1. Overview

Guatemala (Guatemalagwah-teh-MAH-lahSpanish; indigenous names include WatemaalWatemaalkek, IximulewIximulewquc in Kaqchikel and K'iche', and Twitz PaxilTwitz Paxilmam in Mam), officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America, bordered by Mexico to the north and west, Belize to the northeast, Honduras to the east, El Salvador to the southeast, the Pacific Ocean to the south, and the Caribbean Sea (Gulf of Honduras) to the northeast. With an estimated population of around 17.6 million, Guatemala is the most populous country in Central America and the 11th most populous in the Americas. Its capital and largest city is Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, also known as Guatemala City, which is the most populous city in Central America.

The territory of modern Guatemala was historically the core of the Maya civilization. Following the Spanish conquest in the 16th century, it became part of the viceroyalty of New Spain. Guatemala gained independence in 1821, briefly joining the First Mexican Empire before becoming part of the Federal Republic of Central America, which dissolved by 1841. The nation's history has been marked by periods of instability, dictatorships often backed by foreign interests like the United Fruit Company and the United States government, and a lengthy civil war (1960-1996). This conflict involved severe human rights violations, including genocidal acts against the Maya population by the military. Since the 1996 peace accords, Guatemala has pursued democratic development and economic growth, though significant challenges related to poverty, inequality, crime, corruption, and the full realization of human rights and social equity persist. This article explores Guatemala's history, geography, governance, economy, and culture, with a particular focus on its journey towards democratic consolidation, respect for human rights, and the pursuit of social justice for all its citizens, especially its indigenous communities.

2. Etymology

The name "Guatemala" originates from the Nahuatl word Cuauhtēmallān, which means "place of many trees" or "land of trees." This is believed to be a derivative of a K'iche' Mayan phrase also meaning "many trees." Some theories suggest it might refer more specifically to the Cuate or Cuatli tree (Eysenhardtia). The name was reportedly given to the region by Tlaxcalan soldiers who accompanied the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado during the Spanish conquest. Initially, the Mexica (Aztecs) used this name to refer to the Kaqchikel city of Iximche, but its usage was extended to encompass the entire country during the Spanish colonial period. Other interpretations of the name include "land of the eagle" or "mountain that vomits water," the latter possibly alluding to its volcanic landscape, but "place of many trees" remains the most widely accepted origin.

3. History

The history of Guatemala spans from ancient Mesoamerican civilizations to the modern era, marked by indigenous cultures, Spanish colonization, struggles for independence, periods of democratic reform, authoritarian rule, a protracted civil war, and ongoing efforts towards peace and social justice. The nation's past profoundly influences its present social, political, and economic landscape.

3.1. Pre-Columbian era

The first evidence of human habitation in Guatemala dates back to at least 12,000 BC, with archaeological findings like obsidian arrowheads suggesting a presence as early as 18,000 BC. Early Guatemalan settlers were primarily hunter-gatherers. The cultivation of maize (corn) was developed by around 3500 BC, marking a significant shift towards agricultural societies. Archaeological sites dating to 6500 BC have been found in the Quiché region in the Highlands, and in Sipacate and Escuintla on the central Pacific coast.

Mesoamerican pre-Columbian history is generally divided into three periods:

- The Preclassic period (3000 BC to 250 AD): Initially viewed as a formative stage with small farming villages, this perception has been challenged by discoveries of monumental architecture. Notable sites from this era include the Mirador Basin cities of Nakbé (with structures reaching 59 ft (18 m)), Xulnal, El Tintal, Wakná, and especially El Mirador. El Mirador was a massive city, one of the largest of its time, featuring enormous pyramids like La Danta. In the southern highlands, the Kaminaljuyu site, near modern Guatemala City, developed elaborate pottery (Las Charcas phase) and later, under Teotihuacan influence, monumental stone sculptures. Other southern sites like Abaj Takalik and El Baúl also show early sculptural traditions influenced by the Izapan culture.

- The Classic period (250 AD to 900 AD): This period represents the zenith of the Maya civilization and is characterized by widespread urbanization, the rise of independent city-states, sophisticated art and architecture, advanced writing systems, mathematics (including the concept of zero), and complex calendrical systems. The largest concentration of Classic Maya sites is in the Petén lowlands. Tikal, a major Maya city, established a powerful dynasty around 378 AD, possibly with influence from Teotihuacan in central Mexico, and became a dominant regional power, often contending with Calakmul for supremacy. Other important Classic Maya cities in Guatemala include Uaxactun, Piedras Negras, Quiriguá, and Yaxha. Maya influence extended across Mesoamerica, from Honduras and Belize to central Mexico.

The Classic Maya collapse occurred around 900 AD, leading to the abandonment of many major cities in the central lowlands. The exact causes are debated but likely involved a combination of factors, including prolonged droughts, environmental degradation due to overpopulation and intensive agriculture, internal warfare, and disruption of trade routes.

- The Postclassic period (900 AD to 1500 AD): Following the collapse in the lowlands, regional kingdoms rose to prominence in both the Petén (such as the Itza, Kowoj, Yalain, and Kejache) and the highlands. Highland kingdoms included the K'iche' (centered at K'umarkaj or Utatlán), Kaqchikel (at Iximche), Mam, Tz'utujil, Poqomchi', Q'eqchi', and Ch'orti'. These groups preserved many aspects of Maya culture but often engaged in conflict with each other. Influence from northern groups, possibly Toltec-related or other Chichimeca groups, is evident in some Postclassic highland cities. These highland kingdoms were the societies encountered by the Spanish upon their arrival.

The Maya civilization shared many traits with other Mesoamerican cultures due to extensive interaction and cultural diffusion. While advancements like writing, epigraphy, and the calendar did not solely originate with the Maya, their civilization developed them to a high degree of sophistication.

3.2. Spanish colonial era (1519-1821)

Following Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492, Spanish expeditions to Guatemala began in 1519. Hernán Cortés, who led the Spanish conquest of Mexico, granted a permit to Captains Gonzalo de Alvarado and his brother, Pedro de Alvarado, to conquer the Guatemalan highlands. In 1523, Pedro de Alvarado entered the region. Early Spanish contact brought devastating epidemics of European diseases, such as smallpox and measles, to which the indigenous populations had no immunity, leading to a catastrophic decline in their numbers.

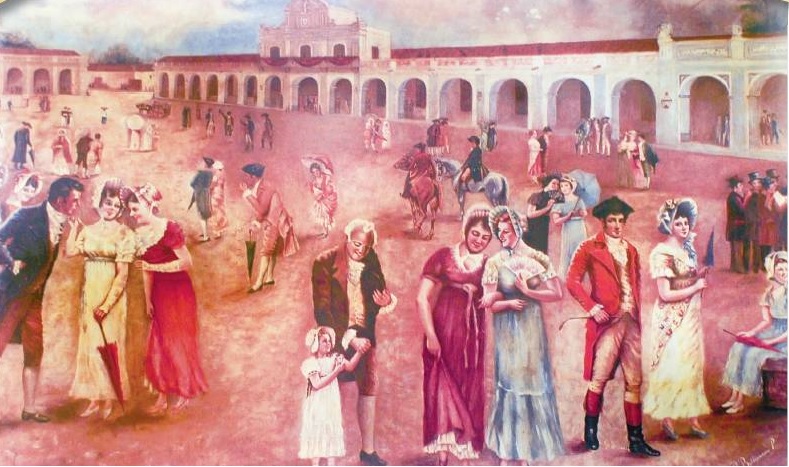

Alvarado initially allied with the Kaqchikel to defeat their traditional rivals, the powerful K'iche' kingdom. The K'iche' were decisively defeated in 1524, and their capital, Q'umarkaj (Utatlán), was razed. Alvarado then established the first Spanish capital, Villa de Santiago de Guatemala, on July 25, 1524, near the Kaqchikel capital of Iximche. However, Alvarado soon turned against his Kaqchikel allies due to his excessive demands for gold, leading to a Kaqchikel revolt. The Kaqchikel abandoned Iximche, which was subsequently burned by deserters in 1526. The Spanish struggled for several years to subdue the Kaqchikel and other resistant Maya groups.

The capital was moved several times:

- To Ciudad Vieja (then known as Santiago de los Caballeros) on November 22, 1527, following the Kaqchikel attack on the Iximche site. This capital was destroyed on September 11, 1541, when a lahar (volcanic mudflow) from the Agua Volcano's crater, possibly triggered by heavy rains and an earthquake, inundated the town. Pedro de Alvarado himself had died earlier that year in Mexico.

- To Antigua Guatemala (then Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala) in the Panchoy Valley, about 4 mile away. This city became the political, economic, religious, and cultural center of the region for over 200 years. It was, however, repeatedly damaged by earthquakes, culminating in the devastating Santa Marta earthquakes of 1773-1774.

- To its current location in the Ermita Valley, founded on January 2, 1776, and named Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción (New Guatemala of the Assumption), now Guatemala City.

During the colonial period, Guatemala was part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain but was administered as the Captaincy General of Guatemala (Capitanía General de Guatemala), also known as the Kingdom of Guatemala. This administrative division encompassed most of Central America, including Chiapas (now in Mexico), Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. While rich in agricultural products like cacao, indigo (añil), cochineal, sugarcane, and precious woods, the region lacked the vast mineral wealth (gold and silver) found in Mexico and Peru, making it of secondary importance to the Spanish Crown. The economy was based on large landed estates (haciendas and plantations) worked by indigenous and later, mestizo labor, often through systems of forced labor like the encomienda and repartimiento. The indigenous population suffered greatly under colonial rule, facing land dispossession, forced labor, heavy taxation, and cultural suppression, including the destruction of Maya codices, though some important texts like the Popol Vuh survived through transcriptions. Guatemala's strategic location on the Pacific Coast also made it a supplementary node in the Transpacific Manila Galleon trade, connecting Latin America to Asia via the Spanish Philippines.

The social structure was rigidly hierarchical, with Spanish-born peninsulares at the top, followed by American-born Spaniards (criollos), then mestizos (mixed European and indigenous), mulattos (mixed European and African), indigenous peoples, and enslaved Africans at the bottom. This system created deep-seated inequalities that would persist long after independence.

3.3. Independence and Central American Federation (1821-1847)

The early 19th century saw growing unrest in Spain's American colonies, fueled by Enlightenment ideas, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and Napoleon's invasion of Spain in 1808, which weakened Spanish authority. On September 15, 1821, prominent criollos in Guatemala City, led by figures like Gabino Gaínza, declared the independence of the Captaincy General of Guatemala from Spain. This declaration encompassed the territories of Chiapas, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica.

Shortly after independence, the region faced political uncertainty. In January 1822, under pressure from Agustín de Iturbide, who had declared himself Emperor of Mexico, the former Captaincy General was annexed to the First Mexican Empire. However, Iturbide's empire was short-lived, collapsing in March 1823.

Following the Mexican Empire's demise, the Central American provinces (excluding Chiapas, which remained part of Mexico) declared their independence from Mexico on July 1, 1823, and formed the Federal Republic of Central America (República Federal de Centroamérica), also known as the United Provinces of Central America. The new federation adopted a constitution in 1824 and initially established its capital in Guatemala City.

The Federal Republic was plagued by internal divisions and conflicts between liberal and conservative factions from its inception. Liberals advocated for a federal system with states' rights, separation of church and state, and free trade, while conservatives favored a strong central government, close ties with the Catholic Church, and protectionist economic policies. Key figures in this struggle included the Honduran liberal Francisco Morazán and the Guatemalan conservative Rafael Carrera.

In 1838, liberal forces under Morazán and Guatemalan José Francisco Barrundia invaded Guatemala. They executed Chúa Alvarez, father-in-law of Rafael Carrera, which fueled Carrera's resolve against Morazán. After initial setbacks, Carrera, a charismatic leader with strong support among the indigenous and mestizo peasantry, launched a counter-offensive. He managed to defeat Morazán's forces and gain control of Guatemala City in April 1839.

The internal strife and military conflicts led to the disintegration of the Federation. Between 1838 and 1840, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Costa Rica formally seceded. El Salvador briefly remained loyal to Morazán, but he was eventually defeated and executed in 1842. On April 17, 1839, Guatemala declared itself independent from the Federal Republic of Central America.

During this period, a secessionist movement in Quetzaltenango led to the formation of the breakaway state of Los Altos (1838-1840), comprising parts of western Guatemala and Chiapas. This state, supported by liberals, was eventually reincorporated into Guatemala by Carrera's forces in 1840. Belgium also showed interest in the region, with the Belgian Colonization Company attempting to establish a colony at Santo Tomas de Castilla in the 1840s, though this effort ultimately failed. Rafael Carrera was elected Guatemalan Governor in 1844.

3.4. Republic

On March 21, 1847, Guatemala formally declared itself an independent republic, with Rafael Carrera becoming its first president. This marked the beginning of Guatemala's journey as a sovereign nation, though it would face continued internal political struggles and external pressures.

3.4.1. Carrera government (1847-1865)

Rafael Carrera dominated Guatemalan politics for nearly three decades. His rule represented a shift towards conservatism, reversing some of the liberal policies of the Federation era. He enjoyed significant support from the rural masses, particularly indigenous communities, partly due to his policies of protecting communal lands and respecting local customs, which contrasted with liberal efforts to privatize land. He also restored the power and influence of the Catholic Church, culminating in the Concordat of 1852 (ratified 1854) with the Holy See, which granted the Church significant privileges.

Carrera's first term as president of the independent republic began in 1847. However, political turmoil led to his resignation in 1848, and he went into exile in Mexico. A liberal regime briefly took power, but Carrera returned in 1849, backed by his rural supporters, and regained control. He defeated an allied army from Honduras and El Salvador at the Battle of La Arada in 1851, a decisive victory that consolidated his power and ensured Guatemala's dominance in the region for a time.

In 1854, Carrera was declared "supreme and perpetual leader of the nation" for life, with the power to choose his successor. His government maintained stability, though often through authoritarian means. He intervened in neighboring countries to support conservative factions and faced military challenges, including a war with El Salvador under Gerardo Barrios in 1863, which Carrera won. He maintained friendly relations with European governments, particularly Great Britain, which was a key trading partner. Carrera died on April 14, 1865, having nominated his loyal general, Vicente Cerna y Cerna, as his successor. His long rule provided a period of relative stability and conservative consolidation, but also entrenched traditional power structures and delayed certain modernizing reforms. From a social equity perspective, while he protected some indigenous land rights, his regime did little to address the fundamental inequalities faced by the Maya population.

3.4.2. Vicente Cerna y Cerna regime (1865-1871)

Field Marshal Vicente Cerna y Cerna continued Carrera's conservative policies after becoming president in 1865. His government maintained a strong alliance with the Catholic Church and the landed elite. Liberal opposition, which had been suppressed under Carrera, began to resurface. Cerna's administration was characterized by some as archaic and oppressive. Liberal party members were often prosecuted and exiled. Economic stagnation and growing discontent among liberal intellectuals and emerging coffee planters created an environment ripe for change. The Consulado de Comercio, a powerful merchants' guild, maintained its monopolistic position during this era, which stifled broader economic development. The period set the stage for the Liberal Revolution of 1871.

3.4.3. Liberal governments (1871-1898)

The "Liberal Revolution" of 1871, led by Miguel García Granados and Justo Rufino Barrios, overthrew Cerna's conservative government. Barrios became president in 1873 and initiated a period of sweeping liberal reforms aimed at modernizing Guatemala, promoting economic development, and reducing the power of the Catholic Church.

Key policies of the Liberal era included:

- Land Reform:** Indigenous communal lands and church properties were expropriated and privatized, ostensibly to promote efficient agriculture. However, this often resulted in the concentration of land in the hands of a few wealthy landowners and foreign companies, dispossessing many indigenous communities and forcing them into a system of debt peonage or migratory labor on coffee plantations. This had a devastating impact on indigenous livelihoods and social structures, exacerbating inequality.

- Economic Development:** Coffee cultivation expanded dramatically, becoming Guatemala's primary export crop. The government invested in infrastructure like roads, railways (including the transoceanic railway project), and ports to facilitate coffee exports. Foreign investment, particularly German, was encouraged.

- Education Reform:** The state took control of education from the Church, promoting secular and supposedly universal education. However, access remained limited, especially for rural and indigenous populations.

- Separation of Church and State:** The liberals curtailed the privileges of the Catholic Church, confiscating its lands, expelling religious orders, and promoting secularism in public life.

Barrios also pursued an ambitious, but ultimately unsuccessful, policy of reuniting Central America by force. He was killed in battle in El Salvador in 1885 during an attempt to achieve this goal.

Manuel Barillas (1886-1892) succeeded Barrios. Uniquely among liberal presidents of this era, he peacefully handed over power to his successor, José María Reyna Barrios (1892-1898), after ensuring Reyna's victory through manipulated elections. Reyna Barrios continued modernizing efforts, particularly in Guatemala City, with Parisian-style avenues and hosting the "Exposición Centroamericana" in 1897. However, his second term was marked by economic problems due to excessive spending and bond printing, leading to inflation and popular opposition. He was assassinated in 1898. The Liberal era brought significant economic changes and modernization but also deepened social inequalities and further marginalized the indigenous population, setting patterns of land tenure and labor exploitation that would have long-lasting consequences.

3.4.4. Manuel Estrada Cabrera regime (1898-1920)

Following the assassination of President José María Reina Barrios, Manuel Estrada Cabrera assumed the presidency. Initially designated as the successor, he asserted his claim and subsequently won a rigged election, ushering in a 22-year dictatorship (1898-1920). His regime was characterized by authoritarian rule, suppression of dissent, and the cultivation of a strongman image.

Economically, Estrada Cabrera continued the liberal emphasis on infrastructure development for export agriculture. A significant and controversial legacy of his rule was the extensive concessions granted to the United Fruit Company (UFCO). In 1904, he signed a contract giving UFCO tax exemptions, vast land grants, and control over railroads on the Atlantic side, particularly for the completion of the railway from Puerto Barrios to Guatemala City. This marked the beginning of UFCO's deep and often criticized involvement in Guatemalan economic and political affairs, contributing to the country's status as a "banana republic."

Estrada Cabrera faced several revolts and assassination attempts (notably in 1907), which he ruthlessly suppressed. His regime became increasingly despotic over time. The 1917 Guatemala earthquake badly damaged Guatemala City, adding to the country's woes. By 1920, his power had waned, and a bipartisan coalition, spurred by widespread discontent, forced his resignation after the national assembly declared him mentally incompetent. His long rule entrenched authoritarian practices and deepened foreign economic influence, with little regard for democratic principles or social equity.

3.4.5. Transition and Instability (1920-1931)

The fall of Estrada Cabrera in 1920 led to a period of political instability and a series of short-lived governments. Carlos Herrera y Luna served as president from 1920 to 1921 but was overthrown in a coup. José María Orellana (1921-1926) followed, during whose term the quetzal was established as the national currency. After Orellana's death, Lázaro Chacón González (1926-1930) became president. This period also saw renewed, but ultimately unsuccessful, attempts to form another Central American federation; Guatemala briefly joined the Federation of Central America with El Salvador and Honduras from September 1921 to January 1922. The era was marked by ongoing political maneuvering and the search for stable leadership, setting the stage for another strongman to emerge.

3.4.6. Jorge Ubico regime (1931-1944)

Jorge Ubico y Castañeda came to power in 1931, winning an election where he was the sole candidate. His 13-year rule was one of the most stringent dictatorships in Guatemalan history. Ubico was known for his efficiency in administration and fiscal management, but also for his cruelty and authoritarianism.

Key aspects of his regime included:

- Economic Policies:** Ubico maintained tight fiscal control and balanced the budget, even during the Great Depression. He continued to favor export agriculture and made further concessions to the United Fruit Company, which expanded its control over land, railroads, and port facilities.

- Social Control:** He replaced debt peonage with a harsh vagrancy law, compelling landless indigenous men to work a minimum of 100-150 days a year, often on public works projects like road construction or on plantations. Wages were frozen at extremely low levels. He granted landowners immunity from prosecution for actions taken to defend their property, effectively legalizing violence against laborers.

- Authoritarian Rule:** Ubico militarized many aspects of society, appointing army generals as provincial governors. He suppressed dissent, censored the press, and outlawed labor unions. His police force was known for its ruthlessness. He cultivated a Napoleonic image, surrounding himself with symbols of power and demanding absolute loyalty.

- Foreign Policy:** Ubico maintained close ties with the United States. When the US entered World War II, he declared war on the Axis powers, arrested Guatemalans of German descent, and allowed the US to establish an airbase in Guatemala. However, he also expressed admiration for European fascists like Francisco Franco and Benito Mussolini.

Growing discontent among students, professionals, and some military officers, fueled by his repressive policies and the desire for democratic change, led to widespread protests and a general strike in 1944. On July 1, 1944, Ubico was forced to resign, ending his long dictatorship and paving the way for the Guatemalan Revolution. His regime, while fiscally sound by some measures, perpetuated extreme social inequalities and severe repression, particularly against the indigenous and working-class populations.

3.4.7. Guatemalan Revolution (1944-1954)

The period from 1944 to 1954 is known as the "Ten Years of Spring" or the Guatemalan Revolution, a time of significant democratic and social reform. After Ubico's resignation, his handpicked successor, General Juan Federico Ponce Vaides, was quickly overthrown in a popular uprising and military coup in October 1944, led by Major Francisco Javier Arana and Captain Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. A revolutionary junta then organized Guatemala's first truly free election.

- Juan José Arévalo (1945-1951):** A university professor and writer, Juan José Arévalo won the 1944 presidential election with a large majority. His philosophy of "spiritual socialism" (inspired partly by the US New Deal) guided his reforms. His government:

Despite his popularity, Arévalo faced numerous coup attempts (at least 25) from conservative elements in the military and the landed oligarchy, and opposition from the Church. He successfully completed his term, a rare achievement for a reformist leader in Guatemala.

- Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (1951-1954):**

Arévalo's defense minister, Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, won the 1950 presidential election and deepened the reform process. His administration focused on economic nationalism and agrarian reform.

- Decree 900 (Agrarian Reform Law of 1952):** This was Árbenz's landmark policy. It aimed to redistribute large, uncultivated landholdings (fallow land) to landless peasants. The law affected haciendas exceeding a certain size that were not fully cultivated. Compensation was offered based on the declared tax value of the land. Approximately 500,000 individuals, mostly indigenous peasants, benefited from the reform, receiving land either individually or through cooperatives.

The agrarian reform, particularly its application to large uncultivated tracts owned by the United Fruit Company (UFCO), provoked strong opposition from the company and powerful elements within the United States government. UFCO launched an extensive propaganda campaign, portraying Árbenz's government as communist or communist-influenced. During the Cold War, the US government, under President Dwight D. Eisenhower and with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and CIA Director Allen Dulles (both of whom had ties to UFCO), viewed Árbenz's reforms with suspicion and hostility. They feared Guatemala was falling under Soviet influence, though Árbenz's government was not communist and maintained diplomatic relations with the US.

The Guatemalan Revolution represented a significant attempt to modernize the country, democratize its political system, and address deep-seated social and economic inequalities. However, its challenge to established domestic and foreign interests ultimately led to its violent overthrow.

3.4.8. Coup and civil war (1954-1996)

The democratic reforms of the Guatemalan Revolution were abruptly ended by the 1954 U.S. CIA-backed coup, codenamed Operation PBSuccess. The coup was orchestrated by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) at the behest of the Eisenhower administration, heavily influenced by the lobbying efforts of the United Fruit Company (UFCO) whose landholdings were affected by Árbenz's agrarian reform (Decree 900).

The CIA armed, funded, and trained a small force of Guatemalan exiles and mercenaries led by Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas. This force invaded Guatemala from Honduras on June 18, 1954. While the invasion force itself was militarily weak, the coup succeeded due to a combination of factors:

- An intense psychological warfare campaign, including a clandestine radio station broadcasting anti-Árbenz propaganda and false news of a major invasion.

- Bombings of Guatemala City by CIA-piloted aircraft.

- The Guatemalan army's leadership, intimidated by the prospect of direct U.S. intervention and influenced by conservative domestic elements, refused to fight effectively to defend the government.

President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán resigned on June 27, 1954, and went into exile. Castillo Armas subsequently became president, reversing Decree 900, returning expropriated lands (including UFCO's) to their former owners, and launching a period of severe repression against suspected communists, labor leaders, intellectuals, and peasant activists. Thousands were arrested, and political parties were banned.

The 1954 coup had profound and devastating long-term consequences for Guatemala:

- It ended a decade of democratic experimentation and social reform.

- It ushered in nearly four decades of repressive military-dominated rule and political instability.

- It directly contributed to the outbreak of the Guatemalan Civil War (roughly 1960-1996).

The civil war was fought between successive U.S.-backed authoritarian governments and various leftist guerrilla groups, which later unified under the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (URNG) in 1982. The conflict was characterized by extreme brutality and systematic human rights violations, predominantly committed by state forces and allied paramilitaries.

Key phases and aspects of the civil war include:

- Early insurgency (1960s):** A failed revolt by young military officers in 1960 (MR-13) marked the beginning of armed struggle.

- Counterinsurgency and State Terror (1960s-1970s):** U.S. military aid and training (including Green Berets) helped the Guatemalan army develop sophisticated counterinsurgency tactics. Right-wing paramilitary groups and death squads (e.g., Mano Blanca) emerged, targeting students, unionists, intellectuals, and political opponents. Presidents during this era included Enrique Peralta Azurdia, Julio César Méndez Montenegro (a civilian who was largely powerless against the military), and Colonel Carlos Manuel Arana Osorio.

- Escalation and Genocide (late 1970s-early 1980s):** This was the most brutal period of the war. Under military dictatorships like those of General Romeo Lucas García (1978-1982) and General Efraín Ríos Montt (1982-1983), the army launched a "scorched earth" campaign, primarily targeting the indigenous Maya population in the highlands, who were perceived as supporting the guerrillas. This campaign involved massacres, forced disappearances, torture, and the destruction of hundreds of villages. The Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH), a UN-sponsored truth commission, later concluded that acts of genocide were committed against Maya groups during this period, particularly under Ríos Montt. Despite widespread human rights abuses, the Reagan Administration in the U.S. provided significant support to Ríos Montt's regime.

- Transition to Civilian Rule and Continued Conflict (mid-1980s-1990s):** General Óscar Humberto Mejía Victores overthrew Ríos Montt in 1983 and initiated a transition to civilian rule, leading to the election of Vinicio Cerezo Arévalo in 1986. However, the military retained significant power, and human rights violations continued, albeit at a somewhat reduced scale. Peace negotiations began in the late 1980s but progressed slowly.

The civil war resulted in an estimated 200,000 deaths or disappearances. The CEH attributed over 93% of the documented human rights violations to government forces and state-sponsored paramilitaries, with indigenous Mayans accounting for 83% of the victims. The conflict caused massive internal displacement and forced many Guatemalans to seek refuge in Mexico and other countries. The Burning of the Spanish Embassy in 1980, where 37 people died after government forces stormed the building occupied by K'iche' protesters, led Spain to break diplomatic relations with Guatemala.

The war finally ended with the signing of the "Accord for a Firm and Lasting Peace" on December 29, 1996, between the Guatemalan government and the URNG, mediated by the United Nations. The accords included commitments to address human rights, indigenous rights, socio-economic reforms, and military reforms. The legacy of the 1954 coup and the subsequent civil war continues to shape Guatemalan society, with ongoing struggles for justice, reconciliation, and the dismantling of impunity.

3.4.9. Post-civil war era (1996-present)

Following the 1996 peace accords, Guatemala embarked on a challenging path towards democratic consolidation, reconciliation, and socio-economic development. While the accords brought an end to armed conflict, the country continued to grapple with the deep scars of war, including widespread poverty, inequality, weak state institutions, corruption, high crime rates, and the need to address past human rights atrocities. The implementation of the peace accords has been slow and incomplete, facing political and economic obstacles.

4. Geography

Guatemala is located in Central America, bordering the Pacific Ocean to the southwest and the Caribbean Sea (Gulf of Honduras) to the northeast. It shares land borders with Mexico to the north and west, Belize to the northeast, Honduras to the east, and El Salvador to the southeast. Its total area is approximately 42 K mile2 (108.89 K km2).

4.1. Topography and Climate

Guatemala is a predominantly mountainous country, with significant coastal plains in the south and a large lowland plain in the northern Petén department. Two major mountain chains traverse the country from west to east, dividing it into three main regions:

1. The Highlands: This region contains the highest mountains and numerous volcanoes, part of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas. The Cuchumatanes range in the west is the highest non-volcanic mountain mass in Central America. This area is characterized by deep ravines, plateaus, and fertile valleys. Major cities, including Guatemala City and Quetzaltenango, are located here. Volcán Tajumulco, at 14 K ft (4.22 K m), is the highest peak in Central America. The highlands have a temperate climate, often described as "eternal spring," though temperatures vary significantly with altitude, becoming colder at higher elevations.

2. The Pacific Coastal Lowlands: South of the mountains, this region is a fertile plain, wider in the west and narrowing to the east. It has a hot, humid tropical climate and is important for agriculture.

3. The Petén Lowlands: This vast, sparsely populated region in the north is largely composed of rolling limestone plains covered by tropical rainforest. It has a hot, tropical climate with high humidity.

The climate varies considerably by region and altitude. The coastal lowlands are tropical, hot, and humid. The highlands experience cooler, drier weather, with temperatures that can drop significantly at night, especially at higher altitudes. The Petén region is generally hot and humid, with a rainy season typically from May to November.

Guatemala has numerous rivers, generally short and shallow in the Pacific drainage basin, but larger and deeper in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico drainage basins. Major rivers include the Motagua River, Usumacinta River (which forms part of the border with Mexico), Polochic, and Dulce River. Lake Izabal is the largest lake, and Lake Atitlán, a deep, highland lake of volcanic origin, is renowned for its beauty.

4.2. Natural disasters

Guatemala's geographical location makes it prone to various natural disasters.

- Earthquakes:** The country is seismically active due to its position at the intersection of three tectonic plates: the North American Plate, the Caribbean Plate, and the Cocos Plate. The Motagua Fault and the Chixoy-Polochic Fault system cut across the country, and the Middle America Trench subduction zone lies off the Pacific coast. Guatemala has experienced numerous devastating earthquakes throughout its history. The 1976 Guatemala earthquake (magnitude 7.5) killed an estimated 23,000 people and caused widespread destruction.

- Volcanic Eruptions:** The highlands are home to 37 volcanoes, several of which are active, including Fuego, Pacaya, and Santiaguito. Eruptions can pose significant hazards to nearby communities. The 2018 eruption of Volcán de Fuego resulted in hundreds of deaths and missing persons. Historically, volcanic mudflows (lahars) have also caused destruction, such as the event that destroyed the second capital, Ciudad Vieja, in 1541.

- Hurricanes and Tropical Storms:** Both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts are susceptible to hurricanes and tropical storms, particularly during the hurricane season (roughly June to November). These events can bring heavy rainfall, leading to severe flooding and mudslides. Notable storms include Hurricane Mitch (1998), Hurricane Stan (2005), which caused over 1,500 deaths primarily due to flooding and mudslides, and Hurricane Eta (2020), which also resulted in significant loss of life and damage.

- Landslides and Floods:** Heavy seasonal rains, often exacerbated by deforestation and steep terrain, frequently trigger landslides and floods in various parts of the country, causing casualties and infrastructure damage.

These natural hazards pose ongoing challenges to Guatemala's development and require significant disaster preparedness and mitigation efforts.

4.3. Biodiversity

Guatemala is recognized as one of the world's biodiversity hotspots, forming part of the Mesoamerican hotspot. Its diverse topography and climates support a wide array of ecosystems and a rich variety of flora and fauna, including many endemic species.

The country encompasses 14 distinct ecoregions, ranging from mangrove forests along both coasts to dry forests, thornscrub, subtropical and tropical rainforests, cloud forests (especially in the Verapaz region), and pine-oak forests in the highlands. Guatemala has 252 listed wetlands, including five major lakes, 61 lagoons, numerous rivers, and four swamps. Six of these wetlands are designated as Ramsar sites of international importance.

Guatemala is home to approximately 1,246 known species of amphibians, birds, mammals, and reptiles. Of these, about 6.7% are endemic (found nowhere else), and 8.1% are considered threatened. The country boasts at least 8,682 species of vascular plants, with 13.5% being endemic. There are 17 species of conifers, including pines, cypresses, and the endemic Guatemalan Fir (Abies guatemalensis), the highest diversity of conifers in any tropical region.

The Maya Biosphere Reserve, located in the northern department of Petén, covers an area of 5.2 M acre (2.11 M ha) and is the largest protected area in Central America. It is a critical habitat for numerous species, including jaguars, pumas, tapirs, scarlet macaws, and howler monkeys. Tikal National Park, situated within the reserve, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site recognized for both its cultural and natural significance. Other important protected areas include the Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve and numerous national parks and wildlife refuges.

Despite its rich biodiversity, Guatemala faces significant environmental challenges, including deforestation (due to agricultural expansion, logging, and fuelwood collection), soil erosion, water pollution, and habitat loss, which threaten many species and ecosystems. Conservation efforts are ongoing but face resource limitations and socio-economic pressures. Guatemala had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.85/10, ranking it 138th globally out of 172 countries.

5. Government and Politics

Guatemala is a presidential republic with a multi-party system. The government is divided into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial, as stipulated by the constitution, which was last promulgated in 1985 and revised in 1993. The current president is Bernardo Arévalo, who assumed office on January 14, 2024.

5.1. Political system

The political system of Guatemala operates under a framework of a constitutional democratic republic.

- Executive Branch:** The President of Guatemala is both the head of state and head of government. The president is elected by popular vote for a single four-year term and cannot be re-elected. The president appoints a Council of Ministers (cabinet). The Vice President is elected on the same ticket as the President. Recent presidents include Otto Pérez Molina (resigned in 2015 due to corruption), Jimmy Morales (2016-2020), Alejandro Giammattei (2020-2024), and the current president, Bernardo Arévalo.

- Legislative Branch:** Legislative power is vested in the unicameral Congress of the Republic (Congreso de la República). It currently has 160 members (diputados), elected for four-year terms through a mixed system of proportional representation from multi-member national and departmental lists. The Congress is responsible for passing laws, approving the national budget, and overseeing the executive branch.

- Judicial Branch:** The judiciary is independent of the executive and legislative branches. The highest court is the Supreme Court of Justice (Corte Suprema de Justicia), whose magistrates are elected by Congress from a list submitted by a postulation commission. The Constitutional Court (Corte de Constitucionalidad) is a separate body responsible for interpreting the constitution and ensuring its supremacy. The judicial system has faced significant challenges, including corruption, inefficiency, and intimidation, which have contributed to high levels of impunity.

Guatemala has a multi-party system, but political parties are often weak, personality-driven, and lack stable ideological bases, leading to a fragmented political landscape and frequent shifts in alliances. Voter turnout can vary, and citizen participation in politics, while growing, faces challenges from historical repression and current social issues. The country continues to work towards strengthening its democratic institutions, combating corruption, and ensuring the rule of law.

5.2. Administrative divisions

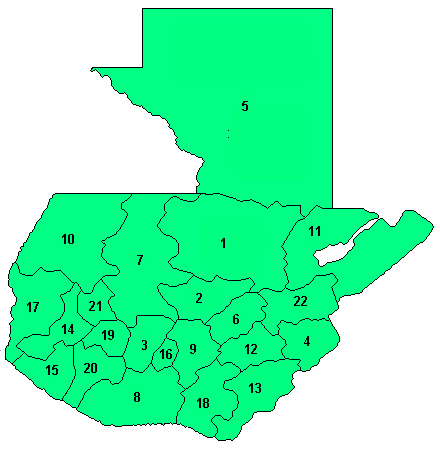

Guatemala is divided into 22 departments (departamentos), which are further subdivided into 340 municipalities (municipios) as of 2024. Each department is headed by a governor appointed by the president. Municipalities are governed by elected mayors and councils.

The 22 departments are:

# Alta Verapaz

# Baja Verapaz

# Chimaltenango

# Chiquimula

# El Progreso

# Escuintla

# Guatemala

# Huehuetenango

# Izabal

# Jalapa

# Jutiapa

# Petén

# Quetzaltenango

# El Quiché

# Retalhuleu

# Sacatepéquez

# San Marcos

# Santa Rosa

# Sololá

# Suchitepéquez

# Totonicapán

# Zacapa

The department of Guatemala, which includes the capital, Guatemala City, is the most populous. The largest department by area is Petén in the north.

5.2.1. Largest cities

Guatemala is a country with significant urbanization, although a large portion of its population still resides in rural areas. The capital, Guatemala City (officially Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción), is the largest urban center not only in Guatemala but also in Central America. Other major cities play important roles as regional economic, cultural, and administrative hubs.

Here are some of the largest cities in Guatemala based on population and importance:

| City | Department | Estimated Population (Urban Area/Municipality) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guatemala City | Guatemala | Approx. 3 million (metro area) / 923,392 (municipality, 2018 Census) | National capital, largest city, primary economic, political, cultural, and transportation hub of Guatemala and Central America. |

| Mixco | Guatemala | Approx. 463,019 (municipality, 2018 Census) | A large municipality forming part of the Guatemala City metropolitan area, primarily residential and commercial. |

| Villa Nueva | Guatemala | Approx. 426,316 (municipality, 2018 Census) | Another major municipality within the Guatemala City metropolitan area, experiencing rapid growth. |

| Quetzaltenango (Xela) | Quetzaltenango | Approx. 180,706 (municipality, 2018 Census) | Second-largest city, important cultural, commercial, and educational center in the western highlands. Historically significant as the center of the Los Altos region. |

| Escuintla | Escuintla | Approx. 156,313 (municipality, 2018 Census) | Major industrial and agricultural center on the Pacific coastal plain, strategically located between the coast and the highlands. |

| Cobán | Alta Verapaz | Approx. 212,047 (municipality, 2018 Census) | Important city in the Verapaz region, known for coffee production and its proximity to natural attractions. |

Other notable cities include Puerto Barrios and Santo Tomás de Castilla (major Caribbean ports in Izabal), Huehuetenango (western highlands), Chichicastenango (known for its indigenous market), and Antigua Guatemala (former capital and major tourist destination in Sacatepéquez). Population figures can vary based on census data and estimates for metropolitan areas versus municipal boundaries.

5.3. Foreign relations

Guatemala's foreign policy generally focuses on maintaining peaceful relations with its neighbors, promoting regional integration, and engaging with international partners on issues of trade, development, security, and human rights. Key aspects of its foreign relations include:

- Central America:** Guatemala is an active member of Central American integration efforts, including the Central American Integration System (SICA). It maintains close ties with neighboring countries like El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua, though historical tensions and border issues occasionally arise.

- Belize:** Guatemala has a long-standing territorial dispute with Belize, claiming a significant portion of Belizean territory. This claim dates back to the colonial era. While Guatemala recognized Belize's independence in 1991, the dispute remains unresolved. Both countries agreed in referendums (Guatemala in 2018, Belize in 2019) to submit the case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for a final resolution, and proceedings are ongoing. This dispute is a central element of Guatemalan foreign policy. From Guatemala's perspective, it exercises de facto control up to its internationally recognized borders but maintains its legal claim over parts of Belize.

- Mexico:** Guatemala shares a long border and significant cultural and economic ties with Mexico. Cooperation on border security, migration, and combating transnational crime is crucial.

- United States:** The U.S. is a major trading partner, source of investment, and home to a large Guatemalan diaspora. Relations have historically been complex, marked by U.S. intervention (e.g., the 1954 coup) and support for counterinsurgency during the civil war. Current cooperation focuses on issues like drug trafficking, migration, economic development, and strengthening democratic institutions. However, differences on issues like corruption and human rights have sometimes strained relations.

- European Union:** The EU is an important partner for trade, development aid, and political dialogue, often emphasizing human rights and democratic governance.

- Taiwan (Republic of China):** Guatemala is one of the few remaining countries that maintain full diplomatic relations with Taiwan (Republic of China) instead of the People's Republic of China. This relationship has been a consistent feature of its foreign policy, though recent administrations, including President Arévalo's, have expressed interest in expanding trade relations with mainland China.

- International Organizations:** Guatemala is a member of the United Nations, the Organization of American States (OAS), and other international bodies, through which it participates in global and regional affairs.

Guatemala's foreign policy aims to navigate a complex international environment while promoting its national interests, which include economic development, security, and the resolution of its territorial claim with Belize.

5.4. Military

The Guatemalan Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas de Guatemala) consist of the Army (Ejército Nacional de Guatemala), Air Force (Fuerza Aérea Guatemalteca), and Navy (Marina de la Defensa Nacional). The President of Guatemala is the commander-in-chief.

- Size and Budget:** The active military personnel is estimated to be between 15,000 and 20,000. Military expenditure as a percentage of GDP has been relatively low in recent years compared to the civil war era.

- Primary Roles:** The primary constitutional roles of the military are to defend Guatemala's sovereignty and territorial integrity. Historically, the military played a dominant role in internal security and politics, particularly during the civil war (1960-1996). The 1996 peace accords included provisions for demilitarization and redefining the military's role to focus on external defense.

- Domestic Activities:** In the post-civil war era, the military has sometimes been deployed to support civilian police in combating organized crime, drug trafficking, and in disaster relief operations. However, its involvement in internal security remains a sensitive issue due to its past human rights record.

- International Activities:** Guatemala has participated in UN peacekeeping missions.

- Legacy and Reforms:** The military's legacy from the civil war, including widespread human rights violations and impunity, continues to be a significant issue. The peace accords mandated reforms aimed at subordinating the military to civilian authority, reducing its size, and strengthening human rights accountability. Progress on these reforms has been mixed.

- Nuclear Weapons:** In 2017, Guatemala signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Efforts continue to modernize the armed forces and align their operations with democratic norms and human rights standards, though challenges related to its historical role and accountability persist.

5.5. Human rights

Human rights in Guatemala remain a significant concern, despite progress since the end of the 36-year civil war in 1996. The country faces a legacy of widespread human rights violations committed during the conflict, particularly against the indigenous Maya population, including acts of genocide. Addressing this legacy and ensuring current protections are ongoing challenges.

Major human rights issues include:

- Impunity and Justice for Past Atrocities:** While some high-profile cases against former military officials for civil war-era crimes (such as the Guatemalan genocide trials) have moved forward, impunity remains widespread. The judicial system is often slow, weak, and susceptible to corruption and intimidation, hindering efforts to bring perpetrators to justice and provide reparations to victims. The work of organizations like the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), before its mandate ended, highlighted the deep-seated nature of clandestine security apparatuses and their influence.

- Violence and Crime:** High rates of violent crime, including homicides, extortion, and gang-related violence, affect citizens' security. Femicide (the murder of women because of their gender) is a severe problem, with Guatemala having one of the highest rates globally. In 2008, Guatemala became the first country to officially recognize femicide as a specific crime.

- Discrimination:** Indigenous peoples, who constitute a large percentage of the population, continue to face systemic discrimination in access to land, education, healthcare, justice, and political participation. Racism remains a significant barrier to social equity. Afro-Guatemalan and Garifuna communities also face discrimination.

- Poverty and Inequality:** Extreme poverty and socio-economic inequality disproportionately affect indigenous and rural populations, limiting their access to basic rights such as food, water, housing, and healthcare. Land disputes, often stemming from historical dispossession of indigenous lands, are common and can lead to conflict.

- Attacks on Human Rights Defenders, Journalists, and Justice Officials:** Individuals and organizations working to defend human rights, expose corruption, or pursue justice often face threats, harassment, intimidation, and violence. This creates a climate of fear and undermines efforts to strengthen the rule of law.

- Judicial System Weaknesses:** The justice system suffers from inefficiency, corruption, lack of resources, and insufficient protection for judges, prosecutors, witnesses, and victims involved in sensitive cases.

- Rights of Vulnerable Groups:** Children, LGBTQ+ individuals, migrants, and persons with disabilities face specific human rights challenges, including violence, discrimination, and lack of access to protection and services.

Efforts by civil society organizations, victims' groups, and international bodies continue to advocate for human rights improvements, accountability for past crimes, and the strengthening of democratic institutions and the rule of law. The government of Bernardo Arévalo has pledged to prioritize human rights and combat corruption, offering a renewed opportunity for progress in this area.

| Extra-Judicial Killings in Guatemala (CALDH Data) | |

|---|---|

| Year | Number of Killings |

| 2010 | 5,072 |

| 2011 | 279 |

| 2012 | 439 |

Note: The significant drop after 2010 may reflect changes in data collection, definition, or actual trends, requiring careful interpretation.

6. Economy

Guatemala has the largest economy in Central America, but it faces significant social problems and is one of the poorest countries in Latin America. Income distribution is highly unequal, with a large percentage of the population living below the national poverty line. The economy is primarily based on agriculture, services, and remittances from Guatemalans living abroad.

6.1. Major industries and Trade

Guatemala's economy is diverse, with key sectors including agriculture, manufacturing, services, and mining. Trade plays a significant role, with both exports and imports contributing to economic activity.

- Major Industries:**

- Agriculture:** This sector remains vital, accounting for about 13.2% of GDP (2010 est.) and employing a significant portion of the labor force (around half).

- Traditional export crops include coffee (Guatemala is known for its high-quality beans), sugarcane, and bananas.

- Other important agricultural products are cardamom (Guatemala is a leading global exporter), fruits (melons, berries), vegetables, and flowers.

- The expansion of crops like palm oil for biofuel and export has raised concerns about deforestation, land displacement (particularly affecting indigenous communities), labor rights, and food security (as land is diverted from staple food production like corn). The social and environmental impacts of large-scale agriculture are critical issues.

- Manufacturing:** This sector contributes significantly to GDP (around 23.8% in 2010 est.) and includes food processing, textiles and apparel (maquila industry, often for export to the US), beverages, chemicals, and construction materials. The maquila sector, while providing employment, has faced scrutiny regarding labor conditions and wages.

- Services:** This is the largest sector of the economy, accounting for about 63% of GDP (2010 est.). It includes retail, wholesale trade, tourism, transportation, communications, financial services, and government services.

- Mining:** Guatemala has mineral resources, including gold, silver, nickel, zinc, and cobalt. Mining activities, often involving foreign companies, have been a source of conflict with local communities due to concerns about environmental damage, water use, land rights, and the distribution of economic benefits. Gold production in 2015 was around 6 tons.

Proportional representation of Guatemala's exports in 2019 - Trade:**

- Exports:** Key exports include coffee, sugar, bananas, cardamom, apparel, fruits, vegetables, and palm oil.

- Imports:** Major imports include machinery and transport equipment, mineral fuels, chemical products, manufactured goods, and food.

- Main Trading Partners:** The United States is Guatemala's largest trading partner. Other important partners include other Central American countries (especially El Salvador and Honduras), Mexico, the European Union, and countries in Asia.

- Trade Agreements:** Guatemala is a signatory to the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA) with the United States and other Central American nations. It also has free trade agreements with countries like Taiwan, Colombia, and the European Union (through the EU-Central America Association Agreement).

- Economic Challenges and Considerations:**

- Poverty and Inequality:** Despite being the largest economy in Central America, Guatemala suffers from high rates of poverty and extreme income inequality. More than half the population lives below the national poverty line.

- Remittances:** Remittances from Guatemalans working abroad, primarily in the United States, are a crucial source of foreign income, constituting a significant portion of GDP and supporting many families.

- Informal Economy:** A large part of the labor force works in the informal sector, with limited access to social security and labor protections.

- Infrastructure:** Deficiencies in infrastructure (roads, ports, energy) can hinder economic growth.

- Corruption and Rule of Law:** Corruption and a weak rule of law are significant impediments to investment and sustainable economic development.

- Social and Environmental Impact:** The pursuit of economic growth through industries like large-scale agriculture and mining needs careful balancing with social equity (especially concerning indigenous land rights and labor practices) and environmental sustainability to ensure long-term well-being.

The government has periodically considered controversial economic measures, such as the potential legalization of poppy and marijuana production for revenue, though these have not materialized into formal policy. In 2024, Guatemala was ranked 122nd in the Global Innovation Index.

- Agriculture:** This sector remains vital, accounting for about 13.2% of GDP (2010 est.) and employing a significant portion of the labor force (around half).

6.2. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing sector of the Guatemalan economy, contributing substantially to foreign exchange earnings and employment. Guatemala's rich cultural heritage and diverse natural landscapes make it an attractive destination for international visitors. In 2008, tourism was estimated to contribute $1.8 billion to the economy, with around two million tourists visiting annually.

- Main Tourist Attractions:**

- Maya Archaeological Sites:** Guatemala is the heartland of the ancient Maya civilization, and its archaeological sites are major draws.

- Tikal: Located in the Petén rainforest, Tikal is one of the largest and most impressive Maya cities, a UNESCO World Heritage Site renowned for its towering pyramids and vast plazas.

- Quiriguá: Another UNESCO site in the department of Izabal, famous for its intricately carved stelae, the tallest in the Maya world.

- Iximché: A Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya capital in Chimaltenango, offering insights into the period just before the Spanish conquest.

- Other notable sites include Yaxha, El Mirador (a massive Preclassic city, less accessible but historically significant), Uaxactun, and Kaminaljuyu (in Guatemala City).

- Colonial Heritage:**

- Antigua Guatemala: The former colonial capital, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is celebrated for its well-preserved Spanish Baroque architecture, cobblestone streets, and stunning volcanic backdrop. It is a major hub for tourism and Spanish language schools.

- Natural Landscapes:**

- Lake Atitlán: A deep, beautiful highland lake surrounded by volcanoes and traditional Maya villages like Panajachel, Santiago Atitlán, and San Pedro La Laguna.

- Semuc Champey: A natural limestone bridge with a series of turquoise pools in Alta Verapaz.

- Volcanoes: Opportunities for hiking active and dormant volcanoes like Pacaya, Acatenango, and Tajumulco.

- Highlands: The mountainous regions offer scenic beauty, indigenous markets (like Chichicastenango), and cultural experiences.

- Pacific Coast: Offers black sand beaches and opportunities for surfing.

- Caribbean Coast: Livingston offers a unique Garifuna culture and access to the Río Dulce.

- Cultural Tourism:** Experiences include visiting indigenous markets, learning about Maya traditions, textiles, and cuisine, and studying Spanish.

- Impact and Current Status:**

The tourism industry provides employment in hotels, restaurants, transportation, and as tour guides. It also supports local artisans and communities. The government, through the Guatemalan Tourism Institute (INGUAT), promotes the country as a tourist destination. There has been an increase in cruise ship arrivals at Guatemalan ports, further boosting tourist numbers.

Challenges for the tourism sector include infrastructure limitations in some areas, security concerns (though tourist areas are generally well-policed), and the need for sustainable tourism practices to protect natural and cultural heritage. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the industry, but efforts are ongoing to revive and further develop tourism as a key economic driver. - Maya Archaeological Sites:** Guatemala is the heartland of the ancient Maya civilization, and its archaeological sites are major draws.

7. Demographics and Society

Guatemala's society is characterized by a rich ethnic and cultural diversity, a young population, and significant social and economic disparities. The country has the largest population in Central America and faces ongoing challenges related to poverty, inequality, education, health, and security.

7.1. Population

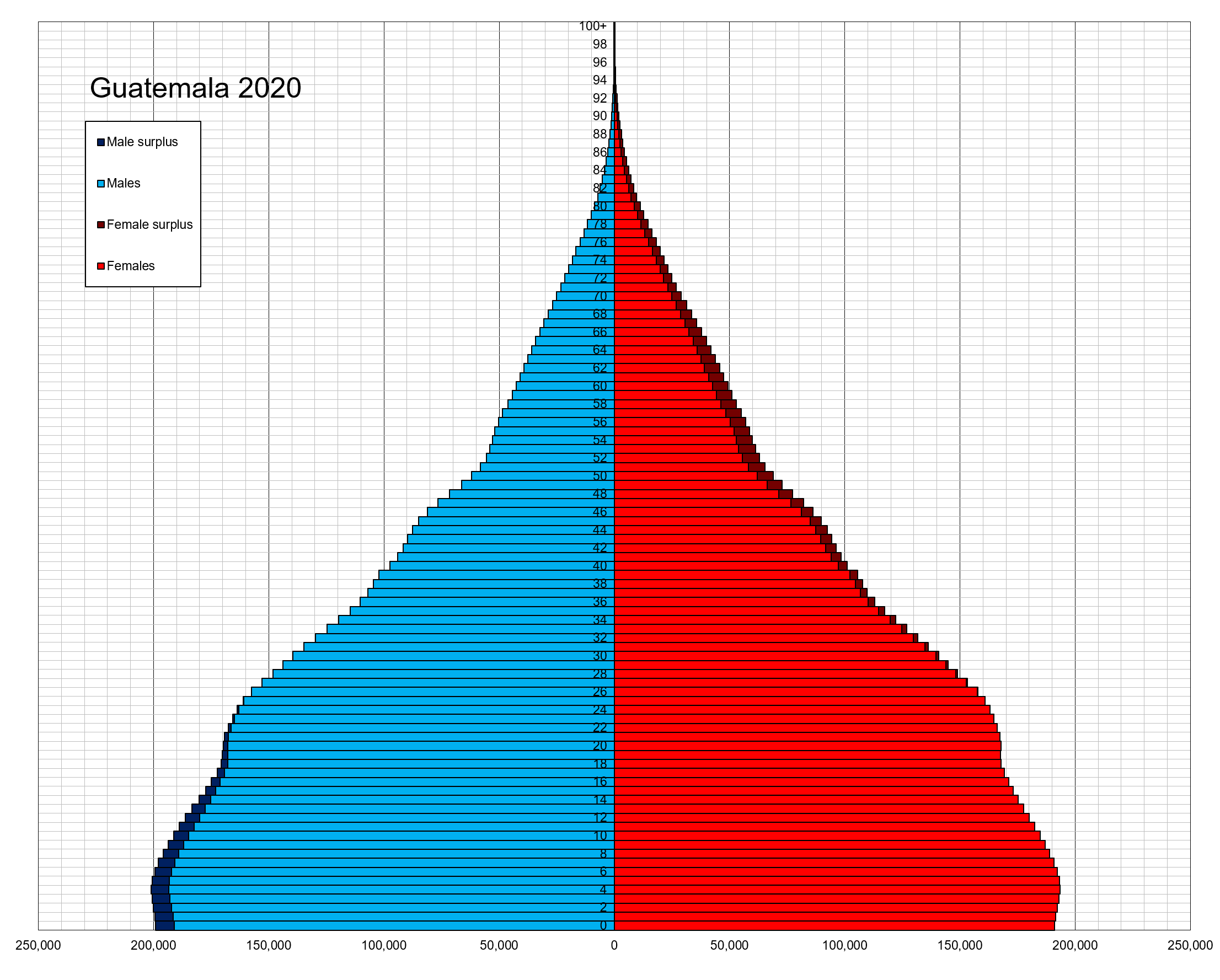

As of recent estimates (around 2023-2024), Guatemala has a population of approximately 17 to 18 million people (some sources state 17.6 million, others like the 2018 census reported 14.9 million, with projections showing significant growth). This makes it the most populous country in Central America. Guatemala experienced one of the fastest population growth rates in the Western Hemisphere during the 20th century, growing from about 885,000 in 1900.

- Key Demographic Characteristics:**

- Population Density:** Varies significantly, with higher concentrations in the highlands, the Pacific coastal plain, and around Guatemala City, while the northern department of Petén is sparsely populated.

- Growth Rate:** Historically high, though it has been gradually declining.

- Age Structure:** Guatemala has a very young population, one of the youngest in the Western Hemisphere. In 2010, approximately 41.5% of the population was under the age of 15, 54.1% were aged 15-65, and 4.4% were 65 or older. The estimated median age is around 20 years.

- Urbanization Rate:** While a significant portion of the population still lives in rural areas, urbanization is increasing. Guatemala City is the largest urban agglomeration and is heavily centralized, serving as the main hub for transportation, communication, business, and politics.

- Historical Population Data:** Censuses have been conducted periodically. Some historical data includes:

- 1778: 430,859

- 1880: 1,224,602

- 1921: 2,004,900

- 1950: 2,870,272

- 2002: 11,183,388

- 2018: 14,901,286 (INE Census)

This demographic profile presents both opportunities (a large youth workforce) and challenges (pressure on education, health services, and employment).

7.2. Ethnic groups

Guatemala is a multiethnic and multicultural nation with a rich tapestry of indigenous and mixed-heritage populations. According to the 2018 National Institute of Statistics (INE) Census:

- Ladino/Mestizo**: Approximately 56% of the population is classified as Ladino. The term "Ladino" in Guatemala typically refers to people of mixed European (primarily Spanish) and indigenous ancestry, as well as culturally assimilated indigenous individuals or those of European descent who do not identify as indigenous.

- Indigenous Peoples:** Approximately 43.6% of the population is indigenous, making Guatemala one of the countries in Latin America with the highest proportion of indigenous people.

- Maya:** The vast majority of indigenous Guatemalans (41.7% of the total population) belong to various Maya linguistic groups. The largest Maya groups include:

- K'iche' (11.0% of total population)

- Q'eqchi' (8.3%)

- Kaqchikel (7.8%)

- Mam (5.2%)

- Other Maya groups (including Tz'utujil, Poqomchi', Achi, Jakaltek, etc.) collectively make up 7.6%.

- Xinca**: An indigenous non-Maya group, historically inhabiting southeastern Guatemala. They constitute about 1.8% of the population.

- Garifuna**: An Afro-descendant group with mixed African and Carib indigenous ancestry, primarily residing on the Caribbean coast, particularly in Livingston. They make up about 0.13% of the population.

- Maya:** The vast majority of indigenous Guatemalans (41.7% of the total population) belong to various Maya linguistic groups. The largest Maya groups include:

- Other groups:**

- Afro-Guatemalans (other than Garifuna) and mulattos, often descendants of colonial-era enslaved people or banana plantation workers, account for about 0.19%.

- Foreign-born individuals represent about 0.24%.

- White Guatemalans of predominantly European descent (e.g., Spanish, German, Italian) are generally included within the Ladino category in census data if they are culturally Guatemalan and Spanish-speaking. German settlers, for instance, played a role in developing coffee cultivation and introduced traditions like the Christmas tree.

It's important to note that indigenous rights activists sometimes estimate the indigenous population to be closer to 60-65%, suggesting potential undercounting or issues with self-identification in official censuses.

Social relations between ethnic groups have historically been marked by inequality and discrimination, particularly against indigenous peoples. The 1996 Peace Accords included provisions for recognizing and promoting indigenous rights and cultural identity, but systemic challenges persist.

7.3. Languages

Guatemala has a rich linguistic diversity, reflecting its multiethnic composition.

- Official Language:** Spanish is the sole official language of Guatemala and is spoken by the majority of the population (around 69.9% according to some estimates, though proficiency varies, especially in rural indigenous areas). Guatemalan Spanish has its own regional variations and influences.

- Indigenous Languages:** There are 24 distinct indigenous languages spoken in Guatemala.

- Mayan Languages:** Twenty-two of these are Mayan languages. These are actively spoken, particularly in rural communities, by about 29.6% of the population. Major Mayan languages include:

- K'iche'

- Kaqchikel

- Q'eqchi'

- Mam

- Tz'utujil

- Poqomchi'

- And many others, each with its own distinct cultural heritage.

- Non-Mayan Indigenous Languages:**

- Xinca: An indigenous language isolate, historically spoken in southeastern Guatemala, now critically endangered with very few fluent speakers.

- Garifuna: An Arawakan language spoken by the Garifuna people on the Caribbean coast.

The Language Law of 2003 (Decree 19-2003) officially recognizes these indigenous languages as national languages and provides for their promotion and use in education, public services, and media, though implementation faces challenges. Efforts towards bilingual education aim to preserve these languages while also ensuring proficiency in Spanish. About 0.1% of the population speaks English, and 0.2% speak other languages; 0.1% are reported as speaking no language (likely referring to pre-verbal children or specific data collection nuances).

7.3.1. Indigenous integration and bilingual education

Efforts towards the social integration of Guatemala's diverse indigenous Maya peoples and the promotion of their linguistic and cultural rights have been a significant, albeit challenging, aspect of national policy, particularly since the 1996 Peace Accords. Bilingual intercultural education is a key component of these efforts.

- Historical Background:**

Historically, state policies often aimed at assimilating indigenous populations into the dominant Ladino culture, with Spanish as the sole language of instruction. This led to high dropout rates among indigenous children and the marginalization of indigenous languages and cultures. Early attempts at literacy in indigenous languages, such as those by the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) in partnership with the Ministry of Education from the 1950s, had mixed results, sometimes still aiming for eventual transition to Spanish.

- The Peace Accords and Legal Framework:**

The 1996 Peace Accords, particularly the Accord on Identity and Rights of Indigenous Peoples, marked a turning point. They recognized Guatemala as a multicultural, multilingual nation and mandated the state to promote indigenous languages, cultures, and access to education in their own languages. The 2003 Language Law (Decree 19-2003) further solidified the status of indigenous languages as national languages and promoted bilingual education.

- Current Status of Bilingual Education:**

Bilingual Intercultural Education (Educación Bilingüe Intercultural - EBI) programs aim to provide instruction in a child's mother tongue (Mayan, Xinca, or Garifuna) during the initial years of primary school, with a gradual introduction of Spanish as a second language. The goal is to improve learning outcomes, reduce dropout rates, strengthen cultural identity, and promote intercultural understanding.

- Achievements:**

- Mayan Languages:** Twenty-two of these are Mayan languages. These are actively spoken, particularly in rural communities, by about 29.6% of the population. Major Mayan languages include:

- Challenges:**

- Funding and Resources:** EBI programs often lack adequate funding, materials, and trained personnel.

- Teacher Training and Availability:** There is a shortage of qualified bilingual teachers fluent in both an indigenous language and Spanish, and pedagogical methods.

- Curriculum Development:** Creating culturally relevant and effective curricula for numerous languages is a complex task.

- Coverage:** EBI programs do not reach all indigenous communities, and implementation quality varies.

- Discrimination and Stigma:** Indigenous languages sometimes still face social stigma, and parents may prefer Spanish-only education hoping it provides better economic opportunities for their children.

- Political Will:** Consistent political support and effective implementation across different government administrations have been variable.

- Standardization vs. Dialectal Variation:** Many Mayan languages have significant dialectal differences, posing challenges for standardized instruction.

Despite these challenges, bilingual education is considered a crucial tool for promoting social equity, preserving cultural heritage, and empowering indigenous communities within Guatemala's diverse society. The ongoing efforts reflect a commitment to a more inclusive and just educational system, aligning with the principles of democratic development and human rights.

7.4. Religion

Guatemala has a diverse religious landscape, predominantly Christian, but with a growing presence of various denominations and the persistence of traditional Maya beliefs.

- Roman Catholicism:** Historically, Roman Catholicism, introduced during Spanish colonization, was the overwhelmingly dominant religion. While it remains the largest single denomination, its proportion of adherents has declined. Recent estimates (around 2012-2018) suggest that Roman Catholics constitute about 45-48% of the population. The Catholic Church continues to play an influential role in society.

- Protestantism:** Protestantism, particularly Evangelical and Pentecostal denominations, has experienced significant growth since the mid-20th century, especially from the 1960s onwards and accelerating during the civil war and its aftermath. Protestants now represent a substantial portion of the population, estimated to be around 38-42%. Guatemala is often described as one of the most heavily Evangelical nations in Latin America. This growth is notable among both Ladino and indigenous Maya populations.

- Traditional Maya Beliefs:** Traditional Maya religious practices, often syncretized with Catholicism, persist, particularly in indigenous communities. These beliefs involve reverence for nature, ancestors, and a complex cosmology. Since the 1996 Peace Accords, there has been greater cultural protection and revitalization of indigenous spiritual practices. The government has even instituted a policy of providing altars at Maya ruins for traditional ceremonies.

- No Religious Affiliation:** A segment of the population, estimated around 11-12%, identifies as having no religious affiliation or being agnostic/atheist.

- Other Religions:**

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) has a growing presence, with tens of thousands of members.

- Eastern Orthodox Church: Has seen notable growth in recent decades, with some reports claiming hundreds of thousands of converts, making Guatemala a significant center for Orthodoxy in the Western Hemisphere.

- Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism are practiced by smaller communities.

The religious dynamism, particularly the growth of Evangelical Protestantism, has had significant social and political implications in Guatemala. Religious affiliation often intersects with ethnic identity, social class, and political orientation.

7.5. Education

Guatemala's education system faces significant challenges in providing quality and equitable access to all its citizens, particularly in rural areas and among indigenous communities. The Ministry of Education is responsible for national educational policy and curriculum.

- Structure of the Education System:**

The system generally follows a five-tier structure:

1. Pre-primary education (educación parvularia)

2. Primary education (educación primaria): Typically six years, compulsory by law but not universally enforced or accessed.

3. Basic secondary education (educación básica): Three years.

4. Diversified secondary education (educación diversificada): Two to three years, offering various tracks (e.g., academic, technical, vocational).

5. Tertiary education (educación superior): Universities and other higher education institutions.

- Key Issues and Challenges:**

- Access and Coverage:** While primary school enrollment has increased, significant disparities exist between urban and rural areas, and between Ladino and indigenous populations. Many children, especially girls and those in remote indigenous communities, do not complete primary education. Access to secondary and higher education is even more limited for disadvantaged groups.

- Quality of Education:** The quality of public education is often low due to underfunding, lack of resources (textbooks, materials, infrastructure), overcrowded classrooms, and inadequately trained teachers.

- Literacy Rates:** Literacy rates have improved but remain a concern. As of 2021, the literacy rate for those aged 15 and above was around 83.3%, up from 74.5% in 2012. However, illiteracy is higher among indigenous women and in rural areas.

- Bilingual Education:** As discussed previously, bilingual intercultural education for indigenous students is an official policy but faces implementation challenges (see Indigenous integration and bilingual education).

- Teacher Training:** Lack of adequate training and professional development for teachers, especially in rural areas, impacts the quality of instruction.

- Funding:** Guatemala's public spending on education as a percentage of GDP (around 3.2%) has historically been lower than the regional average and international recommendations, though recent administrations have aimed to increase it.

- Social Factors:** Poverty, child labor, malnutrition, and long distances to schools contribute to high dropout rates.

- Higher Education:**

Guatemala has one public university, the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (USAC), founded in 1676, making it one of the oldest universities in the Americas. There are also numerous private universities (around 14 others). Access to higher education is limited, largely concentrated among urban and higher-income populations.

Efforts to improve the education system are ongoing, often supported by international organizations and NGOs like Child Aid, Pueblo a Pueblo, and Common Hope. These efforts focus on teacher training, providing resources, promoting bilingual education, and addressing the social barriers to education, all crucial for Guatemala's democratic development and social equity.

7.6. Health

Guatemala faces significant public health challenges, with health outcomes generally lagging behind many other Latin American countries. Disparities in access to healthcare and health status are pronounced between urban and rural areas, and between Ladino and indigenous populations.

- Key Health Indicators:**

- Life Expectancy:** Life expectancy at birth has been improving but remains relatively low for the region.

- Infant and Child Mortality:** Infant and under-five mortality rates are among the highest in Latin America, though they have been declining. Malnutrition is a major contributing factor to child mortality and stunting.

- Maternal Mortality:** Maternal mortality rates are also high, particularly in rural and indigenous communities due to limited access to skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric care.