1. Overview

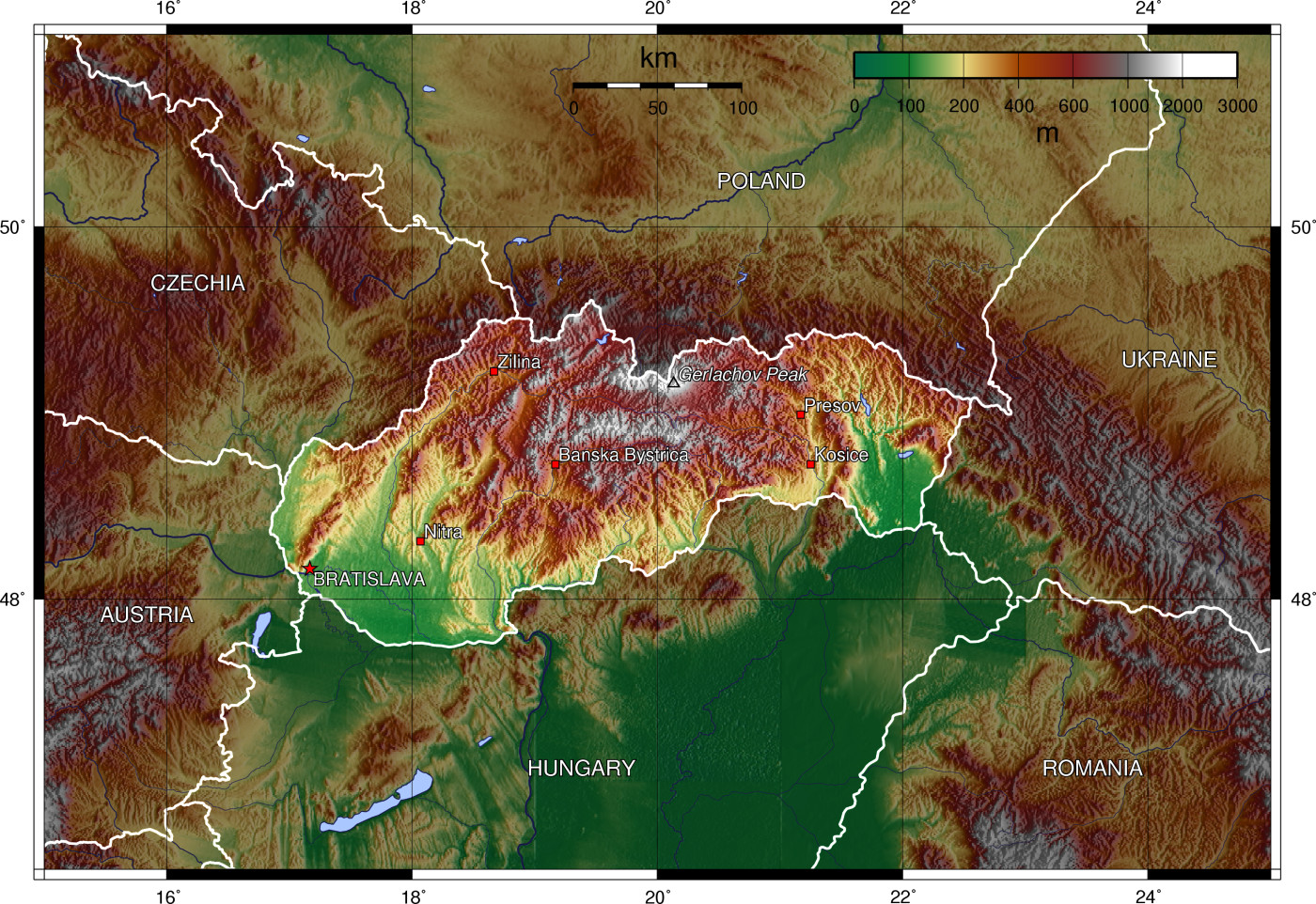

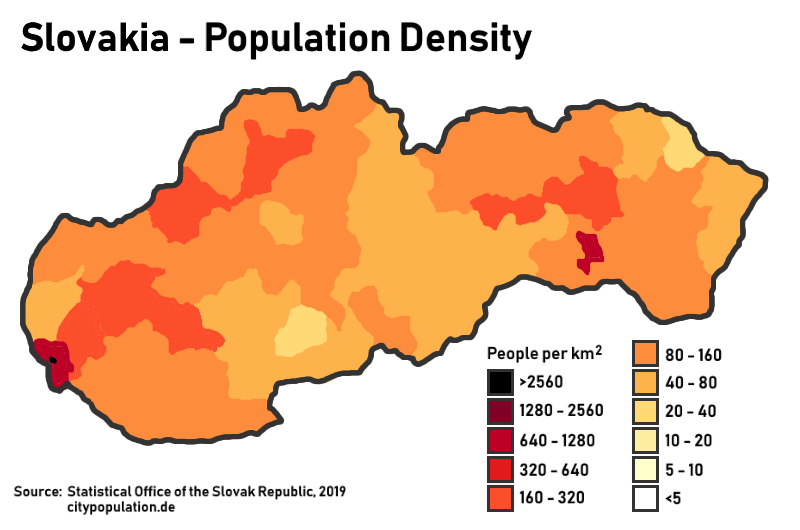

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Spanning approximately 19 K mile2 (49.00 K km2), Slovakia is home to a population of over 5.4 million people. The capital and largest city is Bratislava, with Košice being the second largest. The nation's geography is characterized by the mountainous terrain of the Carpathian Mountains in its northern half and fertile lowlands in the south.

Slovakia's history encompasses early Slavic settlements, the formation of states like Samo's Empire and Great Moravia, a long period as part of the Kingdom of Hungary and later the Habsburg Monarchy and Austria-Hungary. The 20th century saw Slovakia become part of Czechoslovakia, experiencing periods of democratic development, the hardships of World War II under a clerical fascist regime allied with Nazi Germany which involved significant human rights violations, and decades under Communist rule marked by the suppression of civil liberties. The peaceful Velvet Revolution in 1989 led to the end of Communist rule and the eventual dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993, establishing the independent Slovak Republic.

Since independence, Slovakia has pursued democratic development and European integration, joining NATO and the European Union in 2004 and adopting the Euro in 2009. The country has a developed high-income economy, with a strong automotive industry, but faces challenges such as regional disparities and ensuring social equity. Slovakia's political system is a parliamentary democratic republic. The society is predominantly Slovak, with Hungarian and Roma minorities. Culturally, Slovakia has rich folk traditions, a diverse artistic heritage, and numerous historical and natural sites, including several UNESCO World Heritage Sites. This article explores these facets of Slovakia, emphasizing its journey towards democratic governance, the protection of human rights, and the pursuit of social equity.

2. Etymology

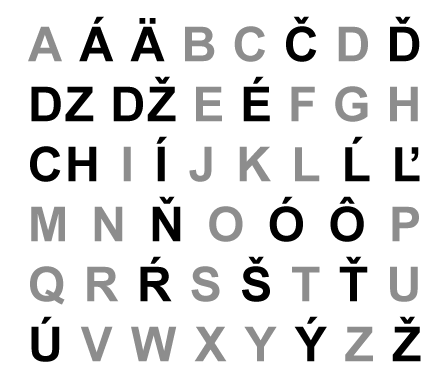

The name "Slovakia" essentially means the "Land of the Slavs". The Slovak term SlovenskoSlovenskoSlovak derives from an older form, Sloven/SlovieninSloven/SlovieninSlavic languages. This makes it a cognate of the names Slovenia and Slavonia. In medieval Latin, German, and even some Slavic sources, the same name was often used to refer to Slovaks, Slovenes, Slavonians, and Slavs in general.

According to one theory, a new form of the national name for the ancestors of the Slovaks emerged between the 13th and 14th centuries, possibly due to foreign influence. The Czech word SlovákSlovákCzech (found in medieval sources from 1291 onwards) is an example. This form gradually replaced the name for male members of the community. However, the name for female members (SlovenkaSlovenkaSlovak), the reference to the inhabited lands (SlovenskoSlovenskoSlovak), and the name of the language (slovenčinaslovenčinaSlovak) all remained the same, rooted in the older form, similar to their Slovenian counterparts. Most foreign translations of the country's name, such as "Slovakia" in English, SlowakeiSlowakeiGerman in German, and SlovaquieSlovaquieFrench in French, tend to stem from this newer form.

In medieval Latin sources, terms like SlavusSlavusLatin, SlavoniaSlavoniaLatin, or SlavorumSlavorumLatin (and other variants, appearing as early as 1029) were used. In German sources, names for the Slovak lands included WindenlandWindenlandGerman or Windische LandeWindische LandeGerman (early 15th century). The forms "Slovakia" and SchlowakeiSchlowakeiGerman began to appear in the 16th century. The current Slovak form, SlovenskoSlovenskoSlovak, is first attested in the year 1675.

3. History

The history of Slovakia spans from prehistoric settlements through antiquity, the Early Middle Ages featuring Slavic states like Great Moravia, a long period within the Kingdom of Hungary and Habsburg Monarchy, its incorporation into Czechoslovakia in the 20th century, and its current status as an independent Slovak Republic established in 1993.

3.1. Prehistory and Ancient Times

The Slovak territory has been inhabited since the Paleolithic Era, with significant cultural developments through the Bronze Age and Iron Age, leading into the Roman Period.

3.1.1. Paleolithic Era

The oldest surviving human artefacts from Slovakia, found near Nové Mesto nad Váhom, are dated to 270,000 BCE, during the Early Paleolithic era. These ancient tools, made using the Clactonian technique, provide evidence of the earliest human presence in the region.

Other stone tools from the Middle Paleolithic era (200,000-80,000 BCE) have been discovered in the Prévôt (Prepoštská) cave in Bojnice and other nearby sites. One of the most significant discoveries from this era is a Neanderthal cranium, dated to c. 200,000 BCE, found near Gánovce, a village in northern Slovakia.

Archaeologists have also found prehistoric human skeletons and numerous objects and vestiges of the Gravettian culture. These findings are principally located in the river valleys of the Nitra, Hron, Ipeľ, and Váh rivers, extending as far as the city of Žilina, and near the foothills of the Vihorlat, Inovec, and Tribeč mountains, as well as in the Myjava Mountains. Among the most well-known finds is the oldest female statue made of mammoth bone, the famous Venus of Moravany, dating to 22,800 BCE. This statue was discovered in the 1940s in Moravany nad Váhom near Piešťany. Numerous necklaces made of shells from Cypraca thermophile gastropods of the Tertiary period have been found at sites such as Zákovská, Podkovice, Hubina, and Radošina. These findings provide the most ancient evidence of commercial exchanges between the Mediterranean and Central Europe.

3.1.2. Bronze Age

During the Bronze Age (2000 to 800 BCE), the geographical territory of modern-day Slovakia underwent significant development in three stages. Major cultural, economic, and political advancements can be attributed to the substantial growth in the production of copper, especially in central Slovakia (e.g., Špania Dolina) and northwest Slovakia. Copper became a stable source of prosperity for the local population. Key cultures from this period include the Otomani and Únětice cultures, followed by the Tumulus culture and later the Urnfield culture. The funeral culture of the Carpathians and that of the middle Danube are also notable from this period.

After the disappearance of the Čakany and Velatice cultures, the Lusatian people expanded the building of strong and complex fortifications, featuring large permanent buildings and administrative centers. Excavations of Lusatian hillforts document the substantial development of trade and agriculture during this period. The richness and diversity of tombs increased considerably, and the inhabitants of the area manufactured arms, shields, jewelry, dishes, and statues, indicating a sophisticated material culture and social organization.

3.1.3. Iron Age

The Iron Age in Slovakia is marked by the arrival of Celtic tribes and the development of distinctive local cultures, such as the Púchov culture. This era is broadly divided into the Hallstatt and La Tène periods, each characterized by unique societal and technological advancements.

3.1.4. Roman Period

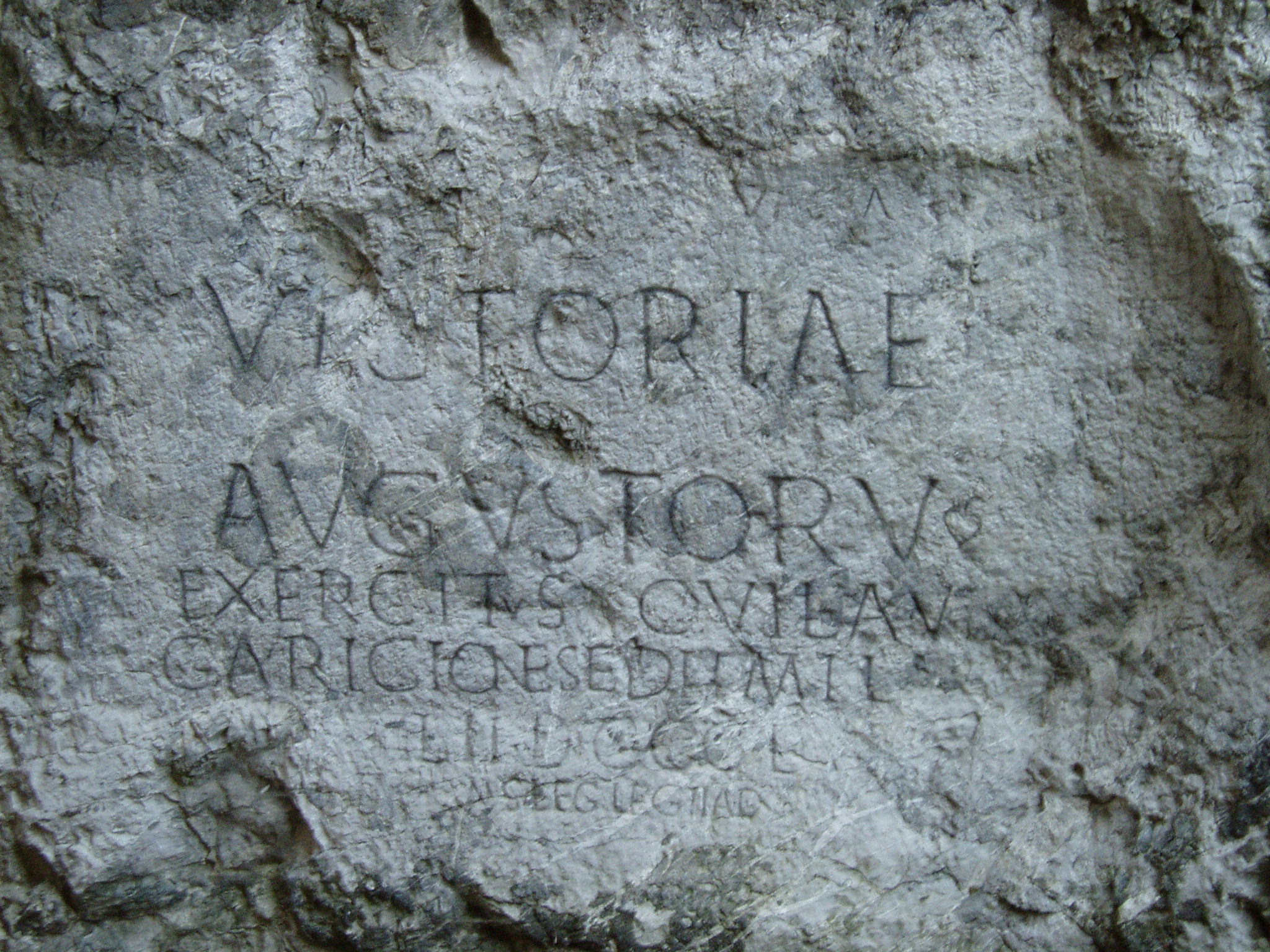

From 2 CE, the expanding Roman Empire established and maintained a series of outposts around and just south of the Danube. The largest of these were Carnuntum (whose remains are on the main road halfway between Vienna and Bratislava) and Brigetio (present-day Szőny at the Slovak-Hungarian border). Such Roman border settlements were also built on the present area of Rusovce, currently a suburb of Bratislava. The military fort there, known as Gerulata, was surrounded by a civilian vicus and several farms of the villa rustica type. Gerulata's military fort housed an auxiliary cavalry unit of approximately 300 horses, modeled after the Cananefates. Remains of Roman buildings have also survived in Stupava, Devín Castle, Bratislava Castle Hill, and the Bratislava-Dúbravka suburb.

Near the northernmost line of the Roman hinterlands, the Limes Romanus, lay the winter camp of Laugaricio (modern-day Trenčín). It was here that the Auxiliary of Legion II Augusta fought and prevailed in a decisive battle over the Germanic Quadi tribe in 179 CE during the Marcomannic Wars. A Roman inscription on the castle rock in Trenčín commemorates this victory. The Kingdom of Vannius, a client kingdom founded by the Germanic Suebi tribes of Quadi and Marcomanni, as well as several small Germanic and Celtic tribes including the Osi and Cotini, existed in western and central Slovakia from 8-6 BCE to 179 CE, interacting with the Roman Empire.

3.2. Early Middle Ages

This period saw major migrations, the settlement of Slavic peoples, the formation of early Slavic states such as Samo's Empire and the Principality of Nitra, and the rise and fall of Great Moravia.

3.2.1. Great Migrations and Slavic Settlement

The period of the Great Migrations, from the 4th to 7th centuries CE, significantly reshaped the ethnic landscape of Central Europe, including the territory of present-day Slovakia. In the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, the Huns began to leave the Central Asian steppes. They crossed the Danube in 377 CE and occupied Pannonia, which they used for 75 years as their base for launching raids into Western Europe. However, the death of Attila in 453 CE brought about the collapse of the Hunnic empire.

Following the Huns, other groups moved through or settled in the region. In 568 CE, a Turko-Mongol tribal confederacy, the Avars, invaded the Middle Danube region. The Avars occupied the lowlands of the Pannonian Plain and established an empire dominating the Carpathian Basin. Their rule exerted considerable influence over the local populations.

The Slavs began arriving in the territory of present-day Slovakia in the 5th and 6th centuries, likely as part of broader Slavic migrations across Europe. They gradually settled the lands, often coexisting or competing with the remnants of Germanic tribes and later the Avars. Western Slovakia became a center of Slavic settlement.

3.2.2. Slavic States

The Slavic tribes who settled in Slovak territory during the 5th and 6th centuries gradually began to form more organized political entities. In the 7th century, the Slavs living in the western parts of Pannonia played a significant role in a revolt against Avar domination, led by Samo, a Frankish merchant. This resulted in the creation of Samo's Empire around 623 CE, considered the first Slavic state-like entity. Western Slovakia was a core part of this empire, which lasted until Samo's death in 658 CE.

After the decline of Avar power, which began after 626 CE and concluded around 804 CE, local Slavic structures strengthened. By the 8th century, a distinct Slavic state known as the Principality of Nitra arose in what is now western Slovakia. Its ruler, Pribina, is a notable figure from this period; he had the first known Christian church on the territory of present-day Slovakia consecrated by 828 CE in Nitra. This indicates early Christianization efforts and the principality's growing political and cultural significance. The Principality of Nitra, along with neighboring Moravia, would later form the core of the Great Moravian Empire.

3.2.3. Great Moravia (830 - before 907)

Great Moravia emerged around 830 CE when Mojmír I unified Slavic tribes settled north of the Danube and extended Moravian supremacy over them. This marked the formation of a powerful early Slavic state. When Mojmír I attempted to secede from the supremacy of the king of East Francia in 846, King Louis the German deposed him and assisted Mojmír's nephew, Rastislav (reigned 846-870), in acquiring the throne. Rastislav pursued an independent policy, successfully stopping a Frankish attack in 855 and seeking to weaken the influence of Frankish priests in his realm. To achieve greater ecclesiastical independence and promote Christianity in the Slavic vernacular, Duke Rastislav requested the Byzantine Emperor Michael III to send teachers.

In response, two brothers, Byzantine officials and missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius, arrived in 863. Cyril developed the first Slavic alphabet, the Glagolitic alphabet, and translated the Gospel into the Old Church Slavonic language. This mission was crucial for the cultural and religious development of Great Moravia, laying the foundation for Slavic literacy and liturgy. Rastislav also focused on the security and administration of his state, evidenced by numerous fortified castles built during his reign, some of which (e.g., Dowina, often identified with Devín Castle) are mentioned in Frankish chronicles in connection with him.

During Rastislav's reign, the Principality of Nitra was given to his nephew Svätopluk as an appanage. Svätopluk, however, allied himself with the Franks and overthrew his uncle in 870. As ruler, Svätopluk I (reigned 871-894) assumed the title of king (rex). Under his reign, the Great Moravian Empire reached its greatest territorial extent, encompassing not only present-day Moravia and Slovakia but also parts of present-day northern and central Hungary, Lower Austria, Bohemia, Silesia, Lusatia, southern Poland, and northern Serbia, though the exact borders remain debated by modern historians. Svatopluk also withstood attacks from Magyar tribes and the Bulgarian Empire, sometimes even hiring Magyars in his wars against East Francia. In 880, Pope John VIII established an independent ecclesiastical province in Great Moravia with Archbishop Methodius as its head, also naming the German cleric Wiching as the Bishop of Nitra.

After the death of King Svatopluk in 894, his sons Mojmír II (reigned 894-906?) and Svatopluk II succeeded him as the King of Great Moravia and the Prince of Nitra, respectively. However, they soon quarreled for domination of the empire. Weakened by internal conflict and constant warfare with Eastern Francia, Great Moravia lost most of its peripheral territories.

Meanwhile, semi-nomadic Magyar tribes, possibly after a defeat by the Pechenegs, left their territories east of the Carpathian Mountains. They invaded the Carpathian Basin and began to occupy the territory gradually around 896. Their advance may have been facilitated by continuous wars among the countries of the region, whose rulers occasionally hired them to intervene in their struggles.

The fate of Mojmír II and Svatopluk II is unknown as they are not mentioned in written sources after 906. In three battles near Bratislava (4-5 July and 9 August 907), the Magyars routed Bavarian armies. Some historians consider this year as the date of the break-up of the Great Moravian Empire due to the Hungarian conquest, while others place its demise slightly earlier (to 902). Great Moravia left a lasting legacy in Central and Eastern Europe. The Glagolitic script and its successor, the Cyrillic script, were disseminated to other Slavic countries, charting a new path in their sociocultural development.

3.3. Kingdom of Hungary, Habsburg Monarchy, and Ottoman Empire (1000-1918)

Slovakia's history from 1000 to 1918 includes its integration into the Kingdom of Hungary during the High Middle Ages, transformations in the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Period including Ottoman interactions and Habsburg rule, and the development of the Slovak national movement in the 18th and 19th centuries.

3.3.1. Early Kingdom of Hungary and High Middle Ages

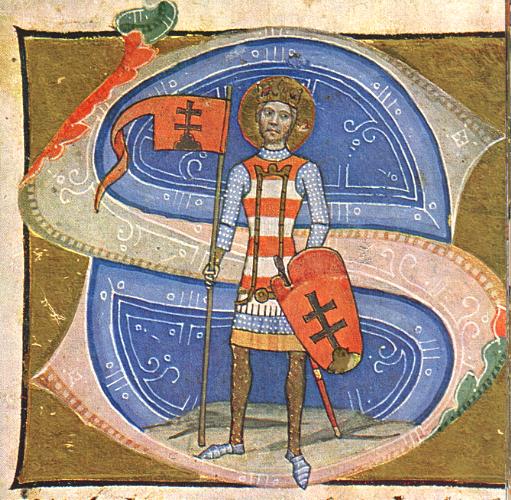

Following the disintegration of the Great Moravian Empire at the turn of the tenth century, the Hungarians annexed the territory comprising modern Slovakia. After their defeat at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955, the Hungarians abandoned their nomadic ways and settled in the centre of the Carpathian Basin. They gradually adopted Christianity and began to build a new state, the Kingdom of Hungary, formally established in 1000 with the coronation of Stephen I.

In the years 1001-1002 and again from 1018-1029, parts of Slovakia were briefly conquered by Bolesław I the Brave of Poland. After the territory of Slovakia was returned to Hungary, a semi-autonomous polity known as the Duchy of Nitra continued to exist or was re-established around 1048 by King Andrew I. This duchy, comprising roughly the territory of the former Principality of Nitra and Bihar principality, formed what was called a tercia pars regni (a third of a kingdom), often governed by a member of the royal Árpád dynasty as an appanage. This polity existed until 1108/1110, after which it was not restored. From this point until the collapse of Austria-Hungary in 1918, the territory of Slovakia was an integral part of the Hungarian state.

The ethnic composition of Slovakia became more diverse with the arrival of Carpathian Germans in the 13th century, who were often invited as settlers to develop mining and urban centers, and Jews in the 14th century. A significant decline in the population resulted from the Mongol invasion in 1241 and the subsequent famine. Much of the territory was devastated, but recovery was aided by King Béla IV, who encouraged resettlement and the construction of stone castles for defense. In medieval times, the area of Slovakia was characterized by German and Jewish immigration, burgeoning towns, the construction of numerous stone castles, and the cultivation of the arts. The influx of German settlers sometimes led to tensions with the autochthonous Slovaks and Hungarians, as Germans often gained significant power in medieval towns. One such conflict in Žilina was resolved by King Louis I with the proclamation of the Privilegium pro Slavis in 1381, which mandated equal representation for Slovaks and Germans on the city council and an alternating mayorship.

3.3.2. Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Period

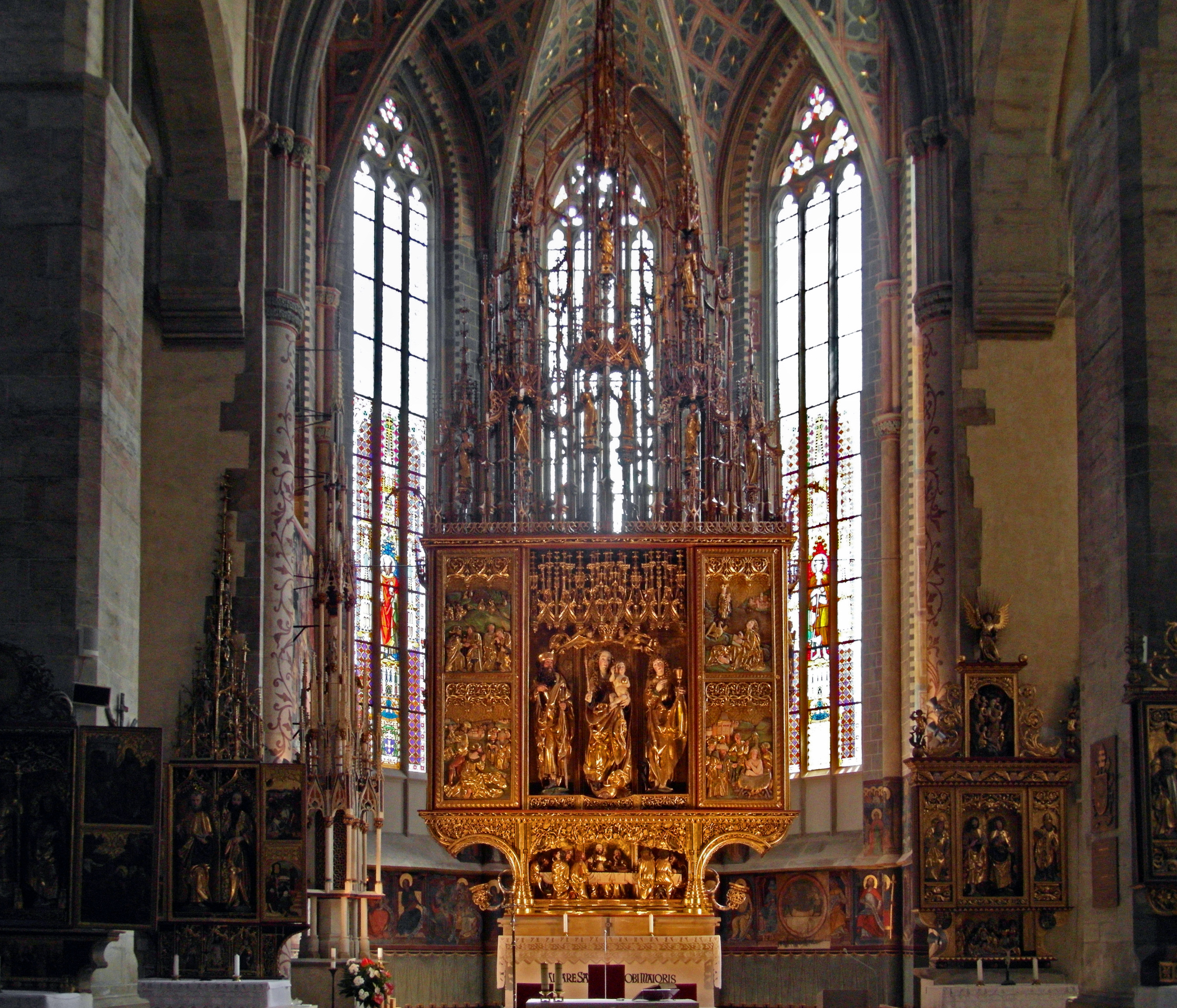

The late Middle Ages and early modern period in Slovakia were marked by continued urban development, further immigration, and significant political and religious upheavals. In 1465, King Matthias Corvinus founded the Hungarian Kingdom's third university, Academia Istropolitana, in Pressburg (Bratislava), but it was closed in 1490 after his death. Hussites also settled in the region after the Hussite Wars, contributing to religious diversity.

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Hungarian territory had a profound impact. After the Battle of Mohács in 1526 and the fall of the old Hungarian capital of Buda in 1541, Bratislava (then Pressburg/Pozsony) was designated the new capital of Royal Hungary (the part of Hungary under Habsburg rule) in 1536. This marked the beginning of a new era, with the territory becoming part of the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy. The region comprising modern Slovakia, then known as Upper Hungary, became a place of settlement for nearly two-thirds of the Magyar nobility fleeing the Ottomans, leading to increased linguistic and cultural Hungarian influence.

This period also saw the growth of Protestantism, partly due to old Hussite families and Slovaks studying under Martin Luther. For a short period in the 17th century, most Slovaks were Lutherans. They often defied the Catholic Habsburgs and sought protection from neighboring Transylvania, a rival Hungarian state that practiced religious tolerance and often had Ottoman backing. Upper Hungary became the site of frequent wars between Catholics in the west and Protestants in the east, as well as against the Ottomans. The frontier was in a constant state of military alert, heavily fortified by castles manned by Catholic German and Slovak troops on the Habsburg side.

By 1648, Slovakia was not spared the Counter-Reformation, which brought the majority of its population from Lutheranism back to Roman Catholicism. In 1655, the printing press at the Trnava university produced Benedikt Szöllősi's Cantus Catholici, a Catholic hymnal in Slovak that reaffirmed links to the earlier works of Cyril and Methodius. The Ottoman wars, the rivalry between Austria and Transylvania, and frequent insurrections against the Habsburg Monarchy (such as the uprisings led by Stephen Bocskai or Emeric Thököly) inflicted great devastation, especially in rural areas. In the Austro-Turkish War (1663-1664), a Turkish army decimated Slovakia. In 1682, the Principality of Upper Hungary, a short-lived Ottoman vassal state under Thököly, was established. Prior to this, regions on its southern rim were already part of Ottoman eyalets like Egri, Budin, and Uyvar. Thököly's Kuruc rebels fought alongside the Turks against the Austrians and Poles at the Battle of Vienna in 1683. As the Turks withdrew from Hungary in the late 17th century, the strategic importance of Slovak territory decreased, though Pressburg retained its status as Hungary's capital until 1848.

Socially, these changes had varied impacts. Urban centers with German populations often prospered, while rural areas, predominantly Slovak, suffered from wars and feudal obligations. The rise and fall of different noble families, religious conflicts, and Ottoman incursions continuously reshaped the social fabric.

3.3.3. 18th and 19th Century National Movement

The retreat of the Ottoman Empire from Hungary in the late 17th and early 18th centuries brought significant changes to the Slovak lands. With the end of constant warfare, there was a period of relative peace and demographic recovery. However, Slovakia remained firmly under Habsburg rule as part of the Kingdom of Hungary. The 18th century saw the early stirrings of a Slovak national consciousness, influenced by the Age of Enlightenment. Figures like Anton Bernolák made efforts to codify a Slovak literary language based on western Slovak dialects in 1787.

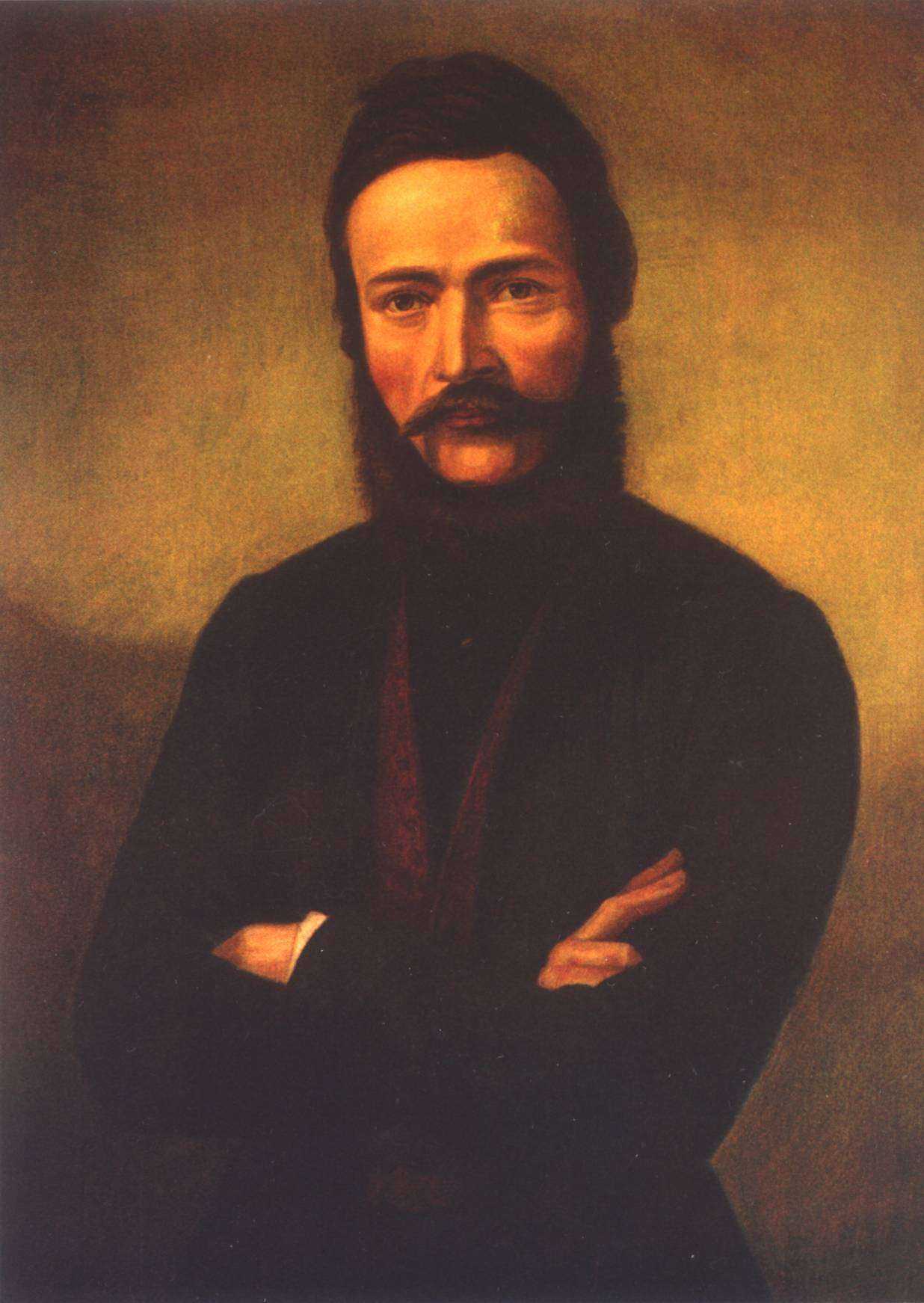

The Revolutions of 1848 across Europe had a profound impact on the Slovak national movement. As Hungarians sought greater autonomy or independence from the Habsburgs, Slovak leaders, such as Ľudovít Štúr, Jozef Miloslav Hurban, and Michal Miloslav Hodža, articulated their own demands for national rights, linguistic recognition, and political representation. They supported the Austrian Emperor, hoping for a degree of independence or autonomy from the Hungarian part of the Monarchy. The Slovak Uprising of 1848-49 saw Slovak volunteers fighting for these aims, though ultimately they failed to achieve full autonomy. Štúr also played a crucial role in codifying a new Slovak literary language based on central Slovak dialects in 1843, which became the foundation for modern Slovak.

Despite the failure of the 1848 revolutions to secure Slovak autonomy, they were instrumental in cementing a Slovak national identity. The subsequent period, especially after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 which created the Dual Monarchy, saw intensified Magyarization policies by the Hungarian government. These policies aimed to assimilate non-Hungarian populations, including Slovaks, by promoting the Hungarian language and culture in administration, education, and public life. This led to increased resistance from Slovak intellectuals and activists, who established cultural institutions like the Matica slovenská (Slovak Foundation) in 1863 to preserve and promote Slovak language and culture, though it was later closed by Hungarian authorities in 1875. The late 19th and early 20th centuries were characterized by ongoing efforts to defend Slovak national rights and push for democratic reforms in the face of these assimilationist pressures, laying the groundwork for future political aspirations that would culminate in the formation of Czechoslovakia after World War I.

3.4. Czechoslovakia (1918-1992)

As part of Czechoslovakia, Slovakia experienced the democratic First Republic, the turbulent World War II era under the First Slovak Republic, decades of Communist rule with periods of reform and repression, and finally, the peaceful dissolution of the federation.

3.4.1. First Republic (1918-1939)

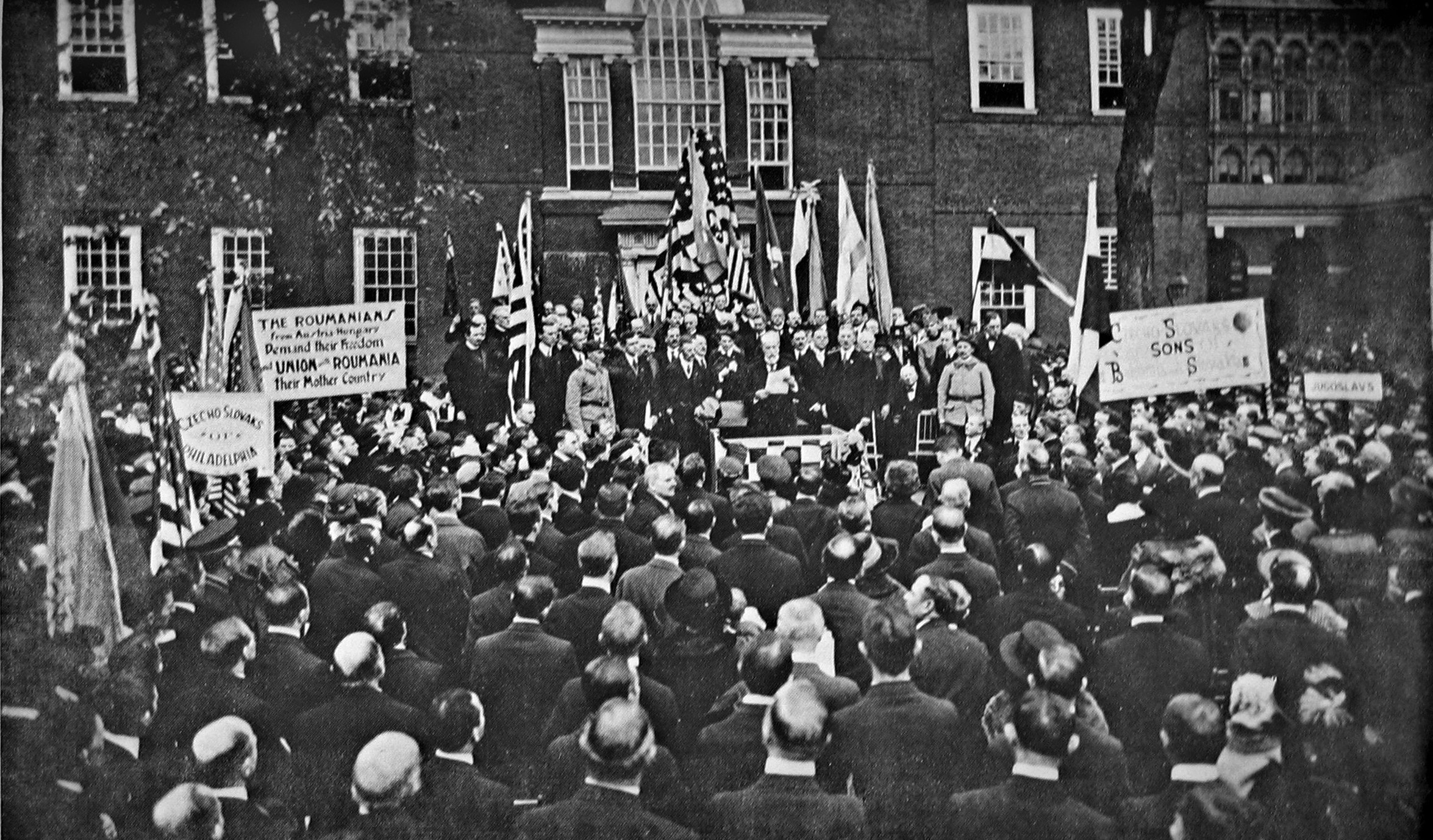

Following World War I and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the state of Czechoslovakia was proclaimed on October 28, 1918. The Czechoslovak National Council, led by figures like Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, Milan Rastislav Štefánik (a Slovak), and Edvard Beneš, successfully advocated for independence. The borders of the new state, incorporating the territory of present-day Slovakia (which had been entirely part of the Kingdom of Hungary), were set by the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and the Treaty of Trianon in 1920.

The First Czechoslovak Republic (1918-1938) was a parliamentary democracy. For Slovaks, it represented a significant step towards national self-determination after centuries of Hungarian rule. However, the concept of a unified "Czechoslovak nation" promoted by the central government in Prague sometimes clashed with Slovak aspirations for greater autonomy. Politically, Slovak parties like Andrej Hlinka's Slovak People's Party advocated for Slovak autonomy within the republic.

Economically, Slovakia was less developed than the Czech lands and remained largely agrarian, though some industrialization occurred. Socially, there was progress in education and culture, with the establishment of Slovak-language schools and institutions. However, significant minorities, including Hungarians in southern Slovakia and Germans, posed challenges to the new state's cohesion. While democratic principles were generally upheld, the centralist tendencies of the Prague government and economic disparities between the Czech lands and Slovakia were sources of tension. The interwar period was also marked by relative prosperity before the Great Depression hit, causing economic hardship and fueling political instability across Europe. The democratic development was notable compared to many other Central and Eastern European countries of the time, but underlying ethnic and regional issues persisted.

3.4.2. World War II and the First Slovak Republic (1939-1945)

The lead-up to World War II saw Czechoslovakia come under increasing pressure from Nazi Germany. The Munich Agreement in September 1938 forced Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland to Germany. This significantly weakened the state, leading to the Czecho-Slovak Republic which granted Slovakia greater autonomy. Subsequently, under German pressure and the threat of partition by Hungary and Poland, Slovakia declared independence on March 14, 1939, establishing the First Slovak Republic. The remainder of the Czech lands became the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia under German occupation.

The First Slovak Republic, led by President Jozef Tiso and Prime Minister Vojtech Tuka of the clerical fascist Hlinka's Slovak People's Party, was a one-party state and a client state of Nazi Germany. It allied with Hitler's coalition and participated in the invasion of Poland in September 1939 and later the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. In November 1940, Slovakia joined the Axis powers by signing the Tripartite Pact.

The regime was responsible for severe human rights violations, particularly the persecution of its Jewish population. The Slovak government enacted anti-Jewish laws, and between 1942 and 1944, approximately 75,000 Jews (out of a pre-war population of about 135,000 in the territory, including those in areas annexed by Hungary) were deported from Slovak territory to German extermination camps. The Slovak state paid Germany 500 Reichsmarks per deported Jew for "retraining and accommodation." Thousands of Jews, Roma, and other political undesirables also remained in Slovak forced labor camps like Sereď, Vyhne, and Nováky. While Tiso granted some presidential exceptions, these saved only a small fraction of the Jewish population.

Resistance to the fascist regime and German influence grew, culminating in the Slovak National Uprising in August 1944. This major armed revolt, involving Slovak army units, partisans, and support from the Allies, aimed to overthrow the Tiso government and restore Czechoslovakia. Although the uprising was brutally suppressed by German forces and their local collaborators (the Hlinka Guard), resulting in widespread massacres and the destruction of numerous villages, partisan warfare continued. The territory of Slovakia was eventually liberated by Soviet and Romanian forces by the end of April 1945. The Czechoslovak government-in-exile in London, led by Edvard Beneš, worked throughout the war to reverse the Munich Agreement and restore Czechoslovakia to its 1937 boundaries.

3.4.3. Communist Regime (1945-1989)

Following World War II, Czechoslovakia saw the re-establishment of the republic, a Communist seizure of power in 1948, and governance under the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic until the Velvet Revolution in 1989.

3.4.4. Democratization and Dissolution of the Federation (1989-1992)

The Communist regime in Czechoslovakia collapsed in late 1989 through the Velvet Revolution, a series of peaceful mass demonstrations and strikes. Sparked by the brutal suppression of a student demonstration in Prague on November 17, the protests quickly spread across the country, including Slovakia (where they were known as the Gentle Revolution). Key dissident figures like Václav Havel in the Czech lands and groups like Public Against Violence (Verejnosť proti násiliu - VPN) in Slovakia played leading roles. The Communist Party relinquished its monopoly on power, and a transitional government was formed. Václav Havel was elected president of Czechoslovakia in December 1989.

The subsequent period was marked by rapid democratization. Free elections were held in June 1990, leading to a non-Communist government. Censorship was abolished, political prisoners were released, and civil liberties were restored. Economic reforms aimed at transitioning from a centrally planned economy to a market economy were initiated. The country was renamed the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic.

However, the democratization process also brought underlying tensions between Czechs and Slovaks to the forefront. Slovak political leaders, notably Vladimír Mečiar and his Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS), increasingly called for greater Slovak sovereignty or full independence. Differences in economic perspectives, historical experiences, and political priorities contributed to growing divergence. Negotiations between Czech Prime Minister Václav Klaus and Slovak Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar failed to find a mutually acceptable model for the continuation of the federation.

On July 17, 1992, the Slovak National Council adopted the Declaration of Sovereignty of the Slovak Republic. In November 1992, the federal parliament voted to dissolve Czechoslovakia. The dissolution, often referred to as the Velvet Divorce, occurred peacefully on January 1, 1993, resulting in the creation of two independent states: the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. This peaceful separation stood in stark contrast to the violent breakups occurring in other parts of post-Communist Europe at the time, such as Yugoslavia.

3.5. Slovak Republic (1993-Present)

Since independence in 1993, the Slovak Republic navigated early systemic transitions in the 1990s, achieved European integration and economic growth in the 2000s, faced political changes and social challenges in the 2010s, and is currently addressing contemporary crises and political developments in the 2020s.

3.5.1. 1990s: Early Independence and Systemic Transition

The Slovak Republic became an independent state on January 1, 1993, with Michal Kováč as its first president and Vladimír Mečiar as its influential prime minister. The early years of independence were characterized by political instability and the challenges of transitioning to a market economy. Mečiar's governments (1992-1994 and 1994-1998) faced criticism both domestically and internationally for perceived authoritarian tendencies, a confrontational political style, and controversies surrounding the privatization process, which was often non-transparent and favored political allies. This period was sometimes referred to as "Mečiarism."

The transition to a market economy was difficult, marked by high unemployment and inflation initially. The rise of organized crime was a significant social problem during the 1990s, often referred to as the "Wild 90s," penetrating various levels of society and even, allegedly, politics. A notable incident was the 1995 abduction of President Kováč's son, allegedly involving the Slovak intelligence service (SIS). These issues led to concerns about democratic backsliding and hindered Slovakia's efforts to integrate into Western European institutions like NATO and the EU. U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright famously referred to Slovakia during this time as a "black hole in the heart of Europe." Socially, vulnerable groups often bore the brunt of economic reforms and instability. The country operated without a head of state for 14 months in 1998-1999 after the parliament failed to elect a new president, leading to constitutional changes for direct presidential elections.

The 1998 parliamentary elections marked a turning point, bringing a broad coalition government led by Mikuláš Dzurinda to power. This government embarked on a series of far-reaching economic and political reforms aimed at stabilizing the country, improving democratic governance, and accelerating integration into Western structures. These reforms, though sometimes socially painful, laid the groundwork for future economic growth and international acceptance.

3.5.2. 2000s: European Integration and Economic Growth

The 2000s were a transformative decade for Slovakia, characterized by successful integration into key Western international organizations and significant economic growth. Under the governments led by Mikuláš Dzurinda (1998-2006), Slovakia implemented comprehensive reforms, including a flat tax, liberalization of the labor market, and deregulation, which attracted substantial foreign investment, particularly in the automotive sector.

Slovakia achieved major foreign policy goals during this period. It became a member of the OECD on December 14, 2000. A landmark achievement was its accession to NATO on March 29, 2004, followed by entry into the European Union (EU) on May 1, 2004. These memberships solidified Slovakia's geopolitical orientation and provided a framework for further democratic and economic development. Ivan Gašparovič became president in 2004 and was re-elected in 2009.

The Slovak economy experienced a period of rapid expansion, earning it the nickname "Tatra Tiger." Average GDP growth was around 6% per capita annually from 2000 to 2008. This growth was largely driven by foreign direct investment and exports. On January 1, 2009, Slovakia adopted the Euro as its national currency, becoming the 16th member of the Eurozone. This was seen as a significant step in its European integration.

While the economic growth brought prosperity and improved living standards for many, social benefits were not always evenly distributed. Regional disparities persisted, and some segments of the population faced challenges adapting to the new economic realities. The global financial crisis of 2008-2009 began to impact Slovakia towards the end of the decade, slowing down the "Tatra Tiger" momentum. In early 2009, Slovakia also faced an energy crisis when Russia cut gas supplies via Ukraine.

3.5.3. 2010s: Political Changes and Social Challenges

The 2010s in Slovakia were marked by shifts in the political landscape, efforts to navigate economic crises, and significant social challenges that tested the country's democratic accountability. Iveta Radičová became Slovakia's first female Prime Minister in 2010, leading a center-right coalition. However, her government collapsed in 2011 over disagreements regarding the European Financial Stability Facility, a Eurozone bailout mechanism.

The 2012 parliamentary election saw Robert Fico's Smer-SD party win an absolute majority, a rare feat in Slovak politics. Fico became Prime Minister for a second time (his first term was 2006-2010). His government focused on social welfare measures while maintaining fiscal discipline. In 2014, Andrej Kiska, an entrepreneur and philanthropist with no prior political party affiliation, was elected president. Fico's Smer-SD also won the 2016 elections, and he formed his third government.

Slovakia, like other European countries, dealt with the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the subsequent Eurozone crisis. The country also faced the European migrant crisis starting in 2015, which became a significant political issue, with Fico's government taking a firm stance against mandatory refugee quotas.

A pivotal and tragic event occurred on February 21, 2018, with the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová. Kuciak had been investigating high-level corruption and alleged links between Slovak politicians and organized crime. Their murders sparked the largest anti-government protests in Slovakia since the Velvet Revolution, with citizens demanding a thorough investigation, justice, and an end to corruption. The protests led to a political crisis, resulting in the resignation of Prime Minister Robert Fico in March 2018. He was replaced by Peter Pellegrini, also from Smer-SD. The murders and subsequent revelations put a spotlight on issues of corruption, press freedom, and the rule of law, significantly impacting public trust in state institutions and demanding greater democratic accountability. In 2019, Zuzana Čaputová, a lawyer and anti-corruption activist, was elected as Slovakia's first female president, her victory seen partly as a response to the public's desire for change.

3.5.4. 2020s: Pandemic, Geopolitical Crises, and Political Developments

The 2020s began with significant challenges for Slovakia. The 2020 parliamentary election brought Igor Matovič and his OĽaNO party to power, forming a new coalition government. Shortly after, the COVID-19 pandemic struck, leading to widespread socio-economic disruption. The government implemented various measures to combat the pandemic, but its handling, particularly Matovič's controversial decision to purchase Russia's Sputnik V vaccine without EU regulatory approval, led to a government crisis and Matovič's resignation in March 2021. He was succeeded by Eduard Heger of the same party. The pandemic resulted in over 21,000 deaths in Slovakia by 2023 and caused a significant economic recession in 2020, followed by a recovery and then a slowdown due to subsequent crises.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 created new geopolitical and economic challenges. Slovakia, sharing a border with Ukraine, became a key transit country for refugees and a significant provider of humanitarian and military aid to Ukraine under Heger's government. The war also led to an energy crisis and an inflation surge, impacting the Slovak economy. Political instability continued, with Heger's government collapsing after a no-confidence vote in late 2022. In May 2023, President Zuzana Čaputová appointed a technocratic caretaker government led by Ľudovít Ódor to lead the country until early parliamentary elections.

The snap parliamentary election in September 2023 saw the return of Robert Fico and his Smer-SD party to power, forming a coalition government. This new government announced a halt to state military aid to Ukraine, while continuing humanitarian aid. In April 2024, Peter Pellegrini, an ally of Fico and former Prime Minister, was elected as Slovakia's sixth president. A deeply shocking event occurred on May 15, 2024, when Prime Minister Robert Fico was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt. The suspect cited opposition to the government's policies, including its stance on Ukraine, as a motive. This event sent shockwaves through Slovak society and raised concerns about political polarization and stability. These developments underscore the ongoing complex political and social dynamics within Slovakia as it navigates domestic issues and a volatile international environment.

4. Geography

Slovakia's geography is defined by its varied topography including the Tatra Mountains, a system of national parks and caves, its network of rivers, a temperate to continental climate, and diverse biodiversity and water resources.

4.1. Topography

Slovakia lies between latitudes 47° and 50° N, and longitudes 16° and 23° E. The Slovak landscape is noted primarily for its mountainous nature, with the Carpathian Mountains extending across most of the northern half of the country. These mountain ranges include the high peaks of the Fatra-Tatra Area (which encompasses the Tatra Mountains, Greater Fatra, and Lesser Fatra), the Slovak Ore Mountains, the Slovak Central Mountains, and the Beskids.

The highest point in Slovakia is Gerlachovský štít in the High Tatras, at 8.7 K ft (2.66 K m). The largest lowland is the fertile Danubian Lowland in the southwest, an important agricultural region, followed by the Eastern Slovak Lowland in the southeast. Forests cover approximately 41% of Slovakia's land surface, contributing significantly to its biodiversity and natural scenery.

4.1.1. Tatra Mountains

The Tatra Mountains, a part of the Carpathian Mountains, form a natural border between Slovakia and Poland and are the highest range in the Carpathians. They are divided into several parts:

- The High Tatras (Vysoké TatryVysoké TatrySlovak) are the most famous and alpine part, featuring 29 peaks higher than 8.2 K ft (2.50 K m) AMSL. They are a popular destination for hiking, climbing, and skiing. This section is home to many scenic glacial lakes (plesá) and deep valleys. The highest peak in Slovakia, Gerlachovský štít (8.7 K ft (2.66 K m)), is located here, as is Kriváň (8.2 K ft (2.50 K m)), a mountain highly symbolic for Slovaks and featured on Slovak euro coins.

- The Western Tatras (Západné TatryZápadné TatrySlovak) lie to the west of the High Tatras. Their highest peak is Bystrá at 7.4 K ft (2.25 K m). They are characterized by grassy ridges and are also popular for hiking.

- The Belianske Tatras (Belianske TatryBelianske TatrySlovak) are located to the east of the High Tatras and are the smallest by area. They are known for their limestone and dolomite formations and rich flora, with restricted access to protect their unique environment.

- The Low Tatras (Nízke TatryNízke TatrySlovak) are a separate mountain range to the south of the main Tatra massif, separated by the valley of the Váh river. Their highest peak is Ďumbier at 6.7 K ft (2.04 K m). The Low Tatras are also a major tourist area, known for skiing, hiking, and cave systems.

The Tatra mountain range is symbolically represented as one of the three hills on the coat of arms of Slovakia. Much of the Tatras area in Slovakia is protected as Tatra National Park (TANAP).

4.2. National Parks

Slovakia has nine national parks, which collectively cover approximately 6.5% of the country's land surface. These parks are dedicated to preserving the nation's diverse natural landscapes, ecosystems, and biodiversity.

| Name | Established | Area (km²) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tatra National Park (Tatranský národný park) | 1949 | 285 mile2 (738 km2) | Highest peaks of the Carpathians (High Tatras), alpine meadows, glacial lakes, unique flora and fauna including chamois and marmots. |

| Low Tatras National Park (Národný park Nízke Tatry) | 1978 | 281 mile2 (728 km2) | Extensive mountain range, forests, karst phenomena, large cave systems (e.g., Demänovská Caves). |

| Veľká Fatra National Park (Národný park Veľká Fatra) | 2002 | 156 mile2 (404 km2) | Large continuous forests, especially beech and fir; rich biodiversity, traditional mountain sheep farming. |

| Slovak Karst National Park (Národný park Slovenský kras) | 2002 | 134 mile2 (346 km2) | Extensive karst landscape with numerous caves and abysses (UNESCO World Heritage site), unique thermophilic flora. |

| Poloniny National Park (Národný park Poloniny) | 1997 | 115 mile2 (298 km2) | Easternmost park, borders Poland and Ukraine, primeval beech forests (UNESCO World Heritage site), presence of European bison. |

| Malá Fatra National Park (Národný park Malá Fatra) | 1988 | 87 mile2 (226 km2) | Diverse relief with rocky gorges (e.g., Jánošíkove diery), alpine meadows, rich flora and fauna. |

| Muránska planina National Park (Národný park Muránska planina) | 1998 | 78 mile2 (203 km2) | Karst plateau with canyons, caves, and endemic flora (e.g., Muránska Daphne), semi-wild horse breeding. |

| Slovak Paradise National Park (Národný park Slovenský raj) | 1988 | 76 mile2 (197 km2) | Famous for its gorges, canyons, waterfalls, and ladder/chain-assisted hiking trails; Dobšiná Ice Cave (UNESCO World Heritage site). |

| Pieniny National Park (Pieninský národný park) | 1967 | 15 mile2 (38 km2) | Smallest national park, known for the Dunajec River Gorge, traditional wooden raft trips, diverse flora and fauna. |

4.3. Caves

Slovakia is renowned for its numerous caves and caverns, with hundreds located beneath its mountains. Many of these are karst caves formed in limestone and dolomite regions. Currently, 30 caves are open to the public, offering visitors a glimpse into these subterranean wonders. Most caves feature impressive stalagmites rising from the ground and stalactites hanging from the ceiling, along with other formations like flowstones and draperies.

Five Slovak caves are part of the "Caves of Aggtelek Karst and Slovak Karst" UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized for their exceptional geological and biological value. These are:

- Dobšiná Ice Cave (Dobšinská ľadová jaskyňa): One of the most important ice caves in the world, with permanent ice fill.

- Domica Cave (Jaskyňa Domica): Known for its extensive passages, rich sinter fill, and significant archaeological finds from the Neolithic period. It forms a transboundary system with Baradla Cave in Hungary.

- Gombasek Cave (Gombasecká jaskyňa): Famous for its unique thin, hollow soda straw stalactites.

- Jasovská Cave (Jasovská jaskyňa): Notable for its historical significance (inscriptions from the 15th century) and rich speleothem decoration.

- Ochtinská Aragonite Cave (Ochtinská aragonitová jaskyňa): One of only a few aragonite caves in the world open to the public, featuring rare and beautiful aragonite formations.

Other notable caves open to the public include:

- Belianska Cave (Belianska jaskyňa): Located in the Belianske Tatras, known for its large domes and sinter waterfalls.

- Demänovská Cave of Liberty (Demänovská jaskyňa slobody): Part of the extensive Demänovská Cave System in the Low Tatras, famous for its rich and varied speleothem decoration.

- Demänovská Ice Cave (Demänovská ľadová jaskyňa): Also in the Low Tatras, featuring year-round ice formations.

- Bystrianska Cave (Bystrianska jaskyňa): Located in the Low Tatras, known for its therapeutic climate used for speleotherapy.

These caves are managed by the Slovak Caves Administration and are important sites for tourism, education, and scientific research.

4.4. Rivers

Most of Slovakia's rivers originate in its mountainous regions and are part of the Black Sea drainage basin (via the Danube) and, to a lesser extent, the Baltic Sea drainage basin (via tributaries of the Vistula). Some rivers only pass through Slovakia, while others form natural borders with neighboring countries for a total length of over 385 mile (620 km). The total length of the river network on Slovak territory is approximately 31 K mile (49.77 K km).

Major rivers in Slovakia include:

- The Danube (DunajDunajSlovak): The second-longest river in Europe, it flows through southwestern Slovakia for 107 mile (172 km), forming part of the border with Hungary and Austria. Bratislava, the capital, and Komárno are major Slovak ports on the Danube.

- The Váh: The longest river entirely within Slovakia, stretching 250 mile (403 km). It is a major tributary of the Danube and flows through much of western and northern Slovakia. Many important cities and industrial centers are located along its banks.

- The Hron: The second-longest river entirely within Slovakia, at 185 mile (298 km). It flows through central Slovakia and is also a tributary of the Danube.

- The Nitra: A 122 mile (197 km) long river in western Slovakia, a tributary of the Váh.

- The Ipeľ (IpeľIpeľSlovak): A 144 mile (232 km) long river that forms a significant part of the southern border with Hungary before joining the Danube.

- The Hornád: A 120 mile (193 km) long river in eastern Slovakia, flowing through the Slovak Paradise National Park before entering Hungary to join the Sajó (Slaná).

- The Slaná (SlanáSlanáSlovak): Flows for 68 mile (110 km) in Slovakia through the Slovak Karst region before continuing into Hungary.

- The Dunajec: Forms a 11 mile (17 km) stretch of the northern border with Poland, famous for its scenic gorge in the Pieniny National Park. It is part of the Baltic Sea drainage basin.

- The Morava: Forms the northwestern border with the Czech Republic and Austria for 74 mile (119 km) before joining the Danube at Devín.

Other important rivers include the Myjava, Orava, Laborec, Latorica, and Ondava. The largest volume of discharge in most Slovak rivers occurs during spring due to snowmelt from the mountains. The Danube is an exception, with its discharge peaking in summer due to snowmelt in the Alps.

4.5. Climate

Slovakia's climate lies between the temperate and continental climate zones, characterized by four distinct seasons. The country experiences relatively warm summers and cold, cloudy, and humid winters. Weather patterns vary significantly between the mountainous northern regions and the plains in the south. Temperature extremes recorded are between -41.8 °F (-41 °C) and 104.53999999999999 °F (40.3 °C), although temperatures below -22 °F (-30 °C) are rare.

The warmest region is Bratislava and Southern Slovakia, where summer temperatures can reach 86 °F (30 °C), and occasionally up to 102.2 °F (39 °C) in areas like Hurbanovo. Nighttime summer temperatures typically drop to around 68 °F (20 °C). Daily temperatures in winter average between 23 °F (-5 °C) and 50 °F (10 °C), with nighttime temperatures potentially freezing but usually not falling below 14 °F (-10 °C).

The country's four seasons each last approximately three months:

- Spring** (starts around March 21): Characterized by colder weather initially, with average daily temperatures of 48.2 °F (9 °C) in the first weeks, rising to about 57.2 °F (14 °C) in May and 62.6 °F (17 °C) in June. Spring weather can be very unstable.

- Summer** (starts around June 22): Usually features hot weather, with daily temperatures often exceeding 86 °F (30 °C). July is typically the warmest month, with temperatures occasionally reaching 98.6 °F (37 °C) to 104 °F (40 °C) in southern regions. Showers or thunderstorms can occur, sometimes associated with a weather pattern known as "Medardova kvapka" (Medard's drop - traditionally 40 days of rain). Summer in Northern Slovakia is generally milder, with temperatures around 77 °F (25 °C) (cooler in the mountains).

- Autumn** (starts around September 23): Mostly characterized by wet weather and wind, although the first weeks can be warm and sunny. The average temperature in September is around 57.2 °F (14 °C), dropping to 37.4 °F (3 °C) by November. Late September and early October can be a dry and sunny period known as Indian summer.

- Winter** (starts around December 21): Temperatures typically range from 23 °F (-5 °C) to 14 °F (-10 °C). Snowfall is common in December and January, which are the coldest months. In lower altitudes, snow may not last the entire winter, alternating between thawing and freezing. Winters are colder in the mountains, where snow cover usually lasts until March or April, and night temperatures can fall to -4 °F (-20 °C) or lower.

Dry continental air brings summer heat and winter frosts, while oceanic air influences bring rainfall and can moderate summer temperatures. Fog is common in lowlands and valleys, especially during winter.

4.6. Biodiversity

Slovakia possesses a rich biodiversity due to its varied topography, climate, and geographical position at the crossroads of different biogeographical regions. The country signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on May 19, 1993, and became a party to the convention on August 25, 1994. It subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, received by the convention on November 2, 1998.

Slovakia's biodiversity includes a wide array of animals (such as annelids, arthropods, mollusks, nematodes, and vertebrates), fungi (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota, and Zygomycota), micro-organisms (including Mycetozoa), and plants. More than 11,000 plant species, nearly 29,000 animal species, and over 1,000 species of protozoa have been described within its territory. Endemic biodiversity is also common, with species found uniquely in this region.

The country is located within the biome of temperate broadleaf and mixed forests and includes terrestrial ecoregions such as the Pannonian mixed forests and Carpathian montane conifer forests. Vegetation associations and animal communities vary with altitude, forming distinct height levels: oak forests at lower elevations, followed by beech, spruce, scrub pine (mountain pine), alpine meadows, and subsoil (areas above the tree line with sparse vegetation). Forests cover approximately 44% of Slovakia's territory, with about 60% being broadleaf trees and 40% coniferous trees. The occurrence of animal species is strongly connected to the appropriate types of plant associations and biotopes.

The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.34/10, ranking it 129th globally out of 172 countries. Conservation efforts are significant, with a network of national parks and other protected areas aimed at preserving these valuable natural habitats and species.

Over 4,000 species of fungi have been recorded from Slovakia. Of these, nearly 1,500 are lichen-forming species. Some of these fungi are undoubtedly endemic, though more research is needed to determine the exact number. Among the lichen-forming species, about 40% have been classified as threatened in some way: approximately 7% are apparently extinct, 9% endangered, 17% vulnerable, and 7% rare. The conservation status of non-lichen-forming fungi is not as well-documented, but a red list exists for its larger fungi.

4.7. Water Resources

Slovakia possesses significant water resources, primarily in the form of groundwater and surface water from its extensive river network. The entire population of Slovakia has access to safe drinking water sources. The country is recognized for having some of the best quality tap water globally and ranks second in Europe (after Austria) for its reserves of drinking water.

Groundwater is the predominant source of high-quality drinking water, accounting for approximately 82.2% of the supply, with surface water making up the remaining 17.8%. The importance of groundwater is underscored by its protection under the Constitution of Slovakia. Since 2014, the export of drinking and mineral waters via pipelines and water tanks has been banned, although this ban excludes bottled water and water for personal use. Žitný ostrov (Rye Island) in southwestern Slovakia is the largest natural groundwater reservoir not only in Slovakia but also in Central Europe, making it a vital resource.

Slovakia is also rich in mineral and thermal springs. Around 1,300 mineral sources are registered, providing curative waters and high-quality mineral water for drinking. There are 21 thermal spa towns built on these mineral springs, which have a long tradition and are important for both health tourism and recreation. Some of the most visited spa towns include Piešťany, Trenčianske Teplice, Bardejov, and Dudince. The utilization of these geothermal resources contributes to the country's tourism industry and wellness sector.

5. Government and Politics

Slovakia operates as a parliamentary democratic republic with distinct executive, legislative, and judicial branches, governed by its constitution. Its administration is organized into regions and districts, and it maintains active foreign relations and a national military, while addressing human rights issues.

5.1. Political System

Slovakia is a parliamentary democratic republic characterized by a multi-party system. The Constitution of Slovakia, ratified on September 1, 1992, and effective from January 1, 1993, establishes the framework for its governance, emphasizing the separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Democratic processes include regular elections for the presidency and parliament, referendums, and mechanisms for citizen participation, although voter turnout and civic engagement can vary.

The President is the head of state, elected by direct popular vote using a two-round system for a five-year term, with a maximum of two consecutive terms. While the president has limited executive powers, they include representing the state abroad, appointing the prime minister and other key officials, vetoing legislation (which can be overridden by parliament), and serving as commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

The Prime Minister is the head of government and holds the most significant executive power. The prime minister is typically the leader of the political party or coalition that wins a majority in parliamentary elections and is appointed by the president. The government, or cabinet, is responsible to the National Council (parliament).

Slovakia's political landscape features a range of political parties, often requiring coalition governments to be formed. This multi-party system fosters political pluralism but can also lead to periods of political instability or complex coalition negotiations. The functioning of democratic processes, including the rule of law, transparency, and accountability, are ongoing areas of development and public discourse, particularly in light of challenges such as corruption and political polarization.

5.2. Executive Branch

The executive branch of the Slovak government is headed by the President of Slovakia, who is the formal head of state, and the Prime Minister of Slovakia, who is the head of government and wields most of the day-to-day executive authority.

The President (currently Peter Pellegrini, since June 2024) is elected by direct popular vote for a five-year term and can serve a maximum of two terms. The president's powers are largely ceremonial but include representing the state internationally, appointing and dismissing the Prime Minister and other members of the government (cabinet), appointing judges (including Constitutional Court judges from parliamentary nominations), signing laws or exercising a veto (which can be overridden by a parliamentary majority), calling referendums, and serving as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

The Prime Minister (currently Robert Fico, since October 2023) is appointed by the president and is usually the leader of the political party or coalition that commands a majority in the National Council (parliament). The Prime Minister selects the cabinet ministers, who are then formally appointed by the president. The Government of Slovakia (the cabinet) is collectively responsible for formulating and implementing state policy and is accountable to the National Council. It consists of the Prime Minister, deputy prime ministers, and ministers responsible for various government departments (e.g., foreign affairs, interior, finance, defense). The government can propose legislation, issues decrees, and manages the state administration through its ministries and other agencies.

5.3. Legislative Branch

The legislative authority in Slovakia is vested in the National Council of the Slovak Republic (Národná rada Slovenskej republikyNárodná rada Slovenskej republikySlovak), which is a unicameral parliament. It consists of 150 members, known as deputies, who are elected for a four-year term.

The election process for members of the National Council is based on a system of proportional representation with a single nationwide constituency. Political parties or coalitions must achieve a minimum electoral threshold (typically 5% for single parties, 7% for coalitions of two or three parties, and 10% for coalitions of four or more parties) to gain seats in the parliament. This system tends to result in multi-party representation and often necessitates the formation of coalition governments. All Slovak citizens aged 18 and over have the right to vote.

The primary functions and powers of the National Council include:

- Enacting laws and amending the constitution (constitutional amendments require a three-fifths majority).

- Approving the state budget.

- Debating and approving the government's program statement and holding the government accountable (e.g., through votes of no confidence).

- Ratifying international treaties.

- Electing candidates for certain state offices, such as judges of the Constitutional Court (who are then appointed by the President) and the Public Defender of Rights (Ombudsman).

- Declaring war (in case of an attack or as part of collective defense obligations) and approving the deployment of armed forces abroad.

The Speaker of the National Council presides over its sessions and is typically elected from the governing coalition. The National Council operates through various committees that scrutinize legislation and oversee government activities.

5.4. Judiciary

Slovakia's judicial system is based on civil law traditions, influenced by Austro-Hungarian and later Czechoslovak legal codes. The judiciary is independent and tasked with interpreting and applying the law.

The structure of the Slovak judicial system includes:

- General Courts**: These are organized into a three-tier system:

- District Courts (okresné súdyokresné súdySlovak): Courts of first instance for most civil and criminal cases.

- Regional Courts (krajské súdykrajské súdySlovak): Act as courts of appeal for decisions from district courts and as courts of first instance for certain more serious or specialized cases.

- Supreme Court of the Slovak Republic (Najvyšší súd Slovenskej republikyNajvyšší súd Slovenskej republikySlovak): The highest appellate court for general courts, reviewing decisions of regional courts on points of law. It also has other specific competencies.

- Specialized Criminal Court** (Špecializovaný trestný súdŠpecializovaný trestný súdSlovak): Deals with serious crimes such as organized crime, corruption, and extremism. Its decisions can be appealed to the Supreme Court.

- Constitutional Court of the Slovak Republic** (Ústavný súd Slovenskej republikyÚstavný súd Slovenskej republikySlovak): This is a separate judicial body responsible for upholding the constitution. Its main functions include:

- Reviewing the constitutionality of laws and other legal regulations.

- Resolving disputes over competencies between state bodies.

- Adjudicating on complaints regarding violations of fundamental rights and freedoms by public authorities.

- Interpreting the constitution or constitutional laws in cases of dispute.

- Deciding on electoral complaints.

The Constitutional Court consists of 13 judges appointed by the President for a 12-year term from a list of candidates nominated by the National Council.

Judges of general courts are appointed by the President upon the proposal of the Judicial Council of the Slovak Republic. The Judicial Council is an independent body responsible for judicial self-governance, including aspects of judicial selection, training, and discipline. Efforts to strengthen judicial independence, efficiency, and public trust in the judiciary have been ongoing themes in Slovakia's democratic development.

5.5. Constitution

The Constitution of the Slovak Republic (Ústava Slovenskej republikyÚstava Slovenskej republikySlovak) was adopted by the Slovak National Council on September 1, 1992, and came into effect on January 1, 1993, coinciding with the establishment of the independent Slovak Republic. September 1 is celebrated as Constitution Day, a national holiday.

The drafting process took place in the context of the impending dissolution of Czechoslovakia. It was influenced by democratic traditions of the First Czechoslovak Republic, as well as contemporary European constitutional models.

The Constitution's main contents establish Slovakia as a sovereign, democratic, and law-governed state. It is divided into a preamble and nine chapters:

- Preamble**: Expresses the Slovak nation's historical aspirations for self-determination and commitment to democratic values, human rights, and cooperation with other nations.

- Chapter One (Basic Provisions)**: Defines the nature of the state, its territory, symbols (flag, coat of arms, anthem), and the official language (Slovak).

- Chapter Two (Fundamental Rights and Freedoms)**: This is a comprehensive section detailing a wide range of human and civil rights, including personal liberty, freedom of expression, assembly, religion, social and economic rights, and rights of national minorities. It reflects international human rights standards.

- Chapter Three (Economy of the Slovak Republic)**: Outlines principles of the market economy, the role of the National Bank of Slovakia, and state property.

- Chapter Four (Territorial Self-Government)**: Provides for local self-government through municipalities and higher territorial units (regions).

- Chapter Five (Legislative Power)**: Defines the structure, powers, and functioning of the National Council (parliament).

- Chapter Six (Executive Power)**: Details the roles and powers of the President and the Government (Prime Minister and cabinet).

- Chapter Seven (Judicial Power)**: Establishes the Constitutional Court and the general court system, guaranteeing judicial independence.

- Chapter Eight (Office of the Public Prosecutor of the Slovak Republic and Public Defender of Rights)**: Defines these independent institutions.

- Chapter Nine (Transitional and Final Provisions)**.

The Constitution has been amended several times since its adoption. Notable amendments include:

- September 1998: Introduced the direct election of the president by popular vote.

- February 2001: Incorporated changes related to Slovakia's accession to the European Union, including the primacy of EU law in certain areas.

- June 2014: An amendment defined marriage as a unique bond between a man and a woman, and also included provisions related to the protection of drinking water resources.

Amendments to the Constitution require a three-fifths majority vote in the National Council. The Constitution serves as the supreme law of the land, and its provisions for fundamental rights are a cornerstone of Slovakia's democratic order.

5.6. Administrative Divisions

Slovakia is divided into several tiers of administrative units for governance and statistical purposes. The primary administrative division is into eight regions (krajekrajeSlovak, singular: kraj). Each region is named after its principal city, which serves as its administrative seat. These regions have had a degree of self-governance since 2002, with directly elected regional parliaments and presidents (chairpersons). Their self-governing bodies are officially referred to as Self-Governing Regions (samosprávne krajesamosprávne krajeSlovak) or Upper-Tier Territorial Units (vyššie územné celkyvyššie územné celkySlovak, VÚC).

The eight regions of Slovakia are:

| English Name | Slovak Name | Administrative Seat | Population (2019 est.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bratislava Region | Bratislavský kraj | Bratislava | 669,592 |

| Trnava Region | Trnavský kraj | Trnava | 564,917 |

| Trenčín Region | Trenčiansky kraj | Trenčín | 584,569 |

| Nitra Region | Nitriansky kraj | Nitra | 674,306 |

| Žilina Region | Žilinský kraj | Žilina | 691,509 |

| Banská Bystrica Region | Banskobystrický kraj | Banská Bystrica | 645,276 |

| Prešov Region | Prešovský kraj | Prešov | 826,244 |

| Košice Region | Košický kraj | Košice | 801,460 |

The regions (kraje) are further subdivided into districts (okresyokresySlovak, singular: okres). Slovakia currently has 79 districts. Districts primarily serve as units of state administration rather than self-governing entities.

The lowest tier of administrative and self-governing units consists of municipalities (obceobceSlovak, singular: obec). There are currently 2,890 municipalities in Slovakia. These include both cities (mestámestáSlovak) and villages. Municipalities have their own elected councils and mayors and are responsible for local services such as primary education, local roads, and public order.

Economically, there are significant regional disparities. The Bratislava Region, being the capital region, is by far the wealthiest, with a GDP per capita significantly higher than the EU average and considerably higher than other Slovak regions. Western regions are generally more prosperous than eastern regions, presenting an ongoing challenge for equitable development and national cohesion. Efforts to reduce these disparities include EU cohesion funds and national development programs.

5.7. Foreign Relations

Slovakia's foreign policy is primarily oriented towards Euro-Atlantic integration and maintaining good relations with its neighbors and global partners. The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs (Ministerstvo zahraničných vecí a európskych záležitostíMinisterstvo zahraničných vecí a európskych záležitostíSlovak) is responsible for conducting the country's external relations.

Key aspects of Slovakia's foreign relations include:

- European Union (EU) Membership**: Slovakia became a member of the EU on May 1, 2004. EU membership is a cornerstone of its foreign policy, influencing its economic, political, and legislative frameworks. Slovakia participates actively in EU institutions and common policies. It adopted the Euro on January 1, 2009, and is part of the Schengen Area since December 21, 2007.

- NATO Membership**: Slovakia joined NATO on March 29, 2004. This membership is central to its security policy, and Slovakia participates in NATO missions and collective defense efforts.

- International Organizations**: Slovakia is a member of the United Nations (since 1993) and participates in its specialized agencies. It served a two-year term on the UN Security Council from 2006 to 2007. Other memberships include the Council of Europe (CoE), the OSCE, the World Trade Organization (WTO), the OECD, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Health Organization (WHO), the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM), Interpol, UNESCO, CERN, and the Bucharest Nine (B9).

- Regional Cooperation**: Slovakia is an active member of the Visegrád Group (V4), alongside the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland. This group fosters regional cooperation on political, economic, and cultural issues.

- Bilateral Relations**: Slovakia maintains diplomatic relations with 134 countries. It has particularly close ties with the Czech Republic, stemming from their shared history in Czechoslovakia. Relations with Hungary have historically been complex due to issues concerning the Hungarian minority in Slovakia and differing interpretations of history, but have generally improved. Relations with other neighboring countries (Poland, Austria, Ukraine) are generally stable and cooperative. Slovakia also maintains important relationships with major global partners like the United States and Germany.

- Stance on International Issues**: Slovakia generally aligns its foreign policy with EU common positions. It has supported international efforts for peace, democracy, and human rights. Its stance on issues like the Russo-Ukrainian War has evolved with changes in government, with recent policy shifts regarding military aid to Ukraine while maintaining humanitarian support.

As of 2024, Slovak citizens had visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to 184 countries and territories, ranking the Slovak passport 10th in terms of travel freedom according to the Henley Passport Index. Slovakia maintains around 90 diplomatic missions abroad and hosts numerous foreign embassies and consulates in Bratislava.

5.8. Military

The Slovak Armed Forces (Ozbrojené sily Slovenskej republikyOzbrojené sily Slovenskej republikySlovak) are responsible for the defense of Slovakia, its sovereignty, and territorial integrity. The President of Slovakia is formally the commander-in-chief. Since Slovakia joined NATO in March 2004, its military policy has been closely aligned with the alliance's objectives and collective defense principles.

Key aspects of the Slovak military include:

- Structure**: The armed forces consist of the Ground Forces, the Air Force and Air Defence Forces, and various support units. Since 2006, the army transformed into a fully professional organization, and compulsory military service was abolished. In 2022, the Slovak armed forces numbered approximately 19,500 uniformed personnel and 4,208 civilians.

- NATO Membership and International Cooperation**: As a NATO member, Slovakia participates in joint exercises, contributes to NATO's rapid response forces, and aligns its defense planning and equipment modernization with NATO standards. The country has been an active participant in US- and NATO-led military actions.

- Peacekeeping Operations**: Slovakia has a history of contributing to international peacekeeping and crisis management operations under the auspices of the UN, EU, and NATO. Notable missions include UNPROFOR in Yugoslavia, SFOR in Bosnia and Herzegovina, KFOR in Kosovo, operations in Afghanistan (ISAF/Resolute Support), Iraq, and Cyprus (UNFICYP). As of early 2025, Slovak personnel were deployed in Cyprus (UNFICYP), Bosnia and Herzegovina (EUFOR Althea), and Latvia (NATO Enhanced Forward Presence).

- Modernization**: The Slovak Armed Forces are undergoing modernization efforts to replace aging Soviet-era equipment with NATO-compatible systems. This includes acquiring new fighter aircraft (such as F-16s), armored vehicles, and other advanced military technology.

- Main Components**:

- The Ground Forces are primarily composed of mechanized infantry brigades.

- The Air Force operates fighter aircraft (transitioning to F-16s), transport aircraft, and utility helicopters. Air defense is provided by SAM brigades.

- Special forces units, such as the 5th Special Forces Regiment, are also part of the armed forces structure.

Defense spending and policy are subject to parliamentary oversight and public debate, particularly concerning alignment with NATO commitments and responses to regional security challenges.

5.9. Human Rights

Human rights in Slovakia are guaranteed by the Constitution of Slovakia (adopted in 1992) and numerous international laws and conventions to which the country is a signatory. Slovakia generally performs favorably in international assessments of civil liberties, Freedom in the World, press freedom, internet freedom, and democratic governance.

However, challenges and concerns remain:

- Corruption**: Corruption in the public sector and judiciary has been a persistent issue, impacting public trust and the effective protection of rights.

- Minority Rights, particularly Roma**: The Roma minority continues to face significant challenges, including social exclusion, discrimination in housing, education, and employment, and occasional instances of police brutality or racially motivated violence. While legal frameworks for minority protection exist, their implementation and effectiveness are often criticized by domestic and international human rights organizations like the European Roma Rights Centre. Efforts to improve Roma integration and address these issues are ongoing but complex.

- LGBT+ Rights**: LGBT+ individuals face social prejudice and legal limitations. Same-sex marriage is not recognized, and public discourse on LGBT+ rights can be polarized. There have been reports of violence and threats of violence targeting LGBT+ persons.

- Freedom of the Press**: While generally respected, journalists have faced pressure, and the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak in 2018 highlighted serious threats to media freedom and safety.

- Judiciary**: Concerns about the efficiency, independence, and accountability of the judiciary have been raised, although reforms are being implemented.

- Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence**: These remain societal problems, with ongoing efforts to strengthen legal protections and support services for victims.

The Slovak government has established institutions like the Public Defender of Rights (Ombudsman) and the Slovak National Centre for Human Rights to monitor and promote human rights. Civil society organizations also play a crucial role in advocating for human rights and providing assistance to vulnerable groups. International bodies, including the Council of Europe and UN human rights mechanisms, regularly review Slovakia's human rights record.

6. Economy

Slovakia's economy is characterized by its main industries, particularly automotive and IT, extensive international trade and foreign investment, a significant energy sector relying on nuclear power, a developing transportation network, a growing tourism sector, and advancements in science and technology.

6.1. Economic Overview

Slovakia is classified as a high-income developed economy. After transitioning from a centrally planned economy to a market-driven one in the 1990s, the country experienced a period of rapid growth in the 2000s, earning it the nickname "Tatra Tiger." Key drivers of this growth included structural reforms, significant foreign direct investment, and integration into the European Union. Slovakia joined the Eurozone on January 1, 2009, adopting the Euro as its currency.

As of 2024, its GDP (PPP) per capita was estimated at around $49,684, and its nominal GDP per capita at $25,809. Its GDP per capita in purchasing power standards was 74% of the EU average in 2023. Major economic sectors include industry (especially automotive), services (which contribute the largest share to GDP), and to a lesser extent, agriculture.