A fellow barrister from the Bombay High Court recalled Jinnah's "incredible" self-faith, recounting an instance where Jinnah retorted to a judge, "My Lord, allow me to warn you that you are not addressing a third-class pleader." Another contemporary described him as a "great pleader" with a "sixth sense," known for his clear thinking and deliberate, precise delivery of points.

Jinnah was also a supporter of working-class causes and an active trade unionist. In 1925, he was elected President of the All India Postal Staff Union, which had a membership of 70,000. He advocated forcefully for workers' rights, striving for "living wage and fair conditions," and played a significant role in the enactment of the Trade Union Act of 1926, which provided legal protection for the trade union movement to organize.

2.2. Entry into Politics and the Indian National Congress

Jinnah's political involvement began in the early 1900s, dedicating much of his time to his law practice but remaining engaged in national affairs. He attended the Indian National Congress's twentieth annual meeting in Bombay in December 1904. A member of the Congress's moderate wing, he initially favored Hindu-Muslim unity in the pursuit of self-government, aligning himself with leaders like Mehta, Dadabhai Naoroji, and Gopal Krishna Gokhale. This moderate faction was in contrast to those like Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Lala Lajpat Rai, who pressed for quicker independence.

In 1906, when the Simla Delegation, led by the Aga Khan III, met with Viceroy Lord Minto to seek assurances for Muslims in future reforms, Jinnah expressed his dissatisfaction. He questioned the delegation's right to speak for Indian Muslims, arguing they were unelected and self-appointed. He initially opposed the formation of the All-India Muslim League in Dacca later that year, which aimed to advocate for Muslim interests, believing that separate electorates would "divide the nation against itself."

Despite his initial opposition, Jinnah used separate electorates to secure his first elective office in 1909, becoming Bombay's Muslim representative on the Imperial Legislative Council. He was a compromise candidate chosen after two older, more prominent Muslims seeking the position deadlocked. The council, expanded to 60 members by reforms enacted by Minto, advised the Viceroy on legislation. In 1911, Jinnah introduced the Wakf Validation Act, aimed at providing legal recognition to Muslim religious trusts under British Indian law. This measure passed two years later, marking the first act sponsored by non-officials to be enacted by the Viceroy. Jinnah was also appointed to a committee that helped establish the Indian Military Academy in Dehra Dun.

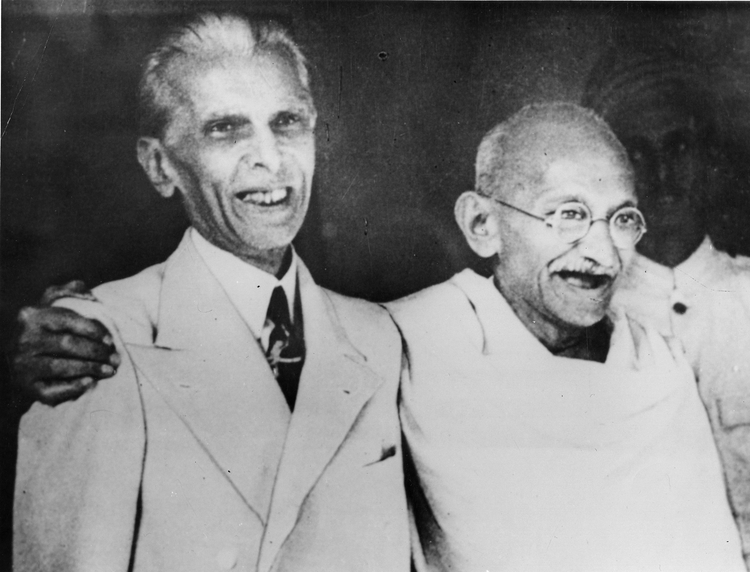

In December 1912, Jinnah addressed the annual meeting of the Muslim League, though he was not yet a member. He joined the League the following year, while still maintaining his membership in the Congress, emphasizing that League membership was secondary to the "greater national cause" of an independent India. In April 1913, he traveled to Britain with Gokhale to meet with officials on behalf of the Congress. Gokhale, a Hindu, remarked that Jinnah possessed "true stuff" and a "freedom from all sectarian prejudice," which would make him "the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unity." Jinnah led another Congress delegation to London in 1914, but with the outbreak of World War I, British officials showed little interest in Indian reforms. Coincidentally, he met Mohandas Gandhi for the first time at a reception in Britain; Gandhi, a lawyer, had become known for advocating satyagraha (non-violent non-co-operation) in South Africa. Jinnah returned to India in January 1915.

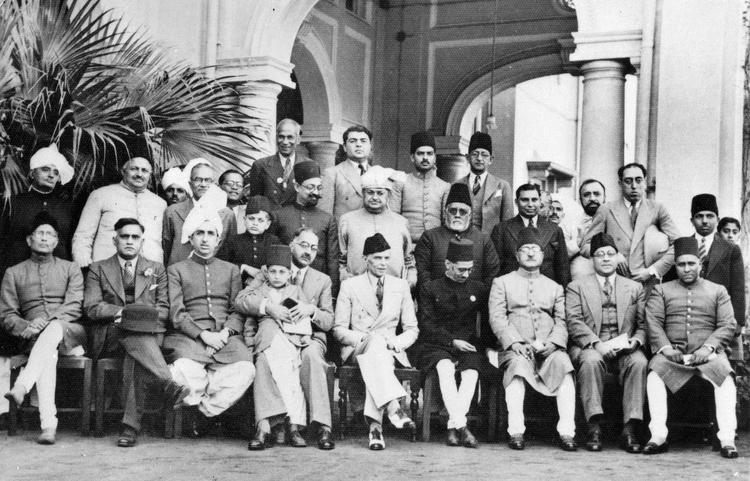

2.3. Lucknow Pact

The deaths of Sir Pherozeshah Mehta and Gopal Krishna Gokhale in 1915, followed by Dadabhai Naoroji's death in 1917, undermined Jinnah's moderate faction within the Congress, further isolating him. Despite this, Jinnah tirelessly worked to foster unity between the Congress and the Muslim League. In 1916, now serving as president of the Muslim League, Jinnah played a pivotal role in the signing of the Lucknow Pact. This significant agreement established quotas for Muslim and Hindu representation in the various provincial legislatures, a move aimed at fostering inter-community cooperation. Although the pact was never fully implemented, its signing ushered in a period of unprecedented collaboration between the Congress and the League, marking a high point in Hindu-Muslim political unity.

2.4. Home Rule Movement

During World War I, Jinnah, like other Indian moderates, supported the British war effort, hoping that India would be rewarded with greater political freedoms for its contributions. Jinnah was instrumental in the founding of the All India Home Rule League in 1916. Alongside prominent political leaders like Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Jinnah advocated for "home rule" for India, seeking the status of a self-governing dominion within the British Empire, akin to Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. However, with the war ongoing, British politicians showed little inclination to consider Indian constitutional reform. British Cabinet minister Edwin Montagu described Jinnah in his memoirs as "young, perfectly mannered, impressive-looking, armed to the teeth with dialectics, and insistent on the whole of his scheme."

2.5. Fourteen Points

In 1927, the British Government, under Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, initiated a review of Indian policy, leading to the appointment of the Simon Commission. Indian leaders, both Muslim and Hindu, largely boycotted the commission due to the British refusal to include Indian representatives. Although a minority of Muslims broke from the League to welcome the commission, most members of the League's executive council remained loyal to Jinnah, confirming him as its permanent president. Jinnah vehemently criticized the commission, declaring that "A constitutional war has been declared on Great Britain" and that the exclusively white commission signified Britain's view of India's unfitness for self-government.

In 1928, Lord Birkenhead challenged Indians to propose their own constitutional changes. In response, the Congress formed a committee led by Motilal Nehru, which produced the Nehru Report. This report favored geographically based constituencies, rejecting separate electorates for Muslims. Jinnah, despite believing separate electorates were necessary for Muslim representation, was willing to compromise. He proposed constitutional reforms that he hoped would satisfy a broad range of Muslims and reunite the League. These proposals, which called for mandatory representation for Muslims in legislatures and cabinets, became known as his Fourteen Points. Despite his efforts, he could not secure their adoption, as the League meeting in Delhi where he hoped to gain a vote dissolved into disarray.

2.6. Farewell to Congress

Relations between Indians and the British government became highly strained in 1919 following the extension of emergency wartime restrictions on civil liberties by the Imperial Legislative Council, prompting Jinnah to resign from it. Widespread unrest across India intensified after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar, where British Indian Army troops fired upon a protest, killing hundreds. In the wake of Amritsar, Mohandas Gandhi, who had returned to India and gained significant influence within the Congress, called for a campaign of satyagraha (non-violent non-co-operation) against the British.

Gandhi's proposal garnered broad Hindu support and attracted many Muslims from the Khilafat Movement, who sought to preserve the Ottoman caliphate. Gandhi's popularity among Muslims grew due to his advocacy for imprisoned or killed Muslims during the war. Unlike Jinnah and other Congress leaders, Gandhi eschewed Western attire, spoke Indian languages, and was deeply rooted in Indian culture, which resonated deeply with the masses. Jinnah, however, criticized Gandhi's Khilafat advocacy, viewing it as an endorsement of religious zealotry and his proposed satyagraha campaign as political anarchy. Jinnah believed that self-government should be achieved through constitutional means.

At the 1920 session of the Congress in Nagpur, Jinnah's opposition to Gandhi's methods was met with rejection by the delegates, who adopted Gandhi's proposal for satyagraha until India achieved independence. Jinnah did not attend the subsequent League meeting, which passed a similar resolution. Consequently, Jinnah resigned from the Congress, retaining only his position within the Muslim League, marking a significant divergence in his political path.

3. Interlude in England and Return to Politics

This period marked Jinnah's temporary withdrawal from active Indian politics and his subsequent powerful re-engagement, culminating in his renewed leadership of the Muslim League.

3.1. Activities in England

The alliance between Mohandas Gandhi and the Khilafat faction proved short-lived, and the non-cooperation campaign yielded less impact than anticipated as India's existing institutions largely continued to function. Jinnah, disillusioned, explored alternative political ideas and contemplated establishing a new political party to rival the Congress. In September 1923, he was elected as the Muslim representative for Bombay in the new Central Legislative Assembly. Demonstrating his parliamentary skills, he collaborated with the Swaraj Party and continued to press for full responsible government. In 1925, Lord Reading, the retiring Viceroy, offered Jinnah a knighthood in recognition of his legislative contributions, but Jinnah politely declined, stating, "I prefer to be plain Mr Jinnah."

Jinnah remained in Britain for most of the period from 1930 to 1934, practicing as a barrister before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, handling numerous India-related cases. Biographers offer differing reasons for his prolonged stay; Stanley Wolpert suggests Jinnah might have stayed for life if offered a Law Lord position or sought a parliamentary seat, while Hector Bolitho denies Jinnah's desire to enter the British Parliament. Jaswant Singh views this period as a break or sabbatical from the Indian struggle. Bolitho characterized these years as "Jinnah's years of order and contemplation, wedged in between the time of early struggle, and the final storm of conquest."

3.2. Personal Life

In 1918, Jinnah married his second wife, Rattanbai Petit ("Ruttie"), 24 years his junior. Ruttie was the fashionable daughter of his friend Sir Dinshaw Petit, belonging to an elite Parsi family in Bombay. Their marriage faced significant opposition from Rattanbai's family and the Parsi community, as well as from some Muslim religious leaders. Rattanbai defied her family, nominally converted to Islam, and adopted the name Maryam Jinnah (though she never used it), leading to a permanent estrangement from her family and Parsi society. The couple resided at South Court Mansion in Bombay and traveled frequently across India and Europe. Their only child, a daughter named Dina, was born on August 15, 1919. The couple separated before Ruttie's death in 1929. Following her passing, Jinnah's younger sister, Fatima Jinnah, moved in with him to care for him and his daughter.

In 1931, Fatima Jinnah joined her brother in England. From this point onward, she provided him with dedicated personal care and support, particularly as his health declined due to lung ailments that would eventually prove fatal. She lived and traveled with him, becoming a close advisor and confidante. Muhammad Ali Jinnah's daughter, Dina, received her education in England and India. Jinnah's relationship with Dina became strained after she chose to marry Neville Wadia, a Parsi from a prominent business family. Jinnah had urged her to marry a Muslim, to which she reportedly reminded him that he too had married a woman not raised in his faith. Despite this personal rift, Jinnah continued to correspond cordially with his daughter. However, their personal relationship remained strained, and Dina did not move to Pakistan during his lifetime, only returning for his funeral.

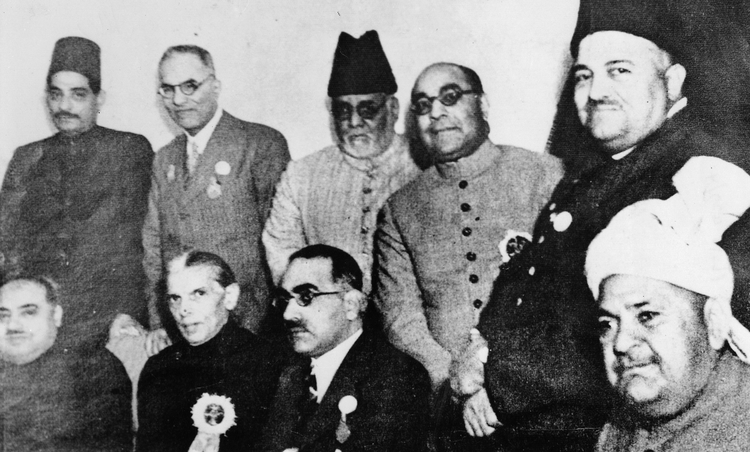

3.3. Return to Politics and Leadership of the Muslim League

The early 1930s saw a resurgence of Indian Muslim nationalism, which gained momentum with the Pakistan Declaration. By 1933, Indian Muslims, particularly from the United Provinces, began to urge Jinnah to return to India and reassume leadership of the All-India Muslim League, which had become largely inactive. Although he remained its titular president, Jinnah initially declined to preside over its April 1933 session, stating he could not return until the end of the year.

Among those who met with Jinnah to persuade him to return was Liaquat Ali Khan, who would become his significant political associate and Pakistan's first prime minister. At Jinnah's request, Liaquat consulted a broad range of Muslim politicians, confirming their desire for Jinnah's return. In early 1934, Jinnah relocated to the subcontinent, though he continued to travel between London and India for business for several years, eventually selling his house in Hampstead and closing his legal practice in Britain.

In October 1934, Muslims of Bombay elected Jinnah as their representative to the Central Legislative Assembly, despite his absence in London. The British Parliament's Government of India Act 1935 granted considerable autonomy to India's provinces, establishing a weak central parliament in New Delhi with limited authority over foreign policy, defense, and much of the budget. Full power remained with the Viceroy, who could dissolve legislatures and rule by decree. The League reluctantly accepted this scheme, expressing reservations about the weak central parliament.

The Indian National Congress was far better prepared for the provincial elections in 1937. The League failed to secure a majority even in the Muslim-majority provinces and could not form a government anywhere, though it joined the ruling coalition in Bengal. The Congress and its allies formed governments even in the North-West Frontier Province (N.W.F.P.), where the League won no seats despite an overwhelmingly Muslim population.

According to Jaswant Singh, the outcome of the 1937 elections had a "tremendous, almost a traumatic effect upon Jinnah." Despite his two-decade belief that Muslims could protect their rights in a united India through separate electorates, preserved Muslim majorities in provincial boundaries, and other minority protections, Muslim voters had not united. The issues Jinnah hoped to advance were lost amidst factional infighting. Singh noted that when the Congress formed governments with almost all Muslim MLAs in opposition, non-Congress Muslims were suddenly confronted with the "stark reality of near-total political powerlessness." This stark realization, that Congress could form a government entirely on the strength of general seats even without winning a single Muslim seat, profoundly impacted Muslim political opinion.

Over the next two years, Jinnah dedicated himself to building support for the League among Muslims. He secured the right to represent the Muslim-led Bengali and Punjabi provincial governments in the central government in New Delhi. He actively expanded the League's reach, reducing the membership fee to two annas (1/8 of a rupee), half the cost of joining the Congress. He also restructured the League along the lines of the Congress, centralizing power in a Working Committee appointed by him. By December 1939, Liaquat estimated that the League had achieved three million two-anna members, indicating significant growth and mobilization under Jinnah's leadership.

4. The Pakistan Movement

The period leading to Pakistan's creation was marked by a fundamental shift in Jinnah's ideology, from advocating for a united India to demanding a separate Muslim state, a journey that defined his central role in the Pakistan Movement.

4.1. Background to Independence and Ideological Formation

Until the late 1930s, most Muslims in the British Raj, along with Hindus and other self-governance advocates, anticipated that an independent India would be a unitary state encompassing all of British India. Nevertheless, alternative nationalist proposals were emerging. In a 1930 speech to a League session, Muhammad Iqbal called for a separate state for Muslims within British India. In 1933, Choudhary Rahmat Ali published a pamphlet advocating for a state named "Pakistan" in the Indus Valley, with other names proposed for Muslim-majority areas elsewhere. Jinnah and Iqbal corresponded in 1936 and 1937, and in subsequent years, Jinnah frequently credited Iqbal as his mentor, integrating Iqbal's imagery and rhetoric into his speeches.

While many Congress leaders sought a strong central government for an independent India, some Muslim politicians, including Jinnah, were unwilling to accept this without robust protections for their community. Other Muslims supported the Congress, which officially advocated a secular state upon independence, although its traditionalist wing, including figures like Madan Mohan Malaviya and Vallabhbhai Patel, sought to implement policies such as banning cow slaughter and making Hindi a national language. The failure of the Congress leadership to disavow Hindu communalists concerned Congress-supporting Muslims, yet the Congress maintained considerable Muslim support until around 1937.

Events that further alienated the communities included the failed attempt to form a coalition government involving the Congress and the League in the United Provinces following the 1937 election. Historian Ian Talbot notes that "the provincial Congress governments made no effort to understand and respect their Muslim populations' cultural and religious sensibilities. The Muslim League's claims that it alone could safeguard Muslim interests thus received a major boost. Significantly, it was only after this period of Congress rule that it [the League] took up the demand for a Pakistan state."

Balraj Puri suggests that Jinnah turned to the idea of partition in "sheer desperation" after the 1937 vote. Historian Akbar S. Ahmed posits that Jinnah abandoned hope of reconciliation with the Congress as he "rediscover[ed] his own Islamic roots, his own sense of identity, of culture and history, which would come increasingly to the fore in the final years of his life." Jinnah also increasingly adopted Muslim dress in the late 1930s. Following the 1937 elections, Jinnah demanded that power-sharing issues be settled on an all-India basis and that he, as League president, be accepted as the sole spokesman for the Muslim community.

4.2. Iqbal's influence on Jinnah

The influence of Muhammad Iqbal on Jinnah regarding the creation of Pakistan is widely regarded as "significant," "powerful," and "unquestionable" by scholars. Iqbal is also credited with convincing Jinnah to end his self-imposed exile in London and re-enter Indian politics. Initially, Iqbal and Jinnah were at odds, as Iqbal believed Jinnah was indifferent to the crises facing the Muslim community under the British Raj. However, this began to change during Iqbal's final years before his death in 1938. Iqbal gradually succeeded in swaying Jinnah to his view, leading Jinnah to accept Iqbal as his mentor. In his annotations to Iqbal's letters, Jinnah expressed solidarity with Iqbal's conviction that Indian Muslims required a separate homeland.

Iqbal's influence also deepened Jinnah's appreciation for Muslim identity, evident from 1937 onwards. Jinnah began echoing Iqbal's ideas in his speeches, incorporating Islamic symbolism, and directing his addresses towards the underprivileged. Akbar S. Ahmed noted a shift in Jinnah's rhetoric: while he continued to advocate religious freedom and minority protection, his aspirational model increasingly resembled that of the Prophet Muhammad, rather than a purely secular politician. Ahmed argues that interpretations of the later Jinnah as purely secular misread his speeches, which, he contends, must be understood within the context of Islamic history and culture. Consequently, Jinnah's vision for Pakistan began to clearly assume an Islamic character, a change that persisted throughout his life. He continued to adopt ideas directly from Iqbal, including those on Muslim unity, Islamic ideals of liberty, justice, and equality, economics, and even practices like prayers.

In a 1940 speech, two years after Iqbal's death, Jinnah expressed his profound commitment to Iqbal's vision, stating, "If I live to see the ideal of a Muslim state being achieved in India, and I was then offered to make a choice between the works of Iqbal and the rulership of the Muslim state, I would prefer the former." This highlights the transformative impact Iqbal had on Jinnah's political and ideological outlook.

4.3. Second World War and Political Strategy

On September 3, 1939, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announced the commencement of World War II with Nazi Germany. The following day, Viceroy Lord Linlithgow, without consulting Indian political leaders, declared India's entry into the war alongside Britain, sparking widespread protests across India. After meetings with Jinnah and Gandhi, Linlithgow announced that negotiations on self-government were suspended for the war's duration. The Congress, on September 14, demanded immediate independence with a constituent assembly, which was refused. Its eight provincial governments resigned on November 10, leading to governors ruling by decree. Jinnah, conversely, was more accommodating towards the British, who increasingly recognized him and the Muslim League as representatives of India's Muslims. Jinnah later remarked, "after the war began,... I was treated on the same basis as Mr Gandhi. I was wonderstruck why I was promoted and given a place side by side with Mr Gandhi." While the League did not actively support the British war effort, it also avoided obstructing it.

With the British and Muslims largely cooperating, the Viceroy requested the Muslim League's position on self-government, anticipating it would diverge significantly from the Congress's. To formulate this, the League's Working Committee met for four days in February 1940, defining terms for a constitutional sub-committee. They sought a proposal resulting in "independent dominions in direct relationship with Great Britain" where Muslims were dominant. On February 6, Jinnah informed the Viceroy that the League would demand partition instead of the federation outlined in the 1935 Act.

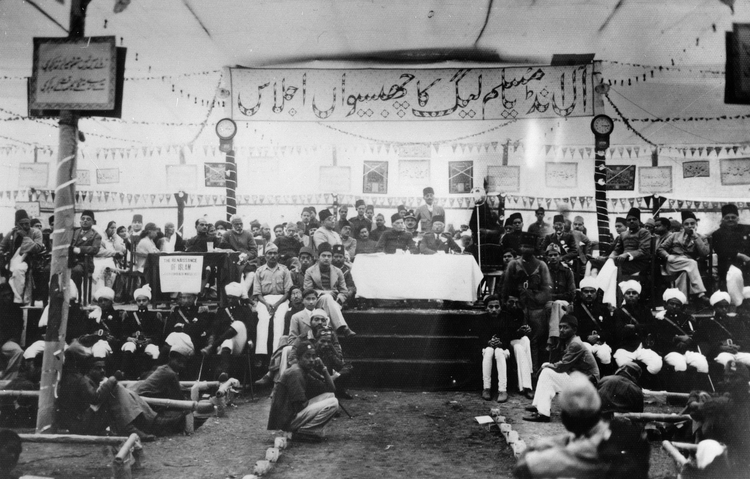

The Lahore Resolution (sometimes called the "Pakistan Resolution," though it lacks that name), based on the sub-committee's work, formally embraced the two-nation theory and called for a union of Muslim-majority provinces in British India's northwest, with complete autonomy. Similar rights were to be granted to Muslim-majority areas in the east, and unspecified protections for Muslim minorities elsewhere. The League session in Lahore passed the resolution on March 23, 1940.

Gandhi's reaction to the Lahore Resolution was muted; he called it "baffling" but affirmed the Muslims' right to self-determination. Congress leaders were more vocal; Jawaharlal Nehru dismissed it as "Jinnah's fantastic proposals," while C. Rajagopalachari called Jinnah's views on partition "a sign of a diseased mentality." Linlithgow met with Jinnah in June 1940, shortly after Winston Churchill became Prime Minister. In August, he offered both Congress and the League a deal: full war support in exchange for Indian representation on major war councils and a postwar representative body to determine India's future, with no settlement imposed against the objections of a large population segment. This satisfied neither party, though Jinnah was pleased that the British were moving towards recognizing him as the representative of Muslim interests. Jinnah was cautious about defining Pakistan's exact boundaries or its relationship with Britain and the rest of India, fearing it might divide the League.

The attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 brought the United States into the war. With Japanese advances in Southeast Asia, the British Cabinet dispatched the Cripps Mission, led by Sir Stafford Cripps, to seek Indian backing for the war. Cripps proposed a "local option" allowing provinces to remain outside a central Indian government, forming their own dominions or confederations. The Muslim League was uncertain of winning the necessary legislative votes in mixed provinces like Bengal and Punjab for secession, and Jinnah rejected the proposals as not sufficiently recognizing Pakistan's right to exist. The Congress also rejected the plan, demanding immediate concessions Cripps wouldn't give. Despite its rejection, Jinnah and the League viewed the Cripps proposal as recognizing Pakistan in principle.

The Congress followed the failed Cripps mission with the "Quit India" demand in August 1942, initiating a mass satyagraha campaign. The British promptly arrested most major Congress leaders, imprisoning them for the war's duration. Gandhi was under house arrest until his release for health reasons in 1944. With Congress leaders absent, Jinnah capitalized on the opportunity, warning against Hindu domination and maintaining his demand for Pakistan without detailing its specifics. Jinnah also worked to strengthen the League's provincial political control.

He helped establish the newspaper Dawn in Delhi in the early 1940s, which disseminated the League's message and eventually became Pakistan's leading English-language newspaper. He also resided on Aurangzeb Road (now Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam Road) in Delhi, near Birla House where Mahatma Gandhi stayed, and was neighbors with Sir Sobha Singh, one of Delhi's wealthiest men. His former residence now serves as the Embassy of the Netherlands in India and is widely known as Jinnah House.

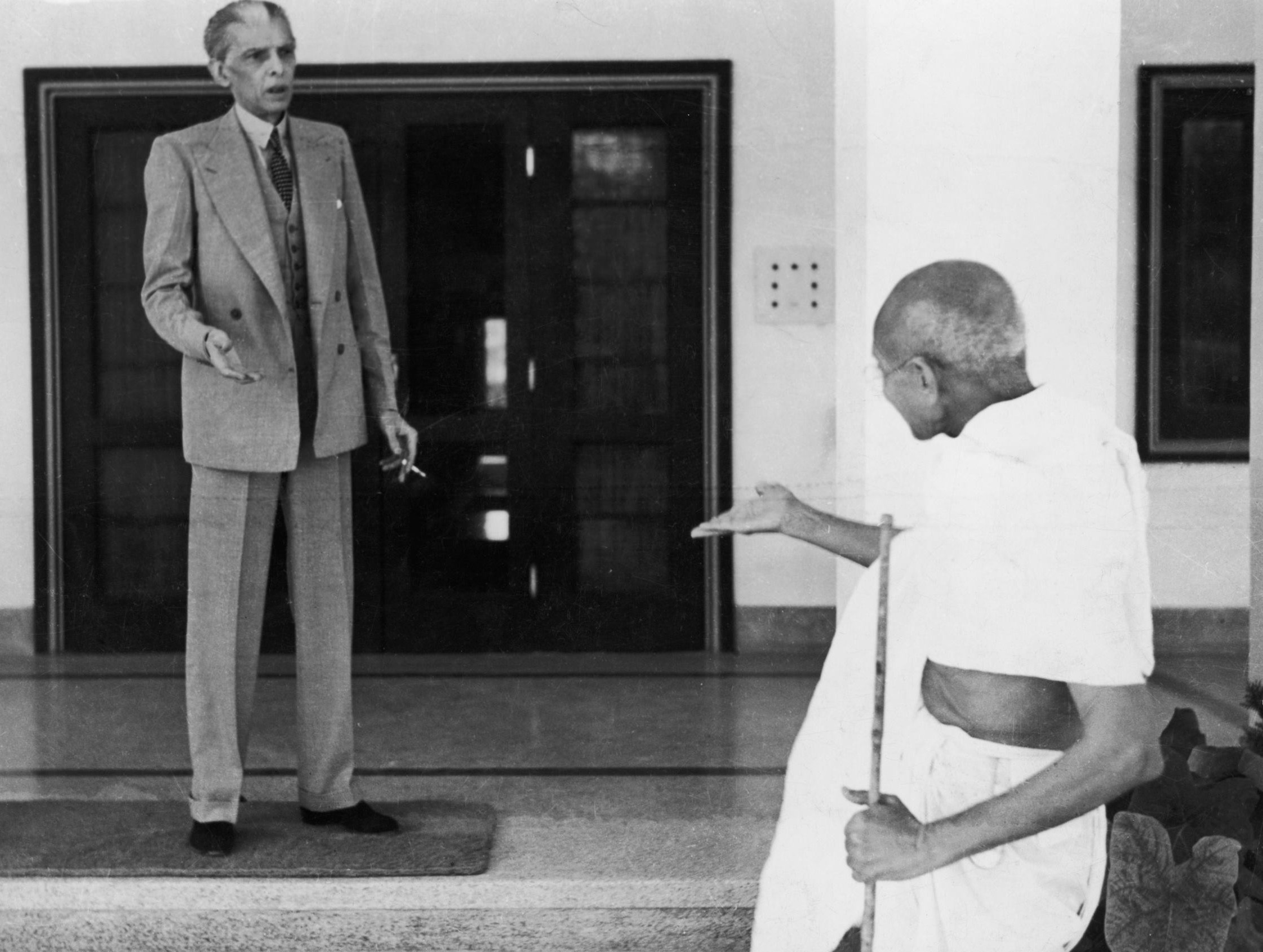

In September 1944, Jinnah hosted Gandhi, recently released from confinement, at his home on Malabar Hill in Bombay. Their two weeks of talks yielded no agreement. Jinnah insisted on Pakistan being conceded prior to the British departure and coming into existence immediately, while Gandhi proposed that plebiscites on partition occur sometime after a united India gained independence. In early 1945, Liaquat and Congress leader Bhulabhai Desai met with Jinnah's approval, agreeing that after the war, Congress and the League should form an interim government with equal representation on the Viceroy's Executive Council. However, upon their release from prison in June 1945, the Congress leadership repudiated the agreement, censuring Desai for acting without proper authority.

4.4. Postwar Developments and Elections

Field Marshal Viscount Wavell succeeded Linlithgow as Viceroy in 1943. In June 1945, after the Congress leaders' release, Wavell convened the Simla Conference, inviting leading figures from various communities to meet him at Simla. He proposed a temporary government aligned with the Liaquat-Desai agreement. However, Wavell was unwilling to guarantee that only the League's candidates would fill seats reserved for Muslims. As other invited groups submitted their candidate lists, Wavell abruptly ended the conference in mid-July without further seeking an agreement, as a British general election was imminent, and Churchill's government felt it could not proceed.

British voters elected Clement Attlee and his Labour Party to government in July. Attlee and his Secretary of State for India, Lord Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, immediately ordered a review of the Indian situation. Jinnah made no comment on the change of government but called a meeting of his Working Committee, issuing a statement demanding new elections in India. The League's influence at the provincial level in Muslim-majority states was mostly through alliances, and Jinnah believed that new elections would improve the League's standing, strengthening his claim as the sole spokesman for Muslims. Wavell returned to India in September after consulting with his new government in London; elections for both central and provincial assemblies were announced soon after, with the British indicating that a constitution-making body would follow the votes.

The Muslim League declared that they would campaign on a single issue: Pakistan. Speaking in Ahmedabad, Jinnah reiterated, "Pakistan is a matter of life or death for us." In the December 1945 elections for the Constituent Assembly of India, the League won every seat reserved for Muslims. In the provincial elections in January 1946, the League secured 75% of the Muslim vote, a significant increase from 4.4% in 1937. According to his biographer Bolitho, "This was Jinnah's glorious hour: his arduous political campaigns, his robust beliefs and claims, were at last justified." Wolpert wrote that the League's electoral performance "appeared to prove the universal appeal of Pakistan among Muslims of the subcontinent." Nevertheless, the Congress dominated the central assembly, although it lost four seats from its previous strength.

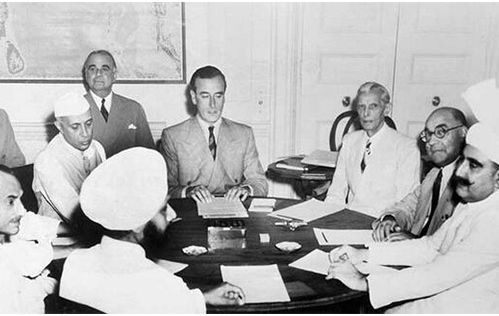

In February 1946, the British Cabinet decided to send a delegation to India to negotiate with leaders there. This Cabinet Mission included Cripps and Pethick-Lawrence, arriving in New Delhi in late March. In May, the British proposed a plan for a united Indian state with substantially autonomous provinces, grouped by religion. Defence, external relations, and communications would be managed by a central authority. Provinces could leave the union entirely, and an interim government with Congress and League representation would be formed. Jinnah and his Working Committee accepted this plan in June, but it collapsed over the number of interim government members for each party and Congress's insistence on including a Muslim member in its representation. Before leaving India, the British ministers stated their intent to inaugurate an interim government even if one major group refused to participate.

The Congress soon joined the new Indian ministry. The League joined later, in October 1946, with Jinnah dropping his demands for parity with Congress and a veto on Muslim affairs. The new ministry convened amidst widespread rioting, especially on Direct Action Day in Calcutta. Congress urged the Viceroy to immediately summon the constituent assembly to draft a constitution, believing League ministers should either join or resign. Wavell attempted to mediate by flying Jinnah, Liaquat, and Nehru to London in December 1946. The talks concluded with a statement that the constitution would not be imposed on unwilling parts of India. Returning from London, Jinnah and Liaquat stopped in Cairo for pan-Islamic meetings.

The Congress endorsed the joint statement from the London conference, despite internal dissent. The League refused, taking no part in constitutional discussions. Jinnah had considered maintaining some links to Hindustan (the Hindu-majority state), such as a joint military or communications. However, by December 1946, he insisted on a fully sovereign Pakistan with dominion status. The Attlee ministry desired a swift British departure but lacked confidence in Wavell. From December 1946, British officials sought a new Viceroy, eventually settling on Admiral Lord Mountbatten of Burma, popular among both Conservatives (as Queen Victoria's great-grandson) and Labour (for his political views).

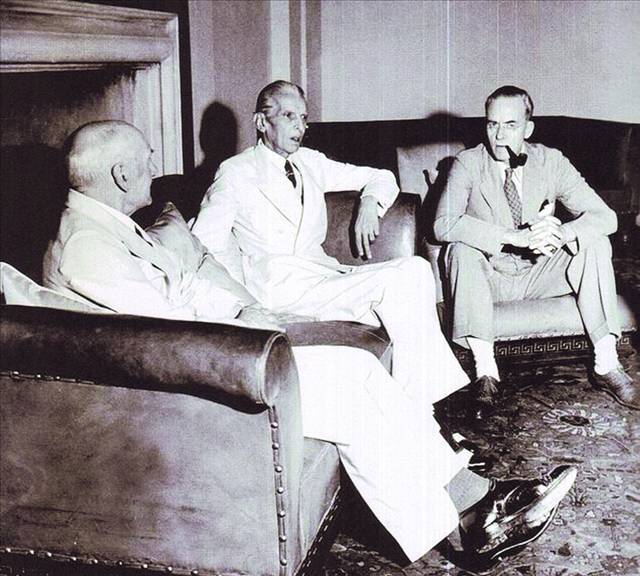

4.5. Mountbatten Plan and Independence

On February 20, 1947, Attlee announced Mountbatten's appointment and that Britain would transfer power in India no later than June 1948. Mountbatten assumed the Viceroyalty on March 24, 1947. By this time, the Congress had largely accepted the idea of partition. Nehru later stated in 1960 that they were "tired men" who took the partition plan as "a way out." Congress leaders concluded that loosely tied Muslim-majority provinces were not worth sacrificing the strong central government they desired. However, Congress insisted that if Pakistan became independent, Bengal and Punjab must also be divided.

Mountbatten's briefing papers warned him that Jinnah would be his "toughest customer," elusive to understand. Their meetings began on April 5, lasting six days. Jinnah, photographed between Louis and Edwina Mountbatten, famously quipped, "A rose between two thorns." Mountbatten was not favorably impressed with Jinnah, frequently expressing frustration to his staff over Jinnah's unyielding insistence on Pakistan.

Jinnah feared that upon British departure, control would be handed to the Congress-dominated constituent assembly, disadvantaging Muslims in their pursuit of autonomy. He demanded the division of the British Indian Army before independence, which would take at least a year. While Mountbatten hoped for a common defense force post-independence, Jinnah deemed it essential for a sovereign state to possess its own military. After meeting with Liaquat, Mountbatten concluded, informing Attlee and the Cabinet in May, that "it had become clear that the Muslim League would resort to arms if Pakistan in some form were not conceded." The Viceroy was also influenced by negative Muslim reactions to the assembly's constitutional report, which envisioned broad powers for the post-independence central government.

On June 2, 1947, Mountbatten presented the final plan to Indian leaders: on August 15, Britain would transfer power to two dominions. Provinces would vote on joining the existing constituent assembly or a new one for Pakistan. Bengal and Punjab would vote on joining an assembly and on partition. A boundary commission would determine the final lines. Plebiscites would occur in the North-West Frontier Province (which had an overwhelmingly Muslim population but no League government) and the Muslim-majority Sylhet district of Assam, adjacent to eastern Bengal. On June 3, Mountbatten, Nehru, Jinnah, and Baldev Singh, a Sikh leader, made the formal radio announcement. Jinnah concluded his address with "Pakistan Zindabad" (Long live Pakistan), a phrase not in the script. Some listeners, however, misinterpreted his Urdu as "Pakistan's in the bag!"

In the subsequent weeks, Punjab and Bengal voted for partition. Sylhet and the N.W.F.P. voted to join Pakistan, a decision also made by the assemblies in Sind and Baluchistan.

4.6. Partition of India and its Consequences

On July 4, 1947, Liaquat, on Jinnah's behalf, asked Mountbatten to recommend to King George VI that Jinnah be appointed Pakistan's first governor-general. This request angered Mountbatten, who had hoped to hold the position in both dominions (he became India's first post-independence governor-general). Jinnah, however, felt Mountbatten might favor the new Hindu-majority state due to his closeness with Nehru. Furthermore, the governor-general would initially be a powerful figure, and Jinnah trusted no one else in that office.

Although the Boundary Commission, led by British lawyer Sir Cyril Radcliffe, had not yet reported, massive population movements and sectarian violence were already underway. Jinnah arranged to sell his house in Bombay and acquired a new one in Karachi. On August 7, Jinnah, accompanied by his sister and close staff, flew from Delhi to Karachi on Mountbatten's plane. As the plane taxied, he reportedly murmured, "That's the end of that."

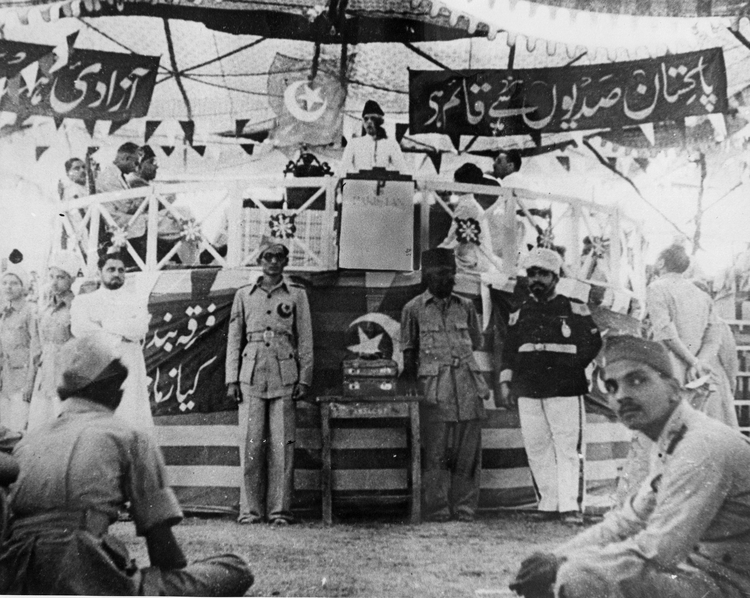

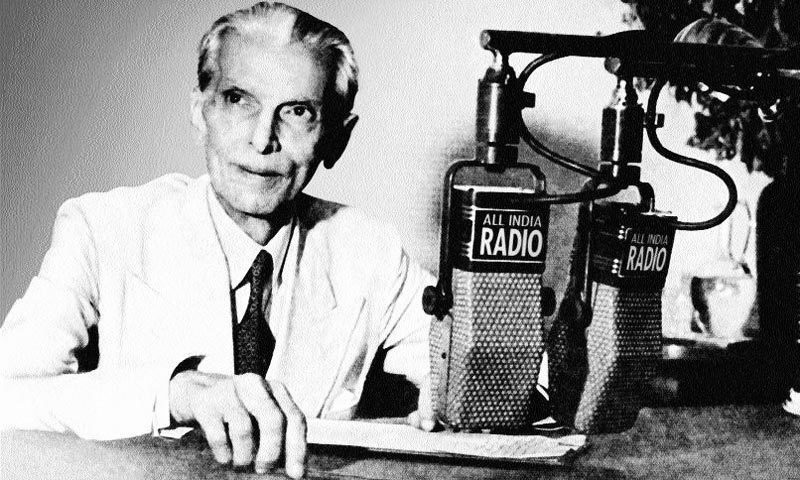

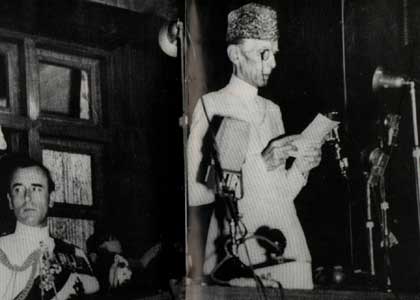

On August 11, Jinnah presided over Pakistan's new constituent assembly in Karachi and delivered his famous August 11 speech: "You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan... You may belong to any religion or caste or creed-that has nothing to do with the business of the State... I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State." On August 14, Pakistan became independent, and Jinnah led the celebrations in Karachi. One observer described him as "Pakistan's King Emperor, Archbishop of Canterbury, Speaker and Prime Minister concentrated into one formidable Quaid-e-Azam."

The Radcliffe Commission, tasked with dividing Bengal and Punjab, completed its work and reported to Mountbatten on August 12. Mountbatten withheld the maps until August 17, seeking to avoid disrupting independence celebrations in both nations. However, ethnic violence and population movements were already rampant; the publication of the Radcliffe Line dividing the new nations ignited mass migration, murder, and ethnic cleansing. Millions on the "wrong side" of the new borders fled or were killed, or participated in violence themselves, in a desperate attempt to alter the commission's verdict. Radcliffe noted in his report that he knew neither side would be satisfied with his award and declined his fee for the work. Christopher Beaumont, Radcliffe's private secretary, later attributed blame, though not sole blame, to Mountbatten for the massacres in Punjab, which resulted in an estimated 500,000 to 1,000,000 deaths. Jinnah, despite being over 70 and frail from lung ailments, personally supervised refugee camps and traveled across West Pakistan to aid the eight million people who migrated to Pakistan. According to Akbar S. Ahmed, "What Pakistan needed desperately in those early months was a symbol of the state, one that would unify people and give them the courage and resolve to succeed."

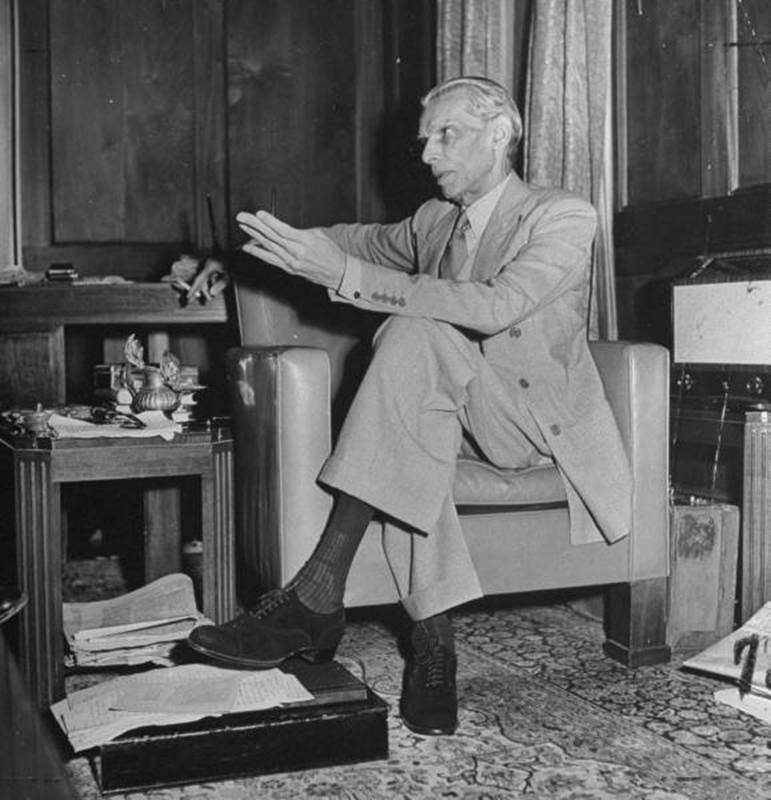

5. First Governor-General of Pakistan

As the first Governor-General of Pakistan, Jinnah embarked on the monumental task of establishing the nascent nation's governance, administrative structures, and key policies, while simultaneously addressing a profound humanitarian crisis.

5.1. Nation-Building and Government Establishment

As Pakistan's first governor-general, Jinnah worked tirelessly to establish the new nation's government and policies. He oversaw the setting up of the governmental framework, administrative structures, and key policies for the nascent state. This included ensuring the smooth functioning of bureaucracy despite severe staff shortages, as few members of the Indian Civil Service and the Indian Police Service had chosen Pakistan. The immediate challenges included creating a new capital, establishing a legal system, and securing international recognition for the new state.

Jinnah's leadership was crucial in these formative months. He provided a unifying symbol for the fragmented population and instilled a sense of purpose and resolve amidst chaos. His efforts were directed at laying the foundations of a functional state, including economic planning and defence establishment.

Among the restive regions of the new nation was the North-West Frontier Province. The referendum there in July 1947 had been marred by low turnout, as less than 10% of the population was permitted to vote. On August 22, 1947, just a week after becoming governor-general, Jinnah dissolved the elected government of Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan. Later, Abdul Qayyum Khan was appointed by Jinnah in the Pashtun-dominated province, despite being a Kashmiri. On August 12, 1948, the Babrra massacre in Charsadda resulted in the deaths of 400 people aligned with the Khudai Khidmatgar movement.

5.2. Refugee Support and State Consolidation

Jinnah's efforts extended to aiding the millions of Muslim migrants who had emigrated from neighboring India to Pakistan after the partition. He personally supervised the establishment of refugee camps, working to manage the massive humanitarian crisis.

Along with Liaquat Ali Khan and Abdur Rab Nishtar, Jinnah represented Pakistan's interests in the Division Council, tasked with appropriately dividing public assets between India and Pakistan. Pakistan was slated to receive one-sixth of the pre-independence government's assets, meticulously divided by agreement down to the number of paper sheets. However, the new Indian state was slow to deliver, reportedly hoping for the collapse of the nascent Pakistani government and a reunion. Partition presented severe challenges, including for farmers whose markets were now across an international border, and shortages of machinery. Besides the refugee crisis, the new government struggled to salvage abandoned crops, establish security in a chaotic environment, and provide basic services. According to economist Yasmeen Niaz Mohiuddin, "although Pakistan was born in bloodshed and turmoil, it survived in the initial and difficult months after partition only because of the tremendous sacrifices made by its people and the selfless efforts of its great leader."

The princely states of India were advised by the departing British to choose whether to join Pakistan or India. Most acceded prior to independence, but the holdouts contributed to lasting divisions. Indian leaders were angered by Jinnah's attempts to persuade the princes of Jodhpur, Udaipur, Bhopal, and Indore to accede to Pakistan-the latter three not bordering Pakistan. Jodhpur, however, bordered Pakistan and had a Hindu majority population but a Hindu ruler. The coastal princely state of Junagadh, with a Hindu-majority population, acceded to Pakistan in September 1947, with its ruler's dewan, Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, personally delivering the accession papers to Jinnah. However, two of Junagadh's vassal states-Mangrol and Babariawad-declared independence from Junagadh and acceded to India. In response, the Nawab of Junagarh militarily occupied the two states. Subsequently, the Indian Army occupied the principality in November, forcing its former leaders, including Bhutto, to flee to Pakistan, marking the beginning of the politically influential Bhutto family.

The most contentious and enduring dispute was over the princely state of Kashmir. It had a Muslim-majority population and a Hindu maharaja, Sir Hari Singh, who delayed his decision on which nation to join. With the population in revolt in October 1947, aided by Pakistani irregulars, the maharaja acceded to India, and Indian troops were airlifted in. Jinnah objected and ordered Pakistani troops into Kashmir. The Pakistani Army, still commanded by British officers, saw its commanding officer, General Sir Douglas Gracey, refuse the order, stating he would not move into another nation's territory without higher authority approval, which was not granted. Jinnah withdrew the order, but the violence escalated into the First India-Pakistan War.

Some historians suggest that Jinnah's courting of Hindu-majority states and his gamble with Junagadh indicated ill-intent toward India, as Jinnah, who had promoted separation by religion, paradoxically sought to gain the accession of Hindu-majority states. Rajmohan Gandhi asserts that Jinnah hoped for a plebiscite in Junagadh, even if Pakistan would lose, to establish a principle for Kashmir. However, when Mountbatten proposed that accession in all princely states should be decided by an "impartial reference to the will of the people" (which would include Junagadh, Hyderabad, and Kashmir), Jinnah rejected the offer. Despite United Nations Security Council Resolution 47, which called for a plebiscite in Kashmir after Pakistani forces withdrew, this has never occurred.

In January 1948, the Indian government finally agreed to pay Pakistan its share of British India's assets. The partition violence subsided by January 18, following Mahatma Gandhi's fast, with religious rioters promising Gandhi to renounce violence. Just days later, on January 30, Gandhi was assassinated by Nathuram Godse, a Hindutva activist, who claimed Gandhi was pro-Muslim. Upon hearing of Gandhi's murder, Jinnah publicly issued a brief statement of condolence, calling Gandhi "one of the greatest men produced by the Hindu community."

In February 1948, in a radio address to the American people, Jinnah articulated his vision for Pakistan's future constitution:

:The Constitution of Pakistan is yet to be framed by the Pakistan Constituent Assembly, I do not know what the ultimate shape of the constitution is going to be, but I am sure that it will be of a democratic type, embodying the essential principles of Islam. Today these are as applicable in actual life as these were 1300 years ago. Islam and its idealism have taught us democracy. It has taught equality of man, justice and fair play to everybody. We are the inheritors of these glorious traditions and are fully alive to our responsibilities and obligations as framers of the future constitution of Pakistan.

In March, Jinnah, despite his declining health, made his only post-independence visit to East Pakistan. In a speech before an estimated 300,000 people, Jinnah stated (in English) that Urdu alone should be the national language, believing a single language was essential for national unity. The Bengali-speaking people of East Pakistan strongly opposed this policy, and the official language issue was a significant factor in the region's secession to form Bangladesh in 1971.

6. Political Thought and Philosophy

Jinnah's political thought evolved significantly throughout his career, initially championing a united India before advocating for a separate Muslim state. His vision for Pakistan, articulated towards the end of his life, emphasized democratic and liberal principles alongside an adherence to Islamic ideals.

6.1. Political Ideology

Jinnah's foundational political philosophy was deeply rooted in constitutionalism and liberal democracy, principles he absorbed during his legal education in England. He believed in achieving political change through legal and parliamentary means, as evidenced by his early career in the Indian National Congress and his consistent emphasis on constitutional reforms. His vision for Pakistan's constitution was explicitly democratic, aiming to embody the essential principles of Islam, which he believed taught "equality of man, justice and fair play to everybody." This indicated a commitment to a modern, democratic state structure rather than a purely theocratic one.

He was a staunch advocate for minority rights and believed in the equality of all citizens before the law. His emphasis on democratic values, rule of law, and a non-discriminatory approach to governance was consistent throughout his public statements on Pakistan's future.

6.2. Views on Religion and State

Jinnah's concept of Pakistan as a state for Muslims was complex and has been subject to varied interpretations. While he sought a homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent, his vision for the state's character, particularly regarding religion, was articulated in his August 11, 1947 speech. In this pivotal address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, he declared, "You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan... You may belong to any religion or caste or creed-that has nothing to do with the business of the State." He further stated, "You will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State." This speech is widely cited by those who argue for Pakistan's secular foundation and Jinnah's commitment to religious freedom and the rights of minorities.

However, others interpret his call for a state based on "the essential principles of Islam" as indicative of an Islamic identity for Pakistan, though not necessarily a theocracy. He believed that Islam's ideals of justice, equality, and fair play were compatible with and conducive to a democratic system. His stance on the role of Islam in governance was seen by some as an ideological framework for a just society rather than a literal imposition of religious law. The tension between Jinnah's emphasis on secular citizenship and the "Islamic identity" of the new state has remained a central debate in Pakistan's history.

6.3. Vision for Pakistan's Constitution

Jinnah's ideas for Pakistan's future constitution underscored principles of equality, justice, and democracy. He envisioned a democratic type of constitution that would embody the essential principles of Islam, which he asserted were timeless and fostered democracy, equality of mankind, justice, and fair play. He saw Pakistan as inheriting "glorious traditions" and recognized the framers' responsibilities and obligations in shaping its future.

His determination to establish a unified national identity led him to advocate for Urdu as the sole national language of Pakistan, a policy he believed was crucial for unity. This view, however, met strong opposition from the Bengali-speaking population of East Pakistan, who felt their linguistic and cultural identity was threatened. This language issue became a significant factor contributing to the Bengali language movement and ultimately to the secession of East Pakistan and the formation of Bangladesh in 1971, highlighting a divergence between Jinnah's vision for national integration and the realities of diverse linguistic identities within the new state.

7. Personal Life

Jinnah's private life, marked by personal relationships and distinctive habits, offers insights into the man behind the political titan, revealing a blend of traditional ties and Westernized sensibilities.

7.1. Marriage and Family

Jinnah's personal life was shaped by two significant marriages and complex family dynamics. His first marriage was an arranged union to his cousin, Emibai Jinnah, two years his junior, just before he left for England in 1892. This marriage was brief, as Emibai died during his absence in England. His mother also passed away while he was abroad.

In 1918, Jinnah married his second wife, Rattanbai Petit (known as "Ruttie"), a fashionable and much younger daughter of his friend, the wealthy Parsi baronet Sir Dinshaw Petit. Ruttie was 24 years younger than Jinnah. This inter-faith marriage faced significant opposition from both Rattanbai's Parsi family and some Muslim religious leaders. Rattanbai defied her family, nominally converted to Islam, and adopted the name Maryam Jinnah (though she never used it), leading to a permanent estrangement from her family and the Parsi community. The couple resided at South Court Mansion in Bombay and traveled frequently across India and Europe. Their only child, a daughter named Dina, was born on August 15, 1919. Despite their initial closeness and extensive travels, the couple separated prior to Ruttie's death in 1929 from peritonitis.

After Ruttie's death, Jinnah's younger sister, Fatima Jinnah, moved in with him. She became his constant companion, providing personal care and unwavering support as his health deteriorated in his later years. She lived and traveled with him, serving as a trusted advisor and confidante, and played a significant role in caring for his daughter, Dina.

Jinnah's relationship with his daughter Dina became strained after she chose to marry Neville Wadia, a Parsi businessman from a prominent family, despite Jinnah's urging for her to marry a Muslim. Dina reportedly reminded him that he too had married outside his faith. While their personal relationship remained distant, Jinnah continued to correspond cordially with her. Dina did not move to Pakistan during her father's lifetime, only returning for his funeral.

7.2. Lifestyle and Habits

Jinnah's time in the Western world not only influenced his political thought but also profoundly shaped his personal preferences, particularly his distinctive sense of style. He abandoned traditional Indian attire for Western-style clothing and was renowned for his impeccable public appearance throughout his life. He reportedly owned over 200 suits, which he wore with heavily starched shirts with detachable collars. As a barrister, he took pride in never wearing the same silk tie twice. His insistence on being formally dressed persisted even as he approached death, reportedly stating, "I will not travel in my pyjamas." In his later years, he was often seen wearing a Karakul hat, which subsequently became known as the "Jinnah cap," a symbol closely associated with him.

Jinnah was a heavy smoker, known to keep a tin of Craven "A" cigarettes on his desk, smoking 50 or more a day for 30 years, in addition to Cuban cigars. This habit contributed significantly to his deteriorating lung health in his final years. He generally disliked frivolous activities and showed little interest in entertainment, dedicating his focus primarily to law, politics, human rights, and nation-building. Despite being from a Muslim background, he was not considered a rigorously observant Muslim in terms of strict adherence to all religious injunctions. This aspect of his personal life, including alleged consumption of alcohol and pork, and engaging in financial practices involving interest, has been a subject of historical debate regarding his religious identity and the character of the state he founded.

8. Illness and Death

Muhammad Ali Jinnah's final years were marked by a severe deterioration of his health, largely kept secret, culminating in his death shortly after Pakistan's independence.

8.1. Deterioration of Health

From the 1930s, Jinnah suffered from tuberculosis, a condition known only to his sister Fatima Jinnah and a select few close associates. Jinnah meticulously kept his lung ailments private, believing that public knowledge of his ill health would politically undermine him. In a 1938 letter, he downplayed his suffering during tours, attributing it to "irregularities [of the schedule] and over-strain" rather than a serious underlying condition. Years later, Mountbatten remarked that had he known of Jinnah's severe illness, he would have stalled negotiations, hoping Jinnah's death would avert partition. Fatima Jinnah later wrote that "even in his hour of triumph, the Quaid-e-Azam was gravely ill... He worked in a frenzy to consolidate Pakistan. And, of course, he totally neglected his health."

Jinnah was a heavy smoker, reportedly consuming 50 or more Craven "A" cigarettes daily for 30 years, alongside Cuban cigars, a habit that undoubtedly exacerbated his lung condition. As his health worsened, he increasingly took longer rest breaks in the private wing of Government House in Karachi, where only he, Fatima, and his servants were permitted. In June 1948, seeking cooler weather, he and Fatima flew to Quetta, in the mountains of Balochistan. However, he could not fully rest there, delivering a speech to officers at the Pakistan Command and Staff College, urging them to be "custodians of the life, property and honour of the people of Pakistan." He returned to Karachi for the July 1 opening ceremony of the State Bank of Pakistan, where he delivered a speech. A reception by the Canadian trade commissioner that evening, honoring Dominion Day, was his last public event.

On July 6, 1948, Jinnah returned to Quetta but soon journeyed to an even higher retreat at Ziarat, on the advice of doctors. Jinnah had always been reluctant to undergo medical treatment, but recognizing the severity of his condition, the Pakistani government dispatched the best available doctors to treat him. Tests confirmed tuberculosis and also revealed advanced lung cancer. He was treated with the then-new "miracle drug" streptomycin, but it proved ineffective. Jinnah's condition continued to deteriorate, despite the widespread Eid prayers of his people. He was moved to the lower altitude of Quetta on August 13, the eve of Independence Day, for which a ghost-written statement for him was released. Despite a slight increase in appetite (he weighed just over 79 lb (36 kg)), his doctors recognized that for him to return to Karachi alive, it had to be very soon. Jinnah, however, was reluctant, not wanting his aides to see him as an invalid on a stretcher.

8.2. Death and Funeral

By September 9, 1948, Jinnah had also developed pneumonia. Doctors urged him to return to Karachi, where he could receive better care. With his agreement, he was flown there on the morning of September 11. Dr. Ilahi Bux, his personal physician, believed Jinnah's change of mind was prompted by an innate foreknowledge of his impending death. The plane landed at Karachi that afternoon, where Jinnah's limousine and an ambulance awaited. The ambulance, however, broke down on the road into town. The Governor-General and his companions waited by the roadside in oppressive heat for another ambulance, as Jinnah could not be placed in the car because he could not sit up. Trucks and buses passed by, their occupants unaware of Jinnah's presence. After an hour, a replacement ambulance arrived, transporting Jinnah to Government House, arriving over two hours after the landing. Muhammad Ali Jinnah died later that night at 10:20 pm at his home in Karachi on September 11, 1948, at the age of 71, just over a year after Pakistan's creation.

Upon Jinnah's death, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru remarked, "How shall we judge him? I have been very angry with him often during the past years. But now there is no bitterness in my thought of him, only a great sadness for all that has been... he succeeded in his quest and gained his objective, but at what a cost and with what a difference from what he had imagined."

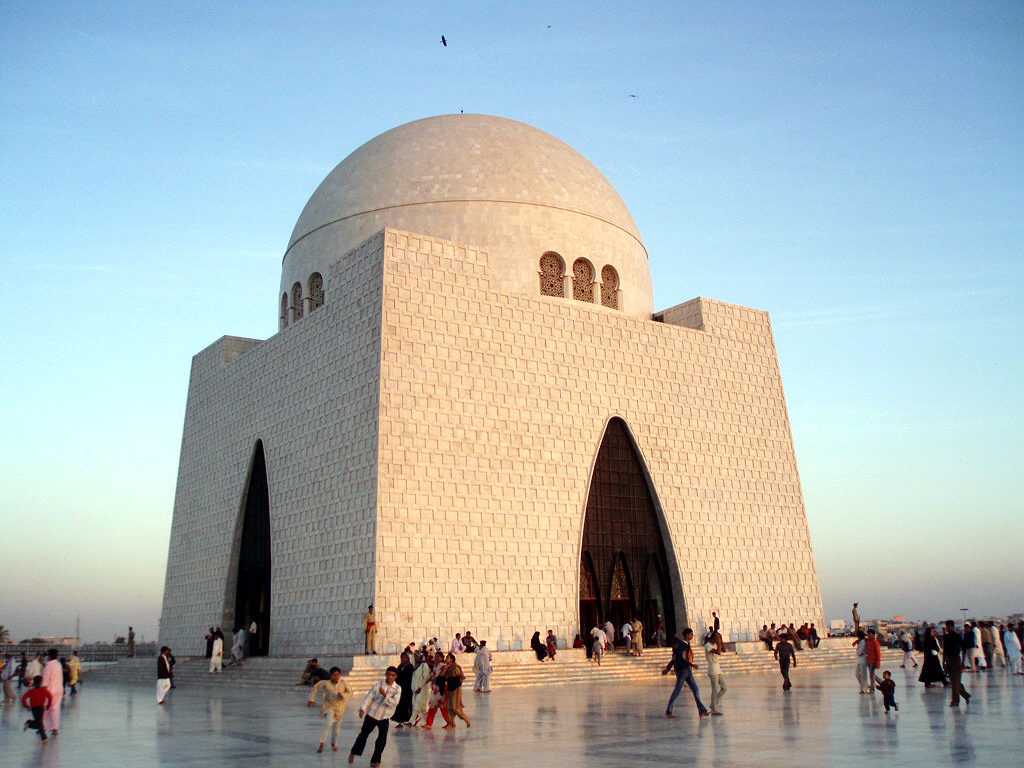

Jinnah was buried on September 12, 1948, amidst official mourning in Pakistan; a million people gathered for his funeral, led by Shabbir Ahmad Usmani. Today, Jinnah's remains rest in a large marble mausoleum, Mazar-e-Quaid, in Karachi, which has since become a notable landmark and a site for official ceremonies.

8.3. Debate on Religious Identity

After Jinnah's death, his sister Fatima Jinnah sought to execute his will under Shia Islamic law, sparking a debate in Pakistan concerning Jinnah's religious affiliation. Vali Nasr, an Iranian-American academic, claimed that Jinnah "was an Ismaili by birth and a Twelver Shia by confession, though not a religiously observant man."

The question of Jinnah's specific sectarian identity became a legal matter. In a 1970 legal challenge, Hussain Ali Ganji Walji asserted that Jinnah had converted to Sunni Islam. Witness Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada testified that Jinnah converted to Sunni Islam in 1901 when his sisters married Sunnis. In 1970, an affidavit jointly submitted by Liaquat Ali Khan and Fatima Jinnah, stating that Jinnah was Shia, was rejected. However, in 1976, the court rejected Walji's claim that Jinnah was Sunni, implicitly suggesting he remained Shia. This was reversed in 1984 by a high court bench that maintained "the Quaid was definitely not a Shia," which suggested he was Sunni.

Journalist Khaled Ahmed notes that Jinnah publicly maintained a non-sectarian stance, striving "to gather the Muslims of India under the banner of a general Muslim faith and not under a divisive sectarian identity." Liaquat H. Merchant, Jinnah's grandnephew, opines that "the Quaid was not a Shia; he was also not a Sunni, he was simply a Muslim." Conversely, an eminent lawyer who practiced in the Bombay High Court until 1940 testified that Jinnah prayed as an orthodox Sunni. Akbar Ahmed concluded that Jinnah became a firm Sunni Muslim by the end of his life. This ongoing debate reflects the complexities of religious identity within the context of nation-building and the diverse interpretations of Jinnah's legacy.

9. Legacy and Honours

Muhammad Ali Jinnah's enduring legacy is intrinsically linked to the creation of Pakistan, where he holds a position of immense reverence, while historical evaluations of his role continue to prompt debate and scholarship.

9.1. Titles and Reverence

Jinnah's most profound legacy is the existence of Pakistan itself. According to Yasmeen Niaz Mohiuddin, "He was and continues to be as highly honored in Pakistan as George Washington is in the United States... Pakistan owes its very existence to his drive, tenacity, and judgment... Jinnah's importance in the creation of Pakistan was monumental and immeasurable." American historian Stanley Wolpert, in a 1998 speech honoring Jinnah, deemed him Pakistan's greatest leader.

Jinnah earned the widely recognized title Quaid-e-AzamQuaid-e-AzamUrdu (meaning "Great Leader"). His other esteemed title is Baba-e-QaumBaba-e-QaumUrdu ("Father of the Nation"). The title "Quaid-e-Azam" was reportedly first bestowed upon him by Mian Ferozuddin Ahmed and became an official title through a resolution passed on August 11, 1947, by Liaquat Ali Khan in the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. Within days of Pakistan's creation, Jinnah's name was read in mosque sermons as Amir ul-MillatAmir ul-MillatUrdu, a traditional title for Muslim rulers. His birthday, December 25, is observed as a national holiday, Quaid-e-Azam Day, in Pakistan.

9.2. Memorials and Institutions

The civil awards of Pakistan include an 'Order of Quaid-i-Azam'. The Jinnah Society also annually bestows the 'Jinnah Award' upon individuals who render outstanding and meritorious services to Pakistan and its people. Jinnah's image is depicted on all Pakistani rupee currency notes, and he is the namesake of numerous Pakistani public institutions. The former Quaid-i-Azam International Airport in Karachi, now known as Jinnah International Airport, is Pakistan's busiest.

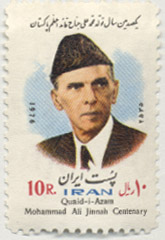

Internationally, one of the largest streets in the Turkish capital Ankara, Cinnah Caddesi, is named after him, as is the Mohammad Ali Jenah Expressway in Tehran, Iran. In the United States, a portion of Devon Avenue in Chicago was named "Mohammed Ali Jinnah Way," and a section of Coney Island Avenue in Brooklyn, New York, was also named 'Muhammad Ali Jinnah Way.' The Mazar-e-Quaid, Jinnah's mausoleum, stands as one of Karachi's notable landmarks. The "Jinnah Tower" in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India, was built to commemorate him. The royalist government of Iran also issued a stamp in 1976 commemorating the centennial of Jinnah's birth.

The Jinnah Mansion in Malabar Hill, Bombay, remains in the possession of the Government of India, but its ownership has been a subject of dispute with the Government of Pakistan. Jinnah had personally requested Prime Minister Nehru to preserve the house, expressing a hope to return to Bombay one day. There have been proposals for the house to be offered to the government of Pakistan to establish a consulate in the city as a goodwill gesture, but Dina Wadia, Jinnah's daughter, also staked a claim on the property.

9.3. Historical Evaluation

There is a considerable body of scholarship on Jinnah, principally originating from Pakistan. In his 1969 book Quaid-e-Azam Jinnah: A Selected Bibliography, Muhammad Anwar listed 1,500 entries, mostly in English. However, Akbar S. Ahmed notes that this scholarship is not widely read outside Pakistan and typically avoids even the slightest criticism of Jinnah. Ahmed points out that books published outside Pakistan sometimes mention Jinnah's alcohol consumption, a detail often omitted from books published within Pakistan, suggesting that depicting the Quaid drinking might weaken his Islamic identity and, by extension, Pakistan's. Some sources allege he gave up alcohol near the end of his life, while professor Maya Tudor concluded that Jinnah "could not be described as a practicing Muslim" due to his consumption of pork, use of alcohol, and engagement in interest-bearing transactions. Conversely, Yahya Bakhtiar, who observed Jinnah closely, concluded that Jinnah was a "very sincere, deeply committed and dedicated Mussalman."

According to historian Ayesha Jalal, while the Pakistani view of Jinnah often leans towards hagiography, he is generally viewed negatively in India. Ahmed describes Jinnah as "the most maligned person in recent Indian history... In India, many see him as the demon who divided the land." Even many Indian Muslims hold a negative view, blaming him for their plight as a minority in India. However, historians like Jalal and H. M. Seervai assert that Jinnah never explicitly desired the partition of India; they contend it was an outcome of the Congress leaders' unwillingness to genuinely share power with the Muslim League. They argue that Jinnah used the demand for Pakistan primarily as a strategic tool to mobilize support and secure significant political rights for Muslims. Francis Mudie, the last British governor of Sindh, once remarked in Jinnah's honor:

:In judging Jinnah, we must remember what he was up against. He had against him not only the wealth and brains of the Hindus, but also nearly the whole of British officialdom, and most of the Home politicians, who made the great mistake of refusing to take Pakistan seriously. Never was his position really examined.

9.4. Influence and Scholarship

Muhammad Ali Jinnah's political career, particularly his advocacy for "Direct Action Day" in 1946, has been widely associated with the subsequent bloodshed and communal violence that escalated into the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan. This incident and Jinnah's perceived role are often viewed with contempt in India.

However, Jinnah has also garnered admiration from Indian nationalist politicians, such as Lal Krishna Advani, whose comments praising Jinnah caused an uproar within his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Indian politician Jaswant Singh's 2009 book Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence sparked controversy in India by arguing that Nehru's desire for a powerful central government, rather than Jinnah's policies, led to partition. Following the book's release, Singh was expelled from the BJP, to which he responded that the party was "narrow-minded" and had "limited thoughts."

Jinnah was the central figure in the 1998 film Jinnah, which depicted his life and struggle for Pakistan. Christopher Lee, who portrayed Jinnah, regarded it as his best performance. Hector Bolitho's 1954 book Jinnah: Creator of Pakistan prompted Fatima Jinnah to publish My Brother (1987), as she felt Bolitho's account failed to adequately capture the political aspects of Jinnah's life. Fatima's book received a positive reception in Pakistan. Stanley Wolpert's Jinnah of Pakistan (1984) is widely considered one of the most authoritative biographical works on Jinnah.

The perception of Jinnah in the West has also been influenced by his portrayal in Sir Richard Attenborough's 1982 film, Gandhi. The film, dedicated to Nehru and Mountbatten and supported by Indira Gandhi, Nehru's daughter and then Prime Minister of India, depicted Jinnah (played by Alyque Padamsee) in an unflattering light, appearing to act out of jealousy of Gandhi. Padamsee later admitted his portrayal was not historically accurate.

Historian R. J. Moore acknowledged Jinnah's universal recognition as central to Pakistan's creation. Stanley Wolpert succinctly summarized Jinnah's profound impact on global history:

:Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three.

10. Criticism and Controversy

Muhammad Ali Jinnah's life and political career, particularly his role in the partition of India, have been subjects of significant criticism and controversy, leading to varied interpretations of his legacy, especially concerning the violence that ensued.

10.1. Responsibility for Partition Violence

One of the most significant criticisms leveled against Jinnah concerns his perceived responsibility for the widespread violence that accompanied the partition of India. The Direct Action Day called by the Muslim League on August 16, 1946, is a particular focal point of this controversy. While Jinnah and the League intended it as a day of peaceful protest to highlight Muslim demands for a separate state, it tragically escalated into severe communal riots, particularly in Calcutta (now Kolkata), resulting in thousands of deaths among both Hindus and Muslims. Subsequent violence spread to other regions like Bihar and Noakhali.

Critics argue that Jinnah's call for Direct Action, even if not intended to incite violence, created an environment that enabled and exacerbated communal tensions, for which he must bear some responsibility. The scale and brutality of the violence, leading to mass migrations and ethnic cleansing, are often attributed by critics to the hardening of positions and the ultimate failure to find a peaceful, united solution, for which Jinnah's uncompromising stance on Pakistan is sometimes blamed. Some scholars, like Yasser Latif Hamdani and Eamon Murphy, specifically associate Direct Action Day with bloodshed and view Jinnah's role in it with contempt in India.

10.2. Controversies Regarding Personal Life

Controversies also touch upon aspects of Jinnah's personal life, particularly concerning his religious observance. Despite being the founder of a state intended for Muslims, Jinnah was not considered a rigorously observant Muslim by some accounts. Historical sources suggest he consumed alcohol and pork, and engaged in financial practices that involved charging interest-practices generally forbidden in orthodox Islam. These aspects of his lifestyle have fueled debates, especially in Pakistan, about his true religious identity and whether his personal practices aligned with the Islamic principles he advocated for the new nation. While some scholars minimize these details or suggest he changed his habits later in life, critics use them to question the depth of his Islamic faith and, by extension, the religious character of Pakistan.

10.3. Indian Perspective

In India, Jinnah is often portrayed in a largely negative light, commonly viewed as the primary architect of the partition and the "demon who divided the land." This perspective holds him responsible for the immense suffering, displacement, and loss of life that resulted from the division of British India into two separate nations. Many Indian historians and political figures emphasize his perceived intransigence and unwillingness to compromise with the Indian National Congress as key factors leading to the subcontinent's violent division. Even many Indian Muslims, who remained in India as a minority, sometimes blame Jinnah for their subsequent challenges and diminished status.

This critical view has occasionally sparked controversy, as seen when Lal Krishna Advani, a prominent Indian nationalist politician, praised Jinnah, causing an uproar within his own Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Similarly, Jaswant Singh's 2009 book Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence, which argued that Nehru's desire for a powerful central government led to partition, also ignited public debate and resulted in Singh's expulsion from the BJP, highlighting the entrenched and often emotionally charged nature of Jinnah's legacy in India.