1. Overview

The Republic of Uzbekistan (Oʻzbekiston RespublikasiOʻzbekiston RespublikasiUzbek), commonly known as Uzbekistan (OʻzbekistonOʻzbekistonUzbek), is a doubly landlocked country located in Central Asia. It is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north and west, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the east and southeast, Afghanistan to the south, and Turkmenistan to the southwest. The capital and largest city is Tashkent. Uzbekistan is a secular state with a presidential republican form of government.

The region of modern Uzbekistan has a rich history, having been settled since the second millennium BC. Early inhabitants included Eastern Iranian nomads like the Scythians, who established kingdoms in Khwarazm, Bactria, and Sogdia. The area was part of major empires, including the Achaemenid Empire, the empire of Alexander the Great, the Parthian Empire, and the Sasanian Empire. The Muslim conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries led to the Islamization of the region, which subsequently became a center of the Islamic Golden Age, with cities like Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva flourishing along the Silk Road. The 13th century saw the devastating Mongol invasion. In the 14th century, Timur (Tamerlane) established the vast Timurid Empire with Samarkand as its capital, leading to the Timurid Renaissance. Later, the region was ruled by Uzbek khanates, including those of Bukhara, Khiva, and Kokand.

In the 19th century, the Russian Empire conquered Central Asia, and Tashkent became the political center of Russian Turkestan. Following the Russian Revolution, the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic was formed in 1924 as part of the Soviet Union. Uzbekistan declared independence on August 31, 1991, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The post-independence era was dominated by President Islam Karimov, whose rule was characterized by authoritarianism and significant human rights concerns. After Karimov's death in 2016, his successor, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, initiated a series of reforms aimed at economic liberalization, improving international relations, and addressing some human rights issues, although challenges to democratic development persist.

Uzbekistan's economy is transitioning towards a market economy, with significant reliance on cotton production, natural gas, and gold mining. The country has a diverse population, with Uzbeks forming the majority, and significant minorities of Tajiks, Russians, Kazakhs, and Karakalpaks. Uzbek is the official language, while Russian remains widely used. Islam, predominantly Sunni, is the majority religion. Culturally, Uzbekistan is known for its historical architecture, traditional music like Shashmaqom, and unique cuisine, with plov (osh) being a national dish.

2. Etymology

The name "Uzbekistan" (OʻzbekistonOʻzbekistonUzbek) is derived from the name of the Uzbek people combined with the Persian suffix "-stan" (meaning "land of"). The term "Uzbegistán" is recorded as appearing in 16th-century literature, such as the Tarikh-i Rashidi.

The origin of the word "Uzbek" itself is disputed among scholars, with several theories proposed:

# One theory suggests it means "free," "independent," or "own master/leader," derived from an amalgamation of the Turkic words uz (meaning "own," "self," or "true") and bek (a title meaning "master," "leader," or "noble"). Thus, "Ozbek" could signify "noble" or "true leader."

# Another theory posits that the name is an eponym derived from Oghuz Khagan, also known as Oghuz Beg.

# A third explanation suggests it is a contraction of Uğuz (an earlier form of Oghuz), combined with bek, meaning "Oghuz-leader."

# Some historical accounts link the name to Uzbeg Khan (Öz Beg Khan) of the Golden Horde, who reigned in the 14th century and played a significant role in the Islamization of the Horde. His influence may have led to his followers, and later other Turkic groups in the region, being identified as Uzbeks.

Regardless of the precise origin, the middle syllable or phoneme is cognate with the Turkic title Beg (or Bek). During the Soviet era, the name of the country was commonly spelled as ЎзбекистонOʻzbekistonUzbek in Uzbek Cyrillic or УзбекистанUzbekistanRussian in Russian.

3. History

Uzbekistan's history spans from ancient civilizations like Bactria and Sogdia, through the Timurid Empire and subsequent Uzbek khanates, to its incorporation into the Russian Empire, the Soviet era, and finally, its emergence as an independent nation in 1991, followed by significant political and social transformations.

3.1. Ancient and Medieval History

The territory of present-day Uzbekistan has been inhabited since the Paleolithic era. The first known settlers in Central Asia were Eastern Iranian nomads, particularly the Scythians (also known as Saka), who arrived from the northern grasslands sometime in the first millennium BC. As these nomads settled, they developed extensive irrigation systems along the rivers. During this period, cities such as Bukhara (Bukhoro) and Samarkand (Samarqand) emerged as centers of government and high culture. By the fifth century BC, the states of Bactria, Sogdia, and Tokharia (comprising the Yuezhi people) dominated the region.

As East Asia developed its silk trade with the West, an extensive network of cities and rural settlements in the province of Transoxiana (the land between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers) and further east in what is today Xinjiang became crucial. Sogdian intermediaries became the wealthiest merchants along this route, which came to be known as the Silk Road. Consequently, Bukhara and Samarkand grew into extremely wealthy cities, and Transoxiana (Mawarannahr) was at times one of the most influential and powerful provinces of antiquity.

In 327 BC, the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire provinces of Sogdiana and Bactria. This conquest faced fierce popular resistance, causing Alexander's army to be bogged down in the region, which later became the northern part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was eventually replaced by the Yuezhi-dominated Kushan Empire in the first century BC. For many centuries thereafter, the region of Uzbekistan was ruled by various empires, including the Hephthalites, the Sasanian Empire, and Turkic peoples like the Göktürks.

The Muslim conquests starting in the seventh century brought Islam to Uzbekistan. Arab forces, notably under Qutayba ibn Muslim in the eighth century, conquered Transoxiana, which soon became a focal point of the Islamic Golden Age. During this period, Islam also began to take root among the nomadic Turkic peoples. The Samanid Empire (9th-10th centuries) further consolidated Islamic rule and Persianate culture in the region. Cities like Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva became centers of learning and culture, producing renowned scholars such as Muhammad al-Bukhari, Al-Tirmidhi, al-Khwarizmi, al-Biruni, and Avicenna (Ibn Sina). In the 10th century, the region was gradually dominated by the Turkic-ruled Kara-Khanids, followed by the Seljuks.

The Mongol conquest under Genghis Khan in the 13th century brought profound change. The invasions of Bukhara, Samarkand, Urgench, and other cities resulted in mass murders and unprecedented destruction, with parts of the Khwarazmian Empire being completely razed. Following Genghis Khan's death in 1227, his empire was divided, and Transoxiana largely fell under the control of the Chagatai Khanate, founded by his second son, Chagatai Khan. For a period, orderly succession, prosperity, and internal peace prevailed in the Chaghatai lands, and the Golden Horde also exerted influence.

3.2. Timurid Empire

In the early 14th century, as the Mongol successor states began to fragment, various tribal groups competed for influence in the Chaghatai territory. From these struggles, Timur (also known as Tamerlane), a tribal chieftain of Turco-Mongol descent, emerged in the 1380s as the dominant force in Transoxiana. Although not a direct descendant of Genghis Khan, Timur became the de facto ruler and embarked on extensive military campaigns, conquering all of western Central Asia, Iran, the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and the southern steppe region north of the Aral Sea. He also invaded Russia and was preparing an invasion of Ming China when he died in 1405. Timur was known for his extreme brutality, and his conquests were often accompanied by genocidal massacres in the cities he occupied.

Despite the violence of his conquests, Timur initiated the last great cultural flowering of Transoxiana, known as the Timurid Renaissance. He gathered numerous artisans, scholars, architects, and physicians from the vast lands he had conquered into his capital, Samarkand, imbuing his empire with a rich Perso-Islamic culture. During his reign and those of his immediate descendants, a wide range of magnificent religious and palatial constructions were undertaken in Samarkand and other population centers. His grandson, Ulugh Beg, was a renowned astronomer and mathematician who built a significant observatory in Samarkand, making the city a prominent center of science. It was during the Timurid dynasty that Turkic, in the form of the Chagatai language, became a literary language in its own right in Transoxiana, with the greatest Chaghataid writer, Ali-Shir Nava'i, active in Herat (now in northwestern Afghanistan) in the second half of the 15th century. The Timurids, while Turkic in origin, were highly Persianate in culture.

3.3. Uzbek Khanates Period

The Timurid state quickly fragmented after Timur's death due to chronic internal fighting among his descendants. This instability attracted the attention of the Uzbek nomadic tribes living north of the Aral Sea. In 1501, under the leadership of Muhammad Shaybani, Uzbek forces began a wholesale invasion of Transoxiana, effectively ending Timurid rule in the region by 1507. The Shaybanids established their own dynasty, and the center of power gradually shifted from Samarkand to Bukhara. Babur, a Timurid prince, was driven out of Transoxiana by the Uzbeks and subsequently moved east to found the Mughal Empire in India.

From the 16th century onwards, the region of modern Uzbekistan was primarily divided among three Uzbek khanates:

- The Khanate of Bukhara (later the Emirate of Bukhara from 1785, ruled by the Manghits)

- The Khanate of Khiva (ruled by a branch of the Shaybanids, later the Qungrats)

- The Khanate of Kokand (emerged in the Fergana Valley in the 18th century, ruled by the Mings)

These khanates were often in conflict with each other and with neighboring Persia. Society was characterized by a feudal structure, with a landowning aristocracy and a large peasant population. The slave trade in the Emirate of Bukhara became prominent and was firmly established during this period. The cities of Bukhara, Khiva, and Kokand became important centers of Islamic culture and trade, though the overland Silk Road had declined in importance with the rise of maritime trade routes.

3.4. Russian Empire and Soviet Era

In the 19th century, the Russian Empire began its expansion into Central Asia, driven by strategic and economic interests. This period is often referred to as the "Great Game," a rivalry between the British and Russian Empires for influence in the region. The Russian conquest of the Uzbek khanates occurred gradually:

- Tashkent was captured in 1865.

- The Emirate of Bukhara and the Khanate of Khiva became Russian protectorates in 1868 and 1873, respectively, retaining nominal autonomy in internal affairs.

- The Khanate of Kokand was fully annexed in 1876 and incorporated into the Governorate-General of Turkestan, with Tashkent as its political center.

By 1912, there were 210,306 Russians living in Uzbekistan. The Swedish explorer Sven Hedin passed through Uzbekistan during his first expedition in the early 1890s.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Central Asia became a battleground. Despite early resistance from the Basmachi movement, by the early 1920s, the Bolsheviks had consolidated control. The Khanate of Khiva and the Emirate of Bukhara were transformed into the Khorezm People's Soviet Republic and the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic, respectively, before being fully absorbed.

On October 27, 1924, as part of the national delimitation in Central Asia, the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR) was created as a constituent republic of the Soviet Union. Initially, Samarkand was its capital, but in 1930, the capital was moved to Tashkent. The Soviet era brought profound social and economic transformations:

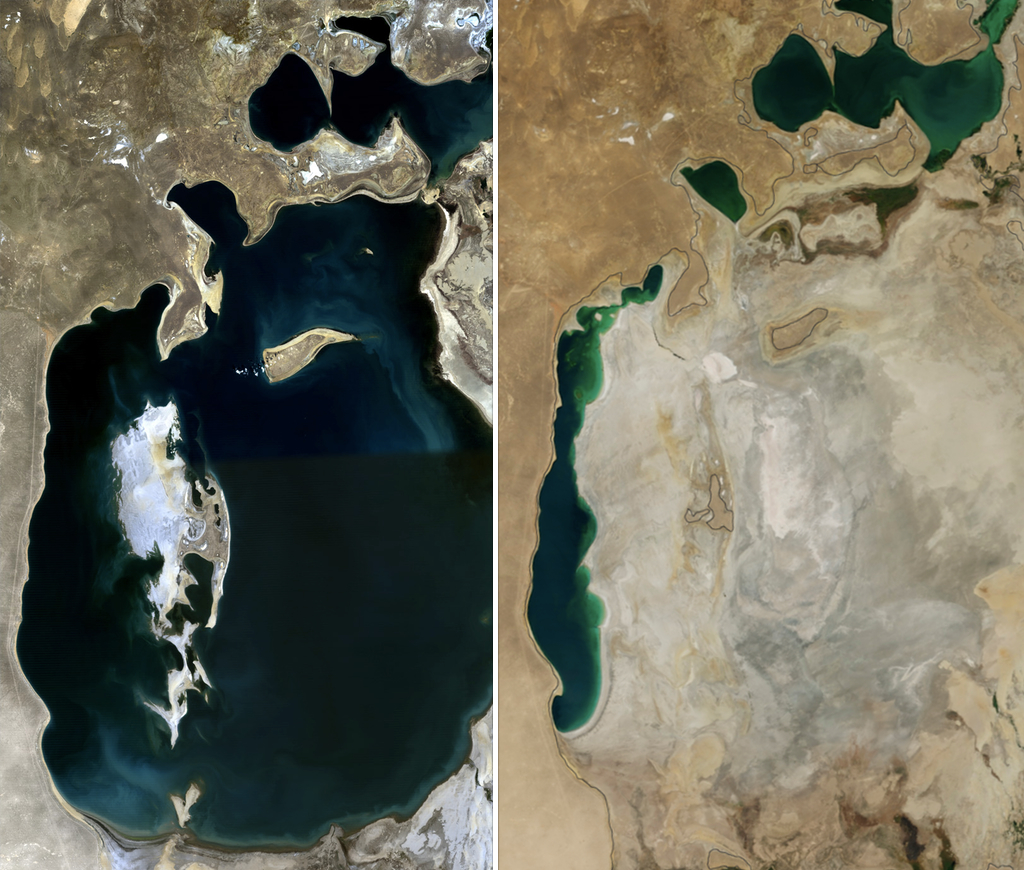

- Collectivization of agriculture:** Traditional farming was replaced by large state-run farms, heavily focused on cotton production, which had devastating environmental consequences, particularly the shrinkage of the Aral Sea.

- Industrialization:** Some industries were developed, particularly related to cotton processing and resource extraction.

- Secularization:** Religious institutions were suppressed, and an atheistic ideology was promoted, though Islamic practices persisted, often underground.

- Education and Healthcare:** Literacy rates increased significantly, and a state-run healthcare system was established.

- Russification:** The Russian language and culture were promoted, and Russian settlers were encouraged.

- Political Repression:** Dissent was suppressed, and the Communist Party maintained tight control.

- Deportations:** During World War II and before, various ethnic groups, including Crimean Tatars, Volga Germans, Chechens, Pontic Greeks, Meskhetian Turks, and Koryo-saram (Koreans), were forcibly deported to Uzbekistan and other parts of Central Asia.

During World War II (1941-1945), an estimated 1,433,230 people from Uzbekistan fought in the Red Army against Nazi Germany. As many as 263,005 Uzbek soldiers died on the Eastern Front, and 32,670 went missing in action. Some Uzbeks also fought on the German side in the Ostlegionen. In the Soviet-Afghan War (1979-1989), a number of Uzbek troops fought in neighboring Afghanistan, with at least 1,500 losing their lives.

The 1966 Tashkent earthquake caused significant destruction in the capital, leading to a massive rebuilding effort with participation from across the Soviet Union.

3.5. Post-Independence Era

On June 20, 1990, Uzbekistan declared its state sovereignty within the Soviet Union. Following the failed coup attempt in Moscow, Uzbekistan declared full independence on August 31, 1991, with September 1 proclaimed as National Independence Day. The Soviet Union was formally dissolved on December 26, 1991.

Islam Karimov, who had been First Secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan since 1989 and was elected President of the Uzbek SSR in 1990, became the first President of independent Uzbekistan. He was re-elected in 1991, 2000, 2007, and 2015, each time with over 90% of the vote in elections widely criticized by international observers as lacking democratic standards. Karimov's rule, spanning a quarter-century, was marked by authoritarianism, limited civil rights, and significant human rights abuses. His government suppressed political opposition, controlled the media, and was accused of systematic torture and the use of forced labor, particularly in the cotton industry. A key event during his presidency was the Andijan massacre in May 2005, where government troops fired on protesters, resulting in hundreds of deaths (the official figure was 187, but independent estimates were much higher). This event led to strong international condemnation and a deterioration of relations with Western countries.

Islam Karimov died in September 2016. He was succeeded by his long-time Prime Minister, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who was appointed interim president and subsequently won the presidential election in December 2016. President Mirziyoyev has initiated a series of reforms, often dubbed an "Uzbek Spring." These reforms have included:

- Economic liberalization, such as making the national currency, the som, fully convertible in September 2017, and efforts to attract foreign investment.

- Some relaxation of state control over the media and civil society.

- Measures to improve the human rights situation, including the release of some political prisoners, the abolition of exit visas in 2019, and steps to combat forced labor in the cotton sector.

- A significant improvement in relations with neighboring Central Asian countries like Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan, resolving long-standing border and water disputes.

- Constitutional reforms, with Mirziyoyev being sworn into his second term in November 2021 after winning the presidential election.

Despite these reforms, international organizations continue to express concerns about the pace of democratic development, ongoing restrictions on fundamental freedoms, and the human rights situation in Uzbekistan. However, a United Nations report in 2020 noted much progress towards achieving the UN's Sustainable Development Goals.

4. Geography

Uzbekistan is a doubly landlocked country in Central Asia, featuring vast deserts like the Kyzylkum and mountainous regions in the east. It has a continental climate with hot summers and cold winters, and faces significant environmental challenges, notably the desiccation of the Aral Sea.

4.1. Topography and Borders

Uzbekistan covers an area of 173 K mile2 (447.40 K km2), making it the 56th largest country in the world by area. It stretches 0.9 K mile (1.43 K km) from west to east and 578 mile (930 km) from north to south.

Uzbekistan is one of only two doubly landlocked countries in the world (the other being Liechtenstein), meaning it is a landlocked country entirely surrounded by other landlocked countries. Furthermore, due to its location within a series of endorheic basins, none of its rivers flow into the open sea.

The country shares borders with five nations:

- Kazakhstan to the north and northwest (along the Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan border)

- Kyrgyzstan to the northeast (along the Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan border)

- Tajikistan to the southeast (along the Tajikistan-Uzbekistan border)

- Afghanistan to the south (a short border of less than 93 mile (150 km) along the Afghanistan-Uzbekistan border)

- Turkmenistan to the southwest (along the Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan border)

Uzbekistan is the only Central Asian state to border all four other Central Asian republics.

The topography of Uzbekistan is diverse. Less than 10% of its territory consists of intensively cultivated irrigated land in river valleys (such as the Fergana Valley) and oases. The majority of the country is dominated by the vast Kyzylkum Desert (Red Sands), which occupies a large part of the central and western lowlands. In the east and southeast, the terrain becomes mountainous, with foothills and ranges extending from the Tian Shan and Pamir-Alay mountain systems. The highest point in Uzbekistan is Khazret Sultan, reaching 15 K ft (4.64 K m) above sea level, located in the southern part of the Gissar Range in the Surxondaryo Region, on the border with Tajikistan. Major rivers include the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, both of which historically fed the Aral Sea.

Uzbekistan is home to six terrestrial ecoregions: Alai-Western Tian Shan steppe, Gissaro-Alai open woodlands, Badghyz and Karabil semi-desert, Central Asian northern desert, Central Asian riparian woodlands, and Central Asian southern desert.

4.2. Climate

The climate in Uzbekistan is predominantly continental, characterized by hot, dry summers and cool, often cold, winters. There is little precipitation annually, typically ranging from 3.9 in (100 mm) to 7.9 in (200 mm).

Summer temperatures, especially in the southern and desert regions, can be extreme, with average high temperatures often reaching 104 °F (40 °C). Winter temperatures vary, with average lows around 28.4 °F (-2 °C) in many areas, but can drop to -9.399999999999999 °F (-23 °C) or even -40 °F (-40 °C) in some northern and mountainous regions.

Regional variations are significant. The deserts experience the greatest temperature extremes and lowest precipitation. The mountainous regions in the east receive more rainfall and have cooler temperatures. The Fergana Valley has a somewhat milder climate compared to other parts of the country. Spring and autumn are generally pleasant, with moderate temperatures, making them favorable seasons for agriculture and tourism.

4.3. Environmental Issues

Uzbekistan faces severe environmental challenges, largely stemming from decades of Soviet-era policies focused on maximizing cotton production and unsustainable resource management.

The shrinking of the Aral Sea is one of the world's most catastrophic environmental disasters. Once the fourth-largest inland sea, it has shrunk to about 10% of its former area. This is primarily due to the diversion of its two main feeder rivers, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, for extensive irrigation of cotton fields. The consequences include the creation of the Aralkum Desert on the former seabed, loss of biodiversity, salinization of land and water, dust storms carrying salt and pesticides, and severe health problems for the local population in regions like Karakalpakstan.

Water pollution is a major issue, with agricultural runoff carrying pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers into rivers and groundwater. Industrial waste and inadequate sewage treatment also contribute to contamination.

Soil salinization and degradation are widespread, particularly in irrigated agricultural areas. Intensive farming practices, especially for cotton, which requires large amounts of water, have led to the accumulation of salts in the soil, reducing fertility.

Desertification is advancing, exacerbated by climate change, overgrazing, and unsustainable land use practices.

Air pollution is a concern in industrial centers and urban areas, largely due to emissions from outdated industrial facilities and vehicular traffic.

One significant environmental disaster was the Sardoba Reservoir collapse in May 2020. The dam failure led to extensive flooding, covering approximately 86 K acre (35.00 K ha) of land, resulting in six deaths and the evacuation of over 111,000 people. The devastation also extended into neighboring Kazakhstan. The estimated cost of recovery exceeded 1.50 T UZS.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has highlighted the need for effective climate risk management in Uzbekistan to ensure ecological safety. Efforts are underway, with international support, to mitigate these environmental problems, including projects to restore parts of the Aral Sea ecosystem, improve water management practices, and promote sustainable agriculture. However, the scale of the challenges remains immense, deeply affecting local populations and ecosystems.

Uzbekistan has also experienced seismic activity, including notable earthquakes such as the 1902 Andijan earthquake, the 1966 Tashkent earthquake, and the 2011 Fergana Valley earthquake.

5. Politics

Uzbekistan operates as a presidential republic with a bicameral parliament, the Oliy Majlis. Its political landscape has evolved from the authoritarian rule of Islam Karimov to a period of reforms under Shavkat Mirziyoyev, though human rights concerns and democratic development challenges persist.

5.1. Government Structure

Uzbekistan's government structure is defined by its Constitution, adopted on December 8, 1992. The country operates as a presidential republic with a formal separation of powers, although in practice, the executive branch, particularly the President, holds substantial power.

- The President: The President of Uzbekistan is the head of state and holds significant executive authority. The President is directly elected by popular vote for a term that has varied (currently set at seven years following a 2023 constitutional referendum, previously five years). The President appoints and dismisses the Prime Minister and cabinet members (subject to parliamentary approval), serves as the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, and has broad powers in foreign policy and national security. Shavkat Mirziyoyev is the current president.

- The Prime Minister and Cabinet: The Prime Minister of Uzbekistan is the head of government and is appointed by the President with the approval of the Oliy Majlis (Parliament). The Prime Minister, along with the Cabinet of Ministers, manages the day-to-day affairs of the government and implements laws and presidential decrees. Abdulla Aripov is the current Prime Minister.

- The Parliament (Oliy Majlis): The Oliy Majlis is the supreme legislative body of Uzbekistan. Since a 2002 referendum and subsequent elections in 2004-2005, it has been bicameral:

- The Legislative Chamber (Lower House) consists of 150 deputies elected for five-year terms. Deputies are expected to be "full-time" legislators.

- The Senate (Upper House) consists of 100 members. Eighty-four senators are elected by regional councils, and sixteen are appointed by the President from among distinguished citizens. Senators also serve five-year terms.

- The Judiciary: The judicial system includes the Supreme Court, the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Economic Court (now part of the Supreme Court structure after reforms), and lower courts. While the constitution provides for an independent judiciary, it has historically been subject to executive influence. Reforms under President Mirziyoyev have aimed to strengthen judicial independence and fairness.

Uzbekistan is divided into 12 regions (viloyatlar), one autonomous republic (Karakalpakstan), and the independent city of Tashkent.

5.2. Domestic Political Situation

Since gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Uzbekistan's domestic political scene was dominated by its first president, Islam Karimov, until his death in 2016. His rule was characterized by a highly centralized, authoritarian system with limited political pluralism and suppression of dissent. Elections during his tenure were widely criticized by international observers as not meeting democratic standards. Karimov's first presidential term was extended to 2000 via a referendum, and he was re-elected in 2000, 2007, and 2015, each time receiving over 90% of the vote.

Following Karimov's death, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, then Prime Minister, became interim president and was subsequently elected president in December 2016. Mirziyoyev initiated a period of reforms often referred to as the "Uzbek Spring." These reforms have included:

- Economic liberalization, including currency convertibility and efforts to attract foreign investment.

- Some relaxation of state control over the media and increased space for public discussion.

- Release of some political prisoners and efforts to improve the country's human rights image.

- Administrative reforms aimed at reducing bureaucracy and combating corruption.

- Improved relations with neighboring countries.

Major political parties in Uzbekistan are generally pro-government. These include the Uzbekistan Liberal Democratic Party (OʻzLiDeP, Mirziyoyev's party), the Milliy Tiklanish (National Revival) Democratic Party, the People's Democratic Party of Uzbekistan (XDP, formerly the Communist Party), the Adolat (Justice) Social Democratic Party, and the Ecological Party. Genuine opposition parties face significant obstacles to registration and operation.

The electoral system has seen some technical improvements, but concerns about the overall fairness and competitiveness of elections remain. Mirziyoyev was re-elected in the 2021 presidential election and secured a further term in a snap presidential election in July 2023 after a constitutional referendum that, among other changes, extended presidential terms to seven years and reset his previous terms.

Challenges to democratic development include a historically weak civil society, persistent restrictions on fundamental freedoms, and the dominance of the executive branch. While reforms have brought some positive changes, transforming the deeply entrenched political system remains a long-term process.

5.3. Human Rights

The human rights situation in Uzbekistan has long been a subject of international concern, particularly during the rule of President Islam Karimov (1991-2016). Non-governmental human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, as well as entities like the United States Department of State and the Council of the European Union, consistently defined Uzbekistan under Karimov as an "authoritarian state with limited civil rights," citing widespread violations.

Key human rights issues have included:

- Torture and Ill-treatment: Systematic use of torture and ill-treatment in detention facilities was widely reported.

- Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions: Critics of the government, human rights activists, independent journalists, and members of unapproved religious groups faced arbitrary arrest and politically motivated imprisonment.

- Restrictions on Freedoms: Severe restrictions were placed on freedom of speech, press, assembly, and association. Independent media was largely suppressed.

- Religious Freedom: While the constitution guarantees religious freedom, unregistered religious groups faced harassment, and individuals were prosecuted for "extremist" religious activity.

- Forced Labor: The systematic use of forced labor, including child labor (though largely eradicated in recent years) and forced adult labor, in the annual cotton harvest was a major concern, leading to international boycotts.

- Andijan Unrest (May 2005): Government forces opened fire on protesters in the city of Andijan, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of civilians (official figures were much lower). The government characterized the event as an anti-terrorist operation and rejected calls for an independent international investigation. This event led to a significant deterioration in relations with Western countries and increased repression domestically.

- Forced Sterilization: Reports emerged of a government program involving the forced sterilization of women, particularly in rural areas, as a means of population control.

- LGBT Rights: Male homosexuality remains criminalized under Uzbek law, punishable by fines or imprisonment of up to three years.

Since President Shavkat Mirziyoyev came to power in 2016, there have been some positive developments. His administration has taken steps to address some human rights concerns:

- Release of numerous political prisoners and human rights defenders.

- Abolition of Soviet-style exit visas in 2019.

- Increased engagement with international human rights organizations and UN bodies.

- Significant progress in eradicating systematic forced labor in the cotton industry, leading to the lifting of some international boycotts. The International Labour Organization (ILO) confirmed in 2022 that systemic child labor and systemic forced labor had been eliminated in the Uzbek cotton harvest.

- Some easing of restrictions on media and freedom of expression, though self-censorship remains prevalent.

Despite these reforms, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch continue to report on ongoing human rights issues, including restrictions on free speech, the lack of genuine political pluralism, impunity for past abuses, and concerns about the fairness of the justice system. The Freedom House has consistently ranked Uzbekistan near the bottom of its Freedom in the World ranking, though there has been some improvement in its scores in recent years. The impact of reforms on vulnerable groups and minorities is an area of ongoing observation.

6. Foreign Relations

Uzbekistan pursues a multi-vector foreign policy, balancing relations with neighbors like Russia and China, as well as global powers such as the United States and the European Union. It is an active member of international bodies including the UN, SCO, and CIS.

6.1. Relations with Neighboring Countries and Major Powers

Uzbekistan's relations with its Central Asian neighbors (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan) have historically been complex, marked by disputes over borders, water resources, and ethnic enclaves. Under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, there has been a significant improvement in regional diplomacy, with active efforts to resolve outstanding issues and enhance cooperation in trade, transport, and security. Relations with Afghanistan have also seen positive developments, with Uzbekistan playing a role in regional peace initiatives and providing humanitarian aid.

Russia remains a key partner for Uzbekistan, reflecting deep historical, economic, and security ties. Russia is a major trading partner, a source of investment, and a destination for Uzbek labor migrants. Military and security cooperation continues, though Uzbekistan withdrew from the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) in 2012 (having previously suspended membership in 1999 and rejoined in 2006).

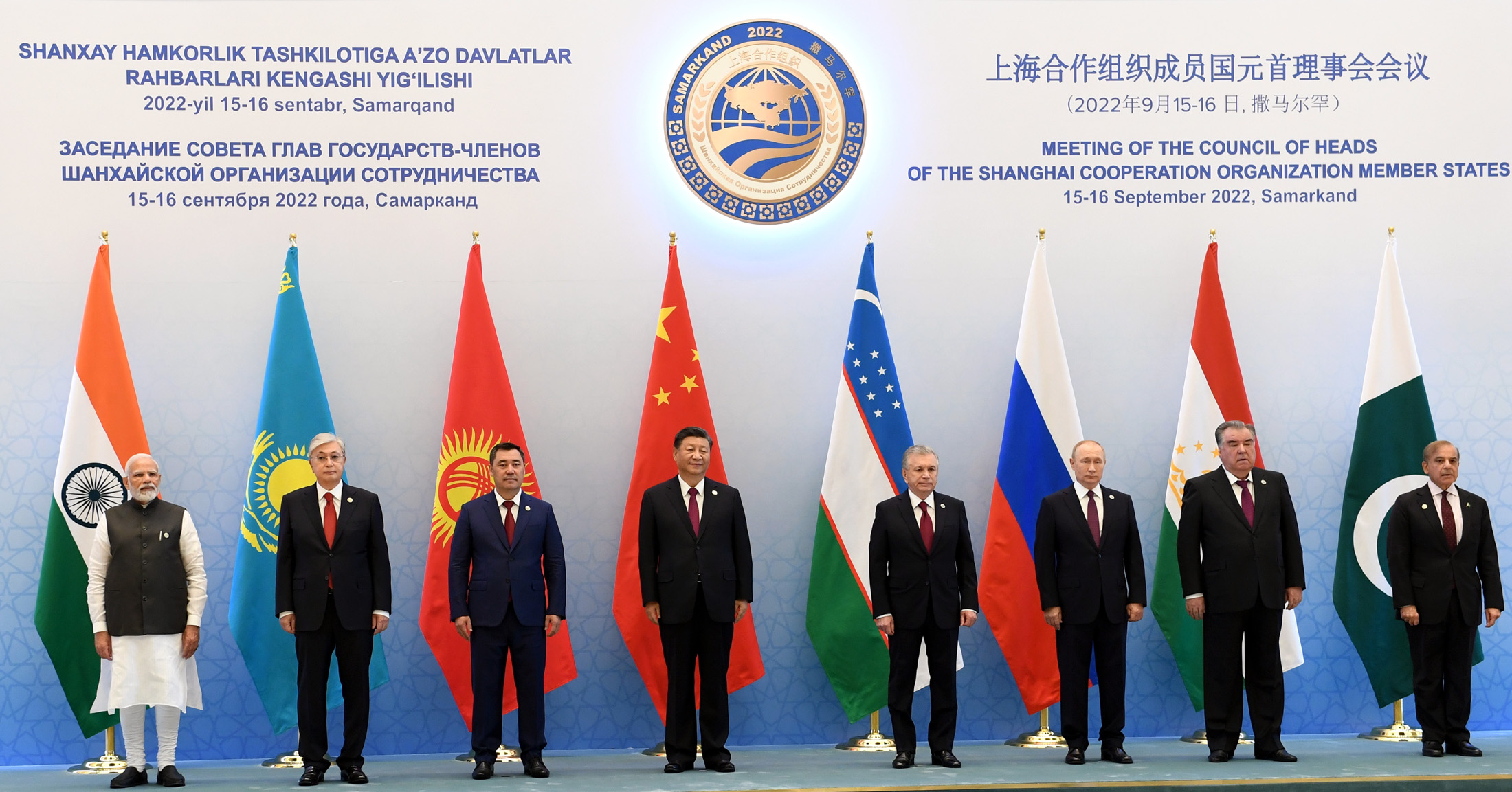

China has emerged as a crucial economic partner, particularly through its Belt and Road Initiative. China is a major investor in Uzbekistan's infrastructure, energy, and transport sectors, and a significant trading partner. Both countries cooperate within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

United States relations have fluctuated. After 9/11, Uzbekistan became a key partner in the US-led campaign in Afghanistan, hosting a US airbase at Karshi-Khanabad (K2). However, relations soured significantly after the Andijan unrest and US criticism of Uzbekistan's human rights record, leading to the closure of the K2 base to US forces in 2005. Under President Mirziyoyev, there has been a cautious rapprochement, with renewed dialogue on security, economic cooperation, and human rights.

The European Union (EU) is an important trading partner and provider of development assistance. Relations were strained after the Andijan events, leading to EU sanctions (later lifted). The EU engages with Uzbekistan through its Central Asia strategy, focusing on areas such as trade, investment, governance, and human rights.

Uzbekistan maintains diplomatic relations with many other countries, including Turkey (with which it shares linguistic and cultural ties through the Organization of Turkic States), South Korea (a significant investor), and countries in the Middle East.

6.2. International Organization Membership

Uzbekistan is an active participant in numerous international and regional organizations:

- United Nations (UN):** Joined on March 2, 1992. Uzbekistan participates in various UN agencies and programs. A UN report in 2020 noted much progress toward achieving the UN's Sustainable Development Goals.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO):** A founding member. Uzbekistan hosts the SCO's Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) in Tashkent. The SCO focuses on regional security, counter-terrorism, and economic cooperation. Samarkand hosted a major SCO summit in 2022.

- Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS):** Joined in December 1991. While participating in economic and humanitarian cooperation, Uzbekistan has maintained a degree of independence within the CIS framework, notably by withdrawing from its collective security arrangements.

- Organization of Turkic States (OTS):** Became a full member in 2019, strengthening ties with other Turkic-speaking countries.

- Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC):** A member, reflecting its Muslim-majority population and cultural heritage.

- Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO):** A regional organization comprising Central Asian countries, Iran, Turkey, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Azerbaijan, focused on promoting economic, technical, and cultural cooperation.

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE):** A participating state. The OSCE is involved in monitoring elections and promoting democratic reforms and human rights.

- World Trade Organization (WTO):** Uzbekistan applied for WTO membership in December 1994 and holds observer status. The accession process has been lengthy but has seen renewed momentum under President Mirziyoyev, with the Working Party on Uzbekistan's accession resuming formal meetings.

Uzbekistan was previously a member of the GUAM alliance (Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Moldova), joining in 1999 (making it GUUAM) but withdrew in 2005. It also joined the Central Asian Cooperation Organization (CACO) in 2002, which later merged with the Eurasian Economic Community (which itself ceased to exist with the formation of the Eurasian Economic Union, of which Uzbekistan is an observer state since December 2020).

7. Military

The Armed Forces of the Republic of Uzbekistan are the largest in Central Asia, with approximately 65,000 active servicemen. The military structure is largely inherited from the Turkestan Military District of the former Soviet Army. The armed forces consist of the Army, Air and Air Defence Forces, National Guard, and border troops.

Uzbekistan's defense policy focuses on maintaining sovereignty, territorial integrity, and regional stability. The country has adopted a policy of neutrality and non-alignment with military blocs, as enshrined in its foreign policy concept. While it was a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) at different times, it suspended its membership in June 2012 and has not rejoined.

Military equipment is predominantly of Soviet and Russian origin, though there have been efforts to modernize and acquire some equipment from other sources, including the United States and China. The government spends approximately 3.7% of its GDP on the military (older estimates, recent figures vary). It has received Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and other security assistance from various partners.

Uzbekistan has cooperated with international partners on security issues, including counter-terrorism and border security. Following the September 11, 2001 attacks, Uzbekistan approved the U.S. Central Command's request for access to the Karshi-Khanabad (K2) air base for operations in Afghanistan. However, after the Andijan unrest and subsequent criticism from the U.S., Uzbekistan demanded the withdrawal of U.S. troops, which was completed in November 2005. In 2020, reports emerged suggesting the former US base might have been contaminated with radioactive materials, a claim denied by the Uzbek government.

The government has accepted the arms control obligations of the former Soviet Union and acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear state. It supported an active program by the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) in western Uzbekistan (Nukus and Vozrozhdeniye Island) related to the dismantling of former Soviet biological weapons facilities. The military plays a significant role in ensuring security in a region facing challenges such as drug trafficking, religious extremism, and instability in neighboring Afghanistan.

8. Administrative Divisions

Uzbekistan is divided into twelve regions, one autonomous republic (Karakalpakstan), and the independent city of Tashkent. Major urban centers include the capital Tashkent, historic Silk Road cities like Samarkand and Bukhara, and regional hubs such as Andijan and Nukus.

Here is a list of the administrative divisions:

| Division | Capital City | Area (km2) | Population (1 January 2024) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andijan Region Andijon ViloyatiAndijon ViloyatiUzbek | Andijan AndijonAndijonUzbek | 1.7 K mile2 (4.30 K km2) | 3,394,400 |

| Bukhara Region Buxoro ViloyatiBuxoro ViloyatiUzbek | Bukhara BuxoroBuxoroUzbek | 16 K mile2 (41.94 K km2) | 2,044,000 |

| Fergana Region Fargʻona ViloyatiFargʻona ViloyatiUzbek | Fergana FargʻonaFargʻonaUzbek | 2.7 K mile2 (7.00 K km2) | 4,061,500 |

| Jizzakh Region Jizzax ViloyatiJizzax ViloyatiUzbek | Jizzakh JizzaxJizzaxUzbek | 8.2 K mile2 (21.18 K km2) | 1,507,400 |

| Republic of Karakalpakstan Qoraqalpogʻiston RespublikasiQoraqalpogʻiston RespublikasiUzbek (Qaraqalpaqstan RespublikasıQaraqalpaqstan RespublikasıKara-Kalpak) | Nukus NukusNukusUzbek (NoʻkisNoʻkisKara-Kalpak) | 62 K mile2 (161.36 K km2) | 2,002,700 |

| Qashqadaryo Region Qashqadaryo ViloyatiQashqadaryo ViloyatiUzbek | Qarshi QarshiQarshiUzbek | 11 K mile2 (28.57 K km2) | 3,560,600 |

| Xorazm Region Xorazm ViloyatiXorazm ViloyatiUzbek | Urgench UrganchUrganchUzbek | 2.5 K mile2 (6.46 K km2) | 1,995,600 |

| Namangan Region Namangan ViloyatiNamangan ViloyatiUzbek | Namangan NamanganNamanganUzbek | 2.8 K mile2 (7.18 K km2) | 3,066,100 |

| Navoiy Region Navoiy ViloyatiNavoiy ViloyatiUzbek | Navoiy NavoiyNavoiyUzbek | 42 K mile2 (109.38 K km2) | 1,075,300 |

| Samarqand Region Samarqand ViloyatiSamarqand ViloyatiUzbek | Samarkand SamarqandSamarqandUzbek | 6.5 K mile2 (16.77 K km2) | 4,208,500 |

| Surxondaryo Region Surxondaryo ViloyatiSurxondaryo ViloyatiUzbek | Termez TermizTermizUzbek | 7.8 K mile2 (20.10 K km2) | 2,877,100 |

| Sirdaryo Region Sirdaryo ViloyatiSirdaryo ViloyatiUzbek | Guliston GulistonGulistonUzbek | 1.7 K mile2 (4.28 K km2) | 914,000 |

| Tashkent (City) Toshkent ShahriToshkent ShahriUzbek | Tashkent ToshkentToshkentUzbek | 126 mile2 (327 km2) | 3,040,800 |

| Tashkent Region Toshkent ViloyatiToshkent ViloyatiUzbek | Nurafshon NurafshonNurafshonUzbek | 5.9 K mile2 (15.26 K km2) | 3,051,800 |

The capital of Tashkent Region was Tashkent until 2017, when it was moved to Nurafshon.

8.1. Major Cities

Uzbekistan has several historically and economically significant cities. The most prominent ones include:

- Tashkent (ToshkentToshkentUzbek): The capital and largest city of Uzbekistan, Tashkent is a major economic, cultural, and transportation hub in Central Asia. It has a history spanning over 2,000 years and features a mix of ancient Islamic architecture, Soviet-era buildings, and modern developments. Key sites include the Chorsu Bazaar, Kukeldash Madrasah, and the Tashkent Metro. It serves as the administrative center of Tashkent City.

- Samarkand (SamarqandSamarqandUzbek): One of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central Asia, Samarkand was a key city on the Silk Road and the magnificent capital of the Timurid Empire. It is renowned for its stunning Islamic architecture, including Registan square, the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, the Gur-e-Amir mausoleum, and the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis. Samarkand is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Bukhara (BuxoroBuxoroUzbek): Another ancient Silk Road city, Bukhara has long been a center of Islamic scholarship, culture, and trade. Its historic center, also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, features numerous mosques, madrasahs, and the famous Kalyan Minaret. Key sites include the Samanid Mausoleum and the Lyab-i Hauz complex.

- Khiva (XivaXivaUzbek): Located in the Khorezm oasis, Khiva is known for Itchan Kala, its walled inner town, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Itchan Kala preserves over 50 historic monuments and hundreds of old houses, presenting a remarkably intact example of a medieval Central Asian city.

- Andijan (AndijonAndijonUzbek): A major city in the Fergana Valley, Andijan is an important industrial and agricultural center. It is known as the birthplace of Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire.

- Namangan (NamanganNamanganUzbek): Also located in the Fergana Valley, Namangan is a significant agricultural and crafts center.

- Nukus (NukusNukusUzbek, NoʻkisNoʻkisKara-Kalpak): The capital of the autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan. Nukus is known for the Savitsky Museum, which houses a unique collection of Russian avant-garde art.

- Fergana (FargʻonaFargʻonaUzbek): The administrative center of the Fergana Region, it is a relatively newer city compared to others, founded during the Russian colonial era. It serves as an industrial hub for the fertile Fergana Valley.

- Qarshi (QarshiQarshiUzbek): An important city in southern Uzbekistan, located in an oasis on the Qashqadaryo River. It has historical significance and is a center for natural gas processing.

- Termez (TermizTermizUzbek): Uzbekistan's southernmost city, located on the Amu Darya river border with Afghanistan. It has a rich Buddhist and Islamic history.

- Kokand (QoʻqonQoʻqonUzbek): Formerly the capital of the powerful Khanate of Kokand, it was a major trade and religious center in the Fergana Valley.

- Shahrisabz (ShahrisabzShahrisabzUzbek): The birthplace of Timur, its historic center is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, featuring monumental ruins from the Timurid era, such as the Ak-Saray Palace.

These cities reflect Uzbekistan's long and diverse history, blending ancient traditions with Soviet influences and modern development.

| City | Region | Population (2023 est.) |

|---|---|---|

| Tashkent | Tashkent City | 2,955,700 |

| Namangan | Namangan Region | 678,200 |

| Samarkand | Samarqand Region | 573,200 |

| Andijan | Andijan Region | 468,100 |

| Nukus | Karakalpakstan | 334,600 |

| Fergana | Fergana Region | 322,600 |

| Bukhara | Bukhara Region | 289,189 |

| Qarshi | Qashqadaryo Region | 288,900 |

| Kokand | Fergana Region | 303,600 |

| Margilan | Fergana Region | 242,500 |

9. Economy

Uzbekistan's economy is transitioning from a state-controlled system to a market-oriented one, with key industries including agriculture (notably cotton), mining (gold, natural gas), manufacturing, and tourism. The country is liberalizing foreign trade but faces challenges like corruption and commodity dependence.

9.1. Economic Structure and Policies

Upon gaining independence, Uzbekistan initially adopted a gradualist approach to economic reform, emphasizing state control, import substitution, and energy self-sufficiency. This "Uzbekistan Economic Model" aimed to avoid the economic shocks experienced by some other post-Soviet states but also led to slower structural reforms and limited foreign investment. Corruption was, and remains, a significant challenge, with a 2006 International Crisis Group report suggesting that revenues from key exports were often not benefiting the general populace. The Economist Intelligence Unit noted government hostility towards an independent private sector.

Since 2016, under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan has embarked on a more ambitious phase of economic liberalization. Key policies include:

- Currency Liberalization:** In September 2017, the Uzbek som became fully convertible at market rates, a major step towards integrating with the global economy and attracting foreign investment.

- Privatization and State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) Reform:** Efforts are underway to reduce the state's role in the economy by privatizing SOEs and improving their corporate governance.

- Improving the Investment Climate:** Measures to simplify business registration, protect investor rights, and reduce regulatory burdens. Uzbekistan improved its ranking in the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business report.

- Tax Reform:** Modernizing the tax system to make it more transparent and business-friendly.

- Foreign Trade Liberalization:** Reducing import tariffs and non-tariff barriers, and actively pursuing World Trade Organization (WTO) membership.

The country has shown robust GDP growth, averaging 4% per year between 1998 and 2003, and accelerating to 7-8% annually in subsequent years. According to IMF estimates, the GDP in 2008 was almost double its 1995 value. Inflation, which was rampant in the early 1990s (around 1000% annually from 1992-1994), was brought under control with IMF guidance, falling to 22% by 2002 and generally remaining in single digits or low double digits since then, though it saw a rise to nearly 40% in 2010 and was around 18.9% in 2017 after some price liberalizations. From 2018 to 2021, Uzbekistan received a BB- sovereign credit rating from both S&P and Fitch. The Brookings Institution noted Uzbekistan's large liquid assets, high economic growth, low public debt, and (historically) low GDP per capita. Projections suggest Uzbekistan could be one of the fastest-growing economies in the coming decades.

Social equity remains a concern. While official unemployment is low, underemployment, especially in rural areas, is estimated to be at least 20%. The government aims for economic development that also improves living standards and reduces income inequality, though these remain significant challenges.

9.2. Major Industries

Uzbekistan's economy is diversified, with key sectors including agriculture, mining and energy, manufacturing, and a growing tourism industry.

9.2.1. Agriculture

Agriculture in Uzbekistan employs about 19-27% of the labor force and contributes around 17-20% to the GDP. Approximately 11 M acre (4.40 M ha), or about 10% of Uzbekistan's total area, is cultivable land, mostly irrigated.

- Cotton:** Historically the dominant crop, Uzbekistan was the world's seventh-largest producer and fifth-largest exporter of cotton (as of 2011). However, production has been linked to severe environmental problems (e.g., Aral Sea desiccation) and, in the past, widespread forced labor, including child labor. Significant reforms have been undertaken to eradicate forced labor, leading to the lifting of international boycotts by entities like the Cotton Campaign in 2022. The government is also diversifying away from cotton monoculture. Uzbek cotton pulp has reportedly been exported to Russia for use in explosives and gunpowder, particularly after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

- Grains:** Wheat is a major crop, cultivated for domestic consumption as part of food security policies.

- Fruits and Vegetables:** Uzbekistan is a significant producer of fruits (apricots, grapes, apples, melons) and vegetables (tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots). Horticulture is a growing export sector.

- Livestock:** Sheep (for mutton and wool), cattle, and poultry are important. Sericulture (silk production) is also a traditional agricultural activity.

Challenges in agricultural reform include improving water management, addressing soil salinity, modernizing farming techniques, and ensuring sustainable labor practices.

9.2.2. Mining and Energy

Uzbekistan is rich in mineral resources.

- Gold:** The country has substantial gold reserves (estimated 1.70 K t, 12th largest in the world) and is a major producer (from 80 t to 102 t annually, ranking among the top 10 globally). The Muruntau gold mine is one of the largest open-pit gold mines in the world.

- Uranium:** Uzbekistan ranks among the top countries for uranium reserves and production (7th globally for production, around 2.40 K t annually).

- Natural Gas:** The national gas company, Uzbekneftegas, is a significant producer (annual output of 78 B yd3 (60.00 B m3) to 92 B yd3 (70.00 B m3)), ranking around 11th-15th globally. The country has 194 hydrocarbon deposits. Major fields are in Kokdumalak and Shurtan.

- Other Minerals:** Deposits of copper (10th largest deposits), silver, lead, zinc, molybdenum, tungsten, and coal are also significant.

- Energy Sector:** With its large natural gas reserves and Soviet-era power generation facilities, Uzbekistan is the largest electricity producer in Central Asia. The energy sector is crucial for domestic consumption and exports. Key international players involved in Uzbekistan's energy sector include China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), Petronas, Korea National Oil Corporation, Gazprom, and Lukoil.

Environmental and social impacts of resource extraction, including land degradation and water use, are considerations in the sector's development.

9.2.3. Manufacturing

The manufacturing sector in Uzbekistan includes:

- Automotive:** GM Uzbekistan (formerly UzDaewooAuto), a joint venture with General Motors, is a major car manufacturer, producing vehicles primarily for the domestic market and export to CIS countries.

- Textiles:** Leveraging its cotton production, the textile and garment industry is a significant employer and exporter. Efforts are ongoing to move up the value chain from raw cotton to finished textile products.

- Food Processing:** Processing of locally grown agricultural products (fruits, vegetables, grains, dairy).

- Chemicals:** Production of fertilizers (nitrogen, phosphate) and other chemical products.

- Machinery and Equipment:** Production of agricultural machinery, mining equipment, and components for various industries.

Challenges include modernizing technology, improving product quality, and increasing competitiveness in international markets.

9.2.4. Tourism

Tourism in Uzbekistan is a growing sector, leveraging the country's rich historical and cultural heritage, particularly sites along the ancient Silk Road.

- Key Destinations:** Historic cities like Samarkand, Bukhara, Khiva, and Shahrisabz (all UNESCO World Heritage sites) are major attractions, drawing tourists with their ancient mosques, madrasahs, mausoleums, and vibrant bazaars. Other attractions include the Fergana Valley (known for crafts), the Aral Sea region (for its unique environmental story), and mountainous areas for ecotourism.

- Government Policies:** The government has actively promoted tourism by easing visa requirements for many countries, investing in tourism infrastructure (hotels, transport), and marketing Uzbekistan as a tourist destination.

- Current Status:** The tourism industry has seen significant growth in recent years (pre-COVID-19 pandemic), contributing to foreign exchange earnings and employment. Efforts are focused on diversifying tourism offerings beyond cultural tourism to include ecotourism, adventure tourism, and MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, and Exhibitions) tourism.

9.3. Foreign Trade

Uzbekistan's foreign trade has been evolving with its economic reforms and efforts to integrate into the global economy.

- Major Export Items:** Traditionally, cotton fiber and gold have been major exports. In recent years, natural gas, energy products, textiles, agricultural products (fruits, vegetables), metals (copper, zinc), and some manufactured goods (cars) have become increasingly important.

- Major Import Items:** Machinery and equipment, chemical products, foodstuffs, metals, and consumer goods.

- Trade Partners:** Key trading partners include Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Turkey, South Korea, and European Union countries (like Germany). Trade with neighboring Central Asian countries has increased significantly since 2016.

- Balance of Trade:** Uzbekistan has often maintained a trade surplus, supported by exports of commodities like gold and natural gas. The current account turned into a large surplus (9-11% of GDP) between 2003 and 2005. Foreign exchange reserves, including gold, totaled around 25.00 B USD in 2018 and 13.00 B USD in 2010.

- WTO Accession:** Uzbekistan applied for World Trade Organization (WTO) membership in December 1994 and holds observer status. The accession process has been lengthy but has been revitalized under President Mirziyoyev's reform agenda, with formal meetings of the Working Party resuming.

- Trade Policies:** The government has historically pursued import substitution policies and restricted imports through high tariffs and non-tariff barriers. However, recent reforms aim to liberalize trade, reduce import duties (e.g., excise taxes on foreign cars were removed in 2020 for a period), and promote export diversification. Uzbekistan has Bilateral Investment Treaties with about fifty countries.

The Tashkent Stock Exchange (Republican Stock Exchange, RSE) opened in 1994. While its volume has grown, the capital market remains relatively underdeveloped.

9.4. Economic Challenges

Despite progress, Uzbekistan's economy faces several significant challenges:

- Corruption:** Pervasive corruption remains a major obstacle to economic development and foreign investment. While the government has launched anti-corruption initiatives, effective implementation and systemic change are ongoing challenges. The country ranked 158th out of 180 in the 2018 Corruption Perception Index. High-profile scandals involving government contracts and international companies (e.g., TeliaSonera) have highlighted these risks.

- Difficulties in Attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI):** Historically, a challenging business environment, currency conversion issues (largely resolved since 2017), and concerns about rule of law have deterred FDI. While FDI inflows have increased with recent reforms, sustained efforts are needed to improve the investment climate further.

- Income Inequality and Poverty:** Despite economic growth, income inequality and poverty persist, particularly in rural areas. Ensuring that growth is inclusive and benefits all segments of the population is a key social and economic challenge. The Asian Development Bank estimated in 2011 that 44.42% of the population lived on less than 2 USD per day in 2010.

- Dependence on Commodities:** The economy remains reliant on exports of commodities like gold, natural gas, and cotton, making it vulnerable to global price fluctuations. Diversification into higher value-added industries is a priority.

- Infrastructure Deficiencies:** While improving, infrastructure (transport, energy, digital) requires further modernization and investment to support sustained economic growth.

- Weak Institutions and Rule of Law:** Strengthening institutions, ensuring the independence of the judiciary, and upholding the rule of law are crucial for long-term economic stability and attracting investment.

- Environmental Sustainability:** Addressing the severe environmental problems, particularly related to water scarcity and land degradation, is critical for sustainable economic development, especially in the agricultural sector.

- Human Capital Development:** While literacy rates are high, improving the quality of education and vocational training to meet the demands of a modernizing economy is essential.

Addressing these challenges is central to Uzbekistan's ongoing reform efforts and its aspirations for sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

10. Demographics and Society

Uzbekistan is Central Asia's most populous nation, with a young, multi-ethnic population predominantly composed of Uzbeks. Uzbek is the official language, though Russian is widely spoken. Islam is the majority religion. The country has high literacy rates but faces challenges in its education and healthcare systems.

10.1. Demographics

As of 2022-2023, Uzbekistan's population is estimated to be around 36 million, constituting nearly half of Central Asia's total population. The population is relatively young, though it is slowly aging; in 2020, approximately 23.1% of the population was under the age of 16. The total fertility rate has declined from Soviet-era highs but remains above replacement level.

The population density varies significantly, with the highest concentrations in the Fergana Valley, Tashkent region, and other irrigated oases. Large desert areas are sparsely populated. The urbanization rate is around 50-51%, meaning a significant portion of the population still resides in rural areas.

Life expectancy in Uzbekistan is around 75 years on average (72 for men, 78 for women, as of 2016).

A national census, the first in over 30 years, was planned but postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and logistical challenges; it is now scheduled for 2025-2026, with results expected in 2027. The last Soviet census providing detailed ethnic data was in 1989.

10.2. Ethnic Groups

Uzbekistan is a multi-ethnic country. According to official 2020-2021 estimates:

- Uzbeks** constitute the majority, at approximately 83-84.5% of the population. They are a Turkic people and their language, Uzbek, is the official state language.

- Tajiks** are the largest minority group. Official figures place their share at around 4.8-5%. However, this figure is contentious, with some Western scholars and Tajik sources suggesting the actual percentage could be much higher, possibly between 10% and 30%. Tajiks are an Iranian people and speak Tajik, a variety of Persian. They are concentrated in cities like Samarkand and Bukhara, as well as in regions bordering Tajikistan. The discrepancy in numbers is partly attributed to Soviet-era census practices where some Tajiks may have been registered as Uzbeks.

- Kazakhs** form about 2.4-3% of the population, primarily residing in regions bordering Kazakhstan.

- Russians** make up about 2.1-2.3%. Their numbers have significantly decreased since independence due to emigration, primarily for economic reasons. In 1989, Russians constituted 5.5% of the population, and in the 1970s, nearly 1.5 million Russians (12.5%) lived in Uzbekistan, with Russians and Ukrainians forming over half the population of Tashkent during the Soviet period.

- Karakalpaks** are another Turkic group, comprising about 2.2% of the population. They predominantly live in the autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan in northwestern Uzbekistan.

- Tatars** (primarily Volga Tatars and Crimean Tatars) constitute about 0.5-1.5%. Approximately 100,000 Crimean Tatars continue to live in Uzbekistan, descendants of those deported in the 1940s.

- Koryo-saram** (ethnic Koreans) number around 180,000-200,000 (about 0.6-0.7%). They are descendants of Koreans forcibly relocated from the Russian Far East by Stalin in 1937-1938. They have largely integrated into Uzbek society while maintaining some cultural traditions.

Inter-ethnic relations have generally been peaceful, though tensions have occurred historically, such as the Fergana pogroms. The government officially promotes inter-ethnic harmony. Minority rights, including language and cultural rights, are constitutionally guaranteed, but practical implementation can vary.

10.3. Languages

The official state language of Uzbekistan is Uzbek, a Turkic language belonging to the Karluk branch. Since 1992, Uzbek is officially written in the Latin alphabet, transitioning from the Cyrillic script used during the Soviet era.

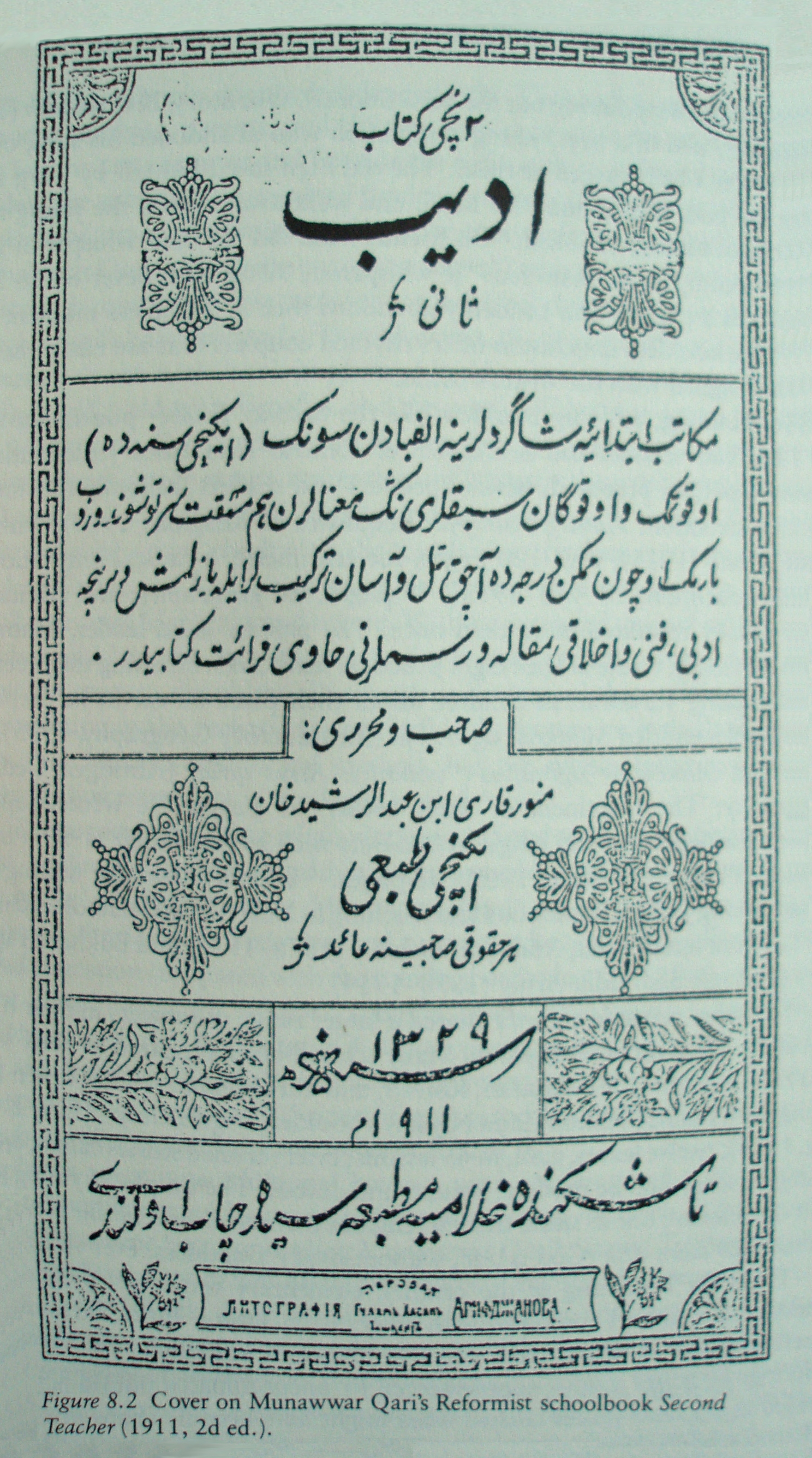

- Uzbek Script Transition:** Before the 1920s, the written form of Uzbek (then often called Turki or Chagatai) used the Arabic script (specifically Nastaʿlīq). In 1926, a Latin-based alphabet was introduced, followed by several revisions. In 1940, the Cyrillic alphabet was imposed and remained in use until after independence. In 1993, Uzbekistan officially adopted a Latin-based script, which was modified in 1996. Educational institutions now primarily teach the Latin script. However, the Cyrillic script is still commonly used, especially by the older generation and in some media and publications. Many signs throughout the country are in both Uzbek and Russian. A 2020 draft bill to regulate the exclusive use of Uzbek in government affairs, which included potential fines for using other languages, faced criticism from Russia and was not fully implemented.

Russian is not an official language but serves as an important lingua franca, especially in urban areas, business, science, and for inter-ethnic communication. It is spoken by a significant portion of the population as a first or second language (approximately 14.2% as a first language according to some older estimates, with many more having proficiency). Digital information from the government is often bilingual (Uzbek and Russian). Many Uzbeks in urban areas feel comfortable speaking Russian.

Tajik, a variety of Persian, is widespread in cities like Bukhara and Samarkand due to their large ethnic Tajik populations. It is also spoken in pockets in the Fergana Valley (e.g., Sokh), Tashkent region, and other areas. Estimates of Tajik speakers vary widely, with some sources suggesting that 25-30% of Uzbekistan's population may use Tajik, reflecting the disputed figures for the ethnic Tajik population. Tajik language education has faced restrictions.

Karakalpak, another Turkic language (from the Kipchak branch, closer to Kazakh), is spoken by about half a million people, primarily in the Republic of Karakalpakstan, where it has official status alongside Uzbek.

Other minority languages spoken include Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Turkmen, Koryo-mar (Korean dialect), Armenian, and others.

There are no language requirements to attain citizenship in Uzbekistan. The government promotes Uzbek as the state language, but the practical role of Russian remains significant.

10.4. Religion

Uzbekistan is a secular state according to its constitution (Article 61), which stipulates the separation of religious organizations from the state and their equality before the law. The state is not to interfere in the activity of religious associations.

Islam is the dominant religion. Estimates from various sources indicate that Muslims constitute around 88-96.7% of the population.

- The vast majority of Uzbek Muslims are Sunni of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence.

- There is a small Shia minority (estimated around 1-5%).

- Sufism also has a historical presence in the region.

Christianity is the second-largest religion, practiced by approximately 2.3-9% of the population.

- The largest Christian denomination is the Russian Orthodox Church, primarily serving the ethnic Russian, Ukrainian, and other Slavic minorities.

- Other Christian groups include Roman Catholics, various Protestant denominations (Baptists, Pentecostals, Lutherans, Seventh-day Adventists), and Armenian Apostolic Christians.

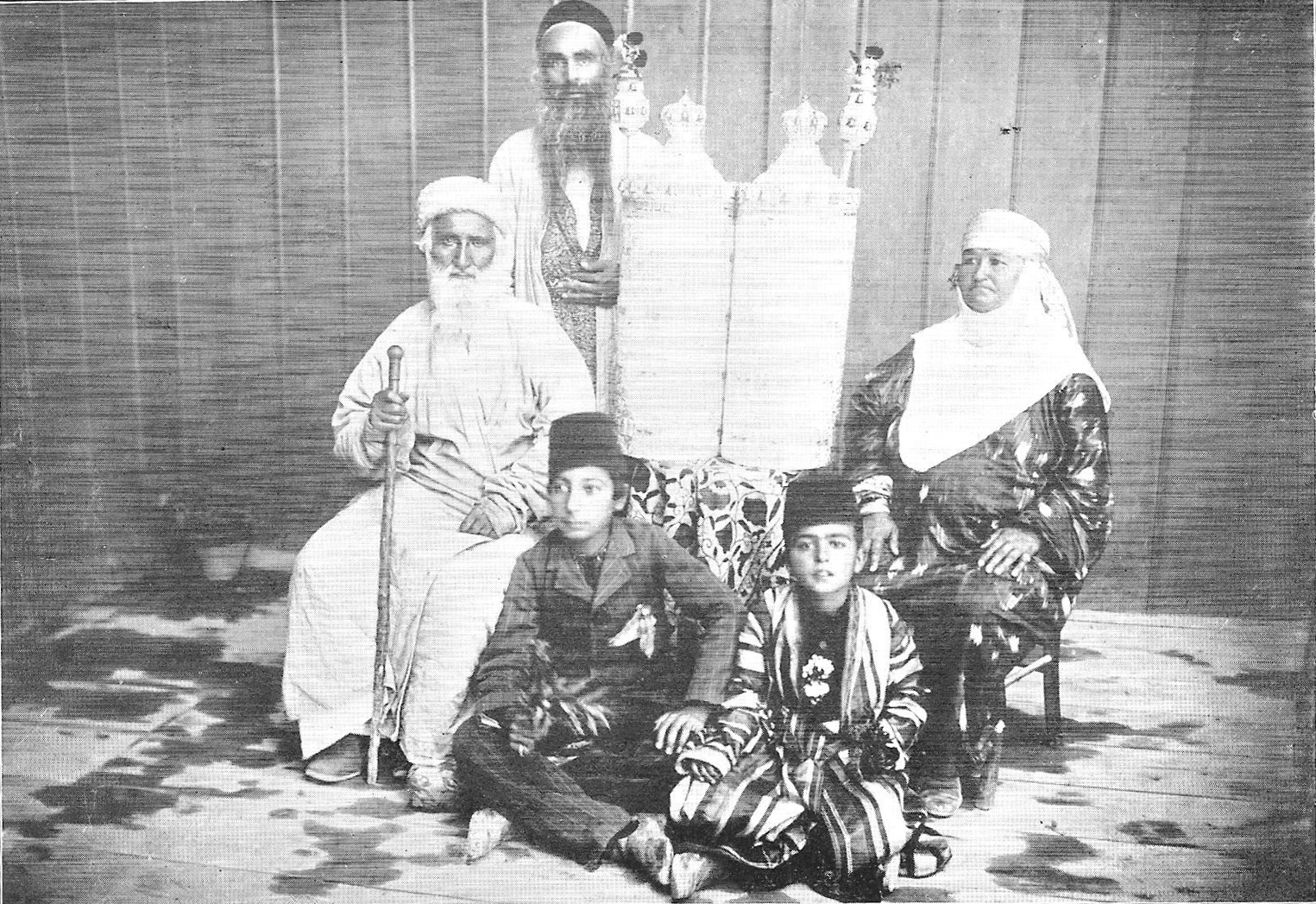

Judaism has a long history in Uzbekistan, with the Bukharan Jewish community residing in Central Asia for thousands of years. In 1989, there were about 94,900 Jews in Uzbekistan (0.5% of the population). Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, most Bukharan Jews have emigrated, mainly to Israel, the United States, and Germany. Fewer than 5,000 Jews remained in Uzbekistan as of 2007, with small communities in Tashkent, Bukhara, and Samarkand.

Other faiths include Buddhism (practiced by some in the Koryo-saram community, estimated at 0.2% by a 2004 report), Baháʼí Faith, and Hare Krishna. There are also an estimated 7,400 Zoroastrians, mostly in Tajik areas like Khujand (though Khujand is in Tajikistan, the source might imply Tajik-populated areas within or near Uzbekistan).

The Soviet era (1924-1991) involved state promotion of atheism and discouragement of religious expression, though practices often continued privately. After independence in 1991, there was a gradual resurgence of religious practice, particularly Islam. The Uzbek government has maintained tight control over religious activities, officially to prevent the rise of religious extremism. Unregistered religious activities are restricted, and groups deemed "extremist" (such as Hizb ut-Tahrir or certain Islamist movements) are banned. While there have been concerns about restrictions on religious freedom, President Mirziyoyev's administration has seen some easing of religious controls compared to the Karimov era.

10.5. Education

Education in Uzbekistan has a strong legacy from the Soviet era, characterized by high literacy rates, but it also faces contemporary challenges.

- Structure and Levels:** The education system generally includes pre-school education, compulsory general secondary education (typically 11 or 12 years, previously 9 years of school followed by 3 years of lyceum/college, now transitioning to a unified 11-year system), vocational training, and higher education.

- Literacy Rate:** Uzbekistan boasts a high literacy rate, with official estimates around 99.9% to 100% for adults (age 15 and over). This is a significant achievement of the Soviet universal education system. However, there are concerns that with only 76% of the under-15 population enrolled in education (and only 20% of 3-6 year olds in pre-school, according to older data), this figure might be challenged in the future.

- Higher Education:** There are numerous state universities and institutes across the country, including the National University of Uzbekistan, Tashkent State Technical University, and specialized institutes for medicine, agriculture, economics, etc. Several international universities have also established campuses in Tashkent, such as Westminster International University in Tashkent, Management Development Institute of Singapore in Tashkent, Turin Polytechnic University in Tashkent, Inha University Tashkent, and Webster University. There are also Islamic institutes and an academy, including the Tashkent Islamic Institute and the International Islamic Academy of Uzbekistan. Universities graduate around 600,000 students annually.

- Language of Instruction:** Uzbek is the primary language of instruction, but Russian-language education is also widely available, particularly in urban areas and at the university level. Many students opt for Russian-medium education due to perceived advantages in higher education and career opportunities.

- Challenges and Reforms:**

- Budget Shortfalls:** The education system has faced severe budget shortfalls, impacting infrastructure, teacher salaries, and curriculum development.

- Curriculum Revision:** Since independence, there has been an ongoing process of curriculum reform to align with national identity and modern educational standards. The transition from Cyrillic to Latin script for Uzbek has also presented challenges in terms of textbook availability and retraining.

- Quality of Education:** Concerns exist about the quality of education, particularly in rural areas and at the tertiary level.

- Corruption:** Corruption within the education system, such as bribery for grades or admissions, has been a reported issue.

- Teacher Shortages and Training:** Attracting and retaining qualified teachers, especially in certain subjects and regions, is a challenge.

President Mirziyoyev's administration has prioritized educational reform, with initiatives aimed at increasing investment, modernizing curricula, improving teacher training, and enhancing the autonomy of higher education institutions.

10.6. Health and Healthcare

The healthcare system in Uzbekistan is largely state-run, a legacy of the Soviet Semashko system, but has undergone reforms since independence.

- Life Expectancy:** Average life expectancy at birth is around 75 years (72 for males, 78 for females, as of 2016).

- Major Health Issues:** Common health problems include cardiovascular diseases, respiratory illnesses, and infectious diseases. Environmental factors, particularly in the Aral Sea region (high rates of respiratory diseases, certain cancers, anemia), contribute significantly to health challenges. Maternal and child health has improved but remains a focus area.

- Healthcare Service System:** The system includes a network of primary healthcare facilities (polyclinics, rural health posts), specialized clinics, and hospitals. Most services are officially free, but informal payments and shortages of medicines and equipment are common. There is a growing private healthcare sector.

- Public Health Policies:** The government has focused on reforms to improve the efficiency and quality of healthcare services, strengthen primary care, combat infectious diseases (like tuberculosis), and promote healthy lifestyles. International organizations like the WHO and UNICEF are involved in supporting health initiatives.

- Challenges:** Key challenges include underfunding, outdated infrastructure and medical equipment, shortages of qualified medical personnel (especially in rural areas), disparities in access to care between urban and rural areas, and the need for further modernization of the system.

There are 16 psychiatric hospitals and approximately 2,834 primary local medical institutions mentioned in one of the sources, indicating a structure for mental healthcare, though details on its quality and accessibility are not provided.

11. Transportation

Uzbekistan's transportation network relies on extensive road and railway systems, including the Tashkent Metro and high-speed rail. Air transport, centered around Tashkent International Airport, connects it internationally.

11.1. Land Transport

Land transport, encompassing roads and railways, forms the backbone of Uzbekistan's transportation system.

- Road Network:** Uzbekistan has an extensive road network connecting major cities and rural areas. The quality of roads varies, with major highways generally being in better condition than rural or regional roads. Efforts are ongoing to upgrade and expand the road infrastructure, including participation in international transport corridors. Buses and taxis (registered and unregistered) are common modes of public transport in cities and for intercity travel. Uzbekistan has a domestic automotive industry, notably GM Uzbekistan (formerly UzDaewooAuto), which produces cars primarily for the local and regional markets. SamKochAvto, a joint venture, produces small buses and lorries, including models under agreement with Isuzu Motors of Japan.

- Railway Network:** The railway system (Oʻzbekiston Temir YoʻllariOʻzbekiston Temir YoʻllariUzbek) is well-developed and plays a crucial role in freight and passenger transport. It connects major Uzbek cities and links the country with neighboring states like Russia, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan.

- Tashkent Metro:** The capital, Tashkent, has a metro system, which opened in 1977. It was the first in Central Asia and currently consists of four lines. The stations are known for their ornate designs. For example, Kosmonavtlar station, built in 1984, is decorated with a space travel theme, commemorating figures like Uzbek cosmonaut Vladimir Dzhanibekov.

- High-Speed Rail (Afrosiyob):** Uzbekistan launched Central Asia's first high-speed railway line in September 2011, connecting Tashkent with Samarkand. The service uses Talgo 250 trains, branded as "Afrosiyob." The line has since been extended to other cities like Bukhara and Qarshi. This has significantly reduced travel times between major tourist and economic centers.

The Afrosiyob high-speed train in Samarkand, used on the Tashkent-Samarkand high-speed rail line. - Several railway projects are underway to improve domestic and international connectivity, including new lines and electrification of existing ones. Some routes historically passed through neighboring countries, prompting projects to create direct domestic links.

11.2. Air Transport

Air transport is vital for international travel and connecting distant parts of the country.

- Airlines:** The national flag carrier is Uzbekistan Airways. It operates domestic flights and international routes to Asia, Europe, North America, and the Middle East. Other smaller airlines also operate in the country.

- Airports:** The main international gateway is Tashkent International Airport (Islam Karimov Tashkent International Airport). Other significant airports are located in major cities like Samarkand, Bukhara, Urgench (serving Khiva), and Fergana, many of which also handle international flights, particularly catering to tourism.

- Aircraft Manufacturing:** During the Soviet era, Uzbekistan hosted the Tashkent Aviation Production Association (TAPOiCh), a major aircraft manufacturing plant. It produced various types of aircraft, including Ilyushin transport planes. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, production declined significantly due to outdated equipment and loss of markets, though it continues some limited production and maintenance work.

The government has been working on modernizing airport infrastructure and improving air traffic management to enhance safety and capacity.

12. Communications

Uzbekistan's communications sector has seen significant development since independence, particularly in mobile telephony and internet access, although it faces challenges related to infrastructure and state control.

- Telephony:**

- Mobile Communications:** The mobile phone market has grown rapidly. As of July 2007, there were 3.7 million users, which increased to 7 million by March 2008, and over 24 million by 2017. Major mobile operators include Beeline (part of Russia's VEON, formerly VimpelCom), Ucell (formerly Coscom, previously a subsidiary of TeliaSonera, now state-owned), UMS (Mobiuz, a state-owned operator that took over from MTS Uzbekistan), and UzMobile (a branch of the national fixed-line operator Uzbektelecom). MTS Uzbekistan (formerly Uzdunrobita) was once the largest operator but ceased operations after disputes with the government.

- Fixed-line Communications:** The fixed-line network, largely inherited from the Soviet era, is less prevalent than mobile services, especially in rural areas. Uzbektelecom is the main provider.

- Internet:**

- Access and Usage:** Internet penetration has increased significantly. As of 2019, the estimated number of internet users was over 22 million, representing about 52% of the population. Broadband access is expanding, but high-speed connectivity is more common in urban areas.

- Internet Censorship and Control:** The government exercises significant control over internet content. Reporters Without Borders has previously named Uzbekistan an "Enemy of the Internet." Access to certain websites, particularly those critical of the government, social media platforms, and proxy servers, has been blocked or restricted at various times. In October 2012, the government reportedly toughened internet censorship by blocking access to proxy servers. While there has been some easing of restrictions under President Mirziyoyev, concerns about online censorship and surveillance persist.

- ICT Development:** The government has policies aimed at developing the Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) sector, promoting e-government services, and improving digital literacy.

- Postal Services:** O'zbekiston Pochtasi (Uzbekistan Post) is the national postal operator.

Challenges in the communications sector include modernizing infrastructure, particularly in rural areas, ensuring affordable and reliable internet access for all, and balancing national security concerns with freedom of information.

13. Science and Technology