1. Overview

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a nation situated in northwestern South America, characterized by its diverse geography, rich cultural tapestry, and a complex history marked by significant social and political transformations. With coasts on both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, its territory encompasses the Andean mountain ranges, vast Amazon rainforest, expansive plains (Llanos), and insular regions. This document explores Colombia's journey from its pre-Columbian civilizations through Spanish colonization, its struggle for independence, and its subsequent development as a republic. It delves into the nation's multifaceted political system, economic structures, and demographic composition, with a particular focus on issues of equitable development, the advancement of human rights, democratic progress, and the impact of historical and ongoing events on minorities, vulnerable populations, and the pursuit of social justice. The narrative emphasizes Colombia's efforts towards peace, reconciliation, and the strengthening of democratic institutions amidst challenges related to internal conflict, social inequality, and environmental conservation, reflecting a center-left/social liberal perspective that prioritizes inclusive growth and the well-being of all its citizens.

2. Etymology

The name "Colombia" is derived from the last name of the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus (Christophorus ColumbusLatin, Cristoforo ColomboItalian, Cristóbal ColónKrisˈtoβal koˈlonSpanish). It was originally conceived by the Venezuelan revolutionary Francisco de Miranda as a reference to all of the New World, particularly the territories and colonies under Spanish and Portuguese rule.

The name was later adopted by the Republic of Colombia of 1819, a federation formed from the territories of the former Viceroyalty of New Granada. This entity encompassed modern-day Colombia, Panama, Venezuela, Ecuador, and parts of northwestern Brazil and Guyana.

When Venezuela and Ecuador seceded in 1830, the remaining core territory, which included the former Department of Cundinamarca, adopted the name "Republic of New Granada." This name was officially changed in 1858 to the Granadine Confederation (Confederación GranadinaConfederación GranadinaSpanish). In 1863, following a civil war, the name was again changed to the United States of Colombia (Estados Unidos de ColombiaEstados Unidos de ColombiaSpanish). Finally, in 1886, the country adopted its present name, the Republic of Colombia (República de ColombiaRepública de ColombiaSpanish). The Colombian government uses both ColombiaSpanish and República de ColombiaSpanish to refer to the country. The origin of the name is also referenced in the second verse of the Colombian national anthem: Se baña en sangre de héroes la tierra de ColónThe land of Columbus is bathed in the blood of heroesSpanish.

3. History

Colombia's history spans from ancient indigenous civilizations, through Spanish colonization and a protracted struggle for independence, to the formation of a republic facing 19th-century nation-building challenges, 20th-century conflicts and economic shifts, and ongoing 21st-century efforts towards peace and social equity.

3.1. Pre-Columbian era

The territory of present-day Colombia served as a vital corridor for early human civilization, connecting Mesoamerica and the Caribbean to the Andes and the Amazon basin. Archaeological evidence indicates human presence since at least 12,500 BCE. The oldest finds, dating to the Paleoindian period (18,000-8000 BCE), come from sites like Pubenza and El Totumo in the Magdalena River Valley, about 62 mile (100 km) southwest of Bogotá. Traces from the Archaic Period (circa 8000-2000 BCE) have been found at Puerto Hormiga and other locations. Early occupation is also evident in the El Abra and Tequendama regions in Cundinamarca. The oldest pottery discovered in the Americas, found at San Jacinto, dates to 5000-4000 BCE.

Nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes at El Abra, Tibitó, and Tequendama sites near present-day Bogotá engaged in trade with each other and with cultures from the Magdalena River Valley. In November 2020, an 8 mile stretch of pictographs at Serranía de la Lindosa was revealed, potentially dating back 12,500 years (c. 10,480 BCE), as suggested by depictions of extinct fauna. This period represents the earliest known human occupation of the area.

Between 5000 and 1000 BCE, hunter-gatherer tribes transitioned to agrarian societies, establishing fixed settlements and developing pottery. Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, various Amerindian groups, including the Muisca, Zenú, Quimbaya, and Tairona, developed sophisticated political systems known as cacicazgos (chiefdoms). These societies had a pyramidal power structure headed by caciques (chiefs).

The Muisca primarily inhabited the high plateaus of what are now the departments of Boyacá and Cundinamarca, known as the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. They formed the Muisca Confederation, a political and social entity. Their economy was based on agriculture, cultivating maize, potato, quinoa, and cotton. They were skilled traders, exchanging gold, emeralds, blankets, ceramic handicrafts, coca, and especially rock salt with neighboring nations. The Muisca had a complex religious system and left behind significant goldwork, much of which is associated with the legend of El Dorado. Their social structure was stratified, and they developed a calendar and a form of hieroglyphic writing.

The Tairona inhabited the northern regions of Colombia, in the isolated mountain range of Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. They were known for their advanced engineering skills, evident in their construction of stone paths, terraces, bridges, and irrigation systems. Their goldwork and pottery were also highly developed. The Tairona fiercely resisted Spanish colonization.

The Quimbaya inhabited regions of the Cauca River Valley, between the Western and Central Ranges of the Colombian Andes. They were renowned for their exquisite goldwork, characterized by intricate designs and technical mastery. Their society was also agricultural, and they produced high-quality ceramics.

Other significant indigenous cultures included the Calima, Zenú, and Nariño peoples, each with distinct artistic traditions and social organizations. The Zenú, for instance, were known for their extensive canal systems for agriculture in the Caribbean plains. Some groups, like the Caribs, were known for being warlike, while others had more peaceful dispositions. These civilizations varied in their social structures and agricultural practices.

Around the 1200s, there is evidence of contact between Malayo-Polynesians and Native Americans in Colombia, leading to the spread of Native American genetics from Precolonial Colombia to some Pacific Ocean islands.

3.2. Colonial period

Spanish exploration of the Colombian coast began in 1499 when Alonso de Ojeda, who had sailed with Columbus, reached the Guajira Peninsula. In 1500, Rodrigo de Bastidas led the first exploration of the Caribbean coast. Christopher Columbus himself navigated near the Caribbean coast of Colombia in 1502.

The first stable European settlement on the American continent, Santa María la Antigua del Darién, was founded in 1510 by Vasco Núñez de Balboa in the region of the Gulf of Urabá. Balboa is also famed for being the first European to see the Pacific Ocean in 1513, which he named Mar del Sur (South Sea), a discovery that significantly facilitated further Spanish exploration and colonization of South America.

The Spanish colonial period was marked by the establishment of cities: Santa Marta was founded in 1525, and Cartagena in 1533. The conquest of the interior was led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, who embarked on an expedition in April 1536. He named the territories he passed through the "New Kingdom of Granada". In August 1538, Quesada provisionally founded its capital, Santa Fé de Bogotá (present-day Bogotá), near the Muisca cacicazgo of Muyquytá.

Other notable conquistador expeditions occurred around the same time. Sebastián de Belalcázar, the conqueror of Quito, traveled north from Peru, founding Popayán in 1537 and Cali in 1536. From 1536 to 1539, the German conquistador Nikolaus Federmann, in service of the Welser banking family of Augsburg, crossed the Llanos Orientales (eastern plains) and traversed the Cordillera Oriental in search of El Dorado, the mythical "city of gold." The legend of El Dorado played a crucial role in attracting Spanish and other European explorers to New Granada throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, fueling expeditions and the exploitation of resources.

The Spanish conquistadors frequently formed alliances with indigenous groups who were enemies of other local communities. These indigenous allies were crucial for the conquest, as well as for the subsequent creation and maintenance of the colonial empire. However, the indigenous populations suffered a catastrophic decline due to the violence of the conquest, forced labor, and, most devastatingly, Eurasian diseases like smallpox, to which they had no immunity. This demographic collapse had profound and lasting impacts on the social and economic fabric of the region.

Viewing the land as largely depopulated or underutilized, the Spanish Crown distributed land grants (mercedes) to settlers and established systems like the encomienda (a grant of indigenous labor and tribute) and later haciendas (large estates) for agriculture and mining. These systems led to the widespread exploitation of indigenous people and natural resources. Gold and emerald mining became particularly important economic activities for the colony.

In 1542, the New Kingdom of Granada, along with other Spanish possessions in South America, became part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, with its capital in Lima. In 1547, New Granada was established as a separate captaincy-general within the viceroyalty. In 1549, the Royal Audiencia of Santa Fe de Bogotá was created, giving the region more administrative autonomy, although important decisions were still made in Spain by the Council of the Indies.

The transatlantic slave trade brought enslaved Africans to Colombia, beginning in the 16th century. Spain, unlike other European powers, did not establish its own trading posts (factories) in Africa to purchase slaves. Instead, the Spanish Empire relied on the asiento system, which granted licenses to merchants from other European nations to supply enslaved Africans to its American territories. This system brought many Africans to Colombia, primarily to work in mines, on plantations, and as domestic servants. Despite the brutality of slavery, resistance was common. Palenque de San Basilio, founded by runaway slaves (cimarrones) in the 17th century under leaders like Benkos Biohó, became the first officially recognized free town in the Americas in 1713, a testament to the resilience and struggle for freedom by Afro-descendant populations. Figures like Saint Peter Claver, a Spanish Jesuit priest in Cartagena, dedicated their lives to ministering to and advocating for the dignity of enslaved Africans, though such efforts did not challenge the institution of slavery itself. Indigenous peoples were legally considered subjects of the Spanish Crown and, in theory, could not be enslaved in the same manner as Africans, though they were subjected to various forms of forced labor. The Spanish colonial authorities established resguardos (indigenous communal lands) to protect indigenous populations and their lands, but these were often insufficient and subject to encroachment.

Spain's colonial trade policies were restrictive. Direct trade between the Viceroyalty of Peru (which included New Granada) and the Viceroyalty of New Spain (which included the Philippines, a source of Asian goods like silk and porcelain) was often prohibited to maintain Spain's monopoly. This led to widespread illegal trade among Peruvian, Filipino, and Mexican merchants, with smuggled Asian goods often passing through regions like Córdoba, Colombia, fostering resentment against Spanish economic control.

In 1717, the Viceroyalty of New Granada was established with Santa Fé de Bogotá as its capital. It was temporarily dissolved and then re-established in 1739. This new viceroyalty included provinces in northwestern South America previously under the jurisdiction of New Spain or Peru, corresponding mainly to modern-day Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama. Bogotá became one of the principal administrative centers of the Spanish Empire in the New World, alongside Lima and Mexico City, though it remained comparatively less developed in economic and logistical terms.

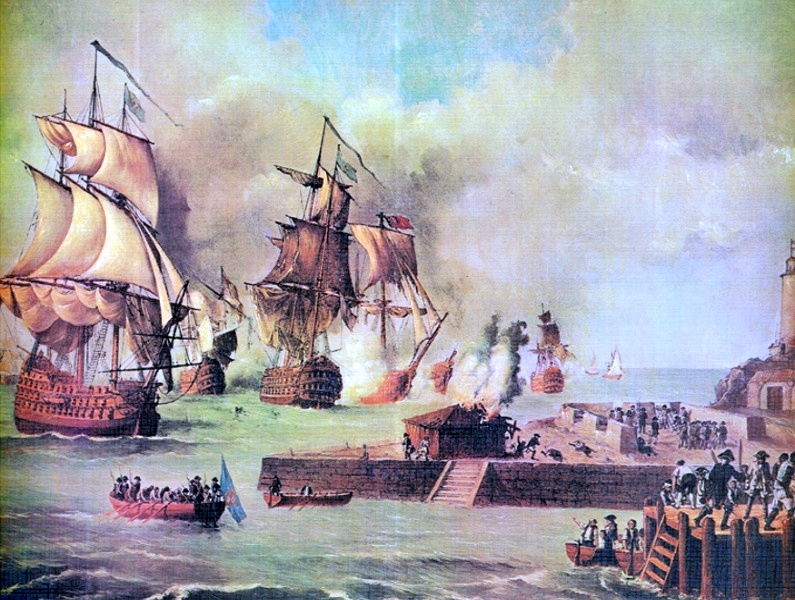

During the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739-1748) between Great Britain and Spain, the strategic port city of Cartagena de Indias became a prime target for the British. In 1741, a massive British expeditionary force attempted to capture the city but was decisively defeated by Spanish forces under Blas de Lezo. This victory secured Spanish dominance in the Caribbean until the Seven Years' War and highlighted Cartagena's military importance.

The 18th century also saw significant scientific and intellectual developments. The Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada, led by the priest, botanist, and mathematician José Celestino Mutis, began in 1783 under the commission of Viceroy Antonio Caballero y Góngora. This expedition aimed to inventory the flora and fauna of New Granada, classify species, and founded the first astronomical observatory in Santa Fe de Bogotá. The expedition played a crucial role in fostering scientific inquiry and produced figures who would later become prominent in the independence movement, such as the astronomer Francisco José de Caldas, the scientist Francisco Antonio Zea, and the zoologist Jorge Tadeo Lozano. The Prussian scientist Alexander von Humboldt visited Santa Fe de Bogotá in 1801 and met with Mutis, further contributing to the scientific exploration of the region.

3.3. Independence

The struggle for independence from Spanish rule in New Granada was part of a broader movement across Spanish America, influenced by Enlightenment ideas, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and Spain's weakening due to the Napoleonic Wars. Rebellions against Spanish authority had occurred throughout the colonial period, but a concerted push for independence emerged around 1810. The Colombian Declaration of Independence is traditionally commemorated on July 20, 1810, following events in Bogotá where criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the Americas) challenged viceregal authority, demanding a local governing junta. This day is now celebrated as Colombia's Independence Day.

Early independence efforts were marked by internal divisions. Antonio Nariño, a proponent of centralism, clashed with federalist factions, leading to a period of instability known as the Patria Boba (Foolish Fatherland, 1810-1816). Cities like Cartagena declared their own independence in November 1811. In 1811, the United Provinces of New Granada was proclaimed, headed by Camilo Torres Tenorio, but unity was elusive.

Following Napoleon's defeat and the restoration of King Ferdinand VII to the Spanish throne, Spain launched a military reconquest of its American colonies. In 1815-1816, Spanish forces under Pablo Morillo retook New Granada, restoring the viceroyalty under Juan de Sámano. This period was characterized by harsh repression of patriots, which, in turn, fueled renewed resistance.

The definitive phase of the independence war was led by Simón Bolívar, a Venezuelan criollo, with crucial support from figures like Francisco de Paula Santander of New Granada. Bolívar, after securing support from Haiti and organizing his forces, launched a daring campaign across the Andes. The victory at the Battle of Boyacá on August 7, 1819, was decisive, leading to the liberation of Bogotá and effectively securing independence for New Granada. The war involved significant loss of life, with estimates suggesting that 12-20% of the pre-war population (between 250,000 and 400,000 people) perished. Pro-Spanish resistance continued in some regions, notably in Pasto in the south, but was largely defeated by 1822.

In 1819, at the Congress of Angostura, Bolívar proclaimed the creation of the Republic of Colombia (historiographically known as Gran Colombia to distinguish it from the modern republic). This new state united the territories of the former Viceroyalty of New Granada, encompassing present-day Colombia, Panama, Venezuela, Ecuador, and parts of Guyana and Brazil. The Congress of Cúcuta in 1821 adopted a constitution for the new republic, with Bolívar as its first president and Santander as vice president.

However, Gran Colombia was plagued by internal political and territorial divisions, regional rivalries, and differing visions for the new state. Tensions between centralists, who favored a strong central government led by Bolívar, and federalists, advocated by Santander and regional leaders, grew. Economic difficulties and logistical challenges in governing such a vast and diverse territory also contributed to its instability. By 1830, Venezuela, under José Antonio Páez, and Ecuador (then known as the District of the South, led by Juan José Flores), seceded from the union. Bolívar, disillusioned, resigned from the presidency and died later that year. Gran Colombia officially dissolved in 1831.

3.4. 19th century

Following the dissolution of Gran Colombia, the remaining central territory, formerly known as the Department of Cundinamarca (which included Panama), became the Republic of New Granada in 1831. Francisco de Paula Santander became its first president (1832-1837), implementing policies that promoted education and a degree of federalism, though the nation was often caught between centralist and federalist ideals. This period laid the groundwork for Colombia's enduring two-party system, with the emergence of the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party in 1848 and 1849, respectively. These parties, representing differing socio-economic interests and ideologies regarding the role of the state and the Catholic Church, would dominate Colombian politics for over a century, often leading to intense and violent conflict. Slavery was formally abolished in 1851, a significant step towards social reform, though Afro-Colombian communities continued to face discrimination and marginalization.

The mid-19th century was characterized by political instability and frequent civil wars as Liberals and Conservatives vied for power and clashed over issues such as federalism versus centralism, the role of the Church in state affairs, and economic policies. In 1858, the country adopted a federalist constitution and became the Granadine Confederation. This was followed by another civil war (1860-1862), which led to the establishment of the United States of Colombia in 1863 under a more radically federalist constitution (the Rionegro Constitution). This constitution granted significant autonomy to the constituent states and promoted liberal reforms, including the separation of church and state and freedom of education.

However, the highly decentralized nature of the United States of Colombia contributed to persistent instability and regional conflicts. By the 1880s, a movement known as the Regeneración (Regeneration), led by Rafael Núñez (initially a Liberal, later aligning with Conservatives), sought to restore central authority and the influence of the Catholic Church. This culminated in the Constitution of 1886, which established a highly centralized, unitary state named the Republic of Colombia. This constitution, which remained in effect with amendments until 1991, strengthened the executive branch, made Catholicism the state religion, and curtailed many of the liberal freedoms granted by the Rionegro Constitution. The establishment of the Republic of Colombia in 1886 marked a significant shift towards conservative, centralist rule, but it did not end the deep-seated partisan divisions that continued to shape the nation's trajectory. These internal divisions frequently ignited bloody civil wars, the most significant of which was the Thousand Days' War (1899-1902). This devastating conflict, primarily between Liberals and Conservatives, resulted in an estimated 100,000 to 180,000 deaths and had profound social and economic consequences, further weakening the nation at the turn of the century.

3.5. 20th century

The 20th century in Colombia was a period of profound political, social, and economic transformations, marked by both progress and intense conflict. The century began in the aftermath of the devastating Thousand Days' War (1899-1902). Weakened by internal strife, Colombia faced a major territorial loss in 1903 when Panama, with the backing of the United States and France, seceded to allow for the construction of the Panama Canal. This event, perceived by many Colombians as a result of U.S. imperialism, strained relations with the United States for years, though a settlement was reached in 1921 with the Thomson-Urrutia Treaty, which included a 25.00 M USD indemnity to Colombia.

The early decades saw the rise of the coffee economy, which became a crucial driver of economic growth and modernization, particularly in regions like Antioquia and the newly established "Coffee Axis." However, social inequalities persisted, and political tensions between the Liberal and Conservative parties remained high. A brief border conflict with Peru, the Leticia Incident (1932-1933), over territory in the Amazon basin was resolved through League of Nations mediation, with the disputed area awarded to Colombia.

The period from the late 1940s to the early 1950s is known as La Violencia ("The Violence"), a brutal undeclared civil war between supporters of the Liberal and Conservative parties. The assassination of the popular Liberal presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán on April 9, 1948, in Bogotá triggered massive riots known as the Bogotazo. The violence quickly spread throughout the country, leading to an estimated 180,000 to 300,000 deaths and widespread displacement. This era left deep scars on Colombian society and contributed to the later emergence of guerrilla movements. Colombia participated in the Korean War under the UN Command, being the only Latin American country to send troops.

To end La Violencia, the Liberal and Conservative elites agreed to a power-sharing arrangement known as the National Front (1958-1974). Under this pact, the presidency alternated between the two parties every four years, and government positions were divided equally. While the National Front succeeded in reducing partisan violence between the two main parties, it largely excluded other political voices and failed to address underlying social and economic inequalities. This exclusion, coupled with the influence of the Cuban Revolution and Cold War ideologies, contributed to the formation of various left-wing guerrilla groups in the 1960s, including the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the ELN, and later the 19th of April Movement (M-19). These groups initiated a new phase of armed conflict against the state.

The latter half of the 20th century was dominated by this asymmetric low-intensity armed conflict involving the state, leftist guerrillas, and, increasingly from the 1980s, right-wing paramilitary groups (such as the AUC) often formed by landowners, business interests, and drug traffickers to counter guerrilla influence. The conflict was further complicated and intensified by the rise of powerful drug cartels, most notably the Medellín Cartel led by Pablo Escobar and the Cali Cartel. These organizations amassed enormous wealth and power through the production and trafficking of cocaine, leading to widespread corruption, violence (narco-terrorism), and a "war on drugs" heavily supported by the United States. The drug trade fueled violence on all sides of the conflict and had a devastating impact on Colombian society, undermining state institutions and leading to countless human rights abuses, including massacres, assassinations, forced displacement, and kidnappings.

The profound social impact of these conflicts included massive internal displacement, turning Colombia into one of the countries with the highest number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the world. Widespread human rights violations were committed by all armed actors, including extrajudicial killings, torture, and violence against civilians, particularly affecting rural communities, indigenous peoples, Afro-Colombians, and social leaders.

Despite the violence, Colombia made efforts towards democratic reform. The Constitution of 1991 was a significant step, introducing mechanisms for citizen participation, recognizing ethnic and cultural diversity, and strengthening human rights protections. However, the implementation of these reforms was often hampered by the ongoing conflict and entrenched inequalities. Peace negotiations with some guerrilla groups, like the M-19, led to their demobilization in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but the larger FARC and ELN remained active. The conflict escalated significantly in the 1990s, with widespread violence affecting many parts of the country.

3.6. 21st century

The 21st century in Colombia has been characterized by significant security improvements, continued economic growth, a landmark peace process with the FARC, and persistent social and human rights challenges. The administration of President Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010) implemented a "Democratic Security" policy, which involved a more aggressive military campaign against guerrilla groups, particularly the FARC, with substantial support from the United States through Plan Colombia. This period saw a reduction in violence and kidnappings in many areas and weakened the FARC militarily. However, it was also marked by controversies, including the "false positives" scandal, where military personnel extrajudicially killed civilians and presented them as combat casualties to inflate success rates, a grave human rights violation. The demobilization process of the AUC (paramilitary groups) during Uribe's tenure was also controversial, with concerns about impunity for human rights abuses and the re-emergence of successor criminal bands (BACRIM).

President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018), Uribe's former defense minister, shifted focus towards a negotiated end to the conflict. In 2012, his government initiated peace negotiations with the FARC in Havana, Cuba. After four years of complex talks, a final peace agreement was announced in 2016. However, in a national referendum in October 2016, a narrow majority of voters rejected the initial deal. Following modifications, a revised peace accord was signed in November 2016 and subsequently approved by the Colombian Congress. President Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. The peace agreement included provisions for FARC's demobilization and disarmament, their transformation into a political party, rural development reforms, victims' rights (including truth, justice, reparation, and non-repetition), and addressing illicit drug cultivation. A Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) was created as a transitional justice mechanism to prosecute serious human rights violations committed during the conflict by all parties.

The implementation of the peace accord has been a complex and challenging process. While FARC officially disarmed and transitioned into a political party (now Comunes), some dissident factions rejected the agreement and continue to engage in violence and illicit activities. The ELN remains an active guerrilla group, though peace talks have been intermittent. Challenges include ensuring security in former FARC-controlled areas, addressing the needs of victims, implementing land reforms, combating illegal economies (coca cultivation, illegal mining), and protecting social leaders and ex-combatants, many of whom have been assassinated. Pope Francis visited Colombia in 2017, paying tribute to victims and encouraging reconciliation.

President Iván Duque (2018-2022), from the right-wing Democratic Center party founded by Uribe, expressed skepticism about parts of the peace deal and faced criticism for perceived slow implementation of some aspects. His term was also marked by significant social unrest, including widespread protests in 2019 and 2021 against economic policies, inequality, and police brutality, highlighting ongoing social discontent. Relations with Venezuela remained tense, with Colombia receiving millions of Venezuelan refugees and migrants fleeing the crisis in their country. Colombia took a leading role in proposing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which were adopted by the United Nations.

In 2022, Gustavo Petro was elected president, becoming Colombia's first left-wing head of state. His running mate, Francia Márquez, became the first Afro-Colombian vice president. Petro's agenda focuses on "Total Peace" (seeking negotiations with remaining armed groups), social and economic reforms to address inequality, environmental protection (particularly the Amazon rainforest), and a shift in drug policy. His government has re-established diplomatic relations with Venezuela. The pursuit of lasting peace, strengthening democratic institutions, ensuring justice and reparations for victims of the long conflict, tackling deep-rooted social and economic inequalities, and addressing human rights concerns remain central challenges for Colombia in the 21st century.

4. Geography

Colombia's geography is marked by diverse natural regions, including the Andean mountain ranges, coastal plains, the Amazon rainforest, and the Llanos. Its topography varies significantly, influencing a range of climates from tropical to alpine, and supporting extraordinary biodiversity which is subject to ongoing conservation efforts.

Colombia is situated in northwestern South America, with an area of 0.4 M mile2 (1.14 M km2). It is the only South American country with coastlines on both the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea (Atlantic Ocean). The country is bordered by Panama to the northwest; Venezuela and Brazil to the east; and Ecuador and Peru to the south. Colombia also possesses insular regions in North America, including the San Andrés and Providencia archipelago in the Caribbean Sea and Malpelo Island in the Pacific Ocean. It shares maritime borders with Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Jamaica, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. Colombia lies between latitudes 12°N and 4°S, and longitudes 67°W and 79°W.

The geography of Colombia is characterized by six main natural regions:

1. The Andean Region: Dominated by three principal ranges of the Andes-the Cordillera Occidental (Western Range), Cordillera Central (Central Range), and Cordillera Oriental (Eastern Range). Most of Colombia's population and major cities, including Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali, are located in these highlands. The Andes are part of the Ring of Fire, making the region prone to earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

2. The Caribbean Coastal Region: Consists mainly of low-lying plains, but also includes the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, an isolated mountain range with Colombia's highest peaks, Pico Cristóbal Colón and Pico Simón Bolívar (both approximately 19 K ft (5.78 K m)). This region is home to major port cities like Barranquilla and Cartagena, and the arid La Guajira Desert.

3. The Pacific Coastal Region: Characterized by narrow, discontinuous lowlands backed by the Serranía de Baudó mountains. It is one of the wettest places on Earth, covered in dense rainforest and sparsely populated. The main port is Buenaventura.

4. The Orinoquía Region (Llanos Orientales): Expansive plains or savannas east of the Andes, part of the Orinoco River basin, shared with Venezuela. This region is important for cattle ranching and agriculture.

5. The Amazon Region: The southeastern part of the country is covered by the Amazon rainforest, the world's largest tropical rainforest, characterized by immense biodiversity.

6. The Insular Region: Comprises islands in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, such as San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina in the Caribbean, and Malpelo and Gorgona in the Pacific.

The main rivers of Colombia include the Magdalena River, Cauca River, Guaviare River, Atrato River, Meta River, Putumayo River, and Caquetá River. Colombia has four main drainage systems: the Pacific drain, the Caribbean drain, the Orinoco Basin, and the Amazon Basin. The Orinoco and Amazon River mark parts of Colombia's borders with Venezuela and Peru, respectively.

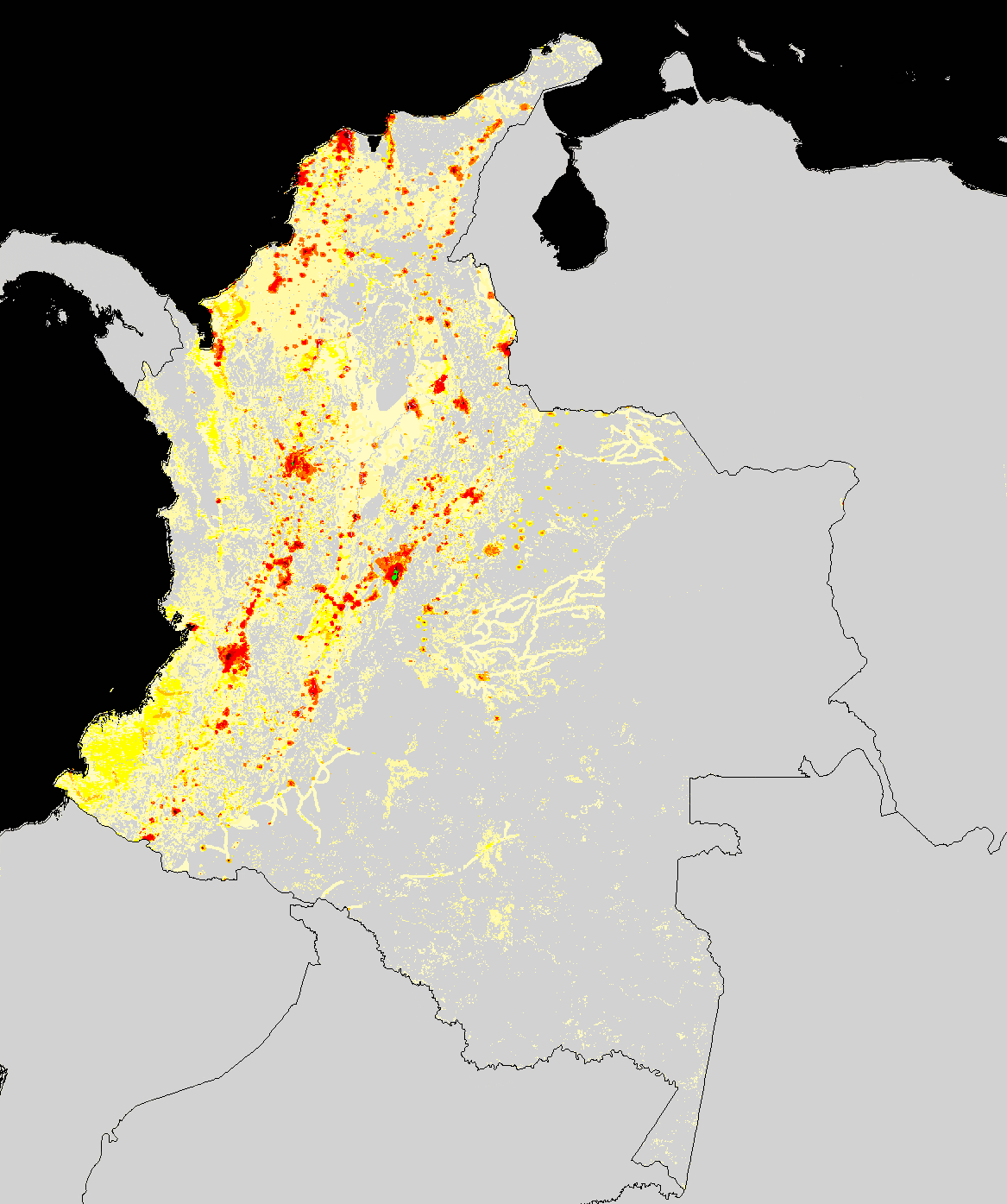

Over half of Colombia's territory is made up of the Llanos and Amazon lowlands, but these regions contain less than 6% of the population.

4.1. Topography

Colombia's topography is exceptionally diverse, dominated by the Andes Mountains in its western and central parts. East of the Andes lie vast lowlands.

The Andean Region is the most populous and is characterized by three parallel mountain ranges (cordilleras) that emerge from the Colombian Massif in the southwestern departments of Cauca and Nariño:

- The Cordillera Occidental (Western Range) runs adjacent to the Pacific coast. It includes cities like Cali. Peaks in this range can exceed 15 K ft (4.70 K m).

- The Cordillera Central (Central Range) runs between the Cauca and Magdalena River valleys. It is home to cities like Medellín, Manizales, Pereira, and Armenia. This range contains numerous volcanoes and high peaks, some reaching over 16 K ft (5.00 K m).

- The Cordillera Oriental (Eastern Range) is the widest of the three and extends northeast towards the Guajira Peninsula. It includes major cities such as Bogotá, Bucaramanga, and Cúcuta. Peaks in this range also reach over 16 K ft (5.00 K m). The Altiplano Cundiboyacense, a high plateau within this range, is where Bogotá (8.5 K ft (2.60 K m)) is situated, making it one of the highest large cities in the world.

The Caribbean Coastal Plains are generally low-lying, except for the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, an isolated massif with Colombia's highest peaks, Pico Cristóbal Colón and Pico Simón Bolívar (both approx. 19 K ft (5.78 K m)). This region also features the arid La Guajira Desert.

The Pacific Coastal Plains are narrow and discontinuous, backed by the Serranía de Baudó. This region is characterized by dense rainforests and extremely high rainfall.

East of the Andes, the topography transitions to vast lowlands:

- The Llanos Orientales (Eastern Plains) are expansive savannas belonging to the Orinoco River basin, characterized by grasslands and gallery forests along rivers. Human settlement is sparse, focused on cattle ranching and agriculture.

- The Amazon Rainforest covers the southeastern part of Colombia. This region is a vast, largely undeveloped area of dense tropical rainforest with numerous rivers, forming part of the larger Amazon Basin. Human settlements are typically found along rivers.

These varied topographical regions create diverse ecosystems and influence human settlement patterns, with the majority of the population concentrated in the Andean valleys and intermontane plateaus.

4.2. Climate

Colombia's climate is predominantly tropical due to its proximity to the equator. However, it exhibits significant variations primarily due to altitude, resulting in diverse climatic zones across its six natural regions. Temperature, humidity, winds, and rainfall patterns differ considerably from one region to another.

The country experiences several climatic zones:

- Tierra caliente (Hot Land): Found below 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m) in elevation. This zone is characterized by average temperatures above 75.2 °F (24 °C). It covers approximately 82.5% of Colombia's total area and includes coastal plains, the Llanos, and the Amazon rainforest. This zone supports tropical agriculture.

- Tierra templada (Temperate Land): Located between 3.3 K ft (1.00 K m) and 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m). Average temperatures range from 62.6 °F (17 °C) to 75.2 °F (24 °C). This zone is ideal for coffee cultivation and is where many major cities are located.

- Tierra fría (Cold Land): Present between 6.6 K ft (2.00 K m) and 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m). Temperatures vary between 53.6 °F (12 °C) and 62.6 °F (17 °C). This zone supports crops like wheat and potatoes and is home to cities like Bogotá.

- Páramo (Alpine Tundra/Moorland): Found above the forested zone, typically between 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m) and 13 K ft (4.00 K m). These are treeless grasslands characterized by unique flora adapted to cold, windy, and humid conditions.

- Tierra helada (Frozen Land): Above 13 K ft (4.00 K m), where temperatures are below freezing. This zone includes areas of permanent snow and ice on the highest Andean peaks and the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

Rainfall patterns are influenced by the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), trade winds, and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Most of Colombia experiences two rainy seasons (typically April-May and October-November) and two dry seasons. However, the Pacific coastal region is one of the wettest places on Earth, receiving extremely high rainfall year-round (often exceeding 0.2 K in (5.00 K mm) annually). In contrast, the La Guajira Peninsula in the extreme north is semi-arid to arid, with annual rainfall sometimes below 30 in (750 mm). The Amazon region also experiences high rainfall.

These diverse climatic conditions profoundly affect agriculture, with different crops suited to specific altitudinal and rainfall zones. They also impact livelihoods, water resources, and biodiversity across the country.

4.3. Biodiversity and conservation

Colombia is recognized as one of the world's seventeen megadiverse countries, boasting an extraordinary level of biodiversity. It ranks first globally in bird species (over 1,900 species, more than Europe and North America combined) and orchid species. The country is home to approximately 10% of the Earth's species, despite its intermediate size. This includes a significant percentage of the world's mammal species (around 10%), amphibian species (14%), and reptile and palm species (ranking third globally for both). Colombia also has about 2,000 species of marine fish and is the second most diverse country in freshwater fish. There are an estimated 7,000 species of beetles and around 1,900 species of mollusks. The country is estimated to host about 300,000 species of invertebrates in total.

This remarkable biodiversity is a result of Colombia's varied ecosystems, which include Amazon rainforests, Andean highlands (with diverse altitudinal zones like páramos and cloud forests), grasslands (Llanos), deserts, mangroves, and coral reefs along both its Caribbean and Pacific coasts. Colombia has 32 terrestrial biomes and 314 types of ecosystems.

Conservation efforts are managed through the "National Natural Parks System," which covers approximately 55 K mile2 (142.68 K km2), accounting for 12.77% of the Colombian territory. These protected areas aim to preserve the country's rich flora and fauna. The national flower, the orchid Cattleya trianae, is an example of its endemic plant life.

Despite these efforts, Colombia faces significant environmental challenges. Deforestation, driven by agricultural expansion (including illicit coca cultivation and cattle ranching), illegal mining, logging, and infrastructure development, is a major threat, particularly in the Amazon and Andean regions. This habitat loss impacts biodiversity and affects the territories and livelihoods of indigenous communities and other local populations who depend on these ecosystems. Other challenges include water pollution, soil erosion, and the impacts of climate change.

Environmental protection policies are in place, and Colombia is a signatory to various international environmental agreements. There is a growing awareness of the need for sustainable development and the protection of natural resources. However, balancing economic development with conservation, addressing the social drivers of environmental degradation, and ensuring the rights and participation of indigenous and local communities in conservation efforts remain critical tasks. Colombia had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.26/10, ranking it 25th globally out of 172 countries. The country also possesses large reserves of freshwater, ranking sixth globally in total renewable freshwater supply. The social and environmental impact of resource exploitation, such as mining and oil extraction, is a significant concern, often leading to conflicts with local communities and environmental damage if not managed responsibly.

5. Government and politics

Colombia operates as a presidential democratic republic with a separation of powers into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The country is divided into departments and municipalities, with several major cities serving as economic and cultural hubs. Its foreign policy focuses on regional and global cooperation, supported by its military forces, while significant attention is given to addressing human rights challenges.

The government of Colombia operates within the framework of a presidential, participatory democratic republic, as established by the Constitution of 1991. This constitution emphasizes the separation of powers among three branches of government: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial.

The executive branch is headed by the President of Colombia, who serves as both head of state and head of government. The President is elected by popular vote for a single four-year term. A 2004 constitutional amendment allowed for a two-term limit, but this was repealed in 2015, restoring the single-term limit. The President is assisted by the Vice President and the Council of Ministers (cabinet). At the provincial level, executive power is vested in department governors and municipal mayors, who are also elected by popular vote. Smaller administrative subdivisions like corregimientos or comunas have local administrators. Regional elections are typically held one year and five months after the presidential election.

The legislative branch is represented nationally by the Congress (Congreso de la RepúblicaSpanish), a bicameral institution.

- The Senate (SenadoSpanish) has 102 members. 100 are elected nationally, and two are reserved for representatives of indigenous communities.

- The Chamber of Representatives (Cámara de RepresentantesSpanish) has 166 members (this number can vary slightly based on population changes and special constituencies). Members are elected from territorial constituencies (departments and the Capital District) and special constituencies (e.g., for Afro-Colombians, Colombians abroad).

Members of both houses are elected by popular vote to serve four-year terms, with elections typically held two months before the presidential election. The Congress is responsible for making laws, amending the constitution, and exercising political control over the government.

The judicial branch is independent and responsible for administering justice. It is headed by four high courts:

- The Supreme Court of Justice (Corte Suprema de JusticiaSpanish) is the highest court for civil and penal matters.

- The Council of State (Consejo de EstadoSpanish) is the highest court for administrative law and also provides legal advice to the executive branch.

- The Constitutional Court (Corte ConstitucionalSpanish) is responsible for ensuring the integrity of the Colombian constitution and reviewing the constitutionality of laws.

- The Superior Council of Judicature (Consejo Superior de la JudicaturaSpanish) is responsible for the administration and auditing of the judicial branch.

Colombia operates under a system of civil law, which has incorporated elements of an adversarial system since reforms in the early 21st century.

Major political parties in Colombia have historically included the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party. However, the political landscape has become more fragmented in recent decades with the emergence of new parties and coalitions, such as the Democratic Center, Humane Colombia, and the Green Alliance. The electoral system involves direct popular vote for most elected offices. Democratic participation is encouraged, but challenges remain, including voter turnout, political polarization, and the influence of illicit money in politics. Accountability mechanisms exist, including oversight bodies like the Inspector General's Office and the Comptroller General's Office, but ensuring effective governance and combating corruption are ongoing concerns. Recent political dynamics have seen a shift with the election of the country's first left-wing president in 2022, Gustavo Petro, signaling a potential realignment in Colombian politics.

5.1. Administrative divisions

Colombia is a unitary republic divided into 32 departments (departamentosSpanish) and one Capital District (Distrito CapitalSpanish) for Bogotá. The Capital District is treated as a department for administrative purposes and serves as the nation's capital. Bogotá also serves as the capital of the surrounding department of Cundinamarca.

Each department is headed by a Governor (GobernadorSpanish) and has a Departmental Assembly (Asamblea DepartamentalSpanish), both directly elected for four-year terms. Departments are responsible for regional administration, development planning, and coordinating services between the national government and municipalities.

Departments are further subdivided into municipalities (municipiosSpanish). There are over 1,100 municipalities in Colombia. Each municipality is governed by a Mayor (AlcaldeSpanish) and a Municipal Council (Concejo MunicipalSpanish), also directly elected for four-year terms. Municipalities are the basic territorial and administrative unit, responsible for local services, urban planning, and local governance. Each municipality has a designated municipal seat or capital town (cabecera municipalSpanish).

Municipalities, in turn, are subdivided into:

- Corregimientos in rural areas. These are often extensive rural territories within a municipality and may include several smaller villages (veredasSpanish). Each corregimiento may have a local administrative board (Junta Administradora Local, JALSpanish) and is headed by a Corregidor, usually appointed by the mayor.

- Comunas in larger urban areas. These are urban subdivisions within a city, also with the possibility of having an elected JAL.

In addition to the Capital District of Bogotá, four other cities have been designated as Special Districts (Distritos EspecialesSpanish) due to their unique historical, cultural, port, or tourism importance. These are Barranquilla, Cartagena, Santa Marta, and Buenaventura. These districts have a special administrative regime.

Some departments with low population density, particularly in the Amazon and Orinoquía regions (e.g., Amazonas, Vaupés, Vichada), have special administrative divisions known as "departmental corregimientos" (corregimientos departamentalesSpanish). These function as a hybrid between a municipality and a regular corregimiento, directly under departmental administration due to their sparse population and limited administrative capacity.

The following is a list of the departments and the Capital District, with their respective capital cities:

| Department | Capital City | Department | Capital City |

|---|---|---|---|

Amazonas | Leticia |  La Guajira | Riohacha |

Antioquia | Medellín |  Magdalena | Santa Marta |

Arauca | Arauca |  Meta | Villavicencio |

Atlántico | Barranquilla |  Nariño | Pasto |

Bogotá, Capital District | Bogotá |  Norte de Santander | Cúcuta |

Bolívar | Cartagena |  Putumayo | Mocoa |

Boyacá | Tunja |  Quindío | Armenia |

Caldas | Manizales |  Risaralda | Pereira |

Caquetá | Florencia |  San Andrés and Providencia | San Andrés |

Casanare | Yopal |  Santander | Bucaramanga |

Cauca | Popayán |  Sucre | Sincelejo |

Cesar | Valledupar |  Tolima | Ibagué |

Chocó | Quibdó |  Valle del Cauca | Cali |

Córdoba | Montería |  Vaupés | Mitú |

Cundinamarca | Bogotá |  Vichada | Puerto Carreño |

Guainía | Inírida | ||

Guaviare | San José del Guaviare | ||

Huila | Neiva |

5.1.1. Major cities

Colombia is a highly urbanized country, with approximately 77.1% of its population residing in urban areas as of 2018. The largest cities are significant centers of economic activity, culture, and population, reflecting diverse social dynamics and development patterns across the nation.

- Bogotá: The capital and largest city, with a population of about 7.4 million in the city proper (2018 census). It is the political, economic, administrative, industrial, artistic, cultural, and sports center of the country. Located on a high plateau in the Andes, Bogotá is known for its historical La Candelaria district, numerous universities, museums, and a vibrant cultural scene. Its rapid growth has presented challenges in terms of infrastructure, housing, and social equity.

- Medellín: The second-largest city, with a population of around 2.4 million (2018 census), and capital of the Antioquia Department. Once notorious for drug-related violence, Medellín has undergone a significant transformation, becoming known for innovation in urban planning, public transportation (including cable cars serving hillside communities), and social programs. It is a major industrial, commercial, and technological hub, with a pleasant climate earning it the nickname "City of Eternal Spring."

- Cali: The third-largest city, with over 2.1 million inhabitants (2018 census), and capital of the Valle del Cauca Department. Cali is known as the "Salsa Capital of the World" due to its vibrant salsa music and dance culture. It is an important industrial and agricultural center in southwestern Colombia, with a significant Afro-Colombian population and a rich cultural heritage. Social dynamics are influenced by its diverse population and proximity to the Pacific coast.

- Barranquilla: The fourth-largest city, with a population of over 1.2 million (2018 census), located on the Caribbean coast where the Magdalena River meets the sea. It is a major port, industrial center, and cultural hub, famous for its Carnival, one of the largest in the world and recognized by UNESCO. Barranquilla plays a vital role in Colombia's international trade and has a diverse population reflecting European, Middle Eastern, and African influences.

- Cartagena: A historic port city on the Caribbean coast with a population of nearly 877,000 (2018 census). Its walled old town is a UNESCO World Heritage site, renowned for its colonial architecture, fortresses, and vibrant atmosphere. Cartagena is a major tourist destination and an important industrial and shipping center. Social dynamics are shaped by tourism, its historical legacy, and significant Afro-Colombian communities.

- Cúcuta: Located on the border with Venezuela, Cúcuta is a significant commercial center with a population of about 685,000 (2018 census). Its economy and social dynamics are heavily influenced by cross-border trade and migration, particularly the recent influx of Venezuelan migrants and refugees.

- Bucaramanga: Capital of the Santander Department, with a population of around 570,000 (2018 census). Known as the "City of Parks," it is an important commercial, industrial, and educational center in northeastern Colombia.

- Ibagué: Known as the "Musical Capital of Colombia," with a population of about 492,000 (2018 census). It is an agricultural and commercial center in the Tolima Department.

- Villavicencio: Considered the gateway to the Llanos Orientales (Eastern Plains), with a population of around 492,000 (2018 census). It is an important center for agriculture and cattle ranching.

- Santa Marta: One of the oldest surviving cities in South America, located on the Caribbean coast near the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, with a population of about 455,000 (2018 census). It is a port city and tourist destination known for its historical sites and proximity to Tayrona National Natural Park.

These major cities face common urban challenges such as managing growth, providing adequate housing and public services, addressing inequality, and ensuring public safety, while also serving as engines of economic development and cultural innovation.

5.2. Foreign affairs

Colombia's foreign policy objectives are centered on promoting national interests, security, economic development, and international cooperation. Key aspects of its foreign affairs include:

1. Relations with Neighboring Countries:

- Venezuela**: Relations have historically fluctuated significantly due to ideological differences, border security issues (presence of armed groups, illicit trafficking), and massive Venezuelan migration into Colombia. Efforts to manage the humanitarian crisis and maintain regional stability are priorities. Under President Gustavo Petro, diplomatic relations, severed in 2019, were restored in 2022.

- Ecuador**: Relations are generally cooperative, focusing on border security, trade, and environmental issues. Past tensions, such as a 2008 Colombian raid against a FARC camp in Ecuadorian territory, have largely been overcome.

- Peru**, **Brazil**, **Panama**: Colombia maintains generally stable and cooperative relations with these neighbors, focusing on trade, security cooperation (especially against drug trafficking and organized crime), and infrastructure projects.

2. Regional Integration Efforts:

- Pacific Alliance**: Colombia is a founding member of this trade bloc (along with Chile, Mexico, and Peru), which aims for deep economic integration, free movement of goods, services, capital, and people, and joint promotion in Asia-Pacific markets. This alliance reflects a strategy to diversify economic partners and enhance competitiveness, contributing to equitable development through increased trade and investment opportunities.

- Andean Community (CAN)**: Colombia is an active member of CAN (with Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru), working on customs union, free trade, and harmonized policies in areas like transportation and intellectual property.

- Organization of American States (OAS)**: Colombia participates actively in the OAS, supporting its pillars of democracy, human rights, security, and development. It has often played a role in regional diplomatic efforts and has been subject to OAS human rights monitoring.

- CELAC** and **UNASUR** (though its participation in UNASUR has been suspended/withdrawn by some members including Colombia): Colombia has engaged in these broader regional forums, though its alignment and level of participation can vary depending on the political orientation of its government and the dynamics within these organizations.

3. Participation in Major International Organizations:

- United Nations (UN)**: Colombia is an active UN member, contributing to peacekeeping operations (historically) and engaging in various UN agencies and programs focused on development, human rights, and peacebuilding. The UN has played a significant role in verifying the Colombian peace process.

- World Trade Organization (WTO)**: Colombia adheres to WTO rules and participates in global trade negotiations.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)**: Colombia became a full member of the OECD in 2020, committing to its standards in areas like economic policy, governance, and social development. This membership is seen as a step towards modernizing its public policies and fostering inclusive growth.

4. Relations with Global Powers and Partners:

- United States**: The U.S. has historically been Colombia's most significant partner, particularly in security cooperation (Plan Colombia for counter-narcotics and counter-terrorism) and trade. The U.S. is a major trading partner and source of foreign investment. Colombia is designated as a Major Non-NATO Ally of the United States.

- European Union**: The EU is an important trading partner and a key supporter of Colombia's peace process and human rights initiatives, providing financial and technical assistance.

- NATO**: Colombia is a NATO Global Partner, the only Latin American country with this status. This partnership involves cooperation in areas like security, demining, and military interoperability, but does not imply NATO membership or collective defense commitments.

- China**: Relations with China have been growing, particularly in trade and investment, reflecting China's increasing economic presence in Latin America.

Colombia's foreign policy often emphasizes multilateralism, the fight against transnational organized crime (especially drug trafficking), promoting foreign investment and trade, and seeking international support for its peacebuilding and development efforts. Human rights considerations and the impact of its policies on vulnerable populations are increasingly important dimensions of its international engagement, aligning with a focus on equitable and democratic progress.

5.3. Military

The Military Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Militares de ColombiaSpanish) are responsible for the defense of the nation, maintaining sovereignty, and contributing to internal security. The President of Colombia is the commander-in-chief. The Ministry of National Defence oversees the military branches and the National Police (which has a gendarmerie role and is part of the defense sector, though it primarily handles law enforcement).

Composition and Roles:

The Colombian Armed Forces consist of three main branches:

1. National Army (Ejército NacionalSpanish): The largest branch, focused on land-based operations, border security, counter-insurgency, and counter-narcotics efforts. It is organized into divisions, brigades, and special units.

2. National Navy (Armada NacionalSpanish): Responsible for maritime security in both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, riverine operations (given Colombia's extensive river network), and coastal defense. It includes the Naval Infantry (Marines), Coast Guard, and Naval Aviation.

3. Aerospace Force (Fuerza Aeroespacial ColombianaSpanish, formerly Air Force): Responsible for air defense, air support for ground and naval operations, reconnaissance, and air transport. It operates various types of aircraft and has air units stationed across the country.

Primary Missions:

- National Defense**: Protecting Colombia's sovereignty and territorial integrity from external threats.

- Internal Conflict Resolution**: Historically, a primary focus has been combating internal armed groups, including leftist guerrillas (like FARC dissidents and ELN) and other illegal armed organizations. This involves counter-insurgency operations and efforts to establish state control in remote areas.

- Counternarcotics Efforts**: The military plays a significant role in combating drug trafficking, including eradication of illicit crops (coca), interdiction of drug shipments, and dismantling drug trafficking organizations. This is often conducted in cooperation with international partners, notably the United States.

- Border Security**: Patrolling and securing Colombia's extensive land and maritime borders.

- Disaster Relief and Humanitarian Aid**: Providing assistance during natural disasters and humanitarian crises.

- International Cooperation**: Participating in regional security initiatives and, in some cases, international peacekeeping or training missions. Colombia is a NATO Global Partner.

Defense Policy and Expenditure:

Colombia has historically dedicated a significant portion of its GDP to military expenditure, largely due to the long-running internal armed conflict. In 2016, military spending was around 3.4% of GDP. Colombia's armed forces are among the largest and most experienced in Latin America in counter-insurgency warfare. Defense policy has emphasized professionalization, modernization of equipment, and strengthening intelligence capabilities. The "Democratic Security" policy under President Uribe (2002-2010) significantly expanded military operations. The subsequent peace process with FARC has led to some shifts in military focus, though challenges from remaining armed groups persist. In 2018, Colombia signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Human Rights Considerations:

The Colombian military's operations, particularly in the context of the internal armed conflict, have faced scrutiny regarding human rights. There have been documented cases of abuses, including extrajudicial killings (the "false positives" scandal), forced displacement, and other violations. Significant efforts have been made, with national and international pressure, to improve human rights training, accountability mechanisms within the armed forces, and adherence to international humanitarian law. Transitional justice mechanisms like the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) are tasked with investigating and prosecuting serious violations committed by all parties to the conflict, including members of the state forces. Ensuring respect for human rights and strengthening civilian oversight remain ongoing priorities for democratic progress and reconciliation.

The National Police, while part of the Ministry of Defence, functions primarily as a law enforcement agency throughout the country, distinct from the military forces, though they often coordinate in security operations. As of 2023, Colombia had approximately 455,461 active military personnel.

5.4. Human rights

The human rights situation in Colombia has been a significant concern for decades, deeply intertwined with the country's long-standing internal armed conflict, pervasive social inequality, and the activities of illegal armed groups and criminal organizations. Despite progress in some areas, numerous challenges persist, affecting various segments of the population, particularly minorities and vulnerable groups.

Impact of the Internal Armed Conflict:

The internal armed conflict, involving state forces, leftist guerrillas (FARC, ELN, and their dissidents), right-wing paramilitaries (historically, like the AUC, and their successor groups), and drug trafficking organizations, has been the primary driver of human rights violations. These include:

- Violence against Civilians**: Massacres, assassinations, forced displacement (Colombia has one of the world's largest internally displaced populations), kidnappings, torture, and sexual violence have been committed by all armed actors.

- Extrajudicial Killings**: The "false positives" scandal, where military personnel killed civilians and presented them as combatants, remains a stark example of state-committed abuses.

- Recruitment of Child Soldiers**: Illegal armed groups have systematically recruited and used children in hostilities.

- Landmines and Unexploded Ordnance**: Extensive use of landmines by non-state armed groups continues to endanger civilian populations.

Rights of Minorities and Vulnerable Groups:

- Indigenous Peoples and Afro-Colombians**: These communities have been disproportionately affected by the conflict, often caught in the crossfire or targeted for control of their resource-rich territories. They face displacement, violence, land dispossession, and threats to their cultural survival. Despite constitutional recognition of their collective rights, effective protection and consultation regarding development projects in their territories remain challenges.

- Human Rights Defenders, Social Leaders, and Journalists**: Colombia is one of the most dangerous countries for human rights defenders, community leaders, environmental activists, and journalists, who face threats, harassment, and assassination for their work in denouncing abuses and advocating for rights.

- Women and LGBTQ+ Individuals**: Women have suffered disproportionately from conflict-related sexual violence and displacement. LGBTQ+ individuals face discrimination and violence, although legal protections have advanced in recent years.

- Children**: Children are affected by recruitment, displacement, lack of access to education in conflict zones, and violence.

Social Inequality and Economic Rights:

Deep-rooted social and economic inequality, including unequal land distribution and limited access to basic services like healthcare, education, and justice for many, particularly in rural and marginalized areas, are underlying causes of social unrest and contribute to human rights challenges. Labor rights are also a concern, with issues related to informal employment and attacks on trade unionists.

Efforts for Protection and Promotion of Human Rights:

- Governmental Institutions**: The Colombian government has institutions dedicated to human rights, such as the Ombudsman's Office (Defensoría del Pueblo) and the Presidential Council for Human Rights. The 1991 Constitution includes robust human rights protections.

- Justice and Accountability**: The peace agreement with FARC established the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), a transitional justice mechanism aimed at ensuring truth, justice, reparations, and non-repetition for victims. The ordinary justice system also prosecutes human rights violations, though impunity remains a challenge.

- Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and Civil Society**: A vibrant civil society, including numerous national and international NGOs, plays a crucial role in documenting abuses, providing legal aid to victims, advocating for policy changes, and promoting human rights education.

- International Community**: International bodies like the UN Human Rights Office, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and various governments provide monitoring, support, and pressure for improvements in the human rights situation.

Despite progress in security in some areas and the peace agreement with FARC, significant human rights challenges persist. Ensuring the safety of social leaders and ex-combatants, effectively implementing the peace accord's provisions on victims' rights and rural reform, combating impunity, addressing structural inequalities, and protecting vulnerable communities from ongoing violence by armed groups are critical for advancing human rights and consolidating peace in Colombia. The center-left/social liberal perspective emphasizes the need for comprehensive state action, robust justice mechanisms, and the strengthening of civil society to address these deep-seated issues and build a more equitable and rights-respecting society.

6. Economy

Colombia's diversified economy, the third-largest in South America, relies on domestic demand and sectors including agriculture, mining, and services. Key areas include abundant agricultural and natural resources, a developing energy and transportation infrastructure, growing science and technology sectors, and an expanding tourism industry. However, the nation faces ongoing socioeconomic challenges related to poverty, inequality, and the need for equitable development.

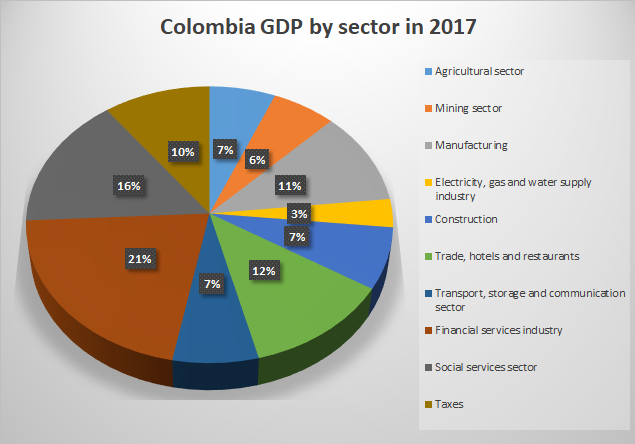

Colombia's economy is the third-largest in South America, characterized by macroeconomic stability and favorable long-term growth prospects, though it faces challenges related to inequality and equitable development. Historically an agrarian economy, Colombia urbanized rapidly in the 20th century. By the late 2010s, agriculture accounted for about 6-7% of GDP and employed around 16% of the workforce. Industry (including manufacturing, mining, and construction) contributed about 25-30% of GDP and employed around 20% of the workforce. Services became the dominant sector, representing over 60% of GDP and employing around 64% of the workforce.

The country's economic production is significantly driven by domestic demand, with household consumption expenditure being the largest component of GDP. Colombia's market economy experienced steady growth for much of the latter 20th century, averaging over 4% per year between 1970 and 1998. It suffered a recession in 1999 but recovered, achieving strong growth in subsequent years, including 7% in 2007. According to IMF estimates, in 2023, Colombia's GDP (PPP) was approximately 1.00 T USD.

Total government expenditures account for around 28-30% of the domestic economy. External debt has fluctuated but has generally been managed within sustainable levels. Fiscal policy aims for stability, though challenges remain in terms of tax revenue and social spending. Inflation has generally been moderate, for example, closing 2017 at 4.09%. The average national unemployment rate was 9.4% in 2017, but high levels of labor informality (affecting nearly half the workforce) remain a significant problem, impacting income security and social protection for many workers. Formal workers' incomes have generally risen more substantially than those of informal workers.

Colombia has established free-trade zones (FTZs) to attract foreign investment and promote exports, such as the Zona Franca del Pacífico in Valle del Cauca. The financial sector has grown favorably, supported by good liquidity, credit growth, and overall economic performance. The Colombian Stock Exchange (Bolsa de Valores de Colombia) participates in the Latin American Integrated Market (MILA), offering a regional platform for trading equities. Colombia has made strides in improving its business environment and legal frameworks for investment.

The country is rich in natural resources and remains significantly dependent on energy and mining exports. Key exports include mineral fuels (oil and coal), coffee, cut flowers, bananas, plastics, precious stones (especially emeralds, being a world-leading producer), metals, and various manufactured goods. Principal trading partners include the United States, China, the European Union, and other Latin American countries. Efforts to diversify exports beyond traditional commodities are ongoing, supported by free trade agreements.

Despite economic growth, socioeconomic challenges persist. In 2017, DANE reported that 26.9% of the population lived below the poverty line, with 7.4% in extreme poverty. The multidimensional poverty rate stood at 17.0%. Income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, remains high, though there have been efforts to reduce it. The government has focused on financial inclusion programs for vulnerable populations. Tourism has become an increasingly important sector, contributing around 2% of GDP and generating significant employment, with foreign tourist arrivals showing substantial growth in the 2010s.

From a center-left/social liberal perspective, while Colombia's economic fundamentals are relatively strong, achieving more inclusive growth requires addressing structural inequalities in income, land distribution, and access to quality education and healthcare. Sustainable development also necessitates careful management of natural resources to mitigate environmental impact and ensure benefits for local communities, particularly indigenous and Afro-Colombian populations often affected by extractive industries. Strengthening social safety nets, formalizing labor, and investing in human capital are crucial for equitable development and improving living standards for all Colombians.

6.1. Agriculture and natural resources

Colombia's economy is significantly endowed with agricultural potential and abundant natural resources. However, the exploitation and management of these resources present ongoing challenges regarding environmental sustainability and social equity.

Agriculture:

Agriculture has historically been a cornerstone of the Colombian economy. Key agricultural products include:

- Coffee**: Colombia is globally renowned for its high-quality coffee. It is one of the world's largest producers of Arabica beans. The coffee sector provides livelihoods for hundreds of thousands of families, particularly in the Andean regions, often on small-scale farms. While historically a dominant export, its relative share has declined with economic diversification, but it remains culturally and economically important. The "Coffee Cultural Landscape" is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

- Flowers**: Colombia is the world's second-largest exporter of cut flowers (after the Netherlands), particularly roses, carnations, and chrysanthemums. This industry is a major source of employment, especially for women, but has faced scrutiny regarding labor conditions and pesticide use.

- Bananas and Plantains**: These are important export crops and staple foods within the country. Large plantations exist, primarily in the Urabá region and the Caribbean coast.

- Palm oil**: Colombia is a significant global producer of palm oil. While providing economic benefits, the expansion of palm oil cultivation has raised concerns about deforestation, biodiversity loss, and land conflicts, particularly affecting Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities in regions like the Pacific coast and the Llanos. Efforts towards sustainable palm oil production are underway but face challenges.

- Other Crops**: Other notable agricultural products include sugarcane (for sugar and ethanol), rice, maize, potatoes, cassava, avocados (a growing export), cocoa, and a wide variety of tropical fruits.

- Livestock**: Cattle ranching is widespread, particularly in the Llanos and parts of the Andean and Caribbean regions. Beef and chicken meat production are significant for domestic consumption and some export. Extensive cattle ranching is a driver of deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions.

Challenges in the agricultural sector include unequal land distribution (latifundia vs. minifundia), limited access to credit and technology for small farmers, infrastructure deficits, and the impact of climate change. Illicit crop cultivation (coca and poppy) in some rural areas, often linked to armed conflict and poverty, further complicates agricultural development and has severe social and environmental consequences. The Colombian agricultural sector contributes significantly to the country's greenhouse gas emissions (around 55%), largely due to deforestation, extensive cattle ranching, land grabbing, and illegal agriculture. Equitable rural development, land reform, and support for sustainable agricultural practices are crucial for social justice and environmental protection.

Natural Resources:

Colombia is rich in mineral and energy resources:

- Coal**: Colombia is a major coal exporter, with large open-pit mines like Cerrejón in La Guajira. The coal industry is a significant source of export revenue but also faces criticism for its environmental impact (water use, dust, habitat disruption) and its effects on local communities, particularly indigenous groups like the Wayuu.

- Petroleum and Natural Gas**: Oil is a primary export, and natural gas is important for domestic energy consumption. Exploration and exploitation occur in various regions, including the Llanos, Magdalena Valley, and offshore. Fluctuations in global oil prices significantly impact the Colombian economy. Concerns exist regarding the environmental effects of oil extraction and the social impacts on local communities. In 2019, Colombia was the 20th largest petroleum producer globally. As of 2020, oil and coal accounted for over 40% of the country's exports.

- Emeralds**: Colombia is the world's leading producer of high-quality emeralds. The mining regions, primarily in Boyacá and Cundinamarca, have a history of conflict and informal mining, though efforts are made to formalize the sector.

- Gold and other Metals**: Gold mining, both formal and informal/illegal, is widespread. Illegal gold mining, often linked to criminal organizations and armed groups, causes severe environmental damage (mercury pollution, deforestation) and social conflicts. Colombia also has deposits of nickel, silver, and platinum. In 2017, the country extracted 52.2 tons of gold.

- Water Resources**: Colombia has abundant freshwater resources, crucial for agriculture, hydroelectric power, and human consumption. However, water management, pollution, and access disparities are challenges.

The exploitation of natural resources has been a driver of economic growth but also a source of social and environmental conflict. Ensuring that resource extraction benefits local communities, respects human rights (especially of indigenous and Afro-Colombian populations whose territories are often affected), minimizes environmental damage, and contributes to sustainable and equitable national development are key ongoing challenges.

6.2. Energy and transportation

Energy:

Colombia's energy matrix is characterized by a high reliance on hydroelectric power, which accounts for approximately 65-70% of its electricity generation. This makes its electricity sector largely based on a renewable source, but also vulnerable to climatic variations like droughts associated with El Niño. The country has significant untapped potential for other renewable energy sources, including wind (especially in La Guajira), solar, and biomass. The government has been promoting diversification and the development of non-conventional renewable energies to enhance energy security and reduce environmental impact.

Fossil fuels, particularly natural gas and coal, also play a role in electricity generation, especially as backup during dry periods or for specific industrial needs. Oil is a major primary energy source for transportation and a key export commodity. Natural gas is widely used for residential cooking, heating, and industrial processes.

The development of renewable energy projects, while environmentally beneficial, must consider social impacts, including land use and consultation with local communities, particularly indigenous groups in areas with high wind or solar potential like La Guajira. Energy efficiency programs and grid modernization are also part of Colombia's energy strategy. The country was recognized in the 2014 Global Green Economy Index (GGEI) for its efforts in greening efficiency sectors.

Transportation:

Colombia's challenging topography, with three Andean mountain ranges, has historically made transportation infrastructure development difficult and costly. The Ministry of Transport and various agencies like the National Roads Institute (INVÍAS) and the National Infrastructure Agency (ANI) regulate and manage the sector.