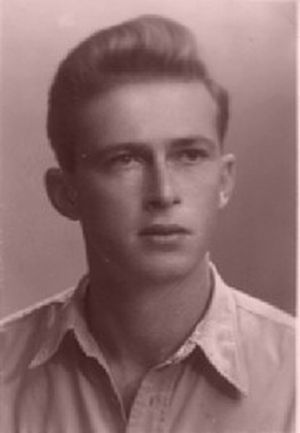

1. Early Life and Education

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Yitzhak Rabin was born at the Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestine, on March 1, 1922. His parents, Nehemiah Rabin (born Nehemiah Rubitzov in 1886 in Sydorovychi, near Ivankiv, Ukraine) and Rosa Rabin (née Cohen, born 1890 in Mogilev, Belarus), were immigrants of the Third Aliyah, a significant wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine from Eastern Europe.

Nehemiah's father, Menachem, died when he was a boy, prompting Nehemiah to work from an early age to support his family. At 18, he emigrated to the United States, where he joined the Poale Zion party and subsequently changed his surname to Rabin. In 1917, Nehemiah volunteered for the Jewish Legion and traveled to Mandatory Palestine. Rosa's father, a rabbi, initially opposed the Zionist movement, but he sent her to a Christian high school for girls in Gomel, which provided her with a broad general education. From an early age, Rosa demonstrated a strong interest in political and social causes. In 1919, she journeyed to Palestine aboard the steamship Ruslan, arriving as a leading figure of the Third Aliyah. After a period working on a kibbutz near the Sea of Galilee, she settled in Jerusalem.

Rabin's parents met in Jerusalem during the 1920 Nebi Musa riots. They later moved to Tel Aviv's Chlenov Street, near Jaffa, in 1923. Nehemiah found work with the Palestine Electric Corporation, while Rosa became an accountant and an active local politician, serving as a member of the Tel Aviv City Council. The family relocated again in 1931 to a two-room apartment on Hamagid Street in Tel Aviv. The Rabin household was characterized by a strong commitment to public service and activism, with both parents dedicating much of their lives to supporting community and Zionist causes. Even after his father's death when Yitzhak was young, his mother remained an active figure in the Mapai (Labor Party) and various defense organizations. Yitzhak's sister, Rachel, was born in 1925 in Tel Aviv, where Yitzhak grew up.

1.2. Childhood and Schooling

Yitzhak Rabin began his formal education in Tel Aviv, where his family had moved when he was one year old. In 1928, he enrolled in the Beit Hinuch Leyaldei Ovdim (בית חינוך לילדי עובדיםBeit Hinuch Leyaldei OvdimHebrew, "School House for Workers' Children"), a school established in 1924 by the Histadrut (General Labor Federation). The school aimed to instill national pride in urban youth and educate a generation capable of governing the nation. It specifically focused on teaching students values of responsibility, collective distribution, and unity, fostering a sense of social activism that students were expected to carry throughout their lives. Rabin spent eight years at this school, later writing that he considered it his "second home" and expressing particular appreciation for its teaching style, which extended beyond the confines of a typical classroom.

After completing his studies at Beit Hinuch in 1935, Rabin spent two years at the secondary boarding school on Kibbutz Givat Hashlosha, which his mother had helped to found. It was here, in 1936, at the age of 14, that Rabin first joined the Haganah, receiving his initial military training, which included learning to use a pistol and standing guard. He also became involved with HaNoar HaOved, a socialist-Zionist youth movement.

In 1937, Rabin enrolled in the two-year Kadoorie Agricultural High School, located at the foot of Mount Tabor. He consistently achieved excellent marks in agricultural subjects but notably disliked studying the English language, which he viewed as the language of the "British enemy." Although he initially aspired to become an irrigation engineer, his interest in military affairs intensified in 1938 as the ongoing Arab revolt worsened. During this period, a young Haganah sergeant named Yigal Allon, who would later become a prominent IDF general and politician, provided military training to Rabin and his peers at Kadoorie. When the British authorities temporarily closed Kadoorie in 1939, Rabin joined Allon as a security guard at Kibbutz Ginosar. Rabin graduated from Kadoorie in August 1940. While he briefly considered pursuing irrigation engineering on a scholarship at the University of California, Berkeley, he ultimately decided to remain in Palestine and contribute to the Zionist struggle. Many of Rabin's fellow Kadoorie alumni would later become commanders in the IDF and leaders of the newly established state of Israel. Rabin never formally pursued a university degree after his agricultural schooling.

2. Personal Life

2.1. Marriage and Family

Yitzhak Rabin married Leah Schlossberg during the tumultuous 1948 Arab-Israeli War. At the time of their marriage, Leah was working as a reporter for a Palmach newspaper. Leah was born in Königsberg, Germany (which later became part of Russia), in 1928, and her family immigrated to Israel immediately after Adolf Hitler's rise to power.

Together, Yitzhak and Leah had two children: their daughter Dalia, born on March 19, 1950, and their son Yuval, born on June 18, 1955. Leah Rabin served as a steadfast supporter of her husband throughout his military and political careers. Dalia later became a lawyer and was elected to the Knesset, founding a peace organization following her father's assassination. Yuval currently represents Israeli companies in the United States.

Rabin himself was a deeply secular individual. He adhered to a secular-national understanding of Jewish identity and was described by American diplomat Dennis Ross as "the most secular Jew he had met in Israel," indicating his non-religious stance. After his tragic assassination, Leah Rabin became a fierce advocate for his legacy of peace, taking up the mantle to promote his vision for the future.

3. Military Career

Yitzhak Rabin's military career was extensive and marked by significant leadership roles and strategic achievements.

3.1. Palmach Service

In 1941, while undergoing practical training at Kibbutz Ramat Yohanan, Rabin joined the newly formed Palmach, the striking force of the Haganah, under the significant influence of Yigal Allon. Despite his initial lack of skills in operating a machine gun, driving a car, or riding a motorcycle, he was accepted by Moshe Dayan as a new recruit. Rabin's first military operation was assisting the Allied invasion of Lebanon in June-July 1941, a territory then held by Vichy French forces. It was during this operation that Moshe Dayan famously lost an eye.

As a Palmachnik, Rabin and his unit operated clandestinely to avoid detection by the British administration, spending most of their time farming while training secretly part-time. They did not wear uniforms and received no public recognition for their efforts during this period. In 1943, Rabin was given command of a platoon at Kfar Giladi, where he trained his men in modern tactics, emphasizing swift, lightning attacks.

After World War II, relations between the Palmach and the British authorities became increasingly strained, particularly concerning the treatment of Jewish immigrants. In October 1945, Rabin planned and successfully led a Palmach raid on the Atlit detainee camp, which resulted in the liberation of 208 Jewish illegal immigrants who had been interned there. During the "Black Shabbat" operation in July 1946, a large-scale British crackdown against the leaders of the Jewish Establishment and the Palmach in Mandatory Palestine, Rabin was arrested and detained for five months. Following his release, he became the commander of the second Palmach battalion, eventually rising to the position of Chief Operations Officer of the Palmach in October 1947. He also served as Deputy Commander of Palmach in 1947.

3.2. Israel Defense Forces (IDF) Leadership

Following the declaration of the state of Israel, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) were formed with the objective of defending the state's existence, territorial integrity, and sovereignty, protecting its inhabitants, and combating all forms of terrorism that threatened daily life. The IDF's predecessors included the Haganah and the Jewish Brigade, which fought as part of the British Army during World War II.

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Rabin played a crucial role, directing Israeli operations in Jerusalem and engaging the Egyptian army in the Negev. At the war's outset, he commanded the Harel Brigade, which fought to secure the road to Jerusalem from the Israeli coastal plain, including the strategic "Burma Road." His brigade also participated in numerous battles within Jerusalem, such as securing the southern flank of the city by recapturing Kibbutz Ramat Rachel.

During the first truce of the war, Rabin commanded IDF forces on the Tel Aviv beach during the tragic Altalena Affair. The Altalena ship carried approximately 1,000 American MAHAL volunteers and a large quantity of weapons and ammunition for the War of Independence. Organized by Hillel Kook of the Irgun, the ship was shelled and set on fire off the Tel Aviv shore on David Ben-Gurion's orders, the day after much of its cargo was offloaded at Kfar Vitkin. It was later towed out to sea and sunk, resulting in numerous casualties among volunteers on board and those who jumped into the sea. Rabin famously referred to the shore gun that fired on the ship as "The Holy Gun." Despite the tension and bloodshed, Menachem Begin, the Irgun leader, broadcast a radio message urging his members not to fight the IDF, stating: "Do not raise a hand against a brother, not even today. It is forbidden for a Hebrew weapon to be used against Hebrew fighters." This plea is widely believed to have averted a full-scale civil war.

In the subsequent period, Rabin served as deputy commander of Operation Danny, the largest-scale operation at that point, involving four IDF brigades. This operation led to the capture of the cities of Ramle and Lydda, as well as the major airport in Lydda. Following the capture of these towns, there was a large-scale expulsion of their Arab population. Rabin signed the expulsion order, which explicitly stated: "1. The inhabitants of Lydda must be expelled quickly without attention to age. ... 2. Implement immediately."

Later, Rabin was appointed chief of operations for the Southern Front, participating in major battles that concluded the fighting there, including Operation Yoav and Operation Horev. In early 1949, he was a member of the Israeli delegation to the armistice talks with Egypt held on the island of Rhodes, which formally ended hostilities of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. After demobilization at the war's end, he remained the most senior former Palmach member still serving in the IDF.

Like many Palmach leaders, Rabin was politically aligned with the left-wing, pro-Soviet Ahdut HaAvoda party and later Mapam. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion distrusted these officers, leading several to resign from the army in 1953 after "a series of confrontations." Those Mapam members who remained, including Rabin, Haim Bar-Lev, and David Elazar, had to endure several years in staff or training posts before resuming their careers.

Rabin was appointed commander of the first IDF course for large unit commanders. With the assistance of his junior officers, he formulated the IDF's combat doctrine, which emphasized instruction and standardized training principles for various army units, from individual soldiers to divisions. Later, he served as head of the Operations Division of the General Staff, managing the administration of temporary reception camps. These camps housed hundreds of thousands of new immigrants, many from Islamic countries, who arrived in Israel after its independence. During severe floods in 1951 and 1952, IDF assistance to these camps was critical.

In May 1959, Rabin became the head of the Operations Branch, the second-highest position in the IDF under Chief of Staff Haim Laskov. In this role, he was tasked with addressing all issues related to the defense forces from a strategic perspective. His priorities included building a superior army, maintaining fluid stability, fostering ties with militaries worldwide, and integrating the political dimensions of military missions. He also attempted to reduce Israel's reliance on France, which was the country's primary arms supplier during the 1950s and 1960s, shifting focus towards the United States instead.

In 1961, Rabin became the Deputy Chief of Staff of the IDF, and from 1964 to 1968, he served as Chief of Staff. He dedicated his first three years in this position to preparing the IDF for all possible contingencies. He sought to strengthen the organization and reshape its structure, developing new training and combat methods along with a revised military doctrine. New weaponry was acquired, with top priority given to the Israeli Air Force and armored units. Arab nations strongly opposed the National Water Carrier project, a pipeline system designed to transport water from the Sea of Galilee to the country's central urban areas and arid lands, enabling the regulation of water use and supply nationwide. Syria attempted to divert the Jordan River tributaries that flowed into the Sea of Galilee, which would have sharply reduced the carrier's capacity, but these efforts failed due to IDF counter-operations under Rabin's command.

3.2.1. Six-Day War (1967)

Under Rabin's command, the IDF achieved a decisive victory over Egypt, Syria, and Jordan in the Six-Day War of 1967. The early 1960s saw escalating tensions in the Middle East, particularly along the Syrian-Israeli northern border, marked by numerous incidents. These clashes intensified in early 1967, including an event where the Israeli Air Force shot down six Syrian fighter jets that had infiltrated Israeli airspace. Soon after, the Soviet Union provided erroneous intelligence to Arab nations, suggesting that Israel was preparing a full-scale assault on Syria. Damascus sought assistance from Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who was then pressured to initiate war against Israel.

Nasser responded by massing troops in the Sinai Peninsula, violating a 1957 agreement. He expelled the UN forces stationed in Sinai since 1957, which had served as a buffer between Egyptian and Israeli armies, and delivered speeches vowing to conquer Tel Aviv. Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq subsequently entered into joint defense treaties, leaving Israel seemingly isolated and at risk of a comprehensive attack.

Rabin advocated for a preemptive strike. However, the Israeli government initially sought to gain international support, particularly relying on a United States commitment to ensure freedom of navigation in the Straits of Tiran, before taking military action. It was decided that Prime Minister Levi Eshkol was unsuitable to lead the nation during this crisis. Under public pressure, a national unity government was formed, with Moshe Dayan appointed Minister of Defense. This new government accepted Rabin's counsel to launch an attack.

On June 5, 1967, nearly all of Israel's air force fighter jets were deployed in a massive raid on Arab air forces. Taken by surprise, most Arab fighters were destroyed while still on the ground. With overwhelming air superiority secured, Israeli armored and infantry regiments encountered minimal resistance during their invasion of the Sinai Peninsula. The Egyptian army was defeated within days and retreated towards the Suez Canal. Despite appeals for Israel to remain uninvolved, the Jordanian army initiated shelling within and around Jerusalem. Within two days, IDF paratroopers stormed and conquered East Jerusalem, reaching the Western Wall in the Old City. Rabin was among the first to visit the Old City after its capture, and he delivered a famous speech on Mount Scopus at the Hebrew University. Soon after, most of the West Bank was invaded and occupied. With Egypt and Jordan neutralized, the IDF then attacked Syrian forces on the Golan Heights, eliminating their threat to the northern Jordan River valley.

Within six days, Israel, having been forced to fight on three distinct fronts, had decisively defeated the armies of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. This victory is widely regarded as one of the greatest military triumphs in world history and was achieved under Rabin's command as Chief of Staff of the IDF. Rabin emerged as a national hero, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem later awarded him an honorary doctorate. The Six-Day War profoundly transformed the state of Israel. In addition to demonstrating an undeniable military dominance over Arab nations, Israel's territory tripled in size. Much of the land of Israel, including a reunited Jerusalem, now came under Israeli control. The issue of the country's borders, which many believed had been settled with the War of Independence, was once again ignited. This military victory ushered in a new era in Israel's political and diplomatic life, and its regional geopolitics continue to be influenced by these events to this day.

4. Diplomatic Career

Yitzhak Rabin's diplomatic career marked a crucial transition from military service to international relations, particularly in strengthening ties with the United States.

4.1. Ambassador to the United States

After 27 years of distinguished service in the Israel Defense Forces, Yitzhak Rabin retired from the military in 1968. He was subsequently appointed Israel's Ambassador to the United States, a position he held for five years, until 1973.

Rabin considered Israel's relationship with the United States to be of utmost importance. The Cold War was at its peak, and a strong relationship with the U.S. was seen as a crucial counterbalance to Soviet support for Arab nations. During his tenure in Washington, D.C., the U.S. solidified its role as Israel's primary supplier of weapons and military equipment. Rabin successfully lobbied to lift the embargo on F-4 Phantom fighter jets, significantly enhancing Israel's defense capabilities. From a diplomatic perspective, Washington, D.C., came to rely on Israel as its most critical and reliable ally in the Middle East. During his ambassadorship, Rabin also made various attempts to open avenues for peaceful engagement with Arab nations. He did not hold an official capacity during the Yom Kippur War in 1973, which occurred shortly after his return to Israel.

5. Political Career

Yitzhak Rabin's political career was marked by his diverse roles and significant contributions to Israeli governance and the pursuit of peace.

5.1. Minister of Labor

Following his return to Israel from his ambassadorship, Rabin joined the Israeli Labor Party. In the elections held at the end of 1973, he was elected to the Knesset as a member of the Alignment (the Labor Party's alliance), placed 20th on their list. In March 1974, he was appointed Israeli Minister of Labor in the short-lived 16th government led by Prime Minister Golda Meir. During this period, Prime Minister Meir was compelled to resign due to widespread public protests concerning Israel's military unpreparedness during the Yom Kippur War, as well as the findings of the Agranat Commission report. Following Meir's resignation, Rabin was elected leader of the Labor Party, paving his way to become Prime Minister.

5.2. First Term as Prime Minister (1974-1977)

On June 3, 1974, Rabin succeeded Golda Meir as Prime Minister of Israel, becoming the first native-born Israeli to hold the office. His election to party leader came after he defeated his long-standing rival, Shimon Peres. The intense rivalry between Rabin and Peres would persist throughout their careers, often involving competition for party leadership and even credit for government achievements. Rabin formed a coalition government that initially included Ratz, the Independent Liberals, Progress and Development, and the Arab List for Bedouins and Villagers. This arrangement, sustained by a narrow parliamentary majority, lasted only a few months and was one of the rare periods in Israel's history when religious parties were not part of the ruling coalition. The National Religious Party eventually joined the coalition on October 30, 1974, while Ratz departed on November 6.

5.2.1. Key Policy Decisions and Challenges

In foreign policy during Rabin's first term, a major development was the Sinai Interim Agreement between Israel and Egypt, signed on September 1, 1975. This agreement, which followed intensive shuttle diplomacy by U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and a threatened "reassessment" of U.S. policy by President Gerald Ford, stated that the conflict in the Middle East should be resolved by peaceful means rather than military force. Rabin remarked that "reassessment" was "an innocent-sounding term that heralded one of the worst periods in American-Israeli relations." Nevertheless, this agreement was a crucial step towards the Camp David Accords of 1978 and the Egypt-Israel peace treaty signed in 1979. During this period, while actively pursuing peace with Arab nations, Rabin maintained a firm policy against the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which he regarded as an international terrorist organization that did not hesitate to attack civilians. However, he was open to engaging with officially recognized Arab leaders, such as King Hussein I of Jordan, with whom he would eventually forge a deep friendship. Rabin indicated a willingness to accept territorial compromises in the West Bank in exchange for peace.

Perhaps the most dramatic event during Rabin's first term was Operation Entebbe in July 1976. Under his direct orders, the IDF executed a daring long-range undercover raid to rescue passengers of an airliner hijacked by militants belonging to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine's Wadie Haddad faction and the German Revolutionary Cells (RZ). The hijacked aircraft had been diverted to Idi Amin's Uganda. The operation was widely celebrated as a tremendous success, becoming a subject of extensive analysis and commentary due to its spectacular nature. Rabin was widely praised for his nation's refusal to succumb to terrorism.

5.2.2. Resignation

Towards the end of 1976, Rabin's coalition government faced a significant crisis. A motion of no confidence was brought by Agudat Yisrael over a breach of the Sabbath when four F-15 fighter jets were delivered from the U.S. to an Israeli Air Force base. The National Religious Party abstained from the vote, leading Rabin to dissolve his government and call for new elections, scheduled for May 1977.

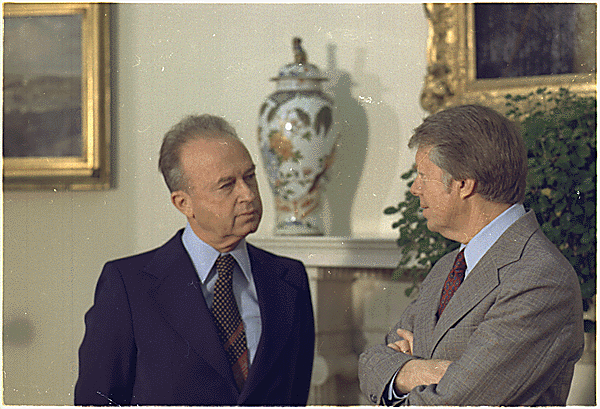

In February 1977, Rabin was narrowly re-elected as party leader over Shimon Peres. However, two unforeseen developments contributed to his eventual resignation. Following a March 1977 meeting with U.S. President Jimmy Carter, Rabin publicly stated that the U.S. supported the Israeli concept of defensible borders. Carter subsequently issued a clarification, leading to a "fallout" in U.S.-Israeli relations that is believed to have contributed to the Labor Party's defeat in the upcoming May 1977 elections.

The second, and more direct, cause of his resignation was the "Dollar Account affair". On March 15, 1977, journalist Dan Margalit of Haaretz revealed that a joint dollar account in the names of Yitzhak and Leah Rabin, opened in a Washington, D.C., bank during Rabin's term as Israeli ambassador (1968-1973), was still active, which was a breach of Israeli law at the time. Israeli currency regulations strictly prohibited citizens from maintaining foreign bank accounts without prior authorization. Rabin initially resigned on April 7, 1977, after Maariv journalist S. Isaac Mekel further disclosed that the Rabins held two accounts, not just one, containing 10.00 K USD, and that a Finance Ministry administrative penalty committee had fined them 150.00 K ILS. Rabin subsequently withdrew from party leadership and his candidacy for prime minister. His decision to take responsibility for the financial impropriety was later hailed by many as a reflection of his integrity and accountability. For the next seven years, Rabin served as a regular member of the Knesset, largely remaining in the background, dedicating considerable time to his family, and writing commentaries on current affairs, politics, and strategy.

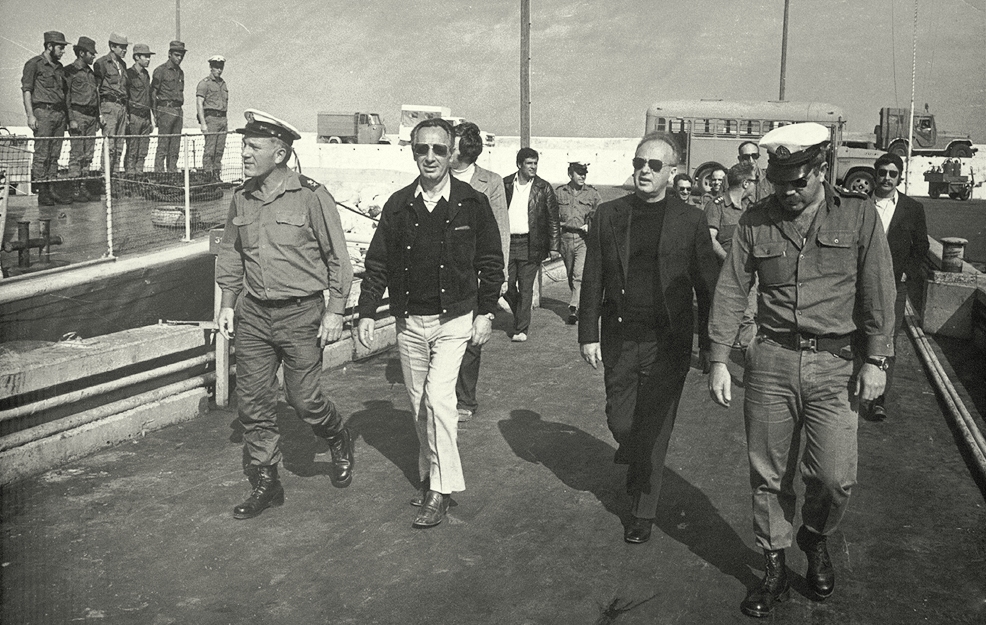

5.3. Opposition Member of Knesset and Minister of Defense (1977-1992)

Following the Labor Party's defeat in the 1977 Israeli legislative election, Likud's Menachem Begin became Prime Minister, and Labor, as part of the Alignment alliance, entered the opposition. From 1977 until 1984, Rabin served as a member of the Knesset, sitting on the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee. During this period, he unsuccessfully challenged Shimon Peres for the Israeli Labor Party leadership in the 1980 Israeli Labor Party leadership election.

From 1984 to 1990, Rabin served as Minister of Defense in several national unity governments led alternately by Prime Ministers Yitzhak Shamir and Shimon Peres. One of his primary responsibilities upon taking office was overseeing the withdrawal of Israeli troops from Lebanon, where they had been engaged in a costly attrition war since the 1982 invasion, which followed the assassination attempt on Israeli Ambassador to the UK, Shlomo Argov, by the Abu Nidal Organization. Known as Operation Peace for Galilee, the war proved burdensome for Israel, and an initial attempt at withdrawal in May 1983 was unsuccessful. Rabin and Peres ultimately began withdrawing the majority of Israeli forces in January 1985. By June 1985, all Israeli soldiers had departed Lebanon, except for a narrow "Security Zone" along the border, which was deemed a necessary buffer against attacks on Israel's northern territory. The South Lebanon Army operated actively in this zone alongside the IDF.

5.3.1. Response to the First Intifada

From late 1987 to 1991, the First Intifada, a Palestinian popular uprising in the occupied territories, erupted, catching Israel by surprise with its unexpected scale and rapid escalation. While Israeli military and political leaders were slow to grasp its magnitude and significance, the uprising quickly garnered significant international attention. The uprising, initially expected to be short-lived by both Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), soon devolved into a prolonged confrontation. Rabin adopted a harsh "Iron Fist" policy to suppress the uprising, authorizing the use of "force, might, and beatings" against rioters. The derogatory term "bone breaker" became an internationally recognized slogan used to criticize his approach.

In August 1985, as Minister of Defense, Rabin formalized the "Iron Fist" policy in the West Bank, reinstating British Mandate-era legislation that allowed for detention without trial, house demolitions, the closure of newspapers and institutions, and the deportation of activists. This policy shift followed a sustained public campaign demanding tougher measures after the May 1985 prisoner exchange, which saw the release of 1,150 Palestinians.

The combination of the "Iron Fist" policy's failure to quell the uprising, Israel's deteriorating international image, King Hussein I's surprising announcement that Jordan was relinquishing its sovereignty claims over the West Bank (which Israel had occupied since the Six-Day War), and the U.S.'s recognition of the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, compelled Rabin to seek an end to the violence through negotiation and dialogue with the PLO. This period marked a significant shift in Rabin's approach, as he came to believe that a solution to the conflict needed to be found through diplomatic means rather than purely military ones.

In 1988, Rabin was responsible for the assassination of Abu Jihad in Tunis. Two weeks later, he personally supervised Operation Law and Order, the destruction of the Hezbollah stronghold in Meidoun, during which the IDF claimed to have killed 40-50 Hezbollah fighters, while three Israeli soldiers were killed and seventeen wounded. On July 27, 1989, Minister of Defense Rabin planned and executed the abduction of Hezbollah leader Sheikh Abdel Karim Obeid and two of his aides from Jibchit in South Lebanon. In response, Hezbollah announced the execution of William R. Higgins, a senior American officer working with UNIFIL who had been kidnapped in February 1988.

Following the 1988 elections, a second national unity government was formed, in which Rabin continued to serve as Minister of Defense. The following year, he submitted a plan for negotiations with the Palestinians, which laid the foundation for the Madrid International Peace Conference and marked the beginning of the peace process. The core of this plan focused on fostering a credible local Palestinian leadership in the territories and called for elections separate from the PLO.

In 1990, the Labor Party's attempt to bring down the government led to its collapse, and Rabin, along with the rest of Labor, returned to the opposition benches. From 1990 to 1992, Rabin remained a member of the Knesset and served on the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee. During these years in opposition, he intensified his efforts to reclaim the leadership of his party, a position that Shimon Peres had held since 1977. Rabin unsuccessfully attempted to persuade the Labor Party to schedule a leadership election in 1990, which had seemed promising for him given Peres's weakened position and Rabin's popularity in polls. Although the party's 120-member Leadership Bureau initially recommended an immediate election in July 1990, the 1,400-member Labor Party Central Committee voted 54% to 46% against it a week later, an upset result that delayed a leadership contest until at least the following year.

5.4. Second Term as Prime Minister (1992-1995)

Yitzhak Rabin's second term as Prime Minister was dedicated to significant reforms and a groundbreaking peace process that reshaped the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East.

In the 1992 Israeli Labor Party leadership election, Rabin was elected chairman of the Labor Party, unseating Shimon Peres. In the subsequent 1992 Israeli legislative election, the Labor Party, led by Rabin, successfully leveraged his widespread popularity. The party secured a clear victory over the Likud of then-incumbent Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir. Although the left-wing bloc in the Knesset achieved only a narrow overall majority, its success was facilitated by smaller nationalist parties failing to pass the electoral threshold. Rabin formed the first Labor-led government in fifteen years, establishing a coalition with Meretz, a left-wing party, and Shas, a Mizrahi ultra-orthodox religious party.

On July 25, 1993, following Hezbollah rocket attacks into northern Israel, Rabin authorized Operation Accountability, a week-long military operation in Lebanon. His first action as Prime Minister was a reorganization of national priorities, with peace with the Palestinians at the top of the agenda. Socio-economic issues also ranked high. Rabin firmly believed that Israel's economic future necessitated an end to the state of war. During this period, Israel experienced a significant influx of immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Resources that had previously been allocated to settlements were rechanneled to support these new immigrants and invest in the education sector.

5.4.1. Economic and Social Reforms

Rabin's second term as Prime Minister saw significant reforms across Israel's economy, education, and healthcare systems. His government substantially expanded the privatization of businesses, marking a notable shift away from the country's traditionally socialized economy, a move described by Moshe Arens as a "privatization frenzy."

In 1993, his government launched the "Yozma" program, which offered attractive tax incentives to foreign venture capital funds that invested in Israel. Critically, the government promised to double any such investment with its own funding. As a direct result, foreign venture capital funds heavily invested in the burgeoning Israeli high-tech industry, significantly contributing to Israel's economic growth and its emergence as a global leader in high-tech innovation.

In 1995, the National Health Insurance Law was enacted, establishing Israel's universal health care system. This reformed the healthcare landscape, moving away from the previously Histadrut-dominated health insurance system. As part of these reforms, doctors' wages were raised by 50%. Education spending also saw a substantial increase of 70%, leading to the construction of new colleges in Israel's peripheral regions and a one-fifth increase in teachers' wages. Additionally, his government initiated major public works projects, including the construction of the Cross-Israel Highway and a significant expansion of Ben Gurion Airport.

5.4.2. Leading the Peace Process

Yitzhak Rabin played a pivotal role in leading the Middle East peace process during his second term. He and Foreign Minister Shimon Peres collaborated closely to implement this process. Rabin's journey to accept the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as a partner for peace was a protracted and challenging one. He ultimately recognized that to negotiate peace, he had to engage with the "enemy," acknowledging that Israel had no other viable partner for an agreement apart from the PLO. Rabin believed that the success of peace initiatives required the Palestinian moderates to prevail over the radicals and fundamentalists within the PLO. Despite his personal reservations about the credibility of Yasser Arafat and the PLO's intentions, Rabin agreed to engage in secret negotiations with PLO representatives.

These clandestine talks, held in Oslo, Norway, during the spring and summer of 1993, resulted in what became known as the Oslo Accords. The agreements were finalized on August 20, 1993, and officially signed on September 13, 1993, in a landmark ceremony in Washington, D.C.. Arafat signed on behalf of the PLO, and Peres signed for the State of Israel. The ceremony was witnessed by U.S. President Bill Clinton, U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher, and Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev. Before the signing, Rabin received a letter from PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat renouncing violence and officially recognizing Israel. On the same day, September 9, 1993, Rabin sent Arafat a letter officially recognizing the PLO. Two days earlier, Rabin had articulated his primary motive for negotiating with Palestinians: "The Palestinians will be better at it than we were, ... because they will allow no appeals to the Supreme Court and will prevent the Israeli Association of Civil Rights from criticizing the conditions there by denying it access to the area. They will rule by their own methods, freeing, and this is most important, the Israeli army soldiers from having to do what they will do."

The Oslo Accords, which guaranteed Palestinian self-rule in parts of the territories for five years, are widely considered one of the major achievements of Rabin's public career. However, the announcement of the accords triggered numerous protest demonstrations within Israel. As these protests persisted, Rabin maintained that as long as he commanded a majority in the Knesset, he would disregard the protests and protesters, famously stating that "they (the protesters) can spin around and around like propellers" but he would continue on the path of the Oslo Accords. Rabin's parliamentary majority crucially relied on the support of non-coalition Arab members. He also dismissed objections from American Jews, referring to such dissent as "chutzpah." The Oslo agreement also faced strong opposition from Hamas and other Palestinian factions, who launched a series of suicide bombings against Israel, which only served to increase Israeli public anger and a sense that the peace process was failing.

After the historic handshake with Yasser Arafat, Rabin, on behalf of the Israeli people, declared: "We who have fought against you, the Palestinians, we say to you today, in a loud and a clear voice; Enough of blood and tears. Enough!"

The Gaza-Jericho Agreement, which initiated the first phase of Palestinian self-rule in Gaza and Jericho, was signed on May 4, 1994. Under this agreement, the IDF withdrew from most of the Gaza Strip but continued to defend Jewish settlements in the area. On September 28, 1995, Israel and the PLO signed the Oslo B Agreement, which further expanded the areas of the West Bank under new Palestinian control.

Rabin's resolute pursuit of peace with Palestinians, even when faced with opposition from some Jewish factions, paved the way for a crucial diplomatic breakthrough: the initiation of peace talks with Jordan. After several months of negotiations between Rabin and King Hussein I, a full peace treaty between Israel and Jordan was signed on October 26, 1994. During this term, Rabin also continued persistent efforts toward peace with Syria, indicating his readiness to exchange territory for a peace agreement, contingent on Israeli public approval. He approved a referendum before any potential withdrawal from the Golan Heights.

5.4.3. Nobel Peace Prize Award

For his pivotal role in the creation of the Oslo Accords, Yitzhak Rabin was awarded the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize, sharing the honor with Yasser Arafat and Shimon Peres. In his Nobel Peace Prize lecture on December 10, 1994, Rabin stated: "Military cemeteries in every corner of the world are silent testimony to the failure of national leaders to sanctify human life."

The Oslo agreement deeply divided Israeli society. While many viewed Rabin as a hero who advanced the cause of peace, others regarded him as a traitor for potentially ceding lands they considered rightfully belonging to Israel. Many right-wing Israelis frequently attributed the deaths of Jewish citizens in terror attacks to the consequences of the Oslo Accords. Outside of his peace efforts, Rabin was also awarded the Ronald Reagan Freedom Award in 1994 by former First Lady Nancy Reagan. This award is given to individuals who have made "fundamental and long-lasting contributions to the cause of global freedom" and who embody President Reagan's conviction that "a man or woman truly can make a difference."

6. Assassination

On November 4, 1995, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin's life was tragically cut short by assassination.

6.1. Events of the Assassination

On the evening of November 4, 1995 (the 12th of Cheshvan on the Hebrew calendar), Rabin was assassinated by Yigal Amir, a law student and right-wing extremist who vehemently opposed the signing of the Oslo Accords. The assassination occurred as Rabin was attending a massive rally at the Kings of Israel Square (now Rabin Square) in Tel Aviv, which was held in support of the Oslo Accords.

As the rally concluded, Rabin descended the city hall steps towards the open door of his car. At this moment, Amir fired three shots at Rabin with a semi-automatic pistol. Two of the shots struck Rabin, while the third lightly injured Yoram Rubin, one of Rabin's bodyguards. Rabin was immediately rushed to the nearby Ichilov Hospital, where he tragically died on the operating table. His death was attributed to massive blood loss and two punctured lungs. Amir was apprehended immediately by Rabin's bodyguards and police. He was subsequently tried, found guilty of murder, and sentenced to life imprisonment. Following an emergency cabinet meeting, Israel's foreign minister, Shimon Peres, was appointed as acting Israeli prime minister.

6.2. Immediate Aftermath and Funeral

Rabin's assassination sent profound shockwaves through Israeli society and much of the world. Hundreds of thousands of Israelis gathered at the square where Rabin was assassinated, as well as at his home, the Knesset, and near the assassin's hometown, to mourn his death. Young people, in particular, turned out in large numbers, lighting memorial candles and singing peace songs. Before leaving the stage on the night of the assassination, Rabin had sung "Shir LaShalom" (the Peace Song) with Israeli singer Miri Aloni; a paper with the song lyrics, stained with his blood, was later found in his pocket.

On November 6, 1995, Rabin was buried on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. His funeral was attended by an unprecedented number of world leaders, including U.S. President Bill Clinton, Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, King Hussein I of Jordan, French President Jacques Chirac, UK Prime Minister John Major, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, and UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali. President Clinton delivered a memorable eulogy that concluded with the Hebrew words "Shalom, haver" (שלום חברShalom haverHebrew, literally "Goodbye, friend"). King Hussein I, in his eulogy, described Rabin as "a man of courage, a man of vision," emphasizing his humility and ability to understand other perspectives to achieve peace. Hussein pledged to continue the legacy of peace, hoping his own end would be "like my grandfather, and like Yitzhak Rabin."

The square where he was assassinated, formerly known as Kikar Malkhei Yisrael (Kings of Israel Square), was renamed Rabin Square in his honor. In November 2000, his wife Leah died and was buried beside him on Mount Herzl. After Rabin's assassination, his daughter, Dalia Rabin-Pelossof, entered politics, being elected to the Knesset in 1999 as a member of the Center Party. In 2001, she served as Israel's Deputy Minister of Defense. As with many political assassinations, the context and surrounding events of Rabin's murder have been subject to much debate, including various conspiracy theories.

7. Legacy and Evaluation

Yitzhak Rabin's legacy is characterized by his profound impact on Israeli society and the Middle East peace process, encompassing both widespread acclaim and significant controversy.

7.1. Positive Legacy

Yitzhak Rabin's legacy is profoundly significant, marked by his transformation from a formidable military general to a dedicated advocate for peace. After his assassination, he was widely hailed as a national symbol, embodying the ethos of the "Israeli peace camp," despite his earlier military career and hawkish views. He is predominantly remembered as a great man of peace in Israel. His crucial contributions to the Middle East peace process, particularly the Oslo Accords and the Israel-Jordan peace treaty, are regarded as monumental achievements that shifted the paradigm of regional conflict. As Israel's first native-born Prime Minister, he also holds a symbolic status as a quintessential Sabra leader. His determined pursuit of peace, even in the face of intense domestic opposition, is a defining aspect of his positive legacy. The peace process he initiated, particularly for the Israeli left, became a national symbol, although it gradually stalled after his death, especially with the rise of the Israeli right in the mid-2000s.

7.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his widely celebrated achievements, Yitzhak Rabin's career was also marked by criticisms and controversies. His resignation from his first term as Prime Minister in 1977 stemmed from a financial scandal involving an unauthorized foreign bank account held by his wife, a violation of Israeli currency regulations at the time.

A significant source of criticism against Rabin arose from his "Iron Fist" policy as Minister of Defense during the First Intifada. His authorization of "force, might, and beatings" against Palestinian rioters led to international condemnation and the pejorative term "bone breaker." This period ignited widespread debate about human rights and the Israeli occupation.

Later in his career, his leadership in the Oslo Accords drew intense opposition from factions within Israel. Many on the right wing vehemently opposed the territorial concessions and compromises with the Palestine Liberation Organization, viewing them as a betrayal of Israeli land and security. These opponents often held him responsible for the subsequent increase in Palestinian suicide bombings and other terror attacks, which they saw as direct consequences of the peace agreements. Similarly, some Palestinians, primarily Hamas and Islamic Jihad, also opposed the Oslo Accords, believing they did not go far enough to secure Palestinian rights, and responded with their own campaigns of violence. His peace policy, though widely supported, angered these factions, including religious right-wingers living in settlements in the West Bank, Gaza, and the Golan Heights. The economic crisis and high inflation following the Yom Kippur War also contributed to his Labor Party's defeat in the 1977 elections.

8. Commemoration

Numerous initiatives and sites commemorate Yitzhak Rabin's life and legacy, particularly emphasizing his pursuit of peace.

The Knesset has officially designated the 12th of Cheshvan, the date of his assassination according to the Hebrew calendar, as his official memorial day. An unofficial, yet widely observed, memorial day also takes place on November 4th, the date of his assassination according to the Gregorian calendar.

In 1995, the Israeli Postal Authority issued a commemorative Rabin stamp. In 1996, Israeli songwriter Naomi Shemer translated Walt Whitman's poem "O Captain! My Captain!" into Hebrew and set it to music to mark the anniversary of Rabin's assassination. This song is frequently performed or played during Yitzhak Rabin memorial day services.

The Yitzhak Rabin Center was established in 1997 by an act of the Knesset, with the mission of creating "a Memorial Centre for Perpetuating the Memory of Yitzhak Rabin." It conducts extensive commemorative and educational activities, emphasizing the principles and practices of democracy and peace. Mechinat Rabin, an Israeli pre-army preparatory program designed to train recent high school graduates in leadership prior to their IDF service, was founded in 1998. In 2005, Rabin posthumously received the Dr. Rainer Hildebrandt Human Rights Award, which is annually bestowed in recognition of extraordinary, non-violent commitment to human rights.

Many cities and towns across Israel have named streets, neighborhoods, schools, bridges, and parks after Rabin. The country's largest power station, Orot Rabin, is named in his honor, as are two government office complexes-one at the HaKirya in Tel Aviv and another at the Sail Tower in Haifa. The Israeli terminal of the Arava/Araba border crossing with Jordan and two synagogues also bear his name. Beyond Israel's borders, streets and squares have been named after him in Bonn, Berlin, Chicago, Madrid, Miami, New York City, and Odesa. Parks have been dedicated to his memory in Montreal, Paris, Rome, and Lima. Additionally, the community Jewish high school in Ottawa, Canada, is named after him. The Cambridge University Israel Society hosts an annual academic lecture in honor of Yitzhak Rabin. Reggae artist Alpha Blondy also recorded a single titled 'Yitzhak Rabin' in tribute to the former Israeli Prime Minister.

9. Published Works

Yitzhak Rabin's notable writings include his autobiography:

- The Rabin Memoirs (1996)

10. Awards and Decorations

Yitzhak Rabin received numerous significant awards and military decorations throughout his distinguished career, recognizing his contributions to both military service and peace.

- Nobel Peace Prize (1994)

- Ronald Reagan Freedom Award (1994)

- War of Independence Ribbon

- Operation Kadesh Ribbon

- Six-Day War Ribbon

11. Electoral History

Yitzhak Rabin participated in several key electoral contests, primarily for the leadership of the Israeli Labor Party.

In the 1974 Israeli Labor Party leadership election, Rabin successfully challenged Shimon Peres, securing 54% of the votes (298 votes) compared to Peres's 46% (254 votes), thus becoming party leader.

He was narrowly re-elected in the February 1977 Israeli Labor Party leadership election, receiving 50.7% of the votes (1445 votes) against Shimon Peres's 49.3% (1404 votes).

However, in the 1980 Israeli Labor Party leadership election, Rabin was unsuccessful in his challenge against incumbent Shimon Peres. Peres won with 70.8% of the votes (2123 votes), while Rabin received 29.2% (875 votes).

Rabin made a comeback in the 1992 Israeli Labor Party leadership election. He won the leadership with 40.6% of the vote, defeating incumbent Shimon Peres (34.5%), Yisrael Kessar (19.0%), and Ora Namir (5.5%). The total turnout for this election was 70.1% of 108,347 votes cast.

12. Overview of Offices Held

Yitzhak Rabin held a range of significant political and military offices throughout his distinguished career.

| Office | Tenure | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces | 1964-1968 | Seventh Chief of Staff |

| Ambassador of Israel to the United States | 1968-1973 | Seventh Ambassador |

| Minister of Labour | March 10, 1974 - June 3, 1974 | Served in the 16th Government under Golda Meir |

| Prime Minister of Israel (First Term) | June 3, 1974 - June 20, 1977 | Fifth Prime Minister, leading the 17th Government |

| Minister of Communications | June 3, 1974 - March 20, 1975 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |

| Minister of Welfare (First Term) | July 7, 1975 - July 29, 1975 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |

| Minister of Defense (First Term) | September 13, 1984 - March 15, 1990 | Served in National Unity Governments under Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Shamir |

| Prime Minister of Israel (Second Term) | July 13, 1992 - November 4, 1995 | Eleventh Prime Minister, leading the 25th Government, until his assassination |

| Minister of Defense (Second Term) | July 13, 1992 - November 4, 1995 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |

| Minister of Labor and Social Welfare (Second Term) | July 13, 1992 - December 31, 1992 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |

| Minister of Jerusalem Affairs | July 13, 1992 - December 31, 1992 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |

| Minister of Religious Affairs | July 13, 1992 - February 27, 1995 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |

| Minister of Education and Culture | May 11, 1993 - June 7, 1993 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |

| Minister of Internal Affairs (First Term) | May 11, 1993 - June 7, 1993 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |

| Minister of Internal Affairs (Second Term) | September 14, 1993 - February 27, 1995 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |

| Minister of Health | February 8, 1994 - June 1, 1994 | Concurrent with Prime Ministership |